Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 13/99/32. The contractual start date was in January 2015. The final report began editorial review in July 2016 and was accepted for publication in February 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Kate Hunt is deputy chairperson of the Research Funding Board for the National Institute for Health Research Public Health Research programme.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by Gray et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2018 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

The problem of obesity and sustained weight loss

Rising levels of obesity are a major challenge to public health. 1 In 2011, it was estimated that there would be 11 million more obese adults in the UK by 2030, resulting in up to 668,000 additional cases of diabetes, 461,000 additional cases of heart disease and stroke, 130,000 additional cases of cancer and up to 6.3 million quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) lost, with associated medical costs set to increase by £1.9B–2B per year. 2

Although the behaviour change techniques (BCTs) and strategies that are effective in helping people achieve clinically significant short-term weight loss (by at least 5%3 of their initial body weight), by increasing physical activity (PA) and improving diet, are now well described,4–6 longer-term weight loss is less well researched and remains a challenge. Weight loss as a result of taking part in behavioural interventions typically peaks at around 6 months, followed by a plateau and then a gradual regain in weight at a rate of 1–2 kg per year (often with larger regains in the earlier years). 7–10 Participants in weight loss programmes typically regain 30–35% of lost weight in the first year post intervention, and most return to their baseline weight within 3–5 years. 11–14

As long-term weight maintenance is essential to maximise the health benefits associated with weight reduction,15 it is important to understand how to support people to sustain their weight loss following behavioural interventions. Systematic reviews indicate that a combination of energy and fat reduction, regular PA and behavioural strategies (such as regular weighing) is required for successful long-term weight loss. 16–18 Other reviews9,19 suggest that short-term weight loss, flexibility and variability in approach to diet and PA, and ongoing self-monitoring are important.

Some researchers have focused on the impact quality of motivation or locus of control on maintenance of behaviour change. Self-determination theory20,21 suggests that an understanding of motivation for behaviour change requires a consideration of innate psychological needs for autonomy (associated with the internalisation of regulation from external regulation, through introjected and identified regulation, to integrated regulation, in which a new behaviour becomes fully assimilated to the self), competence to perform behaviours, and relatedness to others. An empirical study22 of weight loss maintenance in relation to locus of control (the extent to which a person believes that they have control over events in their life) further demonstrated that an internal locus of control was associated with long-term weight loss maintenance.

Meanwhile, a recent systematic review23 of theoretical explanations for the maintenance of behaviour change suggested that people tend to maintain their behaviour if they are satisfied with the behavioural outcomes; if they enjoy engaging in the behaviour, or if the behaviour is congruent with their identity, beliefs and values; if they successfully monitor and regulate the newly adopted behaviour and have effective strategies to overcome barriers; if the new behaviours have become habitual; if their psychological and physical resources are plentiful (i.e. they are not subject to additional stressors such as life events); and if their environmental and social context supports the new behaviour.

Current evidence therefore suggests that fostering an internalised regulation of PA and dietary behaviours and an internal locus of control (which, in turn, are associated with habit formation and the routinisation of behaviours and their incorporation into values, self-identity and beliefs) are important for the long-term maintenance of weight loss. Self-monitoring, satisfaction with changes, and social and other environmental circumstances are also important. Nevertheless, the evidence on long-term weight loss remains limited, particularly in men. 16,24 More can be learned about the factors that are important for weight loss maintenance from follow-up studies of behavioural interventions that investigate who is successful in achieving long-term weight loss and how they do this. This will inform the development of future interventions to improve long-term outcomes.

Men and weight management

Since 1980, the prevalence of obesity in men worldwide has almost doubled. 1 In the UK, male obesity is among the highest in Europe and is forecast to increase at a faster rate than female obesity in the next 20 years. 2 Compared with women, men may be more vulnerable to the adverse health consequences of obesity. The tendency of men to carry excess fat abdominally puts them at greater cardiometabolic risk,25 and they are diagnosed with type 2 diabetes at a lower body mass index (BMI) than women. 26 In Scotland, obesity-related health risk is socially patterned, with men who are less affluent and less well educated at increased risk. 27 Nevertheless, men are under-represented in referrals to commercial weight management programmes (between 11%28 and 13%29 of referrals are men) and in NHS weight management services (23% of referrals are men). 30 A recent systematic review concluded ‘[t]hat men are under-represented suggests that methods to engage men in services, and the services themselves, are currently not optimal’. 31

Men’s reluctance to enrol in weight management programmes may in part reflect the way some men perceive weight management as a ‘diet’ or a ‘women’s’ issue. 32–34 It may also be influenced by the setting in which such programmes are delivered; for example, a Slimming World (Alfreton, UK) initiative35 to target men (by offering men-only groups) failed to increase their engagement by > 2% (i.e. from 3% to 5%). However, the potential of professional sporting organisations to attract men to health promotion activities is now widely recognised. 36–41 A National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Public Health Research programme-funded randomised controlled trial (RCT) (09/3010/06)42 provided evidence of the success of professional football clubs in engaging men in a weight loss and healthy living programme [Football Fans in Training (FFIT)] and supporting them to lose weight42–44 and to make other positive changes to their health and behaviours up to 12 months after baseline measurement. The present study reports on the follow-up study (to 3.5 years post baseline measurement) of participants in the RCT of the FFIT programme at 13 of the top professional football clubs in Scotland (ISRCTN32677491). 45

Football Fans in Training: weight loss, physical activity and healthy eating for men

Here we provide a brief summary of the development of the FFIT programme, the key results from the previously funded evaluation and an update on the FFIT programme since the RCT results were published.

The FFIT programme was specifically designed to work with, rather than against, prevailing conceptions of masculinity, although it also takes account of best evidence in weight loss and behaviour change. 42,46 The FFIT programme is ‘gender-sensitised’ in relation to context (in the traditionally male environment of football clubs and men-only groups), content (for which information on the science of weight loss presented simply: ‘science but not rocket science’), discussion of alcohol, ‘branding’ (e.g. the use of football club insignia on programme materials) and style of delivery (using participative, peer-supported learning that encourages the men to interact for mutual learning and support, and positive male ‘banter’ to facilitate the discussion of sensitive subjects). The programme is delivered free of charge by community coaching staff at professional football clubs to groups of up to 30 men who are overweight or obese (participant-to-coach ratio 15 : 1) over 12 weekly sessions at football club stadia. At the start of the RCT, the coaches were trained over 2 days in the FFIT delivery protocol by the research team.

As Table 1 shows, each FFIT session combines advice on healthy eating and/or BCTs (‘classroom component’) with a coach-led group PA session using football club facilities. The BCTs are those known to be effective in PA and dietary interventions (self-monitoring, goal-setting, implementation intentions and feedback on behaviour)4 and social support, both from other participants and from their wider social networks,5 is also promoted (a full description of the use of BCTs within the FFIT programme is provided elsewhere46). Throughout the FFIT programme, men are encouraged to make behavioural changes that they can sustain long term, and to incorporate PA and healthy eating into their daily lives. The 12-week active phase is followed by a light-touch weight maintenance phase, including six e-mail prompts from coaches until 12 months after the start of the FFIT programme, and an invitation to a group reunion after 9 months. 46

| Classroom | PA | |

|---|---|---|

| Week 1 |

|

|

| Week 2 |

|

|

| Week 3 |

|

|

| Week 4 |

|

|

| Week 5 |

|

|

| Week 6 |

|

|

| Week 7 |

|

|

| Week 8 |

|

|

| Week 9 |

|

|

| Week 10 |

|

|

| Week 11 |

|

|

| Week 12 |

|

|

| Reunion |

|

|

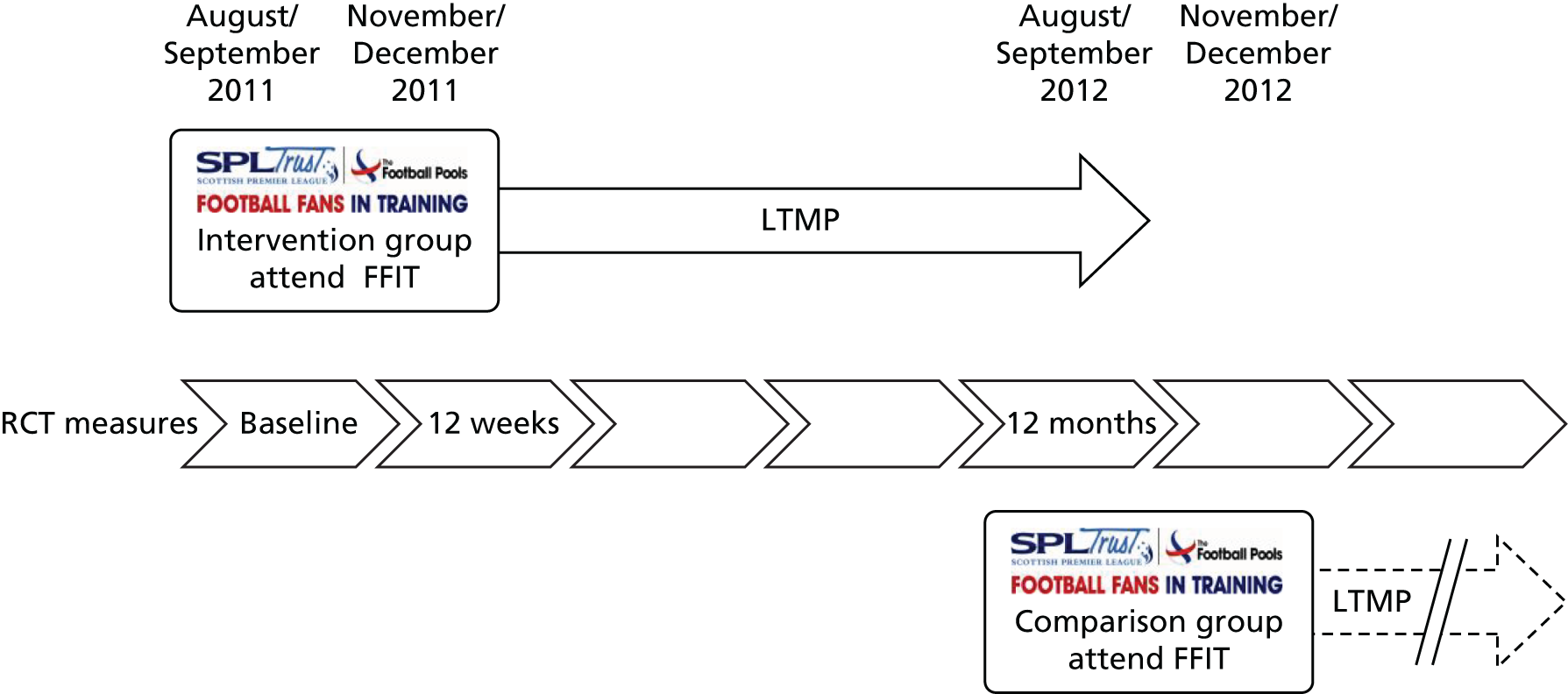

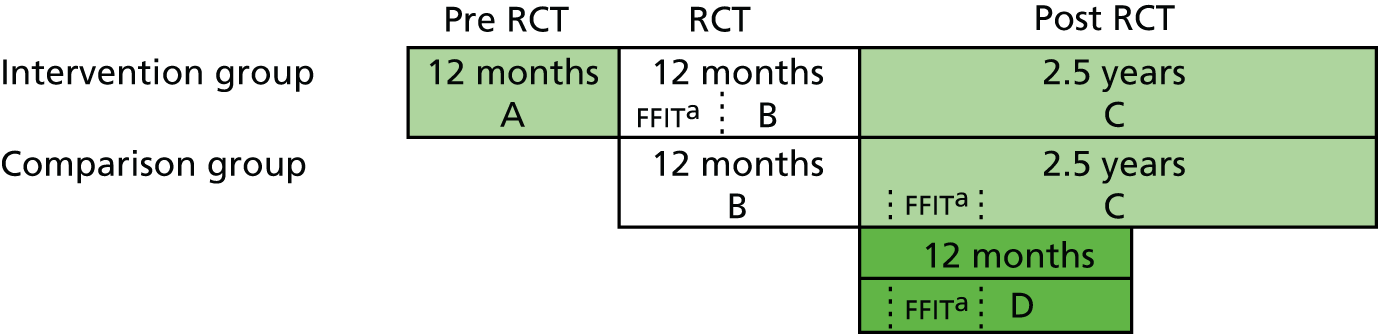

Figure 1 provides an overview of the design of the FFIT RCT conducted in 2011/12; further details are provided elsewhere. 43,44 This was a pragmatic trial, with weight loss at 12 months as the primary outcome, in which 747 men (aged 35–65 years with an average BMI of ≥ 28 kg/m2) were randomly allocated either to the FFIT RCT intervention group (n = 374) or to a waiting list comparison group (n = 373) following baseline measurements at the 13 participating football clubs. The baseline measurements demonstrated that the programme successfully engaged men from across the socioeconomic spectrum43 whose excess body weight put them at a high risk of ill health. 47 At the baseline measurements, all men were given an information book on weight loss and feedback on their weight using a BMI wheel as a visual aid. As Figure 1 shows, men in the intervention group commenced the FFIT programme immediately (within 3 weeks of baseline measurement in August/September 2011) and men in the comparison group were offered a place on the FFIT programme at their football club 12 months later (in autumn 2012).

FIGURE 1.

The FFIT RCT waiting list design and timeline. LTMP, light touch maintenance phase.

Baseline and follow-up measurements at 12 weeks and 12 months (with 92% retention overall at 12 months) were undertaken by a fieldwork team who were trained to standard measurement protocols. The waiting list design meant that all men in the RCT (i.e. the comparison group as well as the intervention group) were offered an opportunity to take part in the FFIT programme. However, because the comparison group took part in the FFIT programme after the end of the RCT [under ‘routine delivery’ (i.e. non-research) conditions], no post-intervention measurements were conducted with them.

During the RCT, the coaches delivering the FFIT programme reported weekly attendance at programme sessions to the research team; four out of five men in the intervention group attended at least 6 out of the 12 sessions during the active phase. 43 Observations of a sample (n = 26) of sessions across all football clubs suggested that the fidelity of delivery was good: coaches delivered 81 out of 93 (86%) key tasks. 43 At 12 months, the mean between-group weight loss difference was 4.94 kg [95% confidence interval (CI) 3.95 to 5.94 kg; p < 0.0001; adjusted for baseline weight and football club] in favour of the intervention group, and 39.0% of men in the intervention group (130/333), compared with 11.3% of men in the comparison group (40/355), had achieved a weight reduction from baseline of ≥ 5%. Significant between-group differences were also observed at 12 months in secondary outcomes including waist circumference, percentage body fat, resting blood pressure (BP), self-reported PA, dietary intake, alcohol consumption and psychological outcomes [self-esteem, affect and physical health-related quality of life (HRQoL)]. 43

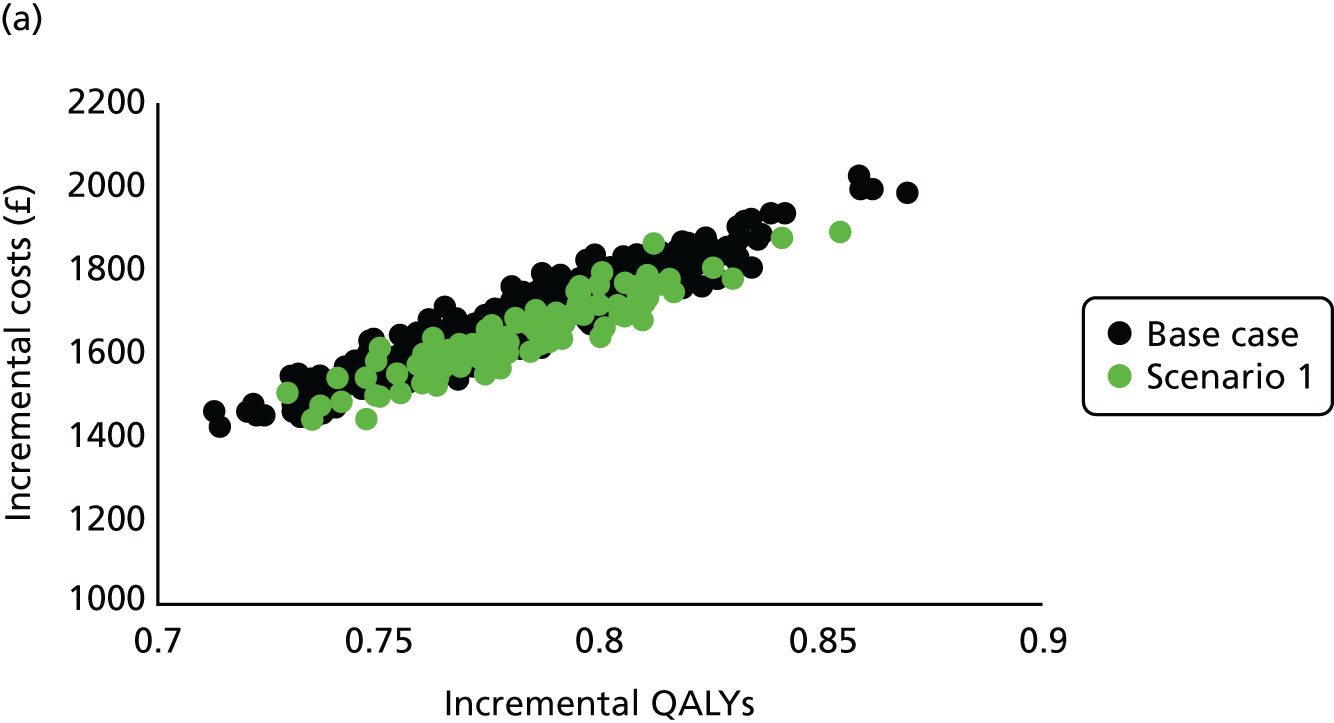

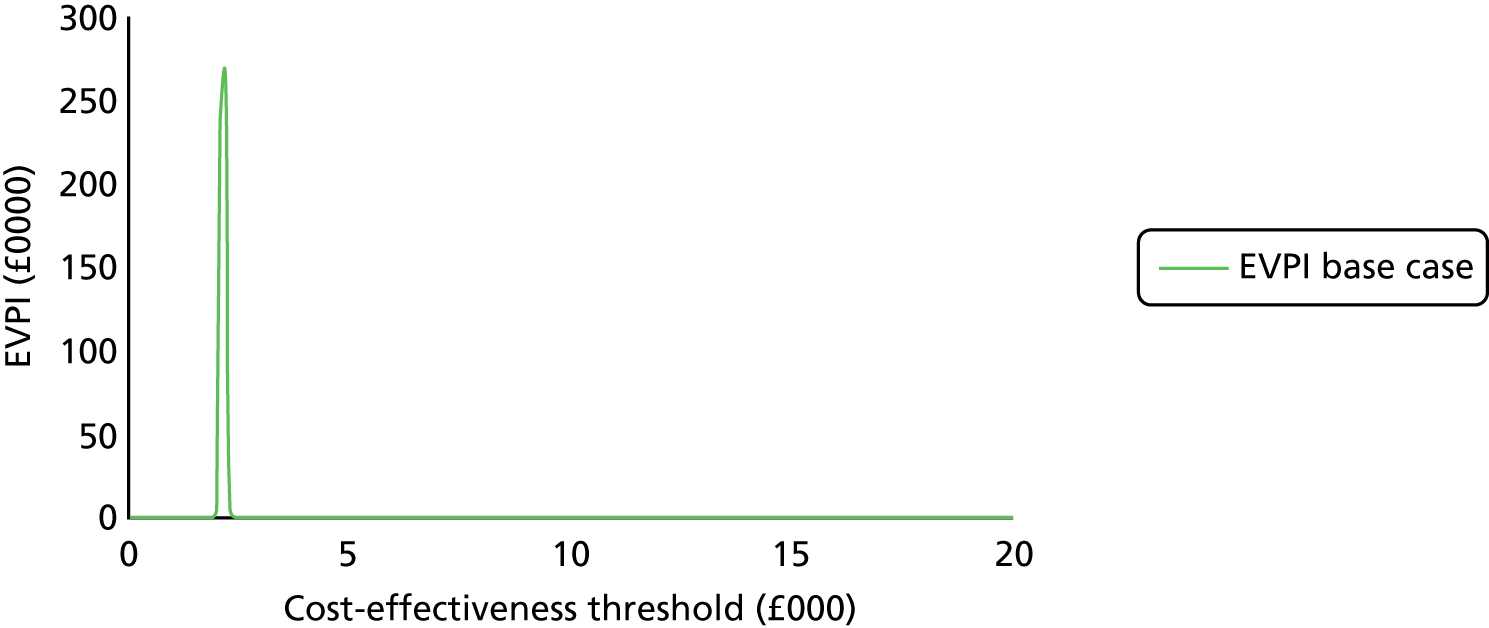

The RCT demonstrated that the FFIT programme was cost-effective, with an incremental cost of £13,387 per QALY gained43 over the 12-month within-trial period. For a cost-effectiveness threshold of £20,000 per QALY, the probability that the FFIT programme was cost-effective, compared with no active intervention, was 0.72. This probability rose to 0.89 for a cost-effectiveness threshold of £30,000 per QALY. Longer-term modelling also showed favourable results. When the longer-term impact of the intervention was limited to 5 years, the cost-effectiveness of the FFIT programme was estimated to be between £1174 and £4475 per QALY gained depending on the assumptions made about the impact that this had on longer-term costs. 44

Focus groups comprising subsamples of men in the intervention group at each of the 13 RCT football clubs were conducted as part of the process evaluation at two time points: immediately post programme and at 12 months (when men were sampled to ensure that a range of experiences of weight loss maintenance were represented). These data suggested that men valued the way that the style of delivery of the FFIT programme and the materials themselves enabled them to build autonomy and take personal responsibility for their own behaviours, choosing which strategies best suited their own lives. 44 Men in the 12-month focus groups reported how focusing on a healthy, balanced diet with structured, organised eating patterns had helped them in their efforts to maintain their weight loss. Many also described how they had succeeded in incorporating new PA and healthy eating habits into their daily routine, and how they were continuing to self-monitor their weight and/or PA. There was evidence from the discussions that those who had successfully maintained their weight loss had, to at least some extent, developed internalised behavioural regulation. Many also spoke about the importance of ongoing social support, either from their partners and children or from fellow FFIT participants (in some football clubs, men had continued to meet up following the initial 12-week active phase of the programme). Some described how aspects of their identity had changed through participation in the FFIT programme, for example that they now saw themselves as an active, fit person. Nevertheless, men also reported a number of barriers to ongoing weight control after the programme, including injury, illness and stressful life events, such as bereavement, which hampered their ability to make long-lasting changes. 44

Similar to other RCTs,48,49 11.3% of men in the comparison group succeeded in losing ≥ 5% weight (as measured at 12 months) before starting the programme. This pre-intervention weight loss may reflect a number of potentially interacting factors. The act of signing up to take part in the FFIT RCT suggests that these men already had some degree of motivation to lose weight, and the experience of the baseline measurement sessions (which included feedback on their BMI status) may have heightened that motivation. Any man with elevated BP at the baseline measurements was advised to consult his general practitioner (GP), which may have acted as a further ‘wake-up call’. All men were also given a standard weight loss advice booklet50 and had the chance to speak briefly to the coach about the upcoming FFIT programmes. Finally, our recruitment activities within football clubs may also have changed men’s views about the acceptability of weight loss among men in general, or among their football-supporting peers in particular. Taken together, these factors suggest that the difference in weight loss between the groups is a conservative estimate of what the FFIT programme can deliver.

The FFIT programme continues to be delivered post RCT. In partnership with the Scottish Professional Football League (SPFL) Trust, the research team has developed a 2-day training package to train new coaches to deliver the FFIT programme, and has entered into an exclusive licence agreement with the SPFL Trust to allow it to oversee training, delivery, and ongoing quality assurance and monitoring of the FFIT programme worldwide. In Scotland, around 4500 men have now taken part in the FFIT programme, and the Scottish Government has funded further deliveries in 33 SPFL clubs. Seven football clubs are delivering the programme in England and 12 football clubs are delivering it in Germany. The Scottish Government has also commissioned an adapted version of the programme for women, which has been delivered in 25 Scottish football clubs.

Rationale for the current study

The FFIT RCT 12-month results compare favourably with those of RCTs of other men-only weight management programmes. 51,52 Nevertheless, longer-term follow-up is necessary to fully understand the potential public health benefit of the FFIT programme. The current study treats the FFIT RCT intervention and comparison groups as two longitudinal cohorts and reports their outcomes at 3.5 years after the RCT baseline measurements.

Aims and objectives

This longitudinal 3.5-year follow-up study had three main aims:

-

to investigate long-term weight trajectories from baseline to 3.5 years in men who were aged 35–65 years with a BMI of ≥ 28 kg/m2 at the start of the FFIT RCT

-

to establish the cost-effectiveness of the FFIT programme over the medium and longer term

-

to investigate the feasibility and utility of establishing low-cost, long-term, passive follow-up of the clinical health outcomes of current and future participants in the FFIT programme via routinely collected NHS records.

We aimed to address six underlying research objectives, as follows.

Objective 1: long-term weight outcomes

To investigate the extent to which:

-

participants in the intervention group achieved objectively measured long-term weight loss (at 3.5 years after baseline measurements and 3.5 years after commencing participation in the FFIT programme)

-

participants in the comparison group achieved objectively measured long-term weight loss (at 3.5 years after baseline measurements and 2.5 years after commencing participation in the FFIT programme)

-

weight trajectories and weight loss differed between the intervention group and the comparison group (at 3.5 years after baseline measurements).

Objective 2: randomised controlled trial secondary outcomes

To investigate the extent to which there were long-term changes in the intervention and comparison groups in the RCT secondary outcomes, and how these differed between the groups:

-

objective physical measurements – BMI, waist circumference, percentage body fat and resting BP

-

health behaviours – self-reported PA, sitting time, diet and alcohol intake

-

psychological outcomes – self-esteem, positive and negative affect, and physical and mental HRQoL.

Objective 3: predictors of long-term weight loss

To investigate:

-

the baseline predictors (age, BMI, education level, socioeconomic status, marital status, number of long-standing illnesses and orientation to masculine norms) of successful long-term weight loss in the two groups, and how these differed between the groups

-

how the following mediator variables predicted long-term weight loss after controlling for the baseline predictors in both groups, and how these differed between the groups –

-

change (from RCT baseline, 12 weeks and 12 months) in health behaviours (self-reported PA, sitting time, diet and alcohol intake)

-

change (from RCT baseline, 12 weeks and 12 months) in psychological status (self-esteem, positive and negative affect, and mental and physical HRQoL)

-

perceived autonomy, competence, relatedness and satisfaction with PA and dietary behaviours, as assessed at 3.5 years

-

the extent to which PA and healthy eating routines were established, the ongoing use of BCTs, ongoing contact with other FFIT participants, and major life events, as assessed by self-report at 3.5 years

-

end-of-intervention weight change (from objective RCT measurements in the intervention group and self-report in the comparison group) and pre-intervention weight change (from objective RCT measurements in the comparison group only)

-

self-reported injury and joint pain, as assessed at 12 months and 3.5 years.

-

Objective 4: men’s experiences

To describe men’s experiences (including their motivations, emotions and relations with others) of attempting to control their weight over the long term, their reasons for achieving or failing to achieve long-term weight loss and the strategies they continued to use or stopped using.

Objective 5: cost-effectiveness

To investigate the medium- and long-term cost-effectiveness of the FFIT programme by:

-

establishing the extent to which weight loss and positive behavioural changes were sustained beyond the first 12 months, and the subsequent impact that these had on the cost-effectiveness of the FFIT programme at 3.5 years

-

updating the modelling of the longer-term health outcomes and resource use of men who participate in the FFIT programme, and assessing the potential for longer-term cost-effectiveness

-

exploring heterogeneity of the cost-effectiveness of the FFIT programme.

Objective 6: long-term follow-up via medical records

To explore the potential of using linkage to routinely collected NHS data sets to allow long-term, low-cost, passive follow-up of future FFIT participants through investigation of the following:

-

utility – long-term clinical health outcomes (through data linkage on hospitalisations, mortality, prescribing, cancers, diabetes and, when possible, blood test results) of RCT participants, and the extent to which these were associated with long-term weight loss and behaviour change

-

feasibility – the extent to which men enrolling in routine implementation deliveries of the FFIT programme (in spring and autumn 2015) were prepared to give permission for transfer of their baseline, post-programme and 9-month weight measurements and BMI (as measured by coaches in participating football clubs) to the research team, and to agree to linkage to their NHS records.

In this report, we describe the methods and processes of data collection and analysis for the long-term weight outcomes, RCT secondary outcomes and predictors of long-term weight loss (see Chapter 2), the results of which are presented in Chapter 3 (objectives 1–3). Chapter 4 reports the qualitative analysis of men’s experiences, including methods and results (objective 4). Chapter 5 reports the economic analysis, including methods and results (objective 5). Chapter 6 reports the methods and results for the utility and feasibility of long-term follow-up via medical records (objective 6).

Chapter 2 General methods

Setting

The setting was the 13 SPFL clubs that took part in the FFIT RCT in 2011/12.

Overview of study design

We undertook a mixed-methods, longitudinal, follow-up study to investigate long-term weight trajectories in participants in both arms of the FFIT RCT. As both groups had taken part in the FFIT programme (the intervention group commenced in autumn 2011 and the comparison group were given the opportunity to do so in autumn 2012), the follow-up was designed as a cohort study.

The current chapter reports on the methods relating to data collection and analysis for long-term weight outcomes, RCT secondary outcomes and predictors of long-term weight loss. Methods relating to data collection and analysis for the qualitative interviews (see Chapter 4), economic evaluation (see Chapter 5) and utility and feasibility of data linkage (see Chapter 6) are presented in the relevant chapters.

The study protocol is available at www.nets.nihr.ac.uk/projects/phr/139932.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval for the study was obtained from the College of Social Sciences Ethics Committee at the University of Glasgow (CSS/400140075), which complies with the Economic and Social Research Council’s research ethics framework.

Retention strategies and contact with men at the 3.5-year follow-up

The personalised approach to recruitment and retention during the 2011/12 FFIT RCT resulted in 89% (333/374) of the intervention group and 95% (355/374) of the comparison group taking part in the 12-month measures. At this time, we asked participants if they would consent to being followed up in future. A total of 95% (316/333) of the intervention group and 98% (349/355) of the comparison group did so. We therefore had a potential FFIT follow-up cohort of 665 (89% of those who took part in the FFIT RCT).

Formal recruitment to the 3.5-year follow-up measures began in February 2015. To maximise attendance at the follow-up measures, we followed the retention protocols that had been successful in the RCT.

-

Measurement sessions were held at football club stadia at which FFIT community coaches were present.

-

At least two measurement sessions were held at each football club.

-

One month before the football club measurement sessions, men received a personalised letter and an information sheet about the follow-up study.

-

Three weeks before the football club measurement sessions, men were contacted individually by telephone to make an appointment, and appointments were confirmed by e-mail/post (in accordance with their preference).

-

Appointment reminder texts and e-mails were sent up to 48 hours in advance of the football club measurement sessions.

-

Men who did not attend their appointment were telephoned either during the football club measurement session to rearrange their appointment or after the session if they could not be reached during the session.

-

Men who were unable to attend football club measurement sessions were offered a fieldworker visit at their home (or at another convenient location if they preferred).

-

Men were offered £20 high street store vouchers (and travel expenses for stadia measurements) for taking part in the follow-up measurements.

In addition, in December 2014, prior to the study commencing, all men in the FFIT follow-up cohort were sent Christmas cards that included a request for any update of their contact details. A summary of the retention procedures and timeline is provided in the retention procedures for the FFIT follow-up study (see Report Supplementary Material 1).

Participants

The participants were men who participated in the FFIT RCT and who consented to being contacted for follow-up research at the RCT 12-month measurements (n = 665). These men were aged 35–65 years and had a BMI of ≤ 28 kg/m2 at RCT baseline.

Intervention

As this study was a longitudinal follow-up of participants in both arms of the FFIT RCT, no further interventions were conducted. A detailed description of the FFIT programme is provided in Chapter 1, Football Fans in Training: weight loss, physical activity and healthy eating for men, and is also available elsewhere. 46

Outcome assessment

The main outcome measures in the 3.5-year follow-up study are the same as those assessed at baseline, 12 weeks and 12 months during the FFIT RCT. They were set with reference to National Obesity Observatory guidance for the evaluation of weight management interventions. 53

Primary outcome

The primary outcome was objectively measured weight change from FFIT RCT baseline to 3.5 years expressed as a mean and as a percentage.

Secondary outcomes

The secondary outcomes were as follows:

-

change from baseline to 3.5 years in objectively measured BMI, waist circumference, percentage body fat and resting BP

-

PA – change from baseline to 3.5 years in self-reported frequency and duration of walking, moderate and vigorous activity and duration of sitting time over the last 7 days measured using the International Physical Activity Questionnaire-Short Form54

-

diet – change from baseline to 3.5 years in self-reported frequency of intake of key contributors to weight gain55 [e.g. fast foods, chocolate bars, chips, pies, sugary drinks and breakfast consumption, using questions adapted from the Dietary Instrument for Nutrition Education (DINE)56], and perceived changes in portion size using eight photographs representing different portions of foods that the research team considered to be important in weight gain (cheese, meat, pasta and chips)57

-

alcohol intake – change from baseline to 3.5 years in self-reported consumption over the last 7 days58

-

psychological outcomes –

-

change from baseline to 3.5 years in positive and negative affect as measured by the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS)59

-

self-esteem as measured by the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSE)60

-

physical and mental HRQoL as measured by the Short Form questionnaire-12 items (SF-12) Health Survey (version 2). 61

-

Baseline predictors

The baseline predictors were age, BMI, education level, socioeconomic status,71 marital status, orientation to masculine norms and number of long-standing illnesses, as measured at FFIT RCT baseline.

Mediators

The mediators measured included change from FFIT RCT baseline in health behaviours (self-reported PA, sitting time, diet and alcohol intake) and psychological outcomes (self-esteem, positive and negative affect, mental and physical HRQoL).

Other mediators were as follows:

-

self-determination theory constructs20 – reported self-regulation of PA and dietary behaviours as measured by the Treatment Self-Regulation Questionnaire (TSRQ),62 perceived autonomy in PA and dietary behaviours as measured by the Locus of Causality Scale (LCS),63 perceived competence in PA and dietary behaviours as measured by the Perceived Competence Scale (PCS)64 and perceived relatedness as measured by the Need for Relatedness Scale (NRS),65 all as reported at 3.5 years

-

perceived satisfaction with current PA and dietary behaviours,66 as reported at 3.5 years

-

self-reported use of behavioural techniques that are likely to be associated with long-term weight loss, including ongoing self-monitoring of weight/PA and the extent of establishment of dietary and PA daily routines, as reported at 3.5 years (see Q1a, Report Supplementary Material 2)

-

self-reported frequency of contact with other FFIT participants, coaches, football club-based initiatives and other health promotion/weight management initiatives since the end of the initial 12-week active phase of the FFIT programme, as reported at 3.5 years

-

self-reported major life events (e.g. bereavement, family illness, separation, divorce, redundancy) since the end of the initial 12-week active phase of the FFIT programme, as reported at 3.5 years

-

end-of-intervention weight change [from objective RCT baseline and 12-week measurements for the FFIT follow-up intervention (FFIT-FU-I) group and from self-reported (at 3.5 years) end-of-programme weight loss for the FFIT follow-up comparison (FFIT-FU-C) group] and pre-intervention weight change (from objective RCT baseline and 12-month measurements for the FFIT-FU-C group)

-

self-reported injury and joint pain, as reported at 12 months and at 3.5 years.

Health-care resource use, GP-prescribed medications and family history of coronary heart disease (CHD)/stroke67 were self-reported for the economic evaluation. Participants were also asked to report any long-standing illnesses (and the extent to which they limited activities) and smoking status at 3.5 years.

Procedures

Outcome and predictor assessment

Stadia measurements were conducted by a team of fieldworkers, trained to standardised protocols, during 29 sessions across the 13 football clubs between March and May 2015. Home visits took place between June and August 2015. Most home measurements were conducted at the participant’s home, but one participant attended at the University of Edinburgh and another requested a visit to his workplace. Percentage body fat was not recorded among these participants. In addition, some men who were contacted for home visits elected to provide only their weight (which was either objectively measured by a fieldworker visiting them at home or self-reported to a fieldworker over the telephone). Men who declined a home visit or giving self-reported weight by telephone and men whom the fieldworkers had been unable to reach by telephone or e-mail during the follow-up study were sent a weight-only self-report form and prepaid return envelope following the completion of home visits. All outcome data collection ended on 25 September 2015.

The fieldwork team

Data were collected by teams of fieldworkers. Each measurement session team had a designated fieldwork team leader and a fieldwork nurse responsible for BP measurement. Fieldworkers were trained to standard measurement protocols by experienced research and survey staff in the Medical Research Council (MRC)/Chief Scientist Office (CSO) Social and Public Health Sciences Unit. Training took place over 2 days for stadia measurement staff. This included a half-day of training for fieldwork team leaders only, and 1.5 days of training for fieldworkers, with training sessions led jointly by the fieldwork team leaders and members of the research team. A further day of training for home visit fieldworkers was provided to emphasise strict adherence to protocol during home visits to minimise detection bias. All fieldworkers wore T-shirts branded with FFIT research logos at in-stadia measurement sessions (Figure 2) and during home visits.

FIGURE 2.

Fieldwork team arriving at a FFIT follow-up 3.5 years in-stadia measurement session.

Measurement protocols

Objectively measured outcomes

The protocols for recording the objectively measured outcomes were identical to those used during the FFIT RCT. Weight (kg) was recorded using electronic scales (Tanita HD-352™, Milton Keynes, UK) and with participants wearing light clothing, not wearing shoes and having empty pockets. Height (cm) was measured without shoes using a portable stadiometer (Seca Leicester™, Chino, CA, USA). Waist circumference was measured twice (three times, if the first two measurements differed by ≥ 5 mm), and the mean was calculated. Resting BP was measured using a digital BP monitor (Omron HEM-705CP™, Milton Keynes, UK) by a fieldwork nurse. Body composition was measured using a Bodystat 1500MDD machine (Bodystat Ltd, Douglas, Isle of Man). All equipment was calibrated before fieldwork commenced.

Outcomes based on self-report

Participants completed two self-administered questionnaires. The first questionnaire included the self-report outcomes from the 12-month RCT measures (see schedule A, Report Supplementary Material 3). It also included additional questions on when participants attended the FFIT programme, their recollection of their weight loss at the end of the FFIT programme, interaction with other FFIT participants or coaches, changes in personal circumstances and family health history (see schedule B, Report Supplementary Material 3). The second questionnaire focused on additional mediator outcomes (see schedule B, Report Supplementary Material 3).

Fieldworkers were trained to assist any man who appeared to have literacy or other problems with questionnaire completion. All completed questionnaires were routinely checked before the participant left the measurement session (or the fieldworker left the home visit) to minimise missing data.

Copies of the two FFIT follow-up study questionnaires are provided (see Report Supplementary Material 2 and Report Supplementary Material 4).

Preparation of self-reported variables for analysis

Physical activity

Following standard procedures described in the International Physical Activity Questionnaire scoring protocol,54 we calculated and reported metabolic equivalent of task (MET) minutes per week for self-reported walking, vigorous, moderate and total PA, and time in minutes for daily sedentary time over the last 7 days. Activity times that exceed 180 minutes (3 hours) per day were truncated to 180 minutes to normalise the distribution of levels of activity, which are usually skewed in large population data sets. 68

Diet

We used the adapted DINE from the FFIT RCT43 to collect self-reported frequency of intake of various fatty and sugary food types, and fruit and vegetables over the previous 7 days (see questions 27–32, Report Supplementary Material 4). From these data, we calculated a fatty food score, a sugary food score, and a fruit and vegetables score (see Report Supplementary Material 5).

Fatty food types

Participants reported how many times, over the previous 7 days, they had eaten a serving of cheese, beef burgers or sausages, beef, pork or lamb, fried food, chips, bacon or processed meat, pies, quiches or pastries and crisps. They also reported the amount of milk, over the previous 7 days, that was used for drinking or in cereal, tea or coffee in a day, and what kind of milk they normally used.

Sugary food types

Participants reported how often, over the previous 7 days, they had eaten chocolate, sweets or biscuits and drunk sugary drinks (fizzy drinks, diluting juice or fruit juice).

Fruit and vegetables

Participants reported how many times a day, over the previous 7 days, they had eaten fruit and vegetables.

When there were missing values, the score was recoded to the smallest possible score (e.g. if number of times of eating cheese was missing, then the assumed frequency was ‘no times’) for all variables except milk. If milk (amount) was missing, then the entire milk score (milk amount × milk type) was assumed to be 1 (lowest possible value) regardless of milk type.

Portion size

We assigned numbers from 1 to 8 to the photographs of each food, with higher numbers representing larger portions.

Alcohol intake

Following Emslie et al. ,58 we converted responses to the 7-day recall diary for alcohol to standard units that are equivalent to 8 g of pure alcohol (e.g. half a pint of ordinary beer, lager or cider, a small glass of wine and one measure of spirit each contain 1 unit of alcohol). We calculated the total number of units reported in the past week.

Psychological outcomes

Scores for both the RSE and PANAS short form were normalised so that values could be calculated for participants who had missed one or two items contributing to each scale. The PANAS normalised scales scores range from 1 to 5, with higher scores indicating higher negative affect and higher positive affect. Higher scores on the RSE (normalised range 0–3) indicate better self-esteem. SF-12v2 scores were summarised separately for mental and physical HRQoL following standard algorithms. 61

Mediators

Treatment Self-Regulation Questionnaires: diet and physical activity

There are three subscales on each TSRQ: autonomous regulatory style, controlled regulatory style and amotivation. The responses to items on the three subscales were averaged (normalised) and reported separately for each behaviour. The scores for the items on the TSRQs range from 1 to 7, with higher scores indicating greater motivation.

Locus of Causality Scale: diet and physical activity

The scores for the three items on the LCS range from 1 to 7. Following the standard scoring protocol, scores were reversed on items 2 and 3, and the mean score for the three items was then calculated. Higher scores indicate greater self-determination or autonomy.

Perceived Competence Scale: diet and physical activity

The scores for the four items on the PCS range from 1 to 7. The mean score for the four items was calculated. Higher scores indicate greater perceived competence.

Need for Relatedness Scale

There are two subscales on the NRS: acceptance and intimacy. The scores for the items on the NRS range from 1 to 7. The responses to items on the subscales were averaged and reported separately for peers (specifically other men from the FFIT programme) and family. Higher scores indicate stronger relatedness.

Satisfaction with changes in physical activity, dietary and weight

The scores for the satisfaction items range from 1 to 9, with 1 being ‘very dissatisfied’ and 9 being ‘very satisfied’. There was also an option for participants to indicate if they had not made any changes (scored as ‘0’). For each item, participants who gave an answer of 0–6 were grouped together and compared with those who gave an answer of 7–9.

Use of behaviour change techniques

Items on the continued use of BCT scales were scored as follows: 1, ‘never’; 2, ‘rarely’; 3, ‘sometimes’; 4, ‘frequently’; and 5, ‘always’. For each item, participants who answered ‘sometimes’, ‘frequently’ or ‘always’ were grouped together and compared with those who answered ‘never’ or ‘rarely’. Strategies included using the pedometer (or self-monitoring of walking), self-monitoring weight, SMART (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Realistic, Time-limited) goal-setting, tips on how to overcome setbacks, and social support for PA or diet.

Routinisation of physical activity and dietary behaviours

Items on the routinisation of behaviours scales were scored as follows: 1, ‘never’; 2, ‘rarely’; 3, ‘sometimes’; 4, ‘frequently’; and 5, ‘always’. For each item, participants who answered ‘frequently’ or ‘always’ were grouped together and compared with those who answered ‘sometimes’, ‘never’ or ‘rarely’. Items for routinisation of PA behaviours included daily walking, gym attendance, cycling, swimming or other forms of exercise, and attending a group programme. Items for routinisation of dietary behaviours included eating regular meals, watching portion sizes, limiting intake of certain types of food (e.g. fats, sugars), limiting overall calorie intake, limiting intake of sugary drinks, limiting intake of alcohol, consciously eating slowly and reading food labels.

Frequency of contact with other Football Fans in Training participants, coaches and health promotion/weight management initiatives since the end of the Football Fans in Training programme

Items on the continued contact scales were scored from 1, ‘very frequently’, to 5, ‘never’. For each item, participants who answered ‘very frequently’, ‘frequently’, ‘occasionally’ or ‘rarely’ were grouped together and compared with those who answered ‘never’.

Major life events since the end of the Football Fans in Training programme

A major life events scale was developed for the FFIT follow-up study, drawing on items from the Psychiatric Epidemiology Research Interview Life Events Scale. 69 Participants were asked to indicate if each of 17 life events had happened to them and, if so, the extent to which it had affected their day-to-day life both at the time, and currently. For the purposes of the mediator analyses, the total number of life events reported was calculated, as was the number of events in each of four categories (own health, personal circumstances, family health and work).

Prior weight change

Post-intervention weight change was estimated as follows: (1) the FFIT-FU-I group from objectively measured weight at 12 weeks minus baseline; and (2) the FFIT-FU-C group from self-reported post-intervention weight loss at 3.5 years. Post-intervention weight change was converted into the following categories for each group: 1, ‘did not lose weight’; 2, ‘lost up to 5%’; 3, ‘lost 5–10%’; and 4, ‘lost more than 10%’. Pre-intervention weight change was estimated in the FFIT-FU-C group only from objectively measured weight at 12 months minus baseline.

Short Form Conformity to Masculine Norms Inventory-22 items (measured at randomised controlled trial baseline)

The 22 items on the Short Form Conformity to Masculine Norms Inventory-22 items (CMNI-22)70 were scored as follows: 0, ‘strongly disagree’; 1, ‘disagree’; 2, ‘agree’; and 3, ‘strongly agree’. Following the scoring protocol, the scoring on nine of the items was reversed before scores on all items were summed to give an overall score. A higher CMNI-22 score indicates greater conformity to masculine norms.

Injury and joint pain as self-reported at 12 months and 3.5 years

For injuries, the number of lower limb injuries, the number of torso or upper body injuries and the total number and type of limitations due to injury were summed separately. In addition, participants were grouped and compared according to whether they had reported any injuries that limited walking, any injuries that limited using stairs and any injuries that limited PA. For joint pain, participants were assigned to groups (n = 7) according to reports of any:

-

upper joint pain (neck, back and upper limb) that persisted all of the time, compared with those who did not report upper joint pain all of the time

-

lower limb joint pain (hip, knee, ankle, foot/toes) all of the time, compared with those who did not report lower joint pain all of the time

-

upper joint pain that limited activities ‘to a moderate degree’ or more, compared with those who did not

-

lower limb joint pain that limited activities ‘to a moderate degree’ or more, compared with those who did not

-

upper joint pain, compared with those reporting ‘never’ or ‘don’t know’ for upper joint pain

-

lower limb joint pain, compared with those with those reporting ‘never’ or ‘don’t know’ for lower limb joint pain

-

joint pain, compared with those reporting ‘never’ or ‘don’t know’ for any joint pain.

Changes to outcomes

Diet

In our protocol we said that we would measure change from baseline to 3.5 years in self-reported frequency of intake of key contributors to weight gain (e.g. fast foods, chocolate bars, chips, pies and sugary drinks) and of breakfast using questions adapted from DINE. However, to be consistent with the reporting of the FFIT RCT,43 we summarised the 17 original variables into three scores (fatty food, sugary food, and fruit and vegetables; see Preparation of self-reported variables for analysis, Diet) indicative of healthy changes that men could have made to their diets.

Satisfaction with behaviour and weight changes

In our protocol we said that we would measure perceived satisfaction with current PA and dietary behaviours. However, given evidence from reviews that suggests that satisfaction with short-term outcomes (including weight) may predict long-term outcomes,19,23 we asked men how satisfied they were with what they had experienced as a result of the changes they had made to their diet, PA and weight at the end of the FFIT programme, as well as currently.

Sample size and power

All 665 men (intervention group, n = 316; comparison group, n = 349) who had consented to being contacted again for future follow-up were invited to participate in the FFIT follow-up study. Assuming an attrition rate of 20%, we estimated that we would have outcome measurements for 532 men (intervention group, n = 253; comparison group, n = 279). The standard deviation (SD) for the percentage change in weight loss during the RCT was approximately 10% in the intervention group. Assuming that this would be higher in the longer term (e.g. 15%) but similar in both groups, we estimated that we would have 80% power to detect a change in weight of 2.65% in the intervention group, 2.52% in the comparison group, and 1.83% overall.

Blinding

As this was not a RCT, and as both groups had had an opportunity to take part in the FFIT programme, blinding of participants was not relevant. Nevertheless, the fieldworkers conducting the measurements were not told to which group the men belonged.

Statistical methods

All participants with available data were included in the analysis. To investigate the long-term outcomes in relation to the primary (weight loss) and RCT secondary outcomes (BMI, waist circumference, percentage body fat, resting BP, and self-reported PA, diet, alcohol intake, positive and negative affect, self-esteem, and physical and mental HRQoL) (objectives 1 and 2), 12-month and 3.5-year outcomes were summarised separately by group (FFIT-FU-I or FFIT-FU-C) and overall. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to test the change from baseline in 12-month and 3.5-year outcomes within groups, and the Mann–Whitney U-test was used to detect differences between groups. All outcomes were continuous. Each group was also analysed separately within mixed-effects (repeated measures) linear regression models, with adjustments for baseline value and visit (12 months and 3.5 years) as fixed effects, and participant and football club as random effects. The mean value (change from baseline), 95% CI and p-value were estimated from these models.

Differences in weight trajectories between the FFIT-FU-I group (who commenced the FFIT programme in September 2011) and the FFIT-FU-C group (who were offered places on the FFIT programme in September 2012) were investigated by considering both groups together and including additional fixed effect terms for group, and a group × visit interaction.

For each group, the predictors of change in weight (objective 3) were investigated by extending the repeated mixed-effects linear regression models described above to include each predictor separately to assess their individual impact. All predictors were then added to the model, and a backwards-selection method was applied to identify the independent predictors of change in weight. To determine whether or not there were different predictors for each group, the data from both groups were considered in a single model, with a predictor × group interaction term added.

When possible, we undertook additional analyses, including a backward-selection data-driven model, which included the following hypothesised predictors/mediators (measured at 12 months or 3.5 years) of long-term weight loss: end-of-intervention weight change; sustained PA and diet change; continued use of self-monitoring; major life events, injury and joint pain; social support; the extent to which behaviour had become routinised; satisfaction with behaviour change; self-regulation; perceived autonomy; perceived competence; and perceived relatedness.

Non-response bias was investigated by comparing the baseline characteristics of participants who agreed to take part in the 3.5-year measurements (total followed-up cohort) with those of participants who did not (not followed-up cohort) using appropriate statistical tests (t-test/Mann–Whitney U-test/chi-squared test/Fisher’s exact test).

The sensitivity of the overall results to a variety of assumptions about the primary outcome of the cohort not followed up was assessed by imputing missing outcome data for the cohort not followed up using the return to baseline and the last-value-carried-forward methods. The analyses described above were repeated for the imputed data.

In addition, sensitivity analyses of the change in primary outcome from baseline to 3.5 years were carried out using the weight measures from immediately before taking part in the FFIT programme as the baseline for both groups (i.e. for the FFIT-FU-C group, the RCT 12-month weight measurements were used as the ‘baseline’). Two sensitivity analyses were performed, the first using the total followed-up cohort, and the second excluding those in the FFIT-FU-C group who had lost ≥ 5% of their baseline weight by the RCT 12-month measures.

All analyses were conducted using SAS® software (version 5.1, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). (SAS and all other SAS Institute Inc. product or service names are registered trademarks or trademarks of SAS Institute Inc. in the USA and other countries. ® indicates USA registration.)

Changes to protocol

There were no changes to protocol except those described in Changes to outcomes.

Public involvement

Extensive public engagement was undertaken throughout the development and evaluation of the FFIT programme. We worked closely with the SPFL Trust while developing the FFIT programme and during the conduct of the FFIT RCT in 2011/12. Subsequent discussions with the SPFL Trust about the value of long-term follow-up of RCT participants and of the potential for data linkage to routinely collected NHS records led to the development of the proposal for the FFIT follow-up study. Members of the SPFL Trust and other lay representatives were involved in the following ways.

Design of the Football Fans in Training follow-up study

The involvement of the SPFL Trust from the earliest stages of the development of the research questions and detailed project description ensured that the follow-up study had real-life application and would benefit the SPFL Trust and football clubs. A FFIT coach and a former FFIT participant also read and commented on the penultimate draft of the detailed project description to ensure that the research was relevant to a non-academic audience.

Management of the Football Fans in Training follow-up study

The SPFL Trust agreed to join the Study Steering Committee, and was represented at meetings by the operations manager, Derek Allison. The FFIT coach and the former participant who commented on the project description were also asked to join the Study Steering Committee. Their representation on this advisory group was important in ensuring that the findings were relevant and accessible to a non-academic audience.

Developing participant information resources

The SPFL Trust commented on the protocol that was developed as part of the data linkage feasibility work (described in Chapter 6, Feasibility of data linkage) for coaches to use to ask participants in the autumn 2015 and spring 2016 deliveries of the FFIT programme for permission to access their NHS records.

Undertaking and analysing the Football fans in Training follow-up study

The SPFL Trust attended all project team meetings (either the general manager, Nicky Reid, or the operations manager, Derek Allison), which allowed it to contribute to key decision-making across the project. It also worked closely with the project manager in facilitating links with, and training of, appropriate football club representatives to allow data collection in the data linkage feasibility study (see Chapter 6, Feasibility of data linkage).

Contributing to the reporting of the Football Fans in Training follow-up study

The SPFL Trust was given an opportunity to comment on all progress reports and this final report. The FFIT coach and the former FFIT participant were also given the opportunity to comment on this final report.

As part of the end-of-project dissemination activities (see Dissemination of research findings), we are working closely with the SPFL Trust FFIT Development Officer (Stevie Chalmers) in preparing a lay report presenting the results of the follow-up study. This collaboration will ensure that the lay report is a useful document for the SPFL Trust and football clubs to use to support their efforts to build partnerships with potential funders and organisations (e.g. the NHS) for future deliveries of the FFIT programme. The FFIT coach and former FFIT participant will also be asked to comment on the lay report.

Dissemination of research findings

We are working closely with the SPFL Trust in the organisation of end-of-project events to disseminate the findings of the FFIT follow-up study to non-academic audiences. FFIT coaches and participants are being invited to attend and play an active part in these events. This approach will ensure that these events have the maximum impact for the SPFL Trust and its member football clubs.

Chapter 3 Results: outcomes and predictors of long-term weight loss

Introduction

This chapter presents the results of the analysis in relation to the primary outcome (change in weight at 3.5 years), secondary outcomes from the FFIT RCT, and the predictors and mediators of weight loss at 3.5 years. Specifically, we aimed to investigate the:

-

extent to which participants in the RCT intervention group and comparison group achieved long-term weight loss, and how weight trajectories differed between the groups

-

extent to which there were long-term changes in the intervention and comparison groups in the RCT secondary outcomes, and how these differed between the groups

-

baseline predictors and mediators (after controlling for baseline predictors) of long-term weight loss, and how these differed between the groups.

Participant flow

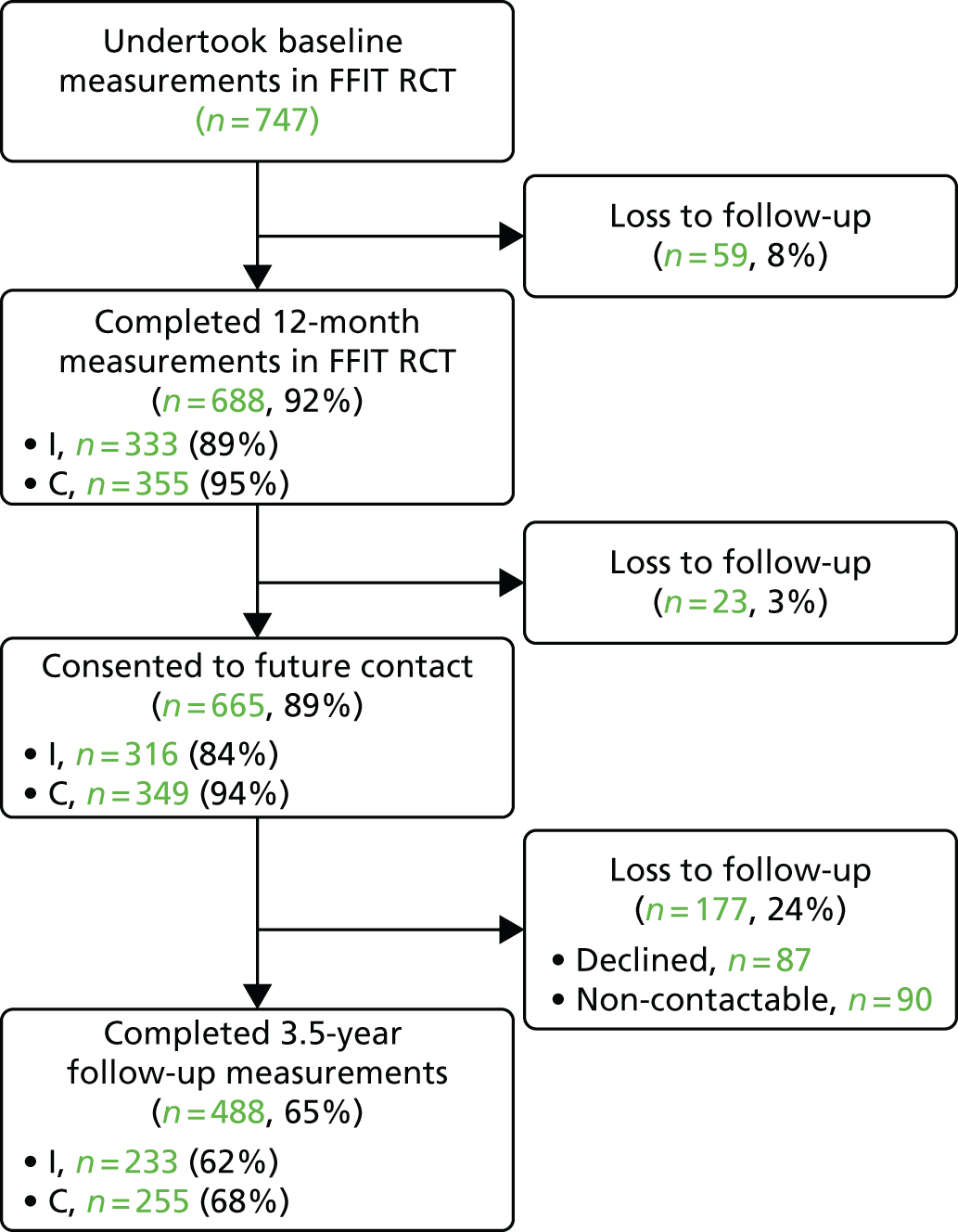

As shown in Figure 3, of the 688 men who took part in the RCT 12-month measurements, 665 provided consent to be contacted again in future. When attempts were made to contact these 665 men in 2015, 87 (13%) withdrew consent [either completely (n = 43) or they did not want to take part in the current measurements but agreed to be contacted again in future (n = 44)]. Another 90 men (13%) could not be contacted despite multiple attempts. Hence, 488 men took part in the 3.5-year follow-up measurements (hereafter referred to as the total followed-up cohort). Of these, 333 attended measurement sessions in the stadia, 118 completed the full set of measurements and questionnaires in home visits and 37 provided weight-only data (three had their weight measured by a fieldworker during a home visit and 34 provided self-reported weight by telephone or post).

FIGURE 3.

Summary of flow of participants through the FFIT RCT and follow-up study. C, comparison group; I, intervention group.

The FFIT-FU-I group comprised 62% (233/374) of men in the RCT intervention group and the FFIT-FU-C group comprised 68% (255/373) of men in the RCT comparison group. This equates to 65% (488/747) of men from the original RCT cohort. Although more participants in the RCT comparison group than in the RCT intervention group were followed up at 3.5 years, among those who consented to future contact at the 12-month measurements, follow-up was similar in both groups (intervention group, 74%; comparison group, 73%). Therefore, the differential follow-up at 3.5 years largely reflects the lower retention in the intervention group at the 12-month measurements (89% vs. 95% retention in the comparison group).

Baseline data

Table 2 shows the demographic characteristics of participants in the FFIT RCT (n = 747) and follow-up study (n = 488) cohorts. Small differences were seen in the age, employment status and housing tenure of those who took part in the 3.5-year measurements (total followed-up cohort) and those who did not (not followed-up cohort).

| Demographic characteristic | Cohort, n (%) | Group, n (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FFIT RCT (N = 747) | Not followed up (N = 259) | Total followed up (N = 488) | FFIT-FU-I (N = 233) | FFIT-FU-C (N = 255) | |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 47.1 (8.0) | 46.2 (7.8) | 47.5 (8.0) | 47.3 (8.2) | 47.7 (7.9) |

| Ethnicity | |||||

| White (British/Scottish/Irish/other) | 735 (99.1) | 256 (99.2) | 479 (99.0) | 228 (98.7) | 251 (99.2) |

| Other | 7 (0.9) | 2 (0.8) | 5 (1.0) | 3 (1.3) | 2 (0.8) |

| Missing | 5 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 2 |

| SIMD71 (quintiles) | |||||

| 1 (most deprived) | 131 (17.8) | 45 (17.7) | 86 (17.8) | 40 (17.3) | 46 (18.3) |

| 2 | 131 (17.8) | 52 (20.5) | 79 (16.4) | 35 (15.2) | 44 (17.5) |

| 3 | 122 (16.6) | 42 (16.5) | 80 (16.6) | 43 (18.6) | 37 (14.7) |

| 4 | 165 (22.4) | 52 (20.5) | 113 (23.4) | 58 (25.1) | 55 (21.8) |

| 5 (least deprived) | 188 (25.5) | 63 (24.8) | 125 (25.9) | 55 (23.8) | 70 (27.8) |

| Missing | 10 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 3 |

| Employment status | |||||

| Paid work | 626 (84.0) | 210 (81.4) | 416 (85.4) | 201 (86.6) | 215 (84.3) |

| Education or training | 8 (1.1) | 8 (3.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Unemployed | 27 (3.6) | 13 (5.0) | 14 (2.9) | 3 (1.3) | 11 (4.3) |

| Not working (long-term sickness/disability) | 16 (2.1) | 3 (1.2) | 13 (2.7) | 8 (3.4) | 5 (2.0) |

| Retired | 32 (4.3) | 9 (3.5) | 23 (4.7) | 10 (4.3) | 13 (5.1) |

| Other | 36 (4.8) | 15 (5.8) | 21 (4.3) | 10 (4.3) | 11 (4.3) |

| Missing | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Education level | |||||

| No qualifications | 71 (9.5) | 32 (12.4) | 39 (8.0) | 17 (7.3) | 22 (8.6) |

| Standard grades/Highers | 241 (32.3) | 83 (32.0) | 158 (32.4) | 73 (31.3) | 85 (33.3) |

| Vocational or HNC/HND | 240 (32.1) | 82 (31.7) | 158 (32.4) | 84 (36.1) | 74 (29.0) |

| University | 156 (20.9) | 53 (20.5) | 103 (21.1) | 48 (20.6) | 55 (21.6) |

| Other | 39 (5.2) | 9 (3.5) | 30 (6.1) | 11 (4.7) | 19 (7.5) |

| Housing tenure | |||||

| Owner occupied | 563 (75.4) | 179 (69.1) | 384 (78.7) | 182 (78.1) | 202 (79.2) |

| Other | 184 (24.6) | 80 (30.9) | 104 (21.3) | 51 (21.9) | 53 (20.8) |

| Marital status | |||||

| Married | 518 (69.3) | 181 (69.9) | 337 (69.1) | 149 (63.9) | 188 (73.7) |

| Living with partner | 95 (12.7) | 31 (12.0) | 64 (13.1) | 39 (16.7) | 25 (9.8) |

| Other | 134 (17.9) | 47 (18.1) | 87 (17.8) | 45 (19.3) | 42 (16.5) |

Table 3 shows that the not followed-up cohort had higher baseline weight, waist circumference, BMI, percentage body fat, and systolic and diastolic BP than the total followed-up cohort. Baseline PA, dietary, alcohol intake and psychological variables are provided in Report Supplementary Material 6. These show that men who took part in the 3.5-year measurements ate breakfast slightly more often than those did not; however, there were no other differences between the cohorts.

| Physical characteristic | Cohort, mean (SD) | Group, mean (SD) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FFIT RCT (N = 747) | Not followed up (N = 259) | Total followed up (N = 488) | FFIT-FU-I (N = 233) | FFIT-FU-C (N = 255) | |

| Weight (kg) | 109.5 (17.3) | 112.6 (17.2) | 107.8 (17.1) | 108.3 (17.9) | 107.4 (16.3) |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 118.4 (11.7) | 120.7 (11.7) | 117.1 (11.6) | 117.5 (12.3) | 116.8 (10.8) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 35.4 (5.0) | 36.3 (5.0) | 34.9 (4.9) | 35.0 (5.1) | 34.8 (4.7) |

| Body fat (%) | 31.7 (5.5) | 32.5 (5.0) | 31.2 (5.6) | 31.3 (6.0) | 31.2 (5.3) |

| Missing | 10 | 3 | 7 | 4 | 3 |

| BP (mmHg) | |||||

| Systolic | 140.3 (16.3) | 142.5 (17.0) | 139.1 (15.8) | 137.5 (16.7) | 140.7 (14.9) |

| Diastolic | 88.8 (10.2) | 90.2 (10.7) | 88.1 (9.9) | 87.4 (10.0) | 88.8 (9.8) |

| Missing | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Participants with a BMI of 28–30 kg/m2, n (%) | 72 (9.6) | 15 (5.8) | 57 (11.7) | 25 (10.7) | 32 (12.5) |

Outcomes

Long-term weight outcomes

Table 4 shows that, at 3.5 years, the mean weight loss from baseline in the FFIT-FU-I group was 2.90 kg (95% CI 1.78 to 4.02 kg; p < 0.0001); the equivalent figure for the FFIT-FU-C group was 2.71 kg (95% CI 1.65 to 3.77 kg; p < 0.0001). There were no between-group differences. Table 5 shows that similar proportions of men (≈32%) in both groups weighed ≥ 5% less than their baseline weight at 3.5 years.

| Change from baseline weight | Group | Difference between groups (FFIT-FU-C – FFIT-FU-I) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FFIT-FU-I (N = 233) | FFIT-FU-C (N = 255) | |||||

| Mean (95% CI) | p-value | Mean (95% CI) | p-value | Mean (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Change to 12 months | ||||||

| Absolute (kg) | –5.49 (–6.51 to –4.47) | < 0.0001 | –0.68 (–1.32 to –0.03) | 0.1244 | 4.81 (3.61 to 6.02) | < 0.0001 |

| Percentage | –4.96 (–5.85 to –4.07) | < 0.0001 | –0.57 (–1.15 to 0.00) | 0.1425 | 4.39 (3.33 to 5.44) | < 0.0001 |

| Change to 3.5 years | ||||||

| Absolute (kg) | –2.90 (–4.02 to –1.78) | < 0.0001 | –2.71 (–3.77 to –1.65) | < 0.0001 | 0.19 (–1.35 to 1.73) | 0.7421 |

| Percentage | –2.52 (3.45 to –1.60) | < 0.0001 | –2.36 (–3.31 to –1.41) | < 0.0001 | 0.16 (–1.17 to 1.49) | 0.7266 |

| Proportion of men | Group, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| FFIT-FU-I (N = 233) | FFIT-FU-I (N = 255) | |

| Achieving at least 5% weight loss | 75 (32.2) | 81 (31.8) |

Table 4 also shows that, at the RCT 12-month measures, the FFIT-FU-I group had lost 5.49 kg (95% CI 4.47 to 6.51 kg) and the FFIT-FU-C group had lost 0.68 kg (95% CI 0.03 to 1.32 kg) from baseline. It is important and reassuring to note that the 12-month weight loss figures for the men who were followed to 3.5 years are very similar to those reported at the end of the trial, at which point the mean 12-month weight loss was 5.56 kg (95% CI 4.70 to 6.43 kg) in the intervention group and 0.58 kg (95% CI 0.04 to 1.12 kg) in the comparison group. 43 Thus, there was no selective loss to long-term follow-up owing to 12-month weight loss outcomes.

Long-term weight trajectories

Table 6 shows that men in the FFIT-FU-I group gained 2.59 kg (95% CI 1.61 to 3.58 kg; p < 0.001) between the 12-month and the 3.5-year measures (i.e. 2.44%, 95% CI 1.61% to 3.27%, of their baseline weight). This equates to a weight gain of 1.04 kg per year. Nevertheless, 3.5 years after baseline measurement, men in the FFIT-FU-I group still weighed 2.90 kg less on average, demonstrating a sustained weight benefit from taking part in the FFIT programme. Meanwhile, men in the FFIT-FU-C group (who had the opportunity to take part in the FFIT programme under ‘routine delivery’ conditions immediately after the 12-month measures) lost 2.03 kg (95% CI 1.08 to 2.98 kg; p < 0.001) or 1.79% (95% CI 0.92% to 2.65%) of their baseline weight during the same time period. The mean between-group difference in weight trajectories was 4.62 kg (95% CI 3.26 to 5.99 kg; p < 0.001) or 4.23% (95% CI 3.02% to 5.43%; p < 0.001).

| Change in weight | Group | Difference between groupsa (FFIT-FU-C – FFIT-FU-I) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FFIT-FU-I (N = 233) | FFIT-FU-C (N = 255) | |||||

| Mean (95% CI) | p-value | Mean (95% CI) | p-value | Mean (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Absolute (kg) | 2.59 (1.61 to 3.58) | < 0.001 | –2.03 (–2.98 to –1.08) | < 0.001 | –4.62 (–5.99 to –3.26) | < 0.001 |

| Percentage (of baseline) | 2.44 (1.61 to 3.27) | < 0.001 | –1.79 (–2.65 to –0.92) | < 0.001 | –4.23 (–5.43 to –3.02) | < 0.001 |

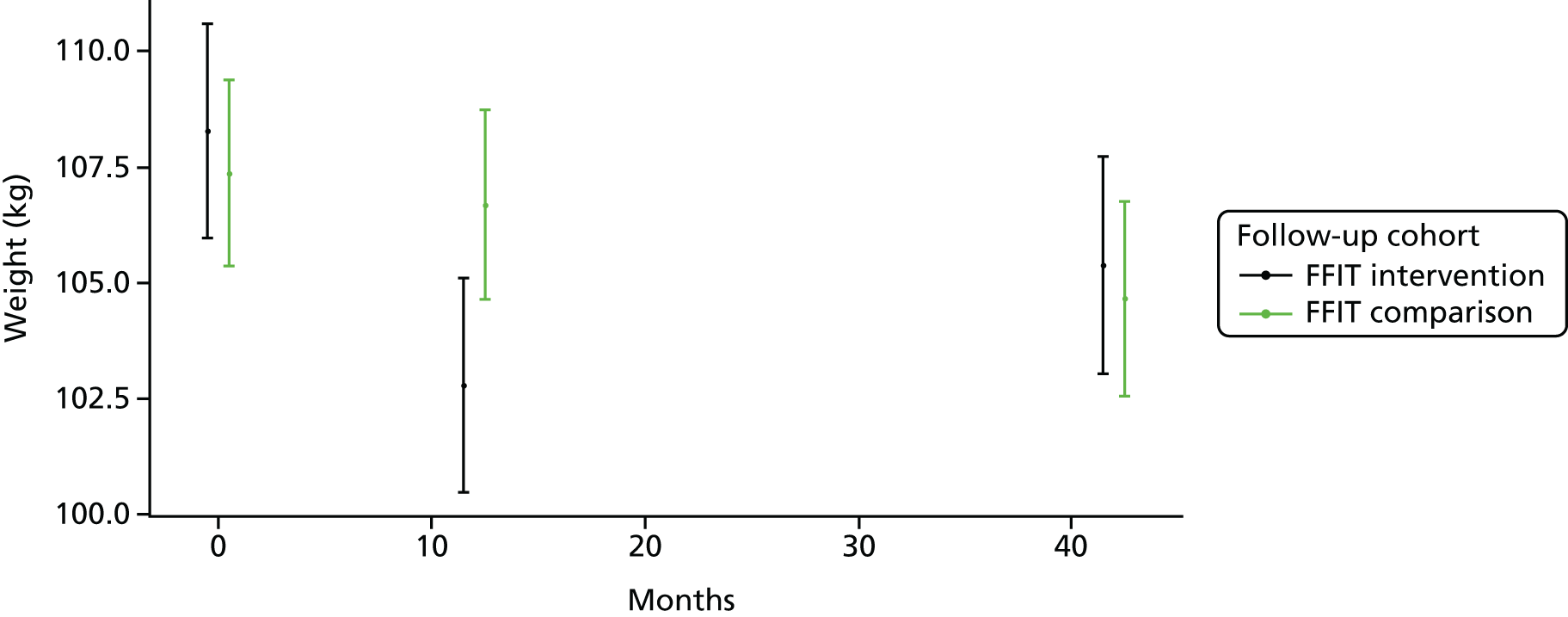

Figure 4 illustrates the data shown in Table 4, and clearly demonstrates that both groups weighed less at 3.5 years than at baseline.

FIGURE 4.

Mean weight (kg, 95% CI) of participants in the FFIT-FU-I and FFIT-FU-C groups at 12 months and 3.5 years after the FFIT RCT baseline measurements. Note that the y-axis [weight (kg)] does not start at zero.

Sensitivity analyses

Sensitivity analyses on the primary outcome (change in weight) were conducted to assess the sensitivity of the main analyses.

-

Loss to follow-up sensitivity analyses used a variety of assumptions about the long-term weight outcomes of men who had not taken part in follow-up measures at 3.5 years.

-

Baseline time points sensitivity analyses assessed the fact that both intervention and comparison groups had the opportunity to take part in the FFIT programme, but at different times.

In the loss to follow-up sensitivity analyses, the return-to-baseline and last-value-carried-forward methods were used to impute missing weight data at 12 months and 3.5 years for men who were not followed up. As men who were not followed up at 3.5 years (the not followed-up cohort) were, on average, heavier than the total followed-up cohort at baseline [112.8 kg (SD 17.2) vs. 107.8 kg (SD 17.1)] and 12 months [109.8 kg (SD 18.3) vs. 104.8 kg (SD 17.3)], the return-to-baseline sensitivity analysis is the most conservative and is reported here. The results of the last-value-carried-forward sensitivity analyses are shown in tables i and ii in Report Supplementary Material 7.

Table 7 shows that, in the return-to-baseline sensitivity analysis, the mean weight loss at 3.5 years was 1.81 kg (95% CI 1.09 to 2.52 kg) in the RCT intervention group (including imputed values) and 1.85 kg (1.12 to 2.58 kg) in the RCT comparison group (including imputed values). As in the main analyses, both figures were still significantly different from baseline, but there was no between-group difference.

| Change in weight | RCT group | Difference between groups (comparison – intervention) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention (N = 374) | Comparison (N = 373) | |||||

| Mean (95% CI) | p-value | Mean (95% CI) | p-value | Mean (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Absolute (kg) | –1.81 (–2.52 to –1.09) | < 0.0001 | –1.85 (–2.58 to –1.12) | < 0.0001 | –0.05 (–1.07 to 0.98) | 0.7984 |

| Percentage | –1.57 (–2.16 to –0.98) | < 0.0001 | –1.61 (–2.27 to –0.96) | < 0.0001 | –0.04 (–0.92 to 0.84) | 0.7898 |

Table 8 shows that, between 12 months and 3.5 years, men in the RCT intervention group (including imputed values) gained 3.15 kg (95% CI 2.37 to 3.92 kg; p < 0.001) and those in the RCT comparison group (including imputed values) lost 1.30 kg (95% CI 0.59 to 2.01 kg; p < 0.001). Although, as expected, there were slight differences in these values from the main analyses, the change in weight over time in each group remained significant, as did the between-group difference in weight trajectories (4.45 kg, 95% CI 3.40 to 5.50 kg; p < 0.001).

| Change in weight | RCT group | Difference between groupsa (comparison – intervention) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention (N = 374) | Comparison (N = 373) | |||||

| Mean (95% CI) | p-value | Mean (95% CI) | p-value | Mean (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Absolute (kg) | 3.15 (2.37 to 3.92) | < 0.001 | –1.30 (–2.01 to –0.59) | 0.0004 | –4.45 (–5.50 to –3.40) | < 0.001 |

| Percentage (of baseline) | 2.84 (2.18 to 3.50) | < 0.001 | –1.12 (–1.77 to –0.48) | 0.0007 | –3.96 (–4.88 to –3.04) | < 0.001 |

Full details of the baseline time points sensitivity analyses are provided in table iii in Report Supplementary Material 7 and confirm sustained weight loss in the FFIT-FU-I group at 3.5 years post intervention.

Randomised controlled trials secondary outcomes

Objectively measured physical outcomes

Table 9 shows that there were sustained improvements in waist circumference, BMI, percentage body fat, and systolic and diastolic BP at 3.5 years and 2.5 years after taking part in the programme (for the FFIT-FU-I group and FFIT-FU-C group, respectively). There were no between-group differences.

| Change in physical outcome | Group | Difference between groups (FFIT-FU-C – FFIT-FU-I) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FFIT-FU-I | FFIT-FU-C | |||||||

| n | Mean (95% CI) | p-value | n | Mean (95% CI) | p-value | Mean (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Waist (cm) | 214 | –2.90 (–3.89 to –1.91) | < 0.0001 | 237 | –2.64 (–3.64 to –1.65) | < 0.0001 | 0.25 (–1.15 to 1.66) | 0.7057 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 233 | –0.96 (–1.31 to –0.60) | < 0.0001 | 255 | –0.88 (–1.22 to –0.54) | < 0.0001 | 0.08 (–0.42 to 0.57) | 0.7010 |

| Body fat (%) | 162 | –1.94 (–2.81 to –1.06) | < 0.0001 | 165 | –1.38 (–2.31 to –0.45) | < 0.0001 | 0.56 (–0.72 to 1.83) | 0.3085 |

| BP (mmHg) | ||||||||

| Systolic | 214 | –3.13 (–5.15 to –1.11) | 0.0080 | 235 | –4.58 (–6.42 to –2.74) | < 0.0001 | –1.45 (–4.17 to 1.27) | 0.1862 |

| Diastolic | 214 | –1.56 (–2.80 to –0.32) | 0.0308 | 235 | –2.95 (–4.24 to –1.67) | < 0.0001 | –1.39 (–3.18 to 0.39) | 0.0920 |

Self-reported physical activity

Table 10 shows that the total PA was significantly higher at 3.5 years than at baseline in both the FFIT-FU-I group [800.0 MET-minutes per week, interquartile range (IQR) –120 to 2514 MET-minutes per week] and the FFIT-FU-C group (919.0 MET-minutes per week, IQR –186 to 2909 MET-minutes per week), and that there were no significant between-group differences. A similar pattern of results was observed for vigorous and moderate PA, and for walking. Table 10 also demonstrates a sustained reduction in time spent sitting in both groups.

| Change in self-reported PA | Group | Difference between groups (FFIT-FU-C – FFIT-FU-I) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FFIT-FU-I | FFIT-FU-C | |||||||

| n | Median (IQR) | p-value | n | Median (IQR) | p-value | Mean (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Total PA (MET-minutes/week) | 213 | 800.0 (–120 to 2514) | < 0.0001 | 232 | 919.0 (–186 to 2909) | < 0.0001 | 148.7 (–427.5 to 724.9) | 0.6055 |

| Vigorous PA (MET-minutes/week) | 213 | 0 (0 to 1320) | < 0.0001 | 232 | 0 (0 to 1140) | < 0.0001 | 140.9 (–235.4 to 517.2) | 0.6872 |

| Moderate PA (MET-minutes/week) | 213 | 0 (0 to 700) | < 0.0001 | 232 | 0 (0 to 630) | < 0.0001 | 6.7 (–229.4 to 242.7) | 0.8298 |

| Walking (MET-minutes/week) | 213 | 297.0 (–66 to 1040) | < 0.0001 | 232 | 297.0 (–132 to 1287) | < 0.0001 | 1.1 (–237.6 to 239.8) | 0.8652 |

| Daily sitting (minutes) | 171 | –30 (–180 to 120) | 0.0389 | 189 | –30 (–180 to 60) | 0.0011 | –12 (–61 to 36) | 0.6121 |

Self-reported eating and alcohol intake

Table 11 shows that the consumption of fatty food and sugary food scores at 3.5 years were significantly reduced from baseline in both groups, and that there were no between-group differences. Fruit and vegetables consumption was significantly higher at 3.5 years in both groups, and, again, there were no between-group differences. Similar sustained improvements were also evident for portion sizes of cheese, meat, pasta and chips, and for alcohol consumption; all showed sustained reductions from baseline, and no between-group differences.

| Change in self-reported food and alcohol consumption | Group | Difference between groups (FFIT-FU-C – FFIT-FU-I) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FFIT-FU-I | FFIT-FU-C | |||||||

| n | Mean (95% CI) | p-value | n | Mean (95% CI) | p-value | Mean (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Score | ||||||||

| Fatty food | 214 | –3.86 (–4.83 to –2.89) | < 0.0001 | 236 | –3.16 (–3.99 to –2.33) | < 0.0001 | 0.70 (–0.57 to 1.97) | 0.3289 |

| Sugary food | 214 | –1.32 (–1.69 to –0.95) | < 0.0001 | 236 | –1.07 (–1.41 to –0.73) | < 0.0001 | 0.25 (–0.25 to 0.75) | 0.4264 |

| Fruit and vegetables | 214 | 0.50 (0.23 to 0.76) | < 0.0001 | 236 | 0.40 (0.14 to 0.65) | < 0.0001 | –0.10 (–0.47 to 0.27) | 0.5596 |

| Portion size | ||||||||

| Cheese | 198 | –1.12 (–1.41 to –0.83) | < 0.0001 | 213 | –1.12 (–1.41 to –0.83) | < 0.0001 | 0.00 (–0.41 to 0.41) | 0.9393 |

| Meat | 205 | –0.98 (–1.18 to –0.77) | < 0.0001 | 232 | –0.83 (–1.03 to –0.64) | < 0.0001 | 0.14 (–0.14 to 0.43) | 0.2017 |

| Pasta | 198 | –1.21 (–1.44 to –0.98) | < 0.0001 | 226 | –1.11 (–1.33 to –0.88) | < 0.0001 | 0.11 (–0.22 to 0.43) | 0.6339 |

| Chips | 183 | –1.08 (–1.32 to –0.84) | < 0.0001 | 217 | –0.84 (–1.07 to –0.61) | < 0.0001 | 0.24 (–0.09 to 0.58) | 0.0911 |

| Total alcohol (units/week) | 207 | –2.68 (–4.52 to –0.83) | 0.0070 | 233 | –4.28 (–6.06 to –2.50) | < 0.0001 | –1.61 (–4.16 to 0.95) | 0.2945 |

Self-reported psychological health and quality-of-life outcomes

Table 12 shows that improvements in self-esteem, positive and negative affect, and physical and mental HRQoL were sustained to 3.5 years in both groups, and that there were no between-group differences.

| Change in self-reported psychological outcomes | Group | Difference between groups (FFIT-FU-C – FFIT-FU-I) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FFIT-FU-I | FFIT-FU-C | |||||||

| n | Mean (95% CI) | p-value | n | Mean (95% CI) | p-value | Mean (95% CI) | p-value | |

| RSE score | ||||||||

| Self-esteem | 214 | 0.23 (0.18 to 0.29) | < 0.0001 | 237 | 0.25 (0.20 to 0.30) | < 0.0001 | 0.01 (–0.06 to 0.09) | 0.5507 |

| PANAS score | ||||||||

| Positive affect | 214 | 0.27 (0.17 to 0.38) | < 0.0001 | 237 | 0.24 (0.16 to 0.32) | < 0.0001 | –0.04 (–0.17 to 0.09) | 0.8715 |

| Negative affect | 214 | –0.17 (–0.24 to –0.11) | < 0.0001 | 237 | –0.11 (–0.17 to –0.05) | < 0.0001 | 0.06 (–0.03 to 0.15) | 0.2429 |

| SF-12 score (HRQoL) | ||||||||

| Mental | 213 | 1.12 (–0.19 to 2.43) | 0.0145 | 235 | 2.63 (1.57 to 3.69) | < 0.0001 | 1.51 (–0.17 to 3.19) | 0.1619 |

| Physical | 213 | 1.98 (0.81 to 3.16) | < 0.0001 | 235 | 1.09 (–0.08 to 2.25)a | 0.0218a | –0.90 (–2.55 to 0.76) | 0.1008 |

Randomised controlled trial secondary outcome trajectories