Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 10/3005/18. The contractual start date was in April 2012. The final report began editorial review in October 2017 and was accepted for publication in June 2018. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Steven Cummins and Alastair H Leyland were members of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Public Health Research Funding Board at the time of application for grant funding; however, they played no role in the discussions or decision on the funding of this project. Steven Cummins is supported by a UK NIHR Senior Research Fellowship. Richard Mitchell, Alastair H Leyland and Aldo Elizalde declare that the Social and Public Health Sciences Unit, University of Glasgow, received core support from the Medical Research Council (reference numbers MC_UU_12017/10 and MC_UU_12017/13) and the Scottish Government Chief Scientist Office (reference numbers SPHSU10 and SPHSU13). Andrew Briggs reports grants from NIHR during the conduct of this study, outside the submitted work. Willings Botha received support from a Forestry Commission Scotland (FCS)-funded studentship during the course of the study, supervised by Andrew Briggs and Richard Mitchell. Catharine Ward Thompson and Richard Mitchell report grants from FCS prior to the commencement of this project and co-supervision of FCS-funded studentships that drew on the project described in the report. Catharine Ward Thompson was lead researcher (2006–11) on commissioned research funded by FCS to undertake an evaluation of some of its Woods In and Around Towns programme. Richard Mitchell is a non-remunerated director of a charity (Paths For All), which delivers, and advocates for, walking for health.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Ward Thompson et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background

This section outlines the wider context and background against which the study was developed. The study’s public health focus (mental health) is presented and the intervention it evaluated is introduced.

Context

High prevalence of poor mental health is a major public health problem in the economically developed world. Approximately 27% (83 million people) of the adult population in the European Union experienced at least one mental health disorder in the past year. 1 The economic cost of poor mental health is high. In Scotland, where this project was based, this cost has been estimated at £10.7B. 2 Improving mental health and well-being is a public health priority.

Environmental influences on health, including mental health, are of particular interest because of their potential to affect large numbers of people. 3 Epidemiological investigation and public health policy have long understood the environment primarily in terms of threats to human health; however, there is now growing interest in the salutogenic properties and capacities of environments – that is, in the potential for environments to maintain and improve health. 4 Good evidence from both individual- and population-level studies suggests, for example, that contact with natural environments and green spaces, such as parks, woodlands and river corridors, brings health benefits. 5–7

How do natural environments affect health? Three principal mechanisms have been proposed. 8 First, they may be conducive to physical activity (PA), for which health benefits are well proven. 9 Second, they may foster and support social contact, again for which there is evidence of health benefit. 10,11 Third, contact with natural environments per se may reduce stress, improve well-being and promote immune response. 12–14 This direct effect of natural environments on human health operates, inter alia, via psychoneuroendocrine pathways and has been demonstrated in both laboratory and field experiments. 7,12,15 Empirical evidence for such psychophysiological benefits is supported by well-developed theories about this effect’s origin, such as the hypothesis that it is a psychoevolutionary response to environments that have proved favourable to humans. 16–18 The balance of evidence currently suggests that the psychophysiological responses may be the most important of the three mechanisms, although they may be additive or supra-additive. 8 In addition, there is evidence that greener environments are less polluted environments in terms of air quality, either because vegetation removes pollutants from the air or because a greener environment has fewer pollution sources within it. 19,20

How useful could these health effects be for population health? Observational studies have found associations between access to natural environments and mortality rates for diseases in which stress, immune function and PA play a role in aetiology (see, for example, Maas et al. ,21,22 de Vries et al. 23 and Coutts et al. 24). Studies in the UK show a typical reduction in risk of mortality from cardiorespiratory disease of 5% to 10% in urban-dwelling populations with good access to natural environments compared with those with poor access. 25,26 In Denmark, Stigsdotter et al. 27 found reported levels of stress to be some 40% lower among those with good access to natural environments (≤ 300-m distance) than those with poor access (> 1 km distance). A number of studies have shown greater use of green space when it is more proximate. 28–30 However, there is also evidence that, within certain distance parameters, quality may be more important than proximity. 31 The positive impacts of access to natural environments appear particularly beneficial for deprived urban populations and this might be one explanation for the evidence that socioeconomic health inequalities appear narrower among urban populations with greater access to natural environments. 25 It is important to note, however, that results from observational studies vary by individual characteristics; in particular, it appears that effects may be greater for men than for women. 26 There is currently no clear empirical evidence as to why this should be, although it is hypothesised that it might be attributable to differences between men and women in the frequency, duration and mode of access to natural environments.

The present evidence base on the population-level health effects of exposure to natural environments is, then, largely observational and is therefore subject to the biases and threats from confounders that characterise observational designs. This evidence base also tells us little about how potential changes in access to natural environments improve health or, perhaps more importantly, how those changes should best be achieved. We do not know, for instance, if it is the provision of natural environments or the promotion of opportunities to access these environments that matters most, or if both are equally important. This evidence gap provided the rationale for this study.

The research took advantage of a rare opportunity for a prospective study. Through its Woods In and Around Town (WIAT) programme, Forestry Commission Scotland (FCS), the Scottish Government’s forestry advisor and regulator and the public body that manages Scotland’s forests and woodlands, planned a set of physical and social interventions in deprived communities to enhance public access to natural environments. The study treated these interventions as a ‘natural experiment’32 and investigated their impacts on mental health, particularly perceived stress, at a community level over time.

Woods In and Around Towns

Woods In and Around Towns is a programme delivered by FCS that targets woodlands near socially deprived urban communities. It operates to improve and promote local woods as safe and accessible places for enjoying the outdoors. 33 WIAT aims to increase local residents’ contact with woodlands that are situated within 1 km of settlements with a population of at least 2000 people, thus enhancing well-being and quality of life in urban Scotland.

In aiming to increase local residents’ contact with their local woodlands, WIAT aims to improve mental health and well-being, including stress regulation. FCS committed > £70M to WIAT between 2005 and 2015. It delivers a suite of physical and social interventions within targeted woodlands. Physical interventions consist of physical changes to enhance sustainable management of the woodlands and improve onsite recreation facilities (new paths, signage, entrances, etc.). Social interventions consist of a programme of publicised and facilitated community-level activities/events (e.g. guided walks, natural play and woodland-based classes for school children) that aim to promote the woodlands and increase use. The social and physical interventions delivered in a given woodland are particular to the needs, challenges and interests of that woodland and surrounding community. WIAT represented a rare and valuable opportunity to carry out a prospective evaluation of the health impacts of change in, and promotion of, woodland environments near deprived communities.

Members of the study team had previously investigated impacts of WIAT interventions in a pilot study completed between 2006 and 2009 in the city of Glasgow. That study focused on one wooded green space that received WIAT interventions and a matched comparison green space that did not. 34 Using a repeat, cross-sectional survey (n = 100) of residents living within 500 m of their local green space, impacts on patterns of use, PA, perceived quality of life, perceptions of the neighbourhood and perceptions of woodland/green space environments were explored. 34 The study revealed that the interventions had a positive impact on use patterns and were associated with improved quality of life and enhanced perceptions of the neighbourhood and woodlands; these are factors that might influence health outcomes. 34

The current study provided an opportunity to investigate these relationships further and, if established, explore whether or not they translated into changes in health and well-being. Within this study, therefore, we evaluated the impacts of physical and social interventions delivered by FCS as part of the WIAT programme within three separate woodlands located in the Central Belt of Scotland. These interventions targeted approximately 38 ha of woodland in total, delivered some 3500 m of new and upgraded path, new seating areas and signage, a restored water feature, repaired fences, tree works and > 60 community engagement activities including photography workshops, health walks and bulb-planting days.

Research aims and objectives

Ultimately, the study aimed to provide robust and generalisable evidence on the impact on mental health of an intervention designed to enhance, and increase engagement with, natural environments. To provide a complete assessment of the WIAT interventions, the study aimed to evaluate the effects of the interventions, the functioning of the interventions35 and the interventions’ value for money through linked quantitative, qualitative and economic evaluations.

The key research objective and questions that steered the study were as set out below.

The study’s main objective was to evaluate the health impacts of an intervention that enhanced woodland environments in deprived communities and sought to increase community engagement with these woodlands. This aim was captured in the following primary research question:

-

What is the impact of the WIAT programme of interventions on mental health (particularly as measured by patterns and levels of perceived stress) in the community?

Several secondary research questions also structured the study:

-

Is any impact on mental health associated with a change in levels of engagement with woodland or other natural environments (physical and/or visual) after implementation of the WIAT intervention?

-

Are changes to the physical woodland environment sufficient to have an impact on mental health and/or woodland awareness and use by the community, or are organised activities such as led walks and other promotional initiatives also required?

-

What is the impact of the intervention on other health and well-being outcomes (i.e. PA levels, sense of connectedness to nature and community cohesion)?

-

What is the impact of the intervention on length and frequency of visits to natural areas and local woods, experience of local woods, awareness of them (knowledge of their qualities and availability for use), activities undertaken there and visual contact with woodland?

-

Are there gender differences in the impacts of the interventions?

-

Are there differences in patterns of woodland use, and in impacts of the interventions, in accordance with distance of woodlands from participants’ homes, and is there any distance threshold for impacts?

-

What are the cost consequences of each stage of the intervention (including time input from FCS rangers) in relation to the primary and secondary outcomes of the study?

Literature review

This study was informed by a review, summarised here, of the relevant literature focusing on the few intervention studies that have considered the effects on mental health of physical changes to natural environments and/or exposure to natural environments.

There is accumulating evidence for the beneficial effects of green space on mental health. 36 Multiple studies have found associations between living in or near green environments and/or visiting green environments and improved mental health, lower levels of stress, depression, anxiety and psychological distress and higher levels of well-being and vitality. 27,37–43 Although the precise attributes of green space associated with these health benefits, and the relative importance of different attributes, requires further research,36,44 studies have identified tree cover, tree canopy density, neighbourhood greenery, visible grass and trees,45,46 the quality of green space and its sensory and spatial characteristics47–49 as important. Different segments of the population experience differential health benefits from these and other attributes, with evidence indicating that gender, age, ethnicity and socioeconomic status may mediate the effect. 36 For example, a significant relationship has been identified between access to ‘serene’ green space (i.e. a ‘holy’, safe, calm, undisturbed, silent green environment) and improved mental health in women but not in men. 40

It is rare for insights into the effect of natural environments on mental health to derive from studies that assess the impacts of natural environment interventions. This may in part be because natural environment interventions rarely focus on impacts on mental health. The World Health Organization (WHO) recently issued a call across European professional and city networks for case studies of urban green space interventions. 50 Of the 48 complete submissions received, sent in by municipal authorities, public agencies and third-sector organisations, only five considered impacts on mental health. 51 Also relevant might be the finding that studies of the impacts of natural environment interventions that deliver physical change rarely focus on changes in mental health; instead, changes in PA or visits to green space are the usual concern. 44 A recent systematic review of interventions that delivered physical changes to urban green spaces identified 38 relevant studies, but just three measured mental health outcomes: two considered self-reported stress levels52,53 and one considered self-reported depressive symptoms. 54 Those studies considering stress levels found that residents reported lower levels of stress in areas where vacant urban lots had been cleaned up and ‘greened’ (trees and grass planted, land graded, low wooden perimeter fences installed)52 and, although not constituting a significant decline, reduced levels of stress in areas where green storm water infrastructure had been installed. 53 In the study that considered depressive symptoms, highlighting the important point that studies do not universally identify a positive relationship between natural environments and improved health, a significant increase in depressive symptoms was identified in adolescents (adolescents and adults were studied) in areas that had received park-based and greening interventions. 54

Studies of the impacts of natural environment interventions that deliver physical change suffer from various methodological limitations that curtail the insights they afford. 44 Studies often operate short follow-up periods, limiting the potential to assess longer-term impacts. 44 Details of sample size calculations are rarely provided and many studies are underpowered. 44 Studies lacking an appropriate sample size calculation are at increased risk of type II errors when the sample is too small to detect an effect. Few studies have considered the economic implications of interventions and studies often provide incomplete accounts of the interventions evaluated, neglecting measures of their implementation (e.g. dose, fidelity, reach). 44

Compared with the number of studies that have considered the impacts on mental health of interventions that deliver change in natural environments, far more studies have evaluated the effects on mental health of interventions that focus on exposure to natural environments. A recent systematic review of trials that compared the effects on well-being of outdoor exercise initiatives with indoor initiatives identified 11 relevant studies and all measured some aspect of mental well-being, usually mood. 55 These studies indicated that, relative to exercising indoors, exercising in natural environments was associated with decreases in tension, confusion, anger and depression, greater feelings of revitalisation and positive engagement and increased energy, although feelings of calmness appeared to reduce. 55 A similar systematic review, which focused on studies that compared the impacts on health or well-being of exercise completed in natural environments with exercise completed in ‘synthetic’ environments, identified 25 relevant studies and 16 of these measured aspects of mental well-being. 56 These studies indicated that exercising in natural environments was associated with beneficial effects on several dimensions of mental health, including measures of anger, fatigue and depression/sadness. 56 However, various methodological limitations restrict the insights afforded by these types of studies. 56 Studies often focus on single exposures to natural environments and effects are often assessed immediately following exposure. 56 As a result, longer-term impacts, and the impacts of repeat exposure, are not considered. 56 Study participants tend to be college students, adult males and physically active adults, limiting the potential to extrapolate to wider populations. 56 Finally, within some studies it is unclear if the selected ‘natural’ environments are sufficiently ‘green’ to provide a test of the effect of ‘nature’ on health. 56

To address gaps and deficiencies in the evidence base, such as those discussed here, there is a clear need for further formal assessments of natural environment interventions that deliver physical change. 44 This study, in seeking to evaluate a natural environment intervention that delivered change in community woodlands, was conceived to help address this need.

Chapter 2 Study design and methods

This chapter describes the study’s overall research design and presents the approach and methods employed to address each of the research questions outlined in Chapter 1. It involved both quantitative and qualitative methods and considerable community and stakeholder engagement. This multimethod approach allowed us to identify the outcome of the interventions in relation to our key health, well-being and quality-of-life measures (see Chapter 3). We explored community perceptions of the environment affected by the WIAT interventions (see Chapter 4) and undertook an economic evaluation (see Chapter 5) of the interventions. The methods used for each are described in turn.

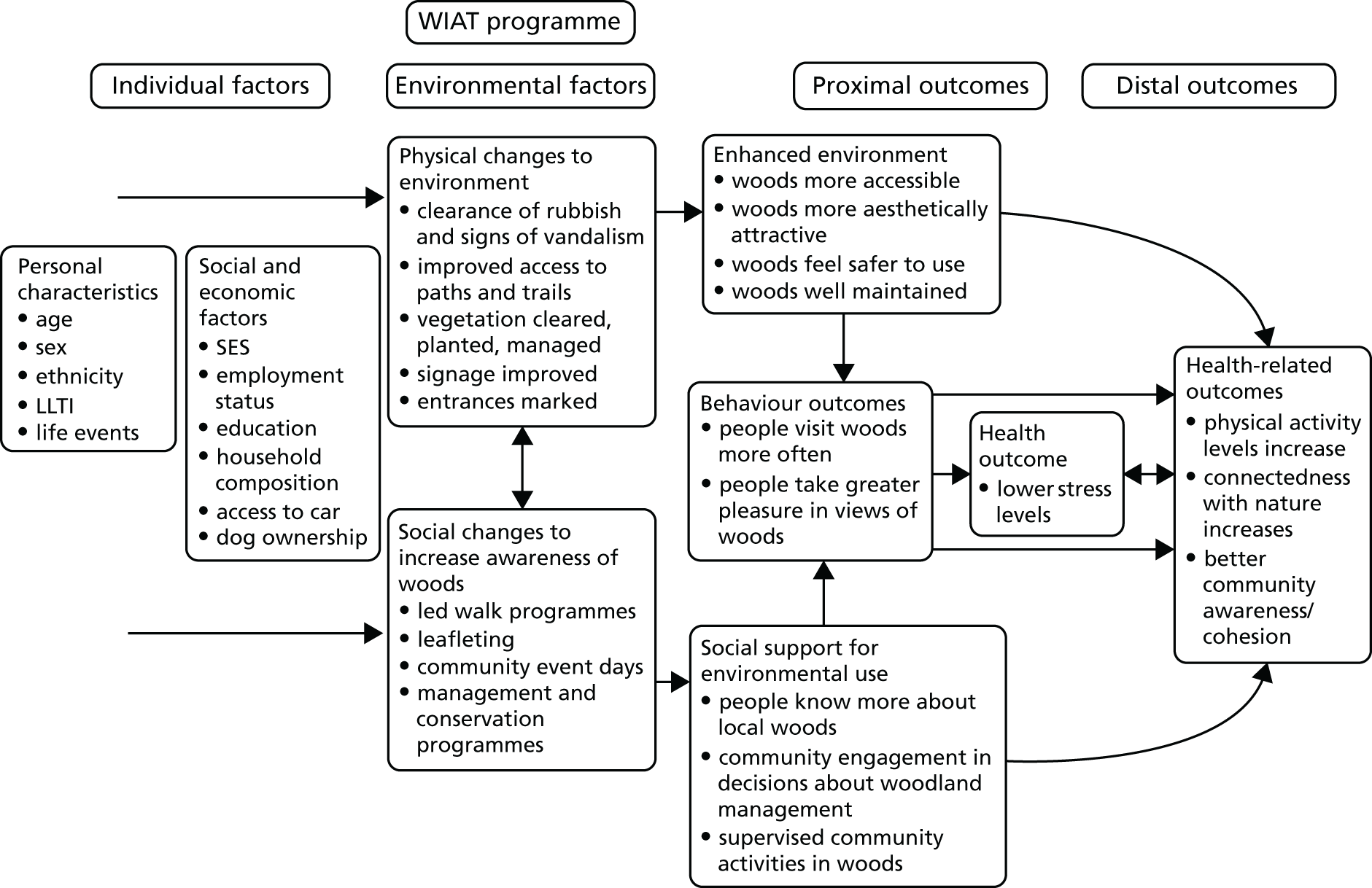

A high-level evidence-based logic model (Figure 1) that hypothesised how the interventions would affect health underpinned and orientated the study. It is an adapted version of the model for this study published by Silveirinha de Oliveira et al. in 2013. 57 This theory posited that the physical changes to the woodlands would make them more accessible, more aesthetically pleasing and safer, and the social interventions would increase awareness of, and engagement with, the woodlands as well as social interactions among community members. Collectively, this would lead to individuals visiting the woodlands more often and taking greater pleasure in views of and use of the woodlands. As a result, there would be measurable reductions in self-reported levels of stress (our primary outcome measure). Other hypothesised pathways to this outcome included increased levels of PA, increased feelings of connectedness with nature and better community cohesion.

FIGURE 1.

Hypothesised impact pathways of the WIAT intervention programme. LLTI, limiting long-term illness; SES, socioeconomic status. Adapted with permission from Silveirinha de Oliveira et al. , 2013. 57 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Overall research design

The study was a controlled programme-level evaluation of the WIAT intervention. The research design was quasi-experimental and included three intervention and three matched control sites. The WIAT intervention was treated as a natural experiment. 32 The study design included repeat cross-sectional surveys of individuals resident in intervention and control communities, with three waves of data collection to assess health impacts. A longitudinal cohort of participants (seen at two or three waves) was nested within the cross-sectional surveys, the size of which was determined by the extent to which we were able to obtain repeat responses. The longitudinal mixed-methods study also tracked the nature and cost of environmental changes in woodlands and promotional activities that took place, the local communities’ perceptions of these interventions and the interventions’ impact on primary and secondary health outcomes.

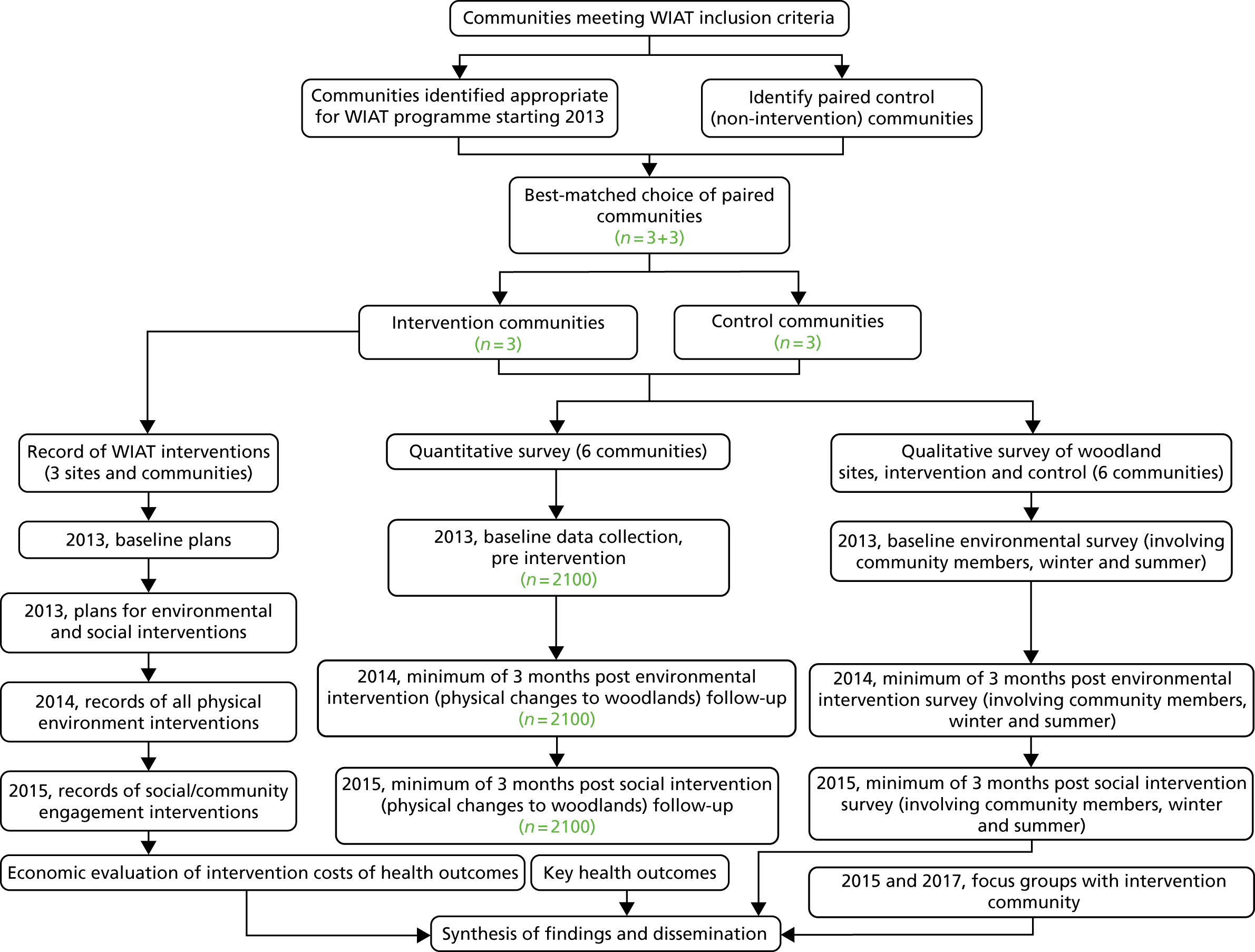

The study contained six main components (Figure 2):

-

A preliminary, geographical information system (GIS)-based assessment of all potentially WIAT-eligible woodlands and their associated communities, using both FCS maps and (in the final stages of site choice) site visits, to identify sites appropriate for intervention starting in 2012/13 and for which comparable control woodlands and communities could be identified in each case.

-

A record of the environmental and social interventions planned and implemented by FCS, under the WIAT programme, including the costs involved at all stages, to ensure that we could identify sites that had not been subject to recent WIAT intervention prior to the commencement of this study.

-

A core survey of the local community in each site, undertaken before and after each of the two phases of WIAT intervention, to record the intervention’s impact on health and well-being outcomes, perceptions and use of local woods and green space, and assessments of the local neighbourhood and the interventions.

-

Audits of the woodlands and associated neighbourhood environment, both by expert auditors and by local community members, in both summer and winter, before and after each phase of the intervention, to evaluate any changes in the physical characteristics of each site.

-

A qualitative study of a subsample of core survey and woodland audit participants from each local community to elicit an understanding of the experience of the intervention and perceptions of its effectiveness.

-

An economic evaluation of the intervention and any associated health outcomes identified.

FIGURE 2.

Study components and sequence.

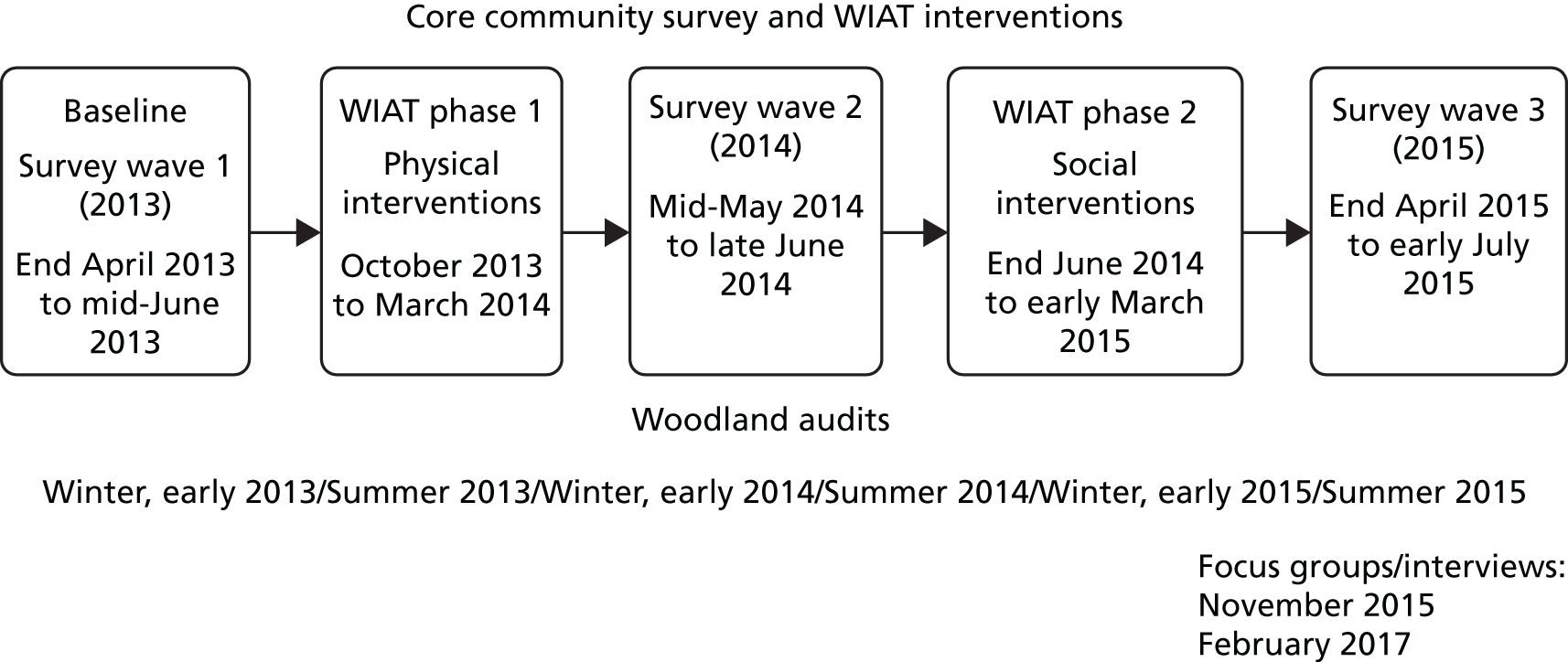

Figure 3 shows the time scale for the data collection components 3, 4 and 5 listed above against the time scale of the WIAT interventions.

FIGURE 3.

Time scale of data collection and WIAT interventions.

Study setting

Six woodland sites (three intervention and three control sites), and associated communities, were included in the study. They were located within the Scottish Lowlands Forest District, a district that covers the Central Belt of Scotland, extending from the west to the east coast and including the major conurbations of Glasgow and Edinburgh. The National Records of Scotland show that, of the 5.37 million people living in Scotland in mid-2015, the Central Belt of Scotland contained > 3.3 million of those people. This highly urbanised part of Scotland, including Greater Glasgow, Renfrewshire, North Ayrshire, North Lanarkshire, Falkirk, the Lothians, Edinburgh and Fife, also contains the majority of the most deprived populations.

Site selection

The woodlands and associated communities were chosen from among those that met WIAT inclusion criteria. At the time of site selection, these required woodlands to lie within 1 km of a settlement of at least 2000 people, for the woodland to cover a minimum of 1 ha and at least 40% of the land had to have tree cover. Furthermore, the WIAT programme targets woodlands in areas of high deprivation.

Our site selection further developed these criteria to choose sites that satisfied the study requirements, including the need to match sites ready for intervention as closely as possible with control sites in terms of a number of environmental and demographic characteristics. The process was as follows.

-

Sites were chosen within the worst 30% of socioeconomic deprivation in Scotland as measured by the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation (SIMD). 58

-

At least 50% of the woodland area had to be within 1.5 km of an urban population of at least 2000 people. We expanded the definition of community within range of woodlands to 1.5 km to ensure an adequate settlement size for sampling purposes and to allow for any effect of distance to be assessed.

-

Woodlands had to have a minimum size of 4 ha (this was deemed more typical of WIAT sites in practice than the FCS minimum criterion of 1 ha for WIAT eligibility) and at least 40% of the land had to have tree cover.

After the application of steps 1, 2 and 3, 40 sites were identified as potential candidates. The selection process was narrowed further by assessing the physical qualities of both woodlands and surrounding communities. To do so, satellite and panoramic images via Google Earth (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA) were used. Factors considered for this analysis included:

-

The maturity and the degree of existing cover of the trees.

-

The height of residential buildings (because high-rise or tower block housing provides particular challenges in terms of access, we excluded areas with this housing).

-

The different ways of accessing the woodlands, including any major physical barriers to access.

-

The number of private or semi-private gardens as well as the quantity of trees there.

-

-

A final shortlist was presented to the FCS to assess the status of each site, potential issues, previous grants and interventions. Woodland sites that had received FCS investment or direct promotion within the previous 5 years were discarded. This resulted in a shortlist of 10 sites from which to choose for the study.

-

Several visits to the shortlisted sites were conducted by researchers and members of the FCS to examine whether or not the characteristics of the sites were fully consistent with the desk-based analysis.

-

Six sites were chosen in December 2012, assigned to the intervention or control group and paired (one each of intervention and control) based on various socioeconomic and demographic characteristics of individuals living in the surrounding communities (Table 1). Three sites were assigned to the intervention group and the remaining three to the control group (Tables 2a and 2b). The intervention sites of each matched pair were chosen based on their readiness for management agreements to be obtained (see point 7), as there was little time for lengthy negotiations on ownership, access and use.

-

Management agreements were prepared between the FCS and the local authorities involved to ensure that no other interventions within the shortlisted sites took place during the time frame of the natural experiment, thus reducing confounding issues in the study design. These efforts also involved close consultation with private land owners as some of the chosen woodlands were not under full ownership of the relevant local authorities.

| Characteristic | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic | Neighbourhood housing | Economic factors | Multiple deprivation | Health |

|

|

Income (number of income-deprived people) | SIMDa | |

| Site | Age, years (%) | Mean age (years) | Ethnicity | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–9 | 10–14 | 15–19 | 20–29 | 30–44 | 45–59 | 60–64 | 65–74 | 75–84 | ≥ 85 | Non-white (%) | ||

| Intervention A | 12 | 8 | 8 | 10 | 21 | 17 | 7 | 11 | 4 | 1 | 39 | 1 |

| Control A | 14 | 9 | 8 | 10 | 22 | 17 | 6 | 9 | 4 | 1 | 37 | 0 |

| Intervention B | 12 | 7 | 7 | 11 | 22 | 16 | 9 | 13 | 4 | 1 | 40 | 1 |

| Control B | 11 | 9 | 8 | 12 | 22 | 21 | 5 | 7 | 4 | 1 | 37 | 2 |

| Intervention C | 16 | 9 | 8 | 13 | 24 | 16 | 4 | 7 | 3 | 0 | 34 | 1 |

| Control C | 15 | 9 | 9 | 14 | 23 | 18 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 34 | 1 |

| Site | Neighbourhood housing type (%) | Economic and deprivation indicators | Health | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Detached houses | Flats/tenements | Semi-detached houses | Terraced houses | Other (e.g. caravan) | Income deprivation scorea (%) | SIMD scoreb | SMRc | Depressed (%) | |

| Intervention A | 4 | 41 | 22 | 32 | 1 | 33 | 49 | 152 | 10 |

| Control A | 8 | 48 | 19 | 24 | 2 | 35 | 49 | 143 | 11 |

| Intervention B | 2 | 50 | 11 | 36 | 1 | 27 | 36 | 111 | 9 |

| Control B | 7 | 13 | 32 | 47 | 1 | 23 | 32 | 120 | 11 |

| Intervention C | 3 | 15 | 22 | 58 | 0 | 22 | 35 | 108 | 10 |

| Control C | 9 | 13 | 17 | 61 | 1 | 25 | 35 | 97 | 11 |

The three matched pairs of sites were located in Glasgow City, Renfrewshire (two sites), North Lanarkshire, Midlothian and Fife. Tables 2a and 2b show the community characteristics of the sites chosen and Table 3 shows the characteristics of the eligible woodlands in each of these sites.

| Site | Woodland overview |

|---|---|

| Intervention A | Total area: 8.5 ha (approximately). The intervention woodland is 5.9 ha, owned by Glasgow City Council; remaining area is in private ownership. Located on a hill – elevation begins at 25 m and rises to 42 m. Located between two deprived neighbourhoods. There are a few other nearby areas of green space, all separated from the site by main roads, including parks and woods |

| Control A | Total area: 4 ha (approximately). Mostly in private ownership. The control woodland is located between a deprived neighbourhood and a main road. Mostly flat, with some elevation on the south and west side, away from the road. A river runs through the woodland. There are a couple of other nearby areas of green space (a park and woods) separated by main roads |

| Intervention B | Total area: 24 ha (approximately). Forms part of a larger woodland that includes a further 11 ha of mature woodland (not part of the intervention site). Owned by Renfrewshire Council. Relatively level terrain (elevation 12 m). Located on the fringe of a deprived community separated from the housing by a sports centre and playing fields. There is only one other green space, at some distance to the south of the neighbourhood, beyond a main road |

| Control B | Total area: 16 ha. Mostly in private ownership. Varied landform including a steeply incised stream and gentle sloping areas. Located on the fringe of a deprived community beyond a local residential road. There is one additional nearby green space, a small park, plus a large golf course with woodland at some distance and beyond a main road |

| Intervention C | Total area: 5.8 ha. Owned by Midlothian Council. Sloping topography. Located next to a deprived community with housing on three sides. Additional nearby areas of green space include an open green space with some small woodland areas, separated from the site by a minor local road, and fields and small woodland strips further away |

| Control C | Total area: 11 ha (approximately). Owned by the Woodland Trust but leased to the GreenBelt Group (which manages green spaces). Mixed terrain including relatively flat areas and a very steep slope. Located between two deprived neighbourhoods. Additional nearby areas of green space include a woodland and further green space beyond main roads |

The Woods In and Around Towns interventions: environmental and social interventions

A record was kept of the interventions, which were planned and implemented in two phases. The aim was that FCS would follow typical procedures for WIAT programme interventions, although the study design placed additional constraints of timing on both phases of implementation.

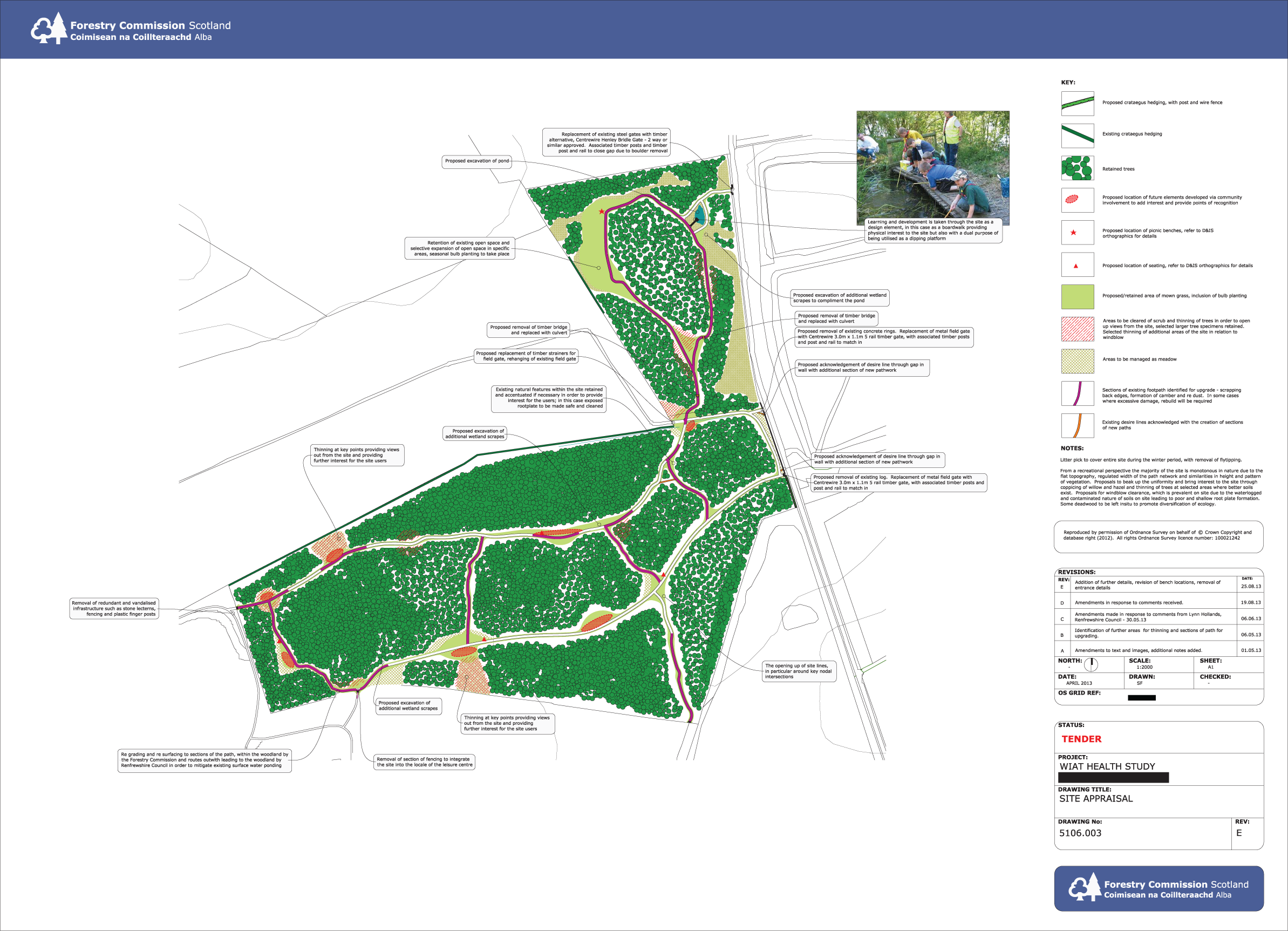

Phase 1: environmental interventions

Phase 1 involved physical changes to the woodland environment, designed to facilitate better access to, and use of, the woods. The interventions took place simultaneously across the three intervention sites over a period of 6 months, between October 2013 and March 2014. As with all WIAT schemes, the interventions were responsive to local conditions and community needs and, therefore, followed WIAT principles but varied in the detail of their design and implementation. The WIAT interventions followed principles defined by FCS in its grant-aid schemes of that time (2010). 33 The FCS guide to developing interventions to enhance the woodland user experience59 also informed the interventions to help ensure that a consistent approach was taken.

Researchers documented the physical state of the sites before and after the first intervention phase of the WIAT programme, undertaking regular checks of the environment in the field. In addition, FCS kept a systematic record of the plans, progress and completion of the works and noted feedback from the rangers involved in the projects as they progressed.

The physical changes to each intervention site were:

-

Intervention site A – upgrading main entrance with stone setts (paving blocks) and bollards (wooden posts to exclude vehicular traffic), surfacing a loop path (i.e. a path taking a more or less circular route to return to its starting point) (approximately 650 m), treeworks (trimming and clearing overgrown vegetation and tree branches), fence repair, installing two picnic benches, installing two benches and litter picking.

-

Intervention site B – upgrading three entrances, surfacing a loop path (approximately 1900 m), treeworks (thinning trees and trimming and clearing overgrown vegetation and tree branches), installing two picnic benches; installing six benches, new signage, restoring pond and creating dipping platform and litter picking.

-

Intervention site C – upgrading one existing entrance, creating one new entrance with stone setts, surfacing a loop path (approximately 990 m), non-surfaced path improvements, treeworks (felling and thinning trees and clearing overgrown vegetation and tree branches), installing one bench and litter picking.

Forestry Commission Scotland produced plans of the interventions and the researchers photographed the physical state of the sites before and after this phase of the WIAT programme. Figures 4–6 show images of typical physical changes to each intervention site in this phase of intervention, all taken in winter months for ease of comparison. See Appendix 1 for plans of the environmental interventions.

FIGURE 4.

Intervention site A before (above) and after (below) environmental interventions. Reproduced with permission from OPENspace.

FIGURE 5.

Intervention site B before (above) and after (below) environmental interventions. Reproduced with permission from OPENspace.

FIGURE 6.

Intervention site C before (above) and after (below) environmental interventions. Reproduced with permission from OPENspace and FCS.

Phase 2: social interventions

Phase 2 involved social interventions via facilitated community engagement activities to advertise and promote woodland use. The social intervention started in June 2014 (4 months after the physical intervention was completed) and took place in the three intervention sites over a total period of 9 months, until March 2015. They were planned around typical interventions used in the WIAT programme and, as with the physical interventions, were responsive to local woodland and community characteristics and aimed to target a variety of different segments, including different age groups, within the community. Typically, they involved one or two forest rangers and up to 1 day of preparation.

Community members were invited to these activities by FCS using a variety of means to engage different groups via both targeted events [e.g. photography workshops, a continuing professional development (CPD) event for nursery teachers and assistants] and more general events aimed at the whole community. Public events were freely open to all and widely advertised, for example through posters on site, in local shops, libraries, health centres, schools, community council Facebook (Facebook, Inc., Menlo Park, CA, USA; www.facebook.com) pages and letter drops to people’s homes.

The FCS rangers completed a form devised by the researchers for each activity undertaken to ensure that a systematic record was kept of the social intervention delivery and the participants engaged. This included a record of:

-

the number of people involved

-

the estimated age group of participants

-

the participants’ genders.

Table 4 summarises the 62 social interventions undertaken and the numbers of participants. For some public events the attendance was so high that only an estimate of numbers was possible. It should also be noted that those participating in some events might be the same people attending repeated sessions, so the numbers reported are not necessarily unique individuals but the sum of those attending any one event. Most activities attracted a reasonable balance of male and female participants, although school and nursery teachers and assistants were predominantly female and health walk participants were predominantly male.

| Social intervention (n) | Number of participants | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention site A | Intervention site B | Intervention site C | |

| Public event (11) | 168 | 272 | 80 |

| Photography workshop (7) | 8 | 10 | 6 |

| Health walk (9) | 14 | 43 | n/a |

| Summer club (during school holidays) (8) | 77 | 51 | n/a |

| School/nursery school session (11) | 108 | 46 | n/a |

| Green gyma (11) | 10 | 12 | n/a |

| Community clean-up/litter picking (2) | n/a | n/a | 20 |

| Dog owners’ event (2) | n/a | n/a | 5 |

| Nursery teachers’ CPD session (1) | n/a | n/a | 9 |

| Total number of attendees | 385 | 434 | 120 |

Public events and those with school or nursery children included activities to introduce children and adults to the natural environment (e.g. ‘The Secret Woodland’, ‘Magic in Your Woodlands’, ‘Winter Woodland Wonders’, ‘Meet the Critters’, family fun day, a ‘Scavenger Hunt’, bulb planting). Art works were also created as part of the activities celebrated in public events (e.g. a wooden carving of a dragon at intervention site A and a woven willow sculpture of a deer at intervention site B).

Recording progress and monitoring of the Forestry Commission Scotland interventions

Forestry Commission Scotland recorded its plans and progress, including budgets and resource allocation for the study interventions, as part of normal WIAT procedures. Feedback included numbers of attendees and community engagement events, as described above, and comments from participants. For example, a participant at an intervention site B public event in September 2014 called ‘Magic in Your Woodlands’ noted ‘Just wanted to say what a wonderful day the boys had. We stayed for over 4 hours’.

In addition, regular progress meetings took place between the researchers and FCS staff managing the interventions to discuss plans for the interventions, progress, any problems or delays, any additional engagement with the local community and current or potential site users and any feedback on the process of intervention implementation. The meetings also ensured that detailed records of the interventions for research purposes were maintained. In total, 12 meetings were held between May 2012 and November 2015, with meetings most frequent during the process of physical and social interventions. At the end of the interventions, a reflective workshop was held in May 2016 by an external researcher from Forest Research with the FCS project management staff to explore the FCS experience of undertaking the interventions and identify good practice and lessons learnt. 60

The records of progress meetings with FCS show that the interventions were planned in accordance with standard WIAT procedures and both physical interventions (see Appendix 1) and social interventions were discussed and agreed by FCS staff and notified to the researchers in advance of implementation. It was, in particular, agreed that, so far as possible, the interventions would be typical of the WIAT programme, drawing on a relatively modest budget rather than being singled out for additional levels of funding or other resources (minutes of progress meeting on 11 June 2013).

The implementation of the physical interventions involved both Forest Enterprise staff and contractors to undertake the construction work, as is typical of WIAT projects. The progress meetings record that the phase 1 physical interventions were carried out as planned, without any significant divergence from the agreed programme of activities (minutes of meetings on 24 January 2014). Minor adaptations to physical interventions were responsive to local conditions and community responses; this is typical of the WIAT programme and would be expected of any such project.

The implementation of the social interventions was so compressed in timing that it was not possible for FCS staff to undertake all the activities, as would normally be the case. An experienced external ranger was therefore contracted by FCS to undertake the social interventions at intervention sites A and B (minutes of meetings on 20 May and 24 July 2014). This proved successful and received positive feedback from the project manager. However, it did mean that the interventions at site C were less numerous and not delivered by the same people as those in sites A and B (minutes of meetings on 29 January 2015).

The desirability of deterring vandalism and maintaining the quality of the site experience is always an issue in WIAT projects. During the two phases of interventions, between 2013 and early 2015, FCS ensured that any items suffering major vandalism were repaired or replaced and the sites were kept at reasonable levels of maintenance. However, once the intervention phases were completed, no further maintenance was carried out by FCS.

In summary, the interventions were not adapted in major ways, other than in the hiring of an external contractor as a ranger to undertake the social interventions at two of the sites. There was a close fit between what was planned and what was delivered under the interventions.

Other contextual factors

As part of the site selection process in 2011, contact (by e-mail or telephone) with the relevant local authority planning departments was necessary to establish that there were no plans for change in the woodland sites under consideration other than the WIAT interventions. We also enquired about any changes planned for the survey communities or the wider neighbourhood context during the course of the study that might influence the study results, but did not identify any factors that appeared likely to do so.

When preparing for community-led audits (see Environmental audits) and focus groups (see Community focus groups and interviews), we again contacted the local authority planning departments and community planning officers to assist in making contact with local community members and facilitators. We also enquired whether or not any important changes had been experienced in any of the communities, such as new building developments or urban renewal projects. In the case of intervention site B, wider community developments were identified that had taken place during the course of the study and may have had an influence on outcomes. The evidence for these comes from personal communications with local authority planners and from local newspaper reports (The Herald, Paisley Daily Express, The Sun) between 2012 and 2014.

In 2012, plans for major redevelopment of the town centre in which intervention site B is located, were approved. Proposals included a new supermarket, town hall, community centre and car park. In March 2013, a new multimillion-pound leisure centre opened next to the intervention site B woodland. In 2014 there was a housing redevelopment programme that required many people to move house within the intervention site B community during the study period, as well as people moving into and out of the area. The extensive town centre redevelopment programme also started in 2014. In May–June 2015 (and coinciding with the 2015 wave 3 core survey; see Core survey of community residents), access paths from nearby car parks to the edge of the intervention site B woodlands were upgraded by the local council. There were concerns about the possible impact of this work on the intervention and its operation, although these paths were outside the intervention woodland under study. As the path upgrade by the council took place only as the final wave survey was being undertaken, it is unlikely to have affected community use of the woodlands in the previous year but may have disrupted or enhanced use during the few weeks prior to some respondents completing the survey.

Core survey of community residents

The health and other impacts of the physical and social interventions were explored primarily through a survey of community residents. The survey was administered in three repeat cross-sectional waves: at baseline and after each phase 1 and phase 2 intervention in the intervention and control areas. Although originally planned as a simple, repeat cross-sectional design, the survey as completed contained a nested longitudinal cohort, as explained in more detail in Sampling strategy and Recruitment.

Questionnaire design

Primary outcome measure

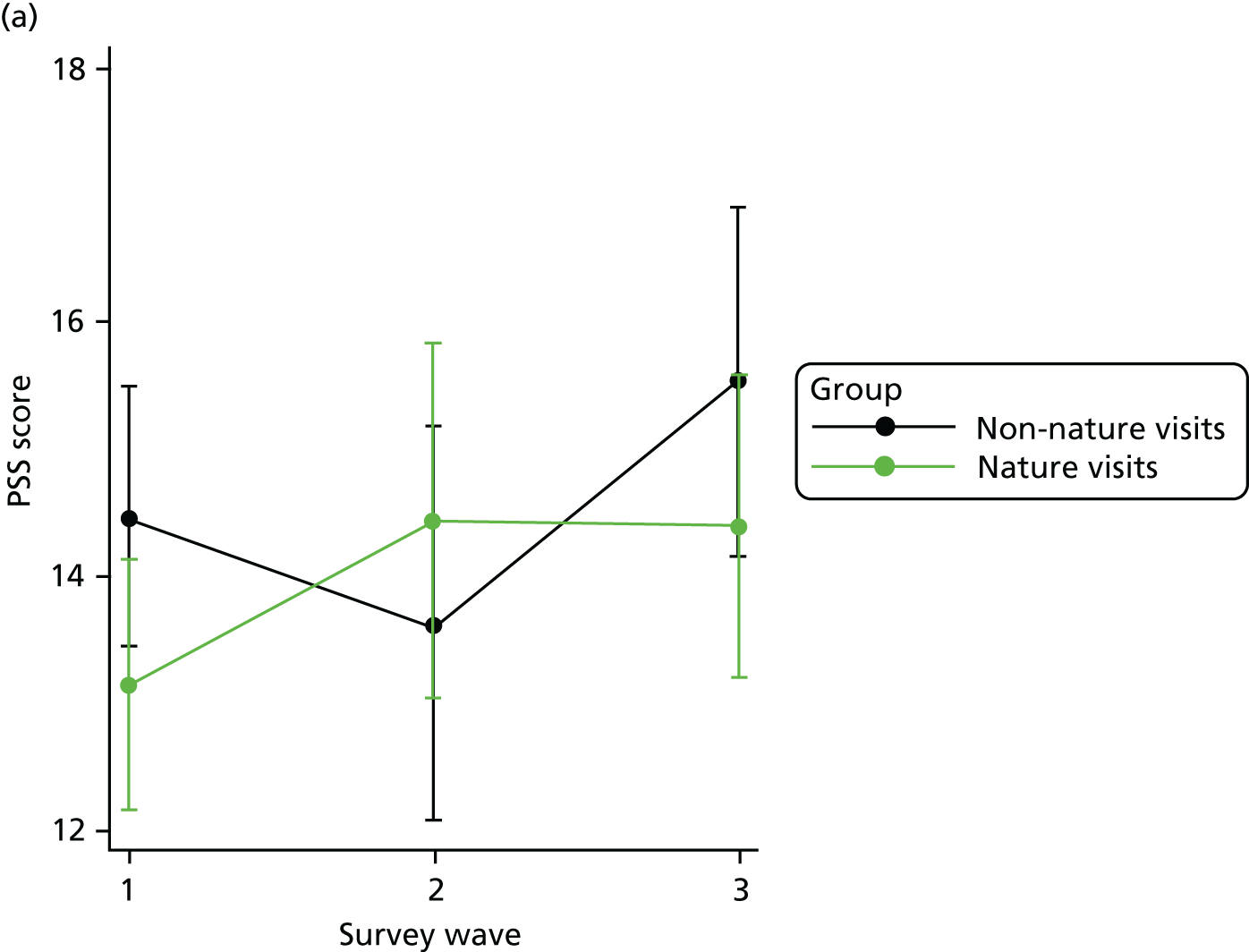

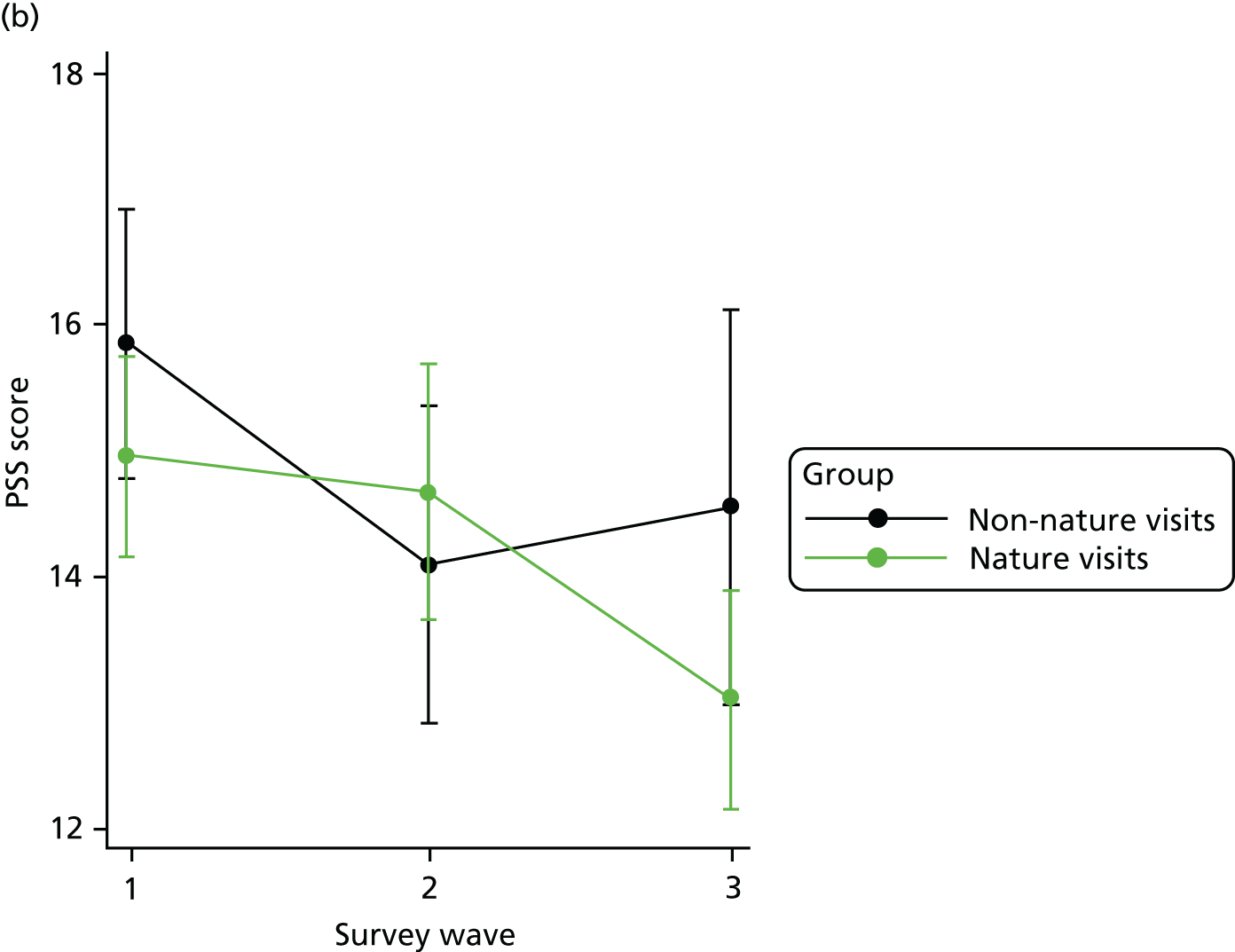

The primary outcome was a measure of perceived stress, assessed using the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS). The PSS is a validated measure of the degree to which situations in one’s life are appraised as stressful by considering coping resources and feelings of control. 61 Previous studies of links between natural environments and stress have used the PSS and evidence indicates that it is sensitive to change over time in relation to therapeutic interventions. 62

Secondary outcome measures

The main secondary outcome measures used were:

-

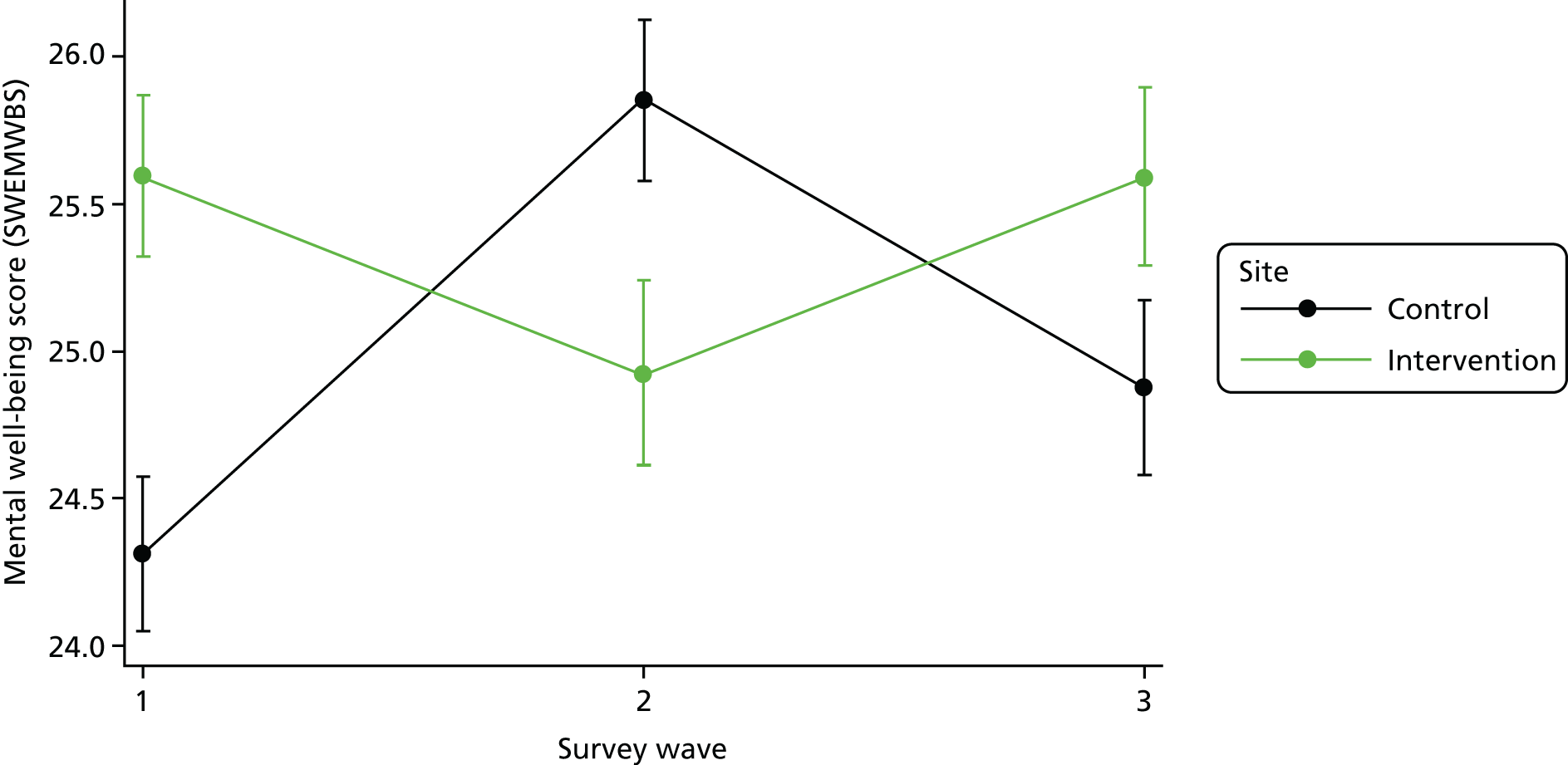

Self-reported health-related quality of life (HRQoL), measured using EuroQol-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D),63 and mental well-being, measured using the Short Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (SWEMWBS). 64

-

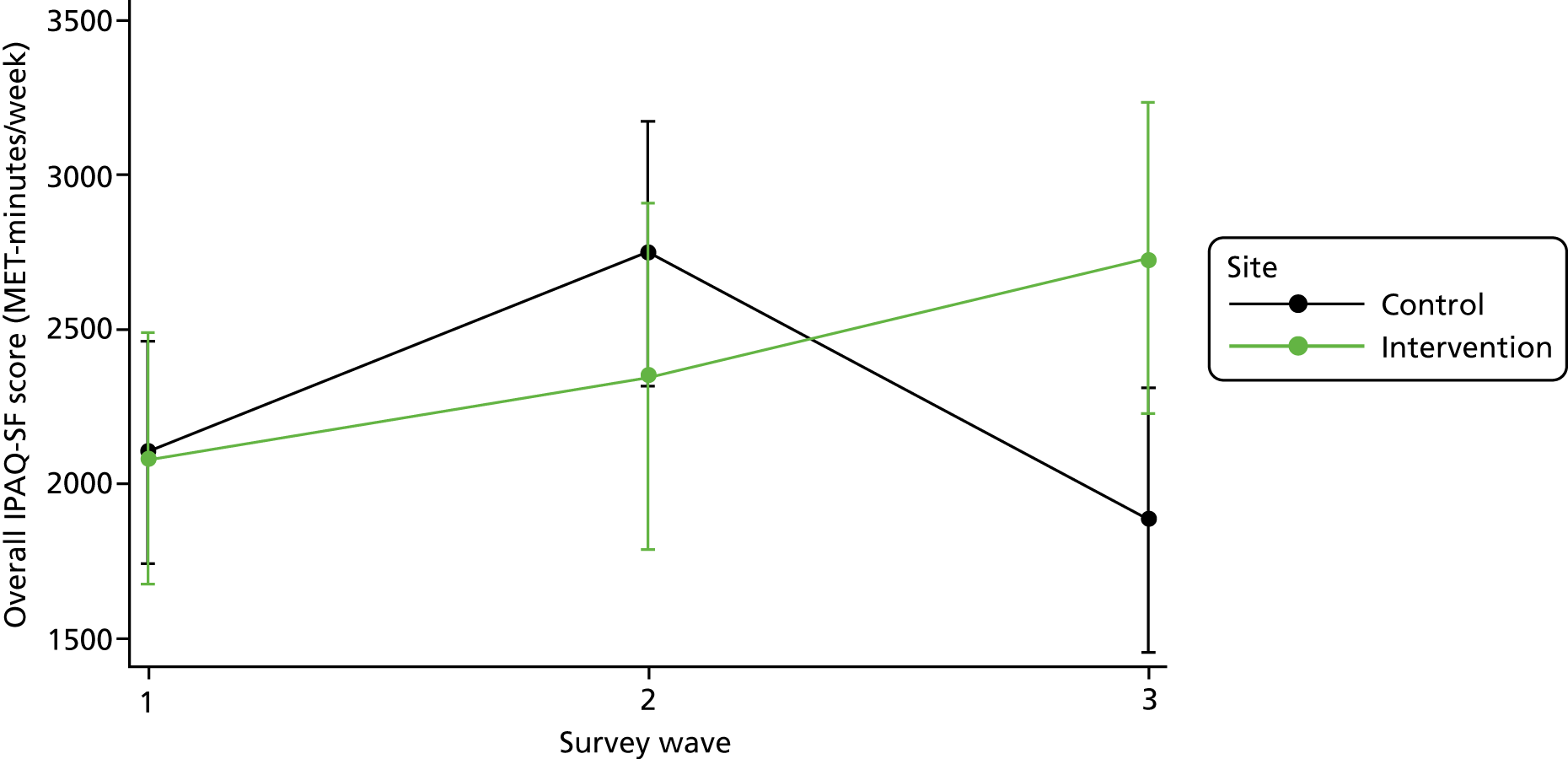

Self-reported PA levels, measured using the International Physical Activity Questionnaire – Short Form (IPAQ-SF), which is able to capture different levels of activity and sedentary behaviour. 65

-

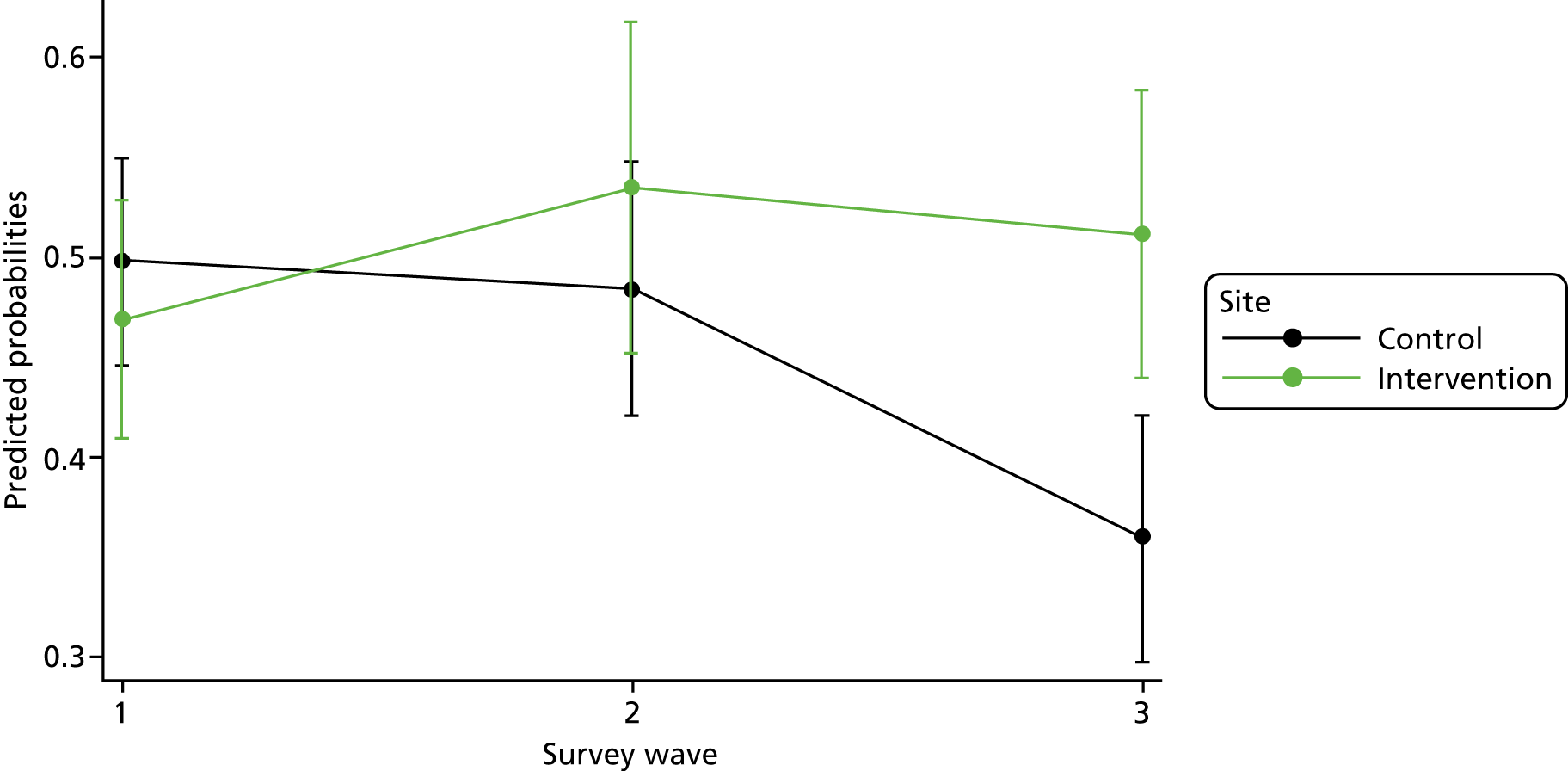

Self-reported visits to the specified (i.e. intervention or control) local woodland site, including frequency of visits in summer (April–September) and winter (October–March), time spent there, activities undertaken there, whether alone or with a companion or dog, and mode of access (e.g. walking, cycling, car). 66,67

-

Self-reported visits to other local (defined as within 10–15 minutes’ walk from home) green spaces, including frequency of visits in summer and in winter, activities undertaken there, whether alone or with a companion or dog and mode of access. 66

-

Perceptions and experiences of the local woodlands, including how easy it is get to the woodlands from home (ease/difficulty and estimated time to get there), perceptions of the woodlands’ qualities (Likert scale items on freedom from litter, quality of entrances, paths, facilities), experience when there (Likert scale items on safety, peacefulness, a place for healthy activities, for visiting with family and friends, enjoying wildlife, natural appearance), whether or not there are direct views of the woodland from home and awareness of views of the woodland when walking around in the neighbourhood and frequency of involvement in community woodland activities (e.g. led walks, community events, educational activities, conservation or woodland management work). 66,68–71

-

Emotional connection to the natural world (connectedness with nature), measured using the Inclusion of Nature in Self (INS) scale. 72

-

Perceived restorativeness of the woodland environment, using four items from the Perceived Restorativeness Scale measuring two core components of psychological restoration (‘being away’ and ‘fascination’). 62

-

Perceptions of the local neighbourhood and social capital and cohesion measured using standard questions from the English Citizenship Survey. 73

-

A range of sociodemographic variables were also collected: gender, age group, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, country of birth, working status, educational level, disability, annual income, financial strain, children in the household, type of accommodation, accommodation satisfaction, whether or not they had a garden, whether or not they owned a dog, whether or not they had access to a motor vehicle, length of time in neighbourhood, home address and postcode.

In the wave 3 survey only, the questionnaire also included questions on awareness of the interventions:

-

awareness of any change in the local woodlands and, if so, ratings of the changes (five-item scale from ‘very negative’ to ‘very positive’) and whether changes were seen in person or heard/read about

-

participation in any organised activity in the woodlands in past year and, if so, with whom and when.

The full questionnaire from wave 3 can be seen in Report Supplementary Material 1.

Sampling strategy

We were interested in community-level change resulting from the same programme of interventions in three different sites with three matched control sites, so our analysis involved comparison of the population sample from the communities that received the intervention with those that did not. We initially selected a repeat cross-sectional survey design rather than a cohort design for pragmatic reasons: a pilot study with two communities that met the WIAT site criteria undertaken in 2006–934 indicated that achieving a longitudinal cohort in these settings was unlikely to be successful owing to the unwillingness of participants to be recontacted and high levels of attrition over time. Recruitment and retention of a cohort of several hundred participants in each community over a multiyear study in this context appeared unfeasible. However, following the first survey wave, at baseline, the researchers revisited the decision to reject a cohort design. Considering again the potential value gained by the inclusion of a longitudinal cohort, it was decided to attempt to establish such a cohort. A longitudinal cohort of participants was therefore targeted, nested within the cross-sectional surveys.

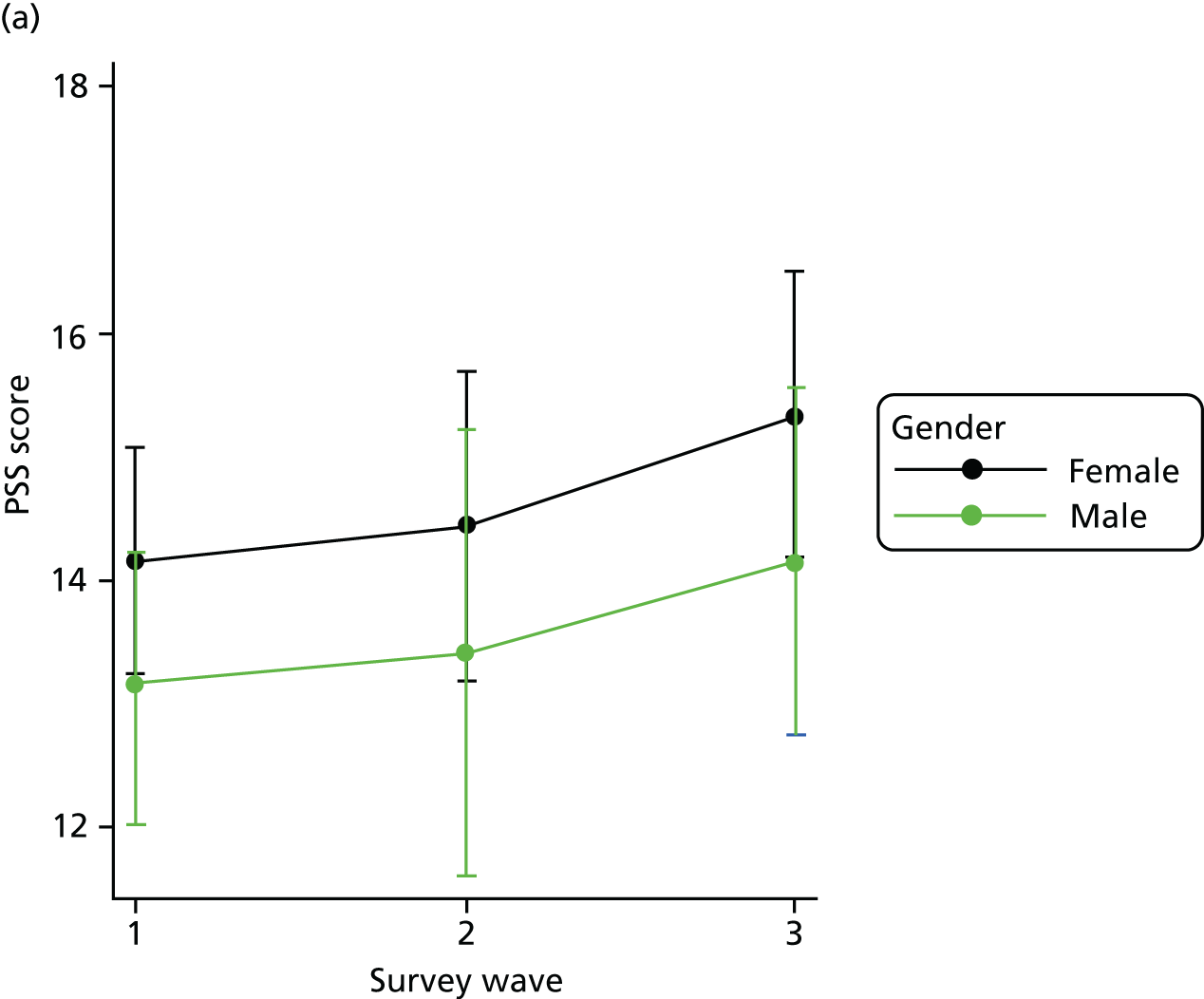

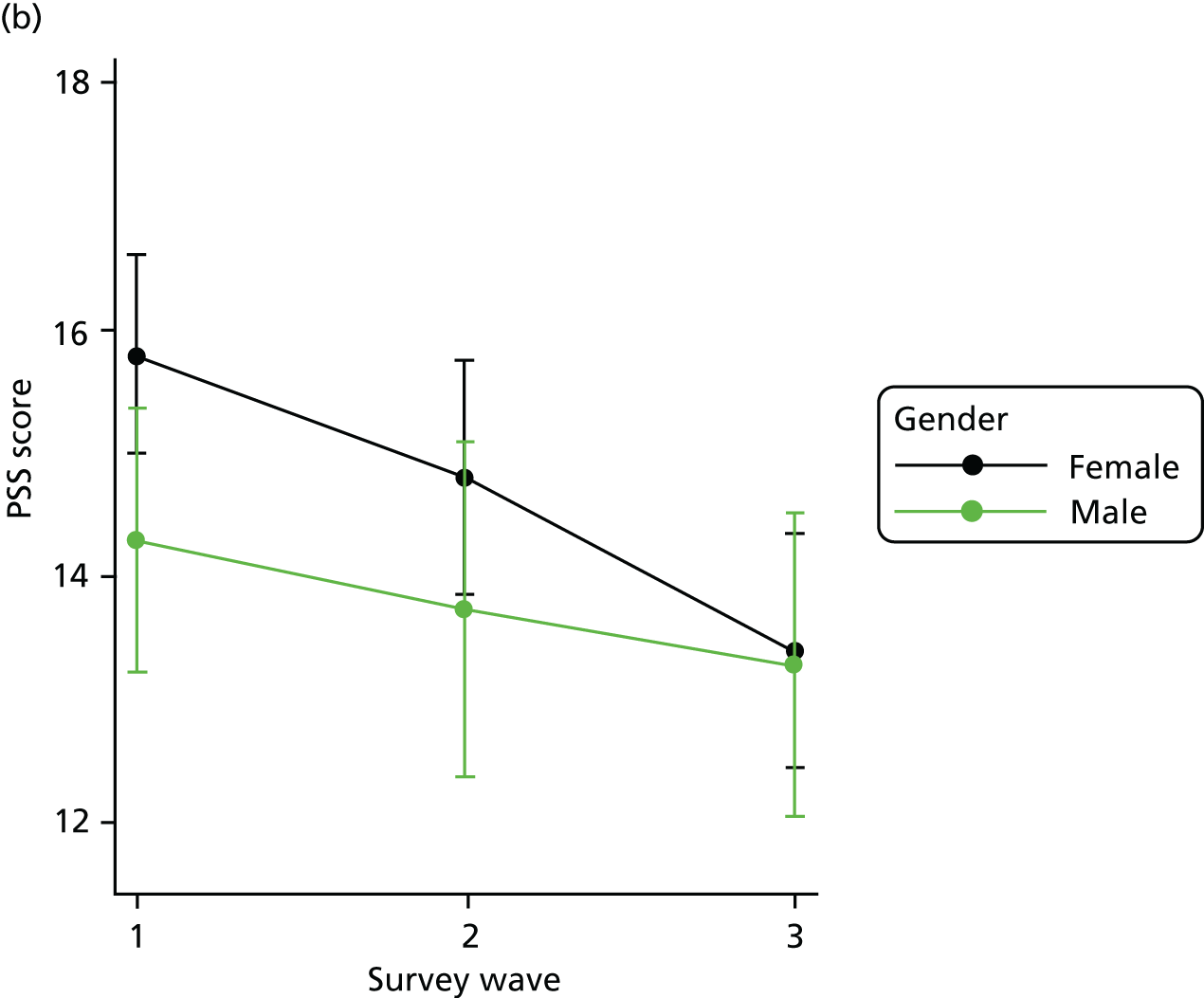

In determining the sample size, the literature suggested that there were likely to be gender differences in the observed effects. 26 To answer the primary research question, our sample size needed to be large enough to (1) detect an effect of the WIAT programme in the intervention group compared with the control group at each post-intervention wave, and (2) allow us to detect a gender difference in that effect. Based on data from Stigsdotter et al. ,27 to detect a male/female difference in means of 1.2 in each group (intervention and control), with a common standard deviation (SD) of 6.2 based on a two-sided, two-sample test with a 5% level of significance and 80% power, would require a minimum of 420 males and 420 females in each arm of the study. Therefore, a total sample size of 1680, comprising 840 intervention group and 840 control group participants, was required, with an equal split of male and female participants in each group. We did not power the study for further subgroup analysis (the added cost to power for different age groups was not considered justifiable). However, we did consider other demographic and personal variables in analysis of the data, the sequential nature of the intervention and confounders, such as life events (see Chapter 3). We could not completely rule out a clustering effect and did not have data available to enable us to precisely calculate the design effect caused by clustering. To take account of this we allowed for a 25% increase in our sample size beyond that based on the above power calculations. Thus, we sought a total sample size at each survey wave of 2100 (1050 per intervention or control group).

The survey was administered in three repeat cross-sectional waves at the same time of year in each case: wave 1 (baseline pre-interventions, late April to June 2013), wave 2 (follow-up, minimum of 2 months post physical environment interventions at each site, May to June 2014) and wave 3 (follow-up, minimum of 2 months post woodland promotion interventions at each site, late April to July 2015).

Recruitment

Face-to-face surveys are a robust method of data collection that maximise the level of response. Other methods, such as telephone and postal surveys that rely on self-completion, have shown declining response rates in recent years, especially in disadvantaged areas. 74 Our questionnaire was designed to be administered in a 25-minute, face-to-face, computer-assisted personal interview (CAPI) completed in the respondent’s own home. The questionnaire was piloted in July 2012 to assess its time burden and participant comprehension of its questions and procedure.

A survey company with experience of recruitment in communities similar to those of the study collected the data. Fieldworkers employed by the survey company were given full training on administering the questionnaire. Surveys were completed in the participant’s own home with fieldworkers moving from door to door, recruiting participants and conducting the survey. A quadruple call-back approach was adopted with fieldworkers making a minimum of four attempts to contact an address before moving on to the next randomly assigned address.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Individuals aged ≥ 16 years living within the intervention and control communities and within 1.5 km of a woodland site were eligible for the study. Individuals were not eligible to participate if they primarily resided outside the study sites. Individuals recruited to the linked community-led audit and community focus group branches of the study (see Environmental audits and Community focus groups and interviews) were excluded from subsequent waves of survey data collection to avoid contamination of response by their experience of in-depth involvement in the research.

Participants were selected from a postcode address file [Address Point – the then definitive Ordnance Survey product that provided a precise grid reference for each address listed in the Postcode Address File (Royal Mail data set)]. Selection used a stratified random sampling approach, stratified in accordance with distance from the WIAT intervention woodlands. This address file lists all deliverable addresses in the UK and can distinguish business and domestic addresses; we focused on domestic addresses only. Each unit postcode has a grid reference and this was used to stratify the sample by distance from the local woodland. We considered stratification by distance necessary because previous research suggests that the use of woodlands for populations living nearby may decline with distance,30 but there is also evidence that the quality of the natural environment may moderate the effect of distance,31 so distance was necessary to consider because the WIAT intervention is aimed at improving woodland quality. We stratified the sample in accordance with five distance points from the six WIAT-eligible woodlands. These distance points were in the range of 150 m, 300 m, 500 m, 750 m and 1500 m. Letters were then sent to the selected households informing them of the research project and that participants were being sought within the communities. The letters also contained the contact details of the research team members and their office, offering participants the opportunity to receive further information about the project or to opt out (see Report Supplementary Materials 2–4). Addresses of those residents who decided to opt out were then removed from the sample. A door-to-door approach and a quadruple call-back system were used to recruit participants. Recruitment was by face-to-face request to the first adult that responded to the door-to-door approach adopted.

Obtaining a longitudinal cohort

To maintain contact with the respondents from previous surveys, a thank-you letter was sent to all the addresses where wave 1 interviews took place. Unless respondents chose to opt out after receiving this letter (the letter described how to do so), the same addresses were visited in subsequent survey waves. Interviewers were instructed to confirm whether or not the person who answered the door was the same person (name, gender, age, address) who was previously recorded in wave 1. When the original respondent could not be found or recruited, recruitment of the new respondent in the household was attempted, if eligibility criteria were satisfied. If new recruits agreed to take part in the survey, a new respondent identifier code was generated. New recruits from the same household were asked to establish the relationship to the person previously interviewed (spouse/partner, child, parent, sibling, other family member or other as specified).

The size of the cohort was determined by the extent to which we were able to obtain repeat responses by this method. The cohort consisted of respondents who had participated in at least two waves of the survey. Once data were collated, checks were undertaken for age, gender and other individual characteristics to confirm that the respondents were correctly matched at each wave. The inclusion of this cohort in the initial cross-section design required changes to the initial analysis plan (see Chapter 5).

Response levels

To ensure that the correct sampling and interview protocols were followed, researchers attended the company’s field workers’ training sessions and took part in some of the visits to interview participants. This also gave insights into the challenges of recruitment in these very deprived urban areas, where, for example, there was a relatively high rate of refusal to answer the door (despite letters being sent in advance to targeted households).

Based on the random sample of addresses taken up by the survey company from the supplied postcode files, the overall response level achieved for the three surveys was 53%, lower than originally targeted. We also calculated the level of co-operation, that is, the proportion of successful interviews achieved once personal contact with a household had been made. The definition of ‘personal contact’ for this calculation includes effective interviews, doorstep refusals, people who wrote to opt out of the survey after receiving the introductory letter (these were comparatively few: 181 in total in wave 1) and those unable to take part owing to language issues or incapacity. The level of co-operation excludes incorrect or unusable sample addresses (empty properties, business premises, etc.), households from which there was no reply on the doorstep (despite quadruple call-back) and households (in waves 2 and 3) at which the named respondent was not available. The overall level of co-operation was 70%.

The response levels by wave and type of site (intervention/control) are shown in Table 5.

| Wave | Site | Total sites | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention | Control | ||||||||

| n | Response level (%) | Co-operation level (%) | n | Response level (%) | Co-operation level (%) | n | Response level (%) | Co-operation level (%) | |

| 1 | 1061 | 52 | 76 | 956 | 48 | 70 | 2117 | 50 | 73 |

| 2a | 1054 | 50 | 70 | 1044 | 54 | 78 | 2098 | 52 | 74 |

| 3b | 1050 | 57 | 61 | 1052 | 61 | 67 | 2102 | 59 | 64 |

Assembling a longitudinal cohort represented a considerable achievement for the study given the challenges in participant recruitment. The availability of repeated measures from the same individuals provided more statistical power for the study and gave greater confidence in interpreting cause-and-effect relationships.

The sample respondents (n = 6317) were classified in accordance with the wave(s) of the study they participated in. This resulted in five different types of respondents across the six sites:

-

respondents who completed waves 1 and 2 (not wave 3) – 217 participants

-

respondents who completed wave 1 (not wave 2) and wave 3 – 235 participants

-

respondents who did not complete wave 1 but completed waves 2 and 3 – 420 participants

-

respondents who completed waves 1, 2 and 3 (the complete cohort) – 277 participants

-

respondents who completed only one wave, whether wave 1, 2 or 3 (cross-sectional data) – 5168 participants.

Data cleaning

The data collected via the core survey were cleaned using range, consistency and logic checks to confirm their quality. These checks involved identifying the correct codification of the responses, examining missing values or abnormal patterns in the data, assessing the average interview length or the performance of the interviewers, etc.

As part of this quality control, abnormal patterns in the data were noted, principally in relation to the score of the primary outcome (PSS). It was detected that an unexpectedly large number of participants appeared to have a PSS score of 0 (indicating no stress at all) at waves 2 and 3. Furthermore (but in wave 2 of the survey only), an unexpectedly high number of participants reported a PSS score of 21. Checks on interviewer identities and process revealed that five interviewers were associated with these suspect cases throughout the follow-up household surveys. A total of 857 cases with apparently unreliable PSS scores were linked to these interviewers, of which 426 corresponded to wave 2 and 431 to wave 3.

Although no other suspicious response patterns were observed in the data sets created by these interviewers, the possibility of data fabrication could not be discounted. It was decided that, to ensure the reliability of the analysis, all data collected by the interviewers whose results for PSS were questionable needed to be excluded. The 857 problematic cases were deleted from the final sample, reducing the original data set from 6317 to 5460. The number of losses from wave 2 and the number of losses from wave 3 (the two follow-up surveys) were about equal. The analyses presented in this report use this reduced sample.

Approach to analysis

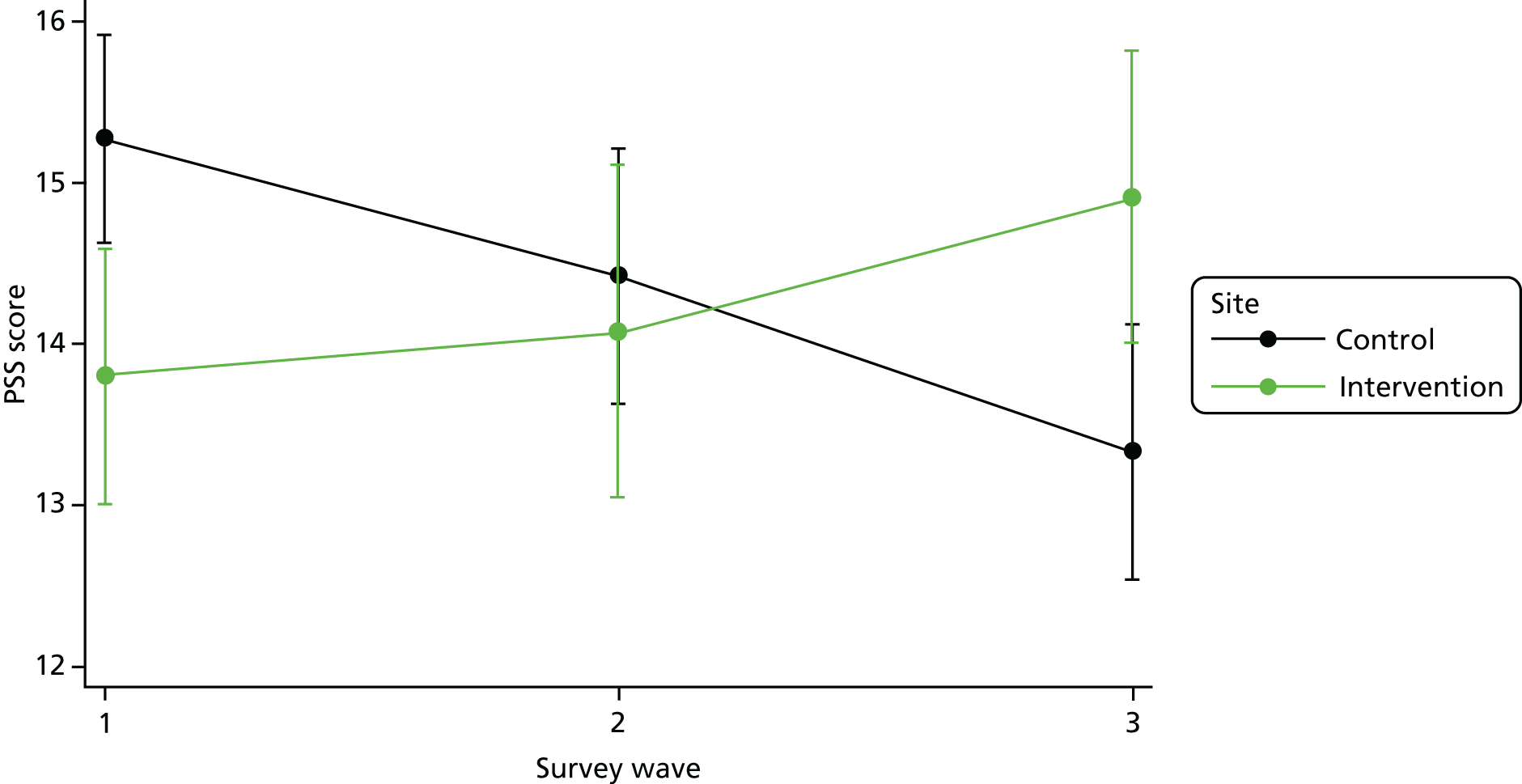

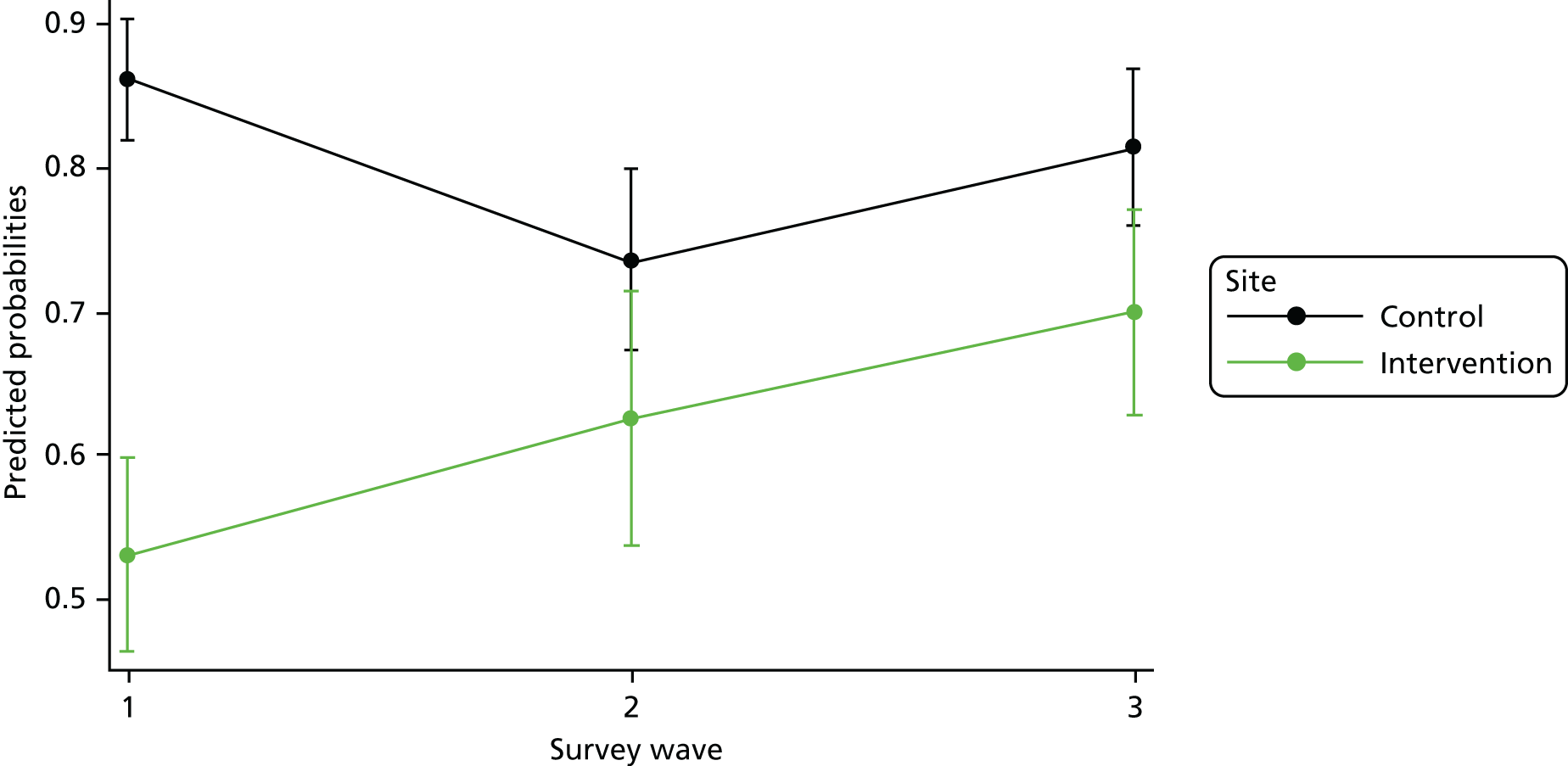

Two general approaches to quantitative analysis informed the detailed statistical analysis undertaken. First, an overall effect was estimated. This was essentially an intention-to-treat (ITT) approach. It tested whether or not living in an intervention site alone was sufficient to produce primary and secondary outcomes of interest, regardless of an individual’s exposure to the intervention (captured by their engagement with woodlands, green space and natural environments).

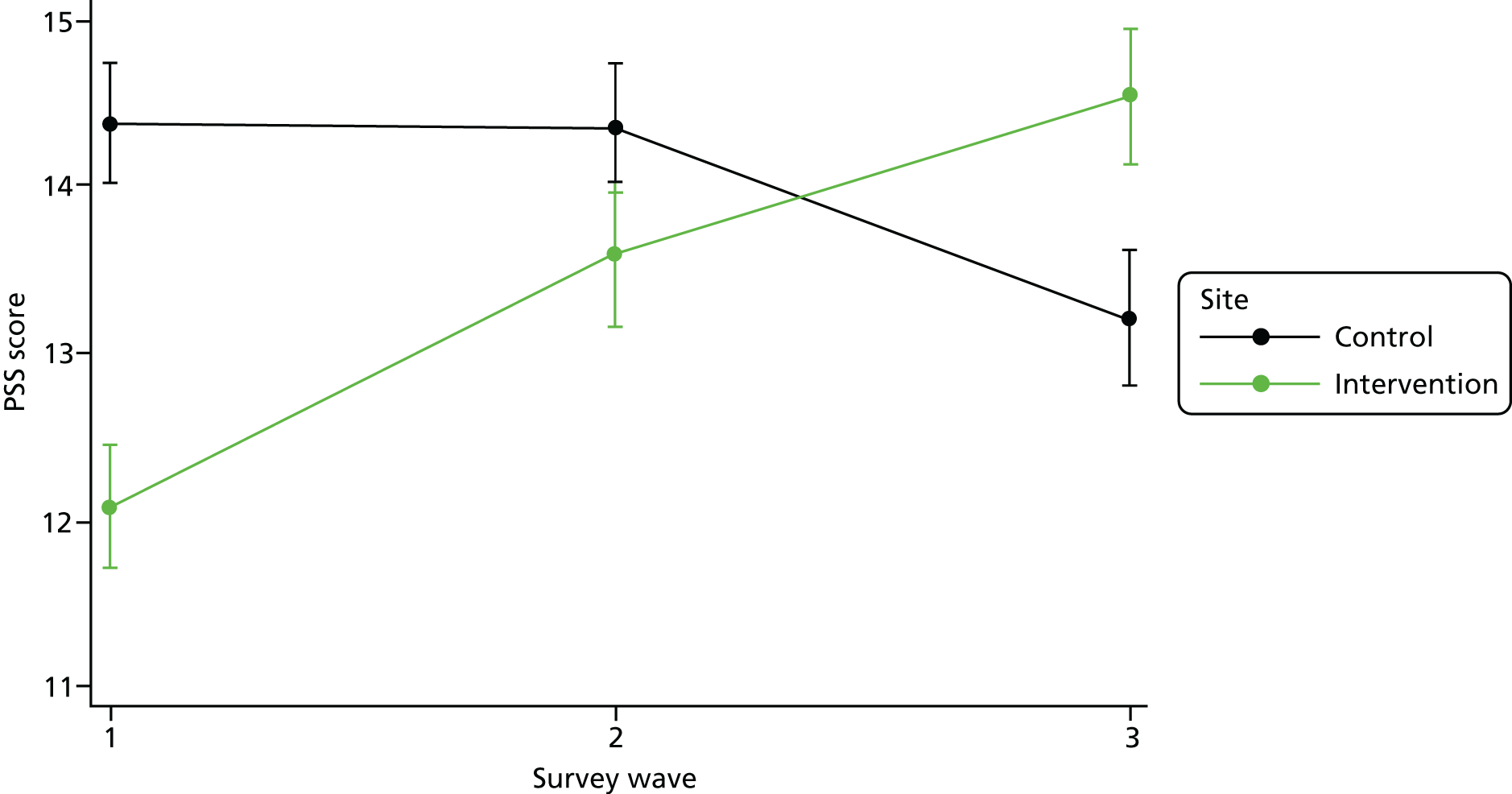

The ITT approach considered the magnitude of the interactions between living in an intervention site (or not) and the wave of the survey. This therefore captured the differential impact between the intervention and control groups, in relation to the effect of the WIAT programme. The models assessed the effect of the WIAT programme by comparing the differential impact after physical (phase 1) interventions (wave 2) and after both physical and social (phase 2) interventions (wave 3) with respect to the baseline (wave 1). For this, although each difference estimate (captured by the interaction terms) was statistically determined by its own p-values in the models, the differences between the two post-intervention phases were established on the basis of the p-values of a conventional Wald test.

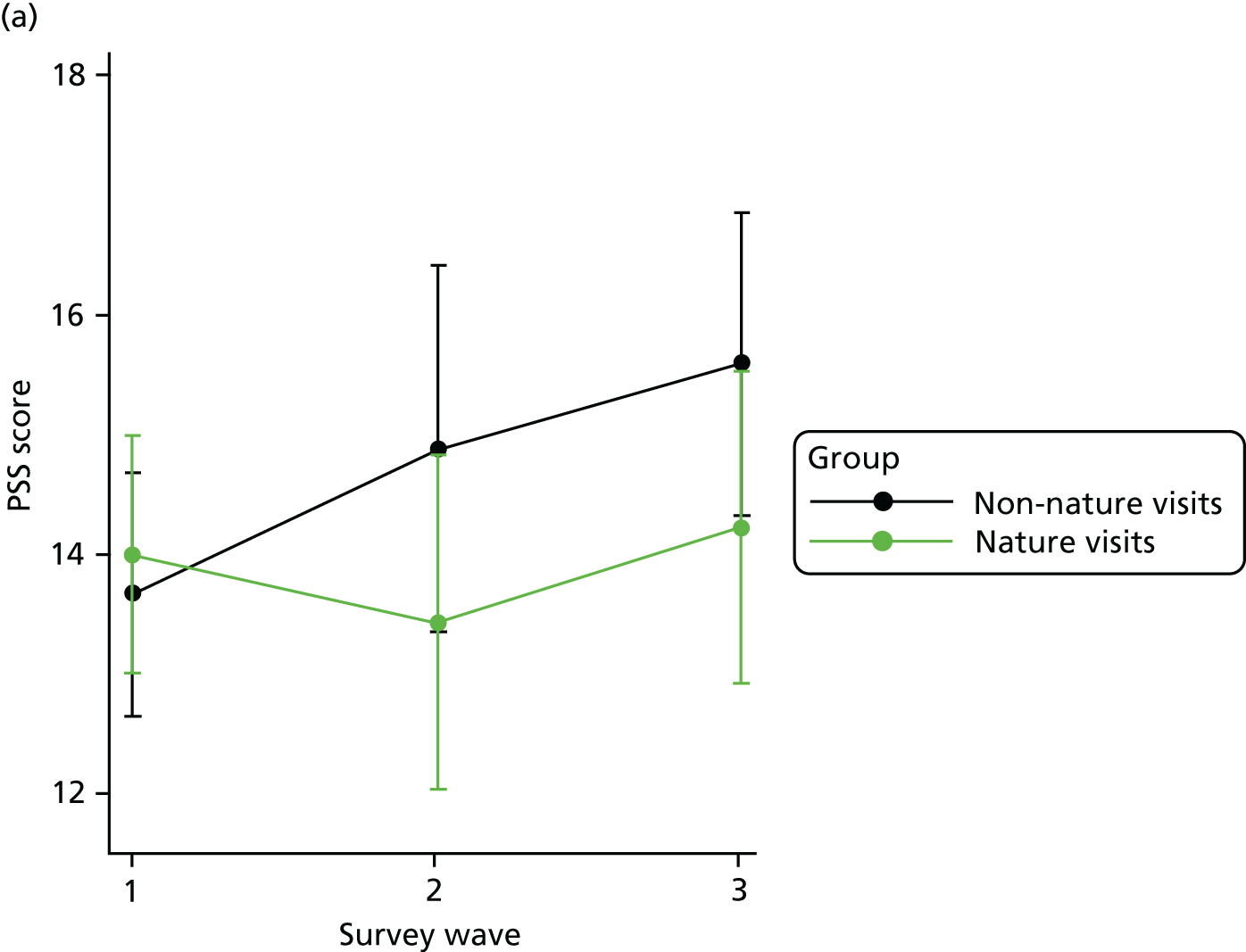

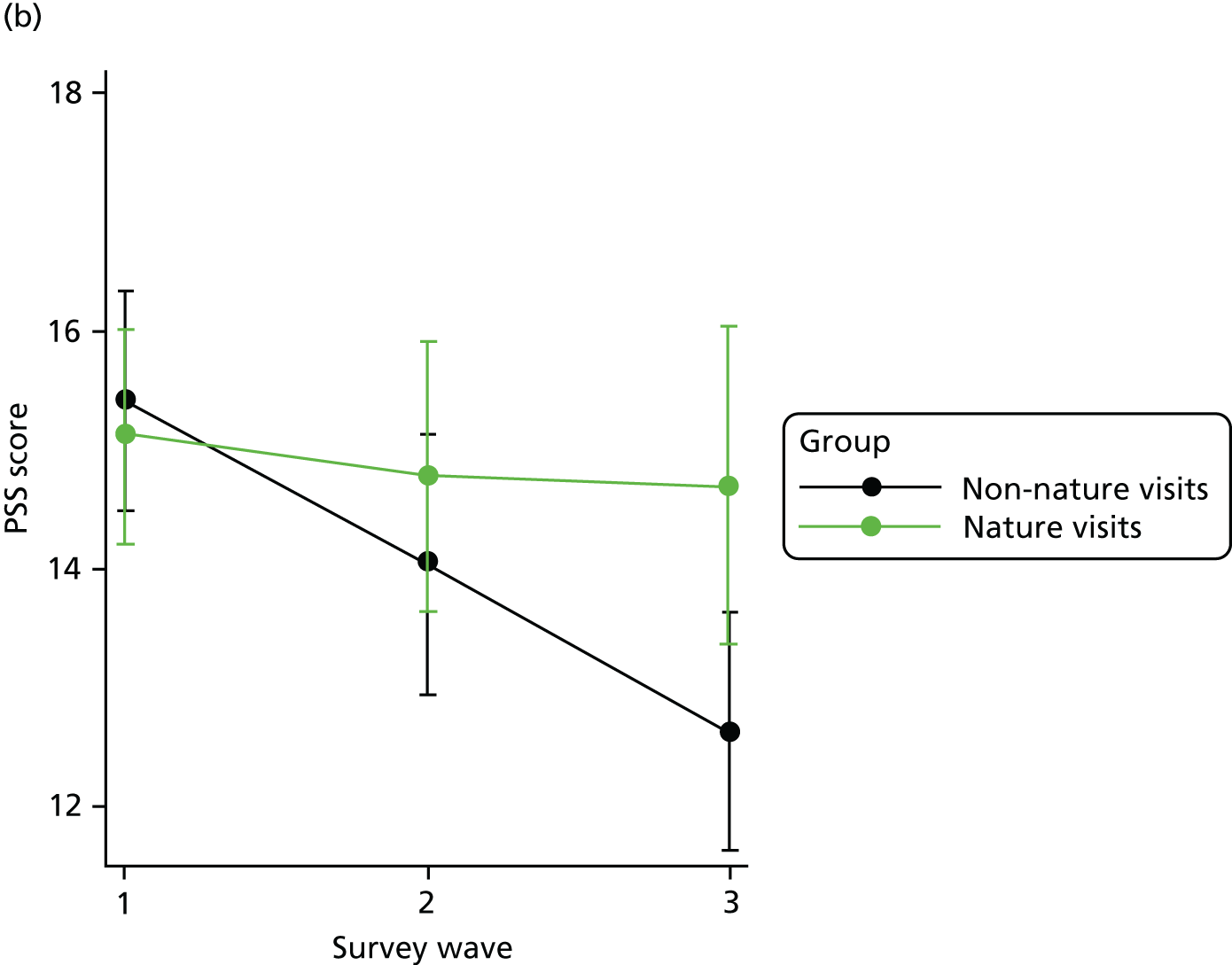

Second, we augmented this analysis by providing a closer inspection of the intervention effect on our primary outcome (perceived stress). This was possible by examining the differential impact of the WIAT programme as a function of three main factors: (1) levels of engagement with the woods (physical and visual), (2) gender and (3) distance to the woods. This augmented approach was used to model our primary outcome and required a rather different analytical strategy to estimate the intervention effect. A three-way interaction term was added in the models, denoted by the binary variables of type of site (i.e. intervention or control) and wave of the survey plus the corresponding indicators on levels of engagement with the local woods, gender or distance to the woods. The ‘main effect’ within each level of these three indicators was then given by calculating a joint test of interaction terms.

The two sets of analyses involved a series of multilevel regression models. The use of a multilevel framework was required because our full sample, created by three repeated surveys sampling individuals within spatially defined communities, also included a proportion of individuals who participated at more than one wave. Therefore, the models needed to allow for repeated observations nested within individuals as well as spatial clustering. Our multilevel approach accounted for the fact that observations made on the same individual at two different waves were likely to be correlated. For this reason, we used individuals – the lowest level in the data – as the clustering variable in all the statistical specifications.

Given the continuous and binary forms of our different outcome measures (see Chapter 3 for details of how these were derived), the analysis involved a combination of linear and logistic regressions. All the models were adjusted for a substantial set of individual-level characteristics considered to be potential confounders for any intervention effect. The selection was made a priori and was based on existing literature describing relationships between sociodemographic variables and both access to and use of natural environments.

As 4410 out of 5460 observations had complete information (81%), imputation techniques were considered to handle missing data. Imputation was used only for data from a particular survey wave that were missing for an individual who had participated in that wave of the survey. In other words, no participant’s data were imputed other than for variables in the survey wave in which they had participated.

Specifically, we followed Rubin’s rules to perform multiple imputations via chained equations. This imputation technique was used owing to its greater flexibility to account for uncertainty in the missing data mechanism; we assumed that the data were ‘missing at random’, meaning that the ‘missingness’ could be determined by known variables. The use of chained equations also had the advantage of being able to include different types of variables in the process (e.g. continuous, categorical, nominal). Appendix 2 provides further information on the approach taken.

All analyses were conducted using the cross-sectional data set (termed panel A) and repeated with the longitudinal cohort (termed panel B). Although the former enabled us to use all individuals regardless of the number of waves in which they participated, the longitudinal cohort (panel B) allowed us to track the same participants across time. Although the cohort was not necessarily a representative subsample, it provided a form of sensitivity analysis to corroborate (or otherwise) findings from the cross-sectional data. All analyses were conducted using Stata® version 14 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Chapter 3 describes the derivation of variables for considering primary and secondary outcomes in the study and details the analytical methods used.

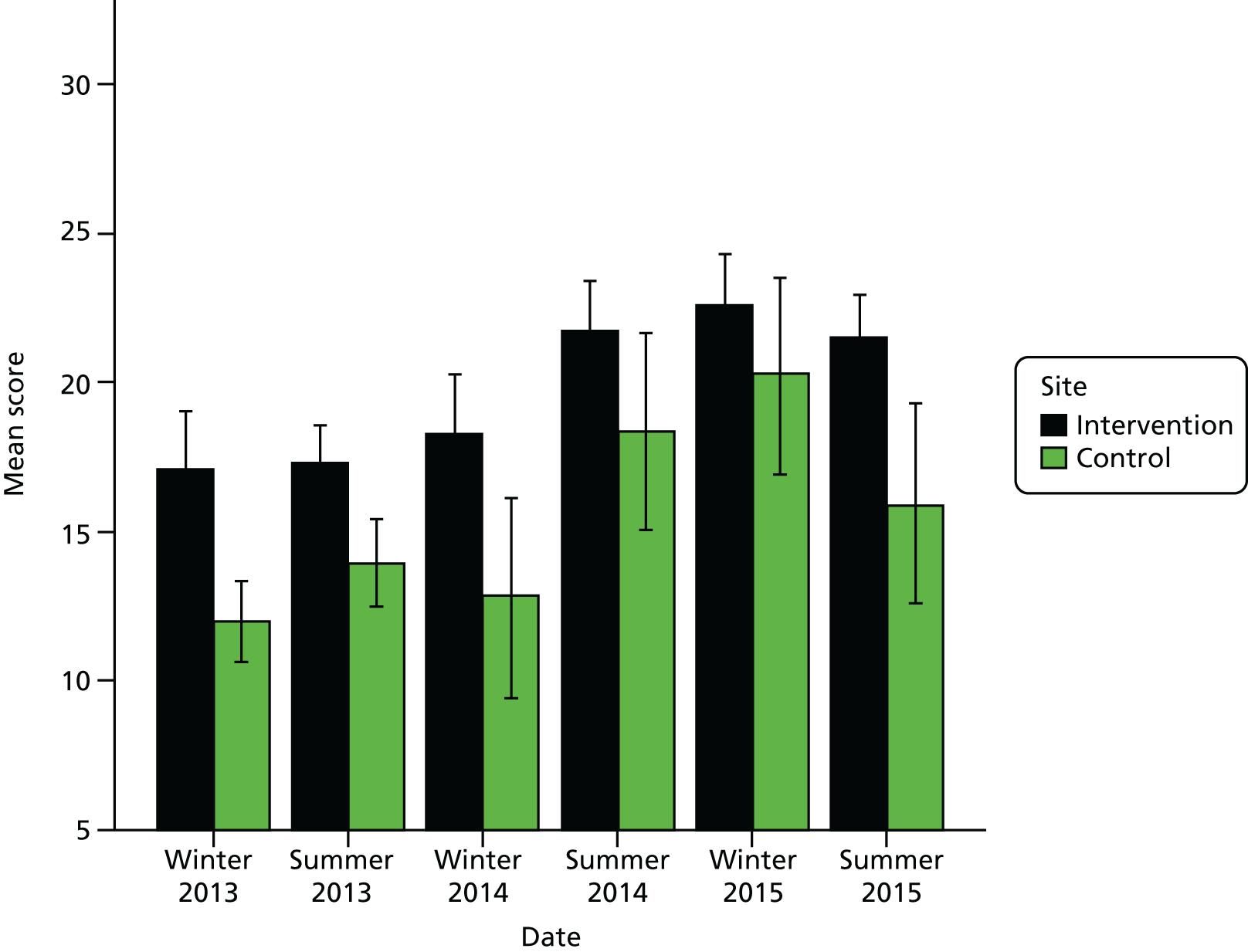

Environmental audits

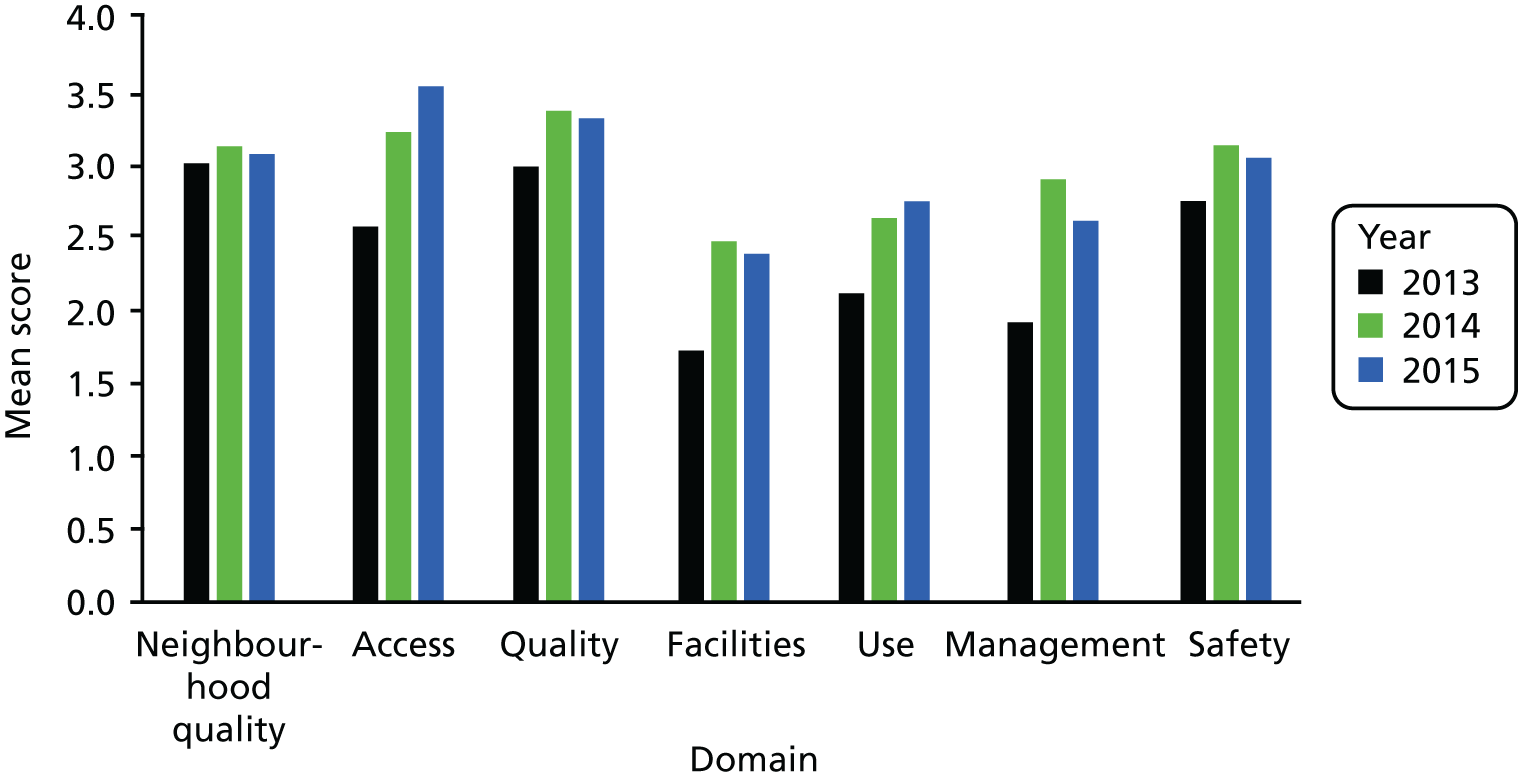

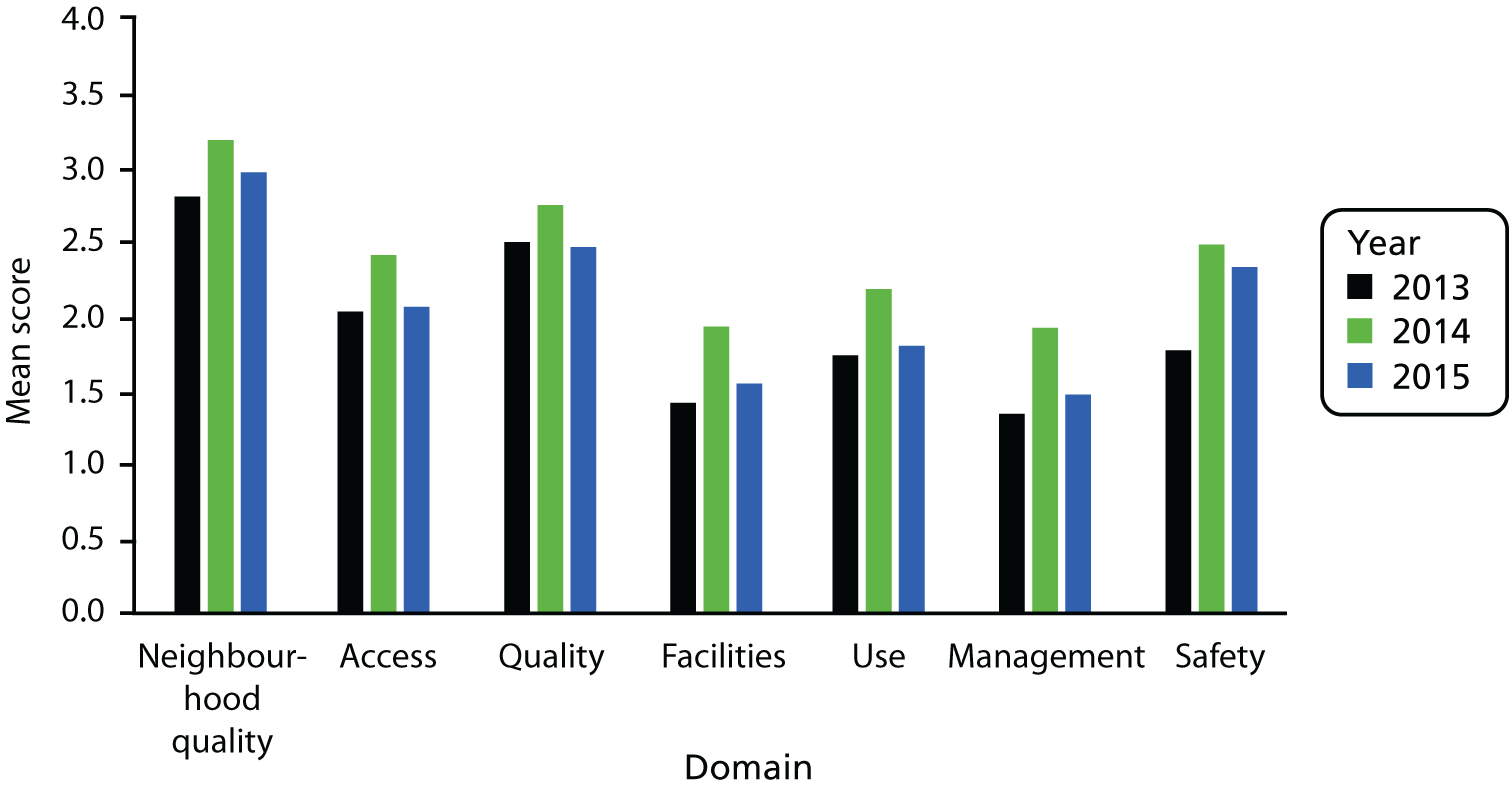

Changes in the nature and quality of the woodland sites were monitored using a site-based environmental audit tool developed by members of the research team for this purpose. 66,68,75 The tool enables change over time at a site to be captured in a systematic manner. The audit tool consists of 25 items aggregated into seven domains: neighbourhood quality, access/signage, woodland/green space quality, facilities, use, maintenance/management and security/safety. Each domain contains between two and six items; for example, the domain ‘neighbourhood quality’ comprises the items infrastructure, appearance, litter and maintenance. For a given woodland, the tool requires auditors to score each item on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (‘poor’, the lowest score) to 5 (‘excellent’, the highest or ‘best’ score). Auditors score the woodland in accordance with their ‘on the day’ experiences rather than previous experiences. In addition to giving scores, the tool allows participants to add textual comments about the woodland, its characteristics and quality.

The tool has been designed and tested for use by both experts (usually landscape architects) and residents of deprived urban communities. Members of the study team, trained in the use of the tool, audited all six sites using the tool; this constituted the ‘expert environmental audits’ record for the study. Two members of the study team were involved in each audit of any site, in which use of the tool achieved high levels of inter-rater reliability. Expert auditors were male and female and came from diverse ethnic and cultural backgrounds.

The tool’s appropriateness for community use was established in the project pilot study34 and it has been tested for sensitivity and reliability in a study of green space in deprived urban areas of England. 66,68 Recruitment of community members undertaking audits is described in detail below; they were male and female and, reflecting the demographic profile of the study communities (see Table 2), were all of white British ethnicity. A copy of the audit tool can be seen Appendix 3.

The woodlands for each study site were audited twice in each year of the study (2013–15) capturing pre- and post-intervention conditions in both the intervention and control sites. Audits by the study team and by community members were completed in both winter (February to March) and summer (June to July) each year to capture the effects of seasonality. Audits took place on a weekday, either mid-morning or early afternoon. Before the community audits took place, members of the study team walked the sites conducting a risk assessment, familiarising themselves with the woodland and noting any potential hazards. Community participants were taken for a walk in each woodland, accompanied by the two experts, and each individual in both groups completed the audit at the site.

Recruitment of community site auditors

Participants for the community-led audits were recruited initially through the baseline survey, in which respondents could indicate their willingness to be recontacted to participate in group walks or focus groups to help with the research. This produced comparatively few positive responses and so additional individuals were recruited through contact with local community groups and facilitators and through local advertising. Participants who took part in the first audit were invited to take part in all subsequent environmental audits. We sought a balanced sample in terms of gender but diversity with regard to age and life stage.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

As with the community core survey, individuals aged ≥ 16 years living within the intervention or control communities within 1.5 km of the study woodland site were eligible to take part in the community-led audit sections of the study.

Sample

We aimed to recruit 10 diverse members of the community to each community-led environmental audit. In practice, we found that attendance varied greatly between sites and over time. It proved very difficult to recruit individuals to the audits programmed for control site A. Despite the best efforts of the study team, no members of the community could be recruited to the winter 2013 community-led environmental audit at this site, and only one community member could be recruited to the summer 2015 audit. Table 6 shows the participant numbers for each site at each audit point.

| Site | Year | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | |||||

| Winter | Summer | Winter | Summer | Winter | Summer | ||

| Intervention A | 9 | 10 | 10 | 14 | 13 | 13 | 69 |

| Intervention B | 3 | 8 | 4 | 7 | 9 | 4 | 35 |

| Intervention C | 7 | 8 | 7 | 7 | 10 | 15 | 54 |

| Control A | 0 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 14 |

| Control B | 11 | 8 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 34 |

| Control C | 9 | 9 | 5 | 8 | 10 | 9 | 50 |

| Total | 39 | 47 | 35 | 44 | 46 | 45 | 256 |

Approach to analysis

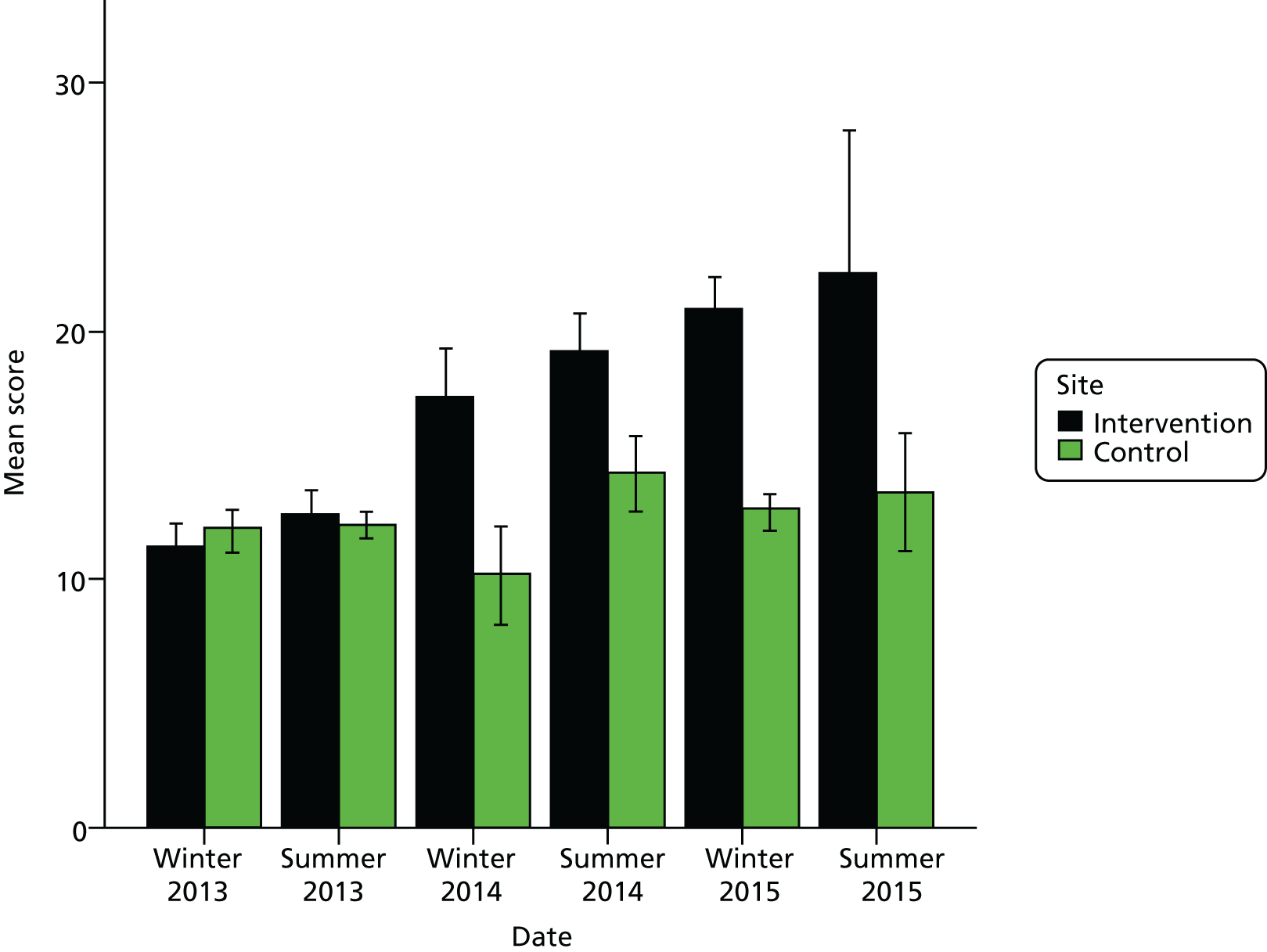

The audit data collected from both expert and community-led audits consisted of Likert scale scores from 1 to 5 for each of the 25 items considered and any additional textual comments. For each audit completed at each site, an average was calculated for each of the seven domains into which these items fall (maximum score of 5). A final score, summed over these seven domains (maximum score of 35), represents the overall perceived quality of the woodland and its immediate surroundings. The means and SDs of total scores were calculated across all community group participants and, separately, across the two expert auditors for each site at each time point. Appendix 3 contains the detailed results of these audits.

The resulting audit scores were used to compare intervention and control sites at each audit time point and to compare any changes over time in perceptions of the woodlands at each site. This allowed an assessment of whether or not the interventions had resulted in perceptions of improved quality of the woodlands over time compared with control sites (which had no interventions). The community audit scores were also compared with the expert scores. The use of both winter and summer audits were important because each woodland site varied in appearance quite markedly between these seasons. For example, features as varied as distant views or local litter, which might be covered by abundant summer vegetation, could be more clearly seen in winter audits. Evidence of types of use were also different between summer and winter.

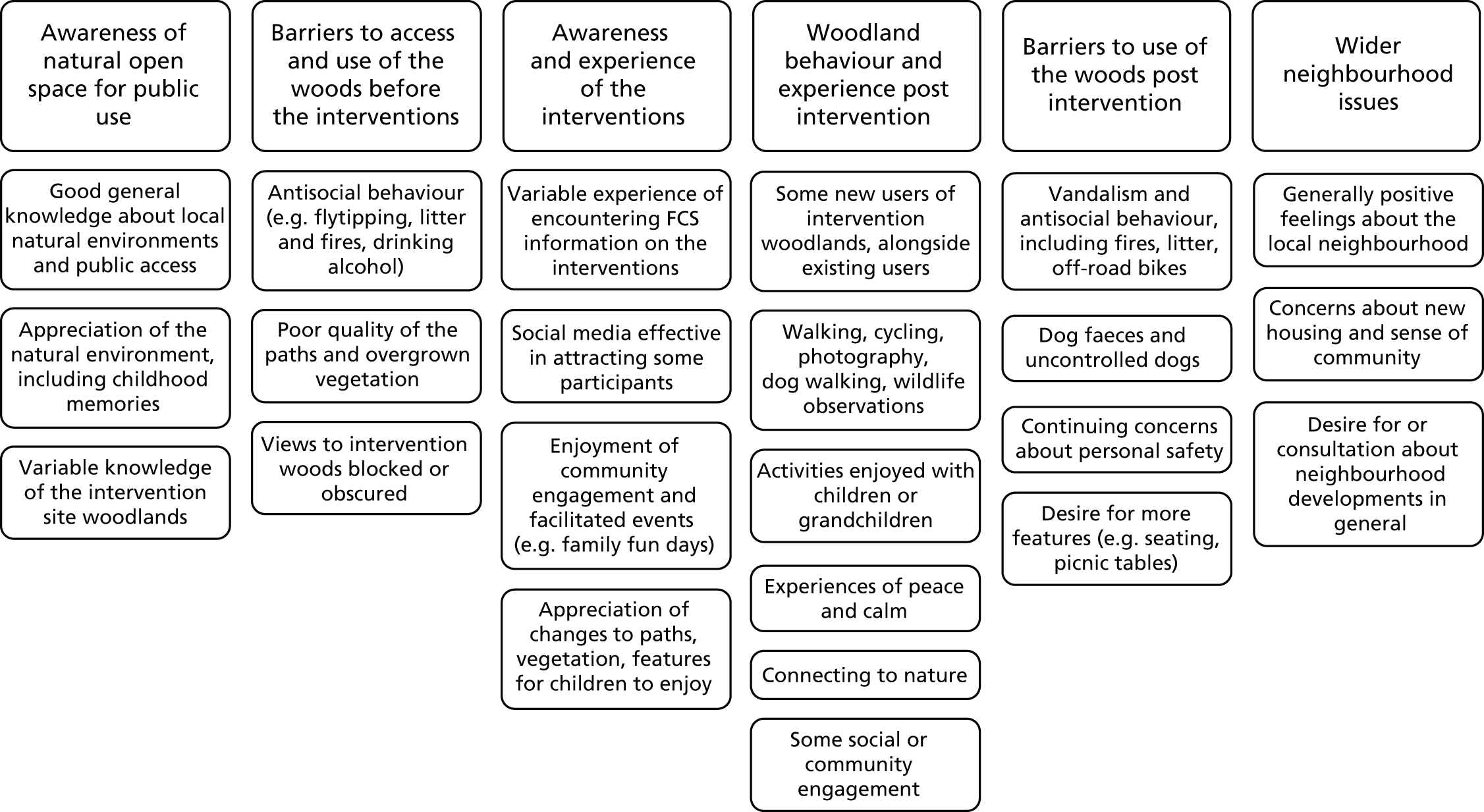

To better understand the perceptions leading to community audit scores, any textual comments were also reviewed under each of the seven domains of the tool. Finally, these were compared with the themes that arose from the community focus groups (see Community focus groups and interviews) to reveal any common themes or disparities in community perceptions.

Community focus groups and interviews

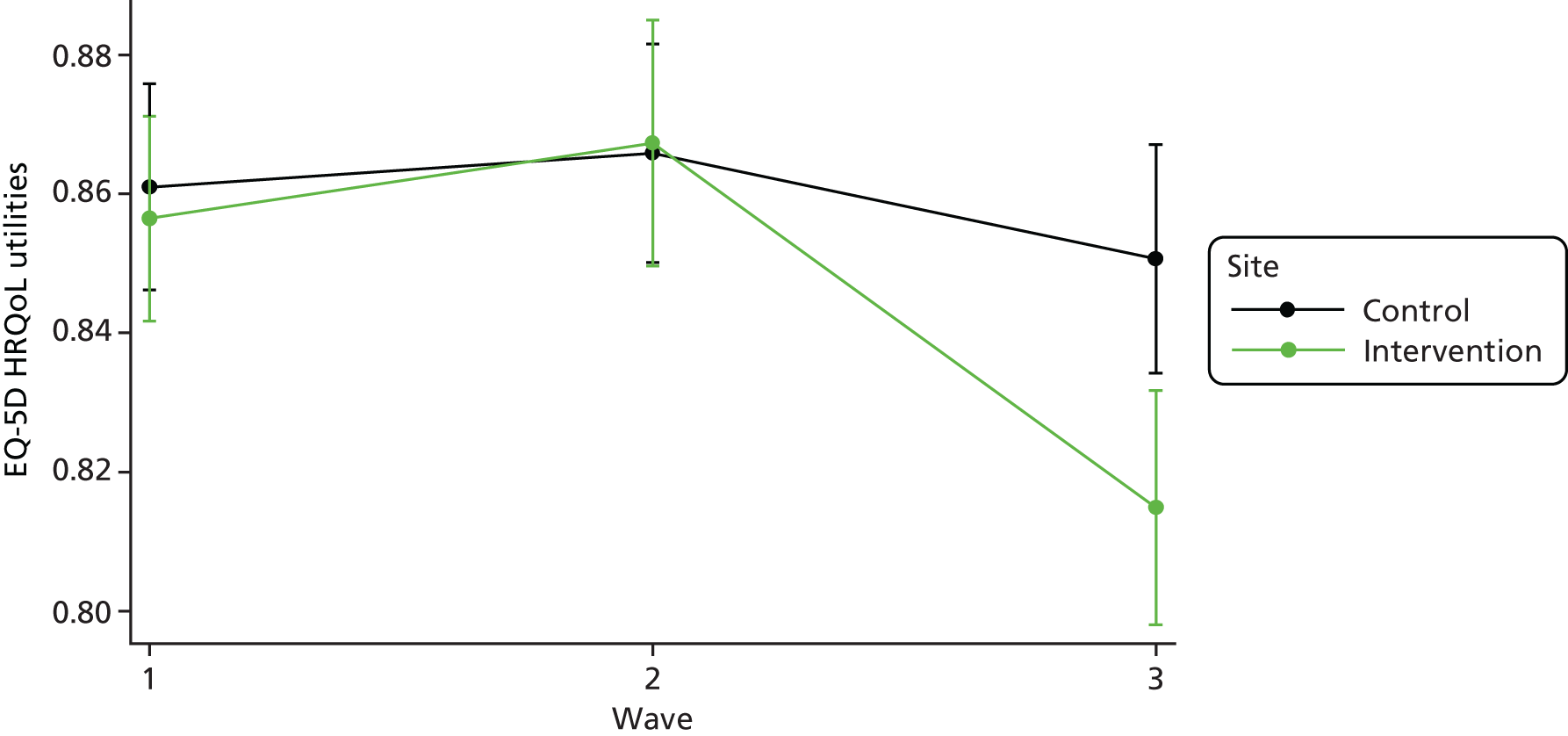

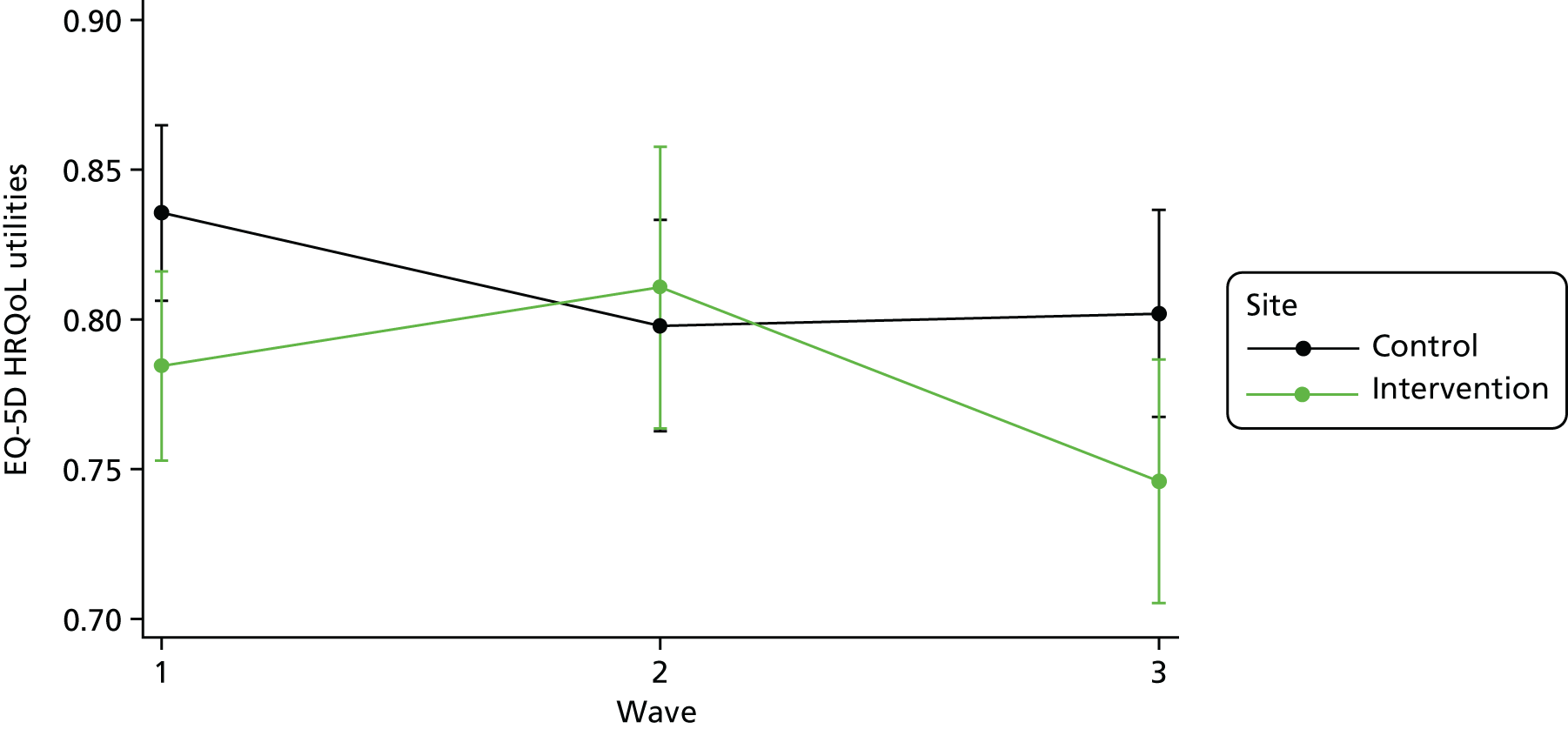

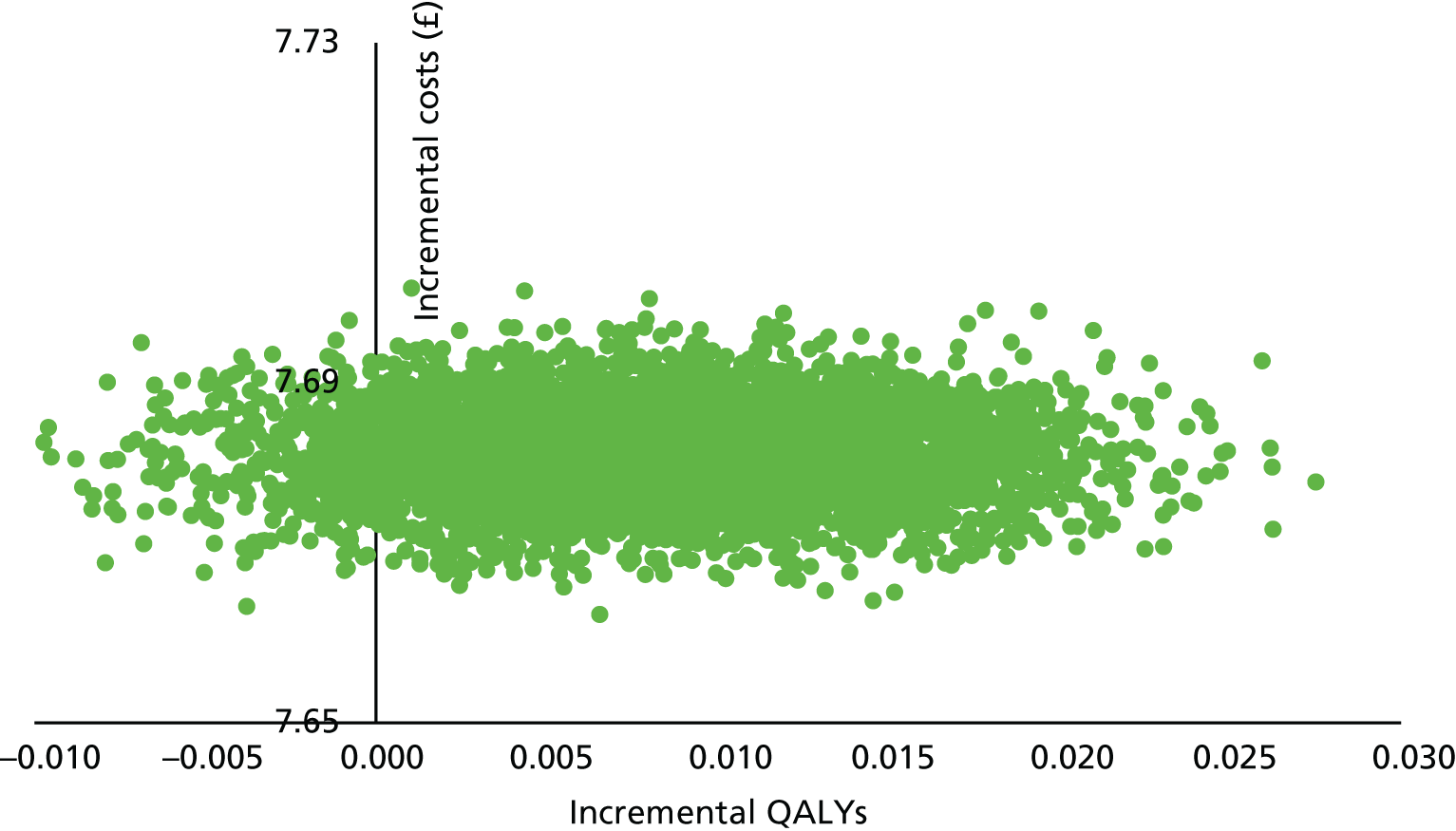

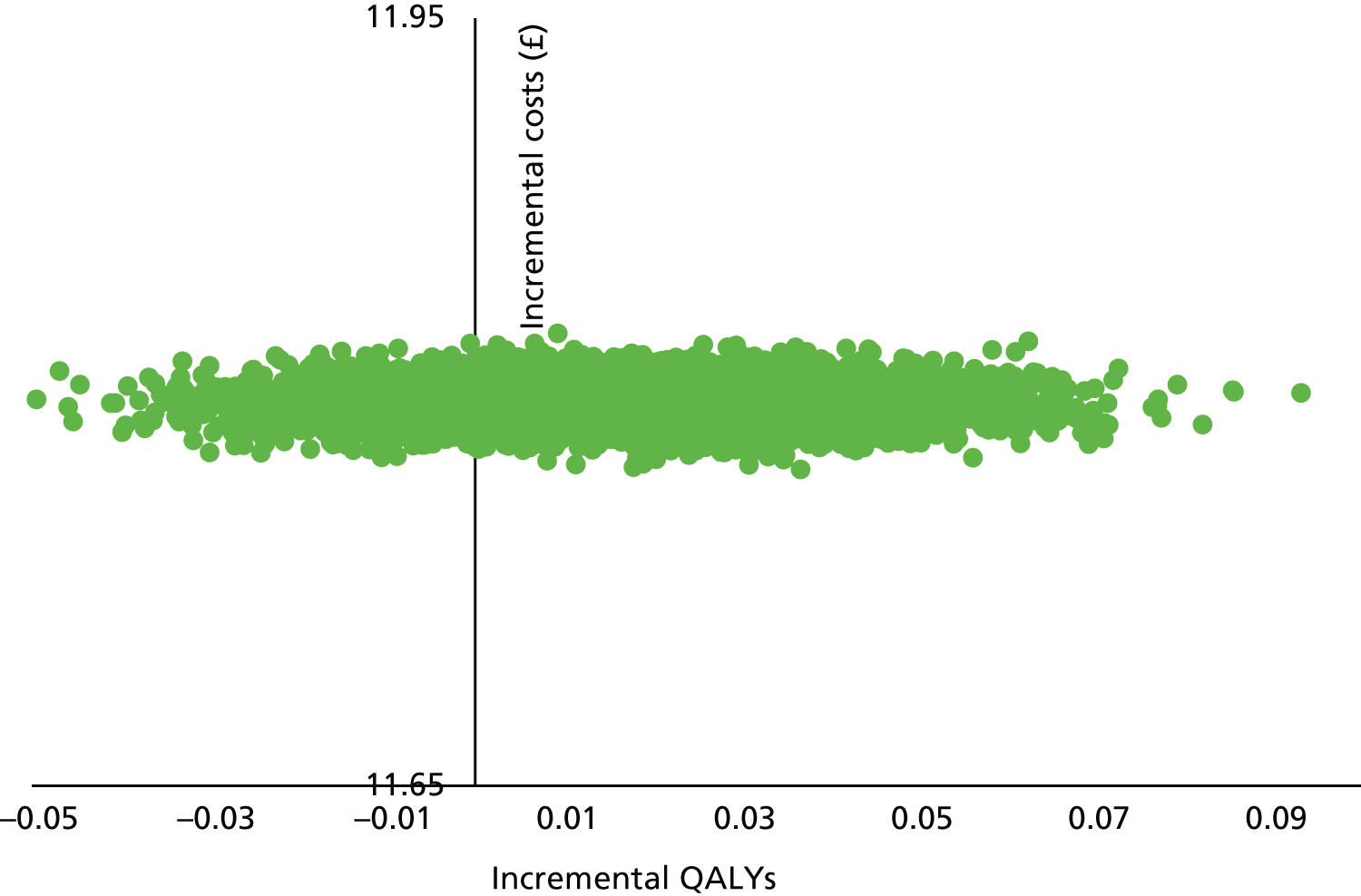

Focus groups with local residents in the three intervention communities were used to gain additional insight into the perceptions, experience and impacts of the physical and social interventions. Qualitative methods, such as focus groups, provide insight into lived experiences and personal narratives and afford opportunities for participants to provide answers in their own words; they are not tied to a fixed set of responses within a survey. Focus groups thus provided an opportunity to investigate the lived experience of the effects of the interventions from the perspective of members of the public resident in the community. They also offered the opportunity to illuminate any findings from the core survey that might otherwise be difficult to understand or explain.