Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 09/3004/01. The contractual start date was in October 2011. The final report began editorial review in July 2013 and was accepted for publication in July 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

The Universities of Sheffield, Bangor, Southampton and Northumbria, Community Network and Age UK received grant funding from the National Institute for Health Research Public Health Research programme for this study. The University of Sheffield also received grant funding from Age UK to pay subcontractors for delivering the intervention. Community Network is a national charity and social enterprise that runs telephone friendship groups and a commercial teleconferencing service for the third sector, which could be perceived as having influenced contributions to the report. As an employee of Community Network, Angela Cairns acknowledges a financial relationship with a commercial entity that might have an interest in the submitted work.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2014. This work was produced by Hind et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Scientific background

There is increasing evidence of a direct association between loneliness and ill health. Loneliness is a strong risk factor for depression and increases mortality rates significantly in older people with depression. 1 Research has shown that loneliness predicts all-cause mortality in older people. 2 Loneliness is associated with poor self-rated health,3 increased blood pressure,4 higher levels of some vascular biomarkers,5 poor sleep quality6 and greater likelihood of health risk behaviours. 7 Greater cognitive decline and an increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease are also associated with loneliness. 1,2 Although previous reviews have considered the effectiveness of loneliness interventions in alleviating loneliness, they have not considered the link between loneliness and the wider public health factors associated with loneliness and ill health, for example health inequalities. With such major impacts on health, an understanding of what, how and why public health interventions prevent or alleviate loneliness in older people is critical. Overall, health and life expectancy are linked to social circumstances. Older people are socially excluded when they experience economic and material deprivation and/or lack access to social networks, services and activities. 7 Therefore, social exclusion can impact on loneliness, which in turn can impact on mental and physical health. Thus, loneliness may mediate the pathway between social inequalities and health inequalities.

The number of older people is increasing globally. In the UK, > 17% of the population is aged ≥ 65 years and this is predicted to rise to 20% by 2024. Life expectancy is also increasing and now stands at 78.1 years for men and 82.1 years for women. The number of older people living alone is currently rising. Among women aged ≥ 75 years, 60% live alone. 8 One of the risk factors for loneliness is living alone, although this may be linked to the time spent alone and the size of an individual’s social network. 9 Loneliness is frequently reported by people living in rented accommodation and in single dwellings, particularly if they have been forced into the situation as a result of widowhood or divorce. 10 Social breakdown, inadequate systems to support older people and lack of infrastructure to maintain social networks can lead to loneliness and social exclusion. 11 Older people are at greater risk of enduring loneliness, because of a reduction in personal and external resources available to them. Between 30% and 40% of older people are sometimes or often lonely,12 and this figure has remained fairly constant for the past 40 years. With the increase in the number of older people, the actual number experiencing loneliness is therefore increasing. Loneliness can occur as a result of one or more event or it can be chronic and made worse by transition into old age. Events that can cause loneliness include loss and bereavement, widowhood, migration and perceived and actual poor health, whereas other risk factors for loneliness include lack of resources, living alone and time spent alone. 12 Physical limitation through loss of mobility and/or sensory impairment is the largest single predictor of loneliness. 13 The prevalence of visual impairment increases exponentially with age, with > 50% of visually impaired older people feeling lonely. 14 With such overwhelming evidence of the societal costs of loneliness, a wide range of interventions has been developed to prevent and/or alleviate loneliness in later life.

Social isolation and loneliness have long been identified as being problems associated with later life. According to Age Concern England,15 many of Britain’s older people are living in isolation, with those aged > 65 years being twice as likely as other age groups to spend > 21 hours of the day alone. Mental illness, low morale, poor rehabilitation and admission to residential care have all been found to be correlated with either social isolation or loneliness or both. 16 Six independent vulnerability factors for loneliness have been identified: marital status, increases in loneliness and time alone over the previous decade, elevated mental morbidity, poor current health and poorer health in old age than expected. 17 In response to research gaps highlighted in National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance on interventions to promote mental well-being in older people,18 this study was funded to provide evidence of population benefit of one home-based intervention that aims to improve the mental well-being of community-living older people who may be vulnerable.

Over the last decade there has been a continued focus on the value of providing health-promoting interventions to older people with the aim of compressing morbidity in the later stages of the life course and promoting quality of life. 7,15,18–21 This is supported by robust evidence that has demonstrated the relationship between extent of social activity and morbidity and mortality. 22 The NICE guidance on interventions to promote mental well-being18 was underpinned by a systematic review of the evidence of effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of interventions. 21 However, the evidence to support the introduction of many interventions in practice, and particularly those that aim to promote socialisation and alleviate loneliness, is lacking. 8,10 A systematic review23 of research into interventions that aim to promote socialisation identified 11 studies with sufficiently robust findings out of 30 that met the review inclusion criteria, with the majority of studies originating from North America. Despite the methodological challenges that this review posed, the review was able to identify that the most effective interventions were those conducted in a group with educational and/or supportive input. Only one study showed that benefit could be derived from one-to-one interventions. Further to this, Cattan et al. 24,25 conducted an evaluation of eight schemes that participated in the Call in Time initiative, promoted through Help the Aged (later to merge with Age Concern to become Age UK), a national charity, and Zurich Community Trust. The results of the evaluation found that telephone befriending can provide a vital lifeline in helping older people who spend a lot of time in their home to regain confidence and increase their levels of engagement and participation. However, older people in the study also emphasised a desire for choice in the types of support services on offer, including face-to-face contact and peer support. A recommendation from the study was therefore for a model that, in addition to one-to-one telephone support, included scope for developing peer support through telephone clubs. This recommendation echoes that given in earlier work conducted in North America. 26 The Foresight report27 also notes that there is a strong case for giving priority to research that assesses the potential use of technologies through the life course, and their impact on individuals; an example cited is social networking for older adults (p. 248).

Rationale

The Putting Life in Years (PLINY) trial was designed to evaluate the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of a 12-week, telephone-delivered, group intervention based on de Jong Gierveld’s loneliness model28 and Bandura’s theory of self-efficacy,29 and delivered by the voluntary sector. The intervention was designed to include a number of short one-to-one telephone calls with a trained volunteer with the purpose of introducing participants to the concept of group telephone calls. Participants received all calls in their own home using their existing equipment and were connected to their volunteer and group participants via the Community Network’s teleconferencing system. The intervention was based on recommendations in the work by Cattan et al. 24,25 All interventions were delivered by trained volunteer facilitators whose competence was assessed using a treatment fidelity framework to evaluate whether delivery was consistent. 17

Funding for intervention delivery was provided by Age UK (national), the national charity formed from Age Concern and Help the Aged in 2009. There is a network of independent Age UK and Age Concern branches across England. One of these, hereafter the service provider, agreed to recruit and manage the volunteers necessary to deliver the intervention. Community Network provided the infrastructure to enable participants and their volunteer to be joined together by telephone. Community Network is a national charity working with local, regional and other national charities to help connect people who may experience social isolation.

Chapter 2 Methods

Methods for the implementation of the intervention

To understand the course of this study and its outcomes it is necessary for the reader to have a clear sense of how the intervention was implemented. For this reason, before presenting the main trial results (see Chapter 3), we provide a narrative summary of the barriers to intervention implementation. Statements are supported, when possible, by e-mail communication, trial management group (TMG) meeting minutes and field notes.

Methods for the main trial

This report is concordant with the extension of the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) statement to improve the reporting of pragmatic trials. 30 This is a pragmatic two-arm parallel-group randomised controlled trial (RCT) with a feasibility phase. Formal stop–go criteria were established to assess the feasibility of the trial: (1) sufficient participants willing to enter the trial and (2) retention of sufficient participants to assess the primary outcome measure. The final study protocol can be found in Appendix 1, along with a table of changes made to the protocol over the course of the project, which were approved by South Yorkshire Research Ethics Committee (REC).

Participants

Two main methods were used to identify potentially eligible study candidates. We worked with an existing research cohort that is following the lives of 20,000 adults in the area over a period of 10 years and includes individuals who have signalled a willingness to be contacted about further research. Between June 2011 and July 2011 we sent letters with a postage-paid response card and a candidate leaflet to 528 participants in the cohort aged ≥ 75 years. We also invited general practices to help identify potentially eligible study candidates. Between June 2011 and December 2012, 18 general practices sent letters to 9051 patients. The letters included the same candidate leaflet and an invitation to complete a postage-paid response card to express an interest in the study. Response cards were returned to the recruiting site (University of Sheffield, Sheffield, UK).

A pack containing the same candidate leaflet and postage-paid response card was also given to workers in services across the city that were likely to come into contact with older people with the aim of asking them to identify potential participants. In many instances, researchers personally delivered packs and spent time with workers explaining the aims of the study and what it entailed. The Community Intermediate Care Service (NHS) was provided with 500 packs, the city council’s main library received 50 packs and the mobile library service received 200 packs. In addition, two A3 and 30 A4 posters were provided for display. The Community Access and Reablement Service (CARS) was given 100 packs and the local Meals on Wheels service received 120 packs. In addition, 200 packs were given to an extra care scheme (housing with care services available if or when required), a local housing association and the local churches council for community care. Research assistants distributed 200 packs at community events in the locality including a Lifewise event, Regenerate RISE (Reaching the ISolated Elderly) and a local well-being festival (150 packs). Two referrer information sheets and 100 packs were sent to the Allied Healthcare Group; one referrer information sheet and a study leaflet were sent to the Older People’s Partnership Board and distributed to its network (22 May 2012); and five packs each were given to nine Healthy Living Pharmacies.

An unknown number of packs was also sent to relevant public and voluntary sector outlets: the local Expert Elders Network, the local Pensioners Action Group, the local Wellbeing Consortium, Age Well, a victim support group, an older adults community mental health team and a black and minority ethnic community mental health development worker.

Information about the study was circulated to local community and media outlets including the city council’s Help Yourself web page and the local newspaper.

Research assistants telephoned all potential candidates who had returned a response card. A number of candidates telephoned the research team directly. Research assistants checked initial eligibility during the telephone call, for example age and living situation. Research assistants arranged to visit those who were identified as being potentially eligible and interested in finding out more about the study. Appointments were arranged approximately 5 days after the telephone call to allow sufficient time for the candidates to receive and read the Participant Information Sheet, which was posted out (or e-mailed on request) by the research assistants. The Participant Information Sheet was reviewed by the lay representative on the TMG as part of the submission of essential documents to the REC. Research assistants visited potentially eligible candidates in their own home to conduct a screening visit. Those eligible to join the study were aged ≥ 75 years; had good cognitive function, defined as having a six-item Cognitive Impairment Test (6CIT) score of ≤ 7; were living independently (including those who were co-resident with others) or in sheltered extra care housing; and were able to understand and converse in English. The exclusion criteria were (1) the inability to use a telephone effectively with appropriate assistive technology; (2) living in a residential/nursing care home; and (3) already receiving a telephone intervention.

Written informed consent was obtained by research assistants either at the screening visit or at a separate visit if additional time was required to make a decision whether or not to participate. Research assistants administered the 6CIT and calculated the score during the visit. Candidates who were ineligible because of a 6CIT score > 7 were subsequently contacted by a clinically qualified member of the research team and told that they were not eligible to be involved and advised to contact their doctor. A letter containing the score was sent to the candidate. For candidates who were eligible, the research assistant taking consent and administering the baseline questionnaires informed another member of the research team (research assistant or trial manager) of the screening identifier so that they could randomise and inform participants of their allocation. On allocation, and before they were contacted by a volunteer, participants allocated to receive telephone friendship (TF) were sent a ‘question and answer’ document about TF groups by the research team (see Appendix 2) and were advised that the service provider’s volunteer would contact them. The research assistants or the study manager informed the service provider of intervention participants by letter. Initially, this was carried out each time a participant was allocated to receive TF. However, the research team and the service provider subsequently agreed to wait until six participants (sufficient to make a group) had been allocated before forwarding details to the service provider.

Participants were able to withdraw from active participation in the study on request. Individuals who withdrew from the intervention were not replaced. Written consent was obtained to share information with the NHS Health and Social Care Information Centre and other central UK NHS bodies to check participants’ health status and help minimise the risk of telephoning or writing to participants who died before follow-up. Both study arms received postal updates on the study at 2 and 4 months after randomisation.

Interventions

The intervention design is detailed in Appendix 3.

Candidates were screened as described in the previous section. Those who consented were randomly allocated to one of two groups (see Randomisaton and blinding):

-

TF group calls provided through the voluntary (charitable) sector

-

a control group who received usual health and social care following randomisation.

The aim of the intervention was to increase contact between individuals with the intention of forming new acquaintances and friendships. By improving perceptions of companionship and support the aim was to reduce perceived isolation and improve participants’ sense of confidence and mental well-being. The intervention was designed by MC and built on the findings of a previous study which suggested that group calls, following one-to-one befriending, may help older adults to share interests. 24,25

The interventions were delivered by trained volunteer facilitators. Volunteers were recruited by the service provider. Volunteers had no previous experience of protocolised befriending or facilitating conversations, either face to face or by telephone.

The one-to-one individual intervention consisted of up to six calls between each participant and a volunteer befriender. The purpose of the one-to-one calls was to support the participant and prepare him or her for the group conversations. One-to-one calls were brief (10–20 minute) friendly conversations that were held each week for a duration of 6 weeks, beginning with familiarisation and everyday conversation and moving towards a focus on the group calls including topics of interest and supporting the participants with concerns about starting group sessions. Volunteer befrienders telephoned participants using the Community Network’s teleconferencing system. Although not designed for one-to-one calls, the use of the system enabled cost-free calls for participants and volunteers. A detailed description of the training is provided in Appendix 4.

Roles and remit of the service provider and Community Network

Implementation meetings of between 1 and 2 hours were held with the service provider or its delegates (the volunteer co-ordinators) every 2–4 weeks between 20 October 2011 and 16 January 2013. The same individuals from the service provider and representatives of Community Network also attended the monthly TMG meetings, at which the perspectives of members of the public about process and documentation were also elicited. At implementation meetings the trial manager provided advice, guidance and additional documentation as required to the volunteer co-ordinators. E-mail and telephone communication was also frequent, including reminders about training date cut-offs and suggestions for promoting the volunteer opportunity to charities and community groups in the city and within the university. The trial manager attended all but one volunteer induction session and all one-to-one training sessions. The chief investigator initiated the meetings with the service provider and attended implementation meetings on request.

A worker from the service provider was responsible for recruiting all volunteers and provided an induction to the organisation, including the provision of information on issues facing older people and shadowing paid workers in day centres. Those who were deemed to be appropriate for the telephone befriending role were then trained by the same member of staff to make the one-to-one calls in accordance with the training manual (see Appendix 4) before progressing to the group training. Volunteers received group facilitation skills training by telephone. The training lasted 4 hours in total and was delivered in 1-hour sessions over the telephone by a professional trainer who delivers training on behalf of Community Network. Training groups were designed to consist of a maximum of five trainee facilitators and the trainer. However, this was difficult to fulfil for this study (see Chapter 3, The contract with the service provider). Group training included how to run groups in a style conducive to creating group cohesion and promoting a safe environment for participants. Volunteers were told that assisting the group to be self-sustaining if possible was an important goal. The trainer from the service provider also committed to offer volunteers ongoing mentoring. The contract with the service provider subsequently included an agreement for volunteer mentoring but did not specify its type and frequency.

Table 1 summarises the facilitation skills training content. Detailed information is provided in Appendix 4.

| Session 1 | Session 2 | Session 3 | Session 4 |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

The group intervention consisted of 12 weekly telephone calls facilitated by the trained volunteer at a prearranged time each week, as agreed between members and the volunteer facilitator. Community Network provided the teleconferencing facility, which involved the volunteer facilitator booking the time/date of group calls in advance. The operator called the volunteer facilitator first and then each participant in turn at the prearranged time. TF groups ideally involved six participants and one volunteer facilitator. Group telephone discussions were designed to last about 1 hour to allow sufficient time for sharing experiences and interests and talking about everyday life. Participants were able to contact Community Network and/or the TF group service provider if they would not be taking part in a call. The purpose of the group discussions on the telephone was to increase social contact and reduce perceived isolation. The intervention was not designed to actively instil major behaviour change. Technical and procedural strategies covered by the facilitation skills training were based on psychological models for how groups develop and how facilitators should run groups in a style conducive to creating group cohesion that provides a safe environment for achieving underlying quality of life goals of the intervention, such as to ‘review life experiences’. 31 Volunteer facilitators were instructed about circumstances in which they should intervene to retain a safe environment, for instance if there was conflict or if the ground rules of the group were broken. Volunteer facilitators were present to make the work of the group ‘easy’ and to allow the group to be self-sustaining if possible.

Participants randomised to the control arm did not receive any study intervention. However, they did participate in the baseline and outcome measurements and the extent of their health and social care service usage was assessed (as for all participants).

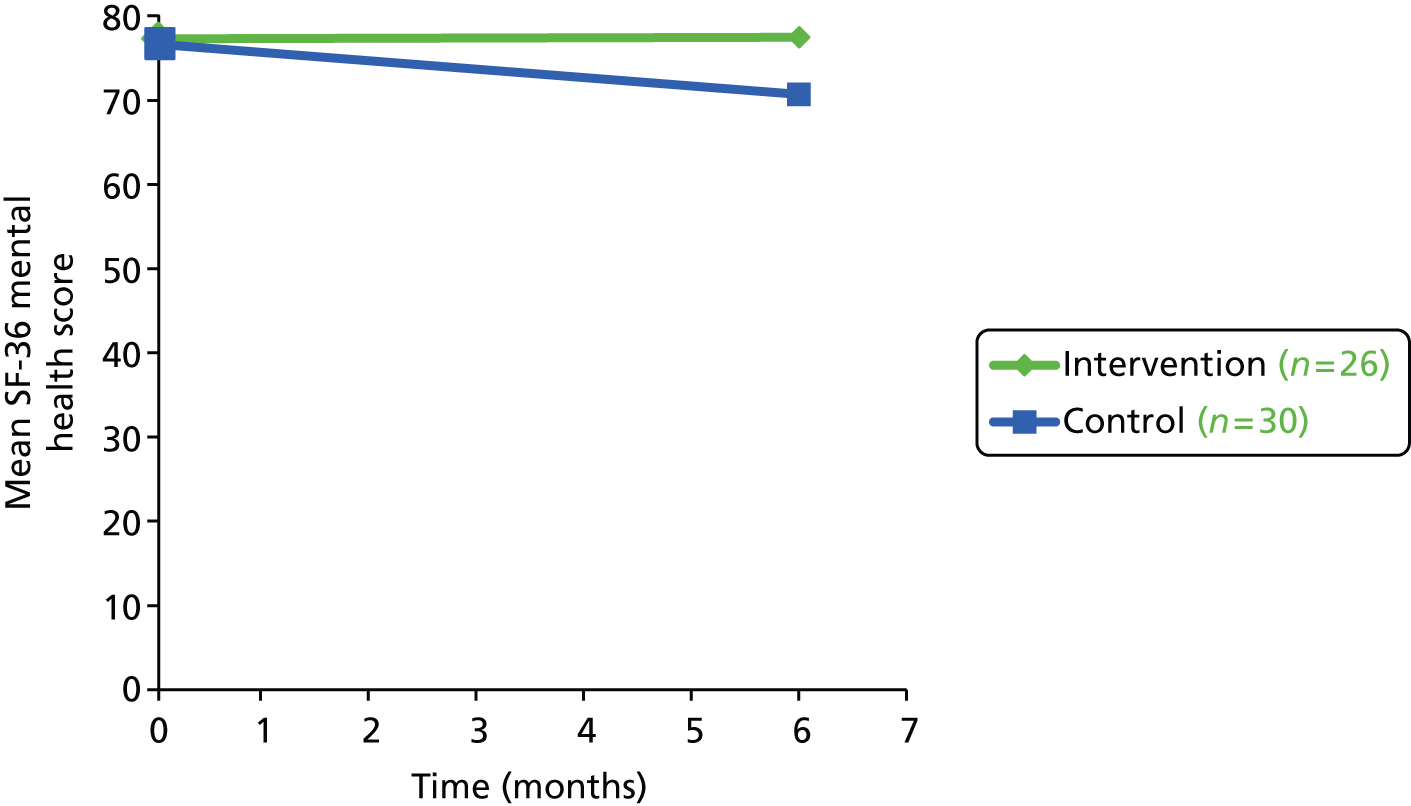

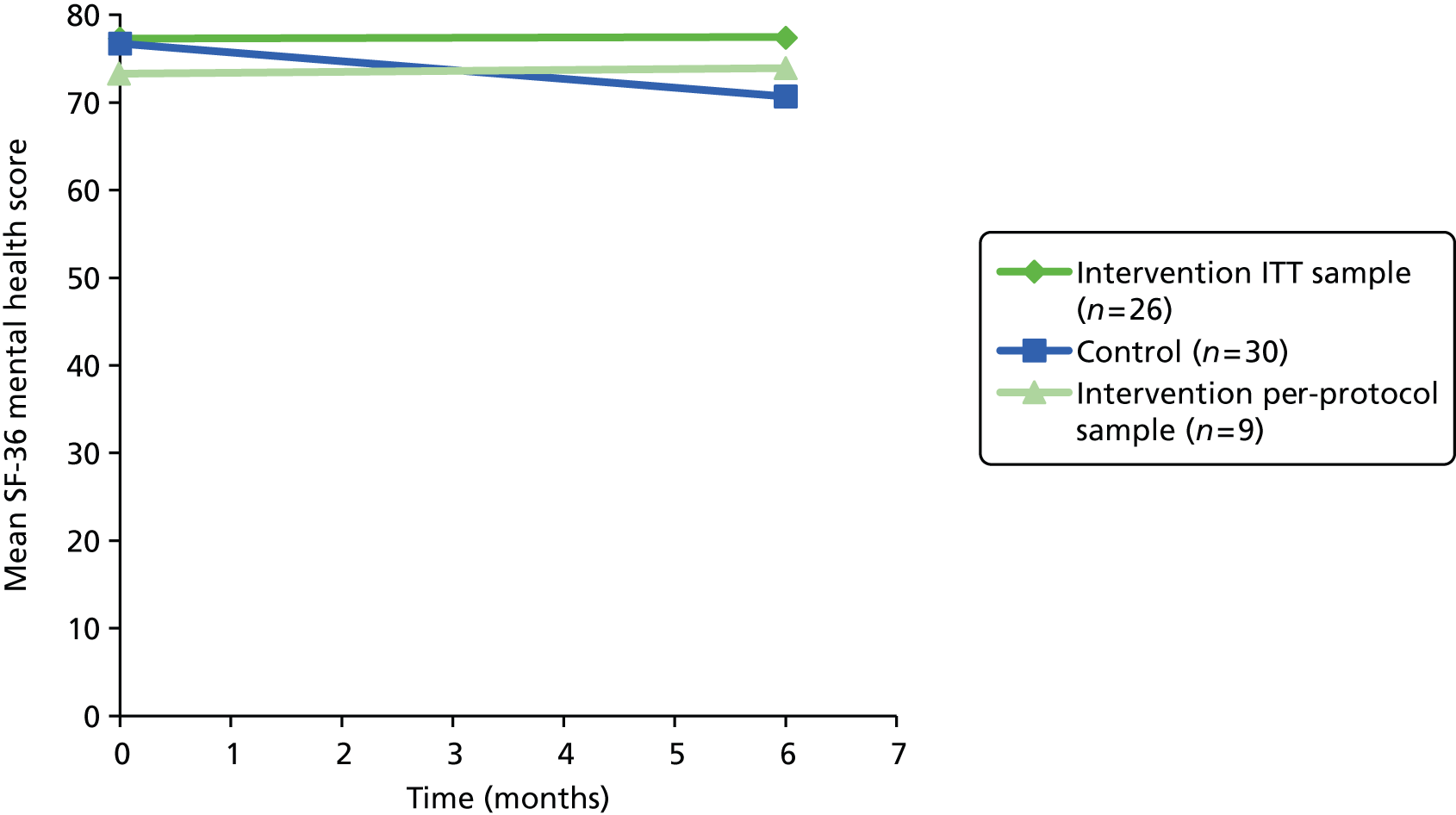

Objectives

The primary objective of the main study, a parallel-group RCT, was to determine whether mental well-being, as measured by the Short Form questionnaire-36 items (SF-36) (mental health dimension) 6 months after randomisation, is significantly increased in participants allocated to receive the TF group intervention compared with participants allocated to a control group (receiving only contact by card/letter at months 2, 4, 8 and 10 with no further contact other than follow-up assessment).

Secondary objectives were to:

-

Identify, using qualitative methods, the psychosocial and environmental factors, as well as implementation issues, that may mediate or modify the effectiveness of the intervention, specifically voluntary sector readiness to take forward new forms of services, the best modes of delivery of telephone support/friendship, how volunteers (facilitators) can be supported and retained, and the extent to which fidelity of the intervention is maintained within and across the participating organisations.

-

To determine any lasting impact on mental well-being by repeat measurement with all participants 12 months after baseline assessment.

-

To examine whether there is any significant improvement in the intervention arm compared with the standard care arm in the physical dimension of the SF-36 at 6 months and 12 months following baseline assessment.

-

To measure the extent of use of health and social care and community facilities by participants over time to determine whether the intervention is cost-effective compared with standard care.

Outcomes

Table 2 shows the timing of the assessments and interventions. All baseline assessments and interventions were carried out in participants’ homes using the case report form (see Appendix 5). Follow-up assessment at 6 months post randomisation was carried out by telephone (unless a home visit was indicated). The primary end point was the level of mental well-being at 6 months post randomisation using the SF-36 mental health dimension. Secondary end points were:

-

other dimensions of the SF-36 to measure all aspects of health including physical health32

-

the Patient Health Questionnaire – nine questions (PHQ-9)33

-

the European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) score (for health economic analysis)34

-

the General Perceived Self-Efficacy Scale (GSE) score35

-

the de Jong Gierveld Loneliness Scale score36

-

Office for National Statistics (ONS) well-being measure37

-

a health and social care resource use questionnaire to collect participants’ use of health, social care and community services (for health economic analysis). 38

| Assessment/intervention | ≈Minus 2 weeks | ≈Minus 1 week | Baseline | 2 months | 4 months | 6 months | 8 months | 10 months | 12 months |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study promotion text/referrer information sheet | ✓ | ||||||||

| Invitation letter | ✓ | ||||||||

| Response card/first contact form | ✓ | ||||||||

| Initial screening | ✓ | ||||||||

| Participant information sheet | ✓ | ||||||||

| Screening visit | ✓ | ||||||||

| Cognitive impairment test (6CIT) | ✓ | ||||||||

| Consent form | ✓ | ||||||||

| Baseline questionnaires | ✓ | ||||||||

| Randomisation | ✓ | ||||||||

| TF group questions and answers (intervention) | ✓ | ||||||||

| Contact card/letter | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Follow-up questionnaires | ✓ | ✓ |

All primary and secondary outcomes were measured at 6 months post randomisation.

Sample size

For the purposes of sample size estimation the primary outcome was the mean SF-36 mental health dimension score at 6 months post randomisation. The SF-36 mental health dimension is scored on a scale from 0 (poor) to 100 (good health). A previous general population survey of residents demonstrated that the SF-36 can successfully be used as an outcome measure for community-dwelling residents aged ≥ 75 years, with a response rate of 82% being achieved. 39 From this general population survey of 3084 community residents, the mean SF-36 mental health score was 68.3, with a standard deviation (SD) of 19.9. 39

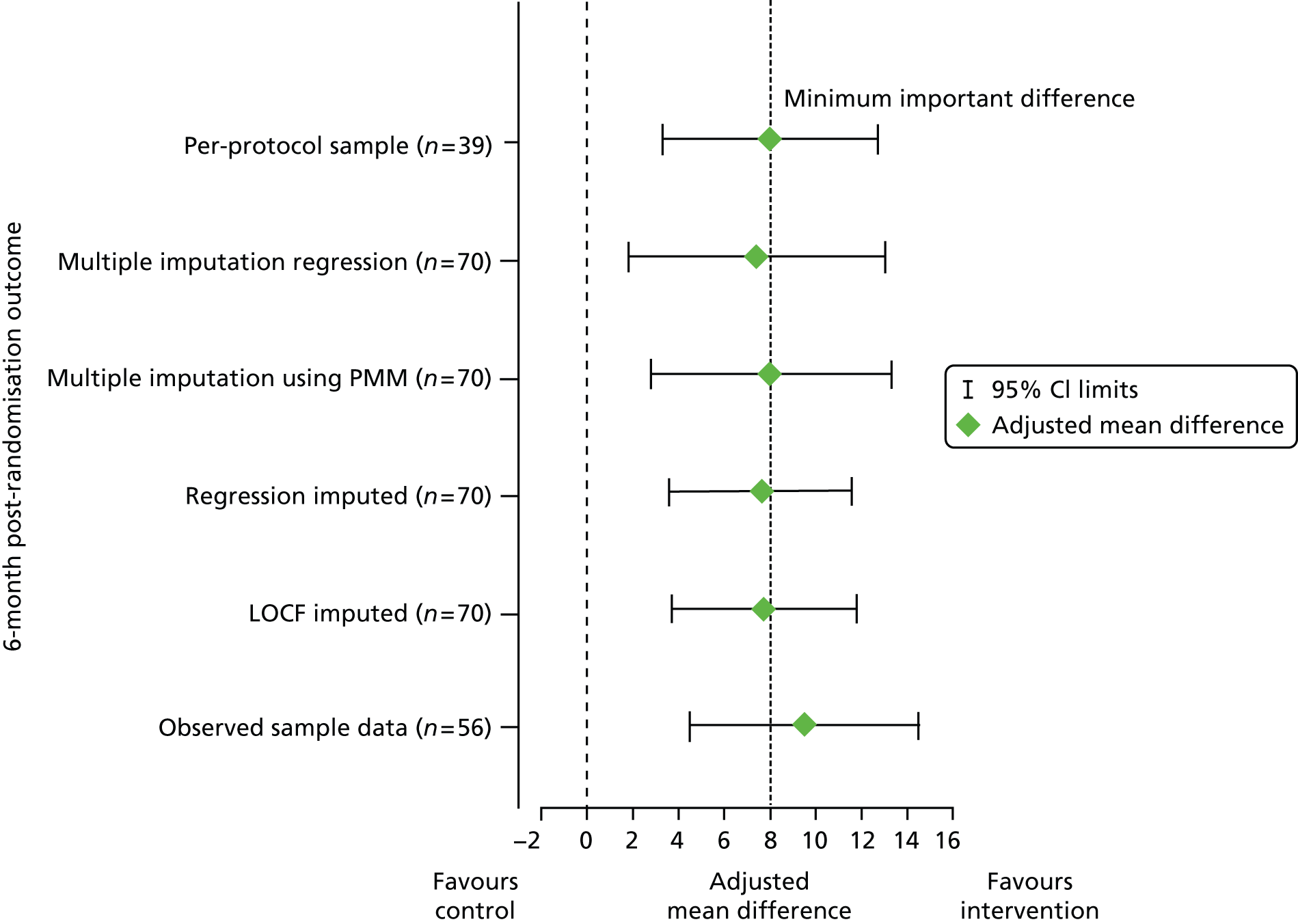

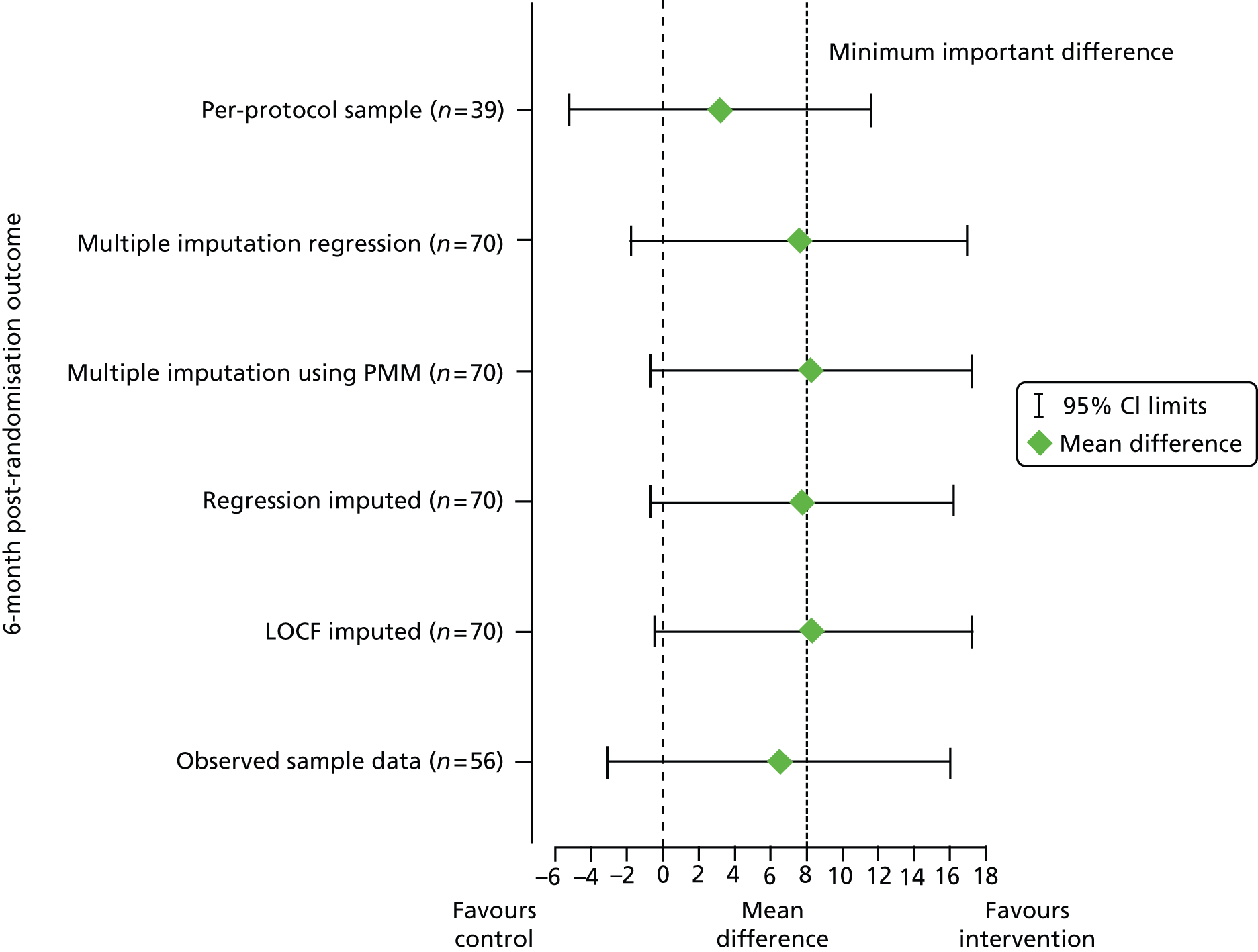

The developers of the SF-36 have suggested that differences between treatment groups of between 5 and 10 points on the 100-point scale can be regarded as ‘clinically and socially relevant’. 40 We assumed a SD of 20 points for the SF-36 mental health dimension at 6 months post randomisation and that a mean difference in mental health score of ≥ 8 points between the intervention group and the control group is the smallest difference that can be regarded as clinically and practically important.

Assuming that a mean difference of ≥ 8 points on the SF-36 mental health dimension between the intervention group and the control group is the smallest difference of clinical and practical importance that is worth detecting, then with 248 subjects (124 intervention, 124 control) the trial was originally determined to have 90% power to detect this mean difference or greater as statistically significant at the 5% (two-sided) significance level using a two independent samples t-test. We assumed a correlation of 0.50 between the baseline and the 6-month SF-36 mental health scores. However, the telephone befriending intervention is a group or facilitator-led intervention. Therefore, the success of the intervention may depend on the volunteer facilitator delivering it so that the outcomes of the participants in the same group with the same volunteer facilitator may be clustered. We therefore assumed an average cluster size of six participants per telephone befriending group and an intracluster correlation (ICC) of 0.04 so the design effect is 1.28. With these assumptions and 99 participants per group, the power of the analysis was reduced to 80% to detect a mean difference of ≥ 8 points in the 6-month SF-36 mental health score. If 20% of the participants drop out and are lost to follow-up then we would have needed to recruit and randomise 124 participants per arm (248 in total).

Randomisation and blinding

Eligible participants were randomised to one of the two arms by the trial manager or a research assistant through a centralised web-based randomisation service provided through the Clinical Trials Research Unit (CTRU). The randomisation sequence was generated in advance by a CTRU statistician, not by the trial team. There were no stratification factors in the randomisation sequence. A sequence of treatment/intervention assignments was randomly permuted in blocks of varying size to ensure that enough participants were allocated evenly to each arm of the trial. Participants, outcome assessors and the trial manager were not blind to treatment allocation because of the practical nature of the intervention. All outcomes were self-reported using validated questionnaires (except for sociodemographics and health and social care resource use, which were assessed using bespoke instruments). Trial statisticians and the principal investigator were blinded to the treatment allocation codes until after the final analysis. Data presented to the trial steering committee (TSC) and the TMG did not identify treatment allocations.

Statistical methods

Analysis population

The intention-to-treat (ITT) data set included all participants who were randomised during the time period when participants were able to receive the intervention (ignoring any occurrences post randomisation such as protocol or treatment non-compliance and withdrawals). This included participants randomised on or before 30 September 2012, plus one participant (R1/081) randomised after this date (who received the intervention because another participant dropped out before receiving the intervention), and followed up for 6 months. Participants randomised to the intervention from October 2012 onwards (with the exception of R1/081) did not receive the intervention because there were not enough volunteers to deliver it. No attempt was made to follow up participants recruited in this time period and they did not form part of the outcome analyses.

The SF-36 mental health dimension data were defined as complete if at least half of the items that make up the mental health dimension score were available. The mental health dimension is made up of five items/questions from the SF-36 questionnaire; if at least three of these items were available then the participant was defined as having complete SF-36 mental health dimension data (see the following section for a description of missing data).

A per-protocol data set was defined as all participants in the control group and participants in the intervention group who completed ≥ 75% of the group telephone calls over the 12 weeks of the group intervention (the one-to-one telephone calls with a volunteer were not included in the definition of ‘per protocol’). This means that, if a TF group completed 12 group telephone calls, individuals were part of the per-protocol data set if they were present for the duration of nine or more of the calls. Sensitivity analysis on the per-protocol data set was performed.

As a pilot study the main trial analysis was largely descriptive and focused on confidence interval (CI) estimation and not formal hypothesis testing. Rates of consent, recruitment, adherence and follow-up by randomised group are reported. Outcome measures are summarised by randomisation group. Data from the pilot study are used to estimate the variability of the continuous outcome (SF-36) in the trial population. As the intervention is volunteer led we also used the data to estimate the ICC. As part of the pilot analysis we estimated the effect size for the 6-month SF-36 mental health outcome with CIs to check whether or not the likely effect was within a clinically relevant range.

Handling incomplete telephone call data or missing measurements

Missing items in the SF-36 mental health dimension were imputed with the mean of the complete items in that dimension, given that at least half of the items in the mental health dimension are completed. If half or more of the items were missing (i.e. three or more) then the mental health dimension score was not calculated. For sensitivity analysis, imputation was used to obtain complete 6-month SF-36 mental health dimension data. Missing data were imputed using three methods: last observation carried forward (LOCF), regression and multiple imputation. The primary analysis was repeated for these imputed data sets and displayed alongside the ITT analysis results.

Statistical analysis

Baseline characteristics

The baseline and sociodemographic characteristics and person-reported outcome data (SF-36, PHQ-9, EQ-5D, GSE, de Jong Gierveld Loneliness Scale, 6CIT) were summarised and assessed for comparability between the TF group and the control group. 41–43 Age and SF-36, PHQ-9, EQ-5D, GSE, de Jong Loneliness Scale and 6CIT scores were presented on a continuous scale. For these continuous variables, summary statistics such as the minimum, maximum, mean, SD, median and interquartile range (IQR) were presented depending on the distribution of the data. Numbers of observations and number and percentage in each category are presented for categorical variables (e.g. sex and ethnicity). All of these summaries are presented by treatment group and overall and are assessed for comparability. No statistical significance testing has been carried out to test baseline imbalances between the arms but any noted differences are reported descriptively. 44,45

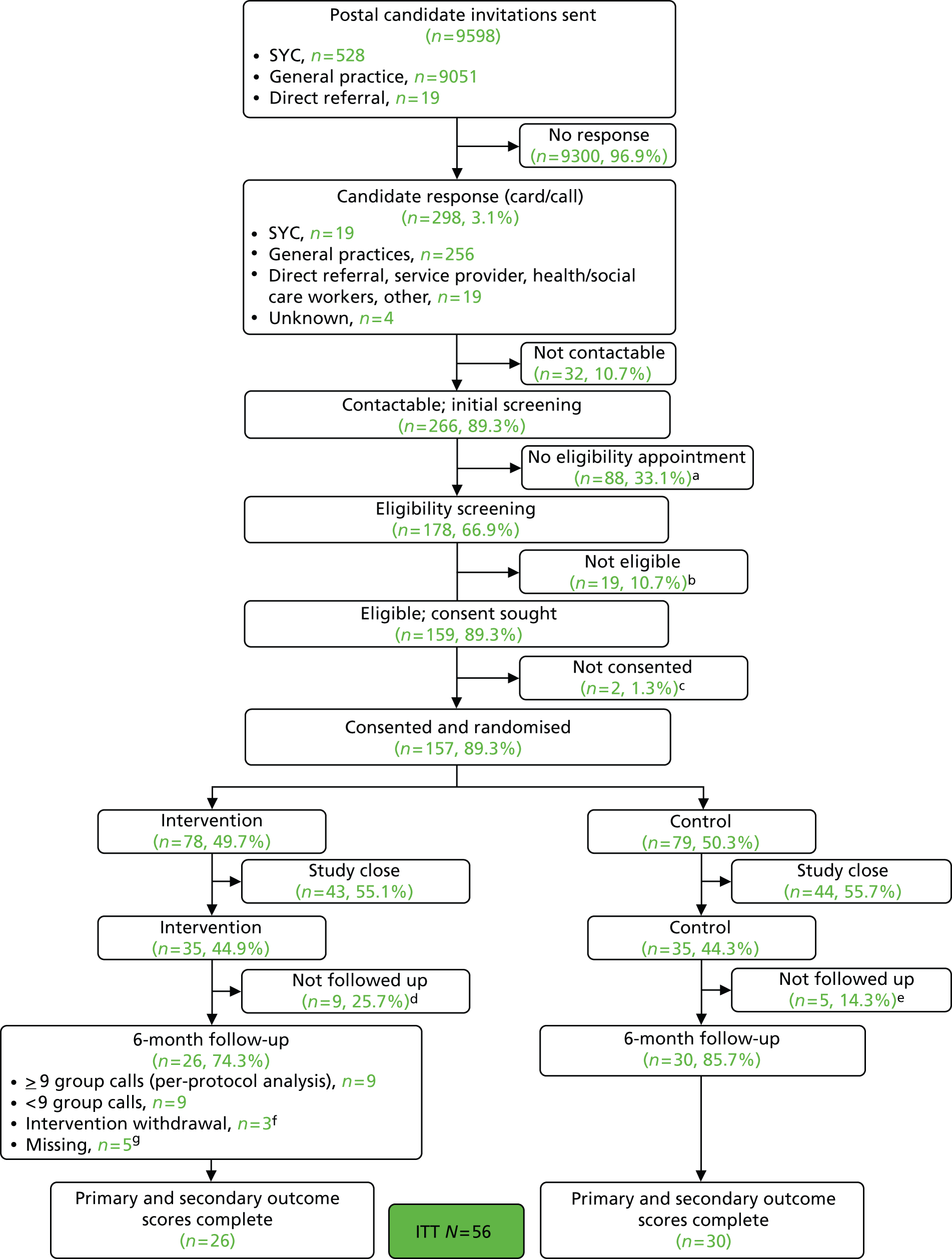

Data completeness

Data completeness is summarised in a CONSORT flow chart, from participants’ enrolment, during follow-up and at the close of the trial. Data completeness is based on the primary outcome (SF-36 mental health dimension score) and having a valid measurement at 6 months post randomisation.

Effectiveness analyses

The mean SF-36 mental health dimension score was compared between participants allocated to receive the TF group intervention and participants allocated to the control group using a marginal general linear model (GLM) with robust standard errors, and an exchangeable correlation. 46 The marginal model used generalised estimating equations (GEEs) to estimate the regression coefficients. The intervention is a group-based intervention with each group led by a single volunteer facilitator. The statistical analysis allows for the possibility that there may be clustering or correlation of the participants’ outcomes within the same telephone befriending group. Participants in each telephone befriending group were regarded as a cluster in the analysis. Participants in the control group were treated as a cluster of size one in the analysis. The exchangeable correlation assumes that individual outcomes in the same cluster (TF group) have the same correlation. A 95% CI for the difference in SF-36 mental health dimension scores between the intervention group and the control group is also reported. An adjusted analysis was performed alongside this unadjusted analysis, which included the potential baseline prognostic covariates of age, sex and baseline SF-36 mental health dimension score in the marginal GLM. The inclusion of baseline covariates was informed by the investigation of baseline imbalance and previous research, which suggested that health-related quality of life varies by age and sex. 39 The mean (SD) SF-36 mental health dimension scores for the treatment and control groups and the number in each group were displayed. This was accompanied by the adjusted and unadjusted mean difference between the intervention group and the control group with the associated CIs (see Table 2).

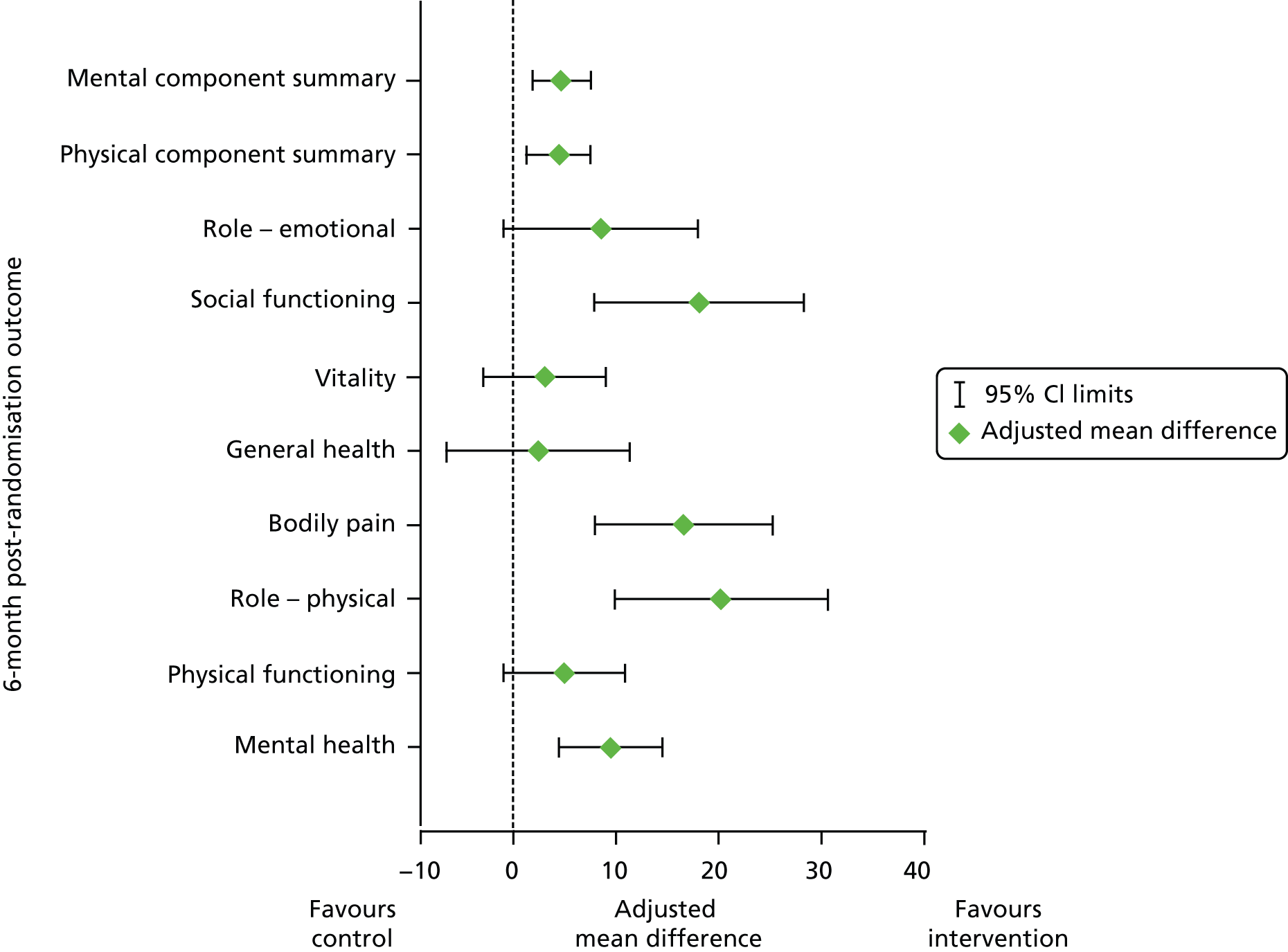

Analysis of secondary outcomes

The remaining SF-36 dimensions (physical functioning, role – physical, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning and role – emotional) were computed and rescaled in the same manner as the mental health scale described in the previous section. The two component scores (physical component summary and mental component summary) were also computed and normalised using data from US norms. 32 The PHQ-9 is calculated as the total score of the nine questions; each is scored from 0 to 3, giving a total score in the range 0–27. The total was calculated only if all nine questions were answered. Two measures for the EQ-5D were analysed:

-

The EQ-5D tariff, derived from five three-level questions using UK norms. 34 The tariff was calculated only if all five questions were answered.

-

The single-item EQ-5D ‘thermometer’ scale.

Three measures from the de Jong Gierveld Loneliness Scale were analysed:

-

Emotional loneliness: this is calculated from questions 2, 3, 5, 6, 9 and 10 and is the number of items scored ‘yes’ or ‘more or less’. It is scored from 0 to 6 and is defined only when all six questions are answered.

-

Social loneliness: this is calculated from questions 1, 4, 7, 8 and 11 and is the number of items scored ‘no’ or ‘more or less’. It is scored from 0 to 5 and is defined only when all five questions are answered.

-

Overall loneliness: this is the sum of the emotional and social loneliness scores. It is defined when 10 or 11 of the questions are answered.

The GSE is the sum of 10 questions, each of which is scored from 1 to 5, giving a total score in the range 10–50. It is defined when at least seven of the 10 questions are answered; if < 10 are answered, the revised total is given by GSE = total × (10/number of questions answered).

Secondary outcomes (other dimensions of the SF-36, PHQ-9, EQ-5D, de Jong Gierveld Loneliness Scale, GSE) at 6 month post randomisation were compared between the intervention group and the control group using a marginal GLM with robust standard errors and exchangeable correlation with and without adjustment for baseline covariates. The means and SDs (and numbers used for each calculation) for the treatment and control groups with adjusted and unadjusted mean differences and associated CIs are reported.

Estimates of the critical parameters that would be used for a sample size calculation (SD, correlation between baseline and 6-month outcomes and the ICC) are also reported.

Economic analysis

The case report form (see Appendix 5) included questions about the use of primary and secondary care health services, social care services and voluntary and private sector services.

The following elements were planned for the health economics analysis:

-

Costing of the TF service.

-

Costing of participants’ health, social care and voluntary service use during the trial.

-

Cost-effectiveness analysis using a range of outcome measures and a cost–utility analysis using the EQ-5D. The resulting cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) would be compared with the NICE threshold of £20,000–30,000 per QALY gained.

-

An exploratory analysis of participants’ willingness to pay for a TF scheme.

Because of the early closure of the trial for reasons outlined in Chapter 4 (see Assessment of study feasibility), a high proportion of participants allocated to the intervention arm did not receive the intervention and it was therefore not appropriate to conduct the planned health economics analysis. Frequency tables for participants’ service use are presented in Chapter 4 (see Health and social care resource use); differences between the intervention group and the control group at follow-up should be interpreted with caution.

Methods for the qualitative research

Background

This report is concordant with Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) guidelines for reporting qualitative research. 47 The purpose of the qualitative research was to evaluate the impact of TF groups on older people as well as their perceived advantages and disadvantages in terms of well-being. The objective was an assessment of the acceptability and appropriateness of the intervention for preventing loneliness and maintaining good mental health. Some aspects of the fidelity assessment (e.g. views on the receipt and enactment of the intervention) were also informed by the qualitative research (see Methods for the fidelity assessment).

Methods for the participant interviews

The aim of the qualitative research was to explore to what extent older people considered TF groups to have made an impact on their well-being. A topic guide (see Appendix 6) was used to undertake semistructured interviews. This was based on a previous study25 and was tailored by MC and RG-W in line with the secondary end points for the trial. The topic guide was not piloted but was reviewed by the lay representative on the TMG as part of the review of essential documents submitted for ethical approval.

The topic guide covered questions regarding participants’ needs and expectations of telephone befriending, its impact on their health and well-being and accessibility and acceptability of the telephone discussion. It also inquired after participants’ experiences of the volunteer facilitator and whether they felt that the telephone discussions were or were not a good way to give them the support that they needed.

All participants allocated to the telephone befriending intervention and provided with a volunteer facilitator were invited (by telephone) to participate in a semistructured interview (24 individuals). We interviewed all 19 participants who volunteered to take part. Reasons for declining a research interview were not elicited but were recorded if volunteered by the participant. One female research associate (RG-W) and one female research assistant (RD) performed the interviews in April 2013. RG-W had studied qualitative research techniques as part of her MA in Research Methods and had experience of in-depth and semistructured interviews. RD had experience of qualitative interviews but was a novice in terms of qualitative analysis. Neither of the interviewers delivered the intervention to the interviewees. RD visited some interviewees to collect baseline data and/or collected 6-month follow-up data by telephone for the main trial. Interviewees would have known that the interviewers were on the research team and were from the University of Sheffield and may have associated them with the volunteers delivering the intervention and/or with delivery of the intervention. The interviewers were asked to withhold their own opinions, personal goals and characteristics and to reiterate the purpose of the research and that this interview was separate from the intervention. No repeat interviews were undertaken or field notes taken.

The interviews lasted between 14 and 63 minutes (median 29 minutes) and were conducted face to face in a place selected by the participants. All were conducted in participants’ homes. Written consent for audio recording was obtained when participants entered the study. For all but three interviews no one was present except for the participant and the researcher. Three interviews were interrupted by (1) a participant’s daughter (bringing a drink), (2) a participant’s cleaner and (3) a visitor. Sociodemographic data were collected from participants as part of the main trial and are reported in Chapter 4. Interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim. Transcripts were not returned to the participants for comment or correction.

Data analysis commenced during the data collection period using a constant comparative method to identify themes and where interviews and analysis each informed the other. Data analysis of the transcripts was conducted using NVivo 9 (QSR International, Warrington, UK). We used a ‘framework’ approach to analysis in which a priori and emergent themes were identified using the following stages: familiarisation, identifying a thematic framework, indexing, mapping and interpretation (charting was not undertaken). 48 A priori themes of interest were acceptability and accessibility of the group telephone discussion; subthemes were derived inductively through familiarisation with the transcripts. 48,49 Results were used to explore factors that may have mediated and moderated the intervention and contributed towards the findings of the trial and to identify any other emerging issues or factors that may have influenced the uptake of the intervention and which had not previously been documented. 50 It is unlikely that data saturation was achieved. 51 Participants were not asked to provide feedback on the identified themes.

Initially, we indexed transcripts using our own thematic framework (see Appendix 7); this was later supplemented with codes based on concepts from the group dynamics literature, relating to characteristics of functioning groups, specifically group cohesion and disclosure. 31

Methods for the volunteer interviews

The aim of the qualitative research was also to explore the experiences of volunteer facilitators in delivering the intervention. A semistructured topic guide was used with themes including the accessibility and acceptability of delivering befriending by telephone and the motivations of volunteers to take part and their experiences of facilitating group discussions, including their perceptions of participant benefit. All volunteers who remained in contact with the service provider were invited to take part in a semistructured interview. This included volunteers who dropped out before, mid and post completion of facilitator training, resulting in a sample of three. Two had completed the one-to-one and group telephone call phases of the intervention and one dropped out during the group facilitator training. We did not elicit reasons for declining an interview. RG-W performed the interviews in April 2013 and had a previous relationship with all volunteers having attended volunteer induction and one-to-one training sessions to support the service provider (by request). Interviewed volunteers knew that the interviewer was on the research team and from the University of Sheffield and not from the service provider. The interviewer was asked to withhold her own opinions and to reiterate the purpose of the research and that the interview was separate from the intervention and the service provider. No repeat interviews were undertaken or field notes taken.

The interviews lasted between 18 and 59 minutes (median 43 minutes) and were conducted face to face in a place selected by participants. Two interviews were conducted at the home of the volunteers and one was conducted at the University of Sheffield. For all interviews no one was present except for the participant and the researcher. Sociodemographic data were not collected for volunteers. A topic guide (see Appendix 6) was used. This was based on the secondary end points of the study and was informed by some elements of the fidelity framework, for instance whether the group experienced conflict or followed ground rules (see Methods for the fidelity assessment). The topic guide was not piloted.

Interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim. Transcripts were not returned to the participants for comment or correction. Data analysis of transcripts was conducted by RG-W by hand using a constant comparative method to identify themes. Analysis and interpretation followed relevant themes from the qualitative research framework developed from the participant interviews (see Chapter 5, Results of the participant interviews). Results were used to explore potential explanations for the quantitative findings and identify other emerging issues or factors influencing volunteer-led interventions. The final outcome was a synthesis of coded data and subthemes including those relevant to the fidelity assessment.

Methods for the fidelity assessment

The importance of describing complex interventions and actual content delivered is well established. 52,53 The fidelity substudy assessed how well the TF intervention was delivered according to the intervention protocol. An intervention fidelity framework based on that identified by the Behaviour Change Consortium54 was developed (see Appendix 1). The framework sets out the parameters by which quality and fidelity would be measured, under the headings of study design, training, delivery, receipt and enactment.

Telephone befriending design

To assess comparable ‘treatment dose’, the number, frequency and duration of one-to-one and group telephone contacts were established. The minimum number of one-to-one contacts was recommended as three on the basis that some participants would need more one-to-one contacts to be sufficiently confident to join the group discussions. A maximum of six one-to-one contacts was set. A maximum of 12 group telephone contacts was established and a minimum (in terms of treatment dose) was set at nine (of 12) group calls. The frequency of all telephone contact was weekly.

Telephone befriending training content assessment and methods

Volunteers were trained by Community Network’s group facilitation skills trainer. Attendance at training sessions was monitored by register taken by the single trainer who trained all volunteer facilitators. The training was delivered over the telephone to a number of trainees (maximum five) over four 1-hour sessions. The session content focused on providing skills and techniques to enable the facilitator to support the group to work well as a group and fulfil its purpose (see Methods for the main trial, Interventions).

The trial manager (RG-W) developed a fidelity checklist based on the standard training delivered to all volunteers who facilitate telephone discussion via the Community Networks’ teleconferencing system. This was reviewed by the content expert (MC) and the Community Network trainer to ensure that core components were included and that materials and practice delivered by the trainer could be assessed for consistency across groups. The checklist also included components to assess volunteer facilitator skill acquisition. The checklist was piloted by RG-W and MC using a sample of audio recordings, with modifications made where necessary (see Appendix 8, Training content checklist).

A purposive sample of training sessions was audio recorded across and within the training groups. RG-W and a research assistant (LN) used the training content checklist to assess the content and delivery techniques conveyed to trainee (volunteer) facilitators and facilitator skill acquisition. Checklists were completed and scored separately by the two coders and scores were compared. All scores were reviewed to ensure consistency in interpretation of the checklist items, with areas of dispute discussed and agreement reached by consensus. When agreement could not be reached the original observations, and therefore scores, remained the same. Median scores were calculated to provide an overall fidelity score for each training group and show the degree of consistency in the content delivered to trainee facilitators.

Treatment fidelity assessment and methods

To ensure that the criteria for treatment fidelity were met, those delivering the group befriending intervention (volunteer facilitators) were assessed for adherence to the intervention protocol across the 12 weeks. The assessment of treatment fidelity by volunteer facilitators used an intervention delivery checklist developed by RG-W based on the techniques delivered in the facilitator skills training and on a one-to-one training manual provided to volunteers (see Appendix 4). The training fidelity checklist was reviewed by MC and the Community Network trainer with modifications made where appropriate (see Appendix 8, Intervention delivery checklist).

According to the facilitation skills training, as groups develop, the level of input required from the volunteer facilitator should diminish over time. Therefore, the sample of audio recordings included three time points (weeks 1, 6 and 12) to assess the degree to which volunteers used their acquired skills and adhered to the intervention protocol during delivery. The checklists were designed to take into account variation in the content of sessions and the fact that, if some scenarios did not arise, volunteer facilitators could not be expected to demonstrate the appropriate response.

Telephone befriending delivery

Attendance at all planned sessions was recorded through call registers completed by volunteer facilitators at every session during both the one-to-one phase and the group phase. Volunteer facilitators recorded any difficulties with the delivery of the intervention protocol on the call registers. Issues arising during delivery of the intervention were noted by the service provider and forwarded to the research team. The challenges of implementation and barriers to uptake were examined with a convenience sample of volunteer facilitators (see Methods for the qualitative research and Chapter 5, Results of the volunteer interviews).

A purposive sample of audio recordings of group sessions was used to assess the match with the intervention protocol in terms of the content and techniques delivered and the extent to which volunteer facilitators enabled choice and decision-making. Note that the protocol (see Appendix 1) also incorrectly refers to the concept of intervention ‘drift’, which implies a trend away from intervention fidelity known to exist at baseline, something not established in this study. Samples were taken at three time points – weeks 1, 6 and 12 – to examine intervention delivery and volunteer facilitator skills and receipt of the intervention and enactment by participants. Checklists were completed and scored separately by the two observers and scores were compared. Coders reviewed scores to ensure consistency in interpretation of checklist items, with areas of dispute discussed and agreement reached by consensus. When agreement could not be reached the original observations, and therefore scores, remained the same. Median scores were calculated to provide an overall percentage score for each facilitated group.

Telephone befriending receipt and enactment

Unlike formal behaviour change interventions, such as cognitive–behavioural therapy or motivational interviewing, the PLINY intervention does not attempt to tightly regulate behaviour outside the delivery setting. The intervention attempts to reduce the discrepancy or (mis-)match between the quality and quantity of existing relationships and relationship expectations. 55 The intervention, through facilitated dialogue between participants, is intended to create a safe environment in which social contact can improve perceptions of available companionship and support (see Appendix 3). It follows that, if the volunteer facilitators are delivering the intervention per protocol, then the group is ‘working’ well and participants should not be exhibiting problem behaviours known to inhibit successful group experiences. For this reason, we limit our assessment of participant receipt and enactment to evidence of their performance as part of a friendship group. To try and identify whether participants found the group intervention to be appropriate, acceptable and beneficial (see Methods for the qualitative research and Chapter 5, Results of the participant interviews), we specifically reviewed interview transcripts with participants and volunteer facilitators for evidence of characteristics which indicated that the groups were in a transitional phase, towards functioning well as a group:31

-

defensiveness and resistance

-

conflict

-

confrontation.

Other characteristics – anxiety, the struggle for control, challenges to the group leader and the leader’s reactions to resistance – were not seen as relevant in this intervention, as the level of disclosure, anxiety and resistance within befriending groups was anticipated to be lower than in a therapeutic group.

Interview transcripts and audio recordings were also reviewed for the following problem behaviours that are counterproductive to group functioning:31

-

silence and lack of participation

-

monopolistic behaviour

-

hostile behaviour

-

dependency

-

acting superior

-

socialising (before the end of the programme)

-

‘band-aiding’ (e.g. try to sooth/lessen pain when someone is upset).

Other behaviours – storytelling, questioning, giving advice, intellectualising, emotionalising (dwelling on getting in touch with their feelings) – were not seen as problematic in this intervention.

Chapter 3 Results of the implementation of the intervention

Interaction with the service funder and service provider

Conditional funding

It was originally intended to use multiple service providers to deliver the intervention. This was not possible for the following reasons. We considered it likely that the delivery at scale of a manualised intervention by volunteers would need the stable base offered by formal training and monitoring by experienced volunteer co-ordinators. For this, it was essential to secure funding. The funding was secured from a national charity on condition that we would use the money to deliver the intervention through one or more of its local branches only; we were unable to use other organisations to deliver the intervention. We looked at the viability of recruiting other branches of the charity to deliver the intervention. Other branches did express an interest but were unable to provide the intervention to participants recruited in the urban centre where the study was ongoing. Each branch of the charity was restricted through its constitution to serve the needs of its (bounded) local population. No branch could provide volunteers to work outside its geographical area. The research team was not adequately resourced to work in other geographical areas, which, in participant recruitment terms, was unnecessary in a conurbation with an estimated population of over half a million people.

An overview of the funding made available by the national charity is provided in Table 3. Detailed breakdowns follow of the resource for (1) the service provider, the local branch of the national charity, to recruit, train and mentor volunteer befriending facilitators (Table 4) and (2) a specialist trainer in group facilitation to support the manualisation of the intervention, provide advice on assessing its fidelity and train the volunteer facilitators (Table 5).

| Item | Cost (£) | Assumptions/notes |

|---|---|---|

| Service provider costs | ||

| Staffing and resources (three recruitment waves) | 6078.60 | See Table 4 |

| Overheads | 1215.72 | |

| Subtotal | 7294.32 | Excluding VAT (service provider confirmed that it would not charge VAT) |

| Group facilitation trainer costs | ||

| Training content | 3300.00 | Assume 5.5 days’ work @ £600 per day |

| Volunteer training | 4200.00 | Based on 30 volunteers retained by the service provider for facilitator training. Training provider – four 1-hour sessions for five people at £700 |

| Manuals/materials | 117.60 | See Table 5 |

| Participant – facilitator training | 700.00 | Assume that five participants will start their own group |

| Fidelity advice | 1200.00 | Advice to content expert and study manager on fidelity – approximately 2 days at £600 per day |

| Subtotal | 9517.60 | |

| VAT @ 20% | 1903.52 | |

| Total | 11,421.12 | |

| Item | Unit | Number of units | Cost per unit (£) | Total cost (£) | Notes/assumptions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Advertising | |||||

| Website | Updates | 1 | 30 | 30.00 | External costs incurred for website support |

| Mail-outs | Mail-outs | 100 | 0.85 | 85.00 | Second-class post and stationary plus return envelopes |

| E-mail-outs | Hours | 2 | 12 | 24.00 | Internal staff time – BDA (includes staff time for postal mail-outs) |

| Window advertisement | Posters | 0 | 0.00 | Internal printing only | |

| VAS | 0 | 0.00 | Assumes no charge for VAS | ||

| Press advertising | Press adverts | 2 | 300 | 600.00 | Estimated costs of local ‘freebies’ |

| Radio | 0.00 | ||||

| Subtotal | 739.00 | ||||

| Initial day course orientation to working with older people and training in one-to-one befriending (assumes 15 volunteers per day) | |||||

| Preparatory work | Hours | 4 | 0 | 0.00 | Induction to working with older people plus summary of the trial |

| Introductory day | Days | 2 | 150 | 300.00 | Assumes 10 volunteers per day can be accommodated in the venue |

| Venue | Days | 2 | 50 | 100.00 | |

| Refreshments | Volunteers | 20 | 3.5 | 70.00 | Includes lunch, tea/coffee/water, biscuits |

| Equipment | 0.00 | Own equipment used | |||

| Handouts | 20 | 2.5 | 50.00 | Handouts printed internally | |

| Subtotal | 520.00 | ||||

| Administration | |||||

| Collate applications | Hours | 3 | 12 | 36.00 | Internal staff time – BDA |

| Invitations to applicants | Invitations | 20 | 0.46 | 9.20 | Second-class post and stationary |

| CRB checks | Volunteers | 10 | 0 | 0.00 | External costs to process – no charge for volunteers |

| CRB checks administration | Hours | 5 | 12 | 60.00 | Internal staff time – BDA |

| Vetting administration | Hours | 5 | 12 | 60.00 | Internal staff time – BDA |

| Subtotal | 165.20 | ||||

| Interim – mentoring and review per wave | |||||

| Mentor and review sessions | Half-days | 4 | 75 | 300.00 | Assumes five volunteers per half-day |

| Venue | Half-days | 4 | 30 | 120.00 | |

| Refreshments | Volunteers × half-days | 20 | 1.5 | 30.00 | Includes tea/coffee/water, biscuits |

| Equipment | 0.00 | Own equipment used | |||

| Handouts | Handouts × sessions | 20 | 1 | 20.00 | Handouts printed internally |

| Follow-up | Hours | 6 | 22 | 132.00 | Internal staff time – CEM |

| Subtotal | 602.00 | ||||

| Total per wave of 20 inducted, 10 retained (excluding overheads) | 2026.20 | ||||

| Overheads | |||||

| Contribution to service provider overheads (20%) | 405.24 | ||||

| Total per wave of 20 inducted, 10 retained (including overheads) | 2431.44 | ||||

| Total across three waves (including overheads) | 7294.32 | ||||

| Item | Cost (£) | Notes/assumptions |

|---|---|---|

| Training content development | 3300 | Assumed 5.5 days’ work @ £600 per day |

| Training | ||

| Four × 1-hour course | 4200 | Based on £700 per four volunteers (n = 30) |

| Subtotal | 7500 | |

| Manual and materials (estimate) | ||

| Cover letter (n = 30) | 3 | |

| Confidentiality sheet (n = 30) | 3 | |

| Facilitator handbook (25 pages; n = 30) | 75 | |

| Facilitator recording sheet (n = 252) | 3 | |

| Certificates (n = 30) | 3 | |

| Content/session sheets (n = 252) | 3 | |

| Postage (n = 30) | 28 | |

| Subtotal | 118 | |

| Fidelity advice | ||

| Advice to content expert on fidelity | 1200 | e.g. Facilitator adherence to intervention protocol |

| Subtotal | 1200 | |

| Volunteer facilitator training | ||

| Train four volunteers as facilitators | 700 | |

| Subtotal | 700 | |

| Total | 9518 | |

The contract with the service provider

Contractual negotiations with the service provider ran between 20 October 2011 and 14 June 2012 when the contract was signed. The service provider was contracted to:

-

Identify and recruit suitable volunteers for the role of volunteer/facilitator for the delivery of the PLINY research intervention, including carrying out Criminal Records Bureau (CRB) checks.

-

Ensure that volunteers are oriented to working with older people and willing to deliver telephone befriending, are trained to carry out one-to-one calls in line with the PLINY research intervention and are ready to receive training in telephone befriending facilitation (to be delivered by a third party) in the numbers and by the dates shown in Table 6.

-

Ensure that volunteers take responsibility for scheduling and (subject to participant adherence) delivery of up to six one-to-one and 12 group telephone sessions for each person recruited to the PLINY research study and randomised to the TF group.

-

Ensure that there are sufficient volunteers to provide cover in the event of volunteer facilitator absence or discontinuation.

-

Provide ongoing ‘mentoring’ to volunteers, in line with the service provider’s policies and procedures and the PLINY research intervention, to ensure a point of contact and support.

-

Provide regular (at least monthly) updates to the research team on levels of volunteer recruitment and retention and feed back information, including the one-to-one and group call registers, to inform the research.

-

Alert the research team at the earliest opportunity if a participant wishes to withdraw or is unable to participate in the intervention (TF groups), with reasons recorded (if provided by the participant).

| Deadline | Recommended number of volunteers recruited and trained | Minimum number of volunteers recruited and trained |

|---|---|---|

| 1 May 2012 | 20 | 10 |

| 1 September 2012 | 20 | 10 |

| 1 January 2013 | 20 | 10 |

Item (3), the delegation of first contact and scheduling of calls, might not be considered best practice for sustaining a volunteer befriending service. For instance, a Delphi survey of volunteer co-ordinators managing befriending services found general agreement that they should be managed either by a full-time or a part-time project co-ordinator. 25 The volunteer co-ordinators also agreed that it was essential to have a monitoring system in place (p. 51). 24 We were unable to broker such an arrangement within the available finances.

Recruitment and retention of volunteers

Recruitment and retention of volunteers was an important criterion for the feasibility of the study (see Chapter 4, Assessment of study feasibility) and for the continuity of the service for individual participants and their groups. Matching service demand (participant recruitment) with the capacity of the service provider was part of the study design. Participant recruitment was intended to be conducted over three waves. It was estimated that a minimum of 10 and a maximum of 20 volunteers would be required in each wave. Therefore, a minimum of 30 (maximum of 60) volunteers was agreed with the service provider as being necessary to facilitate approximately 20 friendship groups over the life of the study. This would ensure capacity to continue the service in the event of dropout or planned and unplanned absences.

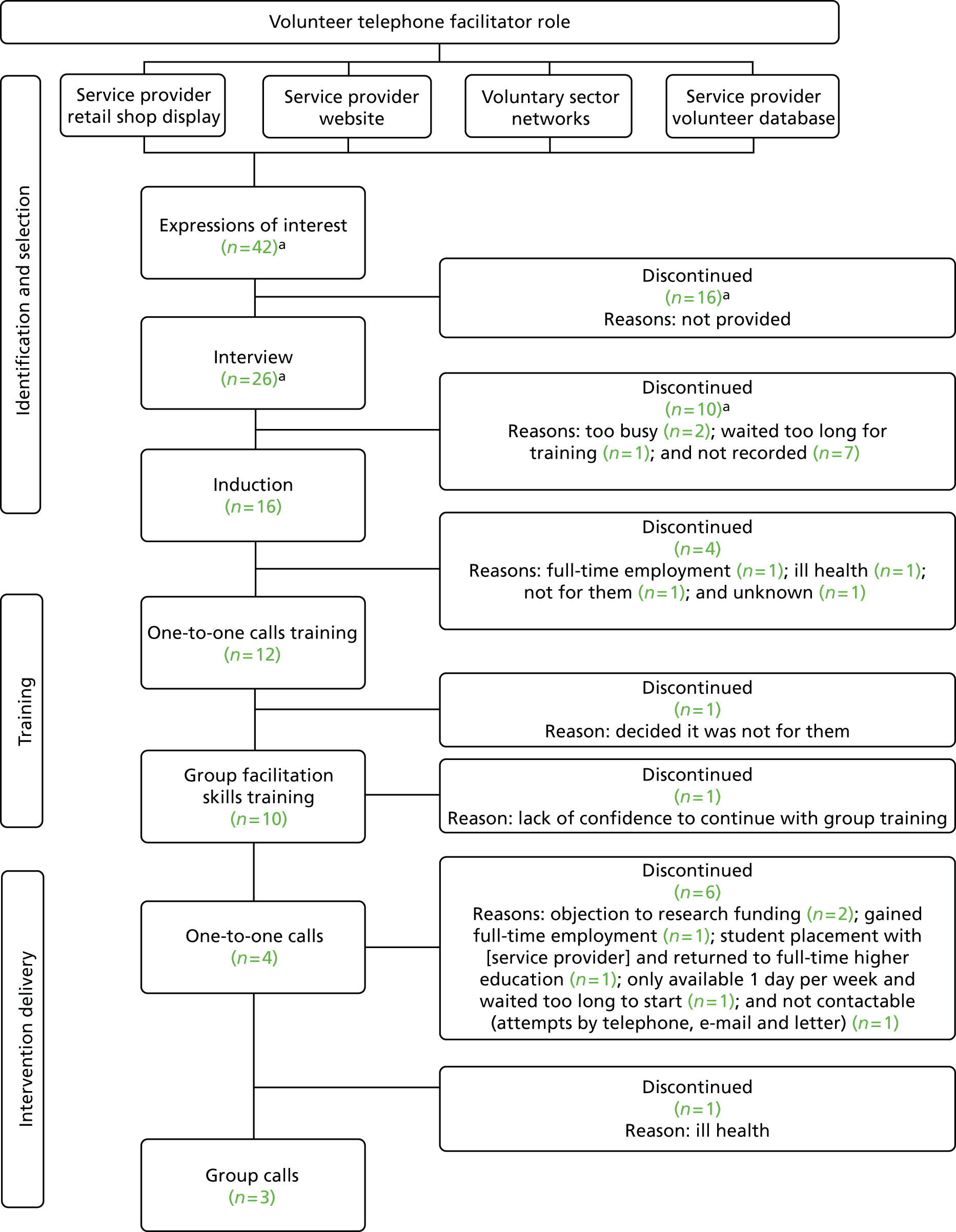

The service provider experienced difficulties with recruiting and retaining a sufficient number of volunteers. These difficulties were explored within the four categories of marketing, training, monitoring and boundaries. Figure 1 shows the flow of volunteers throughout the study. Ten (24%) out of 42 volunteers who expressed an interest in the study completed the training of whom three (33%) delivered the intervention. Reasons for dropping out were captured when possible to provide an indication of the acceptability and accessibility of the volunteer role to those expressing an interest in the role.

FIGURE 1.

Flow of service provider’s volunteers. a, Information supplied by the service provider (field note, 13 November 2012). Detailed information was not captured for all expressions of interest/referrals to the service provider (including agencies, e.g. Jobcentre Plus). The service provider reported that all candidates were screened for suitability for a number of volunteer opportunities, including the telephone group facilitator role.

Marketing

Activity by the service provider to promote the volunteer opportunity included its website (news archive, 25 September 2012; accessed 10 May 2013), the Northern Community Assembly website (field note, 21 November 2012), the local Wellbeing Consortium (field note, 20 November 2012), a local newspaper and a range of community and voluntary networks and organisations available in the locality, which we have not named to preserve the anonymity of the service provider (field note, 14 June 2012; TMG, 15 November 2013). The service provider reported that potential volunteers referred to them by other agencies (e.g. Jobcentre Plus) were often not suitable for the facilitator role (TMG, 19 September 2012).

Suggestions for additional strategies to promote the volunteer role in the locality were made by the study team (e.g. TMG, 15 November 2013).

Training

Training sessions for the group intervention required a minimum of four volunteers for the training group to be feasible. The service provider identified an initial group of six volunteers early in the project (TMG, 20 February 2012) and scheduled one-to-one training for them in March 2012. The charity reported a number of implementation issues including matching the availability of volunteers to training dates (TMG, 20 February 2012). They also found that retaining volunteers between recruitment and training was difficult and required more resources than anticipated (TMG, 20 August 2012). It should be noted that the first group of volunteers (n = 4 in two groups) received induction and one-to-one calls training from the service provider in March 2012, 2 months before the scheduled start of participant recruitment. In fact, participant recruitment did not commence until June 2012, 1 month late, because of delays in contracting. A lower than anticipated response to the initial recruitment strategy (direct mail out to participants of a population cohort) meant a further delay before the research team had recruited and randomised the six intervention-arm participants needed for a group. According to the service provider, this delay caused the attrition of several existing volunteers (see Figure 1). At a time when the rate of participant recruitment was starting to increase, the service provider advised the study team that it was not actively recruiting volunteers (TMG, 19 September 2012) because there was an insufficient number of randomised participants. Instead, the service provider was waiting for candidate volunteers to approach them in response to advertisements.

Once the research team had managed to increase the rate of participant recruitment through general practice mail-outs, the service provider experienced repeated difficulties identifying volunteers to fill facilitator training groups. As a result, the first two training sessions (May 2012) contained only two genuine volunteers; to make the training viable, the service provider’s staff and members of the study team – who did not intend to deliver the intervention – made up the places to make the training viable. A finite training budget meant that running sessions with insufficient numbers of genuine volunteers was not sustainable. As a result, we agreed that the four (ideally five) places on training sessions scheduled for some time in the future had to be filled by a certain date – the ‘book by’ date – or they would be cancelled. ‘Book by’ dates were arranged with the group facilitator trainer to assist the service provider as it reported (TMG, 14 June 2012) practical difficulties in co-ordinating volunteers at the times and pace required by (1) the trial, which had a window of 1 year to recruit 248 participants to test the effectiveness of a public health intervention, which had to be rolled out at scale, and (2) the group training (four 1-hour telephone sessions on different days). The service provider did not always confirm whether sufficient volunteers had been identified by the ‘book by’ date despite reminders from the trainer/study manager (e-mail and telephone, 16 November 2012).

The total number of volunteers group trained between 17 May 2012 and 22 October 2012 was 11, instead of the 20 who should have been trained. Two trained volunteers were not available to take on a group; one was on a student placement with the service provider and needed to return to full-time education and one was available for only 1 day per week, having assumed that they could make befriending calls in the evening. Three training sessions (during which 15 more volunteers should have been trained) were cancelled between August 2012 and January 2013 because of a lack of take-up. Three volunteers facilitated four groups (n = 24) to completion between September 2012 and May 2013 (with up to 6 weeks one-to-one befriending beforehand). One group received one-to-one befriending from a fourth volunteer facilitator who dropped out before the group stage. An existing volunteer took over for the group calls stage (see Monitoring volunteers). The number of days that volunteers ‘survived’ in the project (from completing group training to the day that they dropped out) ranged from 12 to 118 (mean 62 days).

Monitoring volunteers

Feedback from volunteers was collected by the service provider and reported to the TMG and, when relevant, to other volunteers delivering the service. The study team also captured implantation issues during set-up and recruitment in field notes.

The service provider was responsible for providing ongoing ‘mentoring’ to volunteers, in line with its existing policies and procedures relating to volunteers and the intervention protocol, to ensure a point of contact and support for the volunteers whilst they were delivering the TF service. The charity provided a summary of the project in its induction pack together with copies of the one-to-one training manual (field notes, 20 March 2012, 15 June 2012, 9 October 2012). Volunteers often contacted the study team with enquiries about what to do in certain circumstances, for instance if participants missed calls and the facilitator had been only able to contact one (of six) participants in the first week (field note, 30 October 2012), they were going on holiday (field note, 17 September 2012) or if they experienced technical difficulties with audio recording calls (field note, 29 September 12) (see also Boundaries between research and service delivery). The reasons why volunteers contacted the study team rather than the service provider are considered in Boundaries between research and service delivery and Chapter 5 (see Results of the volunteer interviews).

Volunteers reported difficulties in contacting participants to arrange the initial and subsequent one-to-one telephone calls (see Chapter 5, Results of the volunteer interviews). Volunteers reported that it would be better to make calls in the early evening and that some participants had also reported this. however, to safeguard participants using the service the provider did not permit volunteers to make calls before 0900 or after 1700 from Monday to Friday. This resulted in one volunteer dropping out (see Figure 1).