Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 12/133/04. The contractual start date was in December 2014. The final report began editorial review in May 2018 and was accepted for publication in October 2018. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Frank Kee was a member of the Public Health Research (PHR) Funding Board 2009–19 and the PHR Prioritisation Group 2016–19. Ruth F Hunter has received a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Career Development Fellowship. Ruth F Hunter and Wendy Hardeman have received funding from the NIHR Public Health Research programme separately from the current project grant. Wendy Hardeman has received funding from AbbVie Ltd (North Chicago, IL, USA) for consultancy outside the current project. The Northern Ireland Clinical Trials Unit received funds through the NIHR Public Health Research programme for its involvement in the study.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Tully et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Ageing and physical activity

Many countries, including the UK, are facing rapid growth in the proportion of the population aged ≥ 65 years. 1 Within the UK, Northern Ireland is projected to have the most rapid increase in the age of its population, with approximately 25% of the population projected to be aged ≥ 65 years by 2041. 2 Ageing is associated with functional decline, reduced quality of life and increased risk of morbidity, disability and mortality. 3 Payette et al. 3 have called for a renewed focus on the prevention of multimorbidity, which is set to double in the next 20 years. In addition, health problems emerge at a younger age in older adults from socioeconomically disadvantaged backgrounds, indicating the need for interventions targeting these individuals. 4

Physically active older adults are at a reduced risk of developing numerous chronic non-communicable diseases,5,6 all-cause mortality,7 poor self-rated health,8 falls9,10 and sarcopenia. 11 In addition to the physical health benefits, regular activity has been associated with improved cognitive function and reduced risk of dementia,12 and higher levels of health-related quality of life. 13 These associated physical and mental health benefits may lead to lower utilisation and cost of health-care services. 14 In addition, lower levels of physical activity are associated with poorer social health, such as increased social isolation (fewer number of interactions with others) and loneliness (feeling of being alone), in adults aged ≥ 65 years. 15,16

Physical activity levels of older adults in the UK

In the UK, it is recommended that older adults undertake at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity per week. 17 Despite the possible benefits of being physically active, levels of inactivity increase with age. Two-thirds of adults aged ≥ 65 years are not meeting recommended levels, with significant inequalities in participation rates in people from socioeconomically disadvantaged areas. 18 Declining physical activity levels are a major public health concern in the UK due to the associated health-care costs, estimated to be £0.9B per year. 19 Coupled with the anticipated rise in the number of older adults in the UK and half of current lifetime spending on health care being incurred in old age,17 there is a need to develop effective interventions that promote active ageing.

Physical activity interventions for older adults

Systematic reviews of physical activity interventions for community-dwelling older adults20–23 have demonstrated that medium-term (up to 1 year) effects on physical activity are achievable with interventions that encourage older adults to perform some type of aerobic activity, of which walking is the predominant form. These reviews also highlight that many of the included interventions do not reach the people who would benefit the most. 21,22 Therefore, there is a need to develop interventions that specifically target groups who participate in low levels of physical activity, such as those from socioeconomically disadvantaged communities. These ‘hard-to-reach’ groups have their own unique needs that should be considered in designing an intervention.

The barriers to and motivators for physical activity reported by older adults are different from those in younger people. For older people, poor health and a lack of knowledge of, and belief in, the health benefits of physical activity are most frequently cited as the major barriers to regular participation. 24 Inactive older adults have identified their preference for individually tailored physical activity programmes, which take place outside intimidating settings such as gyms and which avoid the concern of slowing down others in group exercise. 25 Devereux-Fitzgerald et al. 26 recently reviewed the experience of older adults in previous physical activity interventions. Older adults’ doubts about their physical capability, or their need to engage in moderate-intensity physical activity in later life, were addressed through their experience of participating in the physical activity interventions. 26 Devereux-Fitzgerald et al. 26 also identified that older adults cited their enjoyment of social interaction with others in the intervention as a motivation to be physically active.

In addition to addressing individual and social determinants in physical activity interventions, research has demonstrated the influence of neighbourhood environments on supporting physical activity in older adults. Living in an area that is supportive of physical activity (i.e. more ‘walkable’) has been associated with higher levels of physical activity, especially in individuals who also have higher self-efficacy and social support. 27 Although it is not feasible to introduce wide-scale changes in the physical environment within behavioural interventions, previous research has shown the potential of physical activity interventions which seek to encourage the use of existing infrastructure for older adults. 28 Therefore, interventions designed on the basis of the socioecological model that seeks to address multiple levels of influence on physical activity behaviours (including individual, social and environmental factors) may have the potential to deliver sustained changes in physical activity. However, there are few interventions designed to address these multiple levels of influence in community-dwelling older adults.

Peer-led physical activity interventions

Peer-led interventions offer a model that may help older adults overcome many of the barriers to physical activity. Peer-led behaviour change interventions are a common and effective means of encouraging behaviour change, including in physical activity. 29,30 Peer mentors are trained, non-professional individuals, who are similar to the target population (e.g. in age and cultural background) and possess experiential knowledge of the target behaviour. 31,32 Peer mentors offer emotional support, motivation through positive reinforcement and relevant knowledge regarding problem-solving strategies. 33

In previous interventions, peer mentors have delivered skills training, provided advice and feedback, and offered social support. 32 The ‘motivational’ peer mentor is therefore an important source of social influence in interventions, addressing behavioural determinants such as self-efficacy, perceived competency to be active and self-determination. 32 However, most of the previous peer-led physical activity interventions did not employ a theoretical framework in their design phase, making it difficult to understand the potential mechanisms through which these interventions may have worked. 32

Aims of the ‘Walk with Me’ project

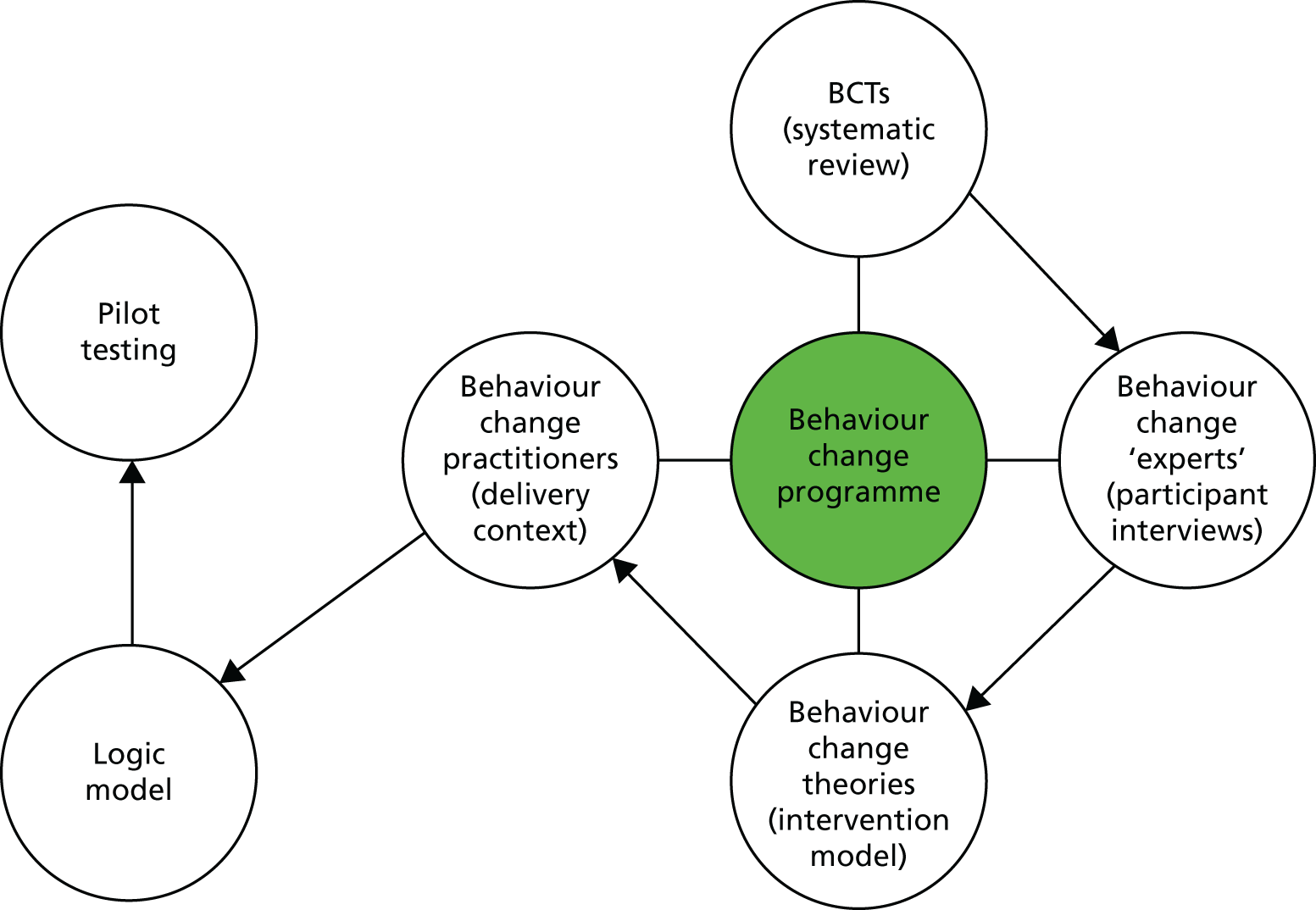

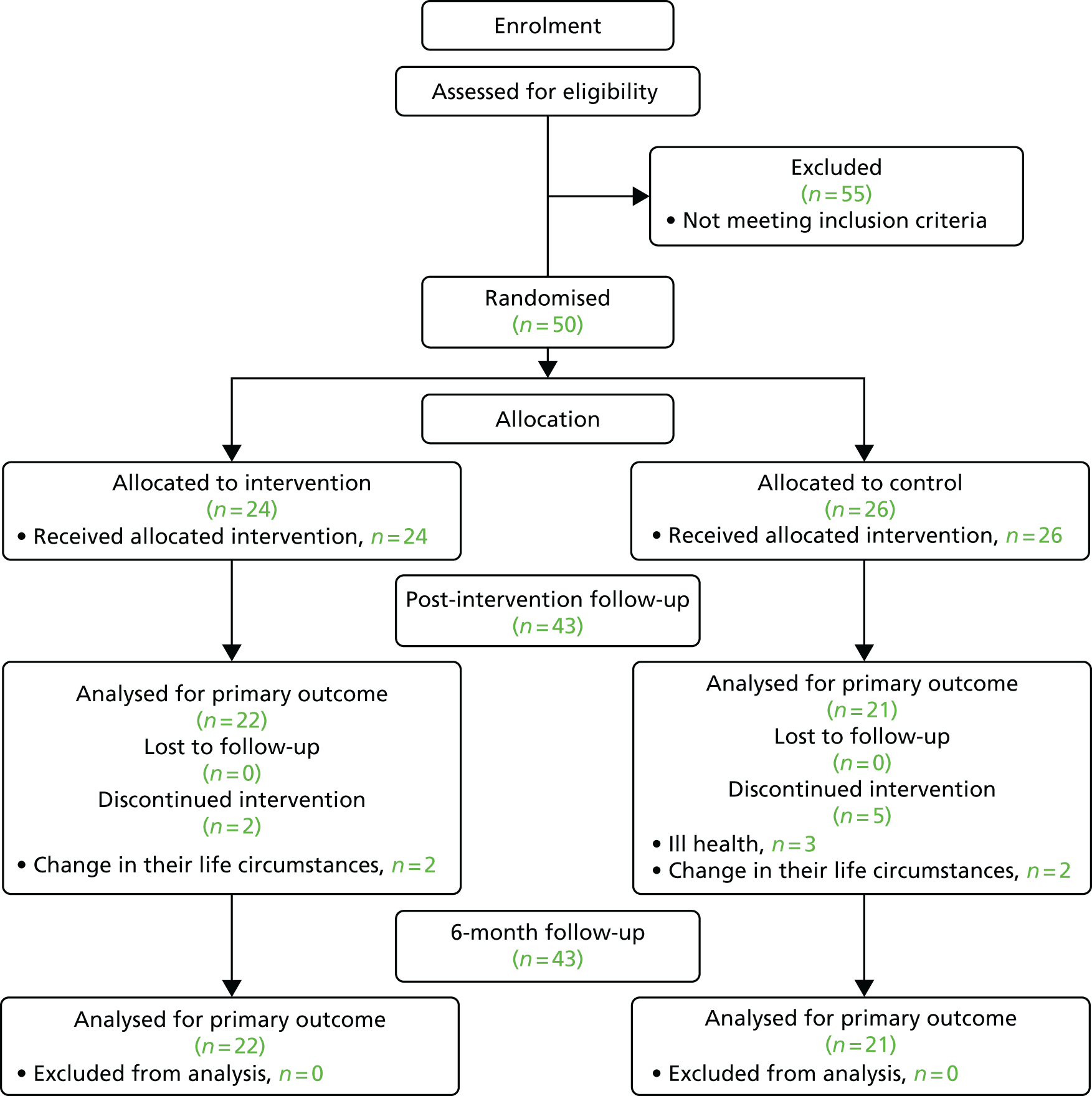

Using the Medical Research Council (MRC) framework for complex interventions,34 we designed and tested the feasibility of a multilevel peer-led physical activity intervention for older adults, tailored to meet the needs of the local community. The intervention package was developed after identifying appropriate behaviour change techniques (BCTs) through a rapid review of previous peer-led interventions. Following this, we conducted interviews with members of the target population to explore their preferences for, and their perceptions of, the feasibility of the BCTs identified in the rapid review. Using information from the first two stages, combined with behaviour change theory [social cognitive theory (SCT)] and input from practitioners regarding the context for the delivery of the proposed programme, we developed a peer-led physical activity intervention and logic model, and tested its feasibility in a pilot randomised controlled trial (RCT) (Figure 1). The aim of the pilot trial was to provide information on recruitment and attrition rates, intervention fidelity, data on the variability in objective physical activity measurements and the resources needed to support the development of a definitive trial. 35

FIGURE 1.

Integrated model to design intervention content.

Changes to the intervention delivery

It was originally planned that peer mentors would be managed under the existing walking group scheme in the Health and Social Care Trust. Owing to governance issues, it was not possible to arrange this in a timely manner, so the ‘Walk with Me’ study protocol needed to be amended. Therefore, some of the peer mentors were also insured and indemnified through Queen’s University Belfast.

Chapter 2 Rapid review to identify components used in previous peer-led interventions

Introduction

The first phase in the MRC complex intervention model is to gather relevant evidence and theory in order to develop a logic model for the implementation of the intervention, which includes the proposed causal pathways and relevant outcome measures. A rapid review approach36 was used to gather evidence and review the BCTs employed in previous peer-led physical activity interventions in adults aged > 18 years.

Peer-led interventions can be considered complex, as they involve multiple interacting BCTs. 34 This makes it difficult to identify the most effective techniques used within peer-led interventions to encourage physical activity behaviour change. 37 To standardise the extraction of components employed in previous interventions, Michie et al. 37 developed the BCT Taxonomy v1. This taxonomy provides standardised labels and definitions for 93 BCTs, hierarchically organised into 16 groupings. BCTs are ‘an observable, replicable, and irreducible component of an intervention, designed to alter or redirect causal processes that regulate behaviour’. 37 Previous evidence demonstrated an association between identification of BCTs and effective interventions for physical activity behaviour change. 38 Presently, there are no published studies identifying which BCTs are most widely used for physical activity behaviour change in peer-led interventions in older adults (aged > 60 years). The aim of our rapid review was to identify the BCTs employed in previous peer-led physical activity interventions.

Methods

Protocol registration

The review protocol was registered and published at PROSPERO (URL: www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/; registration number CRD42014009791).

Identification of studies

The following six databases were searched from inception until March 2015: MEDLINE, EMBASE, SPORTDiscus, The Cochrane Library, Physical Education Index and Web of Science. They were searched using a tailored and sensitive search strategy. Physical activity terms were based on those used in a previous Cochrane review of interventions to promote physical activity. 39 These were combined with peer-led intervention search terms derived from a previous review of peer-led interventions. 29 The search strategy was developed for MEDLINE and adapted for the other databases. A full list of terms is included in Appendix 1. In addition to searching electronic databases, the reference lists of included studies and relevant systematic reviews were searched for appropriate studies.

Inclusion criteria

The review was not restricted to interventions targeting only older adults, as we anticipated there would be very few peer-led interventions in this age group and this might limit the inclusion of potentially useful components. Therefore, studies involving community-dwelling adults aged > 18 years, interventions targeting changes in physical activity and interventions that reported a change in physical activity were included. Studies also needed to include a control or comparison group. No language restrictions were applied.

Study selection

All duplicate studies were removed with RefWorks 2.0 software (ProQuest, Ann Arbor, MI, USA). Two reviewers (ALW and MAT) independently screened the title and abstract of all remaining references to remove those that were obviously not relevant. The full text of remaining articles was obtained and screened for inclusion. When any discrepancies arose, consensus was reached through discussion with other authors.

Data extraction and management

The Cochrane Public Health Group data form was modified to meet the requirements of this review. The form was piloted by two authors (ALW) and (MAT) in a random sample of three studies to confirm that it captured relevant data. Data extracted included method of recruitment, type of peer who delivered the intervention, theoretical basis of intervention components, timing of intervention (frequency, intensity, duration) and method of delivery of outcome assessment.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

The risk of bias in the included studies was examined using the Cochrane risk of bias assessment tool (2014; The Cochrane Collaboration, The Nordic Cochrane Centre, Copenhagen, Denmark). This tool was extended to include risk of bias in specific assessments relating to physical activity interventions (e.g. use of objective measure of physical activity as an outcome measure). Two authors (ALW) and (MAT) independently assessed each study’s risk of bias. All discrepancies were resolved by the reviewers through discussion.

Identification of behaviour change techniques

Two trained reviewers (AW and CC) extracted information of the BCTs in included interventions. A detailed data extraction form was developed by three reviewers (MAT, CC and AW) (see Appendix 2). BCTs were extracted independently by two of the three reviewers (AW and CC), using the published BCT Taxonomy v1. 37 Discrepancies were resolved through discussion with a third reviewer (MAT).

Results

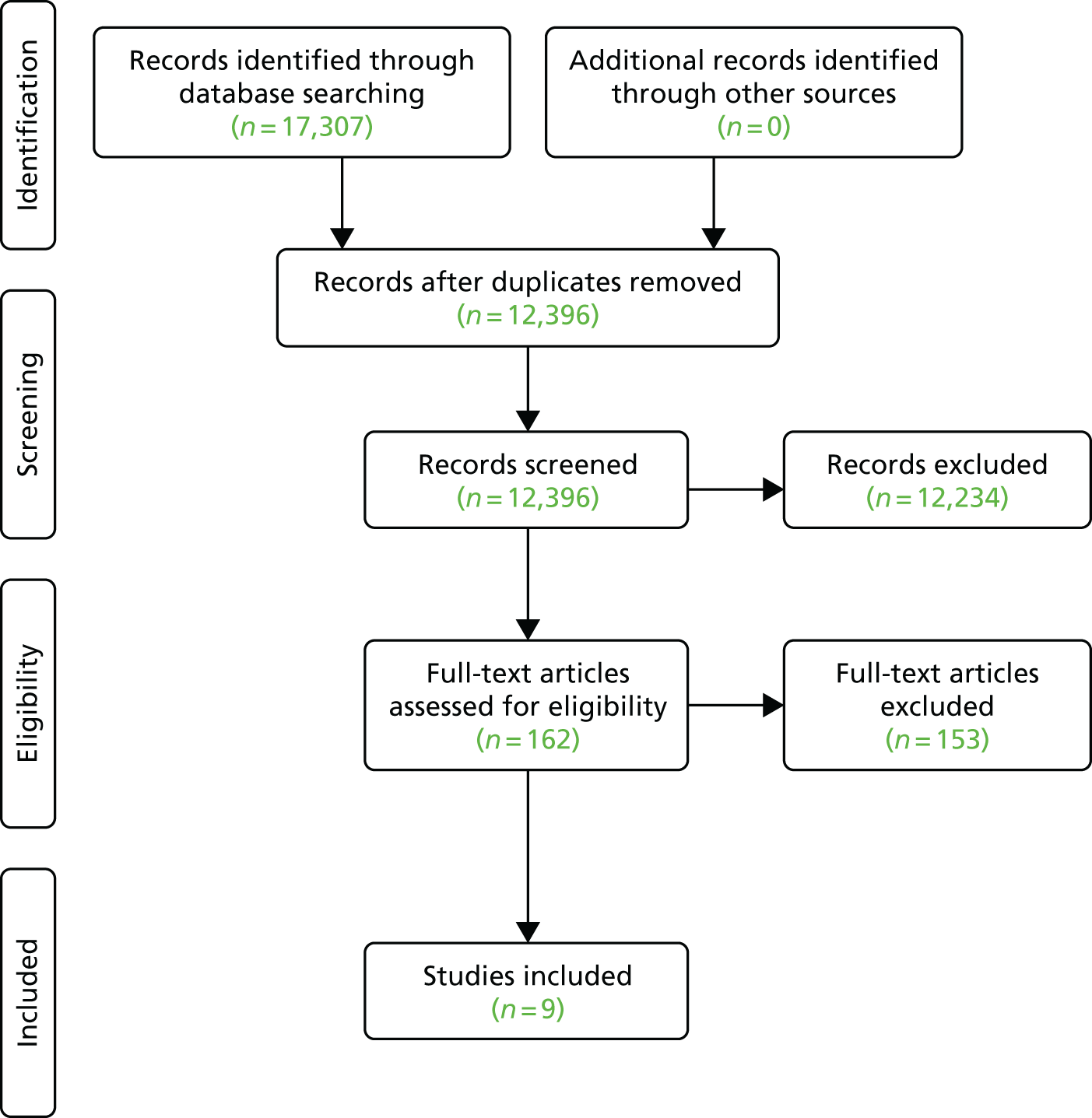

Overall, a total of 17,307 citations were identified from the database searches (Figure 2). After the removal of duplicates, 12,396 citations remained. After title and abstract screening, 162 full-text articles were assessed for inclusion. Most excluded studies did not measure free-living physical activity or were single-arm intervention studies with no control group (see Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram for rapid review.

Characteristics of included studies

Nine studies (1780 participants with a mean age of 54.8 years) met the inclusion criteria and were included in this review. 40–48 Table 1 summarises in detail the key characteristics of included studies. Six of the nine studies were RCTs. 40–42,45,47,48 Two of these studies were conducted in specific groups of patients (male first-time cardiac patients44 and women with stage 0–3 breast cancer43). Most interventions were implemented in the USA (n = 5),40,41,43,44,48 with others in Canada (n = 2),45,46 the UK (n = 1)47 and Hong Kong (n = 1). 42 Overall, 69% of participants were female. Four of the nine studies involved ≥ 70% female participants. 40,41,45,46 One study involved exclusively female participants44 and one involved exclusively male participants. 45 In all studies, the authors reported that they had no conflict of interest to declare.

| Study | Sample population | Age (years), mean (SD) | Target population | Setting | Country | Sample size | Study design |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boyle et al.40 | Students (aged > 18 years) enrolled in a personal health class during the 2007–8 academic year |

Total sample: range not reported, 21.1 (4.47) Intervention: 21.2 (4.28) Control: 21.1 (4.67) |

Female: 74% White: 91% Full-time student: 96% |

University- and home-based programme | USA |

Total sample: n = 178 Intervention: n = 86 Control: n = 92 |

Quasi-experimental design |

| Buman et al.41 | Inactive/insufficiently active community-dwelling older adults living in a university community |

Total sample: range not reported, 63.42 (8.42) Active intervention: 63.49 (8.26) Standard community intervention: 63.35 (9.07) |

Female: 82% Married: 54% White: 91% Ethnicity: Hispanic |

Community-based programme | USA |

Total sample: n = 91 Active intervention: n = 44 Standard community intervention: n = 47 |

RCT |

| Castro et al.42 | Inactive (not active for > 60 minutes per week) older adults and living within San Francisco Bay area |

Total sample: range not reported, 59.1 (± 6.1) Peer mentors: 64.4 (± 5.8) |

Female: 65.8% Caucasian: 67.4% |

Community-based programme | USA |

Total sample: n = 181 Physical activity advice from staff arm: n = 61 Peer mentor arm: n = 61 Attention-matched control arm: n = 59 |

RCT |

| Lamb et al.43 | Inactive male and female middle-aged adults | Total sample: range 40–70 years, 50.8 (7.7) |

Taking < 120 minutes of MVPA Male: 47.7% |

Community-based programme | UK |

Total sample: n = 260 Advice group: n = 129 Health walks group: n = 131 |

RCT |

| Parent and Fortin44 | Male first-time cardiac surgery patients |

Total sample: range 40–69 years, 56.5 (7.7) Experimental: 57.6 (7.4) Control: 55.9 (7.8) |

Male: 100% | Home-based programme | Canada |

Total sample: n = 56 Experimental: n = 27 Control: n = 29 |

RCT |

| Pinto et al.45 | Inactive (< 30 minutes per week of vigorous exercise or 90 minutes per week of moderate intensity exercise for past 6 months). English-speaking women with stage 0–3 breast cancer (diagnosed in the past 5 years) and had completed surgery |

Total sample: range 55–65 years, 55.62 (9.55) Intervention: 55.64 (8.59) Control: 55.59 (10.59) |

White: 98.7% Hispanic: 6.6% Married: 82.9% Female: 100% |

Home-based programme | USA |

Total sample: n = 76 Intervention: n = 39 Controls: n = 37 |

Quasi-experimental design |

| Resnick et al.46 | Inactive urban community-dwelling older adults | Total sample: range 60–85 years, 73.3 (± 8.5) |

Female: 79% African American: 77% |

Community-based programme | USA | Total sample: n = 166 | Feasibility RCT |

| Thomas et al.47 | Inactive older adults (aged > 60 years) with no history of CVD of physical disabilities, from 24 community centres |

Buddy support group and pedometer: 71.7 (5.7) Control: 72.4 (5.7) |

Female: 67% Smoking: 53.7% |

Community-based programme | Hong Kong |

Total sample: n = 399 Buddy support group and pedometer group: n = 193 Control: n = 206 |

Cluster RCT |

| Tudor-Locke et al.48 | Inactive male and female participants with type 2 diabetes |

Total sample: range 38–71 years, 55.7 (7.3) Professional led: range 38–70 years, 54.8 (7.2) Peer led: range 42–71 years, 57.8 (7.4) |

Female: 82% Former smokers: 52.7% |

Community-based programme | Canada |

Total sample: n = 220 Professional led: n = 157 Peer led: n = 63 |

Quasi-experimental design |

Outcomes

Although total physical activity levels were reported in all studies, physical activity measures varied between them. However, all instruments were reported as being valid and reliable. Six studies reported assessing the impact of the intervention only on self-reported physical activity levels, including the National Health Interview Survey,40 the Jenkins Activity Checklist,44 the Stanford Five-City Project Physical Activity Questionnaire43 and the Yale Physical Activity Survey. 46 One study used an objective measure of walking (Yamax SW-200 pedometer; Yamax Corp., Tokyo, Japan). 48 Other studies used a combination of objective and self-report methods. No studies reported the cost-effectiveness of the intervention.

Methodological quality of included studies

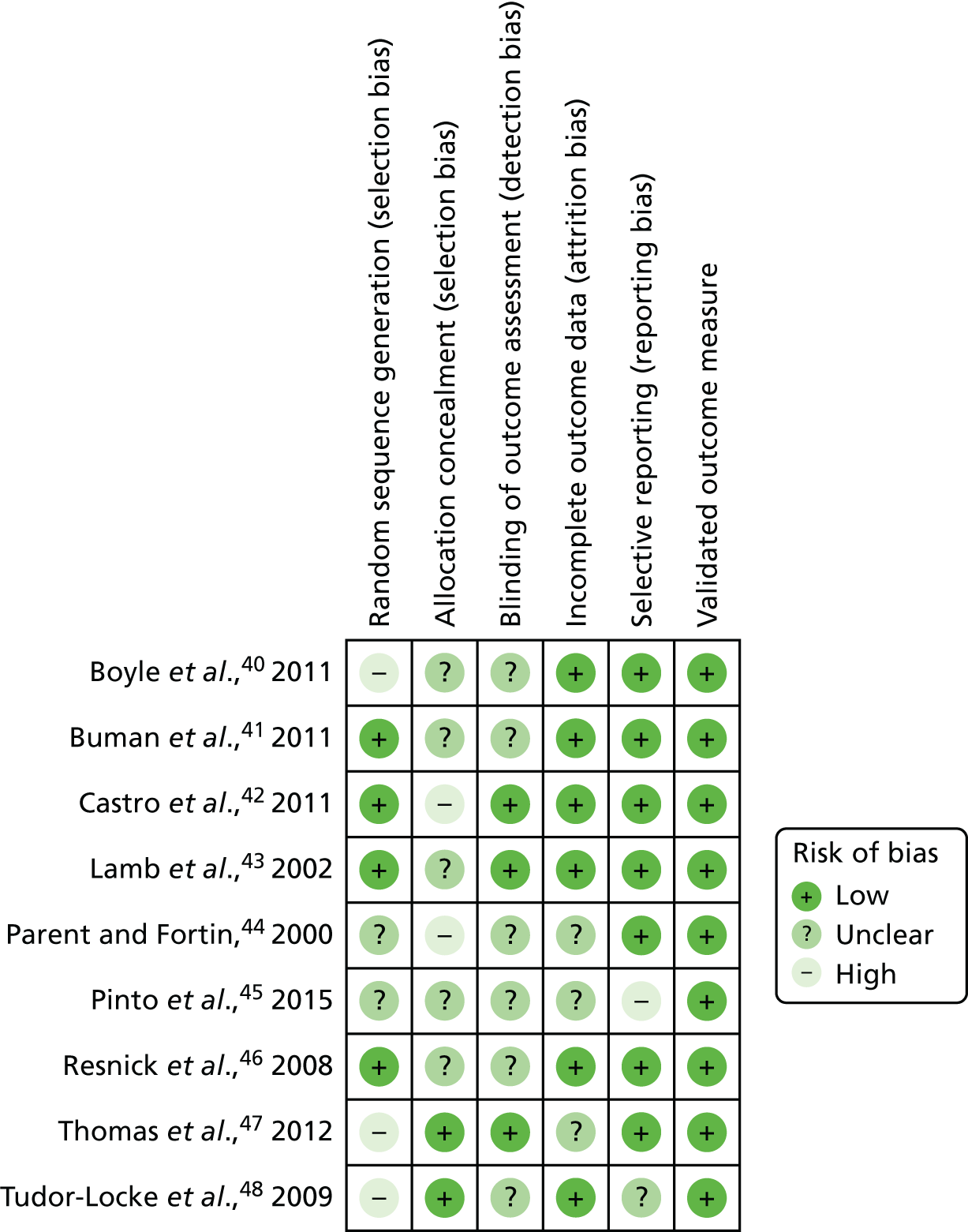

Six of the nine studies employed a randomised controlled design. 40–43,45,46 Allocation concealment was used in two studies. 47,48 A further four studies were rated as having a low risk of bias from random sequence generation. 41–43,46 Outcome assessors were blind to the allocation of participants in three of the nine studies. 42,43,47 It was unclear if outcome assessors were blind to allocation in the other six studies. Six of the nine studies were deemed to have a low risk of attrition bias. 40–43,46,48 Reporting bias was evident in only one study,45 which did not report all of the prespecified outcomes. Finally, all nine studies reported using a validated measure of physical activity (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Risk of bias in included studies.

Intervention components

Several common approaches (models) were used to deliver the peer-led physical activity interventions. The first model identified was the group-based peer education. The role of the peers was to act as group leaders guiding participants to adopt a new behaviour that facilitated healthy outcomes. Five studies used a group-based approach to deliver the intervention, whereby peer mentors acted as group educators, social leaders or walking co-ordinators. 40,42,43,46,47 Another model used was the dyads model, whereby peer mentors offered one-to-one ‘buddy’-type support for participants. Three studies used this approach, with support offered either in person44,45 or by telephone. 41 Finally, one study offered a combination of group and one-to-one support. 48 In both models, peer mentors delivered skills training, goal-setting and feedback on progress, problem-solving activities and social support and acted as a role model for positive behaviour change. Interventions did not appear to include explicit strategies to encourage maintenance of physical activity. Five of the nine studies were based on a behavioural theory. Theories used were SCT,41,46 self-efficacy theory40,45,48 and social learning theory. 45

Characteristics of peer mentors

In four of the nine studies, peer mentors were recruited from the same source as the study participants, such as former patients,44,45 fellow university students40 or members of the same community centre (Table 2). 47 Peer mentors in other studies were former research participants,41,42 middle-aged lay instructors46 or trained peer leaders. 48 They were recruited from lists of participants in previous research studies41,42 or through existing organisations or groups such as university,40 patient groups or community centres,46,47 or peer leadership training courses. 48

| Study | Peer mentor characteristics | Recruitment of peer mentors | Eligibility | Additional training (type and hours of training) | Ongoing management of peer mentors | Incentives for peer mentors | Resources |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boyle et al.40 | Peer educator was a trainee exercise physiologist enrolled in an advanced undergraduate physiology class | Not reported | Not reported | Trained in physical fitness assessment and programming skills | Supervised by researchers | Not reported | Not reported |

| Buman et al.41 | Research participants from previous health promotion studies | Recruited from a registry of research participants from previous health promotion studies and through a local fair | Reported having a regular physical activity routine or had a basic background in health education | Not reported | Quality control checklists and scoring procedures were used to give the peer mentors feedback about ways to improve their efforts to facilitate group meetings. Programme staff met weekly with the mentor after each of the first five sessions to give feedback and coaching. Additional feedback was provided as needed throughout the intervention | Not reported | Volunteered their time without remuneration; however, in a few cases mentors were modestly reimbursed for their travel (approximately US$15 per session) |

| Castro et al.42 | Participants from previous research studies | Mailings to previous research participants and announcements to local active ageing community groups | Physically active (at least 150 minutes of MVPA per week) and willing to volunteer for 4–6 hours per week for a minimum of 1 year | Not reported | Peer mentors were assigned post-training practice sessions identical to professional staff, including assignments to rehearse advice and counselling components and practise completing forms to document the content and delivery of the interventions | Not reported | Peer mentors were provided with pre-paid telephone charge cards if they wished to make telephone calls to their contacts from home |

| Lamb et al.43 | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Parent and Fortin44 | Previous patients who had recovered from cardiac surgery | Recruited by a research co-ordinator | Able to verbalise enthusiasm towards increased activity, stimulate motivation and share their successful rehabilitation after surgery | Given 6 hours’ training by the research co-ordinator on interaction principles (how to listen empathically and to reflect the patient’s feelings) and on cardiovascular disease and treatment | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Pinto et al.45 | Breast cancer survivors who provide information and emotional support for other breast cancer survivors | Recruited from an existing programme run by the American Cancer Society Reach to Recovery programme | Not reported | Trained by the American Cancer Society Reach to Recovery programme on how to deliver the exercise programme | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Resnick et al.46 | Middle-aged lay instructors | Not reported | Not reported | Full-day training session and a detailed procedure manual | Within an ongoing Senior Wellness Project | Not reported | Not reported |

| Thomas et al.47 | Members of community centre aged ≥ 60 years | Through older adults community centres | Aged ≥ 60 years, no history of myocardial infarction or stroke and physical disability | Not reported | Supervised by research assistants. Provided with an instruction manual on how to enlist a walking partner | Not reported | Cost of telephone calls were reimbursed |

| Tudor-Locke et al.48 | Nominated by professionals after the completion of a 16-week peer leadership training course | Recruited by professionals after the completion of 16-week peer leadership training course | Not reported | Additional half-day training on adult learning principles and facilitation skills | Not reported | Not reported | Travel costs. Peers were given the same resources as the professionals (overhead transparencies, checklists) |

Not all of the studies detailed the training offered to peer mentors. Those that did so reported training lasting from 6 hours to a full day. 44–46,48 Moderate-value resources were offered to support peer mentors, including reimbursement of expenses incurred such as travel costs and the cost of telephone calls (see Table 2). 41,42,47,48

Behaviour change techniques in peer-led physical activity interventions

The BCT Taxonomy v1 is clustered into groupings of BCTs that may be commonly used together in physical activity interventions. 37 Agreement between data extractors was fair (κ = 0.5). Therefore, all papers were reviewed a second time with a third reviewer (MT) to ensure accuracy in BCT data extraction.

The results from the assessment of BCTs identified that the most commonly used BCTs were goal-setting (behaviour) (n = 740–42,45–48); social support (emotional) (n = 740–46); instruction on how to perform the behaviour (n = 740,42–47); problem-solving (n = 641,42,45–48); adding objects to the environment (n = 641,42,45–48); demonstration of the behaviour (n = 440,43,46,47); behavioural practice/rehearsal (n = 440,43,46,47); self-monitoring of behaviour (n = 640–42,45,47,48); and social support (practical) (n = 640–42,45,47,48). The most commonly used groups of BCTs employed in peer-led physical activity interventions were (1) goals and planning [goal-setting (behaviour), n = 7;40–42,45–48 problem-solving, n = 6;41,42,45–48 action-planning, n = 2;41,47 and behavioural contract, n = 1];40 (2) feedback and monitoring [feedback on behaviour, n = 2;42,48 self-monitoring of behaviour, n = 6;40–42,45,47,48 self-monitoring of outcome(s) of behaviour, n = 1;45 and feedback on outcome of behaviour, n = 241,45]; (3) social support [social support (practical), n = 6;40–42,45,47,48 and social support (emotional), n = 740–46]; (4) shaping knowledge (instruction on how to perform the behaviour, n = 740,42–47); (5) comparison of behaviour (demonstration of the behaviour, n = 4;40,43,46,47 social comparison, n = 244,46); and (6) antecedents (adding objects to the environment, n = 641,42,45–48) (Table 3).

| BCT label | BCT group | Study | Frequency of BCT/nine studies | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boyle et al.40 | Buman et al.41 | Castro et al.42 | Lamb et al.43 | Parent and Fortin44 | Pinto et al.45 | Resnick et al.46 | Thomas et al.46 | Tudor-Locke et al.47 | |||

| 1. Goals and planning | 1.1 Goal-setting (behaviour) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 7 | ||

| 1.2 Problem-solving | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 6 | ||||

| 1.4 Action-planning | ✓ | ✓ | 2 | ||||||||

| 1.8 Behavioural contract | ✓ | 1 | |||||||||

| 2. Feedback and monitoring | 2.2 Feedback on behaviour | ✓ | ✓ | 2 | |||||||

| 2.3 Self-monitoring of behaviour | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 6 | ||||

| 2.4 Self-monitoring of outcome(s) of behaviour | ✓ | 1 | |||||||||

| 2.7 Feedback on outcome of behaviour | ✓ | ✓ | 2 | ||||||||

| 3. Social support | 3.1 Social support (unspecified) | ✓ | 1 | ||||||||

| 3.2 Social support (practical) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 6 | ||||

| 3.3 Social support (emotional) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 7 | |||

| 4. Shaping knowledge | 4.1 Instruction on how to perform the behaviour | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 7 | ||

| 5. Natural consequences | 5.1 Information about health consequences | ✓ | ✓ | 2 | |||||||

| 5.6 Information about emotional consequences | ✓ | 1 | |||||||||

| 6. Comparison of behaviour | 6.1 Demonstration of the behaviour | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 4 | |||||

| 6.2 Social comparison | ✓ | ✓ | 2 | ||||||||

| 8. Repetition and substitution | 8.1 Behavioural practice/rehearsal | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 4 | |||||

| 9. Comparison of outcomes | 9.1 Credible source | ✓ | ✓ | 2 | |||||||

| 10. Reward and threat | 10.3 Non-specific reward | ✓ | 1 | ||||||||

| 10.9 Self-reward | ✓ | 1 | |||||||||

| 11. Regulation | 11.2 Reduce negative emotions | ✓ | 1 | ||||||||

| 12. Antecedents | 12.5 Adding objects to the environment | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 6 | |||

| 15. Self-belief | 15.1 Verbal persuasion about capability | ✓ | ✓ | 2 | |||||||

| 15.4 Self-talk | ✓ | 1 | |||||||||

Discussion

In this review of peer-led physical activity interventions, nine studies rated as having fair to good methodological quality were identified (i.e. low risk of bias). Interventions were designed around the social support that peer mentors could offer, either within groups or on a one-to-one basis. Intervention strategies were broadly developed to emphasise the peer mentor as a role model for positive behaviour change. Within the interventions, peer mentors delivered skills training, goal-setting and feedback, and problem-solving components. To equip them to do this, they were given short training sessions and offered ongoing support (see Table 2). Peer mentors were recruited either from groups of participants in previous interventions or from community centres. Physical activity was measured using validated instruments, but, as self-reported activity may be biased, there is a need for studies using objective measures of physical activity. A limitation of the study was that BCTs in the control groups were not coded, and thus we were unable to identify BCTs that were unique to the intervention. However, as we were not assessing effectiveness, this does not have an implication on the overall findings.

The BCTs employed in the interventions included in the review were used in the next stage of our study as the basis of interviews with older adults to determine their preferences for what could be included in an intervention.

Chapter 3 Feasibility and acceptability of proposed behaviour change and intervention strategies (qualitative interviews)

Introduction

The rapid review of existing literature (see Chapter 2) reporting peer-led physical activity interventions identified common groups of BCTs employed in previous interventions; these were goals and planning; feedback and monitoring; social support; shaping knowledge; comparison of behaviour; repetition and substitution; and antecedents. This qualitative study aimed to explore the feasibility of using some of the most commonly used BCTs in these groups [goal-setting, self-monitoring (behaviour), social support (practical and emotional), problem-solving, instruction on how to perform the behaviour, demonstration on the behaviour and adding objects to the environment] in a peer-led intervention for older adults. These BCTs aligned to SCT, which emerged from the rapid review as a promising theoretical framework for the design of the intervention. We sought to inform the development of our intervention content by eliciting, through semistructured interviews, the opinions and preferences of older adults living in socioeconomically disadvantaged communities regarding the use of these BCTs.

Methods

The Office for Research Ethics Committees Northern Ireland gave ethics approval for the study (reference number 14/NI/1330).

Participants

This phase of the study was carried out in the South Eastern Health and Social Care Trust (SEHSCT) area. All electoral wards within the SEHSCT area were ranked by quartiles of the Northern Ireland Multiple Deprivation Measure (NIMDM). The NIMDM score is constructed by combining population data relating to seven different domains (income; employment; health deprivation and disability; education, skills and training; proximity to services; living environment; crime and disorder). Community organisations [e.g. Colin Neighbourhood Partnership, The Resurgam Trust (community group), Hillhall Community Resource Centre and St Luke’s Family Centre] located within electoral wards with NIMDM scores in the top 25% (most disadvantaged quartile) were approached to facilitate identification and recruitment of potential participants. They were asked to identify individuals aged between 60 and 70 years living in the target areas (although we accepted some older individuals as they were available). The aim was to recruit a purposive sample of individuals (men and women of different ages and physical activity levels, living in urban and rural settings). None of the participants had experience of walking groups or peer-led health programmes.

Data collection

Semistructured one-to-one interviews were deemed the most appropriate method of gathering detailed information from participants regarding the feasibility and acceptability of BCTs. Interviews were conducted either in participants’ homes or in local community centres. Participants completed a brief questionnaire to provide demographic information and a self-assessment of their current health status (as poor, fair, good, very good). Each interview lasted approximately 1 hour and all were conducted by a female psychology graduate trained and experienced in qualitative methodology (IMcM).

At the beginning of each interview, participants were informed of the research topic and the aims of the study and asked to sign a consent form. All participants were informed that they could withdraw their support at any time during the process, and that their information would be held securely and used anonymously. A flexible interview schedule was developed for the interview (summarised in Box 1). This included questions about the role of physical activity in day-to-day life and participants’ views of setting physical activity goals (goal-setting); using a pedometer to monitor progress (self-monitoring, instruction on how to perform the behaviour, adding objects to the environment); problem-solving; working with a peer mentor (social support, practical and emotional); and going for a demonstration walk with a peer mentor (demonstration on the behaviour). Questions were supplemented with copies of self-monitoring diaries, pedometers and photos to elicit responses. A full copy of the interview schedule is included as Report Supplementary Material 1. After the interview, all participants were debriefed and provided with an opportunity to raise any questions or concerns.

Can you describe your typical day?

When do you feel you are physically active during the day?

Goal-setting and self-monitoringHave you ever heard of a pedometer before?

What do you think are the advantages of using something like a pedometer and diary?

What do you think are the disadvantages of using something like a pedometer and diary?

Problem-solvingCan you think of barriers or obstacles you have faced to increase your physical activity?

Did you find anything that helped you overcome these?

What do you like about this method?

What do you not like about this method?

Peer mentoringWhat do you think about the idea of using a peer mentor?

What would you want them to do with you?

Do you see any problems with using a peer mentor?

Demonstration walkWhat kind of information would people need to increase their walking?

Where would you like to go?

How often would you want to go?

Are there any problems with using a peer mentor?

Data analysis

Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed anonymously. In line with current guidelines;49–51 a directed content analysis approach was adopted to understand the emotional responses and preferences expressed by the participants regarding the feasibility and acceptability of implementing the BCTs being examined. 49–51

Using the transcripts, the lead researcher (IMcM) generated initial codes which highlighted pertinent features of the data. This was achieved in a systematic manner by reading each line of the transcript and placing codes in the margins of the text. These initial codes were then collated into potential themes. The researcher then reviewed the themes in relation to the initially coded narratives and a thematic map was generated. Sufficient time was given to this coding process to ensure that coding was as robust as possible. The codes and themes were then given to another member of the research team (CC) who was familiar with the transcripts and who then confirmed the validity of the key themes. In addition, researchers (MEC and ES) experienced in qualitative analysis also reviewed the themes and subthemes. After 11 interviews, data saturation was achieved; another interview was completed to seek confirmation of the analysis. The findings were discussed with six participants in follow-up meetings during the intervention development phase for validation.

Results

The characteristics of each participant are summarised in Table 4.

| Participant ID | Sex | Age (years) | Employment status | Health status | Health problem limiting normal daily activities | Highest education level | Home owner | Living with partner or living alone | Number of people in household |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Female | 61 | Retired | Fair | No | Secondary school | Own | Alone | 1 |

| 2 | Male | 92 | Retired | Good | Yes | Secondary school | Own | Alone | 1 |

| 3 | Female | 77 | Retired | Fair | No | Secondary school | Own | Alone | 1 |

| 4 | Female | 70 | Retired | Poor | Yes | Secondary school | Rent | Partner | 2 |

| 5 | Male | 80 | Retired | Fair | No | Secondary school | Own | Alone | 1 |

| 6 | Female | 67 | Retired | Good | Yes | Secondary school | Own | Alone | 1 |

| 7 | Female | 60 | Full-time work | Good | No | College | Own | Partner | 3 |

| 8 | Female | 62 | Retired | Excellent | No | Secondary school | Own | Partner | 2 |

| 9 | Female | 65 | Retired | Fair | Yes | Secondary school | Rent | Partner | 2 |

| 10 | Male | 63 | Retired | Fair | Yes | Secondary school | Own | Partner | 2 |

| 11 | Male | 72 | Retired | Fair | Yes | Secondary school | Rent | Partner | 2 |

| 12 | Male | 72 | Retired | Poor | Yes | Secondary school | Rent | Living alone | 1 |

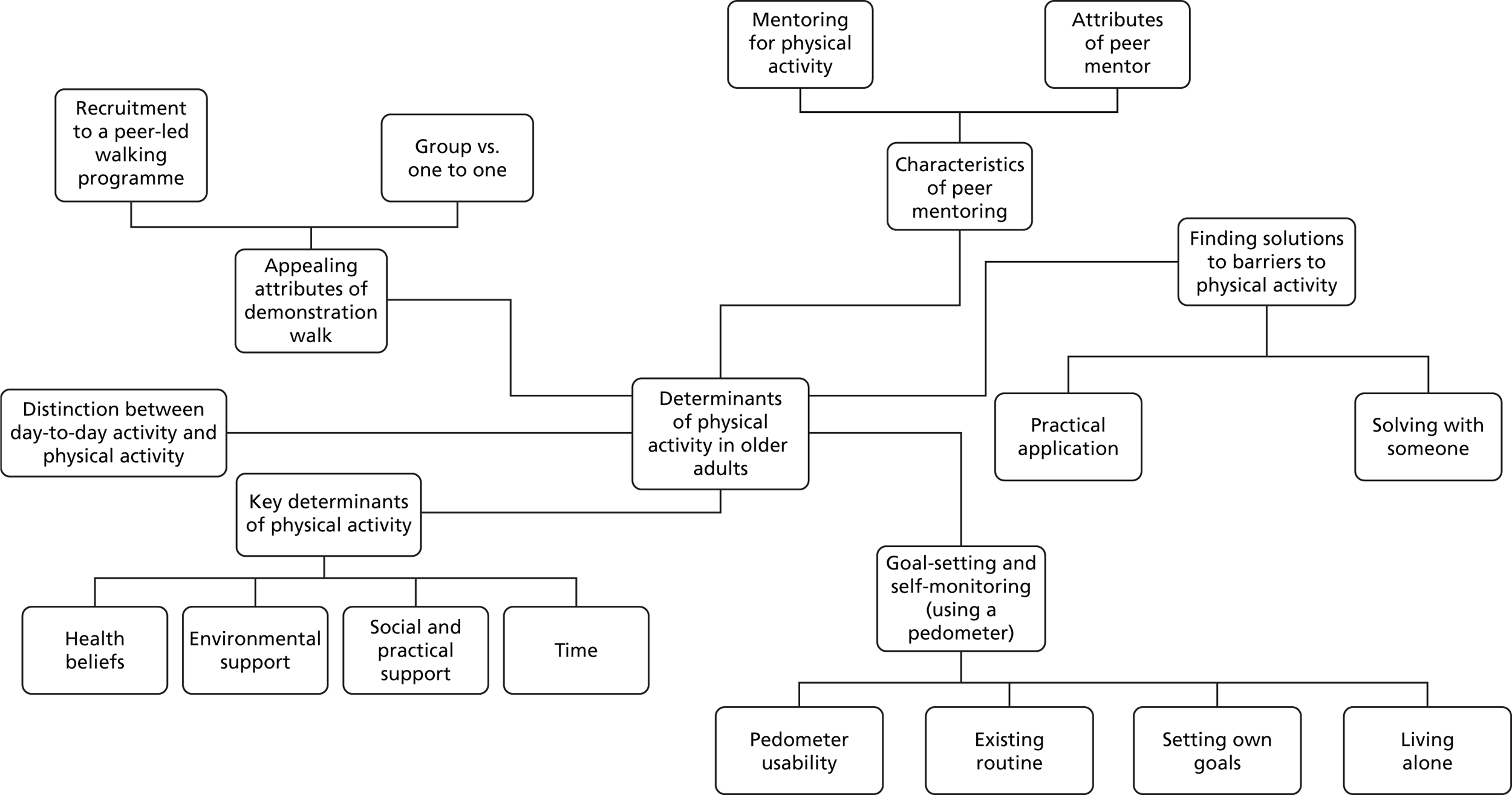

Themes

The key themes and subthemes are depicted in Figure 4. These included a distinction between day-to-day activity and physical activity; key determinants of physical activity; goal-setting and self-monitoring using a pedometer; characteristics of peer mentors; finding solutions to barriers to physical activity; and appealing attributes of demonstration walking. The themes are reported below, supported by relevant quotations, which are anonymised.

FIGURE 4.

Thematic map of ‘Walk with Me’ intervention development interview data.

Theme 1: distinction between day-to-day activity and physical activity

The interviewer clearly defined physical activity as activities in which people were ‘up and about’ and ensured that participants understood that physical activity is not limited to activities that are structured (e.g. going to the gym). In terms of the discussion, individuals echoed this understanding and described their typical day, which consisted of the activities of daily living, including housework (e.g. laundry, cooking and cleaning), as well as carer responsibilities for either grandchildren or partners:

. . . just have breakfast. And so I make my husband’s breakfast cause he’s not in good health . . . going to do the washing . . . go and get your washing upstairs and bring it down . . . I’d be up the stairs all the time . . . And would I never rest. I do knit . . .

Participant 9

The majority of individuals appeared to be busy simply carrying out day-to-day living activities, and physical activity was regarded as something that was for leisure, and not something that was ‘necessary’. It was also mainly limited to a number of physical activities, among which walking and gardening were the most frequently mentioned:

. . . the morning part of it was active enough, certainly, because erm my flower bed had got decidedly overgrown and um it needed a great deal of hoking and poking to get it into any sort of order at all.

Participant 3

My only activity at, at the moment is walking. Walking my dogs.

Participant 4

The findings suggest that older adults are potentially less physically active and may not be meeting the recommended guidelines for physical activity:

Really that’s all my activity because I’m not sport minded or anything [laughing].

Participant 2

Theme 2: key determinants of physical activity

Individual discussions suggested that there was a complex interplay between individuals’ beliefs about their health and how physical activity would affect it; the environment in which they lived and whether or not it allowed access to appropriate areas to walk; the level of support that they received, whether physical or social; and the amount of time that they could devote to physical activity. These various factors all appeared to have a potential influence on physical activity levels.

Health beliefs

Participants expressed feelings about the ‘inevitability’ that physical activity would decline over time as a result of changes in health and in social circumstances:

But unfortunately with erm the deterioration in my wife’s health I was gradually dropping, and the fact that I was getting older anyway (laughs).

Participant 3

Participants also suggested that existing health conditions prevented them from increasing their physical activity level:

Although I haven’t done it [physical activity] in about 2 months. Erm I think that one day I just done a bit too much and then fluid gathered in my knees. So, I need to be careful not to over do it.

Participant 11

However, participants also suggested that poor health could also be a motivator for increasing physical activity in the belief that it could alleviate the symptoms of existing conditions or even prevent new ones from developing:

I’m trying to use the hands. Trying to use the limbs by bending up and down . . . I still do it because I have to do it.

Participant 9

In addition, participants expressed a belief about the benefits of physical activity (e.g. for better mental health and weight management). Participants expressed different beliefs about their level of actual physical activity, with some believing that they should be taking more physical activity and others believing that their physical activity levels were adequate:

You’re out walking, you’re out active, you’re, you feeling better in yourself and your whole head lifts. My husband suffers badly with depression so, when we’re out walking, it lifts him. You’re out. Know what I mean?

Participant 9

I’m conscious that I need some sort of walking. Some sort of activity. I’ve retired now around 2 years. And erm I’ve noticed I’ve put on a bit of weight and I have myself, a certain weight I will not go over and I’m, you know, erm, normally watching my weight. And I am conscious that I need to be more active.

Participant 11

We are active, active enough. At the moment like . . . hopefully it stays that way.

Participant 10

However, the mixed belief regarding adequacy levels of physical activity may have been due to a misunderstanding about or a lack of awareness of the actual physical activity guidelines:

. . . but I don’t know what 300 steps would mean. Would that mean it’s good or bad?

Participant 9

Environmental support

Participants mentioned fear of traffic (cars and bicycles), dogs, antisocial behaviour and bad weather as key barriers to physical activity, even when appropriate places such as parks were available in their local areas:

Erm [coughs] I think that is becoming increasingly difficult as the roads, the roads have got so busy now. Aye. It’s not so pleasant. I can see myself now, um being reluctant enough to walk the roads with my dog because there’s so much traffic and so few now with . . . easy green edges to the roads where you can walk in comfort.

Participant 3

There’s green fields over there . . . But you wouldn’t walk. I mean I could walk about during the day, it’s fine. But at night, no, I wouldn’t.

Participant 9

Well I, I, don’t like walking round tow paths so I do not ‘cause it’s full of dogs’ doo doos and broken bottles. I don’t like that atmosphere along it. I like round [XXXX] bridge. I like places like that. You know, there’s good fresh air and you meet other people. You know what I mean? Somewhere like that you know. Or up the [XXXX] park. Now I would walk round [XXXX] park.’

Participant 11

I used to go to [XXXX] path but erm the amount of cyclists in that area. You’re just constantly stopping and starting and looking round you. And mostly cyclists. They don’t have a bell anymore and erm, . . . , they would probably frighten you sometimes. They’re right behind you before you realise they’re there.

Participant 12

However, having places to walk that were safe and accessible, or places that allowed them to get in touch with nature, could help to increase participants’ physical activity levels:

Well all the trees. There’s trees and nature. You see ducks and you see . . . So you go up there and you see ducks, and cows. Just trees. It’s not vandalised, not wrecked and ruined and destroyed. You know what I mean? So when you go up to the [XXXX] bridge, 10 minutes away in the car, sure it’s like a different world isn’t it?

Participant 13

Social and practical support for physical activity

Participants expressed a preference for combining social interaction with physical activity, thus making physical activity more enjoyable by focusing attention on socialising rather than on the activity itself:

I would like that one if you were going out with friends . . . you wouldn’t realise the distance . . . you don’t see time.

Participant 8

. . . you’re talking away and you’re. I would say, erm, and I would even think a couple of them there people would forget about their ailments when there’s a crowd cause they’re talking about different things.

Participant 12

Comments suggested that increased social support also increases confidence through learning from others or through the feeling of increased safety from the presence of others:

Safety in numbers. People feel safe out walking along with somebody else. Cause we’re afraid of the dogs and young ones and all messing about in the parks. Not so bad if . . . I’m on the toll path. But I’ve walked round [XXXX] park and I’ve felt a wee bit uneasy in it . . .

Participant 10

Physical support was also a motivator to increasing physical activity whereby providing physical aids to carry out gardening or a secure physical environment could increase physical activity levels:

Give me the tools. Instead of you bending down in pain, get the tools to dig but you standing up . . . so that would be. I would need to get out there and buy those tools that would be my solution. That’s my barrier.

Participant 9

However, the intensity of social support was seen as an important determinant of physical activity, and both lack of support and too much support were potential barriers to physical activity:

. . . if I need to go somewhere, to the hospital for an appointment to the clinic, my daughters are down straight away. Pick me up in the car, so, I don’t get to walk, and I would, and that, that would stop me from, you know.

Participant 9

Time

Participants suggested that their lack of physical activity was due to lack of time because of the many other activities that they took part in, as well as the carer responsibilities that they had for either partners or grandchildren:

I would like to have been gone out and having a walk. But that’s like a barrier. I have to stay in and mind three children.

Participant 7

However, even when time was available, participants preferred to take part in less intense physical activities (e.g. knitting and reading), and so appeared to lack motivation to increase their physical activity level:

I put her into the activity centre and then I’d sit and chat to my friends.

Participant 7

. . . drops me off . . . and will come back and pick me up for I wouldn’t walk all the way back.

Participant 7

Theme 3: goal-setting and self-monitoring (using a pedometer)

Self-monitoring and goal-setting were perceived as helpful approaches to increasing physical activity and, in particular, participants perceived that the pedometer would have a positive influence on their activity levels. Four subthemes were highlighted: pedometer usability, existing routine, setting own goals and living alone.

Pedometer usability

In general, participants expressed a positive attitude towards the pedometer:

Yes that would be a good thing. Yes . . . my son . . . uses that at work. He’d walk 5 mile a day.

Participant 11

There was a general awareness of the pedometer among participants, all of whom had either seen or heard of a pedometer before. In fact, one participant had actually used a pedometer for monitoring steps previously for a different study:

. . . and that would keep me active. That would keep me more active than erm because I do walk about a bit in the home . . .

Participant 9

Yes. I’ve seen them before. Our kids got them one time at McDonalds [Chicago, IL, USA] . . . wee wee yellow ones, and they were using them . . .

Participant 10

However, despite the overall positive view regarding pedometers, there were concerns about their actual use in practice:

Sure the last time . . . there wasn’t a step come up on it. So I wonder if this one’s working? That one wasn’t working sure it wasn’t?

Participant 10

In addition, participants also highlighted that pedometers should be simple to use:

I don’t want something like a magic phone . . . because I’ll not be able to use it [laughs].

Participant 4

. . . well that there’s handy . . . where erm you just, say clip it on to your jeans or something, and um, you just push a button and it starts, and pushes a button and it stops. Anything complicated, I wouldn’t be able to use, you know. But something like that there!

Participant 5

Participants also suggested that the device should be easy to wear and easy to see:

You have to be able to see it . . . the other one I used you were constantly putting your glasses on and off so that was a distraction too. But that has a nice clear face.

Participant 8

. . . the way I thought that if you could get like an arm band . . . it’s better than having something clipped on you.

Participant 8

Existing routine

Participants expressed an interest in using the pedometer because they felt that this would fit into their existing routines. For example, participants preferred to, or were more interested in, monitoring or counting current steps rather than trying any additional or new types of activities:

. . . so I really have a routine, most of the week . . . and then I’d be able to see what I’d done one day and what I’m doing on another day. Some days wouldn’t be as many as others. So it would give me a, a bit of a picture.

Participant 10

However, this does show that the provision of pedometer per se may not be sufficient to enact behaviour change and that participants need to be encouraged to use the pedometer to set step goals and monitor their progress:

But I wouldn’t want to be doing this diary all the time.

Participant 10

Setting own goals

Participants expressed a preference for being able to set their own goals, as opposed to having them set by someone else. This was mainly due to the feeling that self-set goals would be tailored to their own physical fitness or capability rather than general goals that might not be achievable:

Well the goal-setting, because it’s, as long as it’s, I set my own goals . . . you know . . . and doesn’t put too much pressure on individuals to achieve them.

Participant 12

It would really encourage you, I’d be ‘here, I gotta go out the night and all. I’ve got to fill this here in. see how many steps I’d done . . . It would encourage me just to be able to look and say ‘Look what I’ve done – 8000 today’, and then when it’s coming up to tea time I’d be going ‘come on let’s go and do another one . . . we’ll maybe try and get up to 10’ . . . I think that would be encouraging.

Participant 12

There was also a feeling that, even if goals were set, there should be flexibility to take account of ‘off’ days when existing conditions or tiredness might prevent them from achieving the targets:

I would get maybe, say for argument’s sake, about 50 yards before the pain, the pain gets gradually worse . . . you know. When would you want me to draw the line?

Participant 12

Finally, participants expressed concern about the added pressure that setting goals might put on them, despite the fact that doing this would motivate them to try to increase their physical activity levels:

I wouldn’t want the guilt on me . . . if I didn’t do the right amount. And I wouldn’t want to be feeling that I’d fallen behind . . .

Participant 12

Living alone

The use of a pedometer to set goals and monitor activity was viewed as a potentially useful solution for people living alone because it was something that could be carried out independently without any additional support:

. . . even in the house, you could do that on your own with the pedometer . . . that would interest me.

Participant 5

Participants expressed a view that people living alone could easily slip into levels of non-activity because there was no one else to motivate or encourage them to take part in physical activity. They saw the pedometer as a source of motivation and encouragement:

And in fact in a family environment possibly the, the advantages might be doubtful. But for anyone living alone. I think it would be a very useful in that it’s quite easy to lapse into a way of life which . . . would predominantly inactive . . .

Participant 3

Theme 4: characteristics of peer mentoring

Social support in the form of peer mentoring was viewed favourably by participants, and comments suggested that, for a peer-led intervention to be successful, the specifics of both the peer and the activity should be considered. In addition, participants suggested that they should have the opportunity to meet with the peer mentor at least once per week. Some participants said they would prefer to have peer contact by telephone, whereas others preferred face-to-face contact, and at a neutral location rather than at their home.

Mentoring for physical activity

Participants identified key components of the activity that needed to be addressed in order to motivate them to take part. First, the activity needed to be well planned, in terms of both timing and route of walking, but arrangements needed to be flexible:

When he phones and lets you know what’s happening in advance then you can pre-plan what’s going to happen or pre-plan to go to these different activities.

Participant 11

In addition, participants felt that the programme planned should create opportunities to try new activities (e.g. swimming), to visit places within their local area or outside their area that they had not been before, or to resume previous activities that they had stopped because their circumstances had changed (e.g. as a result of illness). Attention should also be given to including activities that the participants themselves identified as being pleasurable:

I do feel peer mentoring can introduce you to new ideas. Just because you’re elderly, it doesn’t mean to say you can’t have new ideas . . . you can show the peer something that you enjoy doing . . .

Participant 4

Activities needed to reflect the shared interests and the capabilities of both the peer and the participant:

I’d be interested in what they [the peer mentor?] would like to do too.

Participant 4

People might be reluctant to go out with other people on the basis that they might be . . . walking much further than they would.

Participant 3

In addition, the benefits of any planned activities should be stated at the outset of the programme so that there could be an understanding of the purpose in order to increase motivation to participate:

. . . she said it was good for your health. Good for your mental health, and once she mentioned mental health sort of thing, people listened. And this’ll relax you and relieve stress of the day.

Participant 9

In addition, although the aim of the physical activity intervention may be to increase levels of activity, its other potential beneficial effects were of significance. One interviewee commented on how motivation to continue with the programme long term was derived from their positive experience of it, specifically reporting how it helped promote relaxation:

So relaxing. And that’s what got me motivated.

Participant 9

Attributes of the peer mentor

The attributes of the peer were considered to be key to ensuring the success of a peer-led intervention. Participants expressed a desire for the peer mentor to be not only experienced and well trained but also medically aware to build confidence and trust:

. . . if they have got experience, that can restore your confidence, offering advice, discussing problems . . . Problem-solving with you . . .

Participant 4

. . . the peer would need to know, look this woman has high blood pressure, and this one has diabetes and she needs to carry something . . . Now my friend, she knows me well, and she has asthma and see before we go out like, [XXXX] knows to have all her things with her and she, she lets me know. So, that I’m aware when I’m out with her that this is a bag she has this particular coloured inhaler in . . .

Participant 10

In addition, although participants did not feel that they needed to have the same demographic characteristics as the peer mentors, such as age, they did consider that a peer mentor needs to be someone who is themselves physically active and physically capable to help and provide encouragement. However, it was also noted that other resources should be readily available if help were needed:

Even a young person. It wouldn’t matter what age they were. I think a young person anyway would get you up and get you out.

Participant 9

As long as they were a wee bit more active, . . . that they were able to . . . erm. It would be no good if they were worse than me probably . . . these days we all carry mobile phones.

Participant 5

The only other characteristic of the peer that was identified as important was sex: it was generally felt that the peer mentor should be of the same sex as the participant. However, it was suggested that participants with partners may not need a peer.

The most important component of a peer-led intervention for participants was the relationship that would develop. All participants felt that the relationship should be based on friendship, and a few key components that could secure the success of friendship development were dentified. First, participants identified the need for the peer and participant to have shared interests, and several participants suggested that, similar to dating, the peer’s interests and the participant’s interests should be ‘matched’ to ensure compatibility:

. . . before a peer was selected, that . . . there was a list that you could put down the sort of things that interest you.

Participant 4

Well I would like go out with somebody that’s not doom and gloom. A bit of jokiness . . . that’s what you need. What would be important to walk with is two or three people that you can have a wee bit of banter. You don’t want to hear about the price of tea. You don’t want to hear about their aches and pains. I don’t want to be conferring about aches and pains with anybody. I would avoid having a walk.

Participant 13

Participants suggested that the peer should be voluntarily motivated to spend time with them rather than being paid to do so:

. . . rather than . . . someone who is duty bound, to go ‘walkies’ on Wednesday afternoon, no matter whether it’s pouring or, or the roads are icy or whatever . . .

Participant 4

There was a feeling that friendship would lead to a stronger bond of loyalty, which would act as a physical activity motivator. In other words, friendship would ensure that people would be more reluctant to let others down and incentivise them to meet and carry out activities with the peer:

There’s always the, the feeling that ‘well I should turn up’ because if I don’t I’m letting, letting them down.

Participant 3

Theme 5: finding solutions to barriers to physical activity

Participants were not aware of what problem-solving might involve until it was explained to them. However, it was one of the most preferred options, perhaps because participants felt that it was something that they did on a day-to-day basis anyway. It was considered that problem-solving should be integrated into an overall programme rather than being used as a standalone activity:

I mean, if you’re, you’re getting to the point of deciding that we’re going to have regular walks together you would then come down to the point of where you were actually going to go.

Participant 3

However, participants identified many potential barriers relating to physical activity, including health-related issues; for example, arthritis may prevent walking or gardening, fear for personal safety may prevent walking in areas that were not busy or crowded, and child-minding responsibilities meant that it could be difficult to find time for physical activity. In general, participants felt that finding solutions to barriers was a useful exercise and that problem-solving with another person could help them see the broader picture and find solutions that they may not find by themselves:

It’s great if somebody helps me, because I just see the barrier. You know? And then if somebody like you was to talk about I would go ‘yeah that would be a good solution there’, you know.

Participant 9

However, there was a concern that solutions needed to be applied, progress monitored and feedback given on an ongoing basis to ensure success:

It’s just not practical. No.

Participant 2

Theme 6: appealing attributes of the demonstration walk

The inclusion of a ‘demonstration walk’ as part of the proposed intervention, whereby the peer mentor and participant would go for a walk together, in order to identify potential routes and locations in the local area, was not widely welcomed. The majority of participants suggested that they might consider taking part in a peer-led walk on a weekly basis if the areas outlined in the peer-led activity (above) were addressed. In addition, two areas that could increase motivation to taking part in the demonstration walk were identified.

Group versus one-to-one peer walk

Participants felt that a demonstration walk, if performed as a group activity, could be more enjoyable than walking only with a mentor, as it could provide an opportunity to meet other people with common interests and friendships could be developed within the group:

Where there are other people like yourself who would welcome you, welcome your company.

Participant 4

There was also a feeling that a group could avoid some of the difficulties that perhaps may arise in a one-to-one peer relationship. Thinking of performing the activity as a group was considered to be less daunting and to offer greater opportunity to meet someone with similar interests and capabilities:

. . . maybe even three or four people, . . . because maybe in a group, it’s easier.

Participant 5

However, participants also perceived that, although the group had advantages over a one-to-one peer relationship, it could be less attractive because it felt more like a structured activity and could be a less flexible arrangement:

A structured appointment is, is not a good idea, um, because older people have good days and bad days or don’t fancy putting on a, a waterproof and braving the storm.

Participant 4

I don’t really like the idea of a structured appointment.

Participant 4

Recruitment to a peer-led walking programme

In considering preferred approaches to recruitment, some participants reflected on their experience of joining various clubs. Although they had joined clubs in response to seeing information about them, they knew of other people who would have been eligible to join but did not:

There’s a lot of people in the same situation as what I am in the area but they don’t seem to be coming forward.

Participant 11

There was discussion within the group about the targeted selection of individuals for invitation to join a peer mentoring intervention. It was considered that such an approach from someone from the intervention would have been a more effective method of encouraging recruitment and one participant described how a personal approach had engendered enthusiasm for accepting an invitation to join another group. Such a personal approach to recruitment, rather than relying on posters and leaflets, was considered appropriate in order to ensure common interests or capability among prospective participants:

Well I was stopped one time when, when I was in shopping and this guy stopped me and erm he was telling me that he was trying to set this group up for a certain age, well not a certain age, but a certain gender of people and he was telling me the activities that they plan . . .

Participant 11

It was emphasised in the discussion that information relating to how to join a peer mentor walking group should be made very clear and that the process of recruitment should be as simple as possible for older individuals.

Well, . . . I’m not sure how they get in contact with people or do you have to get in contact with them? They [walking groups] might well make it easier for people to get in touch with them.

Participant 3

Discussion

Interviews revealed that older adults have busy lives, including housekeeping and carer responsibilities, and therefore engaging in other regular physical activity is not seen as a necessity. Walking appeared to be a common and preferred activity across all participants.

Similar to previous research,52 the findings suggest that increasing physical activity in older adults is a complex phenomenon because of the interplay between physical, psychological and environmental factors. For example, the current study identified that health-related beliefs, social support and the characteristics of the local neighbourhood environment are important determinants of physical activity that need to be considered in the development of any physical activity intervention development. However, the current study findings revealed that there were key areas within each BCT which should be explored with a target population, in order to address their barriers to physical activity.

Participants reported leading busy lives, but are not necessarily physically active. To increase physical activity, interventions should seek to increase awareness of the recommended physical activity guidelines and highlight the key health, emotional and social benefits of physical activity for older adults in order to persuade older adults to prioritise physical activity.

Tailoring interventions to personalised physical activity goals, such as step goals,20 can lead to sustained increases in physical activity. Our participants reported that they liked the idea of goal-setting and self-monitoring because they are easy to do and because they can be integrated into existing routines, leading to increased self-efficacy for physical activity. 53 However, the interviews revealed the importance of participants setting their own goals and of the ease of use of monitoring devices, so attention must be paid to selecting the right activity monitor (simple, easy to read, easy to carry and robust) and to delivering appropriate training on how to use it, and allowing participants to set their own goals.

Providing physical activity in combination with appropriate levels of support (whether physical support, such as gardening tools or walking aids, social support, such as peer mentoring or demonstration walking, or simply providing physical activity within a social setting), could decrease feelings of social isolation and loneliness, and increase feelings of motivation, confidence and safety, as well as make physical activity more enjoyable and ultimately increase overall levels of physical activity. Interventions that capitalise on social inclusion, such as peer mentoring or a demonstration walk, have great potential to succeed in increasing physical activity. 52 However, the relationship with the peer or the group is important to ensuring success, so a matching exercise to ensure shared interests between the peer/group and participant is key.

Discussion about the environment identified several defining characteristics which could increase physical activity. For example, individuals suggested that important features of the environment included a facilitated environment (well-maintained paths, aesthetically pleasing, scenic, close to nature, free of pollution), a safe environment (free from traffic, cyclists, dogs and crime), and one that was accessible (local or not). They also mentioned bad weather as a barrier to physical activity. Therefore, planned activities should take place away from traditional physical activity locations (e.g. gyms), but in a physically supportive environment (one that is ‘walkable’), with transport readily available or provided, and which also provides indoor or protected locations to facilitate walking in any weather. In addition, discussions around the demonstration walk identified a need to ensure robust recruitment that was proactive and personal to promote participation.

Interviews revealed conflicting beliefs relating to health, with individuals expressing the belief that physical activity can prevent and improve symptoms of current health conditions, such as arthritis, but can also create health issues through physical exhaustion or make existing symptoms worse, which could result in a lack of independence and the loss of the ability to get out and about. Thus, pain management is key to increasing physical activity, as is the tailoring of physical activity to individual needs. 54

In summary, there is merit in utilising each of the BCTs explored within the context of this study as each addresses barriers to physical activity. Interventions which include goal-setting and feedback, problem-solving, social support through peer mentors and behavioural practice with a peer mentor, as identified through the interview discussions, are perceived to have the greatest likelihood of succeeding in increasing physical activity in an older population living in an area of socioeconomic disadvantage.

Chapter 4 Development of the ‘Walk with Me’ peer-led walking intervention to increase physical activity in inactive older adults

The first phase in developing the complex intervention was to gather relevant evidence and theory to develop a logic model for the intervention, including the proposed causal pathways and relevant outcome measures. From the rapid review of peer-led physical activity interventions, the most common groups of BCTs used previously were related to goals and planning; feedback and monitoring; social support; shaping knowledge; comparison of behaviour; repetition and substitution; and antecedents. The intervention development interviews also identified other BCTs specifically relating to the health benefits of physical activity (information about health consequences). The behaviour change wheel55 was used to map promising BCTs, that is, those that had been successfully used in previous interventions included in the rapid review and that it was deemed could be feasibly delivered within the proposed context, on components of behaviour that reflect multiple levels [motivation (reflective and automatic), opportunities (physical and social environment) and capability (physical and psychological)]. The main output from this stage was a shortlist of proposed BCTs, mapped on to key intervention functions, for inclusion in the design of a pilot RCT.

In the next stage, we explored the perceived feasibility and preferences for strategies, which included particular BCTs, through interviews with older adults from our target communities. Taking account of the interview findings enabled us to avoid and overcome potential barriers to implementation within the intervention design, and to incorporate elements which were perceived to facilitate walking.

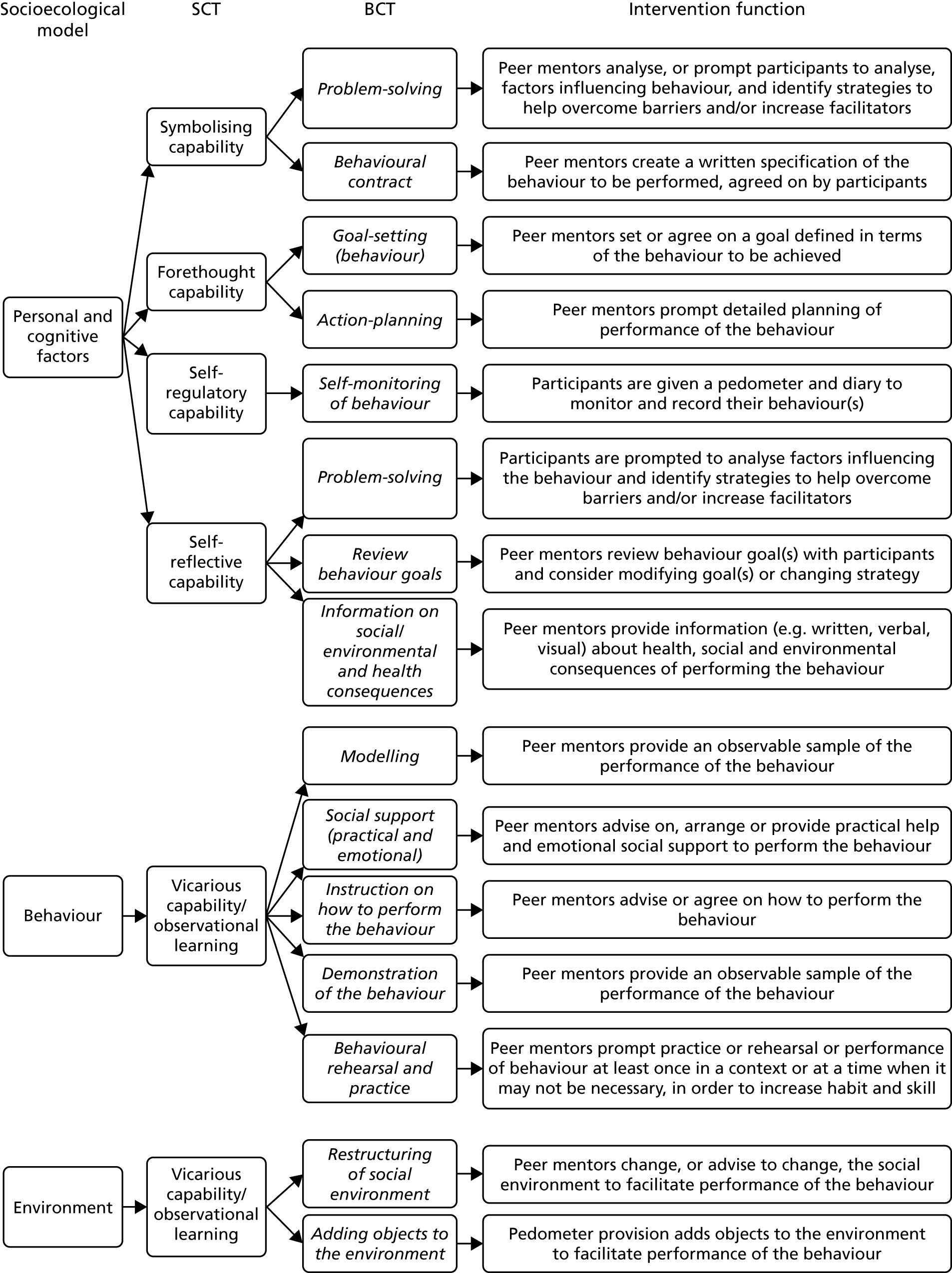

Social cognitive theory56 was used to provide a theoretical framework for designing the intervention as it maps well onto the socioecological model and the role that the physical, psychological and environmental factors identified in the interviews play in physical activity. SCT proposes that personal, environmental and behavioural factors reciprocally influence behaviours. BCTs identified through the rapid review were mapped onto the core set of psychosocial determinants and intervention functions of SCT (i.e. self-efficacy, outcome expectations, goals, and impediments and facilitators) (Figure 5). In addition, the socioecological model was used to provide a framework for a multilevel intervention design57 that addresses multiple levels of determinants, including individual, social and environmental factors. In addition to individual factors (such as feedback on current behaviour), we planned to address social factors, by providing peer mentors to act as a social support for change and environmental factors by matching the programme to local environmental opportunities.

FIGURE 5.

Behaviour change techniques mapped to intervention functions, SCT and socioecological model.

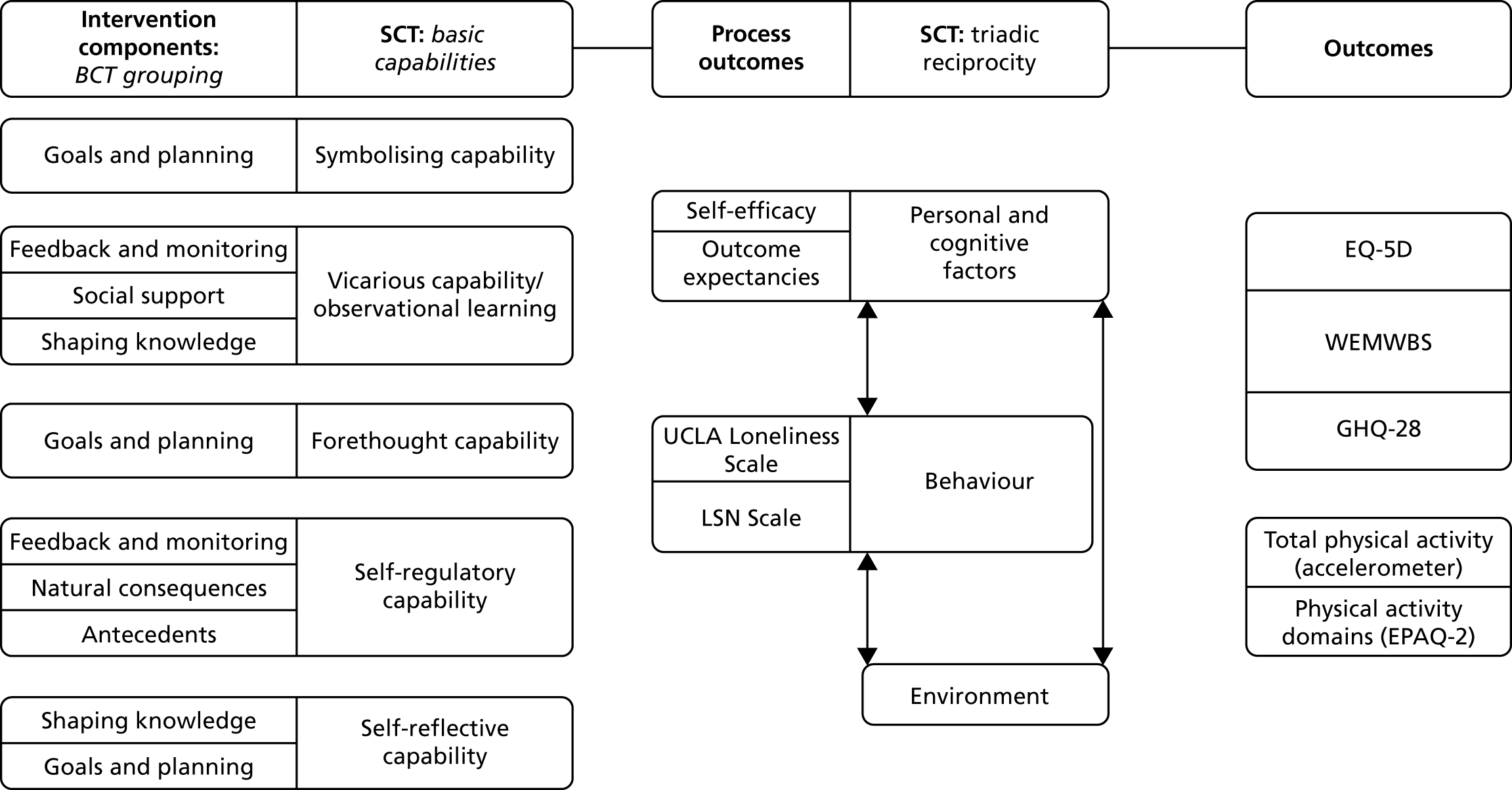

The logic model developed for this study (Figure 6) illustrates how the key intervention functions (BCT groupings) align with the basic capabilities of SCT,56 and how the process and behaviour outcomes of the intervention were measured.

FIGURE 6.

‘Walk with Me’ logic model. EQ-5D, EuroQol-5 Dimensions; GHQ-28, General Health Questionnaire-28 items; LSN, Lubben Social Network; WEMWBS, Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale.