Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 16/122/33. The contractual start date was in July 2018. The final report began editorial review in April 2021 and was accepted for publication in December 2021. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2023 Moffatt et al. This work was produced by Moffatt et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2023 Moffatt et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced with permission from Moffatt et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited, appropriate credit is given and any changes made indicated. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

Introduction

In this chapter, we provide an overview of the background and context of social prescribing in the UK, highlighting the rapidly shifting policy context that has occurred since this evaluation commenced in June 2018. Social prescribing is now firmly embedded within The NHS Long Term Plan2 as a central aspect of the personalisation agenda. Within Primary Care Networks (PCNs) across England, funding to introduce the role of social prescribing link workers into multidisciplinary teams has been available since July 2019. 2,3 In this chapter, we explore how social prescribing is defined and operationalised in the UK. We critically examine the quantitative and qualitative peer-reviewed literature that demonstrates that an evidence base of the effects of social prescribing is derived from a wide range of settings and ‘lags considerably behind practice’. 4 We outline the study design, aims, objectives, study population and intervention, and explain our rationale for the study’s focus on people with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). We conclude the chapter with a description of the intervention and our approach to patient and public involvement (PPI).

Background and context of social prescribing in the UK

Social prescribing grew from a recognition that patients with complex and long-standing problems require a formal ‘gateway to non-medical management’,5 with estimates that approximately one-fifth of GP consultation time is taken up with non-health matters. 6 Social prescribing-type interventions are not particularly new, especially in the field of mental health. 7 In 2006, the Department of Health and Social Care supported the introduction of social prescribing for people with long-term conditions (LTCs), and there has been increasing interest in social prescribing as a means to address complex health, psychological and social issues presenting in primary care. 8 Social prescribing is highlighted as one of the 10 high-impact actions to reduce workload and increase capacity in general practice9 and is regarded as an intervention with the potential to reduce health inequalities. 2,3

Historically, social prescribing schemes in the UK have been commissioned locally by Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) or local authorities (LAs) and have been delivered by voluntary, community and social enterprise (VCSE) organisations. 10 More recently, however, social prescribing has become part of the NHS personalised care agenda,2 securing national funding through newly formed PCNs. These PCNs bring together neighbouring general practices to expand community multidisciplinary teams, typically covering 30,000–50,000 patients. 2 PCNs can claim reimbursement for the cost of a social prescribing link worker, whom they can employ either directly or via the VCSE organisation. It is projected that, by 2023–24, over 1000 link workers will be funded through PCNs, with 900,000 patients referred. 2 PCNs are being encouraged to work with existing schemes to develop a shared social prescribing plan and expand existing provision. 10 In many regions, local arrangements are still evolving, but uptake of this initiative has been rapid.

How is social prescribing defined and operationalised in the UK?

Despite this rapidly emerging policy context, there remains no agreed single definition of social prescribing within the UK or internationally; however, there is a broad consensus that social prescribing helps patients access non-clinical sources of support, predominantly in the VCSE sector, but also draws on resources supplied by health and local government services. To enable this, front-line health staff, primarily but not solely in primary care, refer patients to a link worker. Once the patient is connected to a link worker, which pre COVID-19 was predominantly face to face, a conversation takes place to identify problems and goals, thereby ‘co-producing a social prescription’ designed to find solutions that will lead to improved health and well-being. 11

Currently within UK practice there is no single model of social prescribing. Rather, social prescribing models cover a spectrum12 that varies according to whether programmes focus on individuals, communities or a combination of both; the level of support offered to patients following referral; and the actual activities offered. Usefully, Husk et al. 4 identified multiple pathways from primary care to activities undertaken and reported that current policy supports link worker-based models. Recognising that patients who are simply given information about a service will not necessarily take it up,13 in most schemes the link worker acts as a ‘facilitator’ and offers personal support, although the level of ongoing support varies considerably. Services into which patients are referred vary and can include clubs offering physical activities, such as gyms, walking groups, gardening clubs and dance clubs, and those offering weight management and healthy eating activities, such as cooking clubs. Addressing wider economic and social issues can involve referral into services that address welfare, debt, housing and employment issues. Support and self-help groups, such as those targeted at people with specific LTCs, for example chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or diabetes, may also be accessed via social prescription. 1

The link worker role is central to social prescribing as currently practised in the UK1,14,15 and elsewhere. 16,17 A 2019 survey of UK CCGs reported 75 different terms for this ‘connector’ role,18 and a recent scoping review identified 18 separate terms that described this position. 19 The link worker role is recognised to be ‘complex and demanding’15 and requires a wide range of skills. 20 Executing the link worker role requires time, interpersonal skills and strong community networks and relies on the existence of onward referral services. 15 There is no clear professional pathway into the link worker role, and link workers come from a range of backgrounds, including the social work, teaching, health-care and VCSE sectors,21 which is likely to affect how they perceive and carry out their role. Previous life and work experience are regarded as important;20 link workers employed via the NHS are required to have a National Vocational Qualification (NVQ) at level 3 or above. 13 The relatively limited peer-reviewed literature on the role indicates that link workers can feel inadequately trained to deal with highly vulnerable clients with complex issues that involve time-consuming case management; therefore, link workers can lack capacity to meet the needs of large numbers of referrals and can also face problems related to service cuts or unacceptably long waiting lists for onward referrals. 20,22 There is now a professional membership network for UK link workers23 and, although link working is recognised as a rewarding role,21 lack of clinical supervision and support is commonly reported among link workers based in primary care and is cited as a reason for leaving. 24

Introducing new services into primary care, irrespective of how appropriate they may be, is not straightforward and requires belief in the benefits and ‘buy-in’ from those expected to refer to the service. 14,25,26 Moreover, referrals to PCN link workers can come from hospitals, allied health workers, the police, the fire service, job centres, social services and the VCSE sector, among others. 13 The role of the general practitioner (GP) and other members of the primary care team in relation to social prescribing is not well understood,27 given that overall a relatively small number of GPs have been included in studies about social prescribing26–30 and even fewer studies include other members of the primary care team. 31,32 Enabling linkage between primary care and social prescribing relies on procedures that facilitate appropriate referrals of patients who meet the social prescribing service criteria. This requires co-operation and trust between members of the primary care team and the social prescribing service(s). 32 A recent qualitative study of the barriers to, and facilitators of, social prescribing for patients with mental health problems based on the views of 17 GPs found that most GPs in the study were supportive of social prescribing and reported that it enabled their patients to be better connected to their local VCSE organisations. 27 Link workers were seen to have more time with clients than the GP and, therefore, were able to act as a bridge between the GP and the community. This contrasts with previous findings from interviews with GPs (n = 3) and district nurses (n = 8) in the west of Scotland, who saw their focus as predominantly clinical and expressed concerns about being held accountable for the actions of unknown or unverified organisations that their patients were linked into. 32 In an interesting overlap between the views of GPs,27 link workers33 and the wider VSCE sector,22 capacity, resources and precarity of the VCSE organisation in the context of austerity were seen as significant challenges to social prescribing. 25

Social prescribing has been the topic of a number of editorials in the medical press, with some arguing the case strongly for social prescribing34 and others being more circumspect. 35,36 Concern has also been raised that the use of the term ‘prescribing’ further medicalises problems that require non-medical support. 37,38 Most apparent is unease about the current level of evidence for the effectiveness of social prescribing on health and well-being outcomes and resource use. 35–37,39 It would appear that there is a strong sense of the potential for social prescribing to improve patient well-being and an awareness that conducting robust research on social prescribing is challenging,40 but that obtaining this evidence is necessary for health professionals to more fully engage with social prescribing. 39

What is the evidence for the effectiveness of link worker social prescribing in UK health-care settings?

Quantitative evaluations of the impact of social prescribing

Bickerdike et al. ’s41 systematic review of 15 social prescribing evaluations, published in 2017, included evaluations published between 2000 and January 2016 in which the primary outcome of interest was any measure of health and well-being and/or usage of health services. The authors concluded that there was:

. . . little convincing evidence for either effectiveness or value for money . . . most evaluations are small scale and limited by poor design and reporting . . . common design weaknesses include a lack of comparators, loss to follow-up, short follow-up durations and lack of standardised and validated measuring tools . . . a distinct failure to consider and/or adjust for potential confounding factors, undermining the ability to attribute any reported positive outcomes to the intervention (or indeed interventions) received.

A subsequent evidence synthesis by Public Health England,42 which included eight studies, examined the effectiveness of social prescribing on (1) contact with primary health care and (2) changes in physical and/or mental health. It concluded that there was no clear evidence for effectiveness.

Although the number of peer-reviewed publications on social prescribing has increased considerably since 2017,19 the number of UK peer-reviewed studies using quantitative health-related outcome measures is still relatively small. Focusing on the UK, between the end of Bickerdike et al. ’s41 review period in 2016 and December 2020, we used similar search terms (see Report Supplementary Material 1). We identified 10 peer-reviewed studies that had quantitative outcome measures (five quantitative and five mixed methods) and evaluated the impact of nine UK social prescribing initiatives on clients’ health, well-being or resource use. Our focus was on peer-reviewed studies; however, we did not include a ‘museums on prescription’ intervention43 because this did not involve a link worker-type facilitator and, because of our focus on social prescribing in primary care, we also excluded a social prescribing initiative in secondary care mental health services. 7 The shared characteristic of the social prescribing interventions evaluated (see Appendix 1, Table 36) is that they link primary care and local assets and services via a link worker, connector or facilitator. Thereafter, the similarities end and each study evaluated a different model of social prescribing, funded via different sources and delivered by a different type of ‘facilitator’, including paid staff and a combination of paid staff and volunteers. 44,45 The interventions varied considerably in ‘intensity’, for example six sessions,46 12-week programmes5,45,47,48 or no limits on time with a community links practitioner (CLP). 49 The intervention target populations varied: they were predominantly aimed at adults aged ≥ 18 years, although one intervention was aimed at those aged ≥ 14 years. 46 Most interventions were targeted at people in mid to later life living in areas of high socioeconomic deprivation and experiencing LTCs, multimorbidity, mental health problems, loneliness and social isolation; these people typically have frequent attendance in primary care and polypharmacy.

The specific aims of the evaluated interventions varied. They include supporting people with complex needs and living in deprived inner-city localities;49,50 improving patient well-being, increasing personal self-efficacy, reducing primary care use/health and social care use, addressing polypharmacy;5,44,48 reducing social isolation/loneliness;45,46,51 improving mental health;48,52 and increasing physical activity. 47 A range of study designs and outcome measures were used. Most studies used a before-and-after design. 5,45–48,50–52 Two studies included matched comparison groups: a before-and-after postal questionnaire study design44 and a quasi-experimental cluster-randomised controlled trial (RCT) design. 49 The latter study49 is the most methodologically robust study to date.

Outcome measures included depression and anxiety,44,50 energy expenditure,47 physical activity,49 general/subjective well-being,44,46,48,50,52 loneliness,45 social support,51 social networks46 and health-related quality of life (HRQoL) [as measured using the EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L)]. 46,49,51 However, in some studies it was not clear what the primary outcome was. Three studies examined changes in primary health-care resource use:5,44,48 one examined self-reported GP usage,46 two studies examined accident and emergency (A&E) use44,48 and one study examined change in repeat medication. 5

The two studies with control groups44,49 found no statistically significant differences in patient-reported outcomes between baseline and 8 months44 or in health-related quality of life (as measured using the EQ-5D-5L) between baseline and 9 months. 49 However, in the latter study,49 some improvements were found in those patients who engaged with the programme as opposed to those simply being referred. 49,53 Outcomes for the uncontrolled studies showed a varying picture, with high rates of attrition and relatively small sample sizes at follow-up being common. In one study,48 statistically significant improvements in measures of health, well-being, patient activation and frailty were identified at the 12-month follow-up (n = 86, constituting 57% of the sample). 48 In another study,52 a statistically significant improvement in subjective well-being was reported from baseline to post intervention. However, this study suffered from high rates of attrition, with 87.8% of patients either lost to follow-up or not engaging with the intervention. 52 Statistically significant improvements in subjective well-being, social networks and EuroQol-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) overall health rating were reported in another study. 46 However, the number of clients in this study completing the baseline and post-intervention assessments (n = 265) was considerably smaller than the 2250–3750 users reported as being in contact with the service. Furthermore, these results included only individuals who had engaged with the full six sessions. In a national study in which the primary outcome was loneliness,45 over 70% of clients (n = 1634) reported reduced loneliness (p < 0.0001) immediately post intervention; however, 3-month follow-up data from a subsample of users (n = 101) showed that 60% were experiencing increased loneliness. 45 With regard to primary care use and polypharmacy,5 prescribed medication44 and self-reported health-care utilisation,46,49 no differences were found in these measures from baseline to post intervention. However, a statistically significant decrease in the median number of GP consultations was identified,44 although the authors did not rule out regression to the mean. Overall, this body of peer-reviewed research did not robustly demonstrate beneficial effects on quantifiable health outcome measures or health-care resource use, reinforcing Bickerdike et al. ’s41 systematic review conclusions. However, the challenges in identifying which outcomes to measure and in which ways should not be underestimated. 39

Qualitative evaluations of the impact of social prescribing

Qualitative research with patients who accept their referral and engage with services generally indicates positive evaluations of social prescribing services. 1,53,54 In three of the previously mentioned studies with quantitative components,5,44,49 linked qualitative data about the perceived impact of social prescribing by clients indicated positive narratives that were not reflected in the quantitative data. Of these linked studies, the most detailed qualitative analysis identified considerable variation in the perceived impact of the Glasgow ‘Deep-End’ Link Worker Programme, ranging from no change to moderate/major improvement. 53 Twelve adults aged 34–67 years with a combination of social, psychological and physical problems were interviewed. Some saw the CLP as a catalyst for behaviours and activities that improved their well-being. In contrast, others reported that the CLP had provided practical support, which improved psychological well-being but had no effect on health-related behaviours, or that the intervention resulted in no benefits. 53 Feeling understood and developing a supportive relationship with the CLP were identified as important, but not on their own sufficient to facilitate improvements. A further requirement for improvement was the development of ‘wider social relationships and developing competence to engage in the wider community’. 53

A qualitative study of 30 patients aged 40–74 years with LTCs who engaged with a social prescribing intervention identified that most patients experienced multimorbidity combined with mental health problems, low self-confidence and social isolation, and all were adversely affected by their health problems. 1 The social prescribing intervention, with which it was possible to be engaged for up to 3.5 years, engendered feelings of control, self-confidence and reduced social isolation; had a positive effect on health-related behaviours and LTC management; and improved mental health. 1 A qualitative follow-up study54 of 24 individuals, who had been with the social prescribing intervention for between 12 and 24 months, found that participants reported improvements in condition management and health-related behaviours and reduced social isolation. However, setbacks related to multimorbidity, family circumstances and social, economic or cultural factors were also identified, which highlighted the importance of long-term support and link worker continuity. 54 As has been reported elsewhere,25,53,55,56 the availability of a supportive and easily accessible link worker able to deliver a personalised service that reflect individual goal-setting priorities, enable gradual change and deal with issues beyond health was both positively appraised and seen as important to maintaining positive changes. Hanlon et al. 53 and Wildman et al. 54 emphasise the importance of an approach that addresses both individual behavioural change and wider structural barriers in the context of socioeconomic deprivation. Furthermore, as has already been highlighted by GPs and organisations, the availability of suitable onward referral services is an important consideration for social prescribing at a time of severely constrained public spending. 54,55

Qualitative research that has explored challenges in delivering social prescribing services55 and the uptake of and adherence to social prescribing56 further highlights the importance of the link worker–client relationship, the complexity of the link worker role, patient expectations, the availability and cost of onward referral services, fear of stigma about psychosocial problems, short-term programmes and the need for strong community infrastructure. Husk et al. ’s4 recent realist review indicates that patients are more likely to accept a social prescribing referral if the intervention matches their needs and expectations and is presented to them in an acceptable way; patients are more likely to engage if they are supported to connect with accessible activities; and patients are more likely to adhere to the intervention because of skilled facilitators or condition/symptom change.

Quantitative and qualitative research highlights the complex phenomenon that is social prescribing, which is described as a ‘pathway and series of relationships’4 and not a single intervention, making it challenging to evaluate. As yet, it is not possible to make inferences about the efficacy of any particular model over another. 4 Current research into social prescribing indicates the need for longer-term outcome evaluation using robust routine data and mixed-methods design. If quantifiable effects of social prescribing are identified, the important questions are why, how and for whom these effects are seen. If there are no quantifiable effects, questions remain about why this is the case. The literature also highlights many gaps in our understanding of social prescribing, including the link worker role, service user experiences, the role of VCSE, integration into primary care, impacts on secondary services use, cost implications and cost-effectiveness.

Study design, aims and objectives

The study aimed to evaluate the impact and costs of a community-based link worker social prescribing intervention on the health and health-care utilisation of adults aged 40–74 years with T2DM to observe how link workers delivered the intervention and how patients engaged with social prescribing. A further study was undertaken in response to the COVID-19 pandemic that aimed to capture the experiences of patients with LTCs in receipt of social prescribing during and immediately after the first lockdown period.

This multimethods evaluation comprised three work packages (WPs).

Work package 1

Work package 1 (WP1) had the following objectives:

-

to measure the short-term (i.e. 1-year) and long-term (i.e. 2- and 3-year) effects of the social prescribing intervention targeting adults with T2DM on levels of glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c; primary outcome), body mass index (BMI), blood pressure (BP), cholesterol levels, smoking status and health-care utilisation

-

to provide a range of estimated intervention effects based on comparing the intervention group with a number of relevant control groups

-

to examine differential intervention effects in subgroups by gender, age, ethnicity, multimorbidity and deprivation level

-

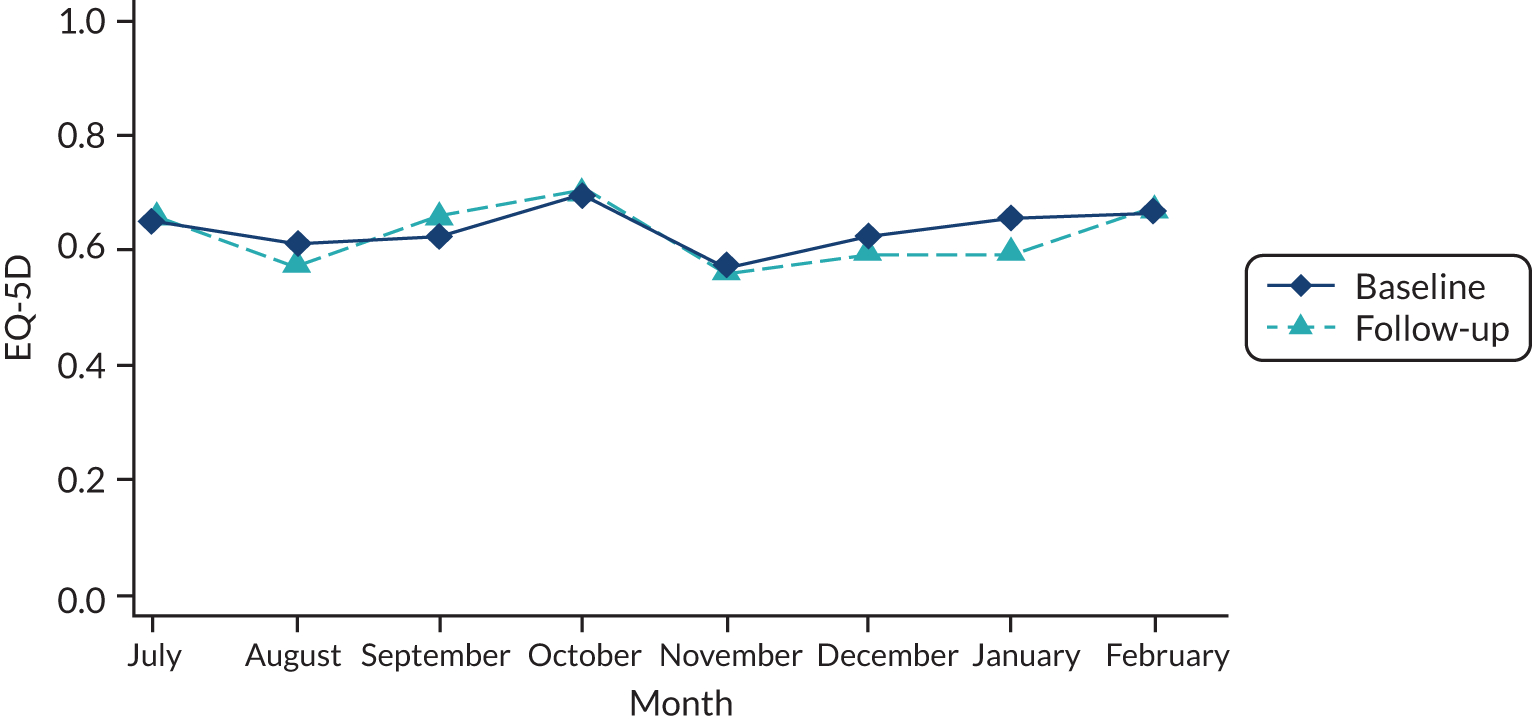

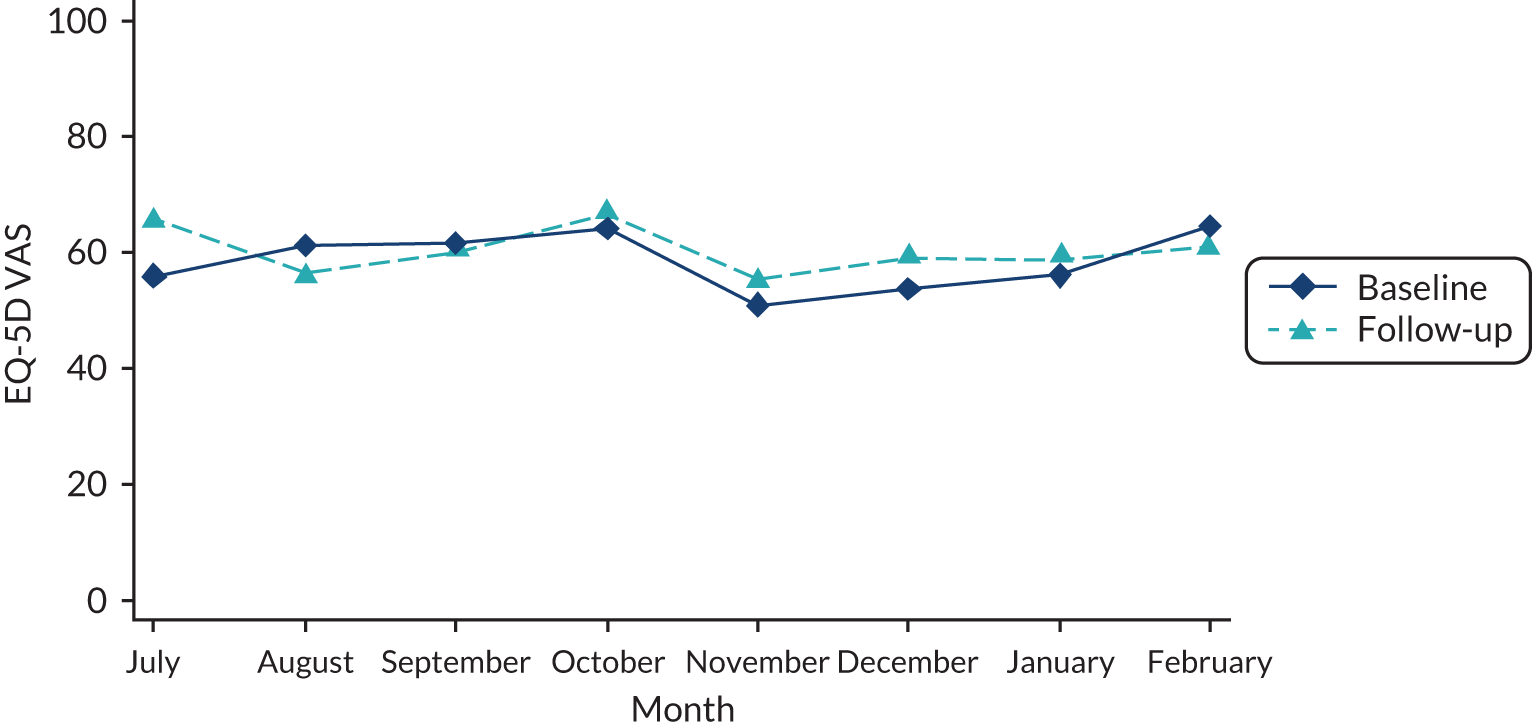

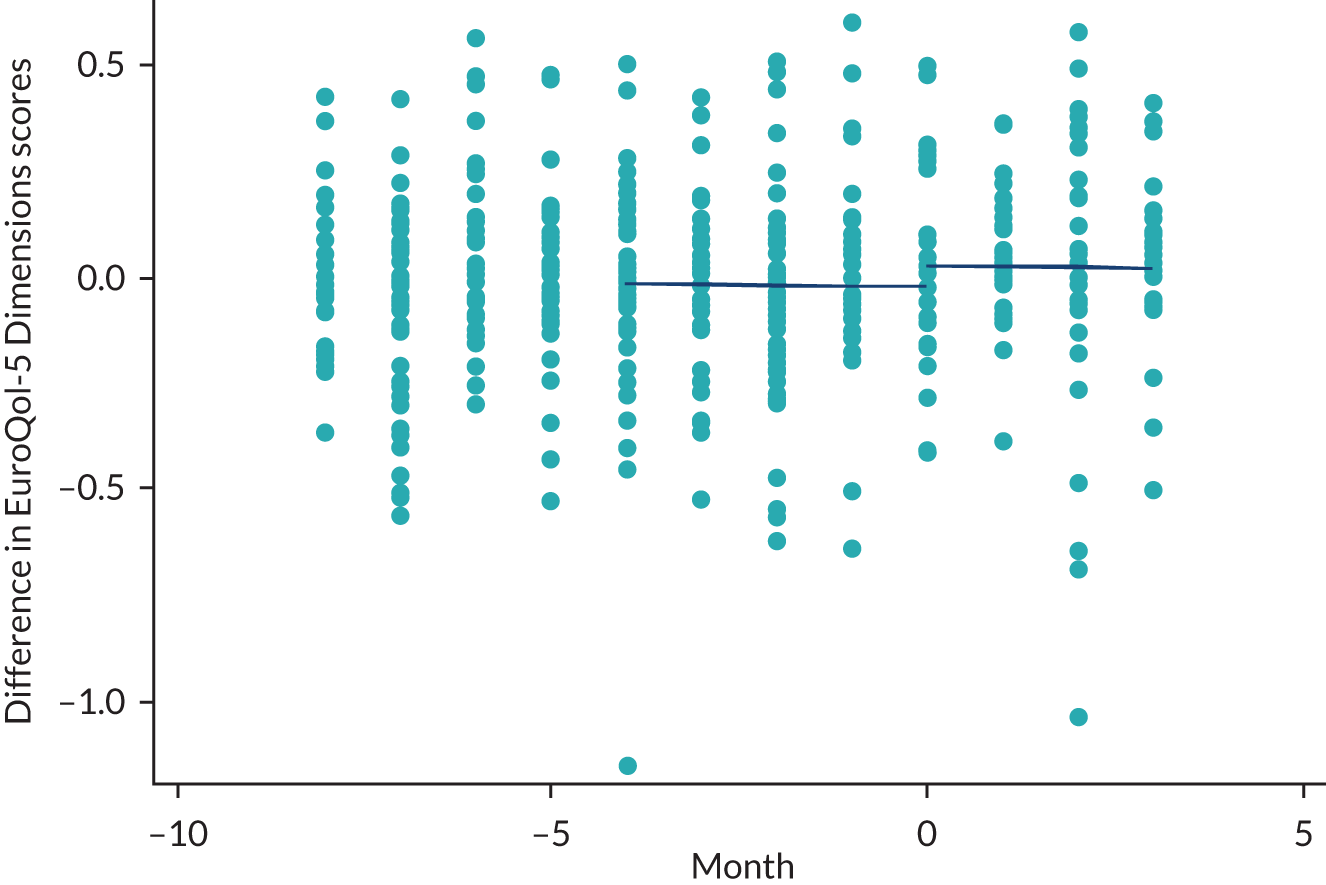

to measure HRQoL as change in EQ-5D-5L score at the 12-month follow-up in the social prescribing intervention clients.

Work package 2

Work package 2 (WP2) had the following objective:

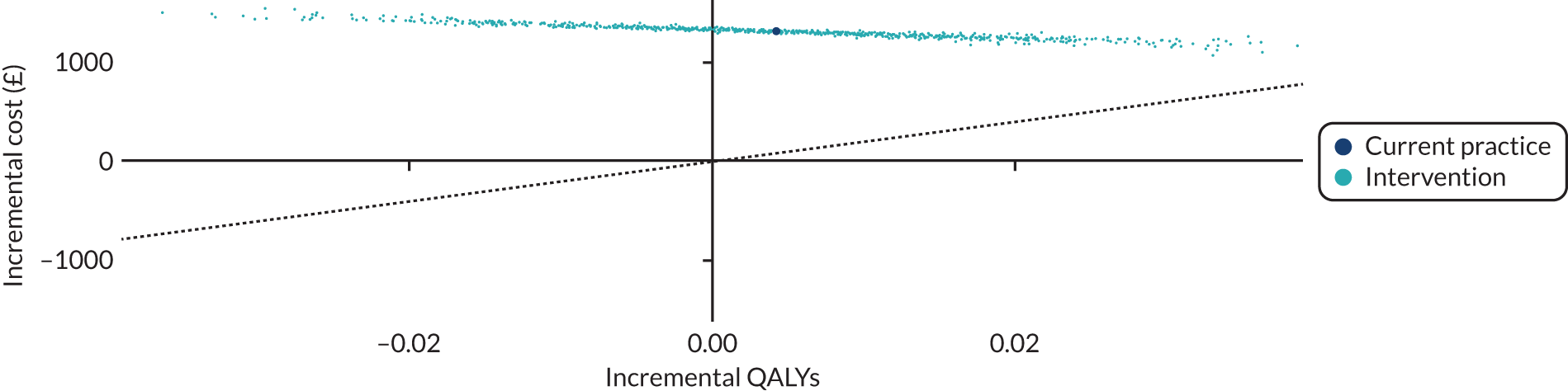

-

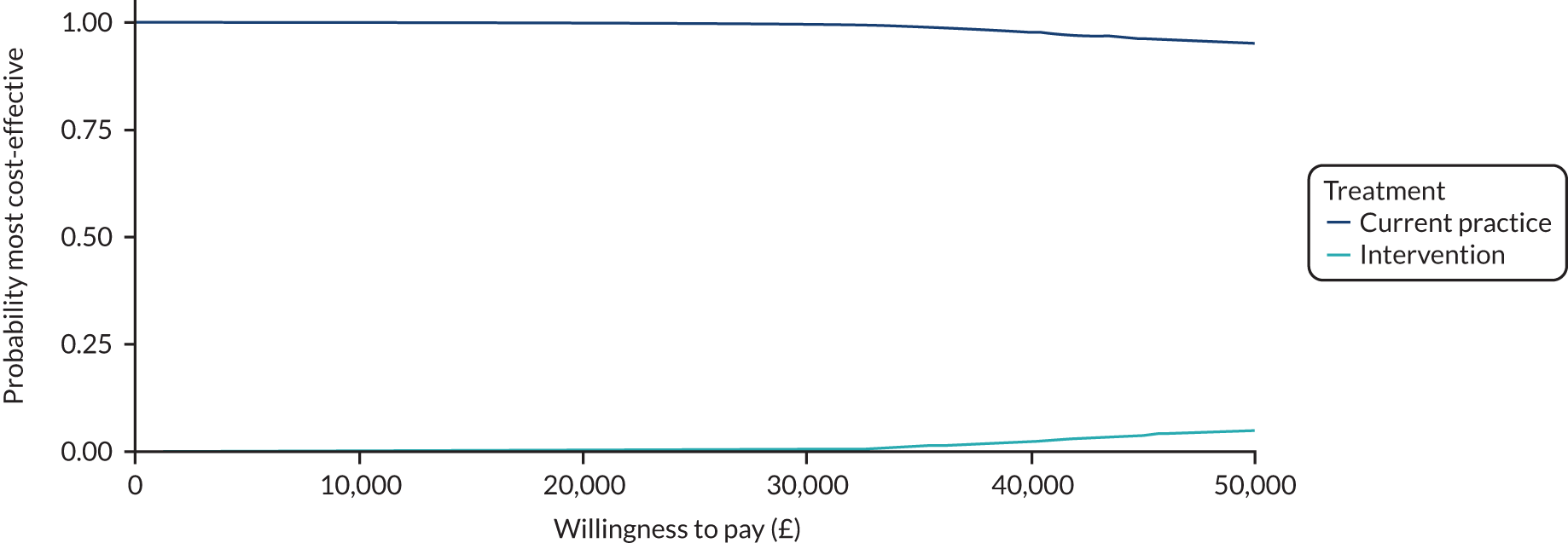

To measure the cost-effectiveness of the social prescribing intervention for health-care utilisation and each of the outcomes. From the perspective of a health service provider, costs and benefits will be compared for individuals in the intervention group and a cohort of individuals who did not receive the intervention. The robustness of the results will be investigated using sensitivity analysis.

Work package 3

Work package 3 (WP3) had the following objectives:

-

to use ethnographic methods to examine –

-

link workers’ experiences of delivering social prescribing

-

patients’ engagement with the social prescribing intervention and whether or not and how social prescribing leads to changes in patients’ lives

-

-

to examine the impact of COVID-19 on people with LTCs and the role of social prescribing during the pandemic.

Study setting

The study setting comprised 10 electoral wards in the inner and outer west of Newcastle upon Tyne in the north-east of East England (with a total population of 100,050; Table 1). Five wards are in the most deprived quintile, four wards are in the fourth-most deprived quintile and one ward is in the third most deprived quintile of the Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD). 57 All but two of the wards have higher than the English average levels of LTCs or disability that limit day-to-day activities. Seven wards have higher than the English average levels of long-term unemployment and six wards have higher than the English average levels of social renting, a further indication of low income. Just under one-third of the inner-city wards’ population are from black and minority ethnic communities. By contrast, all but one of the outer-city wards are predominantly of white ethnicity.

| 2011 ward | Total population (n) | Gender (%)a | Ethnicity (non-white) (%)a | Day-to-day activities limited by LTC/disability, patients aged 16–64 years (%)a | Social rented households (%)b | Long-term unemployed (%)c | IMD scored | IMD quintiled | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | ||||||||

| Benwell and Scotswoode | 12,694 | 48.5 | 51.5 | 9.1 | 48.7 | 40.4 | 3.2 | 43.3 | 5 |

| Blakelaw | 11,507 | 47.7 | 52.3 | 16.0 | 48.1 | 33.6 | 2.3 | 35.8 | 5 |

| Denton | 10,500 | 47.4 | 52.6 | 2.5 | 50.9 | 30.6 | 2.1 | 31.7 | 5 |

| Elswicke | 13,198 | 53.2 | 46.8 | 46.9 | 47.6 | 46.8 | 3.5 | 50.7 | 5 |

| Fenhame | 10,954 | 47.7 | 52.3 | 15.2 | 44.6 | 28.9 | 1.9 | 28.8 | 4 |

| Lemington | 10,228 | 48.2 | 51.8 | 2.3 | 45.2 | 22.1 | 1.9 | 30.4 | 4 |

| Newburn | 9536 | 48.5 | 51.5 | 2.1 | 47.8 | 31.5 | 2.1 | 28.5 | 4 |

| Westerhope | 9196 | 47.9 | 52.1 | 2.3 | 48.5 | 10.2 | 1.0 | 14.8 | 3 |

| Westgatee | 10,059 | 56.0 | 44.0 | 34.9 | 27.3 | 46.1 | 2.5 | 41.1 | 5 |

| Wingrovee | 13,685 | 54.2 | 45.8 | 50.2 | 33.6 | 32.1 | 1.7 | 28.9 | 4 |

| Total (WtW area) | 111,557 | 50 | 50 | 19.8 | 46.8 | 32.9 | 2.3 | – | – |

| England | 53,012,456 | 49.2 | 50.8 | 14.6 | 43.5 | 17.7 | 1.7 | – | – |

Study population

Owing to the large number of people in the social prescribing intervention with a T2DM diagnosis (41%),59 we focused the evaluation on this subsample. The primary outcome was the change in the level of HbA1c, which is a well-recorded objective clinical outcome measure. The study population was identified and selected by North of England Commissioning Support Unit (NECS) and comprised community-dwelling adults aged 40–74 years who had T2DM with or without comorbidity- or disease-related complications or a diagnosis of depression or anxiety.

Diabetes is a major public health issue; some 7% of the UK population live with diabetes, and approximately 1 million people have undiagnosed T2DM. 60 If no changes are made to the way that T2DM is managed and treated, the costs to the NHS are estimated to increase to £17B by 2035, with the associated increases in the wider costs to society estimated to be over £22B. 61,62 Economic analyses show that NHS costs stem mostly from treating diabetes-related complications that are exacerbated by poorly controlled levels of blood glucose. For many people with T2DM, there is scope for improved condition management, resulting in fewer diabetes-related complications and increased cost savings. 63 People with T2DM may have one or more other LTCs64 and T2DM is often associated with mental health conditions, such as anxiety and/or depression, which can negatively affect an individual’s ability to manage their condition. 65 T2DM is socially patterned; the poorest people are 2.5 times more likely to have T2DM66,67 and, once diagnosed, are at increased risk of complications. 68 Although T2DM diagnosis is a criterion for study entry, this does not preclude the co-existence of other physical and mental health conditions. T2DM is also one of the comorbidity risk factors associated with worse COVID-19 outcomes. 69

Intervention

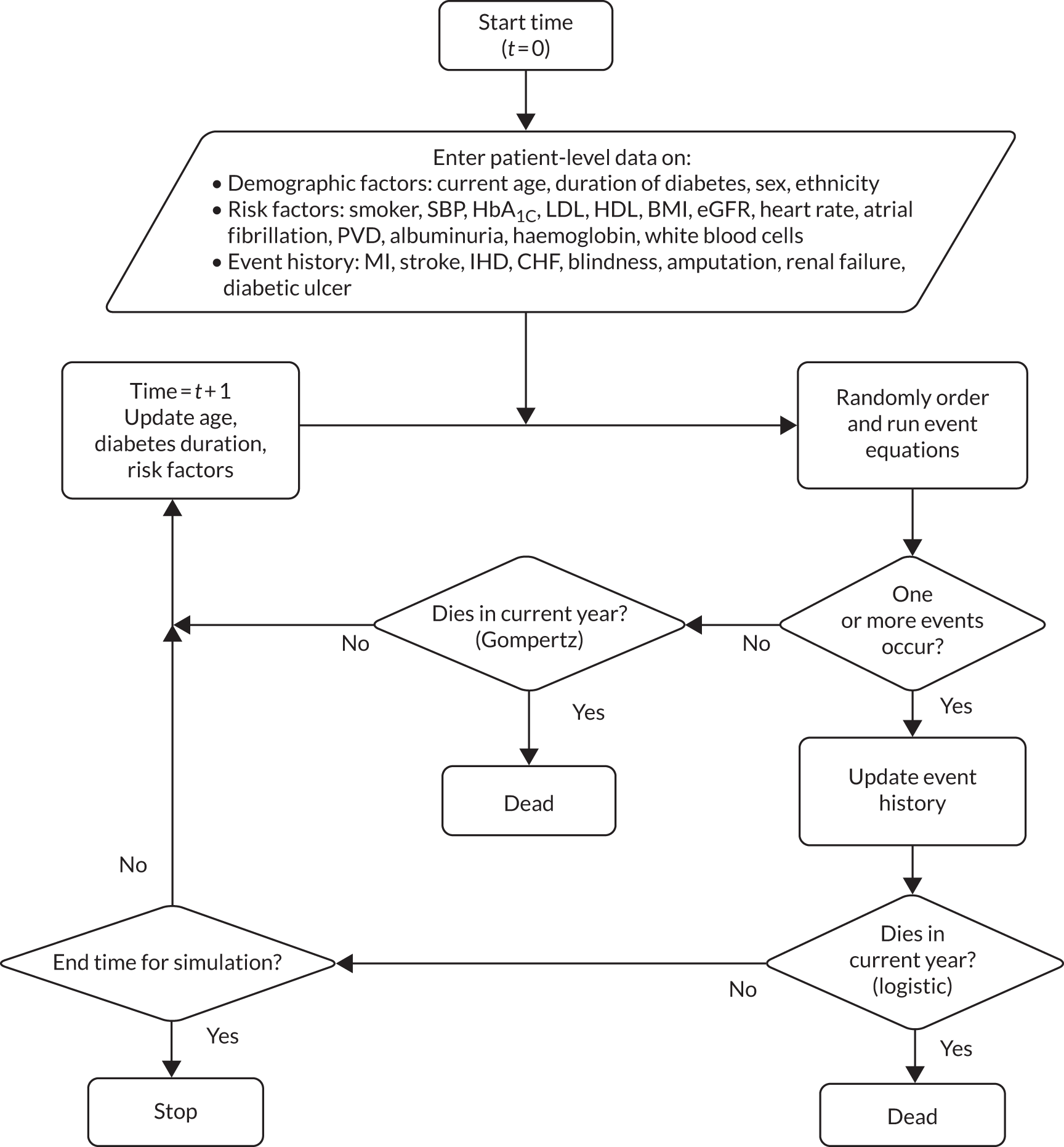

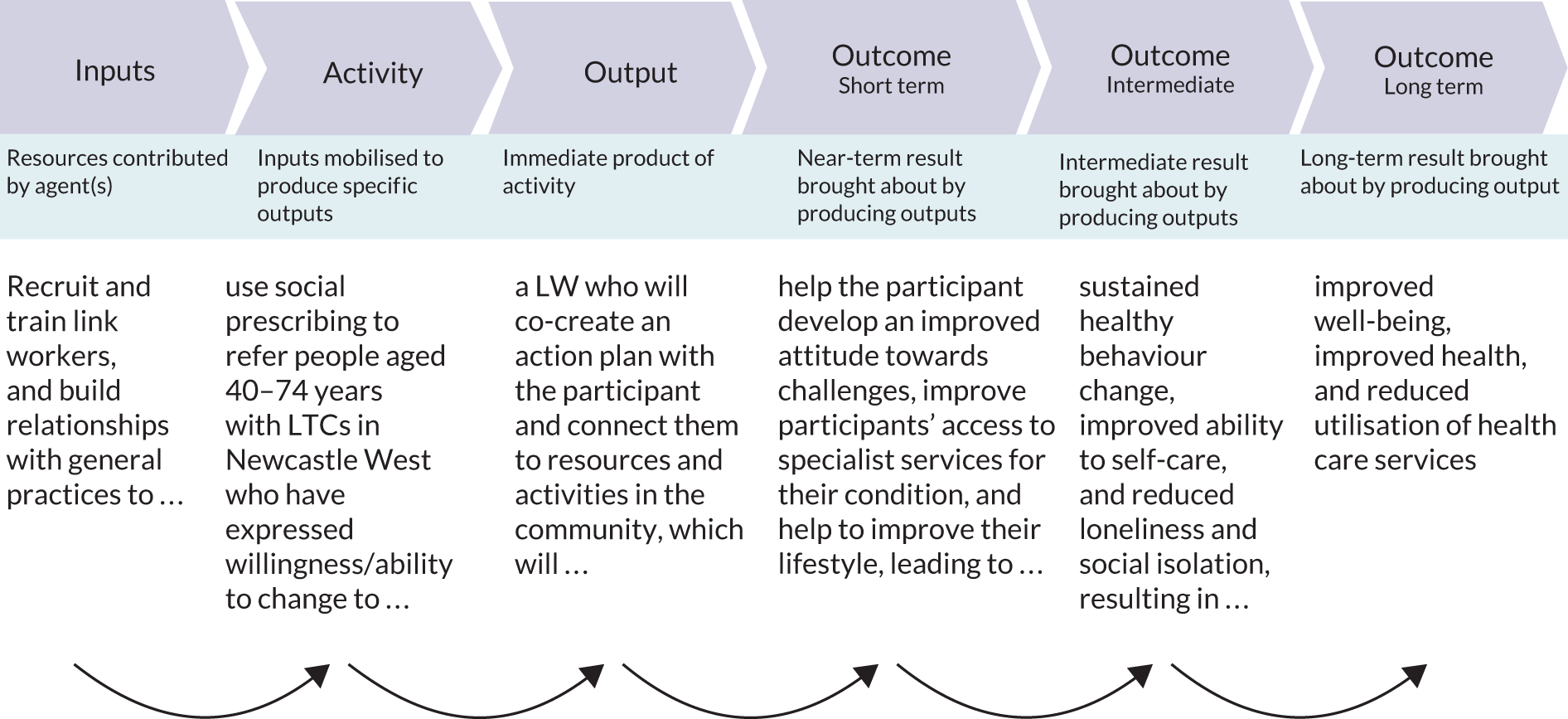

The intervention, detailed in Table 2, is a community-based link worker social prescribing intervention for people aged 40–74 years who have at least one of eight LTCs. 70

| Name | WtW |

|---|---|

| Purpose | WtW social prescribing was based on extensive pilot work and, over an 8-year period (from 2007 to 2015), was co-produced with people with LTCs.72 WtW is a service for people aged 40–74 years in the west of Newcastle upon Tyne who have at least one of eight LTCs (i.e. diabetes type 1 or 2, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, coronary heart disease, heart failure, epilepsy or osteoporosis, with or without anxiety and/or depression). The intervention aims to improve health-related outcomes and the quality of life of people with LTCs by increasing their confidence and ability to manage their illness, and to reduce costs and/or improve value to the NHS in their treatment. The intervention has four key objectives:

|

| Resources | Link workers were attached to clusters of primary care practices and employed by not-for-profit organisations. Link workers had experience of working with individuals and were expected to have had experience and knowledge of the community. Provider organisations were contracted by WtW Management Limited (Newcastle upon Tyne, UK), which was funded for 7 years from April 2015 via the Cabinet Office Social Outcomes Fund, Newcastle West Clinical Commissioning Group (now part of Newcastle Gateshead Clinical Commissioning Group), Big Lottery Fund Commissioning Better Outcomes and Social Outcomes Fund and a SIB.73 WtW Limited is a special-purpose vehicle, the role of which is to contract service providers, receive investments and make outcomes payments. Link worker line management was provided by the aforementioned not-for-profit provider organisations with experience in delivery of community programmes, health-care interventions and staff management. Link worker training and development needs were met by both WtW Management Limited (Newcastle upon Tyne, UK) and provider organisations. A bespoke management information system was used by link workers and WtW Management Limited to manage referrals, store and retrieve information relating to patient journeys, and monitor referral and progress targets |

| Procedures |

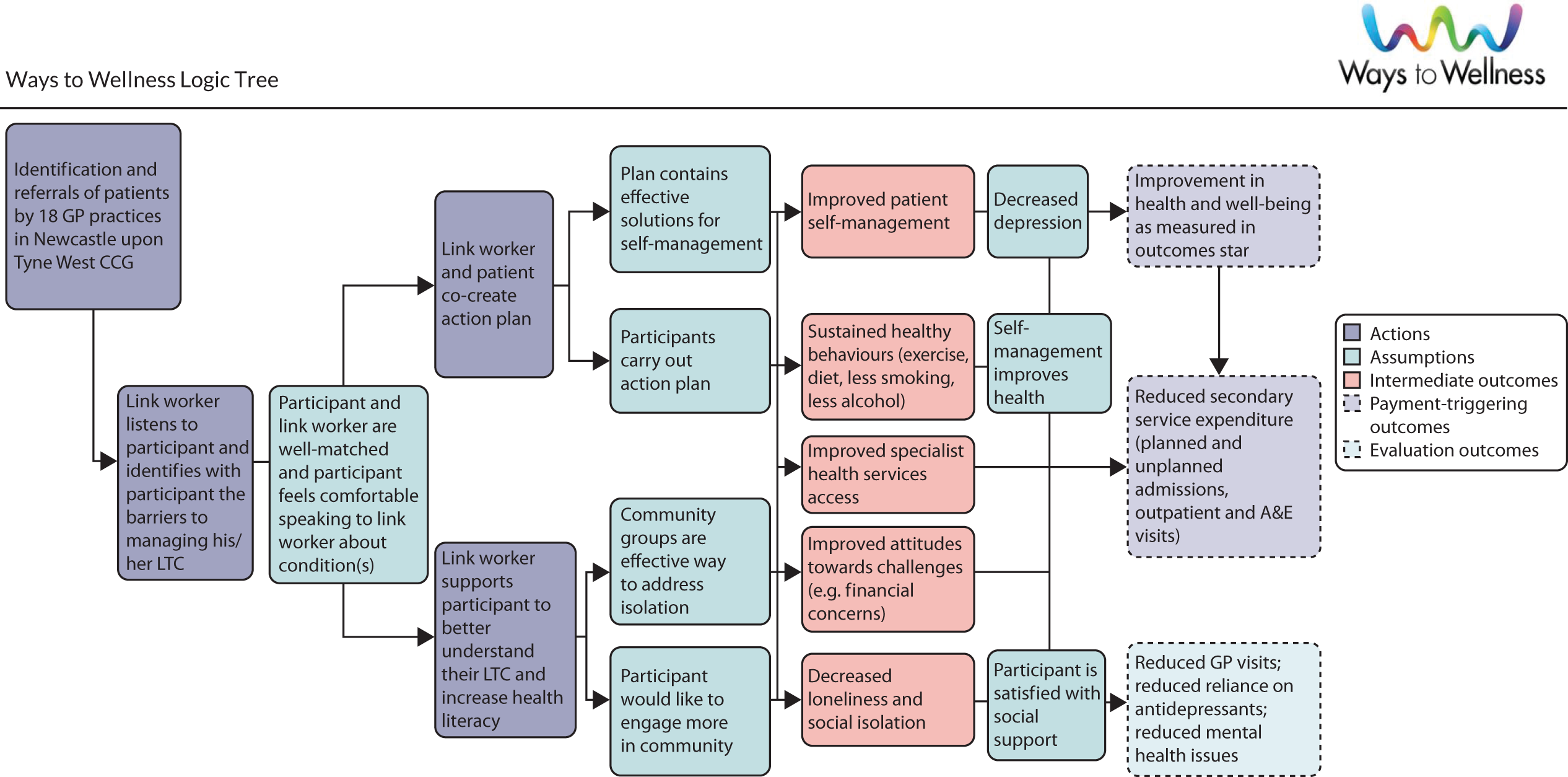

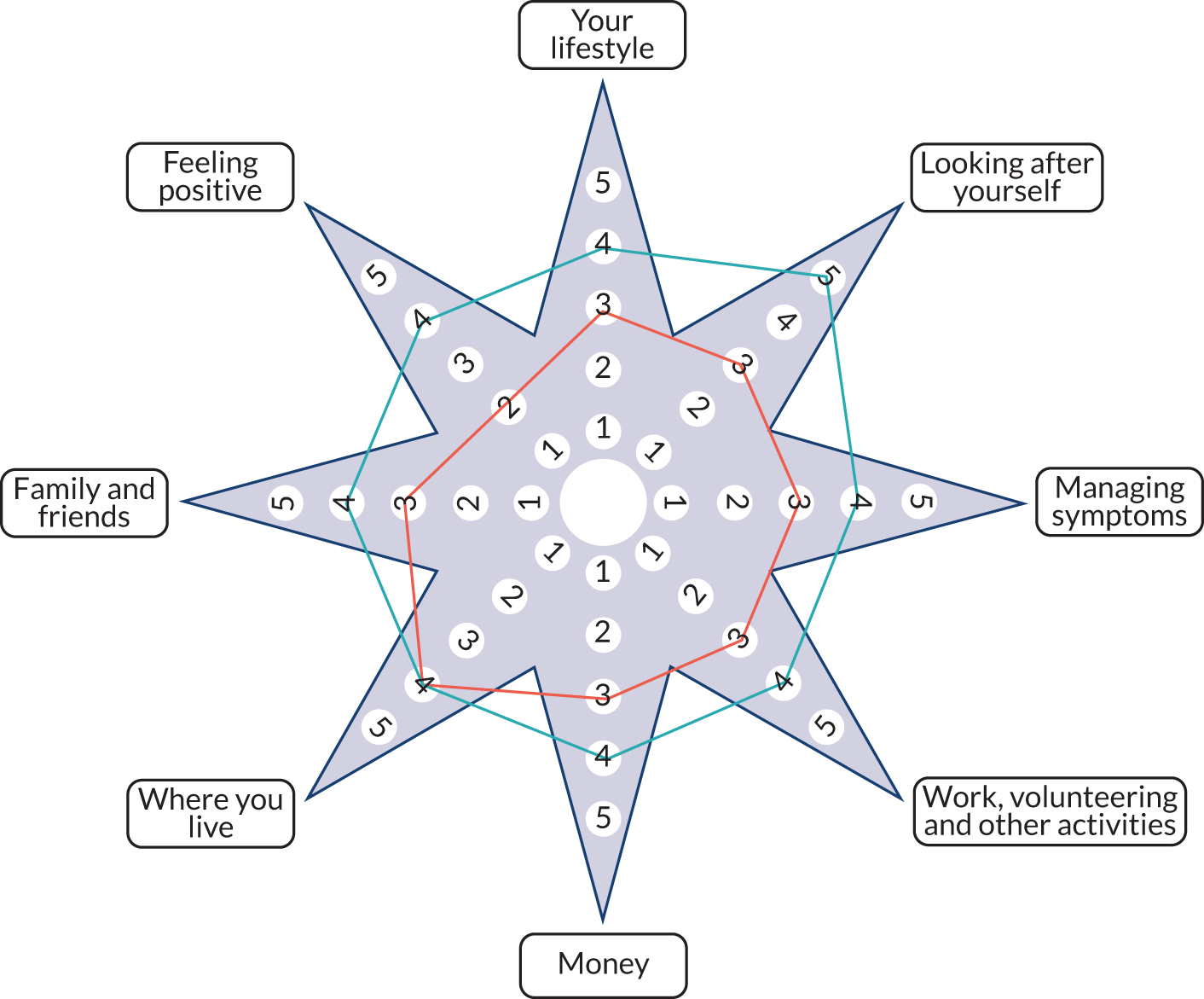

All 18 general practices that were members of the Newcastle West CCG were assigned link workers. Referral to WtW could be made by any primary care professional. Subsequent practice changes reduced practice numbers to 16 in 2018. Practices were encouraged to adapt their clinical computer systems to incorporate and generate a standard referral form to provide an efficient referral mechanism for primary care practitioners. Practices were also encouraged to tag all eligible patients so that in any consultation with HCPs a screen reminder appeared and, if deemed appropriate, a referral to WtW could be offered to the patient with an automated process to decline or accept. If accepted, this triggered a referral to a link worker, via a referral document integrated into the computer system. If the patient declined, a reminder would be flagged on the computing system 6 months later. There was variation in the rate at which practices adapted their computer systems On referral, patients were assigned a link worker who is trained to use the WBS (Triangle Consulting Social Enterprise Ltd, Brighton, UK)74 self-assessment tool (Figure 1). This proprietary tool was conducted approximately every 6 months and aims to help clients to assess their state on a scale of one to five across eight parameters (lifestyle; self-care; symptom management; work, volunteering and activity; money; home environment; personal relationships; and positive feeling). This helps to identify problems and allows the link worker and the patient to co-produce a personalised action plan. The aim is that link workers initiate the intervention by supporting patients to access a range of local community services (e.g. physical activity classes, welfare rights) or, in some cases, by supporting patients to develop self-directed programmes |

| Providers | Link workers come from a range of professional backgrounds, including community work and health care. Over the qualitative study fieldwork period (i.e. October 2018–July 2020), link workers were employed based on pre-existing expertise and experience as there was no recognised qualification. Training in safeguarding, LTCs, the use of the WBS and motivational interviewing was given. Ongoing, in-service training and knowledge exchange events took place regularly |

| How | Initial client contact comprised a one-to-one in-person baseline interview, followed by further contact either face to face or by telephone, text, e-mail or video call. Phases of contact comprised engagement (initial contact and goal-setting), intervention (actively supporting patient to achieve goals), keeping in touch (link worker supports patient to maintain progress and develop new goals if appropriate) followed by discharge. Clients could complete up to seven WBSs, meaning that the maximum length of engagement was approximately 3.5 years |

| Where | Link worker contacts took place in a range of settings, including general practices, provider organisation premises and other community settings. Some home visits could take place. The link worker could accompany patients to support their contact with a community organisation |

| When and how much | Link workers and patients could meet/have contact when they thought necessary. At a minimum, contact was encouraged every 6 months to complete the WBS and this could be either face to face or by telephone |

| Tailoring | The intervention was intended to be personalised to the individual clients’ needs and link workers’ judgements about what help was available |

| Modifications | Although the intervention was not modified during the research, the number of provider organisations fell from four to two. As the intervention was rolled out, recruitment targets and link worker caseload were scheduled to increase within the first year of intervention delivery. Following year 1 of the intervention delivery, the average link worker caseload was 100 (range 80–120) |

| How well | This was a flexible, personalised intervention; fidelity was not assessed |

The intervention began in April 2015 and to the end of our fieldwork period in July 2020 had recruited 5526 patients into the service.

FIGURE 1.

Well-being Star™ (second edition). © Triangle Consulting Social Enterprise Ltd. Authors: Sara Burns and Joy Mackeith. URL: www.outcomesstar.org.uk (accessed 30 May 2020). Reproduced with permission from Triangle Consulting Social Enterprise Ltd (Anna Good, Triangle Consulting Social Enterprise Ltd, 2021, personal communication).

Ethics, governance and sponsor

NHS Research Ethics Committee (REC) approval was obtained for WP1 and WP2 from the Proportionate Review Sub-Committee of the London-Brent REC [REC reference 18/LO/0631; Integrated Research Application System (IRAS) project identification number 238970]. The EQ-5D-5L study was approved by Newcastle University’s Faculty of Medical Sciences REC (reference number 1011), which, via an amendment, approved the COVID-19 study. WP3 was approved by Durham University’s Anthropology Department’s Research and Ethics Data Protection Committee. Newcastle University is the sponsor of the research.

Changes to the protocol

In June 2019, the protocol was amended (version 2) to reflect changes to WP3. The ethnography (WP3) was changed to comprise two separate, but linked, ethnographies: ethnography 1 focused on service user experiences and ethnography 2 focused on link worker roles and practices. In November 2020, the protocol was amended (version 3) to reflect changes to data extraction procedures in WP1 and WP2, to reflect changes to procedures for EQ-5D-5L follow-up data collection measures and to include the additional qualitative fieldwork undertaken as a response to the COVID-19 pandemic. In April 2021, the protocol was amended (version 4) to indicate that a multimethods approach was undertaken for data integration.

Protocol version 4, the final approved version, is available at https://fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/16/122/33 (accessed 19 April 2022).

Independent Study Steering Committee

An independent Study Steering Committee (SSC), which was chaired by Professor Sally Wyke, University of Glasgow, monitored study progress, research standards and conduct. The SSC initially met face to face in June 2019. Two subsequent annual meetings (in March 2020 and January 2021) were held using Zoom (Zoom Video Communications, San Jose, CA, USA) because of the COVID-19 pandemic. See Appendix 2 for SSC membership.

Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee

A Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee was not required because the study did not use a medicinal device and the data for analysis either were anonymised (WP1 and WP2) or were provided with the fully informed consent of the participant (WP3).

Patient and public involvement

The aim of PPI was to involve clients and link workers throughout the study period to optimise the implementation, application and dissemination of the research. Prior to this study taking place, members of the research team had engaged with clients and link workers to execute qualitative interview studies1,15,54 and a quantitative study exploring the feasibility of outcome measurements in impact evaluation. 75 Extensive discussions with link workers in particular, combined with results from our feasibility study, directed us to a design that relied on routine data augmented by EQ-5D-5L data collected by link workers at baseline, rather than relying on self-completion questionnaires. The insights from the qualitative study1 informed the choice of observational/ethnographic methods. As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, a large-scale planned PPI event scheduled for July 2020 was cancelled. Throughout the period of lockdown and government-imposed restrictions, we were unable to undertake PPI activities. However, below we give an account of the activities that took place, together with our critical reflections.

Patient and public involvement methods

Patients and public

We engaged clients via pre-existing service user groups that had been set up by provider organisations. We accessed members of the public via Newcastle University’s Faculty of Medical Science Public Engagement network.

Link workers

We engaged with link workers at their knowledge exchange events and attended meetings on an ad hoc basis. We sent regular newsletters to link workers and provider organisations informing them about the progress of the study.

Patient and public involvement results

Patients and public

Although initial service user input to recruitment materials was useful, to keep PPI and qualitative/ethnographic fieldwork separate, it was decided not to consult within these fora. Subsequently, these groups became important field sites for ethnography.

Facilitated group discussions with over 100 members of the public about the aims and purpose of social prescribing, as outlined in The NHS Long Term Plan,2 yielded useful information helpful to our interpretation.

Link workers

Link workers were engaged in the research in two main ways. First, link workers were involved in the administration of the baseline EQ-5D-5L questionnaire, which required ongoing communication, including regularly reviewing optimal questionnaire administration, giving monthly feedback about response rates and having ongoing discussions about the best way to increase response rates.

Although the provider organisations were reimbursed for link worker time in baseline questionnaire completion, reimbursement was not the key motivating factor. Concerns about interfering with the development of rapport, client vulnerability and overload, capacity and staff turnover were given as reasons for not facilitating completion of baseline questionnaires. From discussions with link workers, it became clear that researcher-led telephone follow-up would be the most likely method to obtain a good follow-up response rate and would also reduce the burden on hard-pressed link workers.

Second, link workers were involved as research participants, both within focus groups and through participant observation at provider organisations and being ‘shadowed’ by the ethnographer. Link workers, therefore, found themselves both facilitating data collection and being research participants. This did not appear to pose problems for focus group participation, but the less common experience of being observed in their routine practice required time to develop trust with the ethnographer.

Reflections on patient and public involvement

There were aspects of PPI that were helpful to the research endeavour. Our ongoing engagement with link workers enabled us to provide feedback about response rates that acted as regular reminders to link workers about data collection and enhanced the baseline response rate. Equally, we realised that link worker-administered questionnaires would be logistically difficult at follow-up and switched to researcher-administered follow-up, which was likely to have enhanced the follow-up response rate.

The inclusion of two ethnographies meant that we were foregrounding the voices and experiences of those receiving and delivering the intervention. Over the period of the ethnographic fieldwork, we did not feel that it was appropriate to share information derived from the ethnographies with clients or link workers.

On reflection, we experienced some ‘blurred boundaries’ as a result of the involvement of link workers both as participants and in their role administering questionnaires. Furthermore, the constraints imposed by lockdown hampered the planned engagement with broader stakeholders throughout the course of the study. Further stakeholder engagement will take place once the research is fully completed, enabling the research team to include a wide range of perspectives, including study participants, providers, VCSE organisations, primary care, public health and local government, and providing input into the findings, interpretation and implications of the research.

Report structure

This chapter has presented the background to the Social Prescribing in the North East (SPRING_NE) study, its aims and objectives, and has provided an overview of the intervention and study context. Methods and results from the quantitative studies are presented in Chapters 2–4; Chapters 5 and 6 present the results of the ethnographies. Chapter 7 presents data from the additional COVID-19-related study undertaken to explore the impact of the first lockdown on people with LTCs and on the intervention. Chapter 8 draws together the results and discusses their implications. The large-scale adoption of social prescribing within UK primary care creates a timely context for our findings.

Chapter 2 Health outcomes and health-care costs

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced with permission from Moffat et al. 76 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited, appropriate credit is given and any changes made indicated. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

Introduction

In this chapter, we outline the methods and results that enable us to answer the following questions:

-

Does a link worker social prescribing intervention, targeting adults aged 40–74 years with T2DM, result in changes to the levels of HbA1c, BMI, BP, cholesterol levels, smoking status and health-care use and costs?

-

Does the intervention demonstrate greater effectiveness in subgroups (i.e. gender, age, ethnicity, deprivation index) of the eligible population?

In the SPRING_NE study, we exploit the geographical introduction of the intervention as a natural experiment, with treatment and control groups. The intervention was introduced into general practices in the west end of Newcastle upon Tyne (the treatment group) and not into general practices in the east end of Newcastle upon Tyne (the control group). Among the population aged 40–64 years in the intervention-eligible practices, the prevalence of T2DM ranged between 36.00% and 66.67%. Using data from the Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF), Secondary Uses Service (SUS) and the intervention provider, we were able to estimate a range of difference-in-difference (DiD) models to estimate whether or not the intervention had any impact on a range of clinical outcomes or on secondary care use and costs, and whether or not the results varied by subgroups.

Methods

The intervention was introduced into a geographical area, the west end of Newcastle upon Tyne, allowing us to use DiD methods, a quasi-experimental technique, to estimate treatment effects. Randomisation is normally desirable for estimating treatment effects because it ensures, in theory, that the treatment and control groups are statistically equivalent pre treatment. However, the introduction of the intervention did not allow for randomisation. DiD models recognise that there is no randomisation and that the treatment and control groups may be systematically different from one another. Normally, this raises the issue that individuals self-select into treatment, meaning that the treated and the untreated are not comparable, leading to biased treatment effects. 77 Geographical assignment of treatment rules out, in our case, one element of sample selection, in that general practices cannot self-select into offering the intervention. In our case, even if the general practices in the west end of Newcastle upon Tyne systematically differ from general practices in other parts of the city, then we can still estimate unbiased treatment effects, as long as two further assumptions hold. These two assumptions are the parallel trends assumption, that in the pre treatment, the trends in the outcomes of interest are parallel for the treatment and control groups; and unconfoundedness, that is, that the intervention did not coincide with other treatments that vary by practice and that could influence the outcome measures. Neither of these assumptions can be formally tested and we rely on falsification tests and our modelling strategy to overcome any areas where these assumptions may not hold.

Difference-in-differences models

Linear models for health outcomes

The basic two-period formulation of a DiD model is given in Equation 1:

where yit is the outcome for individual i at time t; Di is a dummy variable that is equal to one if the individual is in the treatment group, and zero otherwise; Tt is a dummy variable that is equal to one if the data are from the post-intervention time period, and zero otherwise; and Di × Tt is an interaction of these two terms. The associated coefficient for the interaction term, τ, is the DiD estimate and is an estimate of the impact of treatment on the outcome, conditional on our assumptions holding. The treatment dummy (Di) controls for the pre-treatment differences between the treatment group and the control group. The time dummy (Tt) controls for common time effects across both groups. The treatment effect is identified on the basis that the two groups are moving along parallel trends and that factors that affect the two groups are identical apart from the allocation of treatment.

Equation 1 can be extended to longitudinal data with multiple time periods. This gives the model that is now commonly referred to as the two-way fixed-effects model:78

In this formulation, we have Xit, a series of observed time-varying controls (in our final models these comprised age and age squared), and Dit, which, as above, is a dummy representing treatment status. However, this treatment status dummy is now time varying and, when the intervention is introduced, shows the change in treatment status from untreated to treated for the treated group. The treatment status dummy is always zero for the control group. We also include individual (λi) and time (γt) fixed effects. These fixed effects are crucial because the individual fixed effects control for all time-invariant unobservable individual heterogeneity, whereas the time fixed effects take account of time-varying factors that may affect both groups. For example, in 2014, the QOF was changed, with the number of targets reduced by 40;79 however, this will have affected all general practices and should be controlled for by the time fixed effects. The individual fixed effects are particularly important because these also absorb GP fixed effects. One risk to model identification is that some general practices may be more engaged with the intervention or make better use of the intervention than other practices. In our data, however, as no individual changes general practice during the duration of our observation period, individual fixed effects absorb the general practice fixed effects, meaning that time-invariant general practice characteristics are also controlled for in our model.

We estimate versions of Equation 2 for all of our health outcomes. We treat the health outcomes as continuous variables because they are, mostly, continuous in the range of values that we are dealing with. For the binary smoking status outcome, we also estimate linear probability models because these models can accommodate the fixed effects in a way that is not possible with standard binary response models, such as the logit. The application of linear probability models is considered appropriate for DiD models because of the estimation of constant marginal effects. 77

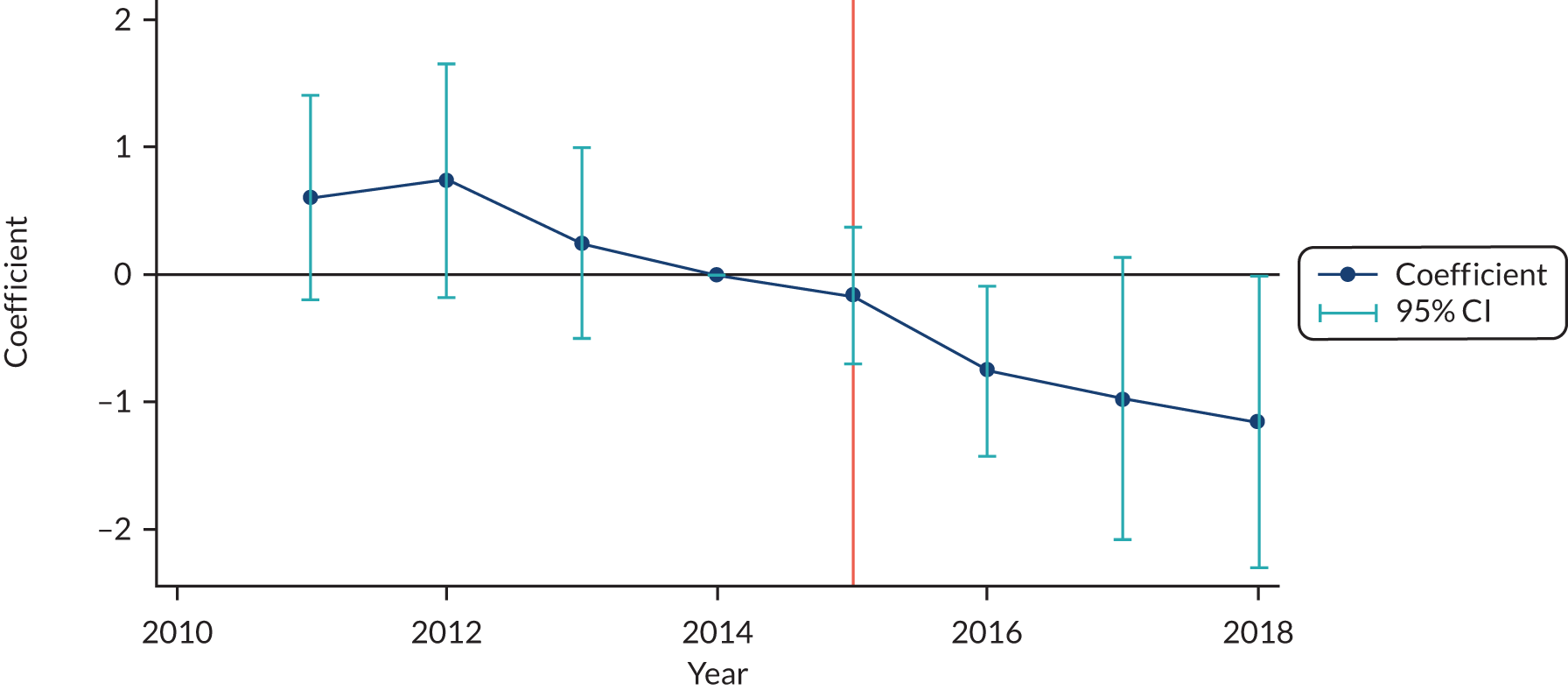

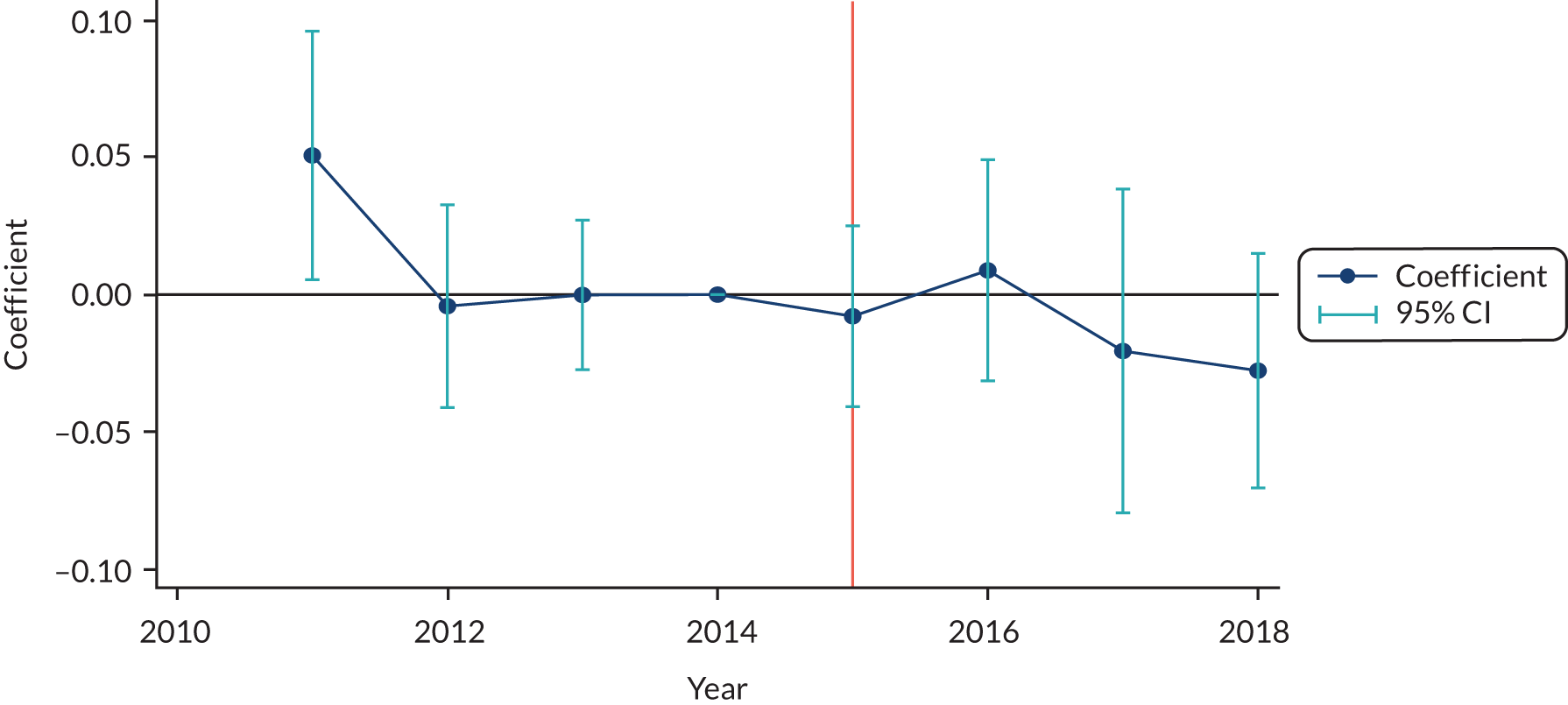

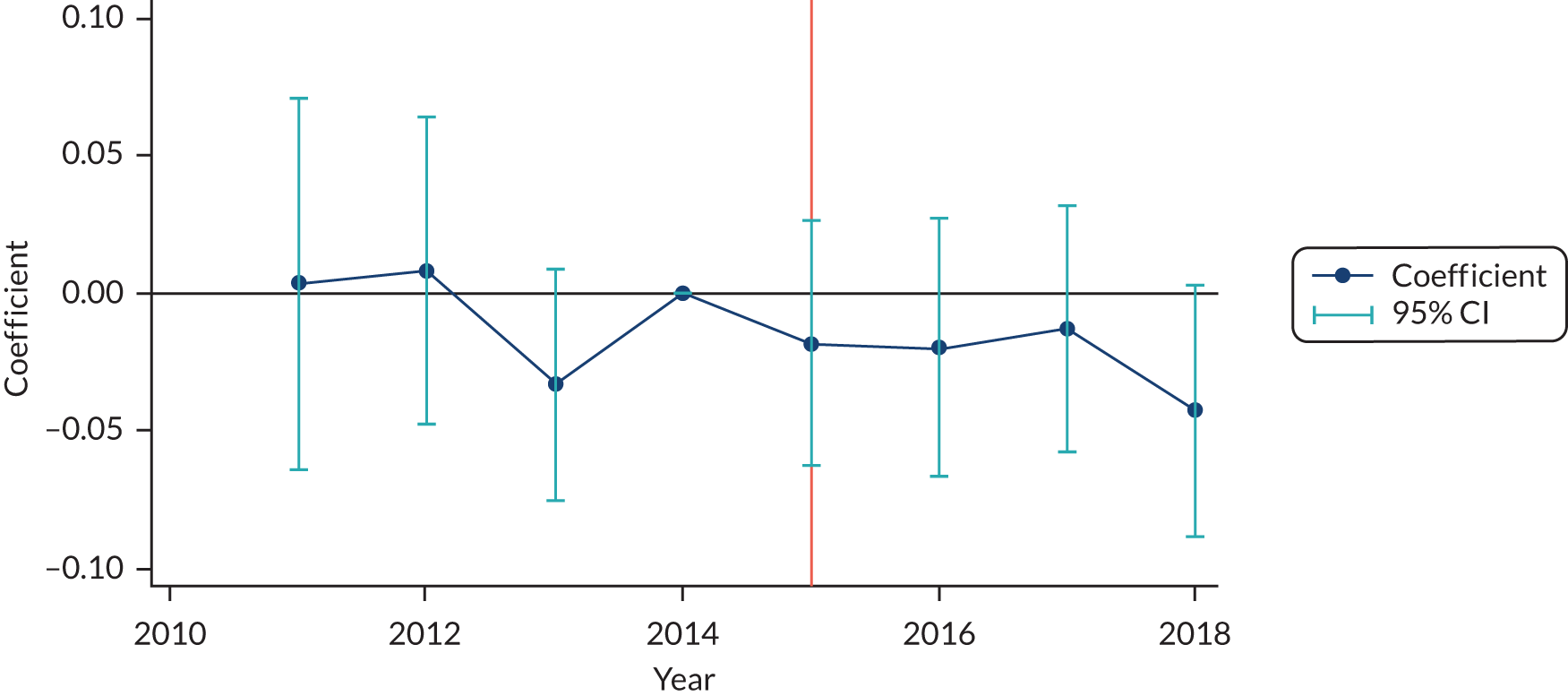

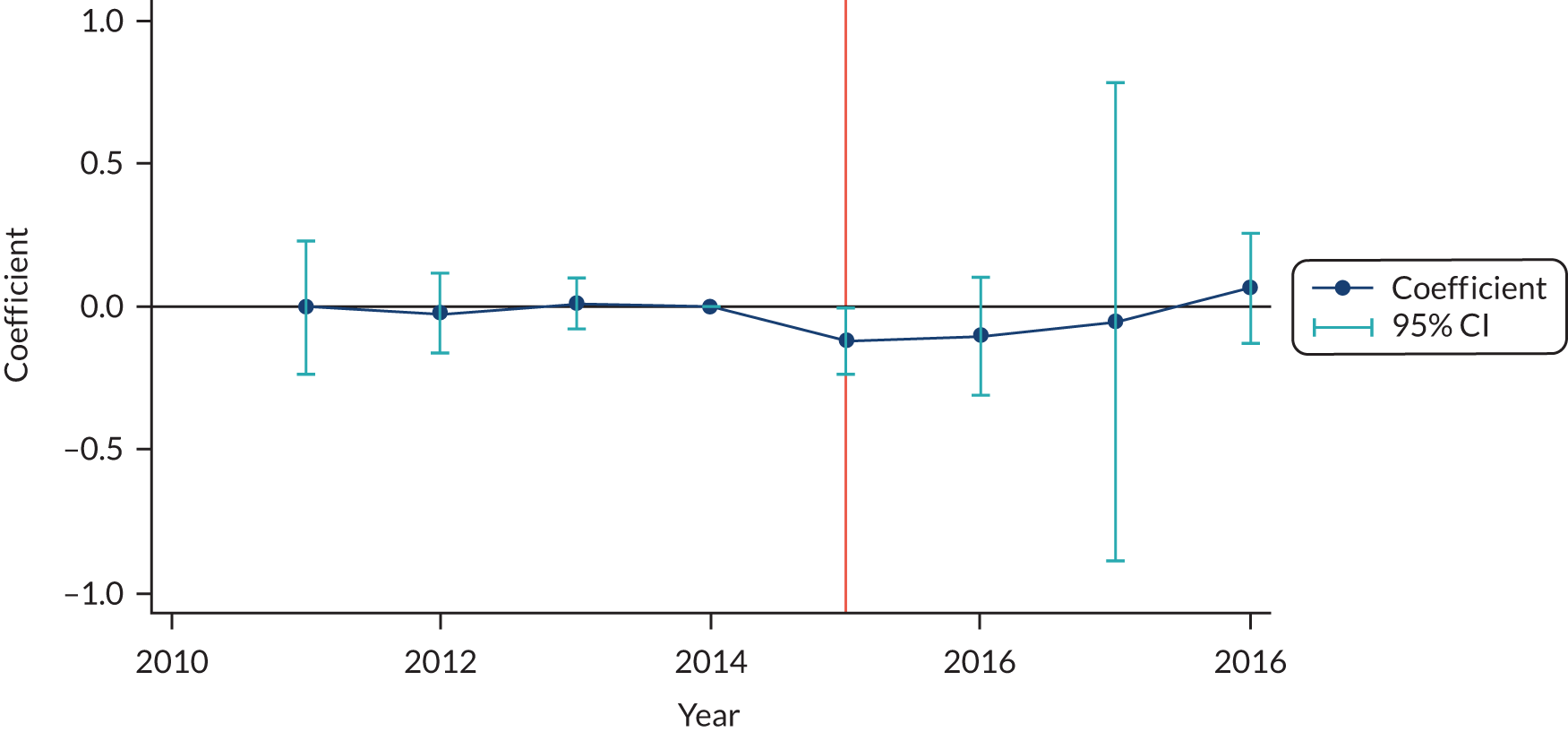

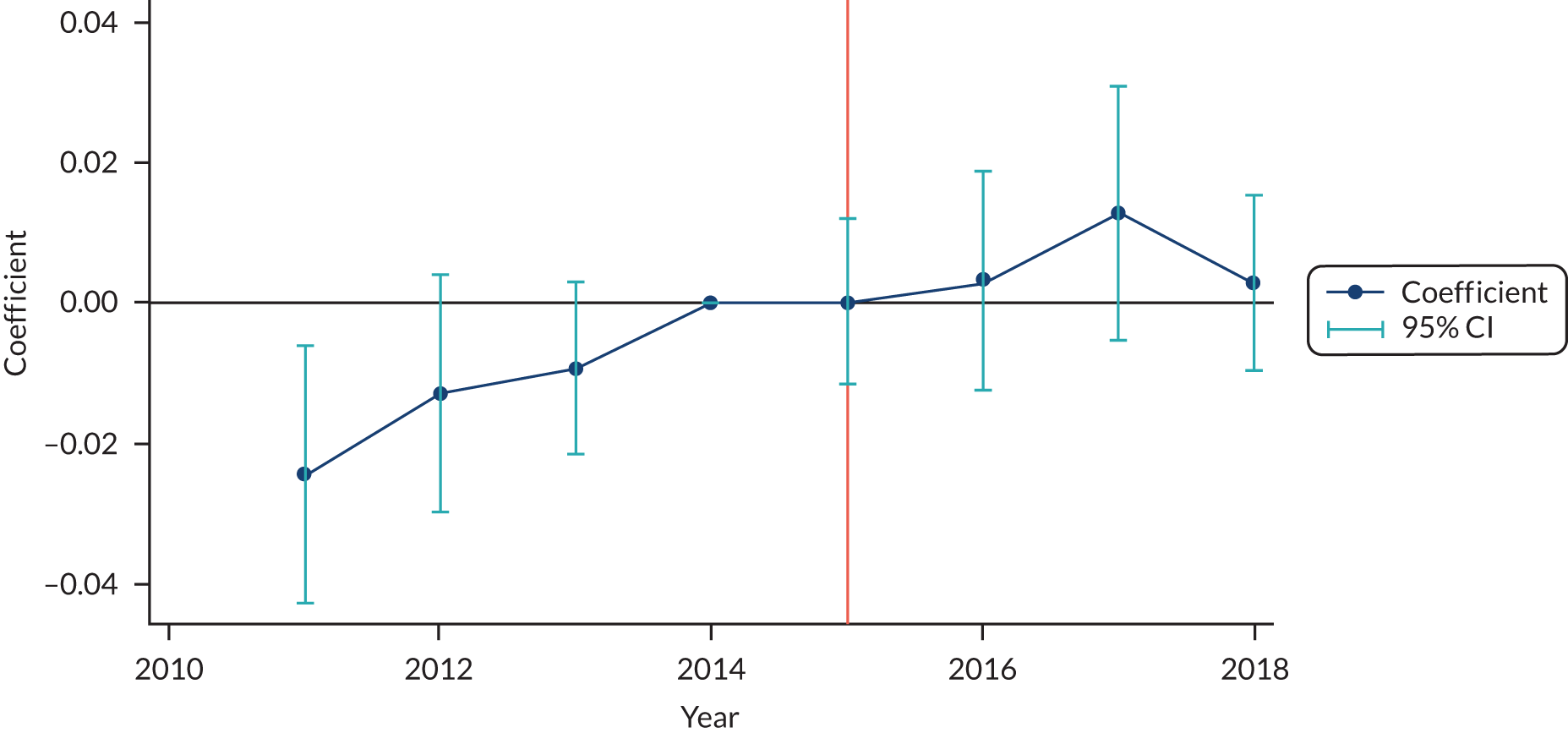

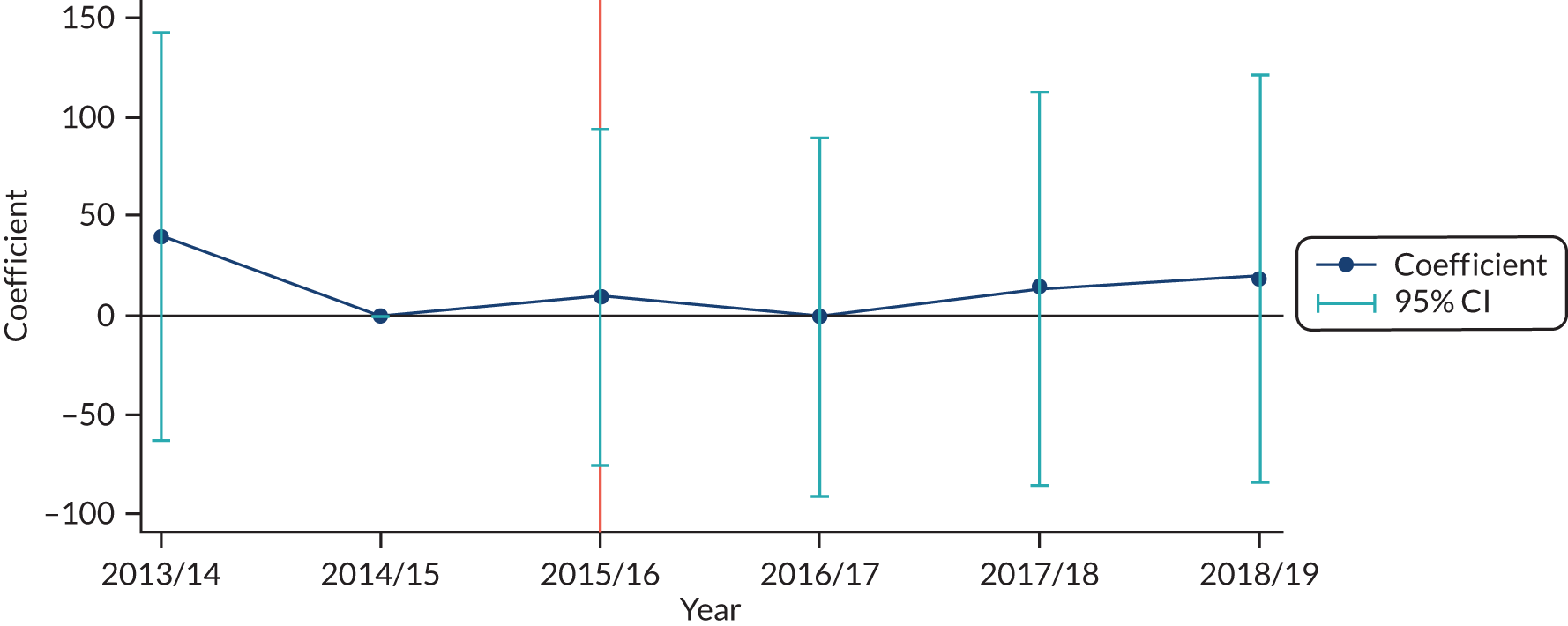

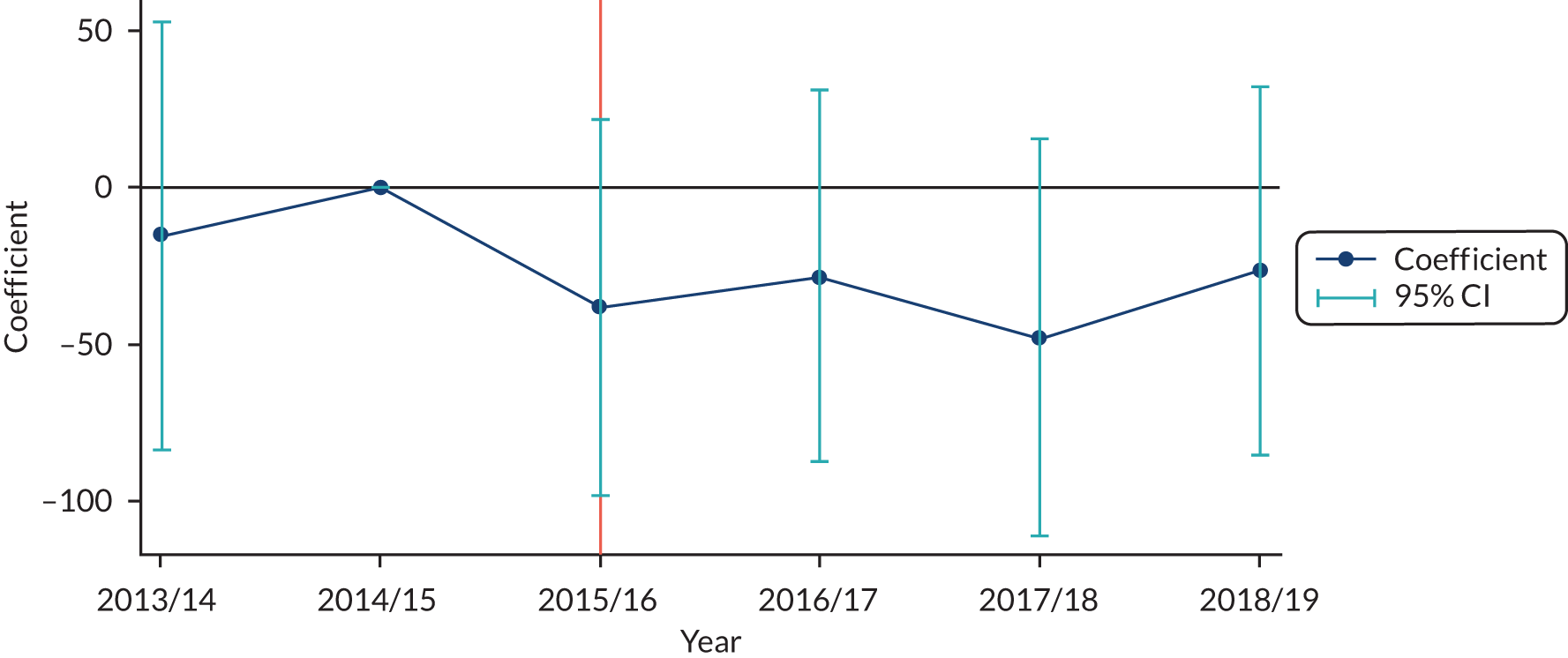

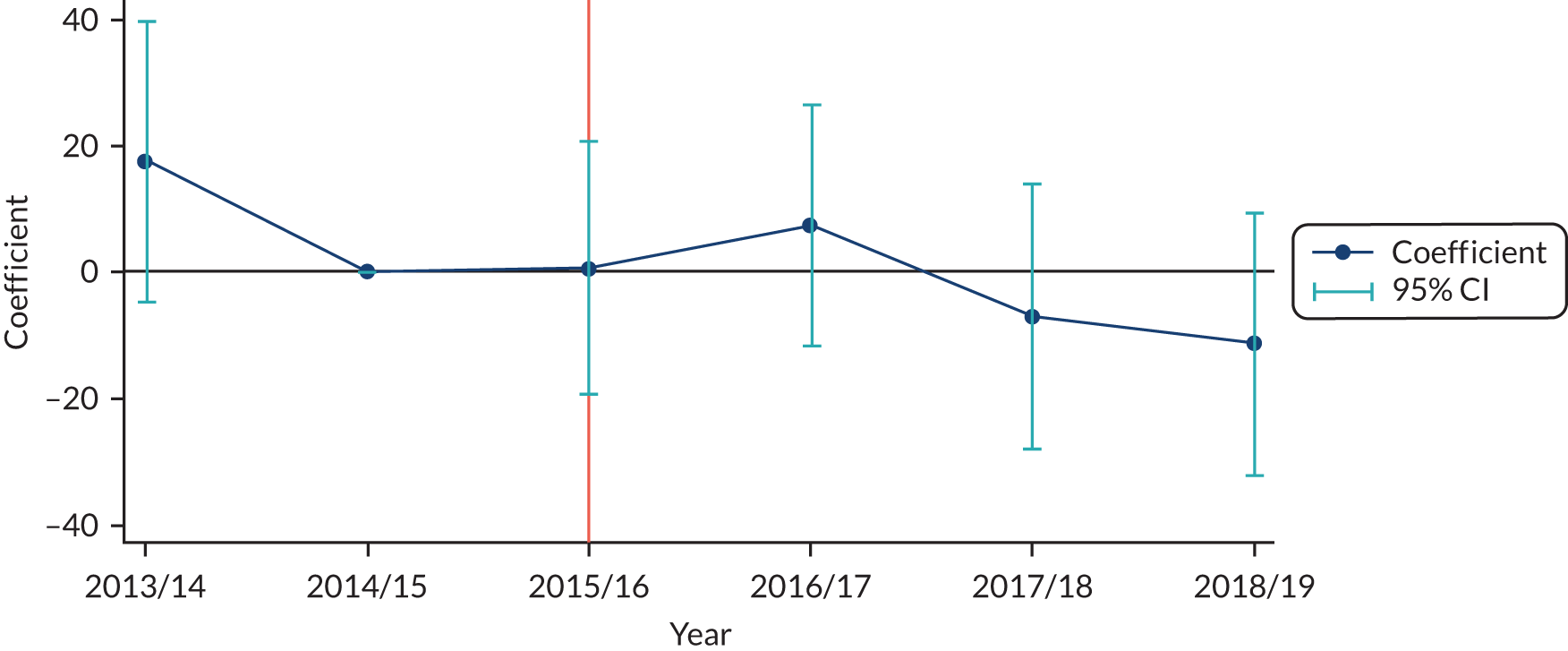

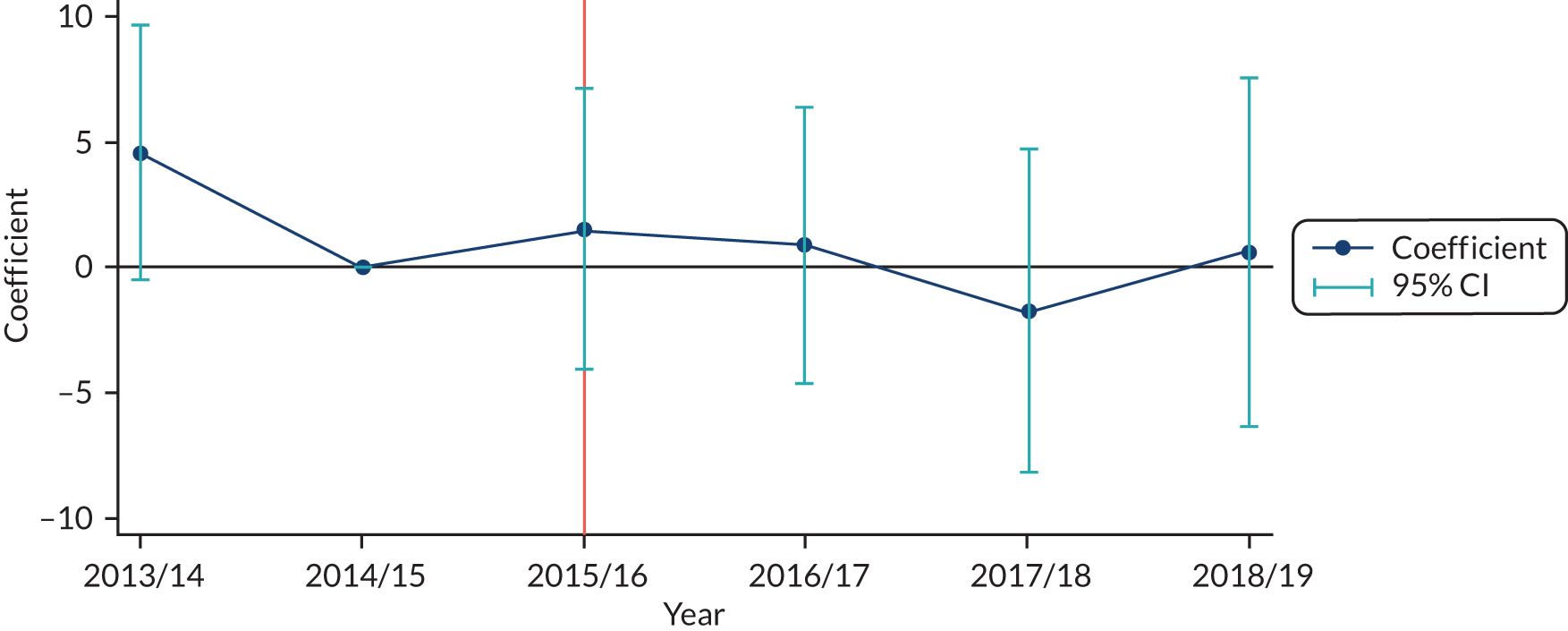

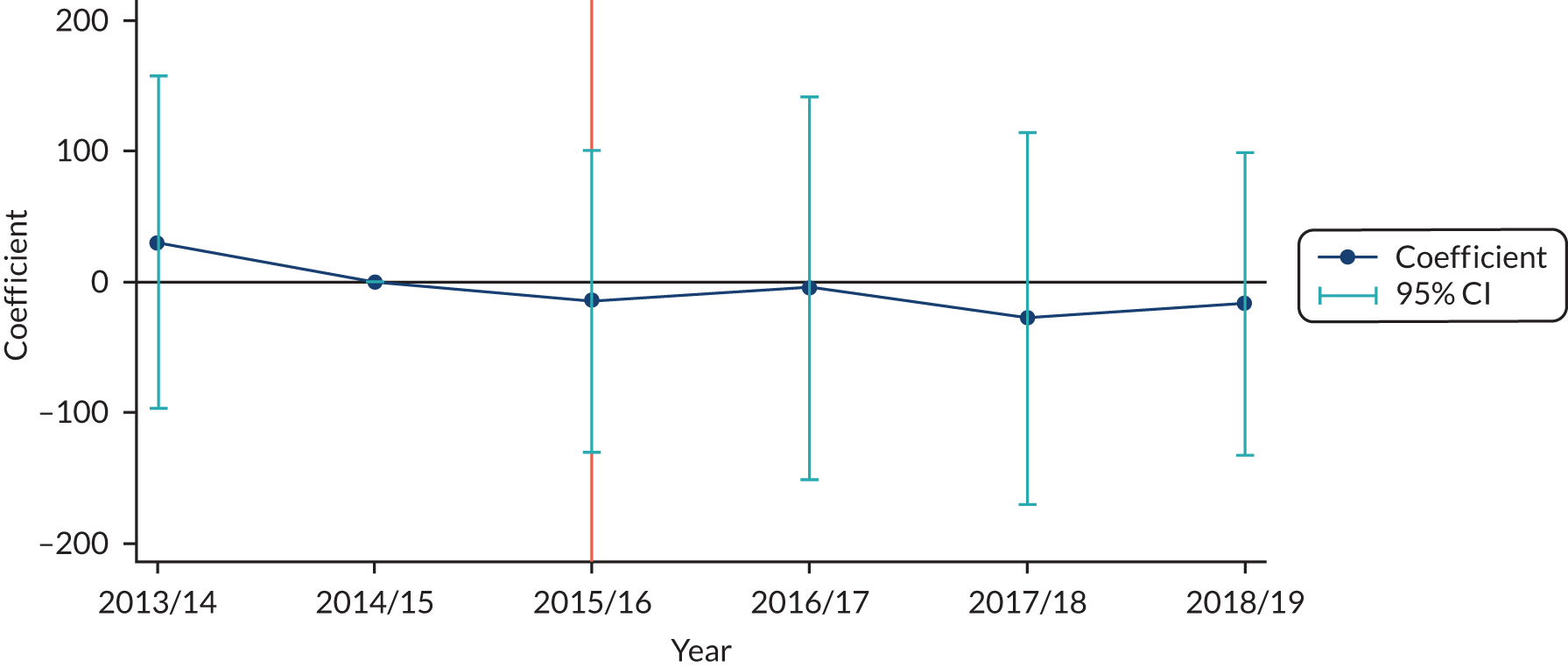

As an extension and falsification test, we extend Equation 2 to include leads and lags of treatment. This event-study approach allows us to investigate whether or not there is evidence of parallel trends pre treatment. 80,81 The model that we estimate is:

The parameters of interest are τ1T and τ2T. We normalise effects to zero in 2014/15, the year prior to the introduction of the intervention. Although this is not a formal test of the parallel trends assumption, we have evidence in favour of parallel trends if the τ1T are positive or close to zero and insignificant. Evidence of a treatment effect would come from negative and significant estimates of τ2T.

Treatment and control groups

To apply the DiD model, it is important that we determine the treatment and control groups. With the intervention introduced into geographically determined general practices, there are a number of ways to consider the compositions of the treatment and control groups. Within our data, we have numerous ways to define treatment and control groups, leading to different possible estimates of the treatment effect. Table 3 outlines the possible treatment groups and the different estimates to which they give rise.

| Treatment group | Control group | Estimate | Bias |

|---|---|---|---|

| Study-eligible patients in WtW general practicesa who were in receipt of the intervention at time tb | Study-eligible patients in WtW general practices who were not in receipt of the intervention at time t and who go on to receive the intervention at time t + 1b | τ 1 |

If the intervention is randomly assigned across patients, this should provide a consistent estimate of the short-run effect of the intervention. If individuals in the greatest need are first to receive the intervention, then any significant finding may be an overestimate As t → t + 1, this comparison estimates an intensity of intervention effect – individuals who have been on the programme for over 1 year compared with individuals who have just started the programme |

| Study-eligible patients in WtW general practices who were in receipt of the intervention during the study period | Study-eligible patients in WtW general practices not receiving the intervention during the study period | τ 2 |

If the intervention is randomly assigned this should provide a consistent estimate of the intervention effect If individuals in the greatest need are first to receive the intervention, then any significant finding may be an overestimate. If individuals who may benefit from intervention refuse the intervention, and this is related to our outcomes of interest, then the bias may be in either direction |

| Study-eligible patients in WtW general practices receiving intervention over the study period | Study-eligible patients not in WtW general practices | τ 3 a |

If, pre intervention, the intervention group and the control group have similar trends in their outcomes, and if there are no changes that may affect the control group differentially to the intervention group, this approach should provide the best estimate of the average effect of intervention on the treated. This would give the complier-average causal effect If there are non-social prescribing interventions for the control group that are beneficial, then we would underestimate the benefits of the social prescribing intervention |

| Study-eligible patients in WtW general practices | Study-eligible patients not in WtW general practices | τ 3 b |

If, pre intervention, the intervention group and the control group have similar trends in their outcomes, and if there are no changes that may affect the control group differentially to the intervention group, this approach should provide the best estimate of an intention-to-treat effect. This will be different, and we expect lower, than the average effect of intervention on the treated (τ3b) as our intervention group contains untreated individuals However, it has the benefit of overcoming any problems regarding intervention assignment in social prescribing practices |

Each of the possible comparisons lead to different potential estimations of the treatment effect and the potential ‘bias’ associated with estimated treatment effect. We give most attention to the value τ3b, the intention-to-treat (ITT) estimate of the treatment effect. The ITT estimate overcomes a number of problems associated with the estimation of treatment effects using observational data. First, any treatment is based on a referral process, so that those individuals who are the most ill/most in need, or incurring the highest costs, are those who are referred first. With regression to the mean, it is possible that these individuals see improvements in their health regardless of the intervention and, therefore, the effect of treatment may be overestimated. The ITT analysis mitigates this somewhat by considering all individuals to be treated at the time that treatment becomes available. Second, the ITT analysis accounts for the fact that the intervention will suffer from non-compliance and wide individual heterogeneity in the intervention composition and level of participant engagement. A final advantage of the ITT analysis is that it provides an estimate of the expected effect of the intervention on an individual drawn at random from the treatment practices. However, the ITT estimate cannot distinguish between the effect of the intervention on the individual and the effect of the general practice. It is possible to specify all of the possible combinations of treatment effects, as outlined in Table 3, as ITT analysis. Individuals in the respective treatment groups are deemed to be treated once treatment is available, despite that it may be some time, even years, before individuals actually receive treatment.

As outlined above, there are good reasons for taking an ITT approach. In addition, in recent years it has been noted that the two-way fixed-effects model is potentially biased when treatment assignment varies across time and there is treatment heterogeneity. 78,82 Essentially, the two-way fixed-effects estimator becomes a weighted average of all of the possible two-by-two combinations of treatment and control groups that are available in the data. This leads to the possibility that even when the treatment effect is negative the final estimated treatment effect from two-way fixed effects can be positive. This result depends on the size of effects and the size of the respective groups. To overcome this problem, de Chaisemartin and D’Haultfoeuille78 propose an estimator that is based on the time that treatment occurs, so comparing treatment changes across consecutive time periods with observations whose treatment status did not change. This allows the researcher to investigate the evolution of treatment across time and for the estimation of placebos that are similar to the event-study approaches outlined in Equation 3. Owing to the small number of switchers into treatment, at some of our time points we estimate these models for the main effects only and not for the subgroups. It follows from these recent modelling developments that it is not possible to rank the direction and sign of the potential treatment effects that can be estimated. It is possible that the direction of the estimates is affected by the relative sizes of the groups, the potential treatment heterogeneity and the possibility of heterogeneity in treatment over time. 78

Two-part models for secondary care expenditure outcomes

One of our aims is to estimate the impact of the intervention on health-care expenditure, taking account of usage and cost. Health expenditure is a mixture of distributions because the costs arise from a two-stage procedure. First, there is health-care use and, second, the costs of the health-care usage. As a result, there is considerable density in the distribution at zero because most individuals, including within our data, do not use secondary health-care services in a given year. A further modelling complication arises because, whereas most secondary health service use is of low cost, there are a significant number of individuals who incur very high health-care costs, giving the distribution of the data a long right-hand tail. The consequence of these distributional problems is that the traditional linear model in Equation 2 is not appropriate for investigating expenditure data.

To accommodate the distributional challenges of expenditure data, we follow83 and estimate two-part models (TPMs). The TPM splits the decision into two stages: a use stage and a cost stage. There were four main modelling decisions to be made: first, whether to apply a logit or a probit for the first part of the model (although the consequences of this decision are trivial). We chose a logit model. Second, we had to decide on the link and distribution family for the second-stage generalised linear model (GLM). We made these choices on the basis of the Box–Cox test and the modified Park test. 83 Following this procedure, we chose a log-link function and the gamma distribution. The final decision relates to which variables to include in the linear index. We tried a range of controls to assess their impact on the estimated treatment effect; all models included age and age squared.

The TPM can formally be considered as:83

In this formulation, f0 is the density of yi when yi = 0 and f+ is its conditional density when yi > 0. There has previously been concern that there may not be independence between the two parts of the mode; however, Drukker84 has formally demonstrated that E(yi|xi) can be identified even if there is dependence between the two parts.

The TPM is a non-linear model and, therefore, the derivation of the treatment effect is slightly different from that of a standard two-way fixed-effects model. Following Deb et al. ,83 we can specify a non-linear conditional expectations function for a simple model as:

The control variables (x′i where bold text is used to denote vectors), and the treatment dummy (Di) are a linear function that is transformed by a non-linear function g(*). Now the treatment effect is the difference between two expected values based on the treatment status:

Therefore, in this case, the treatment effect of interest can be obtained from the sample as:

where N is the sample size. Essentially, as shown by Puhani,85 the treatment effect is the difference between the expected value of the outcome in the post-treatment period and the hypothetical expected value in the post-treatment period had the individual not received treatment. In practical terms, the average impact of treatment on the treated can be estimated by taking the average marginal effect from the TPM.

Data

We use data from three different sources: the QOF, SUS and intervention provider. All of these data were provided by NECS.

The QOF is an incentive programme that financially rewards English general practices for quality of patient care and helps to standardise improvements in the delivery of primary care. Under this programme, sets of targets are used to allocate funds, meaning that there can be excellent reporting of a variety of health outcomes for individuals. During the period of our study, there was only one major reform to the QOF targets that may be an issue for our analysis: a reduction in the number of targets by 40 in 2014–15. However, as these changes affected all practices, we would not expect this reform to affect our identification. The QOF provides data on our health outcomes: levels of HbA1c (our primary outcome measure), blood pressure, cholesterol levels, glucose levels, BMI and smoking status. Where individuals had more than one outcome measure per year as a result of repeat visits to their GP, we took the yearly average as the outcome. The level of HbA1c (a measure of glycaemic control) was chosen as our primary outcome measure because it is a key measure of T2DM control. Data on levels of HbA1c are well collected (i.e. there are clear QOF targets for levels of HbA1c) and glycaemic control has a significant effect on long-term health and even small reductions in HbA1c levels can reduce long-term macrovascular and microvascular complications. 86–88

Quality and Outcomes Framework data are populated with measures and Read codes describing the data collected. There are possibilities of errors in routine data collection. For example, HbA1c level measured using International Federation of Clinical Chemistry (IFCC) units can be recorded in the Read codes as DCCT (Diabetes Control and Complications Trial) units. For these reasons, some top coding was required. HbA1c level was top coded at 120 mmol/mol, BMI was top coded at 50 kg/m2 and bottom coded at 20 kg/m2, and cholesterol level was top coded at 10 mmol/l.

The QOF also provides information on patient characteristics, including age, ethnicity (although there are some recording issues with this characteristic leading to inconsistent categorisation and small sample sizes), sex at birth, area of residence and the presence of additional comorbidities. All of the health outcomes and characteristics were extracted by NECS. The QOF was used to identify our sample of patients: individuals within the eligibility age range (40–74 years), registered at a treatment or control GP practice and with a diagnosis of T2DM on 1 April 2015. The data observation period ran from 1 April 2011–12 to 30 March 2018–19. Under our data-sharing agreements, only comorbidities that were part of the eligibility criteria for the intervention were included in our data sample, that is COPD, asthma, heart failure, coronary heart disease, epilepsy and osteoporosis. The area of residence was given as LSOA (lower-layer super output area) and these LSOA markers were linked to the IMD deciles, with 1 being the most deprived decile. Permission to access patients’ QOF register data were given by 13 out of the 16 treatment practices, covering 80% of those referred into the intervention and 11 out of the 15 control practices, providing information on approximately 8300 individuals, with approximately 58% of individuals in treatment practices. The exact number of observations depends on the outcome under consideration, as can be seen in the results.

Secondary uses services data are a record of secondary health-care use in NHS providers. For our study, we used information on the use and cost of outpatient services, inpatient elective services, inpatient non-elective services and A&E services. The costs were measured as the national tariffs that are paid for services at 2019 costs. To prevent extreme values affecting overall results, all costs were capped at the top percentile value.

Finally, we were able to observe who had actually received treatment from the intervention data that provided dates that an individual completed their initial goal-setting meeting with their link worker. We define this date as the point at which an individual started treatment. For the linear health outcome models, we also test the sensitivity of our results by constructing a new treatment group, where the treated are those individuals who have completed at least two goal-setting meetings with their link worker. These meetings typically occur at least 6 months apart.

The three separate data sets were pseudonymised by NECS, using the same key, and linked to form the complete data set. Table 4 shows the variable names and definitions. The pre-treatment summary statistics for the whole sample, and broken down by treatment and control group, are presented in Tables 5 and 6. Summary statistics for the whole time period are given in Appendix 3, Table 37, and Appendix 4, Table 38.

| Variable | Definition |

|---|---|

| HbA1c level | Concentration (IFCC units: mmol/mol) of glycated haemoglobin in the blood |

| BP systolic | SBP (mmHg) |

| BP diastolic | DBP (mmHg) |

| High blood pressureb | Either SBP of > 140 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure of > 90 mmHg |

| Blood glucose level | Concentration (mmol/l) of glucose level in the blood |

| Cholesterol level | Concentration (mmol/l) of total cholesterol in the blood |

| BMI | Body mass index (kg/m2) |

| Smoking status | Currently smoke (1/0) |

| Age | Individual age, years |

| Age start | Age at the start of the data observation period |

| Female | A dummy (0/1) indicating whether an individual’s recorded sex in the QOF is female (1) or male (0) |

| Comorbidities (based on intervention-eligible conditions) | A categorical variable indicating:

|

| Ethnicity, non-white | Based on QOF-reported ethnicity. A dummy (0/1) variable indicating whether an individual is ethnically non-white (1) or white (0) |

| Deprivation decile (IMD deciles) |

The IMD is the official measure of relative deprivation for small areas in England and ranks every LSOA (a LSOA is a geospatial statistical unit containing an average of 1500 residents) from 1 (most deprived) to 32,844 (least deprived). IMD scores are grouped into deciles (e.g. 1 to 3284 represents the 10% most deprived neighbourhoods). Deciles were linked with LSOA data provided by the NECS. Decile 1 represents being in 10% of the most deprived LSOAs; decile 10 represents being in 10% of the least deprived LSOAs The IMD combines information from the seven domains to produce an overall relative measure of deprivation. The domains are combined using the following weights:LSOA location, and so IMD decile, is taken from the QOF and is time invariant |

| Variable | Count (n) | Mean/proportiona | SD | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control group | |||||

| HbA1c level (mmol/mol) | 2855 | 56.88 | 14.47 | 28.50 | 120.00 |

| BP (mmHg) | |||||

| Systolic | 3170 | 133.54 | 12.27 | 97.33 | 202.75 |

| Diastolic | 3170 | 78.33 | 7.79 | 53.83 | 123.00 |

| High | 3170 | 0.33 | 0.37 | 0 | 1 |

| Blood glucose level (mmol/l) | 1533 | 8.37 | 3.44 | 3.30 | 18.00 |

| Cholesterol level (mmol/l) | 3046 | 4.58 | 1.09 | 2.00 | 9.50 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 3129 | 33.15 | 6.31 | 20.00 | 50.00 |

| Smoker | 3158 | 0.26 | 0.42 | 0 | 1 |

| Treatment group | |||||

| HbA1c level (mmol/mol) | 3989 | 58.17 | 15.03 | 26.02 | 120.00 |

| BP (mmHg) | |||||

| Systolic | 4506 | 133.53 | 12.38 | 90.00 | 220.00 |

| Diastolic | 4506 | 78.56 | 7.86 | 55.00 | 124.56 |

| High | 4506 | 0.33 | 0.37 | 0 | 1 |

| Blood glucose level (mmol/l) | 2543 | 8.41 | 3.50 | 2.60 | 18.00 |

| Cholesterol level (mmol/l) | 4293 | 4.57 | 1.09 | 1.53 | 10.00 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 4374 | 32.61 | 6.37 | 20.00 | 50.00 |

| Smoker | 4483 | 0.25 | 0.41 | 0 | 1 |

| Total | |||||

| HbA1c level (mmol/mol) | 6844 | 57.63 | 14.81 | 26.02 | 120.00 |

| BP (mmHg) | |||||

| Systolic | 7676 | 133.53 | 12.33 | 90.00 | 220.00 |

| Diastolic | 7676 | 78.46 | 7.83 | 53.83 | 124.56 |

| High | 7676 | 0.33 | 0.37 | 0 | 1 |

| Blood glucose level (mmol/l) | 4076 | 8.39 | 3.48 | 2.60 | 18.00 |

| Cholesterol level (mmol/l) | 7339 | 4.57 | 21.09 | 1.53 | 10.00 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 7503 | 32.84 | 6.35 | 20.00 | 50.00 |

| Smoker | 7641 | 0.26 | 0.42 | 0 | 1 |

| Variable | Count (n) | Mean/proportion | SD | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control group | |||||

| Use any HC | 3455 | 0.62 | 0.41 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Total cost | 3455 | 1097.05 | 1958.46 | 0.00 | 14,000.00 |

| A&E use | 3455 | 0.24 | 0.34 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| A&E cost | 3455 | 41.18 | 74.04 | 0.00 | 500.00 |

| IP elective use | 3455 | 0.18 | 0.30 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| IP elective cost | 3455 | 367.15 | 918.39 | 0.00 | 7500.00 |

| IP non-elective use | 3455 | 0.11 | 0.24 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| IP non-elective cost | 3455 | 327.75 | 1100.61 | 0.00 | 1200.00 |

| Outpatients use | 3455 | 0.54 | 0.43 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Outpatients costs | 3455 | 318.01 | 456.71 | 0.00 | 2500.00 |

| Treatment group | |||||

| Use any HC | 4941 | 0.60 | 0.41 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Total cost | 4941 | 1028.57 | 1862.64 | 0.00 | 14,000.00 |

| A&E use | 4941 | 0.23 | 0.33 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| A&E cost | 4941 | 39.92 | 73.86 | 0.00 | 500.00 |

| IP elective use | 4941 | 0.17 | 0.30 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| IP elective cost | 4941 | 365.91 | 937.13 | 0.00 | 7500.00 |

| IP non-elective use | 4941 | 0.10 | 0.24 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| IP non-elective cost | 4941 | 303.17 | 1036.01 | 0.00 | 12,000.00 |

| Outpatients use | 4941 | 0.52 | 0.43 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Outpatients costs | 4941 | 290.01 | 424.12 | 0.00 | 2500.00 |

| Total | |||||

| Use any HC | 8396 | 0.61 | 0.41 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Total cost | 8396 | 1056.75 | 1902.84 | 0.00 | 14,000.00 |

| A&E use | 8396 | 0.24 | 0.33 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| A&E cost | 8396 | 40.44 | 73.93 | 0.00 | 500.00 |

| IP elective use | 8396 | 0.18 | 0.30 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| IP elective cost | 8396 | 366.42 | 929.41 | 0.00 | 7500.00 |

| IP non-elective use | 8396 | 0.11 | 0.24 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| IP non-elective cost | 8396 | 313.29 | 1063.07 | 0.00 | 12,000.00 |

| Outpatients use | 8396 | 0.52 | 0.43 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Outpatients costs | 8396 | 301.53 | 438.02 | 0.00 | 2500.00 |

The data presented in the tables demonstrate that, in terms of average health outcomes, the treatment and control groups are similar, with the treatment group having, on average, slightly higher levels HbA1c. The tables also indicate that the sample size for blood glucose is much smaller than that for the other outcomes; for this reason, we do not analyse the blood glucose outcome. In terms of health-care costs (and, to some degree, health-care use), the treatment group appears to incur, on average, lower costs (and use) than the control group. Finally, Table 7 shows the characteristics of the sample. Compared with the treatment group, the control group is slightly older, more likely to have an extra multimorbidity and more likely to be male. There are considerable differences in ethnicity, with the treatment group more likely than the control group to be non-white. Large proportions of both the control group (55%) and the treatment group (60%) live in areas in the top quintile of deprivation.

| Variable | Count (n) | Mean/proportion | SD | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control group | |||||

| Age (years) | 3455 | 58.54 | 8.94 | 39.50 | 73.50 |

| Age (years) at start | 3455 | 55.04 | 8.94 | 36.00 | 70.00 |

| Women | 3455 | 0.42 | 0.49 | 0 | 1 |

| Multimorbidity | 3455 | 0.58 | 0.49 | 0 | 1 |

| Ethnically non-white | 3424 | 0.12 | 0.32 | 0 | 1 |

| Deprived area | 3455 | 0.55 | 0.50 | 0 | 1 |

| Treatment group | |||||

| Age (years) | 4941 | 57.90 | 9.13 | 39.50 | 73.50 |

| Age (years) at start | 4941 | 54.40 | 9.13 | 36.00 | 70.00 |

| Women | 4941 | 0.44 | 0.50 | 0 | 1 |

| Multimorbidity | 4941 | 0.53 | 0.50 | 0 | 1 |

| Ethnically non-white | 4878 | 0.24 | 0.42 | 0 | 1 |

| Deprived area | 4941 | 0.60 | 0.49 | 0 | 1 |

| Total | |||||

| Age (years) | 8396 | 58.16 | 9.06 | 39.50 | 73.50 |

| Age (years) at start | 8396 | 54.66 | 9.06 | 36.00 | 70.00 |

| Women | 8396 | 0.43 | 0.50 | 0 | 1 |

| Multimorbidity | 8396 | 0.55 | 0.50 | 0 | 1 |

| Ethnically non-white | 8302 | 0.19 | 0.39 | 0 | 1 |

| Deprived area | 8396 | 0.58 | 0.49 | 0 | 1 |

Results

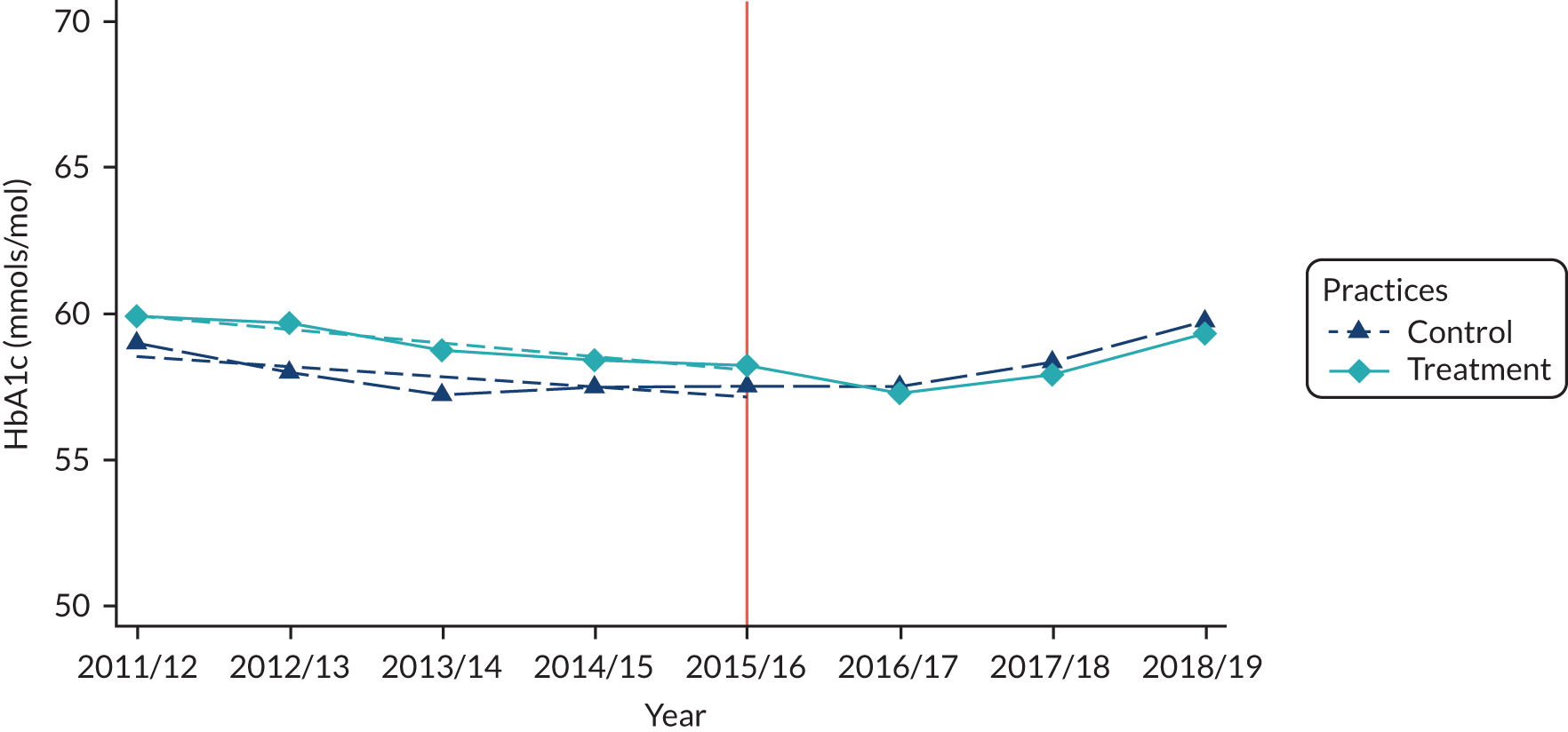

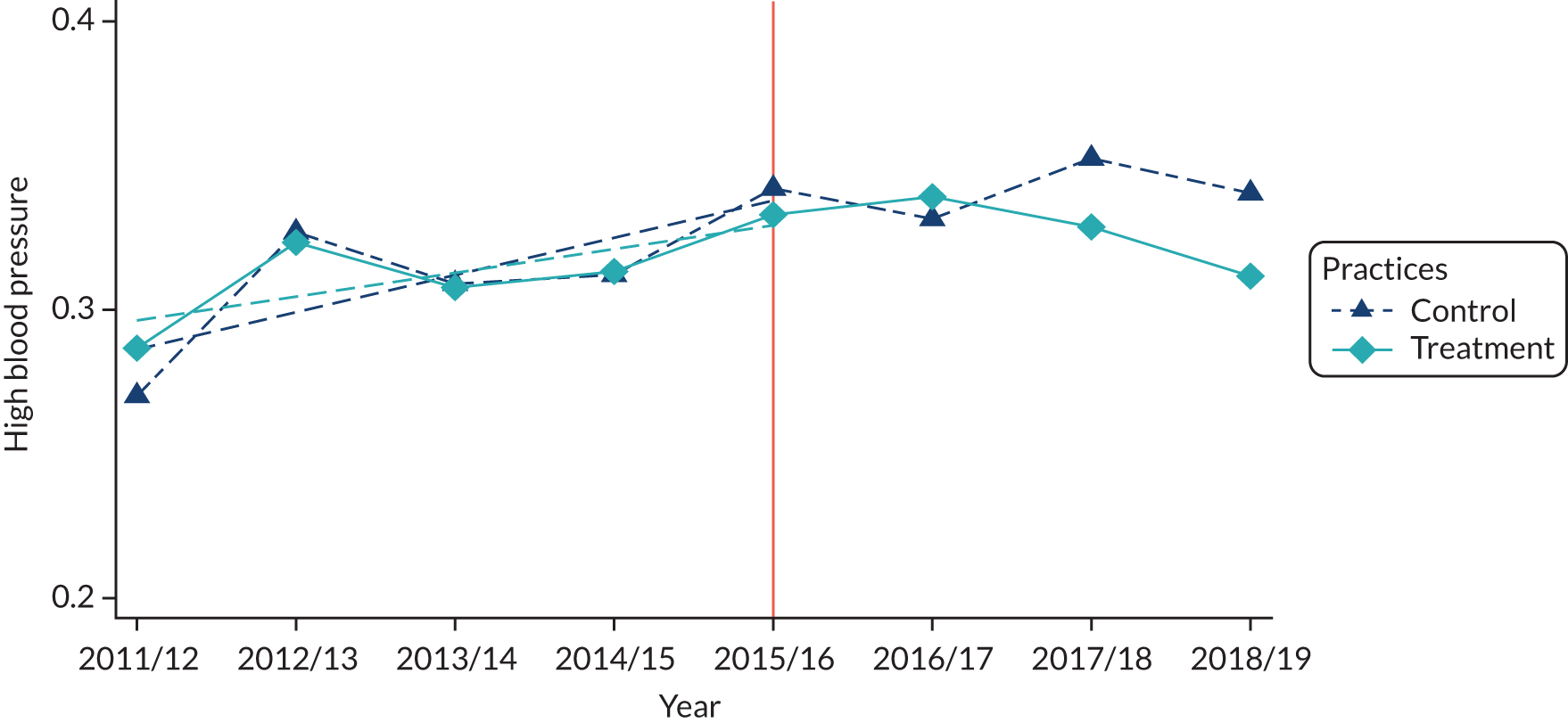

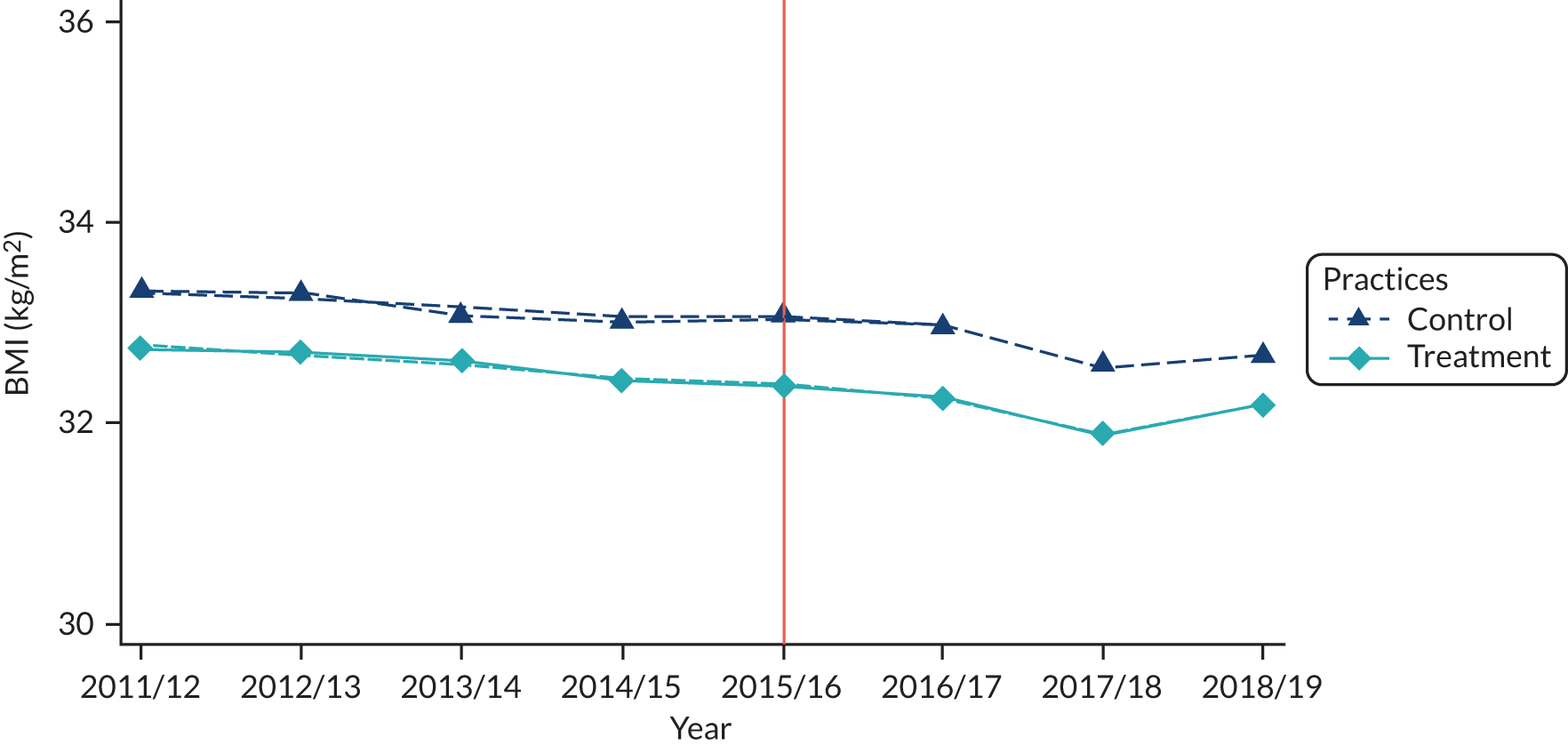

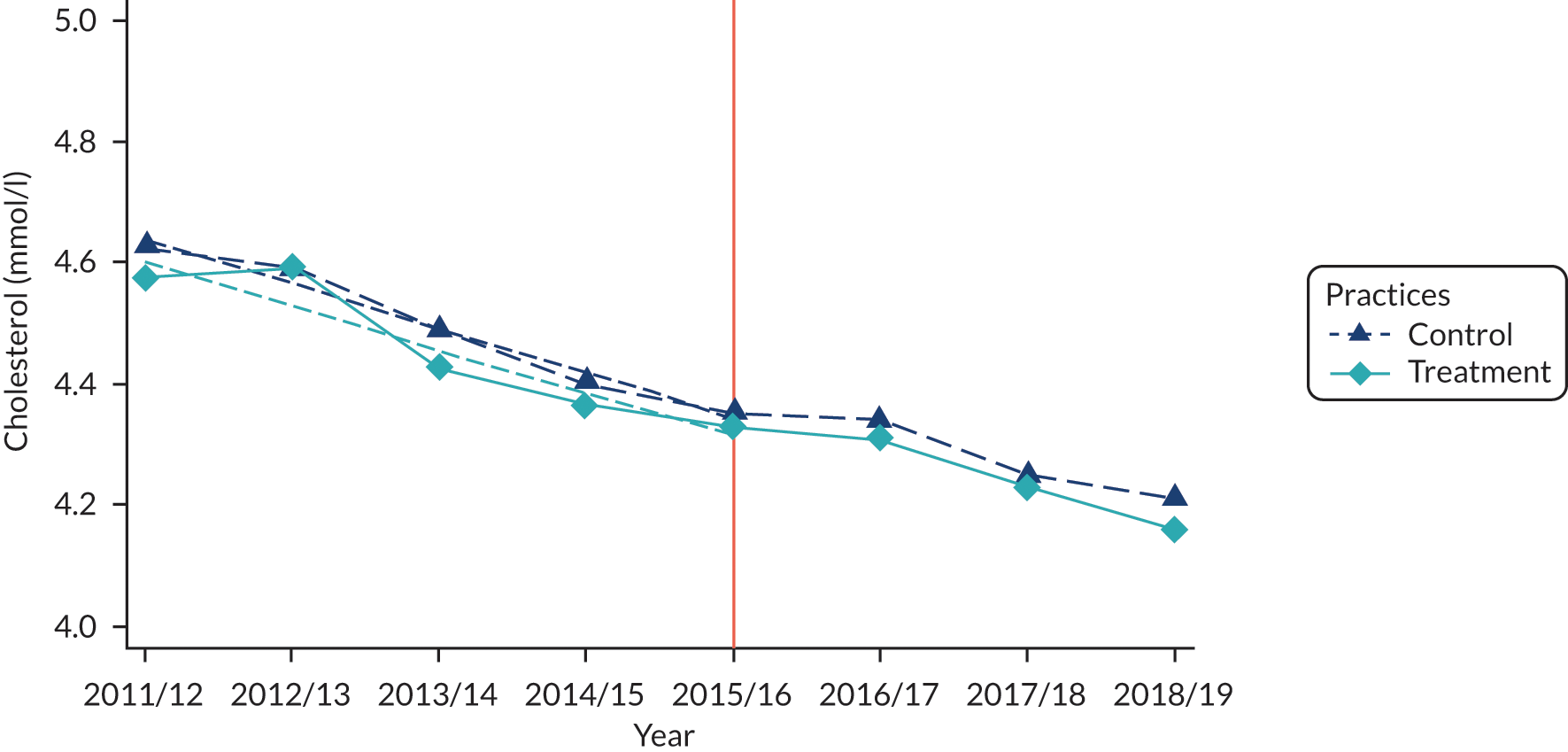

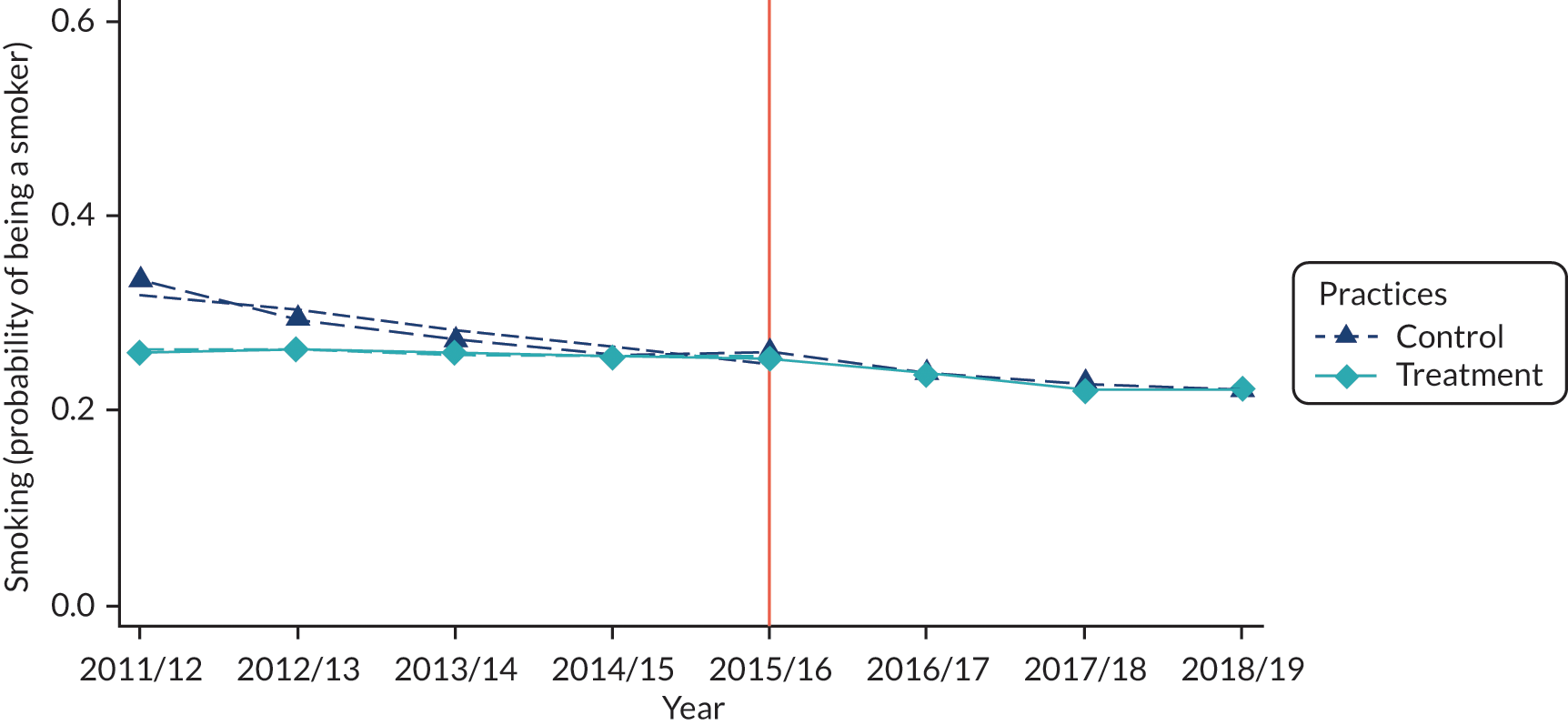

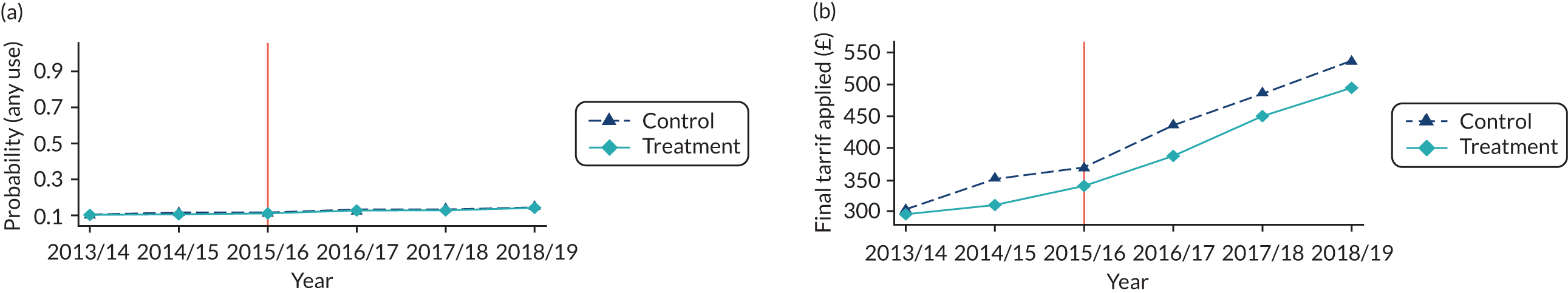

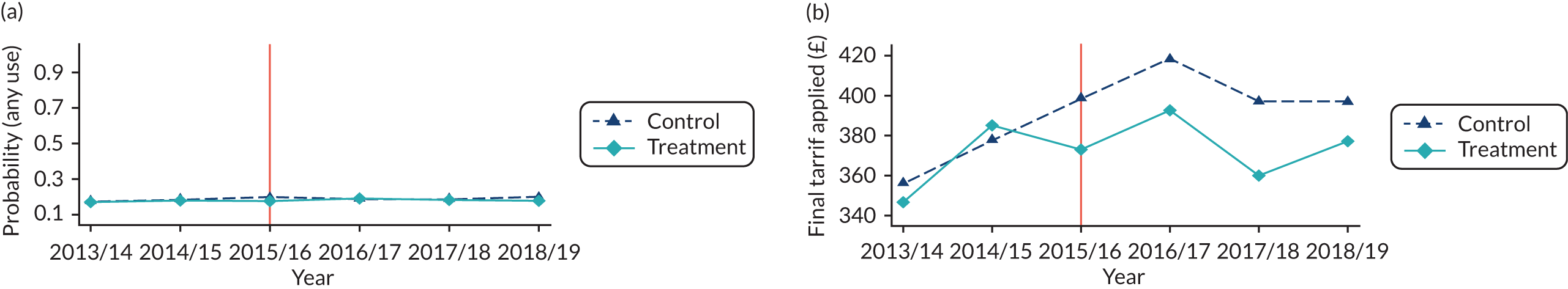

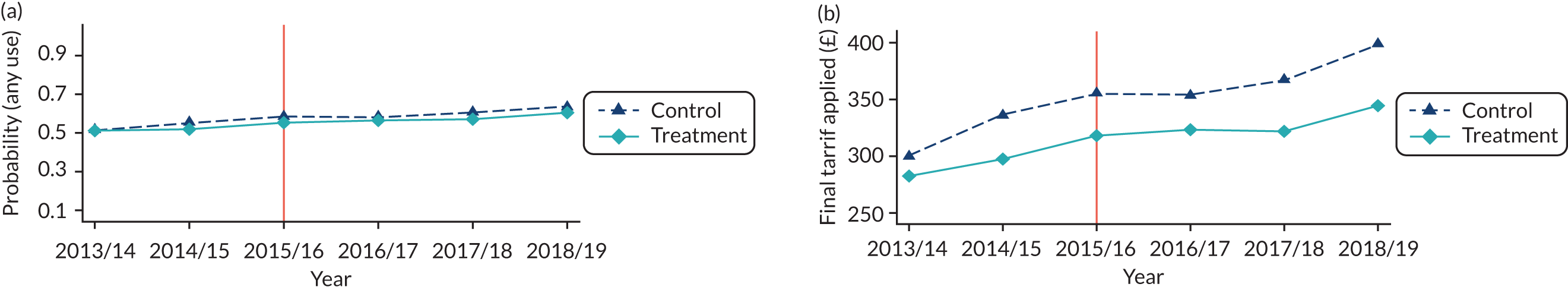

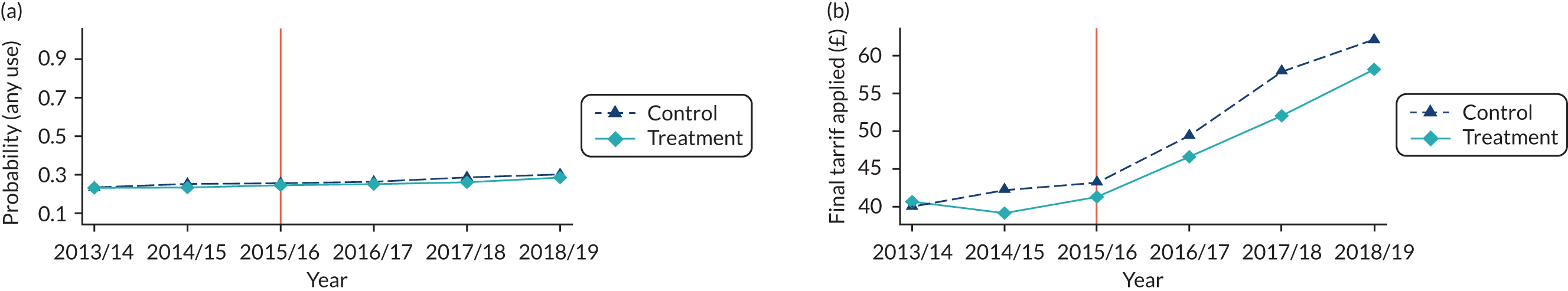

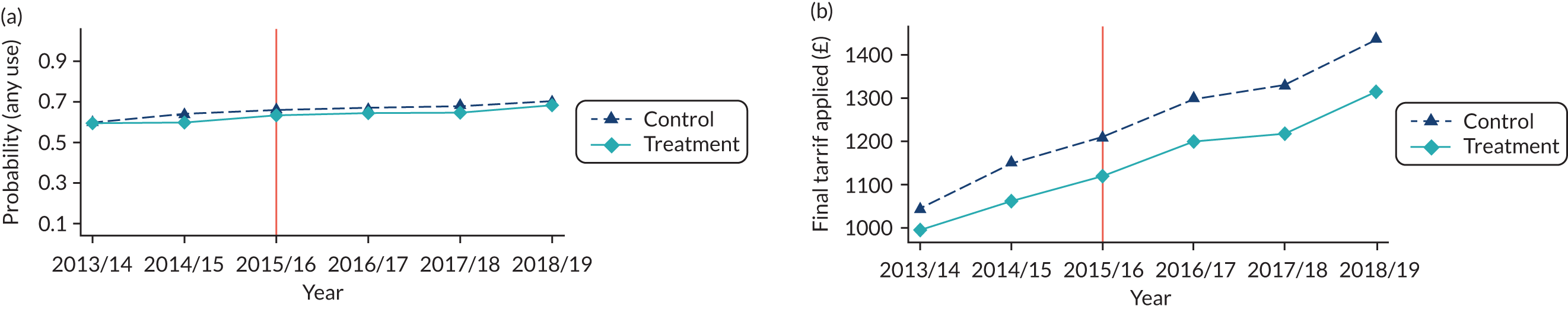

Health outcomes

Figures 2 and 3 and Appendix 5, Figures 11–13, provide the unconditional means for the health outcomes for the treatment and control groups across the whole time period. These are based on the ITT analysis, with individuals classed as being in the treatment group if they are registered with a general practice offering the intervention. We mark the point at which the intervention was available, year 15/16. These graphs help to provide evidence to support our DiD approach. Ideally, the two groups would have similar trends in outcomes in the pre-treatment period. If there is an impact of treatment, we would expect some divergence in outcomes post treatment. However, even if the figures themselves do not demonstrate parallel trends, because these are unconditional trends, it may be that once age, time and individual fixed effects are accounted for the parallel trends assumption holds.

FIGURE 2.

Glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) level: control vs. treatment by year. Mean outcomes plotted against year for the treatment and control practices, with the orange line indicating the year that the intervention became available.

FIGURE 3.

High blood pressure: control vs. treatment by year. Mean outcomes plotted against year for the treatment and control practices, with the orange line indicating the year that the intervention became available.

The trends suggest a mixed picture for the intervention. The average level of HbA1c is lower in the control group than in the treatment group in each year prior to treatment (see Figure 2). The small dashed lines represent the linear trend. Pre treatment, the linear trends are parallel. Following treatment, the average level decreases to below the average for the control group and remains there, suggesting that, on average, the intervention has a role in reducing the levels of HbA1c. However, the range over which levels of HbA1c are changing is very small.

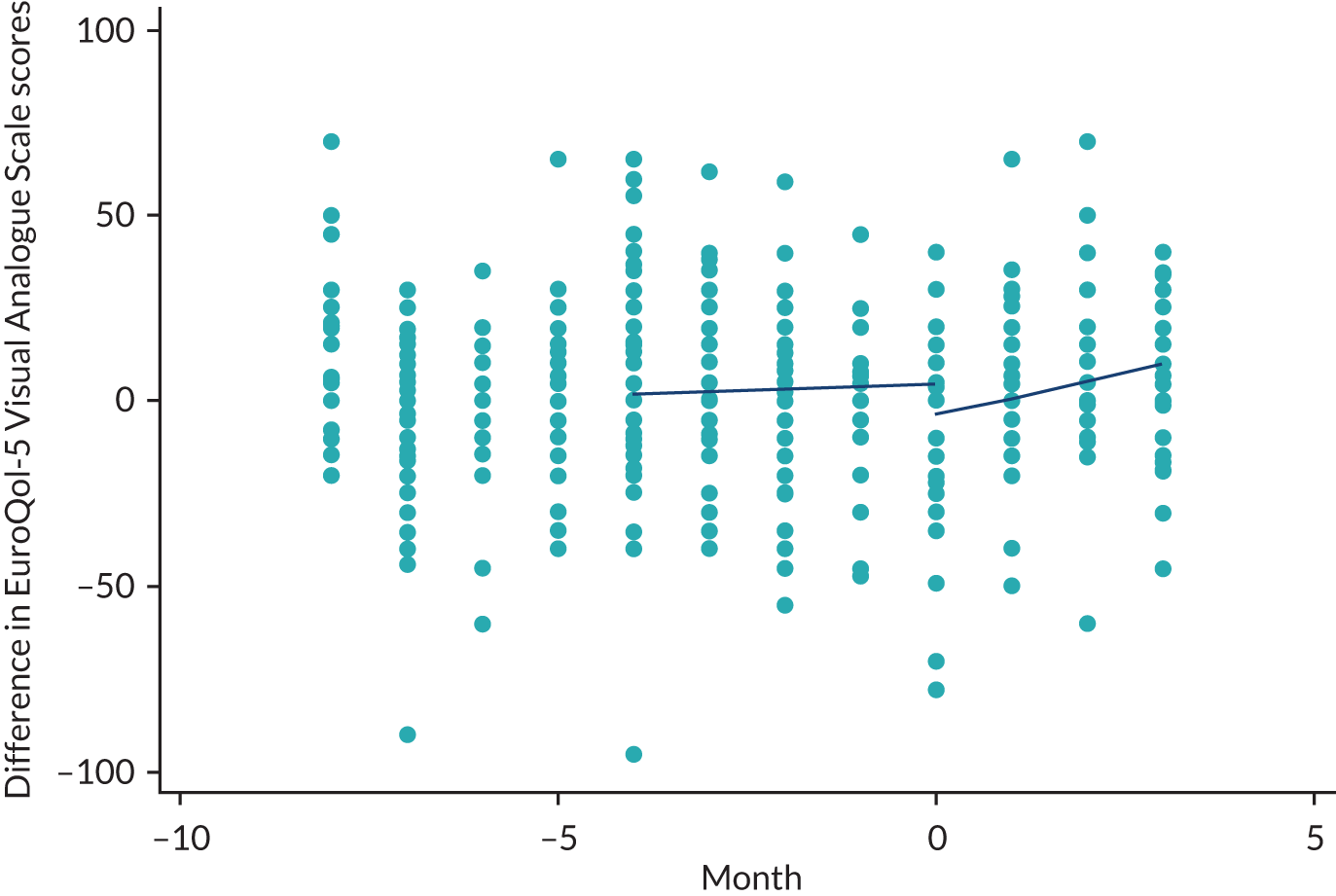

For the probability of having high blood pressure (see Figure 3), we see a similar pattern. Pre treatment, the trends (the small dashed lines) are parallel and the treatment and control groups largely move together. Post treatment, there is a divergence between the treatment group and the control group, with the treated group showing improvements in probability of having high blood pressure. Although, again, this finding is tempered by the fact that the changes are very small in magnitude.