Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 12/153/39. The contractual start date was in April 2017. The final report began editorial review in February 2018 and was accepted for publication in September 2018. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Ruth Kipping received grants from North Somerset Council and Gloucestershire Council. Ruth Kipping and Rona Campbell received grants from Development and Evaluation of Complex Interventions for Public Health Improvement (DECIPHer). Laura Johnson received grants from the Elizabeth Blackwell Institute (University of Bristol) and the Wellcome Trust. Laurence Moore received grants from the Medical Research Council (MRC) and from the Scottish Government Chief Scientist Office. Rona Campbell (2015–current), Laurence Moore (2009–15) and Russell Jago (2014–current) were members of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Public Health Research (PHR) Research Funding Board. William Hollingworth was a member of the NIHR Health Technology Assessment Clinical Evaluation and Trials Board. Rona Campbell was a member of the MRC Public Health Intervention Development (PHIND) Scheme Funding Board and the Board of DECIPHer Impact.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Kipping et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced from Kipping et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Preschool children’s physical activity, nutrition and weight: a national priority

In England, 22.6% of children starting primary school are overweight or obese. 2 Obesity rates increase with deprivation; 12.7% in the most deprived areas are obese, compared with 5.8% in the least deprived decile. It is predicted that 17% of children aged 2–11 years in England will be overweight in 2020 and a further 13% will be obese. 3 Therefore, it is a priority that interventions are developed, tested and implemented with preschool-aged children to reduce their risk of developing obesity and chronic diseases.

Among children, physical activity (PA) is associated with lower levels of cardiometabolic risk factors, including blood lipids, blood pressure and improved psychological well-being. 4 Patterns of PA track moderately from childhood to adulthood, suggesting that it is linked to both short- and long-term health among children. 5 Furthermore, review evidence has identified that preschool children (aged 3 to 4.9 years) who had higher levels or increased amounts of PA were associated with improved measures of adiposity, motor skill development, psychosocial health and cardiometabolic health. 6

The English Chief Medical Officer’s recommendations are that children < 5 years of age who are capable of walking should be physically active for at least 3 hours per day and sedentary time should be minimised. 7 There is no guidance about screen time in the UK. In 2012, only 10% of 2- to 4-year-olds in England were classified as meeting the current guidelines for children < 5 years7 of at least 3 hours of PA per day. In addition, 3- to 4-year-olds in the UK are sedentary for an average of 10–11 hours per day. 7,8

A diet that is high in fruit and vegetables and low in saturated fat has been associated with reduced risk of many forms of cancer, adult heart disease and all-cause mortality. 9 Dietary patterns are often set during childhood. Children aged 1.5–10 years in the UK do not eat sufficient amounts of fruit and vegetables, and 32% of boys and 18% of girls are reported as having eaten no fruit during a 4-day period. 10 The latest national recommendation is that intake of free sugars should provide no more than 5% of total energy intake for adults and children aged > 2 years. 11 Intake of non-milk extrinsic sugars (NMES) is 12% of total daily energy intake for 1- to 3-year-olds and 13% for 4- to 10-year-olds. 12 Soft drinks contribute 10% to the intake of NMES in 1- to 3-year-olds and 13% to the intake of NMES in 4- to 10-year-olds. Saturated fat intake is also higher than the recommended 11% of total daily energy intake, at 14.6% for 1- to 3-year-olds and 13.3% for 4- to 10-year-olds. Preschool-aged children in low-income populations are more likely to consume table sugar and soft drinks than those in more affluent groups. 13

A study of the prevalence of dental caries among a sample of 5-year-old children in state-funded schools in England found that 24.7% of children had some obvious tooth decay in 2014/15. 14 The average number of teeth that were decayed, missing or filled in the whole sample was 0.8, and among those with decay it was 3.4. There is a clear correlation between higher deprivation and dental decay (R2 = 0.47) at local authority level. Poor oral health can have a negative impact on sleeping, eating, speaking, playing and socialising for children. 15 Furthermore, it is the most common reason for admission for hospital in children aged 5–9 years in England. 16 A Public Health England commissioning toolkit for oral health reviewed the evidence for a wide range of oral health interventions and found that there was some evidence for the effectiveness of healthy food and drink policies in early childhood settings and recommended this approach. 17 Furthermore, the review found that oral health training for the wider professional workforce appeared promising although there was a lack of randomised controlled trials (RCTs).

Three systematic reviews of obesity prevention, PA and nutrition in young children each identified a lack of studies in young children and a clear need for more research with robust study designs. 18–20 The 2011 Cochrane review of obesity prevention in children identified research gaps for effective interventions for children aged 0–5 years. 20 In addition, this review recommended that studies must better report the impacts on the environment, setting and sustainability. Studies should also test interventions that are guided by theory-based frameworks such as the socioecological model.

Rationale for a feasibility study on physical activity and improved nutrition in child-care settings

Child-care settings provide opportunities to deliver interventions at the population level. 21 Ninety-seven per cent of children aged 3–4 years in England attend some form of government-funded early years education, of whom 39% attend day-care providers outside school settings. 22 In England, government-funded child care for 3- and 4-year-olds increased from 15 to 30 hours/week in September 201723 (with certain conditions on parental employment), which has the potential to increase the amount of time children spend in child-care settings. However, not all child-care settings are health-promoting environments. Child-care settings provide scalable opportunities to deliver interventions at the population level. 21 The 2012 Early Years Foundation Stage (EYFS) statutory framework sets the standards to ensure that children learn, develop and are kept healthy and safe. 24 The EYFS includes somewhat limited standards for PA and healthy diet and requires nurseries to maintain a high staff to child ratio (1 : 4 for 2-year-olds, and 1 : 13 for 3- to 5-year-olds). 24 This provides nursery staff with contact during mealtimes to apply the techniques of taste exposure, encouragement, praise, and modelling of healthy eating. Furthermore, the settings can constrain or enable PA. A systematic review of the role of peers in eating behaviours and PA found that there was some evidence to support the role of peers. 25 Four out of the six PA studies reported that children were more active when peers were present. However, large peer group size was negatively associated with PA in two cross-sectional studies. 26,27 All nutrition interventions in the review reported that children’s eating behaviours may be influenced by their peers.

The Children’s Food Trust published voluntary guidelines for food in early years settings in 2012. 28 In addition, PA guidelines for young children in England were published in 2011. 7 The English 2016 Childhood Obesity strategy is very limited with respect to preschool children,29 but local authorities in England and Wales are increasingly developing and implementing their own programmes to support healthy interventions in early years settings. We have reviewed the local authority websites for the Core Cities in England and found all (except one) have some form of healthy early years programme. In Wales, the Healthy and Sustainable Pre-School Scheme was started in 2011 on seven health topics: Nutrition and Oral Health; Physical Activity/Active Play; Mental and Emotional Health, Wellbeing and Relationships; Environment; Safety; Hygiene; and Workplace Health and Wellbeing. 30 These programmes all include nutrition and some have additional health topics. However, none of these programmes has been evaluated for effectiveness through a RCT. Therefore, new approaches are required to prevent obesity and reduce inequalities in early years settings.

Assessment of PA in 3- to 5-year-old children at preschool has shown that they are physically inactive during most of their time in preschool, with only 3% of time engaged in moderate to vigorous physical activity (MVPA). MVPA is closely associated with cardiorespiratory fitness and body mass index (BMI) in adolescence; therefore, it is of concern that such a small proportion of time in preschool is spent in MVPA. Furthermore, about 80% of time is spent in sedentary activities. 31 However, studies have found different levels; one study found that children aged 3–4 years in the UK (in particular boys) spent more time in MVPA and were less sedentary when in child care than when at home. 32 The particular preschool that a child attends is a strong predictor of PA levels, and being outdoors is one of the most powerful correlates of PA in children. 31 The lack of MVPA in preschool settings may be influenced by space constraints, a lack of equipment, a lack of policies and a lack of scheduled times for free play and outdoor play and a lack of staff training in PA promotion. 19 A systematic review of interventions to increase PA in child-care settings concluded that regularly provided, structured PA programmes can increase the amount and intensity of PA undertaken. 33

Larson et al. 18 reviewed the regulations, practices, policies and interventions for promoting healthy eating and PA and for preventing obesity in children attending child care. The review identified a lack of strong regulation in child-care settings in relation to health behaviours, such as PA and diet. A 2016 Cochrane review of strategies to improve healthy eating, PA and obesity prevention in child-care services found that:

Weak and inconsistent evidence of the effectiveness of such strategies in improving the implementation of policies and practices, childcare service staff knowledge or attitudes, or child diet, physical activity or weight status. Further research in the field is required.

Wolfenden et al. 33

There is ample opportunity within child-care settings to improve nutritional quality, oral health, time engaged in PA and promotion of health behaviours by caregivers. Other than Nutrition And Physical Activity Self Assessment for Child Care (NAP SACC) (see NAP SACC), a small number of RCTs based in child-care settings that aim to improve nutrition and/or PA or sedentary time with 2- to 4-year-olds have been published (Table 1). The studies focused on education, staff development, and addressing child-care policies or opportunities for increasing PA. Many, but not all, of the studies reported small changes in children’s PA, sedentary time or nutrition in the short term. Only one intervention showed an effect on weight. 40 There was a lack of long-term follow-up or demonstration of effect across a wide range of anthropometric and behavioural changes. Only four of the studies were in the UK and none of these targeted both diet and PA within child-care settings.

| Name of study/first author | Type of intervention | Setting; country (age range) | Results for the intervention arm compared with the control arm |

|---|---|---|---|

| Family Focused Active Play34 | Family-focused intervention to decrease sedentary time and increase PA for 10 weeks | Surestart Centres; England (3–4.9 years) | 1.5% and 4.3% less sedentary time during week and weekend days, respectively, and 4.5% and 13.1% more PA during week and weekend days, respectively |

| Active Play35 | 6-week local authority staff-led training (active play) to help preschool staff deliver 60-minute weekly sessions compared with a resource pack | Preschools attached to Surestart Centres; England (3–4.9 years) | Assessment of 162 children found no evidence for differences in total fundamental movement skill, object control skill or locomotor skills scores |

| Alhassan36 | An increase of 60 minutes per day in time spent outdoors for 2 days | Head Start Centers; USA (3–5 years) | No difference in total daily PA |

| Specker37 | Children assigned to gross motor or fine motor group for 1 year | Nursery; USA (3–5 years) | Time spent in vigorous activity was higher in the gross motor group at 18 months but not 24 months |

| Brocodile the Crocodile38 | Seven educational sessions encouraged to reduce time spent watching TV | Nursery; USA (2.6–5.5 years) | –4.7 hours per week television/video viewing (95% confidence interval –8.4 to –1.0 hours per week; p = 0.02) |

| CHERRY39 | An exploratory trial, focused on family-centred nutrition | Children’s Centres; England (1.5–5 years) | Positive, but non-significant, changes in fruit and vegetables, decreasing sugary drinks and snacks |

| Healthy Caregivers/Children40 | Curricula for teachers/parents, menu modifications and policies for nutrition, PA and screen time | Children’s Centres; USA (2–5 years) | Mean child BMI increased in control centres from 0.43 to 0.55 kg/m2 and smaller increases were seen in intervention centres (0.46 to 0.49 kg/m2). The environmental assessment (EPAO) total nutrition score improved in the intervention centres (12.4 to 13.5) with no change in control schools (12.5 to 12.6). Little changes in the EPAO PA scores |

| Hip-Hop to Health41 | Healthy eating and PA lessons for 14 weeks | Preschools; USA; (3–5 years) | More MVPA (difference between adjusted group means = 7.46 minutes per day, p = 0.02) and less total screen time (−27.8 minutes per day, p = 0.05). No differences in BMI, zBMI, or dietary intake |

| Move and Learn42 | Integration of PA into preschool half-day over 8 weeks | Preschools; USA; (3–5 years) | In 2 out of the 8 weeks, the levels of PA were higher than in the other weeks |

| Munch and Move43 | Professional development to promote healthy eating and PA among children | Preschools; Australia; (mean age 4.4 years) | FMS improved (p < 0.001) and the number of FMS sessions increased by 1.5 per week (p = 0.05). Sweetened drinks reduced by 0.13 servings (46 ml) (p = 0.05) |

| PAKT44,45 | 30-minute/day PA intervention delivered by preschool teachers, with homework over 1 year | Preschools; Germany; (mean age 4.7 years) | The intervention found no evidence for improvement in PA measured by accelerometers between groups |

| Preschool nutritional intervention46 | Sessions by nutritionists with some parent involvement. Activities covered different foods, preparing food and eating behaviour | Preschools; Germany; (3–6 years) | Fruit and vegetable intakes increased by 0.23 and 0.15 portions per day (p < 0.001 and p < 0.05, respectively). No changes in water or sugary drinks consumed |

| MAGIC47 | Nursery and home elements with enhanced PA programme and materials for home | Nursery; Scotland; (mean age 4.2 years) | No differences in BMI, PA or sedentary behaviour |

| SHAPES48 | Ecological PA intervention in preschools: preschool teachers trained to engage children in PA during (1) structured, teacher-led PA opportunities in the classroom; (2) structured and unstructured PA opportunities at recess; and (3) PA integrated into preacademic lessons | Preschools; USA; (4 years) | Children in intervention schools engaged in more MVPA than children in control schools (7.4 and 6.6 minutes per hour, respectively; p = 0.01). In the analysis by gender there was evidence of a difference for girls (6.8 vs. 6.1 minutes per hour of MVPA, respectively; p = 0.04) but not for boys (7.9 vs. 7.2 minutes per hour, respectively; p = 0.1) |

| Tigerkids49 | Modules on PA, fruit and vegetables and waste | Preschools; Germany; (3–5 years) | Higher consumption of fruit and vegetables at 6 months, which was sustained at 18 months |

| Toy box50,51 | Preschool-based, family-involved intervention to influence obesity-related behaviours in 4- to 6-year-olds in Europe | Preschools; six European countries; (4–6 years) | Evaluation of the effectiveness of the study of 472 preschool children (mean age 4.43 years) from 27 kindergartens in Flanders found small increases in PA in the whole sample. The greatest effects were found in boys and in preschoolers from high-SES kindergartens |

Ongoing randomised controlled trials

Internationally, several trials in early years settings or with families of preschool children are currently being conducted with the aim of improving nutrition and/or PA, which further demonstrates the importance of improving health for this age group:

-

Jump Start is a multicomponent PA intervention for children aged 3–5 years in Australia. The intervention uses lessons in preschool and a home-based component with the primary outcome of total activity (accelerometer measured) during centre hours. 52

-

The Healthy Start-Départ Santé intervention is being tested in preschools with children aged 3–5 years in Canada. The intervention aims to enable parents and preschool staff to integrate PA and health eating into the day. 53

-

The DAGIS study (increased health and wellbeing in preschool) is a preschool intervention that is being developed with the aim of reducing inequalities in energy balance-related behaviours in preschoolers aged 3–5 years in Finland. 54,55

-

In Norway, a web-based programme to reduce food-related fears and promote healthy dietary habits in 1-year-olds is being studied through a trial design with two different interventions. 56

-

The physical Literacy in the Early Years (PLEY) Project in Nova Scotia (Canada) is aiming to determine if 3- to 5-year-old children who participate in active outdoor play in Childcare Centres, facilitated by educators trained in embedding loose parts into outdoor play spaces, develop greater physical literacy. 57

-

Smart Moms is a 6-month smartphone intervention in North Carolina (USA) that aims to reduce sugar-sweetened beverage and juice consumption among children aged 3–5 years with overweight or obese mothers. 58

-

The extended Infant Feeding, Activity and Nutrition Trial (InFANT Extend) is a trial in Australia testing a 33-month intervention using web-based materials and Facebook (Facebook, Inc., Menlo Park, CA, USA; www.facebook.com) with parents of infants, alongside the pre-existing six 2-hour sessions given quarterly to first-time parents. 59

NAP SACC

The NAP SACC intervention was chosen to be adapted and piloted in the UK in this study. 60 NAP SACC, which was developed in the USA, is focused on improving nutrition and PA environment, policies and practices in child-care centres through self-assessment and targeted technical assistance. It addresses PA, sedentary behaviours and nutrition by allowing providers to choose where they focus change. The NAP SACC approach, which uses data, evidence-based action-planning, choice, support, engagement and ownership, tailoring and sustained change, has been used in other UK public health interventions. RCTs of NAP SACC in the USA have demonstrated the feasibility and acceptability of the intervention, the effectiveness of improving the environmental audit nutrition score [11% improvement from a baseline Environment and Policy Assessment and Observation (EPAO) score of 8.6],60 increase in nursery staff’s knowledge of childhood obesity, healthy eating, personal health and working with families (all at a p < 0.05 level), decrease in children’s body mass index z-scores (zBMI) (p = 0.02)61 (a measure of relative weight adjusted for child age and sex) and an increase in accelerometer-measured PA by 17% (p < 0.05) and a 46.2% increase in vigorous activity (p < 0.05). 62 NAP SACC was updated in 2014 and the revised online version, called ‘Go NAP SACC’, includes expanded best practices and is the version which NAP SACC UK is based on, excluding the materials for breastfeeding. 63

NAP SACC is one of the few interventions that works with child-care providers to produce sustainable changes in the child-care environment and promote improvements in children’s activity levels and nutritional intake. NAP SACC has been widely adopted throughout the USA, which demonstrates that it is a model that, if shown to be effective, could easily be disseminated in the UK. NAP SACC has not previously been assessed for feasibility or acceptability of use in the UK or with direct measures of nutrition or BMI. In addition, some issues of fidelity to the intervention were encountered in the US trial, which were addressed through this feasibility study.

NAP SACC UK

The development and final version of NAP SACC UK (Nutrition And Physical Activity Self Assessment for Child Care UK version), following the phase 1 study, is outlined in detail in Chapter 2. To orientate the reader, the NAP SACC UK intervention, as used in the feasibility study, involved health visitors (called NAP SACC UK partners) supporting nursery staff to (1) review the nutrition, oral health, PA and screen time environment, policies and practices against best practice and national guidelines, (2) support staff to set goals and (3) provide targeted assistance over 5 months. Two workshops were delivered to nursery staff by local experts. A home intervention [website, short message service (SMS) and e-mails] was developed to support parents to set goals.

The subsequent chapters outline the methods and results for the two phases of the feasibility RCT and the two substudies. This is followed by the lessons learnt and discussion.

Chapter 2 The NAP SACC UK feasibility study overview

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced from Kipping et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

In this chapter the feasibility study aims and objectives, study design, progression criteria, trial registration, governance, ethics, safety and public involvement are outlined.

Study aim and objectives

The aim of the feasibility study was to evaluate the feasibility and acceptability of implementing and trialling an adaptation of the NAP SACC intervention, with a home component in nursery settings. The study had one primary objective and three secondary objectives.

Primary objective

-

To assess whether or not prespecified criteria relating to the feasibility and acceptability of the intervention and trial design are met sufficiently for progression to a full-scale RCT.

Secondary objectives

-

To explore the experiences of nursery staff, the intervention delivery team and parents/carers, in terms of acceptability, barriers, fidelity to and facilitators of the intervention, data collection methods and participant burden, and the feasibility of long-term follow-up with the aim of informing refinement of the intervention and study design prior to a potential full-scale RCT.

-

To pilot primary and secondary outcome measures and economic evaluation methods, and determine the practicality of data linkage for BMI through the Child Measurement Programme in England66 and Wales,67 in advance of a potential full-scale RCT.

-

To calculate the sample size required for a full-scale RCT and to estimate likely recruitment, attendance, adherence and retention rates.

Feasibility study design

The feasibility study had two phases:

-

Phase 1: intervention adaptation and development, in which the NAP SACC materials were adapted for use in the UK and the NAP SACC UK home component to involve parents/carers was created.

-

Phase 2: feasibility cluster RCT with embedded process evaluation and health economic methods (Figures 1 and 2). The logic model for the NAP SACC UK intervention is shown in Figure 3.

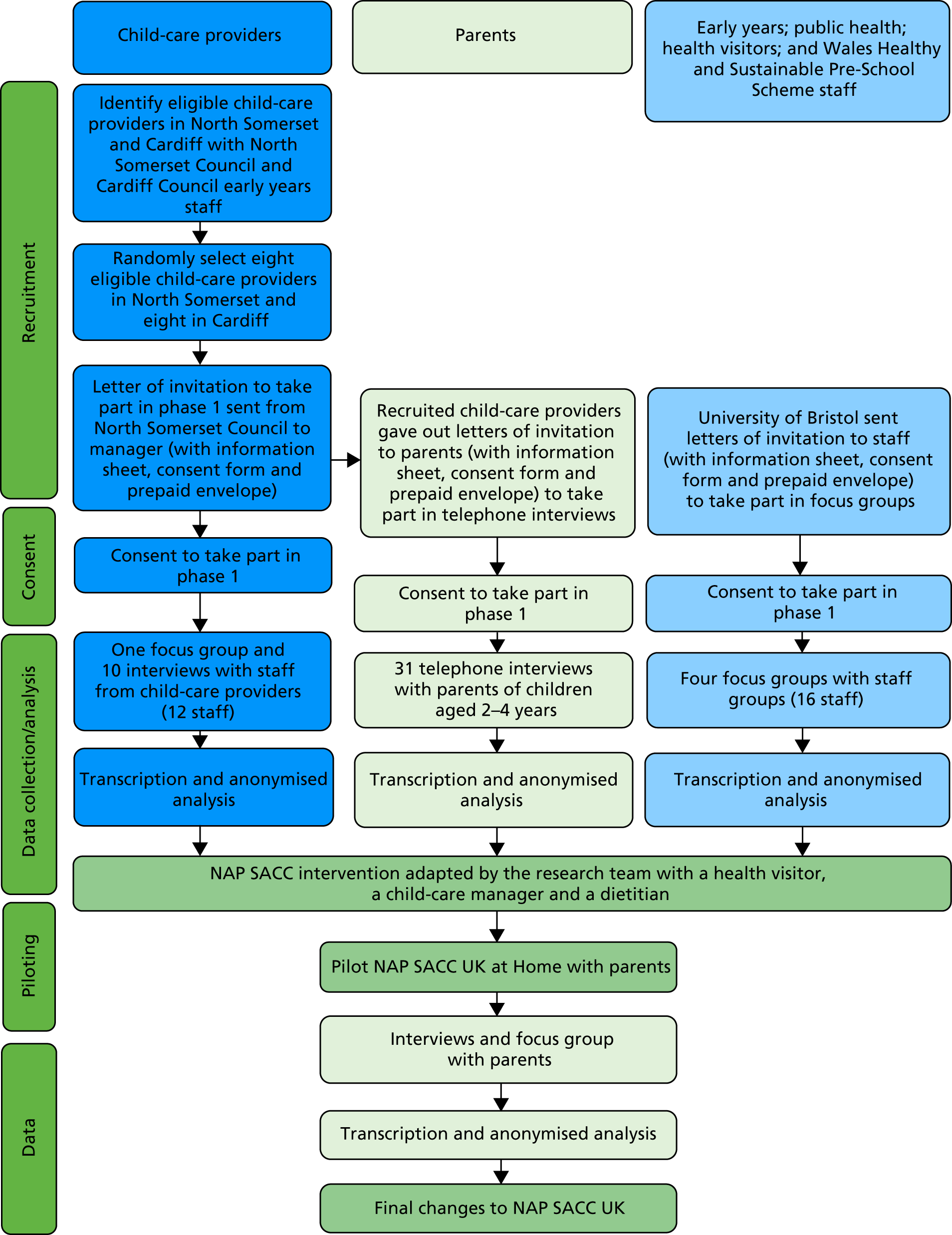

FIGURE 1.

Phase 1 flow diagram.

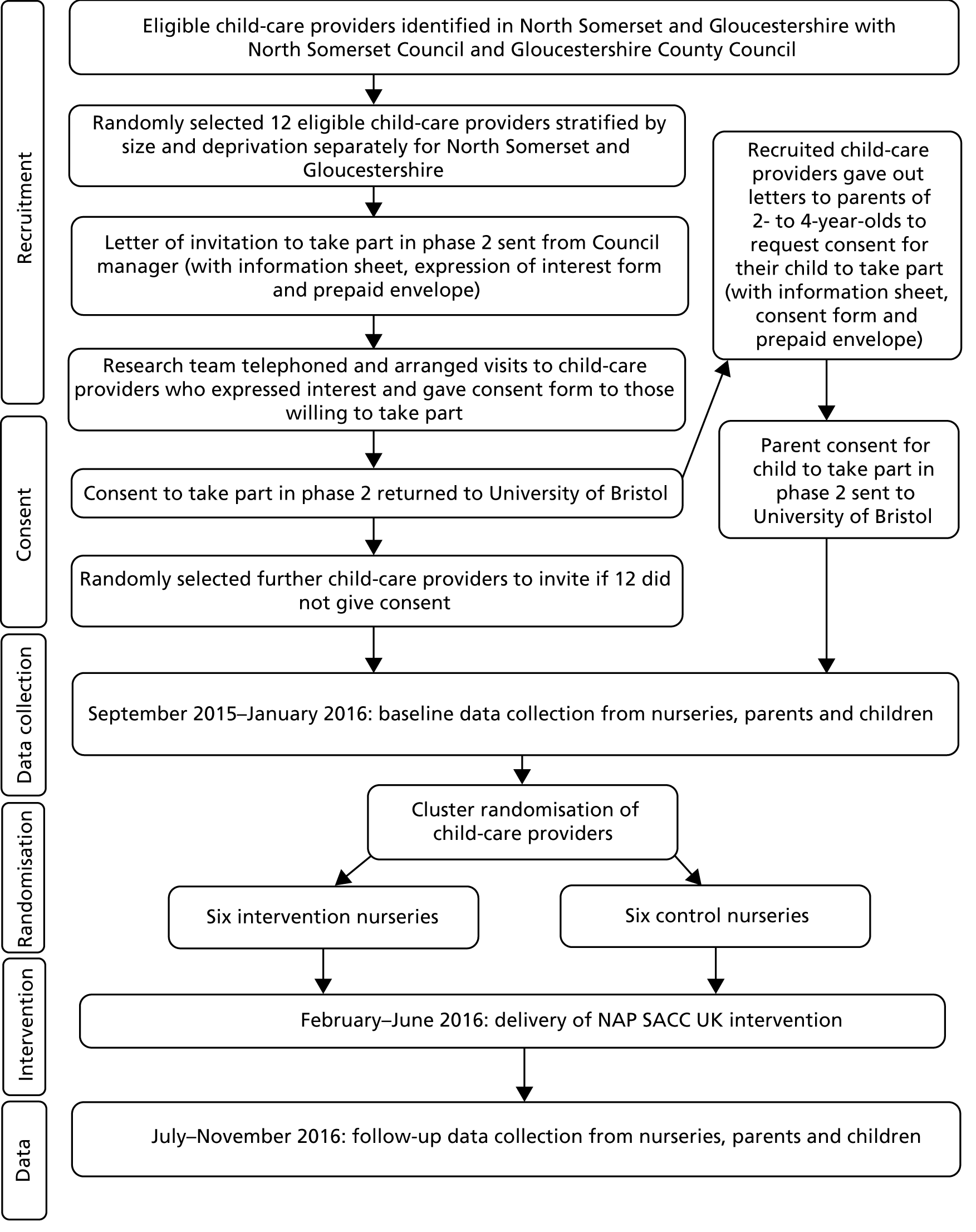

FIGURE 2.

Phase 2 flow diagram.

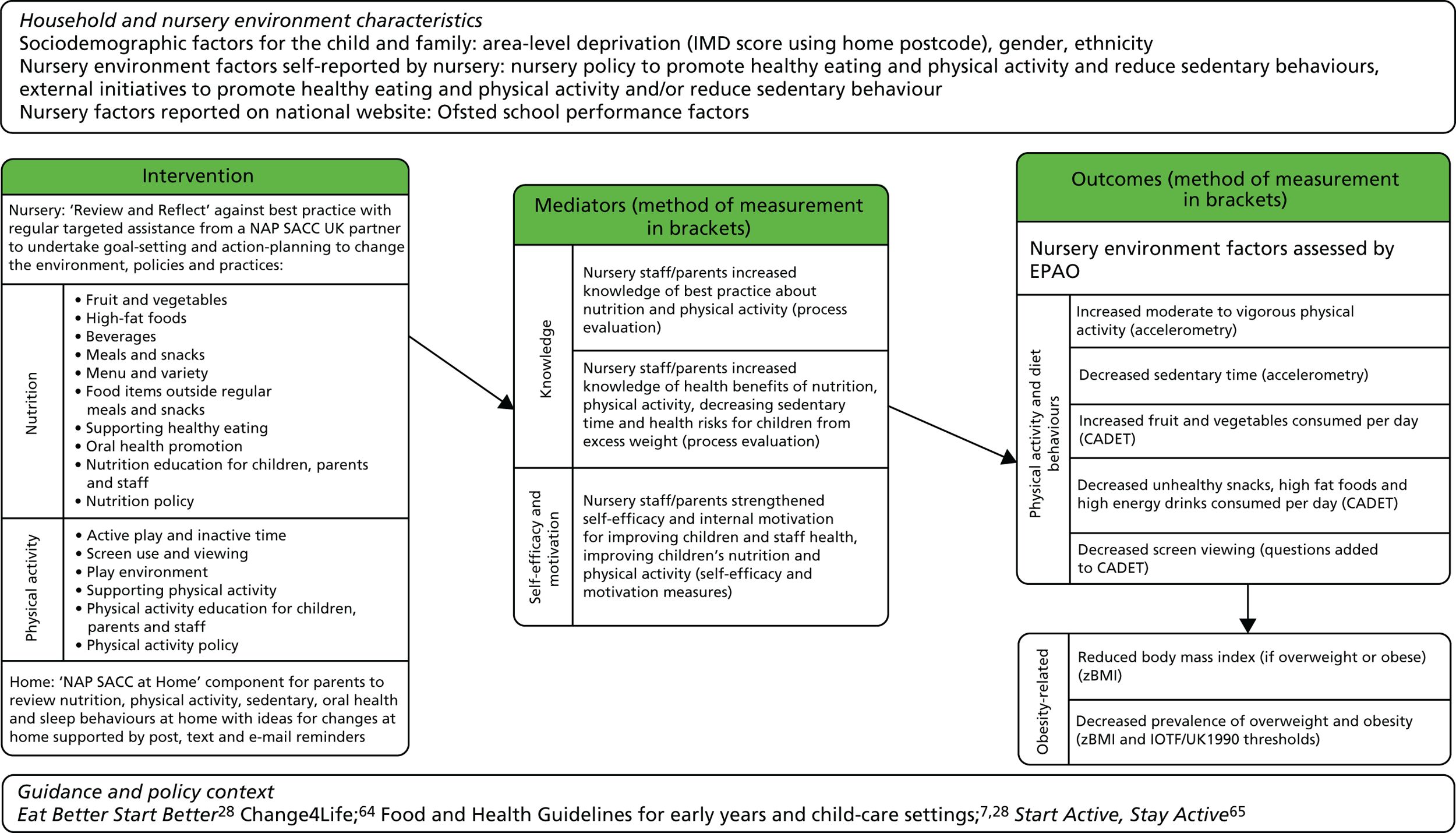

FIGURE 3.

Logic model of NAP SACC UK. IOTF, International Obesity Task Force.

The protocol for the study has been published. 1

Progression criteria

The predefined progression criteria for the trial, as agreed with the external Trial Steering Committee (TSC) and the funder [National Institute for Health Research (NIHR)], were the following.

Criterion 1: feasibility

-

Was it feasible to implement the NAP SACC UK intervention in child-care providers? This was assessed according to (1) at least 40% of contacted eligible child-care providers expressing a willingness in principle to take part in the feasibility trial in response to an invitation to take part; and (2) a synthesis from the different aspects of the process evaluation [observation, interviews and analysis of meeting logs between NAP SACC UK partners (health visitors) and child-care providers].

Criterion 2: acceptability of intervention

-

Was the intervention acceptable to NAP SACC UK partners? This was assessed via interviews with partners and analysis of meeting logs between NAP SACC UK partners and child-care providers.

-

Was the intervention acceptable to the majority of child-care managers, staff and parents/carers? This was assessed via interviews with managers, staff and parents/carers.

Criterion 3: acceptability of the trial design

-

Were the trial design and methods acceptable? This was assessed according to (1) expressions of interest from eligible child-care settings; (2) interviews with child-care providers about randomisation and data collection; (3) at least a 40% parental opt-in consent rate for measurements with eligible 2- to 4-year-old children; (4) a maximum loss to follow-up of three providers (or no more than two in any arm) or 40% of children; (5) a synthesis of interviews with parents/carers about data collection.

Trial registration, governance and ethics

The study was approved by Wales Research Ethics Committee 3 prior to recruitment and data collection commencing (formative work 14/WA/1134; pilot RCT 15/WA/0043; process evaluation 15/WA/035). The trial protocol was registered with Current Controlled Trials (ISRCTN16287377: www.isrctn.com/ISRCTN16287377). Ethics approval for the mediator questionnaire substudy was obtained from the Faculty of Health Sciences Research Ethics Committee at the University of Bristol (reference 41585). Ethics approval for the nursery food photography feasibility substudy was obtained from the University of Bristol School for Policy Studies Research Ethics Committee in November 2017. The feasibility RCT was overseen by a TSC, comprising an independent chairperson and four independent members. The TSC met approximately 6-monthly throughout the study (with one 12-month gap), meeting five times in total, to examine trial progress, conduct and scientific credibility. This was a pilot trial with no interim analysis and, therefore, the TSC and funder agreed that a separate Data Monitoring and Safety Committee was not necessary.

Safety

Child-care providers were given contact details for the trial manager and were able to contact the study team if they had any concerns or parents/carers report concerns. Nursery managers and those delivering the intervention (health visitors and trainers) were asked to contact the study team within 5 working days if any untoward incident or adverse event (AE) occurred to a member of staff or child, as a direct result of taking part in NAP SACC UK, or because of changes that have occurred in the nursery environment as a result of participation in NAP SACC UK. Study-specific AE/incident report forms were available to be used to record information on the event. No AEs or serious AEs were reported associated with the intervention or trial.

Public involvement

A patient and public involvement group was set up early in the project to provide advice and guidance. Parents, child-care staff, health visitors, local authority early years staff, public health specialists, health improvement staff and a dietitian were invited to participate. The first meeting was held in March 2015, during phase 1 of the project, as phase 2 (a feasibility RCT) was being planned. The topics discussed included the wording of parent questionnaires, wording of the questionnaire around future use of anonymised data, the content and delivery of the nursery staff workshops that made up a key component of the intervention, the home component, ‘NAP SACC at Home’, and suitable thank you gifts for the children involved. This first meeting was well attended (nine lay members). The next meeting, held in February 2016 with the same group invited, was very poorly attended (one lay member). This meeting was held after baseline data collection, prior to the intervention. The main topic for discussion was the home component, ‘NAP SACC at Home’, particularly how to engage parents and children, the suitability of sending tips by text and e-mail, how to encourage parents to set goals, and the use of a NAP SACC UK Facebook group.

The final meeting was held in July 2017 at the end of the study. This time only nursery managers were invited (five attended) and the meeting was used to discuss improvements that could be made to the NAP SACC intervention and data collection methods following issues identified during the feasibility study. Topics discussed included how to approach nurseries and parents to improve recruitment, incentives for nurseries to participate, dietary measures and the possibility of weighing or photographing food consumed by children, intervention delivery and the impact of the government-funded 30 hours of child care due to start in September 2017. This was a very useful meeting with good engagement from nursery managers, who provided useful insights.

Changes made to the protocol and intervention following phase 1

Change of phase 2 study site

During the funding process, NIHR suggested that an urban area with greater ethnic diversity be included in addition to North Somerset to ensure greater generalisability. The plan was to keep Bristol available for a full trial and, therefore, we proposed that Cardiff be involved. There was subsequently a change of site from Cardiff to Gloucestershire, which required a protocol amendment. Full details of this decision are shown in Table 30, Appendix 1. This was agreed with the sponsor, TSC and NIHR. The collaborators’ agreement was signed by the two new organisations. This created a delay in recruitment of nurseries in Gloucestershire, but the change improved our understanding of the feasibility of undertaking this study by involving another local authority area in England given the complexity of interventions and different nursery provision encountered in Wales.

Shortening the intervention

As recruitment of nurseries was delayed by the change to include Gloucestershire, we agreed with the TSC to shorten the intervention to 5 months. Therefore, baseline data collection was carried out from September 2015 to January 2016. Randomisation took place in February 2016. The intervention period was 1 February 2016 to 30 June 2016. The NAP SACC UK at Home element was launched to parents in April and May 2016. Follow-up data collection was completed at 8 out of the 12 nurseries in July 2016. The remaining four nurseries were left until September 2016 to assess the feasibility of following up those children who had left nursery to start school.

Chapter 3 Feasibility study phase 1: methods

This chapter provides an overview of the study aims and objectives, study design, methods and results of phase 1 of the study where we adapted NAP SACC to the UK setting and developed a home component.

Phase 1 eligibility and recruitment

A purposive sample of eight child-care providers in North Somerset and eight child-care providers in Cardiff were sent a letter inviting the child-care provider staff to take part in a focus group or telephone interview to inform the development of the NAP SACC UK trial. A letter, project information sheet, reply envelope and form indicating if they wish to participate in a focus group or telephone interview were sent. The sample of child-care providers included private day nurseries as well as community preschools and Children’s Centre nurseries but did not include parent-and-child playgroups or crèches. North Somerset and Cardiff were selected because these are the areas where the RCT was originally intended to take place, Gloucestershire was substituted for Cardiff for phase 2. The two areas provided diverse localities within England and Wales, including urban and rural settings, with a range of deprivation and ethnicity indices.

Health visitors in North Somerset, Wales Healthy and Sustainable Pre-School Scheme (WHASPS) staff in Cardiff and early years staff working at local authorities in North Somerset and Cardiff were sent the same information inviting them to take part in separate focus groups. Written informed consent was taken before the focus groups and telephone interviews commenced.

Phase 1 data collection procedures

Twelve (75%) nurseries were recruited, eight in North Somerset and four in Cardiff. The recruited child-care settings were asked to send parents with children aged 2–4 years a letter, project information sheet, reply envelope and form indicating if they wish to participate in a telephone interview to discuss the NAP SACC UK intervention and trial.

Interviews were conducted with parents in sufficient numbers until saturation was reached and followed a semistructured format with follow-up probes on key topics of interest. Questions focused on ways in which the NAP SACC intervention could be adapted to involve parents and methods of maximising participation in the trial. Each telephone interview lasted 30–45 minutes, was conducted by a trained researcher and was recorded using an Olympus DS-2200 Digital recorder (Olympus DS-2200 Digital recorder, 2 Corporate Center Drive, Melville, NY, USA).

Focus groups were initially chosen as the method of data collection for nursery, early years and public health staff. Focus groups are an effective method of collecting qualitative data as the thoughts and ideas of some members of the group can often encourage others to verbalise their responses in a comfortable, safe and supportive environment. 68 Each focus group lasted 45–60 minutes, was conducted by a trained moderator and was recorded using an Olympus DS-2200 digital recorder.

The focus groups had a semistructured design with follow-up probes on key topics of interest. Questions focused on which aspects of NAP SACC needed to be adapted to incorporate UK guidance, recommendations and terminology; how NAP SACC could be adapted to include parents; what additional training could be provided to child-care staff to increase structured active play; how the intervention could be promoted to child-care providers; what factors might influence low participation and adherence to the programme and study; and what strategies should be used to maximise participation.

Owing to the logistical difficulties of arranging focus groups with nursery staff, it was later decided to hold telephone interviews for most nursery staff. The same topic guides were used for the nursery staff interviews as they were for the focus groups and ethics approval was given for the change.

In addition to discussing how NAP SACC could be adapted to the UK during focus groups and interviews, potential changes to NAP SACC were discussed during meetings with a group of local experts, including a community dietitian, oral health and PA specialists, as well as with the study Trial Management Group, the TSC and the founder of NAP SACC (and co-applicant), Dianne Ward.

Phase 1 data analysis

The interview and focus group recordings were transcribed verbatim and anonymised. Tapes were erased and destroyed after transcription. All identifying data were removed from the transcripts. The qualitative software analysis package NVivo (Version 10, QSR International, Warrington, UK) was used to support analysis and data management. As the data were exploratory, a thematic analytical approach was used. A member of the research team indexed a subset of transcript data to construct a coding framework. Codes were then applied to the remaining transcript data. Codes were assembled to construct emergent themes, which were refined and agreed through discussions between the research team. All participant narratives were equally privileged in the generation of new theoretical and empirical insights. Anonymised data were presented in the form of quotes.

Feasibility study phase 1: results

This chapter presents the results from phase 1 of the feasibility study, which aimed to inform the adaptation of the NAP SACC intervention for use in the UK and the creation of a home component and to refine the RCT methods.

Recruitment

Participant characteristics are shown in Table 2. A total of 12 nursery managers, 31 parents and 15 public health and early years staff participated in the study. More than 90% of the participants were female. Four focus groups were conducted with public health and early years staff, along with one focus group for nursery staff. All 31 parents were interviewed by telephone.

| Place | Group | Number | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In focus groups | Of interviews | |||

| North Somerset | Parents (all) | N/A | 21 | 21 |

| Low-SES parents | N/A | 1 | 1 | |

| Middle-SES parents | N/A | 12 | 12 | |

| High-SES parents | N/A | 8 | 8 | |

| Nursery managers | 2 | 6 | 8 | |

| Public health/early years staffa | 6 | N/A | 6 | |

| Cardiff | Parents | N/A | 10 | 10 |

| Low-SES parents | N/A | 0 | 0 | |

| Middle-SES parents | N/A | 5 | 5 | |

| High-SES parents | N/A | 5 | 5 | |

| Nursery managers | N/A | 4 | 4 | |

| Public health/early years staffb | 9 | N/A | 9 | |

| Total | Parents (all) | N/A | 31 | 31 |

| Nursery managers | 2 | 10 | 12 | |

| Public health/early years staffb | 15 | N/A | 15 | |

Child-care context

Table 3 shows the breakdown of nurseries by location, socioeconomic status (SES), type of nursery, number of 2- to 4-year-old children registered at the nursery, and meal and/or snack provision. The SES of the nursery was based on the Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD)69 in England and the Welsh Index of Multiple Deprivation (WIMD)70 in Wales. The IMD is an English Government-produced measure of deprivation that includes assessments of income, employment, health and education. 69 WIMD is the official measure of relative deprivation for small areas in Wales, which includes assessments of income, employment, health, education, access to services, community safety, physical environment and housing. 70 The IMD/WIMD was obtained for the postcode of each nursery and thus represented a measure of deprivation for the nursery and not the individual participant. The nurseries were then stratified into low-, middle- and high-SES tertiles.

| Child-care setting number | Location of child-care setting | SES of child-care setting | Type of child-care setting | Number of 2- to 4-year-old children at child-care setting | Food provided |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | North Somerset | High | Community preschool | 40 | Meals and snacks |

| 2 | North Somerset | High | Community preschool | 16 | Snack only |

| 3 | North Somerset | Middle | Private day nursery | 48 | Meals and snacks |

| 4 | North Somerset | Middle | Children’s centre nursery | 105 | Meals and snacks |

| 5 | North Somerset | High | Community preschool | 45 | Snack only |

| 6 | North Somerset | Low | Private day nursery | 35 | Meals and snacks |

| 7 | North Somerset | Middle | Private day nursery | 60 | Meals and snacks |

| 8 | North Somerset | Middle | Private day nursery | 42 | Meals and snacks |

| 9 | Cardiff | High | Private day nursery | 50 | Meals and snacks |

| 10 | Cardiff | Low | Private day nursery | 30 | Meals and snacks |

| 11 | Cardiff | Middle | Private day nursery | 63 | Meals and snacks |

| 12 | Cardiff | High | Community preschool | 55 | Snack only |

Eight nurseries were based in North Somerset, of which four were registered as private day nurseries, three as community preschools and one as a children’s centre nursery. Four nurseries were based in Cardiff, of which three were registered as private day nurseries and one as a community preschool. Across both sites, two nurseries were classified as low SES, five were middle SES and five were high SES. The number of 2- to 4-year-old children registered at the nurseries ranged from 16 to 105. A total of 75% of the sample of nurseries provided meals and snacks for children, which were prepared in-house. The remainder, all of which were community preschools offering sessional care, provided snacks only. Information regarding the ethnic diversity of the child-care settings was unavailable but one-third of the nurseries were based in Cardiff, which is ethnically diverse (17.2% from a non-white background). 70

Nursery environment

Healthy nursery environment: nutrition (parents and nursery managers)

Parents and nursery staff generally reported a good standard of nutrition in nurseries:

We take fruit in, in the morning. So that’s part of the routine, is putting the fruit together in a bowl. And . . . if you bring in something more unusual than just an apple or a banana then they . . . sort of talk about it with the children.

Parent_Mid_SES_Nursery_1

With us the majority of the time we have fruit and natural yoghurt for dessert, there’s always veg either in with the meal or as part of the meal.

Manager_High_SES_Nursery_9

However, knowledge of and use of nutritional guidance varied between settings, ranging from specific food safety guidance for caterers, to recipes from early years magazines, to no guidance at all:

. . . the owner and the management team and the cook . . . we all throw ideas about what we are going to provide.

Nursery Manager_High SES_Nurser_9

We usually follow the Safer Food Better Business for Caterers guidance and also the schools’ guidance as well, the local authority guidance as well . . . and of course anything else that comes out via research . . .

Manager_Mid_SES_Nursery_4

. . . that’s between me, as the owner, and my cook as what we can cook and what we can afford . . .

Manager_Mid_SES_Nursery_3

. . . Um at the moment we just get it from, you know, early years magazines, etc.

Manager_Mid_SES_Nurser_4

Interestingly, none of the North Somerset settings had used, or even heard of, the Children’s Food Trust’s 2012 report, Eat Better, Start Better: Voluntary Food and Drink Guidelines for Early Years Settings in England. 28

Healthy nursery environment: physical activity (parents and nursery managers)

Parents and staff of most nurseries reported that there was space and equipment for children to be physically active:

It’s a new building and they’ve got a very large central play area, as well as a separate outdoor play area.

Parent_Mid_SES_Nursery_4

They’ve got an outdoor area at the front and back . . . they are always out on bikes or they have a couple of little plastic cars, so they are always charging around out there.

Parent_Mid_SES_Nursery_7

. . . we’ve got . . . the Sticky Kids’ CDs [compact discs] which we do, and we’re outside nearly all day.

Manager_Low_SES_Nursery_6

However, one setting had only indoor space available to children:

This playgroup doesn’t have a garden . . . so they are very much confined to indoors . . . with regards to physical activity as far as I know there’s not massive of stuff organised.

Parent_High_SES_Nursery_12

The majority of parents also reported that their children spent time outdoors at their nursery, but there was variation in whether this was ‘all weather’ or only on fine days:

My son especially loves the outside and I think that’s why he really enjoys it there. He has in the past got upset because he couldn’t go outside because it’s raining.

Parent_High_SES_Nursery_5

We have to make sure they have wellies and waterproofs so yes they can go out anytime.

Parent_Mid_SES_Nursery_7

Some parents reported that their child’s nursery never took children off premises for PA or outdoor play, which they had mixed reactions to:

Because they’ve got quite good outdoor facilities, the garden is big enough, they don’t really need to. They are in the city centre so I don’t think it’s very practical to be honest.

Parent_Mid_SES_Nursery_11

I don’t think they take them outside. It is a shame . . . there is park land within 2 minutes of where they are, so they definitely could take them outside.

Parent_High_SES_Nursery_12

Screen time mainly consisted of children taking turns on a computer, and was reasonably limited across settings:

We’ve only literally got one computer, and to be fair that’s not on every day.

Manager_ Mid_SES_Nursery_8

However, one nursery reported that they relied on the television to keep children occupied while cleaning the nursery:

This week’s been particularly bad weather, so while I need to clear up my dining room, which is also our playroom, I use the television because it’s been wet and windy and they haven’t wanted to go outside.

Manager_Mid_SES_Nursery_3

NAP SACC intervention

Nursery staff were asked to look at the questions on the self-assessment form and provide feedback on their clarity, appropriateness and fit with UK standards. They were also asked to comment on the length of the draft document. Overall, nursery staff were positive about the NAP SACC approach of self-assessment:

. . . I thought they were quite . . . reflective and . . . not too off-putting either . . . and you just literally tick boxes, which is what we always like.

Manager_Mid_SES_Nursery_3

You know, when you said 70 questions I thought, ‘Ooh’. But actually they’re quite straightforward.

Manager_High_SES_Nursery_2

However, the absence of a section on oral health in the self-assessment form was noted to be a growing concern in nurseries:

. . . one thing that has come to our attention in nurseries . . . is children’s teeth . . . more so than obesity, I feel. We have three children at the nursery . . . one . . . is 2 years old and her teeth are rotten . . . another little boy . . . has a hole in his tooth . . . another little girl . . . has got holes in her teeth . . . to the point where she needs them out. And I think . . . we need to put . . . oral health in there somewhere.

Manager_Mid_SES_Nursery_3

Regarding the action-planning document, nursery staff suggested reducing the number of goals required to be set over a 6-month period:

I don’t know whether 10 would be manageable in 6 months, besides everything else that people have to do as well. 10 just seems quite a lot. I’ve got action plans that I might have 10 on but I’m going to spend a whole year covering those. 6 months to do 10 is quite a lot I think.

Manager_Low_SES_Nursery_10

We usually have, when we do anything in child care, we usually use three or four goals, targets.

Manager_Mid_SES_Nursery_3

They also welcomed improved links with health visitors:

We never ever see a health visitor, so I think that’s amazing.

Manager_Mid_SES_ Nursery_2

However, health visitors and WHASPS expressed concern over their capacity to deliver training workshops for nursery staff:

My area, there’s lots of health visitors, so we’d probably be able to achieve it. But in other places, like here, [town name], they may not be able to because there’s quite a few nurseries and not many health visitors, so they might struggle to get round each one, with getting their work done as well.

Health_Visitor_North_Somerset

I think having to give presentations maybe takes us into a different level of time commitment.

WHASP_Cardiff

When asked if the proposed workshop topics of ‘childhood overweight’, ‘nutrition for children, ‘physical activity for children’ and ‘personal health and wellness for staff’ would be of interest to child-care staff, nursery managers expressed a particular need for more staff training in children’s PA:

. . . although physical development is now a prime area for us to promote, a lot of us have not had any training about how to promote that, you know, the types of activities, and it’s not easily available.

Manager_High_SES_Nursery_5

However, concerns were raised about the sensitivity of the topic ‘personal health and wellness for staff’:

. . . that could be quite a tricky area, couldn’t it? Um especially if you’re modelling the obesity one, because you could have some staff that could be slightly overweight that could take offence at that . . . it would have to be handled very carefully, wouldn’t it?’

Manager_ Mid_SES_Nursery_4

Developing a home component

In general, parents welcomed the idea of including a home learning component in the NAP SACC UK intervention:

If I was given something like that . . . um I’d have just welcomed the advice and I wouldn’t think you were trying to tell me what to do; you’re just trying to help me in the right direction. If there are a few things that I can improve upon, then brilliant.

Parent_High_SES_Nursery_2

However, many parents were concerned that this part of the intervention could be deemed to be invasive or ‘preachy’:

There’s a fine line with becoming too involved with how a parent is raising their child, so I would be cautious.

Parent_High_SES_Nursery_12

I think sometimes some people might think it’s a bit patronising. It’s quite obvious that children shouldn’t just sit around and watch TV [television], they need exercise.

Parent_Mid_SES_Nursery_3

Some parents cautioned that the home component may be received differently depending on social background:

I think there are some types of parents that will be hard to reach, so if you approach it in a non-judgemental way and you make it easily accessible for everyone no matter what background, I imagine there are some people who don’t have much money . . . they will feel different and I think it’s making those people feel welcome because it’s help for everyone.

Parent_Mid_SES_Nursery_11

Healthy/low-cost recipe and PA ideas were reported to be most attractive to parents as part of the home component:

Sometimes it’s cheaper or easier to buy junk food. So I think recipes is a good one, giving ideas.

Parent_Mid_SES_Nursery_11

I think a lot more should be available for children, I’ve been looking at gymnastics and dance classes for my daughter and they are just so expensive . . . you would love to send your children to all these classes, but you need ideas of things that don’t cost, or don’t cost a lot of money.

Parent_Midd_SES_Nursery_4

Many parents welcomed the idea of sharing healthy eating and PA ideas with others, and tip-sharing forums were suggested, either online (e.g. using social media) or at a physical meet-up:

You could probably maybe do workshops for parents, ways of getting vegetables into foods, things like that. It would give you a boost to do the right thing, wouldn’t it?

Parent_Low_SES_Nursery_6

It would be really handy to have a Facebook page with ideas of what you could cook for dinner tonight. A healthy meal that you could do, or something that you could do with the children.

Parent_Mid_SES_Nursery_4

Others suggested that the home component would be most successful if linked in with the nursery’s activities:

You could do something coming from the nurseries, like a welcome pack, or once a quarter maybe linked to the seasons, something like that. Different vegetables and things . . . In that you could have a couple of recipe ideas, or activities you can do at this time of year, or even go for a long walk and collect autumn leaves, pine cones to make Christmas decorations, all that sort of stuff. Seasonal fruit and veg and a couple of nice recipes to do with it. A little fun activity pack.

Parent_Mid_SES_Nursery_7

Parent–child cookery sessions and demonstrations at the nursery were also appealing:

I wonder whether if you had some kind of demo maybe, I don’t know whether the preschool would be involved with that. You could have a kind of demo, someone come along and cook something, and the children and the parents all stay together and have like a buffet or party, that maybe encourages the children to try something they haven’t and maybe the parents as well.

Parent_High_SES_Nursery_1

Finally, parents highlighted the importance of involving children in the home component as much as possible, as they were regarded by parents as ‘key’ to change in the home:

So anything that involves the parent going IN, I think they would be keen on and involving the children as well will mean once you’ve left this event, you take it home and if the children’s imagination has been captured and you’ve been there together, then I think that would be a very good way of getting the information home.

Parent_Mid_SES_Nursery_4

Development of NAP SACC UK and NAP SACC UK at Home

NAP SACC UK

Following discussions with nursery managers, it was decided to change the name of the NAP SACC UK self-assessment form to the Review and Reflect form as the research team felt that the word self-assessment evoked a sense that the nursery was being examined in a manner similar to Ofsted (England) or Estyn (Wales), which was potentially off-putting for staff. The form itself was also revised using the English guidelines Eat Better, Start Better – Voluntary Food and Drink Guidelines for Early Years Settings in England,28 as these are seen as current best practice for nurseries in the UK. This meant including questions on salt, breakfast, types of protein and dairy served, puddings and snacks, as well as adapting foods originating in the USA to UK alternatives. Given the concerns raised by the nursery manager and NHS oral health specialist about oral health in nursery-aged children, three questions on oral health were added to the child nutrition section of the form, including how staff promote oral health to children, capacity for professional development and training in oral health, information and support for families and existence of a policy on oral health. Furthermore, after discussion with Welsh Healthy and Sustainable Pre-School Scheme staff, a question was also added about whether or not the nursery had a PA policy that included active travel. After making these amendments and adaptations, the original Go NAP SACC form (excluding the breastfeeding section) was reduced to 80 items.

Following feedback from nursery staff about the manageable number of goals to be achieved in 6 months, the action-planning document was reduced from 10 goals to 8. Owing to the concerns of some nursery managers about their ability to release staff for training, and also the potential sensitivity of some of the workshop topics, the number of training workshops available to nursery staff was condensed from five workshops on ‘obesity’, ‘healthy eating’, ‘physical activity’, ‘personal health and wellness’ and ‘working with families’, to two workshops, each lasting 3 hours, on ‘nutrition and oral health’ and ‘physical activity’. Instead of being delivered by a ‘nurse partner’, as in the USA, these workshops were delivered by a local expert. This differed to the original plan for workshops to be delivered by health visitors and Welsh Healthy and Sustainable Preschool staff, as feedback suggested that this would be burdensome for staff who already had large caseloads. However, because of the interest from nurseries in improving links with health visitors, these workshops were attended by a health visitor, who then became the NAP SACC UK partner for that nursery, maintaining regular contact with the facility to provide support and guidance in making their improvements over a 6-month period. Table 4 summarises the changes made from NAP SACC US to NAP SACC UK.

| Step | NAP SACC | |

|---|---|---|

| USA | UK | |

| 1 | 99-item self-assessment (excluding breastfeeding section), ‘Go NAP SACC’63 | 80-item Review and Reflect based on ‘Go NAP SACC’63 and revised with UK guidance |

| 2 | Action-planning (10 goals) | Two workshops (3 hours) delivered by local experts with participating health visitors |

| 3 | Five workshops delivered by nurse consultant | Action-planning (8 goals) |

| 4 | Targeted technical assistance from nurse consultant | Targeted technical assistance from NAP SACC UK partner (health visitor) |

| 5 | Evaluate, revise and repeat | Evaluate, revise and repeat |

Development of NAP SACC UK at Home

Drawing on feedback from parents about the proposed home component of NAP SACC UK, a digital media intervention was developed (NAP SACC UK at Home). The steps of NAP SACC UK at Home are outlined below:

-

Sign up: parents are invited to sign up to take part in NAP SACC UK at Home. This involved logging on to the NAP SACC UK at Home website and registering an e-mail address and mobile phone number for correspondence or returning the information on paper to the NAP SACC UK office.

-

Tailoring support: parents were asked to complete a questionnaire about their family habits at home with respect to the areas covered by the home component to allow tailoring of support. An e-mail or text was sent in response, suggesting areas of focus for the goals. The first 50 parents who completed the questionnaire received a free family swimming voucher, redeemable at local swimming pools.

-

Goal-setting and action-planning: parents were asked to set goals for change and plan actions to meet the goals in the areas of eating, drinking, oral health, sleeping, indoor play, outdoor play, television (TV) and screen-viewing behaviours.

-

Tailored suggestions: parents received fortnightly tips and suggestions to prompt behaviour changes in the areas where support was requested. These were sent via Facebook, text and e-mails or by post for those not online.

-

Review: parents were encouraged to review their goals and actions, to consider what worked and what could be approached differently, to set new goals and actions and consider other areas for change.

Summary

The phase 1 study found that nurseries reported a generally good standard of nutrition, but the extent to which nutrition guidance was used varied between settings, with some using no nutritional guidance at all. Most nurseries had space for the children to be physically active, which was usually outdoors. There was variation in the extent to which the outdoor space was used ‘all weather’ or on fine days only. Screen time was limited across settings, with few including television time in their daily routines. Children’s oral health was highlighted to be a growing concern in nurseries, and this concern was reinforced by an NHS oral health specialist, who was a member of our group of expert advisors to NAP SACC UK. Adaptations to NAP SACC were made in the light of the phase 1 study and NAP SACC UK at Home was created.

Chapter 4 Feasibility cluster randomised controlled trial phase 2: methods

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced from Kipping et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

This chapter describes the methods used in the feasibility cluster RCT.

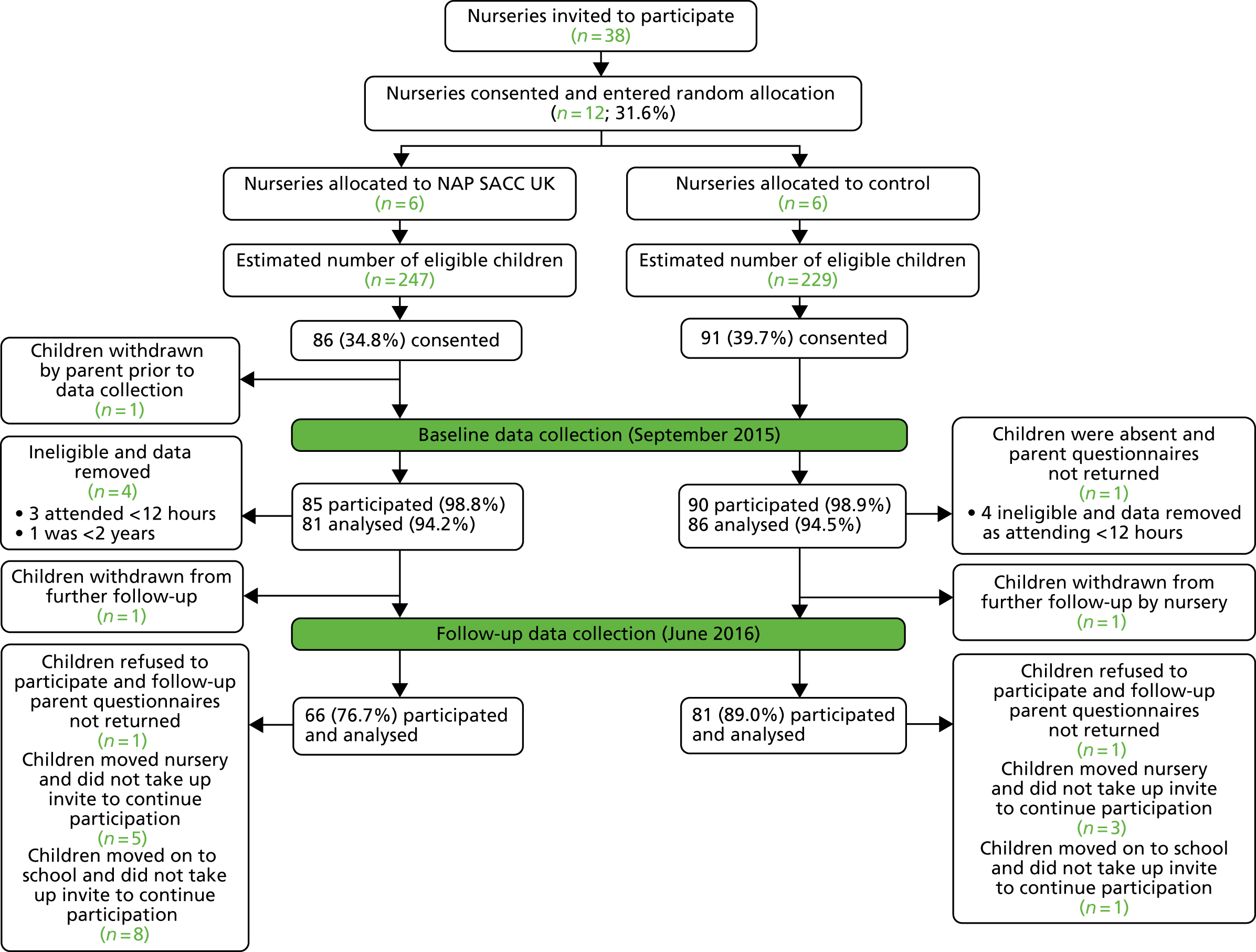

Sample size, eligibility, recruitment and randomisation

The sample size for this feasibility study was not informed by a power calculation. The sample size of 12 nurseries was chosen to provide information on variability within and between nurseries at baseline and follow-up, response rates and intracluster correlation coefficients (ICCs) in anticipation of a larger trial. A larger sample would not have been appropriate for a feasibility study and 12 participants was deemed a sufficient sample for the process evaluation, which was the most important part of this feasibility study.

The study took place in nurseries in two areas of England (North Somerset and Gloucestershire) and in the homes of children recruited to the study. North Somerset is a rural area adjacent to Bristol, with 14.1% of children living in poverty (per cent of children aged < 16 years in families receiving means-tested benefits and low income in 2012). 71 Gloucestershire is a large rural county to the north of Bristol. The health of people in Gloucestershire is generally better than the England average; however, 13.8% of children live in poverty. 72

The inclusion criteria for child-care providers were that they must be a day nursery, private nursery school, maintained nursery school, children’s centre with nursery, or preschool, in North Somerset or Gloucestershire. Excluded child-care settings were child minders, crèches, playgroups, primary school reception classes (where schools operate an early-admission policy to admit children aged 4 years) and au pairs. Settings were eligible if they had a minimum of 20 children aged 2–4 years who attend the child-care providers for at least 12 hours per week over 50 weeks of the year, or 15 hours per week in term time.

The NAP SACC UK study was discussed with North Somerset child-care provider managers at meetings convened by North Somerset Council and advertised in the Council’s early years newsletter. These opportunities were not available in Gloucestershire because of timing of recruitment. Child-care providers were sent a letter from the Council, project information sheet, reply envelope and form indicating if they wish to participate and reason for their response. Non-responders were followed up with a reminder and then a telephone call. All interested child-care providers were contacted by telephone to discuss the study following which, if the provider was still interested, they were offered a visit to discuss the intervention and study in more detail. A £200 incentive was provided to all participating nurseries at the end of the study.

Randomisation involved allocation to two arms: NAP SACC UK or usual practice. Twelve child-care providers (six in each area) were recruited to the trial, of which six were randomised to the control group and six to the intervention (three in each area). Allocation was conducted by an independent statistician at the Bristol Randomised Trials Collaboration, blind to the identity of the child-care providers. Stratified randomisation was used to ensure balance for (1) deprivation (using IMDs for the local super output area for 2010, where the provider is located), (2) size of child-care provider [small (≤ 48 children) or large (> 48 children)] depending on number of children attending, details obtained from the Council, Ofsted website or the nurseries own website] and (3) location (North Somerset and Gloucestershire). To achieve reasonably equally sized groups for randomisation, 12 groups were created across each of the two areas, with six lists created for each of low, medium and high IMD score. Each of the six lists by IMD category combinations was divided into two equal groups according to size.

Parents/carers were given a letter, project information sheet, reply envelope and form indicating if they wish to give consent for their child to take part in the study (sent at the end of August 2015). Research staff attended all nurseries late afternoon on between 1 and 3 days (depending on staff availability) to talk to parents about recruitment and answer any questions. All children received a small thank you gift [packet of stickers or a Mr Men™ (Mister Men Limited, London, UK) book] after each of the two data collections to encourage the prompt return of accelerometers.

The NAP SACC UK intervention

The NAP SACC UK intervention is based on the online Go NAP SACC intervention73 (but delivered in person) and was adapted for use in the UK during phase 1 of the feasibility study. It is based on social cognitive theory and the socioeconomic framework. In the feasibility study, the intervention was delivered by health visitors (NAP SACC UK partners) and local experts delivered the workshops for nursery staff. The intervention used in the NAP SACC UK feasibility trial is summarised using the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR)74 12-item checklist in Table 5. The intervention also contained a home-based component, informed by other studies of behaviour change with parents/carers of young children use of digital media, and interviews and focus groups with parents/carers, nursery managers and health visitors. The intended behaviour change techniques used in the different elements of the NAP SACC UK intervention are outlined in Appendix 5, Table 32.

| Item | Description |

|---|---|

| Name | NAP SACC UK |

| Why |

NAP SACC UK is an intervention delivered in child-care settings with the aim of improving the nutrition, oral health and PA environment, through a process of self-assessment and targeted assistance. NAP SACC UK is a theory-based programme that employs components of social cognitive theory and socioecological framework. The objectives of the programme are to improve the nutritional quality, variety and quantity of food served, increase the amount and quality of PA, and to improve oral health education, staff–child interactions and staff behaviours around nutrition and PA and child-care provider policies on nutrition and PA NAP SACC at Home Phase 1 work included interviews with parents, which indicated an interest in a digital media intervention for parents, where tips and ideas could be given without being invasive or ‘preachy’ |

| What: materials |

The NAP SACC UK intervention is based around a self-assessment tool completed by nursery managers. This document, called the Review and Reflect, is an 80-item multiple-choice questionnaire, completed by the nursery manager, covering areas in nutrition, oral health, PA and play, outdoor play and learning, and screen time Following completion of the Review and Reflect, the nursery manager along with the NAP SACC UK partner agree on eight goals: three nutrition, three PA and a further two of the nursery’s choice. These are recorded on the ‘NAP SACC UK Action-planning’ document Intervention materials are not yet available for access because of the possibility of undertaking a full-scale trial NAP SACC at Home The NAP SACC at Home intervention is based around a website called ‘NAP SACC at Home’. This contains a page where parents can register their details, an initial questionnaire, goal-setting area and information pages. Additional materials included a NAP SACC at Home Facebook page, and paper copies of resources for those without internet access |

| What: procedures |

The NAP SACC UK intervention is a five stage process:NAP SACC at Home The NAP SACC at Home part of the intervention has the following stages: |

| Who provided |

The main part of the intervention was delivered by NAP SACC UK partners, who in this study were health visitors. Health visitors are qualified nurses or midwives who have undertaken further training and qualifications in child health, health promotion, public health and education. Additionally, to undertake the role of NAP SACC partner, health visitors were given further training consisting of a 0.5-day session led by a senior early years nutrition health improvement specialist, a PA specialist and an oral health specialist, and a further 2-hour ‘top-up’ training session mid-way through the intervention Workshops were delivered by specialists. The nutrition workshop was delivered by a senior early years health improvement specialist with a background in paediatric dietetics. The PA workshop was delivered by a PA expert NAP SACC at Home The NAP SACC at Home part of the intervention was delivered remotely via a website (or paper copies) and via Facebook. The content of the website and Facebook page was developed by the study team, and the website was designed and built by a specialist digital media company |

| How |

The main part of the intervention was delivered face to face; this included going through the Review and Reflect and action-planning, and the workshops. Other parts of the intervention, such as on-going support and advice from the NAP SACC UK partner, could be provided over the telephone, or by e-mail All parts of the intervention were delivered to participating nurseries individually. Some parts may have been delivered on a one-to-one basis (e.g. nursery manager and NAP SACC UK partner setting goals), whereas other parts, such as the workshop, would have been delivered to a whole group of staff from one nursery NAP SACC at Home The NAP SACC at Home part of the intervention was delivered remotely via a website (or paper copies) and via Facebook. Parents were able log on at a time convenient to them, on laptops, PCs or mobile devices |

| Where |

The NAP SACC UK intervention is delivered in the nursery itself. The NAP SACC UK partner offers visits to the nursery as necessary, and the workshops take place at the nursery, unless the nursery request otherwise NAP SACC at Home Parents were able access materials via the internet from their own home, or wherever was convenient |

| When and how much |

The NAP SACC UK intervention took place over 5 months. The initial face-to-face meetings between health visitors and nursery managers lasted ≥ 2 hours. The average number of advice/support opportunities given was 2.2 face-to-face meetings, 1.8 telephone calls and 2.8 e-mails The nutrition workshops were 3 hours and the PA workshops were 2.5 hours NAP SACC at Home Parents were able to access the website as often as they liked during the intervention period. Individually tailored texts/e-mails were sent to parents on a fortnightly basis |

| Tailoring |

The technical assistance offered by the NAP SACC UK partner would depend on the goals that the nursery had set NAP SACC at Home The NAP SACC at Home component was specifically tailored to suit the parents’ needs. Parents answered a questionnaire when they registered and this enabled appropriate information, hints and tips to be sent to them, depending on which areas they set goals in |

| Modifications | The intervention was originally intended to be 6 months long. This was reduced to 5 months part-way through the study to allow time for data collection |

| How well: planned | A process evaluation was conducted alongside the RCT, which looked at both adherence and fidelity. This involved the use of observations, logs, semistructured interviews and document analysis |

| How well: actual | The NAP SACC UK intervention was implemented as planned, with two exceptions: (1) the parent website was used by only 14% of parents and (2) one intervention nursery did not fully implement the intervention |

Outcome measures

Primary outcomes

The primary outcome of this feasibility RCT was the acceptability of the intervention and the trial methods, assessed against pre-set progression criteria (see Progression criteria). Progression criteria were agreed with the NIHR Public Health Research funding board and an independent TSC and were assessed using a range of methods.

Secondary outcomes

The secondary outcomes were measured at baseline (T0) prior to the intervention and 8–10 months after the baseline measurements (T1) (follow-up was deliberately staggered to assess the feasibility of following up children aged 4 years as they moved to school). These assessments were to inform the choice of primary outcomes for a full-scale trial and particularly whether or not the outcomes require data collection from parents/carers and children, or if the outcomes could be the environmental audit and zBMI using data linkage from the National Child Measurement Programme (NCMP). The outcomes included:

-

child accelerometer-measured activity

-

children’s height and weight

-

child food and drink intake, specifically of fruit and vegetables, snacks and sugar-sweetened drinks

-

child screen time

-

EPAO instrument score

-

parental and nursery staff mediators

-

family costs

-

health-related quality of life (HRQoL).

Data collection

As this feasibility study was not designed to assess efficacy, effectiveness or cost-effectiveness, data collection was designed primarily to assess feasibility and acceptability. All measurements were completed at baseline and again at follow-up, except for the baseline nursery audits and demographic information provided on consent forms. Data collection methods comprised the following.

Accelerometry measured activity

We used ActiGraph GT1M accelerometers (Actigraph, Pensacola, FL, USA), which have been extensively validated for assessment of PA among children. Accelerometers were fitted by NAP SACC UK researchers on the day of data collection, and instructions for their use were given to parents/carers on the same day.

Anthropometric measures of children

All anthropometric measurements were completed by DBS-checked trained fieldworkers with a member of nursery staff present. Weight was measured without shoes in light clothing to the nearest 0.1 kg using a Seca digital scale (Seca, Birmingham, UK). Height was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm without shoes using a portable Harpenden stadiometer (Holtain Ltd, Pembrokeshire, UK). Fieldworkers were trained to ensure correct position for height assessment. The ethics committee requested that the research team wrote to nursery managers alerting them to any children who were on or above the 99th zBMI centile for their age and sex, with context regarding the concerns about obesity in children, and advising them to follow their usual child protection procedures.

Children’s food and drink intake specifically fruit and vegetables, snacks and sugar-sweetened drinks

Dietary assessment was performed using the Child and Diet Evaluation Tool (CADET) prospective ticklist record for all foods consumed in a 24-hour period, an instrument validated for use in intervention studies with young children. 75,76 The CADET assesses the intake of 15 food groups, and CADET data were recorded by researchers undertaking observation of the children at all snacktimes and mealtimes at the nurseries and by parents/carers completing the CADET form at home for the child’s food and drink consumption before and after nursery. At baseline, the data were collected on paper forms with four children observed by one researcher. At follow-up, the data were recorded on paper and transferred to Google Nexus (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA) tablets in the nursery. In a sample of four nurseries, CADET data collection at home was piloted over a weekend in addition to the weekday of nursery data collection; for two of these nurseries, the data were returned by parents on paper and in two nurseries they were collected from the parents by a researcher over the telephone. For the two nurseries where CADET was provided over the telephone, a NAP SACC UK researcher made up to four attempts to contact the parents/carers by telephone.

Sedentary time

Sedentary time was assessed by gathering details of screen time and quiet play time on a weekend day; the questions were based on those used in the Toybox study. 77 Sedentary time was assessed via questions at the end of the CADET tool completed by parents/carers.

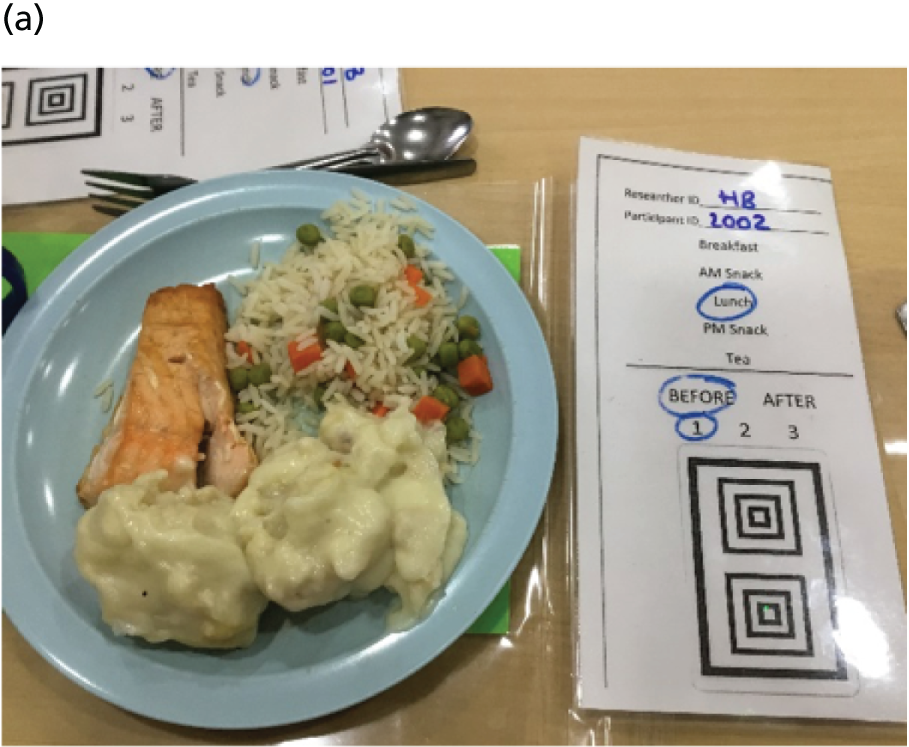

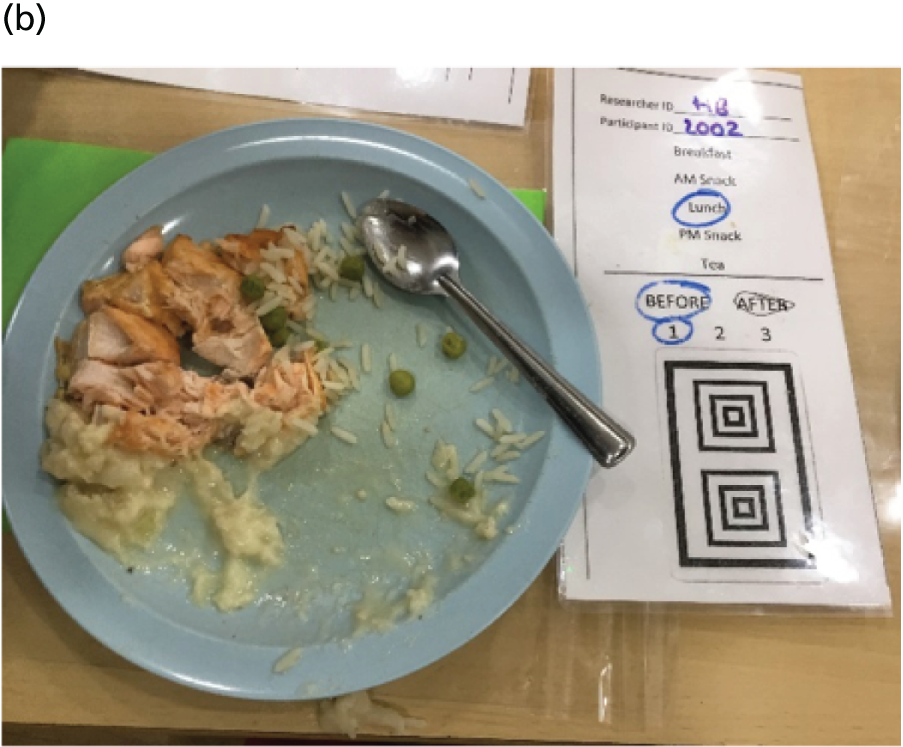

Environment and Policy Assessment and Observation instrument score