Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 17/149/03. The contractual start date was in October 2019. The final report began editorial review in March 2022 and was accepted for publication in November 2022. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Scior et al. This work was produced by Scior et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Scior et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Sections of this chapter have been reproduced from the Standing Up for Myself (STORM) study protocol,1 reproduced under licence CC-BY-4.0 from the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Journals Library.

People with intellectual disabilities are more likely than the general population to experience ‘some of the worst of what society has to offer’, including low incomes, unemployment, poor housing, social isolation and loneliness, bullying and abuse. 2 The NHS commissioned report which presents this conclusion recommended more action to reduce stigma and discrimination as a means to improve lives and health outcomes for people with intellectual disabilities.

Intellectual disability is characterised by an IQ below 70 and associated deficits in everyday adaptive skills, arising before the age of 18, and is estimated to affect 1.4–2% of the UK population. 3 Adults and young people with intellectual disabilities are at increased risk of mental health problems, with recent prevalence estimates of diagnosable psychiatric disorders at 30–50%. 4,5 They face substantial social and health inequalities, at least partly due to stigmatising attitudes and barriers within health, social care and education systems, and wider society. 2,6 The increased risk of mental health problems is due to a range of biological, psychological and social factors – one important social factor is stigma: the negative stereotypes held by society about people with intellectual disabilities, which often lead to prejudice and discrimination. Despite positive changes in policies, service provision and societal views in general, young people and adults with intellectual disabilities still frequently face negative attitudes and discrimination. 7 These in turn render them more vulnerable to a negative sense of self and low self-esteem,2,8,9 poor quality of life2,6,10 and mental health problems. 11,12 Accordingly, interventions that seek to reduce stigma and that ideally empower people with intellectual disabilities to challenge stigma themselves have the potential to improve their well-being and to reduce inequalities.

Stigma

Young people and adults with intellectual disabilities often face attitudinal barriers and negative interactions arising from their stigmatised status in society, including bullying, harassment, hostility and other negative encounters in the community. This is in addition to discrimination in education, employment, access to and receipt of health and social care services, and housing. 13 However, due to social and cognitive skills limitations associated with a diagnosis of intellectual disabilities and reduced social support, their capacity to deal with others’ negative responses is often diminished. In response to not infrequent disability hate crimes, they are often afraid to move freely within their local communities, severely restrict their movements and even move home, if able to do so. 14,15

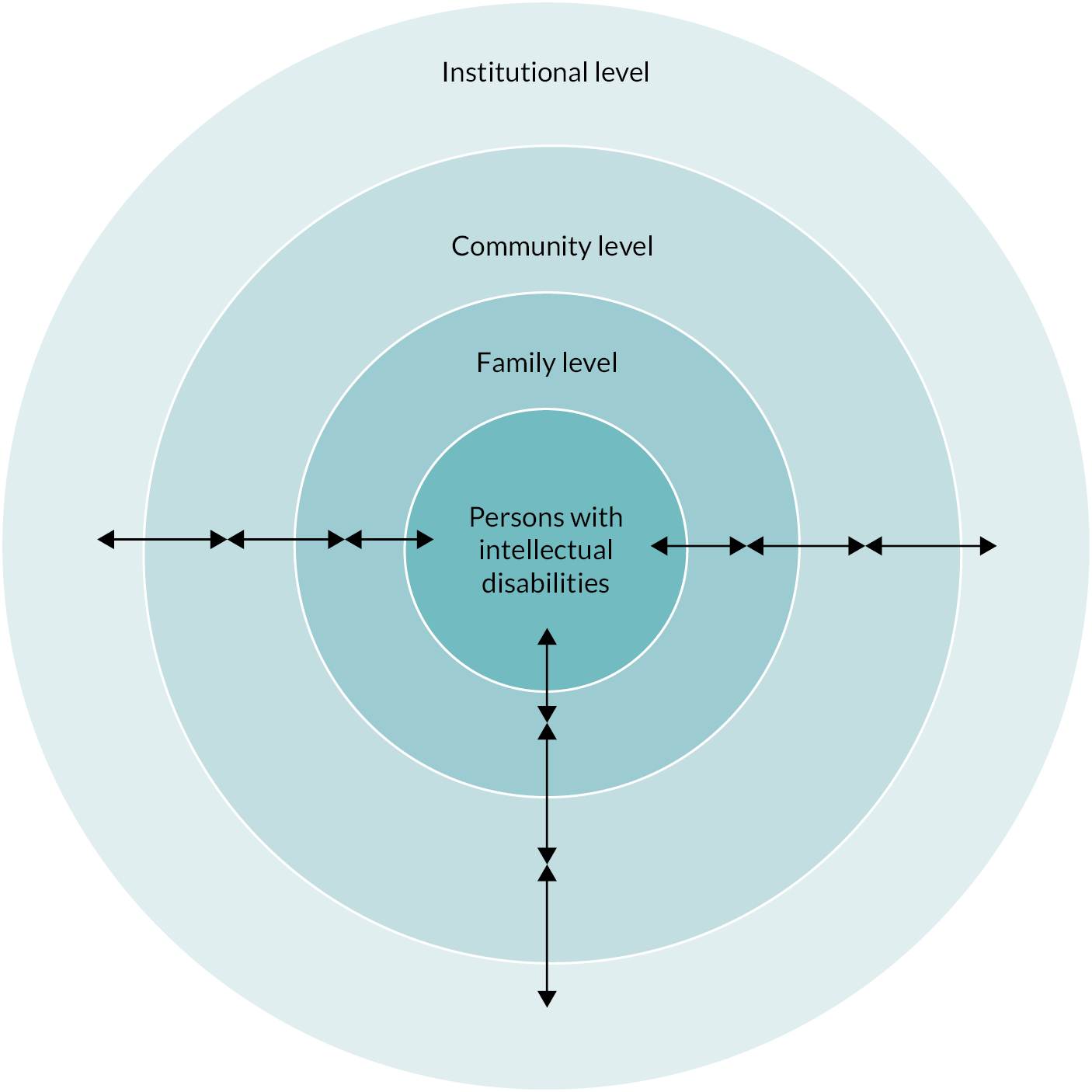

Consistent associations have been reported in this population between stigma and poorer self-reported health outcomes,6 increased anxiety and depression11,12 and lower self-esteem. 8,9 Consequently, intellectual disability stigma needs to be tackled at multiple levels, as articulated in our theoretical framework which calls for evidence production and remedial action at four interlinked levels (Figure 1): the level of stigmatised person, their family who may be subject to courtesy and affiliate stigma themselves,16,17 the community who generates and maintains stigma through prejudicial attitudes and discrimination, and finally the level of society and systems such as legislation and policy. 18

Interventions are in place to tackle such stigma at the institutional level and to promote more positive attitudes towards people with intellectual disabilities among the public and among key target groups. A number of systematic reviews evidence a lack of effective interventions for: (1) the reduction of negative effects associated with stigma as experienced by people with intellectual disabilities, and (2) managing stigma. 18–20 Psychological and psychosocial approaches that are suitable to this end, such as cognitive behavioural, narrative approaches and acceptance and commitment therapy, have been successfully used, for example, in the mental health field to help buffer individuals against stigma and its negative consequences, including low self-esteem. 21,22 Evidence that empowering the target or ‘victims’ of stigma can be effective comes, for example, from meta-analyses of interventions with victims of bullying. 23,24 Developing effective ways of enhancing the capacity of people with intellectual disabilities to manage and resist stigma, both individually and collectively, is likely to have positive effects on their self-esteem, mental health and general well-being. In turn, reducing the negative impact of stigma may reduce demands on (mental) health and social care services as a result of improved well-being (see Chapter 2, Logic model).

A meta-analysis of ‘stigma resistance’ in the mental health field found strong positive associations between stigma resistance and self-stigma, self-efficacy, quality of life and recovery in people with mental health problems. 25 These authors described stigma resistance as an ongoing, active process that involves using one’s experiences, knowledge, and sets of skills at the (1) personal, (2) peer and (3) public levels. 26 They described stigma resistance at the personal level as ‘(a) not believing stigma or catching and challenging stigmatising thoughts, (b) empowering oneself by learning about one’s condition and recovery, (c) maintaining one’s recovery and proving stigma wrong and (d) developing a meaningful identity apart from’ (p.182) one’s condition (in their case, mental health challenges). At the peer level, stigma resistance involves ‘using one’s experiences to help others fight stigma and at the public level, resistance involved (a) education, (b) challenging stigma, (c) disclosing one’s lived experience and (d) advocacy work’ (p.182). 26 As yet though, this understanding has not been translated into evidence-based interventions that seek to increase stigma resistance among members of different stigmatised groups.

Looking to disability stigma specifically, the first Global Disability Summit in 2018 stressed that more action is needed to reduce high levels of stigma faced by people with disabilities around the world. The Summit led to 170 commitments by governments and multilateral organisations, including the World Health Organization and several UN agencies, to do more to reduce disability stigma. As noted, this project is firmly located within an understanding that disability stigma occurs at and needs to be tackled at multiple levels. Hence, the decision in this project to focus on empowering people with intellectual disabilities to resist stigma, if they so choose, does not for a moment suggest that parallel anti-stigma interventions are not also needed at the family, community and institutional levels.

Standing Up for Myself as a public health intervention

In the intellectual disability field, a few interventions have sought to employ psychosocial approaches to enhance the capacity of people with intellectual disabilities to manage their stigmatised status in society. These include psychoanalytically informed consciousness-raising groups,27 and groups drawing on cognitive behaviour therapy. 28 While such interventions may be helpful at an individual level by supporting the person to ‘come to terms’ with their disability and learn to cope with a stigmatised identity, they do not go beyond stigma management, nor do they explicitly name oppression, and thus do not empower people with intellectual disabilities to challenge the status quo. Furthermore, they were designed to be delivered by highly skilled clinicians and are therefore limited in reach.

Standing Up for Myself, a psychosocial group intervention, works directly with groups of young people and adults with intellectual disabilities to enhance their capacity to manage and resist stigma. STORM was designed from the outset to be scalable by being brief (four sessions plus one follow-up session) and suitable for delivery by group facilitators with a modest amount of preparation and training but without requiring any specific qualifications. By being delivered within the context of established groups, STORM provides a safe space to tackle sensitive subjects, maximises the potential for peer support and does not require substantial new delivery mechanisms which would affect its potential future implementation.

The STORM programme

Standing Up for Myself is a manualised psychosocial group intervention developed with close input from people with intellectual disabilities and experienced facilitators of groups for members of this population. STORM was designed for delivery by staff in education, social care and third sector organisations who have experience of facilitating groups for people with intellectual disabilities, without requirement for any specialist qualification. ‘Third sector organisations’ refers to voluntary and community organisations, typically providing services to achieve social goals. These are non-governmental and operate on a not-for-profit basis (unlike the private sector). The STORM intervention is delivered to established groups to ensure members feel comfortable and safe discussing sensitive and potentially distressing topics, to offer peer support, and to ensure that group facilitators who know group members can monitor responses and offer additional support, where necessary. Peer support available through a group intervention is seen as an integral part of STORM with hypothesised benefits for well-being, self-worth and responses to stigma, based on evidence from the mental health field. 29,30

Standing Up for Myself consists of four weekly 90-minute sessions and a 90-minute follow-up session (delivered around 4 weeks after session 4); an overview of the STORM programme sessions and key messages is provided in Table 1. The intervention involves: (1) watching short films of people with intellectual disabilities talking about the meaning of intellectual disability to them personally, their first-hand experiences of social interactions (both positive and negative) and how they deal with negative interactions with others; (2) group discussions of this material, guided by questions posed by the group facilitator as per the manual; (3) sharing of personal experiences relating to the topic under discussion; (4) problem-solving in relation to different possible responses to stigmatising experiences; and (5) action planning for managing and resisting stigma in future either individually and/or as a group. STORM uses existing film footage produced with and by people with intellectual disabilities as stimuli for discussion in sessions 1–3. This consists of short film clips (2–7 minutes in length) used as part of the STORM intervention with permission from the films’ original makers/producers.

| STORM sessions and key messages | STORM activities |

|---|---|

| Session 1: What does ‘learning disability’ mean to people with learning disabilities? What does it mean to me? Key message: My learning disability is only one part of me. |

Videos (4 clips) followed by a discussion to explore:

|

| Session 2: How are people with learning disabilities treated? Key message: It’s not OK for people to treat me badly. I don’t have to put up with it. |

Videos (3–4 clips) followed by a discussion to explore:

|

| Session 3: How do people with learning disabilities respond to being treated negatively? Key message: I can stand up for myself when people treat me badly. |

Videos (× 3/4 clips) followed by a discussion to explore:

|

| Session 4: What am I already doing when others treat me in a way I don’t like? What else do I want to try? Key message: I can make a plan to help me stand up for myself. People I trust can help me with it. |

Begin action planning:

Celebration event. |

| Follow-up session: What worked and what got in the way of my plan? Key message: Things can get in the way of my plan. Talking to others can help me decide what to do next and not give up. |

To review and discuss:

|

Of note, the intervention uses the term ‘learning disability’ as the most commonly used term in the UK to denote ‘intellectual disability’.

The STORM manual is available as a pdf document and is supported by an online web-based version (a Wiki) that contains all training and preparation materials, film clips, session materials, information for participants in an accessible Easy Read format, and optional activity and work sheets in a format designed to make it as easy as possible for facilitators to deliver each session in accordance with the manual. These materials were fully updated following feedback from an initial pilot study. 31

The rise of digital interventions and the impact of COVID-19

The use of digital health (also known as e-health) interventions has grown rapidly over the last decade, a development that has accelerated greatly in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic and associated social restrictions. 32,33 The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic were acutely felt in the UK from March 2020, with the first national lockdown. The way in which services and support were delivered, including to people with intellectual disabilities, has been responsive to successive lockdowns and the need for distancing. Face-to-face (F2F) meetings were largely suspended at times during the pandemic and, wherever possible, organisations shifted to supporting their members and users through virtual methods, in particular, web-based video meetings and WhatsApp calls (see Chapter 3, Usual practice). Consultations with partner and third sector organisations over the course of the COVID-19 pandemic have highlighted that this shift has been successful for many (if not all) people with mild-to-moderate intellectual disabilities. With initial support, many have learnt how to use virtual meeting software/apps. Many individuals with intellectual disabilities have underlying health conditions that place them at increased risk of COVID-19, and many organisations anticipate that they may continue to use virtual methods for the foreseeable future to engage with people with mild-to-moderate intellectual disabilities, and as part of a more diverse offer once they are able to resume F2F meetings. The widespread move towards much greater use of digital technologies, including by people with intellectual disabilities, through force of circumstance has offered an opportunity to assess the use and value of digital methods to promote well-being in this population. This is a priority in current health policy, yet an area where people with intellectual disabilities were largely excluded pre-pandemic. 34,35

Evidence supporting the acceptability and effectiveness of digital mental health interventions among both children and young people and adult populations has been generated in a range of settings. 36–41 However, as Lehtimaki et al. 37 note, the effectiveness of many digital mental health interventions remains inconclusive and more rigorous and consistent demonstrations of effectiveness and cost effectiveness are needed. In addition, further analyses are required to provide stronger recommendations regarding relevance for specific populations. 40 The current STORM study was originally designed as a cluster-randomised feasibility trial of the manualised STORM psychosocial group programme for people with intellectual disabilities, including economic and process evaluation. However, following the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the study was initially paused, and subsequently (in the autumn of 2020) the study design was revised. Adapting STORM so that it would be suitable for digital delivery became the primary aim, followed by a small pilot study to test the feasibility and acceptability of the adapted digital group intervention.

Digital interventions for people with intellectual disabilities

The use of digital health interventions with people with intellectual disabilities has been limited and this population has generally been excluded from e-health research. 42 Even though the scope of digital mental health is vast and people with intellectual disabilities who face multiple threats to their mental well-being might well benefit, they seem to have been relatively neglected in the discourse around digital mental health and the development and implementation of new (digital) interventions. 35 Historically, lower levels of access to the internet among this population have created a ‘digital divide’. 34 In 2019, Ofcom reported that people with intellectual disabilities in the UK had lower access to the internet compared with people without disabilities. This discrepancy was partly explained by lower levels of household ownership of PCs/laptops and tablets among this population (69% vs. 85% of people with no disabilities) and of smartphones (70% vs. 81%). 43 Contextual barriers to the use of digital interventions with people with intellectual disabilities also include concerns among many service providers about their own lack of digital skills which limit their opportunity to support people with intellectual disabilities. 44 However, it has been suggested that such barriers can be overcome with appropriate support and adaptations and a small, but growing, literature attests to the value of digital technologies to improve health as well as educational, vocational and leisure opportunities for this population. 35

The rationale for a digital version of the STORM intervention

The suggestion that the digital divide amongst people with intellectual disabilities needs tackling if we are to further avoid increasing existing health inequities has never been more evident than in the context of the pandemic. Increasing access to digital technology and the internet and generating e-health interventions that can improve the well-being of large numbers of people with intellectual disabilities should be a priority. It is also in line with the need to challenge health inequalities in the UK health and social care system stipulated in the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Evidence Standards Framework for Digital Health Technologies. 45

Having the option to meet virtually can promote self-determination and social participation for people with intellectual disabilities,46 with benefits including increased communication and social interaction. 47,48 Digital technology could also be a means to widen access for members of this population to therapy. 42 The potential benefits of digital interventions for people with intellectual disabilities are supported through consultation work we carried out at various time points since the first UK lockdown (see Chapter 3, Usual practice). Self-advocates and third sector organisations reported that for many people with intellectual disabilities virtual meetings were a preferred means of connecting with others as home was seen as a safe and familiar space to discuss personal experiences, and it could allow increased confidence to speak up and engage in discussions. Many people with intellectual disabilities experience anxiety about moving around their local community or travelling alone or are reliant on support from others to attend services, both of which can act as barriers to joining and attending groups in person. Virtual meetings have been suggested as one way to help overcome this, with some organisations informing us that they have been able to reach more of their members since replacing F2F with virtual meetings. Furthermore, people with intellectual disabilities living in rural areas of the UK are often prevented from using community services and joining groups due to the absence or inaccessibility of public transport and/or support required to travel. Organisations we consulted, particularly those that cover rural areas, informed us that attendance at F2F meetings is lower among their members during the winter months and greater use of digital meetings could fill an important gap. We should stress that digital methods are by no means for everyone. In a recent large-scale study on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the lives of people with intellectual disabilities in the UK, 42% were reported never to have been keen on online activities. 48 Therefore, adjustments to service delivery continue to be called for to meet the diverse needs of this population, and to reduce barriers to the inclusion and active participation of people with intellectual disabilities in their communities, both ‘real world’ and virtual.

The immediate need for and importance of STORM to help people with intellectual disabilities discuss negative experiences with their peers and resist stigma has been highlighted during the COVID-19 pandemic. The discrimination and inequalities people with intellectual disabilities have experienced during this time have also been highlighted. 49,50 Self-advocacy groups have often felt neglected by the government while their members had to shield, and have complained about lack of reasonable adjustments, including a failure to communicate social restrictions and rules. By continuing to meet virtually, these organisations have provided their members with space to connect with others and have sought to reduce the negative consequences of social isolation. They have emphasised the need for a space to discuss negative experiences and the stigma they face more generally, as well as specifically at this time when discrimination and social inequalities have been heightened.

Looking to the future, it seems important to offer a choice of delivery formats to access the STORM intervention to increase inclusion and respond to diverse preferences for engaging with peers. This aligns with our long-term goal to offer STORM as a widely and freely accessible public health intervention that can enhance the ability of people with intellectual disabilities to manage and resist the stigma they often face in their everyday lives. By potentially extending the reach of STORM among this population through the creation of a digital version, we seek to challenge exclusion and promote equality at multiple levels.

Adaptation of STORM for digital delivery and pilot study

In view of the aforementioned issues, the main aim of this project was to (1) adapt the STORM intervention for digital delivery (Digital STORM) to groups of people with mild-to-moderate intellectual disabilities, and (2) test delivery of the adapted intervention and outcome measurement in a virtual environment through a small pilot with four groups. The adaptation process is described in detail in Chapter 2. The pilot study is reported according to the progression criteria set out in the revised study protocol (see Chapter 2, Revised study design). The acceptability, adherence and fidelity of the intervention delivery are detailed in Chapter 3.

Chapter 2 Methods

Sections of this chapter have been reproduced from the STORM study protocol,1 reproduced under licence CC-BY-4.0 from the NIHR Journals Library.

Original study design

Standing Up for Myself was originally designed as a cluster-randomised feasibility trial of the manualised STORM psychosocial group programme for people with intellectual disabilities, including economic and process evaluation. It was planned to invite third, education and social sector organisations that work with groups of people with intellectual disabilities to identify one established group with an average of six to seven members interested in participating in the trial. Groups were to be randomised to STORM or the control arm on a 1 : 1 ratio using variable block randomisation in which the unit of randomisation is the group. STORM was to be delivered via F2F groups as weekly 90-minute sessions over the course of 4 weeks, with a 90-minute follow-up session (delivered around 4 weeks after session 4). The control group would receive usual practice (UP) plus access to STORM after the 10–12 months’ follow-up period (wait-list control). Using mixed methods, we intended to examine delivery of the intervention and adherence, as well as to gain stakeholder views on the acceptability of the intervention and on barriers and facilitators that may affect not only its future implementation but also plans for a future definitive trial.

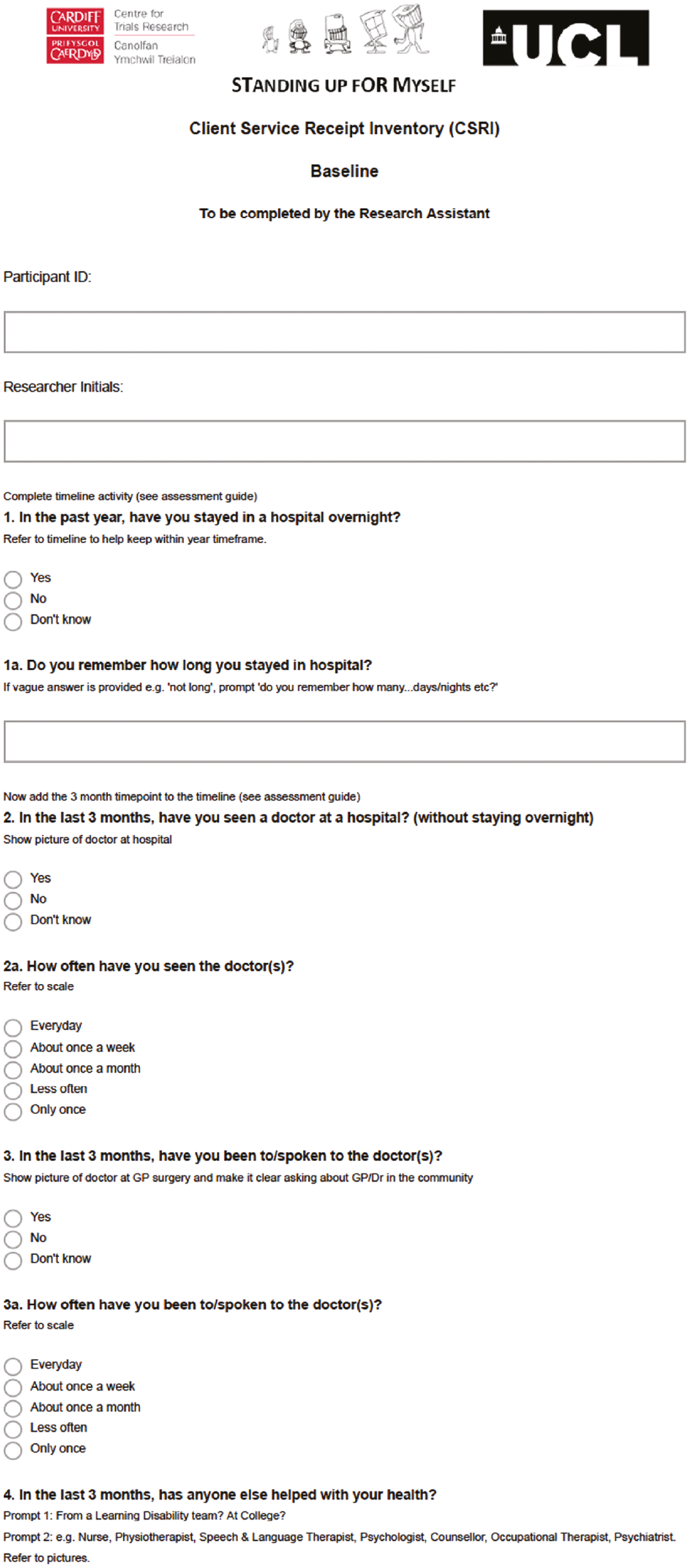

Revised study design

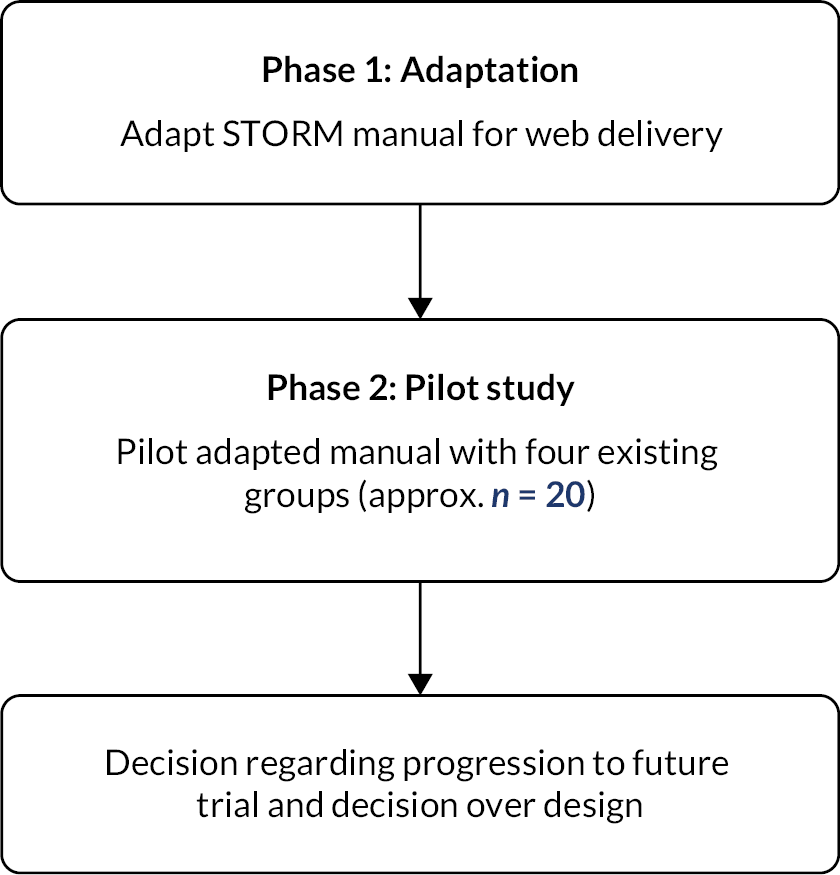

In view of the obstacles that the COVID-19 pandemic posed to delivering the study as originally intended, the study protocol was revised to include work to adapt the STORM intervention to make it suitable for online delivery via web-based meeting platforms to people with mild-to-moderate intellectual disabilities. The adaptation was a 4-month phase of work, undertaken with in-depth input and oversight from a multistakeholder Intervention Adaptation Group (IAG). The outcome of this phase was to produce intervention materials appropriately adapted to the new delivery context and to revise the intervention manual and training materials, where necessary. The newly adapted digital intervention would then be piloted through delivery to groups already meeting online and as part of a pilot study to examine its feasibility and acceptability (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Flow diagram of the digital adaptation and pilot of STORM.

Objectives

The objectives were:

-

To adapt the existing STORM intervention for online delivery (Digital STORM), ensuring the content, number of sessions and direct contact time were the same for both STORM and Digital STORM.

-

To pilot the Digital STORM intervention in order to investigate the feasibility of recruitment to and retention of participants in Digital STORM; and adherence, fidelity and acceptability of Digital STORM, when delivered to groups of people with mild-to-moderate intellectual disabilities online.

-

To test digital administration of the study outcome and health economics measures.

-

To build on community assessments to describe what ‘UP’ for organisations delivering groups for people with mild-to-moderate intellectual disabilities may look like in the wake of COVID-19, to inform a potential future trial.

Progression criteria related to study objectives

Undertaking the pilot study of a digital adaptation of STORM was contingent on the study team being able to meet objective 1, to revise and adapt the intervention materials to the acceptance of the IAG and study management group (SMG). This objective was met by the end of March 2021.

The study progression criteria for objectives 2 and 3 are outlined in Table 2. For objective 2, regarding the feasibility and acceptability of Digital STORM, the progression criteria have been divided into two parts. Part one outlines criteria assessed using data collected from facilitators and through session recordings, and part two focuses on acceptability from the perspective of the pilot participants. Finally, for objective 3, progression criteria are defined to assess the feasibility of digital administration of the study outcome measures.

| Research objective 2: To investigate the feasibility and acceptability of Digital STORM, when delivered to groups of people with intellectual disabilities online. | ||

|---|---|---|

| 2.1. Feasibility of delivery of Digital STORM to participants, assessed via facilitator notes, supervision notes, facilitator interviews and a review of session recordings to demonstrate: | ||

| Progression not indicated | Indicator for progression, with further adaptations needed | Strong indicator for progression |

| Attendance was poor (participants on average attended less than three sessions) and within- session presence and engagement were poor, unlikely to be resolved with adaptations. Technical problems were significant, were not resolvable and likely to severely impair future implementation. |

Good attendance across sessions (participants on average attended at least three sessions), BUT presence and engagement within sessions were somewhat impaired by technical issues. These would be resolvable with some additional modifications/guidance. | Good attendance across sessions (participants on average attended at least three sessions) and presence and engagement within sessions were good, any technical problems were resolvable and did not unduly impact on running the session or engagement (with brief connectivity problems not exceeding 10–15 minutes). |

| Would not recommend Digital STORM to others nor consider running it with other groups. | Would only consider recommending Digital STORM to others or running another group if specific changes were made to the content, structure or accessibility of the technology. | Would recommend Digital STORM to others and consider running it with another group. |

| Facilitators felt unable to monitor participants’ emotional responses during sessions and to respond accordingly, modifications unlikely to resolve this. | Facilitators felt modifications were needed to monitor participants’ emotional responses during sessions and to respond accordingly, but these would be straightforward to implement through additional guidance or adaptations. | Facilitators felt able to monitor participants’ emotional responses during sessions and to respond accordingly. |

| Privacy threats were evident and unmanageable or significantly affected engagement and participation. Further modifications unlikely to adequately resolve this. | Privacy could be better managed with some modifications. | Able to manage any threats to privacy for group members either by following the manual or taking additional steps. |

| 2.2. Acceptability of Digital STORM to participants, assessed via feedback obtained from focus group meetings to demonstrate: | ||

| Progression not indicated | Indicator for progression, with further adaptations needed | Strong indicator for progression |

| A majority of participants judged the delivery format as not acceptable and would not recommend Digital STORM to others. Changes unlikely to remedy this. | 50% or fewer judged the digital delivery format as acceptable and would recommend Digital STORM to others. | A majority of participants judged the digital delivery format as acceptable and would recommend Digital STORM to others. |

| On occasion when participants found intervention contents distressing, they either felt un-supported by the group facilitator and/or their peers, or were unable to access support outside of the group. Changes unlikely to remedy this. | On occasion when participants found the intervention contents distressing, they did not always feel well supported by the group facilitator and/or their peers, or were not able to access support outside of the group when they needed it. Changes would mean that support in this area could be improved. | On occasion when participants may have found the intervention contents distressing, they either felt well supported by the group facilitator and/or their peers, or were able to access support outside of the group. |

| Participant privacy was not maintained in a way that allowed them to fully engage in the sessions. Changes unlikely to remedy this. | Participant privacy was mostly maintained but there were occasions when threats to privacy affected engagement and/or raised concern. Changes in this area could make this more acceptable in the future. | Participant privacy was maintained in a way that allowed full engagement in the sessions. |

| Research objective 3: To test the feasibility of digital administration of the study outcome measures: | ||

| Progression not indicated | Indicator for progression, with further adaptations needed | Strong indicator for progression |

| < 70% of collected outcome data found to be useable. | 70–79% of collected outcome data found to be useable. | 80%+ of outcome data (collected at baseline) found to be useable. |

Three categories of progression indicators are provided, a strong indicator for progression, progression indicated subject to further amendments and progression not indicated. All progression criteria were agreed with the SMG, Study Steering Committee (SSC) and funder as part of the approvals of the amended protocol.

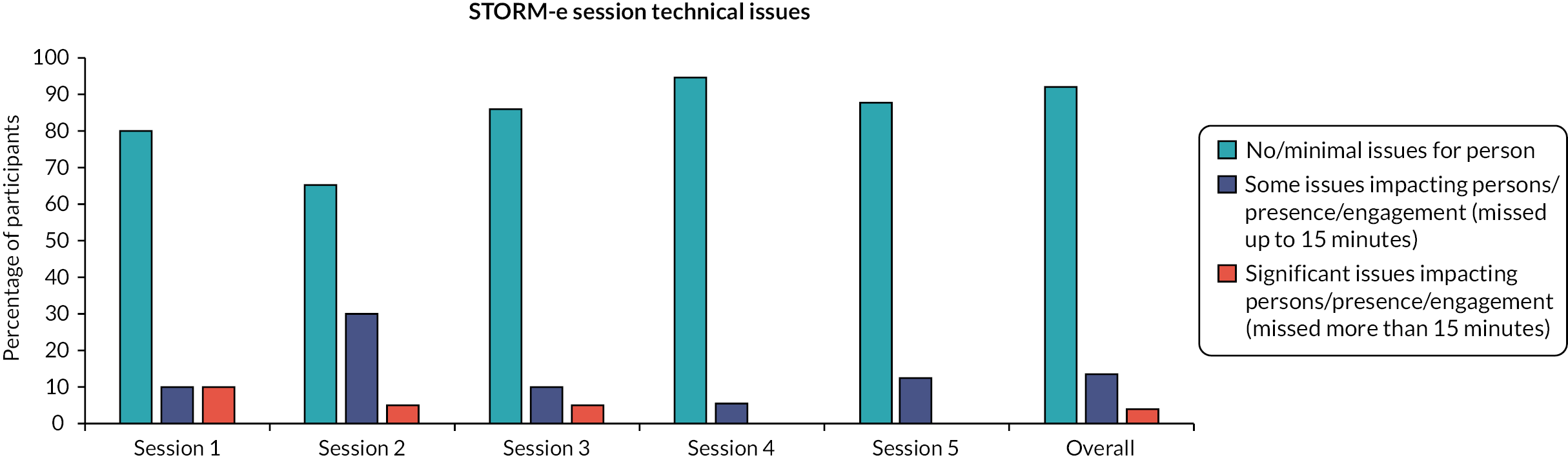

In addition to the above, the risk of exclusion from Digital STORM due to technical issues was considered, and a target was set of no participant missing more than two sessions, or parts thereof, due to technical problems (other than brief connectivity problems not exceeding 10–15 minutes).

Adaptation of STORM for digital delivery

Intervention Adaptation Group

In October 2020, the IAG was established to oversee the adaptation of the STORM intervention. The IAG consisted of our four PPI advisors (STORM expert advisors), the independent co-chair of the PPI group (CB), three group facilitators (from our stakeholder group), two research and impact staff from Mencap (as our intervention delivery partner), members of the research team (KS, LR, ER, MO, KD) and the director and a member of staff of Unthinkable Digital. Digital inclusion experts Unthinkable Digital were commissioned to work with the team because they brought expertise in digital inclusion and learning design specific to people with intellectual disabilities. Their particular knowledge and skills were deemed important to ensure that the adapted digital version of STORM would be optimised for the engagement of people with intellectual disabilities and ease of delivery for facilitators who would all be relatively new to online group facilitation.

Attention to potential risks

In adapting the intervention, careful consideration was given to potential risks to ensure every effort was made to mitigate these. The risks were broadly categorised as falling within the following three areas. Firstly, potential risks to acceptability and inclusion arising from technical barriers to accessing online group meetings due to limited technology/digital equipment (e.g. phone/laptop/tablet), and/or internet connectivity problems (in recognition of the digital divide highlighted in the literature, see Chapter 1).

Secondly, we were concerned about potential risks to confidentiality and privacy while exploring personal and sensitive issues, particularly when participants join web-based meetings from remote environments where threats to privacy can be less controlled than in F2F meetings.

Thirdly, risks related to the facilitator’s ability to monitor and manage any potential emotional distress during the intervention, for example, while sharing information and videos via the screenshare feature in Zoom or MS Teams. Similarly, ensuring group members would feel supported and/or able to access support was seen as very important in the context of digital delivery of the intervention.

Ensuring access and engagement with Digital STORM

Given the above aims and orientation to risks, the IAG reviewed the following aspects of the STORM intervention and made recommendations to the research team regarding necessary adaptations to the manual and other resources:

-

intervention format and structure, including changes to group dynamics and interactions when moving from a F2F to a virtual environment, and mechanisms for managing potential challenges to participants’ right to privacy

-

intervention content, including how to manage demands on group facilitators tasked with delivering Digital STORM

-

delivery mechanisms and resources, including how to ensure participants had access to and familiarity with technology to be used as part of Digital STORM

-

participant needs for support, including the role of carers/family members in supporting participants to engage with the intervention.

Outcomes of the Intervention Adaptation Group meetings

The IAG met four times, at monthly intervals, between November 2020 and February 2021. Each meeting focused on one or several of the topics outlined above. During the meetings, the IAG was able to draw on community assessments already conducted by the research team to identify key considerations in adapting the STORM intervention for digital delivery. Also informing the IAG’s discussions, ideas and plans were insights generated through a web survey disseminated with support from our partner organisations. The survey sought to understand what facilitators had learnt regarding what works in making the shift from F2F to web-delivered activities, including how to prepare and support access to and engagement with web-based meetings and manage privacy concerns (further details about the survey are presented below and in Chapter 3).

A summary of the key recommendations for adaptation from the IAG meetings is provided in Table 3.

| Intervention structure | |

| Number and timings of sessions |

|

| Group sizes |

|

| Intervention content | |

| Videos |

|

| Delivery mechanisms and resources | |

| Zoom/MS Teams or other web-based meeting platforms |

|

| White board/flip chart notes |

|

| Communication cards |

|

| Posters for key messages and worksheets |

|

| Manual and Wiki |

|

| Managing threats to privacy | |

| Facilitator's role in managing privacy |

|

| Participants’ need for support | |

| Monitoring for emotional distress and how to manage this during sessions |

|

Digital STORM intervention

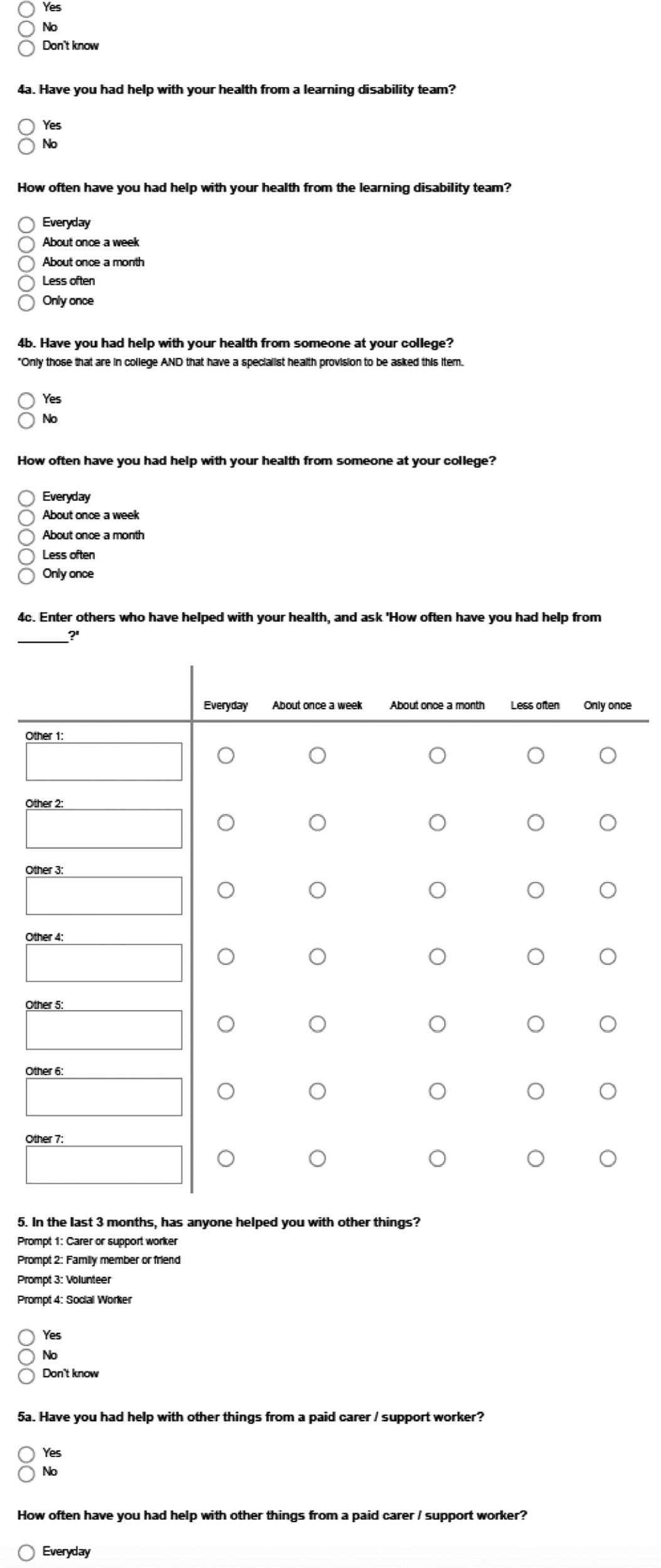

Logic model

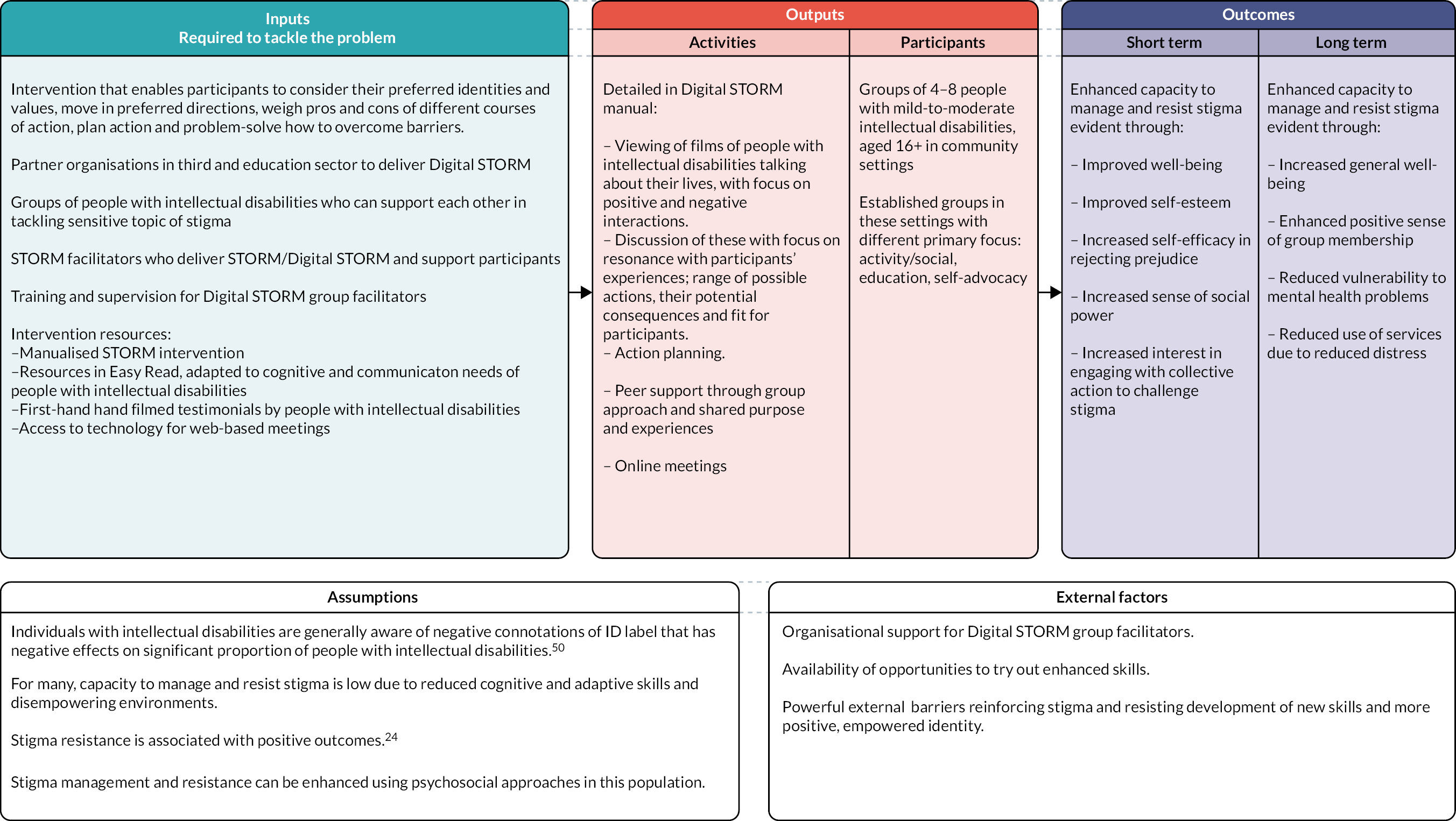

A Logic model for the Digital STORM intervention is shown in Figure 3. The model was somewhat refined from the original version pertaining to the F2F version of STORM to reflect.

FIGURE 3.

Digital STORM intervention logic model.

Digital STORM facilitator training and supervision

Facilitator training

In addition to providing the intervention manual (paper and electronic copy), access to the Wiki and other Digital STORM resources, facilitators were provided with brief training to deliver the intervention. The training was delivered over the course of two 2-hour sessions and was jointly delivered by the Study Manager (LR) and a member of Mencap’s research and impact team (HB) via Zoom. Session 1 provided an overview and background to Digital STORM and an introduction to the resources. A demonstration of the Wiki was provided, as well as an overview of the structure of the Digital STORM sessions and key messages. Guidance was shared about managing the technology involved, followed by a discussion of possible solutions to problems that might present in the course of delivering Digital STORM. Session 2 was designed to be more interactive in nature, providing the opportunity for facilitators to ask questions about Digital STORM resources and providing advice for preparing and delivering Digital STORM sessions. Further detail and discussion around action planning was included, as was detail about the supervision and support available.

Supervision for facilitators

Regular one-to-one supervision sessions with HB were offered to each facilitator throughout the Digital STORM intervention delivery, in addition to ad hoc support via e-mail correspondence. The supervision sessions were designed to be informal in nature, hosted via Zoom or MS Teams (depending on facilitator preference). Each facilitator was offered a ‘check in’ session before they delivered the first session. This was to ensure that they felt prepared and had the opportunity to ask any final questions before starting delivery of the intervention. The other supervision sessions were offered shortly after each STORM session; attendance was not mandatory.

Digital STORM pilot phase

The pilot evaluation of the Digital STORM intervention focused on issues of feasibility and acceptability. As described in Objectives, this study set out to evaluate:

-

recruitment (of organisations, facilitators and participants), retention and adherence (participants);

-

intervention fidelity;

-

feasibility of intervention delivery and acceptability.

Recruitment and retention to the pilot study

Sample size

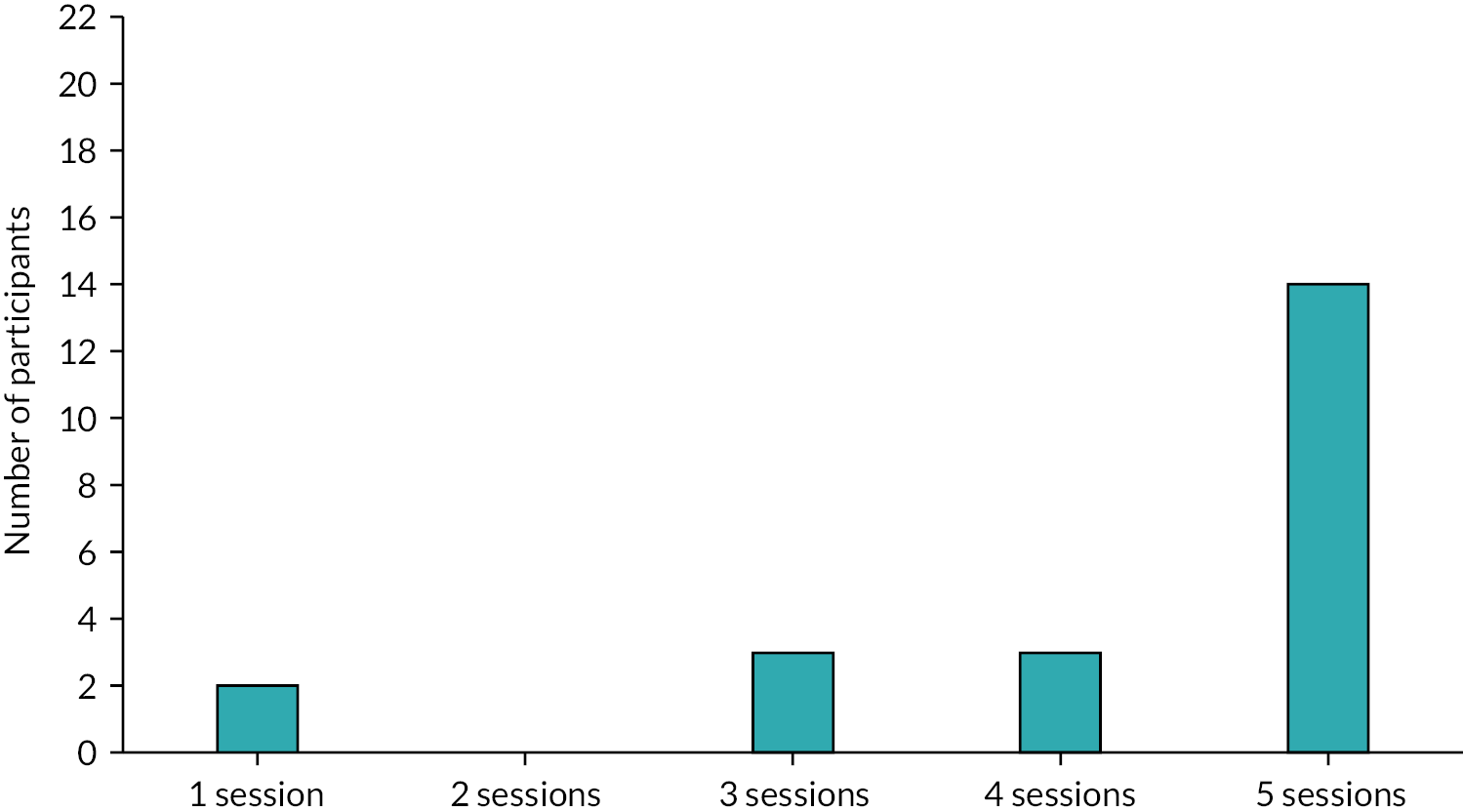

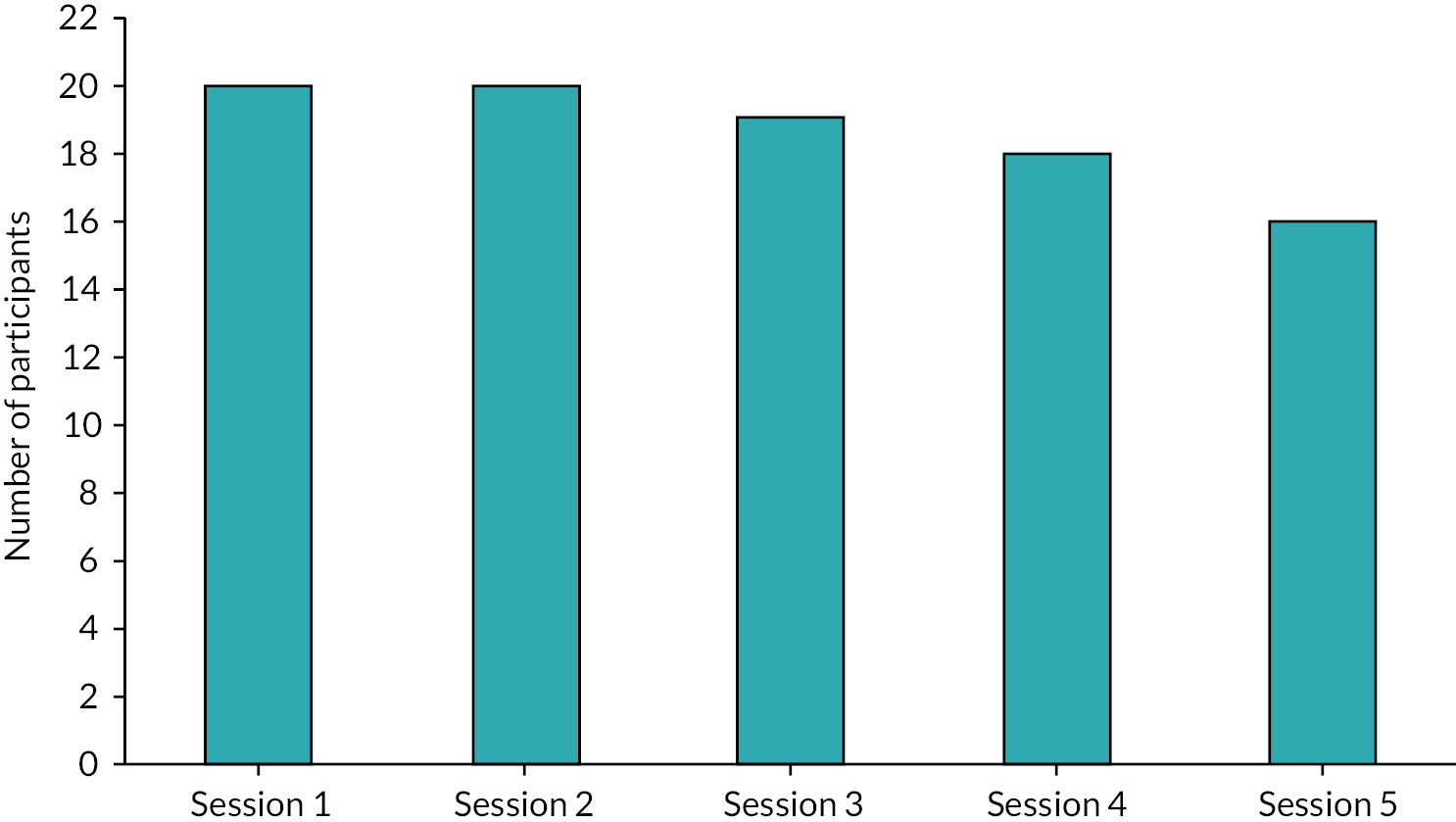

Following the adaptation phase, the Digital STORM intervention was piloted with four groups (N = 22), with the group size ranging from three to seven members. The smaller group size (compared to the 5–10 recommended for the original intervention) was determined by feedback received during our stakeholder consultations that smaller group sizes work better in web meetings.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for groups and participants

The feasibility of recruitment was established through identifying group facilitators and consenting group members who met the study inclusion criteria and did not meet the exclusion criteria. A record of the screening and recruitment processes and outcomes was kept in a database developed and maintained by the research team.

Groups were eligible to take part in the Digital STORM pilot if they:

-

were in place already (although group meetings might have been disrupted due to COVID-19 and associated social restrictions);

-

intended to continue or restart meeting as a group for at least 3 further months;

-

had at least three and no more than eight members with intellectual disabilities who wished to participate in the intervention;

-

were willing to replace five of their usual meetings with Digital STORM;

-

had a group facilitator willing to receive training and facilitate the Digital STORM intervention in digital form and in line with the manual;

-

had organisational support to deliver the study intervention.

Groups were excluded if:

-

they were run as part of the NHS;

-

some of their regular members declined taking part in Digital STORM and it was not possible to find alternative meeting times to run Digital STORM (in the event, this did not occur during the pilot).

Participants were included if they:

-

were aged 16+ years;

-

had a mild-to-moderate intellectual disability as defined by an administrative definition (use of services for people with intellectual disabilities);

-

were able to communicate in English;

-

were a member of an established group for people with intellectual disabilities (educational, activity, social or self-advocacy focused);

-

were able to complete the outcome measures (with or without support) and engage with the STORM intervention;

-

had access to the internet and a device that could access web meetings, be this via Zoom, MS Teams or Google Meet;

-

were able to access support to access web-based meetings, where needed;

-

had capacity to provide informed consent to participation in the study.

Screening groups and participants for eligibility

Facilitators of groups were sent a study information leaflet (see Appendix 1). After they and their group expressed an initial interest in the Digital STORM project, a researcher contacted facilitators individually as part of the screening process to check for eligibility. Questions were asked about the usual activities of the group, including how well established their online meetings were, resources available to them (including digital equipment), group members’ ages, ability to join in discussions, the support available to them (including from carers, and supporters within and beyond the participating organisation). The screening questions were guided by the inclusion and exclusion criteria listed above.

Obtaining informed consent from participants

All potential participants from the identified groups were provided with study information in an accessible (Easy Read) information sheet (this can be accessed at www.storm-ucl.com/). Potential participants had the option of receiving the information sheet by e-mail or post. A researcher also attended one of the groups’ usual (virtual) meetings to present the information to group members and answer any questions they might have, using Zoom or MS Teams, whichever software was familiar to the group. The researcher presented the information verbally while also showing the information sheet using the screenshare function.

Group members were given at least 24 hours to consider the study information before making a decision and informing the group facilitator of this. As part of confirming their interest in participating in the study, group members provided their contact details to the group facilitator to pass on to the researcher. Once this information was provided to the research team, a researcher made contact with group members to set up individual meetings using the online platform they were familiar with.

At the initial individual meetings with potential participants, the researcher shared and read through the information sheet again, checking whether the information was understood by the participant, further explaining anything that the participant appeared unsure about and answering any questions they might have. The researcher proceeded to share the consent form via screenshare and talked through each information point, checking the participant’s retention and understanding. The participant’s verbal responses of ‘yes’/‘no’ to each item on the consent form were recorded (using end-to-end encryption, in line with data protection regulations). Participants were also asked to state their name and the date for the purposes of recording their verbal consent. Recordings of verbal consent were stored on a University College London (UCL) secure research drive and separate from all other data collected.

Retention, attendance and adherence

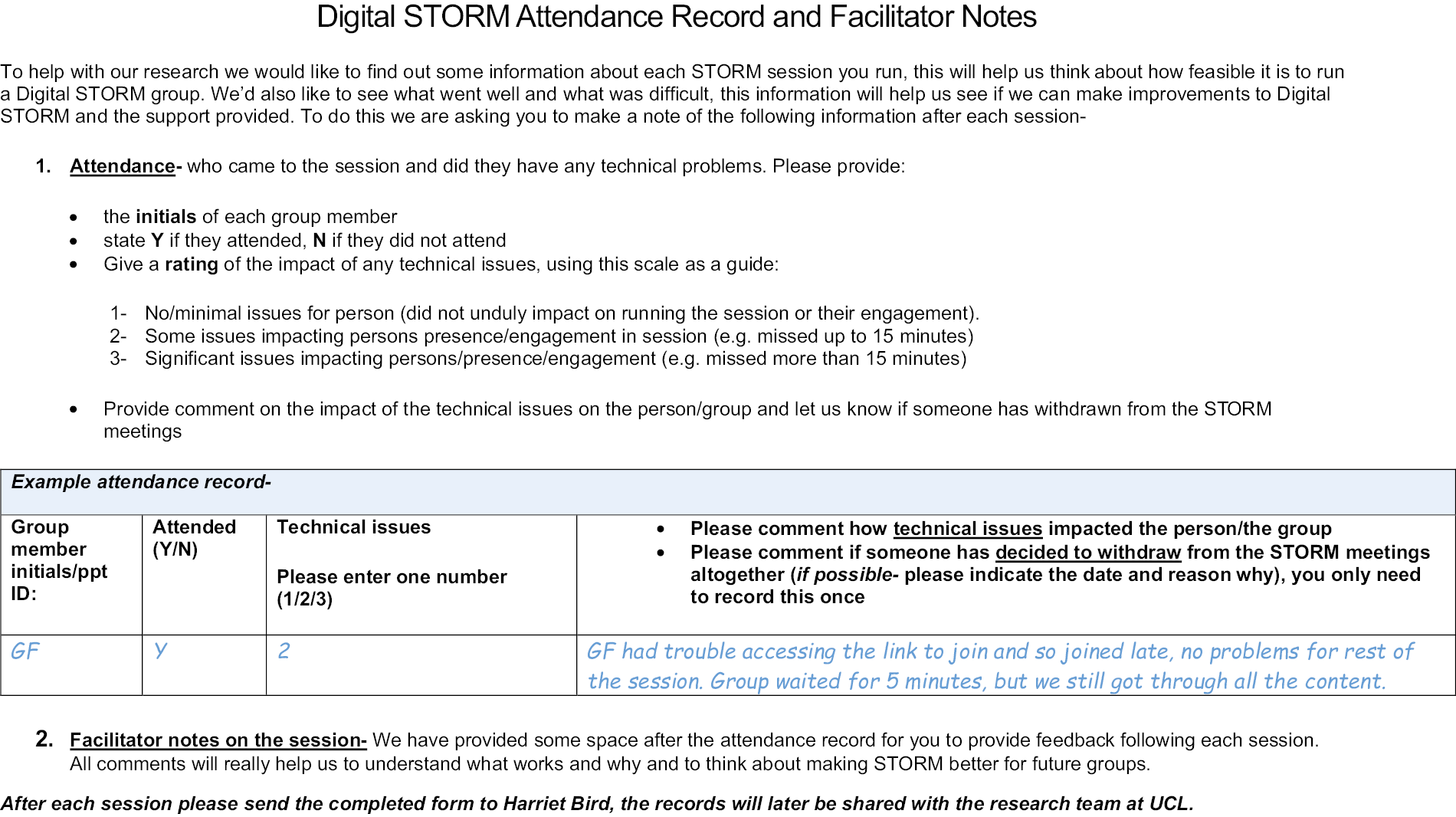

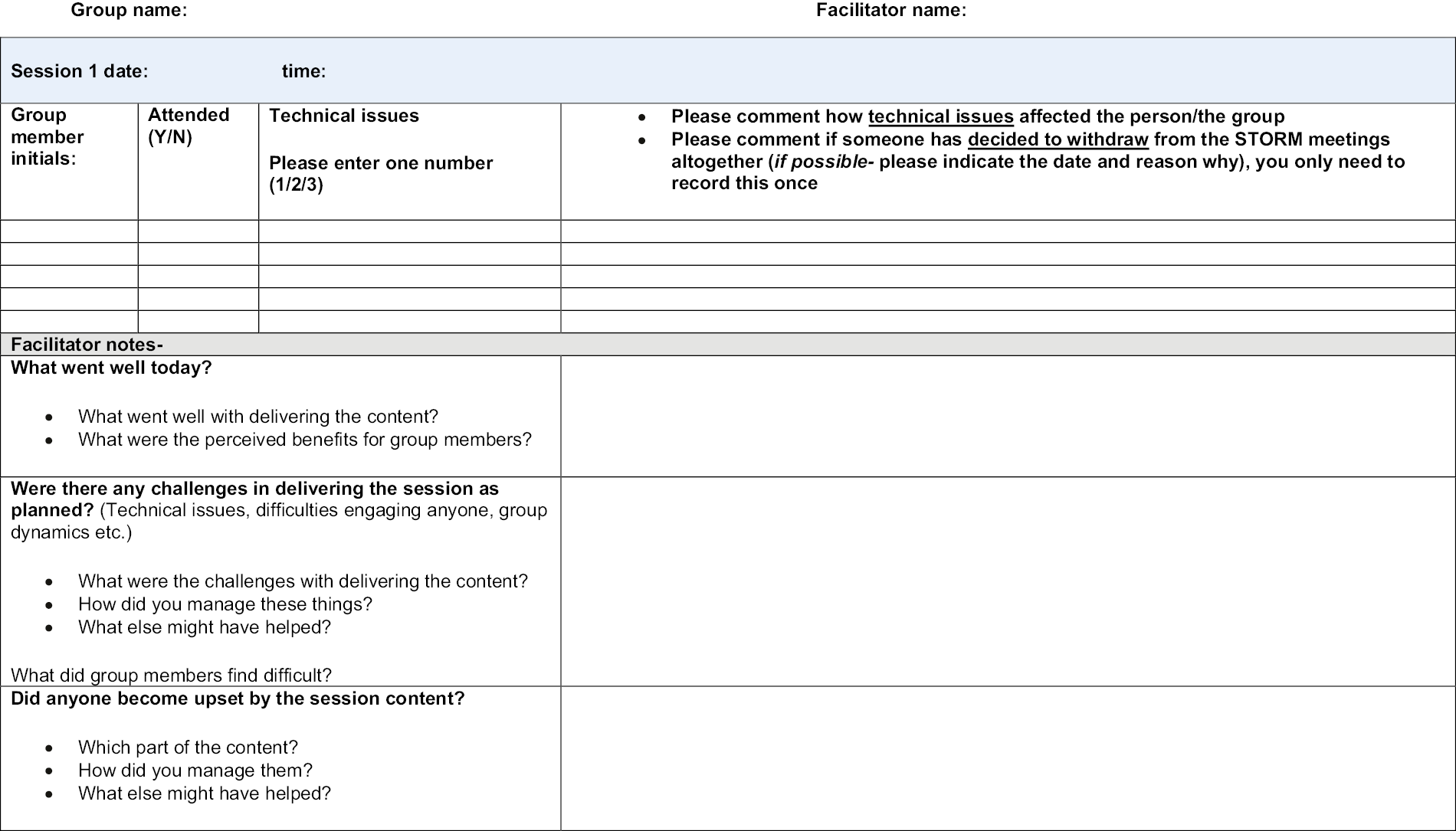

Retention, attendance and adherence were assessed by group facilitators recording participants’ attendance at each session using a bespoke attendance and feedback form (see Appendix 5). The form captured attendance at each session and included a rating by the facilitator for each participant of whether technical issues affected their engagement with the session. Ratings were on a three-point scale; (1) no/minimal issues for the person (did not unduly impact on running the session or their engagement), (2) some issues affecting participants’ engagement in the session (e.g. missed up to 15 minutes) and/or (3) significant issues affecting person’s/presence/engagement (e.g. missed more than 15 minutes). There was space for facilitators to make notes about how the technical issues affected the person. Additional space was provided with prompts for facilitators to comment on: (1) what went well during the session, (2) challenges to delivering the session as planned and (3) whether anyone had become unduly upset during the session due to the session content.

Facilitators were asked to complete the form after each session and to send it to the intervention partner (HB), so as to facilitate an understanding of the experiences and to inform discussions in supervision. Following supervision sessions, the completed document was sent to the Study Manager (LR) with any additional supervision notes added. In case of any missing attendance and engagement data, session recordings were used to assess what proportion of sessions participants were able to attend (to account for participants dropping out at any point, either due to poor internet connectivity or for other reasons).

Intervention fidelity

All Digital STORM sessions were video recorded, to conduct ratings of the intervention’s fidelity. Recordings were made using the record function available in Zoom/MS Teams. To enable recordings to be saved to local UCL computers/secure drives and to negate other more complex data-sharing procedures, a researcher (MO) set up the meetings in the relevant app and sent the joining details to facilitators to share with their group members. MO would then start the meetings, start the recording and then share hosting control of the meeting app with the facilitator. She would then turn off her video, microphone and sound and would not interact with nor observe the group during sessions and inform group members that this was the case. Recordings of Zoom meetings were end-to-end encrypted via Zoom’s recording function, while recordings via MS Teams were stored in the secure UCL cloud.

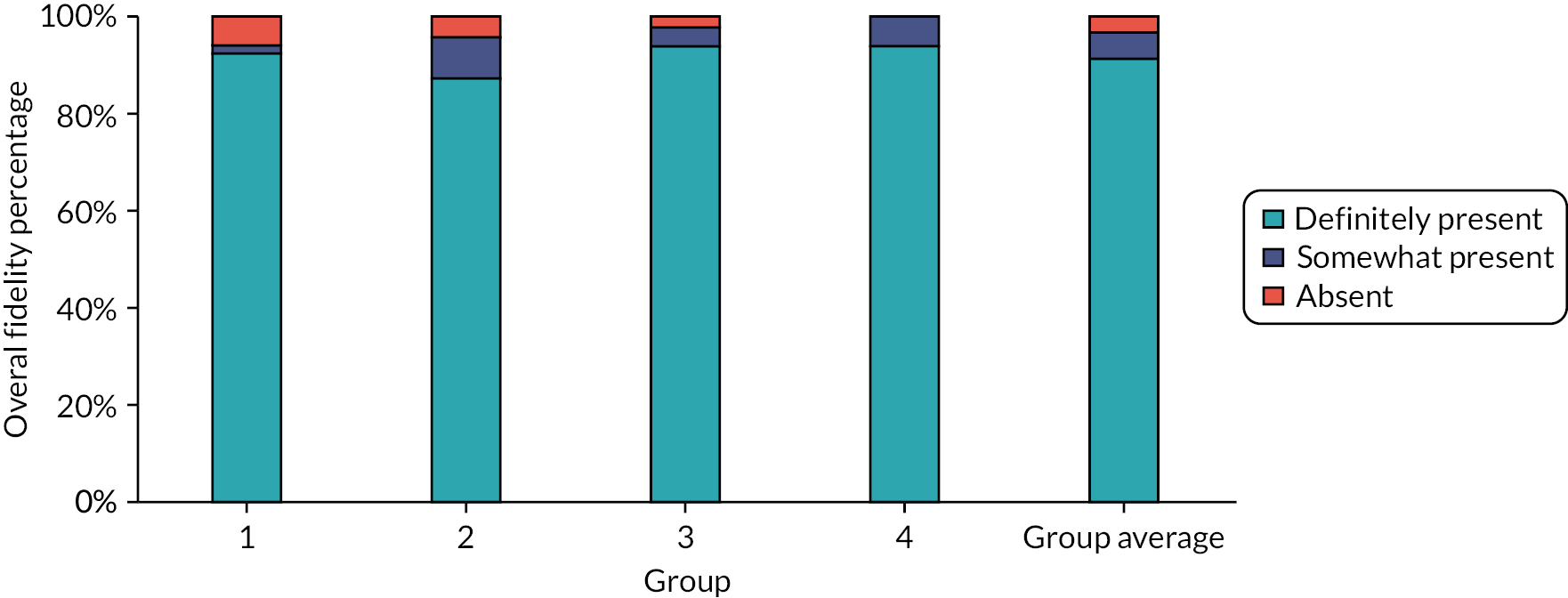

To assess fidelity to the Digital STORM manual, a checklist of core requirements was developed using a coding frame (Microsoft Excel spreadsheet) for (1) adherence to the manual, (2) group process and (3) facilitator engagement with group members (see Appendix 6). The checklist was used to rate the video recordings of sessions to determine whether core elements were definitely present/somewhat present/absent. The checklist was adapted from an existing fidelity instrument developed for group interventions and by taking into account the particular social and communication needs of people with intellectual disabilities. 51 Fidelity ratings were completed by the chief investigator (CI) (KS) and a second rater (KD). Both independently rated a session and discussed points of divergence to achieve a high level of reliability in their ratings. The data manager (SJ) randomised the remaining recordings, to identify session 1 or 2 and session 3 or 4 to be rated for each of the four groups. All follow-up sessions were rated. Rater 1 (KD) rated nine sessions across three groups and rater 2 (KS) rated three sessions from one group. Both raters kept a reflective log while rating the session recordings. Once finalised, the data were sent to the data manager (SJ) for analysis. Quantitative analyses were employed to explore the variation of fidelity scores across groups and the association between fidelity scores and outcomes. Furthermore, the recordings were used alongside the facilitators’ attendance records, notes and log entries to identify what challenges to implementing Digital STORM as planned arose and how these were managed, in order to identify the need for further revisions to the manual and/or delivery mechanisms ahead of a feasibility study.

Feasibility of intervention delivery and acceptability – qualitative methods

All Digital STORM participants were invited to participate in a virtual focus group interview with their fellow group members. STORM facilitators were invited to a virtual individual interview. Views were sought on study participation, barriers/facilitators to the intervention’s implementation, as well as potential future improvements to the content or delivery of Digital STORM sessions (see Appendix 2). During the interviews, we also asked about the perceived value, benefits and harm or unintended consequences of the Digital STORM intervention to develop a full understanding of the likely mechanisms of change and to ensure these are fully measured in a full study.

Both focus groups with participants and individual interviews with facilitators were conducted via Zoom or MS Teams, in line with their preferences. Recordings were made using the record function available in Zoom/MS Teams and later transcribed using Otter for qualitative coding and analysis.

Three of the focus groups were co-facilitated by a peer researcher from the STORM Expert Advisory Panel (HR) and a researcher (MO), and one was conducted by a researcher (MO) alone. The focus group meetings took place following the final STORM session and once all post-intervention data had been collected. Group facilitators were also present for the discussions. Not all group members were present for the full duration of the focus group meetings, with some arriving late, leaving early, or being absent altogether (full details in Appendix 7). Semistructured interviews were conducted with the four group facilitators either by the CI or MO. Both facilitator interviews and focus groups were conducted via a video call platform (Zoom or MS Teams), with facilitator interviews lasting 40–60 minutes and focus groups lasting up to 90 minutes.

Questions were developed to obtain participants’ and facilitators’ views on the feasibility and acceptability of the Digital STORM intervention, informed by the progression criteria set out in Chapter 4, Adapting and piloting the existing STORM intervention for online delivery. This was supplemented with questions to capture the impact of Digital STORM on participants (see Appendix 2). The interviews and focus group recordings were transcribed using the Otter artificial intelligence software and anonymised by a researcher (MO) prior to analysis.

Qualitative analyses

Framework analysis52,53 is a method of thematic analysis which is widely used in health research and is an appropriate approach when multiple researchers are working together. 54 This analytical method was applied to the qualitative data collected via interviews with facilitators and focus groups with group members. In applying this method both inductive and deductive approaches were used. This allowed the identification of themes which address the progression criteria for the study as well as other unanticipated themes which are generated through unrestricted coding of the data. As such, themes were formulated that related to the feasibility and acceptability of the Digital STORM intervention, as well as observations by group members and facilitators that pointed to wider aspects or suggestions for improvement to be held in mind.

Following familiarisation with the transcripts, two researchers (LR and MO) independently rated the same transcripts until any differences in coding had been discussed and resolved. Thereafter the focus group data were coded by one researcher (MO). Facilitator interviews, together with facilitator session and supervision notes, were coded by the Study Manager (LR). Coding involved line-by-line reading of the transcript and applying a ‘code’ describing that passage of text. Initial codes related to issues of feasibility, acceptability and perceived impact of the Digital STORM intervention and were refined through initial open coding. This process was undertaken in MS Word, using the comment function to highlight passages of text and apply a code. A working analytical framework was developed from the progression criteria and further categorisation of the codes identified and agreed on by both researchers in discussion with the CI (KS). Passages of data from transcripts were then charted into a framework matrix using a table in MS Word. During the charting, a content count was made for specific areas of interest, where these would help address questions in the process evaluation or enable the team to report results relating to the progression criteria (it is recognised that producing counts is not typically an outcome of framework analysis). 54 The charted data were then compared and contrasted to support the interpretation of the data and development of themes and subthemes.

Testing digital administration of outcome and economic evaluation measures

The third objective was to test digital administration of the study’s outcome and economic evaluation measures undertaken at baseline and post intervention for all participants. All procedures for supporting remote administration of study measures were finalised as part of the adaptation phase. Concurrently with the adaptation of the intervention, the research team reviewed materials and procedures for supporting administration of study outcome measures using video meeting platforms and the web-based survey platform QualtricsXM.

Health and social outcome measures

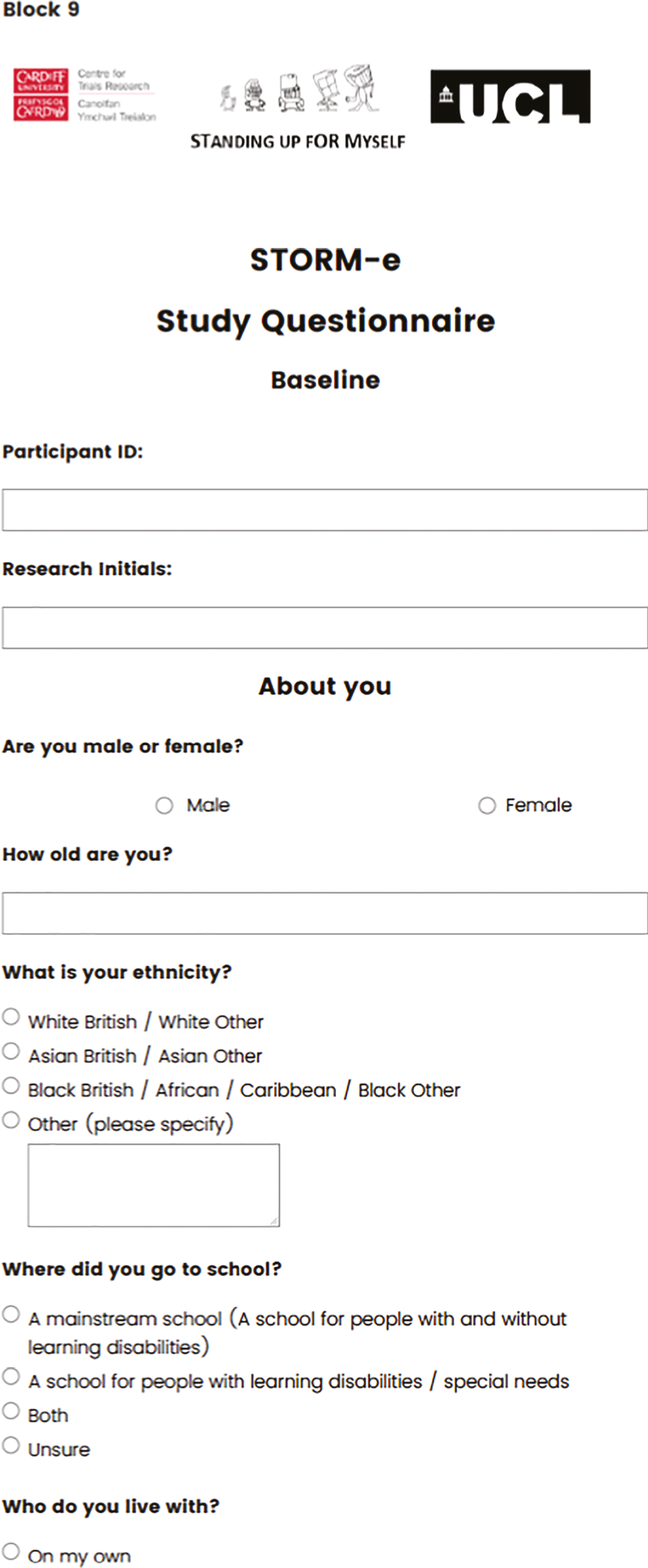

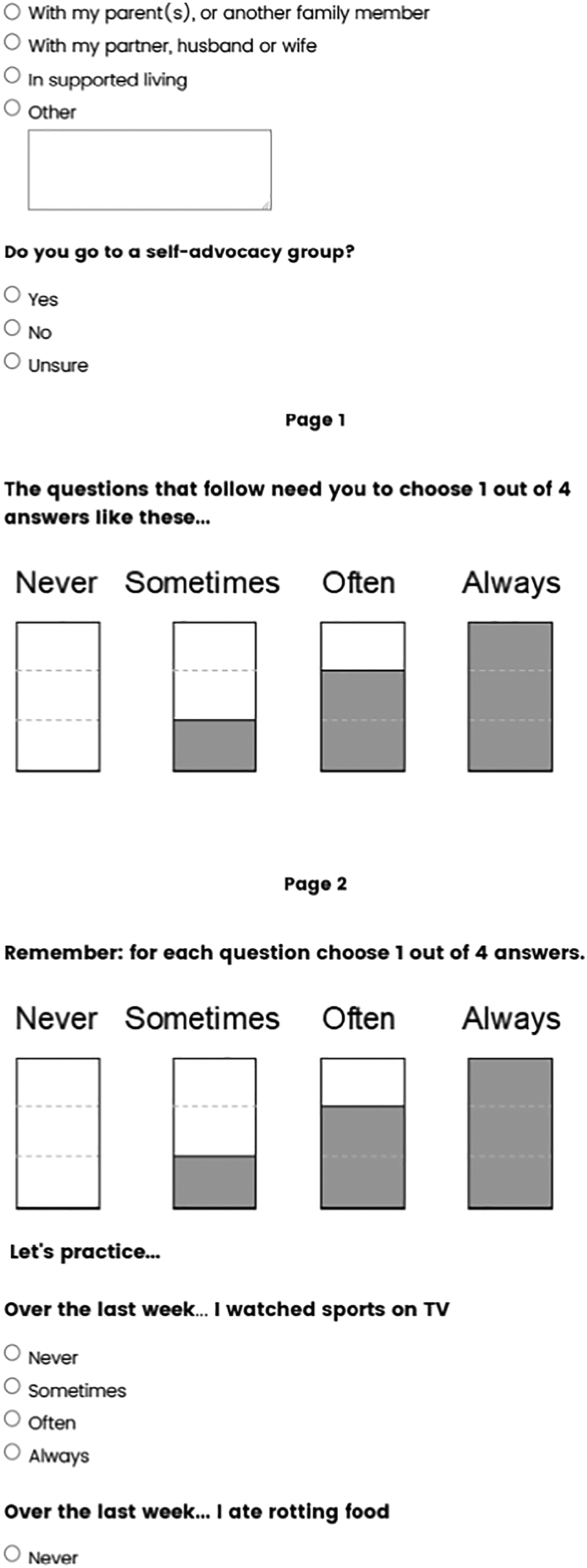

The health-related and social outcome measures used in the pilot were as follows (the combined measures as presented in QualtricsXM are presented in Appendix 3):

-

Mental well-being measured using an adapted version of the Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale (WEMWBS). 55 The WEMWBS is a 14-item scale validated for adolescents aged 13+ and adults. The scale was adapted by the research team by amending the reference period from 2 weeks to 1 week; simplifying the wording of some items, for example, changing ‘optimistic’ to ‘hopeful’ and turning gerunds to simple past tense forms; and reducing the response scale from a five- to a four-point scale.

-

Self-esteem, measured using a six-item version of the Rosenberg self-esteem scale, validated for people with intellectual disabilities. 56

-

Self-efficacy in rejecting prejudice (SERP), single self-rated item used in our pilot: ‘At this moment, how confident do you feel about standing up to prejudice?’, rated on a four-point scale (‘not at all confident’ to ‘very confident’).

-

Reactions to Discrimination (RtD) four-item subscale of the Intellectual Disabilities Self-Stigma Scale, measuring emotional reactions to stigma in people with intellectual disabilities. 57

-

Sense of Social Power: adapted four-item version of the Sense of Power Scale, to date not yet validated for people with intellectual disabilities. 58

The above scales were rated using a four-point Likert response scale; other than for the SERP the response options were ‘never, sometimes, often, always’. The Likert scale for all items was supported by a pictorial representation of the rating scale.

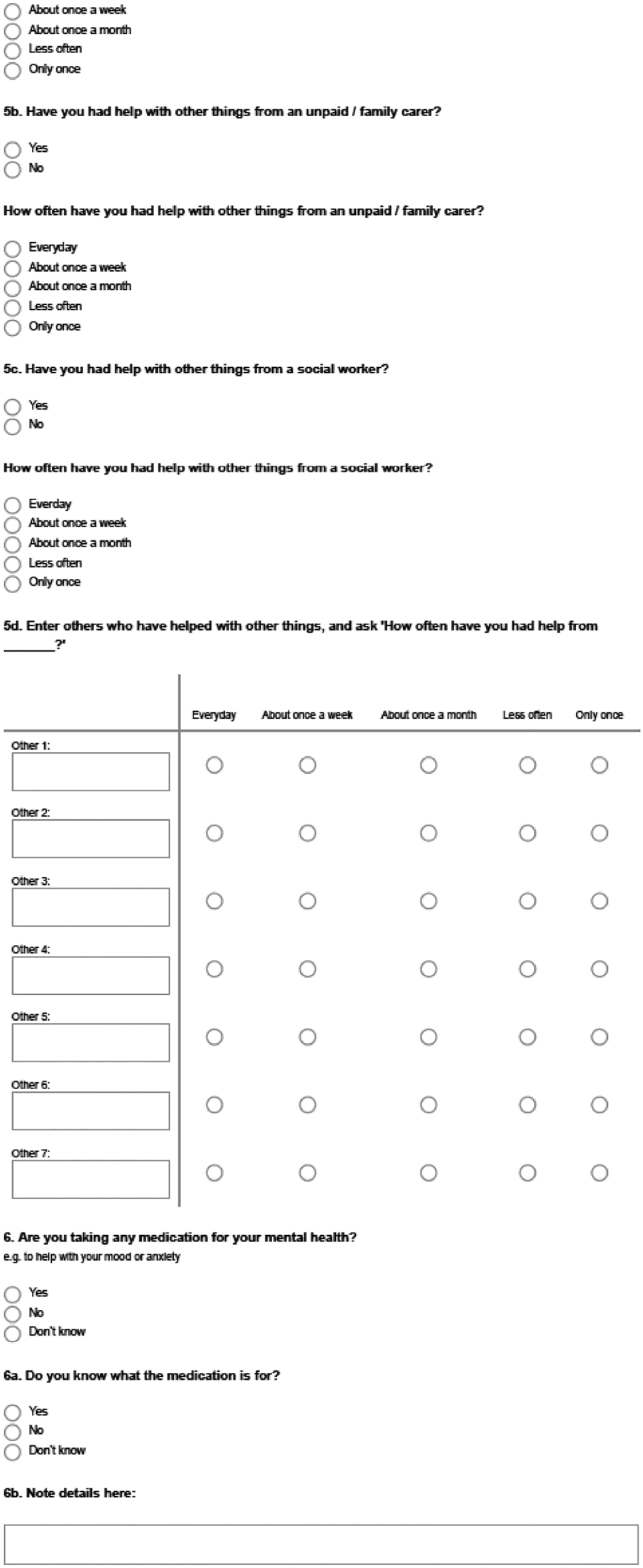

Measures for economic evaluation

The measures for economic evaluation used in the pilot were as follows:

-

A Service Information Schedule (SIS) was developed to capture comprehensive costs associated with the Digital STORM intervention. Information was sought on staff salaries, on-costs, overheads, training costs, materials and postage costs (where applicable). Data were collected from the research team on the adaptation of STORM for online delivery, from the delivery partner on the provision of training, supervision and materials, and from facilitators on time spent preparing for delivery, feedback and follow-up, and materials.

The information on staff involved in intervention-related activities required was as follows:

-

profession/job title (to approximate salaries if missing)

-

salary (annual or hourly)

-

grade where applicable (to approximate salaries if missing)

-

oncosts (employer pension and NI contributions)

-

overheads

-

number of hours spent on each task.

The SIS was completed by intervention providers in collaboration with the research team and further explored during qualitative interviews with facilitators.

-

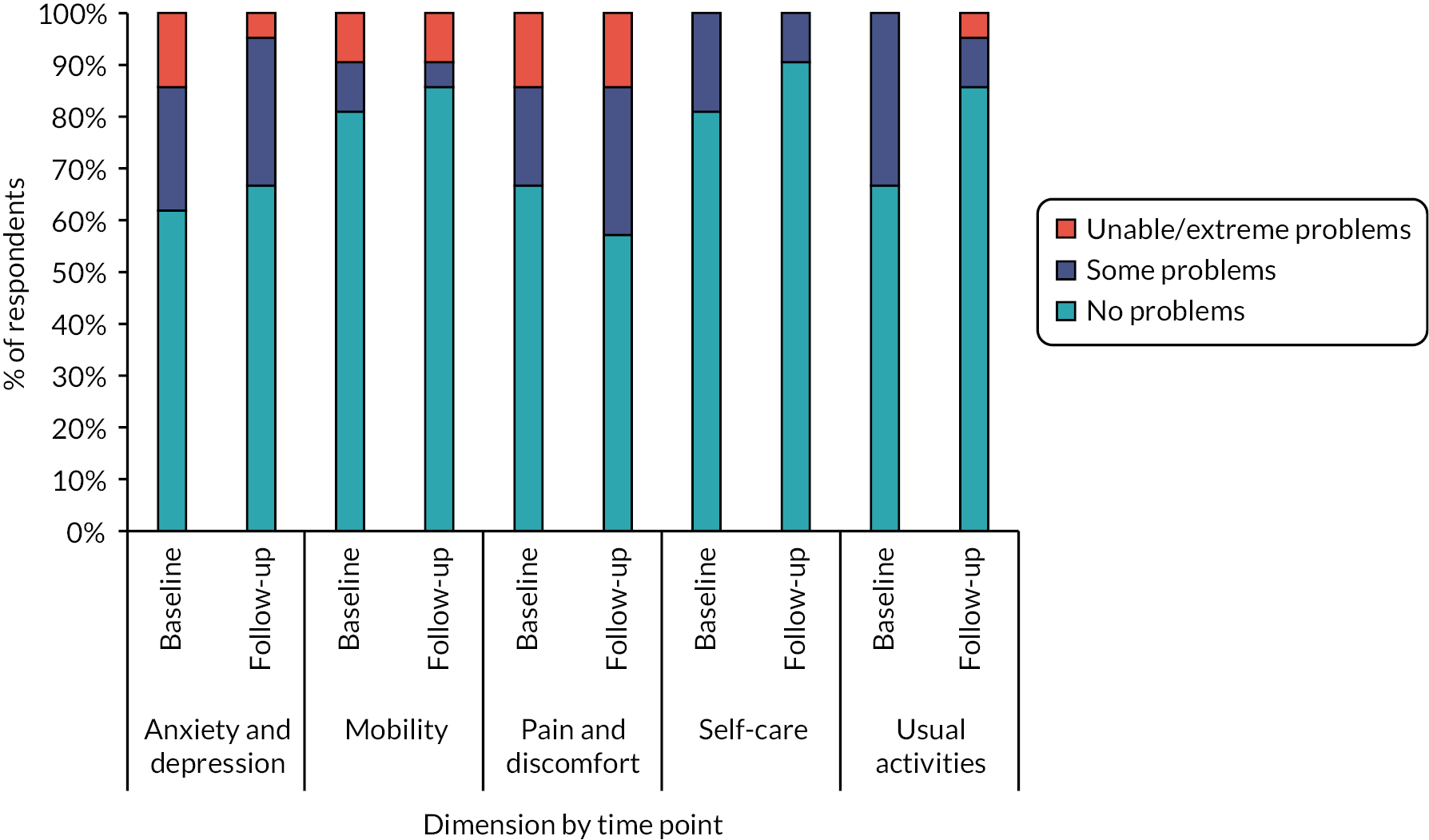

EuroQol-Youth (EQ-5D-Y),59 a self-report measure of health-related quality of life across five domains that are rated on a three-point scale, was administered. The EQ-5D-Y is a version of the EQ-5D-3L aimed at children and adolescents. The main difference is in the wording of questions, aiming to make the measure more accessible for this population. This measure allows for the calculation of quality-adjusted life years a common measure in health economic evaluation.

-

Client Service Receipt Inventory (CSRI),60 a self-report measure of use of services and supports. A short version covering a retrospective 3-month period was developed and adapted for use with input from the PPI Advisory Group. Participants were asked to provide information about contacts with general health services, mental health services, third sector organisations and education support as well as informal help received from supporters/carers and friends (see Appendix 4).

Scoping the acceptability of using data linkage in future studies

As part of the post-intervention data collection, we also asked participants questions to test the potential for consent to accessing routine data concerning health, education and social care use via data linkage methods, to inform the methods to be used in a possible future study.

The question asked of participants was phrased as follows:

Instead of asking you lots of questions, another way for researchers to get this information is from your records. For example, asking your doctor for this information from your medical record. Do you understand this?

If we’d asked to get this information from your medical records, how happy would you be about this?

The response options given were:

-

I would be happy for researchers to ask for this information from my records.

-

I would not be happy with this. I prefer they ask me.

-

I am not sure.

Assessment time points

A schedule of enrolment and assessments for group members at baseline and post intervention is provided in Table 4. The intervention commenced 1–20 days after baseline assessments. All baseline data were collected by the end of April 2021, prior to participants undertaking session 1 of the intervention. Post-intervention data were collected 3 months from baseline, range 10–12 weeks. All post-intervention data were collected following session 5 and before the qualitative focus groups and interviews took place (by the end of June 2021).

| Time point | Screening | Baseline | Post intervention |

|---|---|---|---|

| Informed consent | X | ||

| Demographics | X | ||

| Assessment against inclusion criteria | X | ||

| Mental well-being | X | X | |

| Self-esteem | X | X | |

| SERP | X | X | |

| RtD | X | X | |

| Sense of Social Power | X | X | |

| EQ-5D-Y | X | X | |

| CSRI | X | X |

Procedures for digital administration of study measures

Following informed consent, baseline measures were administered to groups 1–3 by two research assistants (MO, KD), and to group 4 by two Doctorate in Clinical Psychology trainees supervised by the CI and Study Manager. All research staff carrying out data collection were appropriately qualified and completed relevant training. Clarification of any questions relating to STORM that arose during sessions was referred to the CI or Study Manager.

Administration of all measures followed an assessment manual, which allowed for some flexibility depending on participants’ support needs. Items were read by the researcher one by one and visual supports and practice items were used to support understanding and familiarisation. Participants’ responses were entered directly into the study QualtricsXM database via an online link, set up by the data manager at the clinical trials unit (SJ). Data collection sessions were audio-recorded using the record function available in Zoom/MS Teams. Participants provided consent for the recordings to be used for potential training of researchers in the future.

After completing the baseline measures, all participants were asked three questions to assess the acceptability of collecting measures via video meeting platforms:

-

What did you think about doing the interview?

-

Would it be ok for others to do this?

-

Is there anything we could do to make it better?

Participants received a £10 retail voucher for a retailer of their choice at each assessment point in recognition of the time taken to complete the measures.

Outcome data analyses

Descriptive statistics were used to describe baseline demographics and summarise responses on the proposed outcome measures. Statistical methods are therefore descriptive in nature. Significance tests are not reported as this is a pilot study and is not a test of the intervention. Categorical data are presented using counts and percentages and continuous data using means and standard deviations or medians and inter-quartile ranges, as appropriate. For each outcome measure where a participant had completed at least one item, the number and percentage of useable forms are reported. Baseline data completeness results are reported in relation to the progression criteria described in Progression criteria related to study objectives.

Economic evaluation analyses

The feasibility of economic evaluation was assessed using rates of completion of information about the cost of the intervention (SIS), rates of completion of information about access to formal and informal sources of support (CSRI) and rates of completion of the EQ-5D-Y. In addition, an attempt was made to compare index values to other studies that have used the youth version of the measure.

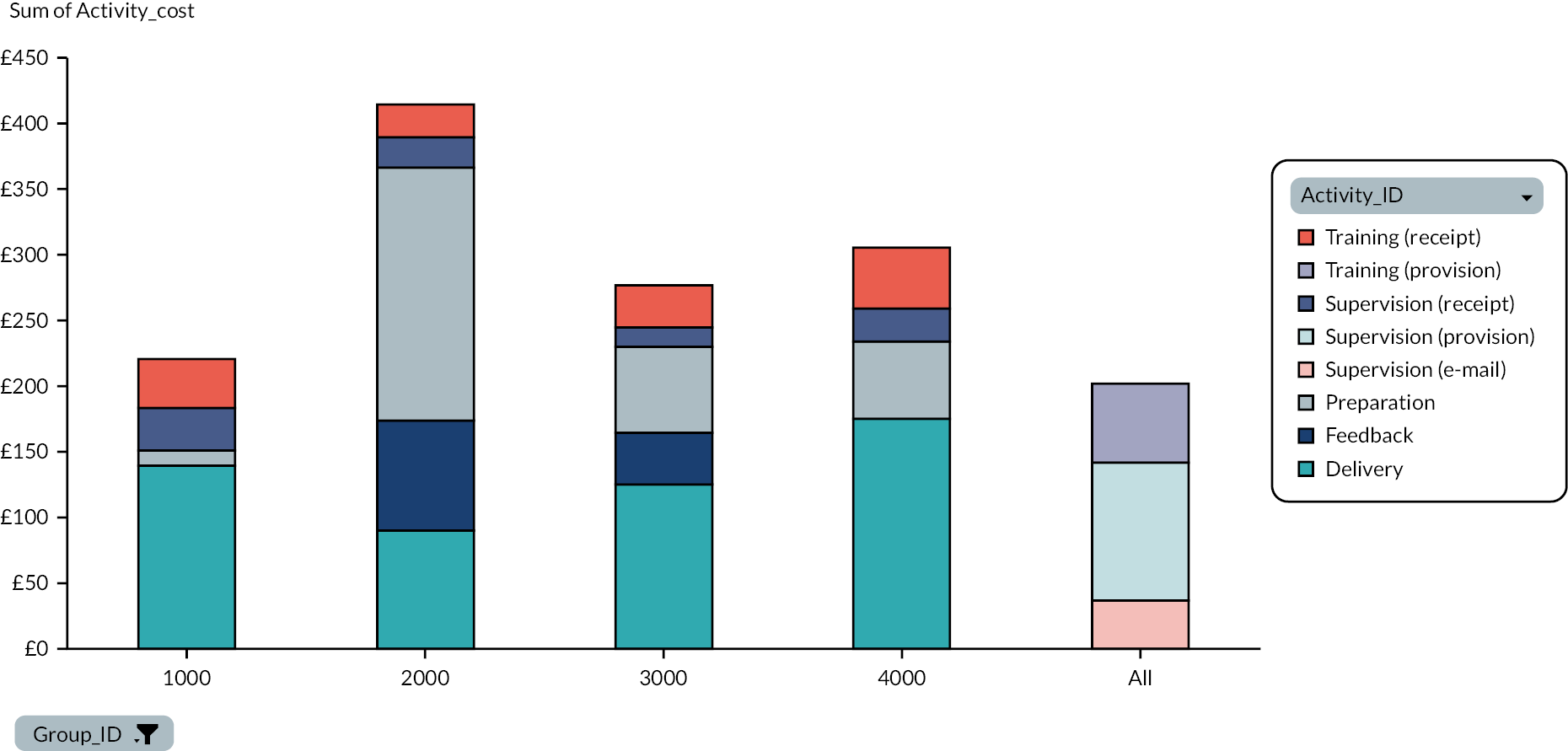

A comprehensive intervention cost for Digital STORM was calculated based on SIS data, including information on staff salaries, on-costs, training costs, materials and travel time.

The proportion of returned CSRIs and the proportion of questions completed at each time point are reported. The proportion of participants reporting contacts with a given service was examined to determine whether it is feasible to assess cost-effectiveness from: (1) a public sector perspective, or (2) a wider societal perspective in a full trial.

Establishing usual practice

The template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR)61 guidance for trials emphasises the importance of a complete published description of interventions to enable implementation and research replication. Having a complete description of a comparator is also good practice for the same reasons. Therefore, objective 4 for this study was to describe what UP, the potential comparator for a future trial, might look like for groups of people with mild-to-moderate intellectual disabilities in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. To achieve this objective, during the adaptation period, information was sought from third sector and education providers to ascertain how the pandemic had affected the offer and format of group meetings for people with intellectual disabilities and what UP looked like in this new context. A survey was designed exploring UP with people with intellectual disabilities who attend groups run by third, education and social sector organisations, both before and since the onset of the pandemic (see Appendix 8). The facilitators were asked to provide details about the nature of the activities their groups were engaged in before and since the COVID-19 pandemic (where they had adapted to meeting online). We also sought to understand how facilitators and group members were adapting to meeting and engaging with their groups on digital platforms to inform the intervention’s digital adaptation. QualtricsXM (web survey platform) was utilised to collect data and included questions about the type of group activities, who delivers them, mode of delivery, group size and details of changes to UP.

An invitation to complete the survey was disseminated between November 2020 and February 2021. Organisations initially contacted with an invitation to complete the survey were known to the research team, including partner organisations [Mencap, Foundation for People with Learning Disabilities (FPLD) and People First Dorset]; groups that had taken part in the original STORM pilot; or organisations that had expressed interest in the feasibility randomised controlled trial (RCT) in January 2020. Additional organisations with large networks were contacted via e-mail, such as Learning Disability England and Choice Forum; these advertised information about the survey via e-mail to their networks. The survey was also advertised on social media.

Data management

Outcome data and economic evaluation data were collected using a web-based QualtricsXM database. The data were saved into a secure, encrypted bespoke online database at the Centre for Trials Research (CTR). This secure encrypted system was accessed by username and password (restricted only to those who needed direct access) according to CTR standard operating procedures (SOPs) and complying with Good Clinical Practice and General Data Protection Regulations (GDPR). Back-up paper case report forms (CRFs) were available in the event the web-based system was not accessible. Fidelity checks and data cleaning were performed as detailed in the data management plan. Following data cleaning, the database was shared with the statistician (MW) and health economist (EB) for analysis. A full data management plan was signed off prior to data collection.

Safety reporting

Procedures were put in place for the reporting of any serious adverse event (SAE) within 24 hours of knowledge of the event to the study team. There were no adverse events (AEs) or SAEs for STORM. Any planned treatments that participants were already receiving at the start of the study were not considered as AEs or SAEs.

Trial registration, governance and ethics

The study was funded by the NIHR PHR programme (17/149/03). The trial protocol was registered with Current Controlled Trials (ISRCTN16056848) and published as an amended version. The adaptation and pilot protocol was approved by the Centre for Trials Research, all co-investigators, the facilitator and STORM expert advisors (PPI), the wider SMG, the SSC, and the funder. The study was overseen by the SSC, comprising an independent chairperson and six further independent members, including two self-advocates with intellectual disabilities, supported in the SSC role by FPLD, an organisation they had previously worked with. The SSC met four times in total to review the study progress, methods and management.

The study was approved by the UCL Research Ethics Committee prior to recruitment and data collection commencing (Project ID 0241/005). An amendment to the study methods was approved by the committee before the start of the pilot of the adapted Digital STORM intervention.

Patient and public involvement and stakeholder involvement

Our reporting of the patient and public involvement (PPI) for this study follows the GRIPP2 reporting checklist.

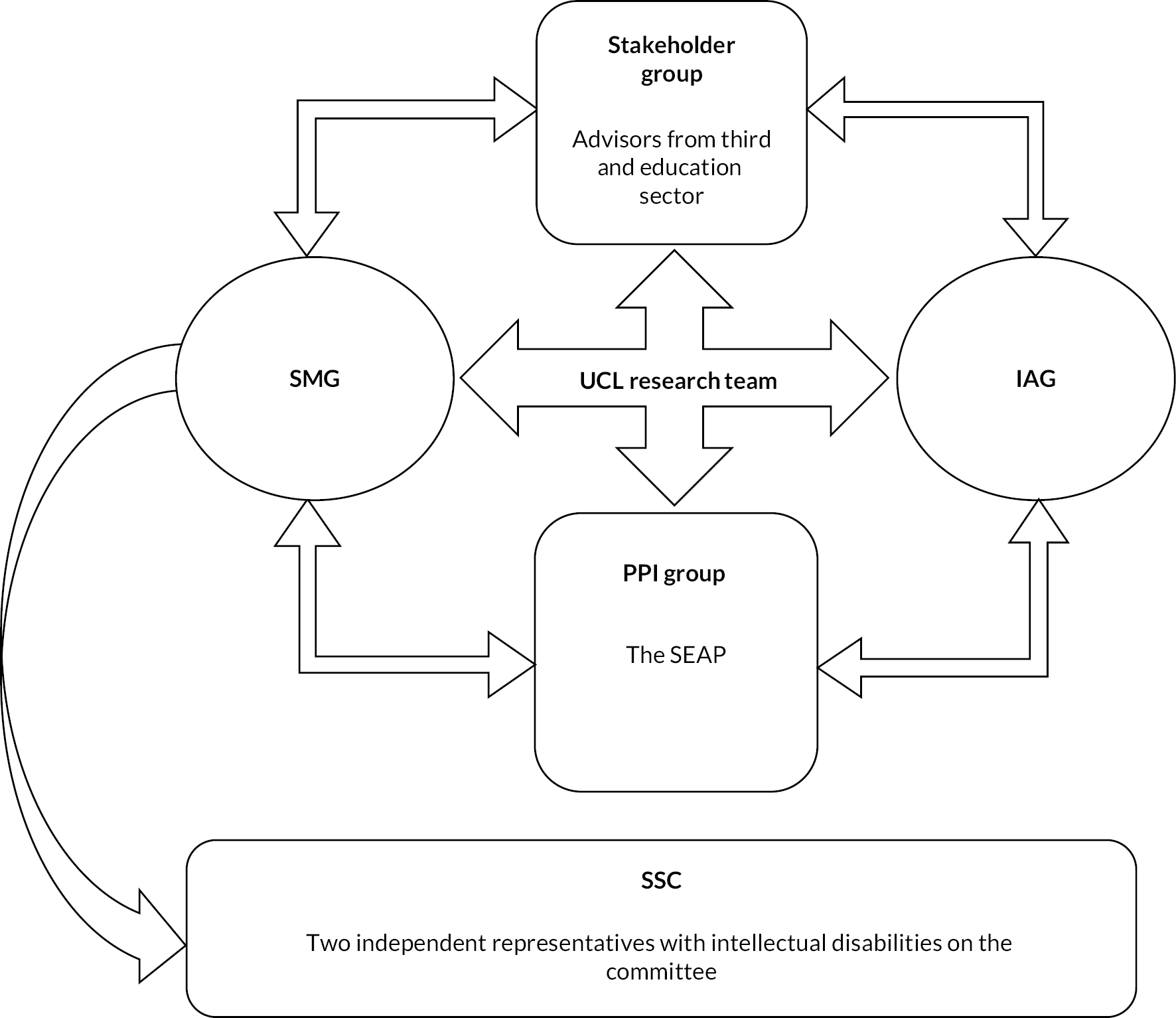

Patient and public involvement for the project overall consisted of an advisory group of four expert advisors with intellectual disabilities. A separate stakeholder group of experienced group facilitator advisors from the third and education sectors was also involved in advising the project team throughout the study. Both groups were familiar with the STORM programme through involvement or participation in an earlier pilot study of STORM. Representatives from the STORM Expert Advisor Panel (SEAP) and all facilitator advisors were invited to SMG meetings. Two STORM experts initially represented SEAP at each SMG meeting and were provided with additional support for this. Following the outbreak of the pandemic, it was not possible to sustain this model in a meaningful and inclusive way and instead, CB represented the views of SEAP at the SMG and provided feedback to SEAP in turn. Members of the stakeholder group also attended SMG meetings. Both groups attended the IAG. Finally, as noted, there were two independent representatives with intellectual disabilities on the SSC. Figure 4 depicts the various PPI and stakeholder groups and their relationships.

FIGURE 4.

Patient and public involvement and stakeholder groups and their relationships to study team and oversight committees.

The patient and public involvement advisory group

The PPI advisory group consisted of three men and one woman with intellectual disabilities, all of whom were advisors during the earlier development and initial piloting of the STORM programme (hereafter referred to as STORM experts). The group named themselves the SEAP. SEAP meetings were co-chaired on a rotational basis by Christine-Koulla Burke (CB), Director of one of our partner organisations, the FPLD, and one of the STORM experts with intellectual disabilities. The meetings were also attended by the Study Manager and Research Assistant to present materials and matters for discussion and feedback to the group.

The aims for PPI in the current project were:

-

to support the inclusion of people with people with intellectual disabilities in research that matters to them;

-

to bring to the team lived experience and knowledge of both intellectual disabilities and stigma. The team sought to engage with this experience and knowledge to:

-

shape the participation of organisations and people with intellectual disabilities in the research;

-

ensure the accessibility of all study materials and processes for potential participants in the research (e.g. information sheets, consent forms);

-

adapt outcome measures where relevant and advise on appropriate data collection processes.

-

Following agreement of the amended protocol to adapt the STORM programme for digital delivery, the aims of the PPI evolved to include:

-

co-design of Digital STORM resources and approaches through participation in an IAG, details of which are provided above.

Patient and public involvement activities

Early SEAP meetings were used to re-familiarise the STORM experts with the STORM programme, discuss the PPI plans, clarify roles and to provide training (e.g. on PPI and research methodology relevant to this study, such as RCTs). The panel discussed and agreed how they wished meetings to be run, including sharing responsibility for co-chairing meetings. To enable this, the co-chairs (i.e. one of the STORM experts and CB) would meet 30 minutes ahead of each meeting to run through the Easy Read agenda and discuss preferences for co-chairing the respective meeting. The co-chairs had an annotated version of the agenda with small prompts (in red text) to help them in the role. For each meeting, a folder with a record of new words and concepts that arose (which might otherwise be considered jargon) was available to support everyone to work together. Easy Read minutes were also produced. At the start of each meeting, the research team provided feedback verbally on actions taken in response to previous input from the STORM experts. At the end of each meeting, dedicated time allowed everyone to reflect on how the meeting had gone. This allowed us to adjust how we worked and to put additional support in place where necessary. We continued to meet with the STORM experts via Zoom following the COVID-19 pandemic outbreak. In addition to Zoom meetings, the research team consulted individual advisors directly by telephone.

To check the materials and processes developed with the STORM experts, the project team made presentations to the FPLD Advisory Group and a group of Mencap Research Champions (a group of Mencap employees with intellectual disabilities who advise on research at Mencap). The team provided a taster of the first STORM session to the Mencap Research Champions to gauge views about presenting intervention resources in the planned format (the STORM Wiki, see Chapter 1). This group also commented on the draft project information sheets to check understanding, especially around the explanation of the RCT methodology. Information about STORM outcome measures was reviewed with both the Mencap Research Champions and the FPLD Advisory group members to ensure wording, practice items and visual supports were easy to understand and accessible. A representative from the FPLD Advisory group also worked with the team allowing them to pilot the online delivery of the study measures. These groups’ comments and feedback were presented back to the STORM experts who agreed the final amendments to be made by the research team.

Stakeholder group involvement

A group of experienced group facilitators from the third sector and education providers was established. The group met at key points during the study. These meetings were more informal and were co-led by the CI and Study Manager. Initially, this group provided input on plans for recruitment, study materials and procedures. As the work evolved to co-designing Digital STORM, the model of separate meetings ceased and all advisors joined a larger IAG. Members of this stakeholder group were also invited to all study steering group meetings and regularly provided input in this forum.

Outcomes from patient and public involvement and stakeholder contributions

The PPI for the study led to significant influence in a number of key areas. First, considering how to help potential participants with intellectual disabilities understand the study design, all advisors shared their thoughts and frustrations in understanding the RCT design themselves and shared ideas for presenting this information to others through project information sheets. This work also led to the production of a video by SEAP members to promote the benefits of taking part in the research, no matter which arm of a trial one might be randomised to. Owing to the pandemic halting recruitment, we did not get to use these resources further.

Significant contributions were made to the adaptation of two study measures (the WEMWBS and the CSRI). The data presented in Chapter 4 on the feasibility and acceptability of the study measures are testament to the impact of the PPI work in these measures’ development.