Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 13/163/17. The contractual start date was in October 2015. The final report began editorial review in October 2017 and was accepted for publication in May 2018. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

The University of Stirling (Martine Stead and Kathryn Angus), the University of Nottingham (Tessa Langley, Sarah Lewis and Ben Young) and the University of Edinburgh (Linda Bauld) are members of the UK Centre for Tobacco and Alcohol Studies (UKCTAS) (http://ukctas.net). Funding for UKCTAS from the British Heart Foundation, Cancer Research UK, the Economic and Social Research Council, the Medical Research Council and the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), under the auspices of the UK Clinical Research Collaboration, is gratefully acknowledged. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, the decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript. Linda Bauld reports that she is a member of the NIHR Public Health Research (PHR) programme Research Funding Board. Srinivasa Vittal Katikireddi reports that he is a NIHR PHR programme Research Funding Board member and received grants from the Medical Research Council and the Scottish Government Chief Scientist Office during the conduct of the study. Sarah Lewis reports that she is a NIHR Health Services and Delivery Research programme Board member.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Stead et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background and existing research

Behaviour change is crucial to preventing the large burden of non-communicable diseases (NCDs). 1,2 Public health organisations recommend, and spend considerable resources on, mass media campaigns to encourage reductions in risky behaviours or adoption of healthier behaviours. 1,3–5 Mass media campaigns can be run via traditional media channels, such as television, radio, cinema, newspapers, magazines and billboards, or via new digital media, including websites, pop-up and banner advertisements, QR (Quick Response) codes, viral marketing and social media. New media often feature an element of interactivity [e.g. liking, sharing or commenting on content and downloading campaign apps (applications)]. Campaigns aim to increase knowledge, influence attitudes and motivate target groups to change health behaviours. 6 Because they can be delivered at the population level, they can reach large numbers of people at a relatively low cost and are widely agreed to have an important role to play in influencing health behaviour change. 7

Evidence suggests that mass media campaigns can be effective in changing individual health behaviours, for example smoking. 8,9 However, there have been few attempts to synthesise evidence of effectiveness across multiple behaviours. An approach that examines intervention effectiveness across several health topic areas is able to offer a broad overview of evidence, and to bring attention to areas in which no systematic reviews have been conducted. 10 When evidence is scarce or highly heterogeneous (e.g. evidence of effectiveness with population subgroups), a broad overview approach allows evidence to be combined more meaningfully. For commissioners, it can help to guide decision-making regarding in what contexts and for what behaviours mass media campaigns may be most useful.

Aim and objectives

The aim of this research was to provide the NHS, local authorities, government and other organisations with evidence on the effective use of mass media to communicate public health messages.

In order to do so, we aimed to systematically review the evidence of effective uses of mass media campaigns to convey messages that lead to health behaviour change in the target audience – by preventing risky or unhealthy behaviours, by encouraging the cessation of existing risky or unhealthy behaviours, by promoting the uptake of healthy behaviours or by raising awareness of key public health issues.

In addition to the overall aim, the study had the following objectives:

-

Assess the effectiveness of mass media campaigns to communicate public health messages.

-

Examine the components of messages that can be effectively communicated through mass media.

-

Explore how different types and forms of media campaigns can reach and be effective with different target populations (particularly disadvantaged groups).

-

Assess new or emerging evidence about campaigns that employ different forms of media (including new media).

-

Examine the relationship between local, regional and national campaigns and evidence of effectiveness where this exists.

-

Assess the extent to which mass media campaigns can interact with other interventions or services to improve health outcomes.

-

Explore the currency, utility and applicability of findings with key stakeholders.

-

Identify key research gaps in relation to mass media campaigns to communicate public health messages.

Most, but not all, of our objectives were addressed in this study. The first reason for not addressing all of the objectives was that our reviews did not identify evidence to address them. This was the case for objective 4, for which we found very limited evidence on new media, and, to some extent, for objective 5, for which some key findings about campaigns of different scope and scale were available but not enough information applicable to the UK context of local, regional or national was identified. The second reason was that it became apparent that some avenues for exploration were beyond the time and resources available for the study when the volume of literature had been initially assessed. This was the case for objective 6, as it emerged that trying to fully address this objective would have required reviewing a very sizeable body of additional literature in which mass media was just one element of much broader multicomponent interventions. These limitations are discussed in Chapter 7.

Overview of the study

The study comprised a series of evidence reviews informed by a logic model. We have been guided in the write-up of this report by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement,11 although, as this report documents a large review of reviews combined with syntheses of primary studies, we had to develop our own structure to some extent.

Review of reviews

Reviews of reviews are becoming an established component in the repertoire of evidence-informed policy and practice. 12–14 They allow key findings from a range of studies to be easily accessed, while also identifying research gaps. We reviewed and synthesised evidence from English-language systematic reviews published between January 2000 and January 2016 on the effectiveness of mass media campaigns across six health topics that represent the main preventable risk factors for disease morbidity and mortality in developed countries:15 alcohol use, illicit substance use, diet, physical activity, sexual and reproductive health and tobacco use. We registered this review of reviews (review A) with PROSPERO (CRD42013004170)16 (see Chapters 2 and 5).

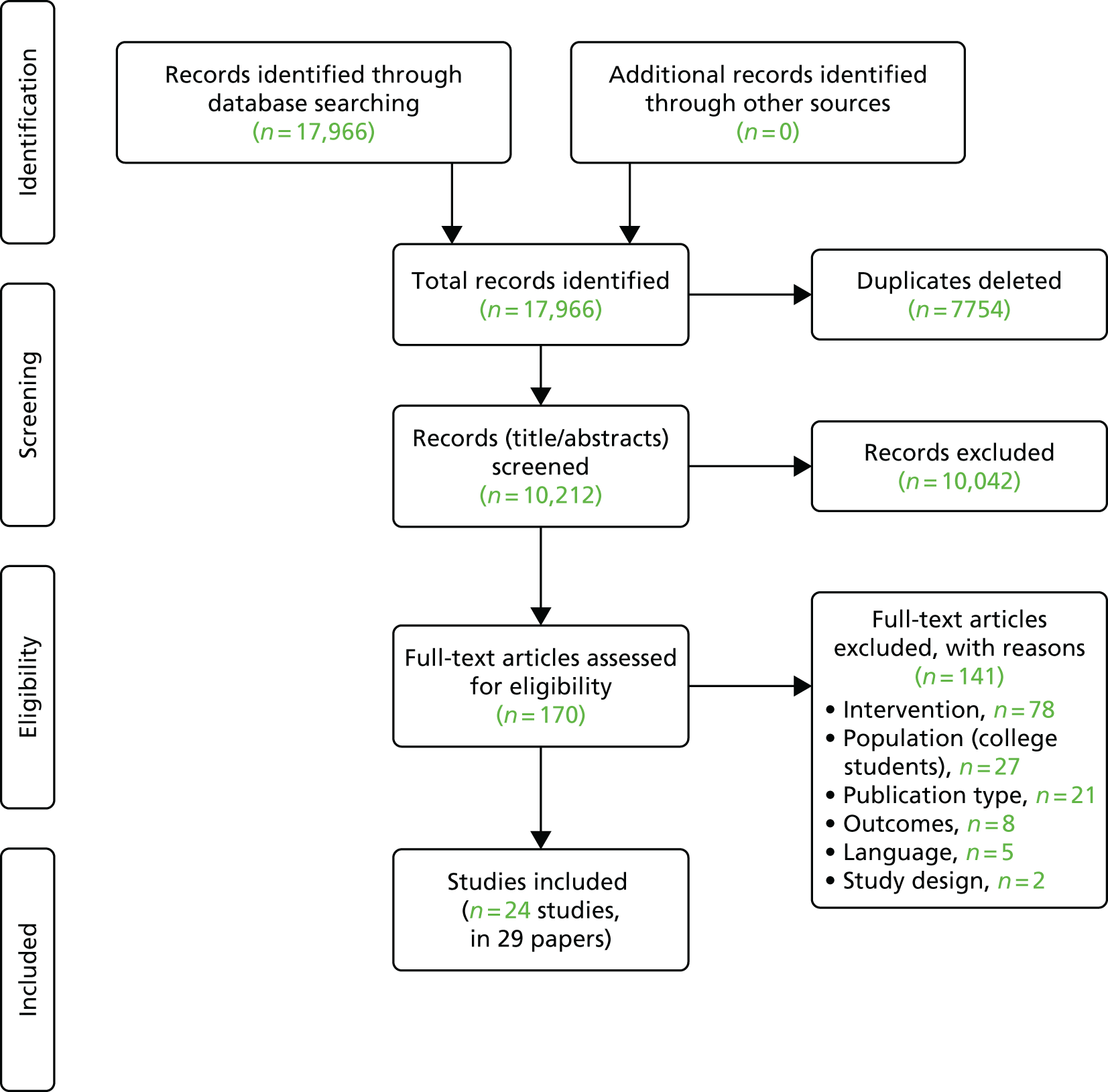

Reviews of primary studies

No systematic reviews addressing alcohol use or diet met our inclusion criteria for the review of reviews described in the previous section. As a result of this, and as anticipated in our protocol,16 we conducted two reviews of primary studies. The first (review B), a systematic review of English-language primary studies (published by July 2016), was conducted to assess the effectiveness of mass media public health campaigns to reduce alcohol consumption and related harms. Studies examining drink driving mass media interventions and college campus campaigns were excluded. We registered this review with PROSPERO (CRD42017054999)17 (see Chapter 3).

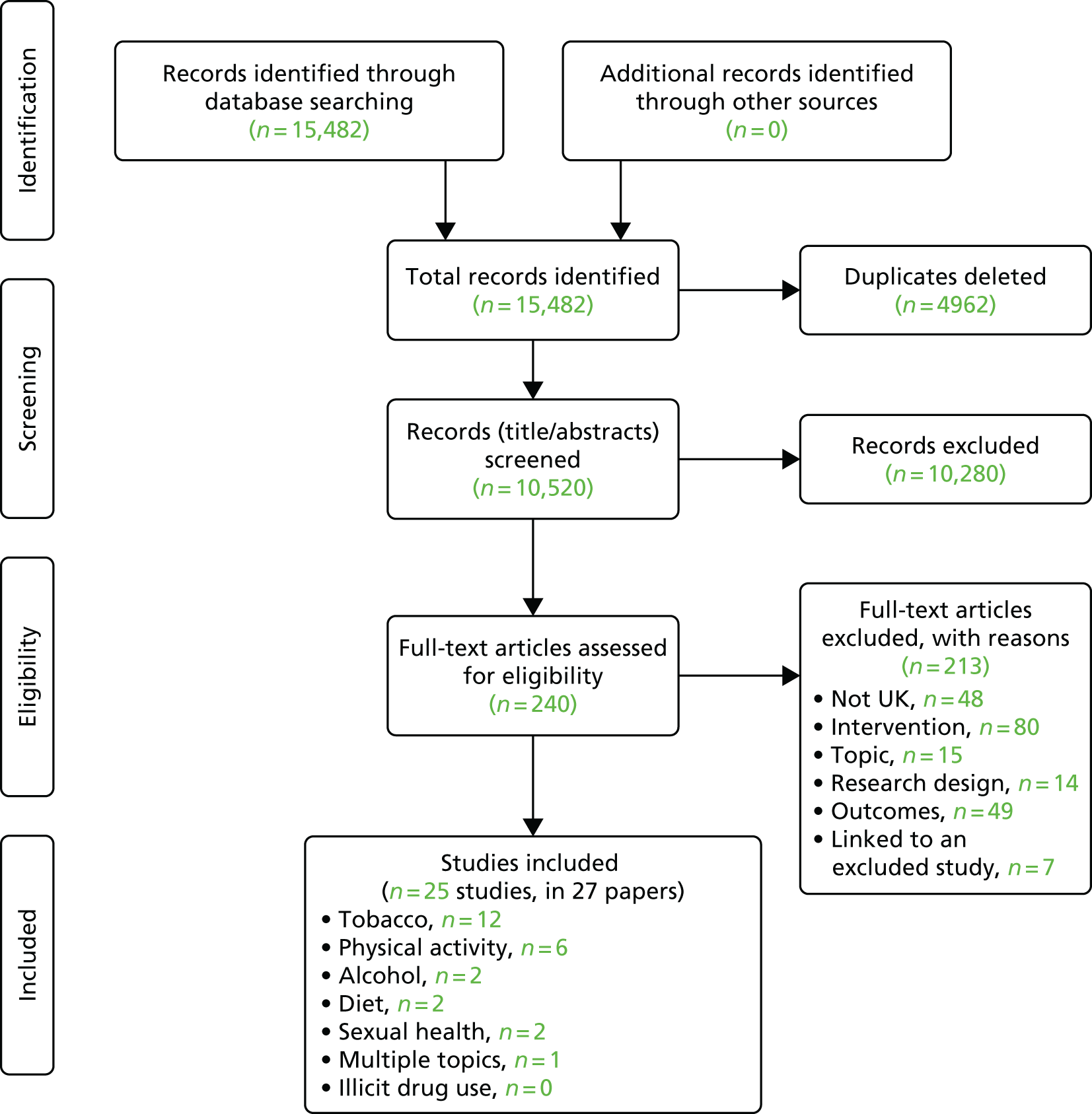

The second (review D) was a systematic review of English-language primary studies of mass media campaigns targeting the same six health topics, conducted in the UK and published between January 2011 and September 2016. The focus of the review was on evidence concerning the characteristics of UK mass media campaigns associated with effectiveness, rather than on the effectiveness of those campaigns per se (see Chapter 5).

Other reviews

We conducted a rapid review of reviews describing the cost-effectiveness of mass media campaigns (review C). We reviewed reviews and systematic reviews, published between January 2000 and January 2017, which assessed economic studies that evaluated both the costs and benefits of mass media campaigns for any of our six health topics of interest (see Chapter 4).

As described previously, no systematic reviews addressing diet met our inclusion criteria for the review of reviews. A scoping search for English-language primary studies (published by August 2016) was conducted for studies of mass media public health campaigns aiming to improve dietary behaviours. The modified search strategy (diet terms and mass media terms) was tested in one database (MEDLINE) and identified > 16,500 hits. A full review and synthesis was too great to conduct within the time and resources of the current project. Project resources were instead directed towards the review of recent UK primary studies (published between January 2011 and September 2016), referred to previously (review D). We focused on UK studies to complement the review of reviews (review A) and enhance the relevance for UK practitioners, policy-makers and commissioners (see Chapter 5).

The logic model

The utility of logic models in systematic reviews

In a broad systematic review such as this, a range of different types of interventions in different contexts are compared and contrasted. Critical to this process is an understanding of how the different interventions are thought (or intended) to work; this provides a conceptual framework to structure the analysis. Based on the idea of programme theory from the evaluation literature, this framework is often described as a ‘logic model’, which is a diagrammatic representation of the key intervention inputs, the activities undertaken in the intervention, and the causal pathway that is triggered by the intervention, resulting in the desired (or not desired) outcome(s). 18 Thinking critically about the causal pathway is important in public health interventions, as there are often long chains of outcomes between the intervention and the ultimate health outcome. For example, in this review, a given mass media campaign might be designed to have a given message to raise awareness about the consequences of a given behaviour. It may adopt a given strategy or intervention theory in order to raise awareness, but merely raising awareness does not necessarily result in improved health. The raised awareness needs to result in a decision to change behaviour; the initial behaviour change, and, ultimately, sustained healthier behaviours, may lead to an improvement in population health.

Many systematic reviews develop a logic model a priori, as this can then drive many of the decisions that need to be made during the systematic review process. First, systematic reviewers need to make consistent decisions about which studies are in the scope of the review and which are not. The logic model can be used to develop inclusion/exclusion criteria in order to delineate the scope of the review. Once the studies for the review have been identified, the logic model can be used to determine what data need to be extracted about studies in a standardised way, in order to structure the comparative analysis. The logic model then helps to structure the analysis, enabling reviewers to identify commonalities and differences in interventions that may help to explain variance between their results. However, although the existence of an a priori logic model can be useful for these reasons, it should be considered provisional and subject to change once the studies have been examined. This is important because once reviewers have seen the range of studies in their review they may find that the logic model does not contain sufficient nuance to capture significant differences in intervention approach, content or in the contextual factors that might influence intervention implementation – or the long causal chain between intervention and health outcome. For this reason, this review contains two logic models: the first, which informed the early stages of the review, helped reviewers to determine what was relevant and irrelevant, and what data should be extracted; the second is based on the first, and also summarised the reviewers’ understanding of the research contained within the review.

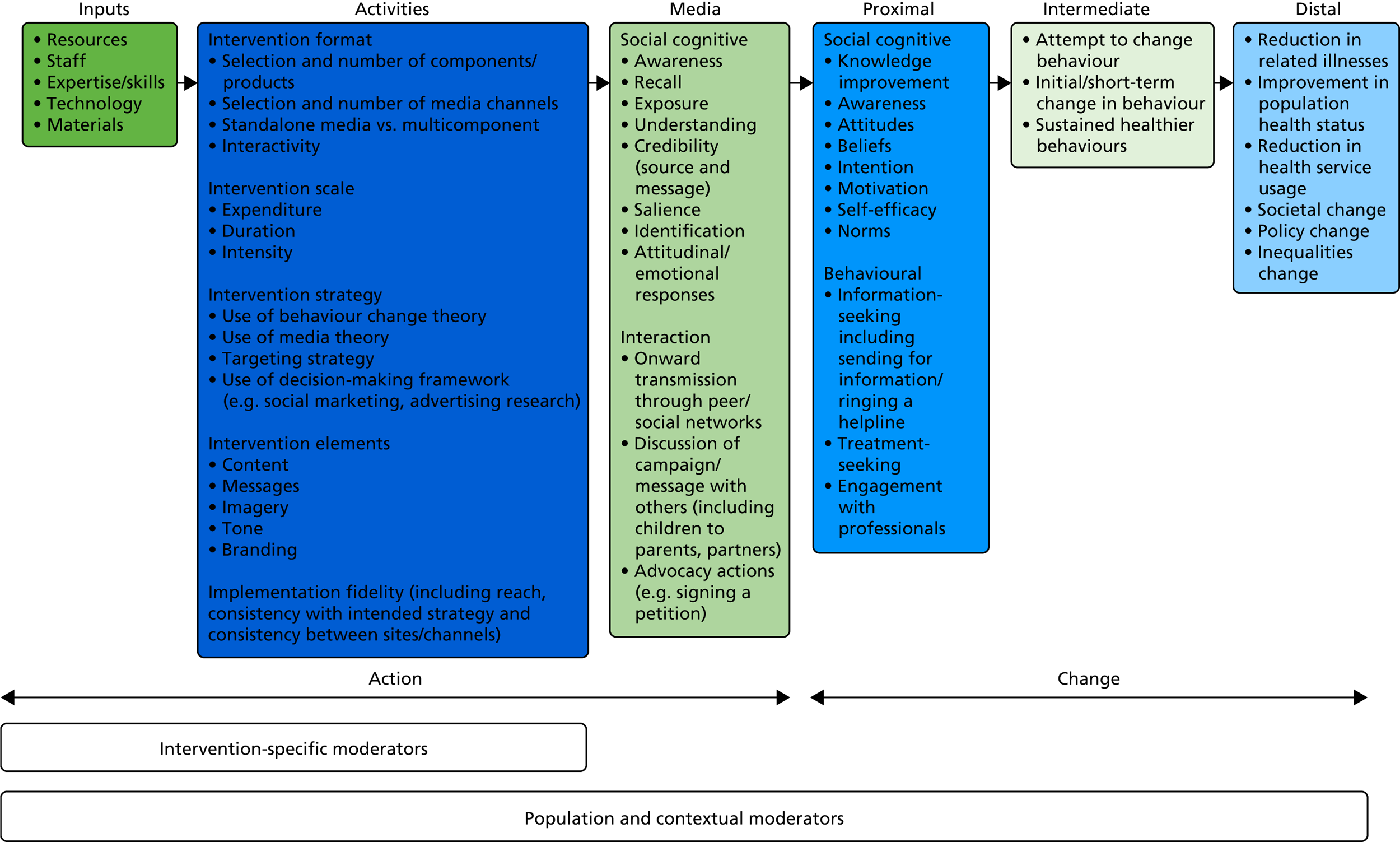

Development of the initial logic model for mass media interventions

The initial logic model owes much of its overarching structure to the work of Chen. 19 We split the model into two major components: the action model (comprising the intervention inputs, activities and media outcomes) and the change model (made up of proximal, intermediate and distal outcomes). Although this may appear to be rather linear, and not cognisant of relevant theorising about complex interventions (e.g. feedback loops, phase changes and emergent outcomes; see Rogers20), we consider mass media interventions as operating in different ways to other public health interventions, and it is possible to conceptualise the intervention as a coherent entity that is implemented, and then the outcomes that result from it in a linear way (i.e. there may be feedback loops and other manifestations of complexity within the change model, but these can be understood as operating downstream of the mass media intervention, and not interacting with it).

We first developed our initial logic model for mass media interventions separately for each of the public health areas of the review before synthesising these into a common logic model. As well as demonstrating how mass media interventions may work, the resulting logic model was used to guide the evidence synthesis through helping to define inclusion and exclusion criteria, identifying moderators (and potentially subgroup analyses if meta-analyses had been possible at a later stage), and identifying mediating factors and guiding the search for evidence. 21 Our initial model represents a synthesis of logic models developed independently of mass media interventions of smoking cessation and mass media interventions of healthy eating/physical activity. In common with the development of logic models more broadly, both logic models were developed through working backwards across an outcome and action chain starting from the distal outcome.

Beginning with smoking cessation, we first located the small number of systematic reviews of mass media interventions for smoking that included a logic model, and used the model included in the review by Niederdeppe et al. 22 as a starting point. This included detail on the change part of a logic model in particular, but was enhanced with further details that helped to disaggregate some of the intermediate outcomes around behaviour change; this corresponded with other models of ‘stages of change’ in health promotion. The action part of the model was enhanced through examining logic models that were developed in other studies of mass media interventions of public health but that were not necessarily specific to smoking cessation (e.g. Huhman et al. 23), as well as significant components that were identified in reviews of mass media smoking interventions, but that were not conceptualised in a logic model (e.g. Durkin et al. 24). Finally, further stages of change of smoking cessation were identified through examining the logic models that were included in reviews of public health and policy interventions for smoking cessation, but that did not necessarily involve mass media. 25 A similar process was employed to develop the logic model for healthy eating/physical activity. To synthesise the models, common components were identified and the language harmonised; for example, both the physical activity and smoking cessation logic models included common stages of change around the attempts at adopting healthier behaviours and reduction in unhealthy behaviours as precursors to successful behaviour change, although these were originally expressed in language specific to each health topic. Even though the two health topics included here were chosen because they were conceptually relatively different and could affect very different populations (making them suitable candidates to pilot this approach), their synthesis was relatively straightforward as both involved synthesising logic models of mass media interventions to stimulate behavioural change for lifestyle behaviours. However, as we expected that some of the health topics that the review would consider may be more complex, we expected that our process of synthesising logic models and developing an overall logic model might result in topic-specific pathways being depicted within the final model; for example, mass media interventions for some health topics might also attempt to change behaviour through an intermediary party, and this might need to be depicted in the logic model. Thus, our initial logic model is presented here (Figure 1), and it was continually challenged and refined throughout the process of the review.

FIGURE 1.

The National Institute for Health Research mass media review: logic model.

Public and stakeholder engagement

Members of the public and stakeholders from a range of organisations were involved in this study. In particular, public and stakeholder engagement informed the development of the research, our refinement of research plans and the interpretation of findings. Stakeholder engagement was particularly important in shaping the focus and scale of our literature searches, in developing and finalising our logic model, and in supporting the research team to reflect on the implications and key messages from our findings, including for the design of mass media campaigns and future research. Chapter 6 describes our engagement activities in more detail.

Chapter 2 What is the impact of mass media campaigns on behaviour and other outcomes? Findings from the review of reviews (review A)

Overview

This chapter reports evidence from the review of reviews on the impact of mass media campaigns on behavioural and other outcomes, and examines evidence of variations in impact between different target populations. The chapter addresses two of the study objectives:

-

1. assess the effectiveness of mass media campaigns to communicate public health messages

-

3. explore how different types and forms of media campaigns can reach and be effective with different target populations (particularly disadvantaged groups).

Methods

Overviews of reviews are becoming an established component in the repertoire of evidence-informed (or evidence-based) policy and practice. 12–14 In order to fulfil the above objectives, we conducted a review of reviews and carried out a high-level synthesis of the evidence on the effects of mass media campaigns across multiple health behaviours. We registered this review with PROSPERO (reference number CRD42013004170). 16

Identification of reviews

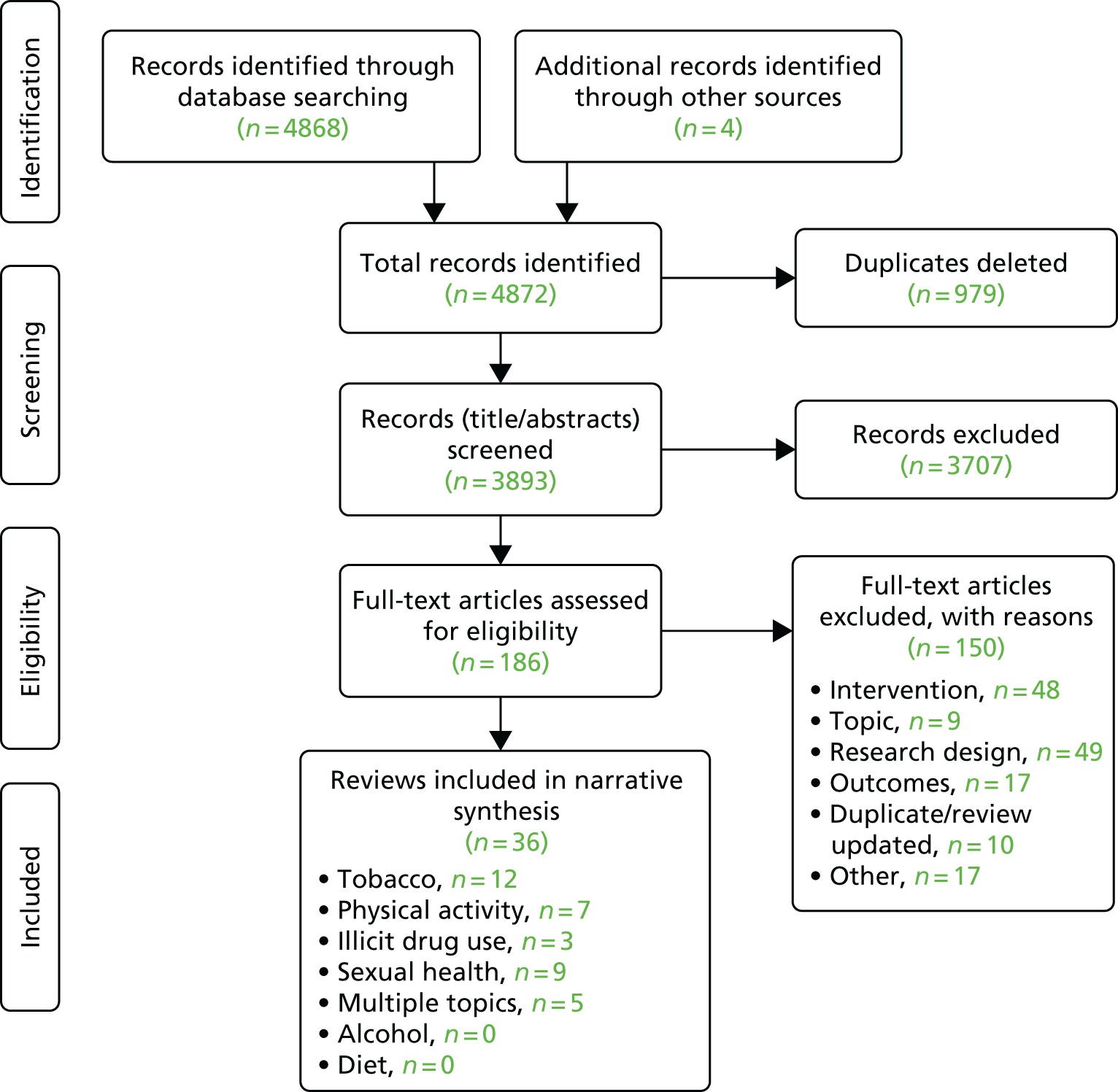

We combined terms concerning mass media campaigns, such as media, ‘mass communication’, ‘social marketing’ and broadcast, with terms denoting systematic reviews and meta-analyses (see Appendix 1). We searched the Database of Promoting Health Effectiveness Reviews, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects, the Campbell Collaboration Library of Systematic Reviews, the Health Technology Assessment database hosted by the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, EMBASE, PubMed, the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, MEDLINE and Web of Science between 10 December 2015 and 5 January 2016. We did not systematically search the grey literature, which was a departure from our protocol; however, systematic reviews published as reports, rather than in peer-reviewed journals, were still identified by the strategy described above. To check the quality of the searches, we searched the results to find systematic reviews already known to the team. The reference lists of any relevant reviews of reviews were also searched. Results were uploaded to an Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Co-ordinating Centre (EPPI)-Reviewer 4 database and deduplicated (Figure 2). 26

FIGURE 2.

The PRISMA flow diagram of the identification and selection of reviews (review A).

Review selection

Records were screened against the inclusion criteria listed in Box 1. Reviews were screened on title and abstract by three reviewers. We carried out comparison coding as an inter-rater reliability test, and, when we agreed on the included and excluded reviews at a 90% rate, the reviewers continued individually. Full-text reviews were then retrieved, and individual expert teams assessed the papers in the different health topic categories to reach the final list of reviews. Two researchers from the wider team adjudicated if there was uncertainty about whether or not to include a review. See Appendix 2 for a list of reviews excluded by full-text assessment.

The review:

-

Was published in or after 2000.

-

Was published in English.

-

Concerned human populations.

-

Included interventions that met the definition of a mass media intervention – the intentional use of any media channel(s) of communication by local, regional and national organisations to influence lifestyle behaviour through largely passive or incidental exposure to media campaigns, rather than largely dependent on active help-seeking (adapted from Wakefield et al. 6 and Bala et al. 27). This excludes, for example, health campaign websites that individuals actively searched for or signed up for.

-

Examined one or more of the following health topics – alcohol use, illicit substance use, diet, physical activity (including sedentary behaviour), sexual and reproductive health, and tobacco use. Reviews examining mass media interventions promoting health screening behaviours (e.g. human immunodeficiency virus testing and cervical screening) are excluded because NHS population screenings are not part of the remit of the National Institute for Health Research Public Health Research programme.

-

Was conducted as a systematic review, which was defined as including a specified search strategy from more than one database, an assessment of the quality of studies and some kind of synthesis of the primary studies.

-

Reported sufficient outcome data on behaviour change and/or its individual determinants. In multicomponent interventions, the outcome data had to relate to the mass media component, not to the whole intervention.

Data extraction

Data from reviews identified as meeting the inclusion criteria were extracted into a standardised data extraction form. Data extracted included review characteristics, participant characteristics, types of study design, types of synthesis and outcome data (particularly social cognitive and behavioural outcomes). For each topic, one reviewer extracted the data, and a sample (≥ 25%) was checked by a second reviewer to ensure the consistency of the extraction.

Quality appraisal and relevance assessment

We used the Risk Of Bias In Systematic reviews (ROBIS) tool to assess the risk of bias of included systematic reviews. 28 Included reviews were assessed by one researcher, and a second researcher checked all their assessments against the full-text review and ROBIS guidelines, with any disagreements discussed between the two researchers. We rated the relevance of the included reviews to our aims (high or low relevance), based on two dimensions: its relevance to an Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) context (included studies conducted in OECD countries versus all studies in the review that were conducted in non-OECD countries)29 and whether or not the review’s main focus was on mass media interventions. We also extracted information on the quality of the included studies in each review as assessed by the review authors: good, medium or low quality or not stated.

Data synthesis

Given the highly heterogeneous nature of the interventions and reviews, we did not attempt to conduct meta-analysis, and a narrative synthesis approach was pursued. 30 We initially tabulated all available data according to topic and tried to identify duplicate results. We then created tabular summaries of the full data, with information on potential bias within the included evidence base retained. We investigated patterns in the available results, making comparisons across topics, outcomes and population subgroups [based on the PROGRESS (Place of residence; Race/ethnicity/culture/language; Occupation; Gender/sex; Religion; Education; Socioeconomic status; Social capital) characteristics],31 with due attention paid to contradictory data. Analysis proceeded iteratively, with the whole team regularly meeting to discuss findings. To summarise the results for the outcomes of interest (behaviours, intentions, awareness/knowledge and attitudes), a symbol was applied to indicate how good the evidence was for a positive or negative effect. 32 This incorporated the risk of bias of the relevant reviews and reported effect sizes/directions. Inconsistency statistics were extracted from relevant meta-analyses.

To make conclusions based on the available evidence, we developed a systematic and transparent approach, building on principles of the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach. 33,34 In addition to risk of bias, we also assessed the domains of inconsistency, indirectness and imprecision for each behaviour. Inconsistency assessed whether or not the reported effects for a behaviour differed between assessments of behaviour change and its determinants, as well as whether or not high statistical heterogeneity was observed within meta-analysis. Directness referred to how directly the evidence related to the health topics examined in this review within the UK context. Evidence on behavioural outcomes was considered ‘direct’ whereas evidence regarding awareness/knowledge, attitudes or intentions only was considered ‘indirect’. Similarly, if available evidence was primarily drawn from non-OECD countries then this was considered indirect. Imprecision was assessed on the basis of the precision of the effect estimate [e.g. did the 95% confidence interval (CI) exclude no effect?]. ‘Overall effect’ was assessed by taking into account the direction of effect for behaviour with consideration of the indirect outcomes and the risk of bias in the evidence available. When there was evidence at a low risk of bias that was directly observed for the behaviour of interest, with little imprecision and inconsistency, we considered this to have a high level of certainty. We downgraded to moderate, low or very low certainty if there was a high risk of bias (by two levels), indirect evidence (by two levels), inconsistency (by one level) and imprecision (by one level).

Overview of the included reviews

Thirty-six systematic reviews were included from the initial 3893 records screened (see Figure 2). The reviews examined mass media interventions for tobacco use (12 reviews),27,35–45 sexual health (nine reviews),46–54 physical activity (seven reviews,55–61 of which one focused on reducing sedentary behaviour)55 and illicit drug use (three reviews),62–64 with five reviews addressing ‘mixed topics’65–69 (i.e. more than one of our six health topics) (Table 1). Although no systematic reviews met our inclusion criteria for alcohol use or diet mass media interventions, studies evaluating campaigns targeting alcohol or diet were included in four mixed heath topics reviews. Fourteen reviews were assessed to have a high risk of bias and 22 were considered to have a low risk of bias (see Appendix 3). Approximately half of the reviews focused solely on mass media interventions (n = 17), and the others reviewed broader ranges of behaviour change interventions including mass media campaigns. When geographical data were provided for mass media studies, 15 of the reviews included at least one study from the UK and four reviews included studies from only non-OECD countries (all sexual health topic reviews); the rest were mainly studies of mass media campaigns from OECD countries. On the basis of the focus of the reviews on mass media and geographical data, 18 of the included reviews were judged as highly relevant to the topic. We searched for reviews published between January 2000 and January 2016; the time period covered by the included reviews’ searches ranged from database inception to January 2015, and the most recent included study was published in 2013.

| Review (first author and year); risk of bias (ROBIS) | Health topic | Was mass media the sole focus? | Aim of the review | Relevance to our review of reviews | Type of synthesis | Number of included studies | Number of relevant studies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abioye (2013);55 low risk of bias | Physical activity | Yes | We searched six electronic databases from their inception to August 2012 and selected prospective studies that evaluated the effect of MMCs on physical activity in adults | High | Meta-analysis | 9 | 9 |

| Bala (2013);27 low risk of bias | Tobacco use | Yes | To assess the effectiveness of MMCs in reducing smoking among adults. Four research questions: i) Do MMCs reduce smoking (prevalence, cigarette consumption, quit attempts and quit rates) compared with no intervention in comparison communities? ii) Do MMCs run in conjunction with tobacco control programmes reduce smoking, compared with no intervention or with tobacco control programmes alone? iii) Which study characteristics relate to their efficacy? iv) Do tobacco MMCs cause any adverse effects? | High | Narrative synthesis | 11 | 11 |

| Bertrand (2006);46 low risk of bias | Sexual health | Yes | To review the strength of the evidence for the effects of three types of [broadcast] mass media interventions . . . on HIV/AIDS-related behaviour among young people in developing countries and to assess whether these interventions reach the threshold of evidence needed to recommend widespread implementation | Low | Narrative synthesis | 15 | 15 |

| Brinn (2010);35 low risk of bias | Tobacco use | Yes | To determine the strength of the evidence that mass media interventions to prevent smoking in young people may: 1) reduce smoking uptake among youths (< 25 years), 2) improve smoking attitudes, behaviour and knowledge, 3) improve self-efficacy/self-esteem, 4) improve perceptions about smoking including the choice to follow positive role models | High | Narrative synthesis | 7 | 7 |

| Brown (2012);56 high risk of bias | Physical activity | Yes | The goal of the systematic review described in this summary was to determine the effectiveness of stand-alone MMCs to increase physical activity at the population level | High | Meta-analysis and narrative synthesis | 16 | 16 |

| Brown (2014);37 high risk of bias | Tobacco use | No | To assess the effectiveness of population-level interventions/policies to reduce socioeconomic inequalities in smoking among adults by assessing primary studies of any intervention/policy that reported differential effects on a smoking-related outcome in at least two socioeconomic groups | Low | Narrative synthesis | 117 | 30 |

| Brown (2014);36 high risk of bias | Tobacco use | No | What is the equity impact of interventions/policies to reduce youth smoking? | Low | Narrative synthesis | 38 | 1 |

| Byrne (2005);65 high risk of bias | Multiple – alcohol use, tobacco use, illicit drug use | Yes | Aims to critically review the literature on past and current drug, alcohol, and tobacco use prevention media campaigns, examining the similarities across health communication programme believed to be effective, with the aim of viewing their applicability for the prevention of youth problem gambling | High | Narrative synthesis | 25 | 25 |

| Carter (2015);47 low risk of bias | Sexual health | No | Community education may involve activities that seek to raise awareness and promote behaviour change, using mass media, social media, and other media or interpersonal methods in community settings. This systematic review evaluated the evidence of the effects of community education on select short- and medium-term family planning outcomes | High | Narrative synthesis | 17 | 14 |

| de Kleijn (2015);38 high risk of bias | Tobacco use | No | The primary aim of this review was to determine how effective school-based interventions are in preventing girls smoking, and the secondary objective was to determine which interventions are most successful | Low | Meta-analysis and narrative synthesis | 37 | 4 |

| Derzon (2002);66 high risk of bias | Multiple – alcohol use, tobacco use, illicit drug use | Yes | A synthesis into the capability of media interventions to reduce youth substance-use | High | Meta-analysis | 72 | 72 |

| Ellis (2003);67 low risk of bias | Topics: multiple – diet, tobacco use | No | (1) to provide an overview of the cancer control interventions (adult smoking cessation, adult healthy diet, mammography, cervical cancer screening, control of cancer pain) that are effective in promoting behaviour change and (2) to identify evidence-based strategies that have been evaluated to disseminate these cancer control interventions | Low | Narrative synthesis | 31 | 8 |

| Ferri (2013);62 low risk of bias | Illicit drug use | Yes | To assess the effectiveness of mass media campaigns in preventing or reducing the use of or intention to use illicit drugs among young people | Low | Meta-analysis and narrative synthesis | 23 | 23 |

| Finlay (2005);57 high risk of bias | Physical activity | Yes | The 1998–2002 studies (interventions) were reviewed for their success in impacting message recall and behaviour change. The newer studies plus those identified by Kahn et al. (2002) and Marcus et al. (1998), were assessed for the presence of a more sophisticated understanding of the media processes of inception, transmission and reception | High | Narrative synthesis | 17 | 8 |

| French (2014);48 low risk of bias | Sexual health | Yes | An exploratory review was conducted to assess research examining awareness, acceptability, effects on HIV testing, disclosure and sexual risk, and cost-effectiveness of HIV mass media campaigns targeting MSM | High | Narrative synthesis | 12 | 12 |

| Gould (2013);39 low risk of bias | Tobacco use | Yes | (a) To systematically review and summarise the literature describing attitudes and key responses to culturally targeted anti-tobacco messages [in indigenous and First Nations populations in Australia, New Zealand, USA and Canada] and (b) identify any differences in effect according to whether the messages were addressed to the target population or . . . general population | Low | Narrative synthesis | 20 | 11 |

| Grilli (2000);49 low risk of bias | Sexual health | Yes | To assess the effects of mass media on the utilisation of health services | Low | Narrative synthesis | 21 | 2 |

| Guillaumier (2012);40 low risk of bias | Tobacco use | Yes | 1. Systematically review the published evidence of the effectiveness of MMCs (with the primary purpose of encouraging smokers to quit) with smokers from socially disadvantaged groups. 2. Critique the methodological quality of the evidence for the effectiveness of MMCs with disadvantaged groups | High | Narrative synthesis | 17 | 17 |

| Hemsing (2012);41 high risk of bias | Tobacco use | No | 1. Do interventions that involve partners’ support of their pregnant partners lead to effective smoking cessation among pregnant partners during pregnancy and postpartum? 2. Are there interventions that are effective in encouraging partners who smoke to stop smoking? . . . Do the intensity and modality of the intervention influence effectiveness? | Low | Narrative synthesis | 9 | 1 |

| Hill (2014);42 high risk of bias | Tobacco use | No | To review and synthesise existing evidence on the equity impact of tobacco control interventions by SES | Low | Narrative synthesis | 77 | 12 |

| Jepson (2006);43 low risk of bias | Tobacco use | Yes | To synthesise evidence evaluating the effectiveness of mass media interventions on helping people to quit smoking/tobacco use and/or to prevent relapse. These interventions were considered for both the effectiveness of the channel of communication and also for the effectiveness of message content | High | Narrative synthesis | 44 | 39 |

| Kahn (2002);58 high risk of bias | Physical activity | No | The Guide to Community Preventive Service’s methods for systematic reviews were used to evaluate the effectiveness of various approaches to increasing physical activity: informational, behavioural and social, and environmental and policy approaches. Changes in physical activity behaviour and aerobic capacity were used to assess effectiveness | Low | Narrative synthesis | 94 | 6 |

| Kesterton (2010);50 high risk of bias | Sexual health | No | This review investigates the effectiveness of interventions aimed at generating demand for and use of sexual and reproductive health services by young people, and interventions aimed at generating wider community support for their use | Low | Narrative synthesis | 74 | 3 |

| LaCroix (2014);51 low risk of bias | Sexual health | Yes | This meta-analysis was conducted to synthesize evaluations of mass media–delivered HIV prevention interventions, assess the effectiveness of interventions in improving condom use and HIV-related knowledge, and identify moderators of effectiveness | Low | Meta-analysis | 54 | 54 |

| Leavy (2011);59 high risk of bias | Physical activity | Yes | To assess progress and quality of (i) campaign evaluation design and sampling, (ii) use of theory and formative research in campaign development and (iii) evidence of campaign effects including proximal, intermediate and behavioural outcomes | High | Narrative synthesis | 18 | 18 |

| Matson-Koffman (2005);60 low risk of bias | Physical activity | No | To review selected and recent environmental and policy interventions designed to increase physical activity and improve nutrition as a way to reduce the risk of heart disease and stroke, promote CVH [cardiovascular health], and summarise recommendations | Low | Narrative synthesis | 64 | 7 |

| Mozaffarian (2012);68 low risk of bias | Multiple – diet, physical activity, tobacco use | No | To identify and assess the evidence for the effectiveness of population approaches in changing dietary, physical activity, or tobacco use habits and related health outcomes. Population strategies were . . . media and educational campaigns . . . consumer information . . . economic incentives, school and workplace approaches, local environmental changes and direct restrictions | Low | Narrative synthesis | ≈100 (not stated) | 31 |

| Ogilvie (2007);61 low risk of bias | Physical activity | No | To conduct a systematic review of the best available evidence across all relevant disciplines to determine what characterises interventions effective in promoting walking; who walks more and by how much as a result of effective interventions; and the effects of such interventions on overall physical activity and health | Low | Narrative synthesis | 48 | 2 |

| Richardson (2008);44 low risk of bias | Tobacco use | No | This review examines the effectiveness of: (a) mass media interventions designed to prevent the uptake of smoking in children and young people and (b) interventions that are designed to prevent the illegal sale of tobacco to children and young people | High | Narrative synthesis | 41 | 37 |

| Robinson (2014);69 low risk of bias | Multiple – physical activity, sexual health, tobacco use | Yes | This review aimed to assess the effectiveness of health communication campaigns that include both mass media and health-related product distribution to increase healthy behaviour change. (The criterion requiring campaigns to use a mass media channel was developed to decrease the challenge of distinguishing campaigns from health education interventions) | High | Meta-analysis and narrative synthesis | 25 study arms in 22 included studies | 11 relevant study arms |

| Speizer (2003);52 high risk of bias | Sexual health | No | We review and synthesise this emerging body of evidence with an eye towards advancing our understanding of ‘what works’ in adolescent reproductive health programming in developing countries | Low | Narrative synthesis | 41 | 6 |

| Swanton (2015);53 low risk of bias | Sexual health | No | The aim of the present research was to examine the effect that new-media-based sexual health interventions have on sexual health behaviours in non-clinical populations and to determine the factors that moderate the effect of technology-based sexual health interventions on sexual health behaviours | High | Meta-analysis | 15 | 12 |

| Sweat (2012);54 low risk of bias | Sexual health | No | To examine the relationship between condom social marketing programmes and condom use | Low | Meta-analysis | 11 | 6 |

| Werb (2011);63 high risk of bias | Illicit drug use | Yes | To investigate the state of the research related to the effectiveness of anti-illicit drug public service announcements in modifying behaviour and intention to use illicit drugs among target populations | High | Meta-analysis | 11 | 11 |

| Werb (2013);64 low risk of bias | Illicit drug use | No | To systematically search the existing peer-reviewed scientific literature in order to identify and assess interventions to prevent the initiation of injection drug use | Low | Narrative synthesis | 8 | 1 |

| Wilson (2012);45 low risk of bias | Tobacco use | No | To evaluate the independent effect on smoking prevalence of four tobacco control policies outlined in the WHO MPOWER Package: increasing taxes on tobacco products, banning smoking in public places, banning advertising and sponsorship of tobacco products, and educating people through health warning labels and antitobacco MMCs | High | Narrative synthesis | 84 | 19 |

The reviews focused on a range of target groups, including studies of mass media campaigns targeting by age group, socioeconomic status, ethnicity, sex, sexual orientation, addictive behaviours, morbidity or parental/pregnancy status, in addition to whole-population, untargeted campaigns. Twelve reviews did not report the sample sizes of their included studies, and a further four reviews only reported some samples sizes. Over the other 20 reviews, the sample sizes of included studies ranged from 27 to 130,245 participants.

Most of the reviews included studies of mass media campaigns that had national reach (n = 22), with a third of these including only national campaigns (n = 7); the rest also included regional and local campaigns. Ten reviews included studies of mass media campaigns that had a local reach only or had a local or national reach. Four of the reviews did not report details on the reach of the campaigns.

Twenty-six reviews presented a narrative synthesis of study results, six reviews completed a meta-analysis of the data and four reviews used both methods to synthesise and present findings. The reviews examined a range of direct behavioural outcomes (reducing harmful behaviours, increasing healthy behaviours and help-seeking), indirect behavioural outcomes and sociocognitive outcomes (intentions, awareness and knowledge, attitudes and beliefs, and norms and self-efficacy), and 16 reviews analysed data for subpopulations (see Table 1).

The types of studies included by the reviews in their syntheses were reported in most of the reviews (n = 34). The majority of syntheses included a mixture of study designs, from randomised control trials (RCTs) and trials, cohort studies, pre–post studies and post-test only studies (n = 23). Four reviews synthesised data from RCTs and trials only, six reported data from pre–post-test studies only and one review reported post-test data only (see Appendix 4 for the detailed characteristics of the included systematic reviews).

Evidence of impact on behavioural outcomes

We examined evidence of the effects of mass media campaigns on behavioural outcomes relating to all of our health topics. Rather than present evidence simply by health topic, we synthesised evidence across three broad categories of behavioural outcome: reducing harmful behaviours, increasing healthy behaviours and treatment-seeking. We were interested in examining whether or not the effectiveness of mass media campaigns differs across these three types of behavioural outcome; for example, are mass media campaigns more effective at encouraging or reinforcing positive behaviours than at discouraging negative behaviours? We defined ‘reducing harmful behaviours’ as bringing about a reduction in behaviours that have harmful effects (e.g. preventing young people from taking up smoking or encouraging smoking cessation, reducing other substance use and reducing sedentary behaviour). We defined ‘increasing healthy behaviours’ as encouraging greater engagement in behaviours that are protective of health, such as engaging in physical activity or using a condom. ‘Treatment-seeking’ was defined as engaging in specific actions to secure information, advice, support or treatment relating to the health topics examined in the review, for example using a sexual health service, seeking testing for sexually transmitted diseases or calling a smoking quitline.

Reducing harmful behaviours

Fourteen reviews reported evidence on whether or not mass media campaigns reduced harmful behaviours, as outlined in Table 2. 27,35,38,40,41,43–45,55,62,63,65,66,68 Eleven focused on a specific health topic and three examined mixed health topics. 65,66,68 All 14 reviews included studies based in OECD countries, and seven included studies conducted in the UK. 27,41,43–45,55,68 Ten of the reviews were rated as having a low risk of bias27,35,38,40,43–45,55,62,68 and four were considered to have a high risk of bias. 41,63,65,66 Eleven reviews focused on a specific health topic and three examined mixed health topics. 65,66,68 Three reviews used meta-analysis,55,62,66 with the remainder presenting results in a narrative synthesis.

| Review topic | Outcome | Review (first author and year) | Result | Risk of bias and quality | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Review risk of biasa | Quality of included studiesb | Mass media focus | ||||

| Physical activity | Reduction in sedentary behaviour | Abioye (2013)55 |

▲ RR 1.15, 95% CI 1.03 to 1.30 (4 studies) ~ I2 = 63% |

✓ | = | All 15 studies on mass media |

| Illicit drugs | Use of illicit drugs | Ferri (2013)62 |

Meta-analysis of RCTs: ● ~ I2 = 70% |

✓ | = | All 23 studies on mass media |

| Illicit drugs | Use of illicit drugs | Ferri (2013)62 |

Other study designs (not RCTs): △ |

✓ | = | All 23 studies on mass media |

| Illicit drugs | Use of illicit drugs | Werb (2011)63 |

▲ ~ I2 = 100% |

✗ | Not stated | All 11 studies on mass media |

| Tobacco | Smoking uptake | Richardson (2008)44 | △ | ✓ | = | 37 of 60 studies on mass media |

| Tobacco | Smoking initiation | Wilson (2012)45 | ◁▷ | ✓ | = | 19 of 84 studies on mass media |

| Tobacco | Smoking uptake | Brinn (2010)35 | ◁▷ | ✓ | ✗ | All 7 studies on mass media |

| Tobacco | Smoking uptake | de Kleijn (2015)38 | △ | ✓ | Not stated | 4 of 37 studies on mass media |

| Tobacco | Smoking prevalence | Bala (2013)27 | ◁▷ | ✓ | ✗ | All 11 studies on mass media |

| Tobacco | Smoking prevalence | Wilson (2012)45 | ◁▷ | ✓ | = | 19 of 84 studies on mass media |

| Tobacco | Smoking consumption | Bala (2013)27 | ◁▷ | ✓ | ✗ | All 11 studies on mass media |

| Tobacco | Quit attempts | Bala (2013)27 | ◁▷ | ✓ | ✗ | All 11 studies on mass media |

| Tobacco | Quit rates | Bala (2013)27 | ◁▷ | ✓ | ✗ | All 11 studies on mass media |

| Tobacco | Quit attempts | Hemsing (2012)41 |

O Based on 1 study |

✗ | = | 1 of 9 studies on mass media |

| Tobacco | Smoking cessation | Wilson (2012)45 | ◁▷ | ✓ | = | 19 of 84 studies on mass media |

| Tobacco | Smoking cessation | Jepson (2006)43 | ◁▷ | ✓ | ✗ | 39 of 44 studies on mass media |

| Tobacco | Smoking cessation | Guillaumier (2012)40 | ◁▷ | ✓ | ✗ | 17 of 17 studies on mass media |

| Tobacco (mixed topics review) | Smoking prevention and cessation | Mozaffarian (2012)68 | △ | ✓ | = | 25 of about 100 studies |

| Mixed topics | Substance use (illicit drugs, alcohol and tobacco) | Derzon (2002)66 | ▲ | ✗ | Not stated | All 72 studies |

| Mixed topics | Substance use (illicit drugs, alcohol and tobacco) | Byrne (2005)65 | △ | ✗ | Not stated | All 25 campaigns in 53 studies |

Effects on sedentary behaviour were examined in one review. A meta-analysis of studies based in OECD countries on the effect of mass media campaigns on physical activity in adults found evidence of mass media campaigns reducing sedentary behaviour [relative risk (RR) 1.15, 95% CI 1.03 to 1.30], with moderate heterogeneity observed (I2 = 63%; p = 0.018). 55

Two reviews reported on whether or not mass media campaigns had an impact on illicit drug use. A meta-analysis of RCT studies of campaigns targeting young people (aged < 26 years) found no effect (standardised mean difference –0.02, 95% CI –0.15 to 0.12), but did find evidence of reductions in the use of illicit drugs in an analysis of non-RCT studies. 62 The other, a review of the effects of anti-illicit drug public service announcements on youth (no definition by age specified) found very small positive reductions in illicit drug use, with considerable inconsistency; however, it should be noted that this review had a high risk of bias. 63

Nine reviews (eight specifically focusing on tobacco27,35,38,40,41,43–45 and one examining a range of health topics68) examined the impact of mass media campaigns on tobacco use. All included OECD-based studies and five included UK studies. 27,41,43–45 Four reviews, all considered to have a low risk of bias, examined the impact on preventing smoking uptake in young people. The review by Richardson et al. ,44 which included one UK study, reported positive results for smoking prevention: the narrative synthesis found evidence to suggest that mass media campaigns can prevent the uptake of smoking in young people (evidence from one review and two studies) and that industry-sponsored studies are less effective (evidence from one study). The other three reviews – Wilson et al. 45 (which included one UK study), de Kleijn et al. 38 and Brinn et al. 35 – all reported mixed results.

Five reviews examined smoking cessation or quit rates. Four reviews with a low risk of bias that included UK or OECD studies reported mixed results. 27,40,43,45 The fifth review reported no effect on quit attempts; the review had a high risk of bias and the evidence was from one study conducted in the UK. 41 Finally, a review that examined a range of health topics reported evidence of mass media campaigns having a positive effect on the combined outcomes of smoking prevention and cessation. 68

The impact of mass media on the use of a combination of substances (alcohol, illicit drugs and alcohol) was examined by two mixed health topic reviews. 65,66 Although both of these reviews reported positive effects, both reviews were rated as having a high risk of bias.

Increasing healthy behaviours

Twelve reviews reported evidence on whether or not mass media campaigns can increase healthy behaviours (Table 3). Ten focused on specific health topics (either physical activity55–61 or sexual health52–54) and two examined a range of topics. 68,69 None of the included reviews focused exclusively on diet/healthy eating, but one of the mixed-topic reviews included evidence on diet-related behaviours. 69 Nine of the reviews included studies conducted in OECD countries,55–61,68,69 four included studies conducted in the UK55,57,58,60 and two did not report the countries. 53,56 Two of the reviews, focusing on sexual health interventions, comprised studies conducted in low- and middle-income countries. 52,54

| Review topic | Outcome | Review (first author and year) | Result | Risk of bias and quality | Mass media focus | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Review risk of biasa | Quality of included studiesb | |||||

| Diet (mixed-topic review) | Consumption of healthy food | Mozaffarian (2012)68 | △ | ✓ | = | 25 of about 100 studies |

| Physical activity | Brisk walking | Abioye (2013)55 |

▲ RR 1.53 (95% CI 1.25 to 1.87) ✓ I2 = 0% |

✓ | = | All 15 studies on mass media |

| Physical activity | Time spent walking | Ogilvie (2007)61 | △ | ✓ | = | 2 of 48 studies on mass media |

| Physical activity | Overall physical activity | Abioye (2013)55 |

● RR 1.02 (95% CI 0.91 to 1.14) ~ I2 = 72% |

✓ | = | All 15 studies on mass media |

| Physical activity (mixed-topic review) | Increases in physical activity | Mozaffarian (2012)68 | △ | ✓ | = | 25 of about 100 studies |

| Physical activity | Self-reported time spent in physical activity | Brown (2012)56 |

▲ Median relative increase of 4.4% |

✗ | = | All 16 studies on mass media |

| Physical activity | Self-reported activity | Brown (2012)56 | △ | ✗ | = | All 16 studies on mass media |

| Physical activity | Changes in physical activity | Finlay (2005)57 | ◁▷ | ✗ | = | All 8 studies on mass media |

| Physical activity | Self-reported activity | Brown (2012)56 | ◁▷ | ✗ | = | All 16 studies on mass media |

| Physical activity | Changes in physical activity | Leavy (2011)59 | ◁▷ | ✗ | ✗ | All 18 studies on mass media |

| Physical activity | Stair use | Matson-Koffman (2005)60 | △ | ✓ | ✓ | 9 of 64 studies on mass media |

| Physical activity (mixed-topic review) | Stair use | Mozaffarian (2012)68 | △ | ✓ | = | 25 of about 100 studies |

| Physical activity | Stair use | Kahn (2002)58 | △ | ✗ | = | 6 of 94 studies on mass media |

| Sexual health | Condom use | Swanton (2015)53 |

▲ OR 1.39 (95% CI 1.06 to 1.83) ~ I2 = 77.2% |

✓ | ✗ | 12 of 15 studies on mass media |

| Sexual health | Condom use – most recent sex encounter | Sweat (2012)54 |

▲ OR 2.01 (95% CI 1.42 to 2.84) ~ (narratively assessed) |

✓ | ✗ | 6 of 11 studies on mass media |

| Sexual health | Condom use – all condom use | Sweat (2012)54 |

▲ OR 2.10 (95% CI 1.51 to 2.91) ~ (narratively assessed) |

✓ | ✗ | 6 of 11 studies on mass media |

| Sexual health | Condom use | Speizer (2003)52 | ◁▷ | ✗ | ✓ | 6 of 41 studies on mass media |

| Sexual health (mixed-topic review) | Condom use | Robinson (2014)69 | △ | ✓ | = | All 22 studies |

Eight of the reviews examined whether or not there was evidence that mass media campaigns could increase physical activity. A range of physical activity outcomes were reported, including walking, overall levels of physical activity, and using the stairs. In reviews that examined impact on stair use, the mass media campaigns typically comprised ‘point-of-decision prompts’, such as posters in locations with high footfall (e.g. public transport hubs and workplaces), encouraging people to use the stairs rather than the lift or escalator.

Two reviews with a low risk of bias reported evidence that mass media campaigns increased walking behaviour. In a meta-analysis of four studies, Abioye et al. 55 found evidence that mass media campaigns could produce an increase in brisk walking (RR 1.53, CI 1.25 to 1.87), whereas Ogilvie et al. 61 found evidence from two studies that mass media campaigns increased the time spent walking. Two reviews with a low risk of bias, one focusing specifically on physical activity60 and one examining a range of topics,68 found that stair use was increased by mass media campaigns comprising point-of-decision prompts (e.g. signs and banners to encourage using stairs). A third review, with a high risk of bias, also reported evidence that mass media campaigns could increase stair use. 58

However, reviews that examined overall levels of physical activity or time spent in physical activity reported generally mixed evidence. A meta-analysis of four studies in one review with a low risk of bias found no clear impact on overall physical activity (RR 1.02, 95% CI 0.91 to 1.14; I2 = 72%). 55 In contrast, a mixed-topic review at low risk of bias found a positive effect on increases in overall physical activity. 68 The evidence from three reviews with a high risk of bias that examined changes in physical activity behaviours was generally mixed. 56,57,59

Four reviews provided evidence on whether or not mass media campaigns could increase healthy sexual health behaviours. Three reviews with a low risk of bias examined the impact of mass media on condom use: two of these reviews conducted meta-analysis and found that media campaigns had a positive effect on condom use, with inconsistency in the effect estimates [odds ratio (OR) 1.39, 95% CI –1.06 to –1.83;53 and OR 2.01, 95% CI 1.42 to 2.84, OR 2.10, 95% CI 1.51 to 2.9154]. The third review, which was of mixed health behaviour topics, also reported positive effects on condom use. 69 The fourth review reported mixed results of the effect of mass media on sexual health behaviours;52 this review was found to have a high risk of bias.

Finally, a mixed-topic review with a low risk of bias reported that mass media campaigns could have a positive effect on the consumption of healthy food. 68

Treatment-seeking

Ten reviews provided information on treatment-seeking: six focused on treatment-seeking in relation to sexual health46–50,52 and four focused on treatment-seeking in relation to tobacco use (Table 4). 27,37,42,43 Seven of the reviews included studies conducted in OECD countries,27,37,42,43,47–49 and all seven included studies conducted in the UK. Six were at a low risk of bias27,43,46–49 and four were at a high risk of bias. 37,42,50,52

| Review topic | Outcome | Review (first author and year) | Result | Risk of bias and quality | Mass media focus | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Review risk of biasa | Quality of included studiesb | |||||

| Sexual health | Use of family planning services | Carter (2015)47 | △ | ✓ | = | 14 of 17 studies on mass media |

| Sexual health | Use of health services | Grilli (2000)49 | ◁▷ | ✓ | ✗ | 2 of 21 studies on mass media |

| Sexual health | Use of health centre | Kesterton (2010)50 |

△ Based on 1 study |

✓ | ✗ | 3 of 74 studies on mass media |

| Sexual health | Use of clinic | Speizer (2003)52 |

△ Based on 1 study |

✗ | ✓ | 6 of 41 studies on mass media |

| Sexual health | HIV testing | French (2014)48 | ◁▷ | ✓ | ✗ | All 12 studies on mass media |

| Sexual health | Use of HIV service/clinic | Bertrand (2006)46 | ◁▷ | ✓ | ✗ | All 15 studies on mass media |

| Tobacco | Calls to quitline | Jepson (2006)43 | △ | ✓ | ✗ | 39 of 44 studies on mass media |

| Tobacco | Calls to quitline | Bala (2013)27 |

△ Based on 1 study |

✓ | ✗ | All 11 studies on mass media |

| Tobacco | Calls to quitline | Hill (2014)42 | ◁▷ | ✗ | ✗ | 12 of 77 studies on mass media |

| Tobacco | Calls to quitline | Brown (2014)37 | ◁▷ | ✗ | ✗ | 30 of 117 studies on mass media |

Of four reviews examining the impact of media campaigns on the use of sexual health services or clinics, one found a positive effect47 and one reported mixed results. 49 Positive results were reported in two further reviews,50,52 but results were from only one study in each review and both reviews were at high risk of bias. The effects of mass media campaigns on the uptake of HIV testing or HIV services was examined in two reviews with a low risk of bias, both reporting mixed evidence. 46,48

There was evidence of mass media campaigns having a positive effect on calls to smoking quitlines from two reviews with a low risk of bias,27,43 although this was based on only one study in one of the reviews. 27 Mixed evidence was reported for the impact of mass media campaigns on smoking quitlines in two reviews with a high risk of bias. 37,42

Evidence of the impact on indirect behavioural outcomes and social cognitive outcomes

We also examined evidence of the effects of mass media campaigns on indirect behavioural outcomes and social cognitive outcomes. Indirect behavioural outcomes were defined as intentions to engage in, reduce or desist from unhealthy behaviours (such as smoking) or to engage in healthy behaviours (such as condom use). Social cognitive outcomes comprised awareness, knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, norms and self-efficacy.

Intentions

Seven reviews examined whether or not there was evidence that mass media campaigns had an impact on intentions to change behaviour (Table 5). 35,39,47,59,62,63,69 All of the reviews included studies from OECD countries but none included studies from the UK. Statistical methods were used in two reviews to assess the impact of mass media campaigns on illicit drug use intentions. 62,63 The remaining five reviews used narrative synthesis. Most of the reviews were of good quality (at a low risk of bias).

| Review topic | Outcome | Review (first author and year) | Result | Risk of bias and quality | Mass media focus | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Review risk of biasa | Quality of included studiesb | |||||

| Illicit drug use | Not to use/to reduce use/to stop use of illicit drugs | Ferri (2013)62 |

◀▶ SMD –0.07 (95% CI –0.19 to 0.04) ~ I2 = 0.0% |

✓ | = | All 23 mass media studies |

| Illicit drug use | To use illicit drugs | Werb (2011)63 |

◀▶ 0.29 (95% CI –0.17 to 0.75) ✓ I2 = 66.1% |

✗ | Not stated | All 11 mass media studies |

| Physical activity | To be more active | Leavy (2011)59 | △ | ✗ | ✗ | All 18 studies on mass media |

| Sexual health | To use contraception | Carter (2015)47 | ◁▷ | ✓ | = | 14 of 17 mass media studies |

| Tobacco use (mixed-topic review) | Intentions to quit, calls to quitlines | Robinson (2014)69 | △ | ✓ | = | All 22 studies |

| Tobacco use | To quit or smoke | Gould (2013)39 | △ | ✓ | ✗ | 11 of 20 studies on mass media |

| Tobacco use | To smoke | Brinn (2010)35 | ◁▷ | ✓ | ✗ | All 7 mass media studies |

Three reviews with a low risk of bias examined tobacco use: two focused solely on tobacco35,39 and one mixed-topic review included tobacco. 69 Positive results for intentions to quit or to smoke were reported in two of the reviews,39,69 whereas one review that focused on reducing smoking prevalence in young people reported largely mixed results for the intention to start smoking. 35 The quality of the included studies was assessed by the reviews themselves as medium to low.

Statistical pooling in two reviews, one at low risk of bias62 and one at high risk of bias,63 found a mixed impact of mass media campaigns on illicit drug use intentions (including not to use, to reduce use or to stop use), with no clear indication of either a positive or negative overall effect.

One sexual health review with a low risk of bias reported largely mixed results for intentions to use contraception,47 whereas a physical activity review reported largely positive results for intentions to be more active,59 but the review had a high risk of bias.

Awareness and knowledge

Fifteen reviews reported on whether or not mass media campaigns had an impact on awareness and knowledge (Table 6). 27,35,39,44,46,47,50–52,57,62,65–68 The reviews had varying levels of relevance to the UK context: three reviews included non-OECD country research only, five reviews included one or two UK studies and the rest were reviews of studies from mainly OECD countries. Two reviews presented statistical results, with the remaining reviews presenting only narrative results. 51,66

| Review topic | Outcome | Review (first author and year) | Result | Risk of bias and quality | Mass media focus | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Review Risk of Biasa | Quality of included studiesb | |||||

| Diet (mixed-topic review) | Healthy diets | Mozaffarian (2012)68 | △ | ✓ | = | 25 of about 100 studies |

| Diet (mixed-topic review) | Dietary counselling helplines | Ellis (2003)67 | △ | ✓ | ✗ | 8 of 31 studies |

| Illicit drug use | Illicit drug effects |

Ferri (2013)62 Effects of illicit drugs use |

◁▷ | ✓ | = | All 23 studies on mass media |

| Physical activity (mixed-topic review) | Physical activity | Mozaffarian (2012)68 | △ | ✓ | = | 25 of about 100 studies |

| Physical activity | Physical activity | Finlay (2005)57 | △ | ✗ | = | All 8 studies on mass media |

| Sexual health | HIV prevention and transmission | LaCroix (2014)51 |

HIV prevention: ▲ d+ = 0.39 (95% CI 0.25 to 0.52), k = 65 HIV transmission: ▲ d+ = 0.30 (95% CI 0.18 to 0.41) |

✓ | Not stated | All 54 studies on mass media |

| Sexual health | Sexual health | Carter (2015)47 | △ | ✓ | = | 14 of 17 studies on mass media |

| Sexual health | Contraception | Carter (2015)47 | △ | ✓ | = | 14 of 17 studies on mass media |

| Sexual health | Health products/service | Bertrand (2006)46 | △ | ✓ | ✗ | All 15 studies on mass media |

| Sexual health | HIV transmission, condom use, HIV risk and prevention methods | Bertrand (2006)46 | ◁▷ | ✓ | ✗ | All 15 studies on mass media |

| Sexual health | How to access services | Kesterton (2010)50 |

△ Based on 1 study |

✓ | ✗ | 3 of 74 studies on mass media |

| Sexual health | Reproductive health |

Speizer (2003)52 Reproductive health |

△ Based on 1 study |

✗ | ✓ | 6 of 41 studies on mass media |

| Tobacco use | Knowledge, attitudes and intentions: towards tobacco use and the tobacco industryc | Richardson (2008)44 | ◁▷ | ✓ | = | 37 of 60 studies on mass media |

| Tobacco use | Knowledge/beliefs: smoking and cardiovascular riskc | Bala (2013)27 | ◁▷ | ✓ | ✗ | All 11 studies on mass media |

| Tobacco use | Smoking | Gould (2013)39 | △ | ✓ | ✗ | 11 of 20 studies on mass media |

| Tobacco use (mixed-topic review) | Smoking cessation helplines | Ellis (2003)67 | △ | ✓ | ✗ | 8 of 31 studies |

| Tobacco use | Smoking | Brinn (2010)35 | ▽ | ✓ | ✗ | All 7 studies on mass media |

| Mixed-topic review | Substance use (illicit drugs, alcohol and tobacco) | Derzon (2002)66 | ▲ | ✗ | Not stated | All 72 studies |

| Mixed topics | Substance use (illicit drugs, alcohol and tobacco) | Byrne (2005)65 | △ | ✗ | Not stated | All 25 campaigns in 53 studies |

There was evidence that mass media campaigns increased knowledge and awareness in relation to sexual health (including knowledge of HIV prevention and transmission, contraception and services). One low-risk-of-bias meta-analysis of 54 studies found consistent positive results for the improvement in knowledge of HIV transmission (d+ = 0.30, 95% CI 0.18 to 0.41, based on 47 reports) and prevention (d+ = 0.39, 95% CI 0.25 to 0.52, based on 65 reports). 51 Positive results regarding sexual health awareness and knowledge outcomes were also reported in four reviews using narrative synthesis,46,47,50,52 but three of these46,50,52 did not include any studies from the UK or other OECD countries, one review had a high risk of bias,52 and both Speizer et al. 52 and Kesterton and Cabral de Mello50 based their results on only one study. The review by Bertrand and Anhang46 also reported some mixed results.

Four reviews with a low risk of bias found mixed evidence that mass media campaigns could improve awareness and knowledge regarding tobacco. Two reviews, which both included studies from the UK,27,44 reported mixed results, whereas the third review reported positive results39 and the fourth review reported negative results. 35 A mixed-topic review with a low risk of bias that examined the effects on knowledge of smoking cessation helplines reported positive results. 67

The effects on knowledge of illicit drugs were examined in one illicit drugs review with a low risk of bias, which reported mixed results. 62 In addition, two mixed-topic reviews65,66 examined the effects on tobacco, alcohol and illicit drugs knowledge. A meta-analysis of the effects on drugs knowledge reported positive results [Δ = 0.05 standard deviation (SD); p < 0.05]66 and a narrative review also reported positive results;65 however, both of these reviews had a high risk of bias.

There was weak evidence that mass media campaigns could have an impact on awareness and knowledge regarding physical activity. Overall positive results, including from UK studies, were reported in one mixed-topic review with a low risk of bias that examined this outcome,68 whereas positive results were also reported by Finlay and Faulkner,57 but the review had a high risk of bias.

Finally, two of the mixed-topic reviews examined evidence of the impact on diet-related awareness and knowledge, both reporting positive results;67,68 the review by Mozaffarian et al. 68 included UK studies.

Attitudes, beliefs, norms and self-efficacy

Ten reviews reported on whether or not mass media campaigns had an impact on attitudes, beliefs, norms and self-efficacy (Table 7). 27,35,44,46,47,52,62,65,66,68 One review conducted a meta-analysis;66 however, only narrative results were presented in the other nine reviews. Most of the reviews were of good quality (low risk of bias), but their relevance to the UK varied.

| Review topic | Outcome | Review (first author and year) | Result | Risk of bias and quality | Mass media focus | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Review risk of biasa | Quality of included studiesb | |||||

| Illicit drug use | Attitudes: illicit drug use |

Ferri (2013)62 Illicit drug use |

◁▷ | ✓ | = | All 23 studies on mass media |

| Illicit drug use | Norms: perceived peer norms | Ferri (2013)62 | ◁▷ | ✓ | = | All 23 studies on mass media |

| Physical activity (mixed-topic review) | Attitudes: physical activity | Mozaffarian (2012)68 | △ | ✓ | = | 25 of about 100 studies |

| Sexual health | Attitudes: use of family planning | Carter (2015)47 |

△ Based on 1 study |

✓ | = | 14 of 17 studies on mass media |

| Sexual health | Attitudes: reproductive health | Speizer (2003)52 |

△ Based on 1 study |

✗ | ✓ | 6 of 41 studies on mass media |

| Sexual health | Beliefs: risk of pregnancy | Carter (2015)47 | △ | ✓ | = | 14 of 17 studies on mass media |

| Sexual health | Beliefs: personal risk of HIV/AIDS | Bertrand (2006)46 | ▽ | ✓ | ✗ | All 15 studies on mass media |

| Sexual health | Self-efficacy: using condoms | Bertrand (2006)46 | ◁▷ | ✓ | ✗ | All 15 studies on mass media |

| Tobacco use (mixed-topic review) | Attitudes: smoking | Mozaffarian (2012)68 | △ | ✓ | = | 25 of about 100 studies |

| Tobacco use | Knowledge, attitudes and intentions: towards tobacco use and the tobacco industryc | Richardson (2008)44 | ◁▷ | ✓ | = | 37 of 60 studies on mass media |

| Tobacco use | Knowledge/beliefs, attitudes, norms and social influences: smoking and cardiovascular riskc | Bala (2013)27 | ◁▷ | ✓ | ✗ | All 11 studies on mass media |

| Tobacco use | Attitudes and norms | Brinn (2010)35 | ◁▷ | ✓ | ✗ | All 7 studies on mass media |

| Tobacco use | Self-efficacy | Brinn (2010)35 | ▽ | ✓ | ✗ | All 7 studies on mass media |

| Mixed topics | Attitudes: substance use (illicit drugs, alcohol and tobacco) | Derzon (2002)66 | ▲ | ✗ | Not stated | All 72 studies |

| Mixed topics | Attitudes: substance use (illicit drugs, alcohol and tobacco) | Byrne (2005)65 | ◁▷ | ✗ | Not stated | All 25 campaigns in 53 studies |

For illicit drugs, the evidence was mixed. A mixed-topic meta-analysis that examined effects on drug use attitudes reported overall positive results (Δ = 0.02 SD; p < 0.05),66 but the review was at high risk of bias, whereas mixed evidence of impact on attitudes to illicit drug use and perceived peer norms was reported in a review with a low risk of bias62 and in a review with a high risk of bias. 65

For sexual health, overall positive results regarding beliefs about risk of pregnancy were reported in one review with a low risk of bias. 47 Positive results regarding other attitude changes were reported in two other sexual health reviews,47,52 but Speizer et al. 52 included only low-income countries and in both cases the reported results were from only one study. Mixed results were reported for the impact on self-efficacy, and negative results were reported for the impact on beliefs by Bertrand and Anhang,46 but this review was limited to low-income country studies and, therefore, it is of less relevance.

The evidence was mixed for tobacco. Three reviews, two including UK studies, reported overall mixed results for the impact on attitudes,27,35,44 and Brinn et al. 35 also reported overall negative results for the impact on self-efficacy. 35 However, a mixed-topic review including UK studies that examined the impact on attitudes to smoking reported overall positive results. 68 The same review also reported overall positive results for attitudes to physical activity.

Evidence of the impact on distal outcomes

In addition to investigating the impact of mass media on proximal outcomes (such as beliefs, attitudes and self-efficacy) and intermediate outcomes (including attempted and sustained behaviour change), evidence on distal outcomes was sought. As noted in the logic model (see Figure 1), this included reduction in illnesses, improved population health, reduced health service usage, societal change, policy change and impact on inequalities. Of all of the systematic reviews included, only one reported on any distal outcomes. 43 The authors noted that:

There is evidence of good quality (1&2 +, C), which shows an effect of mass media interventions on attitudes towards smoking and intentions to smoke among young people under 25 years.

This suggests that mass media programmes may have contributed to the denormalisation of smoking among young people.

Evidence of the impact on different target subpopulations

Summary of the approach to subpopulations in reviews

The majority of the included reviews provide evidence about whether or not the effects of mass media campaigns were comparable across one or more subpopulations. Reviews differ in the extent to which the identification and synthesis of subpopulation differences formed a primary objective. In several reviews, all focusing on tobacco control campaigns, the main aim was to determine the equity or inequity of effects of campaigns across socioeconomic groups. 37,40,42 Some reviews dedicated part of their synthesis to looking at effects in specific subgroups,43–45,54,62 or to looking more generally for factors that moderate sizes of effect51,55 or described results separately for subgroups when this was shown in the original papers. 27,58,61,63 Most reviews provide a narrative synthesis of results for different subpopulations as described by the original studies; very few have conducted a formal statistical subgroup analysis. Some reviews that have included a meta-analysis have examined the factors that cause heterogeneity in study findings,51,55 or analyse in subgroups when available from the original studies. 54,62 A few reviews simply highlighted the subgroups in which statistically significant effects had been found in the original studies; if this was not part of a more formal subgroup analysis, these results have not been included.

When reviews focused on effects of mass media campaigns in a particular target population, those effects have been described earlier according to the relevant outcomes.

The majority of reviews concentrated on behaviour change outcomes, either reducing harmful behaviour or increasing health behaviour, rather than proximal outcomes, when describing and synthesising effects in subpopulations.

Description of the subpopulations that have been considered

The subpopulations considered differ markedly according to health behaviour, with sex27,43,44,51,54,55,58 and age27,44,45,51,55,62 being the only common factors across a number of reviews in different areas. Differences have also been examined according to ethnicity for several health behaviours. 27,39,44,58 Consideration of socioeconomic factors and the equity of effect across socioeconomic groups has been exclusively a feature of reviews of the tobacco control literature, in line with the strong socioeconomic differential in the pattern of smoking and smoking-related morbidity in many developed countries. 27,37,40,42,44 Other subpopulations have been defined according to the pre-campaign level of behaviour, for example by the level of initial physical activity or obesity for campaigns aimed at improving physical activity,58,61 by prior sexual health behaviour for a review of campaigns relating to sexual health,51 and a review of campaigns relating to illicit drugs examined effects according to sensation-seeking behaviour. 63

Effects by subpopulations

Effects by age