Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by PGfAR as project number DTC-RP-PG-0311-12003. The contractual start date was in September 2013. The final report began editorial review in April 2020 and was accepted for publication in February 2021. As the funder, the PGfAR programme agreed the research questions and study designs in advance with the investigators. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PGfAR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2021 Clarkson et al. This work was produced by Clarkson et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2021 Clarkson et al.

SYNOPSIS

Background

‘Living well with dementia’

With the population ageing, dementia represents a significant public health and care challenge. 1 It is a major cause of disability and high-cost care in older people. 2 Finding cost-effective ways to improve care to people with dementia and their families has been termed the £20B question. 3 More recent figures suggest that the cost is around £24B a year in England. 4 Almost half of this cost is attributed to unpaid family care. Social care costs are three times higher than health-care costs. There is a growing body of research that addresses this question, including work on primary prevention (i.e. preventing the development of dementia) and secondary prevention (i.e. offering early treatment). 5 The immediate priority, reflected in policy,6 is one of helping people to ‘live well with dementia’, tertiary prevention, ameliorating difficulties and enhancing well-being. This translates to enabling those with dementia and their family carers to live as well as they can from a humane perspective.

Approximately 60% of people with dementia live at home. Helping people with dementia to live well necessitates establishing appropriate and effective home or personal support, including that from the NHS and social care (often in combination) and taking into account the wishes and views of carers. There is insufficient overview of the different forms of support available, including their relative effects and cost-effectiveness. 2 Studies of psychosocial interventions have identified potentially effective approaches,7 but there has been little or no work translating these into routine home support provided by NHS and social care organisations, nor in evaluating these. For care and support, the evidence base regarding how components (‘active ingredients’) of interventions could be combined into different models of support, and the likely costs and effects of adopting these, is weak compared with treatment for dementia. Translating this evidence into models of support that could benefit the NHS and social care is therefore compromised.

The clinical characteristics of dementia render individuals less able to care for themselves, more prone to emotional and behavioural problems and more likely to have poor physical health. 8,9 Support at home has to respond to these needs appropriately, including enhancing existing coping skills of people with dementia and their carers. Medicines management is one area that can be confusing and burdensome. The needs of individuals and families in accessing appropriate help over the course of life with dementia are changeable and diverse. 10 Support required also needs to be compatible with, and take heed of, existing support networks of people with dementia and their families. 11 Therefore, people with dementia require specialist support from a range of sources, including family, friends, professional health and social care agencies and also charitable organisations. 12

Service reviews have testified to a lack of appropriate home support services for people with dementia. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)/Social Care Institute for Excellence drew attention to the lack of robust data on the organisation and delivery of services for people with dementia and their carers, and the need for specialist support at home. The Association of Directors of Adult Social Services13 reported fragmented services and a lack of clarity about what preventative services are most effective. The National Audit Office10 highlighted the paucity of data about the costs and benefits of home support, causing local decisions on priorities to be ill-informed. We know very little of the range of specialist home care (domiciliary care) for dementia commissioned by local authorities and this is an under-researched area as far as costs and benefits of provision are concerned.

Evidence suggests that although specialist home support for older people with dementia exists in some localities, it is often underdeveloped. Older people with dementia receive a higher level of support than those without. However, this is often less than expected given their level of impairment. 14 Home support to those with dementia is often underdeveloped in comparison with services for older people generally. 15 This is despite the fact that specialist home support is perceived by service users, carers and care workers to deliver better-quality care than standard services. 16

Evaluating home support for dementia

Both the NHS and social care providers provide home support to people with dementia and their families. We appear to know more about unhelpful approaches to supporting people with dementia and carers at home than we do about effective forms of home support. Home support from social care (‘home care’) is provided largely in a ‘generic’ manner to older people, in general, rather than tailored specifically to the needs of people with dementia. This is largely task based, with little heed paid to the particular nuances of individual presentation of the condition,17 and may be indicative of the ‘old culture’ of dementia care. 18 Within the NHS, home support for people with dementia in later stages is provided via Community Mental Health Teams (CMHTs), for example through support workers. This appears not to be co-ordinated well and, in some areas, teams do not provide this support. 10 There appears, therefore, to be scope for more specialist and person-centred approaches to the care of people with dementia at home. The recent Lancet commission on dementia5 articulated principles for such approaches. There is no magic bullet. Interventions should be multicomponent and individualised to need, with support for carers to develop their own coping skills and to modify the environment around the person with dementia.

There are challenges to evaluating such approaches to home support, where they might exist. Existing meta-analyses of studies investigating home support to older people, in general,19–21 have argued for more precise descriptions of the actual components employed (i.e. ‘who, did what, where and how’). An analysis of such components, where these exist within more specialist models of support,22 would be beneficial. For example, for people in the early stages of dementia, early identification through memory clinics has been one development,23 but we know little of the way in which follow-up at home is conducted allied to this. 24 Preliminary studies testify to potential benefits of a home-based information and memory management component at this stage. 25 There is therefore a need for more robust evidence, building on this work. Research also suggests that specialist domiciliary care for people with dementia at later stages can reduce the likelihood of requiring, or delay entry into, long-term care26,27 and enable carers to care for longer. 26 For the NHS, reduction in hospital admissions, which can have a deleterious effect for people with dementia, may be one benefit of developing more intensive or specialist models of home support.

This National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) programme was framed in response to these challenges. It drew on and aimed to extend previous Department of Health and Social Care-funded work17 in marshalling evidence and primary research into the most cost-effective home and personal support approaches for people with dementia.

Effective home support in dementia care programme overview

The programme aimed to discern different models of home support, systematise them, survey their current operation in England and evaluate their cost-effectiveness in providing care for people with dementia and their carers. It also aimed to disseminate findings in the form of guidance for managers and commissioners.

The research was undertaken between September 2013 and March 2020. The main output was to develop evidenced-based guidance on home support models for dementia care, with direct applicability by NHS trusts and partner organisations. Importantly, we included social care and the third sector. We aimed to understand the benefits of different forms of home support in terms of more efficient and effective care and how they might enhance the patient and carer experience.

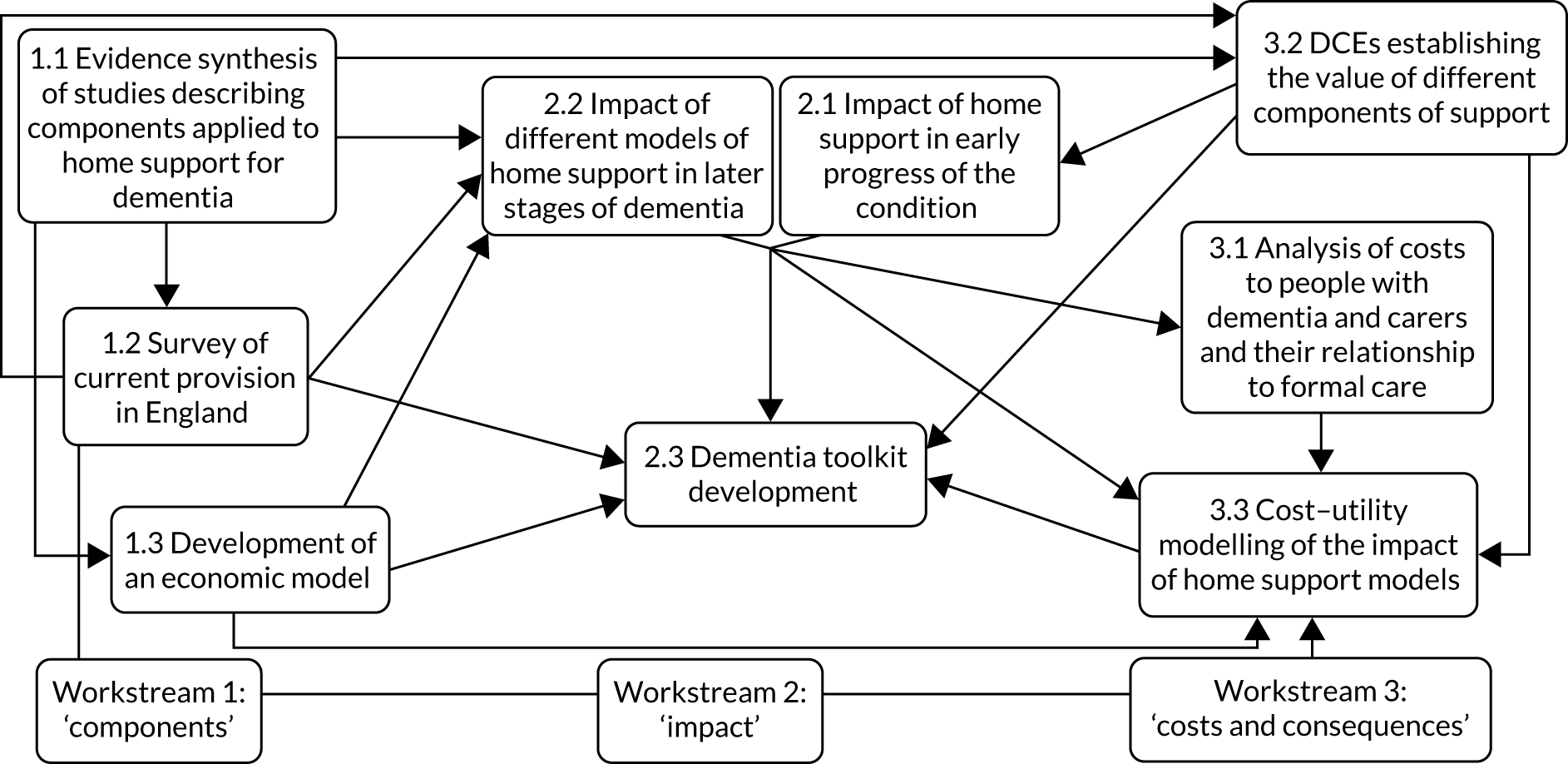

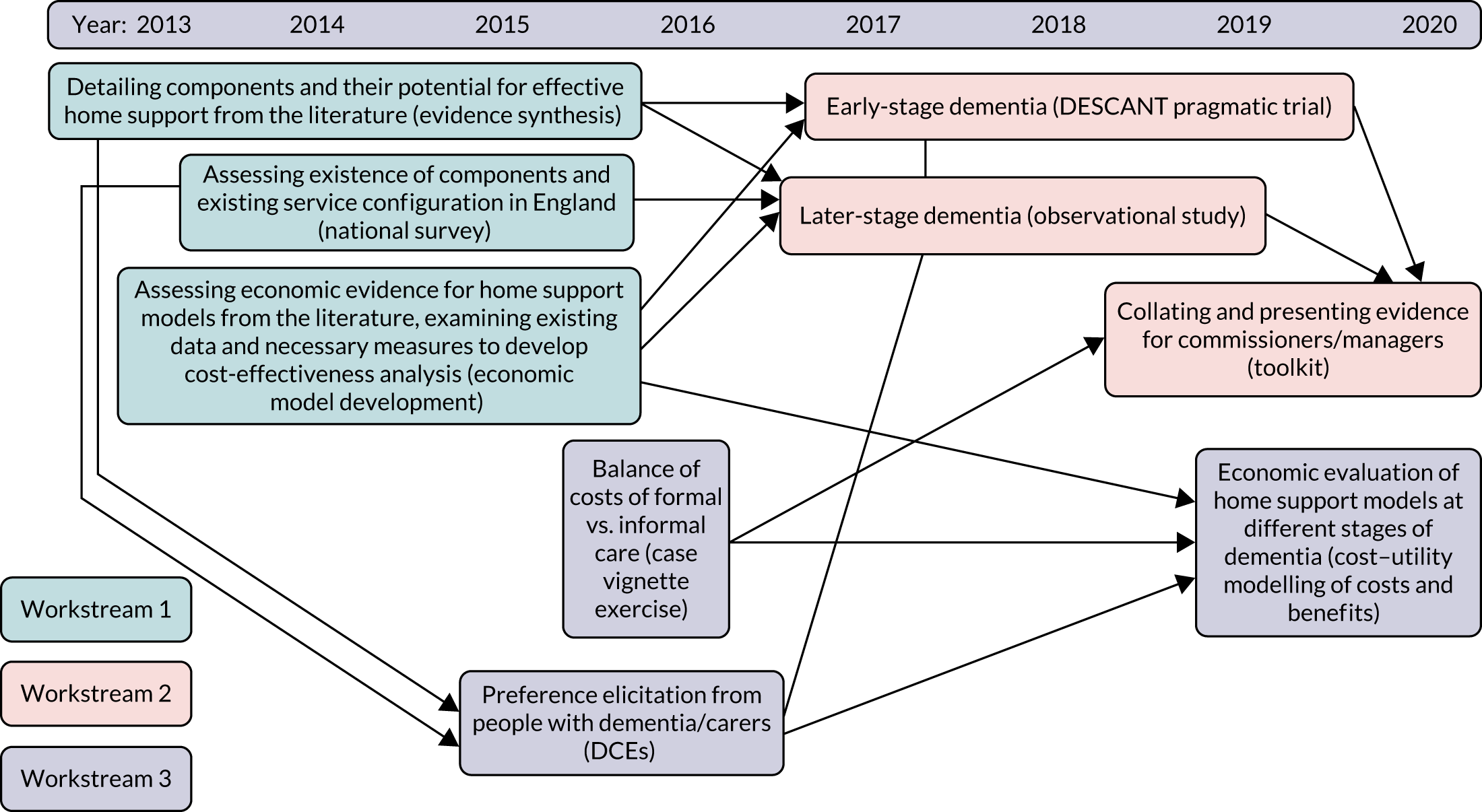

Addressing issues in developing more cost-effective home support approaches in dementia care required a multiphase work programme. Figure 1 outlines the research programme, its constituent parts (i.e. workstreams) and individual projects within them. The programme consisted of three interconnected thematic workstreams that contained nine projects designed to generate an integrated understanding of effective home support for older people with dementia. Each workstream sought to enhance evaluation of one of the three core features of effective home support for people with dementia: (1) the components of high-quality home support, (2) its impact and (3) the costs and consequences of service delivery. The workstreams were thematic and so individual projects within them were not undertaken sequentially. A research pathway diagram of the stages and development of the interconnecting workstreams and how they contributed to the whole programme is shown in Figure 2.

FIGURE 1.

Effective home support in dementia care: workstreams, projects and their relationships. DCE, discrete choice experiment.

FIGURE 2.

Research pathway diagram of stages and development of workstreams. DCE, discrete choice experiment.

Workstream 1

In workstream 1, we identified the components of home support that may benefit people with dementia and their carers through three projects. First, we undertook a narrative synthesis of two literature reviews (an overview of reviews and a systematic review). Second, we conducted a national survey of different components of existing provision in England. Third, we developed an economic model to inform analyses later in the programme.

Workstream 2

In workstream 2, we assessed the impact of two forms of home support. First, a new intervention that was funded at the inception of the programme offered people with early-stage dementia support and guidance on the use of memory aids through dementia support practitioners (DSPs) from memory clinics. We tested the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of this intervention in a pragmatic randomised trial and a process evaluation to investigate fidelity and practice. Second, we examined through a prospective observational study naturally occurring packages of home support for people with later-stage dementia and their carers. Again, we tested the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of these approaches, but this time through multivariate models of effects and costs. The evidence from both these primary studies and other evidence from across the programme was used to develop a toolkit to guide managers and commissioners in how best to provide home support.

Workstream 3

In workstream 3 we evaluated the costs and consequences of different approaches to home support through three projects. First, we undertook an analysis of the balance between costs of informal carer and statutory support by using case vignettes and costing methodology. Second, we examined the preferences of people with dementia and carers through two discrete choice experiments (DCEs) in early- and later-stage dementia. Third, we conducted economic modelling to bring together results from the two primary studies, above, and allied this with data from the economic development work in workstream 1.

Within each workstream, patient, public and carer involvement (PPCI) was crucial to the effective collection and dissemination of evidence. We worked together with established groups in framing the individual studies, designing methods of data collection and in the analysis, interpretation and dissemination of findings.

Programme management

A Programme Steering Committee oversaw the entire programme with a Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC) as a subcommittee, approved by NIHR. The Programme Steering Committee included members with expertise in patient and public involvement, old-age psychiatry, health services research, psychology and biostatistics. The Programme Steering Committee and DMEC met biannually in the early phases of the programme and then maintained e-mail and telephone correspondence once the trial on the programme was underway. A PPCI Reference Group was established and led by two of the investigators (BR and Jean Tottie). Varying numbers of members resident in North West England joined the group, dependent on changing circumstances, and met regularly (at least twice a year) with investigators BR and PC in Liverpool throughout the programme. A Lay Advisory Panel (LAP) of 20 members (carers of those with dementia) was established for consultation and comment, permitting a larger number of carers to contribute to the research across a wide geographical area. Members contributed by e-mail, although paper, telephone or face-to-face communication were also used. The LAP was aligned initially with Uniting Carers (London, UK), part of Dementia UK (London, UK), through the chairperson Jean Tottie, a programme investigator. However, from April 2015, this was hosted by Together in Dementia Everyday (TIDE) (Liverpool, UK), a national community interest company (and now charity), as Uniting Carers ceased operation. Operationally, the entire programme was managed through a Programme Management Group that comprised all investigators. This group met initially every 3 months and then communicated regularly by e-mail and telephone. A Trial Management Group at Manchester University (Manchester, UK) met monthly and liaised with the Clinical Trials Unit at Swansea University (Swansea, UK) [URL: www.swanseatrialsunit.org (accessed 5 April 2021)] and the DMEC on all management matters relating to the trial.

Summary of alterations to the programme

There were no alterations to the original aims and design of the programme. However, recruitment to the trial and observational study suffered from delays caused by Health Research Authority governance changes, recruitment difficulties with this population and staffing changes. We had two extensions to our programme, in May 2017 and November 2018, to deal with these delays. We adapted the original economic model structure, summarising the costs and benefits of home support approaches, from the initial model development (see Workstream 1, Development of an economic model). The form of the model changed in later work because of the lack of appropriate data with which to populate more complex mathematical models. We also took the opportunity afforded to us by the rich primary data from the trial and observational study to implement the model differently.

Workstream 1: identifying components of home support that may benefit people with dementia and their carers

Workstream 1, undertaken during the first 2 years of the programme (September 2013 to September 2015), had the following aims:

-

to investigate the evidence for effective components of psychosocial interventions for dementia in any setting (via an overview of systematic reviews) and to assess the extent to which they can be combined into multicomponent approaches to support people with dementia and their carers at home (via a systematic review)

-

to assess the presence of different components of home support in existing provision in England through a national survey of NHS and social care (local authority) services

-

to develop an economic model to inform later analyses in the programme.

Findings from the systematic reviews were brought together to inform other programme studies [i.e. the national survey and economic model development, evaluation of home support models in later-stage dementia (workstream 2) and DCEs investigating people with dementia and carer preferences (workstream 3)]. The national survey, in turn, informed the choice of which home support models to evaluate in workstream 2 and definitions of attributes for the DCEs in workstream 3. Likewise, the economic model development informed the methods used to evaluate home support models in workstream 2 and was consolidated in workstream 3.

Evidence synthesis of studies describing components applied to home support for dementia

We addressed the difficulties in eliciting firm evidence of the effectiveness of home support by evidence synthesis. This was a review with a specific purpose, that is to examine the components (‘active ingredients’) that may be responsible for the effectiveness of home support approaches for people with dementia or their carers. This informed later stages of the programme and enabled us to discern potential and existing models of home support and to systematise them. The overall aim of the review was to identify, describe, classify and analyse models for delivering home support to people with dementia and their carers in terms of their effectiveness, how and to whom effects are directed, and their cost-effectiveness and acceptability in ameliorating difficulties and improving well-being.

We undertook two systematic reviews to address this aim. First, an overview of systematic reviews to identify components of psychosocial interventions to people with dementia in any setting (e.g. care homes, day care or at home). Second, a systematic review of published studies of support interventions delivered at home, in which we used the components identified in the overview to discern distinct (multicomponent) approaches to home support. Full publications of this work were published in the Journal of Advanced Nursing (the protocol for the evidence synthesis in 201628 and the overview of reviews29 and systematic review30 in 2017). The outputs from these papers are in Appendix 1.

The overview of reviews drew on systematic reviews of randomised controlled trials in any setting. We undertook a narrative synthesis of the evidence because of the heterogeneity of interventions and outcome measures.

We searched CDSR (Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews), DARE (Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects) and EPPI-Centre (Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Co-ordinating Centre) between September 2013 and April 2014 for published systematic reviews in English. We appraised these reviews against Cochrane Collaboration levels of effectiveness. Components of psychosocial interventions were then identified along with their theoretical rationale. Components were defined as the ‘constituents’ or ‘active ingredients’ of interventions that may have an effect on quality of life (including neuropsychiatric symptoms), hospital admissions or time to care home admission. ‘Components’ were conceptualised as ‘common and distinctive techniques across evaluated interventions’. 66 We explored the findings from this identification of components with our PPCI group.

Thirty-six reviews7,31–65 were included in the overview, from 279 references. Over half (148; 53%) of excluded studies were of pharmacological interventions. Of the included reviews, 21 (58%) were of specific interventions (e.g. physical activity programmes), whereas 15 (42%) were reviews of a range of interventions. The reviewed interventions were set predominantly within nursing/care homes (n = 18 reviews) and not at home. The synthesis identified 14 components employed as part of interventions, nine for people with dementia and five for carers (see Appendix 2, Table 2). Our PPCI group articulated that these components could be summarised in a typology referred to as SITE (support, information, therapy or education). Components could reflect the general aims of support, information, therapy or education. For people with dementia, there was evidence of effectiveness for cognitive support, but less evidence for sensory stimulation, emotional support (i.e. reminiscence), behaviour management and daily living assistance [i.e. help with activities of daily living (ADL)]. For carers, there was evidence of effectiveness for behaviour management (i.e. education and training) and emotional support (i.e. psychotherapy and counselling).

Review limitations were that the detail available to describe interventions was variable. The content from which data on components were extracted was based predominantly on descriptions of interventions in the reviews and not in the primary studies on which they were based. Details of who provided the interventions were sometimes partial and there was a lack of evidence about whether or not interventions were undertaken as intended.

This overview provided evidence of several components that may be effective if integrated into home support interventions. However, most reviews investigated were undertaken for studies in settings other than at home. An important evidence gap was therefore identified that could guide practitioners (i.e. nurses, social workers, occupational therapists and voluntary sector support workers) who co-ordinate long-term support to people with dementia at home. This was taken forward to the next stage of the evidence synthesis to discern the clinical effectiveness of different multicomponent approaches to home support for people with dementia and their carers. This was a systematic review of studies, again with a narrative synthesis of the evidence owing to the heterogeneity of interventions, methods and outcome measures. Both quantitative and qualitative studies were included.

PubMed, CENTRAL (Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials), PsycInfo, CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature), Applied Social Science Index (ASSIA) and CSA Sociological Abstracts were searched for studies of support interventions delivered at home to people with dementia or their carers. Databases were searched from inception to April 2014, with no date restrictions to locate studies. Data across studies were synthesised using the 14 components of care for people with dementia and their carers identified previously. We grouped interventions to capture the most prevalent approaches and described them as models of home support, which relied on one or more of the components. We then applied effectiveness ratings to them. Qualitative studies were synthesised using key themes.

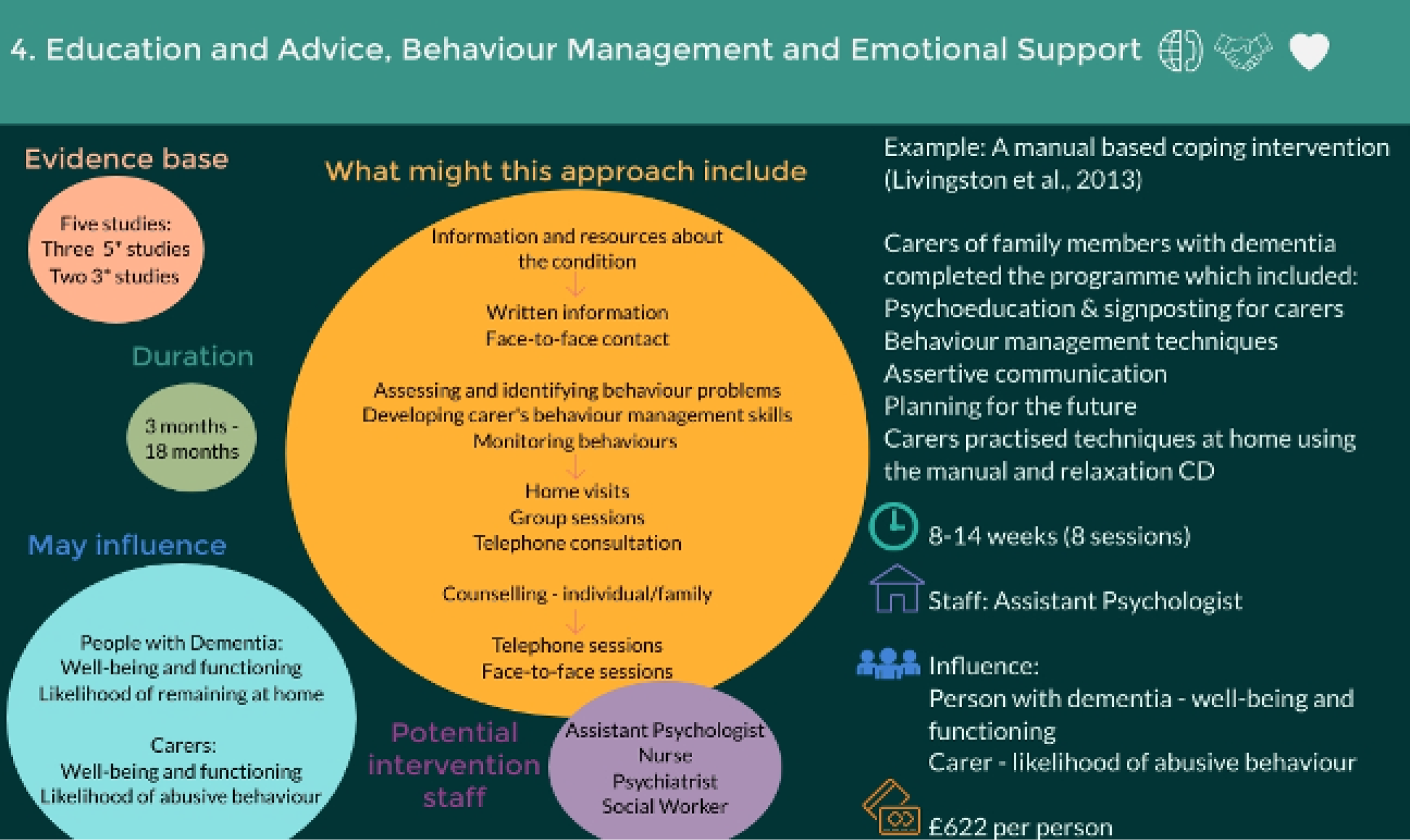

Seventy studies16,26,67–134 (including four qualitative studies) were included in the review from 603 references. There were 52 multicomponent studies for carers, and 15 multicomponent and 21 single-component studies for people with dementia. We identified nine home support models, seven for carers and two for people with dementia, covering 81% of studies (see table 4 in Clarkson et al. 30). Home support models for carers were based on five components: (1) behaviour management, (2) education or advice, (3) social support, (4) emotional support and (5) respite. Home support models for people with dementia were based on two components: (1) environmental modifications and (2) care co-ordination. Three components identified from our overview (i.e. daily living assistance, cognitive support and physical activity for people with dementia) were absent from these home support models. Models containing education, social support and behaviour management appeared most effective.

Limitations of this review were that the interventions presented in studies were not always described with sufficient detail. Data on the stage of dementia (i.e. early progress of the condition vs. later stages) were sometimes not available. The rating of effectiveness of the different home support models was challenging. The number of included studies (n = 70) made it difficult to appraise the effectiveness of each intervention, particularly when they contained multiple components. Data limitations from some studies, in particular, made it difficult to calculate effect sizes. This made it difficult to rate effectiveness comprehensively.

This review provided evidence of potential home support models for people with dementia or their carers. Nine models combined components in different ways. Predominantly, these were to provide support to carers, with environmental modifications and care co-ordination being central components of care delivered to people with dementia. Importantly, we identified a gap in the literature relating to components of daily living assistance, cognitive support and physical activity for people with dementia living at home. This informed the design of the primary studies in the programme (workstream 2). One of the primary studies, the Dementia Early Stage Cognitive Aids New Trial (DESCANT), was designed at inception of the programme, building on an existing Cochrane review (see Appendix 5), but other evidence from this programme review was used to guide the manual for support workers used in the intervention.

Survey of current provision in England

As well as the lack of sufficient evidence of different home support models, collated in our evidence synthesis, there is also little knowledge across the country about the availability of home support to people with dementia. In particular, there is a lack of knowledge about what components are provided by specialist health and social care (local authority) services. We addressed this by undertaking national surveys of NHS and social care services in England in 2014/15. These surveys informed later stages of this programme and contributed to the choice of which home support models to evaluate and the definitions of attributes for the DCEs. The aim of the survey was to assess the presence of different components of home support in existing provision for people with dementia in England and who provides them.

We undertook two surveys. First, to investigate staff roles and tasks provided in specialist NHS services, memory clinics and CMHTs providing early diagnosis and long-term support for older people with dementia in England. Second, to explore the commissioning of social care services for people with dementia living at home. The studies were published in the International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry (the NHS survey in 2018135 and the local authority survey in 2019136). The outputs from these papers are in Appendix 3.

The NHS survey135 investigated how staff in CMHTs and memory clinics support people with dementia in their own homes. We collected data in 2015 through a cross-sectional survey of the 68 NHS trusts that provide mental health services in England. The questionnaire classified home support interventions according to the SITE typology from our evidence synthesis (see Evidence synthesis of studies describing components applied to home support for dementia). We obtained approval for the study from the University of Manchester Ethics Committee on 24 June 2014 (reference 14209). We also received the support of the Research Group of the Association of Directors of Adult Social Services on 22 August 2014 (reference RG14–016). We posted or e-mailed questionnaires to NHS trusts’ chief executives and research and development departments to encourage completion and we registered the survey on the NIHR portfolio in March 2015.

We received responses from 51 (75%) NHS trusts that provided data on 120 (79%) of the 151 local authority areas in England. The support provided by CMHTs and memory services were categorised into 14 indicators of service provision within the SITE typology. Both CMHTs and memory services offered information and advice about dementia, access to relaxation and assistance in managing challenging behaviours. In particular, 110 (92%) of memory clinics and 108 (90%) of CMHTs provided advice on using memory aids. Limitations of this survey included the variation of response rates by region, the need for a single response for all CMHTs and memory clinics within each geographical area, and the danger that, although findings described NHS services for patients in detail, they may have understated services for carers.

The local authority survey136 explored the provision of social care support to people with dementia through a survey to commissioners in English local authorities. An exploratory cluster analysis of nominal data identified similar groups of local commissioning practices. 137 The survey, undertaken in 2014/15, received responses from 122 (81%) of the 151 local authorities. Respite care (in 83% of local authority areas) and day care (in 81% of local authority areas) were the most frequently reported services. Specialist home care, usually provided to people at later stages of dementia, was available in 28% of areas. This showed that joint working between health and social care organisations resulted in a greater range of services for people with dementia, complementing services available to all older people. It confirmed the significant role of health providers in the delivery of social care services for those with dementia. Limitations of this survey included that the data relied on self-reported activities of commissioners working within local authorities, the survey did not identify how specialist services for people with dementia differed from generic services offered to all older people and the potential for changes in practice since the data were collected.

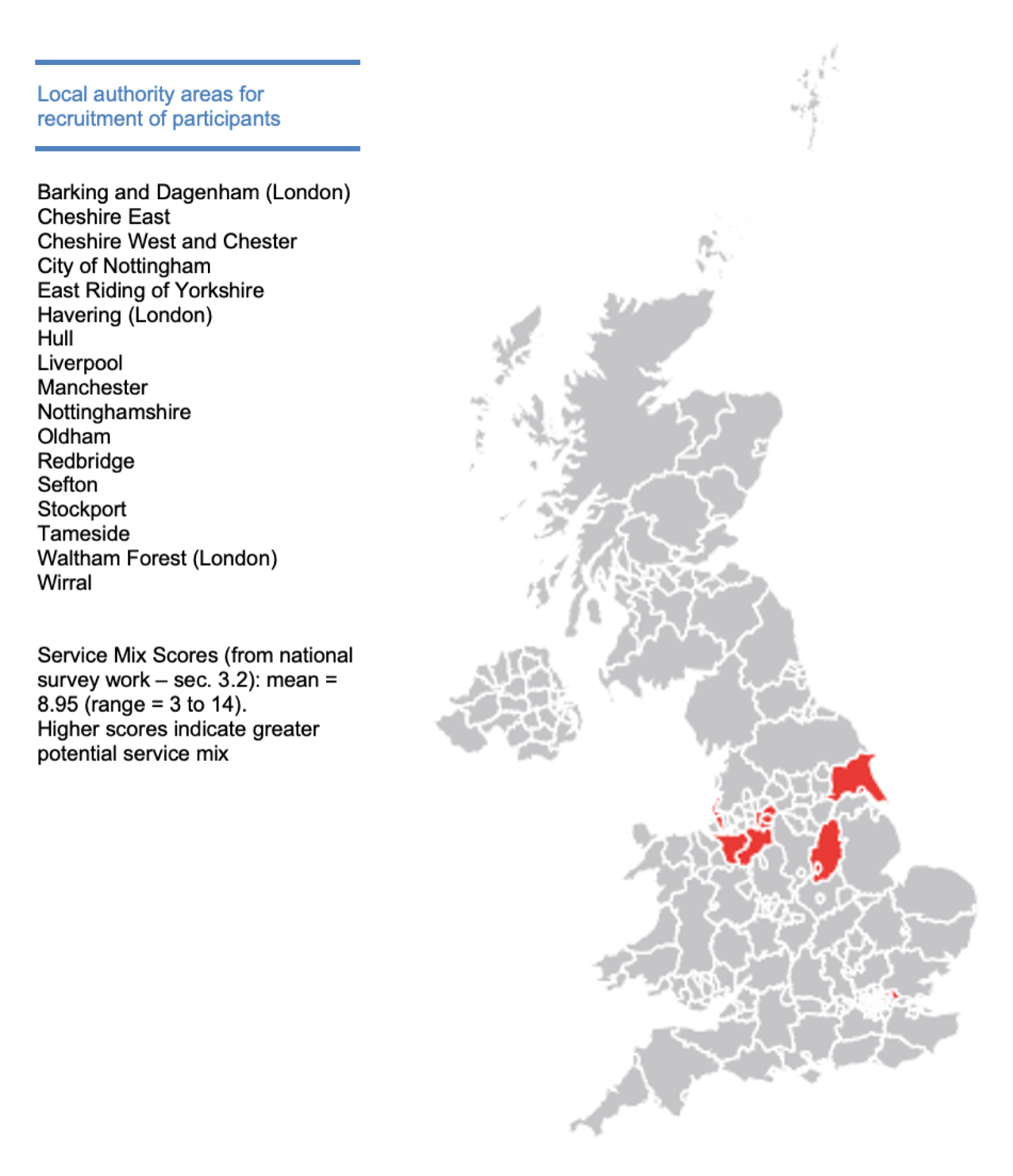

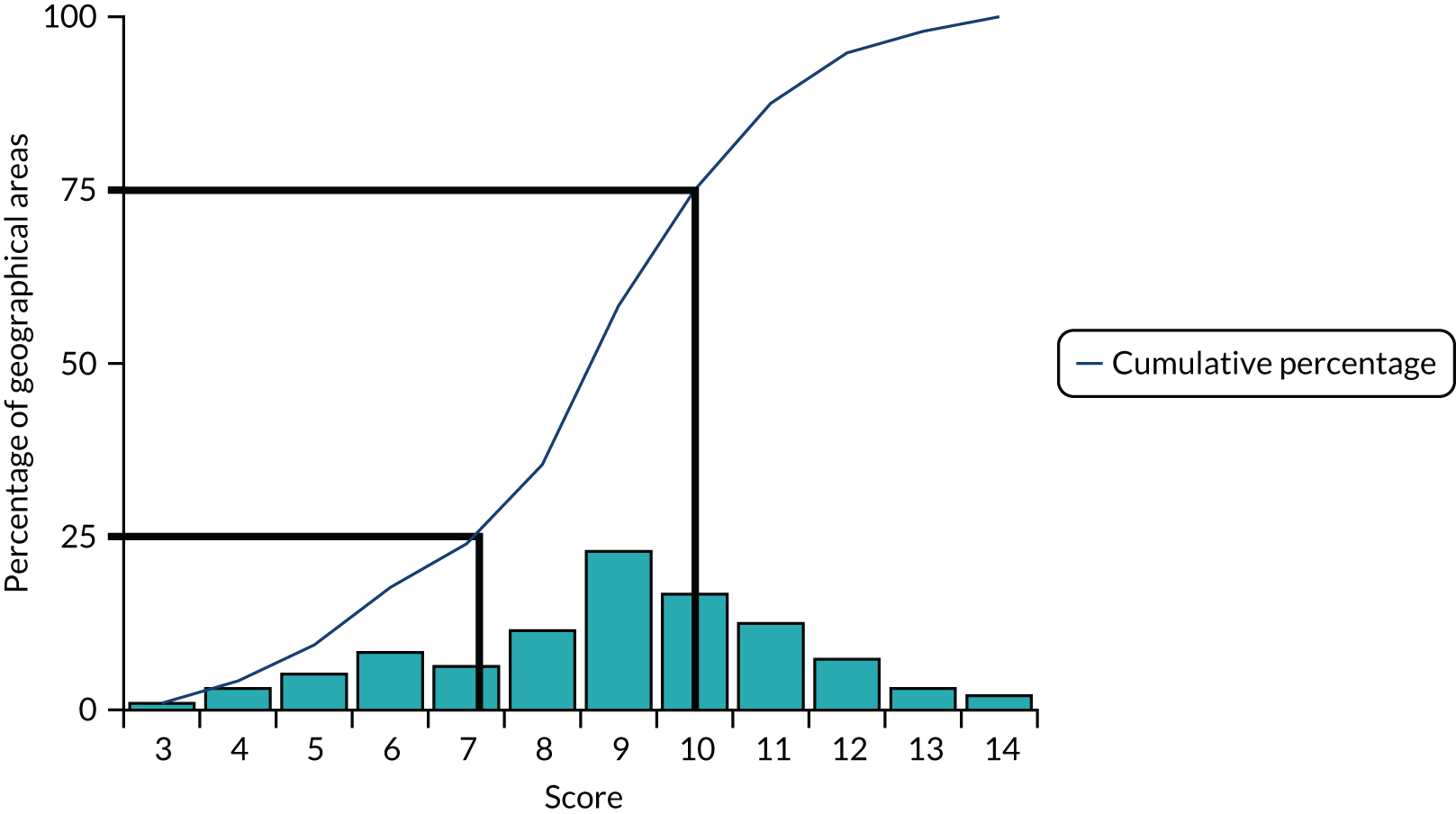

We analysed data from both surveys to produce a ‘service mix score’ for site selection in the observational study of later dementia (see Workstream 2, Effectiveness of home support models in later dementia). We analysed 43 matched local authority and NHS trust areas to create a set of 16 indicators (nine indicators about local authorities and seven indicators about the NHS) to reflect the broad range of services available. We favoured items that provided a good split of the data and for which there was face validity. We could then score areas on the presence or absence of each indicator so that the total score represented the scope for residents to receive a range of different services. No area scored the maximum of 16 points, and the minimum was 3 points. Most areas were in the middle of the distribution, with scores of 8 to 10 points. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test showed that the service mix score followed a normal distribution, with a mean of 8.9 and a standard deviation (SD) of 2.3.

Development of an economic model

As part of workstream 1 (i.e. gathering evidence of different approaches to home support), we began to develop an economic model. This was to be used to synthesise the economic evidence (costs and consequences) for different home support approaches in dementia gathered during the programme. We focused on (1) what data might be currently available concerning typical and potential packages of home support and (2) how we could extrapolate from these approaches to examine the consequences of subsequent pathways of care. In particular, we intended that this developmental work would frame the approaches and methodology used in a full economic model of dementia home support towards the end of the programme, drawing on data from our programme projects, particularly the two primary studies, projects 2.1 and 2.2, in early and later stages of dementia, respectively.

There were therefore two stages: (1) a systematic review to identify current evidence about the cost-effectiveness of home support services for dementia and (2) economic model development, examining the choice of model, the types of data to be used (and any data shortfalls) and what types of home support approaches could have potential benefits versus costs for testing later.

The systematic economic review was a review of full and partial economic evaluations using the NHS Economic Evaluation Database supplemented by additional references. Study characteristics and findings, including incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) when available, were summarised narratively. We appraised study quality using the NHS Economic Evaluation Database critical appraisal criteria and independent ratings, agreed by two reviewers. Studies were located on a permutation matrix, describing their mix of incremental costs and effects to aid decision-making.

Of the 151 articles retrieved, 14 studies met the inclusion criteria (eight concerning support to people with dementia and six concerning support to carers). Five studies were incremental cost–utility analyses, seven were cost-effectiveness analyses and two were cost–consequences analyses. Five studies expressed ICERs as cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) (£6696–207,942/QALY). In four studies, home support interventions were dominant over usual care. Two interventions were more costly but more beneficial and were favourable against current acceptability thresholds. Occupational therapy,138 home-based exercise139 and a carers’ coping intervention140 emerged as potentially cost-effective approaches for which there was better evidence. These interventions used environmental modifications, behaviour management, physical activity and emotional support as active components. There were limitations in the availability of cost or benefits data from which to judge some interventions. This review therefore signalled that more robust evidence was required to judge the value of these and other approaches across the dementia care pathway. This work was published in Value in Health in 2017. 141 The output is in Appendix 4.

A small project team was responsible for the development of the economic model. We concentrated on characterising ‘care as usual’ for people with early- and later-stage dementia, respectively, as a yardstick for the relative effects of a range of models of home support. 142 Our PPCI LAP commented on care at different stages of dementia and the range of different services available. This assisted in establishing what characterised usual care for people with dementia and their families and our search for data to inform this in economic analysis. One conclusion was that usual care varied, both by geography and by dementia stage. Our decisions on the choice of model were informed by existing guidance. 143 We reviewed discrete event simulation models,144,145 which concentrate on sending virtual cases through the care system and analysing the costs and consequences of them receiving different combinations of care. However, we decided, after testing a selection of data from the economic review in a discrete event simulation model, that this model form was too complex to estimate from the data available. There were insufficient data from other sources (e.g. national reports and guidance) to populate more complex decision-analytic models. There were data on service receipt and costs from some studies, but a lack of longitudinal data, particularly on health-related quality-of-life outcomes. This also meant that it was not feasible to model longer-term changes in resources and outcomes for dementia care in our subsequent work. Therefore, we decided to rely on primary data from the two studies, projects 2.1 and 2.2, later in the programme. We concentrated on ensuring that data collection instruments for these studies included the necessary information to generate data for modelling costs and benefits. Cost data needed to include resources consumed from multiple perspectives. These were the NHS, social care, voluntary sector organisations and people with dementia/their carers (i.e. the key actors affected by home support services). The instrument for collecting these data included questions to elicit these perspectives. The measure of benefit for the analyses was the QALY and measures to generate utility values to calculate QALYs were needed.

The eventual economic analyses (described in Cost–utility modelling of the impact of home support models and detailed in Appendix 11) comprised cost-effectiveness acceptability analyses to estimate the incremental cost per QALY gained and the probability that home support models were cost-effective compared with usual care. We aimed to assess this probability against a range of threshold values, reflecting the opportunity costs faced by the NHS and social care in deciding whether or not to fund any approaches to home support for which different organisations are responsible (i.e. whether or not the benefits accrued by new approaches offset the benefits forgone elsewhere). 146 The eventual model incorporated both probabilistic and deterministic sensitivity analyses to quantify uncertainty in the evidence and structural uncertainty. 147 These included varying the source of unit cost and direct cost data, perspective and scope of the analysis (e.g. including impact on families) and alternative measures of benefit. We decided on a time horizon for the primary economic analyses of 6 months.

Summary

Building up the evidence collated in this workstream led to the following summary conclusions. Most approaches where there was evidence of cost-effectiveness data concerned home support at moderate to severe stages of dementia and later in the care pathway. Only two approaches138,148 concerned people in early-stage dementia and it is here that approaches may offer more sustainable benefits to people in terms of them ‘living well’ with the condition. However, the economic evidence around these interventions was far from robust. Three approaches showed more positive cost-effectiveness evidence (i.e. occupational therapy, home-based exercise and a carers’ coping intervention). These approaches relied on the active components of environmental modifications, behaviour management, physical activity and emotional support. Better economic evidence of approaches in early-stage dementia, such as home-based cognitive support, and in late-stage dementia, such as palliative care, is required.

These conclusions were taken forward in designing and analysing our two primary studies in early- and later-stage dementia, which are summarised in workstream 2 in the next section.

Workstream 2: impact of different forms of home support

Workstream 2 was conducted throughout years 4–6 of the programme. We aimed to:

-

evaluate memory aids in early-stage dementia through a pragmatic trial

-

estimate the effectiveness of different emerging models of home support in later-stage dementia

-

disseminate evidence-based guidance through a toolkit developed in one trust area and roll out with commissioners, managers and practitioners.

Effectiveness of home support in early dementia: the DESCANT

Building on the results of our evidence synthesis (see Workstream 1, Evidence synthesis of studies describing components applied to home support for dementia) and economic review (see Workstream 1, Development of an economic model), we identified evidence gaps for the home support of people with early-stage dementia. There was existing preliminary evidence for the potential of memory aids in this population and in our original programme plan we sought to evaluate the success of a novel home-based cognitive support intervention. Our evidence synthesis helped in drafting a protocol that included provision of the aids themselves and also in providing guidance in their use. Despite being widely recommended in practice (see Workstream 1, Survey of current provision in England), the use of aids to assist cognition [e.g. calendars, clocks, whiteboards with electric timers and Post-it® (3M, Saint Paul, MN, USA)] dispensers by those diagnosed with early dementia has not been evaluated robustly. 149,150 We therefore undertook DESCANT, a multisite, pragmatic, randomised trial to evaluate the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of memory aids delivered by DSPs to people with early-stage dementia relative to treatment as usual (TAU).

We published the trial protocol in Trials in 2018. 151 This included the sample size estimation for the primary outcome of the ADL for people with dementia, as measured by the Bristol Activities of Daily Living Scale (BADLS),152 and a description of the intervention and of all trial procedures. The methods of the trial and findings on clinical effectiveness are summarised below. More detail on the trial rationale and findings and a link to the protocol paper are in Appendix 5.

Methods

We calculated that an analysable sample of 360 participants (180 participants in each group) across participating trusts would yield 80% power to detect an effect size (standardised mean difference) of 0.30 on BADLS when using a two-sided significance level of 5%. To allow for 25% attrition (estimated from previous similar studies) between baseline and final interviews, we aimed to recruit 480 randomised pairs of people with mild to moderate dementia and their identified carers. Our prespecified effect size, used in this calculation, corresponds to a 3.5 minimum clinically important difference on BADLS, with a SD of 8.7. 153

We successfully delivered the trial by recruiting participants (people with early-stage dementia and their informal carers) from memory services in nine NHS trusts across England and one health board in Wales. The trial received a favourable Research Ethics Committee opinion on 13/05/16 (reference 16/NW/0389). We negotiated processes to allow the trial to proceed, initially, in two host NHS trusts, with a recruitment start date of 25 November 2016. The first participant was enrolled on 6 December 2016. We then added sites in NHS trusts with the support of their local Clinical Research Network (CRN) teams (and the equivalent in Wales). The trial eventually used 10 local CRNs across England and Wales for consent and recruitment. Capacity to consent for people with dementia was determined by research nurses from the local CRNs who received specific training for research interviews and measures from the University of Manchester research team (i.e. the sponsor), in accordance with the principles of the Mental Capacity Act 2005. 154 Where people with dementia were judged as having capacity, we obtained their informed consent. If people with dementia were assessed as lacking capacity, we asked the primary carer or a personal consultee about the participant’s wishes regarding taking part in research and the primary carer/personal consultee was asked to provide consent. Consent was not assumed at follow-up and additional verbal consent was obtained and recorded at the follow-up interviews. We also recruited from the NIHR Join Dementia Research platform where people with dementia and their carers could register their interest in participating. We randomised participants (i.e. people with early-stage dementia and their informal carers) between the comparator group receiving TAU plus an existing dementia guide155 and the intervention group receiving TAU plus the DESCANT intervention. The rationale for adding a general dementia guide to TAU for the comparator group was informed by our public engagement work. It was thought that additional material, as well as usual care from memory services, would help encourage people with dementia and carers to take part.

In a comprehensive portfolio of outcomes for people with dementia and their carers, the primary outcome was the BADLS, measured at baseline and at 13 and 26 weeks (i.e. the primary end point) after baseline. Secondary outcomes for people with dementia were CASP-19 (Control, Autonomy, Self-Realization and Pleasure) (quality of life), CDRS (Clinical Dementia Rating Scale), DEMQOL (Dementia Quality of Life), ICECAP-O (ICEpop CAPability measure for Older people) (capability measure) and EQ-5D-5L (EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version) (both of which are health-related quality-of-life measures used in the economic evaluation), LSNS-R (Lubben Social Network Scale-Revised), R-IDDD (Revised Interview for Deterioration in Daily Living Activities in Dementia) and S-MMSE (Standardised Mini Mental State Examination). Secondary outcomes for carers were the GHQ-12 (General Health Questionnaire-12 items), which assessed their psychological health, and the SSCQ (Short Sense of Competence Questionnaire), which assessed their sense of competence.

To ensure that the intervention and methods worked in practice, we conducted internal feasibility and pilot studies with 40 participants recruited from the two initial host trusts in equal numbers, completed in August 2017. We adapted the ACCEPT (Acceptance Checklist for Clinical Effectiveness Pilot Trials) criteria156 to assess whether or not the intervention and trial protocol worked in practice and the DMEC accepted these criteria. The only adjustment suggested by the pilot was to reduce the length of follow-up from the initially planned 12 months to 6 months in the main study. This enabled us to meet recruitment targets and tackle the more realistic goal of improving BADLS scores over 6 months. Therefore, we were able to include the pilot data, adjusted to reflect this change, in the main analysis.

We manualised the intervention, which added specialist equipment and advice by trained DSPs to TAU. Training for DSPs was provided by the University of Manchester research team and investigator NK. The intervention provided up to 6 hours’ contact with a DSP for the person with dementia and the identified carer. DSPs designed and delivered a package of memory aids up to a maximum cost of £150 for the person with dementia to use at home. The package for each depended on their needs, preferences and existing use of memory aids. DSPs also advised on improving everyday memory skills and on using these aids to reduce memory lapses. The follow-up sessions addressed queries from participants and recorded whether or not aids were appropriate to identified goals and needs and used accordingly. A concurrent process evaluation provided further insight into the implementation and acceptability of the intervention and details of this are provided in Appendix 6.

Interviewers, trial statisticians, the University of Manchester research team, Programme Steering Committee and DMEC were masked to participants’ allocations. However, masking participants and DSPs was not possible. We took precautions to minimise the risk of bias,157 including randomising after collecting baseline data and asking research interviewers to record after each interview to which group they judged participants belonged and with how much confidence.

We undertook a qualitative analysis, embedded within the trial research interviews, by audio-recording the incidental conversations and comments made by a sample of participants. This analysis was published in Dementia in June 2019158 and the output of the paper is in Appendix 5. The aim was to collect contextual and conversational data from participants (n = 28) during structured interviews for the main study to provide evidence about their experiences and use of memory aids.

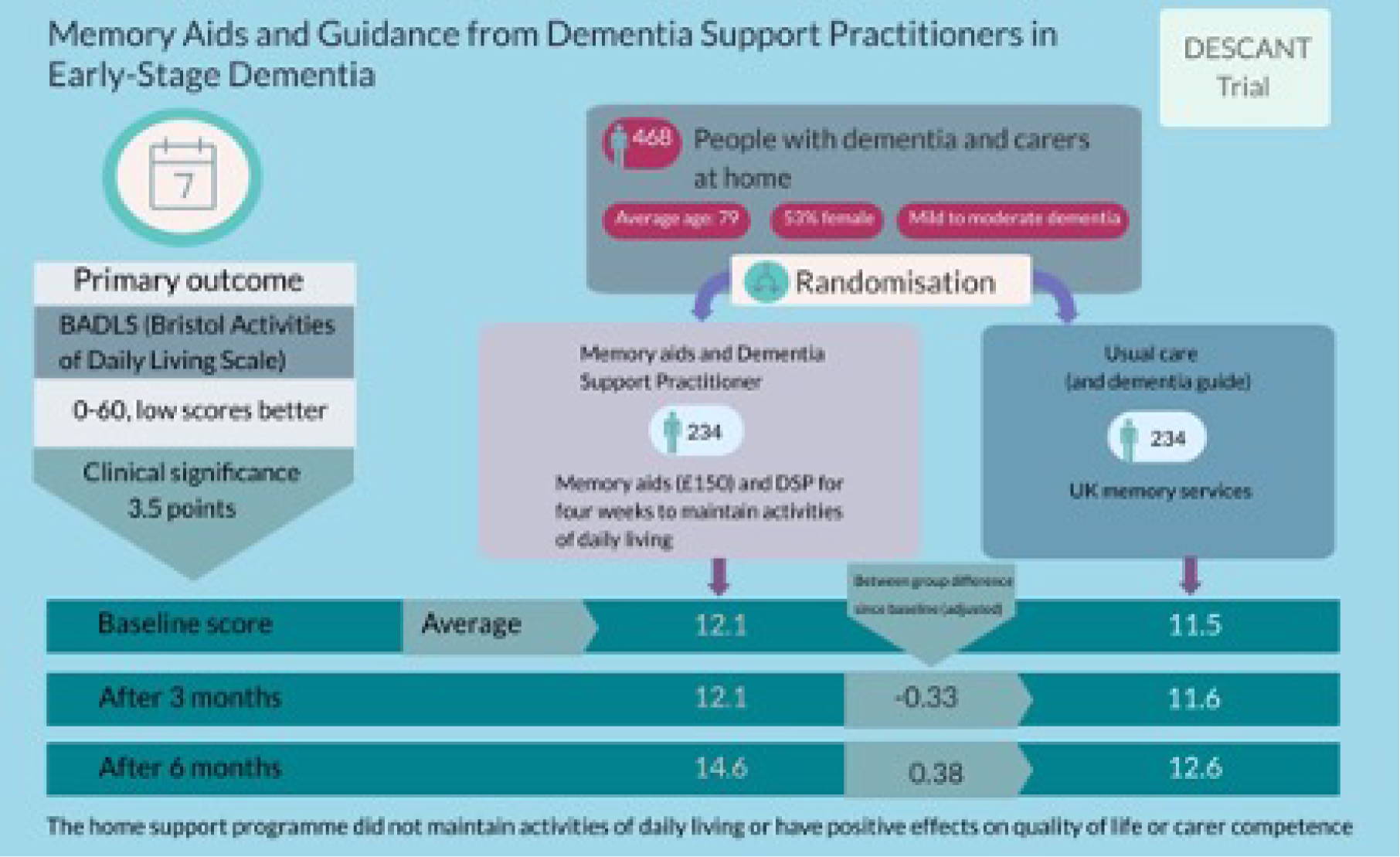

Results

We recruited and randomised 468 people with dementia and their carers at baseline, with 234 pairs in each arm of the study. This was slightly below the 480 people we estimated we would need to achieve our target of analysing 360 participants after allowing for the attrition characteristic of recruitment in this vulnerable population. Attrition at 6 months was in line with that expected (26% rather than 25%) and so the total number of analysable participants with data at baseline and 6 months was 347, also slightly lower than the target.

A multilevel mixed-effects model enabled us to adjust for differences at baseline, notably in age, sex and ethnicity. We used mixed models to examine treatment effect, as these take better account of missing data, particularly if missing at random, and explicitly account for correlations between repeated measurements within each participant. 159 This showed no significant differences between arms over time. Outcomes in both arms reflected increasing dependency by people with dementia, notably in the ADL. In particular, BADLS scores, which range from 0 to 60 with higher scores showing greater dependence, showed a mean difference of only 0.38 at 6 months, slightly but not significantly favouring the comparator group receiving TAU. The 95% confidence interval (CI) ran from –0.89 to 1.65 (p = 0.56). This (non-significant) mean difference of 0.38 was substantially lower than the smallest difference of 3.5 considered important for patient management (see Methods).

A total of 43 serious adverse events (SAEs) were reported for 42 people; one participant had two SAEs. There were more, but not significantly more, SAEs in the intervention arm (n = 24) than in the TAU arm (n = 19). We have no evidence that any SAE was related to the study intervention.

Our process evaluation (see Appendix 6) showed good engagement, with almost all participants completing the intervention, which was delivered as planned with packages individually tailored to participants. Misplacement of items and orientation to date and time were common areas of need. Memory aids that were frequently supplied or supported participants included orientation clocks, whiteboards, calendars and notebooks, as well as bespoke items. These findings suggested a potentially positive impact of the intervention on the well-being of people with dementia and their carers. We identified facilitators of implementation and wider roll-out, barriers to both and strategies to overcome challenges.

Findings from our qualitative analysis highlighted issues concerning the research interview itself and the recruitment of people with dementia to trials. The context and content of the interviews often posed difficulties for participants. People in early-stage dementia struggled with the structured and standardised nature of the research interviews, finding them a linguistic and cognitive challenge. Research interviews addressed sensitive issues that could be distressing for people with dementia and their carers and difficult for interviewers to manage. There was the added tension of the interviewer often having to negotiate the relationships between people with dementia and their carers, and determining whose perspective was being addressed by the questionnaire responses. We return to these issues in Conclusions from the whole programme.

Conclusions

Dementia support practitioners were successfully trained in the DESCANT intervention and delivered it to 98% of participants in the intervention arm. This finding was supported through qualitative findings, which show that implementation was successful and the intervention was well received. However, our main trial failed to show any significant effect of the intervention on the participant outcome measures. The intervention, although well received, did not maintain the ADL or improve other outcomes for people with dementia or carers. Within an expectation of increasing dependency in the ADL over time for dementia,160 any slowing of that dependency is a legitimate aim, with BADLS chosen as the primary outcome to test efficacy of the intervention. However, our intervention did not achieve that aim sufficiently.

Effectiveness of home support models in later dementia

As dementia proceeds in individuals, challenges to everyday living become more apparent and the role of non-health support takes precedence. Informal care by family and friends and social care commissioned or provided by local authorities begins to assume more importance. 161 Our evidence synthesis (see Workstream 1, Evidence synthesis of studies describing components applied to home support for dementia) found a paucity of evidence on home support models addressing daily living activities to help individuals and their families at this stage. We therefore undertook a naturalistic, observational study to discern the naturally occurring home support available in England to people in later-stage dementia and their carers. We then measured the relative effectiveness of these different models. An associated aim of this study was to examine whether or not the models described in the evidence synthesis, and the components thereof, existed in the real world of service delivery across local authority areas of England.

We published the full protocol for the study in International Psychogeriatrics in 2017. The protocol included the final sample size calculation for the primary outcome BADLS152 and a description of data collection and analytic procedures. The output of this paper is in Appendix 7. We summarise below the methods and results of the study in terms of effectiveness of different home support models in later-stage dementia. More detail on the background and findings are in Appendix 7.

Methods

This was a prospective observational study that examined outcomes for people with dementia and their carers after receiving different packages of home support. The outcomes studied were BADLS, DEMQOL, SSCQ and place of residence at 12 months. The analysis plan, contained in the protocol, was to discern the different combinations of home support services received by participants and to aggregate these into separate care package groups (i.e. naturally occurring mixtures of different components of support). 162

Our sampling strategy allowed for potential variation in service mix received by people with dementia living at home. We approached sites (local authority-designated areas) for recruitment with potentially different intensities of service provision, using data from our national surveys (see Workstream 1, Survey of current provision in England). The project received a favourable Research Ethics Committee opinion on 18 December 2015 (reference 15/NW/0822) but Health Research Authority approval was not given until 9 May 2016. Our planned date of recruitment therefore had to be delayed. We negotiated access to participants through home care and respite services, NHS CMHTs and local carer support services. We began recruiting on 10 May 2016, with the first participant enrolled on 31 May 2016. We collaborated with 17 local authority areas and their local CRN teams (following NHS trust boundaries not local authorities) for consent and recruitment. Consent procedures at baseline and follow-up mirrored those in the trial, described above.

The analysis deviated from that described in the protocol for creating the care package groups. We initially planned to use data reduction techniques163,164 on service receipt data to create the packages of care empirically. However, before the end of recruitment, we decided with our statistician that this approach would yield too many groups for analysis and would fail to reflect real-world service mix. This would have compromised the objectives of the analysis (i.e. to examine the approaches occurring naturally to support people in later-stage dementia and their carers at home). We therefore created groups substantively, investigating how the service receipt data mapped on to the approaches identified from our evidence synthesis (see Workstream 1, Evidence synthesis of studies describing components applied to home support for dementia) and how service combinations (‘care packages’) were configured in the real world, described by our PPCI group.

We evaluated the relative effectiveness of the care packages through a multivariate model. We used propensity scores165 to minimise the risk of confounding (i.e. the error of not accounting for variables associated with both receipt of a care package and outcomes). These scores combined the effects of baseline characteristics on receipt of different care packages into one composite measure used to adjust for this in the multivariate models. 166

We undertook an embedded qualitative analysis similar to that in the trial (see Effectiveness of home support in early dementia: the DESCANT) by audio-recording the conversations and comments made by a sample of participants. This analysis was published in BMC Geriatrics in 2019 and the link to the paper is in Appendix 7. Again, the aim was to collect contextual and conversational data from participants (n = 17 carers) during structured interviews. This provided evidence about experiences of the research process and of daily caring for someone with dementia at this late stage.

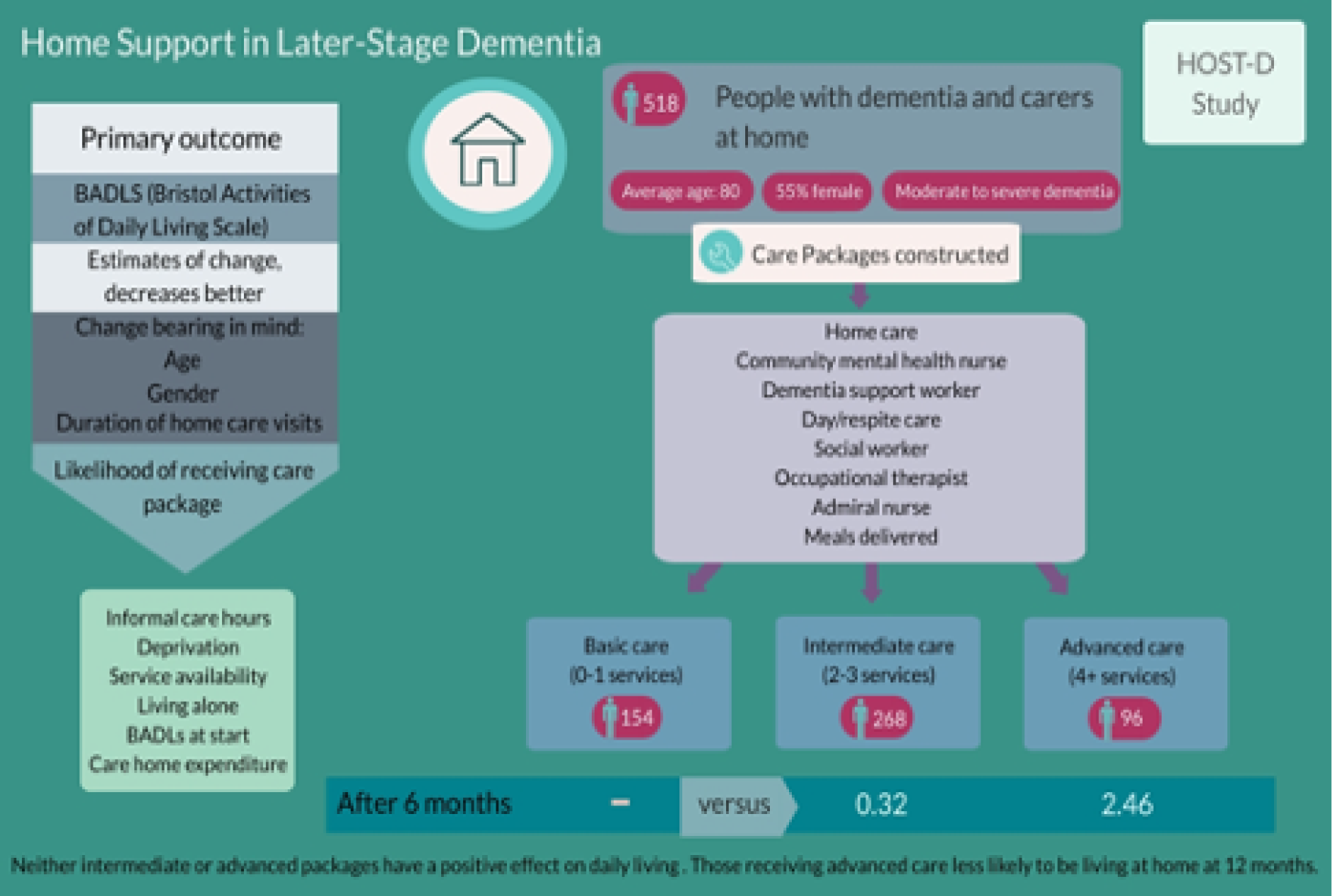

Results

We recruited 518 people with later-stage dementia and their carers at baseline, well above our target sample size of 400, which allowed for attrition. At 6-month follow-up, there was inevitably some attrition, with 389 participants (pairs of people with dementia and their carers) interviewed at both baseline and follow-up to provide data on circumstances, service receipt and outcomes. This sample with follow-up data was still above our initial sample size target of 310 people.

Creating separate care package groups from the data was a challenge. At baseline, service receipt differed between agencies and professional groups. Packages that grouped these data together, overlapped for many participants. This meant that packages including particular components, for example focused on social care or supporting daily living, were not distinct from other packages. Participants tended to receive these services, but also others that could have been grouped into other packages. Therefore, attempting to create distinct care package groups resulted in groups with fewer than 30 participants and the loss of those who belonged to no particular group. To simplify the eventual grouping of services into care packages relied on a measure of service intensity in line with that guiding our sampling strategy from the national survey. We used a subset of eight dementia-specific home support services to create ‘service intensity’ care package groups: basic care (none or one service), intermediate care (two or three services) and advanced care (four or more services). Effectiveness analysis through the multivariate models therefore examined outcomes for each of the intermediate and advanced groups, compared with a reference group of basic care. The models revealed no significant effects of the advanced or intermediate care packages on the primary outcome (i.e. BADLS) or secondary outcomes (see Appendix 7, Tables 8–11). However, participants with more home care visits were more likely, and those receiving advanced care were less likely, to be living at home at 12 months. Whether or not participants changed care package had no effect on these outcomes.

Conclusions

A complex picture emerged of the care packages received routinely by people with later-stage dementia and their carers across 17 areas of England. Home support mixed social care, NHS professional support and voluntary sector contributions, focusing on all components identified in our evidence synthesis for the person with dementia, with the exception of behaviour management. Although the analysis did not show evidence of effectiveness, the data enabled us to investigate the natural patterns of support and how it was targeted on the most vulnerable. The intensity of most people’s care packages did not change over time. Those that did change mostly decreased in care intensity. The study generated a large and comprehensive data set that could be used to examine naturally occurring support in this vulnerable group.

Toolkit to improve management and commissioning

Evidence from across the whole programme was included in the toolkit developed from 2018 to 2020. Its purpose was to present evidence from the programme in a way that was easily accessible to managers and commissioners. We extracted data from the projects across the programme and consulted stakeholders regarding content and presentation. The toolkit provides evidence to inform service specification and to redesign and benchmark practice. The toolkit is available in an accessible web format with the link: https://sites.manchester.ac.uk/home-support-dementia/ (accessed 6 April 2021).

The toolkit had six modules (Table 1). It was designed for the use of commissioners and providers within the statutory and non-statutory sectors, including:

-

Clinical Commissioning Groups (i.e. the NHS bodies responsible for the planning and commissioning of health-care services for their local area)

-

local authorities as commissioners of social care for older people

-

joint commissioners of older people’s services (i.e. commissioners whose responsibilities span Clinical Commissioning Groups and local authorities)

-

provider units within NHS trusts

-

adult social care providers within the statutory and non-statutory sectors

-

commissioners within provider organisations who assume a lead/strategic role in commissioning services within their own organisation and other providers.

| Module | Title | Data source (project number)a | Research question |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Scoping the evidence | Literature review (1.1) | What do we know? |

| 2 | Evaluating the service landscape | Survey of current provision (1.2) | What is the service landscape? |

| 3 | Bridging the memory gap | Trial of home support in early stage dementia (2.1) | What new evidence is there for commissioners and providers to help people in early-stage dementia? |

| 4 | Maintaining well-being at home | Study of impact of different models of home support in late-stage dementia (2.2) | What new evidence is there for commissioners and providers to help people in late-stage dementia? |

| 5 | Preferences for care and support |

Analysis of costs to people with dementia and carers (3.1) Establishing the value of different components of support (3.2) |

What services do consumers (patients/service users/carers) want? |

| 6 | Costs and benefits |

Development of economic model (1.3) Cost–utility modelling of home support models (3.3) |

What is the cost of improving care? |

A small project team, including a stakeholder representative, was responsible for developing the modules for the toolkit by reviewing relevant programme publications and findings, extracting salient data, presenting findings in an accessible format and reviewing each module. To enhance the accessibility of the research findings to commissioners and providers, the material was professionally written in ‘plain English’. Subsequently, a smaller project team designed a set of infographics and web-based tools through Visme™ [2021 Easy WebContent, Inc. (DBA Visme), Derwood, MD, USA] for the toolkit website. A full description of the design and development of the toolkit and a summary of the data within each module is in Appendix 8.

Workstream 3: evaluation of the costs and consequences of different approaches to home support

In this workstream, we aimed to identify the costs of models of home support to public agencies, people with dementia and carers, and their cost-effectiveness. We elicited data on costs and consequences through examining the preferences of staff, carers and people with dementia. This work supported the overall programme aim of examining the success of tertiary prevention for dementia care at home and maintaining well-being, if possible, by minimising people with dementia’s reduced function and ameliorating negative impacts (e.g. by reducing unplanned hospital admissions). Such actions are thought to reduce costs,167 but policy-makers need to understand the consequences for different parties of different forms of home support and their interactions with care provided by carers. To justify the NHS and social care providing more individually tailored care, improvements in the patient–carer experience is required. This workstream generated data on these issues and therefore enabled the economic model, already developed, to evaluate the home support models emerging from the programme.

Analysis of costs to people with dementia and carers and their relationship to formal care

We sought in this study to provide evidence about the transition from informal to formal home support at moderate and later stages of dementia. The relative balance between the costs of formal and informal care has been previously explored,168 but there was a need for evidence about the costs of home support models. This project aimed to do this through the participation of diverse groups of carers of people with dementia recruited via local voluntary organisations, and groups of professional staff in the host NHS trust. The research aims were to investigate which inputs from health and social care and which informal support carers and professional staff considered important to support people with dementia at home effectively. What are the costs of these inputs? What is the relative balance between informal and formal support?

We consulted panels of experts in two senses – carers expert by experience and staff expert by training – between July 2015 and January 2016. The consultations were undertaken through simulation exercises where participants were asked to outline the components they saw as necessary to support people in different circumstances identified through five ‘case vignettes’. These vignettes described circumstances of real cases drawn from the English sample of a European dementia programme169 that were representative of people with dementia at risk of entering care homes. Through the consultations using these vignettes, we collected data on the inputs seen as necessary to support people with dementia at home effectively. We asked participants to consider both formal paid help (e.g. from the NHS or social services) and informal care (i.e. specific inputs from the person living with or offering support to the person with dementia). These inputs were costed using nationally available unit cost data. From this, we analysed the balance of expertly assessed costs between informal care and formal (NHS/social care) support.

The project received a favourable Research Ethics Committee opinion on 29 June 2015 (reference 15/LO/1137). We recruited 14 informal carers of people with dementia via two local community centres and consulted an additional minority ethnic group for guidance. We also recruited 14 professional staff from the host trust through a senior manager who was a member of the programme team. These covered a range of professions in health and social care, including occupational therapists, community psychiatric nurses, social workers and managers. This work was published in Dementia in 2019,170 and is now in Appendix 9.

The vignettes used to collect data represented 42% of people with dementia living at home but at risk of entering care homes in England. The inputs suggested most frequently by both paid staff and informal carers were informal care, personal home care and day-care centres. However, staff suggested an average of 66 hours per week of support across the five case types, whereas informal carers suggested an average of 51 hours. Translating these inputs into average costs at 2014/15 prices, formal care would cost a mean of £719 per week when recommended by staff and a mean of £634 per week when recommended by informal carers. Informal care would cost a mean of £632 per week when recommended by staff and a mean of £391 per week when recommended by informal carers. Therefore, staff recommended informal care costing 88% of formal care, whereas for informal carers the recommended ratio was 62%. Taking recommendations for formal care costs from staff and for informal care costs from informal carers yielded a ratio of 54%.

The limitations of this work included the small sample of 28 participants consulted. We based the case vignettes on a range of people with moderate or advanced dementia judged to be on the margins of care home entry, rather than people with mild or early-stage dementia who may require little or no home support. We derived indicative costs from participants’ judgements. Therefore, they do not represent full societal costs. In particular, they do not include accommodation costs and other social costs, particularly by informal carers.

Nevertheless, data from this study offer insights into the preferences of key actors – informal carers and professional staff – for the inputs and, therefore, costs needed to support people with dementia at home. Informal carers offered different recommendations from those of staff, more frequently identifying provision of hot meals, day care and increased support for carers.

Staff recommended more personal and domestic services than informal carers, probably reflecting carers’ experiences of providing the majority of care. 171 Staff were also more likely to suggest support by speech and language therapists and dieticians, reflecting greater awareness of these services. Carers and people with dementia frequently lack awareness of services, as well as the knowledge of how to access these. 172 Therefore, these data suggest that dementia home support could be more individualised, with the balance between formal and informal care, depending on the needs of the person with dementia.

Discrete choice experiments establishing the value of different components of support

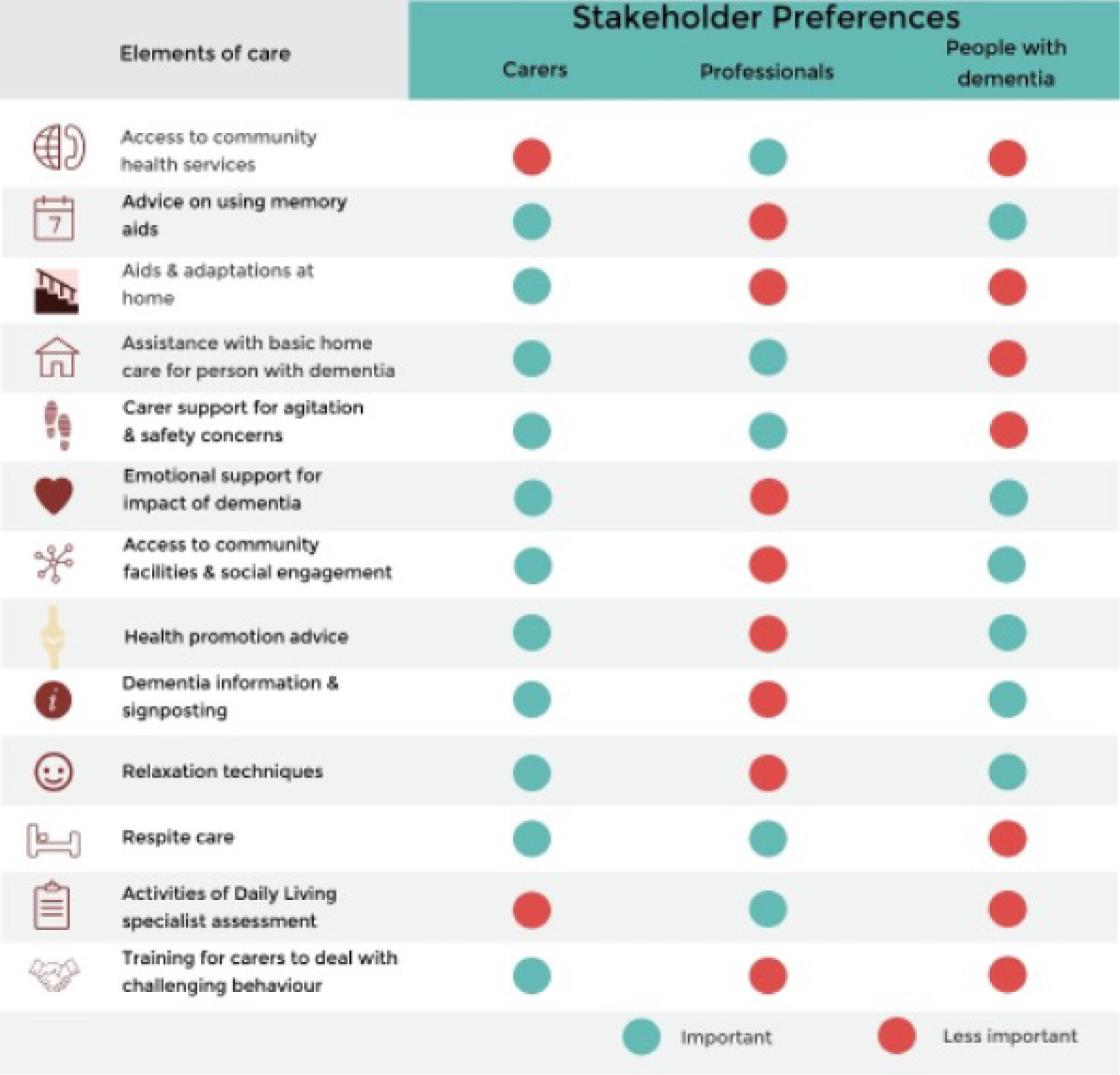

The aim of these two studies was to examine the preferences of people with early- and late-stage dementia and their carers between different home support services. Separate DCEs for early- and later-stage dementia elicited these preferences. Attributes for the DCEs were drawn from the components of care investigated in other parts of the programme (see Appendix 2) and informed by the evidence synthesis and lay consultation with our PPCI group.

We recruited participants to complete DCE questionnaires by a variety of means. For early-stage dementia, we recruited 44 people with dementia and 103 carers through memory clinics and used an online questionnaire. For later-stage dementia, we recruited 100 carers through discussion groups of family carers and used a questionnaire, both online and by post. Analysis used a conditional logistic regression model that examined the strength of preferences for different attributes of home support packages. The project received a favourable Research Ethics Committee opinion on 17 July 2014 (reference 14/NW/1044). The work was published in Ageing & Mental Health for early-stage dementia173 and for later-stage dementia. 161 These outputs are contained in Appendix 10.

We found that the most preferred components for a home support package in early-stage dementia were support with personal feelings and concerns (coefficient 0.67; p ≤ 0.001) and information on coping with dementia provided by a trained worker at home (coefficient 0.59; p ≤ 0.001). For people with dementia, however, opportunities for social and recreational activities were most preferred (coefficient 0.48; p ≤ 0.001). For carers of those in later-stage dementia, the most preferred attributes were regular respite care (coefficient 1.29; p ≤ 0.001) and regular home care (coefficient 0.93; p ≤ 0.001). Cost also had a significant effect, with lower cost packages preferred, and respite care was the most important attribute for all carers. Most carers reported that completing the DCE had been a positive experience.

Cost–utility modelling of the impact of home support models

From the development of the economic model earlier in the programme (see Workstream 1, Development of an economic model), we experienced challenges in evaluating the cost-effectiveness of home support models in dementia. Most approaches we reviewed addressed home support at moderate to severe stages of dementia later in the care pathway, but there were few data about support services offered to those in early-stage dementia. Even the studies identified in our evidence synthesis and economic review lacked reliable data on the costs and benefits of home support models. This was particularly true of social care.

We therefore modelled the economic costs and benefits (cost–utility analysis) of home support models from data collected in our two primary studies (see Workstream 2, Effectiveness of home support in early dementia: the DESCANT, and Workstream 2, Effectiveness of home support models in later dementia). The methods and results of this are summarised below for early- and later-stage dementia, respectively. More details of the methods and findings are in Appendix 11.

Early-stage dementia: within-trial economic analysis

Cost-effectiveness analysis followed an agreed statistical analysis plan, which was summarised in the trial protocol paper in Trials in 2018. 151 The aim was to evaluate whether or not DSPs with guidance in using memory aids were cost-effective compared with TAU for a range of values of willingness to pay (WTP) for a QALY gained. The perspective of the primary analysis was public (NHS and social care), carer (costs) and people with dementia and their carer (health benefits), but multiple perspectives were also presented (see Appendix 11). We estimated QALYs from the EQ-5D-5L completed at baseline, 3 and 6 months, and associated utility tariffs recommended by NICE at the time of analysis. 174–176 We also used dementia-specific utility values from the DEMQOL177 to estimate QALYs, in a sensitivity analysis to examine alternative measures of benefit. We estimated total QALYs from the usual formula:(1)QALY=Σ[(Ui+Ui+1)/2] ×(ti+1−ti)over i=0&1,178

where U is utility and t is time at assessment. The time between assessments is the time from baseline to 3-month follow-up (i = 0), and from 3- to 6-month follow-up (i = 1).

We estimated the direct costs of services used by participants by summing the cost of each resource used to provide health and social care. We collected data from participants and carers on the resources used through the Client Service Receipt Inventory (CSRI)179 to include equipment, adaptations and ambulance use. The Resource Utilisation in Dementia questionnaire (RUD)180 complemented the CSRI by identifying and estimating the volume, duration and cost to participants of support from formal and informal carers. We documented the resources used to provide the DESCANT intervention (e.g. staff time, training and materials) and added them to the services used by participants to estimate the total cost of the intervention. We used national average unit cost data181 to estimate the costs of formal health and social care for each person. The price year for all costs was 2017/18. Costs and effects were not discounted, as the evaluation period was < 1 year.

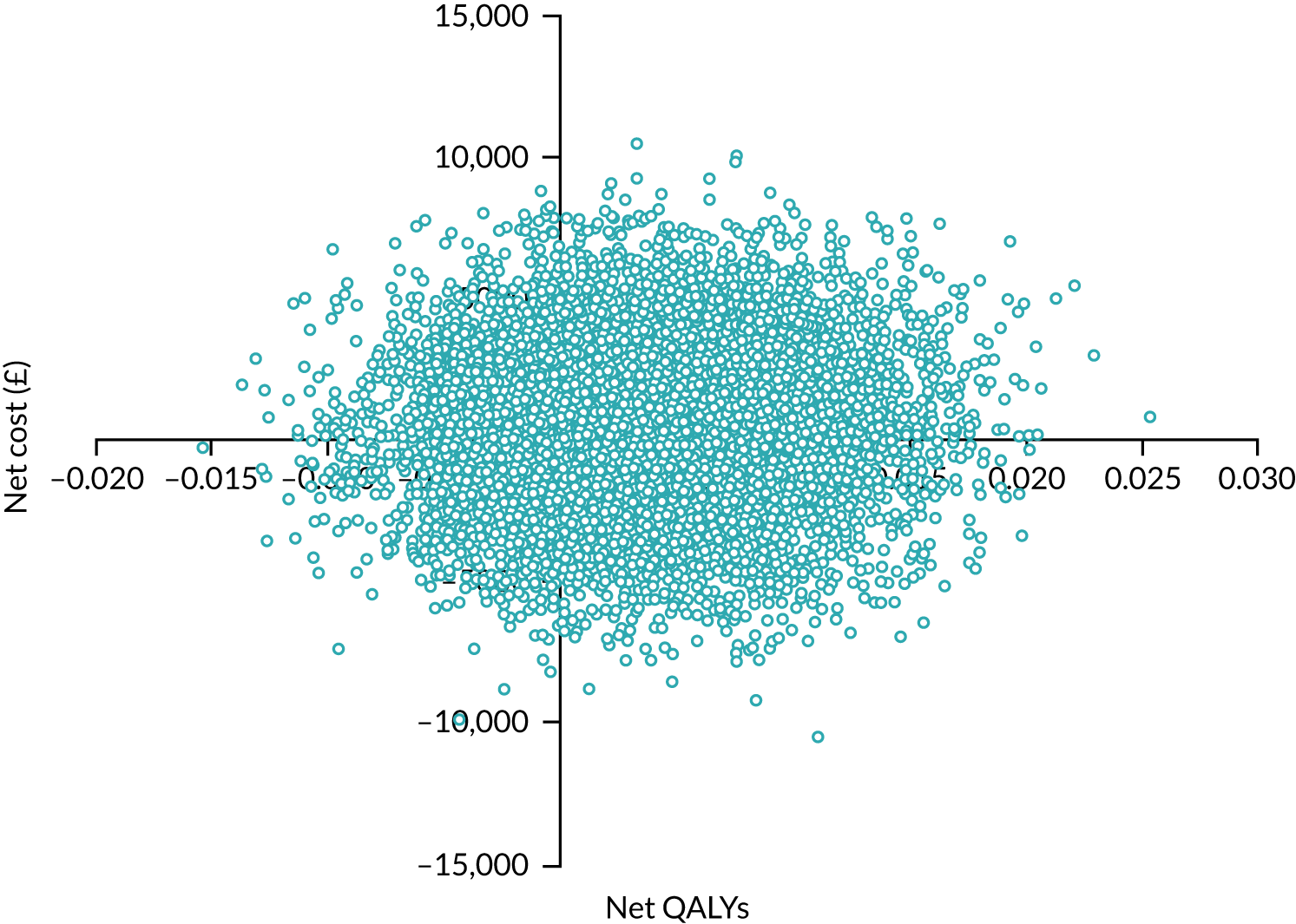

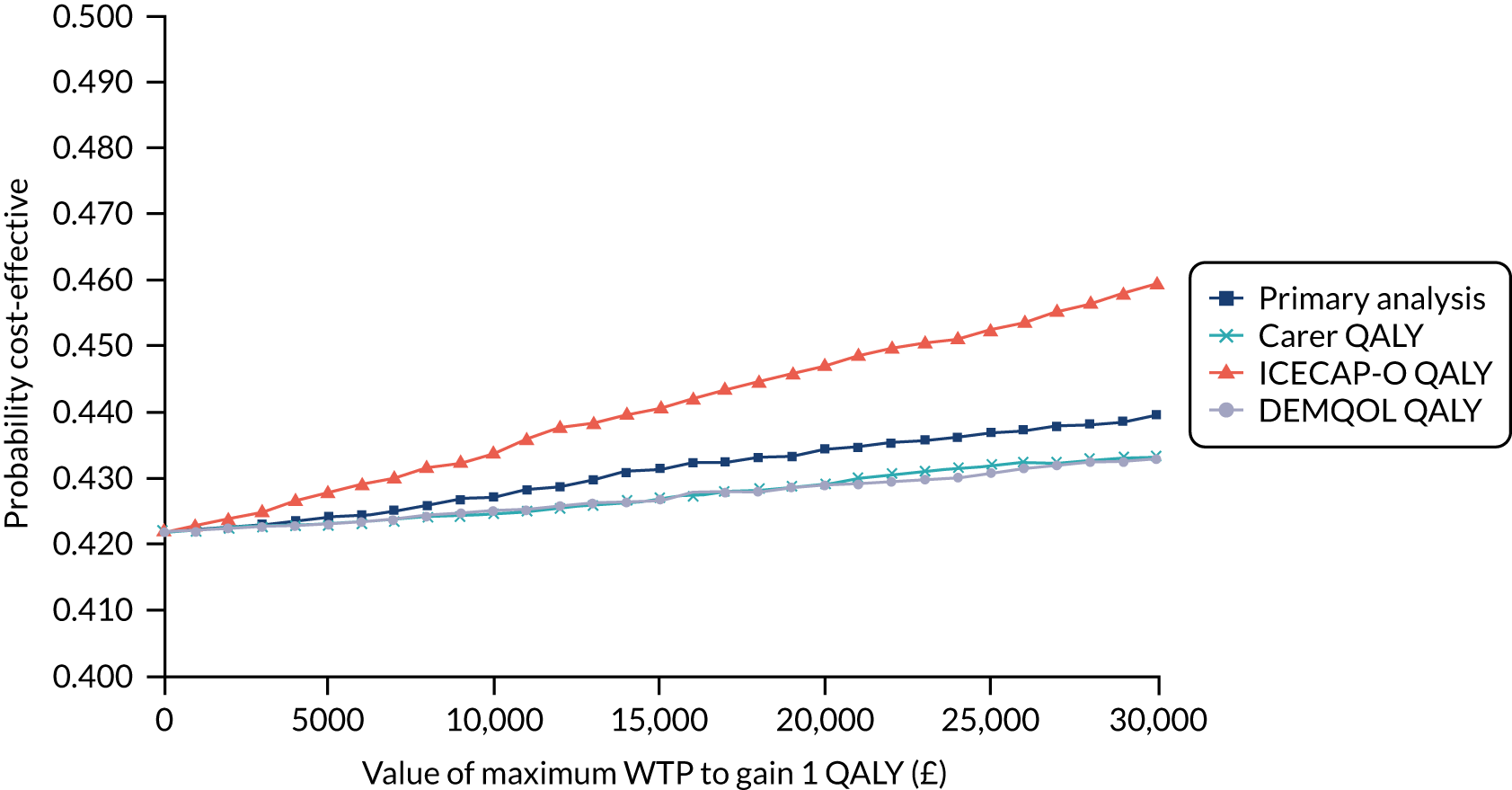

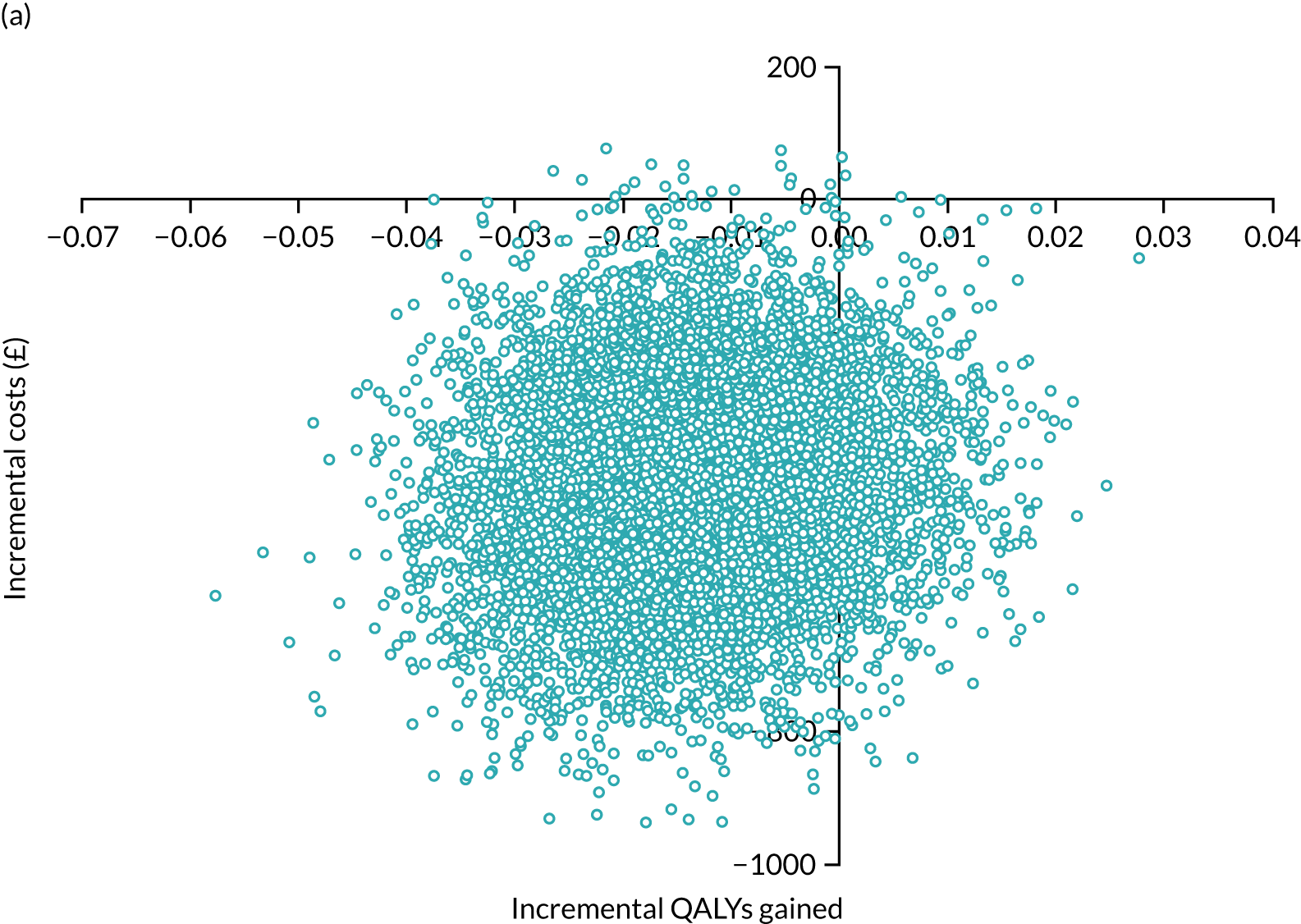

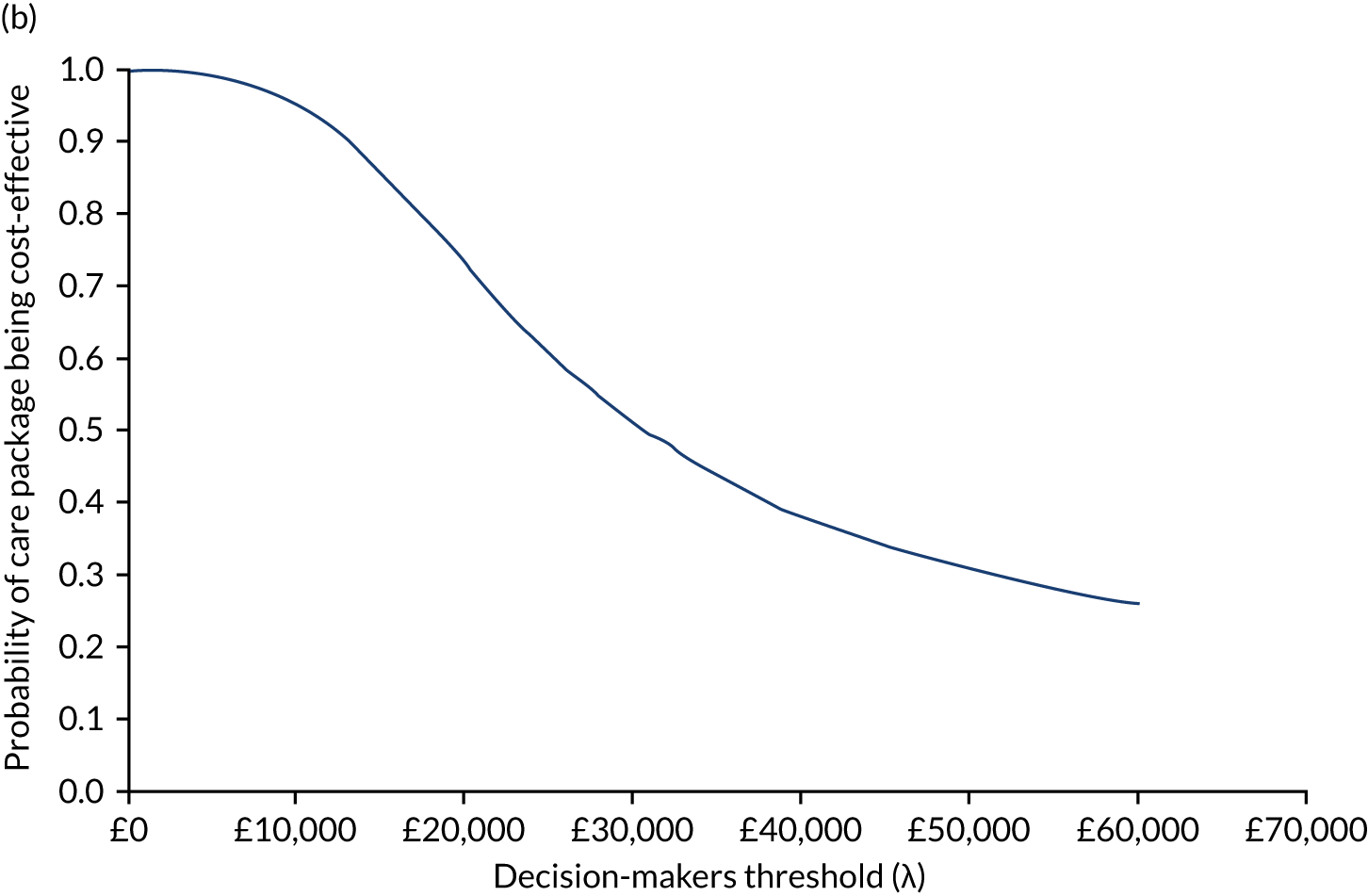

In summary, the results showed that the intervention was, on average, more costly but slightly more effective than TAU. The bootstrapped results, allowing for uncertainty, showed that the intervention had a mean incremental cost (over TAU plus dementia guide) of £412 (standard error £2745, 95% CI –£496 to £5792) and mean incremental QALYs of 0.004 (standard error 0.005, 95% CI –0.006 to 0.014). The intervention was probably not cost-effective at a range of WTP values. Sensitivity analyses, using different measures of utility, did not alter these findings to any degree. At our £15,000 threshold, the intervention had a 42–44% probability of being cost-effective, depending on the measure chosen.

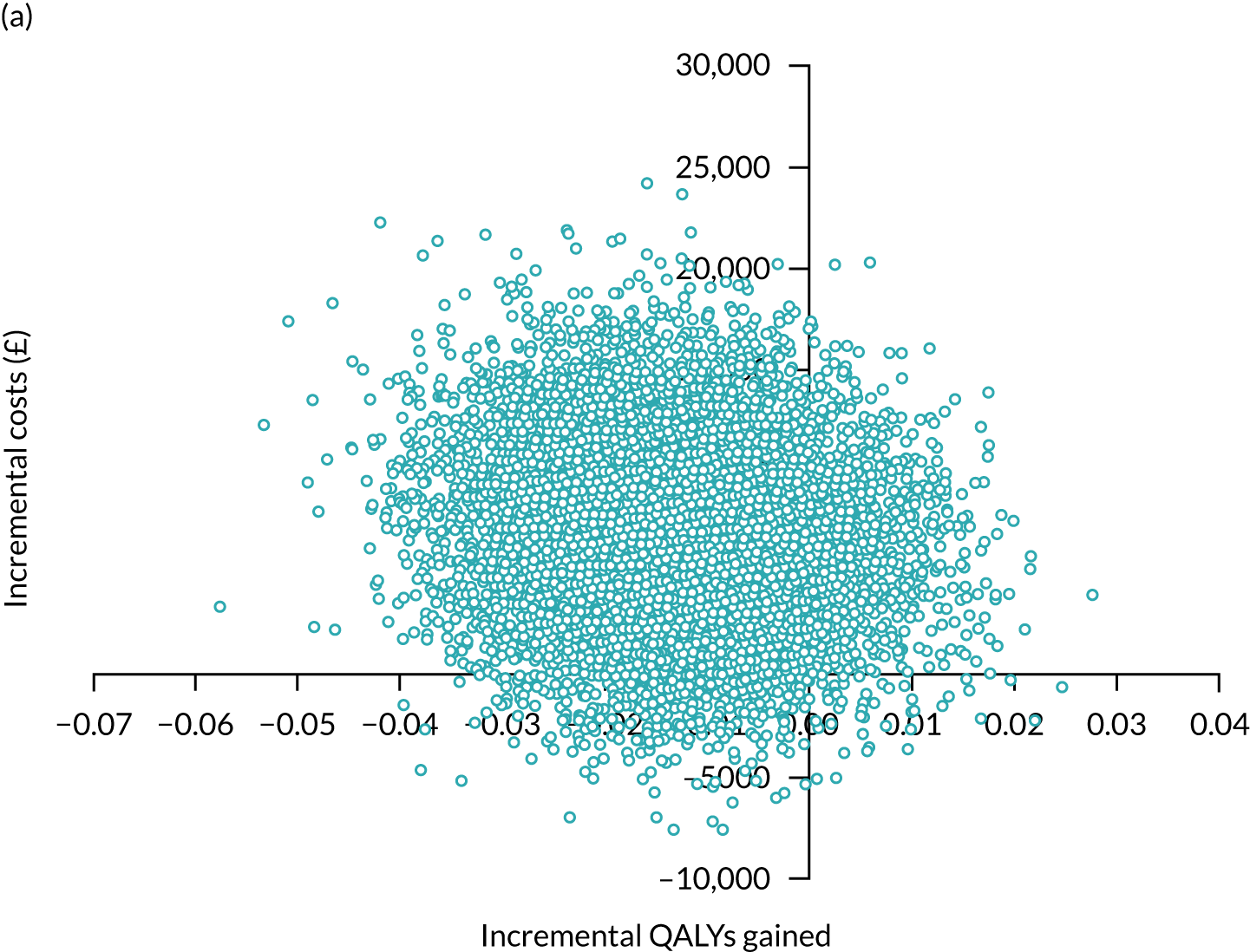

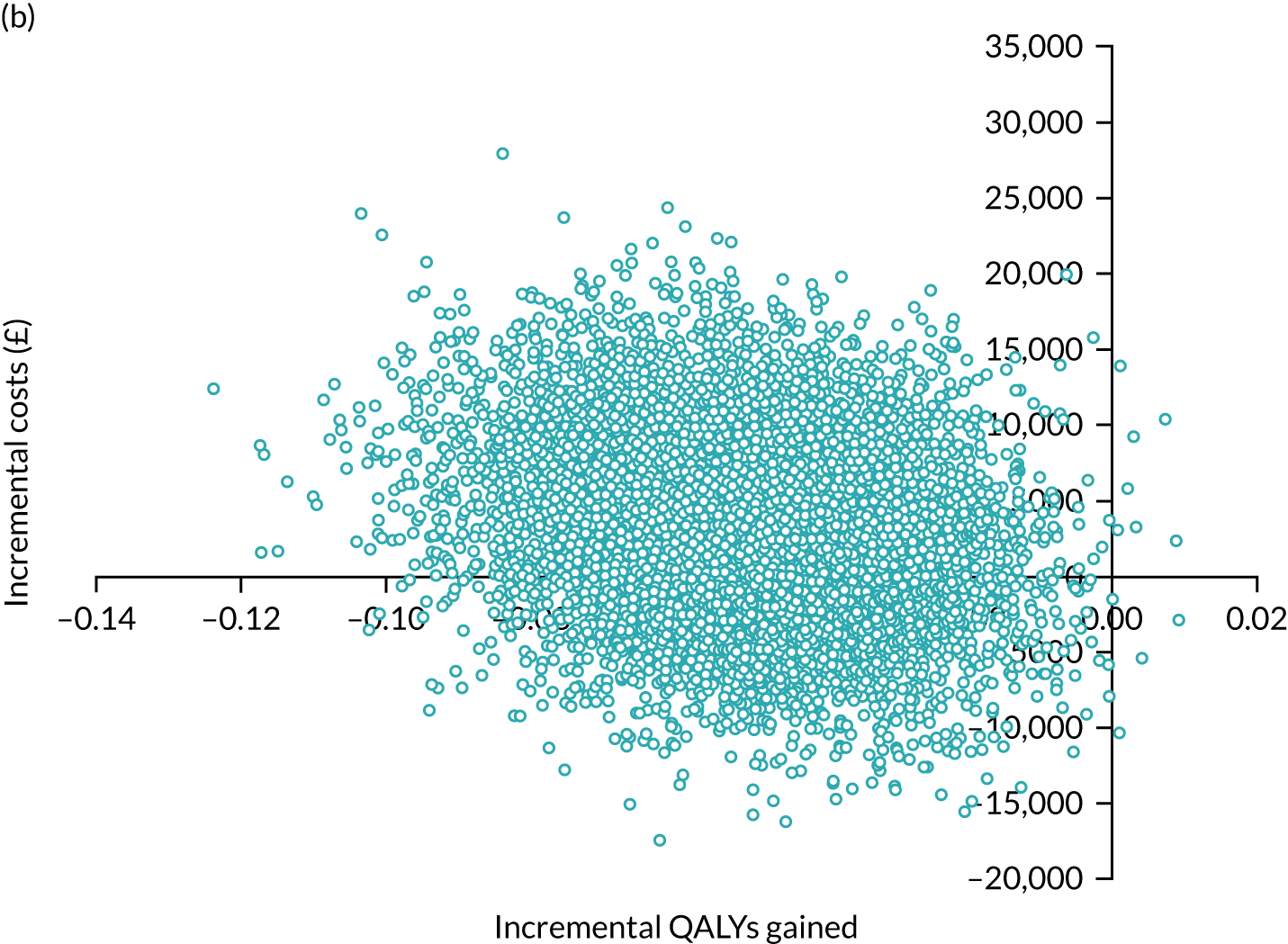

Later-stage dementia: analysing different models of support

Cost-effectiveness analysis again followed an agreed statistical analysis plan. We calculated all resources, costs and QALYs in the same way as in the within-trial analysis above. However, for later-stage dementia, all data from the observational study of home support (see Workstream 2, Effectiveness of home support models in later dementia) related to ‘care as usual’. Therefore, the aim was to examine the cost-effectiveness of different intensities of home support against a minimal model or viable low-cost alternative182 constituting home support from one or no dementia-specific services (e.g. visits only by social workers, community nurses or voluntary sector support workers). We evaluated the incremental costs and benefits of more complex models representing different combinations of services of intermediate and advanced intensity, relative to this minimal model. The perspective of the primary analysis was again public costs to providers (i.e. NHS, social care and third sector), carers (costs) and people with dementia and their carer (health benefits), but multiple perspectives were also presented (see Appendix 11). Again, costs and effects were not discounted, as the evaluation period was < 1 year.