Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by PGfAR as project number RP-PG-0613-20001. The contractual start date was in October 2015. The final report began editorial review in May 2021 and was accepted for publication in June 2022. As the funder, the PGfAR programme agreed the research questions and study designs in advance with the investigators. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PGfAR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2023 Gooberman-Hill et al. This work was produced by Gooberman-Hill et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2023 Gooberman-Hill et al.

Results

Work package 1: systematic reviews

Our systematic review of post-operative risk factors for chronic pain after total knee replacement included 14 studies published up to October 2016, with data from 1168 people. Studies focused on acute pain, function and psychological factors. Risk factor measures and outcomes were heterogeneous. In a narrative synthesis we were unable to draw firm conclusions on potential interventions. The need for further prospective studies in representative populations was clear.

Research published up to December 2018 into pre-operative interventions mainly focused on exercise and education. In the eight trials, with a total of 960 people randomised, there was no association with these interventions and long-term pain outcomes. In the peri-operative setting, we identified 44 trials published up to February 2018, with a range of 10 to 280 people randomised. Unifactorial interventions including some forms of analgesia, early rehabilitation, electrical muscle stimulation and anabolic steroids were associated with improved long-term pain outcomes. However, studies were small and merit further evaluation. There was reassurance that some common peri-operative treatments are not associated with chronic pain. Post-operative interventions evaluated in 17 trials published up to November 2016, with a total of 2485 people randomised, mainly focused on physiotherapy. There was no strong evidence favouring one format of therapy over another.

There has been little research into treatments for chronic pain after total knee replacement. Considering interventions for general chronic post-surgical pain, we identified 66 randomised trials with a total of 3149 participants in our systematic review with searches up to March 2016. A more focused updated search including treatments for chronic pain after arthroplasty of the large joints was conducted in October 2020. Many unifactorial interventions have been evaluated, and specific nerve-focused treatments deserve further research.

Work packages 1 and 2: analysis of national databases

We undertook two analyses of linked databases to identify pre-, peri- and post-operative risk factors for chronic pain outcome. In the first analysis with NJR and HES data, the pre- and 6-month-post-operative Oxford Knee Scores (OKS) was available for 258,386 patients, 43,702 (16.9%) of whom were identified as having chronic pain at 6 months post surgery. Post-surgical predictors of chronic pain were mechanical complication of prosthesis, surgical site infection, readmission, reoperation, revision and an extended hospital stay. However, these post-surgical predictors explained only a limited amount of variability in chronic pain outcome.

In the second analysis, we analysed primary care data from CPRD and secondary care data from the HES–PROMs database and included 4570 patients. At 6 months after surgery, 10.4% of patients were classified as non-responders to surgery regarding their knee pain. Expressing the effects as absolute risk differences allowed us to quantify the relative importance of individual risk factors in terms of the absolute proportions of patients achieving poor pain outcomes. Pre-operative risk factors were having only mild knee pain symptoms, currently smoking, living in the most deprived areas, having a body mass index between 35 and 40 kg/m2 and having had previous knee arthroscopy surgery. Post-operative risk factors were revision surgery and manipulation under anaesthetic within 3 months after the operation, and use of opioids and antidepressants within 3 months after surgery.

Work package 2: long-term follow-up of COASt cohort and analysis of national databases

We characterised the long-term trajectory of chronic pain, including pain characteristics and resource use, through the 5-year follow-up of the COASt cohort of 1581 patients with total knee replacement, and analysis of the linked CPRD and HES databases.

We applied cluster analysis to data on 128,145 patients with primary total knee replacement included in the English PROMs programme to derive a cut-off point on the pain subscale of the OKS. A high-pain group was identified, defined as those with a score of ≤ 14 points on the OKS pain subscale 6 months after total knee replacement. About one in eight people experienced chronic pain 1 year after total knee replacement. Of these patients with chronic pain after surgery, after imputing significant missing data assumed to be missing at random, 65% experienced no-chronic-pain by year 5, 31% fluctuated and 4% remained in chronic pain. People with chronic pain in year 1 had worse quality of life to start with; this improved, but less rapidly than for those not in chronic pain. People with chronic pain reported slightly higher primary care consultation costs than those not in chronic pain but their prescriptions for analgesia were much more frequent, more costly to the health-care system and continued to grow even after surgery, especially prescriptions for opioids.

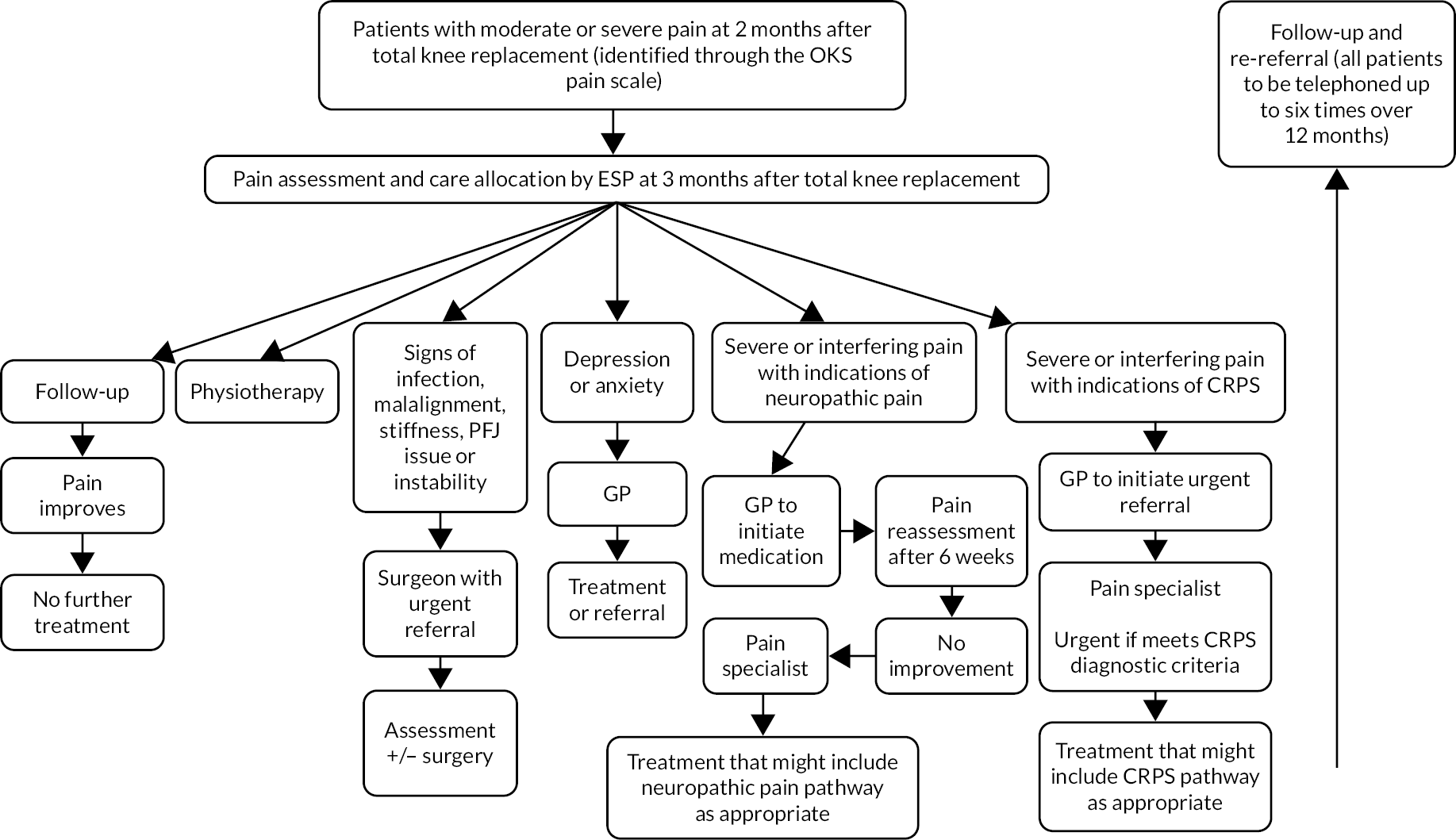

Work package 3: finalisation of an assessment protocol and care pathway

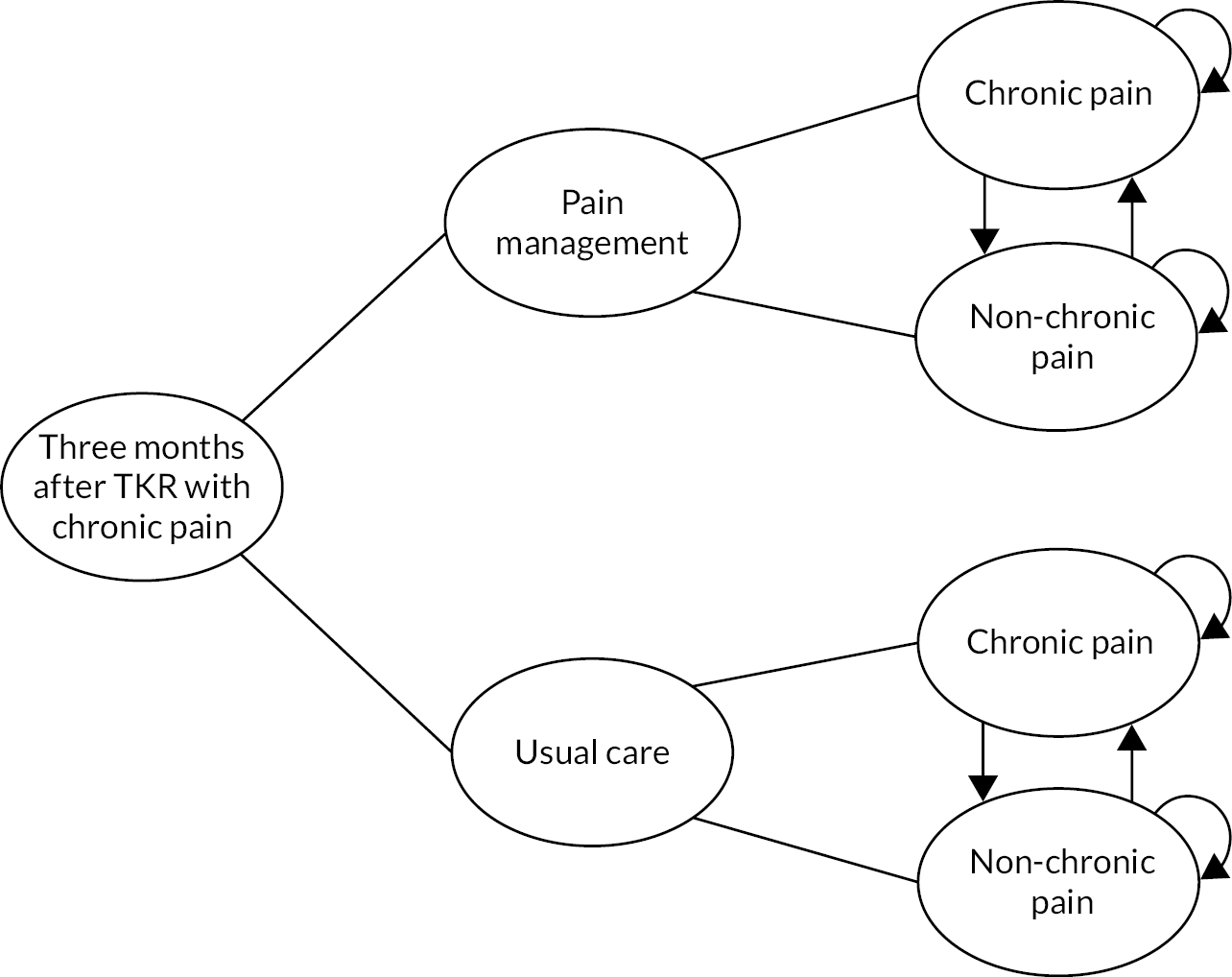

We refined and finalised the novel STAR care pathway and associated training materials. The STAR care pathway involves a clinic appointment for patients who have troublesome pain at 3 months after surgery. A specially trained extended scope practitioner (ESP) conducts a clinic assessment with the patient, comprising history, examination, radiography and questionnaire completion. Based on this assessment, which focuses on understanding the reasons for and impact of the pain, the patient is referred to the appropriate existing services for treatment, such as a surgeon, general practitioner (GP) or specialist, or receives ongoing monitoring. The ESP follows up with patients by telephone for up to 12 months.

Work package 4: randomised controlled trial

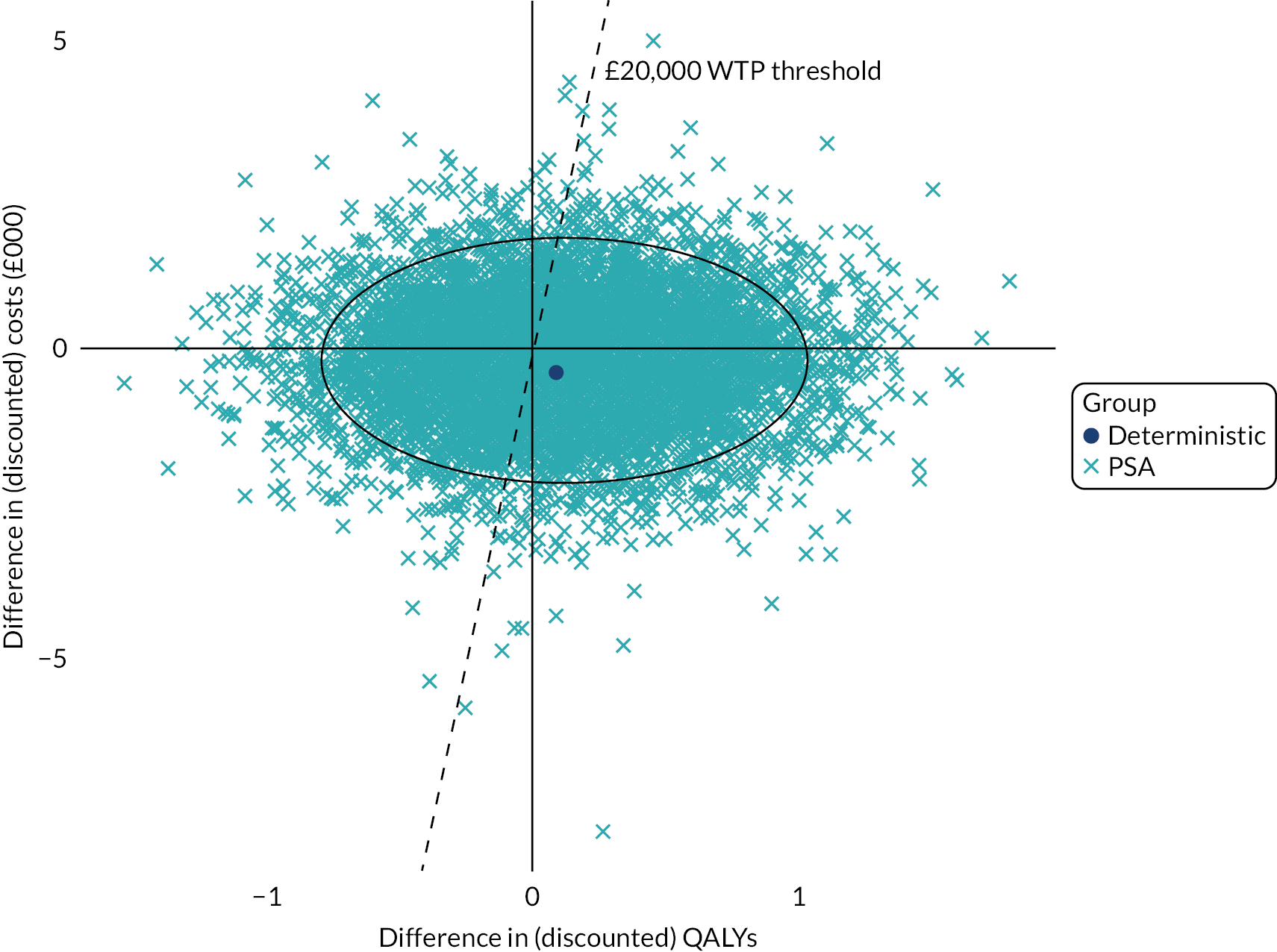

In a multicentre pragmatic, open randomised controlled trial, we evaluated the STAR care pathway. We screened 5036 people, randomised 363 patients with pain at 3 months after knee replacement from eight NHS Trusts in England and Wales and collected 12-month outcomes from 313 (85%) randomised participants. The sample had a mean age of 67 years, was 60% female and 94% white. Our analysis of clinical effectiveness indicated that at 12 months the intervention arm had lower mean pain severity and lower mean pain interference than the usual care arm. For pain interference at 12 months, the adjusted difference in means was –0.68 points on the Brief Pain Inventory pain interference scale [95% CI –1.29, –0.08; p = 0.026]. For pain severity at 12 months, the adjusted difference in means was –0.65 points on the Brief Pain Inventory pain severity scale [95% CI –1.17, –0.13; p = 0.014]. Our analysis of cost-effectiveness indicated that people receiving the STAR pathway from an NHS and personal social services perspective had lower costs (–£724, 95% CI -£1500 to £51) and more quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) (0.03, 95% CI –0.008 to 0.06) than those receiving usual care. The STAR pathway was the cost-effective option: the incremental net monetary benefit at the £20,000-per-QALY threshold was £1256 (95% CI £164 to £2348). This was also the case from a patient perspective. Embedded qualitative research found that patients thought that the STAR pathway was acceptable, and patients described how it provided an opportunity for them to discuss their concerns and to receive more information about their condition while ensuring they received further treatment and ongoing support.

Work package 5: qualitative study

In semistructured interviews with 34 people, we found that people with chronic pain after total knee replacement who made little or no use of services did so because they became stuck in a cycle of appraisal of the validity of their need for help and concern that treatment may not be of benefit. Some were concerned that further treatment may even worsen their pain or cause further harm. When describing chronic post-surgical pain, some participants described sensations of discomfort including heaviness, numbness, pressure and tightness associated with the prosthesis, and some also reported a lack of felt connection with their knee as their movement was no longer natural and required deliberate attention, and that they had a lack of confidence in it.

Work package 6: implementation and dissemination

We found that health-care professionals involved in the delivery and implementation of the STAR care pathway valued its focus on the identification of neuropathic pain and psychosocial issues, enhanced patient care, formalisation and validation of referral practices and an increased knowledge of pain management. Stakeholders supported formal implementation of the STAR pathway. Whether or not this would be supported by hospital management was felt to be dependent on whether or not it was shown to be cost-effective.

Conclusions: implications for health care

After knee replacement, screening for pain with the OKS pain subscale beginning at 2 months after surgery can facilitate the delivery of targeted care from 3 months. Our findings indicate that the STAR care pathway can provide improved care and outcomes for people who have pain after knee replacement. To our knowledge, the STAR care pathway is the first multifactorial intervention for the treatment of post-surgical pain to have been evaluated in a randomised controlled trial. In database analyses and systematic reviews, we identified risk factors for and univariable interventions to prevent or treat chronic pain. After further research these may provide additional components to the care pathway.

Our work also indicates that people with pain could be empowered to seek health care and that health-care professionals can be encouraged provide support. This could include information for people living with chronic pain to inform them that health care may provide benefit and that seeking care is not futile. Informing patients of the likely outcomes after surgery may be a key part of pre- and post-surgical care.

Recommendations for research

We recommend that further research addresses the following points, numbered in descending order of priority:

-

How to implement the STAR care pathway into the NHS.

-

How to improve communication between patients and professionals before surgery.

-

Whether or not patient education and supportive care can enable earlier recognition of chronic pain.

-

The STAR care pathway showed benefit to patients for both pain and interference at 6 and 12 months. Further follow-up would describe the longer-term outcomes of this intervention and the health-care resources utilised by participants.

-

How to reshape the STAR pathway for other surgeries.

-

The STAR programme focused on care after surgery. Future research could make use of the recently developing evidence base about the time before surgery as an opportunity for intervention. Specifically, we now have a greater understanding of risk factors for poor outcome and using this understanding to design and evaluate pre-surgical intervention may prove of long-term benefit to patients and health-care systems.

-

How to better manage patient’s feelings of disconnectedness from the new knee and sensations of otherness to improve incorporation of the prosthesis.

-

Promising interventions, identified in systematic reviews and suggested by our risk factor studies, should be evaluated in appropriately powered high-quality randomised controlled trials.

-

New interventions with evidence of effectiveness in the treatment of chronic pain after knee replacement should be considered as new components of multifaceted personalised care as delivered in the STAR intervention.

Study registration

All systematic reviews were registered on PROSPERO (CRD42015015957, CRD42016041374 and CRD42017041382). The STAR randomised trial was registered as ISRCTN92545361.

Funding

This project was funded by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Programme Grants for Applied Research programme and will be published in full in Programme Grants for Applied Research; Vol. 11, No. 3. See the NIHR Journals Library website for further project information.

Background to the STAR programme

Total knee replacement

Osteoarthritis is the most common joint disease, affecting nearly 10% of adults in the UK1 and about 23% of adults in the USA. 2 The prevalence of knee osteoarthritis depends on its definition: international estimates vary from 8.2% (presence of symptoms) to 9.3% (self reported) to 31.7% (radiographic changes). 3

The primary reason that people choose to undergo total knee replacement is the expectancy of pain relief. 4 In 2019, over 100,000 primary total knee replacements were performed by the NHS,5,6 and it is estimated that about 11% of women and 8% of men will receive a knee replacement during their lifetime. 7

For many people with advanced osteoarthritis, total knee replacement is an effective treatment to relieve pain and improve function. However, some people experience continuing pain in the months and years following surgery.

Chronic post-surgical pain

Chronic post-surgical pain, defined as pain that occurs or increases in intensity at ≥ 3 months after surgery,8 is recognised after a range of surgeries. 9,10 After total knee replacement, average pain severity plateaus by 3 months,11 with overall clinical benefit achieved by 6 months. 12 People with bothersome pain at ≥ 3 months after surgery are often disappointed with their outcome. 4,13 We also know that people with chronic pain after total knee replacement may feel abandoned by health care,14 and struggle to make sense of ongoing pain. 15

In our systematic review bringing together longitudinal studies in representative populations, we found that 10–34% of patients reported unfavourable long-term pain outcomes after knee replacement. 16 The two UK studies included in the review showed that about 20% of patients with total knee replacement had persistent moderate-to-severe long-term pain in their operated knee. 17,18 More recent studies suggest that the prevalence of chronic pain has not changed, with estimates of 15–29%. 19–22 Furthermore, even among those eligible for fast-track total knee replacement, over one-third of patients may require analgesics 1 year after surgery with about half taking opioids. 23

Chronic pain has an impact on many areas of life and is associated with poor general health,24,25 interference with daily activities, disability24 and depression. 26 People with chronic musculoskeletal pain report lower satisfaction with life than the general population. 27–29 Older people with pain may become socially isolated, develop other health problems30 and have limited capacity to bring about change or seek help for their pain.

Economic impact

Chronic pain management has been estimated to account for 4.6 million general practitioner (GP) appointments per year in the UK, which is equivalent to the entire workload of 793 full-time GPs, at a cost of around £69 M. 31 In England in 2005, in addition to over-the-counter purchases, more than 66 million prescriptions were written for analgesic drugs, at a cost of about £510 M. 32 In Europe, the health-care and socioeconomic costs of chronic pain conditions represent 3–10% of gross domestic product, mainly owing to hospitalisations. 33 Although we have some understanding of the economic burden of chronic pain,34,35 up-to-date cost data on chronic pain after total knee replacement is needed.

Aetiology

Chronic pain after total knee replacement may be caused by biological and mechanical factors. Biological causes include the sensitising impact of long-term pain from osteoarthritis,36,37 the development of complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS),38–40 inflammation, infection and localised nerve injury. 41 Mechanical causes include altered gait, prosthesis loosening and ligament imbalance. 42,43 Psychological factors may also influence outcomes. 44–47

Risk factors

To prevent and manage chronic pain after knee replacement, patients, their treating surgeons and health-care professionals need to understand and target the risk factors for and causes of chronic pain after total knee replacement. 48

The potential value of pre-operatively identifying patients at risk of a poor outcome following total knee replacement and using targeted interventions is clear, and much research has focused on pre-operative predictors of outcomes. 45,46,49–51 Potentially modifiable risk factors include pain intensity,45,46,49,50 particularly on movement;52 presence of widespread pain;45,46 and anxiety, depression and pain catastrophising. 44–47,49,53 However, existing multivariable models have low predictive power for pain-related outcomes. 54,55

The operation itself is an important risk factor for chronic pain,56 and factors relating to the operation and recovery may be important. Early post-operative pain is associated with chronic pain,57 and new peri-operative analgesia regimens attempt to limit this. 58–60 In the context of major orthopaedic surgery, it is possible that other post-operative patient factors may be associated with the development of chronic pain.

Prevention

The targeted management of patients with pain after surgery may reduce the risk of longer-term pain and disability. 61 Interventions provided in the knee replacement pathway may have an impact on chronic pain through the modification of risk factors or provision of targeted care to specific patient groups.

Pre-surgical exercise and education interventions have focused on preparing patients for their knee replacement and hospital stay, reducing peri-operative pain, and facilitating early mobilisation and recovery. 49 However, randomised trials and meta-analyses published up to November 2015, when the Support and Treatment After joint Replacement (STAR) programme was developed, had not shown an impact on the key outcome of long-term pain. 49,62

Any treatment in the peri-operative period (including pain management, blood conservation, deep-vein thrombosis and infection prevention, and inpatient rehabilitation) could affect patient recovery and chronic pain. Direct mechanisms of treatments may be through prevention of nerve damage,40 post-thrombotic syndrome,63 reperfusion injury64 and articular bleeding. 65 For other treatments, the pathways leading to long-term pain may be indirect, possibly mediated through increased risks of adverse events. 66

Although early rehabilitation during the hospital stay focuses on regaining range of motion and improving mobility, after discharge treatment aims to enhance recovery through supporting a person to regain function and quality of life, optimising pain relief, and supporting reintegration into social and personal environments. 67 Although physiotherapy often focuses on functional health, another key outcome is the prevention of long-term pain. 68 A recent randomised trial found that a targeted outpatient rehabilitation programme after knee replacement does not improve outcomes in patients at risk of poor outcomes compared with a home-based exercise programme. 69 However, post-operative physiotherapy may be combined with other interventions to provide multidisciplinary comprehensive rehabilitation after knee replacement aimed at improving activity and participation, and reducing the severity of pain. 70

Management

Treatment is difficult once chronic pain is established, and the evaluation of treatments in combination or matched to patient characteristics is advocated. 71 Management of chronic post-surgical pain may focus on the underlying condition leading to surgery or the aetiology of the pain, or be multifactorial in recognition of the diverse causes of post-operative pain.

For patients with total knee replacement, surgical or prosthesis-related problems may require physiotherapy, bracing, arthroscopy or revision surgery. Nerve injury may respond to gabapentin or pregabalin,42 and nociceptive and regional pain may be treated with analgesic and opioid medication. Patients may also benefit from broader pain management approaches including psychological therapies, although high-quality evidence is lacking. 72

In our systematic review of randomised controlled trials published up to October 2014 evaluating interventions for the treatment or management of chronic pain after total knee replacement, we identified a single trial evaluating an intra-articular injection with antinociceptive and anticholinergic activity. 48 No trials of multidisciplinary interventions or individualised treatments were identified, and none was registered.

Health care

Management of chronic post-surgical pain is provided within primary and secondary care. However, not everyone will present at primary or secondary care for treatment of chronic pain. A European survey of almost 6000 adults with musculoskeletal pain suggested that over one-quarter had never sought medical help for their pain, despite many living with constant or daily pain. 73 Our research showed that 75% of adults aged > 35 years experiencing hip or knee pain had not sought help from a GP or allied health-care professional in the previous 12 months. 74 Half of adults with severely disabling knee pain may not consult a GP. 75 In this study, over 85% of participants had consulted about other illnesses and for each contact about knee pain there were 20 contacts relating to other conditions.

The provision of services for chronic pain may also be suboptimal. The 2012 National Pain Audit76 reported significant variation in access to specialist services for chronic pain and variation in levels of care. For example, 67% of services in England were below the minimum recommended levels of staffing, with a notable lack of provision for specialties including psychology and physiotherapy. Under-treatment is also apparent in the primary care setting: an interview study of over 500 GPs found that 81% believed patients received insufficient pain management. 77

Non-use of services is likely to be influenced by individual and social, structural and organisational factors. The average age of patients at knee replacement is 70 years,5 and older people may see pain as a normal part of ageing and may not present to health care. 78,79 Given the high prevalence of chronic post-surgical pain, there is potentially a large hidden population with an unexpressed need for care who are experiencing significant pain and disability.

The STAR programme

The overall aim of the STAR programme was to generate high-quality evidence about how to improve health care and outcomes for people with chronic pain after total knee replacement.

This programme provided the opportunity to conduct a major programme of work addressing multiple important themes. The programme comprised six interconnected work packages, which aimed to improve health care and outcomes for patients with chronic pain after total knee replacement. All work packages were underpinned by collaborative working with patients and full details of patient and public involvement (PPI) are reported in Patient and public involvement.

Specifically, the programme aims were as follows:

-

Synthesise evidence on the prevention of chronic pain after knee replacement and the treatment of chronic pain after diverse surgeries through systematic reviews of published studies. Identify post-surgical predictors of chronic pain after knee replacement through a systematic review and analysis of data from the National Joint Registry (NJR), linked to the Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) and Patient Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs) databases (work package 1).

-

Characterise the long-term trajectory of chronic pain, including an examination of pain characteristics and resource use, through extended follow-up of an existing cohort of patients with total knee replacement up to 5 years after surgery and analysis of the Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD), linked to the HES database (work package 2).

-

Refine and finalise a novel care pathway for patients with chronic pain after total knee replacement through consensus work with health-care professionals. Test intervention delivery and acceptability to patients and evaluate views about implementation of the intervention at future trial centres using the Normalisation Measure Development (NoMAD) tool (work package 3).

-

Evaluate the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the new care pathway for patients with chronic pain after total knee replacement in a pragmatic, open-label, parallel group, multicentre superiority randomised controlled trial with a 2: 1 allocation ratio and embedded economic evaluation and qualitative studies (work package 4).

-

Identify reasons for the non-use of services and how to improve access through a qualitative study with patients living with chronic pain after total knee replacement who make little or no use of formal health-care services (work package 5).

-

Conduct a process evaluation of the implementation of findings into clinical practice and distribute evidence-based information about the identification, assessment and management of chronic pain after total knee replacement (work package 6).

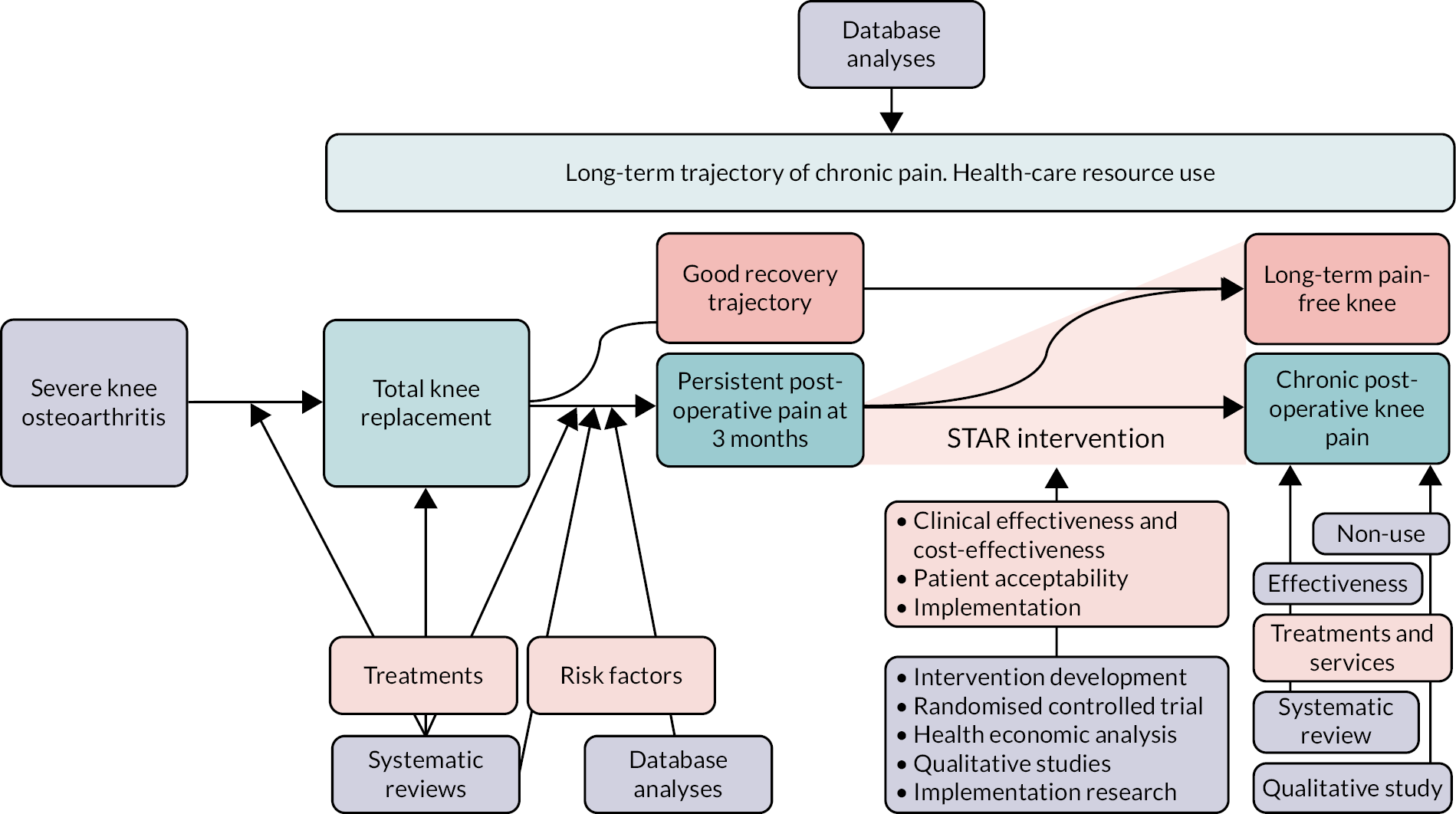

A research pathway diagram is provided in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

The STAR programme.

Changes to the programme and additional research

All planned research has been published or submitted to a journal, or is being written up. Some changes were made to the proposed research and additional investigations undertaken.

In work package 1, we originally planned an overview of systematic reviews looking at the effects of interventions in the knee replacement pathway. The reviews we identified did not focus on the outcome of long-term pain and so we undertook three new reviews of interventions in the pre-, peri- and post-operative setting.

In work package 2, we originally planned to conduct analyses of CPRD–HES data using an algorithm from our National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Programme Development Grant that indirectly identifies patients with chronic pain based on primary care resource use. Ultimately, we identified people with chronic pain directly from patient-reported pain outcomes. To do this, we requested two amendments to the CPRD protocol: (1) to use the CPRD to answer the programme’s specific research questions, and (2) to obtain linked HES–PROMs data that included the patient-completed Oxford Knee Score (OKS). 80 We conducted and published20 a study using publicly available HES–PROMs data between 2012 and 2015 and found that a cut-off of 14 points on the 28-point OKS pain subscale could be used to identify patients with chronic pain following knee replacement. We used this cut-off point in subsequent analyses of CPRD–HES linked patient-level data to evaluate the outcomes, resource use and quality of life of patients with and without chronic pain.

In work package 3 we used the NoMAD survey instrument81 rather than the Normalisation Process Theory (NPT) toolkit. The NoMAD tool had not been developed at the time of our original proposal and enabled us to collect more detailed information about implementation than the NPT toolkit. The questions in NoMAD are based around the four core constructs of NPT that represent different kinds of work that people undertake around implementing a new practice. The 23-item NoMAD survey instrument was developed by the same authors of the NPT toolkit and is a more flexible instrument for measuring implementation potential and implementation processes. To refine the intervention content, we conducted consensus questionnaires and facilitated meetings with health-care professionals. We proposed in the grant application to evaluate inter- and intra-observer reliability of intervention delivery using analysis of variance methods. Instead, we used a more narrative analysis of findings, which more closely aligned with our aims of ensuring the intervention was deliverable and allowed us to identify and address logistical issues with intervention delivery.

At the end of the STAR trial internal pilot phase described in work package 4, enrolment of participants was lower than anticipated. We developed a site feasibility assessment process and recruitment projection tool, increased the number of trial sites from four to eight, and extended the recruitment period for the trial by 3 months. This resulted in the achievement of the intended recruitment target. This change was approved by the Programme Steering Committee, NIHR and the NHS research ethics committee. We also made minor changes to the trial outcome measures at the trial design stage to minimise redundancy and participant burden, while ensuring that all items of the core outcome set for chronic pain after knee replacement were sufficiently represented. We did not include the WOMAC® (Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index), as knee pain and function were assessed with the OKS. Temporal aspects of pain were measured with a single-item question rather than the Measure of Intermittent and Constant Pain, and we did not include single-item questions on pain duration, pain on kneeling or improvement in pain. Additional measures included were the Douleur Neuropathique-482 and a body pain map to assess widespread pain.

Results of a planned cohort-based Markov model to estimate 5-year costs and the (quality-adjusted) life expectancy of patients with chronic pain after total knee replacement under current practice in addition to the STAR intervention is not yet completed.

Impact of COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic impacted on the randomised trial and stakeholder engagement. Adaptations made to the research in relation to this are described in the relevant sections.

In work package 6, we planned to collaborate with local implementation teams in two participating centres to identify ways to deliver the programme findings in practice. Owing to COVID-19, this work was changed to an online meeting with key national stakeholders to communicate findings, including a short, animated video. Participants comprising NHS managers, heads of therapy, physiotherapists, surgeons, pain clinicians, representatives from relevant professional organisations, representatives from Versus Arthritis (Chesterfield, UK) and patients.

Patient and public involvement

Background patient and public involvement work leading to the programme

The STAR programme was developed in collaboration with the University of Bristol’s Musculoskeletal Research Unit patient involvement group, called the Patient Experience Partnership in Research (PEP-R). 49 PEP-R comprises people with experience of musculoskeletal conditions, including pain after surgery. STAR was also developed with input from a representative of Versus Arthritis, the UK’s largest charity dedicated to supporting people with arthritis. Ongoing collaboration with Versus Arthritis shaped the research and provided input into the design of the key implications for research and practice. The STAR programme was preceded by a 1-year NIHR Programme Development Grant that included PPI work. PPI informed the overall design of the programme, with specific input into the study of post-operative predictors and the trial design, including the acceptability of randomisation, timing of data collection, primary outcomes and questionnaire length. The PEP-R group also discussed and approved the PPI plans, specifically requesting a model of ‘taking the research to the patient’ rather than ‘taking the patient to the research’.

The approach to PPI was based on principles of coworking and partnership, in which we aimed to empower the individual patient partners by considering them part of the research team. We worked together to design PPI that resulted in patients having a considerable input into the relevance and quality of our research. 83,84 Our reporting of PPI is in keeping with the recommendations of the Guidance for Reporting Involvement of Patients and the Public 2 (GRIPP-2) short form. 85

Patient and public involvement during the programme

To complement PEP-R’s ongoing engagement, we established a dedicated forum for the programme, comprising four patients with experience of chronic pain after knee replacement. Forum members were offered support and training by an experienced PPI co-ordinator. They received training built into forum sessions, including overviews of qualitative research, systematic reviews, statistics and trial management. Patients were also given information about local PPI events.

During the programme, there were a total of 23 meetings of the STAR patient forum and two one-to-one discussions between the PPI co-ordinator and individual members. STAR was also discussed at six meetings of the PEP-R patient group. Patients were provided with reimbursement for their time in the form of shopping vouchers, as this was their preference. Travel was either reimbursed or arranged for patients to attend meetings. From April 2020 onwards, face-to-face STAR and PEP-R forum meetings were cancelled owing to COVID-19 and we continued to work with the PPI groups remotely. A member of PEP-R attended Programme Steering Committee meetings with the PPI coordinator. STAR PPI activity and its impact in each work package is summarised in Appendix 1 and Box 1.

Researchers worked with the programme’s PPI group to interpret the results of the systematic reviews and database analyses and contributed to summaries of the systematic reviews, which led to improvements in summary clarity and accessibility.

Work package 2The PPI group commented on the use and interpretation of routine health data to ensure that complex findings were accessible to patients. They also gave input into the plain English summary of the analysis of the OKS pain cut-off and its use to identify chronic pain.

Work package 3The PPI group developed and improved the study materials for the refinement of the care pathway, including patient information packs. They also discussed the feedback from 10 patients who attended the STAR clinic and improved the plain English summary of findings.

Work package 4In addition, the PPI group were involved in the development and refinement of trial recruitment and data collection materials. For the trial, this included the review and approval of the screening questions, questionnaire booklet, provision of contact details for support organisations and charities, development of the patient information booklet, trial questionnaire, recruitment and retention methods, and recommendations about the training day sessions for trial staff based at all trial sites. Recommendations included sending a postcard to participants to let them know that they would soon receive the questionnaire, telephoning patients who did not return the questionnaires rather than sending another questionnaire, and including a teabag with the questionnaire. For the economic evaluation work, this included input into revisions of the resource diary to ensure that it reflected the needs and experiences of patients. For the embedded qualitative research within the trial, this included input into the design of interview topic guides and the interpretation of findings, including discussions about the challenge of remembering one clinic among the many appointments a person might have had after a year had passed and how uncertainty about the reason for pain led to confusion and anxiety. PPI members also reviewed newsletters sent to participants.

Work package 5The PPI group gave input into the qualitative research study, including assisting in the design of patient information materials for recruitment such as plain English summaries to enhance clarity and work to interpret interim findings after nine qualitative interviews, in which group members helped to confirm key emerging themes alongside the qualitative researcher.

Work package 6The PPI group gave input into all dissemination through the review of all plain English summaries of findings sent to participants. For example, in work package 4, summaries of screening study findings sent to participants were designed in collaboration with the PPI group, who advised on the layout, wording and infographics. To communicate findings from work packages 3, 4 and 5, summaries for participants were developed in collaboration with PPI members. In addition, ongoing discussions with Versus Arthritis informed work on public dissemination. Finally, at group sessions towards the end of the programme in September and October 2020, patients and other stakeholders worked together to discuss the implementation of the STAR care pathway in practice and future priorities for research and care for chronic pain after knee replacement. One member was interviewed for the STAR film.

Summary of the value of patient and public involvement in the programme

Includes information published in Bertram et al. 86 and Bradshaw et al. 87

Patient and public involvement was an essential part of the programme. We involved patient partners at all stages and this had a significant impact on the study design, such as improvements to patient documents, recruitment and retention methods,86 the communication of results and the planning of next steps (Box 1). Their involvement ensured that patients’ voices were included in the design and delivery of this research and that the outputs were relevant and meaningful to them.

Our patient partners also had an impact on the design of the PPI, as we followed their advice to adopt an approach of ‘taking the research to the patient’, rather than having two PPI members simply attending less frequent and more formal management or advisory group meetings. This had a positive impact on PPI group members as they believed this resulted in improved equality of power and decision-making, an atmosphere of strong collaboration and respect, and the opportunity for them to have a real impact on research. In addition, the research benefited through allowing a greater number of patients with differing experiences to be involved, providing a wider insight into issues of greatest importance to people in chronic pain. The design of the PPI was an ongoing discussion between group members and the PPI coordinator. The STAR forum group members told us that they felt they were working in partnership with the research team and equality was achieved by having the researchers come to them. This approach also had an impact on the research team as they all had the opportunity to attend the regular PPI group meetings and work in collaboration with patients. For some researchers, this was their first opportunity to hear about the experiences of patients with long-term pain and explain their research in plain English face to face. We recommend this approach and continue to use it as our preferred approach to PPI within the Musculoskeletal Research Unit (Translational Health Sciences, Bristol Medical School, University of Bristol, Bristol, UK).

Chronic pain after total knee replacement: risk factors, prevention and management (work package 1)

Background

Although pre-operative risk factors for chronic pain after total knee replacement have been explored extensively, post-operative risk factors have not.

Treatments in the pathway through total knee replacement may potentially modify risk factors for poor patient outcomes and adverse events. These have been reviewed previously, but not with an emphasis on chronic pain.

Little research has focused on the treatment of chronic pain after knee replacement. 48 Interventions for the management of chronic pain after other surgeries may have value in the context of total knee replacement.

Risk factors for chronic pain after total knee replacement: systematic review

This section has been published as Wylde et al. 88

Aims

This systematic review aimed to identify early post-operative patient-related risk factors for chronic pain after total knee replacement.

Methods

A prospectively registered systematic review (PROSPERO CRD42016041374),89 was conducted and reported as recommended by PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines. 90 We searched MEDLINE, EMBASE and PsycINFO from inception to October 2016 with no language restrictions (see Appendix 2, Systematic review search strategy as applied in MEDLINE on Ovid).

Eligible studies were longitudinal in design and met the following inclusion criteria:

-

patients observed within 3 months of knee replacement

-

intervention group – people with a risk factor

-

control group – non-exposed people

-

outcome – chronic pain at ≥ 6 months after knee replacement

Risk of bias was assessed with a non-summative checklist (Box 2),87 based on components of the methodological index for non-randomized studies (MINORS)91 and Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale. 92 Results were reported as a descriptive narrative analysis.

The following checklist components were rated as adequate, inadequate or not reported:

-

inclusion of consecutive patients (consecutive = adequate)

-

representativeness (multicentre = adequate)

-

per cent follow-up (> 80% = adequate)

-

minimisation of potential confounding (multivariate analysis = adequate).

Results

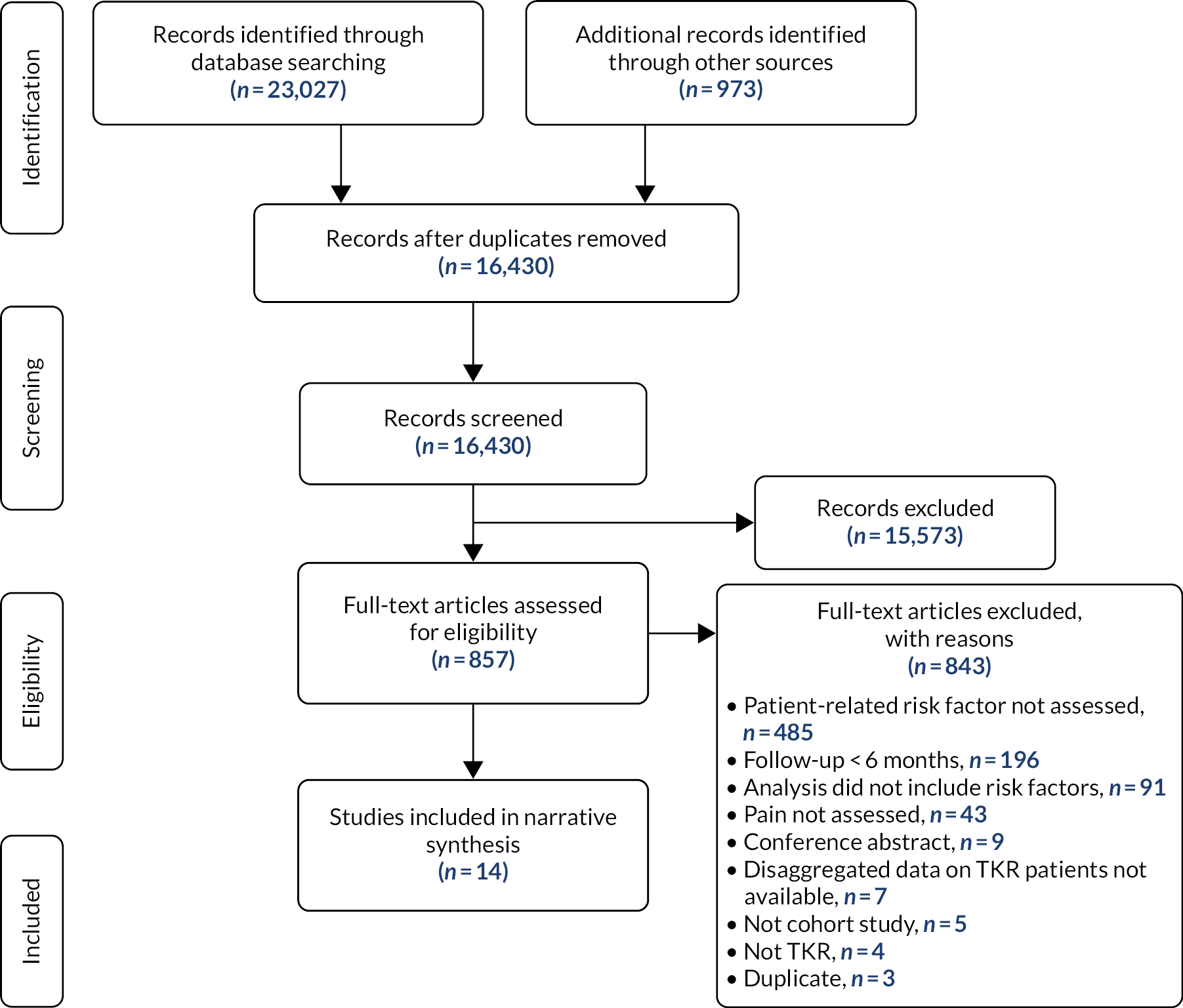

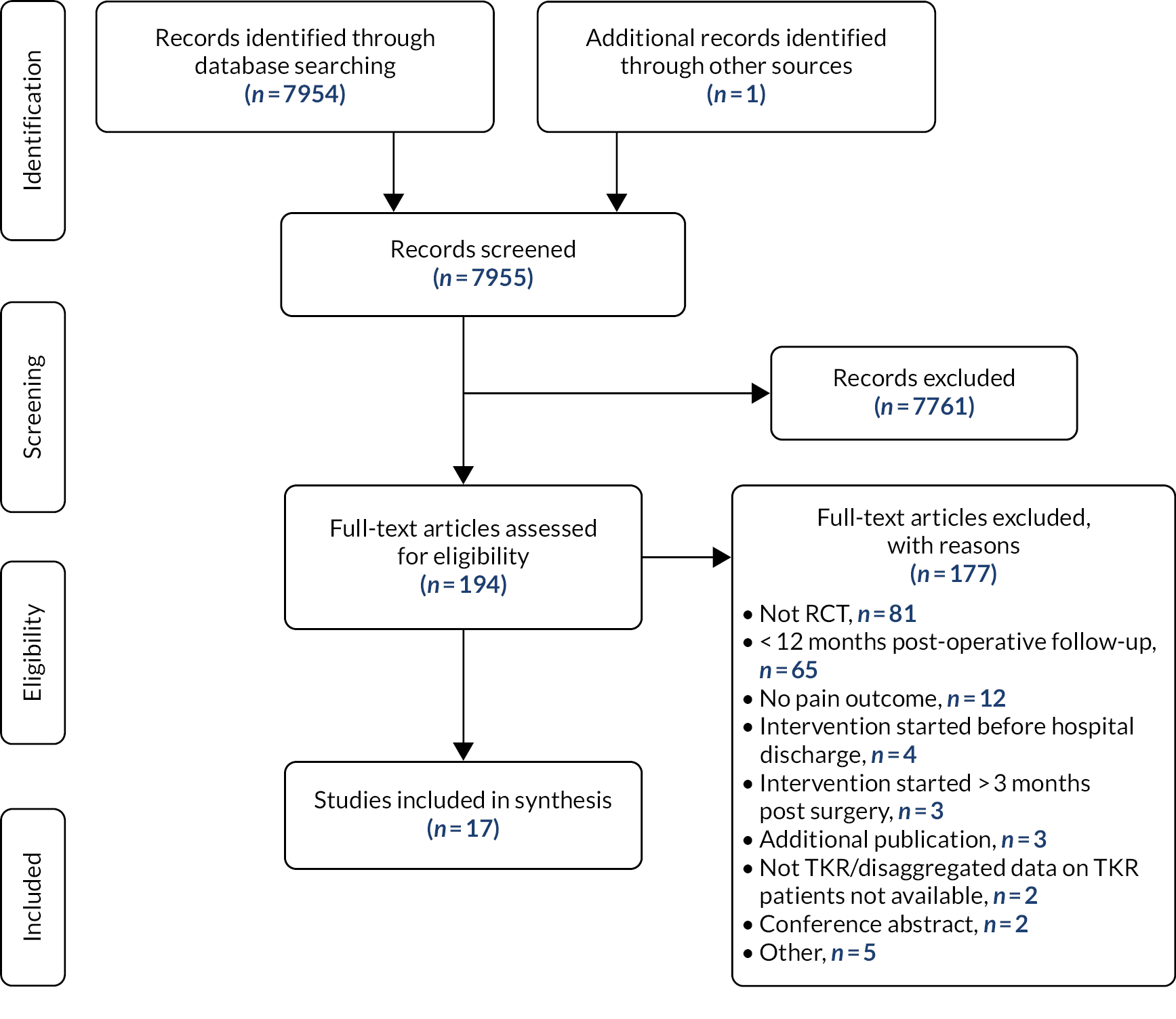

Searches identified 14 cohort studies (1168 patients) evaluating the association between patient-related factors in the first 3 months post operation and pain at ≥ 6 months after primary total knee replacement (see Appendix 2, Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Risk factors for chronic pain after total knee replacement: systematic review flow diagram. TKR, total knee replacement.

Post-operative patient-related factors evaluated included acute pain (eight studies), function (five studies) and psychosocial factors (four studies). In studies with no risk of bias other than patient selection, there was a suggestion that acute post-operative pain during the hospital stay was associated with chronic pain. 52,93 However, in one of these studies, the association was largely explained by pre-operative pain. 52 For all other post-operative patient factors, there was insufficient evidence to draw firm conclusions about an association with chronic pain after total knee replacement.

Risk factors for chronic pain after total knee replacement: database analyses

The NJR/HES analyses are published as Khalid et al. 94 and the HES/CPRD/PROMs analyses are published as Mohammad et al. 95

Aims

These analyses of national databases aimed to identify early risk factors for chronic pain after total knee replacement.

Methods: analysis 1

Primary knee replacements recorded in the NJR were linked with the HES and PROMs databases. We identified primary elective knee replacements performed between April 2008 and December 2016. Predictor variables within 3 months post surgery were surgical complications (i.e. fracture, patella tendon avulsion or ligament injury), medical complications (i.e. myocardial infarction, stroke, acute renal failure, deep-vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism, surgical site infection, respiratory infection, urinary tract infection, wound disruption, mechanical complication of prosthesis, fracture, neurovascular injury, or blood transfusion), length of stay, readmission, reoperation or revision. The outcome was chronic pain measured using the OKS at 6 months after surgery. The associations of the predictors with the chronic pain outcome were explored using logistic regression modelling.

Methods: analysis 2

We conducted a retrospective observational study using anonymised data from the CPRD GOLD database linked to the HES and PROMs databases. Patients were identified using the CPRD GOLD database of individual patient data from electronic primary health-care records from practices across the UK. 96 The CPRD provides a detailed record of both primary and secondary care. 97 Primary care records from the CPRD were linked to secondary care admission records from HES Admitted Patient Care data and the Office for National Statistics mortality data. HES also provides PROMs data before and 6 months after knee replacements.

We included all patients receiving a primary knee replacement between 2009 and 2016. Inclusion in the analysis was limited to patients with HES-linked data (i.e. those in England only) who completed both the pre- and 6-month-post-operative OKS pain subscale (OKS-PS). 80

The treatment effect [(pre-treatment OKS-PS score – post treatment OKS-PS score)/pre-treatment OKS-PS score]98,99 was calculated for each patient. A treatment effect of ≤ 0.2 was used to classify patients as non-responders to surgery regarding their knee pain. Relative risk ratios were generated by fitting a generalised linear model with a binomial error structure and a log link function (log-logistic model) and adjusted risk differences (ARDs) estimated from marginal effects from the regression model.

Results: analysis 1

Pre- and 6-month-post-operative OKSs were available for 258,386 patients and 43,702 (16.9%) of these were identified as having chronic pain at 6 months post surgery. Within 3 months of surgery, complications were uncommon: there were surgical complications in 1224 (0.5%) patients, one or more medical complications in 6073 (2.4%) patients, readmissions to hospital in 32,930 (12.7%) patients, knee-related reoperation in 848 (1.5%) patients and revision knee replacement operation in 835 (0.3%) patients. Post-operative predictors of chronic pain were mechanical complication of prosthesis [odds ratio (OR) 1.56, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.35 to 1.80], surgical site infection (OR 1.13, 95% CI 0.99 to 1.29), readmission (OR 1.47, 95% CI 1.42 to 1.52), reoperation (OR 1.39, 95% CI 1.27 to 1.51), revision (OR 1.9, 95% CI 1.64 to 2.25) and length of hospital stay ≥ 6 days (OR 1.48, 95% CI 1.35 to 1.63). Predictive ability of the model was fair, with an area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve of 0.71, indicating that in respect of discriminatory ability, post-surgical predictors explain a limited amount of variability in chronic pain outcome.

Results: analysis 2

Information was available for 4750 patients between 2009 and 2016. Patients had a mean age of 69 years (standard deviation 9 years) and 56.1% were female. At 6 months after surgery, 10.4% of patients were classified as non-responders. The strongest associations with a non-response to surgery were seen for pre-operative risk factors; these were having only mild knee pain symptoms at the time of surgery (ARD 18.2%, 95% CI 13.6% to 22.8%), smoking (ARD 12.0%, 95% CI 7.3% to 16.6%), living in the most deprived areas (ARD 5.6%, 95% CI 2.3% to 9.0%) and obesity class II (i.e. body mass index between 35 and 40 kg/m2; ARD 6.3%, 95% CI 3.0% to 9.7%). We also identified a range of other risk factors with more moderate effects, including a history of knee arthroscopy surgery (ARD 4.6%, 95% CI 2.5% to 6.6%) and the use of opioids within 3 months after surgery (ARD 3.4%, 95% CI 1.4% to 5.3%).

Effectiveness of interventions to prevent chronic pain after total knee replacement: systematic reviews

These reviews have been published as Wylde et al.,100 Beswick et al.,101 and Dennis et al. 102 A comprehensive overview has been published as Wylde et al. 103

Aim

These systematic reviews aimed to assess the effectiveness of pre-, peri- and post-operative interventions in preventing chronic pain in patients receiving total knee replacement.

Workshop

In March 2016, 57 invited experts and colleagues met with the STAR team at a workshop to discuss interventions for the prevention of chronic pain after knee replacement. Those attending included surgeons, anaesthetists, physiotherapists, nurses and former patients, as well as researchers with interests in randomised trials, health economics, qualitative studies, PPI, systematic reviews and cohort studies.

The systematic review work package lead explained that the aim of the systematic reviews was to identify interventions that may improve long-term pain outcomes after knee replacement. The following definition of an intervention was presented:

Any clinical treatment or public health measure designed to reduce the incidence or modify the effects of particular diseases.

Yarnell and O’Reilly 104

Workshop participants considered that aspects of pre-operative care were potential targets for an intervention to prevent long-term pain. Many patients receive pre-operative education at a single class and from information booklets. Changes to content and interventions to improve uptake of classes were seen as potentially valuable. Pre-operative interventions might include cognitive behavioural therapy, self-management and peer support, weight management, exercise, treatment of comorbidities, nutritional guidance, and intra-articular injections. A multimodal approach might include education, psychological support, management of comorbidities and other components.

In the peri-operative period, workshop participants considered effective pain management important, possibly using gabapentin, nerve blocks and multimodal approaches. Certain anticoagulants are associated with micro-bleeds, which may lead to long-term pain. The use of tourniquets may also be associated with long-term pain.

An enhanced recovery protocol was considered a possible intervention to limit long-term pain. After hospital discharge, workshop participants noted the potential value of mid-term rehabilitation, peer support groups, provision of contact points, an introduction to community services and online resources, and psychological support including cognitive behavioural and mindfulness therapies. Provision of physiotherapy in different formats was also recognised as worth evaluating. Other interventions suggested were intra-articular injections, weight management, podiatry and realignment.

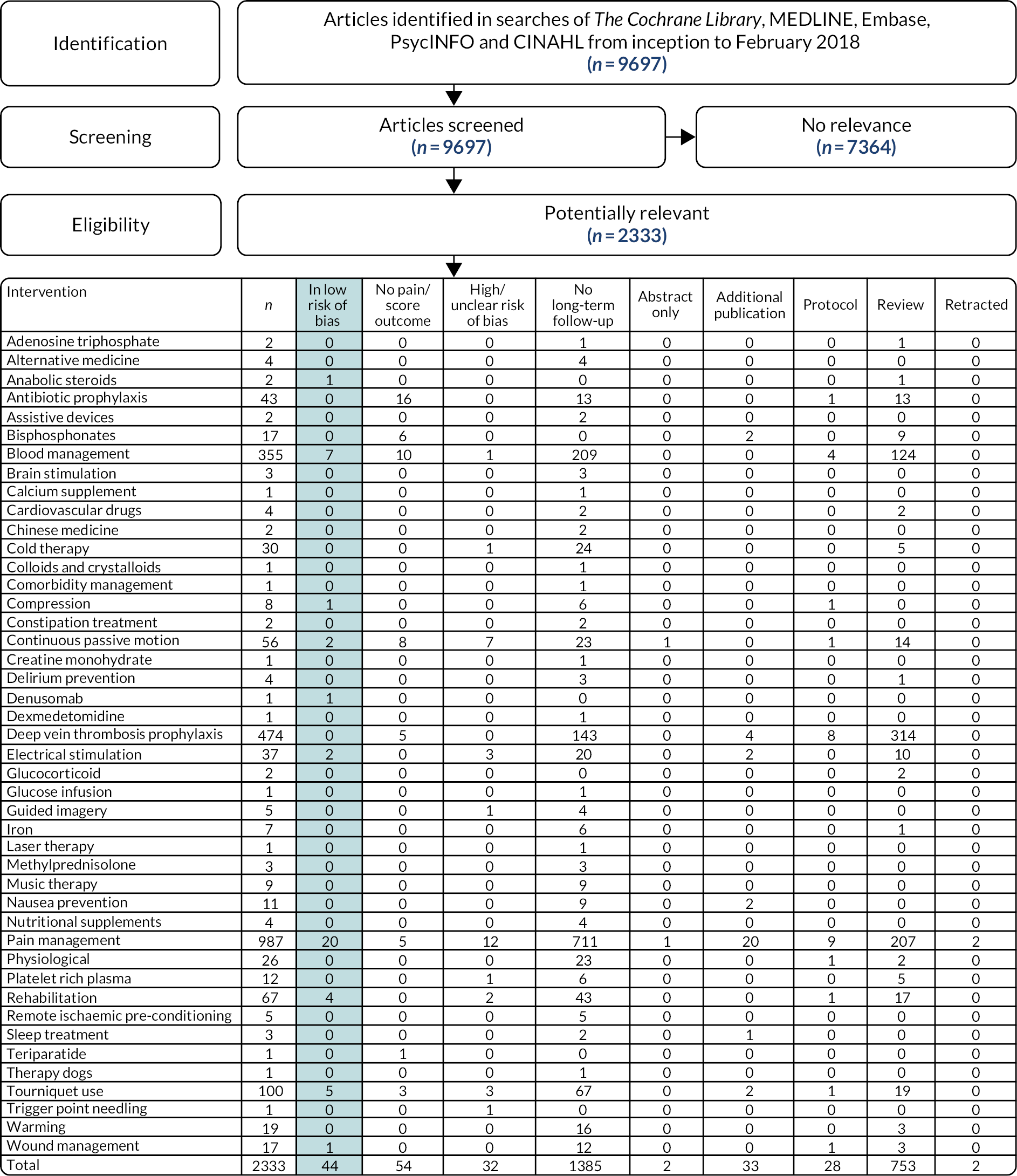

Methods

The systematic reviews were registered prospectively as PROSPERO CRD42017041382. 105 We established a database of all randomised controlled trials and systematic reviews in total knee replacement. These were identified through searches of The Cochrane Library, MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature) and PsycINFO® (American Psychological Association, Washington, DC, USA) in November 2016 (updated February 2018 for peri-operative interventions and December 2018 for pre-operative interventions) (see Appendix 3, Systematic review search strategy as applied in MEDLINE on Ovid).

Eligible studies were randomised controlled trials that met the following inclusion criteria:

-

patients with osteoarthritis awaiting or who have received total knee replacement

-

intervention – treatment in the pre-, peri- or post-operative setting

-

control – usual care or alternative treatment

-

outcomes – chronic pain at ≥ 6 months after knee replacement (≥ 12 months for post-operative interventions), adverse events.

The database was screened, and interventions divided into pre-, peri- and post-operative contexts, and into intervention groups. Risk of bias was assessed using the Cochrane tool. 106

Results: pre-operative interventions

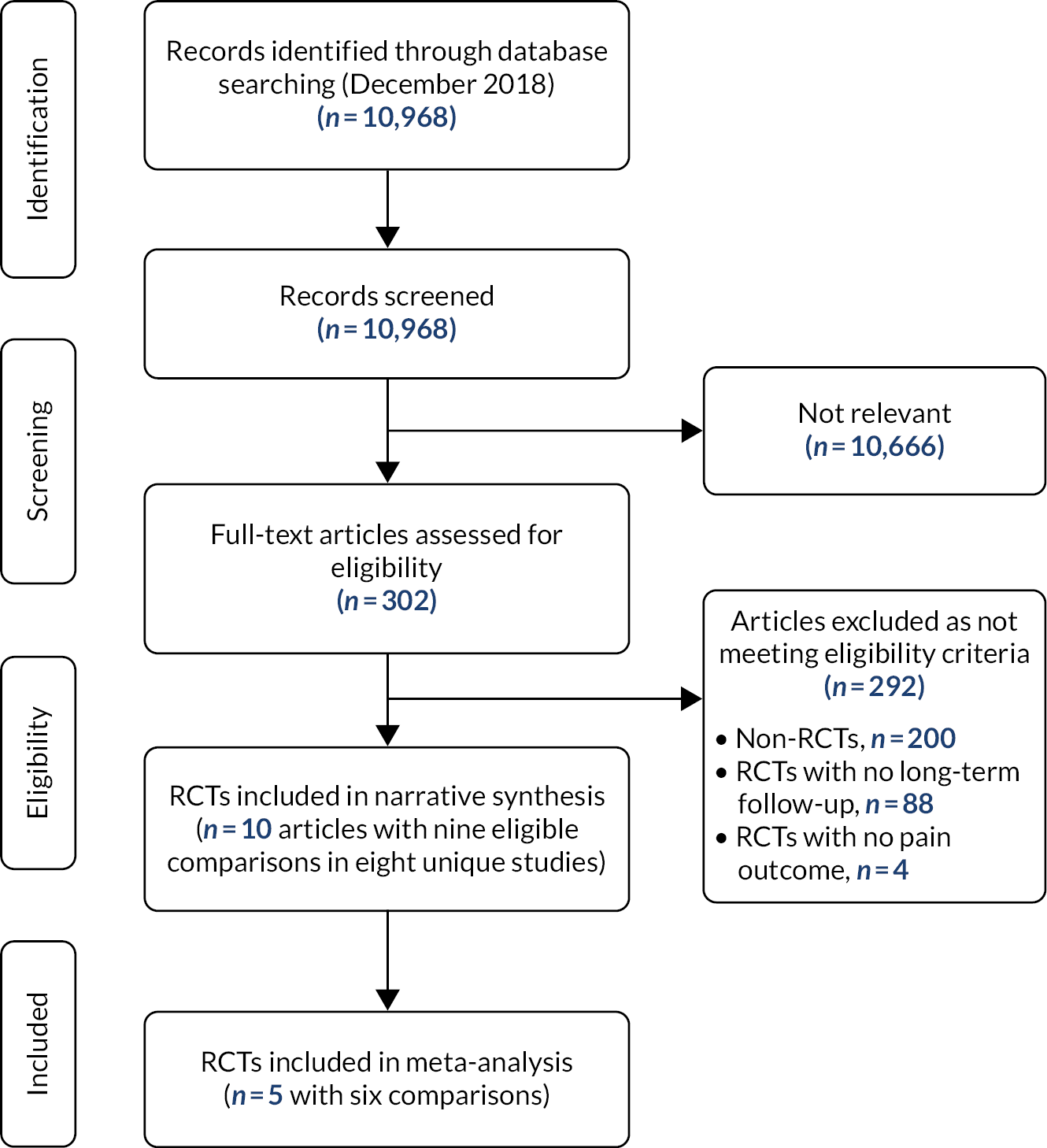

Eight randomised controlled trials with nine comparisons (960 patients) were eligible (see Appendix 3, Figure 3). There was moderate-quality evidence of no effect of exercise programmes on chronic pain after total knee replacement, based on a meta-analysis of six interventions with 229 participants (standardised mean difference 0.20, 95% CI –0.06 to 0.47; I2 = 0%). A sensitivity analysis restricted to studies at low risk of bias confirmed these findings. Studies evaluating a combined exercise and education intervention (one study) and education alone (one study) suggested similar findings.

FIGURE 3.

Effectiveness of pre-operative interventions: systematic review flow diagram. RCT, randomised controlled trial.

Results: peri-operative interventions

Forty-four randomised controlled trials at low risk of bias evaluated interventions in the peri-operative setting with a pain outcome or score with a pain component at ≥ 6 months’ follow-up (see Appendix 3, Figure 4). Intervention heterogeneity precluded meta-analysis. There was weak evidence for small reductions in chronic pain after total knee replacement in people who received peri-operative local infiltration analgesia (three studies), ketamine infusion (one study) or pregabalin (one study). Supported early discharge (one study) showed weak evidence of a small reduction in chronic pain. More clinically important benefits were seen for electric muscle stimulation (two studies), gait training (one study) and a course of anabolic steroids (one small pilot study).

FIGURE 4.

Effectiveness of peri-operative interventions: systematic review flow diagram.

For a range of peri-operative treatments there was no evidence linking them with unfavourable pain outcomes. For example, blood conservation with tranexamic acid during knee replacement was not associated with chronic pain. However, otherwise extensively researched interventions including venous thromboembolism prevention and tourniquet use have not been evaluated in relation to chronic pain.

Results: post-operative interventions

Randomised controlled trials of post-discharge interventions commencing in the first 3 months after total knee replacement were included (see Appendix 3, Figure 5). Seventeen trials with 2485 participants were included. All studies were at risk of bias because participants were not blinded to arm allocation, and five because of incomplete outcome data. Twelve trials evaluated physiotherapy interventions. Other interventions were nurse-led telephone follow-up, neuromuscular electrical stimulation and a multidisciplinary intervention. One study showed benefit for home-based exercises aimed at managing kinesophobia in reducing pain severity compared with no intervention. Otherwise, narrative synthesis found no evidence that one type of physiotherapy intervention is more effective than another. A 10-day multidisciplinary outpatient rehabilitation programme provided between 2 and 4 months after surgery showed no long-term benefit for pain or function. 107 For other interventions, there was insufficient evidence to draw conclusions about effectiveness.

FIGURE 5.

Effectiveness of post-operative interventions: systematic review flow diagram. RCT, randomised controlled trial; TKR, total knee replacement.

Effectiveness of interventions to manage chronic pain after surgery: systematic review

This review has been published as Wylde et al. 2017. 108

Aims

This systematic review aimed to assess the efficacy of interventions to treat chronic pain after non-cancer surgeries.

Methods

The systematic review was registered prospectively as PROSPERO CRD42015015957. 109 We searched MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO, CINAHL and The Cochrane Library from inception to March 2016 (see Appendix 4, Systematic review search strategy as applied in MEDLINE on Ovid). An update in October 2020 was timed to contextualise the STAR intervention.

Eligible studies were randomised controlled trials that met the following inclusion criteria:

-

patients with chronic pain after non-cancer surgery

-

an intervention for pain received by patients at a minimum of 3 months after surgery

-

a comparator of no treatment, placebo, usual care or alternative treatment

-

an outcome relating to pain.

Risk of bias was assessed using the Cochrane tool. 106

Results

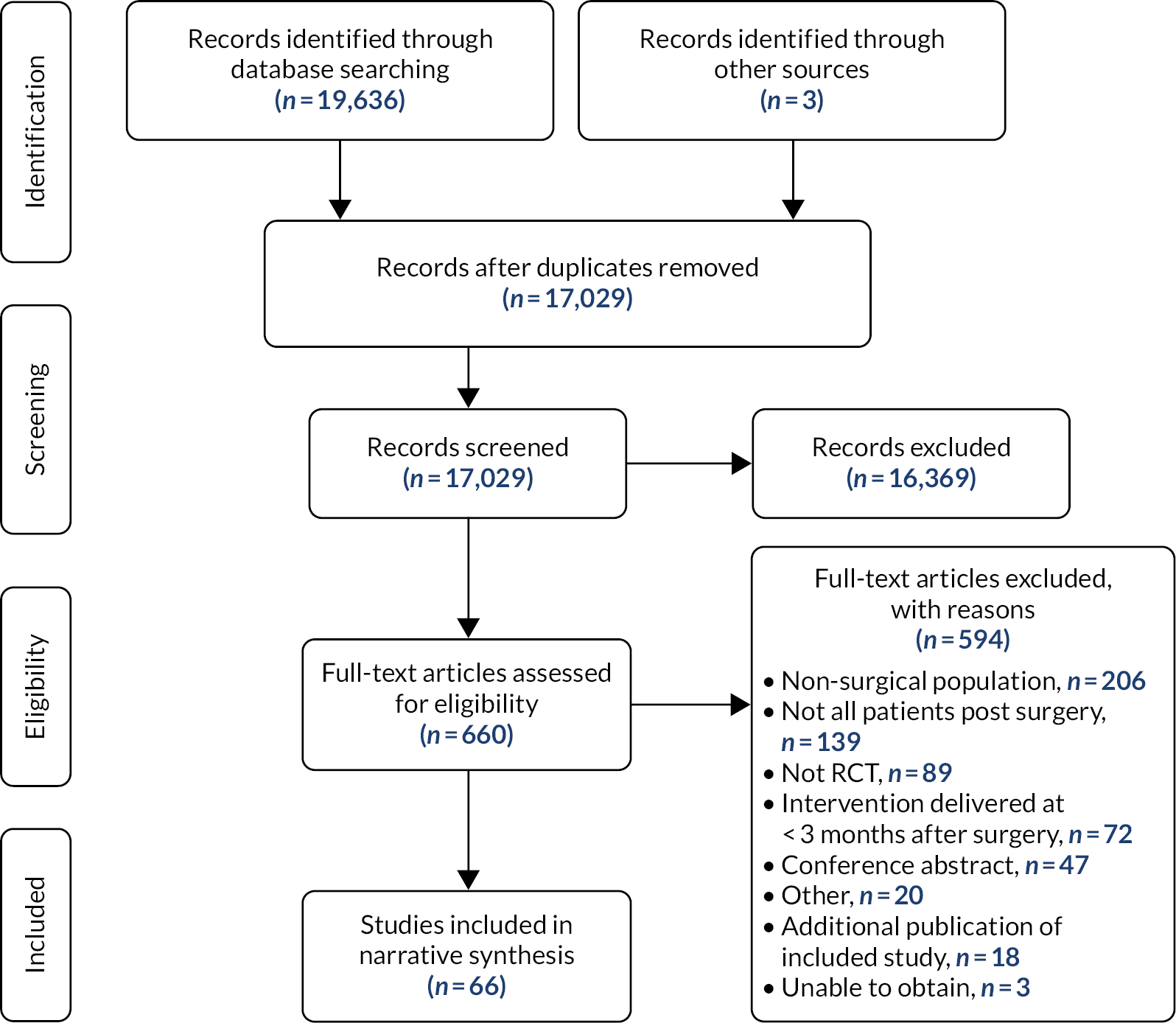

As shown in Appendix 4, Figure 6, 66 trials with data from 3149 participants were included. Most trials included patients with chronic pain after spinal surgery (n = 25) or amputation (n = 21). Interventions were antiepileptics, capsaicin, epidural steroid injections, local anaesthetic, neurotoxins, opioids, acupuncture, exercise, spinal cord stimulation, further surgery, laser therapy, magnetic stimulation, mindfulness-based stress reduction, mirror therapy and sensory discrimination training. Opportunities for meta-analysis were limited by heterogeneity. For all interventions, there was insufficient evidence to draw conclusions on effectiveness but the review provided clear suggestions for future research.

FIGURE 6.

Effectiveness of interventions to manage chronic pain after surgery: systematic review flow diagram. RCT, randomised controlled trial.

Review update

To examine the STAR trial in a contemporary context, we updated searches with terms relating to arthroplasty of the large joints, post-surgical pain, and randomised controlled trials (see Appendix 5, Systematic review search strategy as applied in MEDLINE on Ovid). Systematic reviews and trial registries were checked for studies.

Eligible studies were randomised controlled trials that met the following inclusion criteria:

-

patients with chronic pain after arthroplasty of the large joints

-

intervention – treatment for chronic pain

-

control – no treatment, usual care or alternative treatment

-

outcome – pain.

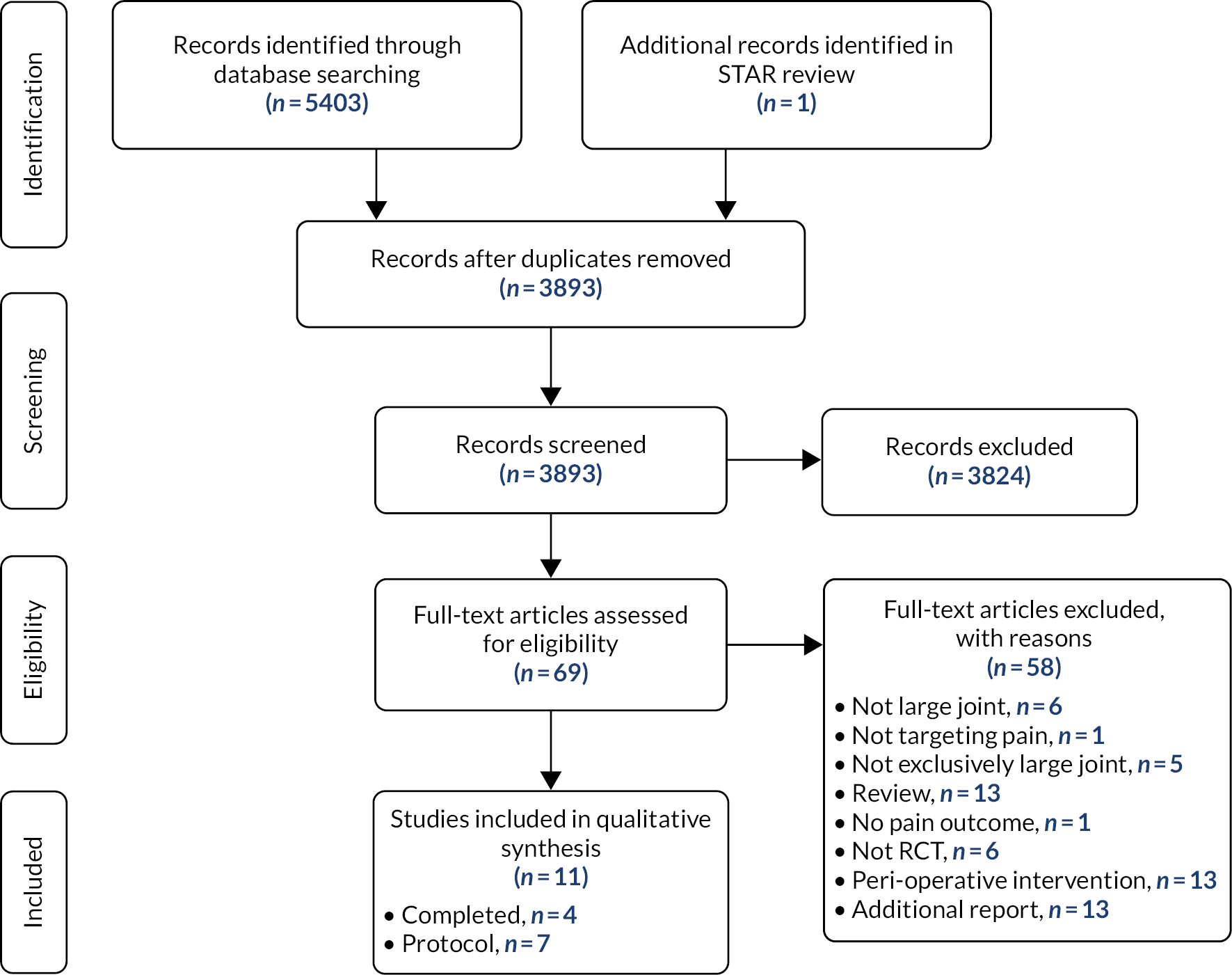

Of 3901 articles identified and screened by one reviewer, 69 were potentially relevant (see Appendix 5, Figure 7). After detailed evaluation by two reviewers, four published randomised evaluations of treatments for chronic pain after knee replacement were identified in the original review and update (see Appendix 5, Table 1). No study was judged to be at high risk of bias. For people with general chronic pain, there were encouraging findings warranting further research into intra-articular botulinum toxin110 and denervation therapy. 111 Radiofrequency genicular nerve treatment showed similar outcomes to treatment with anaesthetic and corticosteroid. 112 No studies were found that evaluated a multifaceted intervention, but one study focusing specifically on treatment of neuropathic pain with topical lidocaine suggested that further research is merited for this personalised treatment. 113

| Study, country, date of recruitment | Inclusion criteria | Number randomised (intervention : control) | Intervention | Comparator | Risk of bias issues | Key results | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Published studies | |||||||

| Singh et al. 2010,110 USA, 2006–9 | Pain after total knee replacement for > 3 months, NRS pain intensity ≥ 6/10 | n = 54; 60 knees (30 : 30) | Single intra-articular botulinum toxin A injection | Single intra-articular injection of saline | Low risk of bias | Reduced pain intensity in botulinum A group after 3 months. Pain relief to around 40 days | |

| Ma et al. 2016,111 China, 2014–15 | Intractable pain of knee joint after total knee replacement | n = 100 (50 : 50) | Denervation therapy | Drug treatment | No losses to follow-up | Denervation therapy associated with improved symptoms | |

| Pickering et al. 2019,113 France, 2016 | Localised neuropathic pain after knee surgery | n = 36 (24 : 12) | 5% lidocaine-medicated plaster for 3 months | 5% plaster with no drug for 3 months | No losses to follow-up | Lidocaine plaster reduced localised neuropathic pain | |

| Qudsi-Sinclair et al. 2017,112 Spain, 2012–14 | Pain after total knee replacement | n = 33 (15 : 18; 14 : 14 received treatment) | Single radiofrequency genicular nerve block | Single analgesic block with corticosteroid | Some concerns: uneven follow-up in small study | Similar pain outcomes in both groups | |

| Wylde et al. 2022120 | Chronic pain 2 months after primary total knee replacement | n = 363 (242 : 121) | STAR intervention | Usual care | Low risk of bias | STAR was clinically effective and cost-effective in improving pain outcomes at 1 year | |

| From trial registries and published protocols | |||||||

| NCT02211534119 | Persistent post-operative pain following total knee replacement | NA | Pulsed electromagnetic energy field therapy | Sham pulsed electromagnetic field | NA | NA | |

| NCT02931435117 | Chronic knee pain despite total knee replacement at ≥ 6 months | NA | Nerve block with radiofrequency ablation | Sham radiofrequency ablation | NA | NA | |

| NCT03825965115 | Persistent post-surgical pain following total knee replacement | NA | Cannabinoids | Placebo | NA | NA | |

| NCT04100707118 | Knee pain 3 months after total knee replacement | NA | Genicular nerve blocks | Sham comparator | NA | NA | |

| NCT03973177116 Crossover |

Refractory chronic knee pain for more than 6 months after total knee replacement | NA | Phenol injection: neurolysis of genicular nerves | Methylprednisolone injection | NA | NA | |

| Larsen et al. 2020114 | Chronic pain after primary total knee replacement | NA | Neuromuscular exercise and pain neuroscience education | Pain neuroscience education | NA | NA | |

| NA, not applicable; NRS, numeric rating scale. | |||||||

FIGURE 7.

Interventions to manage chronic post-surgical pain update: systematic review flow diagram. RCT, randomised controlled trial.

In addition to the STAR trial, six studies were ongoing or not published (see Appendix 5, Table 1). These focus on exercise and education,114 cannabinoids,115 phenol neurolysis of genicular nerves,116 genicular nerve blocks117,118 and pulsed electromagnetic field therapy,119 all in people with general chronic pain after knee replacement.

Strengths and limitations

Our systematic reviews benefited from comprehensive literature searches and broad inclusion criteria to allow for evaluation of diverse interventions. Reviews were conducted according to appropriate guidelines and issues that may have introduced bias were considered. Meta-analysis was conducted, but only when appropriate. A narrative descriptive approach was used in circumstances of high heterogeneity of risk factors, interventions, outcomes and follow-up. Authors were contacted for clarification and missing information at all stages of the reviews. In the review of post-operative risk factors, a limited range of risk factors had been studied. In intervention reviews, our focus was on chronic pain as an outcome, which, although important, may not have been the specific outcome targeted by an intervention.

A strength of our database analyses was the large numbers of patients with linked data. Analyses included multiple centres and results should be generalisable throughout the NHS. Our analyses were limited by the content of data sets. Factors not recorded included implant positioning and surgical technique, pain management and medication use, and psychological, genetic, and environmental factors. Analyses were also limited by the single post-operative knee pain measure, which may not reflect established chronic pain.

Conclusions and inter-relationship with other parts of the programme

Before our comprehensive database analyses, knowledge of post-operative risk factors was limited to the observation that people with acute pain after knee replacement were more likely to report chronic pain. Risk factors identified in database analyses that may have potential for modification or use in the targeting of care included some patient and surgical factors, previous knee arthroscopy, use of opioids and surgical complications.

Randomised trials to assess long-term outcomes after pre-, peri- and post-operative interventions are feasible and necessary to ensure that patients receive care with reduced or no risk of chronic pain. Unifactorial interventions identified in systematic reviews and suggested by stakeholders merit further study.

Although some management strategies for chronic pain after diverse surgeries identified in our systematic review may have limited applicability outside the specific condition for which they were intended, others may be transferable regardless of the surgical procedure. Their value in the personalised prevention of chronic pain requires further research on their individual effectiveness and ultimately their potential as a component in a multifactorial care pathway.

Characterising chronic pain after total knee replacement (work package 2)

Background

Although chronic pain places considerable burden on health-care systems and individuals, little research has characterised chronic pain after total knee replacement and its impact on health-care resource use.

Aims

We aimed to characterise the natural history and course of chronic pain after total knee replacement, including health-care resource use, through additional follow-up of the Clinical Outcomes in Arthroplasty Study (COASt) cohort and analysis of the linked CPRD and HES databases.

Identification of patients with chronic pain after total knee replacement using the Oxford Knee Score

This work has been published as Pinedo-Villanueva et al. 20

We applied cluster analysis to data on 128,145 patients with primary total knee replacement included in the English PROMs programme to derive a cut-off point on the pain subscale of the OKS. A high-pain group was identified, defined by a score of ≤ 14 points on the OKS pain subscale 6 months after total knee replacement. This group comprised 15% of the patient sample and was characterised by severe and frequent problems in all pain dimensions.

Natural history of chronic pain after total knee replacement: extended cohort follow-up

This work has been published as Cole et al. 121

The COASt cohort (n = 1025) contains data from total knee replacement patients with comprehensive pre- and post-operative pain assessments. 122 Recruitment started in 2010 in Oxford and 2011 in Southampton. Patients were recruited pre-operatively and followed up post-operatively at 6 weeks and then annually. In the STAR programme, follow-up was extended to 5 years. This allowed the collection of detailed information on the course, qualities and variability of post-surgical pain. It also enabled the identification of pain patterns, such as late-onset or transient post-surgical pain.

Follow-up questionnaires were received from 580 patients 1 year following their primary total knee replacement and then from 500, 457, 390 and 336 patients for the 2- through 5-year questionnaires, respectively. The data were cleaned and analysed, and summary statistics generated for PROMs [EuroQol-5 Dimensions, three-level version (EQ-5D-3L) and OKS], chronic pain progression, resource use and (community and hospital) costs by chronic pain groups measured using the OKS-PS threshold applied to year 1 values. 20

There were 70 out of 580 participants with chronic pain at 1 year post surgery (12% of the full cohort). Their reported health utility index at 1 year post surgery was 0.39 compared with 0.79 for the non-chronic pain cohort, both reporting an important improvement over their baseline scores (0.27 and 0.48, respectively). Missing data (questionnaires not returned or questions not completed) increased with time to significant levels: 25% of the chronic pain cohort had missing OKS data at 5 years. A predicted means model approach was followed to impute answers to the pain subscale of the OKS and the EQ-5D-3L for all missing values to generate a complete picture of progression into and out of chronic pain over time and associated quality of life. Mean health utility was estimated to slowly improve for the chronic pain cohort, reaching 0.65 by year 5. The increase in the mean score was a reflection of many patients improving their OKS and EQ-5D-3L scores, although not all did. Although 65% of participants with chronic pain at 1 year were estimated to improve their OKS pain subscale beyond 14, never to drop below 14 again, 31% moved back and forth between chronic pain and non-chronic pain, and 4% remained in chronic pain over the 5 years.

In terms of health-care resources, having chronic pain was associated with greater use and costs than not having chronic pain. A larger proportion of participants in the chronic pain cohort than the non-chronic pain cohort reported seeing a GP (63 vs. 34%, respectively), physiotherapist, hospital doctor, nurse or alternative practitioner owing to their knee problem during the first year after surgery. This greater use of health-care services was maintained over the 5-year period. Costs reflected the difference between groups, with the chronic pain cohort reporting mean health-care costs of £1800 during the first year owing to their knee problem, compared with £500 for the non-chronic pain cohort; the gap was still present although significantly reduced at 5 years post surgery (£80 for the chronic pain cohort vs. £25 for the non-chronic pain cohort).

Health-care resource use: analysis of national data sets

This work has been published as Cole et al. 121

Analysis of the CPRD linked to the HES database was undertaken to characterise the natural history of chronic pain after total knee replacement, including resource use. Data from HES–CPRD data set were used to estimate the hospital and primary care costs associated with chronic pain after total knee replacement.

The analysis included patients in the CPRD–HES data set who reported post-operative (6-month) PROMs including the OKS so that they could be classified into chronic pain groups. The sample consisted of 5055 patients, 721 (14%) of whom reported OKS pain scores ≤ 14 and identified as in chronic pain. Hospital costs were estimated based on patient-level data about inpatient hospital stays for their total knee replacement as well as related complications, including revision surgery. Healthcare Resource Groups were generated based mainly on procedure and diagnostic codes reported for each spell. Primary care costs were estimated for reported consultations with GPs and other community health-care professionals as well as the prescription of analgesia.

Mean hospital costs for the primary total knee replacement were very similar for both groups (£6195 for the chronic pain group and £6055 for those not in chronic pain). Revision surgery also cost nearly the same to the NHS for both groups (£9188 for those in chronic pain and £9261 for those not in chronic pain), but its cumulative incidence at 7 years was significantly higher for those in chronic pain (nearly 10%) than the non-chronic pain group (just over 2%). Complications (i.e. myocardial infarction, venous thromboembolism and joint infection) were rare for both groups with less than 1.5% of patients reporting them, although venous thromboembolism and joint infection were more common in the chronic pain group than the non-chronic pain group (1.2 vs. 0.6% for venous thromboembolism, respectively, and 1.1 vs. 0.1% for joint infection, respectively).

In primary care, costs were consistently higher for those in chronic pain. Mean costs (adjusted for exposure) for all reported consultations with any health-care professional in the community and prescriptions of analgesia were estimated up to 10 years before primary total knee replacement and 8 years following surgery. Mean yearly consultation costs per patient for the chronic pain and non-chronic pain groups were, respectively, £244 and £182 at 10 years prior to surgery, £408 and £342 during the 12 months before surgery, £461 and £366 during the 12 months after surgery, and £426 and £325 8 years after primary total knee replacement. GP consultations accounted for 70–80% of the costs for those in chronic pain and generally slightly less for those not in chronic pain.

Prescriptions of antidepressants for pain management, paracetamol, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and opioids were more common (and hence leading to greater costs) for those in chronic pain throughout the 18-year period of analysis. Of particular interest is that those not in chronic pain reported only a small drop in the average yearly cost of analgesia per patient after surgery, only for it to slowly grow again afterwards, reaching levels similar to those immediately before the replacement by the eighth year. Remarkably, those in chronic pain reported a continuous increase of analgesia prescriptions costs from 10 years prior to 7 years after surgery, with an increasing cost of opioid prescriptions after surgery which accounted for 17% of all analgesia prescriptions costs 10 years before the replacement, 50% the year before, and 74% 7 years after.

Economic model

A cohort-based Markov model described in Appendix 6 was developed to estimate the 5-year costs and (quality-adjusted) life expectancy of patients with chronic pain after total knee replacement under current practice as well as the STAR intervention in order to assess the impact of the latter. The model was populated with evidence from the trial and the findings of analysis of both the COASt and CPRD cohorts described above, with scenarios including and excluding the impact on inpatient admissions identified during the trial.

Strengths and limitations

The cut-off point we identified on the OKS pain subscale was derived from patients who completed the post-operative PROMs questionnaires sent out by the NHS. Differences in rates of completion of PROMs questionnaires is known to lead to underrepresentation of some socioeconomic groups and potentially those who feel particularly unsatisfied about their surgery. Using data from over 120,000 patients reported over 4 years reduced this potential bias. Our findings, moreover, were consistent with those of other studies identifying patients with chronic pain.

Findings from the analysis of the COASt cohort were limited by missing data and the potential lack of representativeness from recruiting in just two centres. However, we applied an imputation method that clustered observations by patient and considered completed questionnaires by similar patients. The proportion of chronic pain patients in the cohort (12%) was similar to that found in the England-wide study used to derive the cut-off point (14%).

Although the CPRD population is known to be representative of that of the UK, it lacks long-term data on outcomes beyond the 6-month linked HES–PROMs. To better understand the long-term trajectories of patients in chronic pain following total knee replacement, we combined the representative picture of the CPRD–HES population with the long-term follow-up provided by the COASt cohort. 96

Conclusions and inter-relationship with other parts of the programme

We derived a cut-off on the OKS pain subscale that can be used for patient selection in research settings to design and assess interventions that support patients in their management of chronic post-surgical pain. Patients in chronic pain as identified by this method appear noticeably different from those who are not: their average quality of life (which also captures disability as it includes impact on mobility and the ability to self-care and carry out regular activities) is poorer prior to surgery and it improves after, but not as much as for those not in chronic pain. Most seem to leave the chronic pain category over the subsequent 5 years, but their average quality of life does not reach the level reported by those not in chronic pain just 12 months after their total knee replacement. Patients in chronic pain consume more health-care resources at hospital because they are much more likely to have revision surgery within 7 years, and the costs of their health care in the community are also greater than for those not in chronic pain. Although the average costs of GP consultations per patient plateau after surgery, the costs of opioid prescriptions continue to significantly grow for patients in chronic pain for up to 7 years after surgery. The analysis did not suggest any time points at which poor post-surgical outcome could predict long-term problems; there are, however, signs that long-term problems are associated with pre-operative pain and quality-of-life outcomes as well as health-care resource use, in particular prescriptions for strong analgesia.

Development of a complex intervention for patients with chronic pain after knee replacement: the STAR care pathway (work package 3)

This work has been published as Wylde et al. 123

Background

As part of our Programme Development Grant, we conducted preliminary studies to design an intervention to improve the management of chronic pain after total knee replacement. Studies included a systematic review, a survey of NHS practice, qualitative work with health-care professionals, an expert group meeting and PPI activities. 48,124–126 We found a lack of clear pathways and referral processes for patients with chronic pain after total knee replacement,124,125 hindering patients’ access to targeted and individualised care and highlighting the need for improved access to appropriate pain management interventions for this population.

Aim

The aim of this work package was to refine and finalise a new care pathway for patients with chronic pain after total knee replacement. Specific objectives comprised the following:

-

the refinement of intervention content

-

the testing of intervention delivery and acceptability

-