Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 14/67/20. The contractual start date was in January 2016. The final report began editorial review in February 2019 and was accepted for publication in August 2019. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Emma McIntosh is a member of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Public Health Research (PHR) Research Funding Board. Ian S Young is a member of the Health Technology Assessment (HTA) National Stakeholder Advisory Group (2015 to present). Frank Kee was a member of the NIHR PHR Research Funding Board and PHR Prioritisation Group (2009–19). Dunla Gallagher received funding from Slimming World (Miles-Bramwell Executive Services Ltd, Alfreton, UK) for work conducted prior to her involvement in this study.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by McGirr et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background to the research

The aim of this chapter is to provide a review of the literature related to overweight and obesity in the postpartum period that informed the development of the intervention and the design of the pilot randomised controlled trial (RCT).

Specifically, this chapter describes weight-related trends during and after pregnancy, evidence-based interventions aimed at improving weight and related health outcomes in postpartum women and highlights some gaps in this evidence. The rationale for utilising mobile phone technology as a method of delivering a postpartum weight management intervention is also described. The present study aimed to address the identified gaps in the evidence.

Although no limitations were placed on the country of origin when searching the literature, owing to the nature of the fields of interest (postpartum weight management interventions and using modern technologies to change weight-related behaviour), the majority of the evidence discussed below originates from developed countries including the USA, Australia, countries within Europe and the UK.

Maternal overweight and obesity and the associated risks

Overweight and obesity are one of the major public health challenges of the 21st century, owing to their widespread prevalence and recognised impact on morbidity and mortality. 1 Adult obesity has nearly doubled worldwide since 1980,2 with commensurate trends among women of reproductive age. 3 In the UK, first-trimester obesity increased more than two-fold between 1989 and 2007 from 7.6% to 15.6%. 4

Being overweight or obese at the start of pregnancy is associated with increased risks of adverse health outcomes for mothers and babies. In comparison with women of a healthy weight, women who are overweight or obese and their offspring may be at a significantly increased risk of experiencing gestational diabetes, pre-eclampsia, hypertension, depression, caesarean section, postpartum haemorrhage, induction of labour, preterm birth, stillbirth, foetal defects, congenital abnormalities and infant death,5–8 and there is an increased risk of offspring adiposity continuing into childhood. 9,10 Weight gain between successive pregnancies is associated with increased risk of gestational diabetes, hypertension, caesarean section, large for gestational age birth weight (birth weight above the 90th percentile) and perinatal mortality. 11,12

Weight gain trends during and after pregnancy

Women are at an increased risk for weight gain during the reproductive years, and this weight gain can set women on an upwards weight trajectory for the decades ahead. 13 It has been estimated that between 40% and 65% of women in the UK gain too much weight during pregnancy. 14 This trend is particularly evident in women who start their pregnancy overweight or obese,15 as well as among those of a lower socioeconomic status. 16

Excessive gestational weight gain and a high pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI) are both predictors of postpartum weight retention17–21 and are influenced by many other maternal factors, including diet and physical activity behaviours, breastfeeding, sleep, ethnicity, maternity leave, income and mental health. 13,21 Failure to lose pregnancy-related weight by 6 months post partum is considered an important predictor of obesity and associated conditions in mid-life;22,23 many women with obesity attribute the onset of the condition to weight gained in pregnancy. 24 Between 40% and 50% of women who are overweight pre pregnancy move into the obese BMI category by 12 months postpartum. 25 For women who start pregnancy obese, 97% will remain obese after 1 year26 and 40% may gain two or more BMI units between their first and second pregnancies. 27 Although many women will return to their pre-pregnancy weight within 1 year of delivery, it has been estimated that between 15% and 27% of women have major postpartum weight retention (> 4 kg) at 1 year. 20,25,28 Furthermore, two studies20,29 have identified a risk of additional weight gain between 1 and 2 years postpartum, particularly in women who were overweight or obese at the 1-year postpartum time point.

The postpartum period can also be viewed as the ‘interpregnancy’ period for many women, as they will go on to have more children and will experience subsequent pregnancies. 13 Given that the times during and after pregnancy are periods of significant risk for the onset and maintenance of long-term weight-related issues,21,30 not only will this pose risks to women’s health,15 but it may also increase the risk of adverse outcomes during subsequent pregnancies. 11,12,31,32

The postpartum period represents a unique and challenging period in a woman’s life, both emotionally and physically. Women often struggle with weight management at this stage in life and face many barriers to taking positive action, such as lack of time, tiredness and prioritising their children’s needs. 33–36 Pregnancy and motherhood are major life events, and changes in lifestyle and maternal priorities may help explain postpartum weight retention and further weight gain trends. 19,37

Financial costs associated with pregnancy and postpartum overweight and obesity

The increased prevalence of obesity, in general, is currently estimated to cost the NHS > £6B per year and, by 2050, if we include indirect costs to the wider economy (such as those to social care and education), these costs are forecast to rise to nearly £50B. 38 A UK-based study39 found that a pregnant woman with a BMI of ≥ 25 kg/m2 led to NHS costs of up to 37% more than their those of their counterparts with a healthy weight (BMI of between 18.5 kg/m2 and 24.9 kg/m2). The increased costs were as a result of greater health service utilisation by both mothers and their babies as a consequence of adverse outcomes associated with maternal overweight and obesity. 40–42 Weight reduction prior to women becoming pregnant through pre-conception or interpregnancy/postpartum interventions would be a positive step in reducing these costs. Although it is not possible to fully quantify the direct costs and total savings of interventions seeking to tackle postnatal overweight and obesity, the need for additional health care to treat weight-related conditions is commonly accepted. 43–45 The need to identify cost-effective interventions for reducing weight and to evaluate the associated health-care costs is pressing.

Evidence-based strategies to support postpartum weight management

Current health-care guidance suggests that health professionals should advise women who have had a baby in the previous 2 years to eat healthily and keep active to encourage postpartum weight reduction. 45,46 The postpartum period could be an ideal time to intervene to shape new health behaviours as women have shown motivation for weight loss during this time,47,48 and they may have a heightened awareness of their own and their families’ health, and so may be receptive to information about lifestyle. 13 It is also a time when many women start to prepare for the next pregnancy, so there is the potential to set women on a positive course for subsequent pregnancies. 13 However, women have highlighted a need for additional weight management support during the postpartum period as little is currently provided. 17,49,50

Systematic review evidence49,51–54 and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) public health guidance45 both highlight gaps in knowledge about effective and appropriate weight management interventions for women during the postpartum period. There is systematic review evidence to suggest that diet and physical activity interventions delivered post partum have a moderate but positive influence on maternal weight,51–54 and that interventions combining diet and activity behaviour change may be more successful,49,52,53 as well as interventions that included self-regulatory behaviour change techniques (BCTs), such as self-monitoring of weight. 49 van der Pligt et al. 53 conducted a systematic review of intervention studies in which postpartum weight was a main outcome and any combination of diet, physical activity and weight monitoring were intervention components. Study populations included women with singleton pregnancies who were recruited either during or after pregnancy, provided that the intervention was delivered into the postpartum period. There were 11 studies53 included in the review (n = 1227), 10 of which were RCTs and one was a non-randomised trial. Interventions were delivered by a range of health professionals (nurses, fitness instructors, dietitians, trained counsellors and study assistants). The comparison groups received ‘usual care’, which often involved the provision of some general advice on healthy eating and physical activity, for example a leaflet. Seven of the included studies reported a decrease in postpartum weight retention (i.e. a decrease in the number of participants who did not return to their pre-pregnancy weight) in the intervention group. Six of these seven interventions employed both diet and physical activity components, and five of these seven studies recruited overweight and obese populations only. However, there were shortcomings in the quality of included studies, such as lack of descriptions of the randomisation and blinding processes. The heterogeneity of intervention settings and health professionals responsible for delivering the interventions makes it difficult to determine the important aspects of intervention delivery. Only two studies out of 11 were underpinned by theoretical frameworks, so this evidence limits our understanding of the usefulness of particular theories and BCTs, or how they interact with context, in improving outcomes in overweight or obese postpartum women. In addition, no study examined cost-effectiveness. 53 A later systematic review by Lim et al. 49 included 46 studies using either combined diet and activity, or diet or activity only interventions, to reduce weight in postpartum women within 1 year following birth, compared with usual care control conditions or a comparison of two different interventions. Thirty-three of the studies included were RCTs and were included in a meta-analysis (n = 1892); the other 13 studies that were included were single-arm interventions (n = 6) or non-randomised trials (n = 7). The meta-analysis results indicated that combining diet and physical activity advice may be most effective, resulting in a pooled weight loss of 2.3 kg, with subgroup differences showing greater weight loss as a result of interventions that included self-monitoring. 49 However, this review continued to experience similar methodological shortcomings in the included studies in terms of studies being rated as having high to medium risks of bias as a result of inadequacies in the reporting of randomisation and blinding processes, and heterogeneity in the analyses due to differing intervention approaches, with a lack of detail provided on the active ingredients of interventions.

A notable methodological limitation of the included trials in the presented systematic reviews51–53 is that they have experienced high levels of participant attrition and poor engagement, highlighting the difficulty in engaging and maintaining contact with women in the postpartum period. 13 This period of major physiological, psychological and social change poses many challenges for women’s weight management and their ability to engage in behaviour change interventions; what works at other life stages may not necessarily work at this time. 13 The intervention setting and mode of delivery are key considerations when developing appropriate postpartum weight management interventions. 13 Interventions for overweight or obese postpartum women delivered in community settings, using group approaches, have presented difficulties for new mothers at this challenging time, and have raised concerns about reach and retention, particularly for disadvantaged groups,53,55–58 creating a potential to increase health inequalities. 59,60 For example, despite high initial motivation to enrol in the active mothers postpartum study,55 and the provision of group sessions multiple times per week, at various times of day, women found it difficult to attend owing to the competing needs of their baby and home- and work-life. Thus, despite considerable evidence that group approaches are associated with significant weight loss in the general population,61 they may not be feasible for the postpartum period. Furthermore, given the significant variability in postpartum weight gain trajectories,62 the optimal time to engage women in postpartum weight management during this challenging period is still unknown. 53 It is probable that flexibility regarding time to opt in is needed to engage women in postpartum interventions when they are ready, rather than dictating a narrow opt-in window. 13

The challenges of engaging and retaining women in postpartum weight management interventions has led to the suggestion that a highly flexible and individualised approach to weight loss interventions is needed in the postpartum period, shifting away from structured community-based programmes, to home-based or more adaptable ‘anytime, anyplace’ approaches, such as those enabled by mobile technologies. 53,55–58 However, in the described systematic reviews by van der Pligt et al. 53 and Lim et al. ,49 no study had used modern technologies, such as mobile phones, as an alternative to traditional face-to-face support. One study63 used modern technology (an online diet planner) as an adjunct to traditional face-to-face support. Employing mobile technologies to change diet, weight and physical activity presents a promising and expanding area of behavioural research, but, at the time that our research was conceived, was one that had not been exploited extensively, or trialled in new mothers carrying excess weight. 64–66 Systematic reviews and RCTs published since our funding application for the Supporting MumS are discussed later (see Chapter 5).

Weight management intervention delivery by short message service

The availability, adaptability and low cost of mobile technologies provide a promising format for delivering lifestyle intervention programmes on a sustained basis,67 and the NHS aims to embrace the potential of digital strategies for improving the health of people in the UK. 68 Short message service- (SMS-) delivered interventions have the advantage of wide reach, flexible scheduling and individual tailoring of content, thus making them an attractive proposition to support women in the busy postpartum period and represent an approach that may help address health inequalities. Use of mobile phones and other technical devices has become integral to how individuals communicate and plan their daily lives. Mobile phone ownership is widespread among all sectors of society, irrespective of socioeconomic status, and SMS is available on every type of mobile phone and across all phone companies. Such widespread usage serves to reinforce the image of mobile health (mHealth) becoming an important component of future health-care practice. 69,70 Unlike web-based interventions or applications (hereafter referred to as ‘apps’), which require ownership of a smartphone or tablet, and individuals taking the initiative to use them, SMS is a relatively simple mode of communication that uses basic mobile technology. An intervention using SMS can be reactive as well as proactive, instant, more direct, delivered in a timely manner and does not necessarily rely on initiation by the participant. 66 SMS is an ideal vehicle for reach, engagement and ‘proportionate universalism’, that is SMS can be universally delivered at a scale and intensity that is proportionate to the degree of need to reduce health inequalities, as recommended by Marmot71 and NICE. 72 Exploiting the real-time advantages offered by mobile technologies to deliver weight management support in the postpartum period has the potential to empower women and encourage behaviours that may improve maternal health in both the short and the long term. 67

Early evidence has shown that SMS is an acceptable and feasible mode of intervention delivery and has positive effects on weight management and weight-related behaviours. 64–66,73 Napolitano et al. 73 demonstrated the feasibility and acceptability of SMS as a method for promoting healthy behaviours for weight loss in a group of 52 (mostly female) college students. A systematic review74 of behaviour change interventions using SMS as the main method of intervention delivery (14 studies; n = 3512 participants) highlighted a positive impact on short-term behavioural outcomes, including diet, physical activity, smoking and clinical care, such as diabetes management, in 13 of the included studies. 74 However, study quality was low, with only six of the 14 studies using a RCT design. One study was a clustered randomised comparative trial, one was a randomised crossover trial and the other six were single, pre–post design studies. The ability to compare studies was limited as the interventions were aimed at changing different behaviours. The authors of this review highlighted a need to improve trial methodology to allow the full potential of SMS-delivered interventions to be explored. Another systematic review, by Aguilar-Martínez et al. ,75 specifically examined studies that had used mobile phone technologies as a tool for weight loss in adults with overweight or obesity. Of 10 included studies, two used SMS or multimedia messaging service (MMS) to demonstrate the potential of these methods for supporting weight loss. One of these two studies used a pre–post intervention design (n = 927 participants);76 the intervention involved a 12-week programme of diet, exercise and behaviour modification advice delivered once a week via SMS and was shown to reduce the mean weight, waist circumference and BMI measurements. The other study77 used a RCT design (n = 75 participants) and compared an intervention group which received a 16-week SMS- and MMS-delivered intervention alongside paper-based nutritional advice with a control group which received the paper-based nutritional advice only. The intervention group showed a greater weight loss, on average, than the control group. The remaining studies in the review by Aguilar-Martínez et al. 75 used apps or web-based programmes. However, their review highlighted that frequent self-recording of weight seemed to be important, as was the personalisation of the intervention (counselling and individualised feedback), and that a social support system could act as a motivational tool.

Weight management research has been dominated by trials of interventions mainly focusing on weight loss. Such evidence has illustrated that clinically relevant weight loss is attainable in the short-term, but longer-term (≥ 6 months’) follow-up highlights the challenge of weight loss maintenance,78–80 which is key to maintaining clinical benefits. 81 There is increasing recognition of the need to focus attention on weight loss maintenance and, specifically, the need to design interventions for this purpose. 79 Often, the behaviour change theories that inform intervention research assume that the processes used to initiate behaviour change (such as changes in diet and physical activity to achieve weight loss) also facilitate maintenance of the behaviour. 82 However, accumulating evidence shows that some strategies involved in supporting initial change are qualitatively different from those involved in maintenance of change. 83–85 This suggests that adapted and new BCTs may be crucial to sustain behavioural and weight changes in the long term.

In terms of the evidence for using SMS as a method to encourage behaviours associated with weight loss maintenance, the work of Gerber et al. 86 and Shaw et al. 82 has indicated early feasibility and acceptability of using SMS in this way. Gerber et al. 86 investigated the feasibility of mobile phone SMS to enable ongoing communication with African American women participating in a weight management programme. Ninety-five African American women participated in this pilot study and received regularly scheduled messages; > 4500 messages were transmitted during the first 4 months, with only 114 returned as undeliverable. The participants reported positive attitudes towards incoming messages, with only one participant declining to continue after enrolment. Shaw et al. 82 developed a theoretically driven automated SMS app to deliver weight loss-sustaining messages following a structured weight loss programme, which was found to be acceptable and feasible in a small (n = 16 participants) uncontrolled pilot study. Using technology-based weight management approaches appeared to be well accepted, with up to 74% of participants accessing and reviewing the weight management materials immediately after receipt. 82

Cost-effectiveness of SMS interventions for postpartum weight management and loss

Current guidance from NICE on weight management before, during and after pregnancy45 and its associated review of the cost-effectiveness of weight management interventions following childbirth,87 both outline the potential of postpartum interventions to reduce the long-term risks of heart disease, cancer, obesity and diabetes. In their review, Duenas et al. 87 concluded that weight management interventions following childbirth are shown to be effective in the short term. However, long-term effects were highly dependent on the modelling of key assumptions, and economic results were reliant on the long-term impact of the short-term effects. Thus, although the authors were able to extract data from observational studies that suggested a 15-year impact on weight change and a lifelong impact on survival, definitive causal effects could not be attributed. Therefore, these long-term economic estimates using standard probabilistic sensitivity analysis are likely to have high levels of structural uncertainty. 87 The guidance stipulates that more observational studies are required to aid future clarification of the long-term impact of interventions in this area.

Two studies in postpartum women have examined cost-effectiveness: a cost–utility analysis conducted in Sweden alongside a RCT of a 12-week dietary treatment (involving an initial counselling session, one home visit and SMS support every 2 weeks)88 and a cost-effectiveness review of existing postpartum weight loss RCTs. 89 Both studies found the interventions to be cost-effective. Hagberg et al. 88 calculated (with no remaining effect assumption after the follow-up year) the cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) to be US$8643 (≈£6720.57). With an assumption of 1 year of effect beyond the 1-year follow-up, the cost-effectiveness ratio was US$3477 (≈£2703.62). Rawdin et al. 89 undertook their analysis from the perspectives of the UK NHS and Personal Social Services, and estimated an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of £7355, which is below the NICE guidance90 willingness-to-pay threshold of £20,000.

Searching the existing literature base, no cost-effectiveness studies of a mHealth SMS postpartum weight management intervention were identified. As outlined earlier, postpartum weight management interventions show promise of being cost-effective. However, reviews of digital health interventions have demonstrated that few evaluations have captured data that sufficiently allow for the full consideration of economic outcomes and overall effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the interventions. 91–95 As Graybill et al. 96 emphasise, currently, alternative technologies such as mHealth are in their infancy as they are commonly outside many health-care systems remit and normal practice. The delivery of digital health programmes is currently not standardised and this heterogeneity and uncertainty around the broader societal benefits make it difficult for decision-makers to make fully informed decisions when comparing different programmes. 97

Rationale for the current study

The rationale for this study was to develop and conduct a pilot RCT of a new individually tailored, SMS-delivered weight management intervention for postpartum women, and to include a specifically designed weight loss maintenance intervention component to help women transition from weight loss to weight loss maintenance by encouraging successful and sustainable self-regulation and habit formation. Future research should address the shortcomings noted in previous trials and carefully consider how to make weight management interventions an attractive and attainable proposition for women who are juggling multiple, competing demands in the postpartum period. The use of SMS could offer a flexible approach to weight management for women during this demanding period of their lives, allowing sustained contact over a longer period of time to help support women in changing behaviours for weight loss and weight loss maintenance while allowing for flexible scheduling, individual tailoring and the embedding of evidence-based BCTs. 98–100 Specifically, in our study we aimed to adapt an existing, successful smoking cessation SMS intervention (txt2stop). 98

Txt2stop

The txt2stop intervention is an evidence- and theory-based automated smoking cessation programme comprising theory-based individually tailored messages and behaviour change support, delivered via SMS, that aims to motivate and support adults to continuously abstain from smoking. 98,100 It was shown to be effective in significantly increasing biochemically verified continuous abstinence at 6 months in the intervention group (10.7%) compared with the control group (4.9%), corresponding to a relative risk of 2.20 [95% confidence interval (CI) 1.80 to 2.68; p < 0.0001]. This effect was evidenced in all socioeconomic groups and in younger and older smokers. 98 The success of the txt2stop intervention has resulted in the establishment of new services providing smoking cessation support delivered by SMS in the UK,101 evidencing the scalability and implementation of this intervention design. We chose to adapt this successful pre-existing SMS platform.

Generalisability and sustainability

The economic burden of treating obesity is projected to increase by £1.9B–2B per year in the UK by 2030. 102 Hence, there is a pressing need to identify cost-effective ways of promoting weight loss and, importantly, weight loss maintenance, in different population groups. Some weight loss interventions are very resource intensive and expensive, which can limit their potential for scale-up and implementation,103 and concerns have been raised that other interventions could increase health inequalities. 59,60 From the perspective of health professionals, who have reported multiple barriers to support weight management (such as lack of time and lack of knowledge),61 use of mobile technologies to facilitate the delivery of evidence-based weight management interventions might free up resources to deal with other health needs.

A SMS approach can be delivered flexibly for sustained contact with women over the medium to long term, with the ability to easily re-engage individuals after life events that disrupt weight management progress (e.g. illness, stress), at a low cost that is not attainable with other intervention approaches, such as group-based and in-person interventions. Extended contact following weight loss interventions is considered best practice for weight loss maintenance;80 without it, most individuals will regain weight in the longer term. The present study will inform the available evidence on developing interventions targeting weight loss maintenance. 79 It will also pilot methods for establishing the cost-effectiveness of delivering such an intervention.

Aim of this study

The aim of the present study was to adapt and pilot-test an evidence- and theory-based tailored SMS-delivered intervention supporting behaviour change for weight loss and weight loss maintenance in postpartum women with overweight or obesity.

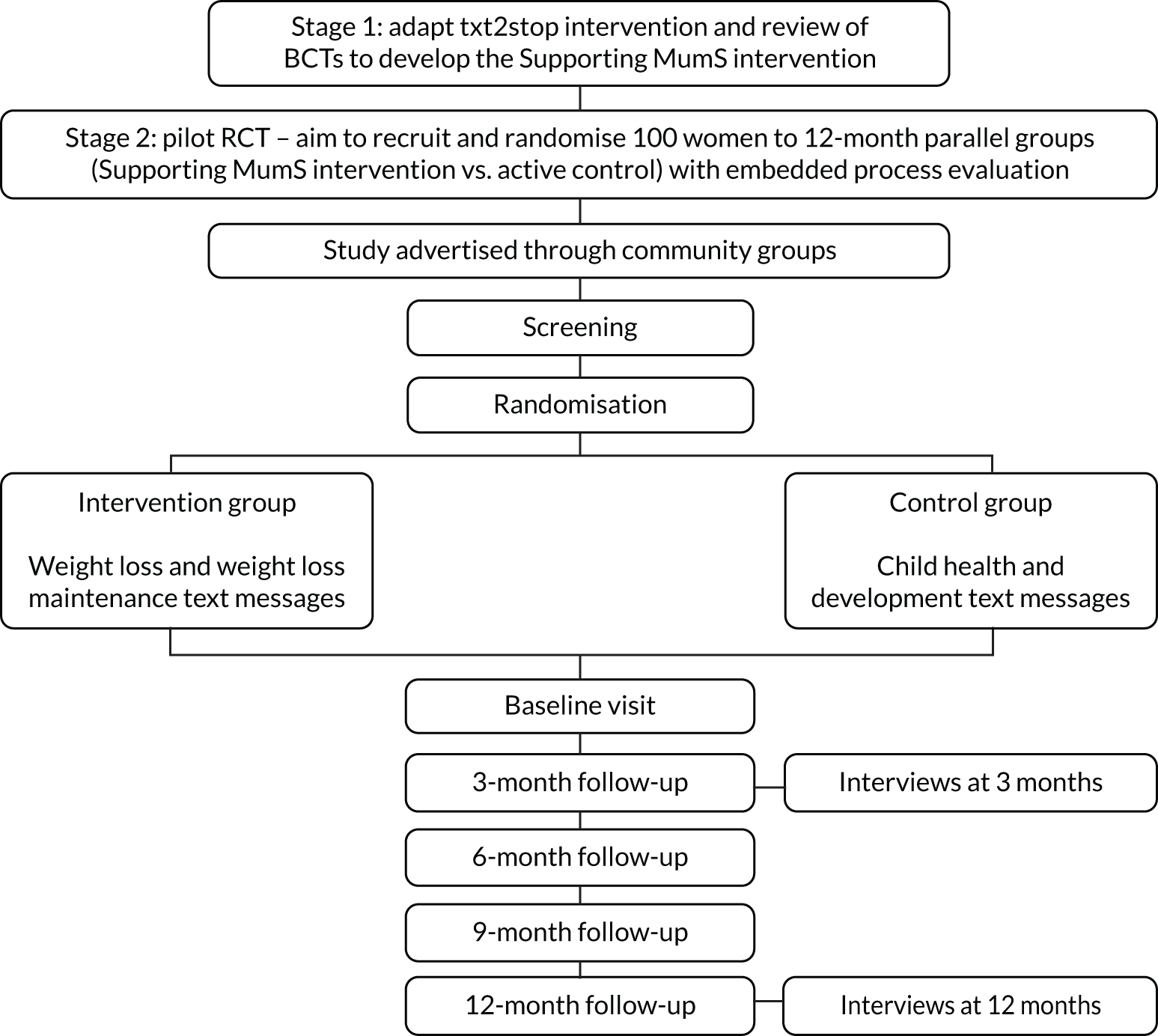

Study design

The study was conducted in two stages. Stage 1 involved the adaptation of the txt2stop intervention98 for the development of a theory-based tailored SMS-delivered intervention supporting overweight and obese women’s behaviour change for weight loss and weight loss maintenance in the postpartum period, along with the development of a SMS-delivered active control focusing on child development (see Chapter 2). Personal and public involvement (PPI) is recommended in the development of new digital interventions;104 this recommendation was considered throughout the design of the study and will be discussed at different stages throughout the present report, where relevant. Stage 2 was a two-arm pilot RCT with an embedded process evaluation (see Chapters 3 and 4). The rationale for conducting a pilot RCT was to examine the feasibility and acceptability of delivering all aspects of a full RCT of the intervention, including a cost-effectiveness evaluation, as recommended by the Medical Research Council (MRC) framework for complex interventions. 105 A process evaluation was conducted to address specific research questions related to the delivery of the intervention and the contextual factors influential in the trial outcomes, as well as to pilot-test measures to be used for assessing mechanisms of impact. 106

Overall objectives

-

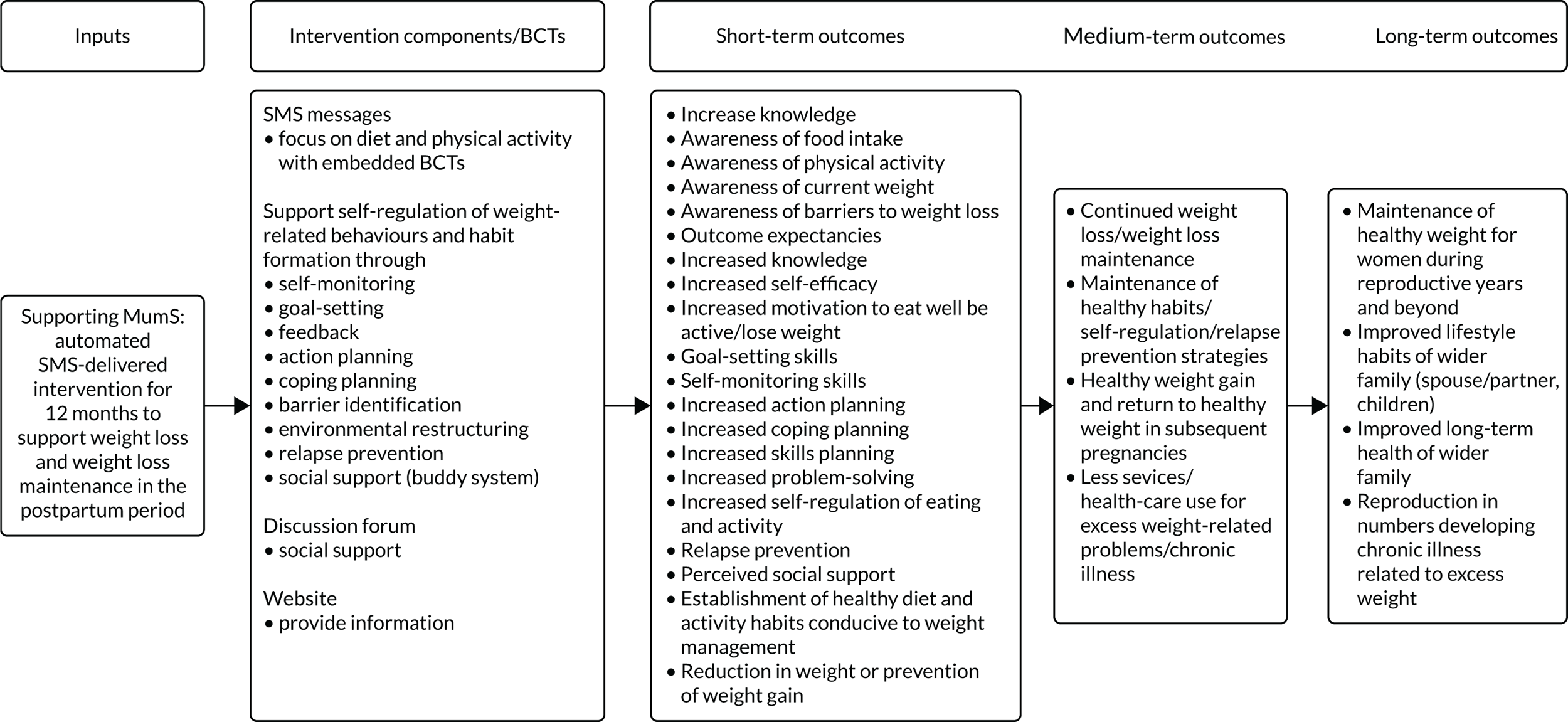

To review BCTs used in the txt2stop intervention and, through assimilation of relevant systematic review evidence, behaviour change theories and the NICE guidance,45 build a logic model for a SMS-delivered weight management intervention in postpartum women who are overweight or obese.

-

To create a library of SMS messages, with PPI, to support weight loss and weight loss maintenance in postpartum women with overweight or obesity.

-

To develop an intervention manual, including a library of messages and recruitment materials and a protocol for a pilot RCT of the SMS-delivered intervention.

-

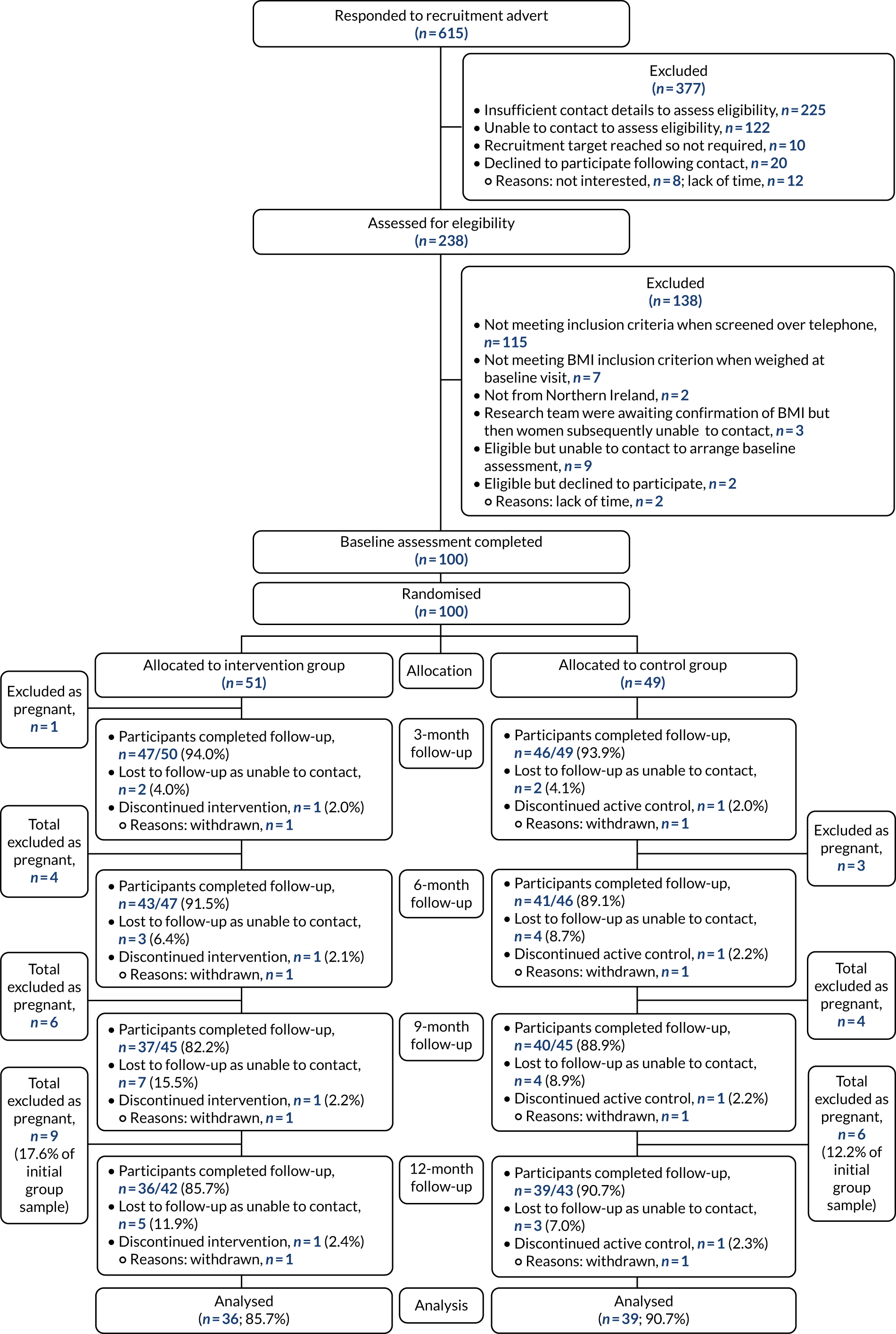

To conduct a pilot RCT to test recruitment and randomisation strategies (including willingness to be randomised to an active control and retention and attrition rates between groups), examine fidelity of implementation and acceptability of the intervention and active control treatments, identify valid and acceptable (to the PPI members) research instruments to be used in a full RCT, provide variability data on weight loss and weight loss maintenance on which to base a formal power calculation for a full RCT, and to assess outcome data collection processes.

-

To assess pilot data in relation to predefined stop/go progression criteria for a full RCT (see Chapter 3) to inform the decision of whether or not to proceed to a full RCT.

Chapter 2 The development and personal and public involvement testing of the Supporting MumS intervention and active control content

The MRC guidance on developing and evaluating complex interventions105 was used to guide the development and pilot testing of the Supporting MumS intervention. This guidance105 highlights that best practice in intervention development is to adopt a systematic approach that uses the best available evidence, has an appropriate theoretical basis and tests the intervention in a phased approach, starting with a pilot, or series of pilots, to address key uncertainties, followed by more definitive evaluation studies.

The present National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) report describes the development and pilot testing of the Supporting MumS intervention, reported in line with the MRC guidance105 (Table 1).

| MRC guidance stage | Activity | Report section |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Developing complex intervention | ||

| Identifying the evidence base | Review of evidence on postpartum weight management – reviewing published literature and existing systematic reviews | Chapter 1: background |

| Identifying and developing appropriate theory | Identifying relevant behaviour change theory for weight management | Chapter 2: intervention development |

| Modelling process and outcomes | Using chosen theory and literature to inform intervention content; testing intervention content with target group; refining intervention according to feedback | Chapter 2: intervention development |

| 2. Feasibility/piloting: pilot RCT | ||

| Pilot RCT | Pilot RCT with specific progression criteria (see Table 5) | Chapter 3: methods; Chapter 4: results |

This chapter reports the development of the Supporting MumS intervention (stage 1 of the MRC guidance). PPI was an integral part of the intervention development process (see Personal and public involvement in intervention and active control development).

Identifying the evidence base

A review of the evidence on postpartum weight management, including consideration of findings from previous RCTs, systematic reviews and qualitative research, was used to inform the key features of the intervention and the pilot RCT (see Chapter 1).

Identifying/developing appropriate theory

The intention from the outset was to develop an intervention that supported weight loss and weight loss maintenance. No single behavioural theory that fully explains the behaviour change process currently exists. The current intervention was based on two complementary theoretical accounts to target specific behaviour change phases: (1) the motivational and volitional phases to support the initiation of change, followed by (2) the maintenance phase to support sustaining change. Modelling of the initiation of change was guided by the health action process approach (HAPA),107 which outlines a motivational and an action-oriented volitional phase in the initiation of behaviour change. The theoretical approach chosen to guide the intervention development for weight loss was the HAPA. 107 HAPA is a comprehensive sociocognitive model that has been successfully used to predict and change lifestyle behaviours, including weight-related behaviours. 108 Moreover, HAPA has successfully informed the content of previous NIHR-funded SMS-delivered interventions. 108–110 The weight loss aspect of the intervention was shaped by the specific behaviour change phases encompassed by HAPA, including the motivational and volitional phases. The specific psychological processes to increase motivation include outcome and risk perceptions, as well as task self-efficacy (i.e. the belief a person has in their ability to perform a behaviour). In the volitional phase, action-focused processes are specified such as action planning (i.e. specifying the necessary steps needed to change behaviour), coping planning (i.e. specifying how to overcome possible barriers) and maintenance self-efficacy (i.e. the belief in one’s ability to continue change in the long-term).

The selection of maintenance processes was based on a systematic review of > 100 behavioural theories that synthesised theoretical explanations for maintenance of behaviour change. 84 Maintenance specific processes include (1) maintenance motives such as appreciation of the behavioural outcomes, enjoyment of the new behaviour and congruence of the new behaviour with one’s identity and values; (2) habits that enable automatic performance of behaviour; (3) resources to uphold behaviour change, both psychological and physical; (4) self-regulation to monitor whether or not the new behaviour is maintained; and (5) social/environmental support for maintenance. These processes are in line with several leading theories of behaviour change maintenance. 84,111–113

Thus, the intervention targeted specific behaviour change phases, including: (1) the motivational and volitional phases to support the initiation of change; followed by (2) the maintenance phase to support sustaining change (Table 2).

| Change phase | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Motivation | Volition | Maintenance | |

| Psychological processesa | |||

| BCTsa (phase specific) |

|

|

|

| BCTsa (universal for diet and activity behaviour change and weight management) |

|

|

|

Modelling process and outcomes

The work conducted in this phase is summarised in the following sections:

-

SMS messages: key considerations (length, frequency, timing, tone, key messages on diet and activity, links).

-

Operationalising the key behaviour change techniques in the weight loss and weight loss maintenance phases [bidirectional messages, targeted messages (breastfeeding, smoking, weight loss, weight loss maintenance), self-monitoring weight, self-monitoring diet and activity, goal setting and feedback, slip-ups and relapse prevention, social support, action planning, coping planning].

-

Additional intervention components: discussion forum and study website.

-

Personal and public involvement in intervention and active control development.

Deciding on relevant behaviour change techniques

The BCTs to be incorporated into the intervention were chosen based on a number of different evidence sources, namely the theoretical basis for the intervention described above, published qualitative research with postpartum women,34,114–118 the NICE guidelines on weight management,119,120 systematic reviews of techniques and components used in successful diet and physical activity interventions,121,122 systematic reviews of weight loss maintenance lifestyle interventions123,124 and mHealth interventions,64,65 and a systematic review of systematic reviews examining the BCTs associated with effectiveness in weight management RCTs [McGirr, Dombrowski, Holmes & McKinley, 2018, Queen’s University Belfast (QUB), manuscript under review]. Based on this literature, a number of BCTs were consistently associated with successful weight loss, notably goal-setting, self-monitoring and feedback. A full list of the BCTs employed, along with examples of SMS messages, are shown in Table 3.

| BCT | Example message |

|---|---|

| Goal-setting (outcome) | We’ve talked the talk, now it’s time to walk the walk :). Set your weight loss target today – text us the weight you hope to be in 6 months’ time. For help with setting a weight target that is realistic for you, check out this link: www.nhs.uk/Livewell/weight-loss-guide/Pages/set-your-target-weight.aspx |

| Provide information on consequences of behaviour to the individual | WEEK 10! Need some extra motivation this week? Make a list of how you’ll feel when you reach your weight loss target, e.g. healthier, more confident. Keep this in mind for the week ahead |

| Goal-setting (behaviour) | WEEK 14. Have you set your activity goal for the week ahead? Text Y11 for yes or N11 for no |

| Prompt self-monitoring of behaviour | Monitoring food intake helps with successful weight loss! Are you still recording what you eat? Let us know – text Y7 for yes or N7 for no |

| Prompt self-monitoring of behaviour outcome | What are the scales saying this week? Text us e.g. 11 st 5, or 73.3 kg |

| Action planning | Check your kitchen – if you have healthy foods in there you are much more likely to eat healthily! Do you have fruit and vegetables in the house this week to snack on? Text Y28 for yes or N28 for no |

| Provide instruction on how to perform the behaviour | When to weigh yourself? Pick a time that suits you each week and stick to it. First thing in the morning, after you go to the loo and before you get dressed is best |

| Barrier identification/problem-solving | Looking after a baby and finding the time to exercise can be hard. One solution is to exercise with your baby. Check this link for fun activities you can try out – www.parenting.com/gallery/exercises-to-do-with-your-baby?page=0 |

| Provide feedback on performance |

What about the goal you set last week, did you reach it? Text Y2 for yes and N2 for no (yes/no reply triggers a feedback message) Want some feedback on your weight? Look no further than your scales! Text us your weight followed by UP, DOWN, SAME (reply triggers a feedback message depending on progress) |

| Stress management/emotional control training | Does your mind often win in the battle against your stomach? It’s easy to eat without hunger. Next time, ask yourself these two Q’s first: ‘Am I really hungry?’, ‘Do I really need it?’ Self-talk helps prevent mindless eating (or, in other words, eating without thinking):) |

| Environmental restructuring | Tempted to buy fizzy drinks? Wait! . . . if it’s not in the house you can’t drink it! Sparkling/soda water with a wedge of lemon/lime (or any fruit you like) is a good swap – gives the zing without calories! |

| Plan social support/social change | If you’re a lone wolf, it’s time to join a pack! Support increases weight loss success, so team up with friends/family, or chat to other mums online. The Supporting MumS forum is a great place to start – http://supportingmums.boards.net |

| Provide information on where and when to perform the behaviour | Info overload? No need to make all changes at once! Small steps go a long way in shifting the lbs! Pick two changes to focus on the next time you are out shopping and then try to repeat each week – it will become a habit before you know it! |

| Set graded tasks | Tummy-toning tip: baby amused on the floor? Set the timer on your phone and try a 30-second plank beside them. Challenge yourself to a longer plank each day |

| Prompt practice | Fill up on fuel, not on calories! Outdo the marketer’s trick of placing unhealthy snacks beside the till at the petrol station. Reach for our good old fruit friends or nuts if you fancy something to munch on |

| Time management | Tired and time-tied? Dinner plans can sometimes go out the window! But who says you have to make a fancy meal? Pasta and pesto, oven chips and fish fingers (with some frozen or tinned peas/beans) make quick and handy dinners |

| Prompting generalisation of a target behaviour | Are you able to manage those tempting food situations any better now than before Supporting MumS? Text Y35 for yes and N35 for no |

| Prompt self-talk | There will be times in your weight loss journey when things won’t be perfect. That’s life! Supporting MumS is about aiming for progression not perfection :) Use this mantra – ‘I’m doing the best I can’ – to keep any negative thoughts away |

| Relapse prevention/coping planning | Mmmm smell it, feel it . . . WANT IT! What do you do next . . . eat it? Next time you are faced with this situation, have a plan of action. Could you walk outside, or do something to distract yourself (e.g. call someone, go online)? Text us what you’ll do next time. E.g. ‘step outside’ |

| Prompt rewards contingent on effort or progress towards behaviour | It’s normal for weight loss to slow down or even stay the same for a while, so don’t let it effect your motivation if this happens – congratulate yourself on your success so far! |

| Prompt focus on past success | Love yourself slim in WEEK 19. Think of a time you achieved something you were proud of and how it made you feel. Keep this is mind :) |

| Teach to use prompts/cues | Are you in an ‘I can do this’ kind of mood? Now is a great time to plan your meals for the week. It will mean you’ll be more likely to make healthy food choices on days when you need that extra little bit of motivation! Here’s a sample meal plan to get you started – www.bhf.org.uk/heart-matters-magazine/nutrition/eat-well-on-a-budget/sample-menus |

| Model/demonstrate the behaviour | Strengthening that all-important core will help your pelvic floor muscles recover. Especially after all it’s been through! Some Pilates moves like the plank are a good place to start. Check out this site to see what you might manage – www.nhs.uk/conditions/nhs-fitness-studio/pages/pilates-for-beginners.aspx |

SMS messages: key considerations

Overall, the intervention was designed to encourage a self-guided approach to lifestyle behaviour change and weight management as supported by the literature. 125–127 In line with existing evidence, the intervention focused on dietary intake as well as physical activity to address energy balance alongside appropriate BCTs to support lifestyle change and weight management. The messages aimed to:

-

contain information for weight loss, including advice, practical tips and external resources

-

provide encouragement and motivation, discourage guilt and encourage self-reflection

-

provide information in layers to avoid overwhelming women with too much at once, with reinforcement of key messages at regular intervals

-

include selected BCTs

-

include real-life situations relevant to postpartum women that they could relate to/address key barriers to weight management for this population, for example family environment triggers such as finishing the kids’ left-overs

-

adopt a friendly accessible tone, including humour, to encourage engagement.

The SMS messages were drafted by three members of the study team and commented on and refined by other members of the multidisciplinary study team, with PPI input (see Personal and public involvement in intervention and active control development).

Key considerations when developing the SMS message library were: (1) message length, (2) message frequency, (3) message timing, (4) tone, (5) key messages on diet and activity to be conveyed and (6) using links to signpost to other information sources and tools.

Message length

One of the challenges in writing the SMS messages was to consider message length. Smartphones can accept messages that are > 160 characters, but, for participants with older models, the messages may come through twice. It was not possible to keep all messages to < 160 characters as some concepts needed some explanation, but message length was kept as tight as possible and was tested with PPI members.

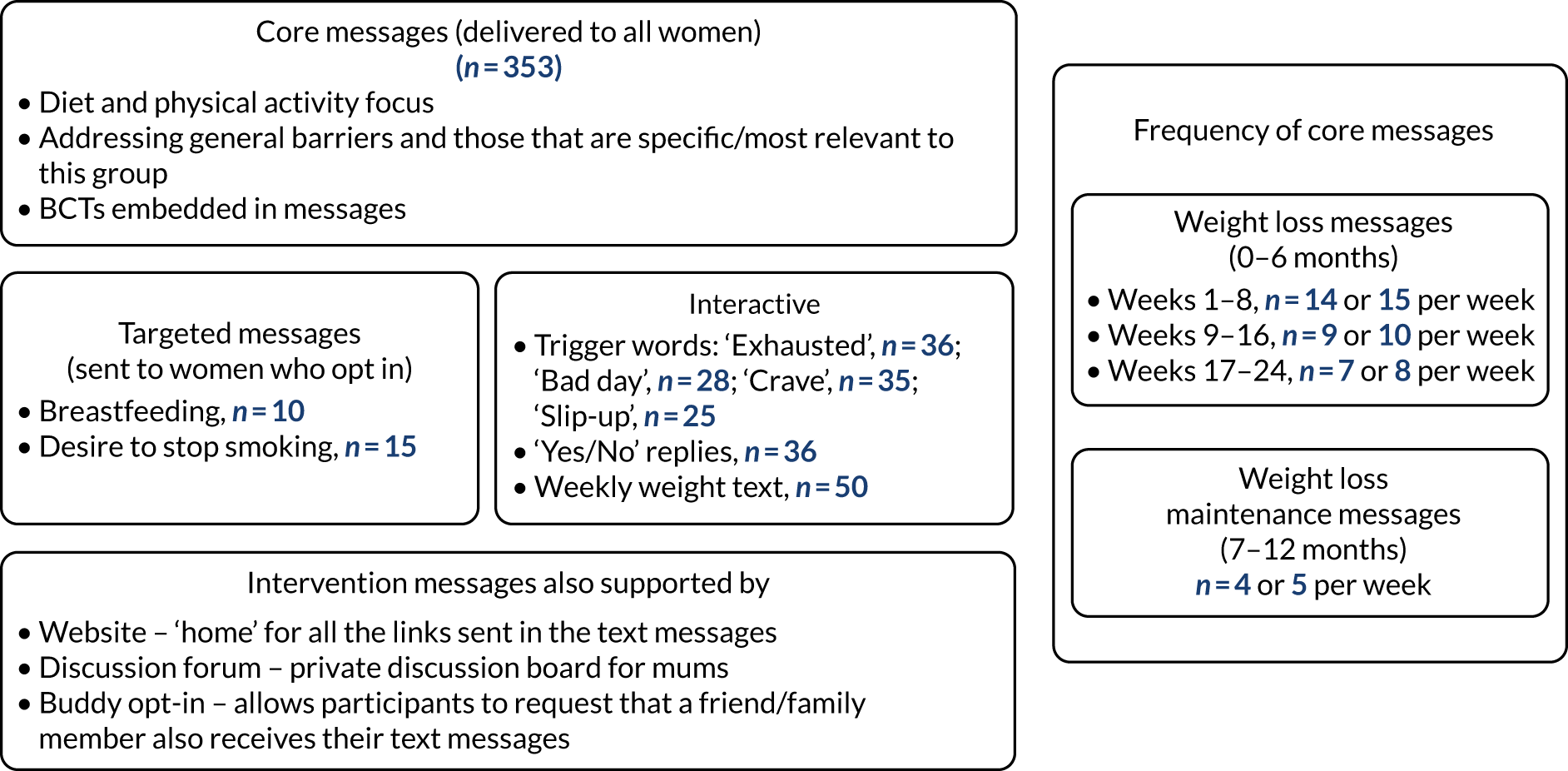

Frequency of messages

For the intervention group, the number of messages was dictated by the nature of the content that needed to be delivered alongside an awareness that too many messages would probably mean messages were ignored. PPI participants were asked for their opinion on the frequency of SMS messages (see Personal and public involvement in intervention and active control development). The intervention consisted of 353 core messages, that is messages that were delivered by the system to all participants: 217 in the weight loss phase and 136 in the weight loss maintenance phase. Given the amount of content to be delivered in the weight loss phase in terms of providing information on diet and physical activity and addressing barriers and embedding BCTs in an engaging and motivational way, a greater number of messages were provided in the weight loss phase (n = 217, months 0–6) relative to the weight loss maintenance phase (n = 136, months 7–12). The number of SMS messages sent during the first 6 months started at a rate of 15 per week and was tapered to eight per week. Fewer messages were sent in the weight loss maintenance phase as the emphasis in this phase was on reinforcing self-regulation techniques, instilled during the first 6 months of the intervention, and focusing more on maintenance-relevant strategies such as relapse prevention and dealing with slip-ups. However, it was also important to maintain enough contact with the participants during months 7–12 to ensure that they still felt supported at this crucial stage in the weight management process, when the potential to return to old ways and regain weight is high. For this reason, the number of messages was kept at four or five per week.

Timing of SMS messages

When participants signed up to the study, they were asked the time of day they preferred to get the message and also what times of day they wanted to be kept message-free, for example 19.00–07.00. The first message was sent to participants on the day they were randomised. Two messages were sent each day between weeks 1 and 8 and they were programmed to arrive at different times to avoid predictability, for example day 1: 11.00 and 20.00, day two: 09.00 and 20.00, day 3: 10.00 and 17.00, day 4: 09.00 and 16.00. As message frequency decreased, SMS messages were sent at various times on different days to avoid predictability; however, the message asking participants to weigh themselves (see Operationalising the key behaviour change techniques in the weight loss and weight loss maintenance phases) was always sent on the same day of the week.

Tone of messages

The messages were written in an informal, friendly style using humour and emojis to engage participants, as evidence indicates that how a message is portrayed can affect how a person responds to that message in relation to changing behaviour. 128 Information on who created the SMS messages (‘nutritionists at QUB alongside other mums’) was provided in the initial messages. To prevent SMS messages from becoming repetitive, some were written as if they came from another mother. These ‘mum’s tips’ were placed sporadically across weeks 1–52, and were included to offer mothers a chance to relate to and learn from another person’s weight management journey and so help to increase self-efficacy.

Key messages on diet and physical activity

The intervention content focused on diet and physical activity, as the effectiveness of targeting dietary change on improving weight outcomes is supported by the literature, see Chapter 1. The key dietary advice incorporated in the intervention focused on creating a calorie deficit, eating regularly (not skipping meals), portion size, healthy snacking, food swaps, social eating, emotional eating, recognising and avoiding food triggers both inside and outside the home environment, shopping for food, cooking, takeaways, drinks, mindful eating, hungry days, weekends and coping/planning for special occasions or other temptations. Barriers to changing diet and activity behaviours were also addressed, including lack of time and tiredness, which are particularly pertinent for this population.

The key messages on physical activity focused on the importance of activity for overall health, guidance on the specific recommendations for physical activity in relation to weight loss and weight loss maintenance, its important role in maintenance of weight loss and a wide range of practical ways for increasing activity, as scheduling activity can be a struggle for women at this stage of life. Walking was introduced first as a form of activity that is accessible to the majority of mothers: they can easily take their baby along with no special equipment required and it is a low-risk activity with recognised health benefits. In line with the self-directed ethos of the intervention, messages also suggested other types of activity throughout the intervention period, encouraging women to find something they might enjoy.

The messages initially focused on dietary change, with messages relating to physical activity being introduced at week 8, in order to focus on one behaviour change before introducing the next activity. Evidence suggests that physical activity on its own is not an effective approach for weight loss, but does become more important in terms of maintaining weight loss. 53,129

Self-monitoring and goal-setting for diet and physical activity were actively encouraged throughout the intervention (see Operationalising the key behaviour change techniques in the weight loss and weight loss maintenance phases).

Using links

Web links were inserted into messages for several purposes, for example to provide more information or guidance on a particular topic such as exercise videos; to signpost to tools to help self-monitor diet and activity; and to give practical advice such as recipe ideas or freezer-friendly meals.

Operationalising the key behaviour change techniques in the weight loss and weight loss maintenance phases

A cluster of BCTs, supported by an evidence base, was selected to be embedded within the Supporting MumS intervention messages and specifically linked to the relevant phases and psychological processes of behaviour change (see Table 3). Intervention BCTs were employed in two ways: (1) phase-specific BCT use and (2) universal BCT use. BCTs specific to a particular phase were operationalised for that phase only. For example, information about the health consequences of obesity (i.e. outcome expectancies) is relevant to motivate people to change, but, once behaviour change has been initiated, this becomes less relevant. Likewise, prompting participants to review their achievements resulting from their weight loss efforts (i.e. satisfaction with outcomes) is only relevant following engagement in behaviour change for some time. Universal BCTs were used throughout the intervention and adapted for the relevant phases of behaviour change. For instance, the setting of weight goals was used throughout the intervention. However, the content of the goals was adjusted depending on whether weight loss was being promoted, or whether participants were being asked to engage in weight loss maintenance.

The BCTs that were considered to be key components based on evidence and theory were operationalised in a number of ways: through the use of bidirectional messages – targeted messages according to weight management progress, eating triggers and other weight-related behaviours (smoking and breastfeeding); self-monitoring weight; self-monitoring diet and activity; and providing social support and messages on action planning and coping planning.

Interactive components: bidirectional messages

Interactive components were included in the core messages that were sent to all participants to encourage engagement and allow provision of feedback. Feedback is important for intervention effectiveness and can serve a number of functions, such as encouraging self-reflection, prompting goal-setting and even preventing a relapse in a trigger situation. One of the interactive features employed questions to emphasise key aspects of the intervention or encourage particular behaviours or self-reflection, for example ‘Did you set a goal this week? Did you achieve your goal? Text us yes or no’.

In total there were 36 ‘yes/no’ messages sent during the 12-month intervention period. When participants replied ‘yes’ or ‘no’, an automated message that was specific for that response was sent to the participant.

Other interactive features included being able to text trigger words and receive an automated reply, and transmission of a weekly weight text, see below.

Targeted messages

Women received targeted messages that were based on data collected at baseline and/or weight loss progress. A bank of text messages was created specifically for women who were breastfeeding and also for women who were interested in smoking cessation. Women opted in to receive these additional messages at baseline, and this was configured on the SMS platform at the time of randomisation.

Breastfeeding

Women who are breastfeeding may be concerned that losing weight will have a negative effect on milk quality and quantity. Evidence to date130 indicates that, once lactation is established, overweight women can restrict their energy intake and exercise aerobically to promote a weight loss of 1 lb/0.5 kg per week, without affecting infant growth. Therefore, a set of SMS messages was created to alleviate participant fears or concerns in relation to weight management while breastfeeding. In total, 10 breastfeeding messages were provided and programmed for delivery in the weight loss phase only, in weeks 1–5, 7–9, 13 and 16. One breastfeeding message was sent each week (except in week 2 when two messages tailored for breastfeeding were sent) so that participants were not overburdened with messages.

Smoking cessation

Smoking cessation is associated with some weight gain and is a barrier to quitting. 131 Therefore, messages were created to provide additional support and encouragement in this regard for women who wanted to stop smoking. Smoking cessation messages were delivered in weeks 1, 14 and 16–24 of the weight loss phase and in weeks 26–28 of the weight loss maintenance phase to encourage and provide sustained support and information to those trying to quit (15 messages in total). One message was sent in each of these weeks so as not to overburden participants. Apart from week 1, messages were not sent about smoking cessation until week 14 in order to avoid overwhelming participants with too many behaviour changes at once; therefore, the intervention conveyed key messages and BCTs related to diet, activity and weight management before addressing smoking cessation.

Weight loss maintenance progress

Weight loss tends to plateau at 6 months and at this stage the focus of the SMS intervention shifted to weight loss maintenance. From month seven onwards, women may have been losing weight or gaining weight or trying to maintain their weight and so they received feedback according to whether their weight had gone up or down or stayed the same (see Self-monitoring of weight). This allowed the provision of real-time feedback, which has been found to be important in effective interventions. 132 The contingent reinforcement highlights achievements or prompts women to take appropriate action. 133

Self-monitoring of weight

Monitoring of weight has been shown to be associated with successful weight loss and weight loss maintenance. 129 Weight self-monitoring was incorporated into the intervention via a weekly message asking women to weigh themselves and send back their weight (e.g. ‘Just a reminder to step on the scales and text us your weight when you do e.g. 11 st 5 or 73.3 kg. All of your texts to SMS will be kept strictly confidential!’) Weekly weight-reporting via SMS has been shown to support self-monitoring and has been found to be feasible in previous trials. 77,133 Reporting weight via SMS was used only for self-monitoring, as weight was measured objectively at study visits (see Chapter 3). In addition to asking women to weigh themselves weekly and respond with their weight, the messages also reminded women why stepping on the scales was important and gave instructions on how to weigh themselves (i.e. preferably the same day of the week, same time and wearing similar clothing), and also reminded women that they could call in to their local pharmacy or shopping centre to weigh themselves.

In the weight loss phase, months 0–6, if women replied with their weight, there was no further message from the system. In the weight loss maintenance phase, the messages reminding women to weigh themselves and report their weight continued, but a feedback feature was added depending on whether women were continuing to lose weight, trying to maintain their weight loss or regaining weight. Hence, in months 7–12, the weekly weight SMS message asked women to send their weight and also add ‘up’ or ‘down’ or ‘same’ in relation to how they did last week (e.g. ‘Weekly weighing = your very own early warning system! Step on the scales today and text us your weight followed by UP, DOWN, SAME. e.g. “10 st 7 SAME” or “66.7 kg SAME”.’). The ‘up’ or ‘down’ or ‘same’ triggered an automated response providing positive encouragement to keep up the good work if their weight went down or stayed the same, or one that offered ideas and information on what to do if their weight went up, as well as messages discouraging feelings of guilt and encouraging them not to dwell on weight gain and to get back on track as soon as possible.

Self-monitoring of diet and activity

Keeping track of diet and activity is known to be positively associated with weight management. 134 Participants were encouraged to monitor their food intake and physical activity to raise awareness of their usual eating and activity patterns and identify where they would like to make changes. The SMS messages suggested a range of options for self-monitoring, such as keeping diaries of food intake and/or activity, using a step counter, using self-monitoring apps or simply recording on paper, for example ‘Keep tabs on your fitness as well as your food. Recording what activities you do, and for how long, will increase your chances of weight loss success. As with food, anything goes- pen & paper, a pedometer, a fitness tracker App on your phone.’. Messages such as this were sent regularly throughout the study to encourage this practice.

Goal-setting and feedback

Participants received guidance on goal-setting for weight loss, dietary change and physical activity via the SMS messages, including examples of how to set specific, measurable, achievable, realistic and timely (SMART) goals, along with guidance on recommended rates of weight loss to help with setting realistic goals. Participants were prompted to set and review goals via prompts, for example ‘Heaps of food for thought this week. Have you thought about what one of your food goals could be? Here’s some inspiration: “I will have a portion of fruit with my breakfast 5 days this week”.’. Messages also asked them to reflect on their progress in relation to the goals they set, for example ‘What about the goal you set last week? Did you reach it? Text Y2 for yes or N2 for no.’. The ‘yes/no’ response triggered an appropriate feedback message, providing support, reinforcement and encouragement; see Interactive components: bidirectional messages.

Slip-ups and relapse prevention

Lapses in good intentions are common in weight loss programmes and can make people feel disempowered, with small slip-ups risking a prolonged return to old and unhelpful behaviours. To support women in such situations, a number of potential trigger points were selected, in conjunction with PPI input (see Personal and public involvement in intervention and active control development). These were ‘slip-up’, ‘crave’, ‘bad day’ and ‘exhausted’. Women could send these trigger words at any time and would receive a reply from a bank of messages specific for that trigger. The real-time responses were designed to provide practical suggestions and support to prevent relapses. This trigger word function has been included in other SMS interventions, such as the txt2stop trial. 98

For messages sent with the word ‘crave’, replies focused on resisting temptation when it was experienced, for example through the use of urge-surfing (allowing cravings to pass without acting on them),135 as well as messages to encourage moderation if they gave in and to ‘get back on track’ again. For ‘slip up’, replies emphasised that it was normal to have slip-ups and encouraged women not to feel guilty. Replies for ‘exhausted’ included suggestions, other than caffeine and sugar, to help combat tiredness, ways of coping with lack of sleep and advice on visiting their general practitioner (GP) if prolonged tiredness persists. ‘Bad-day’ replies included ideas to lift their mood. Women were informed about the trigger words on day 17 of the intervention and were also reminded about them on 8–13 occasions throughout the 12 months of the intervention delivery. From weeks 3–52, participants could send the words ‘crave’ or ‘bad day’; from week 24 they could send the word ‘exhausted’; and in weeks 26–52 they could also send the word ‘slip-up’. Messages were sent out sequentially from a list of available messages. The following numbers of messages for each trigger word were developed: ‘exhausted’, n = 36; ‘crave’, n = 35; ‘bad day’, n = 28; ‘slip-up’, n = 25. Women were not limited in the number of times they could utilise this function.

Social support

Social support was facilitated throughout the SMS intervention using a buddy system (as used previously in txt2stop)98 whereby a participant could nominate a friend or family member to receive the same SMS messages that they were receiving and so be in a better position to provide support to them. Participants were sent the instructions on how to do this in the SMS messages, for example ‘Having support increases weight loss success! Why not have a friend/partner/family member receive the same SMS text messages as you? To do this, reply to this message with Support followed by the person’s mobile number. e.g. Support 07800000000.’. Participants could request a friend/family buddy at any stage and reminders of this facility were sent throughout the intervention period. Messages were also sent to participants to tell them about the value that support can play in weight loss success.

Action planning

Messages were developed to provide participants with knowledge on how they could make plans that would be readily actioned and so would be more likely to lead to achievement of diet and activity goals, for example, ‘Were you able to plan your meals this week? Text Y4 for yes and N4’; ‘Have you made any food swaps recently? Text Y17 for yes and N17 for no’; ‘Keep it, see it, eat it! Check your kitchen– if you have healthy foods in there you are much more likely to eat healthily! Do you have fruit and vegetables in the house this week to snack on? Text Y28 for yes or N28 for no’.

Coping planning

Holiday seasons, special events, social occasions and weekends can all act to undo weight management efforts. 136,137 In line with the theoretical basis of the intervention, support for coping planning was particularly important for maintenance of behaviour to help develop self-efficacy to deal with such situations, and so SMS messages were written to support women in this regard, for example ‘Birthdays? Holidays? Weddings? Do any situations throw your healthy eating plans off track? You’re not alone! Sometimes the best tactic is to accept it, and then plan ahead. If you know you will eat more on a family weekend away, make a plan (e.g. what activity you will do and what you will eat) to get back to your healthy new lifestyle on the Monday’; ‘How have you been coping with tempting situations? Have you been able to resist? Text Y16 for yes and N16 for no’.

Additional intervention components: discussion forum and study website

All the BCTs selected for inclusion in the intervention were embedded in the SMS messages. Two additional components were added to complement the SMS messages with a view to assess how useful these additional elements would be in the pilot RCT.

The first component was a discussion forum, which acted as an additional means of social support. Given the importance of social support for lifestyle behaviour change and weight management, this element was added to allow an opportunity for mothers to talk to other mothers in the intervention, and was complementary to the friends/family social support facilitated via the SMS platform, as previously described. Participants were sent a message informing them of the study forum, along with log-in details. Messages were also sent to remind participants about the forum throughout the duration of the intervention and about the value that support can play in weight loss success.

The other additional component of the intervention was a web page that was established to act as a ‘home’ for all of the web links included in the SMS messages. The web page provided access to the links for participants who might not have been able to access websites from their mobile phone or for those who preferred looking at the internet on larger screens. The web links on the web page were ordered by topic, for easy navigation.

Developing the active control group messages

An active control, as used successfully in the txt2stop trial,98 was developed for the present study. Many similar interventions employ a ‘usual care’ control group; however, the WeighWell feasibility study58 demonstrated the potential for differential attrition rates between the intervention and control groups when a ‘usual care’ control group was used in a postpartum weight loss intervention with women from areas of social disadvantage. Because women volunteering to participate are likely to want to lose weight, being randomised to a usual care or ‘do-nothing’ arm is likely to generate strong patient preferences; employing an active control in these situations might offer an opportunity to create equipoise and enhance satisfaction with randomisation.

As for the intervention messages, the active control SMS messages were drafted by three members of the study team and commented on and refined by other members of the multidisciplinary study team and PPI group (see Personal and public involvement in intervention and active control development). The messages that were developed related to general child care and development, and the content was consistent with evidence-based information provided by the NHS Start4life information service for parents. 138 The active control, therefore, did not mention the target behaviours and did not contain the active ingredients of the intervention (diet and physical activity content and embedded BCTs related to weight loss).

The active control messages were developed for mothers with babies aged ≥ 6 weeks (women had to be at least 6 weeks postpartum to enrol in the study). Relevant messages were created for mothers with a child aged up to 36 months, as women could opt in at any stage up to 24 months postpartum. Women received messages that coincided with the age of their baby, that is if their baby was 6 months old when they were enrolled, they started receiving messages corresponding to this age.

The active control messages were designed to include:

-

A play idea/activity each week.

-

Information on specific milestones, for example developmental steps (crawling, rolling, walking, talking, potty training). Such information was always communicated to mothers with a note of reassurance to assuage concern if their child was not at that stage just yet, as all babies develop differently. Mothers were also advised to speak to their GP or health visitor if they were concerned in any way.

Other messages involved information on home safety, or separation anxiety or information relevant at a particular stage of development. In the Text4baby study139 (the first free, national, health service delivered via SMS in the USA providing information to pregnant women and new mothers to help them improve their health and the health of their babies), three messages per week seemed acceptable to mothers so it was decided to send three messages each week to the active control group in the present study.

There was no bidirectional functionality for the active control messages.

Setting up the SMS platform

The study used the SMS platform used for the txt2stop trial,98 but added to its functionality to allow provision of feedback. The platform enabled messages to be sent to participants at a specified date and time and in a specified order. Other features of the existing SMS platform that were utilised were the trigger-word function described previously; the facility for the participant to text the word STOP at any time if they no longer wanted to receive the messages (in that event, they would still continue in the study unless they also formally withdrew from the study assessments); and the facility to text the word PAUSE if they wanted to pause the messages for a period of time because of planned or unplanned life events, for example holidays or bereavement. If a participant paused the intervention, when they wanted to restart the messages, they contacted the study team who then informed the SMS database programme manager. Messages were restarted from where they left off and the rest of the messages were delivered as for the other participants.

The SMS platform also sent messages on breastfeeding and smoking to women who indicated a desire to receive such messages at their baseline assessments. This was configured on the SMS system at the point of randomisation and the relevant messages were then sent out in addition to the core messages.

Additional programming was carried out to include the participant’s name in the welcome message, as suggested from the PPI work. Feedback from the PPI members indicated that they welcomed the use of some emojis; this was facilitated through the SMS platform using simple symbols, for example a smiley face :), to ensure compatibility across different mobile phones.

Additional programming was also carried out to allow the system to send feedback messages to participants when they responded to the ‘yes/no’ questions or the weight reply messages ‘UP, DOWN or SAME’ in the weight loss maintenance phase. The system was programmed to automatically detect the words ‘UP’, ‘DOWN’ or ‘SAME’ and a message was sent from the appropriate weight reply message library.

Some programming was also required to send the active control messages. This was necessary to adjust message delivery according to the age of the baby at the study outset. Women could opt in to the study any time up to 24 months postpartum, with the study lasting 12 months; therefore, messages were created for babies and toddlers aged from 6 weeks to 36 months. When participants were randomised to the active control, an online calculator selected the appropriate starting point for their messages to ensure that they coincided with the age of their child.

Once set up, the study team tested the delivery of the core messages and interactive features over a period of a few weeks. Issues that were picked up were then resolved before the system went live and the first participant was recruited.

A summary of all the intervention components described is shown in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

The supporting MumS study: summary of the intervention components.

Personal and public involvement in intervention and active control development

The PPI is described in this section according to the GRIPP2-SF (Guidance for Reporting Involvement of Patients and the Public 2-Short Form) subheadings. 140

Aim

The aim of PPI was to help develop a SMS-delivered intervention for weight loss and weight loss maintenance in the postpartum period. To achieve this, the intervention development involved close consultation with postpartum women with respect to the following elements:

-

choosing the name

-

developing initial test SMS messages

-

reviewing the full library of SMS messages.

Personal and public involvement consultations were conducted via a mother and toddler group and a Sure Start group in the Belfast area (Sure Start is a programme that supports parents with children aged < 4 years living in disadvantaged areas in Northern Ireland); in addition, three women who had recently had a baby were recruited, two of whom struggled with their weight. These three women were recruited through word of mouth via QUB researchers and asked to join the study writing team. PPI representatives were paid for their time and input, according to the principles of INVOLVE. 141 Because the PPI representatives had each recently had a baby, they provided input and feedback via telephone or e-mail, as this was the easiest way for them to fit in PPI with their busy lives as new mothers.

Methods and results for the personal and public involvement elements

Choosing the name

The study team created a list of 13 potential study names. The names did not mention weight loss because the study had an active control group. This list was shared with the rest of the project management team, which ranked the names, and a reduced shortlist of eight study names was then tested with PPI representatives. This consisted of one mother and toddler group in Belfast visited by a QUB researcher, together with feedback from other new mothers who were friends or relatives of the QUB study team; in total, 18 women were asked to indicate their preferred study name. The most popular name, based on feedback from postpartum women, was ‘SNAP’. However, subsequent searching showed that various SNAP studies already existed, including a NIHR-funded project examining nicotine replacement therapy in pregnancy. SMS was the second most popular choice, standing for ‘Supporting MumS’.

Reviewing the initial test SMS messages

An initial collection of 30 SMS messages was written by members of the study team; 14 intervention messages and six active control messages were then selected for PPI testing. The aim of this testing was to get initial thoughts from PPI representatives on the tone, length, style and content of messages; the inclusion of links; the use of ‘emojis’; and, importantly, to get an instant reaction from women if they felt that any messages were unsuitable.