Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 12/179/09. The contractual start date was in June 2014. The final report began editorial review in June 2017 and was accepted for publication in October 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Kate Jolly was an investigator on a trial in which the weight loss intervention was donated to the NHS by Slimming World® (Alfreton, UK; www.slimmingworld.co.uk) and Rosemary Conley Health and Fitness Clubs (Tharston, UK; www.rosemaryconley.com). Paul Aveyard reports grants from Weight Watchers® (Maidenhead, UK; www.weightwatchers.com/uk) and Cambridge Weight Plan® (Cambridge Weight Plan Ltd, Corby, UK) and non-financial support from Slimming World, Weight Watchers and Rosemary Conley Health and Fitness Clubs, outside the submitted work.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Daley et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Obesity

Obesity is the most common cause of premature mortality in the UK1 and a significant cause of morbidity in terms of increased risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease and many cancers. 2,3 In the UK, the rates of obesity have more than doubled in the last 25 years, and being overweight has become the norm for adults. 2 Over one-quarter of adults in the UK are obese, and > 63% are either overweight or obese. 4 Obesity is associated with a reduced life expectancy of up to 14 years. 5 Direct costs of obesity are about £5.1B per year, thus placing a significant economic burden on the NHS and society. Given its prevalence and costs, obesity is a significant public health priority in the UK, as well as in other developed countries. Although many behavioural weight loss treatments are effective,6–8 long-term maintenance of weight loss remains a critical challenge. The period after initial weight loss is when people are at the highest risk of weight regain. Few people (1 in 10) recover from even minor lapses of 1–2 kg of regain in weight. 9 On average, people will regain one-third to half of their lost weight within the first year following treatment and will return to their baseline weight within 3–5 years after treatment. 10,11 These data clearly indicate that weight regain is common and efforts are needed to prevent it. Given the large numbers of people who need to lose weight and who need to maintain this weight loss, there is a critical need for low-cost, practical and scalable interventions that can effectively help adults to maintain their weight loss throughout their lives.

Maintenance of weight loss

Compared with weight loss trials, relatively few randomised controlled trials (RCTs) have focused on weight maintenance, and those trials that do exist have tended to evaluate intensive interventions. Over time, it becomes increasingly difficult for individuals to continue to follow the weight management strategies learnt during their attendance at a weight loss programme. This is because most people’s commitment wanes and they drift away from their weight loss eating pattern. This is a problem because a return to former eating and activity habits is associated with weight regain. Ultimately, weight loss will be effective and cost-effective only if weight loss is maintained, but weight loss maintenance is more difficult than weight loss. Therefore, interventions that can successfully help adults to manage their weight throughout their lives are required. The strategies required for weight loss may be different from those required for weight loss maintenance or the prevention of weight gain, and research is required to establish what these particular strategies or approaches might be. Furthermore, there is no consensus about the most effective weight maintenance strategies, the intensity of these strategies and/or the best mode or timing of delivery. Novel interventions are needed to capitalise on the success of individuals’ initial weight loss efforts.

An early meta-analysis12 of 42 RCTs that focused on the effects of extended care on weight loss maintenance reported on strategies that appeared to be useful for weight loss maintenance: taking medication, following a low-fat diet, doing physical activity, having continued contact with others, undergoing problem-solving therapy, increasing protein intake, increasing caffeine intake for those consuming < 100 mg per day, and receiving acupressure. The review authors noted that interventions lacked a theory base and the attrition rate was high in many of the trials (> 35%). Ramage et al. 13 systematically reviewed the evidence (all study designs) for healthy strategies for successful weight loss and weight maintenance. The review concluded that a combination of energy and fat restriction, regular physical activity and behavioural strategies, such as self-monitoring and adhering to a calorie goal, were required for successful weight loss maintenance.

A more recent review14 of RCTs of weight loss maintenance interventions for adults who are obese after clinically significant weight loss found that behavioural interventions that focused on both diet and physical activity led to an average difference of –1.56 kg [95% confidence interval (CI) −2.27 to −0.86 kg; 22 studies, 25 comparisons, 2949 participants] in weight regain in intervention participants compared with control participants 12 months after randomisation. At 18 months (7 studies, 13 comparisons), the mean difference in weight was –1.96 kg (95% CI –2.73 to –1.20 kg). At 24 months, only two studies were found to have reported outcomes and the mean difference in weight change was –1.48 kg (95% CI –2.27 to –0.09 kg). At 30 months, the effect was not significant (–0.85 kg, 95% CI –1.81 to 0.11 kg). No adverse events were reported for any of the behavioural or lifestyle weight loss maintenance trials included in the review. There was no evidence that more intensive interventions were more effective than less intensive interventions, that there were any differences between internet-delivered interventions and comparator groups, or that delivery of the same intervention face to face was more effective than remote delivery (i.e. telephone or via the internet). None of the included review studies had been conducted in the UK. The findings from this review demonstrate that behavioural lifestyle interventions have the potential to be effective in reducing, or slowing down, weight regain after initial weight loss for up to 2 years, but the strength of the evidence is limited because of methodological shortcomings in the included studies. Of particular concern is the fact that many trials reported data only for participants who completed their intervention, introducing the possibility of bias. The review identified that the greatest need for further research was in the area of lifestyle interventions focused on supporting people to manage their weight over the longer term by regulating food intake and increasing physical activity.

A systematic review and synthesis of qualitative research15 identified a wide range of processes and modifying variables involved in weight loss maintenance. Qualitative studies were included if they focused on the experiences of adults who had previously been or were currently obese or overweight. The authors of this review thematically synthesised studies and, from this, developed a model of weight maintenance. The model proposed that making the behaviour changes required for weight loss maintenance generates psychological ‘tension’ because of the need to over-ride existing habits and the incompatibility of the new behaviours with the fulfilment of psychological needs. If successful weight loss maintenance is to be achieved, then management or resolution of this ‘tension’ needs to occur. Management of the tension can be achieved through self-regulation, renewing motivation and managing external influences, but this is likely to require constant effort and resolution through changing habits, finding non-obesogenic methods for addressing needs and, possibly, changes in self-concept.

The reviews presented here concluded that further research is needed on the question of how to successfully help people maintain their weight loss. In particular, authors commented that most trials in the reviews were of low or moderate quality and that many trials of longer-term weight maintenance had been inconclusive. In addition, the review by Dombrowski et al. 14 noted that trials had been heterogeneous in relation to setting, type and duration of interventions and length of time for follow-up. Many trials had methodological issues that could have introduced bias (i.e. inadequate reporting of the randomisation process, blinding or a lack of use of the intention-to-treat principle). Substantial dropout from follow-up was also evident in many trials; this is typically associated with participants’ inability to maintain their weight loss and, therefore, a reluctance to provide data about their weight at follow-up. Loss to follow-up is highly problematic in weight loss maintenance trials because it can lead to an overestimation of the true effects of an intervention.

Since the present study was commissioned, four other trials of weight loss maintenance interventions have been published; three were conducted in England16–18 and one was conducted in the USA. 19 Simpson et al. 16 conducted a three-group RCT of a motivational interviewing-based intervention for weight loss maintenance in adults (n = 170) who had lost at least 5% of their body weight in the previous 12 months. The intervention was based on three main components: motivational interviewing (incorporating implementation intentions), social support and self-regulation/self-monitoring. The intervention used a number of techniques and strategies central to motivational interviewing, for example, promoting intrinsic motivation and encouraging goal-setting and action-planning. Participants were randomised to an intensive intervention group, a less intensive group or a control comparator group. This trial was originally designed as an effectiveness trial with the primary outcome of body mass index (BMI) assessed 3 years after randomisation. Owing to difficulties with participant recruitment, however, the trial was closed early and was reported as a feasibility RCT with the 12-month follow-up as the end point. A total of 170 participants were recruited; retention (84%) and intervention adherence were high (intensive, 83%; less intensive, 91%). The intensive intervention had mean BMI scores 0.96 kg/m2 lower than controls (95% CI –2.2 to 0.2 kg/m2) at the 12-month follow-up. A difference of –0.21 kg/m2 (95% CI –1.4 to 1.0 kg/m2) was reported between the less intensive intervention group and the control group. The average difference in weight was 2.8 kg (95% CI –6.1 to 0.5 kg) between the intensive intervention group and the control group, with a smaller difference noted for the less intensive intervention group (–0.70 kg, 95% CI –4.10 to 2.70 kg). The intensive and less intensive interventions costed £623 and £198, respectively, to deliver. The results of this study are promising, but it was not adequately powered to detect the outcome of interest and the cost of the intensive intervention is likely to mean that it is unlikely to be funded as a routine public health intervention.

The authors of this report completed a RCT (Lighten Up Plus)17 to evaluate a 12-week Short Message Service (SMS) text message weight maintenance intervention that encouraged weekly weighing. The comparator group comprised 380 men and women who were overweight or obese and had completed a 12-week commercial weight loss programme. Participants were eligible to take part in Lighten Up Plus if they had a 12-week weight recorded at their 12-week weight loss programme or had attended a minimum of 9 out of 12 of their weight loss programme sessions and had had their weight measured at their weight loss service in the previous 2 weeks. Participants also had to have access to scales to weigh themselves and needed to own a phone that could receive SMS text messages. The comparator group received a brief weight maintenance support telephone call from non-specialist call centre staff (lasting 10–15 minutes), which gave lifestyle information on a balanced diet, portion control and regular exercise. A brief ‘hints and tips’ leaflet for weight loss maintenance was also mailed to this group. The comparator group received a final call 12 weeks after the initial call, which recapped the hints and tips given during the first call. The intervention group received the same as the comparator group and, additionally, received a SMS-text messaging intervention of 12 weeks’ duration to encourage weekly weighing to prevent weight regain. Text messages that asked participants to reply to the text by sending their weight and whether they had gained or lost weight in the previous week were sent weekly. A reply text was then sent to participants depending on whether or not they had gained weight: a congratulatory message if weight had been maintained or lost; advice about diet and increasing physical activity if weight of < 2 kg had been gained and if this had occurred for < 3 consecutive weeks; or an offer of telephone support if weight had been gained 3 weeks in succession. If participants continued to gain weight, they were offered referral to receive specialist support. The primary outcome was change in weight at the 9-month follow-up, with a follow-up also at 3 months. There was no evidence that the intervention was effective, although the direction of change favoured the intervention group. Data showed that the intervention group adhered well to weekly weighing, with a median of nine weights texted back to the research team out of a possible 13.

Voils et al. 19 assessed the effectiveness of a weight loss maintenance intervention in people (n = 222) who had lost ≥ 4 kg during a 16-week group weight loss programme (nutrition training). The maintenance intervention was delivered primarily by telephone and focused on satisfaction with outcomes, preventing relapse, self-monitoring and obtaining social support. The maintenance intervention was delivered by dietitians and involved both group (three sessions) and individual telephone support (eight sessions) delivered over 42 weeks, followed by 14 weeks of no contact. This was compared with usual care of no further intervention after the initial nutrition training. Follow-up took place at 56 weeks post study randomisation. The mean weight gain was statistically lower in the intervention group (0.75 kg) than in the usual-care group (2.36 kg) (mean difference 1.60 kg, 95% CI 0.07 to 3.13 kg; p = 0.04). Of interest here is that the intervention costs were US$276 (£184) per participant.

Very recently, Sniehotta18 completed the NU Level trial, which investigated an automated remote weight monitoring and feedback intervention using participants’ mobile phones as the mode of delivery over 12 months (n = 288). Participants received wirelessly connected weighing scales that, every time they were used, transmitted participants’ weight in real time to the research team, and these data formed the basis of the automated feedback to participants on their weight maintenance progress. Participants also received an initial individual face-to-face weight loss maintenance intervention session with a psychologist. This intervention was compared with a control intervention comprising quarterly text messages with links to evidence-based weight management guidance. The control group also received the same wireless data transfer weighing scales, but no additional feedback on weight progress was provided. The intervention was ineffective in preventing weight regain, although data indicated that those in the intervention group were able to weigh themselves regularly throughout the intervention (an average of 4.4 times per week).

The trials by Volis and Simpson16,19 highlight that intensive weight loss maintenance interventions might be effective but such interventions would be expensive to deliver at scale. The trial by Sniehotta18 also evaluated an intensive intervention that was ineffective, although this trial does demonstrate that participants are able to adhere to daily weighing. A relatively brief intervention was evaluated by Sidhu et al. 17 and was found to be ineffective, although the results were in the direction that favoured the intervention group and the process data showed that participants were able to engage well with a text messaging system that encouraged them to weigh themselves weekly and to record this weight.

Self-regulation and self-monitoring of weight

Self-monitoring is a key component of self-regulation and has been shown to be important for successful health behaviour change. One promising specific behavioural strategy for weight management is regular self-monitoring to check progress against a target. The potential efficacy of self-monitoring has been based on the principles of self-regulation theory20 and the relapse prevention model. 21 Self-regulation has been described as a process that has three distinct stages: self-monitoring, self-evaluation and self-reinforcement. 20 Self-monitoring is a method of systematic self-observation, periodic measurement and recording target behaviours, with the goal of increasing self-awareness. The awareness fostered during self-monitoring is considered an essential initial step in promoting and sustaining behaviour change. Self-monitoring in the context of self-weighing can show individuals how their behaviour affects their weight and allows them to adjust their behaviour to achieve their goals. In other words, self-regulation theory postulates that motivation for behavioural change results from self-monitoring and observing the comparison of the current recorded behaviour with the desired outcome, along with the interplay between awareness, self-observation, recording and self-evaluation.

Several quantitative and qualitative studies22–25 have reported that individuals who are successful with weight loss and weight loss maintenance frequently monitor their weight. More specifically, there are observational data indicating that a lower frequency of self-weighing is associated with higher fat intake, increased disinhibition and decreased cognitive restraint,26 all of which are behavioural strategies associated with weight gain and regain. Self-monitoring of weight may act as a reward for individuals who control their food intake and physical activity behaviour and who are provided with positive feedback from the scales, thereby enhancing their motivation and reducing the potential for relapse. Frequent self-weighing and reflection of weight progress may also improve self-efficacy for weight maintenance, which, in turn, could improve body image. Encouragement of self-monitoring and recording of weight is a simple concept for a health professional or public health communication to advocate. It is simple for people to understand and implement, and it is the kind of behaviour that could become habitual and, thus, performed throughout life, in the way that cleaning one’s teeth becomes automatic and effortless. Trials have shown that participants can adhere to daily self-monitoring of weight. 16,18,27,28

Data from the US National Weight Control Registry29 indicate that the only factor that people losing weight have in common is that they use both diet and exercise to achieve weight loss. When examining weight loss maintenance, however, there appear to be several common factors, including self-monitoring, having high levels of physical activity, consuming a low-fat diet and eating breakfast. As suggested earlier, strategies needed for successful weight loss and weight loss maintenance may be different because weight loss requires individuals to produce a negative energy balance but weight loss maintenance requires continued and ongoing energy balance. Most importantly, this energy balance needs to be sustained by engaging in behaviours and strategies that can be demonstrated over the long term. Regular self-weighing is a self-monitoring behaviour that can be easily and readily used by people throughout their lives, regardless of whether they are aiming to lose weight or maintain their weight loss.

Data from RCTs30 also show that self-weighing may be an effective strategy within weight loss programmes. Our own systematic review of the effectiveness of self-weighing for weight loss showed that adding advice to self-weigh to a behavioural programme improved its effectiveness when compared with no intervention, but only four trials had assessed this, and the estimate of effect was imprecise and clouded by the use of other self-regulatory components. Another systematic review31 of self-weighing in both weight loss and weight gain prevention interventions reported that 75% of self-weighing-only interventions and 67% of interventions that combined self-weighing with other strategies demonstrated improved weight outcomes. No negative psychological effects were reported.

Potential risks and harms of self-weighing

Although self-weighing may help people control their weight, there may be concerns that it will have negative psychological consequences or lead to the adoption of unhealthy weight control practices. Some researchers have suggested that feedback about body size may result in psychological distress and that self-weighing may worsen body image and/or mood by continuously reinforcing to people that their current body size is not appropriate or ideal32,33 or lead to unhealthy dietary behaviours, such as binge eating and skipping meals. 34 However, there is little evidence to support these concerns. A very recent systematic review and meta-analysis (RCTs and observational studies)35 of the psychological impact of self-weighing found minimal evidence that self-weighing was associated with adverse psychological outcomes in relation to affect, body-related attitudes or disordered eating. There was, however, a small negative association between self-weighing and psychological functioning. Of interest here is that duration significantly moderated the relationship between self-weighing and body-related attitudes: self-weighing over longer durations compared with over shorter durations was associated with more positive and/or less negative body-related attitudes. Study design also moderated the relationship: observational studies tended to report more negative associations between self-weighing and psychological outcomes, and RCTs, which are less prone to bias, tended to report a positive relationship. In a very recent study that post-dates this review,27 49 female university students who were randomised to a daily weight monitoring intervention or a control condition with a 20-week follow-up did not report any harmful effects from regular weighing, and showed high acceptability of and adherence to the intervention. Nevertheless, it is important that trials continue to monitor whether or not self-weighing leads to adverse psychological events.

Chapter 2 Pilot work

In 2009, Birmingham Public Health wanted to evaluate an intervention to facilitate weight maintenance and prevent weight regain over the longer term in users of the Lighten Up service (a weight management service). See Chapter 3 for a detailed explanation of the Lighten Up service. For 1 year the public were offered a 3-month weight maintenance intervention after completing their weight loss programme, and 12-month follow-up data were collected. The intervention focused on encouraging regular self-weighing. Participants who did not own scales were given a voucher to obtain a free set from a local pharmacy, and they were also sent a chart to record their weight and a ‘hints and tips’ booklet about strategies to facilitate weight management. Participants were asked to weigh themselves weekly and to record this on the weight card sent to them. Participants were telephoned 3 months later to encourage regular adherence.

The intervention was delivered by non-specialist call centre staff from Gateway Family Services, a third-sector community organisation [http://gatewayfs.org/ (accessed 12 January 2016)], that, at the time of this study, was contracted by Birmingham Public Health to manage the Lighten Up weight loss service. 5,6 Third-sector organisations are organisations that are neither public sector nor private sector, and include voluntary and community organisations, social enterprises, mutuals and co-operatives. Third-sector organisations are generally ‘value driven’, meaning that they are motivated by the desire to achieve social goals (e.g. improving public welfare, the environment or economic well-being) rather than by the desire to distribute profit. According to the UK government, public services can gain much from working with third-sector organisations, and their benefits include an understanding of the needs of service users and communities that the public sector needs to address; an ability to deliver outcomes that the public sector finds hard to deliver on its own; innovation in developing solutions; and performance in delivering services. As the NHS continues to struggle to meet efficiency targets, third-sector organisations can help to ease the delivery burden. Indeed, the government’s health and social care White Paper36 and subsequent Health and Social Care Bill37 (House of Commons Bill 2010–2011) set out clear aspirations for the voluntary and community sector as a provider of health services, a source of support for commissioning and a partner in tackling health inequalities. Similar models of care in the form of community health workers operate in other countries, where their role is used as means of broadening the reach of health-care systems and as community activists and health educators. For example, in the USA promotoras and promotores de salud are used to address issues such as reproductive health, diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular health and domestic violence within community health systems.

In the pilot, we examined the efficacy of a self-weighing-focused weight maintenance intervention delivered by Gateway Family Services in preventing weight regain at 12 months by comparing the weight of those offered the intervention (intervention group) (n = 3290) with that of participants in the preceding Lighten Up trial38 who had not received a maintenance intervention (control group) (n = 478). Using an intention-to-treat analysis (i.e. regardless of whether participants had lost weight at the end of the weight loss programme or accepted the maintenance intervention), both groups regained weight, but the intervention group regained 0.68 kg (95% CI 0.12 to 1.24 kg) less than the control group. In the per-protocol analysis, comparing intervention participants who had accepted the maintenance intervention with control participants, the mean difference was much larger at 2.96 kg (95% CI –3.67 to –2.25 kg). Although our pilot results are encouraging, and offer preliminary evidence to support the intervention and the use of lay workers from a third-sector organisation for intervention delivery, participants were not randomised to the groups, the intervention was not optimally configured to encourage behaviour change, follow-up data were mostly self-reported and the frequency of self-weighing was not recorded.

Rationale for the study

After the pilot work was completed, the effectiveness of the intervention needed to be tested robustly before it could be implemented. Moreover, at the time of the study, commissioning groups throughout England had begun to offer patients weight loss programmes, which were often provided by commercial weight management providers but had no or minimal provision for weight maintenance support thereafter. If effective, the study would provide information to public health agencies, commissioners or services that may be considering adopting a similar model. The need for evidence about effective weight maintenance interventions delivered within public health arenas will become even more important in years to come as cuts to public spending increase. The need for evidence about effective weight maintenance programmes is also critical to ensure that weight loss is maintained following weight loss interventions given that regain is the norm. This study would provide the public and commissioners with a simple, ‘ready to go’, low-cost weight maintenance intervention that could be implemented immediately, if effective.

The primary aim of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of a theoretically informed brief behavioural intervention delivered by non-specialist staff to promote regular self-weighing to prevent weight regain after intentional weight loss. The intervention was compared with usual care. The research tested a weight maintenance intervention in participants who had successfully completed standard, widely available commercial and NHS weight loss programmes. Although complex, multicomponent, high-intensity interventions may be more effective than the brief intervention we planned to test here, we deliberately chose to test a simple self-weighing intervention, as this has not been done before in a high-quality trial. There are several advantages of testing simple and low-cost interventions. If we test unicomponent interventions and show that they are effective, we can build up to a more complex, multicomponent intervention. It is often difficult to go the other way. Many people in the UK and in other developed countries would benefit from losing weight, and it would not be affordable to deliver intensive interventions to this number of people. Even if our strategy leads to a smaller effect than a complex intervention, the higher reach of the simple, cheap intervention would still result in substantial gains to public health. If we have a range of simple, evidence-based self-help strategies that may prevent weight regain, we can encourage the public to use these outside formal programmes.

Aims and objectives

Primary objective

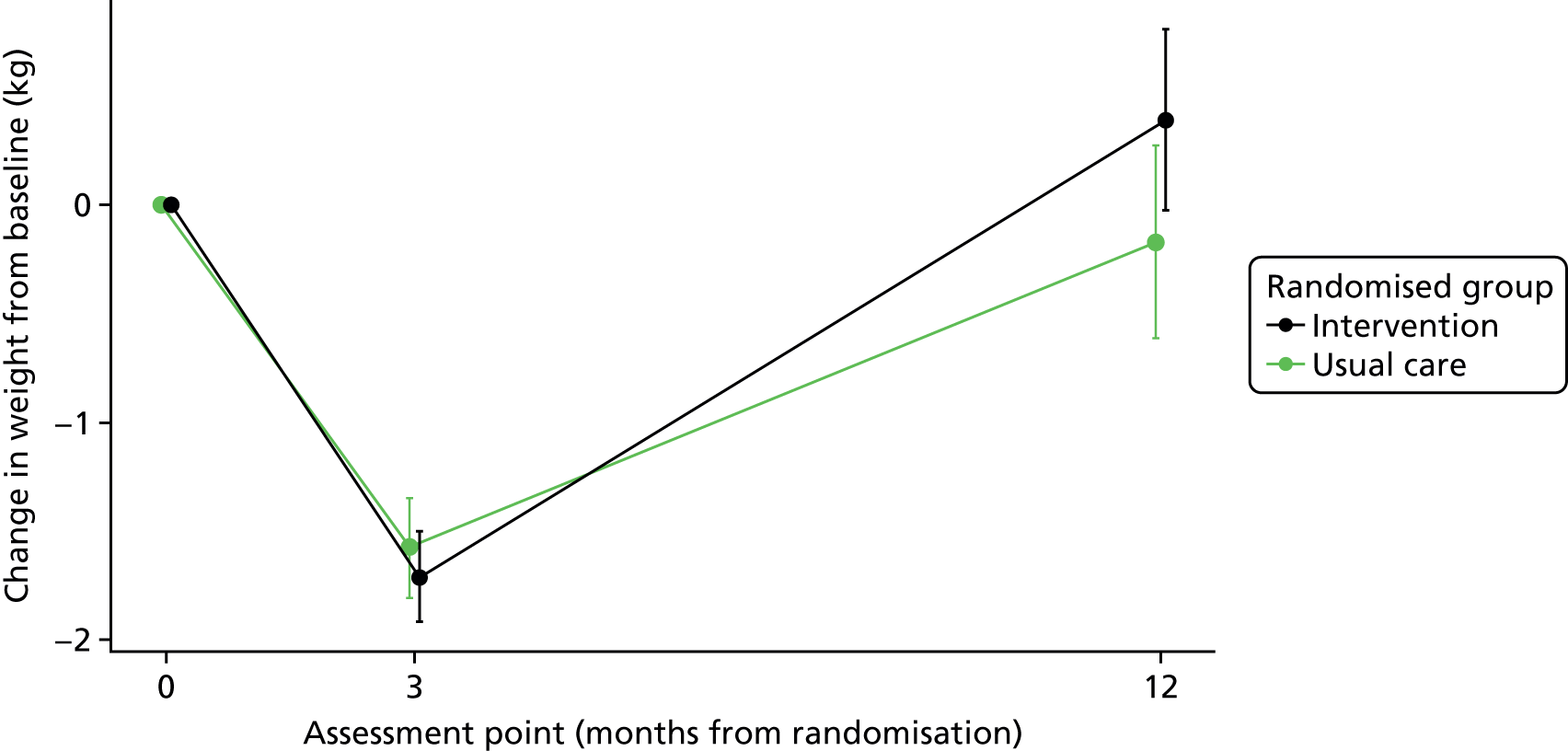

The primary objective was to examine the effect of a brief weight maintenance intervention focused on regular self-weighing, compared with usual care, on objectively assessed mean weight change at 12 month’s follow-up.

Secondary objectives

A series of secondary objectives were outlined in the proposal for this study. These were:

-

to compare the proportion of participants in the intervention and usual-care groups who regained < 1 kg at the 3- and 12-month follow-up points

-

to examine the effect of a brief weight maintenance intervention focused on regular self-weighing compared with usual care on mean weight change at the 3-month (post maintenance intervention) follow-up

-

to assess the cost to the NHS, per kg and per kg/m2, of the additional weight loss maintained for the intervention compared with usual care at 12 months, the cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) during the intervention period and the predicted lifetime QALYs gained

-

to assess the occurrence of adverse effects from the intervention, including uncontrolled eating, emotional eating and body image problems.

Process evaluation objectives

In addition, we planned a process evaluation of the intervention, and a number of objectives in relation to this were preplanned:

-

assessment of the fidelity of intervention delivery to ensure that it was in line with the intervention protocol

-

assessment of whether or not participants received the intervention telephone calls as per the protocol

-

quantification of participants’ adherence to daily self-weighing (objectively verified)

-

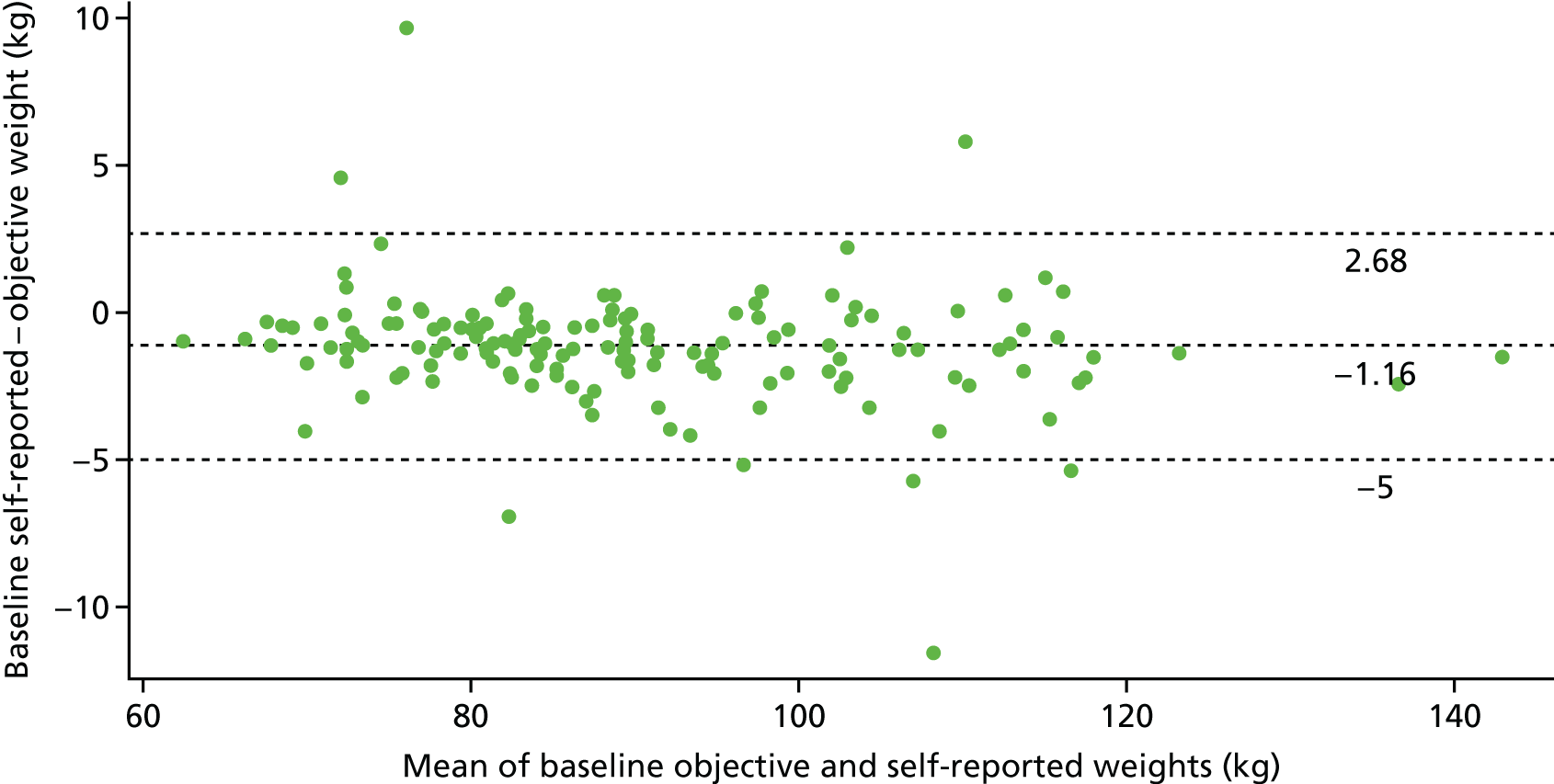

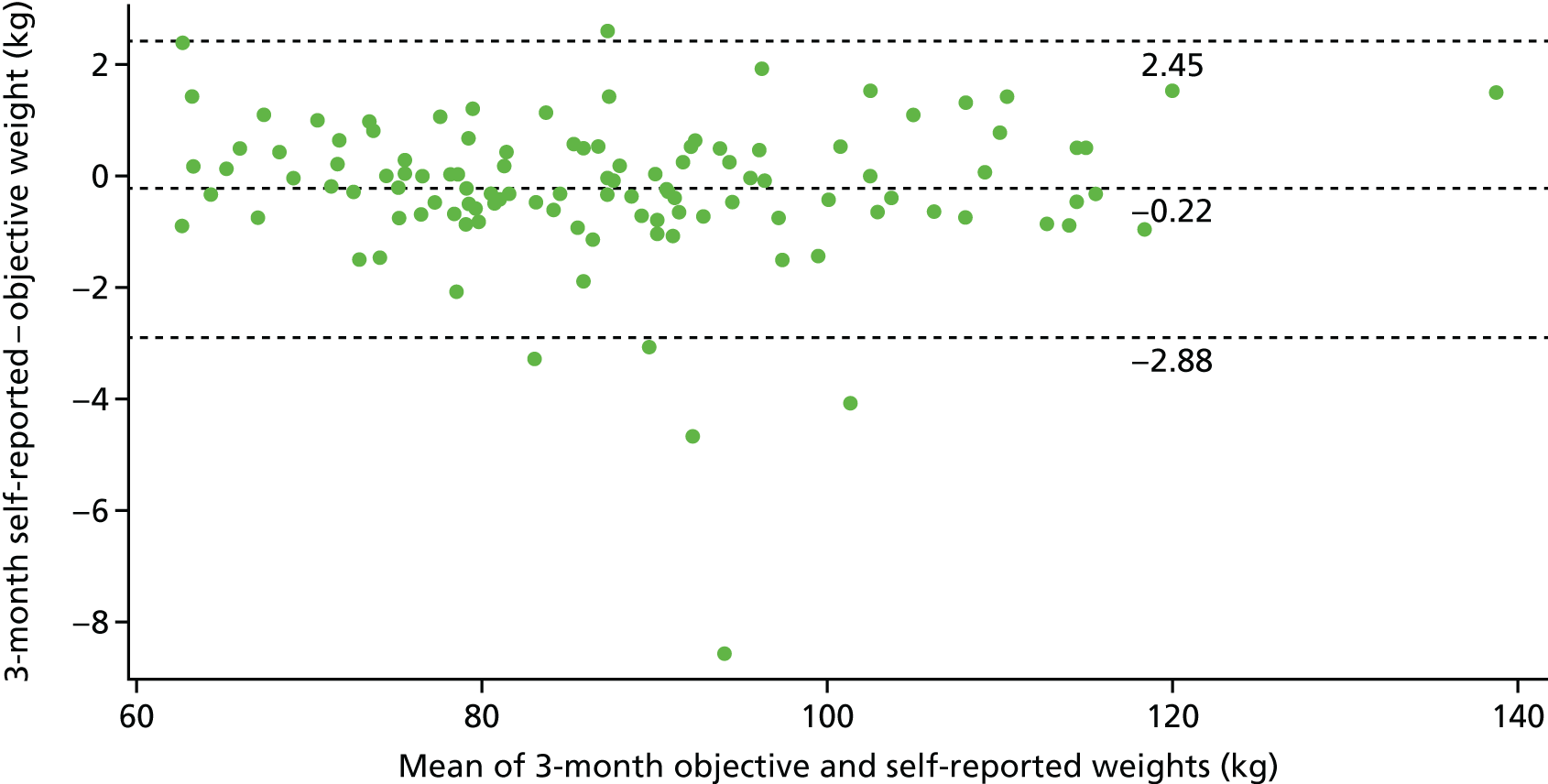

investigation of the relationship between objective and self-reported measures of weighing

-

assessment of whether or not feedback from regular self-weighing led to the development of conscious cognitive restraint of eating

-

exploration of whether the intervention worked by encouraging participants to reapply lessons and techniques they learnt on their weight loss programme or whether it may have worked by encouraging participants to enrol in a weight loss programme once more

-

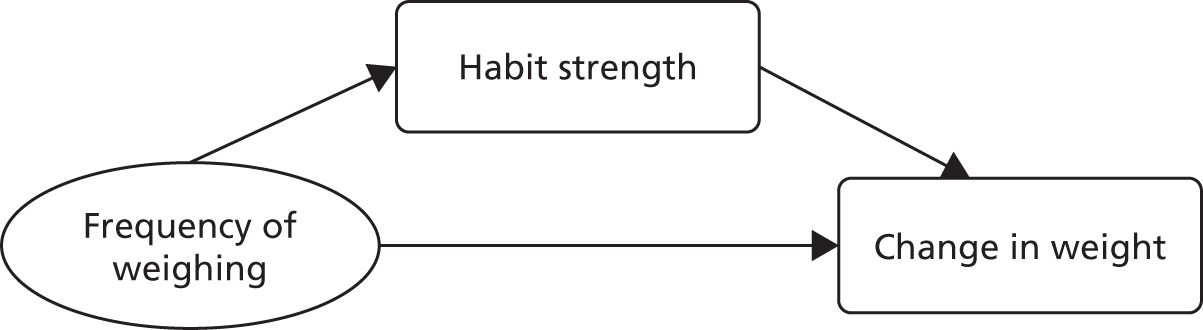

assessment of the degree to which participants developed automaticity (habit index) and the regularity of weighing by interrogating their frequency of self-weighing (objective) data, and the degree to which automaticity was associated with change in weight

-

investigation of whether frequency of self-weighing was related to average change in weight at 3 and 12 months analysed by including frequency of self-weighing (average times per week as reported at follow-up) and its interaction with the intervention group in the mixed-model analysis

-

if the intervention was effective, testing of a logic model with a full mediation analysis.

Chapter 3 Methods

Study design

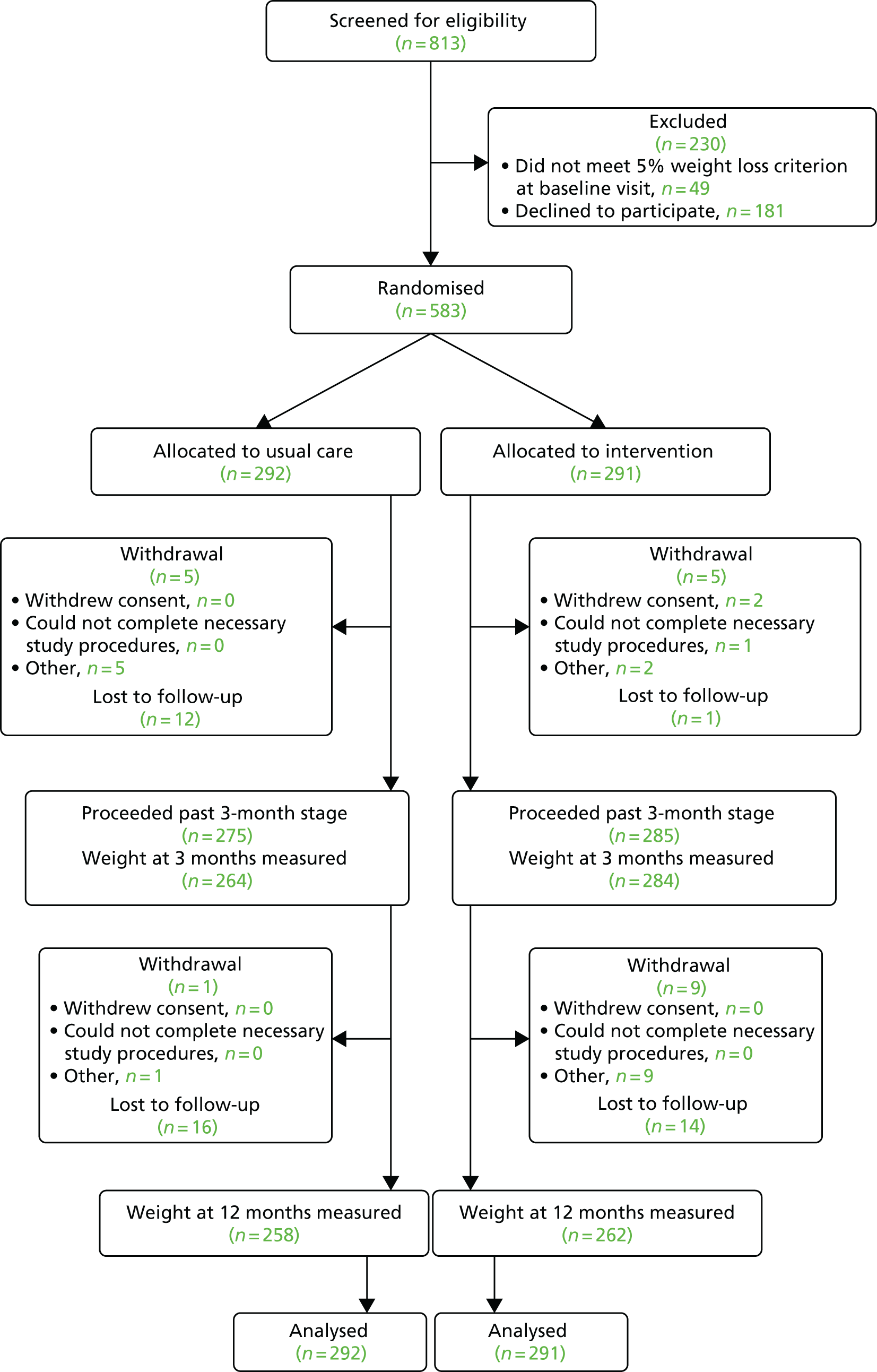

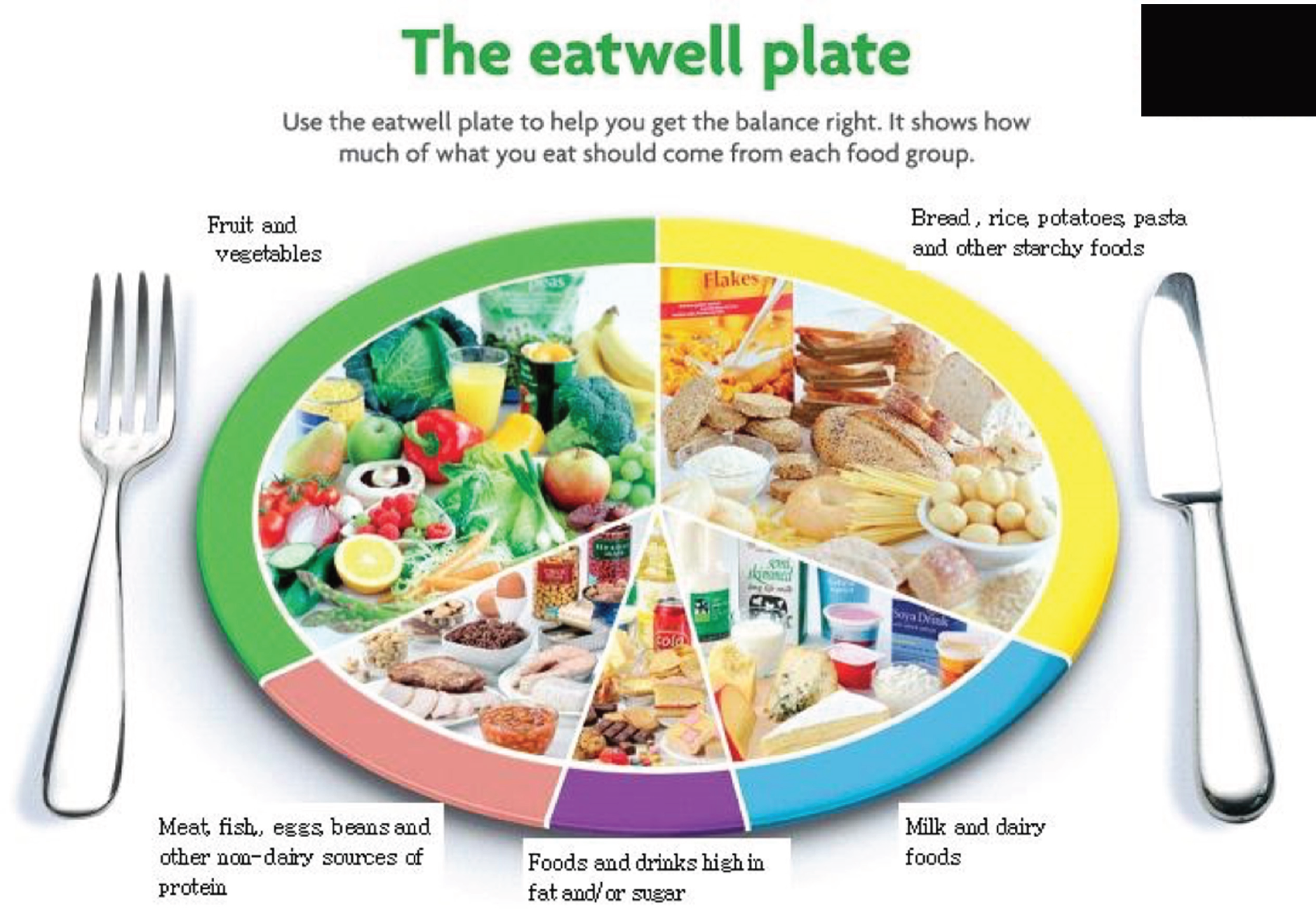

The study design was a RCT in which adults who had received a weight loss programme and had lost ≥ 5% of their initial body weight were allocated to receive a standard weight loss maintenance intervention (a leaflet, the EatWell Plate and a list of useful websites) or an intervention group who received the same written materials plus a 12-week behavioural weight maintenance intervention that promoted daily self-weighing and the recording of weight on a record card. The full trial protocol has been published. 39

Ethics approval and research governance

Ethics approval for the study was obtained from the Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics Ethical Review Committee at the University of Birmingham (ERN-13-1380). The study was conducted in accordance with the recommendations for physicians involved in research on human subjects adopted by the 18th World Medical Assembly, Helsinki, 1964, and later revisions. The trial was hosted by the Primary Care Clinical Research Trials Unit (PCCRTU) at the University of Birmingham and was conducted in accordance with the Research Governance Framework and the standard operating procedures for the PCCRTU. The University of Birmingham acted as the sponsor for the study. Research and development approval from Birmingham City Council was also obtained. An independent Trial Steering Committee was formed to oversee the conduct of the study.

Identifying potential participants and recruitment

In 2008, South Birmingham Primary Care Trust commissioned the Lighten Up service, which provided NHS patients who were obese with a free course of weight loss treatment for 3 months. The Lighten Up service commissioned three commercial weight loss programmes to offer treatment to these patients: Weight Watchers® (Maidenhead, UK; www.weightwatchers.com/uk), Rosemary Conley (Tharston, UK; www.rosemaryconley.com) and Slimming World® (Alfreton, UK; www.slimmingworld.co.uk). Patients could choose their weight loss treatment, and the primary care trust commissioned a telephone call centre to administer the service (Gateway Family Services). Adults who took part in the Lighten Up weight loss programmes were sent an invitation letter and information leaflet when they reached week 9 of their weight loss programme. This letter informed participants about our weight maintenance study and notified them that they would be asked whether they would be willing to take part in a study to prevent them regaining the weight they might have recently lost. During an end-of-programme courtesy telephone call from a member of the study team at Gateway Family Services, participants were asked to report their current weight and their total amount of weight loss since starting their weight loss programme. Those who had lost ≥ 5% of their starting weight were asked to participate in this study about maintaining weight loss. In other sites, namely the Public Health-funded weight management services where recruitment took place, participants were sent a letter, an information sheet, a reply form and a prepaid envelope. The research team at the university contacted these participants on receipt of the reply form to assess their eligibility and, if the participant was eligible, booked a home visit for a baseline assessment.

The eligibility criteria for access to each weight loss programmes can be found in Appendix 1.

Eligibility

The following criteria were used to assess eligibility.

Inclusion criteria

-

Were aged ≥ 18 years.

-

Had lost ≥ 5% of their starting weight by the end of their weight loss programme (based on self-reported weight at a weight maintenance screening call and confirmed during a randomisation home visit that they had lost ≥ 4% of initial body weight).

-

Owned a mobile phone or a landline phone that could receive SMS text messages.

-

Were able to understand English sufficiently to complete the study procedures.

Exclusion criteria

-

Women who were known to be pregnant or who were intending to become pregnant during the study period.

Randomisation

The randomisation list was developed by a statistician within the Primary Care Research and Trials Unit using nQuery Advisor (Statistical Solutions, Saugus, MA, USA). Participants were randomised to telephone support or booklet support (usual care) on a 1 : 1 basis using random permuted blocks of random size (block sizes of 2, 4 and 6). The lists were stratified by whether or not participants intended to continue with their weight loss programme. Separate lists were provided to each researcher undertaking home visits, as recruitment was undertaken concurrently by more than one person. Eligible participants were randomly allocated to either the telephone support or usual care at the baseline visit using number-ordered, opaque, sealed envelopes. Participants were allocated to the groups according to the number order of the batched stratification envelopes that were opened sequentially in number order according to whether or not participants intended to continue to attend their weight loss intervention. Staff undertaking randomisation were trained in the study-specific procedures [see project web page: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/phr/1217909/#/ (accessed 12 February 2015)].

Withdrawal from the intervention and follow-up assessments

Participants were free to withdraw from the study at any time. They could withdraw from receiving the telephone support by calling Gateway Family Services or by making a request to the university research team. When this occurred, the research team asked the participant if they would still be happy to be contacted at the 3- and 12-month follow-up points regarding completion of the follow-up assessments. In addition, the following strategies were used to minimise withdrawal and loss to follow-up at 3 and 6 months:

-

It was emphasised that it was important for the quality of the study to follow up participants even if they did not want to continue to receive the intervention.

-

Participants were informed that if we did not follow up everyone in the study, we could get an overly optimistic view of a new programme, and it was important that ineffective programmes were not recommended to people.

-

All participants received a £20 high-street shopping voucher at the 3- and 12-month follow-up points.

-

One reminder was sent to participants requesting that they return their study questionnaires at the 6-month follow-up.

-

All of the assessments were conducted during the home visit (except the one at 6 months, which was carried out by postal questionnaire) or at a location convenient for participants (e.g. work or general practice).

-

Follow-up home visit appointments were arranged throughout the day and evenings to maximise convenience to participants.

-

Participants were sent a text message reminder of their appointment the day before their scheduled appointment.

-

Participants were sent the follow-up questionnaires 7 days before their scheduled home visit appointment, during which the questionnaires were collected.

-

Follow-up questionnaires that were not completed correctly were returned to participants for completion or participants were telephoned for clarification of their answers.

Blinding

Participants were not explicitly told that this was a trial about target-setting and daily weighing, so they were blinded to group allocation. Rather, participants were told that this study aimed to test two different methods of preventing weight regain after weight loss. We also ensured that the researchers collecting the follow-up data at the 12-month follow-up (primary end point) were blinded to group allocation by providing the case report form (CRF) in a sealed envelope with a sticker on the front to record the weight of the participant, and giving no other information about the participant. After weight was recorded on the sticker, the CRF envelope was opened. Participants were asked not to mention to the researcher which group they were in or indicate whether or not they had BodyTrace (BT003; © BodyTrace Inc., www.bodytrace.com) study weighing scales in their homes until they had had their weight measured. The researcher completing the primary outcome at the 12-month primary end point had not randomised or collected the baseline measurements. The trial statistician remained blinded to group allocation until the analyses were completed.

Intervention

Overview and theoretical approach

Preliminary evidence and our pilot study suggested that regular self-weighing could prevent weight regain. 38,40,41 The proposed intervention was based on our pilot study described earlier and designed such that it would offer support at a time when people are at the highest risk of weight regain. Our intervention was designed to be simple, to address the practical challenges of delivery, to be affordable and so that it could be rapidly implemented if effective. Our intervention would complement current obesity management services and could be offered as a stand-alone or as part of a multicomponent intervention. The overall aim was to minimise lapses/relapses by giving participants feedback on how their behaviour was affecting their weight before too much weight had been gained. Within the field of behavioural medicine there has been considerable focus in recent years on developing behaviour change interventions that are underpinned by a strong theoretical framework. The content and delivery of the intervention was informed by self-regulation theory,20 the relapse prevention model21 and the theory of habit formation. 42 When applied to weight loss maintenance in the context of this study, a key focus of these model was to help participants appreciate and understand the benefits of their weight loss thus far, and to develop a well-maintained (habitual) plan for self-monitoring (self-weighing) progress and responding to gains in weight before they become difficult to reverse.

Intervention components

This study was focused on preventing weight gain and, as such, we did not want participants to regain any weight during the study. However, we felt that 1 kg would allow for some error in measurement and for fluctuations in time of day when weight was recorded by participants themselves during the intervention and also at follow-up assessments. Therefore, the behavioural goal of the intervention was for participants to avoid regaining > 1 kg of their baseline weight (i.e. prevention of relapse).

Lally et al. 43 have shown that habituation of daily health behaviour occurs after an average of 3 months, and hence the intervention lasted 12 weeks. The main element of the intervention was support telephone calls at weeks 0, 2 and 4 that encouraged daily self-weighing, along with reminder text messages every other day for the first 4 weeks, reducing to twice weekly thereafter. We purposefully designed the intervention so that the telephone contacts and frequent texts messages occurred in the first 4 weeks, both because the time after initial weight loss is when people are at highest risk of weight regain, and to maximise the possibility that participants would develop the habit of regularly weighing themselves. The pilot intervention consisted of two telephone calls; we amended this to three calls in this study to provide additional support. The intervention components were mapped against the Coventry, Aberdeen, London Refined (CALO-RE) taxonomy intervention checklist44 (Table 1).

| Behavioural technique | Definition |

|---|---|

| Goal-setting (outcome) | Telephonists will encourage participants to set a weight goal for regain such as ‘in a year I aim to weigh no more than I do now’ |

| Prompt review of outcome goals | Participants will be instructed to remain within 1 kg of their study baseline weight and to review their weight each day against this target |

| Provide information on the consequences of behaviour in general | The telephonist will discuss the benefits of self-weighing with the participant |

| Environmental restructuring | The telephonist will encourage the participant to cue this behaviour: ‘move the scales into your bathroom so when you see them after your shower it will remind you’ |

| Provide information on where and when to perform the behaviour | The telephonist will ask participants to describe when and where the weighing will take place. Participants will be encouraged to weigh themselves at the same time every day |

| Use follow-up prompts | Participants will receive telephone calls at weeks 1, 2 and 4 that encourage daily self-weighing, together with reminder text messages every other day for the first 4 weeks, reducing to twice weekly thereafter |

| Barrier identification/problem-solving | The telephonists will offer practical solutions and give participants ideas and strategies to overcome barriers to daily self-weighing. Participants will be advised that if their current weight is > 1 kg above target weight then they would be best to restart using the plan they followed for eating and physical activity when they were on their weight loss |

| Agree behavioural contract | The telephonist will ask participants if they can commit to a weight change target and to daily weighing |

| Provided general encouragement | The telephonist will encourage the participant: ‘remember every time you record your weight you are one step nearer to this becoming a healthy habit’ |

| Prompt self-monitoring of behavioural outcome | Participants will be instructed to weigh themselves daily and record it on the record card provided |

| Prompt social support | Prompt participants to ask someone they care about to support them, tell this person about their goal and ask the person to remind them of this goal every week |

Telephone calls structure and content

Participants received three support telephone calls in total, once at baseline (week 0), once at week 2 and once more at week 4. The calls lasted about 5–10 minutes each. The callers were non-specialist staff from Gateway Family Services, and not weight loss counsellors. We trained the staff to deliver the intervention as described here. The intervention training manual can be found on the project web page [www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/phr/1217909/#/ (accessed 12 February 2015)]. Some of the advantages of telephone calls over other treatment modalities, including printed materials and internet-based formats, are the possibility of immediate feedback, a reduction in message ambiguity and the opportunity to use natural language and offer a focus that is personal to the individual. 45 Telephone calls also reduce the burden of need for frequent face-to-face contacts and increase the potential for broader public health impact and reach.

The intervention started with the telephonists explaining that weight regain is the norm after weight loss as successful slimmers often feel overly confident about the likelihood that they will keep weight off. Then telephonists encouraged participants to set a weight goal for regain such as ‘in a year I aim to weigh no more than I do now’, although the goal chosen was set by the person. If the person set an ambitious weight loss goal, the telephonist reminded them that the aim of the programme was to prevent weight regain, not to assist weight loss, and encouraged them to set a goal for weight maintenance. The telephonists also explained that weight regain is often not apparent initially and that monitoring weight is important to detect the early signs of this occurring.

Although the goal of the intervention was for participants to avoid regaining > 1 kg of their baseline weight, in a pragmatic trial we accepted that some participants may have had other goals they wanted to achieve, as would be the case if this study was implemented in the population. Thus, the telephonists accepted that some participants may have had alternative goals, but they reminded the participants that it was important to set goals that were realistic and achievable and asked participants to agree that ‘at the worst’ they would avoid regaining > 1 kg of their weight loss. The telephonists explained that weight fluctuates naturally, that variation is normal and that this does not immediately mean that a person has gained fat, which is what damages health. Thus, together, the telephonist and the participant agreed a goal that was somewhere near to weight stability and agreed that frequent monitoring is important to detect early signs of weight gain to allow corrective action to be taken.

After that, the telephonist introduced the concept of daily weighing and explained that it is easier to keep doing something if it becomes a habit and is part of daily routine ‘like brushing your teeth’. The potential benefits of self-weighing for preventing weight regain were also outlined. The telephonist asked participants if they could commit to daily weighing. Assuming that this would be achieved, the telephonist helped participants to make implementation intentions that described when and where the weighing would take place (e.g. ‘every morning after I have had my shower and before I get dressed’). The telephonist encouraged participants to cue this behaviour (e.g. ‘move the scales into your bathroom so when you see them after your shower it will remind you’). This process of implementation intentions is thought to accelerate habit formation. 46

Participants were encouraged to weigh themselves at the same time every day wearing similar amounts of clothing. The telephonist explained that the aim of weighing frequently was to check against the target weight set for weight stability. The telephonist explained that they would send the participant a booklet that would be the participant’s personal weight record. Each page of the booklet represented 1 week and at the top of each page there was a box in which participants were asked to enter the target weight which they aimed to stay within. The telephonist explained that every day the participant should check their recorded weight against the target weight and asked whether the participant could commit to doing this. The telephonist encouraged participants to ‘remember every time you record your weight you are one step nearer to this becoming a healthy habit’. Participants were advised that if their current weight was > 1 kg above their target weight then they would be best to restart the plan they followed for eating and physical activity from when they were on their weight loss programme.

However, there was no specific encouragement for participants to rejoin the weight loss programme and this was not available free on the Lighten Up scheme until participants had completed their 12-month follow-up for this study. In Solihull, participants were able to receive a second set of 12 vouchers to allow free attendance at their weight loss programme following their initial programme. Following this, there needed to be a 3-month gap before they could receive any further free vouchers. In Dudley, if participants achieved a weight loss of ≥ 5% they were able to continue with their weight management programme for a further 12 weeks.

Daily versus weekly weighing

Daily weighing was chosen over weekly weighing (as used in the pilot) for several reasons. Weighing is more likely to become a habit if it is performed daily. Based on self-regulation theory,20 daily weighing is optimal over less frequent weighing because the feedback is immediate about how eating and physical activity is affecting weight, allowing for better self-regulation to ensure that participants remain within their target weight. Observational and pilot experimental evidence has also shown that more frequent weighing is associated with less weight regain than infrequent weighing. 24,26,28,47–50 Daily weighing may be particularly relevant for optimising weight loss maintenance because reversal of weight regain is rare but possible, if people observe their weight regain early on in the process, or address minor lapses.

Week 2 and 4 calls

The telephone calls in weeks 2 and 4 included a review of the frequency of self-weighing and recording of weight over the previous weeks. Those not weighing themselves daily were asked about barriers to this, and the telephonist helped with finding practical solutions, ideas and strategies for how they might overcome them. The telephonist reminded participants of their goals, their commitment to those goals and the value of self-weighing. Participants were further encouraged to self-weigh daily. The importance of using the weight record to prevent relapse was also emphasised. The importance of engaging in regular physical activity/healthy eating to prevent relapse was emphasised again, but the telephonists were not equipped to, and did not, give advice on energy intake or expenditure.

Text messages

Automated reminder text messages were sent every other day for the first 4 weeks, reducing to twice weekly for 8 more weeks. The texts contained changing messages reminding participants to weigh themselves daily [see project web page: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/phr/1217909/#/ (accessed 12 February 2015)]. The text messages also contained words of support and encouragement and reminded participants to revert to using the dietary practices they learnt when attending their weight loss programme if at any time they found that they had regained > 1 kg. Text messages offer the opportunity to provide regular support for habit formation with minimal participant burden, and they negate the need for resource-intensive intervention contacts. Participants chose when they wanted to receive the text messages.

The goal for the intervention was to encourage self-weighing such that it became a habit. Although Lally et al. 43 have shown that habituation of health behaviour occurs after about 90 days, participants may still benefit from some very minimal support to reduce the likelihood of relapse. We therefore continued to send reminder texts twice per month as a ‘top-up’ strategy after the intervention phase until the 12-month follow-up. If this were implemented, the cost would be very low, and it could easily become part of standard care as a strategy for providing longer-term support.

Training and delivery of the intervention

We trained study staff from Gateway Family Services to deliver the intervention in accordance with the intervention manual. At the time of the study, Gateway Family Services managed the Lighten Up weight loss service in Birmingham and they delivered all of the weight maintenance intervention to all participants, including those recruited from Dudley and Solihull. Gateway is a community interest company that operates across the West Midlands. It is a non-profit organisation that works in partnership with local health and social care organisations to support their strategic decisions while empowering people in the community to break social, cultural and economic barriers that can cause deprivation. The Gateway call centre is staffed by employees who are trained in call centre management systems and customer relations, but not in nutrition or weight management. Call centre staff did not offer any opinions or undertake any motivational interviewing, but they listened, offered positive reinforcement about regular self-weighing and setting weight goals, offered advice about intention implementations, gave encouragement and passed on factual information.

Usual-care group

The usual-care group received a leaflet about useful websites about healthy eating and the EatWell Plate (see Appendices 1 and 2). The leaflet is very brief and contains some advice prepared by NHS Birmingham. Other than for follow-up, there was no other contact with the usual-care group and they received no other weight management intervention from either the research team or Gateway Family Services.

Assessments

A list of variables/outcomes and the time points for assessment are shown in Table 2. All staff were trained to collect the study data. A data collection manual was developed [see project web page: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/phr/1217909/#/ (accessed 12 February 2015)] and staff received ‘on the job’ training from the trial co-ordinators (CM or RG).

| Outcome | Measure | Type | Time point | Modifications | Randomisation group | Number of items | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention | Control | ||||||

| Anthropometric measures | |||||||

| Weight change (kg) | Calibrated digital scales | Primary | Baseline and 12-month follow-up | N/A | Yes | Yes | |

| Weight change | Calibrated digital scales | Secondary | Baseline and 3-month follow-up | N/A | Yes | Yes | |

| % who gain < 1 kg | Calibrated digital scales | Secondary | Baseline and 3- and 12-month follow-up | N/A | Yes | Yes | |

| Descriptive information | |||||||

| Demographics | Gender, age, ethnicity, marital status, employment status, derivation quartile | Descriptive | Baseline | N/A | Yes | Yes | 5 |

| Weight management history and aims | Weight loss programme attended, weight loss in programme, continuing to attend weight loss programme, weight management aims, following a weight loss diet | Moderator | Baseline and 3-, 6- and 12-month follow-up | N/A | Yes | Yes | 4 |

| Smoking status | Cigarettes smoked on average each day | Descriptive | Baseline | N/A | Yes | Yes | 1 |

| Medication | Taking medication prescribed by a doctor | Descriptive | Baseline and 3-, 6- and 12-month follow-up | N/A | Yes | Yes | 1 |

| Life changes | Planning any major life changes | Descriptive | Baseline, 3-, 6- and 12-month follow-up | N/A | Yes | Yes | 1 |

| Secondary and process outcomes | |||||||

| Behaviours facilitating weight loss | WCSS | Process | Baseline and 3-, 6- and 12-month follow-up | Reduced from 30 to 27 items [diet (one item) and weight (two items)] owing to error | Yes | Yes | 27 |

| Thoughts about regular self-weighing | Daily self-weighing perceptions scale | Process | 3-, 6- and 12-month follow-up | N/A | Yes | No | 8 |

| Automaticity of self-weighing | Self-Report Index of Habit Strength | Process | 3-, 6- and 12-month follow-up | Shortened from 12 items to 7 | Yes | No | 7 |

| Emotional eating | TFEQ-R18 | Secondary | 3-, 6- and 12-month follow-up | N/A | Yes | Yes | 6 |

| Cognitive restraint | TFEQ-R18 | Secondary | 3-, 6- and 12-month follow-up | N/A | Yes | Yes | 6 |

| Uncontrolled eating | TFEQ-R18 | Secondary | 3-, 6- and 12-month follow-up | N/A | Yes | Yes | 6 |

| Body image | Body Image States Scale51 | Secondary | 3-, 6- and 12-month follow-up | N/A | Yes | Yes | 6 |

| Daily weighing frequency | BodyTrace objective Scales | Process | Baseline until 12-month follow-up | N/A | Yes | No | – |

| Self-weighing frequency | Self-weighing item | Secondary | Baseline until 12-month follow-up | N/A | Yes | Yes | 1 |

| Adverse events | SCOFF questionnaire | Secondary | 3-, 6- and 12-month follow-up | Three items (make yourself sick, worry lost control over how you eat and does food dominate your life) | Yes | Yes | 3 |

Outcome measures

Primary outcome

The primary outcome of change in weight between the start of the maintenance intervention (baseline) and 12 months after randomisation was objectively assessed during a home visit appointment by using calibrated SECA weighing scales (model number 875; SECA, CA, USA). Weight was measured to the nearest 0.1 kg. Participants were weighed in light clothing after removing their shoes, belts, heavy items and jumpers or coats.

Secondary outcomes

Weight and maintenance of weight loss

Change in weight from baseline to the 3-month follow-up (i.e. end of maintenance intervention) was assessed. Maintenance of weight loss was defined as successful when participants’ weight at the 12-month follow-up was ≤ 1 kg of their weight at baseline. The secondary outcomes therefore included the proportion of participants in the intervention and usual-care groups who had regained < 1 kg in weight at the 3- and 12-month follow-up point. We decided not to measure energy intake and expenditure in this study. Assessment of diet and physical activity is onerous for participants and expensive to measure accurately, and we know from past research, and from the laws of physics, that participants who put on less weight must eat less and participate in more physical activity than those who gain more weight. The evidence also raises questions about the validity of current methods of assessing dietary intake in obese adults, who are known to under-report their food consumption. 52,53

Psychological harm and serious adverse events requiring hospitalisation

There was no reason to assume that this study would lead to an excess of adverse events, in this case psychological harm. The treatment consisted of prompting target setting and daily weighing, neither of which seemed likely to cause harm. Some people believe that asking people to weigh themselves daily may cause them to become obsessed with their weight and thus cause psychological harm. Although there is no evidence from RCTs that this is the case, it is important to provide evidence of no harm. Thus, we measured uncontrolled eating and emotional eating in both groups. 54 Body image was also assessed in all participants. 55

Serious adverse events related to bulimia, anorexia and self-harm attributable to body dissatisfaction and necessitating hospitalisation were reported to the trial sponsor (University of Birmingham) and the Trial Steering Committee. The SCOFF questionnaire was used to gather this information. 56 The principal investigator (AD) contacted participants if they had answered yes to two of the SCOFF questions (one of which had to be the first question): ‘Do you make yourself sick if you feel uncomfortably full?’, ‘Do you worry if you have lost control over how much you eat?’ and ‘Would you say that food dominates your life?’.

Self-reported frequency of self-weighing

All participants were asked to report their frequency of self-weighing in the previous month at baseline and at both follow-ups using a single-item measure. This outcome also allowed us to gauge the potential level of intervention contamination in the usual-care group.

Weight control strategies and conscious cognitive restraint of eating

Our hypothesis was that self-weighing leads to the development of conscious cognitive restraint, which the National Weight Control Registry has found to be a key behavioural attribute associated with weight maintenance. 29 Using six items from the Three-Factor Eating Questionnaire Revised 18-item version (TFEQ-R18),54 we examined if feedback from self-weighing led to the development of conscious cognitive restraint of eating (measured in both groups) at 3, 6 and 12 months post randomisation. The use of weight control strategies was also assessed in both groups. 57

Automaticity

In the intervention group, we used seven items from the Index of Habit Strength58 to measure the automaticity of self-weighing.

Intervention fidelity

Delivery of the intervention

Assessment of whether or not participants received the intervention as per the protocol (dose/exposure) was calculated by a summation of the number of intervention calls that were delivered. Gateway Family Services documented the number of intervention telephone calls made to each participant in its database to allow an intervention dose variable for each participant to be calculated. Fidelity was included to ensure that the intervention was delivered consistently and in line with the protocol. As part of the training process, a sample of 36 intervention calls made by Gateway staff (n = 3) delivering the intervention were audio-recorded. Each of these calls was mapped against an intervention content checklist, and an individual score was calculated for each call to assess compliance with the protocol [see project web page www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/phr/1217909/#/ (accessed 12 February 2015)]. Two independent assessors rated each call, and their scores were combined to form an overall score.

Objective recordings of frequency of daily self-weighing

The intervention group received a set of real-time weight tracking scales (BodyTrace scales) as an objective measure of compliance. Every time participants used the scales to weigh themselves, these data were sent to the research team via wireless cellular data transfer. Participants who did not have wireless internet access in their homes were given ION UPS scales, which store 100 recordings of weight on a USB (Universal Serial Bus) stick attached to the scales. The data from these scales were downloaded at the 3-month follow-up visit and every 3 months thereafter. The scales were delivered to participants’ homes and set up by the research team.

Daily self-weighing record cards

As part of the intervention, participants were asked to complete daily self-weighing record cards, which were collected or photographed at the 3-month follow-up visit [see project web page: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/phr/1217909/#/ (accessed 12 February 2015)]. Data from these allowed for the examination of the relationship between objective and self-reported frequency of self-weighing.

Descriptive data and other outcomes

To allow the calculation of BMI, height was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm using SECA 213 stadiometers (SECA, CA, USA) during the baseline home visit. The weight loss service providers in this study routinely collected the following data at the point at which a client entered their service: date of starting weight loss service, name of general practice/general practitioner (GP), date of birth, gender, ethnicity, address (including postcode), contact telephone number(s), information on previous use of weight loss programmes, (including any commercial services), use of antiobesity medication, weight and height at first attendance at the weight loss programme, and weight at the end of the weight loss programme. Participants’ permission to use these data in this study was obtained at baseline [see project web page: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/phr/1217909/#/ (accessed 12 February 2015)]. Gateway Family Services provided the research team with all of the relevant study data, and this information was merged with the main trial study database hosted by the PCCRTU at the University of Birmingham.

At baseline and at follow-up, we collected data on whether participants were trying to lose weight, maintain their current weight or not trying to lose or maintain their weight. We also collected data at each follow-up point on whether or not participants were planning any major life events in the following 3 months and any medication prescribed by their doctor (data not reported). At follow-up, the research team collected data on whether or not participants had attended or were attending a weight loss programme, and, if so, which one, and the number of sessions that they had attended. Participants were also specifically asked whether or not they had reapplied any behavioural techniques they acquired through participation in their weight loss programme and whether or not they had re-enrolled in a weight loss programme. These data could provide the opportunity to examine whether the intervention worked by encouraging people to reapply lessons and techniques that they had learnt on the weight loss programme or whether it worked by encouraging participants to enrol in a weight loss programme once more. Perceptions of daily self-weighing were assessed in the intervention group. 28

Patient and public involvement

We approached previous users of the Lighten Up weight loss programme, who then formed the public and patient involvement (PPI) group (KB and PD); they had successfully lost weight using Lighten Up and, therefore, were similar to the individuals we wanted to recruit. The study was presented to the PPI group and their comments were incorporated into the submitted funding request proposal. Their main feedback was that it was a good idea to involve Gateway Family Services in delivering the intervention because participants would already have had contact with this organisation when attending their weight loss programme. There was some concern that people who did not own scales would be expected to buy some. The PPI group felt that it was important to give participants a choice about when the intervention calls would be made. One member commented that those at risk of relapse often have other issues going on their lives and it would therefore be important to ask about this during the calls. We did not incorporate this suggestion because to do so would be beyond the competence of the telephonists and the scope of the study. However, we included a question on major life events in the study questionnaire. Throughout the trial, Karen Biddle and Polly Dixon attended Trial Steering Committee meetings and we consulted our PPI representatives about any issues on which we needed their input.

Sample size calculation

The standard approach to sample size calculation is to aim to detect a worthwhile intervention effect. This was difficult for this study because there is a linear relationship between being overweight and mortality (30% increase in mortality per 5 kg/m2 increase in BMI). 59 This kind of intervention may be applied broadly in contexts outside the specific behavioural intervention we propose here; in any case, even here, likely at its maximal intensity and cost, it is likely to cost around ≤ £10 per person in public health practice. According to the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, even very small decrements in weight are likely to be cost-effective if they are maintained throughout a person’s life. 60 Consequently, instead of an approach by which we specified a sample size based on a clinically important difference, we proposed a sample size based on the likely size of effect we expected to achieve, namely a 2-kg difference in change in weight at the 12-month follow-up. A total of 280 participants randomised to each group (n = 560) was sufficient to detect a 2-kg difference in change in weight at the 12-month follow-up between the intervention and usual-care groups, with 90% power and 5% significance level. This estimate was based on our pilot trial, in which we found that the standard deviation (SD) of the difference from baseline (i.e. the end of weight loss/start of maintenance programmes) to the 12-month follow up in those who lost at least 5% of their starting weight was 6.3 kg. Having 560 participants also allowed for 20% loss to follow-up at 12 months. In our pilot, the intention-to-treat analysis included all participants regardless of whether or not they had lost weight in their weight loss programme or whether or not they had accepted or received the maintenance intervention; the adjusted mean difference in weight between intervention and control was 0.68 kg. However, in the per-protocol analysis of those who had accepted the maintenance intervention (i.e. those motivated to change), the mean group difference was larger, at 2.96 kg. Similarly, in this study, we planned to recruit participants who had agreed to accept the weight maintenance programme and who showed good adherence to their weight loss programme by losing at least 5% of their starting weight; therefore, we conservatively estimated the likely difference in weight change to be about 2 kg, and more on a par with the findings from the per-protocol analysis in our pilot study. In addition, the intervention group in this study received more contacts than the intervention group in the pilot did, potentially increasing the difference we expected to find.

Changes to the protocol

By March 2015, recruitment had been marginally lower than expected, and we made the decision to recruit from other local programmes. As this study was focused on testing a weight loss maintenance intervention, as long as people purposefully lost weight the method of that weight loss was not important. Participants in programmes funded by Dudley and Solihull City Councils were eligible to join this study if they met the study eligibility criteria. These programmes were either commercial weight loss programmes, as per Lighten Up in Birmingham, or other community programmes (Fit Blokes and SHAPES). Participants recruited from Dudley and Solihull were sent a screening questionnaire and asked to return this to the study team using a Freepost envelope if they were interested in taking part. The research team determined eligibility, and thereafter flow through the trial occurred in the same manner as for those recruited via Lighten Up. Gateway delivered the intervention to all participants.

We also planned a cost-effectiveness analysis with modelling of the long-term health consequences that may follow successful weight maintenance, but this was not completed as the intervention was ineffective.

Partner collaboration

This study was based on a partnership between the study team (Universities of Birmingham and Oxford), Gateway Family Services and Birmingham Public Health.

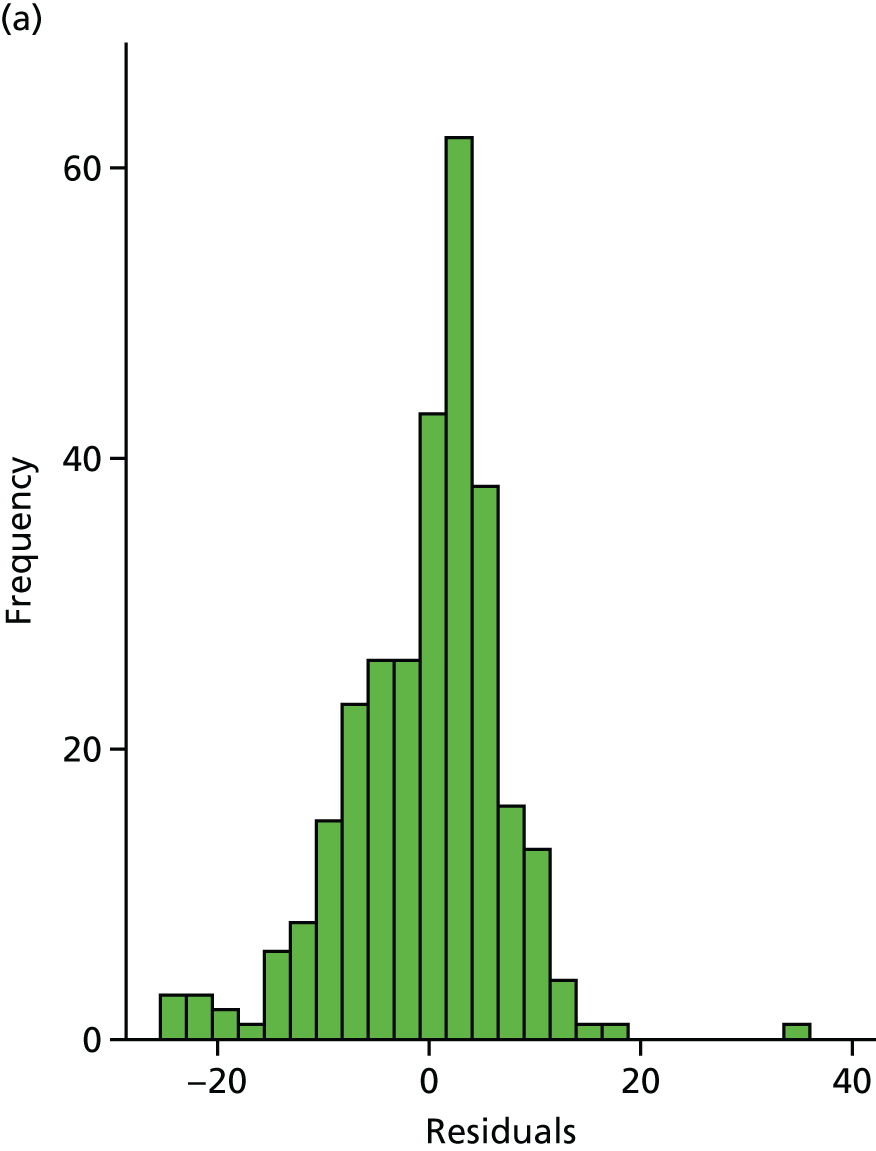

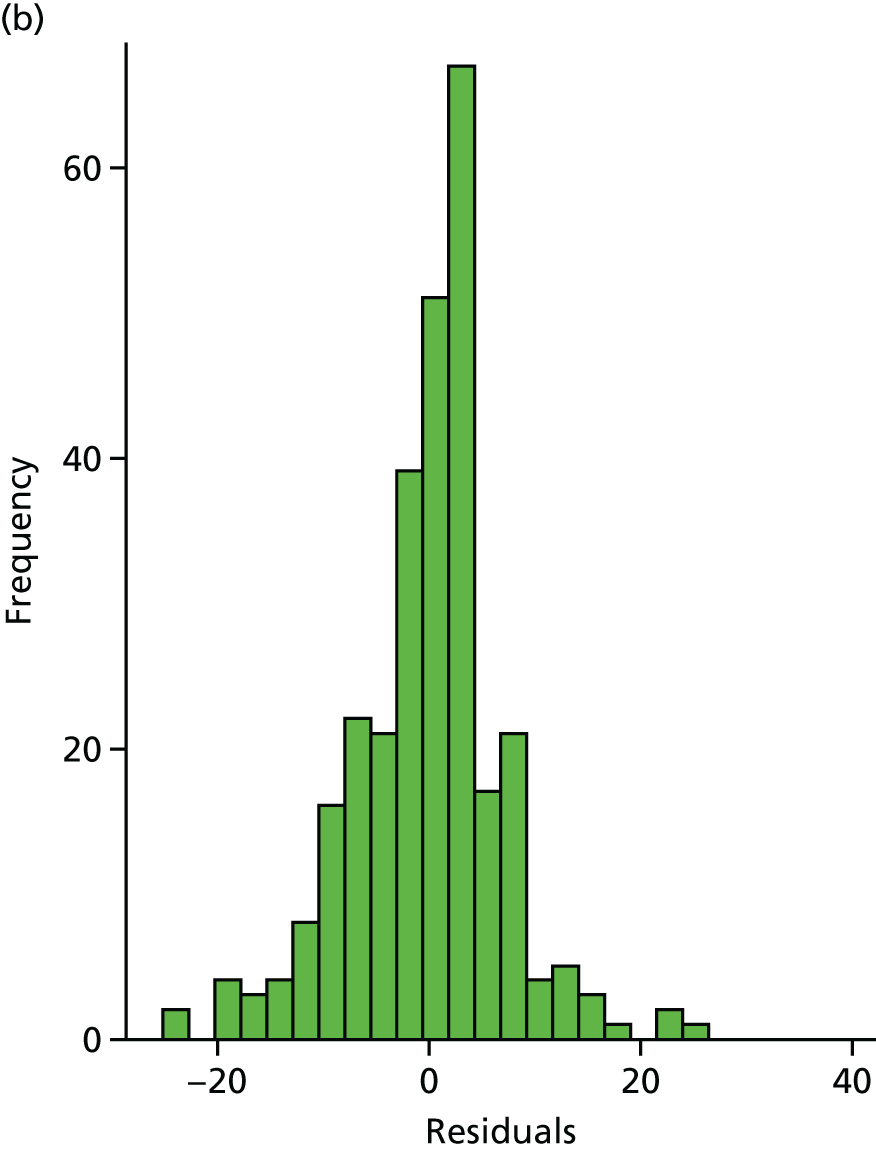

Statistical analysis

Data cleaning

Data underwent statistical data checking by means of distribution analysis and range estimates to ensure that values and dates were valid. Data points identified as out of bounds were flagged and these were sent to the data manager (RG) to be checked against the original CRF. These were performed before the final data lock.

Comparison of baseline characteristics

Participants were summarised by group according to gender, age, ethnicity, index of multiple deprivation quartile, height, employment status, marital status, weight, BMI, whether or not participants were planning to continue to attend a weight loss programme to continue to lose weight or to maintain their current weight, type of weight loss programme attended, number of weight loss sessions attended initially, and self-reported self-weighing frequency.

Dealing with missing data and assumptions of missing data methods

The primary analysis was conducted using the intention-to-treat principle. The primary outcome analysis was conducted initially with imputed missing weight data and then confined to participants for whom weight was reported. Self-reported weight was used in analyses if objective weights were not available. When both objective and self-recorded weights were missing at the 3- and 12-month follow-up points, we used a conservative imputation method proposed by Wing et al. ,24 whereby 0.3 kg per month was added to baseline weight.

Primary analysis/outcome

The primary outcome was assessed by an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) to compare weight change between the groups. Baseline weight and intention at baseline to continue to attend a Lighten Up weight loss programme (stratification variable) were included as covariates. All participants were included in the primary analysis regardless of whether they maintained, lost or gained weight. Self-recorded weight was used in the analysis if objective weights were not available. In the event that both objective and self-reported weights were missing, weights were imputed by adding 0.3 kg per month to the baseline weight. 24

Secondary analysis of weight

A similar analysis to the primary analysis plan was used to compare change in weight from baseline to the 3-month follow-up. An analysis of the proportion of participants in each group who regained ≤ 1 kg from their weight at the end of the weight loss programme (i.e. successful maintainers) at the 3- and 12-month follow-up points was conducted using logistic regression. Those who had continued to lose weight were classified as successful maintainers.

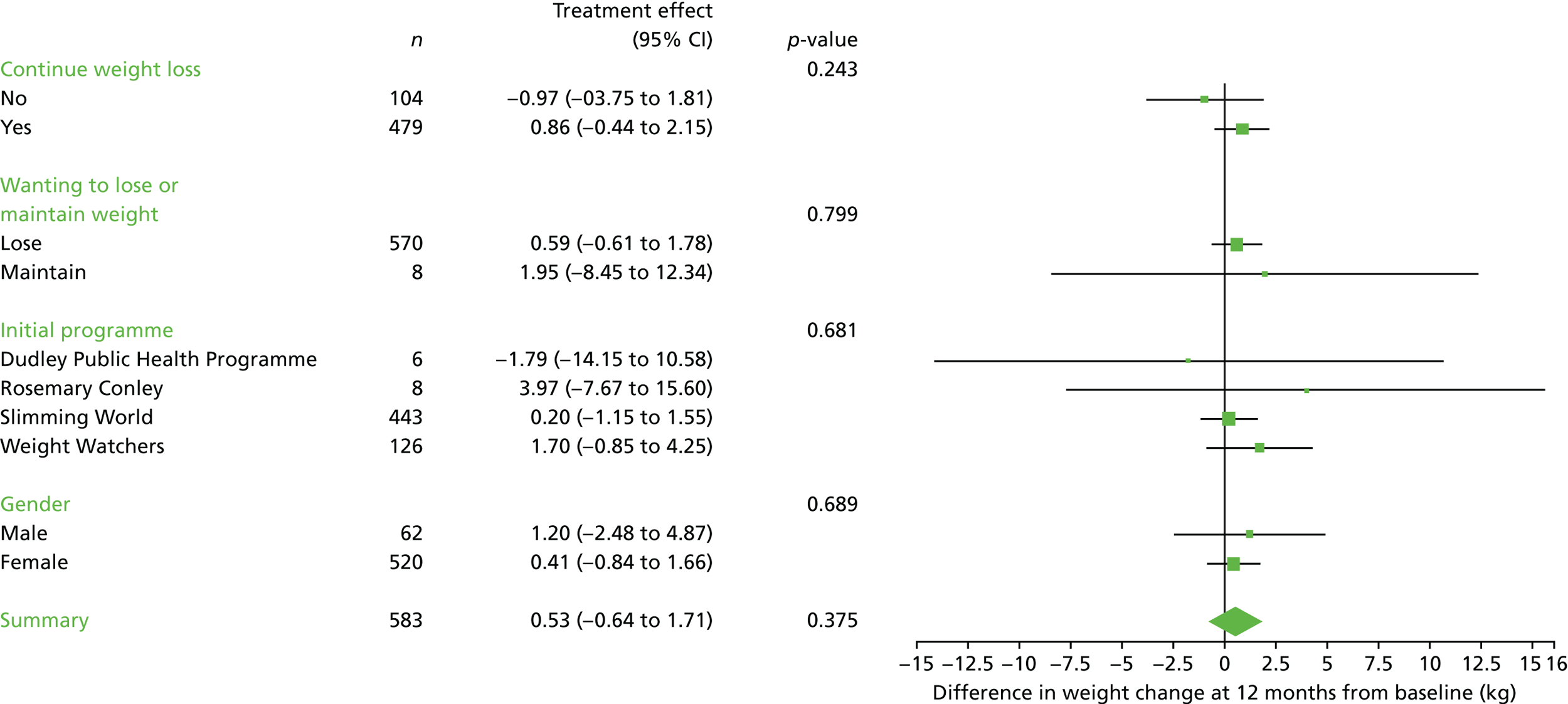

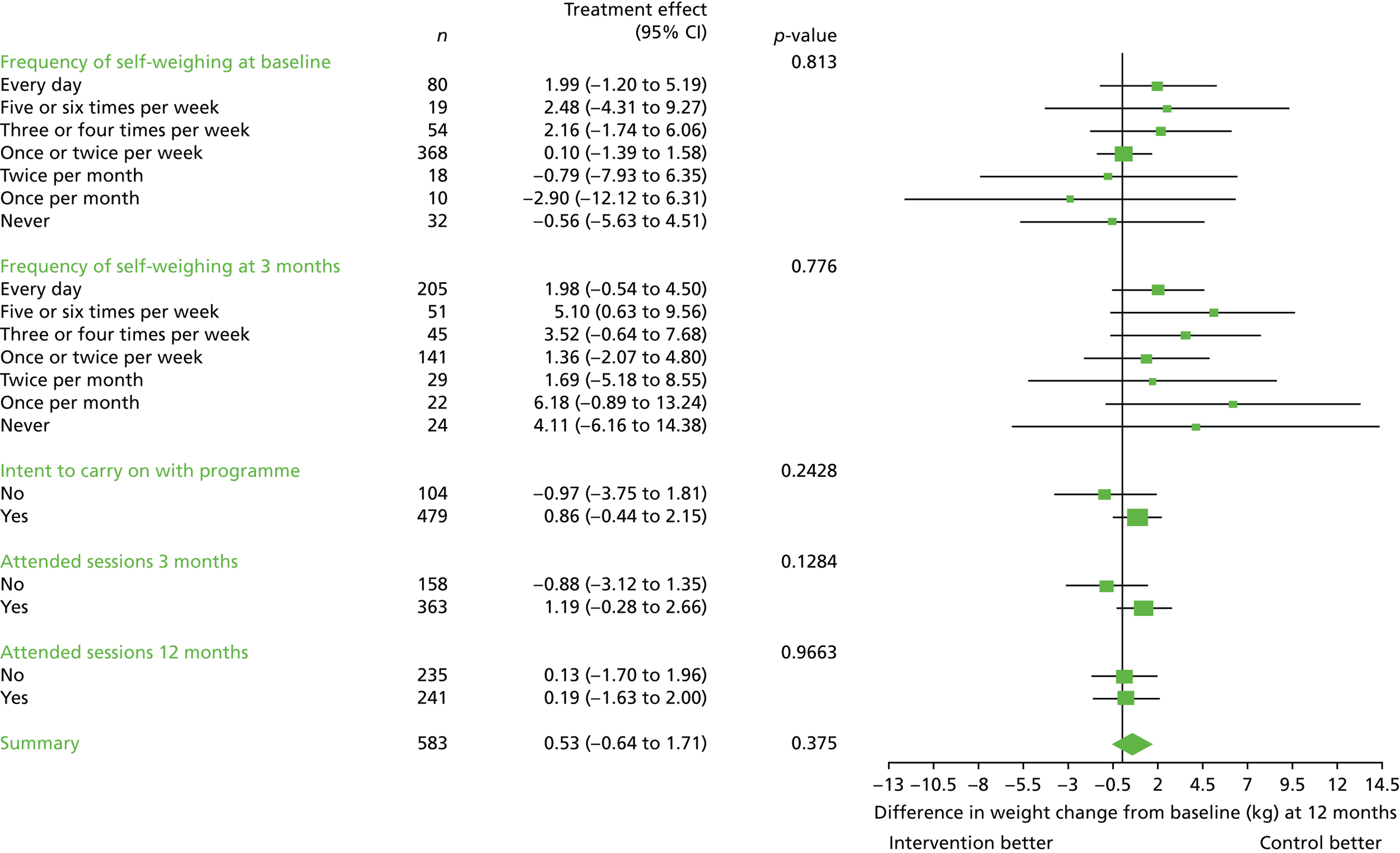

Preplanned subgroup analyses for the primary outcome

We examined the effect of gender, initial weight loss programme attended and whether or not at baseline participants aimed to continue to lose weight or maintain their weight (as a continuous and categorical variable) for the primary outcome in preplanned exploratory subgroup analyses. An ANCOVA model was fitted, similar to the model performed for the primary analysis but including the subgroup categorical variable and an interaction term between the randomised groups and the subgroup categorical variable.

Post hoc analysis for primary analysis

The moderation of the attendance of weight management programmes on weight change at the 12-month follow-up was investigated in a post hoc analysis. The difference in weight change at the 12-month follow-up was also conducted in participants who did and participants who did not return their weight record cards.