Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by PGfAR as project number RP-PG-0612-20001. The contractual start date was in July 2014. The final report began editorial review in October 2020 and was accepted for publication in May 2021. As the funder, the PGfAR programme agreed the research questions and study designs in advance with the investigators. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PGfAR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2021 Knowles et al. This work was produced by Knowles et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2021 Knowles et al.

SYNOPSIS

Background

Burden of disease

Constipation is common in adults and children, and up to 20% of the population (2–28% of adults and 0.7–30.0% children) report this symptom depending on the definition used,1–3 with a much higher prevalence in women. 4–6 Chronic constipation (CC), usually defined as > 6 months of symptoms, is less common7 but results in 0.5 million UK general practitioner (GP) consultations per annum. A proportion (1–2%)8 of the population suffer more disabling symptoms, are very frequently female9 and are usually referred to secondary care, with many progressing to tertiary specialist investigation. Patient dissatisfaction levels are high in this group, with ≈ 80% feeling that laxative therapy is unsatisfactory;10 furthermore, the effect of symptoms on quality of life (QoL) is significant. 11 CC consumes significant health-care resources. In the USA in 2004, a primary complaint of constipation was responsible for 8 million physician visits,12 resulting in (direct and indirect) costs of US$1.7B. Although detailed figures are lacking in the UK, it is estimated that ≈ 10% of district nursing time is spent on constipation13 and that the annual spend on laxatives exceeds £100M. 14

Pathophysiological basis of chronic constipation

The act of defaecation is dependent on the co-ordinated functions of the colon, rectum and anus. Considering the complexity of neuromuscular (sensory and motor) functions required to achieve planned, conscious and effective defaecation,15 it is no surprise that disturbances to perceived ‘normal’ function occur commonly at all stages of life. Clinically, such problems commonly lead to de facto symptoms of obstructed defaecation (e.g. straining; incomplete, unsuccessful or painful evacuation; bowel infrequency), but symptoms such as abdominal pain and bloating are also very common. After exclusion of a multitude of secondary causes (e.g. obstructing colonic lesions; neurological, metabolic and endocrine disorders), the pathophysiology of CC can broadly be divided into problems of colonic contractile activity, and thus stool transit, and problems of the pelvic floor. Thus, with specialist physiological testing, patients may be divided into those who have slow colonic transit, evacuation disorder, both or neither (e.g. no abnormality found with current tests). Evacuation disorders can be subdivided into those in which a structurally significant pelvic floor abnormality is evident, such as rectocele or internal prolapse (e.g. intussusception), and those in which there is a dynamic failure of evacuation without structural abnormality, most commonly termed functional defaecation disorder.

Management of chronic constipation

Management of CC is a major problem because of its high prevalence and lack of widespread specialist expertise. In general, a step-wise approach is undertaken, with first-line conservative treatment such as lifestyle advice and laxatives (primary care) followed by nurse-led bowel retraining programmes, sometimes including focused biofeedback and psychosocial support (secondary/tertiary care). Although these treatments may improve symptoms in more than half of patients, they are far from universally successful. Thus, patients with intractable symptoms and impaired QoL may be offered a range of costly, irreversible surgical interventions with unpredictable results, sometimes resulting in major adverse events (AEs) or a permanent stoma.

The research programme

An evidence-based pathway for the management of CC in adults is currently lacking, although National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance exists for the management of CC in children16–18 and for allied conditions (e.g. faecal incontinence) in adults. This arguably leads to variations in practice, particularly in specialist services. With a number of new drugs gaining NHS approval19–22 and new technologies at a horizon-scanning stage,23–26 it is timely that the currently limited evidence base is developed for resource-constrained NHS providers to have confidence that new and sometimes expensive investigations and therapies are appropriate and cost-effective. A cost-conscious pathway of care may help reduce health-care expenditures by appropriately sequencing the care provided while targeting more expensive therapies at those most likely to benefit from them. Such data could inform the development and commissioning of integrated care pathways. 27

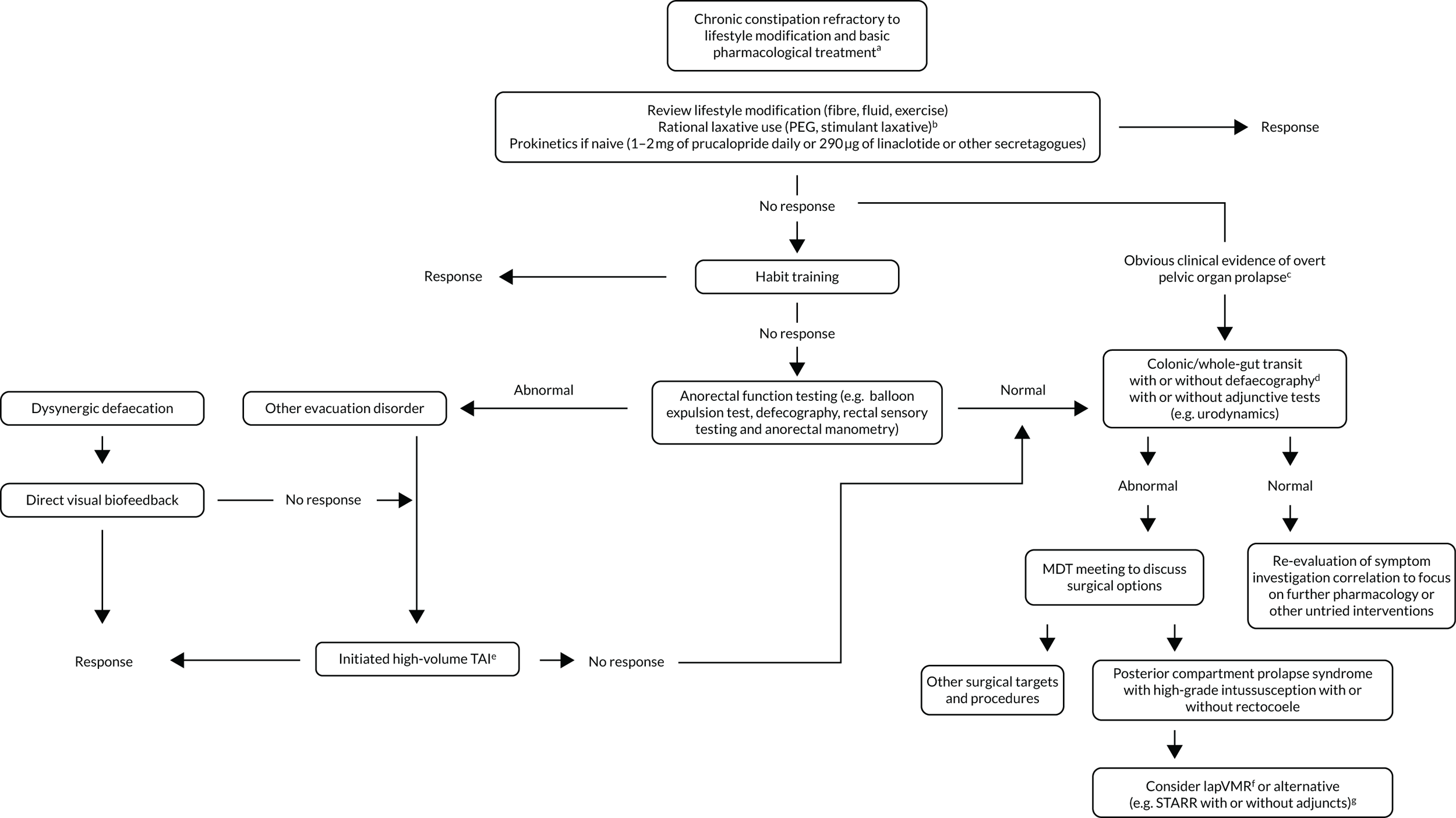

The overall rationale of the Chronic Constipation Treatment Pathway (CapaCiTY) research programme, therefore, was to develop an evidence base for CC management through a series of three randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that answered some of the important questions for sequenced patient care (Figure 1). For each, the focus was on generating real-life evidence based on valid clinical outcome measures, patient acceptability and cost.

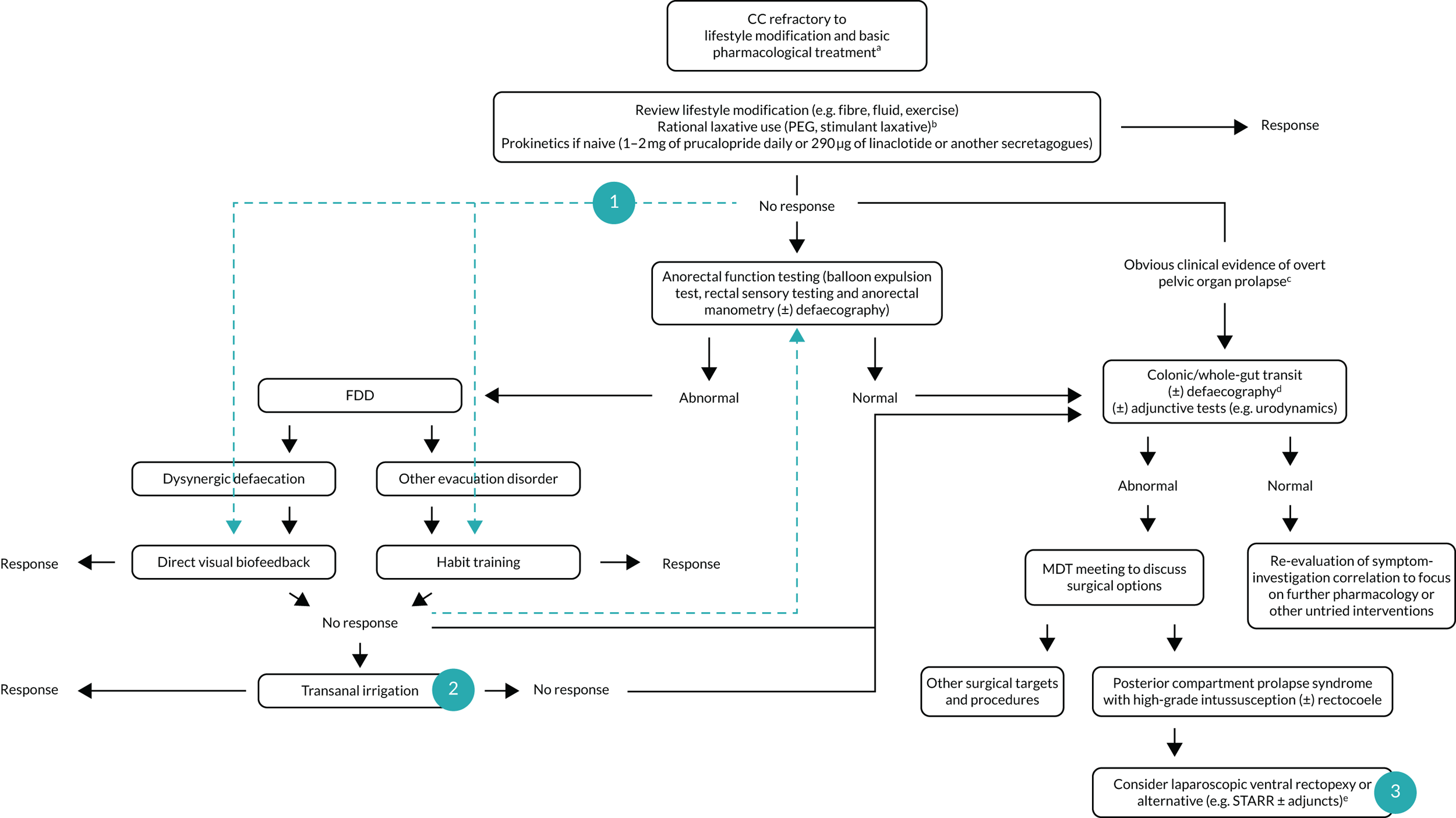

FIGURE 1.

Overview of the CapaCiTY research programme. Green arrows indicate studied pathways in CapaCiTY trials 1–3 (numbered circles). a, Alarm features excluded and secondary causes treated appropriately; b, in IBS-C, consider antispasmodics or neuromodulators in case constipation improves but abdominal pain persists and is dominant symptom; c, examples of overt prolapse include anterior (stage 3 cystocele), middle (stage 3 rectocele, uterovaginal) and posterior compartments (grade IV/V intussusception); d, if not performed previously; e, common adjuncts include sacrocolpopexy, hysterectomy, transvaginal tape and cystocele repair. FFD, functional defaecation disorder; IBS-C, constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome; MDT, multidisciplinary team; PEG, polyethylene glycol[0]; STARR, stapled rectal resection.

The specific objectives were as follows:

-

work programme (WP)1

-

to develop a common methodological framework for subsequent studies

-

to recruit a UK cohort of adults with CC based on strict eligibility criteria and detail the baseline phenotype to identify disease risk factors, symptom burden, QoL and psychological morbidity.

-

-

WP2 (CapaCiTY trial 1)

-

to determine whether or not standardised specialist-led habit training plus pelvic floor retraining using computer-assisted direct visual biofeedback (HTBF) is more clinically effective than standardised specialist-led habit training alone (HT)

-

to determine whether or not outcomes of such specialist-led interventions are improved by stratification to HTBF or HT based on prior knowledge of anorectal and colonic pathophysiology using standardised radiophysiological investigations (INVEST).

-

-

WP3 (CapaCiTY trial 2)

-

to compare the impact of transanal irrigation (TAI) initiated with a low-volume and a high-volume system on patient disease-specific QoL after 3 months of treatment.

-

-

WP4 (CapaCiTY trial 3)

-

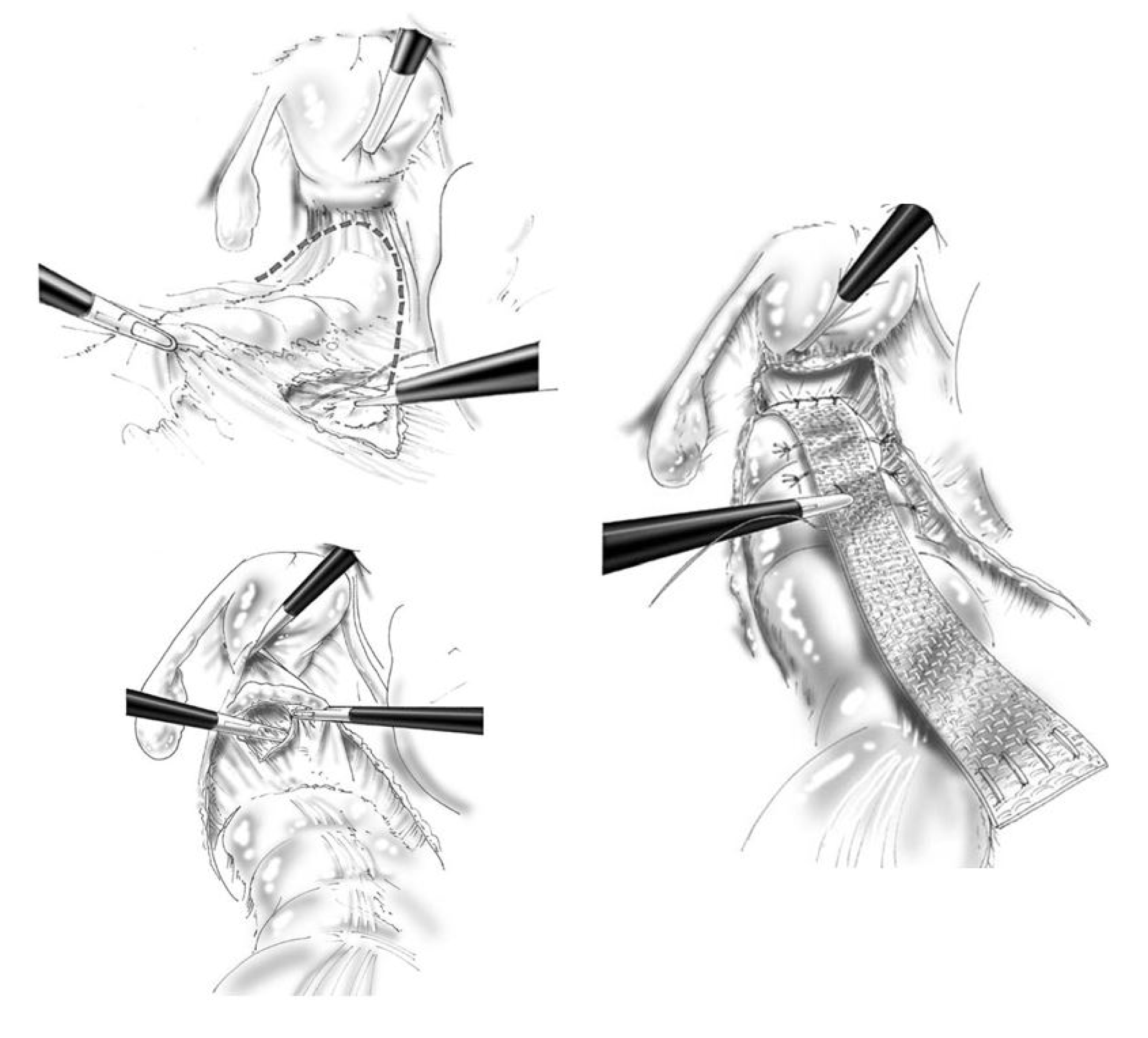

to systematically review the evidence for all common surgical procedures used for adults with CC

-

to determine the clinical efficacy of laparoscopic ventral mesh rectopexy (lapVMR) compared with controls at short-term follow-up (24 weeks).

-

-

WP5

-

to synthesise clinical outcome, patient acceptability and cost data from CapaCiTY trials and to develop an NHS pathway for the management of CC in adults based on data synthesis.

-

Work programme 1: common methodological framework and participant recruitment

Common methodological framework

To permit the synthesis of all data at the end of the programme, we defined eligibility criteria, outcome measures and analytic methods that were common across all three trials. In addition, at the outset it was envisaged that some participants could move sequentially through more than one trial if a prior treatment had failed (although in practice this happened very infrequently because of delays in recruitment to all studies).

Setting

Following scoping during the programme development phase, we pre-identified 10 UK specialist centres that geographically encompass the north and south of England with a mix of urban and rural referral bases. Other centres were recruited for specific studies, especially in CapaCiTY trial 3.

Target population

The programme addressed the NHS management of CC in secondary and tertiary care, rather than the broader patient population with relatively short-lived or mild symptoms, receiving self-care or primary care management. This focus was pragmatic, given the concentration of expertise, diagnostics and biofeedback equipment in hospital settings. Based on well-established epidemiological data28,29 (see SYNOPSIS, Background), the main target population was women of mean age 50 years.

Ethics approvals

The three trials had the following registration details and approvals:

-

CapaCiTY trial 1

-

Research Ethics Committee (REC) reference 14/LO/1786

-

Integrated Research Application System (IRAS) 160709

-

ISRCTN11791740

-

date of REC approval: 6 December 2014.

-

-

CapaCiTY trial 2

-

REC reference 15/LO/0732

-

IRAS 172401

-

ISRCTN11093872

-

date of REC approval: 6 July 2015.

-

-

CapaCiTY trial 3

-

REC reference 15/LO/0609

-

IRAS 171006

-

ISRCTN11747152

-

date of REC approval: 6 July 2015.

-

Eligibility assessments

Patients were recruited at the time of clinical consultation at physician- and nurse-led clinics, and also at the time of investigation in gastrointestinal physiology units. All patients expressing initial interest were referred to the local lead investigator to screen case notes for eligibility.

Good clinical practice-trained local investigators determined eligibility by interview on the basis of defined inclusion/exclusion criteria. Participants were recorded on a screening log and each allocated a unique participant identifier (ID) number. Eligible subjects were then provided with an adequate explanation of the aims, methods, anticipated benefits and risks of the programme, and a participant information sheet. Special emphasis was placed on the long-term nature of the programme, time commitments and number of assessments required. Patients were telephoned 1 week later (or given an appointment) to allow appropriate time for them to consider their participation.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria

Chronic constipation was defined according to pragmatic criteria, broadly, those employed for recent pivotal trials of prokinetics19,22 and US guidance:30

-

age 18–70 years

-

patient self-reported problematic constipation

-

symptom onset > 6 months prior to recruitment

-

symptoms meeting American College of Gastroenterology definition of constipation (‘unsatisfactory defaecation characterized by infrequent stool, difficult stool passage or both for at least previous 3 months’)30

-

constipation that has failed treatment to a minimum basic standard according to the NHS Map of Medicine31 (lifestyle and dietary measures and two or more laxatives or prokinetics tried)

-

ability to understand written and spoken English (for questionnaire validity).

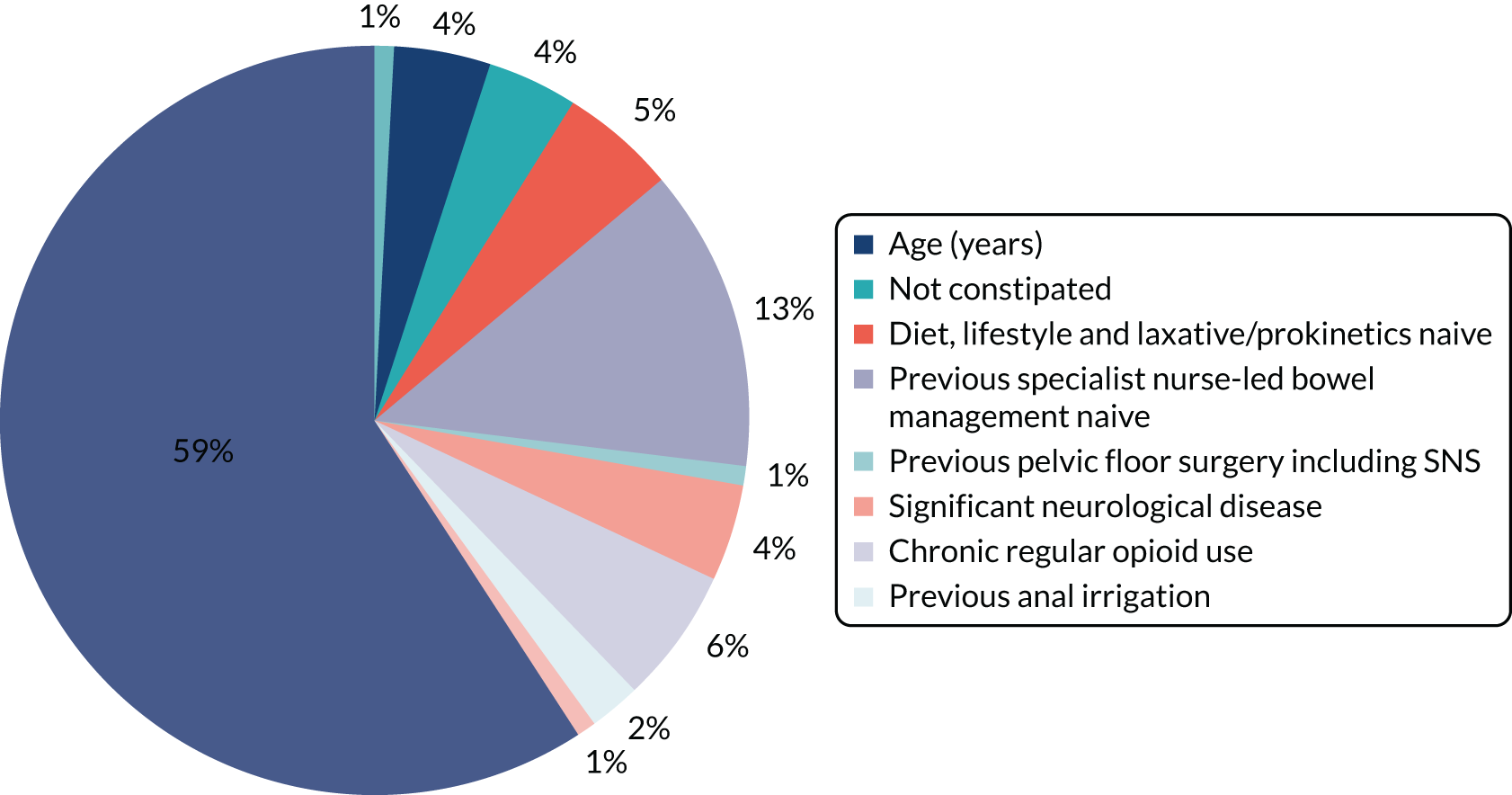

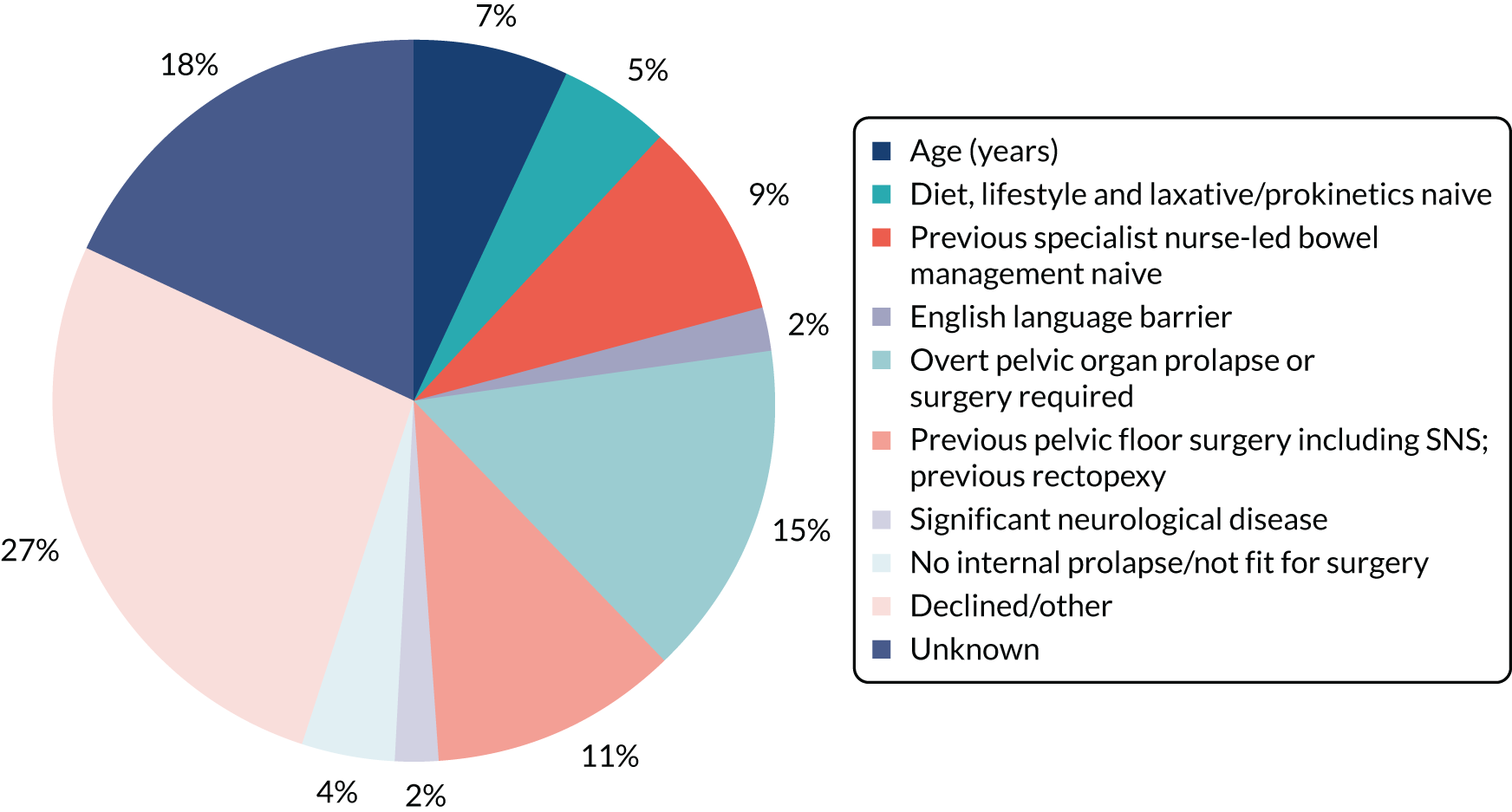

Exclusion criteria

Exclusions included major causes of secondary constipation and specific factors precluding participation in study interventions:

-

significant organic colonic disease (red flag symptoms e.g. rectal bleeding previously investigated); inflammatory bowel disease; megacolon or megarectum (if diagnosed beforehand); or severe diverticulosis, bowel stricture or birth defects deemed to contribute to symptoms (incidental diverticulosis not an exclusion criterion)

-

major colorectal resection surgery

-

current overt pelvic organ prolapse (e.g. bladder, uterus, rectum) or disease requiring obvious surgical intervention

-

previous pelvic floor surgery to address defaecatory problems [posterior vaginal repair, stapled rectal resection (STARR) and rectopexy] or previous sacral nerve stimulation

-

rectal impaction (as defined by digital and abdominal examination, which form part of the NHS Map of Medicine basic standard)31

-

significant neurological disease deemed to be causative of constipation (e.g. Parkinson’s disease), spinal injury, multiple sclerosis or diabetic neuropathy (uncomplicated diabetes alone not an exclusion criterion)

-

significant connective tissue disease – scleroderma, systemic sclerosis and systemic lupus erythematosus (hypermobility alone not an exclusion criterion)

-

significant medical comorbidities and activity of daily living impairment (based on a Barthel index32 score of > 11 in apparently frail patients)

-

major active psychiatric diagnosis (e.g. schizophrenia, major depressive illness and mania)

-

chronic regular opioid use (at least once-daily use) where this is deemed to be the cause of constipation based on temporal association of symptoms with onset of therapy, and all regular strong opioid use

-

pregnancy or intention to become pregnant during study period

-

previous experience of specific therapies included in the programme.

Trial-specific inclusion criteria

-

CapaCiTY trial 1:

-

vision sufficient to undertake visual biofeedback.

-

-

CapaCiTY trial 2:

-

sufficient manual dexterity of patient/carer to use TAI.

-

-

CapaCiTY trial 3:

-

failure of non-surgical interventions (minimum of nurse-led behavioural therapy)

-

internal rectal prolapse, as determined by clinical examination and INVEST, fulfilling two diagnostic criteria – (1) intra-anal or intrarectal intussusception with or without other dynamic pelvic floor abnormalities (e.g. rectocele, enterocele, perineal descent) and (2) deemed (by expert review) to be obstructing on defaecating proctogram (i.e. trapping contrast and/or associated with protracted or incomplete contrast evacuation using normal ranges). 33

-

Baseline clinical evaluation

In addition to screening questions, clinical examination and information obtained by baseline standardised outcome assessments, participants completed a structured interview to document other comorbidities and risk factors (e.g. metabolic, endocrine and neurological disease; obstetric and gynaecological history; joint hypermobility; past surgical history). Clinical examination of the perineum/anus/rectum/vagina was carried forward to baseline from the last clinical consultation to prevent unnecessary repetition of intimate examinations.

Specialist radiophysiological investigations

All three trials required, at least in part (depending on the trial), the results of a number of well-established specialist investigations of anorectal and colonic functions. These investigations were nationally standardised during National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) programme development work, including a consensus meeting (London 2013) highlighting universally discordant current practice; remarkably, no UK centre at that time had the same protocol for any of the four main tests:34

-

Anorectal manometry using high-resolution methods35–37 to determine defined abnormalities of rectoanal pressure gradient during simulated evacuation. 38–40

-

Balloon sensory testing using standardised methods41,42 (2 ml of air per second to a maximum of 360 ml) to determine volume inflated to first constant sensation, defaecatory desire and maximum tolerated volumes. Rectal hyposensation and hypersensation defined in accordance with sex-specific normative data on 91 healthy adults. 43 The rectoanal inhibitory reflex elicited by 50 ml rapid inflation (if necessary, in 50-ml aliquots up to 150 ml).

-

Fixed-volume (50 ml) water-filled rectal balloon expulsion test38,39,44,45 in the seated position on a commode. Abnormal expulsion is defined as failure to expel within 1.0 minute of effort for men and 1.5 minutes of effort for women. 46

-

Whole-gut transit study using serial (different shaped) radio-opaque markers over 3 days, with a single, plain radiograph at 120 hours. 47,48

-

Fluoroscopic evacuation proctography using rectal installation of barium porridge to defaecatory desire threshold (or a maximum of 300 ml) and evacuation on a radiolucent commode33,35–37,49 with pre-opacification of the small bowel (for enterocele). Radiation dose, proportion of contrast evacuated and time taken are recorded, as well as ‘functional’ features (i.e. pelvic floor dyssynergia) and ‘structural’ features (e.g. rectocele, enterocele and intussusception) deemed obstructive to defaecation. 38,43 Although magnetic resonance proctography is now used in some UK centres, with the advantage of no radiation dose, it was not widespread at the time of developing the CapaCiTY programme. There are also differences in sensitivity between fluoroscopic and magnetic resonance proctography, especially if the latter is carried out on a supine patient,50 that could prove difficult for standardisation.

Standardised radiophysiological investigations were performed if results were not already available for participants from tests in the preceding 12 months. In some participants, individual missing investigations were performed. Routine NHS practice (e.g. 10-day NHS rule related to menstrual cycle) was applied in respect of women between menarche and menopause. Participants who could potentially be pregnant had a serum or urine pregnancy test performed as per routine care. Participants were given the results of investigations by the physiologist or radiologist.

Programme outcomes

A common ‘standardised outcome framework’ was used throughout. All questionnaires contained written instructions to be completed by the participant in an undisturbed environment without prompting. Online and postal options were provided for participants who chose not to attend in person.

The plan at the start of the programme was that all outcomes would be recorded for each intervention at baseline, 3 months and 6 months before participants could progress to a further intervention WP. For participants not changing therapy, further outcomes were recorded at 6-month intervals to the end of the programme (to a theoretical maximum of 4 years). Participants who progressed from one intervention to another had a new ‘baseline’ recorded on recruitment. In practice, few participants progressed from one WP to another and follow-up was limited by delays in recruitment to a maximum of about 18 months.

Primary clinical outcome

Patients with CC complain of a multitude of symptoms including infrequent defaecation, pain, bloating, straining, passage of hard stool, incomplete evacuation and systemic symptoms. The relative importance of these varies between patients so that a single symptom, such as bowel frequency, does not adequately describe treatment effect in a population. 51 Symptom diaries have a poor record as primary outcome measures, suffering from incomplete data, retrospective completion, tolerance or sensitisation. 52,53 A number of composite scoring systems have been developed, but only one, the Patient Assessment of Constipation Quality Of Life (PAC-QoL), has been robustly developed and psychometrically validated to a high level, including a comprehensive assessment of effect size. 54–56 The PAC-QoL includes 28 items covering four domains, each item is scored (0–4 points) and items and domains are aggregated to a composite score (0–4 points).

Minimum clinically important differences have been defined for PAC-QoL scores and informed an analysis of responders to treatment. Treatment effects have been characterised using cumulative distribution curves and a 1.0-point reduction has been confirmed as a robust measure of a responder. 57 Furthermore, a minimum clinically important difference can be defined by a 10% change (i.e. 0.4 points in the scale), as reported broadly in the literature. These definitions were used to ensure that the primary outcome measure in each trial was based on magnitude, risk and cost of intervention. Thus, for trials 1 and 2, a ≥ 0.4-point reduction in PAC-QoL score was considered to be a minimally important mean difference between groups, whereas in CapaCiTY trial 3 (surgery) a ≥ 1.0-point difference was chosen to reflect the more costly and potentially harmful intervention posed by surgery.

Secondary clinical outcomes

Given the questionnaire format of most available CC outcome assessments and multiple time points of assessment, we carefully selected and justified each outcome to keep the number and length of assessments to an achievable level (for compliance). The choice of Patient Assessment of Constipation Symptoms (PAC-SYM) and Measure Yourself Medical Outcome Profile 2 (MyMOP2) was specifically informed by qualitative research performed during our NIHR programme development stage on 50 participants with CC:

-

PAC-QoL score – binary responder analyses using 0.4-point and 1.0-point cut-off points

-

PAC-SYM score – individual domains and total score (as continuous variables)

-

2-week patient diary (for 2 weeks prior to each assessment) to record bowel frequency and whether or not each evacuation was ‘spontaneous (no use of laxatives) and/or complete’; the journal also captured concurrent medication, health contacts and time away from normal activities (including work) since the patient’s last visit

-

a validated patient problem-specific measure, MyMOP2, which incorporates the two worst volunteered symptoms and a measure of well-being58 (lower scores represent less symptomatology)

-

a validated QoL cost-effectiveness questionnaire – EuroQol-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D), EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L), and EuroQol Visual Analogue Scale (EQ-VAS)59 (higher scores indicate better QoL)

-

Patient Health Questionnaire-9 items (PHQ-9)60 – nine items measuring level of depression (lower scores indicate less depression)

-

Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7)61 scale (lower scores indicate less anxiety)

-

avoidant and ‘all or nothing’ behaviour subscales of the Chronic Constipation Behavioural Response to Illness Questionnaire (CC-BRQ)62 and Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire for Chronic Constipation (BIPQ-CC)63 (specific analyses required for interpretation)

-

global participant satisfaction (five-point scale from ‘not at all satisfied’ to ‘completely satisfied’) and a global participant improvement score (0–100% visual analogue scale) comparing how the participant feels today compared with before the study (higher scores indicate greater satisfaction).

Health economic outcomes

Resource use at the participant level was captured using trial case report forms (CRFs) at scheduled clinical visits and contacts. Intervention costing was specific to each trial and was detailed in the reporting of findings. Assessments were carried out at 0, 3, 6 and 12 months’ follow-up, augmented by telephone calls (every 12 weeks for the CapaCiTY trial 3). Participant use of prescription drugs related to their condition was recorded and costed using Prescription Cost Analysis (PCA) data. 64 Health service contacts were recorded by asking participants to recall GP, district nurse, pharmacy, accident and emergency department (A&E), outpatient and inpatient visits. Health-care resource use was costed using published national reference costs. Individual patient costs were estimated in 2018 Great British pounds (GBP) as the sum of resources used weighted by their reference costs. Time away from work or usual activities was recorded and costed using national average weekly earnings,65 contributing to a broader societal costing (Table 1).

| Resource | Unit | Cost (£) | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Health-care contacts | |||

| GP | Per visit | 39.00 | PSSRU66 |

| District nurse | Per visit | 41.00 | aPSSRU67 |

| Pharmacist | Per visit | 14.00 | NHS CPCS68 |

| A&E | Per visit | 114.00 | NHS Improvement69 |

| Outpatient | Per visit | 135.00 | PSSRU66 |

| Inpatient | Per visit | 631.00 | PSSRU66 |

| Other resources | |||

| Prescription drugs | Per item | b | NHSD-PCA70 |

| Time off work | Per day | 92.00 | ONS65 |

| CapaCiTY trial 1 | |||

| INVEST | Per procedure | 462.00 | |

| Staff time | Per procedure | 192.00 | NHS Improvement69 |

| Anal manometry | Per test | 50.00 | Personal communicationc |

| Rectal sensation | Per test | 4.00 | Personal communicationc |

| Balloon expulsion test | Per test | 4.00 | Personal communicationc |

| Gut transit study | Per study | 66.00 | NHS Improvement69 and personal commmunicationc |

| Evacuation proctography | Per test | 141.00 | NHS Improvement69 and personal commmunicationc |

| Cleaning/sterilisation | Per procedure | 5.00 | Personal communicationc |

| Habit training (with/without biofeedback) | |||

| Training sessions | Per hour | 135.00 | PSSRU66 |

| Biofeedback | Per session | 70.00 | d |

| CapaCiTY trial 2 | |||

| Low-volume TAI | Per use | 3.93 | eNHSD-PCA70 |

| Per 30-day use | 118.00 | eNHSD-PCA70 | |

| High-volume TAI | Per use | 7.57 | fNHSD-PCA70 |

| Per 30-day use | 227.00 | fNHSD-PCA70 | |

| Training/support sessions | Per hour | 135.00 | PSSRU66 |

| CapaCiTY trial 3 | |||

| LapVMR surgery | Per procedure | 4941.00 | NHS Improvement69 |

Generic health-related QoL was assessed using the EQ-5D questionnaire: a participant-completed two-page questionnaire consisting of the EQ-5D-5L and the EQ-VAS. The EQ-5D-5L includes five questions addressing mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression, with each dimension assessed at five levels, from ‘no problems’ to ‘extreme problems’. EQ-5D-5L scores were converted to health status scores using the mapping function developed by van Hout et al. ,71 providing a single health-related index including 0 (death) and 1 (perfect health), for which negative scores are possible for some health states. Scores were captured in trial CRFs during clinic visits or contacts at baseline, 3 months, 6 months and 12 months for CapaCiTY trials 1 and 2, and at 12-week intervals from the screening visit up to 72 weeks for CapaCiTY trial 3. Using the trapezoidal rule, the area under the curve (AUC) of health status scores was calculated, providing participant-level quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) estimates for the cost-effectiveness analyses. Because AUC estimates are predicted to correlate with baseline scores (and thus potential baseline imbalances), AUC estimates were adjusted for baseline scores in regression analyses.

Patient and health-care professional experience

Qualitative data were obtained to aid the interpretation of outcomes and the development of an authoritative clinical pathway that recognised informational needs of both clinicians and patients. Face-to-face, digitally recorded, semistructured interviews (duration up to 1 hour) were conducted by an experienced nurse with a social science background and involved a purposive, diverse sample of patients and health-care professionals throughout the programme, with participant recruitment reflecting a range of ages, geographical locations and, when possible, other pertinent attributes such as ethnicity and sex, continuing until data saturation when no new themes emerged. All participants were told that they might be invited for interview when they were informed about each trial, but provided separate informed consent for interview (in those agreeing to be approached). A topic guide for each interview, informed by existing literature and patient advisors, was developed and piloted prior to commencement.

Adverse events and other work package-specific data

Adverse events were recorded throughout the programme using an AE log to record the nature, seriousness, causality, expectedness, severity, relatedness and outcome. All serious adverse events (SAEs) that were related or unexpected were reported to the sponsor, REC, quality assurance manager and local research and development (R&D) departments and the participant followed-up until conclusion. Safety was monitored by the Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC) and reported to the REC in the annual progress reports. Other important data such as treatment logs and perioperative courses were WP specific.

Common analytical framework

General

The Pragmatic Clinical Trials Unit (PCTU; a UK Clinical Research Collaboration registered and NIHR-funded clinical trials unit in the Institute of Population Health Sciences, Queen Mary University of London) managed the three trials, including the development and management of secure databases in accordance with standard operating procedures. Automated validation checks were carried out at source data entry and further checks were performed on receipt by the study statistician and data manager. Data queries were addressed to the data manager and participating centres as appropriate. The centrally held database was locked for analysis once the data quality and completeness were assured and on sign-off of the final statistical analysis plan (SAP).

Sample size calculations

Detailed individual justifications for each trial are included in Appendix 1. In brief, sample sizes were calculated using the primary clinical outcome: change in PAC-QoL score based on pre-defined scalar changes. All calculations were performed at 90% power at a 5% significance level and, thence, allowed for 10% drop-out after randomisation.

Baseline characteristics

Numbers and percentages of patients with important baseline characteristics are presented by trial group. Continuous variables (e.g. age) are summarised by treatment group using mean and SD [median and interquartile range (IQR) if non-normally distributed]. No statistical testing was performed.

Clinical outcomes

All analyses were performed by the study statistician after the SAP was reviewed by the DMEC and signed off by the chief investigator and senior statistician. Although exact analyses for each trial differed according to study design, primary outcomes were analysed on an intention-to-treat (ITT) basis at defined time points (3 or 6 months) using linear mixed regression models [using Stata 14.2 (Stata Corp LP, College Station, TX, USA) xtmixed] with a random effect for centre and fixed effects for intervention, sex, baseline PAC-QoL score and breakthrough medication. Secondary outcomes were analysed on an ITT basis. For each outcome, descriptive statistics (as appropriate) by trial group are presented; continuous variables (e.g. PAC-QoL score) are summarised by treatment group using mean, SD, median and IQR. For categorical variables, numbers and percentages of patients reporting each response option were presented by trial group. Given the lower than target number of patients recruited to the trials, adjusted analyses were performed on PAC-QoL-derived secondary outcomes in CapaCiTY trial 1 only (logistic regression models for categorical outcomes). Unadjusted treatment differences and respective 95% confidence intervals (CIs) are presented for all other secondary outcomes. Results obtained using the CC-BRQ and BIPQ-CC have been omitted pending further analysis.

Subgroup analyses

Originally planned subanalyses were restricted after poor recruitment to a small number of specific analyses for major baseline characteristics in the CapaCiTY trial 1 only. A p-value of < 0.05 was taken to indicate statistical significance.

Cost-effectiveness

The economic analysis of the three interlinked CapaCiTY trials followed ITT principles and a prospectively agreed analysis plan. Using the standardised outcome framework for each trial, treatment effects were summarised at the patient level as overall cost and QALYs. Within-trial patient cost-effectiveness analyses were conducted comparing alternative treatments in each trial. Primary analyses took an NHS perspective. 72

Follow-up of trial participants is problematic, particularly over longer periods, making incomplete data a routine challenge. Consequently, the planned base-case analysis for each trial assumed the use of multiple imputation to account for missing data. For each trial, the base-case analysis is presented as the imputed and adjusted within-trial incremental costs and QALYs gained. Supportive sensitivity analyses included participants with complete data; unplanned sensitivity analyses are added if informative. Imputation and estimation were conducted according to good practice guidance73 using the multiple imputation framework in Stata. Multiple imputation provides unbiased estimates of treatment effects if data are missing at random (MAR) (i.e. causes of missingness are captured in observed variables). This assumption was explored in the data using logistic regression of the missingness of costs and QALYs against baseline variables. 74 Patient prognostic variables and trial stratification variables were assessed as potential missingness predictors for use in the imputation, which included outcome measures and costs (at each time point) as predictors and imputed variables. Imputation models used fully conditional (Markov Chain Monte Carlo) methods (multiple imputation by chained equations), which are appropriate when correlation occurs between variables. Multiple imputation ‘draws’ each provide a complete data set, which probabilistically reflects the distributions and correlations between variables. Burn-in traces for imputation variables were visualised to assess the independence of draws. Predictive mean matching drawn from the five k-nearest neighbours (k-NN) was used to enhance the plausibility and robustness of imputed values, as normality may not be assumed. Analysis of multiple draws was conducted with Stata’s multiple imputation framework providing estimation adjusted for Rubin’s rule. 75 In the imputation, missing costs and EQ-5D-5L scores were imputed for each period of follow-up and aggregated to overall patient costs and QALYs for each draw. All imputed variables acted as predictive variables, supplemented by trial baseline variables if significant and plausible predictors of missingness. Analysis of costs and QALYs was conducted primarily using bivariate regression. Multiple imputation estimation models were bootstrapped to provide non-parametric estimates. To minimise the information loss of finite imputation sampling, the fraction of missing information (FMI) was used to ensure that the number of imputed draws exceeded the FMI percentage. The distributions of imputed and observed values were compared to establish the consequences of estimation.

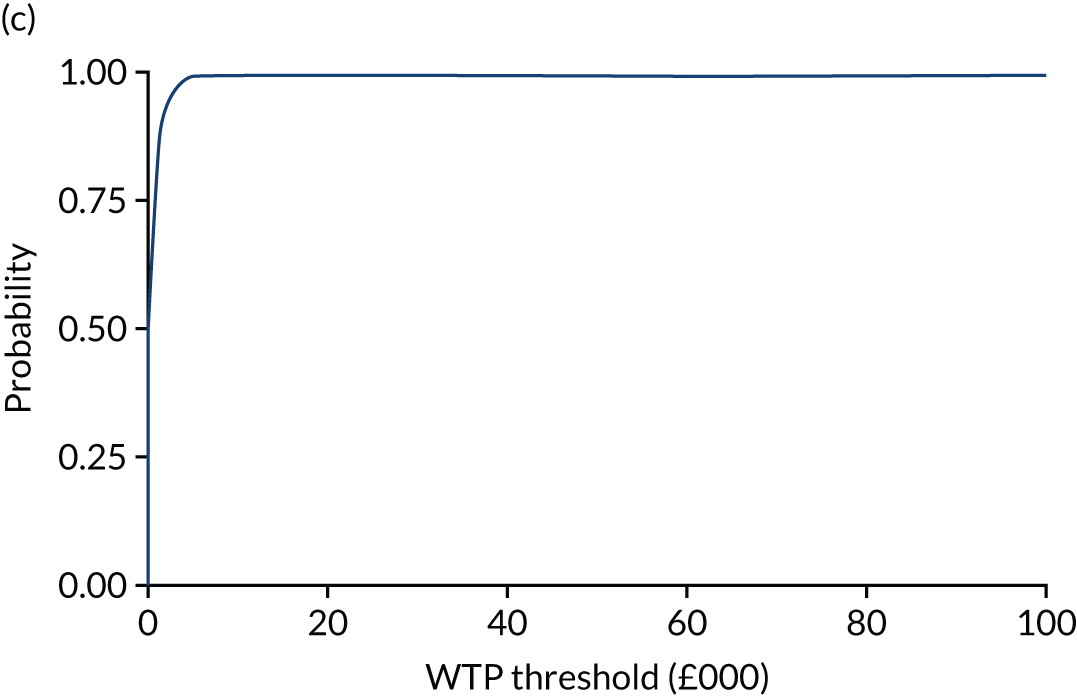

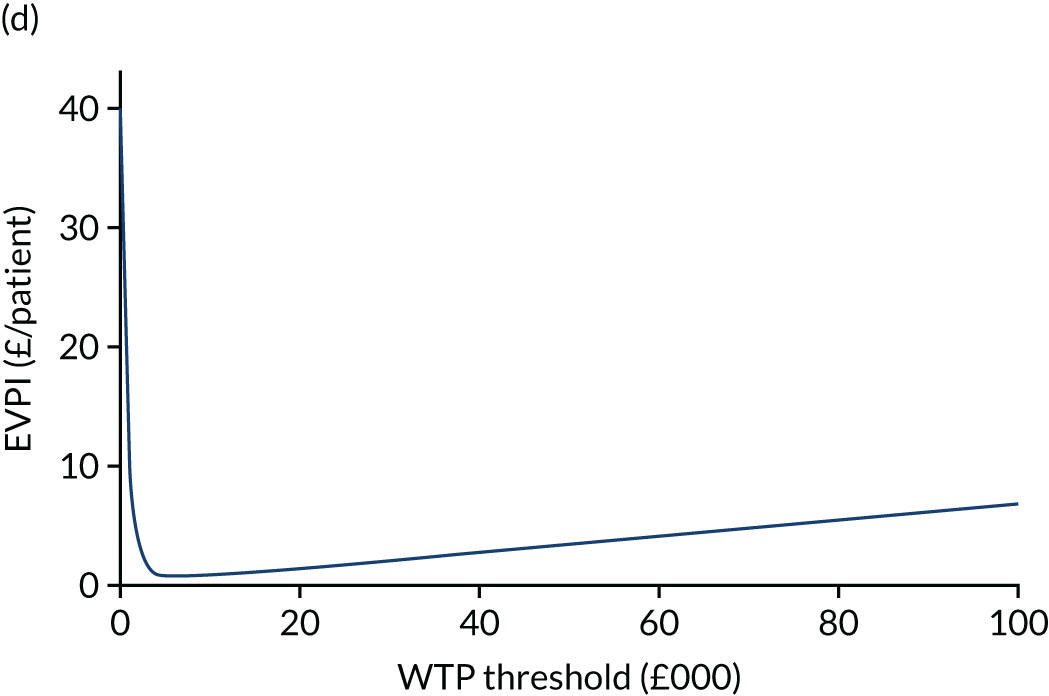

The (bootstrapped) median incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) and CI were estimated from the bivariate analysis. Value for money was determined by comparing the ICER with two willingness-to-pay (WTP) thresholds: the NICE-recommended upper threshold for ‘regular’ approvals of £30,000 per QALY76 and a lower value of £15,000 per QALY, reflecting uncertainty about the true value appropriate to the NHS. 77 The chosen threshold represents the WTP for an additional QALY: an intervention with a lower ICER value than the threshold could be considered cost-effective for use in the NHS. To assess the robustness of findings, base-case assumptions were explored using a range of supportive sensitivity analyses.

Net monetary benefit (NMB) succinctly describes the resource gain (or loss) when investing in a new treatment when resources can be used elsewhere at (or up to) the same WTP threshold. It is calculated as:

where NMB is estimated across a range of WTP thresholds such as from £0 per QALY to £100,000 per QALY. Where an intervention ICER is cost-effective (i.e. lower than the WTP threshold) the incremental NMB will be positive. NMB is routinely estimated from a bivariate regression to help generate a cost-effectiveness acceptability curve (CEAC). The CEAC visualises the likelihood that treatments are cost-effective as the WTP threshold varies. 78 Univariate regression of NMB has several advantages over the bivariate approach: it may be more robust approach with sparse data; it transforms the cost/outcomes data from a ratio into a continuous variable, allowing for easier manipulation and interpretation; it manages the correlation between costs and QALYs; it easily manages covariate imbalances; and repeated estimations explore the WTP threshold. 79 However, it does not allow the cost-effectiveness plane to be visualised, and the univariate distribution varies by threshold. Univariate regression was used as a confirmatory analysis where patient numbers were low or distributions were highly non-normal.

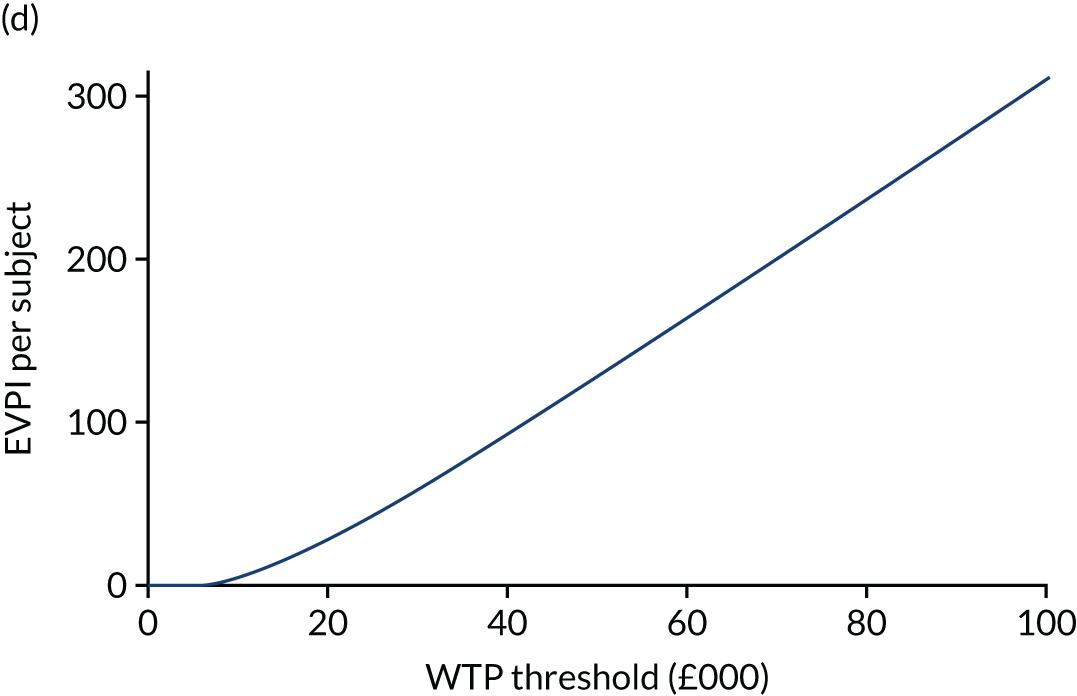

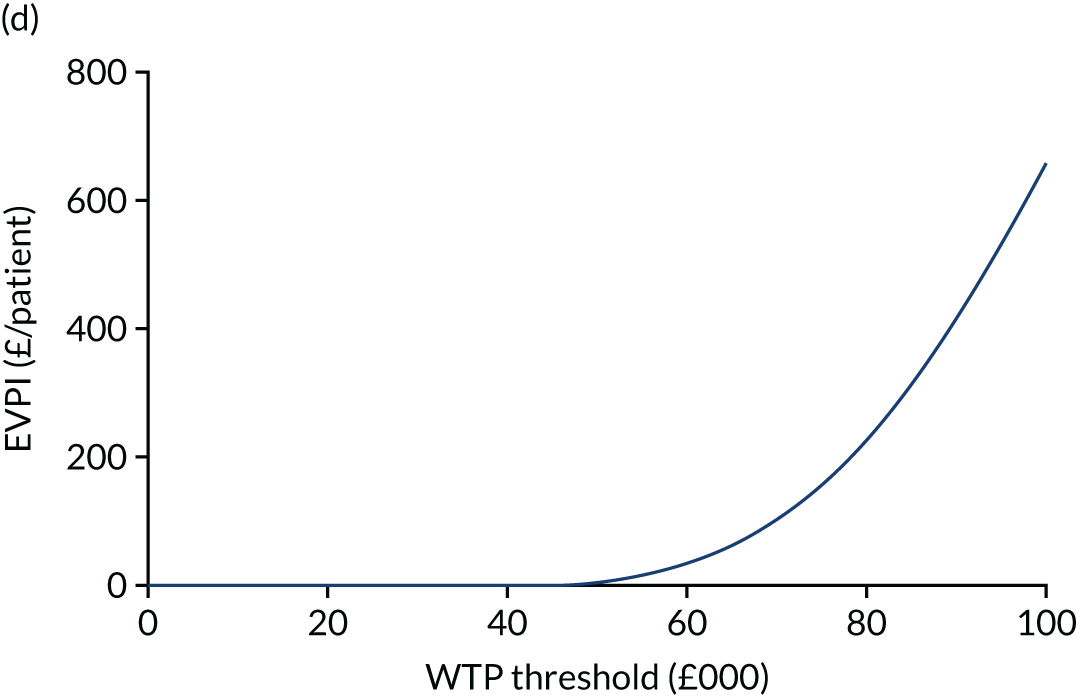

The expected value of perfect information (EVPI) is the upper limit of the value to a health-care system of further research to eliminate uncertainty. 80 Findings from cost-effectiveness analyses remain uncertain because of the imperfect information they use. If a wrong adoption decision (e.g. to make a treatment available) is made, this will bring with it costs in terms of health benefit forgone: the NMB framework allows this expected cost of uncertainty to be determined and guide whether or not further research should be conducted to reduce uncertainty.

Analyses and modelling were undertaken in Stata 16.1 using the portal provided at Queen Mary University of London. Reporting follows the Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS) statement. 81

Patient experience

Interviews were digitally recorded, anonymised, transcribed verbatim and analysed using a pragmatic thematic analysis. Data analysis was developed as outlined by Fereday and Muir-Cochrane82 in the first instance by mapping key concepts derived from the transcripts (‘charting’) and extracting emergent themes from the transcripts. The topic guide was used for the pre-determined codes and supplemented with additional codes that arose from the data. The final analysis combined inductively and deductively derived codes. The qualitative researcher (Tiffany Wade) conducted independent analyses and then compared and refined resulting codes and themes in discussion with the qualitative research study lead (CN). Three members of the patient and public involvement (PPI) panel were shown the qualitative results and participated in an online discussion to refine the messages. Emergent themes formed the basis of analytical interpretation. Challenges to delivering the three trials were also enquired about during the qualitative interviews with participants and research staff, using the qualitative methods described.

Patient recruitment

Challenges to recruitment

Recruitment was poor and negatively affected the whole programme (i.e. all three trials). This reflected several issues with the process and some of the design. Thus, the programme as a whole suffered from the following:

-

Long-term staff [i.e. specialist NHS nurses and Clinical Research Network (CRN)-funded research nurses] sickness and retirements and difficulty in recruiting staff led to shortage of staff to deliver interventions. This was reflected by significant recruitment only at sites where research staff from the directly funded core research team took over delivery (e.g. Barts and the London School of Medicine and Dentistry, Queen Mary University of London, in CapaCiTY trial 1 and County Durham and Darlington NHS Foundation Trust in CapaCiTY trial 2).

-

R&D delays to get the study up and running at many sites (range 6–9 months), with five sites never opening.

-

Lack of funding to cover excess treatment costs (ETCs) [e.g. high-resolution anorectal manometry (HRAM) devices; Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) to allow prescription of irrigation kits].

-

Recruitment targets too high, demotivating staff and pressurising them to start recruitment before they were prepared (according to interviews).

-

Some treatments were available as part of clinical practice immediately if patients refused entry into research, and with some delay if patients agreed to participate. Patients often had a significant burden of symptoms and were unwilling to delay treatment.

Other issues were trial specific. In CapaCiTY trial 1, delays due to infection control variations in approval of HRAM protocol and device cleaning (e.g. local views differed from published national standards and would require the purchase of expensive sterilisation equipment) hindered INVEST. Trial 1 also suffered criticism that the number of outcome questionnaires may have been off-putting to some patients (see Work programme 5, Patient and public involvement). In CapaCiTY trial 2, we underestimated the number of patients who would not be willing to try the irrigation device and the additional staff time above clinical need, making staff reluctant to recruit (both points highlighted in interviews). CapaCiTY trial 3 was seriously hindered by the evolving serious mesh controversy on national and international media. 83 Patients became unwilling to try the intervention and some hospitals were instructed by their lawyers to stop the intervention. A further problem in CapaCiTY trial 3 related to NHS bed pressures: the stepped-wedge design meant that one group of patients was randomised to have surgery caried out in 4 weeks. Some sites were unable to secure a bed in this time frame even with proscribed tolerance.

We took a number of measures to try to mitigate these issues:

-

We provided almost all sites with refresher site initiation visits and guidance in reviewing referral letters to identify suitable patients.

-

We provided all sites with a refresher investigator meeting in December 2017 to get all research staff together from all our sites with the aim to provide them with refresher training on protocol, exchange experience on overcoming recruitment barriers and encourage everyone to recruit.

-

We changed the design of the studies in January 2016 to shorten the time between the follow-up visits from 24 months to 12 months to lessen the burden of the follow-up visits on both patients and research staff, and removed two lengthy questionnaires to reduce file size.

-

We made protocol amendments to make the protocol more compatible with routine practice where possible.

-

We provided sites with support in data entry and administrative work, which would free up the research nurse to do the screening and recruitment.

-

We launched an advertising campaign in summer 2016 to find suitable patients through newspapers.

-

We provided HRAM devices to sites on loan in an effort to help sites meet the requirements of study device (CapaCiTY trial 1). We undertook competitive procurement and assisted sites with business cases to secure funding for HRAM equipment.

-

We secured funding from irrigation device company McGregor Healthcare Ltd (Macmerry, UK) to sponsor sites affected by the lack of prescription funding (CapaCiTY trial 2).

-

We engaged with NIHR to try to encourage CCGs to meet their obligations to fund ETCs. We had letters from the Department of Health and Social Care in this regard but both it and the CRN were unable to mandate ETCs (CapaCiTY trial 2).

-

We requested recruitment extensions for all three trials in an effort to boost recruitment.

-

We regularly presented at national speciality meetings (e.g. the Pelvic Floor Society).

-

We made use of incentives – prizes, a newsletter, social media and professional development opportunities.

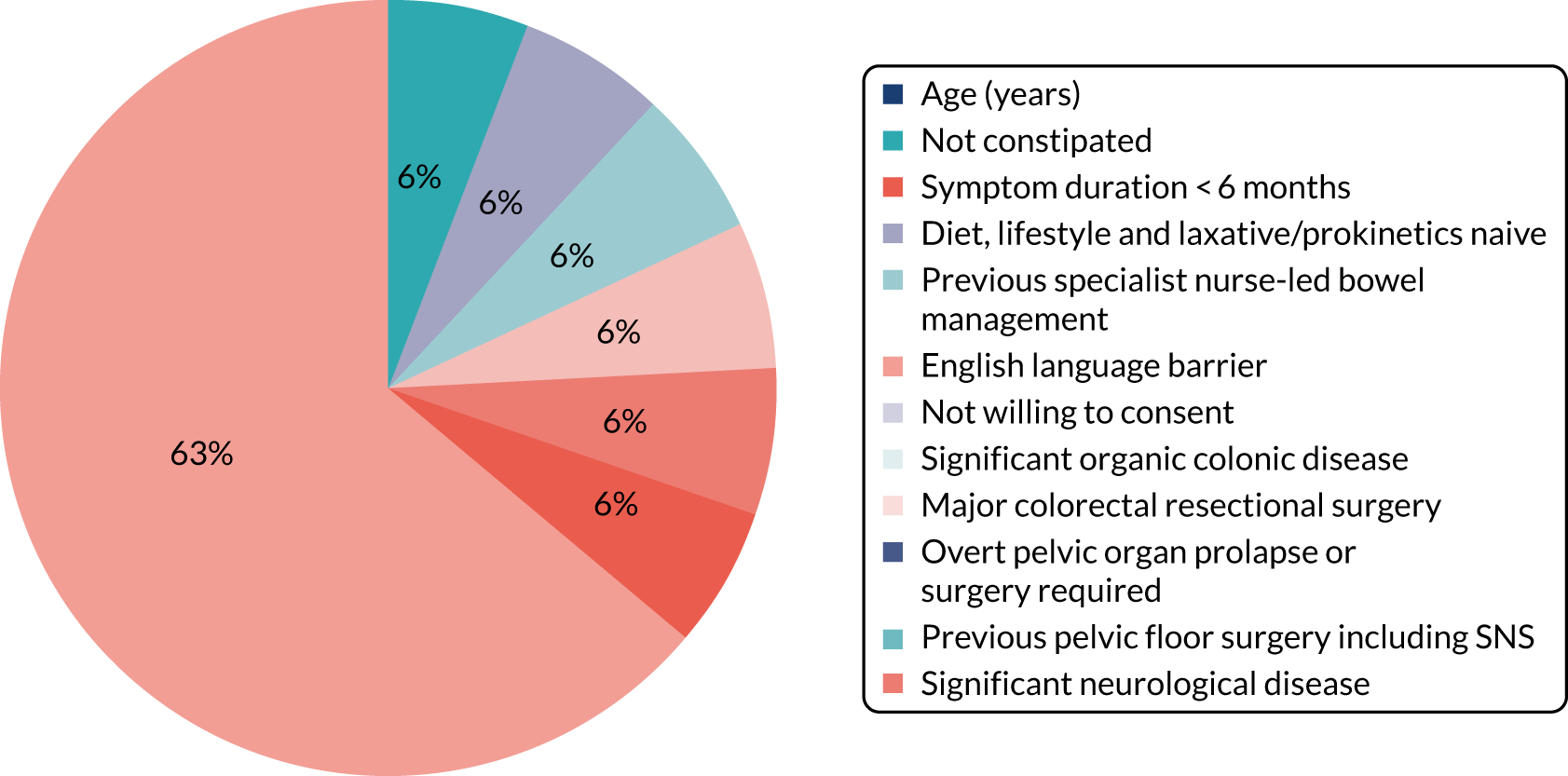

Final programme recruitment

A total of 275 patients was recruited across three trials, representing a major shortfall in relation to the required cumulative sample size (n = 808). These patients were recruited from a total of 733 screened (37.1%); this recruitment rate was lower than the 50% recruitment rate we anticipated. About half of screen failures were due to failed eligibility and about half were due to the patient declining. There was also a problem of patient retention in all trials, with higher than anticipated drop-out rates before primary outcome (actual range 11–43% vs. anticipated range 20%).

A total of 90% of participants were female (100% in CapaCiTY trial 3) and participants had a mean age 45 years (IQR 33–57 years). The majority (70%) of participants were of white ethnicity. Baseline phenotyping indicated high levels of comorbidity in > 70% of patients and a history of previous abdominal and pelvic surgery in > 50%. In terms of other risk factors, psychiatric diagnoses (insufficient for exclusion) and joint hypermobility were each present in ≈ 20% of patients. Approximately two-thirds of participating women were parous. Although the criteria for chronicity of constipation was 6 months’ duration, mean duration was 6 years and almost all patients with CC had constipation that proved intractable to lifestyle modification and laxatives, which was reflected by referral pattern: 80% of referrals were from secondary or tertiary care. Almost 20% had also failed prokinetic therapy. Symptom burden was high, with mean PAC-QoL and PAC-SYM scores of > 2.0 points at baseline. In addition, > 50% of patients had faecal incontinence symptoms, > 30% had urinary symptoms and > 20% had pelvic organ prolapse symptoms (100% in CapaCiTY trial 3).

In CapaCiTY trial 1, data from the PHQ-9, which measures depression, showed that 32.9% of participants scored > 9 points, suggesting that one-third of the sample would meet case criteria for major depressive disorder (MDD). A further 33% had scores indicative of mild depression, suggesting that, overall, around two-thirds of the sample were distressed or depressed. This compares with a point prevalence of MDD in the general population of 5%. The prevalence of MDD is, on average, at least twice as high in people with chronic medical diseases than in those without a chronic medical condition, but, even taking this into account, the rates in the current study are at the high end. 84 The findings for anxiety were similar, with one-third of the cohort (33.6%) scoring above the GAD-7 cut-off point for an anxiety disorder, and a further 25.1% reporting mild symptoms of anxiety.

Interview participants

A total of 45 patients and 23 staff members were interviewed:

-

CapaCiTY trial 1. A total of 24 participants (men, n = 3; women, n = 21) were interviewed: nine participants were allocated to INVEST and 15 participants were allocated to no INVEST, to elucidate the experience of undergoing tests and being given an explanation of results or their feelings about not being tested; 11 participants were allocated to HT and 13 participants were allocated to HTBF, both improved and not improved (at 6 months) for perceptions of treatment. A total of 15 staff members were interviewed: five therapists involved in HT/HTBF to determine the comparative ease of delivery of the two therapies, three research nurses, four CapaCiTY research team members, one biofeedback physiologist, one clinical trials associate and one trainee clinical scientist.

-

CapaCiTY trial 2. A total of 11 patients (men, n = 4; women, n = 7) undergoing TAI were interviewed: seven received high-volume TAI, three received low-volume TAI and one received both high-volume and low-volume TAI. Most (n = 10) patients were continuing to use TAI at the time of interview; however, one had discontinued use by the interview date.

-

CapaCiTY trial 3. A total of 10 patients (all female) were interviewed. Nine patients were interviewed ≈ 1 year after their lapVMR to gain an understanding of what their experiences were prior to, immediately after and 1 year after the operation. One patient who declined surgery was also interviewed. A total of eight staff members (i.e. three surgeons, three research nurses, one gastroenterologist and one research team member) were also interviewed about both the interventional and research element of the study.

Work programme 2: CapaCiTY trial 1 – randomised trial of habit training compared with habit training with direct visual biofeedback in adults with chronic constipation

Specific background and rationale

In most UK practices, patients with CC are first referred to specialist nurses for a variety of nurse-led behavioural interventions to improve defaecatory function. A range of cohort studies,85 RCTs,86–91 reviews,92 guidelines93 and meta-analyses94 attest to the general success of this approach. However, opinion varies greatly concerning the complexity of intervention required and UK survey evidence (performed as part of this programme) indicates that there is remarkable variability of practice. 95

A simple form of behavioural therapy is habit training. This involves optimising dietary patterns to maximise gastrocolic response and the morning clustering of high-amplitude propagated colonic contractions that propel contents towards the rectum for subsequent evacuation. Dietary advice to optimise intake of liquid and fibre is given, as well as advice about frequency and length of toilet visits and posture. Patients are also instructed on basic gut anatomy and function, and gain an appreciation of how psychological and social stresses may influence gut functioning. Simple pelvic floor and balloon expulsion exercises are often included.

More complex forms of therapy include instrument-based biofeedback learning techniques. 85–91 Favoured in the USA and by about half of UK centres, these provide direct visual computer-based biofeedback of pelvic floor activity. Although small RCTs suggest an additive value of biofeedback over habit training alone in the management of selected patient subgroups of CC (e.g. dyssynergic defaecation),87,96–98 there has been no multicentre or adequately powered RCT in unselected patients, despite the uncertainty having significant resource implications. Aside from the issue that there is now considerable disagreement regarding the very diagnosis of dyssynergic defaecation (including from our own study using HRAM),99 most publications advocating biofeedback have come from specialist centres with considerable ‘investment’ in these techniques, with reports much less favourable when biofeedback is the ‘de-vested’ comparator. 100,101 The controversy following a Cochrane review that drew attention to the limitations of the evidence base102 attests to the polarity of opinion on this subject and the need for a more definitive (i.e. a larger, higher-quality) RCT.

This underpinned our first trial-specific research question:

-

In unselected (i.e. no-INVEST group) adults with CC, is HTBF more clinically effective than HT as measured by PAC-QoL score at 6 months’ follow-up?

A further unanswered question regards the utility of behavioural therapies in different subgroups of patients with CC. Well-regarded international consensus (e.g. the Rome VI Criteria)103 supports a view that biofeedback significantly benefits only a subgroup of patients with a form of functional defaecation disorder termed ‘dyssynergic defaecation’ (see Figure 1). This poses the question whether or not further tests are required at an early stage (i.e. before behavioural therapy to select patients for biofeedback). There are significant differences of expert opinion on this subject: some advocate early complex and expensive investigations to guide treatment in most patients,8 whereas others advocate undertaking such tests only in resistant cases or in those progressing to surgery. 104 The advantage of guiding treatment105,106 is balanced against the invasive nature of some tests, radiation exposure, embarrassment and cost (≈ £600–1200 NHS tariff); most also necessitate an escalation of care (i.e. from secondary to tertiary centre). The need to resolve this question has been consistently highlighted38,107 but, to our knowledge, prior to the programme no RCT had stratified treatment selection on this basis.

This underpinned our second trial-specific research question:

-

Is the impact of such specialist-led interventions improved by stratification to HTBF or HT based on prior knowledge of anorectal and colonic pathophysiology using INVEST as measured by PAC-QoL score at 6 months follow-up?

Both research questions were embedded in a single experimental design with three parallel trial groups and required a total sample size of 394 patients. For a full description of this trial, including interventions, trial-specific design procedures and all results and analyses, see Appendix 1. Only the main results and conclusions are summarised in this report.

Results

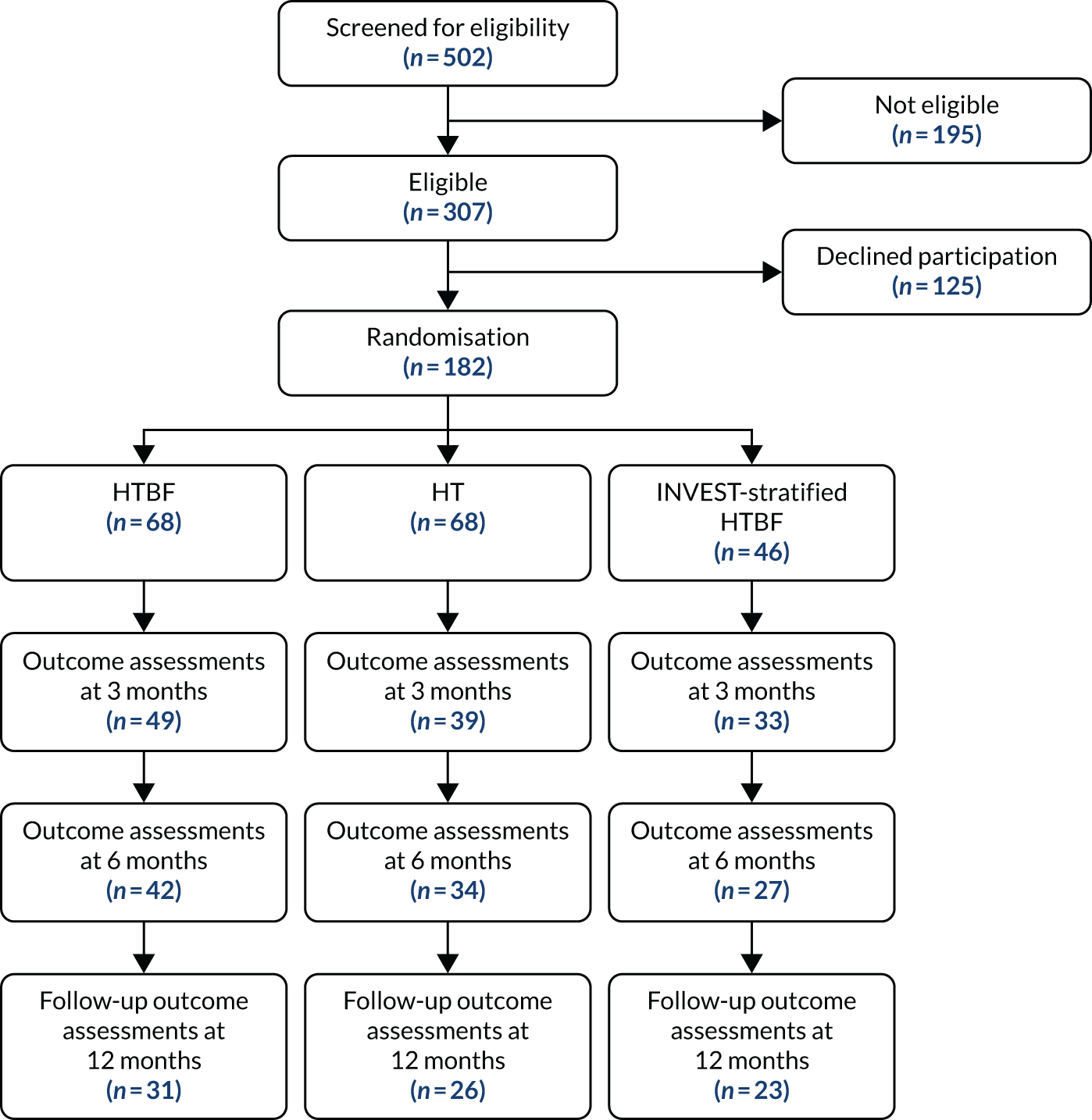

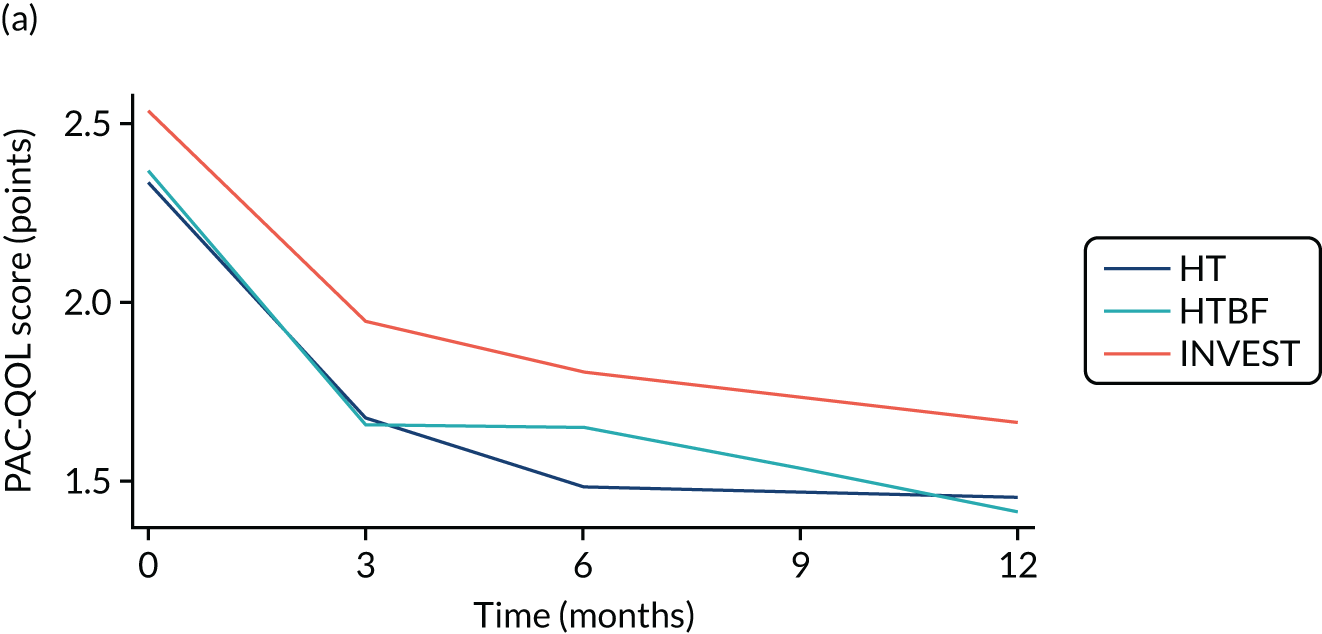

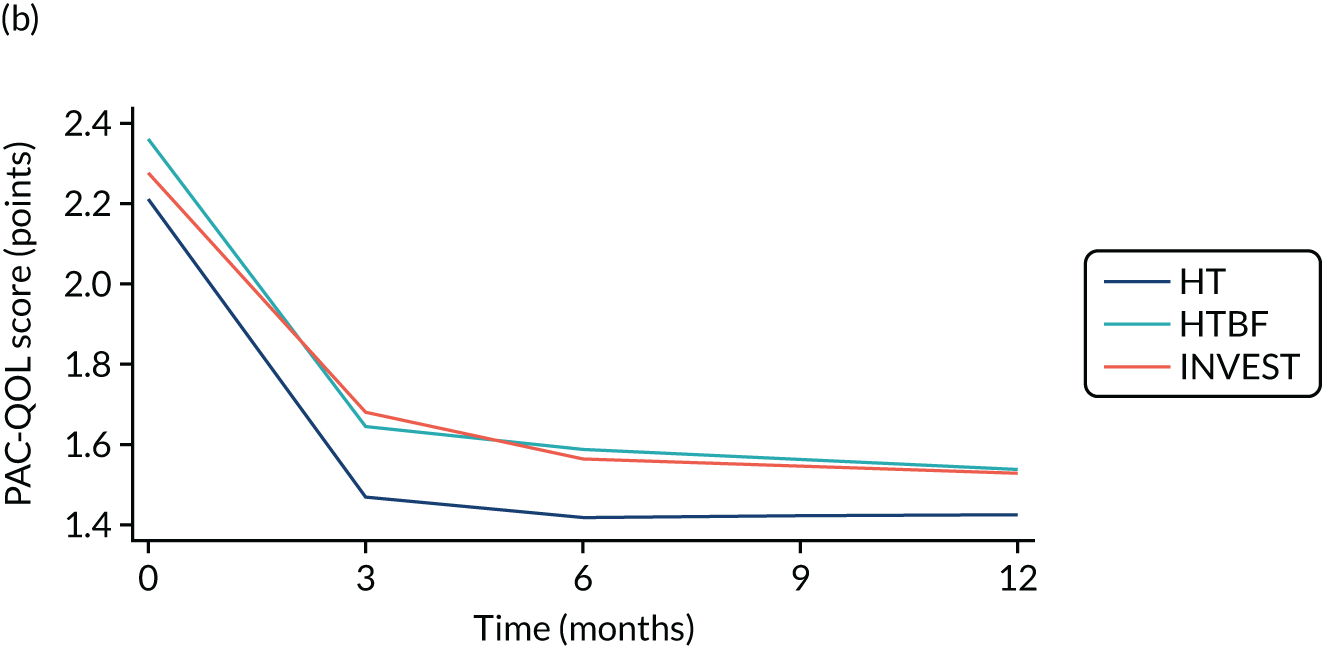

Recruitment started on 26 March 2015 (first intervention 21 May 2015) and ended 30 June 2018. A total of 182 participants (of the target 394 participants) were randomised out of 502 screened (36.3%) from 10 sites. Two sites opened but failed to recruit; the remainder randomised between 7 and 71 participants. A total of 68 participants were randomised to HT, 68 participants were randomised to HTBF and 46 participants underwent INVEST-guided therapy (HT or HTBF based on results) [the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram is shown in Figure 2]. A total of 178 participants provided PAC-QoL data at one or more time points (Figure 3). The primary outcome (PAC-QoL score) was available at both baseline and 6 months for only 103 participants. There was no evidence of an additive effect of HTBF over and above HT (Table 2).

FIGURE 2.

The CapaCiTY trial 1 CONSORT flow diagram.

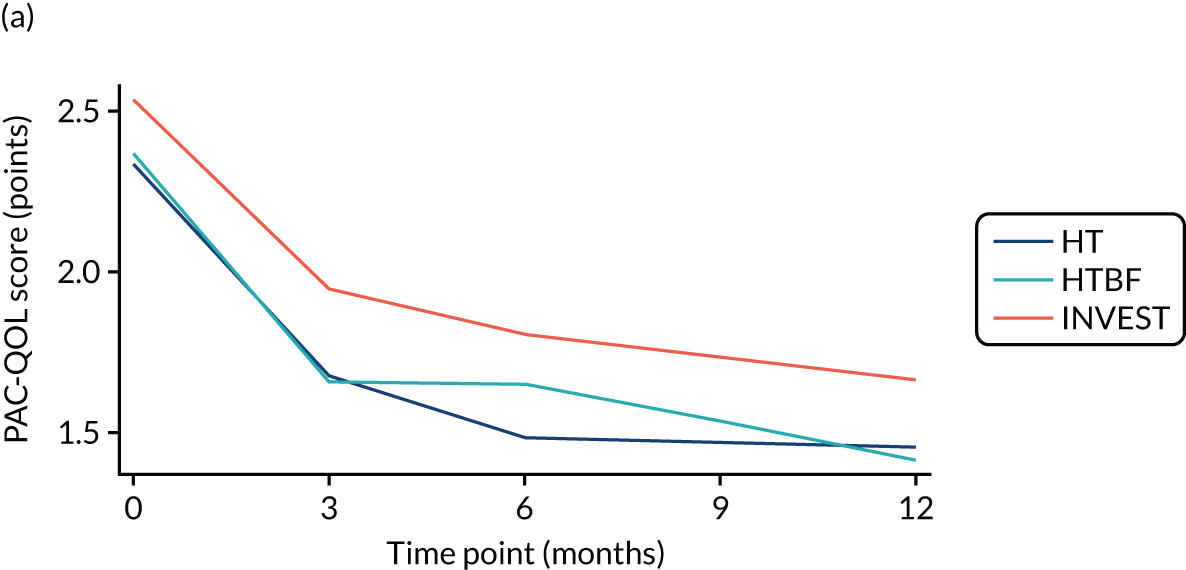

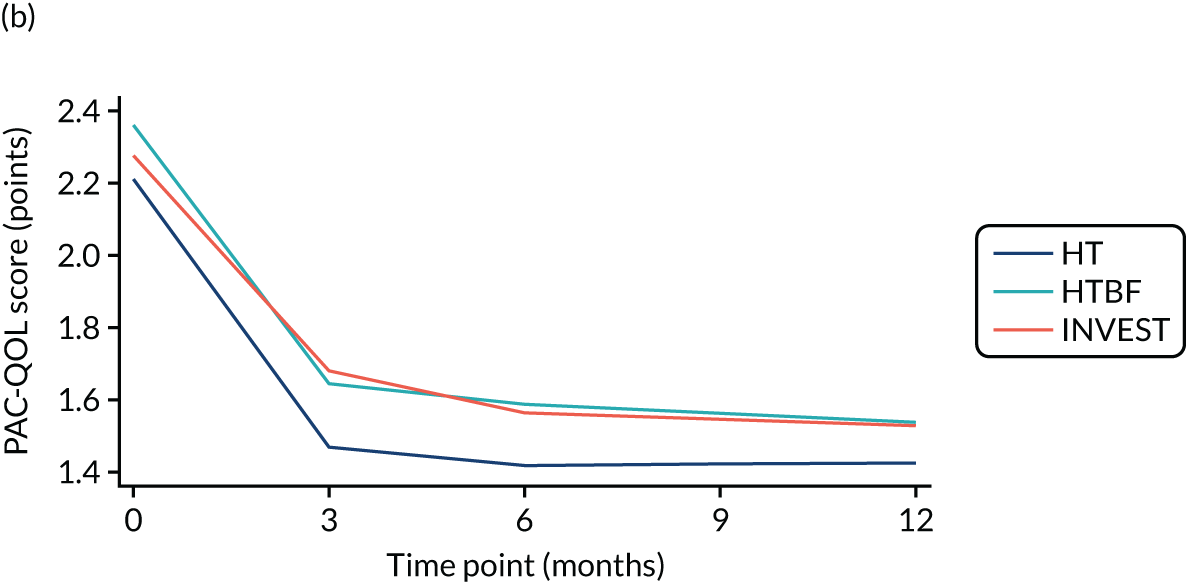

FIGURE 3.

Overall PAC-QoL scores. (a) All participants (n = 178 at baseline); and (b) participants with no missing data to 12 months (n = 54). Both figure parts show reductions in score (i.e. improvement) over time.

| Intervention | PAC-QoL score (points), mean (SD) | Treatment differencea (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 6 months | |||

| HT vs. HTBF | ||||

| HT (n = 38) | 2.26 (0.69) | 1.49 (0.85) | Reference | |

| HTBF (n = 30) | 2.41 (0.81) | 1.65 (1.03) | –0.03 (–0.33 to 0.27) | 0.8445 |

| No INVEST vs. INVEST | ||||

| No INVEST (n = 68) | 2.33 (0.74) | 1.56 (0.93) | Reference | |

| INVEST (n = 22) | 2.36 (0.78) | 1.81 (1.03) | 0.22 (–0.11 to 0.55) | 0.1871 |

A range of secondary outcomes covering symptoms and QoL improved in both the HT group and the HTBF group (e.g. mean PAC-SYM score reduced from 2.2 points at baseline to 1.5 points at 6 months and weekly laxative use reduced fourfold). Interventions led to small reductions in depression but no significant differences between the intervention types. Overall, about 65% of participants were globally satisfied or very satisfied with both interventions and this was reflected by participant experience reported at interview (i.e. similar proportions of participants liked, and a minority disliked, both interventions for a number of reasons).

Similar results were obtained for INVEST versus no-INVEST, with no evidence of a difference in primary outcome (see Table 2): participants provided reasons for liking INVEST (e.g. greater knowledge of their condition and knowing that it was not ‘all in their mind’) and disliking the invasiveness and embarrassment of the tests.

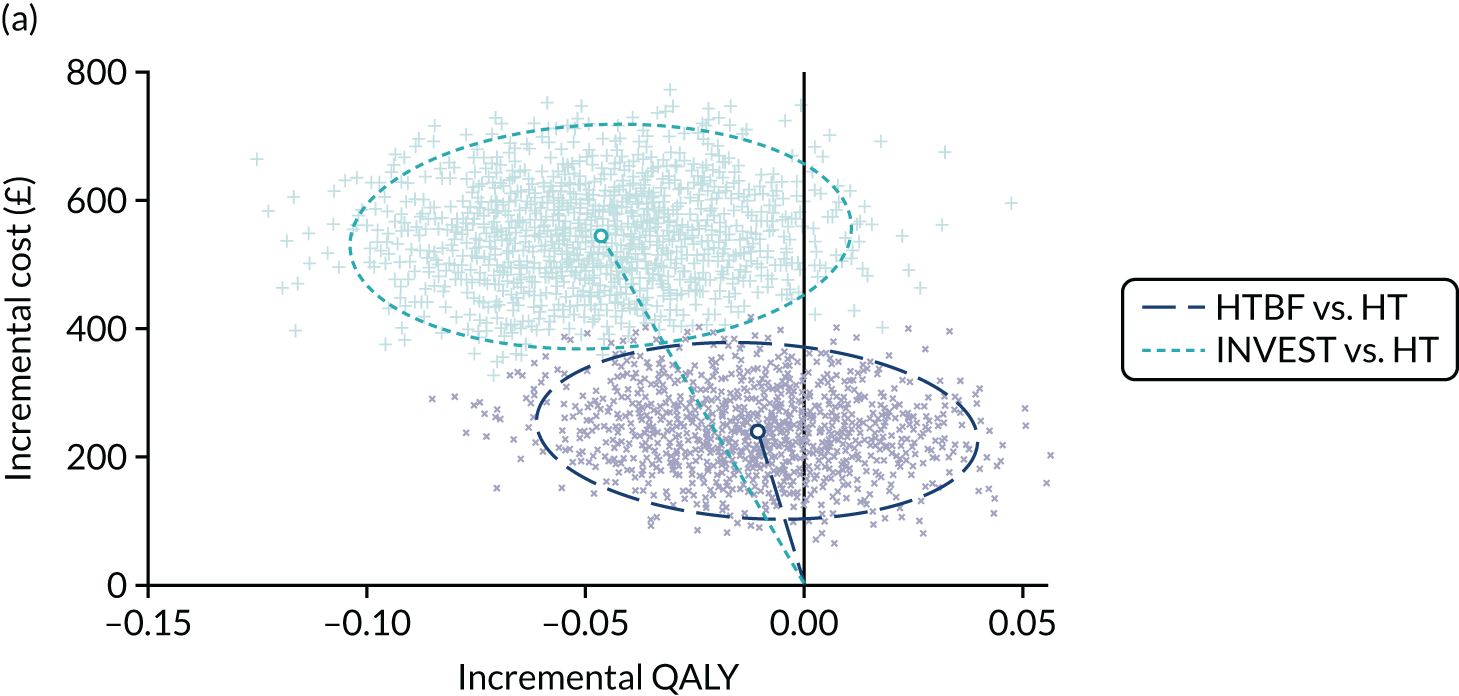

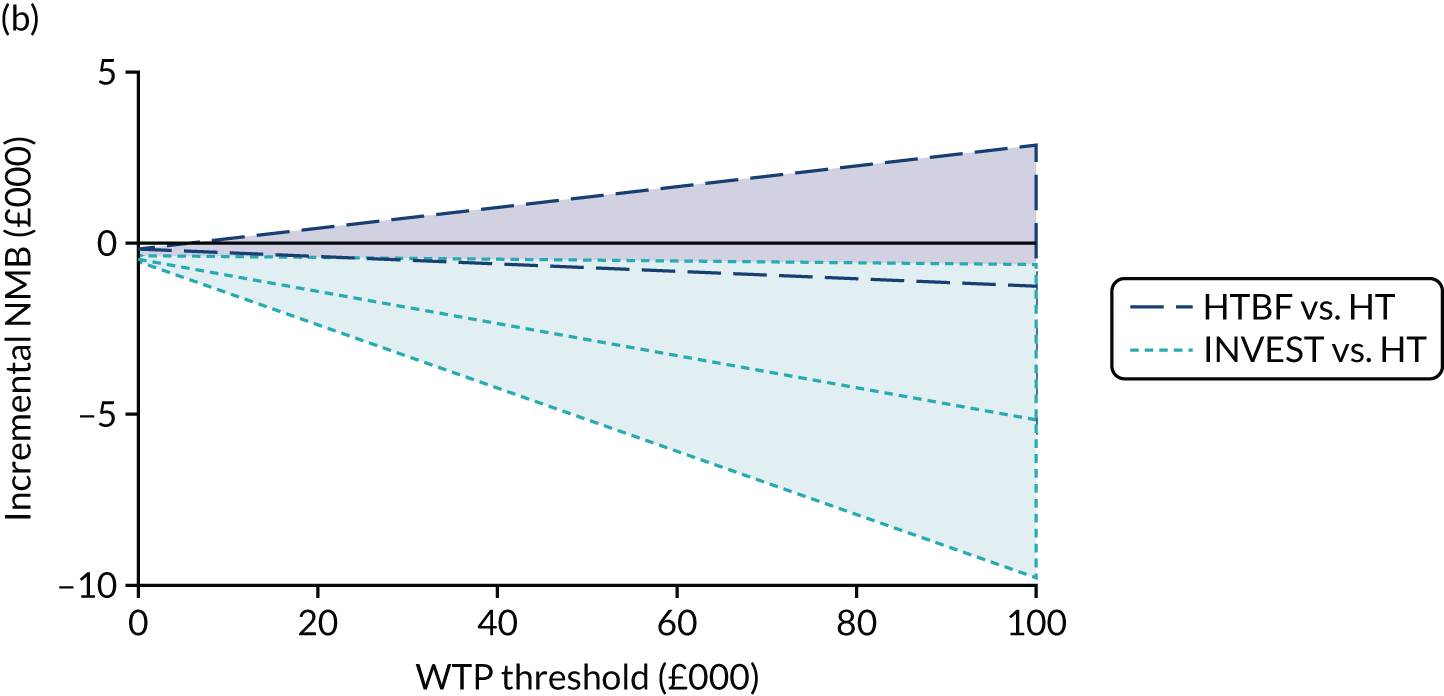

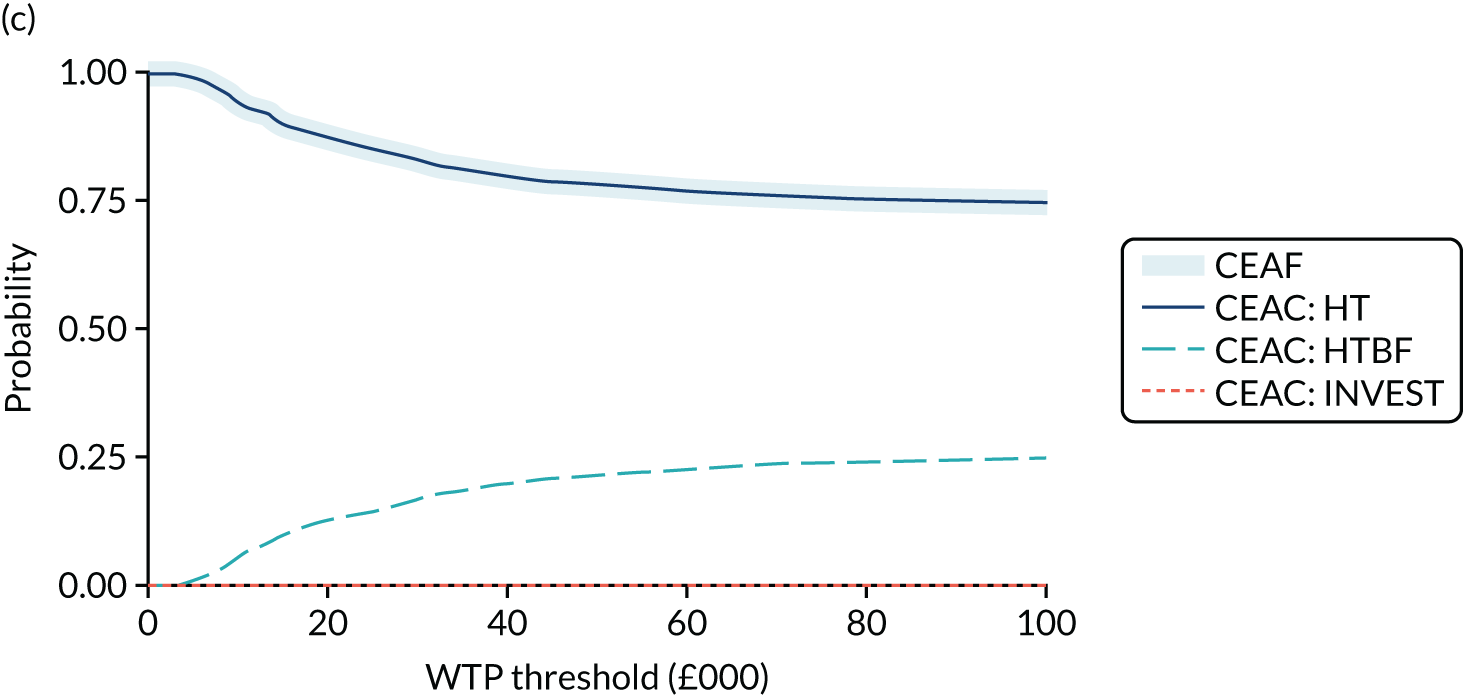

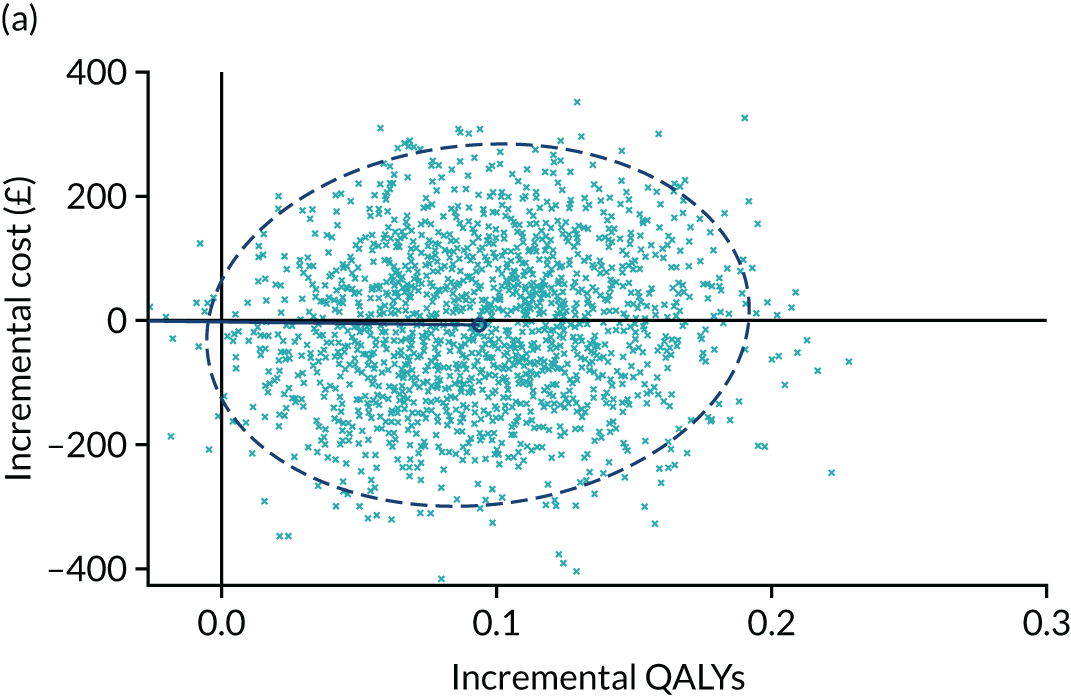

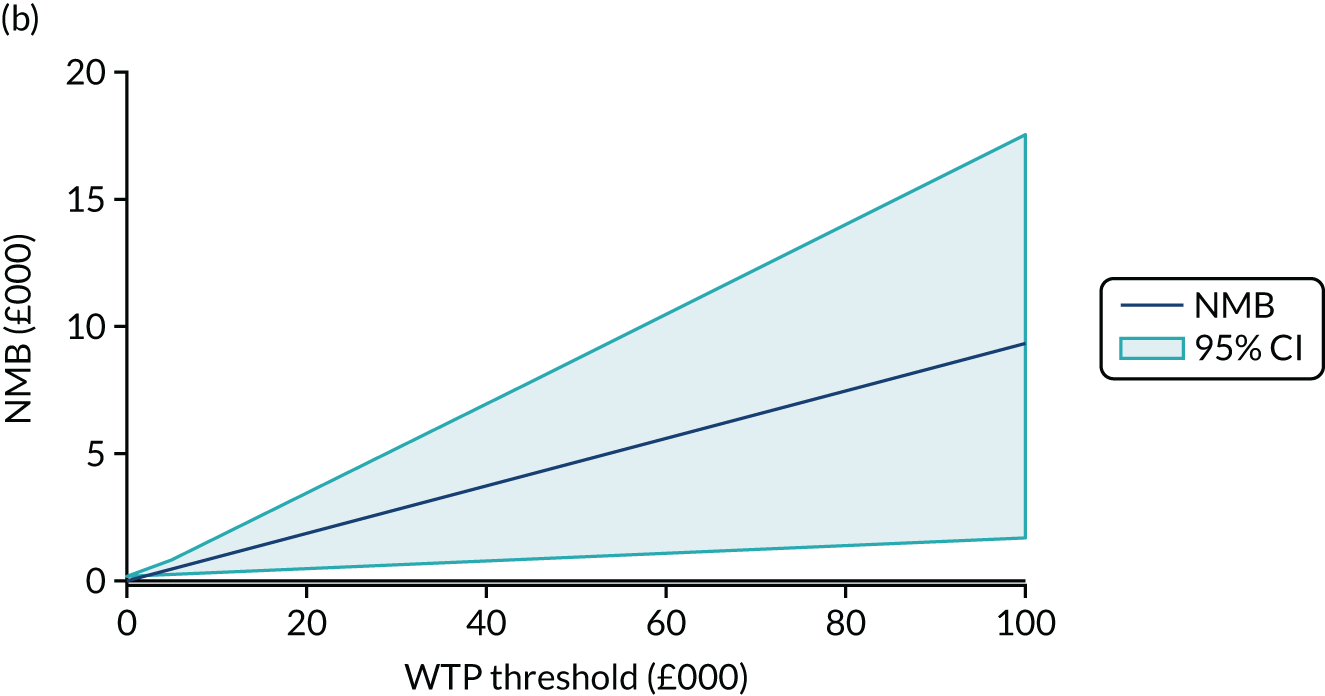

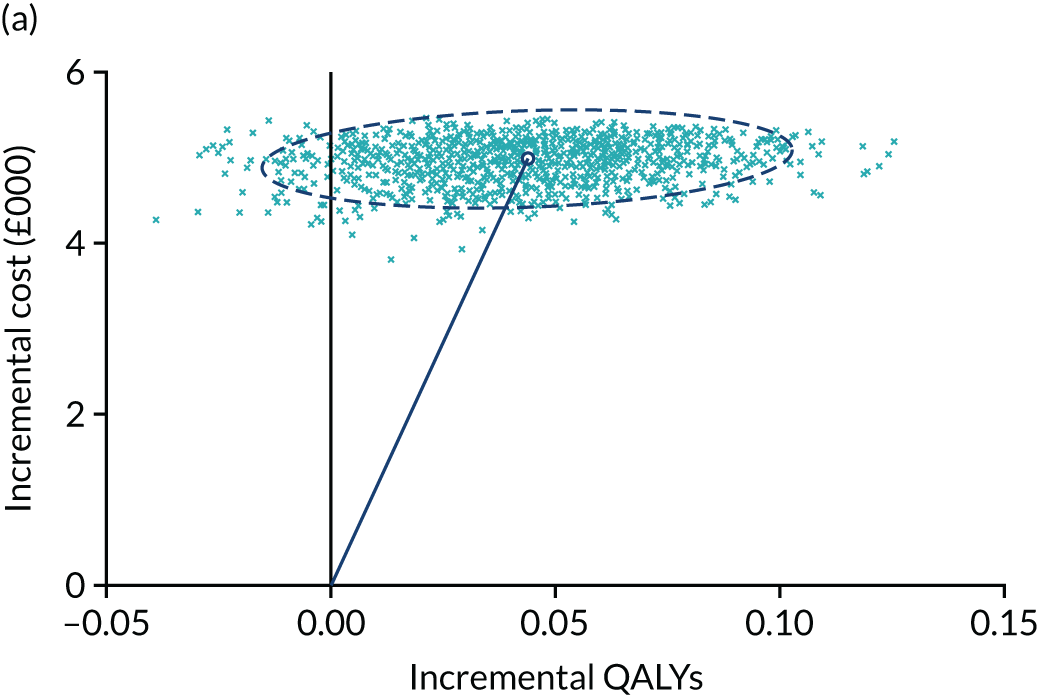

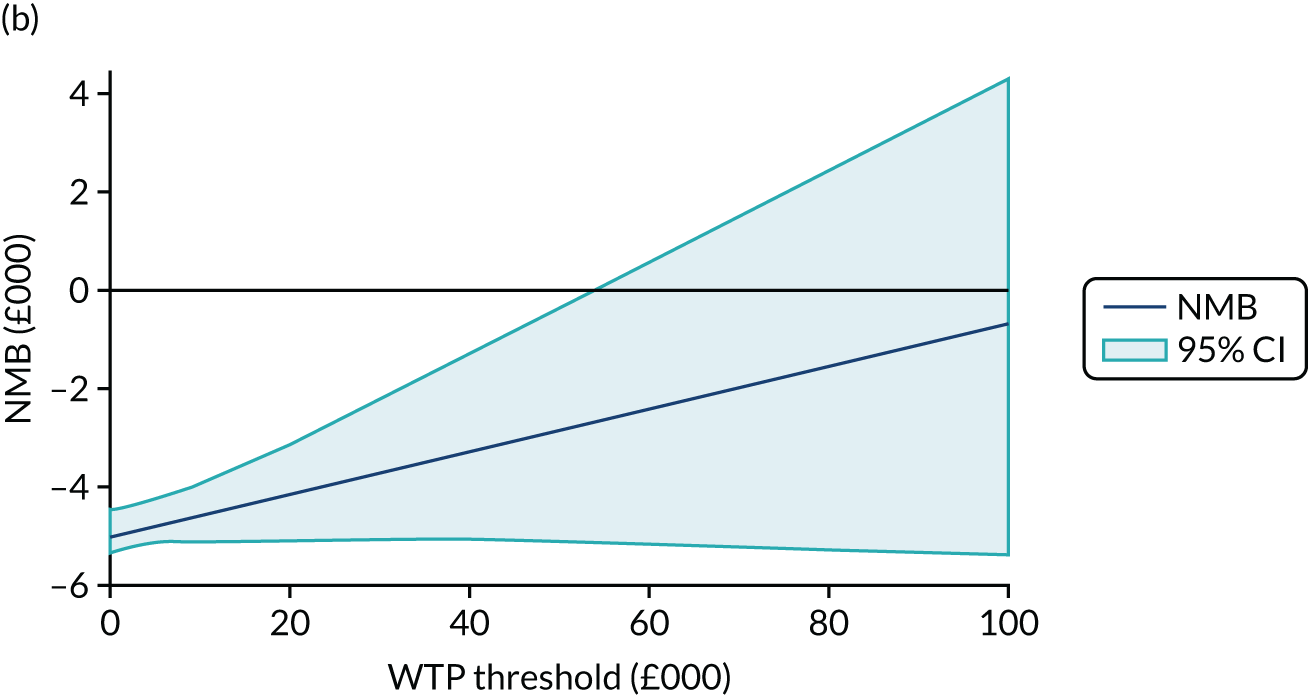

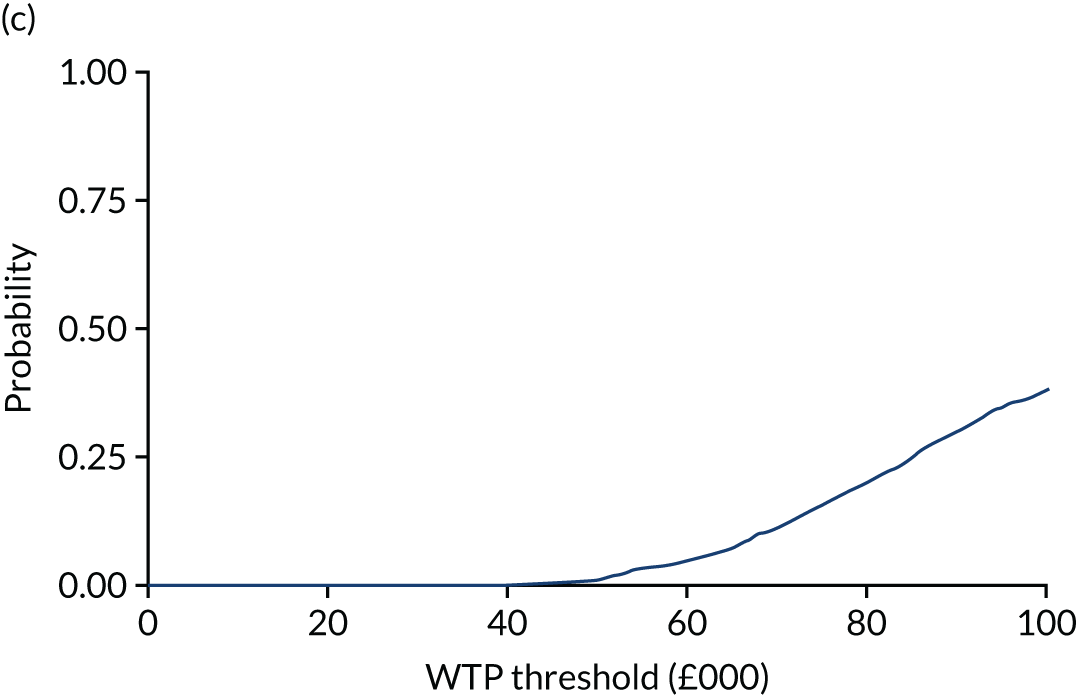

Given similar changes in EQ-5D-5L scores for all interventions, cost-effectiveness analyses favoured the simpler strategies (i.e. HT and no INVEST) as the dominant strategies. In both instances, cost increases were significant (HTBF vs. HT: £239, 95% CI £133 to £354; INVEST vs. no INVEST: £543, 95% CI £403 to £685) and QoL reduced (HTBF: –0.010 QALYs, 95% CI –0.053 to 0.03 QALYs; INVEST: –0.047 QALYs, 95% CI –0.093 to –0.001 QALYs). The probability that HT is cost-effective was a p-value of 0.83 at a WTP threshold of £30,000 per QALY.

Conclusions

Taking together the results from clinical effectiveness, cost-effectiveness and patient experience data, the following conclusions may be drawn while accepting the major caveat of under-recruitment:

-

Included adults with CC had high levels of symptom burden and long durations of symptoms that had been refractory to previous treatments and could therefore be considered ‘hard to treat’. These symptoms were associated with a substantive effect on QoL and psychological well-being. Patient experience reflected the misery of the condition and fear that treatments would be ineffective.

-

Our analysis of clinical effectiveness showed that all interventions trialled (i.e. HT, HTBF with INVEST and HTBF with no INVEST) reduced symptom burden and improved disease-specific QoL. The observed magnitude of these PAC-QoL score changes (≈ 0.8 points) can be considered to be clinically meaningful and represented a greater reduction than the minimum clinically important difference sought between groups by design (mean change 0.4 points). The findings from the primary outcome were coherent with a panel of secondary outcomes, and, overall, such improvements are unlikely to have occurred spontaneously in a condition that is generally considered chronic and stable.

-

Confidence intervals rule out clinically important differences between HT and HTBF for the primary outcome and all main secondary outcomes. The same was true of INVEST and no INVEST.

-

Standardised specialist-led habit training alone and no INVEST are strongly supported by cost-effectiveness analyses. Despite under-recruitment (182 out of a planned 394 participants), participant-level data provided the most robust evidence to date on the first step of care for patients referred to hospital for CC. Neither a complex specialist-led intervention (e.g. pelvic floor retraining using biofeedback) nor stratification to complex or standardised therapy based on prior knowledge of anorectal and colonic pathophysiology (INVEST) were more cost-effective than HT. Analysis suggests that HT is the dominant strategy (i.e. lower cost and greater QoL) at a WTP threshold of £30,000 per QALY.

-

All procedures were safe and well tolerated by patients.

-

Interviews suggested that patient experience was mixed. Some regretted not being allocated to INVEST or HTBF (because they believed that they would have less knowledge of their condition and less likelihood of treatment success), whereas others felt that the tests and biofeedback were embarrassing and intrusive. Most participants reported a positive interaction with staff and at least some symptom benefit. Most would recommend trying the intervention they received to other people with CC.

-

Staff were mostly supportive, but some found that adhering to the agreed intervention protocol constrained their clinical flexibility and they would have preferred to individualise the intervention. The biofeedback element added time to consultations, or limited what they could cover in HT.

-

Because these patients had significant psychological comorbidity, and there is evidence that psychological treatments such as cognitive–behavioural therapy have significant and sustained benefits on symptoms, mood and QoL in people with irritable bowel syndrome (many of whom also experience severe constipation), future work should focus on incorporating psychological methods alongside HT. 108,109

-

Taken together, the cost-effectiveness data (in the absence of differences in clinical effectiveness, patient experience and safety) promote the adoption of the simpler pathway (i.e. HT without INVEST). A revised prototype pathway is provided on this basis in the final conclusions of the synopsis (see Figure 8).

Reflections on work programme 2

This WP was severely hampered by poor recruitment, with many of the general challenges listed in SYNOPSIS. It is not the place here to repeat well-rehearsed arguments about the frailties of delivering a complex research intervention in a resource-strained NHS, but these certainly affected this trial. That noted, with the benefit of hindsight, and even after simplifying the trial design at the award approval stages, the study was probably overambitious in design. We tried to answer two research questions concurrently with one experimental design (HT vs. HTBF and INVEST-stratified vs. no INVEST-stratified treatment). This was laudable and based very clearly on nationally agreed research priorities at the time (e.g. from the American Gastroenterology Association). 93 However, it might have been better to have simplified the design to one that compared only HT with HTBF in a two-group trial without INVEST. This would have not only reduced the sample size (and general complexity) but also avoided some of the issues of equipment shortages and approvals (including infection control procedures) that delayed many centres from opening for as long as 1 year (with some never opening). We considered this option at the second review stage but felt that it was too great a departure from our original application. An alternative design (based on our qualitative data) might have been preference based. Another issue was the complexity of inclusion criteria and the number and complexity of outcome instruments. Despite PPI input at the outset, and changes made (with PPI) during the programme, outcome collection was still burdensome. Although the type of strict inclusion criteria and outcome panel we employed seem to still be the norm in recent pivotal trials, a more pragmatic (relaxed) approach to inclusion and a smaller outcome booklet would (with hindsight) have been preferable.

Despite these challenges, the trial undoubtedly brought together a fragmented community of experts from around the UK and led to the standardisation of practice. Two publications from early in the programme highlight the previous lack of understanding of what actually constitutes biofeedback95 and what investigations tests should be performed and how. 34,110 The former was borne out by our qualitative data (i.e. many practitioners preferred to tailor their approach to each patient). The latter led to an international effort to introduce technical standards on performing and interpreting diagnostic tests of anorectal function, in which the CapaCiTY team were leaders, and these have been published. 111

Finally, it must be recognised that, despite under-recruitment, CapaCiTY trial 1 is, to our knowledge, nevertheless the largest RCT to date in which biofeedback is one of the trialled interventions. A total of 182 patients were randomised; sample sizes in 17 previous RCTs included in a Cochrane review102 ranged from 21 to 119 (and it is noted that the trial with 119 patients101 was focused on surgery with biofeedback as the comparator). Therefore, it is acknowledged that among many UK practitioners there will be a sentiment that the results of CapaCiTY trial 1 do still provide an answer to a major question – namely, that the sort of specialist-led biofeedback practice advocated by a small but very vocal group of experts in the USA is less likely to work in an NHS pathway. The main points are as follows: (1) there is insufficient human resource (trained specialist nurses) and equipment (manometry catheters) to provide it (CapaCiTY trial 1 had three to four sessions; in the USA five to seven sessions are prescribed); and (2) there is a general disbelief (reinforced by the findings of the study and a prior Cochrane review)102 that direct visual biofeedback offers much to patients over and above the panoply of approaches encompassed by HT (including holistic elements of patient support as well as didactic training) when it comes to the average patient (i.e. widespread adoption would be protracted if possible at all).

Research recommendations

The primary outcome effect size was almost identical for all groups and it is unlikely that another trial, even with a much greater sample size, would detect a clinically important difference between interventions. Certainly, the CI for the effect comparing HT and HTBF excludes the difference we initially set as the minimum clinically important difference in our sample size calculation. Thus, it is hard to recommend further investment, even with a more simplified trial design. We cannot comment on whether or not the US expert view is correct; perhaps limitation to highly selected patients with proven dyssynergic defaecation and specialist equipment in the hands of very expert medical practitioners (undertaking multiple sessions of therapy) does result in better outcomes (we did not trial this). However, we believe that this would be difficult to trial successfully in the NHS for the reasons outlined, and were it to produce the same results as CapaCiTY trial 1 it would still be unlikely to influence international opinion owing to the financial reimbursement drivers that promote the US approach. As noted, there may be rationale to include some form of psychological therapy alongside habit training for the large proportion of patients with significant psychological morbidity (akin to trials for patients with irritable bowel syndrome). This is an area for further research.

Work programme 3: trial 2 – pragmatic randomised trial of low-volume compared with high-volume initiated transanal irrigation therapy in adults with chronic constipation

Specific background and rationale

Transanal irrigation, for which there are a variety of commercially available devices, has been rapidly disseminated internationally since about 2000, first in CC patients with neurological injury112,113 and subsequently in other groups CC groups. 114,115 Despite a lack of published data other than from small selected case series, TAI is now available on drug tariff (at a cost of ≈ £2500 per patient per annum) and is generally considered to be the next step for patients failing other nurse-led interventions. TAI has permeated the UK market without robust efficacy data and with ongoing concerns regarding longevity of treatment and complications. 112,116 Retrospective clinical audit data and review116,117 by the applicants suggest a continued response rate after 1 year of ≈ 50%, with patients thus avoiding or delaying surgical intervention, but an accurate assessment of response rate and acceptability of this intervention required confirmation in a trial. In addition, two alternative systems for delivery of TAI exist: low-volume systems delivering ≈ 70 ml per TAI, and high-volume systems delivering up to 2 l of TAI (although typically only 0.5–1.5 l is required per TAI). The theoretical benefit of higher-volume TAI is greater efficacy – simply put, more washout. However, the low-volume system is cheaper, costing ≈£750 per annum, based on alternate-day use, compared with a cost of £1400–1900 per annum for high-volume TAI, and it may also be less traumatic and more acceptable to patients.

This underpinned our first specific research question:

-

In patients with CC who have failed conservative treatment (HT or HTBF), what is the impact on disease-specific QoL of TAI initiated with a low-volume and a high-volume system measured by PAC-QoL score at 3 months’ follow-up?

Transanal irrigation is an invasive therapy that requires, every day or every couple of days, insertion of the device into the anus followed by a period spent filling the rectum with fluid and then evacuating it. It is reasonable to suppose that patients would discontinue therapy that they felt was ineffective or unacceptable, or switch between low-volume and high-volume systems (permissible in the trial design).

This underpinned our second trial-specific research question:

-

What is the survival rate of therapy of TAI initiated with a low-volume and a high-volume system and do patients prefer one system to another?

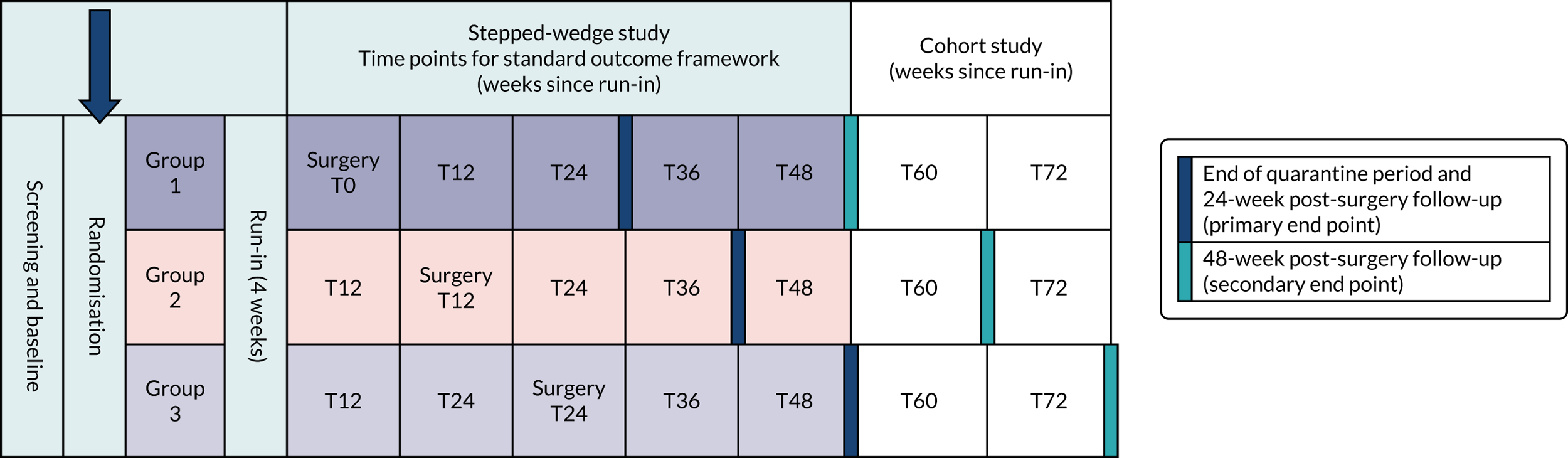

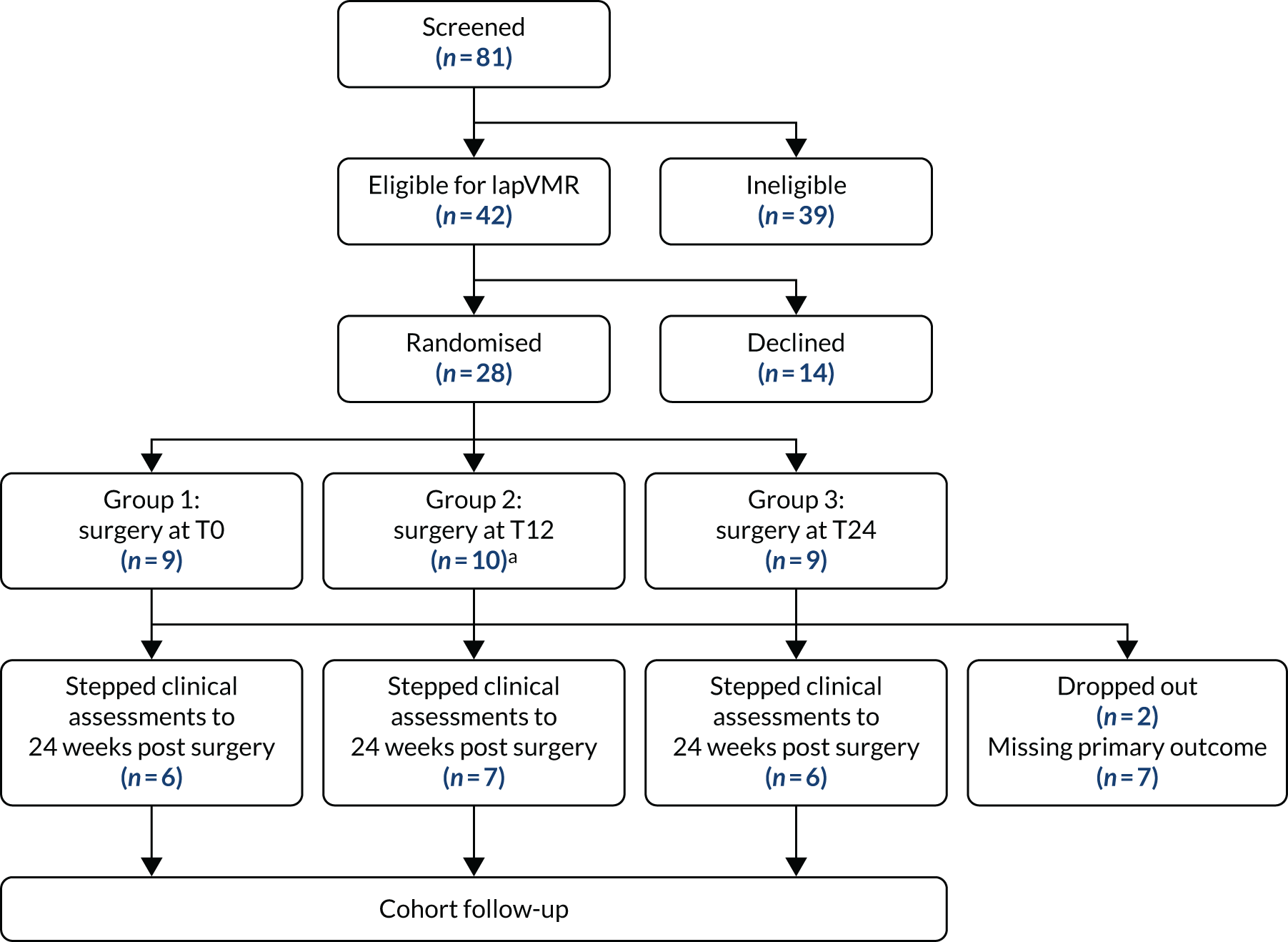

Both research questions were embedded in a single, pragmatic, two-group parallel design (Figure 4) and required a total sample size of 300 patients (150 per group). Patients used one system only (plus defined ‘rescue therapies’) for a minimum of 3 months. After this time point they could switch to the other system if their initial therapy was ineffective/unsatisfactory. This allowed identification of response rates to each system in the short term (3 months) and, thereafter, a comparison between treatment strategies (TAI initiated with low-volume therapy or high-volume therapy) rather than a pure comparison of the two techniques. This was a patient-centred study design aiming to limit the time that patients spent using ineffective therapy without being allowed to try an alternative. Reasons for switching were captured qualitatively.

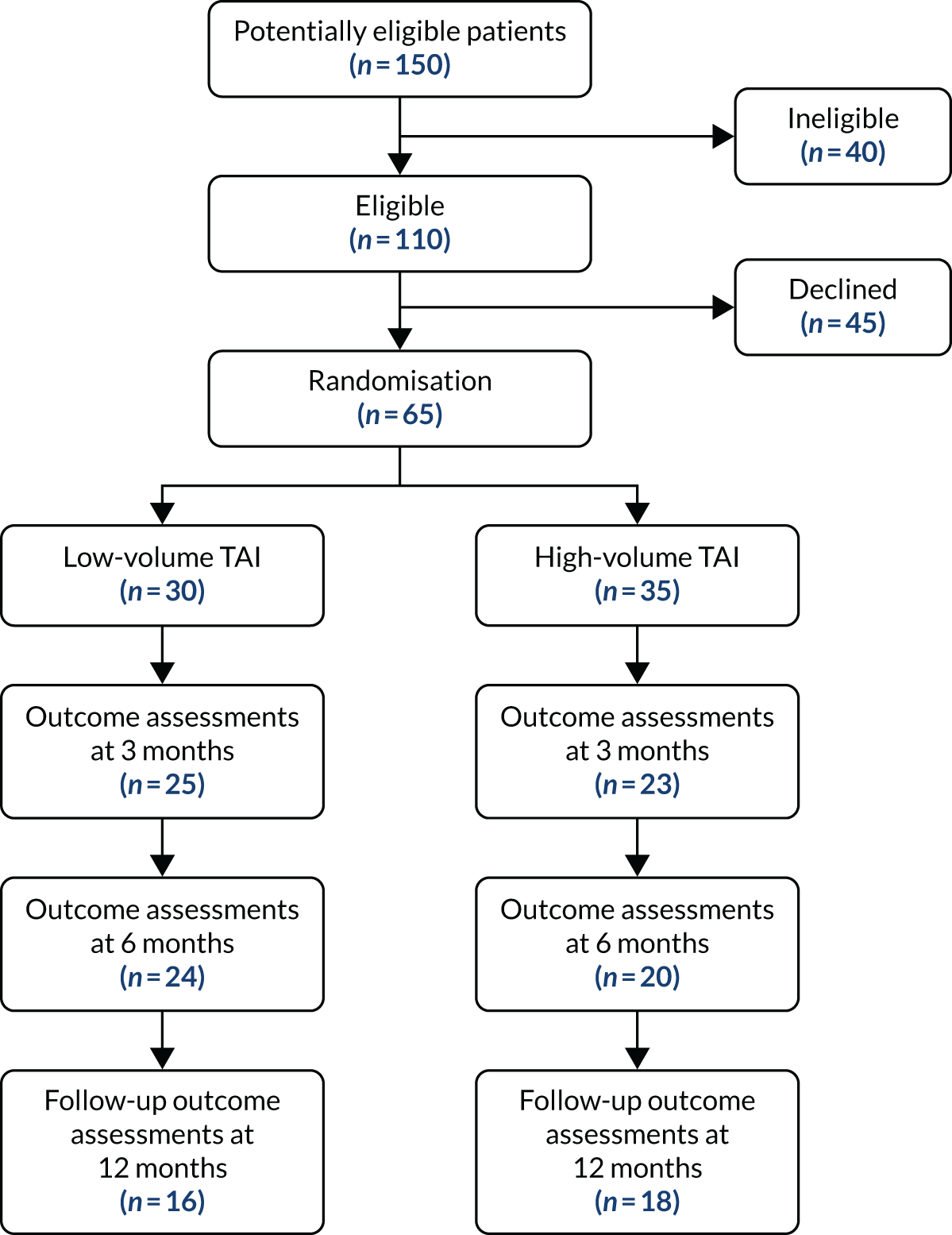

FIGURE 4.

The CapaCiTY trial 2 CONSORT flow diagram.

For a full description of this trial, including interventions, trial-specific design procedures and all results and analyses, see Appendix 1. Only the main results and conclusions are summarised in this report.

Results

High-volume compared with low-volume transanal irrigation

First recruitment and intervention took place on 11 November 2015; recruitment ended 30 June 2018. A total of 65 patients (target 300 patients) were randomised from 150 screened (21.7%) from seven sites. Three sites opened but failed to recruit; the remainder randomised between 1 and 33 patients, with approximately half of the patients recruited from secondary care and half recruited from tertiary care. A total of 30 patients were randomised to low-volume TAI and 35 to high-volume TAI (see Figure 4). The primary outcome (PAC-QoL score) was available at baseline and 3 months for only 43 patients.

At 3 months there was a modest reduction in mean PAC-QoL score from 2.4 points to 2.2 points (SD –0.2 points) in the low-volume TAI group and a larger reduction of –0.5 points in the high-volume TAI group (Table 3). Although this difference was not large there was consistency of findings across some of the other outcome measures. For example, global satisfaction score, global improvement score and EQ-VAS score showed greater improvement in the high-volume TAI group. These results were based on an ITT analysis even though two patients crossed over (from low-volume to high-volume TAI) before the 3-month outcome (possibly diluting the difference in effect).

| Intervention | Baseline | 3 months | Difference in means (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | ||

| Low-volume TAI (n = 19) | 2.4 (0.8) | 2.4 (1.9–2.9) | 2.2 (0.8) | 2.0 (1.5–2.8) | Reference |

| High-volume TAI (n = 25) | 2.3 (0.7) | 2.4 (1.8–2.8) | 1.8 (0.9) | 1.8 (1.1–2.3) | –0.37 (–0.89 to 0.15) |

Some further evidence of the greater benefit of high-volume TAI could be inferred from the fact that, over the follow-up period (with the majority after 3 months), 18 patients switched from low-volume to high-volume TAI but only six patients switched from high-volume to low-volume TAI, and two of these six switched back again to high-volume TAI.

Despite under-recruitment, patient-level data from the trial still provided the most robust evidence available to inform the pathway of care. Despite differences in initial purchase prices of the basic devices, initiating high-volume TAI did not increase study cost but resulted in higher patient QoL, suggesting a dominant interventional strategy (cost-effective at a WTP threshold of £30,000 per QALY; p = 0.99).

The interventions were generally well tolerated considering the invasive nature of the procedure. A total of 16 out of the 65 patients (25%) reported AEs, with a total of 68 AEs. Of these, 40 AEs (59%) were mild and 20 (29%) were moderate. There were six SAEs, of which three were expected. All resolved with no sequelae.

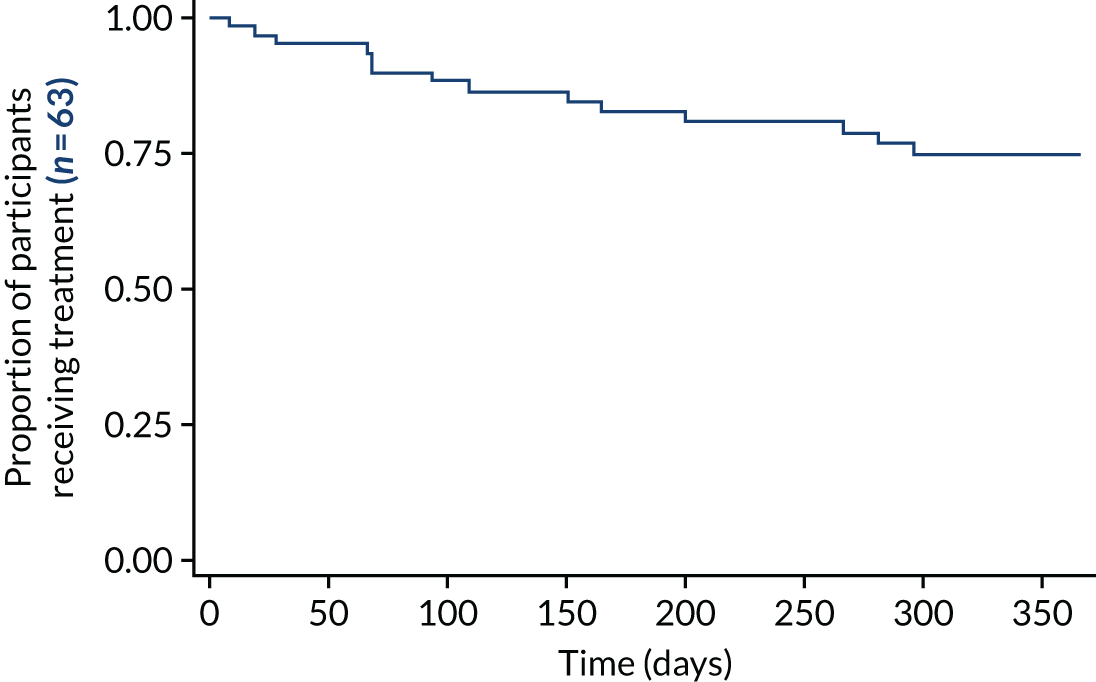

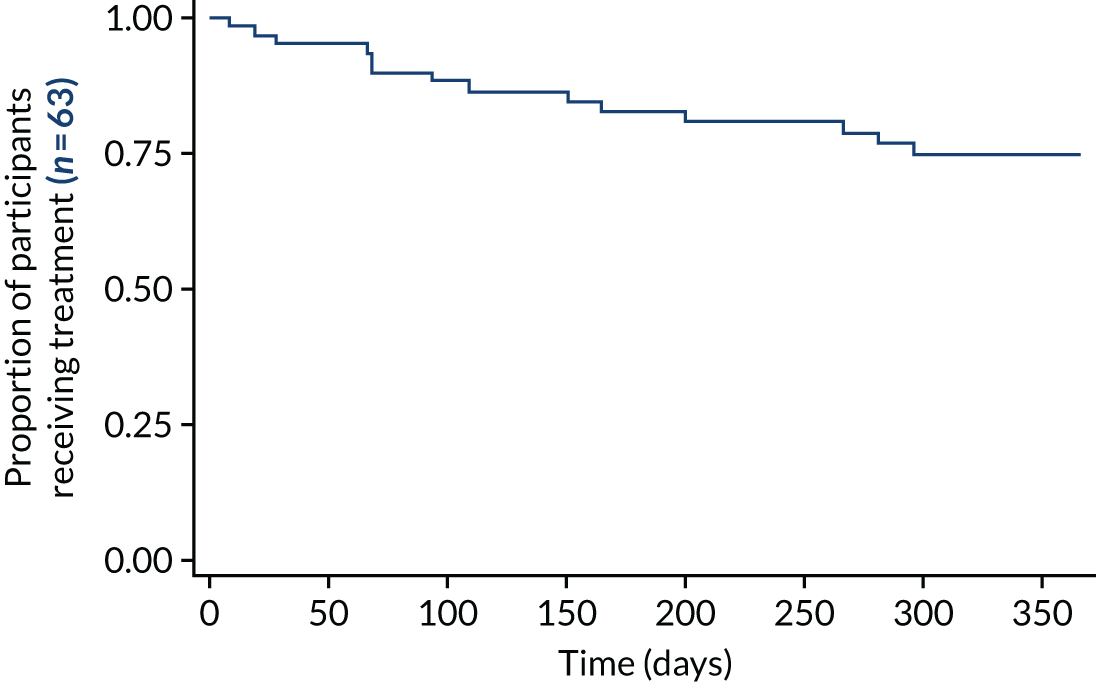

Survival rate of transanal irrigation therapy

In the absence of a sham control (impossible to devise), and with the inability to compare with standard therapy, it was reasonable to use treatment continuation as a marker of efficacy. The treatment is burdensome, and it can be argued that patients who are not receiving benefit would not continue with it. There was no encouragement from research or clinical staff for patients to continue to use ineffective therapy. The 1-year survival rate of the treatment of 76% (Figure 5) implied significant continued effect. A comparison of survival rate plots of low-volume and high-volume TAI that allows for crossover has not been presented at the time of publication. This analysis is planned but was outside the SAP. 118

FIGURE 5.

The CapaCiTY trial 2 survival rate of treatment as a surrogate of ongoing benefit: Kaplan–Meier plot for time to cessation of treatment.

Conclusions

Taking together the results from clinical, cost-effectiveness and patient experience data, the following conclusions may be drawn while accepting the major caveat of under-recruitment:

-

The population studied represented a typical hospital-derived cohort of patients with severe CC that had not responded to conservative therapies.

-

We did not carry out statistical significance tests owing to under-recruitment. Despite this, there is preliminary evidence that high-volume TAI may be more effective than low-volume TAI. Although effect sizes were small for both primary and secondary outcome measures (especially global improvement scores), dominant crossover from low-volume to high-volume TAI and health economic analysis point in the same direction of favouring high-volume TAI.

-

Survival rate data were suggestive of a persisting benefit in the majority of patients, with three-quarters of patients still using TAI at 12 months. Overall, there were fewer patients on low-volume TAI at 12 months than on high-volume TAI. A survival rate analysis allowing for crossover is yet to be undertaken.

-

Some AEs were reported, but, of six SAEs, none was related or life threatening. The most common AEs were rectal bleeding and anal pain (48 events in 16 patients).

-

Despite under-recruitment, patient-level data from the trial still provided the most robust evidence currently available to inform the pathway of care. Initiating high-volume TAI did not increase overall cost (despite slightly higher basic device pricing) and resulted in higher patient QoL, suggesting a dominant interventional strategy (cost-effective at a WTP threshold of £30,000 per QALY; p = 0.99).

-

Although cost-effectiveness base-case findings were robust to the complete-case and sensitivity analyses conducted, the findings should be treated with caution. Small absolute numbers of patients and high levels of missing data as follow-up progressed placed great reliance on the imputation process and output. As with CapaCiTY trial 1, although substantial efforts were made to deliver a robust imputation process, it not possible to prove that a MAR process has been attained. Actual level of TAI use (the predominant cost) was not directly recorded and was instead approximated from available variables.

-

A final consideration in support of high-volume TAI concerns convergence. Health-care costs are similar comparing the two groups, suggesting that differences in health-care costs beyond 12 months are small. However, QoL diverges between groups over 12 months, suggesting that QALY gains may continue to accrue for some time beyond 12 months. Although speculative, any modelling of future cost and benefits would further increase the cost-effectiveness of high-volume TAI.

-

Transanal irrigation often caused initial anxiety, was not always easy to learn and was time-consuming. Ongoing staff support was much appreciated, especially as results were not always immediate. Some found it of no benefit, but many persevered and found that, although not necessarily a pleasant experience, it had an impact (sometimes large) on their symptoms and QoL. Staff were possibly more enthusiastic than patients initially, and this enthusiasm was picked up by patients in some cases and helped them to persevere.

Reflections on work programme 3