Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 12/153/60. The contractual start date was in March 2014. The final report began editorial review in June 2018 and was accepted for publication in November 2018. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Russell M Viner is President of the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health. Stephen Scott reports grants from King’s College London during the conduct of the study. Chris Bonell is a member of Public Health Research Research Funding Board. Deborah Christie reports personal fees from Medtronic plc (Dublin, Ireland), personal fees from Pfizer Inc. (New York, NY, USA) and personal fees from ASCEND (Watford, UK), all unrelated to the submitted work.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Bonell et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced with permission from Bonell et al. 1 This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Scientific background

The study protocol for this trial is available in full in Trials. 1 It is presented again here. Bullying, aggression and violence among children and young people are some of the most consequential public mental health problems apparent today. 2,3 The prevalence and harms of aggressive behaviours among young people makes addressing these a public health priority. 4–7 The World Health Organization (WHO) considers bullying to be a major adolescent health problem, defining this to include the intentional use of physical or psychological force against others. 5,8 This includes verbal and relational aggression that aims to harm the victim or their social relations, such as by spreading rumours or purposely excluding them. 9,10 Some definitions of bullying11 emphasise that bullying refers to abuse that is committed repeatedly over time and that involves a power imbalance between the perpetrator(s) and the victim. The prevalence of bullying among British young people (at around 33%)12 is above the European average,13 with approximately 25% of young people reporting that they have been subjected to serious peer bullying. 14 Cyberbullying, in particular, is rapidly becoming one of the most common forms of bullying. 15 There are marked social gradients: family deprivation and school-level deprivation increase the risk of experiencing bullying. 16 Bullying most commonly occurs in schools17,18 and prevalence varies significantly. 19–22

Being a victim of peer bullying has been associated with an increased risk of physical health problems;23,24 substance use;25–28 long-term emotional, behavioural and mental health problems;29–33 self-harm and suicide;34–36 and poorer educational attainment. 37,38 Students who experience physical, verbal or relational bullying regularly tend to experience the most adverse health outcomes. 39 There has also been evidence that childhood exposure to bullying and aggression may influence lifelong health through biological mechanisms. 23,29,40

The perpetrators of peer bullying are also at risk of a range of adverse emotional and mental health outcomes, including depression and anxiety. 13,19 Therefore, the prevention of bullying, aggression and violence is a major priority for public health and education systems internationally,3,41 with schools a key focus of policy initiatives to improve young people’s mental health and well-being. 42 In England,43 schools have a legal obligation to prevent bullying.

Bullying is often a precursor to more serious violent behaviours. One UK study44 of 14,000 students found that 1 in 10 young people aged 11–12 years reported carrying a weapon, and 8% of this age group admitted that they had attacked another with the intention of hurting them seriously. By the age of 15–16 years, 24% of students reported that they had carried a weapon and 19% had reported attacking someone with the intention of hurting them. 44 Interpersonal violence can cause physical injury and disability, and has been also associated with long-term emotional and mental health problems. Aggression refers to behaviour that is intended to harm, either directly or indirectly, another individual who does not wish to be harmed. 45 There are also links between aggression and antisocial behaviours in young people and violent crime in adulthood. 46,47 This is thought to result from low-level provocation and aggressive behaviours in secondary schools being educationally disruptive and emotionally harmful, and reducing educational attainments and later life chances, and therefore leading to more overt physical aggression over time. 48–50 The economic costs to society as a whole from bullying and violence are extremely high: the total cost of crime attributable to conduct problems in childhood has been estimated to be about £60B per year in England and Wales. 51

Reducing aggression, bullying and violence in British schools has been a consistent priority in public health and education policies. 52–54 The 2009 Steer Review50 concluded that schools’ approaches to discipline, behaviour management and bullying prevention vary widely and are rarely evidence based, and that further resources and research are urgently needed. There is, therefore, a pressing need to determine which interventions are effective in addressing bullying and aggression in schools, and to scale up such interventions to local and national school networks.

Whole-school-based interventions

A number of systematic reviews have assessed school-based interventions to address bullying and aggression. Interventions that promote change across school systems and address different levels of school organisation (i.e. ‘whole-school’ or ‘school environment’ interventions) are particularly effective in reducing victimisation and bullying in comparison with curriculum interventions. 55–57 ‘Whole-school’ or ‘school environment’ interventions are interventions that modify the systemic operations of schools, and they have been shown to have an impact on a range of health outcomes and risk behaviours. 57 A key element of these interventions appears to be increasing student engagement with school, particularly the most socially disadvantaged students, who are at the highest risk of poor health and educational outcomes. 58,59 Two trials have found that such approaches are associated with reductions in risk behaviours, including violence and antisocial behaviour. 60,61

The effectiveness of such interventions may be attributable to the way that they address bullying as a systemic problem meriting an ‘environmental solution’, rather than an individual student issue. 55 Whole-school interventions are also inherently universal in their reach and are likely to provide a cost-effective and non-stigmatising approach to preventing bullying. 56 This is in keeping with other evidence from the UK and internationally, which shows that schools promote health most effectively when they are not treated merely as sites for health education, but also as physical and social environments that can actively support healthy behaviours and outcomes. 62,63

Thus, these school environment interventions take a ‘socio-ecological’64 or ‘structural’65 approach to promoting health, whereby behaviours are understood to be influenced not only by characteristics of individuals, but also by the wider social context. A recent National Institute for Health Research (NIHR)-funded systematic review on the health effects of the school environment found evidence from observational and experimental studies that modifying the way in which schools manage their ‘core business’ (teaching, pastoral care and discipline) can promote student health and potentially reduce health inequalities across a range of outcomes, including reductions in violence and other aggressive behaviours. 63 Other outcomes that are improved by school environment interventions can include mental health and physical activity and reduced substance use, including alcohol, tobacco and drugs. 63

School environment interventions, therefore, are likely to be one of the most efficient ways of addressing multiple health harms in adolescence owing to their potential for modifying population-level risk as well as their reach and sustainability. 63 Multiple risk behaviours in adolescence are subject to socioeconomic stratification, and are strongly associated with poor health outcomes, social exclusion, educational failure, and poor mental health in adult life. 66 A recent King’s Fund report, Clustering of Unhealthy Behaviours Over Time, emphasised the association of multiple risk behaviours with mortality and health across the life-course, and the policy importance of reducing multiple risk behaviours among young people through new interventions that address their common determinants. 67

The INCLUSIVE (initiating change locally in bullying and aggression through the school environment) trial aims to evaluate the Learning Together (LT) intervention. This has been particularly informed by two international evidence-based school environment programmes. The first is the Aban Aya Youth Project (AAYP),61 a multicomponent intervention enabling schools to modify their social environment as well as delivering a social skills curriculum. This approach was designed to increase social inclusion by ‘rebuilding the village’ within schools serving disadvantaged, African American communities. To promote whole-school institutional change at each school, teacher training was provided and an action group (AG) was established (comprising both staff and students) to review policies and prioritise the actions needed to foster a more inclusive school climate. Among boys, the intervention was associated with significant reductions in violence and aggressive behaviour. 61 The intervention also brought benefits in terms of reduced sexual risk behaviours and drug use, as well as provoking behaviour and school delinquency. Second, the Gatehouse Project60,68 in Australia also aimed to reduce health problems by changing the school climate and promoting security, positive regard and communication among students and school staff. As with the AAYP, an AG was convened in each school, facilitated by an external ‘critical friend’ and informed by data from a student survey, alongside a social and emotional skills curriculum. A randomised controlled trial (RCT) found consistent reductions in a composite measure of health risk behaviours, which included violence and antisocial behaviour.

Process evaluation of whole-school health interventions

Most evaluations of interventions taking a whole-school approach to preventing violence and promoting health in schools examine outcomes rather than processes. 63,69 The process evaluation of the Gatehouse Project, which greatly informed LT, found that school staff perceived the various components (needs survey, action team, external facilitator) to function synergistically. Although specific actions varied between schools, these were completed with good fidelity. Implementation was facilitated by supportive school management and the broad participation of staff and students. 70,71 However, this evaluation did not attempt to assess systematically how the completeness of the implementation might have been influenced by schools’ baseline social climate.

The Healthy School Ethos intervention was also informed by the Gatehouse Project and included several elements similar to LT, but without a curriculum or any restorative practice elements. 72,73 Using a structured process modelled closely on the Gatehouse Project, it aimed to enable schools involved in pilots in south-east England to carry out locally determined actions to increase students’ sense of security, positive self-regard, and communication with staff and students. The intervention provided an external facilitator, survey data on student needs and training, and enabled schools to convene action teams to determine priorities and ensure delivery. Students and staff co-revised rules for appropriate conduct and revised policies on bullying and student feedback. Staff were trained to improve classroom management. Process evaluation reported that the intervention was delivered with good fidelity. Locally determined actions (e.g. peer-mediators) were generally more popular than mandatory actions. Implementation was more feasible when it built on aspects of schools’ baseline ethos and when someone on the senior leadership team (SLT) led actions. Student awareness of the intervention was high. Student accounts suggested that benefits might arise as much from participation in intervention processes, such as rewriting rules, as from the effects of subsequent actions. Some components reached a large proportion of students. 72,73

Before the current Phase III trial, the LT intervention had been piloted in four schools. 74 Overall, school staff members were consistently supportive. Although some schools were already deploying some restorative approaches, the intervention was nonetheless attractive because it enabled restorative practices to be delivered more coherently and consistently across the school. The adaptability of the intervention, in contrast to overly prescriptive, ‘one-size-fits-all’ interventions, was also a strong motivating force and a source of acceptability to school managers. Staff valued the ‘external push’ that was provided by the external facilitator. The intervention was highly acceptable to school staff because of its fit with national policies and school metrics focused on attendance and exclusions. Some staff reported that it took time for them to understand how the various intervention components joined up, and this could have been better explained from the outset. Staff were positive about sustainability, with some reporting that activities would continue after the pilot was completed.

Regarding particular components, staff reported that the needs assessment report allowed them to see the ‘big picture’ and identify priorities, but some suggested that the needs assessment could also feel too ‘negative’ at times, especially among established staff, who sometimes viewed this as a reflection on their work at the school. Negative aspects of the needs report could also present problems for schools, because if they were inspected by the Office for Standards in Education, Children’s Services and Skills (Ofsted) they would be expected to share the results with the inspectors. As with the HSE (Healthy School Ethos) evaluation, AGs were viewed positively, and it was suggested that student participation may be an active ingredient in improving relationships and engagement across the school, particularly when these involved students who might be less committed to school and might be involved in antischool peer groups. Again, the presence of a SLT member on the group was seen as critical to driving actions forward. The training, however, was more critically received, with many staff suggesting that this was too didactic and contained too few examples from secondary schools. All schools successfully implemented the curriculum, welcoming its flexibility whereby modules could be implemented using the newly provided or existing materials. The pilot lacked a large enough sample to examine how implementation and processes might vary across a range of different school contexts, and focused only on the first year of implementation, so it could not examine the processes by which the intervention might become normalised within schools’ institutional policies and practices and be sustained once external facilitation is withdrawn.

Restorative justice

The INCLUSIVE trial extends the AAYP and Gatehouse interventions by including a ‘restorative justice’ approach. The Steer Review50 in 2009 called for English schools to consider adopting more restorative approaches to preventing bullying and other aggressive behaviour to help minimise the harms associated with such problems. The central tenet of such approaches is repairing the harms caused to relationships and communities by criminal behaviour, rather than merely assigning blame and enacting punishment. Such approaches have now been adapted for use in schools and can operate at a whole-school level, informing changes to disciplinary policies, behaviour management practices, and the way in which staff communicate with students in order to improve relationships, reduce conflict and repair harm.

Restorative practice aims to prevent and/or resolve conflicts between students or between staff and students to prevent further harms. 75 It enables victims to communicate the impact of the harm to perpetrators, and for perpetrators to acknowledge and take steps to remedy this in order to avoid further harms. Restorative practice can involve methods to prevent incidents (e.g. ‘circle-time’, which brings students together with their teacher during registration periods or other lessons to maintain good relationships) and/or to resolve incidents (e.g. ‘conferencing’, bringing together relevant staff, students, and, where necessary, parents and external agencies such as police or social services). Restorative practice aims to prevent the occurrence or continuation not only of bullying but also of other forms of aggression and classroom disruption. Restorative practice can be delivered instead of, or alongside, more traditional punitive discipline. 76

The theoretical basis for restorative approaches has much in common with the theory of human functioning and school organisation. 59 It is theorised that the process of students coming together, discussing the harm, and working towards a reparative plan develops perpetrators’ competency through accepting responsibility for the actions and contributing to a reparative solution, and develops offenders’ understanding of the realities of others. Victims are also empowered in this process as they become an active participant in the decision-making process, and the acknowledgement of the offenders’ ability to offer some healing to the victim (e.g. via an apology or carrying out a sanction) gives dignity to both parties. This resonates with the ideas of improving relationships as well as promoting practical reasoning and sense of connection to school. By eliciting accountability for the harm caused to the victim and the school community and negotiating a plan for restitution, the young person is encouraged to reclaim an identity as a participant of the school community, not a peripheral outsider. 76 Through this process, the young people involved develop relational competency, and enhance their relationships with staff and other students by improving their ability to empathise and communicate effectively. Restorative approaches might indeed be particularly suitable for ‘alienated’ student offenders as they are given the opportunity to develop the necessary competencies to participate as a responsible member of the school community from which previously they might have felt excluded. 77 It may also be particularly helpful for female young people, as gender theory suggests that female adolescent identity is often based within a framework of relationship and connection. Thus, application of the principles of restorative approaches becomes a natural adjunct to the therapeutic process of self-identity and growth. 77

However, to date, restorative approaches in schools have been evaluated using only non-randomised designs, and systematic reviews have called for more rigorous evaluations of restorative practice in schools. 78 Those studies that have been carried out do suggest that the restorative approach is promising both in the UK79–81 and internationally,82–84 particularly when implemented at the whole-school level. For example, in England and Wales, the Youth Justice Board evaluated the use of restorative approaches at 20 secondary schools and six primary schools, and reported significant improvements in students’ attitudes to bullying and reductions in offending and victimisation in schools that adopted a whole-school approach to restorative practice. Restorative approaches thus appear to have the potential to complement school-environment interventions such as Aban Aya and the Gatehouse Project. They offer a highly promising way forward for reducing aggressive behaviours among British young people. A 2009 Cochrane review85 found no RCTs of interventions employing restorative approaches to reduce bullying in schools and recommended that this be a priority for future research.

Process evaluations report positive results in terms of feasibility and acceptability of restorative practices in schools. In New Zealand,86 case studies of five secondary schools and colleges found that all teachers valued restorative practice and felt that it was a good strategy for managing misbehaviour. In a pilot in London schools,87 students in schools that had implemented restorative practice reported that their school was doing a good job of stopping bullying. Teachers reported that most restorative meetings were effective at addressing bullying, gossiping, and disagreements between students and teachers.

Common challenges reported in process evaluations of restorative practice in schools include consistency in the way restorative practice is implemented. 82,88,89 Evaluations also suggest that restorative practice is implemented most successfully when it is delivered as part of a whole-school approach, when a positive ethos has been established, and when one-to-one problem-solving skills (e.g. listening and responsibility) have been introduced into the curriculum. 90,91

Social and emotional education

Social and emotional education aims to educate students not merely academically but using non-cognitive social skills and emotional self-management skills to enable young people to function at school and in other areas of life and to develop resilience or ‘grit’. There was evidence that classroom curricula that teaches young people the skills needed to manage their emotions and relationships can enhance social relationships, improve mental health and reduce bullying. 92 Many whole-school interventions, including the Aban Aya93 and Gatehouse60 interventions, also include social and emotional education elements, the intention being that these act synergistically with other components, helping students to take part in intervention activities within and beyond the classroom.

Objectives and hypotheses

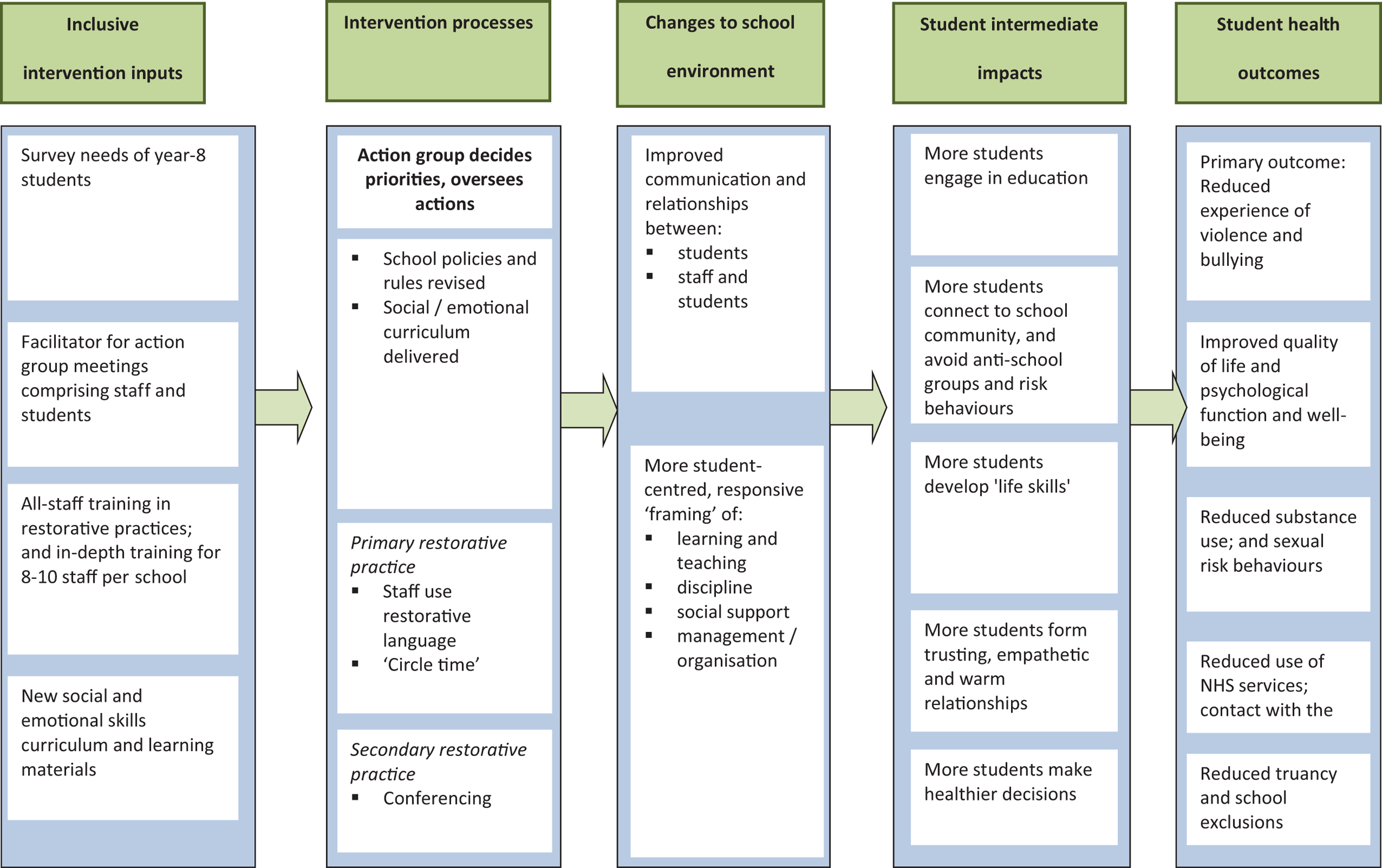

In 2014, we developed the LT intervention, which aimed to modify the school environment by involving students, building better relationships, using restorative approaches, and developing social and emotional skills to reduce a range of risk behaviours including bullying and aggression. 74 The intervention combined AGs of staff and students to modify the whole-school environment; training for staff to implement restorative approaches; and a social and emotional skills curriculum. These components were intended to address school- and individual-level determinants of bullying and aggression and to be synergistic with one another: the AG ensuring that schools took a whole-school approach to restorative practice and the social and emotional skills curriculum enabling students to participate actively in AGs and restorative practices.

A pilot cluster RCT in eight schools met all of the prespecified feasibility and acceptability criteria. 74 We report here the findings of a full-scale cluster RCT of LT (the INCLUSIVE trial).

We hypothesised that in secondary schools randomly allocated to receive LT there would be lower rates of self-reported bullying and perpetration of aggression among students aged 14–15 years at the 36-month follow-up.

We hypothesised that at the 36-month follow-up student and staff secondary outcomes would be improved in intervention compared with control schools. More specifically, we expected improvements in students’ quality of life (QoL), well-being, psychological function and attainments; reductions in school exclusion and truancy, substance use, sexual risk, NHS use and police contacts among students; and improvements in staff QoL and attendance and reductions in staff burn-out.

We hypothesised that individual-level student socioeconomic status (SES), sex, and school-level stratifying factors (single-sex vs. mixed-sex school, school-level deprivation, and value-added strata) would moderate the effectiveness of the intervention for student outcomes.

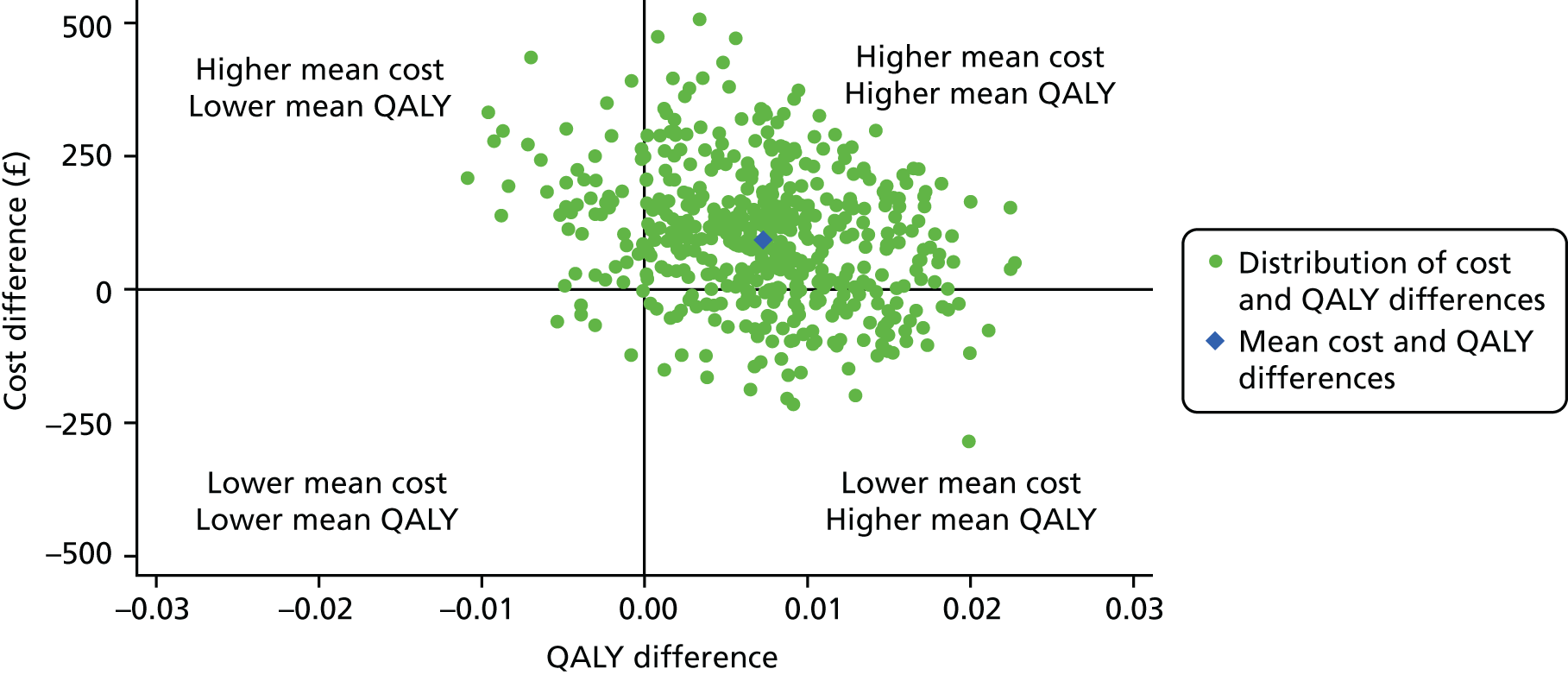

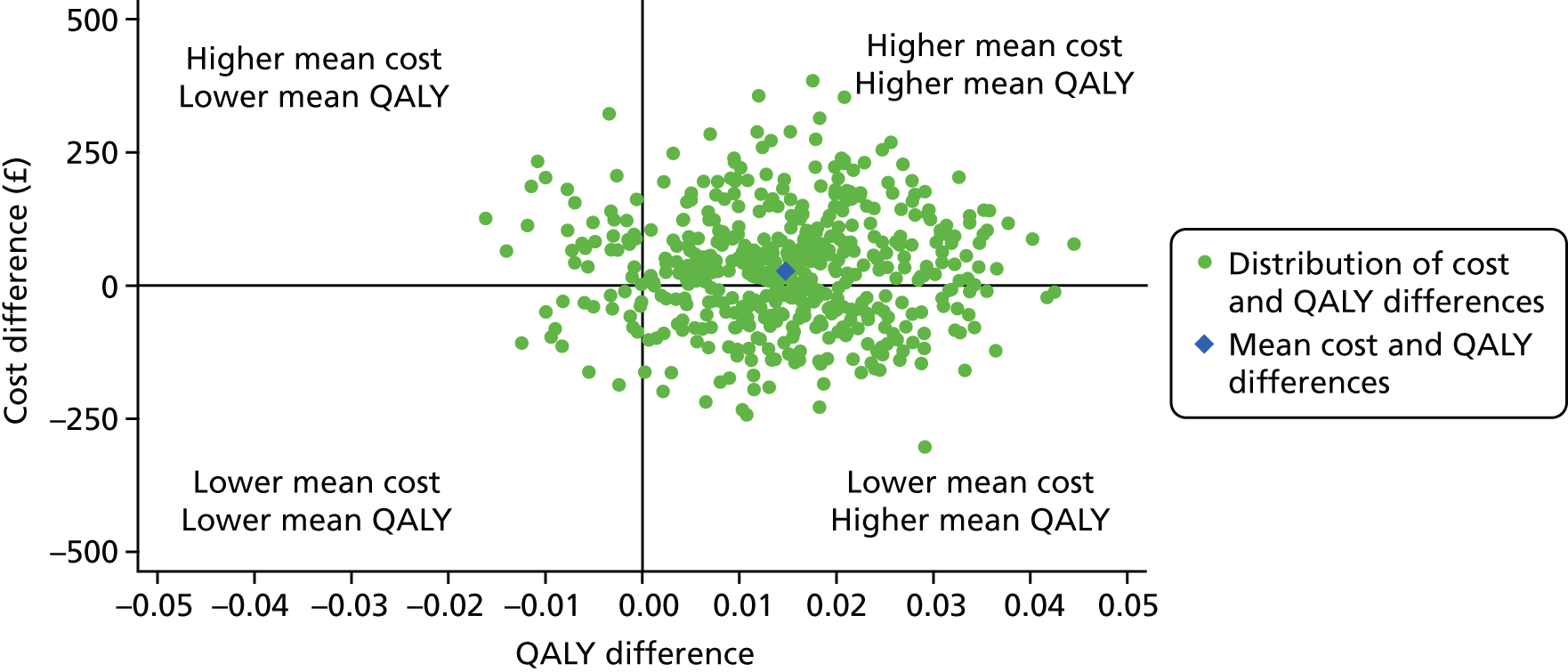

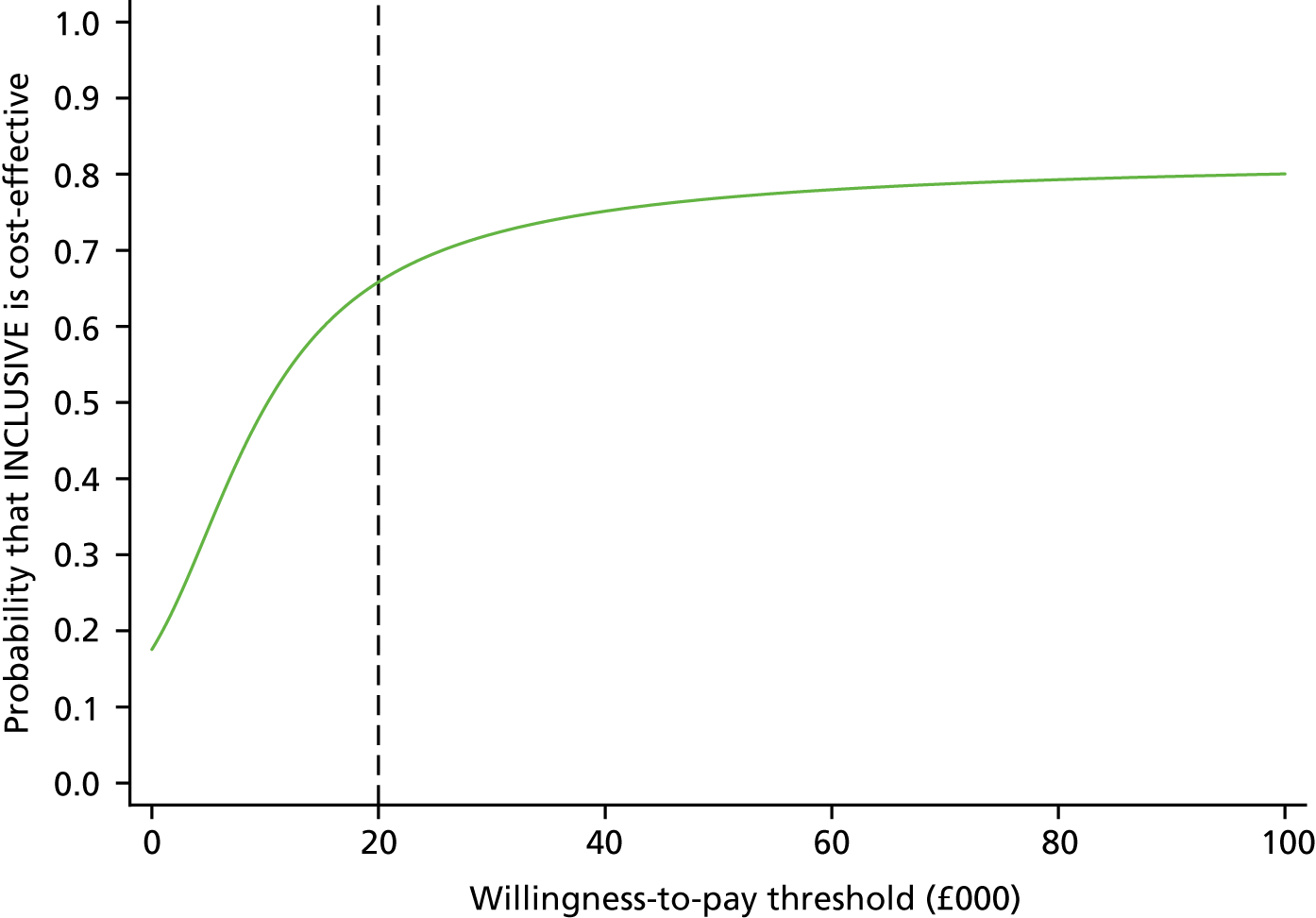

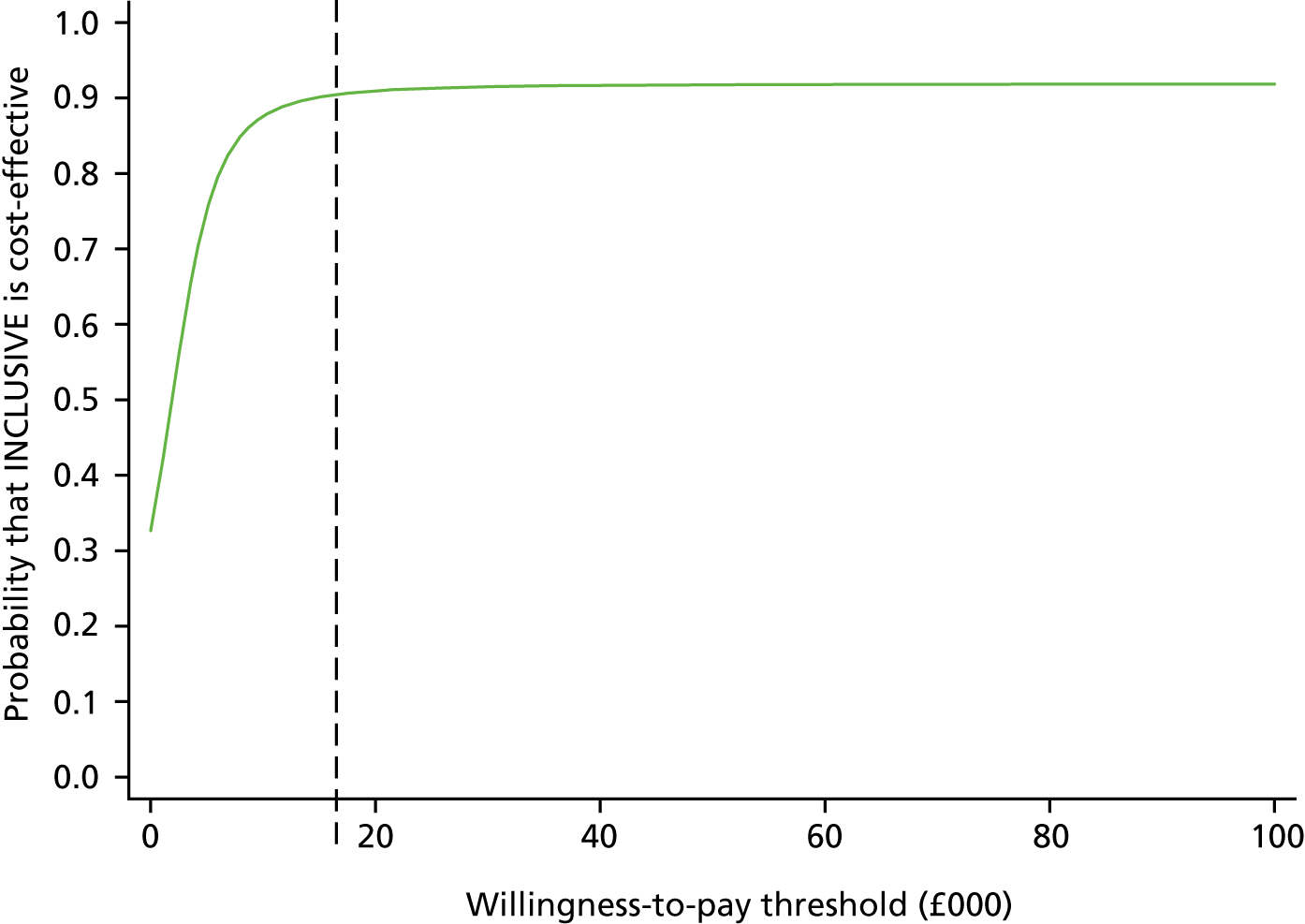

We also hypothesised that LT would be cost-effective compared with standard school practice in terms of student quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) and costs.

Chapter 2 Methods

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced with permission from Bonell et al. 1 This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Trial design

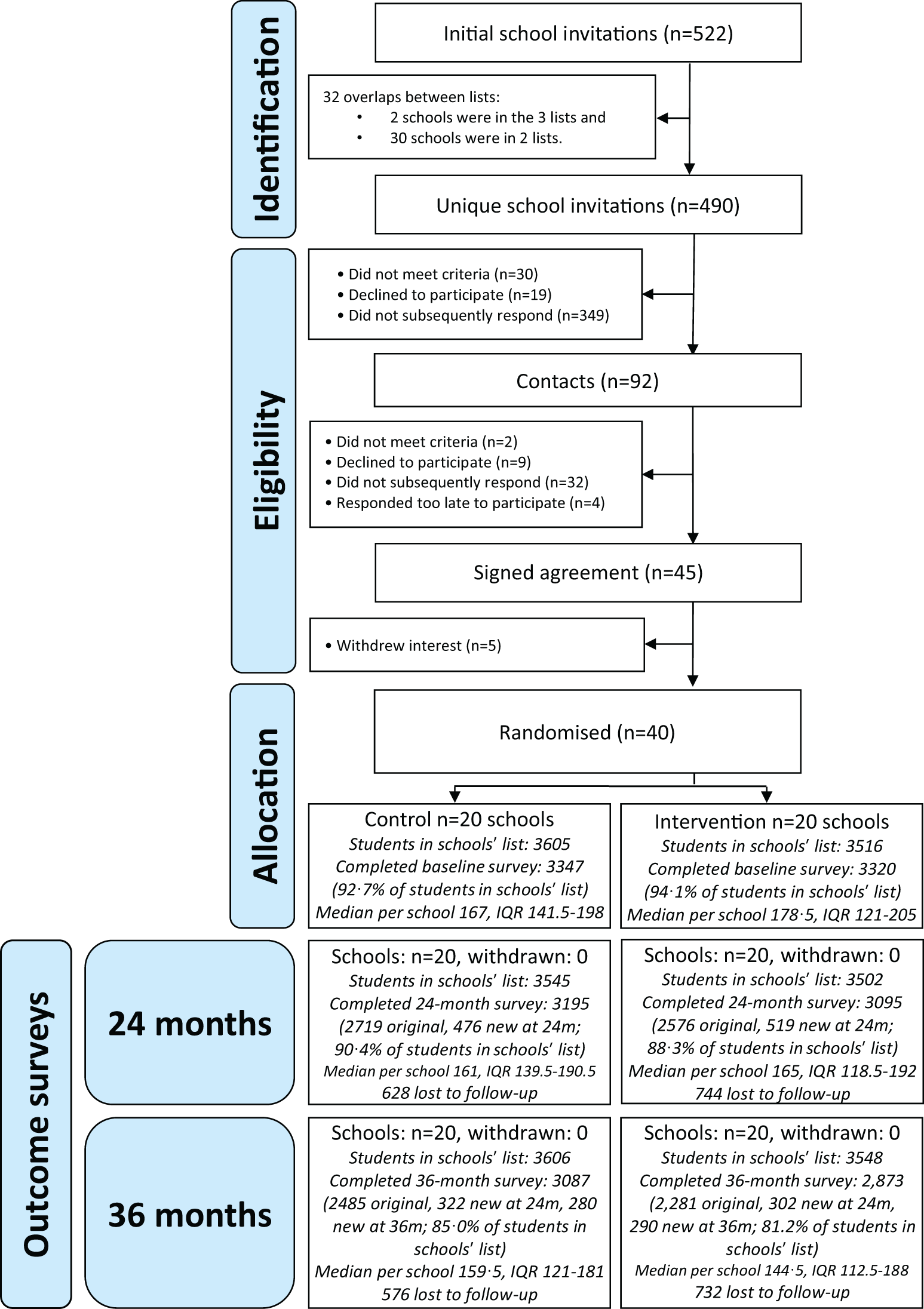

We undertook a two-arm repeat cross-sectional cluster 1 : 1 RCT of the LT trial with an integral economic and process evaluation in 40 secondary schools in south-east England, with schools as the unit of allocation. 1 Our study population consisted of all students in the school at the end of year 7 (aged 11–12 years) at baseline, and at 24-month (end of year 9; aged 13–14 years) and 36-month (end of year 10; aged 14–15 years) follow-up, as well as school teaching and teaching assistant staff at each time point.

Refinements to the trial informed by the pilot

The changes made to the trial informed by the pilot included:

-

identifying the Gatehouse Bullying Scale (GBS) and Edinburgh Study of Youth Transitions and Crime (ESYTC) school misbehaviour subscale as primary outcomes of bullying victimisation and perpetration of aggressive behaviours, respectively

-

including validated measures of drug use, sexual behaviour and educational attendance and attainment as additional secondary outcomes

-

including all ‘state’ schools in the recruitment pool of schools to reflect the overall population profile of schools in south-east England

-

using existing school networks to facilitate timely recruitment

-

using revised timetabling – project initiation in February of the preceding school year, surveys of staff and students to be conducted in the summer term each year, timetabling of intervention and staff training to be undertaken prior to September school-year start

-

enhancing quantitative data on intervention fidelity, including structured independent assessments of intervention delivery

-

undertaking an economic evaluation to use the Child Health Utility 9D (CHU9D) scale and to be supplemented with a cost–consequences analysis.

Refinements to the trial after commencement

During the development of the trial, the following changes to the protocol were made:

-

A meaure of bullying perpetration (the Modified Aggression Scale Bullying subscale) was included after the baseline survey as we elected to add a measure of bullying perpetration as well as one of victimisation.

-

We included administrative documents (e.g. minutes, attendance sheets, training satisfaction feedback) in our assessment of trial arm fidelity to provide us with a wider range of quantifiable data.

The protocol was amended during the trial to refine the methods used. All amendments were approved by the independent study steering committee and the funder of the trial (NIHR). The only change to trial outcomes was the addition of a measure of bullying perpetration (secondary outcome). All refinements were completed before the 36-month surveys were collected and before any trial analyses were conducted.

Participants

The INCLUSIVE trial was a universal intervention aimed at all 11- to 16-year-olds in participating secondary schools in England. Although the intervention was expected to have effects on the whole school, our study population consisted of students at the end of year 7 (aged 11–12 years) at baseline and at the end of year 10 at the 36-month follow-up (aged 14–15 years), as well as all school teaching and teaching assistant staff. This year group should have experienced the intervention for 3 years, including the classroom curriculum for years 8–10. All students in the school in that year and all teaching staff were surveyed at each time point, not only those who participated at baseline.

Eligibility criteria for participants

Participant eligibility was assessed at the school level. Eligible schools were:

-

Secondary schools within the state education system (including community, academy or free schools, and mixed- or single-sex schools) in south-east England. We took the widest definition of a ‘state school’ and excluded only private schools, schools exclusively for those with learning disabilities and pupil referral units. The last two were excluded as the INCLUSIVE study was unlikely to be appropriate for their populations.

-

Schools whose most recent school quality rating by Ofsted was ‘requires improvement’/‘satisfactory’ or better. Schools with an ‘inadequate’/‘poor’ rating were excluded, as these schools would be subject to special measures that were likely to impede LT delivery.

Eligible schools were approached initially by letter and e-mail, with a telephone follow-up, complying with good practice and research governance for undertaking studies within the education system.

As the intervention was delivered at the whole-school level, there were no specific eligibility criteria for students, although parents who did not want their child to participate in the surveys were able to opt out on behalf of their child.

Settings and locations

Schools were recruited between March and June 2014 from secondary schools in Greater London and the surrounding counties (Surrey, Kent, Essex, Hertfordshire, Buckinghamshire and Berkshire) that had a maximum travel time of 1 hour from the study centres in London. To aid recruitment, we partnered with existing school networks, such as the University College London (UCL) Partners Schools Network and the Institute of Education Teaching Schools, and schools that are part of our collaborating schools network, Challenge Partners. We approached approximately 500 eligible schools, initially by letter and e-mail and with a telephone follow-up.

The 40 participating schools did not differ from 450 non-recruited schools in terms of school size, population, deprivation, student attainment or value-added education. However, participating schools were more likely to have an Ofsted rating of good or outstanding (see Appendix 1, Table 26).

Intervention

The INCLUSIVE trial involved 2 years of externally facilitated intervention and a final year without external facilitation. The LT intervention was intended principally to augment, rather than to replace, existing activities (e.g. training and curricula) in intervention schools. However, it was intended to replace existing non-restorative disciplinary school policies and practices when the AG deemed restorative approaches more appropriate. The intervention logic model is shown in Appendix 1 (see Figure 6).

Below we describe the intervention informed by the TIDieR (Template for Intervention Description and Replication) checklist for better intervention reporting. 94 Fidelity assessment is described under process evaluation, the product of which is presented in our results.

Learning Together

Theory of change

Informed by Markham and Aveyard’s59 theory of human functioning and school organisation, the intervention’s theory of change suggests that for young people to choose healthy behaviours over risky behaviours, such as bullying, aggression or substance use, they must possess the autonomy, motivation and reasoning ability to make informed decisions. These capacities and goals are theorised as facilitated by increased engagement with education (the school’s ‘instructional order’) and connection to the school community (the school’s ‘regulatory order’). It is theorised that schools can increase such engagement by improving relationships between students and teachers, between different groups of student and between academic education and broader student development, as well as by reorienting learning and teaching, discipline, social support, and school management and organisation so that these centre on student needs and view conflict as an opportunity for learning. The intervention aims to strengthen relationships between and among staff and students through the use of primary (preventing conflict) and secondary (preventing the escalation of conflict) forms of restorative practice, and by enabling staff and students to work together on an AG co-ordinating intervention delivery in each school (see Appendix 1, Figure 6). AGs also aim to enable student participation in decision-making. Restorative practice aims to increase students’ active participation in discipline systems. A social and emotional skills curriculum delivered in classrooms aims to promote student autonomy and reasoning ability, and to facilitate student participation both in AGs and in restorative practice.

Materials

Schools allocated to receive the intervention were provided with various resources. School staff were offered training in restorative practices, with participants given written summaries of the material covered in training. Schools were provided with a manual to guide the convening and running of an AG. For the first 2 years of the intervention, schools were provided with an external facilitator for the AG. Schools were sent a report on student needs detailing findings from a survey of students aged 11–12 years about their attitudes to and experiences of school, and their experiences of bullying, aggression and other risk behaviours (see Appendix 3). Schools were provided with written lesson plans and slides to guide delivery of a classroom-based social and emotional skills curriculum.

Procedures

Training was given to all staff, and in-depth training was given to selected staff, including training in formal ‘conferencing’ to deal with more serious incidents.

Action groups

Action groups were required to include, at a minimum, six students from the intervention classes (year 7 at the start of the intervention) and six members of staff, including at least one from the senior management team and one member of each of the teaching, pastoral and support staff. Having a member from specialist health staff, such as the school nurse and/or local child and adolescent mental health services staff, was desirable but optional. The AG was required to meet at least six times per school year (approximately once every half-term), and was tasked with developing action plans to co-ordinate the delivery of the intervention outputs:

-

reviewing and revising school rules and policies relating to discipline, behaviour management and staff-student communication to incorporate restorative principles

-

implementing restorative practices throughout the school to prevent and respond to bullying and aggression

-

additional tailored actions to address local priorities

-

delivering the social and emotional skills curriculum for years 8–10.

The facilitator ensured that meetings were scheduled, and attended these to ensure that the meetings were participative and focused on deciding and implementing actions. These actions were informed by findings about their students’ experiences of bullying, aggression and the school environment from our baseline survey (conducted before randomisation) and from a 12-month survey of students at the end of year 8 (aged 12–13 years) in intervention schools only, as well as from the 24-month trial survey. In year 3, facilitation was to be internally led by the AG’s chairperson, usually a SLT member or another experienced staff member. External facilitation in the first 2 years was theorised to be important to enable schools to initiate changes and particularly to empower students to participate in decisions. In year 3, schools were expected to facilitate implementation internally so that the trial could assess whether or not the intervention could be sustained by schools in the absence of an external facilitator.

Social and emotional learning curriculum

Schools delivered classroom-based social and emotional skills education in ‘stand-alone’ lessons, for example ‘personal, social and health education’ (PSHE) lessons, and/or integrated it into tutor time or various subject lessons (e.g. English) to students in the trial cohort as they moved through years 8–10 (aged 12–15 years). They received 5–10 hours of teaching and learning per year on restorative practices, relationships, and social and emotional skills based on the Gatehouse Project curriculum. 60

Schools selected modules for each year from establishing respectful relationships in the classroom and the wider school; managing emotions; understanding and building trusting relationships; exploring others’ needs and avoiding conflict; and maintaining and repairing relationships.

Restorative practice

Primary restorative practices delivered in schools in all three years involved staff using restorative language (the respectful use of language to challenge or support behaviour in a manner that preserves or enhances the relationship) and circle time (classes coming together to discuss their feelings and air any problems so that these may be addressed before they escalate) underpinned by supportive school rules and policies and the social and emotional skills curriculum. Circle time takes place in an informal setting, and is overseen by a member of staff; it provides an opportunity for a class to discuss their relationships in the open. It could be undertaken during registration periods or other lessons and aims to maintain good relationships, or deal with specific problems, as well as making the whole class aware of the issues and responses ongoing.

Secondary restorative practices involve some staff implementing restorative conferences (the parties to a conflict being invited to a facilitated face-to-face meeting to discuss the incident and its impact on the victim and for the perpetrator to take responsibility for their actions and avoid further harms). Conferencing was suggested for use in more serious incidents; this is a more ‘one-on-one’ practice of restorative justice, which brings together relevant staff, students, parents and, where necessary, external agencies to discuss ongoing issues between students.

Training

Staff training was implemented to ensure that teachers understood the necessary skills to engage in restorative practice. Training was provided by trainers accredited by the UK’s Restorative Justice Council. Each school had its own named facilitator, who was a freelance consultant with experience of school leadership or organisational change, co-ordinated by a lead facilitator who trained them in the intervention theory and methods. AGs comprised at least six staff members (including one member of the school’s SLT and one member of the school’s teaching, student support and administrative staff) and at least six students from each school, led by a member of the school’s SLT with support from the external facilitator in the first two years of the intervention but not in the third year. All of these staff attended the all-staff training and some attended the in-depth training. Staff who received basic training in restorative practice implemented this in the form of the use of restorative language and circle time. In addition, 5–10 staff members at each school who received in-depth training in restorative practice implemented this in the form of restorative conferences. The curriculum was delivered by teachers who specialised either in PSHE or in other subjects guided by lesson plans.

Modes of delivery

All intervention components were delivered face to face.

Location

All components were delivered on school premises.

Dose

Training occurred in the first year of intervention, comprising half a day for all staff plus in-depth 3-day training for 5–10 staff members at each school. AGs met six times per year in all 3 years. Restorative practices were delivered as frequently as required in each school. In their curriculum, students received 5–10 hours of teaching per year.

Planned adaptations

The intervention enabled local tailoring, informed by the needs survey and other local data sources. AGs ensured that implementation in their school was appropriate to local needs as identified by members and the survey of student needs. This included ensuring that revisions to policies and rules built on existing work, deciding which curriculum modules to deliver in each year, and implementing locally decided actions aiming to improve relationships and student participation (e.g. cascading restorative practice training to staff who had not attended or to student peer mentors).

Unplanned modifications

There were no unplanned modifications.

Comparator: control schools

Schools randomised to the control group continued with their normal practice and received no additional input. The sample of schools was spread over a wide geographical area and there were no cases in which intervention and control schools were near one another. Head teachers and a small number of staff in control schools were aware that the school was participating in a trial that was described as the INCLUSIVE trial. These individuals were not informed that the name of the intervention was LT and were not informed about the detailed contents of the intervention during recruitment. It is therefore unlikely that schools in the intervention and control arms would have shared information about the intervention.

Assessment and follow-up

Assessment of effectiveness

Student primary and secondary outcomes were assessed at 36 months, at the end of year 10 (when the students were aged 14–15 years), with a baseline survey having been undertaken at the end of year 7 (when the students were aged 11–12 years). Staff secondary outcomes were also assessed at 36 months. Additional student and staff surveys were conducted at 24 months to assess intervention process and intermediate outcomes to be used in the mediation analysis. Student surveys were conducted in exam conditions in schools, maximising privacy. The questionnaires used to collect these data can be found in full in the supplementary material (see Report Supplementary Material 1).

All students in the school in that year and all teachers and teaching assistant staff were surveyed at each time point, not only those who participated at baseline. Paper-based questionnaires were completed confidentially in a 45-minute class session devoted to that purpose. Field workers supervised the class as they completed the questionnaire, with the teacher present (for disciplinary purposes) but unable to see the questionnaires. The field workers assisted students with questions that they did not understand and ensured that the students completed as much of the questionnaire as possible. Students with mild learning difficulties or with limited command of written English were supported by field workers to complete the questionnaires.

We assessed the potential for measurement error and bias by asking the students completing surveys if their responses to questionnaires were completely truthful. We asked students in intervention schools involved in qualitative interviews whether or not their reporting (as opposed to their experience) of bullying and aggression might have been affected by the intervention.

Staff data were often collected on the same days as student data. However, owing to the busy nature of their work, staff questionnaires were often left at the school to be done in private time, and then mailed back to the study team. Staff were allowed to fill in their questionnaires in the staff breakroom, or to take them home to fill in.

Data management

The study centre received class lists for each school in advance of each survey. Participants were allocated a unique identifier (ID) prior to each survey and this ID was recorded on the questionnaire. All questionnaires were anonymous. Questionnaires were completed in classrooms and completed questionnaires were collected in schools on the day of the survey. If a participant was not in school on the day of the survey, a questionnaire was left at the school for them to complete later and was returned to the study centre by post. Completed questionnaires were transported from the school by study personnel to the study centre, where they were stored in a locked room.

Questionnaires were then securely transported for data entry by a third party, where they were double-entered into a database by trained personnel. Each questionnaire was checked at the time of data entry for any handwritten comments. Questionnaires with any additional text, regardless of content, were scanned, and password-protected scans were sent to the study team for safety reporting assessment. Electronic data generated from data entry were transferred via password-protected secure FTP and stored on secure servers at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM).

Following data entry, questionnaires were securely transported to the LSHTM Clinical Trial Unit (CTU) for archiving. An inventory of all questionnaires was maintained by LSHTM CTU.

Electronic data generated from data entry were transferred via password-protected secure FTP and stored on secure servers at LSHTM. Relevant trial documentation will be kept for a minimum of 15 years after study completion.

Ethics arrangements

The trial was approved by the UCL Ethics Committee (reference 5248/001). Ethics arrangements were informed by recent guidance on ethical issues in cluster RCTs.

Informing participants

Details of the research, including the possible benefits and risks, were provided to schools through written information and personal meetings and were provided to student participants through age-appropriate written information.

Consent

Written, informed consent was obtained at school level (chairperson of governors; head teacher) for random allocation and for the intervention, and at the individual student, staff and intervention facilitator level for data collection. For students, written age-appropriate information sheets were provided in class 2–4 weeks before the baseline survey, together with oral explanation by teachers. Written consent was required from all participating young people, which was collected immediately before conducting the baseline survey. Young people were also asked to take home written information sheets for their parents. Parents who did not want their child to participate were asked to notify this opt-out in writing using a prepared form. This ‘opt-out’ consent is standard practice in trials in secondary schools and was used in our pilot study, proving acceptable to schools, young people and families. Only < 1% of parents exercised an opt-out.

Information sheets and consent forms for student surveys were identical in intervention and control schools and did not refer to the intervention. Parents were informed about the study and could withdraw their children from research activities.

Duty of care and confidentiality

The researchers were experienced with the specific ethical issues involved in undertaking research with young people and other vulnerable participants. All work was carried out in accordance with the requirements of the Data Protection Act 1998. 95 Data storage and IT (information technology) systems were secure. All information remained confidential within the research team, except when child protection issues were raised. We consulted with a child protection social worker to define the issues that would prompt an exemption. The chief investigator, Russell Viner, as a paediatrician with training in child safeguarding, oversaw actions when safeguarding concerns were raised, and sought further advice, when necessary, from appropriate authorities. We followed Economic and Social Research Council ethics guidance and sought research ethics approval from the appropriate bodies. We also sought policy approval from local authorities related to each participating school.

Ethics review

Approval for the study was sought and obtained from the research ethics committees of the two lead universities, LSHTM and UCL. Our trial complied with the Economic and Social Research Council research ethics framework.

Assessment of harms

There were no anticipated risks to participants or to schools. However, as with all interventions, there may have been unanticipated risks. Harms were assessed by examining outcomes at 24 and 36 months. An independent Data Monitoring Committee (DMC) examined any potential harms at 24 months. If any major harms were detected, the DMC was to inform the Trial Steering Committee (TSC), which would decide what action should be taken.

Outcomes

Primary outcomes

Outcomes were collected by a research team (led by RV) independent of the intervention team. The primary outcomes were self-reported experience of bullying victimisation and perpetration of aggression measured at 36 months. The questionnaires used to collect these data can be found in full in Report Supplementary Material 1.

-

Bullying victimisation was assessed with the GBS, a 12-item validated96 self-report measure of being the subject of teasing, name-calling or rumours, being left out of things, and receiving physical threats or actual violence from other students within the previous 3 months. The questions and responses were worded to ensure that these assessed bullying occurring either face to face or online. Students reported the frequency of and upset related to each experience. Items were summed to make a total bullying score (higher scores represented more frequent upsetting bullying, with a maximum score of 3).

-

Perpetration of aggressive behaviour was measured using the ESYTC school misbehaviour subscale, a 13-item scale measuring self-reported aggression towards students and teachers. Each item was coded as occurring hardly ever or never, less than once per week, at least once per week, or most days. Items were summed to provide a total score, with higher scores indicating greater aggressive behaviour (maximum score of 39). 97

Secondary outcomes

The GBS and ESYTC outcomes were measured at 24 months as secondary outcomes. In addition, we measured the following at 24 and 36 months.

Student-level self-report outcomes

These were measured through student survey self-reports.

Quality of life

The Paediatric Quality of Life Inventory (PedsQL) version 4.0 was used to assess overall QoL. The 30-item PedsQL has been shown to be a reliable and valid measure of QoL in normative adolescent populations. 98 It consists of 30 items representing five functional domains – physical, emotional, social, school and well-being – and yields a total QoL score, two summary scores for ‘physical health’ and ‘psychosocial health’, and three subscale scores for ‘emotional’, ‘social’ and ‘school’ functioning.

Health-related quality of life

The CHU9D, a validated, age-appropriate measure of students’ health-related quality of life (HRQoL),99 was used to inform the economic evaluation.

Psychological function and well-being

The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ)100 is a brief screening instrument for detecting behavioural, emotional and peer problems and prosocial strengths in children and adolescents. It is brief, quick to complete and validated in national UK samples.

The Short Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale (SWEMWBS)101 is a seven-item scale designed to capture a broad concept of positive emotional well-being, including psychological functioning, cognitive-evaluative dimensions, and affective-emotional aspects, with a total ‘Well-Being Index’ generated.

Risk behaviours

Substance use

Smoking, alcohol use and illicit drug use were assessed. Validated age-appropriate questions were taken from national surveys102 and/or previous trials were used in order to assess smoking (smoking in previous week; ever smoked regularly), alcohol use (use in previous week; number of times really drunk; binge drinking) and illicit-drug use (last month; lifetime use).

Sexual risk behaviours

Age of sexual debut and use of contraception at first sexual encounter were examined with measures used in the RIPPLE trial. 103 We consulted with schools about the acceptability of asking these questions at follow-up (year 10).

The Modified Aggression Scale Bullying subscale (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.83)

This measure came from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s guidance document on bullying measures. 104 It includes a five-item scale assessing the level of bullying perpetration (last 3 months).

Use of NHS services

Self-report use of primary care, accident and emergency, or other service in the previous 12 months.

Contact with police

This was assessed using self-report of whether the young person had been stopped, told off or picked up by the police in the previous 12 months.

Demographic information

Sex and ethnicity

Student self-report.

Socioeconomic status: the Family Affluence Scale

The Family Affluence Scale (FAS) was developed specifically to describe the SES of young people. 105 A composite FAS score was calculated for each student based on his or her responses to four items relating to family car ownership, children having their own bedroom, the number of computers at home, and the number of holidays taken in the past 12 months. For our analyses, scores were collapsed into tertiles of low (score of 0, 1 or 2), medium (score of 3, 4 or 5) and high (score of 6, 7, 8 or 9) family affluence.

Data collected directly from schools

We planned to collect some data directly from schools for each year of the study using data routinely collected by schools:

-

school attendance data, expressed as number of half-days absent over the previous year

-

school rates of temporary and permanent exclusions

-

staff attendance, expressed as number of half-days absent, for which staff members’ informed consent to access was sought.

Individual staff-level outcomes

The following secondary outcomes were measured using survey self-reports from teachers and teaching assistants (the questionnaires used to collect these data can be found in full in Report Supplementary Material 1):

-

staff QoL, measured using the Short Form questionnaire-12 items (SF-12),106 a brief, well-validated measure of adult health-related QoL

-

staff stress and burnout, measured using Maslach Burnout Inventory,107 an established scale that uses a three-dimensional description of exhaustion, cynicism and inefficacy.

School-level outcomes

Value-added education score

School median value-added scores were obtained from UK official statistics108 relating to the progress students make between education Key Stage 2 or 3 (aged 7–14 years) and Key Stage 4 (aged 14–16 years). The value-added score for each student was calculated using the difference between their own output point score (end of Key Stage 4) and the median output point score achieved by others with the same or similar starting point (Key Stage 2 or 3), or input point score. 108 Schools that neither added nor subtracted educational value were given a score of 1000, with positive value added (> 1000) indicating a school where students on average made educational progress and negative value added (< 1000) indicating the reverse.

School size

The total number of students in the school, as identified from the school and college performance tables. 108

School-level deprivation

This was assessed using two variables:

-

Proportions of students eligible for free school meals (FSM) – the percentage of students eligible for FSM at each school at any time during the past 6 years is an accepted summary measure of school deprivation. Data were publicly accessible from the Department for Education. 108

-

The Income Deprivation Affecting Children Index (IDACI) score – a small-area indicator of deprivation specifically affecting children (< 16 years of age), which represents the proportion of children in a postcode who live in low-income households. 109 The value for each school is derived from the school’s postcode and thus represents the deprivation level of the school’s local area, rather than the school itself.

Office for Standards in Education, Children’s Services and Skills rating

Ofsted ratings108 are government inspectorate ratings of the quality of teaching, leadership and management, achievement of students, and behaviour and safety of students of a school. Schools are classified as 1 = ‘outstanding’, 2 = ‘good’, 3 = ‘requires improvement’ or 4 = ‘inadequate’. Owing to eligibility criteria for the INCLUSIVE study, only schools rated from 1 to 3 were included in the sample.

School sex mix

Mixed- or single-sex schools were identified from the school and college performance tables. 108

School type

Our sample comprised five types of school, categorised by the source of school funding. These were (1) converter academy mainstream (n = 18), funded directly from central government; (2) sponsor-led academy (n = 6), which has an independent business or charitable sponsor but is funded directly from central government; (3) foundation (n = 6), where the school owns its premises but is funded by the local authority; (4) community (n = 5), where premises and funding are provided by local authorities; and (5) voluntary-aided (n = 4), where the premises are owned by a charity (e.g. a religious foundation) but funding is at least partly from the local authority. 108

Process evaluation

The process evaluation examined intervention implementation and receipt, and possible causal pathways, in order to facilitate interpretation of the outcome data and enable refinement of the intervention logic model. Informed by existing frameworks,110,111 data were collected to examine the following.

Trial context

We assessed the context of schools in the intervention and control arms, such as discipline systems, staff training, social and emotional skills curricula, and student participation in decision-making. This drew on interviews with intervention facilitators and trainers, members of AGs in intervention schools, staff on school SLTs, and other staff in the intervention and control arms; and focus group discussions with students and staff in schools selected as case studies.

Trial arm fidelity

We assessed the fidelity of intervention delivery by school and facilitator. In addition to the above sources, we drew on follow-up surveys with staff and students; structured researcher observation of AG meetings and staff training; surveys of adults leading curriculum implementation and implementing restorative practice; interviews with adults delivering the curriculum; structured diaries kept by facilitators of AG meetings and by trainers of all-staff training; and administrative documents such as minutes and attendance sheets.

Overall fidelity in the externally facilitated first 2 years was scored out of a possible eight points for each school, as assessed by researchers, based on whether or not (1) at least five staff attended in-depth training (indicated in training registers); (2) each year all six AGs were convened (indicated in minutes); (3) policies and rules were reviewed (indicated in minutes); (4) locally decided actions were implemented (indicated in minutes); (5) AGs were perceived to have had a good or very good range of members (indicated in survey of AG members); (6) AGs were perceived to have been well or very well led (indicated in survey of AG members); (7) schools delivered at least 5 hours and/or at least two modules each year (indicated in survey of lesson deliverers); and (8) at least 85% of staff reported that if there was trouble at the school, staff responded by talking to those involved to help them get on better (indicated in staff survey). Overall intervention fidelity in the internally facilitated third year of the intervention was assessed using a narrower range of data, as the research team’s access to schools was expected to be reduced. Schools were scored out of a possible 4 points, on the basis of interviews with AG members to assess whether or not (1) all six AGs were convened and (2) locally decided actions were implemented; surveys and interviews with curriculum deliverers to assess whether or not (3) schools delivered at least 5 hours and/or at least two modules; and staff survey to assess whether or not (4) at least 85% of staff reported that, if there was trouble at the school, staff responded by talking to those involved to help them get on better.

Participation, reach and dose

We assessed the extent to which students and staff were aware of or involved in intervention delivery. This drew on surveys of AG members as well as follow-up surveys of students and staff and focus group discussions and interviews with students and staff.

Reception and responsiveness

We assessed the experiences of participation in INCLUSIVE, and in school environments shaped by this, to assess acceptability and barriers to facilitators. This drew on satisfaction surveys completed by staff attending in-depth training and of AG members; interviews with AG members, school staff and SLT, and students participating in restorative practice; and focus group discussions with students.

Intermediate outcomes

To assess possible intervention causal pathways, to examine whether or not these might mediate intervention effects, and to assess and refine our logic model, we used the Beyond Blue School Climate Questionnaire 28-item scale to measure students’ perceptions of the school climate, including supportive teacher relationships, sense of belonging, participative school environment, and student commitment to academic values,112 and the Young People’s Development Programme (YPDP) single-item measure of involvement with antischool peer groups. 113

Data collection

The data collection for the process evaluation was prospective and used mixed methods. The process evaluation was designed to explore the same intervention processes using different forms of data, and to compare findings between these. Purposive sampling was used for interviews to involve participants with diversity in terms of characteristics thought important for exploring implementation, and to explore diverse accounts and identify different themes. 114 Samples were large enough to generate diversity, but small enough to keep the analysis manageable. Informed by Medical Research Council (MRC) guidance on process evaluation,115 we sampled participants on the basis of characteristics likely to be associated with diverse perspectives on the intervention and its implementation within schools. We balanced sampling of some participants in all schools to develop an overview of delivery with larger samples in a small number of case study schools to explore processes in more depth. When discrepancies or gaps in the data emerged, these were explored in the next applicable data collection round.

Data collected in all schools

Diaries completed by trainers

Individuals providing the all-staff training in restorative practice were asked to complete a diary for each session delivered, informed by the tool used in the pilot study. They were asked to rate the extent to which they covered topics/materials as intended, and the materials and activities [e.g. Microsoft PowerPoint® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) slides, small-group or paired activities] used. Trainers then sent the diaries to the research team.

Observations of training

Researchers aimed to conduct structured non-participant observations of training so that all schools could be observed at least once. Observation guides included what topics were covered and what activities were used, and were informed by the same tools as used in the pilot study.

Satisfaction survey for in-depth training

An anonymous satisfaction survey was given out to the 5–10 staff members from each school who attended the in-depth training on restorative practice. Informed by the same tool as used in the pilot study, questions assessed whether or not participants felt that the training was useful; whether or not they felt confident about putting into practice the skills learnt; whether or not they would recommend the training; and overall how they rated the training provided. Participants placed the questionnaires in an envelope, which the trainers collected and sent to the researchers.

Interviews with trainers

Semistructured interviews with the two trainers were conducted by telephone in year 1 and lasted between 30 and 45 minutes. These aimed to explore the trainers’ views on participant responsiveness, any adaptations and deviations made, and barriers to and facilitators of delivery.

Diaries kept by facilitators of action groups

Facilitators were asked to complete a diary for each AG meeting they attended. Informed by the same tool as used in the pilot study, these explored general meeting information such as duration, date, number of attendees, chairperson and minute-taker names; members’ roles, year group and gender; how and what data were used to inform setting up school actions; priorities set by the school and actions stemming from these; actions concerning the revision of school rules and school policies; identification of which modules of the curriculum were to be implemented and how this was decided; and the participation of AG members. This information was then sent to the research team.

Minutes of action groups

Facilitators were asked to collect minutes from each AG meeting and send these to the researchers. These were used to triangulate the validity of facilitator diary forms.

Observations of action groups

Researchers aimed to conduct structured non-participant observations of AGs in 10 randomly selected schools for each year of intervention. Observation guides focused on the same areas as diaries and were informed by the same tools used in the pilot study.

Survey of action group members

An anonymous survey was handed out to all members of AGs by facilitators at the end of each year of the intervention. Informed by the same tool as used in the pilot study, this explored its acceptability, functioning and composition. It asked questions, for example, on the diversity of staff and students on the AG, how well led they considered the group to be and how empowered members felt to make decisions, using an existing scale. 116 Participants placed the questionnaires in an envelope, which the facilitators collected and sent to the researchers.

Interviews with facilitators of action groups

Semistructured telephone interviews with facilitators (n = 6) were conducted in years 1 and 2 and lasted between 45 and 90 minutes. These aimed to explore views on school culture, responsiveness and priorities; any adaptations and deviations made; and barriers to and facilitators of delivery.

Interviews with members of action groups

We aimed to interview two members of each school’s AG per year. A member of the evaluation team contacted the member of staff tasked with co-ordinating the intervention at each school and asked them to identify two AG members (staff or student) to be interviewed. Identified staff participants were then contacted by e-mail and/or telephone to schedule an interview, which occurred either in person (if possible) in a private room on school premises or over the telephone and lasted between 30 and 60 minutes. Interviews with students were arranged via staff and were always conducted in the school. Interviews were semistructured and explored views on the acceptability of facilitators and the intervention; barriers to and facilitators of AG meetings and how they might be improved; the extent to which actions arising from meetings were implemented in the school; and their perceived impact on the school environment.

Survey of school staff leading implementation of the curriculum

This survey was sent annually to be completed by the teacher in each intervention school who was acting as the LT social and emotional skills co-ordinator. The research team sent the surveys by e-mail termly in the first and second years of the study, and in the final term of the third year. Staff were asked to complete the survey and return it to the research team by e-mail. Informed by the same tool as used in the pilot study, the survey covered what units and lessons were delivered, when, in which subjects, for how many hours, and what intervention materials (e.g. PowerPoint slides, lesson plans), if any, were used to deliver the content.

Interviews with school staff delivering the curriculum

The research team aimed to arrange semistructured interviews in each year of the intervention with the staff member responsible for delivery of the social and emotional curriculum. The curriculum co-ordinator at each school was contacted by e-mail and/or telephone and asked to identify a member of staff delivering the curriculum to participate. Interviews were carried out over the telephone or face to face in a private office on school premises. The interviews gathered views on the fidelity, reach and acceptability of the curriculum; which materials were used; delivery methods; student responsiveness; and contextual barriers to or facilitators of delivery.

Survey of staff implementing restorative practice

This survey aimed to examine the extent to which staff who attended in-depth training in restorative practices were implementing such practices in school. The survey was initially to be completed termly, but for the third year this was changed so that staff were asked to complete it only in the summer term. Staff who had attended the in-depth training were sent an e-mail inviting them to complete the survey. The survey assessed delivery of the use of affective language, circle time, mediation, restorative conferencing, family group conferencing and community conferencing.

Interviews with other school staff

Semistructured interviews were sought across intervention and control schools with one staff member from schools’ SLT (n = 40) and two teaching staff (n = 80) at the beginning of year 1. Each school’s member of staff liaising with the research team was contacted by e-mail and/or telephone and asked to identify three staff members to participate. A member of the research team then contacted these staff by e-mail to schedule a telephone interview. Interviews explored the context of schools, including their policies and practices relating to behaviour management, social and emotional skills education, staff training, and student participation in decisions. In year 3, such interviews were sought with one SLT member in all intervention and control schools. Individuals in control schools were interviewed in the autumn term and in intervention schools in the summer term.

Data collected in case study schools

Six schools in the intervention arm were selected as case studies in order to gather in-depth qualitative data on intervention processes and school context. In these schools, we aimed to conduct focus groups with staff and students, as well as interviews with students participating in restorative practices. To encompass diverse schools, schools were purposively sampled in terms of diversity in relation to the percentage of FSM (above and below national average in 2012 for secondary schools, 16.3%), type of school, the facilitator assigned to the school, and the extent to which the school was responsive (highly responsive, somewhat responsive, poorly responsive) to intervention activities, as rated by the intervention facilitators 3 months into the intervention start date.

Focus groups with staff

In each year of the intervention, we aimed to conduct one focus group with staff in each case study school, each involving four to six members of staff. Staff were purposively selected and invited to participate by the staff member liaising with the research team to include diversity according to degree of participation in the intervention and role within the school (including senior leaders, pastoral staff and classroom teachers). Focus group discussions aimed to explore school culture and ethos, views about the delivery and impacts of the intervention, how restorative practices were applied, and barriers to and facilitators of their use. Focus groups were conducted in private offices on school premises facilitated by one researcher.

Focus groups with students

Each year, we conducted two focus groups with students in each case study school, comprising 4–12 students each: one with students directly involved in intervention activities (e.g. AGs) and one with students not involved in such activities. Students were purposively selected and invited to participate by the staff member in each school liaising with the research team, such that they reflected the diversity of the school in terms of boys and girls, different ethnic groups, and varying degrees of educational engagement. Focus groups were conducted in private offices on school premises facilitated by one researcher.

Interviews with students involved in restorative practices

We aimed to conduct semistructured interviews with two students at each case study school that had been involved in a restorative practice. The staff member at each school liaising with the research team was asked to invite students to participate, recruiting either one boy and one girl or a perpetrator and victim in the same instance of bullying, where possible. Interviews aimed to understand the processes of restorative practice and assess the acceptability of the approach. Restorative interviews were not limited to cases of bullying or aggression but also included classroom misbehaviour or friendship challenges. These interviews were conducted in private offices on school premises facilitated by one researcher.

Interviews and focus groups were audio-recorded and transcribed.

Ethics

All data were collected with research participants’ informed consent. Student and staff participants received written information beforehand and were given the opportunity to ask questions to a member of the research team. They were then invited to give signed consent and reminded that they could skip any questions and/or end the interview at any time. For telephone interviews with staff, an e-mail from participants indicating consent was generally used instead of a written signature. Before the interview began, they were read a statement relating their rights, how the data would be used, and information about anonymity and confidentiality. They were then asked to give verbal consent, which was recorded. All data collected were stored on password-protected drives within separate password-protected folders. However, had any research participants reported that they had been involved in or were at risk of sexual or physical abuse that the school was not already aware of, the research team would have liaised with the safeguarding lead for the school in question, breaking anonymity. Participants were made aware of this policy as part of the consent procedures. No such reports were made.

Economic evaluation

Economic evaluation of the intervention also took place. In accordance with NIHR guidelines, the methodology and results for the economic evaluation are reported separately in Chapter 4.

Changes to trial outcomes

The following deviations from this plan occurred during data collection.

We were unable to collect school-level data on individual student and staff attendance and school rates of temporary and permanent exclusions, despite multiple attempts to contact schools and obtain these data after the intervention was completed. Small numbers of data on school-level exclusions were provided but these were not sufficient for analysis. In response to requests for data, schools either did not respond or notified us that this was a burden they were not prepared to undertake now that the trial had finished. Data were not available similarly across intervention and control schools. A further offer of money towards school staff funds (May 2018; see above) did not motivate schools to provide these data.

In discussion with NIHR, we came up with the following mitigation plan.

-