Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 11/3050/30. The contractual start date was in September 2016. The final report began editorial review in October 2016 and was accepted for publication in July 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

John Norrie reports that he was a member of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR)/Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Commissioning Board 2010–16, is a member of the NIHR Journals Editorial Board (2015–present) and is deputy chairperson of the NIHR/HTA General Board (2016–present). Carol Emslie reports grants and non-financial support from the Scottish Health Action on Alcohol Problems, grants from the NIHR HTA programme and non-financial support from the British Sociological Association Alcohol Study Group outside the submitted work. She is also a member of the Alcohol Research UK Grants Advisory Panel (unpaid position). Peter T Donnan reports grants from Novo Nordisk Ltd, GlaxoSmithKline plc and AstraZeneca plc outside the submitted work. He is also is a member of the New Drugs Committee of the Scottish Medicines Consortium.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by Crombie et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2018 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Alcohol and disadvantaged groups

Alcohol-related morbidity and mortality represent a major public health challenge. The cost of alcohol to society has been estimated at > £55B per year in England1 and > £3.5B per year in Scotland. 2 These costs occur through lost productivity, increased health-care and other public sector costs, and social disruption.

Brief interventions, based on psychological theories of behaviour change, have been developed to tackle alcohol-related problems. There is extensive evidence that they are effective,3–6 although some recent large studies have found them to be ineffective7–9 or possibly harmful. 10 To date, most studies have been conducted in health-care settings, often with individuals who are seeking help.

The risk of alcohol-related harm is substantially higher in disadvantaged groups. 11,12 Alcohol is a major cause of inequalities in health. 11,13,14 Part of the explanation for this may lie in the patterns of drinking; although socioeconomically disadvantaged individuals may not drink more on average, they are more likely to binge drink. 15–17 Binge drinking used to refer to an extended period of several days’ drinking, but is now defined as drinking more than a specified amount, such as eight UK units of alcohol, in a single session. 18

The group who binge drink most frequently in the UK is young to middle-aged disadvantaged men. 16 They may not be reached by current initiatives to tackle excessive drinking as the uptake of public health interventions among socially disadvantaged men is low. 19 There is a need for an intervention that accesses and effectively reduces binge drinking in this hard-to-reach population.

Interventions to reduce inequalities

Behaviour change interventions are less effective, and often ineffective, with disadvantaged/low income groups. 20–23 Indeed, there is concern that interventions may widen inequalities in health. 24–27 A systematic review of smoking cessation found that there were more barriers to change for disadvantaged groups, particularly pro-smoking norms, additional cues to smoking and increased stress. 23 Evaluations of smoking cessation interventions suggest that the lower effectiveness is due not to lower initial uptake, but to lower sustained compliance with the intervention. 28,29 This could be because disadvantaged individuals are less likely to translate intentions to change into action to modify behaviour. 30 Qualitative research suggests that disadvantaged individuals who live in poorly resourced and stressful environments are isolated from wider social norms and have limited opportunities for respite and recreation. 31 Fear of being judged and fear of failure have also been identified as barriers to change. 32 These findings suggest that interventions should be tailored to disadvantaged groups. 33,34 There is a paucity of evidence on interventions to reduce alcohol consumption or binge drinking in disadvantaged individuals.

Recruitment and retention

Recruitment to randomised controlled trials (RCTs) is a major problem. 35 Only a minority of trials reach their intended sample size on time and many require extensions and additional resources to boost recruitment. 35–37 As a consequence, poor recruitment is the major cause of discontinued trials. 38,39 Several systematic reviews40–43 have sought to identify strategies for increasing recruitment to trials. Recommended strategies include using financial incentives, using opt-out, making trial materials culturally sensitive, and making multiple attempts at contact. Direct personal contact, by telephone or face to face, has been found to be substantially more effective than passive approaches, such as mass media or mail. 44

The recruitment of individuals of lower socioeconomic status to trials is particularly difficult because they are less willing to participate in research studies. 45–49 Barriers to research participation include distrust of research, concern about confidentiality, fear of authority, lack of knowledge, lack of time and perceived lack of benefit from participation. 50–54 Strategies to address the reluctance of disadvantaged groups include those mentioned for trials in the general population, but also stress personal contact, the use of sensitive and culturally relevant communication, and attention to the benefits of participation.

The retention of disadvantaged groups is also challenging. 23,55,56 Several systematic reviews55,57,58 and a survey of clinical trials units in the UK59 have identified strategies to improve retention in general population studies. In addition, strategies for retention of disadvantaged groups have been identified. 52,55,56,60–62 These include maintaining contact during follow-up, several contact strategies, the use of a financial incentive, multiple attempts at contact, sending reminders and making the interview convenient for participants. 52,55,57,58,60,61,63–65

Text message interventions

Text messaging provides a method for delivering brief alcohol interventions that has the potential to reach large numbers of individuals at low cost. Recent systematic reviews have shown that there is good evidence that text messages can promote smoking cessation66–68 and increase adherence to antiretroviral therapy. 69,70 The quality of the primary studies in many other areas is a cause for concern. 66,68 No studies have tackled binge drinking among disadvantaged men, although text messaging interventions are particularly well suited to young to middle-aged men because their ownership of mobile phones is high.

Background to the study

We recently completed a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR)-funded feasibility study that demonstrated that all stages of a trial of a brief intervention delivered by mobile phone could be completed successfully. 71 It identified a high frequency of hazardous drinking among disadvantaged men, creating a pressing need for effective interventions to tackle their binge drinking. The success of the feasibility study led to the recommendation that a full trial to assess the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the text message intervention should be conducted.

Overview of full trial

This study tested the effectiveness of a novel text message intervention designed to reduce binge drinking among disadvantaged men. It was a four-centre, parallel group, pragmatic, individually randomised controlled trial. The four centres covered major regions of Scotland: Tayside, Glasgow, Forth Valley and Fife. Men aged 25–44 years from areas of high deprivation were recruited. Deprivation was measured using the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation (SIMD),72 which is similar to the English Index of Multiple Deprivation. Men were recruited from areas classified as being in the most disadvantaged quintile. The required sample size was 798 men.

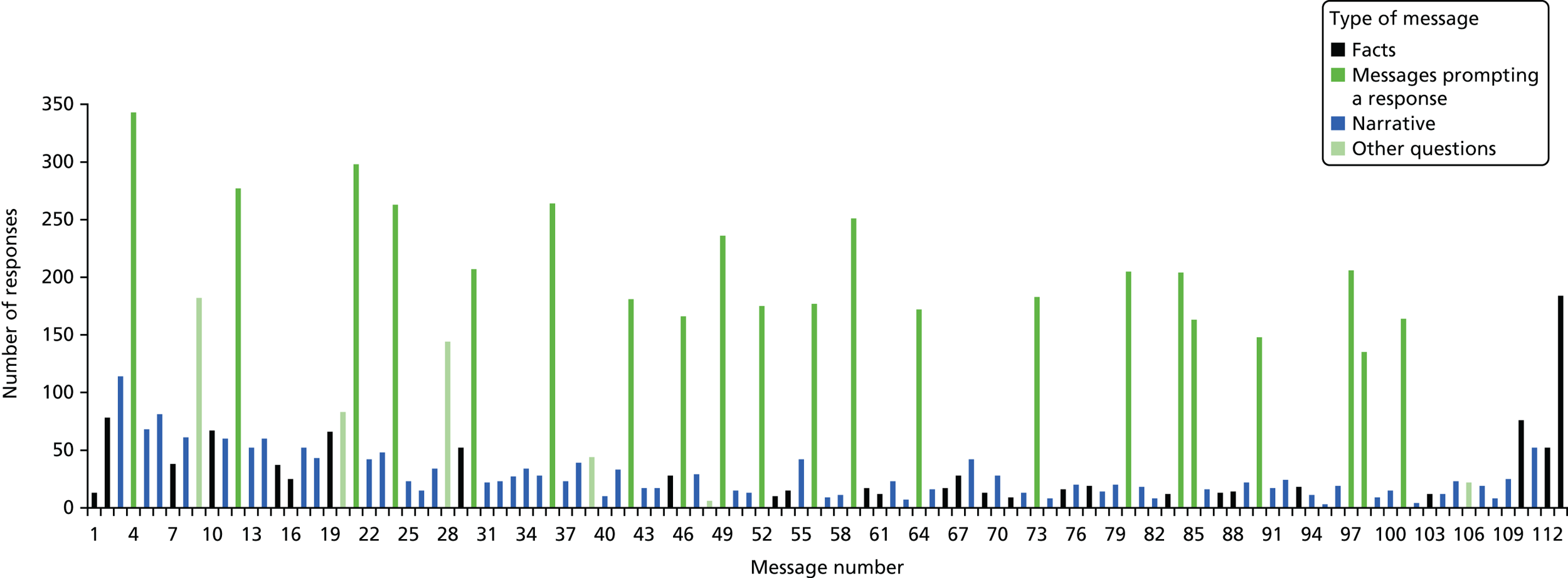

The text message intervention was a series of 112 interactive text messages delivered by mobile phone over a 12-week period. The intervention drew on literature from alcohol brief interventions, communication theory, and behaviour change theories and techniques. The control group received an attentional control comprising 89 text messages on general health topics.

The primary outcome was the proportion of men binge drinking (consuming > 8 units of alcohol) on ≥ 3 occasions in the previous 28 days. It was assessed at 12 months post intervention. Secondary outcomes covered heavy binge drinking (> 16 units of alcohol), total mean consumption and frequency of hazardous or harmful drinking [Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT)] at 12 months post intervention, and binge drinking and heavy binge drinking at 3 months post intervention.

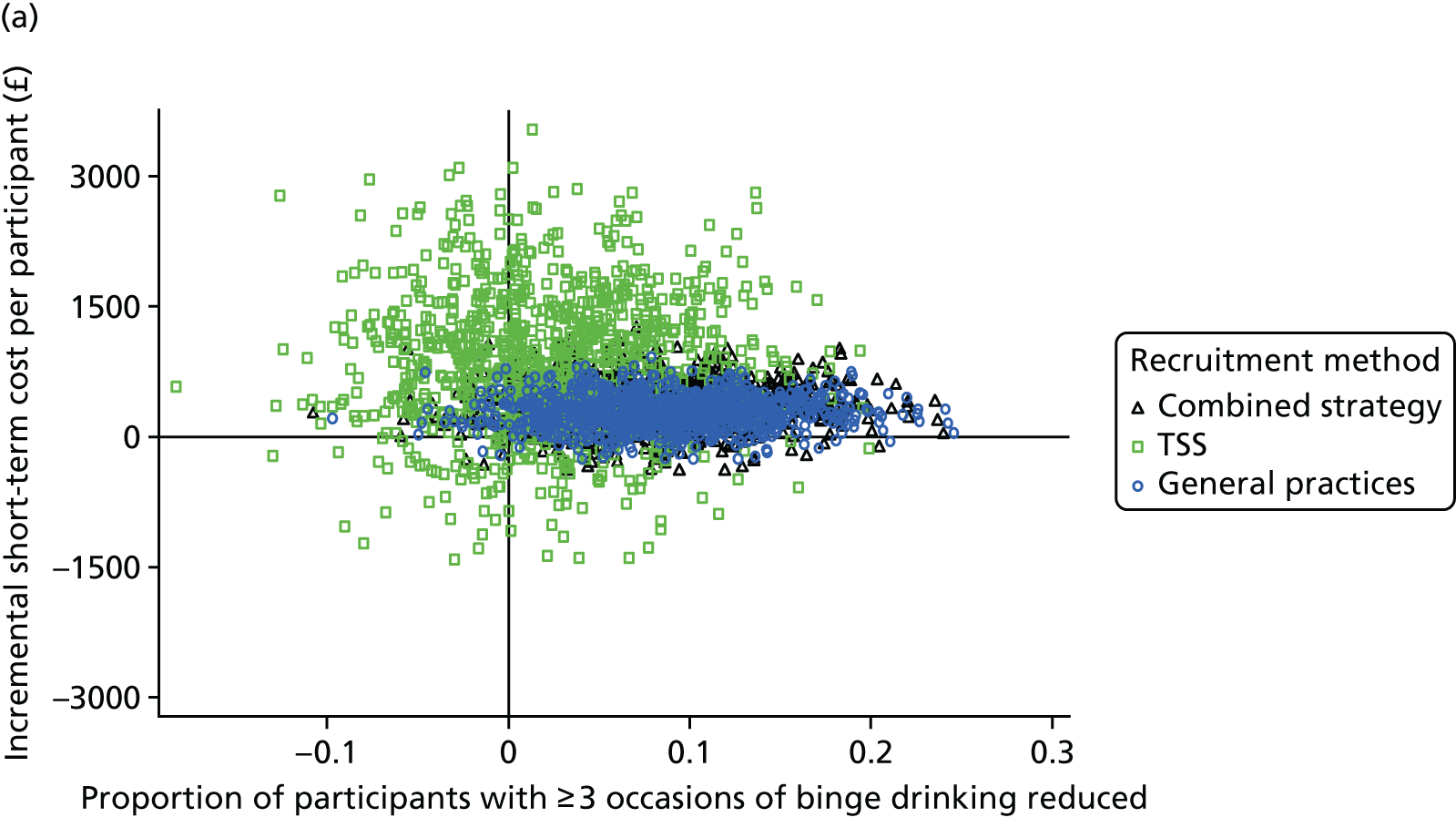

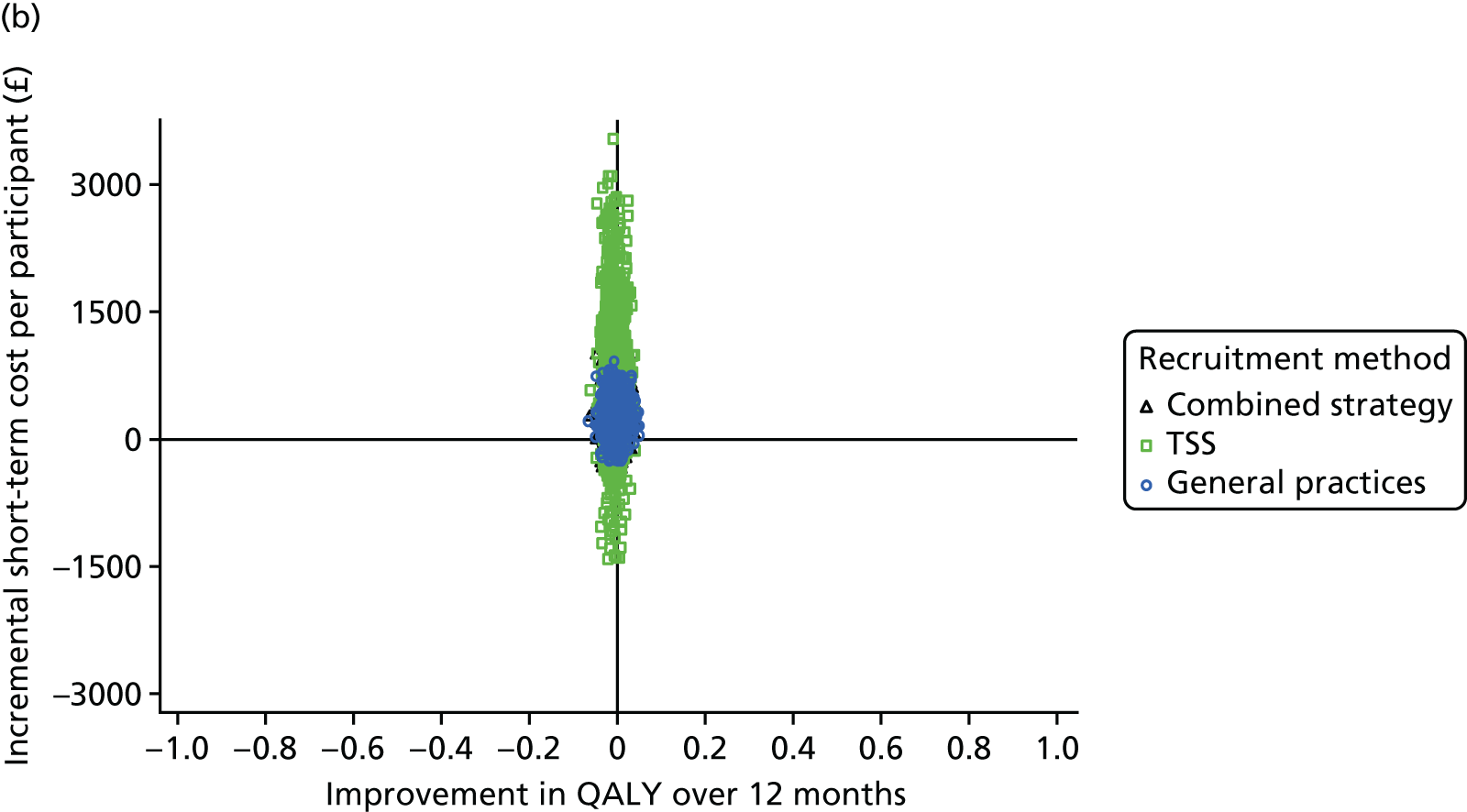

The economic evaluation took a societal perspective and modelled the potential cost-effectiveness of the intervention assuming a nationwide implementation. Data were collected on the resources required for recruitment and the implementation of the intervention. These were used to predict the costs relating to national rollout where resources will be costed according to their opportunity cost.

Research questions

Three research questions were specified in the protocol.

-

Can a brief intervention delivered by mobile phone reduce the frequency of binge drinking among disadvantaged men?

-

Is the intervention cost-effective?

-

Which components of the behaviour change strategy (intentions to avoid becoming drunk, self-efficacy for refusing drinks, goal-setting and action-planning for reducing binge drinking frequency) are associated with changes in drinking behaviour?

Chapter 2 Development of the text message intervention

Introduction

The behaviour change intervention was designed to promote a sustained reduction in the frequency of binge drinking. The challenge was to develop an empirically and theoretically based complex intervention to engage socially disadvantaged men long enough to guide them through the steps to behaviour change. The tailoring of interventions to the needs and circumstances of disadvantaged groups is strongly recommended. 33,34,73 The intervention was developed from the one used in the feasibility study, which was designed in collaboration with the user group. 71 The method of delivery, text messages with no face-to-face contact, proved to be highly acceptable to the target group, so it was used again.

Systematic reviews have shown that text message interventions can successfully modify adverse health behaviours. 66,74 Several recent studies have reported that mobile phone interventions have the potential to modify drinking in people attending emergency departments,75–77 students,78,79 young people,80 adults81 and dependent drinkers. 82 Mobile phone ownership in the target age group in the UK is > 95%,83 and phone users frequently check their phones,84 so study participants would be likely to open and read the messages. Previous studies report that text messages are usually read soon after delivery. 85 Text messaging is particularly suited to the target group because little effort is required to receive the intervention and texts can be accessed at times that suit the participants. In addition, each text message can be read quickly and reread if desired. Men who may not want to commit time to reading leaflets or large sections of text may prefer to receive concise text messages.

Overview

Evidence from several areas was used to create the intervention. Initially, the psychological theory that would underpin the intervention was decided. Evidence from alcohol brief interventions was reviewed and effective behavioural change techniques were included. A narrative was used to structure the text messages and to ensure that the participants’ interest could be maintained over the intervention period. The storyline was designed to increase engagement, provide coherence to the text messages and illustrate the process of behaviour change. Communication theory was reviewed to ensure that the overall ethos of the intervention was engaging for and acceptable to the recipients. Finally, successful techniques used in the design of the text messages for the feasibility study were also incorporated. In particular, focus groups with disadvantaged men, which were conducted in the feasibility study, identified levers for behaviour change, as well as approaches to be avoided.

Key findings from the feasibility study

Focus groups investigated men’s attitudes about taking part in a text message intervention and their beliefs about cutting down. 71 They gave insight into the target group’s patterns of drinking, and their knowledge about alcohol-related harms and the benefits of reduced drinking. The common pattern of drinking was periods of abstinence interspersed with infrequent heavy-drinking days. Many men believed that their drinking behaviours, motives and desire to change were significantly different from when they were younger. They had adopted the role of the ‘mature drinker’, which came with social roles and responsibilities (employee, husband/partner, parent). Most men were aware of the harms associated with alcohol misuse, but had low perceived personal risk. They made it clear that in an intervention they would not want to be preached at or told what to do.

The feasibility study also found that the text message brief intervention could engage participants86 and had the potential to reduce binge drinking. 71 Participants enjoyed the interactive nature of the intervention and gave carefully considered personal responses to the questions asked in the text messages. They engaged with the cognitive antecedents to reducing drinking as they were discussed in the text messages. Although the intervention addressed intention to change, it did not provide sufficient assistance on methods to achieve behaviour change and maintain the new behaviour. The intervention would need to be modified to incorporate a psychological theory that addresses volition as well as motivation to change behaviour. In addition, a period of 1 month would not be sufficient to address all of the steps required to change behaviour, so it should be extended to 3 months.

Psychological theory underpinning the intervention

The behaviour change strategy was based on the Health Action Process Approach (HAPA). 87 The HAPA model suggests that behaviour change occurs through two distinct phases: a pre-intentional or motivational phase and a volitional phase. The volitional phase is made up of separate components: a planning and action phase, and a maintenance phase. HAPA was chosen as it addresses the intention–behaviour gap,88 identified as a weakness in some behavioural change theories. Although HAPA was used as the overarching structure around which the intervention was developed, it drew on other social cognition models, such as subjective norms from the theory of planned behaviour,89 self-monitoring from social cognitive theory90 and control theory. 91 It also used empirical data from the feasibility study. Finally, behaviour change techniques suitable for use in alcohol interventions were incorporated. 92

Alcohol brief interventions

The first trial of a brief intervention for heavy alcohol use was conducted in 1962. 93 Since then, over 50 trials have been conducted in primary care and their results have been synthesised in 26 systematic reviews. 94 The consistent finding is that the interventions were effective for hazardous and harmful drinking in middle-aged men. However, there is insufficient evidence of effectiveness in women and in older and younger drinkers. Evidence from other settings is less persuasive. For example, in patients from emergency departments, trauma care centres, hospitals and community pharmacies, the evidence is mixed. 95,96

Despite the evidence on effectiveness, the mechanism of action of brief interventions is not known,97–99 in part because alcohol brief interventions are very heterogeneous. The time for the delivery of the interventions varies between 5 and 60 minutes, with a median of 25 minutes. 5 The content of the interventions also varies substantially. 5,94 They can contain motivational interviewing, feedback and advice, self-monitoring of alcohol consumption, self-help manuals, counselling and cognitive–behavioural therapy. 5,94,100 It is unclear whether or not interventions based on the principles of motivational interviewing may be more effective than other approaches. 97,99 One review of reviews has suggested that effective interventions contain at least two of three elements: feedback on drinking, advice and goal-setting. 101 A more recent review found that promoting self-monitoring was the only technique that appeared effective. 92 Bien et al. ,100 in their very widely cited paper, summarised the common components of effective brief interventions with the acronym FRAMES: Feedback on current consumption; Responsibility of the individual for his drinking; Advice to change; Menu of change strategies; Empathy in the delivery; and Self-efficacy for action.

Narratives in interventions

A narrative was used to engage the participants and to illustrate the key steps in the behaviour change process. Braddock and Price Dillard102 describe a narrative as ‘a cohesive, causally linked sequence of events that takes place in a dynamic world subject to conflict, transformation, and resolution through non-habitual, purposeful actions performed by character’. Narrative is increasingly being used as a tool for behaviour change. 103 Instead of presenting facts and arguments for changing behaviour, a narrative intervention translates these into actions and experiences of characters within a chronological series of events. 104 Narratives have been used in a range of health behaviour change studies (e.g. risks associated with sunbeds, vaccination for human papillomavirus, smoking cessation and alcohol use104), although none delivered through text messaging has been reported. In the present study, the narrative follows a central character, Dave, as he gradually realises that he drinks too much and decides to reduce his consumption. It charts his efforts, successes and relapses, and concludes with Dave enjoying the financial and social benefits of moderated drinking.

There are several advantages of using narrative. Information presented in a narrative has a stronger effect on knowledge, attitudes and intentions than the same information in a non-narrative format. 105 Narrative is particularly useful for changing perceived social norms and behavioural intentions. 106 It can ‘strengthen existing prosocial beliefs and behaviours as well as counteract unhealthy ones’. 107 Resistance to behaviour change is overcome because individuals are engaged in the narrative. 103

To be effective for behaviour change, the narrative and the characters in it have to engage the reader, a process aided if the protagonists are culturally similar to the target audience. 108,109 The narrative also has to be plausible and internally consistent. 110 The depiction of a character who succeeds against the odds can boost motivation for personal goals. 111

Logic model

A logic model was used to aid the development of the intervention (Table 1). Logic models help to clarify how the intervention will lead to behaviour change and, in the longer term, to improved health and social well-being. 112 A review of a problem (behaviour to be changed and the target group) clarifies what is to be achieved. It can also identify challenges, such as resistance of disadvantaged groups to conventional health-promotion interventions. The intervention strategy, the intervention goals and the outputs specify how the aim will be achieved. In this study, the initial requirements for behaviour change were an increased awareness and personal relevance of the harms of alcohol and the benefits of moderated drinking. Altering risk perception and alcohol expectancies are prerequisites for increased motivation to change. Setting goals and making action plans would lead to reduced drinking, but only if self-efficacy for action was also increased. Furthermore, to prevent relapse, reduced drinking would have to be maintained. This could be achieved by increasing the salience of the benefits of reduced drinking. Thus, the short-term benefits of moderated drinking can be used to encourage longer-term reductions. This will lead to improved health and social well-being for the individual and a reduction in the costs of alcohol-related harms for society.

| Problem | ➡ | Intervention/strategy | ➡ | Intervention goals | ➡ | Output | ➡ | Outcomes | ➡ | Impact | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short term | Long term | ||||||||||

| Binge drinking is common among young to middle-aged disadvantaged men | Design a cost-effective alcohol intervention that will appeal to the target group | Recruit socially disadvantaged men who regularly binge drink | Increased personal relevance of alcohol-related harms | Decrease the number of episodes of binge drinking | Maintenance of healthy drinking patterns | Reduction in inequalities through improved health and fewer social problems and family disruption | |||||

| Disadvantaged men may be reluctant to engage with health-promoting interventions | Incorporate a narrative to engage the men in the steps involved in changing behaviour | Increase awareness of alcohol-related harms | Intentions to drink at safe levels | Reduce/prevent:

|

Prevention of physical, mental and social problems:

|

Reduced costs to:

|

|||||

| Conventional alcohol brief interventions may not reach this group |

The intervention is based on the HAPA and uses behaviour change techniques The causal model: |

Deliver the intervention by text message to make it acceptable to the target group Change alcohol expectancies by encouraging men to consider the benefits of reduced drinking Change drinking behaviour through goal-setting and action-planning Maintain moderate/safe drinking levels |

Goals/action plans to drink at safe levels Strategies to maintain safe drinking levels Moderated drinking by individuals |

Increase salience of benefits of reduced drinking Increase self-efficacy to change |

Increased productivity due to the reduction in sick time taken Shift in attitudes towards alcohol Change in drinking culture |

||||||

Stages in the development of the intervention

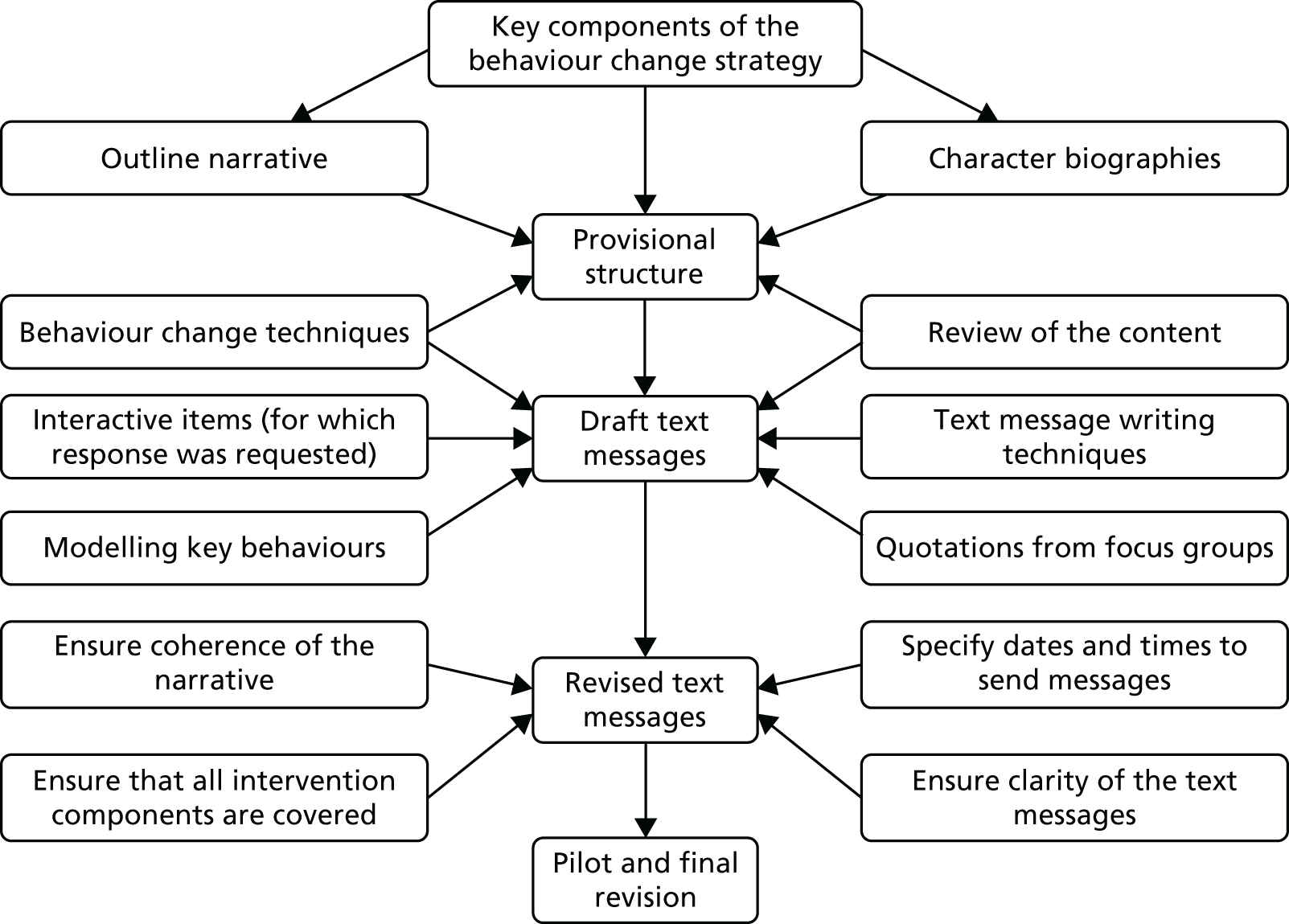

The intervention was developed in four stages (Figure 1): (1) establishing the provisional structure of the intervention, (2) drafting the text messages, (3) revising the content of the text messages and (4) piloting and final revisions. In practice, there was much iteration in the writing process, with modifications made to the narrative and to the text messages as the structure and content of individual text messages were developed. An extended piloting process was required to ensure that the narrative was coherent when rendered into text messages and that all components of the behaviour change strategy were adequately addressed.

FIGURE 1.

Stages in writing the text messages.

Stage 1: establishing the provisional structure

Building on the logic model, key elements of the intervention were reviewed to create a provisional structure. These were the behaviour change model (HAPA)87 and relevant behaviour change techniques. 92 This provided a framework to establish how the narrative would depict the process of behaviour change, who the characters in the narrative would be and how the intervention could be delivered within the time frame of 3 months.

Key components of the behaviour change strategy

To establish a framework and timetable for the delivery of the intervention, the components of HAPA to be incorporated at each stage were addressed in three parts (Box 1). In the motivational phase, the pre-intentional motivational processes that lead to behavioural intentions include changing alcohol expectancies and perceptions of personal risk from alcohol-related harm. Increasing self-efficacy and gaining social support are also essential at this and all subsequent stages of the intervention.

-

Alcohol expectancies.

-

Perception of risk.

-

Action self-efficacy.

-

Social support.

-

Action self-efficacy.

-

Coping self-efficacy.

-

Action control (how to cope in a high-risk situation).

-

Goal-setting.

-

Action-planning.

-

Social support.

-

Recovery self-efficacy.

-

Coping self-efficacy.

-

Action control (how to cope in a high-risk situation).

-

Social support.

The volitional phase of HAPA was divided into two parts. Initially, action-planning and coping-planning were tackled. This included the setting of goals and drawing up of action plans and coping plans. Subsequently, maintenance of the new behaviour, including lapse and relapse, was addressed (see Box 1). A recent review of behavioural theory113 has identified four factors that are important in maintenance. These were incorporated into the intervention: (1) satisfaction with behavioural outcome (e.g. financial gain or weight loss from reduced drinking); (2) self-regulatory processes (e.g. self-monitoring and planning); (3) identity (i.e. ensuring that processes and outcomes of behaviour change are consistent with the attitudes and values of the participants); and (4) social and environmental factors (e.g. making plans for how to deal with high-risk drinking situations).

Character biographies

To enable the detailed storyline to be developed, the number and the nature of the characters were decided. The number of characters was limited to ensure that the study participants could follow their individual stories. Constraints imposed by embedding the narrative in text messages meant that background information on each character was limited.

The feasibility study71 identified distinct drinking behaviours within the target group: men who regularly drank over the binge-drinking threshold (> 8 units of alcohol in a session) and those who engaged in very heavy binge drinking (> 16 units of alcohol in a session). A common pattern of drinking was periods of abstinence interspersed with infrequent heavy-drinking days. Another common feature was that many men believed that their drinking behaviours, motives and desire to change were significantly different from when they were younger. They perceived this as a shift towards the role of a ‘mature drinker’, which came with social roles and responsibilities (employee, husband/partner, parent). This ‘mature drinker’ identity was desirable and important for being able to fulfil responsibilities and commitments to family or work.

The first task was to ensure that the characters in the narrative embodied these characteristics. Participants would be more likely to feel a personal connection if the characters were similar to them. The narrative was portrayed through a lead character, Dave, his wife (Christine) and several minor characters who were friends (Box 2). Dave was presented as someone who believed he was a mature drinker (a family man with responsibilities), but who had been a heavy binge drinker in the past. He was designed to be likeable and someone who would succeed in changing his behaviour. However, so that the participants would empathise with his experiences, he also faced disappointment and failure before finally achieving his goals. Dave was resilient and reflective, allowing him to learn from his failures and disappointments. He modelled the process of reflection on his drinking to encourage participants to review their own behaviour, motivations and circumstances.

Dave is a family man who is married to Christine. He initially believes that he is a mature drinker. He subsequently realises that he is a regular binge drinker and becomes aware of the potential risks from his drinking. He models behaviour change techniques that are likely to work, but also experiences lapses along the way. In the end he achieves his goal to cut down on his drinking and is satisfied with the outcome of the changes he has made.

Peripheral characters (Dave’s friends)Stevie is the unmarried ‘antagonist’ character. He has few responsibilities, is unemployed and lives with his mother. Stevie often encourages everyone around him to drink.

Dougie has had serious alcohol-related problems in the past. He lives with a long-suffering partner (Sadie) but has a troubled relationship. He also tries to change his drinking, but gets it wrong more often than Dave.

Alec is a reformed, now mature, sensible drinker. He is respected by the others and is a role model for Dave.

The minor characters, like the protagonist, were also people with whom the participants could identify (either currently, or as someone who would represent their younger self or an older role model). These characters were more likely to fail in achieving their goals, but they were also designed to elicit empathy and sympathy from participants. Different drinking patterns (e.g. reformed heavy drinker, regular heavy binge drinker) were allocated to the characters, and then other demographic characteristics were introduced (i.e. employed/unemployed; single/in a relationship/family man).

Outline narrative

A narrative, based on the lives of these characters, was written out in full before it was considered how this could be rendered into text messages. Dave set out on a journey to moderated drinking, modelling the key steps in the process to behaviour change (Box 3). For example, action planning to reduce alcohol consumption should specify when a new behaviour will be adopted, where it will be carried out and how it will be achieved. This process of action planning was described in a text message, and then illustrated in a subsequent message by Dave going through the process of identifying the where, when and how he would cut down. Similarly, when relapse prevention was addressed, Dave explained how it had happened to him and why he was determined to keep to his original plan to reduce his drinking. Dave’s fallibility encourages ‘buy-in’, as men identify with him and his determination could inspire them to emulate him. In general, if participants empathise with the character, the texts (e.g. perceived risk, benefits of moderated drinking) become more relevant and concrete and are more likely to lead to behaviour change.

Self-monitoring of drinking.

Risk perception.

Modifying outcome expectancies.

Intention to reduce drinking.

Subjective norms.

Goal-setting.

Action-planning.

Action self-efficacy.

Success at sticking to the plan.

Lapse.

Coping-planning.

Coping self-efficacy.

Satisfaction with changed drinking pattern.

Rewards for achieving goals.

Narratives frequently evoke emotional responses and these can have strong effects over and above more rational cognitive approaches. Thus, emotive topics were used to increase motivation to change; for example, one of the character’s partner and child leave home because of problems caused by alcohol. The character’s setbacks were subsequently resolved after drinking problems had been tackled. The impact of these fraught situations, and their subsequent resolution, will be greater if the participants identify with the character.

Self-efficacy is essential in achieving behaviour change. The intervention aimed to increase self-efficacy throughout the intervention period (task self-efficacy, coping self-efficacy and maintenance self-efficacy). Using characters to model behaviours allowed the intervention to focus on self-efficacy for specific concrete behaviours rather than general self-efficacy beliefs. Furthermore, it can engender self-efficacy through vicarious experience, particularly if the men identify with the characters in the narrative.

Inclusion of behaviour change techniques

Several taxonomies of behaviour change techniques to aid the design of interventions have been published,114,115 including one for alcohol interventions. 92 A list of the relevant techniques that have been suggested for alcohol interventions92 was incorporated into the narrative (e.g. providing normative information about others’ behaviour and experiences and facilitating goal-setting and action-planning).

Review of content

To assess the completeness of the provisional intervention, the sections of the narrative were laid out in a matrix that specified the intended impact of each section, the behavioural construct that was being addressed, the behaviour change techniques employed and the proposed mechanism of change. This ensured that the key components of the behaviour change strategy and the relevant behaviour change techniques were covered in the intervention.

Stage 2: drafting text messages

The complete narrative was rendered in a series of 112 text messages, each with one or more of the following purposes:

-

delivering the narrative (to engage participants)

-

increasing the salience of the harms of heavy drinking and the benefits of moderated drinking

-

modelling steps in the behaviour change process

-

giving information or facts (to augment the behaviour change strategy portrayed in the narrative)

-

asking questions (to monitor, in real time, participants’ reactions to the components of the intervention)

-

comments from other characters (anonymised quotations from the feasibility study participants to reinforce the part of the intervention being delivered)

-

adding humour (to increase engagement).

The salience of harms was increased by asking participants if they or their friends had experienced harms. This avoided the possibly patronising approach of telling experienced drinkers about harms with which they were already familiar. The feasibility study showed that most men were well aware of these harms. 71 It also increased the personal relevance of the harms. A similar approach was used with benefits, in which participants were asked to identify how their lives might be improved if they drank less.

The major constraint in writing the text messages was the permitted length of a text message (160 characters). Thus, the storyline had to be fairly simple and straightforward enough to be delivered in a few words. Although smartphones can send messages that are more than 160 characters (i.e. combining two or more messages at once), there is a danger that the participants will be deterred by large blocks of text.

The text messages were constructed so that the main character, Dave, appeared to be a recipient of the intervention. Thus, he commented on the text messages, answered questions and modelled behaviours that were expected from the behaviour change strategy. To simplify the narrative, Dave was the only character who sent messages, although he discussed at length what was happening in the lives of the other characters. The narrative had to be sufficiently engaging so that participants could remember what was happening from day to day. Achieving this with one or two text messages per day was challenging. Messages containing narrative were identified either by Dave introducing himself or signing off at the end of the message. When possible, messages about changing behaviour and advice about reducing drinking were modelled by the characters. This avoided didactic delivery of the intervention, which preliminary work in the feasibility study had found to be unwelcome.

Interactive items for key components of the intervention

The use of interactive text messages was central to the intervention. Mobile phone etiquette requires reciprocation, so messages that ask questions are likely to be answered. 116 Those in the target group were frequent mobile phone users and, therefore, were likely to engage in text message conversations. The feasibility study showed that participants engaged with the cognitive antecedents to reducing drinking, and with important steps on the causal chain to behaviour change. 86 This feature was capitalised on by asking questions on the key components of HAPA and the behaviour change strategy. For example, participants were asked ‘If you made a goal to cut down a bit on your drinking, what would it be? Text me your answer’ or ‘What would you do if you got into a situation where you were expected to drink far more than you intended? Text me your answer’. The responses to these questions provided an indication of engagement with the intervention in real time.

The feasibility study found that many of the participants gave carefully considered personal responses to the questions set. 86 Participants are likely to spend more time thinking about the content of the message if a response is sought. In addition, committing thoughts to a written response may reinforce the intention or action specified.

Quotations from the feasibility study

The feasibility study produced a wealth of data ‘in the participants’ own words’ both from focus groups and from text message responses from those who received the intervention. 71 Anonymised quotations from the feasibility study delivered information in language appropriate for the target group. Texts that showed other people sharing personal experiences could also give participants confidence to give their own replies. This technique was used to illustrate harms from alcohol misuse, to model new behaviours and to report achievements and benefits from changing behaviour. The quotations were presented as coming from men other than the characters in the narrative. For example, to illustrate risk perception, one message said ‘John from Dundee says “I’ve woke up in the cells a few times because of drink. If i was sober it would never have happened” ’. To reinforce their authenticity, the quotations were not corrected for spelling or grammar.

Specifying dates and times to send messages

The first text message was sent on the Monday evening following randomisation. This enabled messages to be tailored to the day of the week. The feasibility study revealed that a common pattern is heavy drinking at the weekend followed by sobriety during the week. Text messages sent on Friday and Saturday were therefore delivered in the afternoon or early evening before the men went out drinking. Messages sent on Sunday were generally delivered later in the evening to give the participants a little more time to recover from a hangover. Midweek text messages were sent at variable times, often after the working day. Messages were sent at different times and on different days of the week to avoid predictability.

Participants received 112 messages in total. They received at least one message on every day for the first 5 weeks. The maximum number of messages sent in a day was four. From week 6 onwards, occasional days were missed. It is essential to strike a balance between maintaining engagement with the participants, passing on the information necessary, and not overburdening them with the number of messages. Previous research offers differing views on message frequency. One systematic review suggests that retention is higher if the number of messages is varied over time,117 while another reported that interventions when message frequency decreased were more effective than those with constant frequencies. 74 All of the messages in the intervention were unique, although some topics (e.g. self-efficacy and maintenance of a new behaviour) were revisited at different stages of the intervention.

Use of linked messages

On days when more than one text message was sent to participants, the messages were often sent in pairs or groups of three or four. This device has several purposes. Linked messages enabled more complex messages to be sent, as some of the psychological constructs could not be explained in a single message. They were also used to extend the time the participants thought about a topic. The first message was often used to seed an idea, while the follow-up text messages encouraged reflection on the topic. Combinations of messages were also used to add suspense and build a storyline. Paired messages could also pose a question, with the answer provided later in the day. The time delay between linked messages varied from 3 minutes to 4 hours.

Making the intervention acceptable

Communication theory was used to guide the design of the text messages. It proposes that, to be effective, a message must be attended to, comprehended, processed, accepted and acted on. 118 Four features of a message affect the likelihood of behaviour change: the source (i.e. credibility) of the message, its style and content, the nature of the recipient and the context (the circumstances in which the message is received). 67,119 The name of the university was used to give credibility to the study and the intervention, and it was also mentioned on all written material given to the men during recruitment. To establish a relationship, participants were sent a welcoming text message that included their first name. Text messages did not include messaging slang as this could be construed as unprofessional coming from a credible source (i.e. a university). Communication theory suggests that interesting and unexpected statements can be used to maintain interest. Thus, humour was used throughout the intervention period.

Stage 3: revision of the text messages

Ensuring coherence of the narrative and the behaviour change strategy

When the intervention had been rendered into text messages, it was reviewed to ensure that all of the components of the intervention had been preserved (i.e. the key components of HAPA and the behaviour change techniques). The storyline was also checked to ensure the narrative was coherent. The messages were read by colleagues who knew the storyline of the narrative and the behaviour change techniques and processes that should be incorporated into the intervention. They were asked to establish whether or not the behaviour change strategy was intact and addressed in sufficient detail and also whether or not the reader could follow the narrative when it was reduced to a series of text messages. This process was then repeated with colleagues unfamiliar with the narrative and the intervention. Text messages were read and reread to identify any ambiguous statements and to ensure that the unedited direct quotations from the feasibility study were easily understood.

Stage 4: piloting and final revisions

The final piloting used 24 volunteers who were given background information on the study and were told about the fictional characters in the narrative. They were given all of the text messages on paper and asked to provide written comments, both on the overall approach and on individual text messages. The volunteers commonly engaged with the characters and the narrative as if they were real by responding to the text messages rather than commenting on their content. The volunteers’ comments gave reassurance that the texts were clear and readily understood. They also showed that the use of characters made the intervention appear more realistic and less daunting. The volunteers also found the overall approach supportive. Finally, they suggested how the narrative could be amended: for example, one of the minor characters, Stevie, had been left with an unresolved drink problem. The narrative was amended to show that Stevie successfully tackled his drinking and also found a girlfriend.

A second round of piloting involved volunteers who received the text messages on their mobile phones. This was primarily used to test the delivery system, but also helped determine whether or not the frequency and timing of the messages were acceptable.

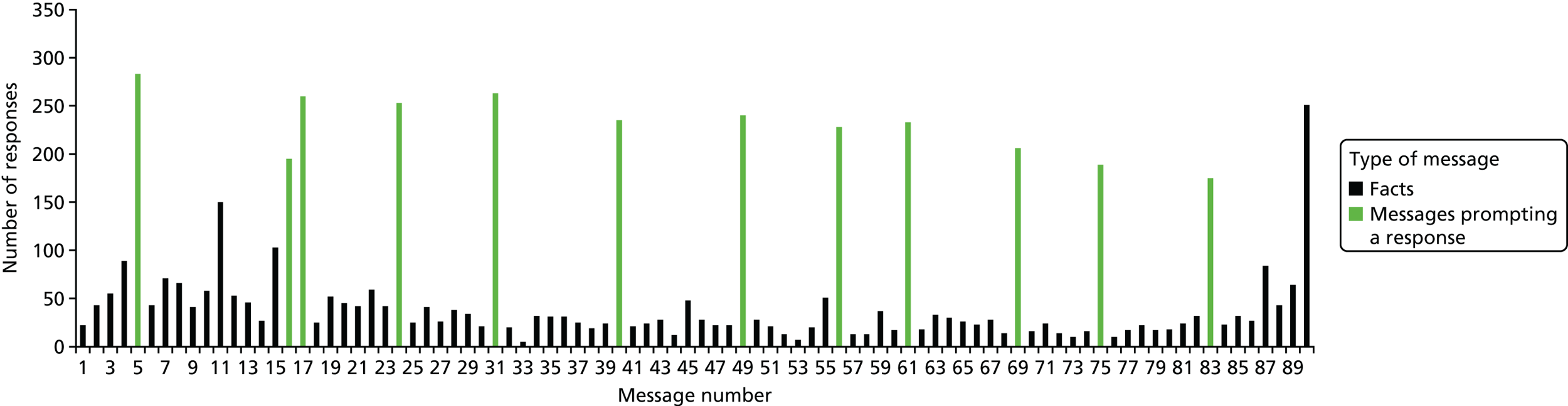

The control package

The control group also received a series of text messages over the 3-month intervention period. This was designed to be an attentional control, which did not mention alcohol or include any messages on changing health behaviour. Every week a different health topic was covered, for example physical activity, sexual health, diet, mental health, sleep quality, hearing and foot health. The text messages provided facts, trivia and jokes on the topics. Although the control messages did not include a narrative, the characters did play a minor role. For example, to increase engagement and introduce humour, some messages appeared to come from Dave in the form of ‘useless information’, such as ‘Dave’s useless information for today: The average person has at least seven dreams a night’ or ‘Dave’s useless information for today: A sneeze can reach 100 mph, a cough only 60 mph’.

To promote engagement, men were asked one question per week. This was usually a multiple-choice question on the topic of the week, for example ’What is the biggest organ in the body? (a) liver (b) lungs (c) skin (d) brain. Text me your answer please‘ and ‘What is bromodosis? (a) painful toes (b) smelly feet (c) ingrown toenails (d) dropped arches. Text me your answer please’. These questions encouraged interaction without asking participants to give the considered personal responses required from the intervention group.

Summary

This structured approach has led to the design of a text message intervention with a strong theoretical basis. The process was highly iterative to enable a theory of behaviour change and a set of behaviour change techniques to be embedded in a coherent narrative. These were successfully rendered in a series of short text messages (maximum length 160 characters). The use of characters helped make the intervention realistic and allowed key behavioural activities to be modelled. Pilot testing revealed strong support for the intervention.

Chapter 3 Study methods

The study was a four-centre, parallel-group, pragmatic, individually randomised controlled trial that sought to reduce the frequency of binge drinking in disadvantaged men. The study protocol is available on the NIHR website120 and was published in the journal Trials. 121 The study was approved by the East of Scotland Research Ethics Service REC1 (REC reference 13/ES/0058).

Recruitment

Study group

Men aged 25–44 years from areas of high deprivation were recruited. Recruitment was conducted in four centres that cover major regions of Scotland: Tayside, Glasgow, Forth Valley and Fife. Level of deprivation was measured using the SIMD,72 which is similar to the English Index of Multiple Deprivation. Men were recruited from areas classified as being in the most disadvantaged quintile. Recruitment was conducted from March 2014 to December 2014.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

Men were included in the study if they had ≥ 2 episodes of binge drinking (> 8 units of alcohol in a single session) in the preceding 28 days. Exclusion criteria were as follows: men who were currently attending care at an alcohol problem service and men who would not be contactable by mobile phone for any part of the intervention period.

Techniques to promote recruitment

Recruitment employed several evidence-based techniques. 40–43 It involved direct personal contact (face to face or by telephone), involved multiple attempts at contact and used an approach based on respectful treatment. 122,123 An opt-out strategy was used. A financial incentive was offered for participating in the study. High-street vouchers to the total of £50 were offered, although this was divided across the whole study: £10 at completion of the baseline questionnaire, £20 during the delivery of the text messages and a further £10 for completion of the questionnaires at 3 months and 12 months post intervention. The incentive was given for continued participation and was not linked to drinking behaviour.

To ensure good coverage of disadvantaged men, two recruitment strategies were employed, each to recruit half of the target of 798 men. One used primary care registers and the other used a community outreach method, time–space sampling (TSS).

Strategy 1: recruitment through general practice registers

Potential participants were identified from the practice lists of 20 general practices by staff from the Scottish Primary Care Research Network (SPCRN). These lists contain data on age, sex and postcode. Postcodes were used to derive the SIMD score. 124 Men who lived in the highest deprivation quintile were randomly selected by SPCRN staff to give a maximum of 200 potential participants from each practice list. General practitioners (GPs) screened the list and sent potential participants a letter inviting them to take part (see Appendix 1). The letter was personally addressed, mentioned the appropriate local university (Dundee, Stirling or Glasgow Caledonian) and stated that a financial incentive would be given. The accompanying participant information sheet (see Appendix 2) carried the university’s logo and stressed the confidentiality of the study. An opt-out strategy was used for recruitment. The name, address and telephone number of those who did not decline to take part were provided to the researchers by the SPCRN. The researchers contacted these individuals by telephone approximately 2 weeks after the GP letter was sent. Attempts at contact by telephone were made at different times of the day and on different days of the week.

Strategy 2: time–space sampling

Time–space sampling125 is a community outreach strategy that recruits participants from a number of venues and involves sampling at different times of the day and on different days of the week. The specific features of the strategy were based on findings from the feasibility study,71 augmented by fieldwork, to identify appropriate venues and suitable times for recruitment. A variety of venues were explored for their potential for recruitment, including town centres, workplaces, community groups, football grounds, charities that support long-term unemployed people, supermarkets, housing associations and main shopping streets in disadvantaged areas.

Fieldwork

Areas classified by the SIMD as being in the most deprived quintile were identified from a government website. 126 Maps of high-deprivation areas within towns were produced using an online mapping resource (Google MapsTM, Google, Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA). The maps were printed with sufficient detail to show street names and reference points to provide a detailed guide for fieldwork. Sources of potential participants were public houses, job centres, community centres, pharmacies, sports facilities, bookmakers and supermarkets. These were identified by using Google Street ViewTM (Google, Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA) and from local authority websites. Google Street View was also employed to identify routes of access and car parking.

The initial fieldwork established that few people were encountered in housing estates in areas of high deprivation. Instead, they tended to congregate in high streets in, or adjacent to, areas of high deprivation, where facilities such as public houses, bookmakers, convenience stores and supermarkets are common. The fieldwork showed that recruiting from the streets around these venues was more productive than recruiting inside the venues. It also established that distributing leaflets and using gatekeepers were largely unproductive.

Initial screening

A researcher approached men in the selected areas who appeared to be in the age range (25–44 years). Potential participants were asked about their age and their current drinking levels. The study was described to those who reported binge drinking (> 8 units of alcohol in a single session) at least twice in the previous 4 weeks. All participants were told that the study was about alcohol and health. They were given a participant information sheet (see Appendix 2) and a consent form (see Appendix 3) to read, and their mobile phone number was obtained. About 24 hours after the potential participants received the participant information sheet and consent form, the researcher telephoned them to discuss the study and ascertain their eligibility by administering the screening questionnaire (see Appendix 4).

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained by text message. This method was successfully used in the feasibility study. 71 Individuals who verbally agreed to take part were sent a text message asking if they understood what was involved and if they were willing to take part. Consent was obtained when the participant positively responded to the text message. These messages were stored electronically. In addition, the research assistant completed the consent form while interviewing the participant and signed and dated the form, including the time at which the text message giving consent was received.

Randomisation

The randomisation was carried out using the secure remote web-based system provided by the Tayside Clinical Trials Unit. Randomisation was stratified by participating centre and the recruitment method and restricted using block sizes of randomly varying lengths. The allocation ratio was 1 : 1, intervention to control.

Allocation concealment

The researchers appointed to carry out the recruitment enrolled the participants. The researchers entered key data items (mobile phone number, study identification number and preferred first name) into the web-based randomisation system. This system automatically assigned men to one of the treatment arms and subsequently delivered the appropriate set of text messages. The researchers who conducted the baseline and follow-up interviews had no access to this system and were unaware to which treatment group the men had been assigned.

Training

The importance of staff training was recently emphasised in a survey of UK clinical trials units. 59 The research assistants who carried out the recruitment and baseline data collection received a formal training programme, comprising three 2-hour sessions of didactic lectures, tutorial sessions and role play. These sessions covered the background to the study and the details of the recruitment strategies and data collection techniques. The need for a sensitive approach to recruitment, based on ‘respectful treatment’,122,123 was described. Researchers were encouraged to value potential participants and to thank them for listening to the outline of the study. In addition to the formal training, two further sessions were held at which progress towards recruitment targets and experience with recruitment techniques were reviewed. Ongoing mentoring formed an important part of training, during which researchers’ recruitment experiences, successes and failures were discussed.

The training on data collection covered the purposes of all of the data items, but focused on the measurement of alcohol consumption. The diversity of alcoholic beverages was described, highlighting how bottled and canned drinks with a specific brand name could vary in volume and strength. The training enabled the researchers to explore this diversity. Role play gave practice in eliciting accurate details of specific drinks consumed, from which detailed drinking histories were prepared. At initial sessions, those playing the role of the drinker were forthcoming with the details of their drinking, but became progressively more reticent in subsequent sessions. This provided those playing the role of the researcher with experience of the careful probing needed to elicit full details of alcohol consumption. Finally, researchers practised calculating the frequency of binge drinking, heavy binge drinking and total alcohol consumption from detailed drinking histories. After each episode of training, supportive feedback was given as part of a group discussion.

Measuring binge drinking

In this study, binge drinking is defined as > 8 UK units of alcohol in a single session. This criterion is widely used in national surveys in the UK. 127 It corresponds to > 64 g of ethanol. The measure used in the USA is ≥ 5 drinks in a single session, which amounts to ≥ 70 g of ethanol. 128 Thus, the definitions are similar but not identical. The study recorded the number of binge-drinking episodes over the 28 days before the interview. Other approaches, such as recording the amount consumed on the heaviest drinking day in the past week, have been criticised. 127

This study also uses > 16 units of alcohol as the threshold for heavy binge drinking to identify those who are consuming very large amounts of alcohol in a single session. There is increasing concern about those who consume sufficient alcohol to be at risk of serious acute adverse effects (e.g. blackout or poisoning). 129 This measure was obtained by doubling the level for binge drinking. The same approach has been proposed for the USA, giving a threshold of ≥ 10 drinks. 129

Data collection methods

All baseline (see Appendix 5) and outcome data (see Appendices 6 and 7) were collected by telephone interview by research assistants blinded to treatment arm. The timeline follow back130 methodology was followed, using the modification for telephone use. 131 Because recent studies have emphasised the importance of measuring the strength and volume of drinks,132,133 the approach was adapted to obtain detailed information on the alcohol consumed on every drinking occasion over the previous 28 days. The initial questions identified how many days in the last 4 weeks participants had consumed alcohol and what they had consumed on each day. Attention was given to eliciting details of the type of drink, for example lager or cider, the brand, the size of servings and the number of servings. Further questions were asked to establish these details. If participants had difficulty describing their drinking, the researcher would ask them to consider the most recent week and then work backwards from there. Once the participant had provided this information, they were asked again about any special occasions not accounted for (e.g. social or sporting events, weddings and drinks with meals out).

When a drink had been poured at home, particularly spirits and wine, participants were asked how their measure compared with a standard pub measure. If consumption was stated as a range of drinks (e.g. ‘2–3 single vodkas’), the mid-point of the range was taken (i.e. 2.5 single vodkas). Similarly, if the number of drinking days was stated as a range (e.g. 2–3 days in a week), this was taken as 2.5 days in a week or 10 days in the last 4 weeks. If the participant could not remember specific drinks (e.g. ‘4 pints of lager, I don’t know which brand’), researchers referred to a ‘standard drinks list’ to ensure consistency.

This detailed questioning provided a list of the type and volume of every drink consumed with sufficient detail for the alcoholic strength to be determined from a look-up table of drinks. The look-up table was compiled from the websites of two major supermarket chains, which provide the volumes and strengths of most common drinks. This was supplemented, when necessary, by the alcohol manufacturer’s own website. The total units of alcohol were calculated for each drinking day. From these data, the number of moderate drinking days (≤ 8 units of alcohol), the number of binge-drinking days (> 8 units of alcohol) and the number of heavy binge-drinking days (> 16 units of alcohol) were established. The data also enabled the total number of units of alcohol consumed over 28 days to be calculated. The process of aggregating drinking and calculating the different measures of consumption was conducted independently by two members of the research team. Differences were resolved by discussion.

Baseline data collection

Alcohol consumption was measured by the methods described above. To minimise research participation effects, which could influence the impact of the intervention, the number of data collected at baseline was kept to a minimum. Recent systematic reviews134,135 indicate that baseline questions can lead participants to re-evaluate drinking behaviour. Thus, questions on topics such as knowledge of the harms of alcohol, or intentions to reduce consumption, were not asked.

Individual-level sociodemographic status was assessed using marital status, employment status and educational attainment. The participants’ postcodes were used to derive the SIMD score. In addition, a single question from the Fast Alcohol Screening Test (FAST)136 was used to determine whether or not participants suffered episodes of memory loss following drinking sessions.

Follow-up methods

Several evidence-based techniques were used in this study to promote retention: financial incentives; credibility of source (the use of the university logo on letterhead); personalised contacts (the use of the participant’s preferred first name); regular contact (through keeping-in-touch text messages); multiple attempts at contact; and the use of multiple methods of contact (letters, texts, telephone calls and, when the information was available, e-mails and partner’s mobile phone). 52,55,57,58,60,61,63–65

The follow-up interviews were conducted by telephone from August 2014 to February 2016. Each week a computer-generated list identified men due to be followed up in the next week. These men were sent a letter 1 week in advance reminding them that they were due to be contacted, and that they would receive a £10 voucher for completing the follow-up interview. An automated text message reminder was also sent 3 days before follow-up was due. Multiple attempts at contact were made at various times of day and on various days of the week. After several unsuccessful attempts, a voicemail message was left and a reminder text message was sent by the researcher. When the information was available, other contact methods were also tried: landlines, mobile phone numbers of partners and e-mail addresses. Subsequently, up to three letters were sent, with reply-paid envelopes, requesting updated contact details and convenient times for contact. Finally, for men recruited through general practice registers, the practice was contacted to request updated contact information.

Data collection at the first follow-up

The first follow-up was carried out 3 months post intervention (see Appendix 6). Data on alcohol consumption were collected, using the method described above. Two secondary outcomes were measured: the proportion of men consuming > 8 units of alcohol, and the proportion consuming > 16 units of alcohol, on ≥ 3 occasions in the previous 28 days. No other data were collected at this follow-up to minimise question behaviour effects. 134,135 Participants were also asked for any change of address to ensure that their gift vouchers would be correctly delivered. The researchers collecting the data were blind to treatment allocation.

Data collection at final follow-up

The final follow-up was carried out 12 months post intervention (see Appendix 7). The primary outcome and three secondary outcomes were measured at this follow-up. The primary outcome was the proportion of men consuming > 8 units of alcohol on ≥ 3 occasions in the previous 28 days. Two secondary outcomes of alcohol consumption were also measured at final follow-up: the proportion of men with ≥ 3 occasions of heavy binge drinking (> 16 units of alcohol in a session) and the mean alcohol consumption over 28 days. The method of collecting the data on alcohol consumption was described above. Finally, the AUDIT137 was used to determine the frequency of hazardous and harmful drinking. Questions were also asked about attempts to reduce drinking and the success of these attempts. Questions on self-efficacy for refusing drinks were taken from a validated questionnaire. 138 Health status was measured by the EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L),139 a validated quality-of-life questionnaire designed to be simple to administer. Contacts with police/criminal justice, plus accident and emergency and other health-care usage, were measured by the widely used short Service Use Questionnaire (S Parrot, Department of Health Sciences, University of York, 2012 personal communication). Well-being was measured using the four Office for National Statistics Personal Well-being questions. 140 Finally, questions were asked about the acceptability of the study methods and recall of the text messages.

The sequence of questions in the follow-up questionnaire was arranged to obtain data on the primary and secondary outcomes first, followed by perceived changes in drinking over 12 months and the data for the economic evaluation, and, finally, participants’ views on the study methods (see Appendix 7). This ensured that questions on alcohol consumption were not influenced by responses to questions on other topics. It also meant that the most important data would be obtained if the interview was terminated early.

Sample size calculation

The sample size calculation is based on the hypothesised difference in the proportion of frequent binge drinking between intervention and control groups at the 12-month post-intervention assessment. It uses the finding from the feasibility study that 57% of men consumed > 8 units of alcohol on ≥ 3 occasions in the previous 28 days. 71 The proposed effect size was that the intervention would reduce the frequency of binge drinking from 57% to 46%, a net reduction of 11%. A recent systematic review of conventional brief interventions5 found an 11% difference in frequency of binge drinking between intervention and control groups. To detect a reduction in the frequency of binge drinking in this way from 57% to 46% (at the 5% significance level with a power of 80%) would require a sample size of 319 per group, or 638 in total. The required sample size was then increased by 20% to allow for losses to follow-up, making the total sample size 798. We expected that the loss to follow-up would be less than this, as the loss in our 3-month feasibility study was only 4%. However, as most alcohol brief intervention trials have a loss to follow-up of > 20%,5 it was prudent to make suitable allowance.

Statistical methods

The analysis of treatment effects was conducted by intention to treat.

Methods for descriptive statistics

Binary variables (including primary and secondary outcomes as well as baseline binary variables) were summarised as number of observations, number of missing values, and number and percentage overall and per treatment group. Continuous variables (total alcohol consumption at 12 months post intervention and total alcohol consumption at baseline) were summarised as number of observations, number of missing values, mean, standard deviation (SD), standard error of the mean, median, and range overall and per treatment group.

Analysis of primary outcome

Logistic regression141 was used to investigate the effect of the intervention on the primary outcome, that is, whether or not the participant had consumed > 8 units of alcohol on ≥ 3 occasions in the previous 28 days at 12 months post intervention (proportion drinking > 8 units of alcohol on ≥ 3 occasions at 12 months). Three models were fitted to the primary outcome:

-

the unadjusted model (only treatment group as a fixed factor in the model)

-

the model adjusted for one baseline drinking variable (whether or not the participant had consumed > 8 units of alcohol on ≥ 3 occasions in the 28 days before the beginning of the study)

-

a full model adjusted for baseline drinking as for model 2 and the baseline covariates of method of recruitment (general practice registers/TSS), recruitment centre, age group, living with a partner (yes/no), employed (yes/no), further education (yes/no), SIMD score (1–10) and question 2 from the FAST. 136

Model 3 is considered the primary analysis and models 1 and 2 are presented for information. The treatment effect of the intervention on the primary outcome was the difference in proportions, or odds ratios (ORs), between the two groups with the 95% confidence interval (CI). Unadjusted treatment effect estimates were compared with corresponding estimates adjusted for baseline and other model covariates.

Analysis of secondary outcomes

The binary secondary outcomes (> 8 units of alcohol on ≥ 3 occasions at 3 months post intervention, > 16 units of alcohol on ≥ 3 occasions at 3 months and > 16 units of alcohol on ≥ 3 occasions at 12 months, and an AUDIT score of > 7 at 12 months post intervention) were analysed using the same analysis plan as for the primary outcome based on the logistic regression model. The adjustment for baseline drinking used the alcohol measure that was the equivalent of the secondary outcome (e.g. for the proportion drinking > 16 units of alcohol on ≥ 3 occasions at 12 months, the adjustment used the proportion drinking > 16 units of alcohol on ≥ 3 occasions at baseline). However, as the AUDIT was not administered at baseline, the adjusted models for the proportion with an AUDIT score of > 7 at 12 months used whether or not the participant had consumed > 8 units of alcohol on ≥ 3 occasions in the 28 days before the beginning of the study (> 8 units of alcohol on ≥ 3 occasions at baseline).

For total alcohol consumption at 12 months post intervention, owing to the skewness of the data, a generalised linear model assuming a gamma distribution and log-link function141 was used in the analysis. Again, three models were fitted as described above to this secondary outcome: the unadjusted model (only treatment group as a fixed factor in the model), the model adjusted for baseline (total alcohol consumption at baseline) and the full model adjusted for baseline and the other covariates listed above for the analysis of the primary outcome. The treatment effect of the intervention on this outcome was measured as the mean difference in consumption between treatment groups with the 95% CI.

Sensitivity analysis for missing data

Multiple imputation methods were used to assess the sensitivity of primary outcome results to missing data. Generalised linear models were used for multiple imputations, assuming that data were missing at random. 142 Multiple imputation included the explanatory variables used in the fully adjusted model above plus the primary and secondary outcomes. All primary and secondary outcome variables at baseline and at the 3-month and 12-month follow-ups were used, as was additional information collected at the 12-month follow-up interviews. This included demographic data at the 12-month follow-up, several questions on participant experiences in the study, and items from the Service Use Questionnaire, the EQ-5D-5L and the Office for National Statistics Personal Well-being questionnaire.

Economic evaluation

The methods for the economic evaluation are presented in Chapter 9.

Patient and public involvement

The trial design was informed by findings from the feasibility study, particularly from the focus groups with disadvantaged men. In addition, the pilot trial with disadvantaged men explored their views of the study design and conduct to identify ways in which these could be improved. Two user group representatives were involved throughout the development and conduct of the full RCT. They attended project meetings and assisted in developing the recruitment methods, reviewing the use of incentives, commenting on the data collection questionnaires and assessing the overall acceptability of the study methods. Volunteers also reviewed the text message intervention and the narrative on which it was based.

Changes to the protocol

The Readiness Ruler143 was not used in the final follow-up questionnaire. This question asks participants to choose one option, from four, that best describes their current drinking status: (1) I never think about my drinking, (2) sometimes I think about drinking less, (3) I have decided to drink less, and (4) I am already trying to cut back on my drinking. This question was not used because it was anticipated that some participants would have made changes to their alcohol consumption, either by cutting down or by stopping completely. Those who had done so might find that none of the options were applicable. Thus, participants in this study were instead asked:

-

Have you tried to reduce your drinking in the past year?

-

Did you set a goal to cut down on your drinking?

-

If yes, how did you try to achieve your goal?

-

If you managed to cut down, have you continued to drink less?

The FAST136 was not used in the final follow-up questionnaire; the AUDIT137 was used instead. The AUDIT comprises 10 questions, all of which are included in the FAST. Many published studies have used the AUDIT, and so, to allow comparison with these, the AUDIT was used in this study. However, the wording of one question common to the FAST and the AUDIT differs slightly. In the AUDIT, the final questions asks ‘Has a relative or friend, doctor or other health worker been concerned about your drinking and suggested that you cut down?’ The three possible responses are no; yes, but not in the last year; and yes, during the last year. In the FAST, the question asks ‘In the last year, has a relative or friend, doctor or other health worker been concerned about your drinking and suggested that you cut down?’ Here the possible responses are: no; yes, on one occasion; and yes, on more than one occasion. This modification was made for the FAST to ensure that the result focused on the last year. 144 This minor difference between the questionnaires means that we cannot report a total FAST score. Thus, the AUDIT is reported instead of the FAST.

The goal-setting and action-planning scales developed by Renner et al. 145 were not used. Initial piloting showed that the burden of answering the many questions on each scale was too great for telephone interviews. Instead, a few specific questions were asked about goal-setting, action-planning and coping-planning.

Chapter 4 Recruitment and baseline assessment

Introduction

This chapter presents the data on recruitment and describes the drinking patterns and demographic characteristics of the study participants. It also explores the implications of the findings for the recruitment of a group usually considered hard to reach.

Results

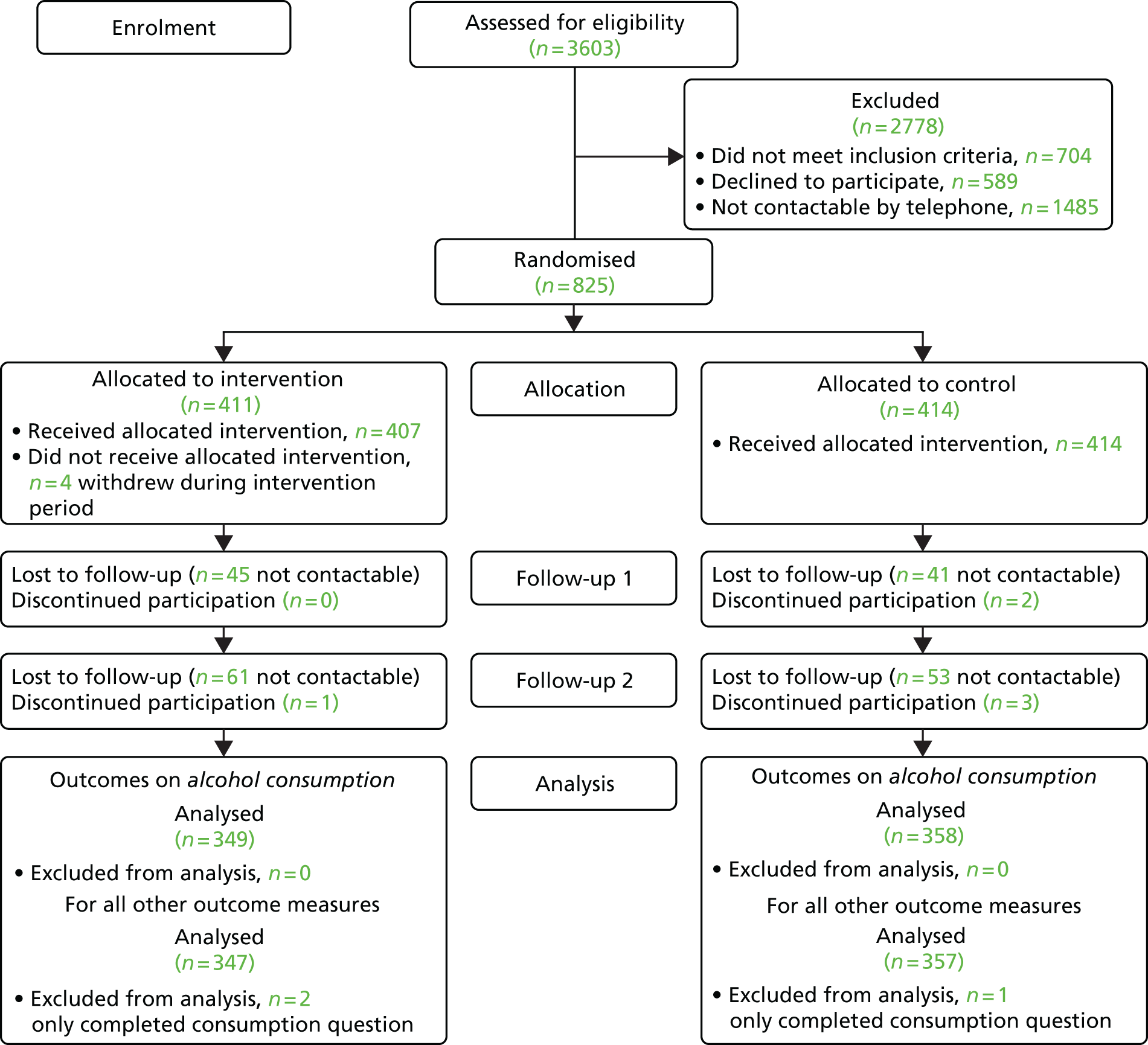

The Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram (Figure 2) shows the passage of individuals through the study. A total of 3603 men were assessed for inclusion in the study, of whom 704 were not eligible (e.g. they had not consumed > 8 units of alcohol on ≥ 2 occasions in the previous 28 days or were not within the target age range). A further 1485 men were not contactable by telephone, and 589 declined. It should be noted that the distinction between not eligible and not interested could be blurred, as some men may have said that they were not interested to avoid discussing their alcohol consumption and others may have said that they did not drink enough as a convenient way of refusing to participate.

FIGURE 2.

The CONSORT flow diagram. Reproduced from Crombie et al. 146 © 2018 The Authors. Addiction published by John Wiley & Sons Ltd on behalf of Society for the Study of Addiction. This is an open access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

The target of 798 men was exceeded, with 825 men recruited in total. Both recruitment strategies were successful (Table 2), although slightly more men were recruited from general practice registers than by community outreach (TSS). Recruitment targets were met in three of the four centres. There was a small shortfall in numbers of men recruited from general practice registers in Forth Valley, but this was compensated by additional men recruited from Fife.

| Centre | Recruitment method, n (%) | Total, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| General practice registers | TSS | ||

| Tayside | 102 (23.9) | 100 (25.1) | 202 (24.5) |

| Fife | 132 (30.9) | 99 (24.9) | 231 (28.0) |

| Forth Valley | 88 (20.6) | 98 (24.6) | 186 (22.5) |

| Glasgow | 105 (24.6) | 101 (25.4) | 206 (25.0) |

| Total | 427 | 398 | 825 |

Most men (84%) had ≥ 3 binge-drinking sessions (> 8 units of alcohol) in the previous 28 days, and almost half had ≥ 3 heavy binge-drinking sessions (> 16 units of alcohol) (Table 3). Participants had almost 20 alcohol-free days over the 28-day period. On average, the participants had 6.6 binge-drinking sessions in 28 days, or 1.65 per week.

| Drinking pattern | Method of recruitment | Total (N = 825), n (%) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| General practice registers (N = 427) | TSS (N = 398) | |||

| Number (%) of men with ≥ 3 occasions of binge drinking (> 8 units of alcohol) in previous 28 days | 350 (82.0) | 346 (86.9) | 696 (84.4) | 0.050a |

| Number (%) of men with ≥ 3 occasions of heavy binge drinkingb (> 16 units of alcohol) in previous 28 days | 171 (40.0) | 221 (55.5) | 392 (47.5) | < 0.001a |

| Mean consumption in past 28 days (units) (SD) | 105.6 (89.0) | 164.4 (162.2) | 134.0 (132.8) | < 0.001c |

| Mean number of binge-drinking sessions (> 8 units of alcohol) (SD) | 5.87 (4.6) | 7.34 (5.8) | 6.58 (5.2) | < 0.001c |

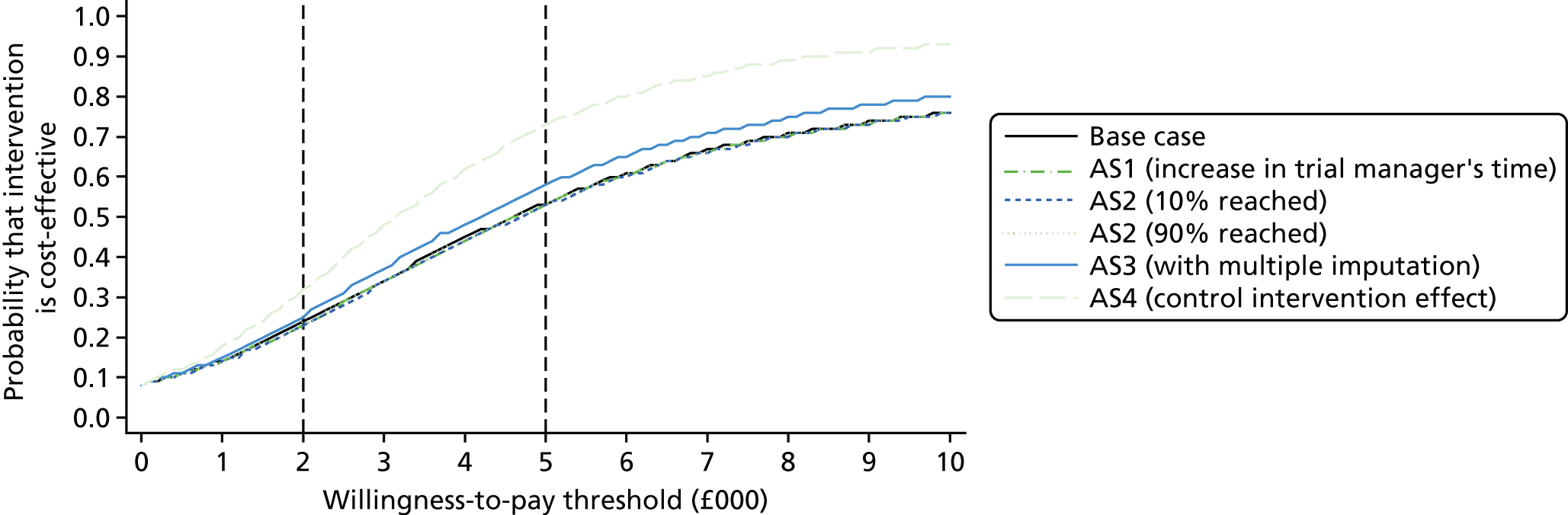

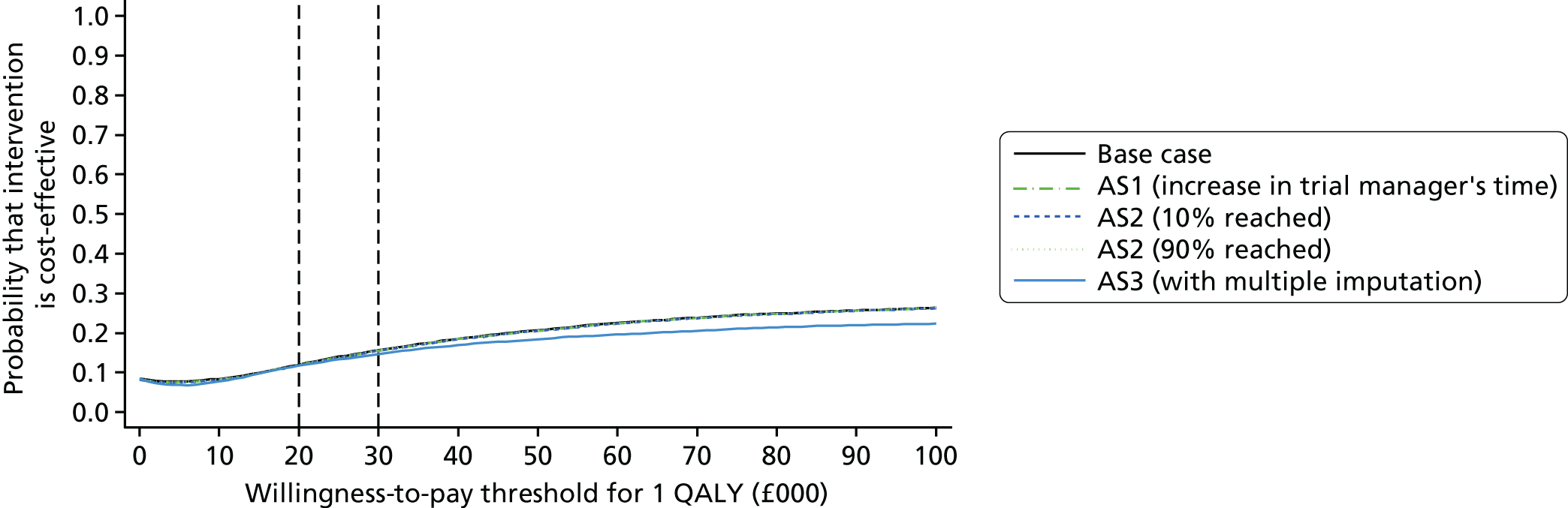

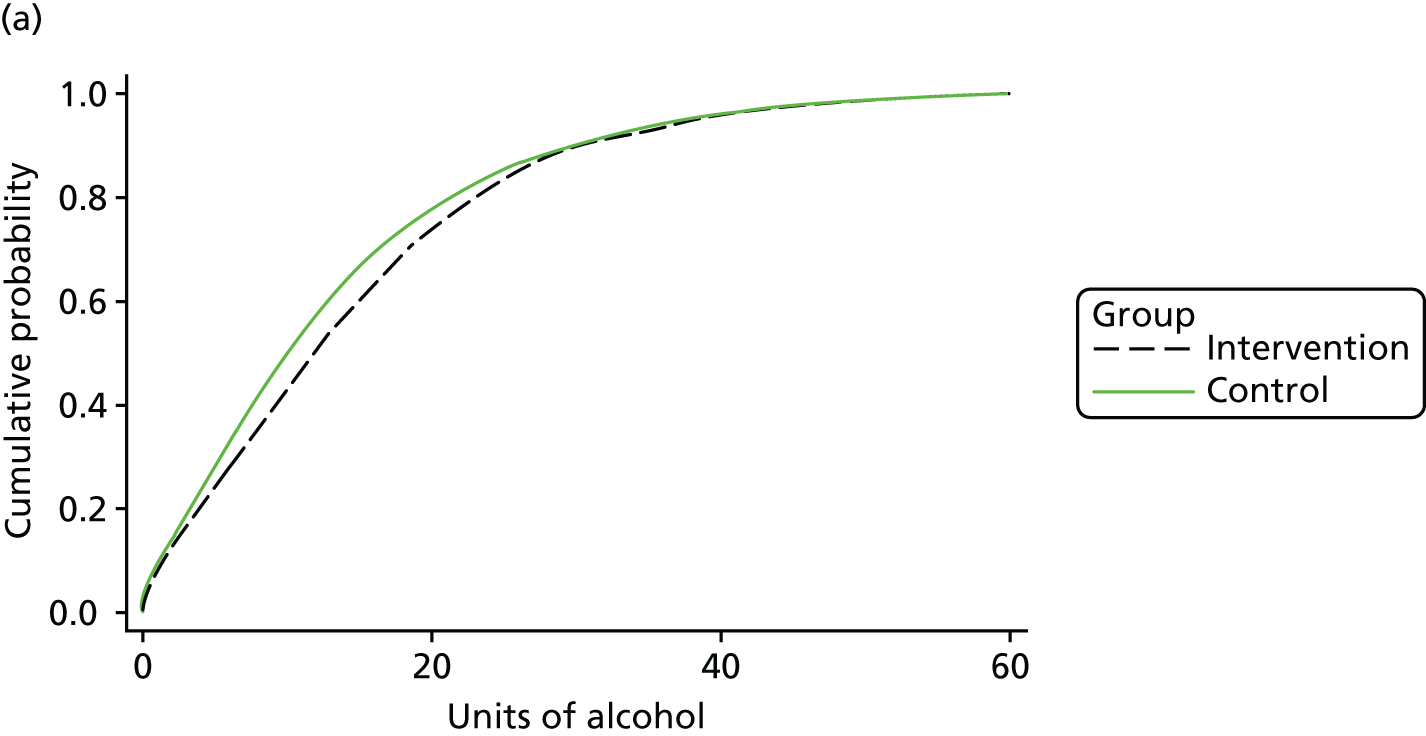

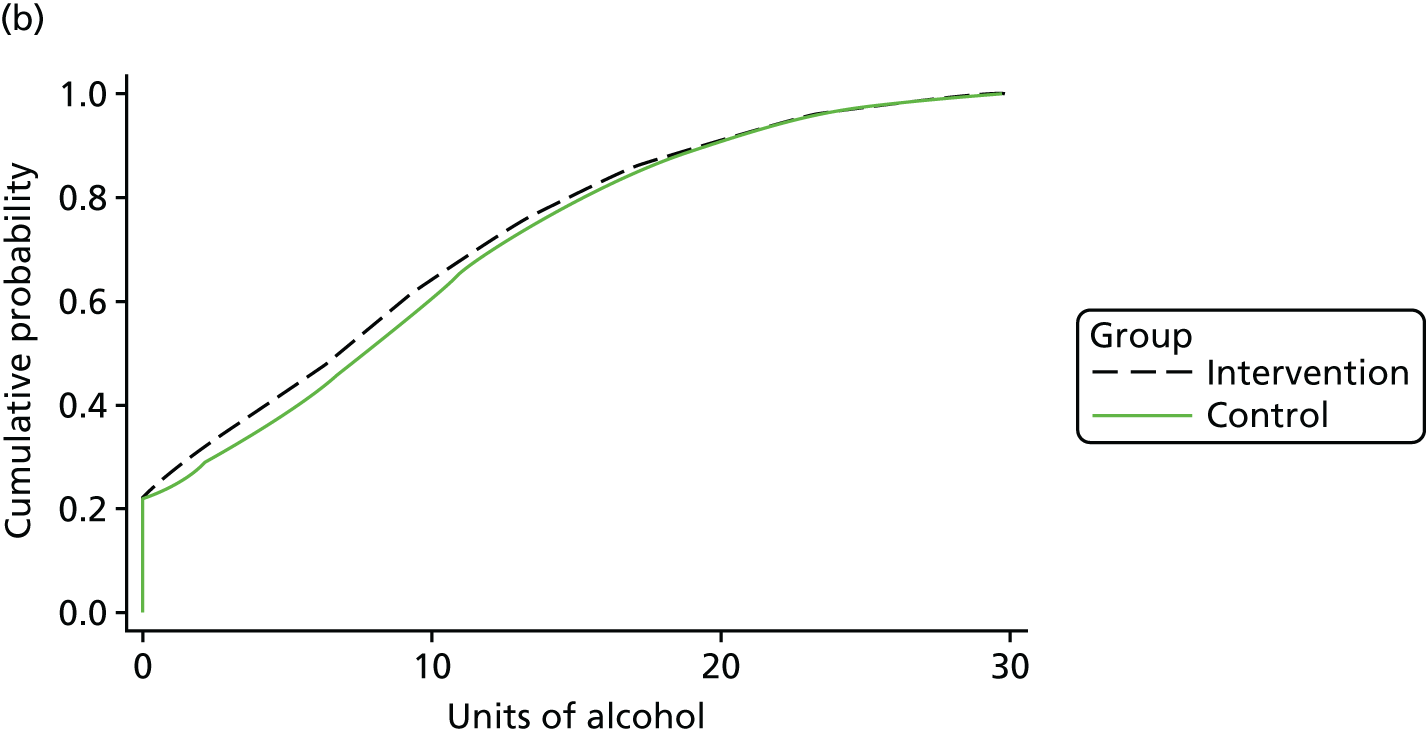

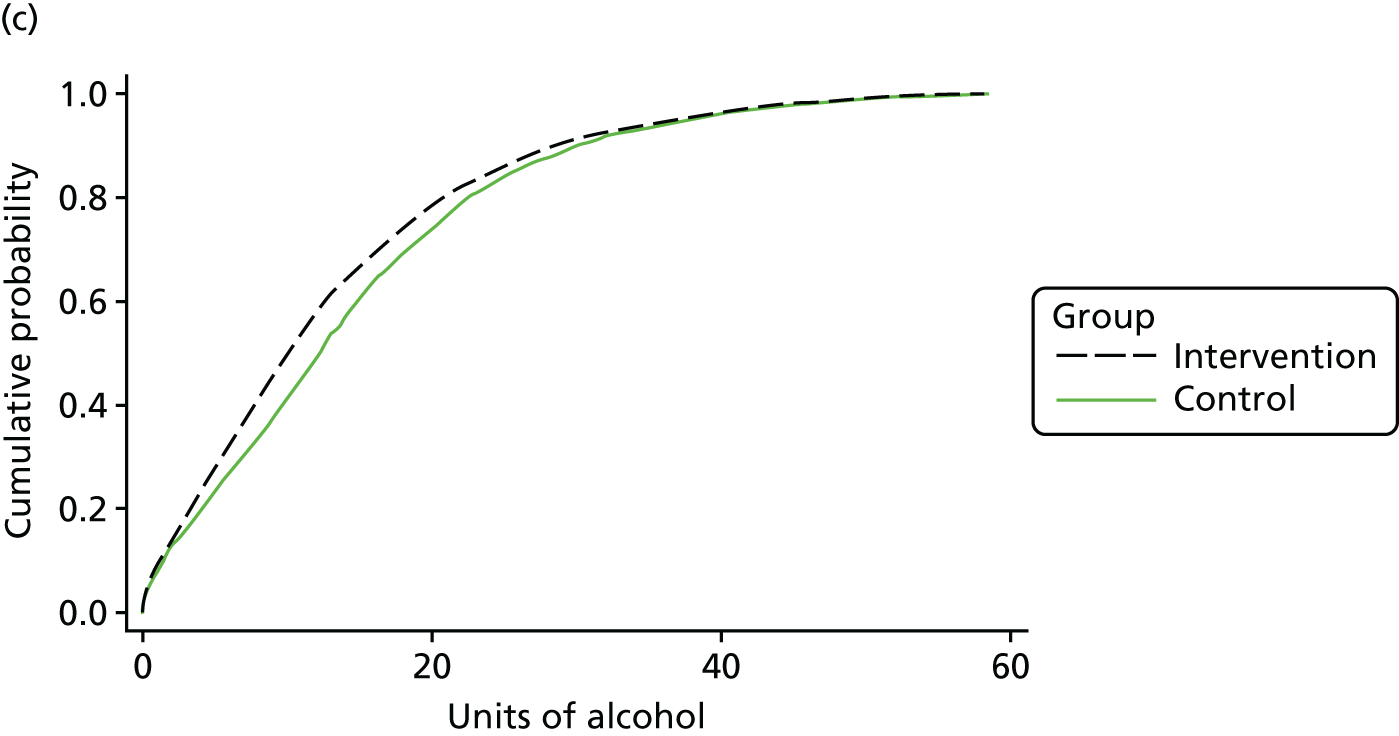

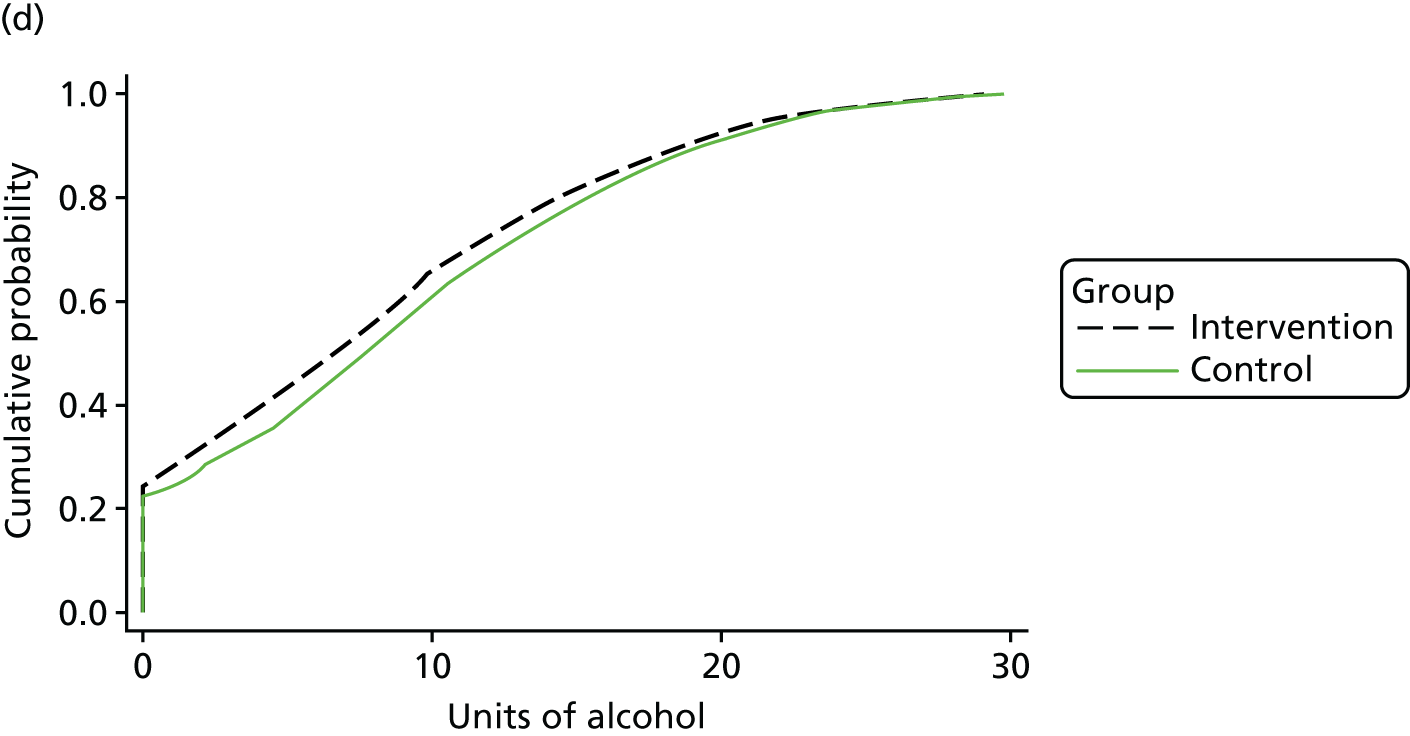

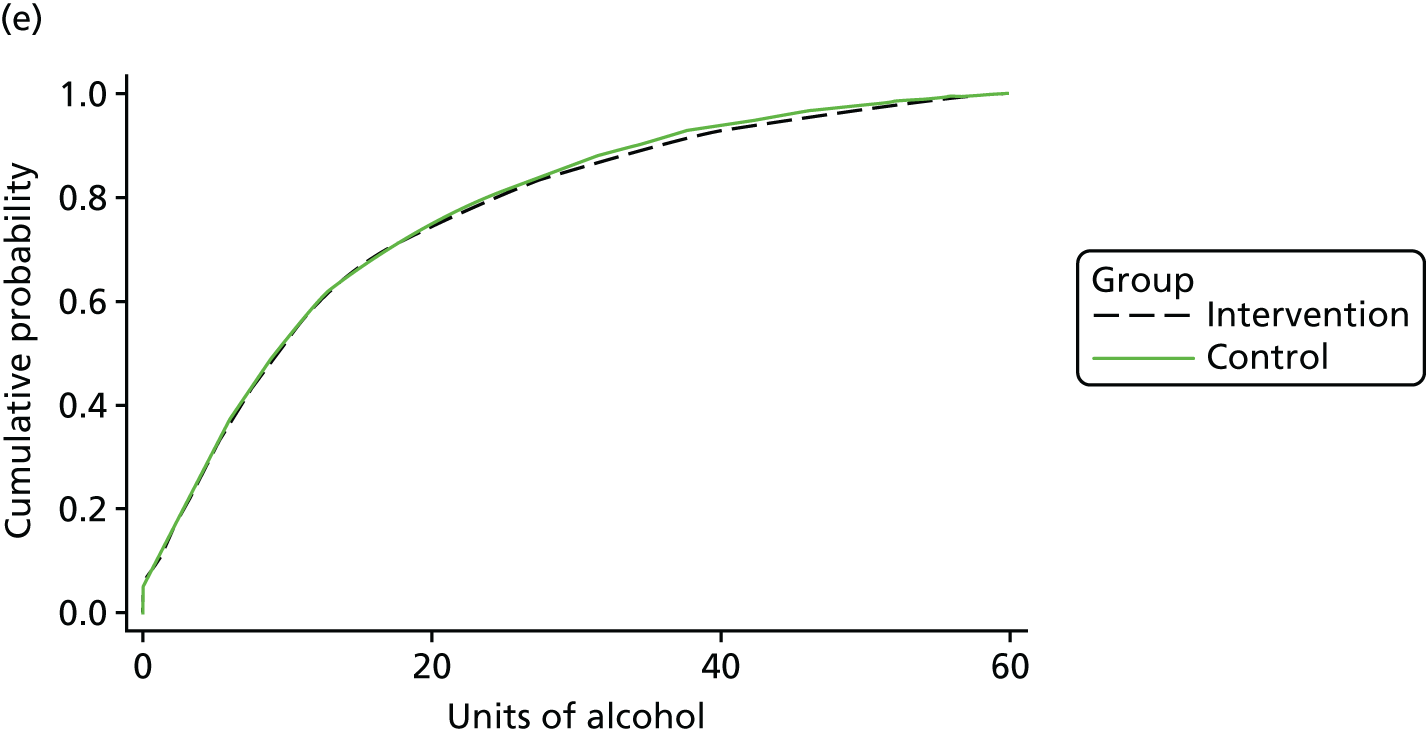

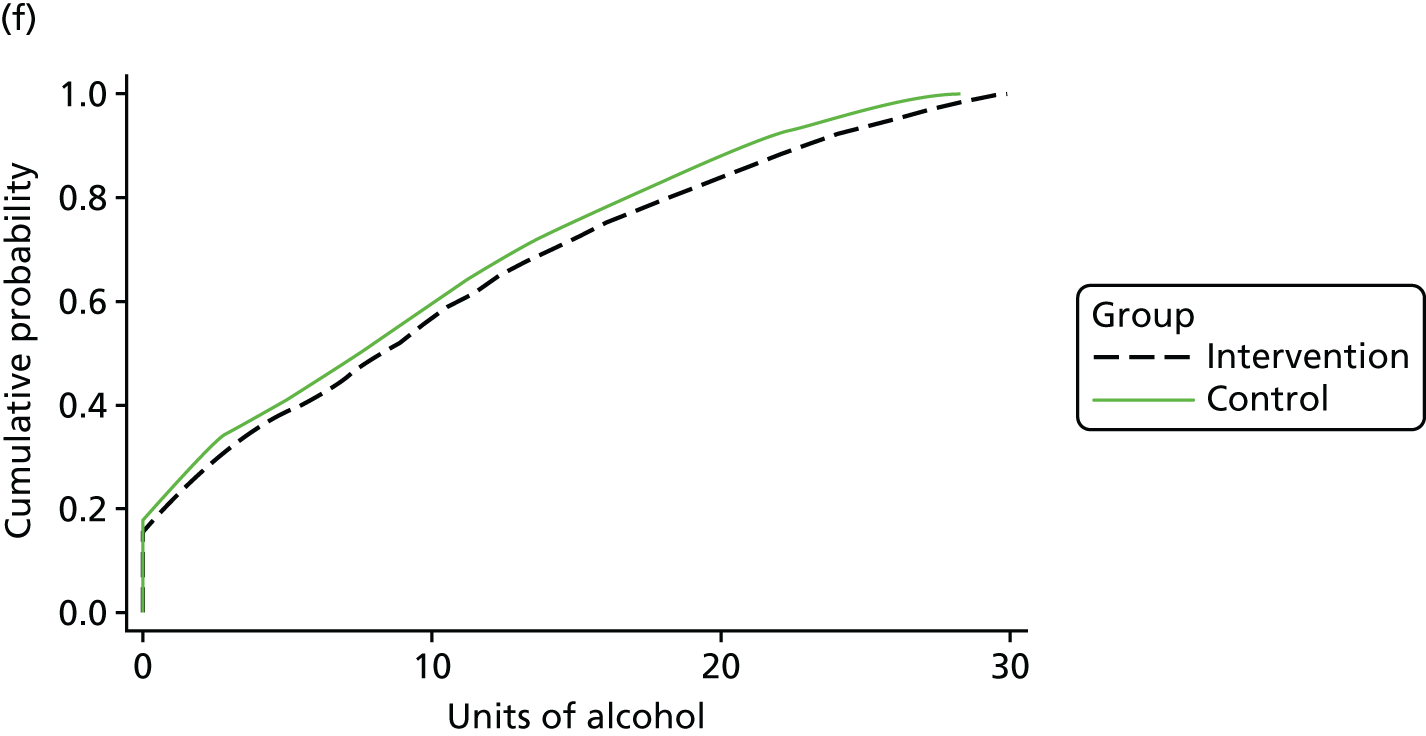

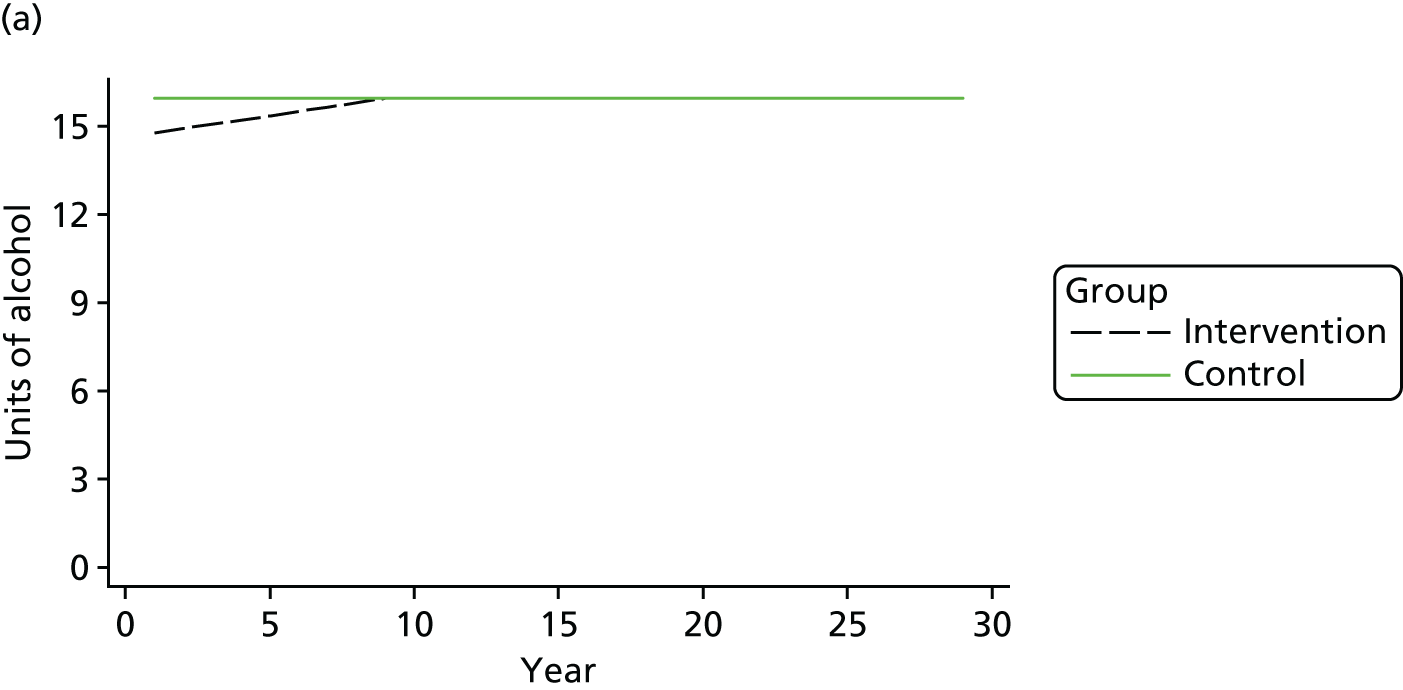

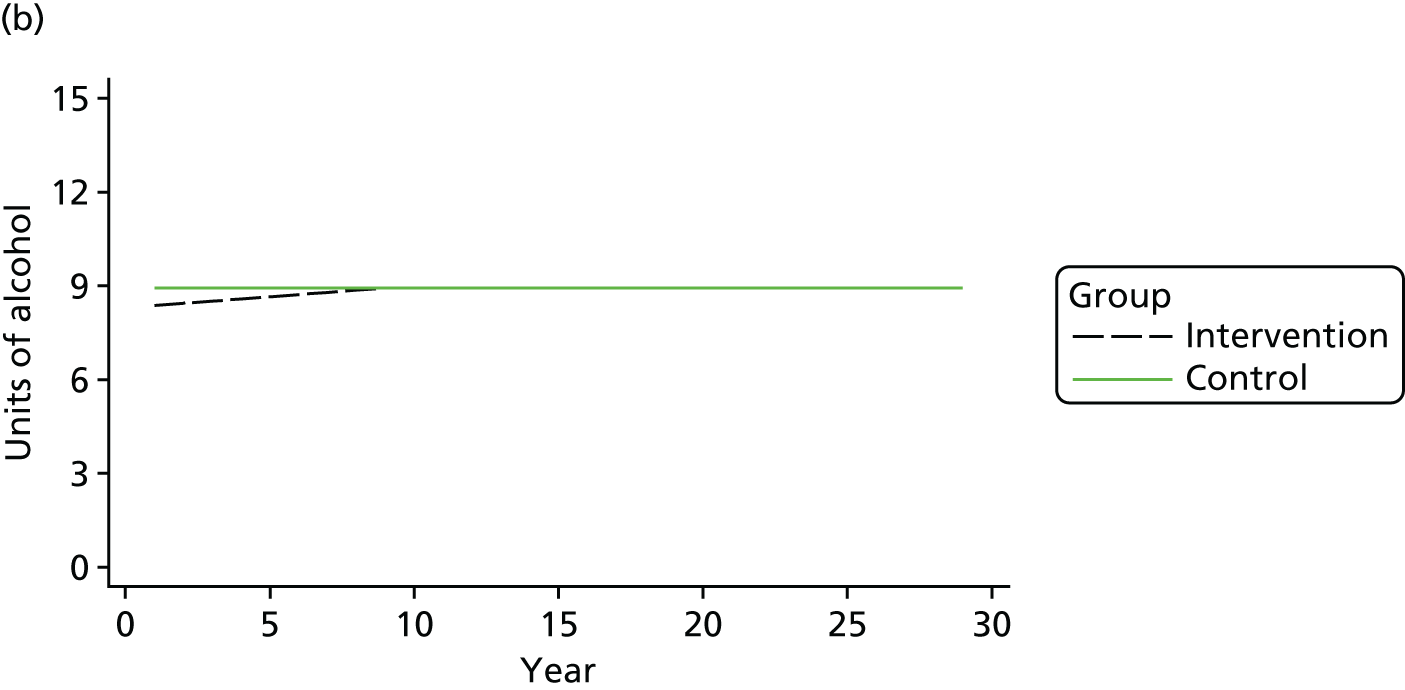

| Mean number of heavy binge-drinking sessionsb (> 16 units of alcohol) (SD) | 2.66 (3.7) | 4.55 (5.7) | 3.57 (4.8) | < 0.001c |