Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 09/3008/11. The contractual start date was in January 2011. The final report began editorial review in September 2012 and was accepted for publication in February 2013. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2013. This work was produced by O’Mara-Eves et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background

Community engagement in health care in the UK

Historically, interventions and actions to promote health were driven by professionals with little or no input from the targeted populations. 1 More recently, community engagement has become central to guidance and national strategy for promoting public health (e.g. Department of Health2). Community engagement has been broadly defined as ‘involving communities in decision-making and in the planning, design, governance and delivery of services’ (p. 11). 3 Community engagement activities can take many forms. Examples of some initiatives in the UK include:

-

service user networks

-

health-care forums

-

volunteering

-

courses delivered by trained peers (e.g. Dudley Primary Care Trust’s Expert Patients Programme)

-

interactive websites that enable the submission of views and opinions on various surveys, polls and public consultations.

Community engagement can also mean involvement in the evaluation of services. Community engagement can be provided alone or in combination with other initiatives. In studies in which community engagement is provided as the sole intervention, evidence of effectiveness can be determined because there is a direct link between community engagement and the outcomes being assessed. In contrast, interventions that are multifaceted and include community engagement as one of a number of components have a less direct link with outcomes being assessed. In such cases, an association between the multifaceted initiative and population outcomes may be seen, but it is not possible to discern with confidence how the community engagement aspect of the intervention may have contributed to this effect (pp. 1–2). 4

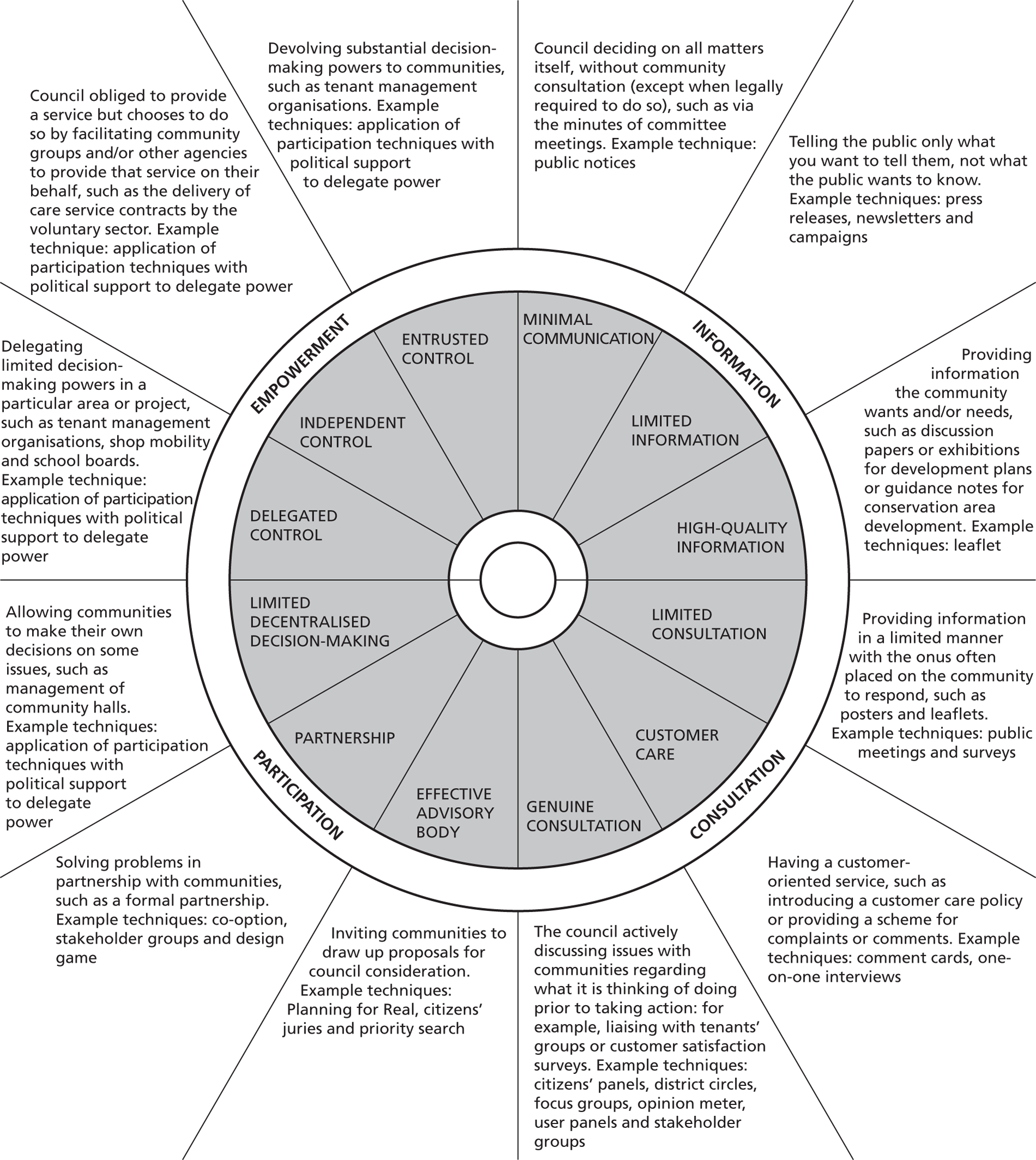

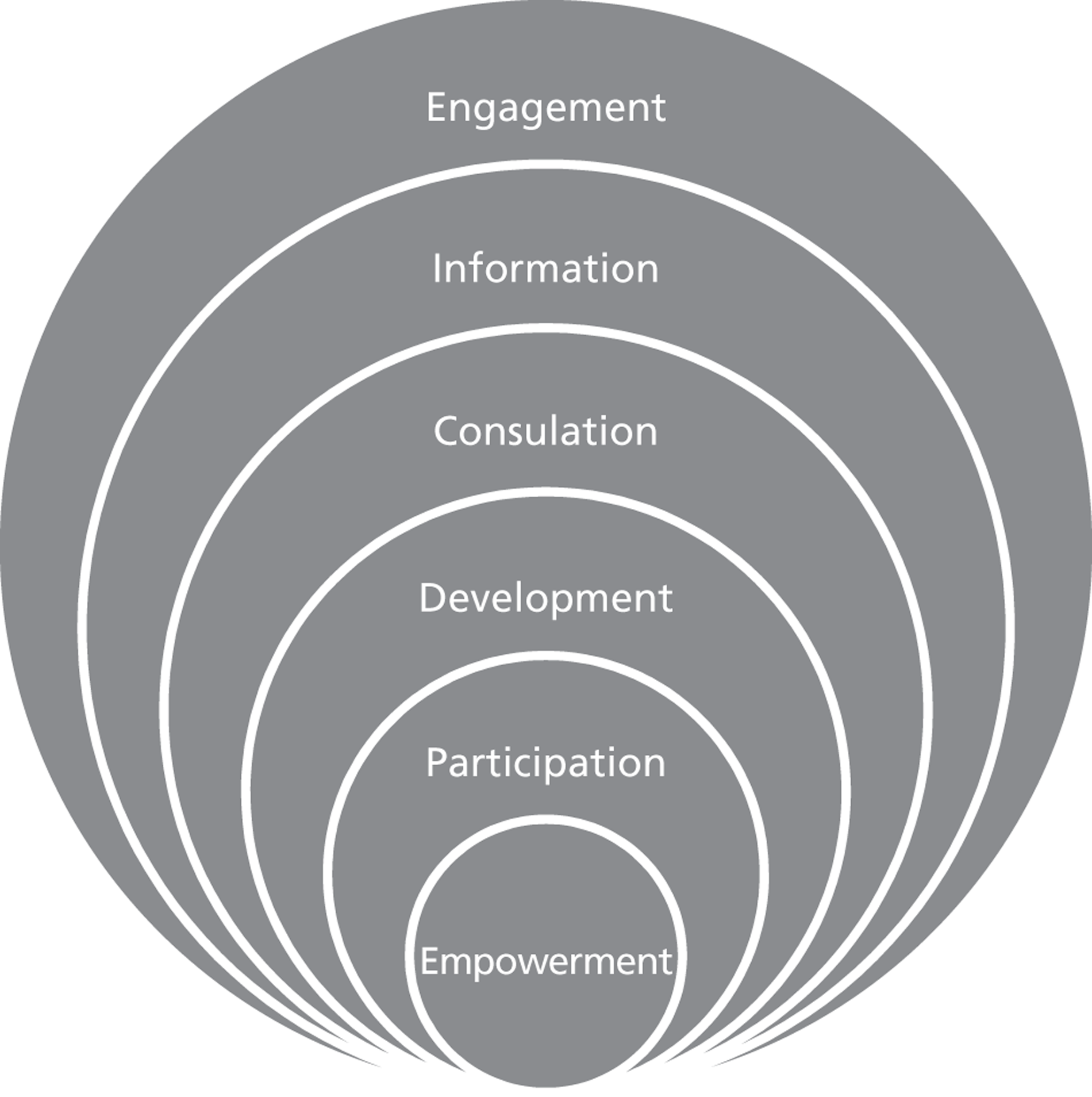

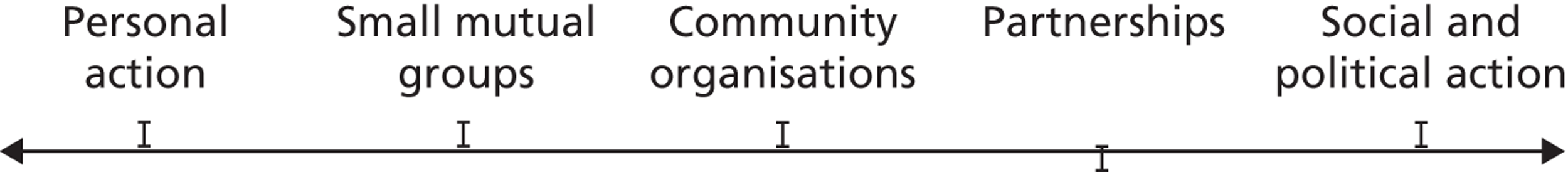

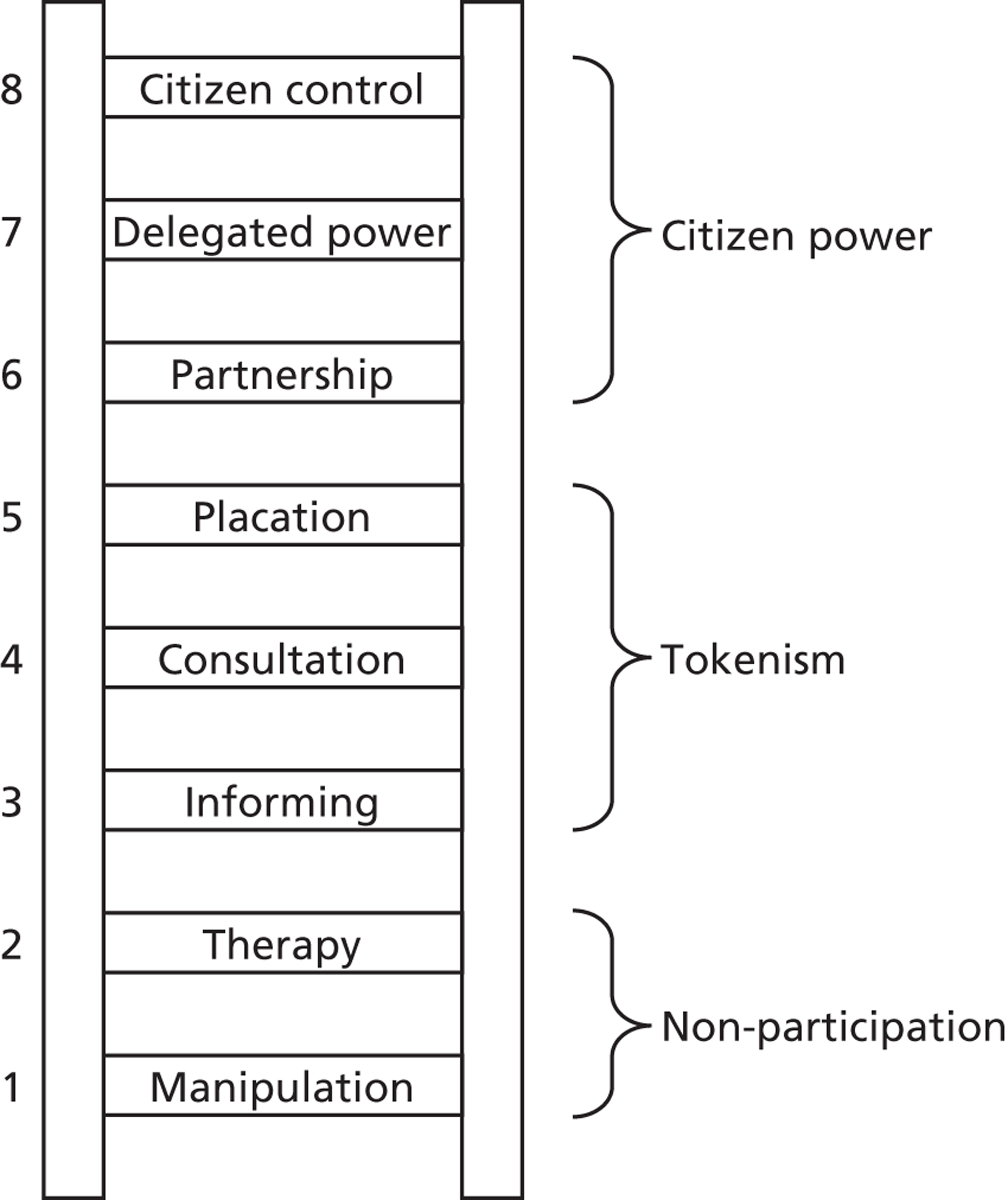

Community engagement can also be seen to operate on different levels, depending on the degree to which community engagement occurs. Wilcox5 describe five levels of increasing community engagement:

-

information-giving, in which people are merely told what is planned

-

consultation, in which people are offered some options and ideas, and organisers listen to feedback, but do not allow new ideas

-

deciding together, in which organisers encourage additional options and ideas, and provide opportunities for joint decision-making

-

acting together, not only to decide together on what is best, but also forming a partnership to carry it out

-

supporting independent community interests, in which local groups or organisations are offered funds, advice or other support to develop their own agendas within guidelines.

A more condensed scale exists for involvement in health research – consultation, collaboration and community control – with information provision not included as a sufficient level of engagement. 6

There is strong policy support for involving people in developing public services and evaluation (e.g. the creation of the Health Inequalities National Support Team7). Various national publications, including Shifting the Balance of Power,8 Commissioning a Patient-led National Health Service,9 the Our Health, Our Care, Our Say White Paper,10A Stronger Local Voice11 and Health Reform in England: Update and Commissioning Framework12 have provided a framework for the engagement of the public in the planning, design and delivery of public health services. Primary care trusts (PCTs) throughout the country have community engagement and public and patient involvement strategies.

Given the increasing policy support for community engagement, it is critical to consider whether such strategies are effective and under what circumstances. The following section outlines the state of research on community engagement in health care.

The evidence base for community engagement

There is some evidence that public involvement in UK health services can be effective. 13 Community engagement is thought to improve health through its impact on the development and delivery of more appropriate and accessible interventions, as well as through its direct positive impact on social cohesion and individual self-esteem and self-efficacy for those who are engaged. 14

Community involvement can be seen as a goal in itself as it encourages public accountability and transparency. 15,16 Through public involvement, communities can have the potential to promote health from the bottom up. 17 Listening to, hearing and acting on the views of the community – particularly those from socially and economically disadvantaged groups – can both empower communities and lead to the co-production and implementation of interventions that are more likely to be feasible, acceptable and ultimately effective in improving health. 4,14 Importantly, community engagement can ‘give a voice to the voiceless’. 18 People with the greatest health needs are often socially excluded and disengaged from services, and their circumstances can make it difficult for organisations to address their needs appropriately. Opportunities to work with their peers through community engagement initiatives may improve the social inclusion of marginalised people.

Although there is a recognised literature recommending community engagement,3,4 there is much uncertainty about how communities might be best engaged; what the results of such engagements are; and how the results should be recorded, analysed and used. 4,19,20 The theory behind recommendations for community engagement is often not linked to empirical evidence.

One of the problems with the current evidence base is a lack of robust synthesis of the research. This makes it difficult to assess the empirical basis for claims about community engagement, as research is scattered across disciplinary and topic-focused boundaries and not pulled together in a coherent way. The few syntheses that have been conducted are helpful, although they have acknowledged limitations, having been completed rapidly from relatively small datasets. 3,4 Limited synthesis in this area also makes it difficult to discern whether community engagement might be an appropriate strategy in any specific situation, as the available evidence is based only on a handful of studies (e.g. Popay et al. ,4 p. 62).

The same lack of high-quality evidence is apparent when looking at the cost-effectiveness of different community engagement strategies, including evidence from the UK. Guidance on community engagement produced by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)21 highlighted a dearth of information in this regard. A review of economic studies on community engagement for health promotion found eight studies, none of which focused specifically on the cost-effectiveness of the community engagement component. 22 A companion systematic review of the economic evidence for community engagement and development strategies to address the wider determinants of health also failed to identify any studies that reported the costs and health benefits of a community engagement approach relative to a comparator;23 some information on the resources required to deliver interventions was, however, reported in 20 studies. A final output of this work for NICE was economic modelling of some community engagement strategies to look at the potential cost-effectiveness of community engagement strategies. 24 However, this was not included in the final guidance because of a lack of robust information on costs and effects; only two vignettes on the role of trained peer educators and community engagement as a way of gaining support for flood defences were included (see also Fischer25).

In summary, the evidence base supporting the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of community engagement strategies is fragmented and of uncertain quality. This review aims to make good some of these deficiencies with a specific focus on whether community engagement is a useful strategy for improving the health of disadvantaged groups.

The challenge of health inequalities in the UK

The quality of health varies from person to person as a result of biological, environmental, social, economic and lifestyle factors. Factors associated with economic and social circumstances are termed the social determinants of health. 26 These refer to a multitude of factors such as family assets, education, security of employment, relative risks at work, housing, family pressures and retirement provision. 27

These disadvantages tend to concentrate among the same people, and their effects on health accumulate during life. The longer that people live in stressful economic and social circumstances, the greater the physiological wear and tear they suffer, and the less likely they are to enjoy a healthy old age (p. 10). 27

The term ‘health inequalities’ refers to gaps in the quality of health of different groups of people based on differences in social, economic and environmental conditions. 28 Health inequalities are evident where disadvantaged groups (e.g. people with low socioeconomic status, socially excluded people) tend to have poorer health than more affluent members of society. Importantly, the term ‘health inequalities’ refers to differences in modifiable health determinants, such as housing, employment, education, income, access to public services and personal behaviour (e.g. use of tobacco)29 as opposed to fixed determinants such as age, sex and genetics. [However, social inequalities are often associated with fixed determinants (age, sex and genetics) and so these fixed factors might have indirect effects on health status.] The fact that many health determinants are modifiable lies at the very heart of all health inequalities strategies; if they are modifiable, then something can be done to improve them. By improving modifiable determinants of health, it is hoped that health inequalities can be reduced and health outcomes enhanced.

Health outcomes that are typically considered when examining health inequalities include life expectancy/mortality rates, disability-free life expectancy and limiting long-term illness. Other health outcomes and health-related indicators can include (but are not limited to) low birthweight, infant mortality, hospital admissions, teenage pregnancy and uptake of health services. In the UK, taking into account variations between local authorities, the average male in the lowest deprivation decile (i.e. the poorest males) will have a life expectancy that is 6.7 years shorter than that of the average male in the highest deprivation decile (i.e. the most affluent). The poorest females will have a life expectancy that is 4.7 years shorter than that of the most affluent females (figures calculated by Alison O’Mara-Eves using multilevel modelling of data from the London Health Observatory available at www.lho.org.uk/LHO_Topics/national_lead_areas/marmot/marmotindicators.aspx, accessed 15 March 2013). When looking at specific local authorities, some of these differences become even larger. For example, Westminster local authority has the widest within-area inequality gap for males, with a life expectancy for the most affluent males that is almost 17 years longer than that for the poorest males. 30 The widest gap for females is in Halton and Newcastle upon Tyne, at just over 11 years’ difference in life expectancy. The average difference in disability-free life expectancy in England between the most affluent and the least affluent, regardless of area or gender, is 17 years. Clearly the life expectancy and quality of health across the lifespan are much lower, on average, for the most deprived populations.

There is no dispute in the UK that health inequalities exist28 and, as a result, health inequalities have been an increasing focus of policy interest. For instance, in 2004, tackling health inequalities was one of the aims underpinning the 11 standards promoted within the National Service Framework. 31 More recently, the Marmot Review of health inequalities, Fair Society, Healthy Lives,28 has afforded even greater attention to the issue of health inequalities (with a particular focus on England). The review identified the evidence relating to health inequalities in England, developed actionable recommendations for practice, produced guidance on possible objectives and measures of inequalities and developed a starting point for a post-2010 health inequalities strategy. The key recommendations made in the report to address health inequalities fall under the following six broad themes:

-

giving children the best start in life

-

enabling all children, young people and adults to maximise their capabilities

-

creating fair employment and good work for all

-

ensuring a healthy standard of living for all

-

developing healthy and sustainable places and communities

-

strengthening the role and impact of health prevention.

The Marmot Review has received broadly positive responses from both public sector (e.g. NICE) and user and community groups (e.g. Citizens Advice Bureau32). Key to the review, and to the ensuing responses, is the belief that reducing health inequalities is one of the key critical social and political issues of our generation.

Reducing health inequalities is often referred to as ‘narrowing the gap’ or ‘reducing the social gradient’. The social gradient of health suggests that the lower a person’s social position, the worse his or her health, and an emphasis on analysing gradients as opposed to gaps exposes differences in health across the spectrum of advantage and disadvantage and not simply poverty and ill health. 33,34 Understanding whether the gradient has reduced involves examining the gradient over time. Recent analyses released by the Office for National Statistics (ONS)35 suggest that, although the quality of health in the population has improved across all social classes from 1982 to 2006, differences in life expectancy between the least and the most deprived social classes have increased during that period. That is, improvements in life expectancy have risen at a higher rate for more affluent people than the most deprived during that 25-year time frame; this finding was particularly true for men.

Considering the social gradient over time raises questions about how best to reduce inequalities. As the Marmot Review28 emphasised:

It is tempting to focus limited resources on those in most need. But . . . we are all in need – all of us beneath the very best-off. If the focus were on the very bottom and social action were successful in improving the plight of the worst-off, what would happen to those just above the bottom, or at the median, who have worse health than those above them? All must be included in actions to create a fairer society.

p. 16

This leads one to conclude that, to reduce the social gradient of health, we need to improve the plight of the most disadvantaged (through targeted interventions) as well as improve the overall health of the population (through universal interventions). The issue of targeted compared with universal approaches to health has received much consideration from NICE. In 2002, NICE invited 30 members of the public throughout the UK to join a Citizens Council. According to NICE,36 ‘The Citizens Council was established to ensure that the views of those who fund the NHS – the public – are incorporated into the decision-making process’. Still in existence today, the Council meets twice a year for three days at a time and has produced 13 reports to date. NICE then issues a formal response to the recommendations made in the report and any actions that they will take as a consequence. At one meeting in 2006, the Council was asked to discuss how health inequalities should be taken into account when developing national guidance. 37 According to the report of the meeting, they were asked which of the following strategies NICE should follow:

whether to issue guidance that concentrates resources on improving the health of the whole population (which may mean improvement for all groups) even if there is a risk of widening the gap between the socioeconomic groups;

or whether to issue guidance that concentrates resources on trying to improve the health of the most disadvantaged members of our society, thus narrowing the gap between the least and most disadvantaged, even if this has only a modest impact on the health of the population as a whole.

p. 437

The Citizens Council was presented with information from various experts (university academics, service providers, etc.) and they engaged in discussions and participated in practical exercises. On the final day they were asked to vote on which of the two broad strategies seemed more appropriate. They were unable to reach unanimous agreement but concluded that:

Despite our many and varied reservations, a majority of the Citizens Council would look with sympathy on NICE strategies intended not only to improve public health for all, but to do so in a way that offers particular benefit to the most disadvantaged.

p. 537

The Marmot Review28 referred to this approach as ‘proportionate universalism’. Although the NICE Citizens Council is an excellent demonstration of the way in which the public can be engaged in the development of national health guidance, the conclusions of their 2007 report also emphasise the difficulty that policy-makers and service providers face when deciding how to address health inequalities. One possibility for addressing the social gradient, discussed below, is through engaging the community in service design and delivery.

Reducing health inequalities through community engagement initiatives

One of the priority objectives advocated in the Marmot Review28 is to ‘improve community capital and reduce social isolation across the social gradient’ (p. 126). By improving social capital and reducing isolation, the social inequalities that underpin health inequalities could be improved – which would have a flow-on effect on health outcomes. The review summarised evidence which suggested that interventions to reduce social isolation are more effective when communities and individuals are included in their design.

Other researchers have advocated community engagement and participation as a strategy to reduce health inequalities (e.g. Wallerstein and Duran,15 Rifkin et al. 38), yet it is difficult to find empirical evidence to support this. Like the Marmot Review, an international literature review for the World Health Organization (WHO) found that participatory empowerment (a facet of community engagement) has been linked to positive outcomes such as social capital and neighbourhood cohesion for socially excluded groups. 15 However, the author noted that links to health outcomes are more difficult to identify. The few examples identified in the review of the effect of participatory empowerment on health outcomes were mostly in developing countries, which have limited transferability to the UK context.

Similarly, Popay et al.’s rapid review4 found some evidence for improvements in social capital, social cohesion and empowerment as a result of community engagement, but little evidence of improvements for mortality or morbidity/health behaviours or impact on inequalities. The authors concluded that the small number of studies addressing the relationship, plus problems with the designs of the primary studies (e.g. the time to follow-up in the mortality studies was too short to expect any change), were the reasons for not observing a relationship.

Rather than searching for evidence of community engagement effectiveness, Arblaster et al. 39 searched for evaluations of health service interventions designed to reduce health inequalities. They included 94 studies in their systematic review and found that successful interventions often had one or more of the following characteristics:

-

systematic and intensive approaches to delivering effective health care

-

improvement in access and prompts to encourage the use of services

-

strategies employing a combination of interventions and those involving a multidisciplinary approach

-

ensuring that interventions address the expressed or identified needs of the target population

-

the involvement of peers in the delivery of interventions.

The last two recommendations echo the general principles underlying community engagement. Although these characteristics alone were not sufficient for success, it is clear that community engagement may be a promising approach to reducing health inequalities.

In summary, it seems that community engagement is likely to have a positive effect on social inequalities,4,15,28 which might in turn reduce health inequalities,28 although the direct effect on health inequalities is still uncertain. 4,15 The present review will attempt to examine both direct and indirect pathways to reducing health inequalities through community engagement approaches.

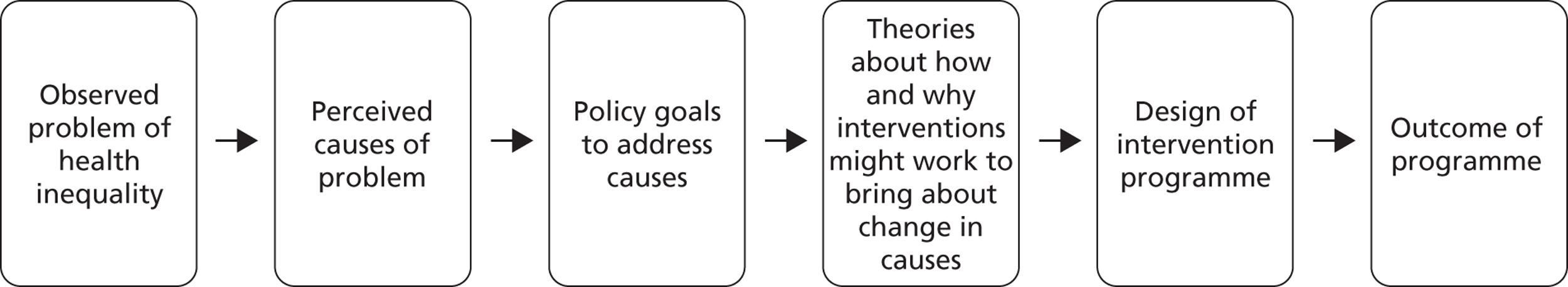

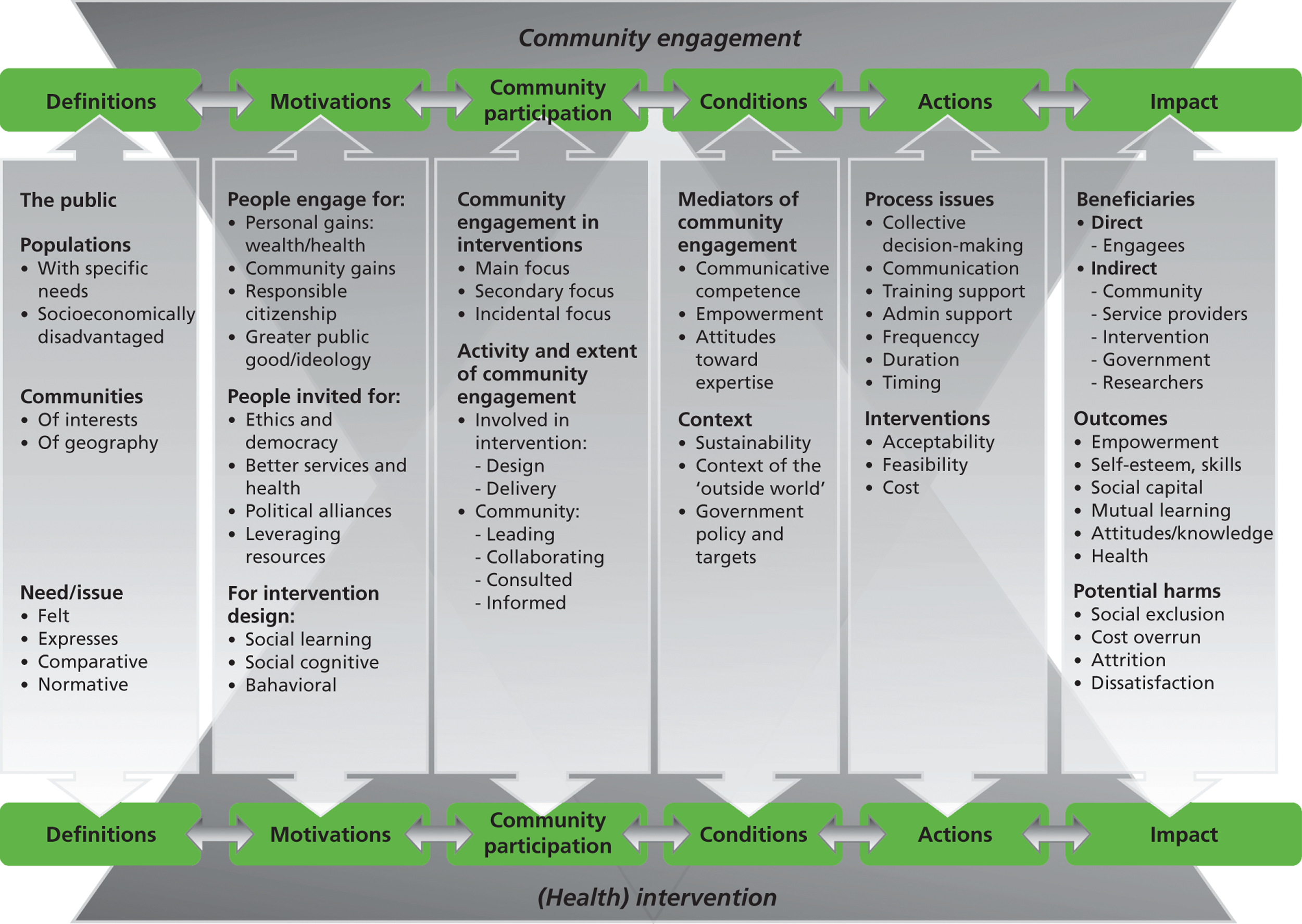

Initial conceptual framework for this research

One of the main outputs from this review is a new conceptual framework that encapsulates the way that different types of community engagement might facilitate interventions to impact on health outcomes amongst disadvantaged groups. The conceptual framework that we finished the project with was therefore quite different from the one that we began with, but for reasons of accountability, and to ensure that it is possible for this report to allow the reader to follow the course of the research, we present here the conceptual framework that informed our search strategies and decisions about which studies to include and exclude.

The commissioning brief for this project defined community engagement as ‘approaches to involve communities in decisions that affect them’. Mason et al. 40 have defined community engagement for health promotion as engaging groups of people who share geographies, interests or identities with the aim of improving health and/or reducing health inequalities. The commissioning brief refers to engagement with any organisations that can provide activities for improving public health. Some non-NHS organisations may be directly health-related, such as sports clubs or food retailers. A healthy public policy approach recognises that it would be helpful if organisations with other aims, such as public transport, workplaces or schools, also considered their influence on health.

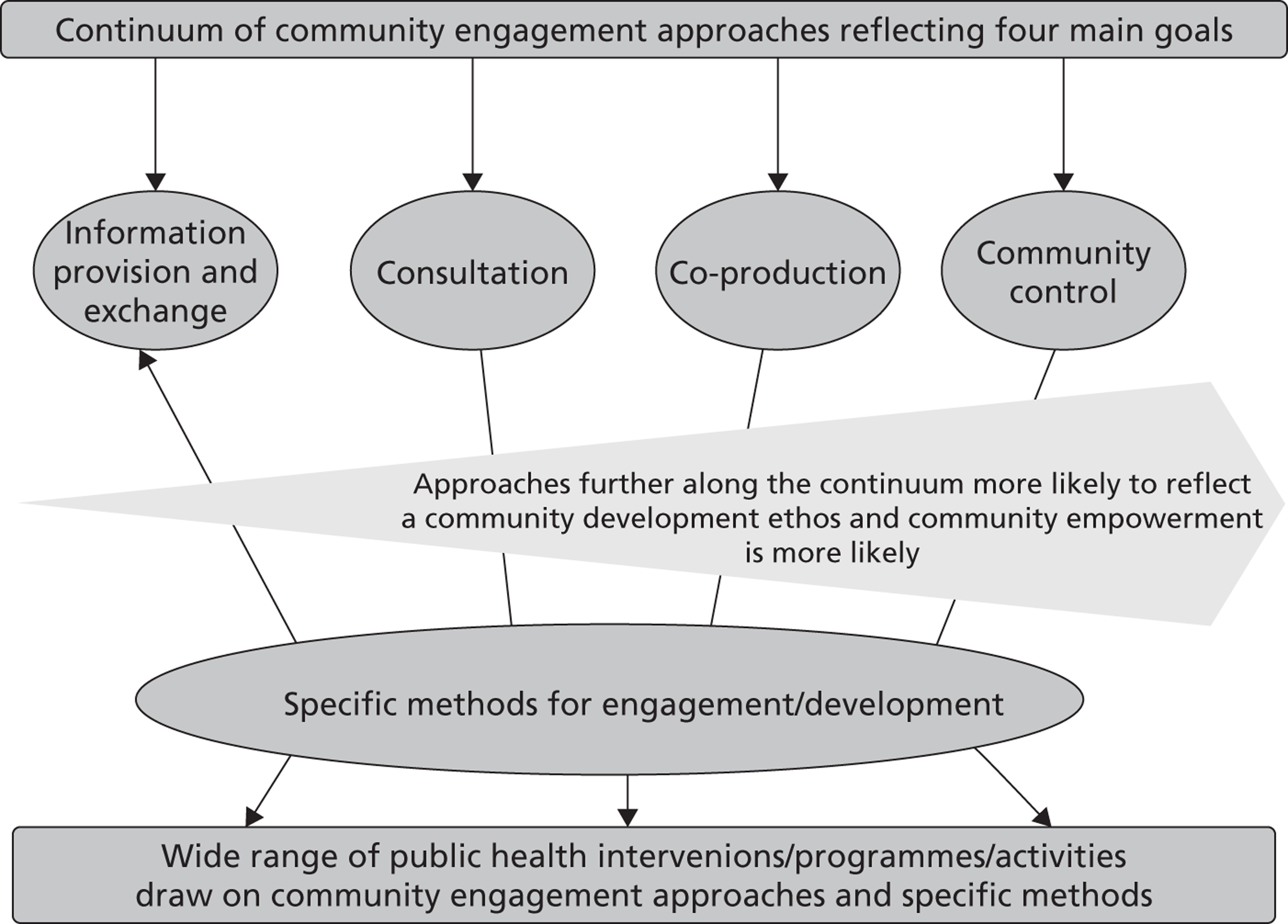

For the purposes of this systematic review, we have defined community engagement as a direct or indirect process of involving communities in decision-making and/or in the planning, design, governance and delivery of services, using methods of consultation, collaboration and/or community control. Information-giving was not seen as an empowering type of engagement, as this approach does not explicitly facilitate any reflection of users’ perspectives in the identification, design or delivery of an intervention.

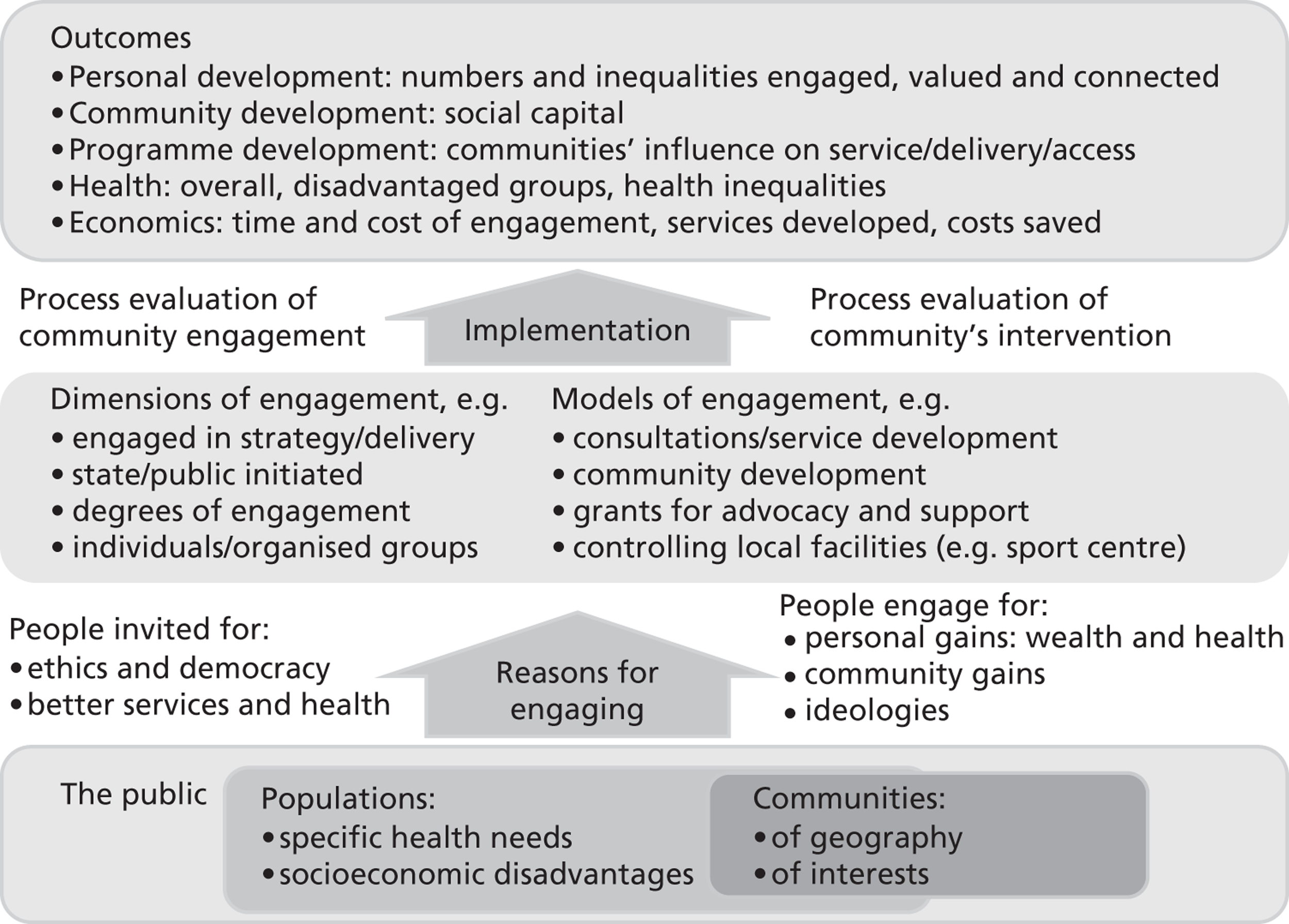

Involving people in decisions that affect them is justified both by ethical and political arguments, and by instrumental arguments asserting that involvement will lead to decisions more relevant to the people being served. Community members are motivated to participate for their own personal material or health benefits, for the gains anticipated for their community or by their own ideologies. 41

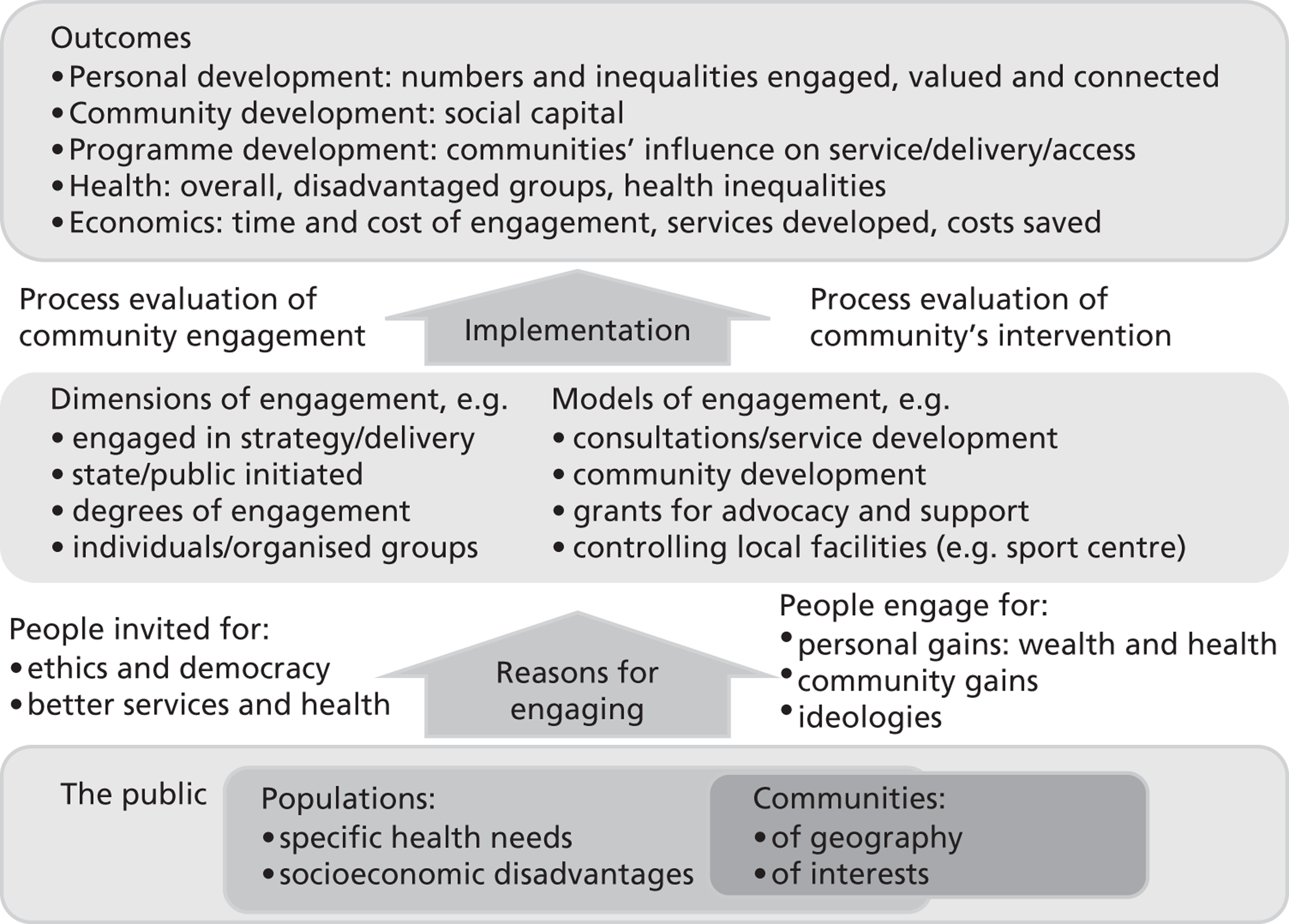

There are a broad range of community engagement models for engaging people in developing strategy or implementing services. Key differences in these models include who initiates the engagement (public service organisations or communities); the degree to which people are engaged (consulted, in collaborative partnerships or in control); and whether it is individuals or organised community members who are engaged. 42,43 Communities may be engaged in consultations, group support and advocacy, service development, controlling local facilities and human resources, and community tier government; any such engagement may be supported by education and networking. 42 Success depends on sound implementation of both the community engagement and any interventions resulting from this engagement.

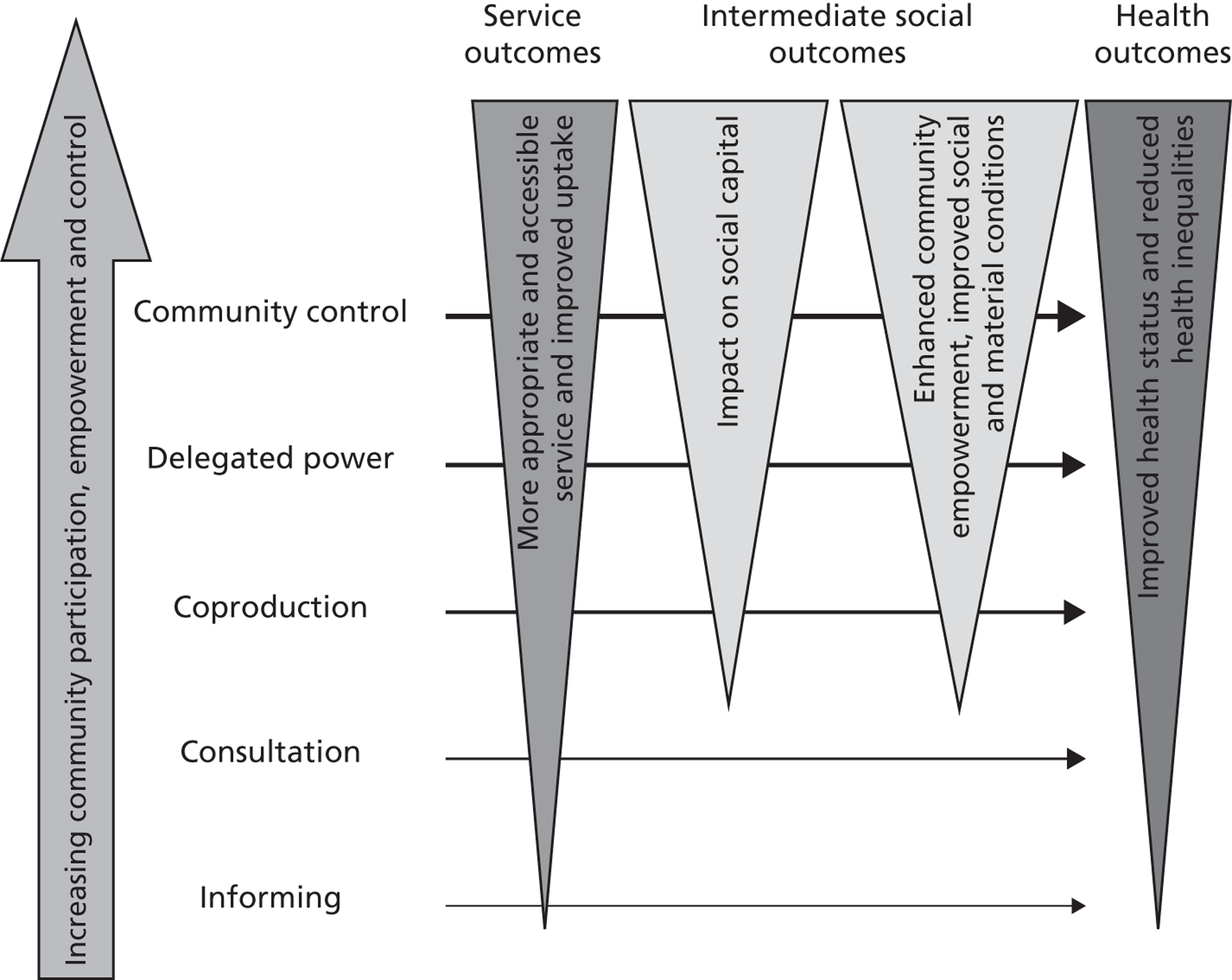

The impact of community engagement can be considered at the level of individuals (personal development), communities (social capital), services (development, delivery, access) and health (population health, health of disadvantaged groups, health inequalities; extended from Slater et al. 44). Ideally, economic analyses would take into account costs incurred by community engagement, subsequent service development and the potential costs that might be incurred/saved as a result of an increased uptake of services that improve health. Data permitting, these are all issues that we proposed to explore in our analyses, and their relationships are summarised in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

The original conceptual framework.

Rationale for this review

Previous work has shown that, if communities are ‘signed up’ to the intervention or programme that they are receiving, people are more likely to participate and better outcomes can result. Community engagement is likely to have a positive effect on social inequalities,4,15,28 which might in turn reduce health inequalities,28 although the direct effect on health inequalities is still uncertain. 4,15 However, without a synthesised evidence base, it is not clear whether specific approaches to community engagement help to reduce inequalities in health; or for whom they work, under what circumstances and with what resources. As it would be difficult and expensive to conduct a very large research project that tests multiple approaches to community engagement in different topic areas with different populations, this project synthesised existing evidence and thereby made use of the investment already made in many published research studies.

Systematic reviews pull together all of the available research on a given topic. Through rigorous, structured approaches to identifying, selecting and analysing the evidence, systematic reviews reduce the biases inherent in more traditional reviews of the literature. They are valuable because they enable us to take stock; when based on the entirety of evidence in a given field they are able to tell us what we do, and do not, know. They are efficient because they valorise previous investments in research and, by virtue of the consistent way that they treat included studies, they are able to recast our view of research in a field, challenging existing assumptions and suggesting new areas for investigation. They also facilitate generalisability by looking for knowledge and findings across individual (and possibly atypical) primary studies.

Synthesising research systematically is recognised internationally as being a valuable and necessary activity for helping us to make sense of existing research and ensure that recommendations for policy and practice are based on the best, and most comprehensive, view of the available evidence. However, before this review was conducted, there was a clear gap in evidence synthesis in the case of community engagement in general, and its impact on health inequalities in particular. There was no synthesis of research able to identify specific approaches to community engagement that are able to reduce inequalities in health – and the resource implications of adopting them. Given the current concerns about health inequalities in the UK28 and the policy emphasis on community engagement as a vehicle for facilitating change (e.g. London Mayor45), it is timely to explore what works in engaging the community to reduce health inequalities.

Review aims and objectives

The overarching aims of this project were to identify community engagement approaches that are effective in improving the health of disadvantaged populations and/or reducing inequalities in health; and to describe the approaches in terms of the circumstances in which they work and the costs associated with their implementation. We accomplished these aims by achieving the following objectives:

-

consulting with relevant stakeholders to ensure that our study was informed by their perspectives and experiences

-

identifying a set of primary research studies that evaluate the effectiveness of interventions with a community engagement component in terms of their impacts on the health outcomes of disadvantaged groups

-

making contact with researchers in the field who have investigated the issues relevant to this study to enhance the data set we draw on

-

describing and synthesising the data that we identify

-

drawing conclusions, verifying our findings with stakeholders and writing up and disseminating our results.

Review questions

Our overarching review question is, ‘Can specific approaches to community engagement help to reduce inequalities in health; for whom, under what circumstances and with what resources?’

To answer this question, the following, more focused research questions (RQs) form the basis of our enquiry:

-

RQ1: What is the range of models and approaches underpinning community engagement?

-

RQ2: What are the mechanisms and contexts through which communities are engaged?

-

RQ3: Which approaches to community engagement are associated with improved health outcomes among disadvantaged groups? How do these approaches lead to improved outcomes?

-

RQ4: Which approaches to community engagement are associated with reductions in inequalities in health? How do these approaches lead to reductions in health inequalities?

-

RQ5: Which types of intervention work best when communities are engaged?

-

RQ6: Is community engagement associated with better outcomes for some groups than others? (In particular, does it work better or less well for children and young people?)

-

RQ7: How do targeted and universal interventions compare in terms of community engagement and their impact on inequalities?

-

RQ8: What are the resource implications of effective approaches to community engagement?

-

RQ9: Are better outcomes simply the result of increased resources, or are some approaches to community engagement potentially more cost-effective than others?

RQ1 and RQ2 are addressed through a map of the evidence and a theoretical synthesis of the models and mechanisms reported in the available literature; RQ3–9 through meta-analysis of the effectiveness data and thematic synthesis of the process data; and RQ8 and RQ9 through an economic analysis of costs and resources data.

Chapter 2 Review methods

The protocol for this review is attached in Appendix 11; although there are no checklists for a complex, multimethod review such as this, we have adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidance46 and the PRISMA checklist can be found in Appendix 10.

Setting

The systematic review includes studies of interventions conducted in any setting.

Design

The project is a systematic review of known existing research. We start with a map of the evaluation studies (see Chapter 3), which describes the scale and range of community engagement interventions (RQ1 and RQ2). This is followed by syntheses detailed across five chapters:

-

a theoretical synthesis of the literature (see Chapter 4) that describes the models and mechanisms of community engagement interventions (RQ1 and RQ2)

-

an aggregative statistical analysis (i.e. meta-analysis) of a subset of evaluation studies that focus on Marmot policy priority areas (RQ3–7; see Chapter 5)

-

a thematic summary of process evaluations that focus on interventions in Marmot policy priority areas (RQ3–7; see Chapter 6).

-

an economic analysis of costs and resources (RQ8 and RQ9; see Chapter 7)

-

additions to the theoretical synthesis that bring together the learning from the above four components to develop a broad conceptual framework (addressing the broader issues within the RQs; see Chapter 8).

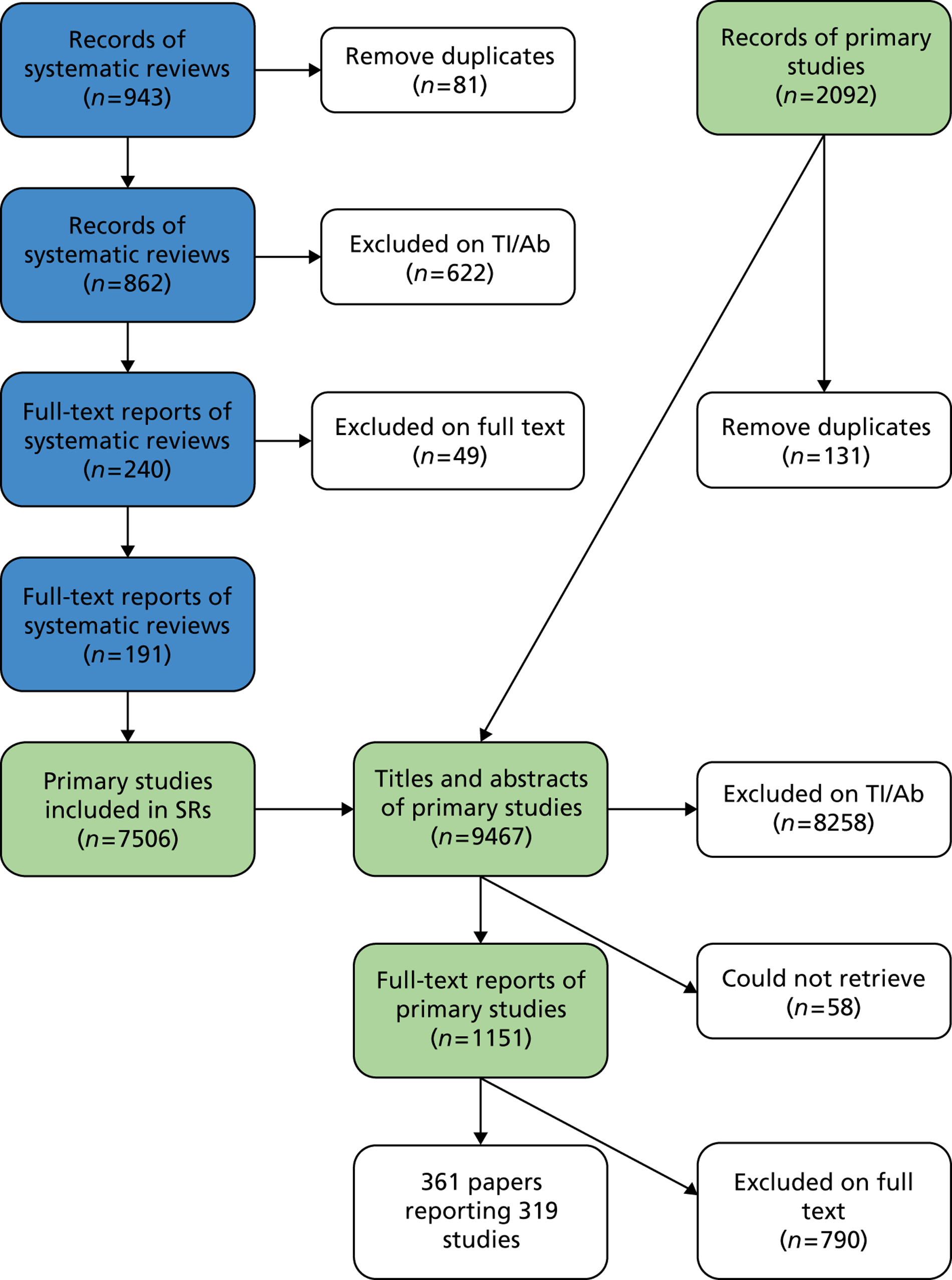

Rather than searching exhaustively for primary studies, which would have meant that most of the project would have been spent searching and screening, we compiled our data set for the analyses from specially selected registers of primary studies and systematic reviews. These registers have been populated using rigorous systematic review search methods.

We considered that a broad range of research was relevant to answering our RQs and thus included three types of research: outcome, economic and process evaluations; we also took account of the existing theoretical literature on community engagement. In the process of identifying the evidence to be synthesised, and before conducting the synthesis itself, we described the evidence with respect to the range of models and approaches underpinning community engagement (RQ1) and the mechanisms and contexts through which communities are engaged (RQ2) in the form of a map of the evidence. We also conducted a theoretical synthesis of the theories evident in the literature, which was the basis of our new conceptual framework.

In the meta-analysis, we analysed many evaluations of community engagement interventions; identified approaches that are most often associated with reductions in inequalities in health; and, to the extent that this was possible over a large number of studies, paid particular attention to the context of the research and the mechanisms by which communities are engaged and the ways this is thought to impact on intervention effectiveness (RQ3–7). The meta-analysis was then complemented with a thematic synthesis of the process evaluations present in the same set of studies. We also analysed the extent to which information on resource use, costs and cost-effectiveness was reported in our data set, as well as identifying data from complementary studies linked to these studies, including the use of modelling approaches to synthesise long-term costs and benefits (RQ8 and RQ9). Following this economic analysis of the literature, the four previous analyses were brought together in a new conceptual framework.

The design and methods were set out in a protocol that was published online on the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) website (see Appendix 11). Our search strategy was far more successful at identifying studies on community engagement and inequalities than we had anticipated at the outset. (We had expected the number of studies that met that joint requirement to be relatively small, and so developed a particularly sensitive search strategy.) Our funders (the NIHR Public Health Research programme) extended the project to enable us to synthesise this larger quantity of literature. The larger quantity of included studies changed our analysis slightly, making it more aggregative than we expected, and it enabled us to conduct a larger statistical analysis that we had planned (which we had planned to conduct ‘if possible’). The project remained faithful to the protocol and any deviations are specified in Chapter 9.

Information management

All records of research identified by our searches were uploaded to the specialist systematic review software, EPPI-Reviewer 4 [Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Co-ordinating Centre (EPPI-Centre), Social Science Research Unit, Institute of Education, University of London, UK], for duplicate stripping and screening. 47 This software recorded the bibliographic details of each study considered by the review, where studies were found and how, reasons for their inclusion or exclusion, descriptive and evaluative codes and text about each included study, and the data used and produced during synthesis. The software enables us to keep track of electronic documents (e.g. PDF files) and take advantage of emerging text mining technologies to help us identify relevant research and efficiently identify commonalities across the studies that we find.

Ethical arrangements

This project was approved by our Faculty Research Ethics board at the Institute of Education (ethics approval reference number FCL 283; copies of the ethics application are available from the report authors). The project complies with the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) Research Ethics Framework.

User involvement

The project advisory group provided feedback on the research in the project. The advisory group includes public health policy and practitioner members. We had regular informal contact with members of the group by e-mail and telephone, and a formal face-to-face (with some attending by teleconference) meeting to discuss the review’s conceptual framework and analytical strategies.

In addition, we explored the review’s interim map findings through consultations with young people through the National Children’s Bureau (NCB) Young Research Advisers group48 and a group for looked-after young people in North London that preferred to remain anonymous. The NCB Young Research Advisers is a group of 18 young people aged 10–17 years from all over England that was established by the NCB to engage young people in the research process. Membership of the group is voluntary and the NCB provides expenses, food and appropriate accommodation when required. In recognition of the young person’s time in taking part in meetings, the NCB also gives members gift vouchers.

The young people’s consultations involved one workshop session for each of the two groups at their own venues, and lasted around 2 hours in length. Sessions were timed to fit in as part of the groups’ existing meeting plans. Content included practical exercises to introduce the project and help group members discuss what helps or hinders them to engage with community activities to improve health or reduce inequalities. These discussions were considered when designing the data extraction tools (e.g. the importance of distinguishing peers from non-peer community members was highlighted, and so we ensured that these were coded separately).

We conducted two seminars in late 2012 at which we discussed our findings and conceptual framework. These seminars were both an opportunity for dissemination and an opportunity for us to obtain wider feedback on our new conceptual framework.

Search strategy

Searching across such a broad topic raises particular challenges. Approaches to community engagement cut across many disciplines, topic areas and outcome domains including, for example, housing, transport, social inclusion, accident prevention and substance abuse. 4 Searching broadly requires the location and screening of many reports to identify a much smaller amount of research evidence that is specifically relevant. This can make exhaustive searching costly and time-consuming.

A further challenge relates to identifying different types of evidence. We wanted to find outcome, process and economic evaluations, and the theoretical literature that applied to them. Not only are these often reported in different sources, which broadens the search scope, but also they use diverse terminology that can make recognition of their relevance difficult. The lack of detail about health inequalities in titles and abstracts can also make it difficult to detect studies that include relevant health equity issues.

Given the above challenges, we identified two practical strategies for identifying relevant studies. First, we identified systematic reviews through searching various websites and databases devoted to systematic reviews. The aim of this step was to capitalise on the systematic searches that have already been carried out for other reviews by identifying relevant primary studies included in those. Second, we used a database of studies in health promotion and public health that the EPPI-Centre has built up over many years as a result of carrying out systematic reviews (known as TRoPHI or, the Trials Register of Promoting Health Interventions). The studies in this database are the product of systematic searches and have already been systematically classified; they thus represent a valuable shortcut to evidence. Importantly, the TRoPHI database is updated several times a year, thereby increasing the likelihood that more recent studies not yet included in a review are identified.

Both approaches to searching are detailed below. The syntax that was used in the search process is presented in Appendix 1. Theoretical literature could be identified from the references in the evaluations and through colleague recommendations, and so the strategy described here focuses on the means by which we found the evaluation literature.

Identifying systematic reviews

We searched a range of registers, websites and databases for systematic reviews that discuss how some or all of their included studies contain interventions that utilise community engagement. The reviews were used to identify included primary studies that are relevant to the scope of this project; the systematic reviews themselves were not included in the syntheses in this project (see Study selection and eligibility criteria).

The systematic review registers, websites and databases that we searched were:

-

Database of Promoting Health Effectiveness Reviews (DoPHER). DoPHER is developed and maintained by the EPPI-Centre. It has focused coverage of systematic and non-systematic reviews of effectiveness in health promotion and public health worldwide. It currently contains details of > 2500 reviews of health promotion and public health effectiveness. All reviews are assessed and coded for specific characteristics of health focus, population group and quality (URL: http://eppi.ioe.ac.uk/webdatabases/Intro.aspx?ID=2, accessed 15 March 2013).

-

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR). CDSR includes all Cochrane Reviews (and protocols) prepared by Cochrane Review Groups in The Cochrane Collaboration. As of Issue 5, 2011, CDSR includes 6641 articles: 4622 reviews and 2019 protocols (URL: www.thecochranelibrary.com/view/0/AboutTheCochraneLibrary.html#CDSR, accessed 15 March 2013).

-

Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE). DARE is developed and maintained by the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) and currently contains > 21,000 systematic reviews. It is focused primarily on systematic reviews that evaluate the effects of health-care interventions and the delivery and organisation of health services. The database also includes reviews of the wider determinants of health such as housing, transport and social care when these impact directly on health, or have the potential to impact on health (URL: www.crd.york.ac.uk/CMS2Web/AboutDare.asp, accessed 15 March 2013).

-

The Campbell Library. The Campbell Collaboration’s library of systematic reviews includes reviews and protocols prepared by Campbell review groups under any of the six co-ordinating group themes: crime and justice, education, international development, methods, social welfare and review users (URL: www.campbellcollaboration.org/library.php, accessed 15 March 2013).

-

NIHR Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme website. The HTA programme produces research about the effectiveness of different health-care treatments and tests for those who use, manage and provide care in the NHS. The HTA website houses all of the reviews published through the HTA programme in the HTA journal series and holds in excess of 550 titles (URL: www.hta.ac.uk/project/htapubs.asp, accessed 15 March 2013).

-

HTA database hosted by the CRD. This database currently holds > 10,000 summaries of completed and ongoing HTAs from around the world. Database content is supplied by the 52 members of the International Network of Agencies for Health Technology Assessment (INAHTA) and 20 other HTA organisations worldwide (URL: www.crd.york.ac.uk/crdweb/AboutHTA.asp, accessed 15 March 2013).

Identifying primary research through the Trials Register of Promoting Health Interventions and NHS Economic Evaluation Database

Searches of the systematic review resources were supplemented by searches of the TRoPHI database and the NHS Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED).

The TRoPHI database includes focused coverage of trials of interventions in health promotion and public health worldwide. It covers both randomised and non-randomised controlled trials and currently contains details of > 4500 trials and is updated four times a year. This source was searched to ensure that relevant trials published outside of the time frame or scope of the reviews identified in the review databases listed in the previous section are detected.

Part of the TRoPHI data set was used in a comparison of randomised and non-randomised trials49 and we proposed to add additional studies from reviews that were carried out since this study. The approximately 300 studies in this data set were already classified using one of two data collection tools that capture detailed information about their methodology, participants, planning and process measures (if any), intervention and outcomes. [Although many of the studies were potentially relevant, surprisingly few passed both our ‘community engagement’ and ‘inequalities’ filter, and so the vast majority (> 99%) of studies synthesised came from our other searches.]

The NHS EED includes records of economic evaluations of health-care interventions, including cost–benefit, cost–utility and cost-effectiveness analyses; the database currently includes > 11,000 economic evaluations. The database is maintained through weekly literature searches that are conducted by the CRD.

Other search sources

The final component in our search strategy was contact with authors of identified studies. We contacted authors of a small number of key studies that were excluded on methodological grounds to ask them if they had outputs that would meet our inclusion criteria, or if they could provide further information about the study to assess its suitability for inclusion. ‘Key studies’ were large-scale UK-based evaluations, such as the Health Action Zones initiative.

Dates of searches

-

DoPHER: 26 July 2011.

-

TRoPHI: 16 August 2011.

-

The Campbell Library, CDSR, DARE, HTA and NHS EED: 17 August 2011.

-

Supplementary search of HTA journal in Web of Knowledge for papers published 2010–11: 18 August 2011.

Study selection and eligibility criteria

The outcome of the search was a database of references and documents that were screened using the review’s inclusion criteria. The inclusion criteria are a list of statements about what the study should contain to be relevant to the review question; studies must meet all of the criteria to be eligible for inclusion in the review. The criteria were applied twice: first, to identify systematic reviews and, second, to identify relevant primary studies.

The criteria were piloted on a sample of studies before being applied to the larger data set and reviewers discussed screening decisions regularly to ensure consistency in the way that studies were being included and excluded. Five reviewers were involved in screening the evidence [three of the report authors (AO, GB and JK) and two research assistants named in the acknowledgements (KT and JW)]. The other report authors were occasionally consulted when inclusion decisions that might affect the scope of the review were encountered.

Selecting reviews

The purpose of this stage was to identify reviews that might include relevant primary studies. The following criteria were applied to titles and abstracts of reviews:

-

published after 1990 (the date cut-off set by other reviews on which we are building, e.g. Popay et al. 4)

-

a systematic review (i.e. describe search strategies and inclusion criteria used)

-

included outcome, economic, or process evaluation studies

-

described at least one intervention potentially relevant to community engagement

-

included at least one study in the results section

-

written in English

-

measured and reported health or community outcomes.

Studies were limited to the English language because of a lack of resources to translate documents. Each systematic review was assessed against these criteria in a stepwise fashion, such that any review excluded because it failed a criterion later in the list must have passed any preceding criterion. We were deliberately inclusive when considering the concept of community engagement at this stage to avoid missing any reviews that might include studies with community engagement even though it was not mentioned in the review’s abstract; as such, reviews that referred to community-level interventions were typically included except when this conflicted with the inclusion criteria above. Indeed, applying a consistent definition of community engagement across reviews was a challenge. In initial stages we relied on reviewers’ previous experience with the literature and developed written guidance on the definition within EPPI-Reviewer 4 as understandings about the concept emerged through group discussion about the interventions, providers, locations and study aims described across the reviews. It is possible that screening titles and abstracts of reviews may have missed some primary studies that had elements of community engagement. However, because of the reflective method used in consolidating our definition of community engagement early on in the screening process, this is more likely to be because of a lack of detail in the reference information available than because of systematic bias from reviewers.

We then retrieved the full-text copy of all reviews that passed these inclusion criteria. A brief screening of the full-text document was then conducted to check that the review was, in fact, systematic and that it included primary studies of relevance to our review. (Relevance at this stage was judged according to the criteria presented in Selecting trials for the map, although the criteria were not applied stepwise and were not recorded.) Potentially relevant primary studies were then added to the EPPI-Reviewer 4 database for the second stage of screening.

Selecting trials for the map

Once the final set of systematic reviews was obtained, we screened within each review to identify potentially relevant primary studies (trials). This involved scanning the evidence tables and reference lists of the reviews for relevant trials. We then located the abstracts for these trials.

The titles and abstracts of the trials identified during this process, plus those identified through TRoPHI and NHS EED, were then assessed for inclusion in the review. Studies were included if they met all of the following criteria:

-

published after 1990 (the date cut-off set by other reviews on which we are building, e.g. Popay et al. 4)

-

includes primary research, in that data have been collected during that study through interaction with or observation of study participants

-

not a Master’s thesis

-

includes outcome, economic, and/or process evaluations of interventions

-

community engagement is the main approach of the intervention

-

for outcome evaluations, study has a control or comparison group (i.e. it must be a controlled trial, either randomised or non-randomised)

-

published in English.

Once all of the studies had been screened on their titles and abstracts, full reports were obtained for those that appeared to meet the criteria or for which there was insufficient information to be certain. The retrieved articles were then screened based on the full-text article.

Three additional criteria were applied at full-text screening which ensured that sufficient detail was present for critical appraisal to take place and that the study participants were relevant to our focus on inequalities:

-

study characterises study populations or reports differential impacts in terms related to social determinants of health that can be captured by the PROGRESS-Plus framework (this framework, which enables us to characterise different dimensions of potential disadvantage, is described in Chapter 3)

-

study reports health or health-related outcomes for the effectiveness evaluation and/or process data in a process evaluation

-

study was conducted in an Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) country (at the time of screening OECD member countries were Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Chile, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Korea, Luxembourg, Mexico, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, UK and the USA).

Those studied that passed the inclusion criteria on the basis of full-text screening were included in the map of engagement models and contributed to the theoretical synthesis.

Selecting trials for in-depth review

With regard to the extraction of outcome data, we carried out a final sift of the studies to determine which would be included in the in-depth review. Some studies were excluded because, on closer inspection, they did not have an adequate (independent) control group or quantitative data from which we could calculate an effect size estimate for the meta-analysis. We also filtered out studies that did not report at least one of the following outcome types:

-

health behaviours (e.g. smoking, food intake, physical activity)

-

community outcomes (e.g. perceived increased access to services in the area)

-

engagee outcomes (e.g. skills acquired by the engagees whilst engaged in the initiative).

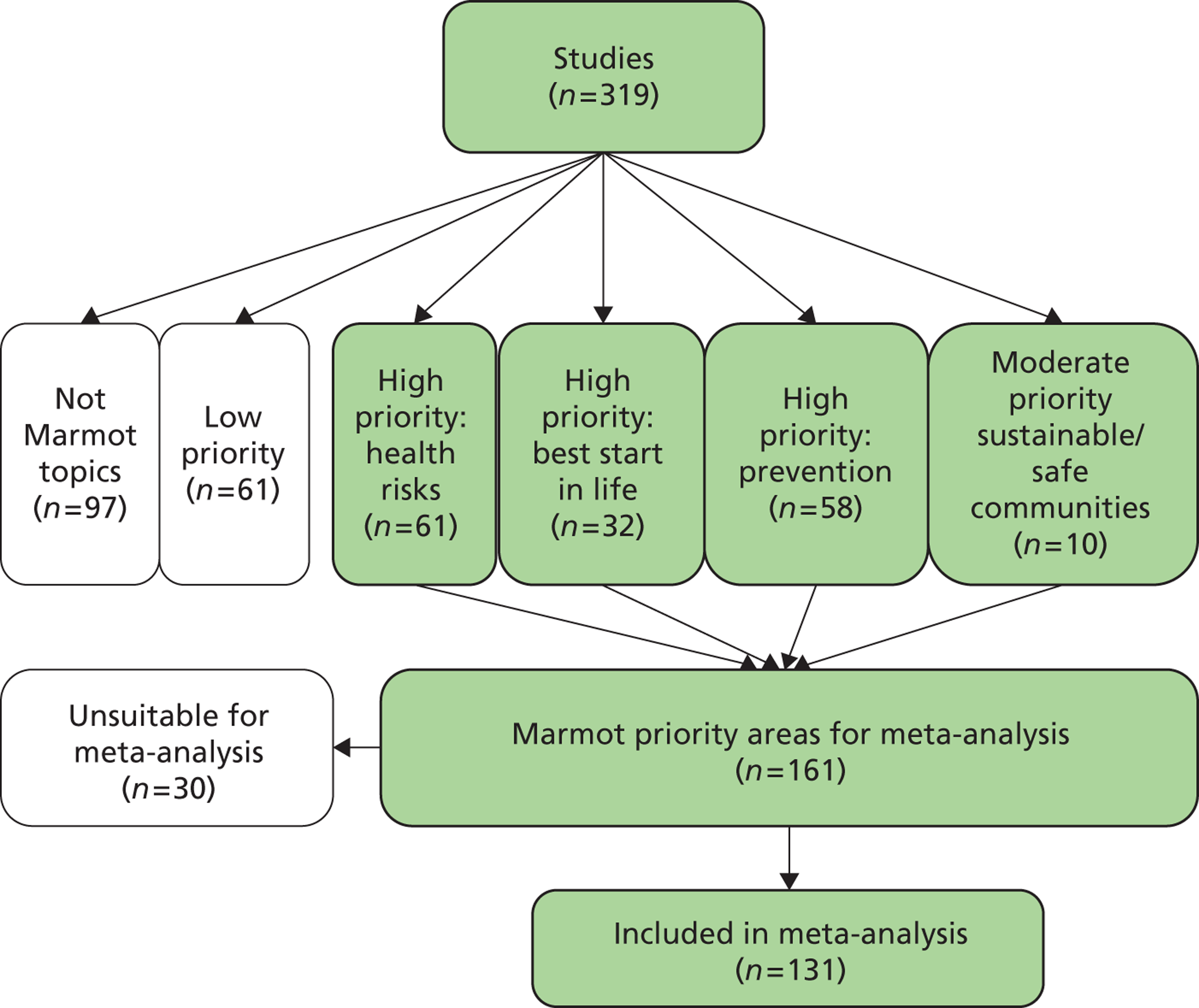

Time constraints meant that we had to further narrow the scope of the studies for meta-analysis – it was simply impossible to extract outcome and risk of bias data for all 319 studies included in the map in the time frame available. It was decided, after consultation with the project advisory group, that a sensible way to identify a manageable set of studies was by focusing on health issues that were emphasised in the Marmot Review28 as being particularly problematic in terms of health inequalities in the UK. To achieve this, we identified any health priority areas in the Marmot Review in ‘health inequalities and the social determinants of health’ (see Chapter 2) and ‘policy objectives and recommendations’ (see Chapter 4) that mapped onto the health topics of the studies included in our review. These are presented in Table 1. Only studies categorised under those health topics were included in the in-depth review.

| Broad theme in Marmot Review | Labels used in Marmot Review | Captured under labels used in our data extraction |

|---|---|---|

| Health risks | Smoking | Smoking cessation |

| Smoking/tobacco prevention | ||

| Alcohol | Substance abuse | |

| Obesity | Obesity prevention/weight reduction | |

| Drug use | Substance abuse | |

| Policy Objective A: give every child the best start in life | Increased investment in early years; quality early years education and child care | Antenatal (prenatal) care |

| Breastfeeding | ||

| Childhood immunisation | ||

| Other child (ill) health | ||

| Supporting families to develop children’s skills | Parenting | |

| Policy Objective C: create fair employment and good work for all | Reducing physical and chemical hazards and injuries at work | Worker injury prevention/safety |

| Policy Objective E: create and develop healthy and sustainable places and communities | Integrate planning, transport, housing and health policies | Housing |

| Neighbourhood renewal/regeneration | ||

| Policy Objective F: strengthen the role and impact of ill health prevention | Increased investment in prevention; implement evidence-based ill health preventative interventions | Public health/health promotion/prevention |

| Cancer prevention | ||

| Cardiovascular disease/hypertension prevention | ||

| Healthy eating | ||

| Physical activity |

Data extraction

Data collection (extraction) process

Mapping stage

The mapping stage of the review describes the scale and range of community engagement interventions and contributes to addressing RQ1 and RQ2. Studies that met our inclusion criteria were stored electronically (when possible) and classified according to a standardised data extraction framework that is detailed in Appendix 2. Information was collected on models of community engagement (consultation, collaboration and community control), approach to community engagement (e.g. formation of community coalition, volunteer intervention provider), mechanism of engagement (how the community was recruited/involved), area of health concern (e.g. breastfeeding, smoking cessation), participants’ PROGRESS-plus characteristics and geographical and other contextual details.

Data extraction for the mapping stage was conducted independently by four different reviewers (AO, GB, JK and FJ). The data extraction tool was piloted on a sample of studies by all four reviewers before being applied to the larger data set. The reviewers discussed ambiguities regularly to ensure consistency in the way that studies were being coded.

Analysis stage

Data items

We extracted further data for those studies included in the meta-analysis, synthesis of process evaluations and economic analysis. Additional information was collected on the potential risk of bias in the study (i.e. methodological features related to the evaluation), the outcomes (see Meta-analysis), process issues (e.g. relationships between service provider and engagee), economic issues (e.g. sufficiency of funds) and costs/resources associated with the intervention (e.g. staff costs). The data extraction and risk of bias tool for effectiveness studies is provided in Appendix 3; the tool for extracting process information is provided in Appendix 4; and the tool for extracting information on resources, costs and consequences is provided in Appendix 5. Before being applied to the larger data set, the data extraction tools were piloted on a sample of studies by all reviewers who subsequently used the tools.

Data for the in-depth review were extracted from each study by two members of the team working independently, before meeting to discuss their findings to ensure quality and consistency of interpretation. The reviewers discussed ambiguities regularly to ensure consistency in the way that studies were being coded. Data extraction for the meta-analysis was conducted by AO, GB, JK and FJ. Data extraction for the economic analysis was conducted by DM and TM.

Data extraction for the theoretical synthesis partially took the form of a narrative that describes the models, context and mechanisms of the participants, interventions and approach to community engagement. This was supplemented with a data extraction of the barriers to and facilitators of implementation, which was taken from the process evaluations using a formally developed tool (see Appendix 4). Data extraction for the thematic synthesis of process evaluations was conducted by GB and JK after the tool had been piloted on a sample of studies.

Summary measures

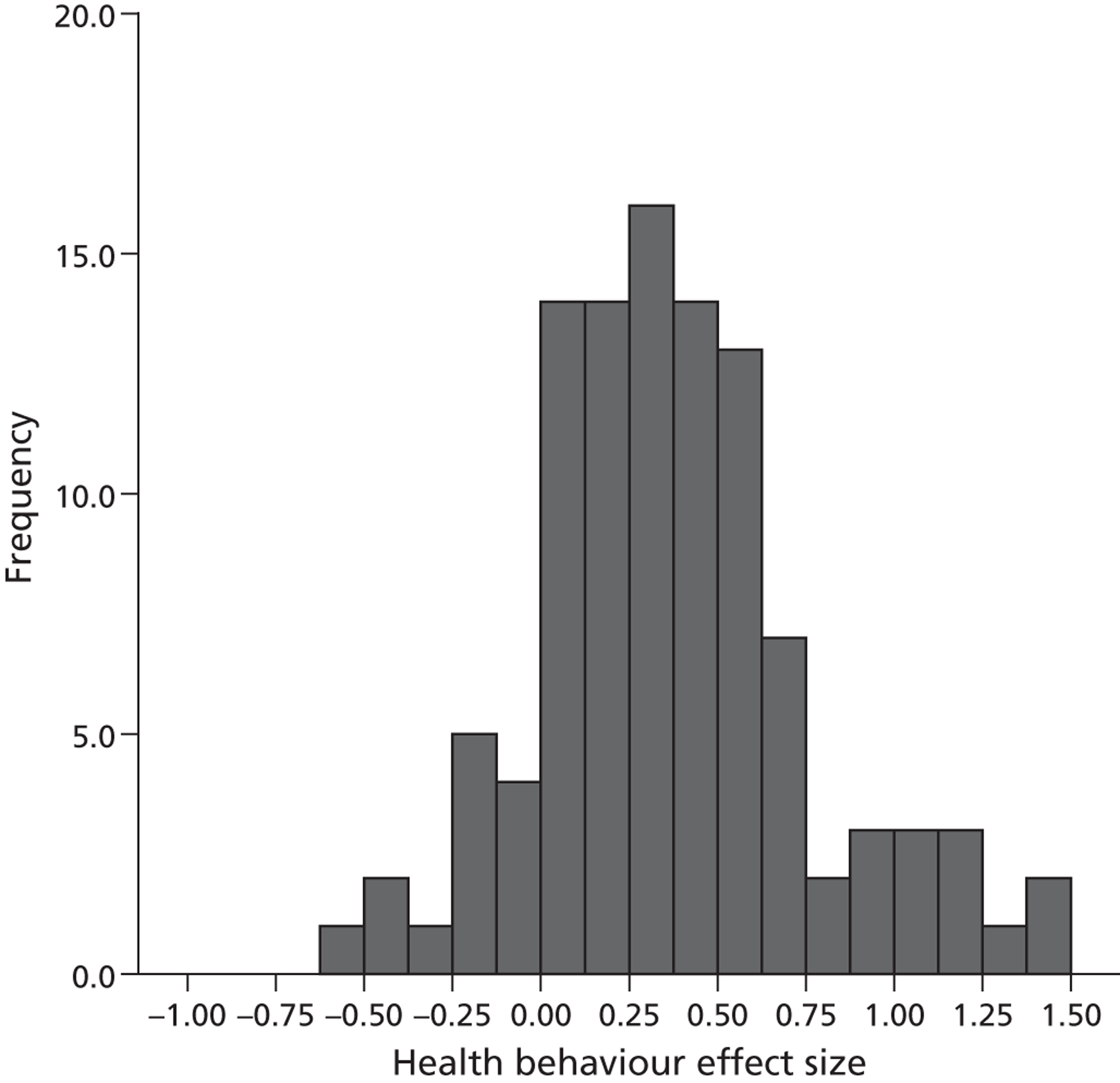

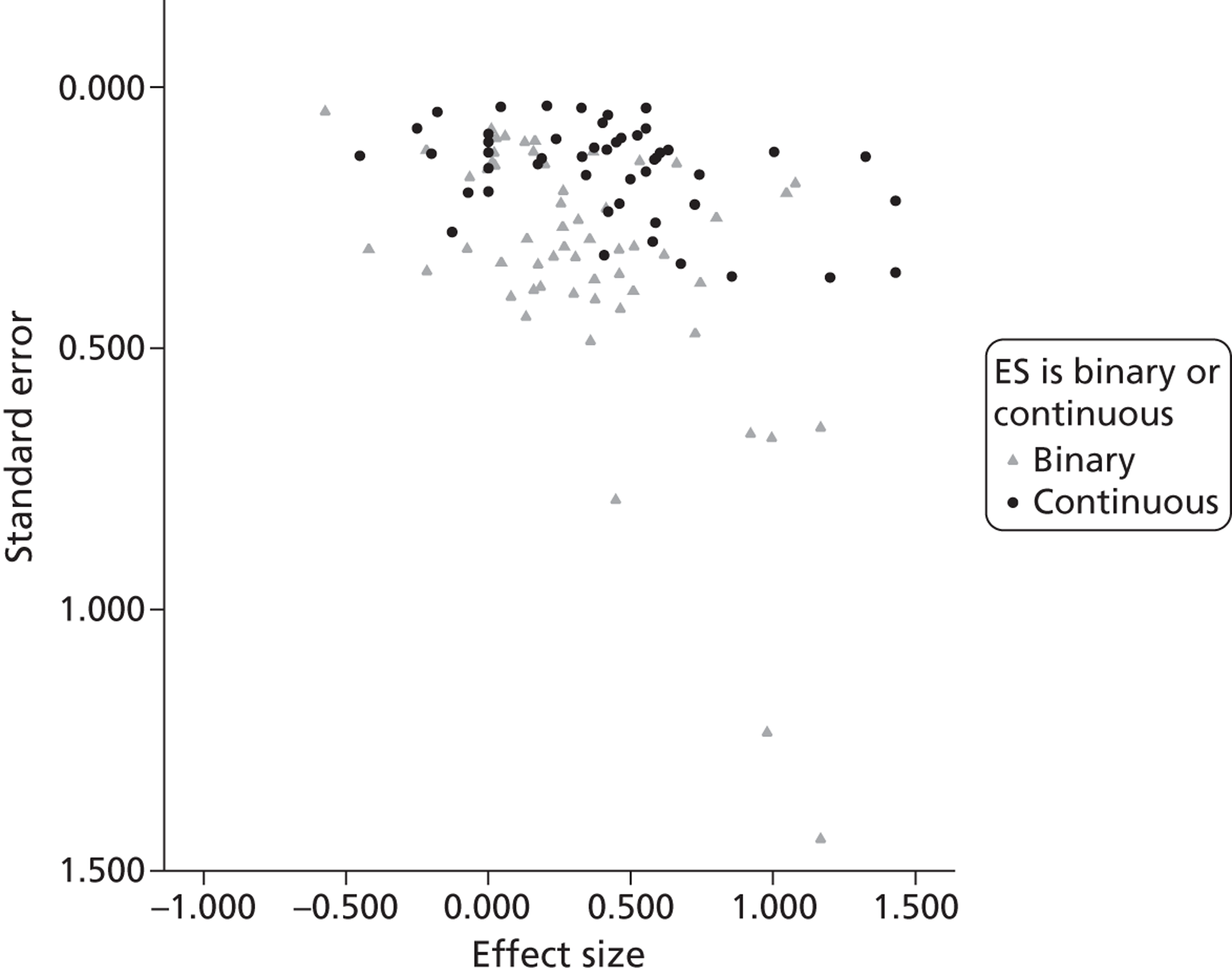

For the meta-analysis, effect sizes were calculated to summarise the impact of the interventions. Because many of the outcomes used different scales and different combinations of continuous and dichotomous data, we used the standardised mean difference50 to enable us to compare and combine results of continuous measures, and odds ratios (ORs) for binary measures. We transformed the ORs to standardised mean difference effect sizes using the methods described in Chinn. 51 The data were screened for outliers and were Winsorised to 2 standard deviations (SDs) from the mean. 52

We also adjusted the standard errors of cluster randomised trials that had a disproportionate weighting. When the intracluster correlation (ICC) was provided, we used the ICC reported by the authors; otherwise, we set the ICC to 0.02. In total, 10 studies were adjusted (two with author-reported ICCs and eight with the imputed ICC).

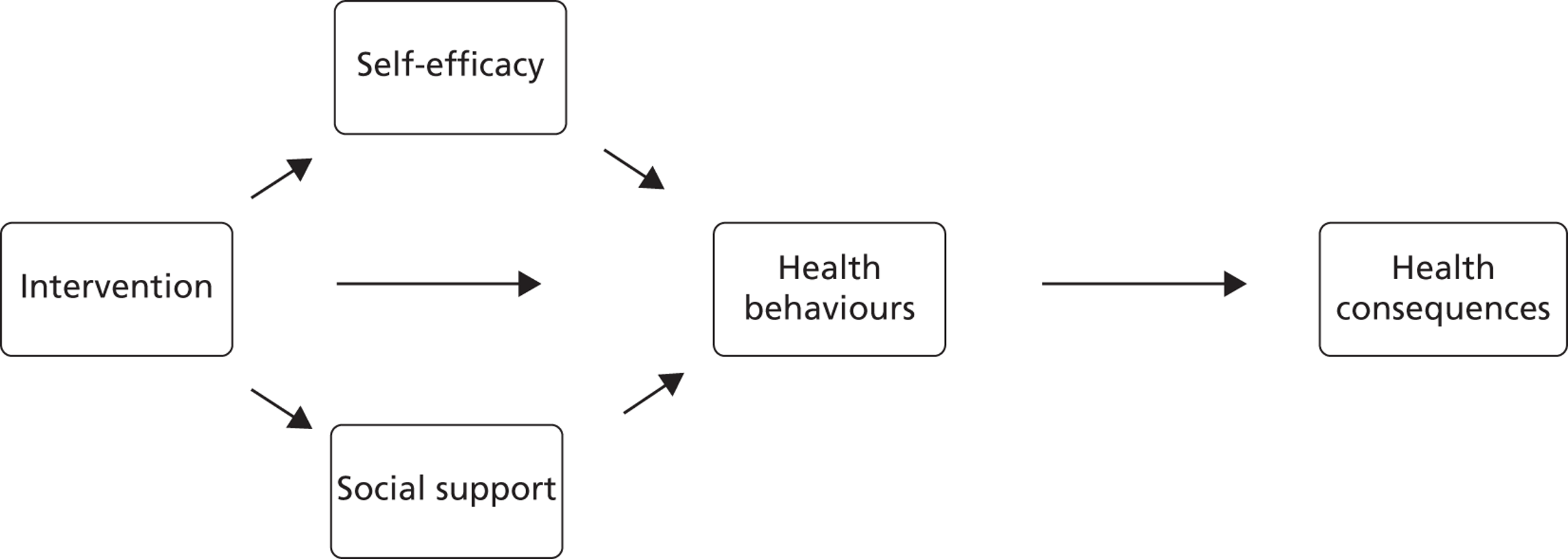

Following the approach we took in a similar meta-epidemiology,49 outcomes were classified into domains according to a conceptualisation of a pathway to behaviour and health change. The domains, in order of the theory of change, were self-efficacy and social support, health behaviour change, physiological consequences and final health state. In the event, all but one of the studies with outcomes in the final two domains reported only one or the other (i.e. physiological consequences or final health state), so these two domains were combined in the meta-analysis.

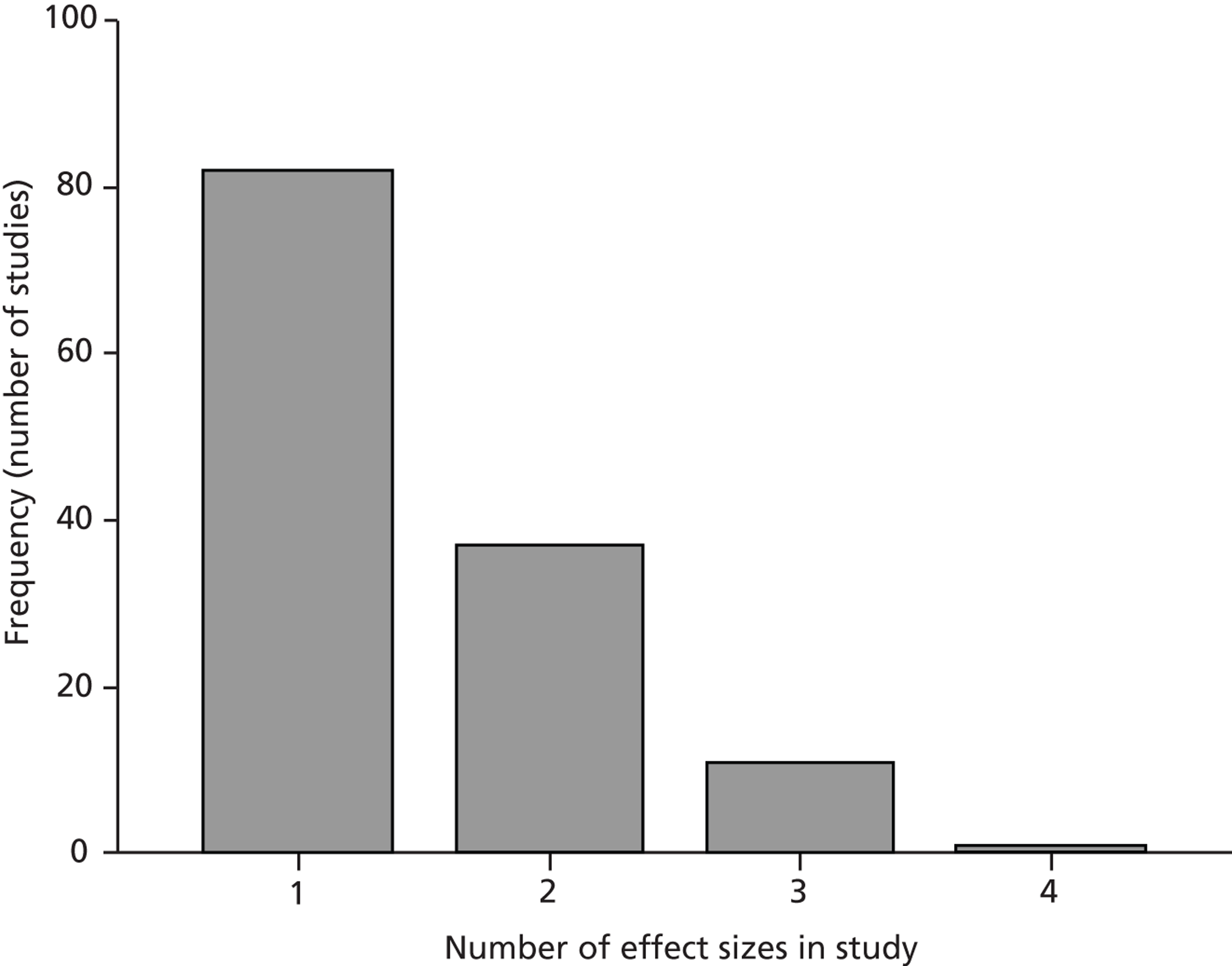

We also calculated effect sizes of outcomes for engagees and communities. As such, studies could contribute more than one effect size estimate to the data set under the following conditions:

-

when there were both immediate post-test and delayed follow-up measures, to test the persistence of effects over time and/or

-

when there were outcomes from different points in the pathway to behaviour and health change (i.e. social support, self-efficacy, health behaviours and health consequences) and/or

-

when there were measures of both engagees and public health intervention participants.

For our economic analysis, data on resources used in community engagement strategies to encourage behaviour change and/or uptake of interventions were extracted from studies using a bespoke data extraction sheet, which was incorporated into EPPI-Reviewer. This included categorisation of funded and in-kind resource use, as well as a value placed on the time of volunteers. We documented whether resource use (e.g. units of equipment, hours of paid staff and volunteers) was reported separately from costs. When possible we aimed to distinguish between those elements of resource specifically for community engagement and resources for any actual health-promoting intervention. This would better enable us to make comparisons between different community engagement mechanisms without this being confounded by the total costs of different interventions. 53

We also categorised budgets from which resources are supported. We made use of The Campbell and Cochrane Economic Methods Group – EPPI-Centre Cost Convertor (http://eppi.ioe.ac.uk/costconversion/default.aspx) to ensure that costs were converted to UK pounds sterling and inflated to 2010 prices using purchasing power parity rates from the International Monetary Fund. If a breakdown of cost data for population subgroups was identified this was also recorded. The economic analysis also extracted data on completed economic evaluations, as well as on some issues concerned with the use of financial and other incentives to encourage community engagement, and analysis of the extent to which the financial and organisational sustainability of effective interventions could be maintained.

Quality assessment

The outcome evaluations (controlled trials) were assessed for methodological quality using an adaptation of the Cochrane risk of bias assessment tool. 54 We examined the studies in a range of dimensions including methods of assignment, the comparison group type, the comparability of groups at baseline/methods of adjustment, attrition and selective reporting. In the meta-analysis, we tested to see whether effect size was associated with methodological quality.

The tool we used to assess the quality of the process evaluations was refined in a recent review55 and assesses whether or not steps were taken to minimise bias and error/increase rigour in sampling, data collection and data analysis; findings were grounded in/supported by the data; there was good breadth and/or depth achieved in the findings; and the perspectives of intervention participants were privileged. The findings from process evaluations that did not score well were included but a sensitivity analysis was conducted to assess their impact on the overall analysis, as findings that depend solely on the evidence of poorer quality process evaluations are more provisional than those coming from stronger evaluations.

We had planned to assess the quality of economic evaluation studies using the Consensus on Health Economic Criteria (CHEC) list. 56 In the event, no such evaluations were identified.

Synthesis of results

Once the relevant data were extracted, we mapped the research that we had identified by producing tables and cross-tabulations to show the frequency of different types of engagement and the contexts in which they occur. We also provide a description of the similarities and differences across interventions. The map is focused on trends and gaps in the evidence base rather than detailing each intervention. We then moved on to synthesise the findings of the studies.

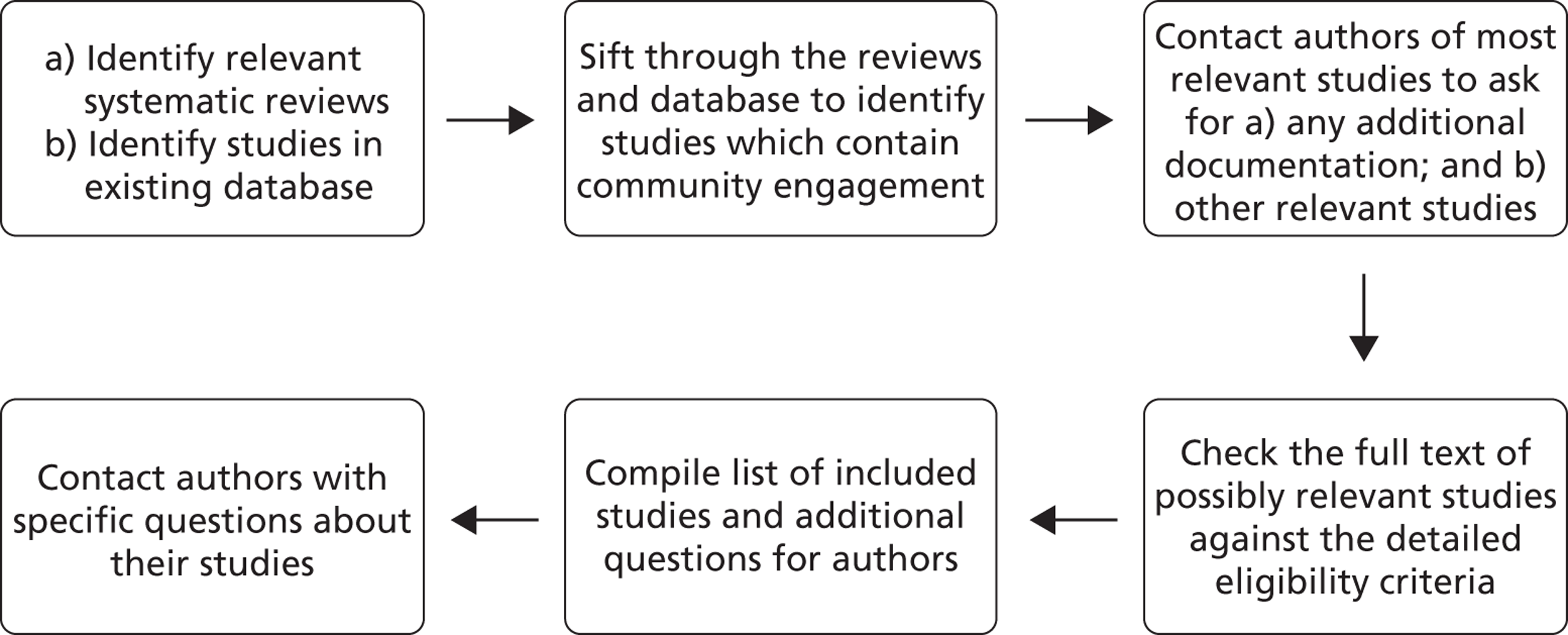

As described in the overview, there are four syntheses (theoretical, meta-analysis, thematic synthesis and economic analysis), which build on one another sequentially. The initial theoretical synthesis informed the subsequent syntheses, whereas the later theoretical synthesis (i.e. development of the conceptual framework) extended on the initial theoretical synthesis to incorporate the findings from the other analyses; there are thus five distinct synthesis chapters in this report. This iterative process is summarised in Figure 2. It shows that, although the emerging conceptual framework informed the statistical and economic analyses, it was then itself developed in the light of these syntheses.

FIGURE 2.

The conceptual framework both informed, and was informed by, the statistical and economic analyses.

Theoretical synthesis (see Chapters 4 and 8)

The theoretical synthesis was the first analysis to be completed. This analysis is similar in some respects to Pawson’s57 work on realist synthesis and examines in particular the theories, mechanisms and contexts of community engagement. It does not, however, attempt to engage in causal reasoning, leaving this task to the meta-analysis. The theoretical synthesis has been split into two parts in the report: Chapter 4 (answering RQ1 and RQ2), which presents the range of models of community engagement that have been presented elsewhere and focuses in particular on the theories of change that underpin each model; and Chapter 8, which presents a broad conceptual framework that encapsulates the studies in the statistical and economic analyses as well as the models of engagement in Chapter 4.

The first synthesis in this review aimed to understand the range of models and approaches underpinning community engagement, and the mechanisms and contexts through which communities are engaged. These aims are a way to gain a conceptual understanding of community engagement, rather than a more aggregative systematic review approach of counting the number of studies representing various models, approaches, mechanisms and contexts. 58,59

The theory-building nature of these aims led the research team to use methods of study identification and synthesis more appropriate for conceptual analysis research synthesis. In this type of synthesis, searching aims to build an understanding of a particular phenomenon by gathering a number of articles that present different perspectives on that phenomenon. Once a sufficient range of ideas have been identified, studies that do not add anything new to the topic are put to one side; in effect, a saturation of perspectives has been reached. 60

Using our data set of included studies along with theoretical literature that we identified alongside them, we adopted a purposive search and inclusion strategy more appropriate to gathering concepts, rather than the more traditional approach of exhaustively accumulating all literature on the topic. 61 A set of included studies was created that had been identified by team members as being examples of each of the different community engagement strategies. These studies were then synthesised in two ways.

The team began with the conceptual framework for community engagement (see Figure 1). First, one reviewer read, summarised and extracted data on community engagement aspects from each study and then compared those findings to the team’s conceptual framework to see whether issues in each paper refuted, confirmed or added new information to the model. The conceptual framework was developed as new issues were discovered. This ‘rolling’ or ‘constant comparative’ method of synthesis has been used in previous EPPI-Centre reviews. 62–64 The emerging conceptual framework and the summaries were read and discussed by the research team, to ensure that the framework reflected the combined expertise and individual perspectives of the whole team. A draft of the conceptual framework was presented to the review’s advisory group and the final framework was revised based on their feedback.

Second, all papers identified before in-depth coding in the map (n = 559) were clustered using the Lingo3G text mining algorithm (Carrot Search s.c., Poznan, Poland);65 these clusters were then manually organised according to the area of health concern, type of community engagement, participants’ PROGRESS-Plus characteristics and country/geographical details. This information was then also used to refine the framework. Each study was then manually coded; each time data were extracted from a study, its mechanisms and contexts were compared with our conceptual framework and the framework checked for its adequacy. After the meta-analysis and economic analysis were completed, the framework was again revised to take account of their findings.

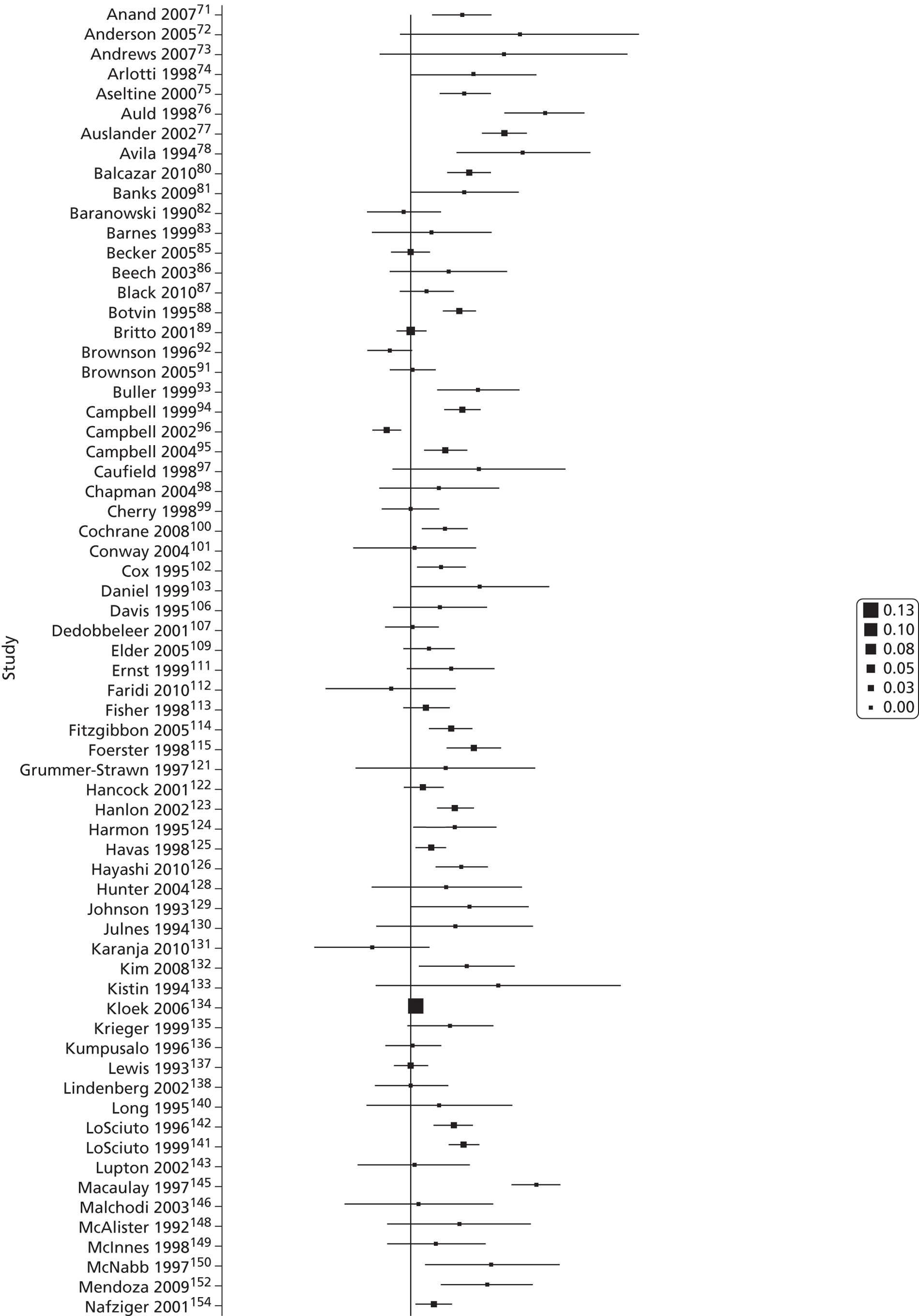

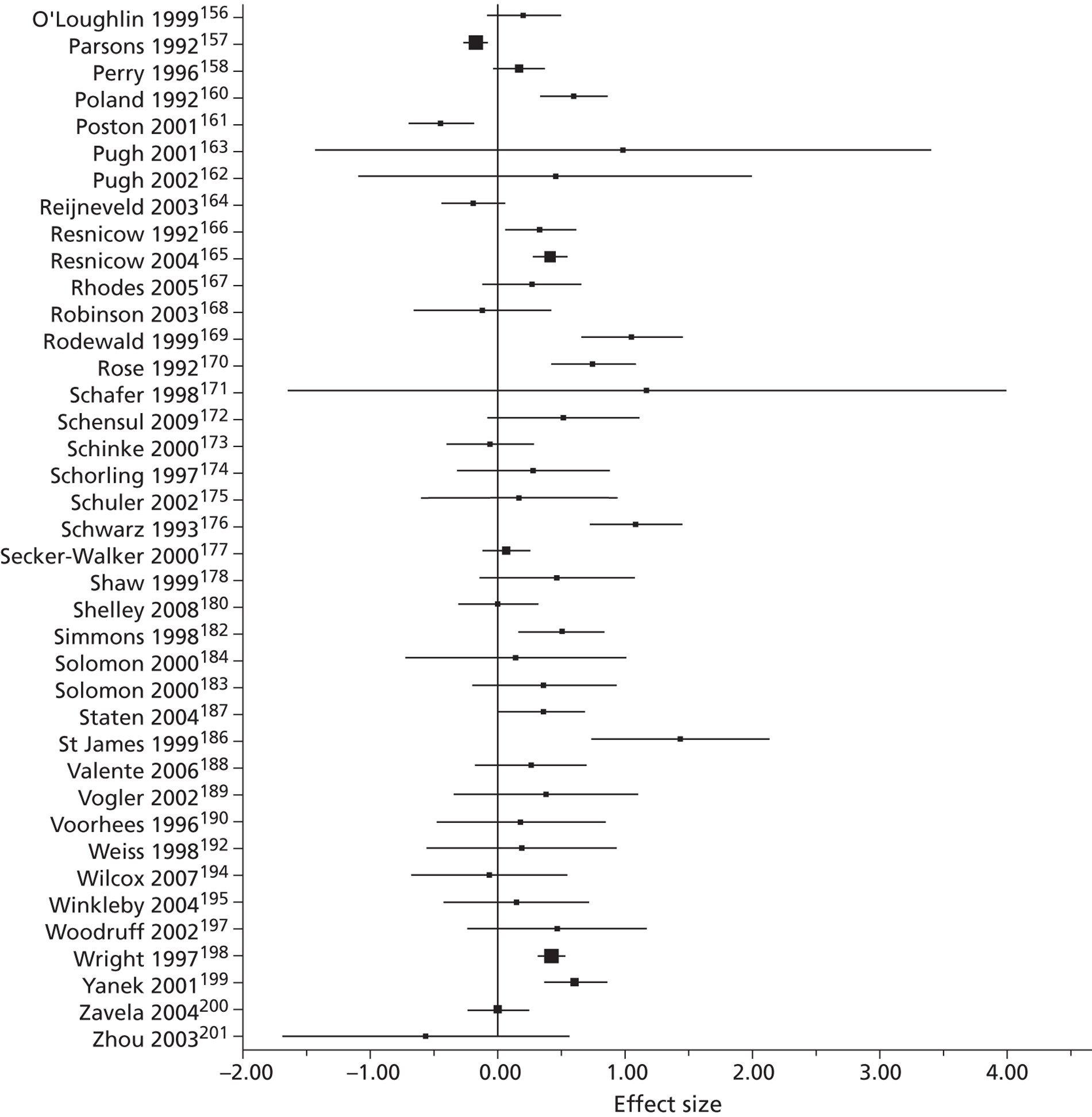

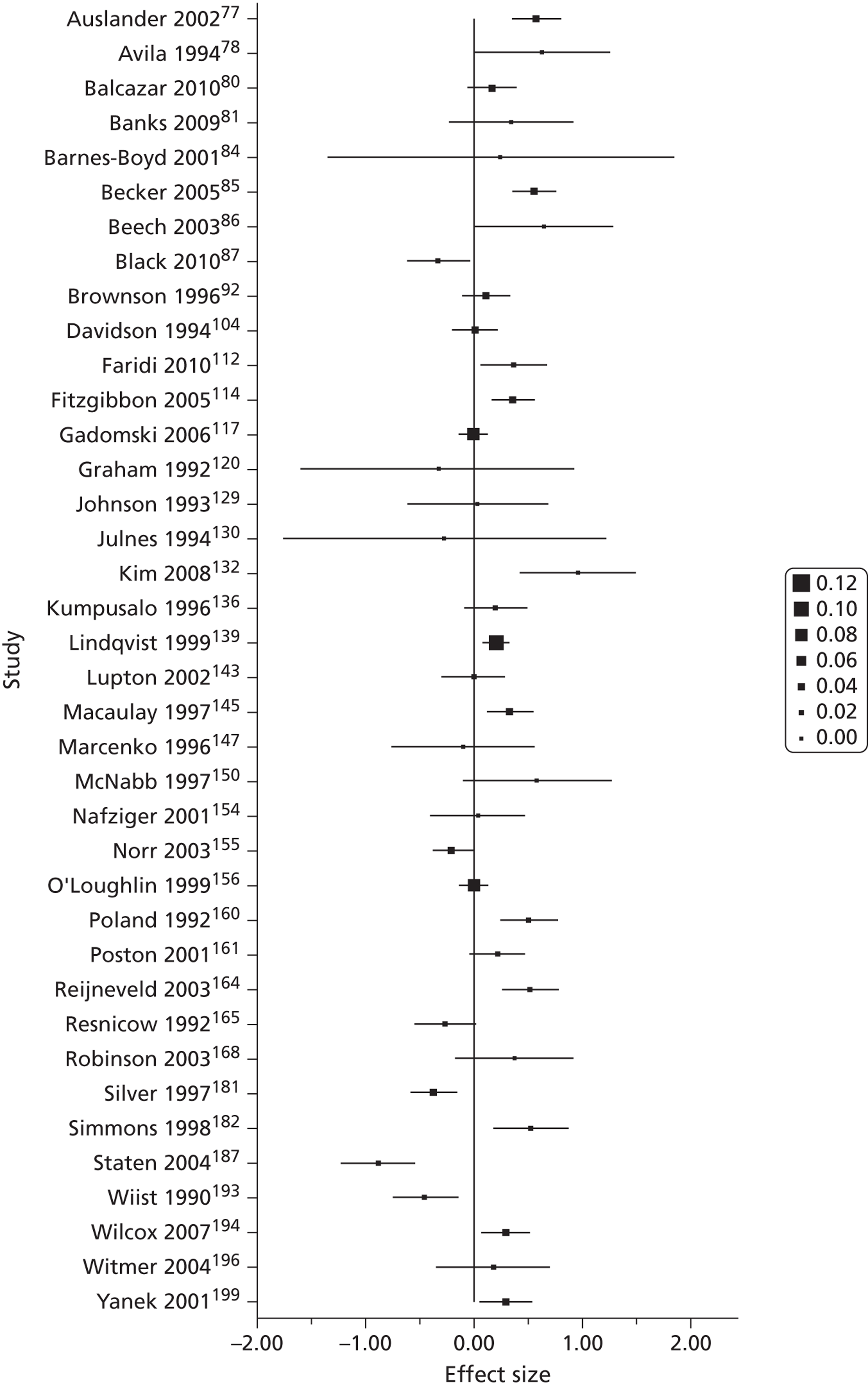

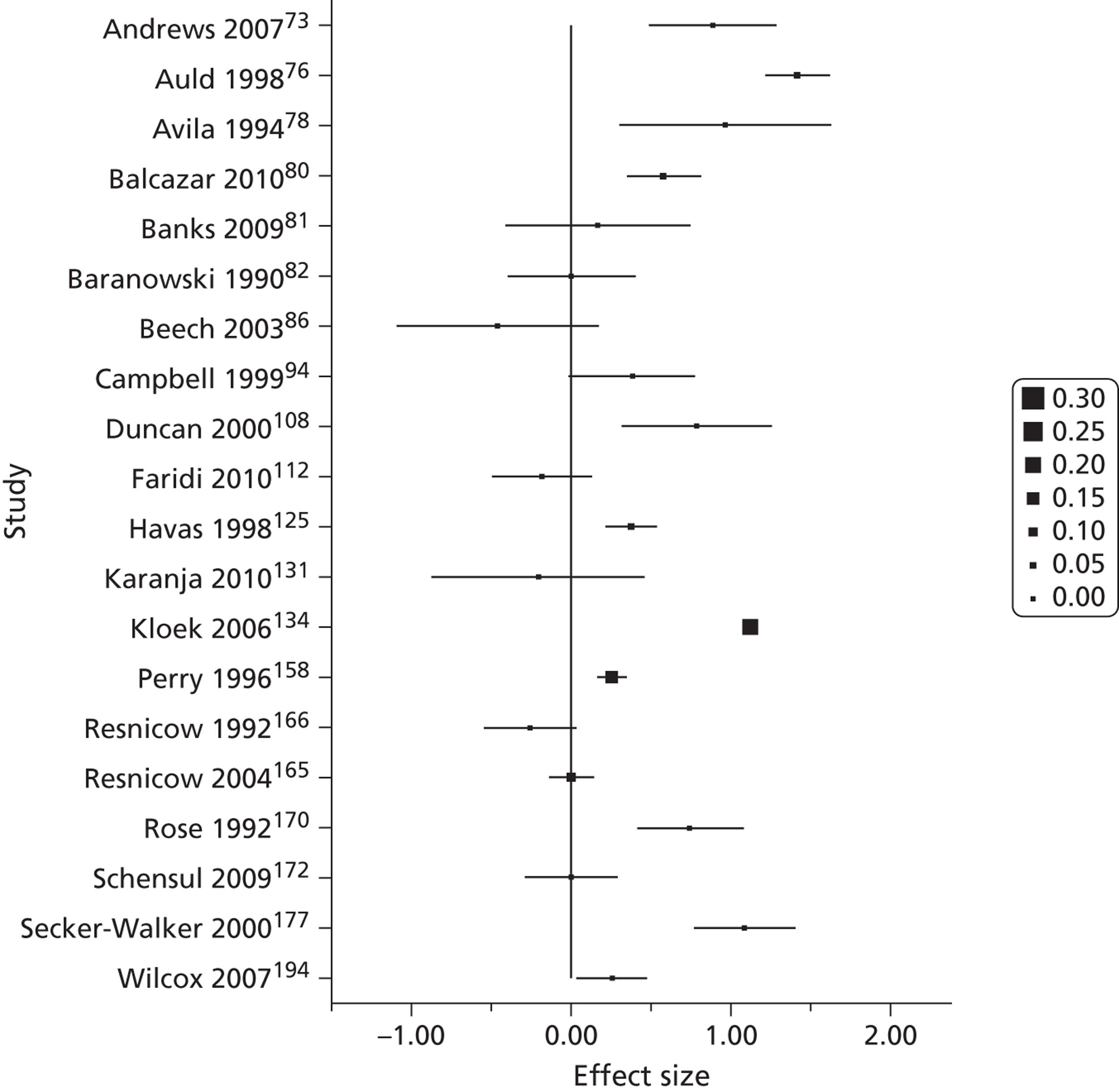

Meta-analysis

The meta-analysis (quantitative synthesis) uses various statistical methods to address RQ3–8, by testing whether any observed differences in the results of included studies might be associated with the type of community engagement they employed. This is reported in Chapter 5. Methods used are descriptive statistics, meta-analysis (homogeneity tests), analysis of variance (ANOVA) and meta-regression. 66 For the random-effects model analyses we followed the methods described in Lipsey and Wilson52 and used SPSS (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) macros written by Wilson. 67 The risk of bias across studies was assessed as described in Quality assessment.

Analyses were conducted separately for the following outcome types:

-

health behaviours at immediate post-test (e.g. fruit and vegetable intake)

-

health behaviours at delayed follow-up

-

health consequences at immediate post-test (e.g. cholesterol levels)

-

participant self-efficacy related to the health behaviours, at immediate post-test

-

social support related to the health outcomes, at immediate post-test

-

engagee outcomes (e.g. skills, empowerment)

-

community outcomes (e.g. perceived improved access to health services in the local area).

Possible moderating or confounding factors included:

-

the community engagement theory of change

-

whether it was a single or multicomponent intervention, and whether community engagement was evident in all components

-

the Marmot Review28 priority health area

-

characteristics of the intervention (setting, strategy, deliverer, duration)

-

characteristics of the participants (age, PROGRESS-Plus health inequality group)

-

whether the intervention was targeted or universal

-

the potential for risk of bias and characteristics of the evaluation.

Moderators and confounders notwithstanding, we aimed to identify the amount of variance (if any) that is explained by different approaches to community engagement with participants within each review, each topic domain and finally across all studies in the meta-analysis. Specific aspects of the analysis, such as data cleaning (identification and treatment of outliers and skewed data), sensitivity analyses and assessment of publication bias, are reported in the results chapter (see Chapter 5) alongside the relevant results to facilitate understanding of the findings.

We chose to focus our reporting of the results on the trends in pooled effect size estimates, rather than between-group statistical significance – as is usually common in meta-analysis. Typical meta-analyses attempt to infer findings from the sample to a hypothetical population. This is problematic for our review because the issues that we are exploring – community engagement and health inequalities – are so broad and difficult to define that it is impossible to know exactly to what population the results of any inferential statistics would apply. Instead, we emphasise observed trends, to help disentangle some of the differences between the types of evidence we have collected. This can help us to understand what might occur in other similar studies not included in the review, but not in any one specific situation because (and as discussed in Chapter 8) the causal pathways are complex and potentially unique to each study.

Thematic synthesis of process evaluations

The thematic synthesis of process evaluations narratively described emerging themes and factors evident across the process evaluations. Our original plan was to conduct a framework synthesis68,69 of process evaluations using a tool that we had constructed based on an earlier synthesis of community engagement process evaluations. 4 We found, however, that, although the framework ‘worked’ for some aspects of the process evaluations that we were synthesising, it did not cover the range of issues that we were encountering. We therefore moved to a more open structure and applied a process evaluation data extraction tool developed and used in previous EPPI-Centre reviews. 55,70 The complete process evaluation data extraction tool is provided in Appendix 4.

The data extraction tool was used to assess 12 criteria, including data collection method (e.g. interviews, surveys); type of stakeholder who provided the process information; the timing of the process evaluation in relation to the intervention; methods and rigour of sampling, data collection and analysis; assessment of how grounded the data were in authors’ findings; assessment of the breadth and depth of findings; and extent to which the process evaluation privileged the perspectives and experiences of the public. An overall rating (low, medium or high) was given to each study in terms of the study’s methods and the usefulness of each study’s findings in drawing conclusions about what works, why and for whom.

Specific content about processes was coded using the following headings:

-

acceptability of the intervention to the participants or providers

-

accessibility/programme reach

-

consultation/collaboration/partnerships

-

programme content (e.g. use of incentives, fit between content and aims of intervention)

-

costs (e.g. issues of sustainability)

-

implementation (e.g. frequency, duration and amount of adherence to programme content)

-

management/responsibility issues

-

quality of programme materials

-

skills and training of intervention providers

-

other issues.

Within each of the process evaluation data extraction questions, responses from each study were summed and frequencies reported. Ratings of overall reliability and usefulness were determined by reviewing responses to each data extraction question. Findings from each data extraction category were assessed and compared to determine whether:

-

lower rigour/lower usefulness studies came to similar or different conclusions to/from higher rigour/higher usefulness studies

-

findings varied by publication date

-

findings varied by health topic

-

findings varied by the type of community engagement model used.

Economic analysis

The final component of our study, the economic analysis, answers RQ8 and RQ9 and investigates the resource implications of various approaches to community engagement. It also reports on the extent to which they have been evaluated in terms of their potential cost-effectiveness.

The data extracted from the studies were synthesised narratively. Two tools were developed specifically for this project to capture data on economic issues (e.g. sufficiency of funds) and resource utilisation, cost and cost–consequences (e.g. staff costs). These tools were then combined into one data extraction tool (see Appendix 5). Items covered the following domains:

-

resourcing and cost breakdown

-

economic consequences of interventions

-

economic evaluation methods and findings

-

availability or flow of funds

-

sufficiency of funds

-

securing additional funds

-

financial sustainability

-

linking investment in intervention with impact on outcomes

-

sources of funds

-

role of volunteers

-

financial and economic incentives

-

other issues.