Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number NIHR130144. The contractual start date was in July 2020. The final report began editorial review in May 2022 and was accepted for publication in April 2023. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final manuscript document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this manuscript.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Melendez-Torres et al. This work was produced by Melendez-Torres et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Melendez-Torres et al.

Chapter 1 Background

Description of the problem

Dating and relationship violence and gender-based violence: joint constructs

Dating and relationship violence (DRV) refers to physical, sexual and emotional violence (including coercive control) in relationships between young people. Critically, it includes those aged under 16, who are not included in UK government definitions of domestic violence. Gender-based violence (GBV) refers to violence rooted in gender inequality and sexuality, such as harassment or bullying on the basis of gender or sexuality, sexual violence, coercion and assault including rape, within or outside dating relationships. 1 Although longitudinal evidence demonstrates that experience of DRV predicts young people’s later GBV victimisation and that they share common risk factors,2,3 they are rarely considered as joint constructs. 4

Previous systematic reviews of interventions for young people have focused on DRV and have not meaningfully considered intervention impacts with GBV. 5–8 This is important because interventions nominally focusing on DRV may impact GBV and vice versa, underpinned by common mechanisms and structural features that lead to high rates of both in schools. Potentially shared aetiological mechanisms include gender norms at the societal level that are inequity-generating (i.e. creating unavoidable and unfair differences between groups); inconsistent development and enforcement of violence prevention policies at school and classroom levels, and the creation of spaces for violence to occur; and, at the individual level, exposure to and reinforcement of antisocial norms relating to gender, sexuality and violence and, conversely, insufficient exposure and reinforcement to prosocial norms relating to the same. 4,9–11 These multilevel influences are experienced across sexual and reproductive health, of which DRV and GBV are important determinants. 12 That is, DRV and GBV have a common basis in exploiting gender and sexual inequalities and in antisocial norms. 13

Dating and relationship violence and GBV are amenable to change in school contexts via a range of approaches, from didactic (e.g. classroom-based) to structural (e.g. school policy changes). 1 Thus, considering DRV and GBV jointly is essential to develop, implement and adapt efficient interventions for schools.

Dating and relationship violence and gender-based violence: public health issues

Dating and relationship violence and GBV are pressing public health problems with manifold and inequity-generating long-term impacts on health. While boys and girls both experience major burdens of emotional and physical DRV, impacts are disproportionately experienced by girls. A cross-sectional study based on a representative sample of 11- to 16-year-olds in Wales found that 28% of girls report emotional victimisation and 12% report physical victimisation by a partner over the course of adolescence, while 20% of boys report emotional victimisation and 17% physical victimisation. 11 However, age-related trajectories in victimisation are steeper in girls than in boys, suggesting that adolescence is a critical period to arrest inequalities arising from DRV and GBV. Girls are more likely than boys to report sexual dating violence victimisation,14 and girls are more vulnerable to experiencing the detrimental impacts of victimisation such as feelings of fear, distress and post-traumatic stress compared to boys. 15 Nationally representative data from the US Youth Risk Behavioral Surveillance Survey from 2001 to 2019 revealed that rates of forced sex were maintained for girls and decreased for boys, and as girls and boys aged, the risk of forced sex increased. 16 In Britain, the median age for most recent occurrence of sex against one’s will, a form of GBV, is 18 among men and 16 among women. 17 In addition, longitudinal evidence suggests that the onset of physical DRV and GBV peaks in mid-adolescence, while onset of sexual DRV and GBV is greatest in late adolescence. 18 This underscores the importance of interventions during school years.

Young people do not report perceived peer sanctions against GBV behaviours,1 and at an individual level, norms accepting of GBV and harassment strongly correlate with DRV perpetration and victimisation, reinforcing the importance of considering these outcomes jointly. 1,13,19,20 In 2021 in the UK, 67% of girls aged 13–18 years reported sexual harassment at school or college; 18% experienced unwanted touching such as being pinned down, having their bra strap or skirt pulled. This increased from 9% for those aged 13–16 years, to 36% for those aged 17–18 years. 21 While it is well understood that sexual minority adolescents experience higher levels of GBV in terms of homophobic and transphobic bullying and sexual harassment,22,23 these adolescents also experience higher rates of physical and sexual DRV. 23–25

Longitudinal impacts of DRV and GBV are numerous. In adolescence, both perpetrators and victims report increased risky sexual behaviour, substance use and depressive symptoms;8,10,23,26 in adulthood, survivors of DRV and GBV are more likely to be re-victimised27 and more likely to report poorer mental and physical health. 28 In particular, a systematic review of longitudinal studies found that both DRV and GBV experiences as adolescents were predictive of adult experiences of domestic violence. 29 Another way in which DRV and GBV are inequity-generating is in their exacerbation of health inequalities between men and women;30 in particular, earlier onset of intimate partner violence leads to greater impacts on mental and physical health in adulthood. 28 In addition, there are strong intersections with other inequalities, such as race/ethnicity and sexuality. 22,23 DRV and GBV generates inequalities between heterosexual and cisgender young people and their sexual minority peers, such as substance misuse and increased burden of suicidal ideation arising from experiences of DRV and GBV. 22,23 Importantly, a key source of these inequalities in mental health is the shared impact of school context, including prevalence and response to DRV and GBV, both of which point to the importance of school-based interventions. 31

School-based interventions for dating and relationship violence and gender-based violence in the UK

Adolescence is a crucial stage for focusing on the prevention of DRV and GBV. Schools, as important sites of gender socialisation (both in the UK and worldwide), have the potential to promote gender-equitable attitudes. In addition, schools are a critical site for the delivery of universal interventions. However, despite their role in establishing prosocial norms and behaviours and their duty of care to prevent violence between pupils, a significant amount of DRV and GBV occurs in schools (e.g. Ofsted 202132). According to a recent report on sexual abuse in schools in England,32 sexual harassment including online sexual abuse is normalised for children in schools and incidents of sexual harassment are so commonplace that they see little point in reporting them. Herbert et al. (2021)33 observe that it is only relatively recently that there has been a sustained UK public health focus on DRV in younger people,10,11,34 with the first trial of a school-based intervention to prevent DRV in young people, Project Respect,35 trialled in the UK.

Description of the intervention

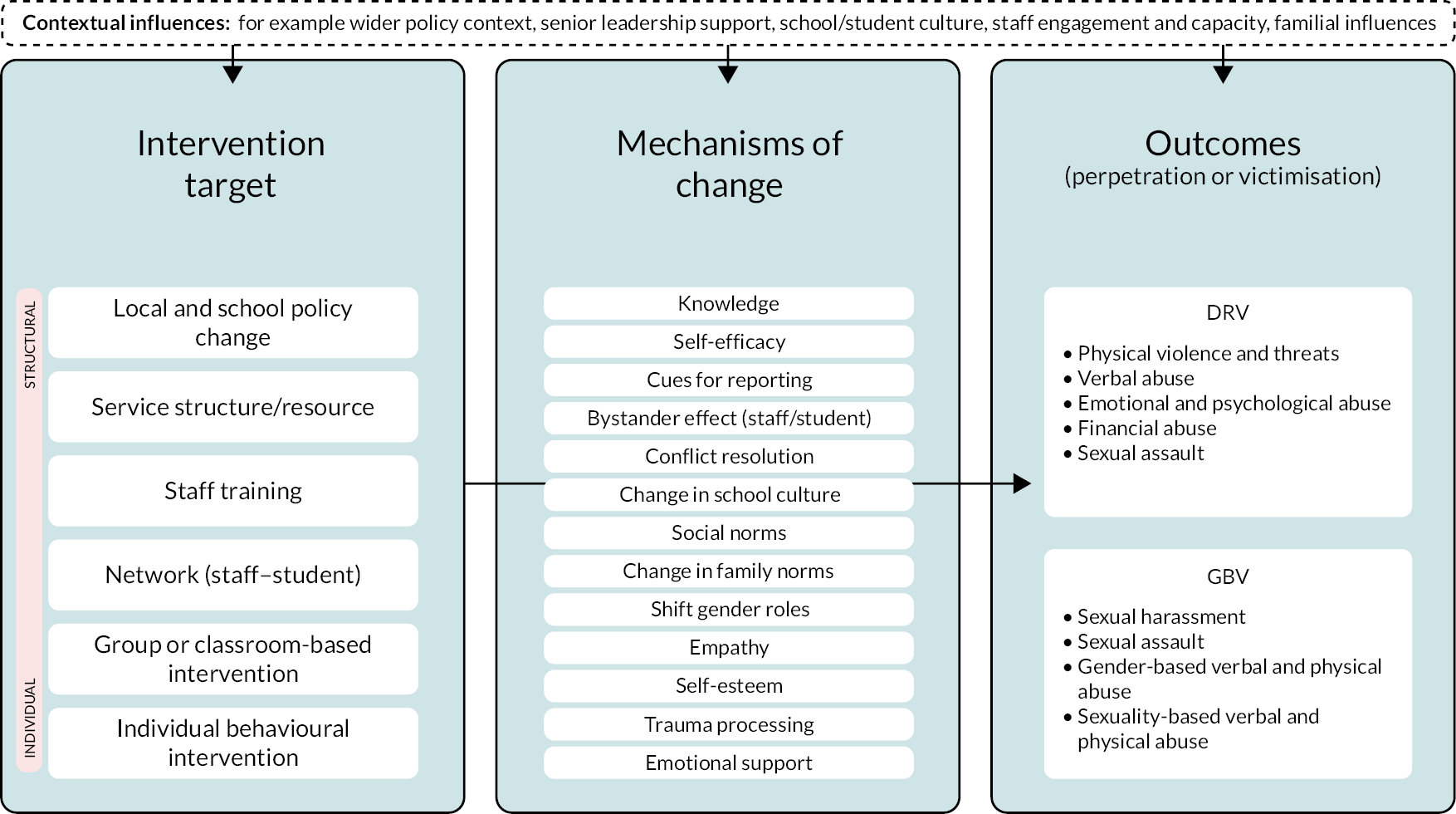

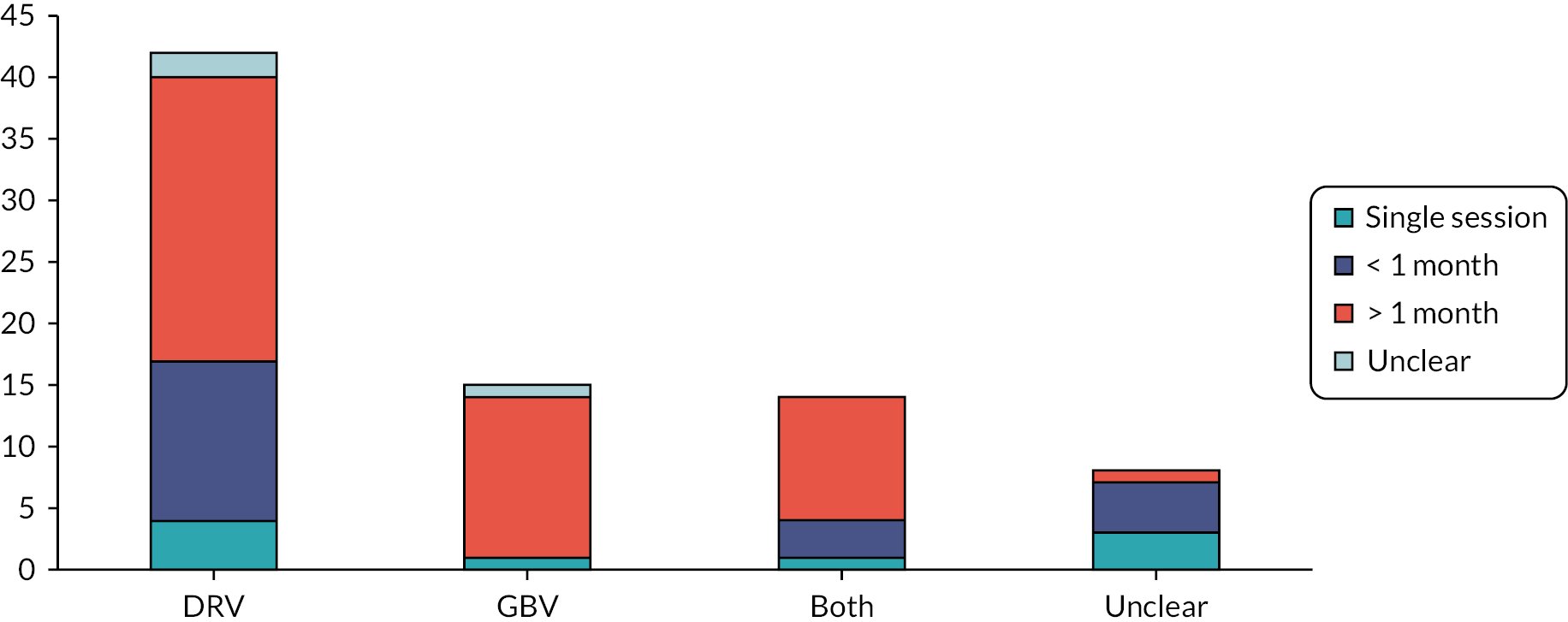

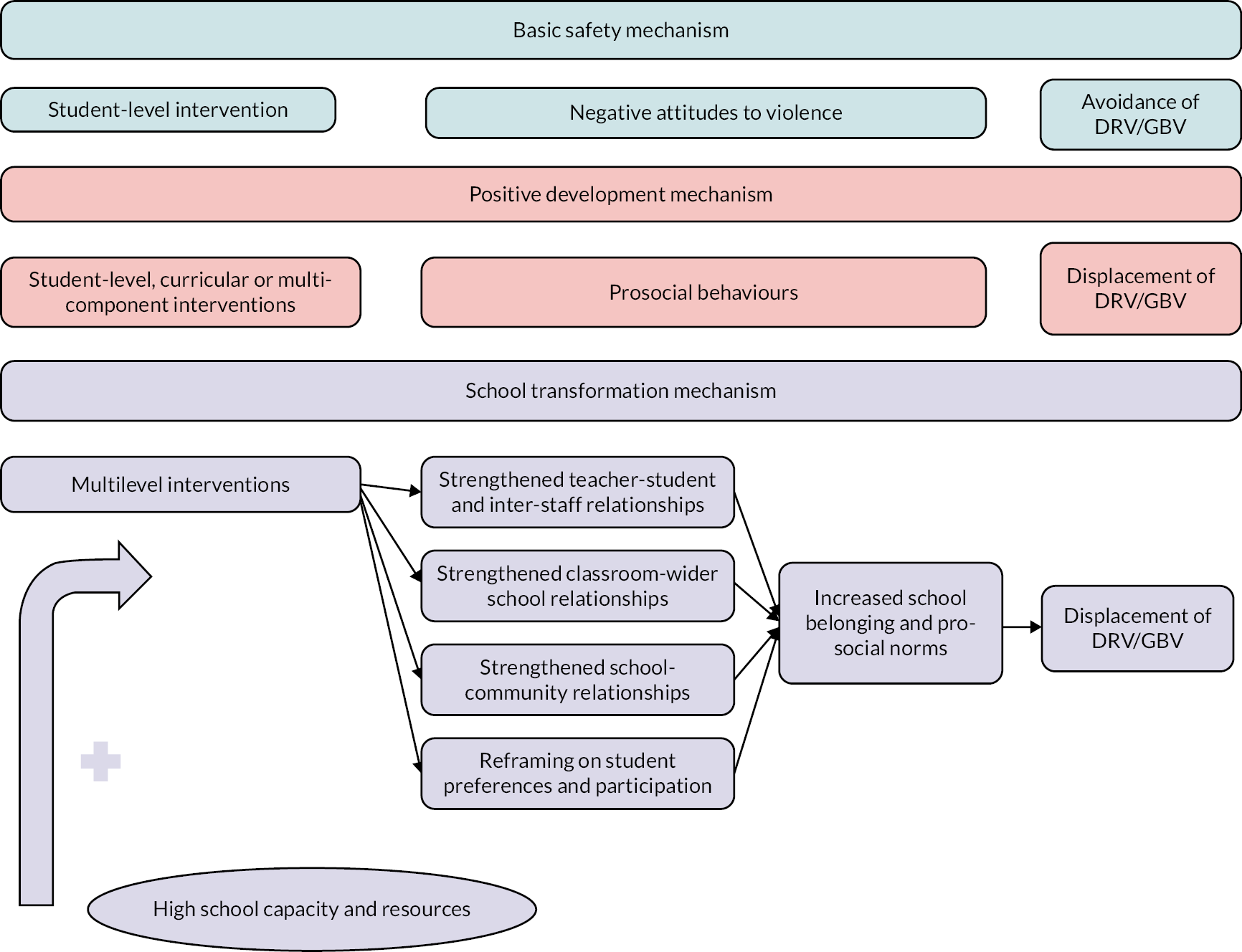

This systematic review focuses on school-based interventions for the prevention of DRV or GBV, provided to students in compulsory education (aged 5–18). An indicative logic model is depicted in Figure 1. These interventions draw on a range of approaches used in the school context, from ‘traditional’ classroom-based instruction as part of, or distinct from, relationships and sex education (RSE) through to school-level resourcing and restructuring. Didactically led programmes have been extensively evaluated. For example, Safe Dates included a RSE curriculum;36 Second Step included classroom-based social and emotional learning;37 and TakeCARE used a video-based programme to teach bystander behaviour, or increased self-efficacy to intervene, with the goal of reducing DRV and GBV. 38 However, explicit consideration of structural components is important given the presence of school ‘hot spots’ for violence, including DRV and GBV,39 and the potential value of staff-led responses in terms of increased monitoring and other place-based approaches. 34 Previous reviews have not attended to these structural components. For example, Safe Dates increased services to adolescents in abusive relationships, and sought to upskill teachers and community service providers. 36 In addition, Shifting Boundaries, which compared a didactic and structural package against a structural-only package (building-based restraining orders, greater faculty and security staff in hot spots, school media campaign) and against no intervention, found reductions in sexual violence perpetration in the structural-only intervention alone. 40 To our knowledge, structural components have not yet been considered in a systematic review. The mechanisms through which interventions may impact DRV and GBV outcomes are accordingly broad, including improved knowledge and self-efficacy, improved reporting and bystander behaviours and better conflict resolution skills through to changes in school culture and responses,31 and social norms at the group level. 12

FIGURE 1.

Initial logic model for understanding DRV and GBV outcomes.

Rationale for the current study

There is no recent systematic review examining the evidence on the effectiveness of school-based interventions for GBV. Systematic reviews published since 2013 have focused on interventions for the prevention of DRV rather than GBV and have not specifically synthesised GBV-related evidence. 5–8,41,42 The search strategies for these reviews did not use comprehensive coverage of search terminology for both DRV and GBV outcomes. Consequently, they provide only a partial picture of the evidence base by omitting relevant studies, either with respect to the range of DRV and GBV outcomes or by restricting to DRV alone. Three reviews5,7,41 also appeared to miss at least one randomised controlled trial (RCT) that was within scope, and since this review began, a further review was published that excluded numerous relevant RCTs. 42 This may be due to variation in the aims of the review authors, though may also suggest that evaluations of school-based interventions may sometimes be harder to identify by common approaches to search strategies (e.g. white papers reporting on the findings of an evaluation may only be found through a comprehensive grey literature search strategy). Reviews also commonly exclude research published not in English, excluding a substantial amount of work on GBV worldwide.

Arguably, artificial distinctions between DRV and GBV have led to variable inclusion of studies, outcomes and effect estimates both across and within reviews. 5–8,43 Furthermore, artificial distinctions between outcomes and intervention strategies preclude a clear picture of the evidence. The shared mechanisms linking DRV and GBV constitute an important reason to consider these outcomes jointly. Some reviews5,6,41 have excluded important forms of GBV that may or may not occur in the context of dating relationships, such as unwanted sexting, coercive control and sexual harassment.

Some of the reviews cited6,8,41–43 have included interventions across age ranges and settings rather than focusing interventions on compulsory education settings specifically, which is most relevant to inform policy. In addition, existing reviews have not synthesised evidence on structural intervention components (e.g. school-level policy change) and have not examined comprehensively heterogeneity in effectiveness by intervention characteristics. 5–8,41–43 Only one review considered implementation aspects and cost effectiveness of interventions but was focused on domestic abuse. 7 Our scoping work suggested that there is a rich evidence base sufficient to go beyond questions of effectiveness and given the size of the evidence base, there is a good rationale for a targeted synthesis that focuses on school-based interventions in compulsory education (as opposed to adolescents generally) to understand how school contexts specifically shape intervention functioning and effectiveness.

A review that addresses these important knowledge gaps is very timely because of the pressing need to prevent DRV and GBV in UK schools. 32 First, as schools move away from single-issue interventions in the context of increasingly crowded timetables, understanding how interventions can target multiple related outcomes will meet a growing policy and practice need. 44,45 DRV and GBV, given potentially shared aetiological mechanisms and risks, form an ideal candidate for ‘joint action’. Similarly, while it is important to consider these outcomes jointly, it is also important to identify which intervention strategies are most effective for one type of outcome or another, and which intervention strategies are best bets across the range of DRV and GBV outcomes. Second, attention to how interventions include multiple and multilevel strategies is important as single-issue, single-component interventions may be more likely to wash out of complex systems such as schools. 46,47 Third, a focus on didactic interventions alone without synthesis of structural and organisational intervention strategies does not account for the potential role of multilevel interventions in reducing health inequalities. 48 Finally, attention to internet-mediated DRV32,49 meets a pressing policy and practice need identified with stakeholders to understand how digital culture in school and youth contexts shapes newer forms of violence.

UK policy context

Importantly, all of this is directly relevant to UK policy and practice. The Department for Education released the final guidance for statutory RSE requiring all schools in England to deliver statutory Relationships Education (RE) in primary schools and RSE in secondary. It came into effect in September 2020, but schools could start using it from September 2019. Those schools not in a position to implement in September 2020 because of the COVID-19 pandemic and closures, had until summer term 2021 to implement. Implementation analysis in schools that adopted the RSE curriculum early shows that challenges were encountered when developing and delivering the RSE curriculum. 50 According to a recent review of sexual abuse in schools in England, children were seldom positive about their RSE lessons and most felt the curriculum did not give them the information and advice they needed to navigate the reality of their lives. 32 This review also highlighted the normalisation of sexual harassment including online sexual abuse in schools for children and recommended that school leaders should take a whole-school approach (WSA) to create a culture where sexual harassment and online sexual abuse are not tolerated, and where they identify issues and intervene early to better protect their students. In light of these findings and in order to fulfil their statutory duties in relation to RSE, schools are likely to need to develop and implement programmes that address DRV and GBV prevention and improve responses to these outcomes.

Thus, there is a good rationale for a new systematic review that provides usable information for practitioners and policy-makers regarding the design and implementation of school-based interventions for DRV and GBV prevention. By synthesising which intervention characteristics are most important for preventing DRV and GBV, what kinds of issues implementers are likely to face, and how interventions are most likely to function in local contexts can support local decision-making and commissioning. Policy and practice stakeholders and young people consulted in preparation for this review identified the need for evidence that could be used to select, develop and implement locally relevant interventions. For example, the statutory guidance on RSE noted that in secondary school, students should understand ‘how stereotypes, in particular stereotypes based on sex, gender, race, religion, sexual orientation or disability, can cause damage (e.g. how they might normalise non-consensual behaviour or encourage prejudice)’ and ‘what constitutes sexual harassment and sexual violence and why these are always unacceptable’. 51 Despite this guidance, policy and practice stakeholders noted a lack of clarity or clear evidence as to the best ways to achieve these goals. These stakeholders also noted the importance of including sexuality-based bullying as part of GBV, especially in light of the Government Equalities Office campaign against homophobic, transphobic and biphobic bullying.

From a research perspective, syntheses that go beyond intervention effectiveness can shape forward development and implementation of best bet interventions against developing evidence of heterogeneity in effectiveness. 43 This review is especially timely given our experience with the recently concluded National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR)-funded pilot trial of Project Respect, a school-based DRV prevention intervention. The first UK trial of an intervention to prevent DRV in young people, Project Respect,35 initially intended to adapt two related interventions found to be effective in the USA: Safe Dates36 and Shifting Boundaries. 40 The adaptation and optimisation process suggested that it would be unlikely to yield an effective intervention in UK school settings. Thus, a systematic review that ‘deconstructs’ existing interventions to better understand intervention functioning would be an essential starting point to develop a relevant evidence base on effective strategies for DRV and GBV prevention specifically in UK school contexts. Indeed, a key finding of Project Respect was that reconsidering types and combinations of components would be critical before undertaking further intervention development.

Finally, the lack of consideration of health inequalities in the evidence base is a major gap as yet unaddressed in a systematic review. This information is vitally important to prevent implementation of interventions that may exacerbate inequalities in respect of a problem already marked by exceptionally large social gradients in long-term impact.

In sum, this mixed-method systematic review including both DRV and GBV as eligible outcomes aims to:

-

address inconsistencies across prior systematic reviews;

-

ameliorate gaps in the understanding of GBV alongside DRV;

-

consider the evaluability of the evidence base across multiple types of evidence;

-

generate timely, relevant and innovative evidence for policy, practice and research.

Review aim and objectives

Our overarching aim is to understand, via systematic review, the functions and effectiveness of school-based interventions for the prevention of DRV and GBV. This aim is supported by the following research questions (RQs):

-

RQ1. What are the theories of change and components of evaluated interventions?

-

RQ2. What factors affect the implementation of evaluated interventions?

-

RQ3. Are interventions effective and cost-effective in preventing DRV and GBV and reducing social inequalities in these outcomes?

-

RQ4. Based on the findings of RQs 1–3, what factors are important for determining the joint effectiveness of interventions for DRV and GBV outcomes?

-

RQ5. What is the comparative effectiveness of different approaches to DRV and GBV prevention?

-

RQ6. What do the different sources of evidence suggest about intervention mechanisms and how these are contingent on context?

Research questions 1–5 are addressed in the main results chapters (see Chapters 4–8), while RQ6 is addressed at the start of the discussion as part of a realist integration of findings (see Chapter 9).

Chapter 2 Review methods

This chapter contains extracts of text that have been reproduced from the review protocol under the Creative Commons licence.

Research design overview

We undertook a mixed-method systematic review in which different types of evidence relating to school-based interventions for the prevention of DRV and GBV were synthesised to understand if, how and in what ways these interventions are effective. Our systematic review followed best-practice conduct (York Centre for Reviews and Dissemination;52 Cochrane Handbook)53 and reporting guidelines (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis,54 including extensions relating to equity; Enhancing Transparency in Reporting the Synthesis of Qualitative Research). 55 This protocol is registered in PROSPERO. Clarification and amendments to the review protocol are provided in Tables 32 and 33 in Appendix 1.

Inclusion criteria for the review

Types of population

We included studies with children in compulsory education (e.g. aged 5–18 years) who are attending school.

Types of intervention

Guided by our logic model, we included evidence relating to interventions implemented in school contexts with students separate from, or as part of, RSE. These interventions could include one or more of:

-

individual behavioural intervention (e.g. individual learning modules or apps);

-

group or classroom-based intervention or practices (e.g. as part of RSE; delivering DRV and GBV prevention content in other academic sessions;44 delivery of content in groups during school hours);

-

network-based approaches, such as public opinion leader interventions;

-

staff training and other service provision in schools (e.g. to recognise and respond better to sexual violence34);

-

local and school policy change56 to address structural factors relating to DRV or GBV, or to change school responses to DRV or GBV.

Interventions could be single-component or multicomponent, or implemented the same type of approach (e.g. group or classroom-based intervention) in a range of ways, for example by differentiating instruction over a range of school years. Included interventions focused in whole or in part on DRV and GBV, and could be universal, selective or indicated; could be primary prevention (reducing incidence of DRV and GBV) or secondary prevention (improving responses to DRV and GBV); and could focus on gender-specific groups (e.g. boys or girls only).

We excluded interventions that:

-

did not seek to address DRV and GBV outcomes, for example interventions focusing on another health promotion topic, such as healthy eating, with an ‘opportunistic’ effect on DRV or GBV outcomes, but that did not describe prevention of DRV or GBV in intervention descriptions;

-

were not delivered in compulsory education (e.g. university-based sexual violence prevention, or youth services);

-

were not delivered at least in part in school contexts.

Types of control

Comparators included business as usual, waitlist control or another active intervention.

Types of outcome

We included outcomes relating to the full scope of DRV and GBV behaviours. These included:

-

DRV perpetration or victimisation, including physical violence; emotional violence, including isolation; coercive control, including internet-mediated DRV; sexual assault in the context of relationships;

-

GBV perpetration or victimisation, including harassment and bullying on the basis of gender or sexuality, including homophobic and transphobic bullying; internet-mediated GBV, such as unwanted sexting or forwarding of sexts; unwanted sexual contact, such as groping; sexual assault; sexual harassment and rape;

-

DRV and GBV-related behaviours, such as harm reduction behaviours, help-seeking behaviours and bystander behaviours;

-

knowledge and attitudes related to DRV and GBV, such as rape myth acceptance, bystander attitudes and GBV-condoning norms.

Outcomes included self-reported behaviours or experiences (e.g. were you groped in the last year; did you call someone names because of their sex or because you thought they were gay), teacher-reported behaviours (e.g. how many times did you see students engaging in sexual harassment) or official reports (e.g. how many sexual harassment incidents were reported in the last year). Included outcome measures were quantitative, expressed as categorical, continuous or count measures. Measures could be composite items (a range of DRV behaviours collected as a count of behaviours) or may be behaviour-specific. Behavioural outcomes could focus on behaviours over a specific period; frequency (monthly, weekly or daily); the number of episodes of a behaviour; or an index constructed from multiple measures. Economic analyses could also include health-related quality of life. We excluded knowledge and attitude outcomes relating to gender, or violence norms generally.

We did not include evaluations where outcomes related only to honour-based violence, forced marriage or female genital mutilation as these outcomes are potentially less amenable to curriculum-based school-based interventions.

Types of study

Types of study included are categorised by research question.

-

For RQ1, we used intervention descriptions and descriptions of theories of change across all included evidence.

-

For RQ2, we drew on process and implementation evidence from eligible interventions that examined intervention delivery or receipt and how delivery was influenced by provider, user or context characteristics. This evidence could be reported in randomised or single-arm trials, retrospective or prospective evaluation studies, and evidence could be qualitative (e.g. description of acceptability of interventions) or quantitative (e.g. measurement of intervention fidelity).

-

For RQ3 and RQ5, we drew on randomised trials, including cluster trials. We also sought any economic evaluations or modelling studies linked to these trials; that is, evidence that seeks to relate intervention costs and savings to health and well-being outcomes or benefits. Finally, we included moderation or subgroup analyses linked to these trials that explore equity-relevant characteristics.

-

RQ4 and RQ6 drew on all included evidence.

Search methods for the identification of studies

Database search strategy

In July 2020, the following bibliographic databases were searched from inception and without limitation on date, language or publication type.

-

MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO, Social Policy and Practice (Ovid).

-

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, Education Resources Information Center, British Education Index, Education Research Complete, EconLit, Criminal Justice Abstracts (EBSCO).

-

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials.

-

NHS Economic Evaluation Database (via the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination).

-

Social Science Citation Index and Conference Proceedings Citation Index (Web of Science, Clarivate Analytics).

-

Australian Education Index, ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global, Sociological Abstracts including Social Services Abstracts, Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ProQuest).

-

Trials Register of Promoting Health Interventions and Bibliomap [Evidence for Policy and Practice Information (EPPI)-Centre].

-

Campbell Systematic Reviews (Campbell Collaboration).

The search strategies were developed by an experienced information specialist following extensive scoping searches and consideration of existing systematic review search strategies. 6,8 The Ovid MEDLINE search strategy was peer-reviewed by another experienced information specialist. The search strategy includes both free-text terms and subject headings for the school setting and DRV/GBV outcomes. In order to identify studies to answer review questions regarding outcome and economic evaluations, intervention theory, process and implementation evidence, and mediation and moderation evidence, no filters for specific study designs were applied. Searches were not restricted by date or language of publication. Full search strategies for each bibliographic database are available in Report Supplementary Material 1.

We searched trial registers to identify ongoing or unpublished research [www.clinicaltrials.gov, WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP)] and we conducted searches for grey literature including conference abstracts, reports and theses from web searches, as well as searches of websites identified in initial scoping searches (including VAWnet; www.vawnet.org).

The bibliographic database searches were updated in June 2021, with a revised strategy developed to improve precision. The revised strategy was based on analysis of titles, abstracts and index terms of included studies. The updated search strategy also incorporated programme names not identified in the initial scoping searches. We created a search summary table for all included studies to identify database sources that retrieved unique records, and this informed bibliographic database selection for update searches. Results from the update searches were not date limited, but instead de-duplicated against previous result sets to ensure records were not missed. Full search strategies for the update searches are available in Report Supplementary Material 1.

Search strategy for other literature sources

Supplementary search methods were used to identify studies not captured by our sensitive database strategies. The reference lists of existing systematic reviews or relevant reports were reviewed for relevant literature. This was the core of our cluster-based approach57 to capture theory underpinning evaluated interventions and identify any missed ‘sibling’ studies. Forward and backward citation chasing was conducted on included studies identified from the June 2020 bibliographic database searches. Scopus (Elsevier), Web of Science (Clarivate) and Google Scholar were used for citation chasing, and bibliographies of included studies were manually checked where this information was incomplete on Web of Science and Scopus.

Targeted searches were conducted in Web of Science and Scopus using first and last author names for studies identified in bibliographic database searches in June 2020. Specific project names (e.g. Project Respect, Shifting Boundaries or Safe Dates) were included in the update search strategies in bibliographic databases, and Google Scholar. Results were screened in Google Scholar, with the first 200 records scanned for each search string. Websites identified in initial scoping searches were browsed or searched for additional reports (including VAWnet: www.vawnet.org; USAID: www.usaid.gov; AVA – Against Violence and Abuse; UNGEI, National Criminal Justice Reference Service: www.ncjrs.gov). Full details of Google Scholar and website searches are available in Report Supplementary Material 1.

Finally, we planned to hand-search journals that published included studies which we found only via reference checking and which are not indexed on databases we have searched. However, due to the exhaustive cluster-based search methods, this was unnecessary.

Information management and study selection

Search results were downloaded into EndNote for deduplication. This was done using EndNote deduplication functionality, plus manual checking. Covidence provided further duplicate matching on import.

Following deduplication, a single search file was uploaded to Covidence software. Two reviewers piloted the screening of successive batches of 100 titles/abstracts, meeting to discuss disagreements, calling on a third reviewer where necessary. Once 90% agreement was reached; each title and abstract were reviewed independently and in duplicate. Records retained after this stage were accessed in full text and assessed against the inclusion criteria in duplicate, and assigned to one or more evidence types (implementation/process, outcome, economic evaluation, mediation and moderation).

Data extraction and appraisal

One reviewer undertook data extraction on study characteristics independently using standardised, piloted forms. All data extraction on study characteristics was comprehensively quality assured by two reviewers for completeness and accuracy.

Further detail about the data extraction tool (DET) is provided in Appendix 2. For all studies where relevant, we extracted information on basic study details (study location, timing and duration; individual and organisational participant characteristics); study design and methods (design, sampling and sample size, allocation, blinding, control of confounding, accounting for data clustering, data collection, attrition, analysis); process evaluation findings and interpretation; outcome measures [timing, reliability of measures, intracluster correlation coefficients (ICCs), effect sizes]; relevant mediation and moderation analyses; and economic data (inputs and outputs relating to costs, consequences/benefits, disaggregated by time period where appropriate). Intervention descriptions and theories of change were extracted as free text across included evidence. When extracting theories of change, we focused on constructs, mechanisms and any contextual contingencies affecting these, as well as other theories cited. Reviewers entered data into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. If included studies were reported in languages that cannot be translated by the review team, a review author completed data extraction in conjunction with a translation of the article.

Published reports may be incomplete in a wide range of ways. For example, they may not: present information on all the outcomes that were measured (possibly resulting in outcome reporting bias); provide sufficient information about the intervention for accurate characterisation; or report statistical information necessary for the calculation of effect sizes. In all cases where there was a danger of missing data affecting our analysis, we contacted authors of papers wherever possible to request additional information. If authors were not traceable, or sought information was unavailable from the authors within 2 months of contacting them, we recorded that the study information was missing on the data extraction form, and this was reflected in our risk of bias assessment for the study. 58

Assessment of quality and risk of bias

Two reviewers assessed the quality of each empirical report. The two reviewers then met to compare their assessments, resolving any differences through discussion and, where necessary, by calling on a third reviewer.

Assessment of process evaluations

Process evaluations were appraised using the EPPI-Centre tool. 59 This addressed the rigour of sampling; data collection; data analysis; the extent to which the study findings are grounded in the data; whether the study privileges the perspectives of participants; the breadth of findings; and depth of findings. These assessments were then used to assign studies to two categories of ‘weight of evidence’ (low, medium or high) to rate the reliability or trustworthiness of the findings (the extent to which the methods employed were rigorous/could minimise bias and error in the findings), and to rate the usefulness of the findings for shedding light on factors relating to the research questions. Guidance was provided to reviewers to help them reach an assessment on each criterion and the final weight of evidence. Findings from critical appraisal were used to inform synthesis, including by describing the qualitative strength of findings in evidence syntheses. The tool was used in this review to assess process evaluations regardless of whether these drew on qualitative or quantitative data, because the criteria were judged applicable to both.

We chose the EPPI-Centre tool given our prior experience with this tool in other NIHR-funded systematic reviews of qualitative research. 39,44,59 A key strength of this tool is that it generates appraisal in terms of both study relevance and study trustworthiness, both of which are important in qualitative evidence synthesis. In addition, the tool reflects the degree to which qualitative findings privilege participant voices, which is important given our focus on generating evidence that speaks to local implementers’ needs.

A final step in quality assessment was to assign studies two types of ‘weight of evidence’. First, reviewers assigned a weight (i.e. low, medium or high) to rate the reliability or trustworthiness of the findings (i.e. the extent to which the methods employed were rigorous/could minimise bias and error in the findings). Second, reviewers assigned an additional weight (i.e. low, medium or high) to rate the usefulness of the findings for shedding light on factors relating to the review questions. The criteria guiding these decisions are shown in Table 1. Quality was used to determine the qualitative weight given to findings in our synthesis, with none of the themes represented solely by studies judged as low on both dimensions. This is relevant because our experience with systematic reviews of process evaluations is that studies relating to exceptionally relevant interventions may not provide rich data; conversely, process evaluations of interventions that only address knowledge and attitudes, rather than behaviours, may provide especially meaningful data that illuminate both how interventions function and how interventions were implemented. Thus, distinguishing between these two weights of evidence sensitised our analysis and helped in prioritising most relevant and most trustworthy findings in synthesis.

| Reliability/trustworthiness of the data | Usefulness of the data | |

|---|---|---|

| High | Rigour in at least three of the first four criteria | Studies privileged the perspectives of participants and to present findings that achieved both breadth and depth |

| Medium | Rigour in two out of the first four criteria | Studies partially met criteria for privileged perspectives of participants and presenting findings that achieved both breadth and depth |

| Low | Rigour in one or none of the first four criteria | Sufficient but limited findings |

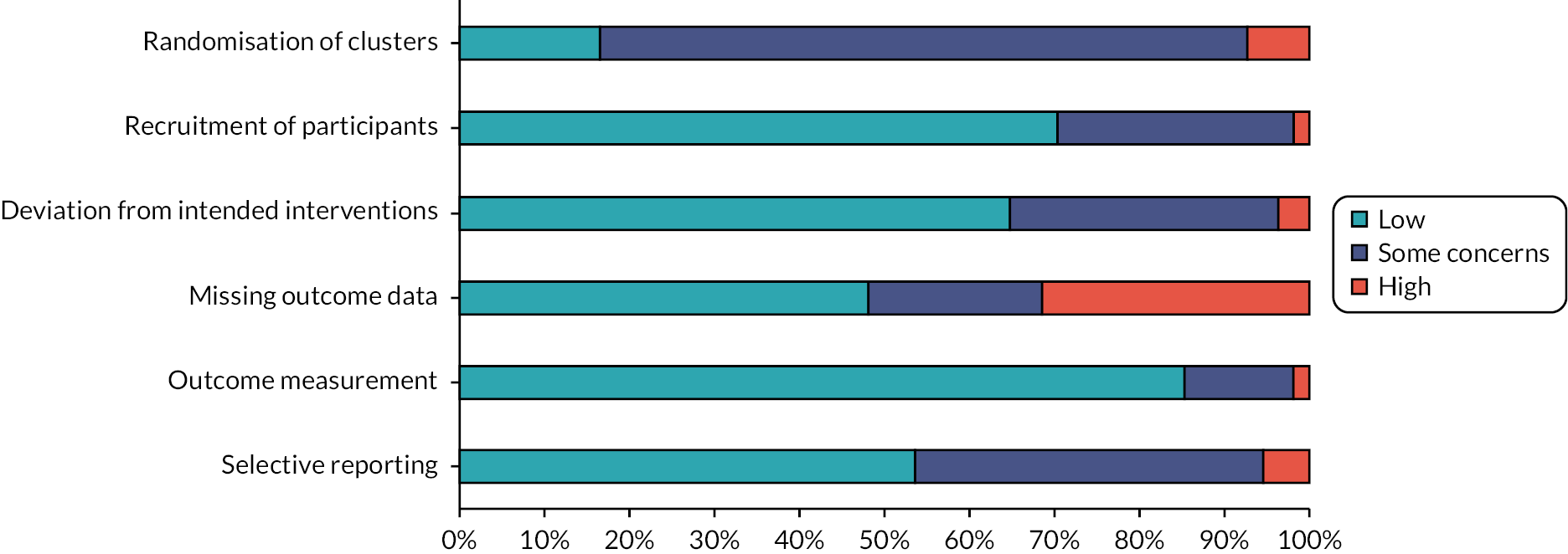

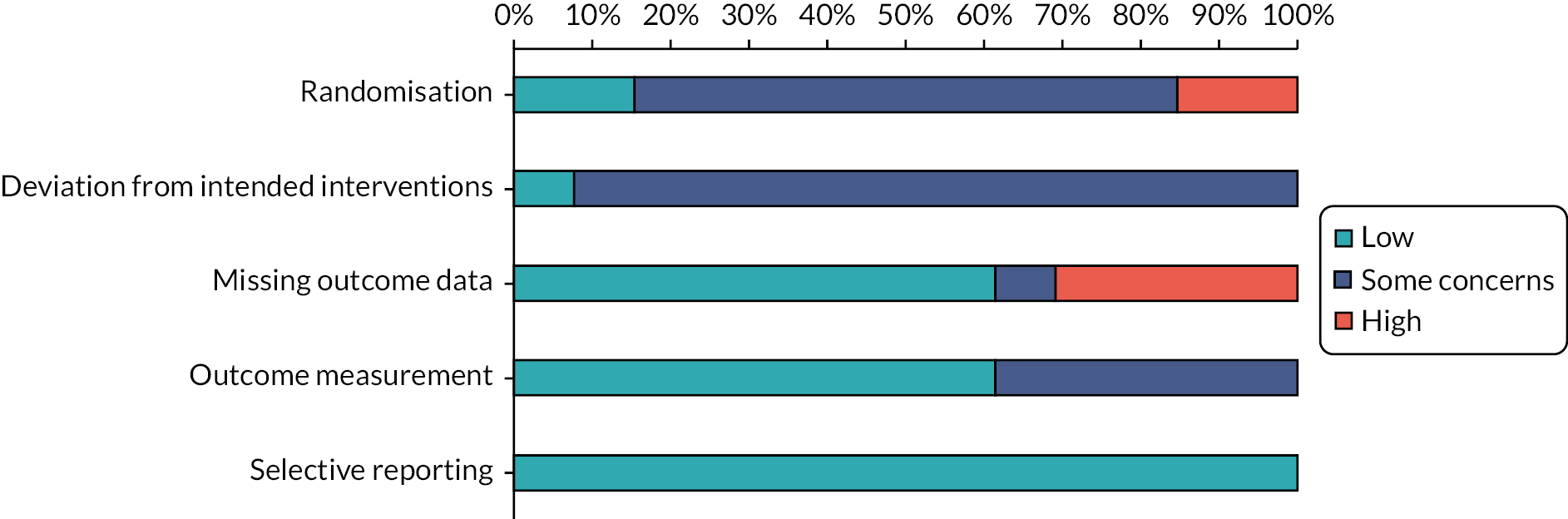

Assessment of outcome evaluations

Critical appraisal of the cluster randomised controlled trials (cRCTs) and RCTs was conducted using the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool version II. 60 For each study, reviewers judged the likelihood of bias for sequence generation and allocation concealment; blinding (of participants, personnel, or outcome assessors); incomplete outcome data; selective outcome reporting; other sources of bias (e.g. recruitment bias in cluster-randomised studies); and intensity/type of comparator. Each study was subsequently identified as ‘high risk’, ‘low risk’ or ‘unclear risk’ within each domain. Decisions were guided by the guidance associated with the tool,53 with the following review-specific adaptations:

-

Where trials did not report baseline characteristics of the included clusters or arms, it was assumed that there were no confounding factors unless the reviewer was concerned that the sample size would undermine effective randomisation.

-

It was assumed that students would likely guess the aims of the intervention, unless evidence to the contrary.

-

There appeared to be a low rate of switching in the trials, but there was limited information about the risk for other protocol deviations that may lead to performance bias. The following were not downgraded for performance bias if there was no switching and an intention to treat (ITT) analysis was reported, as the risk of contamination was considered low:

-

cluster trials where schools were the unit of randomisation

-

interventions lasting one class only.

-

-

An absolute participant attrition rate > 30% was considered problematic.

-

A scale outcomes measure was judged to be acceptable where items were considered by the reviewer to have face validity, and if internal reliability (generally the only psychometric outcome reported) was ≥ 0.7.

-

Trials were not downgraded for unblinded outcome assessors within the outcome measurement domain. Due to the nature of the interventions evaluated, it was not possible for the vast majority of trials to fully blind or obscure students from the intervention they were receiving. This was a limitation noted by many trial authors, who considered there to be a risk that outcomes completed by students could be subject to desirability bias, where students complete outcomes in a way they think is desired by researchers. Trials were not downgraded for this to avoid a floor effect in critical appraisal ratings across the evidence base. However, all trials included in the review are nevertheless considered to be at risk of this bias, in addition to the overall risk of bias across the other tool domains.

Finally, we assessed reporting bias in trials according to Cochrane Handbook guidance. 53 We reduced the effect of reporting bias by focusing synthesis on studies rather than publications and avoiding duplicated data. We attempted to detect duplicate studies and, if multiple articles report on the same study, we extracted data only once. We prevented location bias by searching across multiple databases. We minimised language bias by not excluding any article based on language.

Assessment of economic studies

No formal health economic evaluations were identified by the review. Were we to have identified any eligible economic evaluations and modelling studies linked to randomised trials, we would have appraised them using the Drummond61 or Philips62 checklists, respectively. These checklists require the analyst to answer 24 questions regarding each study, ranging from the type of economic evaluation (e.g. cost–utility analysis) to the time horizon and rationale for the choice of modelling approach.

Data analysis

Our analysis proceeded in a convergent design with RQs 1–5 informing RQ6.

Research question 1: theories and components

We used intervention components analysis63 to analyse intervention descriptions across all included evidence. Intervention components analysis is an inductive approach to comprehensively describing and categorising intervention components in a target body of evidence. This is an appropriate method to describe intervention components when these components do not fit into pre-existing taxonomies of behaviour change, which is especially the case in this review given the diverse, contextually situated and frequently multilevel nature of included interventions. Two reviewers used open coding to generate a comprehensive list of possible intervention descriptors from five different intervention descriptions. The two lists were compared and combined. Using principles of axial coding, the two reviewers proceeded through the remaining intervention descriptions, collapsing codes and adding new ones as required and meeting periodically to compare codes, determine if new axial codes were required and organise axial codes into categories. The final result was a comprehensive list of descriptors to characterise included interventions, organised by relevant categories. Our intervention components analysis ultimately included a set of descriptors for included interventions (type, level, focus), which was analysed across all included evidence, and a set of descriptors for intervention components specifically, which was applied only to outcome evaluations given the size of the evidence based and differences in depth of intervention description.

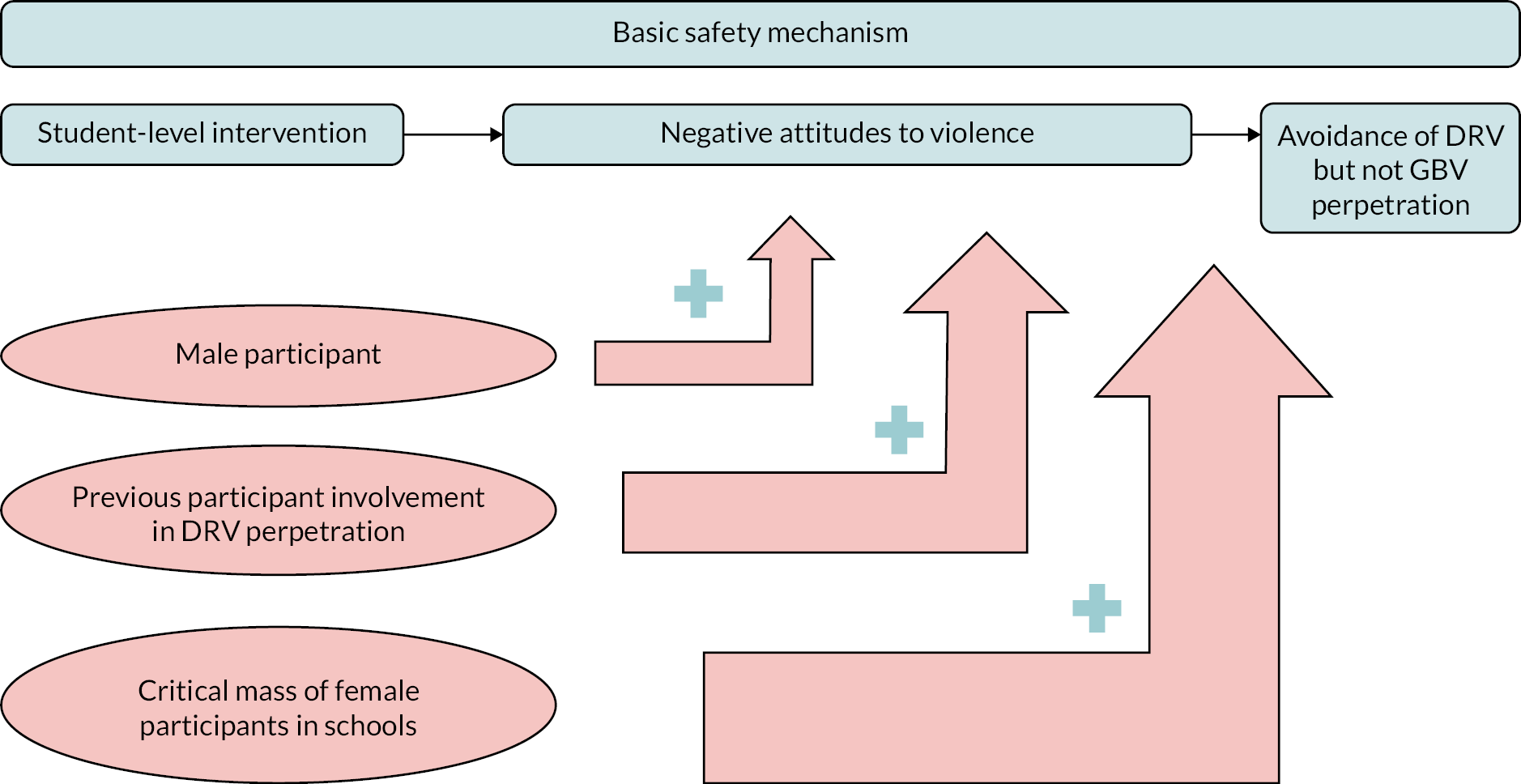

We also synthesised theories of change based on intervention descriptions and accounts embedded in individual studies’ theories of change. Drawing on methods used in previous theory syntheses,64 this inductive analysis included a lines-of-argument synthesis. 65 Lines-of-argument synthesis is an appropriate method based on its understanding that each included study examines a ‘part of the whole’; that is, each study’s account of theory of change represents one possible part of how school-based interventions can work to reduce DRV and GBV broadly. Analysis was undertaken using thematic synthesis and line-by-line coding. 66 We intended to analyse interventions within type first; however, this was not done as it would have limited the breadth of interventions analysed in initial coding, and ultimately did not generate any analytical advantages. Two reviewers began the theory synthesis with a subset of studies first to understand and agree a common approach, prioritising a selection of interventions that (a) were multiply evaluated and (b) represented the breadth of interventions. Subsequently, both reviewers proceeded through each set of studies, meeting to agree findings. The findings from each intervention (second-order constructs) were then compared against each other using a ‘higher-level’ iteration of these thematic grids to produce an overarching theory of change (third-order constructs). Coding unfolded over several cycles, proceeding from initial coding to saturation, followed by confirmatory coding on remaining papers in the analysis. The outcome of this synthesis was a hierarchically organised account of the mechanisms by which interventions are theorised to function in reducing and preventing DRV and GBV and the contexts in which these mechanisms are most likely to operate, broadly across interventions and specifically within intervention types. Specific methods for how the analysis ‘unfolded’ are presented in Chapter 6.

For both the intervention components analysis and the synthesis of theories of change, two reviewers undertook analysis in parallel, with periodic meetings among the analysis team to validate the developing framework. We additionally checked findings with our advisory and stakeholder groups for face validity. These checks focused on identifying which intervention components are most promising in the UK context on the basis of relevance and fit with existing school curricula, intervention strategies and cultures, and which contexts and mechanisms are most likely to be relevant to the UK educational system.

Research question 2: implementation and process evaluations

We synthesised data from implementation and process evidence to identify salient factors affecting intervention implementation and how these relate to context. We used thematic synthesis67 to synthesise these data. Thematic synthesis is apposite as it is a flexible method that seeks to understanding findings across studies, without necessarily imposing a theoretical framework or ‘theorising’ the data, while still preserving the value of reciprocal translation65 in understanding patterns of findings across studies rather than merely summarising these. Thematic synthesis includes both descriptive, or in vivo, themes that describe the specific content in included studies, and analytical themes that cut across findings from multiple studies.

Synthesis of implementation and process evidence began with a tabulation and descriptive coding phase. First, reviewers created a table of included studies reporting information on study type, methods, context and sample; interventions evaluated; and summarised findings. Two reviewers working in parallel then undertook pilot analysis of five reports that were appraised as being of high quality and relevance. The reviewers read and reread the results from these reports, applying line-by-line codes to capture the content of the data, and drafted memos explaining these codes. Coding then proceeded with descriptive codes which closely reflect the words used in findings sections. The reviewers then grouped and organised codes, applying analytical codes reflecting higher-order themes. Subsequently, the reviewers coded remaining studies drawing on the agreed set of codes but developing new descriptive and analytical codes as these arose from the analytical process, and again writing memos to explain these codes. At the end of this process, the two reviewers met to compare their sets of codes and memos. They identified commonalities, differences of emphasis and contradictions with the aim of developing an overall analysis. The outcome of this synthesis was an account of barriers and facilitators that intervention implementers could match to their own context. We sensitivity-analysed all findings by considering whether findings relate to high-income country (HIC) contexts or low-income and middle-income country (LMIC) contexts, in order to better understand the applicability of findings to the UK context.

In addition to routine auditing of findings by the investigator team, we presented findings to our advisory and youth stakeholder groups for feedback. The goal of this was to ensure that findings are relevant to intervention implementers in the UK, and to identify which findings are especially salient in the UK education context.

Research question 3: intervention effectiveness, moderation, mediation and economics

Included trials were organised by intervention type as informed by findings from RQ1, and relevant outcomes were hierarchically categorised by type of DRV or GBV behaviour or experience. We distinguished between different intervention follow-up times (up to 1 year from baseline; more than 1 year from baseline). All time points reported by a study were extracted.

We then meta-analysed study findings where possible. We first analysed within intervention and time-point categories to estimate specific intervention effects on broad outcome categories and then meta-analysed across intervention categories and across outcome categories. Meta-analyses then considered different behaviours, experiences and forms of perpetration and victimisation separately across all intervention types. We originally sought to meta-analyse by intervention type, specific outcome (e.g. physical DRV victimisation) and time point but found that this would be inappropriate given the small number of studies included in any one meta-analysis.

We sensitivity-analysed meta-analyses by whether evidence arose from high-income settings or low-income or middle-income settings, using a standard subgroup difference-based test to identify any statistical differences in effectiveness that may shape the relevance of overall results to the UK context.

The key metric for all meta-analyses was defined in the protocol to be odds ratios (ORs); we ultimately used a standardised mean difference to analyse knowledge and attitude outcomes (i.e. not victimisation or perpetration outcomes). Where victimisation and perpetration outcome measures were continuous, these were converted to ORs using the logistic transformation. We used a random-effects robust variance estimation meta-analysis model to synthesise effect sizes. This is because many outcome evaluations included multiple measures of conceptually related outcomes. Robust variance estimation meta-analysis improves on previous strategies for dealing with multiple relevant effect sizes per study, such as multilevel meta-analysis, meta-analysing within studies or choosing one effect size, by including all relevant effect sizes but adjusting for inter-dependencies within studies. 68 Unlike multivariate meta-analysis, it does not require the variance–covariance matrix of included effect sizes to be known. Where meta-analyses were performed, we included pooled effect sizes in forest plots, with the individual study point estimates weighted by a function of their precision.

We checked that cluster randomised trials have accounted for unit of analysis issues. Prior to synthesis, we checked for correct analysis (where appropriate) by cluster and reported values of ICCs, cluster size, data for all participants or effect estimates and standard errors (SEs). Where proper account was not taken of data clustering, we corrected for this by inflating the SE by the square root of the design effect. 58 Where ICCs were not reported and were relevant to estimating an intervention effect, we imputed an ICC of 0.05, based on values reported in other studies. We planned to undertake sensitivity analysis with respect to ICC values, but this was ultimately unnecessary given that the ICC value was ‘known’ from included studies.

We then produced a narrative account of intervention effectiveness. This narrative account included a comprehensive table of included studies reporting information on study design, methods, context and sample, interventions evaluated and summarised findings, alongside forest plots to describe visually the range and precision of estimates of intervention effectiveness. We then examined the extent of heterogeneity among the studies (as determined both by a Cochran’s Q test and by inspection of the I2). If an indication of substantial heterogeneity was determined (e.g. study-level I2 value > 50%) that cannot be explained through metaregressions, we investigated this further using subgroup and sensitivity analyses.

We used the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions53 to present the quality of evidence, focusing on primary victimisation and perpetration outcomes. The downgrading of the quality of a body of evidence for a specific outcome was based on five factors: limitations of study; indirectness of evidence; inconsistency of results; precision of results; and publication bias. The GRADE approach specifies four levels of quality (high, moderate, low and very low). If sufficient studies are found, we drew funnel plots to assess the presence of possible publication bias (trial effect vs. SE). While funnel plot asymmetry may indicate publication bias, this can be misleading with a small number of studies. 69 We considered possible explanations for any asymmetry in the review in light of our number of included studies. We assessed the impact of risk of bias in the included studies via restricting analyses to studies deemed to be at low risk of selection bias, performance bias and attrition bias; however, risk of bias in included studies was generally poor on these domains and thus a restricted analysis would have been uninformative.

Next, we planned to produce a narrative account of findings from economic evaluations by intervention type. However, as we did not identify any relevant economic evaluations, we instead provided a narrative summary of costing studies linked to included randomised trials. Measures of costs and indirect resource use were summarised using tables. These data were used to inform a narrative synthesis of economic analyses and applicability to the UK context. Because no full economic evaluations were identified, we did not appraise economic studies.

Subsequently, we narratively synthesised evidence of mediation of intervention impacts to demonstrate the degree to which DRV and GBV victimisation outcomes in interventions are mediated by intervening variables.

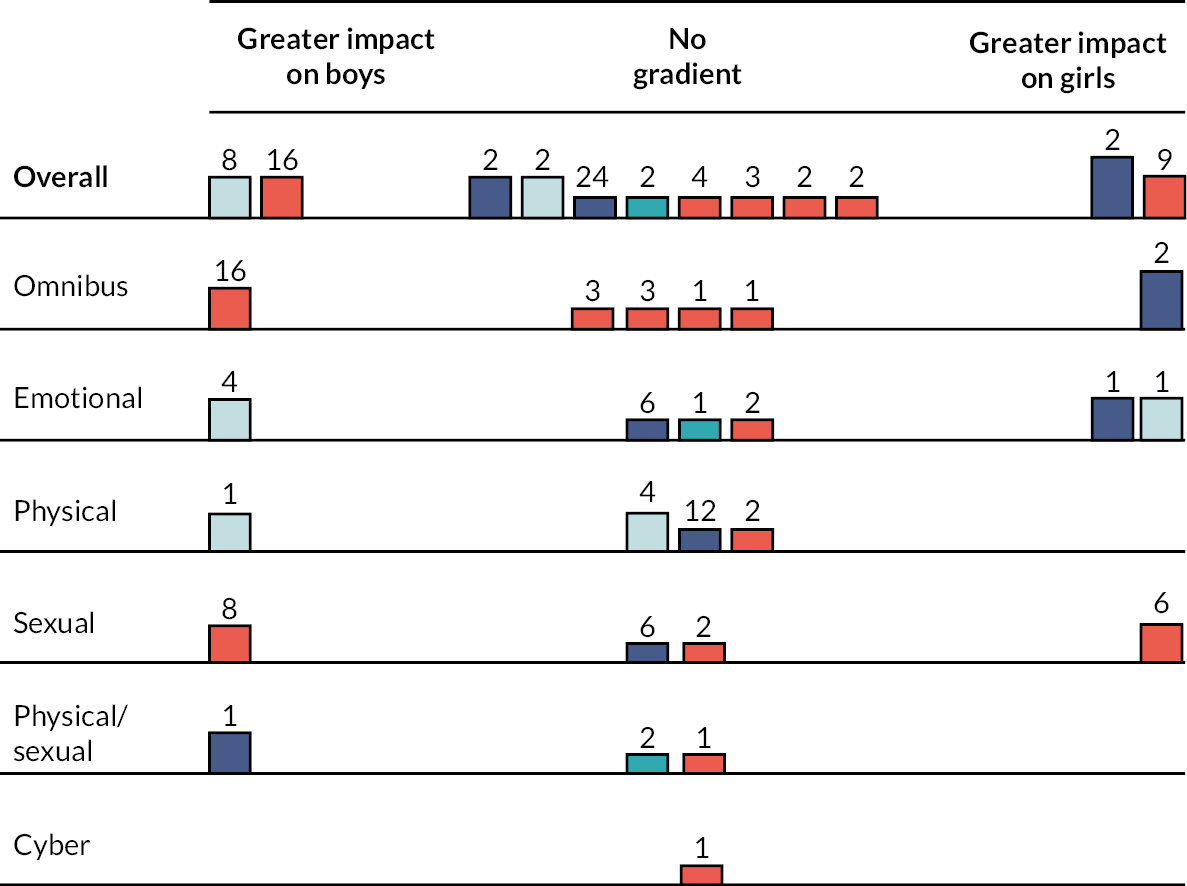

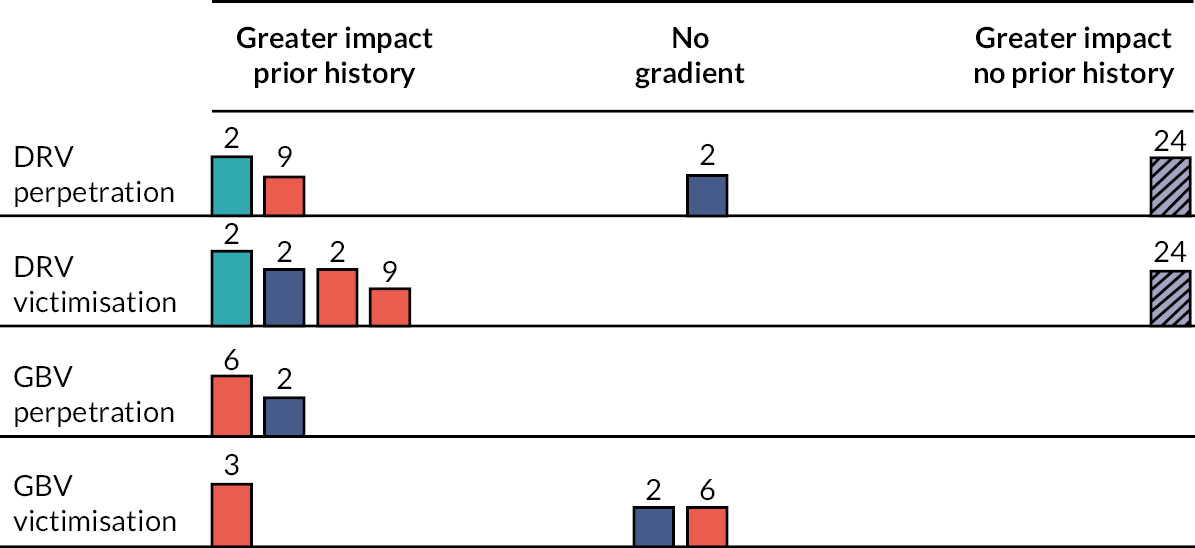

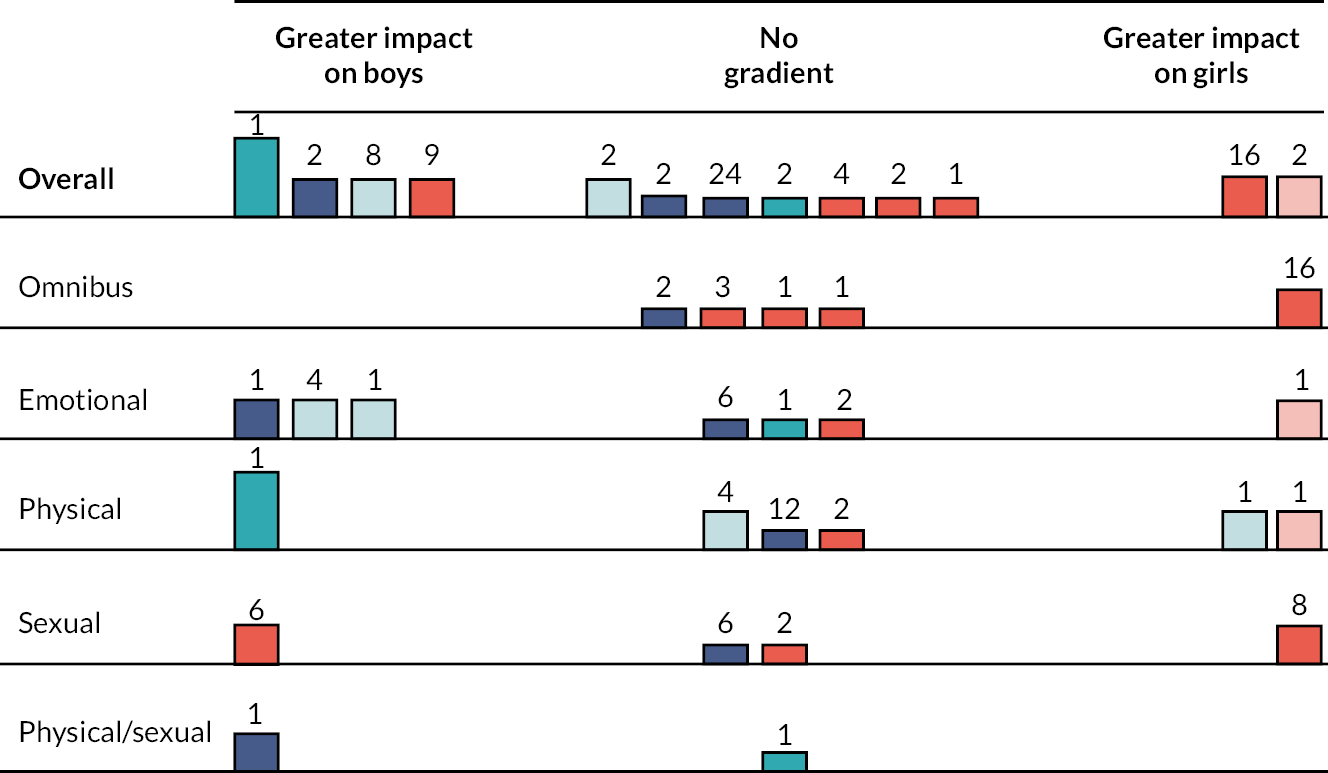

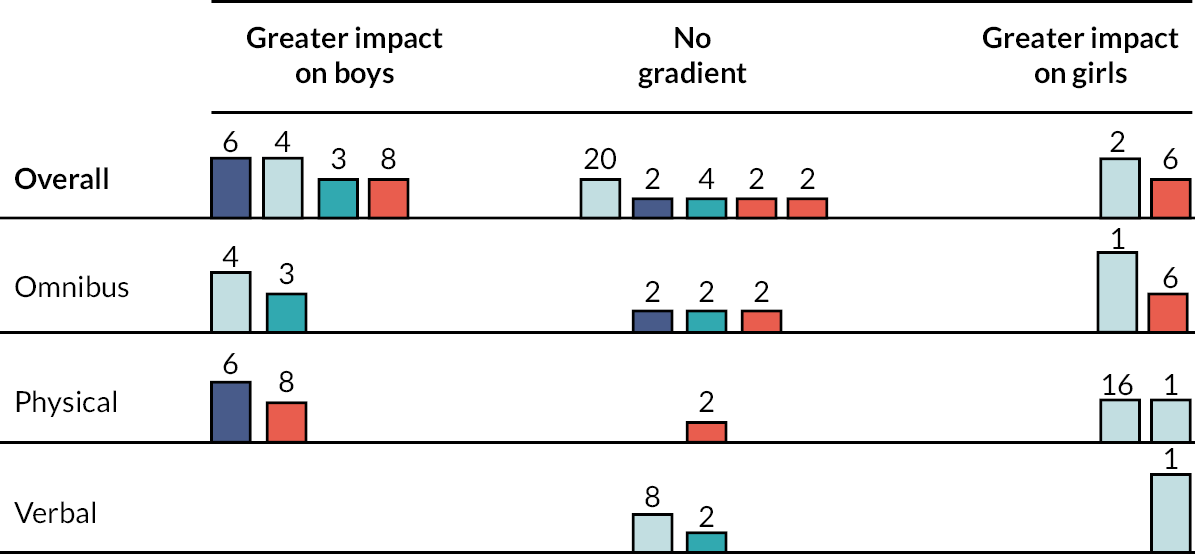

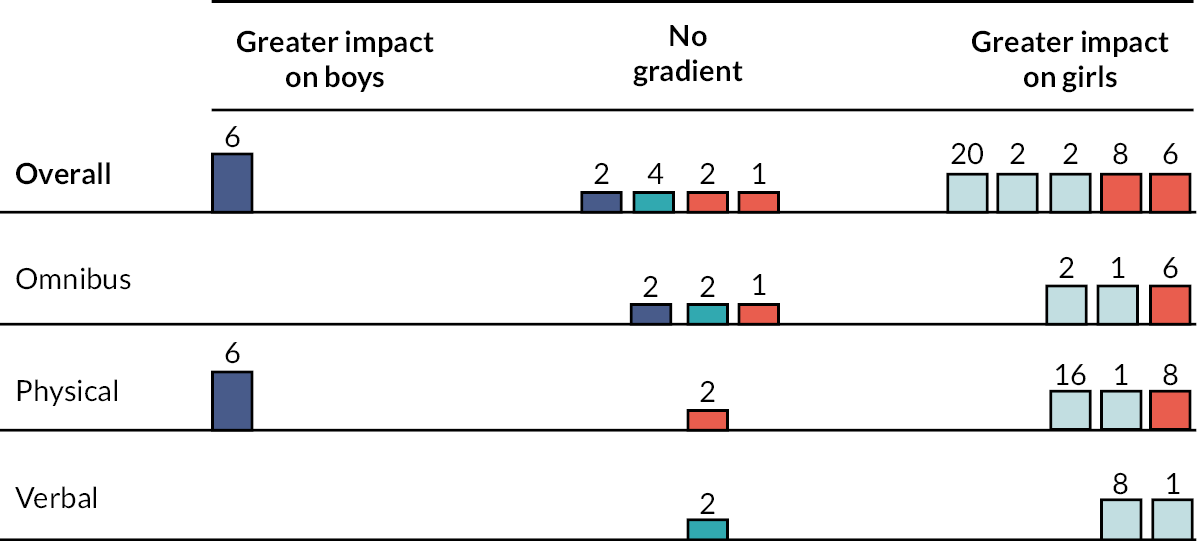

As a final synthesis step, we assessed equity effects by drawing on moderation analyses to illustrate how interventions impact health inequalities, focusing on ethnicity, socioeconomic position, gender, sexuality and age. Our analysis focused on priority outcomes of DRV and GBV victimisation and perpetration. Moderation analyses considering differential intervention effectiveness on these equity-relevant characteristics were organised by intervention type and outcome category and narratively synthesised. Harvest plots were used to graphically depict how interventions ameliorate or worsen social gradients on specific outcomes by equity-relevant characteristics. 70 Where possible and where sufficient data existed, we extended our random-effects robust variance estimation meta-analyses using metaregression to estimate how equity-relevant characteristics of study populations relate to intervention effectiveness.

We presented the findings from meta-analyses to stakeholders in our advisory and youth groups to understand which interventions are ‘best bets’ in the UK context based on both effectiveness and relevance to the UK educational system.

Research question 4: metaregression and qualitative comparative analysis

The next step of the synthesis integrated findings across RQ1–3 to identify how components, mechanisms and implementation factors relate to effectiveness across DRV and GBV outcomes.

First, we used metaregression and pattern matching to understand which components are most effective across both DRV and GBV. We revisited meta-analyses undertaken in RQ3 and used components identified in RQ1 to estimate how inclusion or exclusion of a specific component is associated with intervention effectiveness. These analyses were undertaken by outcome type and time point, but not intervention type, and were estimated using random-effects robust variance estimation meta-analyses. We considered the magnitude, precision and direction of the regression coefficient associated with presence of an intervention component and the reduction in between-study variance resulting from using an intervention component as a metaregressor. We examined the same meta-regressor across a range of outcomes and used pattern-matching71 to identify how specific components are consistently associated with improved or reduced effectiveness across a range of DRV and GBV experiences and behaviours.

Second and where appropriate, we used qualitative comparative analysis (QCA) to identify how different implementation and intervention characteristics combine to form pathways to effectiveness, including on health inequalities. QCA focuses on understanding configurations of conditions that form pathways to effectiveness in interventions. 72 Given that interventions are likely to report diverse types of outcomes using different measurement approaches, QCA is especially apposite as it transforms numerical estimates into a calibrated measure of whether an intervention is effective. QCA focuses on how different implementation and intervention characteristics act in concert to ‘unlock’ pathways to effectiveness. Informed by findings from RQ1 to 3, we developed several candidate groups of implementation and intervention characteristics and considered how these characteristics form pathways to effectiveness. We coded included outcome evaluations as to the presence or absence of these implementation and intervention characteristics where this has not been done already, and classified outcome evaluations as to their effectiveness. We planned to describe effectiveness in several ways, each corresponding to a separate model:

-

interventions that are effective in reducing DRV versus interventions that are not effective in reducing DRV;

-

interventions that are effective in reducing GBV versus interventions that are not effective in reducing GBV;

-

interventions that are jointly effective on DRV and GBV versus interventions that are only effective in one or neither domain.

However, the overlap in interventions testing both DRV and GBV outcomes was insufficient to proceed with this analysis.

We generated truth tables to understand combinations of characteristics by each outcome, and sought to resolve any contradictory configurations (i.e. where combinations of characteristics span both effective and ineffective interventions). We used Boolean minimisation to identify common pathways to effectiveness across each of the three models, and compared findings across models to note which pathways are specific to DRV or GBV outcomes and which pathways are common to effectiveness of DRV and GBV outcomes, and thus should be considered when seeking to address both types of outcomes jointly.

We presented the findings of this analysis to the advisory and youth stakeholder groups to consider how best bet components are relevant in the UK context, and how identified pathways from QCA may be especially important in shaping forward evaluation and implementation in UK schools.

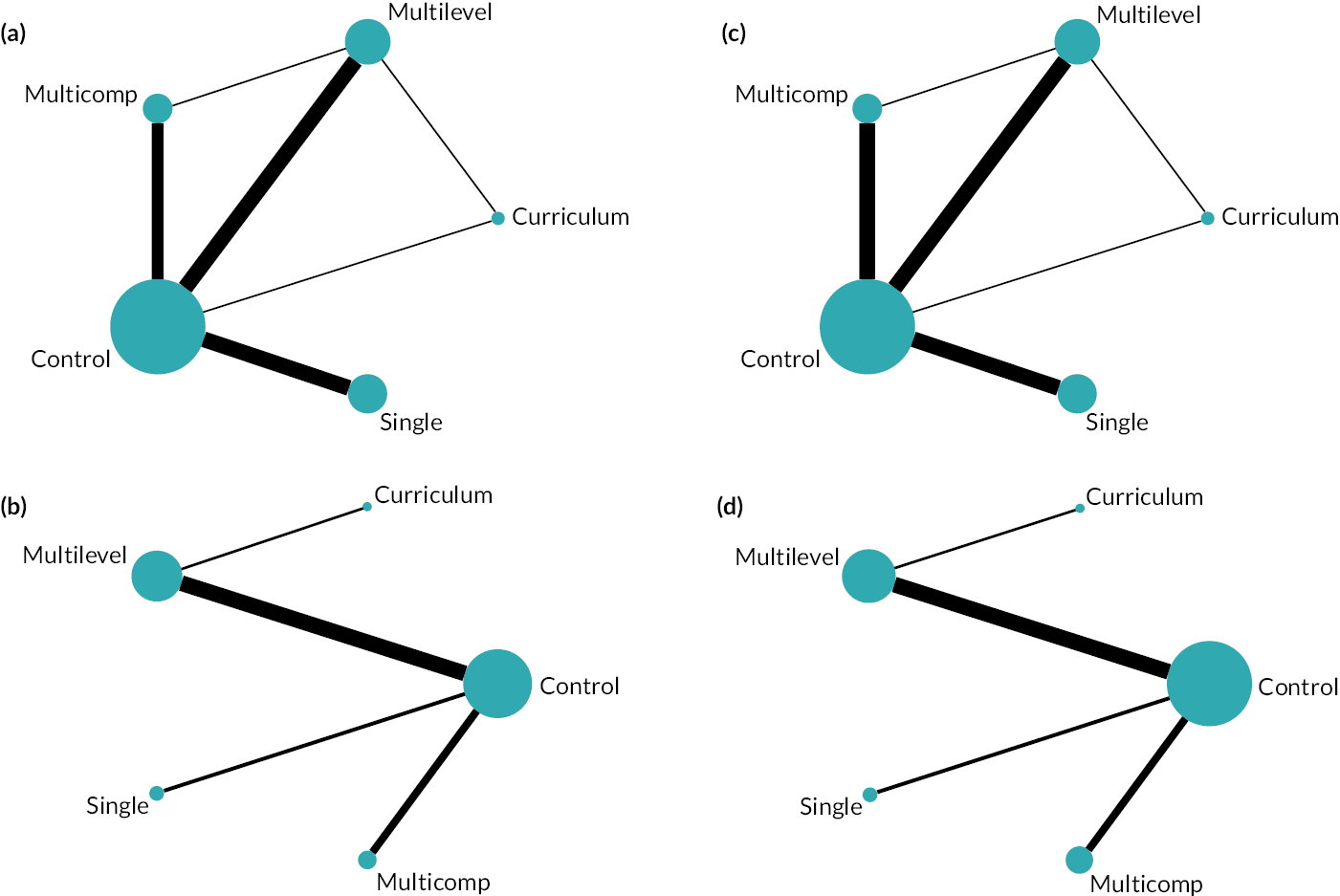

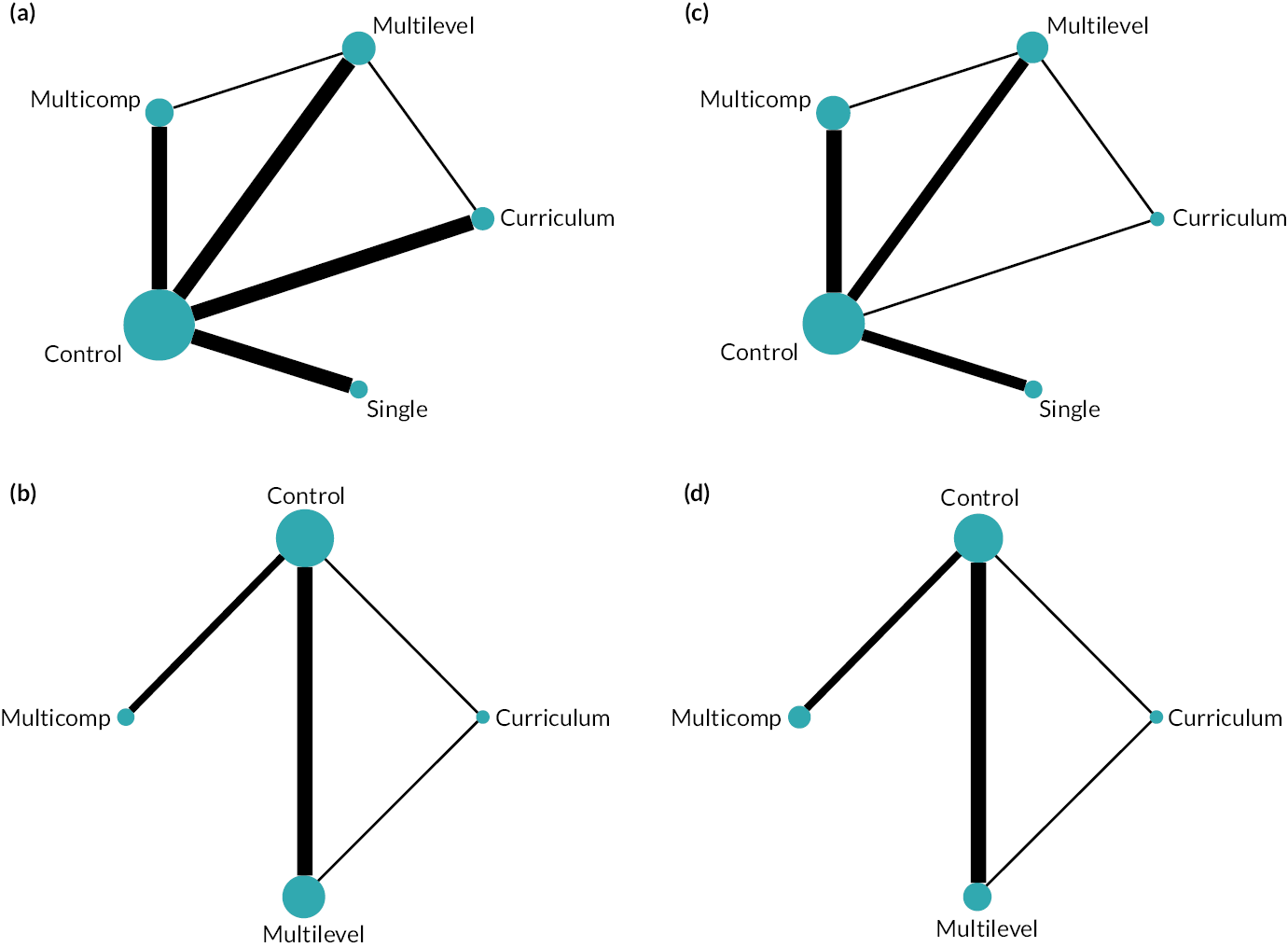

Research question 5: network meta-analysis

Drawing on randomised trials analysed in RQ3, we used the findings from our analysis of intervention typology and intervention components to estimate network meta-analyses (NMAs). For all NMAs, we considered as separate outcomes DRV victimisation, DRV perpetration, GBV victimisation, and GBV perpetration. We considered our intervention typology analyses as primary and our intervention component analyses as exploratory.

All NMAs were implemented in a frequentist framework drawing on methods proposed by Rücker et al. (2012)73 and Melendez-Torres et al. (2015),74 using random effects for all analyses. Implementation used – network – in Stata for typology NMAs and – netmeta – in R for component NMAs. Where trials reported multiple effect sizes for the same outcome (i.e. different estimates of DRV victimisation drawing on, e.g. emotional, physical, sexual DRV), we assumed that outcomes were correlated with ρ = 0.8, consistent with standard assumptions used in robust variance estimation meta-analyses. Analyses were checked for inconsistency statistically using standard design-by-treatment interaction models, and conceptually by considering transitivity with regard to key effect modifiers (principally age, sex, high-income vs. low- and middle-income context). Where necessary, we used network meta-regression to account for plausible effect modifiers unevenly distributed between network comparisons. NMAs were then presented using the standard pairwise comparison league table, with intervention types ranked using a resampling method and surface under the cumulative ranking curve (SUCRA).

Feasibility

We first assessed feasibility for these NMAs, by examining the distribution of typology and components across different outcome domains, and examining where network metaregression may be necessary to balance effect modifiers between nodes in the network. We regarded the typology analyses as primary and the component analyses as exploratory given the number of trials available for each outcome, presenting component NMAs only where enough trials were available to provide a sufficiently rich data structure.

Intervention typology network meta-analyses

Drawing on our findings from RQ1, we used our proposed intervention typology to estimate the relative effectiveness of different intervention types.

Intervention component network meta-analyses

Drawing on our findings from our first research question, we explored where feasible the use of high-level component categories to estimate the impact of each component on intervention effectiveness. We planned to probe potential two-way interactions between components first by probing cross-level (e.g. structural by student) interactions and then considering within-level interactions, but ultimately explored strictly additive models where component NMAs were undertaken.

Research question 6: realist integration of findings

We used implementation and process evidence, mediator and moderator analyses, and ‘informal’ evidence from included studies (e.g. discussion of how interventions were implemented in outcome evaluation discussion sections) to identify mechanisms by which interventions impact DRV and GBV outcomes and associated contextual contingencies. Mechanisms focused on understanding causal chains by which interventions are likely effective, including proximal and antecedent steps (e.g. increasing engagement, addressing social norms, knowledge and attitudes) leading to distal effects on outcomes. Informed by realist synthesis75 and best-fit framework synthesis,76 reviewers used findings from RQ1 as a framework to infer and induce mechanisms from studies. Best-fit framework synthesis is a flexible form of framework analysis for the synthesis of diverse study types. Importantly, it accounts for the possibility that previously ‘untheorised’ findings may emerge as relevant from included study findings. Our approach is informed by realist synthesis in that we aim to understand the links between contexts and mechanisms in generating outcome patterns.

Using the context-mechanism findings from the theory synthesis in RQ1 as a template, reviewers analysed findings from the subsequent syntheses in RQ1–5, working independently and together to understand which causal propositions from the theory synthesis are supported, refuted or unevidenced. This synthesis unfolded collaboratively through meetings of the reviewer team, with an audit trial kept of synthesis decisions made. Analysis could also generate additional context-mechanism-outcome configurations that were not present in the theory synthesis but that reflected learning from other syntheses.

Findings were periodically discussed in meetings of the investigator group and were presented to the advisory and youth stakeholder groups. These groups provided additional insights in revisiting contexts and mechanisms previously discussed in RQ1, and in identifying which previously untheorised contexts and mechanisms are especially salient in the UK context.

Policy and practice consultation

Our review benefited from a robust process of consultation, described in Chapter 11. We convened a policy and practice advisory group, which met three times over the course of the project, and also undertook consultation with different groups of young people in London and Cardiff. These consultations drew on a range of formats and helped in sensitising our analyses and identifying implications of our work.

Ethics approval

The research involved no human participants and drew solely on evidence in the public realm, so ethics approval was not required.

Chapter 3 Overview of included studies

Results of the search

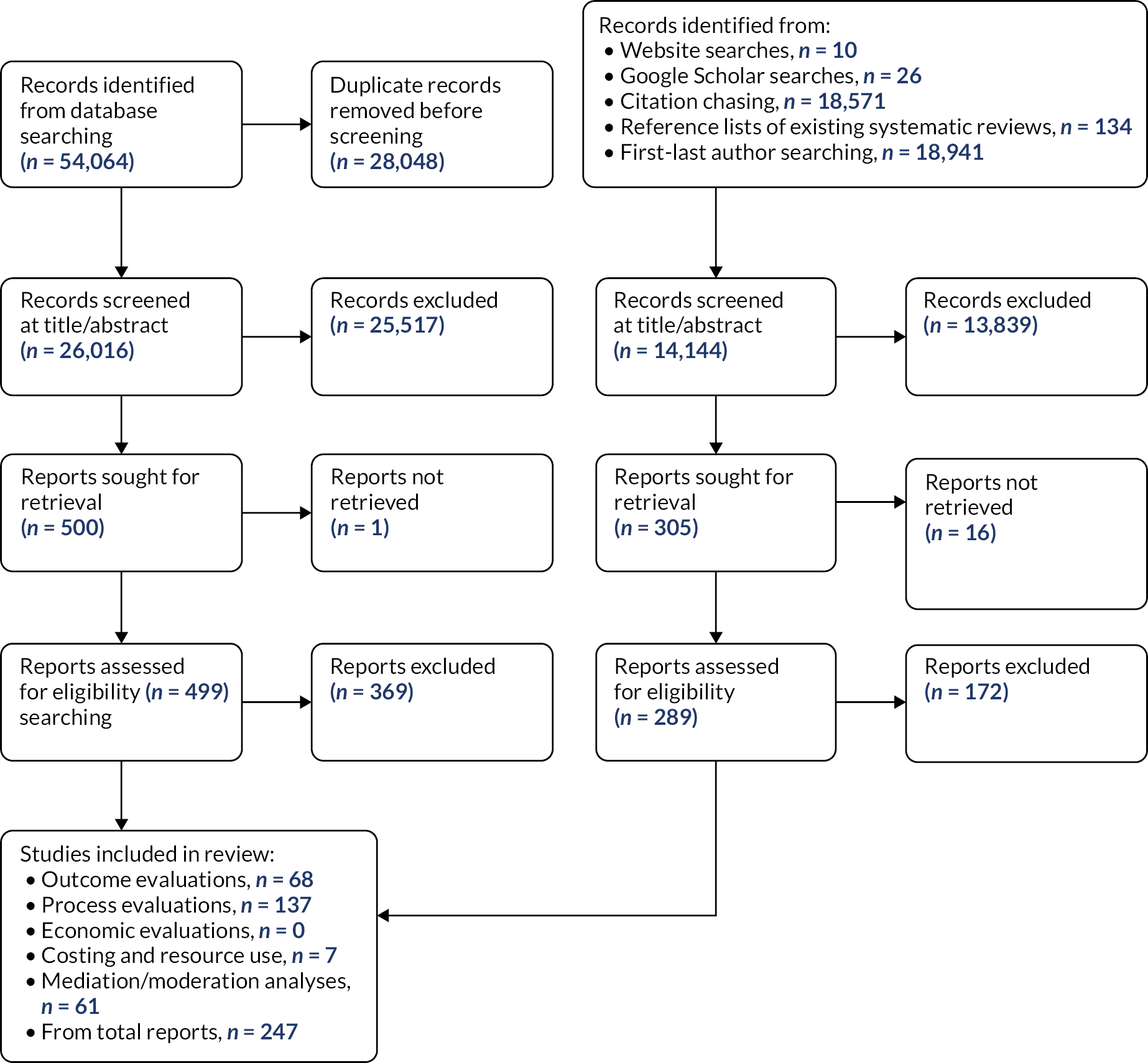

Results of the search are depicted in Figure 2. Up until June 2021, we included a total of 247 reports over 2 rounds of database searching, extensive citation chasing and first and last author searching. It was common for studies to be reported across multiple publications. Some studies were also included in more than one area of the review. An overview of studies included in the review and the type of evidence they reported is provided in Appendix 2.

FIGURE 2.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow chart.

Included studies and reports

The review identified 247 studies that evaluated 211 active interventions. An overview of the studies identified and the types of evidence they reported is provided in the appendix (see Table 34 in Appendix 2), and can be summarised as follows:

-

Fifty-one active interventions described across 75 publications were included in the theory synthesis.

-

One hundred and sixty active interventions evaluated in 137 studies reported in 161 publications were included that reported process or implementation outcomes.

-

Seventy-nine active interventions evaluated across 68 studies reported in 101 publications were included that reported effectiveness data.

-

Twenty-five active interventions evaluated across 24 studies reported in 28 publications were included that reported moderation data.

-

Five active interventions evaluated across five studies reported in seven publications were included that reported mediation data.

-

No studies reporting a formal economic evaluation of a relevant intervention were identified. Instead, we identified eight active interventions evaluated across seven studies reported in seven publications that reported cost and resource use associated with interventions.

Excluded studies are detailed in Report Supplementary Material 1.

Study and intervention characteristics

Study designs

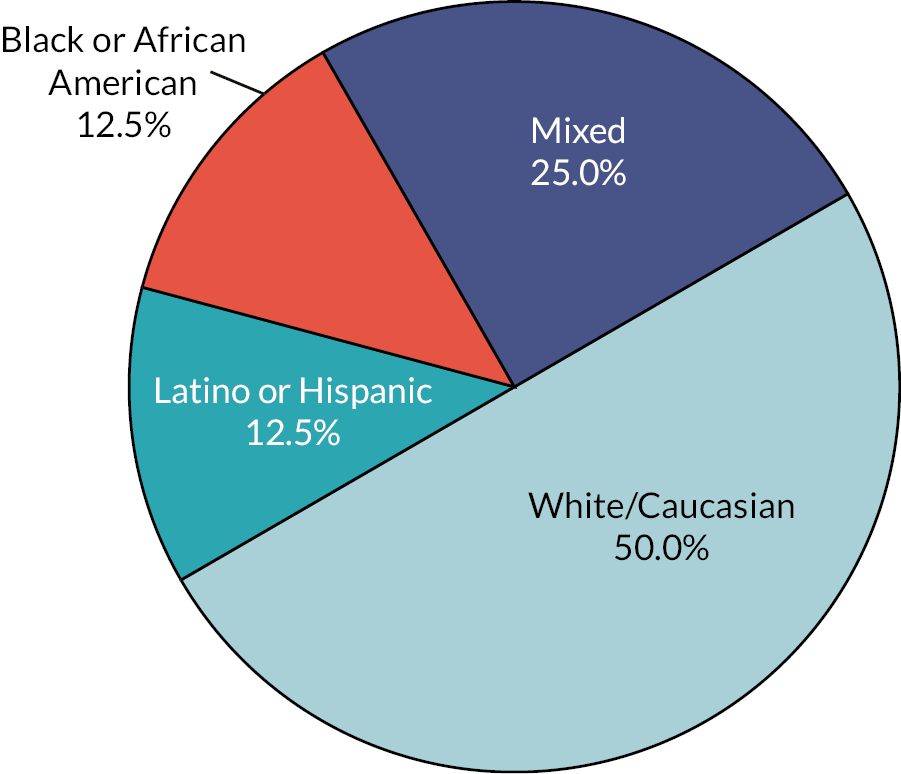

Process and implementation evaluations (RQ2)

One hundred and thirty-seven studies reporting process or implementation outcomes were included. Twenty-nine (21.2%)49,77–101 of the studies were associated with a RCT or cRCT, while others were non-randomised, naturalistic or quasi-experimental studies. Eighty-two studies reported quantitative data and 122 studies reported qualitative data.

Many of the included studies reported incomplete information about the sample included in process evaluations. Where sample size was reported or could be estimated, student sample size ranged from 6 to 5937 (median = 85). Studies evaluating interventions to target both DRV and GBV were generally larger (median = 307) than those targeting DRV only (median = 87) or GBV only (median = 44). Those studies including staff in their evaluations reported a sample size ranging from 1 to 1900 teaching staff or other professional stakeholders (median = 26).

Two studies (1.5%)102,103 were conducted solely with children of primary school age (i.e. < 11 years), and an additional five studies (3.6%)104–108 included students of primary school age or their teachers amongst a broader sample. The other studies were conducted in secondary/high school settings.

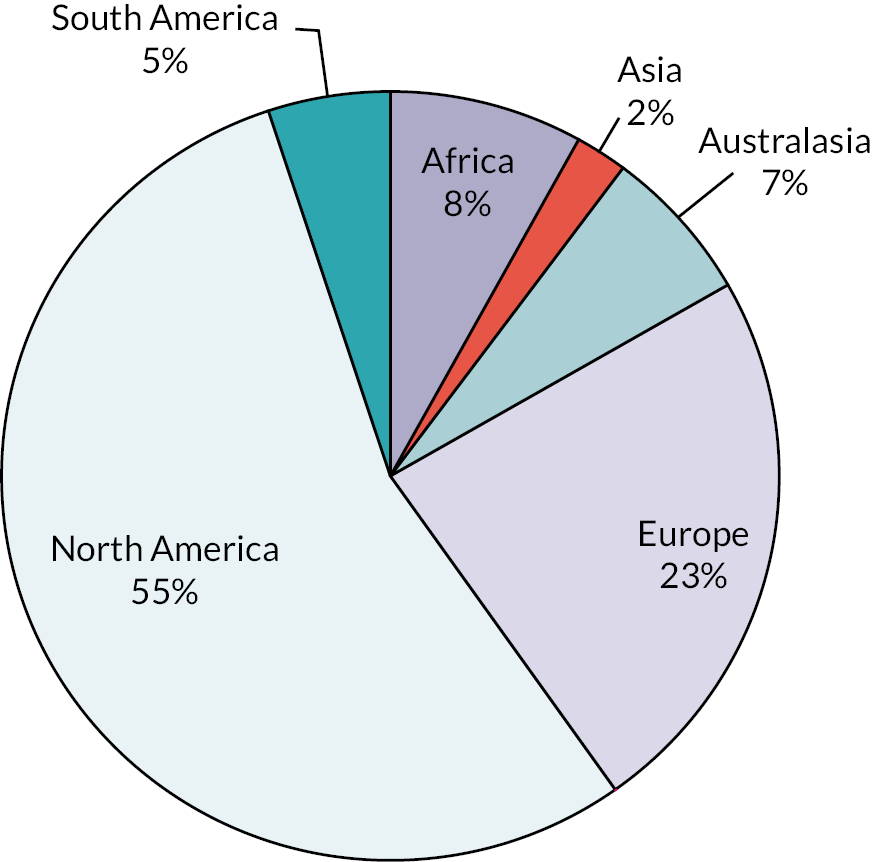

The majority of studies (n = 75, 54.7%) were conducted in North America, with the remaining split across Europe (n = 32, 23.4%),49,79,88,91,94,102,105–107,109–131 Asia (n = 3, 2.2%),78,85,87 Africa (n = 11, 8.0%),90,132–141 South America (n = 7, 5.1%)84,104,142–146 and Australasia (n = 9, 6.6%). 103,147–154 A breakdown of the specific continents and countries in which studies were conducted is provided in Figure 3 and Table 2.

FIGURE 3.

Location of process/implementation evaluations.

| Location | Number of studies | % of total |

|---|---|---|

| Africa | 11 | 8.03 |

| Botswana | 1 | 0.73 |

| Botswana, Malawi and Mozambique | 1 | 0.73 |

| Cameroon, Senegal and Togo | 1 | 0.73 |

| Malawi | 1 | 0.73 |

| Namibia, South Africa, South Sudan, Eswatini, Tanzania, Zambia and Zimbabwe | 1 | 0.73 |

| South Africa | 4 | 2.92 |

| Tanzania | 1 | 0.73 |

| Zimbabwe | 1 | 0.73 |

| Asia | 3 | 2.19 |

| Bangladesh, India, Vietnam | 1 | 0.73 |

| India | 1 | 0.73 |

| Taiwan | 1 | 0.73 |

| Australasia | 9 | 6.57 |

| Australia | 8 | 5.84 |

| New Zealand | 1 | 0.73 |

| Europe | 32 | 23.36 |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Serbia | 1 | 0.73 |

| England | 10 | 7.30 |

| England and Wales | 1 | 0.73 |

| Germany | 1 | 0.73 |

| Ireland | 1 | 0.73 |

| Netherlands | 1 | 0.73 |

| Portugal | 1 | 0.73 |

| Scotland | 1 | 0.73 |

| Serbia | 1 | 0.73 |

| Slovenia | 1 | 0.73 |

| Spain | 7 | 5.11 |

| Sweden | 2 | 1.46 |

| UK | 3 | 2.19 |

| UK, France, Spain and Malta | 1 | 0.73 |

| North America | 75 | 54.74 |

| Canada | 14 | 10.22 |

| Hawaii | 2 | 1.46 |

| Mexico | 1 | 0.73 |

| USA | 58 | 42.34 |

| South America | 7 | 5.11 |

| Brazil | 5 | 3.65 |

| Colombia | 1 | 0.73 |

| Peru | 1 | 0.73 |

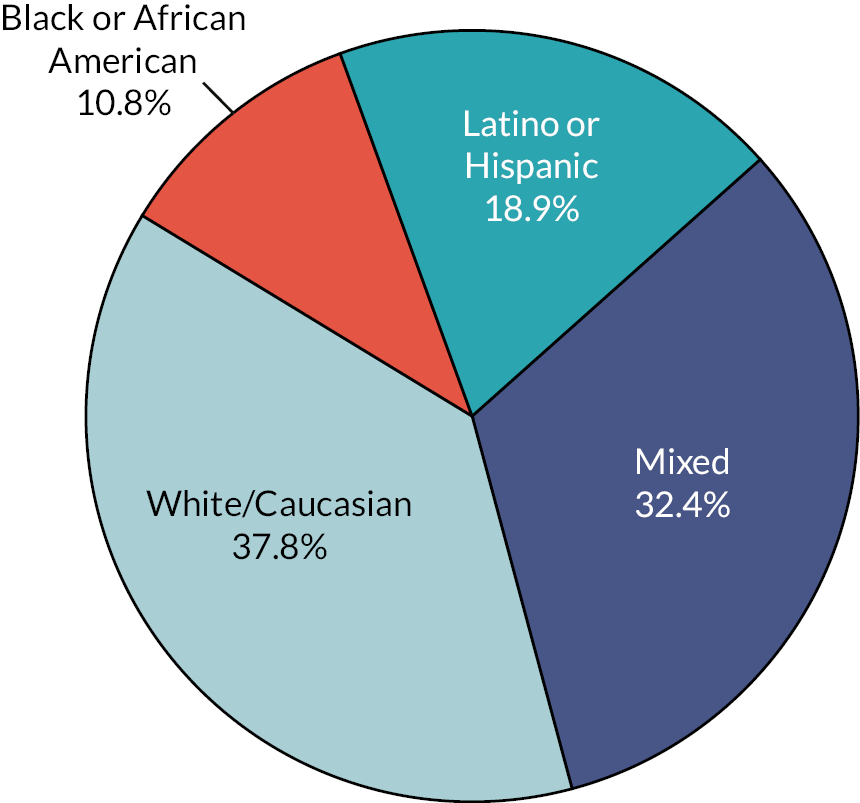

Outcome evaluations (RQ3)

Of the 68 included studies, 14 were RCTs (20.6%) and 54 were cRCTs (79.4%). The majority of studies (n = 61, 89.7%) compared two intervention arms, though five (7.4%)78,94,155–157 and two (2.9%)100,158 studies evaluated three and four intervention arms, respectively. cRCTs ranged in size from 4 to 151 clusters (median 23).

Sample size (ITT population) of the studies ranged from 34 to 89,707 participants, including all groups (median 816). Trials targeting both DRV and GBV were generally larger (median = 2403) compared to trials targeting GBV only (median = 1306) or DRV only (median = 660).

School settings for the included studies are shown in Table 3. Only one study (1.5%)159 was conducted solely in a primary school setting; rather, the vast majority of included studies were conducted in secondary school settings.

| School setting | Number of studies (%) |

|---|---|

| Primary school only (< 11 years) | 1 (1.5)159 |

| Primary and secondary school (≤ 16 years) | 3 (4.4)160–162 |

| Secondary school only (11–16 years) | 57 (83.8) |

| Secondary school and sixth form (11–18 years) | 4 (5.9)49,84,163,164 |

| Sixth form only | 2 (2.9)88,165 |

| Unclear | 1 (1.5)166 |

Where reported, recruitment or data collection for the included studies spanned 1994–2017; there was no clear difference in the age of studies evaluating DRV or GBV.

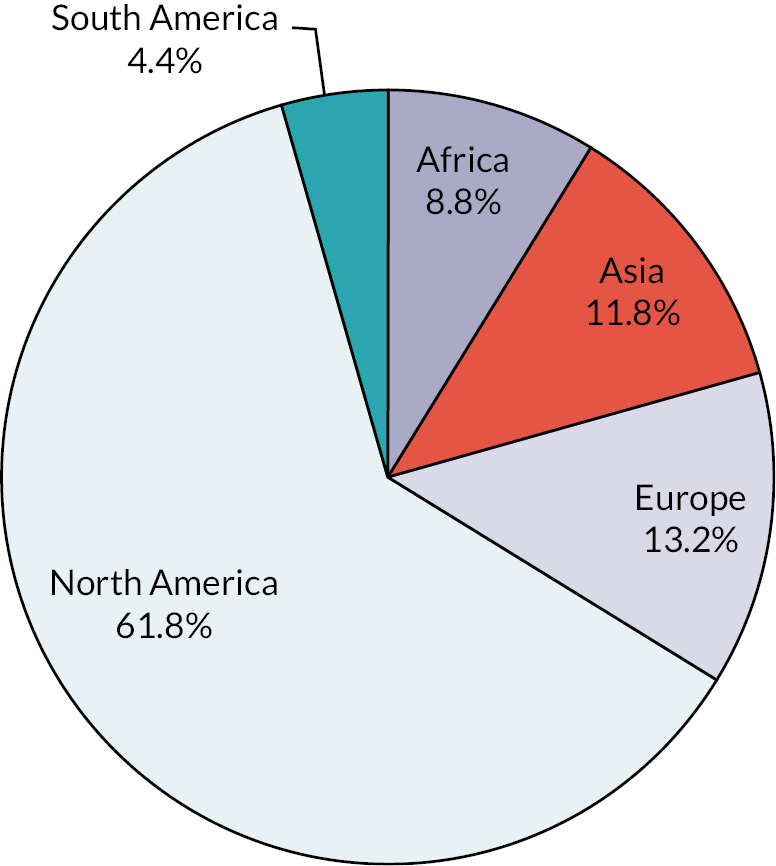

The majority of studies (n = 42, 61.8%) were conducted in North America, with the remaining split across Europe (n = 9, 13.2%),35,49,79,88,94,164,167–169 Asia (n = 8, 11.8%),78,85,87,170–173 Africa (n = 6, 8.8%)90,155,160,174–176 and South America (n = 3, 4.4%). 84,163 A breakdown of the specific continents and countries in which studies were conducted is provided in Figure 4 and Table 4.

FIGURE 4.

Location of outcome evaluations.

| Location | Number of studies | % of total |

|---|---|---|

| Africa | 6 | 8.82 |

| Kenya | 1 | 1.47 |

| Malawi | 1 | 1.47 |

| South Africa | 3 | 4.41 |

| Uganda | 1 | 1.47 |

| Asia | 8 | 11.76 |

| India | 2 | 2.94 |

| Iran | 2 | 2.94 |

| South Korea | 2 | 2.94 |

| Taiwan | 1 | 1.47 |

| Vietnam | 1 | 1.47 |

| Europe | 9 | 13.24 |

| England | 3 | 4.41 |

| France | 1 | 1.47 |

| Germany | 1 | 1.47 |

| Spain | 3 | 4.41 |

| The Netherlands | 1 | 1.47 |

| North America | 42 | 61.76 |

| Barbados | 1 | 1.47 |

| El Salvador | 1 | 1.47 |

| Haiti | 1 | 1.47 |

| USA | 39 | 57.35 |

| South America | 3 | 4.41 |

| Brazil | 3 | 4.41 |

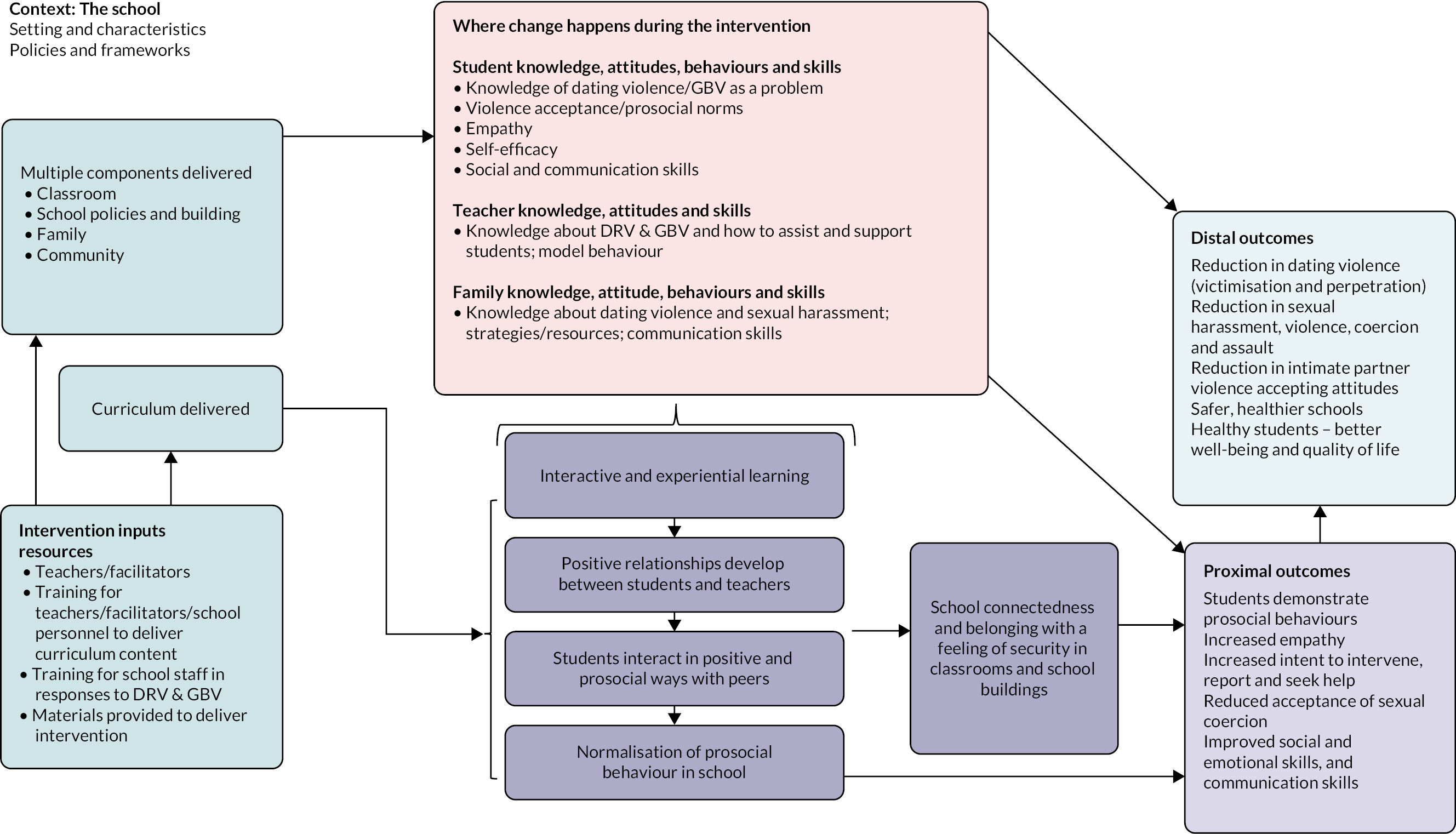

Intervention characteristics

Process and implementation evaluations (RQ2)

One hundred and sixty active interventions were evaluated for process or implementation outcomes. A description of the interventions evaluated is provided in the appendix.

The majority (n = 104, 65.0%) of interventions were evaluated in single-arm studies, while 24 interventions (15.0%)78,80,94,100,105,123,177–179 were compared with at least one other active intervention. Other comparative studies involved a control arm, typically no intervention or waitlist, but process and implementation outcomes were generally only reported for the active arm(s) without any controlled comparison.

Intervention target

Included interventions intended to target DRV (n = 80, 50%), GBV (n = 53, 33.1%) or both (n = 27, 16.9%).

Outcome evaluations (RQ3)

Seventy-nine active interventions were evaluated across 68 included studies. A description of the interventions identified is provided in Report Supplementary Material 1.

Seven interventions were identified as having been evaluated across more than one study: Coaching Boys into Men (CBIM) (n = 2),77,180 Expect Respect (n = 2),95,159 IMPower (n = 2),160,174 Media Aware (n = 2),97,98 Safe Dates (n = 2),36,166 Shifting Boundaries (n = 2)100,156 and TakeCARE (n = 2). 38,181 Other interventions were found to share the same title (e.g. ‘dating violence prevention program’), but were not clearly identified as being the same intervention.

The vast majority of studies (n = 65) compared interventions against a control arm, namely an active control (n = 13),36,38,87,92,160,162,165,169,170,176,181–183 usual practice (n = 12),35,83,98,99,174,184–190 waitlist (n = 17),49,79,84,88,89,94,95,97,167,168,172,175,191–195 no intervention (n = 23)77,78,81,82,84,85,90,96,100,155,157–159,161,163,164,171,173,180,196–198 or ‘control’ (n = 1). 199 For the purpose of this review, one intervention was considered an active control, even though the content of the intervention was targeted towards DRV mechanisms. 36 This was because the intervention was almost entirely conducted outside the school setting, and therefore was not relevant for inclusion in the review. Limited information was typically reported about the nature of non-active control interventions, but often students received their usual classes (excluding topics related to DRV or GBV) over a comparable time period.

Only eight studies included a head-to-head comparison (Table 5). This included comparisons with different methods of delivering the same intervention (e.g. Sabella 1995),158 and comparison of different intensity levels of the same intervention (e.g. Taylor et al. 2017). 156

| Author, date | Comparison | Intervention 1 | Intervention 2 | Intervention 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Achyut 201178 | GEA + CAMPAIGN vs. CAMPAIGN vs. no intervention | GEA + CAMPAIGN | CAMPAIGN | – |

| Jewkes 2019155 | Skhokho vs. Skhokho + caregivers vs. no intervention | Skhokho | Skhokho + caregivers | – |

| Muck 201894 | Scientist-Practitioner Program vs. Practitioner Program vs. control | Scientist-Practitioner Program | Practitioner Program | – |

| Niolon 2019166 | Dating Matters vs. Safe Dates | Dating Matters | Safe Dates | – |

| Sabella 1995158 | Sexual harassment classes: Peer-led vs. Adult-led vs. Self-led vs. control | Peer-led | Adult-led | Self-led |

| Taylor 2010200 | Interaction curriculum vs. law and justice curriculum vs. control | Interaction curriculum | Law and justice curriculum | – |