Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 13/117/01. The contractual start date was in November 2014. The final report began editorial review in January 2018 and was accepted for publication in August 2018. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Suzanne Audrey is a member of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Public Health Research (PHR) Research Funding Committee (2017 to present). Chris Metcalfe is co-director of the Bristol Randomised Trials Collaboration. William Hollingworth is a member of the NIHR Health Technology Assessment Clinical Trials Board (2016 to present). Philip Insall is a member of the NIHR PHR Programme Prioritisation Committee (2014 to present).

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Audrey et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Physical activity and health

Physical inactivity increases the risk of many chronic diseases, including coronary heart disease, type 2 diabetes mellitus, obesity and some cancers. 1,2 It is currently recommended that adults should aim to undertake ≥ 150 minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity in bouts of ≥ 10 minutes throughout the week. 3,4 However, because of increasingly sedentary lifestyles, there are concerns that many adults in high-income countries do not achieve this. 1,4–6 For example, in the UK, 41% of adults aged 40–60 years reported no occasions in which they walked continuously for 10 minutes at a brisk pace each month. 5 Increasing physical activity levels, particularly among the most inactive people, is an important aim of the current public health policy in the UK. 1,7

In addition, there is increasing interest in the relationship between time spent sedentary [defined as any waking, sitting or lying behaviour with low energy expenditure (≤ 1.5 metabolic equivalents of task)] and health outcomes. 8 A large amount of time spent sitting has been associated with a greater risk of cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and cardiovascular and all-cause mortality. The amount of objectively measured sedentary time has been associated with a poorer metabolic profile in healthy adults and those at risk of and who have developed type 2 diabetes mellitus. 9 It is of note that these associations are independent of the level of moderate to vigorous physical activity (MVPA) and, consequently, UK health guidelines recommend that adults should minimise the amount of time spent sedentary (sitting) in addition to increasing physical activity. 1

Walking as active travel

Evidence from systematic reviews suggests that adult populations that use active modes of transport (walking and cycling) for commuting have overall higher physical activity levels than car commuters, and also have a decreased risk of cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality. 10,11 Similarly, there is also evidence that people who use public transport, when a portion of the journey is by foot, accumulate more physical activity than car users. 12

Walking is a popular, familiar, convenient and free form of exercise that can be incorporated into everyday life and sustained into older age. 13 It is also a carbon-neutral mode of transport that has declined in recent decades in parallel with the increase in car use. 1 Even walking at a moderate pace of 5 km per hour (3 miles/hour) expends sufficient energy to meet the definition of moderate-intensity physical activity. 14 Hence, there are compelling reasons to encourage people to walk more, not only to improve their health but to address the problems of climate change. 15–18

In the UK, there are substantial opportunities to increase walking by replacing short journeys undertaken by car. For example, the 2016 National Travel Survey showed that 24.5% of all car trips were shorter than 2 miles (3.2 km), and 13% of trips of less than 1 mile (1.6 km) were made by car. 19 An opportunity for working adults to accumulate the recommended moderate activity levels is through the daily commute, and, in addition, replacing using a car with walking for short journeys is likely to reduce sedentary time. Experts in many World Health Organization countries agree that significant public health benefits can be realised through greater use of active transport modes. 20

Systematic reviews have examined the effectiveness of interventions to promote physical activity in general,21–24 but there is less evidence about how best to promote walking to work. A systematic review of interventions to promote change from car to active transport25 examined 19 studies that included workplace-based interventions, architectural and urbanistic adjustments, population-wide interventions and bicycle-renting systems. Sixteen studies reported positive effects on modal shift, but the reviewers concluded that the methodologies used were not of high quality and the interventions were poorly described. 25

Available systematic review evidence has focused on interventions that promote walking, interventions that promote walking and cycling as an alternative to car use and the effectiveness of workplace physical activity interventions. None focuses specifically on employer-led interventions that promote walking to work, although the studies that have been undertaken are included within the available systematic review evidence.

Workplace physical activity interventions

A systematic review of the literature regarding the effectiveness of workplace physical activity interventions, commissioned by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) graded 14 studies as being high quality or good quality. 26 Three public sector studies provided evidence that workplace walking interventions using pedometers can increase daily step counts. One good-quality study reported a positive intervention effect on walking-to-work behaviour (active travel) in economically advantaged female employees. There was strong evidence that workplace counselling influenced physical activity behaviour but the reviewers indicated that there was a dearth of evidence for small- and medium-sized enterprises.

The NICE public health guidance on workplace health promotion concluded that although a range of schemes exist to encourage employees to walk or cycle to work, little is known about their impact. 27 Few studies used robust data-collection methods to measure the impact of workplace interventions on employees’ physical activity levels (most use self-report) and there is a lack of studies examining how workplace physical activity interventions are influenced by the size and type of workplace and the characteristics of employees. 28

Measuring physical activity

The majority of primary studies have depended on self-report measures of both physical activity and mode of travel, which may not provide reliable estimates. 29,30 A systematic review comparing direct measures with self-report measures for assessing physical activity in adults found that self-report measures were higher than objective measures in some cases and lower in others. 30 This calls into question the reliability of self-report measures, and indicates that there is no approach to correcting for self-report measures that will be valid in all cases. However, few studies have objectively measured the contribution of walking, particularly walking to work, to adult physical activity levels. 28,31

In Sweden, two studies examined the association between neighbourhood walkability [measured using a geographic information system (GIS)] and objective physical activity (measured using accelerometers). 32,33 Both studies demonstrated how increased walking rates translated directly to increased MVPA levels. In the USA, a cross-sectional study34 included 2364 participants enrolled in the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study who worked outside the home during year 20 of the study (2005–6) and found active commuting to be positively associated with fitness in men and women, and inversely associated with body mass index (BMI), obesity, triglyceride levels, blood pressure and insulin levels in men. The authors concluded that active commuting should be investigated as a means of maintaining or improving health. In the UK, researchers used accelerometers to examine associations between walking or cycling to work and objective MVPA levels and found that women who reported undertaking ≥ 150 minutes of active commuting per week achieved an estimated 8.50 additional minutes [95% confidence interval (CI) 1.75 to 51.26 minutes; p = 0.01] of daily MVPA compared with those who reported no time in active commuting, but no overall associations were found in men. 35

Costs and benefits of walking as active travel

Experts agree that significant public health benefits can be realised through greater use of active transport modes, and the ratio of benefits to costs is high. 36 However, more evidence is required on the costs and benefits of active travel interventions; a systematic review of interventions to promote walking included 19 randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and 29 non-randomised controlled studies but only six studies included even rudimentary economic evaluation. 37 Despite studies demonstrating the health benefits of active commuting, assessments of the cost-effectiveness of these interventions are relatively scarce. When economic evaluations have been undertaken, cost-effectiveness analyses have been conducted38 and benefit-to-cost ratios have been calculated. 39,40

There are potential benefits to walkers from reduced commuting costs and greater certainty about the timing of the journey to work. Because morbidity and mortality related to physical inactivity disproportionately affect socioeconomically deprived communities, encouraging and enabling walking as physical activity may help to address health inequalities. The potential benefits to employers who promote walking to work may include reduced in sickness costs and absenteeism, improved staff performance and productivity and reduced staff turnover. 41

Using behaviour change techniques to encourage active travel

Behaviour change techniques (BCTs) have been defined as the ‘active ingredients’ within an intervention designed to change behaviour that are observable, replicable and irreducible components, which can be used alone or in combination. 42 A taxonomy of 26 BCTs was identified in 2008,43 with subsequent work undertaken to improve labels and definitions and to reach a wider consensus of agreed distinct BCTs. 44 The 2008 taxonomy has been successfully used to categorise the BCTs used in healthy eating and physical activity interventions with ‘self-monitoring’ combined with at least one other technique identified as the most effective. 45,46

A systematic review of workplace physical activity interventions confirmed that goal-setting, providing instruction and prompting self-monitoring were the main BCTs used. 28 A systematic review and random-effects meta-analysis assessed the effectiveness of 37 worksite interventions and reported that, overall, worksite interventions have small, positive effects on physical activity: those promoting walking as opposed to other forms of physical activity were more effective, and there was some evidence that goal-setting and goal review techniques may enhance fitness gains. 46 Another systematic review of interventions to promote walking37 identified two general characteristics of interventions found to be effective: targeting and tailoring. A systematic review of promoting walking and cycling as alternatives to using cars27 identified 22 studies that met the inclusion criteria and found some evidence that targeted behaviour change programmes can change the behaviour of motivated subgroups.

Of the 46 walking and cycling controlled interventions coded for BCTs by Bird et al. ,47 21 reported a statistically significant effect using a mean number of BCTs of 6.43 [standard deviation (SD) 3.92]. 38 The most commonly used techniques were ‘self-monitoring’ and ‘intention formation’. 47 NICE has issued recommendations advising that interventions should use BCTs based on goals and planning, feedback and monitoring and social support. 48

The Walk to Work feasibility study

Aim and objectives

The current cluster RCT incorporated lessons learned from the Walk to Work feasibility study [National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Public Health Research (PHR) project number 10/3001/04]. 49 The aim of the feasibility study was to build on existing knowledge and resources to develop an employer-led scheme to increase walking to work and to test the feasibility of implementing and evaluating it in a full-scale cluster RCT. The objectives were to (1) explore with employees and employers the barriers to, and facilitators of, employer-led schemes to promote walking to work, (2) use existing resources and websites to develop a Walk to Work information pack to train work-based Walk to Work promoters, and (3) conduct an exploratory RCT of the intervention to pilot workplace and employee recruitment procedures, examine retention rates, pilot cost and outcome measures and inform a sample size calculation for a full RCT.

Study design

The feasibility study comprised two phases of the Medical Research Council’s framework for evaluating complex interventions. 50 During phase I, a review of resources that promote walking (and in particular the benefits of walking to work) was undertaken. In addition, three focus groups were conducted with employees, and interviews were conducted with three employers, in one small, one medium-sized and one large workplace outside Bristol to finalise the intervention design. Phase II comprised an exploratory randomised trial incorporating process evaluation and an assessment of costs. A cluster trial was required because randomisation of individual employees would risk contamination of the control group: the intervention was to be delivered within workplaces with the potential for employees to share information about the intervention and in which employers would be encouraged to support walking to work.

Recruitment

Workplaces were approached through Bristol Chambers of Commerce for initial expressions of interest. Fifty-five workplaces expressed an interest and were asked to complete a short questionnaire about the size and type of the business. Because the intervention initially aimed to focus on employees within ‘walking distance’ of their workplace, employers were also asked to identify how many of their employees lived within 2 miles of the workplace. This process was aided by the research team supplying the first four digits of postcodes likely to contain employees living within the required range, and an instruction leaflet of how to calculate distance using the website walkit.com (accessed 28 February 2019). Nevertheless, some workplaces found this burdensome and it may have affected recruitment. Of the 55 workplaces initially expressing an interest, 19 were recruited and 17 completed the study. Two workplaces left the study after randomisation to the intervention group: one because of downsizing and one because of heavy workload.

Within participating workplaces, employees living within 2 miles of the workplace were given information about the study and invited to participate. As the study progressed, it was felt that this was too restrictive, and a second round of recuitment was undertaken to include people who lived further away and might be willing to incorporate some walking as part of a mixed-mode commute. A total of 187 participants were recruited to the study: 147 living within 2 miles of the workplace and 40 living further away. In the intervention group, study participants were asked to sign an additional consent form before receiving the intervention. This was also considered to be restrictive and was not thought necessary for a future full-scale trial.

It was felt that naming the study Walk to Work may have restricted interest among some employers and may have encouraged the control group to consider walking to work. Therefore, it was decided to name the full-scale trial the Travel to Work study and to name the intervention the Walk to Work intervention.

Data collection

At baseline, all participating employees were asked to complete a questionnaire giving basic personal data and providing information relating to travel behaviour, costs and health. Participants were also asked to wear accelerometers during waking hours for 7 days to provide an objective measurement of physical activity, and to carry a personal GPS (Global Positioning System) receiver during the commute to confirm the duration of the journey and quantify its contribution to overall physical activity. Post intervention, questionnaires were administered again to explore views and experiences of walking to work, and additional questions about the acceptability of the intervention were included for the intervention group only. The questionnaires, accelerometers and GPS receivers were administered again across the intervention and the control groups (as per the baseline protocol) at a 12-month follow-up data collection point. To examine key issues in more depth, baseline and post-intervention interviews were conducted with employers, Walk to Work promoters and a purposive sample of employees.

The Walk to work intervention

There were several stages of the intervention. Walk to Work promoters, either volunteers or nominated by participating employers, were identified in each workplace in the intervention group of the study. A training session for the Walk to Work promoters was run by experts in the research team and focused on the benefits of walking to work and resources available to promote this, identifying walking routes with participating employees and building confidence to encourage other employees to walk to work. The Walk to Work promoters were provided with the booklets and optional pedometers to assist them in their role. Employees participating in the study were then contacted by the Walk to Work promoter and those who were interested in walking to work were asked to consent to the intervention. The role of the Walk to Work promoter was to distribute booklets and optional pedometers, help identify walking routes, discuss barriers and solutions and encourage goal-setting. The promoters were also asked to provide support through four contacts (face-to-face, e-mail or telephone contacts, as appropriate) with participants over the following 10-week intervention period.

Findings from the process evaluation suggested that the intervention materials were acceptable to participants, with different individuals finding some BCTs more helpful than others. This suggested that a range of BCTs was required to enable participants to choose a ‘package’ to suit their individual needs. Some Walk to Work promoters were more proactive than others. One promoter did not perform the role at all owing to the pressure of work, and others felt that they needed additional support and encouragement during the 10-week intervention period, similar to that provided during the four contacts with study participants. It was also suggested that additional support at an organisational level should be encouraged.

Economic evaluation

All costs (including time, materials, equipment and travel) involved in the intervention were documented. Self-reported general health service use, productivity, absence from work and weekly commuting costs were also measured. The average cost of the intervention for participating workplaces was £441 (with a wide range from £66.33 to £958.38). Costs varied because of different numbers of promoters in each workplace, the number of employees participating in the intervention and the location of promoter training. Mean daily commuting costs were slightly lower in the intervention group than in the control group at follow-up [£2.66 (SD £4.32) vs. £3.64 (SD £12.16)] and mean self-assessed productivity was somewhat better in the intervention group than in the control group [1.51 (SD 1.41) vs. 2.07 (SD 2.24)] (based on a scale of 1 to 10, with 1 being ‘health problems had no effect on my work’ and 10 being ‘health problems completely prevented me from working’), but the study was not powered to provide strong evidence on these outcomes.

Physical activity outcomes

The primary outcome response rate was 80% (149 out of 187 participants) immediately post intervention and 71% (132 out of 187 participants) at the 12-month follow-up. Although not powered to measure effectiveness, the accelerometer data suggested that overall weekday physical activity was lower in the intervention group [434.6 ± 165.0 counts per minute (c.p.m.)] than in the control group (441.9 ± 190.0 c.p.m.) at baseline, but higher in the intervention group (452.0 ± 188.7 c.p.m.) than in the control group (400.6 ± 120.0 c.p.m.) at the 12-month follow-up. MVPA was similar in the intervention (63.4 ± 28.6 minutes per day) and the control (63.3 ± 28.5 minutes per day) groups at baseline, and was higher in the intervention group (61.3 ± 28.4 minutes per day) than in the control group (55.8 ± 22.2 minutes per day) at the 12-month follow-up.

Intracluster correlation coefficient and sample size calculation for a full-scale cluster randomised controlled trial

The intracluster correlation coefficient (ICC) for the fesasibility study was calculated to be 0.12 (95% CI 0.00 to 0.30) and the average cluster size was 8. Based on an ICC of 0.15 to allow for some imprecision in the estimate, it was caluclated that 678 participants across 84 workplaces would be required to give 80% power with a 5% significance level to detect a 15% increase in mean MVPA.

Summary

There are strong public health reasons to promote walking during the commute to and from work, yet there is a paucity of robust evidence relating to the effectiveness of workplace interventions to promote walking to work. A feasibility study showed that a Walk to Work intervention and its evaluation were feasible and acceptable to participants but suggested a need to simplify recruitment procedures and give additional support to the Walk to Work promoters during the 10-week intervention. Qualitative and statistical evidence suggested sufficient evidence of promise to justify a follow-on full-scale cluster RCT. To our knowledge, the Travel to Work cluster RCT is the first study to objectively measure (using accelerometers and GPS receivers) the effectiveness of a workplace intervention to promote walking during the commute to and from work, and to quantify the contribution of walking during the commute to adult physical activity.

Chapter 2 Study design

Trial design

The study was a multicentre, parallel-arm, cluster RCT incorporating process and economic evaluations. The trial protocol was published at the beginning of the study. 51

Aim

The focus of the trial was to evaluate the effectiveness of a workplace-based intervention to increase walking during the commute for adults working in urban and suburban areas.

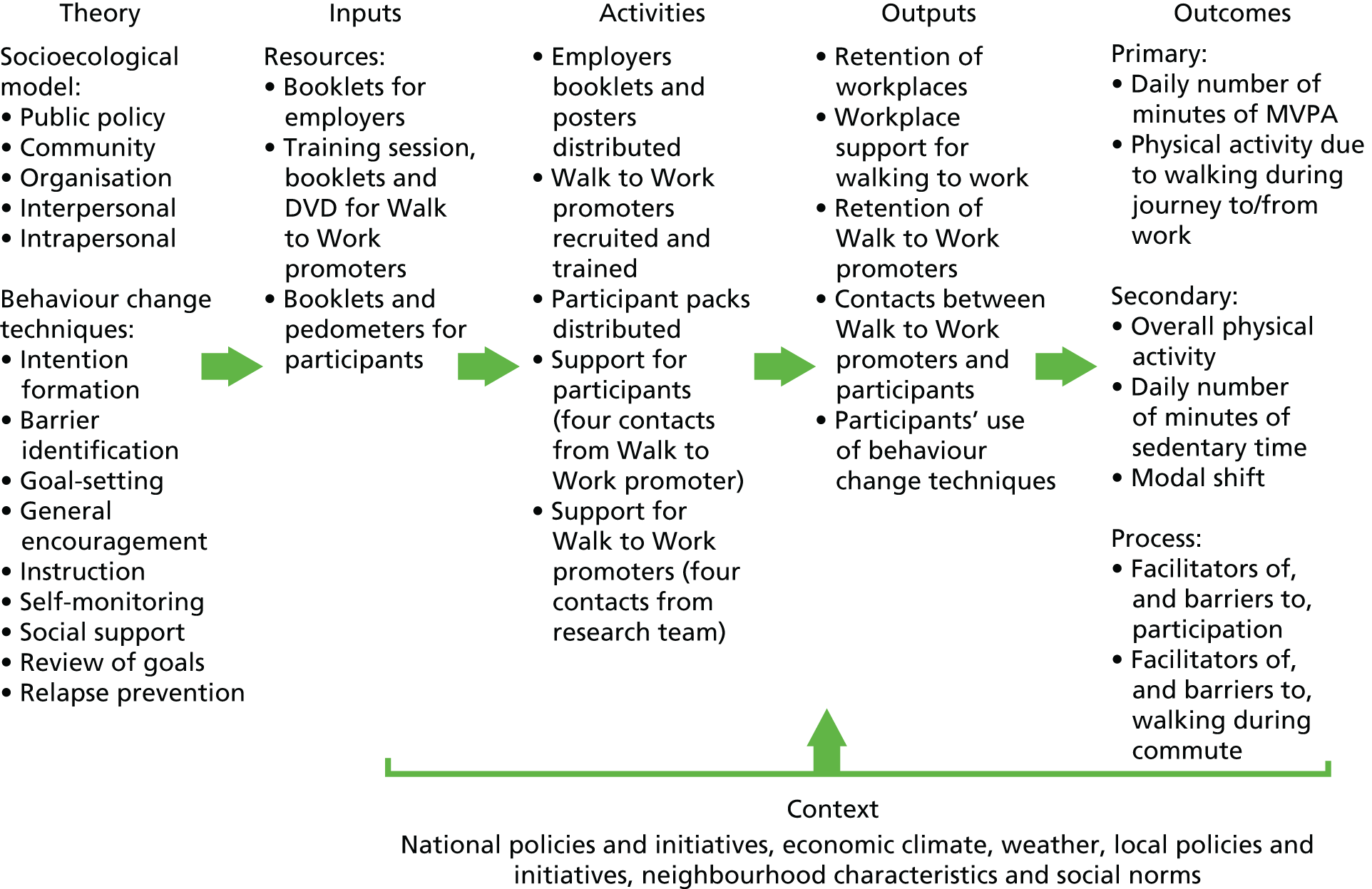

Primary outcome

Does the intervention lead to an increase in the daily number of minutes of MVPA after 12 months compared with the control group?

Secondary outcomes

As well as the primary outcomes, there were several secondary objectives relating to physical activity and travel mode. These were:

-

Does the intervention lead to an increase in overall physical activity compared with the control group?

-

Does the intervention decrease the daily number of minutes of sedentary time compared with the control group?

-

Does the intervention lead to an increased number of journeys in which walking to work is the major mode of travel compared with the control group?

-

Does the intervention increase MVPA attributable to walking on the commute compared with the control group?

Economic outcomes

There were three key economic outcomes of interest:

-

What are the intervention costs to participating employers and employees?

-

Does the intervention lead to increased or decreased costs in terms of health-care use, commuting costs and productivity losses?

-

Does the intervention lead to improved well-being, as measured by the ICEpop CAPability measure for Adults (ICECAP-A) questionnaire?52

Process outcomes

The purpose of the process evaluation was to examine the context of, delivery of and response to the intervention from the perspectives of employers, Walk to Work promoters and employees. There were two main outcomes of interest:

-

What were the barriers to, and facilitators of, walking during the daily commute?

-

Was there evidence of any social patterning in the uptake of the intervention, particularly in relation to socioeconomic status, age and gender?

Sample size and justification

Using the findings from the feasibility study, the sample size for the full-scale trial was based on an average cluster size of eight, an ICC of 0.15 and participant attrition of 25%. The calculation needed to allow equal numbers of workplaces in the intervention and the control groups. We calculated that we needed 339 participants per study group to detect a 15% difference in MVPA levels (equal to a difference of 0.36 SDs) with 80% power at the 5% significance level. Therefore, 678 employees were required from 84 workplaces.

Setting

The aim was to recruit a variety of workplaces from different urban and suburban settings. Workplace recruitment in the first year of the study was in three areas: South Gloucestershire, Bath and Swansea. This was expanded for the second year of recruitment to include Bristol, Swindon, Neath Port Talbot and Newport. A brief overview of each of these areas is provided in the following sections. The workplace characteristics are described in Chapter 3.

South Gloucestershire

South Gloucestershire, in the south-west of England, comprises multiple towns and population centres to the north and east of the city of Bristol. In 2016, the population of South Gloucestershire was estimated to be 277,600, of whom 174,700 people (62.9%) were aged 16–64 years and 146,700 (52.8%) were economically active. 53 Key employers are local and national government departments, engineering and manufacturing industries and large insurance companies. 54 Many employers are located between the northern edge of Bristol and the M5 motorway. This area includes a large regional shopping centre and surrounding retail and business parks. South Gloucestershire contains a network of roads serving the industries, distribution centres and retail centres in the area. The railway network in South Gloucestershire is connected to major cities and towns across the UK.

Bath

Bath is a city in the south-west of England. In 2016, the population aged 16–64 years in the parliamentary constituency of Bath (which includes the city and surrounding suburbs) was estimated to be 64,900, of whom 49,300 people were economically active. 55 The city has strong software, publishing and service-oriented industries. Other important economic sectors in Bath are education, health, retail, tourism and leisure and business and professional services. 56 Major employers are the NHS, the city’s two universities and Bath and North East Somerset council. In an attempt to reduce car use in the historical centre of Bath, park-and-ride schemes have been introduced through which car drivers are encouraged to use car parks on the edge of the city and travel into the centre by bus. Nevertheless, underground city-centre parking was also provided for a recent large shopping centre development. Bath is served by a main railway station providing connections to major cities, as well as some suburban railway services and a network of bus routes to surrounding towns and cities.

Swansea

Swansea is a coastal city and county in south Wales and has the second highest population of the 22 Welsh local authorities. 57 In 2016, the population of the Swansea local authority area was 244,500, of whom 155,300 people (63.5%) were aged 16–64 years and 113,500 were economically active. 57 The Swansea economy has a proportionately large share of jobs in the public administration, health, hospitality, financial services and retail sectors. Of the people in employment, an estimated 87.5% are employed in the service sectors, with 28.2% working within the public sector. Other main business activities are in the construction and scientific and technical sectors. The M4 motorway and several major trunk roads link Swansea to other cities in Wales and England. Bus services include smaller bus and coach operators, a road-based rapid transport route and two park-and-ride services. 58 There is also a main railway station and three smaller suburban stations.

Bristol

Bristol is a city and county in the south-west of England. In 2016, the population of the city of Bristol was 454,200, of whom 309,900 people (68.2%) were aged 16–64 years and 255,400 were economically active. 59 The main employment opportunities are in wholesale and retail, health and social work, administrative and support services and professional, scientific and technical activities. Bristol is connected to London and other major UK cities by two motorways and connecting major roads, as well as through its main railway station. Sustrans (www.sustrans.org.uk; accessed 19 December 2017), a charity promoting sustainable transport, was founded in Bristol. In 2015, Bristol won the European Union’s European Green Capital award (www.bristol2015.co.uk; accessed 19 December 2017), in which sustainable transport was an important focus.

Swindon

Swindon is a large town in the south-west region of England. In 2016, the Swindon area had a population of 217,900, of whom 139,800 people (64.2%) were aged 16–64 years and 120,600 were economically active. 60 The majority of employment opportunities are in manufacturing (including car production plants), wholesale and retail, administrative and support services, health and social work, and finance. Swindon is on the main railway line linking London with the south west of England and south Wales. The town can be accessed by a strategic road network including two junctions along the M4 motorway. 61 The recent transport plan for Swindon indicates that the development of fast and efficient public transport has ‘lagged behind’ because of the relative ease of car use. 61

Neath Port Talbot

Neath Port Talbot is a County Borough and Unitary Authority in central south Wales. The area stretches from the south coast to the borders of the Brecon Beacons National Park. The majority of the population lives in the principal towns of Neath and Port Talbot. In 2016, the population of Neath Port Talbot was recorded as 141,600, of whom 88,000 people (62.1%) were aged 16–64 years and 67,300 were economically active. 62 Regeneration ‘to make Neath Port Talbot a place that is better connected, better for business and a better place to live’ is an important theme for the county borough council (reproduced with permission from Neath Port Talbot Council63). The main employment opportunities are in manufacturing (including steelworks), wholesale and retail trades, and human health and social work. The towns of Neath and Port Talbot both have railway stations, connecting them to major cities in Wales and England, and are also served by a network of buses. The M4 motorway cuts through Port Talbot, linking it to towns and cities along the M4 corridor. The Port Talbot docks complex is used mostly for the import of iron ore and coal for use by the nearby steelworks.

Newport

Newport is a city and unitary authority area in south-east Wales. In 2016, the population of the city was 149,100, of whom 93,100 people (62.4%) were aged 16–64 years and 73,100 were economically active. 64 Newport was once Wales’ largest coal-exporting port, but the docks declined in importance during the 20th century. The main employment opportunities are now in manufacturing, the wholesale and retail trade, and human health and social work. Newport lies within the M4 corridor and is accessed by a network of major roads. A railway line passes through the centre of the city and a network of buses also serves the city. 65

Research governance

Ethics committee approval

As the study was not a clinical trial, and did not involve patients or users of the NHS, it was not necessary to apply for NHS ethics approval. All protocols and relevant paperwork were submitted to the Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry Research Ethics Committee at the University of Bristol in February 2014 and ethics approval was granted on 20 April 2014.

Adverse events

The Walk to Work intervention was considered low risk, involving generally healthy adults, and no adverse events had been reported during the feasibility study. However, there are potential risks to pedestrians in relation to road traffic safety and personal safety. Furthermore, it was possible that people with low activity and no history of walking might suffer initial muscle stiffness. In most cases, this would be mild and a normal consequence of increased physical activity, but participants were made aware that some symptoms might require medical attention, for example when underlying joint weakness is exposed. Such incidents were monitored throughout the trial.

Participating employers, Walk to Work promoters and employees were provided with guidance about adverse events and how to report them. Because available adverse events forms for health research tended to relate to clinical trials rather than low-risk public health interventions, bespoke forms were designed for the current study and agreed with the University of Bristol Research Governance and Ethics officer (see Appendix 1).

It was agreed that adverse events would be recorded by the key researcher for each site and collated by the study manager and principal investigator. When appropriate, adverse events would be reported to the University of Bristol Research Ethics Committee and the chairperson of the Trial Steering Committee. If adverse events were attributable to the intervention, relevant participants would be informed immediately (e.g. if an incident had happened on a particular route, work colleagues using the same route would be provided with relevant information).

It was also acknowledged that Walk to Work promoters might experience difficulties due to disruption to usual working relationships or employers’ concerns about time taken out of usual work activities. The intervention activities might also present problems for employers and employees, such as disruption to work routines as a result of permitting elements of the intervention during working hours. These issues were considered through the qualitative research undertaken as part of the process evaluation.

Participant recompense

A small amount of recompense, a £10 gift voucher, was given to study participants who returned accelerometers and GPS monitors at the baseline and the 12-month data collections, in recognition of their contribution to the research. Interview participants were also given a £10 gift voucher. This was handled discretely by providing relevant individuals with a plain envelope containing the gift voucher thanking them for their help with the study.

Data storage

All data relating to workplaces and research participants are stored at the University of Bristol in accordance with the Data Protection Act 201866 and University of Bristol research governance requirements. Information collected from the paper questionnaires was transferred onto the study database, which is held on secure file storage at the University of Bristol and protected by a combination of user accounts and file access control lists, limiting access to agreed members of the research team. The data set will be kept, with limited access by agreed members of the research team, for 10 years from the end of the study. Following the transcription of interview recordings, all potentially identifiable personal information was removed to ensure anonymity. Personal information required for routine contact was stored on a separate database that could be linked using the unique participant identification number. The hard copies of the questionnaires and consent forms will be kept at the University of Bristol in a locked filing cabinet for at least 3 years after termination of the study.

Trial management and scrutiny

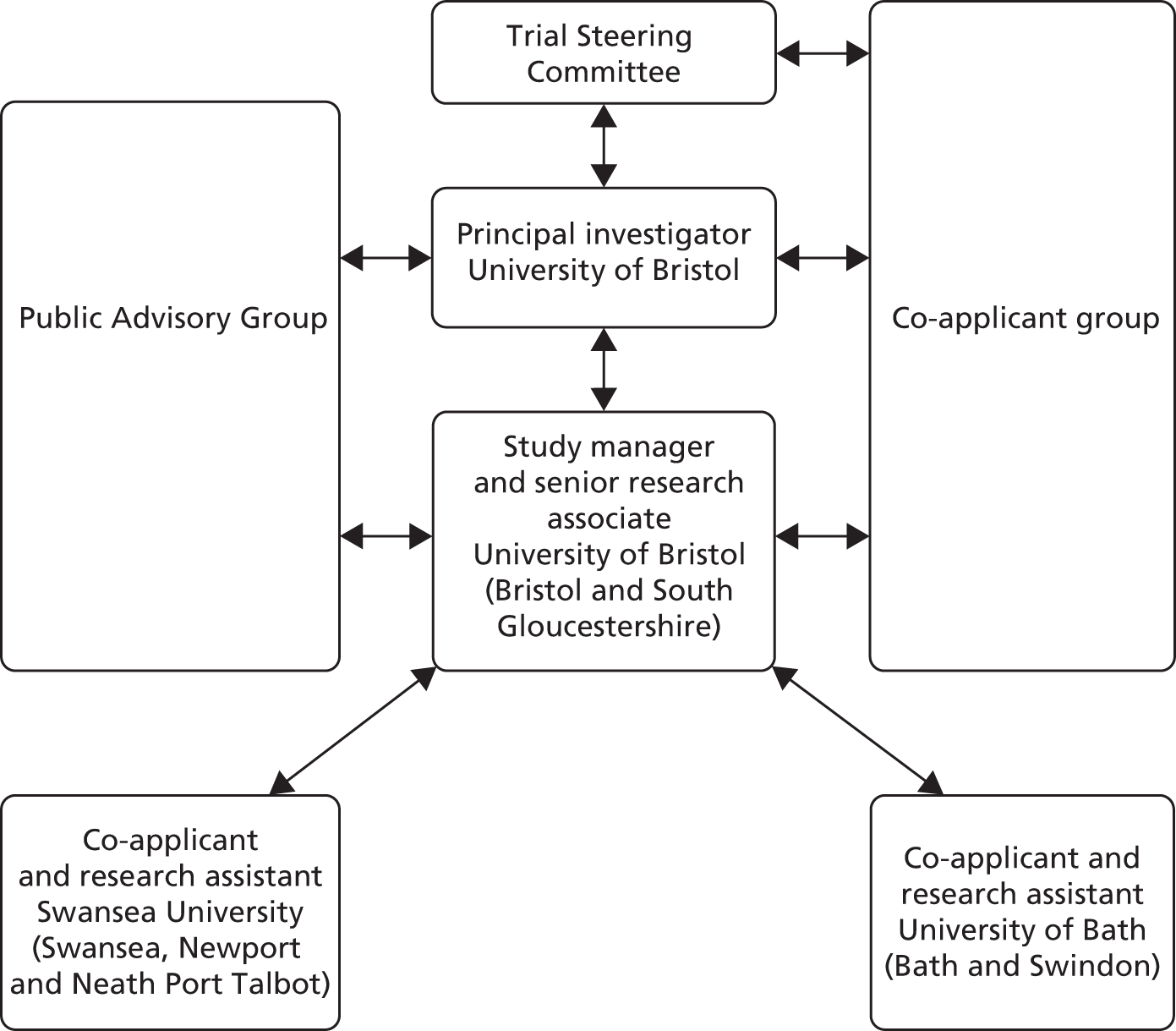

An overview of the study management structure is provided in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Travel to Work study management structure.

Trial Steering Committee

The Trial Steering Committee met with key members of the research team twice a year throughout the study and comprised an independent chairperson, statistician and health economist plus additional independent experts in travel behaviour, research evaluation, physical activity and health promotion.

Study co-applicant group

The research co-applicant group met on a quarterly basis throughout the study and was chaired by the principal investigator. The group comprised co-applicants from each of the research sites (Bristol, Bath and Swansea), the study manager, a representative of the Bristol Randomised Trials Collaboration (BRTC) and co-applicants with expertise in physical activity measurement, statistical analysis, health economics and sustainable transport.

Research team

A research co-applicant and researcher were based at each research centre (Bristol, Bath and Swansea) and the team met on a quarterly basis. There was frequent and ongoing communication, by e-mail or telephone, between the research sites throughout the trial.

Study registration

The study was listed on the ISRCTN (International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number) registry with trial number ISRCTN15009100. 67

Participant and public involvement

The application for a full-scale trial followed on from a feasibility study that included phase I development of the intervention and a phase II exploratory trial. 49 During phase I, focus groups were conducted with employees in three workplaces; their views were sought on the design of the Walk to Work intervention and its evaluation, including the use of accelerometers and GPS monitors. Further interviews were conducted during phase II. A feedback event from the feasibility study was attended by employees, employers and Walk to Work promoters at which the research team presented findings, participants were invited to give feedback on the intervention and its evaluation and we obtained contact details of participants who would consider joining a Public Advisory Group should an application for a full-scale trial be successful.

Data from focus groups, interviews and feedback events helped to shape the intervention and its evaluation for the main trial: the recruitment process was simplified, the arrangements for Walk to Work promoter training were changed to allow group training at an external venue or in-house individual training to suit the workplace and additional booklets were developed that contained information for employers in the intervention group about changes they can make in the workplace to support employees who increase the amount of walking on their commute.

Research co-applicants from non-academic organisations also influenced the feasibility study. A director of Sustrans advised on promoting active travel and a transport consultant with Bristol City Council helped design and implement the training programme. These representatives continued as co-applicants throughout the main trial.

At the beginning of the main trial, 12 people form workplaces involved with the feasibility study were invited to become members of a Public Advisory Group. They were given information about the trial and the role of the group and were informed that reimbursement for time and travel expenses would be provided at a rate of £100 per meeting. Three people accepted membership and fully participated in two meetings towards the beginning of the study. This involved scrutinising the data-collection methods, including questionnaires, travel diary and the instructions for participants using the accelerometers and GPS monitors. They also commented on the intervention materials and suggested that some of the information in the draft booklets for employees, Walk to Work promoters and employers was condescending and repetitive. This was particularly valuable advice and the booklets were shortened and improved as a result.

Project timetable and milestones

The study was originally planned to take 33 months (November 2014 to July 2017) and broadly kept to the proposed timetable for recruitment, delivery of the intervention and data collection. However, a 3-month extension was granted for the core Bristol team to give more time for data analyses and dissemination. The study timetable and key milestones are summarised in Table 1. Because of the potential for seasonality to influence travel behaviour, the study was structured so that the baseline and the 12-month follow-up data collections took place during spring and early summer.

| Milestone | Time point | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | |||||||||

| November to December | January to March | April to June | July to September | October to December | January to March | April to June | July to September | October to December | January to March | April to June | July to October | |

| Staff recruitment (research assistants at three sites) | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Ethics application | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Finalise questionnaires and booklets | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Preparation for baseline data collection | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Prepare Walk to Work packs | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Workplace recruitment | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Participant recruitment | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Baseline data collection | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Randomise workplaces | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Recruit and train Walk to Work promoters | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Implement Walk to Work intervention | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Preparation for post-intervention data collection | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Post-intervention data collection | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Post-intervention interviews | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Data entry and transcription | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Preparation for follow-up data collection | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Follow-up data collection | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Data entry | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Data analysis (qualitative and quantitative) | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Paper writing and dissemination | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

Chapter 3 Recruitment

Methods

Lessons from the feasibility study

Following the feasibility study,49 it was felt that the workplace recruitment process should be simplified so that employers were not required to calculate the number of employees who lived within 2 miles of the workplace before being recruited to the study. This requirement had appeared to be onerous for some workplaces that did not sign up for the study after an initial expression of interest. It was also thought that participant eligibility should be expanded to include people living further away from the workplace who might be willing to incoporate walking as part of a mixed-mode commute. Nevertheless, information about the length of the commute was considered valuable to assess how many participants were within a reasonable walking distance (defined as 2 km for the full-scale trial) and might be encouraged to walk the full distance, and how many might be more suited to a mixed-mode commute. The survey questionnaires, following participant consent, were considered to be the most suitable method of collecting postcodes and enabling study researchers to calculate the distances between home and workplace.

Attrition during the feasibility study (29% at the 12-month follow-up) compared well with other workplace-based physical activity interventions. However, no attempt had been made during the feasibility study to contact employees who left the workplace for other employment between baseline and follow-up. To reduce attrition during the main trial, it was agreed that researchers would ask consenting participants to provide contact details if they left the workplace before the 12-month follow-up. This would enable data-collection packs to be sent to them and returned to the researchers by post.

Eligibility criteria

The following exclusion criteria applied at the workplace level: (1) workplaces with a large proportion of staff on short-term or zero-hours contracts, or workplaces with plans to significantly downsize or relocate during the study period, as follow-up data might not be achievable, and (2) workplaces with fewer than five employees, as there was limited potential to recruit a sufficient number of participating employees into a workplace cluster. All employees within participating workplaces were eligible to take part unless they met any of the following exclusion criteria: (1) they already always walked or cycled to work, (2) they were disabled in relation to walking, (3) they were due to retire before the 12-month follow-up data collection or (4) daily driving was a key part of their role.

Workplace recruitment and consent

The aim was to recruit 84 workplaces of different sizes and industrial classifications. Workplace recruitment took place in two phases during May to July 2015 and March to May 2016. The initial intention was to recruit across three urban areas in south-west England and south Wales: South Gloucestershire, Bath and Swansea (Table 2).

| Recruitment phase | Area | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bath | Swansea | South Gloucestershire | ||||

| Number of workplaces | Number of participants | Number of workplaces | Number of participants | Number of workplaces | Number of participants | |

| 2015 | 14 | 113 | 14 | 113 | 14 | 113 |

| 2016 | 14 | 113 | 14 | 113 | 14 | 113 |

| Total | 28 | 226 | 28 | 226 | 28 | 226 |

For the 2015 recruitment round, lists of employers were obtained from relevant Chambers of Commerce and local authorities. The BRTC generated a list of random numbers (blinded to workplace addresses and contact details) for half of the workplaces to be invited to express an interest in the study, with the intention of sending information out to the remaining workplaces in 2016. However, recruitment in 2015 was insufficient to reach the required sample size. Following discussions within the co-applicant group, and subsequently with the Trial Steering Committee and the funders (the NIHR PHR programme), it was agreed that four additional areas would be included in the second recruitment round. In 2016, employers in the other half of the lists for South Gloucestershire, Bath and Swansea were sent information about the study, in addition to all workplaces on available lists of employers for Bristol, Swindon, Neath Port Talbot and Newport.

Workplace recruitment packs

Workplaces were sent a letter of invitation together with an information leaflet and a short form to return to the research team to express interest and provide basic information about the workplace (see Appendix 2).

Following expressions of interest, eligible workplaces were contacted by telephone or e-mail and a meeting was arranged with one member of the research team at which the trial was explained in more detail and written consent was sought for participation in the study.

Participant recruitment and consent

Employers within participating workplaces were provided with an information leaflet (see Appendix 3), describing the study and eligibility criteria, to distribute to all their employees. All eligible employees were invited to participate in the study and given consent forms for their individual participation. This consent was provided before the baseline data collection and subsequent randomisation.

Baseline characteristics

Study participants were asked to complete baseline questionnaires, which included questions about their sociodemographic characteristics, mode of travel to work and occupation.

Results

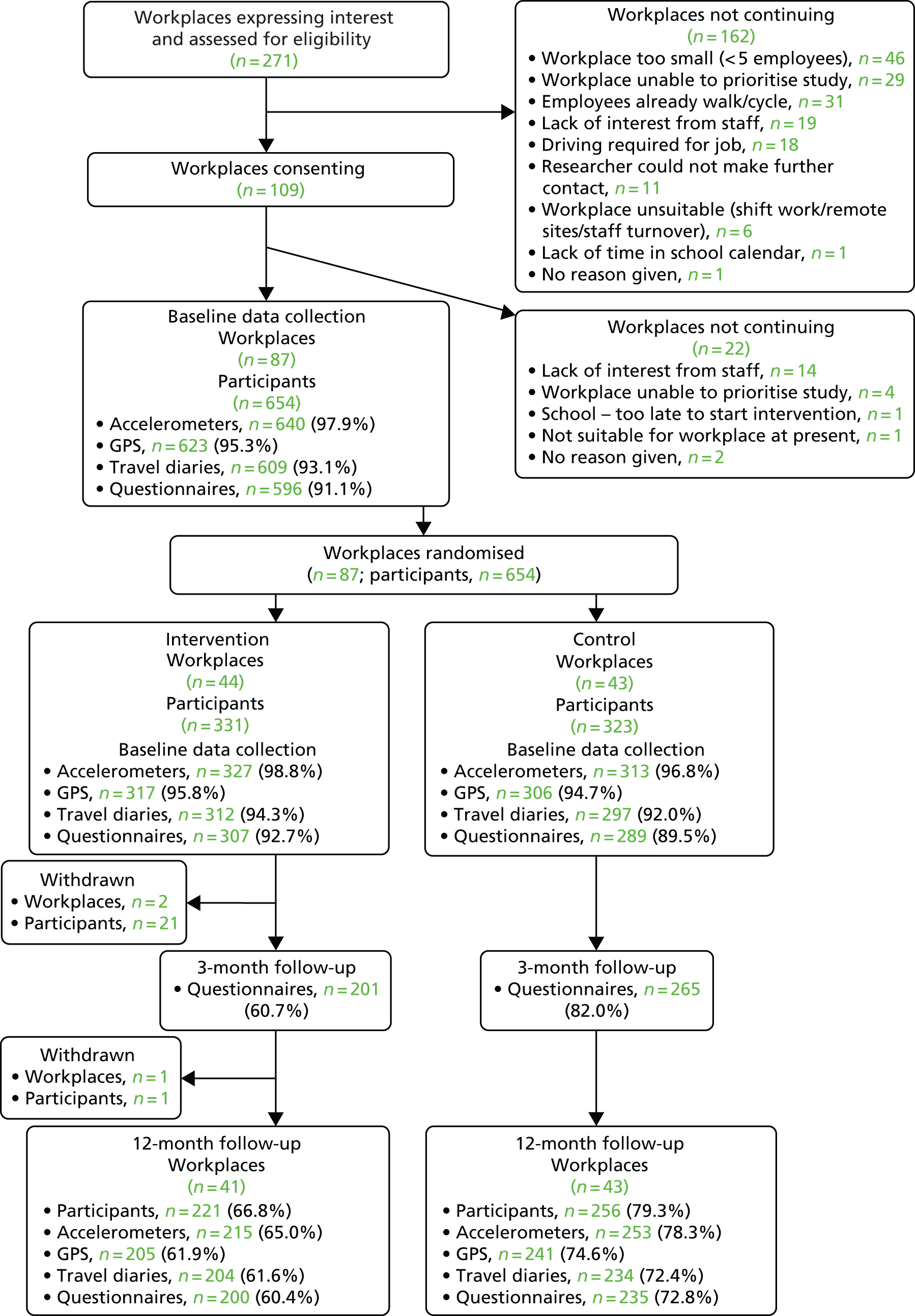

Workplace recruitment

Approximately 9800 invitation packs were sent out over the two recruitment phases (Table 3). Because of time and resource constraints, it was not possible to check whether or not all the workplaces on the lists were still in existence, or whether or not the packs reached an appropriate person with the authority to decide about workplace participation. For example, of 1892 invitations packs sent out in 2015, 114 (6%) were returned undelivered.

| Research centre and area (recruitment phase) | Number of workplaces |

|---|---|

| Swansea | |

| Swansea (2015 and 2016) | 1265 |

| Neath Port Talbot (2016) | 516 |

| Newport (2016) | 1364 |

| Bath | |

| Bath (2015 and 2016) | 1020 |

| Swindon (2016) | 2027 |

| Bristol | |

| South Gloucestershire (2015 and 2016) | 2263 |

| Bristol (2016) | 1348 |

| Total | 9803 |

Workplaces expressing an interest were checked for eligibility by the research team and those meeting the criteria were contacted and provided with further information about the study. As a result of this process, only 29 workplaces were recruited in the first year (Table 4). The number of areas was increased, and a further 58 workplaces were recruited in the second year, making a total of 87 workplaces. This was in line with the target of recruiting 84 workplaces, but there was not an even spread of workplaces across the different areas and the numbers ranged from 35 in Bristol to three in Neath Port Talbot (see Table 4).

| Area | Recruitment status | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consented to participate | Withdrew from study | |||

| Number of workplaces | Number of participants | Number of workplaces | Number of participants | |

| 2015 | ||||

| South Gloucestershire | 10 | 110 | 1 | 12 |

| Swansea | 10 | 64 | 0 | 0 |

| Bath | 9 | 49 | 1 | 9 |

| Subtotal | 29 | 223 | 2 | 21 |

| 2016 | ||||

| South Gloucestershire | 2 | 21 | 0 | 0 |

| Bristol | 35 | 266 | 0 | 0 |

| Bath | 2 | 7 | 0 | 0 |

| Swindon | 3 | 19 | 0 | 0 |

| Swansea | 7 | 79 | 0 | 0 |

| Newport | 6 | 35 | 0 | 0 |

| Neath Port Talbot | 3 | 4 | 1 | 1 |

| Subtotal | 58 | 431 | 1 | 1 |

| Total | 87 | 654 | 3 | 22 |

Reasons for workplace withdrawal following expression of interest

Overall, 271 workplaces expressed an interest in the study. These were checked for eligibility and provided with an opportunity to discuss study participation in more detail. At this stage, 162 workplaces did not continue with the study. Reasons for workplaces not consenting to participation after expressing interest are summarised in Table 5: 28% were deemed ineligible by the research team because there were fewer than five employees, 19% reported that their employees already always walk or cycle, 18% felt unable to prioritise the study activities when they were explained in more detail, 12% had consulted their staff and found a lack of interest in participating and 11% indicated that their employees needed to drive as part of their job.

| Reason | Number of workplaces |

|---|---|

| Workplace too small (fewer than five employees) | 46 |

| Employees already walk/cycle | 31 |

| Workplace unable to prioritise the study | 29 |

| Lack of interest from staff | 19 |

| Driving required for job | 18 |

| Researcher unable to make further contact | 11 |

| Workplace unsuitable (shift work/remote sites/staff turnover) | 6 |

| School – lack of time in academic calendar | 1 |

| No reason given | 1 |

| Total | 162 |

Following workplace consent, a further 22 workplaces withdrew before the baseline data collection (Table 6). The main reason for workplaces withdrawing at this stage of the study related to lack of interest among the workforce, despite their employer having an interest in participating.

| Reason | Number of workplaces |

|---|---|

| Lack of interest from staff | 14 |

| Workplace unable to prioritise the study | 4 |

| Not suitable for the workplace at the moment | 1 |

| School – too late to start intervention in academic calendar | 1 |

| No reason given | 2 |

| Total | 22 |

Workplace characteristics

Workplaces were diverse in relation to their function and included public administration, professional and scientific organisations, retail, services and manufacturing (Table 7). 68 The workplaces varied in size: 10 (11.5%) were micro-sized (< 10 employees), 35 (40.2%) were small (10–49 employees), 22 (25.3%) were medium-sized (50–249 employees) and 20 (23.0%) were large (≥ 250 employees). Table 7 shows a good balance of workplace characteristics between the two groups following randomisation.

| Characteristics | Trial group, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Intervention (N = 44) | Control (N = 43) | |

| Location | ||

| Swansea, Newport and Neath Port Talbot | 13 (30) | 13 (30) |

| Bath and Swindon | 8 (18) | 6 (14) |

| South Gloucestershire and Bristol | 23 (52) | 24 (56) |

| Size of business (number of employees) | ||

| Micro (5–9) | 4 (9) | 6 (14) |

| Small (10–49) | 21 (48) | 14 (33) |

| Medium (50–249) | 9 (20) | 13 (30) |

| Large (≥ 250) | 10 (23) | 10 (23) |

| Most often used method of travel to work by employees | ||

| Car or motorised transport | 32 (73) | 31 (72) |

| Public transport | 1 (2) | 1 (2) |

| Walk or cycle | 1 (2) | 0 (0) |

| Unknown | 10 (23) | 11 (26) |

| Proportion of employees who walk or cycle all the way to work | ||

| None or hardly any | 13 (30) | 12 (28) |

| Fewer than half | 23 (52) | 21 (49) |

| Most | 1 (2) | 0 (0) |

| All | 1 (2) | 0 (0) |

| Unknown | 6 (14) | 10 (23) |

| UK-SIC categories 200768 | ||

| C: manufacturing | 4 (9) | 2 (5) |

| D: electricity, gas, steam and air conditioning supply | 0 (0) | 1 (2) |

| F: construction | 1 (2) | 0 (0) |

| G: wholesale and retail trade; repair of motor vehicles and motorcycles | 4 (9) | 2 (5) |

| H: transport and storage | 0 (0) | 1 (2) |

| K: financial and insurance activities | 2 (5) | 2 (5) |

| M: professional, scientific and technical activities | 10 (23) | 11 (26) |

| N: administrative and support service activities | 5 (11) | 3 (7) |

| O: public administration and defence; compulsory social security | 4 (9) | 4 (9) |

| P: education | 5 (11) | 6 (14) |

| Q: human health and social work activities | 6 (14) | 5 (12) |

| R: arts, entertainment and recreation | 1 (2) | 4 (9) |

| S: other service activities | 2 (5) | 2 (5) |

Participant recruitment and characteristics

Across the 87 workplaces, 654 participants were recruited, with a mean cluster size of approximately 8 (as was the case during the feasibility study). 49 The number of participants in each workplace at baseline ranged from 1 to 28. The average age was 40 years and the majority of participants (455, 65.9%) lived in a household with an income of > £30,000 per year (Table 8). There was a slight balance in favour of females (n = 371, 56.7%) and being educated to at least degree level (377, 57.7%). A large majority of participants, 557 of 626 who gave this information (89%), lived > 2 km from their workplace, and two-thirds travelled to work by car at baseline. Table 8 shows a good balance of key participant characteristics in the intervention and the control groups following randomisation.

| Baseline characteristics | Trial group | |

|---|---|---|

| Intervention | Control | |

| Participant demographic characteristics | ||

| Total number of participants | 331 | 323 |

| Gender: male, n (%) | 143 (43) (N = 331) | 140 (43) (N = 323) |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 41.2 (11.4) (N = 321) | 42.0 (11.3) (N = 314) |

| BMI category, n (%) | N = 331 | N = 323 |

| Underweight and normal | 149 (45) | 144 (45) |

| Overweight | 99 (30) | 92 (28) |

| Obese | 53 (16) | 52 (16) |

| Missing | 30 (9) | 35 (11) |

| Household income, n (%) | N = 313 | N = 305 |

| ≤ £10,000 | 1 (< 1) | 3 (1) |

| £10,001–20,000 | 14 (4) | 25 (8) |

| £20,001–30,000 | 39 (12) | 39 (13) |

| £30,001–40,000 | 51 (16) | 49 (16) |

| £40,001–50,000 | 67 (21) | 53 (17) |

| > £50,000 | 118 (38) | 117 (38) |

| Does not know | 23 (7) | 19 (6) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | N = 317 | N = 310 |

| White British | 288 (91) | 279 (90) |

| White other | 15 (5) | 14 (5) |

| Mixed ethnic group | 4 (1) | 3 (1) |

| Asian or British Asian | 3 (1) | 6 (2) |

| Black or black British | 7 (2) | 5 (2) |

| Chinese | 0 (0) | 3 (1) |

| Education, n (%) | N = 315 | N = 309 |

| Higher degree, degree or equivalent | 195 (62) | 182 (59) |

| A level or equivalent | 74 (23) | 79 (26) |

| GCSE or equivalent | 41 (13) | 43 (14) |

| No formal qualifications | 5 (2) | 5 (2) |

| Current method of travel to work, n (%) | N = 327 | N = 313 |

| Car | 217 (66) | 205 (65) |

| Public transport | 44 (13) | 32 (10) |

| Walk | 32 (10) | 42 (13) |

| Cycle | 34 (10) | 34 (11) |

| Distance between workplace and home (km), n (%) | N = 319 | N = 307 |

| ≤ 2 km | 35 (11) | 30 (10) |

| > 2 km | 280 (88) | 277 (90) |

| Current occupation, n (%) | N = 315 | N = 299 |

| Sedentary | 239 (76) | 237 (79) |

| Standing | 60 (19) | 42 (14) |

| Manual | 15 (5) | 20 (7) |

| Heavy manual work | 1 (< 1) | 0 (0) |

Summary

Workplace and participant recruitment proved more difficult than anticipated but increasing the number of urban areas in the study enabled the recruitment of a range of workplaces of different sizes, locations and business classifications. The number of participants was close to, but just under, the recruitment target. The sample of participants was broadly balanced by gender, and the participants tended to be well-qualified and have a higher than average annual household income. A large majority did not live within ‘walking distance’ of their workplace.

Chapter 4 Baseline characteristics and physical activity

Parts of this chapter are reproduced from Batista Ferrer et al. ,70 published by Elsevier. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Methods

Data collection

Study participants were asked to complete travel diaries, to wear accelerometers (ActiGraph GT3X+) for 7 days during waking hours and to carry a personal GPS receiver (Qstarz BT-1000X), set to record positional data at 10-second intervals, during their commute. Participants were provided with instructions about how to use the monitors (see Appendix 4) and those who returned the equipment were provided with a £10 gift voucher to acknowledge their contribution to the study.

Objectively measured physical activity and main mode of travel during the commute

Raw accelerometer data were downloaded using ActiLife software (version 6.11.8; ActiGraph, Pensacola, FL, USA) and reintegrated to 10-second epochs for analysis. Reintegrated accelerometer data were processed using KineSoft data reduction software (version 3.3.80; KinesSoft, Loughborough, UK) to generate outcome variables. Continuous periods of ≥ 60 minutes of zero values were considered ‘non-wear’ time and removed. To be included in the analysis of daily physical activity and sedentary behaviours, participants were required to provide ≥ 3 days of valid accelerometer data of ≥ 600 minutes in duration. In relation to mode and physical activity during the commute, participants were required to provide at least 1 valid day of combined accelerometer and GPS (accGPS) data on a working day. Days on which cycling was identified as the main mode of travel to work were excluded owing to the inability of waist-worn accelerometers to accurately record physical activity during cycling. 71

Accelerometer and GPS data were combined for every 10-second epoch (accGPS) based on the timestamp of the ActiGraph data. The participant’s workplace and home were geocoded using the full postcode and imported into a GIS (ArcMap version 10.2.2; Environmental Systems Research Institute, Inc., Redlands, CA, USA). The merged accGPS files were imported into ArcMap and participants’ journeys to and from work were visually identified and segmented from other accGPS data using the ‘identify’ tool. Journeys were identified as a continuous sequence of GPS locations between the participant’s home and workplace, and therefore may include trips to other destinations (e.g. shopping).

Mode of travel (walking, cycling, using public transport or driving) for the outward and return journeys over the measurement week was derived from visual analysis using the following variables: counts per 10 seconds (sustained counts per epoch of < 17 were bus, train, car; sustained counts per epoch of > 325 were walking and cycling);72 changes to the sum of the signal-to-noise ratio (approximate threshold of a drop to < 250 was employed to indicate movement from an indoor to an outdoor environment);73 maximum speed of the journey (walking – not > 10 km/hour; cycling – not > 40 km/hour; bus – 10 to 50 km/hour; train and car speeds of > 50 km/hour);74 and GIS location for each epoch.

For participants who used a mixed mode of travel (e.g. walking and travelling by train), the mode of transport covering the greatest distance was considered the mode for that journey. MVPA accrued from walking during the journey was captured in a separate variable. When an outward/return journey was missing, it was assumed to be the same mode of travel as the outward/return journey on the same day. Any remaining missing data were replaced with the corresponding travel diary mode when available. The most frequent mode of travel during data collection was used to derive an overall mode of travel for each participant.

Time spent being sedentary and in MVPA were defined using validated thresholds [sedentary, < 100 c.p.m.; MVPA, ≥ 1952 c.p.m.]. 72 To examine the proportion of participants who met current physical activity guidelines,1 we calculated the total MVPA accumulated in bouts of ≥ 10 minutes over the data-collection week (by multiplying the mean daily number of bouts of MVPA by 7). In line with another study,75 participants were classified as ‘active’ or ‘inactive’ during the commute if their mean daily MVPA accrued during the commute was ≥ 10 minutes or < 10 minutes, respectively.

Variables

Individual characteristics and interpersonal responsibilities

The following variables were derived from questionnaire data: (1) gender, (2) age group (‘below 35 years old’ or ‘35 years or greater’), (3) annual household income (‘£30,000 or below’ or ‘> £30,000’, representing mean UK household income), (4) level of education (‘degree or above’ or ‘below degree’), (5) occupational activity (‘sedentary’ or ‘non-sedentary’), (6) limited access to a car [absence of a current driving licence and/or household access to car (‘yes’ or ‘no’)] and (7) combines commute with school run or caring responsibilities (‘yes’ or ‘no’). Self-reported height and weight were used to compute BMI and were assigned to either ‘normal or underweight’ (BMI of < 25 kg/m2) or ‘overweight or obese’ (BMI of ≥ 25 kg/m2) categories based on internationally recognised cut-off points. 76

Workplace characteristics

Commute distance was estimated using an online calculator (www.google.co.uk/maps; accessed 28 February 2019) and the participant’s home and work postcodes. Commute distance was categorised as ‘2 km or below’, ‘between 2 km and 4 km’ and ‘4 km and above’. Participants were asked about the following policies and facilities at their workplace: (1) free car parking, (2) entitlement to purchase a car parking permit, (3) secure storage for clothing, (4) employer-subsidised cycling schemes, (5) a safe place for bicycles, (6) showers and changing rooms, (7) employer-subsidised public transport schemes and (8) a travel plan or policy. Variables were categorised as ‘yes’ or ‘no’.

Perception of the commuting environment

To describe the commuting environment, participants reported their level of agreement with nine statements using a five-point Likert scale: (1) ‘there are suitable pavements for walking’, (2) ‘the pavements are well-maintained’, (3) ‘there are not enough safe places to cross roads’, (4) ‘walking is unsafe because of traffic’, (5) ‘it is unsafe because of the level of crime or antisocial behaviour’, (6) ‘the routes for walking are generally well lit at night’, (7) ‘the area is generally free from litter or graffiti’, (8) ‘it is a pleasant environment for walking’ and (9) ‘there is a lot of air pollution’. These statements have been used in other studies,74,77,78 and have acceptable test–retest reliability. 79 Negatively worded items were recoded so that a high score equated to agreement with the statements. A mean substitution approach was used for the seven participants who missed a single item on the scale. As the distribution of scores was positively skewed, a binary variable comprising ‘positive perception’ (less than the mean score) and negative perception (greater than or equal to the mean score) was created.

Reasons for car use

To provide additional understanding of reasons for car use, participants whose main mode of travel was driving were asked to indicate all reasons that applied to them from the following list: (1) quicker than alternatives, (2) reliability, (3) comfort, (4) have to visit more than one place, (5) cheaper than alternatives, (6) lack of alternative, (7) personal safety, (8) dropping off/collecting children, (9) work unsociable hours, (10) car is essential to perform job, (11) dropping off/collecting partner, (12) carry bulky equipment, (13) health reasons, (14) giving someone else a lift and (15) often on call. They were then asked to choose the single most important reason from the list.

Analysis

Initially, descriptive analyses comprising counts, percentages, medians and interquartile ranges, were conducted. Differences in physical activity variables (overall and during the commute) were analysed by main mode of travel (car users, public transport users and walkers) using analysis of variance (ANOVA) and chi-squared statistics. Data related to participants classified as cyclists are not presented because of the inability of waist-worn accelerometers to accurately record physical activity during cycling.

Associations with objectively measured physical activity during the commute

To explore associations with levels of physical activity during the commute, logistic univariable analyses and likelihood ratio tests were conducted. The following explanatory variables for analysis were selected a priori: gender, age group, annual household income, education, weight status, occupational activity and commute distance. A multivariable logistic regression model was developed using ‘inactive during commute’ as the reference group. In the order of the strength of association, variables were selected for inclusion and retained in the model if there was an associated improvement in fit (p < 0.05). The final model adjusted for weight status, occupational activity and commute distance.

Associations with objectively measured mode of travel

The objective of the next stage of the analysis was to identify associations between different modes of travel to work and individual, interpersonal and workplace variables. Analyses were restricted to participants who were classified as ‘walkers’ (n = 74), ‘public transport users’ (n = 76) or ‘car users’ (n = 422). Participants classified as cyclists (n = 68) or whose mode of transport was unknown (n = 14) were excluded. Initially, associations were examined using logistic univariable analyses and likelihood ratio tests. Multicollinearity between variables was tested for through correlations. Using the same methodology as described previously, two separate multivariable logistic regression models were developed for ‘walkers’ and ‘public transport users’, both using ‘car users’ as the reference group. Individual, interpersonal and workplace characteristics and perception-of-commute variables were eligible for inclusion if they were associated with an improvement in fit of model (p < 0.05). The final ‘walkers’ model adjusted for limited access to a car, commute distance and availability of workplace car parking. The final ‘public transport users’ model adjusted for age group, limited access to a car, combines commute with caring responsibilities, availability of workplace car parking and perception of commute environment. Finally, a description of reasons for car use by car users was presented as counts and percentages.

Potential clustering by workplace was adjusted for using a robust standard errors approach allowing for workplace-level random effects in the final model. For each model, results were presented as odds ratios (ORs), adjusted odds ratios (aORs) and corresponding 95% CIs and p-values. Through sensitivity analyses, separate logistic models that were restricted to males only and females only were developed, with no major effect sizes by variables observed. Interactions were not fitted owing to small sample sizes. Analyses were undertaken to explore whether or not associations varied by gender. All analyses were conducted using Stata® version 14 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Associations with undertaking physical activity during the commute

Valid accGPS data from at least 1 day were provided by 597 participants. After adjustment for weight status, occupational activity and commute distance, there was strong evidence that participants were more physically active during their commute if they had sedentary jobs (aOR 1.96, 95% CI 1.26 to 3.04) or had a commute distance of < 2 km (aOR 2.73, 95% CI 1.69 to 4.41) or between 2 km and 4 km (aOR 2.74, 95% CI 1.58 to 4.73). There was weaker evidence that participants in the underweight or normal weight category (aOR 1.48, 95% CI 1.04 to 2.12) were more physically active during the commute (Table 9).

| Variable | Participants, n (%) | OR (95% CI); p-value | aORb (95% CI); p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (N = 654) | Inactivea status (N = 349) | Activea status (N = 248) | |||

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 283 (43.3) | 160 (63.0) | 94 (37.0) | – | NI |

| Female | 371 (56.7) | 189 (55.1) | 154 (44.9) | 1.39 (1.00 to 1.93); 0.05 | |

| Age (years) | |||||

| ≥ 35 | 431 (65.9) | 241 (60.6) | 157 (53.5) | – | NI |

| < 35 | 204 (31.2) | 100 (39.5) | 87 (46.5) | 1.34 (0.94 to 1.90); 0.11 | |

| Annual household income | |||||

| ≤ £30,000 | 121 (18.5) | 65 (59.6) | 44 (40.4) | – | NI |

| > £30,000 | 455 (69.5) | 243 (57.9) | 177 (42.1) | 1.08 (0.70 to 1.65); 0.74 | |

| Education | |||||

| Less than degree level | 247 (37.8) | 138 (59.7) | 93 (40.3) | – | NI |

| Degree level or higher | 377 (57.7) | 195 (56.5) | 150 (43.5) | 1.14 (0.81 to 1.60); 0.44 | |

| Weight status | |||||

| Overweight or obese | 296 (45.3) | 179 (64.2) | 100 (35.8) | – | – |

| Underweight or normal | 293 (44.8) | 143 (54.0) | 122 (46.0) | 1.53 (1.08 to 2.15); 0.02 | 1.48 (1.04 to 2.12); 0.03 |

| Occupational activity | |||||

| Non-sedentary | 130 (19.9) | 87 (69.1) | 39 (31.0) | – | – |

| Sedentary | 450 (68.8) | 229 (55.5) | 184 (44.6) | 1.79 (1.17 to 2.74); < 0.01 | 1.96 (1.26 to 3.04); < 0.01 |

| Commute distance (km) | |||||

| > 4 | 455 (69.6) | 276 (64.9) | 149 (35.1) | – | – |

| Between 2 and 4 | 100 (15.3) | 36 (40.9) | 52 (59.1) | 2.68 (1.67 to 4.28); < 0.001 | 2.73 (1.69 to 4.41); < 0.001 |

| < 2 | 71 (10.9) | 20 (40.6) | 38 (59.4) | 2.71 (1.58 to 4.63); < 0.001 | 2.74 (1.58 to 4.73); < 0.001 |

Of 542 participants (82.4%) who provided 3 days of valid accelerometer data, a minority (n = 60, 11.1%) met current UK public health physical activity guidelines. 1 A substantially higher proportion of walkers (n = 24, 38.7%) and public transport users (n = 10, 16.1%) met public health physical activity guidelines than car users (n = 17, 4.7%) (p < 0.001). There were marked differences in time spent in MVPA by main mode of travel. Overall, both walkers (mean 71.3 minutes, SD 21.3 minutes) and public transport users (mean 59.5 minutes, SD 26.6 minutes) accumulated more MVPA throughout the day than car users did (mean 46.3 minutes, SD 20.6 minutes). Walkers (mean 34.3 minutes, SD 18.6 minutes) and public transport users (mean 25.7 minutes, SD 4.0 minutes) were also, on average, more active during the commute than car users (mean 7.3 minutes, SD 7.6 minutes). There was no strong evidence for differences in time spent in sedentary behaviours (p = 0.12) or accelerometer wear time (p = 0.43) by main mode of travel (Table 10).

| Variable | Main mode of travel | p-valuea | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Car | Walking | Public transport | ||

| N = 540 | N = 357 | N = 62 | N = 62 | ||

| Meets public health physical activity guidelines,b n (%) | 60 (11.1) | 17 (4.8) | 24 (38.7) | 10 (16.1) | < 0.001a |

| Overall daily physical activity (c.p.m.), mean (SD) | 385.3 (193.1) | 342.7 (120.1) | 507.2 (151.2) | 405.5 (150.7) | < 0.001c |

| Daily time spent in MVPA (minutes), mean (SD) | 52.9 (28.7) | 46.3 (20.6) | 71.3 (21.3) | 59.5 (26.6) | < 0.001c |

| Daily time spent in sedentary behaviours (minutes), mean (SD) | 580.6 (72.6) | 587.6 (69.5) | 568.1 (62.2) | 585.8 (65.2) | 0.12c |

| Daily wear time (minutes), mean (SD) | 798.2 (75.7) | 800.4 (75.0) | 788.6 (70.9) | 792.7 (72.2) | 0.43c |

| N = 597 | N = 404 | N = 71 | N = 73 | ||

| Daily commute time (minutes), mean (SD) | 85.7 (54.2) | 86.6 (51.0) | 53.8 (29.2) | 116.5 (56.2) | < 0.001 |

| Daily time spent in MVPA during commute (minutes), mean (SD) | 13.0 (14.3) | 7.3 (7.6) | 34.3 (18.6) | 25.7 (14.0) | < 0.001 |

Individual characteristics, interpersonal responsibilities and workplace and environmental characteristics associated with mode of travel

After adjustment for having a current driving licence, household access to a car, commute distance to workplace and free work car parking, there was strong evidence that not having a driving licence (aOR 8.74, 95% CI 2.45 to 31.2) and not having access to a car (aOR 23.1, 95% CI 5.0 to 106.5) were positively associated with walking to work. The workplace characteristics ‘commute distance of less than 2 km’ (aOR 51.4, 95% CI 19.7 to 134.3), ‘commute distance between 2 km and 4 km’ (aOR 15.2, 95% CI 5.84 to 39.4) and lack of free parking (aOR 2.97, 95% CI 1.38 to 6.39) were also positively associated with walking (Table 11).

| Variable | Participants, n (%) | OR (95% CI); p-value | aOR (95% CI); p-value | Public transport users (N = 76), n (%) | OR (95% CI); p-value | aOR (95% CI); p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (N = 654) | Car users (N = 422) | Walkers (N = 74) | ||||||

| Individual and interpersonal characteristics | ||||||||

| Gender: female | 371 (56.7) | 241 (57.1) | 44 (59.5) | 1.10 (0.67 to 1.82); 0.71 | NI | 50 (65.8) | 1.44 (0.87 to 2.41); 0.16 | NI |

| Age: < 35 years | 204 (31.2) | 115 (27.3) | 28 (37.8) | 1.69 (1.00 to 2.85); 0.05 | NI | 38 (50.0) | 2.67 (1.62 to 4.41); < 0.001 | 2.05 (1.05 to 4.02); 0.04 |

| Household income: ≤ £30,000 per annum | 121 (18.5) | 80 (19.0) | 17 (23.0) | 1.34 (0.73 to 2.46); 0.34 | NI | 12 (15.8) | 0.84 (0.43 to 1.65); 0.61 | NI |

| Education: lower than degree level | 247 (37.8) | 169 (40.1) | 32 (43.2) | 1.15 (0.69 to 1.90); 0.60 | NI | 29 (38.2) | 0.88 (0.53 to 1.46); 0.62 | NI |

| Weight status: underweight or normal | 293 (44.8) | 178 (42.2) | 44 (59.5) | 2.31 (1.34 to 3.97); < 0.01 | NI | 28 (36.8) | 0.99 (0.58 to 1.70); 0.99 | NI |

| Occupational activity: sedentary | 130 (19.9) | 288 (68.3) | 50 (67.6) | 1.39 (0.71 to 2.72); 0.34 | NI | 61 (80.3) | 2.54 (1.17 to 5.50); 0.02 | NI |

| Limited access to car: no | 62 (9.5) | 9 (2.1) | 21 (28.4) | 20.4 (8.78 to 47.2); < 0.001 | 20.5 (6.01 to 69.8); < 0.001 | 27 (35.5) | 26.8 (11.8 to 60.7); < 0.001 | 29.2 (10.4 to 81.6); < 0.001 |

| Combines commute with caring responsibilities: no | 485 (74.2) | 308 (73.0) | 59 (79.7) | 2.52 (1.05 to 6.05); 0.04 | NI | 64 (84.2) | 5.47 (1.67 to 17.9); < 0.01 | 4.88 (1.17 to 20.3); 0.03 |

| Workplace characteristics | ||||||||

| Commute distance (km) | ||||||||

| > 4a | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Between 2 and 4 | 100 (15.3) | 48 (11.4) | 21 (28.4) | 11.3 (5.30 to 24.0); < 0.001 | 15.0 (5.55 to 40.6); < 0.001 | 8 (10.5) | 0.87 (0.39 to 1.93); 0.74 | NI |

| < 2 | 71 (10.9) | 26 (6.2) | 35 (47.3) | 34.7 (16.4 to 73.5); < 0.001 | 63.6 (21.5 to 187.9); < 0.001 | 1 (1.3) | 0.21 (0.03 to 1.60); 0.13 | NI |