Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by PGfAR as project number RP-PG-0609-10162. The contractual start date was in June 2011. The final report began editorial review in June 2017 and was accepted for publication in February 2019. As the funder, the PGfAR programme agreed the research questions and study designs in advance with the investigators. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PGfAR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Paolo Deluca acknowledges past and current research funding from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), the Medical Research Council (MRC) and the European Commission. Paolo Deluca is also supported by South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust (SlaM) and by the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre (BRC) for Mental Health at King’s College London and SlaM. Simon Coulton acknowledges past and current research funding as chief investigator and co-investigator from NIHR, Alcohol Research UK, Dunhill Medical Trust, MRC, Lundbeck Ltd (St Albans, UK) and Kent County Council. Mohammed Fasihul Alam acknowledges past and current research funding from Qatar University Internal Grant, NIHR and Community Pharmacy Wales. Kim Donoghue acknowledges past and current research funding from NIHR. Eilish Gilvarry acknowledges grants from NIHR during the conduct of the study. Eileen Kaner is a senior scientist in the NIHR School of Primary Care Research and NIHR School of Public Health Research as part of Fuse, a UK Clinical Research Collaboration (UKCRC) Centre of Excellence in Translation Public Health Research. Eileen Kaner also acknowledges past and current research funding as chief investigator and co-investigator from NIHR, the MRC Public Health Intervention Development Scheme (PHIND), the Department of Health and Social Care, The British Academy, Public Health England, European Research Area Network on Illicit Drugs (ERANID), Policing Research Partnership, North Yorkshire County Council, the Institute of Local Governance, Alcohol Research UK, MRC, the European Commission, Sunderland Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG), the Health Foundation, Research Capability Funding, Diabetes UK and Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust. Ian Maconochie acknowledges grants from NIHR during the conduct of the study. Paul McArdle reports grants from NIHR during the conduct of the study. Ruth McGovern acknowledges past and current research from NIHR, Public Health England, North East and North Cumbria, North Yorkshire County Council, ERANID, the Department of Health and Social Care, the Institute of Local Governance, N8 Policing Research Partnership, Alcohol Research UK, The Children’s Society, Mental Health Research Network – North East Hub and Sunderland CCG. Dorothy Newbury-Birch acknowledges past and current research funding from Public Health England, North Yorkshire County Council, Healum, Alcohol Research UK, County Durham and Darlington NHS Foundation Trust, The Children’s Foundation, NIHR, MRC PHIND, Forces in Mind Trust, the Joseph Rowntree Foundation, The Children’s Society, the European Commission, British Skin Foundation Small Grant and Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust. Robert Patton acknowledges past and current research funding from NIHR, Surrey County Council, the Software Sustainability Institute, Alcohol Research UK and the Higher Education Academy. Ceri Phillips acknowledges past and current research funding from the National Institute for Social Care and Health Research, NIHR, United European Gastroenterology and Asthma UK. Thomas Phillips was funded by a NIHR Clinical Doctoral Research Fellowship. Ian T Russell acknowledges grants from NIHR during the conduct of the study and personal fees from Swansea University outside the submitted work. John Strang reports grants and other funding from Martindale Pharma (Ashton Gate, UK), grants and other funding from Mundipharma (Cambridge, UK), and grants and other funding from Braeburn (Plymouth Meeting, PA, USA) outside the submitted work. In addition, John Strang has a patent Euro-Celtique issued and a patent King’s College London pending, is supported by the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre for Mental Health at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and King’s College London, and is in receipt of a NIHR Senior Investigator Award. He has also worked with a range of governmental and non-governmental organisations and with pharmaceutical companies to seek to identify new or improved treatments from which he and his employer (King’s College London) have received honoraria, travel costs and/or consultancy payments. This includes work with, during the past 3 years, Martindale, Reckitt Benckiser/Indivior (Slough, UK), Mundipharma and Braeburn/Medpace (Cincinnati, OH, USA) and trial medication supply from iGen Networks Corp. (Las Vegas, NV, USA) (iGen/Atral-Cipan, Castanheira do Ribatejo, Portugal). His employer, King’s College London, has registered intellectual property on a novel buccal naloxone formulation, and he has also been named in a patent registration by a pharmaceutical company as inventor of a concentrated nasal naloxone spray. John Strang also acknowledges past and current research funding as chief investigator and co-investigator from NIHR, Mundipharma, MRC, The Pilgrim Trust, Martindale Pharma, the Alcohol and Education Research Council, the Institute of Social Psychiatry and the University of London Central Research Fund. Colin Drummond is partly funded by the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre for Mental Health at SLaM and King’s College London, and partly funded by the NIHR Collaborations for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care South London at King’s College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust. In addition, Colin Drummond is in receipt of a NIHR Senior Investigator Award. Colin Drummond acknowledges past and current research funding as chief investigator and co-investigator from NIHR, MRC, Guy’s and St Thomas’ Charity, Nuffield Foundation, European Union Directorate-General for Justice and Consumers (JUST), Alcohol Research UK, NHS England, the Department of Health Policy Research Programme, World Health Organization, the European Commission and the Alcohol Education and Research Council.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Deluca et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

SYNOPSIS

Setting the scene

The excessive consumption of alcohol is a major global public health issue,1 and, in Europe, alcohol accounted for 6.5% of deaths and 11.6% of disability-adjusted life-years in 2004. 2 Although the main burden of chronic alcohol-related disease is in adults, its foundations often lie in adolescence. 3 The proportion of young people in England aged between 11 and 15 years who reported that they had drunk alcohol decreased from 62% to 54% between 1988 and 2007, but the mean amount consumed by those who drank doubled (from 6.4 to 12.7 units of alcohol per week) between 1994 and 2007. 4 About 10% of 11- to 15-year-olds and 33% of 15- to 16-year-olds in England report alcohol intoxication in the past month. 5,6 Adolescents in the UK are now among the heaviest drinkers in Europe. 6 The Chief Medical Officer for England provided recommendations on alcohol consumption in young people in 2009,7 based on an evidence review. 8 These advise that children abstain from alcohol before the age of 15 years and that 15- to 17-year-olds should not drink, but, if they do drink, then they should consume no more than the recommended limits for adults (currently 14 units per week). 7

Alcohol consumption and related harm increase steeply from the age of 12 to 20 years. 9 In early adolescence, alcohol use and alcohol use disorders (AUDs) (alcohol abuse, harmful alcohol use and alcohol dependence) are relatively uncommon. However, alcohol has a disproportionate effect on younger adolescents, for example by predisposing them to alcohol dependence in later life10,11 and damage to the developing brain. 12 In middle adolescence (ages 15–17 years), binge drinking emerges. Although binge drinking does not necessarily meet the criteria for AUDs, it is associated with increased risk of unprotected or regretted sexual activity, criminal and disorderly behaviour, suicidality and self-harm, injury, drink driving, alcohol poisoning and accidental death. 6,13–16

Alcohol screening

Opportunistic alcohol screening and brief interventions (SBIs) in emergency departments (EDs) capitalise on the ‘teachable moment’ when a connection can be made between alcohol consumption and ED attendance. 17–20 Alcohol SBI in EDs has shown efficacy in adults20 and adolescents,17,18,21 with evidence of cost-effectiveness in adults. 22 Over the past 15 years, the World Health Organization, the US Surgeon General, the American Medical Association and the American Academy of Pediatrics have called for practitioners to carry out SBIs for adolescent drinkers. 23–26 The alcohol strategies for both England and Scotland identify adolescents as a key target group in which to reduce alcohol consumption and related harm. 27,28 However, although there has been an increase in alcohol SBIs for adults, adolescents remain a neglected group. A recent audit of EDs in Scotland found that only 5% of alcohol-related attenders aged < 18 years receive an alcohol intervention before discharge, and that ED staff focus more on those young people presenting with acute intoxication or self-harm. 29 Of the 12 EDs in the north-east of England and London approached during our research programme, none used routine alcohol screening in 10- to 17-year-olds and only three did so in adults.

Several alcohol screening methods have been developed in the USA but have not been evaluated in the UK. A recent systematic review of alcohol SBIs in young people (aged 10–17 years) and adults (aged ≥ 18 years), conducted for the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE),30 examined 51 studies of alcohol screening. Questionnaires were found to perform better than blood markers or breath alcohol concentration in all age groups. In adolescents ,the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) questionnaire was found to have greater sensitivity and specificity than other questionnaires, including CAGE (Cut Down, Annoyed, Guilty, Eye Opener), TWEAK (Tolerance, Worried, Eye-opener, Amnesia, K/Cut Down), CRAFFT (Car, Relax, Alone, Forget, Friends, Trouble), RAPS4-QF (Rapid Alcohol Problems Screen – Quantity Frequency), FAST (Fast Alcohol Screening Test), RUFT (Cut-Riding, Unable, Family/Friends, Trouble, Cut down) and POSIT (Problem Oriented Screening Instrument for Teenagers). AUDIT sensitivities for adolescents range from 54% to 87% and specificities range from 65% to 97%. 31 However, the majority were at the lower end of these ranges and are therefore suboptimal for effective screening.

Additional shortcomings of existing alcohol screening methods for adolescents have been identified. 31 Existing approaches do not sufficiently take into account the age and developmental stage of adolescents. Any alcohol consumption under 15 years of age is of concern, whereas the identification of AUDs is more relevant in older adolescents. There is therefore a need for screening methods that are sensitive to the developmental stage of the adolescent to maximise opportunities for intervention. Alcohol screening has been mostly studied in older adolescents and young adults of college age (18–24 years). Therefore, the validity of alcohol screening methods in younger adolescents is unclear. Questionnaires such as the AUDIT may be too lengthy (10 items) to implement in busy EDs, pointing to the need for briefer tools for routine clinical practice. Methods to increase compliance, particularly by younger adolescents, are also needed. The use of computer screening and interviewing adolescents confidentially and separately from parents has shown some promise in the USA. 32,33

Alcohol brief interventions in health settings

Several systematic reviews have noted the effectiveness of SBIs in adults in health settings. 34–38 Less research in this area has been conducted in adolescents. A systematic review of brief alcohol interventions for young people attending health settings identified nine randomised controlled trials (RCTs) between 1999 and 2008. 30 Eight were based in the USA17–19,21,39–41 and one was based in Australia. 42 Most trials were considered to be methodologically sound, although two were considered to be weak in randomisation and allocation concealment. 40,42 Sample sizes ranged from 34 to 655 and ages ranged from 12 to 24 years. Three trials40–42 targeted socioeconomically disadvantaged groups among whom drug and alcohol misuse were more prevalent. Four trials17–19,21 were based in EDs to maximise the potential for ‘teachable moments’ when the connection between alcohol consumption and its adverse consequences can be more readily highlighted. Two studies39,40 recruited adolescents during routine general check-ups in primary care and one43 recruited in a university health centre. The remaining trials targeted homeless adolescents41 and those attending a youth centre that delivered health services. 42

Six trials17,18,21,40,41,43 tested brief interventions based on one or two sessions of motivational interviewing (MI) that lasted between 20 and 45 minutes. Delivery was carried out by a range of trained professionals, including physicians, nurse practitioners, psychologists, addiction clinicians and youth workers. One trial tested a more intensive programme of four MI sessions over 1 month. 42 Two studies used information technology to deliver brief interventions, one using an audio programme in primary care39 and the other using an interactive computer program in a minor injury unit. 19 The length of follow-up ranged from 2 to 12 months. Loss to follow-up was generally low (0–20%), although the authors of one study40 reported that 34% of their study population were lost to follow-up.

Five trials17,18,21,42,43 reported significant positive effects of brief interventions on a range of alcohol consumption measures. Bailey et al. 42 reported that brief intervention participants showed increased readiness to reduce alcohol consumption, an initial reduction in alcohol consumption and an improvement in knowledge of alcohol and related problems, compared with control subjects. Schaus et al. 43 also reported reductions in blood alcohol concentration, number of drinks per week and risk-taking behaviour. Monti et al. 18 reported that brief intervention subjects were less likely than control subjects to drink and drive or to experience alcohol-related injury, although both treatment groups significantly reduced their alcohol consumption. A subsequent trial, conducted by the same research group,17 reported that alcohol consumption also significantly decreased in both the brief intervention group and the control group. Last, Spirito et al. 21 reported a significant reduction in alcohol consumption at follow-up in both the brief intervention group and the control group. However, adolescents who screened positive for alcohol problems at baseline reported more change after MI than the control subjects.

Three trials reported null effects after brief intervention. 19,40,41 One trial that used an audio-taped programme with 12- to 17-year-old adolescents39 reported an increase in alcohol use and binge drinking among brief intervention subjects, representing a possible adverse effect of this type of intervention.

Summary

In summary, there is a need to develop more effective alcohol screening tools for adolescents in the ED, which are age appropriate and cover a wider range of alcohol consumption and alcohol-related problems than do existing methods. Furthermore, as most of the existing research has been conducted in the USA, screening methods appropriate to EDs are needed in the UK context of the NHS.

Moreover, the majority of alcohol SBI studies among adolescents in health-care settings were conducted in EDs and reported positive outcomes. However, three trials reported alcohol consumption reductions in both the intervention group and the control group, and three more trials reported no effect of brief intervention. None of these trials was in the UK and few studies were conducted in young adolescents. Thus, although there is evidence to suggest that brief intervention may be beneficial for adolescents, particularly in EDs, there is a clear need for a UK trial of this.

This monograph describes the results of our findings linked to the original programme objectives (a full list of publications arising from our programme of work can be found in Overall conclusions, Dissemination).

Work package 1: screening prevalence study of alcohol consumption and alcohol use disorders in adolescents aged 10–17 years attending emergency departments

Introduction

Adolescence is a critical period of development, during which the initiation and continuing use of alcohol may have detrimental consequences for the young person. 44 Several adverse health and social consequences of alcohol use in young people are widely reported in research and health policy, including an increase in depressive feelings, an increase in sexual risk taking, a reduction in educational performance, difficulties in maintaining relationships with peers and friends, and an increase in vulnerability to becoming a victim of crime. 8 Although it is difficult to establish a direct causal relationship between alcohol use in adolescents and social and behavioural problems, several studies have shown that earlier consumption is associated with alcohol-related problems in later life. 45–51 A recent review52 recommended further research to establish the advantages of delaying the onset in drinking when establishing guidelines for drinking in adolescence.

The identification of adolescents who consume alcohol at problematic levels is a key element of any screening and intervention strategy. To offer such interventions, practitioners need access to screening tools that are high in both sensitivity and specificity and are quick and easy to apply at minimal cost. Biochemical markers of alcohol use, such as gamma-glutamyl transferase, aspartate aminotransferase, erythrocyte mean cell volume and carbohydrate-deficient transferrin, are impractical and of little use in this population, and have been found to be inferior to short screening questionnaires in adult populations. 53

The AUDIT54 is a 10-item self-completion questionnaire with established diagnostic properties for hazardous and harmful alcohol use in adults. It addresses three domains: alcohol consumption, harmful consequences and symptoms of dependence. AUDIT is one of the few screening instruments that specifically incorporates consumption into the scoring algorithm and may be particularly suitable for adolescents who are more likely to experience a range of alcohol-related harms as a result of consumption rather than experiencing symptoms of alcohol dependence. Furthermore, it may be the case that the three specific alcohol consumption questions constituting the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test, Consumption (3 items) (AUDIT-C) may be as efficient and brief a screening instrument as the full AUDIT. Previous studies suggest that the AUDIT may be more useful than other brief screening instruments in adolescent populations, but there is limited evidence regarding appropriate cut-off points for different severities of alcohol misuse,55–60 and no previous research has compared the relative effectiveness of AUDIT with that of AUDIT-C in adolescent populations.

Aims

This work package had three principal aims:

-

to estimate and compare the sensitivity, specificity and diagnostic odds ratios (ORs) of the AUDIT and AUDIT-C in identifying at-risk alcohol use, monthly heavy episodic alcohol use, alcohol abuse and alcohol dependence in the context of an opportunistic screening programme for adolescents attending EDs in England

-

to examine the prevalence of alcohol consumption among adolescents (aged 10–17 years) presenting to hospital EDs in England

-

to determine the association between alcohol consumption and age at onset of alcohol consumption with health and social consequences among adolescents presenting to EDs in England.

Findings from aim 1 have been published in Coulton et al. 61 and findings covering aims 2 and 3 have been published in Donoghue et al. 62 These are summarised here and reproduced in full in the appendices.

Methods

Patient and public involvement in work package 1

For work package 1, we collaborated with three organisations to ensure that both parents and young people were engaged in the development of our methodology and materials (the British Youth Council, Parenting UK and the Family and Parenting Institute). We organised focus groups in the north and south of England, at which we presented our planned protocols and then engaged the public to critique our plans and to make suggestions for change. Our work with the parent groups helped to shape the study protocol in terms of the optimal way to introduce the study and obtain informed consent. Consultation with the young people indicated that electronic data capture methods would be better received than interview or paper-and-pencil approaches and, as a consequence, we developed an iPad-based screening and data collection tool (Apple Inc., Cupertino, CA, USA) that we utilised throughout the entire programme of research.

The initial intention of the prevalence study was to examine the prevalence of alcohol consumption and AUDs among adolescents presenting to EDs. The questionnaire included demographic and lifestyle questions, attitude scales and a range of alcohol measures to determine which to use in the main trial, and it was expected to be around 30 pages in length. The patient and public involvement showed that adolescents were unlikely to consent to such a survey and, if consent was given, completion was not likely. A tablet interface and shorter questionnaire were more acceptable and would encourage participation in the study.

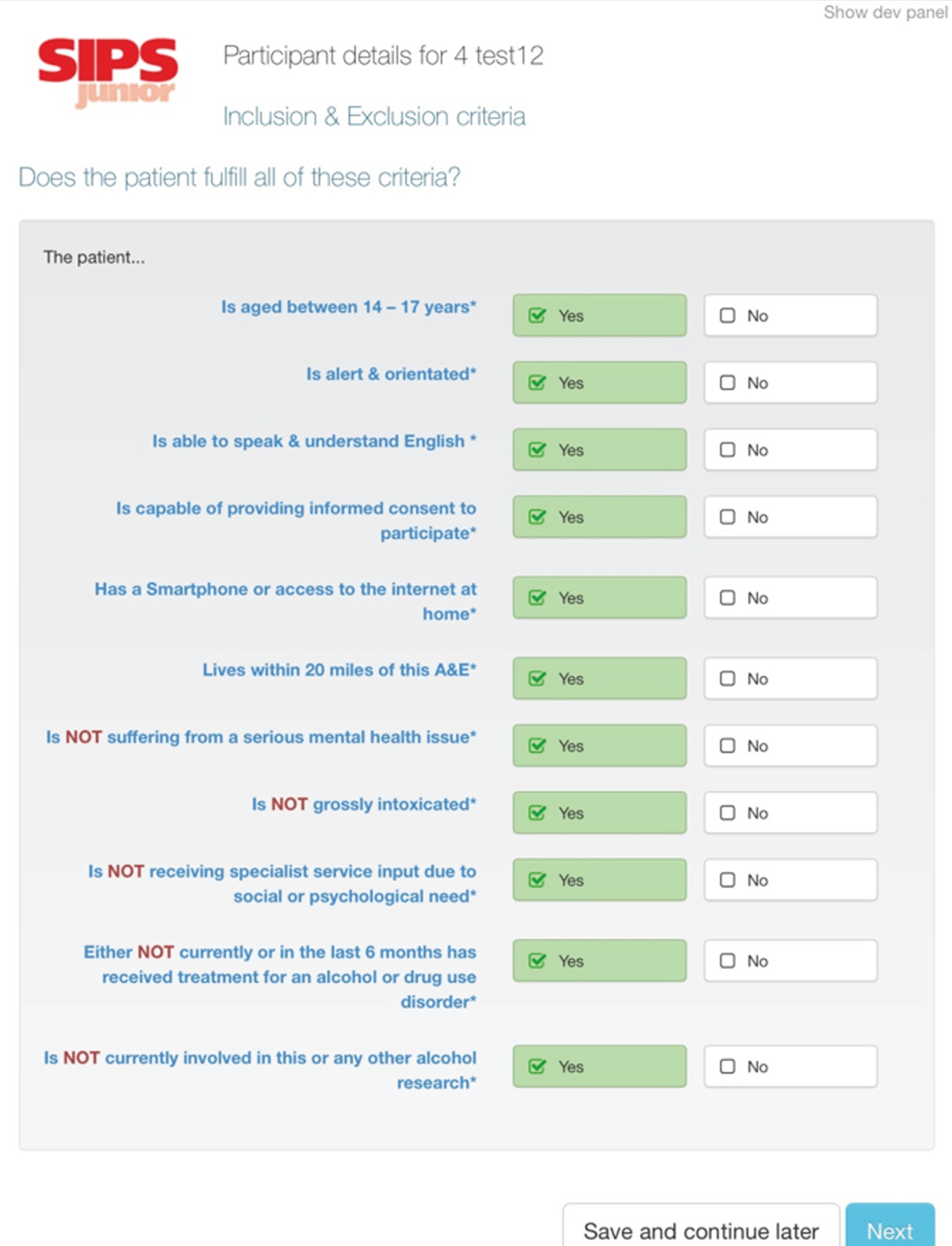

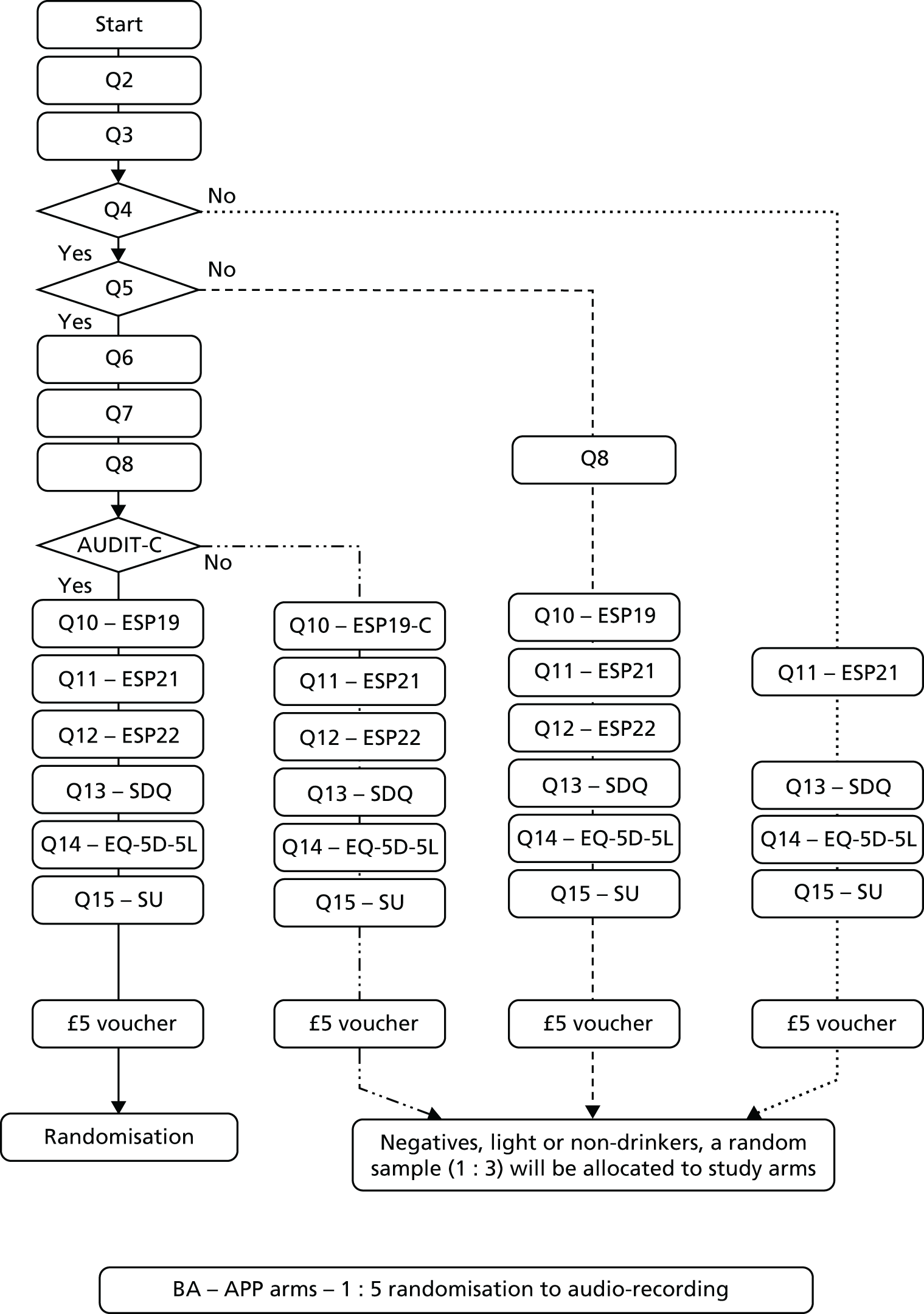

iPad data collection tool

Following a consultation stage with the target groups, we decided to develop an iPad application to better engage adolescents in the prevalence study and to facilitate data collection and improve data quality. The iPad application for the prevalence study has been developed for this research by the software developer Codeface Ltd (Hove, UK) in collaboration with the research team. Codeface Ltd, study investigators and target groups have all been actively involved in its development, testing and piloting. The application provided a flexible approach to conduct the prevalence study and was an innovative method to administer a relatively long battery of measures to this target group (Figure 1). It also had the advantage of automating the routing through the questionnaire, showing the respondent only applicable questions in an engaging and clear layout. Moreover, encrypted data were uploaded securely onto a secure server and could be monitored by the co-ordinating centre in real time. This allowed the research team to check daily when quotas for each year group had been reached. It also reduced the time needed for data entry and cleaning, negating the need for manual data entry for most of the data collected. This data collection application program (app) was further developed and adapted for the data collection and randomisation of participants in the RCTs as part of work package 3.

FIGURE 1.

Screenshot of the data collection app developed for the programme and available from the authors.

Participants

Data collection took place between December 2012 and May 2013. Participants were aged between their 10th and 18th birthdays and were attending 1 of 10 participating EDs across England: in the North East, Yorkshire and The Humber, and London. To be eligible for inclusion in the research, the participant had to be alert and orientated and able to speak sufficient English to complete the research assessments. Participants were not eligible for inclusion if they had a severe injury, were suffering from a serious mental health problem or were grossly intoxicated (as determined by ED staff). Participants were also not eligible to take part if they or their parent or guardian (as applicable) were unable or unwilling to provide informed consent.

We excluded grossly intoxicated patients on the basis that they would not be able to provide informed consent. Clinical protocols for young people presenting to accident and emergency (A&E) departments in a grossly intoxicated state would involve escalation to consider safeguarding concerns and potentially referral to specialist services in most of the hospitals involved in this programme of research. Therefore, the brief interventions being studied in this programme would have been less than the minimal intervention considered necessary for this group.

However, if those patients sobered up during their stay in A&E, then they were approached at a later stage about participating in the research, provided that there were no other clinical concerns or reasons for exclusion.

Procedure

Following clearance by ED staff, a researcher approached consecutive ED attenders meeting the study criteria every day of the week between 8 a.m. and midnight. For those participants aged < 16 years and unaccompanied by a parent or guardian, Gillick competence was assessed by a member of ED staff. Those assessed as Gillick competent were approached by the researcher and invited to provide informed consent for participation. 63

We extended Gillick competency to consent for participation in research on the grounds of minimal/no risk in taking part in this prevalence study. 64

Those aged 16 or 17 years provided informed consent without recourse to a parent or guardian.

Participants completed the study questionnaires independently in a private area of the ED. The researcher was available in case clarification of questions or help with the software program was required. The study data were anonymised and collected using an iPad electronic tablet device, with the exception of the Timeline Followback questionnaire, which was manually administered by the researcher. A £5 gift voucher was given to all participants at the end of the interview to thank them for their time. All young people participating in the study were also given age-appropriate material containing information on alcohol and local services and helplines providing further support.

Measures

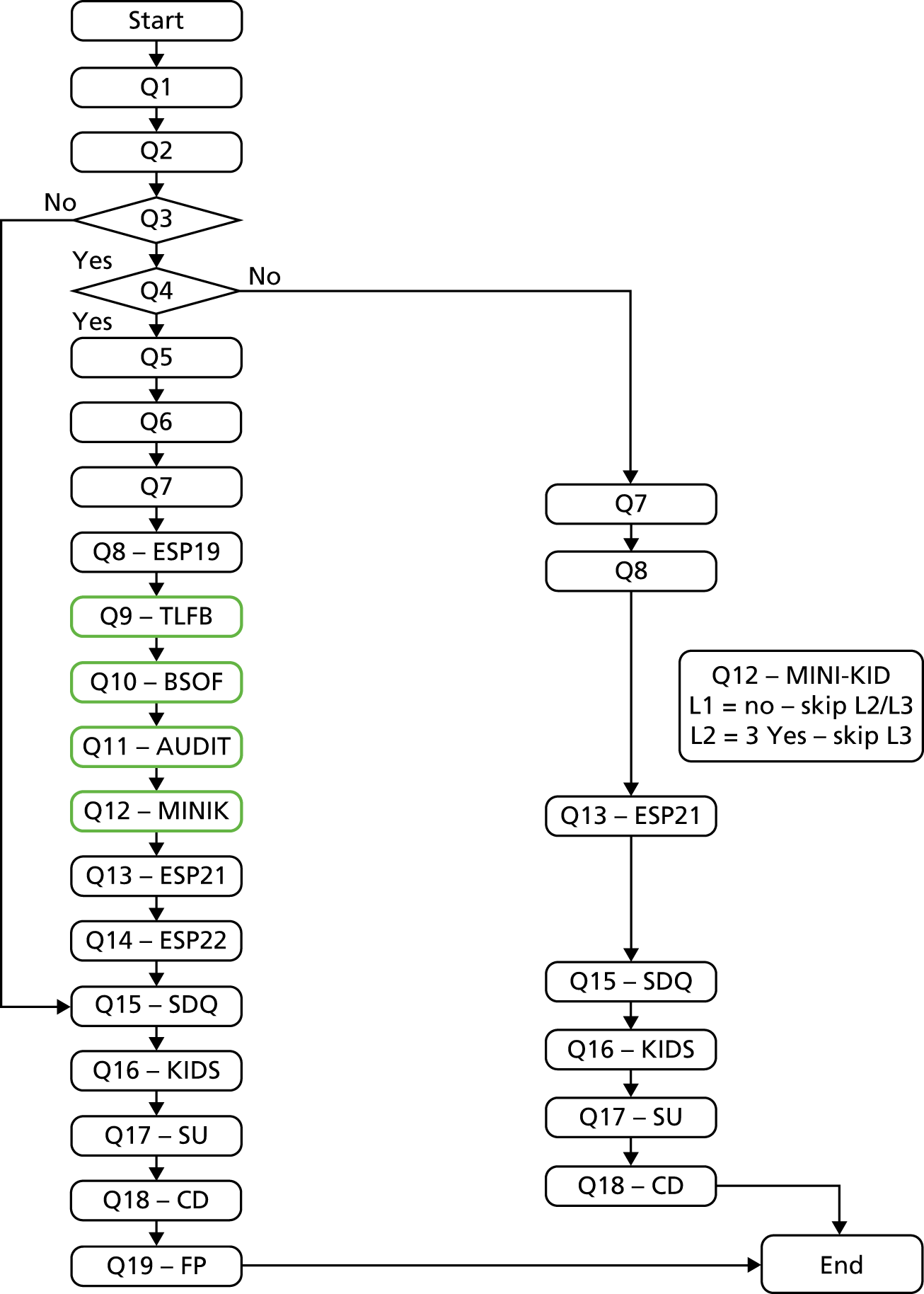

Figure 2 illustrates the flow of research questions. Demographic data, including age, gender and ethnicity, were collected for all participants, as was information on general health behaviours and lifestyle, including tobacco smoking. Health-related quality of life was assessed using the health-related quality-of-life questionnaire for children and young people and their parents (Kidscreen);65 this is a 10-item generic health-related quality-of-life measure, with established validity and reliability in this population. Behavioural and emotional functioning was measured using the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire. 66,67 In addition, several questions relating to age-relevant service use, including questions on previous use of health and social services, school attendance and contact with the criminal justice system, were asked.

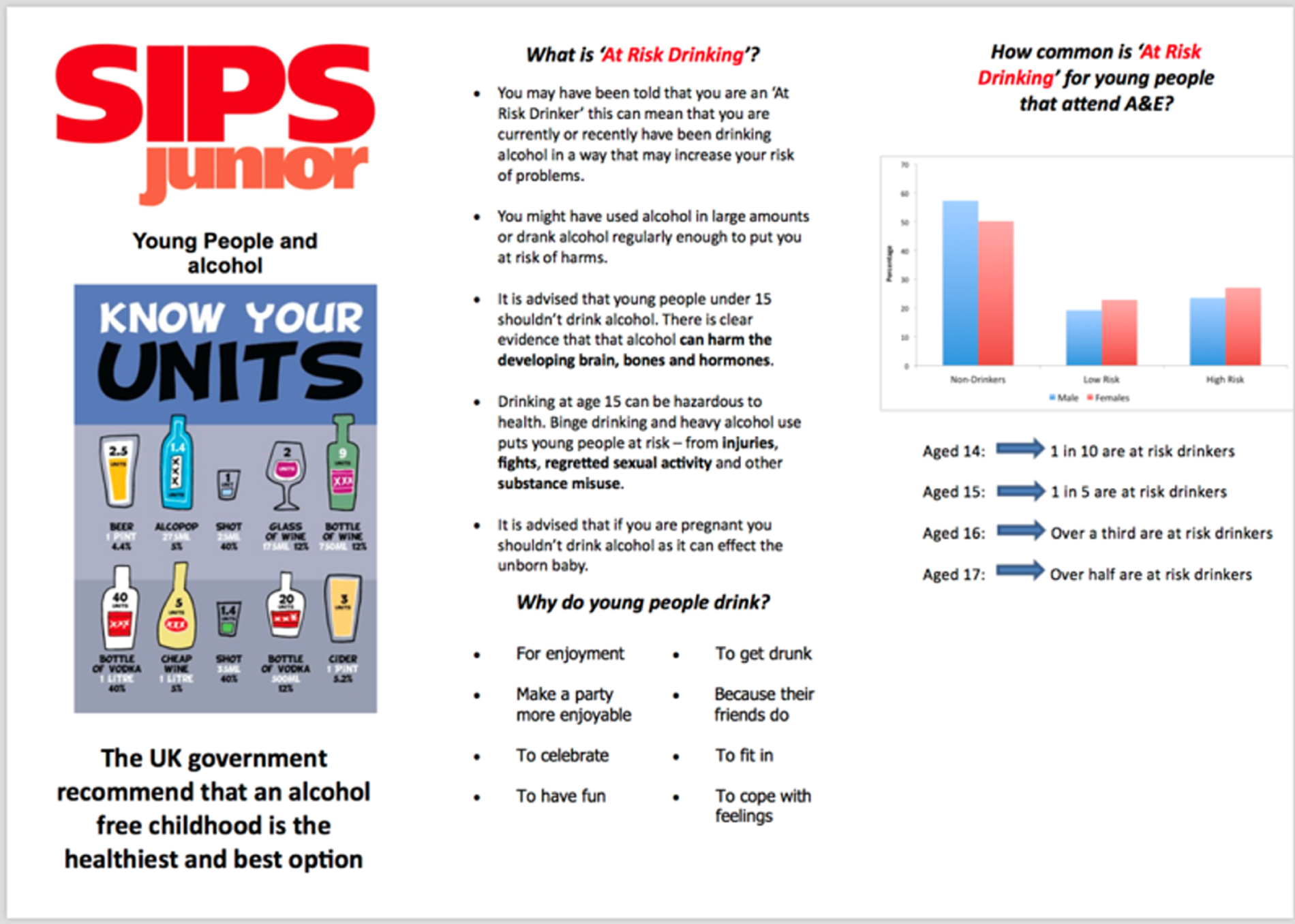

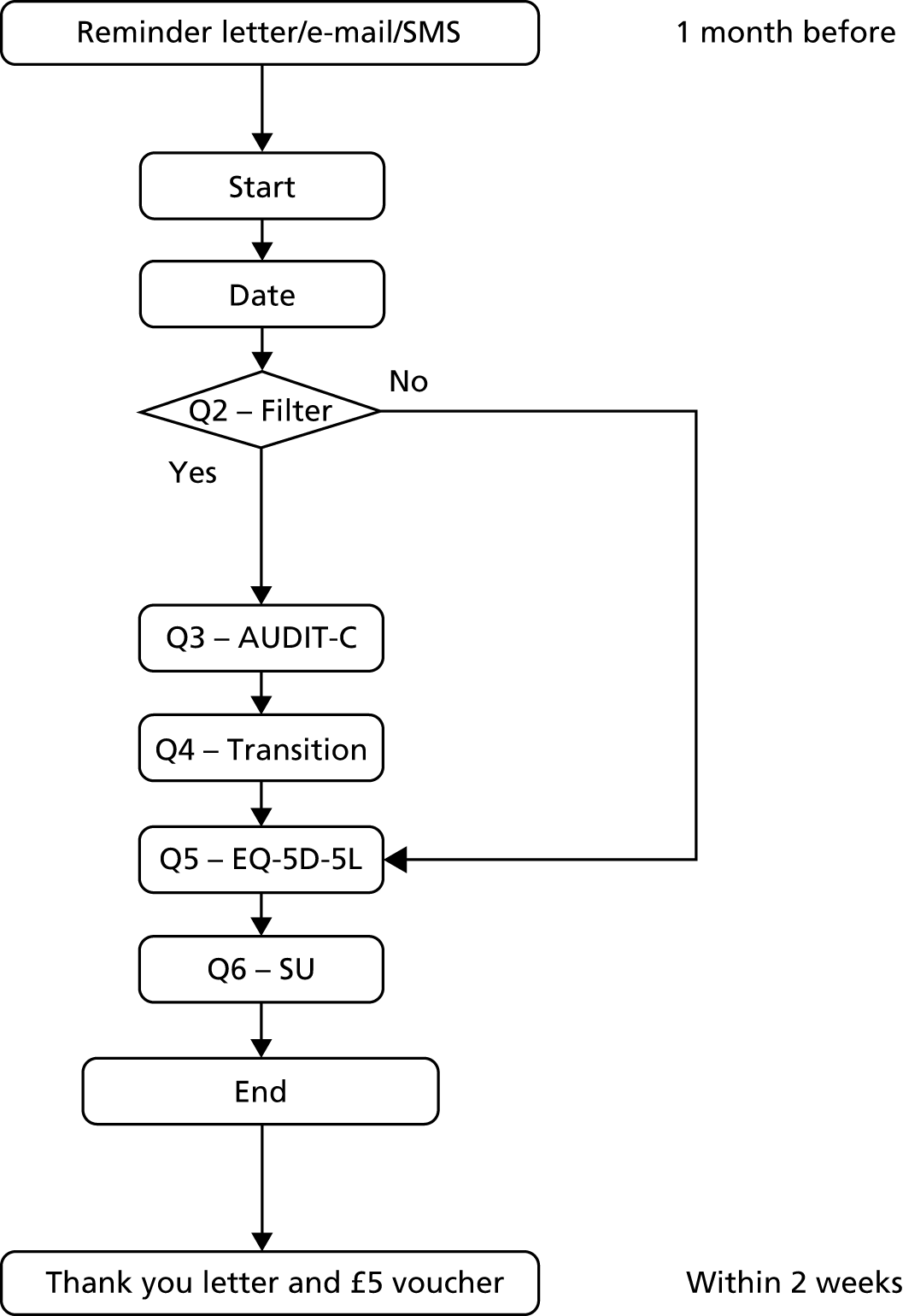

FIGURE 2.

Flow of research questions. Q1, Demographics. Q2, Health and Lifestyle questionnaire. Q3, Filter question 1: have you ever drunk alcohol? Do not include just a sip of somebody else’s drink. Q4, Filter question 2: have you ever drunk alcohol in the past 3 months? Do not include just a sip of somebody else’s drink. Q5, Have you had a drink of alcohol in the past 24 hours? Q6, Have you consumed any alcohol prior to attendance at ED? Q7, How old were you when you had your first sip of alcohol (beer, cider, alcopops, wine, etc.)? Q8, European School Survey Project on Alcohol and Other Drugs Q19 (alcohol intoxication). Q9, Timeline Followback 90. a,c Q10, Beverage Specific Quantity Frequency Questionnaire. a,c Q11, AUDIT. b,c Q12, Mini International Neuropsychiatry Interview for Children and Adolescents (MINI-KID) Alcohol. b,c Q13, European School Survey Project on Alcohol and Other Drugs Q21. Q14, European School Survey Project on Alcohol and Other Drugs Q22. Q15, Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ). Q16, health-related quality of life questionnaire for children and young people and their parents (Kidscreen). Q17, service utilisation. Q18, cognitive debrief. Q19, future participation details. BSQF, Beverage Specific Quantity Frequency; ESP19, European School Survey Project on Alcohol and Other Drugs Q19; L, Level; Q, Question; SDQ, Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire; TLFB, Timeline Followback. a, The order of presentation of quantity–frequency measures (Timeline Followback and Beverage Specific Quantity Frequency Questionnaire) were allocated at random, stratified by age group. b, The order of presentation of diagnostic measures (AUDIT and MINI-KID) were allocated at random, stratified by age group. c, The order of presentation of quantity–frequency measures and diagnostic measures were allocated at random, stratified by age group.

Results

Among participants who reported any alcohol consumption, the age of first consumption in years was recorded using a single question [‘how old were you when you had your first drink of alcohol (beer, cider, alcopops wine, etc.)?’], and further questions about whether or not they had consumed alcohol in the past 3 months and past 24 hours were asked. In addition, all participants who had ever drunk alcohol were asked question 19 (‘experienced alcohol intoxication in your lifetime?’) and question 21 (‘personal experience of alcohol?’) from the European School Survey Project on Alcohol and other Drugs (ESPAD). 68 Further questions were included to assess the feasibility of conducting a future alcohol intervention study, including whether or not the participant wanted further information or advice about alcohol, and whether or not they were willing to participate in an intervention and follow-up study, if this was offered. They were also asked how easy they had found it to complete the questionnaire electronically.

Those participants who indicated that they had consumed alcohol that was ‘more than a sip’ in the past 3 months were asked additional questions about alcohol use. Hazardous alcohol use, harmful alcohol use and harmful alcohol dependence were assessed using the three-item AUDIT-C,54 the full 10-item AUDIT and the alcohol section of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview for Children and Adolescents (MINI-KID), respectively. 69 Quantity of alcohol consumed in the past 90 days was derived from the Timeline Followback Form 9070 and converted to standard units, for which one unit was the equivalent of 8 g of pure ethanol. In addition, beverage-specific quantity and frequency questions were asked for consumption of beer, cider, alcopops, spirits and wine. This is an ad hoc tool developed for this study. The Beverage Specific Quantity Frequency Questionnaire’s measure of alcohol consumption is derived from methods used to measure consumption in adolescent populations6 and conforms with European guidance on the standardisation of measurement of consumption. This questionnaire measures total quantity and frequency of consumption of specific beverages and episodes of excessive consumption over a 90-day period.

The AUDIT has been validated in adolescent populations in EDs in the USA. 56,58 As part of the current programme of research, the shorter, three-question AUDIT-C was validated with a cut-off point of 3 [see Characteristics analysis of screening tools (aim 1)]. The Timeline Followback Form 90 has been validated for use among this population. 71–73 Perceived consequences of alcohol consumption were assessed by question 22 of ESPAD: ‘because of your own alcohol use, how often during the last 12 months have you experienced the following?’. 68

Overall, 5781 participants were asked to participate in the survey, of whom 5377 (93%) consented to participate across the 10 EDs. The mean age of participants was 13.3 [standard deviation (SD 2.1)] years, with similar proportions of male (53.7%) and female (46.3%) participants and a majority of white participants (72.6%). Overall, 2112 (39.3%) participants had consumed alcohol at some time in the past and 1378 (25.6%) participants had consumed alcohol in the past 3 months. Those who had consumed alcohol tended to be older (14.8 years vs. 12.3 years) and were more likely to be white (83.4% vs. 65.6%).

Characteristics analysis of screening tools (aim 1)

A significant positive correlation was identified for AUDIT score for the total number of standard drinks consumed in the past 3 months [Spearman’s r = 0.72, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.71 to 0.73; p < 0.001] and a similar correlation was identified for AUDIT-C score (Spearman’s r = 0.69, 95% CI 0.68 to 0.70; p < 0.001).

Screening properties of the AUDIT-C and the 10-item AUDIT questionnaire were tested against the gold-standard criteria for at-risk drinking, heavy episodic alcohol consumption, alcohol abuse and alcohol dependence, and appropriate cut-off points were identified for each instrument.

The optimum cut-off point for AUDIT in identifying either at-risk drinking, monthly heavy episodic drinking or alcohol abuse was a score of ≥ 4; this provided acceptable sensitivity, specificity and diagnostic odds. An AUDIT-C score of ≥ 3 demonstrated almost identical diagnostic properties but with a significantly better sensitivity for at-risk drinking.

An AUDIT score of ≥ 7 provided a significantly more effective cut-off point for alcohol dependence than any other cut-off point, and demonstrated significantly better diagnostic properties than an AUDIT-C score of ≥ 5.

Sensitivity analysis that incorporated age, gender and ED into the analysis as covariates indicated no influence of these covariates on the observed outcomes.

Prevalence of alcohol consumption (aim 2)

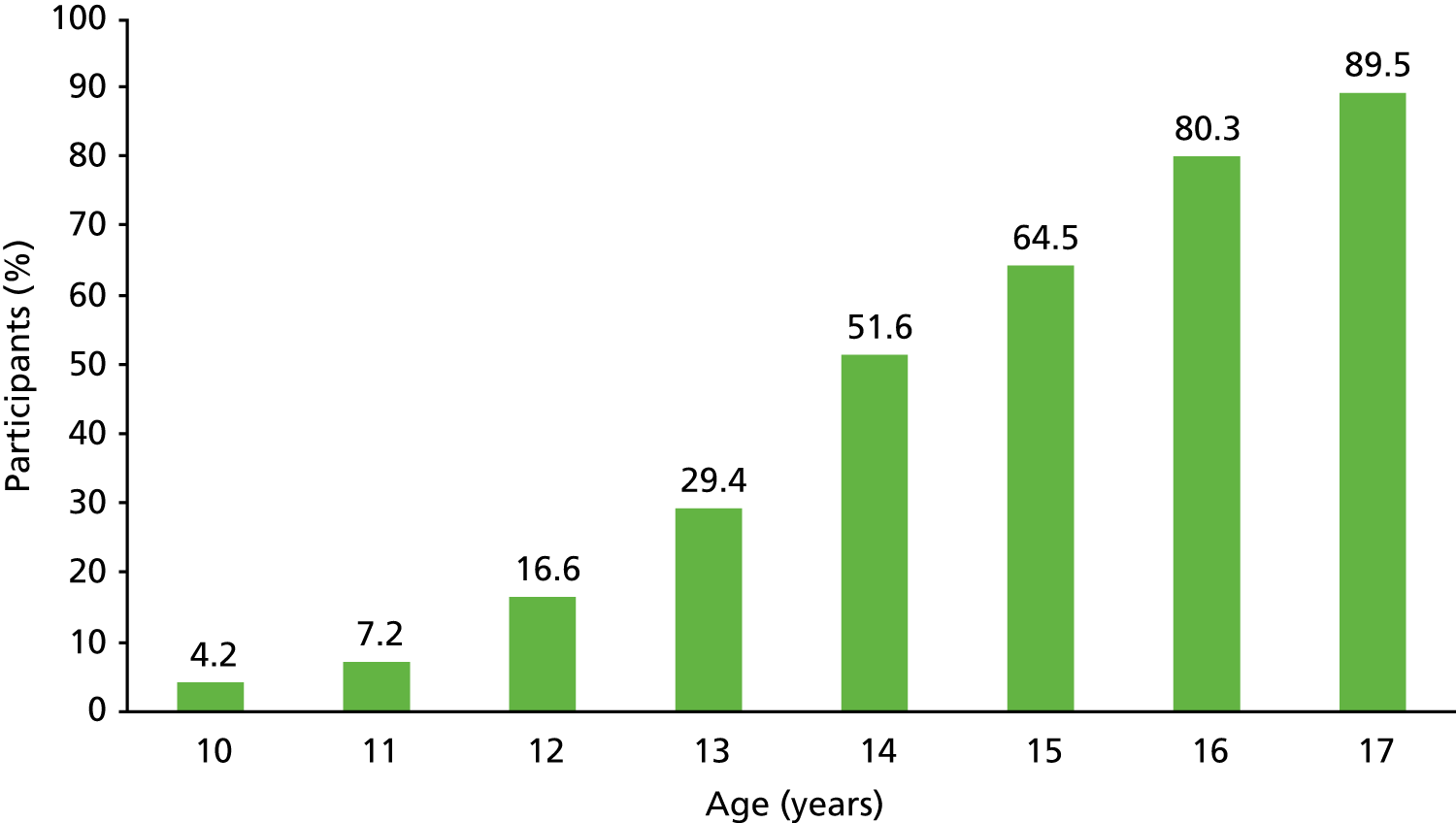

A total of 2112 (39.3%) of the 5377 participants who consented to take part in the research reported having had a drink of alcohol that was more than a sip in their lifetime, with prevalence increasing steadily with age (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Percentage of participants who had a drink of alcohol that was more than a sip in their lifetime by current age. Reproduced from Donoghue et al. 62 Reprinted from Journal of Adolescent Health, vol. 60, Donoghue K, Rose H, Boniface S, Deluca P, Coulton S, Alam MF, et al. Alcohol consumption, early-onset drinking, and health-related consequences in adolescents presenting at emergency departments in England pp. 438–446, 2017, with permission from Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine.

A total of 1374 participants (25.6% of the whole sample) reported drinking more than a sip of alcohol in the previous 3 months. The average age of first alcoholic drink was 12.9 years, ranging from 5 to 17 years of age (17 years was the upper limit for inclusion in this study). The prevalence of at-risk drinking was 14.8% (95% CI 13.9% to 15.8%), of monthly heavy episodic alcohol use was 10.6% (95% CI 9.8% to 11.4%), of alcohol abuse was 2.4% (95% CI 2.0% to 2.8%) and of alcohol dependence was 1.2% (95% CI 0.9% to 1.5%). Among the sample of those who had consumed alcohol in the past 3 months, the prevalence of these behaviours was significantly higher.

Relationship between alcohol consumption and harm (aim 3)

Alcohol consumption in the previous 3 months was associated with older age, being female, being white and having smoked tobacco. In addition, those who had consumed alcohol within the previous 3 months were more likely to report a lower quality of life and to have peer and social problems.

We also found that total alcohol consumed in the previous 90-day period was associated with tobacco use, lower quality of life, poorer general social functioning (conduct and hyperactivity), and the ESPAD questions on health and social problems.

Further analysis investigated the association between age of first alcohol consumption and psychological and social problems. Only participants aged 16 or 17 years who had consumed alcohol in the past 3 months (N = 609, n = 316 female) were included in this analysis. This analysis showed that consumption of alcohol before the age of 15 years was associated with an increased risk of a number of health and social problems. These included a greater risk of smoking tobacco (p < 0.001), lower quality of life (p = 0.003) and a diagnosis of an AUD, as indicated by the MINI-KID (p = 0.002). Consumption of alcohol before the age of 15 years was also associated with a greater risk of experiencing conduct (p = 0.001) and hyperactivity problems (p = 0.001), and more alcohol-related social problems, including having an accident (p = 0.046), problems with a parent (p = 0.017), school problems (p = 0.0117) and experiencing problems with the police (p = 0.012).

Discussion

In this work package, we investigated for the first time the screening properties of a short tool, the prevalence of alcohol consumption, the relationship with emotional and behavioural problems, and alcohol-related harms in adolescents presenting to the ED. The strengths of this study include the large sample size, the wide age range of those studied who were not seeking alcohol treatment and the broad spread of study across 10 EDs in England.

We found that a simple, short three-item self-completed screening instrument, the AUDIT-C, is overall more effective than the longer 10-item AUDIT in identifying adolescents who engage in at-risk alcohol consumption, monthly heavy episodic alcohol use and fulfil the ICD-10 criteria for alcohol abuse. Furthermore, the AUDIT with a cut-off score of 7 is more efficient than the AUDIT-C in identifying adolescents with alcohol dependence. In addition, the AUDIT-C and the AUDIT are widely employed as screening tools for adults in clinical and non-clinical settings and these can be applied equally to adolescent populations with these lower cut-off scores. We conclude that the AUDIT-C should be employed with this population with a cut-off score of 3 as a positive screen for at-risk drinking, monthly heavy episodic alcohol use and alcohol abuse. For those who score ≥ 5 on the AUDIT-C, we recommend that the additional seven questions constituting the full AUDIT be administered. Those scoring ≥ 7 should be clinically assessed for alcohol dependence.

We also found that nearly 40% of the adolescents presenting to the study EDs in England reported that they had consumed a drink of alcohol that was more than a sip in their lifetime. Rates of consumption increased considerably with age, ranging from just 4% for those aged 10 years to 90% for those aged 17 years. Among adolescents who had consumed alcohol in the past 3 months, 14.8% of drinkers screened positive for hazardous alcohol use (≥ 3 on the AUDIT-C).

This work package shows an association between earlier alcohol consumption and harm in adolescents. The prevalence of a diagnosis of harmful alcohol use or dependence was considerably higher among participants who started drinking before the age of 15 years, but it remains to be established whether or not these persist into adulthood. Although the results of this work package do not establish causality, effective interventions to reduce alcohol consumption in this population could potentially mitigate the harmful consequences related to alcohol that are experienced from a young age in this group.

This study identified a high prevalence of AUDs in adolescents attending EDs; we suggest that this setting is relevant for research on alcohol screening in young people. The ED also has a high level of staff expertise, which is well placed to initiate safeguarding procedures when required and provide a good point of onward referral to specialist services. The possibility of conducting alcohol screening among adolescents presenting to the ED and the potential for providing interventions to help reduce alcohol consumption in this population was investigated further in the following work packages of this programme.

The use of technology to collect data was successful in this study, and it is known that technology shows promise as a tool to deliver interventions.

Work package 2: exploratory modelling of the interventions

This work package focuses on the development of age-appropriate alcohol interventions for adolescents. These interventions have been developed with extensive patient and public involvement through a series of focus groups and evaluation work; a review of reviews to explore the evidence base on alcohol SBI for adolescents to determine age-appropriate screening tools; and a systematic review of electronic alcohol interventions.

Systematic review of electronic alcohol interventions

We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of the available literature to determine the effectiveness of electronic screening and brief interventions (eSBIs) over time in non-treatment-seeking hazardous/harmful drinkers.

This systematic review has been published in Donoghue et al. 74

The widespread use of computers, the internet and smartphones has led to the development of electronic systems to deliver alcohol SBIs that can potentially address some of the barriers to implementation of traditional face-to-face SBIs. eSBIs have the potential to offer greater flexibility and anonymity for the individual and to reach a larger proportion of the in-need population. For both adults and adolescents, eSBIs (computer, web and phone based) can offer effective delivery of interventions in both educational and health-care settings, which may prove to be more acceptable than more traditional (face-to-face) approaches. 75–77 In addition, eSBIs could offer a more cost-effective alternative to face-to-face interventions.

A systematic search of the literature was conducted in May 2013 (with no restriction on publication date) to identify RCTs investigating the effectiveness of eSBIs to reduce alcohol consumption through searching the electronic databases PsycINFO, MEDLINE and EMBASE. Two members of the study team independently screened studies for inclusion criteria and extracted data. Studies reporting data that could be transformed into grams of ethanol per week were included in the meta-analysis. The mean difference in grams of ethanol per week between eSBI and control groups was weighted using the random-effects method based on the inverse-variance approach to control for differences in sample size between studies.

We defined an eSBI as an electronic intervention aimed at providing information and advice designed to achieve a reduction in hazardous/harmful alcohol consumption, with no substantial face-to-face therapeutic component. A SBI was defined as screening followed by a brief intervention composed of a single session, ranging from 5 to 45 minutes in duration, and up to a maximum of four sessions aimed at providing information and advice designed to achieve a reduction in hazardous/harmful alcohol consumption. Studies were not deemed eligible for inclusion if participants were alcohol dependent, mandated to complete eSBIs or part of a preselected specific group (e.g. pregnant women). There were no restrictions on age.

A total of 23 studies78–101 were deemed eligible for inclusion in this systematic review. All study interventions were either computer or web based. The content of the interventions included an assessment followed by personalised and/or normative feedback. Control conditions generally consisted of an assessment with no further feedback, but four studies82,85,90,91 included general information on alcohol consumption for those in the control conditions. There was some variation in the dose of the intervention, with the reported time taken to complete the intervention ranging from < 5 minutes91 to 45 minutes. 94 The dose of exposure to the intervention could also be increased through repeated access during the study period81 and/or a printed copy of the personalised feedback provided. 83,88,93,95,97,100 The attrition rate was highly variable between studies, ranging from 1% or 2%87 to > 50%. 99

We found that there was a statistically significant mean difference in grams of ethanol consumed per week between those receiving an eSBI and those in the control group at up to 3 months (mean difference –32.74, 95% CI –56.80 to –8.68), from 3 months’ to < 6 months’ (mean difference –17.33, 95% CI –31.82 to –2.84), and from 6 months’ to < 12 months’ follow-up (mean difference –14.91, 95% CI –25.56 to –4.26). No statistically significant difference was found at a follow-up period of ≥ 12 months (mean difference –7.46, 95% CI –25.34 to 10.43).

The results of this systematic review and meta-analysis suggest that eSBIs are effective in reducing alcohol consumption in the follow-up post-intervention period between 3 months and < 12 months, but not in the longer-term follow-up period of ≥ 12 months.

A review of alcohol screening and brief interventions for adolescents

In addition to the systematic review, we conducted a review of reviews to explore the evidence base on alcohol SBIs for adolescents, and to determine age-appropriate screening tools, effective brief interventions and appropriate locations to undertake these activities, in order to address the lack of consensus about the most effective components of effective interventions. This review of reviews has been published102 and is reproduced in full in Appendix 4.

We conducted a review of reviews based on publications from 2003 to 2013 identified through a search of electronic databases (e.g. PubMed, Web of Science). These were judged to capture all trials of alcohol SBIs in an adolescent population. Thirteen review papers76,77,103–113 were identified and summarised. We also found five additional studies114–118 of alcohol SBIs for adolescents (all published between 2010 and 2012) that were not included in any of the published systematic reviews, and these were also included in this review. Studies that focused on primary prevention of alcohol use were excluded from this review.

Various alcohol screening methods for adolescents have been developed in the USA but have not been evaluated in the UK. Questionnaires were found to perform better than blood markers or breath alcohol concentration in all age groups. The CRAFFT and AUDIT tools are recommended for identification of ‘at-risk’ adolescents. In particular, the AUDIT questionnaire54 was found to have greater sensitivity and specificity than other tools. AUDIT sensitivities for adolescents ranged from 54% to 87% and specificities ranged from 65% to 97%. 31

A number of reviews on effective interventions for adolescents identified as being in need of help or advice about their drinking have now been published; the most recent of these have focused on the use of internet, computer and mobile phone technologies, collectively referred to as electronic brief interventions (eBIs). These reviews present limited evidence that eBIs significantly reduce alcohol consumption compared with minimal or no intervention controls,76,77,104 and our review presented in the previous section extends this work, indicating effectiveness of eBIs in a meta-analysis. 74 However, some caution should be exercised when interpreting these findings, as an earlier meta-analysis by Carey et al. ,119 which compared eBIs with a more traditional face-to-face delivery of interventions, concluded that face-to-face delivery was superior. Indeed, motivational interventions delivered over one or more sessions and based in health-care or educational settings are effective in reducing levels of consumption and alcohol-related harm. 107

Further research to develop age-appropriate screening tools needs to be undertaken. The effect of SBI activity should be investigated in settings in which young people are likely to present; further assessment at venues such as paediatric EDs, sexual health clinics and youth offending teams should be evaluated. The use of electronic (web-/smartphone-based) screening and intervention shows promise and should be another focus of future research.

Overall, this review of reviews and recent RCTs suggests that, despite an increasing interest in applying SBIs to an adolescent population, there are no clear indications of which target population, setting, screening tool or intervention approach can be recommended. The relationship between age, alcohol consumption and harm is complex, and further research is required to establish guidelines for consumption and thresholds of harm for different age groups.

Patient and public involvement in work package 2

In addition to the reviews described above, we engaged with a number of youth organisations (British Youth Council, The Well Centre and Redthread) to help refine our methodology and interventions. There was a clear indication that the stepped care motivational enhancement therapy approach that we had proposed during the application stage was not well received by our target group. As a result, we adopted their suggestions to undertake brief ED-based interaction and to use technology, and we developed a smartphone-based intervention app and a personalised feedback and brief advice (PFBA) (leaflet-based) condition for use in the intervention trials. We have involved young people in the design and content of the app and the leaflet, and have found this to be a particularly useful exercise that has helped us to achieve credibility with young people and to engage young people with our proposed interventions.

The second phase of the patient and public involvement was conducted to develop the interventions. Initially, we had planned to screen adolescents (using the optimal screening method from work package 1) and invite them to participate in a prospective RCT, using therapist-guided brief interventions and, where indicated, intensive motivational enhancement therapy (stepped care intervention). These interventions were to be compared with treatment as usual. The patient and public involvement work showed that young people felt electronic screening and consent was acceptable. A face-to-face brief intervention was acceptable in the ED, but any form of extensive intervention was not. An educational app was recommended by our focus group participants. Furthermore, the prevalence study showed that the questionnaire was too long to be acceptable to participants.

As a result, the iPad screening tool was shortened and refined to include the consent procedure to improve participant management. Participants and parents were e-mailed the information leaflets instead of being given paper copies, with laminated versions kept in the ED for reference. The iPad app was also developed to randomise participants to the different arms of the trial and to record a random sample of brief interventions for fidelity purposes.

The study design was revised so that the intervention comprised a brief intervention (PFBA) with a web-enabled smartphone app (eBI). The smartphone app was not in the initial plan for the trial but was included on the basis of the patient and public involvement, as young people had said that an educative app would be better received than our planned interventions. Adolescents had a preference for images over text, and it was suggested to make the app look and feel like a game.

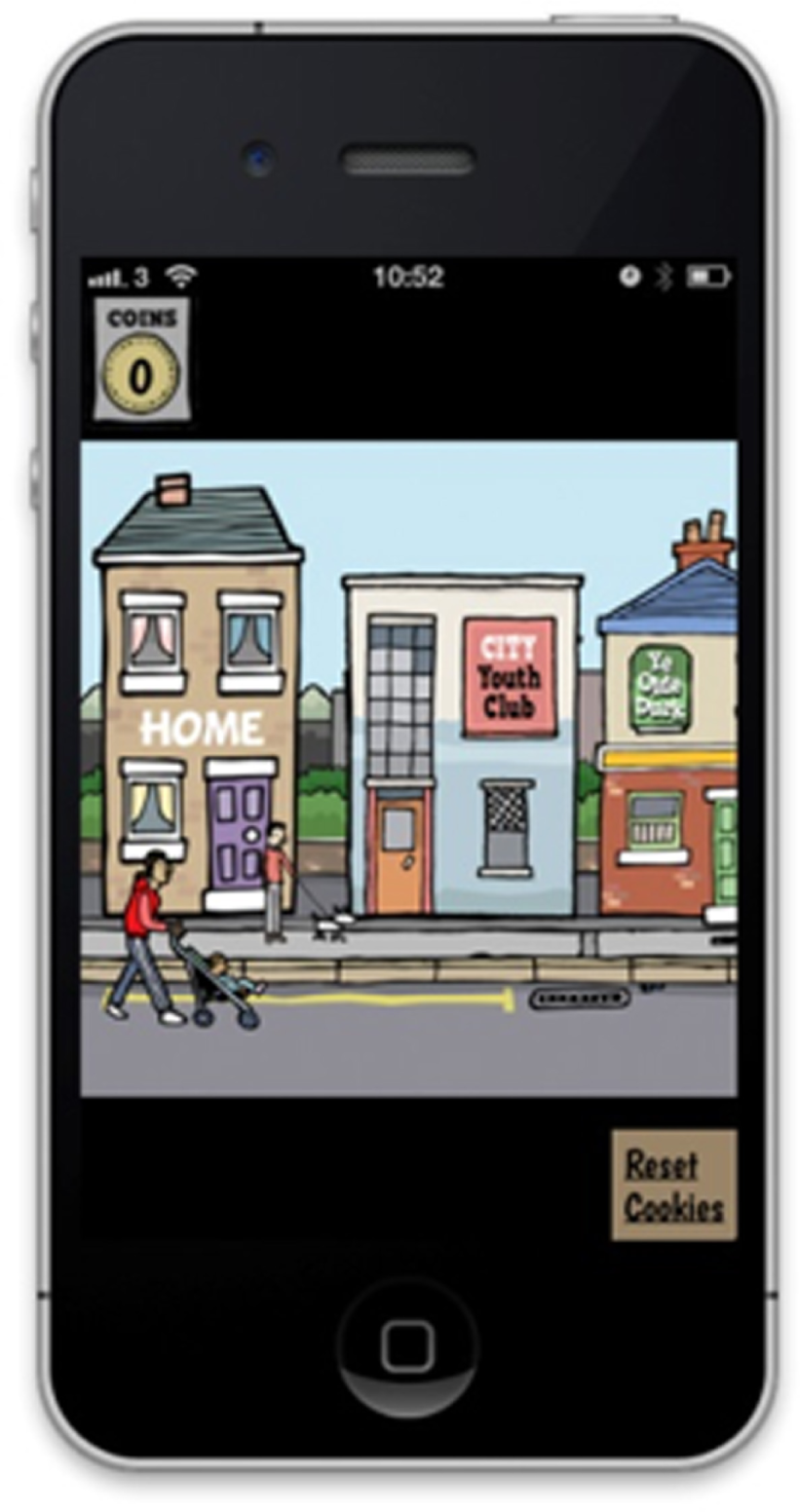

The eBI takes the form of an app called ‘SIPS City’ [Screening and Intervention to Promote Sensible drinking (SIPS)]. The app home screen is a cartoon street with different places for young people to visit (and learn facts about alcohol), and includes gamification features that encourage participants to find and collect coins. It is designed to be engaging and educational, and to provide ongoing feedback and advice about alcohol consumption. It is loosely based on the FRAMES (Feedback of personalized risks: Responsibility, Advice, Menu of options, Empathy, Self-efficacy) motivational brief intervention approach. 120 A demonstration version of the SIPS City app was installed on iPads in the EDs to show to participants randomised to the eSBI arm of the trial, who were not able to access the app on their own smartphone while in the ED. Participants without a smartphone were asked to use an online web browser version of the app; participants who did have a smartphone but were not able to use it while in the ED were sent a link to download the app later.

The final phase of the patient and public involvement was conducted to develop an online self-completion form of the retrospective Timeline Followback-28 (alcohol consumption in the past 28 days), which was later modified in favour of a shorter outcome measure (AUDIT-C).

Work package 3: linked randomised controlled trials of face-to-face and electronic brief intervention methods to prevent alcohol-related harm in young people aged 14–17 years presenting to emergency departments

Background

A number of trials17,18,42,43,117,118 focusing on young people (aged 12–21 years) have reported significant positive effects of brief interventions on a range of alcohol consumption measures. Our systematic review (reported in Work package 2: exploratory modelling of the interventions) suggested that eBIs can significantly reduce alcohol consumption compared with minimal or no intervention controls, and have the added advantage of being more acceptable and easier to implement than more traditional face-to-face interventions. Our study of the prevalence of risky drinking among an adolescent population (aged 10–17 years) reported in Work package 1: screening prevalence study of alcohol consumption and alcohol use disorders in adolescents aged 10–17 years attending emergency departments found that about one in four young people presenting to EDs was consuming three or more drinks on one or more occasion over the preceding month, and that this level of consumption was associated with increased physical, social and educational adverse consequences. We also observed a steep transition in drinking prevalence between 13 and 17 years of age.

Several school-based interventions121 that target non-drinking adolescents have been found to delay the onset of drinking behaviours, and a recent study of adolescents122 found lower rates of substance misuse initiation among those exposed to a web-based intervention. Web-based alcohol interventions for adolescents also demonstrated significantly greater reductions in consumption and harm among ‘high-risk’ drinkers. 123 However, changes in risk status at follow-up for non-drinkers or low-risk drinkers have not been assessed in controlled trials of brief intervention.

Recruitment of both ‘high-risk’ and ‘low-risk’ drinkers has the additional benefit of addressing a major concern among both young people and parents, namely that participation in a trial of this nature may identify the young person as drinking at a level that warrants concern and intervention. Young people interviewed as part of our patient and public involvement work in work package 2 indicated that they would prefer to take part in a trial if there was no implication that they had an ‘alcohol problem’ and were assured that information about their drinking would not be disclosed to parents or health-care staff. Recruitment of both high- and low-risk-drinking young people was more acceptable to both young people and their parents, as was emphasising participant confidentiality.

Thus, we conducted two linked RCTs that included both high- and low-risk drinkers and abstainers, informing them that the study sought to prevent alcohol-related harm in young people. In addition, embedded within the proposed study was an internal feasibility study conducted prior to proceeding to the main trial.

The trials protocol has been published in Deluca et al. 124 and parts of this section have been reproduced from Deluca et al. 124 This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly credited. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Objectives

Primary objective

The primary objective was to conduct two linked RCTs to evaluate the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of brief intervention strategies compared with screening alone. One trial focused on high-risk adolescent drinkers attending EDs and the other focused on those identified as low risk or abstinent from alcohol. In both trials our primary outcome measure was quantity of alcohol consumed at 12 months after randomisation.

Secondary objectives

The secondary objectives of each study were:

-

to identify key predictors of recruitment to the trials

-

to explore the process of intervention through key psychological constructs that may lead to further refinement of the proposed interventions

-

to identify prognostic factors related to better outcomes

-

to explore interactions between participant factors, setting factors, treatment allocation and outcomes.

Our primary (null) hypothesis was similar for both trials: PFBA and personalised feedback plus eBIs is no more effective than screening alone in reducing alcohol consumed at 12 months after randomisation as measured with the AUDIT-C. Our secondary (null) hypothesis relating to health economics states that PFBA and eBIs are no more cost-effective than screening alone.

Methods

The linked trials were granted ethics approval by the National Research Ethics Service London – Fulham (reference 14/LO/0721). The trials comply with the Declaration of Helsinki125 and Good Clinical Practice126 and have been registered as ISRCTN45300218.

Study setting and participants

The trials were carried out in 10 EDs across three regions of England: North East, Yorkshire and The Humber, and London. Data collection was carried out from 10 a.m. to 10 p.m., 7 days per week, over an 8-month period (October 2014–May 2015). During these screening hours, consecutive ED attenders who were between their 14th and 18th birthdays and who met the inclusion criteria but none of the exclusion criteria were approached by a researcher and invited to participate in the study once cleared by ED staff to do so.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion and exclusion criteria were chosen to maintain a balance between ensuring the sample was representative of the ED population while also able to engage with both the relevant interventions and follow-up.

Inclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were being aged between 14 and 17 years inclusive; being alert and orientated; being able to speak English sufficiently well to complete the research assessment; living within 20 miles of the ED; being able and willing to provide informed consent to screening, intervention and follow-up; if under aged < 16 years, being ‘Gillick competent’ or having a parent or guardian who was able and willing to provide informed consent; and owning a smartphone or having access to the internet at home.

Exclusion criteria

The exclusion criteria were having a severe injury; suffering from a serious mental health problem; being grossly intoxicated; specialist services being involved because of social or psychological needs; receiving treatment for an AUD or substance use disorder within the past 6 months; or currently participating in other alcohol-related research.

The inclusion and exclusion criteria were discussed with hospital nurses/doctors before a potential participant was approached and after clinical staff assessed the participant. We relied on their knowledge and professional judgement.

Those who were grossly intoxicated on attendance were not the population of interest. The study addressed those who consumed alcohol at levels at risk to their health, rather than alcohol-related attendances. Although it is possible that these two groups overlapped, we were mindful of the issue of informed consent for those who presented as grossly intoxicated; however, if their intoxicated state reduced to an acceptable level while they were in the ED, they were approached.

Those who met the inclusion criteria and none of the exclusion criteria and scored ≥ 3 on the screening questionnaire, AUDIT-C, were eligible for the high-risk study; those who scored < 3 on AUDIT-C were eligible for the low-risk study.

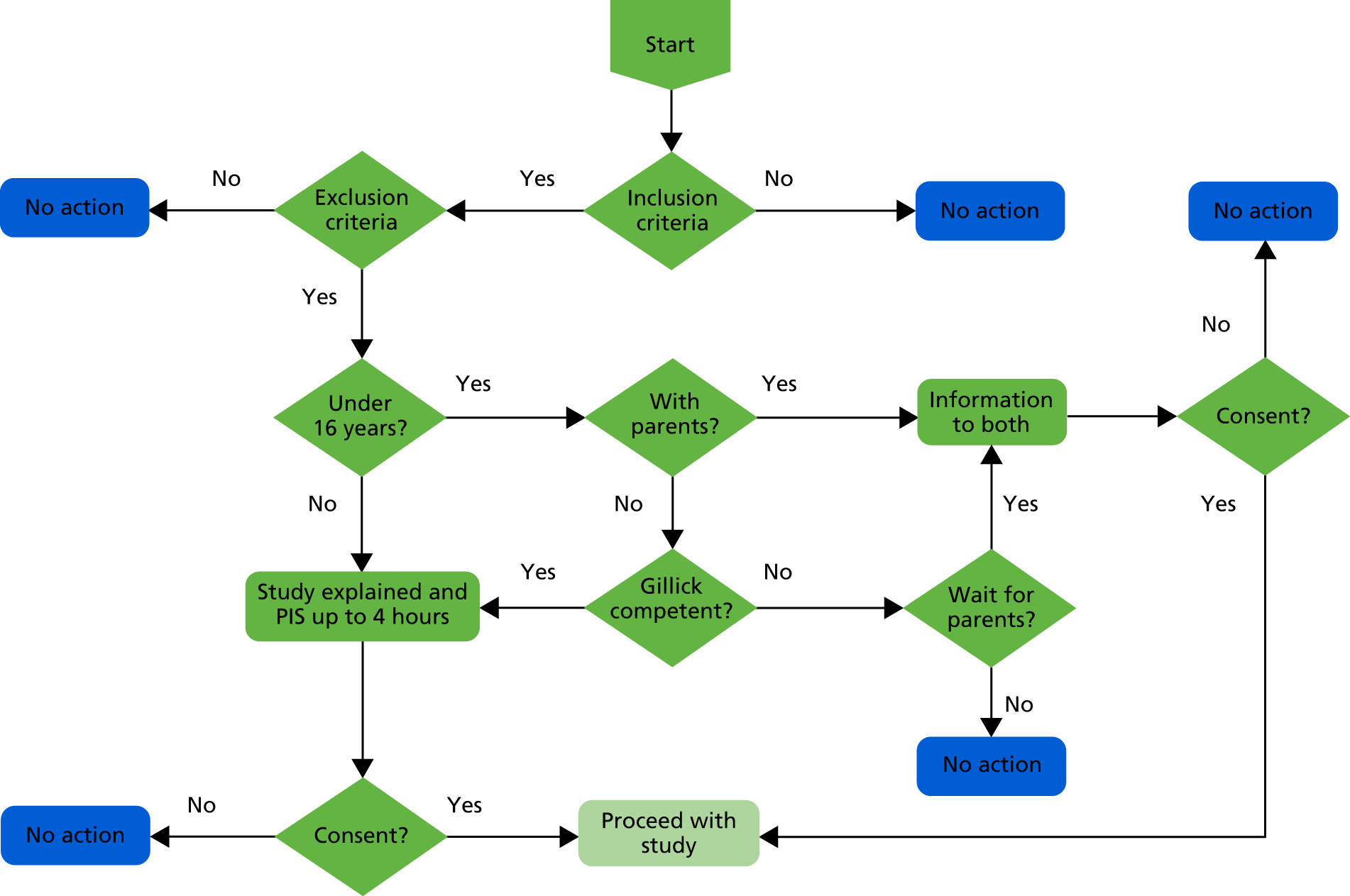

Consent procedure

The study was introduced to patients, and to their parent or guardian if they were aged < 16 years, as a study about alcohol, lifestyle and health, with the focus on preventing alcohol-related harm in all young people attending ED irrespective of their alcohol consumption. Patients aged < 16 years attending the ED without their parent or guardian were also approached to take part if ED staff confirmed that they were ‘Gillick competent’. We extended Gillick competency to consenting for participation in research on the grounds of minimal/no risk in taking part in this study, the potential direct benefit that they would gain from the advice received and the potential benefit to the wider society in the roll-out of the findings. 64

The study was first introduced by ED staff and then explained in more detail by research staff, both verbally and using the patient information sheet. If the patient was under the age of 16 years and accompanied by a parent or guardian, the parent or guardian would also receive the patient information sheet. Patients, and parents or guardians if applicable, had up to 4 hours to ask any questions about the study and to decide whether or not to take part. To obtain the most valid self-report data, patients were told as part of the informed consent procedure that their answers, including those on alcohol consumption, would not be disclosed to their parent or guardian or the ED staff without their consent (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

Decision tree for consent. PIS, patient information sheet.

If patients agreed to participate, their informed consent was recorded using an electronic device (iPad), overseen by a research assistant who also introduced and delivered the allocated intervention to each patient in a private area of the ED. Consent to participate included permission to give the patient’s data and contact details to the research staff, to provide the research team with access to the patient’s ED records, and to participate in follow-up at 6 and 12 months after recruitment.

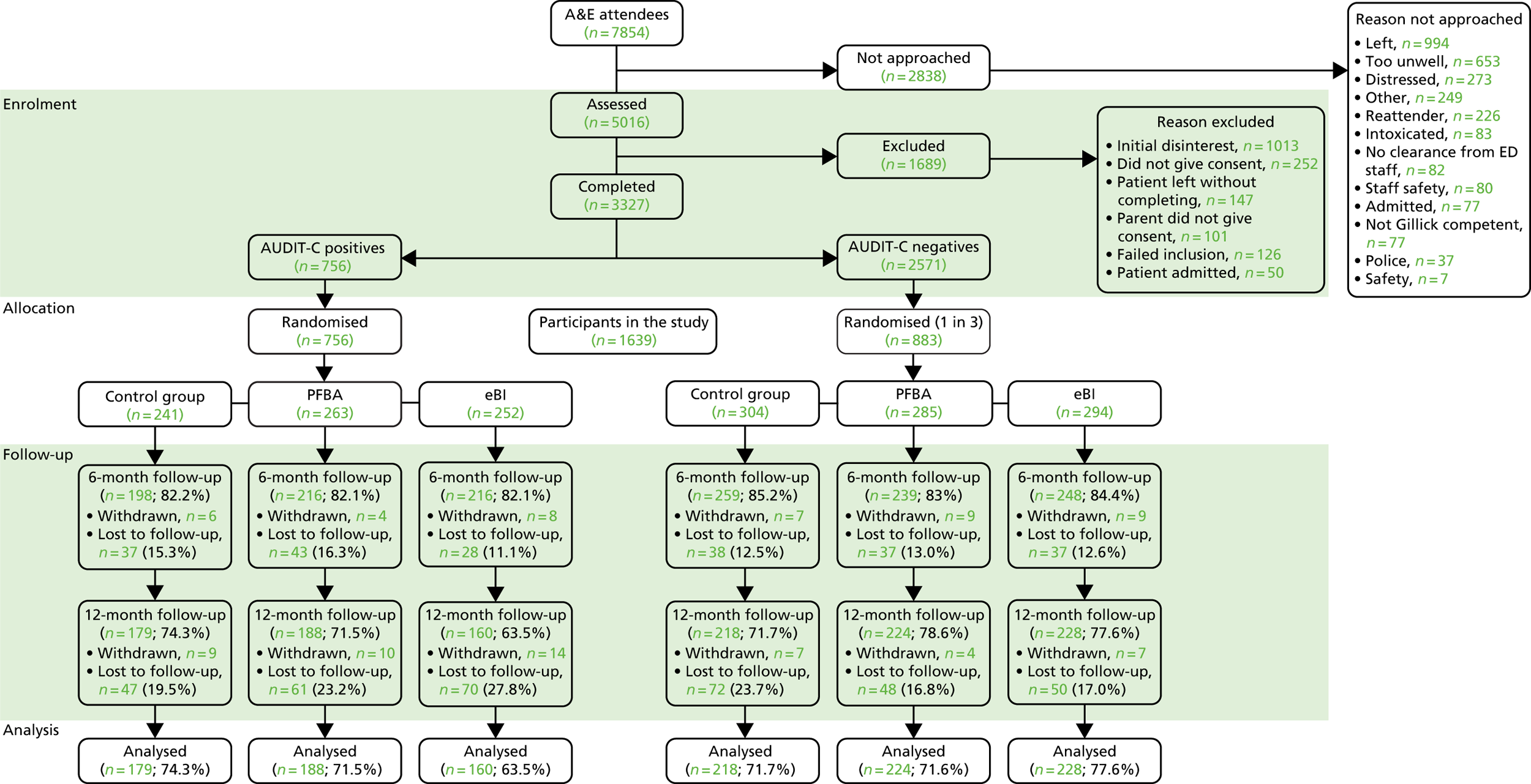

Screening and baseline assessment

After consent was given by the patient or their parent or guardian, as appropriate, the participant completed a screening and baseline assessment (Figure 5 shows the sequence of tools administration). All participants scoring ≥ 3 on the AUDIT-C (high-risk drinkers) were randomised between three groups [two intervention groups (PFBA and eBIs) and the control group receiving screening alone]. Of those scoring < 3 on the AUDIT-C (low-risk drinkers or abstainers), one in three was randomly selected to continue with the study and then randomised between three analogous groups. Participants who scored < 3 but were not selected for the trial were thanked for their participation, given a £5 voucher and returned to the care of the ED staff.

FIGURE 5.

Baseline sequence. APP, SIPS Jr City app; BA, brief advice; EQ-5D-5L, EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version; ESP19, European School Survey Project on Alcohol and Other Drugs Q19; ESP19-C, European School Survey Project on Alcohol and Other Drugs Q19c; ESP21, European School Survey Project on Alcohol and Other Drugs Q21; ESP22, European School Survey Project on Alcohol and Other Drugs Q22; Q, question; SDQ, Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire; SU, Service Use Questionnaire.

The screening and baseline assessment includes demographic information and contact details; health and lifestyle questions; the AUDIT-C;54 questions 19, 21 and 22 from ESPAD;68 the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire,127 the EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L);128 and a short service use questionnaire. 129 This took approximately 10 minutes to complete.

To simplify and enhance data collection, we used a bespoke electronic interface (developed in work package 1), which automated question routing, showing participants only relevant questions. To maximise completion rates, we used an attractive graphical interface. Participants were able to skip questions or withdraw consent at any stage. All of the instruments have been designed and validated for those aged 14–17 years. The screening and baseline assessment was conducted by trained researchers with experience of working with adolescents, and all researchers had completed enhanced Disclosure and Barring Service checks prior to working in the ED. All information that participants gave was treated in confidence.

Participants were remotely randomised with equal probability, stratified by centre, between a screening only control group and one of the two interventions: a single session of face-to-face PFBA or personalised feedback plus a smartphone- or web-based brief intervention (eBI). All participants were eligible to receive treatment as usual in addition to any trial intervention.

Randomisation

Randomisation to trial participant or non-participant was conducted using a simple block randomisation, with a one in three probability of selection. For those selected as participants, randomisation to study group was conducted using strings of randomly selected block sizes, three or six, stratified by ED and gender. Each iPad within a centre had a separate pre-programmed allocation sequence derived by an independent party and made secure using encryption. Researchers engaged in the baseline assessment were not aware of allocated group until after outcomes had been completed. Participants were not blind to allocated group.

Interventions

Screening only group: treatment as usual

After completing the baseline assessment, participants in the screening arm were thanked for their participation, reminded that a member of the research team would contact them in 6 and 12 months to conduct a follow-up interview and returned to the care of the ED staff for usual care.

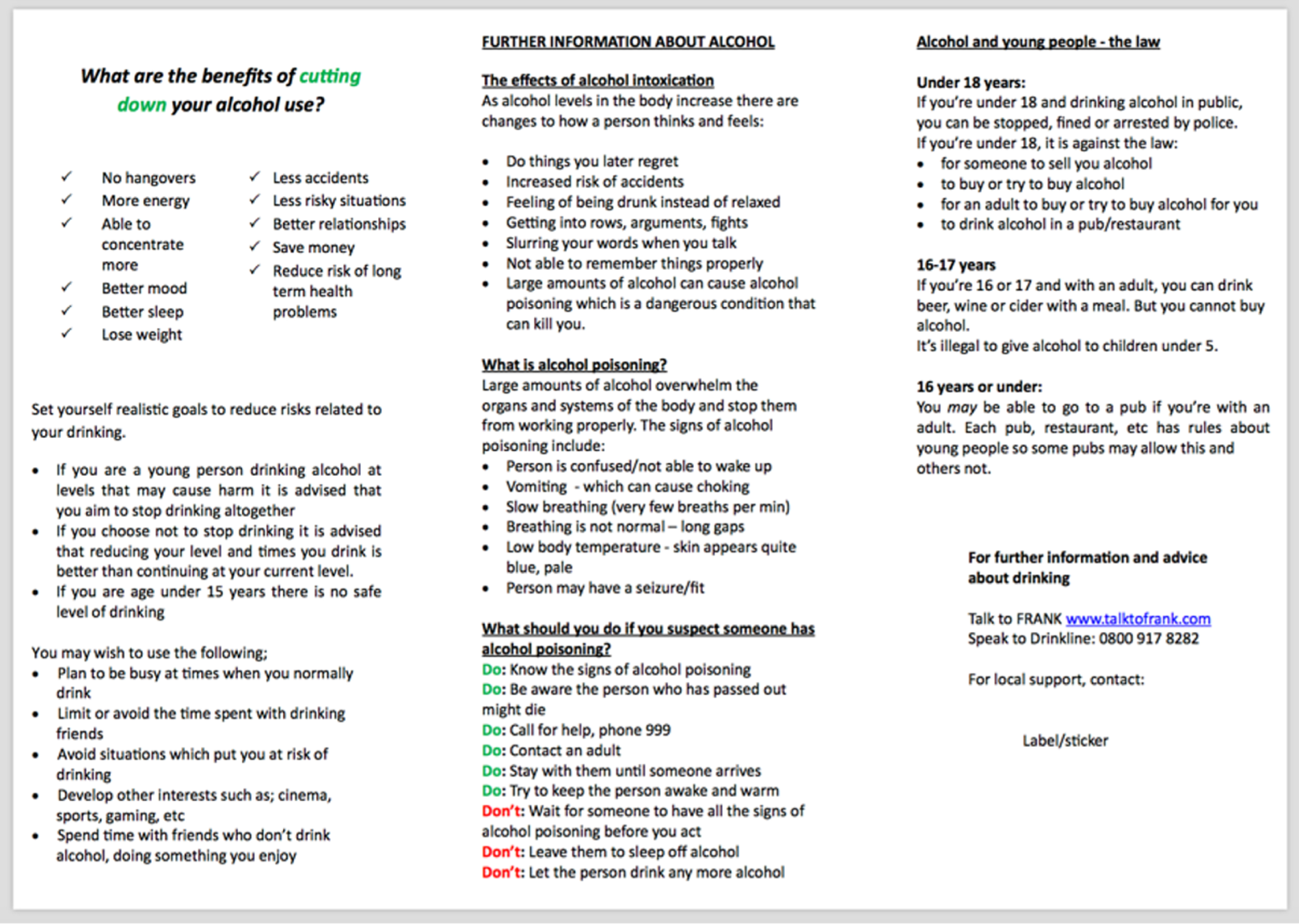

Personalised feedback and brief advice

The PFBA intervention is structured brief advice that takes approximately 5 minutes to deliver (Figure 6) in one session. It is based on an advice leaflet adapted for the target age group in this study from the SIPS brief advice about alcohol risk intervention. 130,131 It is based on the FRAMES model:132

-

Feedback: Give feedback on the risks and negative consequences of alcohol use. Seek the patient’s reaction and listen.

-

Responsibility: Emphasise that the individual is responsible for making his or her own decision about his/her alcohol use.

-

Advice: Give straightforward advice on modifying alcohol use.

-

Menu of options: Give menus of options to choose from, fostering the patient’s involvement in decision-making.

-

Empathy: Be empathic, respectful and non-judgemental.

-

Self-efficacy: Express optimism that the individual can modify his or her alcohol use if they choose. Self-efficacy is one’s ability to produce a desired result or effect.

FIGURE 6.

Brief advice leaflet.

It is conveyed verbally to the participant by trained research assistants or nurses and tailored to their risk status (high or low). It was delivered in a quiet room in the ED.

The advice covers recommended levels of alcohol consumption for young people; gives feedback on the screening results and their meaning; provides normative comparison information on prevalence rates of high- and low-risk drinking in young people; summarises the risks of drinking and highlights the benefits of stopping or reducing alcohol consumption; outlines strategies that they might employ to help stop or reduce alcohol consumption; highlights goals they might wish to consider; and indicates where to obtain further help if they are unsuccessful or need more support.

Each participant received a copy of the leaflet, which included additional information about alcohol intoxication, alcohol poisoning, and alcohol and the law.

Personalised feedback plus a smartphone- or web-based brief intervention

The eBI smartphone intervention SIPS City is an offline-capable mobile web application that works on a variety of platforms but is optimised for recent iPhone (Apple Inc., Cupertino, CA, USA) and Android (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA) phones (Figure 7). It was developed for this research by the software developer Codeface Ltd (Hove, UK) in collaboration with the research team. It followed the recommendations from patient and public involvement, and it was developed using the concept of gamification so that users can navigate, explore, learn facts and figures about alcohol, receive personalised feedback and set goals in an engaging format. The content was adapted to provide the most pertinent information and advice for high- or low-risk drinkers and was similar in content to what was provided in the PFBA intervention arm described above in Personalised feedback and brief advice. Games components of the web application supported high-risk drinkers to reduce or stop their alcohol consumption and low-risk users to maintain abstinence or low-risk drinking.

FIGURE 7.

SIPS Jr Street app with full view of East and West Streets.

The SIPS City app was formatted into a virtual reality of two streets, west and east, in which there were multiple buildings such as a general practice, a pub and a youth centre. To gain access to some buildings, participants had to collect a certain number of coins, which could be obtained from talking to characters on the street or by answering questions correctly. When interacting with people on the street, participants were directed to certain buildings depending on the problem that person was encountering, for example the doctor for alcohol poisoning. It was also possible to drive in the car of ‘Rod McDuff’s School of Motoring’, and facts regarding the risks of alcohol and drinking were portrayed while inside the car.

The first building was the participants’ home, where they could fill out a drinking diary and receive feedback from this. It was also possible to view information on units and a letter from the local A&E about the participant’s drinking. Interaction with a health worker at the general practice allowed a user to follow-up the A&E letter and set personal alcohol goals. There was a sexual health clinic building that provided information on the increase of sexual health risks with increased alcohol intake. After two coins had been obtained, access to East Street was granted. The pharmacy was here, which provided information on how to reduce the effects of a hangover. The school provided information on the harmful effects of alcohol in relation to education, which provided relatable information to those in the age group in this study.

Whenever possible, the app was installed, with the help of a research assistant/nurse, on the participant’s smartphone while they were attending A&E and the participant was encouraged to use it. In the instances when they did not have access to their phone (e.g. flat battery, left at home, no data plan), patients were introduced to a demonstration version of the app on a study device (iPad) and allowed to play with it while in A&E. An e-mail and short message service (SMS) were also sent to the patient within 24 hours with instructions on how to download and install the app on their smartphone once they were at home.

Two further remainders (e-mail and SMS) were sent in the following 2 weeks to those who had failed to install the app on their smartphone.

For participants without access to a smartphone but with access to the internet through other computerised devices, access to a web-based version of the application was provided along with appropriate instructions for its use.

After receiving their allocated intervention (including the screening only group), all participants were thanked for their participation, reminded that a member of the research team would contact them in 6 and 12 months to conduct a follow-up interview, given a £5 voucher to thank them for their time and returned to the care of the ED staff.

Intervention fidelity

Research assistants were responsible for recruiting participants and delivering the interventions. The research assistants were trained during a 2-hour training session, which covered the rationale and procedures of the trial, the importance of reducing alcohol consumption and the correct delivery of the interventions. Filmed examples of delivery were presented and discussed, and role-play sessions were undertaken.

During the trial, we assessed fidelity of the delivery of the PFBA interventions by audio-recording a random sample of 20% of intervention sessions for each researcher. Each recording was assessed by a senior clinician member of the team on whether or not key aspects of the intervention were delivered as intended against a predefined checklist. When necessary, feedback was provided to researchers to improve fidelity. These recordings were prespecified in the protocol analysis plan.

Follow-up assessments

All participants were followed up with a brief set of questions at 6 months after randomisation (Figure 8), and then at 12 months for a full assessment (Figure 9). Follow-up interviews were conducted over the telephone, face to face or electronically via self-completion web survey, as preferred by the participant. The telephone and face-to-face follow-ups were conducted by research assistants trained in the administration of the assessment tools and blinded to the group allocation of the participants. Letters of thanks were sent to participants after each follow-up stage. On completion of each follow-up interview, participants were sent a gift token for £5 by post in recognition of their participation. On completion of the 12-month follow-up, participants were additionally entered in to a prize draw to win an iPad Air (Apple Inc., Cupertino, CA, USA), iPad mini (Apple Inc., Cupertino, CA, USA) or iPod (Apple Inc., Cupertino, CA, USA).

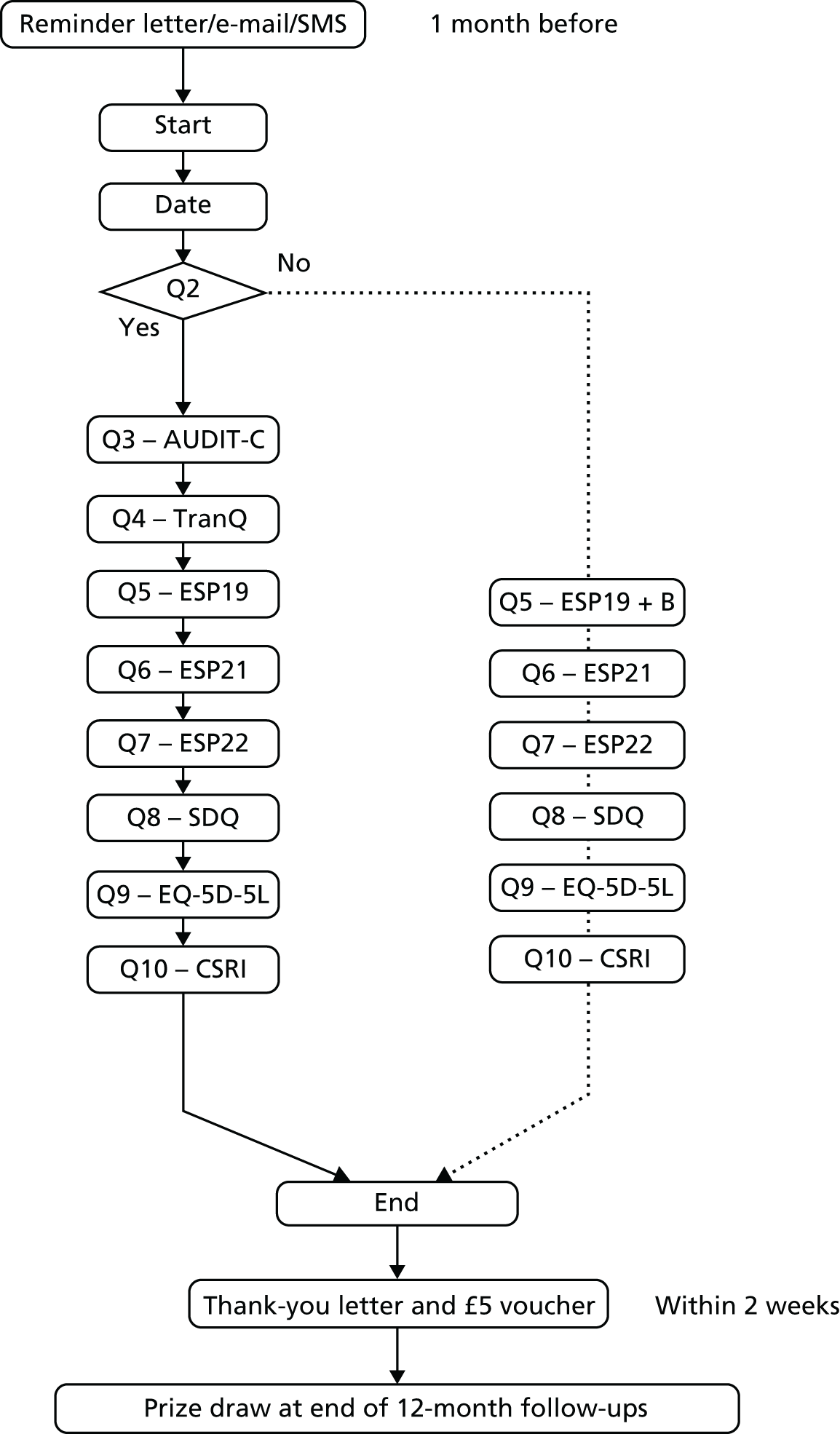

FIGURE 8.

List of tools and order of presentation at 6-month follow-up. Q, question; SU, service utilisation.

FIGURE 9.

List of tools and order of presentation at 12-month follow-up. B, items A (lifetime) and B (last 12 months) in question 19; CSRI, Client Service Receipt Inventory; EQ-5D-5L, EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version; ESP19, European School Survey Project on Alcohol and Other Drugs Q19; ESP21, European School Survey Project on Alcohol and Other Drugs Q21; ESP22, European School Survey Project on Alcohol and Other Drugs Q22; Q, question; SDQ, Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire; TranQ, transition question.

Outcome measures

Primary outcome measure

The primary outcome was the total amount of alcohol consumed in standard UK units (1 unit = 8 g of ethanol) over the previous 3 months, measured at the 12-month follow-up using the AUDIT-C, which was either self-completed by web survey or administered by researchers blinded to treatment allocation.

In the published protocol124 we intended to use the Timeline Followback interview (28-day version). However, this was subsequently changed to the AUDIT-C to facilitate completion rate at follow-up. The AUDIT-C is a much shorter tool (three items) and can be self-administered.

Calculation of weekly units from the AUDIT-C was conducted as follows. The extended AUDIT-C asked two questions regarding frequency and quantity of alcohol consumed. Question 1 asks about frequency, and these values are converted to weekly frequency using the following algorithm: never (0), monthly (0.25), two to four times per month (0.75), two or three times per week (2.5), four or five times per week (4.5) and six or more times per week (6.6). Question 2 asks about quantity on each drinking occasion and is converted to standard units using the following algorithm: none (0), one or two (1.5), three or four (3.5), five or six (5.5), seven to nine (8), ten to twelve (11), 13 to 15 (14) and 15 or more (15). Weekly units are calculated by multiplying converted values for frequency and quantity.

This value allocates participants to 1 of 35 categories of consumption. An ordinal is one in which values are ranked, A is greater than B, but the relative magnitude of A relative to B is unknown. The weekly consumption calculation not only ranks participants but also allows a derivation of the relative difference between participant drinking levels. The large number of data points and the ability to assess relative magnitude means that the weekly consumption can be taken as a continuous measurement variable. This implicit assumption was tested as part of the overall analysis.

Moreover, any ordinal scale with > 11 data points can be treated as continuous. 133

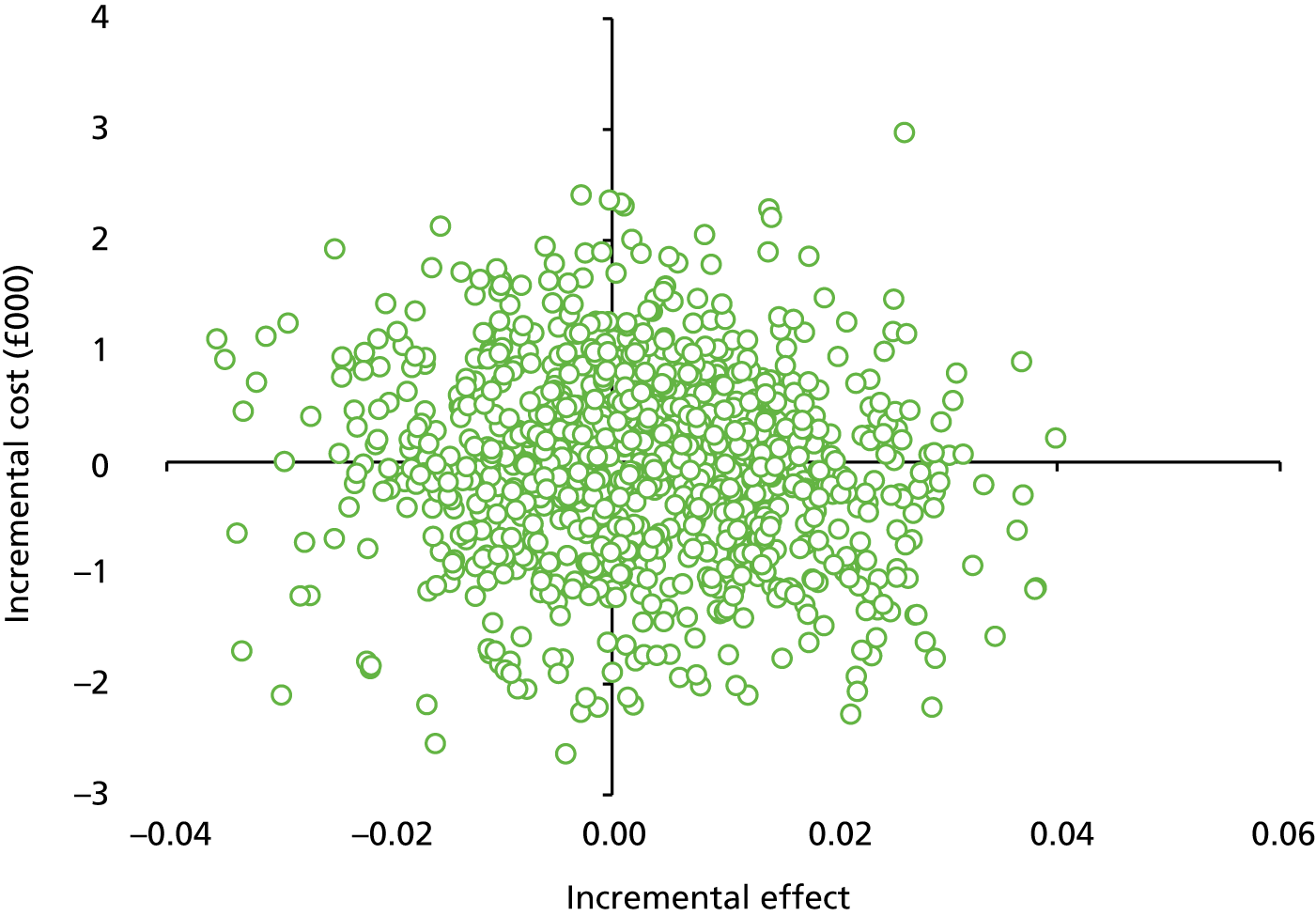

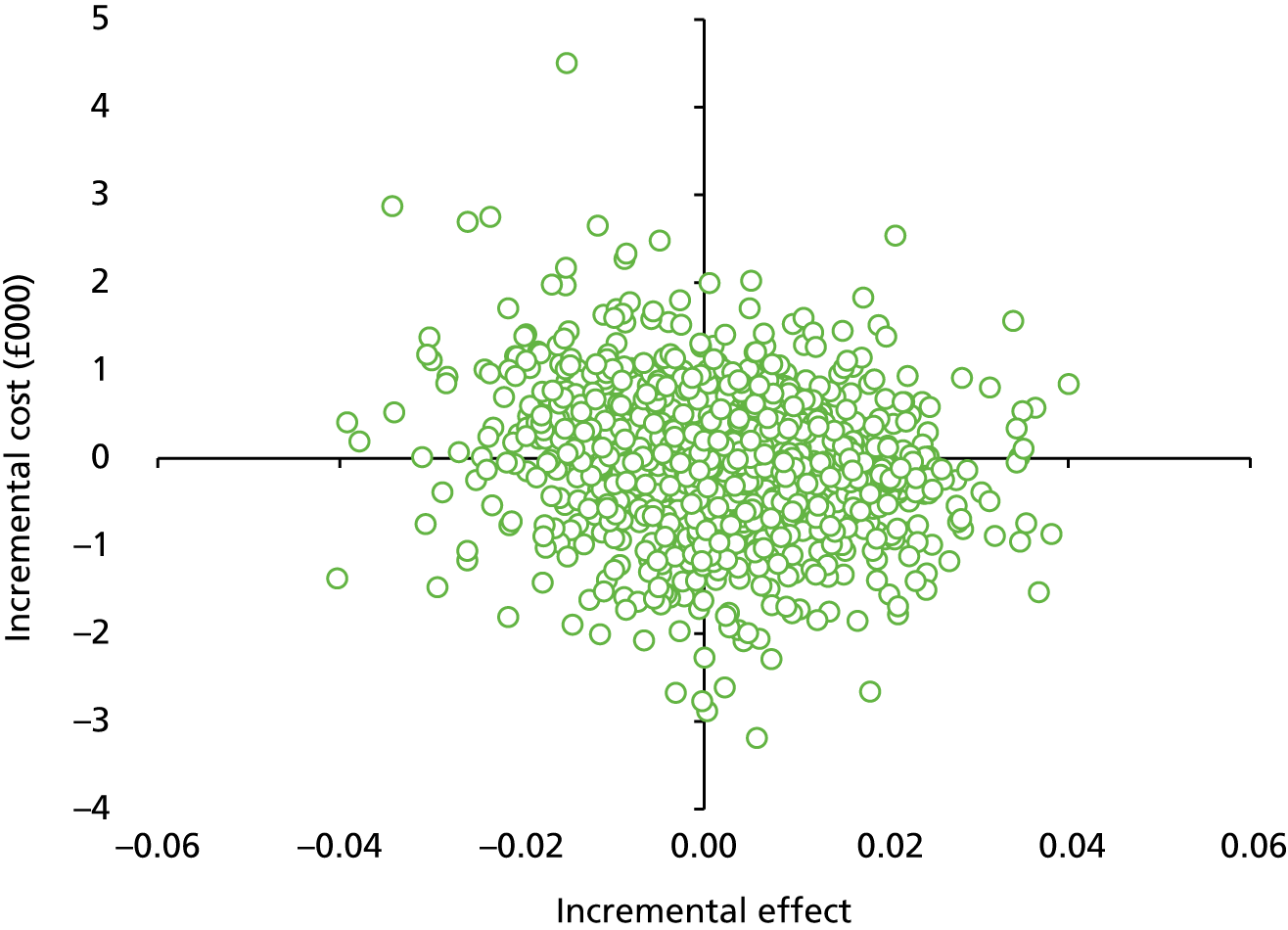

Secondary outcome measures