Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 10/3000/07. The contractual start date was in January 2012. The final report began editorial review in November 2018 and was accepted for publication in September 2019. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Haw et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background and existing research

Parts of this chapter have been adapted from the published protocol by Haw et al. 1 © 2014 Haw et al. ; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly credited. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Exposure to tobacco advertising and promotions increases smoking prevalence by encouraging smoking initiation in young people,2 maintaining smoking in adult smokers3 and precipitating relapse in those trying to quit smoking. 4 Article 13 of the World Health Organization’s Framework Convention for Tobacco Control called for a comprehensive ban on all tobacco advertising and promotions in all media. 5 However, the implementation of legislation to regulate tobacco advertising at a global level is still limited, with only about 15% of the world’s population protected by legislation that bans tobacco advertising and sponsorship. 6 In Europe, the European Union (EU) Tobacco Products Directive 2004 required all member states to implement a ban on tobacco advertising and sponsorship by 2005. 7 A 2008 report from the European Commission on the implementation of the EU Tobacco Advertising Directive concluded that laws to transpose the Directive were in place and had been well implemented, with many Member States having wider advertising and sponsorship bans than those required by the Directive. 8 Within the EU, traditional tobacco brand advertising and direct sponsorship of a cross-border nature has ceased; however, in response to the advertising ban, tobacco marketing and promotion at point of sale (POS) has intensified and POS displays have become critical to the promotion of tobacco products. POS displays not only alert customers to the brands that are available, but, combined with a strengthening of pack design, allow tobacco companies to communicate the values associated with their particular brands. 9 Tobacco products are also displayed alongside ordinary consumer goods, including products targeted at children, such as snacks, soft drinks, toys and collectables. 10 It has been argued that this creates the impression that tobacco is more socially acceptable and commonly used than is the case. 11 Data from the USA suggest that POS tobacco promotion may increase sales by between 12% and 28%. 12

An important development in POS advertising has been the tobacco power wall. Tobacco power walls are typically located close to or directly behind the POS and contain many brands of tobacco that are often organised to make attractive patterns of cigarettes13 and deliberately designed to communicate brand values, thus potentially blurring the line between display and promotion. 11 In the UK they became a common sight in supermarkets, and typically dominated smaller retail outlets, such as convenience stores, which are frequented regularly by young people. Exposure to such displays is thought to normalise tobacco use14 and increase positive brand imagery. 15 Another way in which tobacco companies have succeeded in increasing POS exposure of their brands is by developing new variants of existing brands. Since 1998, brand families have grown in size by > 50%, with popular brands such as Benson & Hedges (Philip Morris International Inc., Neuchâtel, Switzerland) increasing brand variants from four in 1998 to 23 by 2012. The increase in brand variants was intended to maximise their visual impact on shop shelves. 16

There have been two reviews of studies exploring the impact of POS tobacco displays; the first was conducted in 200917 and the second was conducted in 2015. 18 Both found that among young people there were associations between exposure to tobacco promotions at POS and beliefs about the ease of purchasing tobacco, perceived smoking prevalence among peers, smoking susceptibility and smoking initiation. Among adults, images of tobacco packs elicited craving in smokers, while tobacco displays prompted impulse purchasing in smokers and urges to relapse to smoking in recent ex-smokers. The later review, conducted by Robertson et al. ,18 concluded that the more recent studies demonstrated the strongest associations. Paynter and Edwards18 argue in their review that the most common outcome was smoking status, which limited the conclusions that could be drawn about the direction of the association. It is plausible that young people who have just started smoking visit stores more often, thereby increasing their exposure to and awareness of POS displays. By contrast, the later review examined smoking susceptibility in never-smokers, thus eliminating the confounding effect of tobacco purchasing behaviour. Furthermore, the later review included five studies that examined the dose–response relationship, four of which found a positive dose–response effect, strengthening the view that the relationship was causal.

Iceland was the first country to introduce a ban on POS tobacco displays, in 2001. Since then, Thailand (2005), Canada (2005–10), Ireland (2009), Norway (2010), Australia (2010–12), Finland (2012), New Zealand (2012), England, Wales and Northern Ireland (2012–15), Scotland (2013–15), Croatia (2014) and Russia (2015) have followed suit. A small number of studies have examined the impact of POS display bans. 19–22 All have reported high levels of compliance. In addition, following the implementation of bans in Australia and Canada, the exposure of smokers to tobacco advertising from POS displays declined steeply from 74% to 6% in Canada and from 74% to 43% in Australia. 19 In Ireland, the implementation of a comprehensive ban was accompanied by a decline in the recall of POS displays from 49% to 22% in adults, and a decline from 81% to 22% in young people. There was also a reduction in perceived youth smoking prevalence among young people, and an increase in beliefs that the law made it easier for adults to quit smoking and for children not to initiate smoking. 20 In Norway, 20% of smokers/snus users thought that the ban made it was more difficult to buy tobacco products, while 32% said that it had made it more difficult to choose a brand. There was no difference by age group in reported difficulty of purchase, but younger respondents were more likely than older respondents to indicate that it was more difficult to choose a brand. 21 In New Zealand, smoking initiation decreased from 23% in 2011 at baseline to 17% in 2014, 2 years after the ban was implemented. Current smoking prevalence also declined from 9% to 7%, while initiation in the last year decreased from 13% to 11% over the same time period. Between 2012 and 2013, the attempted purchase of cigarettes in the past 30 days by smokers also decreased, from 30% in 2012 to 26% in 2013. 22

Study aims

The aims of the DISPLAY study were to:

-

determine the impact of Scottish legislation to ban POS tobacco advertising on young people’s exposure to tobacco advertising, their attitudes towards smoking and their smoking behaviour

-

identify any ‘unintended consequences’ associated with the implementation of the legislation.

Intervention

The Tobacco and Primary Medical Services (Scotland) Act 2010 includes provisions that prohibit advertising tobacco products at POS (Sections 1 to 3). 23 The legislation also prohibits the display of tobacco products or tobacco-related products in places where those products are for sale and requires retailers to conceal cigarettes from general view, either by covering up gantries/dispensers or by storing cigarettes under the counter. Under the legislation, displays of tobacco products (section 1) or tobacco-related products (section 2) and prices (section 3) are also considered to be advertisements. The overall policy objective of the legislation was to reduce the attractiveness of tobacco products to children and adolescents (i.e. under the age of 18 years), which in turn could contribute to a reduction in smoking initiation and, in the longer term, a reduction in smoking prevalence.

The importance that the tobacco industry places on POS advertising as a mechanism for promoting and maintaining smoking behaviour among adults and children was exemplified by the vigour with which it fought the Scottish legislation. A petition by Imperial Brands plc (Bristol, UK), which sought a ruling that sections of the Tobacco and Primary Medical Services (Scotland) Act 2010 were outside the legislative competence of the Scottish Parliament, was dismissed both at the original hearing and at appeal. Sinclair Collis Limited (Four Ashes, Wolverhampton) also challenged measures in the Act (Section 6) to ban vending machines but, again, this was dismissed. The attempts to disrupt and delay the legislative process were considerable, and Scottish civil servants viewed these as much greater than those in response to the Scottish smoke-free legislation (John Glen, Scottish Government, 2012, personal communication).

The Scottish legislation was implemented on 26 April 2013 in large retail outlets (mainly supermarkets, and referred to as ‘large supermarkets’ from here on) that have > 280 m2 of internal floor area used for displaying goods and serving customers; it was extended to the remaining smaller tobacco retail outlets on 6 April 2015. Similar legislation, the Health Act 2009,24 prohibiting the display of tobacco products was implemented in England, Wales and Northern Ireland in larger stores in April 2012 and in all other retail outlets in April 2015.

The Scottish government has provided guidance on the implementation of the Tobacco and Primary Medical Services (Scotland) Act 2010. 23 The main points are as follows:

-

All tobacco products and smoking-related products covered by the ban must be placed out of sight of customers.

-

Retailers may choose their own means of covering or remove products. When covers are removed temporarily for customer service or for restocking, the area of open display should not exceed 1000 cm2.

-

Any temporary uncovering of products for customer service or for restocking should last only as long as is necessary for the activity to be completed.

-

Smoking-related products and accessories covered by the ban include products designed specifically for smoking tobacco. These include cigarette papers, cigarette holders, tobacco pipes and apparatus for making cigarettes.

-

Smoking accessories that can be used for other purposes, such as matches and lighters, are not covered by the ban. These can continue to be displayed and kept in public view. They should not be stocked in the same storage unit as products covered by the ban.

-

There should be no tobacco branding on price lists or labels. Only three forms of price information are permitted: poster-style lists up to A3 size; a picture price list available on request only; and price labels on shelving, storage units and tobacco jars.

-

All price information should be in a specified standard font. Unbranded generic signs, such as ‘tobacco sold here’, are allowed in any format.

Original research questions

Our original research questions were:

-

Does implementation of the POS regulations of the Tobacco and Primary Medical Services (Scotland) Act 2010 in (1) supermarkets alone (partial ban) and (2) all tobacco retailers (complete ban) result in changes in exposure to tobacco advertising among young people aged 12–17 years (see Chapters 3–5)?

-

Is a reduction in exposure to POS advertising associated with changes in brand awareness, the perceived accessibility of tobacco, the perceived prevalence of youth smoking, susceptibility to smoking, and the incidence and prevalence of smoking among young people aged 12–17 years (see Chapters 6 and 7)?

-

Is there any evidence of socioeconomic patterning in any of the attitudinal or behavioural outcomes in young people (see Chapters 6 and 7)?

-

What is the association between area-level deprivation and (1) levels of POS tobacco advertising and availability of cigarettes pre and post legislation or (2) enforcement of the legislation once implemented (see Chapter 5)?

-

Is there any evidence of a dose–response relationship between changes in exposure to POS advertising and interim and longer-term outcome measures in young people (see Chapters 6 and 7)?

-

Are there any unintended adverse consequences associated with the legislation, for example an increase in cigarette purchases from black-market sources (see Chapter 6)?

-

Is there any evidence of changes in POS advertising and marketing strategies in the lead-up to or after the implementation of measures of the Tobacco and Primary Medical Services (Scotland) Act 2010 in either supermarkets or small retailers (see Chapter 4)?

Changing retail and sociocultural landscapes

Two important developments occurred during the study that affected both the tobacco retail environment specifically and the wider sociocultural landscape. First, there was a rapid increase both in the visibility of e-cigarettes in the retail environment and in the use of these products among both adult smokers and young people. Second, legislation was passed that required all tobacco products to be sold in standardised packaging. This meant that retailers had to implement another major change in relation to their tobacco products shortly after implementing the POS display ban. This further reduced customers’ exposure to branded tobacco products. Thus, at the same time that tobacco products were becoming less visible thanks to the POS display ban and standardised packaging legislation, other nicotine delivery devices were becoming more available and their use was becoming more prevalent. This had implications for the study’s hypothesised causal pathways, as described in the logic model presented in Chapter 2.

E-cigarettes

E-cigarettes, also known as nicotine vapour products, are battery-operated devices that produce a nicotine vapour that is inhaled. The vapour contains far fewer toxins than cigarette smoke and those that are present are far less concentrated. Evidence about the impact of the long-term use of e-cigarettes on health is not yet available; in the UK, vaping is generally regarded as much less harmful than smoking tobacco25 in the short term but could be potentially damaging to health after long-term use. 26 In the UK, e-cigarettes are now more popular as a quit aid than as nicotine replacement therapy and it is estimated that there are about 2.9 million adult users, the vast majority of whom are smokers or ex-smokers. 25 Evidence is still limited and is subject to varying interpretations, but some argue that e-cigarettes show promise both as a quit aid and as a harm-reduction aid27 and, with their considerable reach into the smoking population, should be made widely available and be heavily promoted to reduce morbidity and mortality among smokers who cannot quit smoking. 28

Although e-cigarettes may benefit smokers, they are unlikely to be beneficial for young people. In Scotland, e-cigarette use among young people is mainly experimental or a ‘once- or twice-off’ event29 and is most common among young people who already smoke. Nevertheless, the number of never-smokers experimenting with e-cigarettes is increasing and, by 2015, 8% of 13-year-old and 14% of 15-year-old never-smokers in Scotland had tried an e-cigarette. 29 Direct comparisons with data collected from elsewhere in the UK are difficult to make because of the different age groups surveyed; UK-level surveys conducted in 2016 found that only 4–5% of 11- to 16-year-old never-smokers had tried e-cigarettes, whereas in Wales in 2015, 10% of 11- to 16-year-old never-smokers had. 30 However, vaping is a relatively new phenomenon and it is not possible to predict with confidence how patterns of use will develop. The market is also rapidly evolving, with new products, such as JUUL (Juul Labs, Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA), entering the marketplace, and there is some concern that vaping could become a lifestyle choice for young never-smokers. 31

There is also concern that e-cigarettes could act as a catalyst for cigarette-smoking in young never-smokers. 32 The majority of published data on this are cross-sectional, which does not allow causation to be inferred. However, a growing number of longitudinal studies have found a positive association between e-cigarette use and smoking initiation in young never-smokers at 6- or 12-month follow-up. 33–40 Common liability, where there are common risk factors for both smoking and e-cigarette use, is a plausible explanation of these findings. 41 However, some of the US studies did control for smoking susceptibility. 33,34 Most of the longitudinal studies were conducted in the USA, where policies on tobacco and e-cigarette marketing restrictions are much less stringent than in the UK. However, three studies from the UK have now reported similar findings. 42–44

In 2016, a revised EU Tobacco Products Directive45 came into force that included measures to regulate the sale, promotion and marketing of e-cigarettes. Cross-national marketing of e-cigarettes and refill containers on television and radio, in newspapers and in most magazines is prohibited. These controls came into force in the UK in May 2016, with non-compliant products and refill containers allowed to be sold until May 2017. 46 The new e-cigarette regulations are much less stringent than the regulations for tobacco, and individual jurisdictions may decide whether or not to introduce further restrictions on the domestic marketing of e-cigarettes, for example at POS or on billboards. In Scotland, the government is considering whether or not further restrictions are required to ‘reduce the visibility and attraction of e-cigarettes to children and young people under 18 and adult non-smokers’ (© Crown copyright. Contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0). 47 Unlike in England, external advertising (e.g. billboards and bus shelters) may not be permitted in Scotland in the future.

Standardised packaging

In the face of ever-stricter controls over tobacco advertising, cigarette packs have become a powerful marketing tool. Pack shape and colour increase attractiveness and aid brand differentiation. Recent innovation in pack design, including novel closing mechanisms, textures or coatings to create tactile effects and olfactory and auditory cues, can also reduce risk perceptions and increase brand appeal, purchase interest, sales and market share. 48,49 In December 2012 Australia was the first country to introduce standardised cigarette packs (standard size and colour, no branding and only the brand name in a standard small font) with large graphic health warnings. 50 Early research suggests that, since these packs were introduced, there has been a shift in the attitudes and beliefs of adult smokers, who reported disliking their packs more and that packs had less appeal. The enhanced graphic health warnings also increased motivation to quit. 51 This was accompanied by a decline in expenditure on cigarette products between 2012 and 201552 and a decline in adult smoking prevalence from 16.1% to 14.7% in a similar period. 53 In 12- to 17-year-olds, smoking prevalence also fell, from 7% in both 2008 and 2011 to 5% in 2014 following the introduction of standardised tobacco packs. 54 Survey data suggest that young people find cigarette packs less appealing,55 but, to date, there has been no evidence of increased cognitive processing of the larger graphic health warnings. 56

Following an extensive public consultation, underpinned by a major evidence review,57 standardised cigarette packs were introduced in Scotland and the rest of the UK in May 2016. The new regulations58,59 are compliant with, and go beyond, the requirements of the revised EU Tobacco Products Directive. 45 As in Australia, the pack shape, colour, opening mechanism and font are regulated, together with the size and the position of health warnings and the number of cigarettes in a pack. Misleading descriptors such as ‘lite’ are also prohibited. After May 2016 UK retailers were able to continue to sell branded products to use up old stock, but from May 2017 only the sale of cigarettes and tobacco in standardised packs was allowed.

Report structure and final research questions

The research questions outlined in our original protocol1 were necessarily broad and, as the project developed, these were refined. The structure of the report is as follows.

Following a discussion in Chapter 2 of the study design and research methods used, we present the main outcomes of the study in Chapters 3–8.

In Chapter 3 we focus on retailers’ implementation of and compliance with the POS legislation by answering the following questions:

-

What were the characteristics of tobacco POS displays at baseline, prior to implementation of the POS legislation?

-

What was the level of compliance with the legislation in large supermarkets and small shops?

In Chapter 4 we explore small retailers’ perspectives on the implementation and impact of the POS legislation by answering the following questions:

-

What were small retailers’ expectations about the implementation and impact of the POS legislation?

-

What were small retailers’ experiences of implementing the POS legislation?

-

What were small retailers’ perceptions of the impact of the POS legislation on customers and the retail environment?

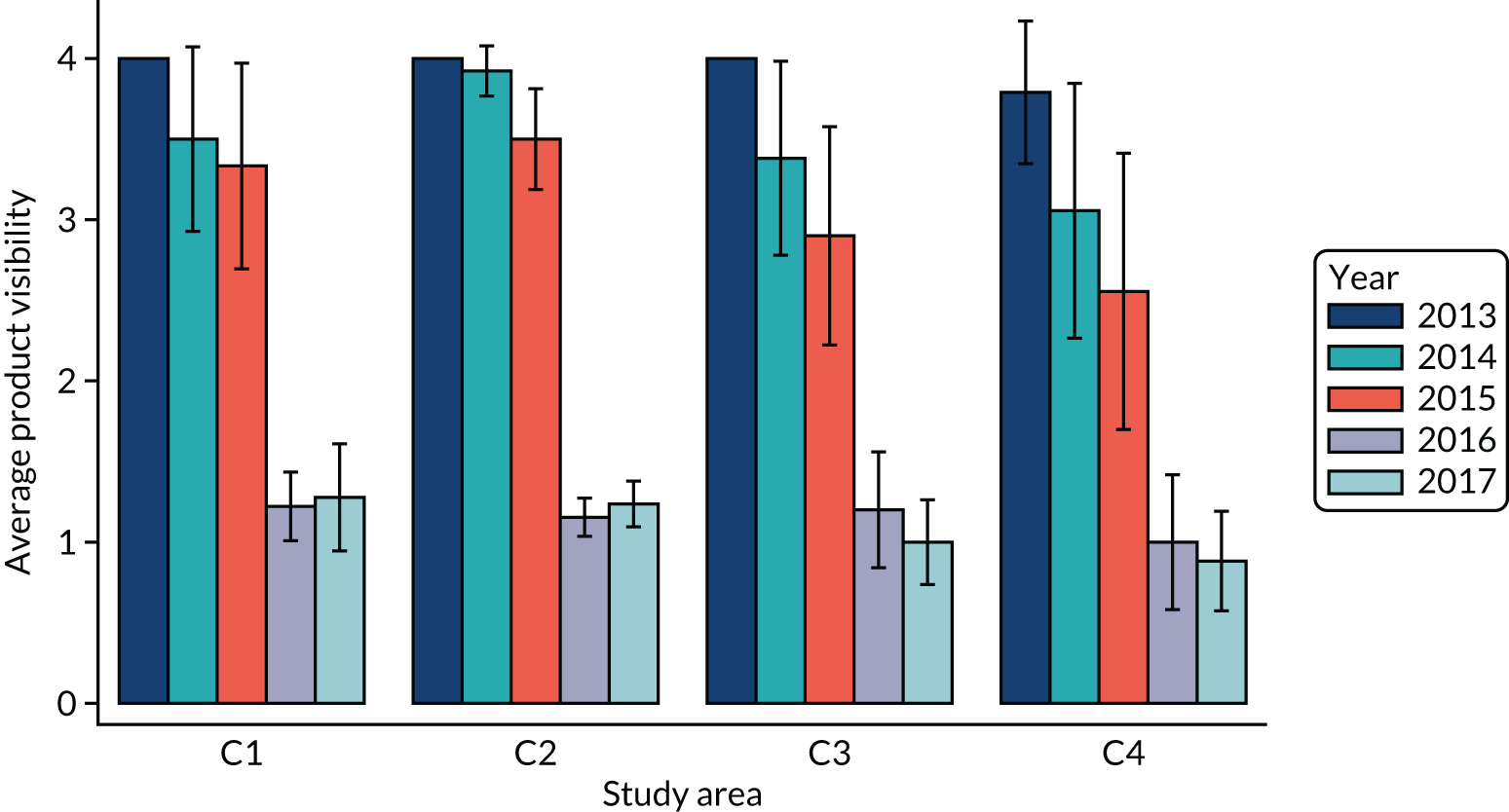

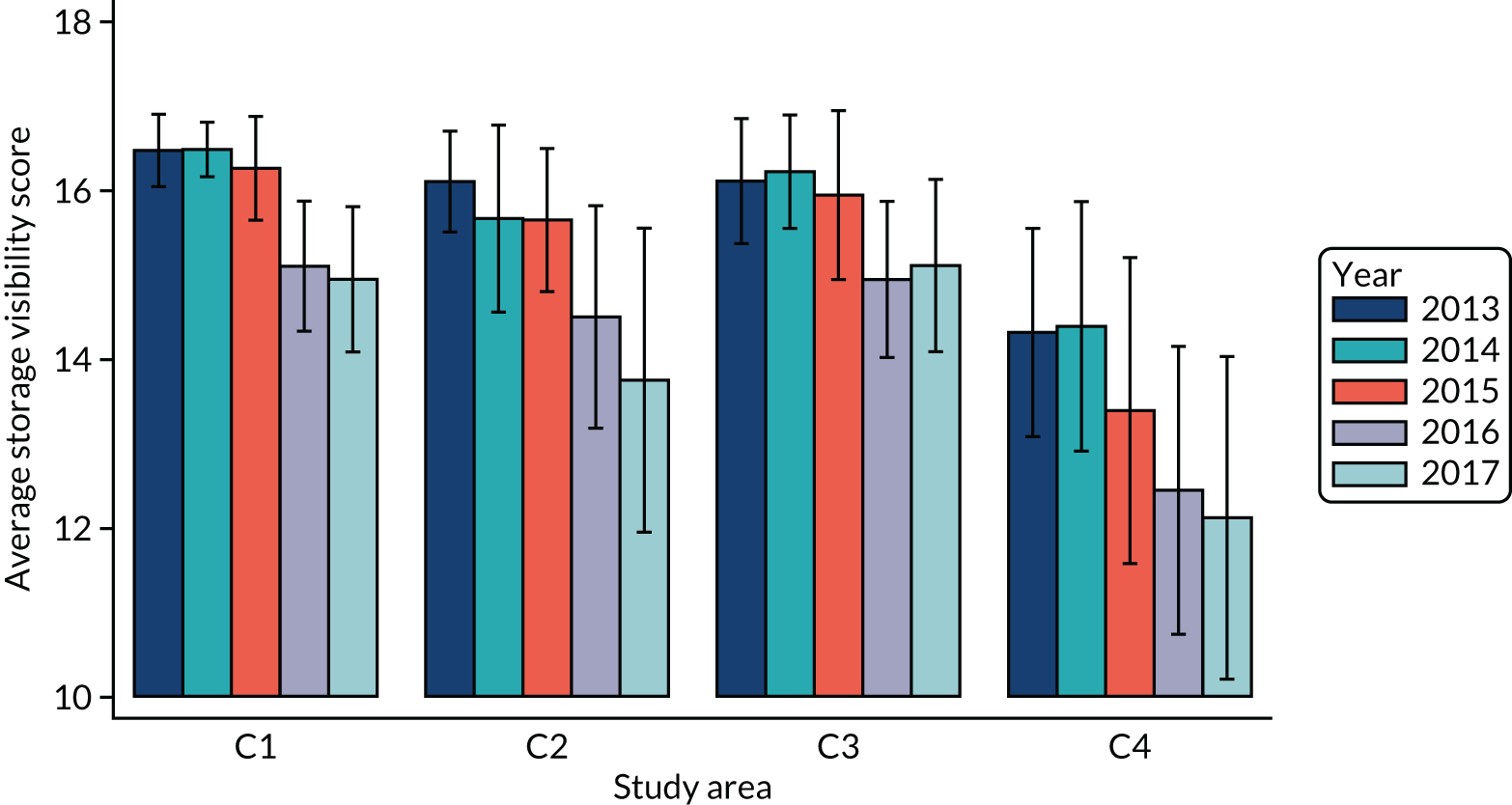

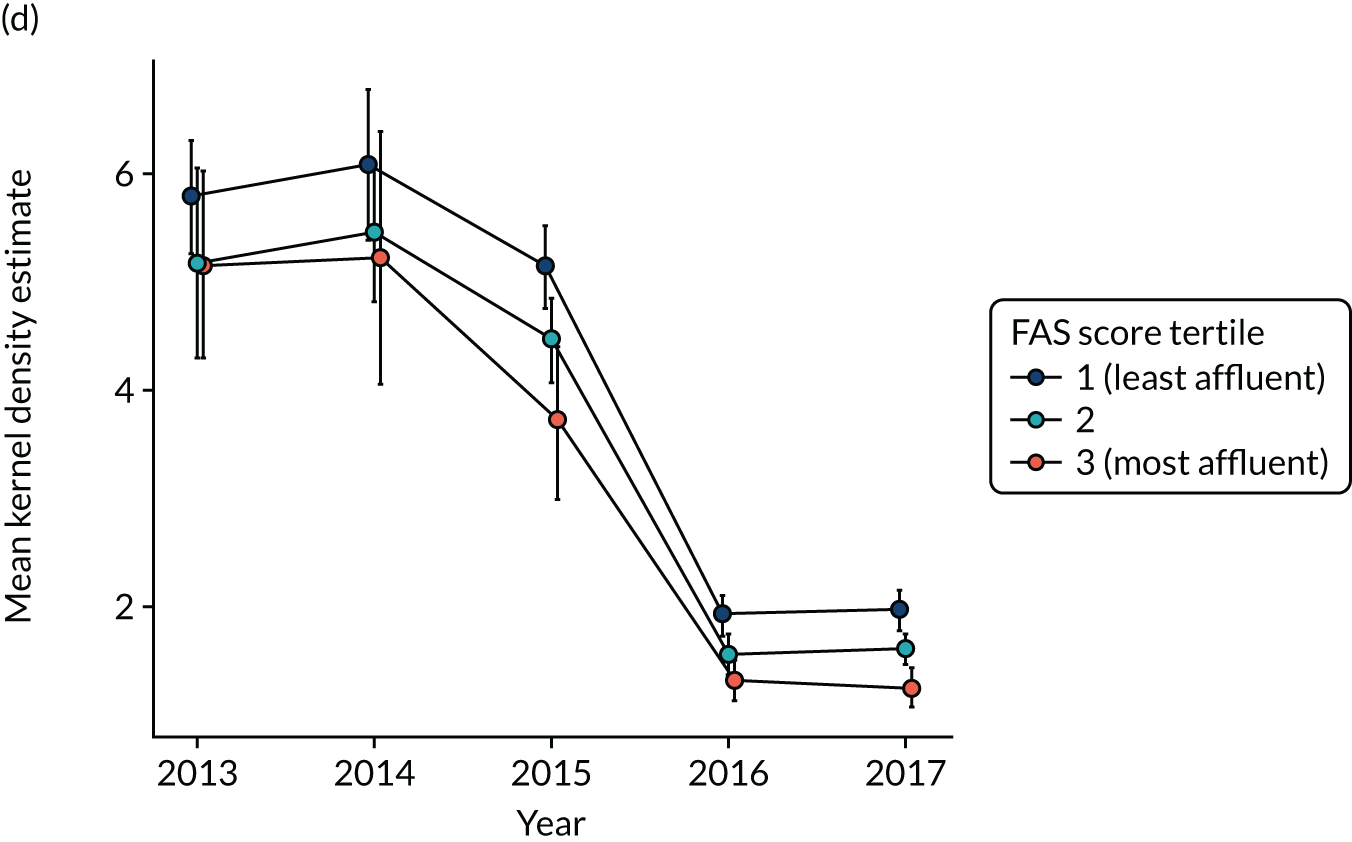

In Chapter 5 we report the findings on the impact of POS legislation on environmental exposure to POS displays. In addition to describing the development of a new visibility measure, we address the following questions:

-

In our four DISPLAY communities, were there changes in exposure to tobacco products either at a community level or for young people in our sample following the implementation of POS legislation?

-

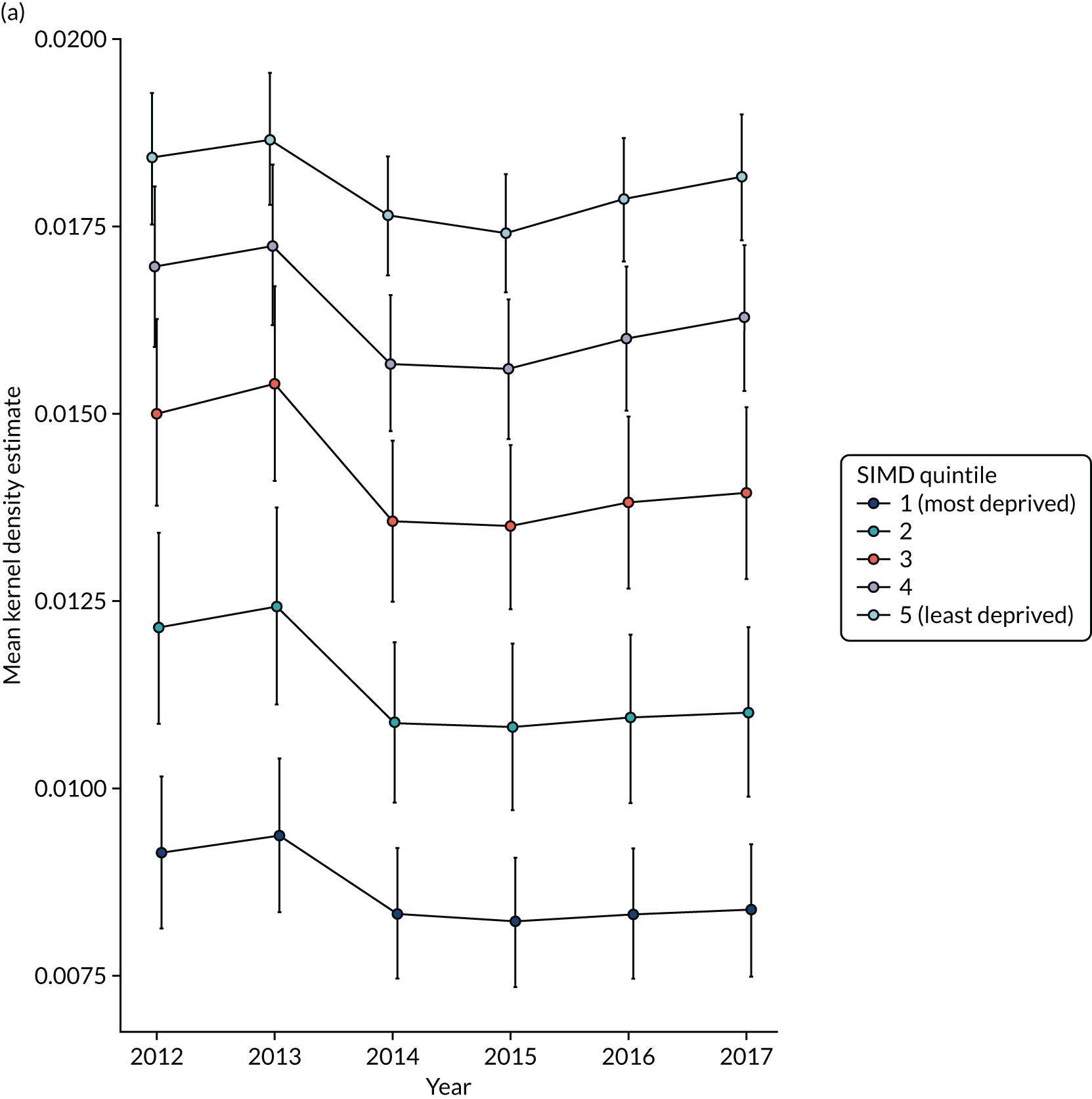

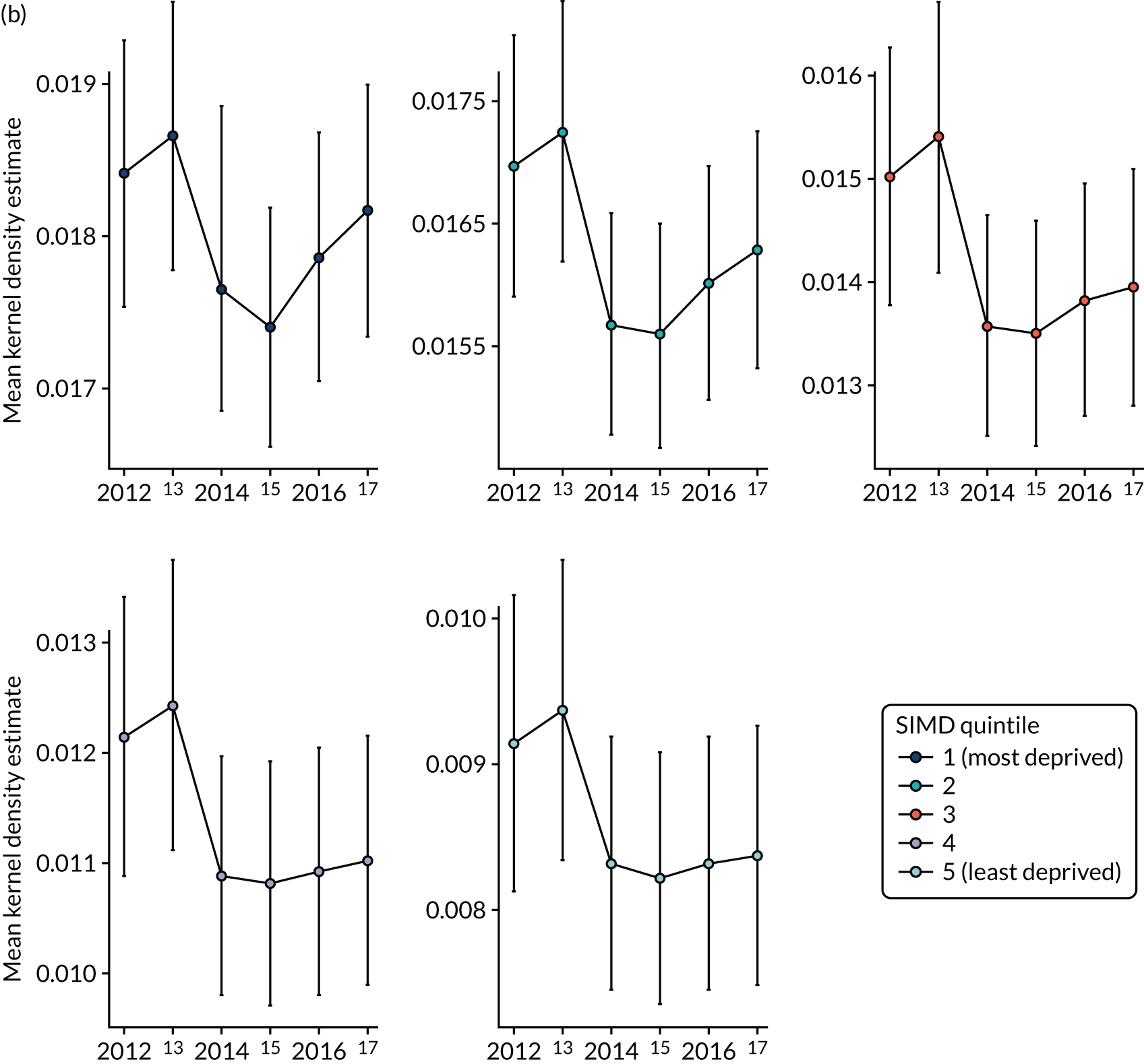

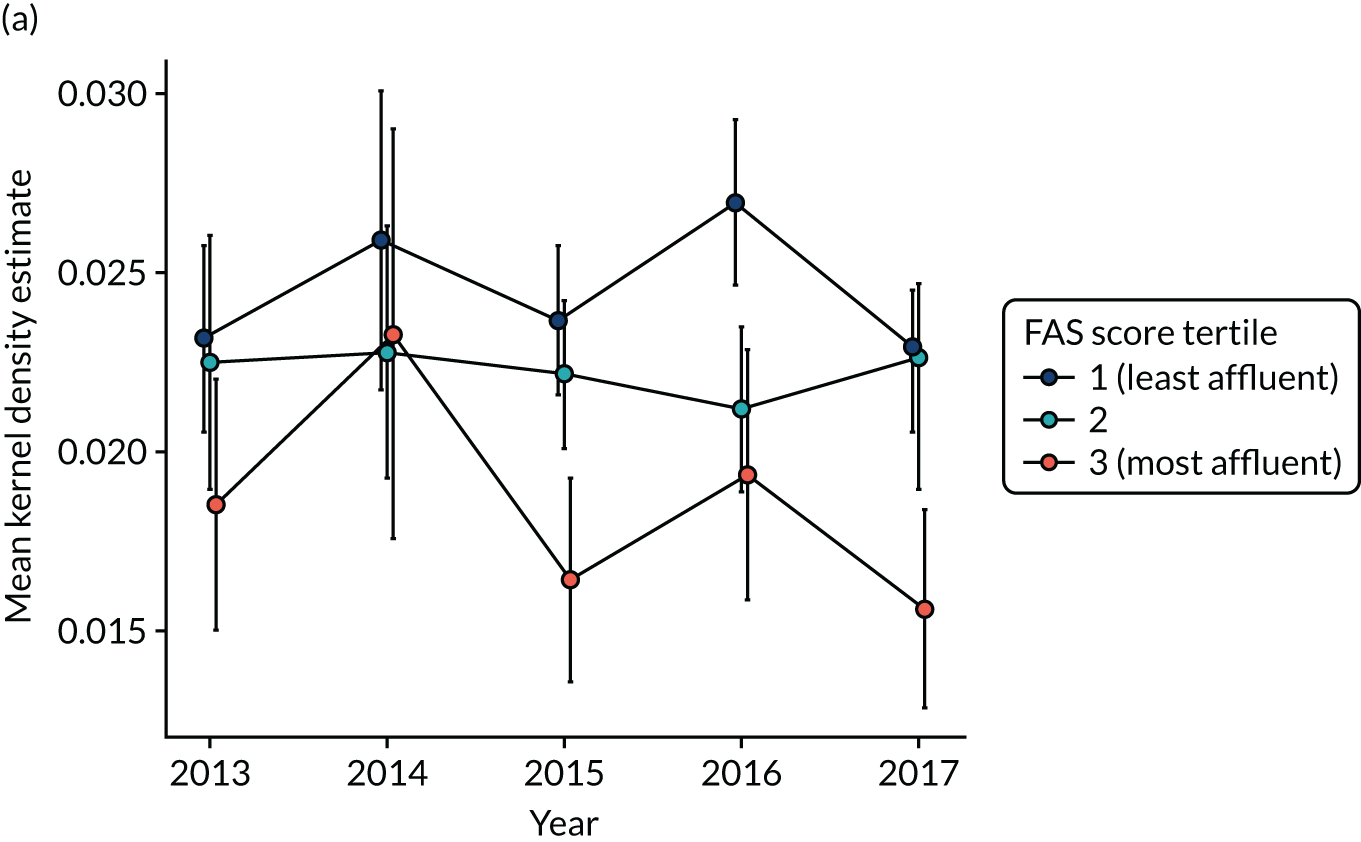

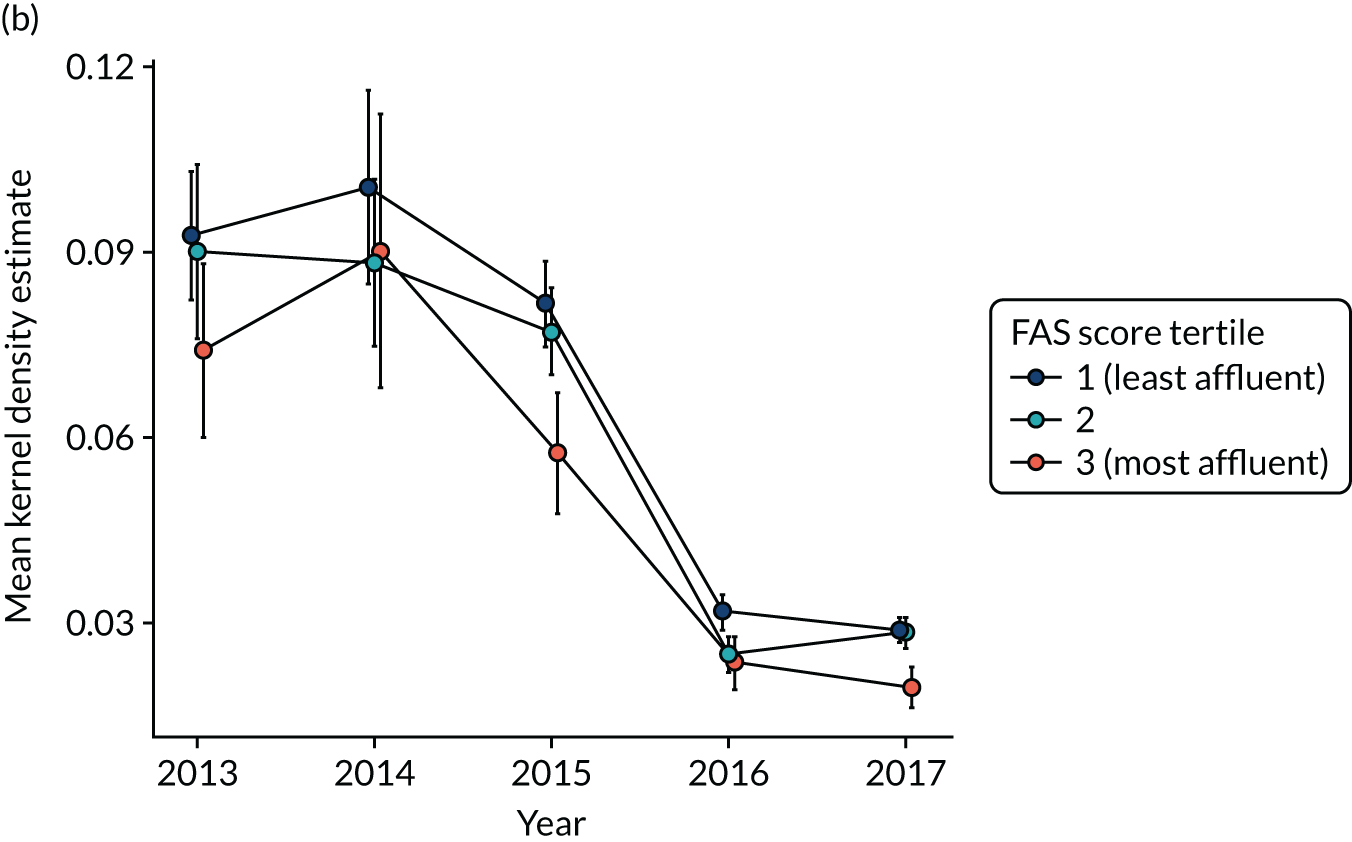

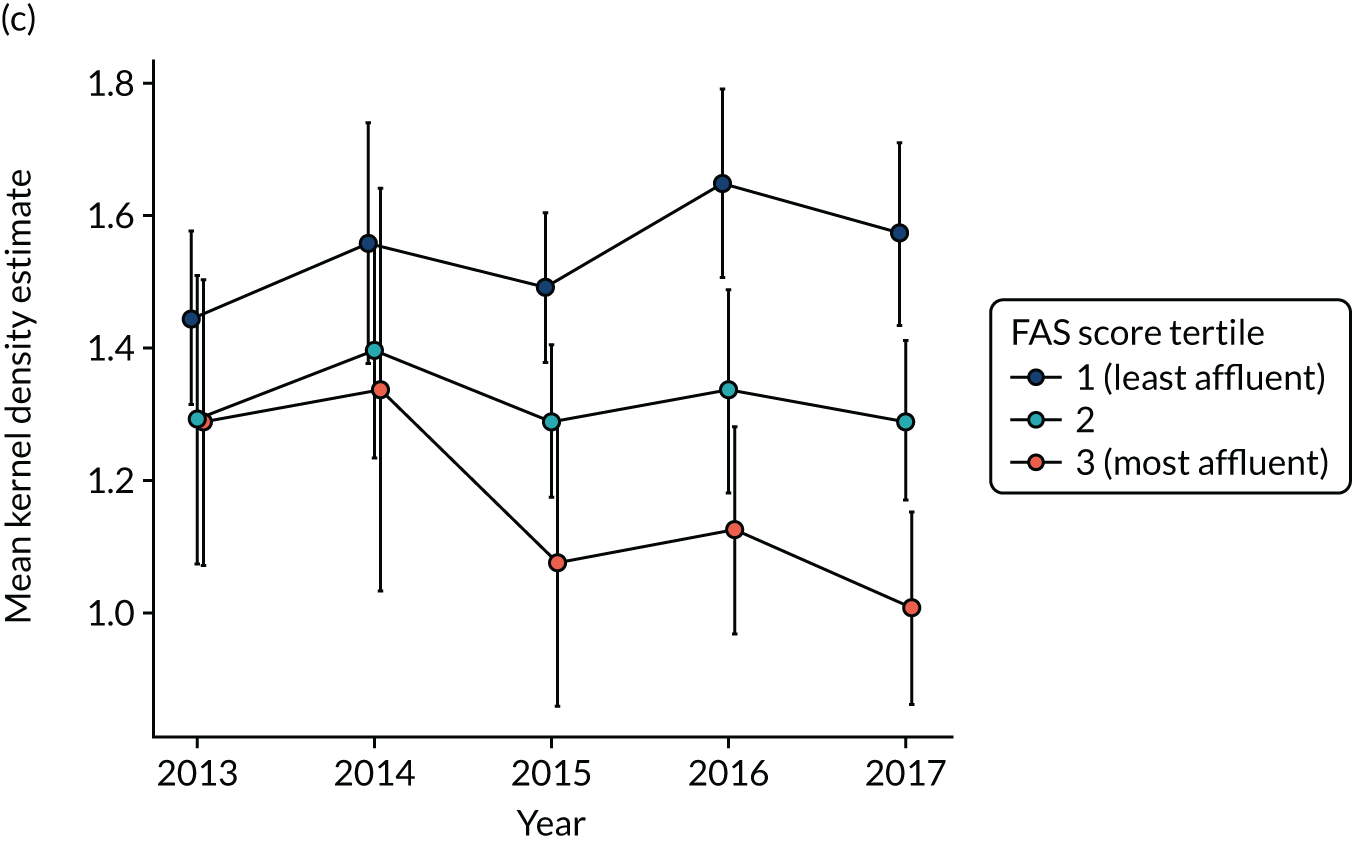

Has there been a change in the national availability of tobacco products in Scotland between 2012 and 2017?

-

To what extent do changes in the national availability of tobacco products vary between local authorities and by area-level indicators of socioeconomic deprivation and urban/rural status?

-

What are the implications of these changes, at both a national and a local level, for social inequalities?

In Chapter 6 we examine the impact of the POS legislation on young people’s brand awareness, perceived accessibility of tobacco and pro-smoking attitudes. The questions addressed are:

-

What was the relationship between POS displays of cigarettes and brand awareness prior to the introduction of the POS legislation in 2013?

-

How did brand awareness change after the introduction of the partial and comprehensive POS bans?

-

What were the trends in perceived tobacco accessibility, pro-smoking attitudes and pro-smoking norms between 2013 and 2017?

-

To what extent did perceived tobacco accessibility, pro-smoking attitudes and pro-smoking norms change after the introduction of the partial and comprehensive POS bans?

-

Did shop visit frequency influence the impact of the legislation on change in perceived tobacco accessibility?

-

Were there any changes in the perceived availability of black-market tobacco associated with the POS legislation pro-smoking attitudes and pro-smoking norms?

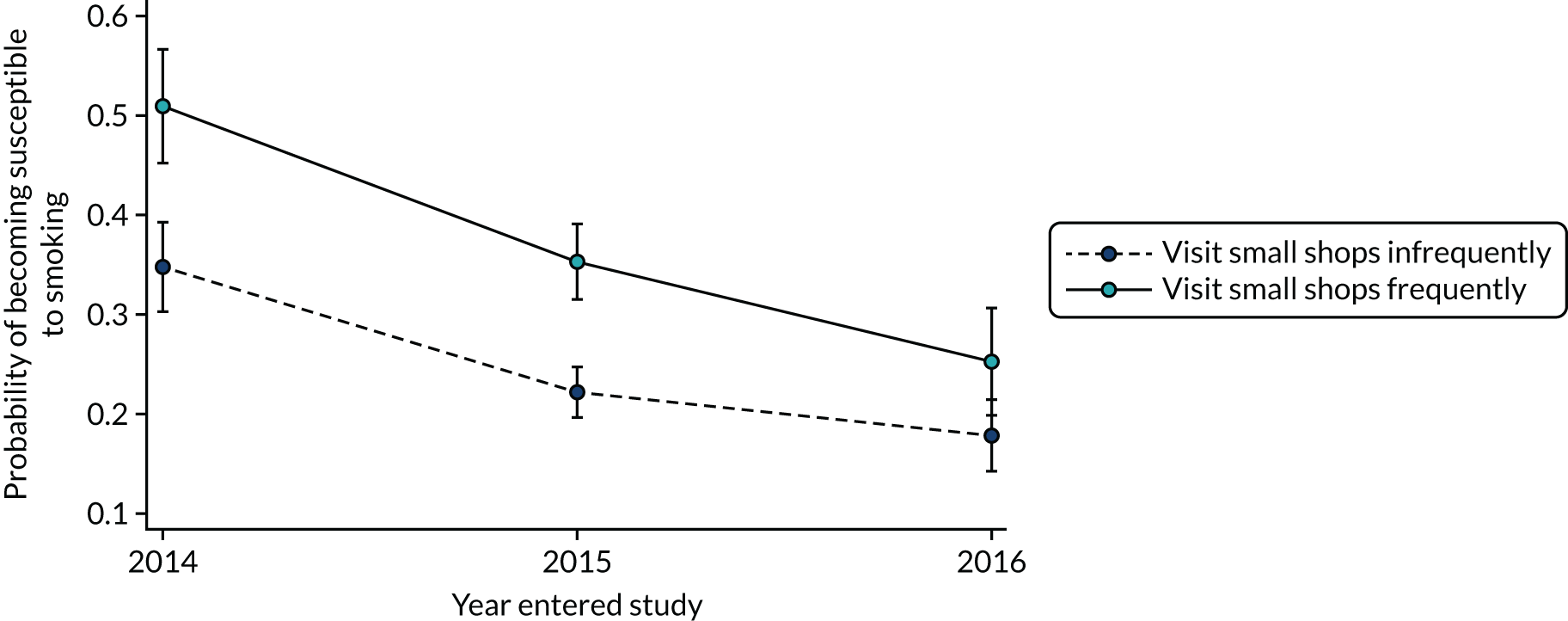

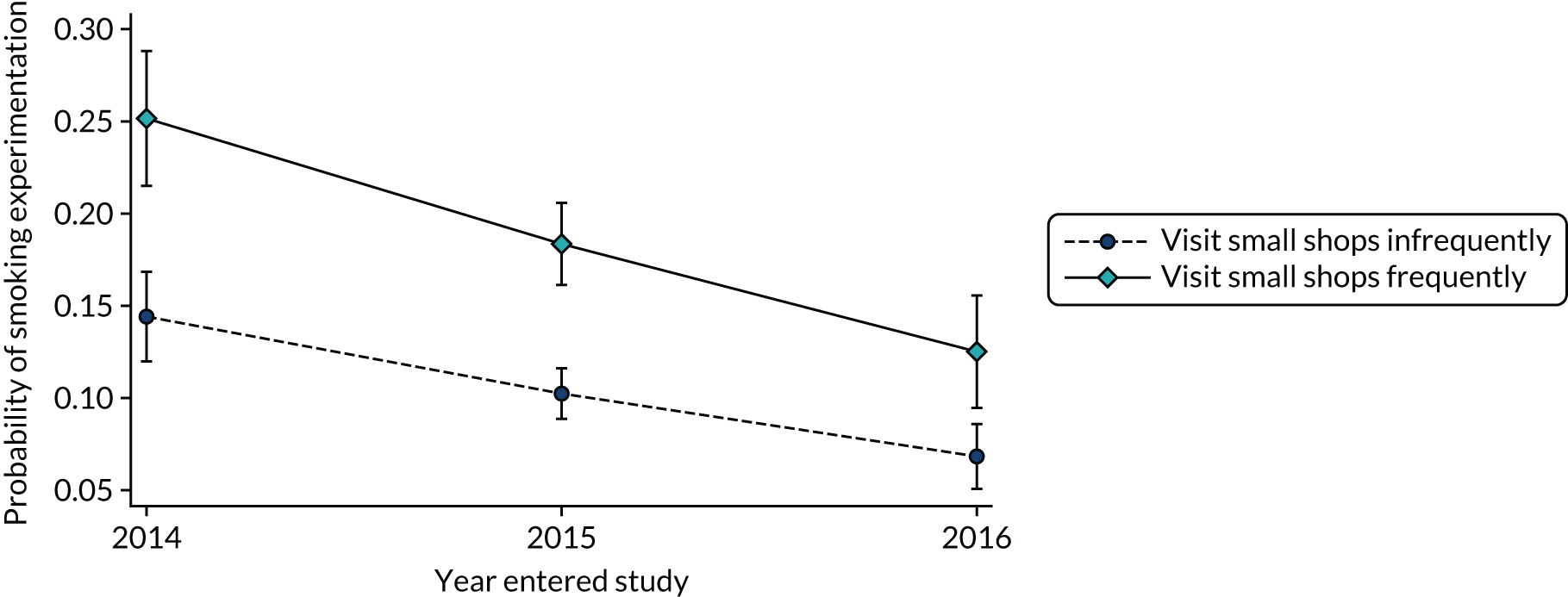

In Chapter 7 we focus on the smoking-related outcomes – perceived smoking prevalence, smoking susceptibility and smoking initiation – and assess their relationship with the implementation of the POS legislation. The questions we answer are:

-

Was the introduction of the partial and comprehensive POS display bans associated with a reduction in perceived youth and adult smoking prevalence?

-

Did shop visit frequency have an influence on these associations?

-

Was the introduction of comprehensive POS legislation associated with a reduction in smoking susceptibility in young people?

-

Did shop visit frequency influence the association between introduction of comprehensive POS legislation and smoking susceptibility?

-

Was the introduction of the comprehensive POS legislation associated with a reduction in the risk of smoking initiation in young people?

-

Did shop visit frequency influence the association between POS legislation and risk of smoking initiation?

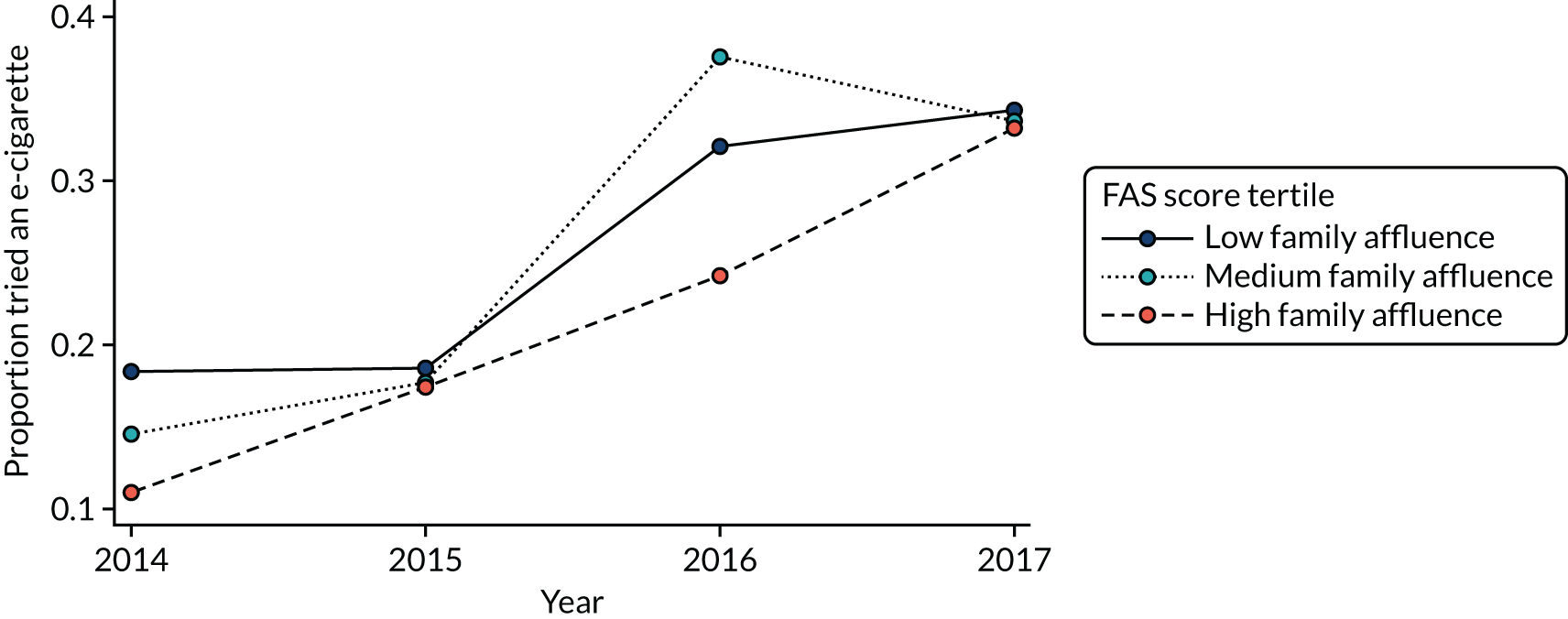

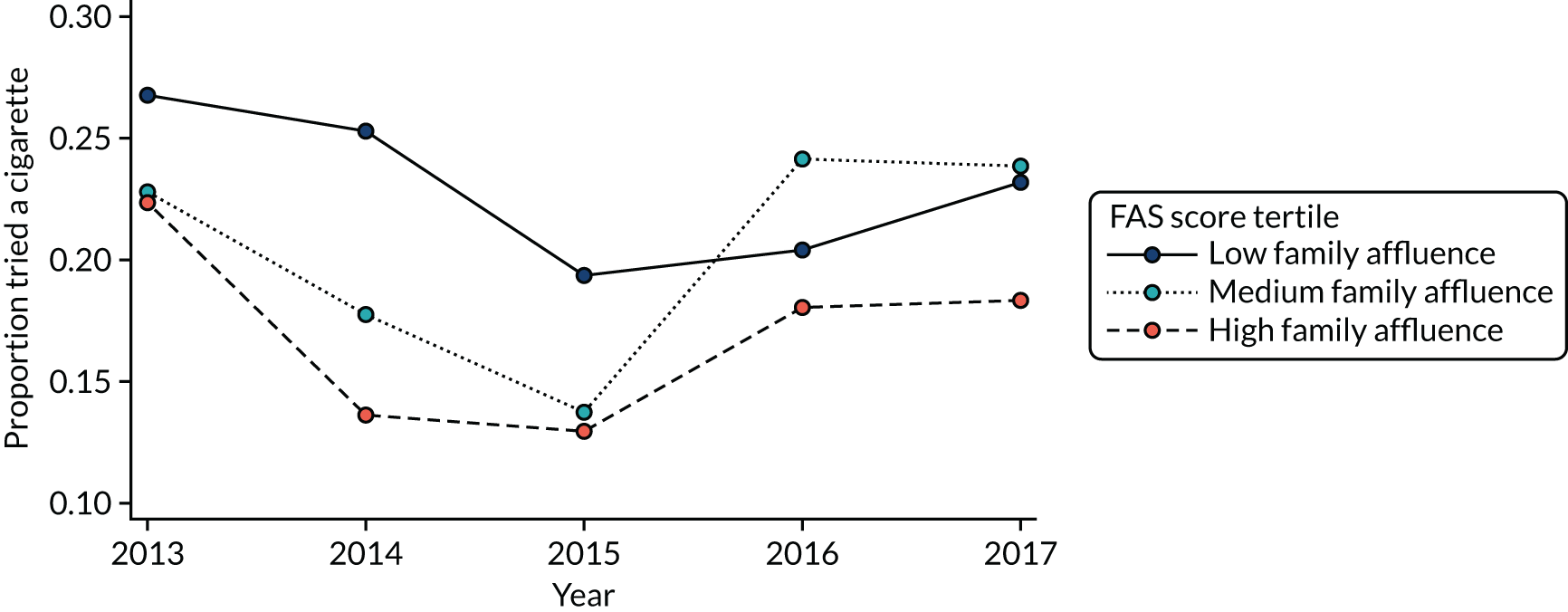

In the last of our outcome chapters, Chapter 8, we consider the impact of the increase in marketing and use of e-cigarettes and the introduction of standardised packaging, and answer the following questions:

-

What are the patterns and trends in e-cigarette use among young people aged 12–17 years?

-

What are the influences on developing social norms among adolescents around e-cigarettes and their use?

-

Is there a relationship between exposure to e-cigarette promotions and e-cigarette use among young people aged 12–17 years?

-

Is there a relationship between e-cigarette use and future smoking initiation in never-smokers aged 12–17 years?

-

What is the level of awareness of standardised packs in young people aged 12–17 years?

-

What are young people’s reactions to the new standardised packs and pictorial health warnings?

Finally, in Chapter 9 we bring together and integrate the findings from across the study components and discuss them in the context of what is already known about the impact of legislation that bans tobacco displays at POS. We then go on to consider the strengths and weaknesses of the study and to consider the implications for future tobacco control policy and research.

Chapter 2 Study design

Parts of this chapter have been adapted from the protocol for the study by Haw et al. 1 © 2014 Haw et al. ; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly credited. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Setting

The study was conducted in four communities on mainland Scotland, UK.

Study design

We regarded the Scottish POS legislation as a complex intervention as it was intended to act on a variety of targets at both the community and the individual level and to have multiple outcomes in the retail environment both among young people and in the community. 60 The legislation was rolled out simultaneously across all areas of Scotland on the same day; hence an experimental design, such as a randomised controlled trial, to evaluate the legislation was not possible. Instead, we conducted a longitudinal study in four purposively selected communities using a multimodal before-and-after design and mixed methods to collect data. 61 Mixed methods were chosen to collect data as this allowed us to collect a range of quantitative and qualitative data and thus answer a much broader range of questions than would otherwise have been possible. This was necessary to make a comprehensive assessment of the effects of the POS legislation in the retail environment and on young people. The collection of qualitative data from both young people and tobacco retailers was intended to provide important contextual information with which to interpret some of the findings on outcomes.

For the purposes of the study, ‘community’ was defined as the catchment areas of the secondary schools selected for study. Schools were purposively selected according to set criteria. Candidate schools were initially identified from those in the central belt of Scotland that had a school enrolment of > 1000 (about 46% of Scottish secondary schools fell into this category at the start of the study), were non-denominational and had an ethnic minority population of < 10%. An upper limit was placed on schools’ ethnic minority population because in Scotland ethnic minority pupils represent only 4% of the total Scottish secondary school population. 62

Schools were then classified by level of social deprivation using the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation (SIMD). 63 The estimate was based on the mean (population-weighted) of the deprivation scores for the data zones (a small-area statistical geography) that fell within the school catchment areas. The schools were also classified by level of urbanisation using the Scottish Government Urban/Rural Classification, which combines measures of population and accessibility64 to give six categories of urbanisation: large urban, other urban, accessible small town, remote small town, accessible rural areas and remote rural areas. In total, 61 schools met the size (pupil roll of > 1000) and ethnicity (< 10% non-white) criteria. Eight were then shortlisted that best met the deprivation (high vs. medium to low) and urbanisation (large urban vs. other urban/small town) criteria, as well as giving a reasonable spread within the central belt of Scotland. The team selected four first-choice schools and four second-choice schools. The final school sample consisted of three first-choice schools and one second-choice school. The fourth first-choice school declined to participate in the study because of pressure of work. Table 1 gives the characteristics of the catchment areas served by the study schools.

| Community characteristic | Study communities (urban/rural classification) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1 (large urban) | C2 (large urban) | C3a (small town) | C4 (small town) | |

| Socioeconomic deprivation | High | Medium/low | High | Medium/low |

| Population 10–19 years old in 2013 | 4817 | 3427 | 2307 | 2226 |

| Geographic area (km2) | 10.0 | 21.17 | 19.06 | 910.57 |

There were four main components to the study:

-

mapping and spatial analysis of the location and density of tobacco retail outlets

-

marketing audits of tobacco retail outlets most used by young people, comprising observational audits in the study communities, and interviews with a panel of retailers in four matched communities

-

cross-sectional school surveys of pupils, with embedded pupil cohorts

-

focus group discussions with purposive samples of pupils.

Data platform and measures

In each study community, data for all components were collected annually for 5 years between 2013 and 2017. With the exception of the marketing audits (see Tobacco advertising and marketing audits of tobacco retail outlets), data collection took place between February and March of each year. Data collected in 2013 prior to the implementation of a partial POS display legislation in large supermarkets on 29 April that year formed the first baseline, with follow-up data collected between February and April in 2014 and 2015.

Data collected in 2015 also provided a second baseline against which to assess the impact of the implementation of the POS legislation in smaller retailers on 6 April 2015. Two further years of follow-up data were collected in 2016 and 2017. Table 2 shows the timeline of the study and when data collection took place.

| Year and quarter | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | ||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| Partial POS display ban in place | Comprehensive POS display ban in place | |||||||||||||||||||

| Mapping and spatial analysis | W1 BP | W2: FP | W3: FP/BC | W4: FC | W5: FC | |||||||||||||||

| Marketing audit | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Observational panel | W1: BP | W1aa | W2: FP | W3: FP/BC | W3a:b FC | W4: FC | W5: FC | |||||||||||||

| Retailer panelc | W1 | W2 | W3 | W4 | W5 | |||||||||||||||

| School survey | W1: BP | W2: FP | W3: FP/BC | W4: FC | W5: FC | |||||||||||||||

| Focus groups | W1: BP | W2: FP | W3: FP/BC | W4: FC | W5: FC | |||||||||||||||

Outcome measures

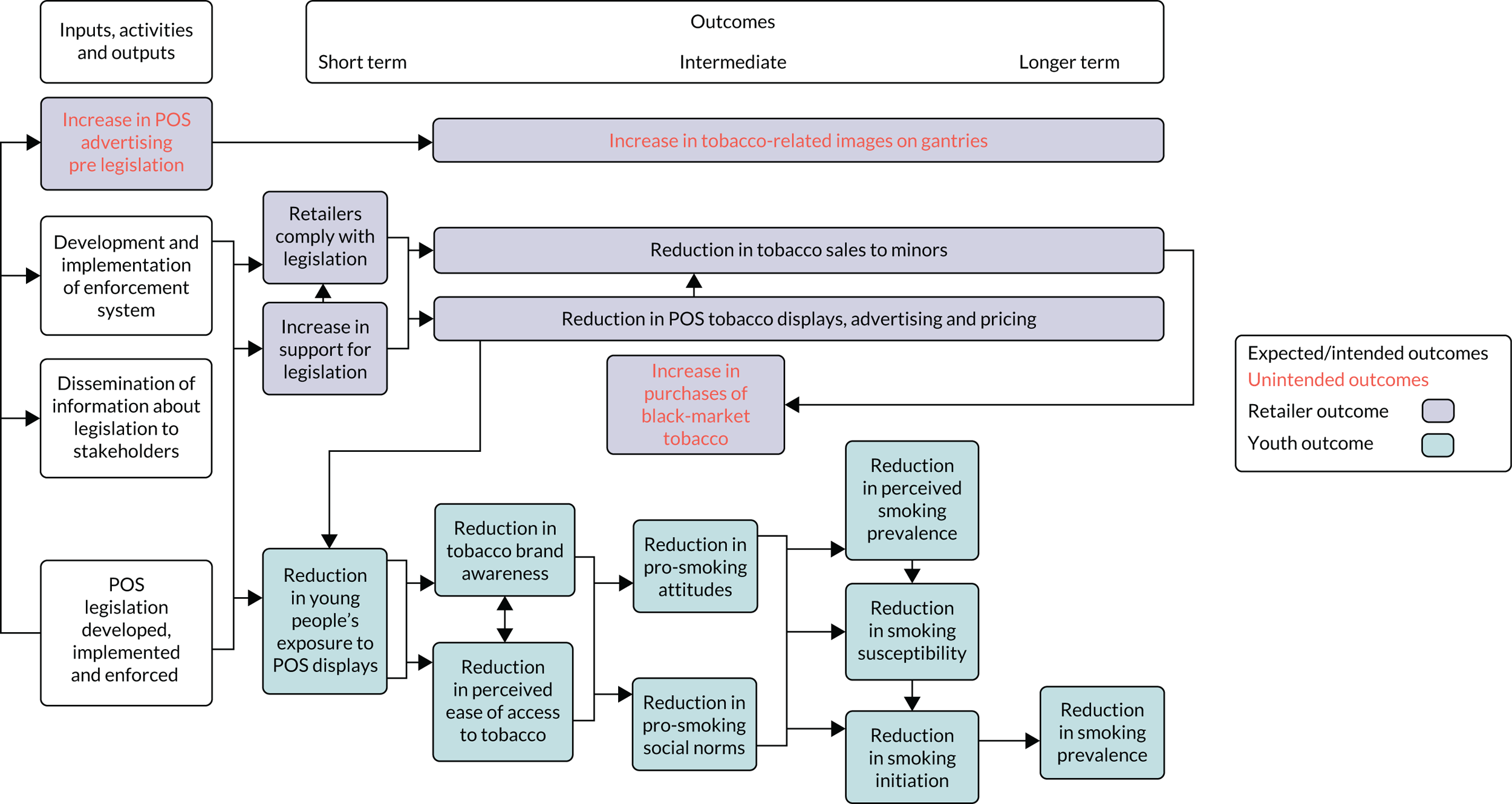

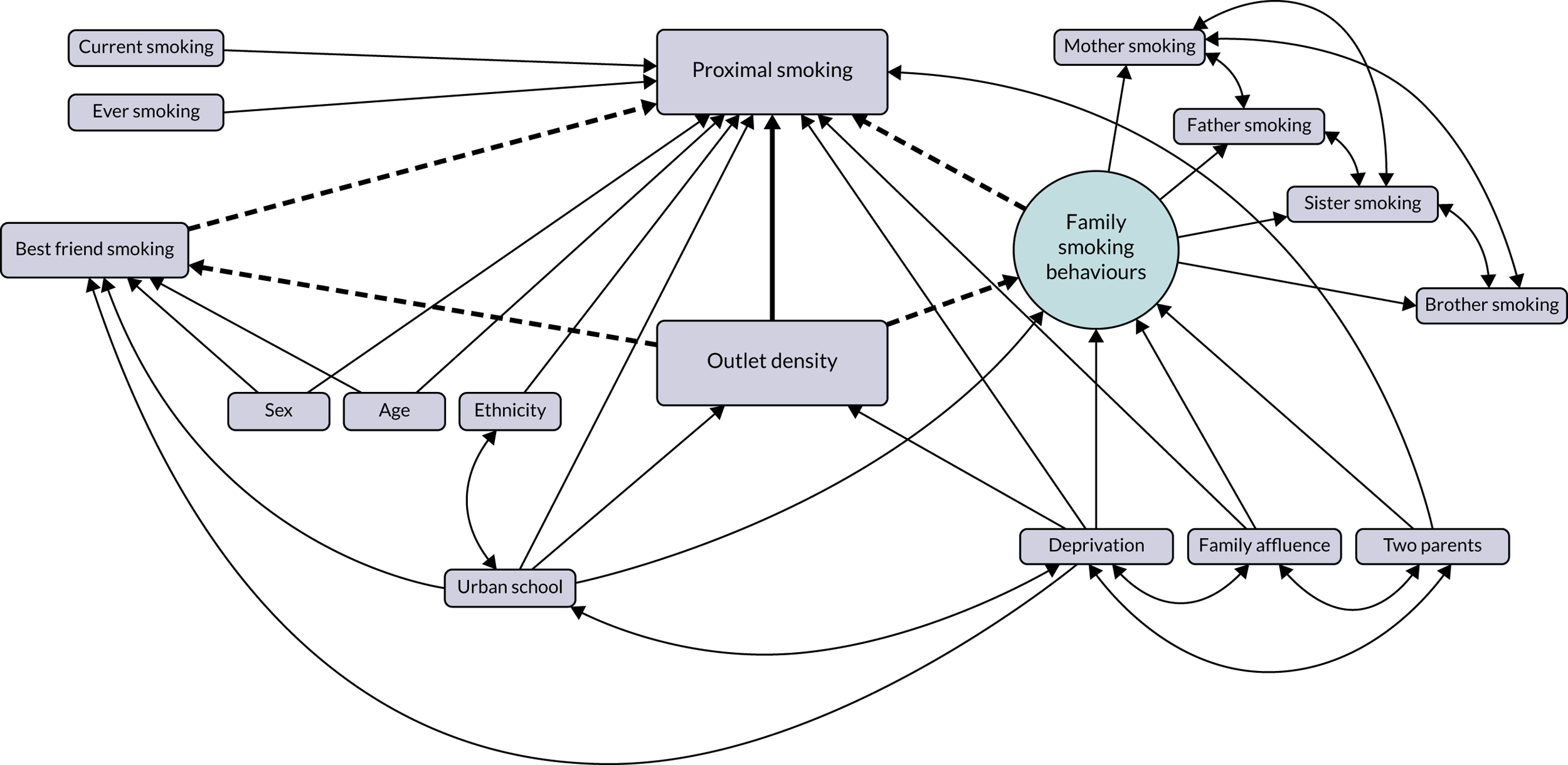

A logic model was developed to provide a framework for the evaluation (Figure 1). It proposed pathways that linked together the implementation of the POS legislation with a set of short-term, intermediate and longer-term outcomes, which were to be assessed by the four study components. Rather than defining primary and secondary outcomes, we set out a time frame within which we believed the outcomes would occur. We classified outcomes as short term if they were likely to occur within 3 months of implementation of the legislation, as intermediate if they were likely to occur up to 1 year post implementation and as longer term if they were likely to occur more than 1 year post implementation. Short-term outcomes of interest were prevalence of POS advertising in tobacco retail outlets (assessed by components 1 and 2) and exposure to POS advertising (assessed by components 1, 2 and 3). Intermediate outcomes of most interest were awareness of POS advertising, tobacco brand awareness, perceived accessibility of cigarettes, perceived youth smoking prevalence, pro-smoking norms and pro-tobacco attitudes. Long-term outcomes of most interest were smoking susceptibility, smoking initiation and prevalence of smoking.

FIGURE 1.

Logic model of activities, outputs and outcomes associated with POS legislation.

Data obtained from the retailer panel interviews (component 2) and focus group discussions with young people (component 4) provided contextual qualitative data facilitating the interpretation of findings about outcomes. In addition to the outcomes outlined above, the study design enabled us to identify, to a limited extent, any unintended or adverse consequences associated with the legislation. We hypothesised that if the ban on tobacco displays reduced perceived accessibility, then smokers (including young smokers) might turn to other sources of tobacco, including the black market. Retailers or the tobacco industry might also increase tobacco promotions before the new regulations were implemented or might develop strategies to circumvent them. Indeed, this was observed in Ireland, where, following implementation of POS legislation, images of tobacco-related paraphernalia such as cigarette lighters regularly appear on the blank covers of the cigarette gantries. 20

Data collection

Mapping and spatial analysis of the location and density of tobacco retail outlets

For each year of the study, geographical data on the tobacco retailers were collected, geocoded and integrated into a Geographical Information System. Data (including address and full postcode) for all tobacco retailers in the study communities were extracted from the Register of Tobacco and Nicotine Vapour Product Retailers65 and mapped at baseline (January 2013) and then annually to 2017. These data were then verified through field visits during which every street in the four communities was inspected. The community-level data enabled the monitoring of the number and rate (per population) of tobacco outlets in each wave. In addition, it provided a verified list of outlets to be visited and observed as part of the observational audit of all retailers in each community (see Tobacco advertising and marketing audits of tobacco retail outlets). This in turn ensured the accuracy of the number and rate per head of population of outlets selling tobacco in each community during the study period.

Baseline tobacco outlet data were geocoded using Code-Point® [Ordnance Survey Limited, Southampton, UK; www.ordnancesurvey.co.uk/business-government/products/code-point (accessed 16 December 2019)] to provide geographical co-ordinates and then integrated into the Geographical Information System. These data were combined with data from the marketing audits (see Tobacco advertising and marketing audits of tobacco retail outlets) and analysed to provide an assessment of changes in tobacco retailing and advertising over the study period. In the analysis, the focus was restricted to large supermarkets and small retailers most likely to sell cigarettes to young people, including off-licences; confectioners, tobacconists and newsagents (CTN); small grocers (including licensed); petrol stations; and fish and chip shops. In the final stage, the outlet data were integrated with the audit data to provide information on exposure to tobacco retailing (combining availability with visibility of tobacco products).

National-level data were also extracted from the Register of Tobacco and Nicotine Vapour Product Retailers65 and used to assess changes in the availability of tobacco products across Scotland. This information provided broader insights into how the availability changed during the study period in response to new tobacco control policies, sector-wide interventions and/or the economic climate. The national availability of tobacco products was compared across local authorities and across neighbourhoods, stratified by a measure of area-level deprivation and by urban/rural status.

Full details of all methods are provided in Chapter 5.

Tobacco advertising and marketing audits of tobacco retail outlets

Some material in this section has been adapted from Stead et al. 10 with permission from The Royal Society for Public Health. © 2016 The Authors. Published by Elsevier Ltd on behalf of The Royal Society for Public Health. This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

As with the mapping and spatial analysis component, the tobacco marketing audit focused on large supermarkets and small shops, including off-licences, CTN, small grocers (including licensed), petrol stations, and fish and chip shops.

There were two parts to this study component.

Observational audit

The observational audit included all tobacco retail outlets in the study communities that fell into one of the six categories identified above. Baseline data (February to March 2013) were collected by experienced researchers using an audit tool informed by previous studies of tobacco exposure. 14,66,67 The researchers visited all outlets in pairs to record brief information about tobacco product availability and display. This included data on the visibility and placement of tobacco products in the store; whether or not and how tobacco products were displayed; whether or not and how tobacco products were actively promoted for sale (both externally and internally); branding of display units and pack sizes available; the most prominent brand, if any; the communication and visibility of pricing information; and tobacco control signage.

The audits were discreet and did not require retailer co-operation, and data collection was facilitated by a token purchase made in each retail outlet to gain access to the tobacco counter. Observers also devised memory aides and techniques to accurately recall and unobtrusively record marketing and advertising information. Mobile phones were used to record key numeric data, and audit protocols were completed away from the retail sites immediately following each observation, with observers comparing notes to verify key characteristics. Where inconsistencies or gaps emerged, these were addressed by an immediate follow-up visit to the study outlet. For most items, observers simply noted the presence or absence of particular features.

The observational audit was repeated immediately after the implementation of the POS legislation in large supermarkets in April 2013 and in small shops in April 2015. As well as assessing exposure, this audit assessed degree of compliance with both the current and the new POS legislation, along with any evidence of strategies used to circumvent the legislation. The observational audit was repeated annually until 2017.

The data collected were used to develop a metric for POS exposure, with measures developed to assess location, size, proximity and visibility of displays from key reference points such as till points and entrance areas. Where appropriate, measures were developed with the aid of visual prompts, for example to indicate the relative visibility of the display. We anticipated that POS exposure would be affected by a number of factors, including increased industry activity, particularly in the lead-up to full implementation in 2015, and retailer non-compliance (e.g. delays in removing gantries or gantries being reused for other non-tobacco products) or poor implementation (e.g. leaving sales shutters open after a sale is made).

Retailer panel interviews

A panel of 24 retailers (representing the main retail types) was recruited from four communities matched to our four main study areas. The communities selected were those that were in our original shortlist of eight communities (see Study design) but were not selected for the main study. They were adjacent to their matched main study areas, but geographically discrete, and had a similar population profile. We chose not to recruit the retailer panel from the main study communities in order to minimise the likelihood that the identities of the study areas would be made public and thereby compromise the integrity of the study. Large supermarkets were excluded from the panel sample for the same reason.

The retail panel sample was purposively selected to represent the range of small stores (CTN, convenience stores, petrol stations and off-licences) found in the main study areas using a combination of making contact using details provided in the Register of Tobacco and Nicotine Vapour Product Retailers65 and cold-calling at the retail premises.

The decision was taken not to recruit the managers of large supermarkets to the retailer panel, as contacting their head offices would risk disclosing the study areas, which again might potentially compromise the integrity of the study. Managers were, however, included in the discreet audit, which indicated that supermarkets made up only 10% of the tobacco retail outlets in the study communities and therefore represented a relatively small subgroup of tobacco retailers.

As in the observational audit, but later in the year (between July and August), the retail panel outlets were visited annually to collect observational data on POS advertising and marketing strategies. An adapted version of the audit tool was used, as described above. In addition to the in-store observations, in-depth interviews were conducted with retail managers/owners of each outlet. These were audio-recorded and again were repeated annually to explore views and experiences before, during and after the implementation of the POS ban and to assess changes from the retailers’ perspective. This included exploring their experiences of preparing to and eventually implementing the ban, and identifying any problems that arose and how retailers dealt with these. Additionally, the data enabled us to understand how the sales process changed and to examine how customers dealt with a new procedure for asking for cigarettes. Data governance required that the identity of all retail sites audited, and of all retailer panel members interviewed, remain confidential.

Cross-sectional school survey of school children with embedded cohorts

Survey design

The school survey had a repeat cross-sectional design with embedded cohorts, with data collection at baseline and longitudinal follow-up for 4 years in each community. Details of the sample size calculation are given in Appendix 1. We hypothesised that the implementation of a partial ban on POS adverting (larger retailers only) would have only a small impact on young people’s outcomes. Therefore, the school surveys conducted in February and March 2013 and 2014 included only young people in Secondary 2 (i.e. 13-year-olds) and Secondary 4 (i.e. 15-year-olds). To assess the impact of the implementation of POS legislation on smaller retailers in 2015, a second baseline survey was conducted with all pupils (Secondary 1 to Secondary 6) (i.e. aged 12–17 years) from study schools in February and March 2015, with repeat surveys conducted for 2 years post implementation in smaller retail outlets. From here on, school years will be referred to as S1, S2, and so on.

The smaller samples in 2013 and 2014 helped to minimise both the resource requirements of the study and disruption to the schools participating in the surveys, while at the same time allowing the follow-up of different cohorts across the school years. Table 3 gives details of the embedded cohorts and the phases of the legislation.

| Survey year | S1 | S2 | S3 | S4 | S5 | S6 | Phase of legislation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 | Baseline pre implementation in large supermarkets | ||||||

| 2014 | Post implementation in large supermarkets (partial POS ban) | ||||||

| 2015 | Post implementation in large supermarkets (partial POS ban) | ||||||

| Pre implementation in small shops | |||||||

| 2016 | Post implementation in small shops (comprehensive POS ban) | ||||||

| 2017 | Post implementation in small shops (comprehensive POS ban) |

Pupil questionnaire

Data were collected using an anonymous self-complete questionnaire administered by class teachers under exam conditions. The questionnaire included questions on sociodemographics; pupils’ smoking behaviours and attitudes towards tobacco use, as well as families’ and peers’ smoking behaviours and attitudes; access to tobacco products; brand awareness; frequency of visits to large supermarkets and smaller retailers; and exposure to tobacco marketing and advertising. In response to the changing retail and sociocultural landscape, questions on patterns of e-cigarette use were included from 2014 onwards, questions on exposure to e-cigarette marketing were included from 2015 onwards and questions on awareness of standardised packs were included in 2017.

Validation exercises were conducted during questionnaire development and throughout the study period. Focus groups and cognitive interviews were conducted to validate new questions. A total of five pilot studies were conducted to finalise the questionnaire: three before the baseline in 2013, one in 2014 and one in 2016. The pilots were designed to assess the appropriateness of question items and time to complete the questionnaire. The number of questions varied from 59 to 66 across the survey waves and the average time taken to complete the questionnaire was 20–35 minutes.

An additional School Level Questionnaire intended for the head teacher or deputy head teacher was used to gather information on the characteristics, resources and health-promoting aspects of all the participating schools. However, it proved not possible to control how the data were compiled, and the consistency and quality of information provided varied considerably across years. We therefore decided not to use any of these data in our analyses; however, the details are presented in Report Supplementary Material 1.

Details of the pupil survey administration and images of standardised packs used in the school survey are given in Report Supplementary Material 1.

Response rates

Response rates to the survey were high across all survey years and ranged from 86% to 87%. Full details of response rates by school are given in Appendix 2. A total of 6612 pupils completed the surveys over the 5 years, and 14,344 completed questionnaires were collected. A total of 4513 pupils (68.3%) completed questionnaires on more than one occasion (Table 4).

| Surveys completed (N = 6612) | n (%) |

|---|---|

| 1 | 2099 (31.7) |

| 2 | 1944 (29.4) |

| 3 | 1919 (29.0) |

| 4 | 650 (9.8) |

Focus group interviews with purposive samples of pupils

Sixteen focus groups were conducted every year with S2 and S4 pupils in each study community. All were single-sex groups of between 3 and 9 participants, and they lasted between 30 and 50 minutes. Focus group participants were recruited with the help of teachers in the study schools so that they included young people who were smokers or had regular contact with smoking, such as having friends who smoke or living in a home with smoker(s). The aim was to include young people who were most at risk of becoming adult smokers. These recruitment methods have been used successfully in a recent study by one of the research team (AA) on young people’s sources of cigarettes. 68 The focus groups were repeated annually until 2017 and provided more detailed and nuanced contextual information and insights into young people’s experiences and perceptions.

In order that the pupils’ discussions did not influence their questionnaire responses, the focus groups were conducted 1–2 weeks after the school survey and were audio-recorded with the permission of group participants. The topic guide included general discussion about the community; leisure time activities; local smoking behaviours and cultures; access to tobacco products including direct, indirect/proxy and black-market; awareness of and views on tobacco promotion, including POS, other direct marketing methods, packaging, branding; awareness and perceptions of the impact of the legislation; and views about preventing youth smoking.

Table 5 shows the number of focus groups achieved and the number of participants involved.

| Sample size | Year | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | |

| Number of focus groups | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 |

| Number of participants | 86 | 72 | 63 | 79 | 82 |

Data analysis

A range of quantitative and qualitative analytical strategies were used. Details of the approaches taken in the development of the visibility tool are given in Chapter 5, Point-of-sale tobacco visibility tool and details of the mapping study are given in Chapter 5, Changes in the availability and visibility of tobacco products between 2012 and 2017, Methods. A range of approaches was used in the schools survey data and an overview is given below.

School survey data analysis

As previously described, the school survey sample was mixed longitudinal and cross-sectional in design (see Cross-sectional school survey of school children with embedded cohorts, Survey design). That is, some young people took part in the survey only once, whereas others were followed up annually for 3 or 4 years consecutively. The DISPLAY study examined a range of outcomes. The analysis approach by outcome type is described below.

Incident outcomes

Outcomes that could be described as one-off irreversible events were analysed as time-to-event data in a survival analysis. This category includes outcomes such as a ‘never-smoking’ young person becoming susceptible to smoking or a never-smoker progressing to trying smoking. Although it would be possible to change in the opposite direction (from being susceptible to non-susceptible), we followed the idea of a staged progression towards becoming a regular smoker. Becoming susceptible and having tried smoking are acknowledged risk factors for future progression to regular smoking and, as such, represent distinct thresholds. In a sample that is mostly longitudinal (i.e. the majority of young people take part in multiple surveys), there would be no point in repeatedly asking the same young people whether or not they have ever tried smoking. This is because we would be able to detect change only in those who had never smoked at baseline. Therefore, the analysis would reduce to a discrete time survival analysis in baseline never-smokers. Thus, we conducted a survival analysis and compared the hazard for the event of interest before the POS ban with the hazard after.

Prevalence outcomes

These outcomes described the proportion of the sample meeting some criteria in a given survey wave, for example the proportions of pupils who thought that they could easily buy tobacco, that smoking was acceptable and that their friends thought that smoking was acceptable. These were not theorised as unidirectional changes because new legislation could theoretically make young people believe that cigarettes would be harder to obtain or that smoking was less acceptable. The main question related to these outcomes concerned whether or not the POS display ban had changed the proportion of young people who held these views. Therefore, we used a repeated cross-sectional approach but focused on only two school year groups, S2 and S4, as these years had data for 2013 and 2014. Using only two school years minimised the repeated-measures element in the data; however, it did not completely eliminate it. To account for the remaining non-independence among the measurements, we used generalised estimating equations for the analysis. Generalised estimating equations produce marginal or population-averaged estimates appropriately adjusted for correlated outcomes. Population-averaged estimates are appropriate for the research question, which focused on how the prevalence of these attitudes in young people was influenced by the POS ban.

Continuous outcomes

Outcomes such as estimated smoking prevalence were analysed as continuous measures. Estimated smoking prevalence, that is, asking young people what percentage of people they think smoke, measures social norms as it reflects how common young people believe smoking to be. We would expect that this could increase or decrease in response to policy. Therefore, we included the full longitudinal and cross-sectional sample. We were interested in how the ban affected individual young people’s estimates of smoking prevalence; therefore, we used a multilevel model with a random intercept for individuals. This model produces subject-specific parameter estimates.

Missing data

In common with most longitudinal samples, subject attrition differentially affected male young people, young people from lower socioeconomic groups and young people with more smokers in their social circle. The data were tested for missing completely at random by conducting multiple logistic regressions on the ‘missingness’ of each variable using all of the other variables in the model. The proportion of significant results suggested that the hypothesis of missing completely at random should be rejected. ‘Missingness’ in the recording of smoking status was associated with the observed variables ‘age’ and ‘low family affluence’ and therefore likely to be missing at random. As there was information in the observed data that predicted ‘missingness’, the data were assumed to be missing at random. 69

Multiple imputation by chained equations was used where there was concern about numbers of missing data (e.g. for e-cigarette longitudinal analyses and the smoking prevalence models) so that the effect of missing data on the parameter estimates could be assessed. All dependent and independent variables in the estimation models were included in the imputation model with the following auxiliary variables: mother in employment, father in employment, entitlement to free school meals and whether or not lives with both parents. One hundred imputed data sets were produced with a burn-in of 10. Trace plots were inspected to confirm the stationarity of each chain by the end of the specified burn-in period. This results in valid statistical inferences that properly reflect the uncertainty due to missing data. 70 Few differences were found between the imputed and the complete-case analysis results.

Analyses were conducted in IBM SPSS Statistics versions 21 and 23 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) or in Stata® version 15 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Project management

The University of Stirling was the sponsor for the study, with the University of St Andrews, the University of Edinburgh and the Scottish Centre for Social Research (ScotCen) acting as subcontractors. A Steering Committee was set up at the start of the project with representatives from the Scottish Government, NHS Health Scotland and ASH Scotland and experts in tobacco control and youth behaviours. The Steering Committee met at the start of the project and then annually to review the progress of the study. A list of Steering Group members is given in Report Supplementary Material 1. In addition, we appointed a Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC). Ordinarily, the appointment of a DMEC is limited to clinical trials; however, there was concern that the DISPLAY study might be subject to freedom of information inquiries from the tobacco industry or from organisations linked to the tobacco industry, and so advice on procedures that should be put in place was sought. The DMEC met on three occasions during the study. A list of DMEC members is given in Report Supplementary Material 1.

Service users and public involvement

With the exception of the schools involved in the study, there was no service user or public involvement either in the development of the study protocol or during data collection between 2013 and 2017. Such involvement is usually highly desirable, if not essential, in most studies. However, as noted previously, there was considerable concern that if the identity of the study communities became widely known, this might compromise the integrity of the study. This was particularly the case with the marketing audit, as normal retailer behaviour might have been disrupted had the study or the researchers’ presence become known.

During the study, the research team responsible for the school survey kept in close contact with participating schools to ensure the smooth running of the surveys. In addition, annual meetings were held with head teachers and/or school representatives a few months before each wave of data collection to discuss planned procedures and iron out any problems. Following the completion of the study, the study schools are being consulted about what dissemination activity they would prefer. This is likely to take the form of bespoke data sets for schools to use with their pupils and a dissemination event to be held at each school.

To ensure co-ordination of all components of the study, a Research Co-ordination Group was set up. This was chaired by the lead applicant (SH), with at least one representative from each of the study component’s research teams attending each meeting. The Research Co-ordination Group met three or four times per year to ensure complete integration of the study components and to provide a vehicle for the detailed monitoring of the study’s progress, the development of a co-ordinated analytical strategy and the sharing of interim findings. Another function of the group was to make decisions about the feedback of interim findings to the Scottish Government.

Finally, a biweekly teleconference was held with the school survey, mapping study and audit teams, and study analysts from the third year of study onwards to co-ordinate data entry and data linkage and the analytical strategy for the quantitative data.

Ethics

Ethics approval was sought for each of the study components from the institutions leading on the individual study components, as follows.

Mapping and spatial analysis

Ethics approval for the mapping study was confirmed by the School of GeoSciences Ethics Committee, University of Edinburgh. No ethical issues were identified.

Marketing audit

The protocol for the marketing audit and retailer panel interviews was approved by the University of Stirling School of Management Research Ethics Committee. In relation to the discreet audit, we argued that conducting observational research without consent was in the public interest (the legislation was passed to protect the health of young people) and that disclosing the observational research would have risked jeopardising the whole study. The ethics application made it clear that all observations would be restricted to spaces readily accessible to members of the general public, that no retailer or premises could be identified, that no retailer or customer behaviour would be recorded and that researchers would use memory aids to enable them to record information after leaving the premises (i.e. no photographic records would be made). The approach taken in this study is consistent with accepted norms within the retail sector, where it is standard practice to collect information in store from rival chains. Similar precedents have also been set with regard to research studies involving test purchasing of age-restricted goods, where pre-notification would have confounding effects. As previously indicated, the study was not designed to assess brand-level or pricing effects and photographic data were not collected.

In line with ethics requirements, all sites and participants were assigned non-identifiable codes to maintain their anonymity. Identifiable data (e.g. participant names and premises names and addresses) were held in a separate database and were linked to electronic data files using these non-identifiable codes. Technical reports, presentations and publications ensured that no participants or retail premises could be identified. Appropriate measures were in place to ensure the safety of fieldworkers. These procedures have been developed and tested as part of other studies undertaken by the research team.

School survey

The survey research protocol was approved by the University of St Andrews School of Medicine Ethics Committee. In addition, research approval was obtained from all local authorities (for both first- and second-choice schools). The research team also made contact with all of relevant health boards to obtain ‘unofficial’ support and backing for the study. For each validation and pilot study, ethics approval was gained from the St Andrews School of Medicine Ethics Committee.

In all survey waves, parental opt-out consent was gained before survey completion. This is the standard consent procedure used in the majority of national school surveys and is believed to result in less biased samples in terms of pupil demographic characteristics and health behaviours. 71 Parents were given 2 weeks to decide whether or not to provide consent. Pupils were also given the opportunity to withdraw from the survey on the day of the survey.

Data were collected using the anonymous self-completed pupil questionnaire, which was administered by class teachers under exam conditions. Each pupil was given an envelope in which to place and seal the completed questionnaire. Therefore, teachers did not have access to the data provided by the pupils. In Scotland, all school pupils have a unique Scottish Candidate Number (SCN). This was linked to the questionnaire serial number. The SCN was used to link questionnaires completed in different years using a deterministic linkage process. The SCN and questionnaire serial numbers were stored on a secure server, separate from the questionnaire data. Data sets were shared with the research team without identifiers (date of birth and postcode); date of birth was converted to age, and postcode was converted to the SIMD quintile.

Focus group study

Ethics approval for the focus group interviews was obtained from the National Centre for Social Research (NatCen) Research Ethics Committee. This committee reviews research projects conducted by NatCen and ScotCen that are not subject to the committee’s approval, has a membership comprising senior NatCen staff, external research experts and external professional experts and is consistent with the requirements of the Economic and Social Research Council and Government Social Research Professional Guidance. Opt-out consent was sought from participants before they took part in the focus groups using the same approach as with the school surveys. At the start of each focus group, participants were assured that their anonymity would be maintained, and ground-rules were established about disclosure.

Chapter 3 Retailers’ implementation of and compliance with point-of-sale legislation

Key findings

-

Before the legislation was implemented, tobacco displays were highly visible in small shops, placed at customer eye level and next to products of particular interest to children, most notably confectionery.

-

The majority of young people in the 2013 school survey (80%) recalled seeing tobacco products displayed for sale both in supermarkets and in smaller shops, with young people from the least affluent backgrounds more likely to recall seeing them.

-

Compliance with the legislation was high when this was assessed 2 weeks after the implementation deadlines in both supermarkets (in April 2013) and small shops (in April 2015). However, two small shops that had a limited range of tobacco products were observed to display them on open shelves. Some other instances of non-compliance were observed, which were mostly minor and temporary.

-

Although compliance with the legislation was found to be high, tobacco as a generic product continued to maintain a strong visible presence. Storage units were still clearly visible, with most located in a prominent position behind the service counter and continuing to carry large generic signage promoting tobacco availability. These features may continue to convey the message that tobacco is an important and normal retail product.

Introduction

To assess the impact of the implementation of POS legislation in tobacco retail outlets, it is important to understand how retailers implemented the legislation and their degree of compliance with the regulations. In this chapter, we use data from the observational audit and retailer panel interviews (see Chapter 2, Tobacco advertising and marketing audits of tobacco retail outlets) and from the school survey (see Chapter 2, Cross-sectional school survey of school children with embedded cohorts) to answer the following questions:

-

What were the characteristics of tobacco POS displays at baseline, prior to the implementation of the POS legislation?

-

What was the degree of compliance with the legislation in large supermarkets and small shops?

Characteristics of tobacco point-of-sale displays at baseline

The following findings on the characteristics of tobacco POS displays at baseline have been published in full in Stead et al. 10 © 2016 The Authors. Published by Elsevier Ltd on behalf of The Royal Society for Public Health. This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/). Adapted with permission from The Royal Society for Public Health.

Methods

In examining POS tobacco display characteristics we focused on seven key features: internal and external visibility of storage units and products (i.e., whether they could be seen both inside the shop and from the street outside); any internal and external tobacco advertising (e.g., on the window or door); the style of storage unit; any brand advertising on the storage unit itself; the visibility of on-pack health warnings when packs were stocked in the unit; storage unit size; and proximity of tobacco products to products with potential appeal to children. For most items, observers simply noted their presence or absence, while overall visibility inside the outlet was rated on a scale of 1–5 and visibility from outside the shop was rated as ‘not very visible’, ‘fairly visible’ or ‘very visible’. Retail outlets were linked to the SIMD63 by their postcode and grouped by SIMD quintile for the purpose of analysis by area deprivation. Data analysis was conducted in IBM SPSS Statistics version 21.

The methods for the school survey are described in Chapter 2, Cross-sectional school survey of school children with embedded cohorts. The findings in this paper focus on young people’s recall of tobacco POS displays and their frequency of visiting small shops and supermarkets. The data presented are from February 2013, wave 1 (see Table 2), before the legislation was implemented in large supermarkets.

Results

Characteristics of tobacco displays in retail outlets

In total, 96 outlets were mapped and observed across the study areas: grocery/convenience stores (n = 58), CTN (n = 16), large supermarkets (> 280 m2 of retail space) (n = 9), petrol station forecourt shops (n = 10) and fast-food/takeaway outlets (n = 3).

The internal main tobacco display was visible from the main entrance of most (69%) outlets. Displays were nearly always positioned behind the main service counter, at customer eye-level and within arm’s reach of the server. Tobacco displays were rated to be most prominent in supermarkets (mean 4.3) and petrol station forecourt stores (mean 3.5), and less prominent in grocery/convenience stores (mean 3.0) and CTN (mean 2.6). External visibility of tobacco products or descriptors was noted in only a small minority of outlets.

Nearly all of the displays were purpose-designed storage units with the cigarette packs displayed upright, facing forwards and with branding clearly visible. However, over one-third of storage units were designed in such a way that pack health warnings were wholly or partially obscured by the front shelf strip. Half of the storage units featured brand advertising, typically on shelf-edge strips. The majority of units also featured generic tobacco messages such as the words ‘cigarettes’ or ‘rolling tobacco’ on the top panel. Storage units ranged in size from 0.0 m2 (where tobacco products were stored out of customer sight) to 6.9 m2, with an average of 2.0 m2. Price information was provided on shelf strips on 90% of the units, and on price-marked packs on 64% of the units. In the majority of outlets, tobacco products were displayed in proximity to products with potential appeal to children and young people. There was higher proximity of tobacco products to confectionery in CTN (81%) and grocery/convenience stores (72%) than in other outlets.

Young people’s frequency of visiting different retail outlets and recall of tobacco displays

In the school survey, young people were asked ‘How often, if ever, do you visit?’ the following shop types: newsagents/corner shops; garage shops/petrol stations; grocery shop or mini-marts; large supermarkets; fish and chip shops; takeaway shops; and mobile ice cream/burger vans. Response options were on a seven-point scale (every day; most days; about two or three times per week; about once per week; less than once per week; never; and don’t know). They were also asked whether they could remember seeing cigarette and tobacco packs in large supermarkets or small shops in the past 30 days. The response options were ‘yes’, ‘no’ and ‘don’t know’. In 2013, young people visited large supermarkets and small shops (including CTN and grocery/convenience stores) more often than they visited other types of outlet. Overall, boys visited all retail outlets more often than girls, particularly CTN and fast-food/takeaway outlets. Eighty per cent of young people recalled noticing tobacco products for sale in both supermarkets and small shops, and there was higher recall among young people living in areas of greater socioeconomic deprivation (p < 0.007). Those aged ≥ 15 years were more likely to recall displays in small shops than were those aged < 15 years (p < 0.004). In the stores young people visited more often (large supermarkets, CTN, grocery/convenience stores), tobacco displays were less likely to be visible from outside the store (p < 0.001), and pack health warnings were more likely to be visible (p < 0.001). There were few significant differences in tobacco display characteristics by level of deprivation, but, as area deprivation increased, the likelihood that cigarette pack warnings were obscured by the design of the display unit decreased (p < 0.001). When the analysis by area-level socioeconomic deprivation included only CTN and groceries (two of the three categories of outlet more frequently visited by young people), tobacco display units were on average significantly larger in areas of more deprivation than in areas of less deprivation (p = 0.03).

Compliance with the legislation

Compliance with the legislation was assessed in two observational audit waves: wave 1a (see Table 2) was conducted in April 2013, 1–2 weeks after the implementation deadline for large shops, and wave 3a was conducted in April 2015, 1–2 weeks after the implementation deadline for small shops.

Compliance in large supermarkets

Nine large supermarkets (i.e. > 280 m2) were in the sample at wave 1a; these represented five supermarket chains. An additional supermarket opened at a later wave but was not in operation at wave 1a. All nine large supermarkets audited were 100% compliant for all measures relating to displaying tobacco products and price information. Three out of the nine stores also had petrol station shops that were classed as small shops (i.e. ≤ 280 m2) and these, therefore, were not assessed for compliance at wave 1a.

Compliance in small shops

Findings on small retailers’ compliance with the legislation have been published in full in an article in PLOS ONE by Eadie et al. 72 © 2016 Eadie et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Methods

The findings in this section are from wave 3a of the observational audit, which was conducted in April 2015, 7–14 days after the display ban came into force in small shops. Only outlets classified as small shops (n = 83) in the sample were audited. We recorded whether or not the retail outlet had modified its tobacco storage unit to comply with the ban, and we assessed compliance against four measures of potential non-compliance: (1) any permanent displays of products covered by the ban (e.g. cigarettes, loose tobacco, cigarette papers, cigarette filters); (2) the effectiveness of storage unit maintenance and design at covering products; (3) any exposure to display of banned products as a result of poor server practices; and (4) any exposure to display of banned products as a result of poor storage practices.

Results

Physical changes

Nearly all outlets (96.4%) had made some form of physical change to the way tobacco products were stored to comply with the ban, with around four-fifths (80.7%) placing tobacco products in new, professionally adapted storage units, most of which were in a prominent position at eye level directly behind the till point. Seven shops (8.4%) had made ‘do-it-yourself’ adaptations to the storage unit, while the remaining six shops (7.4%) had removed their tobacco stock completely away from public view, typically placing their tobacco products in pull-out drawers under the service counter.

Nearly three-quarters of shops (71.1%) used horizontal hinged flaps of the type used in large supermarkets in the UK; 8.4% used vertically suspended blinds, which enabled retailers to access products from between the individual slats; and 9.6% used a combination of these.

Areas of non-compliance

Two outlets (a café/grocery store and a fish and chip shop) continued to display tobacco products on generic shelf units. Both stocked relatively small ranges (three or four cigarettes brands). Thirteen outlets had other smoking-related products, typically cigarette papers and filters, on open shelves, often below eye level. Seven outlets had vertical slats that were only partially effective at concealing products. In five outlets, products were visible because storage unit flaps were poorly fitting or in a poor state of repair. Three outlets used flaps that appeared to reveal an area greater than was permitted under the ban (no more than 1000 cm2 at any one time). The display legislation requires that smoking-related products and accessories covered by the ban, such as pipes and paraphernalia for making cigarettes, are not stored in the same covered space as other products used for other purposes. Seventeen outlets were found to breach this part of the legislation, in most cases by storing matches and lighters alongside cigarette papers and cigarette filters. In seven other cases, retailers were observed storing cartons containing tobacco products on an open storage unit or on a shelf underneath the main storage unit. Eight minor contraventions were observed regarding server/assistant practices, such as opening more than one flap at a time, or storage unit flaps and blinds being left open at the time of visit.

Price information and tobacco signage