Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as award number NIHR129064. The contractual start date was in March 2020. The draft manuscript began editorial review in July 2023 and was accepted for publication in March 2024. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Stenfert Kroese et al. This work was produced by Stenfert Kroese et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Stenfert Kroese et al.

Chapter 1 Background to the research

Why is this research important?

A learning disability is characterised by an intelligence quotient below 70 and associated deficits in adaptive functioning, arising before the age of 18 years. It is estimated to affect 1.4–2% of the UK population. 1 Children with a learning disability are four to five times more likely to have a mental health disorder compared with other children and account for 14% of all children with mental health problems. 2 Their parents, especially mothers, are also more likely to report psychological problems. These health inequalities for children with a learning disability and their parents emerge early in the child’s life. 2

Social exclusion and poverty are more likely to be experienced by children and young people with a learning disability, along with other negative life experiences, such as health issues, abuse and bereavement, as well as having fewer friends than other children. These biological, psychological and environmental factors increase their risk of developing mental health difficulties. 2 At least half of children with a learning disability are victimised, rejected or mistreated by peers3 and, compared with their typically developing peers, 75% of children and young people with a learning disability have low social competence4 and low levels of emotional literacy and coping skills, which further increases their risk of developing mental health difficulties. 5 These early negative experiences have long-term consequences, as young people with mental health difficulties are more likely to have further negative life experiences and unequal life chances as they progress into adulthood. 6

Access to specialist mental health support poses challenges and it has been reported that fewer than 30% of children have access to such services. 7 Thus, children with a learning disability and their parents face significant health inequalities and problems gaining access to appropriate and timely services.

For the general population, there is compelling and consistent empirical evidence that social and emotional competencies can be taught and that these competencies lead to positive and significant improvements in mental health and well-being, behaviour and academic achievement. 6 Improved social and emotional literacy may therefore mitigate some of the impact from inequalities experiences by children with a learning disability. Given this evidence, interventions are needed that aim to protect and improve the mental health and resilience of children with a learning disability. Despite higher prevalence rates of mental health problems in children with a learning disability2 and research demonstrating a link between emotional literacy and mental health in adults and adolescents in the general population, there has been limited research that has examined the link between emotional literacy and mental health in children with a learning disability.

A recent systematic review of randomised controlled trials (RCTs)8 indicates that most reported interventions (including school-based interventions) designed to improve psychosocial–behavioural functioning of school-aged (5–18 years) children with a learning disability may be effective. However, the studies included in this review only report on intellectual functioning and adaptive skills (e.g. communication, social skills and educational/vocational functioning) and were not designed to measure impact on emotional literacy.

The findings of our early (uncontrolled) pilot work5 suggest that an adapted school-based intervention, a programme called Zippy’s Friends (ZF) adapted for children with special educational needs and disabilities (SEND), is acceptable to and valued by teachers, with some promise of improvements in mental well-being, social interactions and problem solving in children with a learning disability. It is therefore important to establish in a controlled and systematic manner whether a school-based emotional literacy intervention such as ZF can be effective in protecting and improving the mental health and resilience of children with a learning disability.

Before such research is conducted, a feasibility study is required to investigate whether ZF-SEND can be delivered successfully to small groups of children in special schools by teachers in a classroom setting, and whether it would be feasible to conduct a large-scale RCT of the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of ZF-SEND.

Conceptualisation of emotional literacy

Emotional literacy has been defined as:

the ability to perceive accurately, appraise and express emotion, the ability to access and/or generate feelings when they facilitate thought, the ability to understand emotion and emotional knowledge; and the ability to regulate emotions to promote emotional and intellectual growth. 9

Bar-On’s10 model of emotional literacy is the most comprehensive and inclusive conceptualisation of this construct, including an array of emotional, personal and social abilities and skills that influence an individual’s ability to cope effectively with environmental demands and pressures. The key factors involved in this model include intrapersonal capacity (understanding, awareness and expression of one’s emotions), interpersonal skills (understanding, awareness and appreciation of others’ feelings), adaptability (altering one’s feeling and thoughts according to different situations and solving interpersonal problems), stress management (coping with stress and strong emotions) and motivational and general mood factors.

Evidence for the positive effects of improving emotional literacy on mental health

Emotional literacy skills have been shown to be associated with resilience to mental health problems. 11 When individuals have a broad repertoire of coping skills they are considered to have ‘coping flexibility’ and research12 has shown that having such flexibility is associated with positive short- as well as long-term outcomes. Studies on coping distinguish between strategies that focus on decreasing the negative feelings a person has after a difficult or stressful situation (‘emotion-focused coping’) and those which attempt to improve or change the situation (‘action-focused coping’). Emotional literacy is associated with (and ZF addresses) both these types of coping strategies.

Research findings suggest that high emotional literacy reduces stress, improves self-esteem and reduces rates of emotional difficulties later in life. A meta-analysis conducted in 2010,13 which includes adult and adolescent participants (from the general population) found evidence that higher emotional literacy is linked to better mental health. A more recent study14 also suggests that emotional literacy predicts mental health in adolescents (without a learning disability) and concludes that teaching emotional literacy is an effective preventative intervention, as emotional literacy was a significant predictor of psychological well-being and adjustment.

Zippy’s Friends, a school-based intervention designed to enhance emotional literacy

Schools have an important role to play in helping to identify mental health difficulties. Early detection and intervention are key so that children get the support they need, when they need it. 6 The UK Government’s Green Paper ‘Transforming Children and Young People’s Mental Health Provision’15 proposes a new joint working approach between schools and the NHS in England to help children and young people live fulfilling and happy lives. National guidance on the social and emotional well-being of children by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends that priority should be given to those children most at risk of mental health problems. 6 However, the recent government ‘SEND and Alternative Provision Improvement Plan’16 fails to mention mental health or emotional literacy promotion as a priority area for children with SEND or a learning disability.

A systematic review17 concludes that schools that promote positive mental health and help children to cope with negative life experiences can create psychological resilience. This review shows school-based psychoeducational interventions to have positive effects on outcomes, including mental health, social, emotional and educational factors for families, children and communities, with the most effective interventions including skills teaching, liaison and education of teachers and parents, involvement in the community, continuity of interventions starting with young children, long-term whole-school approaches, adaptations to the curriculum and a focus on positive mental health. A recent systematic review of classroom-based mental health interventions for children in adverse environments18 also found evidence that such interventions can promote resilience to psychological problems. However, the authors stressed that risk of bias, especially due to confounding variables and deviation from intended intervention delivery, suggests that the findings of most of the 17 included studies should be interpreted with caution.

Zippy’s Friends for mainstream schools has been extensively evaluated in a number of studies in and outside the UK. 19–24 An early (2010) systematic review found support for the effectiveness of ZF for children in mainstream schools, improving coping skills and increasing emotional vocabulary and positive behaviours. 25 The review identified four controlled studies, conducted between 2000 and 2010. Subsequently, research published in 2010 on the effect of ZF on the emotional well-being of 523 primary school children in ‘disadvantaged’ schools in Ireland found a significant positive effect of ZF on emotional literacy, with significant increases in the intervention group’s scores for self-awareness, self-regulation, motivation, empathy and social skills. 20 In 2014, the same authors reported that the significant increase in emotional literacy in the intervention group was maintained at 12-month follow-up. 23 A large RCT with 7- to 8-year-old children (N = 1483) in Norway also found ZF to have a significant positive impact on coping and mental health outcomes. 22

The studies mentioned so far have all been conducted in mainstream schools. Other than the small pilot study carried out by ourselves5 (with no control condition and no recording of feasibility outcomes), to date we have found no studies reporting on trials of whole-class or school-based mental health interventions for children with a learning disability and/or for special schools. Thus, an evidence inequality exists and research on early school-based interventions designed to improve social/emotional functioning and mental health is needed urgently for children with a learning disability.

Rationale for the study

In brief, conducting a feasibility study of ZF-SEND is important because:

-

children with a learning disability experience a range of inequalities, which puts them at greater risk of mental and physical health problems in adulthood;

-

children and young people with a learning disability experience negative life events and adversity more frequently than their non-disabled peers;

-

the construct of emotional literacy has been shown to be a distinct and moderating factor of how life stress affects mental health and well-being;

-

there is evidence that teaching emotional literacy in primary schools is an effective early intervention to promote positive mental health and help children cope with negative life experiences, resulting in better mental health in later life;

-

in mainstream schools, the ZF programme has been shown to be an effective way in which to improve emotional literacy, coping skills and mental health outcomes;

-

emotional literacy is underemphasised in the SEND curriculum and mainstream emotional literacy programmes (except ZF-SEND) do not have SEND adaptations;

-

NICE recommends that help should be given to those most at risk of mental health problems;

-

lack of investment in mental health promotion in primary schools, particularly special schools, has significant costs for society;

-

there is an identified need for SEND-adapted emotional literacy programmes in special schools.

Chapter 2 Study aims, objectives, primary and secondary outcomes

Aims

The primary aim of the study was to evaluate whether it is feasible to conduct a large-scale RCT of the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of ZF-SEND for children with a learning disability in special schools. We aimed to assess the acceptability and feasibility of: (1) participating in the trial; (2) data collection and (3) the ZF-SEND intervention, through a feasibility RCT which aimed to recruit and randomise 12 special schools to either deliver the ZF-SEND intervention over 1 academic year (6 schools) or continue with practice as usual (PAU; 6 schools) and to collect data from 96 pupils at baseline (pre randomisation) and 12 months post randomisation.

The study explored the following, in relation to each aim:

Participation in the trial:

-

Feasibility of recruiting and retaining eligible schools and participants to the study and to identify the most effective recruitment pathways

-

The acceptability of study processes, including randomisation, to schools, teachers and parents/carers.

Data collection:

-

Feasibility and acceptability of the proposed outcome measures as methods to measure the effectiveness of the intervention and to conduct an embedded health economic evaluation within a large-scale RCT.

The ZF-SEND intervention:

-

The feasibility of recruiting suitable schools and teachers to deliver the intervention

-

Adherence to the intervention and fidelity of implementation

-

Acceptability of the intervention to teachers, pupils and parents/carers.

Objectives

-

To collect quantitative data using a range of standardised measures at baseline and 12 months post randomisation from teachers, pupils and parents/carers.

-

To conduct qualitative interviews with pupils, teachers, senior leadership staff and parents/carers to explore their experiences of participating in the feasibility study (two pupil participants in each ZF-SEND school, one teacher in each school, a senior member of staff in each school and one or two parents/carers in each school).

-

In the ZF-SEND arm, to assess intervention delivery, fidelity and adherence, and factors influencing implementation, mechanisms of impact and context using data from multiple sources, including teacher-completed session records, qualitative interviews and observations of two ZF-SEND lessons in each ZF-SEND school.

-

In the ZF-SEND arm, to explore how children, parents and teachers experience the intervention through qualitative interviews with 10–12 pupil participants, 10–12 parents/carers, 5–6 teachers and 5–6 senior staff.

-

To investigate the validity and reliability of the self-report measure of mental health (‘Me and My School’; MAMS) and its relationship with other (proxy report) measures of mental health and behaviour.

-

To establish what constitutes education as PAU for emotional literacy in special schools for children with a learning disability through a survey of 20 special schools involved in the trial and external to the trial.

-

To undertake a nested ‘study within a trial’ (SWAT) to explore the acceptability of two different study designs: one where PAU does not come with the offer of delayed access to ZF-SEND, and one where it does. The aim of this SWAT will be to explore the extent to which offer of a ‘waitlist’ comparator influences recruitment and retention of schools. The findings from this SWAT will be used to inform the design of a subsequent large-scale effectiveness study, if indicated.

-

To review the feasibility study against the progression criteria and ascertain whether progression to a large-scale RCT is feasible.

Primary outcomes

The primary outcome is to determine the feasibility of conducting a future large-scale trial to establish the impact of ZF-SEND on mental health, behaviour/emotional/social functioning and quality of life and its cost-effectiveness (economic evaluation). To determine these outcomes, the following were assessed:

-

Recruitment of schools, pupils and parents/carers: What are the most effective recruitment pathways to identify special schools? What recruitment rate for parents can be achieved? What are the characteristics of schools and families of children with a learning disability approached and recruited?

-

Recruitment of schools and teachers: Can schools and teachers be recruited to run the ZF-SEND programme over 1 academic year? What factors influence schools’ willingness to take part in the research? Can sufficient teachers be recruited and trained?

-

Acceptability of research design: Are schools and parents willing to be randomised within the context of a RCT? Do they prefer a design with delayed access (after follow-up data collection) to ZF-SEND in the PAU arm or will they accept PAU with no access to ZF-SEND? How does the offer of delayed access to ZF as part of PAU influence recruitment and retention of schools and pupils?

-

Fidelity of implementation: Can teachers deliver ZF-SEND with a high degree of fidelity to the programme manual? What are the key barriers/facilitators for successful implementation of ZF-SEND and how does this vary across different school contexts? Does the implementation of ZF-SEND support the logic model?

-

Adherence: What proportion of children with a learning disability in the intervention arm schools complete the ZF-SEND programme?

-

Retention: What proportion of schools, children and parents/carers are retained in the research study up to the 12-month post-randomisation follow-up?

-

Usual practice: What does PAU consist of for promoting mental health and well-being on a class-wide curriculum basis for children with a learning disability in special schools? How is PAU different from the programme content of ZF-SEND? Does the offer of delayed access to ZF-SEND as part of PAU alter what is offered as part of PAU in the year following randomisation?

-

Estimation of parameters to inform a definitive sample size calculation: What are the estimated standard deviation (SD), intracluster correlation coefficient, average cluster size and coefficient of variation of cluster size for the strengths and difficulties questionnaire (SDQ) at 8–12 months post randomisation?

-

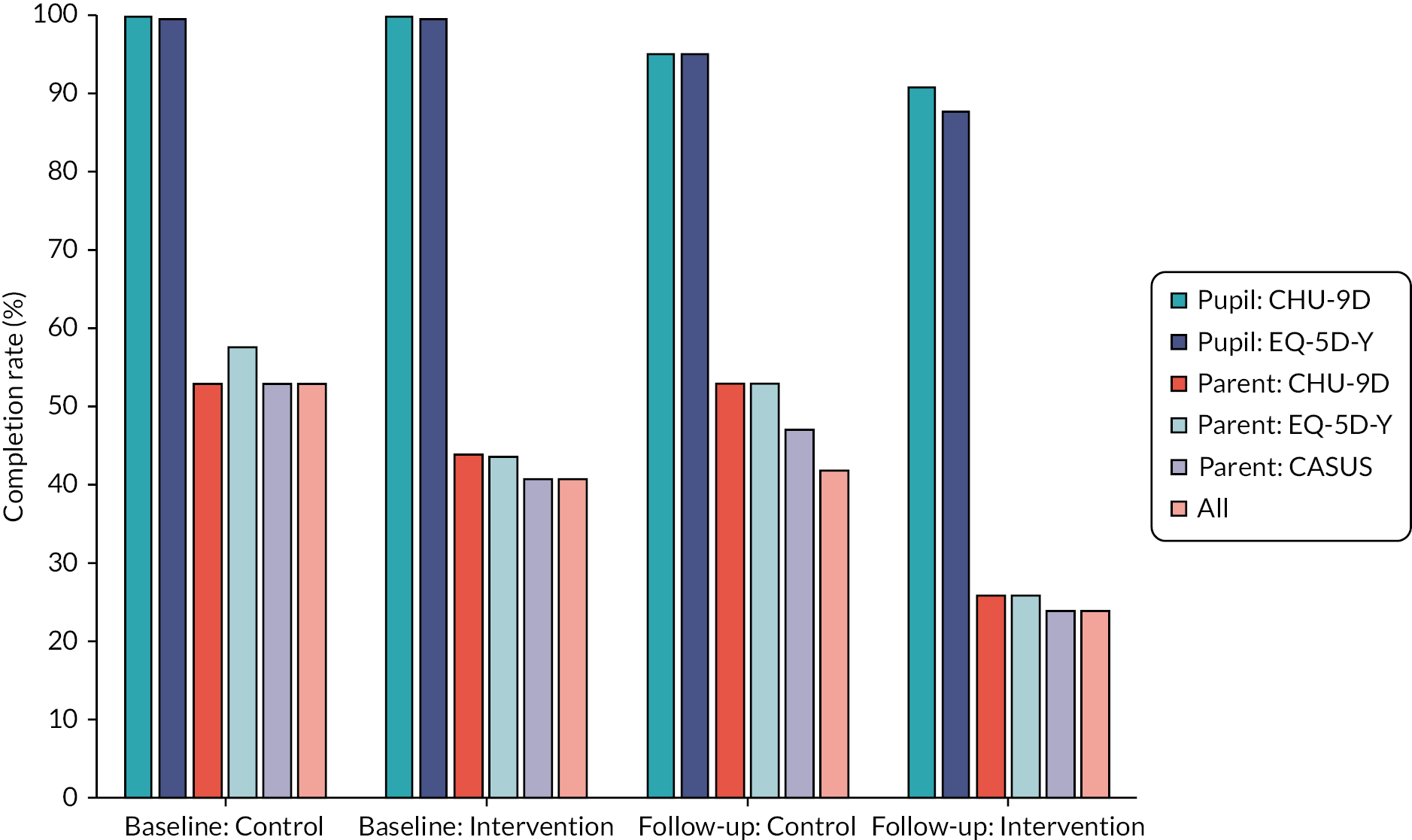

Feasibility of outcome measures: Do children, teachers and parents complete the outcome measures for the study?

-

Design and methods for health economic analysis: What is the feasibility of collecting resource use and health-related quality of life data for parents and the child participants? What sources of unit costs for potential resource consequences are appropriate, and how much primary costing research will be required for a later large-scale trial? What is the most appropriate approach for measuring and valuing child, family and school outcomes for incorporation into a subsequent trial-based economic evaluation?

-

Evidence of harm: Is there evidence on the basis of the outcome measures that the ZF-SEND programme results in harm, in which case progression to a full trial would not be recommended.

Progression criteria

The following progression criteria were determined to inform the feasibility of progression to a large-scale RCT. We used Avery et al. ’s traffic light system26 to prespecify the feasibility outcomes and indicated satisfactory performance that would suggest progression to a large-scale trial is warranted without any amendments (green), progression is only warranted with an amendment to study design and/or processes (amber), or progression is not warranted (red). See Table 1 for each criterion.

| Outcome: metric | Green (%) | Amber (%) | Red (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recruitment of schools: schools randomised/approached | ≥ 50 | 20–40 | ≤ 20 |

| Retention of schools: schools that remain in the study until the end/schools randomised | ≥ 75 | 50–74 | ≤ 49 |

| Recruitment of pupils – consent obtained from parents: parents providing consent for their child to participant/parents approached to provide consent | ≥ 75 | 50–74 | ≤ 49 |

| Fidelity of ZF-SEND delivery: sessions delivered with fidelity to the manual/sessions assessed | ≥ 75 | 50–74 | ≤ 49 |

| Pupil engagement with ZF intervention: pupils actively taking part in at least 50% of sessions/pupils enrolled in the study and in schools allocated to the intervention | ≥ 60 | 40–59 | ≤ 39 |

| Collection of outcome data: pupils with strengths and difficulties questionnaire data available at 8–12 months post randomisation/pupils included in the study | ≥ 75 | 50–74 | ≤ 49 |

Secondary outcomes

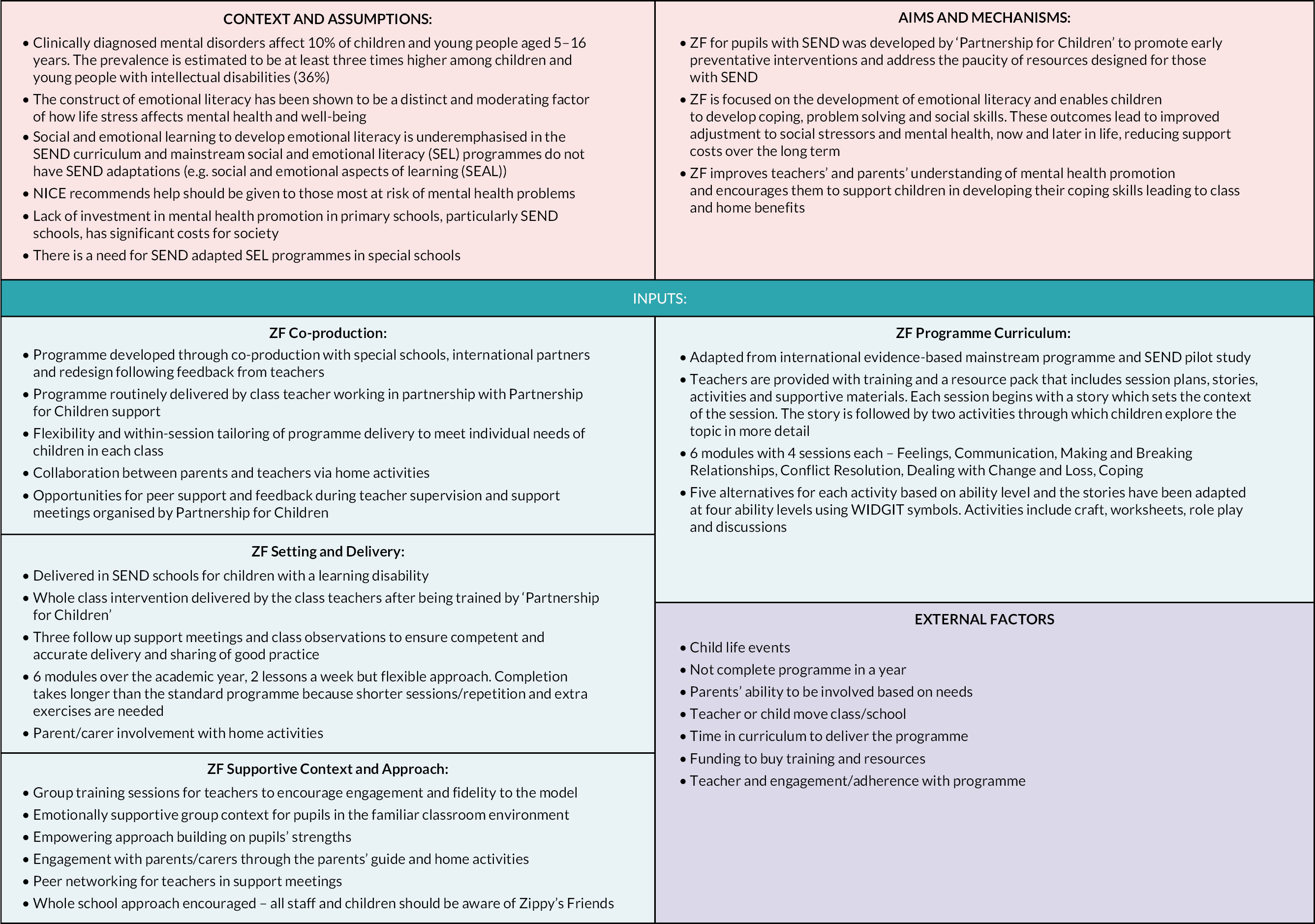

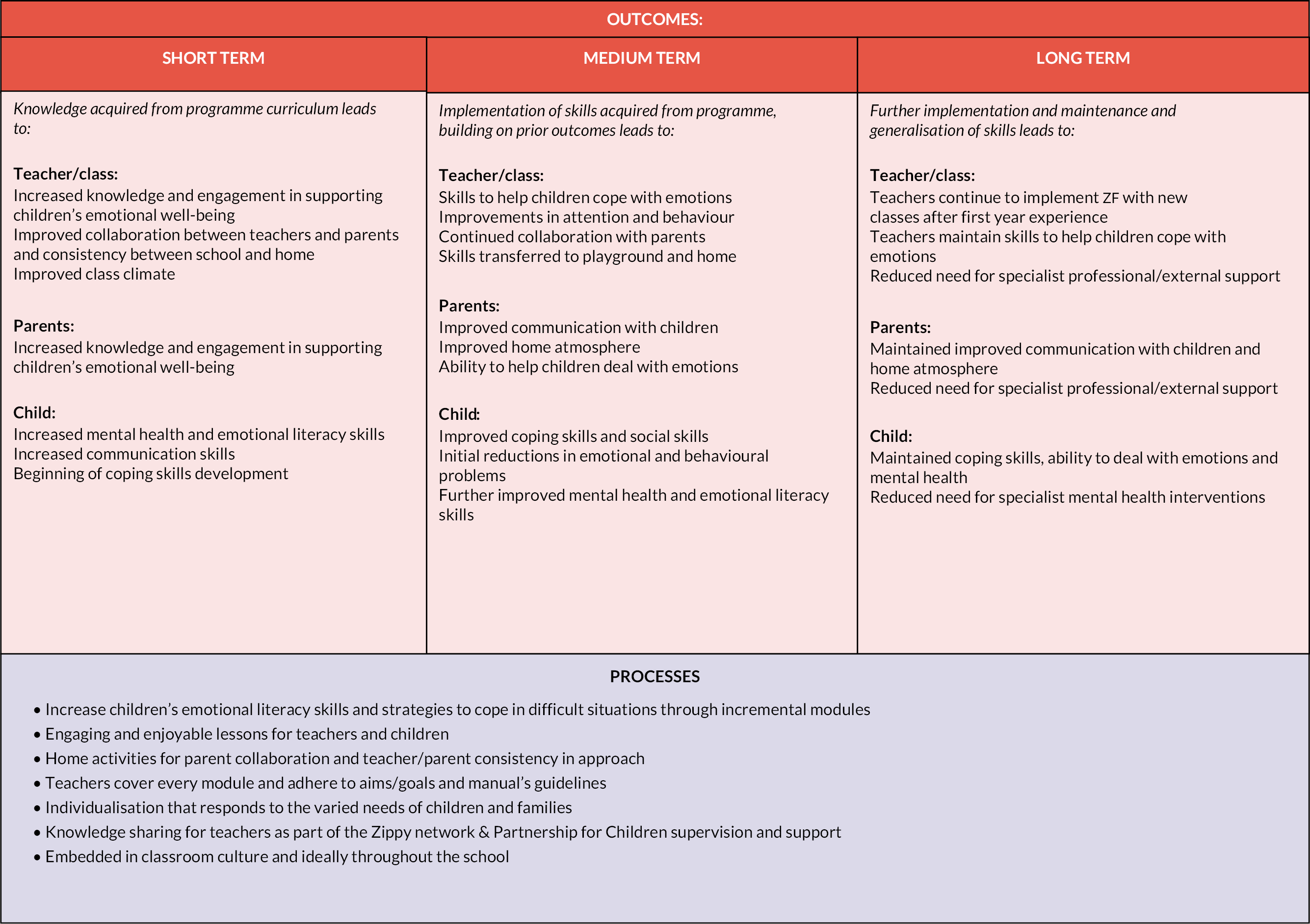

The SDQ27 total difficulties score as reported by teachers and parents/carers was anticipated as the primary outcome for a future trial. The SDQ total difficulties score includes 20 behavioural and emotional problems items (5 each for hyperactivity, conduct problems, emotional problems, peer problems). The SDQ is a mental health screening questionnaire used extensively in UK child mental health settings and in research. The SDQ has also been used in research with children with a learning disability in the UK and internationally,28–31 and maintains good psychometric properties with this population including associations with psychopathology scores from the Developmental Behaviour Checklist (a measure that has four times the number of items but was developed specifically for children with a learning disability and validated against clinician-rated psychopathology judgements). Other outcomes (likely to be secondary outcome measures in a large-scale RCT) were selected based on experience in research with children with a learning disability, brevity but with good psychometric properties and match to the key domains of the logic model (see Appendix 1). To inform the design of a future trial, secondary analyses compared the outcomes of each of the secondary measurements from baseline to follow-up between the study arms.

Patient and public involvement

The study had a robust programme of patient and public involvement (PPI) built in. The aim was to gain advice from PPI partners (including teachers and parents of children with a learning disability) in the design and delivery of the study. As the study was carried out during the COVID-19 pandemic, PPI advice was essential to help us understand the pressures on teachers and parents and then plan the study processes accordingly.

Chapter 3 The intervention

Partnership for Children

Zippy's Friends for Special Educational Needs and Disabilities is provided by Partnership for Children, a charitable organisation based in the UK that works in schools and internationally, and trains teachers to promote mental health in children. The ZF and ZF-SEND programmes were developed jointly by Partnership for Children and academics and educational resources specialists. ZF has been implemented around the world since 1998, currently in over 30 countries. To date, the programme has been offered to over 1.6 million children.

The Zippy’s Friends programme

Zippy’s Friends is a manual-based, classroom programme that aims to develop children’s emotional literacy through improving children’s repertoire of coping skills and their ability to adapt those coping skills to various situations. ZF consists of six modules: feelings, communication, making and breaking relationships, conflict resolution, dealing with change and loss and coping.

The ZF programme uses a problem-solving (as opposed to a rule-bound) approach and teaches children to develop different ways of dealing with social and emotional problems and to self-evaluate. The manual comprises session plans and activities. Each session begins with a story about a group of children to introduce a number of situations and concepts relevant to emotional literacy. These situations and concepts are then explained and consolidated by means of a range of exercises. By hearing how the children in the ZF stories cope with interpersonal problems and with their emotions, and by roleplays and other activities, children are taught to choose effective coping strategies and deal with real-life situations. There is evidence that the ZF programme has a number of beneficial outcomes relevant to mental health,19–24 quality of life and relationships, and that mainstream pupils generally like to participate in ZF activities. 20

In mainstream schools, teachers and teaching assistants deliver the programme during routine classroom time over a 24-week period with 45-minute weekly sessions (four sessions per module).

The Zippy’s Friends for Special Educational Needs and Disabilities programme

While the mainstream programme is designed for children aged 5–7 years, our pilot study5 indicated that ZF-SEND, which was adapted from the original ZF programme by the charity Partnership for Children (www.partnershipforchildren.org.uk), caters best for an older age range (9–11 years) with the proviso that teachers take a flexible approach and ensure that the programme is age appropriate, yet at the same time considering levels of cognitive and emotional functioning. The ZF-SEND programme closely aligns with the mainstream programme but has additional resources and supplements developed by Partnership for Children in consultation with teachers of children with SEND to cater for children with a wide range of special needs. It provides a selection of alternative activities (approximately five for each of the mainstream activities to cater for varying levels of learning disability) and the stories have been adapted at four different ability levels and using Widgit® (Widgit Software Ltd, Warwick, UK) symbols. The activities include craft sessions, completion of worksheets, roleplays, discussion and use of metaphors. Completion of ZF-SEND takes longer than the mainstream programme owing to the increased complexity of running the programme with pupils with SEND and to allow for shorter sessions, repetition of sessions and a range of extra activities. Teachers deliver two 45-minute sessions a week to cater for this and to ensure adequate time for completion within 1 academic year. Teachers are asked to send ZF-SEND materials to parents/carers throughout the programme, to be used in the home to reinforce and generalise the principles of ZF-SEND.

In summary, the ZF-SEND programme is an adaptation of the original ZF. The main difference is that the ZF-SEND version has materials and exercises that cater for children with SEND. The content of each of the sessions remains the same as the original but the ZF-SEND programme takes longer to deliver due to shorter sessions, and the need for repetition and more activities to consolidate learning and memory.

Prior to running the ZF-SEND programme, teachers are required to attend a 1-day training course organised by Partnership for Children. Support and supervision via Partnership for Children is available to teachers throughout the six modules.

A logic model was developed (see Appendix 1) to describe the anticipated mechanisms and processes for the ZF-SEND intervention, how this translates into short- and long-term outcomes and the role of other personal, contextual or situational variables.

Programme fidelity and adherence

Programme fidelity

The following statement on fidelity for ZF-SEND was discussed and agreed by the ZF-SEND research team and Hannah Baker from Partnership for Children in October 2022 and subsequently approved by the study management group on 26 January 2023.

The ZF-SEND programme can be implemented flexibly to suit the varying needs of individual pupils and the group as a whole, in fact this is encouraged. For example, teachers can use different ‘levels’ of complexity of the story and choose if and when to the repeat the story. Teachers can also choose how many lessons and how much time is spent on a specific session plan, including the number and range of activities that are used to deliver the session content. The activities themselves can also be adapted to meet the needs of pupils. However, there is a set of minimum requirements for fidelity relevant to the structure and content of delivery that should be met. In the training, teachers are not given a set of rules on fidelity, but rather the programme materials are presented and it is stressed that there is scope for adaptation, as long as it is in line with the lesson objectives.

Essentially, delivery of the ZF-SEND programme should include:

-

Sessions structured to include an introduction followed by activities and feedback.

-

An anchor or introduction to each session is ideal, but there may be occasions, or even a general approach where teachers choose to jump straight into quick activities rather than have lengthy sessions. This would be dependent on the group’s ability to engage for a certain time period.

-

Teachers should work through the manual sequentially; in the order it is presented.

-

The stories are a key component of the intervention and should be presented within each module. Stories may not feature in every session and different levels of story can be used, as presented in ZF-SEND.

-

At least one activity should be used for each part (parts A and B) of each session. This can be selected from all the alternatives within the programme supplement manual or adapted by the teacher to suit the needs of the pupils. However, it should meet at least 50% of the core components of the activity (as identified in the teacher session records). Teachers can edit and modify the activities so long as they meet a majority (at least 50%) of these core components.

Programme adherence

For the present trial, the definition of programme adherence was based on schools’ progress through the programme, and pupils’ attendance in and engagement with the programme, as follows:

-

Completion of/progress through the programme by the school

-

Percentage of children who attend at least one session (i.e. start the intervention)

-

Percentage of children who complete all the sessions delivered by the school

-

Level of engagement of children in the programme.

Chapter 4 Methods

Trial design and setting

The design is a two-arm cluster feasibility trial of the ZF programme adapted for special schools/units (ZF-SEND), with clear progression criteria and incorporating a process evaluation.

Following recruitment, enrolment of pupils, and collection of baseline data, schools were randomised either to receive training in ZF-SEND and implement the programme plus PAU for 1 academic year or to provide PAU. Partnership for Children trained and supervised teachers delivering ZF-SEND. PAU for emotional literacy in special schools/units for children with a learning disability was established through a survey of special schools/units (including the three PAU schools/units) and a sample of teachers and members of senior leadership/teachers with management responsibilities were interviewed for this purpose.

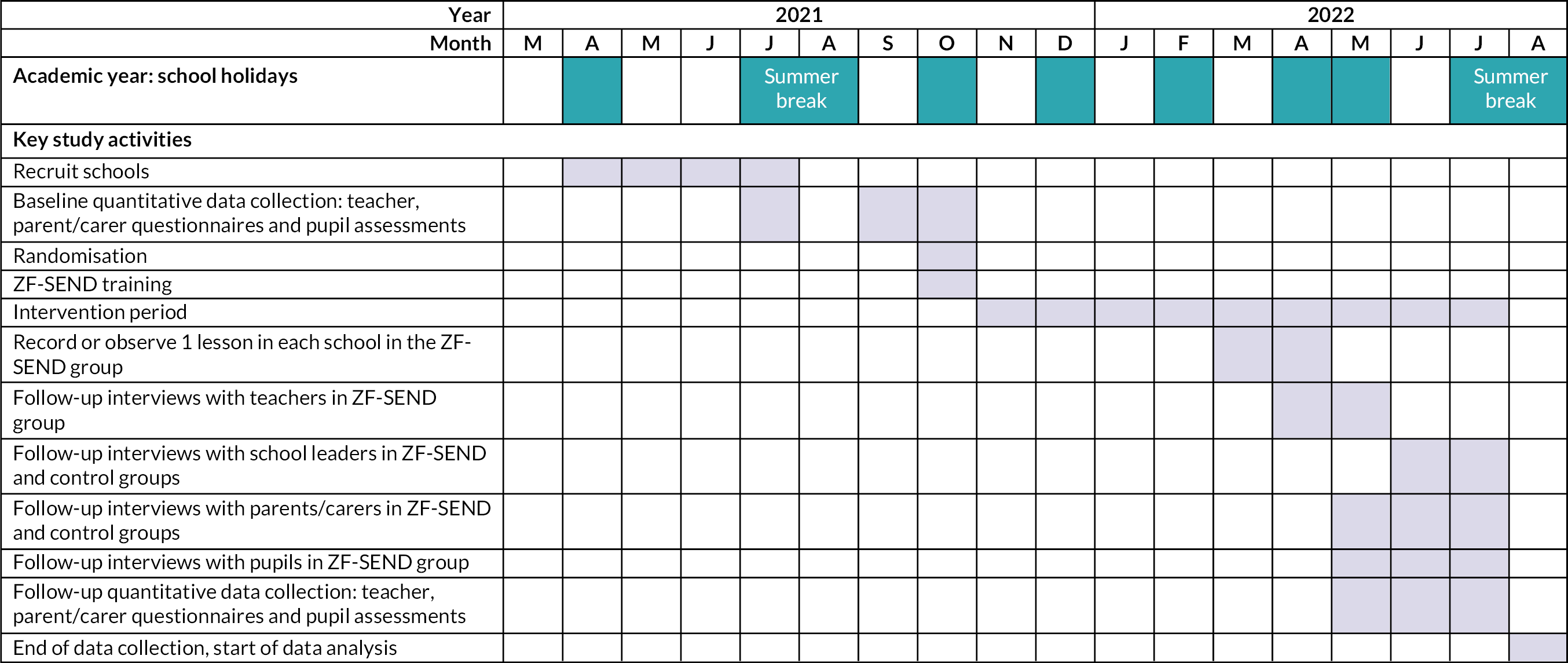

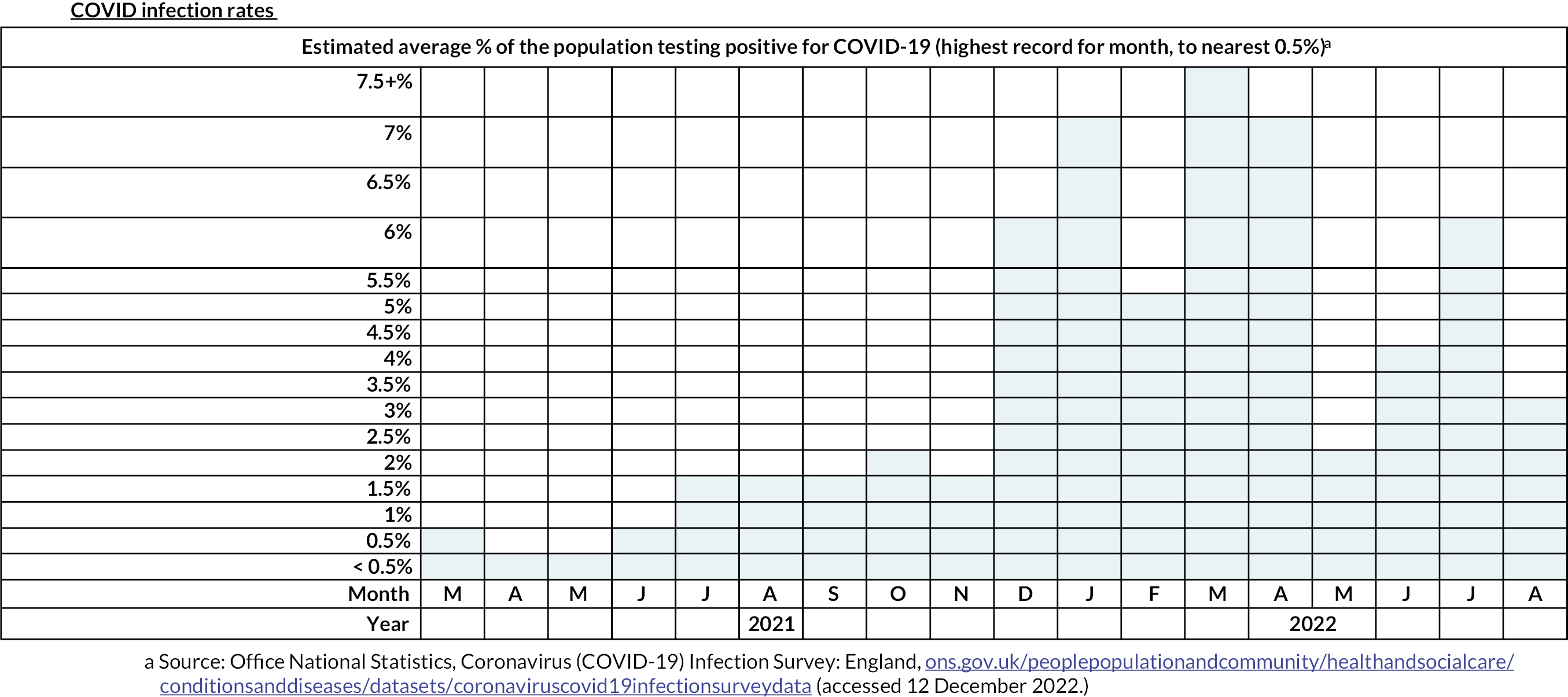

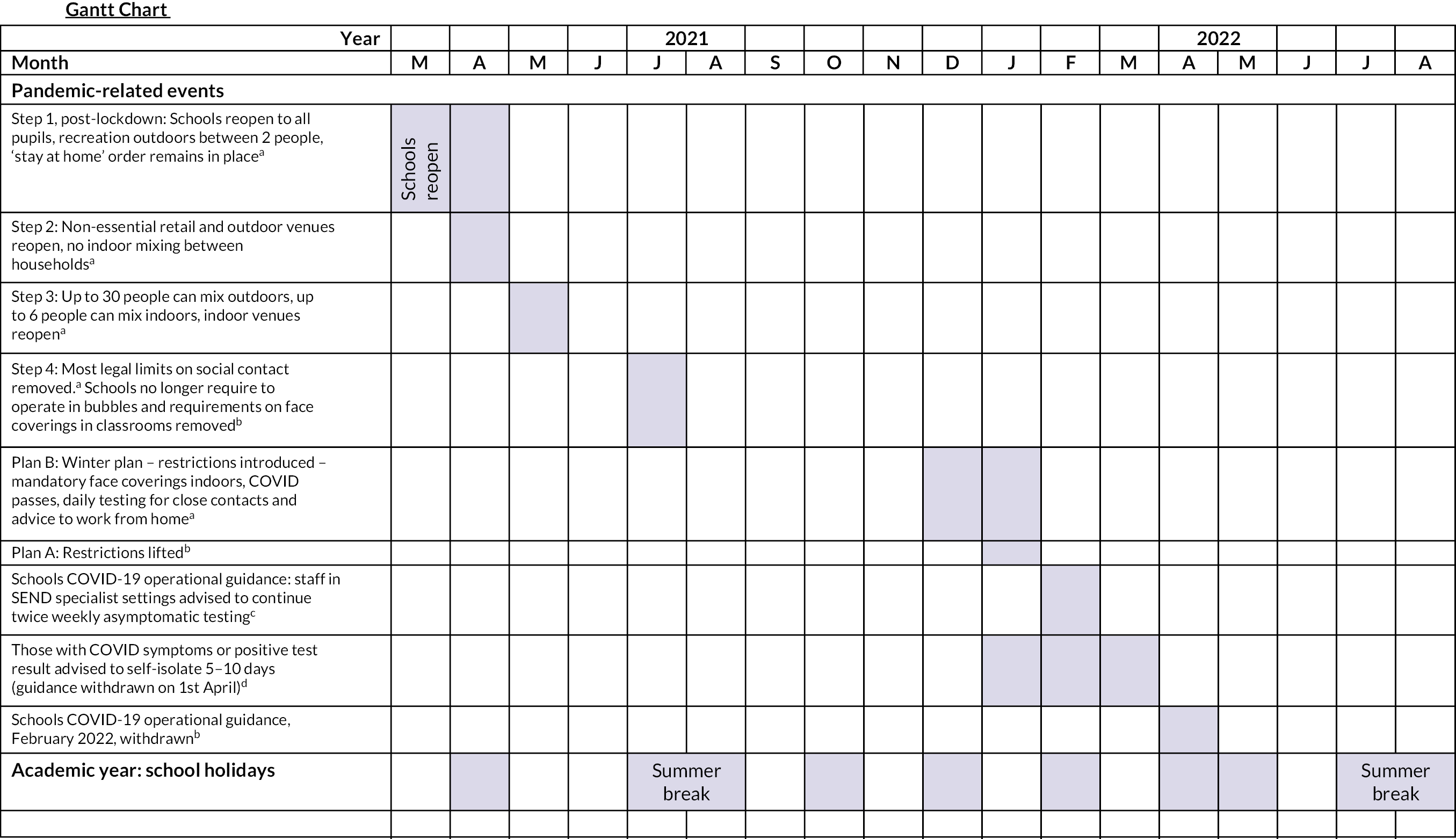

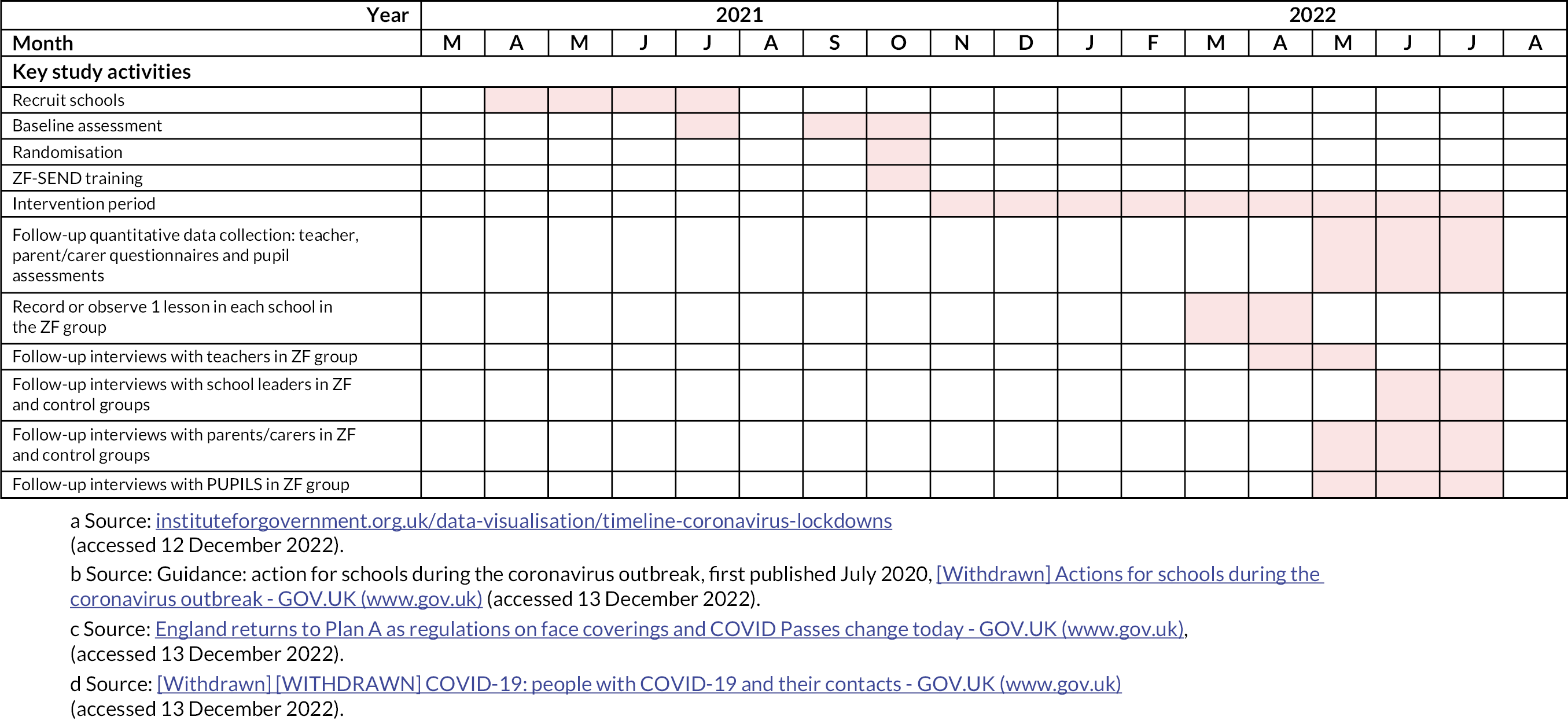

Researchers blind to allocation assessed school-related well-being by interviewing pupil participants. Teacher- and parent-reported data were collected through self-completed questionnaires. Quantitative outcome data were collected at baseline (prior to randomisation) and at 8–12 months follow-up (8–9 months post randomisation). The statisticians remained blind to allocation prior to analysis. Online randomisation used minimisation with a random element, balanced by size of school. Figure 1 provides an overview of the study timeline.

FIGURE 1.

Overview of study timeline.

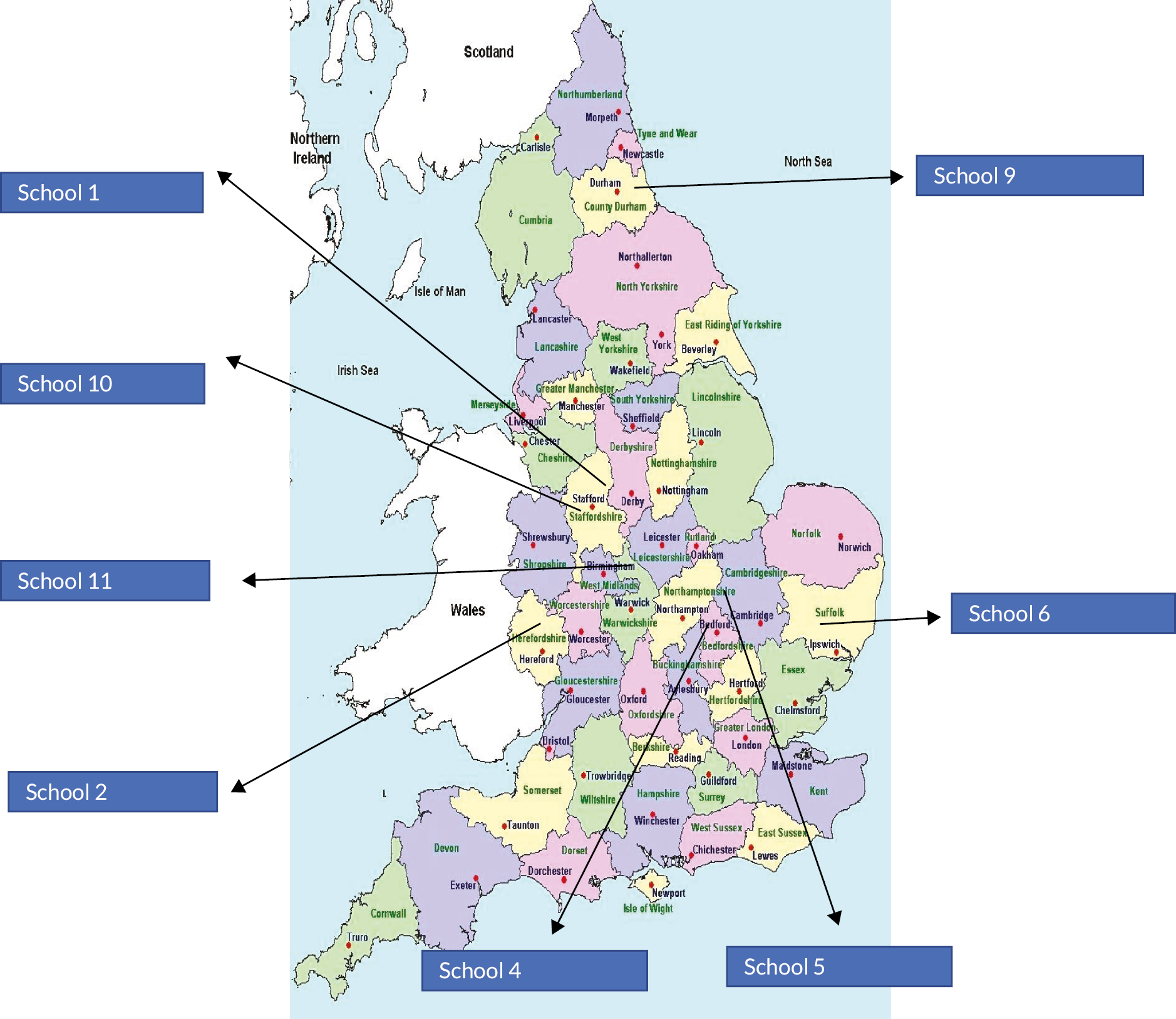

Training in ZF-SEND was provided to schools in the ZF-SEND arm after randomisation. As Partnership for Children are the only organisation providing the programme there was minimal risk of contamination between arms. Furthermore, the schools were widely spread geographically (Figure 3) and schools were not in contact with each other, further reducing any risk.

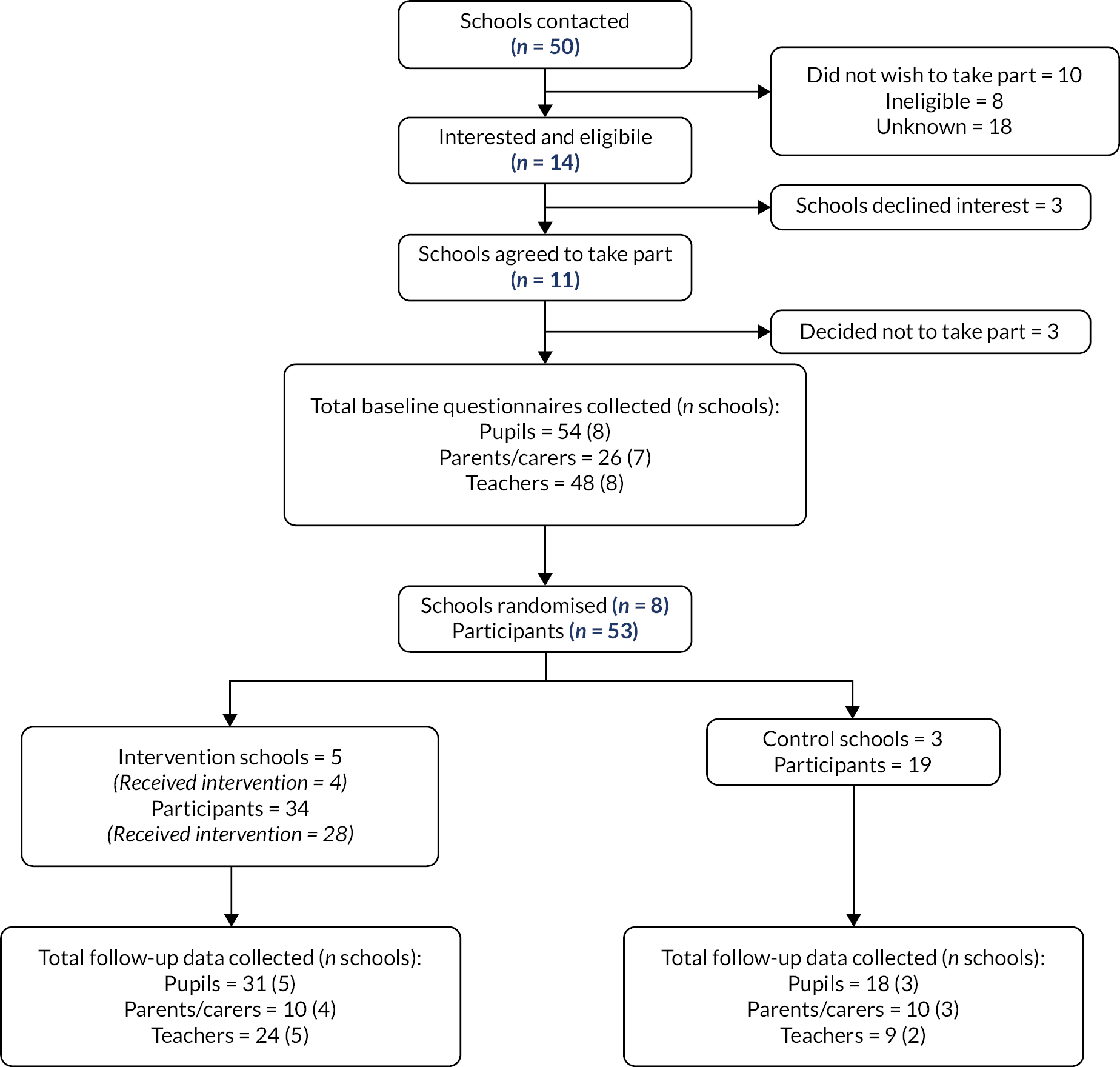

FIGURE 2.

CONSORT diagram of recruitment and data collection process.

Study within a trial

A SWAT was included to assess recruitment strategies. For the SWAT, a sampling frame of potentially eligible schools was established and the order in which they were approached was predetermined. The schools were allocated at random to receive information sheets describing a study where PAU either does or does not offer delayed access to ZF-SEND. Following the completion of data collection, all schools in the control arm were offered the programme as delivered by Partnership for Children, whether or not they received an information sheet which described delayed access.

Context for the trial

The study took place during the COVID-19 pandemic. The start of the study was delayed due to the pandemic and subsequently commenced in spring 2021, shortly after schools had reopened after the national lockdown in England at the beginning of 2021. National restrictions were in place throughout the study period and schools and the study team had to respond to changes in these restrictions and fluctuations in COVID-19 infections leading to staff and pupil absence. See Appendix 2 for an overview of the study timeline set against COVID-19 infection rates and national restrictions.

The delayed start and impact of the COVID-19 pandemic affected the anticipated timeline for the study and various study procedures, as discussed throughout this report. For example, recruitment was delayed as schools had just reopened and therefore baseline data collection was not completed before the end of the 2020–1 academic year. Baseline data collection carried over into the 2021–2 academic year and so the follow-up period reduced to 8–12 months rather than 12 months post randomisation. Delays to baseline data collection had a ‘knock on’ effect for randomisation, which was scheduled after data collection was complete, which then impacted on training for those allocated to the ZF-SEND arm of the trial. Training also had to be adapted to be delivered online because of the pandemic and Partnership for Children could only offer one session before the October half-term break. This in turn delayed the start of the ZF-SEND programme and significantly shortened the time ZF-SEND schools had left to deliver the programme, which resulted in some schools not completing the programme before follow-up data collection. Furthermore, adaptation had to be made to data collection procedures to allow remote (online) collection of data from pupils and remote (online) observations of ZF-SEND lessons.

A key aim of this report is therefore to consider the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the feasibility study. A summary of the key changes to the protocol are listed on page 28 (Figure 1).

Study setting

Special schools in England. The ZF-SEND intervention was delivered in schools by teaching staff.

Recruitment and follow-up

It was anticipated that 12 schools would be recruited in the summer term starting in April 2021 (8 from England and 4 from Scotland). From each school, a class with 6–10 children eligible to participate and their parents/carers were recruited into the study. Following baseline data collection, those schools allocated to the intervention arm delivered ZF-SEND across the 2021–2 academic year. Follow-up assessments were conducted 8–12 months after baseline data collection in June–July 2022. Data collection concluded in August 2022.

The process evaluation took place throughout the study, from the first approach to schools through to collection of follow-up data and data analysis. Interviews with class teachers and school personnel with management responsibilities were carried out at various time points throughout the follow-up period. Class teachers in the ZF-SEND arm completed session checklists throughout the delivery of the intervention. In addition, observations of ZF-SEND lessons were conducted approximately mid-programme. Data on PAU delivered in the control arm as well as at other special schools were collected at various time points during the 2021–2 academic year.

Research ethics

Prior to opening the study to recruitment, an application was made to University of Birmingham Research Ethics Committee, who reviewed and approved the study (8 March 2023, application number: ERN_20-0191). The study was conducted in accordance with the University of Birmingham’s code of practice for research. In addition, as the study was undertaken during the COVID-19 pandemic, a risk assessment was undertaken in line with the University of Birmingham’s restarting research process.

Risk assessment

A study risk assessment was undertaken prior to commencement to identify the potential hazards associated with the study and to assess the likelihood of those hazards occurring and resulting in harm. This risk assessment included:

-

the known and potential risks and benefits to participants

-

how high the risk is compared with normal standard practice

-

how the risk will be minimised/managed.

The study was categorised as a low risk, where the level of risk is comparable to the risk of usual care or practice. The study risk assessment was used to determine the intensity and focus of monitoring activity. It was therefore agreed that the study steering committee would meet every 6 months throughout the study duration.

Eligibility criteria

The study had three types of participants: pupil participants, parent/carer participants, teacher participants and senior teaching staff participants. In addition, heads of school had to consent to their school taking part in the study. Schools and participants were eligible for the study if they met all of the following inclusion criteria and none of the exclusion criteria applied.

Inclusion criteria for schools

-

Schools must have firm commitment to the research and agree to be randomly allocated to either the intervention or the usual practice arm (either delayed or no access to ZF-SEND) of the study.

-

They should have pupils with a learning disability and be able to identify two teachers who consent to taking part and who are willing to deliver the ZF-SEND intervention over 1 academic year to a group of children with learning disabilities.

-

The teachers must also be willing to complete a 1-day training session, to receive supervision from Partnership for Children and to complete the study records, be video-/audio-recorded and participate in a qualitative interview at follow-up. Where teachers consented to participate in the study but not to having ZF-SEND sessions video-recorded, alternative ways to assess fidelity were explored, for example self-report or through a member of the research team observing sessions with the head teacher’s and teacher’s consent.

-

The schools which host ZF-SEND must have the resources to support the study and must be willing to free up the teachers for training and supervision.

Exclusion criteria for schools

-

Delivering other manual-based classroom interventions designed to address mental health, well-being or emotional literacy.

Inclusion criteria for pupil participants

-

Children with a learning disability in years 5–6 (aged 9–11 years; at the top end of primary school) attending special schools. A learning disability (learning disability/difficulty in UK services terminology) was administratively defined by virtue of attending a special school/unit in England or Scotland.

-

Pupils with the cognitive and communication skills to engage in the intervention, to provide assent and to complete the pupil-completed outcome measures.

Exclusion criteria for pupil participants

-

No parental consent to participate in the research (although this would not exclude the pupil from the intervention).

-

Current child protection concerns relating to the pupil at the point of recruitment or the family are reported by the school to be in a state of current crisis (although this would not exclude the pupil from the intervention).

-

Unable to assent to the pupil-completed outcome measures or to communicate using English (and adaptations to meet their communication needs cannot be put in place in the classroom setting).

-

Specific diagnoses and any comorbid conditions were recorded but not used as a basis for inclusion/exclusion.

Inclusion criteria for parent/carer participants

-

Biological, step-parent, adoptive parent or foster carer, or adult family caregiver of pupil participants.

-

Parents/carers with ability to provide informed consent and a level of English language enabling (verbal) completion of outcome measures. Note that reading skills were not required as measures could be administered via structured telephone interview.

Exclusion criteria for parent/carer participants

-

Insufficient command of the (spoken) English language to complete the outcome measures or lacking capacity to give informed consent to take part in the research.

Recruitment

Recruitment of schools

Special schools in England and Scotland were approached to take part in the study. For schools in England, the National Association for Special Educational Needs (nasen) provided a list of 39 schools that had previously indicated that they were interested in taking part in research. For schools in Scotland, members of the research team worked with colleagues from the University of Glasgow the University of Strathclyde, and the British Institute of Learning Disabilities (BILD) to draw up an initial list of 39 potential schools. This list of Scottish schools was refined to only include schools that were eligible for the study and likely to be open to participating in research, resulting in a list of 11 schools which was passed to the research team.

Each of these 50 schools was contacted by the research team by e-mail and provided with an information sheet describing the study including the process of randomisation to intervention or a control group. For the SWAT, schools were sent, at random, one of two information sheets, which described whether or not, if allocated to the PAU group, they would have access to the intervention at the end of the study. The initial contacts were made after the spring break (i.e. late April 2021). Schools were subsequently followed up by phone call up to a maximum of four times. Initial follow-up phone calls took place between 17 May and 3 June 2021 for schools in England and 5 May and 10 May 2021 for schools in Scotland. As Scottish schools closed earlier for the summer break, they were contacted first. A log of all contacts with schools was kept to allow assessment of the feasibility of recruiting schools and the most effective recruitment pathways.

Recruitment of teachers and selection of classes

Schools interested in the study were provided with the inclusion criteria and asked to select at least one class group of pupils who would be in years 5–6 (aged 9–11 years) at the start of the 2021–2 academic year (September 2021). Teachers of these class groups were given information about the project and asked if they agreed to take part.

Recruitment of pupil participants

A member of the research team discussed the study and inclusion criteria with the selected teachers. They described the communication skills required of the pupils to participate in the study and provided some examples of tasks similar to those used in the ZF-SEND intervention and measures to check that potential pupil participants were likely to have the cognitive and communication skills required to give assent, engage with the intervention and complete the outcome measures. Schools sent out information sheets to parents/carers of all eligible, potential pupil participants, on behalf of the research team.

Teachers in the ZF-SEND group were asked to introduce the intervention to their class as a whole, even if some pupils did not meet the inclusion criteria and were therefore ineligible to participate in the study.

Recruitment of parent/carer participants

To protect potential participants’ (pupils’ and parents’) privacy, schools liaised with parents/carers on behalf of the research team. Materials were distributed using the schools’ usual communication systems including electronic ‘parent mail’ and newsletters. Where parents/carers did not receive information using routine communication systems, schools were asked to use alternative methods of communication. Schools were also asked to display information on school wide forums, for example, school bulletins, to ensure that all parents/carers of children at Key Stage 2 were informed about the trial and were provided with the opportunity to complete a ‘right to object’ form.

Parents/carers for each potential pupil participant were sent information sheets that described how their child would be involved in the study, as well as their involvement in data collection.

Recruitment of participants for interview

All class teachers involved in the study were invited to take part in an interview. A member of senior leadership or a teacher with management responsibilities from each school was also invited to take part in an interview. All parents/carers were invited to take part in an interview through the follow-up questionnaire form. In addition, class teachers were asked, via e-mail, to liaise with parents/carers and pass contact details of those interested in taking part in an interview to the research team. For pupil participants in the ZF-SEND group, class teachers were asked to select two pupils for interview based on their expressive verbal communication.

Agreement and consent

Agreement from schools

Information sheets, outlining the study, were provided to schools that expressed an interest in taking part. For the SWAT, two different information sheets were provided to schools at random: one which described a waitlist control where the school would be offered the intervention after the end of the study, should they be allocated to the control group; and one which did not make such an offer. Informed consent was provided by the head teacher of participating schools and recorded on a memorandum of understanding.

Consent from teachers

After head teachers consented to the participation of their school, class teachers were approached and provided with one of two versions of an information sheet, depending on whether they were in the waitlist control or not. Teachers provided their consent, which was recorded on a consent form. Teachers were asked to consent to receiving appropriate training, running the ZF-SEND programme, providing reports on ZF-SEND sessions and having a session observed, if allocated to the intervention group; and completing assessments and being interviewed by research staff.

Assent from pupil participants

As pupil participants were under 16 years of age, they did not provide informed consent for their participation in the research. Instead, parent/carer consent was provided (see below). Prior to the pupil taking part in the baseline and follow-up assessment, the researcher verbally explained what would be involved, using simple language, and asked if the pupil agreed to take part. This was recorded on an ‘assent form’. In addition, implicit non-assent was tested before each outcome assessment. If pupil participants showed verbal or non-verbal signs of not wanting to take part in the study, the assessment was stopped immediately. Similarly, pupil participants taking part in an interview provided verbal assent prior to interview. Pupil assent was not required to take part in the ZF-SEND programme as this was part of routine school activities.

Consent from parent/carer participants

Parents/carers were provided with information sheets via their child’s school. Information was provided on the aims of the study, the nature of data being collected, how data would be collected, confidentiality, potential benefits of the research and names and contacts for future enquiries. To ensure parents/carers received the information, schools were asked to use multiple methods of communication, such as e-mail, written information, newsletters and displays on notice boards.

Parents were provided with the opportunity to ‘opt out’ of their child taking part in the research study via an ‘opt out’ form attached to the information sheet. Parents/carers were given at least 2 weeks to opt out prior to baseline data collection. The children of parents/carers who opted out were not involved in any of the research processes (namely data collection) but did take part in any emotional literacy programmes, including the ZF-SEND programme, that were delivered in the school. Parent/carer consent for children to take part in the ZF-SEND programme was not required as the programme falls within usual curriculum and other institutional activities.

A subgroup of parents/carers was interviewed about their experiences of the study and the intervention. Prior to interview, these parents/carers were provided with an information sheet about the interview and asked for their consent, which was recorded on a consent form.

Sample size

The target sample size was 12 schools (8 in England and 4 in Scotland) with 6 randomised to each arm of the trial. Based on the pilot study, it was estimated that there would be one class/group per school and an average of eight pupils per class (and therefore eight pupils per school). Recruiting 12 schools would therefore provide a pupil sample size of 96 in total (48 per arm). As this is a feasibility study, a formal, a priori power calculation was not conducted. Instead, this feasibility study aimed to provide estimates of key parameters for a future trial. If two-thirds (66.7%) of schools approached agreed to take part (i.e. 12 of 18 approached), the 95% confidence interval (CI) around the percentage was estimated within ± 21.8% (i.e. 44.9–88.5%). Assuming that 12-month follow-up data were obtained for 75% of children, randomising 96 allowed the 95% CI for retention, to be estimated within ± 8.7%.

Randomisation and masking

For the SWAT, a sampling frame of 50 potentially eligible schools was established. Schools were then allocated at random to information sheets describing a study where PAU either does or does not offer delayed access to ZF-SEND. This randomisation process was carried out by the lead statistician using random permuted blocks with varying block sizes (two and four). Schools were stratified by region (England/Scotland), whether the schools was part of a mainstream school or a standalone special school and school size (< 100 pupils, 100 + pupils).

Following recruitment, enrolment of pupils and baseline data collection, schools were similarly randomised to ZF-SEND or PAU using random permuted blocks. Block sizes were fixed at two, owing to the large number of strata and small overall sample size. Schools were similarly stratified by region, type of school and school size. Randomisation was carried out by a member of staff who was not involved in recruitment or data collection. A member of the research team then informed the schools of their allocation via e-mail.

In the majority of cases, baseline assessments were carried out prior to randomisation, and this was the aim. However, owing to time pressures, randomisation was carried out on some schools before all parent/carer and teacher data were returned. However, the risk of bias was deemed to be low in these circumstances as individual class teachers were not informed of their allocation until after they had completed the baseline assessments and completion of these assessments was not administered by a member of the research team, instead, teachers completed the assessments independently. The same applies for parent/carer assessments.

Pupil assessments were administered by a member of the research team, and these were all completed prior to randomisation. At follow-up, a new member of the research team, who was masked to allocation, administered the pupil assessments and a record was kept of any unmasking.

Withdrawal/changes to participation and loss to follow-up

Withdrawal/changes to participation

Participants (pupil, parent/carer, teacher, senior staff) had the right to withdraw consent for participation in any aspect of the study (except pupil participation in the ZF-SEND programme) at any time, up to the end of follow-up and data collection (August 2021). Participants could withdraw from further data collection with or without permission to use the data already collected. Teacher participants in the ZF-SEND arm could also withdraw from providing the programme and schools could withdraw their involvement in the study. In the case of the latter, contact with parents/carers and pupil participants would also cease as all contacts were made through schools.

While no explicit option for withdrawal from the ZF-SEND intervention was provided to pupils and their parent/carers, teachers were encouraged to follow the same principles as they would for routine lessons. They therefore responded to pupils’ preferences, made accommodations and allowances and, if indicated, allowed pupils to not take part in a lesson or the whole programme.

Attrition

A record of participants lost to follow-up was kept, along with reasons for dropping out of the study.

Experimental intervention: Zippy’s Friends for Special Educational Needs and Disabilities

Those in classes allocated to the intervention arm received the ZF-SEND programme in the 2021–2 academic year. Class teachers were provided with training in ZF-SEND through a 2-hour remote training session, delivered by Partnership for Children in October–November 2021. The session was recorded so that those who were unable to attend could watch the recording. Four teachers from three schools attended the remote session. An additional two teachers from two schools watched the video. These plans were adapted due to the COVID-19 pandemic, as limiting non-essential in-person contact was still preferred by many. The aim was to provide training to at least two teachers from each ZF-SEND class; however, owing to time constraints and capacity of schools to release staff, this was only possible for one class. Follow-up interviews with class teachers in the ZF-SEND arm examined the perceived quality and value of the training. The trainer was also interviewed to explore their experience of delivering the training and the extent to which it was delivered as intended.

Zippy's Friends for Special Educational Needs and Disabilities classes started the intervention between 15 November 2021 and 15 January 2022. It was recommended that schools deliver the ZF-SEND programme at least twice weekly throughout the academic year. However, flexibility was offered in how schools arranged delivery. Schools were encouraged to spend as many lessons as required to work through a session plan as detailed in the manual. However, it was expected that classes would work through the session plans and modules in the specified order, using a variety of activities to explore the topic and provide opportunities for learning. Telephone supervision and support was offered by Partnership for Children on an ad hoc basis and teachers could contact Partnership for Children for advice as required.

Comparator intervention: practice as usual

Classes that were not allocated to receive ZF-SEND received PAU alone. Participants attended their usual classes as well as other services, outside school. No limitations or stipulations were placed on PAU group schools in terms of the emotional literacy initiatives they could implement in the school year. PAU may include any services (mainstream and specialised) provided to families and their children with a learning disability as a part of an education health and care plan in England or equivalent in Scotland. Any schools already delivering a manualised, lesson-based emotional literacy programmes were ineligible to participate. Because Partnership for Children is the only organisation in the UK offering training in the intervention, there was no possibility of contamination within the PAU schools during the study.

Information on PAU in emotional literacy among control schools was collected through three short interviews with one school staff per school: at the end of the winter term (6–15 December 2021) after the spring term (27 April–4 May 2022) and in the follow-up interviews (conducted 27 June–18 July 2022).

Data collection

Data were collected during recruitment, at baseline (pre-randomisation) and throughout the course of the 8- to 12-month follow-up. Baseline quantitative outcome measurement, collecting data from pupils, parents/carers and teachers, was conducted either at the end of the preceding school year (July 2021) or beginning of the new school year (September–October 2021). The same outcome measures were repeated at follow-up towards the end of the 2021–2 academic school year (June–July 2022). The process of follow-up outcome measurement started in June 2022 to allow adequate time for teachers to respond, making allowances for the last few weeks of the school year, which are often off timetable and include special activities and trips.

Measures completed by teachers and parents/carers were self-completed via online or paper questionnaire. Parents/carers were also offered the option to complete via a structured interview over the telephone. Pupil measures were conducted through structured interview by a member of the research team who remained masked to allocation. They were face to face or remote, during school time. Teachers or teaching assistants were available to support the pupil, if required; however, this support was limited to helping the pupil feel comfortable rather than being involved in conducting the assessment. Observational notes were made by the researcher to allow an evaluation of this element of data collection, including the feasibility of conducting remote assessments in this way.

To monitor delivery of the ZF-SEND programme, data were collected throughout the school year through a specially designed session checklist, completed by class teachers. In addition, observations of one ZF-SEND lesson in each ZF-SEND school were made around halfway through the school year.

Qualitative interviews were conducted during the summer term, from April 2022 until the end of the school year. Interviews with teachers from ZF-SEND schools were conducted from the start of the summer term to minimise the competing demands we placed on teachers in these schools as they were also involved in intervention delivery and follow-up outcome assessment. Teachers, members of senior management teams or school staff with managerial roles, parents/carers and pupils from ZF-SEND schools were interviewed about their experience of taking part in the research and, if relevant, the ZF-SEND programme. In addition, a series of interviews with schools involved in the trial as well as other special schools explored PAU in terms of emotional literacy initiatives implemented in schools.

Secondary outcome measures

Questionnaires were completed at baseline and follow-up by the teacher, the parents/carers, and the pupils. Teachers were asked to complete the SDQ, the Emotional Literacy Assessment (ELA), and the Nisonger Child Behaviour Rating form (NCBR); parents/carers were asked to complete SDQ, ELA, the child-friendly EQ-5D version (EQ-5D-Y-3L; Euroqol, Rotterdam, Netherlands), the Child Health Utility instrument (CHU), and the Child and Adolescent Service Use Schedule (CASUS); and pupils were asked to complete EQ-5D-Y, CHU, and the MAMS questionnaire.

Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire

The SDQ27 is a behavioural screening questionnaire aimed at 2- to 17-year-old children. The SDQ asks about 25 attributes (some positive and some negative) divided into five scales, each with five items: (1) emotional symptoms, (2) conduct problems, (3) hyperactivity/inattention, (4) peer problems and (5) prosocial behaviour. Each question has three levels: (1) not true, (2) somewhat true or (3) certainly true. Individual scores for each scale were generated by summing the items within that scale, and items 1–4 were summed to generate a total difficulties score. Therefore, the individual scores could range from 0 to 10, whereas the total difficulties score could range from 0 to 40, where higher scores indicate more problems for all subscales, except for the prosocial behaviour scale.

Emotional literacy assessment

The ELA32 is a questionnaire used to identify pupils’ level of emotional literacy and covers five scales, each with four items of emotional literacy as addressed in the social and emotional aspects of learning curriculum. These scales include (1) self-awareness, (2) self-regulation, (3) motivation, (4) empathy and (5) social skills. Each question has four levels: (1) not at all true, (2) not really true, (3) somewhat true or (4) very true. Individual scores for each scale were generated by summing the items within that scale, and all items in all scales were summed to generate a total score for emotional literacy. Therefore, the individual scores could range from 4 to 16, whereas the total score could range from 20 to 80, where a higher score indicates better emotional literacy.

Nisonger Child Behaviour Rating form

The NCBR33 is a questionnaire used to assess the behaviour of children with a learning disability and covers two areas of behaviour including (1) positive social behaviour, which contains two subscales including (a) compliant/calm behaviour (five items) and (b) adaptive social behaviour (five items); and (2) problem social behaviour, which contains six subscales including (a) conduct problems (13 items), (b) insecure/anxious (15 items), (c) hyperactive (8 items), (d) self-injurious/stereotypic behaviour (9 items), (e) self-isolated/ritualistic behaviour (11 items) and (f) irritable behaviour (6 items). Each question has four levels: (1) not true, (2) somewhat or sometimes true, (3) very or often true and (4) completely or always true, scored from 0 to 4, respectively. Individual scores for each scale were summed to generate a total score within that scale which could range from 0 up to a maximum score of 60 for the insecure/anxious subscale.

Me and My School

The MAMS34 questionnaire is a self-reported measurement of social, emotional and behavioural challenges in primary school children. The questionnaire consists of two domains, including emotional difficulties and behavioural difficulties. The emotional difficulties domain consists of 10 questions, whereas the behavioural difficulties domain consists of 6 questions, each with 3 possible responses including: (1) never, (2) sometimes or (3) always. The final scores for each domain were summed to produce scores that range from 0 to 20 for the emotional difficulties domain, or 0–12 for the behavioural difficulties domain. A higher score indicates worse emotional or behavioural problems. An adaptive administration, developed for children with a learning disability was used. 35

EQ-5D-Y-3L

The child-friendly version (EQ-5D-Y-3L)36 of the EQ-5D questionnaire was designed as a measurement of quality of life and covers five questions relating to quality of life including: (1) mobility, (2) self-care, (3) usual activity, (4) pain/discomfort and (5) anxiety/depression. Each question had three levels: (1) no problems, (2) some problems or (3) a lot of problems. A total score for EQ-5D-Y-3L was generated using the EQ5D command in Stata 17® (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA), which ranges from –1 to 1, where a higher score indicates better quality of life.

Child Health Utility instrument

The CHU37 is a paediatric generic preference-based measure of health-related quality of life and consists of nine questions with five possible responses to each, scored from 1 to 5. A set of preference weights using values from a sample from the general population to give utility values for each health state described by the descriptive system, which allows the quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) for use in cost analyses. Coefficients given in previous research38 were used as decrements to calculate utility, which could range from 0.3251 (worst state) to 1 (perfect health).

Child and Adolescent Service Use Schedule

The CASUS39 questionnaire is a parent-reported measurement which reports whether a child has used any health or social services in the past 3 months and, if so, how often they have used them. The questionnaire covers whether the child has had any overnight stays in hospital, hospital appointments that did not require admission, accident and emergency visits, ambulance use, community and school health services not within a hospital setting, use of medication, additional teaching support and living away from home.

Go4Kidds Brief Adaptive Behaviour Scale

The Go4Kidds (Great Outcomes for Kids Impacted by Severe Developmental Disabilities)40 questionnaire includes three questions about a child’s adaptive skills, which includes their support needs, communication, social and self-help skills.

Follow-up interviews

Semistructured interviews were conducted with school staff (class teachers and members of senior leadership/those with managerial responsibilities), parents/carers and pupils. The interviews with school staff and parents/carers were conducted via online video calling. Interviews with pupils were either remote or face to face. All interviews were video- or audio-recorded. Topic guides were developed for each stakeholder group on each arm of the trial to address the feasibility questions. As the study was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, interviews also explored the impact of the pandemic on schools and on the conduct of the study (see Appendix 3 for the qualitative results relating to the pandemic). All interviews were transcribed by an external transcription service to allow data analysis.

Interviews were conducted with:

-

eight pupils from four ZF-ZEND schools

-

four parents/carers (two from PAU and two from ZF-SEND schools)

-

seven teachers (three from PAU and four from ZF-SEND schools)

-

four members of senior leadership or teachers with management/oversight roles (two from PAU and two from ZF-SEND schools).

Interviews with school staff

Interviews with school staff on both arms of the trial explored the acceptability of the trial design including recruitment, randomisation and data collection methods. The aim was to interview one class teacher and one member of senior management/teacher with management responsibilities from each school. Follow-up interviews with school staff in the ZF-SEND arm also explored: adherence to the ZF-SEND manual and key influences on implementation; any additions/adaptations made to the manualised content and the reasons for these; attendance and engagement in the intervention by pupils and their parents/carers; the perceived value of ZF-SEND, and its fit with existing school policies/priorities; staff views on intervention aims and the mechanisms through which it operates; and the perceived quality and value of the training.

Interviews with parents/carers

Interviews with parents/carers explored factors affecting recruitment and retention, experiences of being involved in the study and acceptability and feasibility of the outcome measures. In addition, interviews with parents/carers in the ZF-SEND arm also explored the extent to which intervention content was used or discussed at home, and the extent to which schools have involved them in the intervention. The aim was to interview two parents/carers from each of the ZF-SEND schools and one parent/carer from PAU schools. Interviews could be single or joint if two parents/carers wanted to participate together.

Interviews with pupils

Interviews with pupils from ZF-SEND schools explored their experiences of participating in the intervention, acceptability of intervention content and activities, understanding of key intervention messages and the extent to which they used strategies taught. The aim was to interview two pupils from each of the ZF-SEND schools.

Session checklists

To monitor implementation of the ZF-SEND programme and to evaluate adherence and fidelity (see definition in Statistical analysis: primary statistical analysis), class teachers who were responsible for delivery of ZF-SEND were asked to complete session checklists, which were aligned to each of the session plans in the ZF-SEND programme. These checklists were developed with Partnership for Children to evaluate adherence and fidelity to the programme as well as pupil engagement in sessions. Items on the checklists followed the structure of the programme to ascertain the proportion of sessions that were delivered with fidelity to this structure (use of story in module, rules and review of previous sessions, introduction to session, use of activities aligned to each part of the session, and opportunity for review and feedback). Further items explored fidelity of the programme implementation in relation to the key features/processes of the introduction, rules and review, activities and feedback for each session. They also provided information on attendance at each lesson in line with our assessment of adherence. Pupil engagement in each session was assessed by means of four items tailored to the specific session activities (rated as none, some or all pupils engaged). The session checklists were developed to allow analysis that would produce quantitative measures of fidelity, adherence and pupil engagement.

The session checklists were organised into module booklets comprising checklists for each session in the module. These were e-mailed to teachers at appropriate intervals, depending on their progress through the programme. Teachers were asked to complete the checklist as soon as possible after delivery of the session and to return, via e-mail, the completed booklet after each module. As teachers were given flexibility in how many lessons they used to deliver each session plan, the checklists were completed per session rather than per lesson; however, a record was made to capture how many lessons were used for each session. The checklists were designed to be simple and quick to complete, requiring only tick box responses, but with space at the end for teachers to record qualitative observations.

Observations of Zippy’s Friends for Special Educational Needs and Disabilities sessions

Observations were made of one ZF-SEND lesson at each school assigned to the ZF-SEND arm of the trial. Observations took place between 8 March and 29 April 2021. This timing was selected so that schools would be approximately mid programme. Observations were coded initially by two members of the research team (BSK and MS) using a specially prepared checklist and the session checklist corresponding to the session being taught in the lesson. After the first observation, comparisons were made to check interrater agreement. The remaining observations were carried out independently by one researcher (MS).

Observations could be made in one of three formats: direct (live) observation in person, direct (live) observation via remote video call, or through a video recording of the lesson. Increased flexibility was offered in response to the COVID-19 context as some schools were still limiting non-essential, in-person contact/access to school grounds. The observation checklist covered aspects of fidelity including quality of delivery, adaptations made to the materials during delivery, class dynamics, and contextual issues, with space for free-text qualitative observations in relation to lesson delivery, pupil response and environment and context. Rates of agreement to allow observation and the preferred format were recorded to inform the procedures for assessing fidelity within a future large-scale trial. Analysis of the observation notes was undertaken to produce a qualitative understanding of feasibility of implementing ZF-SEND.

Practice as usual interviews

To establish what is currently delivered as PAU for emotional literacy in special schools, a survey of special schools/units (including the control schools) was conducted through short semistructured interviews. A representative from each PAU school was interviewed at the end of each term over the academic year about the emotional literacy initiatives at their school. In addition, special schools known to the research team were also interviewed at one time point about the emotional literacy initiatives in their schools. The follow-up interviews with parents/carers also posed questions about any home-based initiatives to address emotional literacy. The interviewer recorded responses in the form of handwritten notes which were promptly typed up to provide a summary of the interview and a list of all the emotional literacy initiatives mentioned. These interviews provided detailed information about the comparator condition, including any overlap with the experimental intervention, as well as an insight into the emotional literacy initiatives generally in use in special schools.

Statistical analysis

Primary statistical analysis

The primary outcome was to determine the feasibility of conducting a future large-scale RCT to establish the impact of ZF-SEND on mental health, behaviours/emotional/social functioning and quality of life, and its cost-effectiveness (economic evaluation). This included analyses of recruitment rates, retention rates, adherence and fidelity.

Recruitment and retention rates were represented using a Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) diagram to demonstrate figures overall and by trial arm, including schools contacted, eligible and recruited.

Adherence (attendance) data was summarised by the percentage of sessions in which at least ‘some’ pupils engaged in at least 50% of the core activities of that session; the percentage of children who attended at least one session (i.e. they started the intervention); percentage of children who completed all of the sessions that were delivered (and rated) by the school; and the average number and range of sessions that were completed by the children, difference between schools, and patterns of completion and engagement over time. Where relevant, proportions are presented alongside two-sided 95% Wilson score CIs. 41

Fidelity of the implementation of the ZF-SEND programme was described using the percentage of ZF-SEND sessions that were delivered with fidelity to the manual, as assessed by teachers (self-rated) on the session checklists. ‘Fidelity’ for these analyses was based on the agreed definition outlined in Chapter 3 and was operationalised as a session meeting the following criteria:

-

session was introduced

-

session included at least two different activities

-

at least some pupils engaged in at least 50% of the core elements of the session.

Secondary analysis

Secondary analyses provided baseline demographics for teachers (who completed the form, how long the teacher has known the pupil, what school year the pupil was in, what the pupil’s primary and secondary needs were and whether the child was eligible to free school meals) and parents/carers (age of the pupil; gender of the pupil; ethnicity of the pupil; the pupil’s current living situation; what the pupil’s primary need was; and whether the pupil had any genetic syndrome, epilepsy or sensory impairments).

Individual measurements and final indices at baseline and follow-up were presented for EQ-5D-Y-3L (as answered by the pupils and parents/carers), SDQ (as answered by the teachers and parents/carers), MAMS (as answered by the pupils), ELA (as answered by the teachers and parents/carers), CHU (as answered by the pupils and parents/carers), NCBR (as answered by the teachers), CASUS (as answered by the parents/carers) and Go4Kidds (as answered by the teachers). Two-level analyses of covariance were performed to compare the outcomes of each of the secondary measurements from baseline to follow-up between the trial arms. It was planned that models were adjusted by balancing factors at randomisation including school size (fewer than 100 pupils compared with 100 or more pupils) and study site. However, all schools recruited were based in England and so the models were only adjusted by school size.

Qualitative analysis