Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 15/55/09. The contractual start date was in April 2017. The final report began editorial review in September 2018 and was accepted for publication in April 2019. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Russell Jago has been a member of the Research Funding Board for the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Public Health Research (PHR) programme since October 2014. He is also partly funded by the NIHR Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care West (CLAHRC West) at University Hospitals Bristol NHS Foundation Trust. Jane E Powell was a member of the NIHR PHR Funding Board from June 2011 to September 2015. Chris Metcalfe is a member of the Clinical Trials Units funded by NIHR.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Jago et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction and background

Benefits of physical activity

Physical activity is associated with a reduced risk of heart disease, stroke, type 2 diabetes mellitus, obesity and some cancers. 1 Physical activity is also associated with improved profiles for a number of risk factors, including insulin, glucose, blood pressure, body composition2 and emotional well-being in young people3 and adults. 1

Children’s physical activity levels

Despite the widely demonstrated benefits associated with being regularly physically active, data from the UK Millennium cohort study4 show that only 51% of 7- to 8-year-olds meet the recommendation of 1 hour of moderate to vigorous physical activity (MVPA) per day. Primary school is a key time for developing motor co-ordination and sport-related skills and for building children’s confidence and interest in physical activity. Physical activity levels in children have been shown to decline during primary school. 5,6 Making the most of these ‘skill-hungry’ years could be essential to the development of positive physical activity skills and attitudes. There is moderate evidence of physical activity behaviours tracking from childhood to adulthood;7 therefore, finding ways to foster physical skills and positive attitudes during these early years may help children engage in regular physical activity at secondary school and on into adulthood.

Previous school-based physical activity interventions

The primary school setting provides opportunities to reach large numbers of children in order to implement public health interventions. 8 Systematically reviewed evidence9 has indicated that the effectiveness of school-based physical activity interventions delivered during the curriculum is limited. The review concluded that where there was an effect this was mainly in studies of poor methodological quality. 9 Identified limitations included short follow-up, inadequate adjustment for potential confounders, lack of adjustment for children clustered in schools and the use of self-report measures of physical activity. 9 A 2012 review10 of physical activity interventions for children and adolescents, which included an objective assessment of physical activity, reported an average improvement of 4 minutes of MVPA per day in intervention participants compared with control participants. Of the 30 studies included in the review, only 16 were deemed to be of high methodological quality. Contributory factors to low-quality scores included high attrition, lack of intention-to-treat (ITT) analyses and no adjustment for the clustered nature of the data.

There is an absence of child physical activity programmes that have been shown to be effective and that are ready to be implemented by local public health teams. 11 The RE-AIM (Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, Maintenance) framework was developed to translate research into practice. 12 The RE-AIM framework strikes a balance between public health-focused interventions that have good internal validity (as examined in effectiveness trials) and public health-focused interventions that have good external validity (can be nationally implemented). 12 Numerous physical activity interventions have shown promise at the pilot/feasibility stage, but either they failed to achieve an impact in a definitive trial10 or, if an impact was achieved throughout a trial, this was not sustained during implementation. 13 As such, it is important to design physical activity interventions with future implementation in mind. A feasibility study can be used to identify changes to the study/intervention design that can enhance the external validity of the definitive trial evaluation. 14 One way to achieve this is to identify whether or not all elements of the RE-AIM framework can be assessed and then use the information to guide changes to the design. 11

Rationale for extracurricular interventions

The primary school curriculum is limited to 2 hours of physical education (PE) per week, making it challenging to implement curriculum-based physical activity interventions and providing little opportunity for children to meet public health guidelines or to develop their physical literacy. 15 Time immediately after school is discretionary time for children16 and could be utilised to promote physical activity. 17 Evidence shows that children who are inactive after school are less likely to meet physical activity guidelines;16 therefore, organised after-school programmes that maximise the opportunities for physical activity could be an effective means of engaging primary school children in more physical activity. 8,18 Owing to a lack of capacity among teaching staff, the current provision of extracurricular physical activity in primary schools is dominated by expensive external practitioners, such as football coaches,19 which is costly to the school or to parents, and caters primarily to children who are already active. Provision may have been enhanced since the UK government doubled the primary school PE Premium to £320M for all primary schools in England, which was available from September 2017;20 however, the external provider model remains expensive for schools.

Use of teaching assistants

Teaching assistants (TAs) are an important part of the school system. TAs support teachers in class management and teaching. The number of TAs has significantly increased in the UK since 2000 and they now constitute one-third of the workforce in UK schools. 18 Streamlined staff numbers in schools highlight the importance of utilising existing staff to deliver extracurricular programmes. Therefore, training TAs to deliver after-school programmes could be a low-cost means of helping children to be active. An aim of the study is to assess the feasibility, potential sustainability and cost-effectiveness of an after-school physical activity intervention delivered by TAs.

Use of self-determination theory

Interventions have been more successful when they are based on psychological theory than when they are not. 21 Psychological theory can be used to inform intervention design and facilitate the identification (ID) of key mediators of behaviour change. 21 Self-determination theory (SDT)22 may be particularly appropriate for understanding children’s physical activity. SDT focuses on motivation for behaviour and argues that those with autonomous motivation (i.e. doing physical activity because it is fun or personally valued) have more positive behavioural, cognitive and affective outcomes than those with controlled motivation (i.e. doing physical activity because of feelings of guilt or pressure from others). Evidence from the PE and sport psychology literature demonstrates that autonomous motivation is associated with positive physical activity outcomes in children and adolescents. 23 Previous research into UK primary school children shows that having intrinsic motivation is associated with higher levels of objectively measured physical activity. 24 Autonomous motivation and psychological well-being can be achieved when three innate needs are met: (1) autonomy (i.e. having choice about and ownership over one’s behaviour), (2) competence (i.e. feeling able and effective in one’s environment) and (3) relatedness (i.e. feeling a mutual sense of connectedness with others). Cross-sectional evidence supports the positive relationship between psychological need satisfaction and autonomous motivation in primary school children. 24 Thus, programmes that help children feel part of the decision-making process, confident and competent in their physical ability and part of a supportive team will increase their motivation to be and remain active.

Another feature of SDT is that it suggests that motivational quality is determined partly by the motivational climate created by leaders. 25 This is particularly appropriate for Action 3:30R (hitherto referred to as Action 3:30 for simplicity), as previous research has shown that TAs can be trained to provide curricular content in a safe environment, using a delivery style that fosters optimal motivation and development. 26 For example, TAs can enhance autonomous motivation by (1) being autonomy-supportive (e.g. involving children in decision-making), (2) providing structure (e.g. giving clear expectations, reasoning and guidelines) and (3) being interpersonally involved (e.g. showing empathy and interest). By doing this, TAs can have a positive effect on pupils’ motivation, behavioural engagement and psychological well-being. 25

Summary of formative work

An evaluation was recently completed of an after-school intervention, Action 3:30. 18 The original feasibility study was conducted in 20 schools and participants were Year 5 and 6 pupils (aged 9–11 years). Ten schools were allocated to the intervention arm and 10 schools were allocated to the control arm (normal practice). The intervention consisted of training TAs to deliver 60-minute after-school physical activity sessions twice per week for 20 weeks. The intervention was based on SDT. TAs were trained to facilitate sessions that covered a range of activities and provided support for pupils’ autonomy, competence and relatedness. 27 The results showed that the Action 3:30 intervention holds promise as a scalable physical activity approach. 26,28 The adjusted difference in weekday MVPA was 4.3 minutes higher [95% confidence interval (CI) –2.6 to 11.3 minutes higher] at the end of the intervention in the intervention arm. Sex-stratified analyses indicated that the intervention may hold more promise for boys (8.6 more minutes of weekday MVPA than control, 95% CI 2.8 to 14.5 more minutes) than for girls (0.15 more minutes of weekday MVPA than control, 95% CI –9.7 to 10.0 more minutes). The results from the process evaluation suggested that the intervention was implemented as planned and well received by schools, TAs and pupils. 26,28 Although the effect on mean levels of MVPA among boys was among the best that has been shown for physical activity interventions in children,21 more work is needed to improve the content for girls. In addition, findings from the process evaluation showed that improvements are required to improve attendance, recruit less active pupils and increase TAs’ ability to manage disruptive behaviour.

Rationale for the trial

The evaluation of the original Action 3:30 programme showed that training TAs to deliver after-school physical activity sessions holds promise. The issues raised from the original programme have been addressed in a revised intervention. The aim of the study is to test, in a feasibility study, whether or not the revised intervention leads to increases in the physical activity of both boys and girls, as well as whether or not it results in the recruitment of less active children and in higher attendance levels. In addition, the study aims to test whether or not it is possible to use the RE-AIM framework to assess the implementation potential of the intervention.

Chapter 2 Trial design and methods

Aims and objectives

The study had six research objectives, underpinned by seven research questions.

Objective 1: optimise the intervention to increase activity in boys and girls

1. How can the intervention materials be optimised to increase activity in boys and girls?

Objective 2: identify effective means of recruiting less active children

2. How can recruitment be optimised to recruit less active children?

-

Is it feasible to collect self-reported activity data from Year 4/5 pupils using ‘opt-out’ consent?

-

Is it feasible to collect accelerometer data from all Year 4/5 pupils using an ‘opt-out’ consent procedure at baseline and follow-up in a subgroup of pupils in four schools?

-

Does an ‘enhanced recruitment approach’ facilitate recruiting less active children?

-

Is it feasible and acceptable for schools and pupils to provide opportunities for enrolment at the mid-point of the intervention?

Objective 3: assess intervention fidelity

3. To what extent was Action 3:30 delivered as intended?

-

What proportion of the Action 3:30 sessions were delivered?

-

What was the mean attendance and were there differences by sex?

-

To what extent was the intervention delivery consistent with the underpinning theory?

Objective 4: estimate the effect of allocation to the Action 3:30 intervention on weekday moderate to vigorous physical activity of participants and related physical activity behaviours

4. What is the difference in mean accelerometer-assessed MVPA of boys and girls in the intervention and control arms in the last few weeks of the intervention when the programme was still running (follow-up)?

-

Is there any evidence that intervention participants’ school travel mode or organised club attendance changes as a result of attending Action 3:30?

Objective 5: collect the information needed to assess the feasibility of conducting a definitive trial and assess the implementation potential of the Action 3:30 intervention

5. How many data can be provided for secondary outcomes?

-

Is it feasible to collect information on how costs of implementation are influenced by school infrastructure, staff leadership/participation and overall extracurricular club provision/cost in schools?

-

Is there any evidence of contamination between intervention and control schools?

-

What are the factors that need to be addressed to minimise health inequalities?

6. What would the sample size for a definitive trial be?

7. Is it feasible to collect all data on all dimensions of the RE-AIM framework to estimate the potential population impact of Action 3:30 in a definitive trial?

Objective 6: assess whether or not the five progression criteria for conducting a definitive trial are met

Progression criteria

-

At least 25% of schools that are approached agree to join the study.

-

At least 25% of eligible Year 4/5 pupils express an interest in the study by returning consent forms.

-

At least 40% of participants expressing an interest in the study are girls.

-

At least 50% of the participants in the intervention arm attend 50% of the sessions.

-

At follow-up, at least a small benefit for weekday MVPA is observed for each of boys and girls, comparing intervention schools with control schools, and the upper bound of the 95% CI exceeds 10 minutes.

Research design

The study had two components. Component A, intervention optimisation, is described in Chapter 3. Component B, detailed in this chapter, was a cluster randomised controlled feasibility study in primary schools to compare the Action 3:30 intervention with a usual-practice control. The trial included quantitative, qualitative, process and economic evaluations.

Protocol amendments

The original study protocol (version 1.0) was submitted to NIHR on 3 March 2017. Version 1.1 was submitted on 21 September 2017 with one change, and version 1.2 was submitted on 19 April 2018 with one further change. These revisions are detailed in Table 1.

| Date | Original protocol point | Amendment | Approved |

|---|---|---|---|

| 9 August 2017 | On page 15 of the approved study protocol (version 1.0) it states that in the four ‘opt-out’ schools we will collect data on school travel mode from all children who do not opt out | Data on school travel mode will be collected via the parental questionnaire from all children in all 12 schools who opt in at baseline and follow-up, but not specifically from all children in the opt-out schools | Uploaded to NIHR in version 1.1 on 21 September 2017 |

| 6 November 2017 | Page 10 states: ‘One session will be conducted with parents that received recruitment strategy A with the other conducted with parents in a school that and one school that received recruitment strategy B. The sessions school will be used to understand in more detail how to overcome the issues that were raised in the surveys. We will then repeat the process with Year 4 and 5 pupils in the same schools to understand how recruitment could be improved’ |

One session will be conducted with parents that received recruitment strategy A, and the other will be conducted with parents in a school that received recruitment strategy B. The sessions in each school will be used to understand in more detail how to overcome the issues that were raised in the surveys Exclude final sentence as it was pasted from exemplar text elsewhere out of context, and we are addressing children’s opinions of how to optimise recruitment in our Children’s Advisory Group meetings |

Uploaded to NIHR in version 1.2 on 19 April 2018 |

Ethics

The study was granted ethics approval from the School for Policy Studies, University of Bristol. The trial was registered with Internal Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Register under the reference number ISRCTN34001941. The project was funded by the NIHR Public Health Research (PHR) programme (project number 15/55/09). It was agreed that any adverse events during data collection would be recorded and reported to the chairperson of the Ethics Committee and the chairperson of the Trial Steering Committee (TSC), but there were no such events.

Study population and recruitment

The study sought to recruit 12 primary schools in two local authorities (South Gloucestershire and North Somerset). The number of schools approached and the proportion recruited were recorded, as was the percentage of their pupils claiming free school meals (an indicator of socioeconomic status of the pupils’ families, i.e. higher is more deprived). To participate, schools needed to be willing to allocate space for two after-school sessions per week for 15 weeks between November 2017 and March 2018. To ensure that the sample represented local diversity, half of the schools recruited were above the local authority median for free school meals. Eight schools were recruited in South Gloucestershire and four were recruited in North Somerset (as the latter is a smaller local authority).

The study aimed to recruit 30 Year 4 and 5 pupils (aged 8–10 years) in each school, and 40% of the sample was to comprise girls. The pupils were recruited when they were in Years 3 and 4 (aged 7–9 years) during the summer term ahead of the intervention starting the following autumn. The only exclusion criterion was that pupils who were unable to participate in standard PE lessons could not take part. If more than 30 eligible pupils signed up to the study, pupils were randomly selected using a computer-based algorithm.

Two recruitment methods were tested to examine which was more effective in order to inform a recruitment strategy in a definitive trial. The two methods were designed to ensure that we recruited participants with a range of physical activity levels. Recruitment method A (briefing) involved a short briefing in each class to explain the study and to give out pupil and parent information sheets and consent forms. Recruitment method B (briefing plus taster session) involved the same as recruitment method A plus a 20- to 30-minute taster session led by coaches from Bristol City Council. The taster session aimed to give the pupils an idea of what the Action 3:30 after-school intervention would be like. It was also intended to allay any concerns about the level of physical activity that might be required to take part in the study and to highlight that the sessions would be enjoyable. Four schools in South Gloucestershire and two schools in North Somerset were randomly selected to receive recruitment method B. Written parental consent was obtained for each child. A brief ‘reason for non-consent’ questionnaire was sent home to parents who did not give their consent in order to explore why they did not want their child to take part.

Pre-baseline data (opt-out)

Before the main study commenced, all Year 3 and 4 children in all 12 schools were asked to complete the validated Physical Activity Questionnaire for Older Children (PAQ-C). 29,30 Data were collected in an opt-out consent process. Parents were informed of the measures on an information sheet and asked to return an opt-out form if they did not want their child to participate. In four of the schools in South Gloucestershire, accelerometer data from all Year 3 and 4 pupils were also collected via this opt-out process. This process was conducted in only four schools to assess the utility of the approach and to provide an indication of the potential additional resources that the research team would need if such an approach were used in a larger trial. These data were used to compare the levels of physical activity between pupils who did and pupils who did not consent to take part in the main study and they were treated as the baseline values for participants who subsequently took part in the randomised controlled trial.

Baseline data

Following recruitment and before randomisation, baseline data were collected from the selected children in each school. A summary of the measures can be found in Box 1. Participant age at baseline was calculated from parent-reported date of birth. Parental ethnicity was self-reported by selecting one of 13 descriptions based on the UK census. Pupils’ socioeconomic status was estimated using two measures: parent-reported highest level of education (i.e. up to General Certificate of Secondary Education or similar; Advanced levels/National Vocational Qualifications; first degree/diploma/Higher National Certificate/Higher National Diploma; or higher degree); and parent-reported postcode, which was used to ascertain Index of Multiple Deprivation (see Appendix 1) using English Indices of Deprivation 2010. 31 Accelerometer data that had been collected in the four schools during the opt-out process were used for baseline.

Local authority.

Percentage of free school meals (indication of deprivation).

Total number of Year 3/4 pupils.

Participant level Objectively measuredAccelerometer data for 7 days.

Height (cm) and weight (kg) to calculate standardised BMI z-score (kg/m2).

Child self-reportedPsychosocial questionnaire (on tablet device).

KIDSCREEN score (on tablet device).

CHU9D score (on tablet device).

Parent reportedHome postcode.

Child’s date of birth.

Number of siblings.

Highest level of parental education.

Parents’ ethnicity.

School travel mode.

Child’s current participation in after-school clubs.

BMI, body mass index; CHU9D, Child Health Utility 9D.

Parent public and patient involvement

Two public and patient involvement meetings were held with parents in two schools following recruitment and randomisation. Both meetings were held in control schools, one of which had received recruitment method A and the other of which had received recruitment method B. The aim of the meetings was to gather more information about why parents had not given consent for their children to join the study (following the completion of the reason for non-consent questionnaire) and how to overcome these issues, as well as the parents’ thoughts about the recruitment methods and materials.

Measures

Data were collected from all of the selected children (intervention and control) at two time points:

-

baseline – June 2017

-

follow-up (weeks 13–15 of the intervention) – February/March 2018.

Accelerometer-determined physical activity

Pupils wore ActiGraph GT3X+ accelerometers (ActiGraph, Pensacola, FL, USA) for 7 consecutive days to assess their physical activity levels. Periods of ≥ 60 minutes of zero counts were recorded as ‘non-wear time’ and were removed. 32 Pupils were included in the analysis if they provided ≥ 3 valid days (500 minutes of data between 6 a.m. and 11 p.m.). Minutes in MVPA were estimated for weekdays and weekends using the Evenson cut-off point. 33 In addition, total physical activity was derived from accelerometer counts per minute (c.p.m.) and sedentary time was estimated based on a cut-off point of < 100 c.p.m.

Objective measures

Pupils’ height and weight were measured to the nearest 0.1 m and 0.1 kg, respectively, with their shoes, coats and jumpers removed, using a portable Seca stadiometer and digital Seca scale (both Seca United Kingdom, Birmingham, UK), respectively. Body mass index (BMI) (kg/m2) was calculated and converted to an age- and sex-specific standard z-score. 34

Self-reported measures

Pupils completed a tablet device-based questionnaire assessing their motivation to undertake physical activity and their activity-based perceptions of autonomy, relatedness and competence need satisfaction, using established scales that have been developed and used with a similar age group successfully,24 as well as self-esteem and peer support. Pupil-reported questionnaire data were collected and managed using REDCap35 (https://brtcclinical.bris.ac.uk/redcap/; accessed 20 April 2018) hosted at the University of Bristol.

Physical activity motivation was assessed36 using a five-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (not true for me) to 4 (very true for me). Four types of motivation were assessed via three items each: (1) intrinsic (e.g. because I enjoy being active), (2) identified (e.g. because it is important to me to do active things), (3) introjected (e.g. because when I’m not active, I feel bad) and (4) external (e.g. because other people pressure me to be active). The mean of the three items was calculated for each type of motivation. Composite scores for autonomous (mean of intrinsic and identified) and controlled (mean of introjected and external) motivation were calculated. This scale has been previously validated with primary school-age children. 24

Autonomy37 (six items, e.g. I can decide what activities I want to do), competence38 (six items, e.g. I think I do well, compared with other children my age) and relatedness37 (six items, e.g. I am supported by others) were assessed using a 6-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (not like me at all) to 6 (really like me). A mean score for each variable was calculated.

Self-esteem was assessed using a 10-item Likert scale, ranging from 1 to 5, where pupils had to state how true or false each statement was. 39 Eight items were positively worded (e.g. I do lots of important things) and two items were negatively worded (e.g. I can’t do anything right). Negatively worded items were reverse coded and the mean of all items was calculated.

Peer support was assessed using a four-item Likert scale, ranging from 0 to 4 (0 – no, never; 1 – not much; 3 – quite a lot; 4 – all the time). All items started with ‘Thinking about your good friends, do they . . .’, followed by a statement (e.g. ‘encourage you to be active’). The sum of all four items was calculated.

Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) was assessed using the KIDSCREEN-1040,41 and Child Health Utility 9D (CHU9D)42,43 questionnaires as part of the economic evaluation. The economic evaluation is described in Chapter 5.

Parent-reported measures

Pupils’ parents completed a questionnaire to enable the collection of demographic data (baseline only). In addition, data on daily travel mode to and from school and child’s current participation in after-school clubs were collected at baseline and follow-up. Daily travel mode was assessed for weekdays only, with four response options (i.e. walk, cycle/scoot, car, and public transport). Data on usual travel mode and participation in after-school clubs were collected to capture whether or not attending Action 3:30 affected these in intervention pupils.

Randomisation

School was the unit of randomisation. Schools were randomised to the control (n = 6) or intervention (n = 6) arm after baseline data had been collected. Randomisation was stratified by local authority (South Gloucestershire or North Somerset at a ratio of 2 : 1 in each arm) and recruitment method (recruitment method A or recruitment method B at a ratio of 1 : 1 in each arm). Randomisation and allocation were conducted by an independent member of the Bristol Randomised Trial Collaboration using Stata version 15.1 (2017; StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). Two of the intervention schools were unable to provide staff to attend the intervention training programme and therefore did not deliver the intervention. This is described in more detail in Chapter 4. Therefore, four schools were intervention schools and six schools were control schools.

Blinding

Because of the nature of the study, it was not possible to blind the schools or the pupils, as they had to know whether or not they had been allocated to the intervention. It was also not possible to blind the trial manager or field workers, as they collected the outcome and process evaluation measures. The randomisation processes and primary and secondary analyses were conducted blind by the statistician in the Bristol Randomised Trials collaboration, who was then unblinded to conduct the complier-average causal effect (CACE) analysis.

Sample size

As this was a feasibility trial, no formal sample size calculations were performed. For safety reasons, the maximum number of pupils that could be enrolled in the main study was 30 per school, giving a maximum sample of 360 pupils. Potential sample sizes for a definitive trial were estimated using the derived intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) for MVPA from this study and published ICCs from comparable studies and based on combinations of key parameters (type I and type II error).

The Action 3:30 intervention

Teaching assistant training

Nine TAs from the four intervention schools (two from three schools and three from one school) attended a 25-hour (5-day) training programme in September/October 2017. TA time to attend the training was covered by the schools. The training programme also met the requirement of the Community Sports Leader award. The training programme was delivered by the coach development manager at Bristol City Council, a very experienced senior coach who has led training courses for a number of sports. Action 3:30 is based on the principles of SDT22 and therefore the programme focused on promoting children’s autonomy, relatedness and competence in relation to being physically active. To promote autonomy, TAs were taught to empower pupils by offering choice within activities, such as leading warm-ups, adapting games and controlling the speed at which activities progressed. They were encouraged to invite ideas for designing games and to help children to set their own goals. They were discouraged from using prizes or promised rewards to incentivise club members. A section of the training also focused on how to run child-led sessions in which the pupils choose the activities. TAs were encouraged to create relatedness through empathetic TA–child interactions, and through emphasis on co-operation rather than competition. TAs were trained to support competence by setting progressive activities targeting success balanced by optimal challenge, and by using specific praise to reinforce a message of quality over quantity. A learning point from the previous Action 3:30 pilot study was that TAs needed more support to manage disruptive behaviour. 28 In response to this need, a section of the training was tailored with input from the coach development manager at Bristol City Council, who co-designed the original training materials, to prepare TAs for how to best manage disruptive behaviour in different scenarios. TAs also received a training guide, a comprehensive reference document that reinforced all of the content in the training.

The after-school club

Once trained, the TAs delivered the Action 3:30 after-school club twice per week for 15 weeks between November 2017 and March 2018. To mirror usual school provision, each session lasted 1 hour, commenced immediately after school and was available to all pupils in the year group. TAs received a leader’s manual, which included 30 detailed session plans, a range of games and activities, and reminders about how to embed the key principles of SDT. TAs were asked to deliver the sessions in the prescribed order. Video recordings of model delivery were supplied for 22 games/activities within the sessions using a secure online platform, and links to online resources were given for 19 of the sessions to aid delivery. In addition, pupils were provided with home activity cards every three sessions. These cards aimed to reinforce session content and advise pupils about how they could practise the activities at home with friends and family.

The intervention was refined and improved following the original Action 3:30 study based on findings from the primary analysis18 and process evaluation. 28 Table 2 highlights the changes made to the intervention content.

| Issue raised | Change made |

|---|---|

| Sessions not appealing enough to girls | All session plans were reviewed by three independent physical activity experts to identify ways in which appeal to girls could be increased. Sessions were refined by local advisory groups and TAs who took part in public and patient involvement work. Key changes included adding activities that girls could do in girl-only groups initially to build confidence, ensuring exposure to a variety of activities to find those the children enjoyed and providing more options in sessions for pupils to choose or modify the activities |

| Content better pitched at younger children | Target population was changed to Years 4 and 5 (from Years 5 and 6) |

| Prioritising the Action 3:30 club | TAs felt that ensuring that the school leadership team was aware of the sessions and had commitment to the intervention was essential and that it was important to ensure that other important activities for children in Years 4 and 5 did not clash with Action 3:30. The school/study agreement was refined to reflect these, and specific contingency plans were developed in each intervention school to ensure that the club could always run as planned, even when other activities were taking place, such as a school performance |

| It would help to see exemplar sessions being delivered | 22 model activities/games included in the session plans were video-recorded and uploaded to an online platform. The videos were signposted in the leader’s manual |

| Signpost additional resources | ‘Skill links’ were added to all session plans; these are links to third-party websites that highlight content that could aid delivery |

| TAs needed more help with managing disruptive behaviour | A ‘managing disruptive behaviour’ section was added to the training guide and this was taught during the training programme. Eight TAs reviewed this and commented on its acceptability and how it could be improved. A ‘warning sign’ system was added to flag sessions that could be susceptible to disruption. It was suggested that TAs form close links with classroom teachers so that they were aware of arguments and disruptions during the school day. TAs were asked to ensure that classroom teachers did not use the threatening to ‘take away’ Action 3:30 as a form of punishment. It was suggested that TAs used sanctions for disruptive behaviour that were consistent with school policy. To gain attention in noisy groups, it was suggested that TAs used consistent signals in each session |

| Enhance embedding of motivational content | A ‘star’ symbol was added to each session plan that details where and how TAs can build ‘want to’ motivation and embed the key principles of SDT that was taught during training |

School/pupil appreciation in the intervention and control arms

Intervention schools received £200 to spend on equipment, which they used to cover any school-specific gaps in the equipment that was necessary to deliver the Action 3:30 sessions. Schools were reimbursed for 2 hours per week for two TAs at the TAs’ usual pay rate to cover their time spent delivering the club. Control schools and the two former intervention schools received a £300 donation in recognition of the time spent by school staff to accommodate data collection. Each child (control and intervention) received a small gift at each data collection. The gift was used to encourage the prompt return of accelerometers and was selected to promote physical activity.

Re-enrolment

Data from the original Action 3:30 study and a recent evaluation of an extracurricular dance programme18,44 highlighted that schools usually provide an opportunity for pupils to re-enrol in after-school programmes every term to allow more children to join the programme if others drop out. To enhance external validity, attendance rates in each intervention school were assessed after session 12 (December 2017/January 2018). In each club, if there were spaces available, information sheets and consent forms were sent home with all remaining eligible Year 4/5 pupils. Demographic data were collected from pupils who joined the study at the enrolment point and participated in the follow-up measures.

Process evaluation

Overview

A process evaluation using the RE-AIM framework, reporting on recruitment, dose, intervention effectiveness, fidelity and adoption, was conducted in the four intervention schools. It had both quantitative and qualitative components, which are described below.

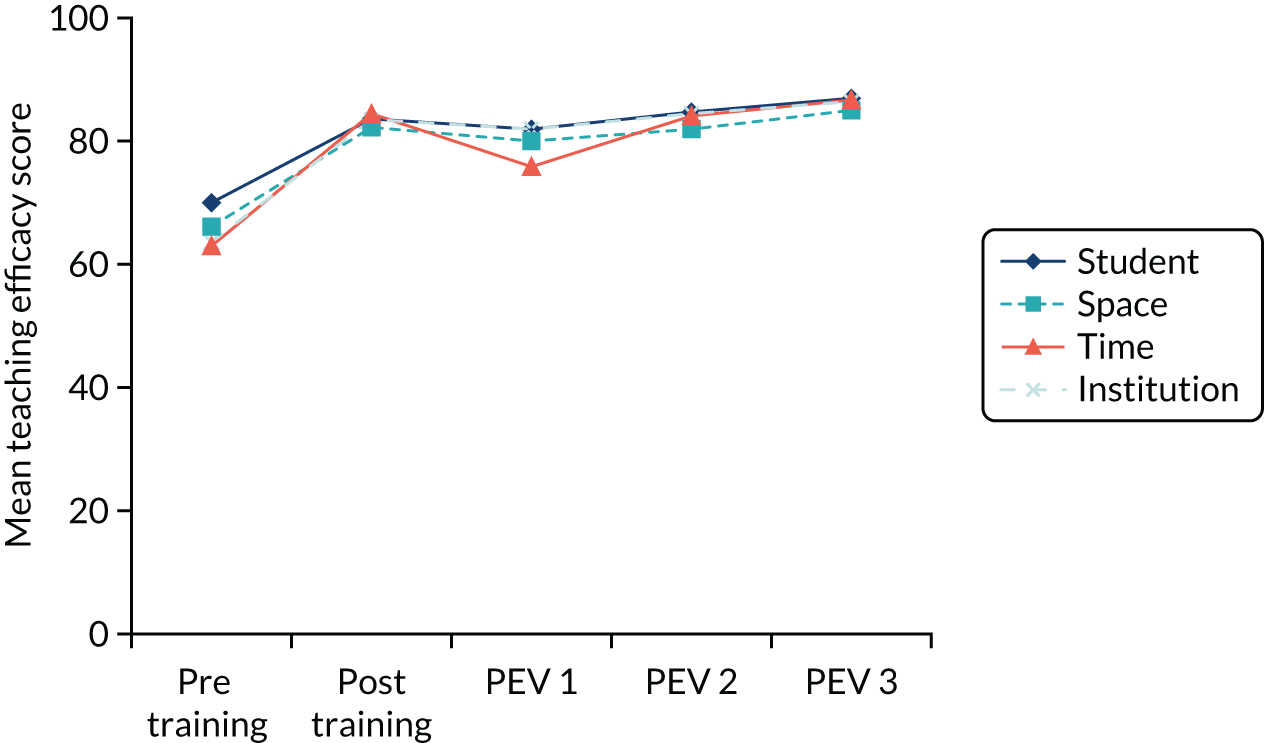

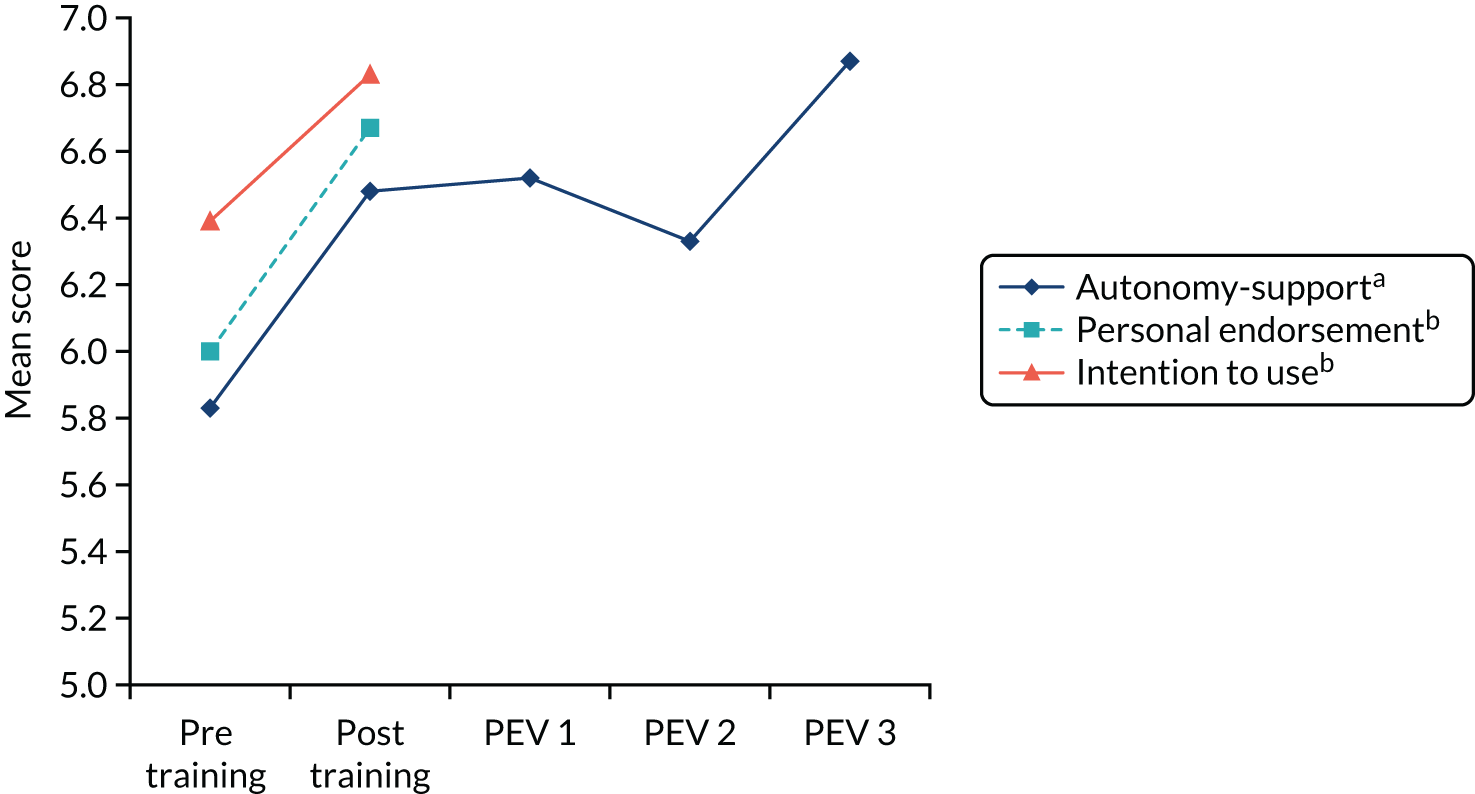

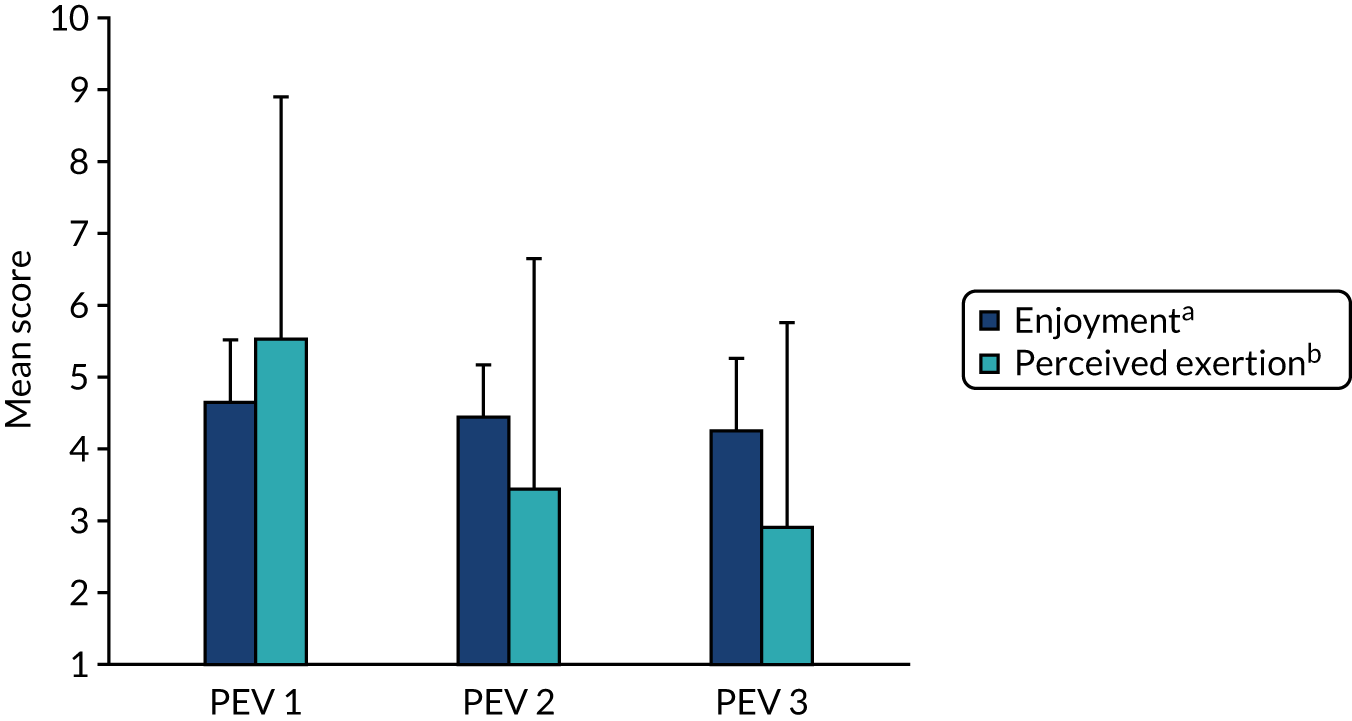

Quantitative process evaluation measures

The quantitative component was conducted using self-report questionnaires and observations. TAs were asked to complete a log book, which recorded attendance and the dose of the intervention (whether each session was delivered fully, partially or not at all to plan). A member of the research team observed three randomly selected sessions (one per half-term) in each intervention school during the 15 weeks. The visits were spaced evenly in each school: approximately 4 school-term weeks apart, starting at or near week 5 of the intervention. During the three observation visits, pupils completed the Sport Climate Questionnaire45 to assess their perceived autonomy support of the TAs, which consisted of six questions on a seven-point Likert scale. Pupils also completed an enjoyment and exertion questionnaire at these observation time points, which consisted of two items referring to their enjoyment of that day’s session and how tiring they perceived that session to have been. Pupils responded using a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (‘not at all’) to 5 (‘a lot’) for the enjoyment item and an 11-point Likert-type scale ranging from 0 (‘not tired at all’) to 10 (‘very, very tired’) for the exertion item. The dose of the intervention was also assessed by the researcher. TAs were asked to complete a validated self-efficacy questionnaire, made up of an adapted version of the Physical Education Teacher’s Physical Activity Self-Efficacy Scale46 and a vignette about autonomy-supportive teaching style and eight items referring to this. 47 The questionnaire was completed before and after the intervention training and during the three observation visits. A researcher assessed school context in all 12 schools using a validated school physical activity environment scale. 48 Data on school physical activity policy context were collected by soliciting information from a school contact about physical activity policies and curriculum. These data were used to examine whether or not differences in the social/physical environment and in school policy strategies could have an impact on the delivery of the intervention. Adoption of the intervention was assessed by recording the number and proportion of schools and TAs who stated that they would continue to deliver a version of Action 3:30 once the intervention period had ended.

Qualitative process evaluation measures

Following completion of the intervention training programme, the coach development manager at Bristol City Council (lead trainer) took part in an interview with the trial manager, which focused on the delivery of the training and whether or not it could be improved. He also completed a checklist to assess whether or not training had been delivered as planned.

Once the 15-week intervention was finished, all TAs (n = 9) and intervention school key contacts (staff members who act as the primary liaison between the school and the study team; n = 4) were asked to take part in semistructured interviews, and selected children (six boys and six girls in each intervention school) were asked to take part in focus groups. Children were purposely selected based on their attendance at the club. The mean number of sessions attended was calculated for all pupils. Pupils with low, medium and high attendance rates were then selected. One pupil who joined at the second enrolment in each intervention school was also purposively selected. School key contacts (n = 4) and Year 3/4 classroom teachers (n = 2) in schools who took part in the accelerometer opt-out process were asked to take part in an interview to discuss the burden associated with this process, and how to mitigate it in future studies. One intervention school also took part in the accelerometer opt-out process, and so that school’s key contact was asked about this process in the same interview. Eight external stakeholders were also asked to take part in an interview. After two schools withdrew from the intervention, a school key contact from each school was asked to take part in an interview to explain the reasons for withdrawal and how this could be prevented in future trials. Two researchers with master’s-level qualitative experience (BT, male; and AP, female) conducted all of the interviews and focus groups. All informants received information about the research aims and the researchers and provided written consent prior to interview. Field notes were made during and after each interview or focus group by the researcher present.

Interview topic guides

Interview topic guides were developed for each informant group (five guides in total). Child focus groups were conducted in school with just the researcher present. The focus groups explored recruitment, attendance, delivery, enjoyment and possible improvements to the intervention. Pupils were asked what they enjoyed the most and least about the intervention and what motivated them to attend. Pupils were also asked to comment about their physical activity context and environment in school.

Face-to-face paired in-depth interviews49 were conducted with TAs in each school, which involved interviewing TAs from the same school together50 for the purpose of gathering information about how the pair/trio perceived the same event(s),51 in this case the training programme and the intervention delivery. The topic guide explored the content and delivery of the training programme, with a focus on the managing disruptive behaviour section. Regarding the intervention, TAs were asked about attendance, delivery, theoretical fidelity and potential improvements. They were also asked to comment on recruitment (TAs and pupils), the re-enrolment strategy and potential contamination between schools.

Face-to-face interviews were conducted with intervention school key contacts in school. The topic guide addressed their involvement in the study, thoughts about the recruitment, content, delivery and enjoyment of the intervention, potential to continue the Action 3:30 programme, potential contamination between schools, and suggested improvements. If applicable, they were also asked to comment on the accelerometer opt-out process.

School key contacts and classroom teachers involved in the accelerometer opt-out process were interviewed face-to-face in school. The topic guide explored the logistics and potential burden of the process.

Face-to-face (n = 3) or telephone (n = 5) interviews were conducted with external impact stakeholders, including regional public health leads, school sport co-ordinators and directors of public health non-profit organisations. The topic guide examined the sustainability, future commissioning and dissemination opportunities of Action 3:30, as well as potential improvements.

Qualitative analysis

To synthesise the wide range of qualitative data collected, the framework method52 was used, as it enables the production of a matrix of the data (from different participant groups), which allows for constant comparison between groups. The framework method also allowed a combined approach to the analysis, enabling themes to emerge inductively from participant accounts and specific issues to be explored deductively. Data were analysed using the following steps:

-

Researchers from the study team (BT and AP) thoroughly read and re-read each transcript and listened back to audio-recordings to become familiar with the data set. Their initial impressions of the data were recorded.

-

Initial codes were created from the central tenets of the underlying intervention theory (SDT22) to interpret the data. These codes examined whether or not the intervention supported autonomous motivation among the participants and the three needs support constructs (autonomy or feelings of choice; relatedness – a feeling of connection between the participants and the instructor; and competence). In addition, a predefined code, ‘school context’, was included to assess the differences between schools in intervention experience and implementation linked to their physical/social/policy environment. For the deductive analysis, the predefined codes were broad, the primary purpose being to categorise relevant information to be further interrogated to elicit more refined codes and interpretations. The deductive analysis codes are presented in Appendix 2.

-

An analytical framework was developed to fit each informant group to avoid losing any key data. Four researchers (BT, AP, SS and RJ) met to discuss and refine a set of codes that could be applied to all transcripts using the following process:

-

Two researchers (BT and AP) independently read and analysed two transcripts from each informant group, met, and discussed and created draft frameworks for each informant group.

-

A third researcher (SS) read two transcripts from half of the informant groups (e.g. boy pupils, TAs) and a fourth (RJ) read the other half (e.g. girl pupils, school contacts) and made notes of the key codes/themes.

-

All four researchers met to discuss and refine draft frameworks.

-

-

The two primary researchers then applied frameworks to remaining transcripts (with some level of double coding, i.e. each researcher coded two more transcripts from each stakeholder group) using NVivo (QSR International Pty Ltd, Warrington, UK). Any new codes that emerged were discussed, and amendments were made to each framework.

-

Coded data were then charted into a framework matrix in NVivo. This summarised the data for each informant by category and included representative quotations. To ensure consistency within the research team, summarising techniques were compared.

-

Data were interpreted and themes were generated in frequent meetings to review the matrix. The two primary researchers agreed on illustrative quotations to show the nature of each theme.

-

The frameworks were triangulated to compare the codes for each informant group to assess the degree of convergence.

The qualitative analysis is reported in accordance with the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) guidelines53 (Table 3) to optimise the credibility and transparency of the research.

| Domain (COREQ) | How we established credibility and transparency |

|---|---|

| Research team and reflexivity | Our researchers’ credentials, experience, sex and relevant training were declared in research outputs to contextualise their perspective and approach to the interview/focus groups and to the analysis of the data resulting from them |

| Study design |

Interviews and focus groups took place in settings of the participant’s choosing in order to make the participant feel empowered Voice recorders were used to record interviews/focus groups to ensure that all data were available for use in analysis Topic guides are attached as standalone documents |

| Analysis and findings |

Double coding on a sample of transcripts from different informant groups reduced researcher bias in coding Participant feedback on results were sought to ensure that interpretation was representative of their perspective |

Statistical analysis

Stata statistical software was used for all statistical analyses. Summary statistics were presented comparing the control and intervention arms at baseline and follow-up on demographics [age, ethnicity, socioeconomic status (using Index of Multiple Deprivation)] (baseline only), psychosocial variables and accelerometer variables, including MVPA. Where the distribution of the outcomes was approximately normal, mean values and standard deviations (SDs) were presented; otherwise, medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs) were presented. For binary/categorical variables, a number and percentage were presented. As this was a feasibility trial, the primary and secondary outcomes were reported using basic statistics to describe the recruitment, session attendance, accelerometer and questionnaire data. To avoid losing power when calculating average scores for the measure of autonomy-supportive teaching experienced by pupils (Sport Climate Questionnaire collected at three process evaluation time points), a multiple imputation approach was taken, which provides a more realistic representation of what would have been provided had all of the children provided complete data at all time points (see Table 17). Non-imputed data are also presented in Appendix 4.

For the accelerometer-assessed mean minutes of weekday MVPA outcome, the following analysis procedures were undertaken. All pupils providing measurements were included, as per their allocation, in an ITT primary analysis to assess the effectiveness of the Action 3:30 intervention to improve the mean minutes of MVPA per weekday among Year 4 and 5 pupils at follow-up using multivariable mixed-effects linear regression. Multivariable mixed-effects linear regression considers the hierarchical nature (i.e. the clustering) of participants within schools. The model included covariates for intervention arm, local authority (South Gloucestershire or North Somerset), recruitment strategy (taster session or not) and the baseline measurement of mean minutes of weekday MVPA. The difference in mean weekday MVPA between the two allocated arms was presented with its 95% CI. This was repeated with stratification by sex, with the differences in mean weekday MVPA between the two allocated arms being presented with 95% CIs for boys and girls separately. This model was adapted to secondary measures based on accelerometer estimates such as sedentary time. The total proportion of pupils meeting the UK recommendations of 60 minutes of MVPA per weekday was calculated based on the average minutes of MVPA across all valid weekdays.

The large majority of trial participants had indicated a willingness to join the Action 3:30 programme at the outset, before the allocation of their school to intervention or control, thereby ensuring allocation concealment. The ITT estimate was based on a comparison of these participating children between those whose school was allocated to intervention and those at schools allocated to control. Children who later joined their school’s ongoing programme at ‘re-enrolment’ made this decision knowing that they were at an intervention school; this fundamental difference prompted us to prespecify a separate analysis of the outcomes in these children, which, if justified, would then be combined using meta-analysis techniques with the ITT estimate.

A key issue when estimating the effect of the intervention in those children joining at re-enrolment is identifying an appropriate comparison group. It is not known which children in the control schools would have joined the intervention at the later opportunity, so the only unbiased comparison based on randomly allocated groups is between all children who did not indicate a willingness to join the Action 3:30 programme at the outset, comparing those at schools allocated to intervention with those allocated to control. This estimate is not equivalent to our primary ITT estimate; here we pilot a CACE method to obtain an unbiased estimate of the effect of the intervention in those who joined the intervention at re-enrolment. This CACE estimate is comparable with the ITT estimate from those children indicating a willingness to enrol at the outset. It is worth noting that both the ITT estimates and the CACE estimates disregard the number of sessions each child attends: the intervention effect is calculated for those children intending to join the programme, whether this is at the outset or the later opportunity.

The CACE estimate and its CI were obtained using the two-stage least squares approach. This method needs all eligible children at each school to provide the necessary measurements; in this pilot, we did this for four schools. The key aim here was to specify the method and consider the feasibility of the approach, as the estimates produced at this stage would not be usefully precise.

Sample size

The sample size for a future definitive trial was estimated using the ICC for weekday MVPA. The school-related ICC was estimated for daily weekday MVPA to power a definitive trial to detect a difference in 10 minutes MVPA per weekday between the two arms. A variance component random-effects model was used to estimate the ICC. As the ICC for MVPA was estimated using data from only 12 schools, the school-related ICC was compared with that observed in other studies.

Compliance and missing data

Accelerometer compliance was measured by the number of valid days of accelerometer data provided by each pupil enrolled in the study at each time point. At minimum of 3 valid days of accelerometer data were required for compliance. Questionnaire compliance was measured by the number and percentage of pupils enrolled in the study who provide questionnaire data. Data provision rates for accelerometer (missing, invalid, valid) and questionnaire data (missing, not missing) were recorded for baseline and follow-up. There were missing data because some participants did not wear their accelerometer for enough time for data to be valid and some did not return their accelerometer (see Table 11 for data provision at each time point).

Governance

A local advisory group was formed, which included local authority physical activity staff from the two local authorities. The group met three times during the study: once during baseline data collection, once during the intervention delivery period to advise on school-related/intervention issues and once at the end of the project to provide feedback about the interpretation of the findings and the future sustainability and dissemination of Action 3:30. A Children’s Advisory Group was formed with children in the four intervention schools. Four children in each school (two boys and two girls) were recruited, one high active and one less active of each sex, to provide feedback about the intervention and raise any logistical issues. Three Children’s Advisory Group meetings were held during the intervention. A Trial Management Group was formed, comprising all of the applicants, the trial manager and the field worker. The Trial Management Group met once per month to discuss key issues. A TSC was formed, comprising an independent chairperson, two independent members and the study team. The TSC met three times during the study and provided independent scientific scrutiny of the study, support to the study team and guidance on how to progress to a definitive trial. A member of the local advisory group was invited to attend the TSC meetings to provide input.

Chapter 3 Intervention optimisation

Aim

The aim was to ensure that the intervention was optimised for participants and that its interest and appeal was maximised for both boys and girls.

Method

A sample session of the intervention was conducted in two schools in the summer term. One Year 5 class in each school was chosen to take part, as these pupils were of the target age but would not be eligible for the study because they would be in Year 6 when the intervention commenced in the autumn term. The sessions were delivered by Bristol City Council staff during a PE lesson. After the sessions, two separate focus groups (one with six boys and one with six girls) were conducted. Class teachers selected pupils with a range of activity levels for the focus groups. The pupils were asked to comment on their enjoyment of the session, their perception of how boys and girls interacted with each other, the teaching style and the ways in which the session could have been improved. Feedback from the first focus groups was used to improve the second sample session. Lessons learnt from all of the focus groups were used to improve the 30 session plans before the intervention commenced.

Focus group discussions were transcribed verbatim and anonymised.

Results

The analysis of the focus groups (n = 4) showed that all pupils were very positive about the sessions and rated them highly. There was no evidence of differences in response from boys and from girls, and therefore data are presented for each theme with indicative quotations from boys and girls where appropriate. The researcher-identified themes were agreed to be (1) variety, (2) teamwork, (3) level of activity, (4) potential improvements and (5) coaching style.

Variety

When the pupils were asked to comment on what they enjoyed, the variety and uniqueness of the activities was a theme that emerged in each of the focus groups. The games were different from those they usually played during PE, and the variety of activities prevented the pupils from getting bored:

I enjoyed the way it was very creative, and it brought new things to our school.

School 2, girl

I thought the different activities were good. Say if you started getting bored of the frisbee, you could go onto the other activity.

School 2, boy

Teamwork

Another theme that emerged was that pupils enjoyed working in a team and socialising with their classmates. The pupils liked working with others with whom they did not usually socialise and preferred that they did not pick their own teams (i.e. that they were not in a team with just their friends):

Because you get to work as a team and it’s all really fun.

School 1, boy

I think it’s good because people you don’t normally spend a lot of time with, you’re on the same team as them.

School 2, girl

When asked to comment on the sessions being for boys and girls, all of the pupils agreed that they preferred mixed-sex teams and that they would not have enjoyed the sessions as much had they been single sex. The pupils felt that a mixed session gave them the opportunity to work with pupils of the opposite sex, which they may not always choose to do:

I think it was good to mix up it all together because we might learn to get along more with boys.

School 2, girl

Boys don’t normally play with girls and they don’t really work together with them. So, I think it’s good to have a chance to learn and do something with them.

School 1, boy

The pupils felt that having mixed teams made the activities and games fairer and that sports should not be exclusive to sex:

I think it’s better with boys because they can catch more and they’re better at stuff.

School 2, girl

If they [girls] were playing something, for example, tag and the boys were playing football, if a girl wanted to come in, you wouldn’t say, ‘No, you’re a girl’. You would say, ‘Yeah, come in’.

School 1, boy

However, the pupils did sometimes feel that the girls and boys grouped together, despite being on a mixed team:

Some of the girls didn’t pass to the boys and some of the boys didn’t pass to the girls. It did make it a bit unfair.

School 2, boy

Level of activity

Most of the pupils thought that the sessions were active and involved plenty of running around:

I think it was really pulse-raising.

School 1, girl

It gives you a lot of exercise.

School 2, boy

However, some pupils felt that certain aspects of the game or certain people were not active enough:

I don’t think it was active enough because, as he said, if you’re in the goal the whole game, you can’t get out and run.

School 2, boy

In particular, the female pupils in school 2 did not think that the session was active enough. They commented that the lack of space and the size of teams limited their ability to be active, and they suggested possible improvements:

There’s always a big huddle. There’s always space over there but we’re always over here.

School 2, girl

We could change the size because there were a lot of us and maybe we could do two games at once.

School 2, girl

Potential improvements

Several recurring suggestions were made of ways to improve the sessions. Pupils proposed that smaller teams and more space would allow more people to get involved:

You might be able to have two teams which would be better. Instead of everybody being rammed in one game.

School 2, boy

Adding more rules to the games was suggested as a way of improving the organisation and structure of the sessions, as well as increasing the level of activity:

I would say everyone at least has to throw it to every person in their group.

School 2, girl

The first goal, a girl would have to score it and then once a girl had scored, for the next half of the game, it could then be a boy who scores it.

School 1, boy

Other potential improvements included ways in which the games could have been made easier, for example by having bigger balls and bigger goals. The pupils also liked the idea of having more and longer games; however, this would have been difficult within the allocated time.

Coaching style

Pupils were asked to comment on how the Bristol City Council coaches delivered the sessions. In general, the pupils liked the coaches and were very positive about their coaching style. The pupils thought that the coaches gave clear instructions without being too strict:

They were very specific on what you had to do and what the rules were.

School 1, boy

They had a way of getting people’s attention . . . and they weren’t strict.

School 1, girl

The pupils felt that the coaches were very encouraging with regard to their skill development and keeping everyone active. They liked that the coaches gave good critical feedback and encouraged them to adapt the activities to progress their skills:

. . . if someone had done it wrong, he [the coach] would say, ‘Ah, unlucky. What you could next time is . . .’ He wouldn’t say, ‘Oh, that was really bad’.

School 2, boy

I liked the way that when we were doing frisbee they were helping us, giving us techniques.

School 1, girl

The only aspect of the coaches’ delivery that the pupils did not like was that the coaches let the pupils choose their own teams and nominated people to be team captains, which they felt made the games slightly unfair:

They made one captain and it made all unfair because we couldn’t say what we wanted.

School 2, boy

They [the coaches] could be team leaders and then go, ‘One, two, three. One, two, three’.

School 1, boy

Summary

The results from the focus groups with Year 5 pupils showed that the sample sessions were well received by both girls and boys. The pupils enjoyed the sessions because they were fun, varied and different from usual PE lessons and encouraged teamwork with others with whom they did not usually play. Boys and girls enjoyed interacting and felt that the session would not have been as enjoyable had it been single-sex. The pupils liked that the coaches were encouraging and gave good critical feedback, which enabled them to improve their skills. Some of the pupils thought the sessions were active; however, others did not. Girls specifically suggested that smaller teams and more space to spread out would have improved the sessions because this would have enabled more people to get involved simultaneously. Introducing more rules into the games was also suggested, as this could have increased the activity level as well as adding more structure to the sessions. Pupils preferred that teams were chosen for them, rather than choosing their own teams, so that the games were equal and fair.

Results from these focus groups suggest that the revised session content appeals to both boys and girls but highlighted further refinements that were used to improve the 30 session plans and the intervention training programme. Table 4 presents the lessons learned and the changes that were made to the intervention to reflect these.

| Learning points | Intervention implementation |

|---|---|

| Children, especially girls, preferred smaller teams | Communicated to TAs during leader training |

| Boys and girls preferred working in mixed-sex teams | Communicated to TAs during leader training |

| Children preferred teams to be picked for them to make them fair | TAs were provided with options for ways to pick teams fairly, supported by examples in the training guide |

| Children valued autonomy, for instance by inventing rules to progress activities | This was highlighted during the motivation section of TA training, reminding TAs of where they could incorporate autonomy-supportive techniques during sessions. Case studies were added into the training guide that reflected this. Session plans already included suggestions for autonomy support within each activity |

| Children valued specific and constructive feedback from coaches | This was highlighted during the communication section of training and reinforced during the feedback and evaluation section of training. Examples of how to provide this type of feedback were provided in the leader’s manual and training guide |

| Children liked to stay active for more of the session | Of the original 40 sessions, the 10 least active sessions were removed. The remaining sessions were edited to enhance the potential for suitable activity by offering suggestions to make each activity/game more or less active as needed |

Chapter 4 Quantitative results

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced from Jago et al. 54 © 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

This chapter provides the quantitative results from the study. The recruitment data are presented first, followed by data provision and study results. Where findings specifically relate to progression criteria, these are clearly shown.

School recruitment

The study required participation of eight primary schools from South Gloucestershire and four from North Somerset, making a total of 12 study schools. Schools were approached based on the percentage of their pupils claiming free school meals and their intake size. Eleven schools in South Gloucestershire were invited to participate. Two schools did not respond to the invitations, one school declined to take part after the initial meeting and eight signed study agreements to take part. The agreements outlined the study role and what was expected of the school in terms of allocating space and staff time for the clubs and also the expectations that the school could have of the project team. In all schools, members of the project team met with the head teacher, provided an overview of the study and answered any questions during a face-to-face meeting. Sixteen schools in North Somerset were invited to participate. Eight schools did not respond to the invitations, four declined to take part after receiving the study information and four signed study agreements to take part. It is notable that the recruitment rate of South Gloucestershire schools was considerably higher than that of North Somerset schools. We believe that this reflects our long-established working relationship with South Gloucestershire Council and support from council staff in approaching schools. Table 5 presents the recruitment rates.

| Local authority | Schools approached (n) | No response (n) | Declined (n) | Schools consented (n) | Recruited (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| South Gloucestershire | 11 | 2 | 1 | 8 | 72.73 |

| North Somerset | 16 | 8 | 4 | 4 | 25.00 |

| Total | 27 | 10 | 5 | 12 | 44.44 |

Progression criterion 1 of the study was to recruit at least 25% of the schools approached. Forty-four per cent of all schools that were approached agreed to take part, so this criterion was met. An aim of the recruitment process was to recruit half of the schools in each local authority from above the median free school meals percentage of that local authority. The median free school meals percentage is 8.5% in South Gloucestershire and 9.3% in North Somerset. Six and four schools in South Gloucestershire and North Somerset, respectively, were above this level, indicating that these schools were in more disadvantaged areas.

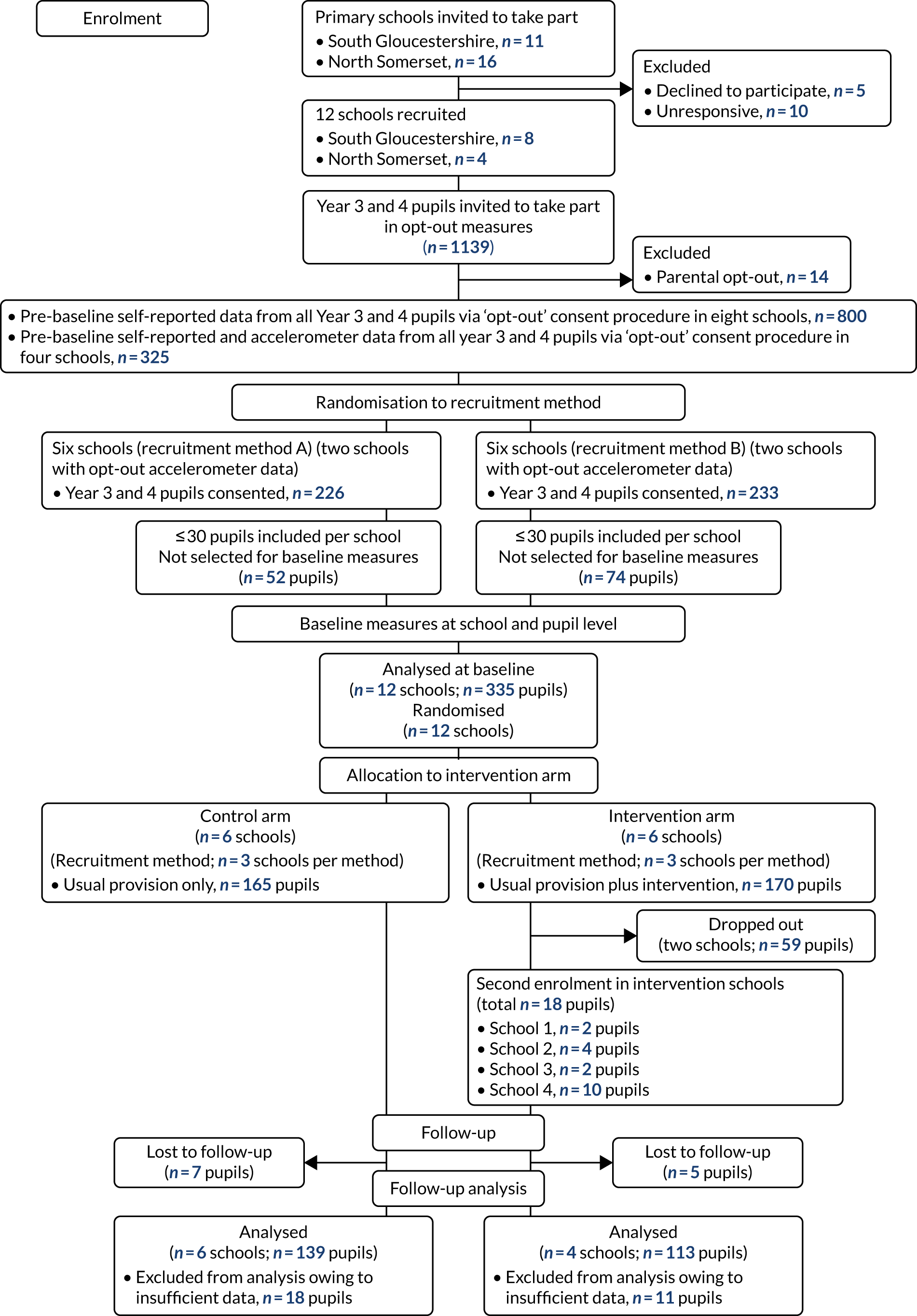

Participant (pupil) recruitment

Opt-out: pre baseline

All Year 4 and 5 pupils had been asked to take part in the opt-out phase when they were in Years 3 and 4. Across all 12 schools, 1139 pupils were eligible to participate, and 1125 pupils participated (98.77%). Table 6 presents the number of eligible pupils, the number of pupils recruited (those who did not opt out), the number of pupils who opted out (those who did not want to take part) and the recruitment percentage for each school in the opt-out phase. The percentage of pupils recruited was similar when they were asked to wear an accelerometer for 7 days and complete the PAQ-C survey (99.01%) and when they were asked to complete only the survey (98.19%).

| School ID | Method | Eligible (n) | Recruited (n) | Opt-outs (n) | Recruited (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 21 | Survey | 131 | 131 | 0 | 100.00 |

| 22 | Accelerometer and survey | 112 | 111 | 1 | 99.11 |

| 23 | Survey | 171 | 170 | 1 | 99.42 |

| 24 | Survey | 78 | 78 | 0 | 100.00 |

| 25 | Accelerometer and survey | 48 | 46 | 2 | 95.83 |

| 26 | Accelerometer and survey | 58 | 58 | 0 | 100 |

| 27 | Survey | 108 | 104 | 4 | 96.30 |

| 28 | Accelerometer and survey | 113 | 110 | 3 | 97.35 |

| 31 | Survey | 57 | 57 | 0 | 100.00 |

| 32 | Survey | 53 | 52 | 1 | 98.11 |

| 33 | Survey | 156 | 156 | 0 | 100.00 |

| 34 | Survey | 54 | 52 | 2 | 96.30 |

| Survey-only total | 808 | 800 | 8 | 99.01 | |

| Accelerometer and survey total | 331 | 325 | 6 | 98.19 |

Baseline

All eligible Year 4 and 5 pupils were asked to take part in the main study when they were in Years 3 and 4. Across the 12 schools, of the 1139 pupils eligible to take part, 459 pupils expressed an interest in doing so by returning study consent forms (41.39%). Owing to health and safety, a maximum of 30 children per school were selected to participate (the maximum was set at 32 in one school because this was the total number of interested pupils and the school approved the inclusion of two extra pupils rather than turning down two pupils). Of the 459 pupils who returned consent forms, 48.66% were girls. In one school (school 31), only 36.36% of pupils who returned consent forms were girls. Table 7 presents the number of eligible pupils, the number and percentage of pupils who returned consent forms, the number and percentage of girls who returned consent forms and the number of pupils in each school who were selected to take part in the study.

| School ID | Eligible (n) | Returned forms (n) | Eligible (%) | Girls, n (%) | Pupils measured at baseline (n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 21 | 131 | 61 | 46.56 | 31 (50.82) | 30a |

| 22 | 112 | 38 | 33.93 | 18 (47.37) | 30 |

| 23 | 171 | 70 | 40.94 | 36 (51.43) | 30 |

| 24 | 78 | 28 | 35.90 | 13 (46.43) | 28 |

| 25 | 48 | 19 | 39.58 | 8 (42.11) | 19 |

| 26 | 58 | 27 | 46.55 | 14 (51.85) | 27 |

| 27 | 108 | 40 | 37.04 | 20 (50.00) | 30 |

| 28 | 113 | 31 | 27.43 | 14 (45.16) | 31 |

| 31 | 57 | 22 | 38.60 | 8 (36.36) | 22 |

| 32 | 53 | 32 | 60.38 | 18 (56.25) | 32 |

| 33 | 156 | 65 | 41.67 | 34 (52.31) | 30 |

| 34 | 54 | 26 | 48.15 | 14 (53.85) | 26 |

| Total | 1139 | 459 | 228 | 334 | |

| Average | 41.39 | 48.66 |

Progression criterion 2 of the study was that at least 25% of eligible pupils express an interest in the study by returning consent forms, which was achieved (41.39%). Progression criterion 3 was that at least 40% of participants expressing an interest were girls, which was also achieved (48.66%).

An aim of the study (objective 2c, which studied an enhanced recruitment approach) was to compare two recruitment methods: briefing against briefing plus taster (see Chapter 2, Study population and recruitment section). A comparison of the two methods is shown in Table 8. The number and percentage of pupils recruited was similar using both recruitment methods. The mean PAQ-C score shows an indication of physical activity level. The score is on a scale of one to five, one being low and five being high. Standard procedures were followed to complete the scoring. 30 There was no difference in mean PAQ-C score between the briefing plus taster and the briefing-only recruitment methods.

| Recruitment method | Schools (n) | Eligible pupils (n) | Recruited pupils (n) | Recruited (%) | Girls (%) | PAQ-C score, mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Briefing only | 6 | 557 | 226 | 40.57 | 51.32 | 3.2 (0.12) |

| Briefing plus taster | 6 | 582 | 233 | 40.03 | 48.07 | 3.08 (0.14) |

Another aim of the study (objective 2c) was to compare physical activity levels between pupils who expressed an interest in the study and pupils who did not. In particular, the study aimed to appeal to and recruit less active children. Table 9 compares the mean PAQ-C score and MVPA, assessed objectively with accelerometers, between pupils who did and pupils who did not consent to take part in the study. Minimal differences were seen between those who did and those who did not consent, which indicated that those who consented to the study were unlikely to have higher physical activity levels than those who did not consent. The data in the table also show that the participants were, on the whole, active and that the consented participants engaged in slightly more minutes of MVPA than non-consented participants (66.8 vs. 63.2 minutes of MVPA per day), but this difference was small.

| Type of data | Non-consented participants | Consented participants |

|---|---|---|

| PAQ-C (n) | 681 | 443 |

| Mean PAQ-Ca (SD) | 3.13 (0.71) | 3.21 (0.68) |

| Accelerometer (n) | 167 | 100 |

| Mean MVPA minutes per weekday (SD) | 63.23 (19.69) | 66.75 (18.77) |

Reasons for non-consent

During the participant recruitment process, brief letters were sent home to parents to collect data on why children did not want to take part in the study. Table 10 presents the number of consent forms that were not returned (i.e. the number of pupils who did not express an interest), and the number and percentage of reasons for non-consent forms returned, for each school. The most common reasons for non-consent were ‘my child does enough activities already’ (38 responses) and ‘my child is not interested in Action 3:30’ (23 responses). Thirteen responses reported reasons related to the letters sent home about the study: parents misreading the information sheet or not receiving it, or not returning the consent form on time.

| School ID | Eligible (n) | Returned forms (n) | Forms not returned (n) | Reason for non-consent forms returned (n) | Eligible (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 21 | 131 | 61 | 70 | 12 | 9.16 |

| 22 | 112 | 38 | 74 | 7 | 6.25 |

| 23 | 171 | 70 | 101 | 13 | 7.60 |

| 24 | 78 | 28 | 50 | 3 | 3.85 |

| 25 | 48 | 19 | 29 | 3 | 6.25 |

| 26 | 58 | 27 | 31 | 2 | 3.45 |

| 27 | 108 | 40 | 68 | 4 | 3.70 |

| 28 | 113 | 31 | 82 | 13 | 11.50 |

| 31 | 57 | 22 | 35 | 7 | 12.28 |

| 32 | 53 | 32 | 21 | 4 | 7.55 |

| 33 | 156 | 65 | 91 | 7 | 4.49 |

| 34 | 54 | 26 | 28 | 8 | 14.81 |