Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by PGfAR as project number RP-PG-0611-20005. The contractual start date was in October 2013. The final report began editorial review in May 2019 and was accepted for publication in May 2020. As the funder, the PGfAR programme agreed the research questions and study designs in advance with the investigators. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PGfAR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Louise Robinson was a member of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Programme primary care themed call board from 1 October 2012 to 18 February 2014. Claire Goodman was a trustee of the Order of St John Care Trust from 2016 to 2019, a NIHR Health Services and Delivery Research (HSDR) Programme Commissioning Board member from February 2012 to 30 June 2015 and a NHS Service Delivery and Organisation (SDO) Commissioning Board member from 1 April 2009 to 1 January 2012; she is currently a NIHR senior investigator (since 2016). Denise Howel was a member of the NIHR SDO Commissioning Board from April 2009 to December 2011, a member of the NIHR HSDR Programme Commissioning Board from January 2012 to November 2015 and a member of the NIHR Programme Grants for Applied Research (PGfAR) Programme funding subpanel from February 2016 to present. Luke Vale was a member of the NIHR HTA Clinical Evaluation and Trials funding panel from 2014 to 2018 and a member of the NIHR PGfAR Programme funding subpanel from 2008 to 2016.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Robinson et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

SYNOPSIS

Background

Our ageing societies and prevalence of dementia

The number of people living with dementia is predicted to double by 2040. 1,2 Dementia has the greatest disease burden of all long-term illnesses. 1,3 Nationally, the cost of dementia care is estimated to be £26B, with community care costs accounting for almost half of this. 2,4 More older people are experiencing a slower, more unpredictable, dying pathway5,6 as a result of multimorbidity,7 age-related illnesses such as dementia8,9 and frailty, leading to an increased need for better-integrated community care, especially if the preferred final outcome is death in the usual place of care. 5,10–12

Dying with dementia

In the UK, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) considers end-of-life care (EOLC) to include all health and social care provided in all settings to the following groups of people: those who are likely to die within 12 months, those with advanced, progressive, incurable conditions, and those with life-threatening acute conditions. 13–15 EOLC also covers support for families and carers. More recently, NICE has provided separate evidence-based care recommendations for patients whom professionals consider to be in the last few days of their life, when more intensive support is needed. 13,14 Because of the unpredictable dying trajectory in dementia, professionals often find it difficult to predict when a person is dying. 16,17 EOLC can, therefore, be considered more than the last few days of life: the term ‘supportive care’ was coined to reflect the need for sustained care throughout the illness trajectory. 18 In terms of the quality of care, evidence consistently shows that people with advanced dementia experience poorer EOLC than those with cancer, with increased hospitalisation, inadequate pain control and fewer palliative care interventions. 19–21 In addition, family carers of people with advanced dementia require more emotional support prior to the person’s death than afterwards;22 many do not consider dementia as a terminal illness and know little about the symptoms and prognosis of the advanced illness. 23 With respect to place of death for people with dementia in the UK, few people die at home. Nearly half die in care homes and around one-third die in hospital;24–26 very few people with a primary diagnosis of dementia use hospice care. 27

Palliative care in dementia

Palliative care is defined as:

An approach that improves the quality of life of patients and their families facing the problem associated with life-threatening illness, through the prevention and relief of suffering by means of early identification and impeccable assessment and treatment of pain and other problems, physical, psychosocial and spiritual.

World Health Organization. 28 © Copyright World Health Organization (WHO), 2020. All Rights Reserved. URL: www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/

People with advanced dementia experience symptoms that are comparable to the symptoms of those dying with cancer. 12 Professionals experience a number of difficulties in meeting the palliative care needs of people with advanced dementia; for example, pain and symptom management is particularly difficult, as people with dementia may not be able to verbalise their symptoms. Despite this, however, the use of evidence-based pain assessment tools in community settings is low. 29 In addition, some professionals do not consider dementia a terminal illness30 and find prognostication difficult. 20,21,31 Both medical and nursing home staff consistently overestimate prognosis in advanced dementia. In one US study,31 only 1% of care home residents at admission were thought to have a life expectancy of < 6 months, yet 71% died in that period. A palliative care approach as dementia progresses is recommended both nationally29,32 and internationally;33 however, the evidence base to inform translation of these recommendations into practice is still limited.

End-of-life care in dementia in the UK: current service provision and commissioning

In the UK, access to specialist palliative care by families caring for people with advanced dementia is limited. 34 The quality of EOLC, in general, has been strongly influenced by the introduction of a national End of Life Care Strategy and programme,35 with associated quality markers to measure care outcomes. 36 These include the use of advance care planning (ACP), to promote patient choice, and EOLC pathways, for example the Liverpool Care Pathway for the Dying Patient (LCP)37 and the Gold Standards Framework (GSF). 38 However, the national End of Life Care Strategy35 was developed from cancer care, and directly transferring interventions may not be appropriate in dementia, for which the dying trajectory is longer and more unpredictable. 39,40 In a UK population, median survival time in dementia is 4.1 years from diagnosis,41 but this can be up to 7–10 years in younger age groups (60–69 years),42 or as low as 1.3 years in an older care home population. 43 Evidence has been slow to emerge of the effectiveness of ACP in dementia care44–46 in terms of reducing potentially harmful interventions such as hospitalisation, but few families living with dementia seem to want to complete formal ACP documents. 47–49

In England, guidance on commissioning dementia services is available from several sources,50 and NICE reiterated the need to follow other relevant existing guidance. 32,51 Currently, health and well-being boards in England do not prioritise EOLC in their strategies. 52 The Department of Health has developed dementia commissioning resources on early diagnosis and intervention, better care in acute hospitals and support for people in the community,53 but none of these documents covers EOLC in detail.

End-of-life care in dementia in the UK: research to date

Despite increasing international research, there has been little UK research in this area,20,54–56 even though EOLC was highlighted as a national research priority. 57 The Marie Curie, Alzheimer’s Society James Lind Alliance Priority Setting partnerships, which worked with the public, have also prioritised research in this area. 58,59

One UK-based study explored what constituted good EOLC in dementia with bereaved carers and professionals. 47 Family carers felt that people with dementia should die free from pain and surrounded by their relatives, whereas professional carers identified physical needs, emotional and spiritual issues, and care planning. However, general practitioners (GPs), who provide most of the EOLC in dementia,60 were not included.

England still has a high rate of hospital death in dementia (40%),61 and few people with dementia die at home. 35,62 Avoiding care transitions is important, but policy has focused mainly on promoting death in the usual place of care, rather than on the quality of dying. 35 Carers and people with dementia report comfort and QoL as the main goals of care. 43 Updated NICE dementia guidance states that people with dementia should receive flexible, needs-based palliative care that addresses the unpredictable progression,29 but models of how to achieve this in practice are lacking. Recent (2013–18) UK research has found high levels of persistent pain in care home residents with severe dementia,63 increasing anguish for carers,64,65 and rising numbers of people with dementia attending emergency departments in the last year of life. 66 Realist methods have increased understanding of integration67 and the barriers to and facilitators of good dementia palliative care,68,69 but significant research gaps remain. These include the following:

Programme aim and objectives

The overall aim of the Supporting Excellence in End-of-life care in Dementia (SEED) programme was to support professionals to deliver good-quality, community-based care towards, and at, the end of life (EOL) for people living with dementia and their families. Specific objectives were to:

-

identify which aspects of existing care towards, and at, EOL in dementia are effective and efficient

-

develop, implement and evaluate an evidence-based intervention, and associated resources, to support good-quality care towards, and at, EOL in dementia

-

determine how community-based EOLC in dementia should be organised and commissioned.

Programme design and methods

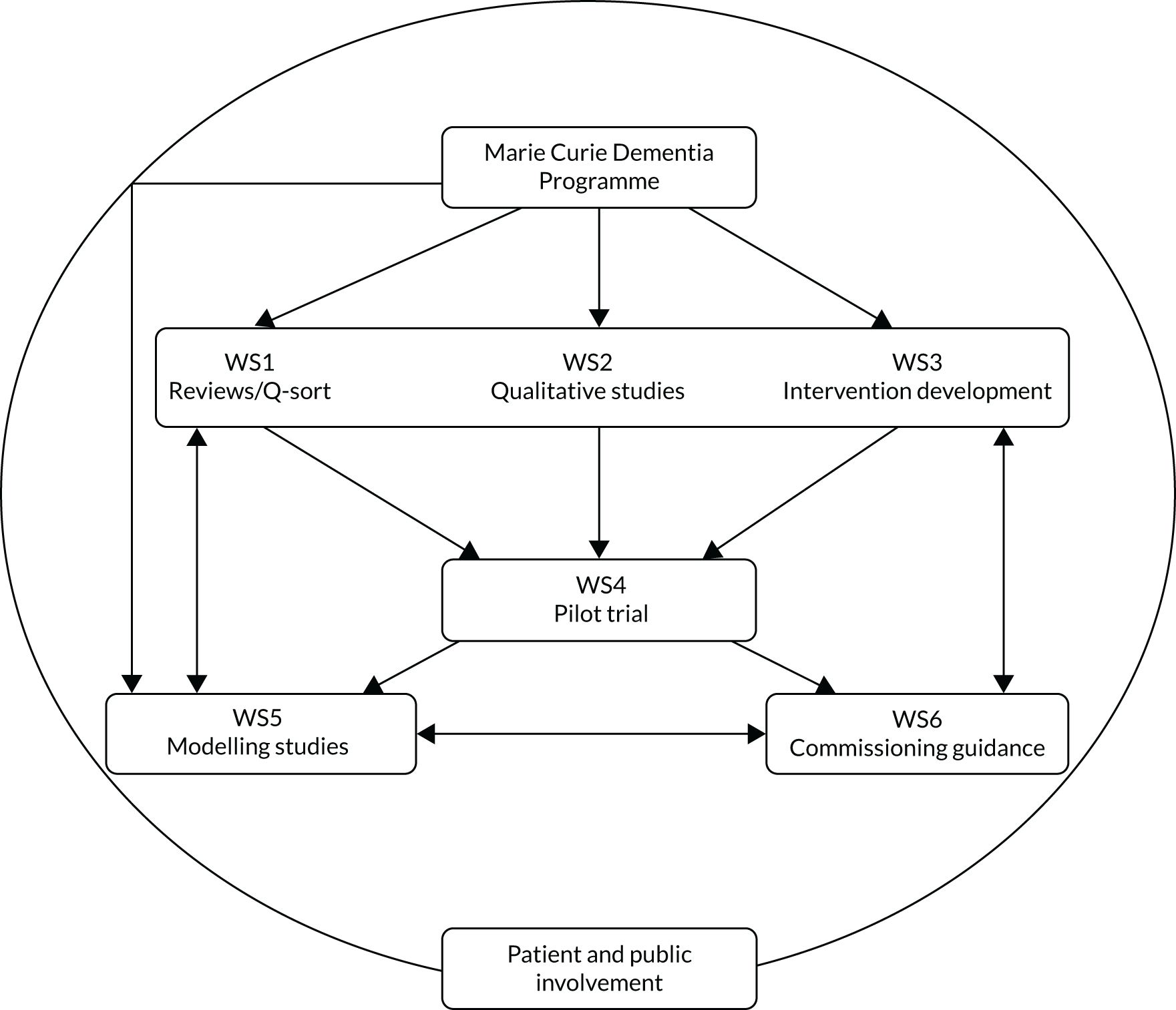

The SEED programme comprised six separate and interlinked workstreams (WSs); Figure 1 illustrates the relationship between individual WSs. We utilised the Medical Research Council (MRC) guidance on the development, piloting, implementation and evaluation of complex interventions. 72–74 The intervention development phrase comprised evidence synthesis (WS1) and a qualitative exploration of current care (WS2) to describe core processes, structures and outcomes. Individual WSs comprised the following:

-

WS1 – mapping current evidence and identifying quality indicators and/or outcome measures for EOLC in dementia

-

WS2 – qualitative studies to identify components of good EOLC in dementia

-

WS3 – development of the SEED intervention using data from WSs 1 and 2 and the Marie Curie Dementia Programme (MCDP)

-

WS4 – pilot trial of the SEED intervention, with process evaluation, to ascertain feasibility and acceptability

-

WS5 – economic modelling of the SEED intervention, including a willingness-to-pay (WTP) exercise to explore cost versus consequences

-

WS6 – commissioning good-quality, community-based EOLC in dementia.

FIGURE 1.

Inter-relationship of WSs in the SEED programme.

Patient and public involvement

Patient and public involvement (PPI) has been pivotal to the creation and subsequent development of this programme. The initial idea for this research originated from Alzheimer’s Society’s Research Network carer groups. A series of collaborative workshops between several representatives from these carer groups and the programme leads ensued to further develop the programme. To ensure that this level of PPI continued throughout the programme, one of the members of the original Alzheimer’s Society Research Network carer groups (ST) became programme co-lead for PPI. In addition, some of the carer group members also joined the external patient and public advisory board (PPAB).

The PPAB met a total of seven times throughout the programme: the initial two meetings were held in the first 6 months, subsequent meetings were held annually and two meetings were held in the final year. Alzheimer’s Society Research Network volunteers already receive training in basic dementia science, research methodologies, ethics and governance and reviewing funding bids. The first meeting was an educational session on EOLC in dementia and the purpose of the group. The second meeting focused on enhancing knowledge and the PPAB management role in terms of:

-

individual members’ roles and responsibilities

-

monitoring individual WSs

-

provision of ongoing support for members.

As required by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), we established an External Steering Committee (ESC), which also included PPI representation. This group met a total of five times during the programme to review progress and provide critical advice. We also had a local PPI group, which provided more in-depth ongoing input, for example providing constructive comments on topic guides. Therefore, each WS benefited from regular insightful feedback grounded in the views and experiences of families living with dementia. The PPI contributions to individual WSs are described in the specific WS sections. The continuing engagement and enthusiasm of PPAB and PPI group members is demonstrated by their contributions to the development and piloting of the massive open online course (MOOC) and their agreement to join new projects.

Major changes to the proposed programme

Workstream 3

The original proposal aimed to develop and evaluate an integrated care pathway (ICP) for professionals to use with people dying from, or with, dementia in community settings. This was grounded in the palliative care intervention, the LCP,37 which provided professionals with advice on how to provide better care in the last days of life. The LCP had been widely implemented on a national level. However, following the recommendation of a national review in 2013, the LCP was withdrawn from practice. 75 The SEED programme team, advised by the ESC, thus avoided any future use of the phrase ‘care pathway for the dying’, or ICP, and developed the intervention from the empirical data.

Workstream 6

In 2015, NICE announced that its dementia care guidelines were to be updated. As this national guidance was anticipated to include evidence-based recommendations on care towards, and at, the EOL in dementia, the ESC recommended postponing the development of any guidance for commissioners based on the SEED intervention findings until the updated guidance was published (in June 2018). 29

Workstream 1: mapping current evidence and identifying quality indicators and/or outcome measures for end-of-life care in dementia

Overview

We utilised the MRC guidance on the development and evaluation of complex interventions72–74 to inform intervention development, beginning with evidence synthesis (WS1). This WS comprised (1) updated systematic reviews to identify existing relevant guidelines, quality indicators and outcome measures, (2) a national online survey to identify current examples of good and sustainable practice (to inform WS2 sampling), and (3) a Q-sort study, with people with dementia, current carers and bereaved carers (n = 57), to explore their views on important outcomes for EOLC. Existing guidelines recommended that care towards, and at, the EOL for people with dementia be community based for as long as possible. As we had identified a number of existing, recent reviews of outcome measures for EOLC in dementia, we did not repeat this work; our article on the systematic review of quality indicators has now been published. 76 No dementia guidelines included any quality indicators to measure, and thus drive, improvement in this area of care. However, current palliative care quality indicators are not entirely suitable as they do not incorporate key aspects of dementia, such as person-centred care or behaviours that challenge. Results from the national survey showed that examples of current good practice rely heavily on (1) non-commissioned, non-recurrent funding and (2) leadership from an interested clinician or ‘local champion’. People with dementia and their families consider compassionate care and informed shared decision-making as important outcomes of good-quality EOLC.

Patient and public involvement

Significant PPI contributions to WS1 included discussion of the content and format of the relevance of existing outcome measures and/or quality indicators, testing the Q-methodology approach and advising on statements to be used, and informing the participant sampling frame for the Q-sort.

Research aim

To inform the development of the SEED intervention, WS1 sought to determine what is already known about the organisation and provision of EOLC for people with dementia and their families. Specific objectives were to:

-

map the evidence base for existing EOLC guidance and care pathways in dementia

-

identify national examples of good and sustainable practice

-

identify outcome measures and indicators to measure good-quality EOLC in dementia

-

elicit the views of people with mild dementia and carers on the elements of the care pathway(s) and outcomes important to them.

Existing end-of-life care guidance and models of care in dementia

Further details of existing EOLC guidance and models of care in dementia are provided in Appendix 1.

Methods

We built on a previous systematic review of dementia practice guidelines. 77 The original review retrieved 27 sets of dementia practice guidelines, 12 of which were eligible for inclusion [i.e. scored at least four on the Appraisal of Guidelines for REsearch and Evaluation II (AGREE II) instrument78]. Of these, five guidelines specifically addressed palliative care and EOLC:

-

Clinical Practice Guidelines and Care Pathways for People with Dementia Living in the Community79 (Queensland University of Technology, 2008)

-

guideline on supporting people with dementia and their carers in health and social care80 [NICE–Social Care Institute for Excellence (SCIE), 2007]

-

Guideline for Alzheimer’s Disease Management81 (California Workgroup on Guidelines for Alzheimer’s Disease Management, 2008)

-

Ministry of Health’s Dementia: MOH Clinical Practice Guidelines82 (Singapore, 2013)

-

Ministry of Health’s Clinical Practice Guidelines, Management of Dementia, 2nd edition83 (Malaysia, 2009).

In collaboration with WS5, we further examined the content in each guideline, looking specifically at setting, content, timing, care model(s), staff and resource implications, and clinical audit parameters. This exercise helped inform WS5 in terms of cost estimation and subsequent modelling.

Key findings

Existing guidelines recommended that people with dementia be managed as far as possible in the community. Recommendations varied as to when palliative care for people with dementia should be introduced, ranging from as early as diagnosis through to < 6 months to live. Only UK guidelines did not make any clear recommendations on the timing of the introduction of palliative care. Guidelines covered a range of aspects of palliative dementia care, including assessment, access to services, ACP and symptom management. Guidelines varied in the level of primary care involvement and support, and included shared care and case management models. Finally, no guideline incorporated any quality indicators/outcomes specific to the palliative care phase of the dementia care trajectory.

Mapping UK end-of-life care services in dementia

This study has been published as Amador et al. 84 For a full-text version of this paper see Appendix 2.

Methods

To map national initiatives, including examples of good and sustainable practice in EOLC in dementia, we updated and repeated the National Council for Palliative Care 2008 local practice online survey from October 2014 to the end of February 2015. We enquired about (1) general information regarding the service (i.e. title, contact information and location), (2) service activities and referral criteria, (3) team size and composition, (4) situation, funding mechanisms and sectors of operation and (5) dissemination and evaluation activities. 84 More than 60 services, set up specifically to provide EOLC to people with dementia, were purposively sampled via targeted e-mail invitation, in addition to open-call invitations.

Key findings

Fifteen respondents representing discrete service initiatives responded. Two-thirds of returns were received in response to targeted e-mail invitations, and one-third in response to open calls. Initiatives engaged in a wide range of activities, predominantly providing direct care and workforce development/advisory or educational activities. Findings suggested that sustainability of services was reliant on (1) enthusiastic clinicians with a leadership role, (2) wider system support through reliable funding mechanisms and (3) a minimum level of integration with normal service provision. More recent initiatives were largely built on the expertise of the nursing professions, and driven mainly by charity and hospice sector funding.

Identifying quality indicators/outcome measures to measure good-quality care

This work has been published as Amador et al. 76 (see Acknowledgements, Publications).

Quality indicators are defined as measurable elements of work/practice performance for which there is evidence or consensus that they can be used for assessing and changing the quality of care being provided. Quality indicators can be related to three key elements of care: process, outcomes and structure. 85,86 Outcome measures, more specifically patient- or public-related outcome measures, assess changes at an individual level in terms of health status or health-related QoL. Both types of measures were considered to be equally important when assessing the impact of a complex, community-based intervention that could potentially affect service users (i.e. patients and their families) as well as service providers and commissioners.

Methods

We had previously identified a number of existing systematic reviews of outcome measures for EOLC in dementia and, therefore, did not repeat this work. 87–89 To identify quality indicators to measure good-quality EOLC in dementia, we built on a previous systematic review of quality indicators for palliative care by de Roo et al. 90 The original review identified 17 sets of quality indicators for palliative care, containing 326 unique indicators. After screening, we excluded over half of the indicators because they were not applicable to long-term care settings, lacked procedural relevance or were specific to a particular scale. In addition, other indicators excluded at this stage were not applicable to UK care settings or lacked conceptual clarity. The remaining indicators (n = 156) were mapped against the European Association for Palliative Care (EAPC) framework for optimal palliative care in older people with dementia, which was developed through a rigorous international consensus process. 33 The framework comprises 11 domains:

-

applicability of palliative care

-

person-centred care, communication and shared decision-making

-

setting care goals and ACP

-

continuity of care

-

prognostication and timely recognition of dying

-

avoid aggressive treatment

-

comfort and optimal symptom treatment

-

psychosocial and spiritual support

-

family carer involvement

-

education of the health-care team

-

societal and ethical issues.

Key findings

Overall, quality indicators available to assess optimal palliative care in older people with dementia covered some of the EAPC domains, including ACP (domain 3), continuity of care (domain 4), prognostication and timely recognition of dying phase (domain 5) and family carer involvement (domain 9). However, existing indicators would need to be further developed in order for each to comprise the necessary elements (i.e. numerator, denominator and performance standard) and have its fundamental properties assessed (i.e. feasibility, acceptability, reliability, sensitivity to change and predictive validity).

There were major gaps in existing quality indicators in the following areas: (1) person-centred care, especially in specific aspects of dementia care (behaviour that challenges), (2) non-pharmacological interventions, (3) the appropriateness of pharmacological and other interventions at EOL (i.e. use of restraints, tube nutrition and the use of antibiotics), (4) the need for appropriate skill mix in health-care teams, including specialist nursing care and dementia care to support optimal symptom management, and (5) the quality of the dying environment.

Developing person-centred outcome measures: views of people with mild/moderate dementia and carers

This work has been published as Hill et al. 91 (see Acknowledgements, Publications).

Methods

Q-methodology is a mixed-methods approach combining qualitative and quantitative techniques to study subjectivity. 92 In this study, it was used to identify the views of people with mild dementia, family carers and bereaved carers on what is important (or unimportant) to them about the care provided to people with dementia approaching the EOL. In the first stage, participants ranked in order, from the most important to the least important, a set of 24 cards printed with statements about the type of care patients could receive (the statements are available in Report Supplementary Material 1). By-person factor analysis was used to identify clusters of respondents who completed the Q-sort in a similar way,92 and these clusters helped define the different factors. Short interviews were conducted following the card sort to provide additional information to aid interpretation of the factors.

Key findings

Four distinct viewpoints were identified:

-

Family involvement – decisions should be made by, and with, the family, and the wishes of people with dementia should be documented in advance to help families with this process. Family carers do not see caring for their relative as a burden: it is more important to keep the person with dementia in their own home and have the family with them at the EOL.

-

Living in the present – people with dementia live life day by day, and carers are more concerned with ensuring the comfort and safety of the person with dementia at that moment in time rather than planning ahead.

-

Pragmatic expectations – carers acknowledge their limits as carers for their relative with dementia and give high priority to having processes in place to provide the best possible care. This may include moving the person with dementia to a care home.

-

Autonomy and individuality – people with dementia want a significant level of autonomy and individuality, with their opinions and choices respected and integrated into their EOLC plans.

These findings reveal several different views on what is important about EOLC for people with dementia; therefore, a one-size-fits-all approach to care is unlikely to be the most appropriate. However, areas of consensus across all views did emerge, including the provision of compassionate care and ensuring that relevant information was available to people with dementia and their families when making decisions.

Workstream 1 conclusions

Existing guidelines recommend that people with dementia be cared for as long as possible in the community. These guidelines include key aspects of care, such as access to key services, ACP and optimal symptom management. Examples of sustainable national good practice are dependent on reliable funding streams, and local clinical leadership, hospice and charity sectors play a key role in the development and sustainability of such services.

No guidelines provided any quality improvement indicators specific to the palliative care phase of dementia. Current palliative care quality indicators may not be entirely suitable for use as they do not include key aspects of dementia care, such as behaviours that challenge and person-centred care. In the design of future services for EOLC, the Q-methodology study highlighted that there is no single way of providing care that will suit everyone. Outcomes for measuring EOLC that are important to people with dementia and their families include the provision of compassionate care and facilitating informed, shared decision-making.

Reflections on workstream 1

There persists a lack of empirical data to inform policy and clinical guidelines in this area of dementia care. Although a consensus framework has been developed, which identifies 11 domains for optimal palliative care for people with dementia, further research is needed to develop appropriate outcome measures or quality indicators to better assess both the quality of EOLC in dementia and outcomes that are important to people with dementia and their families. Q-methodology has the potential to identify person-centred outcomes; unfortunately, this study was limited to a small, selective sample of people with mild dementia and carers who were recruited from a dementia research network. To be generalisable, the study should be replicated with a larger and broader sample to capture additional viewpoints.

Workstream 2: defining and delivering good practice for care towards, and at, end of life in dementia

This work has been published as Bamford et al. ,93 Lee et al. 94,95 (see Acknowledgements, Publications) and Poole et al. 96 (see Appendix 2).

Overview

We used the MRC guidance on the development and evaluation of complex interventions72–74 to inform intervention development. The evidence synthesis (WS1) was followed by a qualitative exploration of current care delivery (WS2). This provided new insights into the key components that are essential for good-quality EOLC in dementia by using qualitative methods (i.e. interviews, focus groups and observation) to explore and compare the perspectives of different stakeholder groups. Three published papers from this workstream separately describe the views of key groups: national experts,94 service managers and front-line staff,95 (see Acknowledgements, Publications) and people with dementia and family carers96 (see Appendix 2). These individual WS2 studies contributed to a final data set that comprised 119 interviews, 12 focus groups, 256 hours of observation and three case studies. The findings of the integrative analysis are summarised in this section, with full details available in the published paper93 (see Acknowledgements, Publications), which drew together the findings of the three studies to identify seven key components of good EOLC:

-

timely planning discussions

-

recognising EOL and providing supportive care

-

co-ordinating care

-

working effectively with primary care

-

managing hospitalisation

-

continuing care after death

-

valuing staff and ongoing learning.

These key components then informed intervention development (described in Workstream 3: development of the SEED intervention).

The integrative analysis highlighted discrepancies between the data, policy objectives and existing literature. Although policy, national experts and service managers often emphasised ACP as crucial to delivering good EOLC,35,44,45 whereas many people with dementia and their families preferred to focus on the present or considered future planning only in relation to wills and funeral arrangements. 96 Providing timely opportunities to discuss future care preferences is challenging in a context in which people with dementia generally receive little support during the mid-stage of the illness trajectory. 97,98 The uncertainty of the dying trajectory in dementia has been identified as a key barrier to good EOLC. 20,21,31,99 However, care home staff did not necessarily view uncertainty as problematic, partly because they were comfortable with the lack of a clear trajectory and partly because they felt that they were often able to identify when individuals were approaching the EOL, but also because following the principles of person-centred care would ensure that needs were recognised and met at all stages of the illness.

Patient and public involvement

Members contributed to WS2 by advising on recruitment approaches and materials, discussing sampling for services to be included in focus groups and the comparative case studies, and reviewing emerging themes from the qualitative analyses.

Research aim

The aim of WS2 was to develop a detailed understanding of good practice in EOLC in dementia to inform development of an intervention (WS3), which would subsequently be tested (WS4). This was achieved through a series of qualitative substudies, with the objectives of:

-

defining good practice from the perspectives of key stakeholders, including national experts, service managers, front-line staff and people with dementia and their family carers

-

understanding existing approaches to EOLC in dementia

-

exploring challenges and unmet need in EOLC in dementia

-

exploring the value and relevance of current tools for EOLC in dementia.

Methods

Qualitative methods were used throughout WS2, including semistructured interviews (face to face and telephone), focus groups, informal discussions and non-participant observation. Data were collected between October 2013 and January 2016 for four substudies that explored:

-

the range of approaches to EOLC in dementia with national experts (WS2.1)

-

service manager approaches to providing EOLC in dementia (WS2.2)

-

the views and experiences of EOLC from the perspectives of people with dementia, family carers and front-line staff (WS2.3)

-

day-to-day practice in EOLC in dementia (WS2.4).

Topic guides are available in Report Supplementary Material 1. The principles of purposive sampling were used in all substudies. 100 Interviews and focus groups were transcribed verbatim and analysed thematically. 101 Episodes of observation were recorded in anonymised field notes. Analysis was iterative and interspersed with data collection. To avoid imposing ideas from one group of stakeholders onto subsequent groups, data sets from individual studies were initially analysed independently. Further details of methods and participants are available in the publications of this work. 93–96 The subsequent integrative analysis involved reconceptualising and developing themes to reflect the nuances in the data from different stakeholders. 93

Key findings

The integrative analysis led to the identification of seven key components of good EOLC for people with dementia. These were central to the development of the intervention in WS3. Table 1 illustrates how themes from different data sets were combined and reconceptualised to produce the seven key components. The original themes from individual data sets often contributed to more than one of the seven components. For example, the theme ‘planning for EOL’ from the comparative case studies was relevant to both timely planning discussion and managing hospitalisation. The mapping was sometimes less intuitive, reflecting nuances within themes that were not necessarily reflected in the overall theme title.

| Seven key components | Interviews and focus groups with | Comparative case studies | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| National experts | Service managers and front-line staff | People with dementia and family carers | ||

| Timely planning discussions | Leadership and management | Communicating with families | Uncertainty about planning ahead/difficulties planning ahead | Planning for EOL |

| Continuity of care | Expectations about decisions and decision-makers | |||

| Recognising EOL and providing appropriate care | ||||

| Recognising EOL and providing supportive care | Use of guidelines | Supporting families | The value of practical support | Recognising EOL and providing physical care |

| Integrating clinical expertise | Ensuring comfort at the EOL | Emotional support towards and after EOL | Planning for EOL | |

| Continuity of care | Communicating with families | Reliance on family at EOL | Access to clinical care | |

| Leadership and management | Recognising EOL and providing appropriate care | Confidence in standards of future care | Emotional work at EOL | |

| Continuity of care | ||||

| Co-ordinating care | Integrating clinical expertise | Collaborative working | Reliance on family at EOL | Access to clinical support |

| Continuity of care | Continuity of care | Challenges in accessing and co-ordinating care | Planning for EOL | |

| Recognising EOL and providing appropriate care | Equipping staff with appropriate skills and knowledge | |||

| Ensuring comfort at the EOL | ||||

| Working effectively with primary care | Integrating clinical expertise | Collaborative working | Challenges in accessing and co-ordinating care | Access to clinical support |

| Continuity of care | Planning for EOL | |||

| Recognising EOL and providing appropriate care | Equipping staff with appropriate skills and knowledge | |||

| Ensuring comfort at the EOL | ||||

| Developing and supporting staff | ||||

| Managing hospitalisation | Continuity of care | Recognising EOL and providing appropriate care | The value of practical support | Access to clinical support |

| Collaborative working | Reliance on family at EOL | Planning for EOL | ||

| Continuity of care | ||||

| Communication with families | ||||

| Continuing care after death | Supporting families | The value of practical support | Emotional work at the EOL | |

| Ensuring comfort at EOL | Emotional support towards and after EOL | Recognising EOL and providing physical care | ||

| Developing and supporting staff | ||||

| Valuing staff and ongoing learning | Leadership and management | Developing and supporting staff | Confidence in standards of future care | Equipping staff with appropriate skills and knowledge |

| Continuity of care | Recognising EOL and providing appropriate care | Skilled and empathic staff | Emotional work at the EOL | |

| Use of guidelines | Continuity of care | Access to clinical support | ||

| Communicating with families | ||||

| Ensuring comfort at EOL | ||||

Although there were differences in emphasis between data sets, the relevance of the seven components to all stakeholder groups is largely demonstrated in Table 1. The integrative analysis was also helpful in refining minor themes within data sets. For example, the emotional work in providing EOLC for front-line staff was a strong theme in the comparative case studies, but was not identified as an explicit theme in other data sets. The integrative analysis drew attention to the presence of this theme in other data sets and helped to ensure that it was embedded in the theme of valuing staff and ongoing learning.

Workstream 2 conclusions

There were some important discrepancies between the findings, policy objectives and existing literature. Although planning for EOL is promoted as best practice,33,35,45 the findings confirmed that people with dementia often prefer to live in the moment, and some had strong reservations about planning for the future. 47,49,62 In terms of practical implications, this suggests the need for planning discussions to be conducted with a professional who has time to get to know the individuals, understands the barriers to planning and is able to approach topics over a period of time (while recognising that it may never be appropriate for some families). Although national experts emphasised skills and training, they paid less attention to the relational context needed to support discussions about future care. 94 The integrative analysis promoted a more detailed understanding and provided insights into how to translate the components into practice. Seven key components were identified as being core to the provision of good-quality EOLC in dementia: (1) timely planning discussions, (2) recognising EOL and providing supportive care, (3) co-ordinating care, (4) working effectively with primary care, (5) managing hospitalisation, (6) continuing care after death, and (7) valuing staff and ongoing learning.

The uncertainty of the dementia trajectory is often cited as a key barrier to good EOLC in dementia. 20,21,31,99,102 However, data from front-line staff, particularly care home staff, suggested that uncertainty may be less relevant than was previously thought. Many staff anticipated and were accepting of fluctuations in people with dementia, and were able to explain these to family carers. Experienced staff often used a combination of their personal experience and knowledge of the individual, subjective changes (e.g. seeming more withdrawn) and objective measures (e.g. weight loss and decreased appetite) to identify people potentially approaching the EOL. 95

Reflections on workstream 2

The integrative analysis promoted a more detailed understanding of key components of EOLC in dementia than would have been achieved through individual data sets. Observation provided valuable insights into how to translate these components into practice. The findings, therefore, highlight the value of including multiple stakeholder groups and different methods to inform complex interventions. A key limitation was the relatively small numbers of people with dementia involved in interviews. It proved difficult to recruit participants through the services taking part in the focus groups; this may have been because of workload, desire to ‘protect’ people with dementia or a lack of confidence in the research team. These difficulties were offset, to some extent, by the involvement of a considerable number of people with dementia in the observations, which often included informal conversations about the care they received and their views on the components of good care.

Workstream 3: development of the SEED intervention

This work has been published as Macdonald et al. 103 (see Acknowledgements, Publications). A detailed description of the SEED intervention is provided in Appendix 3.

Overview

In WS3, we developed an intervention that is grounded in the key findings of WS1 and WS2, and that builds on the results of the MCDP. Using a co-design approach, the seven key components identified in WS2 as underpinning good-quality EOLC in dementia were operationalised into a primary care-based intervention to be piloted in WS4. The primary care-based intervention, delivered by a DNS, targets two key groups of people: (1) those in the earlier stages of the dementia trajectory, with mental capacity to address future care planning; and (2) those in the more advanced stages of dementia, who would benefit from a palliative approach to their care. Findings also suggested the need for a care resource kit, containing current and possibly new resources, targeting the seven key components. As an integral part of the SEED intervention, the resource kit supports intervention delivery, enables effective working with people with dementia and their families, and improves the knowledge and skill set of community-based health and social care professionals. WS3 used an inclusive design-led approach103–105 to co-develop blueprints for a number of new EOL resources that could be included in the care resource kit.

Patient and public involvement

This was integrated throughout WS3. Specific PPI contributions included discussing and advising on the emerging intervention, testing workshop-based activities to inform future stakeholder involvement methods, advising on acceptability of existing resources for the care resource kit, providing detailed feedback on the draft care plan guide and advising on the concept of developing a MOOC.

Research aims

The research aims were to:

-

develop an evidence-based intervention to support professionals to provide good-quality EOLC in dementia

-

co-develop new resources to support implementation of the intervention

-

identify key determinants of costs and outcome to inform WS5 (to prevent duplication, this element is described in Workstream 5: economic modelling study, Valuing the consequences of the SEED intervention).

Developing an evidence-based intervention (see Appendix 3)

The MRC guidance on developing complex interventions includes three key activities relating to intervention development: (1) identifying the evidence base, (2) identifying/developing theory and (3) modelling process and outcome. 74 In the SEED programme, the first activity took place in a series of workshops with the full SEED programme team to review the evidence from WSs 1 and 2 and to generate and prioritise ideas for possible intervention. The broad concept of the intervention was then operationalised through small group co-design workshops, which included modelling process and outcome using the theory of change. 106 Although we had intended to develop the intervention within the team and then conduct task groups with stakeholders, this process was adopted to ensure more integrated involvement of stakeholders (i.e. PPI members, clinical specialists and service providers) throughout the second phase of intervention development.

Phase 1: generating and prioritising ideas

A series of five workshops with the full SEED programme team was undertaken (November 2014 – December 2015). The initial five workshops involved early and ongoing discussions of the existing evidence base (WS1 reviews) and qualitative findings (WS2). The focus was to identify possible frameworks for the intervention, and appropriate methods and processes to inform its development. A brief summary of each workshop is provided in Appendix 3, Developing an evidence-based intervention. Following this series of workshops, the co-design process then continued in a smaller group to develop the intervention in more detail and facilitate translation into practice.

Phase 2: prototype development

The smaller group met every few weeks over a 12-month period, with a 5-month gap between months 4 and 9 (when Sandra Neves was on maternity leave). Members included the design team, PPI members, key researchers, clinical experts and service providers. The main focus of the smaller group was to consider how the ideas identified in the workshops linked to existing theoretical frameworks and could be operationalised in terms of what the intervention would comprise, who it would be targeted at, where it would be based, who would deliver it and how intervention delivery could best be supported. A summary of each of these areas is provided in the following sections.

What theoretical approaches could inform the SEED intervention?

We did not have an explicit theoretical framework to inform the intervention at the outset. Relevant theoretical frameworks to inform the intervention were identified from the literature reviews, qualitative interviews and case studies. These included extending the ideas of person-centred care107,108 to person-centred death and to other key individuals (family members and professionals) involved in EOLC. 109,110 We also drew on ethnomethodological ideas about the social organisation of death. 111 Other aspects of the intervention were informed by complexity theory,112,113 recognising the need for the intervention not only to address individual needs but to enhance systems to support EOLC. The SEED intervention was, therefore, informed by a range of blended theories. With the exception of the social organisation of death, each of the remaining theories informed all of the seven components comprising the intervention.

We subsequently used the framework of normalisation process theory (NPT)114,115 to understand whether or not and how the intervention was implemented (see Workstream 4: pilot trial of the SEED intervention, with process evaluation, to ascertain feasibility and acceptability).

What components would comprise the SEED intervention?

It was agreed that the SEED intervention would focus on the seven key components of care identified in WS2 and would consist of:

-

direct work to support people with dementia and carers towards, and at, the EOL

-

developing a supportive context for EOLC in dementia by –

-

mapping and co-ordinating local services

-

developing the workforce through co-working, training and development

-

improving systems to enhance EOLC, for example improving use of the general practice palliative care register, or improving links between general practices and local care homes

-

a care resource kit.

-

Who would the SEED intervention focus on?

As the aim of the programme was on improving care towards, and at, the EOL in dementia, the consensus of the small co-design group was that the intervention would focus on two groups of people with dementia and their families: (1) those in the earlier stages of the dementia trajectory with mental capacity, to address future care planning; and (2) those in the more advanced stages of dementia, who would benefit from a palliative approach to their care. The ambition was that the intervention would also focus on improving the delivery of EOLC to people with dementia through more strategic work. Although this would be tailored to the local context, we anticipated that this systems-level work might include building capacity of existing staff or enhancing use of the general practice palliative care register for people with dementia.

Where would the SEED intervention be based?

Alzheimer's Disease International has urged implementation of a task-shifted model of dementia care whereby the majority of post-diagnostic care is delivered in community settings by a generalist workforce such as primary care teams. 116,117 In England, this approach has been widely implemented for a range of long-term conditions, usually with a specialist nurse co-ordinating care and facilitating links and knowledge exchange between the general practice and secondary care. 118 To date, dementia has generally been excluded from this model. The findings of WS2 suggested that an intervention based in primary care could address a number of existing shortcomings in EOLC in dementia. For example, better community support was needed to facilitate care in place and obtaining timely support from primary care was a recurrent issue for some care homes. Although the MCDP tested a care home-based intervention,119 this excluded those people with dementia living in their own homes. Basing the intervention in primary care was therefore supported both by the empirical data and the increasing policy emphasis on a primary care-led model of dementia care.

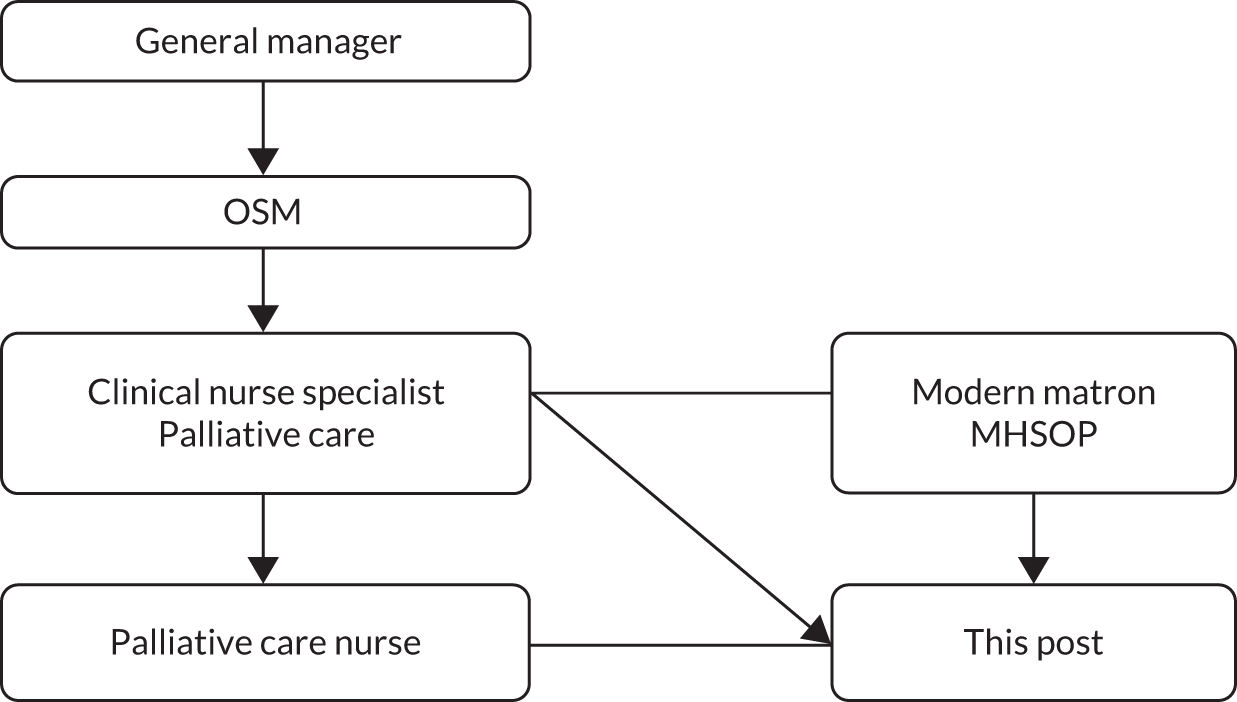

Who would deliver the SEED intervention?

As the seven key components of care largely involved clinically related duties such as future care planning, care co-ordination, working effectively with primary care and supporting/training generalist staff, it was agreed that the SEED intervention should be delivered by a professional with clinical knowledge and expertise. The recently completed MCDP intervention study had tested a non-clinical care co-ordinator role. 119 However, as the SEED intervention would comprise independent working in the community, it was considered that it should be delivered by an experienced nurse, particularly as this was consistent with the role of specialist/nurse practitioners in delivering most chronic care in the community. The post was termed a DNS.

Further discussion led to the development of a job description and person specification outlining the prior knowledge and expertise required and responsibilities of the role (see Appendix 3, Job description provided to NHS trusts and person specification). Existing job specifications for similar community-based, specialist nurse roles (e.g. Macmillan nurse for cancer and Admiral nurse for care of people with dementia and their families) were used to inform the job description.

What support will be needed to deliver the SEED intervention?

To enable the DNS to deliver the SEED intervention, a range of support needs were identified:

-

training and supervision

-

practical support in negotiating the new role

-

an accessible manual describing the SEED intervention [see Report Supplementary Material 2 and Appendix 3, Example of SEED activities and outcomes for one key component (timely planning discussions), and Example of SEED activity checklists for one key component (timely planning discussions)]

-

care resource kit [see Appendix 3, Example of resources for one key component (timely planning discussions)].

Practical issues included secondment arrangements, equipment required, induction and training, and anticipated caseload. Training needs were identified and prioritised using an educational needs assessment (see Appendix 3, Educational needs assessment for dementia nurse specialist). An induction period of 4–6 weeks was agreed to enable the DNSs to meet key professionals in the locality and to build relationships with their general practice. A bespoke SEED manual was developed to introduce the DNSs to the research programme and the intervention, and to help guide them through the role (see Report Supplementary Material 2). This included a description of the intervention using the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) checklist. 120

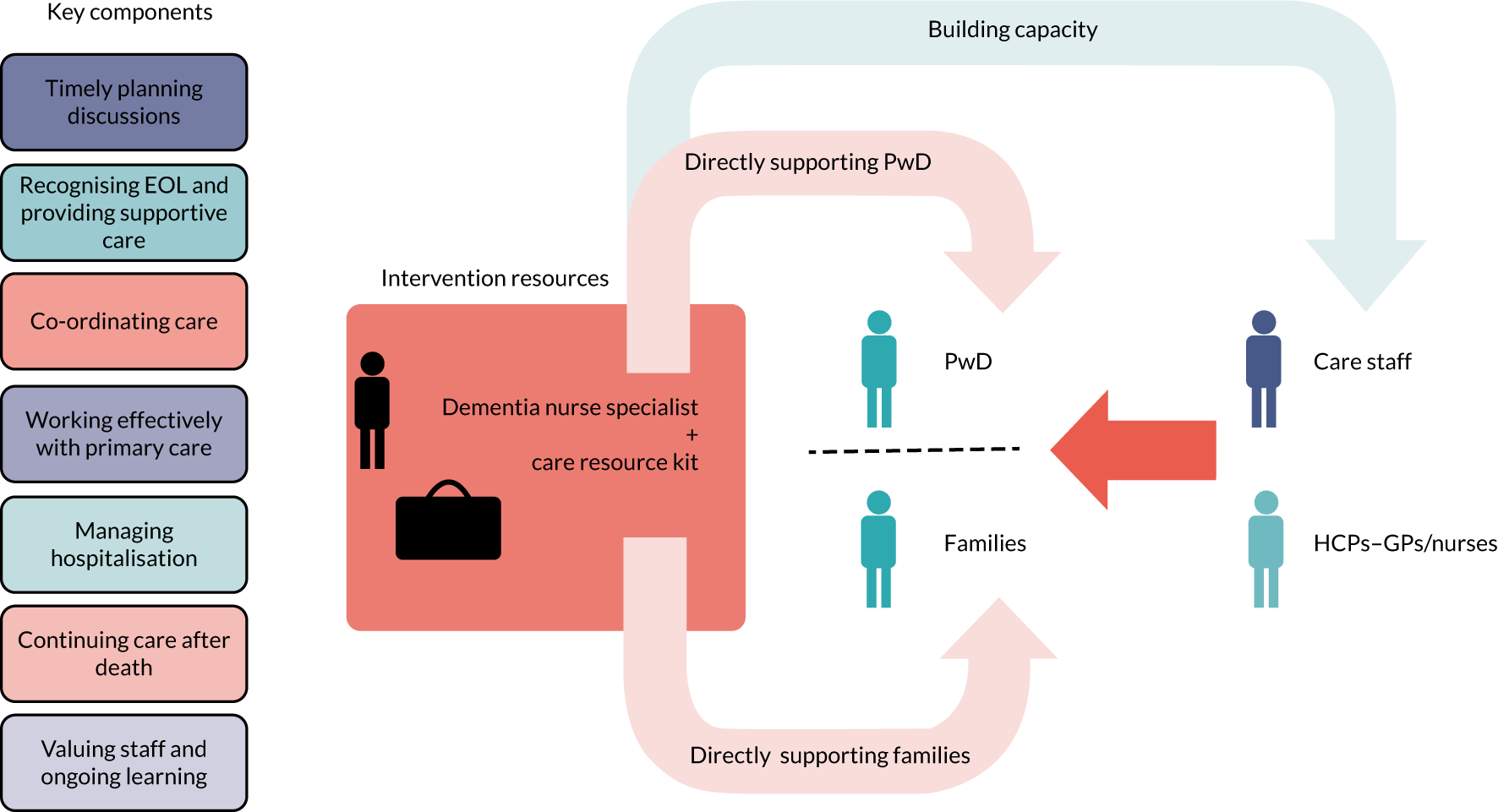

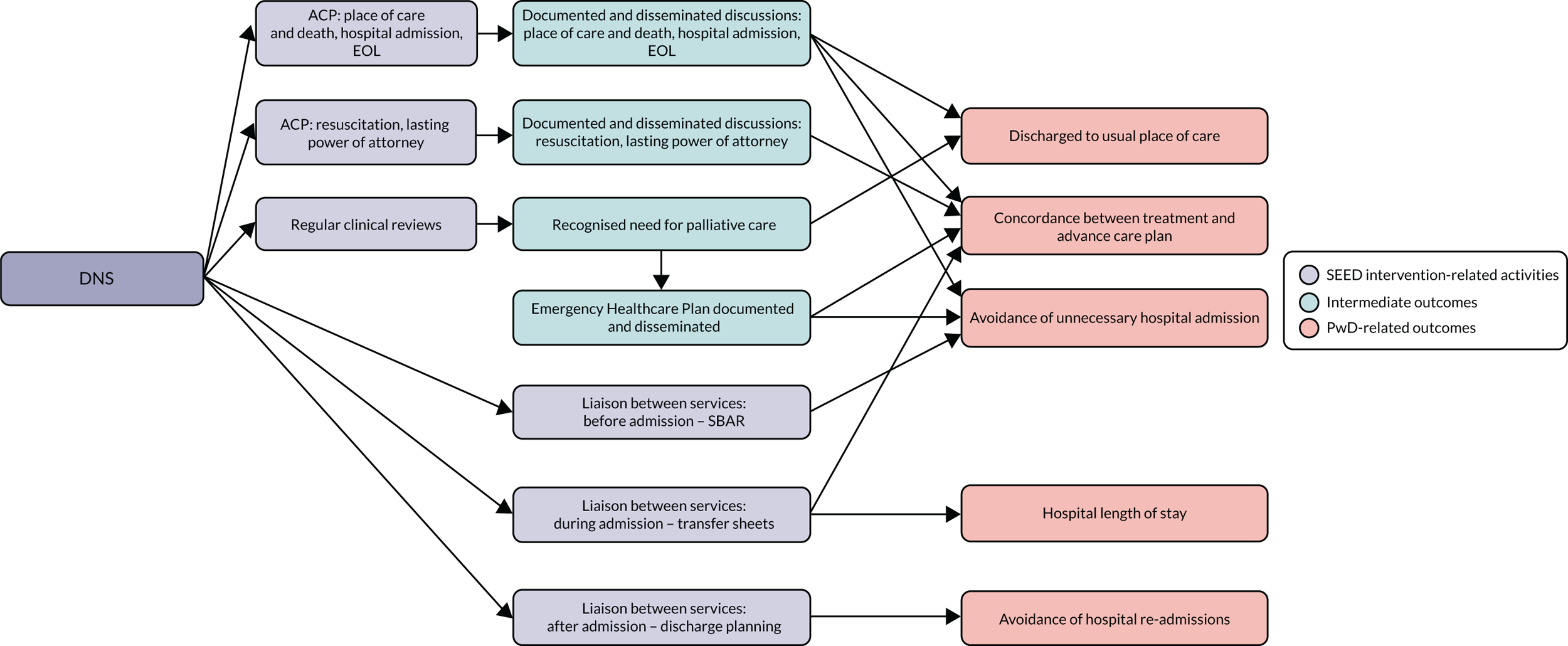

The SEED intervention

The SEED intervention comprised a DNS to focus on the seven key components of good EOLC, identified in WS2, through working with individual people with dementia and family carers and working at a more strategic level to build capacity. A conceptual model of the SEED intervention is provided in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2.

The SEED intervention. HCP, health-care professional; PwD, people with dementia. Reproduced from Macdonald et al. 103 with permission from The Journal of Dementia Care.

Using the theory of change to translate theory into practice

The next stage of intervention development involved translating the conceptual model into practical activities. For each of the seven components, we began by identifying objectives for working (1) with individual people with dementia and their families and (2) at a strategic level (Box 1). The activities were also presented as checklists that could be used by the DNSs to document activities and plan their work. These documents were included in an appendix to the SEED manual [see examples in Appendix 3, Example of SEED activities and outcomes for one key component (timely planning discussions), and Example of SEED activity checklists for one key component (timely planning discussions)].

-

To provide opportunities for discussions about EOLC with patients and families.

-

To provide opportunities for documenting preferences for EOLC.

-

To ensure appropriate dissemination of completed documents.

-

To ensure the timely review of completed documents.

-

To identify people with dementia approaching the EOL and add them to the palliative care register.

-

To share prognosis with families and prepare them for EOL.

-

To ensure the timely recognition and management of pain and discomfort at EOL.

-

To review EOL planning documents.

-

To ensure that all staff are aware of, and follow, relevant documentation.

-

To improve co-ordination between multiple services and agencies.

-

To improve communication within and between services.

-

To improve access to continuing health-care funding.

-

To refer appropriately to specialist services.

-

To provide a conducive environment in care homes for GP visits.

-

To have a named GP and alternate identified.

-

To ensure regular (e.g. 3-monthly) proactive clinical review of people with dementia.

-

To review medications towards EOL.

-

To ensure that a clear rationale is provided for hospital admissions.

-

To ensure that preferences regarding hospitalisation are reviewed and documented.

-

To identify a range of options to support families and care home staff in the event of unanticipated changes.

-

To ensure that professionals who do not know the patient have access to key information.

-

To prepare families for what will happen following the death of the person with dementia.

-

To support families in the immediate post-death period.

-

To assess the need for ongoing bereavement support.

-

To value the emotional work involved in EOLC.

-

To recognise the personal strengths of staff.

-

To establish routine post-death reviews.

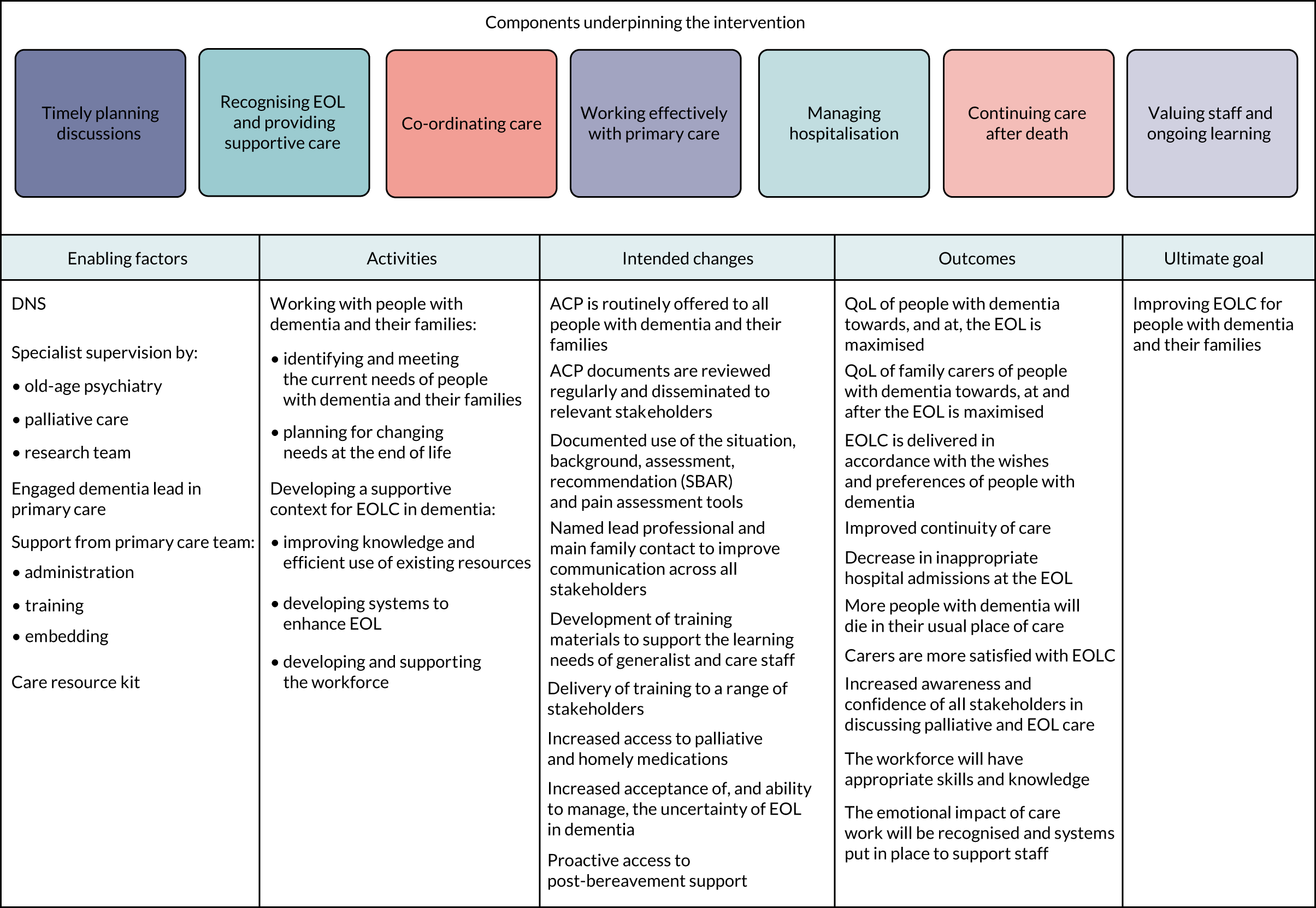

We then summarised the intervention using the theory of change. 106,121 This was used because it focuses on desired outcomes, adopts a collaborative approach and explicitly explores the rationale underlying interventions. Developing a theory of change for the SEED intervention involved an iterative and collaborative process between the research team and key local stakeholders, including a palliative care clinical lead, who would support the DNSs, and a specialist dementia nurse (who was subsequently seconded to the role of DNS for the pilot trial).

The stages involved in developing the theory of change included:

-

identifying a realistic and definite goal for the SEED intervention (Figure 3 presents the ultimate goal)

-

working backwards from the goal to identify outcomes that would contribute to achieving the goal

-

summarising activities needed to achieve these outcomes and the intended changes through which the outcomes would be achieved

-

identifying resources required for the intervention.

FIGURE 3.

Theory of change for the SEED intervention.

In addition, we explored the assumptions underlying the links between activities and the overall goal. The theory of change aimed to provide an overview of the intervention. Individual activities included in Figure 3 are, therefore, not specifically linked to individual components of the SEED intervention (e.g. planning for changing needs at the EOL is clearly linked to timely planning discussions, but is also likely to affect other components, such as providing supportive care, working effectively with primary care and managing hospitalisation). Similarly, the intended changes may result from one or more of the activities (e.g. increased acceptance of, and ability to manage, the uncertainty of EOL in dementia may result from developing and supporting the workforce and/or from planning for changing needs at the EOL). The outcomes and ultimate goal are, therefore, achieved through a combination of activities, rather than being directly linked to a specific activity.

Co-development of the care resource kit

A key role of the DNSs was to provide appropriate information to the right people at the right time. Therefore, we developed a care resource kit containing examples of existing resources to facilitate intervention delivery, and identified potential new resources to address any gaps.

Existing resources

Existing resources were identified through online searches, targeting key websites (e.g. Alzheimer’s Society, Alzheimer’s Association and the National Council for Palliative Care) and using the keywords ‘end-of-life care’ and ‘dementia’. A small group of SEED programme team members with personal and professional experience of EOLC in dementia reviewed the suitability of resources for (1) people with dementia and their families and (2) professional carers. Selected resources were grouped according to:

-

relevance to one or more of the seven key components

-

whether the resource focused on EOLC in general or was specific to dementia

-

target audience (people with dementia, family carers and professionals)

-

country of origin.

The accessibility of the resources was also considered in terms of format and availability (e.g. downloadable, free or paid for). The quality of the identified resources was then reviewed by considering whether and how research evidence had informed their development. In view of the large number of resources identified, many of which covered similar areas, we then selected the most appropriate existing resources for inclusion in the care resource kit, based on the following criteria: dementia-specific, freely available, UK based and evidence based. International resources for professionals were selected if they were of high quality with a strong evidence base. International resources for people with dementia and their families were included if they were accurate, of high quality and judged acceptable by the PPI member of the SEED team.

This process resulted in a detailed table of resources, which was included in the appendices to the SEED manual [see Appendix 3, Example of resources for one key component (timely planning discussions), for an example]. Different ways of enabling the DNSs to quickly identify and access the resources were considered. One suggestion was to develop a web portal to facilitate searching and retrieval of documents, which could be used by people with dementia and their families, as well as professionals. A preliminary structure for the web portal was agreed, in which resources would be organised by their intended audience, the seven components and format (e.g. booklet or video). Although a blueprint for the portal was developed, there were insufficient resources to develop it further.

New resources

The review of existing resources highlighted gaps in three key areas:

-

a simple introductory guide to planning for the future

-

clinical scenarios illustrating common issues in EOLC in dementia and strategies to address these

-

online training for both family carers and professional carers focused on advanced dementia and EOLC.

The rationale for selecting these areas and description of the progress made in developing new resources are described in detail in Appendix 3, Development of new SEED resources. Only one of these new resources, a MOOC on advanced dementia, was successfully completed and marketed.

Massive open online course

This work has been published in Poole et al. 122,123 (see Acknowledgements, Publications and Appendix 2).

The major gap identified by the review of existing resources was the absence of educational resources for both family and professional carers on advanced dementia and the provision of care as the illness progresses. A MOOC was seen as the most appropriate way of addressing this gap. A MOOC is an online course aimed at unlimited participation and open access via the web. In addition to traditional course materials, such as filmed lectures, many MOOCs provide an interactive forum for users.

The SEED-based MOOC, Dementia Care: Living Well as Dementia Progresses, aims to help family carers of people with advancing dementia to feel prepared and supported towards, and at, the EOL. Although primarily designed for family carers, the MOOC was a useful resource for professional carers, particularly care home staff. The content is underpinned by the seven key components that informed the SEED intervention, and addresses three main areas:

-

understanding the progression of dementia and planning for the future

-

working together to ensure the care and comfort of the person with dementia

-

looking after yourself as a carer.

Participants involved in the MOOC included members of the SEED project team (Marie Poole and Louise Robinson), DNSs, family carers, a range of health-care professionals who participated in SEED and additional professionals to ensure that key organisations were represented. The resources included in the MOOC aim to be engaging and informative, and comprise short videos, articles, images, quizzes, animations and interactive forums. Dementia Care: Living Well as Dementia Progresses was launched in March 2019; the 3-week course is now delivered twice-yearly and has been completed by > 3000 participants from 130 countries. To date, the MOOC has been promoted at a range of national and international conferences and with organisations including Dementia UK, Health Education England, local NHS foundation trusts and local dementia services.

Workstream 3 conclusions

Following an extensive co-design process involving all key stakeholders, the seven key components identified in WS2 as underpinning good-quality EOLC in dementia were operationalised as a primary care-based, nurse-led intervention. From a theoretical perspective, we utilised the theory of change106,121 as it allows a collaborative and iterative process and focuses on desired outcomes. A training and supervision programme was developed along with an intervention manual. Findings also indicated the need for a care resource kit to help the DNSs deliver the intervention, work more effectively with people with dementia and their families, and improve the knowledge and skills of family carers and community-based care professionals. An extensive review was undertaken of existing resources, information and tools focused on supporting the delivery of good-quality dementia care towards, and at, the EOL. This indicated a number of gaps, in particular the absence of educational resources for both family carers and professional carers on advanced dementia and the provision of care as the illness progresses. Using the empirical data from earlier WSs, we developed a MOOC to address this gap. The MOOC, Dementia Care: Living Well as Dementia Progresses, was launched in March 2019.

Reflections on workstream 3

Development of the intervention required considerable time and effort that, in hindsight, we underestimated. In addition, the length of the process was increased because of (1) the design researcher undertaking maternity leave mid-way through WS3 and (2) a recommendation from our ESC to extend intervention development time to ensure that key aspects that were essential for operationalisation in practice were completed. Developing new, relevant and innovative educational resources was another key challenge during WS3. Considerable effort was put into searching for and retrieving existing resources, tools and information on EOLC in dementia. However, even once we had identified potential areas for the development of new resources, it was difficult to determine if there were any resources already under development that would address these gaps. Consequently, considerable time and effort were spent creating potential new resources and tools, only for updated review searches, which also required considerable time and human power, to identify new resources that had just been published.

Workstream 4: pilot trial of the SEED intervention, with process evaluation, to ascertain feasibility and acceptability

Further details on WS4 are provided in Appendix 4.

Overview

Workstream 4 comprised a pilot trial to assess the feasibility and acceptability of recruitment and retention, the SEED intervention and outcome measures. Key success criteria for recruitment and retention were generally achieved, but operationalising the eligibility criteria was time-consuming. Many stakeholders thought that all people with dementia would benefit from the intervention and that this would offer a potential strategy for meeting the NICE recommendation for a named care co-ordinator for all people with dementia throughout the illness trajectory. 29 Despite the complexity of the SEED intervention and the requirement for the DNSs to adapt it to the local context, it proved both feasible and acceptable. The DNSs made significant changes at a strategic level (e.g. introducing a template for the annual dementia review in primary care), in addition to working with individuals and their families. None of the outcome measures was considered suitable as the primary outcome measure for a future trial. In the light of these uncertainties, we do not intend to proceed to a definitive trial of the SEED intervention at this stage.

Patient and public involvement

The views of PPI members were sought on progression to a future trial. In particular, we explored extending the intervention to all people with dementia, advantages and disadvantages of alternatives to the current model of one DNS for each general practice, and their views on appropriate outcome measures.

Research aim

The aim of WS4 was to investigate the feasibility of a definitive multicentre RCT of the SEED intervention. Specific objectives focused on three areas:

-

recruitment and retention of people with dementia, family carers and key informants, specifically to –

-

test the feasibility of recruiting 66 people with dementia (with at least 11 from each practice)

-

ascertain whether or not we could collect 12-month follow-up data from at least half (n = 33) of the people with dementia who were recruited

-

-

the implementation of the SEED intervention, specifically to –

-

explore the feasibility and acceptability of the SEED intervention and supporting educational resources

-

explore how and to what extent the intervention was implemented in practice

-

identify, describe and explain factors influencing the implementation of the SEED intervention

-

-

capturing outcome data, specifically to –

-

investigate the feasibility and acceptability of available outcome measures

-

assess the feasibility of collecting resource use data and health-related QoL for people with dementia and family carers

-

explore ways of capturing data on future care planning.

-

Methods

The MRC guidance on developing and evaluating complex interventions emphasises the importance of pilot work to address key uncertainties before progressing to a full trial. 74 Key functions of feasibility/pilot studies are estimating recruitment/retention, testing procedures and estimating sample size. 74 In the present study, there was a high level of uncertainty over each of these areas, in particular over whether or not the intervention could be delivered in practice and whether or not available outcome measures would prove feasible and acceptable in a UK community context. These uncertainties indicated that a pilot trial with an embedded process evaluation was required to inform whether or not progression to a full trial was appropriate.

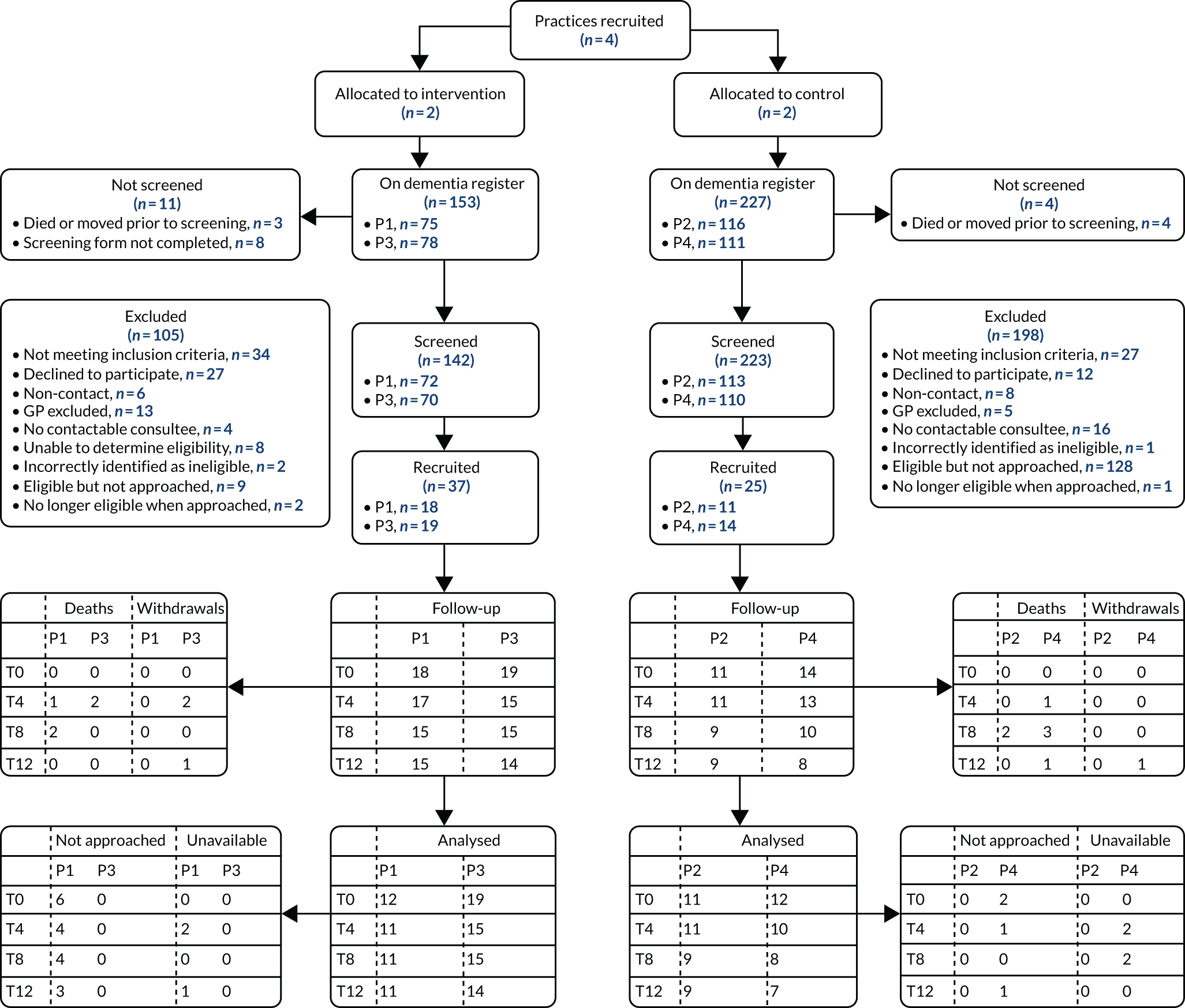

The strategic focus of the intervention could potentially lead to changes in general practices, local care homes and joint working arrangements with other professionals. Because these changes would affect all participants regardless of their allocation, randomising individual participants was not appropriate. Therefore, we used a cluster design, with clusters comprising individual general practices. Each cluster contained two general practices from North East England, one of which was allocated to receive the intervention, whereas the other acted as a control, providing usual care. The trial methods are described in full in Appendix 4, Pilot trial methods, including key areas from the relevant reporting guidelines. 124–127 Details of approvals and trial management by the Newcastle Clinical Trials Unit are provided in Appendix 4, Trial management. Data collection tools (e.g. activity logs and topic guides) are available in Report Supplementary Material 1.

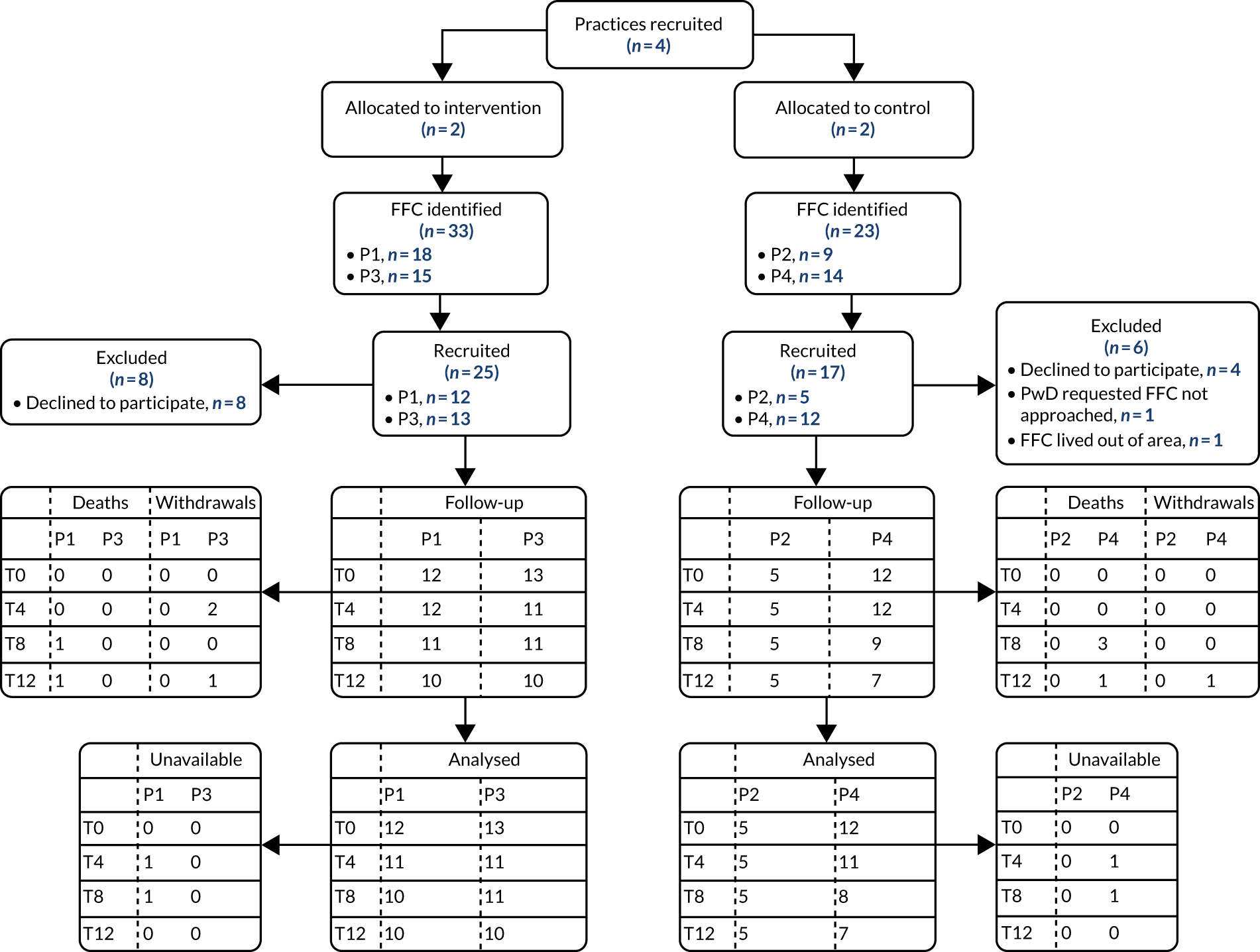

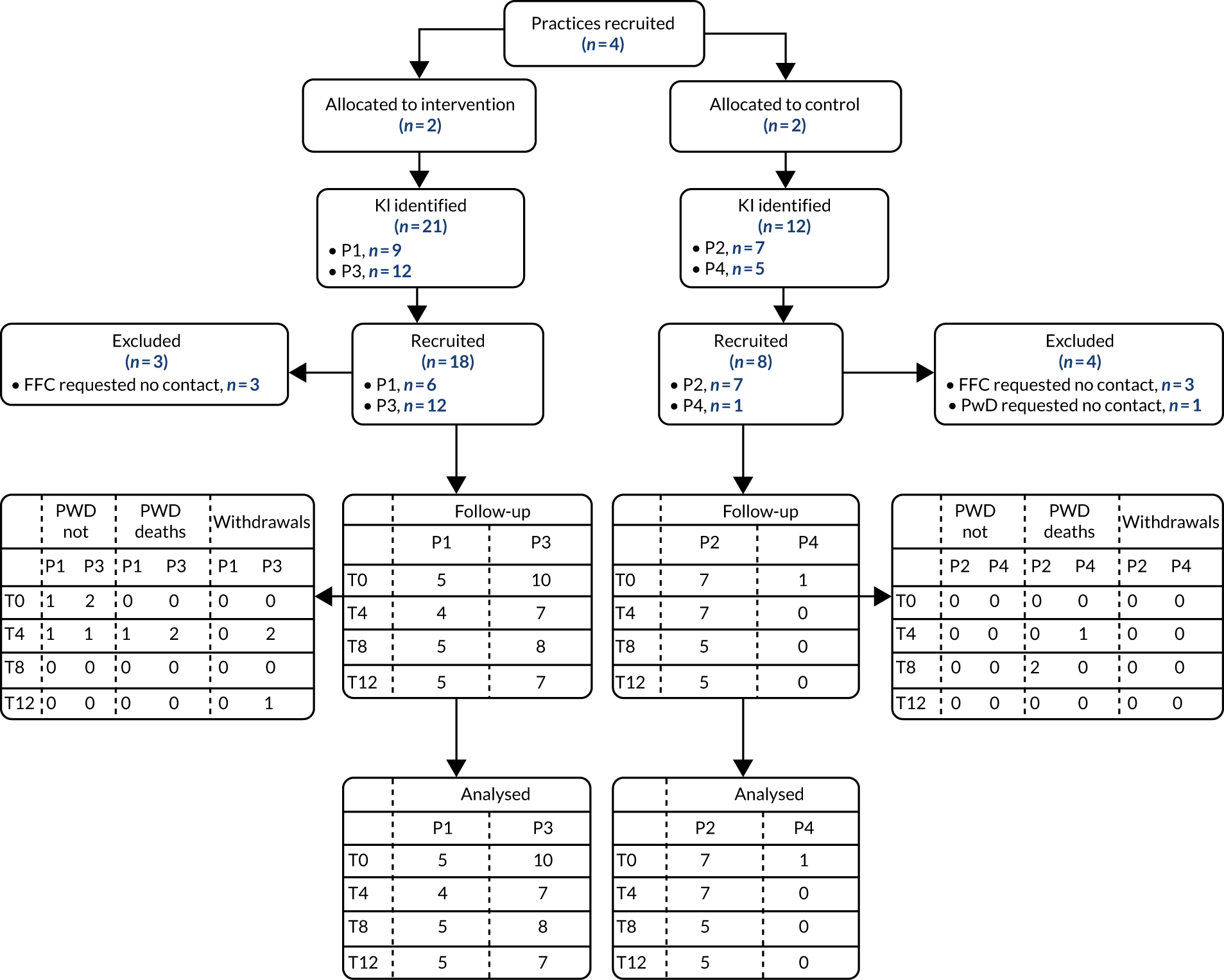

Recruitment

Allowing for 10% attrition, we aimed to recruit a total of 66 people with dementia, to meet the recommended minimum sample size of 30 participants per trial arm. 128 To test the feasibility of recruitment, we aimed to recruit at least 11 people with dementia from each practice. People with dementia were initially identified from the practice dementia register and were screened by a GP to ascertain whether or not:

-

they had been diagnosed within 2 years (hereafter termed ‘recently diagnosed’)

-

they were on the palliative care register

-

they were thought to be approaching EOL, as judged by the question ‘Would you be surprised if this patient were to die in the next 12 months?’129 (hereafter termed ‘potentially approaching EOL’).

Those on the palliative care register were assumed to be approaching EOL and were, therefore, combined with the third group. We anticipated that the intervention would focus on future care preferences with the recently diagnosed group and on the co-ordination of care and supporting non-specialists caring for those potentially approaching EOL. Full eligibility criteria are provided in Appendix 4, Pilot trial methods.

Following screening, selected eligible participants were sent a participant information sheet (PIS) giving them the opportunity to opt out of further contact. The remainder were contacted by a member of the practice team to seek verbal consent to pass their contact details to the research team. The researchers then telephoned potential participants to discuss the study further, and, if appropriate, arranged a home visit to take formal consent and complete the baseline outcome measures. We followed the provisions of the Mental Capacity Act 2005130 for those people with dementia thought to be unable to give informed consent; in such cases, we approached either a personal or a nominated consultee.

Although not essential to participation, for each person with dementia we sought to recruit a family carer and, for those living in care homes, a key informant. They were identified by the person with dementia, the general practice or the care home managers. Family carers and key informants were provided with a PIS, then followed up by the research team, as described previously. We analysed the numbers of eligible participants seen over the recruitment period, and the resulting rates of recruitment, and retention, both by intervention arm and by practice.

Process evaluation

Although the primary focus of the process evaluation was on the implementation, feasibility and acceptability of the intervention, it also provided insights into recruitment and outcome measures. The consent form for people with dementia, family carers and key informants asked if they were also willing to participate in the process evaluation. Additional health and social care professionals for the process evaluation were identified through the DNSs, lead GP and/or practice manager and non-participant observation. The principles of purposive sampling100 were used to obtain a maximum variation sample of people with dementia and family carers in terms of demographic factors, social arrangements, stage of dementia and types of engagement with the DNS. Health and social care professionals (e.g. social workers, members of community palliative care and mental health teams, home care and care home staff) were sampled in terms of level and type of involvement with the DNS. We also interviewed both DNSs at different time points during the study and members of the supervisory team.

All potential process evaluation participants were sent a PIS and followed up by the researcher, and consent was sought prior to data collection. People with dementia who lacked mental capacity to consent, as judged by the researcher and in line with guidance,130 were eligible to participate in observation.

Interviews with professionals were informed by NPT,114 for example by asking about whether or not and how the SEED intervention was distinct from existing services, whether or not and how host general practices supported the DNSs, skills displayed and required by the DNSs, and ways in which the intervention evolved over time. All interviews and informal discussions covered selected areas from the following list, tailored for different types of participant:

-

recruitment processes

-

views on outcome measures and perceived impacts

-

feasibility and acceptability of the SEED intervention

-

fit with existing services

-

factors influencing implementation.

For the process evaluation, we continued data collection until data saturation was reached; we estimated that this would be achieved with up to 10 people with dementia, 15 family carers and 30 professionals.

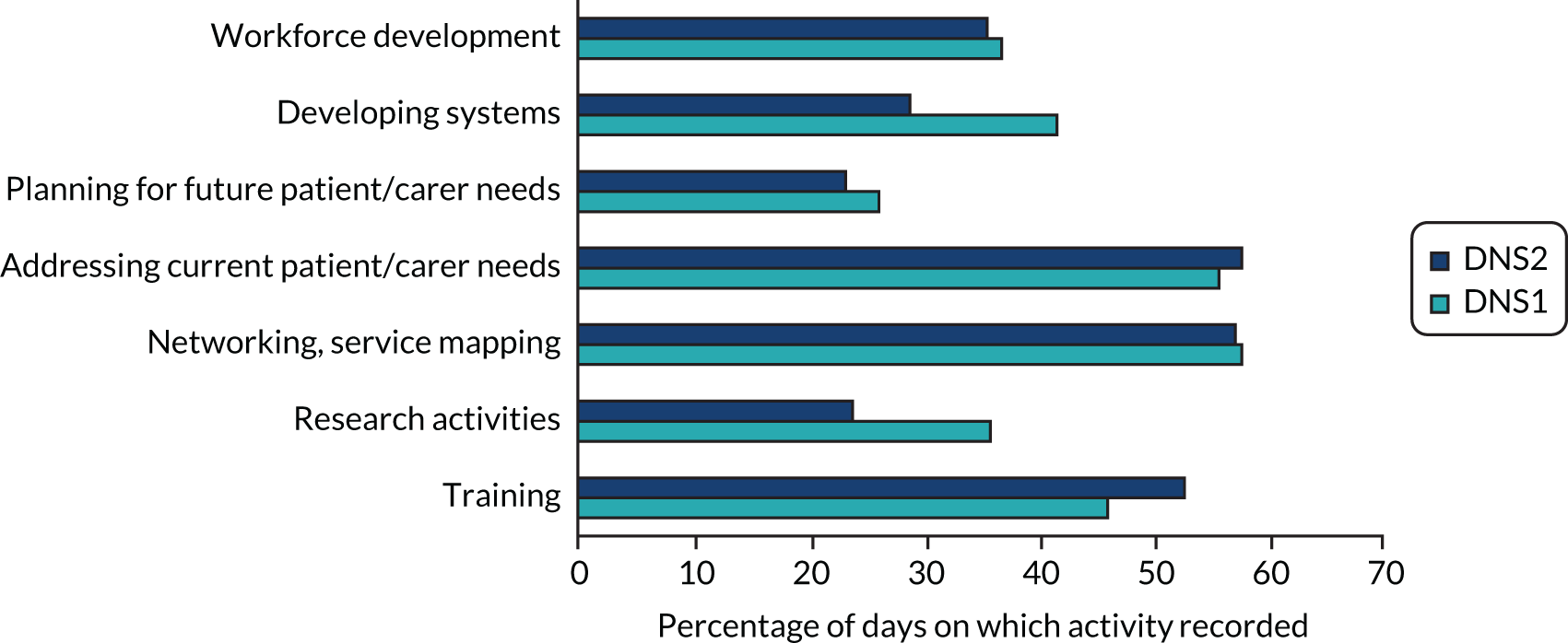

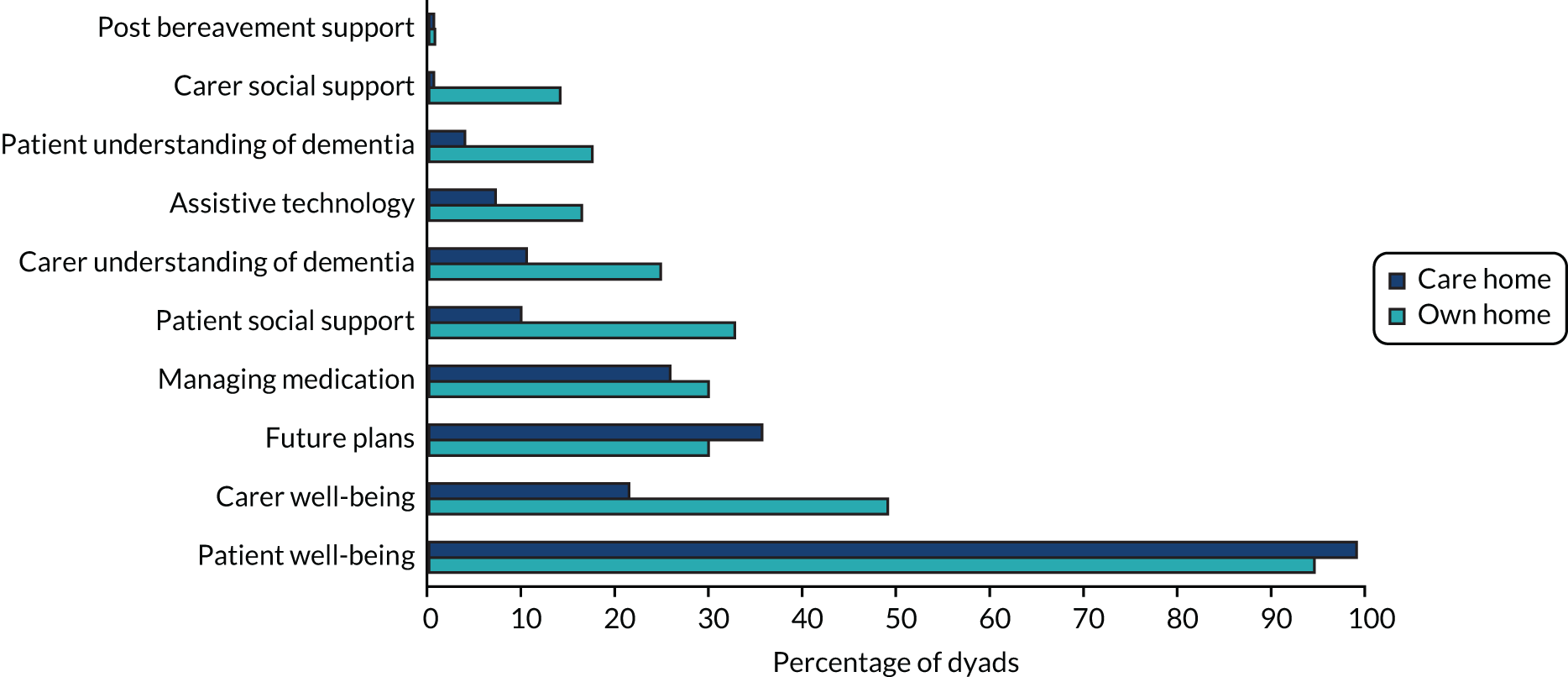

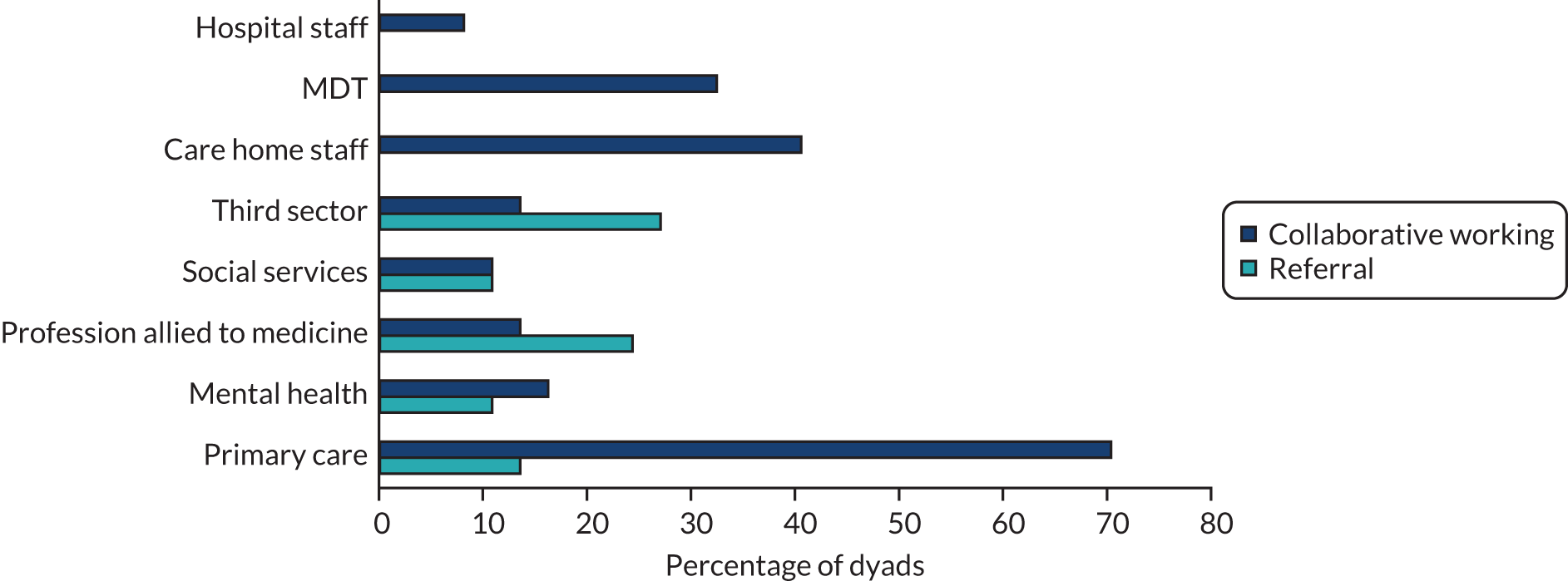

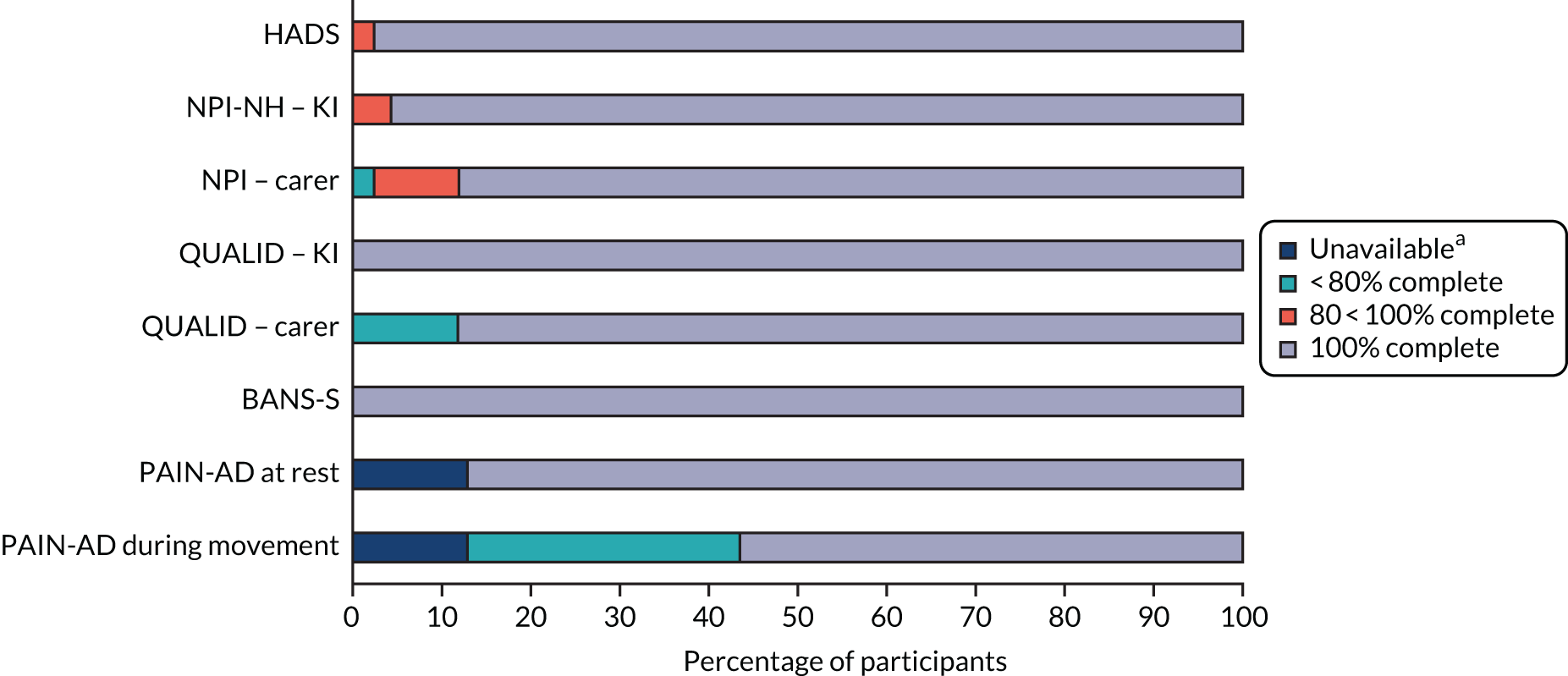

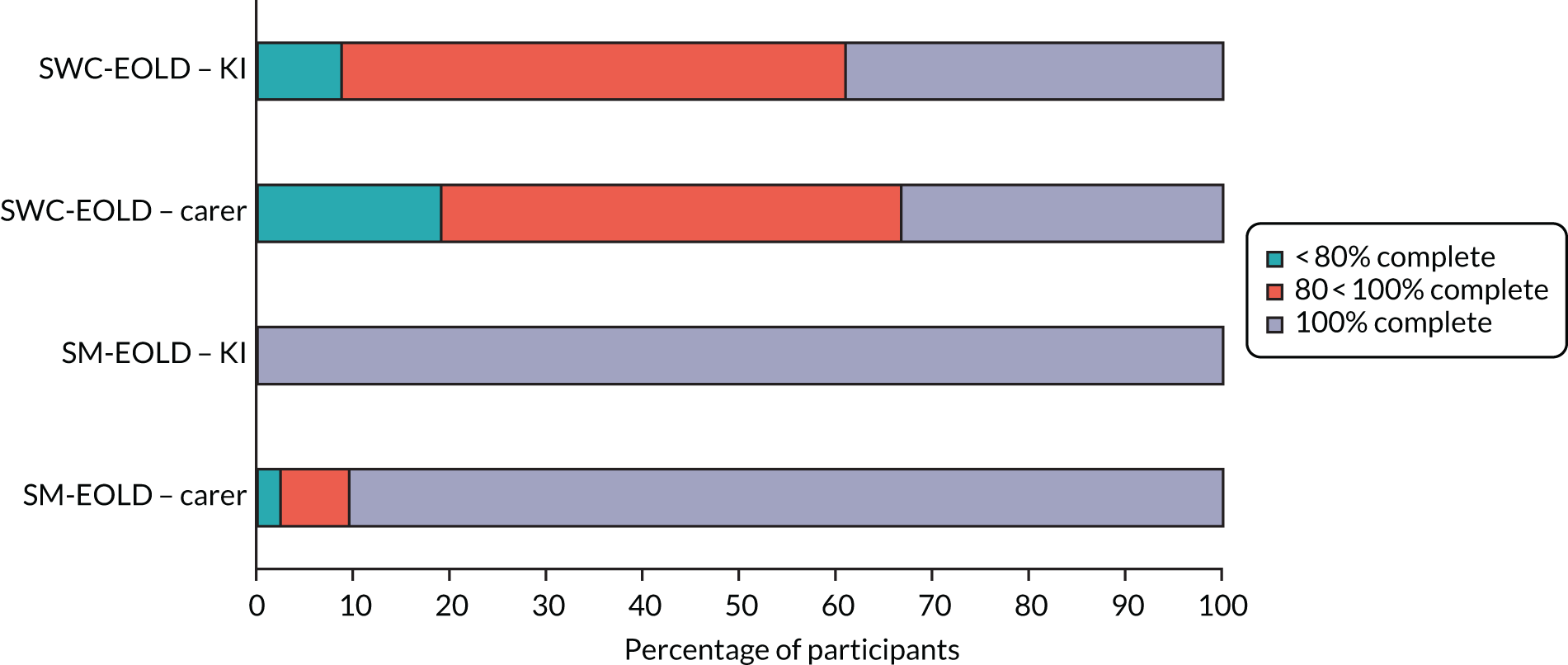

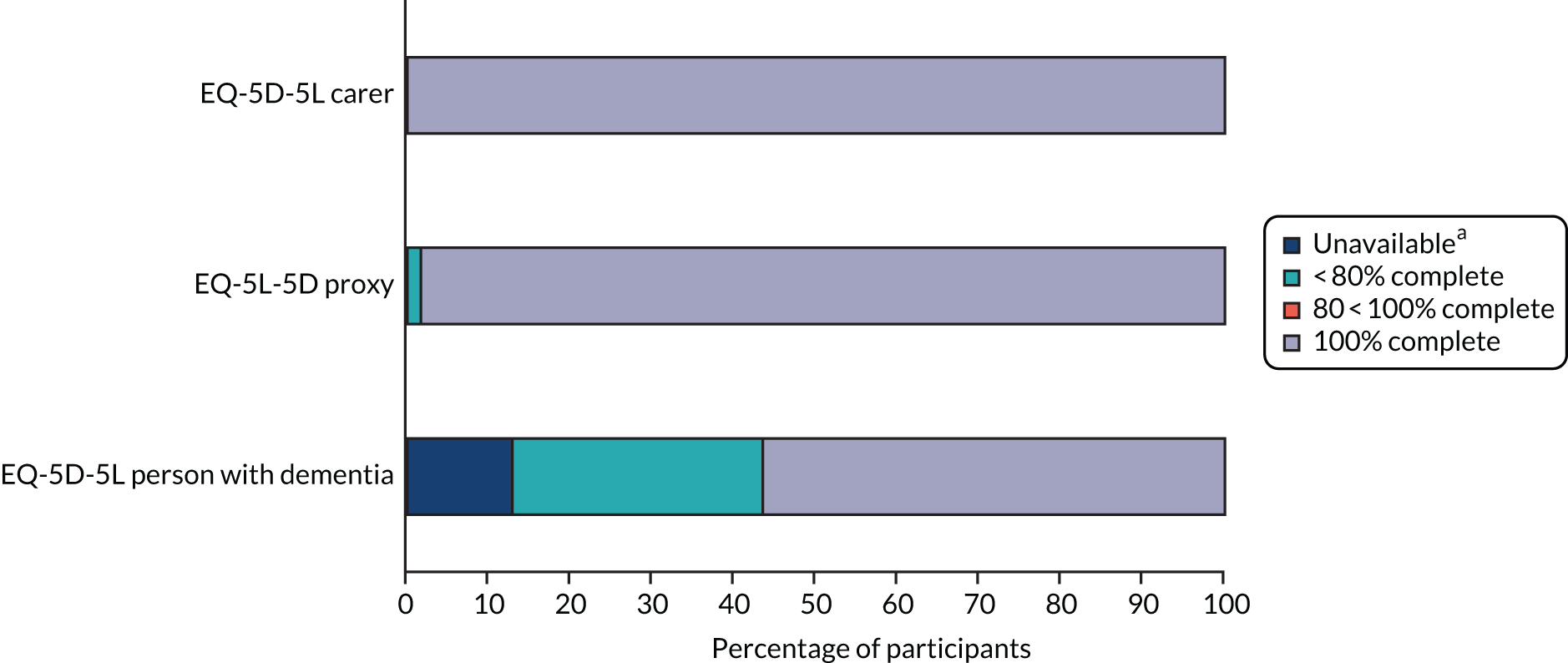

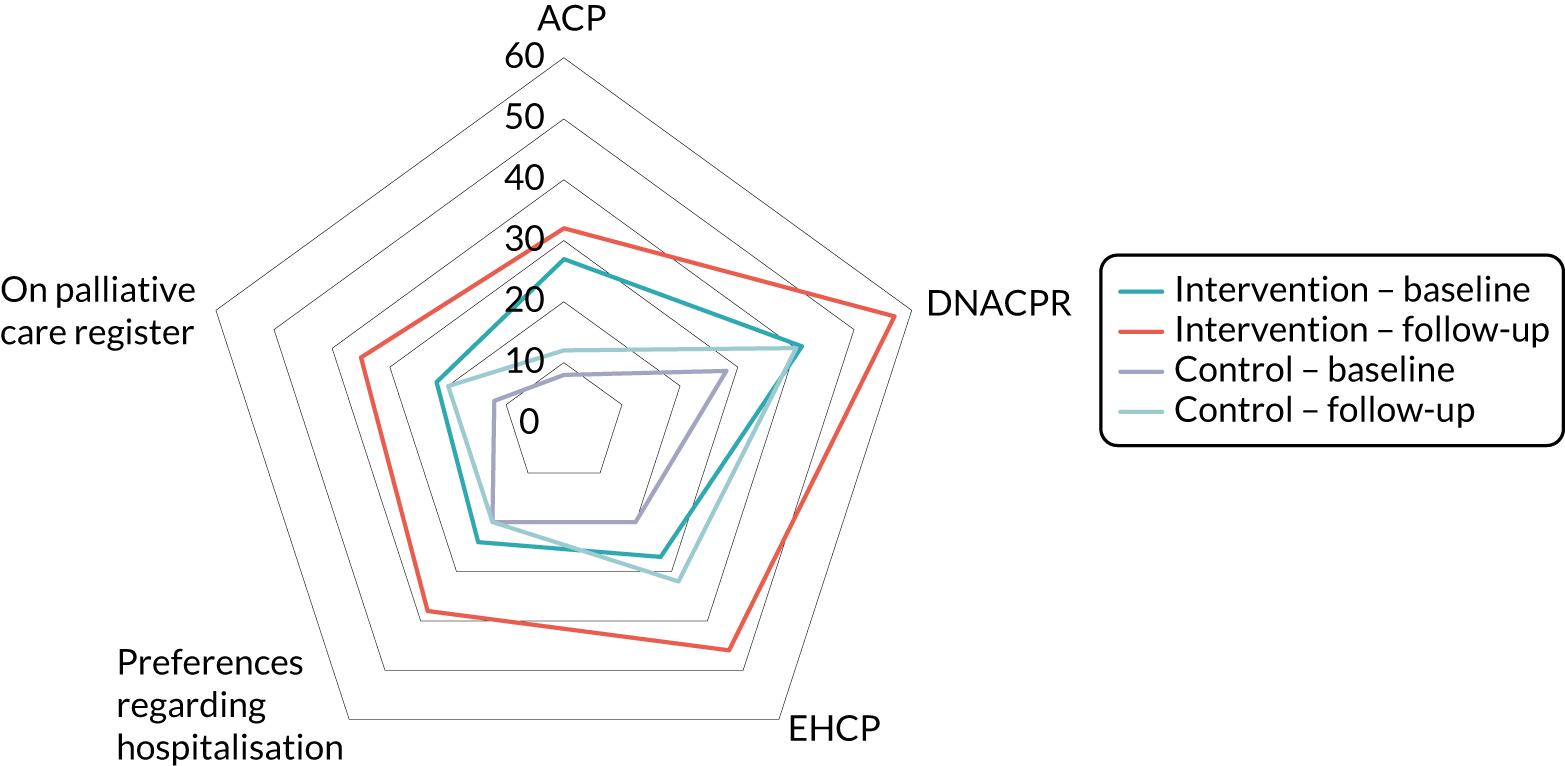

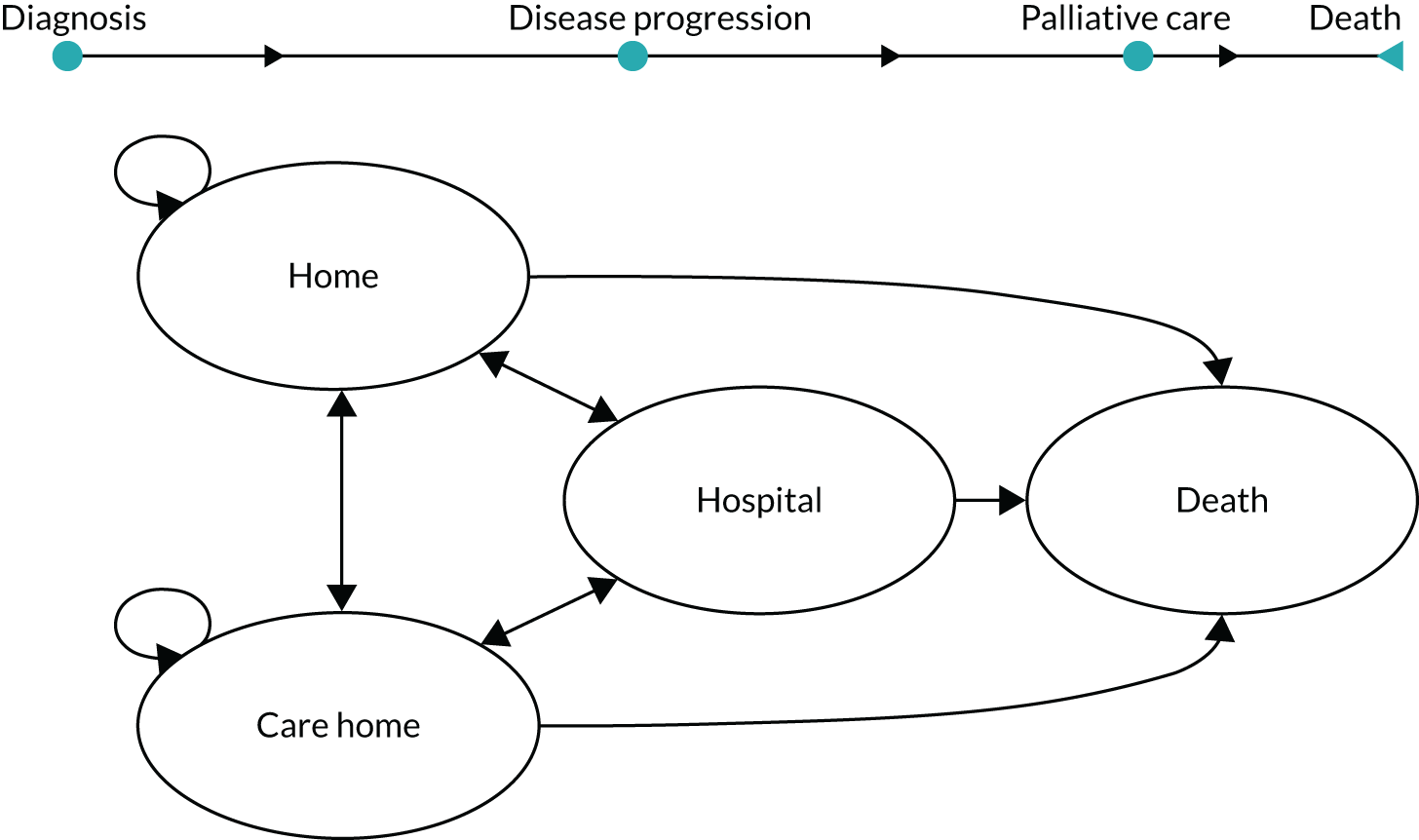

We also captured intervention delivery through intervention supervision and activity logs (see Appendix 4, Delivery of the SEED intervention). Initially, the DNSs kept weekly activity logs using a predefined list of categories. As the role evolved, additional activity logs were introduced to capture, in more detail, interactions with people with dementia and family carers, care home staff and other professionals.