Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 09/3005/12. The contractual start date was in March 2011. The final report began editorial review in October 2012 and was accepted for publication in January 2013. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors' report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen's Printer and Controller of HMSO 2013. This work was produced by Shepherd et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background and rationale for the research

The importance of teachers as health promoters

The role and importance of school health education has been recognised internationally for over 50 years (World Health Organization (WHO) 1951,1 1954,2 cited in Tones and Tilford3). The early focus on health education and hygiene grew over time to recognition of the need to consider the role of the whole school environment in relation to children's health behaviours. The concept of the health-promoting school emerged in the 1990s,4,5 in which all members of the school community (pupils, parents, staff) have the opportunity to contribute to a healthy school environment. During this time there has been a growing recognition of the importance of the school as a setting for health promotion, and the integral role of teachers as promoters of health. In many countries health-promoting schools programmes were established, including the National Healthy Schools Programme (NHSP) in England. 6

Within the school curriculum issues relating to health and well-being can be addressed in a number of ways, including through personal, social, health and economic (PSHE) education (formerly referred to as personal, social and health education – more recently the term economic has been incorporated). PSHE education is a planned, developmental programme of learning designed to help learners develop the knowledge, understanding and skills they need to manage their lives, now and in the future (as defined by the PSHE Association, see www.pshe-association.org.uk). PSHE education includes the concept of personal well-being, which draws together personal, social and health education, including sex education and the social and emotional aspects of learning (SEAL). Although PSHE education is a curriculum-based activity, it may extend to broader school-based activities. Because of its broad nature, health and well-being may also be addressed by the wider curriculum, including subjects such as science, physical education (PE), citizenship and the humanities. The extent to which PSHE education is provided in schools, and more broadly health and well-being is promoted, varies for a number of reasons. Yet teachers are seen to have an increasingly important role in the wider public health workforce. A number of policy strategies have underlined the importance of the school in child health in recent years.

Health and education policies in England

One of the most influential strategies in the area of child health, education and welfare in the last 10 years was Every Child Matters (ECM). 7 ECM stressed the importance of health and safety in all aspects of children's lives, including the school, and underpinned the qualified teacher status (QTS) standards for health.

The NHSP, set up in 1999, was a major initiative to improve health, raise pupil achievement, improve social inclusion and encourage closer working between health and education providers. The NHSP had four themes, including PSHE education, healthy eating, physical activity and emotional health and well-being. A target was set for at least 75% of schools to be accredited with National Healthy Schools status. The Children's Plan: Building Brighter Futures8 emphasised the pivotal role of schools in ensuring that children are healthy and safe. It introduced the concept of ‘extended services’ with its focus on improving access to school activities for disadvantaged children and young people to reduce attainment gaps. It also set a goal for all schools to work with the NHSP. In 2009 the NHSP began rolling out its enhancement model, a universal and targeted approach to pupil well-being offering schools the challenge of meeting specific needs-led healthier behaviour outcomes. Since April 2011, with the new coalition government, the organisation of the NHSP has changed to being a voluntary schools-led initiative rather than one that is centrally driven. The resources to support schools are now in the form of the Healthy Schools toolkit, which is available to schools through the Department for Education (DfE) website. 9

Effective health promotion with children and young people, particularly the early identification and prevention of health inequalities, was also a key aspect of the Choosing Health public health strategy, launched in 2004. 10 The overall aim of the strategy was to develop and build capacity for health improvement at all levels of the system, and to better equip the wider workforce to promote health by ensuring basic skills and knowledge for more people. Furthermore, Healthy Weight, Healthy Lives: a Cross-government Strategy for England11 stated that all schools should be healthy schools, and recognised the need for improvements in staff skills and capabilities.

The Healthy Child Programme from 5 to 19 Years Old, published by the Department of Health and the Department for Children, Schools and Families (DCSF; now the DfE) in 2009,12 set out the early intervention and prevention public health programme for children, young people and their families. It highlighted the need for schools to work together with parents, carers and health professionals and to have an understanding of how to promote health and well-being.

In 2009 the Macdonald review of PSHE education13 recommended that it should be a statutory subject in the curriculum and that all initial teacher training (ITT) courses should include some focus on PSHE throughout the school life. The Macdonald review also recommended that there should be, in time, ‘a cohort of specialist PSHE education teachers’ (p. 8). However, negotiations in April 2010 between the former UK Labour government and opposition parties on the Children, Schools and Families Bill resulted in the removal of the clauses to introduce PSHE education as a statutory subject in the national curriculum at primary and secondary level.

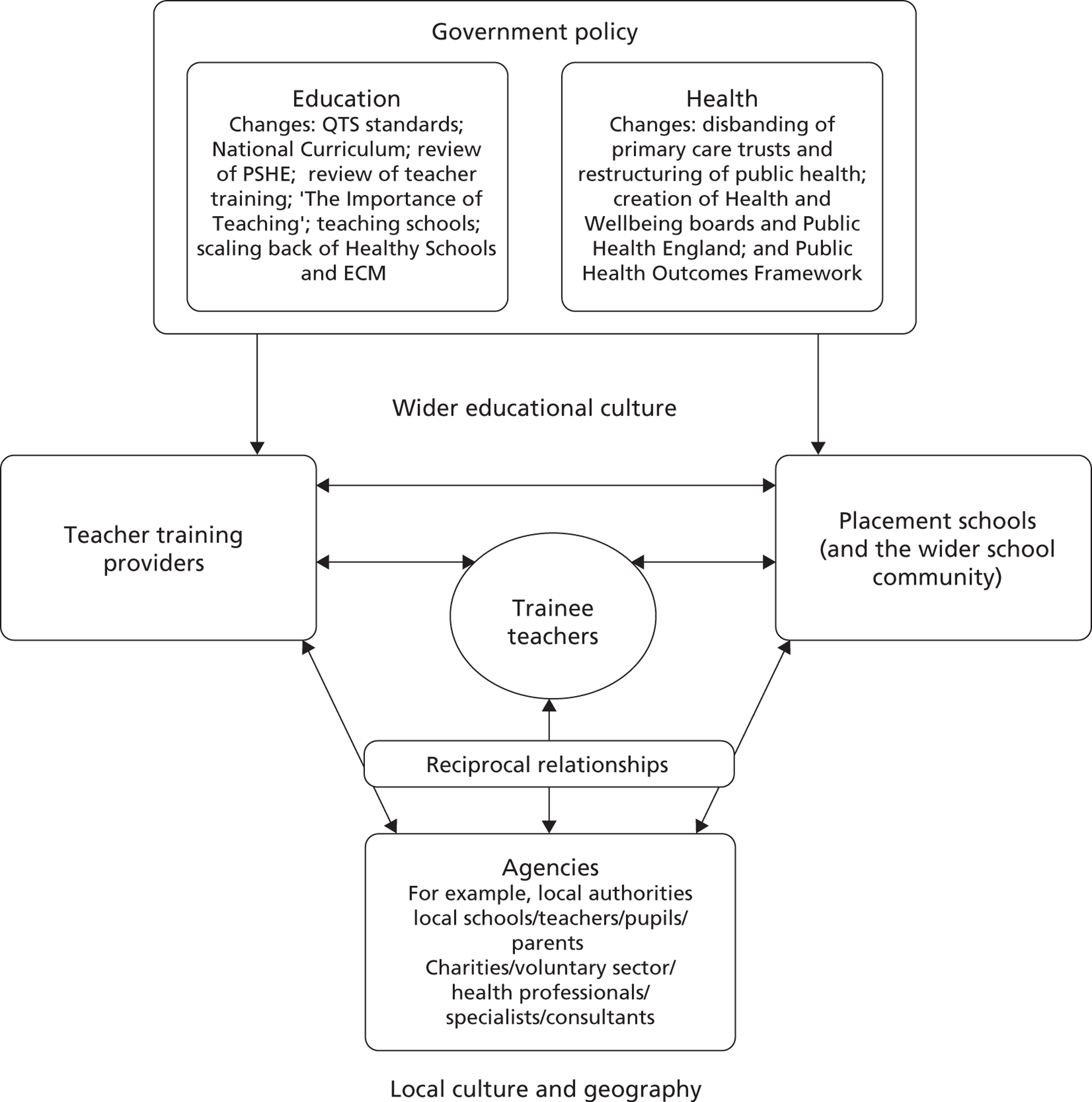

Since the election of the coalition government in 2010, the broad landscape and relationships both within and between education and health has changed. The government published its White Paper, The Importance of Teaching, in November 2010,14 which aims to set out a radical reform programme for the schools system, with schools freed from the constraints of central government direction. It also outlines how the quality of initial training and continuing professional development (CPD) will be transformed. The emphasis will be on more school- or employment-based training. Although the specific focus on health and well-being in this White Paper is less clear, it does acknowledge the fundamental role of school in a pupil's health and well-being:

Good schools play a vital role as promoters of health and wellbeing in the local community and have always had good pastoral systems. They understand well the connections between pupils’ physical and mental health, their safety, and their educational achievement.

2.48, p. 28

In 2011 the DfE published a review of the primary and secondary National Curriculum. 15 The review considered that schools should be given greater freedom over the curriculum, and that the National Curriculum should not absorb the overwhelming majority of teaching time in schools, allowing for a broad and balanced whole school curriculum. The report outlines the requirements for the National Curriculum, to be supported by programmes of study and attainment targets, and the Basic Curriculum, which describes statutory requirements in addition to those for the National Curriculum, which, although compulsory, can be locally shaped by schools. The Basic Curriculum includes sex education. In addition, schools can develop a Local Curriculum, which is non-statutory. The principles underpinning the report's recommendations demonstrate the perceived importance given to PSHE education within the Basic Curriculum. The principles acknowledge the importance of schools contributing to pupils' personal, social and emotional development as well as cognitive development and the crucial role of PSHE education, alongside subject knowledge, in supporting education and learning. Further, the report's overarching aims include:

2.16 The school curriculum should develop pupils' knowledge, understanding, skills and attitudes to satisfy economic, cultural, social, personal and environmental goals.

4. Support personal development and empowerment so that each pupil is able to develop as a healthy, balanced and self-confident individual and fulfil their educational potential.

p. 16

It is suggested that aspects of PSHE education should be included in the Basic Curriculum, and the report welcomed the DfE's internal review of PSHE education. The report also noted that it is important that PSHE education is provided in all stages of education.

The White Paper for public health, Healthy Lives, Healthy People, published in November 2010,16 set out the proposed substantial changes to the public health system in England. It is proposed that joint commissioning of health services will be carried out by local authorities in conjunction with a new body, Public Health England, and the current directors of public health will be employed within local authorities. Health and Wellbeing Boards are being set up in local authorities, comprising local authority directors of public health, social services, children's services, members of local clinical commissioning groups and elected local representatives. The boards will have strategic influence over commissioning decisions across health, public health and social care, with the emphasis on integrated services. These proposed changes will no doubt have a major impact on the way that public health and health-promotion activities are managed, and implications for the support for improvement of health education in schools. The focus will be on local commissioning of services to meet the needs identified in the Joint Strategic Needs Assessment (JSNA) and the Joint Health and Wellbeing Strategy (JWBS). However, although education is mentioned as being represented on the board, there are outstanding questions about how much of the children's agenda the board will cover, and currently little indication of what the relationship will be between schools (maintained or other) and their Health and Wellbeing Board.

Local authorities, through the Health and Wellbeing Board and direct commissioning of public health services, will be held accountable for the delivery of public health outcomes. 17 There are two main public health outcomes: increased healthy life expectancy; and reduced differences in life expectancy and healthy life expectancy between communities. There are four domains (e.g. improving the wider determinants of health, health improvement), each with detailed indicators. Some of these indicators are relevant to children's health and schools (e.g. school readiness, pupil absence, behaviour).

It is unclear how relationships will be sustained across the diversity of types of schools (education authority, academy, free, etc.) and with the Health and Wellbeing Boards and local public health services. The experience of trainee teachers will also vary considerably according to the type of school and locality. As a driver, however, the government's Public Health Outcomes Framework17 – which states the overarching aims of the reformed public health system in England for 2013–16 – may provide some support for the continued emphasis on PSHE education and health-promoting schools. Further, the lack of centralised guidance and direction on healthy schools' implementation policies places more responsibility on teachers and schools to have the skills and knowledge to formulate and deliver their local responses to this agenda.

Organisation of teacher training in England

Initial teacher training

Initial teacher training in England is currently predominantly provided by higher education institutions (HEIs) at undergraduate (e.g. Bachelor of Education, BEd) or postgraduate (e.g. Postgraduate Certificate in Education, PGCE) level. Some postgraduates choose school-centred initial teacher training (SCITT) courses, which provide a greater degree of practice-based learning, while allowing them to retain their student status. An alternative route is through employment-based initial teacher training (EBITT) whereby trainees are employed by schools and train through the Graduate Teacher Programme (GTP) or the Registered Teacher Programme (RTP). Teacher training is funded by the Teaching Agency (part of the DfE and formerly the Training and Development Agency, TDA), but additional health content may be funded from other agencies. Until September 2012, to qualify as a teacher all trainees had to meet QTS standards. 18 The standards specified 33 competencies that teachers need to attain, categorised as professional attributes, professional knowledge and understanding, and professional skills. Standard 21 related specifically to health and well-being, stating that teachers need to know about frameworks and policies around safeguarding and children and young people's health and wellbeing, and how to identify and support pupils' experiencing educational or personal difficulties, including when to refer to other professionals.

New teachers' standards were launched in September 2012, replacing the QTS. 19 Teacher training providers will need to ensure that their programmes are designed and delivered in such a way as to allow all trainees to meet these standards. Newly qualified teachers (NQTs) will also be assessed against the standards at the end of their induction period of employment. Unlike the QTS standards, the new standards do not make explicit reference to health, aside from mentioning the need to create a safe environment and to contribute to the wider life and ethos of the school. Health will be regarded as implicit throughout the standards, as exemplified in phrases such as ‘communicate effectively with parents with regard to pupils' achievements and wellbeing’ (p. 9) and ‘having regard for the need to safeguard pupils' wellbeing’ (p. 10).

A new framework for school inspection came into force in 2012. 20 Again, there is less explicit mention of health but the Office for Standards in Education, Children's Services and Skills (OFSTED) will be considering fundamental aspects such as the behaviour and safety of pupils at the school, including pupils' ability to assess and manage risk appropriately and to keep themselves safe; and the spiritual, moral, social and cultural development of pupils at the school.

The structure of ITT in England is likely to change in the future. In the Importance of Teaching14 the government states that it will reform ITT, to increase the proportion of time that trainees spend in the classroom, focusing on core teaching skills. It will also develop a national network of ‘teaching schools’, based on the model of teaching hospitals, to lead the training and professional development of teachers and head teachers, and increase the number of National and Local Leaders of Education – head teachers of excellent schools who commit to working to support other schools.

It is therefore a changing and challenging time for teacher training in England, and on the surface there appears to be a less explicit role for health and well-being within the framework for training and assessment. This raises questions about the extent to which teacher training providers will feel able to include issues relating to health within their curricula. However, it is also clear that, although less explicit, health and well-being delivered through PSHE education and the wider school ethos is understood to be fundamental to excellent education and improving pupil achievement. The move towards greater self-determination in schools will place more emphasis on teachers and other school staff having the appropriate knowledge and skills, and therefore understanding more about how teachers are currently being trained and how ITT providers are facing up to the future challenges is important. These recent changes to education and health policy are also likely to affect access to training and support around health for qualified teachers in terms of their professional development.

Continuing professional development

Qualified teachers develop their knowledge and skills as part of CPD. Within the context of health, CPD may address the provision of PSHE education or more specifically train teachers to deliver a specific health-promotion intervention (e.g. around a drugs and alcohol initiative, or a sexual health campaign). Training may also encapsulate broader school-wide health-promotion interventions (‘whole-school approaches’) involving others involved in schools with a responsibility for health (e.g. learning assistants, support staff, governors). A variety of people may train teachers around health issues, including Healthy Schools co-ordinators, health professionals (e.g. health-promotion practitioners, health advisers), youth workers, psychologists and educational professionals. Training can be provided in-service (i.e. organised by the school) or externally organised by the organisations responsible for developing specific interventions or teaching methods.

The evidence base for teacher training and health

Early attempts to assess the effectiveness of school health interventions cited a number of effective approaches, but also indicated factors that were not effective and should be discouraged. Amongst other factors, failed programmes were shown to have had little or no investment in teacher training and provision of support resources. 21 These largely related to school-based, mostly intervention-specific training programmes; even less has been written about the initial training of teachers. WHO issued a call for action for schools globally to help them respond more effectively to health, education and development opportunities. Amongst many evidence-based actions, it called for investment in capacity to support professional development programmes to build the capabilities of teachers and health professionals to plan, implement and evaluate school health initiatives. 22

To explore these issues further, ITT and CPD will be considered separately.

Initial teacher training

Since the mid-1980s, research in England and Wales has indicated that teacher education and training in health-related areas is poor and has mostly relied on in-service training, which teachers may or may not receive. 23 Progress on including knowledge and skills regarding health and well-being in the initial training and education of teachers entering the profession has been slow, both in England and elsewhere. 24 There are unanswered questions about the provision and quality of health promotion within ITT courses across England. Our previous survey research has shown that coverage of health and well-being in teacher training curricula is limited and variable in the South East of England region. 25 Using a questionnaire we surveyed 35 organisations offering ITT in 2007 (10 HEIs, 25 employment-based schemes). Fifteen (43%) organisations responded, representing 50% of the total number of trainees in the region (83% from HEIs and 17% from employment-based schemes). The results demonstrated the enormous variability of teacher training provision across the region and the lack of any consistent approach to educating student teachers about their potential roles in promoting children's health. Most organisations were found to be incorporating ECM supported by the NHSP and other external specialists, but to varying extents. Provision of information about the NHSP was also extremely variable, from nothing at all to inclusion in PSHE education or emotional health and well-being. Employment-based training organisations (i.e. EBITT providers) were more likely to have connections with the NHSP. Reasons for lack of inclusion of health issues included insufficient time in a busy curriculum and the extent to which placement schools were actively involved in the NHSP.

The extreme variability found in our survey in the amount of time allocated to health topics demonstrates a lack of consistency in interpretation of the requirements of training, leading to very little provision in many institutions compared with careful attention and innovative good practice in a few others. The survey was limited by the relatively low response rates, its timing (just before a holiday period), the length of the questionnaire (on reflection relatively lengthy) and its confinement to the South East of England. There remains, therefore, a need to assess the adequacy of provision of health initiatives within ITT curricula across England, with a sampling strategy that ensures representation from different types of providers (HEI based, employment based) and types of course (early years, primary, secondary). Such a survey will illuminate variations in practice, identify barriers and facilitators and generate recommendations for effective training and models of effective practice suitable for further evaluation.

More recently there has been further interest in researching ITT, for example considering student teachers' ways of experiencing health education as a school subject26 and guidance for teacher training for health education in France. 27

Continuing professional development and school-based health-promotion training

Personal, social, health and economic education

The 2009 Macdonald review13 suggested that there is wide variability in PSHE education conducted in both primary and secondary schools across England, in terms of content, delivery models and approaches. The DfE commissioned a mapping study of PSHE education in England to determine the prevalent models of delivery and their effectiveness for children and young people. The study, by Formby and colleagues,28 was based on a nationally representative survey of schools in England (with response rates of 22% and 34% for primary and secondary schools respectively) as well as a follow-up case study of 14 schools and sought to address a number of research questions. Three of the questions are particularly pertinent to this report: (1) what are the current skills and qualification levels of PSHE educators? (2) how do staff perceive the professional development that is currently available? and (3) what sources of support are teachers currently using? The survey found that the most effective PSHE education was delivered by well-qualified staff. However, investigation of the skills and qualifications of the PSHE workforce revealed that the vast majority of teaching staff had no PSHE education qualifications, accreditation or CPD training. Only 28% of primary schools had at least one member of staff (including nurses) with the national CPD qualification, largely because it was not easy for primary teachers to be released or funded for PSHE education CPD. The proportion was higher in secondary schools, with 45% of those surveyed reporting that one or more members of staff had the national CPD qualification. Taken as an average across the samples, these figures equate to only 3% and 5% of PSHE education staff in primary and secondary schools, respectively, holding the national qualification.

Although many staff reported good knowledge of available training opportunities, access to training and funding difficulties were rated as perceived barriers to PSHE training, particularly for secondary schools, with over half of schools reporting difficulties in releasing staff and funding them for PSHE education training. Non-accredited CPD PSHE education provided by local authorities was highly valued by primary school staff, particularly in areas where teachers were often lacking in confidence and skills [e.g. sex and relationships education (SRE) and drugs, alcohol and tobacco education]. However, for secondary school teachers, PSHE education was viewed as a low overall priority compared with training for core subjects, even in those schools in which PSHE education had a positive status.

School-based health-promotion training

There is a sizable international evidence base on the effectiveness of school-based health-promotion interventions worldwide. Stewart-Brown29 conducted a synthesis of systematic reviews of school-based health-promotion interventions and health-promoting schools [an update of the previous National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme-funded systematic review published in 199930]. Fifteen systematic reviews were included, between them comprising approximately 750 primary evaluations of school-based interventions on a variety of health issues (e.g. mental health, healthy eating, physical activity), although not all of these interventions would have been delivered by teachers.

Little has been published, at least in terms of evidence synthesis, on the effectiveness of training teachers to deliver such initiatives (either ITT or CPD), and of the barriers to and facilitators of effective teacher training and their subsequent provision of health promotion. There do not appear to be any published systematic reviews of the evidence for the effectiveness of programmes to train teachers to promote health in schools. However, some relevant primary evaluations have been published in this area evaluating teacher training to deliver specific health-promotion interventions. For example, outcome evaluations compared the effectiveness of different types of teacher training (e.g. video instruction compared with workshop training) on a range of teacher outcomes (e.g. implementation, morale, motivation, self-efficacy). 31,32

In terms of theory, the interventions have been based on a range of well-known theories of education, health and health-related behaviour change such as social learning theory, social cognitive theory, the theory of reasoned action/planned behaviour, diffusion of innovations theory and the social–ecological model. 33 Many of these theories predict the necessary mediators of effective health-related behaviour change. The training that the teachers received was designed to equip them with the knowledge, motivation, confidence and skills to facilitate, in turn, desirable improvements in mediators of pupils' behaviour, such as increasing their knowledge, their self-efficacy and their behavioural skills. For example, Kealey and colleagues,34 who evaluated the Hutchinson Smoking Prevention Project in the USA, conceptualised teacher training as a behaviour change process with a strong emphasis on teacher motivation to facilitate the intended behaviour (i.e. the teacher's effective implementation of the curriculum). Theories such as those mentioned above form part of the conceptual framework for this project.

All studies provided evaluation data on the implementation of the intervention, with varying detail given on the training received by teachers. One of the studies that provided detailed information on training was a Scottish trial of a sexual health education initiative called SHARE (Sexual Health and Relationships – Safe, Happy and Responsible). 35 An extensive process evaluation was carried out, comprising observation, questionnaires and interviews with teachers. The teachers reported that they valued and enjoyed the training very much and felt more confident to teach sex education, but a number of barriers to effective delivery of the curriculum emerged, including a lack of understanding by the teachers of the guiding theory of behaviour change and a lack of confidence to teach behaviour change skills (the key element of the intervention).

These findings, although perhaps not necessarily representative of the wider literature, suggest that additional training and support may be necessary to enable teachers to facilitate health-related behaviour change, an outcome that is considered a key marker of effectiveness by many decision-makers. 3 For example, they may require professional input from health educators to deliver skills-building exercises in the classroom, which may be essential for encouraging healthy behaviours. This will have resource and, therefore, cost implications and it underlines the need for a systematic review of the evidence to identify common overarching barriers to and facilitators of effective and efficient teacher training across a range of health topics. Recommendations would be made for health and education professionals, policy-makers and researchers to ensure that teachers fulfil their potential in promoting health and well-being in schools, ensuring that children adopt and maintain healthy lifestyles into adulthood.

Research objectives

The research questions that this research sought to answer were:

-

In what ways does teacher training prepare teachers to promote health and well-being in schools?

-

How effective are interventions to train and support teachers in health?

-

What are the barriers to, and facilitators of, effective training and delivery?

To answer these questions the project has two research objectives:

-

to conduct a survey, using quantitative and qualitative methods, of a sample of ITT providers in England to assess how health and well-being is covered in teacher training

-

to conduct a systematic review of the effectiveness of and barriers to facilitators of teacher training around health and well-being.

This project adopts a broad concept of health and well-being, based on the definition of health used by the WHO as ‘a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity’. 36 Similarly, a broad perspective on the promotion of health is taken, adopting the definition of Green and Kreuter:37 ‘any combination of educational, organisational, economic and environmental support for conditions of living and behaviour of individuals, groups or communities conducive to health’ (p. 2).

Chapter 2 Methods overview

This chapter provides an overview of the design of the project and the methods used. Further detail on the methods used in each of the components of the project can be found in subsequent chapters of this report.

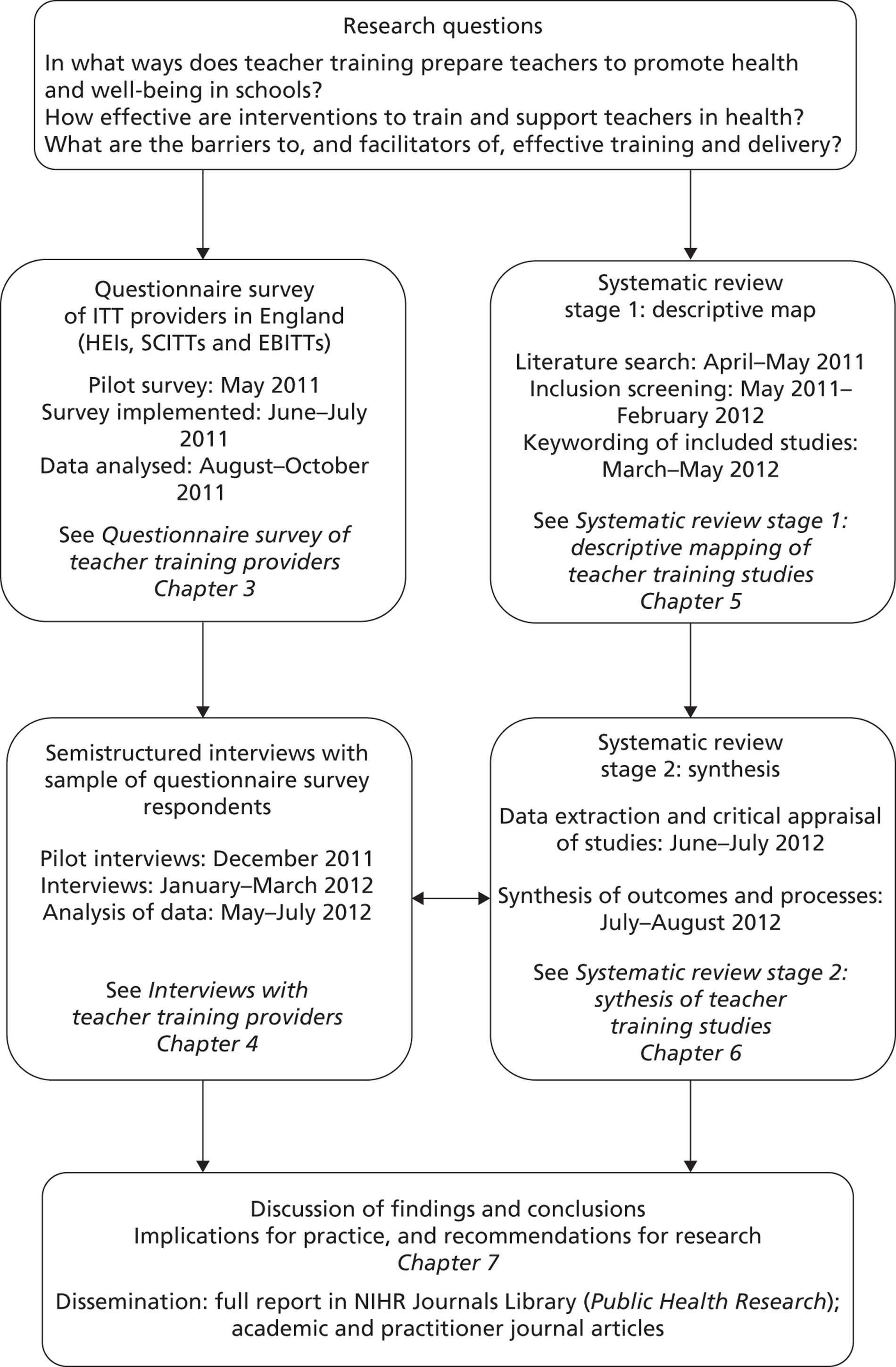

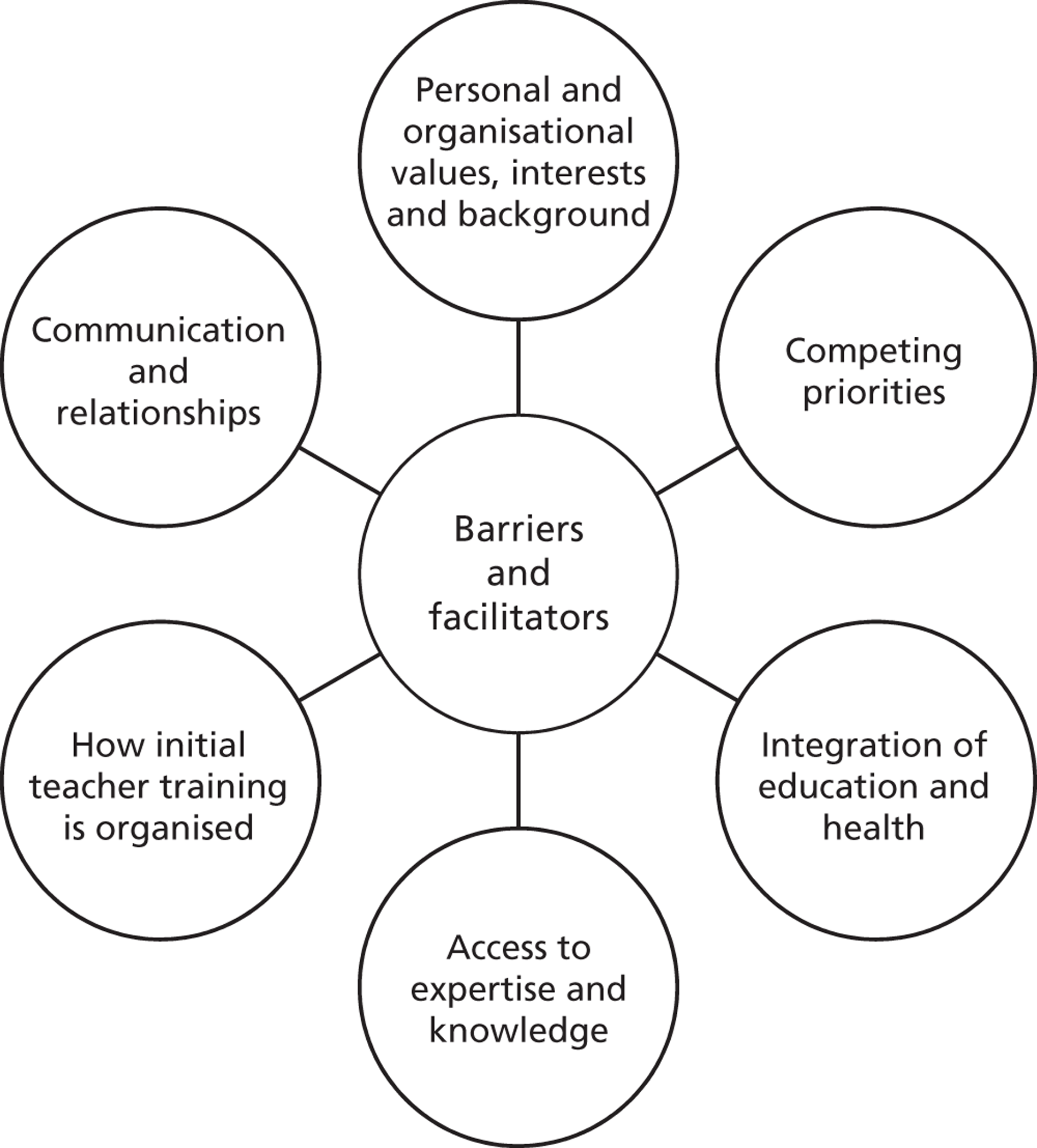

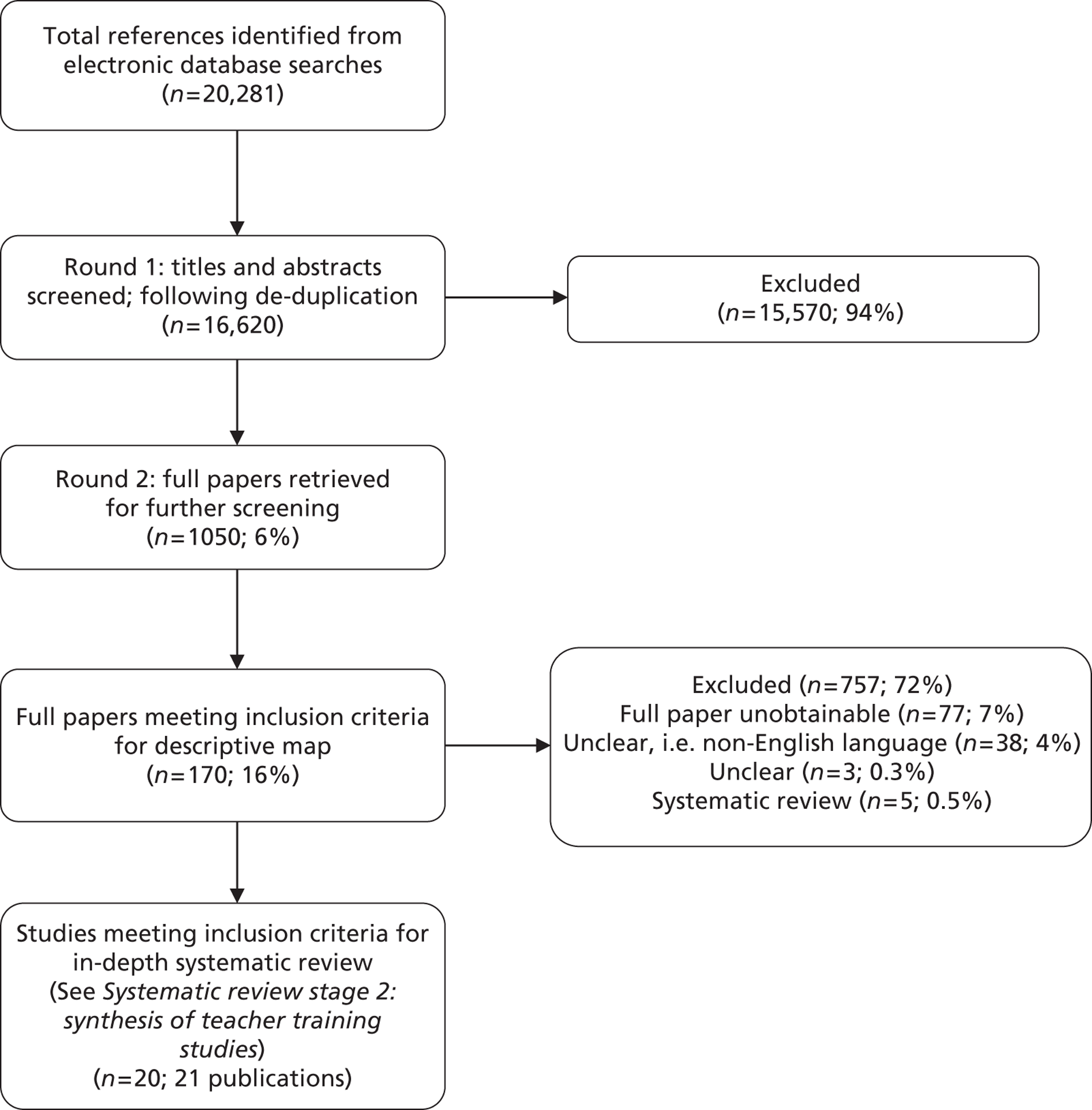

The project comprised two main components: a questionnaire and interview survey of teacher training providers and a two-stage systematic review (descriptive map of study characteristics, followed by an in-depth synthesis of prioritised studies). Figure 1 illustrates the design of the project, showing the stages of the research, including the dates that they were conducted. The two components of the project were designed to complement each other in answering the three research questions. For example, to answer ‘In what ways does teacher training prepare teachers to promote health and well-being in schools?’, the questionnaires and interviews with course managers were able to describe current practice in English ITT institutions. The systematic review was also designed to shed light on this through a descriptive mapping of the characteristics of international research studies evaluating teacher training around health and well-being. The in-depth synthesis of studies included in the systematic review was able to assess ‘How effective are interventions to train and support teachers in health’ through examining the outcomes of the studies (e.g. for teachers and pupils). The questionnaires and the interviews were also able to illuminate effectiveness through course managers' perspectives on the success of their own training in preparing teachers to promote health. Finally, the barriers to and facilitators of effective training and delivery could be assessed from the questionnaires and interviews with the course managers by asking them to discuss the factors that they consider have helped or limited their coverage of health within their training. Barriers and facilitators could also be identified from the studies included in the in-depth synthesis of the systematic review, in terms of process evaluation of training. Chapter 7 of this report discusses the findings of the survey and the systematic review together in relation to each of the three research questions.

Although the two components of the research ran broadly in parallel (see Figure 1), a reciprocal relationship between the two was intended. For example, the findings of the in-depth synthesis of the systematic review were interpreted in terms of the emerging analytical themes from the analysis of the interviews with course managers. The chapters of this report are therefore sequenced to reflect the evolution of the project (i.e. the survey and interview findings followed by the systematic review results).

FIGURE 1.

Overview of the study design.

The protocol for the research was published on the NIHR Public Health Research programme website when the project commenced, and was also registered on the PROSPERO database (international prospective register of systematic reviews; www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero) (see Appendix 1).

Chapter 3 Questionnaire survey of teacher training providers

Methods for the questionnaire survey of teacher training providers

Questionnaire development

The questionnaire was devised between April and May 2011 and was designed to cover a range of issues in keeping with the aims of the study (e.g. how health and well-being is covered in ITT courses, in terms of who provides training, topics, methods and assessment, and any barriers and facilitators). The questionnaire was based on the one used in our previous survey of ITT providers in the South East of England,25 although it underwent extensive adaptation with the addition of a number of questions (e.g. asking respondents to describe how they think current policy changes in education will affect their courses). A range of question types was used including closed-ended questions, questions with pre-coded response categories, Likert scales and open-ended questions. The draft questionnaire underwent a number of revisions with input from all team members and the project's advisory group, who suggested minor changes. It was intended that the questionnaire would take around 10 minutes to complete and would be administered online via the internet using specialist survey software (SelectSurvey.net, version NETv4.068.002; Classapps, Kansas City, MO, USA).

Once internal revision was complete, the questionnaire was piloted in May 2011 with a sample of one HEI, one EBITT provider and one SCITT provider, randomly selected (using a random number generator in a spreadsheet) from each of the nine English regions (formerly known as the Government Offices for the Regions) (see following section for more detail on sampling). The purpose of piloting was to assess the effectiveness of the questionnaire itself in eliciting relevant information, as well as the process of recruiting, sampling and questionnaire administration. In the first wave of sampling the EBITT and SCITT providers were sent the questionnaire by e-mail, and the head of the education department of each HEI was contacted to introduce the study and to ask for the names and contact details of their course managers. In the second wave the course managers whom the HEI heads of department had named in their institution were sent the questionnaire by e-mail.

The response rate to the pilot was 37% (13/35 course managers surveyed). The data elicited from the questionnaires were variable in terms of the level of detail of the responses to the open-ended questions and the proportion of missing data. Following some minor revisions (e.g. removal of less relevant questions to shorten the questionnaire, some reordering of questions) we considered the questionnaire to be of suitable standard for full implementation. The final version is in Appendix 2.

Sampling

Sampling and recruitment of ITT providers began in May 2011 ready for a planned June survey launch. Our sampling frame was the 208 ITT providers in England listed on the TDA (now the Teaching Agency) website (as of May 2011). This included 74 HEIs, 57 SCITT providers and 77 EBITT providers. It was considered that surveying all providers would not be feasible in terms of time and resources (except for SCITT providers; see later in this section) and so a sampling approach was undertaken.

Initial teacher training courses vary in their duration from a 1-year PGCE to 3- or 4-year undergraduate degrees (BA/BSc with QTS or BEd). There are also variations in the level of education that they specialise in (e.g. primary, secondary, key stage 2/3) (Table 1).

| Type of provider and level of education | Undergraduate | Postgraduate |

|---|---|---|

| HEI (e.g. university) | ||

| Early years | BA/BSc, BEd, RTP | PGCE |

| Primary | BA/BSc, BEd, RTP | PGCE, GTP, OTTP |

| Secondary | BA/BSc, BEd, RTP | PGCE, GTP, OTTP |

| Key stage 2/3 | BA/BSc, BEd, RTP | PGCE |

| Post-compulsory | BA/BSc, BEd, RTP | PGCE |

| SCITT | ||

| Primary | – | PGCE (with QTS)/QTS |

| Secondary | – | PGCE (with QTS)/QTS |

| EBITT | ||

| Primary | RTP | GTP, OTTP |

| Secondary | RTP | GTP, OTTP |

School-centred initial teacher training programmes are designed and delivered by groups of neighbouring schools and colleges. SCITT courses lead to QTS, and some will also lead to a PGCE validated by a HEI. EBITT courses are run by consortia of schools, colleges and local authorities (although note that some universities also offer EBITT courses). On the GTP, graduates can attain QTS while training and working in a paid teaching role. The GTP normally takes between 3 months and 1 school year, working full-time, to complete. The RTP combines work-based teacher training and academic study, allowing non-graduates with some experience of higher education to complete their degree and qualify as a teacher at the same time. This course normally takes 2 years to complete. The Overseas Teacher Training Programme (OTTP) is for qualified teachers from overseas who wish to attain qualified teaching status in England. Courses can last up to 1 year. Key stage 2/3 courses cover children in the age range 8–11 years (key stage 2) and 11–14 years (key stage 3). Early years generally covers the 3–7 years age group.

The ITT providers in England were classified according to the nine English regions. Table 2 shows that the number of providers in each region varied from 14 (North East) to 36 (Eastern). We sampled ITT providers within each of the regions to ensure that all areas of England were represented, given that there may be geographical variations in teacher training practice in relation to health and well-being.

| Region | Type of provider | No. of providers |

|---|---|---|

| Eastern | HEI | 6 |

| SCITT | 15 | |

| EBITT | 15 | |

| Total | 36 | |

| East Midlands | HEI | 7 |

| SCITT | 4 | |

| EBITT | 8 | |

| Total | 19 | |

| London | HEI | 13 |

| SCITT | 7 | |

| EBITT | 12 | |

| Total | 32 | |

| North East | HEI | 4 |

| SCITT | 6 | |

| EBITT | 4 | |

| Total | 14 | |

| North West | HEI | 7 |

| SCITT | 1 | |

| EBITT | 6 | |

| Total | 14 | |

| South East | HEI | 10 |

| SCITT | 5 | |

| EBITT | 14 | |

| Total | 29 | |

| South West | HEI | 8 |

| SCITT | 13 | |

| EBITT | 5 | |

| Total | 26 | |

| West Midlands | HEI | 9 |

| SCITT | 5 | |

| EBITT | 7 | |

| Total | 21 | |

| Yorkshire and the Humber | HEI | 10 |

| SCITT | 1 | |

| EBITT | 6 | |

| Total | 17 |

Our sampling strategy varied according to the type of provider in each region, as follows:

-

Random sample of 50% of each of the HEIs within each region. Our initial course mapping showed that the number and range of courses on offer varied considerably by HEI. For example, in the South East region of England, the University of Portsmouth offered (at that time) just two courses, both at postgraduate level. In contrast, Canterbury Christchurch University offered 10 courses covering undergraduate and postgraduate level. To obtain balance we took a random sample of 50% of HEIs classified as offering a ‘low’ number of courses and 50% of those classified as offering a ‘high’ number of courses (low and high to be determined by the average number of courses per provider in a region). We identified the number of courses offered by a HEI through a systematic mapping of each institution's website, with details logged in a spreadsheet database. A questionnaire was to be sent to each QTS-bearing course offered by the sampled HEIs, resulting in sampling of approximately 50–60% of available courses in each region.

-

A random sample of 50% of EBITT providers in each region. As EBITT providers generally offer fewer courses we did not classify them as high or low. (Note: HEI-run EBITT courses, such as the GTP, were sampled as above in 1.)

-

Survey of all SCITT providers. This was considered feasible as there are relatively fewer of them and they offer only a limited range of courses (e.g. one to two courses per SCITT provider).

Recruitment

Recruitment followed a similar approach to that described in the previous section for the pilot questionnaire. For HEIs we first e-mailed the head of the education department in each institution to introduce the project and to ask them to complete a short structured online proforma providing us with the name and contact details of the tutor of each of their ITT courses. This was primarily to ensure that we had accurate details of all courses, as the institutions' websites did not always appear to be up to date. It was also a courtesy so that the departmental head was aware that staff members were being surveyed, and it was anticipated that their support might potentially increase the response rate. A reminder e-mail was sent 2 weeks after the initial e-mail where a response had not been received. If a response was not received following the reminder we obtained the details that we required from the institution's website, supplemented when necessary with a telephone call to the department administrator to clarify which courses were offered and/or the contact details of the course managers.

When a response had been received from the relevant departmental head we e-mailed the course managers whose details had been provided, asking them to complete the online questionnaire. The e-mail briefly specified the purpose of the study and why they had been chosen, and provided a guarantee that their responses would remain confidential and anonymised in the dissemination of the project. Again, after 2 weeks, if no response had been received an e-mail reminder was sent. If no response was received following the reminder they were logged as a non-responder in our database.

We contacted the course managers directly in each randomly sampled EBITT provider and in each SCITT provider, again by e-mail, and asked them to complete an online questionnaire using the same process as that for the HEI course managers. They were contacted at the same time as the heads of department in the HEIs. In all cases consent to participate in the study was assumed by the response to the questionnaire.

To enhance response rates the course managers were offered a monetary incentive. All responders were entered into a prize draw to win an Amazon gift voucher. The first prize was a £50 voucher and the second a £30 voucher.

Ethical approval for the survey and the subsequent interviews (see Chapter 4) was provided by the University of Southampton Faculty of Medicine Ethics Committee (ethics approval number: SOMSEC080.10). Insurance for the study was provided by the University of Southampton, who acted as research sponsor.

Data analysis

Data were downloaded from the online questionnaire tool (SelectSurvey.net) directly into a spreadsheet. The quantitative questionnaire data were analysed using standard descriptive statistics (e.g. counts and percentages). The data were tabulated and for some questions transformed graphically in bar charts. The qualitative data elicited from the open-ended questions were analysed using a basic content analysis approach, with similar responses grouped together in summary categories.

Results of the questionnaire survey of teacher training providers

Response rates

Table 3 shows the survey response rates stratified according to type of teacher training institution provider sampled and English region. The overall response rate was 34%. As the table shows, the percentage response rate varied by type of provider and by region. The regions with the highest percentage responses were Yorkshire and the Humber (56%), followed jointly by the North East (42%) and the South West (42%). No responses were received from any of the providers sampled in the West Midlands region. The highest rate of response was from the SCITT providers, followed by the HEI course managers and then the EBITT providers.

| Region | HEI (first contact), n/N (%) | HEI (course managers), n/N (%) | SCITT, n/N (%) | EBITT, n/N (%) | Total (not including first contact), n/N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eastern | 1/3 (33) | 3/12 (25) | 6/14 (43) | 3/8 (38) | 12/34 (35) |

| East Midlands | 0/3 (0) | 4/12 (33) | 0/3 (0) | 0/4 (0) | 4/19 (21) |

| London | 2/6 (33) | 6/13 (46) | 3/6 (50) | 0/3 (0) | 9/22 (41) |

| North East | 0/3 (0) | 2/12 (17) | 4/5 (80) | 2/2 (100) | 8/19 (42) |

| North West | 0/0 (0) | 1/10 (10) | 1/1 (100) | 2/3 (66) | 4/14 (29) |

| South East | 1/6 (17) | 13/33 (39) | 0/3 (0) | 1/5 (20) | 14/41 (34) |

| South West | 2/4 (50) | 7/17 (41) | 6/12 (50) | 1/4 (25) | 14/33 (42) |

| West Midlands | 1/5 (20) | 0/14 (0) | 0/4 (0) | 0/4 (0) | 0/22 (0) |

| Yorkshire and the Humber | 1/5 (20) | 7/12 (58) | 1/1 (100) | 1/3 (33) | 9/16 (56) |

| Total | 8/35 (23) | 43/135 (32) | 21/49 (43) | 10/36 (28) | 74/220 (34) |

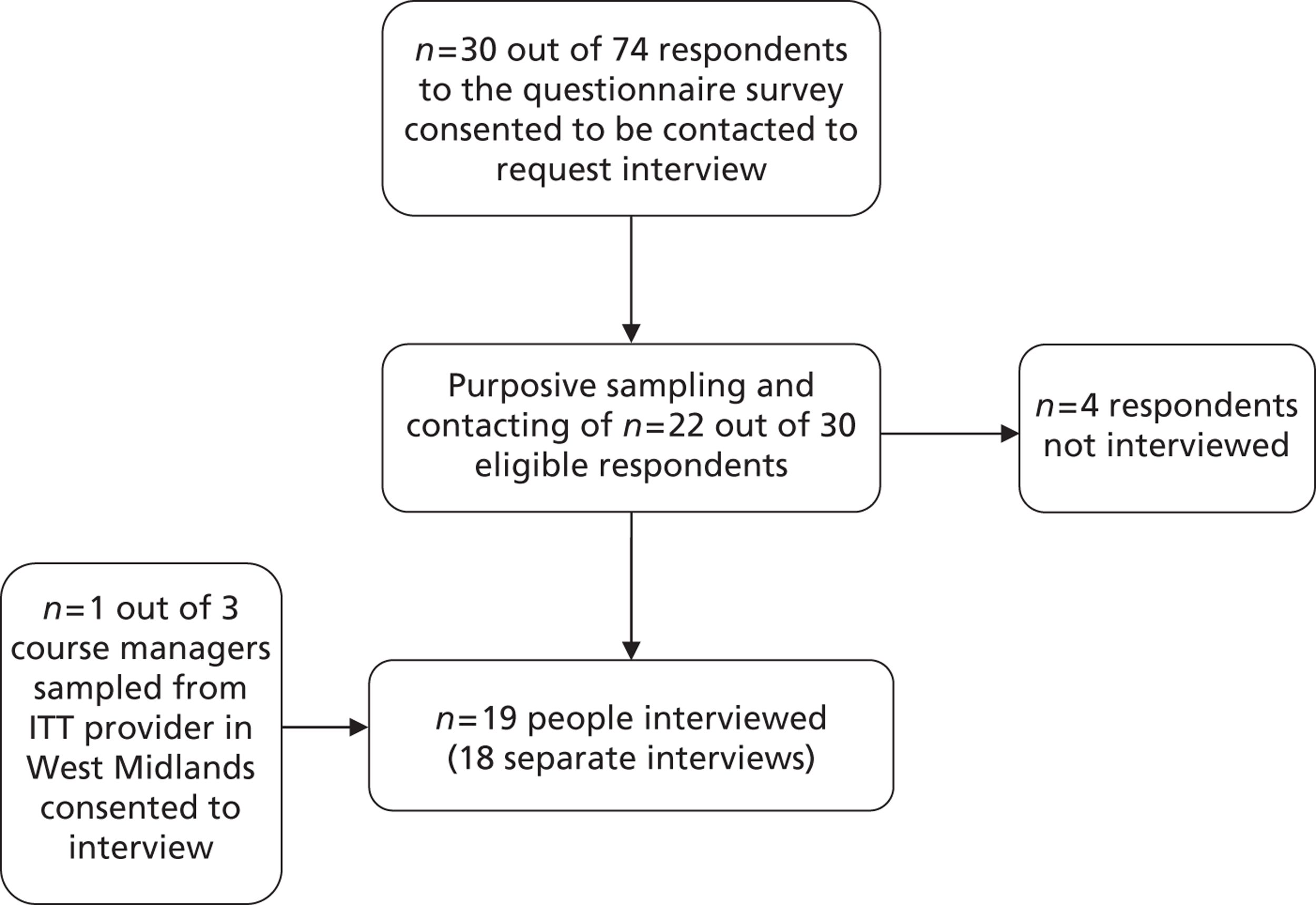

The respondents were asked if they would be willing to be contacted to take part in the follow-up interviews planned for this project (see Chapter 4). Of the 38 HEI respondents who answered this question, 19 (50%) agreed to be contacted; of the 16 SCITT respondents who answered this question, seven (44%) agreed to be contacted; and of the nine EBITT respondents who answered this question, four (44%) agreed to be contacted. The total number of survey respondents who agreed to be contacted was therefore 30.

Details of the respondents

Amongst the HEI respondents, when asked to describe their role, all reported that they managed, led or directed one or more teacher training courses. In some cases this was in addition to other duties such as senior management, assuring the quality of teaching across their institution, developing appropriate CPD and training for staff and conducting research. In some cases more than one person from each HEI sampled responded to the questionnaire. This was a result of the sampling strategy in which providers were sampled at random and all of their course managers were sent questionnaires. Of the SCITT and EBITT respondents, all described themselves as having responsibility for one or more teacher training courses. In addition, some of them also had responsibility for overall management of the organisation itself.

Respondents were asked to tick the ITT course(s) that they managed. Of the 43 HEI course managers who responded, 22 (51%) reported managing one course, 14 (33%) managed two courses, six (14%) managed three courses and one (2%) managed four courses. Between them they managed a total of 72 courses.

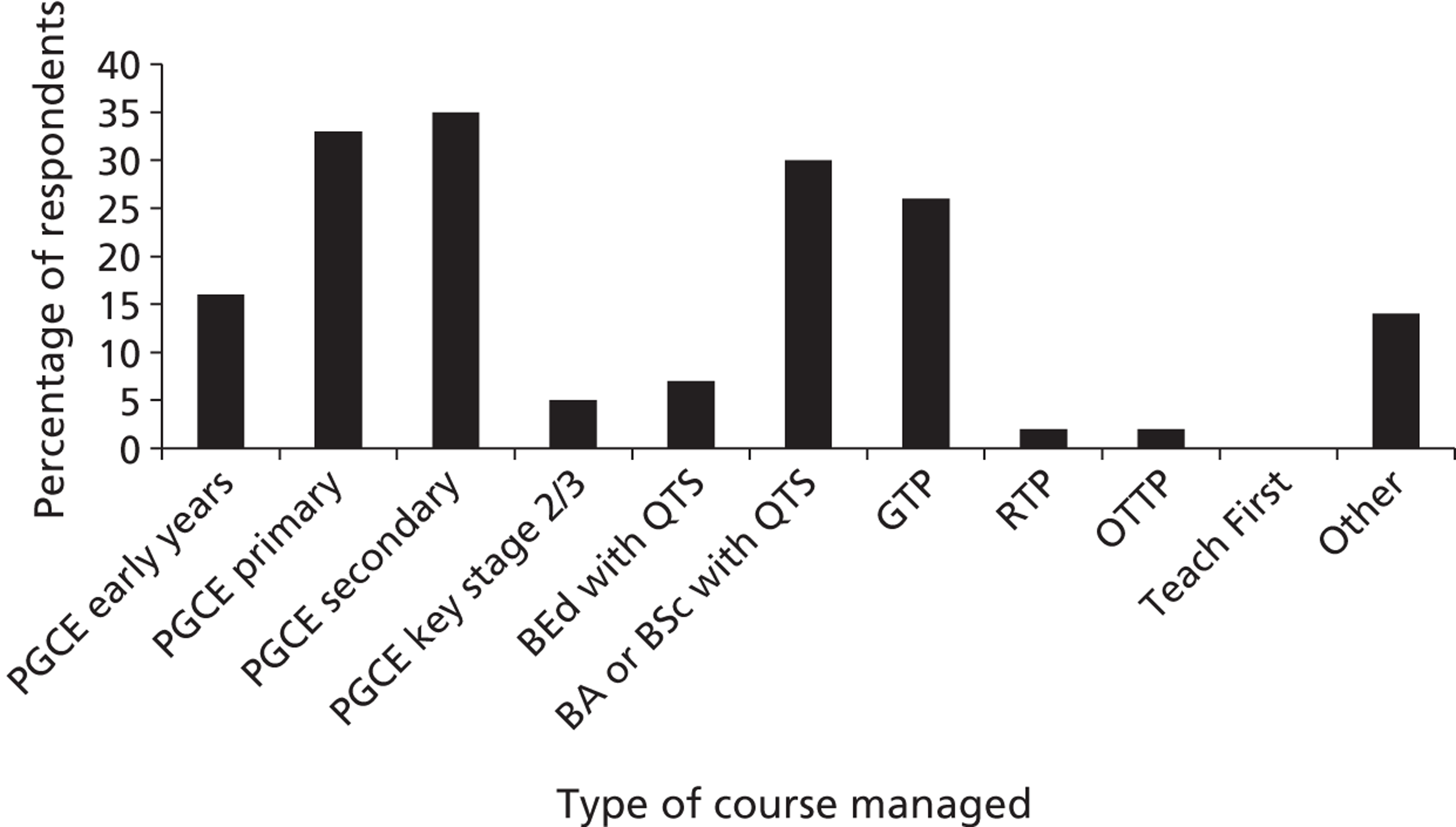

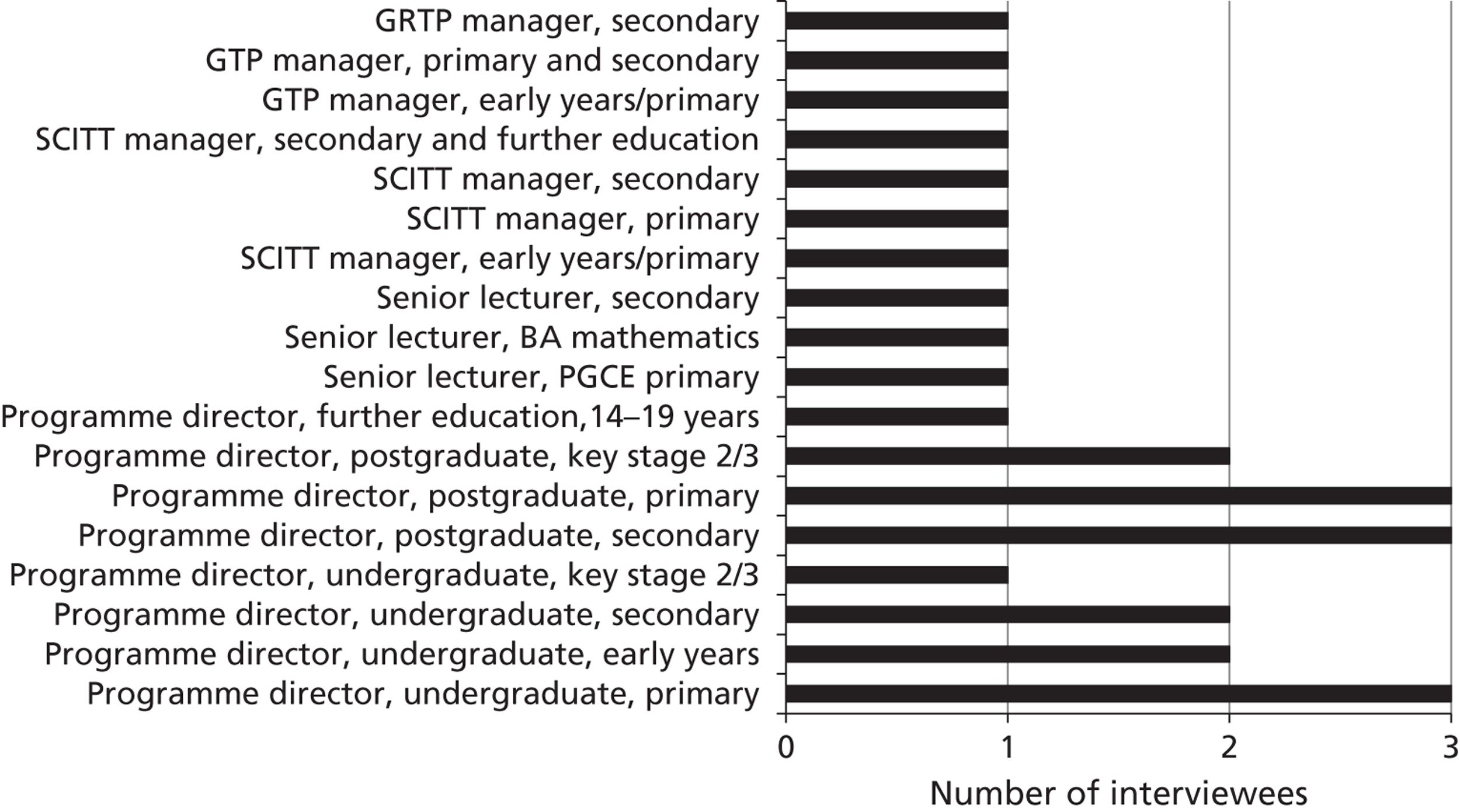

Figure 2 displays the number of HEI respondents who managed each type of course.

FIGURE 2.

Types of courses that respondents were responsible for managing: HEIs (n = 43 respondents).

The most commonly managed course was the PGCE (secondary closely followed by primary). At undergraduate level the most commonly managed course was the BA or BSc. Courses classified as ‘other’ included a Training Grant Only Programme and Assessment-Only Route to QTS.

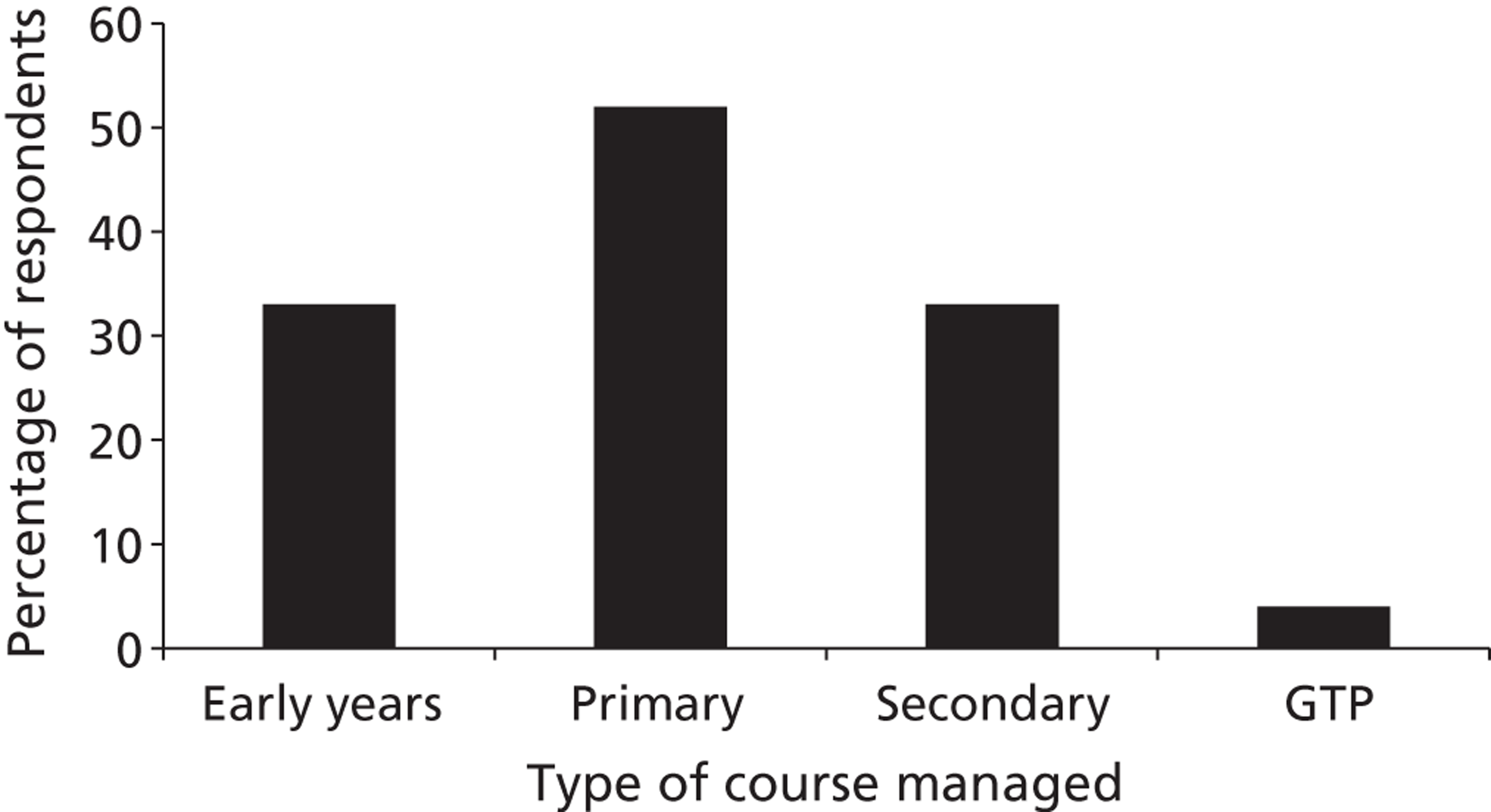

Of the 21 SCITT respondents, 17 (81%) reported managing just one course, three (14%) managed two courses and one (5%) managed three courses. Between them they managed a total of 26 courses. Figure 3 shows the numbers of respondents who managed each type of course. The most common course was the primary course, followed jointly by the early years and secondary courses. One respondent mentioned managing a GTP course under ‘other’. In many cases the respondents mentioned that they managed courses that had PGCE status.

FIGURE 3.

Types of courses that respondents were responsible for managing: SCITTs (n = 21 respondents).

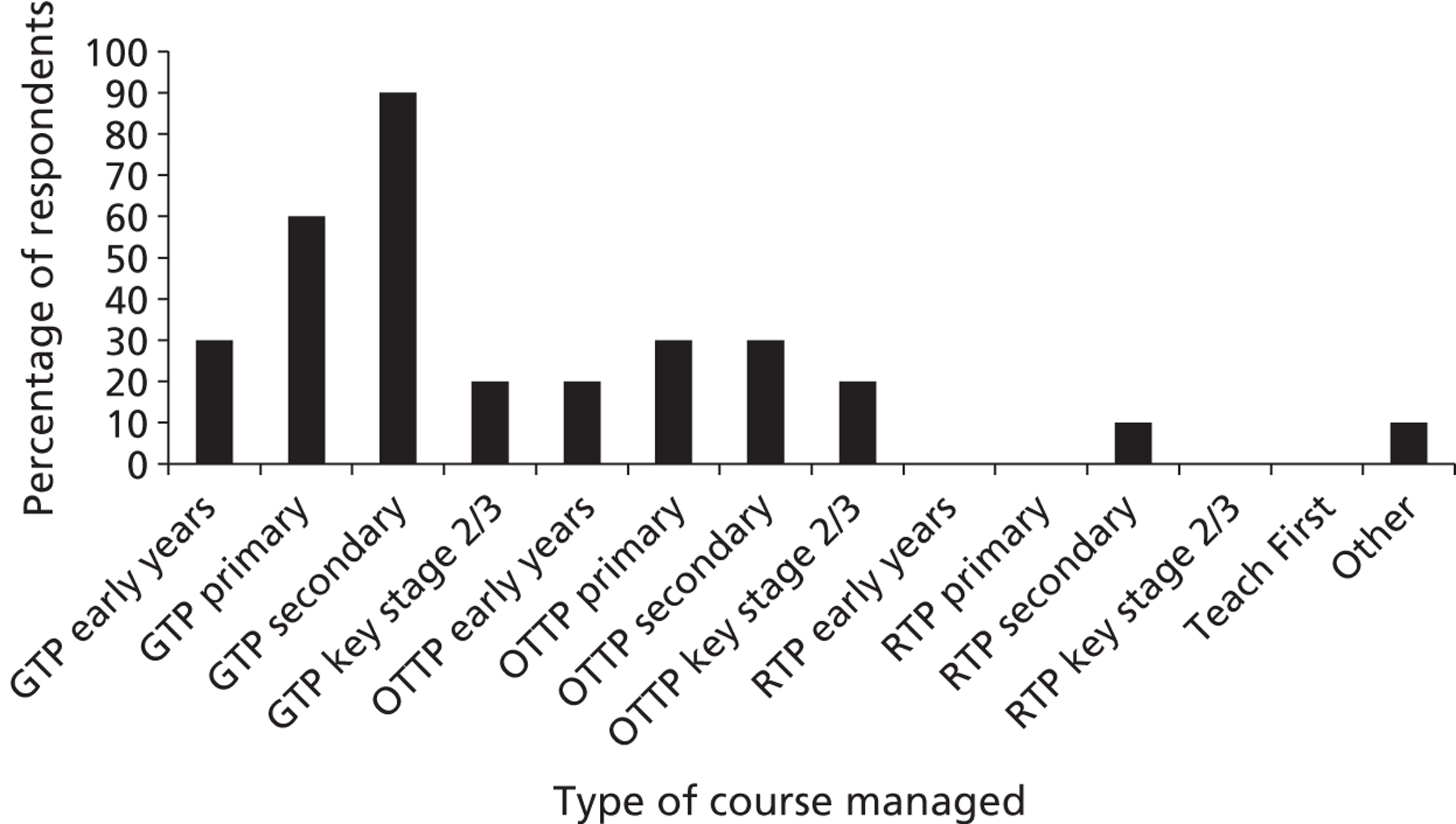

Of the 10 EBITT respondents, two (20%) reported managing one course, five (50%) managed two courses, one (10%) managed four courses and two (20%) managed eight courses. Between them they managed 32 courses. Respondents most commonly managed GTP courses, of which the secondary level was most common, followed by the primary level (Figure 4). They less commonly managed OTTP courses, and only one respondent reported managing a RTP course.

Respondents were asked to specify the numbers of students enrolled on their courses during the 2010–11 year. Table 4 provides the total numbers of students with means and ranges enrolled on courses by respondents in HEIs. In general, more students were enrolled on primary and secondary courses than on early years or key stage 2/3 courses. At postgraduate level, more students were enrolled on primary than on secondary PGCE courses. At undergraduate level, more students were enrolled on BA than on BEd courses, with BSc enrolees in a minority. In terms of employment-based training run by HEIs, students were reported as being enrolled on GTP courses only.

FIGURE 4.

Types of courses that respondents were responsible for managing: EBITTs (n = 10 respondents).

There was considerable variation in the numbers of students enrolled on certain courses. For example, amongst primary BA courses, the lowest number of enrolled students reported was 30, with the highest at 800. For primary and secondary PGCE courses, the lowest number was < 20 and the highest number was > 200.

Table 5 provides the total numbers of students with means and ranges enrolled on courses by respondents in EBITT providers. More students were enrolled on primary and secondary courses than on early years courses and there were none enrolled on key stage 2/3 courses, even though two of the respondents had reported that they had responsibility for courses at this level (see Figure 4). The GTP was the most commonly enrolled EBITT course, followed by the OTTP, although the number of enrolees on the latter was very low. The total number of GTP enrolees was lower at the primary level in the EBITT courses than it was for HEI primary-level GTP courses (see Table 4); however, at the secondary level the opposite was true.

| Course | Early years | Primary | Secondary | Key stage 2/3 | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Min. | Max. | Total | Mean | Min. | Max. | Total | Mean | Min. | Max. | Total | Mean | Min. | Max. | Total | |

| PGCE | 49.3 | 12 | 107 | 493 | 115 | 16 | 225 | 1961 | 101 | 10 | 204 | 1614 | 46.5 | 30 | 63 | 93 |

| BEd | 80 | N/A | N/A | 80 | 292 | 214 | 356 | 1170 | 12 | N/A | N/A | 12 | – | – | – | – |

| BA | 112 | 52 | 280 | 560 | 256 | 30 | 800 | 2049 | 255 | 25 | 500 | 1021 | 40 | N/A | N/A | 40 |

| BSc | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 210 | N/A | N/A | 210 | – | – | – | – |

| GTP | 6 | 4 | 8 | 12 | 36 | 8 | 97 | 181 | 21 | 3 | 47 | 147 | – | – | – | – |

| Course | Early years | Primary | Secondary | Key stage 2/3 | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Min. | Max. | Total | Mean | Min. | Max. | Total | Mean | Min. | Max. | Total | Mean | Min. | Max. | Total | |

| GTP | 3 | 1 | 4 | 8 | 14 | 7 | 24 | 72 | 31 | 13 | 87 | 248 | – | – | – | – |

| OTTP | – | – | – | – | 2 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 4 | – | – | – | – |

| RTP | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1 | N/A | N/A | 1 | – | – | – | – |

Table 6 provides the total numbers of students with means and ranges enrolled on courses by respondents in SCITTs. The SCITT course with the largest total number of students was the primary-level course, followed by secondary and then early years courses.

| Course | Mean | Min. | Max. | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early years | 22 | 9 | 35 | 153 |

| Primary | 34 | 15 | 78 | 372 |

| Secondary | 34 | 22 | 61 | 236 |

| Key stage 2/3 | – | – | – | – |

| Other | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

Health and well-being topics covered

The respondents were asked to indicate which specific health and well-being topics were covered by their courses. This question was answered by 40 out of the 43 HEI respondents, 19 of 21 SCITT respondents and 9 out of 10 EBITT respondents. Table 7 reports the frequency with which topics were covered by the three types of ITT provider and the overall (ranked) totals. Coverage of topics appeared to be generally similar across the different providers. ECM and child protection were covered by all providers. Comments made in response to open-ended questions illuminated the perceived importance of topics such as ECM, with one respondent stating that it is a:

Strong theme running through all professional . . . modules.

HEI 5

There was also an indication of its changing status:

ECM permeates the programme and was an important assignment (now shifting with ECM no longer core government policy, but principles of ECM remain).

HEI 28

Other commonly covered topics (covered by at least 90% of providers) were SEAL/emotional health, antibullying and working with parents (e.g. seeking parental views on school health policies and initiatives). Some lifestyle-related topics such as healthy eating, SRE, drugs, alcohol and smoking received comparatively less attention. Topics were generally more often reported to have been covered during the college-based component of the course than during the school teaching placement, except for EBITT courses where topics were generally more often covered in the schools that the trainees were working in (data not shown). As discussed later in this report, course managers did not always have full knowledge of how health and well-being was covered in placement schools and so the frequency of topics covered in placement schools may be under-reported.

| Topic | Total (n = 68) | HEIs (n = 40) | SCITTs (n = 19) | EBITTs (n = 9) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Covered, n (%) | Unsure/not reported as covered, n (%) | Covered, n (%) | Unsure/not reported as covered, n (%) | Covered, n (%) | Unsure/not reported as covered, n (%) | Covered, n (%) | Unsure/not reported as covered, n (%) | |

| ECM | 68 (100) | 0 | 40 (100) | 0 | 19 (100) | 0 | 9 (100) | 0 |

| Child protection | 68 (100) | 0 | 40 (100) | 0 | 19 (100) | 0 | 9 (100) | 0 |

| SEAL/emotional health | 67 (99) | 1 (1) | 39 (98) | 1 (3) | 19 (100) | 0 | 9 (100) | 0 |

| Antibullying | 66 (97) | 2 (3) | 38 (95) | 2 (5) | 19 (100) | 0 | 9 (100) | 0 |

| Working with parents | 65 (96) | 3 (4) | 38 (95) | 2 (5) | 18 (95) | 1 (5) | 9 (100) | 0 |

| Environment education | 55 (81) | 13 (19) | 33 (83) | 7 (18) | 16 (84) | 3 (16) | 6 (67) | 3 (33) |

| Physical activity | 55 (81) | 13 (19) | 33 (83) | 7 (18) | 15 (79) | 4 (21) | 7 (78) | 2 (22) |

| Healthy Schools | 51 (75) | 17 (25) | 29 (73) | 11 (28) | 14 (74) | 5 (26) | 8 (89) | 1 (11) |

| Healthy eating | 43 (63) | 25 (37) | 26 (65) | 14 (35) | 12 (63) | 7 (37) | 5 (56) | 4 (44) |

| SRE | 42 (62) | 26 (38) | 24 (60) | 16 (40) | 13 (68) | 6 (32) | 5 (56) | 4 (44) |

| Trainee teachers' health | 39 (57) | 29 (43) | 20 (50) | 20 (50) | 12 (63) | 7 (37) | 7 (78) | 2 (22) |

| Drugs education | 38 (56) | 30 (44) | 20 (50) | 20 (50) | 11 (58) | 8 (42) | 7 (78) | 2 (22) |

| Careers education | 36 (53) | 32 (47) | 21 (53) | 19 (48) | 10 (53) | 9 (47) | 5 (56) | 4 (44) |

| Alcohol education | 28 (41) | 40 (59) | 14 (35) | 26 (65) | 9 (47) | 10 (53) | 5 (56) | 4 (44) |

| Smoking prevention | 23 (34) | 45 (66) | 10 (25) | 30 (75) | 8 (42) | 11 (58) | 5 (56) | 4 (44) |

| Economic education | 21 (31) | 47 (69) | 8 (20) | 32 (80) | 9 (47) | 10 (53) | 4 (44) | 5 (56) |

| Other | 8 (12) | 60 (88) | 3 (8) | 37 (93) | 3 (16) | 16 (84) | 2 (22) | 7 (78) |

The topics that the respondents specified as ‘other’ were children's and young people's rights; mental and psychological health issues; care for children from vulnerable families; young carers; loss and bereavement; children and cancer; unmet attachment needs and therapeutic approaches; active global citizenship; equality, diversity and discrimination; restorative practice; and trainee health.

Ways in which health and well-being is covered in teacher training

The respondents were asked to ‘Please describe, as fully as possible, examples of how some of the health and well-being/PSHEE (personal, social, health and economic education) topics (as listed in questions 7/8) have been covered in your course’. (Note: the topics listed in questions 7/8 are those discussed in the previous section). In total, 34 of 43 HEI respondents (79%), 16 of 21 SCITT respondents (76%) and 7 of 10 EBITT respondents (70%) answered this question. The responses varied in terms of comprehensiveness, with some people summarising their activities in a few words and others providing more comprehensive accounts. In general, the level of detail provided was considered sufficient for meaningful data analysis.

Following examination of the data the responses were categorised into the following general themes: methods employed, people involved and context. Subthemes (and the frequency with which they were mentioned) were generated for each. The themes are now discussed in turn.

Table 8 provides a classification of the different methods that teacher training providers have used to teach health and well-being. In HEIs, health and well-being was covered generally through a wide range of methods such as lectures, seminars and tutor-led workshops. Some universities commit whole days within their courses to health issues or PSHE education. For example, in one university the students have a joint day-long conference with social work students exploring health (including mental health) and child protection. In several HEIs some health and well-being topics, such as SRE and drugs, are addressed in a lecture to the whole cohort. Topics may then be discussed in cross-curricular group workshops or in subject-specific areas. Some placement schools, which are linked to university courses, have their own professional studies programme, including school-based lectures and seminars.

| Methods | Number (%) of respondents mentioning | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| HEIs (n = 34) | SCITTs (n = 16) | EBITTs (n = 7) | |

| PSHE education and health and well-being are taught in modules/designated sessions | 7 (21) | 4 (25) | 1 (14) |

| Use a combination of some or all of the following: lectures, seminars, presentations, discussion, interactive workshops, e-learning | 22 (65) | 6 (38) | 1 (14) |

| Tutor-led workshops | 1 (3) | – | – |

| Whole cohort/multidisciplinary lectures | 5 (15) | – | – |

| Presentations on PSHE education from trainees, micro-teaching | 3 (9) | 1 (6) | 1 (14) |

| Teach PSHE education in school placement | 1 (3) | – | 1 (14) |

| All students attached to tutor groups in school placement | 1 (3) | – | – |

| Classroom observation/model lessons, directed tasks | – | 3 (19) | – |

| Whole day on PSHE education/citizenship (includes, for example, SRE, drugs and alcohol) | 4 (12) | 1 (6) | 1 (14) |

| Whole day on communicating with parents including SEAL, bullying | – | 1 (6) | – |

| Whole-day workshops organised by trainees | 2 (6) | – | – |

| Whole-group training sessions for lecturers and students | 1 (3) | – | – |

| Whole day on equality and diversity | – | – | 1 (14) |

| Group work | 1 (3) | – | – |

| One-to-one sessions | – | 1 (6) | – |

| Professional studies sessions on PSHE education in university | 4 (12) | – | – |

| Seminars in schools (partnership programme scheme) | 1 (3) | – | – |

| School-based tasks/activities | 8 (24) | – | – |

| School-based professional studies sessions | – | 3 (19) | 2 (29) |

Table 9 provides a classification of the different types of people who were mentioned as participating in teaching around health and well-being.

| People | Number (%) of respondents mentioning | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| HEIs (n = 34) | SCITTs (n = 16) | EBITTs (n = 7) | |

| Use of consultants from the local authority to lead sessions, e.g. ECM, child protection, PSHE education | – | 3 (19) | 1 (14) |

| Working in partnership with other ITT organisations | – | 2 (13) | – |

| Sessions led by university staff | 1 (3) | – | – |

| PSHE education, ECM, SEAL, child protection, teacher health and well-being by leads/experts in own/local schools | 3 (9) | – | 2 (29) |

| Other external organisation/charity | 2 (6) | – | – |

| Guest speakers, not specified | 9 (26) | 1 (6) | – |

| Pupil-led session, e.g. antibullying | – | 1 (6) | – |

| Researcher in SRE-led training (based on research evidence and good practice) | 1 (3) | – | – |

| Peer training | – | – | 1 (14) |

A variety of agents were mentioned, including people from local authorities, schools, charities and within ITT organisations themselves. In some cases the trainee teachers were actively encouraged to carry out the presentations on health topics themselves. For example, at one university the science and PE students organise a health day and there is a focus on the trainees as role models for health:

The aim is to prioritise the corporate responsibility for modelling healthy lifestyles and draw attention to key topics.

HEI 8

‘Micro-teaching’ was another method used in training whereby the student is filmed teaching and later evaluated. At one university (HEI 39) the students are encouraged to work in pairs to produce a lesson for their assessed presentation at the end of the cross-curricular module, which is often on health/PSHE education. On some courses there was an expectation that trainees will teach some PSHE education in their school placements, or through attachment to a tutor group in school, for example:

Teach the full curriculum at 90% contact for the final five weeks of the course, including all PSHCE [personal, social, health and citizenship education] in that part of the year.

SCITT 5

Classroom observation and practice was also mentioned as an important aspect of training.

Employment-based initial teacher training providers tended to use a variety of methods in their training. Several used experts in PSHE education from their own school or from other local schools. One respondent commented:

Our partnership has a core of outstanding and good schools which offer a full range of training to back up central sessions.

EBITT 10

One respondent mentioned that the training involved someone from a research background, taking an evidence-based approach:

A colleague who conducted research on SRE in schools leads session for trainees based on research findings and good practice.

HEI 34

Table 10 reports a classification of issues relating to the context in which health and well-being is addressed, specific to HEIs.

| Context | Number (%) of respondents mentioning |

|---|---|

| Global dimensions | 1 (3) |

| Cross-curricular activities/workshops | 3 (9) |

| Covered through science | 6 (18) |

| Humanities, health and social care, psychology, social work | 2 (6) |

| Child development | 1 (3) |

| Inclusion module | 1 (3) |

| Professional modules/GPS/education studies | 6 (18) |

| Business | 1 (3) |

| PE | 4 (12) |

| PSHE education course | 1 (3) |

In some cases training around health issues was mentioned as being covered in science or PE courses. For example:

Primary science covers healthy eating and environment education.

HEI 7

Sex and drugs are part of a science module in the final year.

HEI 28

However, health was also covered in other areas of the curriculum such as the humanities. One respondent commented:

There are also elements explored in the science sessions e.g. global dimensions’ cross curricula session on science and DT [design technology] related to sustainability and environmental education. Some of these concepts are also explored through the humanities.

HEI 25

Some health topics were covered through broader professional themes in which students from all subject areas are involved. However, the integration of health into broader areas of the ITT curriculum mentioned by some respondents was not universal. One respondent cited evidence to suggest barriers to the infusion of health throughout their programme:

Having completed our own small scale research project on this topic this year, we have identified that beyond PE, geography and science our other training subject areas do not see how this aspect of education is their responsibility. They had little interest in engagement and did not see it as part of the learning package within their area.

HEI 11

Some of the HEI respondents discussed at what stage in their courses health and well-being is addressed. Health topics were covered at various stages of courses, from the first year and beyond. For example, in a BEd course:

In Year 1 an Introduction to PSHE and Citizenship which explores the coverage and what it incorporates and some of the debates around this area of education. We also look at circle time as one way of building relationships with young children. We explore well-being of themselves and children and consider the self-esteem cycles. In Year 2 we have covered a range of things and is usually covered by an outside provider e.g. RSPCA [Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals], SRE, DARE [Drug Abuse Resistance Education].

HEI 25

Assessment

The respondents were asked whether any of the health and well-being aspects of the course were assessed (in general and/or in relation to QTS). In total, 39 out of 43 HEI respondents (91%), 17 out of 21 SCITT respondents (81%) and 9 out of 10 EBITT respondents (90%) answered this question. The majority indicated that assessment was undertaken [overall 44/65 (68%), HEIs 25/39 (64%), SCITT 12/17 (71%) and EBITT 7/9 (78%)]. Those that indicated that assessment took place were then asked to specify which methods were used. Table 11 shows the frequency of use of different methods, overall and for the three types of teacher training providers.

| Assessment method | Total (n = 44), n (%) | HEIs (n = 25), n (%) | SCITTs (n = 12), n (%) | EBITTs (n = 7), n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Examination | 3 (7) | 2 (8) | 1 (8) | 0 |

| Portfolio | 21 (48) | 8 (32) | 9 (75) | 4 (57) |

| Assignment | 17 (39) | 10 (40) | 4 (33) | 3 (43) |

| Questionnaire | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Teaching observation | 22 (50) | 11 (44) | 9 (75) | 2 (29) |

| Presentation | 15 (34) | 8 (32) | 5 (42) | 2 (29) |

| Other | 13 (30) | 10 (40) | 2 (17) | 1 (14) |

The majority of teacher training providers specified using more than one method of assessment, with the modal class being use of two methods (range 1–5, data not shown). Teaching observation and submission of a portfolio of activities relating to health and well-being were commonly used methods of assessment, particularly so for SCITTs. Less common were methods such as presentations or assignments. Examinations were used by a minority of providers, and no respondents mentioned using questionnaires. In terms of methods listed as ‘other’, the most commonly reported method was the compilation of evidence to support attainment of QTS standards (n = 7, all HEIs). Evidence against the standards could be derived from school placement lesson plans or observational feedback and in some cases students were given the opportunity to select a health and well-being topic for an assignment, essay or their dissertation. Other methods of assessment included ‘professional dialogue’, ‘focused teaching evaluations and reflection’, ‘one-to-one assessments’, ‘tasks during placements assessed as part of their planning files’, ‘online bullying training assessed and certificated’ and ‘implicit through assessment of other aspects of the course’.

External support for teaching health and well-being

The respondents were asked whether they used any external organisations to provide information, resources or teaching to support the delivery of the health and well-being aspects of their courses. In total, 39 out of 43 HEI respondents (91%), 16 out of 21 SCITT respondents (76%) and 9 out of the 10 EBITT respondents (90%) answered this question. For all three types of provider the majority reported use of external organisations [31/39 (79%) HEIs, 10/16 (63%) SCITTs, 6/9 (67%) EBITTs]. Those that indicated that external organisations had been used were then asked to specify which types of organisation were used. Table 12 shows the frequency of use of different external organisations, overall and for the three types of teacher training providers.

| External organisation | Total (n = 47), n (%) | HEIs (n = 31), n (%) | SCITTs (n = 10), n (%) | EBITTs (n = 6), n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health professional | 10 (21) | 4 (13) | 6 (60) | 0 |

| Youth service | 5 (11) | 4 (13) | 0 | 1 (17) |

| Local authority | 35 (74) | 23 (74) | 8 (80) | 4 (67) |

| Voluntary/charitable group | 17 (36) | 13 (42) | 1 (10) | 3 (50) |

| Local university/college | 2 (4) | 3 (1) | 0 | 1 (17) |

| Sports organisation | 10 (21) | 19 (61) | 3 (30) | 1 (17) |

| Local school | 29 (62) | 18 (58) | 7 (70) | 4 (67) |

| Other | 11 (23) | 6 (19) | 4 (40) | 1 (17) |

The majority of respondents specified working with more than one external organisation. For HEIs the median number of external organisations was two (range 1–4, data not shown), for SCITTs the median was three organisations (range 1–4, data not shown) and for EBITTs the median was 2.5 (range 1–5, data not shown).

Local authorities were the most common external organisation that ITT providers worked with to support the health and well-being aspects of their course(s). The delivery of lectures, taught sessions, seminars and workshops by experts were mentioned. These included Healthy Schools co-ordinators, special needs advisors, 14–19 advisors, child protection officers and police liaison officers.

Local schools were also a commonly used external source of support for health and well-being, mentioned by around two-thirds of SCITTs and EBITTs and just over half of the HEIs. The school staff involved included PSHE education experts, PE teachers, senior or head teachers, a teacher specialising in cancer care and teachers with a responsibility for child protection.

Voluntary/charitable groups were used by just over one-third of ITT providers. Specific groups mentioned covered a wide range of health-related issues and included the Teenage Cancer Care Trust, Barnardos, the Red Cross, Rethink Mental Illness (mental health), Nelson's Journey (bereavement), Young Carers, Daisy Chain (autism) and the ABLE project (environmental education). The proportion of ITT providers who worked with health professionals was low overall, and more common for SCITTs. Specific types of health professional mentioned included a clinical psychologist, a speech and language therapist and a cognitive behaviour therapist. The SCITTs who responded did not have any input around health and well-being from a local university or college or youth organisation. The EBITTs made little use of local universities or colleges, sports organisations or youth services (only one used each one).

‘Others’ who support the health aspect of the curriculum in HEIs were the National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children (NSPCC), trade union representatives, police officers responsible for child protection and Association of Teachers and Lecturers (ATL) (education union) consultants. ‘Others’ who were mentioned by SCITTs included child protection specialists (e.g. from the local authority) and ‘the five voices for effective teaching’, a voice development programme for trainees. The only ‘other’ mentioned by an EBITT was a community police officer.

Time spent on health and well-being in the curriculum

The respondents were asked to ‘Please estimate the approximate percentage of time spent, as a whole, covering health and well-being in your course’. In total, 37 of 43 HEI respondents (86%), 16 out of 21 SCITT respondents (76%) and 9 out of 10 EBITT respondents (90%) answered this question. Table 13 presents the percentage of time spent on health by type of provider.

| Time spent on health and well-being (%) | Total (n = 62), n (%) | HEIs (n = 37), n (%) | SCITTs (n = 16), n (%) | EBITTs (n = 9), n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 5 | 14 (23) | 7 (19) | 3 (19) | 4 (44) |

| 5–9 | 26 (42) | 17 (46) | 6 (38) | 3 (33) |

| 10–14 | 16 (26) | 9 (24) | 5 (31) | 2 (22) |

| 15–19 | 4 (6) | 3 (8) | 1 (6) | 0 |

| 20–24 | 2 (3) | 1 (3) | 1 (6) | 0 |

| 25–49 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ≥ 50 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

The highest percentage of respondents indicated spending 5–9% of time on health and well-being, followed by 10–14% of time. A higher percentage of EBITTs reported spending < 5% of time on health and well-being, and several respondents from EBITTs felt that the health and well-being aspect was mostly the responsibility of the placement schools. The figures presented must be interpreted with some caution as some respondents commented that it was difficult to calculate as aspects of health are embedded throughout the course.

Importance of health and well-being in teacher training

The respondents were asked, ‘How important in your view is it to emphasise the health and well-being of pupils and staff/PSHE in the initial teacher training curriculum?’ In total, 37 out of 43 HEI respondents (86%), 16 of 21 SCITT respondents (76%) and 8 out of 10 EBITT respondents (80%) answered this question. Table 14 illustrates the degree to which respondents considered health and well-being important, by type of provider. For each type of provider, the majority considered health and well-being to be important or very important (although a relatively smaller majority of EBITTs), with only a minority considering it to be of some importance. No respondents indicated that it was not important, although, as acknowledged in Chapter 7 of this report, people who regard health as less important may have chosen not to complete the questionnaire.

| Importance | Total (n = 61), n (%) | HEIs (n = 37), n (%) | SCITTs (n = 16), n (%) | EBITTs (n = 8), n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Very important | 23 (38) | 15 (41) | 7 (44) | 1 (13) |

| Important | 31 (51) | 18 (49) | 8 (50) | 5 (63) |

| Of some importance | 7 (11) | 4 (11) | 1 (6) | 2 (25) |

| Not important | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Several respondents commented that the health and well-being aspects of the course are important. For example:

Health and well-being goes across all curriculum subjects. It is something we as tutors are passionate about.

HEI 19

We do a great deal on the pedagogy of these subject areas, how to deal with controversial issues, how to conduct circle time etc.

HEI 14

However, one respondent was open about the fact that she did not focus enough on health and well-being, but completion of our questionnaire had prompted her to re-evaluate her provision:

In reviewing the list of dimensions provided in this survey I feel that there are areas we have neglected to date and will endeavour to supplement our existing provision accordingly.

HEI 39

It was noted by some respondents that, despite the recognised importance of health, lack of funding and time pressures limited the extent to which it could be covered:

With additional resources (i.e. more time and money) we would focus more on this aspect of the course.

SCITT 8

Future changes to teacher training courses

The respondents were asked, ‘In what ways do you anticipate that the content, delivery or structure of your course is likely to change in the near future? (e.g. in response to changes in educational policy or funding?)’. In total, 30 out of 43 HEI respondents (70%), 13 out of 21 SCITT respondents (62%) and 6 out of 10 EBITT respondents (60%) answered this question. The responses given were examined and a number of key themes to emerge were noted. Subthemes were identified and the frequency with which they were mentioned was noted. Table 15 presents these themes, each of which is discussed in further detail below.

| Theme | HEIs (n = 30), n (%) | SCITTs (n = 13), n (%) | EBITTs (n = 6), n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|