Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as award number NIHR128607. The contractual start date was in July 2020. The draft manuscript began editorial review in September 2022 and was accepted for publication in August 2023. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Blanchard et al. This work was produced by Blanchard et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Blanchard et al.

Chapter 1 Background

Description of the problem

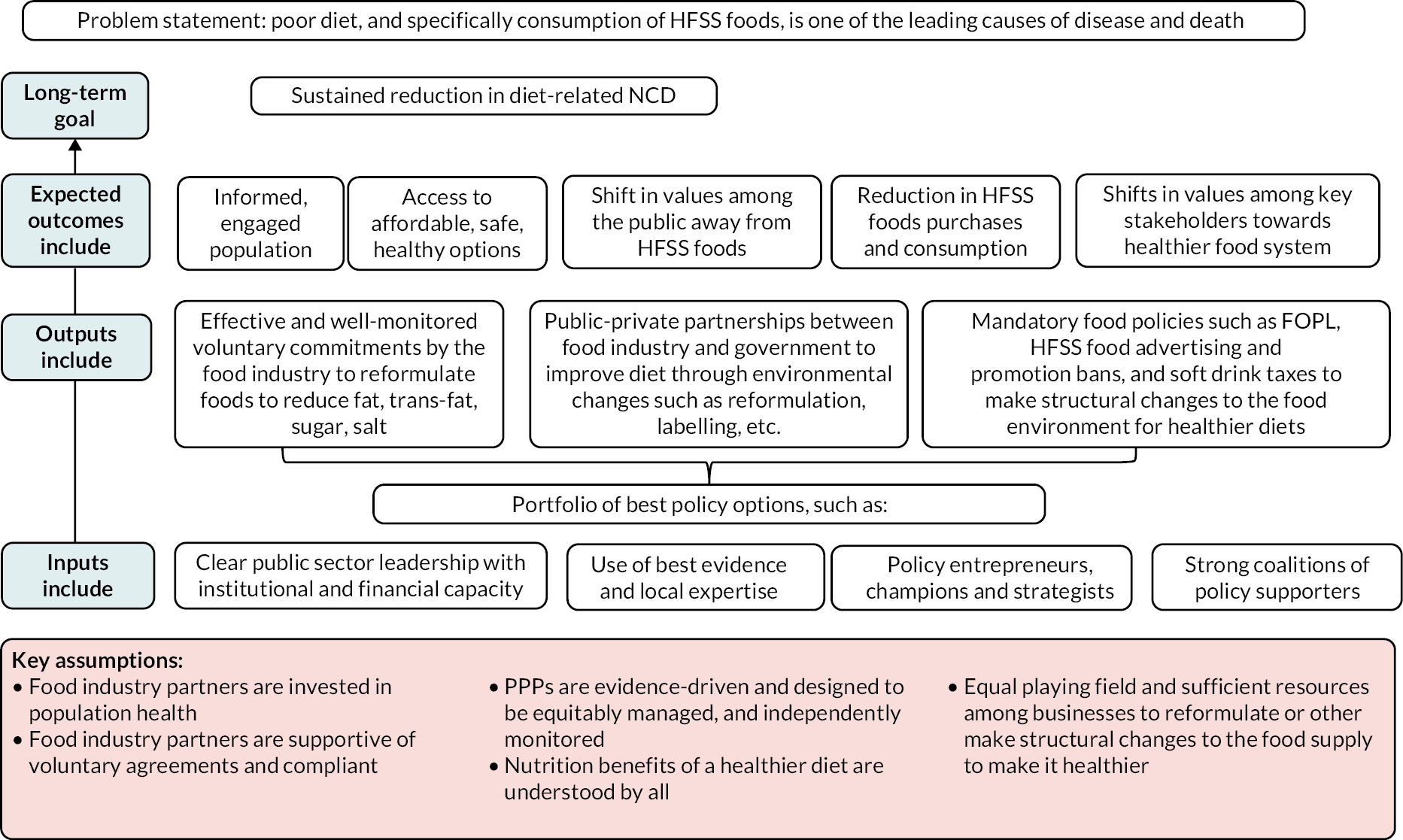

This study synthesises the evidence on effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of population interventions to improve diet, as well as understanding policy processes, with a view to informing the most effective responses to unhealthy diets in England. This report details the systematic review of different types (regulatory, voluntary or partnerships) of population interventions to improve diet, and examines effectiveness, cost-effectiveness, and a range of factors influencing effectiveness.

It is difficult to overstate the role that unhealthy diet plays in human ill health, made worse by a strong social gradient in access to healthy foods and in diet-related diseases. 1 Poor diet is now estimated to be responsible for more deaths than any other risk globally. 2 This is also true for England, with diet driving the major chronic diseases currently faced by the population, estimated to be the largest contributor to overall disease and to have the highest impact on the NHS budget. 3,4 Obesity continues to be one of the most challenging long-term population health problems across England, experienced by both adults and children,5,6 and felt more acutely in areas of greater deprivation. 7 Much of this is because high fat, sugar and/or salt (HFSS) foods are often inexpensive, easily accessible, highly promoted and therefore highly consumed. Most of the salt consumed by the English population is already in the foods people purchase. 8 The consumption of free sugars by adults accounts for 16–17% of their total energy intake9more than triple the 5% maximum recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO). 9,10 Intake of free sugars fails to meet the recommendations in all age groups, with unhealthy diet starting at a very young age. Children consume suboptimal fruit, vegetables and fibre and this worsens along the social gradient as with adults. 9 Poor diet during preschool years has been associated with poorer school attainment, and both dietary patterns and diet-related disease have been shown to track from childhood into adulthood. 11

It is in this context that the English government is implementing a range of population interventions to promote diets, which aim to be health-promoting, support physical well-being, and reduce diet-related non-communicable diseases (NCDs), by reducing consumption of energy-dense, nutrient-poor foods, such as free sugars, salt, saturated and trans-fats, and increasing consumption of fruit and vegetables (FV), lean protein and other nutrient-dense foods. Several of these interventions aim to improve population diet by modifying food environments. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization, the food environment refers to food availability and physical access (proximity), economic access (affordability), the promotion, advertising and information about products and health (marketing and information), as well as food quality and safety. 12

The interventions to improve food environments include voluntary reformulation programmes to reduce ingredients like sodium and sugars in foods, alongside regulatory policies, such as the Soft Drinks Industry Levy (SDIL) implemented in 2019. Indeed, population interventions to improve diet can be broadly categorised by ‘governance’ type: (1) regulatory interventions (public regulation with no involvement of private sector actors); (2) public–private partnerships (PPPs) (public and private sector organisations collaborate in the establishment of collective initiatives to improve health) and (3) voluntary approaches (whereby the private sector designs and monitors its own standards of conduct). Though all three types of interventions have demonstrated varying degrees of effectiveness and therefore potential, there are also risks and challenges to all, with studies indicating that they are not yet optimally designed and/or implemented to meet public health goals. 13,14 The authors’ earlier work indicates that a population intervention to improve diet will be most successful if underpinned by clear accountability, monitoring and evaluation processes, as well as a stated public health objective and sufficient political will to sustain it in the face of resistance. Voluntary commitments and PPPs often lack in accountability and oversight mechanisms; moreover, they often do not include the most effective interventions, or well-defined, evidence-based, quantitative targets, which push partners to go beyond ‘business as usual’ and require them to demonstrate progress against the targets, nor do they sufficiently involve the public in the development and monitoring of the interventions. 15

Thus, this evidence synthesis assesses the evidence of effectiveness of such population interventions with a view to informing more effective responses to unhealthy diet in England, and with lessons and implications for the wider world. We reviewed the different types (mandatory, voluntary or partnerships) of population interventions to improve diet, and examine implementation, effectiveness, and cost-effectiveness, and factors influencing effectiveness.

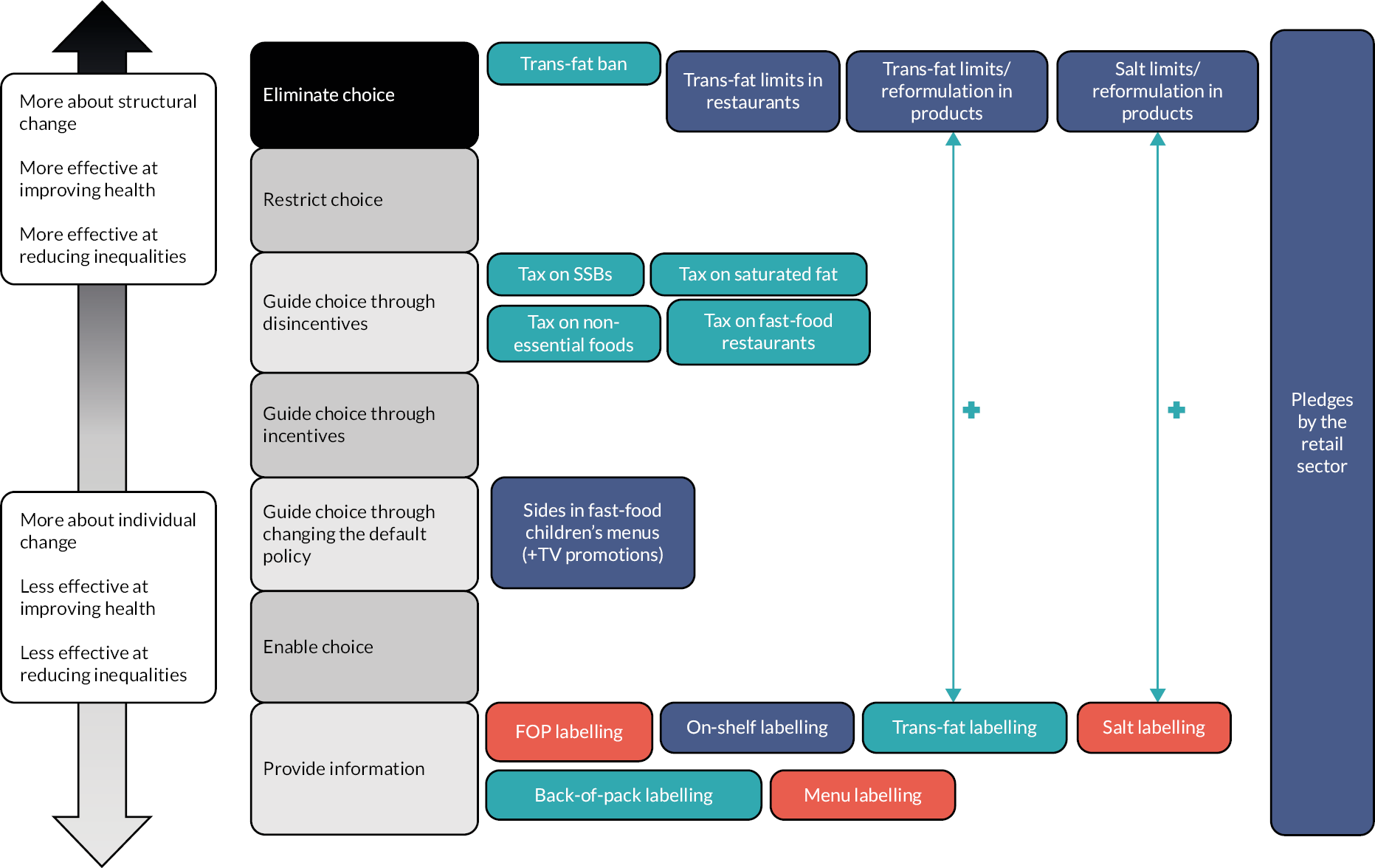

Description of the intervention

Over the past decade, the effectiveness of a range of population interventions to improve diet has been evaluated. Those with most long-term promise are those targeting upstream determinants of poor health, aiming to improve conditions and opportunities, so that the majority of the population can eat healthily. Population interventions can be driven by different types of actors and designed in various ways, ranging from regulatory interventions (where action is required by government and regulated by public authorities), to PPPs (collaborative efforts primarily between private industry and government actors but also including other actors), to voluntary approaches (which are industry-led and without involvement from the public sector). This evidence synthesis will assess the effectiveness of all three types of population interventions, and here below we look at each of these in turn.

Voluntary approaches entail actions by the private sector to create and/or enforce their own initiatives or rules, with no public involvement. Voluntary approaches have been shown to be effective when monitored by arms’ length public health bodies. However, there are also risks and challenges to voluntary agreements, with studies indicating that in their current formats, voluntary agreements to improve diet are usually based on vague commitments, focused on easy but ineffective approaches (such as information sharing), and often hampered by limited monitoring and reporting, generating poor data.

Public–private partnerships Population interventions can be neither entirely regulatory nor voluntary, but with formalised agreements entailing a degree of oversight from a public body, such as a government department of health. These arrangements are most usually referred to as PPPs, involving public and private sector organisations (to varying degrees) in the establishment of collective initiatives to improve health. A PPP in health involves collective work between at least one private for-profit organisation with at least one public (not-for-profit) organisation to jointly share efforts and benefits, with a common commitment to a health outcome. PPPs can be a promising middle option between industry-led voluntary approaches, which are argued to lack sufficient oversight, and regulatory interventions, which can be effective but politically contentious. The rationale for PPPs is that health problems and their solutions should involve all key stakeholders, and that these mechanisms may be cheaper, quicker alternatives to introducing and monitoring legislation, and may help to harness the private sector’s efficiency, cost-saving and expertise to help achieve public health nutrition goals. However, the fundamental purposes of being in PPPs may diverge significantly between the public and private sectors. For public sector partners, PPPs can be a way to supplement funding for research on diet. For private sector partners, PPPs open opportunities to promote their brand and image, and present themselves as legitimate actors in the policy-making processes. While PPPs have had some success in other fields, particularly in the field of environmental policy, some evaluations have shown limited positive impact of PPPs in diet improvement.

A regulatory intervention entails public regulation with no involvement of private actors other than as observers or contributors to consultations. It is an initiative, rule or action by government in which participation is required and there is public sector enforcement. Regulatory population interventions are considered the most effective at meeting objectives but may be politically or commercially unacceptable. Regulatory attempts to reduce consumption of harmful commodities are often met with opposition from producers and marketers of those commodities, and those stakeholders have been shown to use common strategies in resisting the introduction of such upstream regulation.

Reasons for conducting this review

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first comparison of evidence of effectiveness of voluntary, regulatory and partnership approaches to improving diet. It is also the first review that attempts to synthesise evidence to help us understand the theories that underpin these different approaches, and the implementation and monitoring issues that contribute to their impact.

In 2013, we conducted a scoping review of voluntary agreements and their success criteria. The scoping review was an important start but an incomplete exercise, in that it was not a comprehensive, systematic review, and it was not specifically focused on diet. Moreover, and crucially, it only reviewed the evidence of effectiveness of voluntary agreements. Finally, the review was published in 2013, and an update of the latest literature is now warranted. 15

As noted below in the section on the size of the literature, other reviews exist on specific intervention types (e.g. voluntary agreements), and on the effectiveness of interventions to address specific aspects of the diet (e.g. comparisons between regulatory and voluntary approaches to reducing consumption of trans-fatty acids). However, we do not know of any review examining the evidence on the effectiveness of these different intervention approaches to improving diet through the same lens.

It was essential to understand how different policy instruments are meant to work in theory or practice. This evidence synthesis will lead to subcategorisations of approaches, which cut across different governance arrangements: for example, incentive-based mechanisms can be employed in mandatory or partnership arrangements, but be quite different in their construction, that is be driven by different actors and motivated by incentives of a different nature. For example, the SDIL establishes a clearly defined incentive to act (with manufacturers needing to reduce sugar in products by a certain date, at the risk of costing them a certain amount if this is not achieved); the Responsibility Deal (RD) was also an incentive-driven mechanism yet the parameters of that incentive were far less clearly outlined. Thus, we categorise interventions first in terms of governance arrangements to enable an understanding not only of impact of effectiveness, but also the implementation and monitoring issues that contribute to their impact. We believe this to be a major added value of the review. Governance is a key overlooked mechanism in these interventions and reviews of these interventions, and it is a key part of the context, which is rarely discussed. We are confident that studies identified in the systematic review will help to throw light on whether and how governance arrangements have an impact on effectiveness, by understanding what factors relating to interventions, providers, populations and settings affect implementation of such population interventions to improve diet.

Given the range of population interventions to improve diet in England, and the urgent need to resolve the disease burden related to unhealthy diet, it is now essential to understand the effectiveness of different arrangements, levels and types of involvement of the public and/or private sector in improving diet, and what we can learn from the literature about how these could be made more effective at improving diet in England.

Research aims and questions

Aims

To search systematically for, appraise the quality of and synthesise evidence on the effectiveness, cost-effectiveness and policy process of population interventions to improve diet, including regulatory interventions, voluntary approaches and PPPs, and to share the evidence synthesis, and formulate recommendations to improve interventions, with stakeholders with a view to informing more effective responses to unhealthy diet in England.

Research questions

-

How are regulatory interventions, voluntary approaches and PPPs to improve diet assumed to work in theory?

-

What regulatory interventions, voluntary approaches and PPPs to improve diet, and reduce inequalities in diet improvement, have been evaluated?

-

What factors relating to interventions, providers, populations and settings affect implementation of such population interventions to improve diet?

-

Have such population interventions improved process, impact (intermediate and distal) and cost outcomes?

-

Are there any reported unanticipated effects of such population interventions?

-

What is the cost-effectiveness of such population interventions?

-

How can the findings of the evidence review be translated into recommendations for improved interventions?

Chapter 2 Overarching methods

This chapter describes the overarching study design and methods for the series of evidence syntheses, including approaches to the literature search, data extraction and analysis, and a description of the individual evidence syntheses.

Research design overview

This project consists of six distinct evidence syntheses (Table 1) of real-world evaluations of policies aiming to improve population diets by targeting the food environments, published between 2010 and 2020, all of which draw on a common systematic literature search strategy. They consisted of a systematic evidence map of primary research (see Chapter 3), an overview of reviews of the effectiveness of regulatory, voluntary and PPP approaches (see Chapter 4), two systematic reviews of the effectiveness of PPPs (see Chapter 5), and voluntary approaches by private actors (see Chapter 6), a systematic review of the cost-effectiveness of regulatory, voluntary and PPP approaches (see Chapter 7), and a qualitative review of policy process (see Chapter 8).

| Individual outputs | Relevance to research questions and objectives | Report chapter |

|---|---|---|

| Systematic evidence map of regulatory, voluntary and PPP approaches aiming to improve food environments. | Research question 2 Objectives: (1) To map global evidence reports on the breadth, purpose and extent of primary research evaluating the development, implementation, effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of regulatory, voluntary and PPP diet-related policies from both a policy and evaluation perspective; (2) To inform the next stages of the review. |

Chapter 3 |

| Overview of reviews on the effectiveness of regulatory, voluntary and PPP policies to improve food environments. | Research questions 3, 4, 5 Objective: (1) To assess the effectiveness of regulatory, voluntary and PPP diet-related policies; (2) To document how these policies may work (mechanisms of action). |

Chapter 4 |

| Systematic review on the effectiveness of PPPs to improve the food environments. | Research questions 4, 5 Objective: To compare the effectiveness of PPPs targeting the food environment. |

Chapter 5 |

| Systematic review on the effectiveness of voluntary approaches by commercial actors to improve food environments. | Research questions 4, 5 Objective: To compare the effectiveness of voluntary approaches by commercial actors to improve food environments between participants and non-participants, including compliance to the policy guidelines and effects on the food environment, dietary intake and health. |

Chapter 6 |

| Systematic review on the cost-effectiveness of policies to improve food environments. | Research questions 5, 6 Objectives: (1) To assess the cost-effectiveness of regulatory, voluntary and PPP diet-related policies; (2) To identify factors that make some interventions more cost-effective than others. |

Chapter 7 |

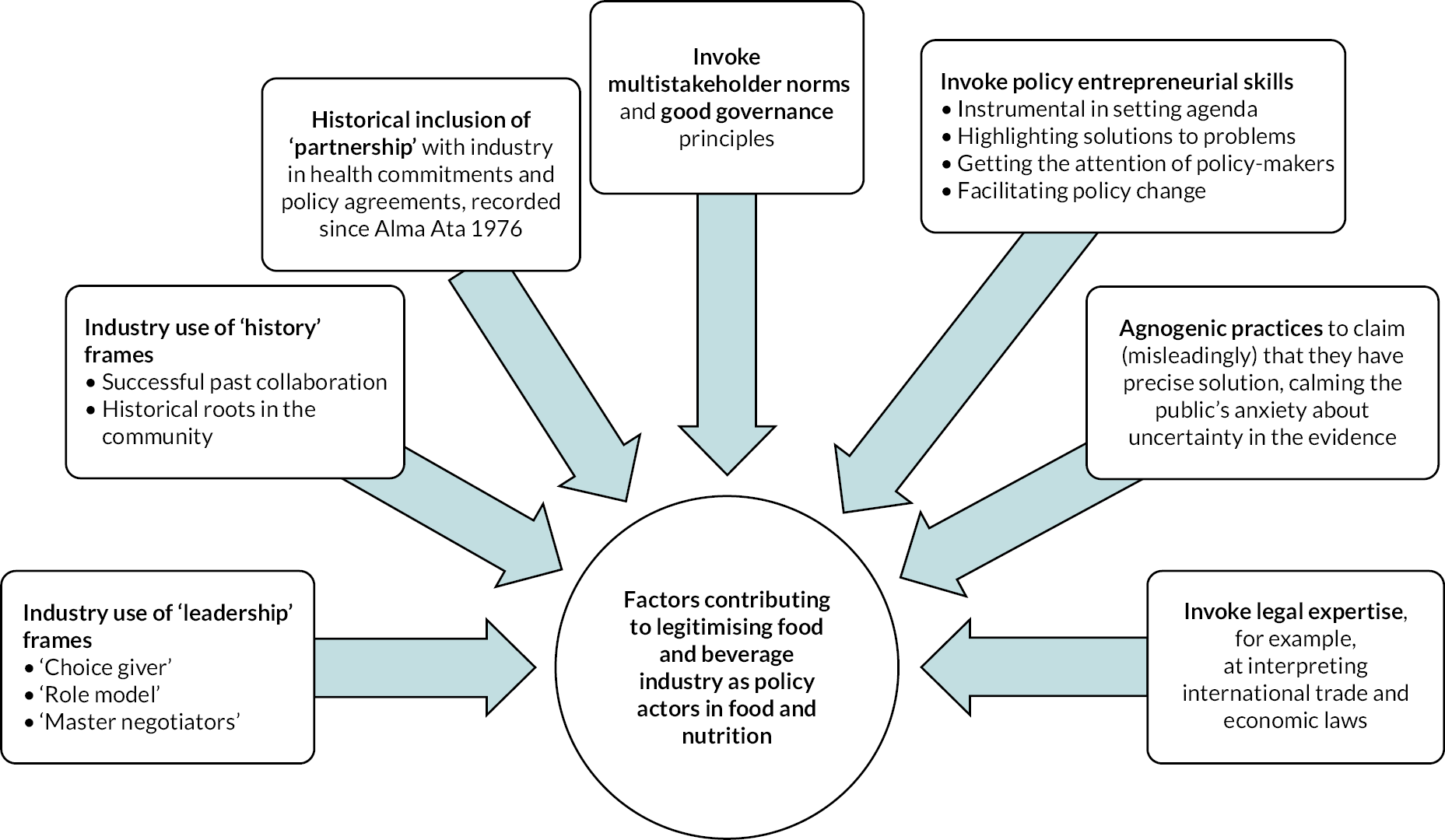

| Qualitative systematic review of policy process in regulatory, voluntary and PPP approaches to improve food environments. | Research questions 1, 3, 5 Objectives: (1) To assess factors shaping regulatory, voluntary and PPP diet-related policies, from design to implementation; (2) To advance out understanding of phenomena and mechanisms underpinning the policy process for improving diet, in particular how large food and beverage industries have become legitimate actors in policy interventions to improve diets. |

Chapter 8 |

| Discussion and conclusions. | Research question 7 Objective: To integrate the findings and propose recommendations. |

Chapter 9 |

Eligibility criteria

This series of reviews focuses on ‘real-world’ studies published between 2010 and 2020 and assessing policies promoting healthy food environments. The year of 2010 was chosen for pragmatic reasons: it allowed us to cover the most recent decade fully while limiting the number of records to deal with given the particularly wide scope of topics searched. By food environment, we refer to food availability and physical access (proximity), economic access (affordability), and the promotion, advertising and information about products and health (marketing and information) as defined by the Food and Agriculture Organization,12 with some exceptions listed in Table 2, and we did not consider food quality and safety neither as a topic nor an outcome. Policies had to target the general public, for example, those focusing on athletes, the army, workplaces and other specific groups were excluded. No restriction on language and country was applied. To be considered ‘real-world’, data had to be collected either at least once when the policy was adopted or implemented, or as part of a state or national public consultation. Experiments, simulations and projections were therefore ineligible, unless they were based on ‘real-world’ policy data. Both policies and evaluations had to be conducted at the international, national, or state level. However, assuming that the characteristics of food and drinks offered in supermarket chains or advertised on major TV channels are similar across a region or country, audits of food products, shops and TV adverts could be conducted at any level unless the evaluation specified that they focused on local independent companies or channels.

| Exclusion code | Included | Excluded |

|---|---|---|

| EX 1: Publication date | Between 2010 and 2020 | Before 2010 and after 2020 |

EX 2–3:

|

Policies that …

|

|

|

||

| EX 4: Not general population | The policies aim to improve the health of the general public, including

|

The policy only targets

|

| EX 5: Not real-life policy | Includes data collected

|

|

| Experiments, simulations and projections are included when based on ‘real-world’ policy data defined as above. |

|

|

| EX 6: Local POLICIES |

Policies implemented at the

|

|

| EX 7: Local EVALUATIONS | Evaluations conducted:

|

|

| EX 8: Not evaluation |

|

|

| EX 9: Policy mapping | Studies assessing effectiveness, cost-effectiveness, factors influencing policy development or implementation (including how a policy was covered in media), responses to public consultations. | Studies solely inventorying (‘mapping’) the presence of policies in countries or regions and/or benchmarking their implementation. |

| EX 10: Views of the general public |

|

|

| EX 11: Insufficient focus on governance |

|

Primary research and evidence syntheses of multiple policies that either have unclear governance or do not consider the governance approach in their analysis. |

| EX 12: Overviews of reviews |

|

Overview of reviews (also called umbrella reviews) and other types of evidence syntheses of literature reviews. |

| EX 13 - UK local level and views of the public |

(This was simply to group the following studies about the UK together)

|

|

| Duplicate | Documents that are not identical. | Identical documents (only keep one of them). |

In addition to primary studies, evidence syntheses other than overview of reviews (also called umbrella reviews) were included if they (1) involved a search in at least two bibliographic databases, (2) mentioned the eligibility criteria (3) clearly indicated which studies were included (e.g. in a table or with a series of references at the start of the results section or within each subsection without needing to track down each reference to recreate a full list of included studies manually). Protocols, working papers, dissertations and pre-prints were excluded. Studies and sections of studies assessing the views of the general public outside public consultations were also not considered, as well as studies solely inventorying (‘mapping’) policies or benchmarking their implementation.

Lastly, given the focus of this project on governance, primary research and evidence syntheses of multiple policies that either have unclear governance or do not consider the governance approach in their analysis were excluded. The eligibility criteria are summarised in Table 2 and detailed in Appendix 1 (see Table 24). Note that the criteria were followed in order – that is the papers had to meet criterion 1 before being assessed for criterion 2.

Search strategy

Fourteen databases were searched in November 2020: ABI/INFORM Global, Campbell Collaboration, Cochrane Library, EconLit, EMBASE, Epistemonikos, MEDLINE, PsycInfo, Science Citation Index Expanded, Social Sciences Citation Index, Arts and Humanities Citation Index, Conference Proceedings Citation Index-Science, Conference Proceedings Citation Index-Social Science and Humanities, and Emerging Sources Citation Index. Given the focus of the overarching project on policy governance approaches (i.e. whether policies are regulatory, voluntary or PPPs), the search was structured around the three following ‘blocks’ of terms using various free text and controlled vocabulary for each of them: (regulatory OR PPP OR voluntary) AND policy AND diet. Considering that some terms refer to several of these concepts at once (e.g. taxes are both a policy and generally regulatory), eight different Boolean phrases were conducted and combined at the end (see Appendix 1, Table 24). The search strategy in MEDLINE was tested on a sample of 38 publications that had been identified as potential studies in our funding application (see Appendix 1, Table 24) and was peer-reviewed by a librarian using the Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies (PRESS) statement. Additionally, we screened the publication lists on the NOURISHING database (https://policydatabase.wcrf.org/) and the Global Food Research Program websites (www.globalfoodresearchprogram.org/); as well as the reference lists of the overviews of reviews retrieved; studies in the systematic reviews of voluntary policy commitments by private actors and of cost-effectiveness, and studies in the evidence syntheses about cost-effectiveness excluded from the overview of reviews.

Data management and screening

Records were uploaded to the Evidence for Policy and Practice Information (EPPI)-Reviewer Web (EPPI-Centre, University College London, UK) for the removal of duplicates, screening, as well as part of the data extractions for the different reviews of the series. Using the eligibility criteria outlined above, a first screening was performed for the overarching project. On top of this, additional screening was performed for each review according to their additional specific eligibility criteria. Details are specified in the methods section of each review. For the overarching project, at least 12% (n = 3346) of titles and abstracts and 33% (n = 637) of eligible full texts were screened by at least two reviewers independently (SR, LB, MJVS, CK, CL). The remaining were screened by one reviewer after reaching a 90% agreement rate. The records excluded because they were ‘not a policy’ were all checked by a second reviewer since disagreements were more common for that criterion. Disagreements were discussed with a third reviewer.

Outputs of literature search

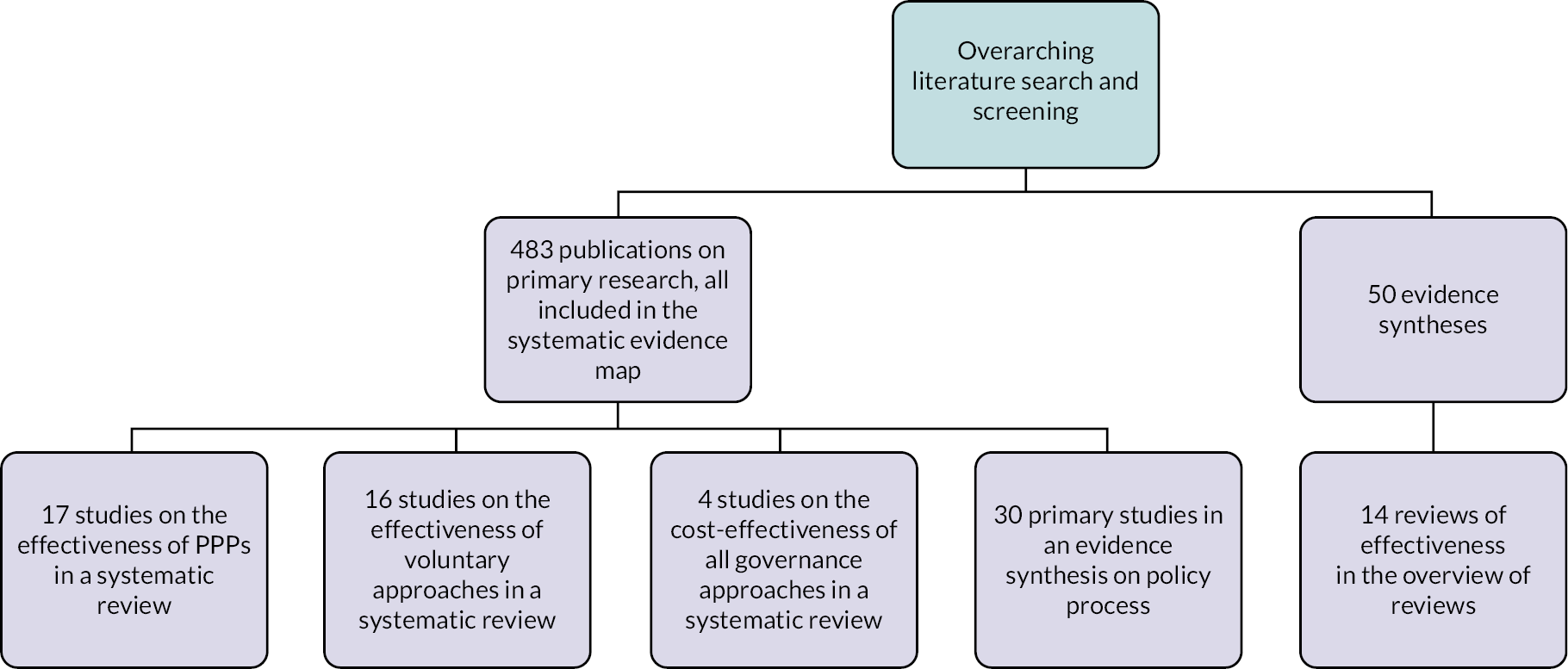

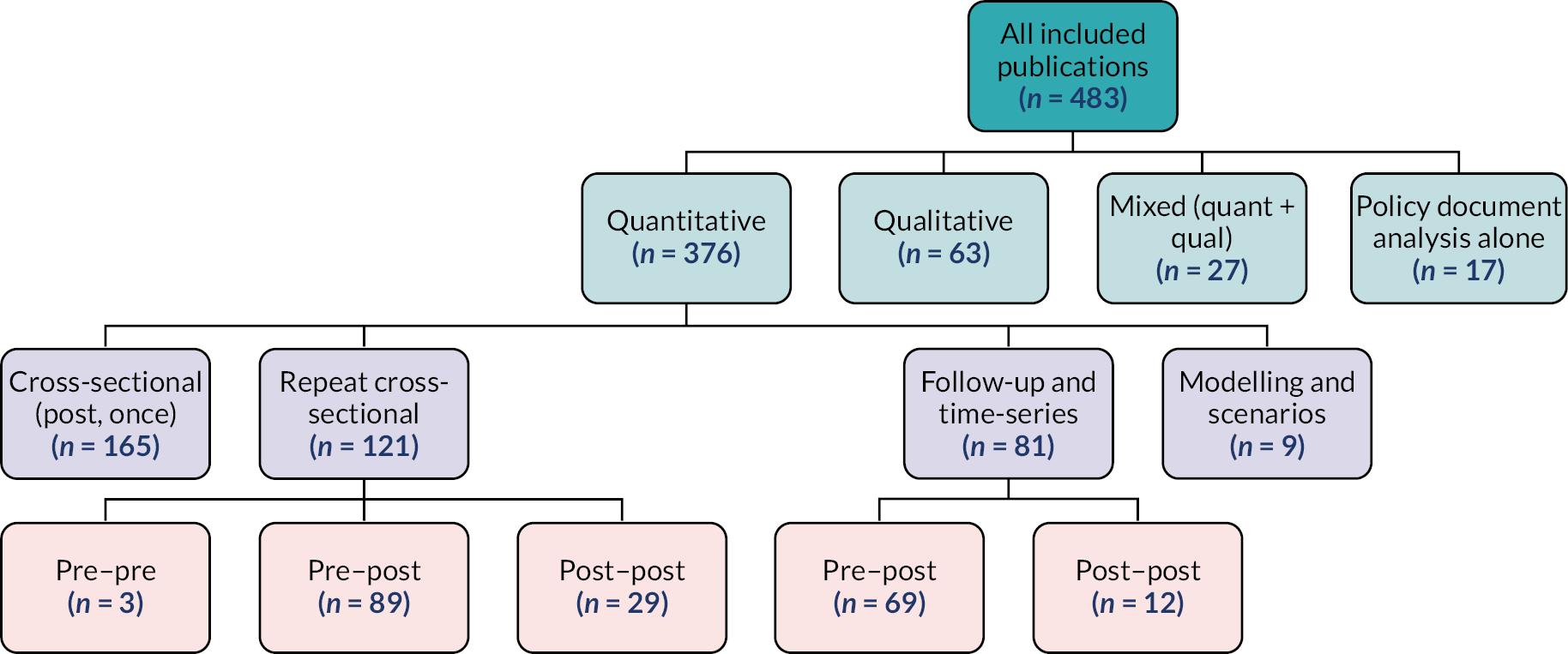

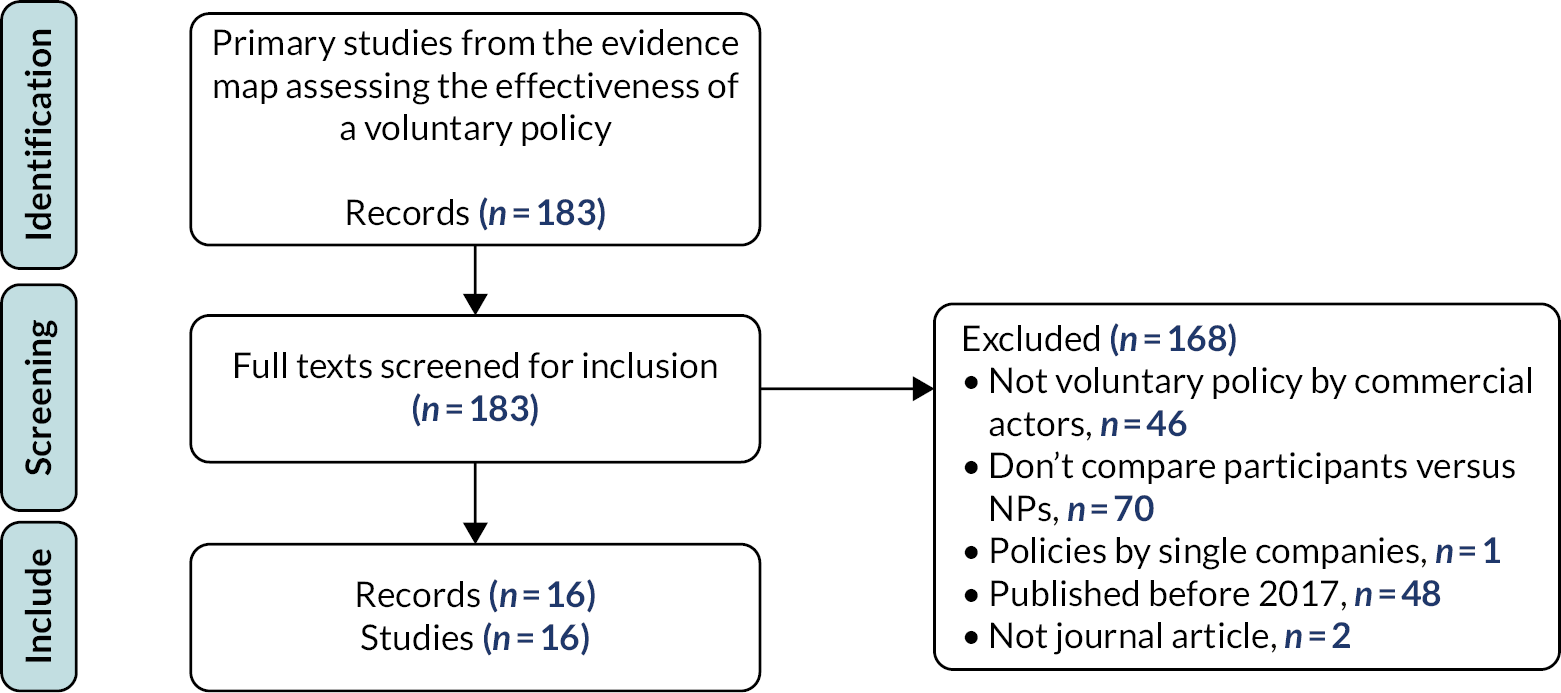

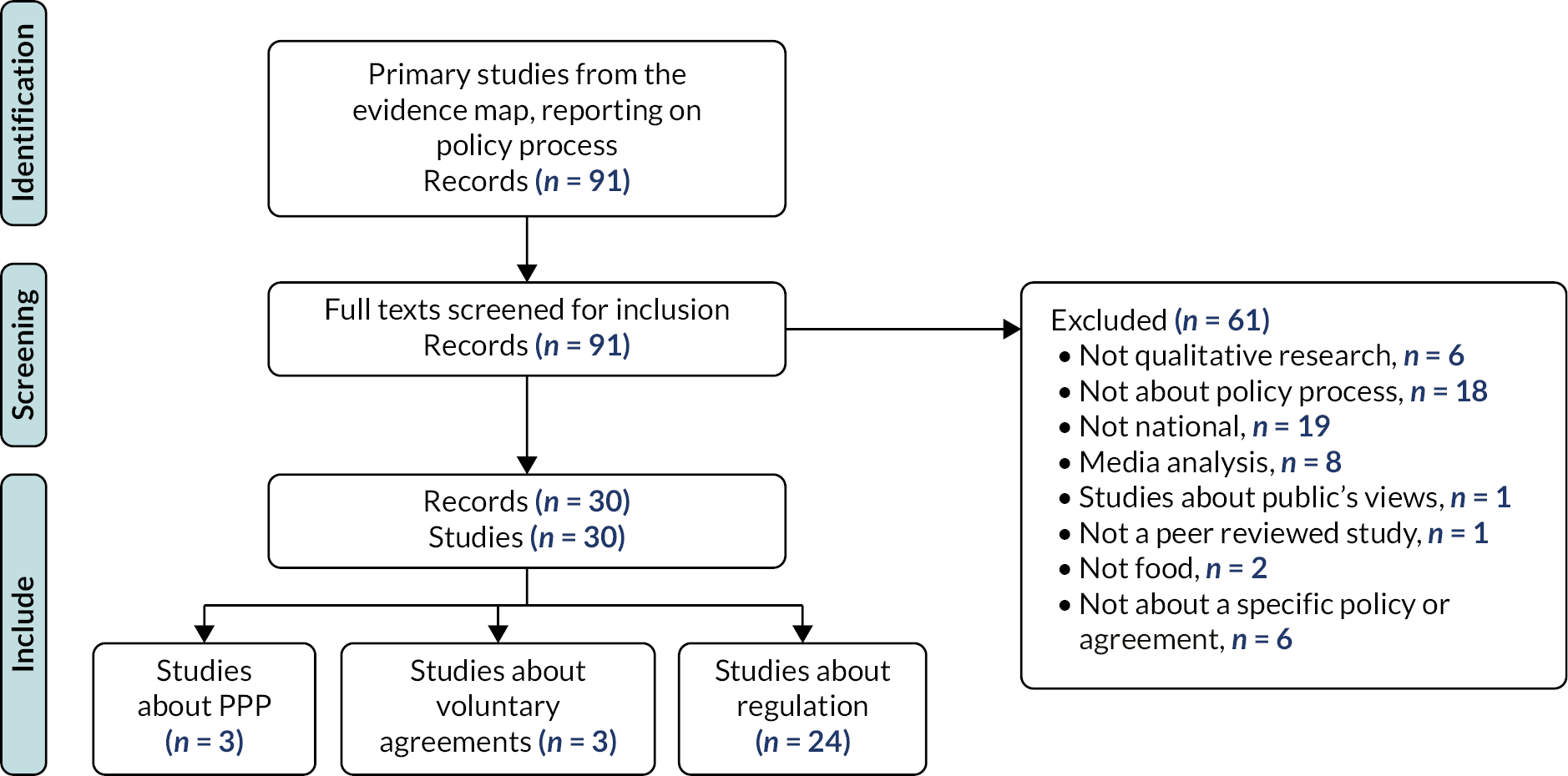

We retrieved 38,209 records from the databases; 27,887 remained after removing duplicates and had their title and abstract screened against the eligibility criteria. Of these, 1859 met the criteria and had their full text screened, resulting in 500 records being included. In parallel, 72 additional full texts were retrieved by screening websites, and reference lists. Of these, 33 met the eligibility criteria, contributing to a total of 533 publications: 483 reporting on primary research evaluations and 50 on evidence syntheses. These became the starting point of all six evidence syntheses. The detail of the selection process for the whole series of reviews is illustrated in Figure 1. The processes and results for each review according to their specific eligibility criteria are presented in the results sections of their respective chapters.

FIGURE 1.

PRISMA flow chart representing the selection process for the entire review. Included Science Citation Index Expanded, Social Sciences Citation Index, Arts and Humanities Citation Index, Conference Proceedings Citation Index-Science, Conference Proceedings Citation Index-Social Science and Humanities, and Emerging Sources Citation Index. Adapted from the PRISMA template by Page et al. (2021). 16

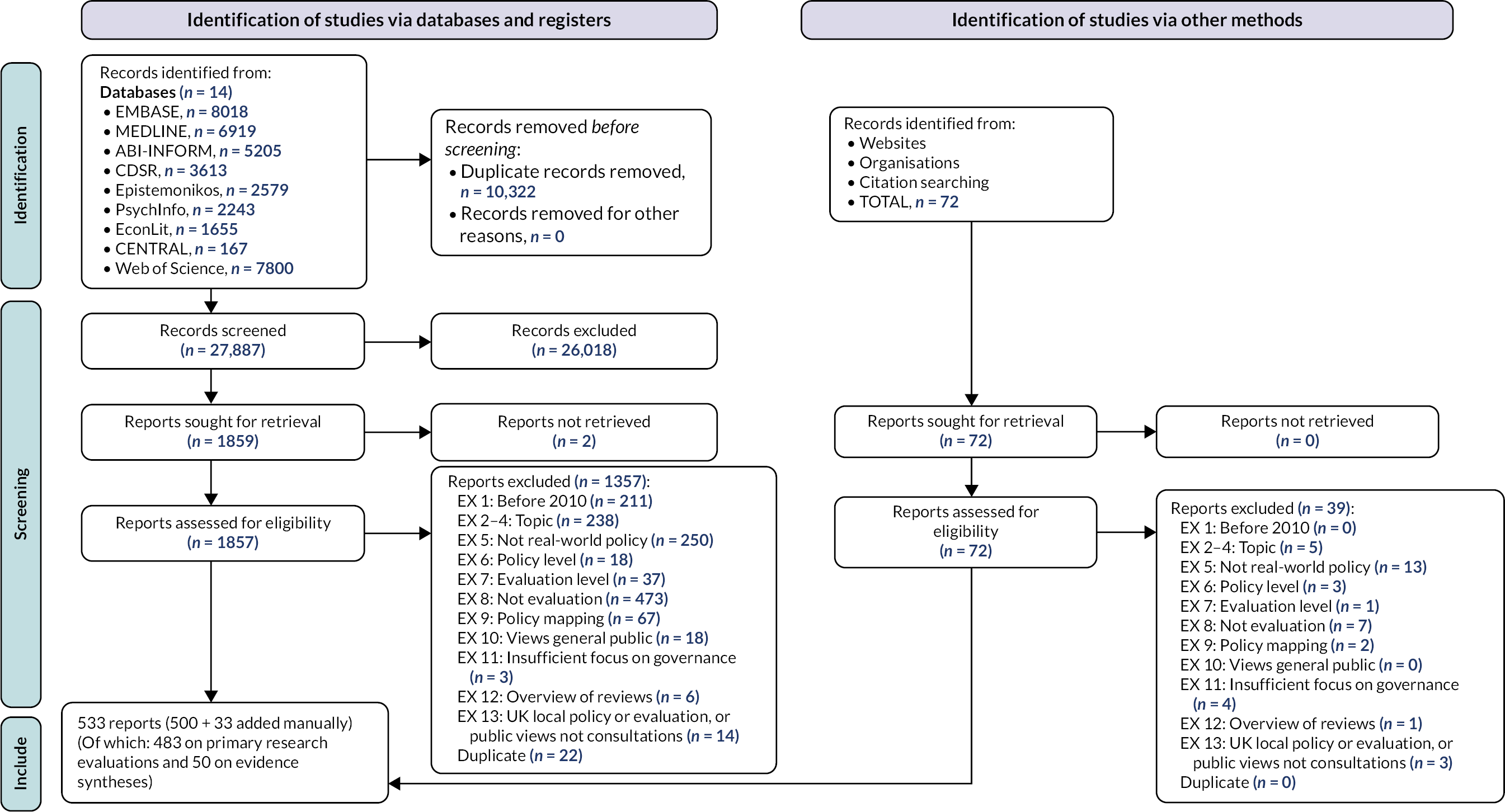

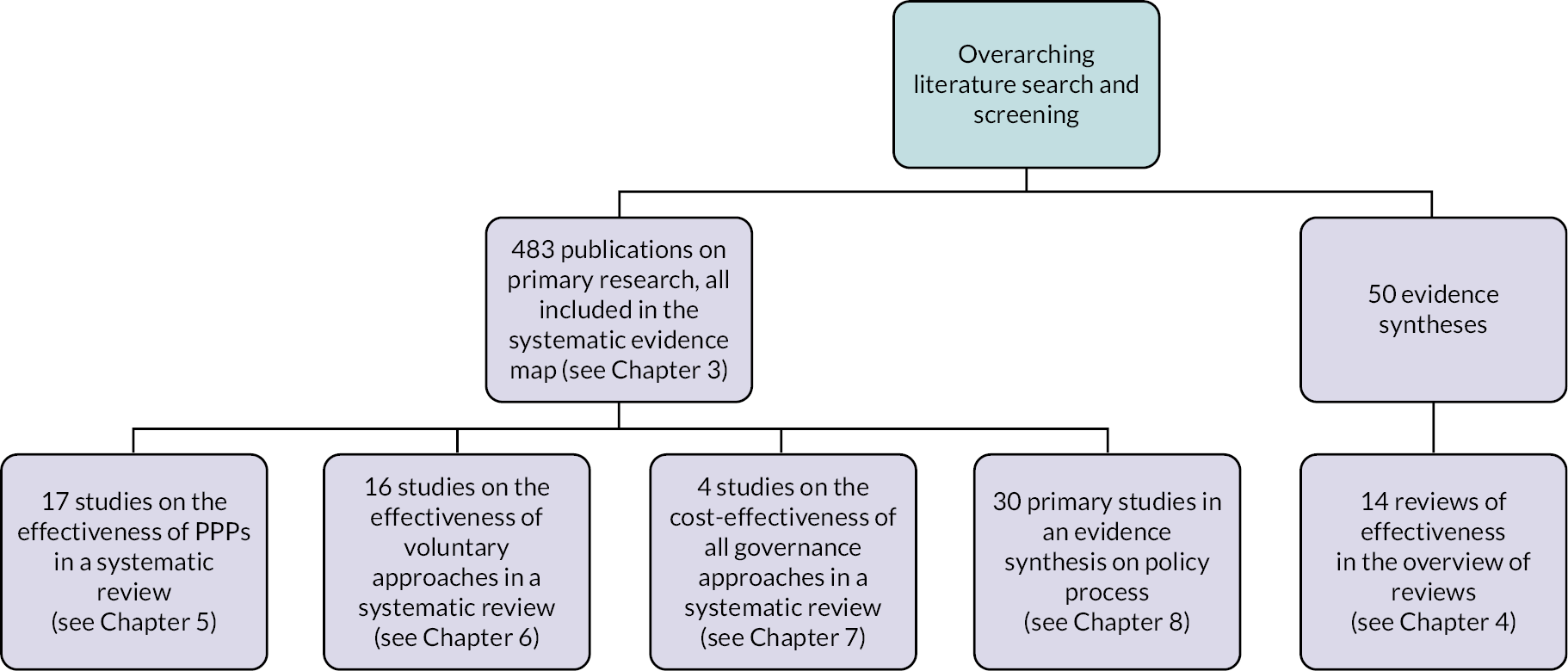

Review outputs’ relationships

Figure 2 illustrates how the different review outputs are related along with the number of studies they include. As explained in Chapter 3, for the systematic evidence map of primary research, given its size, we did link publications reporting on the same studies. Thus, numbers for this output represent publications, not studies. All publications retrieved on primary studies were included in the systematic evidence map, while further screening was applied on the evidence syntheses found for the overview of reviews. Some primary studies and evidence syntheses were also included in additional evidence syntheses specific to a governance approach (e.g. PPP) or study aim (e.g. cost-effectiveness). The systematic reviews in Chapters 5 and 6 addressed gaps in the overview of reviews (see Chapter 4). All evidence syntheses contributed to a systems map.

FIGURE 2.

Relationships between review outputs.

Data extraction

General policy and evaluation characteristics were extracted for all primary studies in the EPPI-Reviewer Web by one reviewer and checked by another (LB, SR, CL). There was one exception: the specific study designs of quantitative studies were extracted by one reviewer (LB) and 10% were checked by a second reviewer (CL), although study designs of studies included in Chapters 5–7 were all further checked by two reviewers separately. Information extraction for each specific review is detailed in their respective chapters. Information was taken at face value unless otherwise specified. A third reviewer was involved to resolve disagreements.

The general policy characteristics extracted included the countries and World Bank regions, the name of the national and international policies (for pragmatic reasons, we did not identify the name of every state policy; instead we grouped them by topic and country regardless of the states), their policy level (international, national, state), the governance approach (regulatory, voluntary, PPP; inspired by a framework by Risse and Börzel17), and policy categories by adapting the ‘NOURIS’ part (which focuses on the food environment) of the NOURISHING framework:18 N-Labelling (excluding health and nutrition claims); O-Specific settings, including schools, child care, health care and leisure; U-Economic tools (which was narrowed down to taxes and price reductions on healthy items); R-Advertising and marketing control; I-Product reformulation by manufacturers; I-Retail and food services environment (excluding those considered under ‘O’ and ‘I’). Subcategories for each policy category were created iteratively. To limit ‘policy noise’, policies had to be the focus of the evaluation, for example, the European Union (EU) pledge (an advertising control policy in the EU) was only captured when specifically evaluated; not every time an advertising control policy was assessed in an EU country. The more we coded publications on governance, the blurrier the line became between voluntary policies and PPPs, and information on the actors involved was scarce. Thus, PPPs became a subcategory of voluntary policies and was joined with two new subcategories: (1) voluntary policies by the private sector (i.e. pledges and self-regulation, in which typically private organisations design their own initiative or their own criteria within an initiative), and (2) voluntary policies by the public or not-for-profit sector. To be qualified as PPPs, policies had to be clearly identified as such or a collaboration between the public and private sectors.

Evaluation characteristics consisted of the publication date; general study aim (e.g. effectiveness, cost-effectiveness, implementation); study design including for quantitative studies the classification of natural experiments by Leatherdale (2019)19 and the presence of a comparison group enabling comparison of either policies, policies versus absence of policies, or participants/products within a policy versus non-participants (NPs)/products; the types of participants and outcomes assessed; and in some of the reviews the health equity dimensions measured as policy outcomes.

The health equity dimensions examined were those from the PROGRESS-Plus framework,20 which stands for Place, Race, Occupation, Gender, Religion and culture, Education, Socioeconomic status (SES) at the individual level, and Social capital. Age and disability were considered for the ‘Plus’. In ‘Place’, in addition to place of residence we included where shops are located. In ‘Age’, we also considered comparisons between media and menus targeting children versus adults, between households with and without children, and data presented for baby and infant products separately. In ‘Education’, we also considered comparison of school characteristics, for example middle versus high schools. Deprivation indices that encompass a range of PROGRESS-Plus dimensions were coded as SES since they generally mostly refer to the latter overall. Health equity domains were searched in each publication by checking figures and tables and searching a list of keywords. A study was considered as exploring an equity dimension when it compared a policy outcome between different groups by the said dimension.

All data extraction categories were non-mutually exclusive, that is a publication could have more than one answer, except for study design.

Study quality appraisal

All studies included in one of the four effectiveness and cost-effectiveness reviews were independently critically appraised by two reviewers (LB, SR, JB, GB, CL) using a tool according to their study design.

The quality of evidence syntheses in the overview of reviews was appraised using the checklist for systematic reviews and meta-analyses by the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) (see Chapter 4 and Appendix 3, Table 25, for more details).

For the systematic reviews of PPP evaluations (see Chapter 5) and of voluntary approaches (see Chapter 5), study quality was assessed using a modified version of the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale for cross-sectional studies21 (see Appendix 4, Table 26). The use of this tool represents a deviation from the protocol: it was planned to use Risk Of Bias In Non-randomised Studies of Interventions (ROBINS-I),22 but the latter was discarded after trialling it on a few studies. The main challenge was that ROBINS-I was designed for follow-up (cohort) studies of interventions that are assumed to be planned or managed by researchers to some extent. This assumption did not apply well to the policy evaluations that we had, making the questions about cointerventions, classification of interventions and deviations from intended interventions difficult to judge meaningfully. We chose instead the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale, which has been widely used and allows identification of the main weaknesses of studies in a pragmatic manner. We selected a version for cross-sectional studies to match with the study designs included in the reviews. We developed additional guidance for studies of documents and environmental features (and one question focused on vaccines), which is lacking in most tools, and for providing an overall judgement given that the original tool uses a scoring system and this is now discouraged by Cochrane. 23

Our modifications to the tool were tested in an iterative process, during which we conversed and agreed on the items and their interpretation. Like the original Newcastle–Ottawa Scale for cross-sectional studies, the final tool that we used included seven items grouped into three risk domains: (1) selection (including representativeness of sample, sample size, non-response/missing data, and ascertainment of the exposure), (2) comparability of subjects in different outcome groups on the basis of design or analysis and confounding factors controlled and (3) the assessment of the outcome and the statistical analysis. Each item was rated as having a high, moderate or low quality, or insufficient information to judge. The same categories were applied for the overall ratings. Studies that included at least one item rated ‘low’ were attributed an overall low quality. Studies attributed a moderate or unclear quality for the two key domains judged the most important – ascertainment of exposure and statistical tests – could only be rated ‘moderate’ or ‘unclear’ at best overall, respectively. Studies with more than one ‘unclear’ item were attributed an ‘unclear’ quality.

The quality of the cost-effectiveness analyses was assessed with Drummond’s 10-criteria checklist version 2015 (see Chapter 7), while the quality of the studies in the thematic synthesis (see Chapter 8) was appraised using the 10 questions for qualitative studies by the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP). 24

Data synthesis

This review in essence comprises a number of different reviews, the methods for which are described in respective chapters, and summarised here. The evidence map is descriptive (see Chapter 3), and so data were synthesised narratively using descriptive statistics, and visual maps were produced with EPPI-Mapper (EPPI-Centre, UCL, UK) and Excel. The four effectiveness and cost-effectiveness evidence syntheses (see Chapters 4–7) include quantitative findings, which, based on the initial scope (and confirmed by the subsequent review), were not suitable for statistical pooling techniques, such as meta-analysis. We synthesised findings by adapting narrative synthesis approaches in the three systematic reviews and overview of reviews of effectiveness (see Chapters 5 and 6). 25 For a graphical representation of the summary findings, in the two systematic reviews and the overview of reviews about effectiveness (see Chapters 4–6), we also used the effect direction plot developed by Thomson et al. 26 to represent graphically the summary findings. The effect direction plot displays non-standardised effects across the multiple outcome domains assessed in a review. Studies were grouped by policy and ordered by overall study quality, publication date and study design; with those considered to provide the best and most recent evidence listed first. According to Cochrane’s guidance and the revised guidance for the effect direction plot, the directions of effect are presented independently from statistical significance for domains of outcomes. 26,27 To mark an effect as being positive or negative, at least 70% of the outcomes within the category represented needed to point towards the same direction. When a study compared multiple outcomes between participants and NPs, we split them into categories following those used by the study authors; this was for both increased transparency and for avoiding results to be inconsistent because a wide range of outcomes were considered together. The p-value of each outcome domain was not calculated due to important limitations in the methodology as explained elsewhere27 (studies with conflicting or unclear effects cannot be included). Instead, we used the effect direction plot as a visual tool to present jointly the direction of effect, study quality and indirectness. As for the qualitative review (see Chapter 8), we employed a qualitative synthesis.

Issues with the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation approach

In the three reviews assessing effectiveness (see Chapters 4–6), we had planned that the effect direction plots would have informed assessments with the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach. 28 However, the application of GRADE itself was not possible. In the overview of reviews (see Chapter 4), there were insufficient details in most of the systematic reviews to proceed. In the systematic reviews on private commitments and PPPs (see Chapters 5 and 6), the framework was judged unfit for purpose given the nature of the studies used, and this despite the modifications suggested in the protocol.

The GRADE framework helps determining the level of certainty in the evidence (rated as high, moderate, low, very low) for each outcome. Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) start at the highest certainly level (high) while observational studies start at ‘low’. Certainty in the evidence is then rated down by considering the methodological limitations of the studies (risk of bias), indirectness (applicability and how it represents the research question elements), imprecision [number of events and confidence intervals (CIs)], inconsistency (heterogeneity in results) and likelihood of publication bias. Certainty can also be rated upwards, but this is an exception. As explained in the protocol, we believe that GRADE’s hierarchy of evidence is inappropriate for policy evaluations. It does not reflect the best possible type of evidence that can realistically be obtained for a research question by considering both practical and ethical implications. Thus, in addition to RCTs, we had planned to also attribute a ‘high’ certainty to the following study designs at the start: (1) pre–post time-series analyses and (2) (potentially) cohorts/follow-up studies involving both a comparison group and data collected before and after policy implementation. Eligible comparisons included (1) comparing a policy to either another policy, the absence of a policy, or the same policy but in another location (e.g. different states or countries); (2) comparing participants in a voluntary policy to NPs; (3) comparing products or audience (e.g. TV audience) targeted by the policy to some not targeted by the policy.

However, these modifications did not address the problem. The main issues were that (1) the GRADE framework was developed for specific or narrow research questions while the review included a wide range of heterogeneous interventions and outcomes. The latter is common for policy topics since decision-makers are interested in a range of outcomes, and the policies from which we can learn can be quite different across settings and time. The assessment of publication biases and inconsistency were particularly problematic for this reason; (2) it does little to differentiate levels of certainty in evidence from observational studies. They all are rated as ‘low’ or ‘very low’, and this despite being the best sources that we can sometimes realistically obtain for some policy topics; (3) the exceptions of study designs outlined above were mostly inapplicable to the research questions of the studies included in the systematic reviews in Chapters 5 and 6. Overall, given the nature of the research questions, we could only obtain ‘low’ or ‘very low’ statements no matter what the studies did. We felt that this led to the production of statements on the certainty of evidence that appeared absolute but were in fact uninformative at best, and misleading at worst. It could send the message to decision-makers that there is no good evidence, and that they might as well consider non-evidence-based sources, such as opinions, instead.

Regarding the exceptions outlined in the protocol (i.e. to also attribute a ‘high’ certainty at the start for pre–post time-series analyses and cohorts/follow-up studies involving both a comparison group and data collected before and after policy implementation) (see Appendix 2), they were proven useless because most studies, including all those in Chapter 6, sought to investigate whether a policy had led to improvements in the nutrient content, advertising content or labelling practices. These are outcomes of interest for policies aiming to improve food environments. However, these studies tend to be repeat cross-sectional, not cohort/follow-up studies. They compare the offer of products or adverts available at one point in time to that at another point in time. In this case, examining different products and adverts through time does not represent a methodological weakness. There were also a few document analyses investigating whether a policy was doing what it pretended or was on track. There is currently no guidance for the latter. To avoid producing statements of certainty of evidence that risk misleading decision-makers, a wider discussion about GRADE for policy evaluations in the systematic review community is needed.

Chapter 3 Systematic evidence map of regulatory, voluntary and public–private partnership policies to improve food environments and population diet

Introduction

This chapter reports the systematic evidence map of the included literature, which exposes regional differences in existing across geographical regions, as well as by equity dimension and governance approach.

Evidence map methods

What is a systematic evidence map?

Systematic evidence maps, also known as evidence gap maps, are a type of evidence synthesis and research translation tool that visually presents the breadth of research available on an area using a systematic approach. While they are generally used to produce high-level descriptions and identify gaps in evidence, we believe that they can also be employed from a critical perspective to question practices both in research and in the field. 29 In the present case, examining the characteristics of both the policies that have been evaluated, and of the evaluations themselves, can shed light on the body of evidence that countries have at their disposal to make decisions about policy design and effectiveness. Thus, this systematic map of global evidence reports on the breadth, purpose and extent of primary research evaluating the development, implementation, effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of regulatory, voluntary and PPP diet-related policies from both a policy and evaluation perspective.

Methods overview

This systematic evidence map used the literature search, eligibility criteria, screening and data extraction strategies detailed in Chapter 2. As a reminder, the data extracted consisted of (1) general policy characteristics, including countries and World Bank regions, policy names, policy levels, governance approaches and policy categories by adapting the ‘NOURIS’ part of the NOURISHING framework:18 N-Labelling, O-Specific settings including schools, child care, health care and leisure, U-Economic tools (narrowed down to taxes and price reductions on healthy items), R-Advertising and marketing control, I-Product reformulation by manufacturers, I-Retail and food services environment; (2) evaluation characteristics, including publication date; general study aim, study design; and for studies assessing policy effectiveness, the types of participants and outcomes assessed and health equity dimensions measured using a generous interpretation of the PROGRESS-Plus framework,20 which stands for Place, Race, Occupation, Gender, Religion and culture, Education, SES at the individual level, and Social capital as well as Age and Disability for the ‘Plus’. A study was considered as exploring an equity dimension when it compared a policy outcome between different groups by the said dimension.

Data were synthesised narratively using descriptive statistics based on the data extraction categories. Visual maps were produced with EPPI-Mapper (EPPI-Centre, UCL, UK) and Excel.

Findings

Included and excluded studies

In addition to the 483 publications reporting on primary studies, the 15 excluded full texts reporting on UK local policies and/or evaluations (see Report Supplementary Material 1, Table S1) (which were part of the 15 UK publications excluded because they were either about the local level or views or the public at the state or national level) were set aside for further analyses. The characteristics of the 483 included publications are described in Report Supplementary Material 2, while those on the local evaluations in the UK and on the excluded publications are listed in Report Supplementary Material 1 (see Table S2). In accordance with Cochrane’s guidance,30 only the characteristics of the full texts excluded for the least apparent reasons are listed, that is because of their policy level (EX 6), evaluation level (EX 7), policy mapping (EX 9), views of the general public (EX 10), evidence synthesis not considering governance (EX 11), UK local policy or evaluation, or public views not consultations, or full texts not obtained (n = 172).

Given the size of this evidence synthesis, we did not attempt at this stage nor for the systematic evidence map of primary research to link publications reporting on the same studies. Thus, the number of ‘includes’ are publications, not studies.

Regional differences across publications

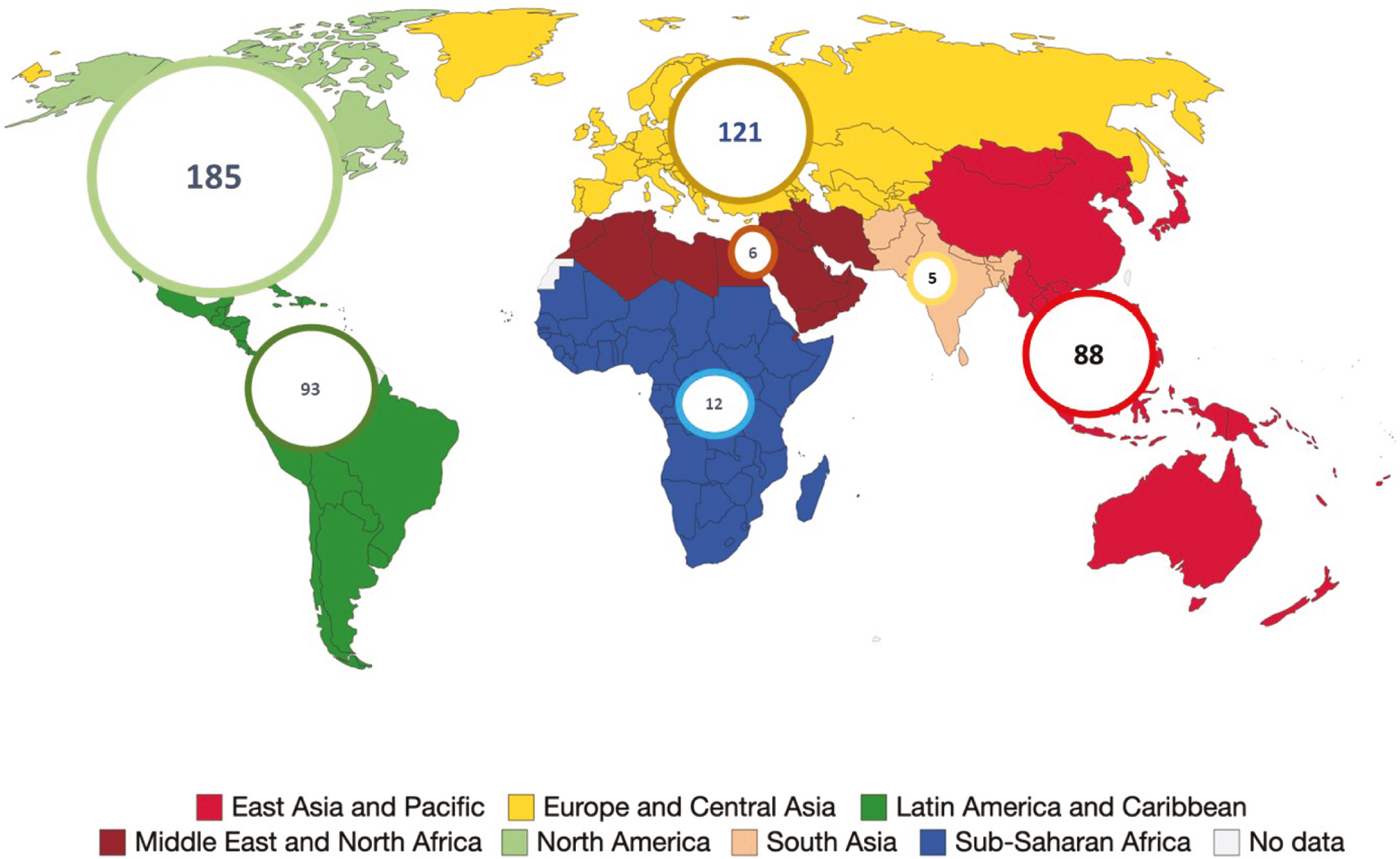

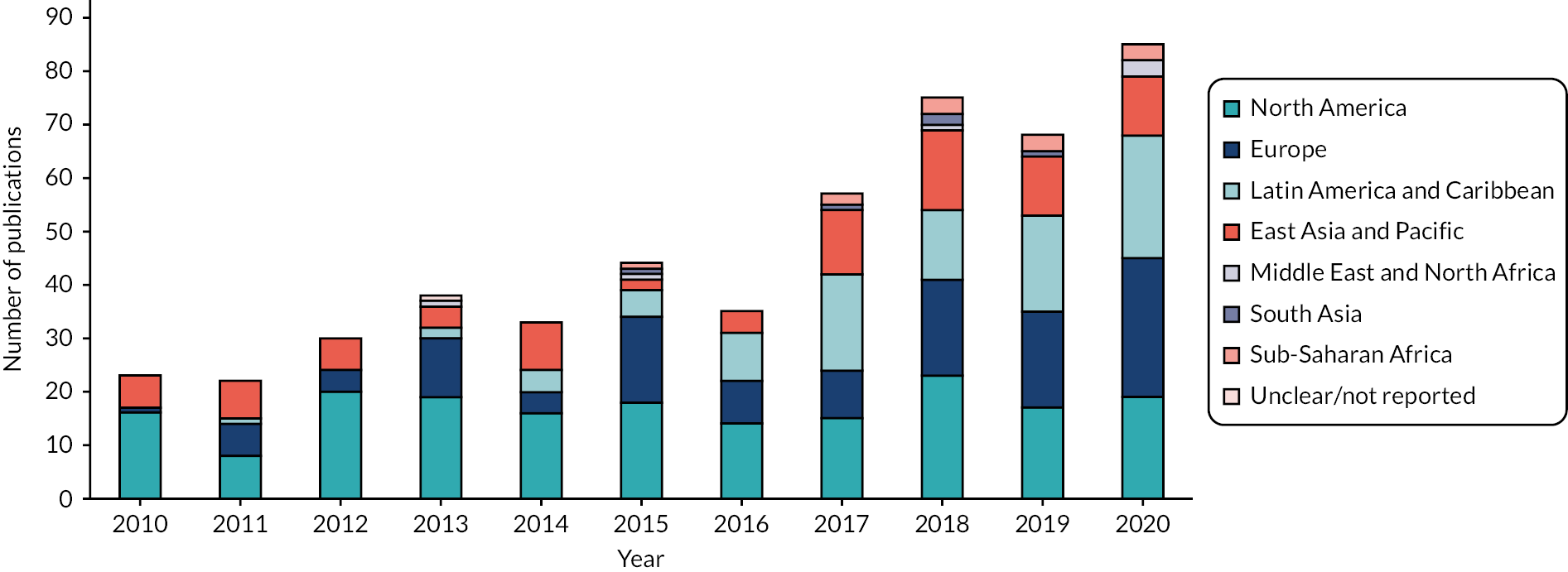

Overall, 70 countries were documented. As shown in Figure 3, there were apparent inequalities in coverage between countries and world regions. The number of evaluations published each year on eligible real-world policies has nearly quadrupled over 11 years, ranging from 23 in 2010 to 85 in 2020 (Figure 4). Studies examining North American countries (38% of publications overall) dominated throughout the period except in 2017 and 2020. The increase in publications worldwide was mainly driven by the World Bank regions of Europe and Central Asia, and of Latin American and the Caribbean (25% and 19% of total publications, respectively), although no Central Asian country was documented and only three studies assessed the Caribbean. East Asia and the Pacific were covered in 18% of total publications. Regarding countries, 30% (n = 146) of publications included the USA, 11% (n = 54) the UK, 11% (n = 51) Australia, 8% (n = 41) Canada, 8% (n = 40) Mexico, 5% (n = 25) Brazil, 4% (n = 19) Chile, 3% (n = 14) France and Spain each, 3% (n = 13) Denmark, and 2% New Zealand and South Africa each (n = 12 and n = 11, respectively). Eighty-one per cent (n = 390) of publications considered these 12 countries alone (without any other country). By contrast, 32 countries were included in only 1 or 2 publications each. While some of these were high-income countries, disparities with and within the least-documented world regions was startling: 12 publications were found about Sub-Saharan Africa (all but 1 about South Africa), 6 about the Middle East and North Africa (4 of which about Saudi Arabia), and 5 about South Asia (all about India). Given that some of these evaluations included multiple countries, the level of details available for some of these countries was particularly limited. One publication had unclear countries and world regions because it assessed companies’ stock markets. 31 Nearly all publications were in English (n = 417), nine were in Spanish, two in Portuguese and one in French.

FIGURE 3.

Number of publications by World Bank world region (n = 482 because it is unclear in one publication). Note: the same publication can include more than one world region (non-mutually exclusive categories).

FIGURE 4.

Number of publications by world region and year (n = 483). Note: since the same publication can include more than one world region (non-mutually exclusive categories), this graph does not reflect the actual total number of publications per year.

Characteristics of policies assessed

The policies examined included 236 national policies (assessed in 73% of publications), 26 groups of state policies (assessed in 26% of publications) and 9 international policies (assessed in 6% of publications). One policy had both a national and a state component. All state policies were implemented in dominant countries (Australia, Brazil, Canada, Spain, the UK and the USA). The five most assessed policies consisted of American state school food standards (n = 37), the Children’s Food and Beverage Advertising Initiative (CFBAI; a national voluntary self-regulation advertising industry code in the USA, n = 21), the Mexican tax on sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs) (national, n = 19), the UK SDIL (national, n = 14), and various American state SSB taxes (n = 14). Together, these three taxes represented 54% of publications about economic interventions (see below). The three most examined international policies were the Australasian Health Star Rating (HSR) (Australia and New Zealand, n = 11), the EU Pledge (n = 5) and the WHO Code of marketing breastmilk substitutes (n = 5).

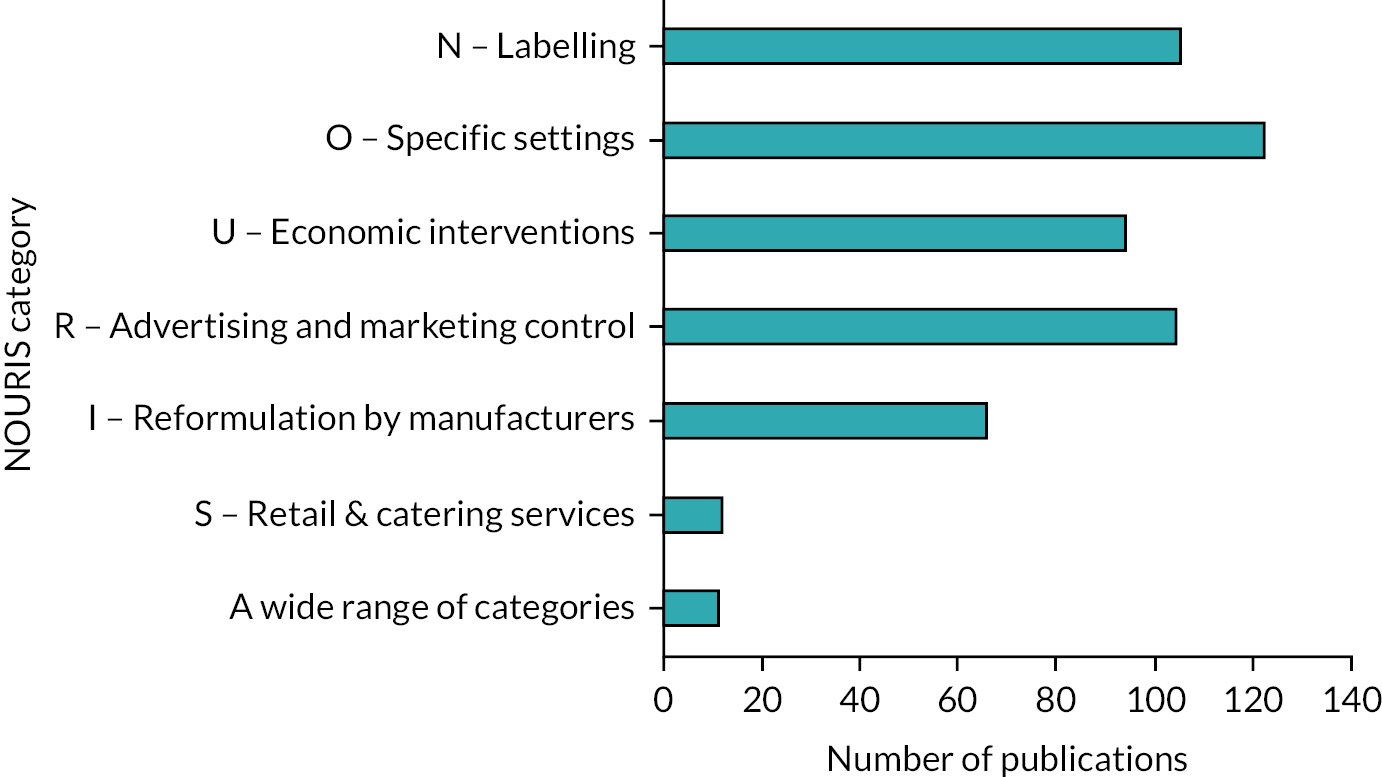

Using the six ‘NOURIS’ categories, as shown in Figure 5, the most assessed policy categories were those specific to school, child care, health care and leisure settings (O, n = 122, 76% of which on schools), followed by labelling [N, n = 105, 39% of which about front-of-packs (FOPs)], advertising and marketing control (R, n = 104, 55% of which about television alone) and economic interventions (U, n = 94, 86% of which about SSB taxes). Evaluations of product reformulation by manufacturers were much less common (I, n = 66, 61% of which about salt) as well as those on the retail and catering sectors (S, n = 12, 83% of which at least aimed to increase the availability of healthy options). Eleven assessed policies that covered a wide range of NOURIS domains (these were grouped separately).

FIGURE 5.

Number of publications by NOURIS category (n = 483). Note: a publication can include more than one policy category (non-mutually exclusive).

Governance arrangements assessed

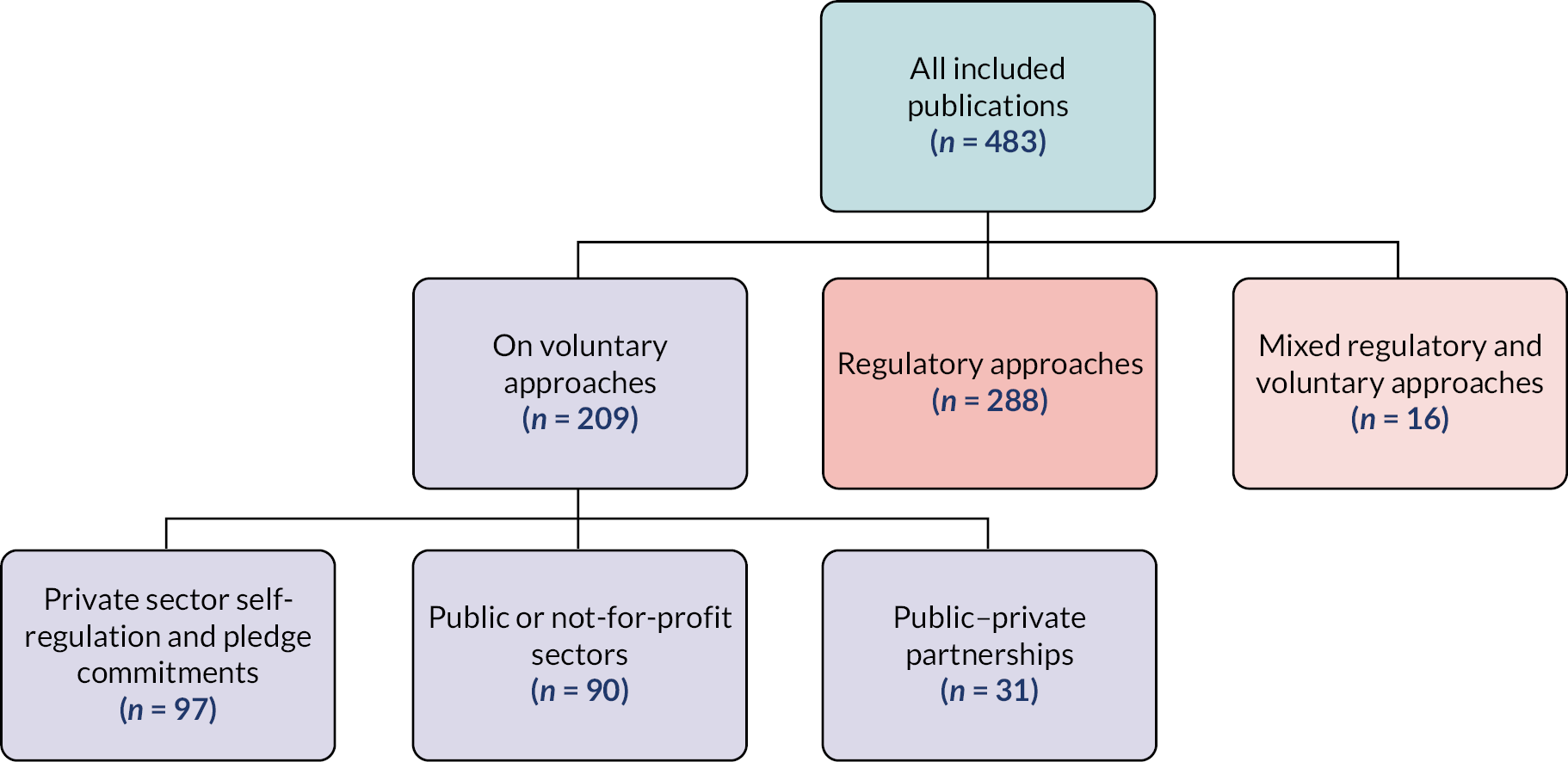

Sixty per cent (60%, n = 288) of publications reported on at least one regulatory initiative, 43% (n = 209) on at least one voluntary action, and 16 assessed mixed governance policies (e.g. the combined use of regulatory labelling and voluntary limits for trans-fats in Canada) (Figure 6). Evaluations of voluntary policies mainly consisted of those led by the private sector (self-regulation and pledges, n = 97) and actions by the public or not-for-profit sector (n = 90), while a minority has investigated PPPs (n = 31). Most publications on PPPs were about the RD in England, UK (n = 12) or the Australian Food and Health Dialogue (FHD) and/or its updated version, the Healthy Food Partnership (n = 10).

FIGURE 6.

Number of publications by governance mechanism (n = 483). Note: a publication can include more than one governance approach (non-mutually exclusive categories).

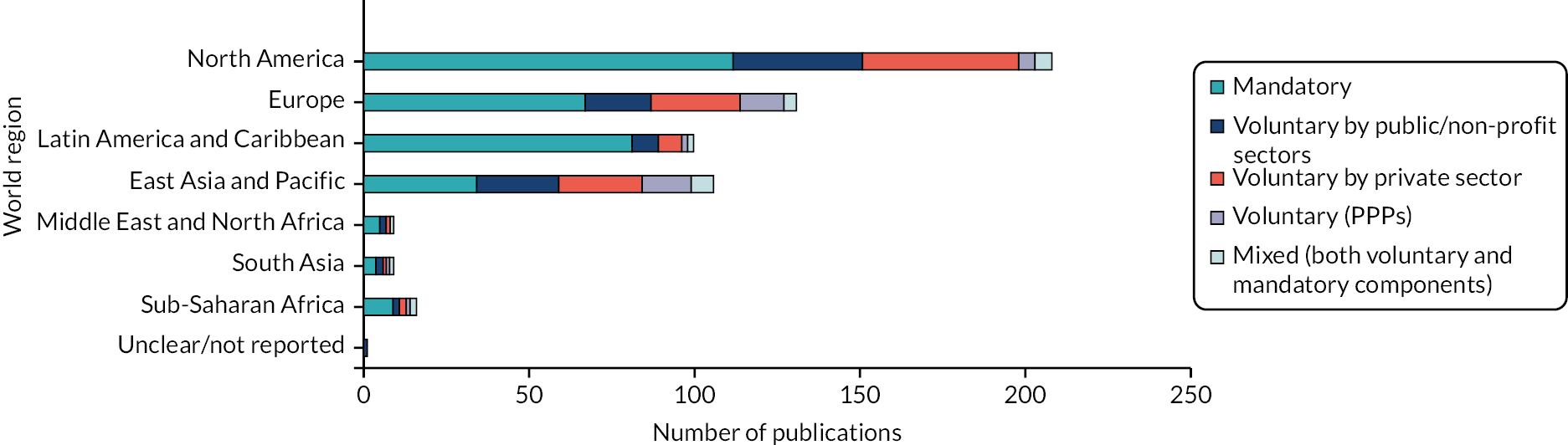

Figure 7 shows the distribution of publication by governance approach and world region. Regulatory approaches represent the majority of publications in all World Bank regions, ranging from 39% in East Asia and the Pacific to 87% in Latin America and Caribbean. East Asia and the Pacific is the region where governance approaches have been assessed the most evenly. Voluntary actions by the private sector were the second most assessed approach in North America and Europe, voluntary actions by the public and not-for-profit sectors were second in Latin America and Caribbean, the Middle-East and North Africa, and South Asia, and the two voluntary categories were equal in East Asia and Pacific and Sub-Saharan Africa, although the sample size in some regions is too small to draw conclusions. As highlighted previously, most PPP evaluations were conducted in Europe (especially the UK) and East Asia and Pacific (especially Australia). There were few evaluations of mixed approaches across all world regions.

FIGURE 7.

Number of publications by world region and governance approach (n = 483). Note: a publication can include more than world region and governance approach (non-mutually exclusive categories).

When combining information on governance approach, world region and policy category together, evaluations about labelling (N) were mainly about regulatory initiatives in North America (especially menu labelling) and Latin America [especially front-of-pack labelling (FOPL)], followed by the voluntary FOP HSR in Australia and New Zealand. Most publications on specific settings (O) evaluated regulatory interventions in schools in North America, then in Europe. Evaluations of economic interventions (U) were mostly concentrated in Latin America, Europe, and the USA, most of which were regulatory since they were taxes. Publications on advertising and marketing control (R) were mainly in North America, followed by East Asia and Pacific and Europe, and were predominantly voluntary actions by the private sector in all three regions. In fact, 53% of evaluations of voluntary approaches by the private sector in this policy category consisted of the CFBAI in the USA; the CFBAI in Canada; the Publicidad, Actividad, Obesidad, Salud code in Spain; and both the Australian Responsible Children’s Marketing and Australian Quick Service Restaurant Industry’s Initiatives (QSRI). Evaluations of product reformulation (I) were about equally distributed across governance approaches in the four dominant world regions, with slightly more PPP evaluations in East Asia and Pacific. The few evaluations of policies targeting the retail and catering sectors or using a wide range of policy categories were only in North America, East Asia and Pacific and Europe, with various distributions of governance approaches. We formulated the hypothesis that evaluations of the least assessed world regions and countries focused on back-of-pack labelling, assuming that it might be the most frequently implemented policy given its simplicity and neutrality. This was not the case: the 18 evaluations covering Africa, the Middle East and South Asia documented a variety of policy areas, which were mainly regulatory (including five on SSB taxes). Similar conclusions were made for the 24 publications that included the 32 least evaluated countries (countries assessed once or twice, in any world region).

We explored whether similar trends applied for local policies and/or evaluations using the 15 publications that were excluded because they were about the local level in the UK. One focused on Scotland, another on Wales, and the rest on England. Together, they examined nine different policies in only two categories: specific settings (O, n = 8; six regulatory about schools, two voluntary by the public sector in hospitals) and the retail and catering sector (S, n = 7; three regulatory, two voluntary by the public sector, two voluntary by the private sector). The number is substantial given that only 12 publications were identified for that category in the whole evidence map. This potentially reflects the greater capacity to implement such initiatives at the local level, whereas other policies such as taxes and TV advertising control are easier to establish at a higher level. The local regulatory initiatives in the retail and catering sectors included planning regulations within the healthy weight strategy and takeaway planning restrictions. The voluntary approaches by the private sector consisted of the Change 4 Life programme, the Healthy Catering Commitment in London, and self-regulated checkout policies by some supermarket chains.

Study aims, participants and outcomes assessed

The vast majority of evaluations (n = 389, 81%) assessed the effectiveness of a policy, followed by factors affecting their implementation (n = 67, 14%), factors influencing their development (n = 34, 7%), how a policy was portrayed in the news (n = 11, 2%), responses to public consultations (n = 10, 2%) and cost-effectiveness analyses (n = 4, 1%). The remaining study investigated whether the New Zealand Advertising Standards Authority self-regulation code protects child rights. Only the fifth (n = 25) of the 119 evaluations assessing other aspects than effectiveness covered other countries than the 12 dominant countries (i.e. USA, UK, Australia, Canada, Mexico, Brazil, Chile, France, Spain, Denmark, New Zealand and South Africa). Given that these types of studies aim generally to employ qualitative or mixed methods, unsurprisingly, the latter study designs were also mostly employed in these countries (as well as Fiji). Figure 8 shows the number of publications by governance approach and study aim category. PPPs were those that were the most assessed holistically with 32% of publications assessing factors influencing implementation and 16% assessing policy development. They were followed by regulatory policies (12% on implementation, 9% on development, and representing most studies on media coverage and public consultations). By contrast, policies led by private actors (mainly self-regulations and pledges) were particularly underevaluated on these aspects with only 7% of publications on implementation and one evaluation of policy development.

FIGURE 8.

Number of publications by study aim category and governance approach (n = 483). Note: a publication can include more than one study aim and governance approach (non-mutually exclusive categories). Dark green: ≥ 100 publications; pale green: 75–99; yellow: 50–74; red: 25–49; white: < 5.

Studies assessing effectiveness focused on a wide range of ‘participants’ or samples: out of 389 publications, 43% (n = 166) relied on data collected data via humans only, 57% did not involve humans at all (i.e. they collected data directly on the environment, in the news or documents, n = 182), and 11% (n = 41) involved both. Consequently, the type of outcomes evaluated also varied. Nine per cent (n = 35) have investigated health-related outcomes [e.g. mortality, diseases, disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs), nutritional status and anthropometric]; these were nearly all conducted in the USA, followed to a smaller extent by Denmark (n = 4) and Portugal (n = 3). The other types of outcomes considered included human behaviours (e.g. dietary intake, sales, purchases, advertising viewing and use of labels; 35%, n = 137), environment features (66%, n = 256), policy characteristics or implementation status (6%, n = 22) and other outcomes (2%, n = 9). All policy categories mainly assessed environment features except for U-Economic interventions, which mostly examined human behaviours.

Study designs employed

As explained in Chapter 2, study design was documented for all primary studies. The design of 67% (n = 254) of quantitative studies was further extracted using the classification of natural experiments by Leatherdale19 as well as presence of a comparison group enabling comparison of either policies, policies versus absence of policies, or participants/products within a policy versus NPs/products.

As described in Figure 9 and more detailed in Table 3, 78% (n = 376) of publications employed a quantitative design, 13% (n = 63) a qualitative method and a minority either used both (mixed methods; 6%, n = 27) or analysed policy documents alone (4%, n = 17). Among quantitative studies, most were single post cross-sectional studies (one data collection, 44%, n = 165), followed by repeat cross-sectional studies (32%, n = 121), follow-up and time series (22%, n = 81), and modelling studies and scenarios (n = 9). Note that the label ‘follow-up studies’ was only applied to human participants because non-human ‘participants’, such as products and adverts, are generally not the same through time. Pre–post studies (n = 160) were more common than post–post (n = 41). Three studies focused on the implementation phase alone (i.e. before the official policy implementation date).

FIGURE 9.

Publications by study design (n = 483). Note: a publication can only include one study design (mutually exclusive category).

| Study design | N (%) for the whole map | N (%) for publications only covering the 12 dominating countries (out of n = 390) |

N (%) for publications only covering the USA (out of n = 141) |

N (%) for publications covering other countries than the 12 (out of n = 93) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | ||

| Quantitative (all) | 376 | 78 | 310 | 79 | 121 | 86 | 66 | 71 | |

| Follow-up studies and time series | (All) | 81 | 17 | 68 | 17 | 22 | 16 | 13 | 14 |

| Pre–post | 69 | 14 | 58 | 15 | 13 | 9 | 11 | 12 | |

| Post–post | 12 | 3 | 10 | 3 | 9 | 6 | 2 | 2 | |

| Repeat cross-sectional | (All) | 121 | 25 | 101 | 26 | 41 | 29 | 20 | 22 |

| Pre–pre | 3 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Pre–post | 89 | 18 | 74 | 19 | 30 | 21 | 15 | 16 | |

| Post–post | 29 | 6 | 24 | 6 | 10 | 7 | 5 | 5 | |

| Cross-sectional, post, once | 165 | 34 | 134 | 34 | 58 | 41 | 31 | 33 | |

| Modelling and scenarios | 9 | 2 | 7 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | |

| Qualitative | 63 | 13 | 44 | 11 | 13 | 9 | 19 | 20 | |

| Mixed methods (quantitative and qualitative) | 27 | 6 | 21 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 6 | 6 | |

| Policy document analyses | 17 | 4 | 15 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | |

| Total | 483 | 100 | 390 | 100 | 141 | 100 | 93 | 100 | |

Table 3 shows the number of publications by study design for the whole map (n = 483), for the publications only focusing on the 12 dominant countries (n = 390, 81% of the map), those focusing only on the USA (n = 141, 29% of the map) and those including other countries than the 12 (n = 93, 19% of the map). According to Leatherdale, the most robust natural experiments are those that include a control (or comparison) group, a pre–post design, as well as time series and follow-up studies. 19 The most used study designs in publications covering only the 12 dominating countries were single cross-sectional studies (34%), followed by repeat cross-sectional studies (26%) and follow-up studies and time series (17%). The same trend was observed for publications on the USA alone, although with a higher proportion of single cross-sectional studies in the American studies (41%). Publications on other countries also had a majority of cross-sectional studies (33% single, 22% repeat) but these were followed by qualitative studies (20%) and then follow-up studies and time series (14%). Quantitative studies in all three categories of publications all tended to use more pre–post designs than post–post. However, nearly all policy analyses, mixed-methods studies, modelling studies and scenarios were about the 12 dominating countries alone. Regarding the use of comparison groups, we documented the number of publications reporting on a quantitative study comparing two policies (or more), a policy versus none, or participants or products targeted by a policy versus some not targeted. Overall for the whole map, 57% of quantitative studies involved such a comparison compared with 60% for the 12 dominating countries alone, 66% for the USA alone and 44% for other countries. Thus, except for pre-post designs, publications focusing only on the 12 dominating countries tend to employ more frequently the most robust quantitative designs or features (i.e. follow-up studies and time series, and comparison groups) compared with publications covering other countries, as well as policy document analyses. However, a smaller proportion of their publications employ qualitative methods. The majority of the publications covering the least documented world regions (i.e. Africa, the Middle East and South Asia) were single cross-sectional or qualitative, although the latter were mainly about South Africa.

Regarding the use of quantitative study design by governance approach, 81% of follow-up studies and time-series analyses, and seven of the nine modelling studies assessed regulatory policies. Very few follow-up studies and time series investigated voluntary policies by the public/not-for-profit or private sectors (7% and 11%, respectively). PPPs were mostly assessed with pre–post cross-sectional studies (n = 6). By policy category, most follow-up studies and time-series analyses, and most modelling studies were employed to evaluate economic interventions. Since these were mainly taxes, it explains why these study designs primarily focused on regulatory interventions.

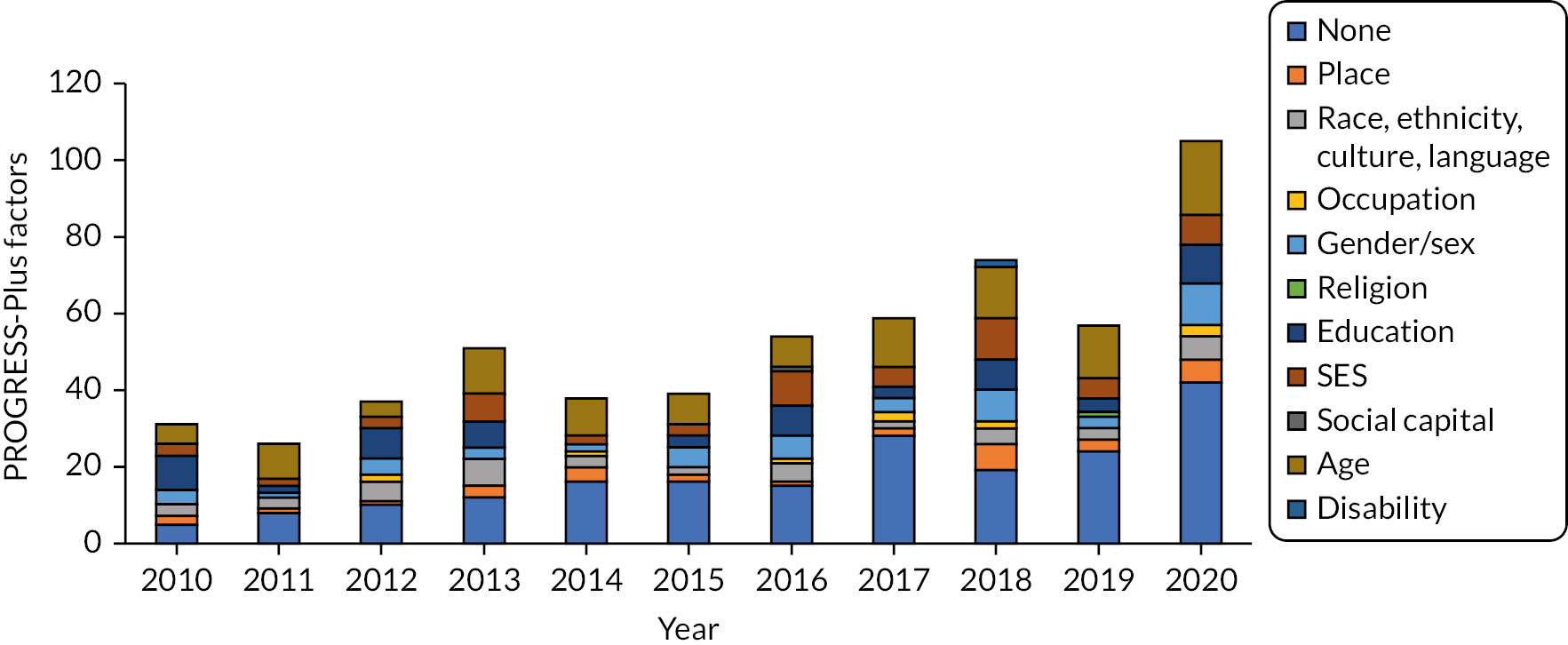

Health equity as a policy outcome

We documented the number of evaluations assessing policy effectiveness comparing a policy outcome between groups by PROGRESS-Plus equity domains. Overall, out of 389 studies used, 50% did not consider any equity domain, 50% assessed at least one, and 21% measured two or more. Age was the most assessed (30%), followed by education (16%, although these mainly related to school characteristics), SES at the individual level (15%), gender/sex (13%), race and culture (11%) and place (8%), whereas only 11 publications considered occupation, and 1 or 2 examined religion, social capital and disability each. This was using a generous interpretation of the PROGRESS-Plus framework, which also considered characteristics of products and places (rather than just humans) and those contributed to higher numbers for age and education. Equity was most frequently considered in the USA (n = 75 with at least one equity dimension), Australia (n = 20), Canada and Mexico (n = 18 each), the UK (n = 17), as well as Chile and France (n = 8 each). Figure 10 illustrates the distribution of publications by year and equity dimension assessed. While the number of quantitative and mixed-methods studies reporting on at least one dimension has increased from 2018, the proportion to the number of studies of effectiveness published per year has reduced, from 72% (n = 13 out of 18) in 2010 to 40% (n = 28 out of 70).

FIGURE 10.

Number of publications comparing policy outcomes by PROGRESS-Plus factors, by publication year. Note: a publication can include more than one health equity dimension (non-mutually exclusive category).

We explored whether evaluations conducted at a smaller scale could capture equity more frequently. In the 15 publications on local policy and/or evaluation in the UK, 8 assessed the effectiveness of a policy. Only four reported on at least one equity dimension: SES (n = 4), place (n = 1), and age (n = 1) representing a similar proportion than for the evidence map, albeit the very small sample size limiting such conclusions.

Conclusions

We found imbalances across the 483 included studies, suggesting that policy evaluations are conducted and published inequitably across the world both in terms of quantity and quality. Though 70 countries were represented overall, 81% of publications focused on only 12 countries (USA, UK, Australia, Canada, Mexico, Brazil, Chile, France, Spain, Denmark, New Zealand and South Africa), and 30% included the USA. Few evaluations were found about Africa, Central and South Asia and the Middle East. Inequities were also detected in the study designs, with the most quantitative robust methods mainly documenting the abovementioned 12 dominant countries. Few publications reported on PPPs (n = 31), and only one assessed the development of voluntary policies led by the public and private sectors each. Using a generous interpretation of the PROGRESS-Plus equity dimensions, we found that not only 50% of publications assessing policy effectiveness did not compare outcomes by any equity domain, but that the proportion of those doing so has decreased over time. Age, education (mainly school characteristics) and SES at individual level were the most frequently assessed dimension, while occupation and education at individual level, religion and culture, social capital and disability were barely considered.

Chapter 4 Overview of reviews of the effectiveness of regulatory, voluntary and public–private partnership policies to improve food environments and population diet

Introduction

This chapter reports the methods and findings of the overview of reviews, including direction of effect stratified by population, and by equity dimension, for regulatory, voluntary and partnership approaches.

Methods

Eligibility criteria and quality appraisal

Fifty initial systematic reviews were identified in the overarching search strategy (see Chapter 2). Additional screening was comprised first, considering only those assessing the effectiveness of interventions. Within these, only the results sections or subgroup analyses containing a majority of studies meeting the project’s eligibility criteria (screened by one reviewer LB) were included. Second, the evidence syntheses without quality or risk-of-bias appraisal were excluded. Third, to limit primary study overlap between systematic reviews, as recommended by Cochrane,32 the ‘most recent, highest quality, “most relevant”, or “most comprehensive” systematic review for groups of overlapping reviews’ were selected.

The quality of each systematic review was assessed using the checklist for systematic reviews and meta-analyses developed by the SIGN with minor modifications, first, excluding systematic reviews without a quality or risk-of-bias appraisal, and second, merging the two lowest of four categories of overall quality proposed by SIGN. 33 The three resulting categories were as follows: ‘high’, ‘acceptable’ and ‘low’. We also added guidance for some of the questions to limit variations in interpretation between reviewers (see Appendix 3, Table 25). Three independent reviewers performed quality appraisal in pairs (LB, SR, CK) in the EPPI-Reviewer Web.

Primary study overlap is a frequent issue in an overview of reviews consisting of having the same primary studies included in multiple systematic reviews. This gives more weight to their findings than those of other primary studies, thus introducing biases, and making data extraction and data synthesis challenging to perform. 32 To overcome this, we employed Cochrane’s approach to ‘all non-overlapping reviews’, and selecting the most recent, highest quality, ‘most relevant’, or ‘most comprehensive’ systematic review for groups of overlapping reviews. The strategy for following this recommendation in the overview of reviews was as follows: First, we extracted general policy and study characteristics for all potentially eligible systematic reviews at this point (see Data extraction for more details). Second, following Cochrane guidance30 we documented primary study overlap in the systematic reviews by creating a matrix and calculating the ‘corrected covered area’. The latter considers the number of publications (including double counting) in evidence syntheses, the number of unique studies, and the number of reviews. 34 Overlaps ranging between 0% and 5% are considered as slight, 6% and 10% as moderate, 11% and 15% as high and more than 15% as very high. Additionally, we documented the number of reviews that overlap with others, the percentage of studies in each review that overlap with others, and the percentage of unique studies that overlap overall. Third, in each group of overlapping reviews, we selected the review that had the highest overall quality (for ‘most robust’), the most recent search date (for ‘most recent’), and that contributed most to the body of research evidence in terms of the number of studies included, topic (NOURISHING policy categories covered) and place (World Bank world regions covered) (for ‘most relevant or comprehensive’). Justifications for the choices were recorded for reasons of transparency. The selection was made by one reviewer (LB).

Data extraction

General review characteristics extracted in a standardised form consisted of which results sections or subgroup analyses were included and excluded, the number of studies included in these analyses, literature search dates in databases, funding, competing interests, and authors’ affiliations. Characteristics of the policies assessed within the selected results sections consisted of countries, policy categories using the NOURISHING framework,18 the types of outcomes assessed, and the equity domains (or effects for population groups that are prone to health inequalities) represented using the PROGRESS-Plus framework. 20 Data were extracted by one reviewer (LB) and a sample verified by another (CK).

The results of the interventions in the eligible results sections were extracted by policy governance approach, type of outcome and equity domain. Some results sections included non-eligible policies. To keep it simple, we extracted information for the whole section; however, results of policies that did not focus on the food environment were disregarded. Given that the results extracted by equity only covered three of the ten domains (gender, SES, age) of PROGRESS-Plus, we also extracted data on equity from the systematic reviews that had been excluded for reducing primary study overlap. This led to the documentation of two additional domains (race and education) as well as additional outcomes within the domains already covered. We also noted that some systematic reviews had assessed their data or drawn conclusions in relation to a hierarchy or ‘level’ of interventions and we documented these instances. Lastly, we briefly documented how the policies work (their mechanisms of action) as described by the review authors (usually as part of their results or discussions).

Data synthesis

As expected, a high degree of heterogeneity was observed among the primary studies and systematic reviews in terms of types of policies and outcomes evaluated. We adapted the effect direction plot developed by Thomson et al. 26 and Boon et al. 27 to visually display non-standardised effects by governance approach, type of outcome and quality rating, but at the review level rather than primary study level. We classified the direction of effect by type of governance approaches compared (regulatory vs. voluntary, regulatory alone, or voluntary alone). Direction of effect was documented independently from statistical significance, consulting primary studies when not reported in the systematic reviews where necessary. The same approach was applied to reporting the number of studies and total participants by outcome. We had planned to assess the level of certainty in the evidence for each outcome using the GRADE framework but information available was insufficient. Thus, as a compromise, the effect direction plot was also used to present jointly the direction of effect, review quality and indirectness.

Findings

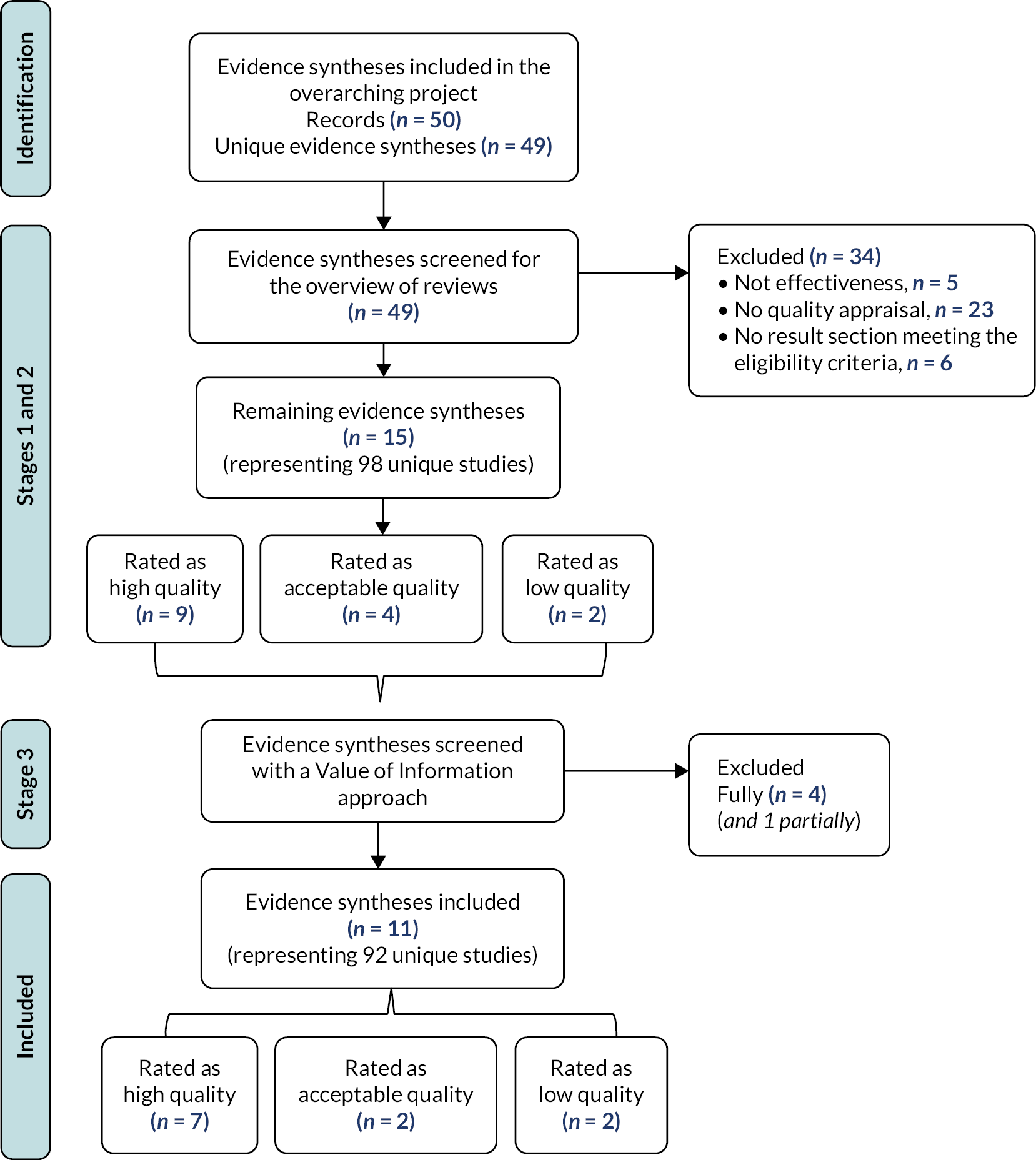

Included studies

As outlined in Figure 11, of the 50 (49 unique) evidence syntheses identified in the overarching search, 5 were excluded as they did not evaluate the effectiveness of policies, 23 for not appraising study quality and 6 for not including a results section meeting the eligibility criteria. This left 15 systematic reviews, which were assessed for primary study overlap. Nine were rated high quality (including three Cochrane reports), four as acceptable and two as low. The assessment of primary study overlap and selection of reviews in each overlapping group of reviews is presented in Appendix 5, Tables 27 and 28. The latter process led to the full exclusion of 4 additional reviews35–38 (2 of high quality, 2 of acceptable quality) and of 1 results section in an additional review39 leaving 11 reviews in the overview of reviews (see Appendix 5, Table 30). However, as explained in the methods, three of the reviews35,36,38 excluded because of primary study overlap were used to document effects on specific population groups (equity). The excluded evidence syntheses along with the justifications are listed in the Report Supplementary Material 1. For the sake of transparency, the latter also lists the five publications representing four systematic reviews that were excluded as part of the screening for the overarching project (see Chapter 2) because of an insufficient focus on governance (i.e. governance was either not documented or documented but not considered in the analysis).

FIGURE 11.

PRISMA flow chart representing the selection process. Adapted from the PRISMA template by Page et al. (2021). 16

Primary study overlap