Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by PGfAR as project number RP-PG-1209-10071. The contractual start date was in July 2012. The final report began editorial review in February 2021 and was accepted for publication in February 2022. As the funder, the PGfAR programme agreed the research questions and study designs in advance with the investigators. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PGfAR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2022 Wyld et al. This work was produced by Wyld et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2022 Wyld et al.

SYNOPSIS

Research summary

The original proposal has largely been adhered to in the programme grant, with a few minor variations.

Prospective cohort study

The study recruited 3450 (with a target of 3500) women aged ≥ 70 years, but recruitment was slower than expected and an extension was required from the original 5 years to 6 years. We also increased the number of centres from 22 to 56 to enhance recruitment. A further delay was caused by the UK Cancer Registry, where we planned to get our survival data updated before final analysis. Legal changes caused by the new General Data Protection Regulations1 meant that, although our study was legally compliant with the old legislation, it no longer complied with consent requirements in the new system. A lengthy negotiation process was required to permit access, which added 9 months to our timelines. In total, the study ran for 7 years, rather than the original estimate of 5 years.

Decision support intervention development

The development proceeded to time and target, resulting in the production of decision support interventions (DESIs) suitable to trial in the cluster-randomised controlled trial.

The cluster-randomised controlled trial

The trial started later than expected owing to a delay in receiving National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) approval for phase 2 of the programme, and compounded by slower than anticipated recruitment. Therefore, an extension and an increase in centre numbers were required. However, we did ultimately recruit to target: 1330 out of the target 1328 women.

Health economic analysis

This was completed, but delayed by the registry data access issue noted in Prospective cohort study.

Variation study

This is completed and published.

Overall

The programme has met all of its targets, but was delayed by 24 months. All expected outputs have been published in scientific journals. The online tool has been Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) approved, is available on the web and is in regular clinical use.

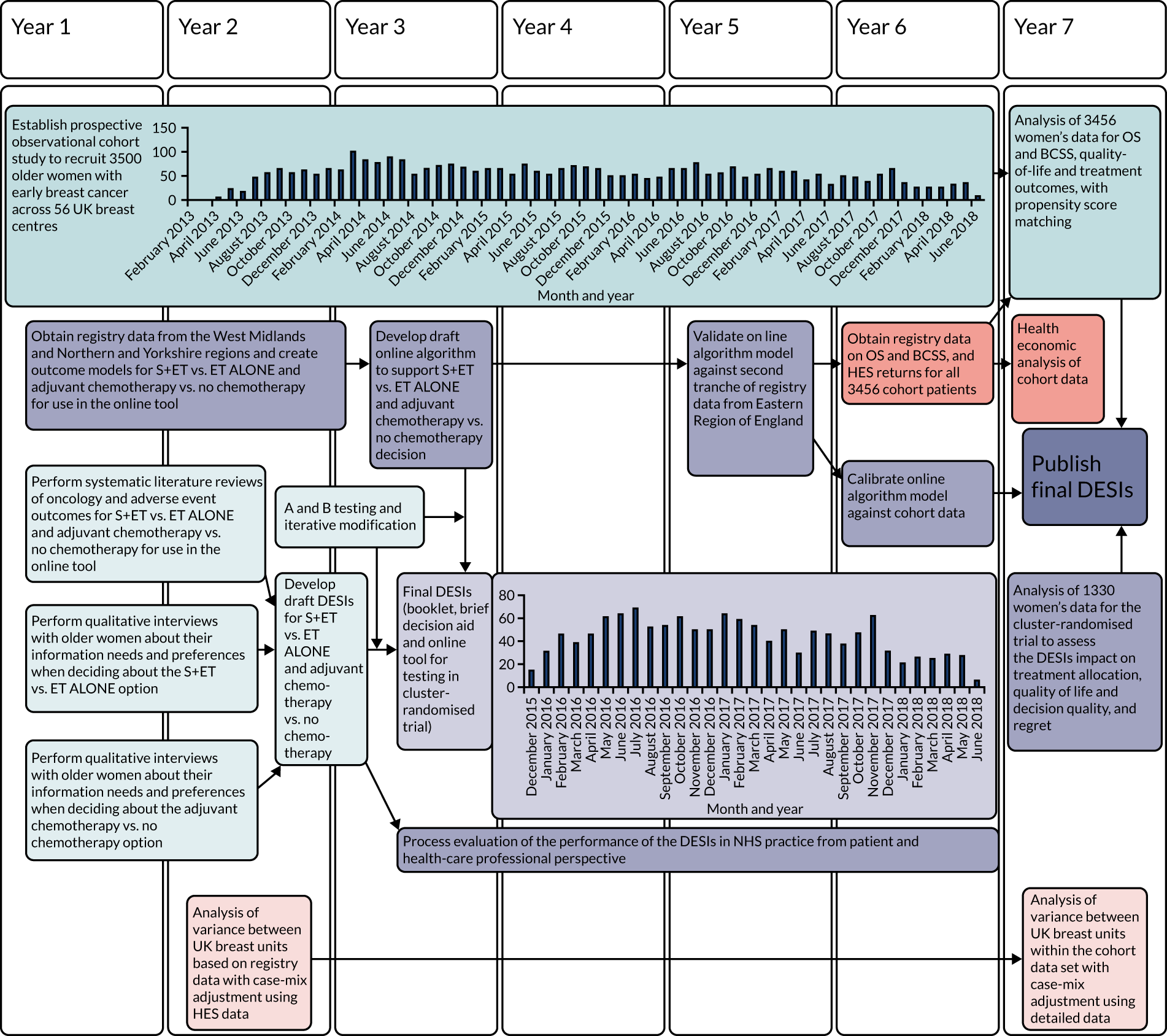

Research pathway diagram

The research pathway diagram is presented in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Research pathway diagram: summary of the relational timelines for the Age Gap programme grant. BCSS, breast-cancer-specific survival; ET ALONE, primary endocrine therapy; HES, Hospital Episode Statistics; OS, overall survival; S+ET, surgery plus adjuvant endocrine therapy. Light-blue shading indicates development of the DESI. Mid-blue shading represents the cohort study. Light-purple shading indicates the cluster RCT. Mid-purple shading indicates development of the models. Light-orange shading indicates analysis of variance. Mid-orange shading indicates health economic analysis.

General background introduction

Breast cancer in older women

Breast cancer is the most common cancer to affect women, with over 55,000 women diagnosed annually,2 and one-third of cases being in women aged ≥ 70 years. The clinical significance of breast cancer is proportionately less in older women, as breast-cancer-specific mortality is overtaken by other-cause mortality once a woman is in her eighties. However, women aged > 80 years still have a higher risk of dying from breast cancer than women in their seventies, which may be because of suboptimal treatment. 3 It is equally important to avoid overtreatment and causing unnecessary harms in women who are very frail. 4 There are currently no tools available that specifically support decision-making in older women with early-stage breast cancer who are faced with a choice of primary endocrine therapy (ET ALONE) or surgery plus adjuvant endocrine therapy (S+ET). The Adjuvant! Online tool5 and the NHS PREDICT tool6 provide survival estimates only for women who have had surgery. This programme of research has developed, validated and trialled an online tool specifically for supporting decision-making in older women.

Surgical treatment of breast cancer in older women

Surgery may be unnecessary for some frailer older women, as disease control may be achieved using antioestrogens alone (ET ALONE). Up to 90% of breast cancers in older women are oestrogen sensitive7,8 and therefore respond well to antioestrogens, potentially allowing women to avoid surgery.

A systematic review of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) evaluating the role of S+ET versus ET ALONE demonstrated no survival difference between the two treatments, but inferior local control for ET ALONE compared with S+ET. 9–12 Longer-term follow-up and a patient-level meta-analysis have recently suggested that survival is superior with S+ET than with ET ALONE (Richard Gray, University of Oxford, 2019, personal communication). These trials were methodologically flawed, and it is therefore not justified to suggest that ET ALONE is not appropriate for any older women. Overtreatment with surgery for very frail older women may be harmful. A recent study of 6000 nursing home residents with breast cancer, all of whom were treated with surgery, reported high morbidity and mortality rates and high levels of long-term functional impairment, although the authors acknowledge that some of the deterioration and deaths may have occurred regardless of their breast cancer treatment. 4

Since these trials were performed in the 1980s, the practice of ET ALONE has changed and is now usually offered only to women with oestrogen-receptor-positive (ER+) cancers, and aromatase inhibitors have largely replaced tamoxifen. 13–16 ET ALONE may, therefore, be more efficacious if potential candidates are selected appropriately, based on health status and tumour biology. From a patient’s perspective, older women express high levels of satisfaction with both S+ET and ET ALONE. 17 Factors cited in favour of ET ALONE are avoiding hospitalisation and surgery, and a desire to retain independence. 17

The purpose of the Age Gap study was to gather data to guide treatment selection for both patients and clinicians to avoid women being overtreated or undertreated.

Adjuvant chemotherapy in older women

Adjuvant chemotherapy is usually advised for high-recurrence-risk breast cancer; however, in women aged ≥ 70 years, there is less certainty about the survival benefits of adjuvant chemotherapy owing to the lack of trial data and to toxicity concerns. 18 The Oxford overview of adjuvant chemotherapy demonstrated reduced mortality for women up to age 69 years,19,20 but there were insufficient data regarding women aged ≥ 70 years to draw firm conclusions. 20

As a result of this uncertainty, in the UK, the National Audit of Breast Cancer in Older Patients (NABCOP) found a two-thirds reduction in chemotherapy use in women aged ≥ 70 years with high-risk disease. 21 Avoidance of chemotherapy in some women may be justified by concerns about poor treatment tolerance; for others, treatment may be well tolerated and improve survival. Rates of mortality and morbidity associated with chemotherapy are higher in women aged ≥ 70 years, with higher rates of haematological toxicity, febrile neutropenia22 and early discontinuation. 23 There is wide variation in chemotherapy rates across the UK,24 which suggests that age- and health-stratified guidelines are required. Generating evidence to support guideline development was one of the aims of this study.

Clinician practice variation in the UK

There is wide variation in rates of non-surgical treatment of breast cancer in the UK, ranging from 5% to 50%,21 suggesting that some women may be overtreated and others undertreated, and highlighting the need for age- and health-stratified guidelines. A similar picture is also seen in the use of adjuvant chemotherapy, with wide variation in rates of use between UK breast units. 24

One of the aims of the Age Gap study was to assess the extent and causes of these variations.

Shared decision-making and decision support

Shared decision-making is joint decision-making by a patient and health-care professional(s) in which they are both experts: the patient on what matters most to them and the health-care professional on the clinical evidence. It can be particularly beneficial in the context of treatment decisions that are preference sensitive, such as those described above for older women with breast cancer. DESIs aim to support shared decision-making and improve the quality of treatment decisions. A systematic review of DESIs showed that they lead to several benefits, such as increased knowledge, greater participation in decision-making, greater comfort with decisions and more accurate risk perceptions. 25

One of the aims of the Age Gap study was to develop DESIs to support older women and their clinicians when engaging in shared decision-making regarding breast cancer treatment.

Aims and objectives

Aims and objectives

-

To provide guidance for the treatment of frailer older women with ER+ breast cancer to ensure optimal treatment with either S+ET or ET ALONE.

-

To provide guidance on the treatment of fitter older women with high-recurrence-risk breast cancer to ensure optimal use of adjuvant chemotherapy with or without trastuzumab.

-

To design, validate and evaluate (in a RCT) a DESI for older women faced with either of the above choices.

-

To determine the health economics of S+ET compared with ET ALONE in older women with ER+ early-stage breast cancer.

-

To determine the extent and causes of variation in UK practice relating to older women with breast cancer.

Work packages

-

Summation of evidence of current UK practice for older women with early-stage breast cancer.

-

Determination of the information needs and preferences of older women when deciding on their preferred breast cancer treatment using a mixed qualitative and quantitative methodology.

-

Development of DESIs, including an online tool (using the above models), to be evaluated in a randomised trial.

-

Development of outcome models in older women with breast cancer, comparing S+ET with ET ALONE, or adjuvant chemotherapy with no chemotherapy, using UK registry data.

-

Acquisition of data from a cohort study of older women with breast cancer to validate the treatment thresholds identified above.

-

Cluster-randomised trial of the DESIs’ impact on treatment allocation and outcomes for older women with breast cancer.

-

Health economic analysis comparing the cost efficacy of ET ALONE with that of S+ET in older women, based on a mixture of published data, registry data and cohort study data.

-

Study of the degree and causes of variation in treatment allocation between UK breast units using registry data, cohort study data and mixed-methods research.

Evidence summary of current UK practice in older women with early-stage breast cancer

Three systematic reviews were undertaken of the evidence relating to the oncological efficacy of and adverse events related to ET ALONE compared with S+ET, and adjuvant chemotherapy compared with no chemotherapy in older women. The three reviews are:

-

a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised trials comparing ET ALONE and S+ET11

-

a systematic review of cohort studies comparing ET ALONE with S+ET10

-

a systematic review of the efficacy and side effects of chemotherapy for breast cancer in older women (not published, see Appendix 1).

The data from these reviews were used to develop an evidence summary on which the factual content of the decision support tools was based.

Defining the information needs and preferences of older women with breast cancer

The next stage in the development of the DESIs was to determine the information needs and preferences of older women. These DESIs focused on two key decisions:

-

whether to have S+ET or ET ALONE

-

following surgery, whether or not to have adjuvant chemotherapy.

A multicomponent mixed-methods study was undertaken to acquire this information, and design and refine the DESIs. The components of the study were:

-

a systematic review of literature on intervention efficacy and adverse events (see Evidence summary of current UK practice in older women with early-stage breast cancer)

-

qualitative interviews with patients regarding information needs and preferences (see Patient interview study to determine the preferred format and content for the surgery plus adjuvant endocrine therapy versus primary endocrine therapy decision support intervention and Patient interview study to determine preferred format and content for the adjuvant chemotherapy versus no chemotherapy decision)

-

a quantitative survey of patient information needs and preferences (see Questionnaire study to determine the preferred content for the surgery plus adjuvant endocrine therapy versus primary endocrine therapy decision support intervention)

-

draft decision support tools (see Development and testing of the decision support interventions)

-

DESI modification based on interviews and focus groups with healthy, age-appropriate volunteers and health-care professionals (see Development and testing of the decision support interventions)

-

DESI modification based on interviews with patients (see Development and testing of the decision support interventions)

-

DESI modification based on field testing with patients (see Development and testing of the decision support interventions)

-

language review by the Plain English Campaign (Stockport, UK; see Development and testing of the decision support interventions)

-

graphic and web design input

-

evaluation of final DESIs in a cluster-randomised controlled trial (see Cluster-randomised controlled trial).

These components are described below.

Patient interview study to determine the preferred format and content for the surgery plus adjuvant endocrine therapy versus primary endocrine therapy decision support intervention

Introduction

The aim of this study was to explore information needs using in-depth qualitative interviews and then to quantify preferences using a bespoke questionnaire. This work has been published. 26

Methods

Women aged > 75 years who were under follow-up after treatment for early-stage breast cancer and had been offered a choice of S+ET or ET ALONE at diagnosis were recruited for interview.

A topic guide was developed by the expert reference group and patient and public involvement (PPI) panel. Topics included sources of information used; information they were given or would prefer to aid their decision-making; their preferences about the process of decision-making; and their preferred format for information, that is booklets, verbal, digital versatile disc (DVD), audio, internet or mobile applications (apps). Interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim. A framework approach was used for analysis.

Results

Thirty-three older women were interviewed (median age 82 years, range 75–95 years) at a median of 20 months after diagnosis. Twenty-two women underwent ET ALONE and 11 underwent S+ET. The median interview duration was 50 minutes (range 23–85 minutes). There were three interview themes:

-

the decision-making process

-

satisfaction with the decision-making process

-

the impact of breast cancer.

The majority of women were pleased with their decision and the decision-making process. The majority preferred a shared decision-making model in which they had significant involvement, although a minority preferred a passive role. Women wanted the information to be jargon free, concise, personalised and in everyday language. For information delivery, they prefered face-to-face discussion, booklets and a question-and-answer format; they wished to avoid online material, ‘apps’ and DVDs. For information graphics, they preferred verbal descriptors, and to avoid percentages and frequencies.

Conclusion

The information needs of the majority of older women were focused on the practical implications of treatment and its impact on physical function and independence. They wanted information presented in a simple, jargon-free manner, ideally face to face. These preferences were taken into account when developing the DESIs, which would comprise a booklet; brief decision aid; and a personalised printout from an online tool, which would be used by the clinician, inserted in the booklet and given to the patient.

Questionnaire study to determine the preferred content for the surgery plus adjuvant endocrine therapy versus endocrine therapy alone decision support intervention

The above qualitative findings were quantified using a bespoke patient questionnaire used with a larger cohort. This study has been published. 27,28

Methods

A cohort of older women (aged > 75 years) were recruited across 10 UK sites. Eligibility criteria were identical to those in Patient interview study to determine the preferred format and content for the surgery plus adjuvant endocrine therapy versus primary endocrine therapy decision support intervention. Questionnaire face and content validity were based on the interviews (see Patient interview study to determine the preferred format and content for the surgery plus adjuvant endocrine therapy versus primary endocrine therapy decision support intervention), and included 30 items relating to preferred information content and nine items relating to preferred media and presentation. An integrated, previously validated, decision-making-preference questionnaire assessed whether older women wanted a passive, active or shared role. 29

Results

A total of 247 women were invited to take part, of whom 101 returned questionnaires (41% response rate). The median age was 82 years (range 75–99 years).

Desired treatment information included the safety and side-effects of surgery, post-operative pain and duration of hospitalisation, fitness for surgery ‘at their age’, impact on independence, availability of support and oncological efficacy.

The majority of women preferred face-to-face informaton provision from doctors (81%), with fewer preferring face-to-face provision from nurses (37%) or the use of a booklet or leaflet (33%). There was little interest in information online or via an app, DVD or video. Very few women had access to the internet (29%). In terms of preferred display of data, verbal descriptors were strongly preferred (e.g. ‘breast cancer is common’), followed by use of proportions (e.g. ‘1 in 8’). Pictograms, bar and pie charts were not highly rated, with < 10% preferring information in this format.

In terms of preferred decision-making style, 35 out of 93 (38%) women preferred the health-care professional to choose the treatment, 36 (39%) preferred to decide themselves and 22 (24%) preferred shared decision-making. 28

Conclusion

Older women expressed their preferences regarding the information they desired to support decision-making about the S+ET versus ET ALONE decision, and their preferred format of information. These data were used to develop a draft DESI, which was then field tested, as described in Development and testing of the decision support interventions.

Patient interview study to determine preferred format and content for the adjuvant chemotherapy versus no chemotherapy decision

Introduction

A similar method was used to derive the information needs and preferences of older women facing a decision about adjuvant chemotherapy after surgery. A series of qualitative interviews, not part of this programme, regarding the factors influencing older women’s choices had been performed30 and these transcripts were reanalysed to extract specific information relating to information needs and preferences.

Methods

The study was part of a larger multicentre observational study [Adjuvant chemotherapy in elderly women with breast cancer (ACHEW)] across 24 UK breast units. 30 Patients who had received adjuvant chemotherapy were recruited for interview. Interviews were based on a topic guide, including provision of information and participation in decision-making. Interview transcripts were re-read for the Age Gap study to focus on informational needs and preferences, which were then used in DESI development.

Results

A total of 58 out of 95 (61%) eligible women participated. The median age was 73 years (range 70–83 years). The majority (58.5%) of women preferred to make the decision in collaboration with a clinician, 22.6% preferred to delegate responsibility to a clinician and 18.9% wanted to make their own decision. Shared decision-making was the preferred choice in women accepting adjuvant chemotherapy (63.9%). The main reasons for accepting adjuvant chemotherapy were prevention of recurrence and clinician recommendation. Women were interested in the side effects of treatment, duration of treatment, route of administration, impact on quality of life (QoL), impact due to their age and comorbidities. Low survival benefits and clinician recommendations influenced decisions to decline adjuvant chemotherapy. Information sources were usually written, and those available were generally viewed positively (56%) and well read (96%). Many wished for personalised information, which was often lacking. There was little interest in information from the internet (17%).

These items were used to develop the DESIs.

Conclusion

The derived information was used to develop the Age Gap decision tool. The focus was on personalised, age-specific information, available in a printed format (a booklet and personalised printout from an online tool) and giving detailed practical information about adjuvant chemotherapy, its benefits and side effects.

Development and testing of the decision support interventions

Introduction

Data from the literature reviews, expert reference group, patient interviews and questionnaires were used to draft decision support tools for both the S+ET versus ET ALONE decision and the adjuvant chemotherapy or no chemotherapy decision. These were then tested with patients and clinicians for content, comprehensibility and accuracy, before being field tested with patients and clinicians. The resulting DESI were then finalised by English language review and graphic design input prior to being trialled in the cluster-randomised controlled trial.

This process has been published. 31

Usability testing

Following initial development, prototype DESIs (brief decision aid, booklets) were tested for usability, acceptability and utility using semistructured interviews. Preliminary testing was first conducted among healthy volunteers aged ≥ 70 years. This was followed by testing with patients who had made a decision regarding breast cancer treatment in the last 12 months, before finally testing the DESI with those currently facing the treatment decision. Iterative modifications were made between each phase.

Sample recruitment

Volunteers

Female volunteers were recruited from breast cancer charities and local community groups.

Patients

Patients were recruited via five UK breast units: Cardiff, Brighton, Doncaster, Sheffield and Southampton. Recruitment continued until data saturation.

Interviews and analysis

Semistructured interviews based around an interview topic guide regarding the DESIs were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Interview topics included DESI content, layout, usefulness, comprehension and potential improvements. Transcripts were analysed using a framework approach.

Results

Sample characteristics

Primary endocrine therapy versus surgery plus adjuvant endocrine therapy decision support intervention

Twenty-two women were interviewed who were aged between 75 and 94 years (median 82.5 years).

Adjuvant chemotherapy decision support intervention

Interviews were completed with 14 women aged between 70 and 87 years (median 74 years).

Surgery plus adjuvant endocrine therapy versus primary endocrine therapy, and adjuvant chemotherapy decision support intervention content feedback

The content of the DESIs was viewed positively, with the right amount of clear, relevant information, which was easily understood. There were some alterations to the text and images to make it more easily understood, and other text items were emphasised further to reflect their importance based on feedback.

Decision support intervention use/implementation

The DESIs were generally thought to be helpful. The importance of discussion with health-care professionals was highlighted.

Discussion

Feedback from participants about the DESIs included many positive comments, but areas of confusion were noted and amendments were made.

Conclusion

Using an iterative process of feedback and improvements, the DESIs were found to be acceptable to and usable for patients. These DESIs were then trialled in the cluster-randomised trial (see Cluster-randomised controlled trial).

Developing outcome models for older patients with early-stage breast cancer

The final component of the decision support package was an online, interactive algorithm, allowing cancer and non-cancer survival prediction, tailored to the age, tumour characteristics and health of the patient. The resulting online tool would be part of the DESI package tested in the cluster-randomised trial. The initial models were developed using retrospective UK registry data from two of the largest UK registry regions, Northern and Yorkshire [Northern and Yorkshire Cancer Registry and Information Service (NYCRIS)], and the West Midlands [West Midlands Cancer Intelligence Unit (WMCIU)], validated using data from a third region [East Anglia; Eastern Cancer Registry and Intelligence Centre (ECRIC)]. Development had three components:

-

development of the first draft of the S+ET versus ET ALONE model using WMCIU and NYCRIS data on 23,849 women aged ≥ 70 years between 2002 and 2010 (see Development of a survival outcome model for surgery plus adjuvant endocrine therapy versus primary endocrine therapy for breast cancer in older women using UK registry data)

-

internal model validation using a more recent tranche of WMCIU/NYCRIS data up to January 2017 using Flexsurv (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) (see Validation of the statistical predictive model)

-

external model validation using registry data from ECRIC (see Adjuvant chemotherapy model development).

These models have been published,32–34 and the process and outcomes are described in more detail in the subsequent sections. The models performed well in terms of survival prediction and were used to populate the algorithm for the Age Gap decision tool, which was used in the cluster-randomised controlled trial.

Development of a survival outcome model for surgery plus adjuvant endocrine therapy versus endocrine therapy alone for breast cancer in older women using UK registry data

Introduction

A retrospective cohort analysis was conducted using UK Cancer Registry data from two English cancer registration regions that are demographically representative of the wider UK population (West Midlands, and Northern and Yorkshire). The effect of ET ALONE versus S+ET on survival outcomes was assessed and a model developed to provide data for an online algorithm to be tested in the cluster-randomised controlled trial. This work has been published. 32,35

Methods

Data on all invasive breast cancer in women aged ≥ 70 years between 2002 and 2010 were acquired from two UK cancer registries (West Midlands, and Northern and Yorkshire). Variables in the analysis included age, tumour stage and oestrogen receptor status, comorbidity index and whether treated with surgery or not. Survival data were derived from death certifications. Cause of death was classified as either ‘breast cancer related’ or ‘not breast cancer related’. Only women with ER+ disease were included. Comorbidity was derived from linked Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) and aggregated using the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI)36 by counting diagnostic codes recorded in the 18 months prior to diagnosis. 37

A full prognostic survival model was constructed by combining the hazards predicted by two submodels. The breast-cancer-specific model was a Royston–Parmar, restricted, cubic spline model. 38 This model had eight covariables (treatment, age, comorbidity, mode of detection, deprivation, lymph node status, tumour grade and size). 32 The other-cause-mortality model had three covariates: age, comorbidity and frailty; these were modelled with the proportional hazards assumption. Frailty was approximated using a version of the activities of daily living (ADL) score. 39 This variable was not recorded in the registry data; therefore, a Markov chain Monte Carlo approach was adapted from Koissi and Högnäs40 to infer frailties.

Results

The 5-year breast-cancer-specific survival (BCSS) in the ET ALONE and S+ET arms was 69% and 90%, respectively, which was in favour of S+ET. Analysis of subgroups according to age or comorbidity stratification demonstrated that, as age or comorbidity increased, the degree of separation between the survival curves lessened, and, in the oldest and least fit groups, there was less benefit from undergoing surgery, regardless of cancer stage at diagnosis.

Conclusion

This analysis suggests that, for older breast cancer patients with ER+ disease, the hazard of breast cancer death was greater with ET ALONE than with S+ET. Findings from this analysis were used to develop a web-based clinical algorithm to aid decision-making (see Design of an online tool to support decision-making for older women with early-stage breast cancer). The final model used in the online tool differed slightly from the above, as, during validation, a technical problem was identified, which was rectified in the final version used in the online tool. The validation process of this model is described in the next section.

Validation of the statistical predictive model

Background

The statistical models for the Age Gap online tool were developed to predict risk of breast cancer and non-breast cancer deaths over time for an individual woman given her age, breast cancer status and comorbidity. Phase 1 of the validation involved internal validation and phase 2 involved external validation using cancer registry data. This work has been published. 34

Phase 1: validation using registry data (internal)

Internal validation was undertaken using the updated registries data set. In the case of breast-cancer-specific mortality results, comparison of observed and predicted 2- and 5-year survival outcomes were well matched, with discrimination of between 0.73 and 0.77. The model was also well calibrated. There was a slight overestimate of breast cancer mortality, with an overestimation of 0.2 and 0.9 percentage points at 2 and 5 years, respectively. All-cause mortality was underestimated by 1 percentage point at 2 years and overestimated by 0.7 percentage points at 5 years.

Phase 2: external validation

External validation was undertaken using a data set from the ECRIC of breast cancer in women aged ≥ 70 years registered from 2002 to 2012.

The model performed well, with discrimination results ranging from 0.75 to 0.80. Overall calibration of the model in the external data set was also good. At 5 years, predicted breast cancer mortality exceeded that observed for the training data by 4%, with the absolute breast cancer mortality rate difference being 0.2%.

Conclusion

The developed model, which was both internally and externally validated using registry data, performed well, with a high degree of prognostic accuracy. The model permits outcome stratification for age and comorbidity according to whether a woman has S+ET or ET ALONE. This model was used to develop the age- and fitness-stratified online outcome tool for the cluster-randomised controlled trial.

Adjuvant chemotherapy model development

Introduction

Adjuvant chemotherapy is recommended for high-recurrence-risk, early-stage breast cancer patients. Meta-analysis41 reported that adjuvant chemotherapy was associated with a reduced risk of recurrence (12%) and death (13%) in patients aged ≥ 70 years, compared with no chemotherapy.

A survival outcome model was, therefore, developed using retrospective analysis of data for breast cancer patients aged ≥ 70 years, from two English cancer registry regions, diagnosed between 2002 and 2012. This compared the effects of adjuvant chemotherapy or no chemotherapy in women aged ≥ 70 years. The outcomes were stratified by age, cancer stage and biology, and health status. The resultant outcome model was used in the Age Gap online algorithm. The work has been published. 33

Methods

Cancer registration records were obtained for all breast cancer diagnoses in women aged ≥ 70 years between 2002 and 2012 from two English registries. Comorbidity was derived from linked HES data and aggregated into a proxy CCI. English indices of deprivation42 (2010) were derived from postcodes.

Analyses were restricted to women diagnosed with stage I–III disease, treated with surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy or no chemotherapy. Some analyses were restricted to patients at high risk of recurrence.

Associations between patients, treatment characteristics and survival were investigated using multivariate proportional hazard regression, using Royston–Parmar, restricted, cubic spline parametric models. 38 Missing data were handled using multiple imputation with chained equations.

Results

Between 2002 and 2012, a total of 29,728 women were diagnosed with breast cancer, of whom 11,735 were included in analysis (stage I–III disease, treated with surgery). Very few patients aged ≥ 80 years received adjuvant chemotherapy, precluding meaningful analysis (n = 122; < 1%), so analyses were restricted to patients aged 70–79 years. Women who had adjuvant chemotherapy were generally younger, were in better health, and had worse disease stage and adverse biology [oestrogen receptor negative (ER–), human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 positive (HER-2+)].

The logistic regression confirmed that a younger age at diagnosis, increased nodal involvement, tumour size and grade, and having ER– or HER-2+ disease were all associated with increased probability of receiving adjuvant chemotherapy. For example, the odds ratio (OR) of adjuvant chemotherapy receipt for each year that the woman was aged ≥ 70 years was 0.763 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.741 to 0.787; p < 0.001]. Having an ER+ cancer was associated with an OR of adjuvant chemotherapy receipt of 0.305 (95% CI 0.261 to 0.357; p < 0.001); conversely, for HER-2+ disease, the OR was 2.904 (95% CI 2.476 to 3.406; p < 0.001). Similarly, node positivity (1–3 nodes positive: OR 3.739, 95% CI 3.120 to 4.483; p < 0.001) and increased tumour size (per mm increase in tumour size: OR 1.015, 95% CI 1.011 to 1.019; p < 0.001) were also associated with increase adjuvant chemotherapy use.

Naive comparison of survival outcomes between the two treatment groups showed that BCSS and overall survival (OS) were worse for patients who received adjuvant chemotherapy than for those who did not. However, this arises from the difference in risk profiles between the two groups. When all high-risk patients were considered, adjuvant chemotherapy was associated with reduced BCSS compared with no chemotherapy. However, when the analysis was repeated with higher-risk-scoring patients only, the positive effect of adjuvant chemotherapy becomes clear.

The Royston–Parmar model results showed that adjuvant chemotherapy was associated with a significant reduction in the hazard of breast-cancer-specific mortality compared with no chemotherapy, after adjustments were made for patient-level characteristics [hazard ratio (HR) 0.74].

Discussion

This study found that adjuvant chemotherapy was associated with a reduction in breast-cancer-specific mortality for patients aged 70–79 years with high-recurrence-risk cancer, after adjustment for patient characteristics.

High-recurrence-risk disease characteristics were associated with adjuvant chemotherapy use. However, many high-risk patients did not receive chemotherapy, in particular those patients aged > 80 years. This may be justifiable given that older patients are more likely to die of other causes than of breast cancer, so the absolute gains in survival may be small.

This age-, comorbidity- and tumour-characteristic-stratified outcome model was, therefore, suitable to use in the online Age Gap tool that would be tested in the cluster-randomised controlled trial.

Design of an online tool to support decision-making for older women with early-stage breast cancer

Introduction

An integral component of the DESI was an online tool to permit personalised survival prediction, stratified according to tumour stage, biology, fitness and frailty. The models described previously were used to ‘power’ the online tool, with stratification for patient age and comorbidity based on the CCI score. The tools were developed to be useable for both health-care professionals and patients. The development process has been summarised in a publication. 31

Methods

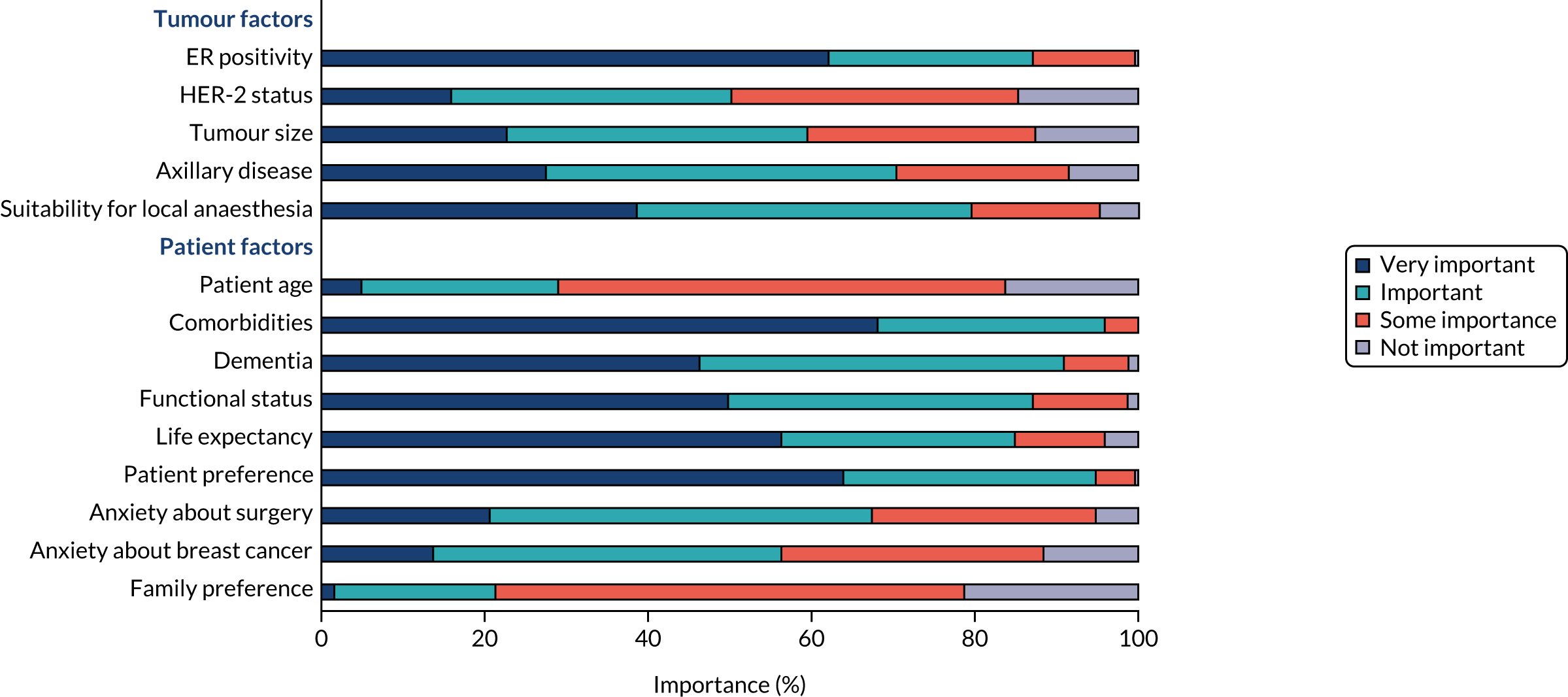

The design of the online tool was based on data derived from the developed models for the ET ALONE versus S+ET, and adjuvant chemotherapy models (see Developing outcome models for older patients with early-stage breast cancer and Adjuvant chemotherapy model development), supplemented with published frailty data39 and evidence from patient interviews about preferred formats for data presentation (see Defining the information needs and preferences of older women with breast cancer). The output from the tool presented data in text, pictogram or bar chart formats. In addition, in response to patient feedback, stratified outputs could be printed off in an easy-to-read format that could be inserted in the booklets developed for the tool, allowing outcomes to be personalised. A draft version was user tested with both health-care professionals and patients, and modified according to feedback.

Three focus groups were undertaken, including six surgeons, seven clinical nurse specialists and nine oncologists.

Results

Feedback from clinicians

The tool was welcomed. All clinicians liked the layout and found it intuitive, quick and easy to use. The printout of the personalised risk sheet was also welcomed. Some clinicians felt that their current pathway of care would make using the online tool difficult, with most stating they would work around the problems.

Items of concern and the responses made by the team are shown in Appendix 2, Table 1.

Feedback from patients

Eight patients were interviewed, with varied feedback regarding data display formats, which were amended. Items of concern and the response made by the team are shown in Appendix 3, Table 2.

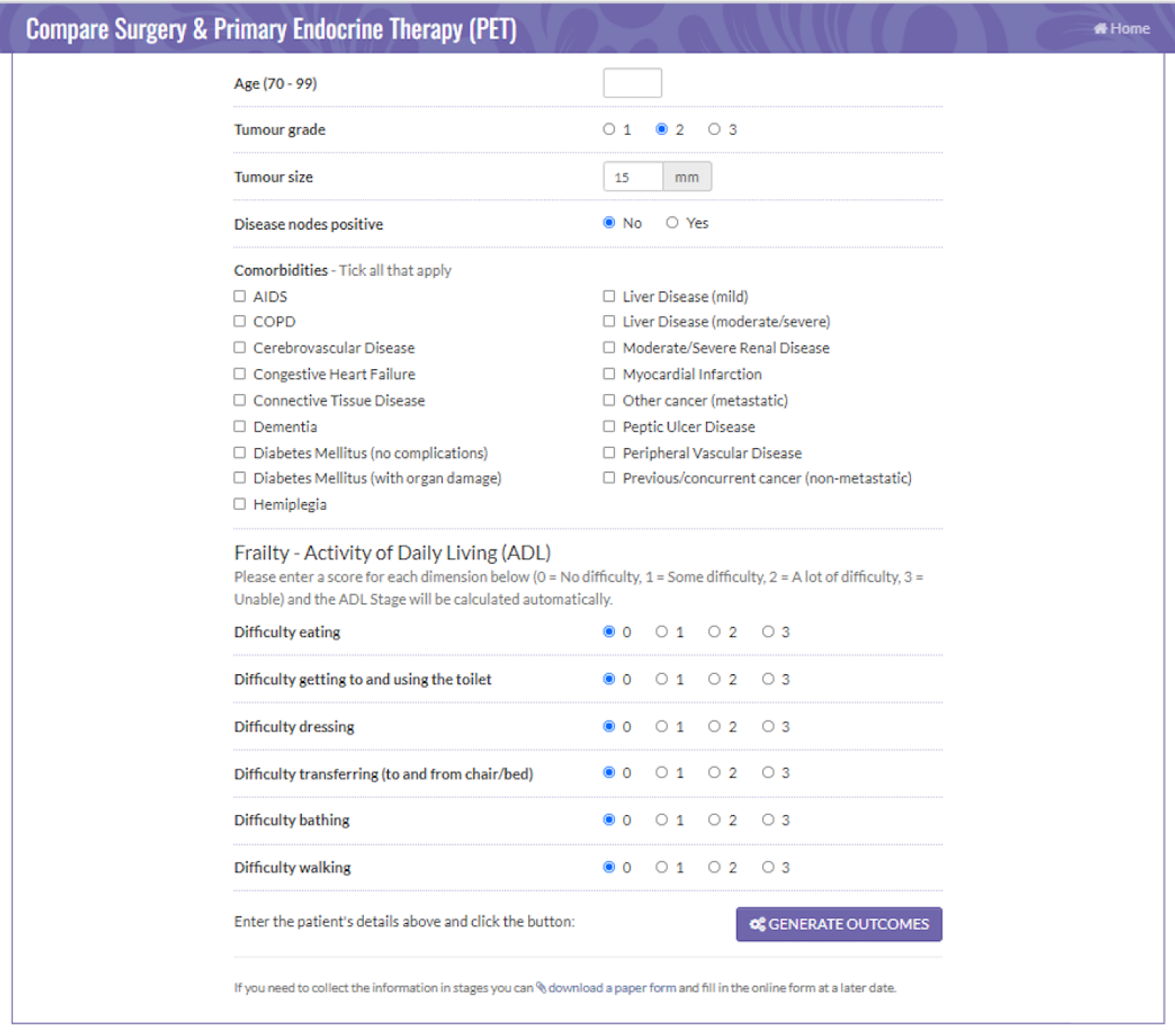

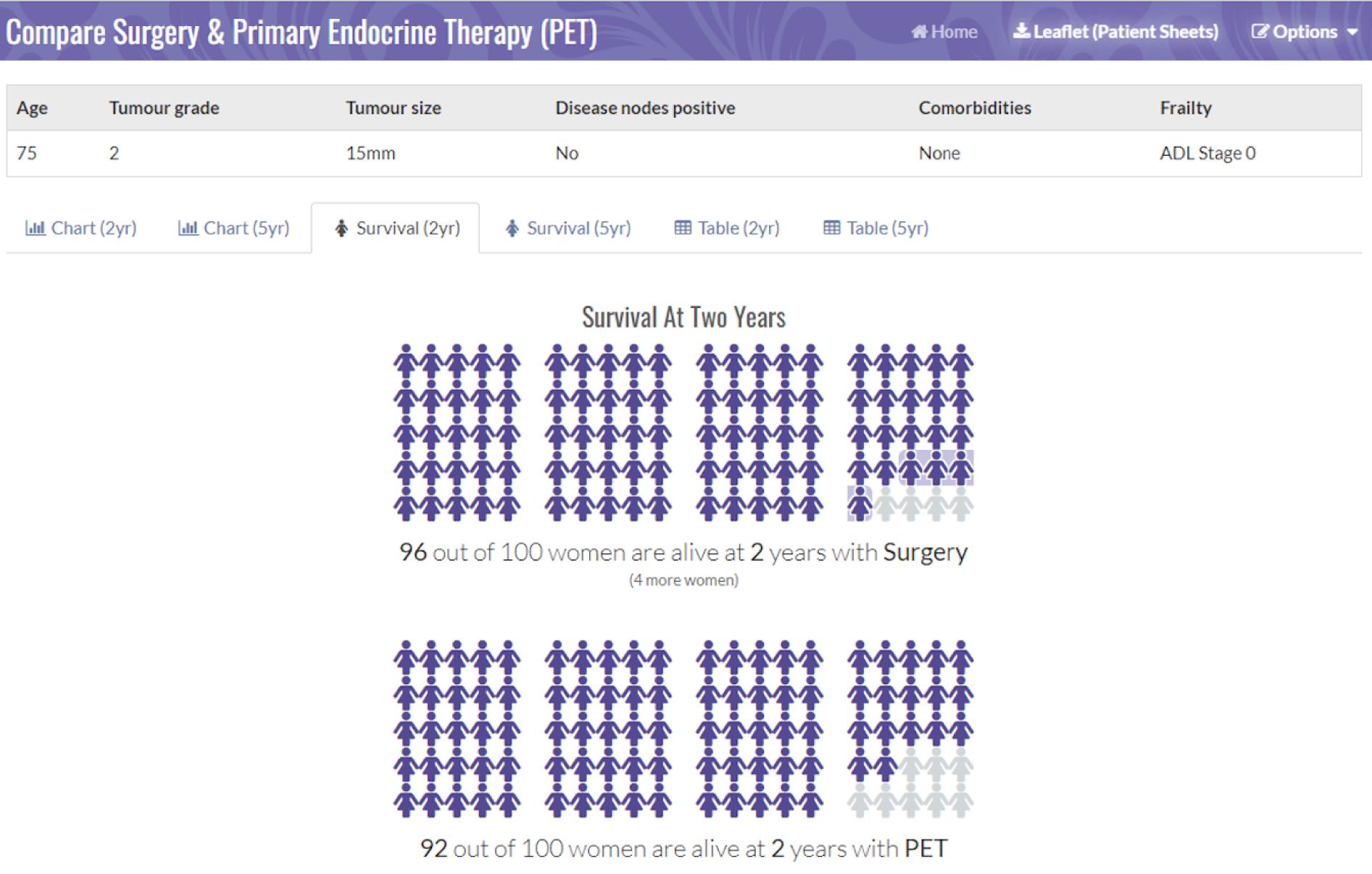

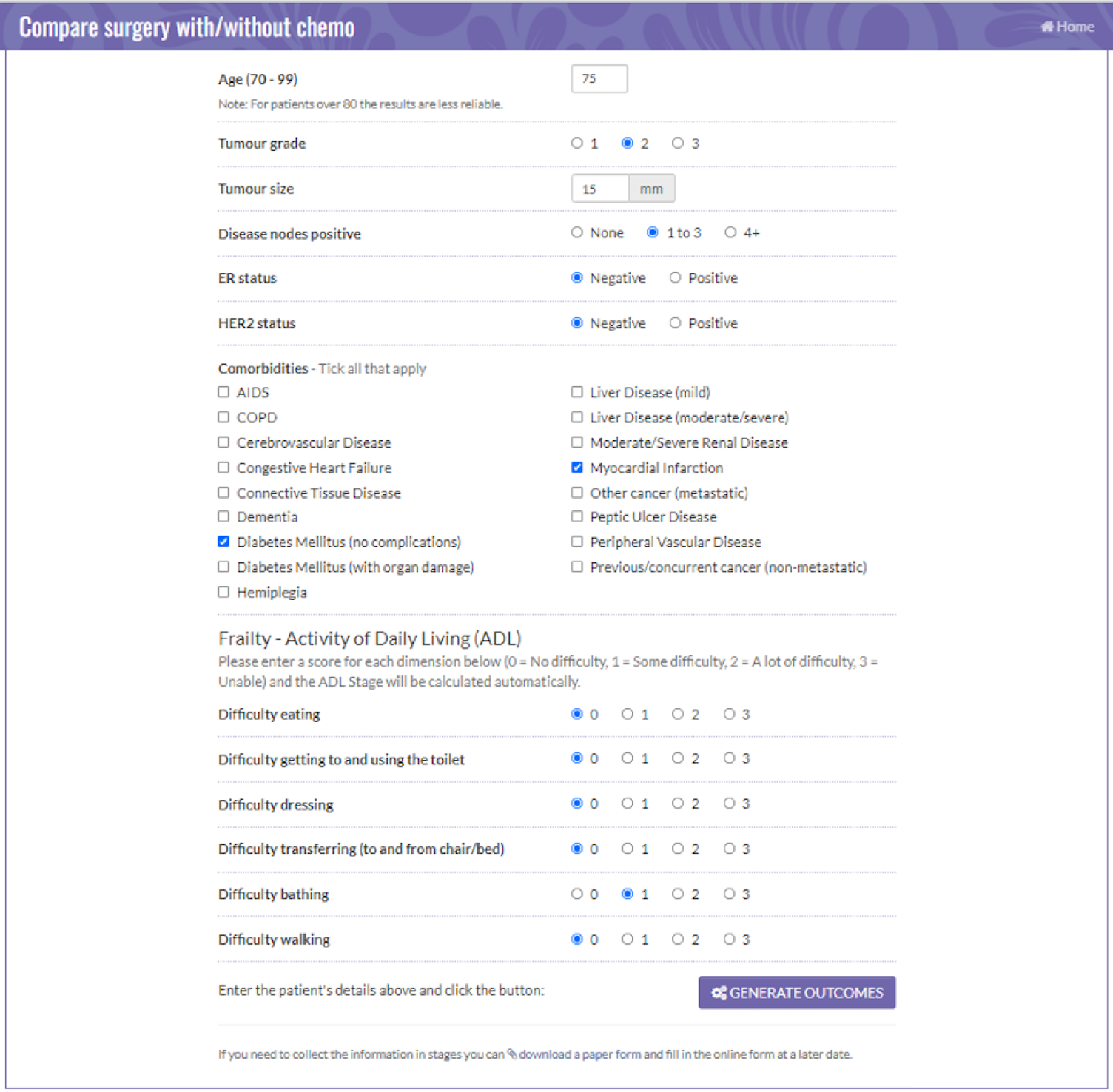

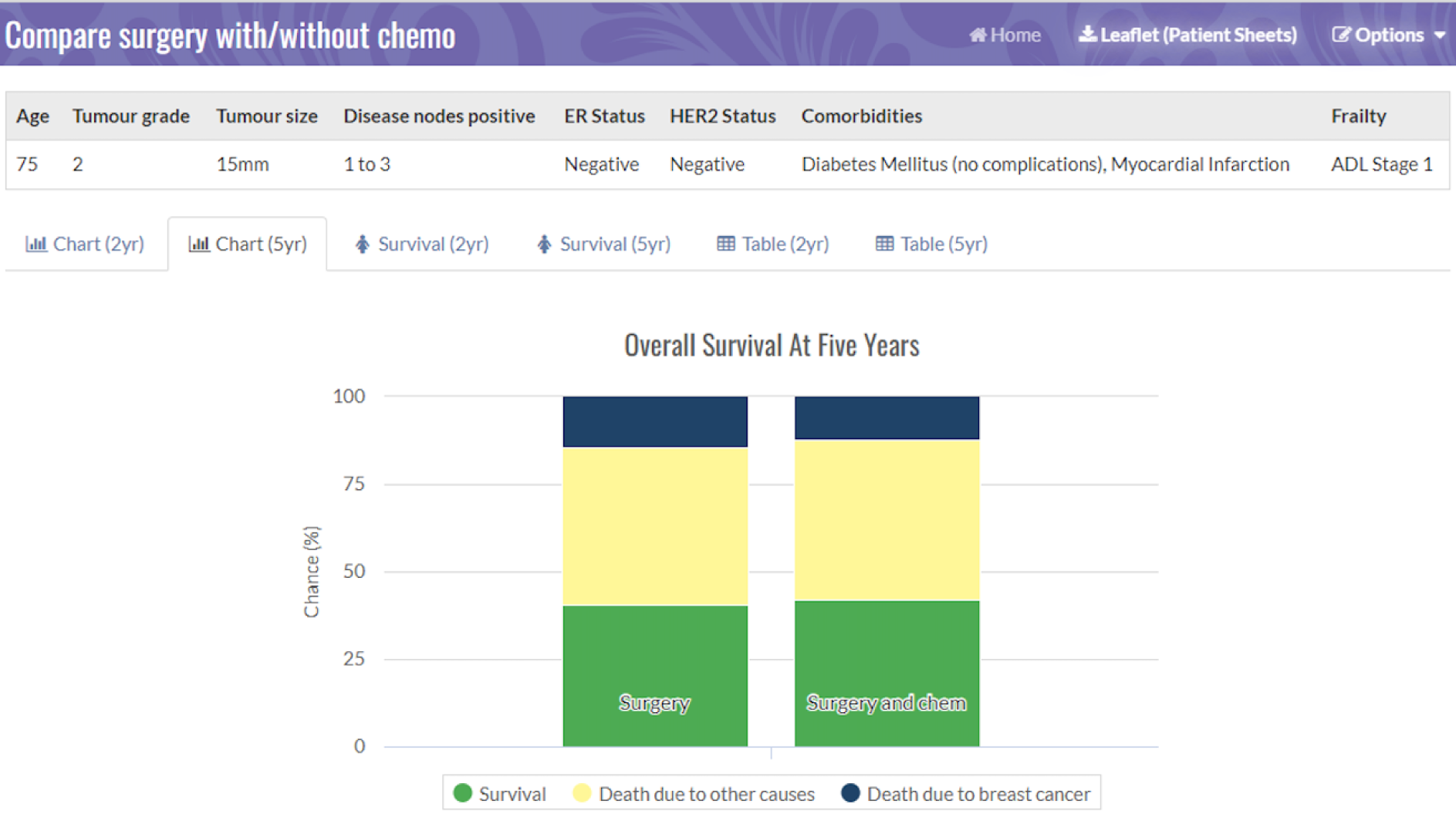

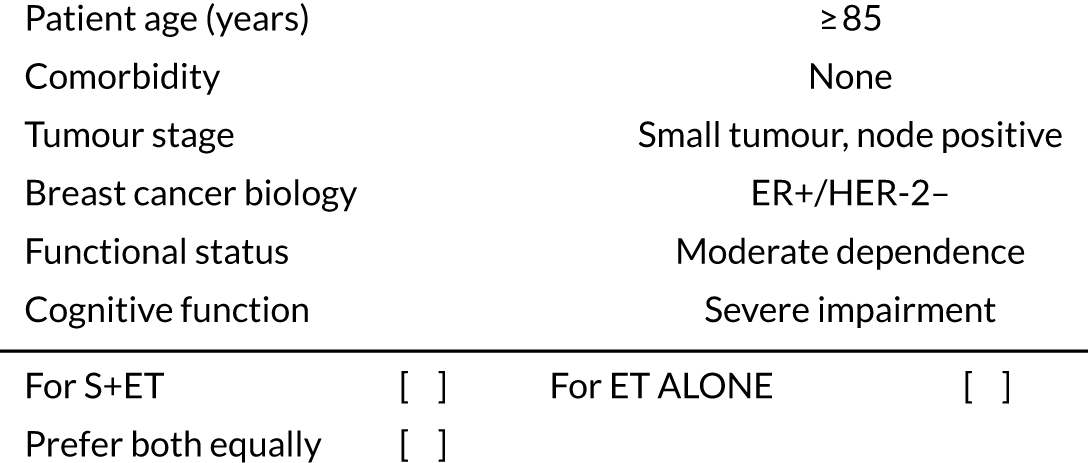

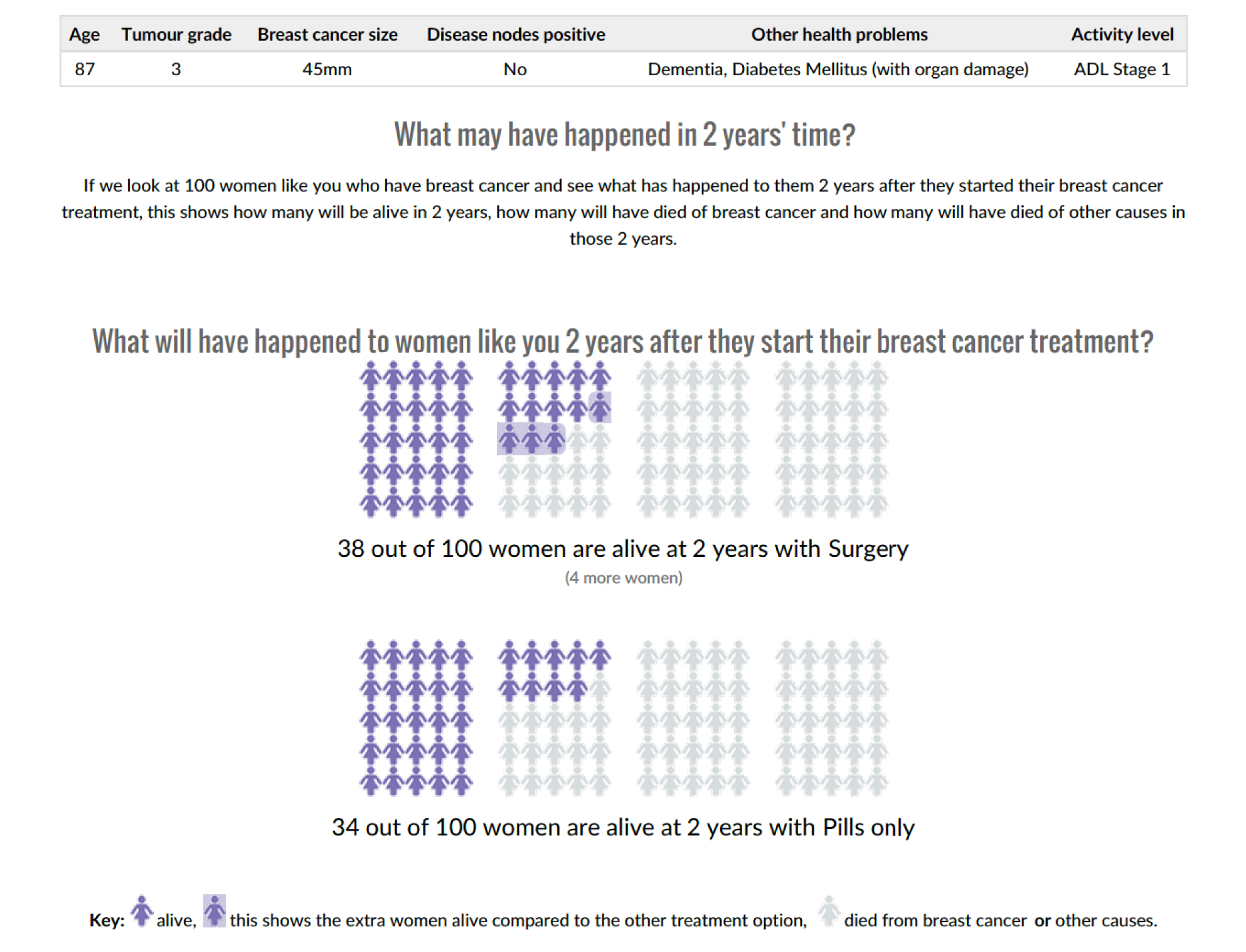

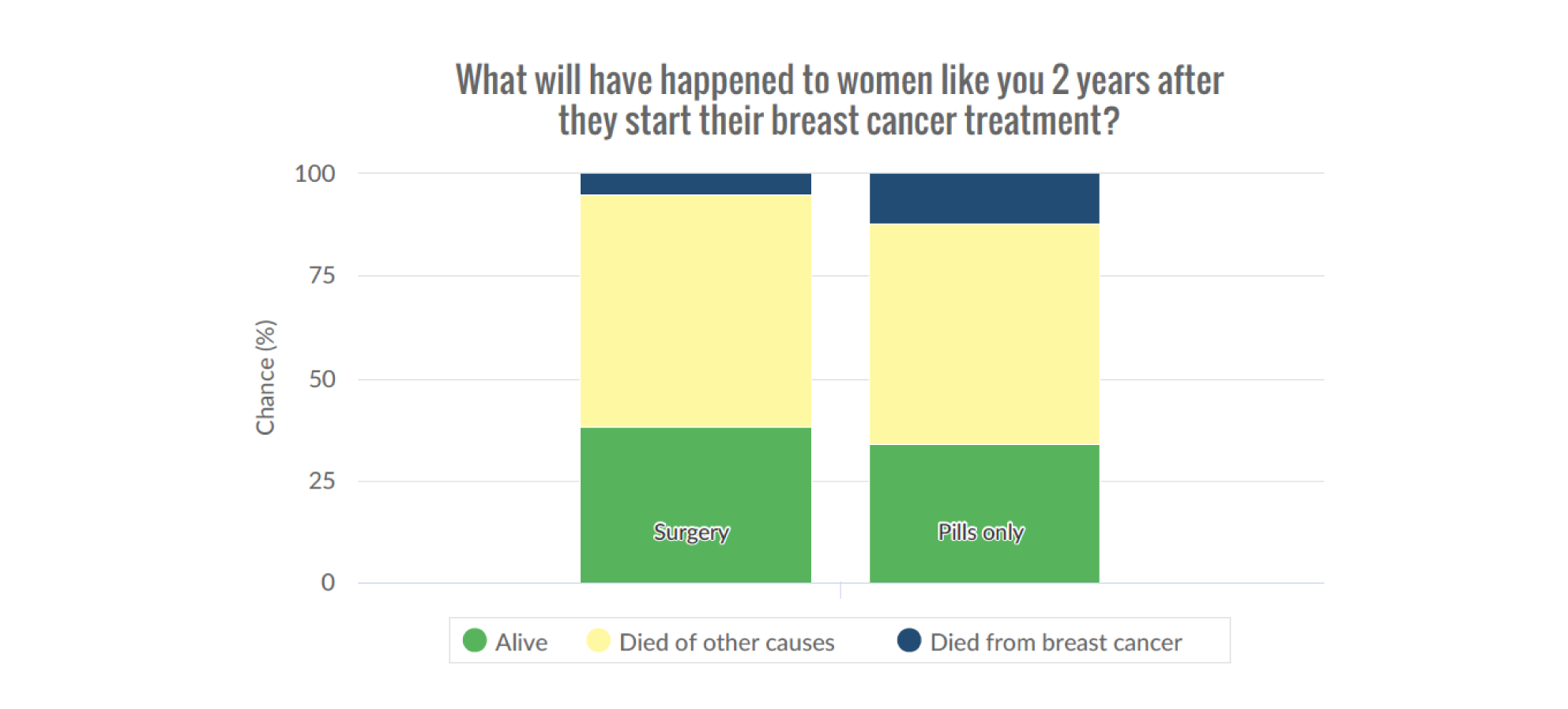

Figures 2 and 3 are screenshots of the final online tool for the S+ET versus ET ALONE tool used during interviews. Figures 4 and 5 are screenshots of the adjuvant chemotherapy tool. Screenshots of the booklets are shown in Appendix 6, Figure 19.

FIGURE 2.

Data collection sheet: comparing S+ET and ET ALONE. Reproduced with permission from the University of Sheffield.

FIGURE 3.

Pictogram showing the survival estimates at 2 years, comparing S+ET and ET ALONE. Reproduced with permission from the University of Sheffield.

FIGURE 4.

Data collection sheet: comparing adjuvant chemotherapy and no chemotherapy. Reproduced with permission from the University of Sheffield.

FIGURE 5.

Pictogram showing the survival estimates at 2 years, comparing adjuvant chemotherapy and no chemotherapy. Reproduced with permission from the University of Sheffield.

The tool now has MHRA approval and can be accessed online. 43

Examples of the brief decision aid for ET ALONE versus S+ET, and for the adjuvant chemotherapy or no chemotherapy decision are shown in Appendix 4, Table 3, and Appendix 5, Table 4, respectively. Images relating to the booklets are shown Appendix 6, Figure 19, and images relating to the outputs from the online tool are shown in Figure 2 and Appendix 7, Figure 20.

The Age Gap prospective observational multicentre cohort study general methods and results

Introduction

The purpose of this study was to recruit a large prospective cohort of older women with early-stage breast cancer with baseline information regarding health, cancer stage, biology and treatment. These data were analysed using propensity score matching to adjust for baseline variation in health and fitness to determine outcomes (survival and QoL) between women treated with S+ET versus ET ALONE, or adjuvant chemotherapy versus no chemotherapy. This would allow us to determine optimal age- and health-stratified thresholds for treatment allocation. Several specific, focused analyses were performed, which are summarised in subsequent sections, including:

-

general cohort methods and results

-

surgery outcomes (see Outcomes from surgery for older women with early-stage breast cancer)

-

overall and BCSS outcomes for women having S+ET versus ET ALONE (see Endocrine therapy alone versus surgery plus adjuvant endocrine therapy: survival analysis)

-

QoL outcomes for women having S+ET versus ET ALONE (see Quality-of-life variation between primary endocrine therapy and surgery plus adjuvant endocrine therapy)

-

overall and BCSS outcomes for women following surgery who did or did not have adjuvant chemotherapy (see Adjuvant chemotherapy versus no chemotherapy in women with high-recurrence-risk breast cancer using both unmatched and propensity-score-matched analyses)

-

QoL outcomes for women following surgery who either did or did not have adjuvant chemotherapy (see Quality-of-life impacts of chemotherapy)

-

treatment allocation and survival outcomes in women with or without cognitive impairment (see Analysis of the impact of cognitive impairment on outcomes for older women with early-stage breast cancer)

-

health economic outcomes for women who had S+ET versus ET ALONE (see Cost-effectiveness analysis comparing surgery plus adjuvant endocrine therapy with primary endocrine therapy).

General methods

Study design

This was a prospective, pragmatic, multicentre, observational UK cohort study.

The cohort study has been published in various component parts, detailed in each section as listed above. A more detailed overview of methods is given in Appendix 8, and described in a published paper that summarises both the cohort and cluster methodologies. 44

Aims

To determine overall and propensity-score-matched outcomes for older women (aged ≥ 70 years) with early-stage breast cancer according to whether they receive ET ALONE or S+ET, and, for women with high-recurrence-risk breast cancer, whether or not they received adjuvant chemotherapy.

Objective

To undertake propensity-score-matched analysis of prospectively collected cohort data to allow risk-stratified comparison of outcomes between women receiving ET ALONE and those receiving S+ET, and those receiving adjuvant chemotherapy and no chemotherapy.

Outcomes

Primary outcome

The primary outcome was OS.

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes were BCSS, failure-free survival (FFS), time to local recurrence (progression in ET ALONE), time to metastatic recurrence, QoL and adverse events [Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) classification]. 45

Propensity-score-matched analysis was performed to adjust for baseline variation in patient and disease characteristics between treatment groups.

Levels of participation

Women were invited to participate after diagnosis but before treatment commencement.

Patients with full cognitive capacity could select one of two levels of participation: full participation (including QoL forms) or partial participation (excluding QoL). Women with significant cognitive incapacity did not complete QoL questionnaires.

Baseline data collection

At baseline, women underwent assessment using a series of validated tools, including the:

-

CCI36

-

abridged Patient-Generated Subjective Global Assessment (aPG-SGA)46,47

-

ADL48

-

Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL)49

-

Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE)50

-

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status (ECOG-PS). 51

In addition, QoL was assessed using the:

-

European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire-C30 (EORTC-QLQ-C30),52 a generic cancer QoL tool

-

European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire-BR23 (EORTC-QLQ-BR23),53 a breast-cancer-specific QoL module

-

European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire-ELD14 (EORTC-QLQ-ELD14),54 an older-person-specific module

-

EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L)55 to permit calculation of quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) for health economics assessment.

Baseline data were collected regarding primary tumour stage and biotype.

Follow-up assessments

Patients were followed up at 6 weeks, and at 6, 12, 18 and 24 months.

Patients could also consent to accessing cancer registry data for long-term follow-up to 10 years.

Participating UK breast units

The study recruited from 56 breast units in England and Wales (see Appendix 8, Table 5).

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria

Women aged ≥ 70 years with operable breast cancer were eligible.

Study treatments

This was a pragmatic cohort study with no change to normal treatment.

Statistical analysis

Propensity-score-matched analysis

Two analyses were performed:

-

In the case of women with ER+ breast cancer, we compared the survival and QoL outcomes in those who received S+ET with the outcomes in those who received ET ALONE.

-

In the case of women with high-recurrence-risk cancers, following surgery [i.e. patients who met any of the following criteria: (1) HER-2+; (2) ER–; (3) ER+ and a histological grade of 3; (4) nodes positive or (5) a high Oncotype DX™ recurrence score], we compared the survival and QoL outcomes for those treated with adjuvant chemotherapy and those treated without chemotherapy.

Overall survival and BCSS were calculated according to treatment allocation. Kaplan–Meier curves were derived for each treatment type by age, disease characteristics, comorbidity and frailty subgroups. OS was compared between treatment groups using a Cox proportional hazards model, adjusting for important prognostic factors.

General cohort results

Recruitment

The study recruited 3416 women between January 2013 and June 2018. The median age was 77 years (range 69–102 years). The median follow-up was 52 months. The age distribution of the cohort was slightly skewed relative to that of the wider population of older UK women with breast cancer, with a slight preponderance of women in the 70–80 years age group and a slight deficit of women aged > 90 years. This was due to selective recruitment and retention. These results have been published. 59

Conclusion

The Age Gap cohort study recruited 3414 women aged ≥ 70 years, demonstrating that recruitment in this age group is feasible. Recruitment was slightly skewed towards younger, fitter women, which must be considered when interpreting the generalisability of the results.

Various specific analyses of the cohort study are presented in the subsequent sections.

Outcomes from surgery for older women with early-stage breast cancer

Introduction

This analysis was performed to describe the allocation of surgery (mastectomy vs. wide excision, and sentinel node biopsy vs. axillary clearance) and the safety and adverse events associated with it. This may enhance understanding of the impacts of surgery. These data have been published. 60

Methods

For this analysis, surgery was classified as major (i.e. mastectomy and/or ALND) or minor (i.e. BCS with or without SLNB). In the case of patients who had a bilateral procedure for invasive breast cancer, surgery was assessed as two unilateral procedures.

Outcomes

Mortality related to surgery was defined as death within 30 days of surgery or surgery being documented as contributing to cause of death. Death from breast cancer was assessed by death certification and expert review of all causes of death. Causes of death were categorised as breast cancer-related or other causes. Complications, obtained by follow-up to 2 years, were categorised using the CTCAE28 and as systemic (i.e. atelectasis, stroke, infarction, deep vein thrombosis/embolism, arrhythmia, allergic reaction or somnolence) or local (i.e. lymphoedema, neuropathy, functional difference, wound pain, wound, necrosis, infection, haematoma, seroma or haemorrhage).

Results

This analysis examined the data from 2816 women who underwent surgery. Of these, 62 had bilateral surgery; therefore, 2858 surgical events are reported. The median age of the surgical cohort was 76 years (range 70–95 years). The majority underwent breast conservation surgery (n = 1716) and 1138 underwent a mastectomy. For axillary surgery, 575 women underwent axillary clearance, 2203 underwent sentinel node biopsy and 76 underwent no axillary surgery.

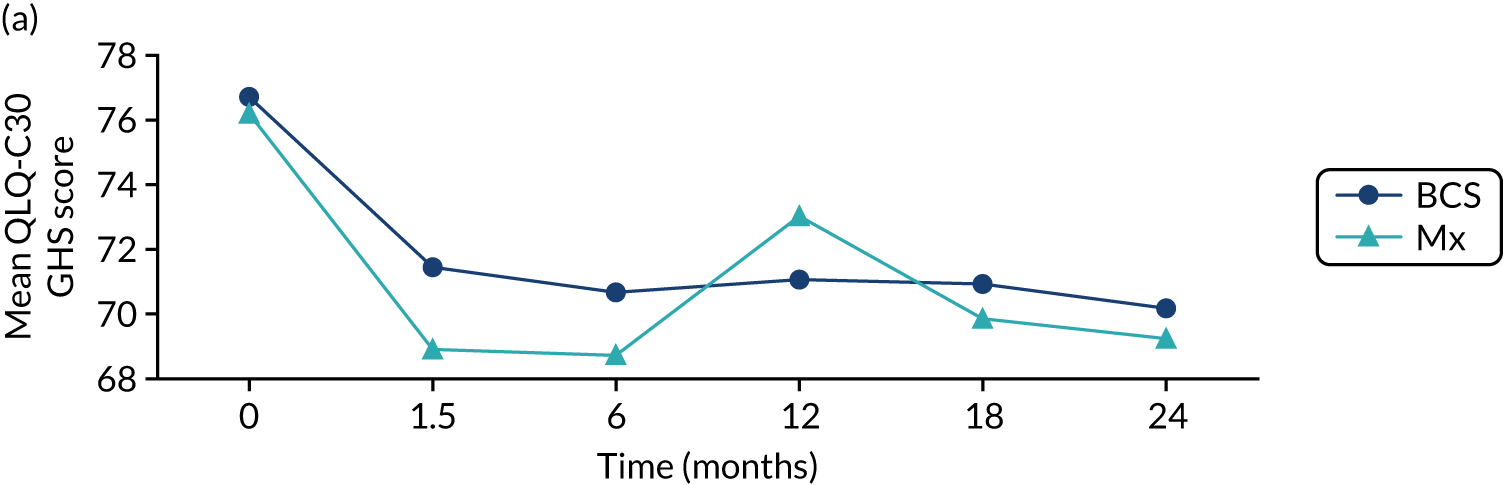

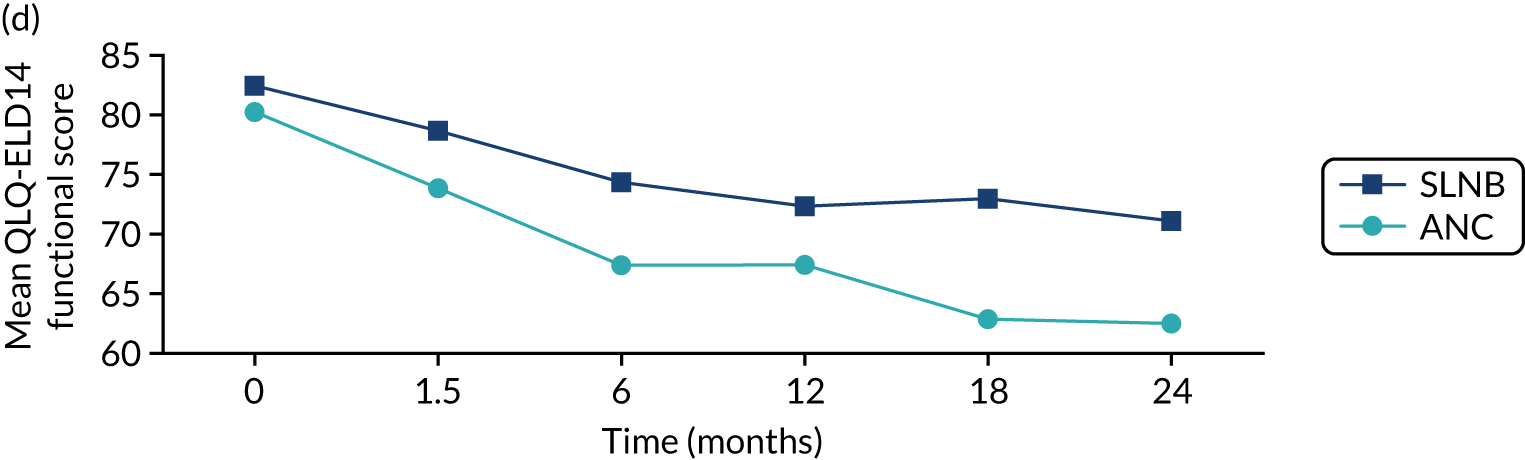

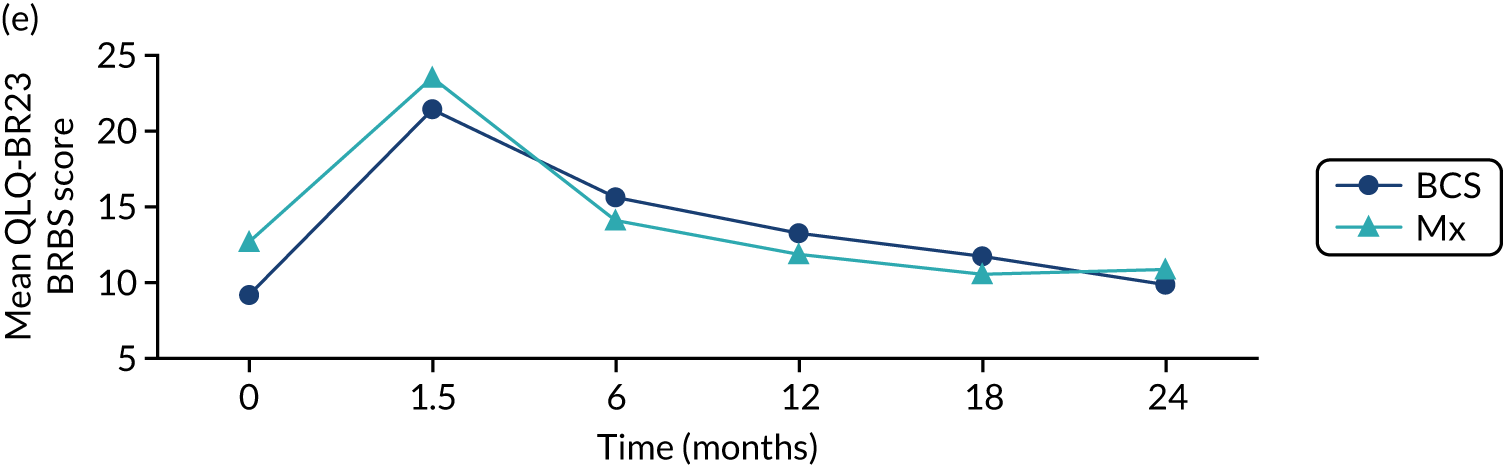

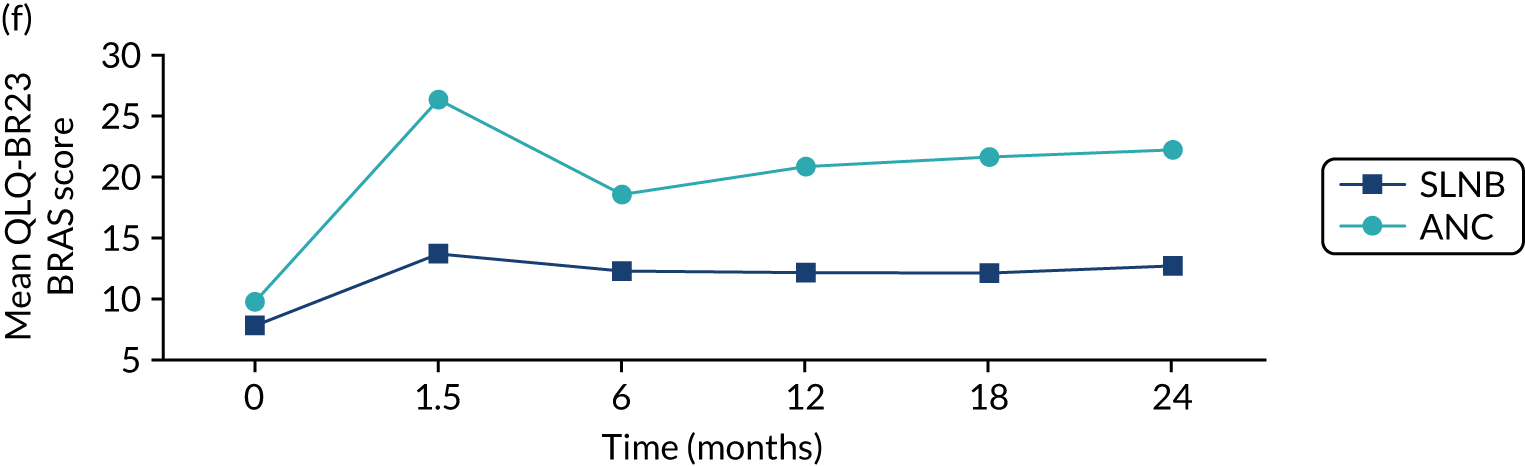

There were no deaths directly attributable to surgery, although there were three deaths within 30 days of surgery (to which surgery theoretically may have contributed). There were 551 adverse events recorded from these 2858 procedures (19.3%), although the majority of these were simple wound complications. Only 2.1% of women had more serious systemic adverse events, such as cardiac, respiratory or cerebrovascular events. QoL was adversely affected by surgery, with impacts clearly seen in the post-operative period (the 6-week time point; Figure 6). These were usually transient, but some residual negative impact was seen in some domains up to 2 years. Negative QoL impacts were more likely with major surgery (i.e. mastectomy, axillary clearance). There was also a long-term negative impact on physical function, implying a lack of resilience in this age group.

FIGURE 6.

Selected mean QoL domain scores following different types of surgery. (a) Axillary clearance vs. sentinel node biopsy: global health status; (b) mastectomy vs. breast conservation: global health status; (c) axillary clearance vs. sentinel node biopsy: functional QoL score; (d) mastectomy vs. breast conservation: breast symptoms; (e) axillary clearance vs. sentinel node biopsy: arm symptoms; and (f) mastectomy vs. breast conservation: body image. ANC, axillary node clearance; BCS, breast conservation surgery; Mx, mastectomy; SLNB, sentinel node biopsy. Surgery usually occurred between 0 and 1.5 months.

Conclusions

In this cohort, breast surgery is generally safe and well tolerated, with few serious adverse events and no deaths. However, there is a negative impact on QoL that is more significant in women who have more major surgery. These risks need to be communicated to women before surgery as part of shared decision-making. We are in the process of developing the online tool to include risk-stratified QoL and adverse event outcomes to be displayed alongside survival outcomes.

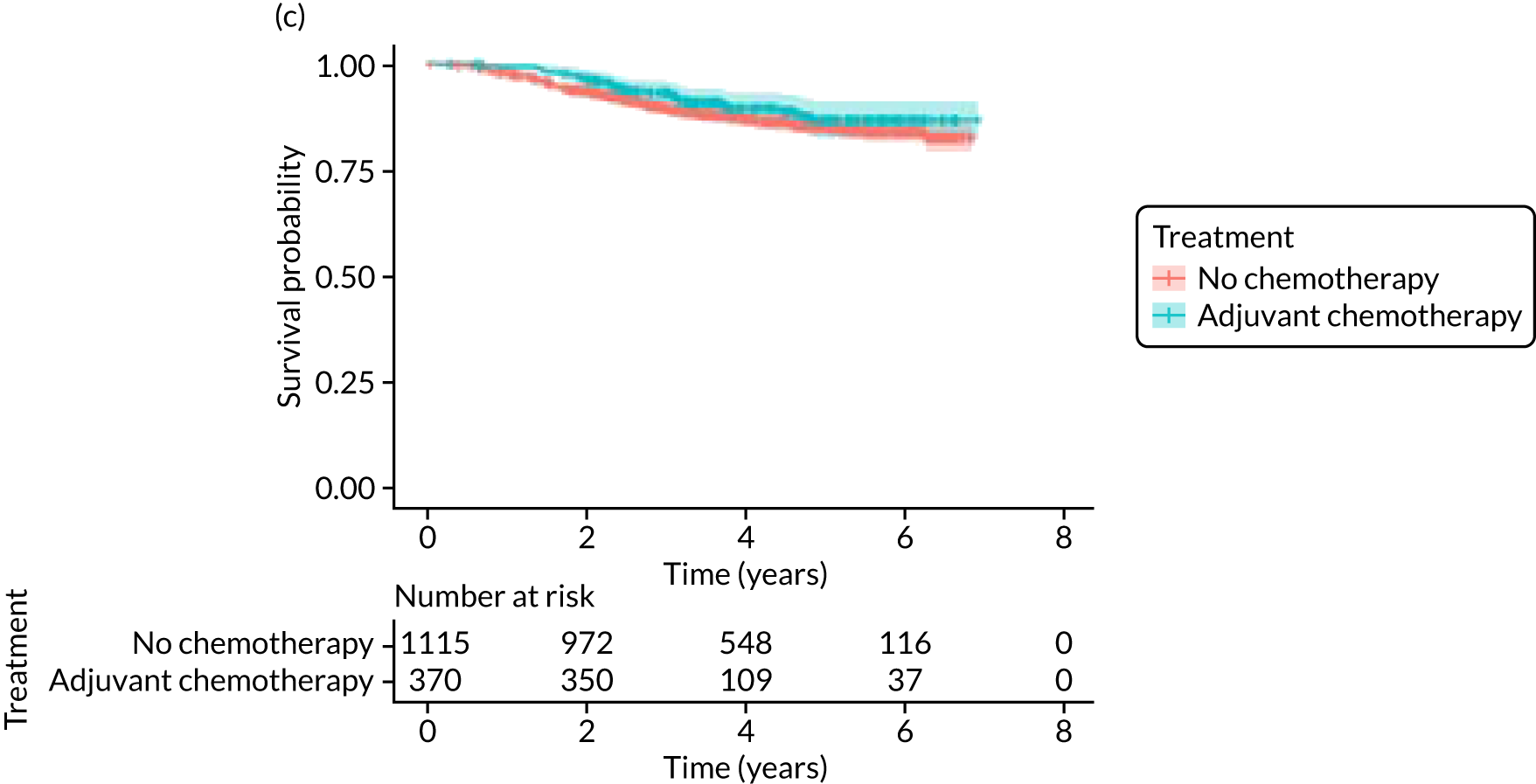

Endocrine therapy alone versus surgery plus adjuvant endocrine therapy: survival analysis

Introduction

This study has used real-world data reflecting current UK practice to determine whether or not there is a group of older women who may be safely offered ET ALONE with little negative impact on their risk of death from breast cancer. The analysis corrected for treatment selection bias using propensity score matching and included only women with ER+ cancers. This analysis has been published. 61

Methods

The cohort recruited women aged ≥ 70 years with operable breast cancer and collected detailed baseline data regarding health, frailty, tumour stage and biology. Normal treatment allocation was permitted to derive a real-world cohort. Analysis of unadjusted outcomes is reported; in addition, to correct for baseline variation in patient allocation to these two treatment arms, propensity score matching was used to create a matched cohort of women with similar baseline characteristics. 61

Results

Recruitment

This analysis was confined to women with ER+ cancer. Of the 2854 patients with ER+ cancer, 2354 (82%) received S+ET and 500 (18%) received ET ALONE. The median follow-up was 52 months. The two treatment cohorts differed significantly in their characteristics. The median age of the ET ALONE group was 84 years (range 70–102 years), whereas the median age of the S+ET group was 76 years (range 69–94 years). In addition, the burden of comorbidity was higher in the ET ALONE group, with a median CCI score of 6 [interquartile range (IQR) 4–7] for ET ALONE, compared with 4 (IQR 3–5) for S+ET. Tumour stage and biology were broadly similar.

Because of this variation in cohort characteristics, baseline adjustment was achieved using propensity score matching. Logistic regression was used to calculate propensity scores for treatment allocation using the ADL, the IADL, the MMSE, the ECOG-PS, the aPG-SGA, the CCI, number of medications and age as covariates.

In the final matched data set, a suitable match was found for 240 (48%) ET ALONE patients: 184 were matched with two S+ET patients and 56 were matched with only one. The resulting matched cohort characteristics were excellent.

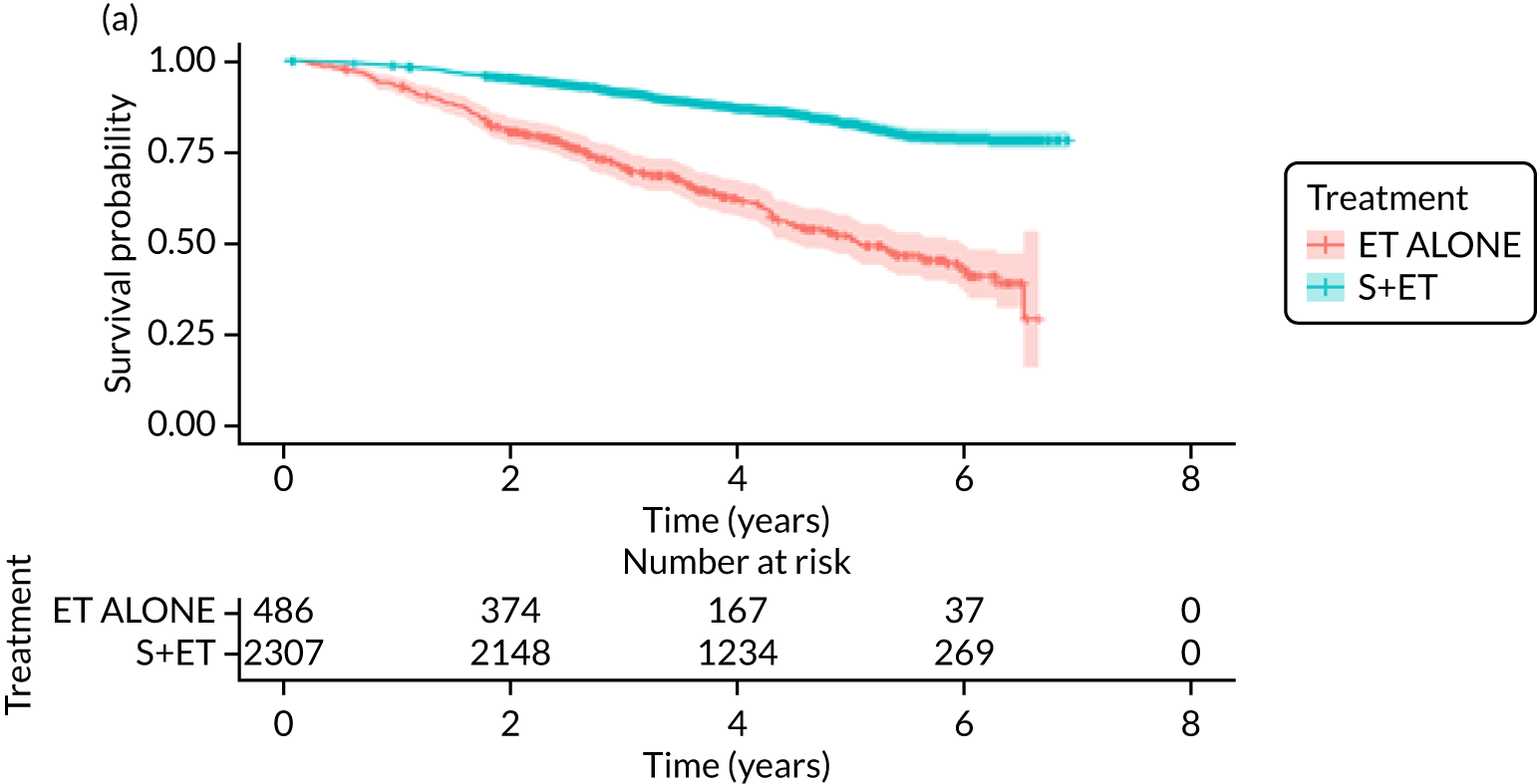

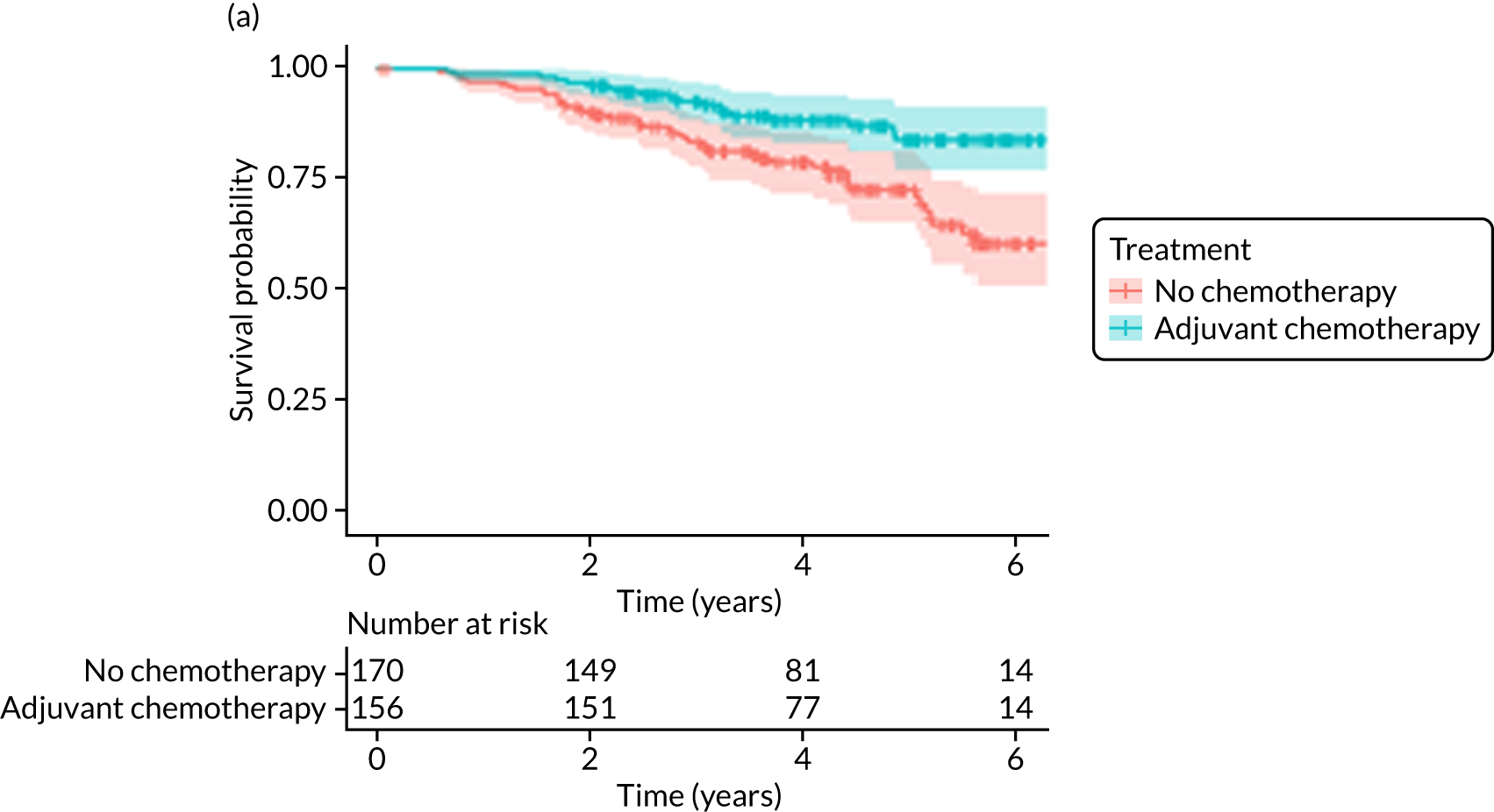

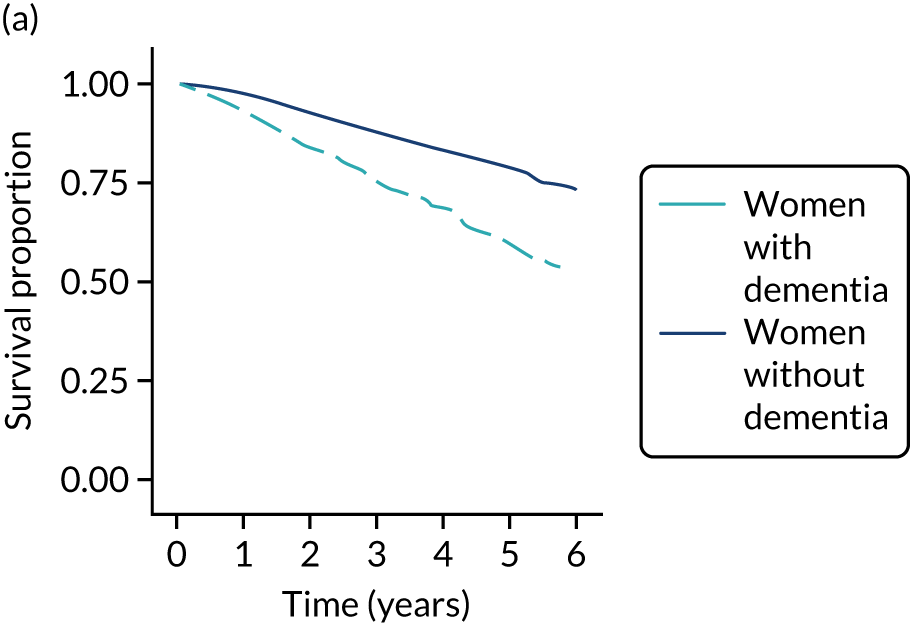

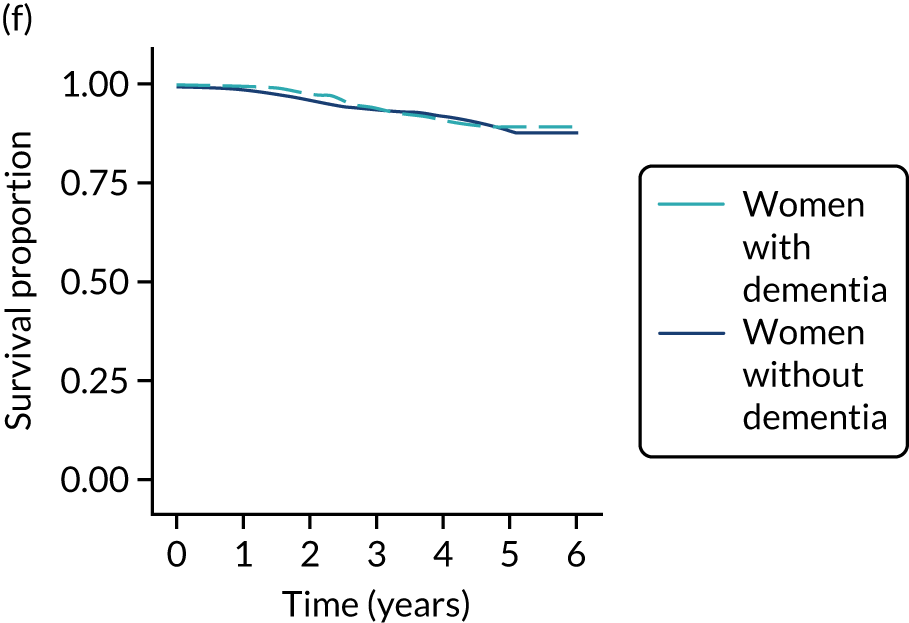

Overall survival (unmatched analyses)

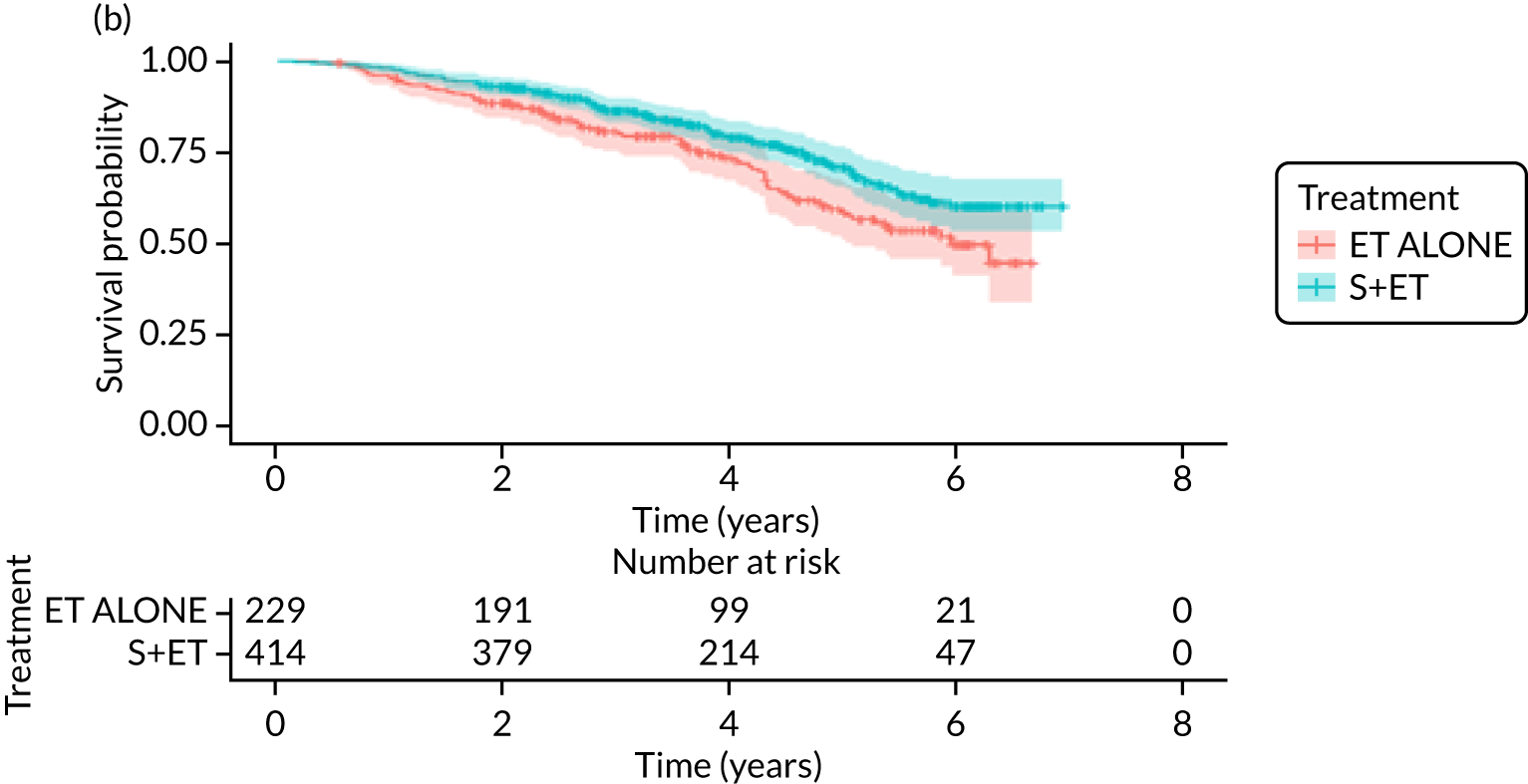

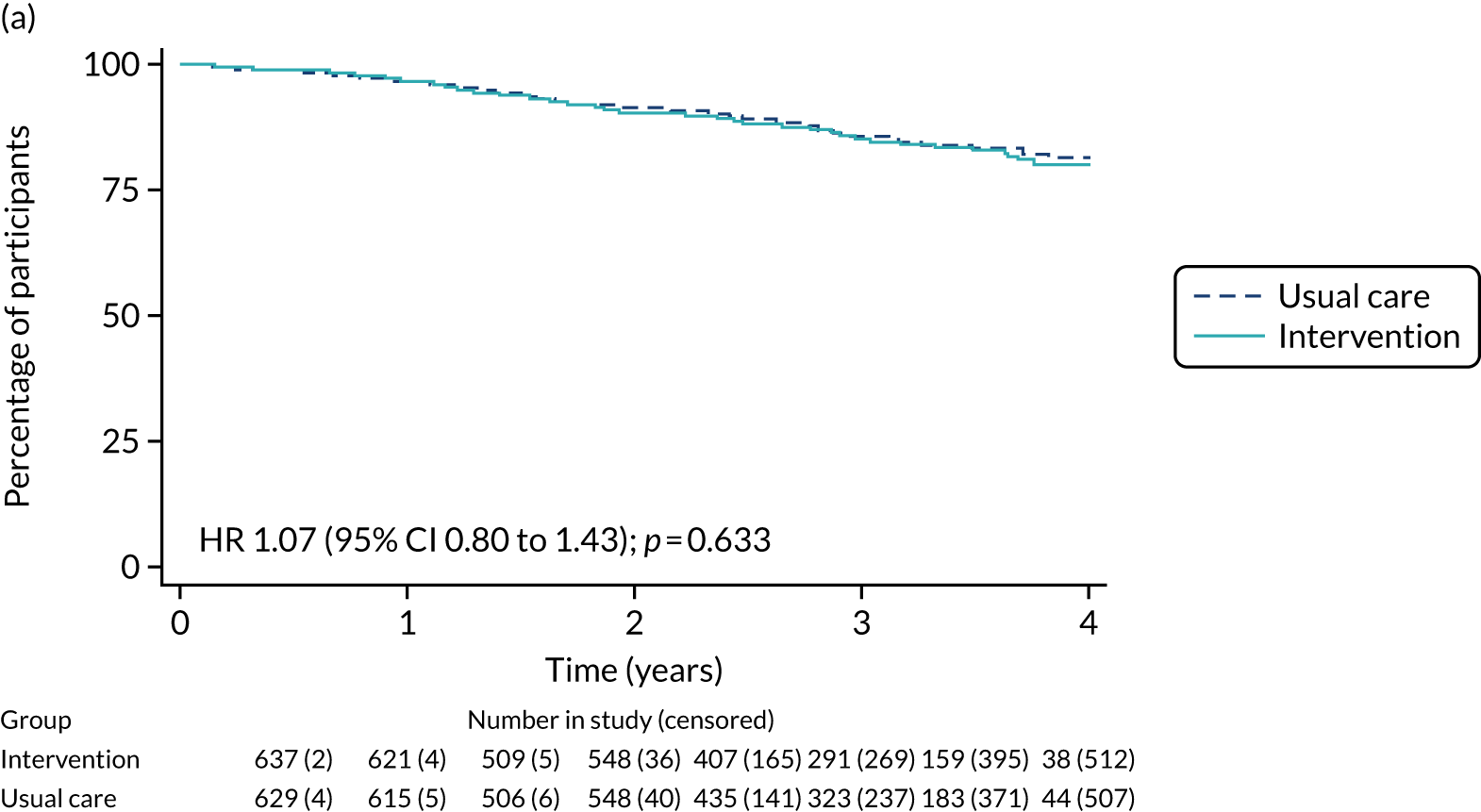

Of the 486 patients who received ET ALONE, 203 (41.8%) died during follow-up, compared with 336 out of 2307 (14.6%) of the S+ET patients. Patients treated with ET ALONE had inferior OS compared with those treated with S+ET (unadjusted HR 0.27, 95% CI 0.23 to 0.33; p < 0.001), but adjusting for case mix via multivariable Cox regression reduced this difference (adjusted HR 0.83, 95% CI 0.63 to 1.09; p = 0.18). The survival curves are shown in Figure 7.

FIGURE 7.

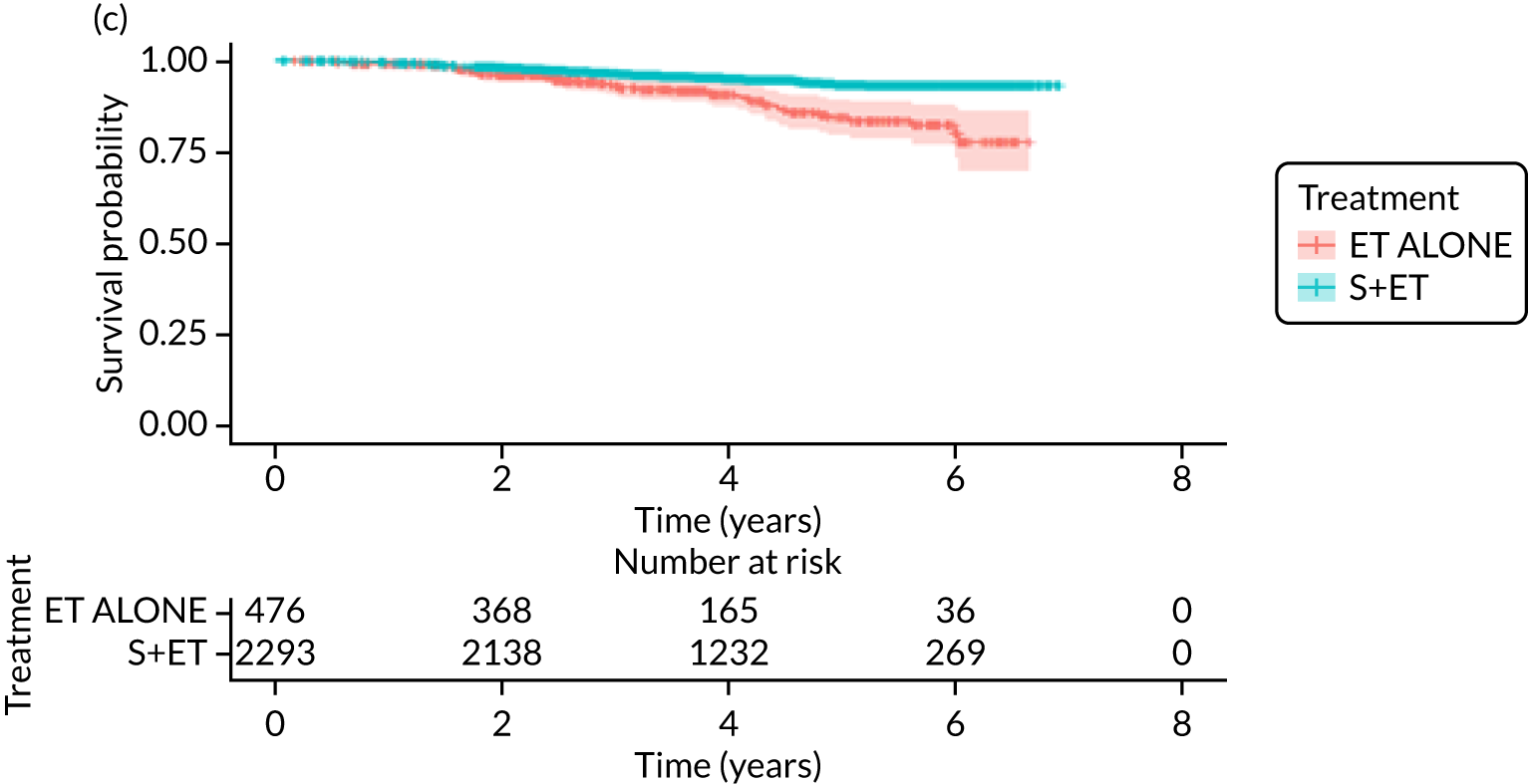

Kaplan–Meier survival curves for women with ER+ breast cancer treated with either S+ET or ET ALONE in matched and unmatched cohorts. (a) OS: unmatched; (b) OS: matched; (c) BCSS: unmatched; and (d) BCSS: matched.

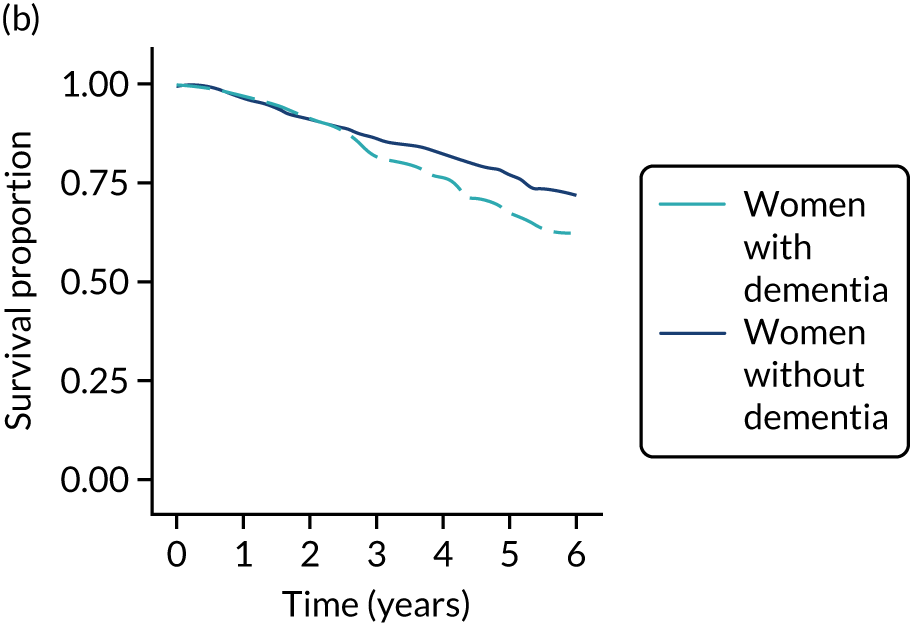

Overall survival (matched analyses)

Of the 229 patients who received ET ALONE, 79 (34.5%) died from all causes during follow-up, compared with 106 out of 414 (25.6%) S+ET patients (matched, unadjusted HR 0.66, 95% CI 0.49 to 0.90; p = 0.008). Matched patients treated with ET ALONE had inferior OS compared with those treated with S+ET. Further adjustment for case mix reduced, but did not remove, this difference (matched, adjusted HR 0.72, 95% CI 0.53 to 0.98; p = 0.037).

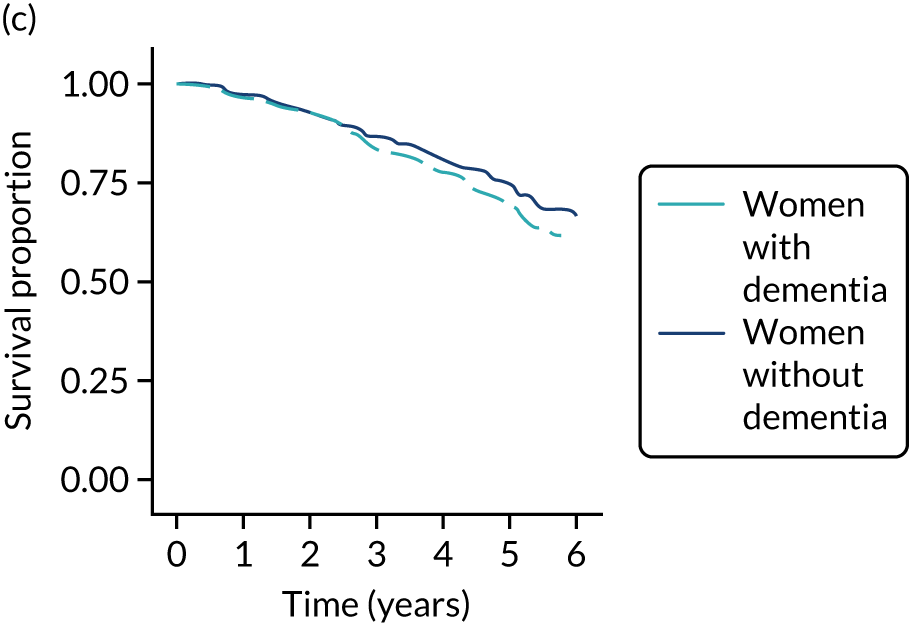

Breast-cancer-specific survival (unmatched analyses)

A total of 45 out of 476 (9.5%) patients died from breast cancer in the ET ALONE group, compared with 113 out of 2293 (4.9%) in the S+ET group (unadjusted HR 0.41, 95% CI 0.29 to 0.58; p < 0.001). The BCSS of patients treated with ET ALONE was inferior to that of those treated with S+ET, but adjusting for case mix reduced this difference (HR 0.89, 95% CI 0.52 to 1.53; p = 0.68).

Breast-cancer-specific survival (matched analyses)

In the matched analysis, of the 223 women, there were 17 (7.6%) breast cancer deaths for ET ALONE, compared with 27 (6.6%) deaths among 408 women for S+ET (HR 0.80, 95% CI 0.43 to 1.47; p = 0.46). Adjusting for residual imbalance via multivariable regression provided similar findings (HR 0.74, 95% CI 0.40 to 1.37; p = 0.34).

Recurrence and progression

Unmatched analyses

Rates of overall (locoregional and metastatic) recurrence in the unmatched cohort were higher in patients in the ET ALONE group (33/451; 7.3%) than the S+ET group (113/2325; 4.9%). Locoregional recurrences (progression in ET ALONE) were experienced by 6 out of 451 (1.33%) women for ET ALONE and 25 out of 2325 (1.07%) women for S+ET. After adjusting for age, baseline health status, physical function and Nottingham Prognostic Index (NPI), S+ET had no effect on the rate of recurrence (HR 1.01, 95% CI 0.52 to 1.95; p = 0.981).

Matched analysis

On matching, the differences in rates of recurrence were not significant and the HR for recurrence between the two treatments was 1.11 (95% CI 0.55 to 2.26; p = 0.775).

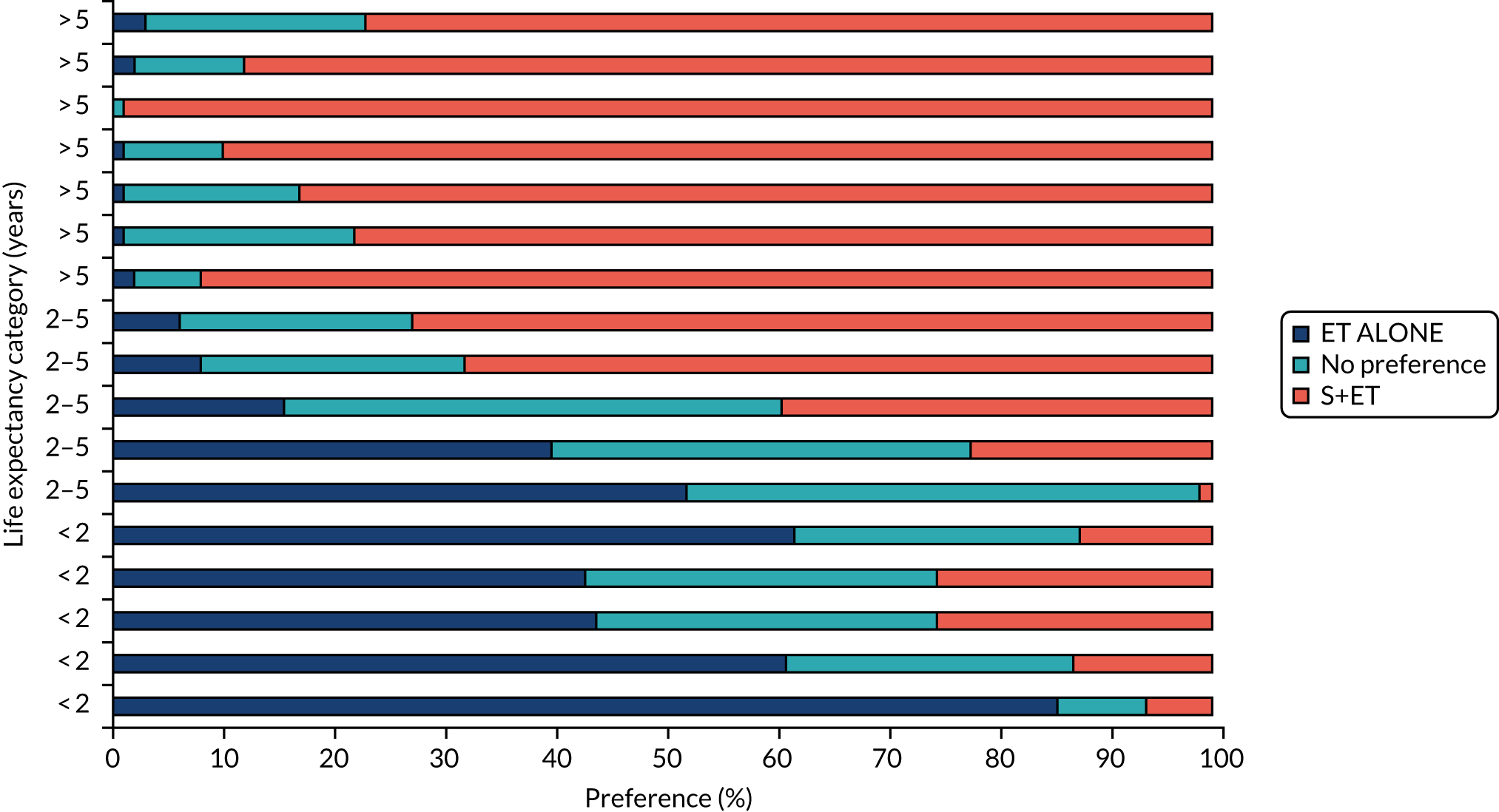

Discussion

Patient characteristics differed significantly between groups, with ET ALONE generally allocated to older, frailer women than those allocated S+ET. Propensity matching allowed creation of well-matched cohorts of women, although some degree of bias persisted, as demonstrated by the residual variation in OS, where the impact of non-breast-cancer causes of death was still slightly higher in the ET ALONE group than the S+ET group. As a result, although S+ET was still associated with an OS benefit, this difference disappeared in both BCSS and recurrence-/progression-free survival at 52 months’ follow-up.

Surgery plus adjuvant endocrine therapy was the primary treatment modality in 82% and ET ALONE in 18% of women, which is slightly lower than a recent national audit,62 which reported a ET ALONE rate of 24%. This variation may reflect selective recruitment of the less frail into the trial and the technical challenge of recruiting women receiving ET ALONE, in whom treatment often starts on the day of diagnosis, leaving a very narrow window for recruitment.

This study suggests that older women with a short life expectancy of ≤ 5 years derive little survival benefit from S+ET, but women likely to survive > 5 years may start to see endocrine resistance develop on ET ALONE. This accords with previous RCTs63–65 in which survival outcomes at 5 years were equivalent between S+ET and ET ALONE, but outcomes diverged over the longer term.

One of the key aims of this work was to identify a subgroup of women who may safely be offered ET ALONE. It would appear that women with a life expectancy of ≤ 5 years (aged ≥ 85 years with significant comorbidities, or aged > 90 years) should be offered an informed choice, highlighting the potential differences in survival, adverse events and QoL.

Quality-of-life outcomes between treatment groups are presented in Quality-of-life variation between primary endocrine therapy and surgery plus adjuvant endocrine therapy.

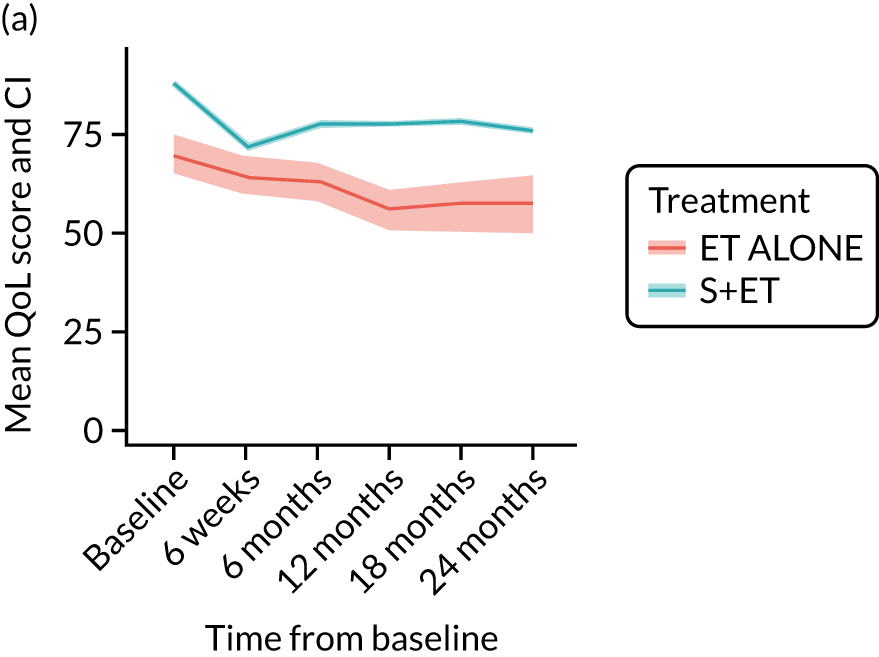

Quality-of-life variation between endocrine therapy alone and surgery plus adjuvant endocrine therapy

This analysis has been published. 66

Background

There are very few published data regarding QoL outcomes in older women comparing S+ET and ET ALONE. One previous randomised trial comparing ET ALONE and S+ET measured psychiatric morbidity using the General Health Questionnaire-28 (GHQ-28)67 score up to 2 years after diagnosis. 68 The study found that 9 out of 49 (18%) surgical patients and 2 out of 49 (4%) ET ALONE patients had scores indicative of psychiatric morbidity, whereas, by 2 years, there were 6 out of 49 (12%) patients with scores indicative of psychiatric morbidity in both arms. The GHQ-28 has no domains that would reflect the specific impacts of breast cancer. The European Organisation for Research and the Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) QoL instruments are much more specific to the impacts of breast cancer treatment (i.e. the EORTC-QLQ-BR2353) and the QoL concerns relevant to older people (i.e. the EORTC-QLQ-ELD1454). The purpose of this study was to explore the QoL differences between S+ET and ET ALONE in older women with early-stage breast cancer using highly specific QoL tools.

Methods

Quality-of-life assessment was performed on the matched and unmatched cohorts from the ET ALONE versus S+ET analysis using the validated European Organisation for Research and the Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC-QLQ) instruments described in The Age Gap prospective observational multicentre cohort study general methods and results.

Owing to significant baseline variation between the unmatched groups in all QoL domains, analyses are largely descriptive and map the changes caused by treatment in each group. In the smaller matched cohort (matched as described in Endocrine therapy alone versus surgery plus adjuvant endocrine therapy: survival analysis), comparative analyses are presented.

Results

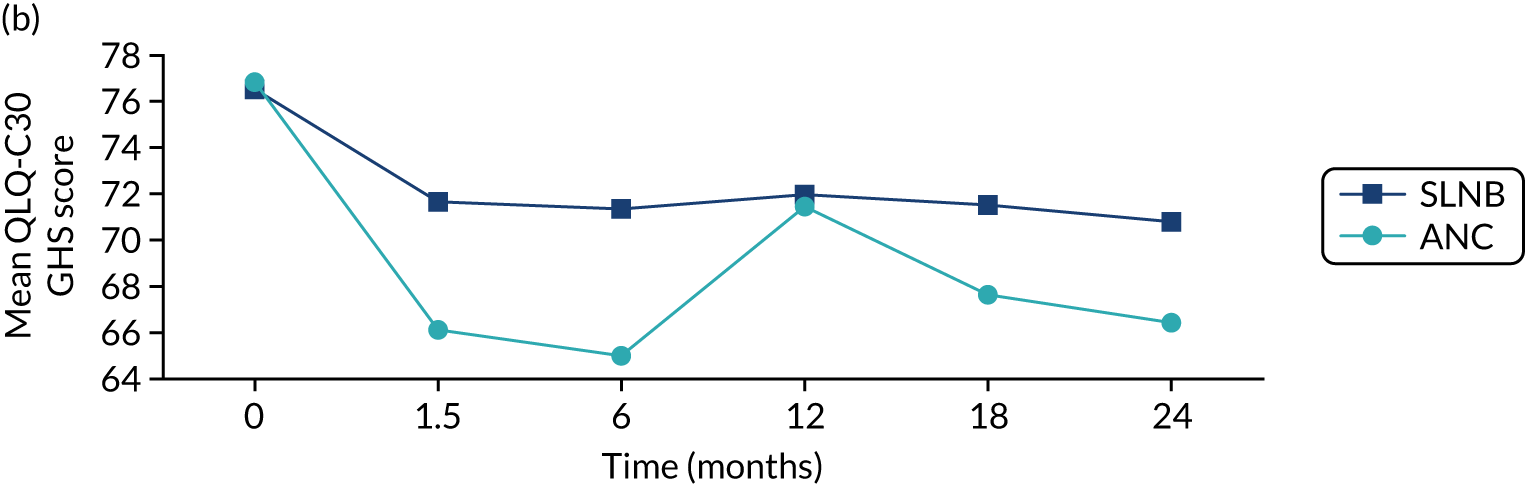

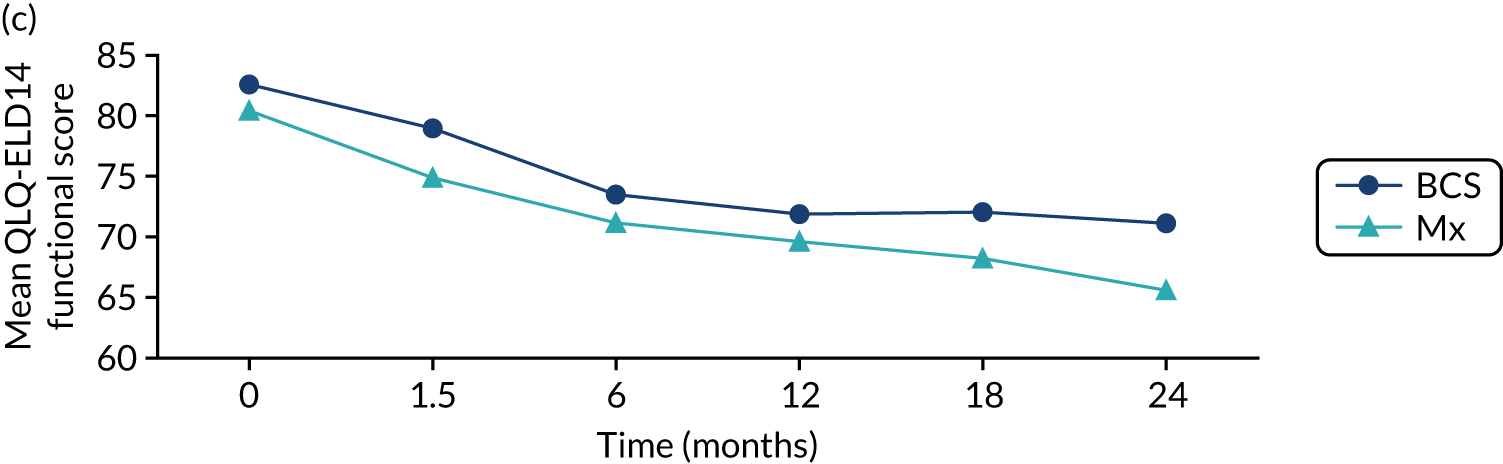

EORTC-QLQ-C30: unmatched analysis

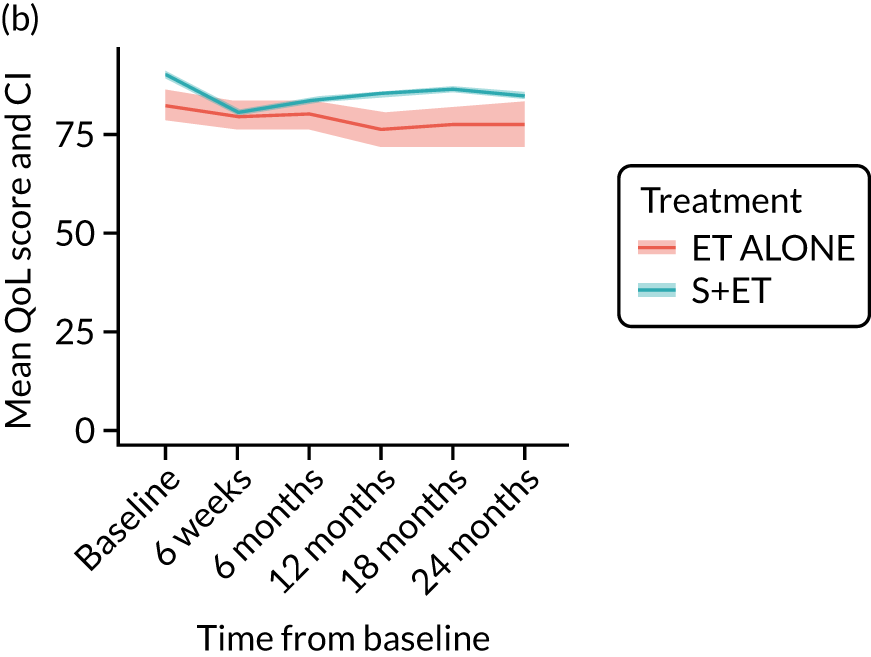

The number of patients completing the EORTC-QLQ-C30 global health status at baseline was 1902 out of 2854 (67%): 1644 received S+ET (70% of the total of 2354 patients) and 258 received ET ALONE (52% of the total of 500 patients). Patients treated with ET ALONE had worse baseline scores than those treated with S+ET across all domains of the EORTC-QLQ-C30. In the S+ET group, a steeper change in mean scores between baseline and 6 weeks is apparent in the role functioning, social functioning and fatigue domains (Figure 8).

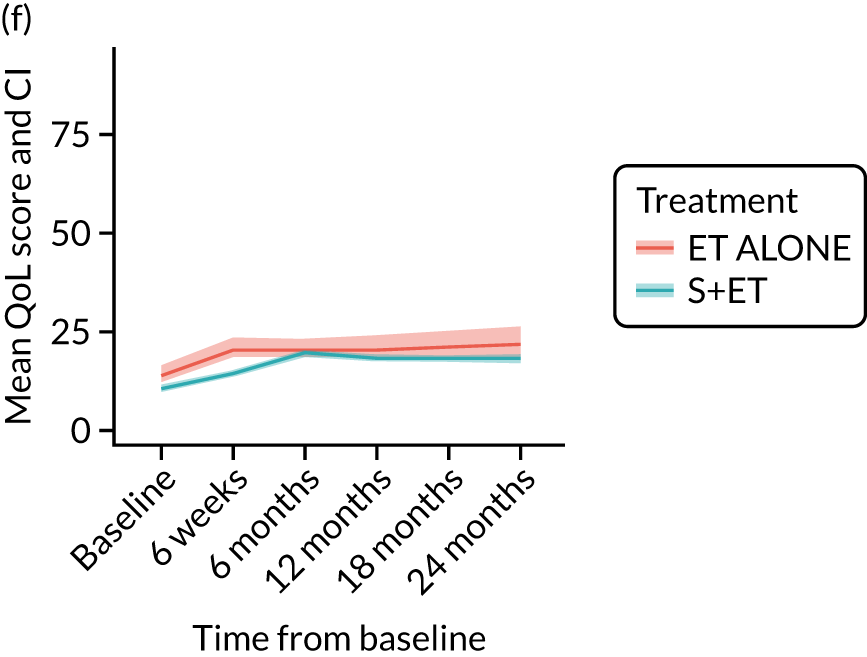

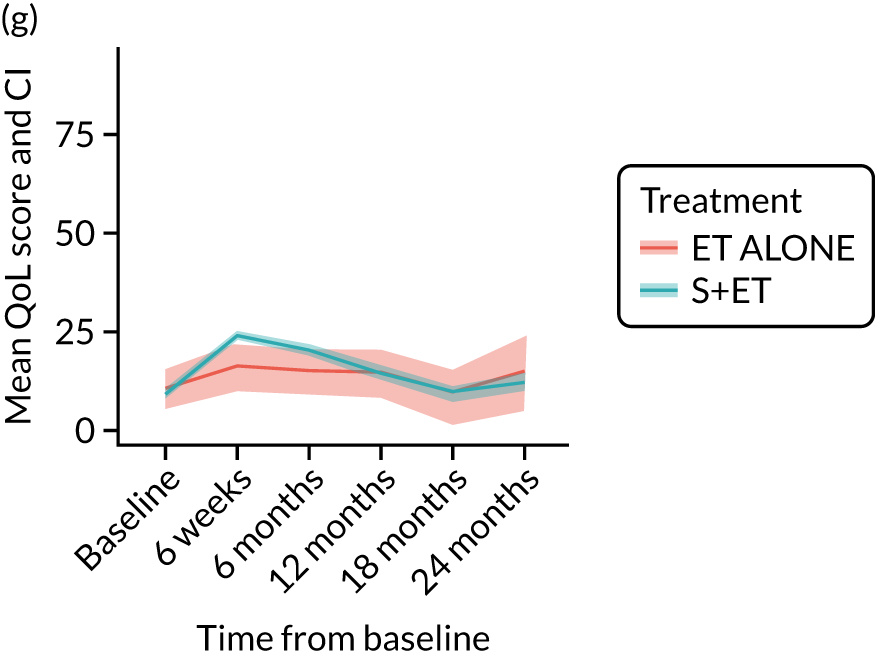

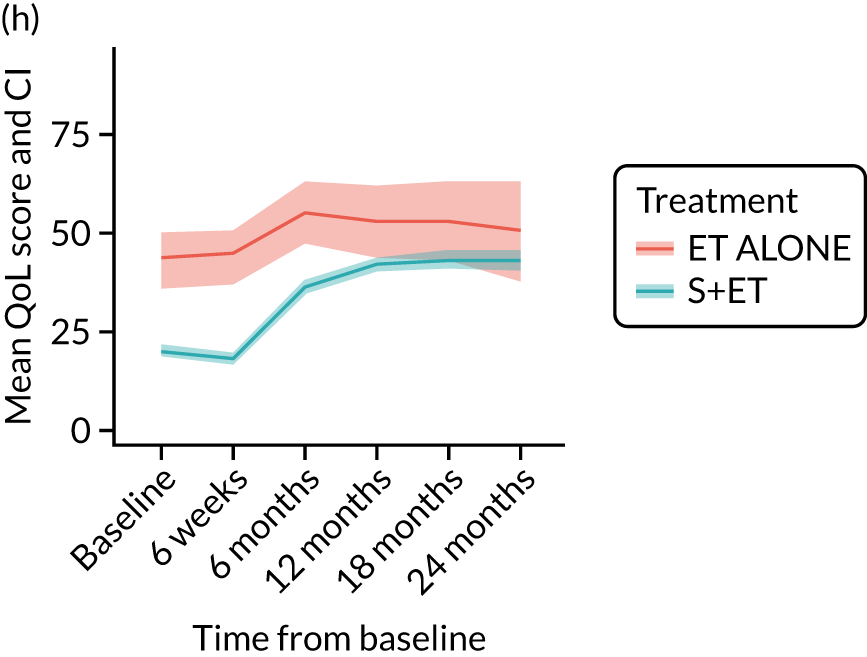

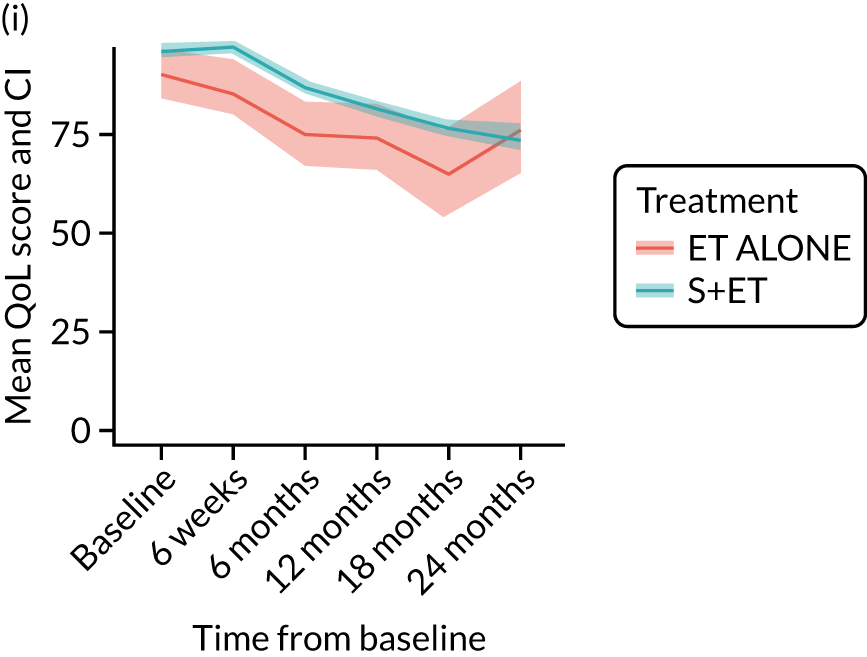

FIGURE 8.

Summary of key changes in QoL during treatment for breast cancer using the EORTC instruments. (a) Role functioning (EORTC-QLQ-C30 domain); (b) social functioning (EORTC-QLQ-C30 domain); (c) fatigue (EORTC-QLQ-C30 domain); (d) arm symptoms (EORTC-QLQ-BR23 domain); (e) breast symptoms (EORTC-QLQ-BR23 domain); (f) systemic therapy side effects (EORTC-QLQ-BR23 domain); (g) burden of illness (EORTC-QLQ-ELD14 domain); (h) joint stiffness (EORTC-QLQ-ELD14 domain); and (i) family support (EORTC-QLQ-ELD14 domain). Surgery took place between baseline and 6 weeks.

EORTC-QLQ-C30: major or minor surgery (plus adjuvant endocrine therapy) versus endocrine therapy alone analysis (matched)

Analysis according to whether the surgery was major (mastectomy and/or axillary clearance) or minor (wide local excision and/or sentinel node biopsy) or ET ALONE highlighted the impact of major surgery compared with ET ALONE on key domains of the EORTC-QLQ-C30 instrument. Major surgery has a more notable negative impact than ET ALONE on global health status and role function at 6 weeks (HR –9.59, 95% CI –16.96 to –2.21).

EORTC-QLQ-BR23 outcomes: breast-cancer-specific quality-of-life outcomes

EORTC-QLQ-BR-23: unmatched analysis

The mean scores for each domain of the EORTC-QLQ-BR23 at each time point (see Figure 8) show that there were several domains in which surgery had an impact (6-week time point). Mean breast symptom scores increased between baseline and 6 weeks for both groups: S+ET patient scores increased from 10.3 [standard deviation (SD) 13.2] to 23.0 (SD 18.8) and ET ALONE patient scores increased from 10.1 (SD 15.7) to 10.8 (SD 15.7). The score for the S+ET group returned to normal by 24 months.

The arm symptom scores increased between baseline and 6 weeks: S+ET patient scores increased from 8.4 (SD 14.1) to 16.6 (SD 18.3) and ET ALONE patient scores increased from 12.5 (SD 18.1) to 14 (SD 18.9). S+ET scores did not return to baseline levels even at 24 months, suggesting a long-term impact of axillary surgery.

For other domains, scores were similar.

EORTC-QLQ-BR23: major versus minor surgery analysis – matched cohort

In the matched cohort, women having major surgery had significantly worse arm symptoms (HR 8.85, 95% CI 3.63 to 14.07) than ET ALONE patients, and the symptoms did not return to baseline even at 2 years. Minor surgery had a lesser effect that, again, persisted to 2 years.

EORTC-QLQ-ELD14 outcomes: older-age-specific quality-of-life domains

EORTC-QLQ-ELD14: unmatched data

In the unmatched data, differences in baseline scores were apparent for the majority of domains. Following surgery, at the 6-week time point, burden of illness scores increased from 21.1 (SD 23.8) to 25.2 (SD 27.5) in the ET ALONE group, compared with a change from 20.3 (SD 23.5) to 30.4 (SD 24.7) for the surgery group. The burden of illness scores returned to baseline levels in the surgery group by 18 months.

EORTC-QLQ-ELD14: major versus minor surgery analysis – matched cohort

In the matched cohort, comparison of major surgery and ET ALONE caused a significant increase in the burden of illness (HR 7.57, 95% CI 0.58 to 14.56) at 6 weeks that, although it improved with time, did not fully return to normal even at 24 months. By contrast, comparison of minor surgery and ET ALONE had a less marked impact (HR 5.17, 95% CI –1.99 to 12.32), which did return to normal.

EQ-5D-5L and visual analogue scale outcomes

EQ-5D-5L: unmatched data

Analysis of unmatched data by domain shows the impact of surgery on several domains, notably ability to perform usual activities, pain and discomfort, and anxiety and depression. All these scores become more adverse between baseline and 6 weeks, which is when surgery usually occurrs. It is noteworthy that, for all these domains, the scores do not return to baseline levels after this treatment-induced deterioration. In ET ALONE patients, the pattern is a slow decline over the 2-year period.

Discussion

Surgery has a clinically relevant impact on a range of QoL domains. Most of these impacts return to baseline levels by 24 months, but there may be some permanent impairment. In ET ALONE patients, the pattern of changes are those of a slow decline across all domains over the 2-year period. These impacts need to be considered and discussed with older women when deciding treatment options. Considering the survival benefit seen in fitter, older women with breast cancer, for most women, despite the largely transient negative impacts of surgery, surgery will be the better option.

However, for older, frailer women with significant comorbidities, for whom any survival benefit may be small, these QoL impairments become more significant. For some of these women, surgery will have no benefit and impair the quality of their remaining lifespan. Older women need to be made aware of this, and we plan to develop the online decision tool to include QoL data so that this may be factored into the decision-making process.

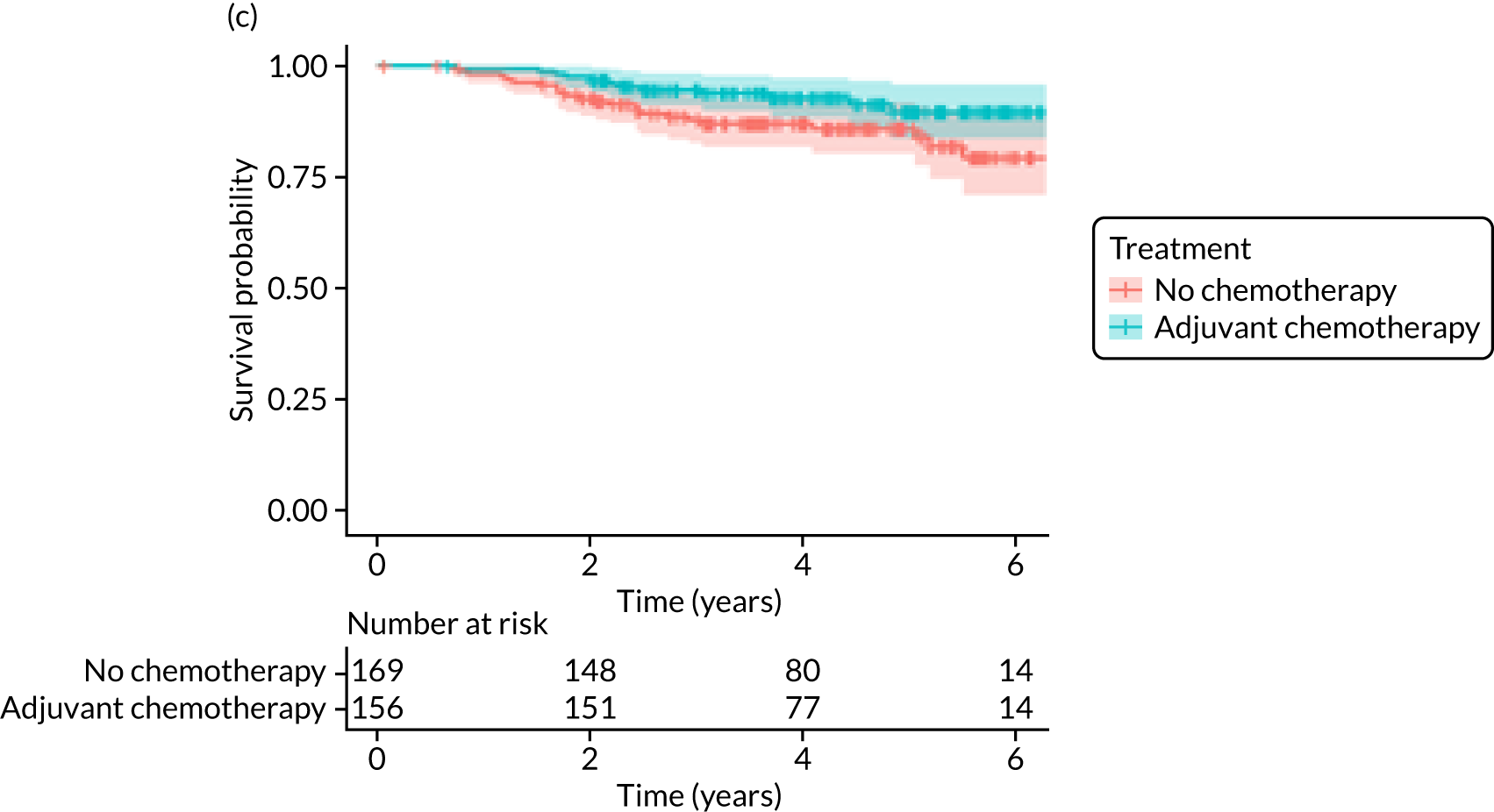

Adjuvant chemotherapy versus no chemotherapy in women with high-recurrence-risk breast cancer using both unmatched and propensity-score-matched analyses

Introduction

The available evidence relating to adjuvant chemotherapy in older women suggests that there is a reduced level of benefit for older women compared with younger women. Nevertheless, benefit is present in some women aged between 70 and 80 years, although there are very limited data for those aged > 80 years. 69 The objectives of this analysis were to determine health-status-stratified outcomes for older women (aged ≥ 70 years) with breast cancer according to whether or not they received adjuvant chemotherapy. This analysis has been published. 70

Methods

General methods

See The Age Gap prospective observational multicentre cohort study general methods and results.

Statistical analyses for the adjuvant chemotherapy survival analysis

The relationships between systemic therapy use and tumour and patient characteristics were evaluated using univariable and multivariable logistic regression. High-risk breast cancers were defined as nodal involvement, ER–, HER-2+, grade 3, or an Oncotype DX score of > 25.

For both OS and BCSS, a Cox proportional hazards model was fitted using regression-based adjustment based on covariates of treatment; age; categories of the aPG-SGA, ADL, IADL, CCI, MMSE and ECOG-PS; number of medications; and NPI71 and human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 (HER-2) status for all high-risk patients.

In addition, a propensity-score-matched analysis of high-risk patients was performed, with exact matching on NPI and HER-2 status, and logistic regression was used to calculate propensity scores for treatment in relation to age, aPG-SGA category, ADL category, IADL category, MMSE category, CCI category, ECOG-PS category and number of medications.

Results

Characteristics of patients

A total of 1520 out of the 2811 patients who underwent surgery had high-recurrence-risk cancer. Of those, 381 (25%) patients subsequently underwent adjuvant chemotherapy within 6 months. As expected, patients undergoing adjuvant chemotherapy were typically younger and fitter and had cancer with a worse prognosis. The median age was 73 years (IQR 71–76 years) for the adjuvant chemotherapy group and 76 years (IQR 73–80 years) for the no chemotherapy group. The median CCI score was 0 (IQR 0–2) for the adjuvant chemotherapy group and 1 (IQR 0–2) for the no chemotherapy group. Tumour stage was generally higher and tumour biology more adverse in women having adjuvant chemotherapy than woman not having chemotherapy.

Only 150 out of 332 (45.1%) women with HER-2+ cancers received adjuvant chemotherapy plus trastuzumab. Only women with high-recurrence-risk tumours (1520/2811; 54%) were analysed. Of these, 376 (25%) received adjuvant chemotherapy.

Propensity matching

In a propensity-score-matched analysis, 200 patients who received adjuvant chemotherapy were matched to 350 who did not.

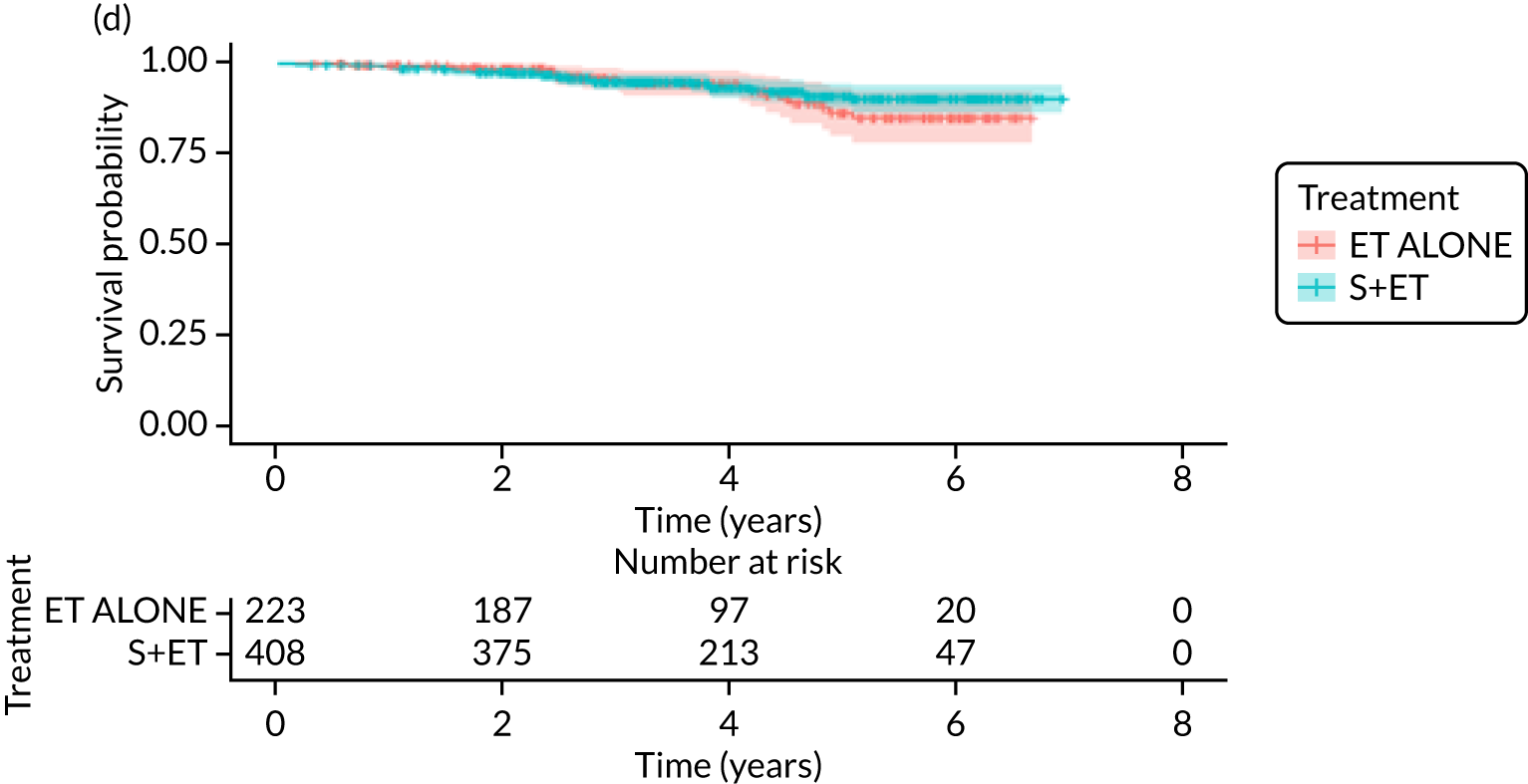

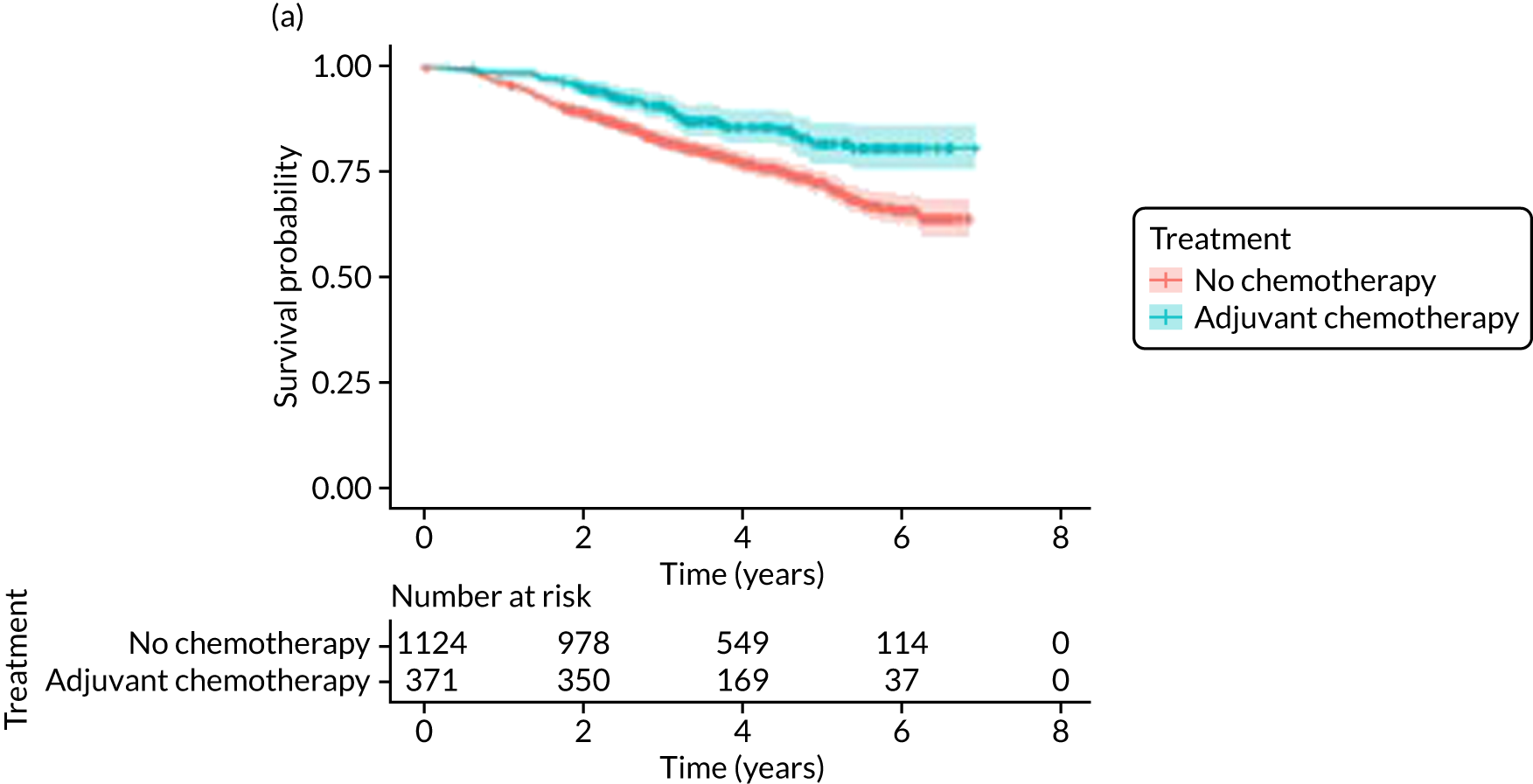

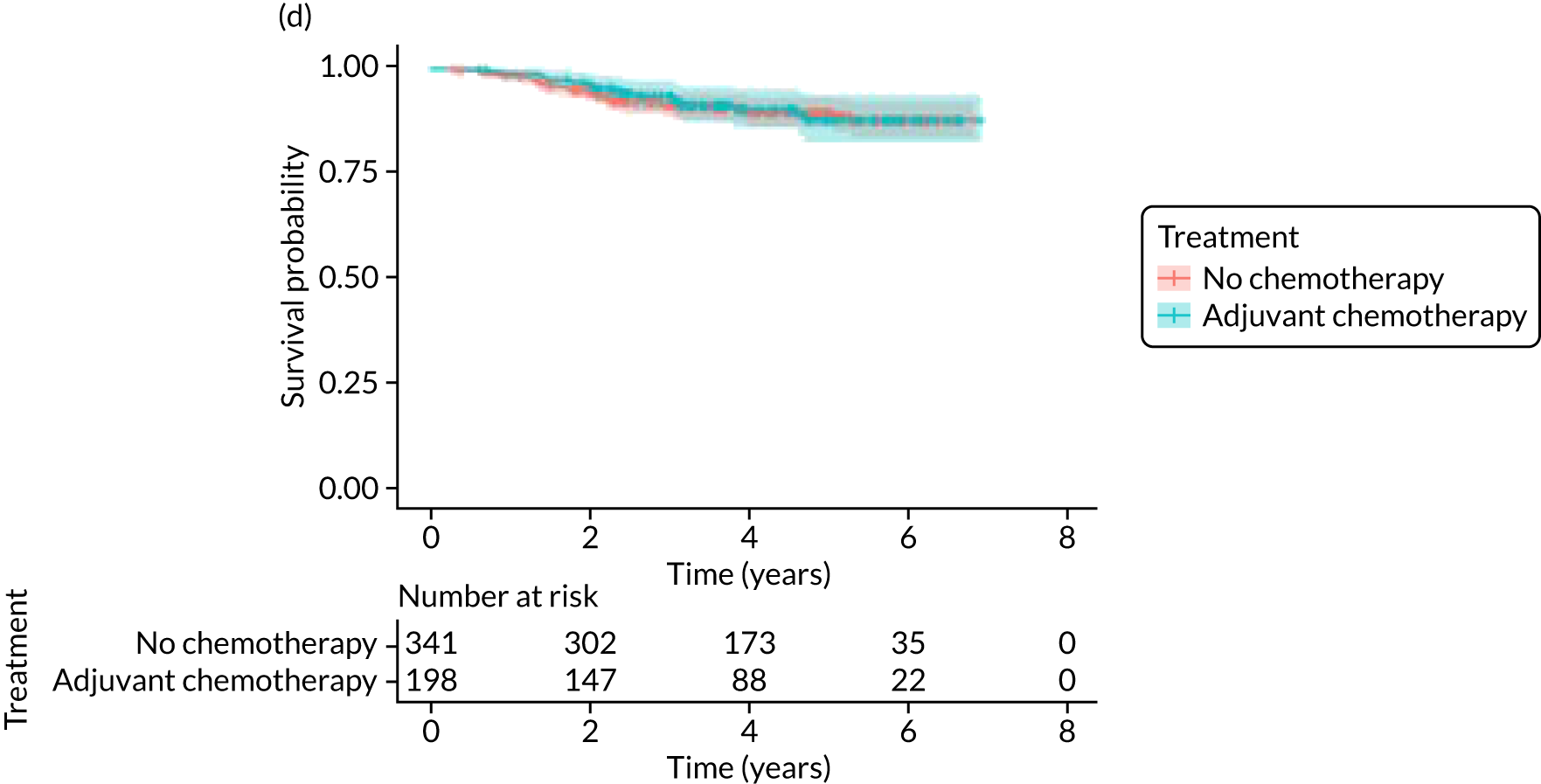

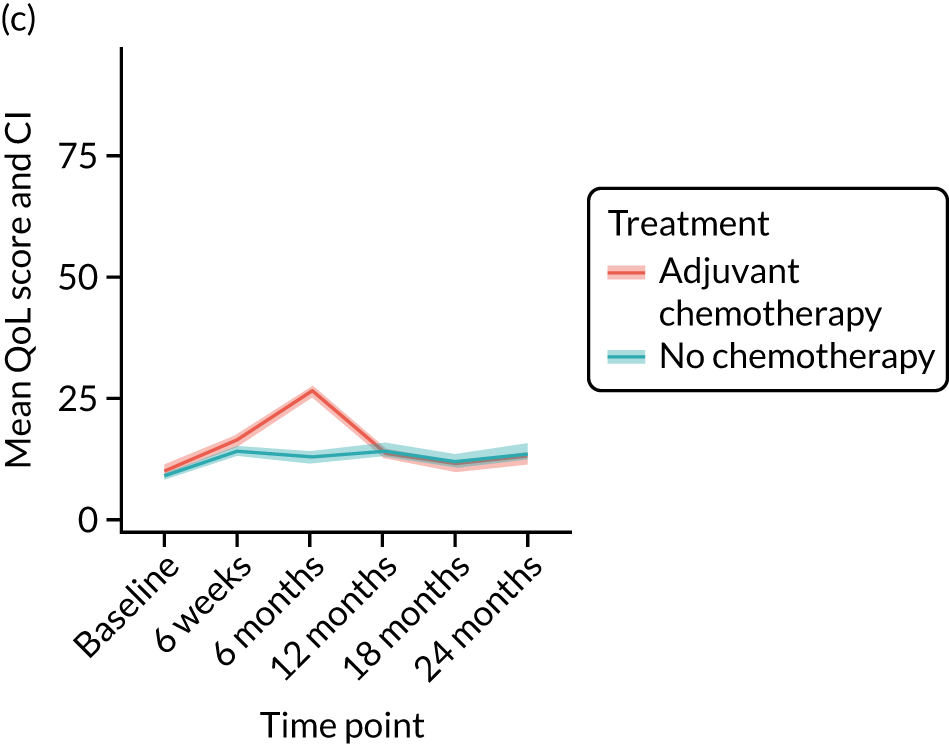

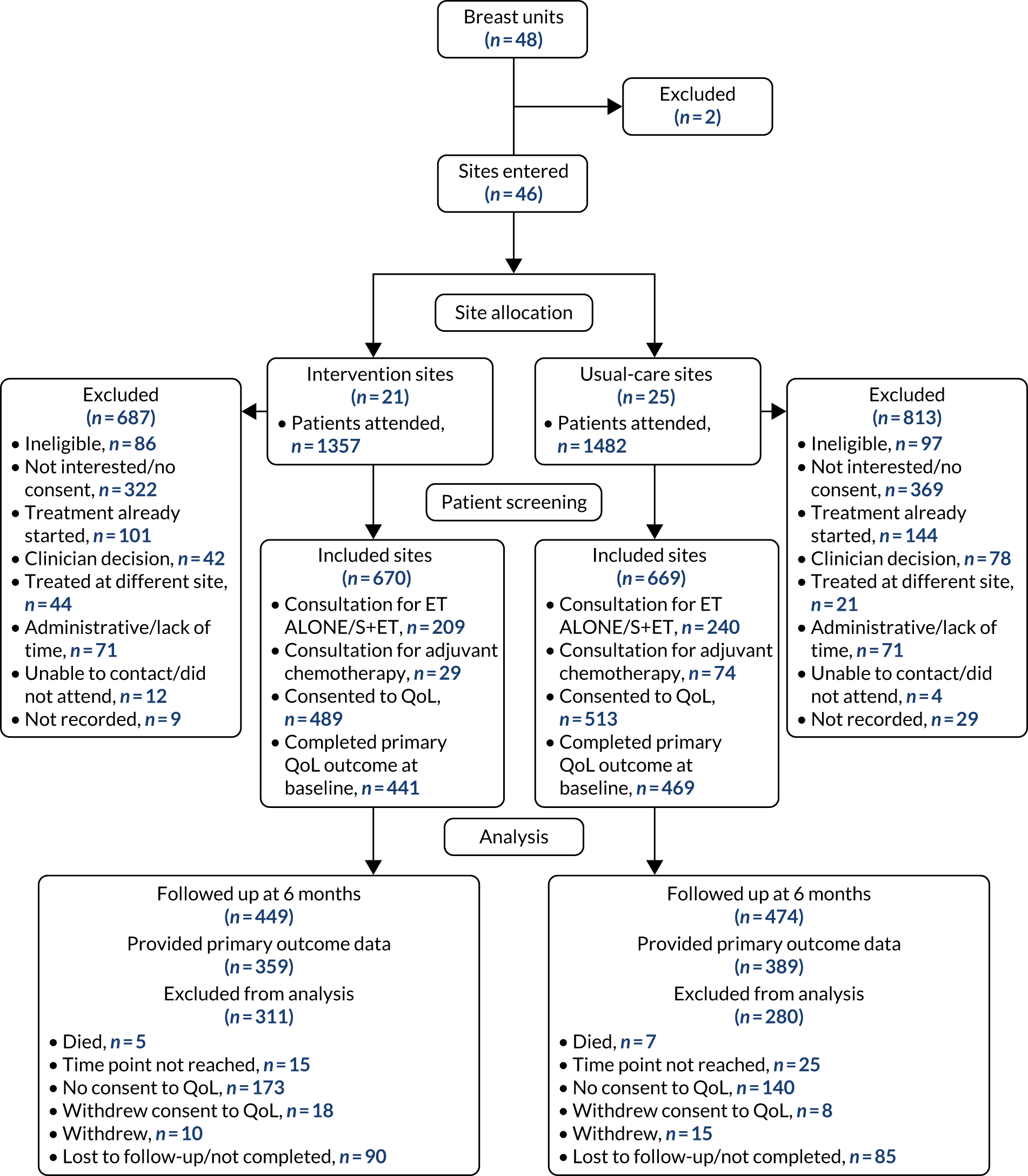

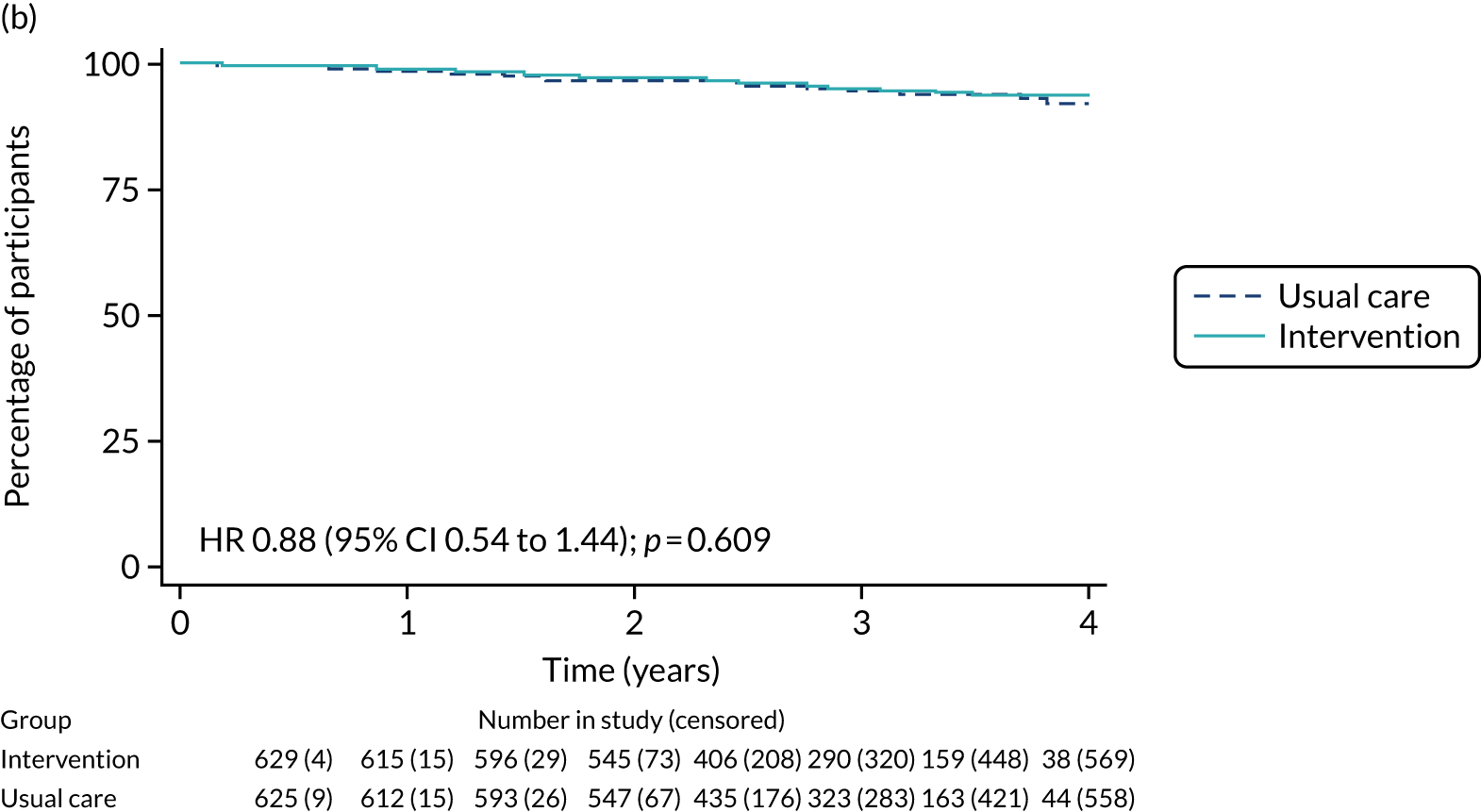

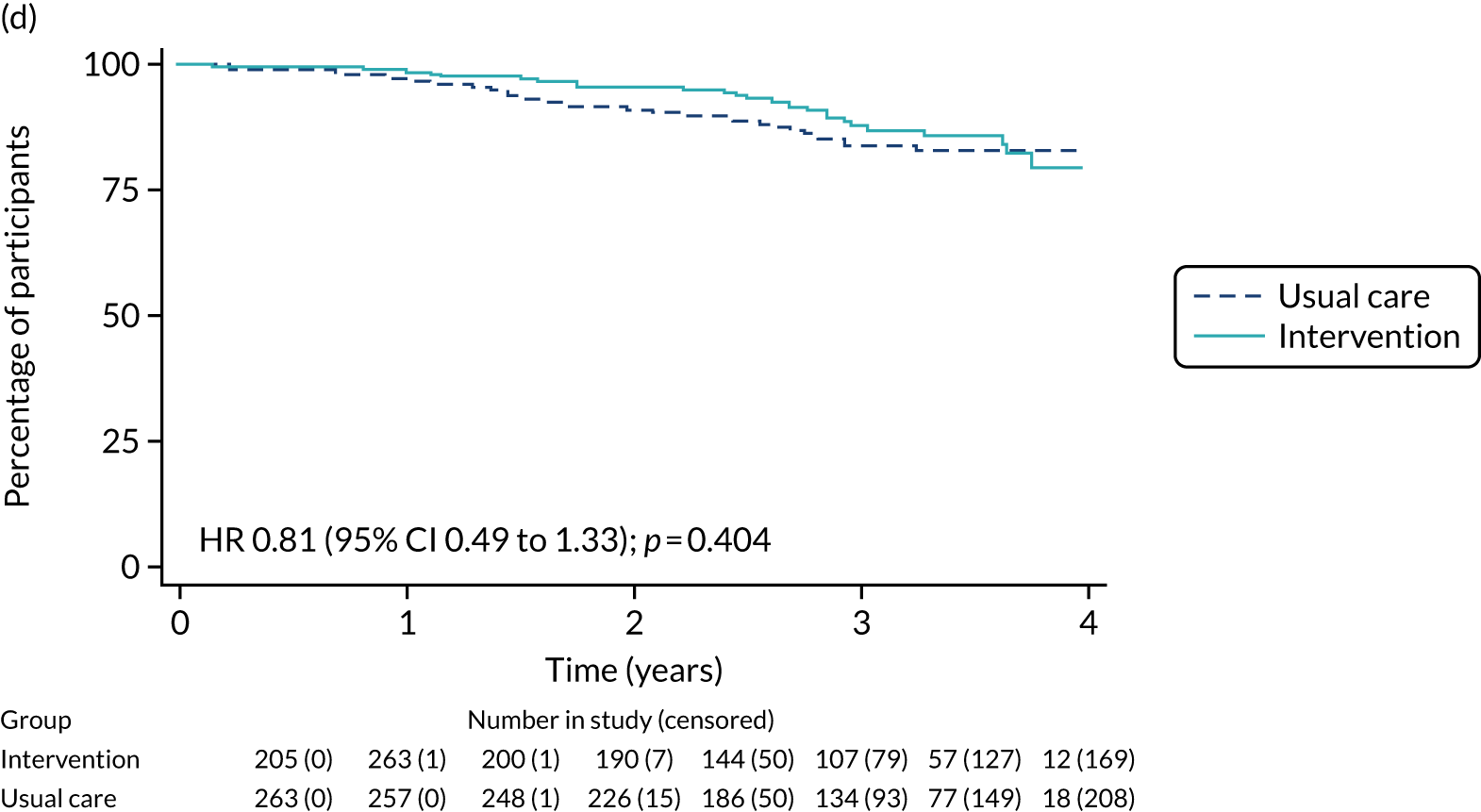

Overall survival

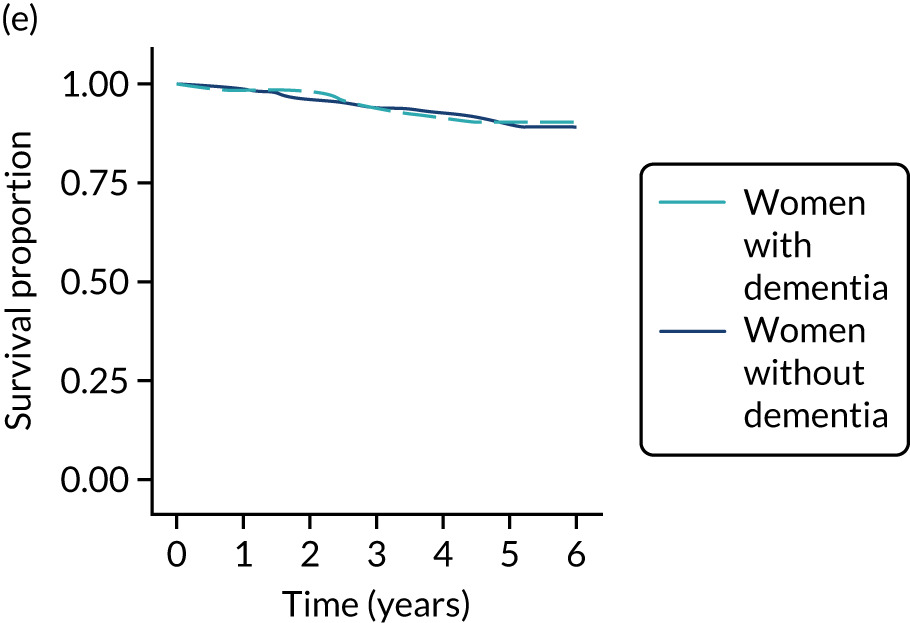

The median follow-up of 52 months is reported for 1495 out of 1520 high-risk patients (adjuvant chemotherapy, n = 371; no chemotherapy, n = 1124). Receiving adjuvant chemotherapy was associated with a longer OS than not receiving chemotherapy, but the difference was not statistically significant when adjusted for other covariates: unadjusted HR 0.545 (95% CI 0.40 to 0.73; p < 0.001) and adjusted HR 0.87 (95% CI 0.58 to 1.28; p = 0.47; Figure 9).

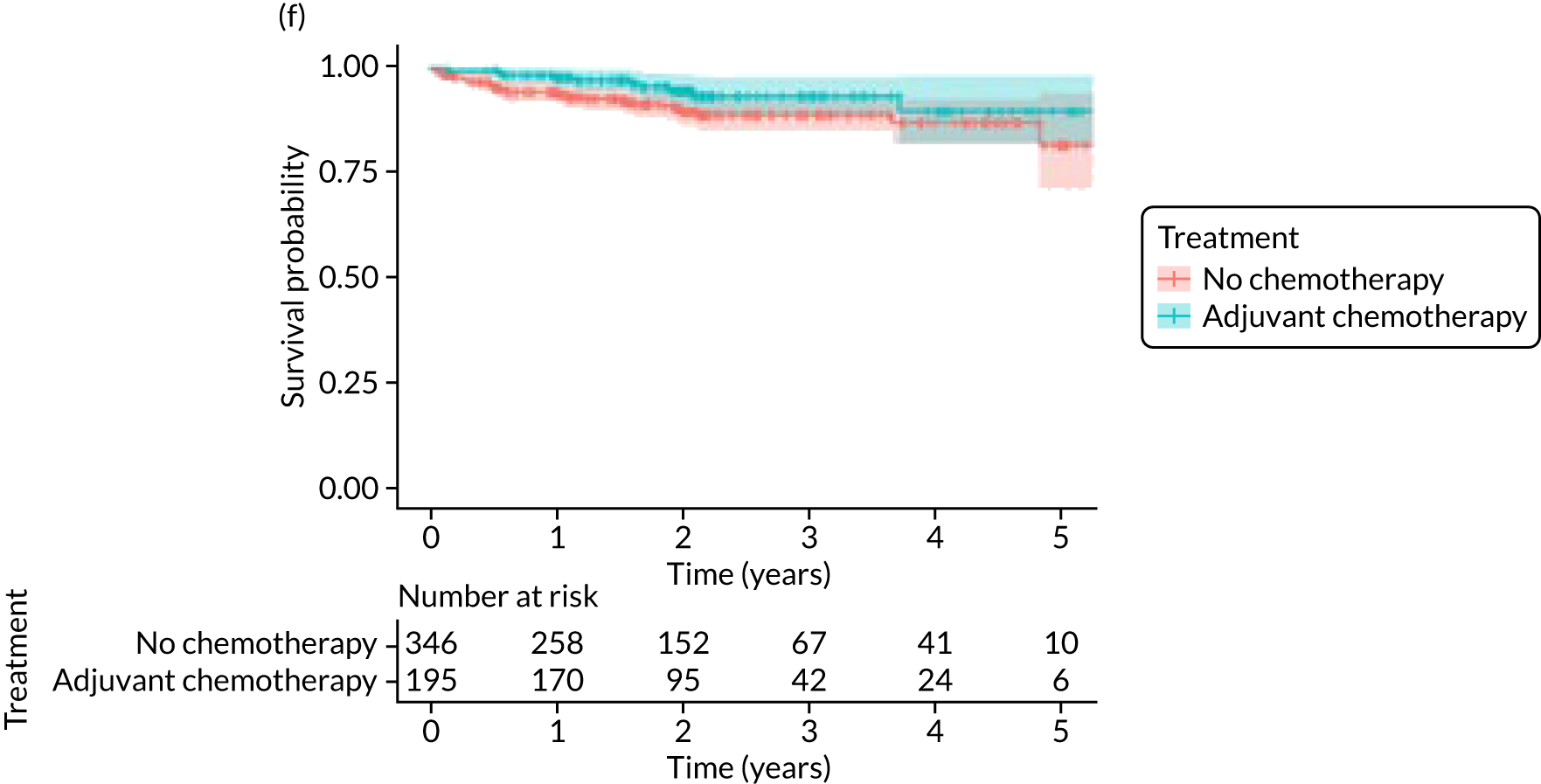

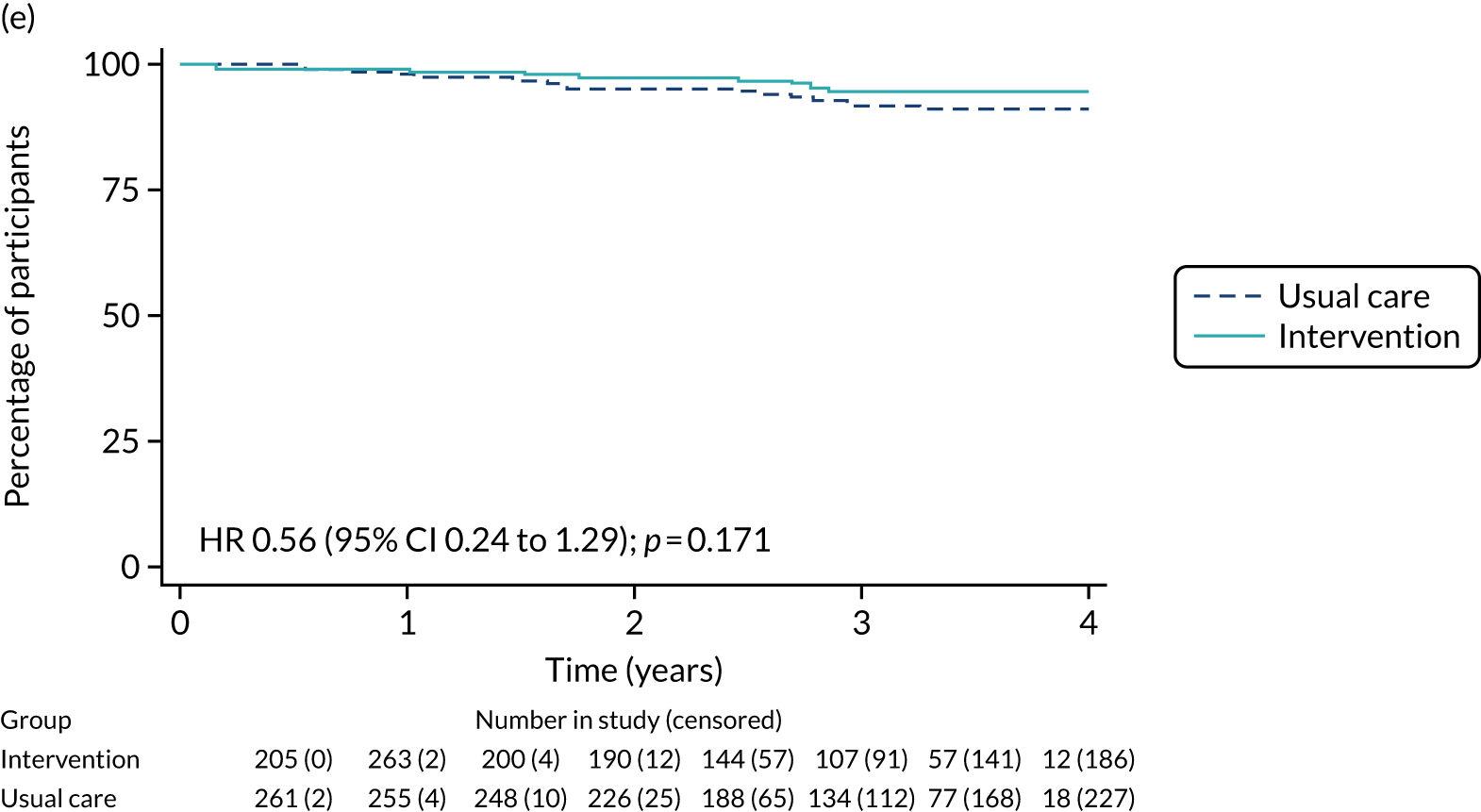

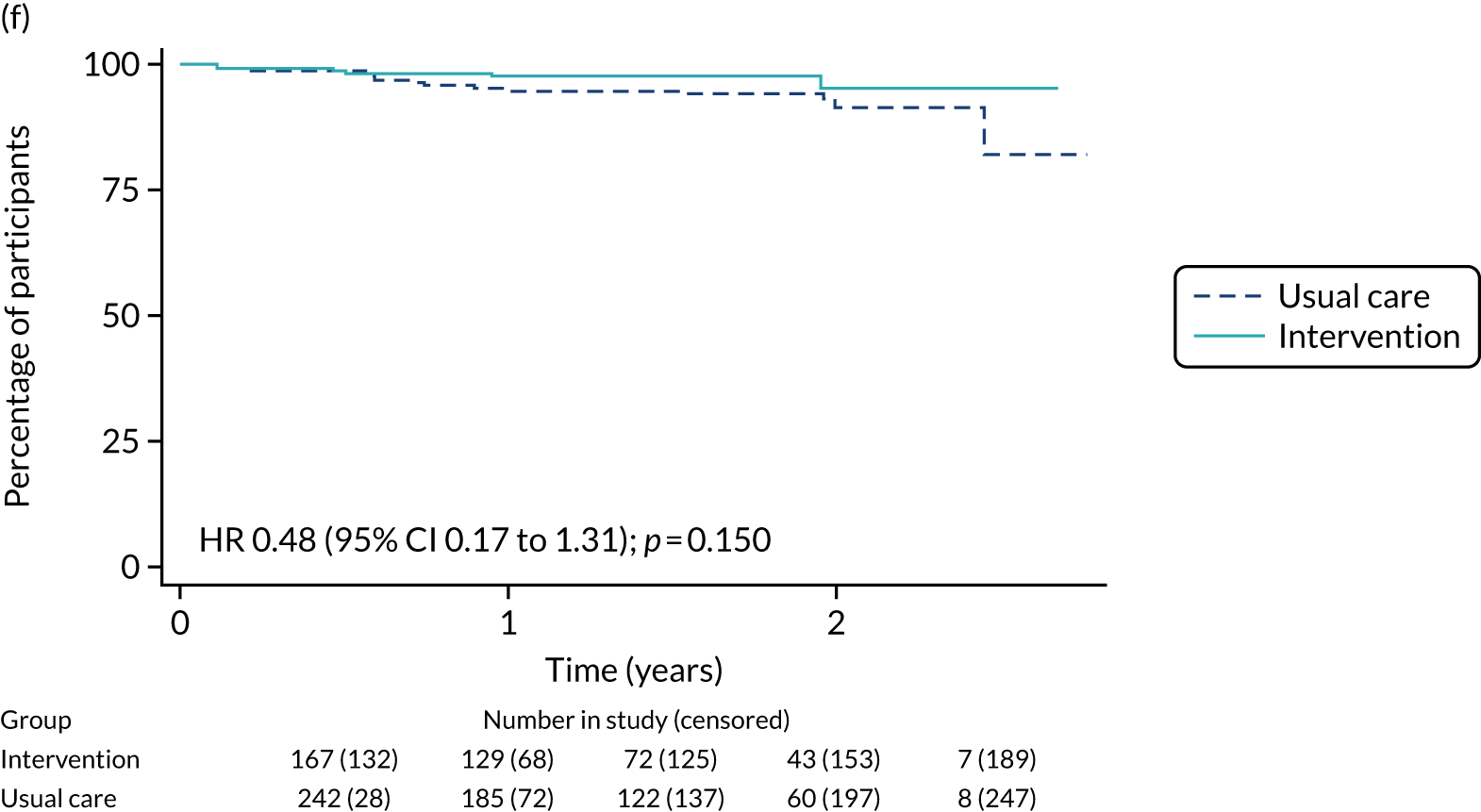

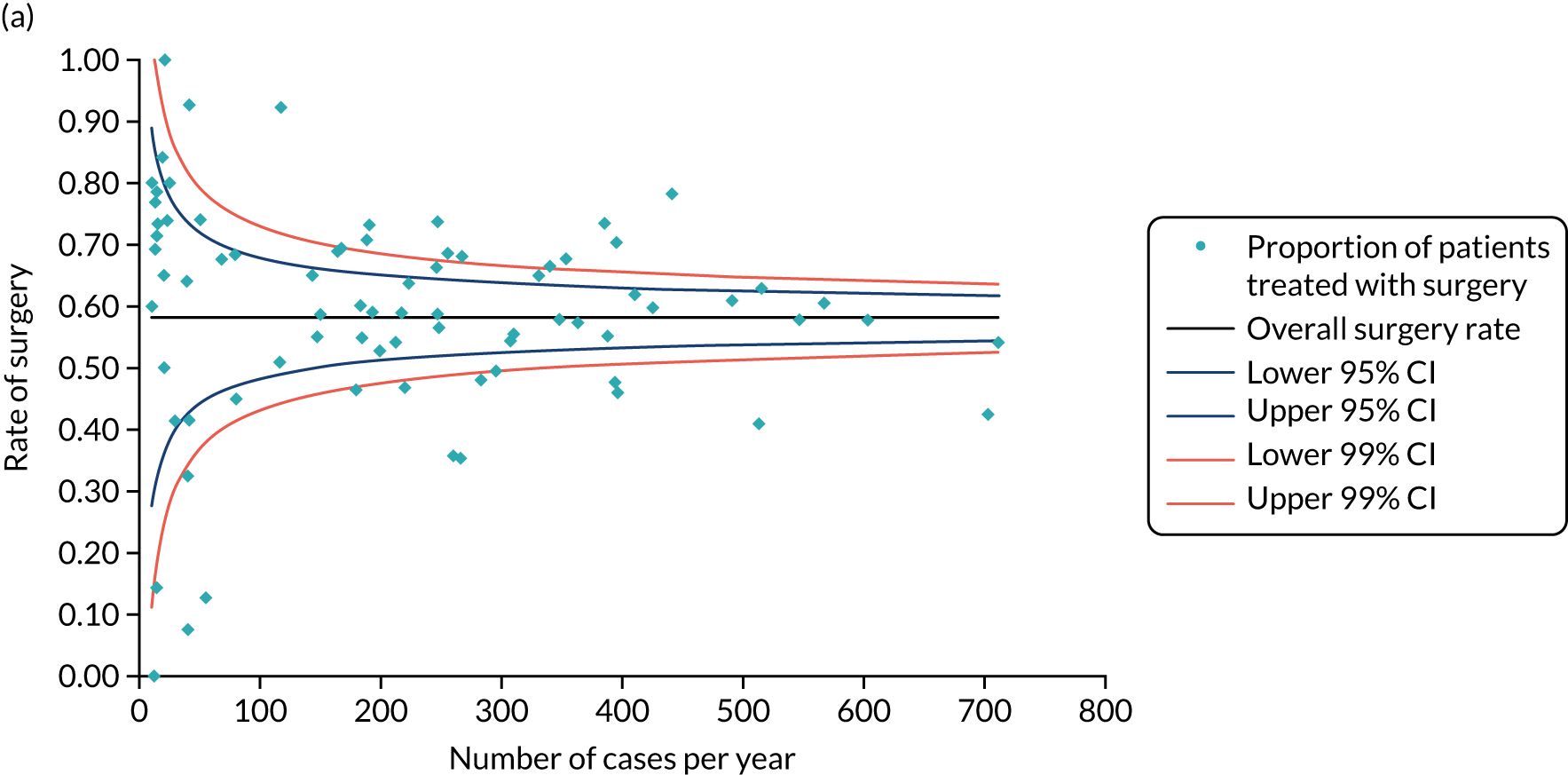

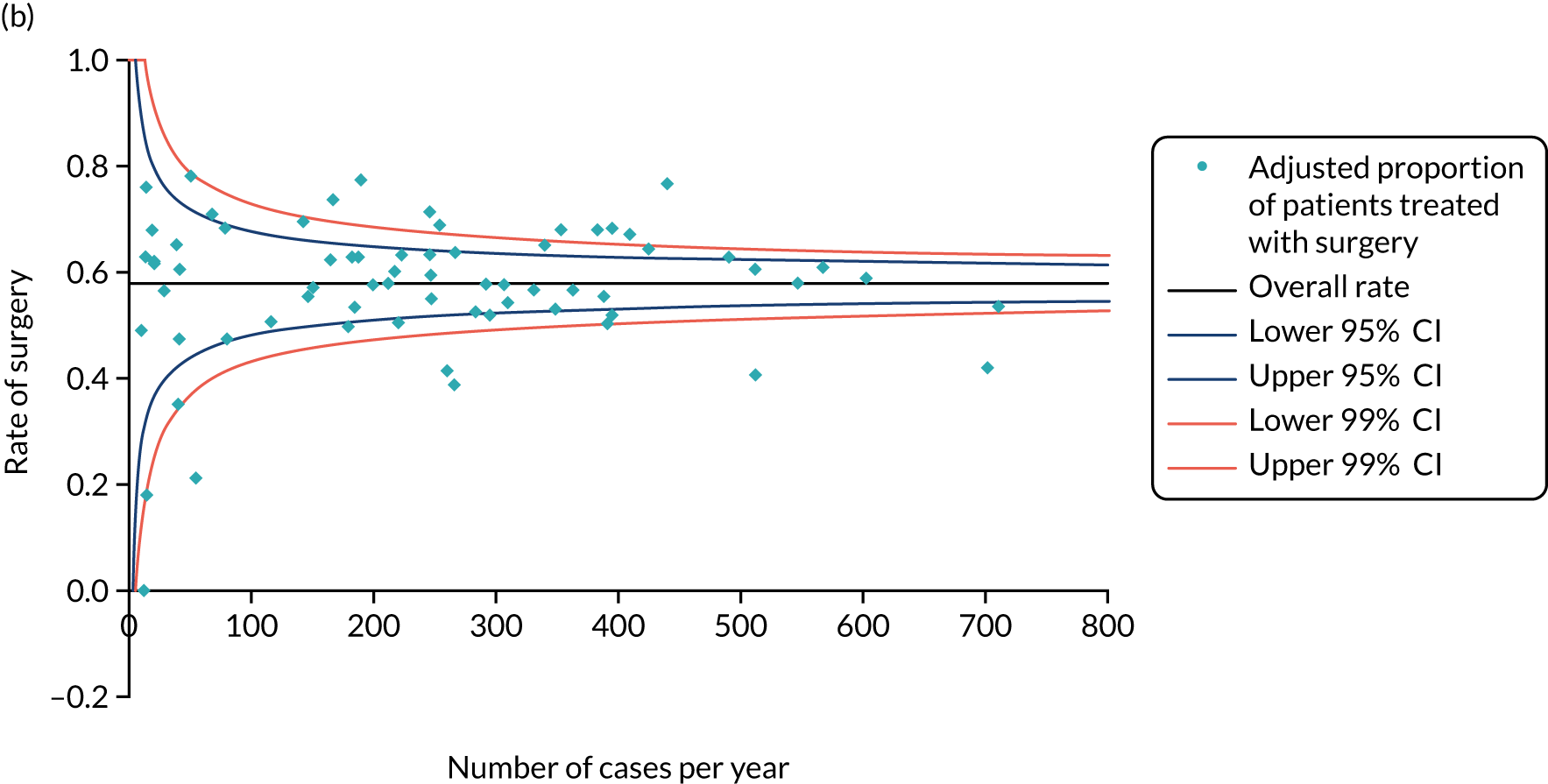

FIGURE 9.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves for adjuvant chemotherapy or no chemotherapy in matched and unmatched groups. (a) OS: unmatched 1; (b) OS: matched 1; (c) BCSS: unmatched 2; (d) BCSS: matched 2; (e) metastatic recurrence-free survival: unmatched 3; and (f) metastatic recurrence-free survival: matched 3.

In the matched population, adjuvant chemotherapy was associated with a longer OS than no chemotherapy, although this was not statistically significant: unadjusted HR 0.79 (95% CI 0.50 to 1.3; p = 0.32) and adjusted HR 0.81 (95% CI 0.50 to 1.31; p = 0.38; see Figure 9).

Breast-cancer-specific survival

Adjuvant chemotherapy did not improve BCSS in the non-matched (unadjusted HR 0.76, 95% CI 0.53 to 1.1; p = 0.15; adjusted HR 0.92, 95% CI 0.56 to 1.53; p = 0.76) or matched populations (unadjusted HR 0.93, 95% CI 0.52 to 1.66; p = 0.80; adjusted HR 0.92, 95% CI 0.50 to 1.69; p = 0.77; see Figure 9), compared with no chemotherapy.

Metastatic-recurrence-free survival

Adjuvant chemotherapy was associated with a lower risk of metastatic recurrence than no chemotherapy in the unmatched population (unadjusted HR 0.67, 95% CI 0.43 to 1.04; p = 0.08; adjusted HR 0.36, 95% CI 0.19 to 0.68; p = 0.002). In 541 matched patients, adjuvant chemotherapy was associated with a lower risk of metastatic recurrence than no chemotherapy (unadjusted HR 0.53, 95% CI 0.26 to 1.07; p = 0.08; adjusted HR 0.43, 95% CI 0.20 to 0.92; p = 0.03; see Figure 9).

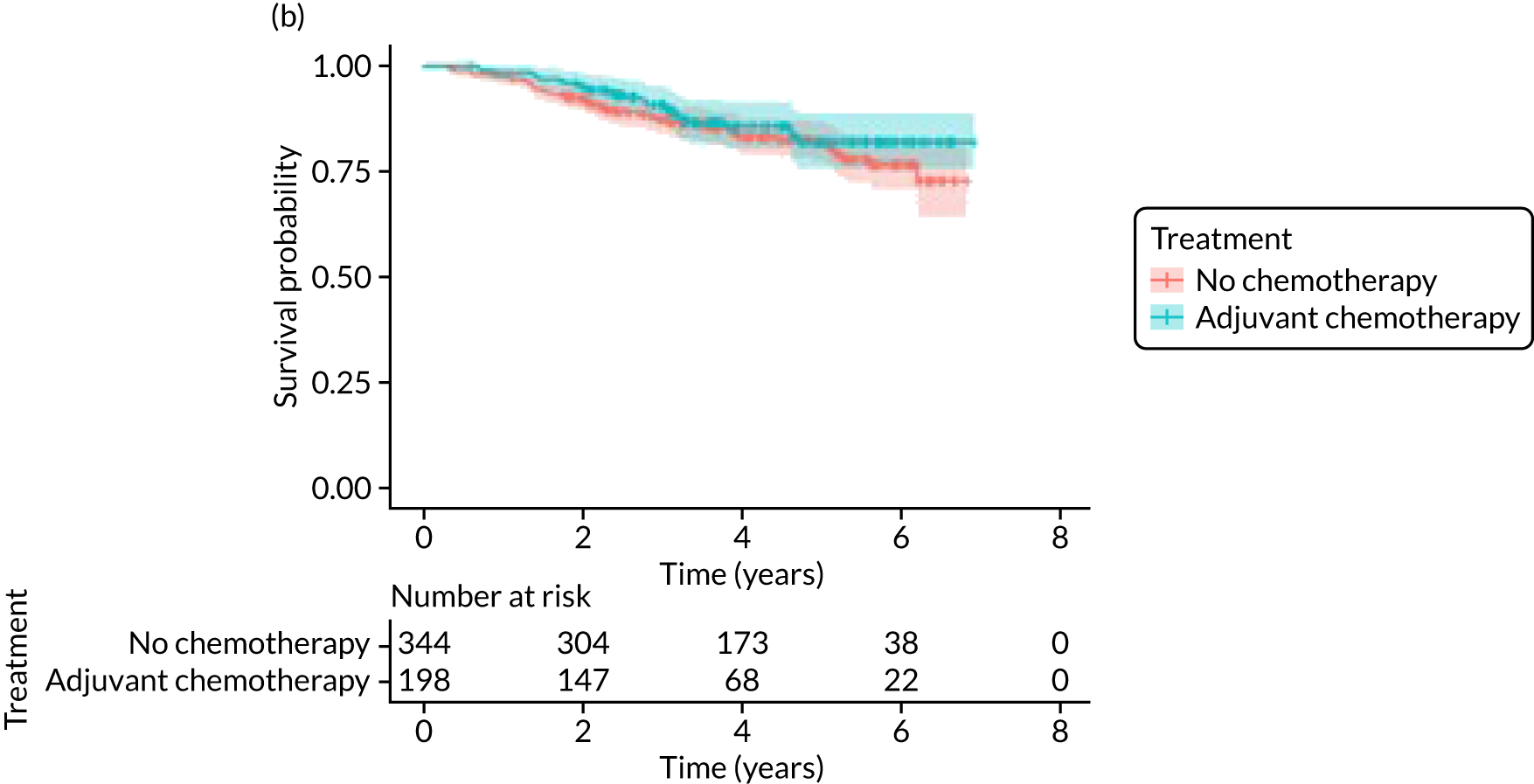

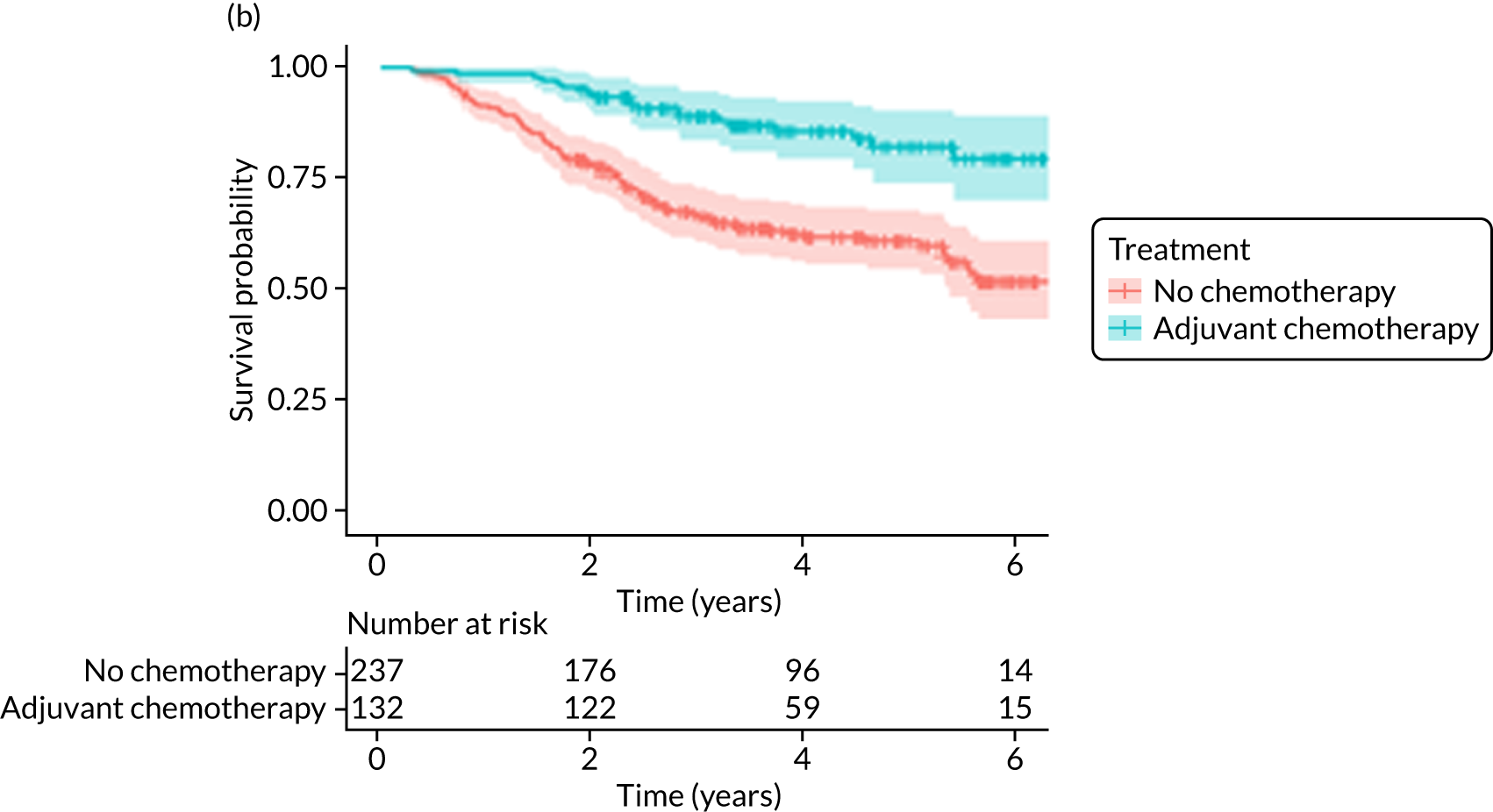

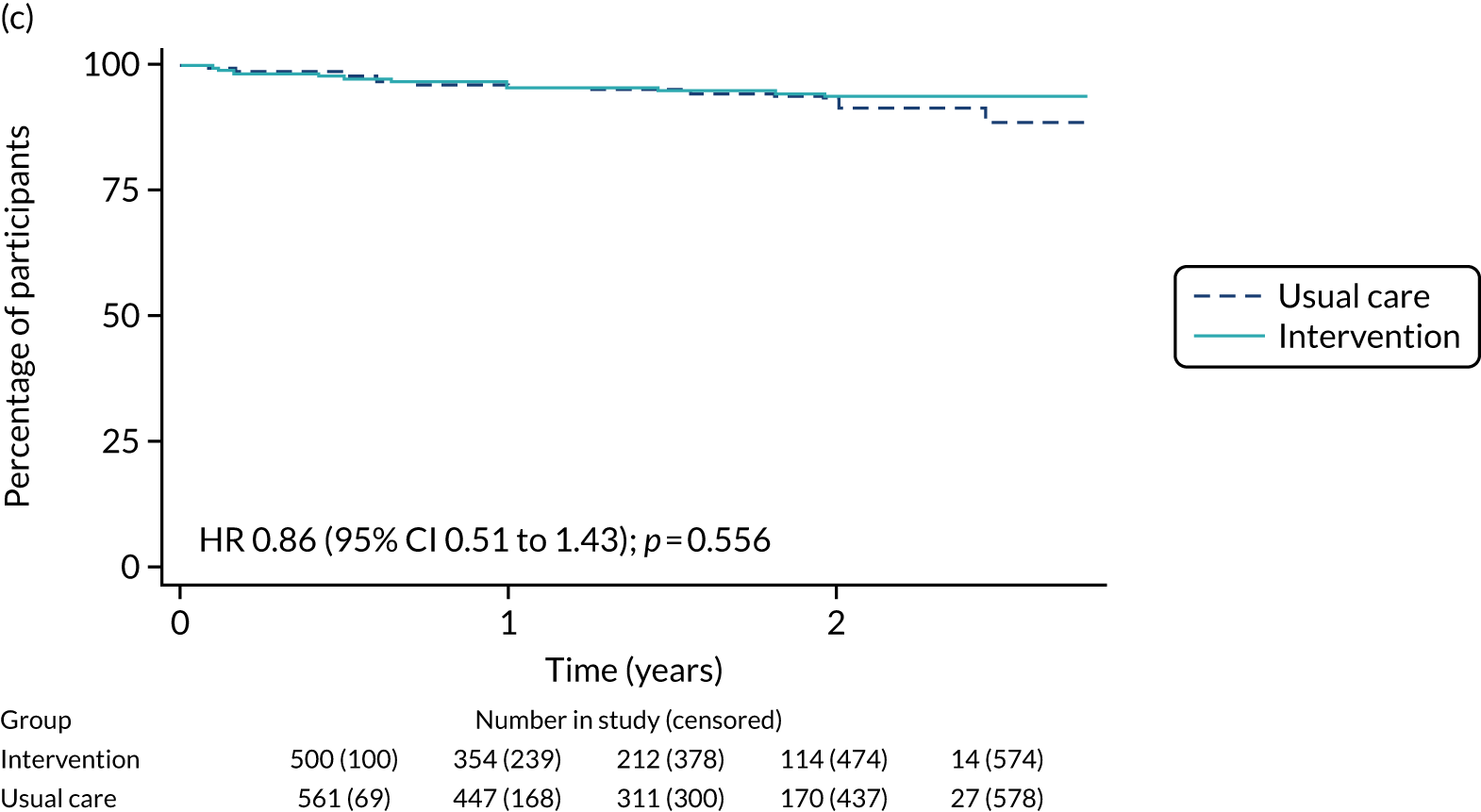

Breast-cancer-subtype-specific analysis of survival

Breast cancers that are ER– and/or HER-2+ are particularly chemosensitive. Therefore, additional exploratory analyses were performed in these subgroups (Figure 10).

FIGURE 10.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves for OS and BCSS in patients treated with adjuvant chemotherapy or no chemotherapy in subgroups with ER– or HER-2+ cancers. (a) OS: HER-2+; (b) OS: ER–; (c) BCSS: HER-2+; and (d) BCSS: ER–.

There were 369 patients with ER– breast cancer with known mortality status, of whom 132 (35.8%) received adjuvant chemotherapy. In a propensity-score-matched analysis of 136 patients, adjuvant chemotherapy was associated with improvements in OS (HR 0.20, 95% CI 0.08 to 0.49) and BCSS (HR 0.12, 95% CI 0.03 to 0.44).

There were 326 patients with HER-2+ breast cancer and known mortality status, of whom 156 (47.9%) received adjuvant chemotherapy with or without trastuzumab. There were fewer deaths from breast cancer and other causes in those who received adjuvant chemotherapy with or without trastuzumab, but, in a matched analysis of 137 patients, the differences were not statistically significant for OS (HR 0.63, 95% CI 0.27 to 1.48) or BCSS (HR 0.50, 95% CI 0.16 to 1.63).

Adjuvant chemotherapy toxicity

Among the 397 patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy, there was one death (0.25%) due to adjuvant chemotherapy (due to congestive heart failure) and 117 (29.5%) patients had an episode of infection. Among the 144 patients who received trastuzumab, four (2.8%) experienced cardiac failure within the first 6 months and 10 (7%) experienced cardiac failure within the first 12 months.

Discussion

Older women treated with adjuvant chemotherapy are younger and fitter and have higher-risk breast cancer (i.e. higher stage, more adverse biology) than those not treated with chemotherapy. When matching for these baseline characteristics is performed, the OS and BCSS benefits disappear. However, in metastatic-recurrence-free survival, a small difference persists in favour of adjuvant chemotherapy in the population of all women, unselected for tumour biology. This apparent benefit did not translate to a survival benefit at 52 months’ follow-up, but longer-term follow-up will be needed to clarify this. 72

It is recognised that the benefits of adjuvant chemotherapy are small for patients with ER+, human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 negative (HER-2–) breast cancer. This study found a benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy in women with ER– breast cancer, with a reduction in the number of breast cancer deaths. These data are consistent with an analysis of US Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) data, which suggested that the benefits of adjuvant chemotherapy in older women were restricted to those with ER– breast cancer. 73

These data relate to women aged between 70 and 79 years. No comment can be made about women aged > 80 years, as there were insufficient patients aged > 80 years receiving adjuvant chemotherapy to permit analysis.

It is clear that the risks of adjuvant chemotherapy must be considered and balanced against these survival benefits for certain subgroups of women. The present study found that mortality rates from adjuvant chemotherapy were very low and side effects were consistent with previous analyses in this setting. 18 QoL outcomes are reviewed in Quality-of-life impacts of adjuvant chemotherapy.

Quality-of-life impacts of adjuvant chemotherapy

Introduction

There are few data about QoL outcomes during adjuvant chemotherapy in older women. 74 This study has evaluated QoL in the Age Gap cohort, comparing women who did and did not receive adjuvant chemotherapy. Considering the high priority that older women give to maintaining their QoL, these data are of great clinical value. This article has been published. 75

Methods

General methods

See The Age Gap prospective observational multicentre cohort study general methods and results.

The Age Gap cohort was analysed, comparing women who did or did not have adjuvant chemotherapy after surgery who had a high risk of recurrence. Both matched and unmatched analyses were performed.

Propensity score matching

The matching process is as described in Adjuvant chemotherapy versus no chemotherapy in women with high-recurrence-risk breast cancer using both unmatched and propensity-score-matched analyses.

Quality-of-life assessment

This is as described in Quality-of-life variation between primary endocrine therapy and surgery plus adjuvant endocrine therapy.

Statistical analyses

The analysis was conducted for patients with high-recurrence-risk cancer for whom QoL questionnaires were available. The mean difference (MD) and 95% CI in the domain scores at each time point, adjusted for baseline scores, were calculated using linear regression models.

The effect of adjuvant chemotherapy on global health scores over time for participants considered as being at high risk was estimated using a mixed-effects linear model that allowed for time, treatment, treatment–time interaction and baseline global health status score. The model was fitted to all high-risk patients and to the propensity-score-matched patients only. For the unmatched analysis, the model also adjusted for age and baseline functionality scores.

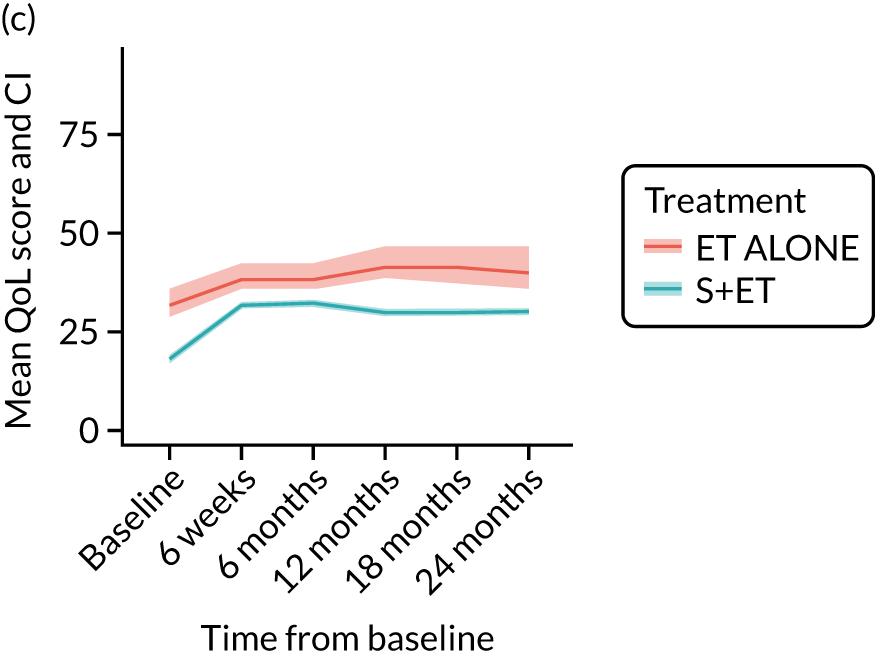

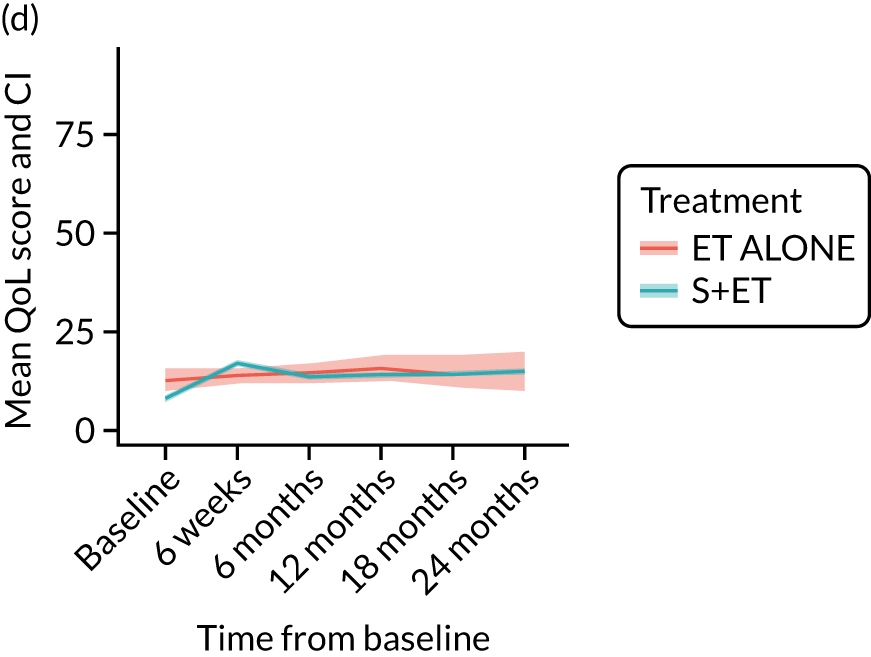

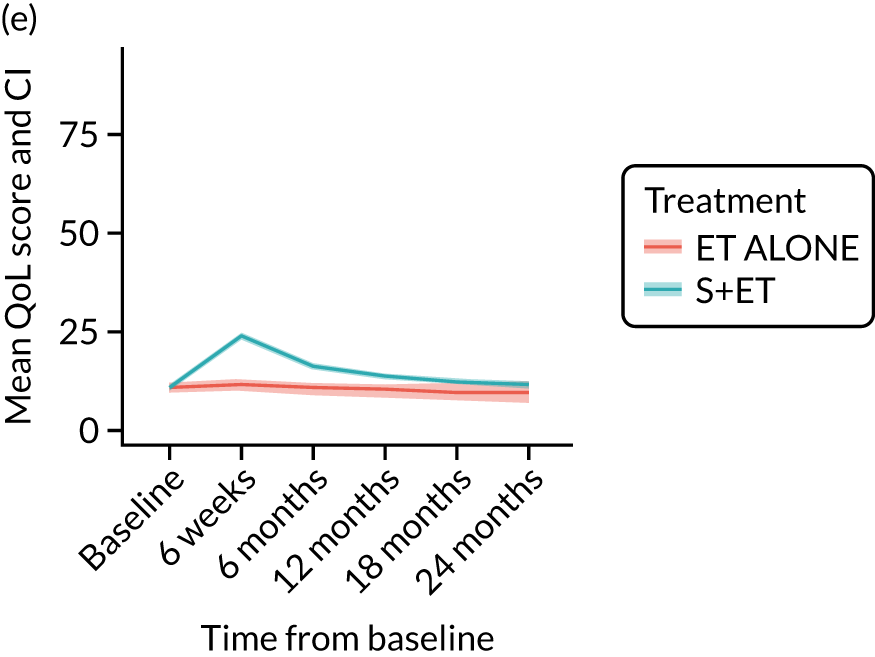

Results

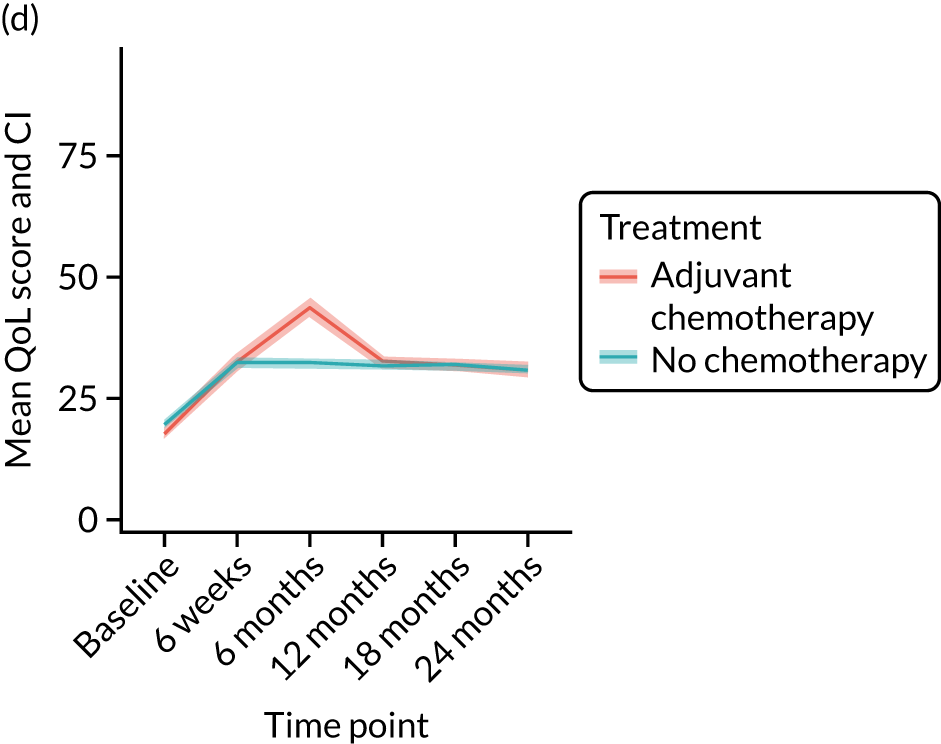

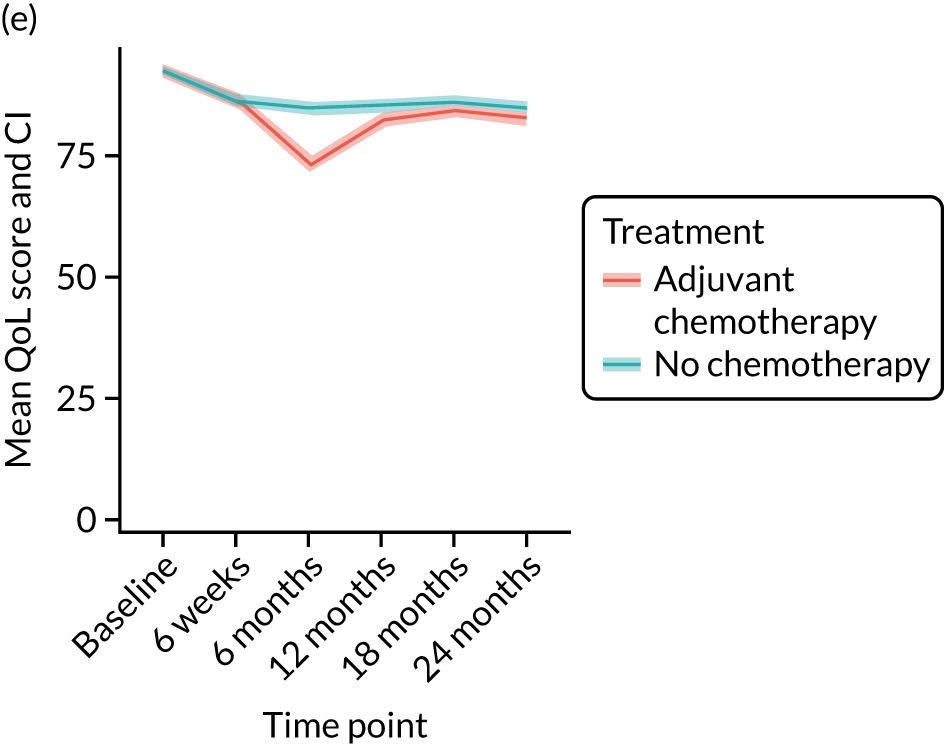

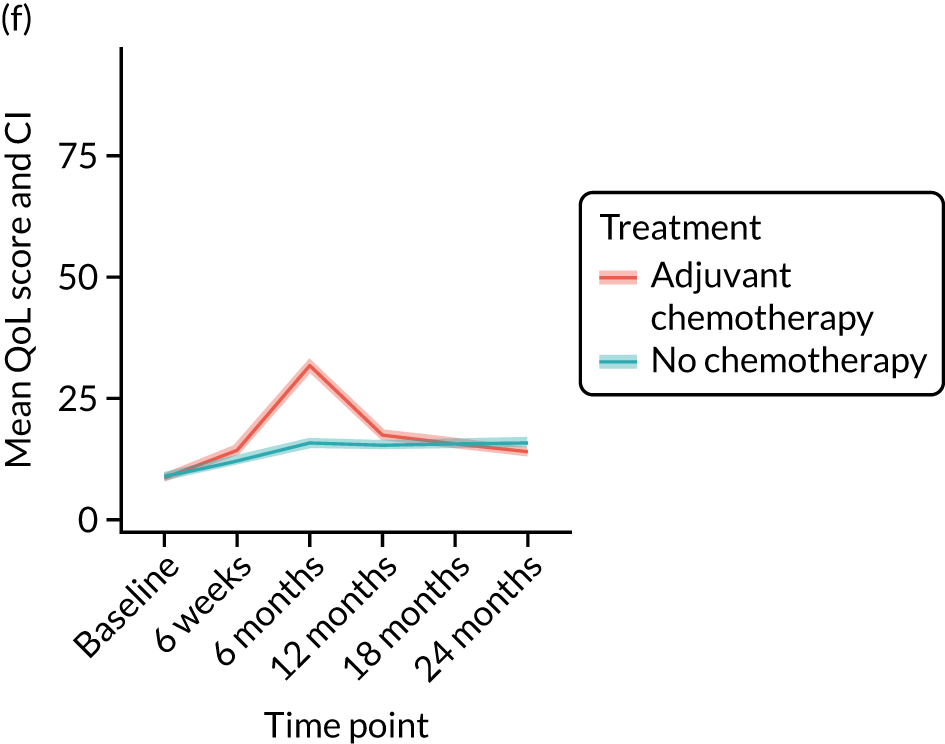

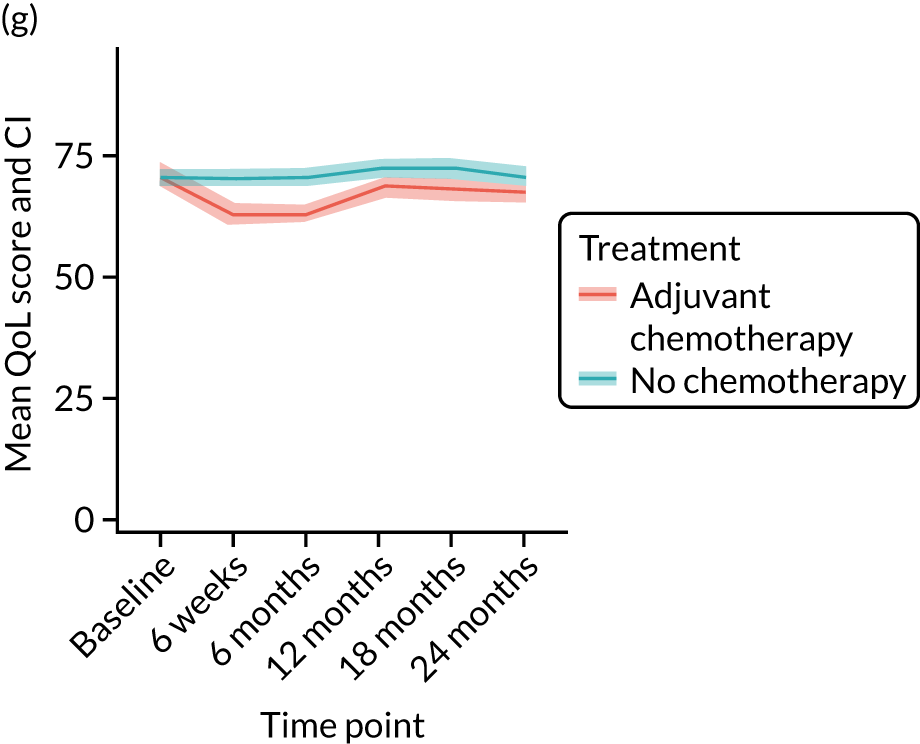

Cohort characteristics

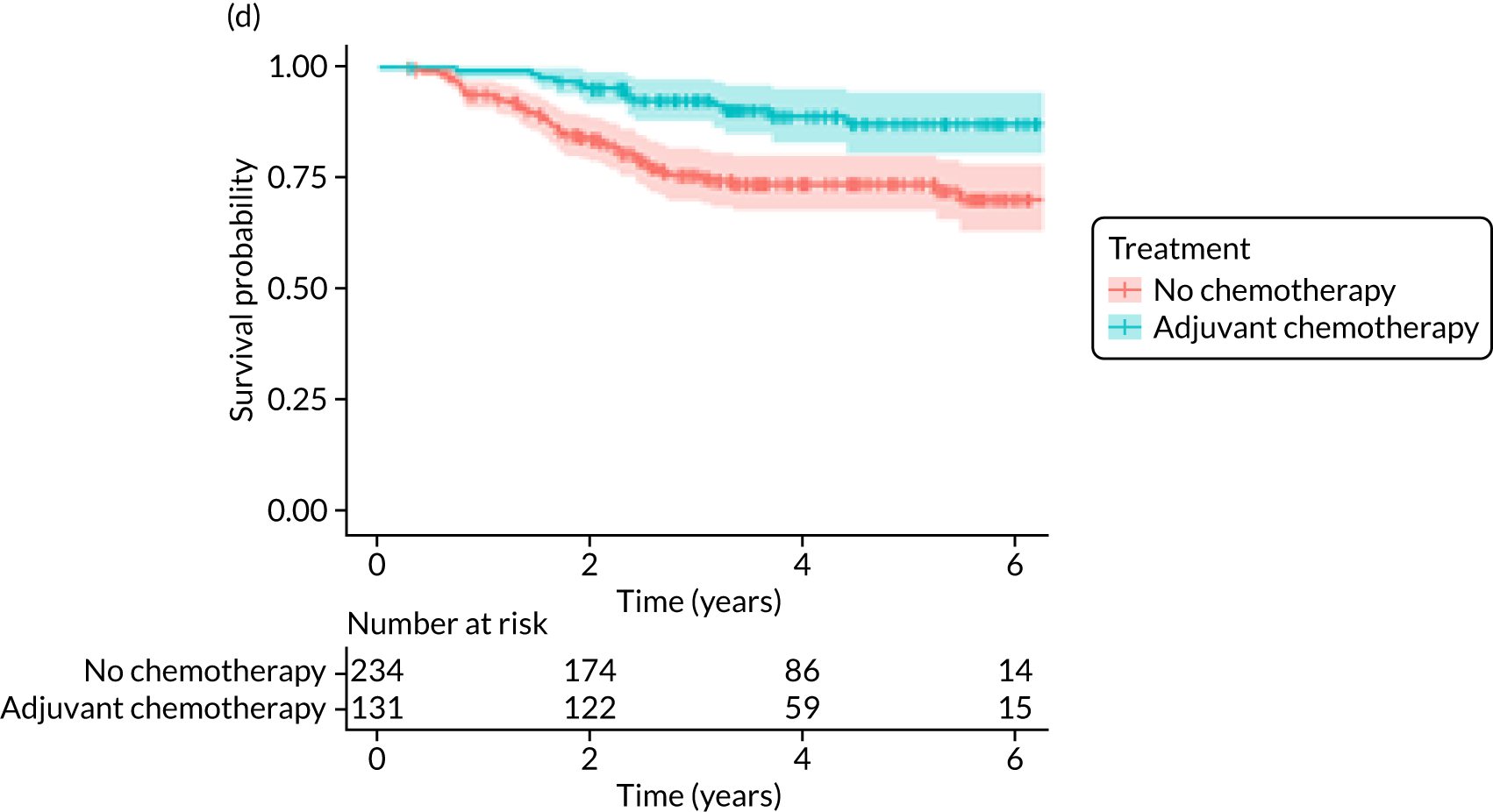

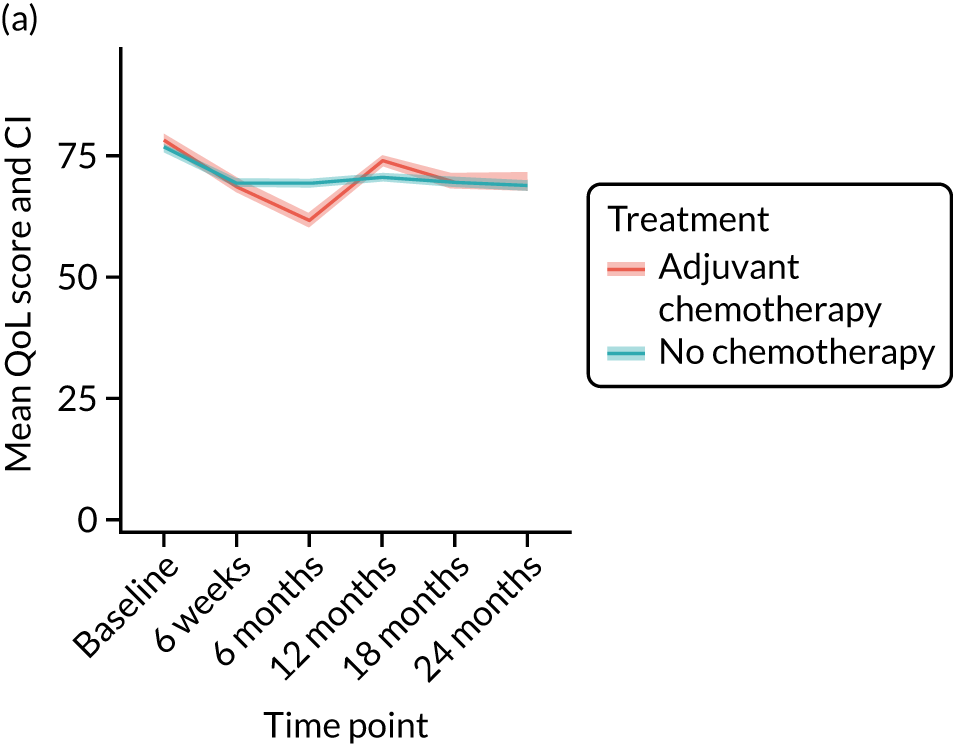

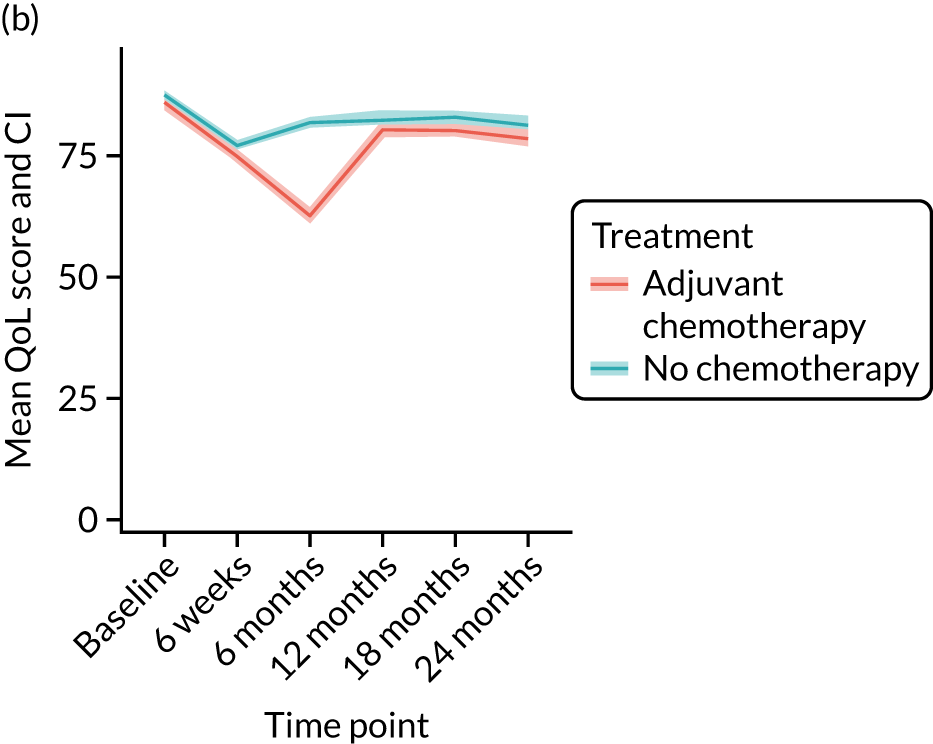

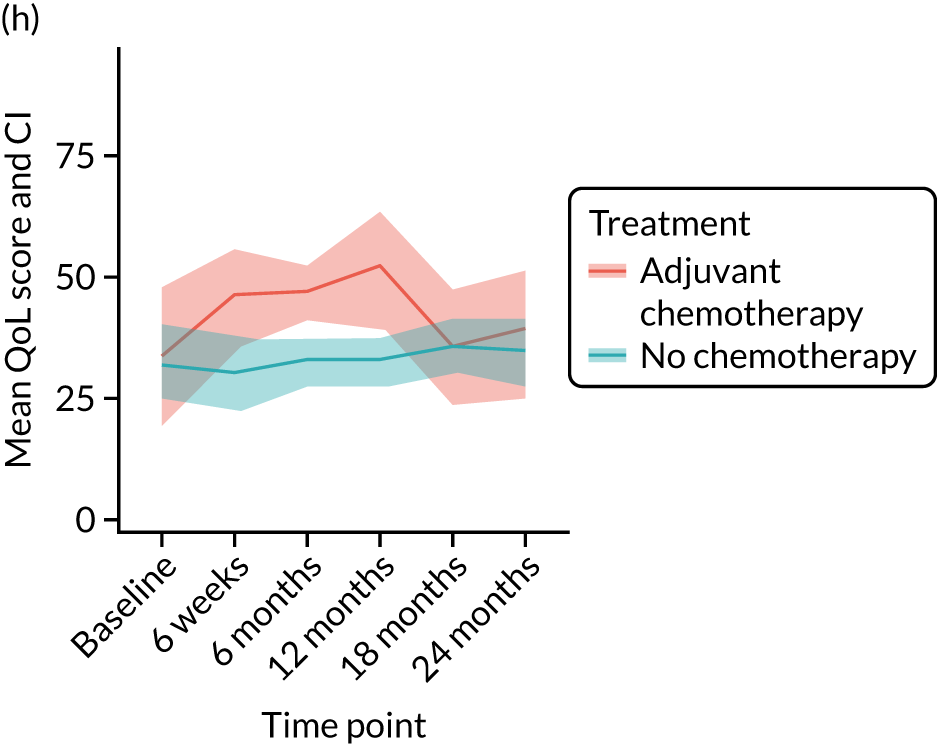

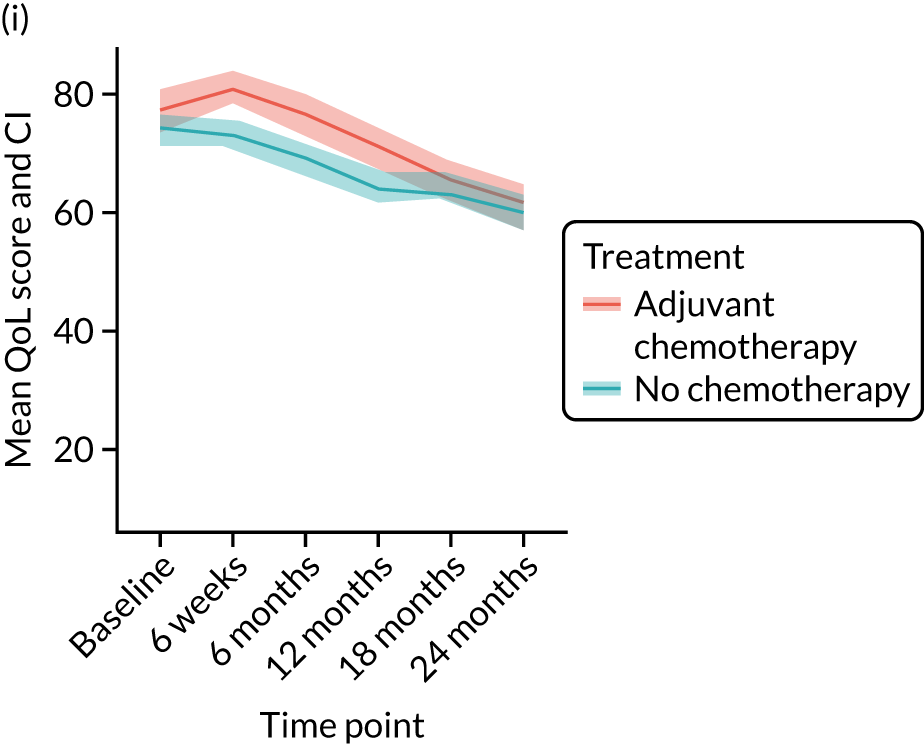

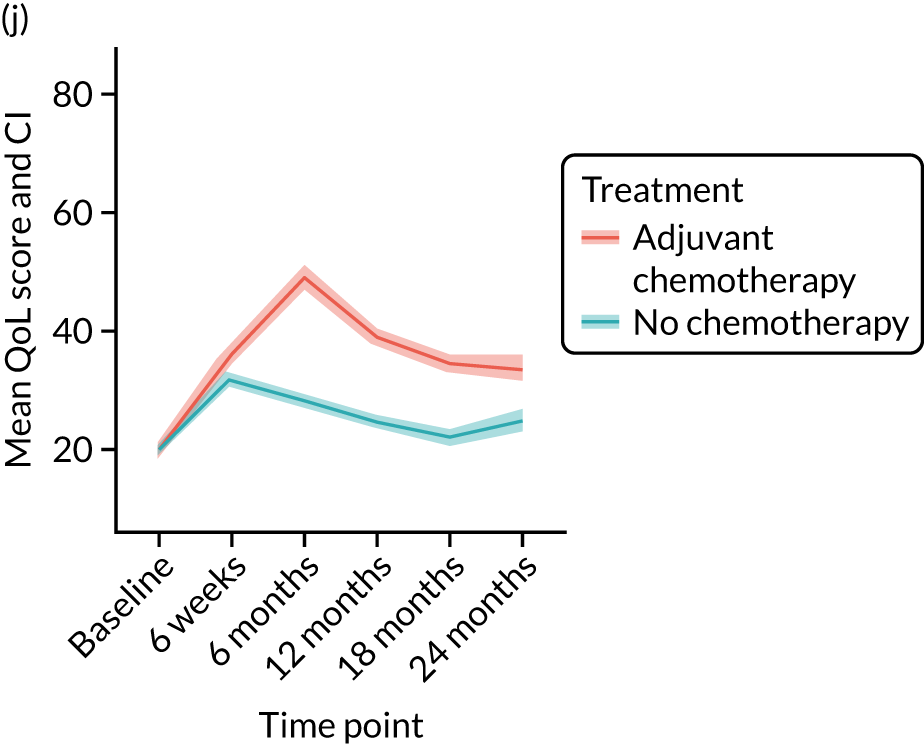

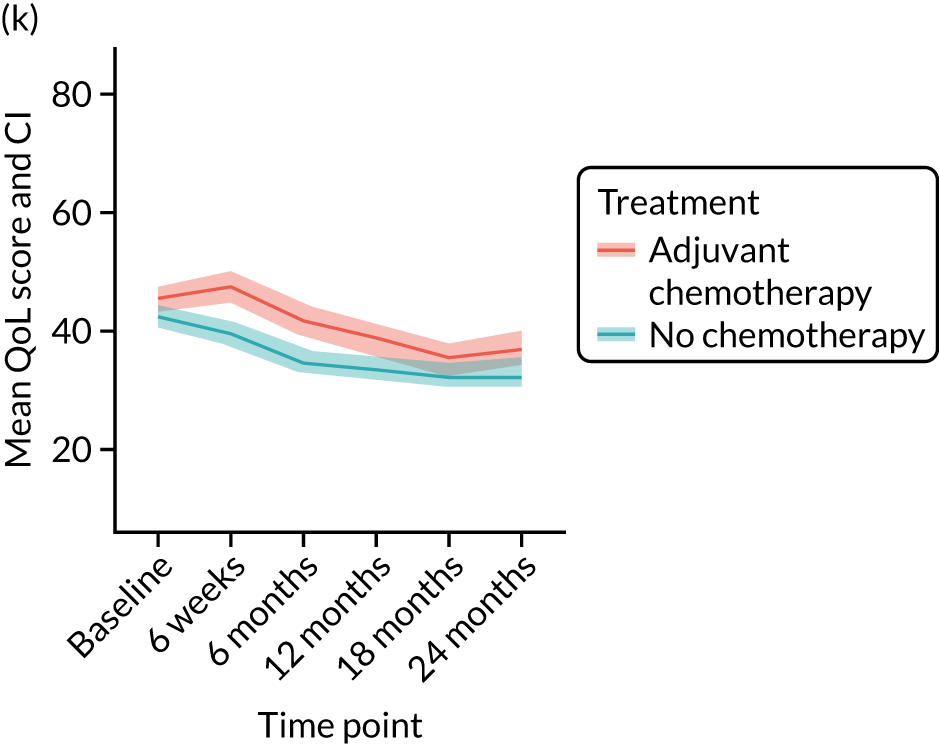

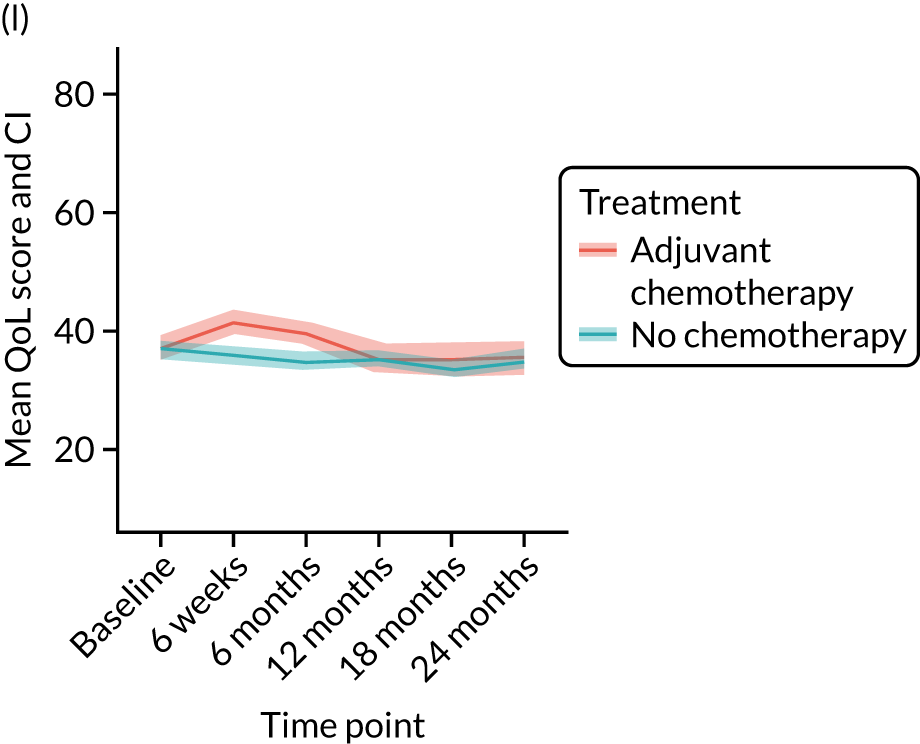

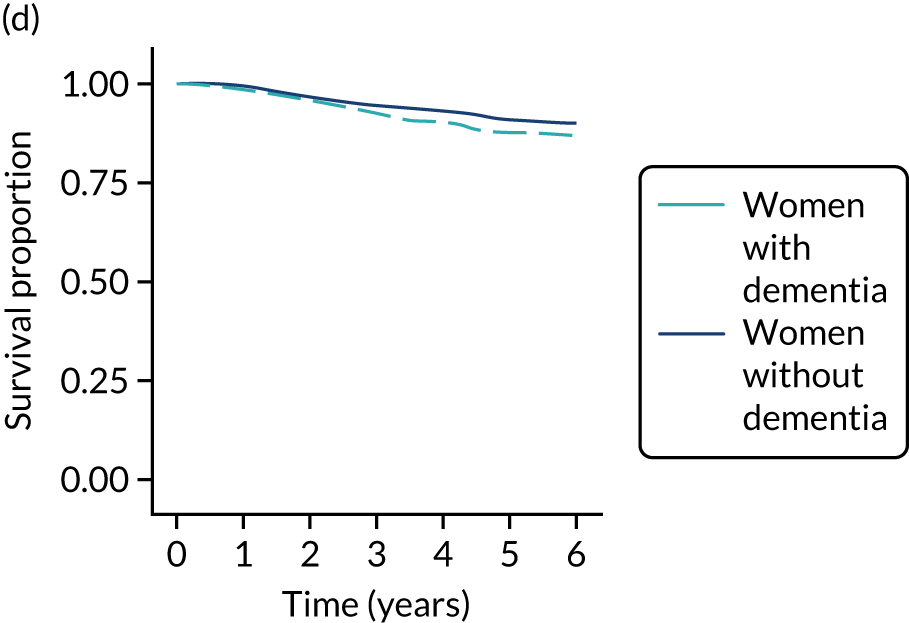

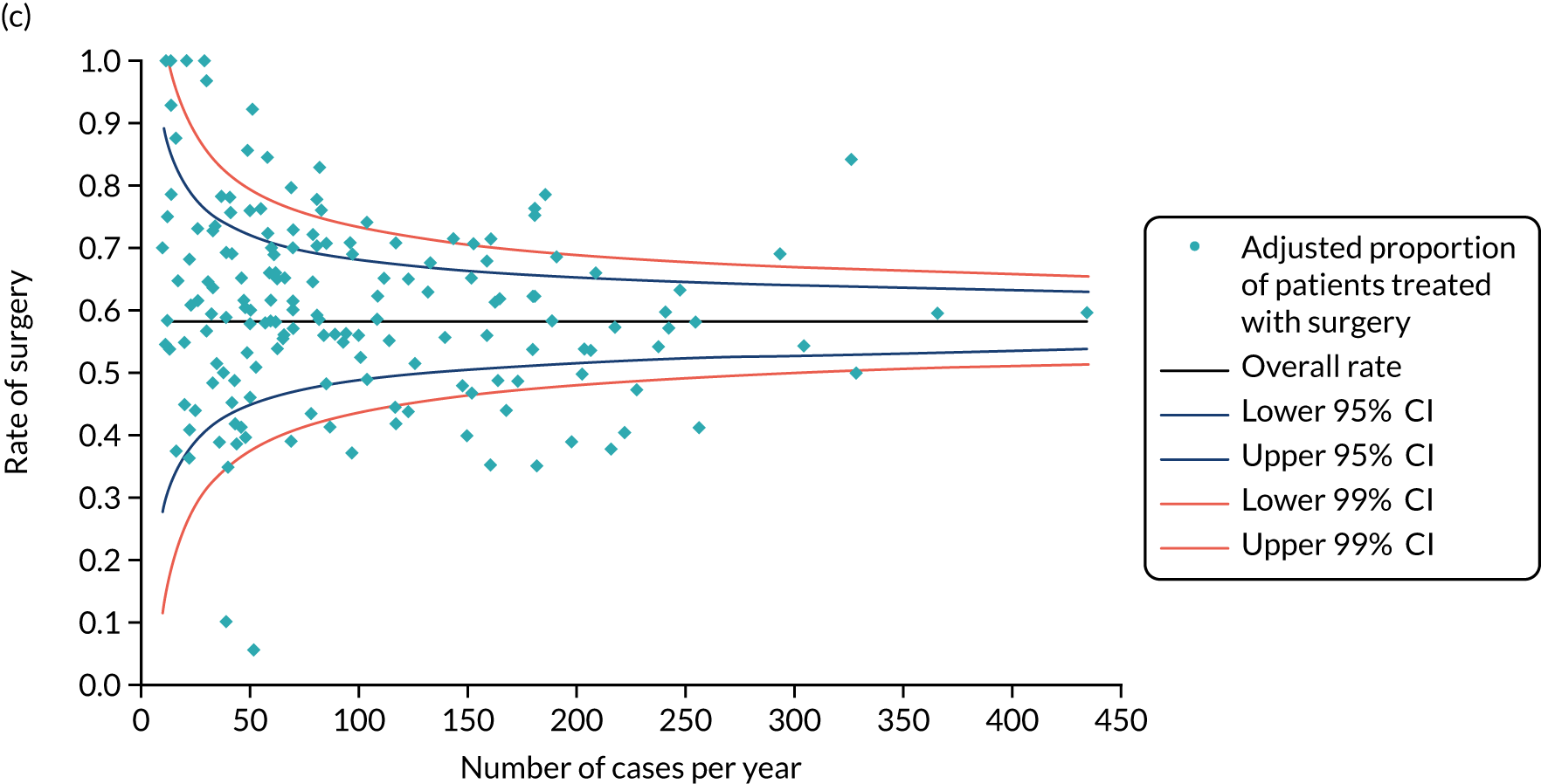

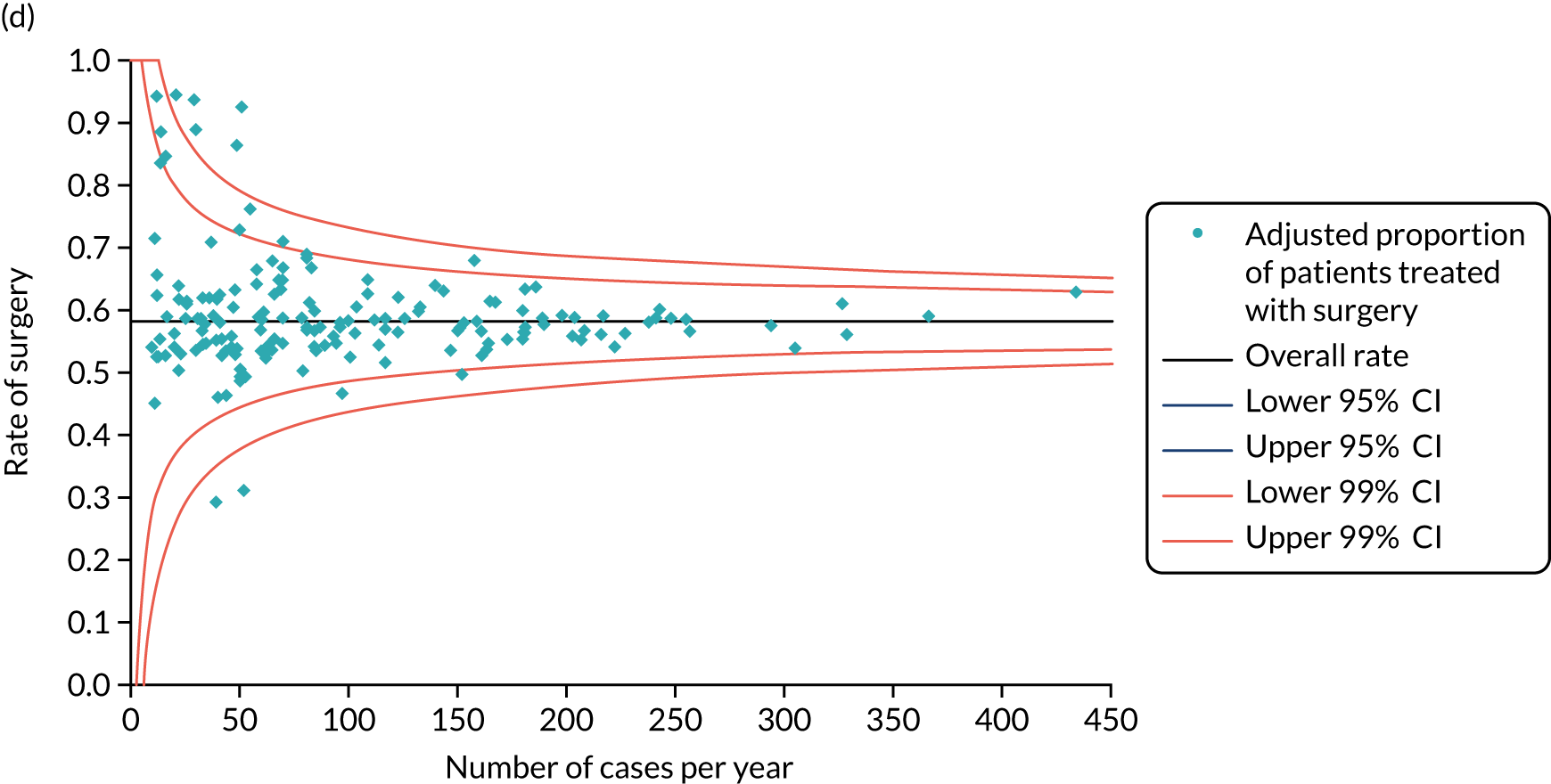

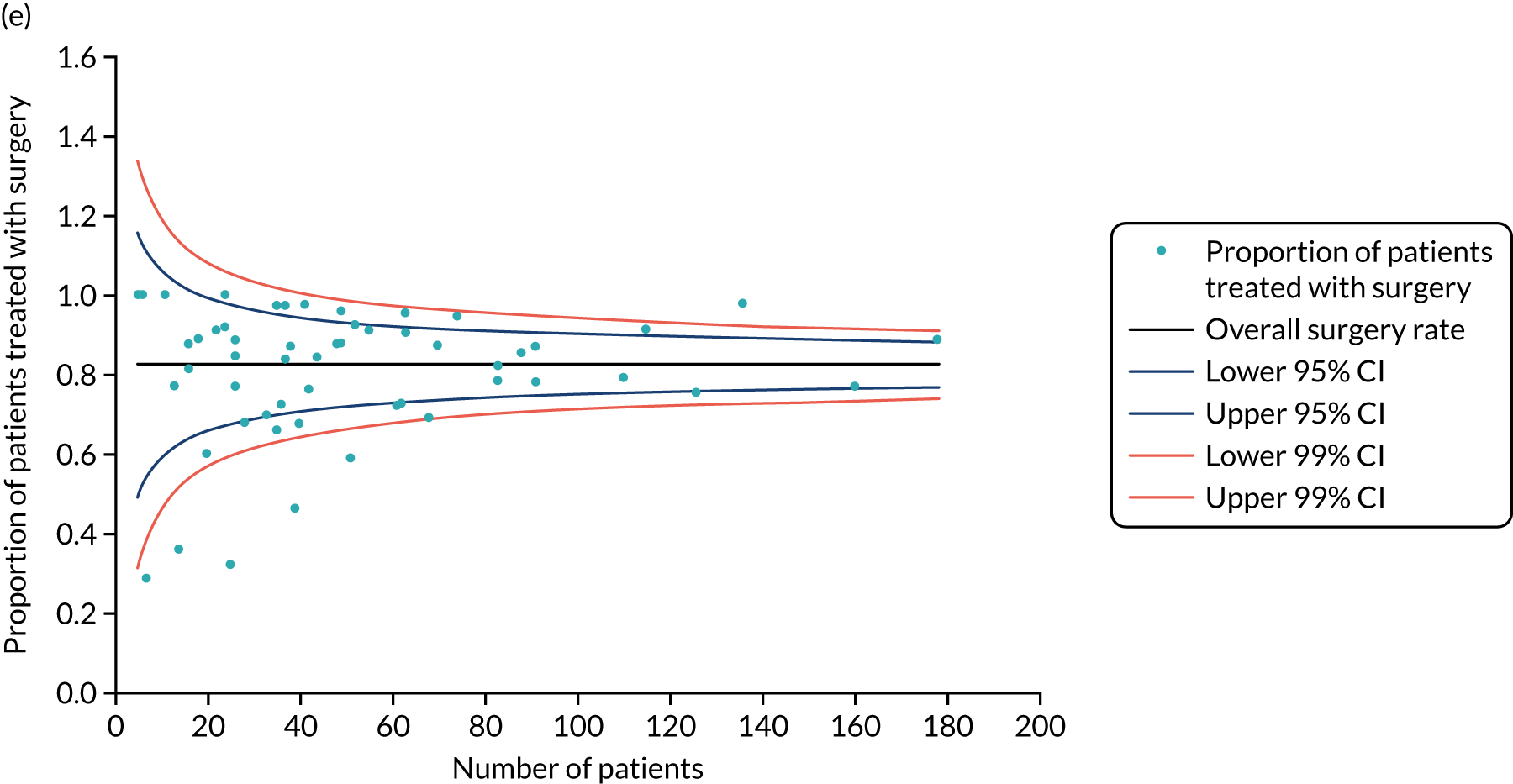

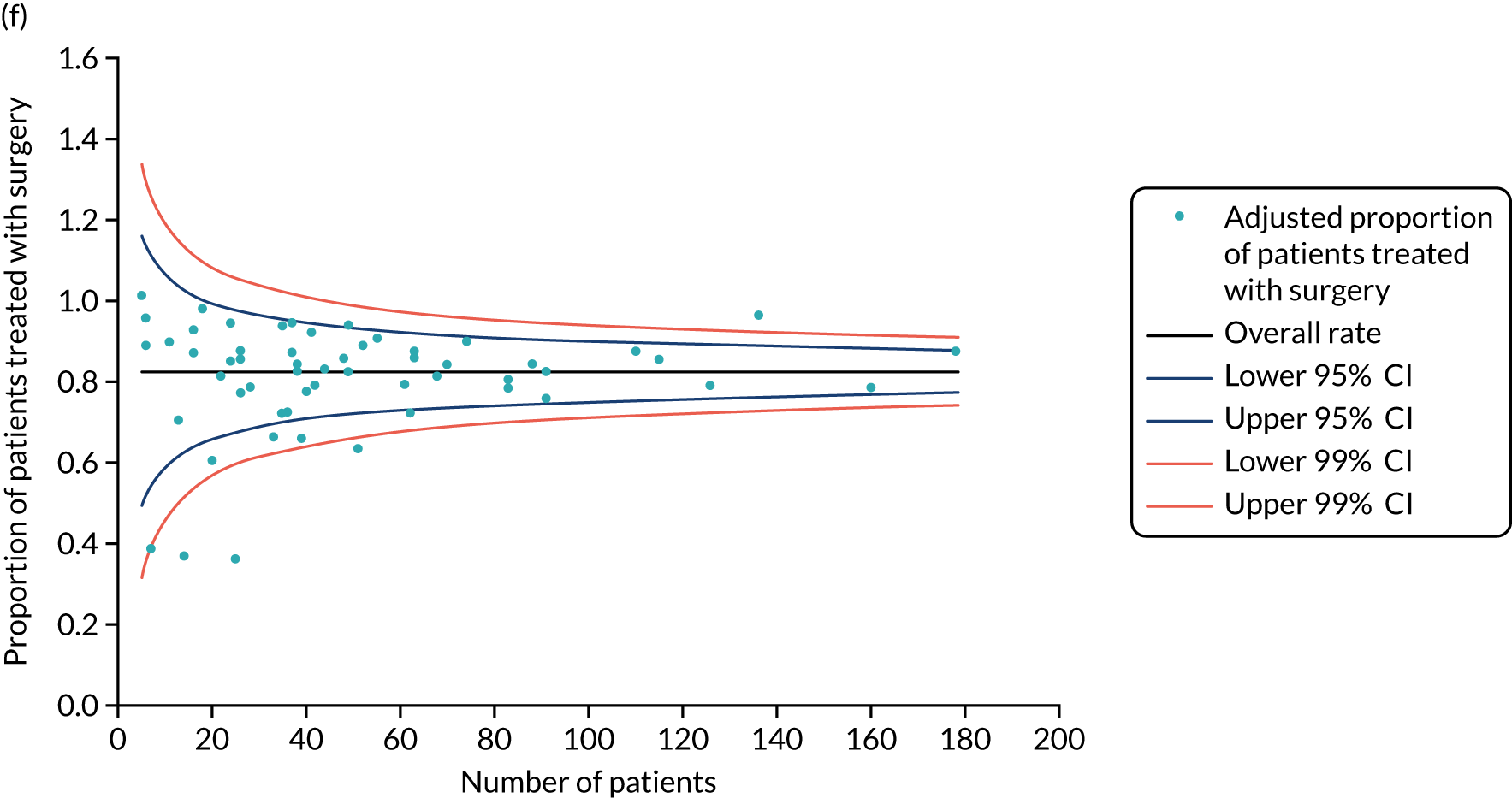

Women receiving adjuvant chemotherapy were younger and fitter and had higher stage disease and more adverse biology. Consequently, matching was used to correct for this baseline variation. Most adjuvant chemotherapy was administered between baseline and 6 months (n = 393), with only four women having adjuvant chemotherapy between 6 and 12 months. The impact of adjuvant chemotherapy is, therefore, most apparent at the 6-month time point.