Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 10/3006/13. The contractual start date was in August 2012. The final report began editorial review in June 2021 and was accepted for publication in April 2022. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Blair et al. This work was produced by Blair et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Blair et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

In 2007, the UK was ranked bottom of 21 nations in a United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) report on child and adolescent health and well-being in high-income countries,1 stimulating the development of national initiatives to improve children’s and young people’s health. A subsequent UNICEF report in 20132 revealed an improvement since this first study, with the UK ranked 16th out of 26 nations. Although there have been some improvements in child health and well-being, the UK has the lowest rate of young people going into further education across all 26 countries and some of the highest child alcohol abuse and teenage pregnancy rates3 (although recent evidence suggests teenage pregnancy rates in the UK have halved since 20074). The current intervention was developed in this context, but remains relevant today.

Social and emotional well-being (SEW) comprises (1) emotional well-being: being happy, confident and not anxious or depressed; (2) psychological well-being: managing emotions, autonomous problem-solving, experiencing empathy and resilience; and (3) social well-being: forming good relationships with others and avoiding behavioural problems, including violence or bullying. 5 It enables people to function well and meet the challenges of life.

The importance of primary-age children’s SEW has been recognised by the UK and Scottish governments and is reflected in a strong body of current and recent government policy and initiatives. For England and Wales, this includes ‘Every Child Matters’, ‘Social and Emotional Aspects of Learning’ and ‘Your Child, Your Schools, Our Future: Building a 21st Century Schools System’. 6–12 Scottish initiatives include ‘Early Years and Early Intervention’, ‘Equally Well’, ‘Getting It Right For Every Child’ and the ‘Curriculum for Excellence’s Health and Well-being Outcomes’. 13–16 The Curriculum for Excellence (CfE) is the Scottish Government’s framework guidance for education, which aims to achieve a transformation in education in Scotland by providing a more coherent, more flexible and enriched curriculum from ages 3 to 18 years. 17

Many of these policies are informed by the World Health Organization’s health-promoting schools framework,18 which requires schools to address, simultaneously, the domains of school ethos, curriculum and family/community involvement. In Scotland, SEW aspects of learning are embedded within the CfE, with health and well-being as important as literacy and numeracy. There are also a number of localised curriculum programmes that have been used successfully within primary schools in Scotland, including Creating Confident Kids (a programme based on the English and Welsh Social and Emotional Aspects of Learning programme), The Motivated School and Being Cool in School. These programmes lack robust evaluation but are currently supported by the Scottish Government’s Rights, Support and Wellbeing Team (previously the Positive Behaviour Team), which adopts both universal and targeted approaches to positive behaviour through improving relationships and environments in schools.

Scientific background

Traditionally, school-based public health interventions aimed at improving the health and well-being of young people have focused on the prevention or reduction of specific health conditions or behaviours, such as obesity; inactivity; alcohol, tobacco and illicit drug use; and sexual risk taking. However, systematic reviews have shown that these interventions have had very mixed and often limited effects on outcomes, with few interventions proving to have a strong long-term impact. 19–25 In addition, there is growing evidence that universal interventions addressing the underlying determinants of non-communicable health conditions and risk behaviours might have greater impact and be more cost-effective at improving health and well-being than approaches targeted at the most vulnerable or those already experiencing problems. 26 In this chapter, we provide a scientific rationale for this study, which evaluated an intervention for primary school children that aims to improve their Social and Emotional Education and Development (SEED). We also describe the aim and research questions for the study. The key components of the SEED intervention and the underpinning theory of change are explained in more detail in Chapter 2. For an overview of the literature search strategy, see Appendix 1.

The primary school setting

There is evidence that programmes addressing the underlying determinants of non-communicable health conditions and risk behaviours need to be introduced in the early years of primary school and sustained over time to include key transition periods. 7,10,27 Improved SEW during primary school has been shown to have an impact on physical health and to be a protective factor against a range of risk behaviours in later years, including tobacco use, illicit drug use and alcohol misuse; violence and crime; and teenage pregnancy. 7,10,28–32 A 2011 review and meta-analysis including > 200 controlled studies of school-based interventions designed to enhance the social and emotional skills of children aged 5–18 years27 found positive benefits on a range of outcomes, including significant improvements in social and emotional skills, attitudes and positive social behaviours, and academic performance. Maximum benefits were observed when the programmes were evidence based and well implemented by school staff. In addition, there is strong evidence that interventions with a longer duration (i.e. multiyear interventions) are likely to have a greater effect than shorter-term programmes. 7,10,33

Other systematic reviews of the effectiveness of universal interventions to improve the mental well-being (encompassing emotional, psychological and social well-being) of children in primary education found that curriculum-only interventions appear to be effective only in the short term. In contrast, there is good evidence to support the use of programmes that combine a social and emotional development curriculum with components that focus on behaviour management and improvement of child–teacher relationships. 7,10,28–32,34 Furthermore, programmes that include a significant teacher training component show considerable promise, as do those that include a parenting support component. 7,10,28–32,34 The multicomponent intervention approach appears to be particularly effective in improving mental health, as well as reducing bullying and violence. 7,10,28–32 One of the key studies in this area is the Seattle Social Development Project (now known as Raising Healthy Children), which was implemented in year 1 of elementary school for 6 years, with follow-up into adolescence and young adulthood. The programme sought to promote connectedness to school and family and to strengthen children’s social competencies. It consisted of three components: teacher training, child social and emotional skill development, and parent training. Follow-up at age 21 years revealed significant reductions in the intervention group, compared with the control group, in health risk behaviours (including alcohol, tobacco and illicit drug use and sexual risk behaviour), violence and crime, and emotional and mental health issues, and increases in positive functioning in university or work. 7,10,35–38 Some of these effects remained significant when the study population was followed up at age 30 years. 39

When devising the SEED intervention, there was little robust evaluation of interventions aimed at improving SEW in UK primary schools. One exception is a recent cluster randomised controlled trial (RCT) of the Roots of Empathy (ROE) intervention, carried out in 74 primary schools in Northern Ireland. 40 ROE is a Canadian programme designed to promote empathy in children through demonstration of the attachment relationship. 41 It consists of annual visits from a mother and infant to the school over the course of a year and is designed to facilitate the labelling of feelings and the exploration of the relationship between feelings and behaviour. The investigators found that, among the intervention group, children (year 5, aged 8–9 years) were rated by their teacher as being more prosocial and exhibiting less difficult behaviour post intervention. However, only the latter was sustained over the 36-month follow-up period. No difference in effect by gender or socioeconomic status was observed. An economic analysis indicated that the ROE intervention was cost-effective. These findings are in accordance with those of the only other cluster RCT of ROE,42 which reported improvements in prosocial behaviour (although this was not maintained over time) and reduction in aggressive behaviour in the short and longer terms.

Whole-school intervention approaches

Whole-school interventions aim to adjust the school environment in an effort to improve health and have been shown to improve social competence and reduce aggression and health risk behaviours. 43–50 A comprehensive review of the impact of school environment interventions in both the primary and secondary school settings on health and well-being51 identified 10 experimental or quasi-experimental studies with a variety of outcomes. Interventions fell into one of three categories: promotion of sense of community and better interpersonal relationships to reduce aggression and other risk behaviours; encouragement of advocacy by staff and pupils for healthier eating and physical activities; and improvement of school playgrounds. Results were mixed, with many studies having important methodological limitations. The authors51 concluded that school environment interventions have the potential to reduce violence and aggression, but highlighted the need for more robust intervention studies. A parallel Cochrane review synthesised the evidence from cluster RCTs of multicomponent interventions aiming to improve health in schools that included input to the curriculum, changes to the school ethos, and family or community engagement. 52 Although the authors found some evidence for effectiveness, such as reduced bullying and improvement in some health behaviours, including smoking, physical activity and dietary outcomes, there was little evidence of effect on other outcomes, such as alcohol use and mental health. Few studies reported on these last two outcomes, and the methodological quality of included studies was generally considered to be low to moderate.

Some of the best evidence for the effectiveness of the whole-school approach within the secondary school setting comes from the Australian Gatehouse Project, which was designed to improve SEW through the promotion of a sense of social inclusion and connection in secondary schools. 53–56 Importantly, the strategies used to achieve this varied between schools, according to pupils’ perceptions of need, with the conceptual framework focusing on three ways of strengthening connectedness to school: (1) building a sense of security and trust, (2) enhancing communication and social connectedness and (3) building a sense of positive regard through valued participation in aspects of school life. 57,58 The effectiveness of the Gatehouse Project was evaluated using a RCT design. 57 Although the Gatehouse Project did not affect depressive symptoms or social and school relationships,53–56 it reduced substance use for a cohort of pupils in the intervention schools followed up longitudinally 2 and 3 years after the intervention began. 53–56 Subsequent year-8 pupils (aged 13–14 years) in intervention schools, surveyed 5 years after the trial began, also reported lower rates of substance use than those surveyed in the control schools. 57,58 Both the Seattle Social Development Project8,11,36–39 and the Gatehouse Project included changes to the school curriculum that focused on developing or improving SEW.

There is also some evidence that targeted programmes can have an impact on SEW. A review of targeted programmes in primary schools reported modest improvement, particularly in social problem-solving and development of positive peer relations, with lengthy, multicomponent programmes. 59 The evidence therefore supports an integrated approach that provides targeted support for those experiencing particular difficulties within a supportive whole-school approach to promote mental well-being. 26,43 Furthermore, a review of family-based programmes to promote mental well-being10,60 supports the need for generic programmes to promote mental well-being at a population level and more intensive programmes for more serious problems among individuals. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance on promoting children’s SEW in primary education strongly supports the adoption of universal approaches, which have the capacity to address emotional well-being in a connected way that reduces potential for stigmatisation, but which also include provision of targeted approaches and early identification of children at risk. 61

Scientific rationale

Although the evidence base suggests several promising intervention approaches, there are limitations and gaps that need to be addressed. Most of the evidence for improving SEW among primary school children is non-UK and largely US-based, and many of the programmes evaluated (particularly family or parenting programmes) target vulnerable children only, as opposed to taking a universal approach. The effectiveness of universal approaches that incorporate elements such as parent support has rarely been investigated in the UK and needs to be determined through robust evaluation. In addition, the cost-effectiveness of addressing health and well-being in general, and SEW in the primary school years in particular, has rarely been determined. However, economic evaluation of the Seattle Social Development Project revealed the substantial economic benefits of such an approach in the US setting, which were far greater than those of basic curriculum-based programmes implemented during early adolescence. 62 To date, evaluation studies have rarely examined the differential effects of specific programmes according to gender and socioeconomic status. It is essential to evaluate the effectiveness of programmes on these subgroups to ensure that there is no widening of health inequalities between these groups, and to identify whether or not programmes may be effective in narrowing health inequalities. Finally, many studies have been criticised for methodological limitations, including having short-term follow-up only, participant attrition and not including key transition periods within the duration of follow-up. 47–52 The transition period between primary and secondary has been shown to be an important indicator for well-being and attainment in later life;7,10,63–65 therefore, it is important to include this key period within the follow-up period of any primary school-based intervention.

The SEED intervention was developed for Scottish primary school children based on the evidence already outlined. For the development, components and theoretical underpinning of the SEED intervention, see Chapter 2.

Study aim and research questions

The overarching aim of this study was to rigorously evaluate the impact of the SEED intervention on improving pupils’ SEW via a stratified cluster RCT. The main research questions were addressed by the complementary outcome, process and economic evaluations.

The pupil-related research questions were as follows:

-

Does the SEED intervention improve pupils’ SEW?

-

If so, is the impact different for specific subgroups of pupils (gender, deprivation)?

-

-

Is the SEED intervention more effective if started with younger children [SEED younger cohort (YC) vs. older cohort (OC)]?

-

What is the duration of the SEED intervention effect?

-

Does the SEED intervention improve the social and emotional experience of transition from primary to secondary school?

-

What is the impact on health behaviours of the SEED intervention during early secondary school years?

-

What are pupils’ experiences of the SEED intervention?

The teacher-related research questions were as follows:

-

Are there changes in teachers’ knowledge, attitudes and behaviour relating to developing pupils’ SEW?

-

Were teachers involved, and, if so, how were they involved, in selecting initiatives to respond to the pupils’ needs assessment?

-

What contextual factors facilitate or inhibit the delivery of the SEED intervention?

-

What contextual factors support or hinder the ability of the SEED intervention to improve pupils’ SEW?

-

Which teachers engage best with the SEED intervention?

-

What are teachers’ experiences of the SEED intervention?

The parent-related research questions were as follows:

-

Do parents report a difference in their child(ren)’s emotional and social development?

-

If applicable, what are parents’ experiences of the SEED intervention?

The economic research question was as follows: is SEED cost-effective?

Chapter 2 The Social and Emotional Education and Development intervention

The development of the Social and Emotional Education and Development intervention

The SEED intervention is designed to promote SEW among primary school pupils. The primary aim of the SEED intervention is to change the school environment (policy-making, teacher and pupils’ relationships and actions) to bring about improvements in SEW. It does so by supporting staff to examine data from their school community, identify the SEW needs of pupils and develop plans to address those needs. 66

The development of the SEED intervention was funded by the Medical Research Council (MRC)/Chief Scientist Office (CSO) Scottish Collaboration for Public Health Research and Policy and was based on a systematic search of the published literature, grey literature and websites to identify existing interventions that aimed to improve the SEW of schoolchildren. We also consulted educational psychologists (EPs), education researchers and other education professionals in Scotland, the USA and Australia to identify promising interventions.

The general model of the SEED intervention is encapsulated by the communities of care, in which the use of intelligence (research or other information) to identify local needs, co-production of priorities and actions to address those needs, and the evaluation of the impact are of fundamental importance. 67 One community of care in particular, known as the Gatehouse Project, was instrumental in helping us design the SEED intervention. Developed in Australia and co-led by the SEED RCT co-investigator and co-author Lyndal Bond, it aimed to build capacity in secondary schools to improve the emotional and mental health needs of young people and was successful in reducing cigarette and drug use, antisocial behaviour and sexual risk behaviour. 53–58

The Gatehouse Project aimed at improving emotional well-being by promoting pupils’ connectedness and belonging to their school. It did so through identification of the relevant risks and protective factors, co-production of an action plan (AP) with teachers and identifying evidence-based interventions to improve relationships between teachers and pupils and pupils’ life skills, all within an evaluative action research cycle. The essential elements were (1) a conceptual and operational framework that made sense to teachers and health researchers, (2) the active combination of health promotion with education reform, (3) an educator working closely with schools as a facilitator or critical friend, (4) establishment of an implementation team, (5) the use of local data to inform direction and strategies and prioritise actions and (6) integration of the curriculum component with the classroom and whole-school context. In so doing, the Gatehouse Project introduced standardised functional components while providing flexibility to accommodate and adapt to local circumstances. 53–58

An early model of the SEED intervention was evaluated in four primary schools in Glasgow. 68 The staff in the pilot schools welcomed the SEED intervention, mainly because it met the existing requirements to enhance health and well-being as part of the Scottish Government’s CfE. 17 EPs also welcomed the intervention. Head teachers (HTs) wanted more flexibility in managing the feedback loops and adapting the programme to the requirements of their schools.

Preliminary discussions and the formative evaluation resolved several aspects of delivery of the SEED intervention. It was decided to assess schools’ organisational needs by means of a survey of all school staff, including classroom assistants and support staff. Pupils’ needs assessments were based on the key outcome measure for the trial [i.e. the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ)]32,69–71 in primary school year 1 (P1) (ages 4–6 years) and primary school year 5 (P5) (ages 8–10 years) classes, with the option to include year-2 and year-6 pupils for very small schools. The SDQ data would be reported with minimal interpretation, without prescribing specific new programmes. Instead the emphasis would be on self-reflection, solution-focused discussion and appreciative inquiry. 72 EPs linked to the school would play a central role in facilitating the SEED intervention, given their role in supporting pupils and staff. Quality improvement officers (QIOs) would be encouraged to support the implementation of agreed initiatives.

Key components of the Social and Emotional Education and Development intervention

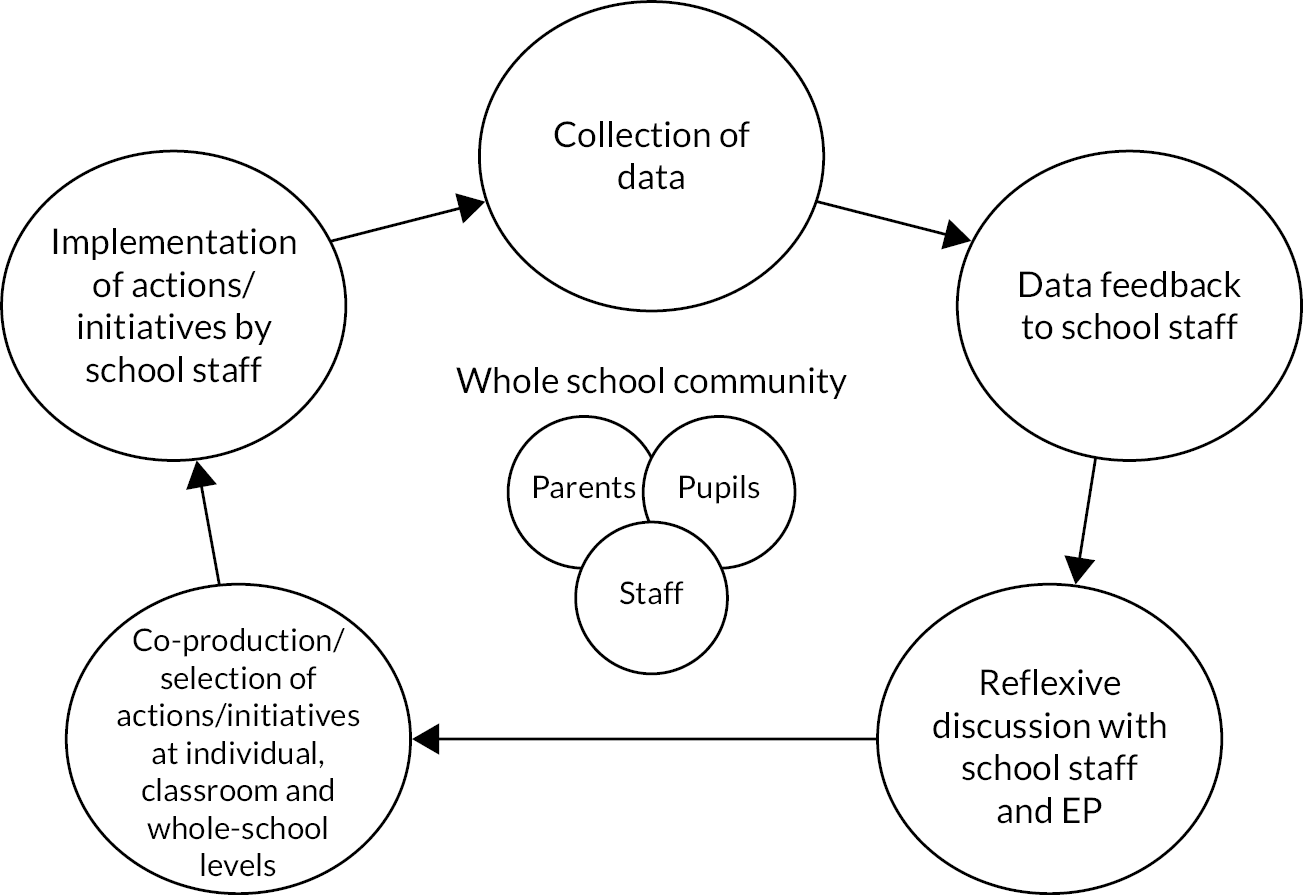

The SEED intervention comprises five components (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

The key components of the SEED intervention.

Component 1: data collection – pupils’ social and emotional well-being and school culture

Pupils’ SEW was assessed using the SDQ. Data were gathered as part of the trial at baseline [i.e. time 0 (T0)] and at follow-ups 1 and 2 [i.e. time point 1 (T1) and time point 2 (T2), 2 years and 3 years post T0, respectively], which allowed three intervention cycles over the course of the study. Additional questions captured data on pupils’ friendships with peers, relationships with staff and expectations of transition to secondary school. Staff perspectives of school culture were assessed through a survey that included the HTs, teaching staff, classroom assistants and support staff. The survey questionnaire included questions on staff stress and distress, whole-school relationships, perceptions of pupil behaviour and well-being, and school ethos. Parents’/carers’ perceptions of the school were captured in a parent survey that included questions on school ethos and environment. For further details of the questionnaires and survey methods, see Chapter 3.

Component 2: feedback reports – analysis and feedback to schools

The data from component 1 were analysed and compiled into individualised reports for each school. To facilitate comparison and reflection, the data were aggregated by cohort (i.e. P1, P5, staff and parents). For T1 and T2, the reports depicted the changes in scores from T0 to T1 and T2. In addition to the individual school reports, an ‘all schools’ report was produced depicting the same data collated across all intervention schools involved in the SEED RCT. Each school was positioned relative to the others in either graphic or tabular form to facilitate comparison (two examples relating to T0 and T2 are available in Report Supplementary Material 1 and 2, respectively).

A SEED resource guide (see Report Supplementary Material 3) was also provided to staff that contained an up-to-date and comprehensive review of programmes to help pupils improve their social and emotional education and well-being. All known programmes delivered to pupils, staff or parents in Scotland that were evidence based or had a strong theoretical underpinning were included. The content of the resource guide was identified through our systematic search and a review of relevant websites, and further information was sought from programme providers if possible. The resource guide was greatly assisted by two existing reviews: the American website Collaborative for Academic, Social and Emotional Learning (CASEL)33,73 and the Australian website KidsMatter. 74 All resources included in the guide were rated in terms of the strength of evidence of effectiveness and were ideally endorsed by the Scottish Government as aligning with the central ethos of the CfE. 75 Summary information was provided for each programme, including the target population, the aim, key components, effectiveness and links to further information. The guide was updated after 2 years.

Component 3: presentation and reflective discussion

Staff from each school chosen to implement the SEED intervention were invited to a presentation and reflective discussion (RD) session in school. The data outlined in component 1 were presented, followed by a discussion, aimed at providing a safe space for open discourse and identifying and prioritising key actions. EPs were included because of their pivotal role in providing additional support to pupils and staff. The teaching staff were encouraged to co-present the data (with the research team); when possible, the EPs co-led the RDs with teaching staff.

The RD sessions aimed at developing a commitment to positive change, co-producing tailored school-wide initiatives and establishing broad support for those initiatives. An assets-based approach was adopted whereby feedback was provided using positive language with reference to best hopes and preferred futures. When considering how to respond to feedback, staff were encouraged to be aware of their goals, considering their preferred options and existing teaching commitments. Reflection was encouraged as part of a continual process of change and development and not an annual event, nor an end in itself.

It was recognised that reflective sessions could be considered sensitive; therefore, the senior management team of each school was given the option of having a separate presentation and RDs. It was impractical to invite parents to the feedback sessions, but schools were encouraged to share results of the needs assessment with parents in other ways, for example through newsletters or electronic communications.

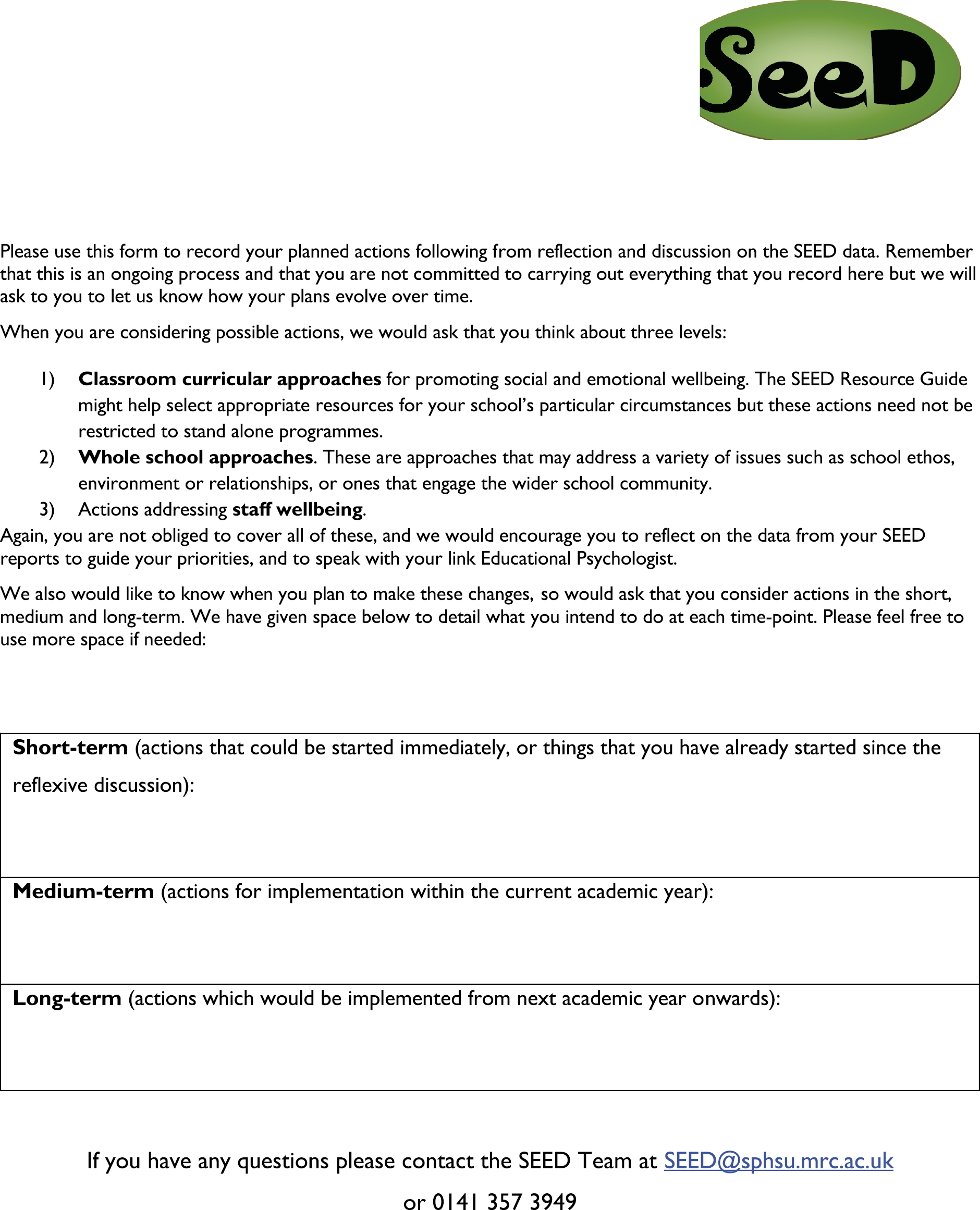

Component 4: selection of actions

There were several co-produced ground rules when selecting actions. Agreed actions should be practical and not add excessively to existing workloads, and preferred options should be aligned with the ethos and strategic goals of the school. The RDs should lead to the formulation of an AP (see Appendix 5), either by all staff or through an ‘action team’ subgroup, which was sometimes the senior management team. Staff were encouraged to use the SEED resource guide to help in their selection of appropriate actions and activities with short-, medium- and long-term time frames. It was recommended that the key priorities, and how these would be implemented, be set out in the APs and focus on:

-

the classroom, for example use of existing interventions such as Creating Confident Kids and Cool in School

-

whole-school initiatives, including training for staff and parents, supporting the implementation of restorative practices aimed at promoting proactive classroom management and interactional instruction, the understanding of the importance of the SEW of children and the opportunity of being positive role models. 18

When possible, the APs were incorporated into the school improvement plan, which schools are obliged to submit to their local authority (LA), typically in a 1- to 3-year cycle.

Component 5: implementation

After the development of APs, schools implemented their activities, supported by their EP and, when appropriate, QIO. The SEED RCT researchers maintained contact with schools during this period, but the intention was that schools should use their usual support systems to implement and maintain initiatives to replicate how the intervention would work in a real-life setting.

Meetings were held with EPs from LAs to discuss the delivery of the intervention and the role of the EP in that delivery. The dominant role of the EP was that of facilitation based on appreciative enquiry, principles that would be familiar to EPs and therefore require minimal training. EPs working in Scottish schools are commonly accredited as chartered psychologists by the British Psychological Society and have membership of the Scottish Division of Educational Psychology. QIOs were also invited to these meetings, although they were less involved. Qualifications for QIOs are unclear, but this role would be likely to require a formal teaching qualification and extensive experience in LA educational settings, including leadership roles and meeting national education priorities.

Underpinning theory of change

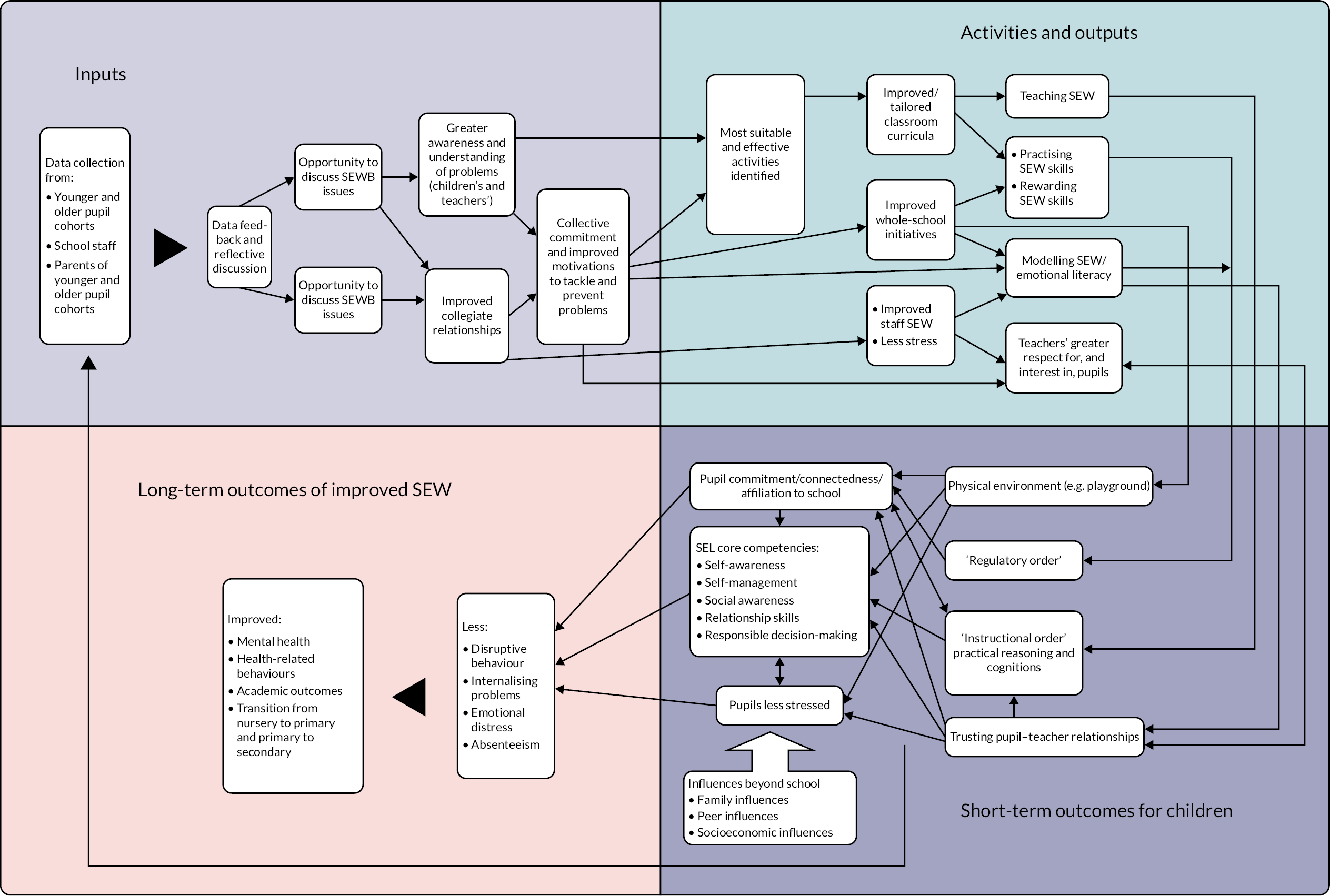

The SEED intervention draws on several theories, outlined in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2.

The SEED intervention theory of change model. SEL, social and emotional learning.

Socioecological framework

The socioecological framework76–78 distinguishes different levels of social influence that operate simultaneously and interact with each other. The levels are commonly described as intrapersonal (e.g. genetics, personality), individual (biographical factors, attitudes and beliefs), interpersonal, community, organisational and macro. The SEED intervention operates at four of these levels:

-

The individual, for example changing pupils’ and staff cognition and attitudes. These include raising staff members’ awareness of SEW as a result of participating in the presentations and RDs, and improving pupils’ core competencies such as self-awareness and social awareness through tailoring the classroom curricula.

-

The interpersonal, such as improving relationships between staff and pupils through greater focus on SEW and between staff by engaging in RD.

-

Organisational, for example changing the culture of a school through a collective commitment to address SEW and develop trust between staff and pupils.

-

The SEED intervention also interacts with macro-level influences, in particular the policy environment as set by the Scottish Government’s CfE17 and education authorities’ translation of that policy at local level.

Co-production

The term ‘co-production’ describes an equitable approach to intervention innovation, development and evaluation. The fundamental principle is that users design and deliver services in equal partnership with professionals. 67 Greenhalgh et al. 79 set out three key principles required for effective co-production in community-based research:

-

A systems perspective comprising an iterative and flexible design that adapts an intervention to local need. This was of central importance to the SEED intervention, including the choice of activities through RD.

-

The framing of research as a creative enterprise with human experience at its core. Research based on pupils’ SEW was the starting point of each of the intervention cycles in the SEED intervention.

-

An emphasis on process, including the framing of the programme, the nature of relationships, and governance and facilitation arrangements, especially the style of leadership. HTs and EPs were identified as local leaders and facilitated the SEED intervention through appreciative enquiry.

Social learning theory

Social learning theory posits that new behaviours can be learnt, and existing behaviours changed, through modelling behaviour, either by demonstration or being taught. 80,81 The concept of ‘modelling’ involves the development of self-efficacy, intentions and planning, and modification through social approval. 80,81 People observe credible role models, with whom they can identify, engaging in particular behaviours. They see the benefits of these behaviours and are motivated to adopt similar behaviours. This learnt behaviour is then positively reinforced by significant others. For example, it was important that staff took ownership of the SEED intervention, and, as part of their collective commitment, they modelled SEW by demonstrating their emotional competency to each other and their pupils.

School connectedness

Connectedness refers to diverse aspects of people’s social experiences, ranging across systemic dyadic relationships, perceptions of relationships, satisfaction with institutions and feelings of belonging. It is associated with a host of positive health outcomes for children and young people. 82 The concept of connectedness is very similar to Markham and Aveyard’s,83 Bonell et al. ’s,47,48,51 Jamal et al. ’s49 and Naghieh et al. ’s50 notion of pupils being ‘committed’ to their school, in that they are able to meet the challenges of learning and accept the school’s norms of behaviour and ethos.

It was decided that dedicated time for staff to better understand the school’s SEW needs, to reflect on these and to discuss how to respond would have a favourable impact. First, the SEED intervention was designed to enhance staff awareness and understanding of both pupils’ and staff members’ SEW problems. Second, the discussion of SEW was expected to lead staff to express and share problems, which would, in turn, improve collegiate relationships. These two processes would enhance motivation and collective commitment for positive change to tackle and prevent SEW problems.

Delivering classroom and environmental SEW interventions should lead both staff and pupils to become more aware of, and practise, their SEW skills and lead staff to reward pupils who exercise these skills. If successful, this should develop pupils’ core competencies such as self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, relationship skills and responsible decision-making, thus contributing to the ‘instructional order’. 83 Another pathway to these outcomes is through the ‘regulatory order’,83 whereby rewarding SEW skills contributes to pupils’ connectedness and commitment to their school. 47–51,82 Theoretically, improvement in school connectedness should lead to reductions in disruptive behaviour, poor well-being and absenteeism among pupils. 84

The next chapter will present the methods for the outcome, process and economic evaluations.

Chapter 3 Methods

Trial design

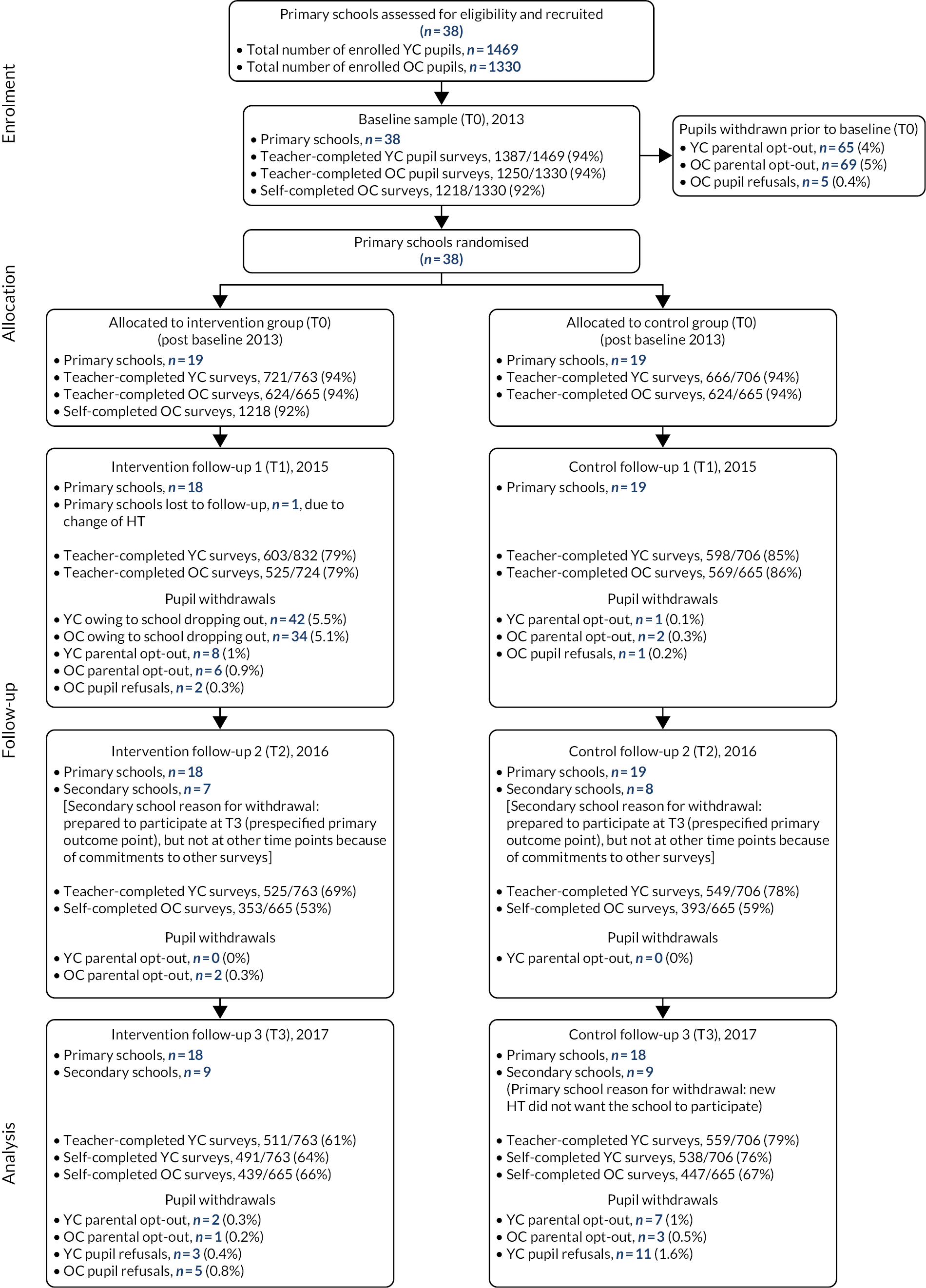

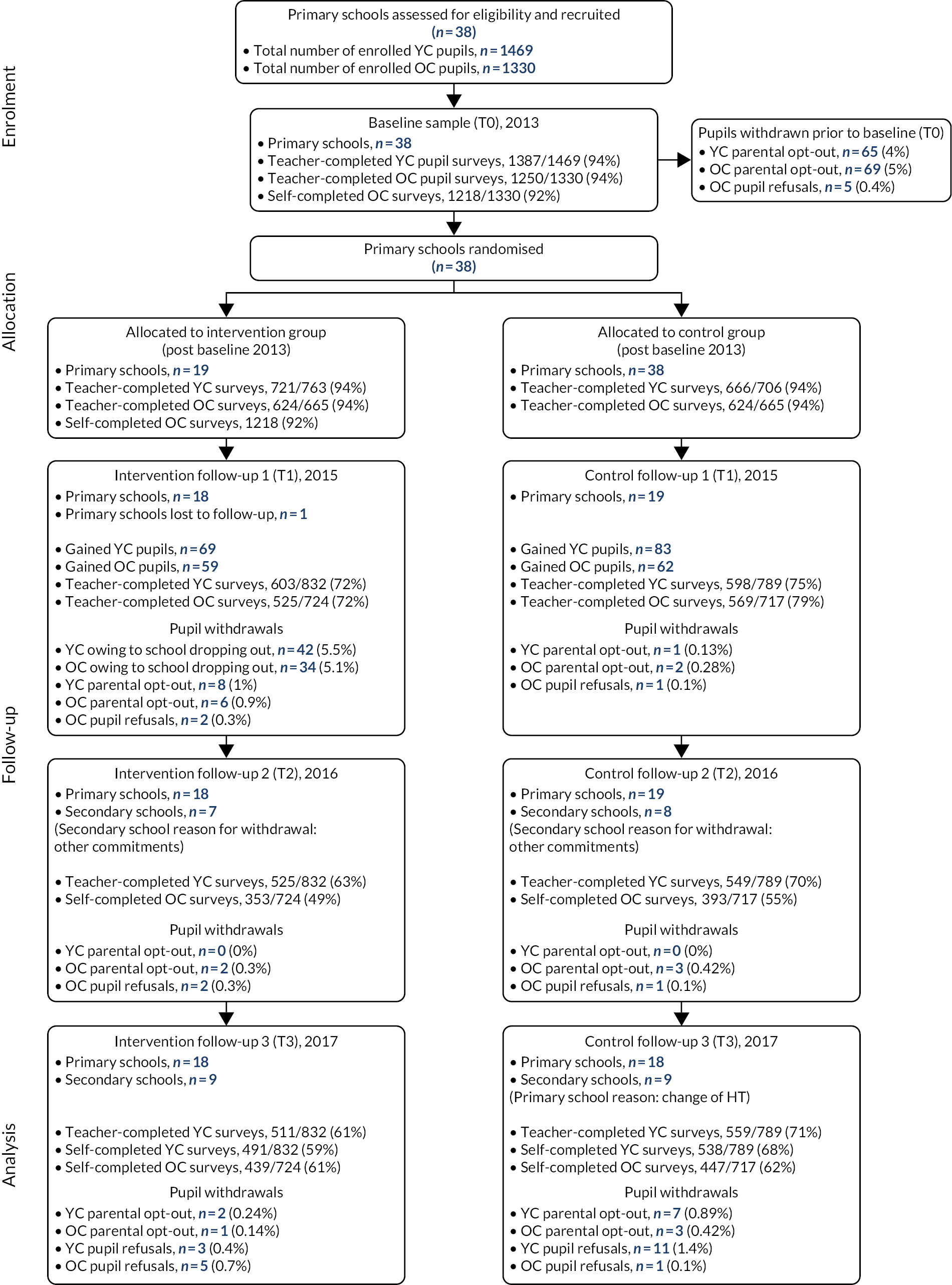

The SEED intervention was a stratified cluster RCT of a multicomponent primary school intervention in Scotland. Process and economic evaluations were conducted as part of the trial. Randomisation was carried out at the level of secondary school learning communities (clusters comprising the primary schools that feed into each secondary school) to minimise contamination; all participating primary schools within a learning community were allocated to the same arm of the trial. The allocation ratio was 1: 1. Once randomised, the intervention schools received the SEED intervention (see Chapter 2) and the control schools continued with their SEW activities as normal. 66

Trial setting

The trial recruited 38 primary schools from 18 learning communities across three Scottish LAs, anonymised as LA1, LA2 and LA3 in this report. There were four waves of data collection in the main study [baseline (T0) and three follow-ups: T1, T2 and time point 3 (T3)] and a further fifth wave [time point 4 (T4)] following the prespecified primary outcome at T3. The baseline (T0) and the first follow-up (T1) data collection and intervention delivery took place in primary schools. Data collection for the OC of pupils at the second (T2), third (T3) and fourth (T4) follow-ups took place in secondary schools.

Changes to trial design

The SEED intervention was registered with an International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number (ISRCTN) in April 2013 (see https://fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/10/3006/13 and https://doi.org/10.1186/ISRCTN51707384). No changes were made to the trial design, aims or primary and secondary outcomes after registration. However, we did secure additional funding, also from the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR), to conduct longer-term follow-up (T4) with the OC just before they reached the end of compulsory education (aged 16 years).

Participants

Eligibility criteria for local authorities

Any LA within a reasonable geographical location accessible to the main study site was eligible for participation. Any LA with involvement in the SEED pilot was excluded, as were LAs that required opt-in consent for parents. LAs known to be taking part in studies similar to the SEED RCT were also excluded. Three eligible Scottish LAs were selected based on the spread of urban and rural populations, socioeconomic diversity and reasonable proximity to the research unit base.

Eligibility criteria for schools

Within each of the three selected LAs, all state primary schools and associated secondary schools were eligible. Special schools (offering specialist education independently of mainstream school base), independent schools and home-educated children were excluded (accounting for ≈ 4.3% of primary school children in Scotland85–88).

Eligibility criteria for participants

Eligible staff included all teaching and non-teaching staff within study primary schools. At T0 all primary school pupils in P1 (aged 4–6 years; YC) or primary school year 5 (P5) (aged 8–10 years; OC) in the 2012–13 academic year were eligible to participate. Baseline (T0) measures were collected in academic year 2012/13, and follow-up 1 (T1) measures were collected in academic year 2014/15. Because teachers or classroom support assistants completed the SDQ on behalf of their pupils, individual pupils were not excluded on the basis of additional support needs or language difficulties unless it was decided, in liaison with the class teacher and HT, that the SDQ would not be a valid measure for a particular child. Pupils completing the self-completed questionnaire were given additional support when needed, unless it was decided, in liaison with the class teacher and HT, that the pupil’s level of understanding of the questions would not allow them to complete the questionnaire accurately (e.g. not understanding spoken English or severe learning difficulties) or when participation would be detrimental to the young person’s well-being.

Sample size

Based on an average of 38 pupils per year at each school and the initial estimate of 36 schools participating, we estimated that there would be a potential 2736 pupils for recruitment at baseline. We expected few pupils to opt out of participation and assumed that 75% of the target population could be followed up for 4 years, meaning a total of 2052 pupils, 1026 from each age group, with an average 28.5 pupils per year per school.

A cautious intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) of 0.05 was assumed (i.e. 5% of the variation in the primary outcome will be attributable to school- and class-level variability), giving a design effect of 2.37. Therefore, with 513 pupils followed up in both the intervention and control arms of the trial (allowing for attrition), the effective sample size was 216 per group (513 ÷ 2.37) within both the YC and the OC.

This sample size would provide 95% power at a 5% significance level to detect a between-group difference of 0.35 standard deviation (SD) units, within each age band. Assuming the SD of the primary outcome [i.e. the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire-Total Difficulties Score (SDQ-TDS)] to be 6 points, this equated to an average between-group difference of 2.1 points. There was also 80% power to detect differences of 0.27 SD units (i.e. 1.6 points on the SDQ-TDS).

Assuming an equal split between boys and girls, then, within each gender, the study had 95% power to detect intervention effects of 0.49 SD units (3.0 SDQ-TDS points), or 80% power to detect an effect of 0.38 SD units (2.3 SDQ-TDS points).

We aimed to recruit 38 primary schools to minimise the impact from any school dropping out during the trial. We expected 1026 P1 (aged 4–6 years) and 1026 P5 (aged 8–10 years) pupils to participate (allowing for 25% attrition), and 1094 sets of parents (allowing for 60% attrition). We estimated that there would be 200 teachers of the OC and YC, but all staff would be invited to complete evaluation questionnaires.

Recruitment, consent and retention

Local authorities level

The directors of education in the selected LAs were approached by e-mail and telephone. This was followed by meetings with nominated EPs and QIOs. Three LA directors of education granted permission, and we were instructed to contact primary schools directly, inviting them to take part. One LA refused because it was in the middle of a restructure.

School level

Purposive sampling was used to recruit 38 schools across the three LAs between November 2012 and February 2013. Demographic information for the participating LAs was collated for all potential primary schools, and clustered learning communities were identified. We prioritised inviting schools that enabled us to represent LA levels of rurality, denomination, school size and proportion of pupils eligible for free school meals (as a proxy for deprivation).

We aimed to recruit up to three primary schools belonging to the same learning community to limit the number of secondary schools needed for data collection following the OC’s transition from primary to secondary school, and owing to limits on the number of learning community clusters available in each LA. Invitation letters and participant information sheets (see Report Supplementary Material 4) were sent to primary school HTs by post, with follow-up telephone contact and visits in person by the research team if requested by the school. Two further rounds of selection and invitation were necessary owing to lack of response or schools declining to participate. In total, 91 schools were approached, and recruitment stopped (in February 2013) when 38 primary schools from 18 learning communities had agreed to participate: 15 schools in LA1, 13 in LA2 and 10 in LA3. Once a school agreed to participate, it was sent an information pack with a checklist of next steps and asked to nominate a key contact to liaise with the trial team.

At the end of T1 (early summer 2015), link secondary schools in participating primary schools’ learning communities were contacted to give notice of the trial and to invite them to support the ongoing data collection for the participating pupils joining their schools in August 2015.

Individual level: school staff, pupils and parents

As the SEED intervention operated at the whole-school level, once a school had agreed to participate, it was not possible for school staff or parents/carers of individual pupils in intervention schools to opt themselves or their child out of the intervention itself, only the data collection for evaluation. For the data collection, individual-level recruitment was required for two cohorts of pupils in each school, their parents/carers and all primary school staff; informed consent was sought for all.

Pupils

In early 2013, parents/carers of pupils in both cohorts at participating primary schools were sent invitation letters and participant information sheets (see Report Supplementary Material 4) seeking opt-out consent for their child to be part of the data collection for the SEED intervention and evaluation. Opt-out consent was critical because previous research over many years has shown that the lower participation with opt-in consent is strongly biased away from the most vulnerable children. 89 Letters were produced with both the school and the MRC/CSO Social and Public Health Sciences Unit (SPHSU) logos and were signed by both the school HT and trial chief investigator. Letters were sent to pupils’ home addresses via the school office. A date was given on the letter by which opt-out slips should be returned, giving parents/carers at least 2 weeks to consider the information and ask questions before data collection would commence. Opt-out slips were collated by the schools and reported to the research team or returned directly to the research team by parents/carers. Ahead of each wave of data collection, participant lists of consented pupils were sent by the trial team to the school’s key contact confirming trial participants. Participant information sheets explained that pupils could be withdrawn from the evaluation at any time by their parents/carers.

Before the first follow-up data collection (T1, 2015), this process was repeated for pupils who were new to the participating primary schools since baseline. No new participants were recruited to the study at T2 or T3. Parents/carers of existing participants were sent letters at each follow-up wave of data collection reminding them of the trial, explaining the process for the current wave of data collection and reminding them of their right to withdraw their child from this.

In addition to parental consent, pupils at classroom sessions were reminded that completion of the self-completed questionnaire was voluntary, even if their parent had not opted them out. Pupils at these sessions (OC at all waves; YC at T3 only) were read an age-appropriate information sheet (see Report Supplementary Material 4) by a member of the research team and given an opportunity to ask questions before beginning the questionnaire. If pupils were absent, an ‘absentee pack’ containing their questionnaire, information and instructions for their teacher was left with the school and returned at a later date via post or collected from the school (see ‘instructions for absentees’ in Report Supplementary Material 4).

Parents/carers

Parents/carers of the two cohorts of pupils were invited to complete parent surveys related to their school and their child at T0, T1 and T3. In the initial letter to parents asking for consent to include their child in the trial, parents were informed that, if their child took part in the trial, parents/carers would also be sent voluntary questionnaires. Parents/carers were not assigned separate identifiers, but were given questionnaires with the identifier of their child; therefore, no record was made of the name of the completing parent/carer. Parent/carer questionnaire packs were sent via school bags (‘pupil post’) with a covering letter and prepaid envelopes for return to the research unit. Consent to participate was assumed by return of completed questionnaires.

Primary school staff

At each wave, the school’s key contact was asked to provide a list of current staff whom they wished to include in the staff survey. A recommendation was made that all teaching and non-teaching staff be included, but this was ultimately at the discretion of each school. Thus, the number of additional staff, such as auxiliary, janitorial or visiting staff (e.g. part-time music teachers), varied between schools. All staff identified by the school were sent a participant information sheet, a letter and a copy of the staff questionnaire (see staff questionnaire in Report Supplementary Material 5 and subsequent changes listed in Report Supplementary Material 6). Consent to participate was assumed by return of completed questionnaires at each wave. This recruitment process meant that there were new staff participants in all four waves.

Retention

To optimise retention among trial schools, each participating school was given £500 on completion of baseline data collection and a further £500 following the final follow-up (T3). In addition, a payment at each wave was made to compensate for the time taken by teachers to complete SDQs for their pupils at a rate of £4.38 per participating pupil, calculated on the basis of the cost of 10 minutes of primary teacher cover.

Throughout the life of the trial, the research team maintained communication with schools, staff and parents, providing periodic updates on the status of the trial and responding to any requests for information in a timely manner. Christmas cards were sent to all participating schools each year. During the trial, several primary schools changed HTs or key trial contacts. The new HTs were contacted by e-mail in the first instance, and this was followed up by telephone calls and/or meetings in person to explain the trial and the school’s involvement in it. In all these instances, these schools were retained in the trial.

For staff and parents, reminder letters were sent with the questionnaires in each wave. Schools were encouraged to let parents of the participating cohorts know of the trial through school newsletters to raise awareness and encourage participation. When possible, schools were asked to set aside collegiate time to complete the SEED survey to optimise participation. Regardless of how it was administered, staff were told that they could return their questionnaires in a prepaid envelope directly to the research unit to reassure about confidentiality of responses.

Over the course of the four waves of data collection, a small number of pupils who had previously been opted out were opted back in by their parents/carers, and a small number of pupils were opted out. Some pupils moved between trial schools, and some pupils left trial schools and were not located in other trial schools.

Withdrawals

The right to withdraw from data collection was emphasised to all individual pupils, parents/carers and staff at each wave. Pupil and parental opt-outs, withdrawals and pupil refusals (pupils who had been consented by parents/carers, but who opted themselves out of the self-completed questionnaire) were recorded with reasons for withdrawal, when known, and a check to ensure that this was actioned on the trial participant database.

Data collection

Questionnaire data were collected via two main methods: classroom-based fieldwork sessions supporting self-completion of pupil questionnaires, and self-completion of questionnaires by adults and return via post or school collection (teacher-completed SDQs, staff questionnaires and parent/carer questionnaires). For example copies of the questionnaires used at T0, see Report Supplementary Materials 5, 7 and 8. All changes to questionnaires from T0 can be found in Report Supplementary Material 6.

In the final follow-up at T4, questionnaires were primarily administered electronically on tablets or on pupils’ own phones.

Confidentiality and anonymity

All data were anonymised. Pupil and staff participants were allocated unique identification numbers (IDNOs) and barcodes were used on all questionnaires and detachable pages to account for and track returned data. Identifying information linking participants to IDNOs was stored securely in a database accessible only by main research and Population Health Research Facility (PHRF) staff at the MRC/CSO SPHSU, University of Glasgow, and held separately from participant questionnaire responses. Questionnaires for parents/carers of participating pupils were allocated the IDNOs for the pupil they were being asked to complete questionnaires about. All questionnaires were designed with detachable pages so that names could be removed from blank questionnaires before completion and identifying data (e.g. postcode or job title) would be returned, processed and stored separately from other non-identifying questionnaire responses.

Results forming part of the intervention were fed back to schools randomised to the intervention in aggregate form, broken down by year group. Neither staff nor parents were informed of individual pupils’ SDQ scores. If parents contacted the trial team requesting to know their child’s SDQ scores, we reminded them of our commitment to confidentiality regarding individual scores. Responses from free-text fields in the staff and parent questionnaires were fed back to schools in a way that removed any identifying information.

Care was taken to conduct interviews ethically and sensitively. Complete confidentiality of interview content and recordings was ensured, and best efforts were made to ensure that quotations and comments could not be traced back to the interviewee. Participating schools will not be identified in any publication and pseudonyms will be used when necessary.

Classroom-based fieldwork

Pupil self-completed written questionnaires (including, but not limited to, the SDQ) were administered in a classroom session lasting approximately 1 hour, supported by a team of trained fieldworkers from the PHRF.

Classroom sessions were scheduled in liaison with the school for a suitable time during school hours and a detailed overview of the session was given to schools in advance. For primary school sessions, schools were asked to block off 1 hour. For secondary school sessions, two periods (40–50 minutes each) were usually allocated, with pupils returning to class either at the end of the first period or whenever they completed the questionnaire during the second period.

In both primary and secondary settings, at the beginning of the session, fieldworkers introduced their team to the pupil group; explained what the session would entail; emphasised that consent had been given by their parents/carers, but that pupils could opt not to complete the questionnaire if they wished; and answered questions. Throughout the session, pupils completed their individual questionnaires supported by fieldworkers who answered questions as they arose or offered one-to-one support if pupils required it (e.g. reading the questions aloud). During questionnaire completion, care was taken to ensure that pupils had as much privacy as possible. Pupils were requested and encouraged to complete questionnaires quietly on their own and not to confer with neighbours. At the end of the session, pupils and staff were thanked for their participation and support and pupils were given a debrief leaflet (see Report Supplementary Material 9) that included a telephone number for ChildLine, and a verbal explanation of the leaflet.

Returned questionnaires

Teacher-completed SDQs (for YC pupils in all waves and OC pupils at T0 only) were delivered to the school along with instructions on how these should be completed, deidentified and returned. The majority of these were then collected in bulk from the school by fieldworkers, but small numbers were returned in Freepost envelopes to the research base.

Staff and parent/carer questionnaires were packed in individual questionnaire packs containing a participant information sheet (see Report Supplementary Material 4) and Freepost return envelopes. Staff and parents/carers were given the option of returning these individually by post in the envelopes provided or by leaving them with the school office, where a SEED fieldworker would collect them. Instructions were given on how to detach pages that contained identifying data, and participants were asked to return these in Freepost envelopes separate to the main questionnaire.

Data processing, entry and management

A Microsoft Access® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) database was used to generate IDNOs, to securely store participants’ names (and associated school details) and to log and track questionnaires via barcodes attached to each questionnaire/detachable page. Anonymised questionnaires were passed to the Robertson Centre for Biostatistics (RCB) Clinical Trials Unit at the University of Glasgow for data entry, then returned to the SPHSU for further data entry and later archived. The detached identifying data and all free-text data were entered in a blind two-pass system by two different PHRF staff members onto a Microsoft Access database. Any disagreement between these passes resulted in the entries being flagged for a third pass. If there was any further disagreement about what had been written by participants or uncertainty about what should be entered, the research team was consulted.

Pupil self-completed questionnaires that were completed electronically at T4 were transferred directly to a secure PHRF database, removing the need for manual entry. Anonymised data were then passed via secure file transfer to the RCB.

On return from the RCB, anonymised paper questionnaire data were stored in a locked, secure data room in the PHRF. Electronic questionnaire data entered by the PHRF were stored confidentially on password-protected servers. All data collected were stored securely in compliance with the General Data Protection Regulations for the European Union and UK (URL: https://gdpr-info.eu). Data were kept in either locked filing cabinets or password-protected databases accessible only by main researchers and PHRF staff. The final data set was accessed only by approved members of staff from the research team and the RCB. All data will be kept for 10 years, in line with University of Glasgow research governance framework regulations for clinical research.

Randomisation

Schools were randomised to control or intervention arms after collection of baseline data in April 2013.

Randomisation was performed when school-level data were available for 38 consenting primary schools. These schools were clustered within 18 learning communities. This was achieved using a computer program written by co-investigator and author Alex McConnachie, within the RCB, using the following procedure.

There were 48,620 possible ways of allocating nine learning communities to the intervention and control groups, from the 18 learning communities involved in the study. Of these, 13,050 possible allocations would achieve an equal allocation of primary schools into each arm of the trial. Of these, 792 achieved the minimal imbalance of primary schools within each LA. Of these, 384 allocations minimised the imbalance with respect to urban/rural classification. Minimising imbalance in terms of school denomination (Roman Catholic or non-denominational) reduced the number of potential allocations to 240. A total of 68 possibilities minimised imbalances within each stratum of minority ethnic populations, and 36 minimised imbalance with respect to the percentage of the school population with free school meal entitlement. Finally, 14 potential selections were identified that ensured that the total expected number of children in each arm of the trial differed by no more than 10%, within both the P1 and P5 cohorts. One of these sets of allocations was then selected at random as the final allocation of schools to the intervention and control arms of the trial.

Once generated, the allocation list was stored in a secure area of the RCB network, with access restricted to those responsible for generating school feedback reports. The statisticians responsible for producing the final analysis report did not have access to the random allocations until all statistical programming had been completed and checked, and the trial database had been locked.

Outcome measures

Primary outcome measures

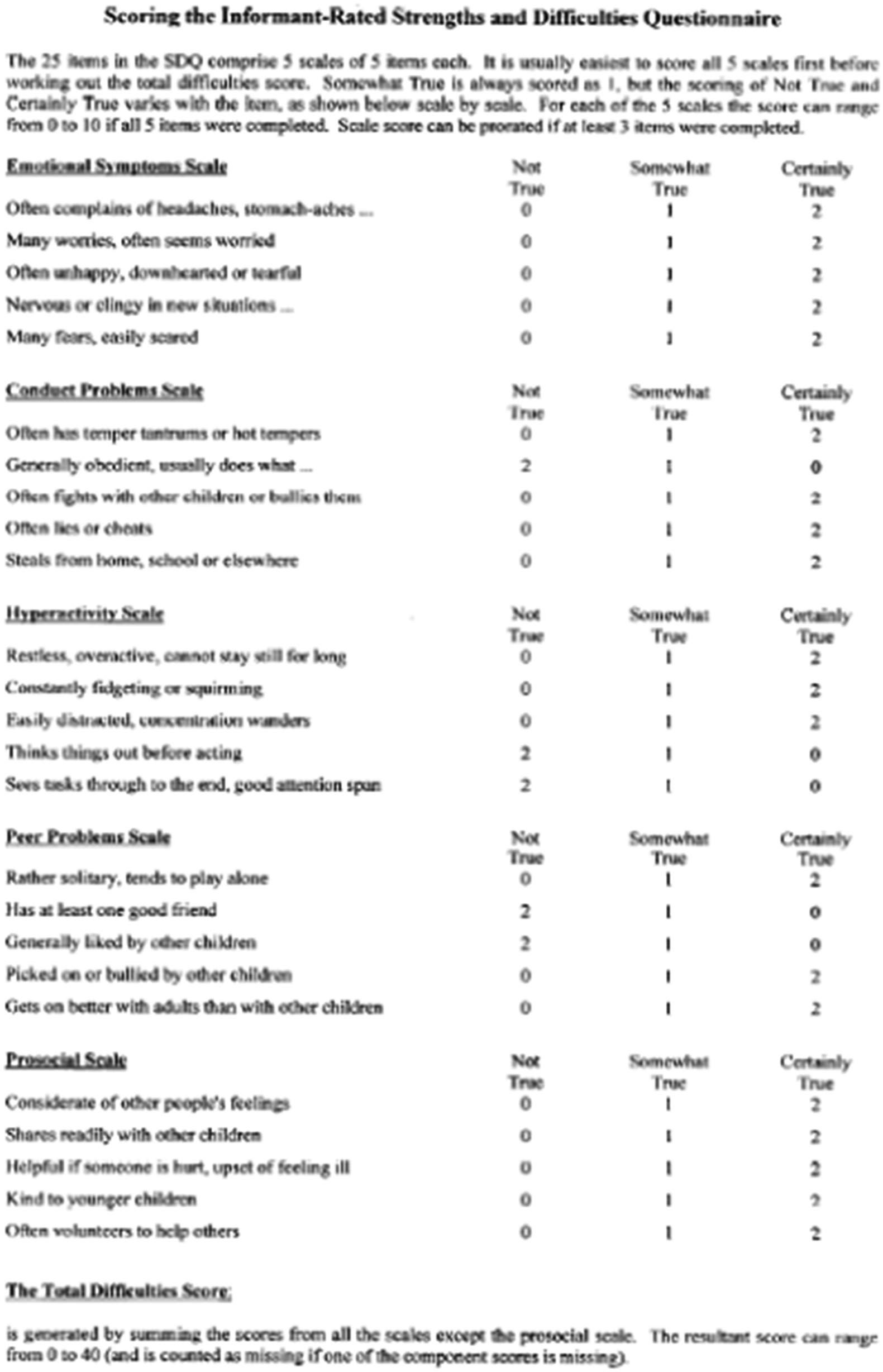

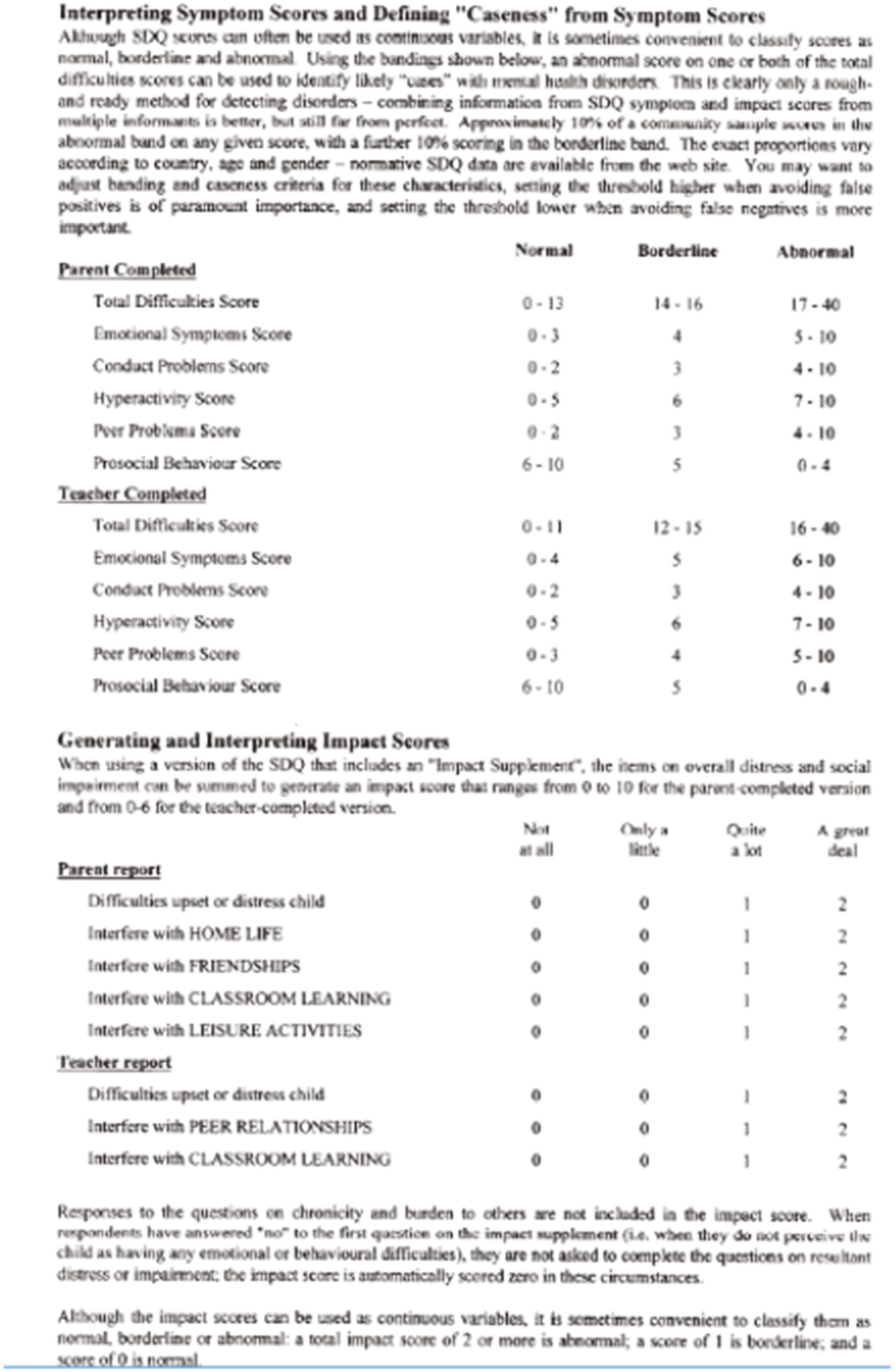

The primary outcome measure for pupils was the SDQ-TDS. 32,69–71 This is an internationally validated, publicly accessible 25-item behavioural screening questionnaire designed to assess levels of emotional and behavioural problems comprising four ‘difficulties’ subscales and one ‘strengths’ subscale. The SDQ-TDS is calculated by summing the scores on the four difficulties subscales.

The pupil self-completed and parent/carer SDQs were administered as part of the larger pupil/parent questionnaires (see the T0 pupil questionnaire in Report Supplementary Material 7, the T0 parent/carer questionnaire in Report Supplementary Material 8 and all changes to questionnaires from T0 in Report Supplementary Material 6). The teacher-completed SDQ was administered as a stand-alone assessment measure given to teachers to complete in class time (see Report Supplementary Material 10). For the OC, the SDQ was self-completed at all five time points (including T4, when only the OC were surveyed), was completed by teachers at T0 and was completed by parents at T0, T1 and T3. The YC SDQs were teacher-completed at four time points (T0 to T3), self-completed at T3 only and parent-completed at T0, T1 and T3. See Appendix 2 for details of the SDQ scoring.

Secondary outcome measures

For pupils, the secondary outcome measures assessed in the pupil questionnaire were as follows:

-

The five validated SDQ subscales: four difficulties subscales (emotional symptoms, conduct problems, hyperactivity/inattention and peer relationship problems) and one strengths subscale (prosocial behaviour). Higher scores represent greater issues in all the difficulties subscales, whereas lower scores represent greater challenges in the prosocial ‘strengths’ scale.

-

Pupils’ social and emotional skills: self-awareness, social awareness/empathy, self-management, responsible decision-making, emotional regulation and self-esteem.

-

Pupils’ well-being and relationships at school – school relationships; whole and class level, liking school, happy friendships, school climate, experience of antisocial behaviour and participation in antisocial behaviour.

-

Pupils’ well-being and relationships at home – family relationships, materialism and daily quality of life.

These measures were collected through pupil self-completed questionnaires. The questionnaires were designed (some for previous studies such as Healthy Respect Phase 2,90 which involved some of the SEED RCT co-investigators) and refined through piloting. 68,91

The secondary outcome collected from the OC at T2 and T3 was the impact of the intervention on health-related behaviours (smoking, drinking and drug use).

For staff, the secondary outcomes were staff attitudes towards pupil behaviour, pupil confidence, pupil engagement and pupil relationships.

Additional quantitative staff measures were collected on staff–staff relationships, school ethos, self-efficacy, staff mental health [Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (WEMWBS),9,10,92 used, with permission, from T1 onwards], perceptions of management, staff–pupil relationships, staff support, training opportunities, staff who played a key role in developing SEW in the school and school support for SEW. For a full list of measures, including sources (when applicable), see the T0 staff questionnaire in Report Supplementary Material 5 and all changes to questionnaires from T0 in Report Supplementary Material 6.

Changes to outcomes

The pupil domain scores were refined between baseline and the first follow-up to validate the groupings of questionnaire items fed back to schools as part of the intervention. Confirmatory factor analysis was carried out, which did not alter the items included in questionnaires, but changed the membership of items within some of the secondary outcomes (see Report Supplementary Material 5 for the T0 staff questionnaire and Report Supplementary Material 6 for all changes to questionnaires from T0).

Blinding

The trial researchers were not blind to intervention arm. PHRF fieldworkers were kept blind to which schools were intervention or control, but it was occasionally necessary for unblinded trial researchers to accompany and support fieldwork. EPs supporting the intervention delivery were not blinded.

Statistical methods

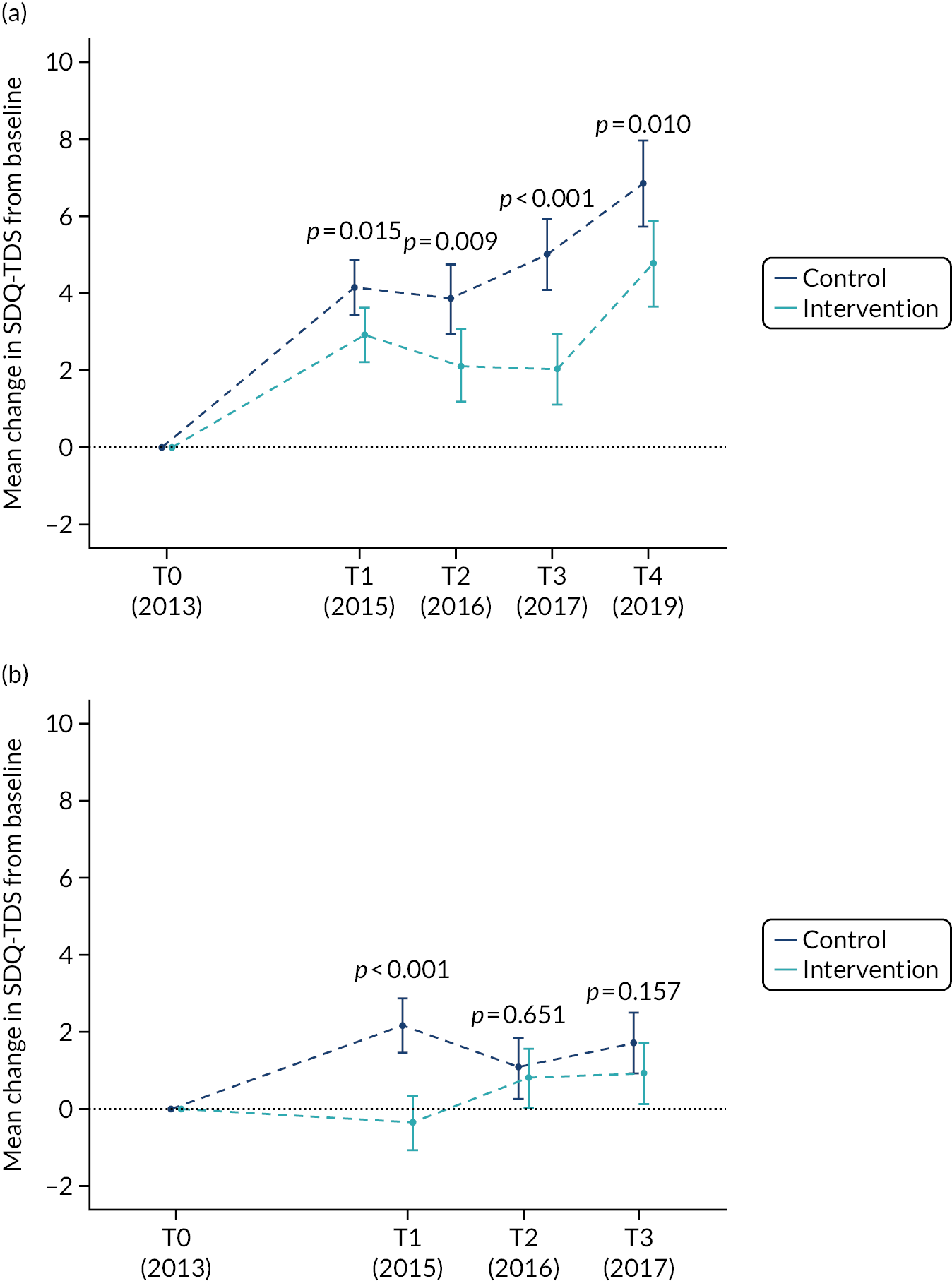

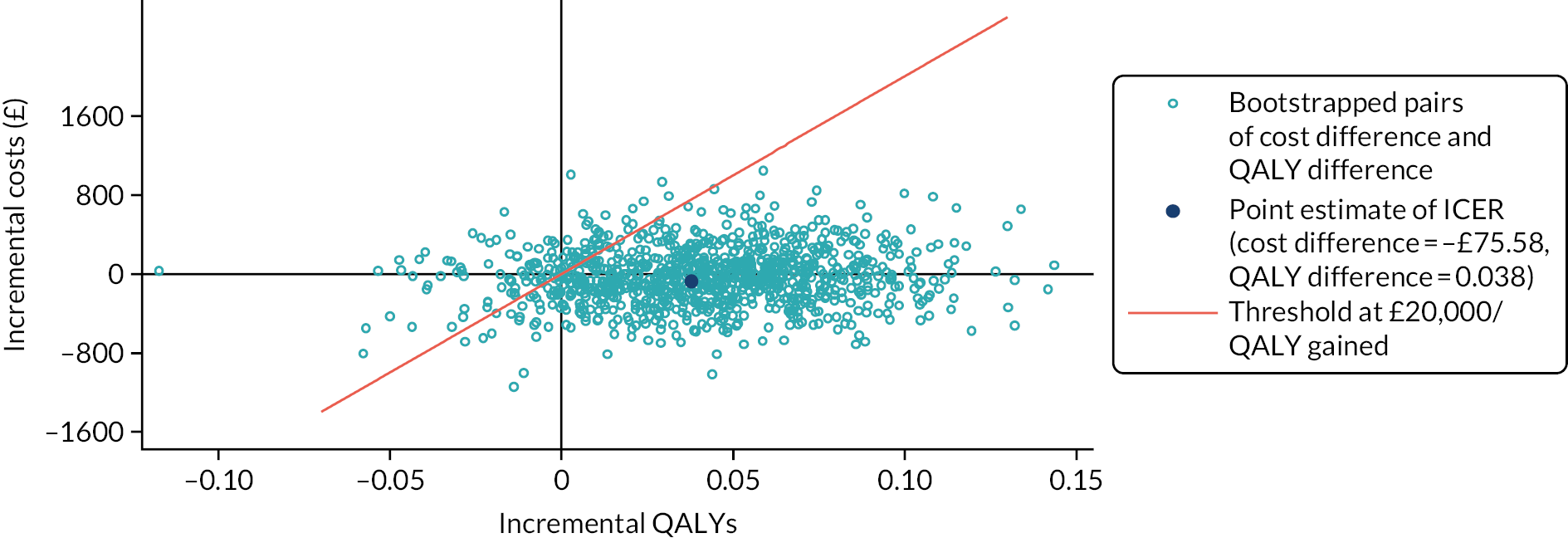

Analyses were conducted to compare the mean SDQ-TDS at T3 between the intervention schools and control schools. For the YC, teacher-completed SDQs were used for the analysis at all visits; for the OC, teacher-completed SDQs were used at the baseline visit, with self-completed questionnaires being used at the follow-up visits. The treatment effect estimate, 95% confidence interval (CI) and p-value were estimated from a multilevel linear regression model with mean SDQ-TDS as the outcome. Predictors within the model were baseline SDQ-TDS, trial arm, cohort, gender and stratification variables that were used when carrying out the randomisation (see above).

In the model, hierarchical random effects were included to account for the clustering of pupils within primary schools and secondary schools. Components of variance and ICCs were reported. In the prespecified analysis plan, there was no plan to adjust the p-values for multiple testing; therefore, all p-values have been reported without adjustment.

This model was extended to estimate the intervention effects within subgroups of the population defined by cohort (younger/older), gender (male/female) and deprivation level (deprived/not deprived). Interaction terms were added to the model to provide separate intervention effect estimates for each subgroup. These analyses were repeated for T1 and T2 data.

In addition, repeated measures analyses were carried out for the primary outcome at all time points (baseline and three follow-ups) simultaneously. Time point was included as a categorical variable, and intervention effects were estimated by including intervention-by-time point interaction terms. Models were adjusted for cohort, gender and the randomisation stratification variables. Gender and cohort were further examined using subgroups of the population (younger male/older male/younger female/older female) and extending the model to estimate the intervention effects within these subgroups.

Analyses of all secondary outcomes (apart from health-related behaviours for the OC) were carried out using a repeated measures analysis over all time points, as for the primary outcome. For all analyses, ICCs were estimated. OC pupils’ health-related behaviours were summarised at each time point (T2, T3 and T4 only) and trial arms were compared using Fisher’s exact tests.

Additional analyses

To test the robustness of the analysis, sensitivity analyses were performed by looking at alternative assumptions regarding missing outcome measures. Assumptions included last observation carried forward and return to baseline. This analysis was carried out on the primary analysis results only.

The secondary outcome repeated measures analysis models were extended to estimate the intervention effects within the gender, cohort and deprivation level subgroups by including interaction terms for each group in the model to provide separate intervention effects.

For the staff domain scores that were not included as secondary outcomes (staff–staff relationships, school ethos, self-efficacy, perceptions of management, staff–pupil relationships, staff support, training opportunities, valued member of staff and school support for staff emotional well-being), repeated measures analyses were carried out at all time points, as for the primary and secondary outcomes.

The SDQ-TDS was split into two groups using cut-off points (normal: 0–15; not normal: ≥ 16); using these subgroups at baseline, interaction terms were added to the SDQ subscale repeated measures models to determine the intervention effect within these subgroups. In addition, the responses to staff questionnaires were examined for the subgroups of teaching and non-teaching staff.

The OC had the additional T4 visit when the pupils were in fourth year of secondary school. Data collected at T4 were used in the analyses only if the pupil had data recorded for at least one of the first three follow-up visits. The main analyses conducted for the primary outcome were repeated to include these additional T4 data. This model was extended to estimate the intervention effects within subgroups of the population defined by gender (male/female) and deprivation level (deprived/not deprived). Repeated measures analyses were carried out at all time points (T0 to T4) to determine the effect of the intervention over the duration of the trial.

The analyses conducted for the secondary outcomes were repeated to include the data collected at T4, and the health-related behaviours were summarised for this follow-up visit, with Fisher’s exact tests carried out to compare the trial arms.

Process evaluation

A process evaluation was embedded in the trial to interpret the trial outcomes and to answer secondary research questions related to process. The delivery of the SEED intervention was monitored in all intervention schools primarily through observation of data feedback and RD sessions in all schools, and in-depth interviews with key contacts (usually the HT or depute HT) at the start and the end of the trial, when possible. Additional data collected included qualitative and quantitative data from staff, pupil and parent questionnaires and researchers’ perceptions of schools. For details on data sources, see Appendix 5, Table 55.

In addition, in-depth data were collected from four case study schools, which were purposively selected from the intervention and control arms of the trial in year 2 of the trial. The case studies represented schools that were active in engaging with the SEED evaluation and schools with reluctant engagement, and schools with high versus schools with low SDQ scores at baseline (Table 1). Engagement was measured by the response rate to the baseline staff survey. One intervention case trial school was replaced in year 3 and we had limited data for another school owing to difficulties arranging interviews with the key contacts. In response, we decided to supplement the four original intervention case study schools in year 5 of the trial with two additional schools based on the original selection criteria. In the case study schools, additional data were collected, including interviews with EPs and focus groups with pupils from both cohorts (see pupil focus group and EPs interview topic guides in Report Supplementary Material 11). Four control schools were selected as case studies. However, for the purposes of this report, data from all control schools were analysed because of the relatively small number of data available for control schools. No process evaluation data were collected or reported at T4.

| School ID | When selected | Selection characteristics | LA | School demographics (size, rurality, denomination, level of deprivation) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IC3P | Year 2 (after baseline) | Active engagement, high SDQ scoresa | C | Very large school, large town, non-denominational, low deprivation |

| IB1P | Year 2 (after baseline) | Active engagement, low SDQ scores | B | Large school, city, Roman Catholic, high deprivation |

| IB2P | Year 2 (after baseline) | Reluctant engagement, high SDQ scoresa | B | Very large school, city, non-denominational, high deprivation |

| IA6P | Year 2 (after baseline) | Mixed engagement (started active, ended up reluctant), low SDQ scores | A | Large school, large town, non-denominational, medium deprivation |

| IA3P | Year 5 (after final follow-up) | Active engagement, medium SDQ scores | A | Small school, rural, non-denominational, low deprivation |

| IA8P | Year 5 (after final follow-up) | Reluctant engagement, high SDQ scoresa | A | Large school, large town, non-denominational, high deprivation |

In the original trial protocol,66 we planned to undertake observations of teachers’ classroom management skills. Once the first round of data feedback and schools’ APs was complete, it became clear that classroom management was only one type of classroom initiative that schools chose to implement (others selected other initiatives from the SEED Resource Guide, available in Report Supplementary Material 3); few did so, and thus there was limited value in observing lessons. Instead, this resource was transferred to observe and record all the RD sessions, as these are a critical and consistent component in the implementation of the intervention. Questions on the type of classroom or whole-school SEW initiatives being implemented were included in the staff survey, and additional questions were asked on fidelity and breadth of implementation across the school.

For topic guides for HT interviews, see Report Supplementary Material 11. Note that ‘baseline’ interviews were collected at T1 and covered perspectives on taking part in the SEED RCT in the baseline wave (and throughout the trial for the T3 interviews). The interviews also explored the school’s context and practices around SEW prior to the SEED intervention, reasons for taking part in the SEED trial and (for intervention schools) the process of implementing the intervention and perceived impact. All schools were invited to participate in interviews; when possible, these were carried out in person for the case study schools and over the telephone for the other schools. Baseline interviews were carried out in five case study schools (two intervention and three control schools) and 17 non-case study schools (seven intervention and 10 control schools). T3 interviews were carried out in six case study schools (four intervention and two control schools) and 19 non-case study schools (11 intervention and eight control schools). All pupil focus groups were conducted by research staff and/or fieldworkers in person following a data collection visit (see Report Supplementary Material 11 for focus group topic guides). Interviews and focus groups were conducted by members of the research team, digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim. Observational notes were taken and written up by members of the research team.

Ethics and consent

For the HT interviews, staff members were given information sheets and sufficient time to ask questions before deciding if they wished to take part. Written consent was obtained prior to conducting the interviews if held face to face. Verbal consent was obtained for telephone interviews and written consent forms returned by post following completion of interviews. Prior to interviews, informed consent was gained from the school HT and interviewee (if different). Parental consent was gained for participation in pupil focus groups and informed written consent was also sought from pupils in person (see the consent forms in Report Supplementary Material 4 and process evaluation consent forms in Report Supplementary Material 11). Information on storage of data can be found in Data processing, entry and management.

Analysis

A coding framework was developed through initial exploration of the data, pilot coding and by discussion between Sarah Blair, Daniel Wight, Marion Henderson, Susie Smillie, Carrie Parcell and Craig Macdonald, and was informed by MRC guidance on process evaluation in RCTs of complex interventions. 93 The coding framework was structured into six sections: (1) the context for SEW in schools (pre-existing situation prior to involvement in the SEED trial); (2) methodological issues of participation in the SEED trial; (3) implementation processes for the SEED intervention; (4) results of the SEED intervention (immediate effects of the SEED intervention or other SEW programmes that are observable/visible, are attributable to the SEED intervention/SEW programmes and can be directly influenced by school); (5) implementation processes of SEW programmes in control schools; and (6) results of SEW programmes in control schools. For more detail on the full coding framework, see Appendix 5, Proposed simplified Social and Emotional Education and Development coding framework.

A first stage of analysis was carried out prior to knowing the outcomes of the trial, to avoid bias in the analysis. 93 Case study data were coded to the agreed framework by Sarah Blair and Carrie Parcell using NVivo 10 (QSR International, Warrington, UK). The coding framework was mapped to the principal research questions from the protocol and to a set of enhanced research questions. These additional research questions explored the differences between the arms of the trial in SEW activities implemented, the extent to which the SEED intervention worked as intended, the degree to which the SEED intervention was embedded in intervention schools and the contextual factors that may have facilitated or obstructed the implementation of the SEED intervention (see Appendix 5, Table 55). The relevant codes were then extracted, and analysis of the case study schools was conducted independently by Sarah Blair, Daniel Wight, Sally Haw and Lawrie Elliott. An interim report was produced following discussion and consensus.

Following the main trial outcomes, a further stage of analysis was conducted to help interpret the findings. This stage focused on the SEED theory of change (see Figure 2) to assess the strength of existing data and the evidence available to explore further. Each proposed pathway within the theory of change was mapped to the existing data; if there were sufficient data from the case studies to provide evidence for the proposed pathways in the theory of change, no further analysis was undertaken. If evidence was moderate or weak, additional coding and analysis were performed on the data available from all schools using the existing coding framework. At this stage, selected data were also explored thematically to gain a more nuanced understanding of the mechanisms of change underpinning the intervention and to allow the generation of themes that could explain pathways beyond those proposed in the theory of change.

Further details on the methods employed in the analysis of the mixed-methods and quantitative data can be found in Chapter 6.

Economic evaluation

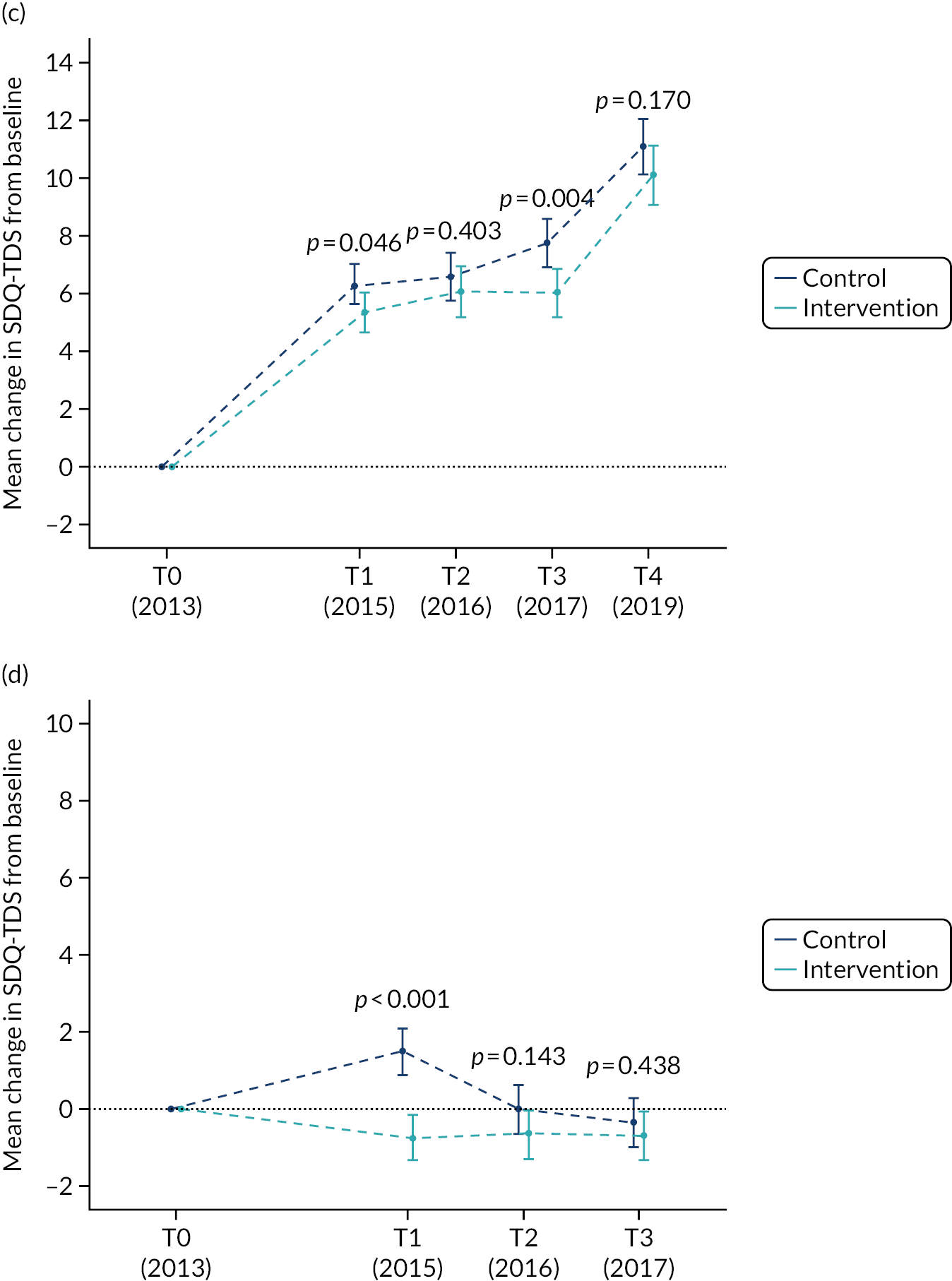

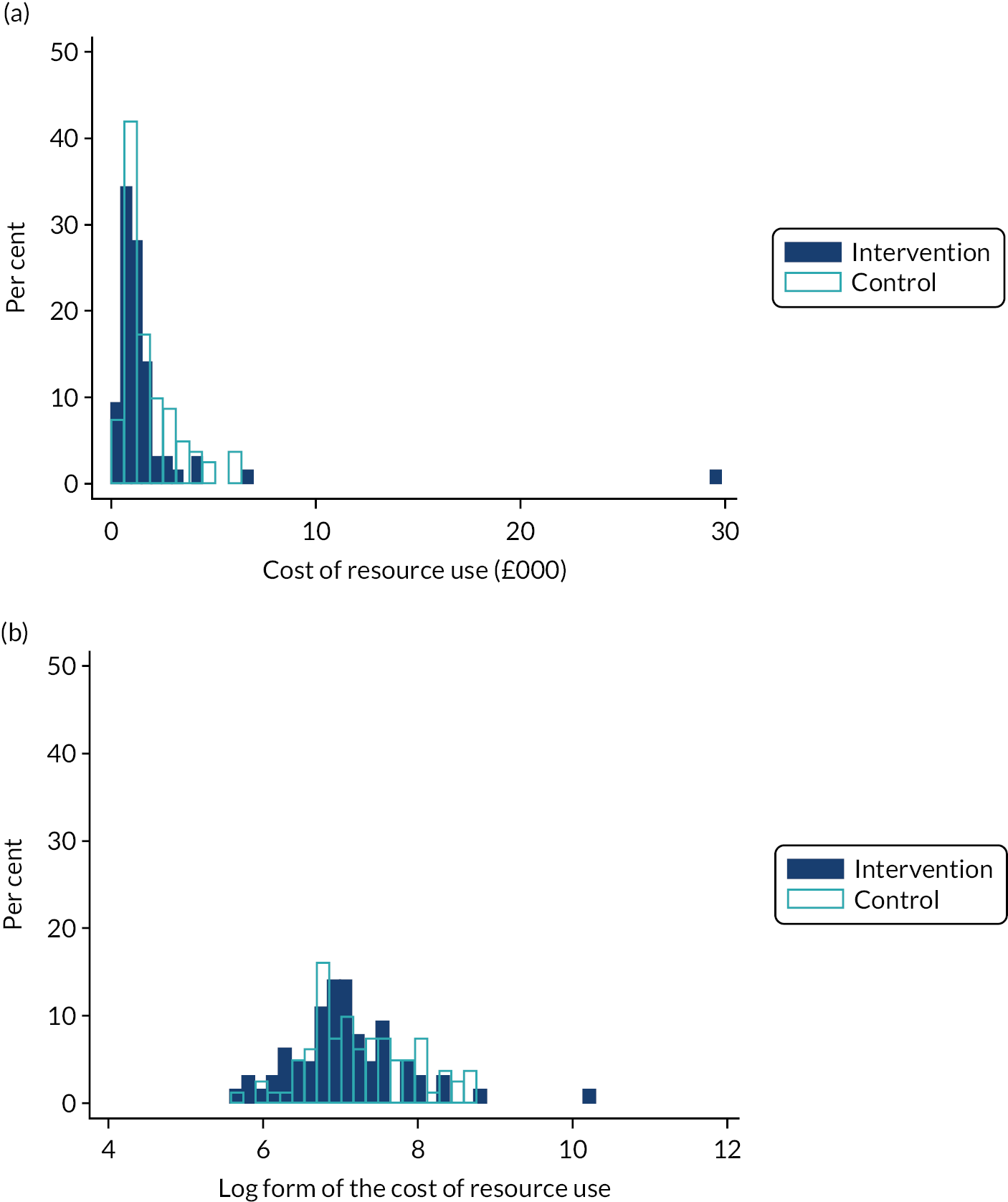

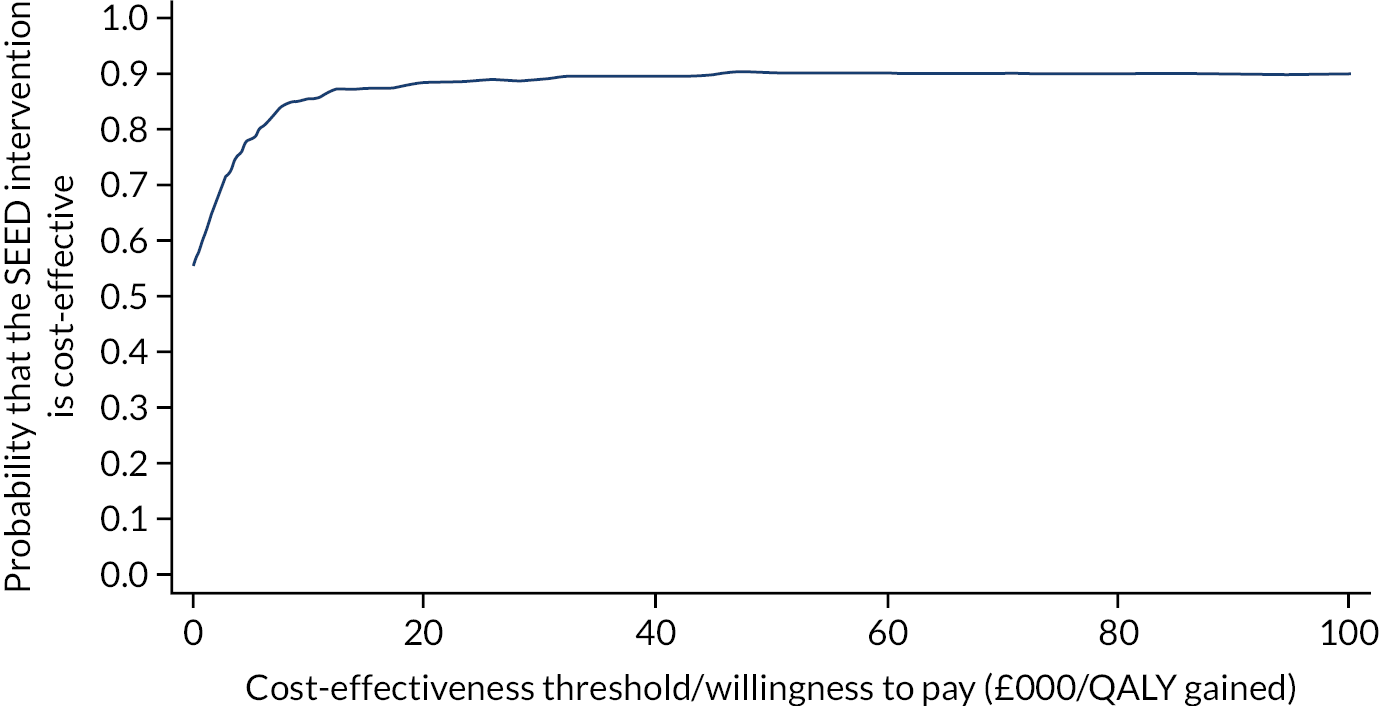

Overview