Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 10/3006/07. The contractual start date was in June 2012. The final report began editorial review in March 2018 and was accepted for publication in September 2018. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Stuart Logan was a member of the Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Commissioning Board 2003–10, the HTA Medicines for Children Themed Call 2005–6 and the Rapid Trials and Add on Studies Board 2012.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Ford et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

This chapter explains the problem that the study was investigating, what previous research has been carried out on this, the intervention that it was thought might help and the reasons why this was thought to be the right intervention to study.

Disruption in school

Disruption in the classroom can undermine the quality of teaching and interrupt the learning of all children in a class. 1 Conduct disorder (or behaviour that consistently violates social norms to the extent that a child’s ability to function is impaired) is the most common childhood mental health problem, with a prevalence of 5–6% in the UK and high levels of comorbidity. 2,3 Furthermore, levels of disruptive behaviours are normally distributed throughout the population. 4 This means that in each classroom in the UK there is likely to be at least one child with a diagnosable conduct disorder, as well as several others who are disruptive to their classmates and teachers at lower levels. 5 Parent training is the evidence-based treatment for childhood behaviour problems6 but this has limited impact on school-based problems. 7 A recent systematic review of teacher-led interventions for internalising and externalising symptoms reported weak evidence for the effectiveness of interventions on internalising problems (Cohen’s d = 0.13) and no evidence for programmes on externalising problems. 8

Teachers report that disruptive behaviour and the task of managing the classroom can lead to high levels of stress and burnout. 9–12 Teachers themselves note the lack of training that they receive in the area of classroom management. 13 Improving the skills of one teacher to manage their classroom effectively would have an impact not only on the children they currently teach but also on children they will teach in the future: assuming one primary school teacher has a new class of 30 children every 2–3 years, within 10 years they will teach > 100 individuals.

A universal intervention that trains teachers has the potential to reach many thousands of children. Interventions that promote socioemotional competencies will affect children at high risk of later mental health problems, as well as their peers who may not have early indicators of risk but who still make up a substantial proportion of those with later mental health difficulties. 14 Promoting resilience at an early stage in life could lead to a population-level reduction in the burden and cost associated with mental ill health. In addition, poor mental health is highly associated with lower levels of academic attainment,15–17 and recent work has demonstrated that improving a child’s mental health will lead to subsequent improvements in their levels of attainment. 18 Therefore, an effective intervention that can be applied and delivered in an ordinary school setting, with no cost other than to train the teachers delivering it, would incur minimal costs for a wide-reaching population health benefit.

Universal interventions in the school setting: the Incredible Years® Teacher Classroom Management programme

There are a variety of universal interventions in existence that are delivered in school settings in order to promote child socioemotional competencies and minimise disruptive behaviour. Those that are led by teachers, and, therefore, may benefit many children rather than targeting individual children who are ‘high risk’, are more limited. A systematic review of teacher-led interventions that target children’s social and emotional behaviour found that only two existing programmes had been evaluated in a controlled design (randomised and non-randomised or pre–post quasi-experimental designs): the Incredible Years® (IY) Teacher Classroom Management (TCM) programme,19 and the Good Behaviour Game. 20,21 Of these two programmes, the systematic review found that the evidence for TCM was the most robust. 21 Importantly, this programme aims not only to improve the socioemotional skills and behaviour of children with externalising disorders but also to promote socioemotional skills in all children, with the aim of preventing poor outcomes in the future. 19

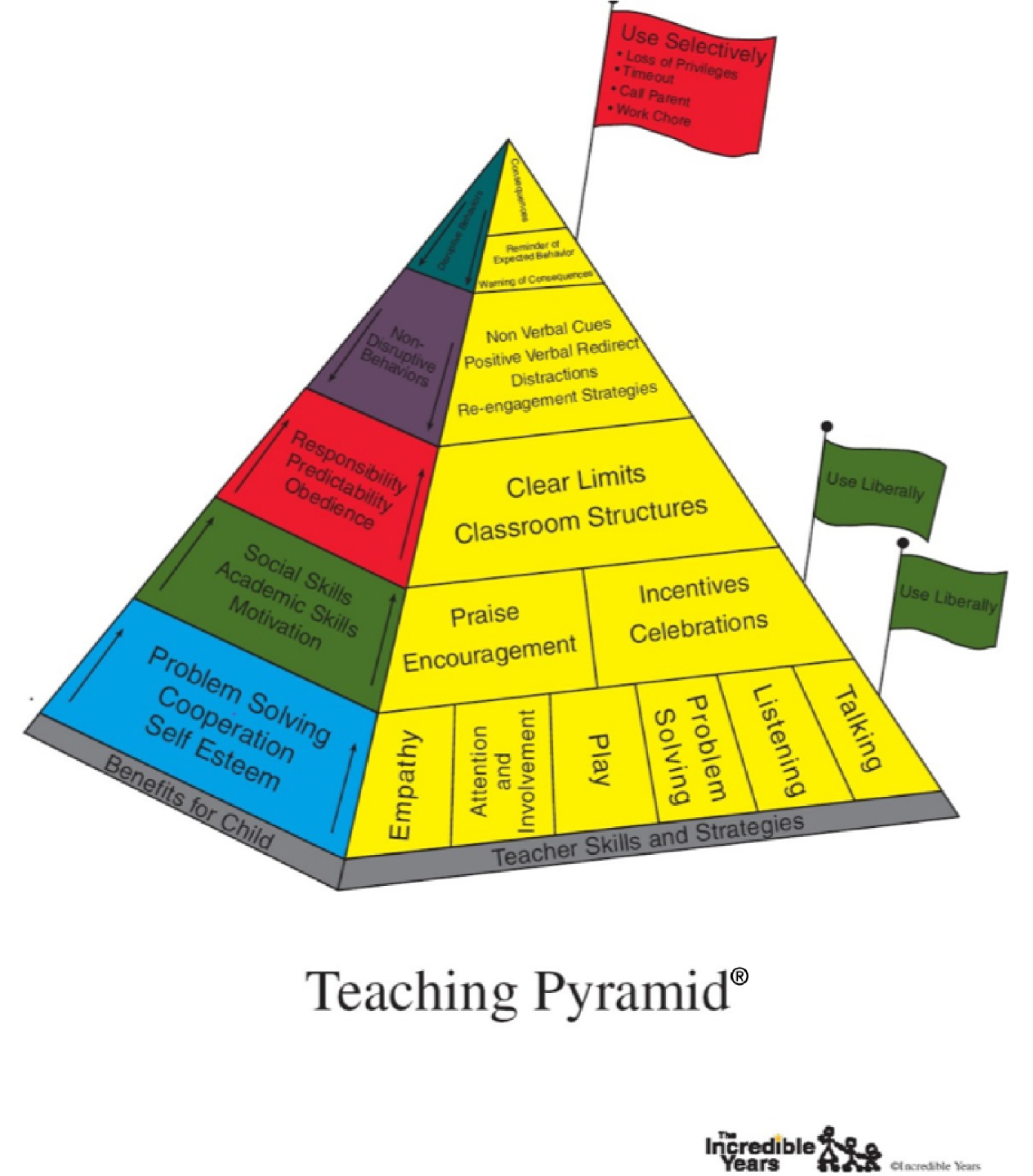

Description of Teacher Classroom Management training

Like the IY parent and child programmes, TCM training was initially developed for individual children with conduct disorders but has been extended to children with risk factors that increase their likelihood of going on to develop a psychiatric disorder or to have other poor social outcomes, such as delinquency or substance use. 22 It is believed that, by helping teachers to support these children, TCM will reduce disruption to the rest of the class, leading to a general improvement in all of their pupils’ socioemotional skills. The focus of the TCM training is on collaborative learning, discussions of teachers’ own experiences and group work to find solutions to problems encountered in the classroom.

The TCM training has four explicit goals:

-

to enhance teacher behaviour-management skills and improve teacher–pupil relationships

-

to help teachers to develop effective individual and group behaviour plans in order to enable proactive (as opposed to reactive) classroom management

-

to encourage teachers to adopt and promote social and emotional regulation skills

-

to encourage teachers to strengthen positive teacher–parent relationships (the promotion of positive relationships between parents, children and teachers is a central tenet of the IY series). 23

Research to date suggests that, although teachers already use a lot of these techniques, TCM training can increase their skills and confidence in using them sufficiently to produce significant improvements in the behaviour of their pupils. TCM uses a range of methods to deliver manualised training designed to improve classroom management. TCM draws on cognitive social learning theory, particularly Patterson’s theories24 about how coercive cycles of interaction between adults and children reinforce unwanted behaviour patterns, Bandura’s ideas25 about the importance of modelling and self-efficacy, and Piaget and Inhelder’s developmental interactive learning methods. 26 In addition, it incorporates strategies for challenging angry, negative and depressive internal dialogue in adults while interacting with children that are drawn from cognitive behavioural approaches. 27

The delivery of the TCM teaching objectives follows these theoretical perspectives and includes problem-solving, role-play, modelling, goal setting, reflective learning, group discussion and support. Cognitive and emotional self-regulation training is also included in the course. 23

The manualised version of TCM is intended to be delivered in a collaborative style to groups of teachers by a trained group leader over 6 full days, with time between each session for teachers to practise the new strategies they have learnt. 23 Table 1 outlines the key concepts that are covered in each of the six TCM workshops.

| Workshop | Workshop title | Key concepts |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Building positive relationships with students and the proactive teacher | Building relationships:

|

| 2 | Teacher attention, coaching, encouragement and praise |

Value of praise and encouragement being used by teachers to increase children’s positive self-talk, to help them learn to self-evaluate and to promote prosocial behaviours Help teachers understand the perspective of children, and the importance of using academic, persistence, social and emotion coaching with children Model ways to promote positive self-praise |

| 3 | Motivating students through incentives |

Dispel notion that praise and tangibles are bad for children Explain pitfalls of negative messages and negative notes to parents Importance of positive messages going home to parents Discuss different incentive systems and how to set them up Discuss teachers reinforcing themselves and other teachers |

| 4 | Decreasing inappropriate behaviour – ignoring and redirecting |

Discipline hierarchies How to give effective instructions and use distractions and redirections Understanding the importance of starting with the least intrusive approach Teaching both teachers and children to understand how to ignore inappropriate behaviour effectively |

| 5 | Decreasing inappropriate behaviour – follow through with consequences |

Helping children learn to self-regulate using calm-down areas in the classroom The importance of the ignoring technique as a strength How to use logical and/or natural consequences (not loss of privileges or work chores) |

| 6 | Emotional regulation, social skills and problem-solving training |

Children need lots of practice to learn social skills The importance of encouraging children’s responsibility and co-operative behaviour in classroom Social, emotion and persistence coaching to help children learn self-regulation and maintain focus Recognition of how powerful a child’s reputation is on other people’s interactions with them |

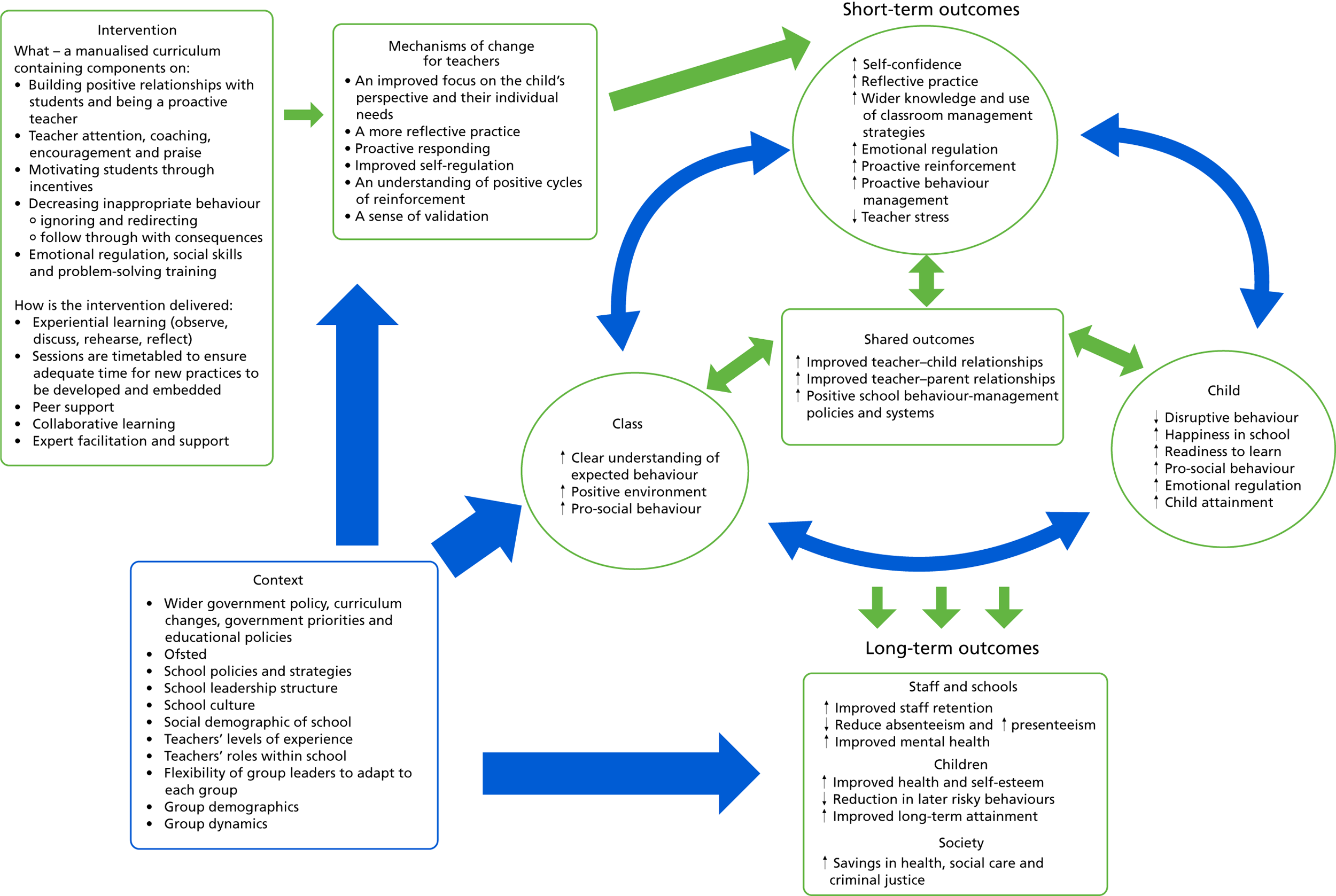

We have proposed a number of mechanisms of change in the logic model shown in Figure 1. We hypothesise that TCM will produce changes in the teachers’ behaviour in the classroom that will lead to positive changes in the children within the classroom. We anticipate that any changes that the teacher makes will have an impact both on individual children and on their class as a whole. It is likely that a reinforcement loop will be in operation, exemplifying positive changes between all three groups. It is important to consider the wider context and what impact this may have on TCM’s mechanisms of change. Certainly, the identified external factors may support or damage this proposed theory of change, and these factors are ones that are explored as part of the process evaluation work.

FIGURE 1.

Teacher Classroom Management training logic model highlighting the proposed mechanisms of change. ↑, increased; ↓, reduced.

Published studies using TCM vary in terms of whether they adhere strictly to the advised training and implementation or adapt the TCM training for individual contexts, as well as in terms of whether TCM is applied as a stand-alone intervention or in conjunction with other IY components or adaptations.

Existing research on the Teacher Classroom Management programme

At the time of writing, 21 independent data sets had been identified that report on the use of the TCM training, and two reviews had been identified that each aimed to collate the evidence around TCM. 28,29

Three initial randomised controlled trials (RCTs) conducted by the IY developers tested the effects of the TCM training in conjunction with other IY components in high-risk samples. The studies reported that children in the intervention arms had significantly fewer teacher-reported symptoms of hyperactivity and antisocial behaviour,22 more social competencies22,30 and better emotion regulation30 and were more co-operative with their teachers and less aggressive with peers. 31 Teachers who received the TCM training were observed to use more positive and fewer harsh and critical techniques,22 and more praise, as well as to be more confident, consistent and nurturing. 31 There was tentative evidence that classrooms with higher levels of conduct problems benefited most from the intervention. 30 As these initial studies evaluated TCM with the parallel parent programmes or mentoring support, it is impossible to know which IY components were responsible for changes in child and teacher behaviour.

Pre–post studies of Teacher Classroom Management

Four non-RCTs utilising pre–post study designs,32–34 in one case with a control group,35 have reported on TCM delivered as intended by the developer. 32–35 In one study, the mental health, ability to concentrate, and peer relationships of target children who were selected by teachers to test their new classroom-management strategies significantly improved. 33,36,37 In contrast, Kirkhaug et al. 35 did not detect significant improvements in their sample of 83 children with severe externalising problems following TCM. Children in the intervention group had improved academic performance and less student–teacher conflict than children in the control group. 35

Fergusson et al. 34 made use of data collected on 237 primary school teachers who received TCM training and reported a significant increase in the frequency and usefulness of positive strategies to manage behaviour. Similarly, a study of 24 pre-school teachers reported that they used more positive strategies and praise following TCM training. 32 In contrast, a small (n = 15) non-peer-reviewed study reported no significant improvements in teacher strategies. 33

Randomised controlled trials of the Teacher Classroom Management programme in primary school-aged children

We identified four RCTs of TCM as a stand-alone intervention that have explored the impact of TCM on primary school-aged pupils and their teachers. 38–41 A summary of these trials is given in Table 2.

| RCT (country, author and year) | Participants/method | Measures | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wales, Hutchings et al.38 (2013) |

12 teachers; 107 selected target children aged 3–7 years Schools paired – one of each pair randomly assigned to TCM or wait-list control |

T-POT42 Teacher-completed SDQ36 IY TSQ and workshop evaluations |

Teachers Fewer commands following TCM Teacher behaviours explicitly targeted by TCM (e.g. use of specific commands) changed in expected direction No impact on teacher behaviour towards whole class. May be because teachers were aware of the target children and may have focused on the study children to the detriment of the wider class during observations Children Compliance to commands increased in intervention group; no change in control group Significantly less off-task behaviour in intervention group following TCM Negative responses to teachers significantly decreased among target children |

| USA, Murray et al.41 (2018) |

45 intervention teachers and 46 control teachers; 1276 students aged 5–7 years In addition to training, each TCM teacher received two consultation sessions within their classroom during the delivery of the programme |

CLASS43 Teacher coder impressions measure43 |

Teachers High levels of satisfaction with the training Significant effect on positive climate from the CLASS for the TCM group was reported post intervention, but this did not sustain into the following year Children Those who had high baseline social or behavioural difficulties improved relative to those in the control group |

| Ireland, Hickey et al.39 (2017) | 22 teachers (one intervention and one control from each of the 11 participating schools); 12 children from each class |

T-POT42 Teacher-completed SDQ36 TSQ |

Teachers Reported significantly more frequent use, and perceived usefulness, of positive management strategies Significantly less use of harsh and critical strategies among intervention teachers relative to control teachers Few changes were observed using the T-POT: TCM teachers used significantly fewer negative strategies at follow-up; however, they also used more negative strategies than the control group at baseline Children Children in the control group had significantly higher SDQ scores at follow-up on the internalising problems subscale than intervention children High-risk children in TCM classrooms scored significantly lower than the control high-risk children on the SDQ-TD and impairment scores at follow-up Cost analysis TCM programme estimated to cost an average of £1682.31 per teacher |

| USA, Reinke et al. (2018)40 | 105 teachers across nine schools; 1817 children aged 5–8 years |

The TOCA-C44 T-COMP45 Children completed standardised maths and reading academic assessments (there were no blinded observations) |

Children Children in the TCM group significantly improved on emotional self-regulation, pro-social behaviour and social competence relative to control children No significant effects on teacher-reported conduct or disruptive behaviours Children who initially scored poorly on teacher-reported measures of social and academic competence improved more in the TCM condition than their peers in the control condition; however, this did not hold when using standardised academic measures of competence |

These studies suggest that TCM training may improve teachers’ abilities to manage their classroom positively by increasing the use of praise and proactive strategies, and by applying fewer harsh, negative and critical strategies. Children in TCM classrooms may derive benefits in the areas of social skills, in particular peer relationship and emotional regulation skills. Disruptive behaviour and negative responses towards peers and teachers may decrease following TCM. Specific findings vary by study design, population and context, with some studies reporting that TCM benefits those considered high risk most, and some finding that TCM prevents deterioration in the classroom environment across the school year. Many existing studies focus solely on the benefits of TCM for high-risk children, pre-school-age groups and education systems outside the UK.

Need for the current study

There are substantial gaps in the evidence base for TCM as a stand-alone intervention delivered as intended by the programme developers. The most recent systematic review of TCM29 includes two of the studies discussed in this chapter38,41 in quantitative meta-analyses and is supported by the wider research base on TCM. There is evidence that TCM reduces negative and increases positive classroom-management strategies, reduces child conduct problems and child behaviour difficulties more broadly, and is effective in both high-risk and community samples of children. Both of these studies were published after the current study began.

The current study was needed to demonstrate whether or not TCM may be an effective universal intervention for child and teacher mental health in the context of the UK primary school system. Existing studies of TCM conducted in Wales and Ireland38,39 are limited by small sample sizes (12 and 22 teachers in total), and, to date, there are only four RCTs of TCM applied in the primary school context. 38–41 Academic outcomes of children whose teachers have received the TCM training have been studied on only one other occasion35 and no study has investigated cost-effectiveness.

The Supporting Teachers And childRen in Schools (STARS) trial aimed to address these evidence gaps by including children up to 9 years of age, including child- and parent-reported measures of child mental health, examining the impact of TCM on child academic attainment, examining the effect of TCM on teachers and all children within their classes, and exploring whether or not TCM has more impact on children who are considered as being at high risk for later poor outcomes.

Chapter 2 Child outcome methods

This chapter details what happened to the children in the trial and demonstrates what questions were asked and how often we asked them.

Study design

The STARS trial was a two-arm, pragmatic, parallel-group, superiority, cluster RCT designed to evaluate whether TCM training (delivered at class level) improves the mental health of individual children. Schools were randomly allocated to the intervention arm (TCM training) or the control arm [teaching as usual (TAU)]. The trial included a parallel economic evaluation to examine the cost-effectiveness of the TCM training and a mixed-method process evaluation that used qualitative methods to assess the acceptability of the TCM training; these are reported on in Chapters 4 and 6, respectively.

Setting, participants and recruitment

We recruited 80 primary schools across the south-west of England in Devon, Torbay and Plymouth in three separate cohorts: September 2012 (cohort 1), September 2013 (cohort 2) and September 2014 (cohort 3). One class (teacher and all pupils) was selected by the headteacher from each school independently of the research team.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Schools were considered for inclusion if they had a single-year class with ≥ 15 children aged between 4 and 9 years who were taught by a teacher who held classroom responsibility for at least 4 days per week. Schools were excluded if they primarily taught pupils with special educational needs (SEN), lacked a substantive headteacher or had been judged as failing at their last Office for Standards in Education, Children’s Services and Skills (Ofsted) inspection.

All children in the selected classes were eligible for inclusion provided that the class teacher judged that they and their parents had sufficient English-language comprehension to understand recruitment information and complete outcome measures.

Recruitment of schools

Schools were approached through unsolicited contact with headteachers, publicity at local education conferences and contacting learning communities. Schools were recruited in three separate cohorts between April 2012 and June 2014, with a waiting list of schools for each cohort in the event of last-minute drop-out before the first data collection period.

Written consent was obtained from the headteacher for the school’s participation and from the class teacher for their involvement after nomination by the headteacher. Parent information leaflets were sent home with children and parents were given 2 weeks to ‘opt out’ their child from the research. In order to opt out their child, parents could return a ready-prepared letter or contact the research team directly. Verbal assent was obtained from children each time they were asked to complete a questionnaire.

Randomisation and concealment

Randomisation of schools, using computer-generated random numbers, was carried out by an independent researcher based at the University of Exeter who was masked to the identity of the schools to ensure allocation concealment. The allocation was passed on to the trial manager, who then informed the schools. Randomisation was completed after baseline data collection to avoid recruitment and response bias. 46 Allocation was completed separately for each cohort, with all schools in a given cohort allocated en bloc. An equal number of schools were allocated to each arm overall, but unequal allocation ratios were used for cohorts 1 and 3 to ensure that there was an adequate number of intervention teachers to fill each TCM training group, with the ratio of intervention to TAU schools being 10 : 5 in cohort 1, 15 : 15 in cohort 2 and 15 : 20 in cohort 3.

Allocation was balanced on the following school factors: urban versus rural/semi-rural area, key stage (KS) 1 (Reception to Year 2) versus KS 2 (Years 3 or 4) and deprivation (whether the percentage of children eligible for free school meals was > 19%, the UK national average in 201247). Because there were relatively few clusters within each cohort, there was a high chance that random allocation using standard stratification or minimisation methods would not have yielded trial arms that were similar on the balancing factors. To overcome this, we used the approach of randomly selecting an allocation sequence for each cohort from the 5% with the least imbalance out of one million randomly generated potential allocations (permutations). Imbalance was quantified by the sum of the mean differences on the three balancing factors between trial arms weighted by the inverse of the variance of those factors. 48

We were unable to mask the schools and teachers because the school needed to release the class teacher to attend the training. Children and parents were not informed about whether or not the teacher attended training. Baseline measures were completed before randomisation. Even following randomisation, parents and children were unlikely to be aware of whether or not their child’s teacher had completed TCM training. The follow-up measures were questionnaires that were completed independently of the researchers (with the exception of the service-related interviews, which were completed by a subsample of parents, and the child measures, as younger children might require support) and thus difficult for the core team of researchers to influence. In addition, the teacher-completed follow-up measures in the second and third years of each school’s participation in the study (18 and 30 months post baseline) were completed by a teacher who did not access the intervention, although they were likely to have known whether their colleague who taught the class in the first academic year of the study did or did not.

Intervention

In the STARS trial, TCM was delivered to groups of up to 12 teachers in 6 whole-day sessions between October and April of each academic year. The sessions took place during the school day but at an external venue. The facilitating group leaders, who delivered the training in pairs, were behaviour support practitioners, had completed the mandatory TCM basic training and had led at least two previous courses prior to the start of the trial. They received monthly supervision from the programme developers, which included video reviews of each session, to ensure fidelity.

As recommended by the education community, and to incentivise recruitment and retention, TAU schools were offered TCM training during their second year of involvement in STARS as long as the attending teacher did not teach the study children during the 30-month follow-up period. All training costs were met for both intervention and TAU schools, including the provision of a £160 payment for each day the teacher attended TCM training to support the provision of a replacement teacher for their class. Our process evaluation involved interviews with headteachers and suggested a number of factors to consider when making their choice of teacher to nominate, including newly qualified teacher (NQT) status, allocation of a class known to be particularly challenging or a known teacher interest in behaviour management. No restrictions were placed on schools about access to other training and support services.

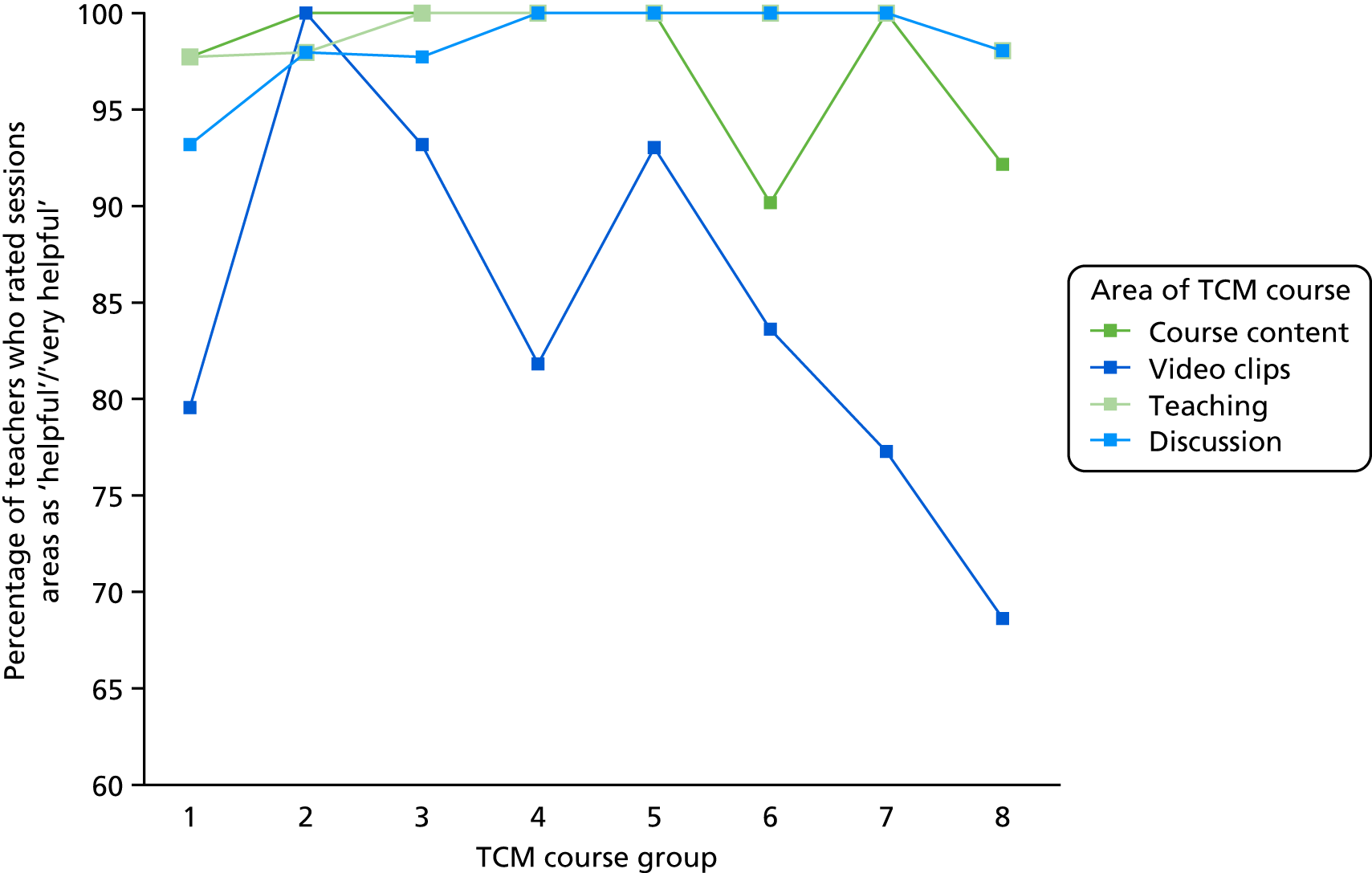

A total of eight TCM groups were delivered; in order that each group contained at least 10 teachers, the number of intervention and TAU teachers varied by cohort and year of the trial. In cohort 1, 15 schools were randomised: 10 to the intervention group and 5 to the TAU group. During this first year of the trial only one TCM group was delivered to these 10 intervention teachers. During cohort 2, 30 schools were randomised: 15 to the intervention group and 15 to the TAU group. During this second year of the trial, two TCM groups were run, which contained a mix of the 15 cohort 2 intervention teachers and the five cohort 1 TAU teachers. During cohort 3, 35 schools were randomised: 15 to the intervention group and 20 to the TAU group. During this third year of the trial, three TCM groups were run, which contained a mix of the 15 cohort 3 intervention teachers and the 15 cohort 2 TAU teachers. During the fourth year of the trial, two TCM groups were delivered to the cohort 3 TAU teachers.

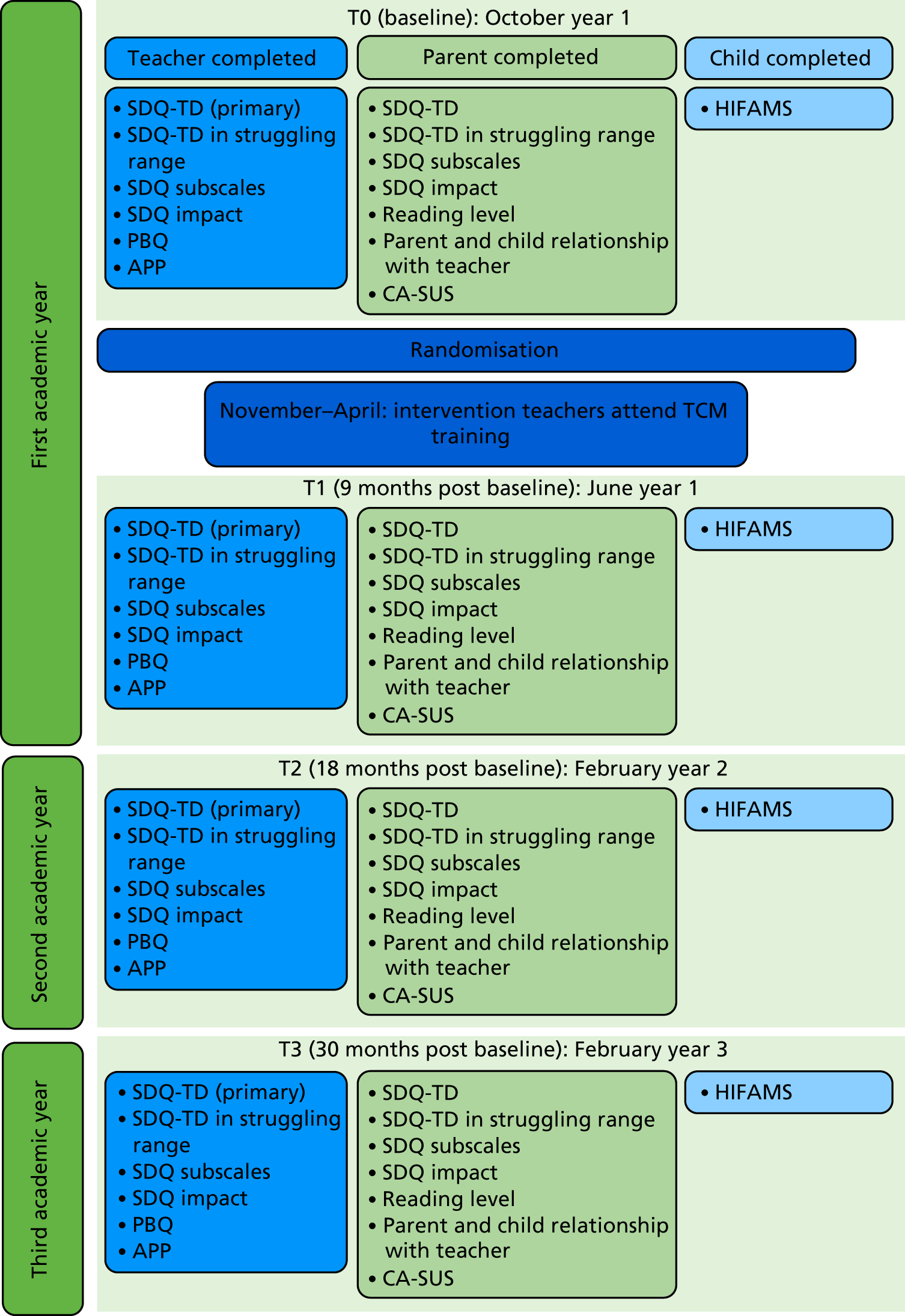

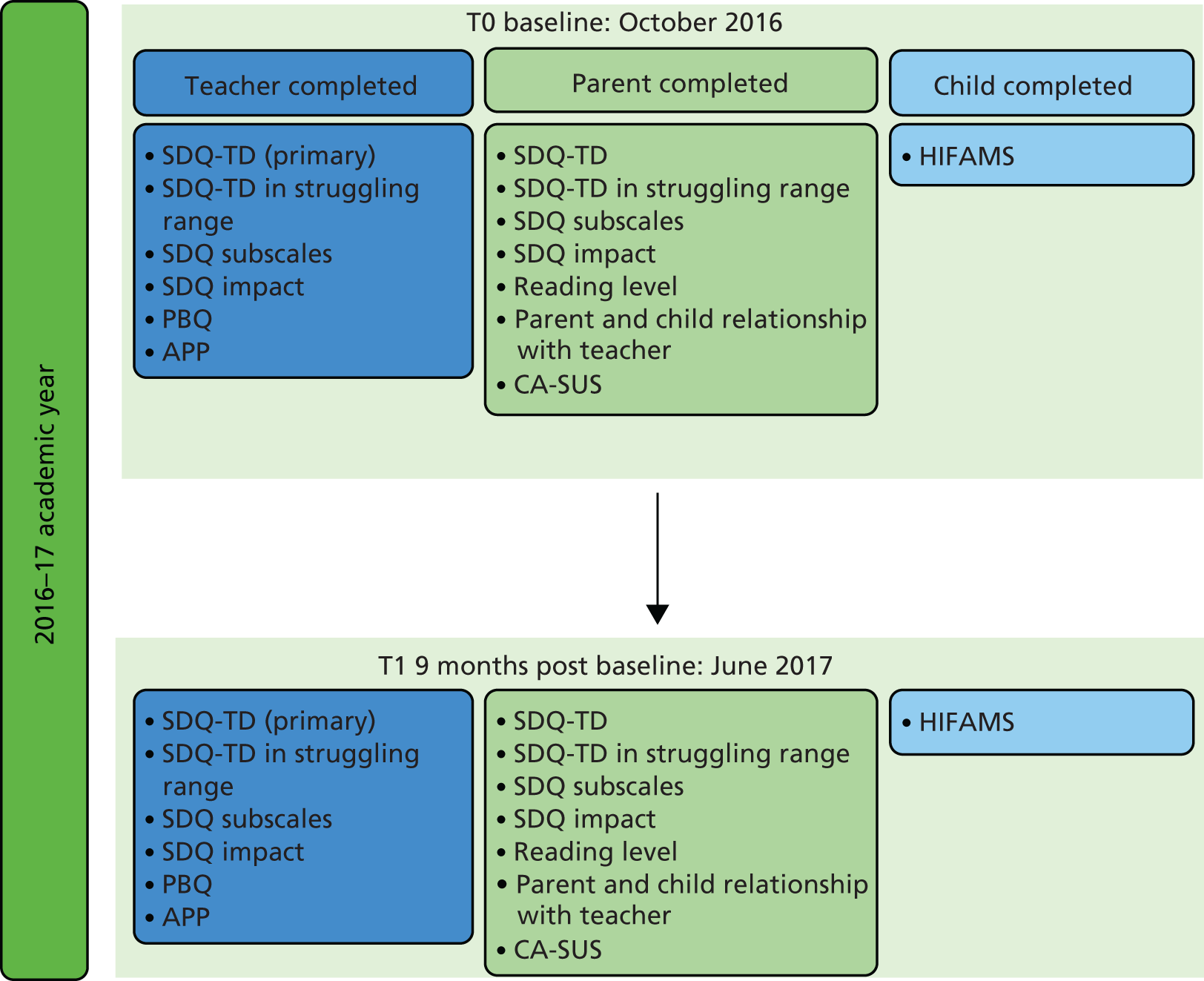

Data collection

All baseline (T0) measures were collected before the end of the first academic half term of the schools’ involvement, usually in October. Follow-up measures were then completed 9 [June, time point 1 (T1)], 18 [February, time point 2 (T2)] and 30 [February, time point 3 (T3)] months later. The 9-month time point was chosen to capture any initial impact the training may have had. Longer-term follow-up was important to see if potential impacts were sustained, reduced or potentially accelerated and the 18- and 30-month time points were chosen as they were mid-way through the following two academic years. Although additional time points during the first year would have been beneficial to track potential change, including any mediators of this change, we were mindful of the need to reduce the response burden on teachers, parents and children, and, therefore, we chose fewer time points that were optimally placed to capture change. Baseline and 9-month assessments took place during the first academic year of participation, before and after the intervention, respectively, so were completed by the same teacher at both these time points. The 18-month and 30-month assessments occurred during the children’s second and third academic year of the trial and were therefore completed by different teachers (Figure 2). It was not possible to ask the original teacher to complete the 18- and 30-month assessments because, in order to complete the measures, teachers must spend a large amount of time with the child to accurately assess their current development. Teacher measures were completed on an online database built for the trial (see Report Supplementary Material 1). To enable a supply teacher to supervise the teacher’s class, schools received £80 for each time point at which teachers completed the outcomes (£320 in total) and £160 for each training day attended (£960 in total). Teachers also personally received a £10 gift voucher after outcome completion at each wave. Parent questionnaires were sent home with participating children. Parents received reminders via the school office and, where possible, second questionnaires were posted directly to the home. Parents received a £5 gift voucher for every completed questionnaire (£20 in total). Child-reported outcome data were collected during school time by researchers as a classroom activity for children aged ≥ 7 years, or individually for younger children. School staff were present but instructed not to assist the children.

FIGURE 2.

Schematic detailing the timing of outcome measures. APP, assessment of pupil progress; CA-SUS, Child and Adolescent Service Use Schedule; HIFAMS, How I Feel About My School; PBQ, Pupil Behaviour Questionnaire.

Outcome measures

Primary outcome

Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire Total Difficulties score (teacher completed)

The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) is a widely used measure of mental health in childhood containing 25 Likert items (each scored 0 to 2) comprising five scales (each with five items). 37 Our primary outcome was the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire Total Difficulties (SDQ-TD) score completed by the children’s class teacher, which sums four of these five scales and has a possible score ranging from 0 to 40.

Secondary outcomes

Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire Total Difficulties score (parent completed)

Parents and teachers were asked to complete the SDQ about children at each time point, and the parents’ SDQ-TD score was a secondary outcome in the analysis.

Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire Total Difficulties score above the clinical cut-off point (parent and teacher completed)

The SDQ-TD score was dichotomised to indicate those with clinically high scores (scored ≥ 12 on the teacher report and ≥ 14 on the parent report) as struggling compared with those with scores in the normal range (scored ≤ 11 on the teacher report and ≤ 13 on the parent report) as normal. 49

Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire subscale scores (parent and teacher completed)

The following subscale scores of the SDQ (each containing five items with a possible score ranging from 0 to 10) were compared between the TCM and TAU trial arms: Behaviour, Emotions, Hyperactivity, Peer Relationships and Pro-social. 37

Teacher-reported Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire impact score (teacher completed)

The teacher-reported SDQ impact score (three items with a possible total score from 0 to 9) quantifies the extent to which difficulties in the areas of emotions, concentration, behaviour or being able to get on with other people have an impact on a child’s everyday life in terms of peer relations and classroom learning. The measure was dichotomised into those whose life was affected by difficulties (scoring 1 to 9) and those whose life was not (scoring 0).

Parent-reported Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire impact score (parent completed)

The parent-reported SDQ impact scale (five items with a total possible score from 0 to 15) quantifies the extent to which difficulties in the areas of emotions, concentration, behaviour or being able to get on with other people affect a child’s everyday life in terms of home life, friendships, classroom learning and leisure activities. The measure was dichotomised into those whose life was affected by difficulties (scoring 1 to 15) and those whose life was not (scoring 0).

Adapted Pupil Behaviour Questionnaire (teacher completed)

The Pupil Behaviour Questionnaire (PBQ) was developed for and used extensively in school effectiveness studies and is based on the findings of the Elton Report. 50 It measures the types of classroom-based disruptive behaviours of particular concern to school staff and has been validated as part of the trial. 51 The adapted version contains six items with the following scoring categories: 0 = never, 1 = occasionally, 2 = frequently. Items are summed, with a higher total score (possible range: 0–12) indicating more disruptive behaviour.

How I Feel About My School (child completed)

Children completed the How I Feel About My School (HIFAMS),52 which measures children’s attitudes towards school, with higher scores indicating greater happiness. The HIFAMS is a 7-item measure of a child’s attitude towards school, with scores ranging from a possible 0 to 14 (summed across seven items each scored from 0 to 2).

Teacher assessment of pupil progress (teacher completed)

Teachers rated the children on sublevels according to their academic progress. These sublevels were mapped on to two categories (below expectation or at or above expectation) and analysed as a binary outcome.

Parent assessment of reading level (parent completed)

Parents rated the children on sublevels according to their reading ability. These sublevels were mapped on to six levels (categories) ranging from ‘cannot read’ to ‘reads very well’ and then grouped further into two categories (developing reader vs. fluent reader) and analysed as a binary outcome.

Assessment of pupils’ relationships with teacher (parent completed)

Parents rated their child’s relationship with their teacher on one of three ordinal categories. This was analysed as a binary outcome [poor or satisfactory (categories one and two) vs. good (category three)].

Assessment of parents’ relationships with teachers (parent completed)

Parents rated their own relationship with their child’s teacher on one of three ordinal categories. This was analysed as a binary outcome [poor or satisfactory (categories one and two) vs. good (category three)].

Child and Adolescent Service Use Schedule (parent completed)

Parents completed a brief, self-report version of the Child and Adolescent Service Use Schedule (CA-SUS)53–55 to collect data on children’s use of key services (high cost, high frequency of use) of relevance to this population; full details are presented in Chapter 4.

Child- and school-level demographics

Parents were asked to provide the following demographic details: child’s eligibility for free school meals, postcode [to link to the Income Deprivation Affecting Children Index (IDACI)], the number of children living in the household, housing tenure (rented or not) and the highest level of qualification of the parent(s) or carer(s). Data on a number of socioeconomic indices that might be related to outcomes were collected for all trial schools. We gathered school-level data on the percentage of children eligible for free school meals at recruitment and the IDACI at lower super output area as a proxy for the school catchment area according to the school’s postcode. 56

National Pupil Database

We asked parents for opt-in consent to access their child’s details from the National Pupil Database (NPD). This is a nationally held database to which all schools in the UK are required to submit data about the children in their school on a termly basis. The NPD includes information about characteristics such as gender, ethnicity, first language, eligibility for free school meals and SEN requirements, and detailed information about any absences and exclusions. Individual-level data on school attendance, exclusions and SEN status were obtained from the NPD for all children whose parents provided appropriate consent.

Sample size

As previously reported in our procotol,57 40 schools (clusters) were randomised to each of the intervention and TAU arms, using one class (teacher and pupils) from each school. Assuming that each class contains 30 pupils and that the recruitment rate is 70% (achieved among parents in the Helping Children Achieve trial58), we anticipated that 21 (i.e. 30 × 0.7) children from each class of 30 and a total of 840 (i.e. 21 × 40) children in each trial arm would participate in the study. Assuming 10% attrition for the children, we expected 19 of them to be followed up at T3 in each class and a total of 760 (i.e. 19 × 40) children to be followed up at T3 in each trial arm. As clusters were randomised, the sample size was calculated taking account of the correlation between pupils’ responses within clusters (or equivalently the variation between clusters). The variance inflation factor (VIF) (design effect) is given by VIF = 1 + [(n-1) × ICC], presented in Donner and Klar,59 where n is the number of pupils providing outcome data at follow-up in each school and ICC is the intracluster (intraschool) correlation coefficient for the primary outcome. Nineteen children in each school were expected to provide follow-up data at T3 and the ICC for the SDQ-TD score (the primary outcome) was assumed to be 0.15 based on analysis of data from Sayal et al. 60 The assumed ICC value takes account of both the inherent variability across schools and the additional variability resulting from the fact that only one classroom was included in the study from each school. The VIF was 3.7 {i.e. 1 + [(19 – 1) × 0.15]} and the target sample size therefore has the same effective sample size as an individually randomised trial with 205 (= 760/3.7) participating pupils at follow-up in each arm, providing 85% power at the 5% level of significance to detect a difference between trial arms of 0.3 standard deviation (SD) units (Cohen’s d = 0.3), or a difference of 1.8 points on the raw SDQ scale (the SD of the teacher-reported SDQ has been estimated to be 5.9 for 4801 UK children aged 5–10 years). 61 This effect would reduce the percentage of children classified in the borderline/abnormal range from 19.7% to 13.7%,61 where borderline/abnormal is defined as those scoring 12 or more out of 40 on the teacher-reported SDQ-TD score. Data from Goodman and Goodman49 suggest that the odds of psychiatric disorder decrease by 33% for each two-point decrease on the teacher SDQ and by 40% for each two-point decrease on the parent SDQ.

Statistical analysis

All analyses, performed using Stata® version 14.2 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) software, were pre-specified in a statistical analysis plan that was reviewed by the independent Data Monitoring Committee (DMC) and the Trial Steering Committee (TSC).

Baseline characteristics of the schools, teachers and children were summarised for each trial arm, reporting means and SDs [or medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs)] for quantitative variables, and numbers and percentages for categorical variables. The characteristics of participating schools were compared with those reported in the 2012 school census for England. 47

The trial outcomes at follow-up were compared using the intention-to-treat principle; children were analysed strictly according to the trial arm to which their school was randomised. The main findings presented are based on analyses of complete cases. In addition, we carried out sensitivity analyses based on 50 multiply imputed data sets using the chained equations approach. 62

Quantitative outcomes were compared between trial arms using random-effects linear regression models, and binary outcomes were compared using marginal logistic regression models using generalised estimating equations with information sandwich (‘robust’) estimates of standard error assuming an exchangeable correlation structure. These methods allow for the correlation of children’s outcome scores within schools. The primary analyses were those in which potential confounders were adjusted for, specified a priori in the analysis plan as the following: the three school-/class-level factors used to balance the randomisation, cohort, child gender, baseline score of the outcome, Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) score based on the child’s address, number of children living in their household and whether or not the child’s household was rented. The last three of these nine prognostic factors had a large number of missing data because they were parent reported. Adjusting for these would have resulted in the loss of one-quarter of the sample in the complete-case analyses (CC1). On this basis, and after discussion with our DMC (5 June 2017), we agreed the primary analysis as the CC1 adjusted for only the six a priori prognostic factors that were not parent reported (CC1). For completeness, we also report the findings from the complete-case sensitivity analysis (CC2) and the analysis of imputed data with all nine prognostic factors included [multiple imputation (MI)].

For all outcomes, tests of interaction were used to assess whether or not there was evidence that the effect of the TCM intervention differed across the three follow-up time points. When the interaction effect is statistically significant at the 5% level, we report the effect at each wave; otherwise, we report an estimate of the average intervention effect across the three follow-up waves.

In an ancillary analysis we used the two-stage least squares instrumental variable method63 to calculate the complier average causal effect (CACE) estimate of the intervention effect on the primary outcome teacher-reported SDQ-TD score that would have occurred if all the teachers in the intervention arm had attended all six TCM training sessions.

Tests of interaction were used in pre-specified exploratory analyses to assess whether or not the effect of TCM on the primary outcome differs across subgroups defined by the following potential moderator variables: school- or child-level deprivation status (in bottom two deciles vs. otherwise), whether or not the child scored in the struggling range on the teacher-reported SDQ-TD score at baseline, the length of the study teacher’s experience (> 5 years vs. ≤ 5 years), KS status (KS 1 vs. KS 2), the child’s gender and cohort status. In a further sensitivity analysis, a test of interaction was used to assess whether or not the effect of TCM on the primary outcome differed between the subgroup defined as having a primary or secondary SEN category of social, emotional or mental health, as classified by the NPD, versus those who did not.

Random-effects Poisson regression was used to compare the pupil-level rates of absence obtained from the NPD between the intervention and TAU arms in years 1 and 2 of the trial. We report crude rate ratios (RRs) and RRs and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) that are adjusted for school-/class-level factors [urban vs. rural/semi-rural area, KS 1 vs. KS 2, deprivation (% of children eligible for free school meals in 2012)], cohort and child gender.

Given the relationship between emotional health and educational attainment,15–18 tests of interaction were also carried out to assess whether or not the effect of the intervention on the assessment of pupil progress (APP) outcomes is modified by whether or not the child scored in the struggling range on the teacher-reported SDQ-TD score at baseline.

Data management

Data entry and cleaning was overseen by the trial manager. All data were stored on a custom-built password-protected database maintained by the Peninsula Clinical Trials Unit (CTU), a UK Clinical Research Collaboration-accredited CTU.

Missing outcome measures

The majority of teachers used a web-based electronic data-capture system to complete all questionnaire measures on the children, which did not allow for any items to be missed. Where this was not possible, teachers were asked to complete paper measures, which were double-entered on to the web-based database. Parents and children completed paper measures, which, again, were double-entered on to the database.

Paper questionnaires were checked for missing data on receipt and efforts were made to obtain these data from participants. In cases in which ambiguous data were not clarified with the participant, items were marked as ‘spoiled’ and recorded as missing.

Missing items within outcome measures were marked in accordance with the established conventions for that measure and overall totals and subtotals were imputed as instructed.

Where possible, teacher-reported outcomes were collected for children who had left their study school. This was achieved by asking the child’s former teacher to complete the measures if the period between the child leaving the study school and data collection was less than one academic term. If the period between the child leaving the study school and data collection was greater than one academic term, we attempted to trace their current teacher in their new school and ask them to complete the measures.

Ethics approval and research governance

This study was granted ethics approval by the Peninsula College of Medicine and Dentistry Research Ethics Committee, now under the auspices of The University of Exeter Medical School Committee on 8 March 2012 (reference number: 12/03/141). The University of Exeter acted as the sponsor for the study. The trial was registered with the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Register with the reference number ISRCTN84130388. STARS was hosted in the Child Health Research Group at the University of Exeter, which has experience in the successful delivery of community-based paediatric trials. The trial was overseen by the independent TSC [Paul Stallard (chairperson), Gail Seymour, Shirley Larkin, Tobit Emmens and David Glenny] and the DMC [Paul Ewings (chairperson), Siobhan Creanor and Andrew Richards]. A summary of the changes made to the original protocol57 is given in Table 3, and the complete final trial protocol can be found in Report Supplementary Material 2.

| Changes to protocol | Date |

|---|---|

| Removal of child quality-of-life measure, extra detail of randomisation procedures and adaptation of two questionnaires | September 2012 |

| TAU schools can choose to send a different teacher to the TCM training, as long as this teacher does not teach the children in the trial | May 2013 |

| Collection of class-level attendance was added as an outcome | July 2013 |

| Alternative method of gaining consent for telephone interviews with parents or teachers using either consent via e-mail (parent CA-SUS interviews) or verbally (teacher or SENCo interviews) was added | May 2014 |

| Qualitative interviews to be completed with teaching assistants and an additional process evaluation FG with the TCM group leaders were added. Additional consenting of parents to allow the research team access to the NPD was added | January 2015 |

| Post-TCM extension study was added | August 2016 |

Confidentiality

All of the information collected was kept strictly confidential and held in accordance with the principles of the Data Protection Act 1998. 64 Each participant was assigned a research number and all data were stored without subject identification. Data were held on a secure database on a password-protected computer at the University of Exeter. Access to data was, and continues to be, restricted to the research team.

Informed consent

Obtaining consent for this trial was a four-stage process:

-

headteachers – after receiving the information leaflet and having the opportunity to discuss the implications of the study, headteachers provided written consent for the school to participate in the trial.

-

teachers – after receiving the information leaflet and having the opportunity to discuss the implications of the study, the nominated teacher provided written consent for their participation in the trial.

-

parents – an information leaflet about the trial was sent via the schools to the parents of all children in the nominated teacher’s class. This explained that if parents wished to opt their child out of the trial, they needed to return a form by a specified date (2 weeks later), otherwise consent would be inferred. Parents were able to opt themselves and their child out of the measurements but were not able to opt the teacher or school out of the study.

-

children – if parents had not opted their child out of the trial, the child’s verbal assent was obtained before they completed the questionnaire measure on each occasion. If a child became distressed or appeared reluctant during data collection, this was assumed to indicate their wish not to complete the measure.

Assessment of harms and adverse effects

Child-completed questionnaires were screened for signs of severe distress and where children reported feeling sad in response to all seven questions of the HIFAMS measure, a conversation was held with the class teacher, headteacher or nominated deputy to ensure that they were aware of any difficulties that the child was facing and that they could put in place plans to support the child.

All researchers in contact with children and schools had the necessary Criminal Records Bureau checks and received training in child safeguarding. The trial had a specific safeguarding policy, but this was never enacted.

Adverse events

We followed Good Clinical Practice guidelines for identifying, acting on and reporting adverse events: we adopted the guideline definitions of adverse events and serious adverse reactions, reporting a total of one adverse event, which the TSC and DMC classified as unrelated to the trial.

Patient and public involvement

Public involvement has been key at all stages of the design, planning and implementation of the STARS programme of work. A User Advisory Group (UAG) was established comprising parents, teachers, headteachers and behavioural support network teachers who were delivering the TCM intervention. The UAG provided key advice on the acceptability of the study to parents and teachers, recruitment and data collection procedures. Specifically, they provided advice on:

-

trial design – the UAG proposed that the TAU schools should be offered the opportunity to receive TCM training as an incentive for recruitment

-

costing – the UAG was insistent that the funding for supply teacher cover should be provided as part of the trial as it was considered that schools would be unable to cover these costs themselves and that this would be a barrier to recruitment

-

consent procedure – the UAG was fully consulted about the proposed consent process; they commented from their own (teacher/parental) perspective, and the process was adapted as a result of their advice

-

outcome measures/questionnaires – the UAG commented on the outcome measures and instructions for completion

-

trial literature – the UAG was involved in the development of the trial literature, including information literature and consent forms.

In addition to the UAG, we worked with the school councils of three local primary schools to develop the HIFAMS measure to ask for children’s perceptions of attending school and we asked the children for their views on how it could be adapted to make it more ‘user-friendly’ for children.

Chapter 3 Child outcome results

This chapter describes the results that were found when considering the impacts of TCM training on children.

Participants

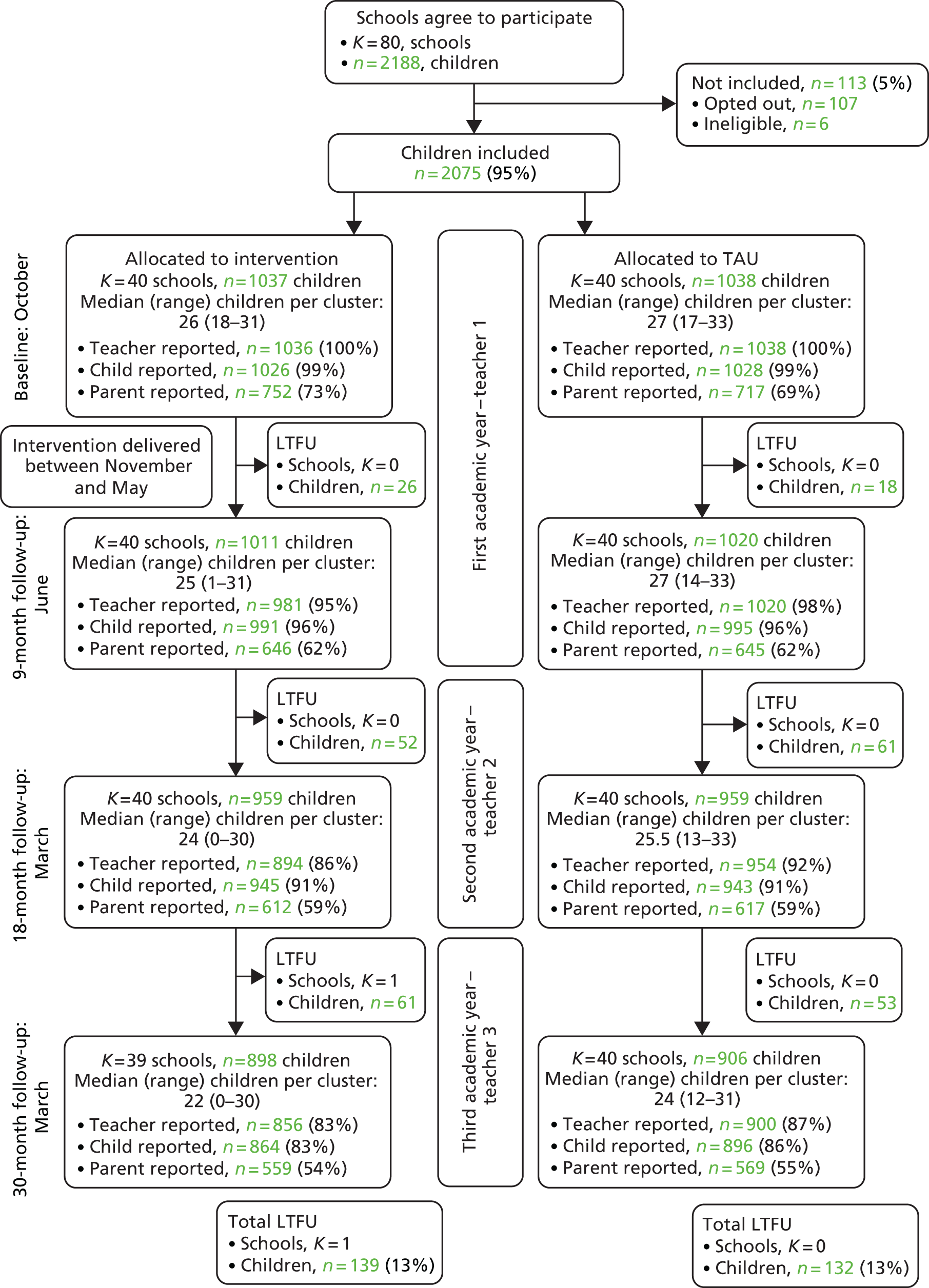

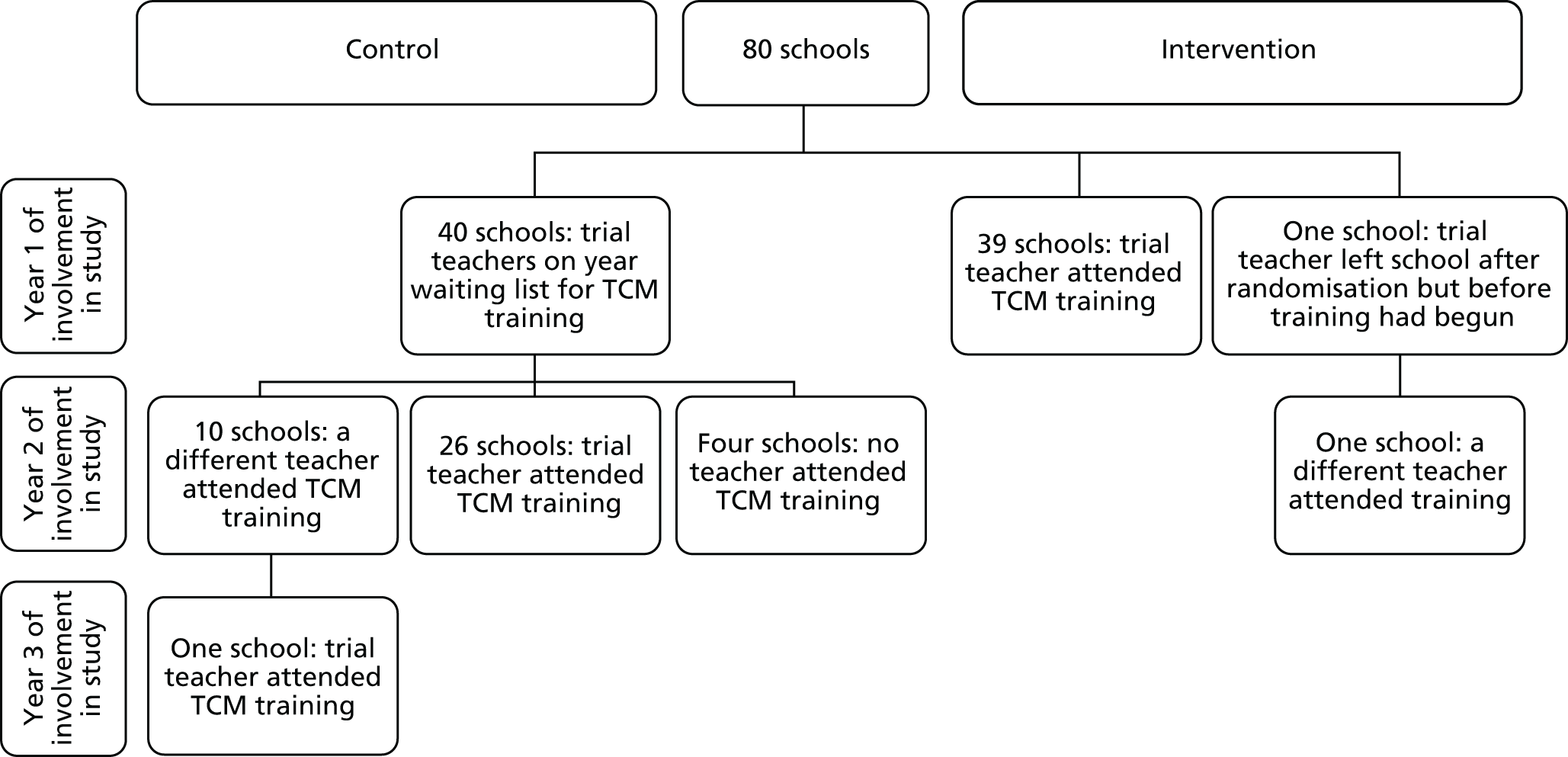

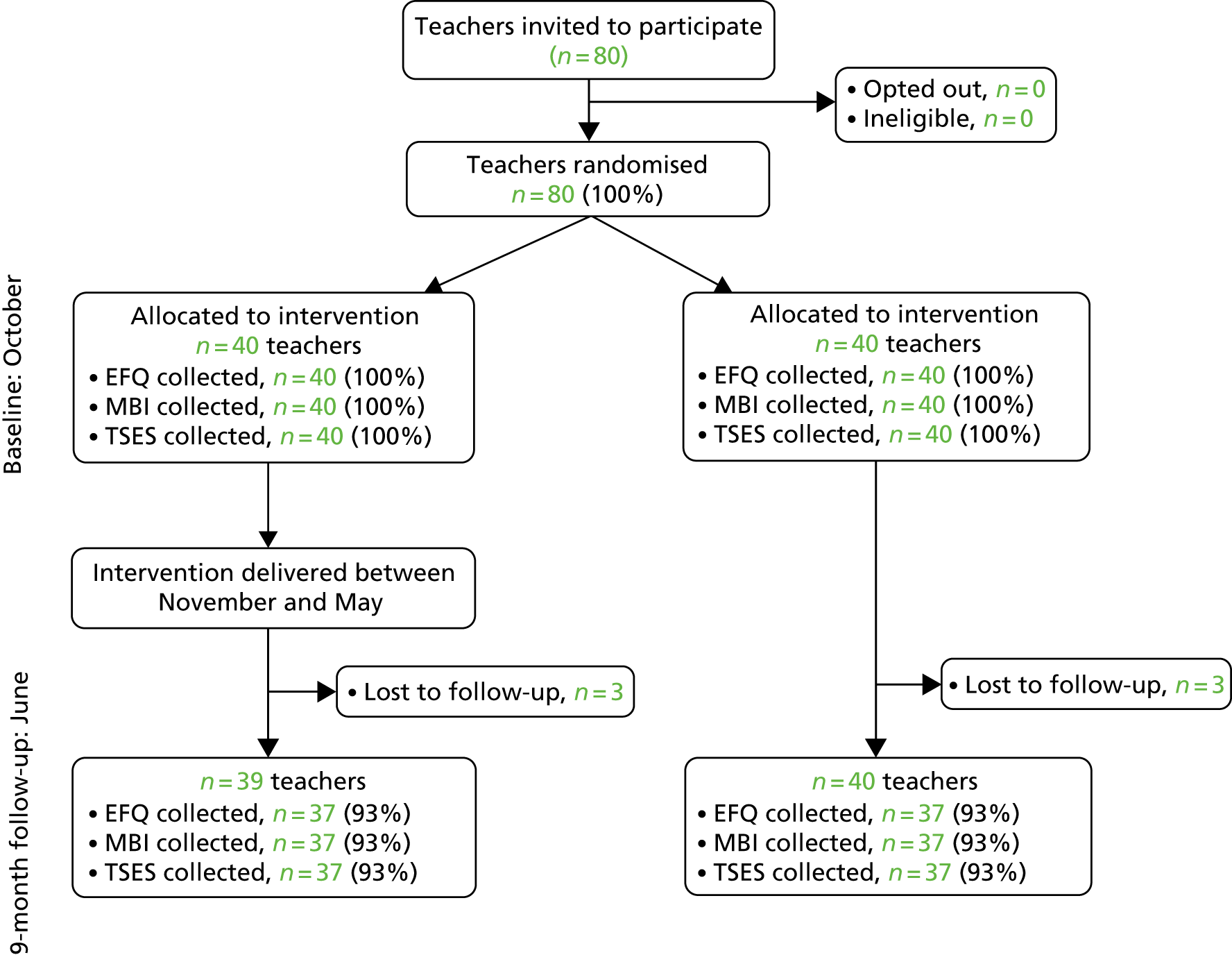

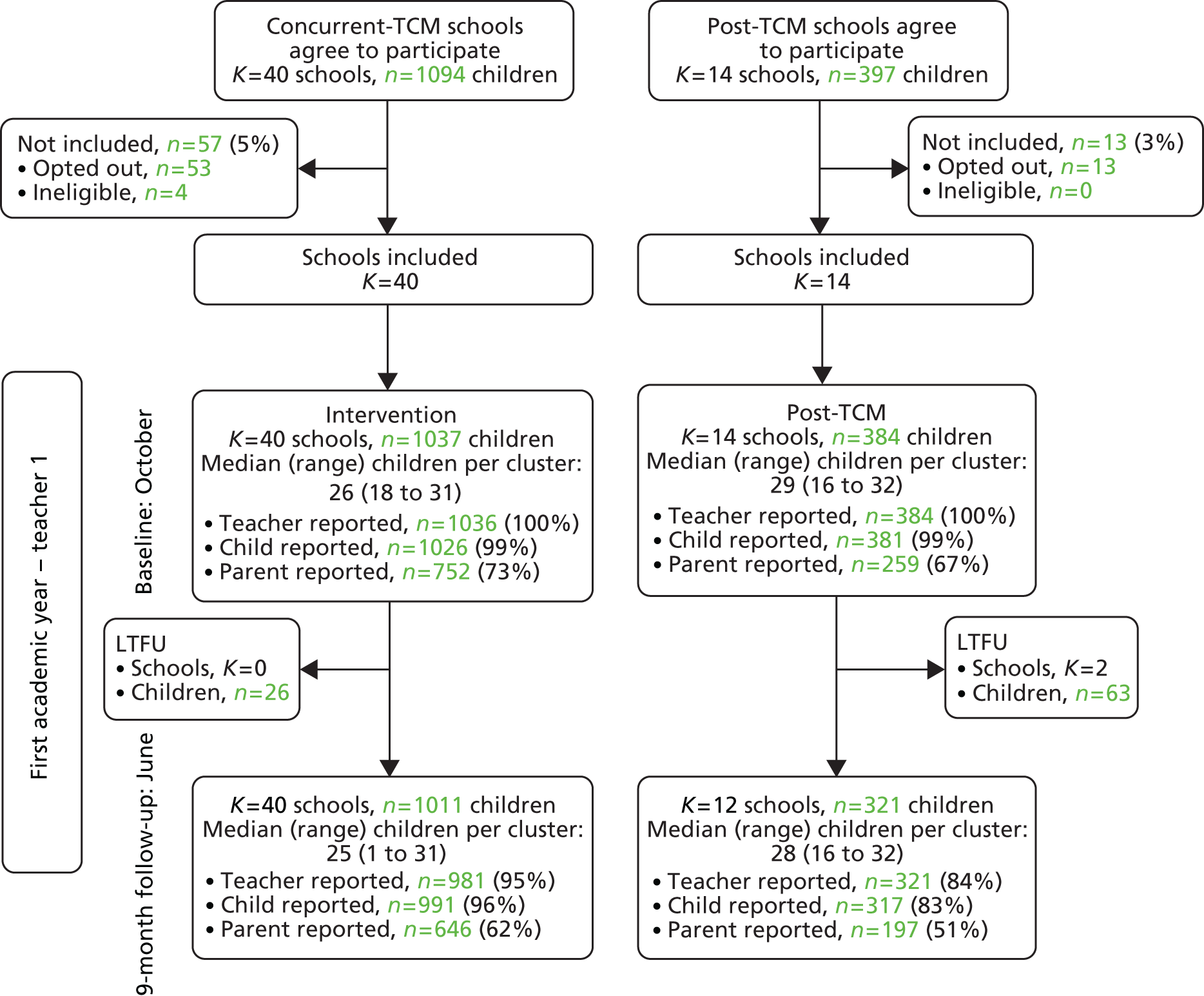

During the 26 months of recruitment, between April 2012 and June 2014, we recruited a total of 80 schools; 40 were allocated to each trial arm across all three cohorts (10 and 5 schools in the TCM and TAU arms, respectively, for cohort 1; 15 and 15 schools in the TCM and TAU arms, respectively, for cohort 2; and 15 and 20 schools in the TCM and TAU arms, respectively, for cohort 3). During the trial some schools did not provide teacher-completed data on child outcomes at the 9-month (n = 1), 18-month (n = 2) and 30-month (n = 1) assessments. In addition, one intervention school withdrew from the trial after completing the 18-month assessment (Figure 3) as a result of a change in headteacher who did not wish to uphold the agreement made by their predecessor. A total of 2075 children were recruited to the trial (1037 in the TCM arm and 1038 in the TAU arm). A further 113 children were either opted out by their parents (n = 107) or ineligible (n = 6). We lost contact with 271 (13%) children over the 30-month follow-up period and two parents withdrew permission for parent-reported outcomes but permitted the collection of teacher- and child-reported outcomes.

FIGURE 3.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials diagram. K, number of schools (clusters); LTFU, lost to follow-up; n, number of children.

Baseline comparability

Compared with the national average,47 participating schools had similar class sizes (trial mean 27.4 vs. national mean 26.8 children) and eligibility for free school meals (trial mean 18.3% vs. national mean 19.3%), but the sample included fewer voluntary controlled schools (5% trial schools vs. 14.4% national schools) and more community (61.3% trial schools vs. 55.3% national schools) and academy schools (10% vs. 6%). Baseline characteristics were generally balanced between the two arms (Table 4). Primary outcome data were collected at 9-, 18- and 30-month follow-up for 96%, 89% and 85% of participants, respectively. The proportion of children scoring in the struggling range on the teacher-reported SDQ-TD questionnaire in both arms approached the expected 20% (cut-off point at the 80th centile)49 but was lower according to parent-reported SDQ-TD (TCM, 16.5%; TAU, 15.5%), which suggests that we lacked parental data on some vulnerable children. No serious adverse events were reported in either trial arm.

| Variable | Intervention (TCM) | Control (TAU) |

|---|---|---|

| School (cluster) characteristics | NS = 40 | NS = 40 |

| Rural/semi-rural vs. urban school, n (%) | ||

| Urban | 22 (55) | 21 (53) |

| KS, n (%) | ||

| 1 | 20 (50) | 21 (53) |

| 2 | 20 (50) | 19 (48) |

| Percentage of children eligible for free school meals, median (IQR) | 12 (8–24) | 14 (10–23) |

| IDACI, median (IQR) | 0.17 (0.08–0.24) | 0.16 (0.10–0.27) |

| Teacher (cluster) characteristics | NT = 40 | NT = 40 |

| > 5 years of teaching, n (%) | 20 (50) | 27 (68) |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 34.5 (9) | 31.4 (9) |

| Female, n (%) | 32 (80) | 33 (83) |

| NQT, n (%) | 2 (5) | 0 (0) |

| Management position, n (%) | 4 (10) | 2 (5) |

| Teacher Self-efficacy Questionnaire | ||

| Student Engagement subscale, mean (SD) | 6.8 (1.0) | 7.1 (1.0) |

| Instructional Practice subscale, mean (SD) | 6.9 (1.0) | 7.2 (0.9) |

| Classroom Management subscale, mean (SD) | 7.3 (0.9) | 7.5 (0.9) |

| MBI | ||

| Exhaustion, mean (SD) | 2.9 (1.4) | 2.5 (1.4) |

| Cynicism, mean (SD) | 1.2 (1.0) | 1.1 (1.0) |

| Professional Efficacy, mean (SD) | 4.2 (1.0) | 4.6 (0.8) |

| EFQ (teacher well-being), mean (SD) | 17.2 (6.9) | 13.9 (6.6) |

| Pupil characteristics | NP = 1037 | NP = 1038 |

| Female, n (%) | 483 (47) | 491 (47) |

| Age in years at last birthday, mean (SD; range) | 6.2 (1.4; 4–9) | 6.4 (1.3; 4–8) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | NP = 721 | NP = 701 |

| White | 689 (96) | 663 (95) |

| Black | 4 (1) | 4 (1) |

| Asian | 5 (1) | 11 (2) |

| Mixed | 20 (3) | 18 (3) |

| Other | 3 (0) | 5 (1) |

| NP = 595 | NP = 502 | |

| Eligible for free school meals, n (%) | 70 (12) | 64 (13) |

| NP = 860 | NP = 844 | |

| IDACI, median (IQR) | 0.16 (0.08–0.64) | 0.15 (0.09–0.25) |

| Number of children in household, n (%) | NP = 770 | NP = 747 |

| 1 | 125 (16) | 122 (16) |

| 2 | 403 (52) | 389 (52) |

| 3 | 175 (23) | 158 (21) |

| 4 | 45 (6) | 49 (7) |

| ≥ 5 | 22 (3) | 29 (4) |

| Housing | NP = 766 | NP = 744 |

| Lives in rented housing, n (%) | 475 (62) | 423 (57) |

| Qualifications | NP = 758 | NP = 734 |

| Parent’s highest qualification, n (%) | ||

| None | 29 (4) | 46 (6) |

| GCSE or equivalent/A level or equivalent | 377 (50) | 377 (51) |

| University degree or equivalent and above | 352 (46) | 311 (42) |

| SDQ score | NP = 1036 | NP = 1038 |

| SDQ-TD score (teacher report), mean (SD) (clinical cut-off point ≥ 12) | 6.8 (5.6) | 6.6 (6.1) |

| SDQ-TD in struggling rangea (teacher report), n (%) | 206 (20) | 200 (19) |

| SDQ behaviour score (teacher report), mean (SD) (clinical cut-off point ≥ 3) | 0.8 (1.5) | 0.9 (1.6) |

| SDQ Emotions score (teacher report), mean (SD) (clinical cut-off point ≥ 3) | 1.5 (2.0) | 1.4 (2.1) |

| SDQ Overactivity score (teacher report), mean (SD) (clinical cut-off point ≥ 6) | 3.3 (3.0) | 3.1 (3.2) |

| SDQ Peer Relationships score (teacher report), mean (SD) (clinical cut-off point ≥ 3) | 1.2 (1.5) | 1.1 (1.7) |

| SDQ Pro-social score (teacher report), mean (SD) (clinical cut-off point < 6) | 7.3 (2.5) | 7.6 (2.4) |

| SDQ Impact score > 0 (teacher report), n (%) (clinical cut-off point ≥ 1) | 395 (38.1) | 373 (35.9) |

| SDQ score | NP = 733 to 752 | NP = 706 to 715 |

| SDQ-TD score (parent report), mean (SD) (clinical cut-off point ≥ 14) | 7.8 (6.0) | 7.8 (5.9) |

| SDQ-TD in struggling rangeb (parent report), n (%) | 124 (16.5) | 111 (15.5) |

| SDQ Behaviour score (parent report), mean (SD) (clinical cut-off point ≥ 3) | 1.5 (1.6) | 1.4 (1.6) |

| SDQ Emotions score (parent report), mean (SD) (clinical cut-off point ≥ 4) | 1.8 (2.0) | 1.8 (2.0) |

| SDQ Overactivity score (parent report), mean (SD) (clinical cut-off point ≥ 6) | 3.3 (2.6) | 3.3 (2.6) |

| SDQ Peer Relationships score (parent report), mean (SD) (clinical cut-off point ≥ 3) | 1.2 (1.6) | 1.3 (1.6) |

| SDQ Pro-social score (parent report), mean (SD) (clinical cut-off point < 6) | 8.4 (1.7) | 8.5 (1.7) |

| SDQ Impact score > 0 (parent report), n (%) (clinical cut-off point ≥ 1) | 244 (33.3) | 209 (29.6) |

| NP = 1036 | NP = 1038 | |

| PBQ, mean (SD) | 2.0 (2.4) | 1.9 (2.4) |

| NP = 1025 | NP = 1028 | |

| HIFAMS, mean (SD) | 10.9 (2.5) | 11.1 (2.3) |

| Assessment of pupil reading level (parent report) | NP = 746 | NP = 713 |

| Fluent reader, n (%) | 320 (43) | 349 (49) |

| Assessment of pupil relationship with teacher (parent report) | NP = 753 | NP = 713 |

| Good relationship, n (%) | 632 (84) | 622 (87) |

| Assessment of parent relationship with teacher (parent report) | NP = 731 | NP = 703 |

| Good relationship, n (%) | 465 (64) | 485 (69) |

| Literacy and numeracy | Np = 1036 | Np = 1037 |

| Below average on literacy, n (%) | 440 (43) | 451 (44) |

| Below average on numeracy, n (%) | 343 (33) | 353 (34) |

Adherence to intervention

Thirty-six (90%) of the 40 teachers in the intervention arm attended four or more TCM sessions; 23 teachers (58%) attended all six sessions (Table 5).

| Number of TCM sessions attended | Number of teachers (%) |

|---|---|

| 0 | 4 (5) |

| 1 | 2 (2) |

| 2 | 1 (1) |

| 3 | 2 (2) |

| 4 | 4 (5) |

| 5 | 16 (20) |

| 6 | 52 (64) |

| Mean: 6 | |

Data completeness

The numbers and percentages of participants with completed data are reported for each time point in Table 6.

| Outcome | Time point, n (%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 9 months | 18 months | 30 months | |||||

| TCM | TAU | TCM | TAU | TCM | TAU | TCM | TAU | |

| Primary outcome: teacher-reported SDQ-TD score | 1036 (100) | 1038 (100) | 981 (95) | 1020 (98) | 894 (86) | 954 (92) | 856 (83) | 900 (87) |

| Secondary teacher-reported outcomes | ||||||||

| SDQ Behaviour score | 1036 (100) | 1038 (100) | 981 (95) | 1020 (98) | 894 (86) | 954 (92) | 856 (83) | 900 (87) |

| SDQ Emotions score | 1036 (100) | 1038 (100) | 981 (95) | 1020 (98) | 894 (86) | 954 (92) | 856 (83) | 900 (87) |

| SDQ Overactivity score | 1036 (100) | 1038 (100) | 981 (95) | 1020 (98) | 894 (86) | 954 (92) | 856 (83) | 900 (87) |

| SDQ Peer Relationships score | 1036 (100) | 1038 (100) | 981 (95) | 1020 (98) | 894 (86) | 954 (92) | 856 (83) | 900 (87) |

| SDQ Pro-social score | 1036 (100) | 1038 (100) | 981 (95) | 1020 (98) | 894 (86) | 954 (92) | 856 (83) | 900 (87) |

| SDQ Impact score > 0 | 1036 (100) | 1038 (100) | 981 (95) | 1020 (98) | 894 (86) | 954 (92) | 856 (83) | 900 (87) |

| PBQ score | 1036 (100) | 1038 (100) | 981 (95) | 1020 (98) | 894 (86) | 954 (92) | 856 (83) | 900 (87) |

| APP – Literacy | 1036 (100) | 1037 (100) | 953 (92) | 1019 (98) | 862 (83) | 897 (86) | 794 (77) | 843 (81) |

| APP – Numeracy | 1036 (100) | 1037 (100) | 953 (92) | 1019 (98) | 862 (83) | 897 (86) | 794 (77) | 843 (81) |

| Secondary parent-reported outcomes | ||||||||

| SDQ-TD score | 751 (72) | 715 (69) | 644 (62) | 641 (62) | 610 (59) | 615 (59) | 558 (54) | 567 (55) |

| SDQ Behaviour score | 752 (73) | 715 (69) | 645 (62) | 642 (62) | 611 (59) | 617 (59) | 558 (54) | 569 (55) |

| SDQ Emotions score | 752 (73) | 715 (69) | 645 (62) | 641 (62) | 610 (59) | 617 (59) | 558 (54) | 568 (55) |

| SDQ Overactivity score | 751 (72) | 715 (69) | 645 (62) | 642 (62) | 611 (59) | 616 (59) | 558 (54) | 569 (55) |

| SDQ Peer Relationships score | 751 (72) | 715 (69) | 644 (62) | 642 (62) | 611 (59) | 616 (59) | 558 (54) | 568 (55) |

| SDQ Pro-social score | 752 (73) | 715 (69) | 645 (62) | 642 (62) | 611 (59) | 617 (59) | 558 (54) | 569 (55) |

| SDQ Impact score > 0 | 733 (71) | 706 (68) | 624 (60) | 637 (61) | 600 (58) | 606 (58) | 550 (53) | 557 (54) |

| Assessment of pupil reading level | 746 (72) | 713 (69) | 639 (62) | 638 (61) | 605 (58) | 610 (59) | 557 (54) | 567 (55) |

| Assessment of pupil relationship with teacher | 753 (73) | 713 (69) | 643 (62) | 642 (62) | 608 (59) | 617 (59) | 556 (54) | 565 (54) |

| Assessment of parent relationship with teacher | 731 (70) | 703 (68) | 646 (62) | 641 (62) | 609 (59) | 612 (59) | 555 (54) | 565 (54) |

| Secondary child-reported outcomes | ||||||||

| HIFAMS score | 1026 (99) | 1028 (99) | 991 (96) | 995 (96) | 945 (91) | 943 (91) | 864 (83) | 896 (86) |

Primary outcome

Table 7 summarises the comparison between the trial arms at follow-up for the primary outcome measure. The primary complete-case analysis is labelled CC1 in the table. TCM improved child mental health according to the teacher-reported SDQ-TD score by 1.0 point (95% CI 0.1 to 1.9; p = 0.03) at the 9-month follow-up. There was little evidence, however, of an effect at the 18-month (p = 0.85) and 30-month follow-ups (p = 0.23). The findings from the fully adjusted CC2 analysis were similar, except for the fact that there was only weak evidence of an effect at 9 months on the teacher-reported SDQ-TD (adjusted mean reduction 0.8, 95% CI 0.1 to 1.6; p = 0.09). Post hoc analysis showed that this is because the large number of children lost from the fully adjusted analysis, lost as a result of missing data on the three parent-reported potential confounders, were also those in whom the TCM effect was greatest. The intervention effect on teacher-reported SDQ-TD was –1.6 (95% CI –2.8 to –0.4) for the 534 children with missing data on the three parent-reported potential confounders and –0.8 (95% CI –1.7 to 0.1) for the remaining 1467 children with complete data. Finally, the fully adjusted analysis of imputed data (MI analysis) provided very similar results to our primary partially adjusted analysis (adjusted mean reduction 1.0, 95% CI 0.2 to 1.9; p = 0.02). All of the remaining findings are based on the approach used in the partially adjusted analysis (CC1 analysis). Findings from the CACE analysis were almost identical to those from the primary intention-to-treat analysis, which suggests that the estimated effects would have been no different had all the teachers in the TCM arm attended all six sessions.

| Follow-up | Trial arm | Analysis, AMD (I – C) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention | TAU | CC1: primary analysis | CC2: sensitivity analysis | MI: sensitivity analysis | |||||||||||

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | n | Estimate | 95% CI | p | ICCa | n | Estimate | 95% CI | p | n | Estimate | 95% CI | p | |

| 9 months | 5.5 (5.4) | 6.2 (6.2) | 2001 | –1.0 | –1.9 to –0.1 | 0.03 | 0.18 | 1467 | –0.8 | –1.6 to 0.1 | 0.09 | 2075 | –1.0 | –1.9 to –0.2 | 0.02 |

| 18 months | 6.7 (6.9) | 6.5 (6.3) | 1848 | –0.1 | –1.5 to 1.2 | 0.85 | 0.18 | 1371 | –0.2 | –1.5 to 1.1 | 0.75 | 2075 | –0.1 | –1.4 to 1.1 | 0.82 |

| 30 months | 6.1 (6.0) | 6.5 (6.6) | 1756 | –0.7 | –1.9 to 0.4 | 0.23 | 0.12 | 1318 | –0.6 | –1.8 to 0.5 | 0.30 | 2075 | –0.8 | –1.9 to 0.3 | 0.14 |

Subgroup analysis

Tests of interaction indicated that TCM led to greater reductions in the teacher-reported SDQ-TD score at 9 months (interaction p < 0.001) for children who were classified by their teacher as struggling with their mental health at baseline (mean difference –2.6, 95% CI –4.6 to –0.6) than for children who were not (mean difference –0.4, 95% CI –1.2 to 0.4). A subgroup effect was also found at 30 months (p < 0.001) but not at 18 months (p = 0.10). TCM may also have greater benefits at 30 months (interaction test p-value of 0.02) for children taught by teachers with > 5 years’ experience (mean difference on teacher-reported SDQ-TD score –2.1, 95% CI –3.8 to –0.4) than for children taught by teachers with ≤ 5 years’ experience (mean difference 0.3, 95% CI –1.3 to 1.9). TCM appeared more effective for cohort 2 schools than for cohorts 1 and 3 schools (interaction p-value of 0.02), but there was little evidence of subgroup effects for the other potential moderator variables.

Secondary outcomes

Table 8 summarises the findings from the teacher-reported secondary outcomes. There was evidence, based on the PBQ score, of reduced disruptive behaviour across all three follow-ups (p = 0.04). Likewise, there was evidence that TCM reduces the percentage of children who are classified as struggling according to the SDQ-TD score (p = 0.05) and reduces the Inattention/Overactivity score (p = 0.02) across all waves. At 9 months only, there was also evidence of a reduction in peer relationship problems (p = 0.02) and an improvement in pro-social behaviour (p = 0.02). There was little evidence of effects on teacher-reported Emotions and Impact scores, APP, parents’ assessment of their child’s mental health or the child-reported outcome HIFAMS (Table 9).

| Outcome | Intervention, mean (SD) or % | TAU, mean (SD) or % | AMD/ORa | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | 95% CI | p-value | ICC | |||

| SDQ-TD score in struggling rangeb | ||||||

| 9–30 monthsc | 16.7 | 19.2 | 0.70 | 0.48 to 0.99 | 0.05 | 0.06 |

| SDQ Behaviour score | ||||||

| 9 months | 0.7 (1.5) | 0.9 (1.6) | –0.1 | –0.3 to 0.1 | 0.27 | 0.09 |

| 18 months | 1.0 (1.8) | 0.9 (1.7) | –0.03 | –0.3 to 0.3 | 0.86 | 0.12 |

| 30 months | 0.9 (1.5) | 1.0 (1.8) | –0.2 | –0.5 to 0.1 | 0.18 | 0.10 |

| SDQ Emotions score | ||||||

| 9 months | 1.3 (1.9) | 1.5 (2.2) | –0.3 | –0.6 to 0.1 | 0.14 | 0.20 |

| 18 months | 1.7 (2.2) | 1.6 (2.1) | 0.1 | –0.3 to 0.6 | 0.63 | 0.18 |

| 30 months | 1.6 (2.1) | 1.6 (2.1) | –0.005 | –0.4 to 0.3 | 0.98 | 0.09 |

| SDQ Overactivity score | ||||||

| 9–30 months | 2.7 (2.9) | 2.8 (3.0) | –0.4 | –0.7 to –0.1 | 0.02 | 0.08 |

| SDQ Peer Relationships score | ||||||

| 9 months | 0.8 (1.4) | 1.0 (1.7) | –0.2 | –0.4 to –0.03 | 0.02 | 0.12 |

| 18 months | 1.1 (1.7) | 1.0 (1.6) | 0.1 | –0.2 to 0.4 | 0.62 | 0.13 |

| 30 months | 1.1 (1.6) | 1.1 (1.7) | –0.07 | –0.4 to 0.2 | 0.60 | 0.10 |

| SDQ Pro-social score | ||||||

| 9 months | 8.2 (2.3) | 8.0 (2.3) | 0.4 | 0.1 to 0.8 | 0.02 | 0.25 |

| 18 months | 7.8 (2.4) | 8.0 (2.3) | –0.1 | –0.6 to 0.4 | 0.67 | 0.20 |

| 30 months | 8.1 (2.2) | 7.6 (2.3) | 0.5 | –0.03 to 1.0 | 0.06 | 0.16 |

| SDQ Impact score > 0 | ||||||

| 9–30 months | 34.5 | 37.3 | 0.80 | 0.61 to 1.05 | 0.11 | 0.05 |

| PBQ score | ||||||

| 9–30 months | 1.8 (2.4) | 1.9 (2.6) | –0.3 | –0.5 to –0.01 | 0.04 | 0.04 |

| Below average on literacy | ||||||

| 9–30 months (T1 to T3) | 32 | 36 | 0.91 | 0.64 to 1.31 | 0.62 | 0.07 |

| Below average on numeracy | ||||||

| 9–30 months (T1 to T3) | 30 | 33 | 0.91 | 0.64 to 1.31 | 0.62 | 0.07 |

| Outcome | Intervention arm, mean (SD) or % | TAU arm, mean (SD) or % | AMD/ORa | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | 95% CI | p-value | ICC | |||

| Parent-reported outcomes | ||||||

| SDQ-TD score | ||||||

| 9–30 months | 7.7 (6.5) | 7.6 (6.4) | 0.1 | –0.3 to 0.5 | 0.64 | 0.01 |

| SDQ-TD score in struggling rangeb | ||||||

| 9–30 months | 18 | 15 | 1.24 | 0.92 to 1.67 | 0.16 | 0.03 |

| SDQ Behaviour score | ||||||

| 9–30 months | 1.4 (1.7) | 1.3 (1.6) | 0.03 | –0.1 to 0.1 | 0.63 | 0.03 |

| SDQ Emotions score | ||||||

| 9–30 months | 2.1 (2.3) | 2.0 (2.3) | 0.02 | –0.2 to 0.2 | 0.86 | 0.02 |

| SDQ Overactivity score | ||||||

| 9–30 months | 3.0 (2.7) | 3.0 (2.6) | 0.1 | –0.1 to 0.3 | 0.30 | 0.004 |

| SDQ Peer Relationships score | ||||||

| 9–30 months | 1.3 (1.7) | 1.3 (1.8) | –0.03 | –0.2 to 0.1 | 0.66 | 0.03 |

| SDQ Pro-social score | ||||||

| 9–30 months | 8.6 (1.7) | 8.7 (1.7) | –0.04 | –0.2 to 0.1 | 0.54 | 0.002 |

| SDQ Impact score > 0 | ||||||

| 9–30 months | 33 | 31 | 0.94 | 0.71 to 1.25 | 0.69 | 0.04 |

| Assessment of pupil reading level | ||||||

| Fluent reader | ||||||

| 9–30 months | 64 | 68 | 0.96 | 0.75 to 1.23 | 0.75 | 0.08 |

| Assessment of pupil relationship with teacher, good relationship | ||||||

| 9–30 months | 86 | 84 | 1.20 | 0.93 to 1.54 | 0.16 | 0.03 |

| Assessment of parent relationship with teacher, good relationship | ||||||

| 9–30 months | 73 | 73 | 1.12 | 0.87 to 1.45 | 0.39 | 0.04 |

| Child-reported outcomes | ||||||

| HIFAMS score | ||||||

| 9 months | 10.8 (2.5) | 10.9 (2.4) | 0.02 | –0.3 to 0.3 | 0.89 | 0.08 |

| 18 months | 10.5 (2.5) | 10.4 (2.8) | 0.3 | –0.1 to 0.7 | 0.17 | 0.11 |

| 30 months | 10.4 (2.8) | 10.3 (2.8) | 0.2 | –0.2 to 0.7 | 0.35 | 0.11 |

National Pupil Database analysis

We received parental consent to access the NPD for a total of 1178 children; this represents 57% of all participating children, with only 71 (3%) parents refusing consent; the remaining 826 parents (40%) did not respond to the invitation.

There was little evidence that the intervention had any effect on the rate of overall absence during either the first (adjusted RR 1.08, 95% CI 0.95 to 1.24; p = 0.24) or second (adjusted RR 1.1, 95% CI 0.72 to 1.7; p = 0.65) year of the trial or on the number of unauthorised absences during the first (adjusted RR 1.03, 95% CI 0.90 to 1.18; p = 0.62) or second (adjusted RR 0.96, 95% CI 0.75 to 1.22; p = 0.74) year of the trial (Table 10). School exclusions were reported on 22 separate occasions (2 in the intervention arm and 20 in the TAU arm), which resulted in a total loss of 64 separate school sessions, morning or afternoon (3 sessions in the intervention arm and 61 sessions in the TAU arm). These exclusions were issued to a total of six children, two from the intervention and four from the TAU arm of the trial. Tests of interaction did not indicate any subgroup effects for children whose primary or secondary category of SEN was social, emotional or mental health, but this analysis lacked power owing to the small number of children with social, emotional and mental health SEN (Table 11).

| Year | Median | IQR | Maximum | Median | IQR | Maximum | Crude RR (I/C) | Adjusted | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR (I/C) | 95% CI | p-value | ||||||||

| Year 1 | Intervention arm (N = 490) | TAU arm (N = 522) | ||||||||

| Absences | 10 | 4–16 | 83 | 9 | 4–16 | 93 | 1.04 | 1.08 | 0.95 to 1.24 | 0.24 |

| Unauthorised absences | 0 | 0–4 | 55 | 0 | 0–2 | 68 | 1.44 | 1.10 | 0.72 to 1.70 | 0.65 |

| Year 2 | Intervention arm (N = 591) | TAU arm (N = 586) | ||||||||

| Absences | 10 | 4–18 | 87 | 9 | 4–17 | 93 | 1.04 | 1.03 | 0.90 to 1.18 | 0.62 |

| Unauthorised absences | 4 | 0–12 | 65 | 2 | 0–10 | 65 | 1.25 | 0.96 | 0.75 to 1.22 | 0.74 |

| Outcome | Presence | Intervention | TAU | AMD (95% CI) | p-value for interaction | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) | ||||

| 9-month follow-up | |||||||

| Social, emotional and mental health SEN | Present | 17 | 13.1 (8.1) | 14 | 18.2 (5.4) | –0.1 (–5.4 to 5.1) | 0.89 |

| Not present | 554 | 4.6 (4.5) | 572 | 4.9 (5.0) | –0.9 (–1.7 to 0.0) | ||

| 18-month follow-up | |||||||

| Social, emotional and mental health SEN | Present | 15 | 14.8 (5.0) | 14 | 15.9 (4.5) | 0.5 (–3.4 to 4.4) | 0.33 |

| Not present | 530 | 5.7 (6.2) | 564 | 5.3 (5.4) | –0.3 (–1.7 to 1.0) | ||

| 30-month follow-up | |||||||

| Social, emotional and mental health SEN | Present | 16 | 14.8 (7.2) | 12 | 19.8 (5.4) | –1.4 (–5.4 to 2.7) | 0.91 |

| Not present | 526 | 5.2 (5.4) | 548 | 5.4 (6.1) | –0.7 (–1.8 to 0.4) | ||

Sensitivity analysis of pupil progress

Although there was no main effect of the intervention on APP in either literacy or numeracy, subgroup analysis did indicate that the intervention’s effect on APP differs between those who were and were not classified by their teacher as struggling with their mental health at baseline, for both literacy (interaction p = 0.04) and numeracy (interaction p = 0.03). The intervention arm had lower odds than the TAU arm of below-expectation assessments in literacy [odds ratio (OR) 0.77, 95% CI 0.53 to 1.12] and numeracy (OR 0.82, 95% CI 0.59 to 1.14) among those not classified as struggling, but it had greater odds of below-expectation assessments for literacy (OR 1.17, 95% CI 0.70 to 1.94) and numeracy (OR 1.35, 95% CI 0.88 to 2.06) among those who are classified as struggling. All four of these CIs, however, include unity, so it is difficult to interpret these findings, other than to comment that there seems to be a differential effect according to baseline mental health.

Chapter 4 Economic evaluation

Aim

The aim of the economic evaluation was to assess the cost-effectiveness of the TCM course compared with that of TAU over the short- and long-term periods.

Methods

Perspective

The prespecified economic evaluation took a broad public-sector perspective and included the use of all health, education and social care services, plus criminal justice sector resources and criminal activity. In addition, productivity losses of parents relating to the needs of their child were identified as relevant by the research team and subsequently included in the broad perspective.

Method of economic evaluation

Within-trial cost-effectiveness analysis

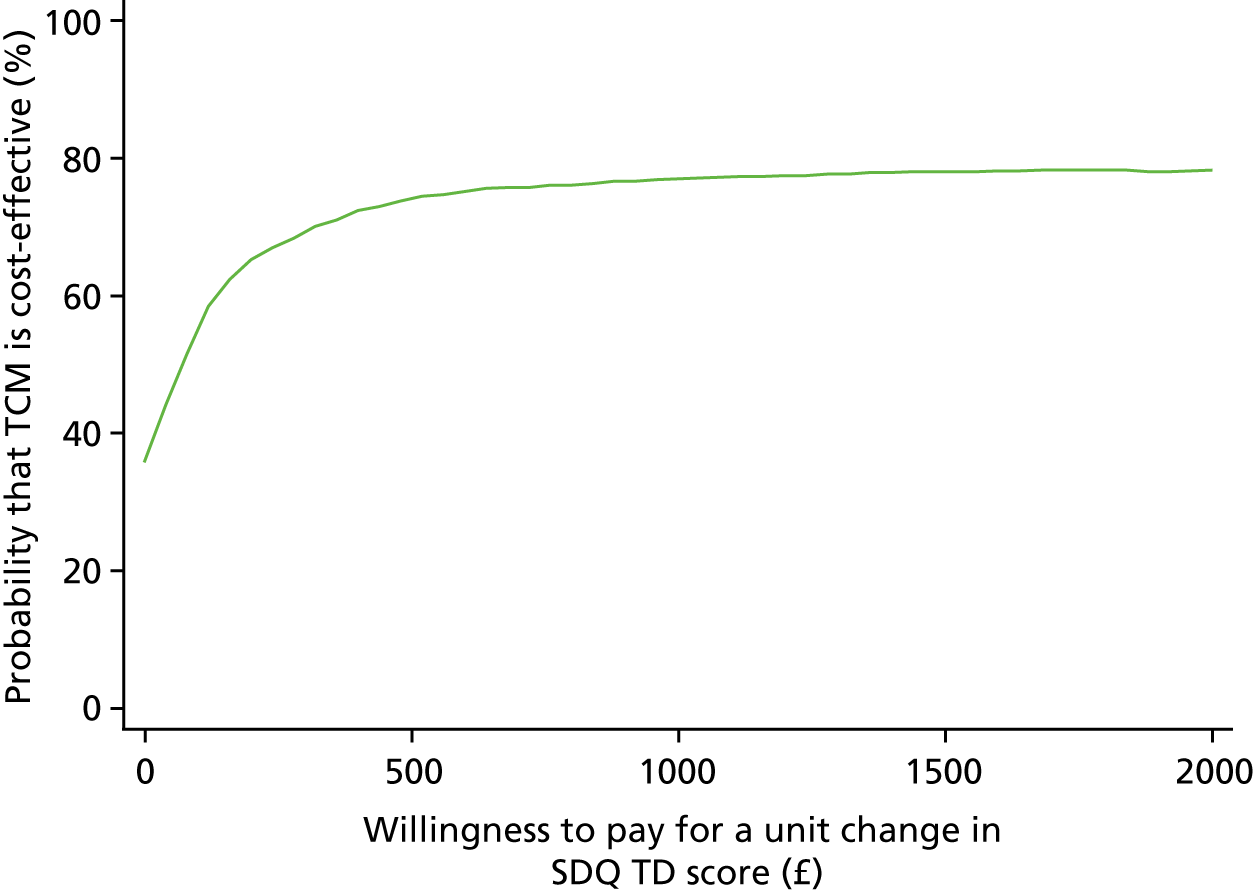

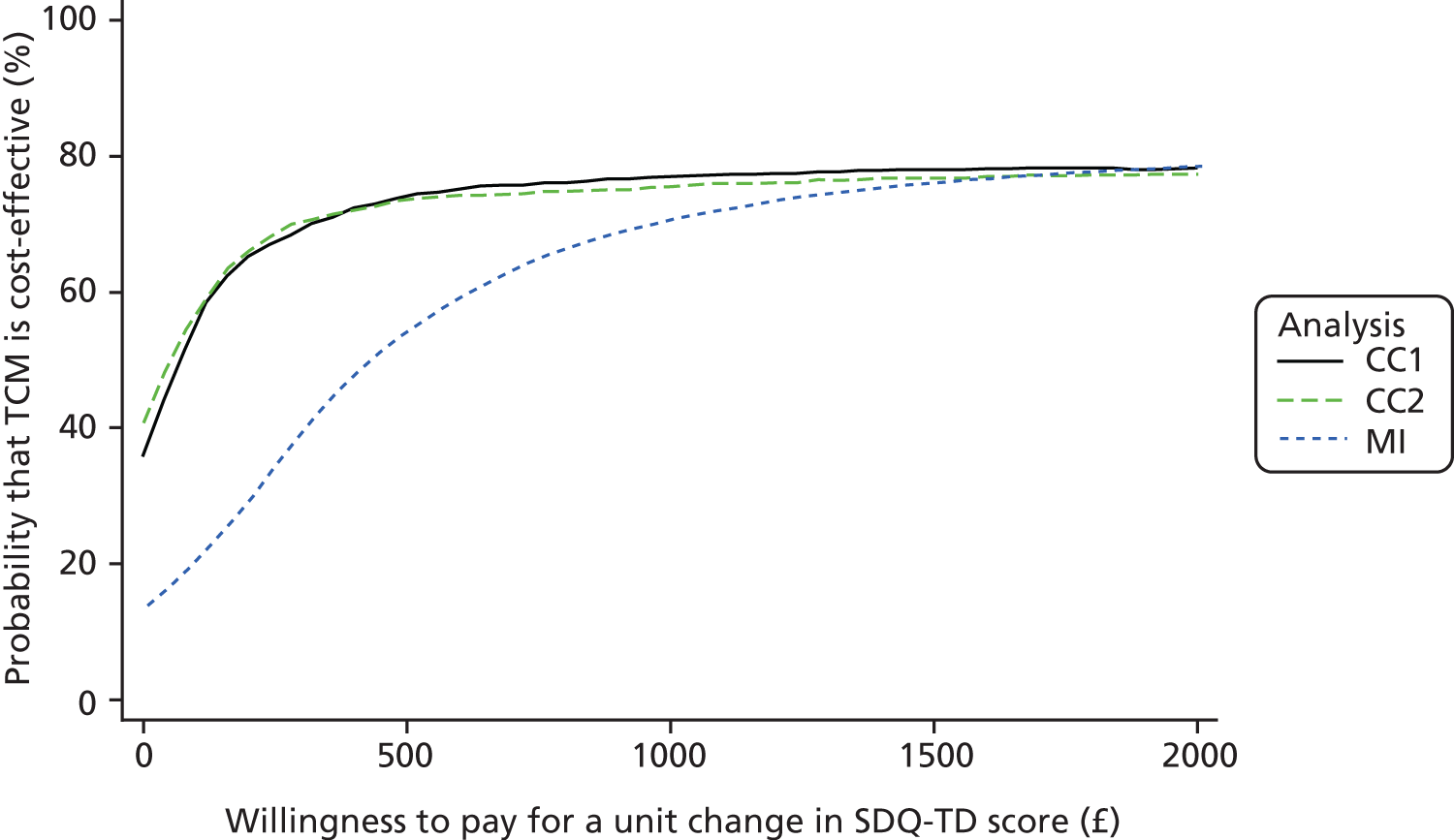

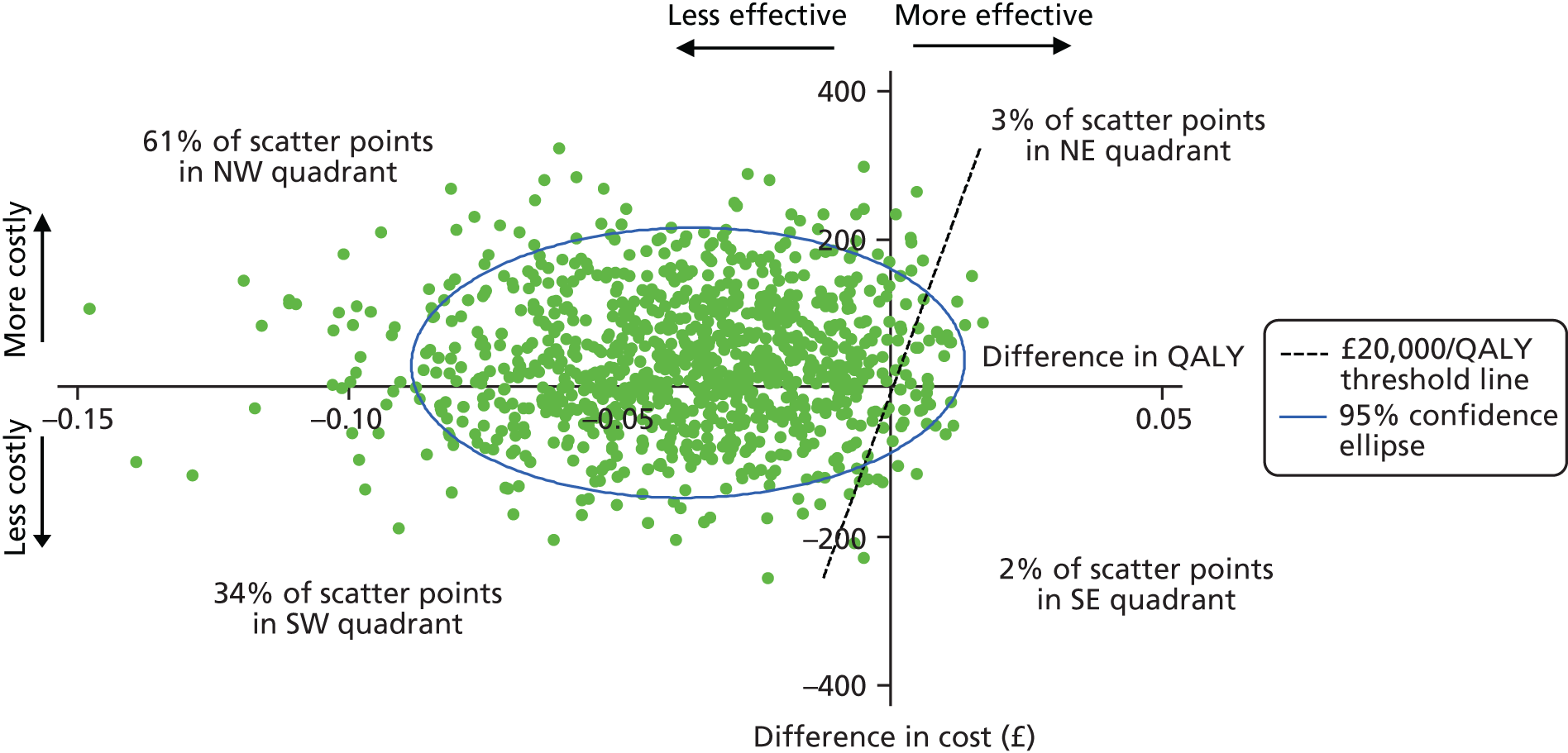

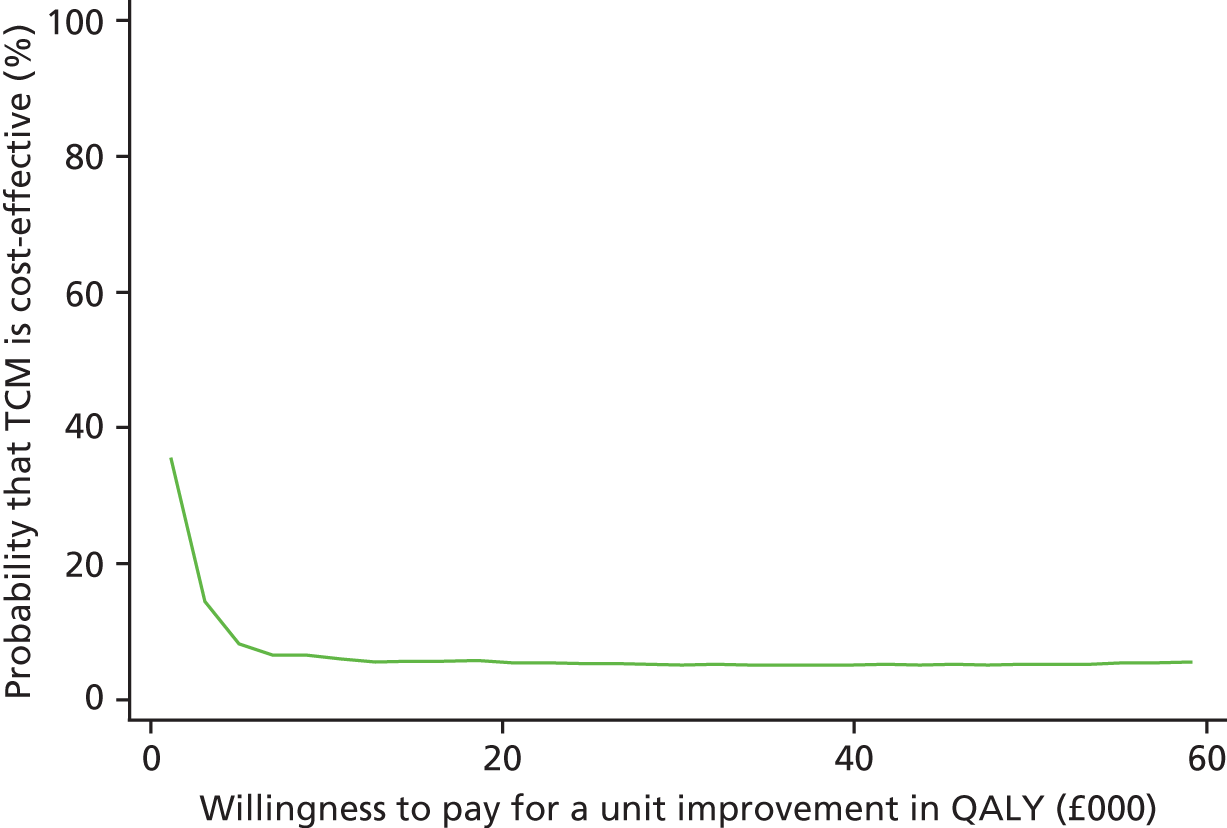

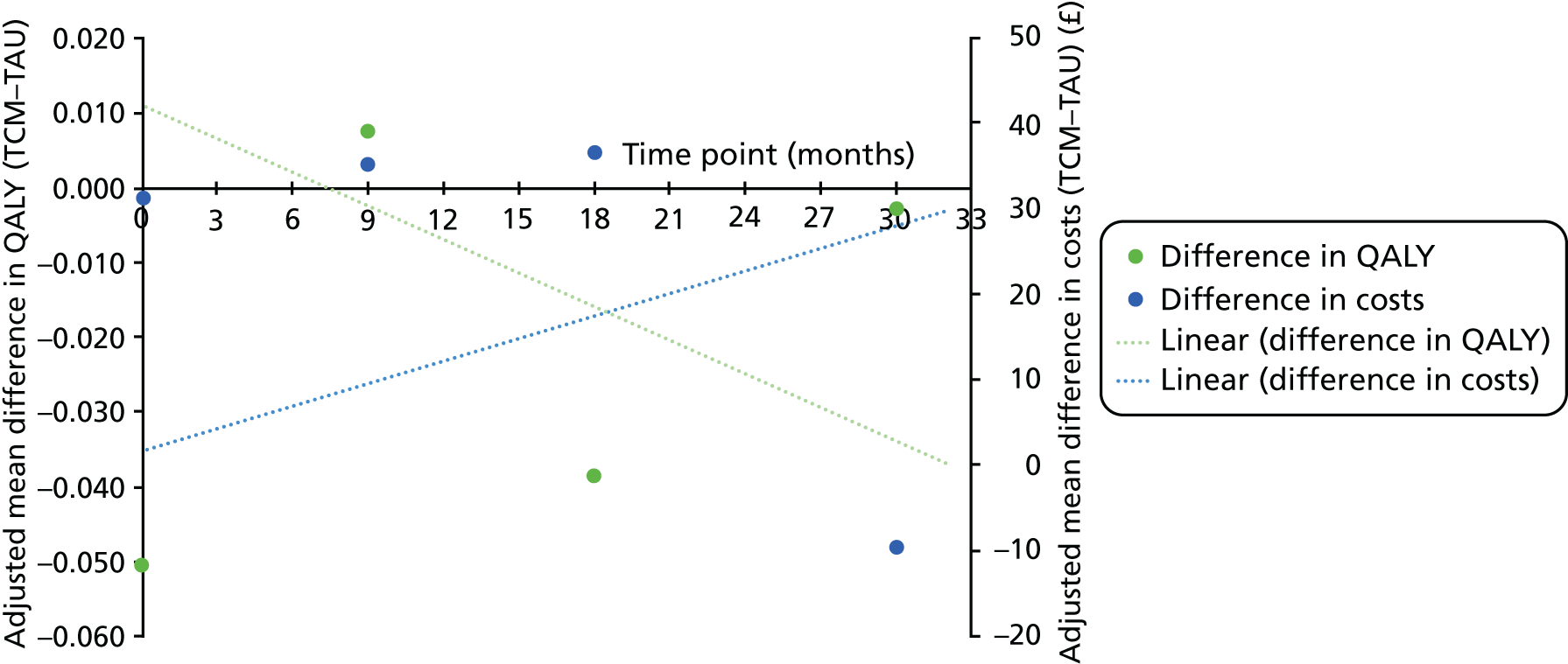

The primary economic evaluation was a trial-based cost-effectiveness analysis of TCM (intervention) compared with TAU (control) at 30-month follow-up, explored in terms of the primary outcome measure, the SDQ-TD score. A secondary cost–utility analysis using quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) based on the EuroQol-5 Dimensions Youth version (EQ-5D-Y)65 was proposed, on the assumption that feasibility testing of the measure prior to the start of the trial proved successful.

Long-term cost-effectiveness analysis

A secondary economic evaluation aimed to examine the expected cost–utility of TCM compared with TAU over the longer term, by extrapolating data from the RCT supplemented with data from the literature using decision-modelling techniques,66 should the cost-effectiveness analysis of TCM prove promising in the short term.

Costs

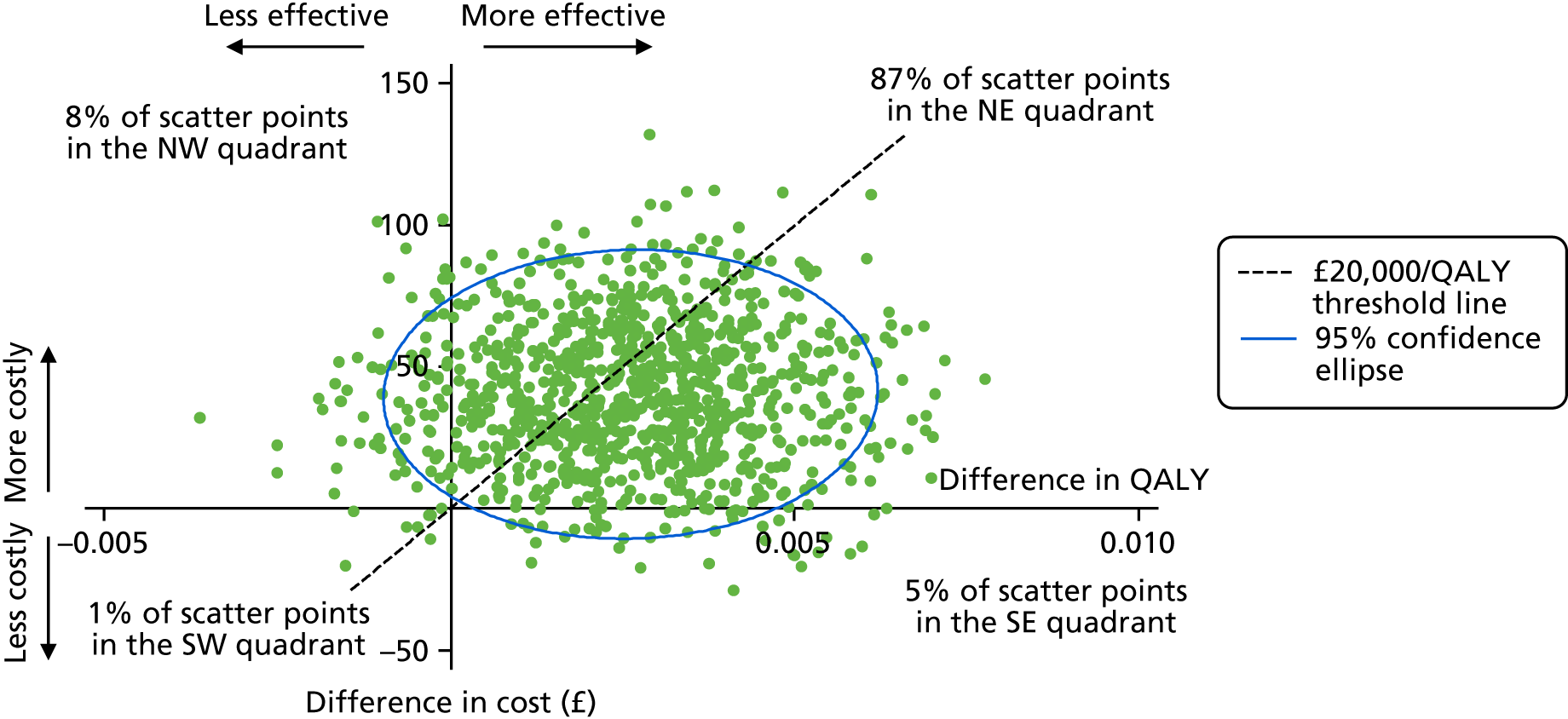

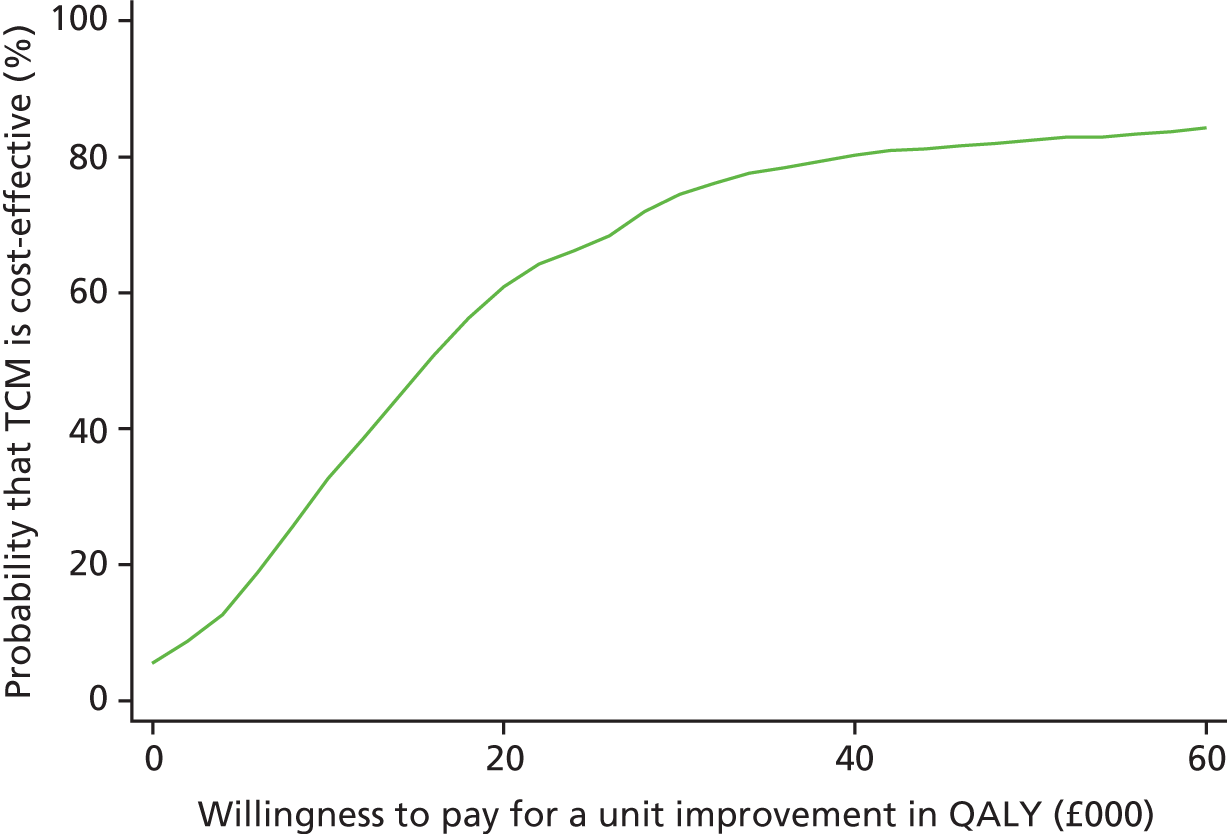

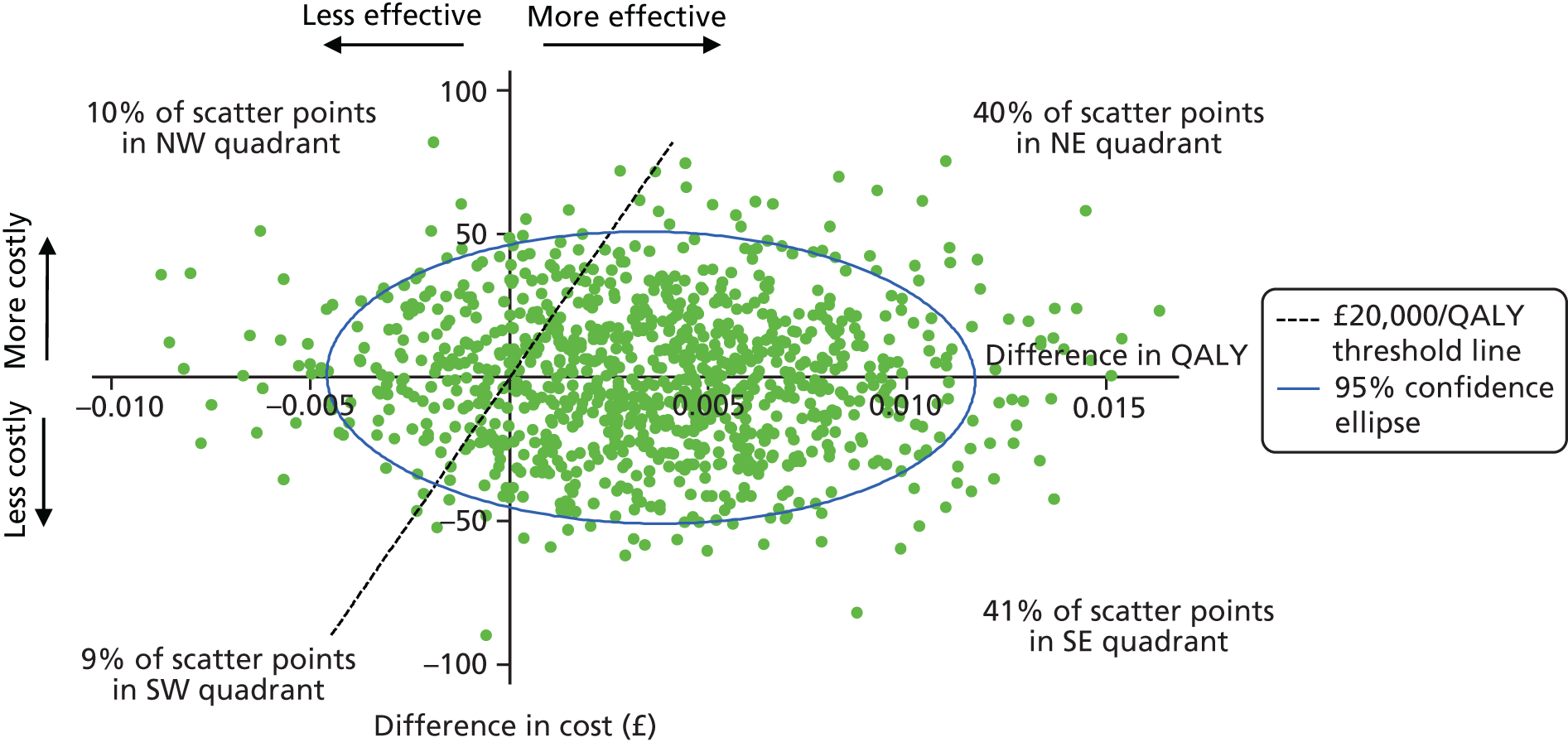

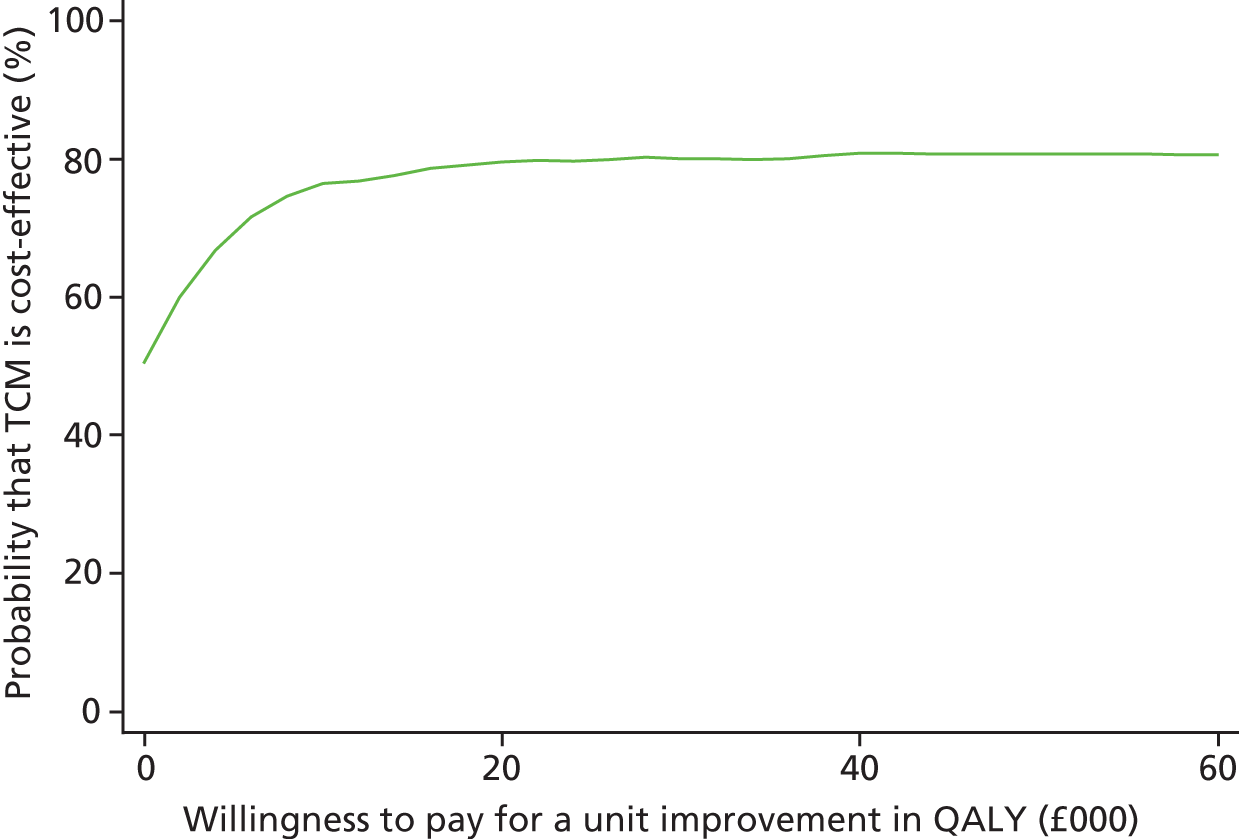

Measurement of resources