Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by PGfAR as project number RP-PG-0608-10133. The contractual start date was in April 2010. The final report began editorial review in September 2018 and was accepted for publication in January 2020. As the funder, the PGfAR programme agreed the research questions and study designs in advance with the investigators. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PGfAR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Clive Ballard reports grants from Novo Nordisk (Bagsværd, Denmark); grants and personal fees from Acadia Pharmaceuticals (San Diego, CA, USA) and from Lundbeck Pharmaceuticals (Copenhagen, Denmark); and personal fees from Pfizer Inc. (New York, NY, USA), Roche Holding AG (Basel, Switzerland), Eli Lilly and Company (Indianapolis, IN, USA), Heptares Therapeutics (Hertford, UK), Otsuka Pharmaceutical (Tokyo Japan), Novartis (Basel, Switzerland) and Allergan (Dublin, Ireland), outside the submitted work. Esme Moniz-Cook held National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) funding for a programme grant during this period (RP-PG-0606-106). Anne Corbett reports personal fees from Lundbeck Pharmaceuticals, Novartis, Bial (Trofa, Portugal) and Acadia Pharmaceuticals, outside the submitted work, and a NIHR Programme Development Grant held during the study period (RP-DG-1212-10004). Dag Aarsland has received research support and/or honoraria from AstraZeneca (Cambridge, UK), Lundbeck Pharmaceuticals, Novartis and GE Healthcare (Chicago, IL, USA), and serves as a paid consultant for Lundbeck Pharmaceuticals and Axovant Gene Therapies (Hamilton, Bermuda), outside the submitted work. Zoe Hoare reports associate membership of the Health Services and Delivery Research programme board (2016–20). Jane Fossey reports a grant from the Alzheimer’s Society (London, UK) outside the submitted work.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Ballard et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

SYNOPSIS

Background

Dementia is characterised by the progressive loss of cogition and function, leading to the loss of independence and communication ability, and eventually to death. Dementia exerts an enormous impact on the individuals affected and their families, many of whom provide informal care for long periods of time. In the context of an ageing population, dementia is also a critical public health issue with considerable financial implications at a societal level. There are 46 million people with dementia worldwide, including 850,000 people in the UK, of whom an estimated 250,000 live in care homes. 1,2 In the USA, 64% of people receiving Medicare in nursing homes have dementia. 3 Care homes provide full-time residential and nursing care, and represent a unique challenge for health care. There is an increasing focus in research and policy on the improvement of institutionalised care and the need for evidence-based interventions for people with dementia that are tailored to this setting.

Dementia in health-care provision and policy

Dementia has a vast impact on health and social care services in the UK. The direct cost of dementia is £42B per year,1 which is higher than the cost of stroke, heart disease and cancer combined. This was the basis of the UK’s national dementia strategy for England, developed by the Department of Health and Social Care in partnership with stakeholder organisations, such as the Alzheimer’s Society (London, UK). 4,5 The strategy laid out a unique vision for people with dementia and provided a 5-year plan for building health and social services for people with dementia that are fit for the 21st century. 4

The strategy included two key objectives with particular relevance to care home settings, with strategies to achieve them. ‘Improving the quality of care for people with dementia in care homes’ (Contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0)4 – objective 11 – involved a government directive to include specialist mental health teams in dementia care within a range of other measures. ‘The development of an informed and effective workforce for people with dementia’ (Contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0)4 – objective 13 – aimed to provide training and skills for health and social care staff to enable them to deliver the best possible care.

The importance of providing high-quality care for people with dementia who are living in residential and nursing homes received less attention in the subsequent Prime Minister’s Challenge on Dementia 20205 and the related implementation plan. 6 However, the value of an adequately trained workforce and the provision of evidence-based training was highlighted, and the focus on minimising unnecessary prescribing of antipsychotic medications to people with dementia was maintained,6 in line with international recommendations. 7 A subsequent report from The King’s Fund, Social Care for Older People: Home Truths,8 has shown the substantial pressures facing the care home sector and the urgent need to use limited resources more effectively to achieve high-quality care.

People with dementia have complex care needs, particularly those residing in care homes. The majority of these individuals have moderate or severe dementia and their care needs are influenced by a combination of cognitive, functional and communication impairments, and medical comorbidities, and a high frequency of behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD). 3,7,9 The NHS provides for these complex health needs largely through primary care and specialist service consultancy. Some specialist teams have introduced more proactive liaison services, but these are not widespread. An effective solution is needed to enable consistent and effective NHS support for people with dementia and staff, particularly in care home settings where specialist staff are rarely available. Such an NHS service would need to improve the general quality of care, the skill base of care staff and the availability of non-pharmacological interventions and reduce the frequency of potentially harmful antipsychotic prescribing to improve health and quality of life (QoL) for people with dementia in care homes.

The Well-being and Health for people with Dementia (WHELD) programme grant was run in parallel with the national dementia strategy for England and the Prime Minister’s challenge on dementia implementation activities, and within the context of a national drive to improve health-care service provision and care home services for people with dementia. The programme represents an important example of the development of a robust evidence-base for dementia care and the improvement of services in care homes.

Behavioural and psyschological symptoms in dementia

Neuropsychiatric symptoms, often referred to by consensus as BPSD, include aggression, agitation and restlessness, psychosis, depression, anxiety, elation, disinhibition, sleep disturbance and apathy. BPSD affect 90% of people with dementia at some point during the course of their condition. 10 These BPSD are critical indicators of QoL and well-being, and have clinically significant effects on the individual and their caregivers. They present a substantial challenge for health and care professionals, as there are limited treatment options. 10

Current best practice guidelines promote non-pharmacological interventions as the first-line approach for the treatment of BPSD, and there is a growing evidence base to support the value of this approach. 11 However, there is little guidance on how to implement non-drug treatments and no structured framework for their widespread use in practice.

The use of antipsychotics in people with dementia

Current best practice guidance limits the use of antipsychotics to short-term prescription (up to 12 weeks) of risperidone (Risperdal®, Janssen Pharmaceutica, Beerse, Belgium) in intractable cases that are causing risk to the person or others.

Clinical effectiveness of antipsychotic medications

Systematic reviews have analysed the clinical effectiveness of antipsychotics in people with dementia. Most studies have focused on the treatment of agitation, aggression, psychosis or overall BPSD. 12,13 These analyses are based on 18 placebo-controlled randomised trials, most of which were conducted over a 10- to 13-week period; however, many of these trials have not been published in full. The best evidence base exists for risperidone, with five fully published good-quality randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and a total of 1761 participants. 12,13 Adverse events were comprehensively reported in all five studies. 12,13 A meta-analysis reported a significant advantage for risperidone in the treatment of aggression {–0.84 points on the Behaviour in Alzheimer’s Disease (BEHAV-AD) scale [95% confidence interval (CI) –1.28 to 0.40 points] at a dose of 1 mg and –1.5 points (95% CI –2.05 to –0.95 points) at a dose of 2 mg}. 12 This threshold of change indicates a statistically significant difference but only borderline clinically meaningful benefit at the 2-mg dose of risperidone. Evidence of a clinically meaningful benefit is restricted to aggression; no clinically meaningful benefit was seen for non-aggressive symptoms of agitation. Effectiveness is even more limited for the treatment of psychosis with risperidone: statistically significant benefit but no clinically meaningful benefit was reported in one trial only at 1 mg of risperidone (BEHAV-AD mean difference –0.14. points, 95% CI –0.25 to –0.03 points). 12,13

There are important issues to highlight in the evidence base that relates to antipsychotic drug use in dementia. First, the evidence for benefit is not equal for all antipsychotic drugs. For example, a meta-analysis of published trials found no evidence that quetiapine (Seroquel, AstraZeneca, Cambridge, UK) confers benefit in the treatment of BPSD. 13 A meta-analysis of risperidone studies indicates that there is statistically significant benefit in risperidone treatment, but with a small effect size [Cohen’s d effect size (ES) of 0.18 for the treatment of psychosis and 0.2 for treating aggression]. 12,13 Olanzapine (Zyprexa, Eli Lilly) and aripiprazole (Abilify, Otsuka) appear to have similar effect sizes, but based on a smaller number of studies. Other atypical antipsychotic drugs have not been evaluated in RCTs. Second, all published antipsychotic trials have reported a high placebo response rate (e.g. 45% vs. 55% for risperidone), indicating that benefit is often related to the general benefits of good clinical practice.

Safety concerns for antipsychotics

The evidence of modest clinical effectiveness of antipsychotics must be balanced against the considerable risk of adverse events. There are established safety concerns associated with these medications, including worsening of cognitive decline, cerebrovascular events, sedation, falls and an increased risk of mortality. 14 A systematic review15 of 15 RCTs of antipsychotics in people with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) reported a 1% attributable risk of mortality over 12 weeks of treatment (risk difference 0.01, 95% CI 0.004 to 0.02; p = 0.01). A 12-month double-blind RCT16 examining antipsychotic discontinuation in people with AD, with a follow-up of participants for up to 5 years, found a significant reduction in mortality associated with discontinuation (hazard ratio 0.58, 95% CI 0.36 to 0.92), with a risk difference in mortality of 29% after 36 months. 16 A subsequent meta-analysis13,17 of all 18 RCTs of atypical antipsychotics for the treatment of BPSD also found a clinically significant acceleration of cognitive decline in people taking antipsychotics (Mini Mental State Examination mean difference 0.73 points, 95% CI 0.38 to 1.09 points; p < 0.0001) over 12 weeks.

Reporting of adverse events is the most complete for risperidone. Full data are not available for other antipsychotics as a result of the large number of unpublished studies. Of particular concern, meta-analyses have established a threefold increased risk of cerebrovascular events in people with AD who take risperidone compared with those taking placebo (odds ratio 3.43, 95% CI 1.60 to 7.32; z = 3.18; p = 0.001), with a risk difference of 3.1% compared with 1.0% in a pooled analysis. 11 Another important risk is an increased frequency of extrapyramidal symptoms (risk difference by meta-analysis 0.06, 95% CI 0.03 to 0.09, over 12 weeks). Peripheral oedema, sedation, prolonged QTc interval, infections and abnormal gait have also been identified as potential problems of atypical antipsychotics. 13 None of the RCTs of antipsychotic treatment for people with AD reported the impact on well-being or QoL. However, the relationship between the prescription of antipsychotics and well-being has been examined in one cohort study18 of 209 people, which suggested that there is lower well-being in people taking these medications in an analysis controlling for BPSD. 18

Long-term use of antipsychotics

Although more limited, evidence on the long-term use of antipsychotic drugs is also beginning to emerge. Only three trials12,16,19 have evaluated a range of atypical antipsychotic drugs over periods of 6 months and longer. Adverse events are more marked with longer-term use, with one RCT16 reporting 59% mortality in an intervention group compared with 30% in a placebo group after 36 months. In another 9-month RCT12 of 421 people with AD, 18% of patients receiving risperidone withdrew from the trial because of adverse events compared with 5% of those patients receiving placebo. Only one RCT19 has directly evaluated the impact of an antipsychotic (quetiapine) on agitation, reporting no benefit of the antipsychotic compared with placebo over 6 months. Overall, these studies have reported no benefit or very modest benefit in the treatment of BPSD over 6–12 months. The exception is one recent trial20 that compared the effect of withdrawal with the continuation of haloperidol, which indicated ongoing benefit of continuation in people who had initially responded to haloperidol treatment. A Cochrane review21 of nine randomised placebo-controlled trials concludes that long-term prescriptions of antipsychotics can be discontinued without a detrimental effect on BPSD. 21

The changing landscape of antipsychotic use

The lack of efficacy and the established safety concerns associated with antipsychotics is the basis of recommendations that these drugs are not to be used in people with AD. Only risperidone is licensed for use in this patient group, for cases of severe BPSD that are causing significant distress or risk to the individual and where other treatment approaches have failed. 7 Despite this, antipsychotic prescribing has been very common because of the lack of other treatments and the considerable pressure that is experienced by health professionals to prescribe medication. To address this issue, many governments and health authorities have promoted initiatives to reduce the unnecessary prescribing of antipsychotics, including the national dementia strategy for England. 7,17,22 These initiatives were supported by evidence that showed that there were no detrimental effects of withdrawing prescriptions on BPSD. 21 As a result, there has been a marked reduction in antipsychotic use in people with AD and dementia. An audit23 conducted in the UK in 2012 showed a 50% reduction in use of antipsychotics, with 16% of people with dementia continuing to receive antipsychotics. Similar trends have been documented across Europe and the USA. 24–26 It will now be imperative for authorities to support this success in reducing the unnecessary prescribing by adapting and updating guidance to reflect the altered landscape of antipsychotic use in dementia. For example, automatic withdrawal of antipsychotics may not be the best course of action given that the larger proportion of existing prescriptions may be appropriate for the individuals. Instead, it will be essential for guidance to focus on continued review of prescriptions and careful monitoring. The change in policy and pressure to reduce prescriptions also shows the importance of training for staff in care home settings and the need to enable their access to other effective therapies.

Non-pharmacological treatments for behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia

All best practice guidance for the management of BPSD recommend the first-line use of non-pharmacological approaches unless the symptoms are so severe that they are causing great distress or risk. 11 Although more severe and challenging agitation and aggression often require pharmacological intervention, this level of BPSD does also respond to intense psychological approaches when tailored to the individual.

Person-centred care

Person-centred care dictates that all care planning and therapies are embedded within a framework that is tailored to the needs and wishes of each individual. This personalised approach involves taking a full history and record of the person’s interests, preferences and abilities, including their hobbies, culture and religious beliefs, previous employment and their medical and physical status. When working with people with dementia it is important to involve family members or close friends in discussions about the person to ensure that a rich life history is created. Person-centred care also requires a comprehensive medical review to ensure that the care and treatment is appropriate to their current and ongoing status (see the review by Fazio et al. 27 for an excellent overview of person-centred care). The value of a person-centred care approach is clearly established in the literature;28–31 however, a systematic review32 has shown a critical issue in how person-centred care is delivered. Of the 170 identified person-centred care training manuals available for use in care settings, only 30 met quality criteria and of these only four were supported by evidence of effectiveness. 32 This disconnect between available programmes and evidence is concerning and emphasises the importance of a standardised approach to person-centredness and the use of non-pharmacological approaches. All of the person-centred training programmes supported by a robust evidence have shown improvement in outcomes related to BPSD. In one RCT28 of an intensive 9-month training programme, the Focused Intervention for Training and Support (FITS) programme showed a significant 50% reduction in antipsychotic prescriptions without worsening of BPSD in 347 care home residents. A trial30 of dementia care mapping, an in-depth care-planning approach that is based on observation of care followed by planning to optimise it, reported improvements in agitation (Cohen’s d ES of > 0.5) but no reduction in antipsychotic use in 298 residents with dementia in 15 care homes. Finally, a cluster RCT33 of an enriched person-centred care programme that focused on improving QoL for care home residents with dementia reported significant improvements in mood and numerical benefit in QoL that did not reach statistical significance in > 200 residents in 10 care homes. The evidence base also supports the use of focused interventions using an ‘antecedent, behaviour, consequence’ approach to create individualised charts for care; these focused interventions are usually delivered by a clinical psychologist. 34 A meta-analysis of these studies highlighted significant improvements in agitation and a significant reduction in antipsychotic use, but no overall significant benefit in mood or QoL. 32

Specific non-pharmacological interventions

In addition to person-centred training interventions, which promote a holistic approach to person-centred care, there are a number of simple approaches available that can be used by health and care professionals or even family members. These include the Seattle Protocols,35 an approach that focuses on increasing physical and cognitive activities for people with dementia, such as balance exercises, gardening or walking; personalised social interaction, an approach that aims to ensure that each individual has dedicated time when they are interacting with other people through a personalised programme; and simulated presence therapy, an approach that uses recordings of conversations or events to promote conversation. More complex approaches include the Needs, Environment, Stimulation and Techniques (NEST) intervention, which is usually delivered by a recreational therapist, and the brief psychosocial treatment, an approach that creates a tailored programme of social interaction, which has been used as a lead-in phase in a clinical trial to effectively reduce placebo response to a drug treatment. 29,36

Non-drug approaches to improve well-being are frequently used as part of a person’s care plan. When non-drug approaches are used within a person-centred care framework these interventions provide an effective means to control for any unmet need that may lead to BPSD. Some specific interventions have also been evaluated for their effect on BPSD. Most of these interventions focus on promoting ‘pleasant activities’, either with or without elements of social interaction. The majority of trials of these approaches have shown improvements in both agitation and depression;37–41 for example, reminiscence therapy involves working with an individual to recall life events and memories, often through the use of props such as photographs or mementoes. Reminiscence therapy may also be enhanced through the use of audio- or video-recordings of events or family members, as in the simulated presence therapy described above. 42 For this reason, the reminiscence therapy approach also involves a great deal of social interaction. There is good evidence to support this approach in addressing symptoms of depression, with six out of seven published studies showing benefit. 43 A similar approach is used in validation therapy, although the evidence base for this is more limited. However, two small trials have reported beneficial effects on behaviour, including agitation, apathy and sleep disturbance. 44 The effect on other BPSD is less clear. The use of music in the care of people with dementia has shown some success in a number of trials that report improvements in both agitation and anxiety, but not depression. 43,45,46 A number of studies have also examined the use of physical exercise, although few have reported significant improvements in BPSD. 44

This emerging evidence base suggests that a number of interventions confer some benefit, but no single intervention has achieved improvement of mental health and reduction of antipsychotic use and none of the interventions conferred a direct benefit to the QoL of people with dementia in care homes.

Rationale for the WHELD programme

Key NHS priorities include improving mental health and the treatment of mental health problems to further reduce antipsychotic use and improve the QoL for people with dementia in care home settings. There is strong evidence that a number of specific person-centred care interventions confer some benefit, but no single intervention has achieved both an improvement of mental health and a reduction in psychotropic drug use in people with dementia. Furthermore, none of the interventions evaluated prior to this programme conferred a direct benefit to the QoL for people with dementia who were living in care homes. Most importantly, none of these interventions had achieved widespread implementation in a clinical or care setting as part of routine NHS practice.

Further research is, therefore, urgently needed to address these key issues. Such research will need to develop an optimised therapy that combines the most effective elements of the currently available evidence-based interventions to maximise the breadth of benefit. The intervention needs to be conceptually integrated, practical to implement in an NHS and care home setting and be cost-effective.

Achieving these objectives will require an integrated programme of research. We tackled this using the Medical Research Council (MRC)’s framework for complex interventions to model, develop, adapt, evaluate and disseminate the intervention.

The final stage of the MRC pathway, overcoming the barriers to enable widespread implementation, is also a major challenge, which cannot be overstated, as this has never been achieved for any therapy in a care home setting. Research is needed to tailor an optimised therapy to the needs of NHS staff, care home staff and people with dementia who are living in care homes and their families. In addition, research is also imperative to understand and overcome the potential obstacles to implementation and to refine the intervention model through an extensive period of testing in the field. Although much is known about the effectiveness of interventions, which benefit specific aspects of health and mental health, any intervention is of limited value unless it is practical and can be implemented routinely in clinical practice. A comprehensive programme of research is essential to overcome these barriers and to develop and implement an effective intervention that can be rolled out nationally as an NHS service to people with dementia in care homes, conferring the benefits to real people in everyday care settings. This is the basis for the design and delivery of the WHELD programme, which was funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Programme Grants for Applied Research programme in 2012.

Aims and objectives

The overarching aim of the WHELD programme was to improve mental health and reduce the prescription of antipsychotic drugs for people with dementia living in care homes, by developing and evaluating an optimised intervention that is based on the most effective currently available therapies that can provide a broad range of benefits and can be routinely implemented as part of NHS care. We will also determine whether or not the intervention improves QoL.

To achieve these aims, the specific obectives for the WHELD programme were to:

-

update current systematic reviews regarding the most effective interventions to reduce BPSD experienced by people with dementia in care homes

-

optimise the most promising interventions and adapt them for an NHS and care home context through expert consenus and consultation with health and care professionals

-

determine the specific benefits of the interventions in incremental evaluation studies

-

develop an optimised intervention that is supported by an operationalised manual, with the specific aim of maximising the breadth of benefit while remaining practical and cost-effective

-

evaluate the optimised intervention and determie the cost-effectiveness in a well-powered, cluster RCT

-

understand the factors that contribute to feasible implementation and sustainability through consultation with study participants, and to field test the intervention to customise it as a practical NHS intervention

-

proactively disseminate the findings and intervention to enable widespread implementation.

In addition, the WHELD programme aimed to support capacity development within dementia reserach by providing research training to postdoctoral researchers to enable them to develop careers as independent researchers, and to build skills and knowledge among NHS care staff through study participation.

Guiding principles for the design of the WHELD programme

The design and approach taken for the WHELD programme followed a number of guiding principles to maximise the impact and relevance of the reserach to current practice and evidence. These guiding principles were as follows:

-

Development of interventions – it would have been inefficient and unneccesary to develop new interventions to promote mental health from basic principles, as effective interventions already existed at the commencement of the programme. However, these interventions required adaption for a UK NHS and care home setting and optimisation to improve the breadth of benefit.

-

Evaluation of QoL – previous trials had not been able to demonstrate improvement of care home residents’ QoL. The WHELD programme was, therefore, adequately designed and powered for such an effect to be demonstrated.

-

Meaningful evaluation of interventions – prior to a large RCT, incremental evaluation was prioritised as a means of determining the effective elements within the overall WHELD programme intervention, how these elements improve the breadth of benefits and which of these key elements deliver value for money.

-

Importance of field testing – it was deemed essential to undertake an extensive period of field testing to ensure that the WHELD programme intervention was fully tailored to the needs of the NHS and the care home sector, and that an intervention was delivered that could be a nationally implemented cornerstone of NHS treatment for people with dementia who are residing in care homes. This was particularly important, as it has not previously been possible to achieve widespread implementation of any intervention in a care home setting.

-

Dovetailing with national strategy and ongoing research – the WHELD programme recognises the need to work within the dynamic climate in UK health-care provision and alongside ongoing complementary research. The programme was designed to address the priorities published in the national dementia strategy for England and dovetails with studies examining specialist approaches for the psychological and pharmacological management of BPSD and other physical and mental health problems.

Work plan

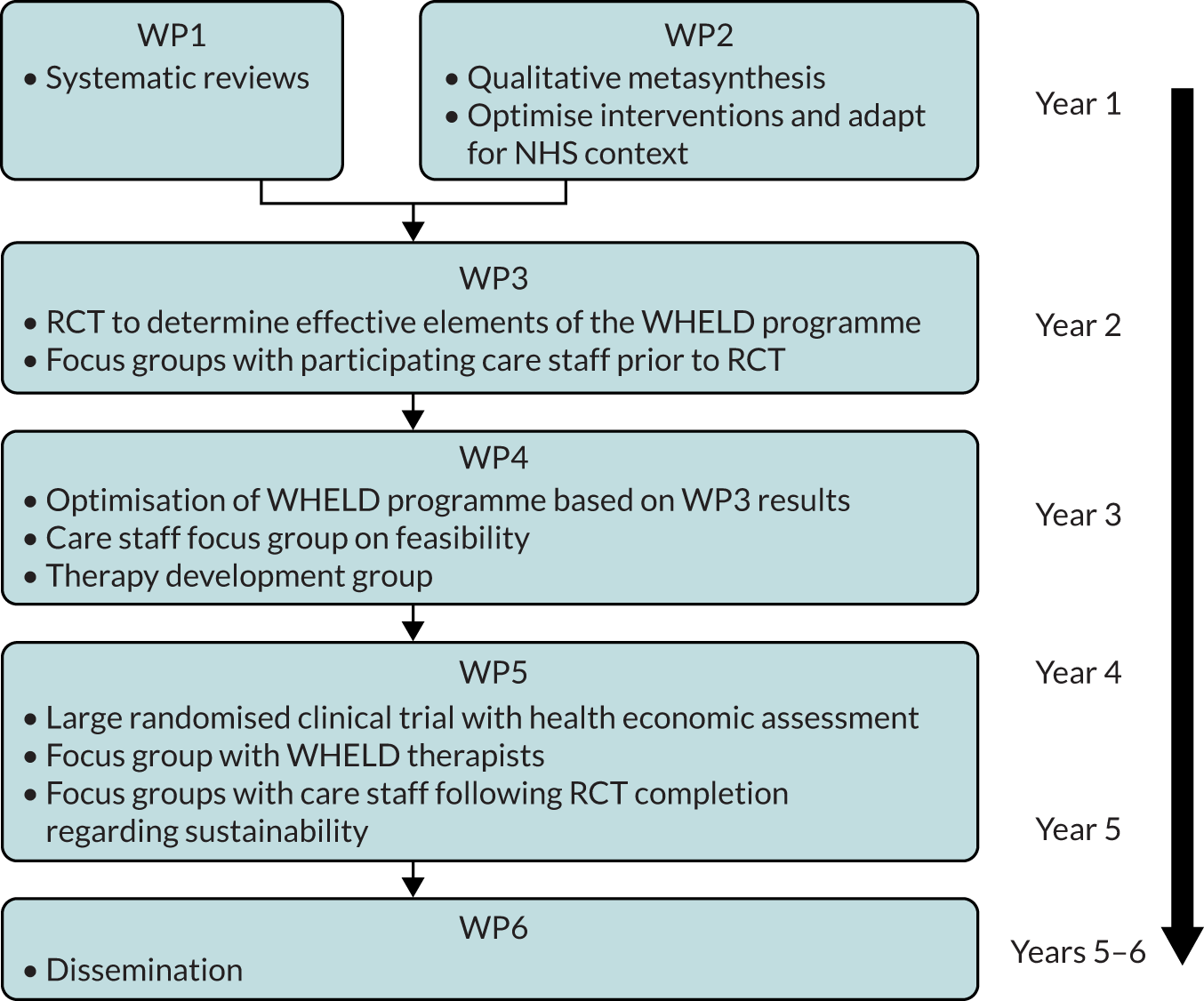

The WHELD programme followed a pathway through modelling, feasibility, evaluation, dissemination and implementation, as illustrated in the MRC framework for complex interventions. The programme, which involved six work packages (WPs), is summarised in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Research pathway diagram.

A description of each WP is as follows:

-

WP1 – update and publish a systematic review to show the service models and interventions for people with dementia living in care homes with the best available evidence base.

-

WP2 – model and adapt exisiting effective interventions to a UK NHS context.

-

WP3 – evaluate the breadth of benefits in an incremental design to establish the most effective and cost-effective combination of intervention elements (factorial study).

-

WP4 – develop an optimised intervention (WHELD), ‘welding together’ the most effective elements of the best available interventions, and develop a standardised manual and training programme for care staff.

-

WP5 – evaluate the full breadth of benefit conferred by the intervention through a large cluster RCT with parallel cost-effectiveness and process evaluations.

-

WP6 – disseminate the findings and the WHELD programme to enable widespread national implementation.

Limitations in design

In designing the study, we were mindful of the challenges of measuring QoL in people with moderate to severe dementia and, therefore, relied predominantly on a proxy measure. Within any RCT of a non-pharmacological intervention, it is a difficult decision whether to opt for treatment as usual or for an active control in the comparision arm. We used an active control (person-centred care) in WP3, which involved 16 care homes, but opted for a treatment as usual control in WP5, as a result of the scale of the study in 69 care homes. This may have inflated the magnitude of observed benefits with the WHELD programme in WP5.

The training and supervision in the intervention was delivered directly to care staff, who participated in qualitative work. However, we recognise that residents with dementia who received the intervention that was delivered by the staff were not included in the qualitative studies and could provide a valuable perspective.

The details of each WP are discussed in the following sections.

Work package 1: systematic reviews of psychosocial and person-centred care interventions for people with dementia living in care homes

Abstract

Objectives: WP1 sought to ask two specific research questions: (1) what is the evidence supporting the use of psychosocial interventions for BPSD? and (2) what is the quality and efficacy of existing psychosocial interventions and staff training programmes in person-centred care in improving BPSD and antipsychotic use?

Methods: Two systematic reviews were conducted. One examined publications relating to psychosocial interventions and the other conducted a search to identify person-centred care training manuals. Quality criteria were applied and the efficacy of manuals was considered.

Results: The systematic review of psychosocial interventions identified 40 studies and highlighted the evidence supporting the use of reminiscence therapy (ES 0.33), personalised pleasant activities (ES 0.46) and training in person-centred care. The modest number of adequately powered RCTs was highlighted. The efficacy and quality review identified 30 manuals meeting the quality criteria, of which only four were supported by RCT evidence. The studies reported benefit to agitation, depression, overall BPSD and antipsychotic use.

Conclusions: The reviews showed the limitations of the evidence base related to person-centred care training, but the combined reviews indicate that there are some benefits in the use of psychosocial interventions for people with dementia living in care homes.

Background

Behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia represent a major challenge to dementia care and are associated with important clinical outcomes. 14,47 There is a high level of unmet need, particularly for individuals living in care homes. 2

A major element of dementia care is the development of safe, effective psychosocial interventions that improve residents’ care, reduce behavioural and psychological symptoms in people with dementia and offer an alternative to antipsychotic medication. There is a growing focus on a personalised approach to these interventions. Another element of dementia care is the need for high-quality training, in addition to effective support for clinicians. These requirements are highlighted in government directives worldwide. 7,17,48

As the starting point for the WHELD programme, WP1 aimed to synthesise the landscape of non-pharmacological treatment approaches and the resources that are currently available. This work directly informed decisions regarding the design and delivery of the WHELD programme.

Aim and objectives

The aim was to address and update gaps in the evidence base to inform the development of the WHELD programme.

The two major objectives were to:

-

update a systematic review highlighting service models and interventions for people with dementia living in care homes

-

conduct a two-pronged systematic review of quality and efficacy of existing person-centred care interventions, with a focus on the impact on BPSD and antipsychotic use.

Systematic review of psychosocial interventions to address behavioural and psychological symptoms experienced by people with dementia living in care homes

Rationale

The relevant literature includes a substantial number of studies investigating treatment approaches for BPSD. However, the majority of these studies focus on pharmacological intervention and of those evaluating psychosocial approaches only a fraction use robust, good-quality methodology to investigate effectiveness. 49–52 Of the recent systematic reviews, only O’Neil et al. 53 focused on the treatment of individual BPSD and none focused on the benefits of personalised psychosocial interventions. Despite the high profile of antipsychotic use as an issue in clinical practice, to our knowledge, no systematic reviews have considered this outcome. 28 A considerable number of new studies have been published since the most recent systematic reviews, which include studies published before 2009. 53

Methods

The work followed a systematic review protocol43 and focused on studies published from 1 January 2012 to 31 December 2012.

Development of review criteria

A preliminary search was undertaken to identify studies that examined the impact of psychosocial interventions on BPSD and antipsychotic use in people with dementia living in care homes. The search was subsequently refined by a specialist panel to focus on personalised psychosocial interventions.

Selection of included studies

A qualified librarian and one investigator performed the initial search. Two investigators examined these results and excluded irrelevant articles. Personalised psychosocial interventions were grouped into six categories of interventions.

Quality of included studies

A traffic-light system was used to describe a risk-of-bias analysis, using an adaptation of the 2008 Cochrane review framework (as reported in 2012 by Corbett et al. 54). The six criteria (adequate sequence selection, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data, freedom from selective reporting and freedom from other bias) were each rated as green, amber or red to produce an overall rating.

Data analysis

Quality assessment used operationalised Cochrane criteria54 and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidance. A descriptive summary was developed for the impact of each type of intervention. Where available, the ES was included.

Results

Studies included in the review

In total, 641 studies were identified in the initial search, of which 597 were excluded. A total of 40 studies were included, of which nine were rated green, eight were rated amber and 23 were rated red. None of the included studies contained a health economic analysis.

Description of studies

The 40 studies comprised 26 RCTs and 14 studies with quasi-experimental designs. The studies were performed in 13 different countries, using 66 different outcome measures. A total of 20 (50%) were published in the last 4 years. The studies were distributed into the six categories: reminiscence (n = 6), personalised music (n = 7), personalised pleasant activities with or without social interaction (n = 10), validation therapy (n = 2), personalised exercise/physical activities (n = 12) and person-centred care training and practice development (n = 3).

Reminiscence

Six studies55–60 evaluated reminiscence. Two studies had a parallel-group RCT design. 55,58 There was substantial variability in sample size (range 30–115 participants, median 67 participants), duration (range 3–8 weeks, median 7 weeks), frequency of intervention and session length (30–60 minutes). Results consistently showed significant benefit to depression (ES 0.33). 56–59 Other outcomes were less consistently evaluated and benefit was variable. One of two studies examining BPSD reported benefit. 60 None evaluated agitation.

Personalised music

Personalised music was examined in seven studies,45,46,61–65 including four parallel-group RCTs. 45,46,61,65 The studies included 20–104 participants (median 55.5 participants) and lasted 4–42 weeks (median 6 weeks), with variable frequency and session length (30–50 minutes). Benefit was identified in three studies that examined agitation,45,46,64 including two RCTs. 46,64 There was no difference in treatment ‘dose’. The ES of personalised music on agitation ranged from 0.43 (in favour of the control) to 0.66 (median 0.21). There was some evidence of benefit to overall BPSD46 and anxiety,45 but not depression. 46 Subsequent work has suggested that there is a possible impact on depression. 66

Personalised activities

Ten studies were included,37–39,41,67–72 of which seven were RCTs. The studies had 37–231 participants (median 147.5 participants) and lasted 1–36 weeks (median 4 weeks), with variable frequency and session length (30–240 minutes). Four studies37–39,67 reported benefit to agitation (ES 0.24–0.91, median 0.46). One study41 reported benefit to depression and four studies37,38,69,71 reported benefit to mood.

Validation therapy

Two studies44,73 analysed validation therapy. One 12-week trial of 30 patients (session length 45–60 minutes) showed benefit to BPSD in combination with reminiscence therapy. 73 Another 16-week trial of 50 patients also saw benefit to agitation, apathy, irritability and night-time behaviour. 44

Personalised exercise

In total, 12 trials of exercise interventions were identified,74–85 including 11 RCTs. Only four74,76,78,82 met criteria for personalised approaches; these involved 56–682 participants (median 205 participants) over 5 weeks (median 15 weeks), varied in frequency and session length (30–60 minutes) and showed limited benefit.

Person-centred care training and practice development

Three cluster RCTs focused on person-centred care training,28,30,33 which included 289–349 participants (median 293 participants) and lasted 4–18 months. Two evaluated the impact on antipsychotic use, with one indicating a significant reduction in use. 28 One study30 reported benefit to agitation. All examined mood, but only one33 reported significant benefit.

Further evaluations were undertaken for interventions that showed significant benefit to explore factors associated with favourable treatment response, defined as at least four studies examining the same outcome, with > 50% of studies indicating benefit. Reminiscence had a beneficial impact on mood in all studies, indicating a broad spectrum of benefit; however, further work is needed to clarify whether or not reminiscence benefits people living at home, younger individuals and those with severe dementia. Studies of personalised pleasant activities, with or without social interaction, indicated significant benefit for people with moderate to severe dementia who were living in nursing homes. Further work is needed to clarify whether or not there are benefits in other settings, in people with severe dementia or in younger individuals.

Discussion

This WP successfully completed and published a systematic review of the evidence supporting the use of psychosocial interventions for BPSD in care home settings. 43

This review has progressed the understanding of the potential differential benefits of interventions on specific BPSD, in particular through reminiscence on mood and depression (ES 0.33)55–57 and personalised pleasant activities on agitation (ES 0.46). 37–39,67 This provides valuable new evidence on the best use of psychosocial interventions for BPSD.

Only three RCTs28,30,33 were identified that evaluated person-centred care training interventions. Although all three RCTs reported benefit in at least one key outcome, benefits were inconsistent. One RCT reported reduced antipsychotic use,28 one improved agitation30 and one improved mood. 33 Further work is needed to optimise these interventions. Evidence regarding personalised music was inconsistent and mainly focused on the treatment of agitation, although interpretation was challenging and further work is needed. Despite the larger evidence base for exercise, only four studies43 focused on personalised approaches to exercise and the impact on BPSD and showed that there was limited benefit. Importantly, there is no evidence that any of the interventions specifically conferred benefit to psychosis.

Limitations

The outcome measures and trial duration in the included studies varied considerably, precluding a meta-analysis. In addition, we did not examine health economic outcomes. Only one study43 examined continued benefit beyond the period of the intervention, which is a key consideration for the development of the WHELD protocol.

It should also be noted that the study limited the period of inclusion to studies published after 2000, to focus on more recent and relevant studies. However, pre-2000 studies were consistent with our conclusions; for example, benefits were reported for social interaction,86 personalised pleasant activities without social interaction,86 personalised physical activity,87 an educational programme88 and reminiscence. 89

An additional limitation is the variety in theoretical frameworks underpinning the interventions and their frequency, session length and duration. Despite this, the review presents clear information to inform clinical practice and the next phases of the programme. This work is valuable in improving the targeting of individual BPSD with specific personalised psychosocial interventions, and in driving key research questions.

Implications for delivery of the WHELD programme

This review demonstrated valuable differential effects between different personalised psychosocial interventions that could have implications for the tailoring of care packages according to symptoms. It showed the importance of person-centred care interventions, pleasant activities for the treatment of agitation and the use of reminiscence therapy for mood. These findings were pulled through to WP2 and directly informed the development of the WHELD programme.

In addition, the review indicated areas of need for the design of the WHELD programme and protocol, including the need to focus on health economics, to improve the understanding of the impact of duration and frequency of specific interventions on ES and to develop a more detailed understanding of the impact of the conceptual frameworks on the outcome, and whether or not this can be used to optimise interventions. The review also emphasised the importance of understanding the level of care staff education that is needed to deliver specific interventions effectively, as well as the effect of the care environment and leadership on implementation.

The review was conducted based on a literature search up to December 2012, as part of the WHELD programme and to inform therapy development. A rapid updating search in October 2019 and citation tracking from out-published papers did not identify any relevant new studies that would change our conclusions.

Systematic review of person-centred interventions and training manuals for care home staff working with people with dementia

Rationale

Global government initiatives emphasise the importance of training for care staff and the need to improve access to effective psychosocial therapies for people with dementia. 5–7,48 These recommendations have resulted in a proliferation of training programmes that are promoted to care providers; however, the evidence to support the effectiveness of these programmes is unclear.

In the UK, increasing the skills of the workforce through training would cost an estimated £546M. Therefore, it is vital to have a clear understanding of the available training courses and their evidence base to support clinical and care interventions.

In line with the overall WHELD objectives, we focused on the implications for BPSD and antipsychotic use for this element of WP1.

Methods

See the published output for the full methodology. 32

The review had two objectives:

-

quality review – to review the quality of the available training manuals for person-centred care of people with dementia

-

efficacy review – to undertake a systematic review of RCTs that deliver training interventions to improve person-centred care.

Quality review

Manuals and training packages were identified through electronic searches, screened for eligibility and scored for comprehensiveness and degree of operationalisation. Studies scoring ≥ 3 for both criteria were deemed to provide broad person-centred interventions to address BPSD and/or antipsychotic use and were suitable for implementation. All papers and manuals that were published up to 30 June 2012 were included.

Data were extracted and manuals were separated into categories according to the type of intervention or training. They were rated independently by three investigators. The type of research evidence available was noted and summarised as anecdotal, qualitative study, open trials, quasi-experimental or RCTs.

Efficacy review

All RCTs and quasi-experimental studies that had a control group that addressed BPSD and/or antipsychotic use were included in the efficacy review. The methodological quality of studies was assessed applying the Cochrane system. 54

Data that pertained to BPSD or antipsychotic prescribing were extracted for meta-analysis. The meta-analysis was undertaken with the Comprehensive Meta-analysis package (version 2, Hewlett Packard, Palo Alto, CA, USA) for key outcomes (agitation, depression and total neuropsychiatric inventory) reporting standardised mean differences with 95% CIs and for antipsychotic drugs when data were available from two or more studies.

Results

Quality review

In total, 170 packages were identified. In total, 63 met the screening criteria and 30 were shortlisted, having obtained sufficient criteria scores. Of these, four were supported by RCT evidence.

Efficacy review

Seven studies were identified,28,30,37,90–93 of which five were parallel-group RCTs. Three studies28,30,93 evaluated the impact of person-centred care training on antipsychotic use, with two studies indicating significant reductions of 12.8%93 and 21.5%,28 which was confirmed by a meta-analysis (standard difference in means 1.08, z = 2.97; p = 0.003). Quantitative evaluation of agitation was available for four studies,28,30,37,92 with an overall significant benefit. Benefit to depression was reported in assisted living environments, but not in care home settings. One trial reported global impact on BPSD and showed a significant 8.7-point improvement. All six studies received a ‘green’ score for quality and risk of bias using the Cochrane quality review process. 54

Excluded studies

Several other interventions did not meet the inclusion criteria, including Reducing Disability in Alzheimer’s Disease (RDAD)31 and cognitive stimulation therapy. 94 Reasons for exclusion included focusing on specific domains, not focusing on BPSD or antipsychotic use, being in non-care home settings or interventions delivered directly to people.

Outcome of combined quality and efficacy review

Only four manuals met the quality criteria and had published clinical trial evidence of efficacy:

-

Focused Intervention of Training for Staff28,95 – a 10-month person-centred care training package that was delivered by a mental health professional, conferring a 19.1% reduction in antipsychotic use (95% CI 0.5% to 37.7%).

-

A collection of evidence-based protocols for non-drug strategies – NEST29,91 and the manual ‘Simple Pleasures’,90 conferring improvements in agitation [Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory (CMAI); p = 0.01] and depression (Geriatric Depression Scale; p = 0.001). 91

-

Dementia Care Mapping – a detailed observational and care planning approach for care homes that showed a significant reduction in agitation (CMAI; p = 0.01) and falls (p = 0.02). 30

-

Improving Dementia Care96 – a practical training and staff development resource that showed a reduction in agitation, although the outcomes varied between sites (CMAI; p = 0.01). 30

Discussion

This review identified evidence that demonstrated the benefits of person-centred care interventions on agitation and antipsychotic use in people with dementia living in care homes. However, this was based on intervention studies that were performed on only a fraction of the training programmes that are currently available. Only 30 (18%) of the manuals followed good educational and person-centred care principles and only four (2.3%) had clinical trial evidence. Thus, over 80% of the available training packages are of variable quality and 98% are not evidence based; this is extremely concerning. Health care and care home sectors are investing in training following government directives, largely in programmes that carry no evidence of benefit. There is a need for person-centred care intervention training to be evidence based if it is to provide better social and medical care. Of note, interventions for which there is evidence of benefit were delivered over a period of at least 4 months, and involved ongoing clinical supervision or support to embed implementation into care home practice. This suggests that one-off training packages or classroom-based training would probably be ineffective.

The literature does not currently provide any evidence for effectiveness on psychosis, depression and QoL. This is an important priority for further research, as highlighted by the Department of Health and Social Care. 97

Limitations

Although the review incorporated national and international manuals, the review was limited to the English language. The search for published manuals was complemented by a search for RCTs, focusing on training and activity-based trials, thereby mitigating the limitations and ensuring a broad international perspective. In addition, training programmes without available manuals were excluded. Several manuals had a broader framework for care delivery rather than a specific focus on BPSD. It is, therefore, likely that wider benefits were not captured.

Implications for delivery of the WHELD programme

This review showed the major disconnect between the interventions that are routinely available and commissioned and the evidence base. This added further weight to the overall rationale of the WHELD programme.

The review provided key indicators of elements that are required for a successful person-centred intervention, including the importance of consistent, long-term support for staff. It indicated the need to evaluate effectiveness on psychosis, depression and QoL, in addition to agitation and antipsychotic use.

The limited number of available training manuals without direct clinical trial evidence of benefit for people with dementia is alarming, and emphasises the importance of a feasible, effective training programme.

Concluding remarks from work package 1

Work package 1 successfully delivered the objective of updating the current evidence base with systematic reviews. It highlighted pleasant activities and social intervention as priority areas for addressing agitation, and reinforced our view that augmentation of existing interventions is needed to deliver comprehensive benefit and improve QoL.

Finally, WP1 identified an alarming number of available training manuals that are not evidence based, and strongly emphasised the need for an evidence-based manual. These findings were taken forward by the Therapy Development Group (TDG) in WP2.

Work package 2: modelling and adaptation of interventions for use within an NHS context

Abstract

Objectives: WP2 sought to identify the factors that influence implementation of psychosocial interventions in care home settings and to develop the WHELD programme for evaluation, based on the outputs and findings from WP1.

Methods: A metasynthesis approach was used to conduct a review of studies that examine the implementation of psychosocial interventions in care homes. Data were analysed by thematic analysis using an interpretive method of metadata synthesis, grouping themes where they had the greatest explanatory power. These findings and WP1 results were used by a TDG to create and protocolise a WHELD programme package.

Results: The meta-analysis revealed key issues in promoting the use of interventions in care homes, including the core involvement of staff, buy-in by family members, flexibility of care home working arrangements, training, supervision and support for staff and the need for cultural change. These findings, combined with WP1, informed development of the intervention. The WHELD programme involved four key elements: person-centred care training that was based on adapted versions of published manuals, antipsychotic review by general practitioners (GPs) that was based on national best practice guidelines, social interaction and exercise, both of which were adapted from published interventions.

Conclusions: The work completed in WP2 follows a clear pathway, from theoretical basis to conceptual framework to a tangible operational intervention. The WHELD programme represents a synthesis of knowledge that was drawn from clinical trial data, existing resources and qualitative analysis, and was collated for use by a broad expert consensus process.

Background and rationale

Work package 1 illustrated the strength of evidence for several psychosocial interventions and manualised person-centred care programmes that confer benefit on mental health and antipsychotic medication use for people with dementia living in care homes. Promising interventions were identified, including staff training, person-centred care and structured social interaction approaches and exercise. Importantly, none of the interventions directly improved QoL for care home residents or achieved widespread implementation as part of routine care practice. WP1 also showed the lack of evidence-based training programmes and the importance of an integrated approach to ongoing support for care staff.

The work carried out in WP1 pointed towards the need for a whole-systems approach to improve person-centredness in care homes with integration of the most effective individual interventions, and to develop an understanding of the factors that influence implementation.

Therefore, WP2 encompassed a further review to gather qualitative data on aspects of psychosocial intervention design, followed by a series of therapy development steps to adapt and combine the key components of established effective interventions.

Aim and objectives

The overall aim of WP2 was to create a conceptually integrated evidence-based intervention that was practical to implement in UK care home settings.

The objectives of WP2 were to conduct a:

-

systematic review and metasynthesis of qualitative research to identify factors that influence the implementation of psychosocial interventions.

-

series of expert panel and TDG sessions to develop a person-centred care intervention by combining the best elements of existing interventions in a way that is both conceptually integrated and practical.

Implementation of psychosocial interventions: systematic review and meta-analysis

Rationale

Qualitative methods are the most appropriate approach for addressing complex questions regarding the implementation and acceptability of psychosocial interventions in care homes. Individual studies provide insight into how different psychosocial interventions are used and experienced within residential settings. Integrating these findings in a qualitative metasynthesis promises to enhance their implementation and impact on health policy and clinical practice. 98,99 WP2 used this approach to help to understand and overcome the potential obstacles to implementing psychosocial interventions as part of routine practice. To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review and metasynthesis of the qualitative evidence in this field.

Methods

Full details of the methodology are provided in a published output. 100 Systematic review methodology was used to identify relevant research regarding the use and effectiveness of psychosocial interventions that were designed to improve outcomes for people with dementia in care homes, from the perspective of people with dementia, relatives or care staff. 101 Papers published between 1 January 1995 and 31 January 2011 were included in the review.

Two investigators independently assessed relevant papers for methodological quality using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) checklist. 102 We opted for an inclusive strategy103 and, in common with another synthesis,99 the quality appraisal process was used as a criterion to judge the value of papers with respect to their contribution to the synthesis. Themes were included in the meta-synthesis if they were supported by data from at least one article that was judged as being of reasonable quality.

A description of the main concepts derived from each paper was recorded,104 and shared constructs across studies and areas of discordance were noted. The themes were combined using an interpretive method of metadata synthesis by grouping themes where they had the greatest explanatory power. A taxonomy was constructed that categorised findings in three domains, which are discussed below.

Results

The review identified 39 papers (34 studies),105–143 of which 29 were rated as being of reasonable quality or better (CASP ≥ 7), with a good level of agreement between reviewers (weighted Cohen’s kappa = 0.66). The 10 papers that did not meet the quality criteria were primarily rated as weak, owing to a lack of rigour in data analysis or a failure to comment on the bias in the study design. 108,116,117,120,123,124,126,128,133,134

The 34 studies spanned a broad range of psychosocial intervention types, which included exercise and other therapeutic activities (n = 6),110–112,117,125,138 music (n = 5),129–132,136 reminiscence (n = 4),113,121,128,135 communication strategies (n = 3),106,108,141 models of dementia care (n = 3),114,133,143 methods of orientation (n = 2),109,124 animal interventions (n = 2),122,123 staff training and supervision (n = 3),118,127,140 and other (n = 6). 105,115,119,137,139,142 Common themes were identified in three overarching categories: elements of a successful intervention, conditions required for a successful intervention and challenges to a successful intervention.

Elements of a successful intervention

Aspects that predicted successful interventions were categorised by whether they elicited benefit to people with dementia or to care staff.

People with dementia

Beneficial interventions often supported people with dementia in ‘connecting with others’ by enhancing communication. Conversation was stimulated between residents, staff and family through various means, including animals, dolls, music, reminiscence items or ‘memory boxes’. 107,116,122–124,128,136,139 Studies reported particular success with volunteer-led approaches. 122,123,137 Music and dance interventions were useful in supporting people to better express emotions,107,111,112 with group activities improving co-operation and a sense of inclusion. 125,131,139,143

Successful interventions also focused on ensuring that participants felt that they were making a meaningful contribution to an activity, for example through taking care of an animal. 107,113,122,128,135,137,139,143 Structured or spontaneous reminiscence was also a valuable element. 112,116,122,123,132,135,139

Care staff

There was a consensus that care staff find psychosocial approaches valuable in enabling them to build better relationships with individuals and their families. 113,115,118,119,128 Closeness between staff and residents was fostered by experiential learning, which encouraged staff to consider the perspectives of a person with dementia114,118,143 and gave them the opportunity to reflect on their approach to residents and the likely impact on them. Reflection reportedly led to changes in care-giving behaviour,118,127,128 particularly when supervision from senior staff was available. 113,127,140

Conditions required for a successful intervention

All of the studies illustrated the reliance on staff to support people with dementia to access the psychosocial interventions. 107,125,126,134 Person-centredness and the importance of relationship building was a major theme, as both a benefit and a determinant of being able to individualise their approach. 107,111,112,117,121,125,132,134,135,138

The involvement of family members was also key to personalising care107,136,142 and a source of mutual appreciation and respect. 121,127,142 A number of studies described successful approaches to stimulate collaboration between relatives and staff. 111,114,122,125,141

Challenges to a successful intervention

A number of challenges were identified, many of which related to the additional work, the requirement for flexibility of team rotas111,136,142 and low levels of staffing as significant barriers to implementation. 119,120,136,140,142 However, with the exception of two studies,126,134 the benefits conferred were thought to over-ride the difficulties. 111,120,136,140,142

The wide range of staff responsibilities and reporting requirements were frequently cited as a barrier to the implementation of psychosocial approaches. 119,133 Staff reported a perceived pressure to focus on responding to challenging behaviour, physical care and safety, rather than supporting individual interactions. 106,115,119,134,138

Finally, a number of challenges were described regarding negative attitudes towards psychosocial interventions and a general lack of knowledge about their potential benefit. 111,126,129,134,142

Discussion

Overall, the metasynthesis identified how important positive benefits from psychosocial interventions can be achieved. The major learning outputs that were taken forward were as follows:

-

It is critical to involve staff and care home managers as active participants and to ensure that they have personal investment in the intervention through collaborative, sympathetic approaches that openly accept the burden and challenges that they experience.

-

Buy-in by family members is also critical – workshops and group events are effective in promoting this.

-

Flexibility is an essential aspect – ensuring that the intervention is adaptable to different home structures and staffing levels, and tailored to resident abilities and interests.

-

Organisational support is required to sustain learning and change in practice, particularly given that training and mentoring involve considerable time investment by staff. It is important to make a clear health economics argument to support this.

-

Cultural change is required to encourage staff to think about residents individually and to address concerns about a new intervention alongside identifying benefits.

-

Person-centred care is fully accepted as the framework for intervention, with established means of tailoring interventions to an individual’s needs.

-

Training is critical and particularly effective when it includes scenario-based, interactive elements and the opportunity for staff to reflect on their practice.

Limitations

Qualitative metasynthesis offers a systematic, relevant overview of international qualitative research, while retaining much of the detail that individual studies provide. However, there is a risk that synthesising across qualitative studies could compromise the integrity of the individual projects, as well as their emphasis on context and holism. 98 We are mindful that this review identified a heterogeneous set of studies that varied in care setting, intervention type and methodological design. To convey the context of the study, comprehensive details are published in Lawrence et al. 100

We also recognise that the sample size is large for a metasynthesis, but are satisfied that the scope of the review was sufficiently focused and believe that the range of data assisted in identifying the properties and key concepts that can be applied across groups and settings.

Implications for the WHELD programme

The recommendations outlined above were taken forward to the intervention development phase of WP2 (described below). The identification of key elements of successful interventions, combined with the outputs of the review in WP1, indicated the need for incremental evaluation of individual elements of psychosocial interventions to enable an examination of the breadth of their benefits.

The WHELD therapy development

Rationale

The work completed in WPs 1 and 2 provided a comprehensive picture of the requirements and existing resources that are available for the creation of an optimised person-centred care intervention. The next phase of the work sought to operationalise this information through a period of collaborative development work with a TDG and associated expert panel.

Aim and objectives

The aim was to develop an optimised person-centred care intervention for people with dementia living in care homes, which would include a training programme for care staff.

Specific objectives within this aim were to:

-

co-ordinate a large-scale expert consultation and TDG to gather informed opinion on the most appropriate design and content for the WHELD programme

-

operationalise the WHELD programme by developing a manual for use in care homes

-

finalise the design of the evaluation of the WHELD programme for WP3.

Methods

Selection and scrutiny of the interventions

During October and November 2010, a TDG was convened that consisted of the WHELD investigators, lay representatives and care home experts, including providers and inspectors.

The expert panel reviewed existing programmes that had evidence of efficacy, to identify elements to be included in a person-centred care programme. The FITS28 and NEST,29 including the Simple Pleasures90 and Improving Dementia Care,30 interventions were scrutinised to identify which elements had proven to be the most effective, which could also be combined into a consistent conceptual framework for person-centred care. The manuals were also reviewed against the emerging literature identified in WP1 and the metasynthesis in WP2. The language and style of the interventions were reviewed, with consideration of the UK context of delivery.

Expert consultation: workshops

A series of workshops was co-ordinated to gather opinions and experience from a wide audience. In total there were 89 workshop participants, including national and international experts from research backgrounds; clinicians from nursing, occupational therapy, physiotherapy, clinical psychology and psychiatry; care home managers and practitioners; and family carers. Two group workshops were conducted with 40 participants in each group to achieve a robust consensus.

The meetings commenced with a presentation of work from WP1 and an overview of the evidence base. Participants were asked to consider the evidence and provide recommendations regarding the selection of interventions to include in the WHELD programme. In a second session, participants developed recommendations for refinement of the person-centred care training that was outlined in the FITS programme,28 to improve implementation. Suggestions were prioritised by consensus, working to create a list that informed the manual development for the intervention.

Intervention creation

The TDG collated and operationalised the outcome of the expert panels to produce the WHELD programme. Manuals of the four selected interventions and overall protocol were produced. Members of the TDG also liaised with three key external experts (Linda Buettner, Jiska Cohen-Mansfield and Linda Teri) regarding their existing interventions and how they might be adapted for the WHELD programme. 29,31,37 The formative materials were then edited to reflect UK practices where necessary. When there was overlap between materials, a decision was made based on the workshop feedback about which material would best meet the criteria for being effective and feasible for a UK care home setting. The full intervention was circulated to all WHELD study investigators for comment and, finally, to members of the TDG. The final version of the manual was approved by the WHELD Programme Management Group (PMG).

Results

Intervention selection

Four key interventions were to be used within the WHELD programme (person-centred care training for staff), which acted as the underpinning framework for the delivery of all interventions, social interaction, physical exercise and review of antipsychotic medication.

Four existing evidence-based interventions were identified for the adaptation to create the WHELD programme. These were the FITS person-centred care manual,28 a non-drug protocol focusing on pleasant activities,37 the NEST intervention29 and the Seattle Protocols. 35 Specific recommendations were made for refinements to individual elements based on safety and UK context-specific considerations.

Adaptation of interventions for the WHELD programme

The TDG developed a manual of the four interventions and the overarching delivery protocol, which are outlined below.

Person-centred care training for staff

This intervention combines elements of several effective interventions that promote person-centred care. These included the FITS person-centred care training package28 and opportunities for experiential learning about adapting care practice to meet the needs of someone with dementia. Using residents’ life stories was a foundation to understand individuals’ needs and preferences. A structured assessment of unmet needs29 underpinned positive individualised care planning by using specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, time-bound (i.e. SMART) goals to implement activities based on a person’s preferences. 90

Review of antipsychotic medication

Previous studies28 that have achieved a reduction in antipsychotic use have incorporated a formal review of antipsychotic medications according to standardised protocols. The National Service Framework recommend that reviews take place every 3 months. The TDG agreed that a review would be undertaken using best practice guidelines for the prescription of antipsychotics to people with dementia. 27 The aim was for care staff to understand the need for regular review and develop a process that was led by the care home that enabled this to be undertaken by the resident GPs. Workshops were also designed for GPs to support care staff in following the best practice guidelines.

Social interaction

This intervention was based on the Positive Events Schedule, the NEST intervention, the Seattle Protocols and Cohen-Mansfield’s ‘toolbox’ of psychosocial interventions, which were individualised to the needs of a particular individual. 29,35,144,145 A version of the ‘toolbox’ approach had been evaluated in several small pilot studies, as well as in a large, open, 4-week trial as part of the CALM-AD clinical trial146 and as part of the FITS study. 28 Activities promoting social interaction were adapted for a UK care setting, with the aim that the activities should be delivered for 60 minutes per week or that there would be a 20% increase in activity if the resident already engaged in this level of activity.

Exercise

The RDAD programme,147 which focuses on activities, strength, balance and flexibility training, was identified as the best evaluated programme for people with dementia, showing significant benefits for activity, mood and health in a RCT. 31 RDAD exercises were adapted to be simply and safely delivered by care staff who had no formal physiotherapy or exercise training. Walking or pleasant activities of the residents’ choice, including seated exercise or circle dance, were incorporated from the exercise section of the NEST protocols. 29 The aim was that this should be delivered for 60 minutes per week or that there would be a 20% increase in activity if the resident already engaged in this amount of exercise.

Operationalisation of the WHELD programme

The TDG produced a manual for the delivery of the WHELD programme as an incremental intervention for evaluation. The delivery was designed as a training programme that was co-ordinated by a central WHELD therapist, who then provided support and supervision for care home staff. Care homes also nominated WHELD dementia champions to act as internal mentors who had responsibility for the implementation of interventions within the care homes. The TDG, therefore, produced one detailed therapist manual, which provided detailed information on the delivery of each intervention, and one dementia champion manual, which was for care home staff. The manuals aimed to maintain distinctiveness between the elements that were delivered, but did not preclude homes from developing activities and interventions of their own volition.

Discussion

The work completed in WP2 follows a clear pathway, from a theoretical basis through a conceptual framework to a tangible operational intervention. The WHELD programme represents a synthesis of knowledge that is drawn from clinical trial data, existing resources and qualitative analysis, and is collated for use by a broad expert consensus process.

Concluding remarks for work package 2

Work package 2 successfully collated evidence from different sources, including systematic reviews, qualitative reviews, expert consensus and existing operationalised interventions, to prioritise interventions for the new WHELD programme. The large consensus process gives additional validation to the final intervention, which was taken forward for evaluation in WP3.

Major outputs of work package 2

The WHELD programme materials

The major outputs of WP2 were the WHELD Therapist Manual and the WHELD Dementia Champions Manual.

Work package 3: factorial pilot evaluation of non-pharmacological interventions in combination with person-centred care training in care homes

Abstract

Objectives: To establish the feasibility, effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of person-centred care training for care staff alone and in combination with antipsychotic review, social interaction and exercise.