Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 17/151/05. The contractual start date was in January 2020. The final report began editorial review in November 2021 and was accepted for publication in May 2022. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Ponsford et al. This work was produced by Ponsford et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Ponsford et al.

Chapter 1 Background

Introduction

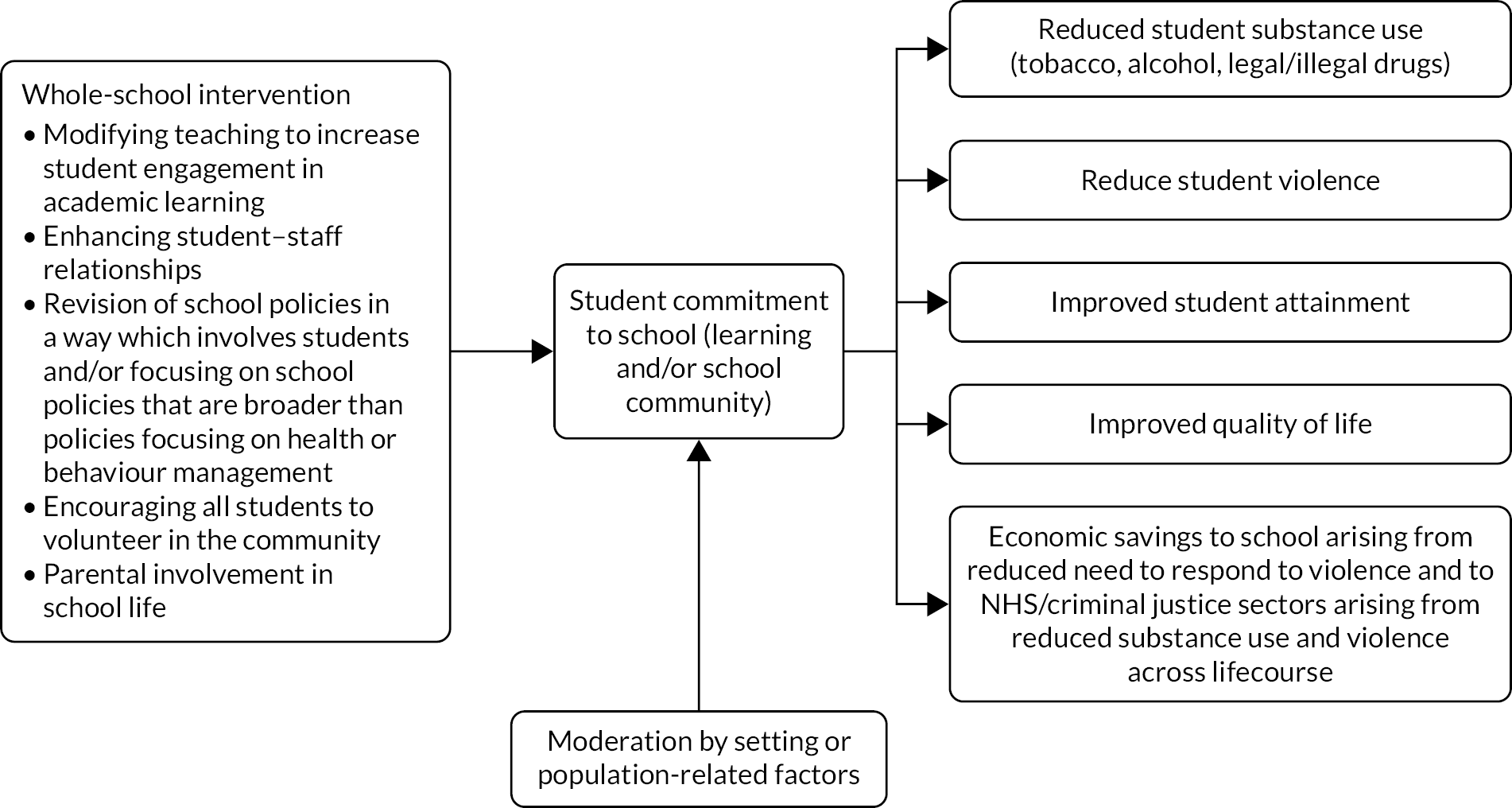

Whole-school interventions aim to modify the school environment to promote health. 1 A subset aims to promote student commitment to school to prevent outcomes such as substance use (i.e. tobacco, alcohol and other drugs) and violence, which are important, intercorrelated outcomes2–5 often associated with disengagement from school. 6,7 Such interventions are informed by theories of change that postulate that interventions build student commitment to school, and therefore prevent substance use and violence by improving relationships within schools and between schools and local communities,8 for example via improving pedagogy, revising school policies, encouraging student volunteering or increasing parental involvement in school. This review synthesises evidence on such interventions. It categorises such interventions into subtypes, examines theories of change, explores factors affecting implementation and assesses effectiveness and cost-effectiveness in preventing violence and substance use, as well as improving educational attainment.

Description of the problem

Substance use and violence among young people remain important public health problems, hence our focus on them in this review. According to English surveys,9 rates of regular drinking have decreased in recent years, with only a small proportion (7%) of young people aged 11, 13 or 15 years reporting that they drank alcohol three or more times during the preceding month. About one-quarter of those aged 15 years reported that they had been drunk at least twice ever. 9 Alcohol has been suggested to be the most harmful substance in the UK. 10 Treating alcohol-related diseases costs the NHS in England an estimated £3.5B annually. 11 The annual societal costs of alcohol use in England are estimated at £21B. 12 Alcohol-related harms are strongly stratified by socioeconomic status. 13 Early initiation of alcohol use and excessive drinking are linked to later heavy drinking and alcohol-related harms14,15 and poor health. 16 Alcohol use among young people is associated with truancy, exclusion and poor attainment, unsafe sexual behaviour, unintended pregnancies, youth offending, accidents/injuries and violence. 17

Preventing young people from initiating smoking is another key public health objective, with 80,000 deaths due to smoking annually. 18 Rates of regular smoking have also decreased, with 3% of young people aged 11, 13 or 15 years reporting that they smoked. 9 Smoking has been estimated to cost the NHS £5.2B per year, and wider societal costs amount to £96B. 19,20 Of smokers, 40% start in secondary school21 and early initiation is associated with heavier and more enduring smoking and greater mortality. 22,23 Smoking among young people is a key driver of health inequalities. 21

Among UK 15- to 16-year-olds, 21% have used cannabis9 and 9% have used other illicit drugs. 22 Early initiation and frequent use of ‘soft’ drugs may be a pathway to later, more problematic, drug use. 24 Drugs such as cannabis and ecstasy are associated with increased risk of mental health problems, particularly among frequent users. 24–27 Young people’s drug use is also associated with accidental injury, self-harm, suicide28–30 and other ‘problem’ behaviours. 31–34

The prevalence, harms and costs of violence among young people indicate that addressing this is a public health priority. 35,36 The most recent evidence shows that, in England, 17% (24% of boys vs. 9% of girls) of young people aged 11, 13 or 15 years reported involvement in a fight two or more times in the preceding 12 months. 9 A UK study found that 10% of young people aged 11–12 years reported carrying a weapon and 8% reported attacking someone with intent to hurt them seriously. 37 By age 15–16 years, 24% of students report that they have carried a weapon and 19% reported attacking someone with the intent to hurt them seriously. 37 There are also associations between aggression and antisocial behaviours in youth and violent crime in adulthood. 38,39 In addition to leading to further health inequalities, the economic costs to society of youth aggression, bullying and violence are high. For example, the cost of crime attributable to conduct problems in childhood is estimated at about £60B a year in England and Wales. 40

Description of the intervention

There is increasing interest in whole-school interventions promoting student commitment to school as a means of addressing complex public health problems and improving educational attainment. Interest in such interventions reflects awareness that health education lessons struggle to find a place in school timetables and have patchy results that tend to dissipate with time. 41–44 It also reflects interest in socioecological determinants of health including the school environment. 45 If effective, such interventions might represent a pragmatic and efficient means of addressing multiple intercorrelated risk behaviours.

Theory of change

According to a previous review we conducted on the effects on student health of the school environment and interventions to address this,1 the theory of human functioning and school development46 provides the most comprehensive theory of how schools can influence student commitment to school and, consequently, students’ health behaviours. In the present review, we therefore use this theory to define our initial theory of change and inclusion criteria for the interventions examined. We also draw on this theory as a starting point for synthesising intervention theories, in the course of which we refine the theory of change. The starting theory of change is also used to help inform our categorisation of interventions, which, in turn, we use to inform our syntheses of evidence about effectiveness. In the discussion section, we reflect on what the evidence synthesised in this review suggests about the usefulness of this theory of change.

What then does the theory of human functioning and school organisation propose as to how school environments might be modified to increase student commitment to school and thereby prevent substance use and violence, and improve educational attainment? The theory proposes that, to promote students’ health, schools should help students build their capacity for practical reasoning and affiliation. Practical reasoning concerns the ability to think and reason. This allows them to make choices, including about their health. Capacity for affiliation involves a concern for other humans, and to experience mutually satisfying interactions and attachments. Such affiliation provides a sense of belonging and feeling of being socially supported, which can protect heath.

The theory proposes that students are more likely to develop these assets if they feel committed to two school ‘orders’. The school ‘instructional order’ is concerned with learning and involves the relay of knowledge and skills. The school ‘regulatory order’ is concerned with conduct and involves the relaying of values and beliefs. Committed students are theorised to feel connected to these orders, enabling the realisation of their capacities for practical reasoning and affiliation.

Students who do not commit to the instructional or regulatory orders are theorised to fall into three categories, depending on the orders to which they are not committed. Alienated students are disconnected from both, either not understanding or rejecting the instructional and regulatory orders. The theory proposes that working-class students are more likely to fall into this category because of the lesser cultural alignment between working-class values and the middle-class values of school. Detached students can meet the demands of the instructional order but do not understand or share the values of the school’s regulatory order. Finally, estranged students cannot meet the instructional order’s demands but share the values of the regulatory order. The theory suggests that schools can promote health by increasing the extent to which students commit to these orders, and thereby realise their capacities for practical reasoning and affiliation.

This is theorised to occur via a number of specific processes. First, schools can modify ‘classification’: the boundaries that exist between the school and the outside world, and boundaries within the school that occur between teachers and students, between students and between subjects. Weakening boundaries between the school and the surrounding community is theorised to increase student commitment via increasing alignment between the school culture and that of the community and families in which students live. This could occur via students volunteering in local communities or via parents being involved in school activities. Weakening boundaries between teachers and students, or among students, is theorised to occur through improved staff/student relationships and co-operation, which will promote greater insights of both students and staff into each other’s realities. Such co-operation and relationship-building could occur via staff involving students in classroom decisions or whole-school policy-making, or via school policies aiming to improve relationships, for example via changes to school discipline systems. 47 This is theorised to promote commitment and facilitate realisation of students’ capacity for practical reasoning and affiliation. Weakening boundaries between subjects is theorised to occur through cross-subject teaching and learning, which will increase student engagement in learning and facilitate the development of the capacity for practical reasoning.

Second, schools can increase student commitment by modifying ‘framing’: reducing teaching that is didactic and teacher-led, and increasing student input into learning. This is theorised to increase student commitment to the school instructional and regulatory orders by communicating the school’s commitment to students and their values and needs.

Thus, the theory proposes that schools engaging in these processes will engender student commitment to school and increase the extent to which students realise their potential for practical reasoning and social affiliations. The theory proposes that, because alienation and detachment are more likely to occur among working-class students, weakening classification and reframing are likely to be more important for schools serving working-class students.

Intervention components

A systematic review requires clear inclusion criteria for interventions that are applicable to all potentially relevant study reports. Rather than requiring interventions to be informed by theories of change with similar constructs to the theory of human functioning and school organisation (which could not be applied because of inconsistencies in how studies report these), we defined inclusion criteria for interventions in terms of intervention activities that aligned with this theory, as this will be more consistently and clearly described in study reports. Therefore, informed by the theory of human functioning and school organisation,46 this review focuses on whole-school interventions aiming to reduce violence or substance use via:

-

modifying teaching to increase student engagement in academic learning

-

enhancing student–staff relationships

-

revision of school policies that involves students and/or that goes beyond health or behaviour management policies

-

encouraging all students to volunteer in the community

-

increasing parental involvement in school.

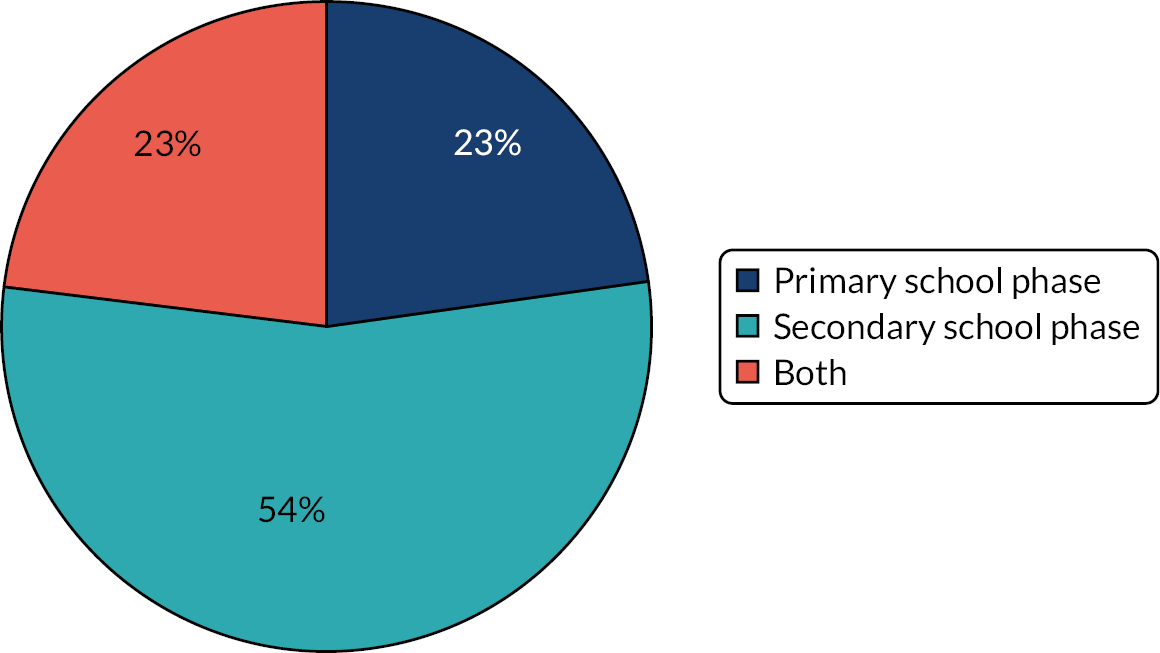

In line with the theory of human functioning and school organisation, these actions are theorised to promote young people’s health by modifying the whole-school environment to engender student commitment to learning and to the school community, thus increasing their capacity for practical reasoning and affiliation and to make healthier choices (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Initial logic model for whole-school interventions that promote student commitment to school to address health problems and achieve educational benefits.

Rationale for the current study

As mentioned, we previously conducted a systematic review of the effects of schools and school-environment interventions on a broad range of student health outcomes. 1 The review synthesised existing theory, identifying the theory of human functioning and school organisation as the most comprehensive theory of how schools might engage in whole-school actions to promote health. 1,46

This review synthesised evidence from trials of interventions modifying the school environment and studies of how school environments influenced health. These syntheses provided evidence that school environments that developed student commitment to school, and whole-school interventions that aimed to increase student commitment to school, were associated with reduced rates of alcohol use, smoking, drug use and violence among students. 48,49

The review was influential on research50 and policy,51 but is now a decade old and was exploratory in scope. Its inclusion criteria for interventions were not informed by a theory of change and it examined student outcomes across a breadth of health domains. It found only a few outcome studies and included no economic evaluations or evaluations assessing educational outcomes. It was thus limited in its ability to test whether or not the theory of human functioning and school organisation is a sound basis on which to inform intervention theories of change, and to determine the best ways for schools to promote student commitment and thereby reduce substance use and violence. The review also excluded interventions that included health education components so that the review could assess whether or not school environment action alone could affect health. With hindsight, it is clear that curriculum and school environment components are potentially synergistic (e.g. a social and emotional skills curriculum preparing students to engage in whole-school change52) and the decision to exclude such interventions led to the exclusion of many otherwise relevant studies.

Finally, the review was limited in not synthesising process evaluations, and therefore not being able to examine factors affecting implementation of interventions. Previous reviews have examined what factors influence the initial delivery and sustained implementation of school-based health interventions,53,54 reporting that key enablers are supportive senior management, alignment of the intervention with school ethos and priorities, positive pre-existing student and teacher attitudes, and parental support of interventions. Given the greater complexity of whole-school interventions as opposed to the largely curriculum-based interventions examined in previous reviews, a review of what factors affect the implementation of whole-school interventions is warranted.

A Cochrane review conducted at about the same time55 synthesised evidence on the effectiveness of ‘health-promoting schools’ interventions (defined as those comprising school environment, curricular and parent/community components). This reported significant effects of such interventions on bullying victimisation and tobacco use, as well as emerging evidence for effects on alcohol and drug use, bullying perpetration and other violence. Although presenting promising evidence, the review was limited by the inclusion of interventions with a variety of school environment components ranging from posters to changes in student participation in decisions. These lacked a common theory of change and this limited the review’s ability to test specific theories of change or recommend which specific whole-school interventions should be implemented. This review also did not synthesise process or economic evaluations.

Since these reviews were published, there has been an upsurge in evaluations of whole-school interventions aiming to prevent student substance use and violence by building student commitment to school. In the light of this and the limitations of earlier reviews, we undertook this new review to focus on such interventions. Unlike the previous reviews, this review focuses on interventions involving activities that align with a specific theory of change informed by the theory of human functioning and school organisation. 46 This was intended to ensure that the review could draw more specific conclusions about which approaches to whole-school change are likely to be effective in preventing student substance use and violence and achieving educational benefits. The review does not exclude whole-school interventions that also include health curricula for the reasons discussed previously.

Review aim and questions

The aim was to search systematically for, appraise the quality of and synthesise evidence to address the following research questions (RQs).

-

What whole-school interventions that promote student commitment to school to prevent student substance use and/or violence have been evaluated, what intervention subtypes are apparent and how closely do these align with the theory of human functioning and school organisation?

-

What factors relating to setting, population and intervention influence the implementation of such interventions?

-

Overall and by intervention subtype, what are the effects of such interventions on student substance use, violence and educational attainment?

-

What is the cost-effectiveness of such interventions, overall and by intervention subtype?

-

Are the effects of such interventions on student substance use and violence mediated by student commitment to school, or moderated by setting or population?

Review objectives

-

To conduct electronic and other searches.

-

To screen references and reports for inclusion in the review.

-

To extract data from and assess the quality of included studies.

-

To synthesise intervention descriptions to describe subtypes and alignment with theory.

-

To synthesise process evaluations to explore factors influencing implementation:

-

To consult with policy/practice and community stakeholders on the results of these analyses.

-

-

To synthesise outcome evaluations to examine effects, mediators and moderators:

-

To consult with policy/practice and community stakeholders on the results of these analyses.

-

-

To draw on the above work to draft and submit to the National Institute for Health and Care Research a report addressing our RQs.

Chapter 2 Review methods

Research design overview

We carried out a multimethod systematic review examining intervention types, theories of change, influences on implementation, outcomes and cost-effectiveness of whole-school interventions promoting student commitment to school to prevent substance use and/or violence, and improve educational attainment. The review followed existing criteria for review conduct and reporting of systematic reviews (e.g. Centre for Reviews and Dissemination56 and Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses). 57 The protocol was registered with PROSPERO (International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews) on 14 October 2019.

Inclusion criteria for the review

Types of participant

Studies were included for which children and young people aged 5–18 years attending mainstream school were the intervention targets.

Types of intervention

The review focused on whole-school interventions aiming to reduce student violence or substance use via actions aligning with the theory of human functioning and school organisation:

-

modifying teaching to increase student engagement in academic learning

-

enhancing student–staff relationships

-

revision of school policies that involves students and/or that goes beyond health or behaviour management policies

-

encouraging all students to volunteer in the community

-

increasing parental involvement in school.

We excluded studies of interventions that:

-

involved health or social and emotional skills curricula only

-

targeted selected students or parents rather than being universal interventions

-

addressed behaviour management in the classroom or school-wide without addressing student engagement or commitment to school

-

involved students as peer educators or peer social marketers without being involved in school policy- or decision-making

-

involved revising policies or procedures relating purely to health or behaviour management without student input.

Types of control

The review focused on treatment-as-usual, no-treatment or other active-treatment control groups.

Types of outcome

Substance use and violence are important intercorrelated outcomes often associated with lack of school commitment. 2–7 Studies focused on violence and/or substance use. We also synthesised evidence on educational attainment, but included studies were not required to focus on this. Our definition of violence includes interpersonal physical, emotional or social abuse. Substance use included use of tobacco, alcohol or other drugs. Outcome measures were quantitative and could be self- or teacher-reported via questionnaires or diaries, or drawn from clinical or administrative data. Outcome measures could draw on dichotomous, categorical or continuous variables. Behavioural outcomes could focus on the following: behaviours over a specific period, frequency, the number of episodes of a behaviour or an index constructed from multiple measures. Violence measures could combine indicators of behaviour and the upset or injury this caused. Measures could examine particular or general forms of behaviours or convictions. Violence measures could combine interpersonal violence with other forms of antisocial behaviour if the former constituted a majority of items. Educational outcomes could be assessed via research-administered tests or routine data on academic progress or performance in tests or exams. Economic analyses could examine the above outcomes and/or health-related quality of life.

Types of study

To address RQ1, we drew on descriptions of interventions and theories of change from included studies. To address RQ2, we included process evaluations that drew on quantitative and/or qualitative data to examine how intervention planning, delivery or receipt was affected by factors relating to interventions, populations or settings. To address RQs 3 and 5, we included cluster randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and/or quasi-experimental evaluations in which schools were allocated non-randomly to intervention and control groups. Studies addressing RQ4 included economic evaluations that related costs to outcomes or benefits.

Search methods for the identification of studies

Database search strategy

Search terms

A draft search strategy was compiled in the OvidSP MEDLINE database by an information specialist (JF). This included strings of terms, synonyms and controlled vocabulary terms (when available) to reflect:

-

population (children and young people aged 5–18 years attending school)

-

intervention (whole-school interventions aiming to prevent violence or substance abuse)

-

evaluation methods.

These concepts were combined using the Boolean operator AND.

Search terms were determined via a text analysis of 77 known articles featuring terminology relevant to the review,58–132 using NVivo 12 Plus software (QSR International, Warrington, UK). Titles, abstracts and keywords were imported and word frequency and cluster analyses were used to create an OvidSP MEDLINE search string that included common subject headings and incorporated relevant words in proximity. These were augmented by additional terms and synonyms so that the search terms adequately described the search topics. These were then combined together and tested systematically. 133 This search strategy was refined with the project team until the results retrieved reflected the scope of the project. When run in an education-focused database, rather than a health one, it became apparent that the sensitivity-to-specificity ratio of the search was too high, resulting in many irrelevant results. Therefore, the search strategy for concept 2 was narrowed. This search was peer reviewed by a librarian not involved with the project using the Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies guidance. 134 The agreed OvidSP MEDLINE search was adapted for each database to incorporate database-specific syntax, controlled vocabularies and search-interface limitations. Details of the search strings used for each database can be found in Report Supplementary Material 1, and in the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine’s data repository. 135

Databases

The following databases were searched in full between 16 and 27 January 2020:

-

ProQuest Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ASSIA) (1987 to 23 January 2020)

-

ProQuest Australian Education Index (complete database as of 23 January 2020)

-

EBSCOhost British Education Index (complete database as of 16 January 2020)

-

EBSCOhost Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) Plus (complete database as of 16 January 2020)

-

Wiley Online Library Cochrane Library (issue 1 of 12, January 2020) was used to search for results from the following databases:

-

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews

-

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials

-

-

Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Co-ordinating Centre (EPPI-Centre) database of health promotion research (BiblioMap) (complete database as of 23 January 2020)

-

EPPI-Centre Database of Promoting Health Effectiveness Reviews (DoPHER) (complete database as of 23 January 2020)

-

OvidSP EconLit (1886 to 9 January 2020)

-

EBSCOhost Education Abstracts (HW Wilson) (complete database as of 17 January 2020)

-

ProQuest Education Database (complete database as of 24 January 2020)

-

EBSCOhost Educational Administration Abstracts (complete database as of 17 January 2020)

-

EBSCOhost Education Resources Information Center (ERIC) (complete database as of 17 January 2020)

-

OvidSP EMBASE® (1947 to 14 January 2020)

-

OvidSP Global Health (1910 to 2020, week 1)

-

OvidSP MEDLINE ALL (1946 to 14 January 2020)

-

OvidSP PsycInfo (1806 to 2020, week 1)

-

Elsevier Scopus® (complete database as of 16 January 2020)

-

OvidSP Social Policy & Practice (October 2019)

-

Clarivate™ Web of Science™ and Social Sciences Citation Index (1970 to present; data last updated on 9 January 2020)

-

EBSCOhost Teacher Reference Center (complete database as of 24 January 2020).

These databases were selected to retrieve literature from the fields of health and education. We amended the list of databases originally intended to be searched (see Appendix 1, Table 8, for deviations from, and clarifications of, protocol) on the advice, informed by initial pilot searches, of the information scientist (JF).

The searches were updated between 11 and 19 May 2021. The search strings used for the updated searches can be found in Report Supplementary Material 1. The updated searches used the following databases:

-

EBSCOhost CINAHL Plus (complete database as of 11 May 2021)

-

Wiley Online Library Cochrane Library (issue 4 of 12, April 2021) was used to search for results from the following databases:

-

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews

-

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials

-

-

EPPI-Centre database of health promotion research (BiblioMap) (complete database as of 13 May 2021)

-

EPPI-Centre DoPHER (complete database as of 13 May 2021)

-

OvidSP EconLit (1886 to 29 April 2021)

-

EBSCO ERIC (complete database as of 19 May 2021)

-

OvidSP Embase (1947 to 10 May 2021)

-

OvidSP Global Health (1910 to 2021, week 18)

-

OvidSP MEDLINE ALL (1946 to 10 May 2021)

-

OvidSP PsycInfo (1806 to May 2021, week 1)

-

Elsevier Scopus (complete database as of 13 May 2021)

-

OvidSP Social Policy & Practice (January 2021)

-

Clarivate Web of Science and Social Sciences Citation Index (1970 to present; data last updated 13 May 2021).

Owing to COVID-19 restrictions, visitor access to libraries was not allowed. Therefore, it was not possible to update searches on the following databases:

-

ProQuest ASSIA

-

ProQuest Australian Education Index

-

EBSCOhost British Education Index

-

EBSCOhost Education Abstracts (HW Wilson)

-

ProQuest Education Database

-

EBSCOhost Educational Administration Abstracts

-

EBSCOhost ERIC

-

EBSCOhost Teacher Reference Center.

Search strategy for other literature sources

The following clinical trials registers were searched for relevant ongoing and unpublished trials on 27 January 2020:

-

ClinicalTrials.gov (complete database as of 27 January 2020)

-

EPPI-Centre Trials Register of Promoting Health Interventions (TRoPHI) (complete database as of 27 January 2020)

-

World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (complete database as of 27 January 2020).

The searches for the following clinical trials registers were updated on 11 May 2021:

-

ClinicalTrials.gov (complete database as of 11 May 2021)

-

EPPI-Centre TRoPHI (complete database as of 11 May 2021).

Because the World Health Organization ICTRP was not returning results, this source could not be updated.

We attempted to search the US Institute of Education Sciences, What Works Clearinghouse on 27 January 2020, but the website was unavailable.

Search terms were derived from the OvidSP MEDLINE search compiled for database searching. Details of the search strings used for these can be found in Report Supplementary Material 1 and in the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine’s data repository. 135 All trial details were examined for their relevance and associated papers were included if they met our inclusion criteria.

We also searched the following websites to identify relevant studies between 17 and 20 January 2020, with updated searches occurring between 20 and 25 May 2021:

-

Cambridge Journals Online (www.eifl.net/e-resources/cambridge-journals-online)

-

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Smoking and Tobacco Use (www.cdc.gov/tobacco/index.htm)

-

Child and Adolescent Health Research Unit (www.cahru.org/)

-

Childhoods Today (www.childwatch.uio.no/publications/journals-bulletins/childhoodstoday.html)

-

Children in Scotland (https://childreninscotland.org.uk/)

-

Children in Wales (www.childreninwales.org.uk/)

-

European Union Community Research and Development Information Service (https://cordis.europa.eu/)

-

Database of Education Research (EPPI-Centre) – not available

-

Drug and Alcohol Findings Effectiveness Bank (https://findings.org.uk/e-bank.php)

-

Google (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA)

-

Google Scholar

-

Welsh Government (https://gov.wales/)

-

Scottish Government (www.gov.scot/)

-

Joseph Rowntree Foundation (www.jrf.org.uk/)

-

National Criminal Justice Reference Service (www.ncjrs.gov/)

-

National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children (www.nspcc.org.uk/)

-

National Youth Agency (https://nya.org.uk/)

-

Northern Ireland Executive (www.northernireland.gov.uk/)

-

OpenGrey (www.opengrey.eu/)

-

Personal Social Services Research Unit (www.pssru.ac.uk/)

-

Project Cork (www.centerforebp.case.edu/resources/tools/project-cork-clinical-screening-tools; accessed 8 November 2021)

-

University College London-Faculty of Education and Society (UCL-IOE) Digital Education Resource Archive (https://dera.ioe.ac.uk/)

-

UK Clinical Research Network Portfolio (www.nihr.ac.uk/researchers/collaborations-services-and-support-for-your-research/run-your-study/crn-portfolio.htm)

-

University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (https://illinois.edu/)

-

US Center for Substance Abuse Prevention (www.samhsa.gov)

-

Social Issues Research Centre (www.sirc.org/)

-

The Campbell Library (www.campbellcollaboration.org)

-

The Children’s Society (www.childrenssociety.org.uk/)

-

Open Library (https://openlibrary.org/)

-

Schools and Students’ Health Education Unit Archive (https://sheu.org.uk/)

-

World Health Organization ICTRP (www.who.int/clinical-trials-registry-platform)

-

Young Minds: Child and Adolescent Mental Health (https://youngminds.org.uk/).

The following search terms were used: (school) AND (teaching OR teacher OR engagement OR engaging OR commitment OR relationships OR policies OR policy OR volunteer OR parent environment OR whole school OR health promoting school) AND (evaluation OR effectiveness OR outcomes OR process OR intervention OR programme OR program). Results were screened in batches of 50. When no relevant results were returned from the last batch of 50, researchers did not progress to the next batch of 50.

Subject experts in the field known to the research team were contacted to identify additional reports. See standalone project information for the experts contacted and a template of the e-mail sent to them (www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/phr/AHSN4485). We also searched reference lists from all reports to identify further studies. The protocol specified that we would hand-search journals that published included studies found only via reference checking, and not indexed on databases we had searched, but none met this criterion.

Information management and study selection

All citations identified by our 2020 searches were uploaded to EndNote X9 (Clarivate) for duplicate removal using existing methods. 136,137 De-duplicated results were then uploaded to EPPI-Reviewer (version 4.0) software (EPPI-Centre, University of London, London, UK). The updated search results were uploaded to the same EndNote library as those identified in 2020. Duplicates found within the results of the 2021 search were removed. Again, de-duplicated results were uploaded to EPPI-Reviewer software.

Two reviewers (CB and RP) piloted the screening of successive batches of the same randomly generated 50 titles/abstracts, discussing disagreements over inclusion and calling on a third reviewer (GJMT) when necessary. Once a batch-level agreement rate of > 90% was reached, the remaining references were screened on title and abstract for inclusion by a single reviewer (RP or CB). Full reports were obtained for references judged, based on title and abstract, as meeting our inclusion criteria or for which there was insufficient information to judge. Screening of full study reports was then carried out by two reviewers (CB and RP), applying a comparable dual piloting process before moving to independent screening. We maintained a record of the selection process for all screened material.

Data extraction

Two reviewers independently extracted data from included theory (CB and RP), process (CB and RP), outcome (CB and GJMT) and economic (CB and AM) evaluation reports, using existing tools. 138–141 When reviewers disagreed on data extraction, they met to resolve this, referring to a third reviewer when necessary.

For intervention descriptions, date were extracted on domains included in a standard framework. 141 For intervention theories of change, we extracted data on constructs, mechanisms, contextual contingencies affecting these and scientific theories informing theories of change. For all studies, we extracted information on the following: study details (study location, timing and duration; individual and organisational participant characteristics); study design and methods (design, sampling and sample size, allocation, blinding, control of confounding, accounting for data clustering, data collection, attrition, analysis); process evaluation findings and interpretation; outcome measures (timing, reliability of measures, intraclass correlation coefficients, effect sizes); relevant mediation and moderation analyses; and economic data (inputs and outputs relating to costs, consequences/ benefits, disaggregated by time period when appropriate). Pairs of reviewers independently entered data into EPPI-Reviewer 4 for each study. We would have involved a translator when necessary, but this issue did not arise. Data extraction tools for the theory of change and for the process, outcome and economic evaluations are provided as part of the standalone project information (www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/phr/AHSN4485).

When reports were incomplete and there was a risk of missing data affecting our analysis, we contacted authors to request additional information (see standalone project information for template: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/phr/AHSN4485). If authors were not traceable or if the sought information was unavailable from the authors within 2 months, we recorded that the study information was missing in EPPI-Reviewer, and this was included in our risk-of-bias assessment.

Assessment of quality and risk of bias

Drawing on Sterne et al. ’s142 guidance, we reduced the effect of reporting bias by focusing synthesis on studies rather than publications. Following the Cho et al. 143 statement on redundant publications, we attempted to detect duplicate studies and, if multiple articles reported on the same data, these data were extracted only once. We minimised location bias by searching across multiple databases. We minimised language bias by not excluding articles based on language.

All included studies were subjected to quality assessment by two independent reviewers using existing tools. Chris Bonell and Ruth Ponsford assessed descriptions of theory and process evaluations, outcome evaluations were assessed by Chris Bonell and GJ Melendez-Torres and economic evaluations were assessed by Chris Bonell and Alec Miners. Each pair then met to compare their assessments, resolving any disagreements through discussion, when necessary calling on the judgement of a third reviewer.

Assessment of theories of change

We assessed the quality of descriptions of intervention theories of change using a modified version of the criteria developed in our previous systematic reviews,144–146 informed also by our prior work on realist evaluation methods. 147 The assessment focused on the extent to which the theory of change described a path from intervention to outcomes; the clarity with which constructs were defined; the clarity with which causal inter-relationships between constructs were defined; the extent to which underlying mechanisms were explained; and the extent to which the theory of change considered how mechanisms and outcomes could vary with context (see standalone project information for tool used: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/phr/AHSN4485).

Assessment of process evaluations

We assessed the quality of process evaluations using the EPPI-Centre tool148 addressing the rigour of sampling, data collection, data analysis, the extent to which the study findings were grounded in the data, whether or not the study privileged student perspectives, and the breadth of findings and depth of findings (see standalone project information for tool used: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/phr/AHSN4485). These assessments were used to assign studies to two categories of ‘weight of evidence’. First, reviewers assigned a weight (low, medium or high) to rate the reliability or trustworthiness of the findings (the extent to which the methods employed were rigorous/could minimise bias and error in the findings). Second, reviewers assigned an additional weight (low, medium or high) to rate the usefulness of the findings for addressing the RQs. Study reliability was judged as being high when steps were taken to ensure rigour in four or more assessment criteria, as medium when addressing only three and as low when addressing two or fewer. To achieve a rating of ‘high’ usefulness, studies needed to be judged to have privileged student perspectives and to present findings that achieve both breadth and depth. Studies that were rated as having ‘medium’ usefulness only partially met this criterion, and studies rated as having ‘low’ usefulness were judged to have sufficient, but limited, relevant findings.

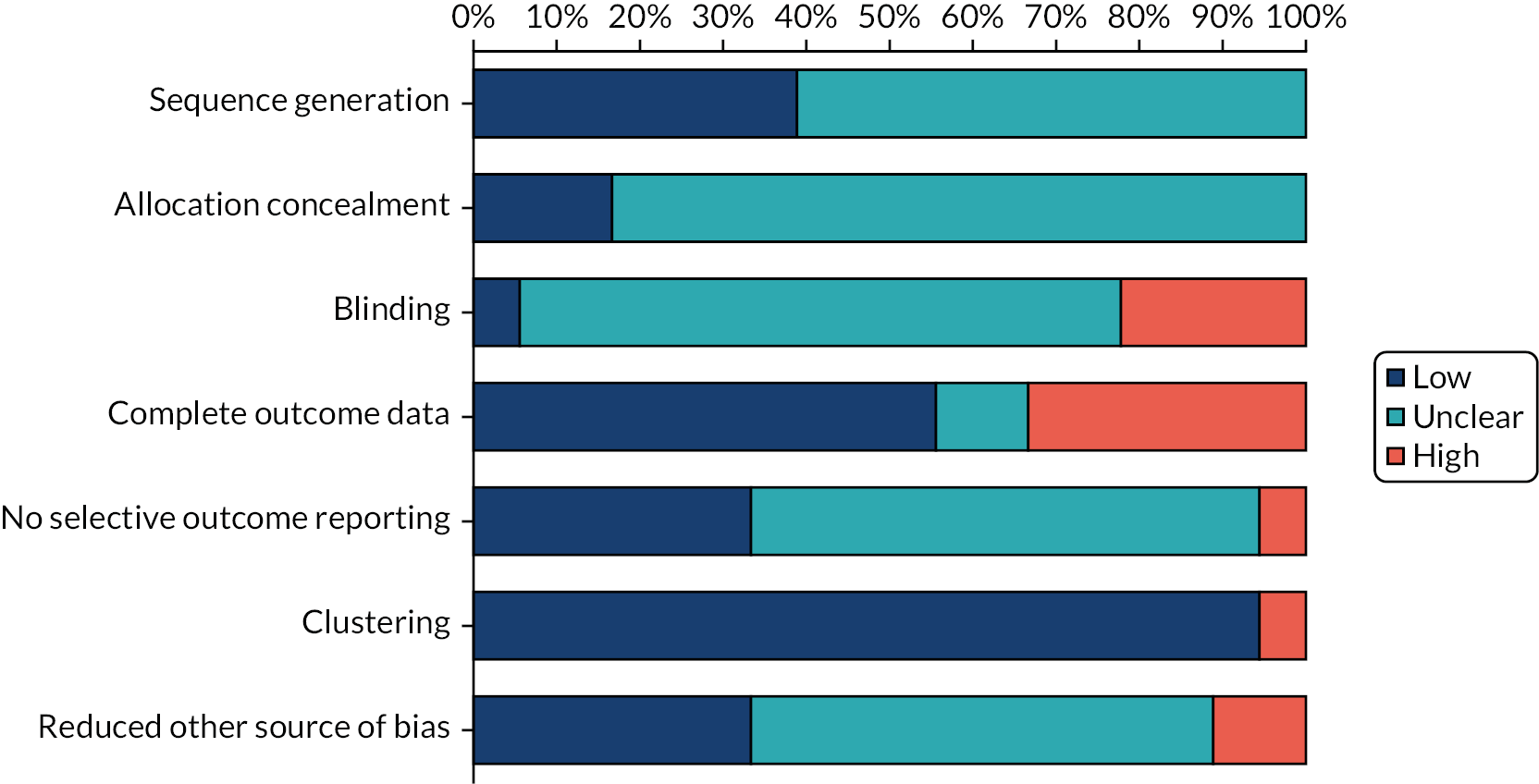

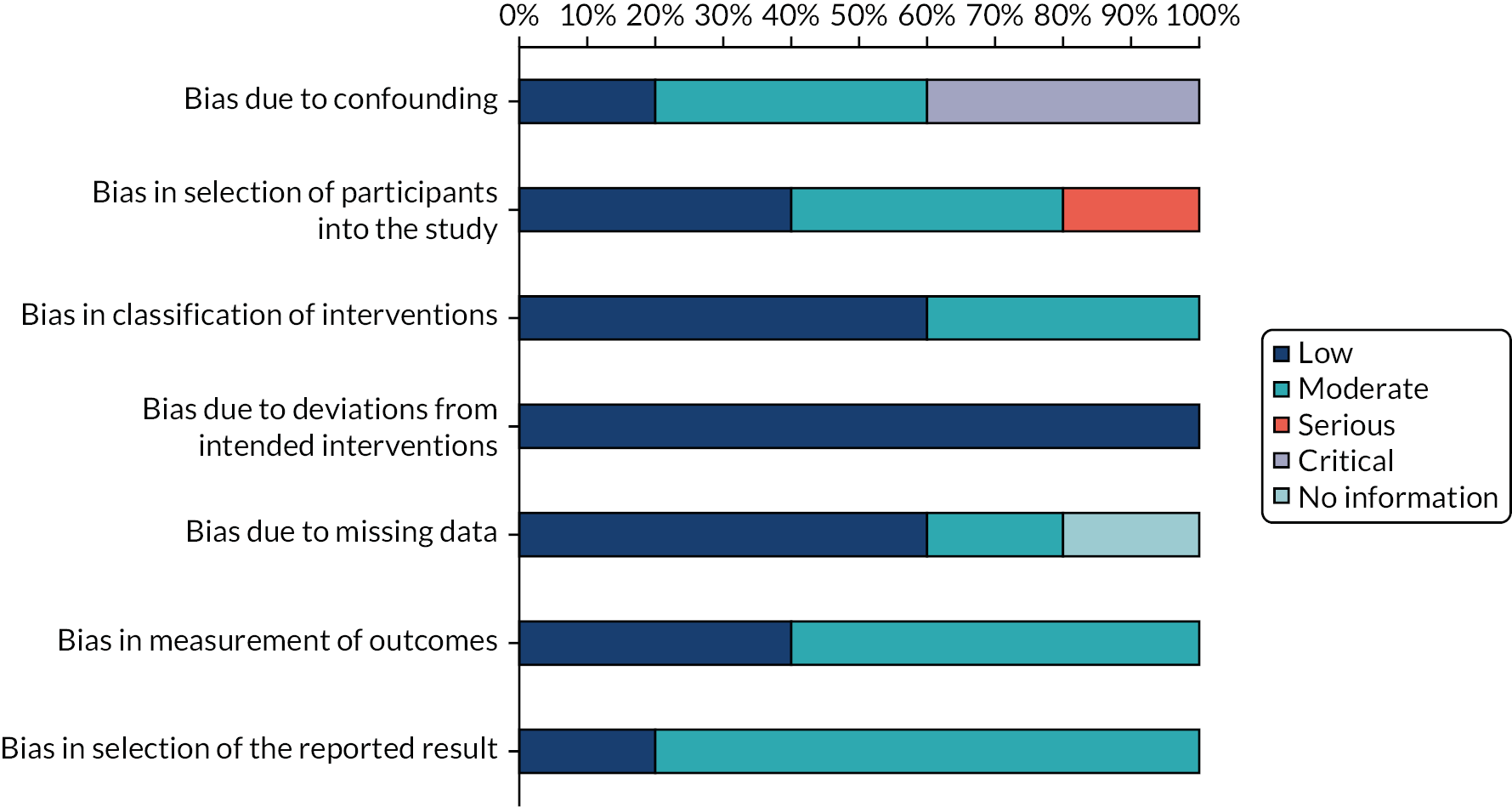

Assessment of outcome evaluations

For RCTs, we assessed risk of bias within each included study using the tool outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. 138 For each study, reviewers judged the likelihood of bias in seven domains: sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding (of participants, personnel or outcome assessors), incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting, other sources of bias (e.g. recruitment bias in cluster randomised studies) and intensity/type of comparator (see standalone project information for tool used: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/phr/AHSN4485). Each study was subsequently identified as having a ‘high risk’, ‘low risk’ or ‘unclear risk’ of bias within each domain. For non-random evaluations, we assessed quality using the Risk Of Bias In Non-randomized Studies – of Interventions (ROBINS-I) tool149 (see standalone project information: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/phr/AHSN4485).

Assessment of economic evaluations

We assessed the quality of economic evaluations using an adapted version of the Drummond et al. 150 checklist. This required reviewers to answer questions regarding each study, ranging from the type of economic evaluation [e.g. cost–utility analysis (CUA)] to the time horizon and rationale for the choice of modelling approach. However, we altered the wording in one question to ensure that information particularly relevant to this review was extracted (see standalone project information for tool used: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/phr/AHSN4485); 31 questions were listed in total.

Data analysis

Typology of intervention approaches

To categorise intervention subtypes (RQ1) we drew on intervention descriptions and theories of change using intervention component analysis. 151 Intervention component analysis is a systematic approach enabling identification of critical features of interventions. As a starting point, we took the intervention description outlined in Chapter 1, which was informed by the theory of human functioning and school organisation,46 to define intervention elements promoting student commitment to school. These included activities involving changes to teaching to increase student engagement in academic learning, enhancing student–staff relationships, revision of school policies that involves students and/or that goes beyond health or behaviour management policies, encouraging students to volunteer in the community and promotion of parental involvement in school. This set of definitions informed line-by-line coding of intervention descriptions and corresponding theories of change by two reviewers (CB and RP), who also used inductive coding to capture the full content of interventions, and refine and subdivide the a priori list of key intervention elements to better reflect the descriptions of interventions in included studies. When more than one report addressed the same intervention, reviewers drew on the descriptions of interventions and theories of change from all relevant reports to inform their analysis.

The two reviewers then met to discuss and refine their coding, accounting for inconsistency in the description of concepts across reports to agree a final, detailed list of key intervention elements and sub-elements that aligned with the descriptions of interventions evaluated in the included studies. Elements were also categorised according to the school subsystems (individual student, classroom or school) they targeted. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion, drawing on the judgement of a third researcher when necessary. The reviewers then worked together to describe interventions in terms of whether or not they included these key elements, creating detailed tables to map the presence and absence of different components contained in each intervention (see Chapter 4). These provided a visual resource to compare and contrast content across interventions. Although grouping interventions into discrete, non-overlapping categories was not straightforward, given the wide variety of intervention strategies used and level of overlap of these across interventions, drawing on this analysis, the two reviewers were able to identify key aspects of difference and similarity between interventions to group them into discrete categories and subcategories forming a final typology of intervention subtypes, described in Chapter 4.

Synthesis of theories of change

To synthesise theories of change (RQ1) we used a form of best-fit framework synthesis. 152 This approach is appropriate when seeking to understand the applicability of an existing conceptual model to a body of evidence and enables the building on of a priori models through the elaboration and incorporation of additional concepts from other sources included in a review. The method begins by defining a priori themes based on an existing conceptual framework and then coding data from included studies against these themes. When concepts from the included studies cannot be coded with the a priori codes, these are coded using inductive thematic analysis. This inductive coding is then used to augment, modify or elaborate the existing model to produce a refined conceptual model that better fits the evidence present.

For this synthesis, one reviewer (CB) reduced the theory of human functioning and school organisation46 to its key elements to form a set of a priori themes for use in the coding of theory reports. Two reviewers (CB and RP) undertook pilot analysis on two reports deemed to include high-quality descriptions of theory of change. The reviewers independently coded the reports using the a priori framework, generating new codes when concepts in theories of change were not captured by the a priori framework. Each reviewer also created memos to explain new codes. These new codes could reflect a rejection, augmentation, refinement or elaboration of concepts within the theory of human functioning and school organisation, based on reviewers’ interpretations and constant comparison of themes across the included theories of change. 153

The two reviewers then met to compare and contrast their application of a priori themes and the emergence of new codes, developing a refined set of themes before going on to code the remaining reports for each intervention, exploring the extent to which theories of change differed between intervention subtypes. Further analysis drew on the agreed set of themes, with reviewers continuing to augment and develop new codes as these arose during the analytic process, and again writing memos to explain these codes. At the end of this process, the two reviewers met again to compare and modify their code sets and application of these, thereby agreeing a final framework composed of a priori and new themes; inconsistencies and disagreements were through discussion, calling on the judgement of a third reviewer when necessary.

Then, drawing on concepts from meta-ethnography used in our previous reviews,145,146 the reviewers developed a synthesis of themes identified through coding for each intervention subtype. This involved identification of patterns of ‘reciprocal translation’ within subtypes whereby similar concepts were expressed across theories of change for different interventions, as well as cases of ‘refutational synthesis’ whereby concepts expressed in some descriptions of intervention theories of change conflicted with other descriptions. This enabled us to build an overall ‘line-of-argument synthesis’ describing two distinct theories of change across intervention subtypes, one of which elaborated the theory of human functioning and school organisation and one of which did not align with this prior theory (see Chapter 5).

When more than one report addressed the same intervention, reviewers used theory of change descriptions from all relevant reports to inform their analysis. The synthesis was also not restricted to reports judged as being of high quality. Instead, conclusions drawing on poorer-quality descriptions were given less interpretive weight.

Synthesis of process evaluations

We synthesised process evaluation findings and interpretations on factors influencing the implementation of interventions (RQ2), again using meta-ethnographic synthesis methods. As with earlier reviews,154 these were applied to textual reports, not only of qualitative research, but also of quantitative research (as it is not possible to synthesise quantitative findings from process evaluations using statistical pooling because of the heterogeneity of research aims, methods and measures). In the case of findings from quantitative elements, we coded author interpretations, first checking as part of quality assessment whether or not these aligned with the quantitative data presented. Meta-ethnography examined themes across sources, identifying cases of ‘reciprocal translation’, whereby similar concepts were expressed in different ways in different sources, and cases of ‘refutational synthesis’, whereby concepts from different sources contradicted one another. We then developed a ‘line-of-argument’ synthesis drawing together concepts from different sources to develop an overall account of factors influencing the implementation of interventions evaluated in included studies.

Second-order constructs (authors’ interpretations of qualitative data) were distinguished from first-order constructs (directly quoted data). The synthesis was not restricted to studies judged to be of high quality. Instead, conclusions drawing on poorer-quality reports were given less interpretive weight.

In terms of procedure, the following steps were taken for the synthesis of process evaluations. First, two reviewers (CB and RP) prepared detailed tables to describe the quality of each report, its empirical focus and study site/population. Second, the two reviewers undertook pilot analysis of two high-quality reports. They read and re-read the results from these reports, applying line-by-line codes to capture the content of the data. They then drafted memos explaining these codes. Coding began with in vivo codes that closely reflected the words used in the findings sections. The reviewers then grouped and organised codes, applying axial codes reflecting higher-order themes. The two reviewers then met to compare and contrast their coding of these first two high-quality studies, developing an overall set of codes from their discussion. Two reviewers went on to code the remaining studies drawing on the agreed set of codes, but developing new in vivo and axial codes as these arose from the analytic process, and again writing memos to explain these codes. At the end of this process, the two reviewers met to compare their code sets and memos. They identified commonalities, differences of emphasis and contradictions in the code sets with the aim of developing a single set of overarching themes drawing on the strengths of the two sets of codes, resolving any contradictions or inconsistencies and drawing on a third reviewer if necessary. Analysis produced tables demonstrating how first-, second- and third-order constructs related to one another, enhancing transparency about these emergent themes.

Analysis of process evaluations was also informed by May’s155 general theory of implementation. This was not part of our protocol, but we found that it provided a useful heuristic for interpreting and organising the emerging themes.

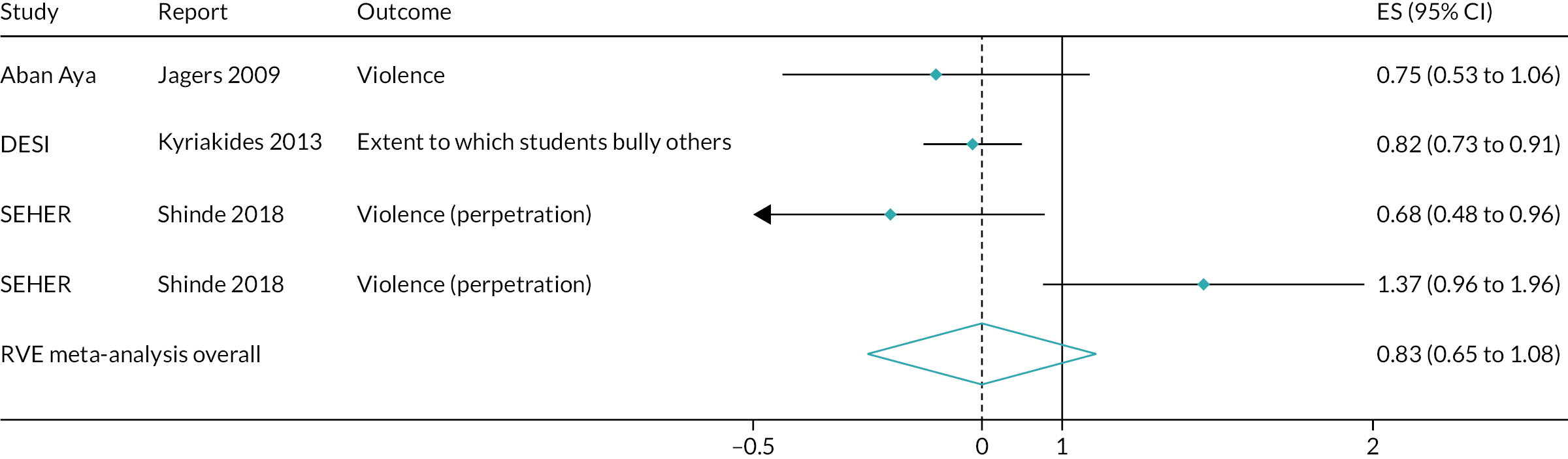

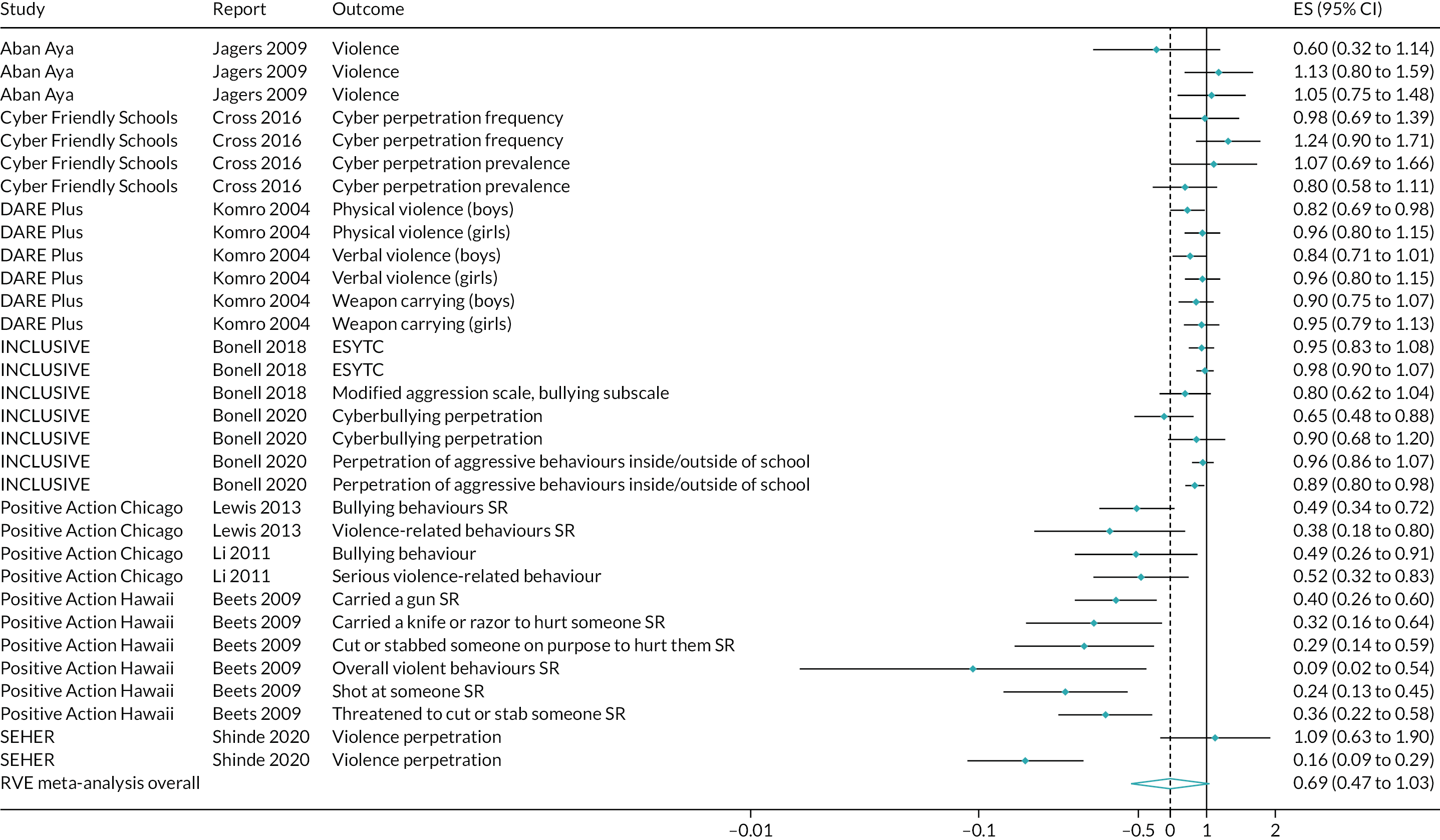

Synthesis of outcome evaluations

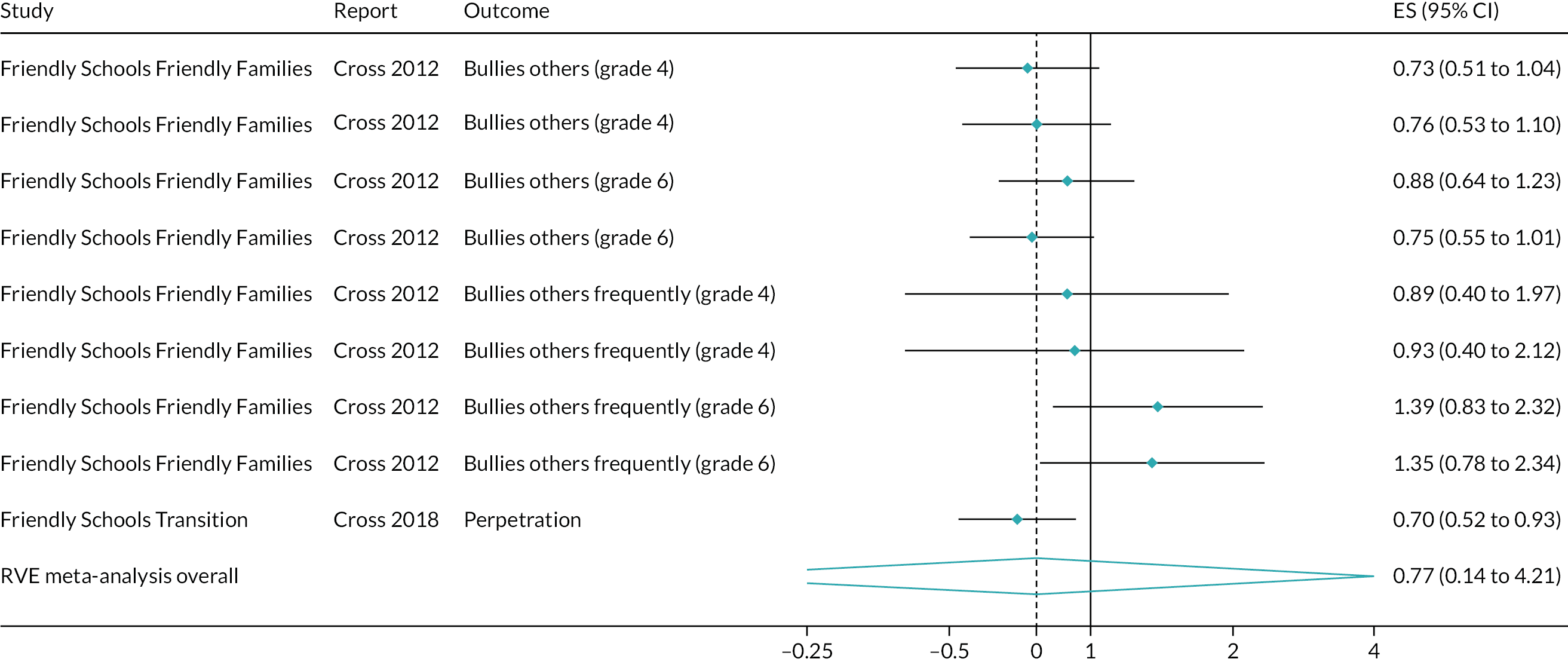

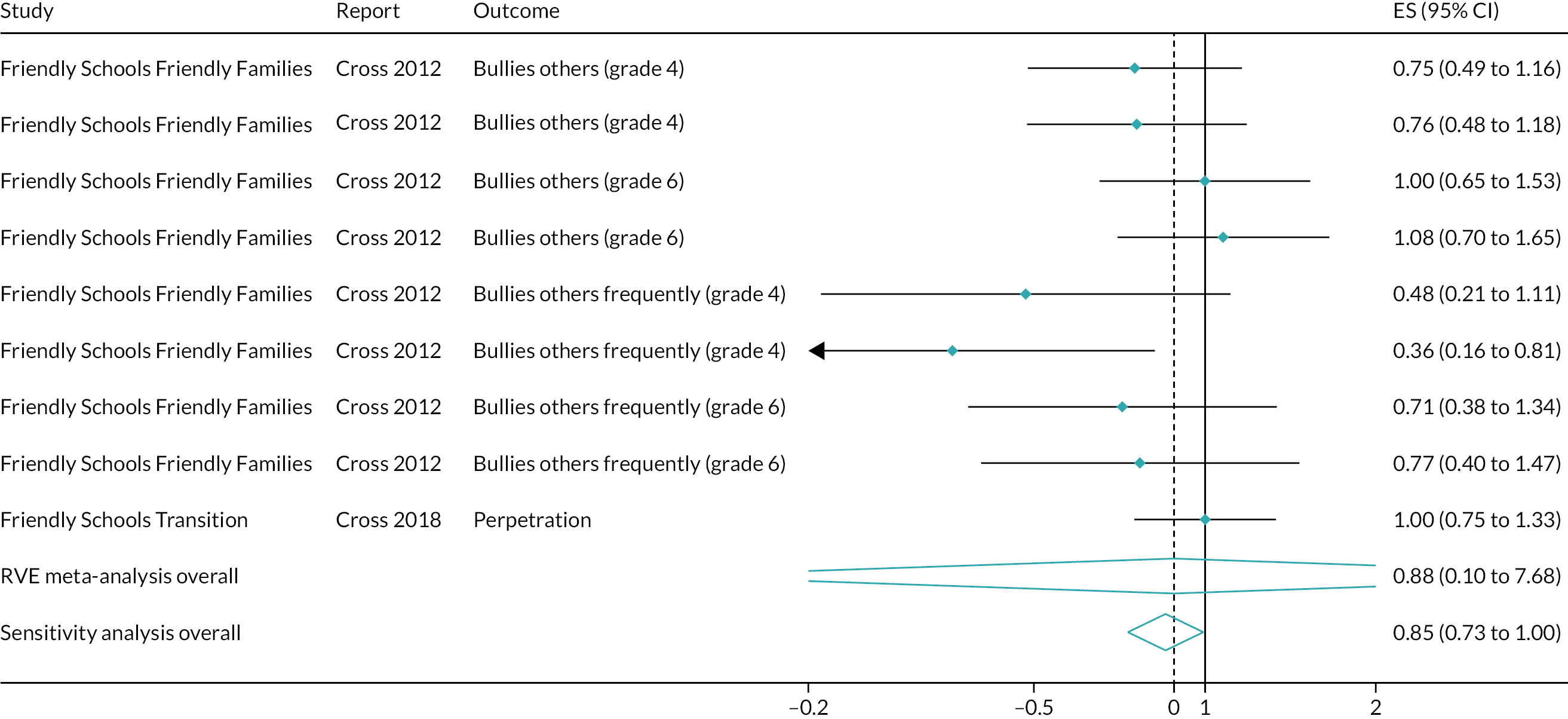

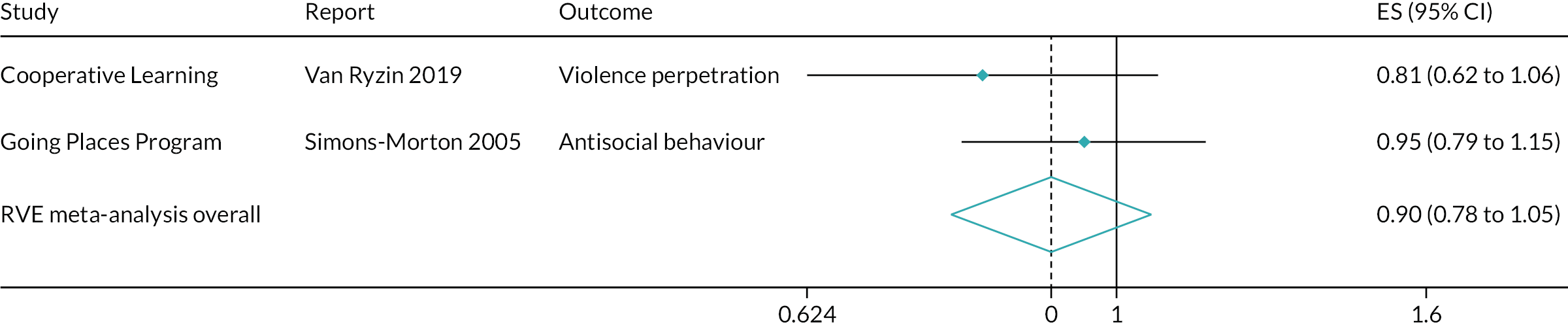

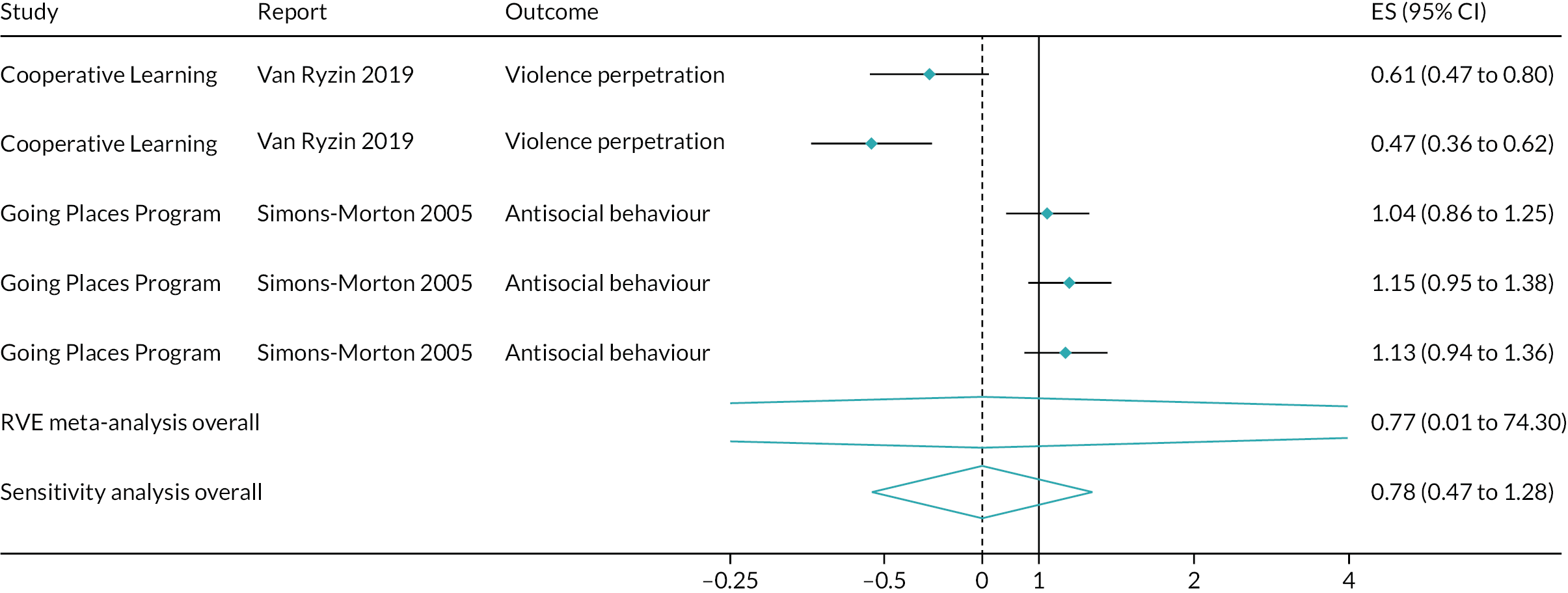

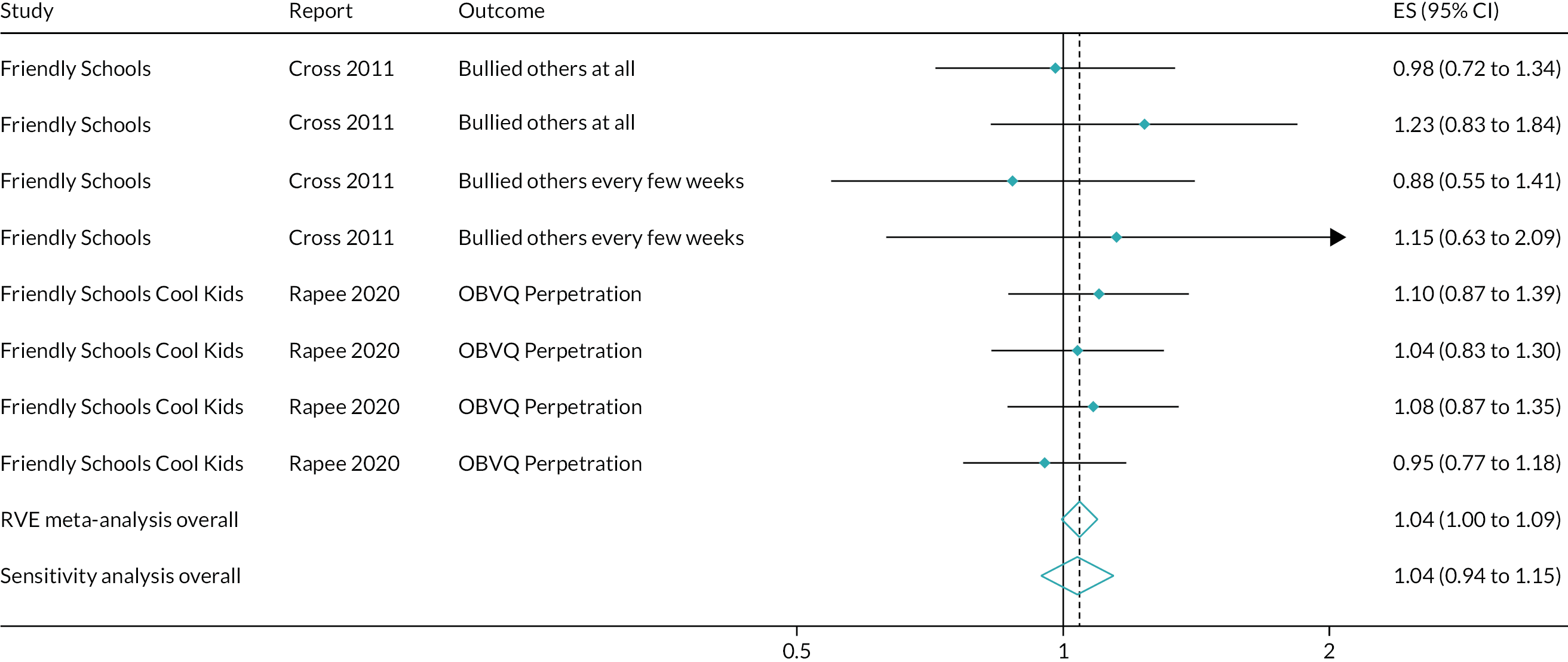

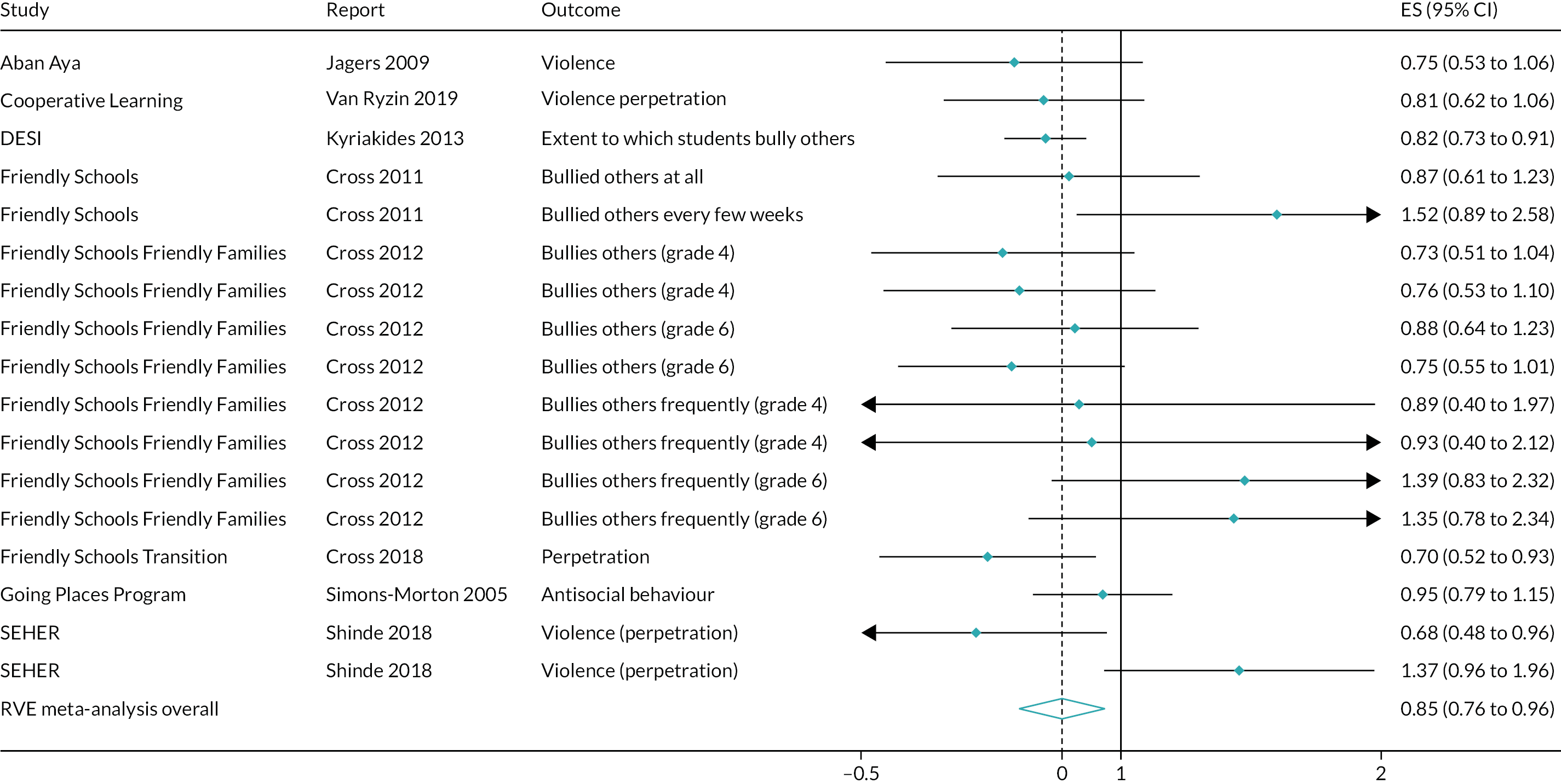

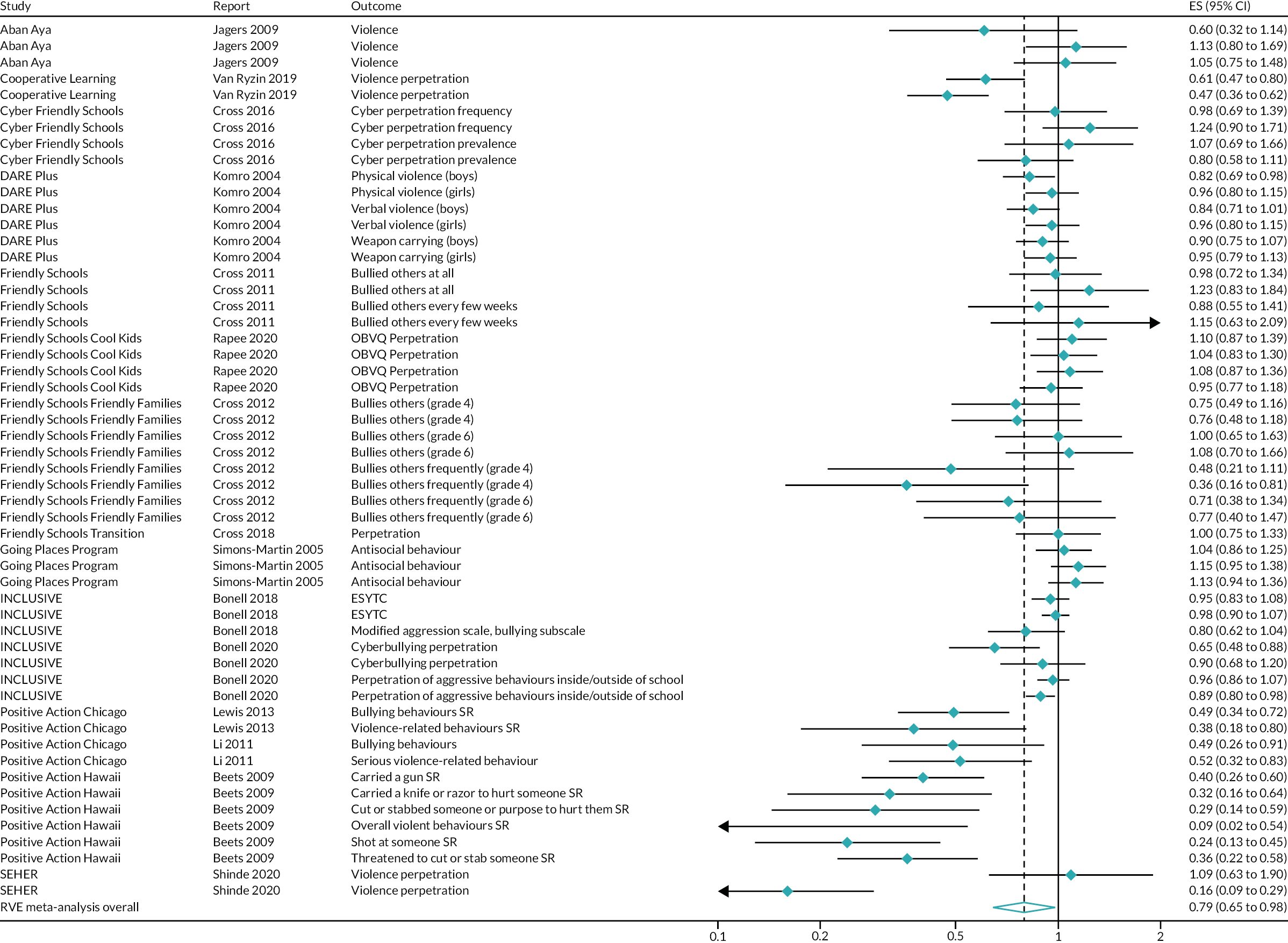

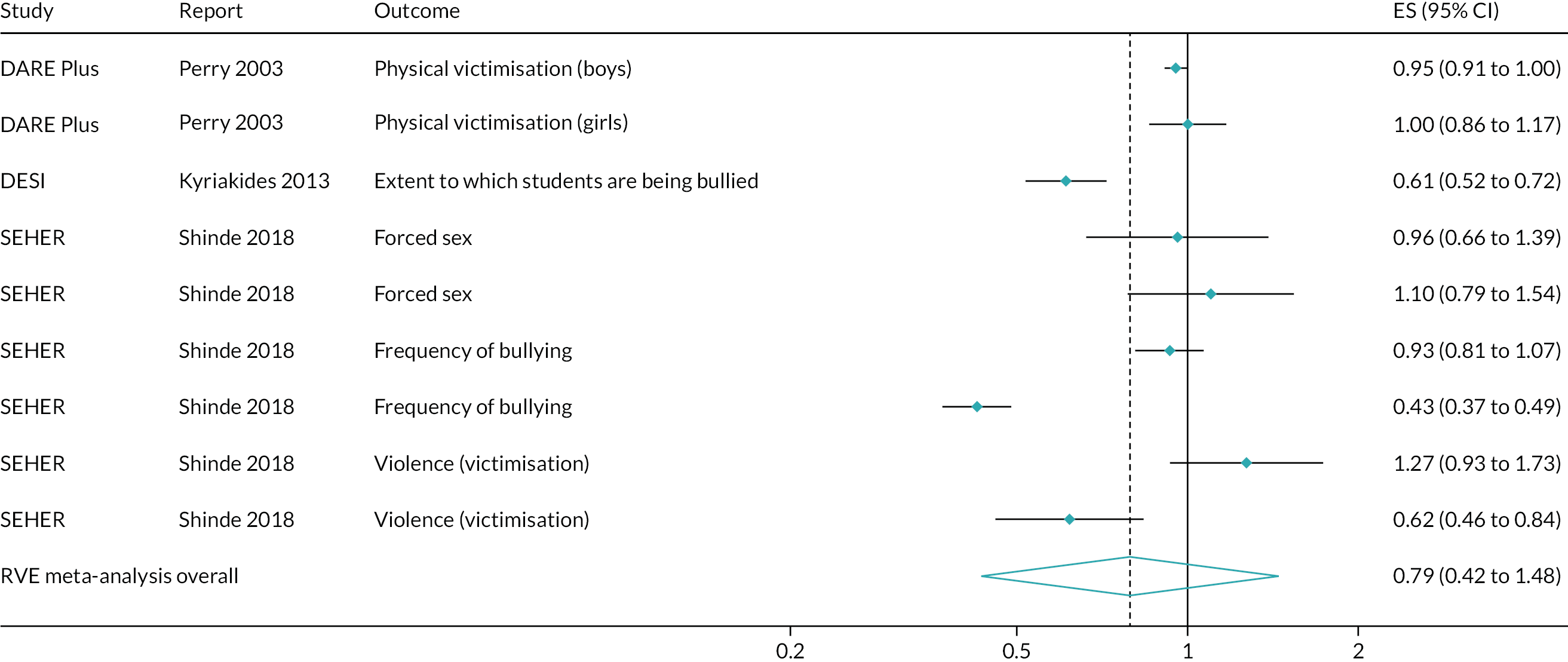

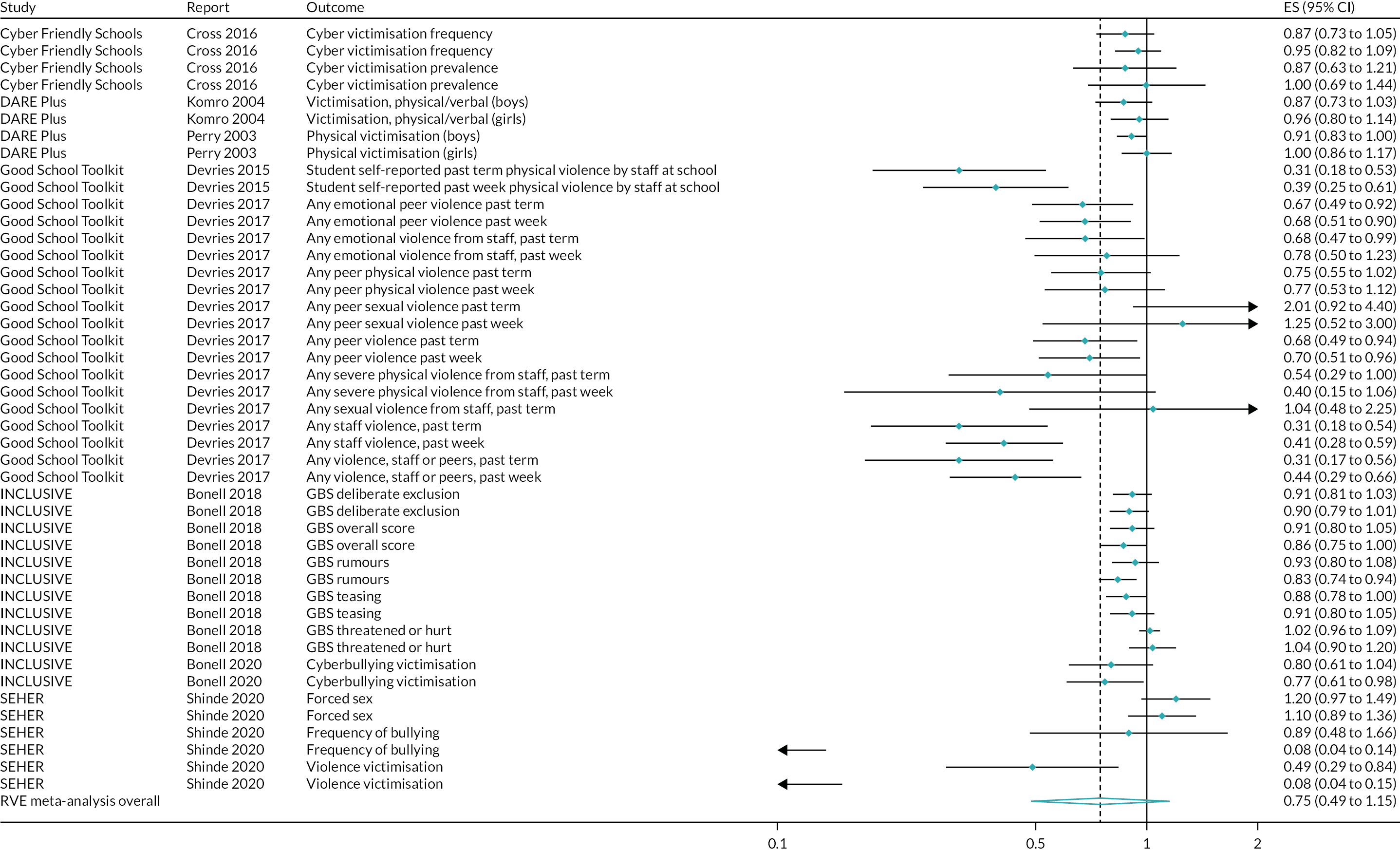

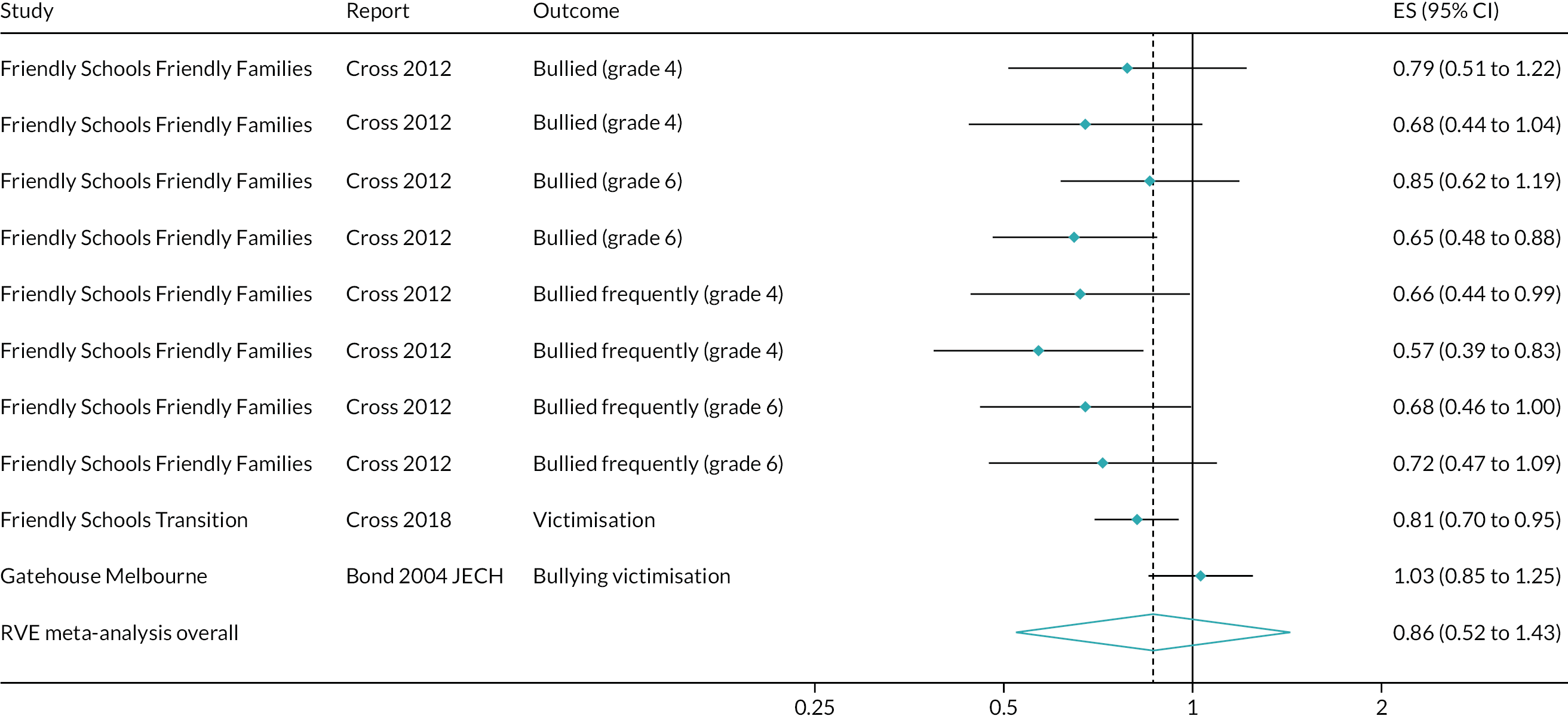

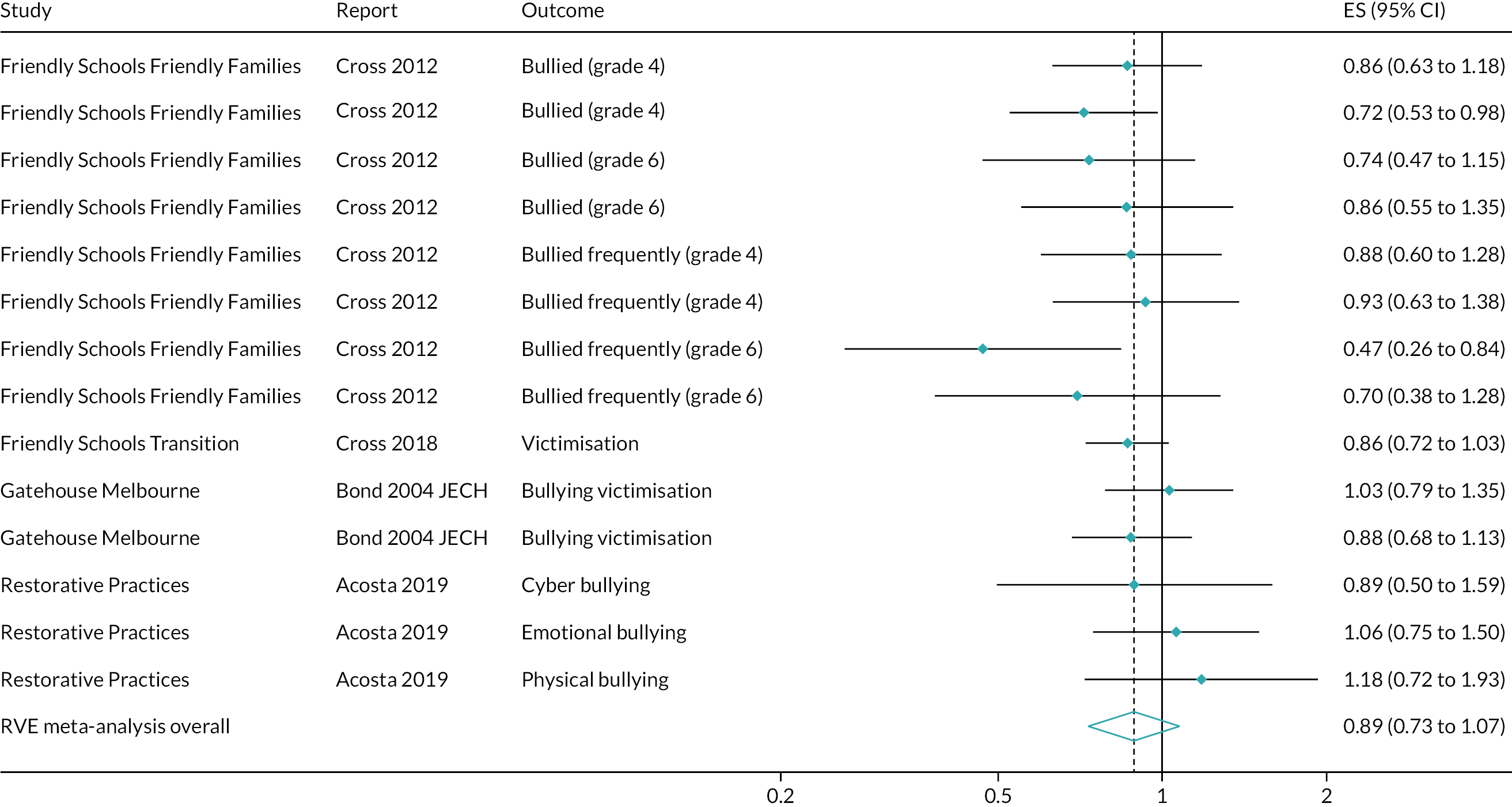

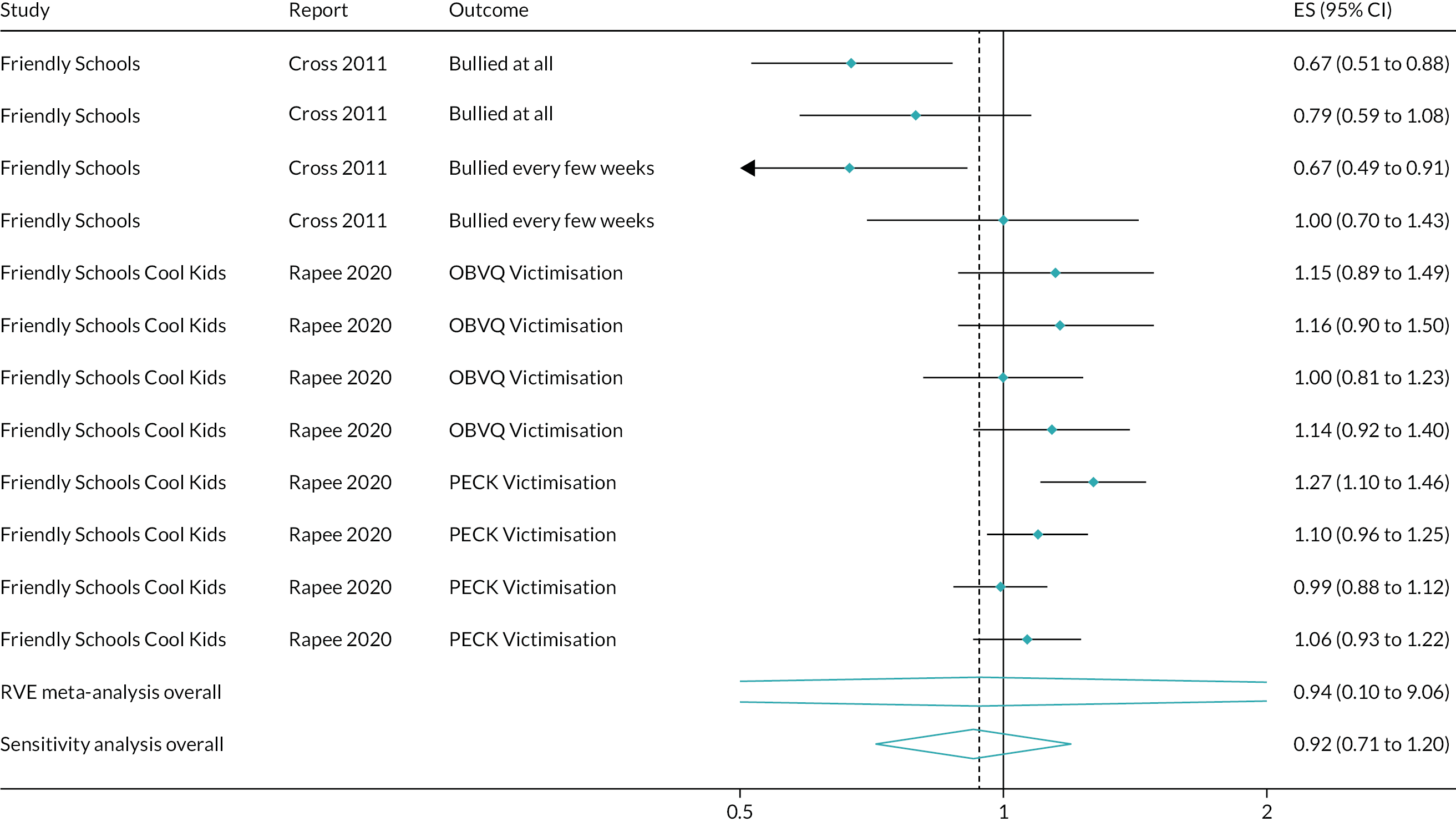

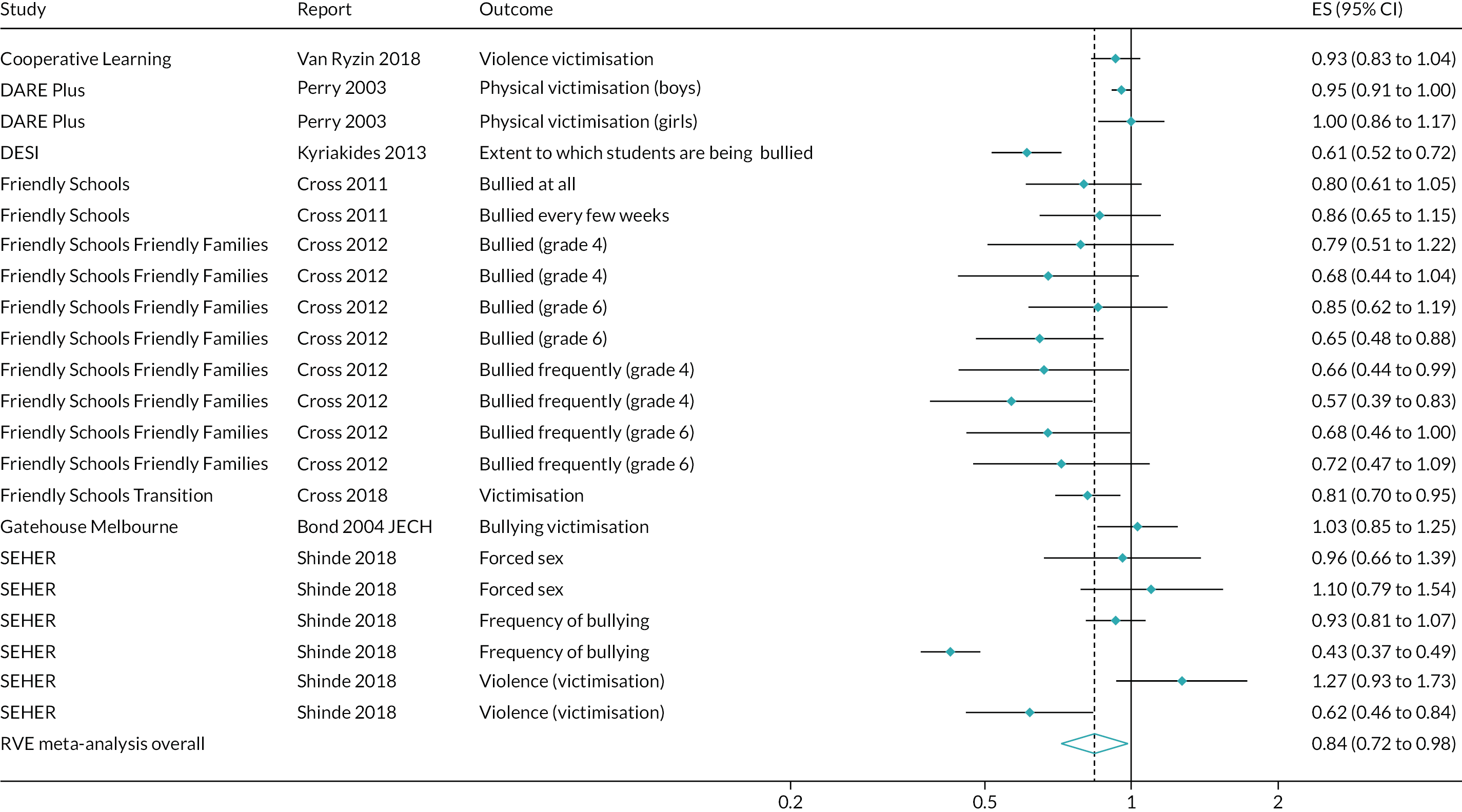

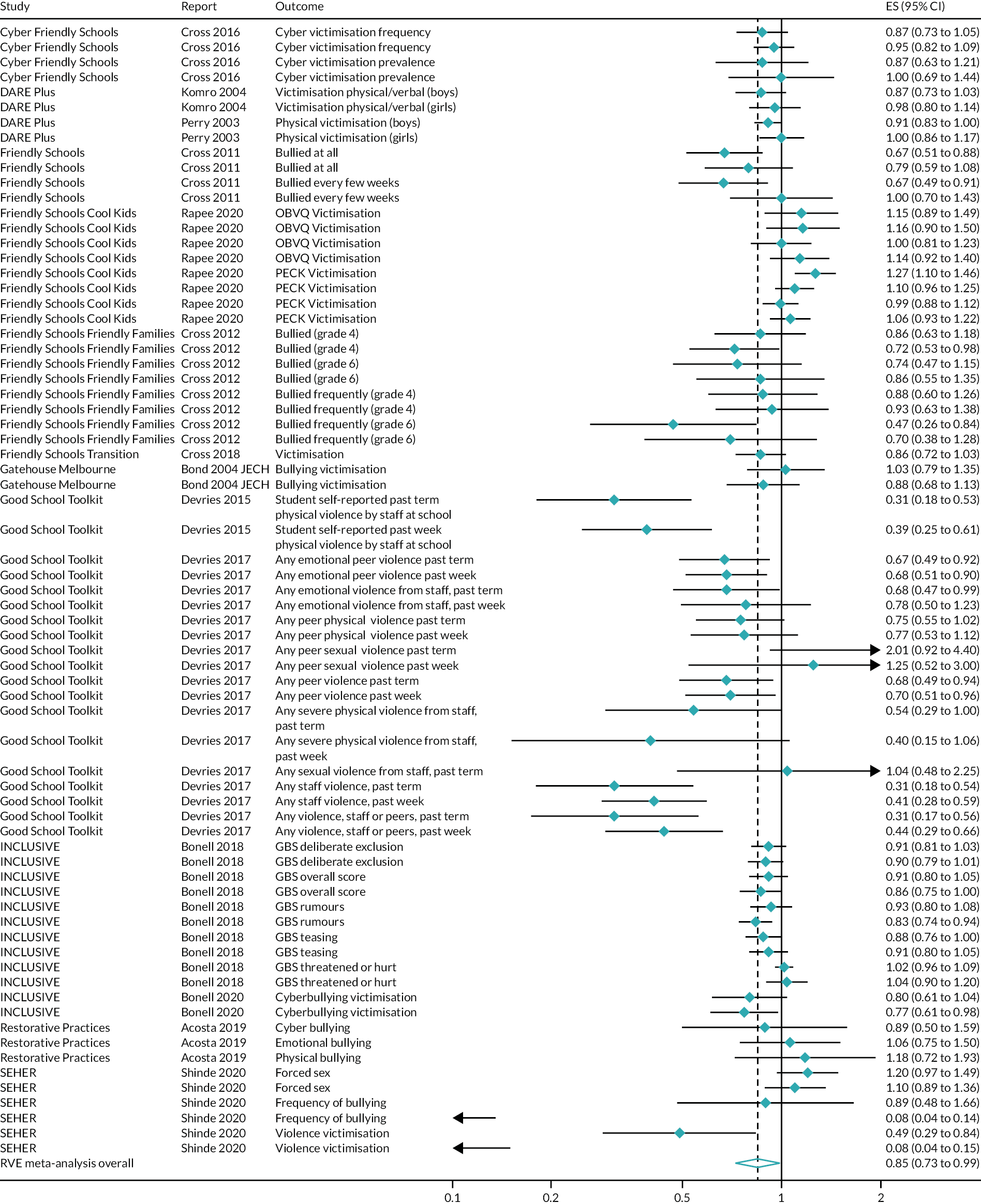

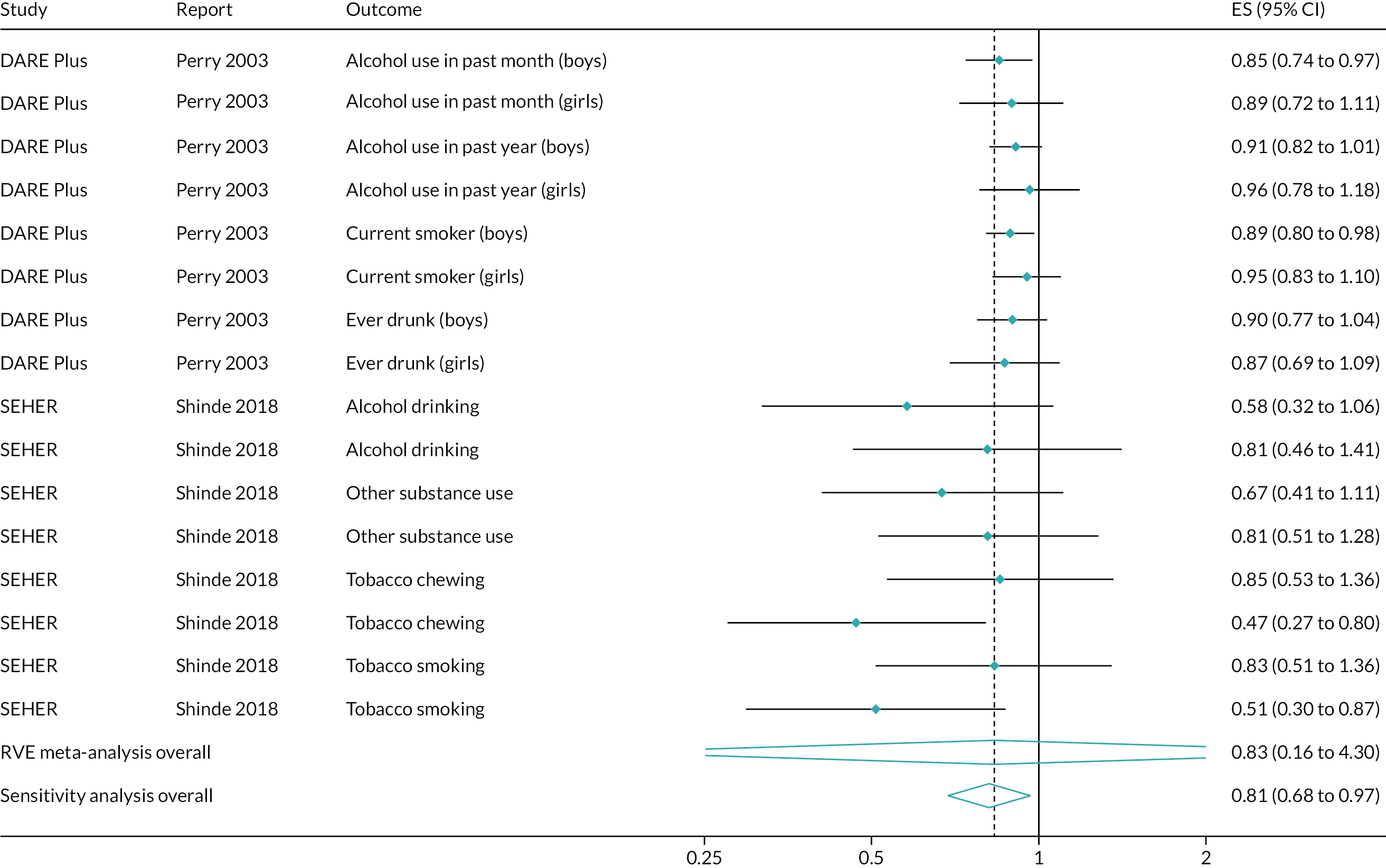

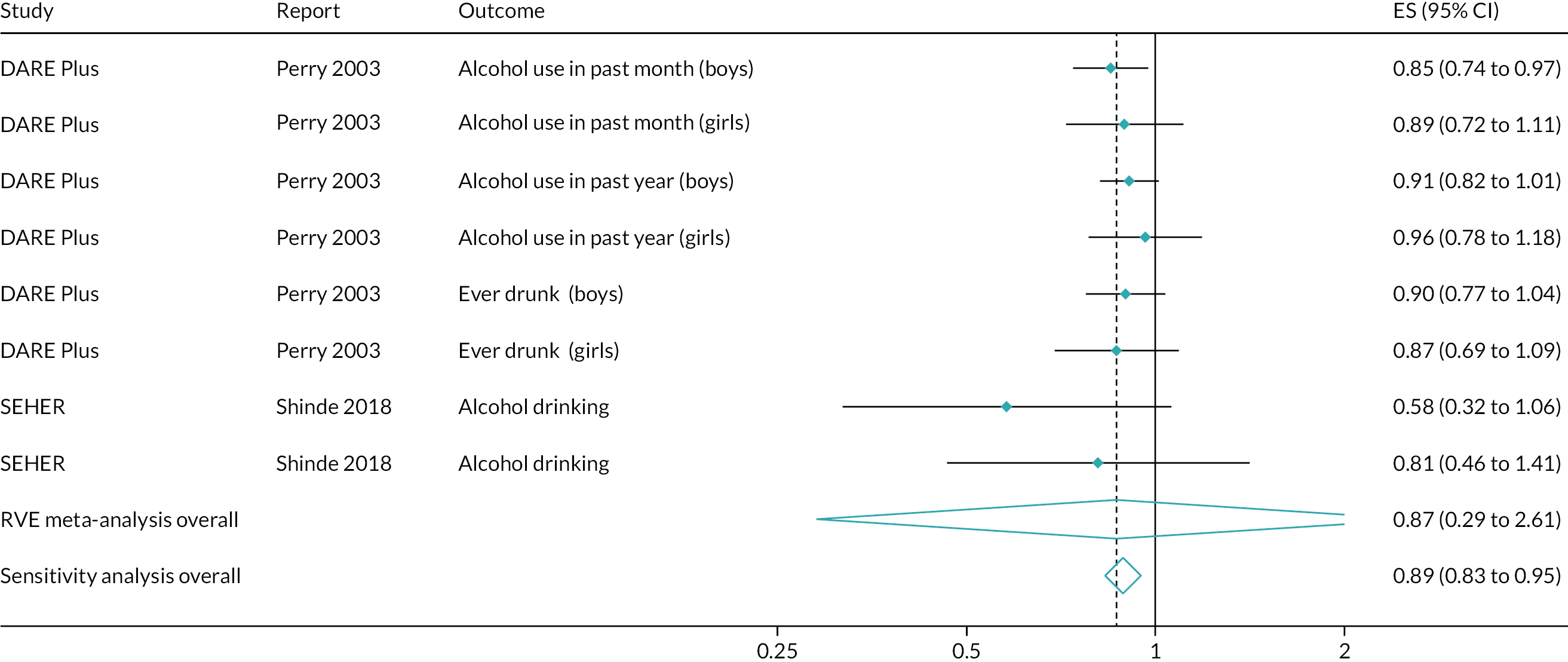

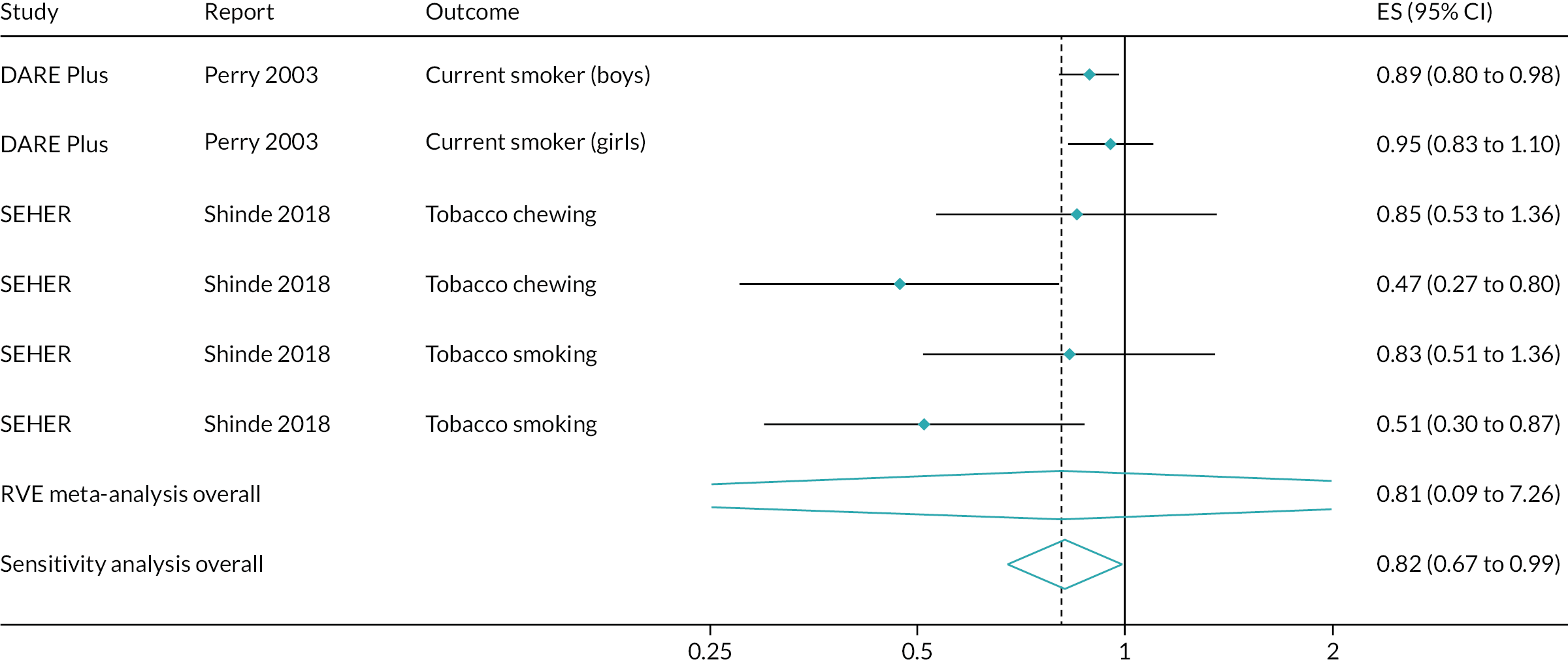

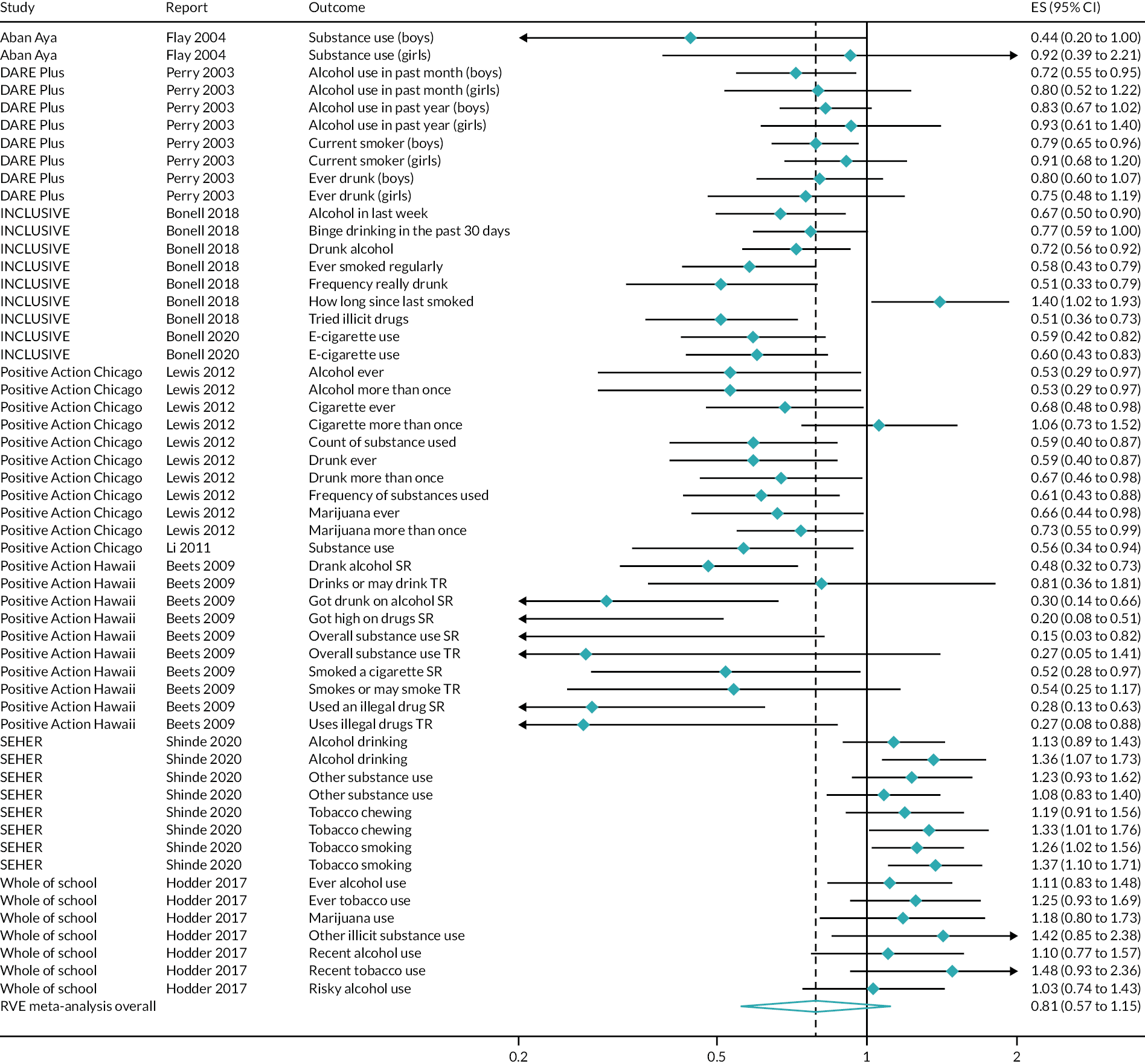

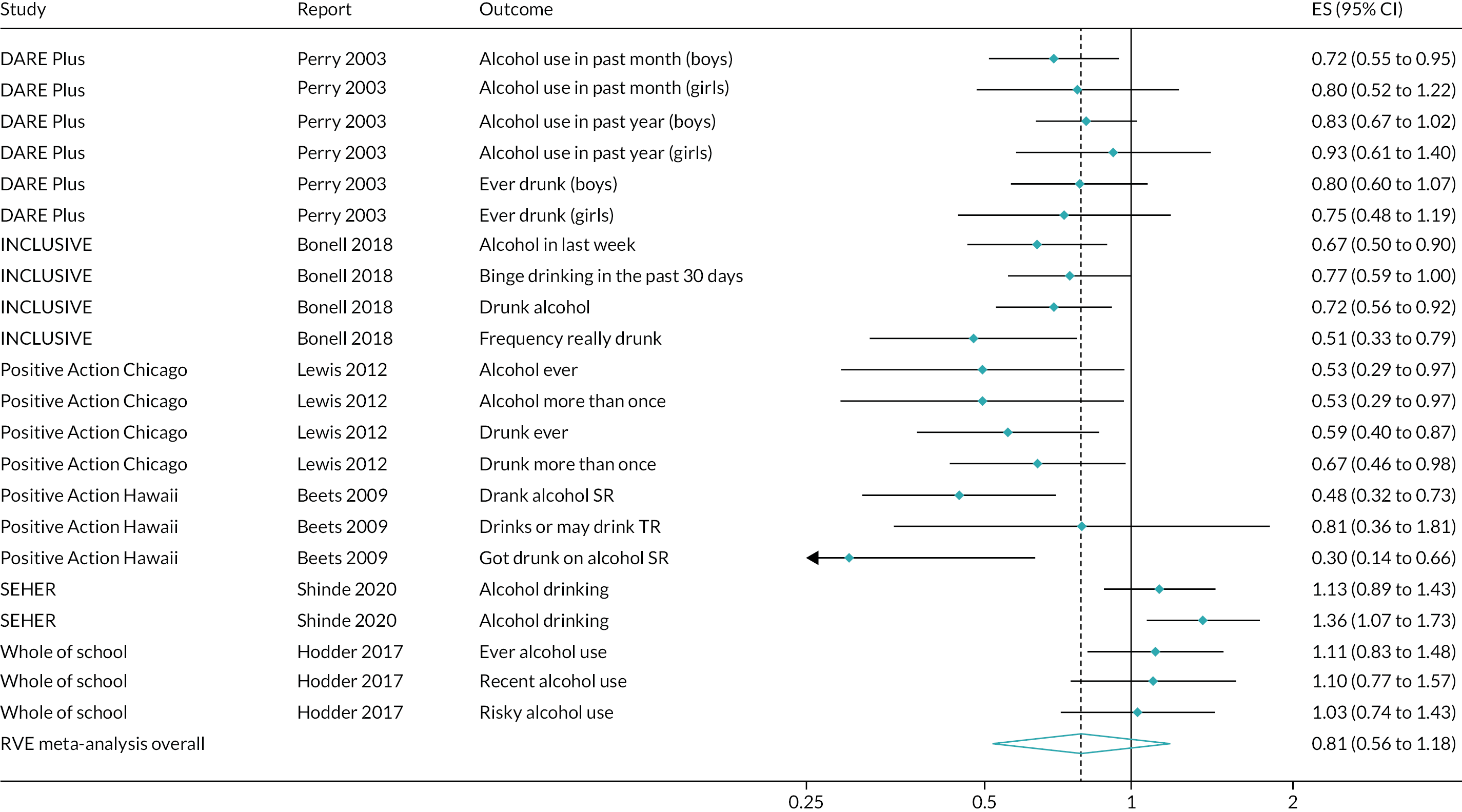

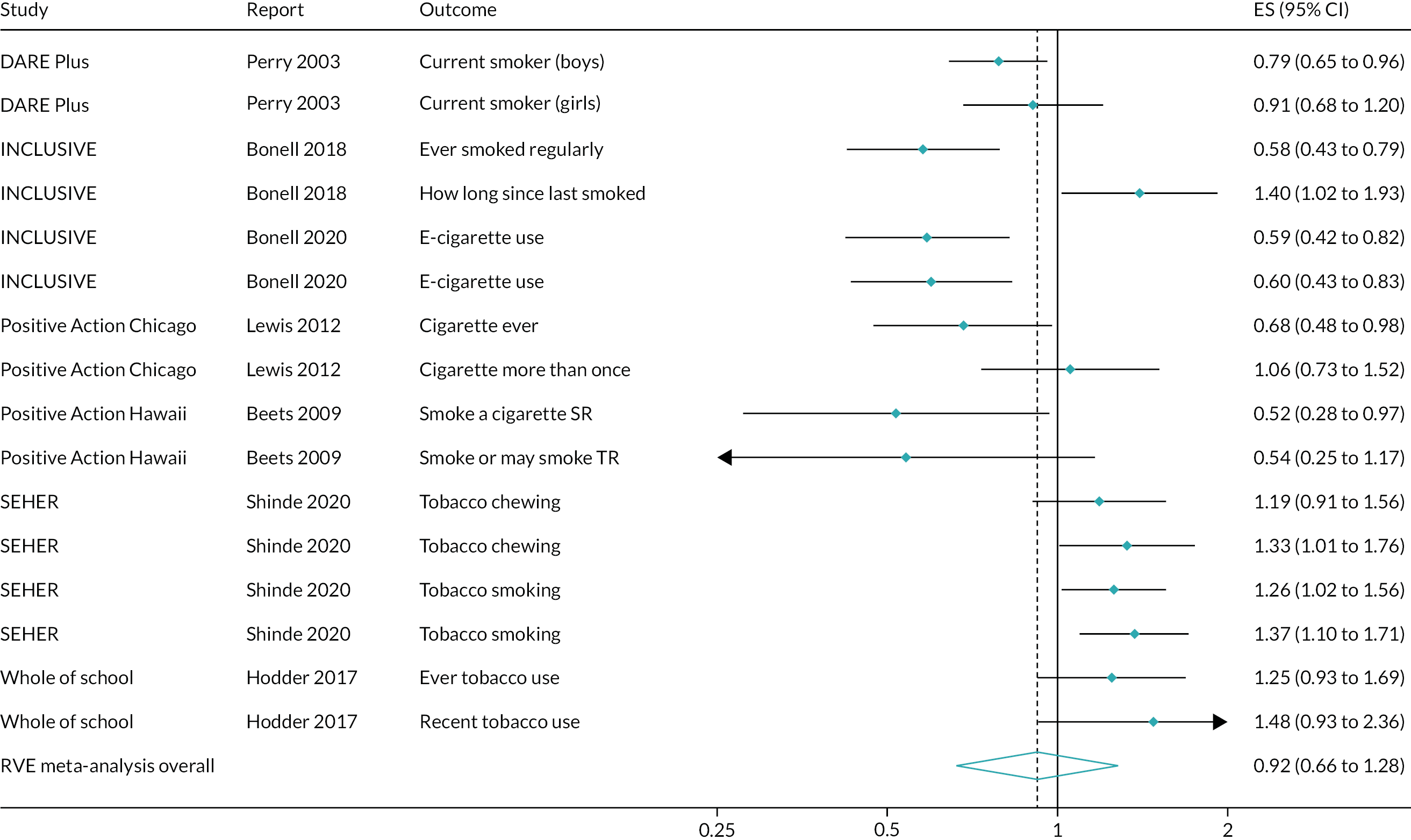

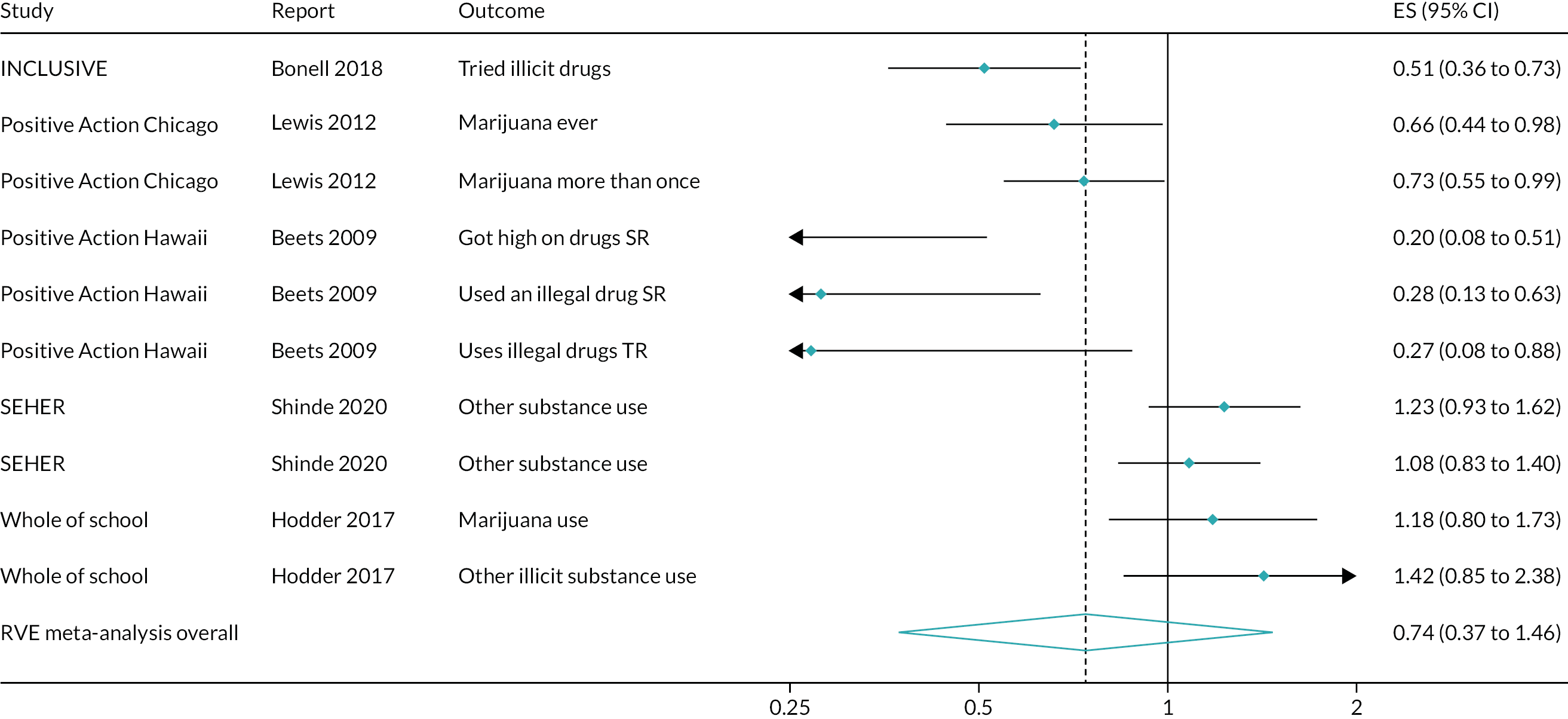

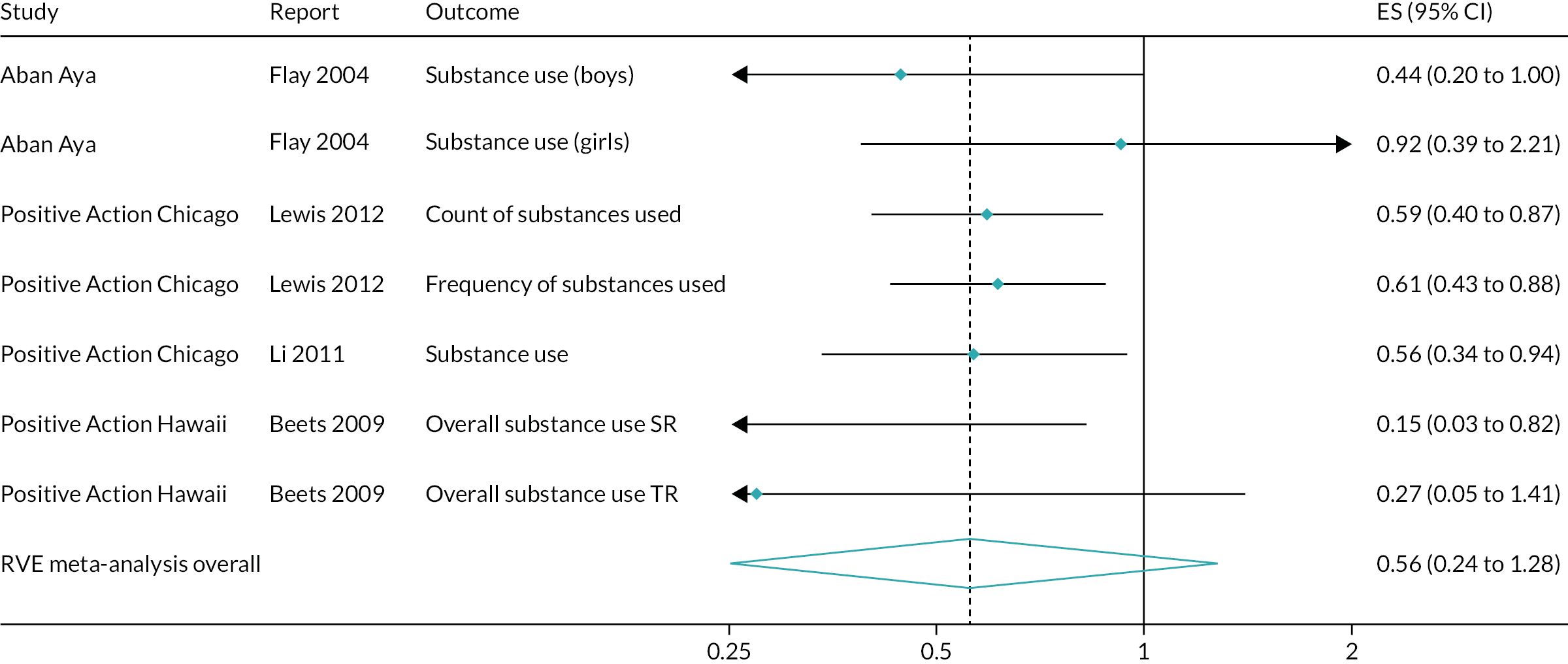

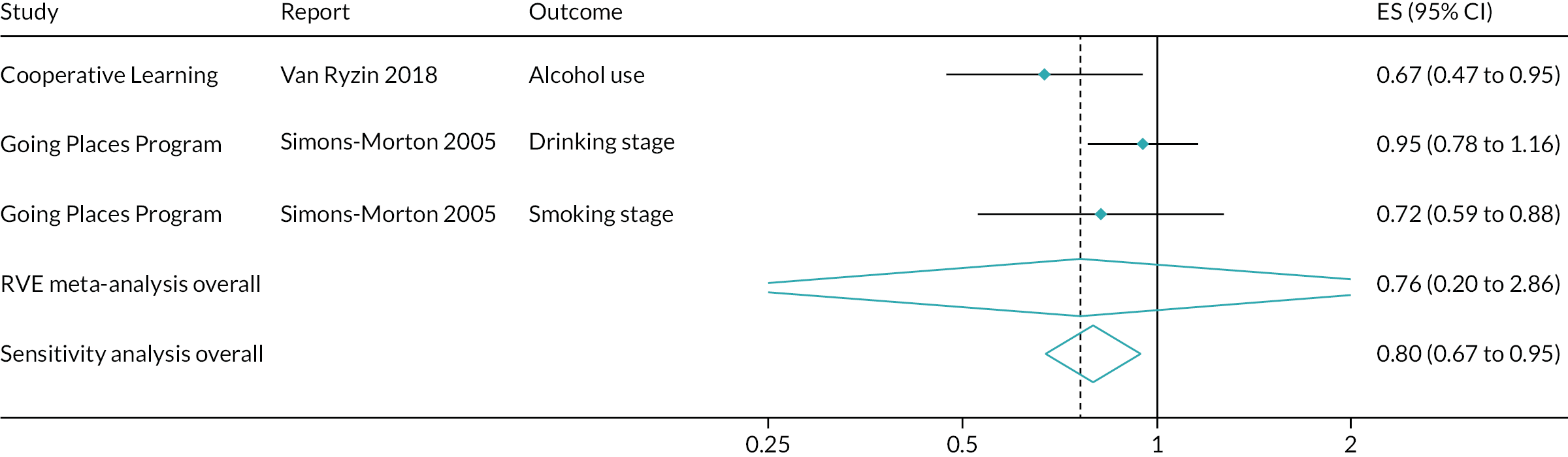

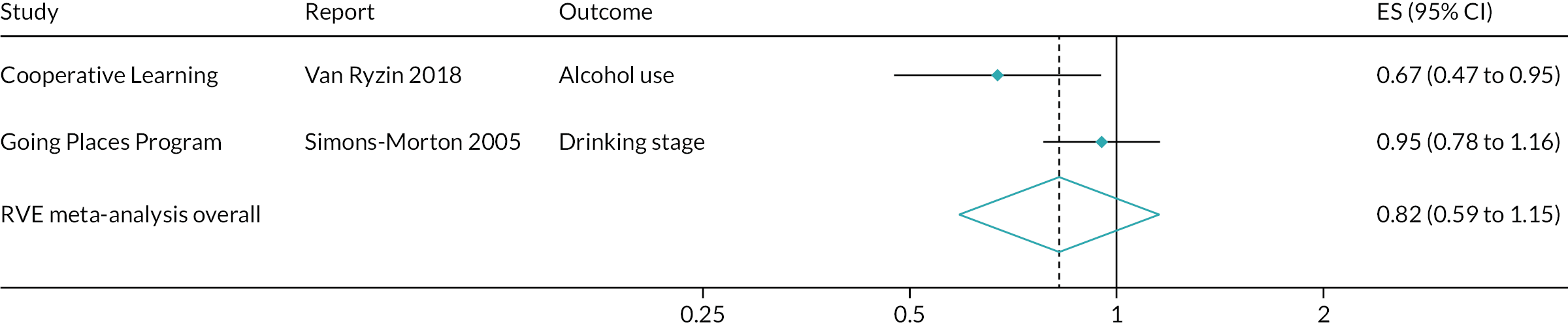

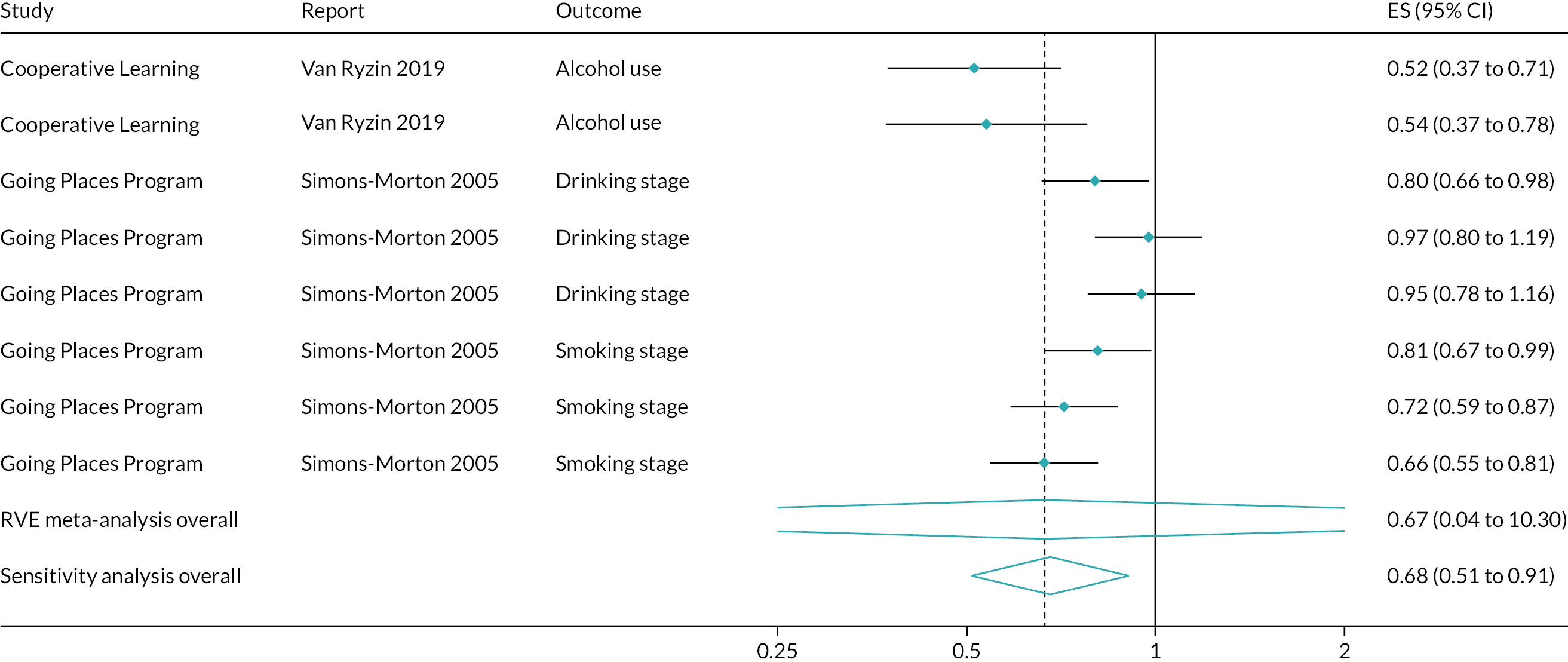

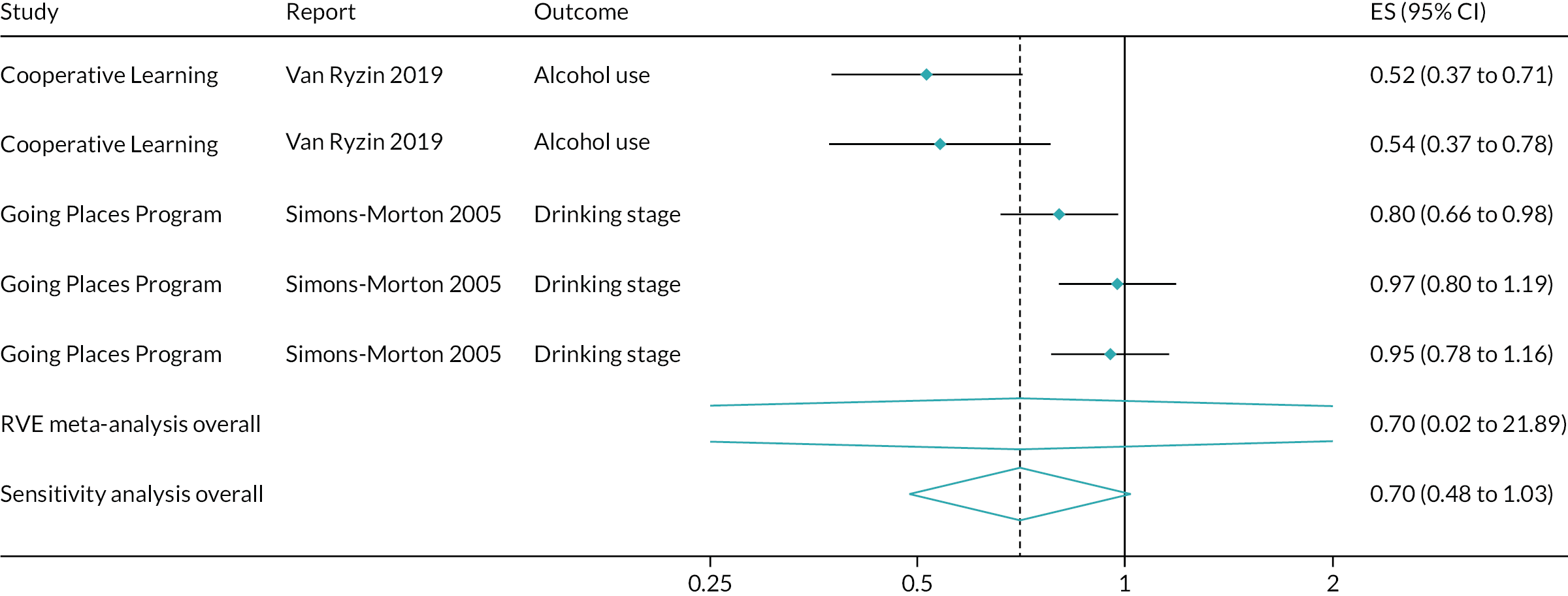

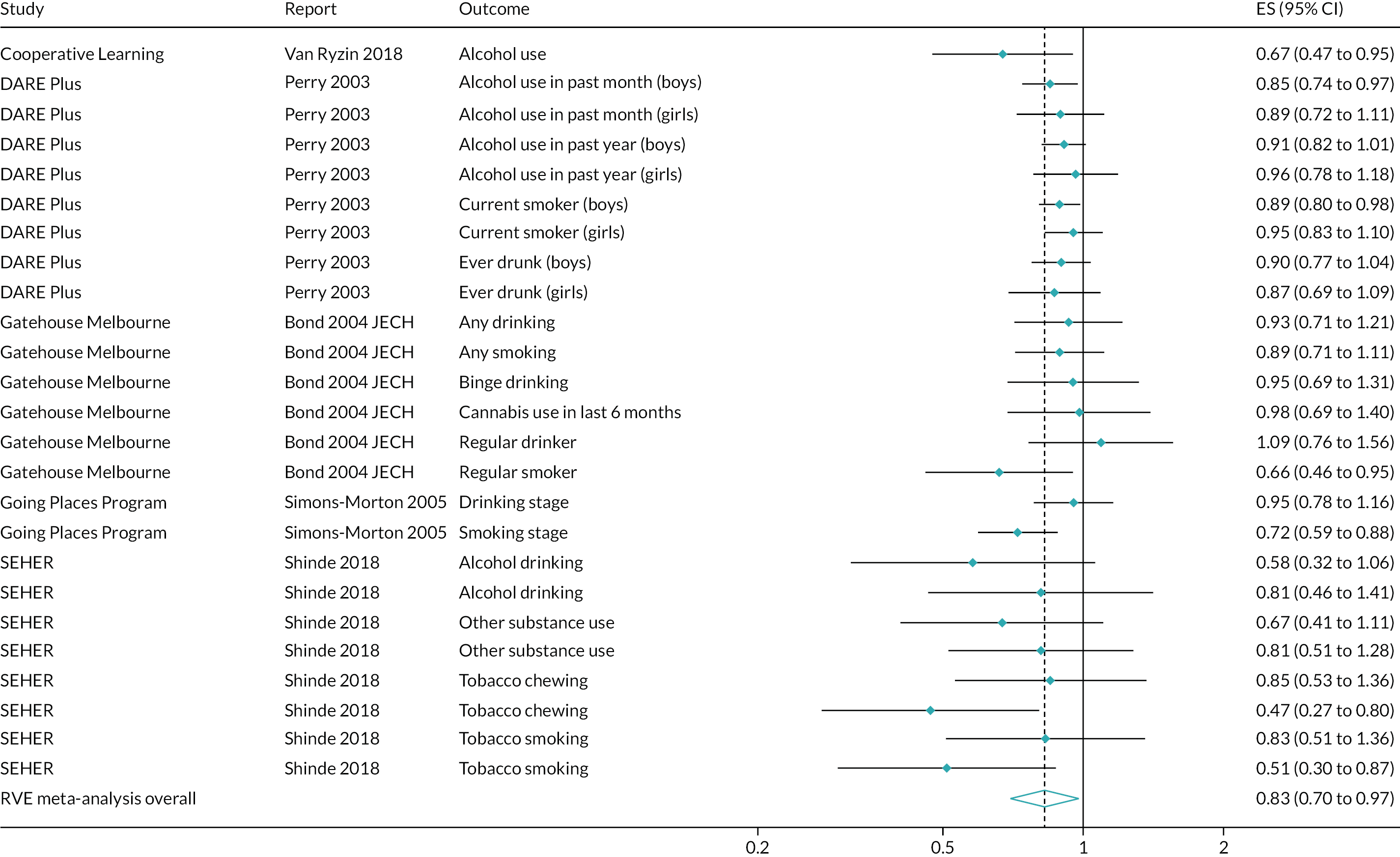

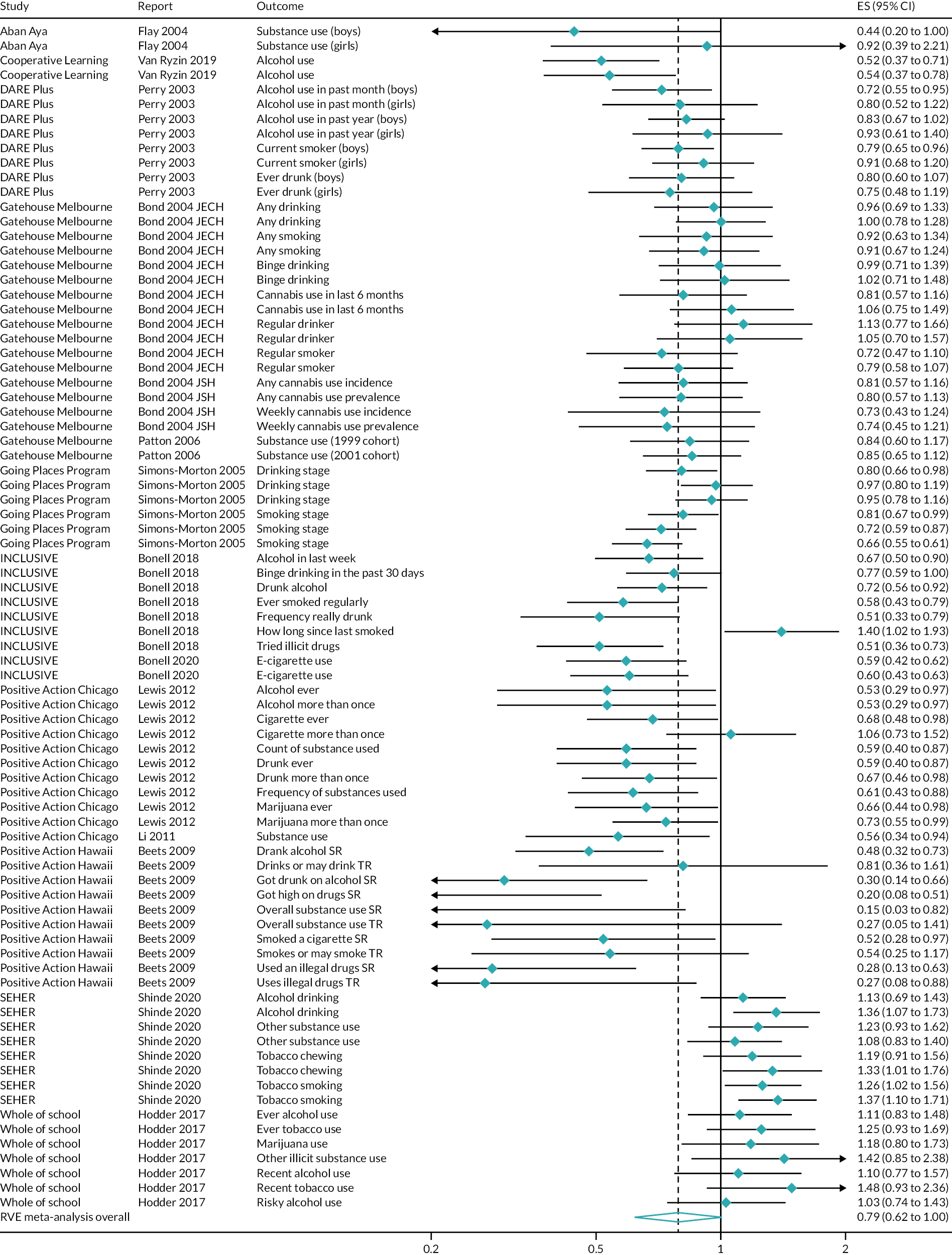

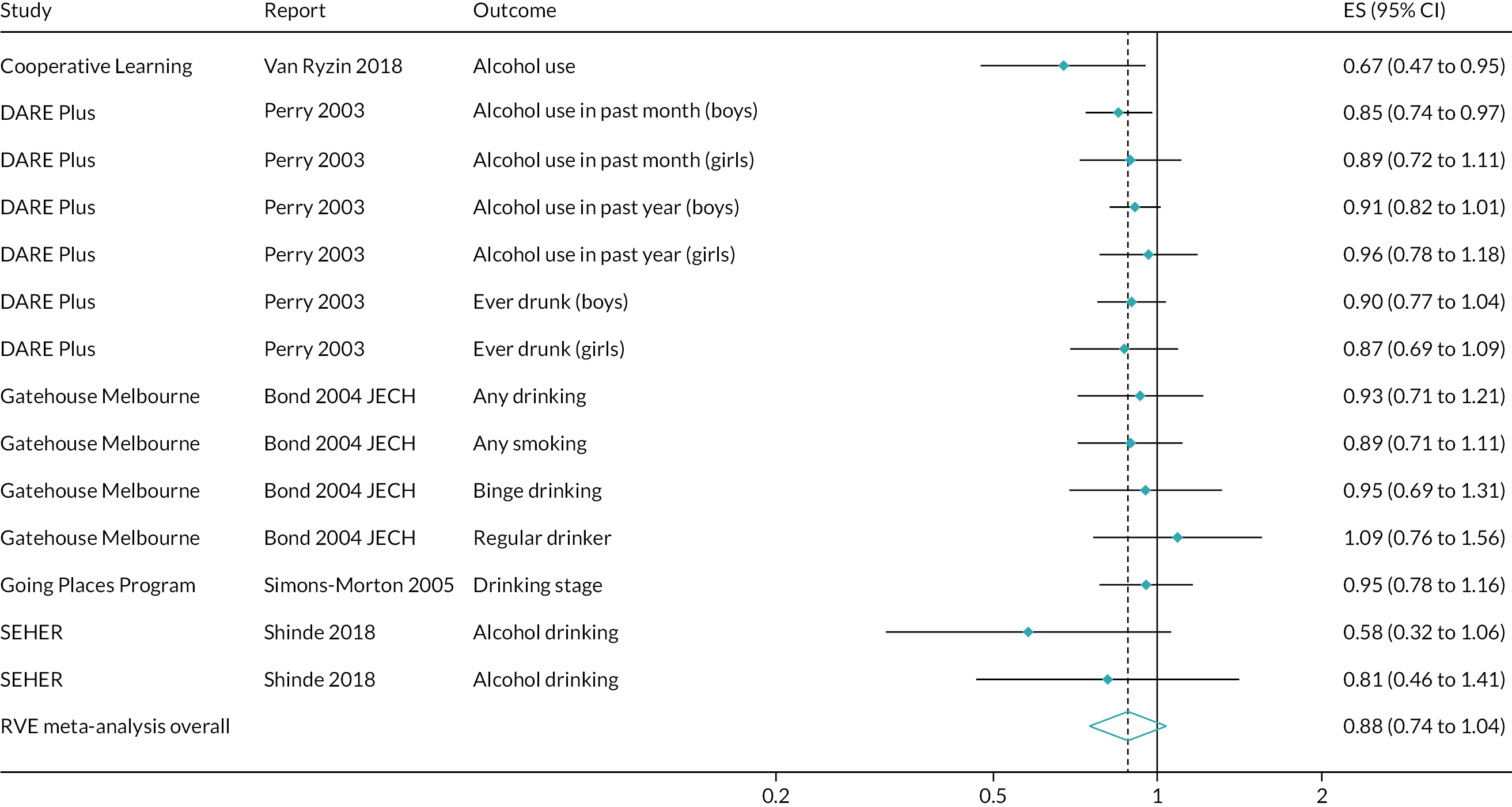

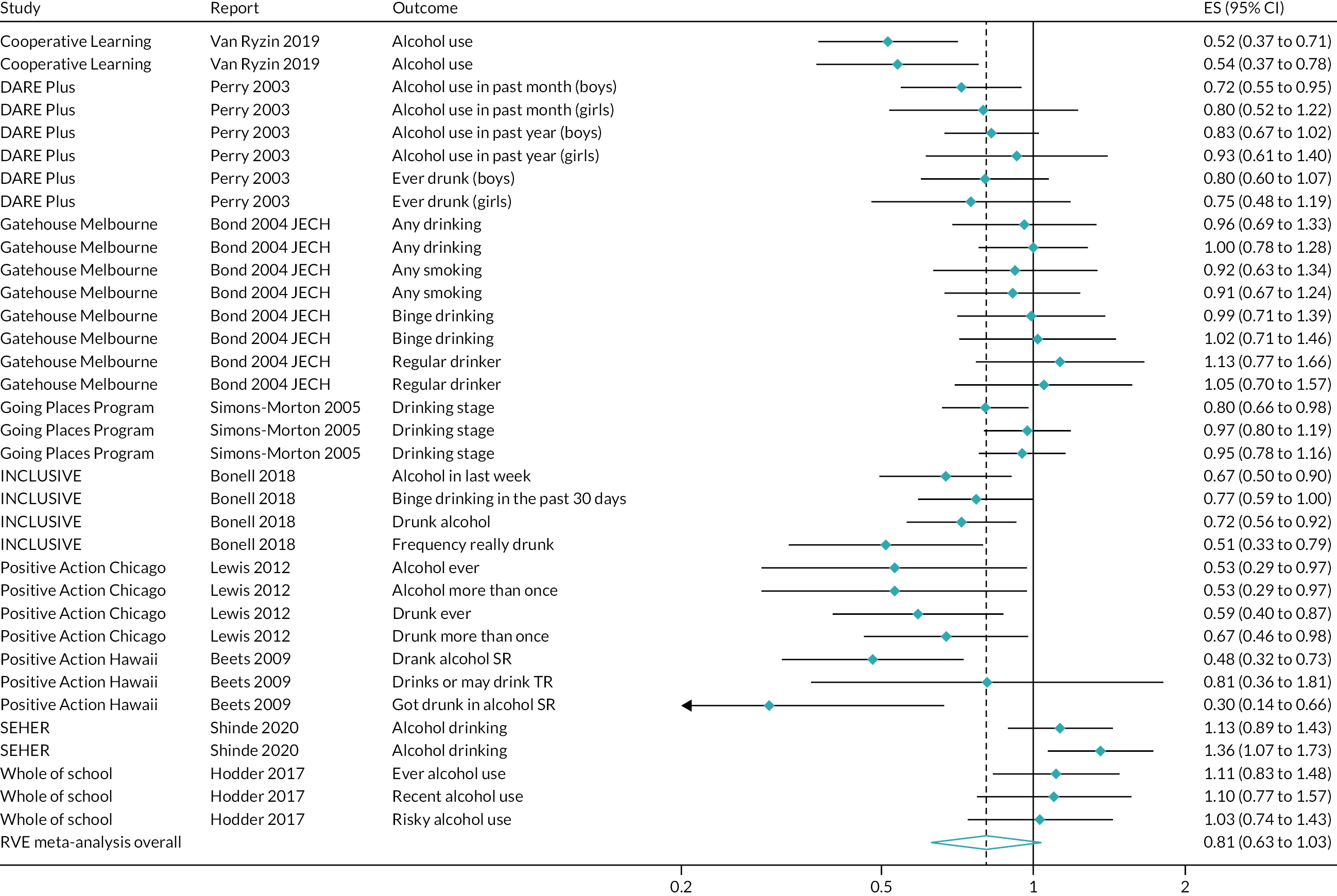

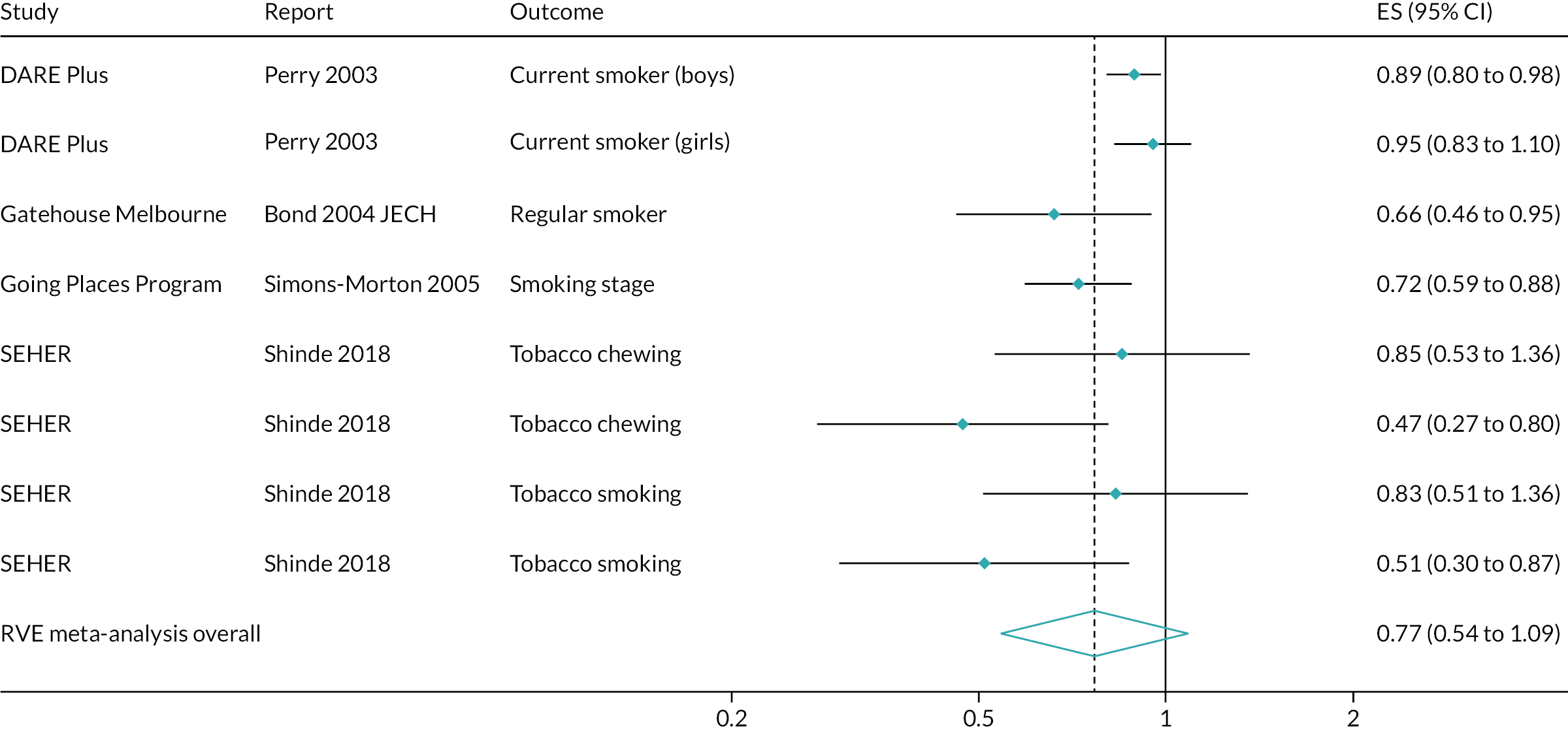

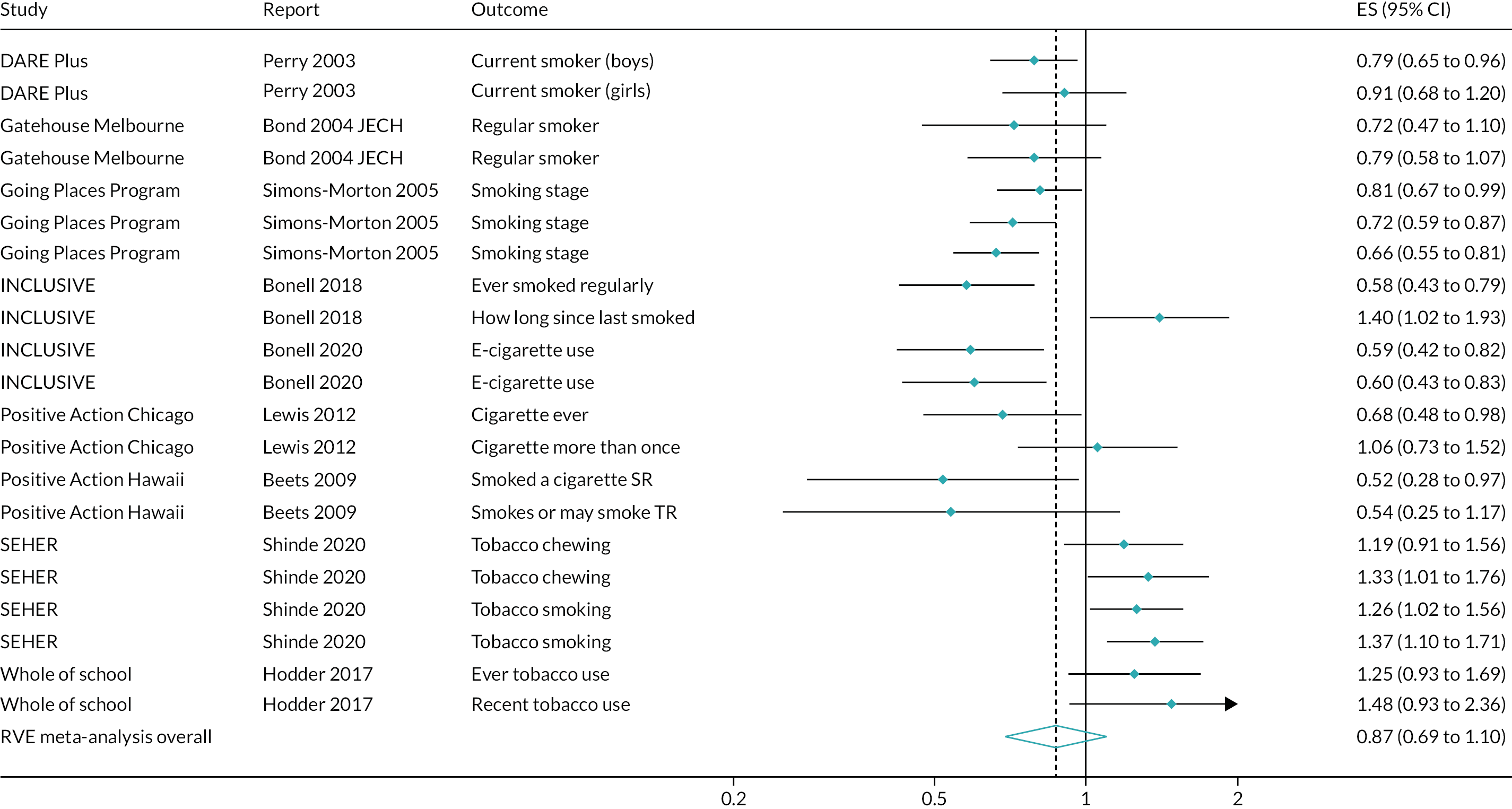

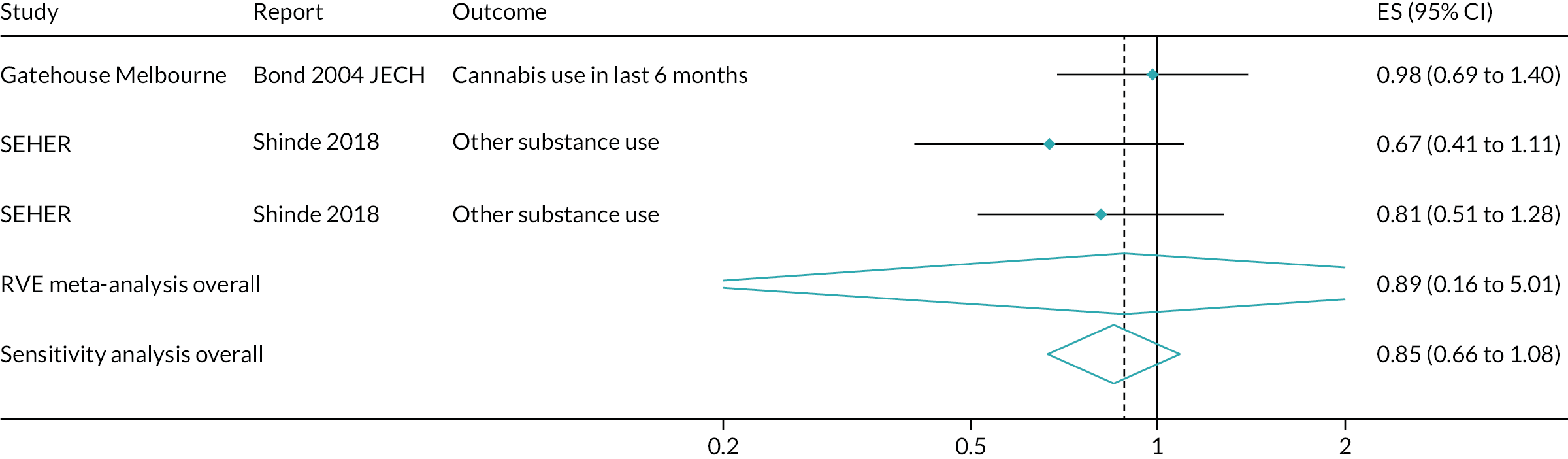

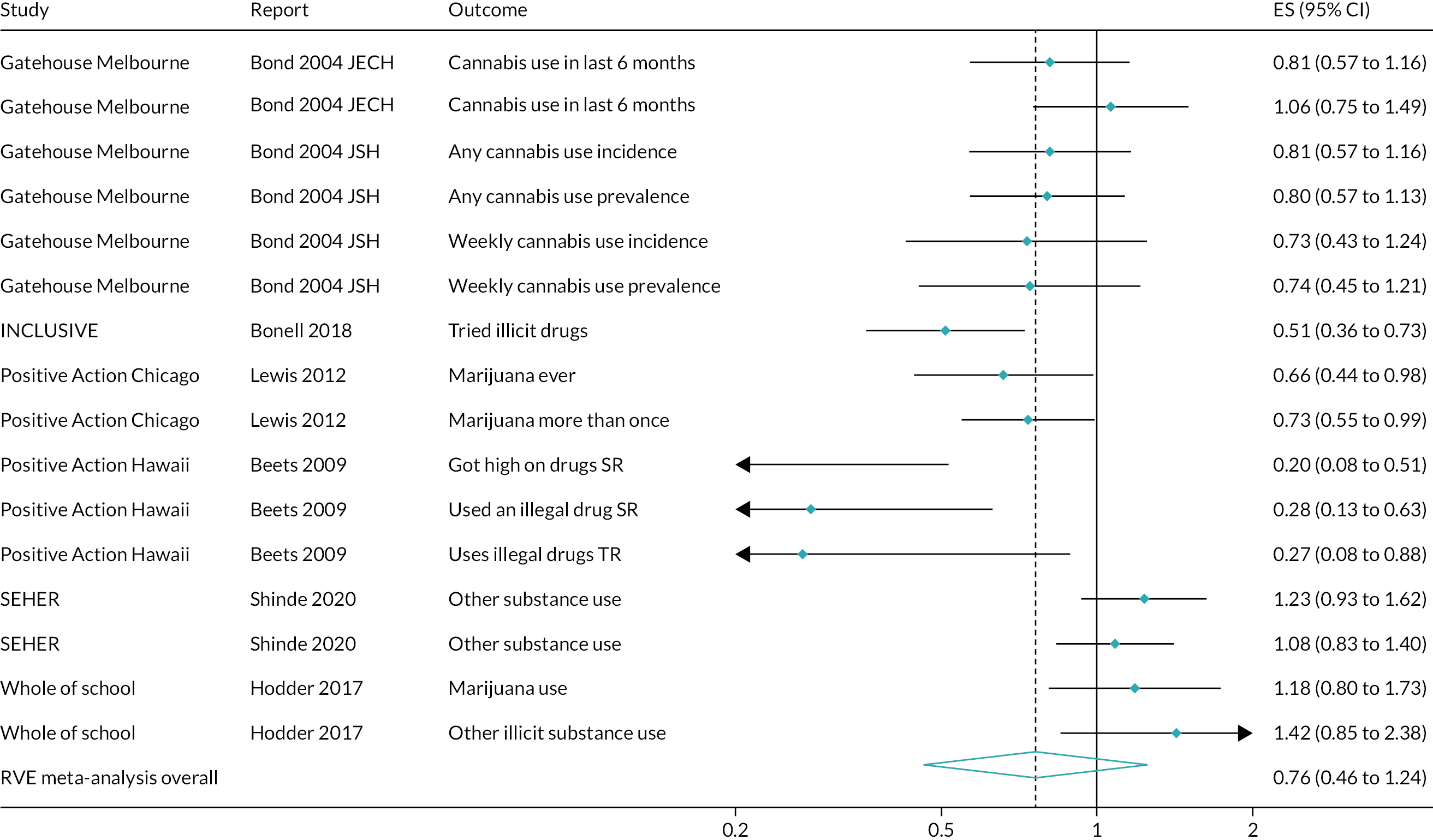

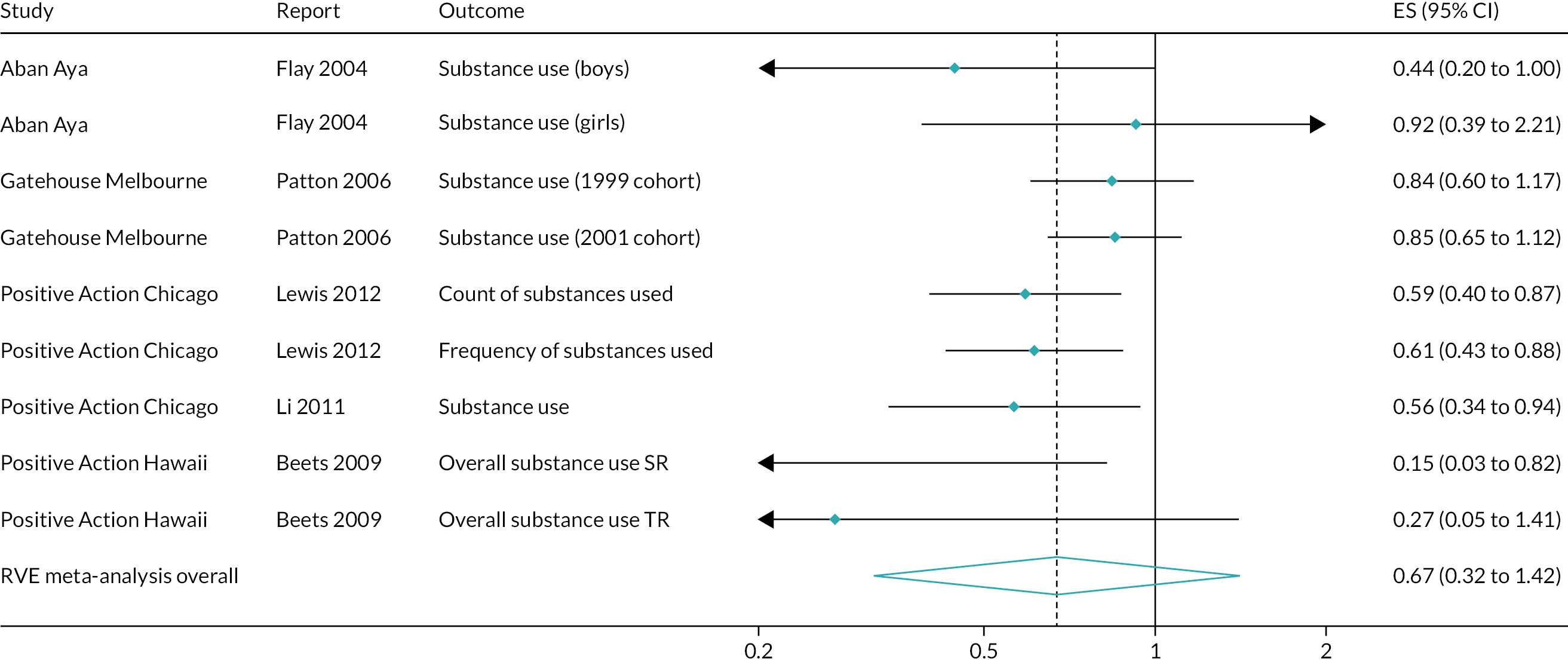

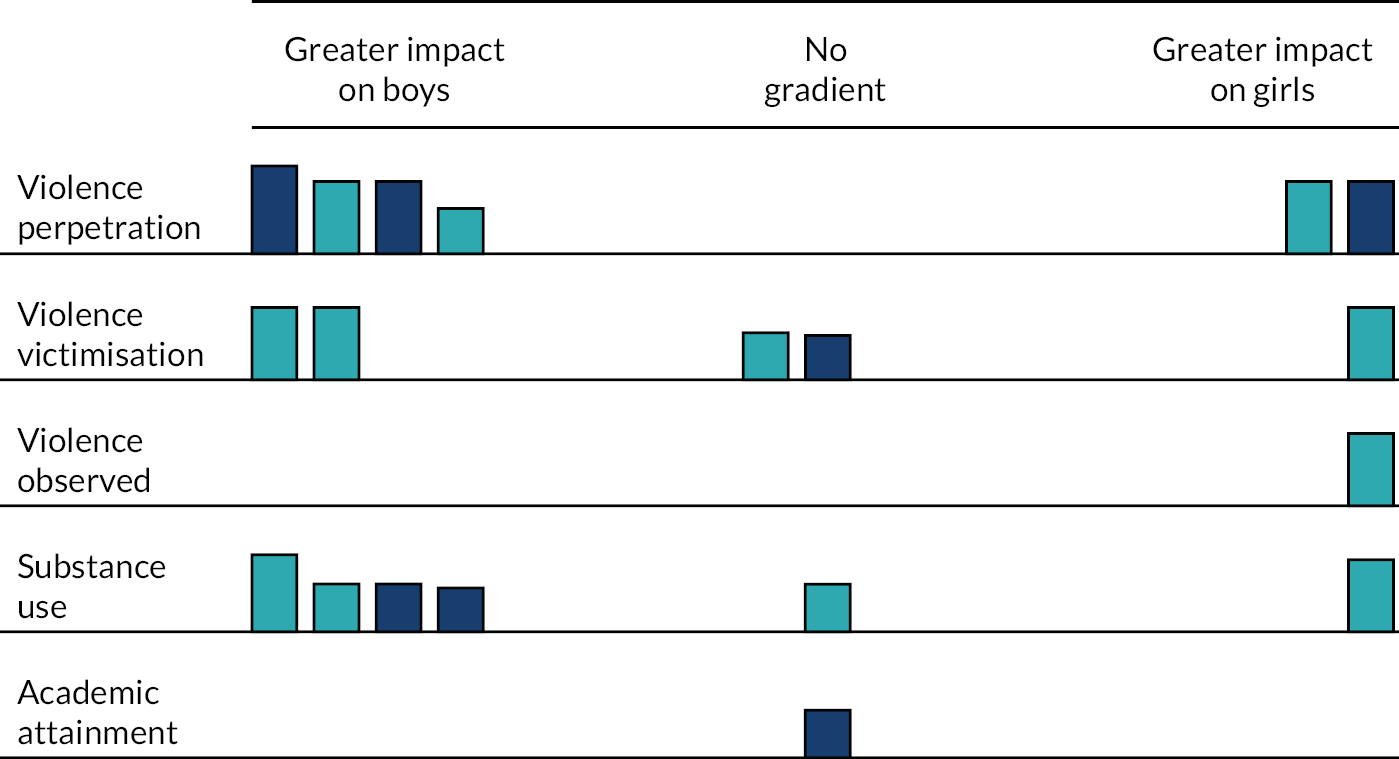

To address RQ3, we first produced a narrative account of the effectiveness of these types of interventions overall and by intervention subtype. This narrative synthesis was ordered by outcome then, within this, by age group, intervention subtype, follow-up time and study design. Outcomes were categorised into violence, smoking tobacco, drinking alcohol, using other drugs and academic attainment. We were not able to categorise by key stage as many interventions spanned multiple age groups and included multiyear longitudinal follow-up. This is explained further in Chapter 7 and is summarised in the deviations and clarifications to the protocol in Appendix 1, Table 8. Categorisation by intervention subtype was informed by our prior categorisation of intervention descriptions and theories of change (RQ1). For a description study characteristics and results, see Table 7. We then produced forest plots for each of our review outcomes, with separate plots for different outcomes and age groups, intervention subtypes and follow-up times (see Figures 11–47). Plots included point estimates and standard errors (SEs) for each study, such as risk ratios for dichotomous outcomes or standardised mean differences (SMDs) for continuous outcomes.

We then examined the extent of heterogeneity among the studies (as determined by both Cochran’s Q test and inspection of the I2-value). If an indication of substantial heterogeneity was determined (e.g. study-level I2-value of > 50%) that could not be explained through meta-regressions, we investigated this further using subgroup and sensitivity analyses. We then undertook meta-analysis to generate pooled estimates of intervention effects. We estimated separate models for substance use and violence. We examined substance use outcomes together in one analysis, as well as separated into smoking tobacco, drinking alcohol, other drug use and any ‘omnibus’ measures of substance use. We regarded follow-up times of up to 1 year and those of > 1 year post baseline as different outcomes, this being a deviation from our original protocol, so that follow-up times better aligned with those provided in the studies reviewed. We ran these models for interventions overall and, when sufficient studies were found, we ran separate models for different intervention subtypes and comparators. This categorisation was informed by our analysis of intervention descriptions and theories of change (RQ1).

When studies were found to be statistically heterogeneous, we used a random-effects model; otherwise, we used a fixed-effects model. When using the random-effects model, we conducted a sensitivity check by using the fixed-effects model to reveal differences in results. We considered using a robust variance estimation meta-analysis model to synthesise effect sizes. This was because outcome evaluations included multiple measures of conceptually related outcomes and robust variance estimation meta-analysis improves on previous strategies for dealing with multiple relevant effect sizes per study, such as meta-analysing within studies or choosing one effect size by including all relevant effect sizes, but adjusting for interdependencies within studies. 156 Unlike multivariate meta-analysis, it does not require the variance–covariance matrix of included effect sizes to be known. Where meta-analyses were performed, included pooled effect sizes were presented in forest plots, with the individual study point estimates weighted by a function of their precision.

Prior to synthesis, we checked for correct analysis by cluster, and report values of intracluster correlation coefficients, cluster size, data for all participants or effect estimates and SEs. When proper account of data clustering was not taken, we corrected for this by inflating the SE by the square root of the design effect. 156 When intracluster correlation coefficients were not reported, we contacted authors to request this information or imputed one, based on values reported in other studies. When imputation was necessary, we undertook sensitivity analyses to assess the impact of a range of possible values. In other instances of missing data (such as missing population information), it was not possible to include a study in a particular analysis if, for example, it was impossible to classify the population using our equity tool.

We used the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions138 to present the quality of evidence and summary-of-findings tables. The downgrading of the quality of a body of evidence for a specific outcome was based on five factors: limitations of the study, indirectness of evidence, inconsistency of results, precision of results and publication bias. The GRADE approach specifies four levels of quality (high, moderate, low and very low). If sufficient studies were found, we drew funnel plots to assess the presence of possible publication bias (trial effect vs. SE). Although funnel plot asymmetry may indicate publication bias, this can be misleading with a small number of studies. In Chapter 7, we discuss possible explanations for any asymmetry in the review in the light of the number of included studies. We assessed the impact of risk of bias in the included studies via restricting analyses to studies deemed to be at low risk of selection bias, performance bias and attrition bias.

Finally, we undertook further work to examine mediation and moderation of effects (RQ5). Mediation analyses involved a narrative synthesis reporting whether or not, within studies, measures of student commitment to school appear to mediate intervention effects on student violence, substance use or educational attainment outcomes. Moderation analyses examined what factors relating to setting and population moderated intervention effects within and between studies. To examine within-study moderation, we narratively synthesised evidence from relevant subgroup analyses conducted within primary studies to explore what subgroup characteristics explain heterogeneity of effects within studies, assessing whether or not interactions are significant. To examine between-study moderation, we aimed to use meta-regression to examine what factors related to setting and population influenced intervention effectiveness157,158 (as long as there are not too many confounders or insufficient data, or if meta-regression is unable to account for interdependencies in complex interventions), or qualitative comparative analysis, adapted for use in research synthesis,159,160 to assess necessary and sufficient conditions related to setting and population for intervention effectiveness. Any meta-regression and qualitative comparative analyses would be exploratory, hypothesis-building analyses because these drew on observational rather than experimental comparisons.

Synthesis of economic evaluations

Measures of costs and indirect resource use and cost-effectiveness were summarised using tables. When information was available, the tables are presented by time horizon so that both the short-and longer-term economic effects could be identified. If measures of resource use had been judged to be sufficiently homogeneous across studies, these would have been synthesised using statistical meta-analysis,140 although the paucity of evidence found precluded this. Measures of costs, indirect resource use and cost-effectiveness were adjusted for currency and inflation to the current UK context. These data were used to inform a narrative synthesis of economic analyses and applicability to the UK context. We did not perform de novo economic modelling because the identified interventions and their outcomes were too heterogeneous.

Policy and practice consultation

We consulted a group of policy and practice stakeholders (representatives from Public Health England, Department of Health and Social Care, Department for Education, Association for Young People’s Health, Healthy Schools London, Education Endowment Foundation and the National Association of Head Teachers), and consulted a separate group of young people under the auspices of the Advice Leading to Public Health Advancement (ALPHA) Centre for Development, Evaluation, Complexity and Implementation in Public Health Improvement (DECIPHer) group of young researchers.

Both groups were consulted only once, rather than the planned two consultations. This was because of disruption to the project arising from the COVID-19 pandemic and the challenges this raised for those working in public health and education. Each group reviewed the results of our syntheses of intervention descriptions, and process, outcome and economic evaluations to inform any refinements to the analysis and drafting of the report. The groups considered and advised us on whether or not the evidence of effectiveness and cost-effectiveness overall and by subgroups suggested that it would be worth investing in the development of a new intervention to be evaluated in the UK. We name stakeholders by their organisation only and do not attribute specific comments to individuals or organisations.

Chapter 3 Results: included studies

Results of the search

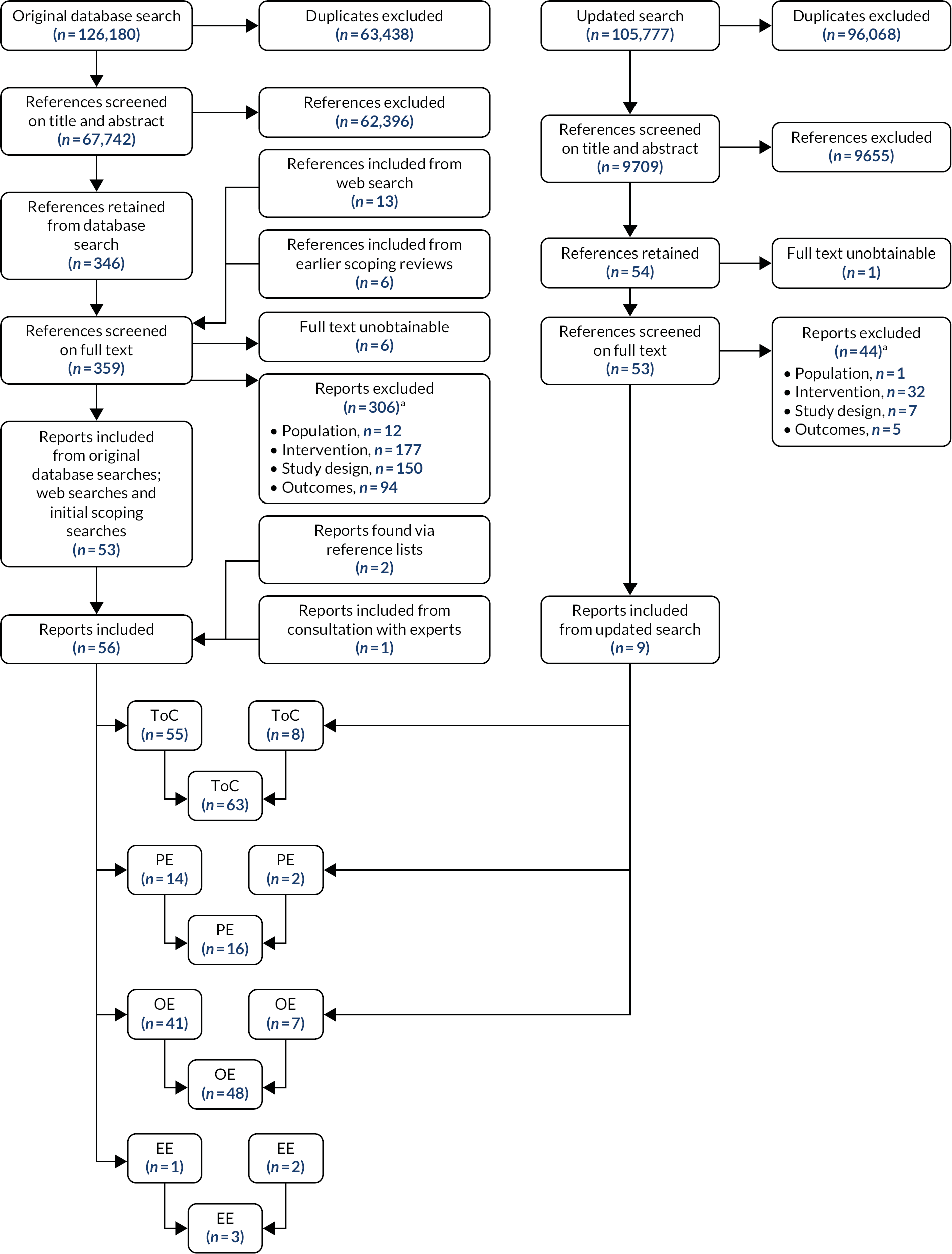

In total, 126,180 references were identified from the electronic literature searches run in January 2020. Of these 63,438 (50%) were identified as duplicates and removed. The updated May 2021 search identified 105,777 results. Of these, 96,068 (91%) were duplicates or already retrieved by the earlier search. This left 9709 new references, giving a total of 72,451 references that were screened on title and abstract. The numbers of results pre and post de-duplication for the 2020 and 2021 searches are listed in Table 1.

| Database name | Number of results retrieved in 2020 | Number of results once duplicates removed | Number of results retrieved in 2021 | Number of new results retrieved in 2021 once duplicates removed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ProQuest ASSIA | 7627 | 3444 | N/A | N/A |

| ProQuest Australian Educational Index | 4738 | 4414 | N/A | N/A |

| EBSCO British Education Index | 440 | 199 | N/A | N/A |

| EBSCO CINAHL Plus | 6011 | 1728 | 7075 | 745 |

| ClinicalTrials.gov | 991 | 935 | 1162 | 165 |

| EPPI-Centre database of health promotion research (BiblioMap) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| EPPI-Centre DoPHER | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Wiley Online Library Cochrane Library (includes results from Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials) | 3316 | 268 | 3736 | 989 |

| OvidSP EconLit | 223 | 208 | 268 | 33 |

| EBSCO Education Abstracts (HW Wilson) | 4567 | 2056 | N/A | N/A |

| ProQuest Education Database | 9115 | 2209 | N/A | N/A |

| EBSCO Educational Administration Abstracts | 1429 | 511 | N/A | N/A |

| EBSCO ERIC | 14,891 | 10,140 | 15,414 | 1301 |

| OvidSP Embase | 11,214 | 4746 | 12,630 | 1536 |

| OvidSP Global Health | 3512 | 1030 | 3988 | 455 |

| World Health Organization ICTRP | 601 | 384 | N/A | N/A |

| OvidSP MEDLINE | 8646 | 8007 | 9589 | 970 |

| OvidSP PsycInfo | 17,477 | 13,548 | 19,126 | 1387 |

| Elsevier Scopus | 17,484 | 4832 | 19,365 | 1096 |

| OvidSP Social Policy & Practice | 722 | 441 | 743 | 64 |

| Clarivate Web of Science and Social Sciences Citation Index | 11,189 | 3232 | 12,681 | 970 |

| EBSCO Teacher Reference Center | 1987 | 410 | N/A | N/A |

| EPPI-Centre TRoPHIct | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 126,180 | 62,742 | 105,777 | 9709 |

Following de-duplication, 62,742 references from the original search and 9709 references from the updated search were screened for inclusion on title and abstract. Pilot screening of four batches of 50 (carried out by CB and RP) revealed consistent (> 90%) agreement between reviewers over which references should be excluded on the basis of title and abstract. Disagreements were discussed between reviewers and the meaning of inclusion and exclusion criteria clarified. As per the protocol, given consistent batch-level agreement of > 90%, the remaining references were screened by a single reviewer (either CB or RP), with each checking with the other if they were unsure about the exclusion of a report.

After screening on title and abstract, 346 references were retained for full-text screening from the initial database searches and 54 were retained from the updated searches, making a total of 400 references from database searches to be screened on full text.

Thirteen additional references were identified from the web searches as includable for full-text screening (Table 2).

| Website name | Number of papers identified for full-text screening |

|---|---|

| Cambridge Journals Online (www.eifl.net/e-resources/cambridge-journals-online) | 0 |

| Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Smoking and Tobacco Use (www.cdc.gov/tobacco/index.htm) | 0 |

| Child and Adolescent Research Unit (www.cahru.org/) | 0 |

| Childhoods Today (www.childwatch.uio.no/publications/journals-bulletins/childhoodstoday.html) | 0 |

| Children in Scotland (https://childreninscotland.org.uk/) | 0 |

| Children in Wales (www.childreninwales.org.uk/) | 0 |

| European Union Community Research and Development Information Service (https://cordis.europa.eu/) | 0 |

| Database of Educational Research (EPPI-Centre) | Not available |

| Drug and Alcohol Findings Effectiveness Bank (https://findings.org.uk/e-bank.php) | 0 |

| 0 | |

| Google Scholar | 0 |

| Welsh Government (https://gov.wales/) | 0 |

| Scottish Government (www.gov.scot/) | 0 |

| Joseph Rowntree Foundation (www.jrf.org.uk/) | 2 |

| National Criminal Justice Reference Service (www.ncjrs.gov/) | 10 |

| National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children (www.nspcc.org.uk/) | 0 |

| National Youth Agency (https://nya.org.uk/) | 0 |

| Northern Ireland Executive (www.northernireland.gov.uk/) | 0 |

| OpenGrey (www.opengrey.eu/) | 0 |

| Personal Social Services Research Unit (www.pssru.ac.uk/) | 0 |

| Project Cork (www.centerforebp.case.edu/resources/tools/project-cork-clinical-screening-tools) | 0 |

| UCL-IOE Digital Education Resource Archive (https://dera.ioe.ac.uk/) | 0 |

| UK Clinical Research Network Portfolio (www.nihr.ac.uk/researchers/collaborations-services-and-support-for-your-research/run-your-study/crn-portfolio.htm) | 0 |

| University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (https://illinois.edu/) | 0 |

| US Center for Substance Abuse Prevention (www.samhsa.gov) | 0 |

| Social Issues Research Centre (www.sirc.org/) | 0 |

| The Campbell Library (www.campbellcollaboration.org) | 1 |

| The Children’s Society (www.childrenssociety.org.uk/) | 0 |

| Open Library (https://openlibrary.org/) | 0 |

| Schools and Students’ Health Education Unit Archive (https://sheu.org.uk/) | 0 |

| World Health Organization ICTRP (www.who.int/clinical-trials-registry-platform) | 0 |

| Young Minds: Child and Adolescent Mental Health (https://youngminds.org.uk/) | 0 |

| Total | 13 |

A further six records already known to reviewers from earlier scoping searches were also added for full-text screening.

Full texts for six references from our initial searches and one reference from our updated searches were unobtainable online or through interlibrary loans, leaving 412 records available for full-text screening, 359 from the original searches and 53 from the updated searches. Double-screening of a set of 50 full-text papers (carried out by CB and RP) revealed > 90% agreement on which items to include from the review. Following this, the two reviewers (CB and RP) moved to independent screening of the remaining references, resolving any uncertainties with each other as the arose. Sixty-two reports remained after full-text screening. 52,61,63,64,66–69,71,73,80,85,87–89,98,103,108–110,113,115,117,123,124,161–197 An additional two reports were added from reference-checking,198,199 and one further article was added from the consultation with subject experts. 200

The 65 reports52,61,63,64,66–69,71,73,80,85,87–89,98,103,108–110,113,115,117,123,124,161–200 deemed eligible for inclusion in the review were then coded according to which review question they answered. Sixty-three reports were identified for inclusion in the review of theories of change (RQ1),52,61,63,64,66–69,71,73,80,85,87,88,98,103,108–110,113,115,117,123,124,161–195,197–200 16 for inclusion in the review of process evaluations (RQ2)63,66,69,71,88,98,110,113,167,189–195 and 48 for inclusion in the review of outcome evaluations (RQ3 and RQ5). 52,61,64,67,68,73,80,85,87,103,108,109,115,117,123,124,161–188,197–200 Three reports were included for inclusion in the review of economic evaluations (RQ4). 89,167,196

Figure 2 summarises the flow of references through the review and the number of studies included in each synthesis. The left side of the diagram describes the original search, and the right side depicts the updated search. Each identified included studies addressing each of our RQs, which is indicated at the bottom.

FIGURE 2.

Searches and screening. EE, economic evaluation; OE, outcome evaluation; PE, process evaluation; ToC, theory of change. a, Total is more than the number of studies excluded because some studies were excluded based on more than one criterion.

Included studies and reports

Overview

The 65 reports included in the review covered 22 distinct interventions examined in 27 separate empirical studies. Six interventions were each the subject of one study report. 161,170,174,189,193,197 The remaining 59 reports covered 16 interventions, examined in 21 separate studies. Only three interventions were evaluated in more than one study. One intervention (Learning Together) was the subject of two separate studies, one pilot and one full trial in the UK, covered by nine included reports. 71,88,89,165,166,168,194,196 A further intervention (Positive Action) was examined in 13 publications from five separate empirical studies (four in the USA and one in the UK) 52,61,63,64,85,108–110,113,123,124,173,179 One paper reported on a study carried out in Australia evaluating two relevant interventions (the Friendly Schools intervention and the combined Friendly Schools and Cool Kids Taking Control interventions),197 one of which (Friendly Schools) was also the subject of a separate study and report. 169

The reports and the interventions and studies they correspond to are reported in Table 3, organised according to the RQ they answer. These are summarised as follows: included reports that describe theory of change, which helped answer the second part of RQ1 (how closely do interventions align with the theory of human functioning and school organisation?); included reports that evaluate processes, which helped answer RQ2 (what factors relating to setting, population and intervention influence the implementation of interventions); included reports that evaluate outcomes, which helped answer RQ3 (overall and by intervention subtype, what are the effects of interventions on student substance use, violence and education?) and/or RQ5 (are these effects mediated by student commitment to school or moderated by setting or population); and included reports that evaluate economic outcomes, which helped answer RQ4 (what is the cost-effectiveness of interventions, overall and by subtype).

| Intervention name | All included reports | Included reports that | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Describe theory of change | Evaluate processes | Evaluate outcomes | Evaluate economic outcomes | ||

| AAYP school/community intervention | Not applicable | Not applicable | |||

| CDP | Not applicable | Not applicable | |||

| Cooperative Learning | Not applicable | Not applicable | |||

| CFS | Cross 2018;191 Australia/Perth |

Cross 2016;191 RCT: Australia/Perth | Not applicable | ||

| DARE Plus programme | Bosma 2005;190 USA/Minnesota |

Not applicable | |||

| DASI | Not applicable | Not applicable | |||

| Friendly Schools | Cross 2011;169 Australia/Perth Rapee 2020;197 Australia/New South Wales and Western Australia |

Not applicable | Not applicable | ||

| Friendly Schools and Cool Kids Taking Control combined | Rapee 2020;197 Australia/New South Wales and Western Australia | Rapee 2020;197 Australia/New South Wales and Western Australia | Not applicable | Rapee 2020;197 RCT: Australia/New South Wales and Western Australia | Not applicable |

| FSFF | Cross 2012;171 Australia/Perth Cross 2018;192 Australia/Perth |

Cross 2018;192 Australia/Perth |

Cross 2012;171 RCT: Australia/Pertha | Not applicable | |

| FSTP | Cross 2018;170 Australia/Perth | Cross 2018;170 Australia/Perth | Not applicable | Cross 2018;170 RCT: Australia/Perth | Not applicable |

| Gatehouse Project | Bond 2001;66 Australia/Victoria Bond 2004;67 Australia/Victoria Bond 2004;68 Australia/Victoria Patton 2006;115 Australia/Victoria |

Bond 2001;66 Australia/Victoria |

Not applicable | ||

| Going Places programme | Simons-Morton 2005;182 USA/Maryland Simons-Morton 2005;183 USA/Maryland |

Not applicable | Not applicable | ||

| GST | Knight 2018;98 Uganda/Luwero District |

Greco 2018;89 Uganda/Luwero District |

|||

| HSE | Bonell 2010;69 UK/SE England |

Bonell 2010;73 QE: UK/SE England | Not applicable | ||

| Learning Together | |||||

| PPP | Mitchell 1991;193 USA/Portland | Mitchell 1991;193 USA/Portland | Mitchell 1991;193 USA/Portland | Not applicable | Not applicable |

| Positive Action |

|

|

Not applicable | ||

| Project PATHE | Gottfredson 1986;174 USA/Charleston | Gottfredson 1986;174 USA/Charleston | Not applicable | Gottfredson 1986;174 QE: USA/ Charleston | |

| Responsive Classroom | Anyon 2016;189 USA | Anyon 2016;189 USA | Anyon 2016;189 USA | Not applicable | Not applicable |

| Restorative Practices Intervention | Acosta 2019;161 USA/Maine | Acosta 2019;161 USA/Maine | Not applicable | Acosta 2019;161 RCT: USA/Maine | Not applicable |

| SEHER programme | Not applicable | Not applicable | |||

| Whole-of-school intervention | Not applicable | Not applicable | |||

| Total (n) | 65 | 63 | 16 | 48 | 3 |

All 65 reports included in the review described an intervention that helped to address the first part of RQ1 (what whole-school interventions that promote student commitment to school to prevent student substance use and violence have been evaluated and what subtypes are apparent?). Sixty-three reports covering all 22 interventions evaluated in the review were included in the synthesis of theories of change (RQ1). 52,61,63,64,66–69,71,73,80,85,87,88,98,103,108–110,113,115,117,123,124,161–195,197–200 Two reports were not included in the synthesis of theories of change as they did not add any new information to more detailed descriptions provided in other reports. 89,196 Sixteen reports covering 13 studies of 10 interventions evaluated processes and all of these also described a theory of change, addressing both RQs 1 and 2. 63,66,69,71,88,98,110,113,167,189–195 Forty-eight reports covering 23 studies and 20 interventions evaluated outcomes (including moderator and mediator analysis) and all of these were also included in the synthesis of theories of change, addressing RQs 1 and 3. 52,61,64,67,68,73,80,85,87,103,108,109,115,117,123,124,161–188,197–200 Of these, 19 reports were included in the synthesis of moderator analysis61,64,68,80,85,87,103,108,117,163,166,168,171–173,176,177,181,186 and three were included in the synthesis of mediator analysis,124,165,184 addressing RQ5. These are marked with an asterisk in Table 3. No publications reported only on theory, processes or outcomes. Two publications reported on economic outcomes only, addressing RQ489,196 and one publication reported on theory, processes, outcomes and economic outcomes, addressing all RQs. 167

Twelve interventions were examined in outcome evaluations only,87,161–164,169,170,174–178,180–188,197,198,200 two were examined in process evaluations only189,193 and six were examined in both outcome and process evaluations. 52,61,63,64,66–69,73,85,103,108–110,113,115,117,123,124,171,173,179,190–192,199 Two interventions were examined in outcome, process and economic evaluations. 71,80,88,89,98,165–168,172,194–196

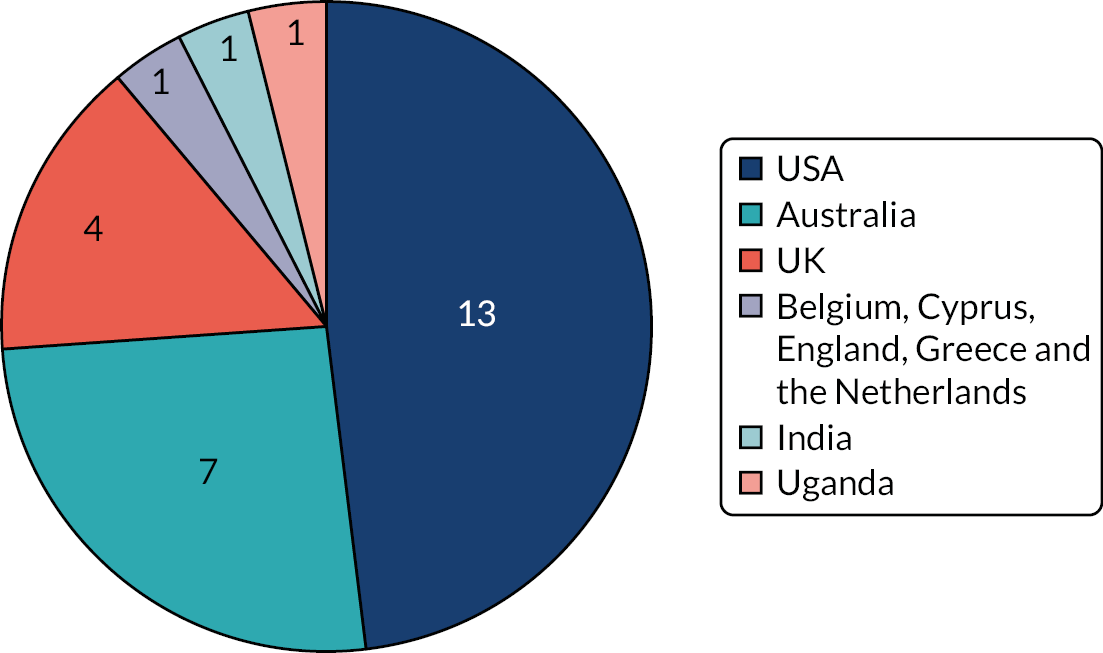

Study and intervention characteristics

The following summaries provide details of the rate of report publication, the geographical location of each empirical study, their study designs, the outcome interventions targeted, who delivered the interventions, intervention components and the duration of interventions.

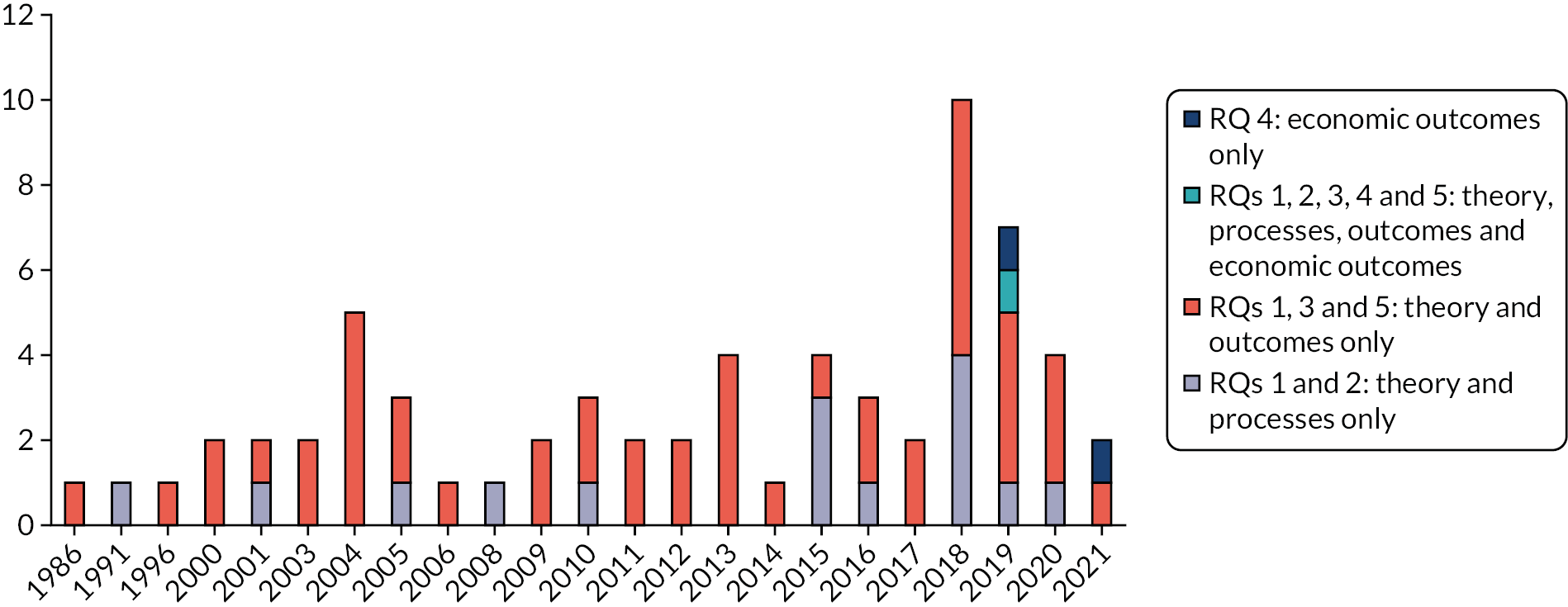

Rate of report publication