Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as award number 15/126/05. The contractual start date was in October 2018. The draft manuscript began editorial review in September 2023 and was accepted for publication in May 2024. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Thompson et al. This work was produced by Thompson et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Thompson et al.

Introduction

This report details the work undertaken to establish the clinical and cost-effectiveness of the Mellow Babies parenting intervention for women experiencing psychosocial stress and their 6- to 18-month-old babies. It arose from a call commissioned by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Public Health Research (PHR) programme ‘15/126 Group-based parenting programmes for improving psychosocial health’. Although the disruption of the COVID-19 pandemic meant the trial was closed before reaching a fully powered sample, there is still significant learning to be gained from the data gathered and the experiences of the research team.

Rationale for research and background

Problems in children’s early social and emotional development are likely to have major long-term consequences for the individual and society;1–6 parental emotional well-being is a major determinant of a child’s social and emotional development. 7,8 Our work with data from the Growing Up in Scotland9,10 and Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children cohorts11–15 demonstrates strong associations between parental mental health, parenting behaviours and children’s psychiatric outcomes. Interventions designed to improve both parental mental health and the parent–child relationship are thus likely to produce substantial benefits in terms of child development and are potentially valuable public health interventions. 16

At the time of instigation this was the first definitive trial of a postnatal group-based parenting programme specifically designed for mothers with psychosocial difficulties who have children aged under 2 years, although we were aware of ongoing Incredible Years for Babies studies (NIHR PHR-13/93/10; ClinicalTrials.gov NCT01931917) and one on Circle of Security (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT02497677), both now completed. A recent (November 2022) topic scoping report commissioned by NIHR highlighted the continued need for randomised controlled trial (RCT)-level evidence for programmes with positive pilot studies, and Mellow Babies was listed as one such programme where more robust evidence was needed. 17

Mellow Babies is a group-based intervention programme with a dual focus on maternal mental well-being and parent–infant interaction. The programme involves attendance on 14 consecutive weeks between roughly 9.30 a.m. and 2.30 p.m. (during school hours) and there is a reunion 1–3 months later. Groups are kept to between 4 and 10 participants, with an ideal group size of 6. Groups can be offered at weekends, and transport, meals and a crèche are provided. Prior to the start of a Mellow Babies group, the group facilitator will visit the mother and child at home on at least one occasion to build rapport and address any anxieties or practical concerns the mother has about attending. During one of these visits, a video of a mealtime will be made for later use in the group, and key interactions in the video will be discussed on a one-to-one basis in preparation for the group. Mellow Babies is always offered as a single-sex group due to the need to create a safe space where participants can relate to each other’s experiences. Many women who have taken part in Mellow interventions will have experience of intrafamilial abuse and post-traumatic stress disorders (PTSDs). While work with fathers is extremely important, it remains true that mothers tend to be the primary caregivers of babies and the typical participant in Mellow interventions.

This research project builds on a large number of before-and-after evaluations of Mellow Babies (Mellow Parenting for children under 18 months) as well as a small-scale waiting list trial. 18 This review by MacBeth et al. (2015) points to some evidence of effectiveness, and subsequent studies have continued to develop this evidence base. 19–21 There nevertheless remains a need for more methodologically robust research trials. The intervention is fully manualised and has been delivered to many thousands of families: it is sufficiently mature to merit a definitive trial.

Objectives

The trial aimed to establish the clinical and cost-effectiveness of delivering Mellow Babies for mothers who are anxious and depressed, along with their 6- to 18-month-old baby. Specifically, it aimed to establish if attending Mellow Babies can improve maternal mental health and child social, emotional and language development at 8 months post randomisation and when the child reaches 30 months of age. Due to the early closure of the trial, prior to the sample being fully recruited, the objectives relating to outcome analysis were removed, and amendments made to the remaining objectives to focus on a series of process-related questions.

The final objectives aimed to maximise learning from implementation of the trial and focused on: (1) the effectiveness of recruitment and retention methods; (2) characterising use of other services during trial participation; (3) sociodemographic characteristics, mental health and participant experience in relation to trial/intervention participation; and (4) the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the operation of the trial. We aimed to address the questions below. This report was prepared with reference to the CONSORT and SPIRIT Extension for RCTs Revised in Extenuating Circumstance 2021 statement for reporting completed trials modified due to the COVID pandemic. 22

-

Which eligible mothers agree and which decline to participate in the intervention, and what reasons do they give?

-

Which recruitment methods were most effective and was there any variation in participant characteristics by means of recruitment?

-

How do sociodemographic characteristics and maternal mental health at baseline relate to:

-

level of participation in Mellow Babies?

-

group composition?

-

changes in parenting behaviours?

-

maternal mental state at 8 months post recruitment?

-

child development at 30 months

-

whether recruited pre-pandemic (to March 2020) or post (since Nov 2021)?

-

-

What is the nature of usual care offered to participants?

-

How do participants describe their experience of participating in Mellow Babies, which elements of the intervention are considered most influential, and is participation stigmatising?

-

Are there family characteristics associated with greater adherence to Mellow Babies?

-

Are there family characteristics associated with greater retention of follow-up?

-

How are the features (in terms of process and outcomes of care) of Mellow Babies valued by mothers?

-

What contextual factors facilitate or hinder the delivery of, and engagement with, Mellow Babies?

-

What specific impact did the COVID-19 pandemic have on the ability to run intervention groups and the trial?

The report has been structured around the four areas detailed in the preceding paragraph to provide a smooth structure and to avoid duplication of content. Each of the four areas pertains to an appendix, which provides more detailed methods and findings, and each of the appendices indicates which of the above questions it pertains to.

Methods

This was a single-centre RCT comparing outcomes for mothers and babies offered the Mellow Babies parenting intervention plus usual care with mothers and babies receiving usual care only. Participants were randomised 1 : 1 with minimisation to reduce imbalance between groups in terms of maternal age (< 25 years; ≥ 25 years), deprivation (working household yes/no) and age of child (≤ 12 months; > 12 months).

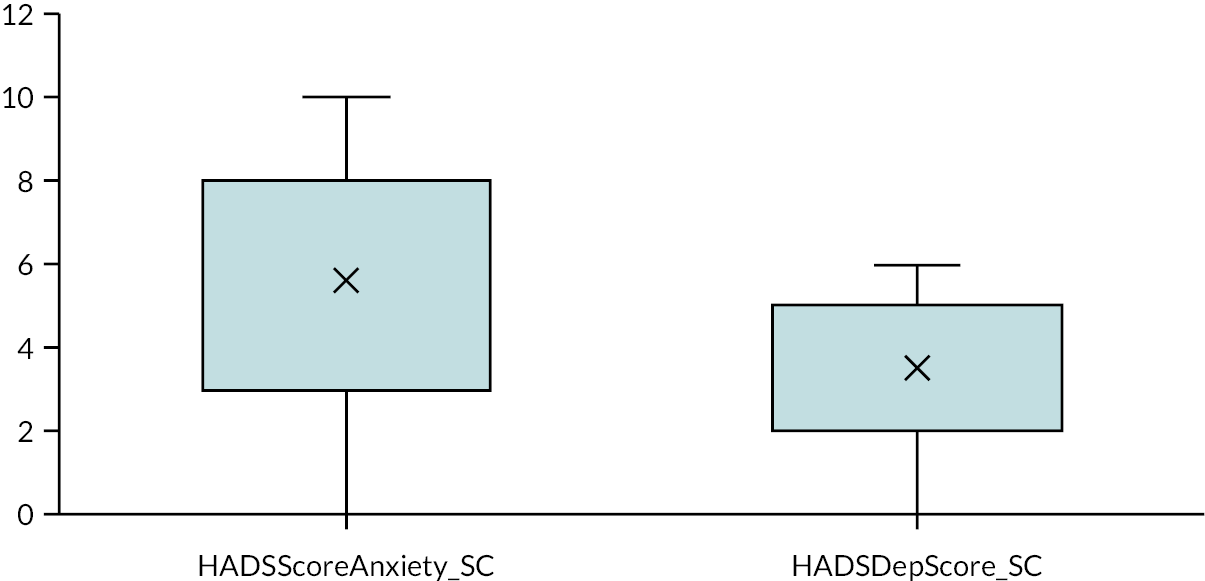

Eligible participants were women aged ≥ 16 years with primary caregiving responsibility of a child aged 6–18 months at the time of randomisation, who resided in Highland Council area (Scotland) and who scored above a defined threshold (≥ 85th centile) on either the anxiety (≥ 11) or depression (≥ 7) subscales of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). 23 Women who were substance dependent (if not stable on recovery programme); were unable to speak or write in English language; who had twins or other multiple births; or who had a baby with significant learning difficulties were excluded from the trial. Women could only take part in the trial once and therefore were excluded from participation for subsequent children. Participants were identified via three core recruitment strategies: health professional referral [e.g. health visitor (HV) or general practitioner (GP)]; self-referral having received a letter of invitation via NHS Patient Identification Centre (PIC) sites; or self-referral through response to advertisements on social media or posters within the local community.

For full details of the trial protocol (v20) see https://fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/15/126/05. Screening and baseline data collection were conducted according to the original protocol. Recruitment was paused, and follow-up data collection commenced in a revised form during 2020 and 2021 due to COVID-19 pandemic restrictions. While the original protocol featured home visits, these data collection appointments had to be conducted remotely. Video conferencing [Zoom (Zoom Video Communications, San Jose, CA, USA) or Teams (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA)] was offered to all participants, but most elected for a phone appointment. All measures for the 8-month post-randomisation assessment could be completed by phone, whereas the 30-month measures were amended because the Bayley Scales required direct interaction with and observation of the child. This was replaced by the Ages and Stages Questionnaire, Third Edition (ASQ-3)24 and the Ages and Stages Questionnaires: Social-Emotional, Second Edition (ASQ-SE2). 25 Although we were able to return to home visits in 2022, the ASQ remained in place as the first 30-month follow-ups for the new cohort took place after we were initially asked to close the trial down and it was thought best to not increase participant burden if outcome analyses would not take place. All follow-up data collection ceased at the end of March 2023 when the final close-down plan was approved by Research Ethics Committee (REC) and the funder. Note, although an add-on study regarding Mellow Babies online had been included in the final protocol, delays in research governance processes, and the subsequent early closure of the trial, meant this work did not take place.

The research team was unable to conduct outcome analysis as was originally planned due to the sample size being too small. No between-group clinical or cost-effectiveness analyses were conducted. Data collected from participants at baseline, 8 months post randomisation and when the child reached 30 months of age were analysed descriptively and subgroup comparisons were conducted based on the revised set of questions above. Note that, due to the small sample size and limited value in comparing subgroups from this sample, no correction for repeated testing nor replacement of missing values has taken place. Any descriptive data are presented at face value as a basis for further discussion. This report provides a synopsis of the findings. Full results are presented in a series of appendices grouped around themes among the research questions.

Process evaluation interviews

Process evaluation interviews were conducted with trial participants and group facilitators. Interviews were conducted by the PhD student (JT) and took place face-to-face, via telephone, or via video call, depending on the preference of the participant. Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed and analysed using thematic analysis. 26 The number of each type of interview is shown in Table 1.

| Type of interview | Number |

|---|---|

| Pre-group interviews with mothers | 1 |

| Telephone fidelity checks | 9 |

| Mid-group interviews with facilitators | 2 |

| End group interviews with mothers | 14 |

| End group interviews with facilitators | 6 |

| Total | 32 |

Results summary

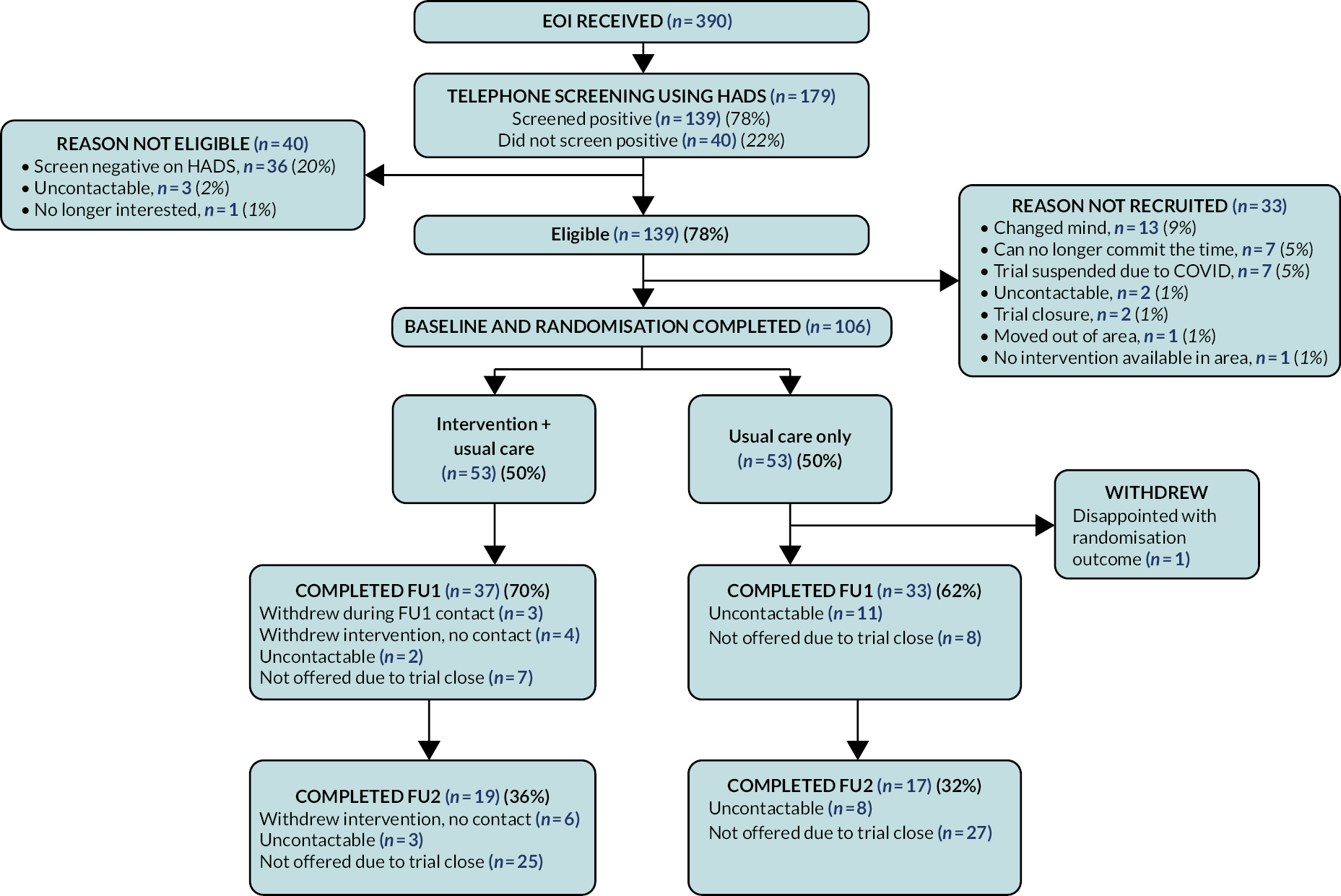

Trial recruitment and retention

With reference to Appendix 1, we successfully recruited 106 participants for the trial (53 per arm). It took several months to establish the most effective recruitment strategy, but once this strategy was in place the system worked well with high throughput. The most successful method of recruitment was PIC letters which led to the recruitment of 75 women, representing 1.7% of all those approached using this method. HV referrals were comparatively few (26 of those eligible), highlighting the importance of approaching potential participants directly and not relying solely on practitioners as gatekeepers. However, qualitative interviews with women who participated suggested having a PIC letter in tandem with a HV flagging up the trial to a participant seemed to be perceived as particularly effective. The screen positive rate was 78%, indicating that using mainly self-referral did not lead to a disproportionate number of ineligible individuals expressing interest in trial participation.

Descriptive subgroup analyses show little variation across key sociodemographic characteristics or mental health measures for this participant group. It is noteworthy that, although the majority of participants were ‘doing well’ in relation to sociodemographic characteristics such as employment status, socioeconomic deprivation, relationship status, and social support, there were still significant levels of mental ill health. We have demonstrated that it is possible to recruit and retain a good proportion of participants even when they are experiencing mental ill health. Future studies should take care to focus on the specific issues being faced by families rather than using sociodemographic characteristics exclusively as a proxy measure for likely level of need. This analysis also showed little association between any of the sociodemographic characteristics and mental health indicators at baseline and outcomes at either of the follow-up points. While there appears to be a direct relationship between relative affluence and taking part in a wider range of activities more frequently with their child, there are few direct associations on other measures. Together, these findings reflect the views of Goyder and colleagues,17 that it is important to adopt a flexible approach sensitive to families’ individual needs.

Overall, our methods of recruitment and retention in this study were successful, although some trial and error was required to refine these, and they required more time and resources than had been anticipated by the recruitment team. There is a clear need for significant investment in good research infrastructure to allow a flexible and personalised approach to recruitment and study engagement.

Health economic evaluation

With reference to Appendix 2, response rates to the EuroQol measure of overall health and quality of life [EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L)] and Participant Cost Questionnaire (PCQ) were high, with no missing item data for EuroQol-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) and very limited missing data for the PCQ. For EQ-5D, 100% of participants completed this questionnaire at baseline and 8-month time points, reducing to 92% at 30 months. For the PCQ, 93% of participants completed this questionnaire at 8-month time point, reducing to 86% at month 30. This suggests that both questionnaires were appropriate for this population and respondent burden was not an issue. In addition, in a future trial, a simplified PCQ may be appropriate given few participants reported accessing NHS or other services during the trial. Further, augmentation with qualitative data would be useful to fully elucidate participants’ experiences of the nature and accessibility of NHS services available to them, especially as these questions focused specifically on maternal mental health and concerns about their child’s development (where services are often difficult to access or simply unavailable). While we did not report EQ-5D data by the arm of the trial, but rather overall summary statistics, on average, these scores increased at the 8-month time point, but they then decreased at the 30-month time point, albeit remaining above baseline scores. Further research is needed to determine the cost-effectiveness of the Mellow Babies intervention.

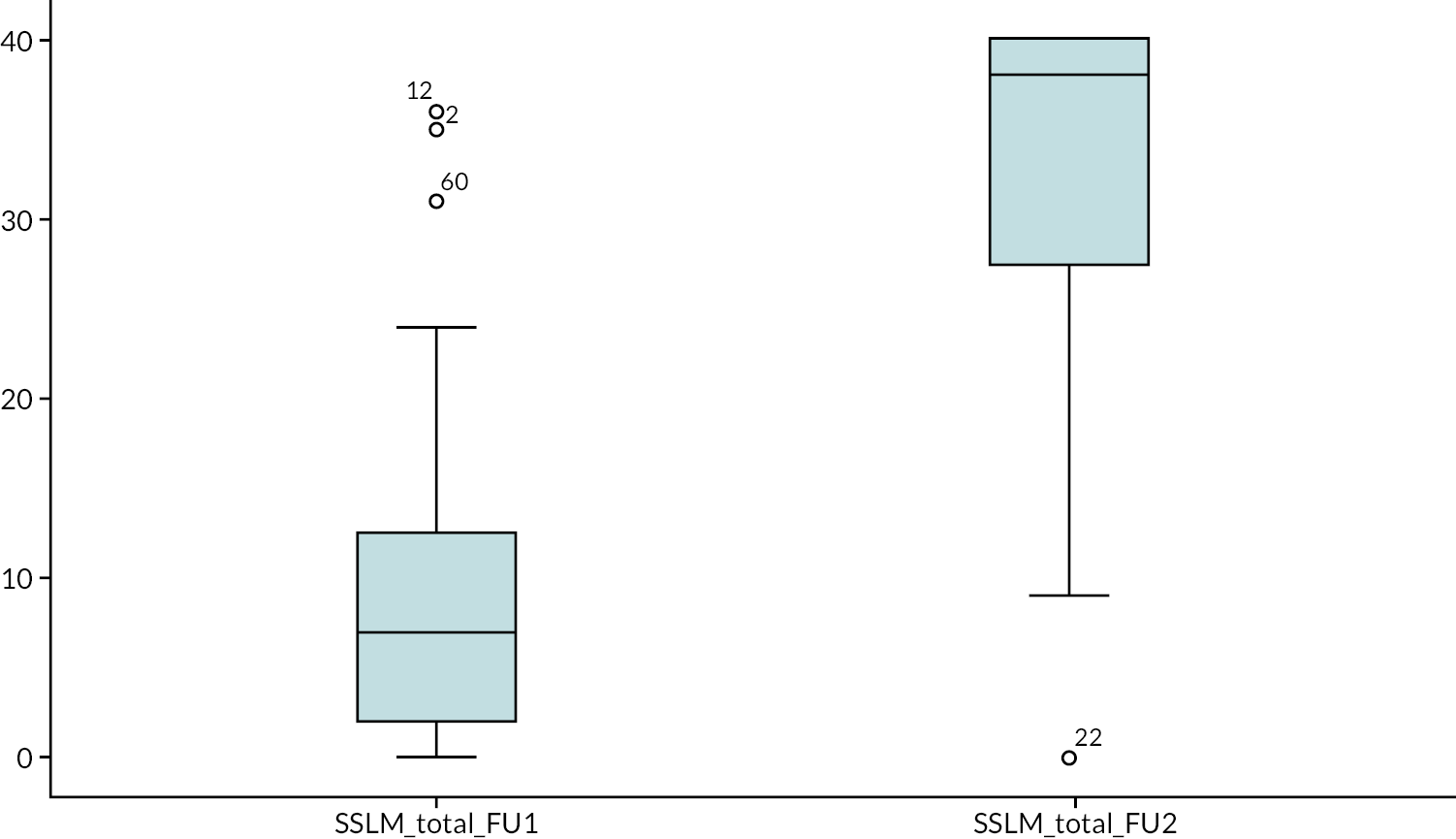

Intervention participants: characteristics, cohesion and process

With reference to Appendix 3, the characteristics of the five intervention groups which were able to take place (group 3 could not operate due to COVID-19 pandemic restrictions, and group 7 could not due to trial close-down) varied in a number of ways: participant characteristics and group practicalities were different. Only two group sessions took place over the usual full 14 sessions, with the remaining groups having to curtail material for logistical reasons relating to the pandemic (group 2), participant absence (group 5) and facilitator availability (group 6). Most participants took part in at least one session, and the proportion maintaining involvement until intervention completion was good in three of the groups. Participants tended to live in less rural areas of Highland, most likely due to the limited capacity to offer groups in remote areas (i.e. lack of critical mass of participants, lack of appropriate venue and childcare, long travel distances for facilitators). Qualitative interviews with intervention participants and facilitators highlighted a range of important themes around recruitment, delivery, participation and impact of the intervention.

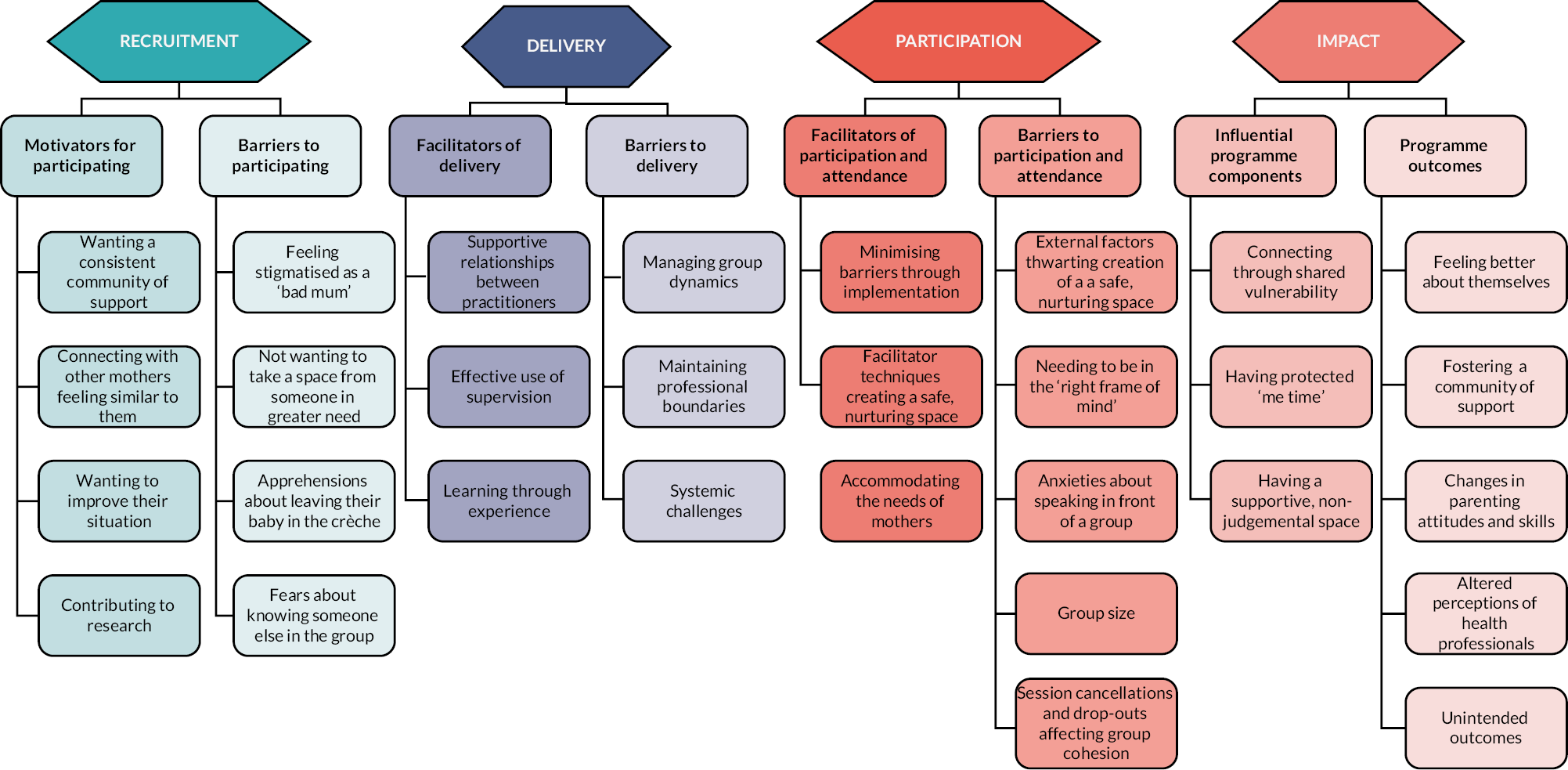

Participants discussed being motivated by a need for a sense of community, connection and support, as well as a desire to contribute to the research. They also discussed barriers to participation, including a sense of stigma (being a ‘bad mum’) and a concern they would know people in their group, as well as concern that they would be taking the place of a ‘more deserving’ participant. Group delivery was facilitated by the practitioners supporting each other, capitalising on their accumulation of experience, and being able to access good supervision to discuss any issues. Managing group dynamics and maintaining professional boundaries were challenges faced by facilitators which may have been improved with enhanced training and increased experience. Other challenges related to the logistics of trying to work part-time as a group facilitator, requiring a lot of non-contact work time, on top of other jobs/work tasks. The flexible and accommodating approach of the intervention (e.g. providing transport and adapting content to meet individuals’ needs) as well as the warm and nurturing approach of the facilitators were highlighted as significant positive factors for participants, and these are key to the ethos of the Mellow Parenting approach. Participants discussed external factors, such as the nature of the venue, and internal factors, such as needing to be in the right frame of mind, as sometimes hindering the intervention. There were anxieties about speaking up in a group which was naturally impacted by group size and the specific dynamics within each group. Group cohesion was also felt to be impacted by participants not attending all sessions and some sessions needing to be cancelled. Finally, a range of positive aspects of the intervention components and outcomes were discussed, including a sense of cohesion through shared vulnerability and the value of a safe, protected time and space. Participants reported feeling better about themselves, having developed a sense of community, having positively altered their perception of health care professionals and having developed new skills in parenting. There were also some negative outcomes discussed, including the impact of PTSD on the experience of group participants, highlighting the need for wrap-around support of mothers and awareness of individual vulnerabilities. Sharing more details about the intervention content and style (e.g. the use of the crèche) with potential participants could also help mothers take part in the intervention feeling more informed.

Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic

With reference to Appendix 4, the COVID-19 pandemic had a significant impact on the trial. Although the trial had been established by February 2020, with the recruitment milestone of 40 participants and 2 established intervention groups met, this activity was forced to cease in March 2020. Recruitment, intervention groups and face-to-face follow-up visits were suspended due to the implementation of lockdown for the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020. Due to the nature of data collection (within participants’ homes) and of the intervention (requiring face-to-face group interaction), it was not possible to recommence recruitment until restrictions were almost completely lifted. Recruitment recommenced in November 2021 and ran until September 2022, when we were asked to cease recruitment due to the decision not to provide further funding to allow the trial to recruit to completion. We were able to run five intervention groups (with a further two recruited but unable to commence), although one of these had to stop midway through in March 2020. As 14 participants randomised to the intervention then could not receive the full intervention, our Data Monitoring Committee advised we exclude those participants and associated controls from any outcome analysis, reducing our sample size by 28 (leaving us with 78).

There were no differences between the participants recruited pre and post pandemic on any of the key sociodemographic or mental health characteristics measured at baseline. Retention to follow-up was equally good pre and post pandemic. Use of primary care services as measured at follow-up (during pandemic restrictions) was low in general, which is most likely due to the reduced availability of primary care services both during and since restrictions. Trial logistics were severely impacted, with a need for the study team and intervention team effectively to plan from the bottom up in a new, post-COVID context, including changed primary care priorities, different perceptions of potential participants, new intervention venues, new crèche arrangements, new group facilitators, and increased workloads for the [NHS research, development and innovation (RD&I)-based] recruitment staff. The importance of working across agencies and pulling together as a team with a shared goal was important, and we were able to re-establish a viable trial within a relatively short period. Nevertheless, the extra time and funding required to complete the trial to protocol was prohibitive, and the funder decided to close the trial as close to the original end date as possible.

Overall, the COVID-19 pandemic had a devastating effect on what was otherwise a viable trial which would have gone a long way to answering a range of questions, not only about the effectiveness of Mellow Babies for mothers experiencing psychosocial stress, but about the lived experience of this population and how we might better engage them in research in future.

Discussion

This trial was not able to establish the clinical and cost-effectiveness of the Mellow Babies parenting intervention for women experiencing psychosocial stress and their 6- to 18-month-old babies. Due to the close-down of the trial prior to recruiting to the planned sample size, we were unable to conduct any outcome analyses due to insufficient statistical power. There has been some scope for learning, primarily in terms of recruitment and retention strategies, and the rich qualitative data collected through interviews has allowed a thorough exploration of the intervention, including group process.

The recent scoping review by Goyder and colleagues,17 ‘Parenting engagement and support interventions for high risk groups’ provides a useful overview of the current state of the field, and suggests some research questions that could be included in future studies:

-

What are the most effective strategies for identifying and engaging families at increased risk in order to offer parenting interventions?

-

How feasible, acceptable and effective are the assessment tools currently in use to identify those who benefit most from the offer of additional support?

-

What forms of support or content do parents want and need most from parenting programmes; what aspects of current programmes do they value most?

-

What factors make it easier for families to accept or sustain engagement with parenting interventions? What are the reasons that families find it difficult to accept or sustain engagement with parenting interventions?

The present report offers data in relation to each of these questions, although this is limited in the context of an incomplete trial and without having had the time to interview control participants as well as those randomised to the intervention arm.

In terms of recruitment (Q1 above), there is a need to have both direct communication with potential participants (e.g. the PIC letter system) and engagement from practitioners working with families (HVs, GPs and third-sector support staff) to optimise the approach. We are aware that HVs were less engaged with the trial than we had anticipated for a range of reasons, not least the extreme pressure that services were under in terms of reduced resources, reduced staffing capacity and increased needs in the population. We also learnt that the element of randomisation was a significant deterrent to referral by practitioners: they were simply unhappy with suggesting to women in their care that they put themselves forward for a 50 : 50 chance of receiving an intervention they would likely benefit from (in the practitioner’s perception). This aligns with recent findings from Rose et al. 27 that practitioners experience role conflict when asked to recruit to clinical trials, and raises issues around how to manage equipoise when trialling an intervention already popular in practice. One solution to this would be to conduct trials such as this on a regional/service cluster randomisation basis, so that no practitioner is facing this perceived dilemma: the intervention is either available in their area or not. Additionally, feedback from participants indicated that when engaging women, the description around improving bonding with babies may lead to negative feelings about participation, particularly where HVs had made the referral, while reassuring women about how the crèche operates and that babies can come into the group if they do not settle, may reduce anxieties in attending groups. The potentially pivotal role of clinicians/practitioners in recruiting to clinical research studies is clear, and it is important to consider the specific needs/concerns within the context of each given study. 28,29

In relation to the feasibility and acceptability of the assessment tools used in screening for trial eligibility (Q2 above), although we did not gather formal data on this, we received no negative feedback. Prospective participants understood that the trial was aimed at women who were experiencing symptoms of anxiety and/or depression. Some women chose not to go ahead with screening once they had discussed eligibility with the recruiting research nurse and better understood this criterion. There is clearly a balance to be gained where recruitment materials make it clear that the research is aimed at women in psychosocial distress, but does not serve to stigmatise or prevent women from coming forward. Recent work in Highland has shown a strong tendency for women to self-censor their requests for mental health care: there was an expressed sense, especially in a climate of low resource, that women compare themselves to those in more extreme distress and this serves to minimise their own. 30 In the case of The Mellow Babies Trial, recruitment materials were designed with patient and public involvement (PPI) input to ensure language struck an appropriate balance, and the research nurse conducting initial phone calls could then explain more fully the criteria, and use the conversation in the context of her clinical experience to help mothers decide if it was worth going ahead with screening.

In relation to which aspects of the programme were most valued by parents (Q3 above), there was a clear recognition of the need for support, which was often reported to be lacking (or experienced negatively) through established services (e.g. health visiting). The fact that other women within intervention groups were also facing challenges in new parenthood was highlighted as a key strength, with other parent and baby/toddler groups being perceived to be full of parents who were happy and knew what they were doing. The context and ethos of the Mellow Babies group seemed to act to remove the stigma and allow participants to express their challenges and feel a sense of normalisation and validation. Other key positive areas of the intervention highlighted by participants were the sharing of life stories by both participants and facilitators, which reduced barriers within the group, and the provision of the crèche, both of which may be challenging to implement in mainstream services.

We have not been able to fully explore factors that encourage sustained engagement (Q4 above) with the data we have. We did not interview mothers who dropped out of the intervention/research (although simple comments were recorded where possible, such as ‘no time to take part as maternity leave has ended’). Some of the qualitative analysis on group process indicates that group composition, including number of participants, age of children and personal characteristics, were key in the intervention groups becoming cohesive (or not) which was perceived by the participants to have encouraged their sustained participation. As it stands, we had very good retention in the face of significant mental health needs in our sample, possibly due to women having otherwise good support in their lives, as indicated by sociodemographic data. Where women did drop out, it tended to be due to mental well-being concerns or life being too overwhelming and group participation having to be de-prioritised. Outside of a trial setting, and in the context of a sustained intervention programme, there is more likely to be the opportunity for such participants to come back to the intervention (i.e. attend a subsequent group) as strict age and other eligibility criteria would be less likely (e.g. Mellow Parenting tends to be more flexible with its age criterion).

The main challenges to this trial were pragmatic, including difficulty establishing a fruitful recruitment strategy and establishing the infrastructure for intervention delivery in the early months, and the interference of the COVID-19 pandemic once systems were in place and the trial was running successfully. The challenges are outlined in greater detail in Appendix 4 and include a need to redirect our recruitment efforts away from relying solely on HVs and other practitioners towards direct communication with potential participants (PIC letters), difficulties in obtaining critical mass of participants within a reasonable time frame in a low population region, and having to establish an infrastructure for intervention delivery where none previously existed. Nevertheless, the trial was established as viable on two separate occasions (initial start-up and post-pandemic re-start): the final challenge was the need for a longer time period and therefore funds to be able to recruit to power.

There are of course some limitations to consider, which are relevant despite no primary outcome analysis. The sample, although showing significantly poor mental well-being, was otherwise relatively advantaged from a sociodemographic perspective. The applicability of these findings to a wider sociodemographic group is therefore limited. Similarly, this trial focused on mothers for pragmatic reasons (see Publications), so findings cannot be extended to fathers or other adults with parental responsibility. The pragmatic difficulties faced in implementing the intervention raise questions about its viability as a sustained programme within usual services, especially in a region like Highland with a relatively small population size and lack of relevant infrastructure. Specialist practitioner posts are often vulnerable, where there are services essentially offered by lone individuals or very small teams (e.g. infant mental health service). However, this is difficult to assess concretely within the artificial context of a RCT: our findings show, for example, that HVs would have been much more willing to refer mothers had there been the certainty of receiving an intervention. Further qualitative data collection would have been useful to help elucidate the experiences of those who left the intervention early, of those in the control group, and of HVs and other practitioners in the field. Had we been able to interview representatives from each of these groups, our understanding in relation to the secondary questions addressed in this report would have been more comprehensive.

The research team and the intervention team worked extremely hard to engage with key partners and stakeholders in the research to ensure the delivery of intended outcomes. Our connection to NHS Highland and Highland Council was critical: NHS Highland RD&I was the only local organisation able to provide an appropriate infrastructure for recruiting and retaining intervention practitioners, and we relied on the collaboration with the public health department to access the PIC letter system. Health visiting is managed by Highland Council, where key stakeholders were included at the planning stage and as co-investigators in the trial. Their input in overcoming pragmatic barriers was invaluable. Similarly, establishing and maintaining good relationships with these stakeholders allowed a smoother interaction with HVs and other practitioners in participant-facing roles. Although we did connect with colleagues in third-sector services as part of our engagement work, recent Highland-based work, in the post-pandemic, post-Brexit climate, has highlighted how central the role of the third sector is in supporting young families. 30

There are several take-home messages from this research:

-

There is scope to conduct a new trial of Mellow Babies, ideally multisite and including cluster randomisation to facilitate recruitment.

-

It is possible to recruit and retain mothers who are experiencing significant psychosocial stress into trials, provided the infrastructure is realistic and flexibility in approach can be employed.

-

Recruitment needs to be direct, with potential participants being trusted to be their own gatekeepers when putting themselves forward for research. We need to avoid potential paternalism/maternalism in parenting support research.

-

Trials need to be realistically resourced/have a robust infrastructure. Recruitment and group facilitation should ideally be carried out by staff dedicated to these roles – a larger trial would help this.

-

The need for a larger trial with better infrastructure brings the focus back to conducting trials in large urban areas and marginalising those in more remote or rural areas. We need to be more thoughtful about how to ensure all participants meeting clinical eligibility have the chance to participate in an intervention that could realistically and sustainably be delivered to them as part of usual services.

-

Solid engagement with the third sector will be critical for the above.

Patient and public involvement

Both the original Chief Investigator (CI) (PW) and the final CI (LT) had already been investigators on other similar trials [e.g. Trial of Healthy Relationship Initiatives for the Very Early years (THRIVE); Henderson et al. , 201931] which we used to inform our approaches to effective engagement, recruitment, and retention in designing our materials and methodological approach. We recruited a previous THRIVE trial participant to offer PPI input at the start of the trial: she gave feedback on our recruitment posters and methods. We were not able to recruit any further PPI group members before we had to pause study recruitment during the COVID-19 pandemic (March 2020).

We worked closely with the local family nurse partnership (FNP) practitioners who kindly recruited teenage mothers on our behalf in order for the trial manager to meet with them to discuss their thoughts and opinions on various aspects of our recruitment approach. The trial manager met with two teenage mothers identified by FNP in August 2019 to discuss material the team were preparing for Facebook, as well as discussing how best to target their peers for recruitment. The meeting was extremely helpful, and we received insightful comments. They suggested that face-to-face engagement within established community groups would be more effective than social media advertisements, as they did not tend to engage online. They suggested local parent/family groups which the trial manager made contact with/met the facilitator of. There was a need for both virtual and face-to-face approaches. Over time, the research team built a network of third-sector contacts and attended local community groups (run by NHS early years practitioners and third sector) in tandem with social media and other advertisement. Although the families we met in August are not permanent members of the trial’s PPI group, the FNP has assured us they are happy to continue to work with the trial team in order to source young mothers for any future service user meetings.

We successfully recruited four participants from the pre-pandemic period to take part in a discussion about their experiences of participating in the trial and to provide direct feedback on recruitment methods and research procedures in the post-pandemic period. We met with two of them in July 2022 and there were some suggestions for small amendments to our documentation, which could not be implemented as we were asked to stop recruitment soon after. On the whole, the feedback from these participants was positive about their experience as trial participants. The two participants who were unable to attend this session were sent a summary of the discussion via e-mail and given the opportunity to comment (no comments were received).

We plan to generate a brief version of this report to make available (online) to all study participants and any member of the public who might be interested. Although we had planned to have a public-facing dissemination event, there may be little scope for this given the changed research questions and limited resources available. While we are unable to report on the original intended outcome for the trial, there would be merit in discussing the findings in the context of other work happening locally (i.e. the development of perinatal and infant mental health services). LT is working with NHS Highland on the perinatal and infant mental health workstream at present and will liaise with them around effective dissemination.

Equality, diversity and inclusion

Participants: The study was open to any mother meeting the inclusion criteria, including via self-referral. Highland is not an ethnically diverse region, with ˂ 2% of residents not of white European extraction. 32 We considered the main barriers to participation to be stressful lives, mental health, social isolation, literacy/education and living rurally or remotely. There is evidence that parents experiencing these stressors are less likely to engage in parenting interventions. 33–36 Measures to overcome these as much as possible were incorporated into the study design, partly based on the design of the Mellow Babies intervention model. Specifically, home visits were used for obtaining consent and gathering baseline and follow-up data. This meant that all measures, although mostly questionnaires, were conducted in an interview style with the researcher taking time to fit with the participant’s schedule. The participant information sheet was designed to be accessible to those with literacy difficulties, and we sought PPI input into its design. A flexible approach to communication, including the use of whichever means was preferred by the participant and the adoption of a patient approach to reminders (i.e. no ‘three strikes and you’re out’ type rule) allowed us to work around participants’ busy and often stressful lives. Critical to this study, it also allowed mental well-being to be considered: if a participant was having a difficult day and needed to reschedule a visit, we accommodated this. Although living remotely will have been a barrier for some potential participants (i.e. too far to travel to a more populous area with enough critical mass to establish an intervention group), we were careful to target recruitment to areas closer to the urban centres. Where participants did not have access to a car, transport was always provided to allow participation in intervention groups.

We successfully enrolled 106 women with babies 6–18 months old living across the Highland Council region in Scotland. Women enrolled in the trial all scored above the threshold for anxiety and depression, 61% stated they had a diagnosed mental health condition (usually depression or anxiety), and 50% had been prescribed a mental health medication since the birth of their baby. Baseline data showed a high level of education, a high level of paid employment and a high level of home ownership among participants, and most were currently in a relationship with their baby’s father. There were also low levels of stress in terms of life events. This suggests that there is more work to be done to ensure that those experiencing adversity in sociodemographic terms have the opportunity to participate and that barriers to participation need to be better understood. However, while the sample as a whole appeared to be ‘doing well’ on these measures, some participants faced specific challenges. What we do know from those who were screened or recruited is that mothers’ non-attendance when randomised to the intervention arm was linked to life stressors, including moving house, returning to full-time work after maternity leave, not feeling able to commit the time to the group, planned absences during the group, and living too far away from where the group was being delivered. Mothers withdrew from the programme due to life stressors, mental health and child factors. Reasons included experiencing a family bereavement, finding the group made PTSD symptoms worse, and the child not being able to settle in the crèche. Lack of participation in follow-up appointments was also predominantly due to life stressors and participant mental health, including experiencing a recent miscarriage, the birth of a child, time pressures, or not ‘being in a good place’. However, the majority of participants who did not take part in a follow-up did not respond to contact from the research team, so we are unable to determine the reasons for non-participation from these mothers.

Research team: The CI for the majority of the trial was a senior, white, male, medically qualified professor. Once he retired (December 2022), this role was taken over by one of the senior co-investigators, a white female senior research fellow, for the final few months of the trial. The rest of the staff on the trial were female, all of white European ethnicity. Our team included staff from different disciplines (e.g. psychology graduates, medical doctors, nurses) and with a range of experience. The main posts for the running of the trial, the Trial Manager/Research Fellow, Research Assistant, and PhD student, were all young, female, early career researchers. We believe the trial has contributed to developing their careers and capacity within the field. We ensured all staff had the opportunity to contribute to key trial decisions and to train in new areas of skill development. The trial was presented at international conferences by the early career researcher staff members. As well as our PhD student, we had a master’s student (a young female medical student) work on the process evaluation in the first year of the project, and she presented her paper at a conference.

Impact and learning

The main impact of The Mellow Babies Trial has been to demonstrate that complex intervention trials of this nature can be viable in areas lacking a large or diverse population or significant trial infrastructure. It is possible to recruit mothers experiencing psychosocial stress, especially when approaching them directly (i.e. no dependence on a ‘gatekeeper’). It is important to be able to conduct trials away from the main population centres if we are to be confident that our findings are truly applicable to the population more widely. Trials need to be realistically planned, and funded, to be able to allow people from remote and rural areas to participate, or for smaller population centres without the level of trial infrastructure of larger cities to be able to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions in a real-world setting.

Although the participant group was representative of the local population in demographic terms, they showed a relative advantage compared to the target population for the intervention (which is likely to experience a greater disadvantage). 20,21 It is likely more mothers experiencing sociodemographic disadvantage might have been recruited if practitioners working with families had more capacity to recruit to the trial. While the PIC letter has been the most effective means of recruitment, it may be that a formal letter would have been off-putting to some potential participants. A two-pronged approach, involving a letter and direct practitioner contact, would be ideal. It could also have been useful to work more directly with third-sector organisations, who often have more direct contact with families, in recruiting participants. Although we did make contact with as many organisations as possible, in both the pre- and post-pandemic phases of the trial we were just getting to the stage of establishing procedures when we had to stop recruitment.

Regarding trial infrastructure, conducting a trial in Highland meant planning based on tenuous resources. For example, when we submitted the funding application, there was a mobile crèche in operation locally that would have been able to staff the intervention crèche facility. By the time the trial started, this business was no longer in operation and there was no alternative. We worked with local nurseries to develop a preferable alternative (hosting the intervention groups within nurseries where child care could be absorbed), but this could not be reinstated post pandemic partly due to the continued restrictions on adults entering the nursery buildings, but also due to new national legislation increasing early education provision meaning that nurseries no longer had the capacity to host the intervention group or to absorb the child care. Staffing the intervention also presented significant challenges, and ultimately the NHS was the only organisation with the size and infrastructure to accommodate staff in secure posts to allow their sustained involvement in the trial.

The Mellow Babies Trial has been able to demonstrate considerable desire for this type of intervention in the community. Almost 400 mothers expressed interest in the trial. Although only 25% of these ultimately became participants, the artificial barrier created by trial recruitment procedures is almost certainly a significant factor.

We have actively disseminated the learning from this work as much as possible and will continue to do so in the coming months to ensure learning is maximised among key stakeholders. We have presented the protocol and aspects of the development at the following conferences:

-

Thompson L, Buchanan L, Christie H, Wilson P. The Mellow Babies Trial: Early Process Evaluation of a Complex Intervention. Oral presentation at the NHS Highland Research, Development, and Innovation Conference, 2019.

-

Thompson L, Wilson P, The Mellow Babies Trial team. The Mellow Babies Trial Protocol. Poster presentation at the NHS Highland Research, Development, and Innovation Conference, 2019.

-

Tanner J, Wilson P, Thompson L. Group Processes and Interpersonal Change Mechanisms Within a Group-based Intervention for Mothers and Their Infants. Oral presentation at the World Association for Infant Mental Health Congress, 2023.

There are no plans to publish any of the findings contained within this report separately. The interview data have been used in a separate analysis (i.e. different research questions and methods) by Jessica Tanner, a PhD student, as part of her thesis focused on group processes in parenting interventions, successfully examined on 29 April 2024. The paper titles are:

-

Tanner J, Wilson P, Wight D, Thompson L. The importance of group factors in the delivery of group-based parenting programmes: a process evaluation of Mellow Babies. Front Child Adolesc Psychiatry 3:1395365. https://doi.org/10.3389/frcha.2024.1395365

-

Tanner J, Wilson P, Wight D, Thompson L. The Mellow Babies parenting programme: role of group processes and interpersonal change mechanisms. Front Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2024;3 https://doi.org/10.3389/frcha.2024.1395363

As stated in Patient and public involvement, we plan to generate a brief version of this report to make available (online) to all study participants and any member of the public who might be interested. Although we had planned to have a public-facing dissemination event, there may be little scope for this given the changed research questions and limited resources available. While we are unable to report on the original intended outcome for the trial, there would be merit in discussing the findings in the context of other work happening locally (i.e. the development of perinatal and infant mental health services). LT is working with NHS Highland on the perinatal and infant mental health workstream at present and will liaise with them around effective dissemination to key stakeholders.

Implications for decision-makers

Due to the close-down of the trial prior to recruiting to the planned sample size, we were unable to conduct any outcome analyses due to insufficient statistical power. This limits our capacity to make recommendations for decision-makers. There is, nevertheless, some scope for learning, primarily in terms of recruitment and retention strategies, and the rich qualitative data collected through interviews have allowed a thorough exploration of the intervention, including group process. As articulated in the Discussion section, there is scope to continue to conduct trials of parenting interventions, including of Mellow Babies, taking into account the learning from this trial regarding logistics and the acceptability and effectiveness of our approach to recruitment and retention. Indeed, research evidence regarding the impact of Mellow Babies continues to accumulate,19–21 which provides useful information for decision-makers, but not at the level of a definitive effectiveness trial. Our take-home messages from the Discussion form the basis of implications for decision-makers:

-

There is scope to conduct a new trial of Mellow Babies, ideally multisite and including cluster randomisation to facilitate recruitment.

-

It is possible to recruit and retain mothers who are experiencing significant psychosocial stress into trials, provided the infrastructure is realistic and flexibility in approach can be employed.

-

Recruitment needs to be direct, with potential participants being trusted to be their own gatekeepers when putting themselves forward for research. We need to avoid potential paternalism/maternalism in parenting support research.

-

Trials need to be realistically resourced/have a robust infrastructure. Recruitment and group facilitation should ideally be carried out by staff dedicated to these roles – a larger trial would help this.

-

The need for a larger trial with better infrastructure brings the focus back to conducting trials in large urban areas and marginalising those in more remote or rural areas. We need to be more thoughtful about how to ensure all participants meeting clinical eligibility have the chance to participate in an intervention that could realistically and sustainably be delivered to them as part of usual services.

-

Solid engagement with the third sector will be critical for the above.

In addition to the above specific implications, there is a need to think more generally about the context and infrastructure around trials of complex interventions such as Mellow Babies. The trial was in many ways constrained by resource availability locally. In order to ensure we reach underserved populations there need to be higher-level actions (infrastructure/funding) that take into account the added contextual barriers (e.g. outsourcing of resources at extra cost), in keeping with NIHR INCLUDE guidance37 and the ongoing NIHR Under-served Communities Programme. 38

Although recruitment was successful in this study, it involved considerably more staff time and logistical effort than anticipated. Despite any efforts made, the trial was not able to reach those in the most remote areas, which in part was due to logistics and resources, but also the constraints related to eligibility criteria (age of child) and needing a critical mass for groups within a short time frame. Rurality has been a barrier to implementation of intervention groups outwith the context of a trial in Highland before, so there is a need to learn directly from those experiences to allow appropriate trial design in future.

Those who did not complete the intervention or were lost to follow-up cited mental health and/or life stressors as the underlying reasons. There is scope to explore more thoroughly how best to retain participants in interventions which are designed to be accessible regardless of these stressors. Outwith the rigid constraints of a conventional RCT design, interventions such as Mellow Babies tend to offer as flexible an approach as possible to allow for continued participation. It may be most prudent to ensure that future trials/interventions exist as part of a wider programme where, for example, those unable to maintain participation in a 14-week whole-day programme may still be able to obtain other relevant support (i.e. an online group) that is more accessible. Having trials more embedded with usual care (such as health visits) without compromising scientific validity would seem to be beneficial not only to trial success but also to participant welfare.

Research recommendations

As this trial was unable to recruit to the planned sample size, there is still ample scope for the original question to be addressed: What is the clinical and cost-effectiveness of the Mellow Babies parenting intervention for women experiencing psychosocial stress and their 6- to 18-month-old babies? This is supported by the review by Goyder and colleagues,17 which highlights the need for higher-level evidence for a number of existing programmes, including Mellow Babies. With thoughtful design, a trial could address not only this primary question, but also several secondary questions along the lines of those proposed by Goyder et al. (see Discussion).

Beyond this specific area of enquiry, our recommendations for future research align with those proposed by Goyder et al. Specifically, the example questions posed in their review present an ideal foundation on which to build on the learning from The Mellow Babies Trial (see Discussion).

-

What are the most effective strategies for identifying and engaging families at increased risk in order to offer parenting interventions?

-

How feasible, acceptable and effective are the assessment tools currently in use to identify those who benefit most from the offer of additional support?

-

What forms of support or content do parents want and need most from parenting programmes; what aspects of current programmes do they value most?

-

What factors make it easier for families to accept or sustain engagement with parenting interventions? What are the reasons that families find it difficult to accept or sustain engagement with parenting interventions?

The learning from The Mellow Babies Trial, detailed in previous sections, serves to reinforce the statement made by Goyder et al. , with reference to Hackworth et al. :33 ‘Enabling parents to engage with the offered support requires an understanding of their most immediate support needs and an understanding of the practical, social, economic and cultural barriers that may make it more difficult for parents to accept support or engage with programmes’.

Conclusions

This trial was not able to establish the clinical and cost-effectiveness of the Mellow Babies parenting intervention for women experiencing psychosocial stress and their 6- to 18-month-old babies. Due to the close-down of the trial prior to recruiting to the planned sample size, we were unable to conduct any outcome analyses due to insufficient statistical power. There has been some scope for learning, primarily in terms of recruitment and retention strategies, and the rich qualitative data collected through interviews have allowed a thorough exploration of the intervention, including the group process. Key learning from interviews with intervention participants included the importance of the social cohesion/community the groups offered, having a safe shared space to focus on themselves, as well as the need to be mindful of not only group size but group composition and their potential impact on the intervention experience. Barriers to participation included a sense of stigma, not wanting to deprive those more in need of support, reluctance to use the crèche, and concern about lack of anonymity and speaking out in a small group. Group facilitators need to be carefully selected and trained, as well as provided with ongoing support from each other and professional supervision. Pragmatic issues related to delivering an intervention which is not embedded in services were discussed, including having to work part-time around other commitments and not always being able to be as flexible as the intervention/participants’ needs might require.

There is no doubt that more trials of parenting support interventions are needed, especially where public services are already investing in well-liked programmes lacking a robust evidence base. Any future trial must take on board the recommendations of Goyder et al. ,17 including the need for proper consideration of contextual barriers to participation. This should include consideration of the need to ensure that those in underserved populations, such as those in remote and rural areas, have the chance to meaningfully participate in research.

Additional information

CRediT contribution statement

Lucy Thompson (https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7461-3262): Conceptualisation, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Visualisation, Writing – original draft, Writing – reviewing and editing.

Jessica Tanner (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1290-9700): Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Validation, Visualisation, Writing – original draft, Writing – reviewing and editing.

Matthew Breckons (https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3057-6767): Data curation, Formal analysis, Validation, Visualisation, Writing – original draft, Writing – reviewing and editing.

Naomi Young (https://orcid.org/0009-0001-1941-0275): Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Validation, Visualisation, Writing – original draft, Writing – reviewing and editing.

Laura Ternent (https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7056-298X): Conceptualisation, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – reviewing and editing.

Thenmalar Vadiveloo (https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5531-6289): Data curation, Formal analysis, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – reviewing and editing.

Philip Wilson (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4123-8248): Conceptualisation, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – reviewing and editing.

Danny Wight (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1234-3110): Conceptualisation, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – reviewing and editing.

Louise Marryat (https://orcid.org//0000-0002-6093-4679): Conceptualisation, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – reviewing and editing.

Iain McGowan (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7778-8065): Conceptualisation, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – reviewing and editing.

Graeme MacLennan (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1039-5646): Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – reviewing and editing.

Angus MacBeth (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0618-044X): Conceptualisation, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – reviewing and editing.

James McTaggart (https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7960-148X): Conceptualisation, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – reviewing and editing.

Tim Allison (https://orcid.org/0009-0003-0175-6977): Methodology, Resources, Writing – reviewing and editing.

John Norrie (https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9823-9252): Conceptualisation, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – reviewing and editing.

Acknowledgements

Philip Wilson was the chief investigator (CI) until December 2022, when he retired. Lucy Thompson worked closely with Phil throughout the trial and took over as CI in January 2023 to manage the trial close-down and prepare the final report.

Other contributions

NHS Highland Research, Development and Innovation team provided study recruitment (Avril Donaldson, Shona MacLeod) and managed the intervention (Frances Hines and her team). Mellow Babies group facilitators were recruited and managed within this team: our thanks to them for their commitment to the trial.

Other members of the University of Aberdeen research team included Dr Hope Christie (Trial Manager 2018–20), Fiona Farrell (Admin support 2019–close), Theresa Hamilton (Admin support 2018–20), Charlotte Murray (research assistant, 2021–3), the late Pam Sherriff (Admin support from bid development to 2019).

Colleagues within the University of Aberdeen Health Services Research Unit/the Centre for Healthcare Randomised Trials (CHaRT) provided invaluable support throughout: Dr Lorna Aucott (Senior Statistician), Dr Seonaidh Cotton (Senior Trial Manager), and Mark Forrest (Senior IT Development Manager).

Previous co-investigators who helped shape the trial: the late Prof James Law, Dr Jing Shen, Clare Simpson, Dr Hugo van Woerden.

Trial Steering Committee: Dr Nick Axford (chair), Matt Forde, Prof Stavros Petrou, Dr Maiken Pontoppidan, and Prof Anna Sarkadi.

Data Monitoring Committee: Prof Jane Barlow (chair), Dr Carole Cummins, and Dr Tim Morris.

Thanks to Mellow Parenting for providing practical advice on intervention implementation.

We would like to acknowledge the contribution of all the practitioners who took the time to learn about the trial, to spread the word and to refer patients.

Finally, we would like to thank all the participants and their babies who took the time to participate in the research.

Data-sharing statement

All data requests should be submitted to the corresponding author for consideration. Access to anonymised data may be granted following review.

Ethics statement

The Mellow Babies Trial was reviewed and approved by NHS East Midlands – Nottingham 1 Research Ethics Committee on 13 December 2018, ref 18/EM/0304. All subsequent protocol amendments were reviewed and approved by the same committee. Any modifications made were planned by the chief investigator (PW to December 2022, LT thereafter) with the project management group, co-investigators, Trial Steering Committee and Data Monitoring Committee as required.

Information governance statement

The University of Aberdeen is committed to handling all personal information in line with the UK Data Protection Act (2018) and the General Data Protection Regulation (EU GDPR) 2016/679. Under the Data Protection legislation, University of Aberdeen is the Data Controller, and you can find out more about how we handle personal data, including how to exercise your individual rights and the contact details for our Data Protection Officer here (www.abdn.ac.uk/about/privacy/).

Disclosure of interests

Full disclosure of interests: Completed ICMJE forms for all authors, including all related interests, are available in the toolkit on the NIHR Journals Library report publication page at https://doi.org/10.3310/KCVL7125.

Primary conflicts of interest: John Norrie is in receipt of the following NIHR grants to: Long-Term Outcomes of Synthetic Mid-Urethral Slings (Mesh Tapes) in Surgical Treatment of Stress Urinary Incontinence in Women – A Long-term Follow-Up of the SIMS RCT. NIHR133092; Glucocorticoids in Adults With Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome: Randomised Clinical Trial (GuARDS Trial). NIHR151601; Inpatient GRAduated Compression stocking use as an adjunct to Extended duration pharmacoprophylaxis for venous thromboembolism prevention – the GRACE multicentre randomised controlled trial. NIHR155294; Early Vasopressors in Sepsis (EVIS) trial. NIHR132594 (19/162/02); Thromboprophylaxis in individuals undergoing superficial endoVEnous treatment (THRIVE). NIHR152877; Examining the benefit of graduated compression stockings in the Prevention of vEnous Thromboembolism in low-risk Surgical patients: a multicentre cluster randomised controlled trial (PETS Trial). NIHR133776; ESPriT2: A multi-centre randomised controlled trial to determine the effectiveness of laparoscopic treatment of isolated superficial peritoneal endometriosis for the management of chronic pelvic pain in women. NIHR129801; A randomised Placebo-Controlled Trial of Antenatal Corticosteriods for Planned Birth in Twins: STOPPIT-3. C-10333879 NIHR131352; Duration of External Neck Stabilisation following odontoid fracture in older or frail adults: a randomised controlled trial of early versus late collar removal. NIHR131118; A Placebo Controlled Randomised Trial of Intravenous Lidocaine in Accelerating Gastrointestinal Recovery After Colorectal Surgery. 15/130/95; A parallel group, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial comparing the effectiveness and cost effectiveness of low-dose oral modified release morphine versus placebo on patient-reported worst breathlessness in people with chronic breathlessness: Morphine and BrEathLessness trial (MABEL). 2019-002479-33; Designing a platform trial to assess the effectiveness of interventions for peripheral arterial disease: The PAEDIS trial Development Project. NIHR155342; Venous leg ulcErs: management and eradIcatioN (VEIN Platform Study). NIHR155477; Alpha 2 Agonists for Sedation to produce Better Outcomes from Critical Illness (A2B TRIAL): A Parallel Group Randomised Controlled Trial Comparing Clonidine, Dexmedetomidine and Current Usual Care. 16/93/01; Diagnostic tools to establish the presence and severity of peripheral arterial disease in people with diabetes. NIHR131855; CHAPS – Compression Hosiery to Avoid Post-Thrombotic Syndrome. 17/147/47; The CATHETER II Study: Randomised Controlled Trial Comparing the Clinical and Cost-Effectiveness of Various Washout Policies Versus No Washout Policy in Preventing Catheter Associated Complications in Adults Living With Long-Term Catheters. 17/30/02; Female Urgency, Trial of Urodynamics as Routine Evaluation (FUTURE). 15/150/05; Feasibility and design of a trial to determine the optimal mode of delivery in women presenting in preterm labour or with planned preterm delivery. 17/22/02 125193; Cervical Ripening at Home or In-Hospital – Prospective Cohort Study and Process Evaluation (CHOICE Study). NIHR127569; NIHR Global Health Research Group on Preterm Birth and Stillbirth at the University of Edinburgh (the DIPLOMATIC Collaboration). 17/63/08; I-Minds: A Digital Intervention to Improve Mental Health and Interpersonal Resilience for Young People Who Have Experienced Online Sexual Abuse – A Non-randomised Feasibility Study With a Mixed-methods Design. NIHR131848; Metformin in Li Fraumeni (MILI) trial: A Phase II randomised open-label cancer prevention study of metformin in adults with Li Fraumeni Syndrome. NIHR131239; Building an international precision medicine platform trial for the acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). NIHR154493; Implementation of Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment based perioperative medicine services to improve clinical outcomes for older patients undergoing elective and emergency surgery with cost effectiveness. [Short title; Perioperative medicine for Older People undergoing Surgery Scale Up (POPS-SUp)]. NIHR157443; NIHR Global Health Research Unit on Respiratory Health (RESPIRE-2). NIHR132826; NIHR Global Health Research Unit on Respiratory Health (RESPIRE) at The University of Edinburgh. 16/136/109; Infant Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal Axis Responses Following Antenatal Corticosteroids and Perinatal Outcomes: A Mechanism of Action of Health Intervention Study. NIHR133388; John Norrie has been a member of the following NIHR committees: Chair of MRC/NIHR Efficacy and Mechanism Evaluation Board, 2019–present; EME Funding Committee Sub-Group Remit and Comp Check (August 2019–current); HTA General Committee (1 November 2016–30 November 2019); HTA Post-Funding Committee teleconference (POC members to attend) (1 November 2016–30 November 2019); HTA Funding Committee Policy Group (formerly CSG) (1 November 2016–30 November 2019); COVID-19 Reviewing (1 June 2020–30 September 2020); HTA Commissioning Committee (18 January 2010–28 February 2016); HTA Commissioning Sub-Board (EOI) (1 April 2016–31 March 2017); NIHR CTU Standing Advisory Committee (1 May 2018–1 May 2023; NIHR HTA and EME Editorial Board (1 November 2015–31 March 2019); Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis Impact Review Panel (1 May 2017–1 June 2017); EME Strategy Advisory Committee (2019–present); EME – Funding Committee Members (1 August 2019–1 August 2022). Angus MacBeth is involved with ongoing research collaboration with the organisation Mellow Parenting, for which he receives no direct financial remuneration. No other interests declared.

Publications

This article is the sole publication from the outcome of the trial. We have also presented the study at conferences:

Thompson L, Buchanan L, Christie H, Wilson P. The Mellow Babies Trial: Early Process Evaluation of a Complex Intervention. Oral presentation at the NHS Highland Research, Development, and Innovation Conference, 2019.

Thompson L, Wilson P, The Mellow Babies Trial team. The Mellow Babies Trial Protocol. Poster presentation at the NHS Highland Research, Development, and Innovation Conference, 2019.

Tanner J, Wilson P, Thompson, L. Group Processes and Interpersonal Change Mechanisms Within a Group-based Intervention for Mothers and Their Infants. Oral presentation at the World Association for Infant Mental Health Congress, 2023.

Our PhD student, Jessica Tanner, has published the following papers related to the study:

Tanner J, Wilson P, Wight D, Thompson L. The importance of group factors in the delivery of group-based parenting programmes: a process evaluation of Mellow Babies. Front Child Adolesc Psychiatry 3:1395365. https://doi.org/10.3389/frcha.2024.1395365

Tanner J, Wilson P, Wight D, Thompson L. The Mellow Babies parenting programme: role of group processes and interpersonal change mechanisms. Front Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2024;3 https://doi.org/10.3389/frcha.2024.1395363

Disclaimers

This article presents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR). The views and opinions expressed by authors in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the NHS, the NIHR, the PHR programme or the Department of Health and Social Care. If there are verbatim quotations included in this publication the views and opinions expressed by the interviewees are those of the interviewees and do not necessarily reflect those of the authors, those of the NHS, the NIHR, the PHR programme or the Department of Health and Social Care.

List of abbreviations

- ADHD

- attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder

- ASQ

- Ages and Stages Questionnaire

- ASQ-3

- Ages and Stages Questionnaire, Third Edition

- ASQ-SE2

- Ages and Stages Questionnaires: Social-Emotional, Second Edition

- CI

- chief investigator

- EQ-5D

- EuroQol-5 Dimensions

- EQ-5D-5L

- EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version

- FNP

- family nurse partnership

- FU1

- follow-up 1

- FU2

- follow-up 2

- GP

- general practitioner

- HADS

- Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

- HADS-A

- Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale – Anxiety subscale

- HADS-D

- Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale – Depression subscale

- HV

- health visitor

- NICE

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence

- NIHR

- National Institute for Health and Care Research

- PCQ

- Participant Cost Questionnaire

- PHR

- Public Health Research

- PIC

- Patient Identification Centre

- PPI

- patient and public involvement

- PTSD

- post-traumatic stress disorder

- QALY

- quality-adjusted life-year

- RCT

- randomised controlled trial

- RD&I

- research, development and innovation

- REC

- Research Ethics Committee

- SDQ

- Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire

- SIMD

- Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation

- SSLM

- Sure Start Language Measure

- THRIVE

- Trial of Healthy Relationship Initiatives for the Very Early years

- VAS

- visual analogue scale

References

- Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Harrington H, Milne BJ. Males on the life-course-persistent and adolescence-limited antisocial pathways: follow-up at age 26 years. Dev Psychopathol 2002;14:179-207.

- Jokela M, Ferrie J, Kivimӓki M. Childhood problem behaviors and death by midlife: the British National Child Development Study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2009;48:19-24.

- Wilens TE, Biederman J, Mick E, Faraone SV, Spencer T. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is associated with early onset substance use disorders. J Nerv Ment Dis 1997;185:475-82.

- Milberger S, Biederman J, Faraone SV, Chen L, Jones J. ADHD is associated with early initiation of cigarette smoking in children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1997;36:37-44.

- Miniscalco C, Nygren G, Hagberg B, Kadesjö B, Gillberg C. Neuropsychiatric and neurodevelopmental outcome of children at age 6 and 7 years who screened positive for language problems at 30 months. Dev Med Child Neurol 2006;48:361-6.

- Law J, Plunkett C, Taylor J, Gunning M. Developing policy in the provision of parenting programmes: integrating a review of reviews with the perspectives of both parents and professionals. Child Care Health Dev 2009;35:302-12.

- Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, Shepard SA, Guthrie IK, Murphy BC, Reiser M. Parental reactions to children’s negative emotions: longitudinal relations to quality of children’s social functioning. Child Dev 1999;70:513-34.

- Tough SC, Siever JE, Leew S, Johnston DW, Benzies K, Clark D. Maternal mental health predicts risk of developmental problems at 3 years of age: follow up of a community based trial. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2008;8:1-11.

- Wilson P, Bradshaw P, Tipping S, Henderson M, Der G, Minnis H. What predicts persistent early conduct problems? Evidence from the Growing Up in Scotland cohort. J Epidemiol Community Health 2013;67:76-80.

- Scott S, Lewsey J, Thompson L, Wilson P. Early parental physical punishment and emotional and behavioural outcomes in preschool children. Child Care Health Dev 2014;40:337-45. https://doi.org/10.1111/cch.12061.

- Allely CS, Johnson PC, Marwick H, Lidstone E, Kočovská E, Puckering C, et al. Prediction of 7-year psychopathology from mother-infant joint attention behaviours: a nested case-control study. BMC Pediatr 2013;13.

- Marwick H, Doolin O, Allely CS, McConnachie A, Johnson P, Puckering C, et al. Predictors of diagnosis of child psychiatric disorder in adult-infant social-communicative interaction at 12 months. Res Dev Disabil 2013;34:562-72.

- Allely CS, Purves D, McConnachie A, Marwick H, Johnson P, Doolin O, et al. Parent-infant vocalisations at 12 months predict psychopathology at 7 years. Res Dev Disabil 2013;34:985-93.