Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 10/3004/02. The contractual start date was in June 2011. The final report began editorial review in October 2013 and was accepted for publication in March 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Dr Jean Adams has received funding from NIHR Health Technology Assessment, grants from British Heart Foundation, Cancer Research UK, Economic and Social Research Council, Medical Research Council and the National Institute for Health Research for research activity during the conduct of this study.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2014. This work was produced by Carr et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

This chapter discusses the background to, and an overview of the focus of, this review. Definitions and distinguishing characteristics of Traveller Communities, the demographics of these populations and their commonalities are first discussed. This is followed by an illustration of the health inequalities experienced by these groups and the limited amount of evidence examining the effectiveness of interventions to improve the health of Traveller Communities. Finally, the complex and undertheorised nature of outreach is described, alongside the challenges this poses for evaluation.

Background

Traveller Communities

Definitions and distinguishing characteristics

The term ‘Traveller Communities’ refers to a complex population group that can be characterised by multiple and diverse dimensions. As such, defining Traveller Communities is not straightforward,1 and the use of terms such as ‘Gypsy’ and ‘Traveller’ is contested both within and outside Traveller Communities. 2 The phrase ‘Traveller Communities’ is used as an overarching term to describe multiple cultural and ethnic groups with diverse histories and customs, including Romani Gypsies, Irish Travellers, Welsh Travellers, Scottish Travellers, Roma, New Travellers, Travelling Showpeople, Circus People and Boat Dwellers. 1 While a nomadic lifestyle is one distinguishing dimension of Traveller Communities, frequency of travel may vary within these groups, classified by Niner3 as follows:

-

full-time Travellers

-

seasonal Travellers

-

holiday Travellers

-

special-occasion Travellers

-

settled Travellers.

Although nomadism is often an important component of Traveller Community lives, a definition of Traveller Communities which rests solely on the basis of a travelling lifestyle is inadequate. Ethnic identity is not lost when members of the Communities settle,1 and cultural practices, the importance of extended family, language and preference for self-employment have all been highlighted as important aspects of Traveller Community identity regardless of the frequency of travel. 4 Given this complexity, the definition of Traveller Communities in legal terms has been difficult. 5 The Race Relations Act recognises Roma, Gypsies and Irish Travellers as distinct ethnic groups, but does not afford the same protection to New Travellers and Occupational Travellers. 6 The following definition of Traveller Communities provided by the Housing Act was adopted for this review because of its inclusivity:

Persons with a cultural tradition of nomadism or of living in a caravan; and all other persons of a nomadic habit of life, whatever their race or origin, including: i) such persons who, on grounds only of their own or their family’s or dependent’s educational or health needs or old age, have ceased to travel temporarily or permanently; and ii) members of an organised group of travelling showpeople or circus people (whether or not travelling together as such).

Great Britain 20047

For the purpose of this report, the terms ‘Traveller Communities’, ‘Traveller Community’, ‘Gypsies and Travellers’ will be used to refer to all Traveller Community subgroups, except where referring only to a specific group (e.g. Roma or Showpeople). The term ‘settled community’ will be used to refer to non-Traveller community members.

Population size

Although it is estimated that there are between 10 and 12 million Roma and Travellers in Europe8 and between 120,000 and 300,000 members of Traveller Communities living in the UK,9 no definitive figures exist. The most recent figures from the biannual Gypsy and Traveller caravan count report 18,730 Gypsy and Traveller caravans in England,10 924 caravans in Wales11 and 684 Gypsy and Traveller households living on sites or encampments in Scotland. 12 However, the caravan count has been criticised for its reliability on account of the fact that it counts caravans rather than people and excludes the estimated two-thirds13 of Traveller Community members who live in housing. 14 , 15 Following the longstanding absence of Traveller Communities from national population surveys, Gypsy and Irish Traveller Communities were included as ethnic categories in the national census, the General Household Survey and the Health Survey for England in 2011. 16 The 2011 UK Census reports 57,680 Gypsies and Irish Travellers living in England and Wales. 17 However, this is likely to be a significant underestimate owing to reluctance of Traveller Community members to self-identify due to fear of discrimination, low levels of literacy impacting on ability to complete census forms, failure to engage marginalised groups such as members of Traveller Communities living on unauthorised sites, and the inclusion of only those Traveller Communities recognised as ethnic groups. 18 Drawing together the figures from Local Authority Gypsy and Traveller Accommodation Assessments across England, the Irish Traveller Movement in Britain18 reports that the total population of Traveller Communities in England in 2012 was 122,785.

The lack of reliable data on the demography of Traveller Communities, combined with the mobility of these groups, may lead to their invisibility throughout the planning of health service provision and result in needs being unmet. 19 Dar et al. 16 conducted a geographical mapping of the numbers of Traveller Communities using existing data sources and compared this with knowledge of Traveller Communities, immunisation service provision and estimated immunisation rates among Health Protection Units surveyed in England. Knowledge of Health Protection Units of Traveller Community populations and their uptake of immunisation was found to be low in a number of areas and there was no apparent association between service provision and numbers of Traveller Community members in a local area. Traveller Communities account for a small proportion of the total current UK population of 63.2 million, even when considering upper estimates of numbers. Any intervention targeted at improving Traveller Community health is, therefore, likely to have a very limited impact on overall population health.

Commonalities with other marginalised populations

While Traveller Communities represent a small proportion of the overall population, health policy highlights a number of commonalities with regard to needs and challenges for service provision across a range of socially excluded groups, including Traveller Communities. 20 The synthesis of evidence on outreach interventions for the health improvement of Traveller Communities, therefore, contributes to understanding what works to improve the health of other disengaged or marginalised groups, and therefore to the achievement of ‘resulting economies of scale and purpose by identifying common needs and service specifications across groups’ (p. 6). 20 The life circumstances of marginalised groups and the corresponding lack of responsiveness by services often results in costly patterns of service use by these groups, for example multiple or frequent attendance and reliance on acute services such as accident and emergency (A&E) as opposed to utilisation of primary care. 20 As such, efforts to improve the health of excluded groups and the accessibility and uptake of health services may contribute to reducing costs associated with the treatment of illness. The focus on subsections of the population who experience particularly acute health disparities can also be justified morally. As Marmot21 comments, ‘Reducing health inequalities is a matter of fairness and social justice’ (p. 15). While a focus only on the most disadvantaged sections of the population will not alone alleviate the social gradient of health inequalities, it is acknowledged that the intensity of intervention needs to be tailored to the degree of disadvantage experienced, and that more concentrated efforts will be needed to tackle the multiple and extensive disadvantage experienced by some groups. 21

Health needs of Traveller Communities

This report does not attempt to provide a comprehensive overview of the health status and needs of Traveller Communities, which is reported extensively elsewhere. 6 , 14 , 22–24 Rather, it aims to illustrate the spectrum of health inequalities experienced by Traveller Communities which outreach interventions might be seeking to address.

Traveller Community health status

The lack of data on the Traveller Community population has limited the generation of robust evidence on their comparative health status14 and, as such, findings need to be interpreted with caution. However, the available evidence points to inequalities experienced by Traveller Communities across many domains of health.

General health and well-being

Traveller Communities have been reported to have poorer general health and well-being than other groups. The mortality of Traveller Communities in the Republic of Ireland (ROI) was found to be three and a half times greater than that of the general population, dropping only 13% compared with a decline of 35% in the general population over the last 20 years. 25

The health status of Traveller Communities in the UK is also significantly worse than that of other socioeconomically disadvantaged or ethnic minority groups. 19 , 26 Traveller Communities scored poorer on measures of overall health than age–sex matched comparators [assessed using the European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) measure of health, mean difference 0.12; p = 0.001] as well as on all individual dimensions of mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain or discomfort and anxiety and depression. 19 These differences in health status between Traveller and settled communities remain even after controlling for smoking status as well as age and sex. 26 Peters et al. 26 also found Traveller Communities to have significantly poorer health than African Caribbean, Pakistani Muslim and white ethnic groups, as assessed using the EQ-5D (mean scores of 74.9, 83.5, 92.6, and 85.5, respectively; p < 0.001).

Traveller Communities reported higher levels of anxiety (mean scores of 9.0 compared with scores of 6.2 for African Caribbean and Pakistani Muslim participants, and 5.7 for white participants) and depression (mean scores of 6.3 for Traveller Communities, 4.2 for African Caribbean participants, 3.8 for Pakistani Muslim participants and 3.1 for white participants), as assessed using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). 26 Qualitative studies which found that Traveller Communities clearly identified with symptoms of mental health and distress27 , 28 provide further evidence in support of concerns around mental health in these groups. Furthermore, high rates of suicide are reported among Traveller Communities, with three times the rates of suicides among Irish Travellers between 2000 and 2006 compared with the general population. 29

Long-term conditions and specific illnesses

Members of Traveller Communities are more likely to have a long-term illness, health problem or disability that limits their everyday activities (42% of Traveller Communities and 31% of age–sex matched comparators; p = 0.009). 19 Traveller Community members more often reported experiencing a number of conditions, including chronic cough (49% vs. 17%), chronic sputum (46% vs. 15%), bronchitis (41% vs. 10%), asthma (65% vs. 40%) and arthritis (22% vs. 10%), than did the comparator group. 19 This study, by Parry et al. ,19 found no difference between Traveller Communities and comparator groups in the prevalence of diabetes, stroke or cancer. However, the authors report that this may be a result of premature death or a reluctance to disclose conditions such as cancer. 19 Since the publication of this study, evidence from Gypsy and Traveller Accommodation Assessments suggests a higher prevalence of diabetes among Traveller Communities (4.6% of those surveyed in Cambridge and 11% in Dorset compared with 3.5% of the general population). 30 A smaller difference was found between Traveller community and African Caribbean and Pakistani groups for health in the past year, asthma and depression after adjustment for age, sex and smoking status. However, significant differences between these groups remained for the cough and sputum items of the respiratory questionnaire. 26 The collation and review of case-management information over a 4-year period revealed a disproportionate incidence of measles among Traveller Communities of more than 100 times that found in the wider population. 31

Maternal and child health

Studies have also raised concerns around the health of Traveller Community mothers and children. A disproportionate number of Traveller Community mothers were represented in the UK maternal mortality statistics for 1997–9 according to the Confidential Enquiry into Maternal Deaths. 32 Members of Traveller Communities more often reported having experienced one or more miscarriages than the comparator group (29% and 16%, respectively; p < 0.001) and the premature death of a child (6.2% of Traveller Community women compared with none of the comparator women; p < 0.001). 19 Results from the All Ireland Traveller Health Study, which suggest that infant mortality is almost four times greater than that of the general population, corroborate these findings. 33

An increased risk of low birthweight (< 2500 g) has been reported among Roma infants in Europe. For example, 14.1% of Roma infants were born with a low birthweight compared with 3.6% of non-Roma infants in the Czech Republic, with a difference of 373 g in birthweight. 34 Similar results have been reported in Hungary, where 26.2% of Gypsy infants were of low birthweight compared with 11.0% in the national sample, and where an overall difference in mean birthweight of 377 g was found. 35 However, the average birthweight of Traveller infants in Ireland was similar to that of the general population, and the growth rate for Traveller children was found to be comparable with the general population at 9 months,33 suggesting that the evidence may be more mixed in this area.

Intragroup differences

A limited amount of evidence exists from which to establish differences between Traveller Community subgroups. Parry et al. 19 found no significant differences between Irish Travellers and English, Welsh or Scottish Gypsies, suggesting that these groups are likely to experience comparable health status. However, there is a lack of evidence on the health of non-ethnic groups, such as Showpeople and Occupational Travellers,16 who share many of the risk factors for health experienced by other Travellers.

Studies suggest a relationship between frequency of travel and health, with those who travel reporting better health status;19 , 36 however, causality is not clear, and this association could reflect a necessity for Traveller Community members with poorer health to settle in order to be close to services. 37

Inequalities of health appear to be particularly great among Traveller Community men. 26 Abdalla et al. 25 report the mortality rate of Traveller Community men in Ireland to be significantly higher than that for women (standard mortality rate of 469 compared with 232 respectively). Traveller Community men have been reported to be over nine times more likely than women to die by suicide, with these gender differences mirroring those found in the general population. 29

Determinants of Traveller Community health

Traveller Communities experience inequalities across the multiple determinants of health represented on Dahlgren and Whitehead’s Social Model of Health. 38 The contributions of these determinants to the poorer health of Traveller Communities are now explored in more detail.

Lifestyle factors

Individual members of Traveller Communities have been found to accept ill health and normalise signs of distress. 37 , 39 Poor health expectations, fear about potential diagnoses and structural constraints resulting from eviction or difficulties in finding appropriate stopping places have all been suggested as factors leading to a lack of prioritisation of preventative health care and services such as screening. 39 , 40 In addition, the literature highlights cultural beliefs of Traveller Communities that govern the body and have a bearing on health practices and which are important for health advisors to be aware of, albeit with the proviso that cultural beliefs and practices may vary across different Traveller Communities and the individuals within them. Okely41 demonstrates the ways in which beliefs about pollution and associated rituals around washing, eating, use of space and placement of objects enacted serve to reinforce a distinction between Travellers and settled communities. For example, the outer body and skin (the interface for engagement with settled community members) is distinguished from and viewed as potentially polluting to the inner body. 41 These beliefs are embodied in practices such as the use of separate washing bowls for items used for cooking and eating from those used for washing the body, and ensuring that anything entering the body through the mouth is ‘ritually clean’. 41 Health practices such as immunisation might, therefore, be viewed as polluting because they transgress the distinction between inner and outer body. While pollution beliefs apply to both men and women, the potential for women to be polluting is greater during menstruation and childbirth as bodily waste from the lower body poses a particular threat of pollution. 41 Women’s sexuality is also potentially polluting and codes of behaviour may be evident to protect against this, for example not revealing certain body parts and women not spending time alone with men other than their husbands. Concerns relating to modesty are likely to impact on the acceptability of behaviours such as breastfeeding and have consequences for health service delivery, including the need to ensure that Traveller Community women are able to access a female health practitioner.

The literature points to a higher number of modifiable risk factors that may contribute to the poorer health of these groups. A greater proportion of Traveller Communities than the general population are current smokers (around 50% compared with around 37%, respectively). 42 Smaller numbers of Traveller Community members report drinking alcohol than the general population, but those who do consume alcohol do so more often (around 65% of male and 40% of female Travellers drink six or more alcoholic drinks on days when they are drinking alcohol compared with around 35% of men and 17% of women in the comparator population). 42

Compared with the general population, fewer Traveller Community members reported eating at least five portions of fruit and vegetables in Ireland (65% and 45%, respectively). 42 A smaller-scale study conducted in Wrexham also reported that Traveller Communities have a poorer diet and lower levels of physical activity than the Welsh and UK population, as well as residents from a deprived local area. 43 Traveller Communities more often reported high blood pressure or cholesterol in the past year (36.5% of Traveller Community members compared with 28.3% of medical card holders in the general population). 42

The literature reports a low uptake of immunisation and well-women services among Traveller Communities. 44 Only around 2.2% of Traveller mothers initiate breastfeeding compared with around 50% of those in the general population. 33

Social and community networks

Extended family provides an important source of social support among Traveller Communities, with family members often expected to provide care for family members who are older or unwell. 37 As such, a positive model of ageing is cited among Traveller Communities, with older Traveller Community members less likely to experience social isolation and loneliness. 45 In addition, elder members of Traveller Communities are often important sources of advice on health, with a higher number of Traveller Community members reporting being supported by parents than the general population (69.6% of Travellers compared with 38.3% of the general population). 42 However, owing to a lack of space on authorised sites, and as Traveller Community members often resort to housed accommodation in order to avoid cycles of frequent eviction, members often find themselves separated from family and community support systems. 46

Living and working conditions

Around one in four Traveller Community members living in caravans do not have a legal place to park their home,5 and are thus forced to live on unauthorised encampments from which they are frequently evicted. Many of the sites provided are of poor quality, are built on contaminated land, are close to motorways, pose significant fire safety risks, are contaminated by vermin, have poor-quality utility rooms, and have chronically decayed sewage and water fittings. 3 , 5 , 6 , 47–49 Traveller Communities experience difficulties in obtaining planning permission for privately owned land due to opposition from local residents. 6 Large numbers of Travellers surveyed in the All Ireland Traveller Health Study who lived on sites or in group housing schemes (designed to enable Travellers to live together in extended family groups) reported a lack of footpaths [40.8% in ROI and 33.0% in Northern Ireland (NI)], public lighting (39.4% in ROI and 20.7% in NI), fire hydrants (73.7% in ROI and 60% in NI) and safe play areas (77.5% in ROI and 79.9% in NI). 42 Places of living were viewed as unhealthy or very unhealthy by around 24.4% of Travellers in the ROI and 24.8% in NI, while 26.4% of Travellers in the ROI and 29% in NI considered thier place of living to be unsafe. 42

Traveller Communities face practical challenges in accessing mainstream services owing to discrimination faced on registering with services, lack of a permanent address and high levels of illiteracy. 6 , 39 Peters et al. 26 report that only 69% of Traveller Communities were permanently registered with a general practitioner (GP) compared with ≥96% of Pakistani Muslim, African Caribbean and white participants. By contrast, findings on Traveller Community access to services in Ireland suggest that Travellers do access preventative screening42 and have similar use of GP services to comparators among the general population (unadjusted rates of 74.2% vs. 75.3%). 50 However, despite these higher rates of access, Traveller Community members rated their experiences of accessing health services less positively. 50 Traveller Communities were less likely than other ethnic groups to have accessed dental services (47% of Gypsies and Travellers compared with 77% of white, 67% of African Caribbean and 63% of Pakistani Muslim participants) or opticians (14% of Gypsies and Travellers compared with 43% of white, 42% of African Caribbean and 49% of Pakistani Muslim participants). 26 As a consequence of difficulties in accessing GP services, Traveller Communities may be more likely to attend acute or reactive services. Beach51 reports that children from Traveller Community sites attend A&E departments twice as often as settled children in the neighbouring areas. Peters et al. 26 found that Gypsies and Travellers had been in contact with A&E departments more often (24% of Traveller Communities) than had African Caribbean (21%), Pakistani Muslim (16%) and white participants (12%) (p = 0.025).

The decline in traditional trades undertaken by Traveller Communities has resulted in many families becoming economically excluded and has necessitated their adaptation or assimilation into mainstream modes of employment. 52 Although there is diversity within the Community with respect to socioeconomic status,52 Travelling Communities overall are cited as experiencing high levels of poverty and low employment. 6 In response to such changes, education is viewed as increasingly important in order to secure the welfare of future generations. 53

Gypsies and Travellers have much poorer educational outcomes, with < 10% of Traveller Community pupils attaining five GCSEs (General Certificates of Secondary Education) or equivalent at A* to C grades, including English and maths, compared with over 50% of the average population. 54 Traveller Community children are noted to have the worst school attendance profile of any ethnic minority group. 55 Absence rates for the years 2007–8 were higher than for other groups for both primary (24.2% for Travellers of Irish heritage, 19.0% for Gypsy/Roma, 5.3% for all pupils) and secondary school (27.3% for Travellers of Irish heritage, 23.5% for Gypsy/Roma, 7.4% for all pupils). 56 Gypsies and Travellers are four times more likely to be excluded from secondary school than any other group. 57 In addition, Traveller Community children are more likely to attend schools with below average results. 56

General socioeconomic, cultural and environmental conditions

There is explicit racism and discrimination directed towards Traveller Communities in society, with this being regarded as the last accepted form of prejudice in England. 58 There is little recognition of the culture or heritage of Traveller Communities and an absence of positive portrayals of Traveller Community lifestyles in mainstream society. 6 A study of media coverage of Traveller Communities in Scotland found a disproportionate amount of coverage relating to these groups (an average of 1.5 articles per day), with nearly half (48%) classified as overly negative portrayals. 59 The under-representation of Traveller Community members in political activities means that they have little voice to challenge such representations. 6 Systems of health service provision contribute to the exclusion of Traveller Communities. For example, it is suggested that GP surgeries might be reluctant to register Traveller Communities due to the extra paperwork required when taking on temporary residents and perceptions that registering Traveller Community members will affect GPs’ ability to meet performance targets around immunisation. 60

Research on the effectiveness of outreach interventions for Traveller Communities

There are efforts to tackle health inequalities faced by Traveller Communities, as evidenced through recent funding sources. 20 , 61–63 Examples of outreach programmes cited as offering potential are diverse, including, for instance, a Community mothers programme,64 trained outreach workers from Traveller Communities,6 , 22 and mobile health clinics or play buses. 6 , 22 A review of health-care interventions for Traveller Communities recommended outreach and the employment of trained health workers from the Community as culturally appropriate and promising components of interventions. 22

However, most initiatives aiming to improve health for Traveller Communities have been initiated in recent years and are as yet unlikely to have yielded significant evidence of impact. Few published reports with robust study designs, such as randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and controlled trials, examine the effectiveness of interventions to improve health in Traveller Communities. A review of the range and quality of evidence on the health of Traveller Communities reveals that studies are rarely well designed and tend to use process rather than outcome measures as indicators of success. 14 While this provides important indicators of culturally sensitive interventions, there is a dearth of reported evidence of improvements in health status. 14 , 65 The heterogeneity of the evidence base, combined with contextual intricacies of a diverse and complex population, raised significant challenges for evidence synthesis.

Outreach

Defining outreach and its purpose

A number of challenges have been identified in meeting the health-care needs of the most socially excluded and vulnerable groups in society. For Traveller Communities and other socially excluded groups who have multiple and complex needs, engagement with and access to preventative care may be afforded a low priority. 66 Mainstream health service provision is often ill adapted to the complicated everyday lives of these groups, for which flexibility and co-ordination across different health- and social-care systems is required. 20 Outreach has, therefore, been utilised as a key strategy to engage those who, through processes of social exclusion or socioeconomic deprivation, occupy a position on the margins of society and are considered ‘hard to reach’. 66 While outreach approaches have, in general, been endorsed in commissioning guidance for improving the health of marginalised groups,67 at present, little detail is given around the specific strategies that are likely to make outreach effective in different contexts.

Owing to the focus of outreach on engagement, and responding to the unique needs of individuals and groups, conceptualisation of approaches to outreach have often been couched in terms of the personal and attitudinal qualities of outreach workers, rather than in terms of methods. 68 For example, the unidirectional nature of the vulnerability between outreach workers and those they attempt to engage, as well as the shared experiences during encounters, are important aspects of the outreach dynamic. 68 However, it is precisely these aspects of outreach that are difficult to articulate and which introduce hidden variability in outreach programmes.

Further diversity in implementation results from the inability to predict the problems that outreach work will need to address. Mackenzie et al. 66 present the following ‘continuum of complexity’ to describe the potential reasons for a lack of engagement that outreach might need to address and the different shapes outreach might take in response:

-

Not receiving engagement invitation letter: outreach works as a ‘health-care postal worker’ to deliver the invitation personally and overcome information gaps in service systems.

-

Literacy or health literacy barriers: outreach worker acts to ‘bridge gaps in understanding’, providing information and responding to questions about services.

-

Lack of priority afforded to preventative health: outreach worker takes a ‘translational role’ to highlight an individual’s candidacy for preventative treatment amid other lifestyle pressures.

-

Psychosocial barriers to engagement: outreach worker utilises strategies such as motivational interviewing and/or signposting to other services to alleviate barriers preventing access.

-

Structural barriers to engagement: outreach workers use signposting, referral and mobilisation of community networks to address broader issues relating to housing, unemployment and debt and co-ordinate the involvement of different agencies.

-

Hidden and multidimensional nature of problem: outreach workers take the role of ‘assessing readiness for action or change’, treating engagement as a process and working incrementally to address multiple issues.

The conditions in which outreach is delivered can be highly unpredictable and beyond the outreach worker’s influence. 68 In addition, the extension of outreach into people’s personal spaces might display aspects of their vulnerability more clearly and evoke feelings of intrusion and potentially unwelcoming responses in those approached. 68 As a result, outreach workers need to be accustomed to the ‘spatial organisation’ of their surroundings and have awareness of social networks and potential change agents, group movements and meeting points. 68 For example, outreach workers in the study reported by Dickson-Gómez et al. 69 had to be sensitive to the social codes and dynamics operating in areas of injection drug use, including the impact that outreach had on the business of drug use through attracting crowds and inviting police attention. In the case of outreach with Traveller Communities, outreach workers may need to demonstrate awareness of the ways Traveller sites and personal spaces are organised to uphold cleanliness and avoid pollution,41 as described above.

Challenges to the evaluation of outreach

The emphasis on the specificity of outreach to particular target groups or contexts has been argued to limit possibilities for the conceptual development of outreach. 68 Indeed, the distinctiveness between outreach implementation models and the boundaries between outreach and other forms of interventions, such as peer support interventions, are not always clear in the literature.

Outreach fits into the category of a complex intervention as defined in the Medical Research Council (MRC) guidance,70 in that it is not standardised and is highly sensitive to local contextual issues. As described above, interventions are often highly individualised,71 implemented in diverse settings and delivered by several different people. 72 In addition, implementation fidelity may be problematic in outreach interventions, as greater flexibility and variability is required in delivery. 71 , 73

The lengthy chain of causality between the delivery of outreach interventions and outcomes also presents a challenge for evaluation. Given the role of outreach in facilitating access to mainstream services, the role of the outreach programme in generating concrete improvements in health behaviour or outcomes may be difficult to disentangle from the impact of other interventions or organisations. 68 Thus, the success of outreach workers in terms of making and sustaining contacts is argued to be a key intermediary outcome in assessing the effectiveness of outreach interventions. 68

Such characteristics pose challenges for articulating71 and documenting the processes of outreach,74 thereby placing it at odds with the emphasis on standardisation in clinical trials. 75 As Mackenzie et al. 66 summarise:

Outreach has been described as eclectic in its purpose, client group and specific mode of practice and, as a direct result of this heterogeneity, little is known about its effectiveness.

Mackenzie et al. 2011,66 p. 352

There is, therefore, a need for greater theoretical development on the particular approaches and underpinning mechanisms of outreach most likely to lead to positive outcomes in particular contexts. 66 , 68 , 76 In doing so, there appears to be a need to achieve a balance between the generalisation and specificity of understandings of outreach across different contexts. 68

Definition of outreach adopted for this review

In order to provide greater focus for this review, and in line with the agenda to tackle health inequalities, the current work will be focused on outreach efforts that aim to engage Traveller Communities in a health-related agenda. For the purpose of this review, the following broad definition of outreach was adopted:

[A] process that involves going out from a specific organisation or centre to work in locations with sets of people who typically do not or cannot avail themselves of the services of that centre.

McGivney 2000,77 p. 11

In addition, following MacKenzie et al. ,66 outreach was considered to involve the alleviation of both ‘physical as well as ideological gaps between services and users’ (p. 2).

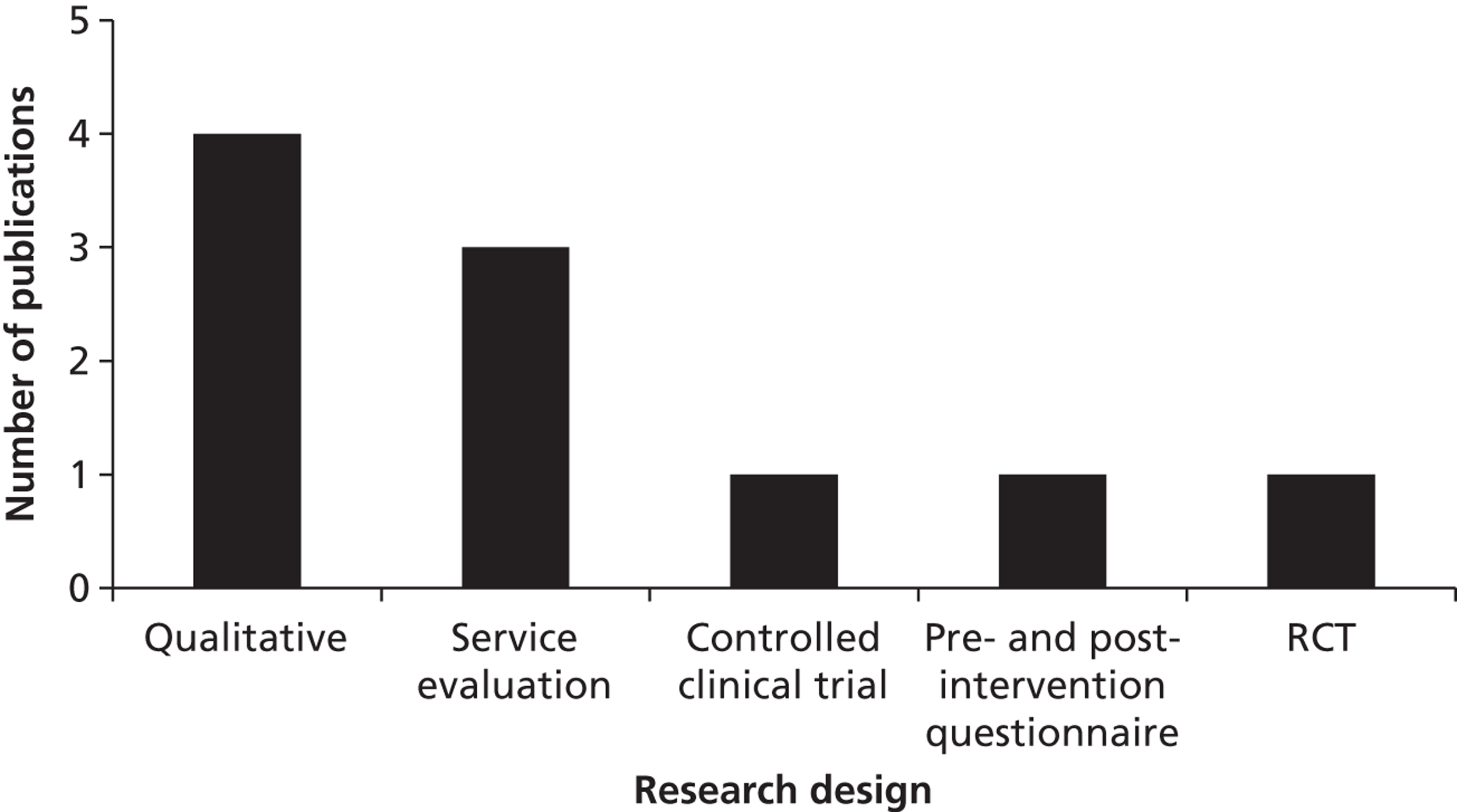

Changes in the review process

Initially, it was proposed that a meta-analysis or narrative synthesis (dependent on data quality) and realist synthesis of evidence on outreach interventions for health improvement of Traveller Communities would be undertaken. However, following the processes of searching for and appraising the quality of evidence, it became clear that it was of insufficient quality to lend itself to a narrative synthesis. Of the 407 studies obtained and assessed on full text, only 12 articles described and evaluated outreach interventions and would have been eligible for inclusion in a narrative synthesis. A process of quality assessment categorised two of these 12 items as ‘moderate’ and 10 items as ‘weak’ using the Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies78 for quantitative studies and the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme checklist for qualitative research. 79 Furthermore, the studies focused on disparate topics, including teenage health, primary health care, support following childbirth, oral health, drug use, prevention of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, domestic violence, health advocate training, and a health mediator programme. The small number of robust studies examining diverse programmes meant that it would have been impossible to identify patterns of effectiveness of component intervention techniques for the health improvement of Traveller Communities. It was therefore decided to undertake a scoping review in conjunction with the realist synthesis. The study protocol is presented in Appendix 1 .

Characterised by breadth rather than depth of approach,80 the scoping review identifies the extent and range of research activity81 on outreach programmes for the health improvement of Traveller Communities. Scoping reviews are noted to be particularly insightful for areas of emerging evidence not amenable to systematic review,82 as for outreach interventions for Traveller Communities, and have been used successfully to capture the sense of a broad disparate literature base83 such as that described above. The wide-ranging coverage of the literature offered by the scoping review, therefore, provides a comprehensive overview of the available evidence in the area, and scaffolds the realist synthesis by situating the evidence on outreach programmes for Traveller Communities within the wider body of literature on Traveller health.

Objectives and focus of the review

Scoping review

The scoping review aimed to examine the extent, range and nature of research activity and map the range of research rather than describe key findings, in accordance with Arksey and O’Malley’s84 recommendations. It aims to answer the following research question:

What is the extent (quantity) and content of available research evidence concerning the health of Traveller Communities?

Economic evaluation

Following the scoping review, the economic evaluation classifies the different types of outreach interventions, estimates their cost and provides an estimate of whether or not interventions might be considered cost-effective.

Realist synthesis

A realist synthesis acknowledges the complexity of interventions and focuses on the explanation of how, for whom and in what circumstances they work. 85 As such, a realist synthesis necessitates the clarification of the purpose of the review, research questions and key theories that will be addressed, a process that often continues to the later stages of the review. 85 This phase involves ‘a careful dissection of the theoretical underpinnings of the intervention, using the literature in the first instance, not to examine the empirical evidence but to map out in broad terms the conceptual and theoretical territory’ (p. V). 85 In order to facilitate reading and transparency of this continual process, the conceptual and theoretical territory is detailed in Chapter 3.

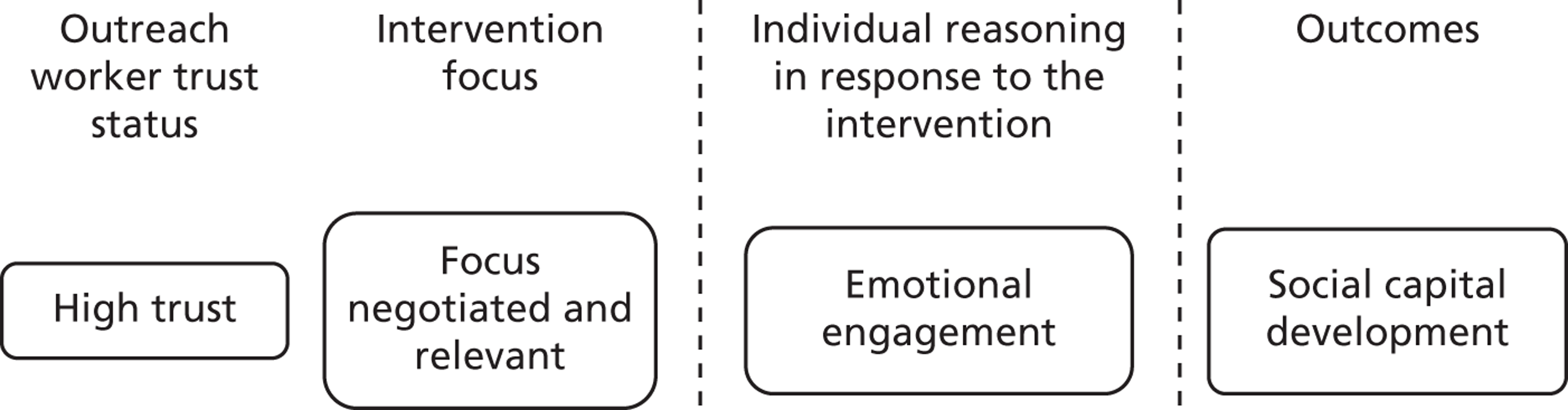

Four initial theories

An initial exploratory scoping of the literature to clarify the focus of the research concentrated on the origins and nature of Traveller Communities as an ethnic group, their differential health status and outreach as a health intervention. This process was partly formalised through the scoping review and completed by consultation with expert members of the project steering group. This led to the articulation of the following initial programme theories on outreach interventions in Traveller Communities:

-

The cultural distinctiveness and particular needs of Traveller Communities mean that outreach forms a key ‘bridge’ between them and statutory health services (‘by whom’).

-

The cultural background (being a peer) of outreach workers is key to the success of their intervention because that enables them to use the right communication tools to reach out to individual Travellers (‘to whom’).

-

Degree of formality and responsiveness to need are key levers for participation (‘how’).

-

Key aims of outreach are to tackle health inequalities through engagement, advocacy and education (‘what for’).

The focus on Traveller Communities in theory 1 offers an insight into the context of outreach interventions. The reviewers’ expertise in peer and lay intervention guided the formulation of theories 2 and 3 as potential mechanisms of outreach and theory 4 offers an opportunity to delve into the purposes and achievements of outreach in this group (outcomes). Thus, these theories offer an avenue to formulate the kinds of Context–Mechanism–Outcome (CMO) configurations that are the cornerstone of realist thinking. These four initial theories clearly are not designed to be tested against null hypotheses, but rather are explanatory in their formulation. The distinguishing feature of a realist synthesis is the theories it develops, which aim to explain why interventions such as outreach lead to particular outcomes in particular contexts. The overall purpose of the review is to neither confirm nor refute them but rather to improve their explanatory potential. They are designed as a guide to frame the subsequent phases of the research, articulate questions posed of the evidence and refine our understanding of how and in what circumstances outreach interventions in the Communities ‘work’. These initial four theories are also used over and again in the process of extracting and synthesising the evidence, as a way of describing different modes of outreach and as explanations of why some programmes seem to flourish better than others. They therefore form the key objectives and focus of the realist review.

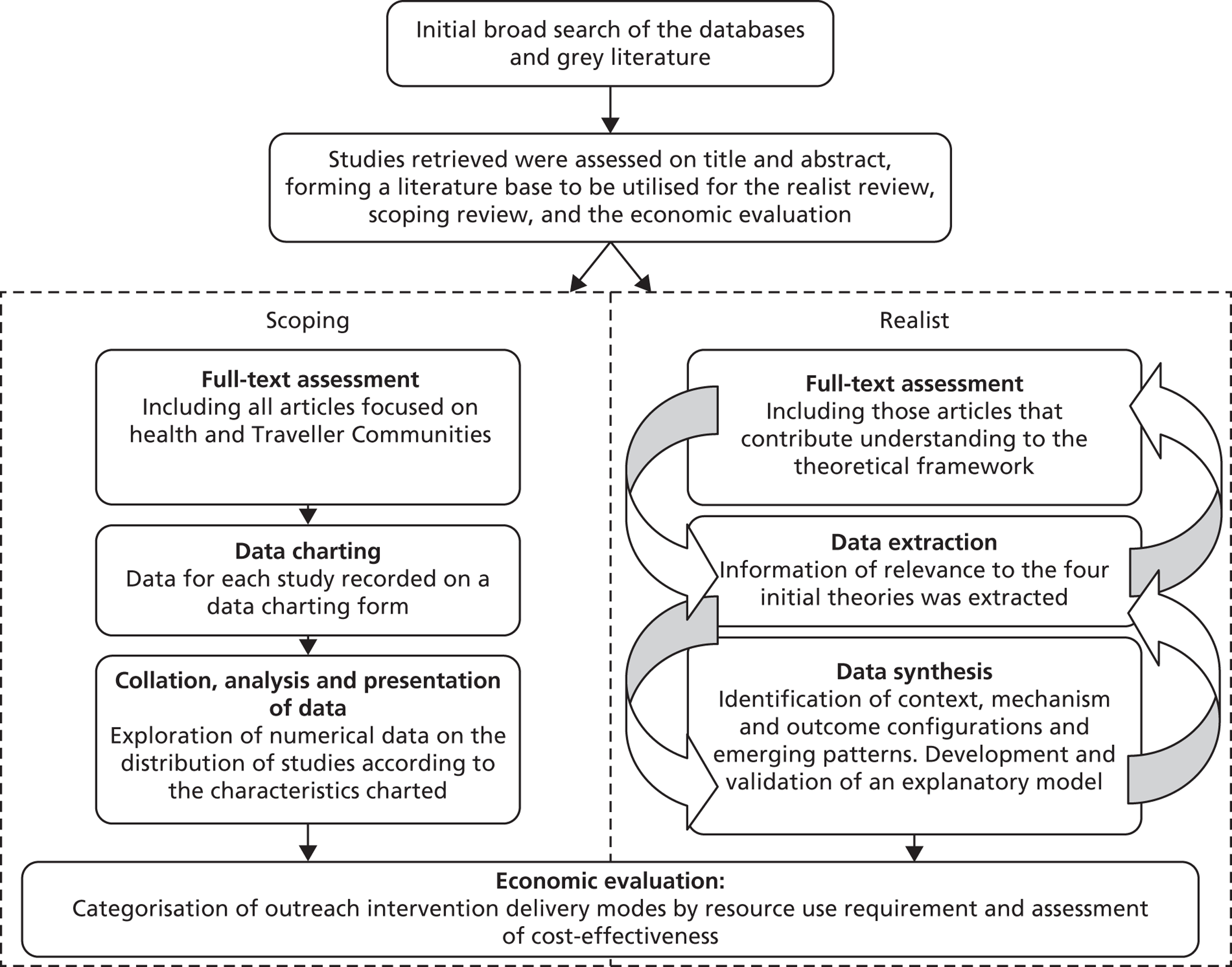

Chapter 2 Methods

The processes of the primary searching of the evidence base and the screening of studies according to title and abstract are first described, as they informed all review strands. The processes of selection, appraisal on full text and analysis of studies are then discussed independently for the scoping and realist synthesis, respectively, as well as for the economic evaluation. Figure 1 provides a summary of the stages taken for each strand.

FIGURE 1.

Summary of stages for each study strand.

Search strategy development

A short phase of problem definition (2 months) was undertaken in order to refine search strategies and data sources to be utilised, drawing on the expertise of an information specialist as well as the combined knowledge and experience of the project team and steering group members on appropriate terminology for searches.

The search features and structure of the proposed databases were examined to identify and compare keywords, subject headings and thesaurus/index terms. Test searches were undertaken for terms referring to the different Traveller Community groups, such as Romani, Roma, Sinti, ‘Irish Travellers’, ‘Scottish Highland Travellers’, Ceardannan, ‘New Age Travellers’, ‘Bargees’, ‘Pavees’, ‘Showpeople’, ’Circus People’ and Yeniche. The databases examined tended to use used the term ‘Gypsies’ as an overarching term to refer to these different groups. References retrieved by using wider terms, for example ‘transients and migrants’, ‘nomads’, ‘itinerants’ and ‘minority and ethnic groups’, were examined for relevance and found to be beyond the scope of the study. The term ‘outreach’ did not appear as a subject heading term in our sample of databases. The preliminary searches revealed examples of articles describing health interventions for the Traveller Community that featured a number of initiatives, only some of which were termed ‘outreach’.

A ‘citation pearl growing’ exercise was also conducted to identify search terms through examining the terms used to index articles which are relevant to the review (referred to as ‘pearls’). 86 , 87 Pearl articles (see Appendix 2 ) were identified through checking citations in a review of health interventions for Traveller Communities22 and through suggestions for relevant articles from representatives working with Traveller Communities, including those that described a health intervention for Traveller Communities. Pearl articles were indexed under the term ‘Gypsies’ or ‘Travellers’, despite focusing on different subgroups of Traveller Communities such as Roma. While the pearl articles referred to examples of outreach interventions for Travelling Communities, none of the studies were indexed under this term ‘outreach’ in Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) or MEDLINE. The piloting of searches on the proposed databases and the citation pearl growing exercise, therefore, contributed to the development of a final search strategy which was comprehensive, yet not too unfocused. Together, these exercises suggested that the use of the term ‘outreach’ only in combination with terms for Gypsies and Travellers would be too limiting, leading to the omission of studies describing outreach that were not indexed as such, and that search terms referring to specific groups of Traveller Communities were likely to contribute few unique items.

Searches of electronic databases

Taking the above findings into account, and considering the differing search features provided by the different databases, the following broad and comprehensive approach to searching the literature was taken.

Structured searches were conducted in the following 12 subscription databases available via the University of Northumbria: Web of Knowledge, MEDLINE, The British Library’s Electronic Table of Contents (Zetoc), CINAHL, Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ASSIA), Social Services Abstracts, British Humanities Index, PsycArticles, Allied and Complementary Medicine Database (AMED), Proquest Nursing and Allied Health Source, International Bibliography of the Social Sciences (IBSS), and Sociological Abstracts.

The searches were conducted between August 2011 and November 2011 by an information specialist working with the research team in order to identify English-language items using the following search strategy: ab,ti(roma or romanies or romany or gipsy or gipsies or gypsy or gypsies or traveler or traveller or travelers or travellers or “travelling community” or “travelling communities” or “traveling community” or “traveling communities”) and (health or outreach).

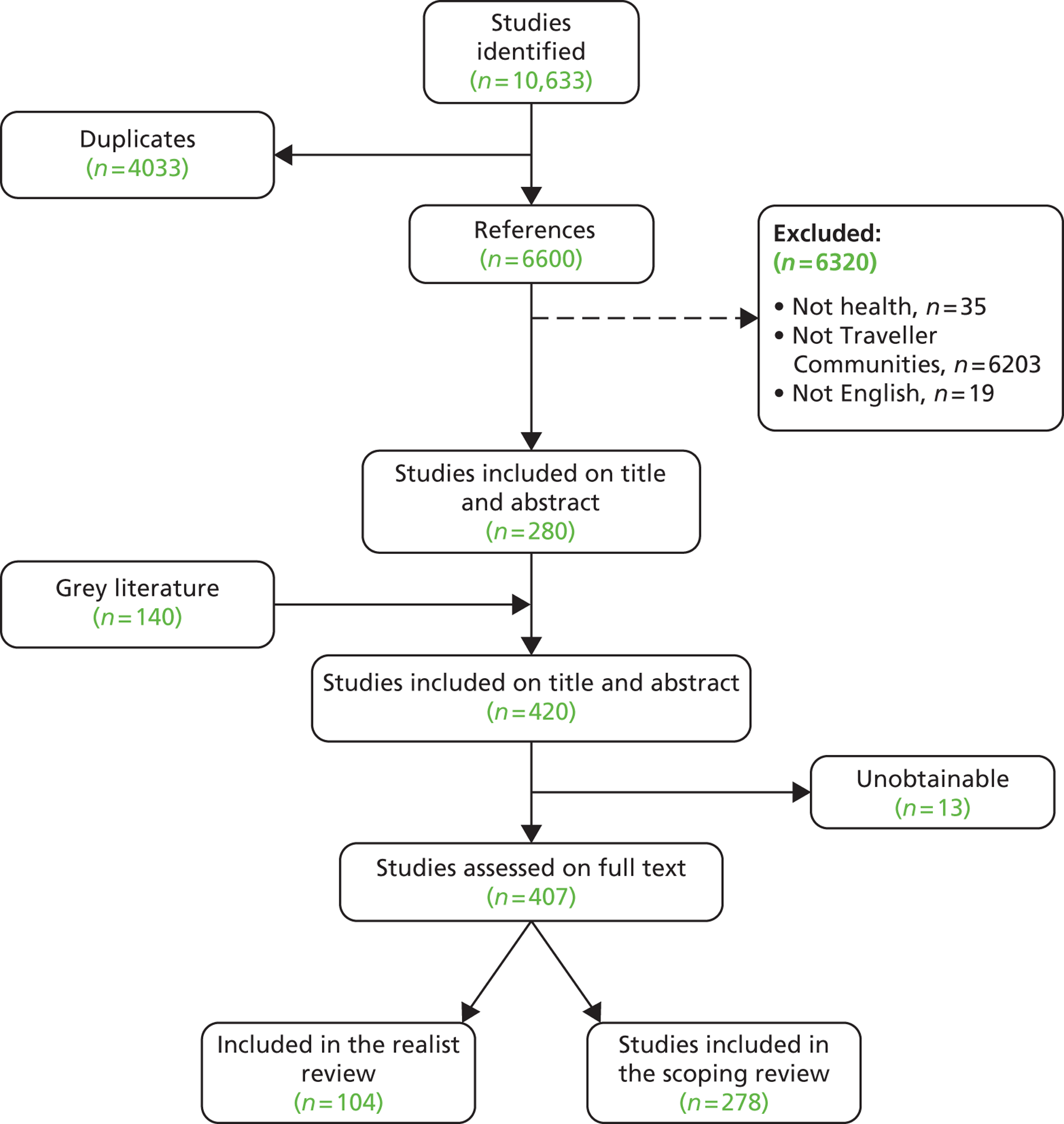

These database searches gathered 10,633 references, of which over 4033 were identified as duplicates (see Figure 3 ). The remaining references were stored in an EndNote library (EndNote, Thomas Reuters, CA, USA). While this strategy resulted in a relatively broad set of references in the first instance, it prevented the exclusion of relevant articles through the adoption of a narrowly focused search strategy.

Searches were also made by two reviewers using The Cochrane Library, The Campbell Collaboration Library of Systematic Reviews, Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD)/Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE) and Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Co-ordinating Centre (EPPI-Centre) databases.

Searches for grey literature

Initial literature searches prior to the study suggested that the formal literature base (i.e. from peer-reviewed journals) on outreach in Traveller Communities is relatively small. However, there appeared to be a substantial amount of ‘grey’ literature on this subject. A number of search strategies were utilised between July 2011 and November 2011 to retrieve grey literature. Websites of organisations that sponsor and/or conduct relevant research (listed in Box 1 ) were searched to identify publications of interest. Where the function was available, RSS (Really Simple Syndication) feeds or e-mail alerts were set up in order to keep appraised of new literature.

Equality and Human Rights Commission: www.equalityhumanrights.com

Friends Families and Travellers: www.gypsy-traveller.org

Intute: www.intute.ac.uk

Irish Traveller Movement in Britain: www.irishtraveller.org.uk

Local Government Association: www.idea.gov.uk

NHS Evidence: www.evidence.nhs.uk

Pavee Point (human rights organisation for Irish Travellers in Ireland): www.paveepoint.ie

Race for Health: www.raceforhealth.org

Department of Health: www.dh.gov.uk

Home Office: www.homeoffice.gov.uk

Joseph Rowntree Foundation: www.jrf.org.uk

MRC: www.mrc.ac.uk

National Audit Office: www.nao.org.uk

The National Federation of Gypsy Liaison Groups: www.nationalgypsytravellerfederation.org

Department for Communities and Local Government: www.odpm.gov.uk

Society of Behavioural Medicine: www.sbm.org

Urban Institute: www.urban.org

Wellcome Trust: www.wellcome.ac.uk

Searches were also undertaken of the Fade Library, a grey literature library for health (http://fadelibrary.wordpress.com/), as well as of a number of open access resources, including the Directory of Open Access Journals (www.doaj.org/), UK Higher Education Repositories (www.opendoar.org/), BioMed Central Open Access (www.biomedcentral.com/) and UK theses (http://ethos.bl.uk/). The Northumbria University HSWE (Health, Social Work and Education) database, an up-to-date bibliographic database of all journal articles relevant to health, community and education studies, and Government policies, reports and legislation, was also utilised. In addition, contact was made with key representatives working with Traveller Communities to ask for suggestions for relevant literature including unpublished practice accounts or evaluation reports.

In cases where both an internal report and a peer-reviewed paper on the same study were retrieved, both documents were scrutinised.

Screening of studies according to title and abstract

The titles and abstracts of studies identified were scanned by two reviewers to make an initial assessment of relevance. As initially it was envisaged that a meta/narrative synthesis would be undertaken, the Population, Interventions, Comparators, Outcomes and Study design (PICOS) framework88 was used to define inclusion/exclusion criteria at this stage (see Appendix 3 ). However, once it became clear that there was insufficient evidence to undertake a meta/narrative synthesis, eligibility for inclusion was broadened to meet the criteria of the scoping review (i.e. the inclusion criteria was no longer limited to interventions but was broadened to include any article pertaining to the health of Traveller Communities). For the realist synthesis, studies were included if they contributed an understanding to at least one area of the initial theories. If there was any doubt at this stage concerning the relevance for inclusion in the review, the full text of the studies was obtained for assessment. No restrictions on inclusion were imposed according to type of journal, publication date (up to the date of searches) or country of research or practice. Foreign-language publications were excluded. Any disagreements between reviewers with respect to the inclusion or exclusion of studies were resolved by consensus or through consultation with a third reviewer. Thirteen articles included on title and abstract were unobtainable (see Appendix 4 ). The publications included on title and abstract then formed a core set of studies which were assessed on full text according to the specific requirements of each review strand.

The methods of the scoping review and realist synthesis in terms of the selection, appraisal and analysis of studies are now discussed in more detail for each strand. The reporting here follows the methodological framework set out by Arksey and O’Malley84 and Levac et al. 82 for conducting scoping reviews and the Realist And Meta-narrative Evidence Syntheses: Evolving Standards project (RAMESES) publication standards for the reporting of realist syntheses. 89

Scoping review

Study selection

In scoping reviews, as with other systematic review methods, relevant studies are found and considered for inclusion/exclusion in relation to the research question. Poth et al. 90 propose that as scoping reviews are exploratory, all studies on a topic are included in order to identify gaps in research, regardless of study design. As such, the broad search strategy described above generated a comprehensive picture of the available evidence on the health of Traveller Communities, the characteristics of which could then be described and summarised. Thus, the scoping review included all those articles which were screened and included on title and abstract which focused on members of Traveller Communities and which had a health focus. The decision to include not only studies that described outreach interventions but also those that focused more broadly on the health of Traveller Communities was made in order that the evidence on outreach interventions could be placed in the context of the wider literature. As a broad search strategy was used, it is unlikely that any references will have been excluded that would be relevant for the scoping review. Completeness of searching, however, was determined by time and scope constraints.

As in scoping reviews generally, no formal quality assessment of included studies was undertaken. While the challenges in assessing quality among the vast range of published and grey literature that may be included in scoping studies are readily recognised, they have not been resolved, and this lack of quality assessment and the resultant limits on data synthesis and interpretation are known weaknesses. 82 , 91 In this review, key features that characterise the quantity and quality of the literature, such as study design and provenance, are examined in a process that sought to include and classify items rather than exclude them.

Charting the data

The studies included in the scoping review were charted according to the ‘descriptive analytical’ method outlined by Arksey and O’Malley,84 whereby ‘a common analytical framework’ is designed to classify and organise studies according to key issues and themes. The following information was collected from each study and recorded onto a ‘data charting form’84 using NVivo software (QSR International, Warrington, UK):

-

date of publication

-

country of publication

-

type of author (e.g. academic, government/local authority, health service providers, Traveller/third-sector organisations)

-

evidence type (e.g. research study, anecdotal account, literature review, policy/guidelines for practice, theoretical/opinion paper)

-

study design (e.g. qualitative study, controlled clinical trial, pre- and post-intervention study, RCT)

-

whether or not outreach is described

-

outreach worker (e.g. Traveller Community member, health visitor)

-

health focus (e.g. women’s health, child health, dental health).

An early case study of using NVivo for a literature review was presented by di Gregorio92 and while a small amount of published material has since developed this process,93–97 the use of such software does not appear to be commonplace. The use of NVivo software for this review facilitated the management and description of the large number of studies, provided a useful operational tool for the manipulation of data during the analysis process, and helped to ensure transparency in the classification of studies.

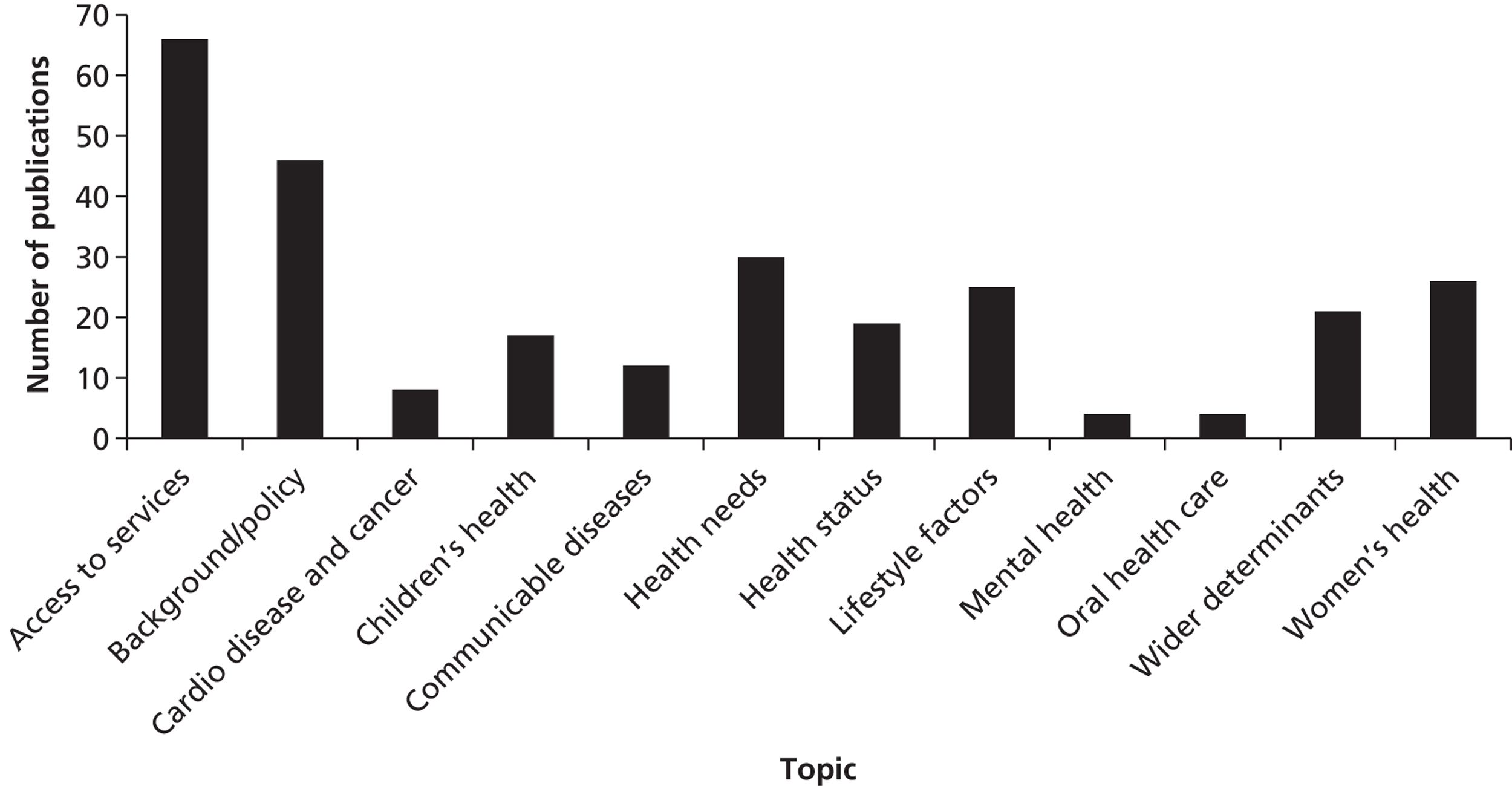

Collating, summarising and reporting results

A numerical approach was taken to the collation and presentation of data, which examined the distribution of studies according to the characteristics charted and illustrated these graphically rather than organising the data according to key themes or findings. This approach enabled the presentation of information around how much and what types of evidence is available on the health of Traveller Communities, how much of the overall research evidence on Traveller health reports on the evaluation of outreach interventions, what research designs have been used to do so, who outreach workers are, in which countries are the most/least publications being published, and what kind of authors are publishing on the health of and outreach interventions for Traveller Communities.

Realist synthesis

A realist synthesis is inherently a highly iterative process, each step cumulatively enriching the previous one and informing the following, and each having to be undertaken a number of times over the course of the study. Reporting is, consequently, a recognised challenge. 98 A degree of sanitisation was thus applied in reporting this study, in order to strike a balance between transparency in exposing the methodological audit trail and readability.

Selection and appraisal of documents

The 407 articles selected on title and abstract formed a core set of studies which were then examined for inclusion in the realist review. There was, naturally, significant overlap between the two review strands, but there were exceptions. For example, some outreach interventions could be excluded from the scoping review if they focused on education, but included in the realist review if they gave detailed descriptions of the outreach process. On the other hand, some studies included in the scoping review lacked sufficient detail to inform any of the realist theories and were thus excluded, even if they focused on outreach. A realist synthesis does not seek to come to a verdict about the relevance or quality of whole studies, but ‘requires a series of judgements about the relevance and robustness of particular data for the purposes of answering a specific question’ (p. 8). 89 Study appraisal is, therefore, guided by judgements on the potential for a study to contribute to theoretical developments rather than standard quality assessment tools. The full text of each study was assessed by two reviewers. The Mendeley reference manager programme, which enables the highlighting and annotation of articles as well as the grouping and organisation of articles according to ‘tags’, was used to record decisions about inclusion/exclusion for the different arms of the study, and the particular initial theory to which the studies or section(s) of reported data were thought to contribute. Appendix 5 lists the studies included in the realist review, with comments about the study design, links between articles (when they relate to the same study or organisation) and comments about the particular learning that they could contribute.

Data extraction

Four initial theories (p. 10) guided the data extraction and analysis stages. These formed a framework to extract data as well as offering early explanatory potential. For the purposes of clarity, we report the steps of data extraction, analysis and synthesis as distinct, without all of the iterations that took place in practice. However, in the interest of a decision audit trail, we have sought to thoroughly expose our decision-making process. Pawson et al. 85 state: ‘The process is, within each stage and between stages, iterative. There is a constant to-ing and fro-ing as new evidence both changes the direction and focus of searching and opens up new areas of theory’.

A data extraction sheet was adapted from that reported by McCormack et al. 99 (see Appendix 6 ), developed to mirror the four initial theories. Data extraction was undertaken systematically, by two researchers (periodically reviewing each other’s extraction sheets) until data saturation was reached, that is no new learning was emerging through the studies85 , 98 (38 studies; see Appendix 5 ). The studies were selected for their potential to contribute understanding on each of the four theories. An iterative approach to data extraction was used, with the data providing new insights into the initial theories, and questions to be asked of the data changing in response to the development of our understanding as the analysis progressed. We consulted our Mendeley database regularly in order to ensure that the studies which had not been data extracted could not contribute new insights in the light of emerging findings. An audit trail was kept of all of the decisions that were made during this process, and reviewed regularly by the wider team. This process led to the decision, for example, to focus on perceived and expressed needs in our exploration of ‘to whom’. An extract of our decision trail regarding this is presented in Appendix 7 .

Analysis and synthesis process

This section needs to be preambled by a note on what is expected of a synthesis process in a realist review. There is no pooling of net effects, no ‘aggregation’ or setting of implementation guidelines. Instead, the purpose of the review is a refinement of the initial four theories.

The steps taken to synthesise the data are now described, although in reality the synthesis did not proceed in such a linear sequence, but rather with considerable overlapping or moving back and forth between the different steps. Here, again, the audit trail memos were used to maximise wider team input in the analysis process.

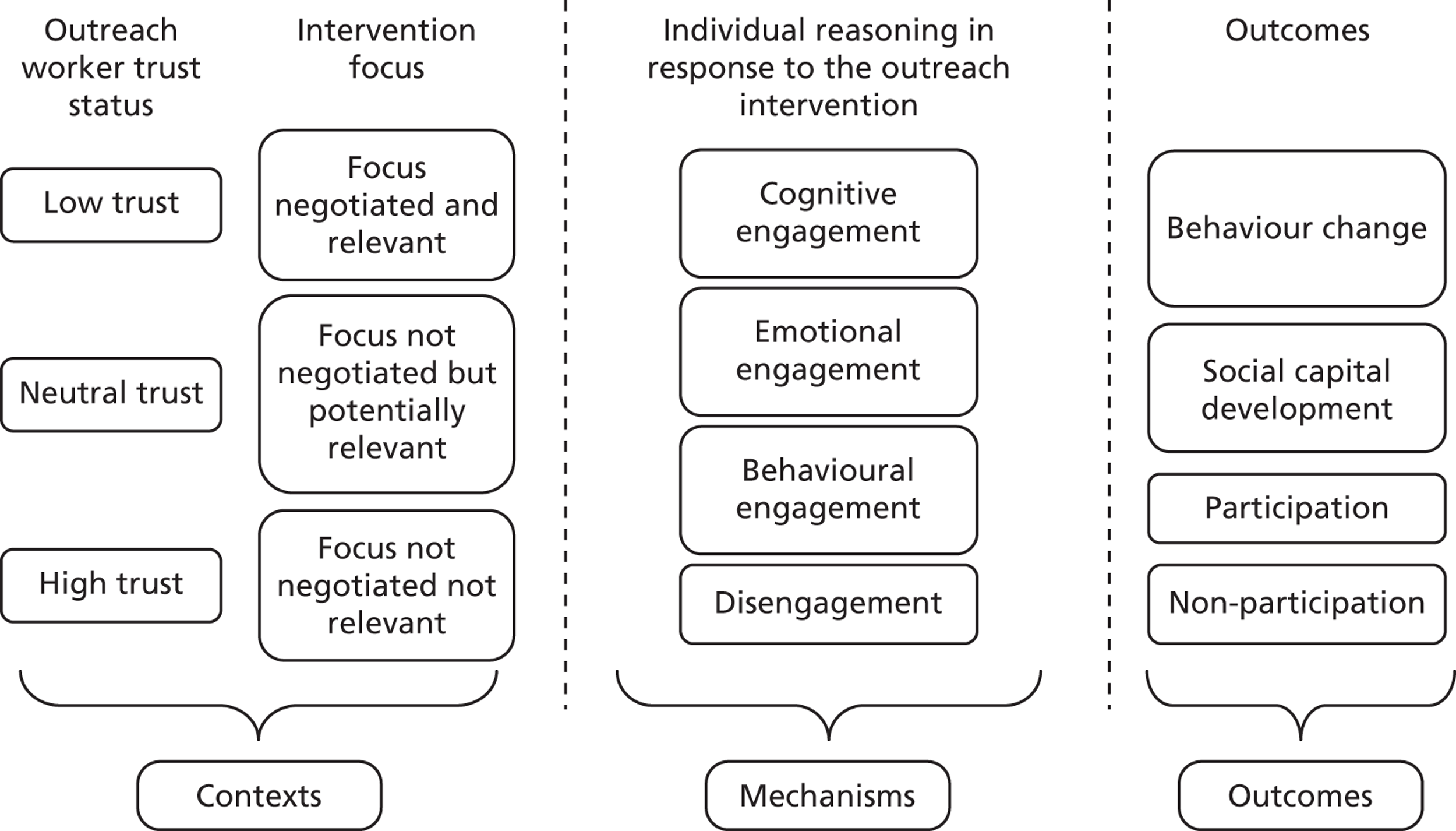

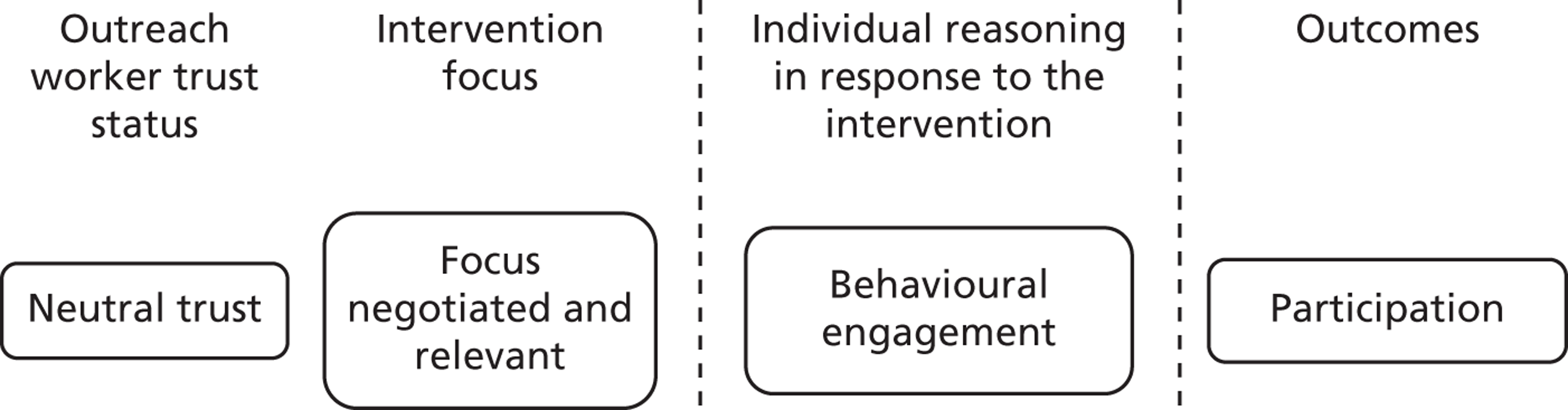

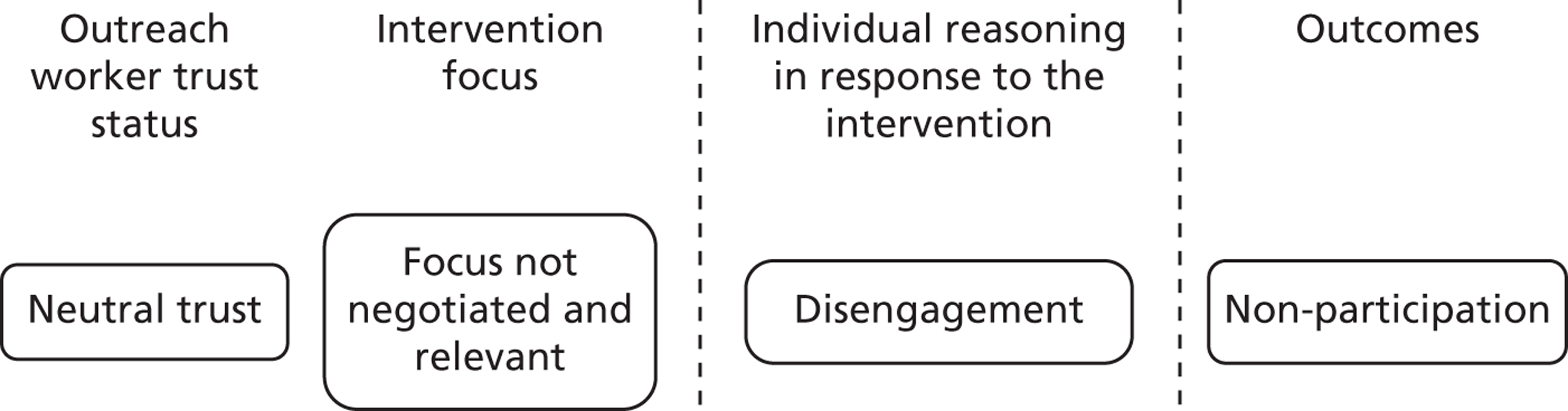

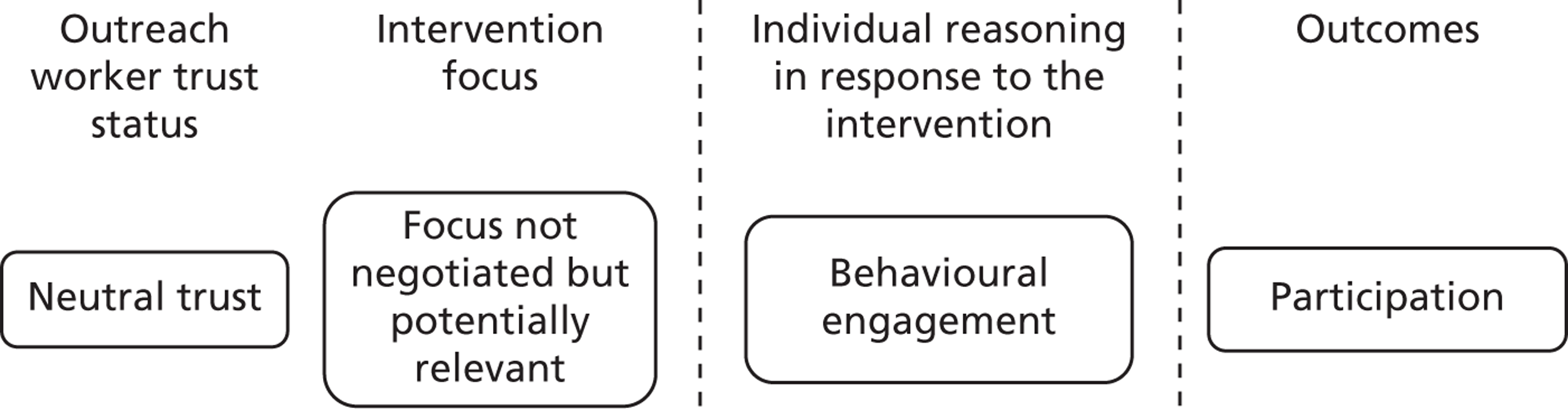

Thematic analysis of the data extracted

The data extracted from each article were separated into the four initial theories (‘to whom’, ‘by whom’, ‘how’ and ‘what for’), and these data were collated and thematically analysed. The list of themes were then classified according to whether they described contexts (C), mechanisms (M) or outcomes (O), and were merged into C, M and O files from which we began to formulate potential CMO configurations. This process enabled immersion in the literature and the search for key terms, abstract ideas and hypotheses that might provide explanatory purchase on how outreach might ‘work’ in Traveller Communities. The net effect of this exercise was, thus, a ‘deconstruction’ of the articles along the lines of our initial theories.

Classifying outcomes

Outcomes were classified following the Dahlgren and Whitehead38 diagram of the social model of health in order to situate intervention impact from the perspective of health inequalities aetiology. Outcomes were thus classified as tackling:

-

General socioeconomic, cultural and environmental conditions. Examples of these include improved communication between members of the Traveller Community and service providers, Community members engaging in a representational role and increased awareness of Traveller culture and needs among service providers.

-

Social and community networks. Examples include building capacity in the Community, participation of Traveller Community members in activities to raise awareness of their culture among the wider community and changing perceptions in the Community about the respective roles of men and women.

-

Individual lifestyle behaviours. Examples of these include improved adherence to prescribed treatment, participants who are engaging and confident to articulate their needs and increased uptake of services.

Working back from outcomes to generate Context–Mechanism–Outcome configurations

Working from this database of classified outcomes, we scrutinised studies for the potential mechanisms that might have led to these outcomes, in context. This was a highly iterative process, whereby theories were developed, populated or countered by a detailed analysis of the studies.

Numerous such CMO configurations were developed from the data extracted, in conjunction with their substantiation and verification through bringing to bear theoretical literature and evidence from interventions in parallel populations. This led to the development of more refined explanatory theories through which outreach interventions may work in Traveller Communities. The net effect of this stage was thus a ‘reconstruction’ of meaning from the previously disaggregated pieces of evidence.

Validation and refining of theories through expert hearings and alternative literature sources

A number of ‘expert hearings’ (EHs) with key stakeholders, including Traveller Community members outreach workers and members of Traveller organisations, were also conducted in order to test and refine the developed theories. Key organisations and individuals were identified and recruited through Internet searches, review of initial documentation and research team networks in the field. The EHs varied in format and consisted of:

-

five consultations with steering group members (Traveller Community members, specialist workers and members of Traveller organisations) (EH1, EH2, EH3, EH4 and EH5)

-

one consultation with a research members’ contact (Gypsy and Traveller liaison officer) (EH6)

-

two focus groups with members of Traveller Communities, facilitated by members of the researchers network (EH7 and EH9)

-

guided discussion around scenarios relating to health needs and services with nine Czech Roma Gypsies (EH8) and five Traveller Community members at Appleby Fair (a traditional horse fair held in Appleby, Cumbria, which is a major annual holiday event and gathering point for members of Traveller Communities) (EH10).

Further detail on EH activities, including the rationale for decision-making about the stakeholders involved, the timing of events and key outcomes, are detailed in Appendix 8 . Given the limited number of outcome data available and as the reporting of outreach interventions tended to describe programme strategies and provided a limited amount of insight into underpinning mechanisms, stakeholder involvement was key to eliciting mechanisms leading to particular outcomes. Access to Traveller Communities and facilitation of consultation with them was negotiated by those with established relationships with Community members. This enabled Traveller Communities to have an active role in the validation and refinement of theories. Examples of consultation focus included:

-

trust: what could health-care professionals do to gain the trust of the Community

-

health improvement: what could be done to improve the health of Travellers

-

patterns of nomadism and their impact on access

-

what kinds of services Travellers would access and in relation to what kinds of needs

-

vignettes, used to elucidate what kind of intervention would trigger different levels of engagement.

Appendix 9 provides an illustration of a discussion guide for a focus group with Traveller Communities and how it was informed by the analysis process.

These data were examined in detail and used to substantiate or invalidate our emergent understandings. For example, participants consistently referred to their preference for outreach workers to come from the Community, but some could think of Traveller Community members who would not be accepted because of prior conflicts within the Community. This shaped our understanding of ‘by whom’ in moderating the necessity to belong to the Community in order to offer effective outreach. The emphasis shifted, instead, to the need to have developed trusting relationships with the Community. Trust, in its own right, emerged in the EHs as having crucial importance, as it had in the Traveller Community literature. We searched the broader literature for existent models of trust and how it might be developed, and then subsequently consulted our EH data again, checking if we had evidence of each subdomain of trust.

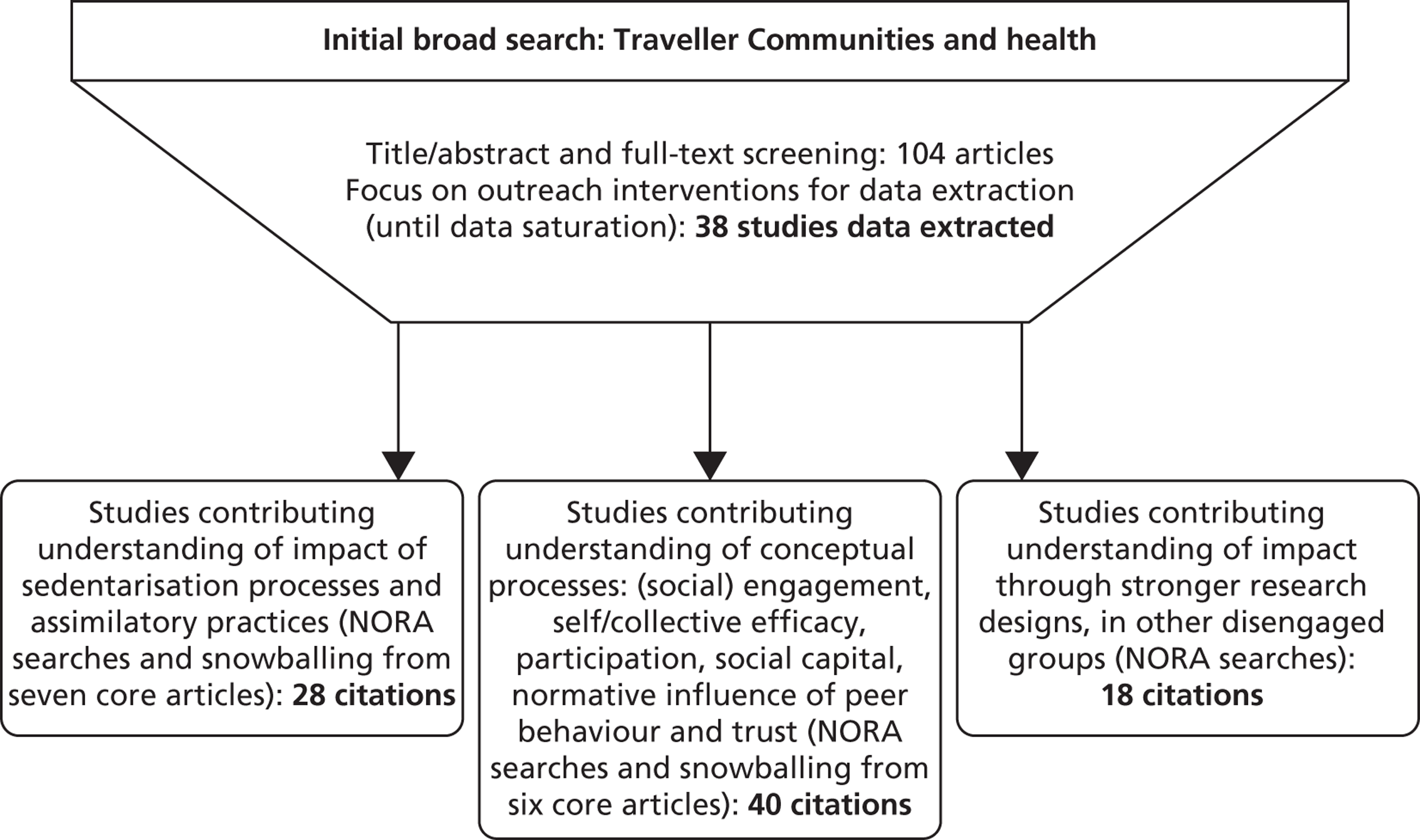

In realist syntheses, the search process is iterative89 and spans the entire project from the development of research questions through to refining the theories developed through the synthesis. 100 As such, for the realist synthesis the initial search was a preliminary one, which provided the reviewers with a literature base to populate and refine the theories described earlier. Subsequent literature searches were undertaken in order to inform the development of initial theories in the subscription databases detailed on p. 11. At this stage in the process, search strategies are required to be purposive rather than systematic in order to allow the development and substantiation of each initial theory. Three iterative searches focused on:

-

developing an understanding of commonalities in all Traveller Community subgroups, and also what distinguishes them and other disengaged groups (C)

-

understanding of potential underlying mechanisms (M)

-

outcomes (O) measured through ‘stronger’ research designs than those which are predominant in the literature on Traveller Communities ( Figure 2 ).

FIGURE 2.

Flow of citations through the realist review.

Each subsequent search strategy led to the identification of a number of studies. They all shaped the developing theories, but Figure 2 highlights the citations that provided us with the most explanatory purchase about that particular theory, and that are explicitly cited in this report. However, all of the 28 citations focusing on the particularities of Traveller Communities were used in developing the ‘to whom’ initial theory (see Chapter 3 , ‘To whom’: the context of outreach work), the 40 citations contributing some theoretical understandings contributed to the development of the explanatory framework for outreach detailed in Chapter 3 (see Explanatory framework). The 18 studies featuring stronger research designs (from RCTs to phenomenological studies) included outreach type interventions in aboriginal communities in Australia and Canada,101 homeless people,102 native American,103 , 104 and refugee groups105 as well as disaffected drug users. 106 These studies were used to substantiate the developing theories, for example on p. 57 and p. 64.

Pawson98 notes that in realist syntheses ‘The presentation of the synthesis is difficult because the process of going back and forth from hypothesis to evidence results in the continuous refinement of those hypotheses’ and that the reporting ‘inevitably and like all scientific research, tidies up that process by freezing the running order of hypotheses and evidence’ (p. 13). For example, EHs that have happened chronologically later in the project nevertheless might confirm or illustrate some of the points made earlier in the theory development process. Where this is the case, they are reported in support of the theory in question as if it had been a linear process, for ease of reading. The same applied to additional literature searches as, for example, while the intent of one particular search might have been to elicit measured outcomes of outreach, the results might have shown up the role of trust development in the process.

Economic evaluation

A lack of economic evaluations of outreach interventions was anticipated, hence the original aim of the economic evaluation component was to build on the narrative review of the effectiveness of outreach interventions. This would involve estimation of intervention costs and then evaluation of the potential cost-effectiveness of different modes of intervention and different health behaviours targeted. This approach, which blends evidence review and data synthesis, was used successfully to highlight which health promotional activities undertaken by lay health advisers might be considered cost-effective. 107 However, the lack of quantitative evaluation of the effectiveness of outreach in Traveller Communities rendered this approach infeasible. To maximise learning from the available literature, the initial criteria for inclusion of only articles describing the evaluation of outreach interventions for Traveller Communities was relaxed to include any article that provided a description of the delivery of outreach, the impact of outreach or the resource implications. A table of the studies included in this analysis is presented in Appendix 10 . The available literature was used to define the principal modes of delivery of outreach interventions, to aid estimation of the resulting resource implications and to provide an indication of effectiveness.

The titles and abstracts of all 407 articles unearthed in the literature review were scrutinised to determine the nature and likely content of the article. Articles describing any aspect of outreach were read. Key articles reporting the health of members of Traveller Communities were also read. Information on outreach interventions was extracted, including budgets and indications of resource use; practicalities of delivery; whether or not specific health behaviours were targeted; training and qualifications of staff; the size of the population served; and any measures of outcomes achieved. After extraction, the main modes of delivery were determined and the information previously abstracted was categorised accordingly. Some articles provided information for more than one mode of delivery. Articles within each mode of delivery category were then evaluated. Given the scarcity of data, no formal attempt was made to assess the quality of information. Data on resource use and budgets were assumed to be correct and to represent the cost of delivery of the intervention described. Data on outcomes were scrutinised for potential bias, but the uniformly weak nature of the evidence presented little opportunity to discriminate according to perceived quality of studies.

Chapter 3 Results

A summary of the identification, screening and selection of studies is provided in Figure 3 .

FIGURE 3.

Summary of the systematic identification, screening and selection process.

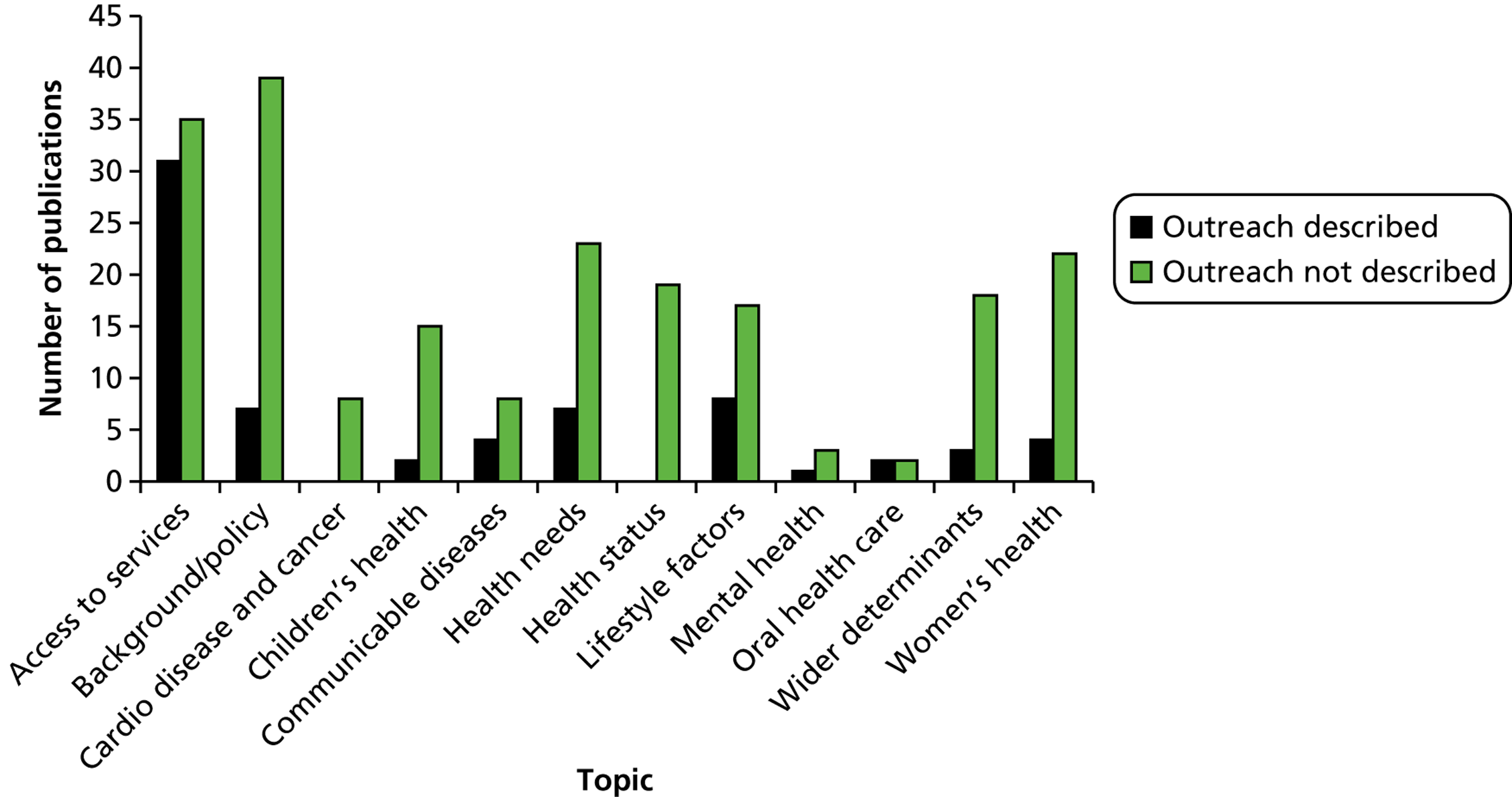

Scoping review

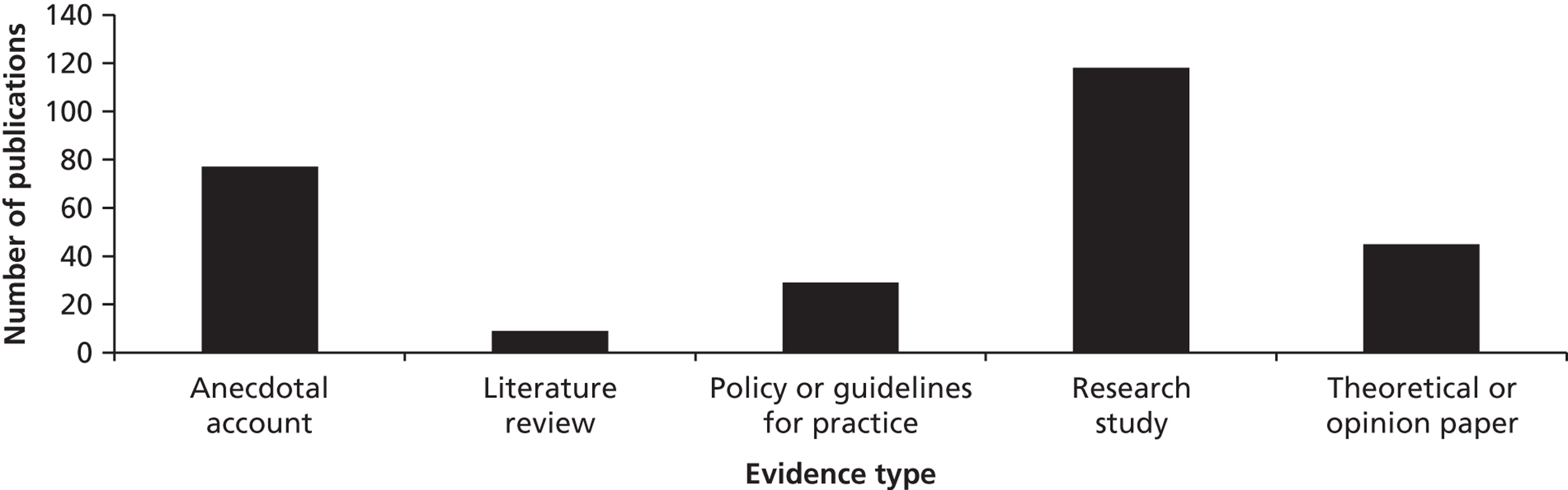

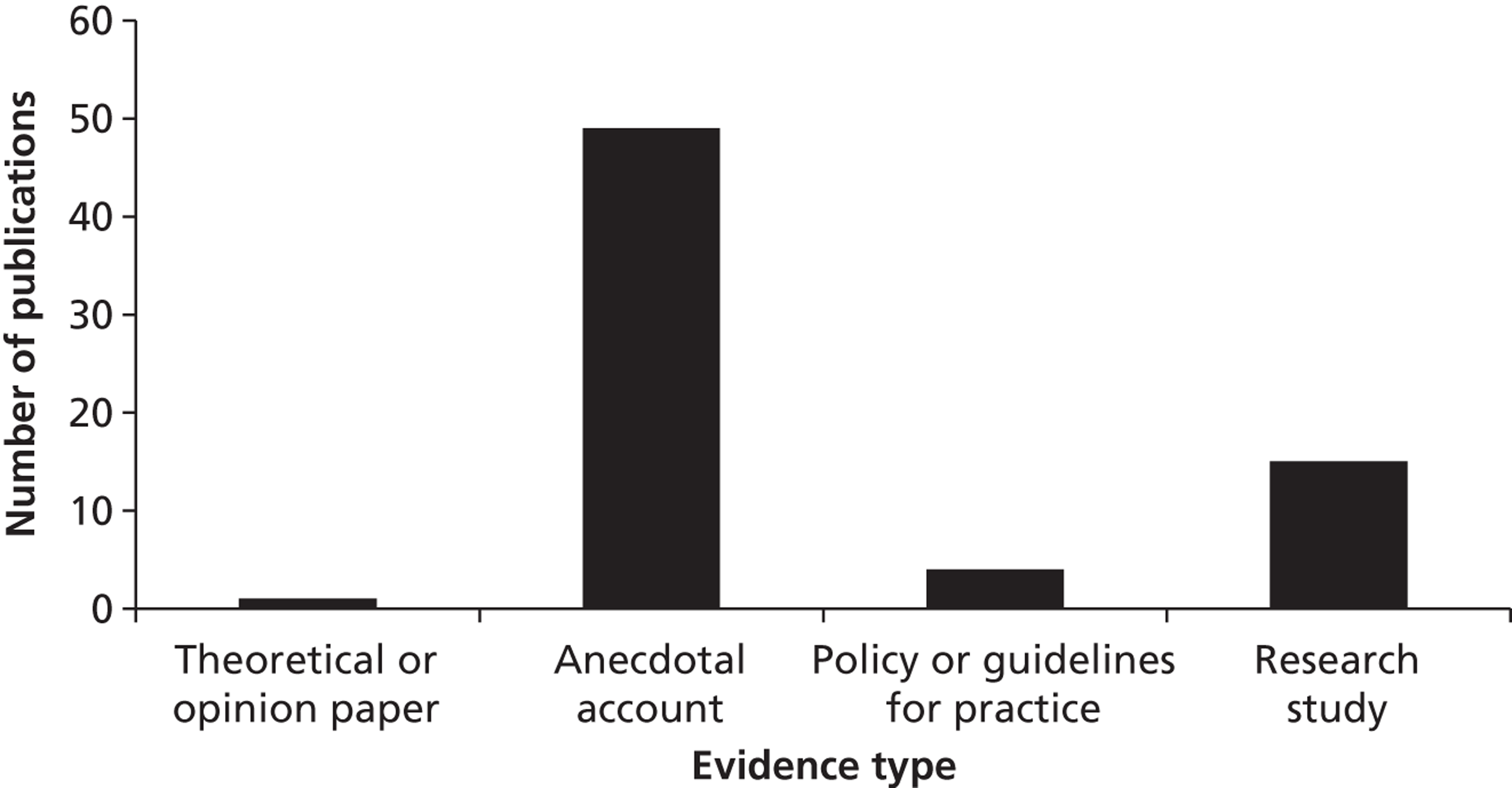

A total of 278 publications focused on the health of Traveller Communities and formed the evidence base for the scoping review (a list of included studies can be found in Appendix 11 ). As noted earlier, a decision was made to include all articles focused broadly on Traveller health in order to situate the evidence on outreach for Traveller Communities in relation to wider research and practice activity. Of all the articles which focused on the health of Traveller Communities, only around one-quarter (24.8%) described the implementation of outreach. This section describes the characteristics of the overall evidence base on the health of Traveller Communities and on outreach interventions for Traveller Communities according to year of publication, country of research or practice, authors and practitioners, and type of evidence.

Key findings

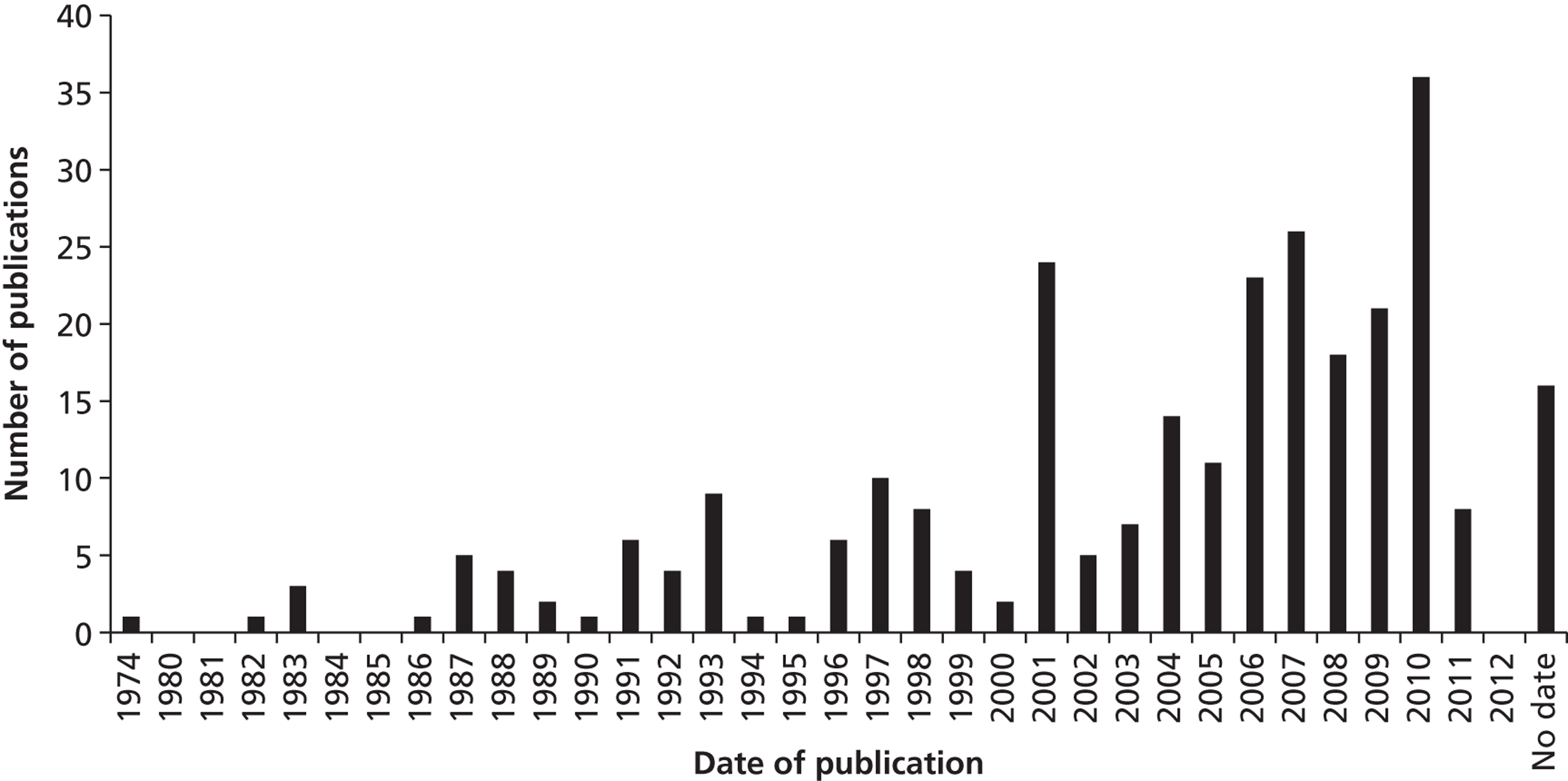

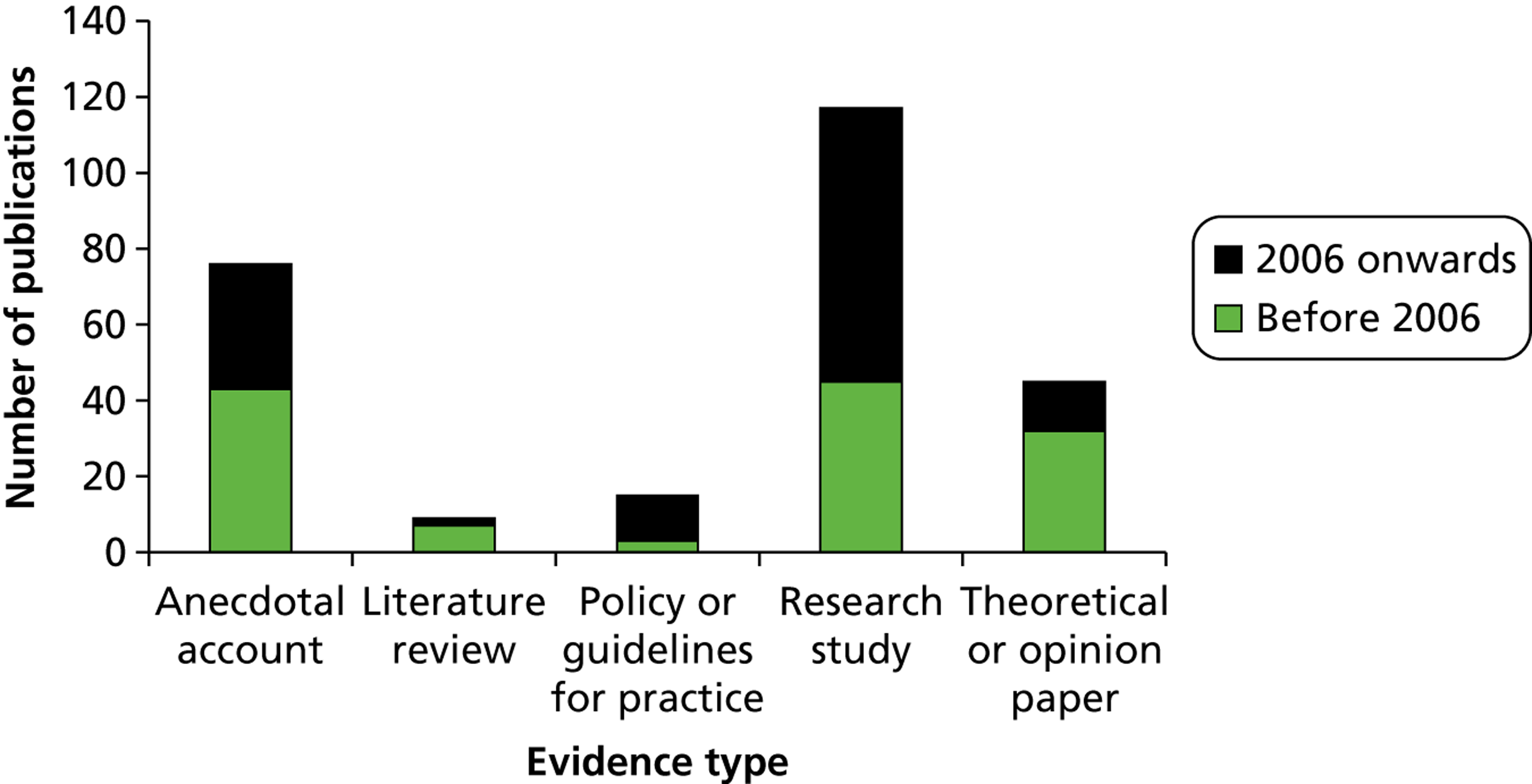

Year of publication

Interest in improving the health of Traveller Communities appears to have increased in recent years. Half (50.4%) of the articles with available dates were published from 2006 onwards (as shown in Figure 4 ). The publication of a seminal study on the health status of Traveller Communities in England in report form in 200437 , 108 and as peer-reviewed publications in 2007,19 , 39 as well as the initiation of the Decade of Roma Inclusion in 2005,109 are developments that may have contributed to this increasing attention to health of Traveller Communities. Although there appears to be a peak of activity in relation to Traveller health in 2001, this is likely to be an artefact of the separate classification of 13 articles all reported in a journal special issue.

FIGURE 4.

Distribution of publications according to year of publication.

When examining only those articles focused on outreach, a similar distribution is evident, with half (50.7%) published from 2006 onwards.

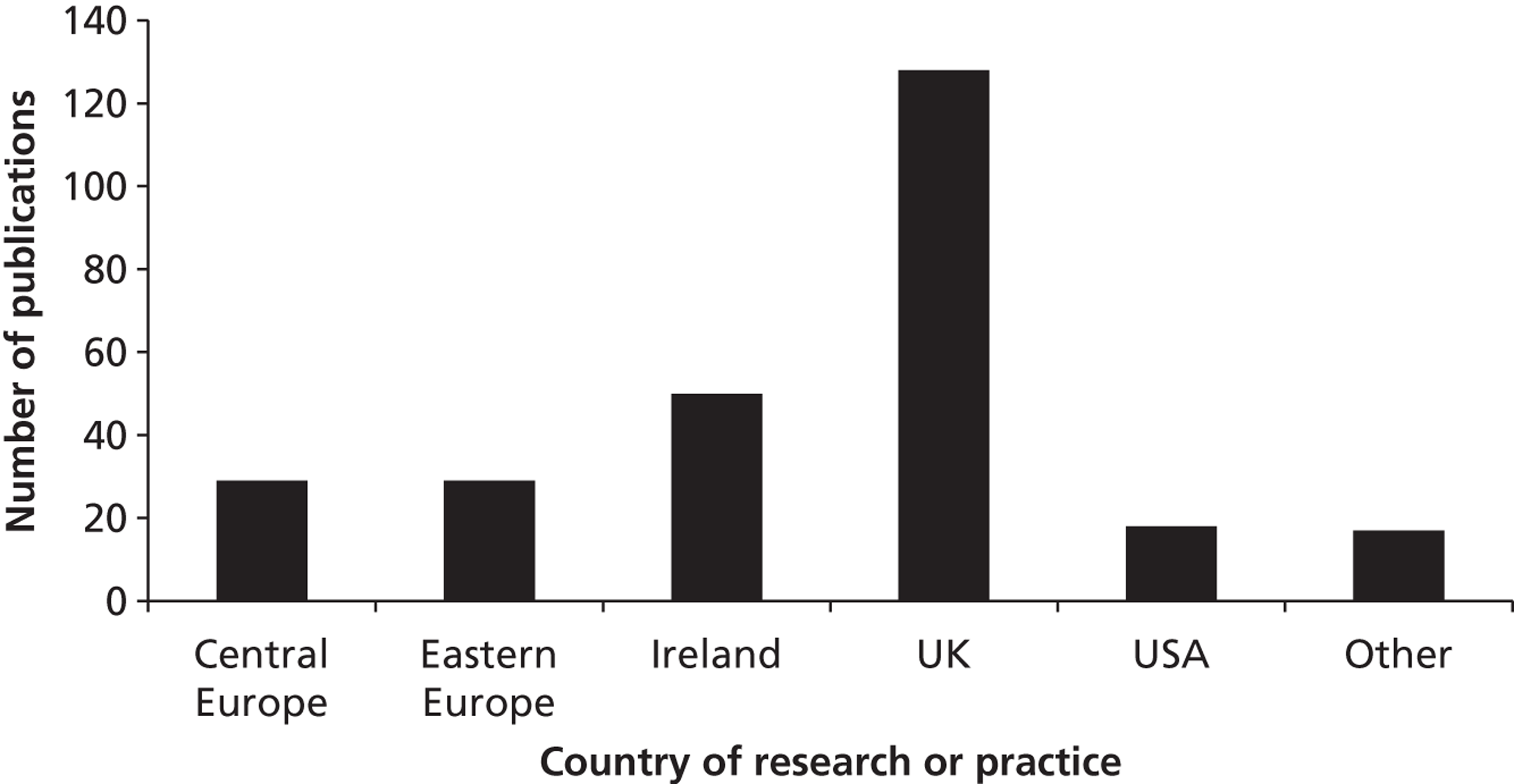

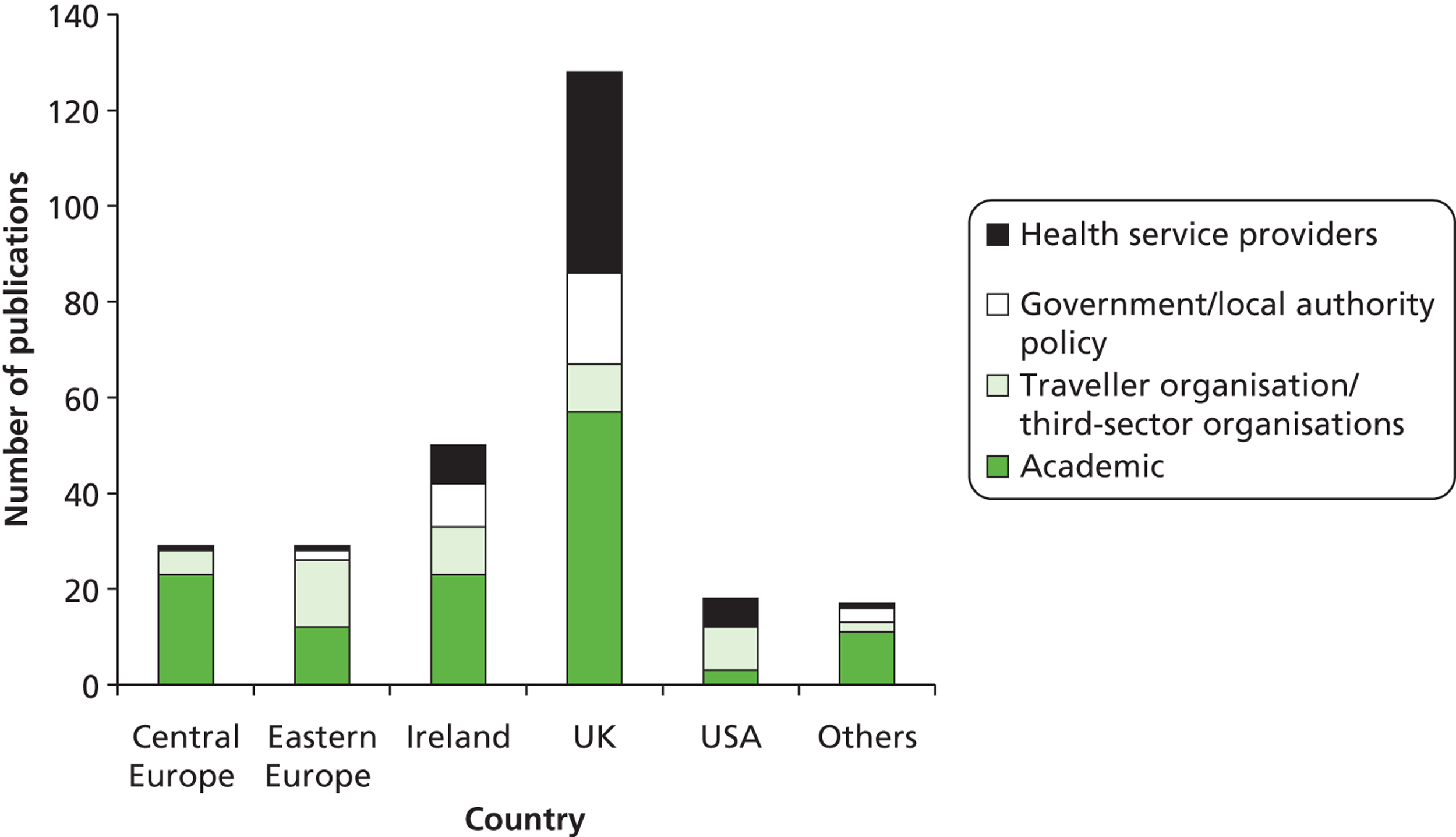

Country of research or practice

Articles were classified according to the country in which the research or practice was conducted (shown in Figure 5 ). The majority of publications (47.2%) emanated from the UK. Articles from Ireland accounted for the next greatest proportion of articles (18.5%). Taken together, central (10.7%) and eastern Europe (10.7%) contributed just over one-fifth of the overall articles, and only a small proportion of articles originated from the USA (6.6%).

FIGURE 5.

Distribution of publications by country of research or practice.

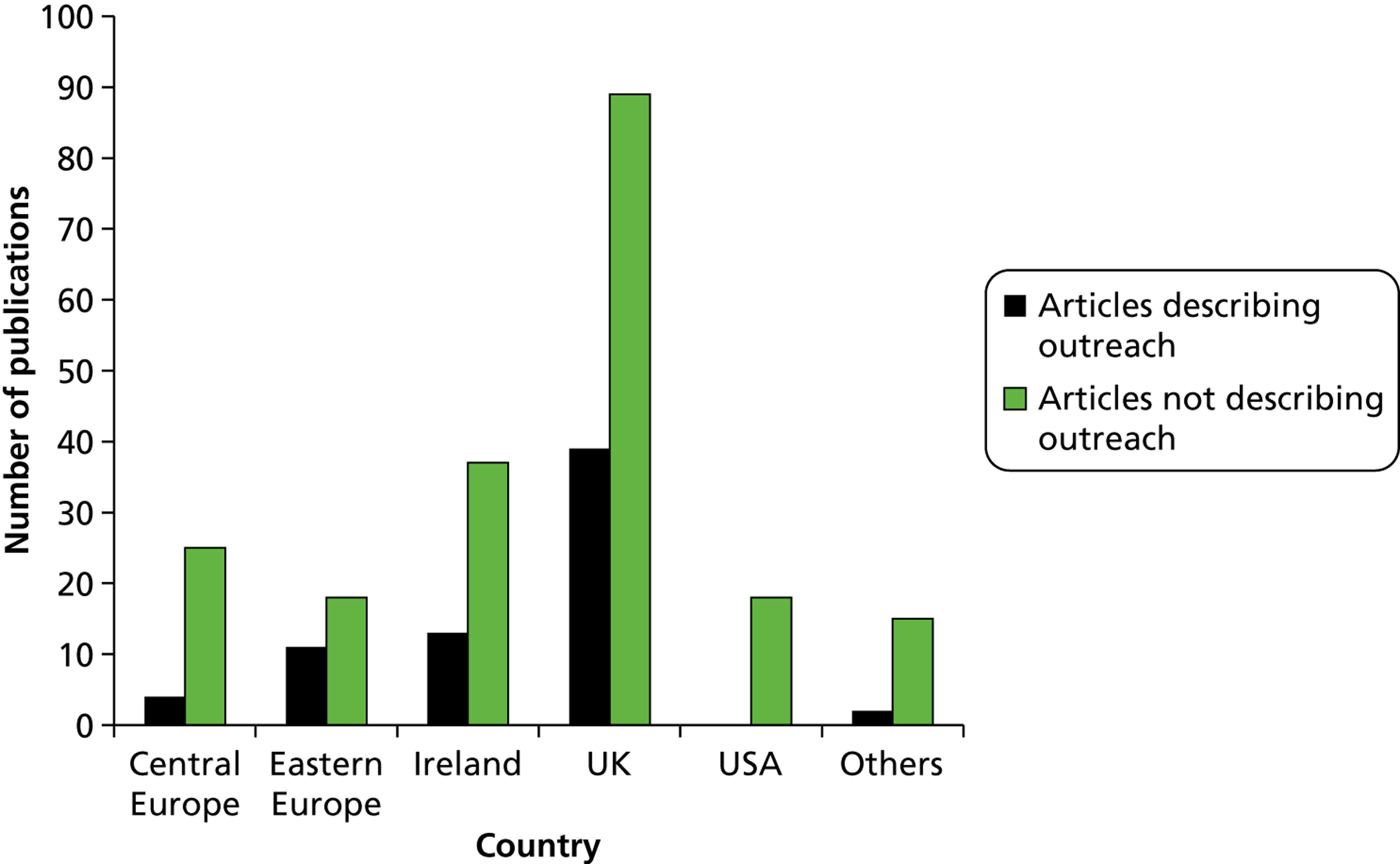

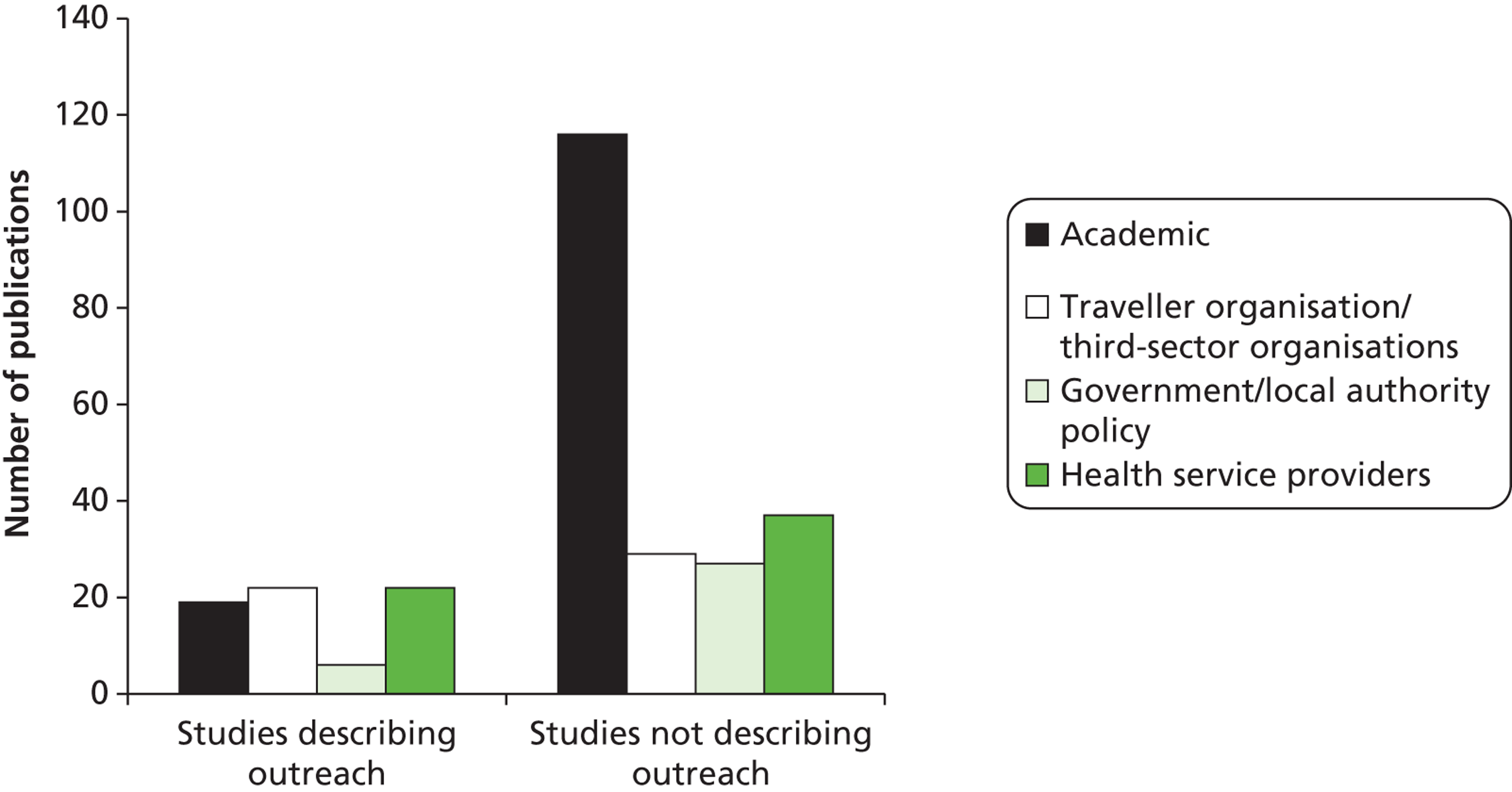

Figure 6 compares the distribution of articles describing outreach with those that do not describe outreach according to country of research or practice. The small amount of evidence describing outreach overall is reflected when studies are broken down by country. However, this difference is particularly pronounced in the USA, in which none of the 18 studies described outreach interventions, and in central Europe, in which only 13.8% of all publications described outreach. Eastern Europe had the highest proportion of articles focused on outreach (37.9%), followed by the UK (30.5%) and Ireland (26%).

FIGURE 6.

Distribution of publications according to country of research and practice and description of outreach.

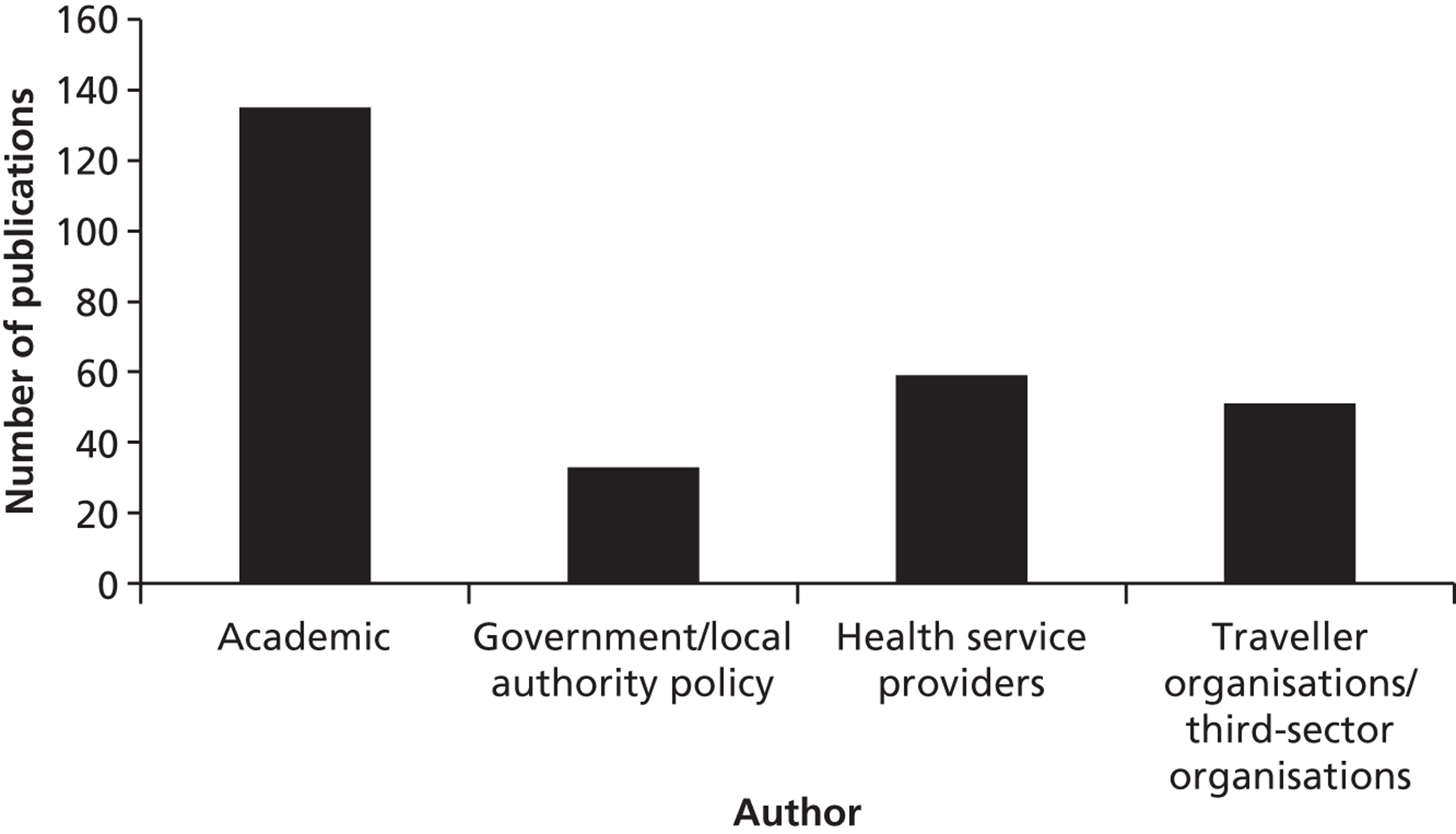

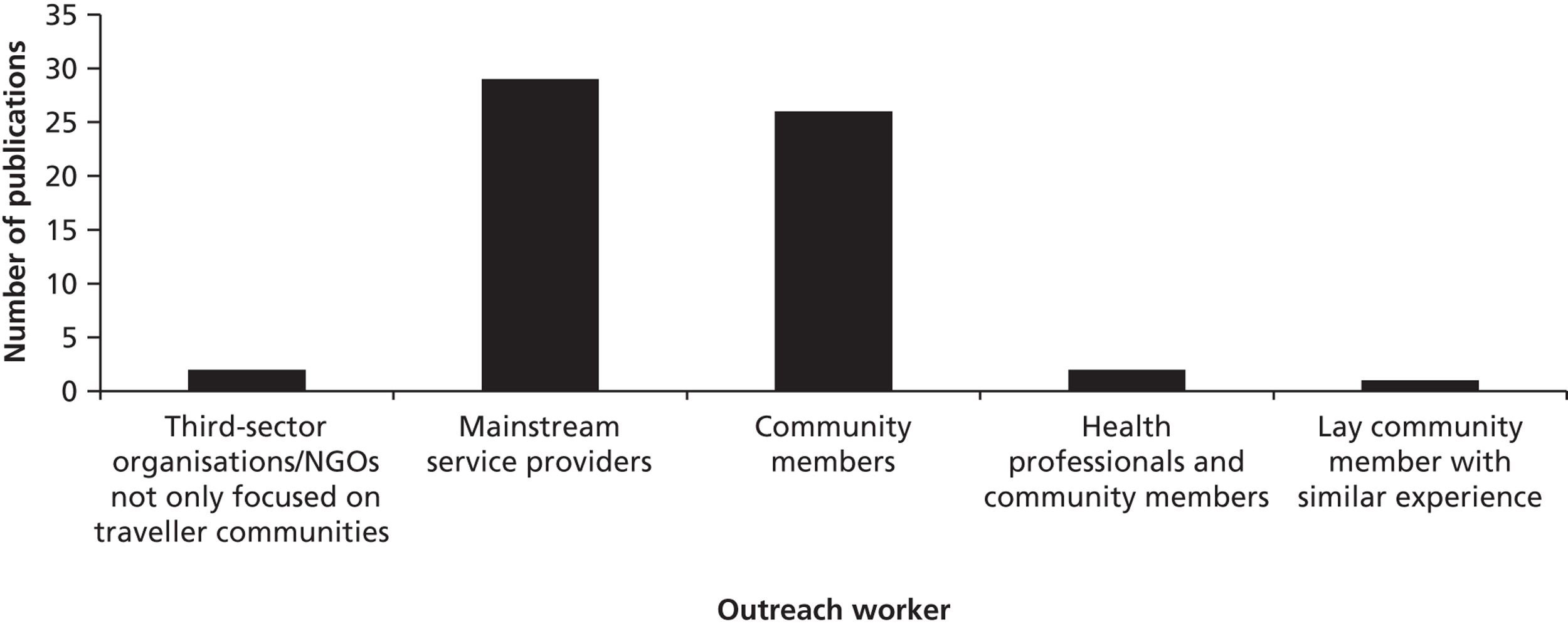

Authors and practitioners

Almost half of the publications were written by academic authors (48.6%) (described in Figure 7 ). There were also considerable numbers of publications written by Traveller Community specific or third-sector organisations (18.3%) and health service providers (21.2%). Governmental or local authority publications accounted for a much smaller proportion of the overall evidence base (11.9%).

FIGURE 7.

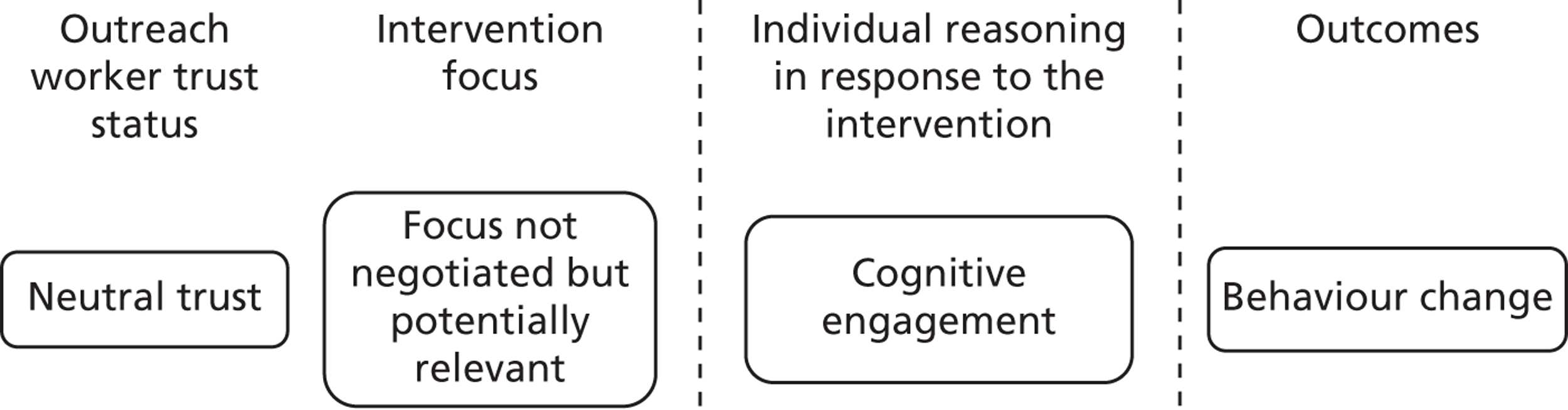

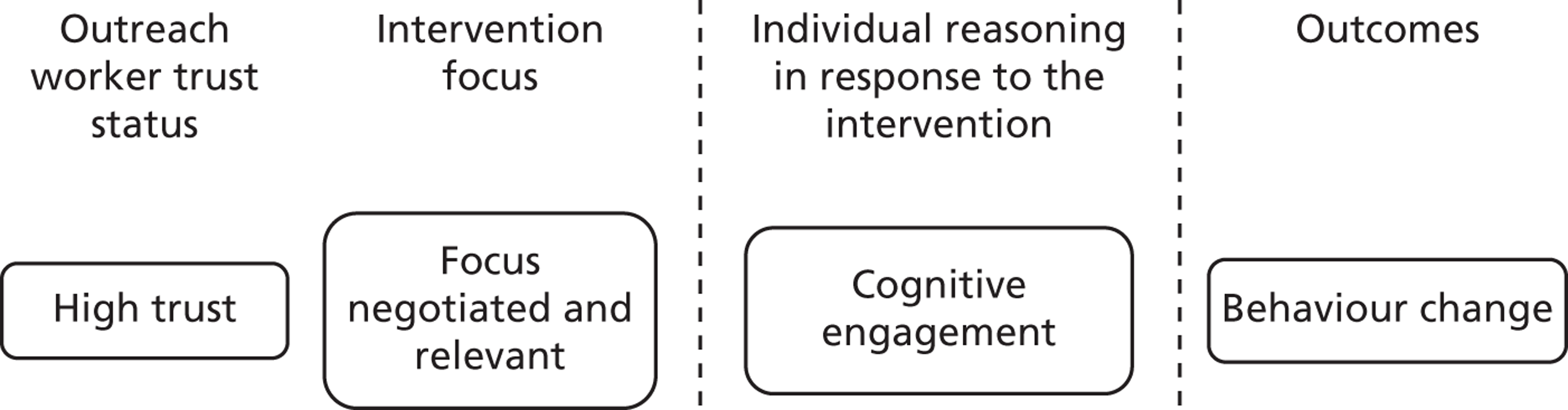

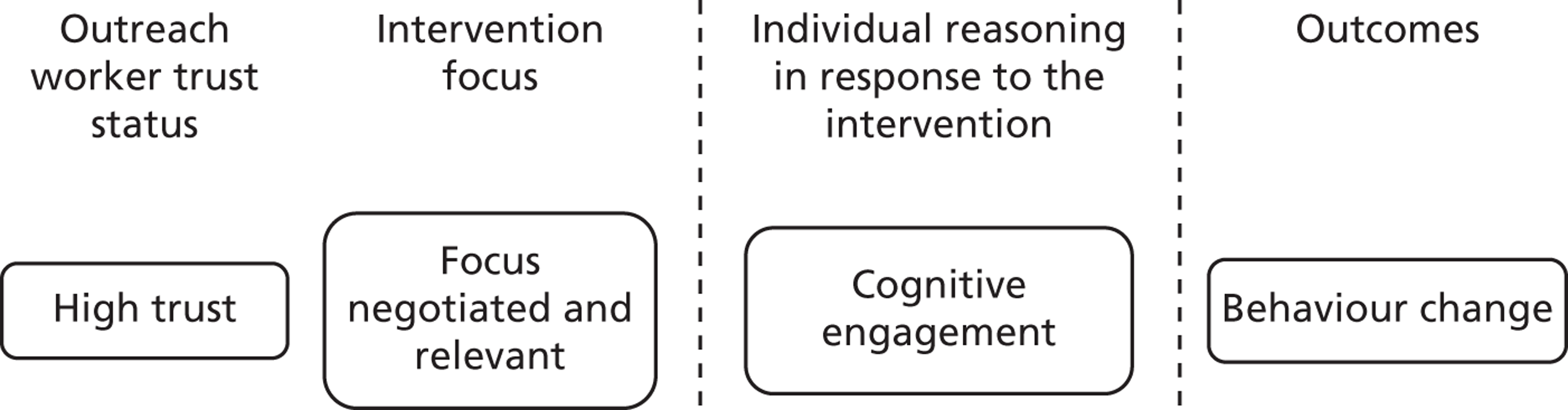

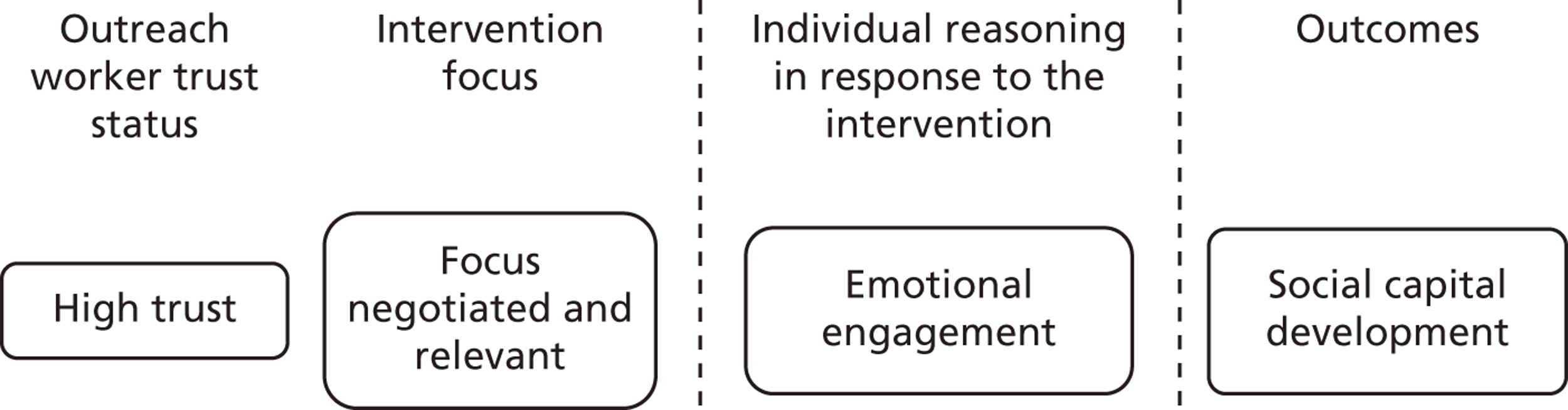

Distribution of publications according to type of author.