Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 17/44/42. The contractual start date was in September 2018. The final report began editorial review in July 2021 and was accepted for publication in March 2022. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2022 Dowrick et al. This work was produced by Dowrick et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2022 Dowrick et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

Parts of this section have been adapted with permission from Rawlinson et al. 1 Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

The prevalence of psychological morbidity, including depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and functional impairment among asylum seekers and refugees (AS&Rs) is higher than among other migrant groups and local majority populations. 2–4 Mental health problems are particularly prevalent among war refugees,5 with rates of PTSD up to 10 times higher than in the general population. 6,7 Persistence of mental health problems after resettlement is related to poor socioeconomic conditions, acculturation-related stressors, economic uncertainty and ethnic discrimination. 4,8 As a result, AS&Rs encounter extensive barriers to accessing health care4 and their mental health needs are largely unmet. 9

Making psychological therapies more accessible for AS&Rs is a national research priority. 10 Psychosocial interventions for AS&Rs resettled in high-income countries may provide significant benefits; however, there are few studies of good quality. 11 Evidence of the applicability of psychological interventions by non-specialists in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) has increased significantly. 12–14 Many countries, including the UK, are seeking to improve health-care delivery by extending the roles of health professionals. 15 Innovations developed in LMICs, including task-sharing,16 have the potential to address current challenges for mental health care in high-income countries. 17

Problem Management Plus (PM+) is a low-intensity, transdiagnostic psychosocial intervention designed to be delivered by lay therapists, who can apply the same treatment principles across common mental health problems without tailoring treatment to a particular diagnosis. 18 PM+ incorporates task-sharing strategies, drawing on evidence of mental health interventions delivered by non-specialists in LMICs12,19,20 and the UK. 21

PM+ aims to help adults experiencing symptoms of common mental health problems, including depression, anxiety, stress and grief, as well as with practical problems, such as unemployment and interpersonal conflict. It therefore offers a potentially appropriate approach for AS&Rs living in high-income settings. PM+ involves five weekly sessions during which psychoeducation is provided and the therapeutic approaches are introduced, with subsequent weeks reinforcing the application to participants’ self-identified problems, and the final session revising learning and identifying future goals and signs of relapse. The PM+ therapeutic approach integrates problem-solving and behavioural treatment principles, including a slow-breathing stress management technique, problem-solving strategies, behavioural activation and strengthening social support. 18

PM+ is a manualised intervention, with separate manuals for the training of trainers and for individual and group PM+ training. It also incorporates the use of lay therapist reference manuals, participant worksheets and group PM+ case study materials. The group and individual PM+ programmes deliver the same content but in different formats: individual PM+ sessions last 90 minutes and involve only the lay therapist and participant, while group PM+ sessions last 2 hours to accommodate group dynamics, and are co-delivered by two lay therapist facilitators. To engage illiterate participants and those whose first language is not English, as well as support disclosure through affiliation with the case study experience, group PM+ adopts a case study format with pictorial materials and an accompanying narrative that follows a person progressing through PM+.

Developed by the World Health Organization (WHO) as part of its Mental Health Gap Action Programme (mhGAP) using the GRADE (Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation) evidence base,22 PM+ has shown significant benefit in trials in LMICs,18,23–28 and the group version is being tested with Syrian refugees in Jordan. 29 However, at present, there is limited evidence of the effectiveness or cost-effectiveness of interventions such as PM+ offered by lay therapists to AS&Rs in high-income countries. A pilot randomised trial of peer-provided PM+ for 60 Syrian refugees in the Netherlands indicated potential effectiveness in improving mental health outcomes and psychosocial functioning, and potentially cost-effectiveness,30 but further studies are needed with diverse AS&R populations in high-income countries.

Rationale for study

The Red Cross estimates that 65 million people throughout the world have been forced to flee their homes as the number of protracted conflicts has increased. 31 This has created more than 22 million refugees worldwide, of whom an estimated 118,995 live in the UK (2017 figures). 31 The UK received 38,500 asylum applications in 2016. Home Office figures show that in 2012–14, 36% of asylum applications were granted initially, rising to 49% after appeal. 32 Many applications are initially refused because it is difficult for applicants to provide the evidence needed to meet the strict criteria for refugees. The area of England with the largest number of asylum seekers in dispersal accommodation is the north-west (9524 in the first quarter of 2017).

Asylum seekers and refugees experience much higher levels of emotional distress and functional impairment than other migrant groups and local majority populations. 3,6,11 These are related to their reasons for leaving their country of origin and their experiences in transit and on arrival. 4 There may also be inequalities in mental health and well-being between asylum seeker and refugee groups depending on their age, gender, nationality, education, occupational status, length of stay, access to resources and current legal status in the UK. There are particular reasons for concern over the mental health of asylum seekers without leave to remain, who are at risk of destitution as they are neither eligible for state benefits nor allowed to undertake paid employment.

As a result of these factors, AS&Rs commonly have inadequate access to mental health care appropriate to their needs. 4 Their contact with statutory agencies is often crisis driven and mediated through voluntary third-sector organisations, whose staff – although highly motivated – lack knowledge and skills in the management of psychosocial distress. The situation is especially problematic for asylum seekers without leave to remain, who have been required to pay for specialist health care since August 2017. 33

There is, therefore, a need to offer and evaluate an accessible intervention designed to address the mental health and associated practical problems experienced by AS&Rs in the UK.

Aim and objectives

The aim of the PROSPER study was to assess the feasibility of conducting a randomised controlled trial (RCT) in the UK of an evidence-based psychosocial intervention based on PM+, delivered by lay therapists for distressed and functionally impaired AS&Rs.

The objectives of the study were to:

-

adapt the form and content of PM+ to the needs of AS&Rs in the UK

-

assess the feasibility of the proposed training procedures (including the involvement of refugees as lay therapists)

-

assess the feasibility of the proposed procedures for recruiting distressed AS&Rs as study participants

-

assess the feasibility of retaining both lay therapists and study participants through to trial completion

-

assess the fidelity of delivery of the intervention

-

assess the acceptability and utility of the proposed study measures, considering any linguistic and cultural barriers

-

assess how service use data can be measured.

In working towards these objectives, we aimed to specify the parameters of a full RCT to test the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of PM+ in reducing emotional distress and health inequalities, and improving functional ability and well-being among AS&Rs.

Research design

Following Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) extension guidelines,34,35 we undertook a feasibility study of PM+, within which we included a pilot study of the design features of a future definitive RCT.

The feasibility study involved adaptation of PM+, using two parallel and interlinked elements:

-

evidence synthesis to identify the barriers to and facilitators of the uptake of psychosocial interventions delivered by lay therapists to improve the mental health and well-being of asylum seekers and migrants, including how idioms of distress are incorporated into assessments and interventions

-

stakeholder engagement with local stakeholders (migrant service users, care providers and policy-makers) using focus group methodology to ensure that PM+ is adapted for use with AS&R populations in the UK.

We also assessed the feasibility of a two-stage PM+ training procedure, with master trainers providing a training course tailored to the needs of well-being facilitators from a counselling non-governmental organisation (NGO), who in turn provided an 8-day training course and ongoing supervision for lay therapists in NGOs that support AS&Rs.

The pilot trial was designed to assess:

-

Feasibility of recruitment, with procedures based on a partially nested design to adjust for clustering by intervention provider in the test arm, with the client as the unit of randomisation. We assessed the feasibility of recruiting participants through collaborating NGOs and other health and welfare agencies,

-

Feasibility of a randomisation procedure in which participants are randomised using a secure 24-hour web-based randomisation system controlled by Liverpool Clinical Trials Centre (LCTC).

-

Feasibility of the proposed delivery model in relation to three key issues –

-

Retention of lay therapists and study participants through to trial completion. For therapists, this may be an issue, given that refugees recently granted leave to remain may wish to seek paid employment and/or relocate geographically. For study participants, retention may be affected by prioritisation of immediate needs regarding housing and benefits, concerns about the well-being of family members, outcomes of appeals procedures, or official policies on dispersal, resettlement and access to health care.

-

Individual compared with group approaches with regard to relative acceptability, participant preferences, linguistic and cultural issues (e.g. gender and language matching) and hence, retention.

-

Fidelity of intervention delivery – the extent to which lay therapists are able to control risk and stay ‘on message’.

-

-

Relevance and acceptability of the proposed study measures, with reference to –

-

technical aspects of translation

-

how epistemic differences relating to experience of distress are negotiated across language and culture

-

and hence their potential acceptability and suitability for a subsequent definitive trial.

-

Risks and benefits

Asylum seekers and refugees

Risks

For those not granted leave to remain, participation in an officially sponsored trial may raise anxieties about public visibility and heightened risk of deportation. This risk can be mitigated by participants using the contact details of their NGO or primary care team to register. A potential risk for all participants is being offered support from a lay therapist who has a similar linguistic and cultural background but antithetical political or religious views; however, this risk can be mitigated by careful vetting at the therapist–client allocation stage. The risk of stigma associated with mental illness in some cultures, meanwhile, can be mitigated by the focus in PM+ on problems of living rather than on illness. There is also a risk for lay therapists of being overwhelmed by their clients’ distress; however, this can be mitigated by training and supervision, including focussing on boundary issues of who they can and cannot feasibly support; the provision of ongoing support mechanisms; and the development of appropriate care pathways. 36–38

Benefits

This study is intended to offer support to distressed and functionally impaired AS&Rs, who may otherwise have no means of receiving evidence-based psychosocial support. It will offer the lay therapists training and experience in a set of transferable skills. If this study enables a full trial to be implemented, we anticipate benefits in terms of improving the mental health and functioning of AS&Rs and reducing the mental health and well-being inequalities faced by this population. If the effectiveness of PM+ is demonstrated, AS&Rs can expect reduced symptoms of anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress disorder, as well as improved functioning and subjective well-being. This in turn is likely to enhance their equity of access to existing statutory health and social care services.

Society and NHS

Risks

Given the current level of political controversy over the status of AS&Rs, there is a risk that this study may generate adverse publicity and lead to policy decisions designed to make life in the UK more difficult, especially for asylum seekers who have been refused leave to remain. Given that the participating NGOs are subject to the vagaries of external funding during a period of sustained austerity, and that one or more of those NGOs could reduce or cease their function during the lifetime of the study, there is a risk that their involvement in the management and delivery of PROSPER may compromise our ability to deliver on our objectives. This risk will be mitigated by paying careful attention to NGO funding sources and, if necessary, by advocacy to commissioners and funding agencies. There is also a risk that participants who undertake a psychosocial intervention designed to empower them will make greater use of health and social care services, generating extra demand on these already overburdened services. However, this risk is likely to be mitigated by a reduction in the use of unplanned and emergency care. Beyond the lifespan of the project, there might be an expectation from AS&Rs and organisations supporting them that the intervention can still be accessed, which will not be the case. However, this risk can be mitigated by careful explanation of the time-limited nature of the intervention.

Benefits

The PROSPER study is intended to generate new knowledge of benefit to the NHS and to society. PM+ is recommended by the WHO as an intervention that can be delivered by lay therapists and is an effective intervention for vulnerable populations living in conditions of adversity. It is innovative in that it takes task-sharing strategies that have been used in LMICs and applies them to a high-income country, bringing global mental health to high-income countries. This study is intended to ascertain whether or not lay therapists in NGOs can be trained to deliver PM+ with demonstrable evidence of capacity. It is also intended to provide early indications of whether or not PM+ can lead to demonstrable improvements in mental health and function for distressed AS&Rs in current UK settings. It has the potential to take forward the Increasing Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) initiative by identifying prospective new access to care pathways for these vulnerable groups.

We anticipate that this research will provide value for money by establishing the feasibility of conducting a trial of an evidence-based psychosocial intervention delivered by lay therapists for distressed and functionally impaired AS&Rs. There is a lack of evidence on the feasibility of conducting research into psychosocial interventions in these circumstances and this study is intended to address this gap in the evidence base.

Looking further ahead, such a definitive trial has the potential to improve mental health, well-being and functional ability among AS&Rs, and to reduce health inequalities. This may lead to the more equitable and effective use of health care by AS&Rs, with a shift from their receiving emergency care to receiving managed, proactive and preventative care. From a societal perspective, cost-effectiveness and cost–benefit analyses following the definitive trial will indicate the extent to which the intervention confers both direct and indirect benefits.

Patient and public involvement is intended to ensure that the project delivers high-quality, original evidence that has the potential to have a significant impact on the design of the definitive intervention and, subsequently, on policy and practice.

Chapter 2 Feasibility study

Evidence synthesis

We conducted a systematic review of the barriers to and facilitators of the uptake of psychosocial interventions delivered by lay therapists to improve the mental health and well-being of AS&Rs. The systematic review followed the guidance of the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. It was registered with PROSPERO in 2018 as CRD42018104453.

Definitions

Psychosocial intervention was defined as any type of therapy, education, training or social support aimed at improving mental health symptoms, behaviour and general functioning without the use of psychopharmacological agents.

An asylum seeker was defined as a person who has fled their own country and formally applied to the government of another country for asylum, but whose application is not yet concluded. They remain asylum-seekers while they are awaiting a decision about their application for refugee status. A person moves from asylum seeker status to refugee status when the country in which they have applied for asylum accepts their claim.

A lay health worker was defined as a health worker who performs functions related to health-care delivery and is trained in some way in the context of an intervention, but who has not received a formal professional certificate, paraprofessional certificate, or tertiary education degree. This includes community health workers, village health workers, birth attendants, peer counsellors, nutrition workers and home visitors.

Inclusion criteria

Types of participants

We included studies that focused on the experiences and attitudes of stakeholders about lay health worker programmes in any country. Participants could include lay health workers, refugees, asylum seekers and their families, policy-makers, programme managers, other health workers or any others involved in or affected by the programmes.

Types of interventions

We included studies of programmes that were intended to improve AS&R mental health and well-being, for example sociotherapy, multifamily interventions, PM+, stepped-care approach, peer-to-peer group intervention, Self-Help Plus, and Friendship Bench. Other examples were programmes that had used any type of lay health worker: including community health workers, village health workers, birth attendants, peer counsellors, nutrition workers and home visitors.

Databases

We searched the following electronic databases for literature published between January 2007 and July 2018: MEDLINE (National Library of Medicine, Bethesda, MD, USA), PsycInfo® (American Psychological Association, Washington, DC, USA), CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature), the Cochrane Library (Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects), the Health Technology Assessment (HTA) database, NHS Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED), EMBASE® (the Excerpta Medica dataBASE; Elsevier, Amsterdam, the Netherlands), BNI (British Nursing Index), ERIC (Educational Resource Index and Abstracts), SocAbs (Sociological Abstracts), ASSIA (Applied Social Sciences Abstract & Indexes), BiblioMap [the Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Co-ordinating Centre (EPPI-Centre) register of health promotion and public health research], Scopus® (Elsevier) and the Social Sciences Citation Index™ (Clarivate™, Philadelphia, PA, USA).

We also searched Evidence Aid (www.evidenceaid.org) for evidence synthesis resources relating to mental health in humanitarian crises. In addition, OpenGrey (GreyNet International, Amsterdam, the Netherlands), Scirus, Social Care Online (Social Care Institute for Excellence, London, UK), the National Research Register, National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) portfolio database, and the Electronic Theses Online Service (EThOS) were searched for grey literature. Trial and research registers were searched for ongoing studies and reviews, including ClinicalTrials.gov, metaRegister of Controlled Trials, the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number (ISRCTN) register, the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (WHO ICTRP) and the PROSPERO systematic review register.

Data extraction forms were developed and piloted in a Microsoft Excel® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) spreadsheet using a sample of included studies. Data were extracted on study design, population characteristics and outcomes by one reviewer and independently checked for accuracy by a second reviewer, with disagreements resolved through discussion with a third reviewer, where necessary.

Quality assessment

Two review authors independently assessed studies meeting the inclusion criteria for methodological quality using criteria proposed in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews or, for qualitative papers, the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) quality assessment tool for qualitative studies. We used GRADE as the accepted approach to assessing the certainty of findings of reviews of effectiveness and, for qualitative evidence, the CERQual (confidence in the evidence from reviews of qualitative research) approach, based on the methodological limitations of individual studies contributing to the review finding.

Findings

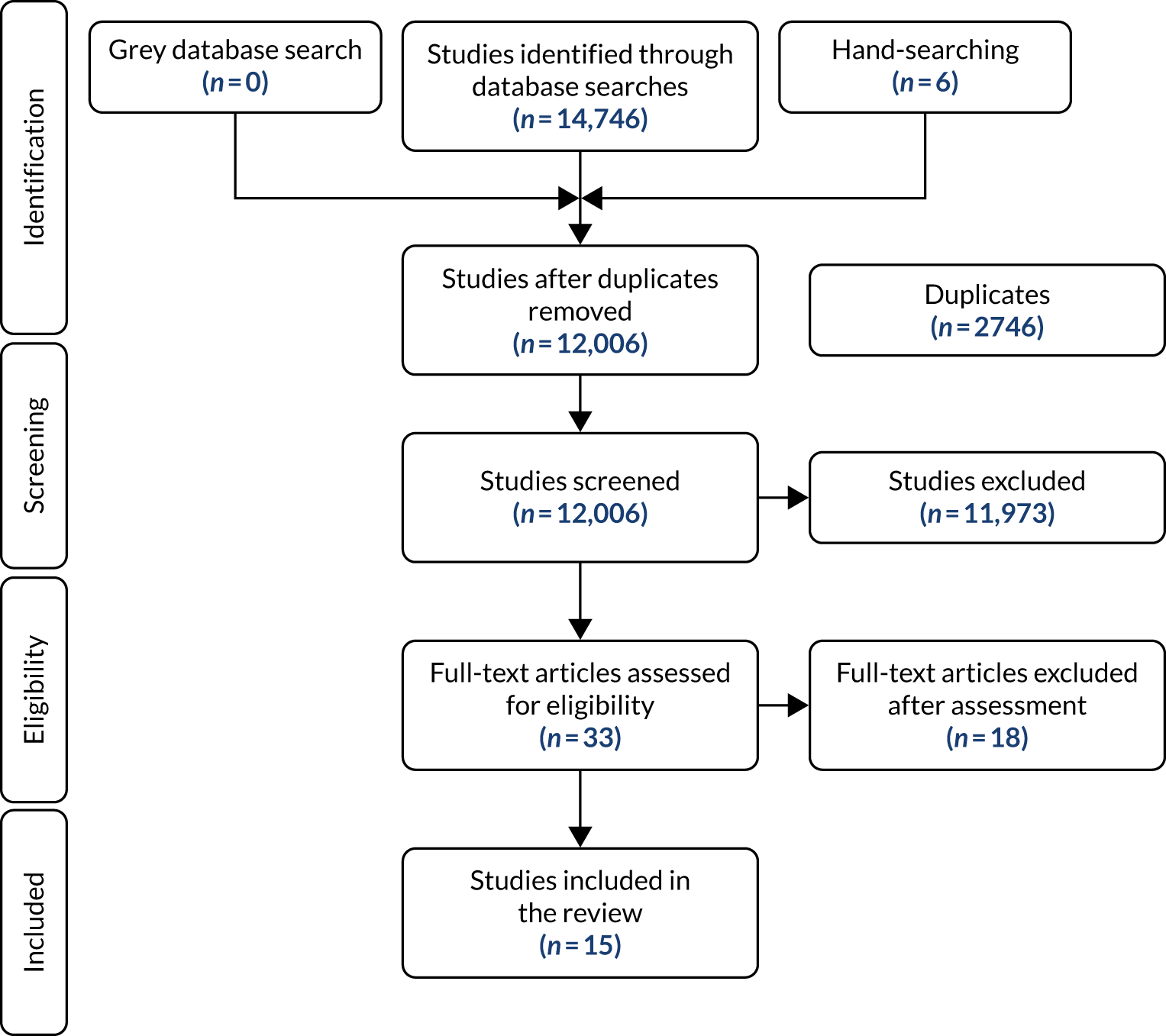

A total of 14,746 titles and abstracts were shortlisted for further assessment, from which 15 papers were identified as suitable for detailed analysis. The pathway from identification to inclusion is shown in the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) flow diagram in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

The PRISMA flow diagram for the PROSPER systematic review.

The host countries were Australia, Canada, Jordan, Sweden, Thailand, the UK and the USA. The refugee populations were from China, the Sudan, Burma, Iraq, Bhutan, Liberia, Viet Nam, Cambodia, Somalia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Owing to the heterogeneity of the included studies and the limitations of the available data, statistical analyses were neither possible nor appropriate. The results of the data extraction and quality assessment for each study are, therefore, presented as a narrative summary. This examines the barriers to and facilitators of the uptake of psychosocial interventions, first from the perspectives of AS&Rs and then from the perspectives of lay health workers.

Barriers for asylum seekers and refugees

Beliefs about mental health can be a barrier. Some AS&Rs do not feel that being sad and stressed is a true mental illness and think that it will diminish with prayer and time. 39,40 Others regard trauma symptoms as non-addressable, unlike depressive symptoms. 41

A lack of trust and privacy and not feeling safe are also important barriers. 42 Some AS&Rs are reluctant, or even afraid, to describe their own experiences. They prefer to talk about people they knew and to describe living in a context where such mistreatment is commonplace. 39,43 In some cases, this is exacerbated by political, ethnic, clan and religious divisions within the AS&R communities.

Many are negotiating a sense of loss and isolation, experiencing a conflict between sense of dependence and independence, or experiencing a sense of inferiority in relation to the indigenous population. 44,45

Uncertainty about legal status makes some less willing to seek help, as do a wide variety of stigmatising and discriminatory experiences. 46 Lack of finance or inadequate access to insurance-based care can also be major barriers. 47

A lack of well-trained interpreters, assigned appropriately to AS&Rs in need of assistance can adversely affect the latter group’s ability to find the help they need. 48 In one such instance a man was detained for being suicidal, when in fact he was trying to describe how he would like sleeping pills as he was experiencing worries that were keeping him from sleeping:

Had it been a Karen interpreter the interpreter would interpret that he was not able to sleep because of worries and that would be all. His main concern was to get sleeping pills. [. . .] The interpreter however interpreted that the person wanted to [take their own life].

Power and Pratt49

Facilitators for asylum seekers and refugees

Asylum seekers and refugees are seen as likely to benefit from interventions that are adapted to their local context and are culturally and linguistically appropriate. 50 Uptake is increased by addressing mental health stigma through educational panels and workshops, community gatherings and dialogues, film screenings and cultural shows.

The free-listing of problems is useful,12,51 as is addressing social problems (e.g. income, poor housing, family problems and violence) before mental health. Some favour multiethnic peer support groups, and others emphasise understanding the needs of different groups, especially women. Community advocacy is useful, especially with facilitators who are drawn from AS&R communities. 52

Asylum seekers and refugees are more likely to participate in and benefit from interventions if they feel supported by other asylum seekers, are able to build rapport in a safe setting and have a sense of family comfort with discussing trauma. 53,54 Knowing how others cope with problems encourages AS&Rs to seek help for their own issues. Other important facilitators of AS&R participation in psychosocial interventions include the knowledge that they are not alone in experiencing a specific problem, and an understanding of the connection between mental and physical health.

Barriers for lay health workers

Lay health workers are less likely to engage in or persist with the delivery of psychosocial interventions for AS&Rs if they experience problems with the work itself. Problems include a lack of management direction, conflicts with co-workers, excessive workload, being asked to undertake duties beyond their abilities, and a sense of powerlessness. External barriers include experiencing their own economic and financial problems, travel difficulties, separation from relatives, their own temporary status in the host country and working in a hostile environment. 55

Facilitators for lay health workers

Lay health workers are more likely to engage in or persist with the delivery of psychosocial interventions for AS&Rs if they are invested in outcomes and understand that their main role is to connect and focus on objective, non-judgemental participation. Team cohesion, social support and supervision all mitigate stress in lay health workers.

Lay health workers value being recognised as a resource in their society. Engagement is most effective when people from AS&R communities who have been in the host country for a few years become bridge-builders, co-creating new ways of working and building refugees’ trust in their relationships with staff. In these ways they may become culturally competent paraprofessionals working with their own communities. 56–59

Stakeholder engagement

Stakeholders (including service providers and service users) were recruited from asylum seeker and refugee support organisations across Liverpool City Region in north-west England using purposive sampling via a convenience approach. The research team directly contacted service providers, who comprised social workers, community workers, nurses, psychological therapists, a clergyman, a doctor, a case worker, a health professional, a child psychiatrist and a health service commissioner. Service users were approached during drop-in sessions at the community organisations, and the study was also publicised on a flyer distributed to the four support organisations collaborating in the research project and on social media.

The study received ethics approval from North West – Greater Manchester East Research Ethics Committee (reference 18/NW/0441). All participants provided written informed consent to participate in focus groups and have anonymised quotations reported.

The research is embedded within a social constructionist paradigm. There was emphasis on the meaning-making of people’s perceptions and experiences. Data were collected and analysed following the principles of interpretative phenomenological analysis. 60

We chose to conduct focus groups instead of individual interviews because we wanted to initiate a dialogue between the members of the group. 61 Using focus groups can cause tension when interpretative phenomenological analysis is used to capture individual sense-making. To limit the impact of this tension, careful attention was paid to ensure that data analysis captured the ‘voice’ of the individual rather than being lost at the group level. 62

The interactions that develop from utilising focus groups allow participants to listen, express their views, question others, ask for clarification, encourage others and reflect on what is being verbalised, which in turn can solidify or challenge their own views. 63 Hence, the group context fosters a deeper and reflexive response. 64 This makes the data unique and simultaneously elucidates the research matter:65

Because they involve discussion, and hearing from others, they give participants more opportunity to refine what they have to say.

Ritchie and Lewis61

Twenty-four individuals (16 women and eight men) participated in six focus groups. The participant age ranged between 27 and 76 years. Participants comprised 13 service providers (white, n = 11; Asian, n = 2; African, n = 1) and 11 service users: seven asylum seekers and four refugees. The primary languages spoken by the AS&Rs were Albanian (n = 1), Arabic (n = 3), English (n = 1), Hindi (n = 1), Shona (n = 1) and Urdu (n = 4). Groups comprised three, four or five participants. Three focus groups were conducted with service providers, and three were conducted with service users so that a balanced account of data could be gathered by allowing AS&Rs a safe space in which to express themselves. The focus groups were led by two moderators (NK and CD) using a semistructured guide. All focus groups were moderated and audio-recorded in English. The transcripts were transcribed verbatim.

Data analysis

A thorough group-level analysis was conducted, with the data approached as a whole entity. In brief, Naila Khan began the analysis by reading each transcript several times; this enabled her to become familiar with the transcripts. She then noted preliminary codes followed by interpretations, and later identified emerging themes. The researcher’s preconceptions were managed through the process of bracketing. This involved keeping a reflective journal throughout the analysis and writing up stages of the research.

The next stage involved meticulously highlighting connections, the intention being to develop the master and subordinate themes. This process was iterative, with themes identified in initial transcripts being revised and refined in the light of data in subsequent transcripts. The final step entailed reconsidering the original themes in consultation with Lois Orton and Christopher Dowrick to enhance inter-rater reliability and conduct further analyses to refine, merge and clarify the final themes, and also to establish the superordinate themes and subthemes. Disagreements were resolved and consensus reached through discussion. 60,66 This process of analysis allows researchers to immerse themselves in the findings and in doing so, ascertain an in-depth understanding of how individuals construct knowledge and meaning of their lived experiences. 67. 68

During this process, key quotations were chosen to illustrate the themes identified and preserve the sense-making of the individual. 62 Participants were coded using ‘service provider’ (statutory or voluntary) and ‘refugee/asylum seeker’ identifiers instead of pseudonyms in order to assist the reader in contextualising the narrative.

Researcher reflexivity

Reflexivity forms a significant part of the qualitative researcher’s process. Our identities and professional roles may have had an impact on the data collated. Therefore, we will briefly make our positions as the facilitators clear to enable the reader to understand who the moderators were and how that possibly impacted on the findings. 69 Moreover, ‘to be reflexive we need to be aware of our personal responses and to be able to make choices about how to use them. We also need to be aware of the personal, social and cultural contexts in which we live and work and to understand how these impact on the ways we interpret our world’. 70 Gender, ethnicity, culture, age, socioeconomic status and educational background are all significant facets of one’s identity. 71

All the contributors to this report share knowledge and skills in relation to mental health and a commitment to the welfare of AS&Rs. Our professional backgrounds encompass clinical psychology, counselling, medicine, nursing, politics, public health and sociology. Our authorial team includes people with membership of minority ethnic communities and lived experience of the UK asylum process.

The contributors who facilitated the focus groups (NK and CD) worked to enhance positive relationships and reduce potential power imbalances with participants, ensuring that the groups were arranged to the convenience and comfort of participants, paying careful attention to shared meaning and evolving shared understandings of what was being heard. At times – especially, but not exclusively – in relation to the focus groups with refugees and asylum seekers, this involved empathising with, and later processing, highly distressing narratives of displacement, suffering and loss.

Naila Khan is a British-born second-generation Pakistani woman and the research associate on the project. To counteract the possibility that her gender and ethnicity might have an impact on the research process, she used the process of bracketing. This was the first time she had conducted research in relation to AS&Rs. She had limited awareness of the asylum process, and consciously did not read much literature prior to conducting the focus groups to avoid bias and assumptions.

Christopher Dowrick is an Irish-born, older, white man. Before the focus groups took place he was concerned that these traits, alongside his role as a professor, might prevent participants from freely giving their opinions. However, except for one service provider who directed their remarks to him, his presence did not appear to affect participants. There may indeed have been an opposite effect in that his presence conferred further significance to the focus groups, and participants therefore felt that their views would carry more weight.

Findings

Five superordinate themes were identified: (1) mental health, community and the asylum process; (2) medical and psychological support; (3) religion and culture; (4) the feasibility of PM+; and (5) loss of profession and identity. Here we focus on stakeholder perspectives on the acceptability and feasibility of PM+ (unpublished data).

The content of PM+

Stakeholders generally expressed positive views about PM+ and its usefulness for distressed AS&Rs:

For asylum seekers to know there is something going on they will come, it’s good for everything, I know as an asylum seeker I would go [. . .] If you go the wrong way it’s not good for their future, their future is this place and like you say help those who help themselves.

Service user

I find it empowering to asylum seekers and refugees that when they are able to resolve their problems they are able to put in a position to have high self-esteem and be integrated, be happy.

Service provider

They identified potential advantages over existing service provision, which was often seen as difficult for AS&Rs to access and (for many) available only in crisis:

Used to work in Kensington with a high number of asylum seekers, there would be somebody who kept coming for sleeping tablets, and kept asking for repeat prescriptions and was met strongly with no, can’t give more sleeping tablets but there was nothing to send him to.

Service provider

What we offer with a couple of sessions is good but after that there’s such a long gap on waiting lists and missing out because we don’t have standard processes, so would be beneficial to anyone arriving. They all have some level of anxiety and stress.

Service provider

They saw the delivery of PM+ as beneficial for lay therapists themselves, as well as for their clients:

I think this in being signed up and trained, it’s actually you that benefits first, you get therapy first, and then like anything you want to share with others.

Service provider

The psychoeducation element was considered to be helpful. Stakeholders approved of stress reduction techniques, and the emphasis on managing problems was seen to assist with establishing realistic expectations:

Most people don’t realise they are breathing wrong, you get stressed, you breath shorter and shorter, you think ‘What’s happening to me? Am I going to pass out?’ That’s a very good start. They need to understand the little things.

Service user

I think it’s much, much needed, and the psychoeducation element is often at the bottom of the getting stuck with a GP [general practitioner] because there’s a kind of ‘no I need any pills’ but actually pills won’t make you better, but that bit on psychoeducation can really help that.

Service provider

Some stakeholders raised questions about the scripted nature of PM+ and whether or not this might inhibit the essential therapeutic element of relationship-building:

I’m thinking about the things that seem to help are about establishing relationship, I’m not sure how that happens here [. . .] It seems it has to be quite scripted to be able to pack all of that in, so I just wonder about that kind of wonder about that.

Service provider

Others were concerned about the risks of lay therapists going beyond the limits of PM+, offering bad advice in relation to legal issues and triggering trauma:

I would be cautious about practical help that goes beyond Problem Management Plus. I’m also worried that bad advice in relation to anything legal . . . can be damaging.

Service provider

. . . within trauma therapy one of the things that this seems to sit well within for stabilisation, the initial phase where you’re not moving into reprocessing or triggering traumatic memory as that might be difficult.

Service provider

Still others questioned the therapy orientation of PM+, suggesting that open, friendship-based approaches would be more suitable for their cultural group:

To me it’s just not our thing as Africans to have therapy-type thing, it’s not our thing at all. My opinion what would work for me is a friendship-type thing [. . .] Feels like there is a gap between the person and me, want to develop the common [g]round, good being asylum seeker to asylum seeker, the language as well having walked in my shoes, but not formally, sit there, what have you done.

Service user

Barriers to implementing PM+

There was a common view that the daily lives of AS&Rs were very busy, that regular attendance at sessions could often be problematic for clients, and that PM+ would need to be fitted into other commitments, including child care, education and the asylum system:

It depends on how through the asylum system they are but lots of them have meetings whether signing up at the Home Office or with their solicitor, they’re really good at navigating through things like this so in one way it would fit in very well, in another [it] could be another stressful thing.

Service provider

Stakeholders also noted the ever-present threat of dispersal to another part of the country, which would interfere with clients’ ability to complete a course of PM+ sessions.

There was concern that cultural differences in understandings of mental health or depression may inhibit people from seeking help in this way:

Is the model culturally accessible to all populations living here? We know that mental health models are culturally determined, different countries have really different kind[s] of model so they’re not there’s no such thing as a culturally neutral mental health service, so it’s interesting, it brings out a challenge I completely identify with.

Service provider

First thing is it’s getting to know them, they have their own tradition and culture and have some different things, something they feel may be a threat, how we can get this is with ourselves [. . .] I know people from Albania, I’m the only one involved in and it’s difficult to engage them, there are so few. They don’t get involved because of culture, they are used to a set way of eating they won’t try [anything other than their] own things, it’s very hard to understand.

Service user

It was felt that it was more difficult for women to talk openly about their mental health problems:

It’s a cultural thing they don’t speak openly, and also they think it’s not important to talk about it sometimes, if I’m just depressed and sad they just feel it’s not they are at risk, or [a] state they have, they must do something for their well-being they don’t realise it’s important for them.

Service user

Some noted the possibility of cultural or religious conflicts between therapists and clients, especially for clients who had been forced to flee their home countries following a change in religion:

Other issue will be how to ensure the lay therapists engage and turn up themselves, and sort of the cultural conflict with the therapist and client. Those are the thing[s] you may not know about, you might not ever understand what they are talking about. A lot of people have fled due to changed religion and the sensitivity of it.

Service provider

Confidentiality was raised as an issue when lay therapists and clients came from the same community and also when interpreters were involved in the sessions. Issues raised were not only personal, but also political:

OK, so my only thought is, you’ve got someone that has trained through this to be a lay therapist and is an asylum seeker, we are such a small community and even now, people chat openly, and some people share in houses, if you have a lay therapist in that community, obviously taught about confidentially, people have supported each other with health problems back off from one another.

Service provider

The lady didn’t want face-to-face interpreter, because of her community, the likelihood was it would be someone from her community and therefore she thought she may be poorly viewed in her community with a face-to-face interpreter.

Service provider

The European Kurdish group are absolutely paranoid about meeting other people to begin with, still happening now, for fear they have fled, two of our families are from [city] and they fear that message will get back home that they are here, they are anxious about translators.

Service provider

Facilitators of implementing PM+

Stakeholders recommended that initial contact be by telephone rather than letter, as many AS&Rs associate mail with official communications from the Home Office:

We get a letter and see it on paper, it’s the first sight for every asylum seeker, there are a lot of them to say can you open I don’t want to open it, they are scared, that sends you to anxiety.

Service user

They proposed locating the PM+ sessions in a familiar environment with easy access, such as a voluntary agency with which the client is already in contact. They also emphasised the importance of practical help with childcare and transport (so that clients are not left financially out of pocket as a result of having to attend sessions) and recommended flexibility around appointments to fit in with clients’ busy lives.

Emphasising the confidential nature of the sessions was important in building trust:

Not enough to give them a piece of paper to say it’s confidential. They have to recognise and develop trust.

Service user

Matching the therapist and the client in terms of gender was seen as important, especially for women:

I think for female clients have a female person, will be more open to person of same gender . . .

Service user

Matching language and culture between therapist and client was often, but not always, seen as helpful:

Yes, the idea is lay therapists coming from same or similar cultural background will have more experiences and ability to developing trusting relationships that might make it come through more quickly.

Service provider

You speak their language and are needed at so many levels, but just through speaking Arabic you would work as a social worker just by being from the same language and culture. But sometimes the opposite, they want someone outside their community.

Service provider

Stakeholders felt that, if interpretation services were needed, it would be safer to use a telephone translation service such as LanguageLine (London, UK).

They also offered practical advice on how to publicise the project, including attending community meetings and placing posters in voluntary organisations working with AS&Rs.

Training procedures

Adaptations to the PM+ manuals to fit the lives of AS&R in the UK for the PROSPER study were approved by the WHO. Examples of group PM+ adaptations include creating a male case study and amending the case study narrative and images to reflect the UK context (e.g. replacing reference to help-seeking from a ‘village elder’ with ‘voluntary or statutory organisations’).

PROSPER PM+ training model

PM+ training and supervision broadly followed the cascade apprenticeship model72 outlined in Table 1.

| Components of apprenticeship model in mental health interventions | Application in PROSPER study |

|---|---|

| Selection of apprentices |

|

| Training |

|

| Application of training ‘on the job’ under direct supportive supervision |

|

| Ongoing expansion of training, knowledge and skills under supportive supervision |

|

| Mutual problem-solving |

|

The apprenticeship model foregrounds supportive supervision,73 promoting cycles of experiential learning, doing and reflecting74 as foundations for enhancing lay therapist competency and fidelity while encouraging motivation and job satisfaction. 75 Supportive supervision explicitly values and integrates ‘tacit knowledge’ gained through experiential practice, which is melded with intervention principles to enhance the skills, knowledge and values of those delivering the intervention. 76 Recognising the importance of training and supportive supervision and the need for further evidence on approaches,75 we describe and reflect on our experiences of cascade apprenticeship training and supervision to draw recommendations for others implementing this model, focusing on adjustments when working with lay therapists who are AS&R.

Recruitment

Well-being mentors

The well-being mentors were the PM+ lay therapists’ trainers and supervisors, and they are themselves ‘lay’ professionals in that they are not mental health specialists. For the PROSPER study, no specific qualifications were expected, with the emphasis in the recruitment of well-being mentors being on experience of training and supporting volunteers from diverse communities within health and social care.

The two recruited well-being mentors had counselling qualifications, and between them they also had qualifications in education and youth work and work experience in voluntary mental health settings. They were recruited and employed by the PROSPER intervention partner Person Shaped Support (PSS) in Liverpool, a social enterprise providing mental health and social care services, including to AS&R. The well-being mentors (AM and LB) receive day-to-day support from their PSS team leader (RMcC) and joint monthly supportive supervision from the master trainer (AC) and participated in PROSPER Project Management Group (PMG) meetings. Initially envisaged as part-time, the well-being mentors’ role was extended to a full-time commitment to ensure that they would be available to support lay therapists’ delivery of PM+.

Lay therapists

The recruitment of 12 volunteer lay therapists was conducted by PSS. It began with the distribution of e-mails, posters and information sheets among NGOs supporting AS&Rs in Liverpool. Over 20 AS&Rs attended information sessions at PSS led by the well-being mentors, at which they were introduced to the PM+ intervention and the lay therapist role and criteria (i.e. age > 18 years; knowledge and/or lived experience of migration and/or the asylum process; sufficient ability in speaking, reading and writing English; and residing in Liverpool, UK). Fifteen candidates who met these criteria and expressed an interest in becoming lay therapists attended individual interviews conducted at PSS by the two well-being mentors and their team leader. The interviews commenced by tasking the candidates with producing an origami object, testing their English-language skills and ability to follow instructions; the candidates were then asked five questions about the skills, knowledge, experience and personal qualities that they would bring to the lay therapist role. Following the interviews, 12 candidates were selected to participate in the PM+ lay therapist training (Table 2).

| Gender | Age (years) | Native language | Education level | Employment/voluntary role in UK | Individual or group PM+ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Female | 30 | Urdu | Undergraduate | Trainee dental assistant | Individual |

| 2 | Female | 30–40 | Farsi | Graduate | Studying fashion, English, maths | Individual |

| 3 | Male | 30–40 | Arabic | Graduate | Studying English and enrolled in pre-studies for pharmacy | Individual |

| 4 | Male | 30–40 | Urdu | Graduate | Business owner | Group |

| 5 | Female | 30–40 | Arabic | Graduate | Studying English, preparing for master’s studies | Group |

| 6 | Female | 40+ | Turkish | Graduate | Studying English and transferring social work qualifications | Group |

| 7 | Female | 30–40 | Thai | Graduate | Studying English and working in hospitality | Group |

| 8 | Male | 20–30 | Farsi | Not known | Studying | Individual |

| 9 | Male | 20–30 | Farsi | Graduate | Studying pharmacy | Individual |

| 10 | Female | 40+ | English/French | Not known | Working | Individual |

| 11 | Female | 20–30 | Urdu | Not known | Studying | Individual |

| 12 | Male | 40+ | Urdu | Not known | Teaching English in conversation groups | Group |

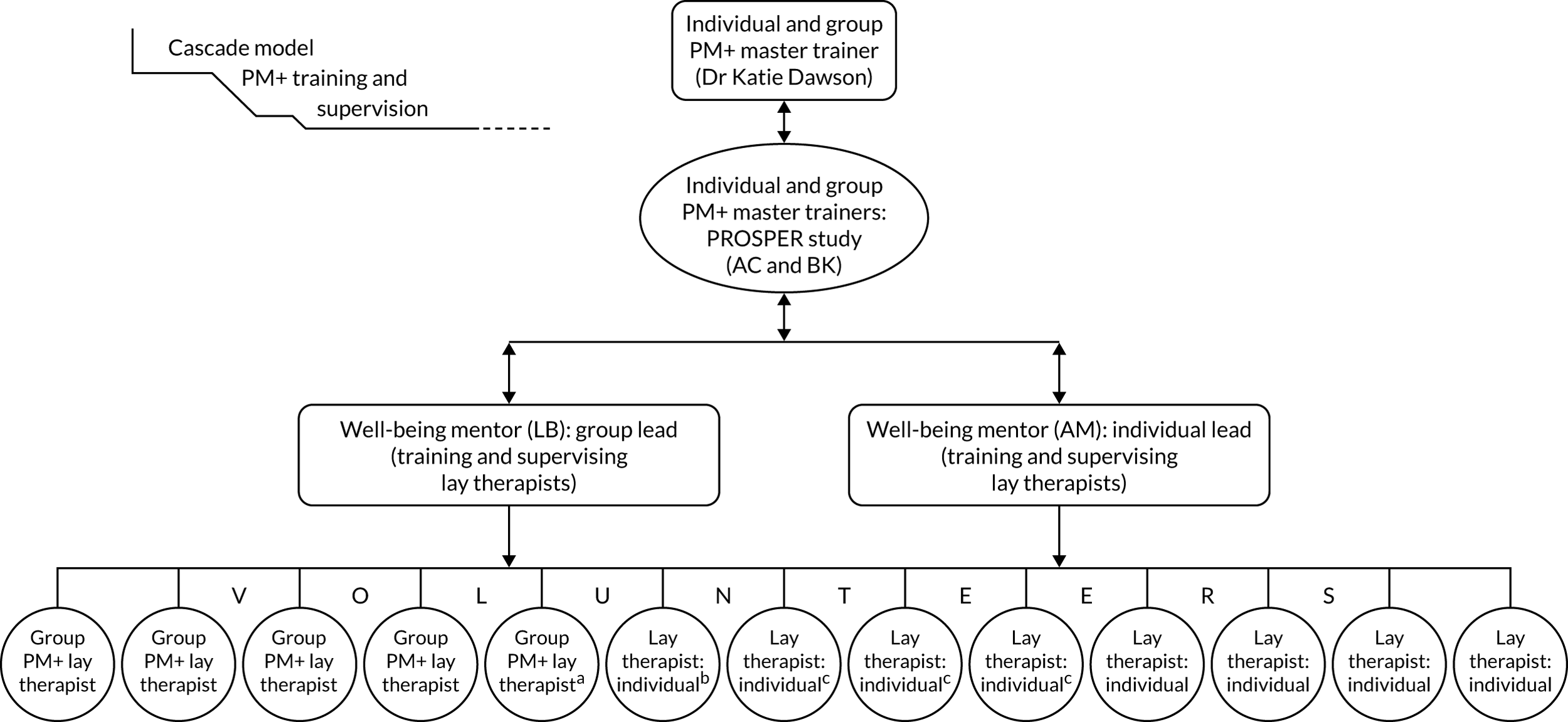

Training

Figure 2 summarises the PM+ cascade training and supervision model.

FIGURE 2.

The PROSPER study PM+ training model. 77 a, Reason for leaving: ill health; b, reason for leaving: moved area; c, reason for leaving: disengaged. Reproduced from Chiumento et al. 77 This article is available under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike License (CC BY-NC-SA), which permits non-commercial use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Well-being mentor training and practice cases

A 5-day well-being mentor training course was led by two master trainers (including AC) in October 2018. Training followed the PM+ training of trainers programme, which foregrounds basic helping skills, and the PM+ intervention sessions, emphasising the core content and underlying rationale. Training highlighted the different individual and group delivery modalities and skills in training others, such as conducting role-play and providing feedback, and leading supportive supervision. The training situated PM+ in the context of the PROSPER study, exploring the relevance of PM+ to AS&R lives and clarifying the intervention and research relationship. All training was experiential and concluded in role-play with volunteers who had no prior experience of PM+.

Following training, the well-being mentors each completed three individual PM+ practice cases with volunteers (including a medical student with lived experience of migration, social work students, and PSS staff). The practice cases embedded knowledge of and skills in implementing the PM+ intervention, equipping the well-being mentors with experiences of common challenges to PM+ delivery such as participant engagement, responding to difficult disclosure and time management. These experiences were invaluable for the subsequent lay therapist training and supervision.

Following the training and practice cases, the well-being mentors spent time networking with AS&R voluntary organisations. This formed a crucial foundation of the well-being mentors’ role as they became familiar and trusted faces at organisations from which lay therapists (and subsequently, PROSPER research participants) were recruited.

Well-being mentor supportive supervision

Following training, the well-being mentors received monthly supportive supervision from one master trainer and the PSS team leader: this lasted between 1.5 and 2 hours and was complemented with e-mail and telephone discussions where required. Additional PROSPER PMG meetings were conducted bimonthly. These meetings provided a forum for input into the lay therapist team development, and well-being mentors with a space to reflect and learn about PM+ implementation (both in context of the research design and AS&R voluntary organisations and statutory health-care systems). 78

Supervision content was tailored to the project stage,77 moving from an initial focus on embedding PM+ knowledge and skills to planning for the lay therapist PM+ training (including enhancing training skills) and then concentrating on skills for leading supportive supervision with lay therapists. This supportive supervision enhanced the well-being mentors’ knowledgeable application of skills to practice. Specifically, the supportive supervision enabled experiential and reflective learning, supporting the lay therapists to enhance their skills in cascade supervision. 74 Finally, well-being mentor supervision incorporated logistical research planning and additional training (e.g. in good clinical practice, data protection and basic first aid).

Lay therapists’ training and practice cases

The lay therapist training was separated into group PM+ (led by LB) and individual PM+ (led by AM), with six lay therapists trained in each modality. Allocation to each modality was based on availability to attend training on a given day and any expressed preferences of the lay therapist themselves. Training was delivered 1 day per week (10 a.m. to 4 p.m.) over 8 weeks from March to May 2019, with scheduling to accommodate the availability of the AS&R lay therapists around other family, work or education commitments.

The training followed the individual or group PM+ training manuals, covering basic helping skills and experiential learning of PM+ sessions summarised above, and was reinforced through discussions and role-play of the PM+ strategies and sessions for the relevant PM+ modality. The master trainer (AC) visited to observe training and provide feedback to the well-being mentors, to meet the lay therapists and to answer questions about the relationship between the PM+ intervention and PROSPER research. At the end of training, the well-being mentors conducted competency assessments with each lay therapist to ensure that they had the knowledge and skills to deliver PM+ to participants safely. Following this, lay therapists were presented with a certificate attesting to their successful completion of PM+ training.

The training was completed by 11 lay therapists; one person dropped out owing to ill health. These 11 lay therapists then completed one individual or group PM+ practice case with PSS staff and student volunteers.

Lay therapists’ supportive supervision

Lay therapists’ group supportive supervision took place throughout the practice cases and was led by the well-being mentors. In addition to discussing how PM+ sessions were progressing and delivering top-up training in PM+ strategies, the well-being mentors incorporated self-care tasks to equip the lay therapists with techniques to promote their own well-being, which is important in therapeutic interventions. 79 A second lay therapist dropped out during the practice cases owing to their compulsory relocation to another city.

PM+ sessions were delivered by lay therapists at PSS offices, with the well-being mentors available before and after sessions. It became natural for supervision to take place immediately after PM+ sessions, with lay therapists eager to reflect with well-being mentors on their delivery of PM+, including which parts went well, where they encountered challenges, and why they felt they had encountered challenges or had successfully delivered intervention components. The lay therapists sometimes asked the well-being mentors for clarification of a strategy, or checked that they had responded appropriately to participants’ questions or responses to PM+ strategies. This supervision allowed space for the lay therapists to build confidence, gain a focus for the next session and offload before returning to their day-to-day life. This individualised supervision approach immediately after PM+ sessions was found to be highly effective and was complemented by group supervision when logistically feasible (i.e. multiple lay therapists delivering sessions at the same time). This demonstrated flexibility in supervision structures79 and attention to feasibility, as individual supervision avoided the travel time and costs that the lay therapists would have incurred in attending separate group sessions.

Well-being mentors conducted fidelity checks through observation of a random selection of PM+ sessions, assessing lay therapist delivery of PM+ against a structured checklist. These checks provided an important mechanism for the well-being mentor to monitor PM+ quality79 and learn where PM+ knowledge and skills may have been misinterpreted. As above, individual supervision of the lay therapist occurred immediately after the fidelity check, ensuring that experiences of the session were fresh and clear. Before giving fidelity check feedback, self-care activities were completed jointly by the well-being mentor and the lay therapist and this was found to enhance supportive feedback and reflection.

Reflections on PM+ training and supervision

We share some reflections based on our experiences that address themes that emerged in reflective workshops: (1) logistical challenges to working with AS&R lay therapists, (2) strategies employed to encourage lay therapist engagement and (3) team and personal growth (Table 3). We identify examples to illustrate these reflections, focusing on considerations relevant to implementing a task-sharing intervention with AS&R lay therapists.

| Reflection | Specific considerations |

|---|---|

| Logistical challenges | Synchronising schedules with lay therapists’ educational, family and personal responsibilities |

| Mitigating financial hardship | |

| Remaining aware of, and responsive to, the impact of personal asylum journeys | |

| Responding to delays in research timelines | |

| Lay therapist engagement strategies | Collective informal engagement through, for example, shared lunches and joint sightseeing tours |

| Positive recognition of the cultural and linguistic diversity of the PM+ intervention team | |

| Allowing lay therapists to set the level and format of communication with well-being mentors | |

| Team and personal growth | Recognising the unique strengths of each member of the PM+ intervention team |

| Shared learning across the PROSPER research and intervention teams | |

| Active development and implementation of well-being mentor ideas and approaches to lay therapist training and supervision | |

| Skills development of PM+ lay therapists |

Logistical challenges

The lay therapists were enrolled on free and fee-charging English-language, educational and vocational courses as it was important for them to improve their English, and to upskill and adapt their qualifications to UK education and employment systems. Some lay therapists also had families (including school-aged children) to care for, and these factors presented challenges to be worked around when synchronising training schedules. Furthermore, recognising that AS&Rs are provided meagre financial benefits,80 financial hardship was mitigated through the reimbursement of travel expenses and provision of lunch and childcare during training. It is likely that most AS&Rs would have been unable to take on the lay therapist role without financial and childcare support. In addition, many lay therapists were experiencing the uncertainties of personal asylum cases. This could have an impact on their well-being and flexibility, and PROSPER schedules needed to account for this.

Delays in ethics approval meant that PROSPER research timelines were extended and PM+ delivery to participants was delayed, leading to a decrease in project activity, at which point several lay therapists left their roles. To maintain commitment, interactions between the well-being mentors and lay therapists involved supportive supervision to review the PM+ intervention, practise self-care strategies and socialise. The lay therapists also made an information video about PM+ aimed at service providers, offering an opportunity to reinforce their knowledge of PM+ strategies and the research design while ensuring active contributions to the PROSPER study and building their confidence.

The impact of delays reflects broader challenges at the research/service delivery interface. While the research and intervention teams’ relationship has been supportive and provided opportunities such as additional training, it has also led to frustration due to the processes required to adhere to clinical trials regulations, the time for ethics approval, and slow initial recruitment. To navigate this, the well-being mentors have played an important role in balancing the rigid timelines and complex governance processes of a research trial against the expectations of lay therapists keen to commence PM+ delivery.

Lay therapist engagement strategies

Collective informal engagement, such as shared lunches during training (with attention to cultural appropriateness by offering halal meals and respecting fasting during Ramadan) and going on sightseeing tours, helped build intervention team cohesion within and beyond PM+ roles. The linguistic and cultural diversity of the lay therapists added value to the PM+ intervention team and promoted a lively training atmosphere. The lay therapists displayed a comfortable vulnerability when talking about cultural differences and migration experiences, complemented by discussions with the well-being mentors about the local Scouse dialect, which indicated the presence of an open and trusting relationship between lay therapists and well-being mentors. Positively recognising this diversity provided bonding experiences, helping the lay therapists to understand the local culture and the well-being mentors to appreciate the lay therapists’ migration experiences.

During initial stages of PROSPER recruitment, the lay therapists were encouraged to set the level and type of interaction with the well-being mentors; for example, some requested weekly check-in telephone calls or meeting the well-being mentor for coffee, whereas others preferred contact by text message or only when there was a participant for them to deliver PM+ to. Tailoring engagement to each lay therapist has avoided problems of over- or undercommunication, demonstrating the mutual respect that is essential for trusting peer and supervisory relationships. 79,81

Team and personal growth

The PM+ training of trainers programme was intensive and demanding, with a breadth of material to cover and knowledge, skills, and confidence to build. Training delivery was aided, however, by a supportive, open and trusting training atmosphere which facilitated the open acknowledgement of areas of confusion and collective problem-solving. Therefore, although intensive, this training rapidly built relationships, establishing a cohesive intervention team that recognised the strengths of each lay therapist.

During the PM+ training and supportive supervision, the lay therapists benefited from the opportunity to improve their English and communication skills and confidence. Initially, many lay therapists were shy about PM+ role-play but they overcame this through encouragement and support from well-being mentors and their peers, developing confidence in delivering individual or group PM+.

Well-being mentor supportive supervision has facilitated approaches to lay therapist training and supervision that draw on the well-being mentors’ personalities and strengths, such as bringing together individual and group lay therapists to share PM+ delivery skills that both groups could draw on; for example, individual PM+ lay therapists demonstrated effective explanation of key strategies, and group PM+ lay therapists demonstrated facilitation skills such as bounce-back questions. This incorporation of peer- and supervisor-led training in dynamic individual and group supervision formats has proven effective in expanding the knowledge, skills and confidence of lay therapists. 79

Shared learning across the PROSPER intervention and research teams has included taking account of lay therapists’ English literacy levels and familiarity with form-filling, and the logistical co-ordination of delivering PM+ sessions at AS&R voluntary organisations. The PMG meetings have provided a forum to discuss and agree research design, with the well-being mentors and master trainer providing ‘on-the-ground’ insights to ensure that these remained practical for AS&R lay therapists unfamiliar with research procedures. 79

Chapter 3 Pilot trial

Parts of this chapter have been adapted with permission from Rawlinson et al. 1 Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Contextual modifications

As a result of the findings from the feasibility study, we made the following contextual modifications to promote the uptake and relevance of the PROSPER pilot trial:

-

Focusing on English, Arabic, Farsi and Urdu, which were identified as the four languages that are currently most commonly spoken by AS&Rs in Liverpool City region.

-

Excluding new arrivals and those in temporary accommodation on grounds of (1) high probability of dispersal and hence unavailability for intervention and/or follow-up, and (2) low probability of being registered with a GP and hence unable to access trial safeguarding procedures.

-

Altering the text of PM+ manuals to reflect life in Western urban settings rather than South Asian rural settings (e.g. ‘home’ not ‘hut’, ‘reading’ not ‘rearing poultry’, ‘visit job centre’ not ‘speak with village elder’).

-

Adapting the group PM+ case studies to include men.

-

Matching therapists and participants on the bases of gender and language, but not on the bases of religion, politics or culture.

-

Identifying accessible ‘safe spaces’ for research interviews and delivery of PM+ sessions, including availability of childcare.

-

Reimbursing travel expenses for lay therapists and participants.

-

Supervising and supporting lay therapists in the inclusion of boundary issues between therapy and involvement in participants’ lives, as the shared lived experience of the asylum process takes this study beyond the boundaries that have been apparent in other contexts.

On this basis, the PROSPER trial protocol was approved by University Sponsor and Liverpool Research Ethics Committee (reference 19/NW/0345) and subsequently published in Trials. 1

Trial protocol

Aim and objectives

This pilot trial was part of the PROSPER feasibility study, the overall aim of which was to determine whether or not it is possible to conduct a RCT in the UK of the evidence-based PM+ psychosocial intervention delivered by lay therapists, for distressed and functionally impaired AS&Rs.

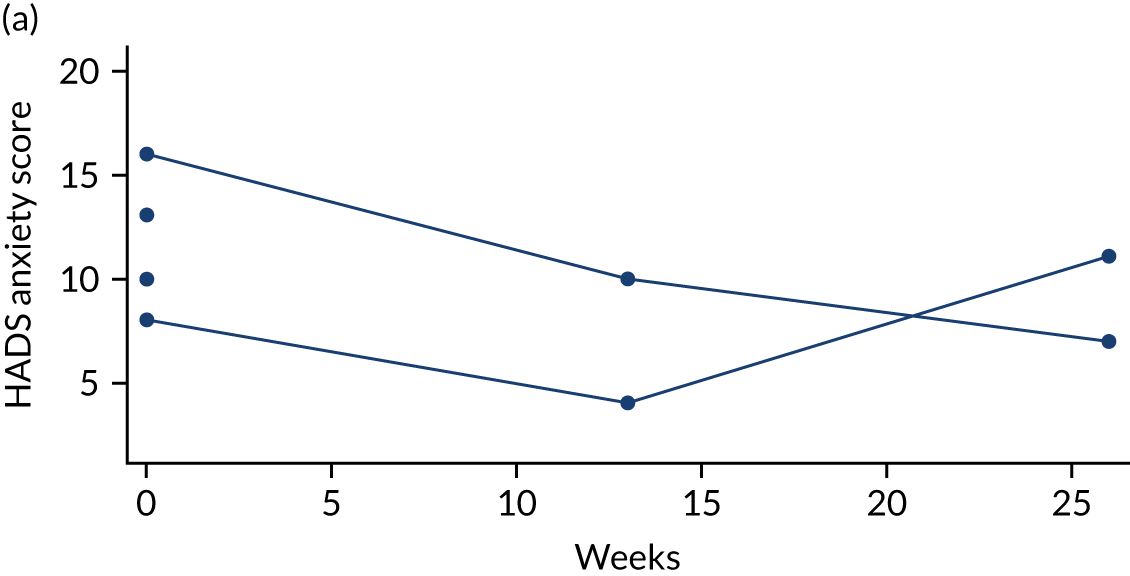

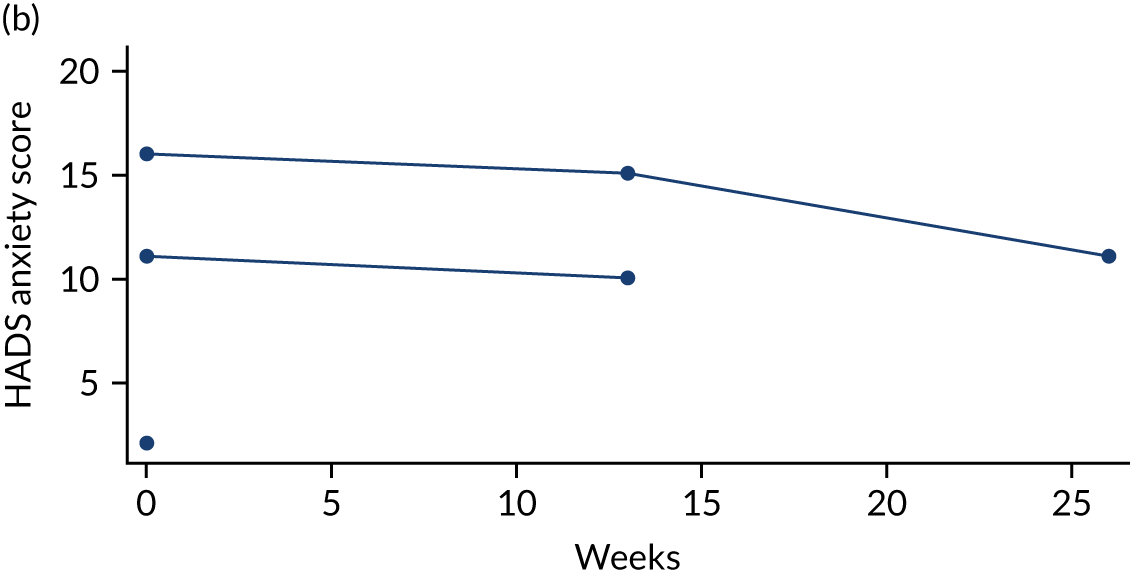

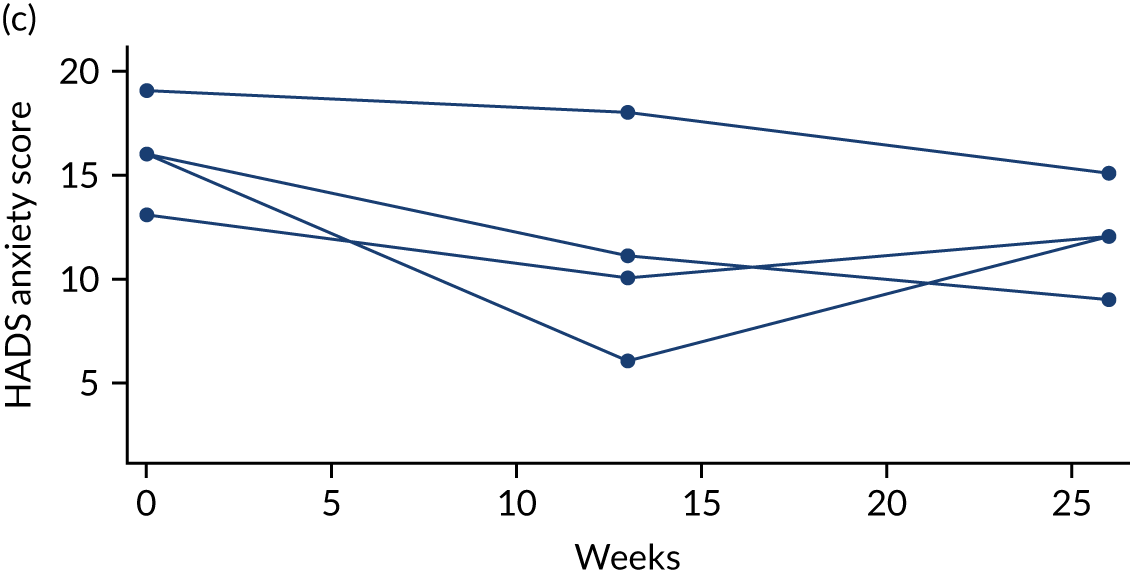

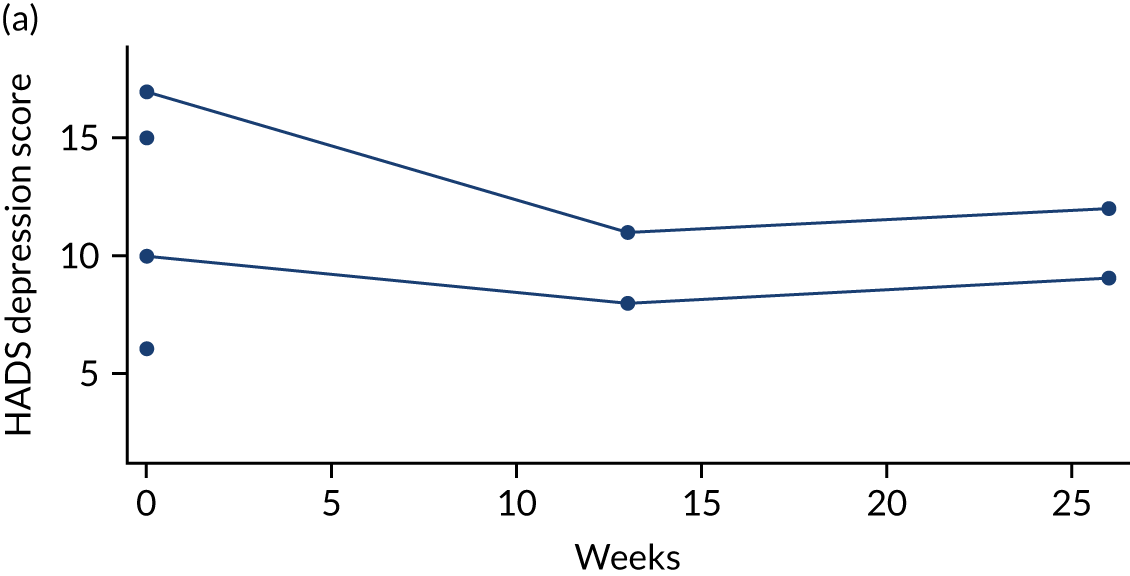

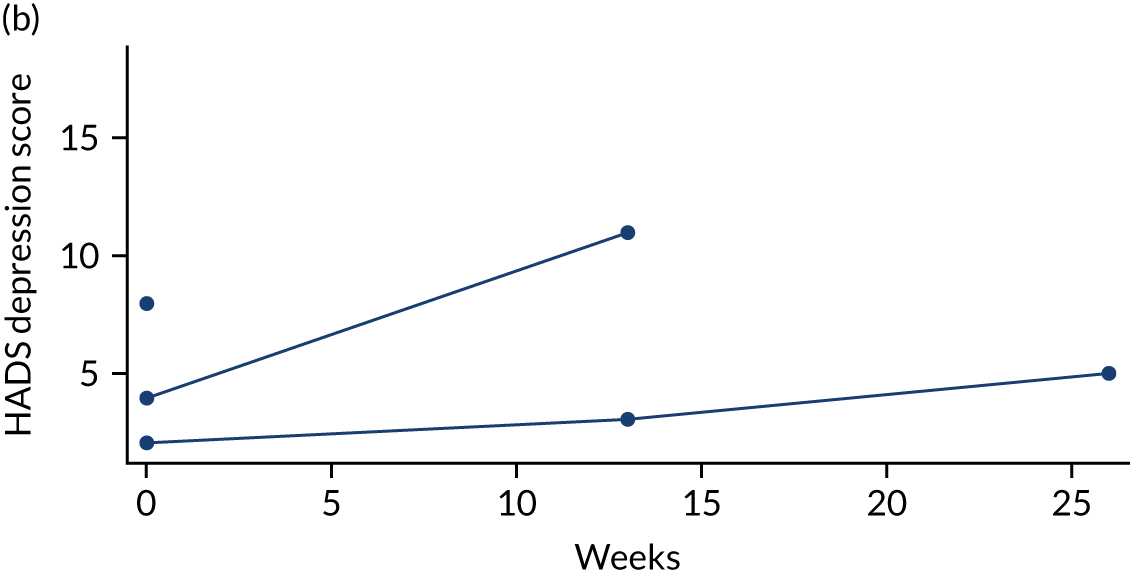

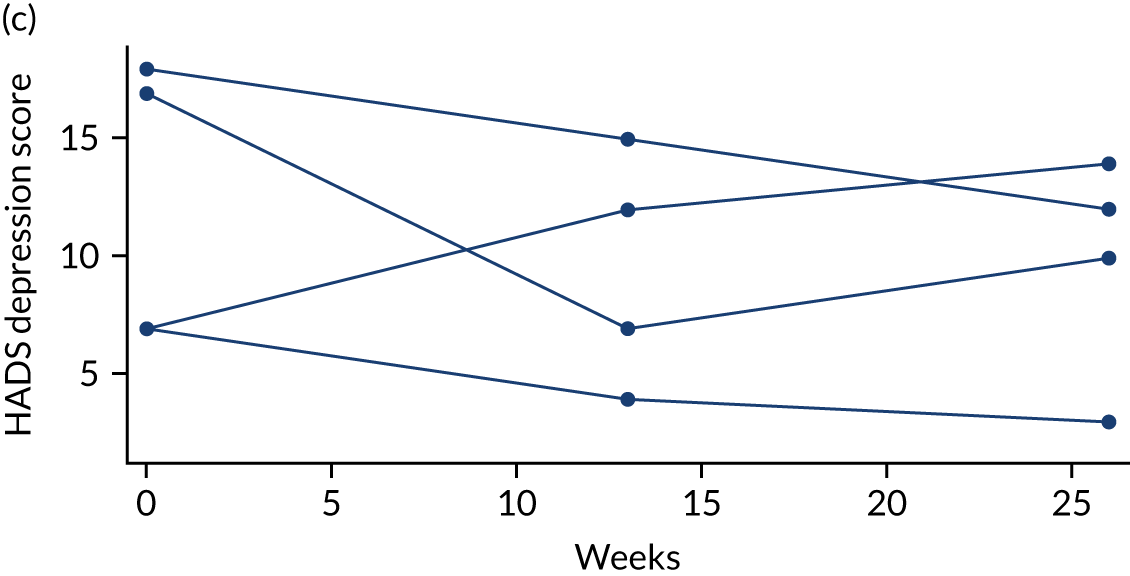

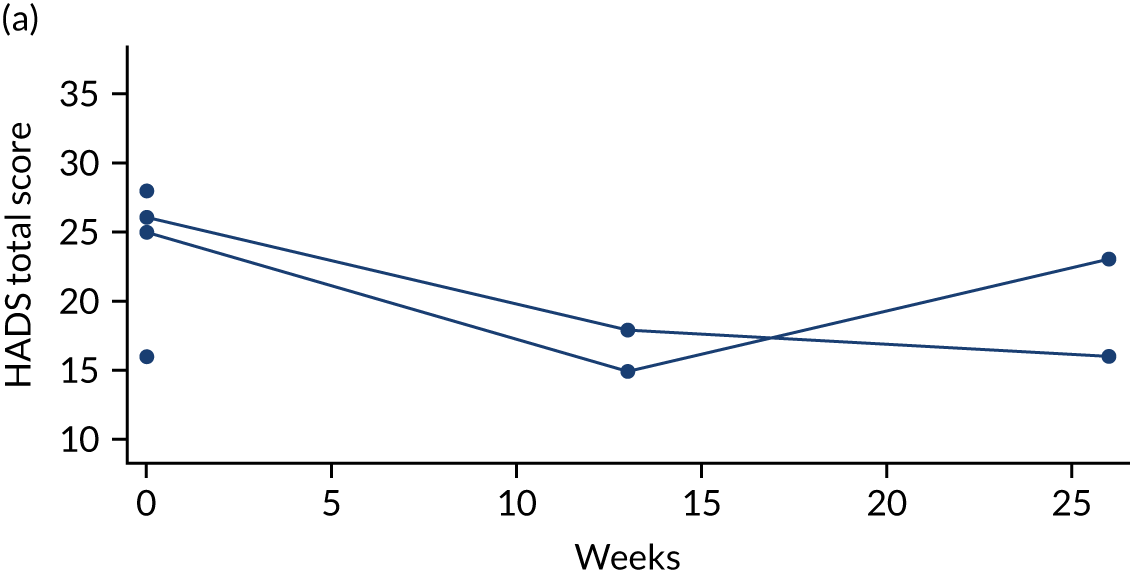

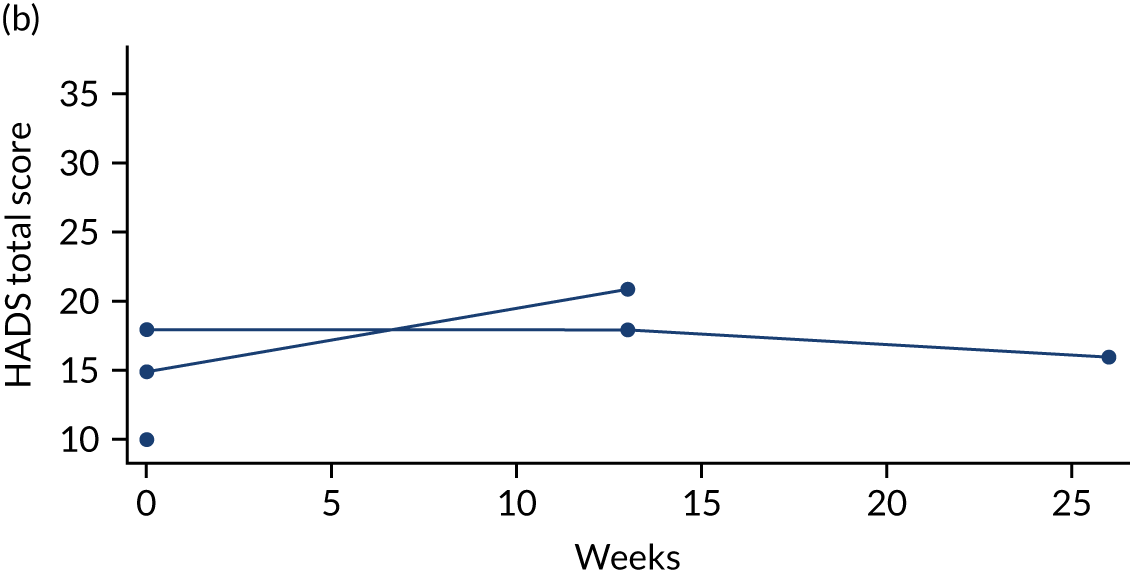

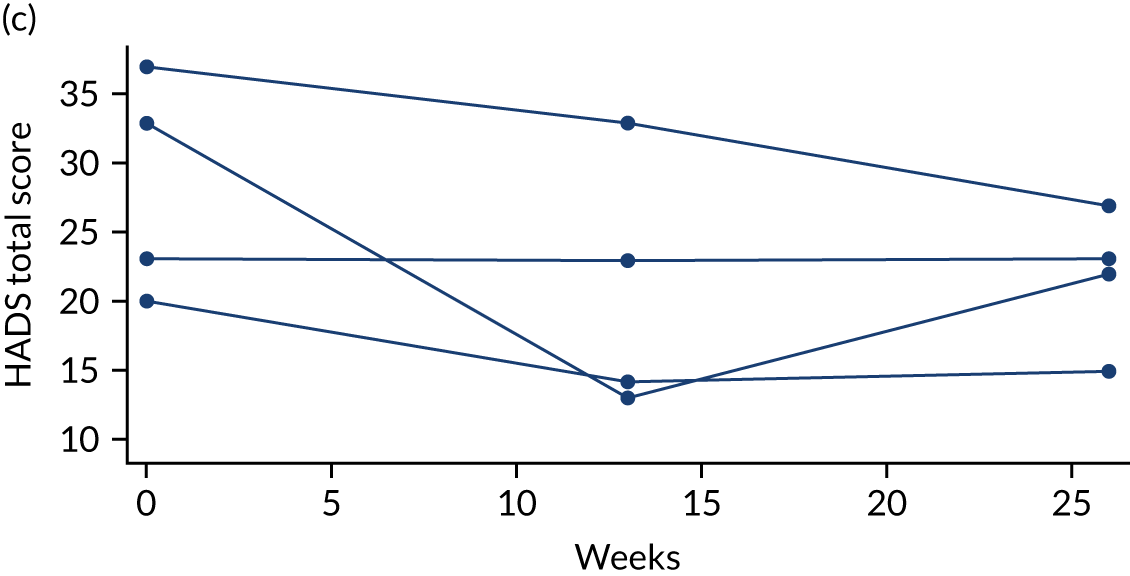

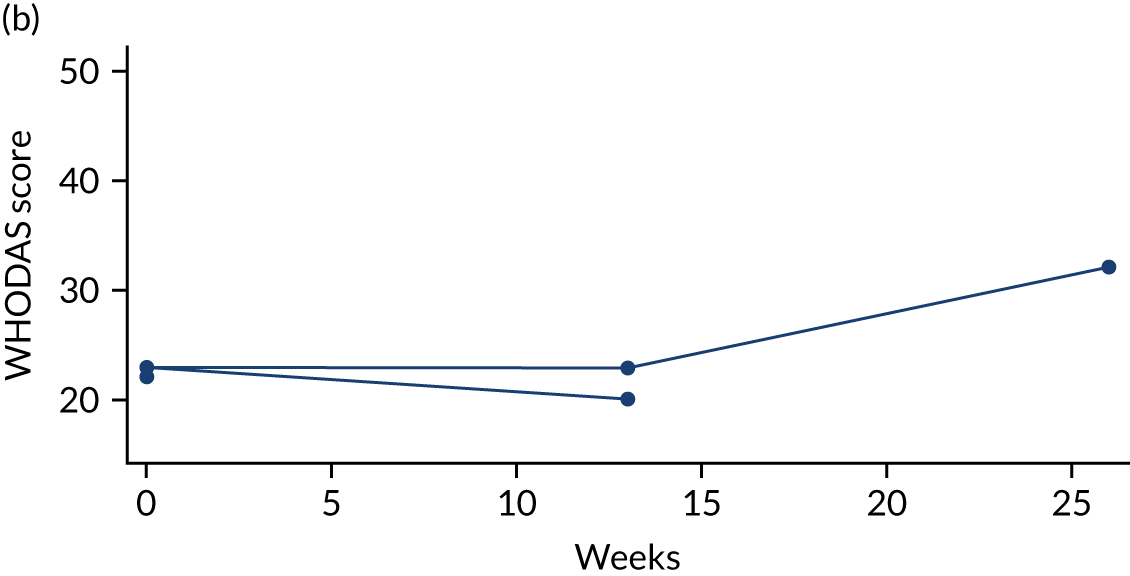

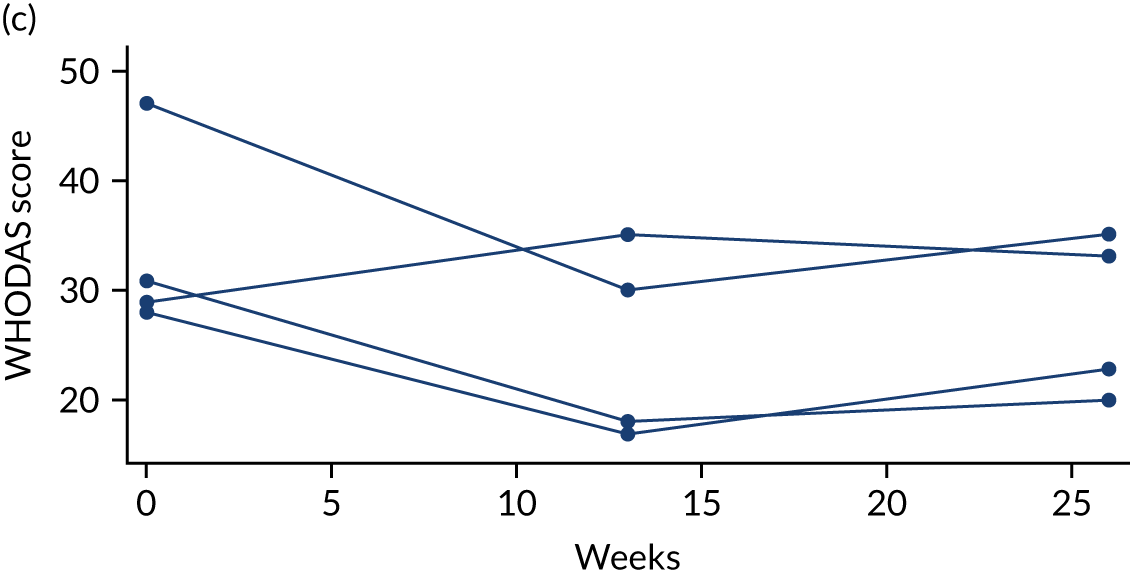

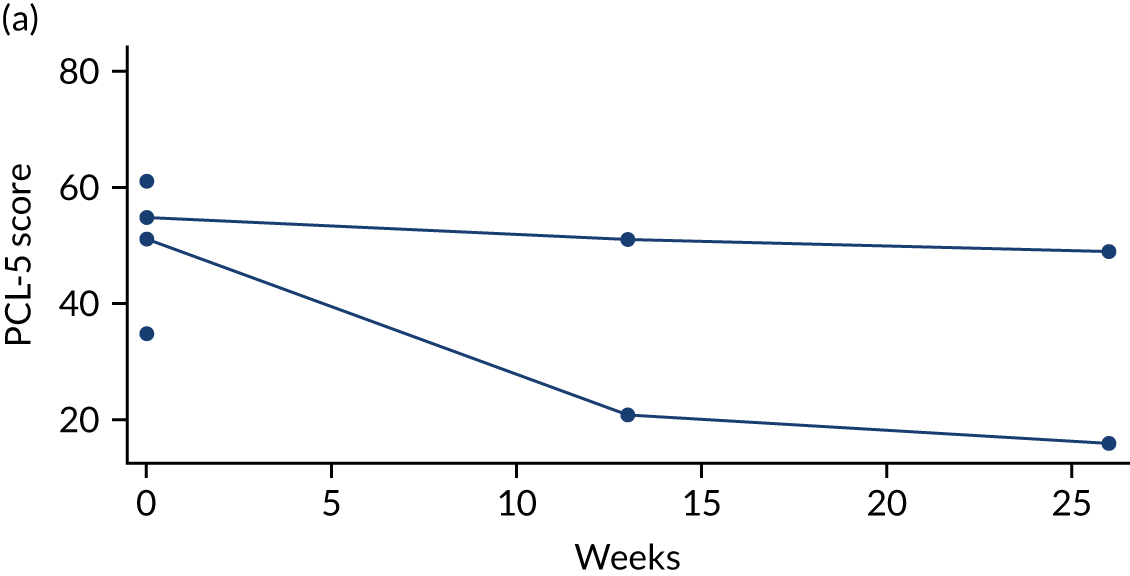

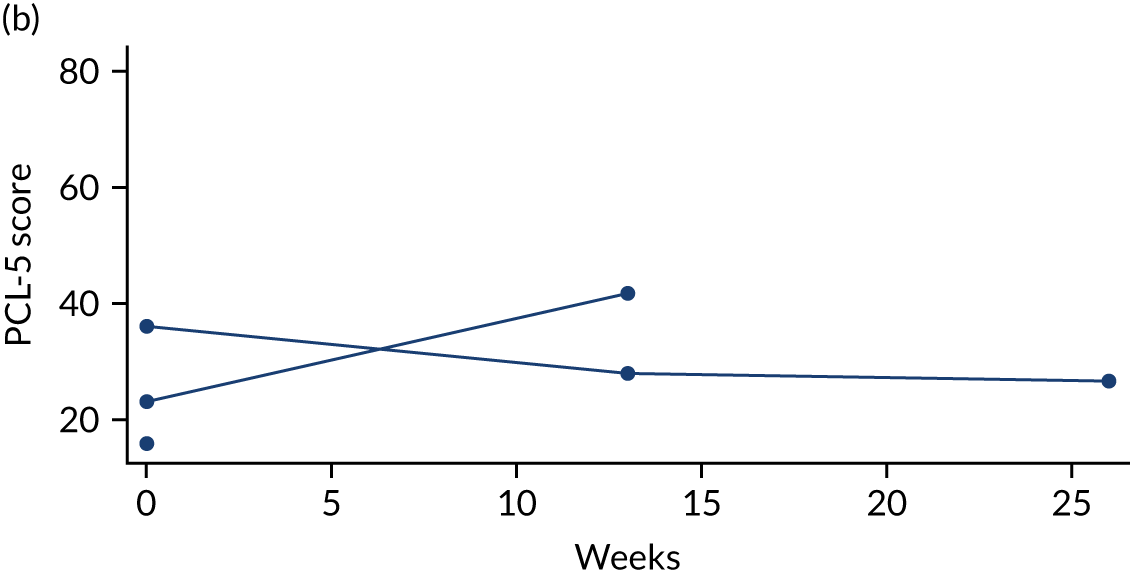

The primary objective of the PROSPER Pilot was to provide preliminary information on the potential effectiveness of group or individual PM+ compared with standard care for AS&Rs, assessed on the severity of combined anxiety and depressive symptoms at 13 weeks post baseline measured using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). 82

The secondary objectives were to provide preliminary information on the potential effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of group or individual PM+ compared with standard care for AS&Rs with regard to:

-

severity of combined anxiety and depressive symptoms at 26 weeks

-

subjective well-being

-

functional impairment

-

progress on problems for which an individual has sought help

-

post-traumatic stress disorder

-

depressive disorder

-

use of services and supports from NHS, social care and voluntary organisations.

Design and setting

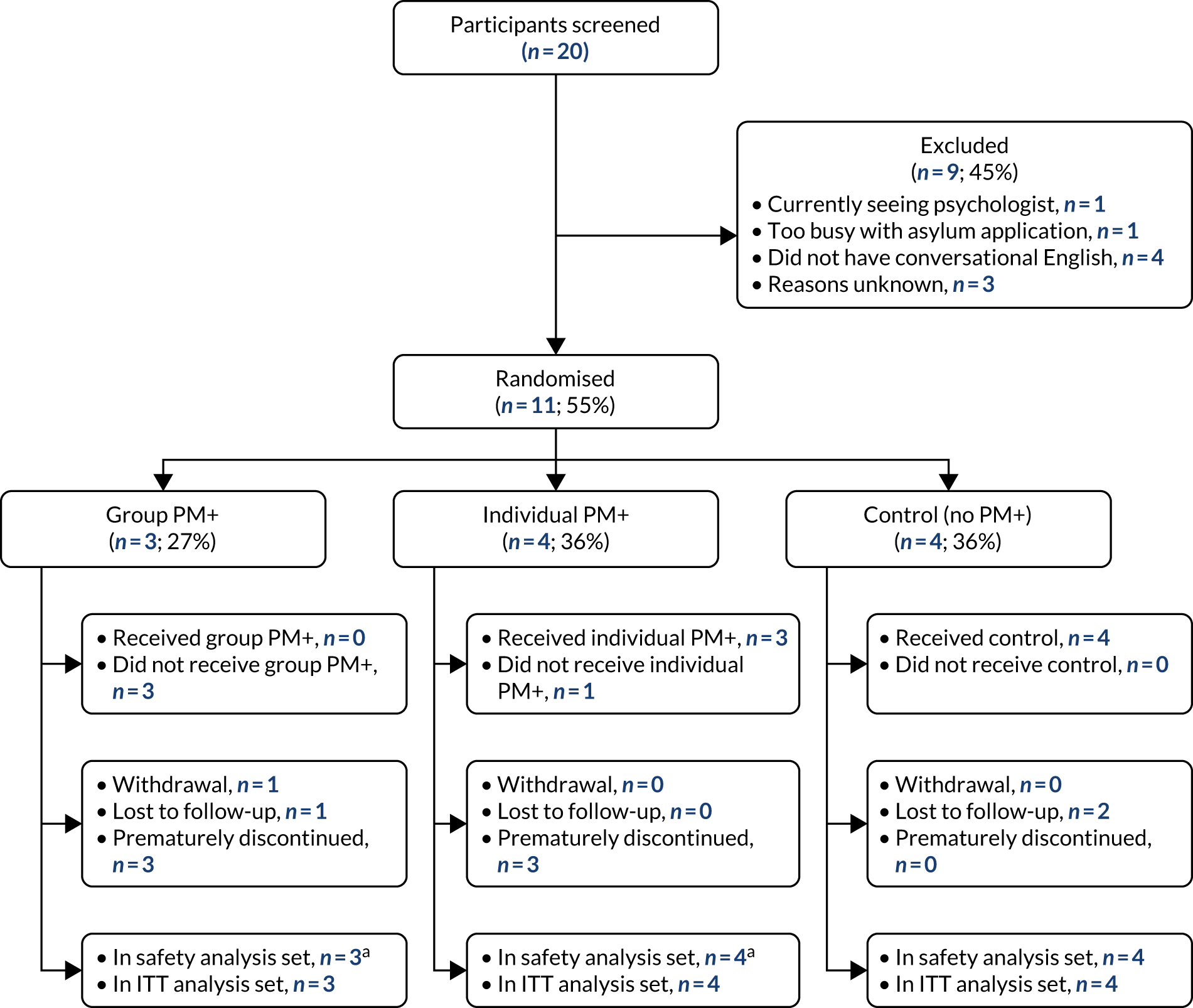

The PROSPER Pilot trial was designed as a three-arm, parallel-design pilot RCT with the features of a proposed future definitive RCT. Participants were to be randomised to receive individual PM+, group PM+ or the control (no PM+) in a ratio of 1 : 1 : 1. Appendix 2 lists all protocol amendments.

The pilot trial was conducted in Liverpool City Region. It utilised collaborative working between three universities (University of Liverpool, Liverpool John Moores University and Bangor University) and three NGOs offering advice and support to AS&Rs: PSS, Asylum Link and British Red Cross, local NGOs whose primary function is to provide advice and support to AS&Rs.

Participants

Trial participants were AS&Rs. This included those with pre-asylum status; those who had been offered either discretionary or indefinite leave to remain in the UK; those whose applications for leave to remain were pending or had been refused; those with humanitarian protection; those with refugee status; stateless people; and people in the Vulnerable Persons Resettlement Scheme.

The other inclusion criteria were:

-

aged ≥ 18 years (self-reported)

-

score of ≥ 8 on either the depression or the anxiety subscale of the HADS,82,83 and score of ≥ 17 on the WHO Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0 (WHODAS)84

-

conversational English, as self-assessed by the potential participant

-

registered with a GP in Liverpool City Region

-

willing to provide relevant socioeconomic data

-

provided written informed consent.

The exclusion criteria were:

-

New arrivals to the UK (< 28 days), owing to the high likelihood of dispersal outside the region.

-

In reception centres, usually known as initial accommodation and receiving temporary financial support under section 98 of the Immigration and Asylum Act 199985 for < 28 days: again, because of the high likelihood of dispersal outside the region.

-

Imminent risk of suicide – assessed by researcher using formal protocols, with supervision and arbitration from qualified health-care professionals.

-

Complex mental disorder (bipolar disorder/manic depression or schizophrenia) – assessed by researcher on basis of participant self-reporting a diagnosis and/or participant currently in receipt of antipsychotic medication, defined as medication listed in the British National Formulary, chapter 2 sections 2.3 (bipolar disorder and mania) and 2.6 (psychoses and schizophrenia). If required, further clinical assessment was to occur using standard formal protocols.

-

Cognitive impairment (moderate/severe intellectual disability, any dementia) – assessed by researcher on basis of participant or carer self-report.

-

Substance misuse – assessed by the researcher on basis of participant’s response to the question ‘are you currently having problems with alcohol, cocaine, marijuana or any other drugs?’ If the response was yes or equivocal, then the participant was excluded. If required, further clinical assessment occurred using standard formal protocols.

-

Currently receiving formal psychological therapy, to avoid potential confounding effects.

Outcome measures

Specific outcome measures, which are candidates for inclusion in any future definitive trial of PM+ for AS&Rs, were tested as part of the PROSPER Pilot trial. These measures are summarised in Table 4:

| Objective | Outcome measures | Time point(s) of evaluation |

|---|---|---|

| Efficacy | ||

| Severity of combined anxiety and depressive symptoms | HADS | Baseline, 13-week and 26-week follow-up assessments |

| Functional impairment | WHODAS | |

| Subjective well-being | WHO-586 | |

| Progress with problems for which participant has sought help | PSYCHLOPS87 | |

| PTSD | PCL-588 | |

| Depressive disorder | PHQ-989 | |

| Health economics | ||

| Use of services and supports from NHS, social care and voluntary sectors | Adapted CSRI90 | Baseline, 13-week and 26-week follow-up assessments |

-

HADS is a well-established 14-item scale consisting of two subscales: HADS-A (anxiety; seven items; possible score range 0–21) and HADS-D (depression; seven items; possible score range 0–21). Higher scores indicate more anxiety and/or depression. HADS has been widely used across cultures. It is sensitive to change over time and has good internal consistency, reliability and validity. 83

-

WHO-5 is validated in international studies for both clinical and psychometric properties and is available in many languages.

-

WHODAS is applicable across all health states, including mental disorders. It has good validity in terms of internal consistency, test–retest reliability and agreement with other measures of disability across countries.

-

The Psychological Outcomes Profile (PSYCHLOPS) has internal consistency and convergent validity with measures of emotional distress and is sensitive to change. It covers three domains: problems (two questions), functioning (one question) and well-being (one question).

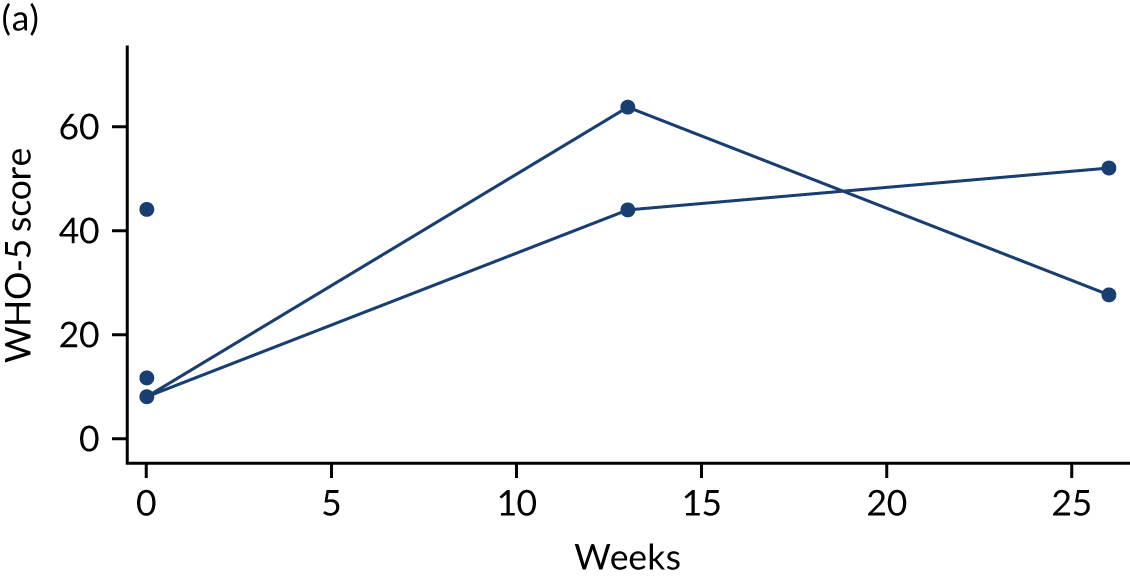

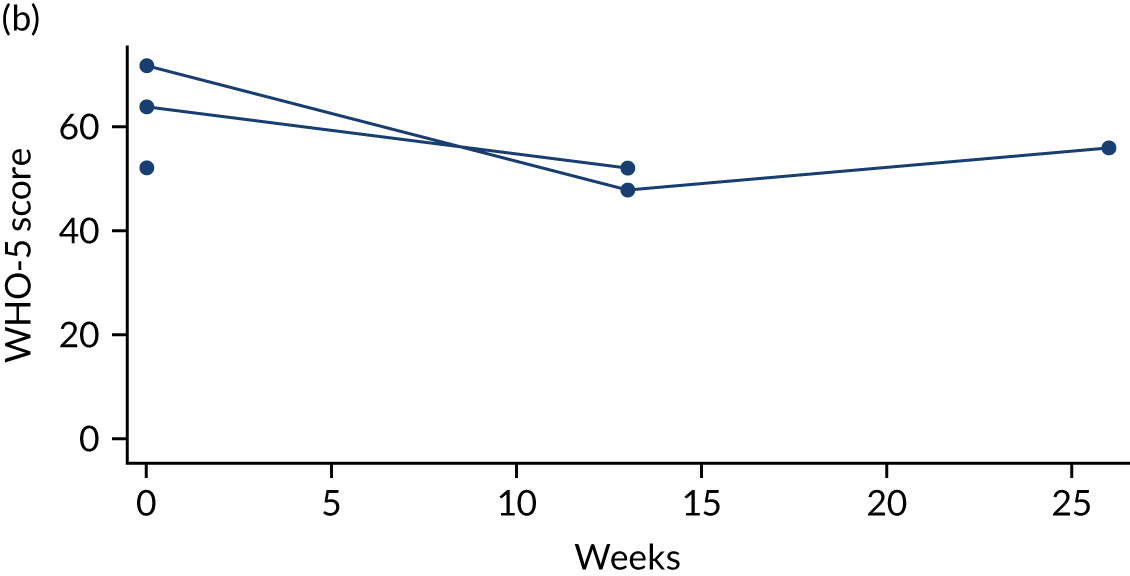

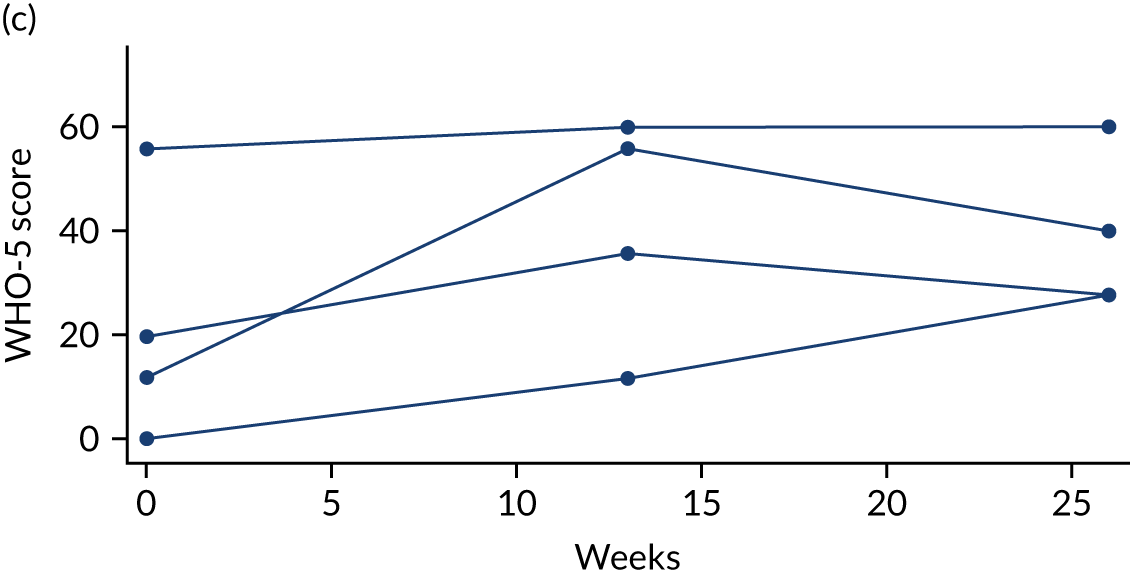

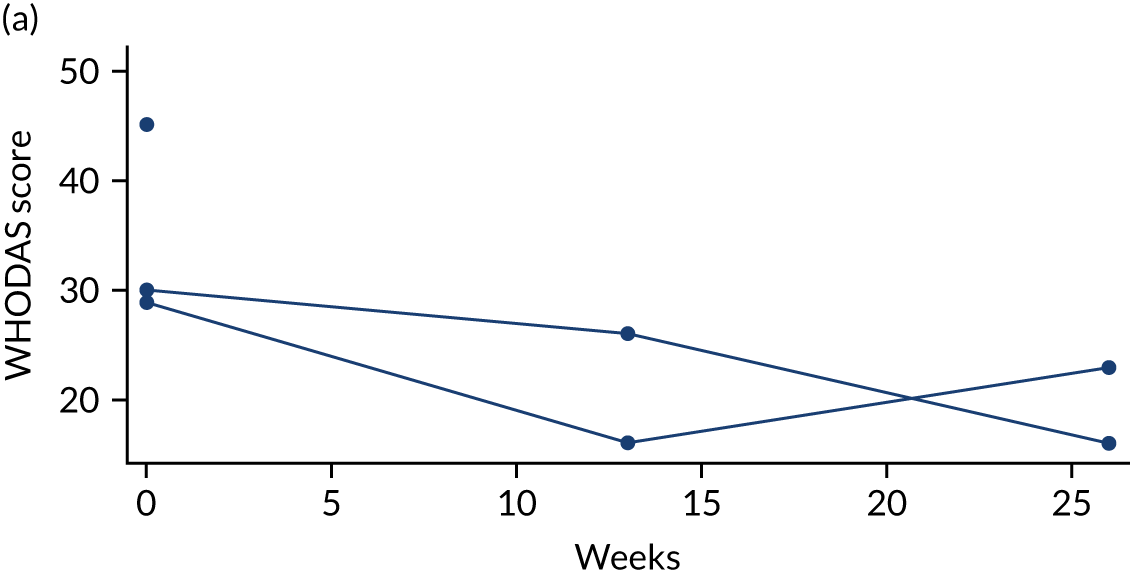

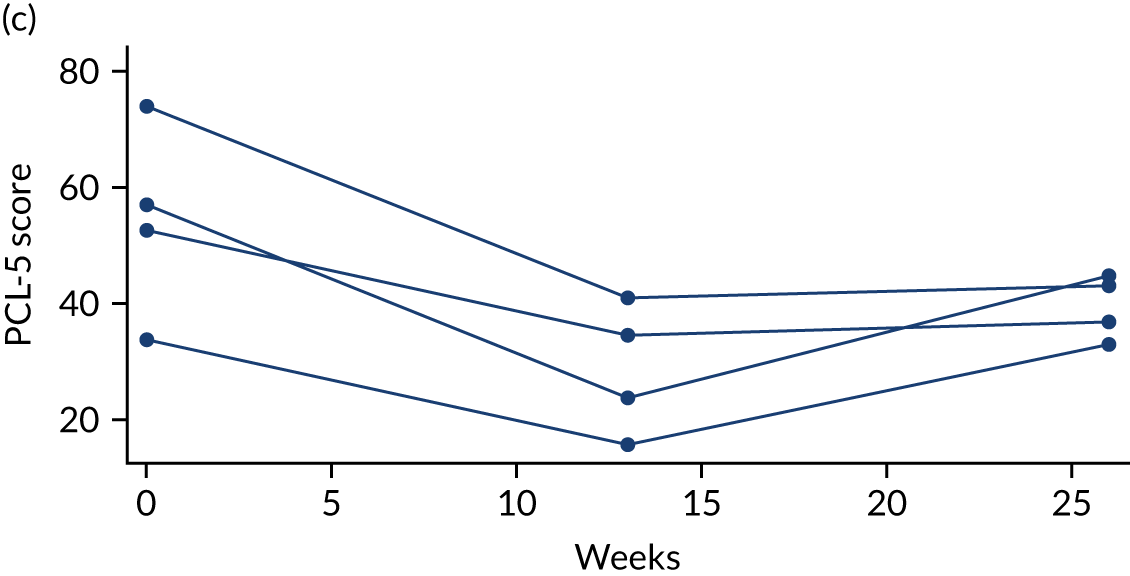

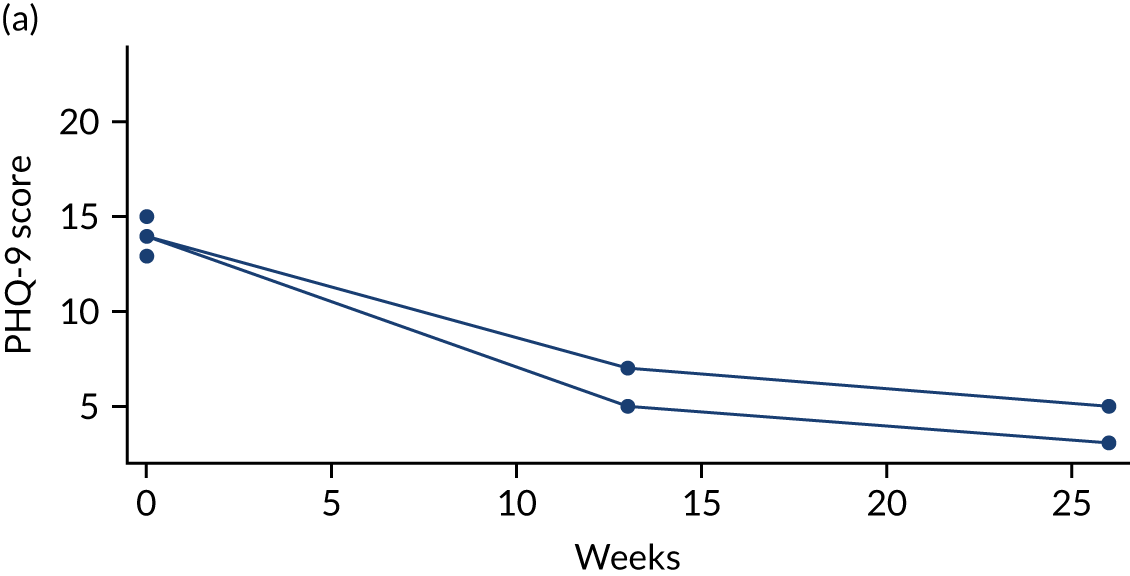

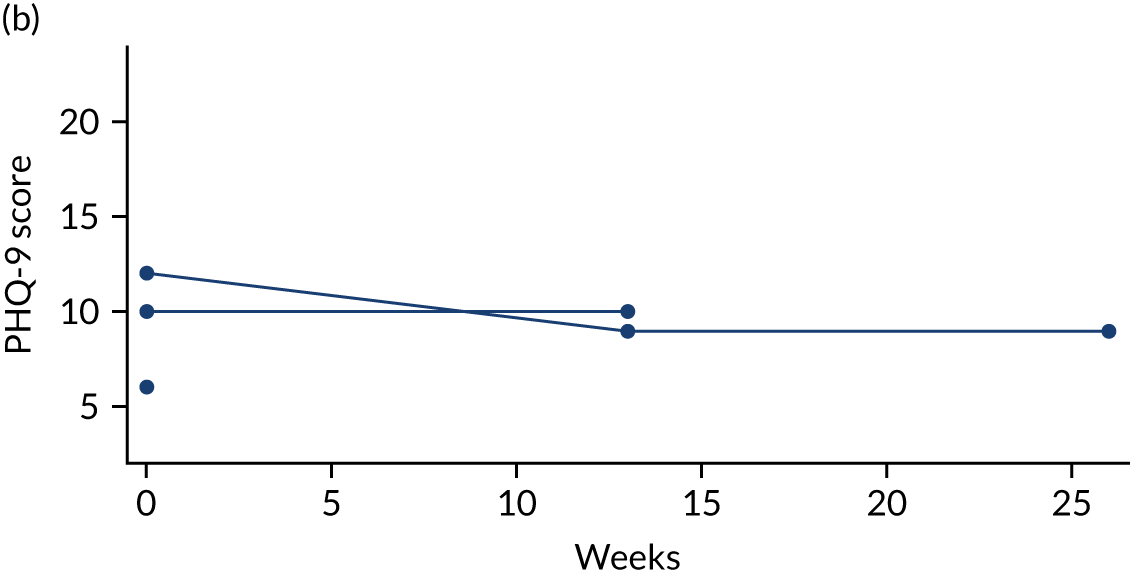

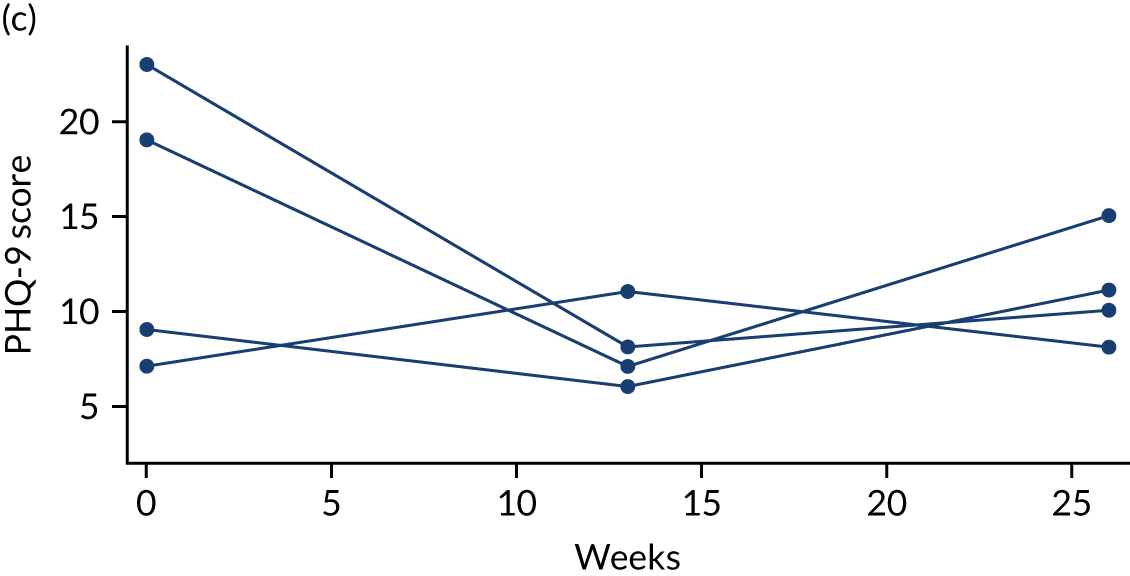

-