Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 13/43/58. The contractual start date was in September 2014. The final report began editorial review in September 2018 and was accepted for publication in July 2019. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

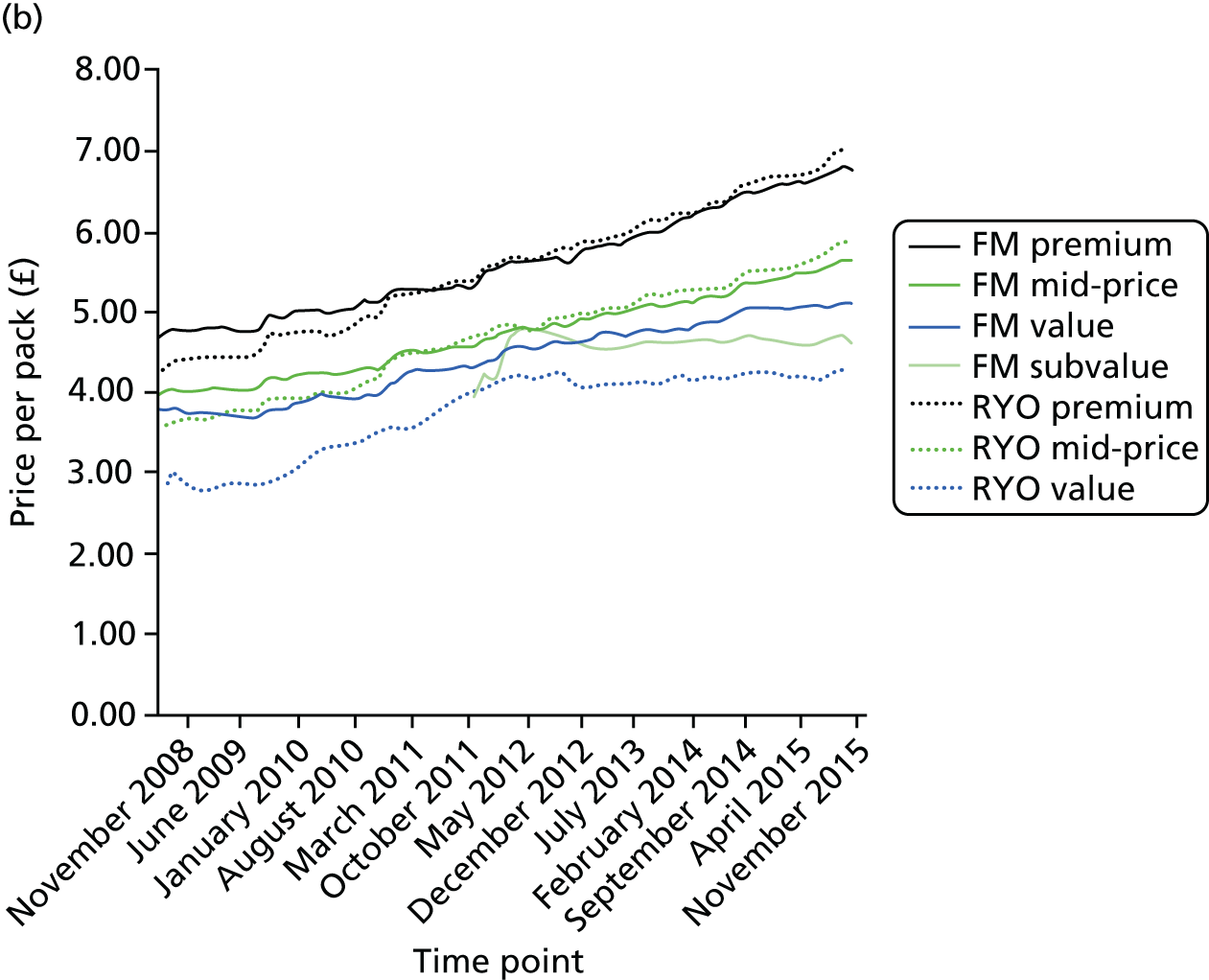

Ann McNeill is a National Institute for Health Research Senior Investigator.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Partos et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction and aims

Background

Health and economic impacts of tobacco

Smoking remains the leading preventable cause of death, disease and health inequalities in the UK. 1 Over 100,000 people in the UK are killed by smoking every year. 2 Smokers lose an average of 10 years of life expectancy, and exposure to other people’s smoke also causes death and disease among non-smokers. In England, the annual cost to the economy is estimated to exceed £11B a year, including cost to the NHS, employers and to the wider economy. 3 In 2017, 14.9% of the adult population in England were current smokers, but this figure masks large disparities in smoking across socioeconomic groups (e.g. 26% smoking prevalence among routine and manual vs. 10% among managerial and professional occupations). 4 Any public health intervention that reduces tobacco use or prevents uptake will lead to significant benefits by reducing premature mortality and morbidity and, consequently, lower NHS costs and increased economic output.

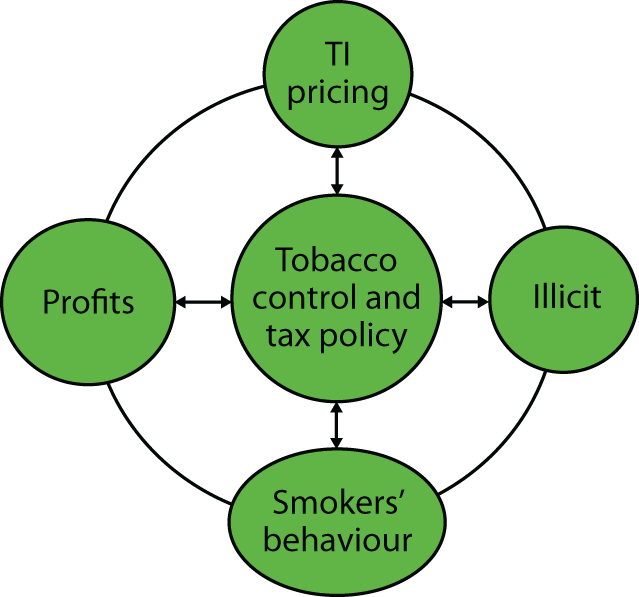

The importance of tobacco tax and price

Tobacco tax increases have been shown to be the most effective and cheapest way of reducing tobacco smoking prevalence,5–13 consumption,14,15 initiation16,17 and inequalities in smoking. 18–21 Tobacco tax has been identified by the World Health Organization as a critically important tobacco control intervention22 and the UK has real tobacco prices that are among the highest in the world. 23,24 The public health impact of tobacco taxation can, however, be reduced by the availability of cheap tobacco. The tobacco industry (TI) is aware of the importance of price and its internal documents show that pricing and price promotions are among its most important marketing tools25–28 in order to reduce the effectiveness of tobacco tax increases. 29,30 Hence, research needs to assess the extent to which the effectiveness of tobacco tax increases is influenced by TI pricing strategies and the effect this has on smokers’ behaviour and socioeconomic inequalities in smoking.

The UK tobacco industry

The main tobacco companies involved in the UK market are Imperial Tobacco (now Imperial Brands) and Japan Tobacco International (JTI). 31 In 2008, JTI became a major player in the UK market through purchasing Gallaher. British American Tobacco (BAT) and Philip Morris, also known as Philip Morris International (PMI), have smaller shares. 31 PMI’s main contribution to the UK market is its iconic brand Marlboro (Philip Morris, New York, NY, USA). Scandinavian Tobacco Group (STG) (Copenhagen, Denmark) was previously involved in the UK through its distribution of Natural American Spirit [chiefly roll your own (RYO)], and currently via sales of cigars and cigarillos. The annual profits generated by the UK TI have been estimated to be £1.5B in 2012 and 2013, with profit margins estimated at approximately 50%. 31

Tobacco industry segmentation and pricing strategies

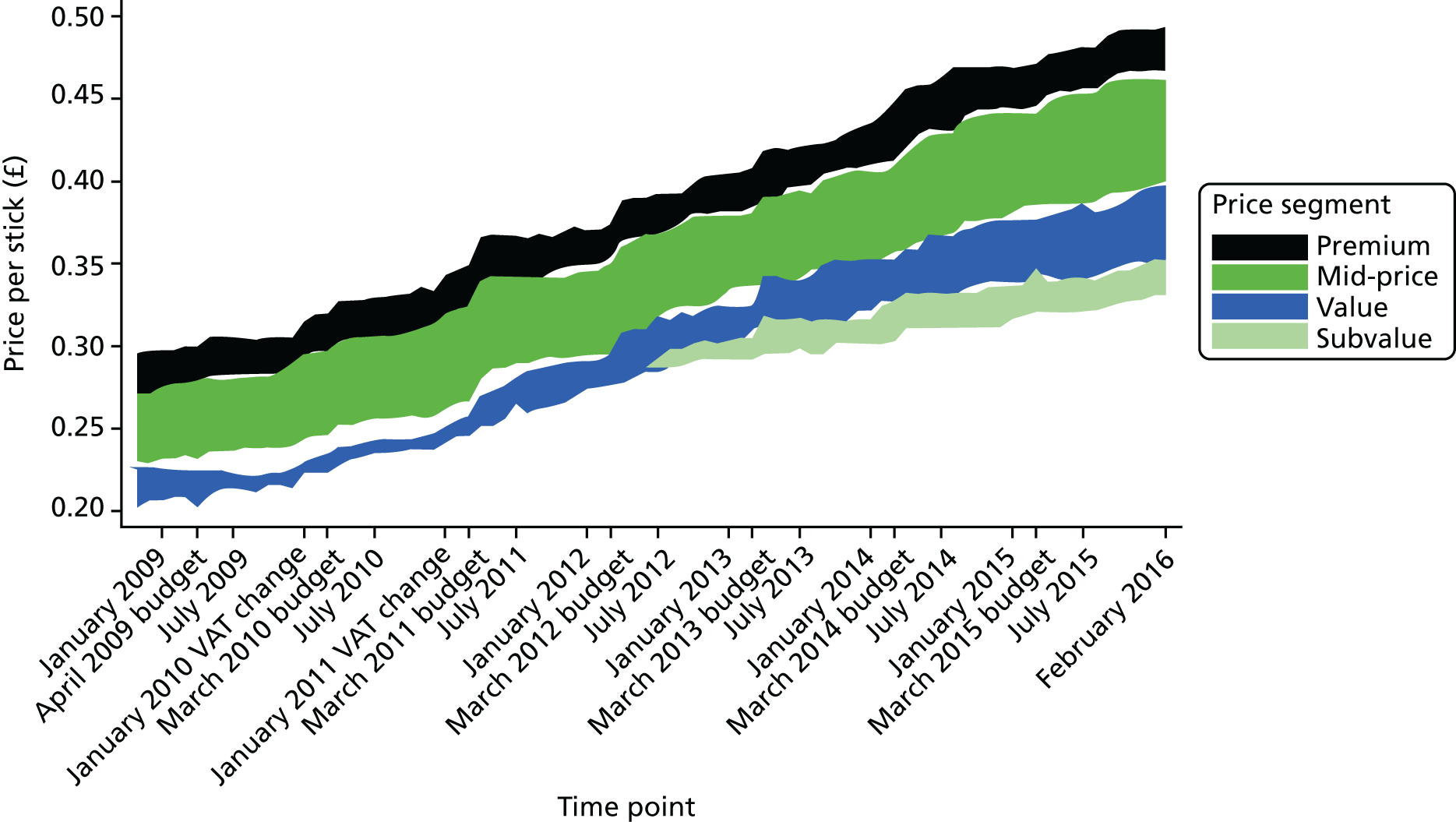

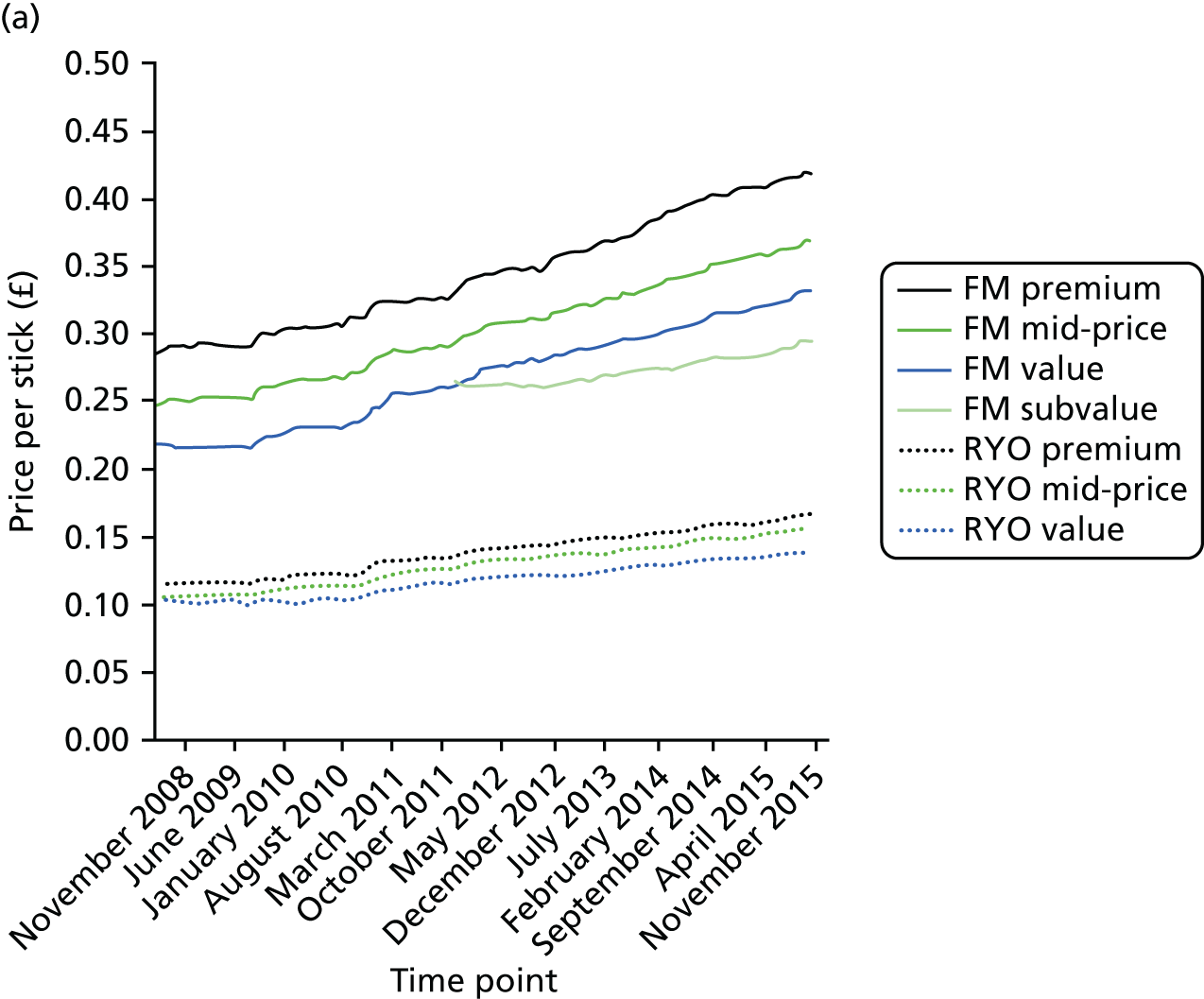

The TI offers a variety of different tobacco products, including factory-made (FM) or manufactured cigarettes, RYO tobacco, cigars, cigarillos and waterpipes. FM cigarettes and RYO tobacco are by far the most popular tobacco products, particularly in the UK. For each tobacco product, the industry offers a number of different brands and it also segments the market into different price categories. Our previous work reviewed the industry literature and sales data on FM segments and identified four price segments: premium, mid-price, economy and ultra-low-price (ULP) brands. 32

When tax increases are announced in the Budget each year, tobacco companies can do one of three things: (1) increase prices on top of tax increases, so that both the price and tax increase are passed on to consumers (known as overshifting), (2) absorb the tax increase so it is not passed on to consumers (undershifting) or (3) pass the tax increase on to consumers in full (fully shifting). 33 The extent of ‘tax pass-through’ to consumers will reflect economic conditions, competition in the market and the extent to which manufacturers are willing to adjust their profits in order to absorb some of the tax increases.

We previously revealed that, between 2000 and 2009 in the UK, the TI undershifted taxes and cut prices on cigarettes in the cheapest segments to keep them cheap, while overshifting taxes on more expensive cigarettes to maximise profits. 32,34,35 Approximately, only half of the price increases were needed to meet tobacco taxation increases, consistent with evidence from Ireland between 2000 and 2010. 36 The range between the cheapest and most expensive cigarettes (the ‘price gap’) therefore increased. Similar TI pricing strategies have now been confirmed in other jurisdictions,37–39 where tobacco companies have also been introducing increasing numbers of lower priced products. 37–39 Smokers are therefore incentivised to down-trade from expensive to cheap cigarettes, rather than quitting smoking.

UK smokers’ behavioural responses to price increases

When faced with a tobacco tax and price increase, smokers may do nothing, quit, reduce consumption or engage in price-minimising behaviours by switching to one of a number of cheaper sources of tobacco. This might include:

-

cheaper legal products (e.g. cheaper manufactured/FM and/or RYO cigarettes12,40–44)

-

tax avoidance – travellers returning from other European Union (EU) countries (which typically have lower tobacco duties) can legally purchase tobacco for personal use in line with guidelines for reasonable personal use,45 or smokers can purchase tobacco in duty-free shops46

-

tax evasion – changing to illicit sources,47 including purchases of a genuine TI product that has entered the illicit market or of counterfeit or ‘illicit whites’

-

purchasing larger quantities which afford economies by buying in bulk (e.g. by the carton, rather than the pack). 40,41

The growing availability of legal cheap cigarettes in the UK is therefore a major public health concern, as it provides options to smokers other than changing their smoking behaviour. If this differentially affected smokers in lower socioeconomic groups, it would drive smoking inequalities further. 32,34,35 The use of cheaper tobacco products has indeed increased, particularly by the poorest. 10,12,42–44,48 The same concerns apply to tobacco tax evasion, also used more frequently by lower socioeconomic groups. 49–52 By contrast, tax avoidance is more common among higher socioeconomic groups consistent with their greater propensity to travel. 46 However, self-reported tax avoidance and evasion by UK smokers declined from 2002 to 2011,53 in contrast to TI arguments that they would increase in response to higher tobacco taxes (see Illicit tobacco: tobacco industry complicity and UK government strategies).

It is, however, unclear whether the decline in use of expensive FM cigarettes is due to a decline in uptake, users quitting or trading down to cheaper products. 12 Evidence indicates that the availability of cheap tobacco reduces motivation to quit and quit success. 54–59 Our work, to date, had used repeat cross-sectional data to examine cheap cigarette use in the UK and could therefore not directly determine the impact that tax and industry price changes had on smokers’ behaviour. Two US studies40,60 found mixed results: one60 found smokers using cheaper FM cigarettes were less likely than those using premium brands to quit or reduce smoking between 1988 and 1993, and the second, more recent, study40 found no direct association between use of cheap FM brands or RYO tobacco in 2009 and quitting outcomes in 2010. Evidence from the International Tobacco Control Policy Evaluation Project (ITC), using data prior to 2008, across four countries (Canada, Australia, the USA and the UK), found a lower likelihood of successful quitting among smokers of cheaper compared with more expensive FM cigarettes. 56 However, in comparison with these other countries, the use of cheap tobacco has been found to be significantly higher in the UK. 57

Factors that might influence smokers’ inclinations to switch to cheaper products rather than quitting also remain largely unexplored. For instance, smokers who are brand-loyal,61,62 or loyal to a specific product type (FM cigarettes or RYO tobacco, rather than smoking both63) might be less likely to switch to a cheaper product. To the best of our knowledge, existing research has provided only limited insights into the purchasing patterns among UK smokers of tobacco on which UK tobacco duties have not been paid,46 and no studies have examined trends in tax evasion separately from tax avoidance, or how these purchasing patterns might change in response to tobacco tax increases.

Affordability

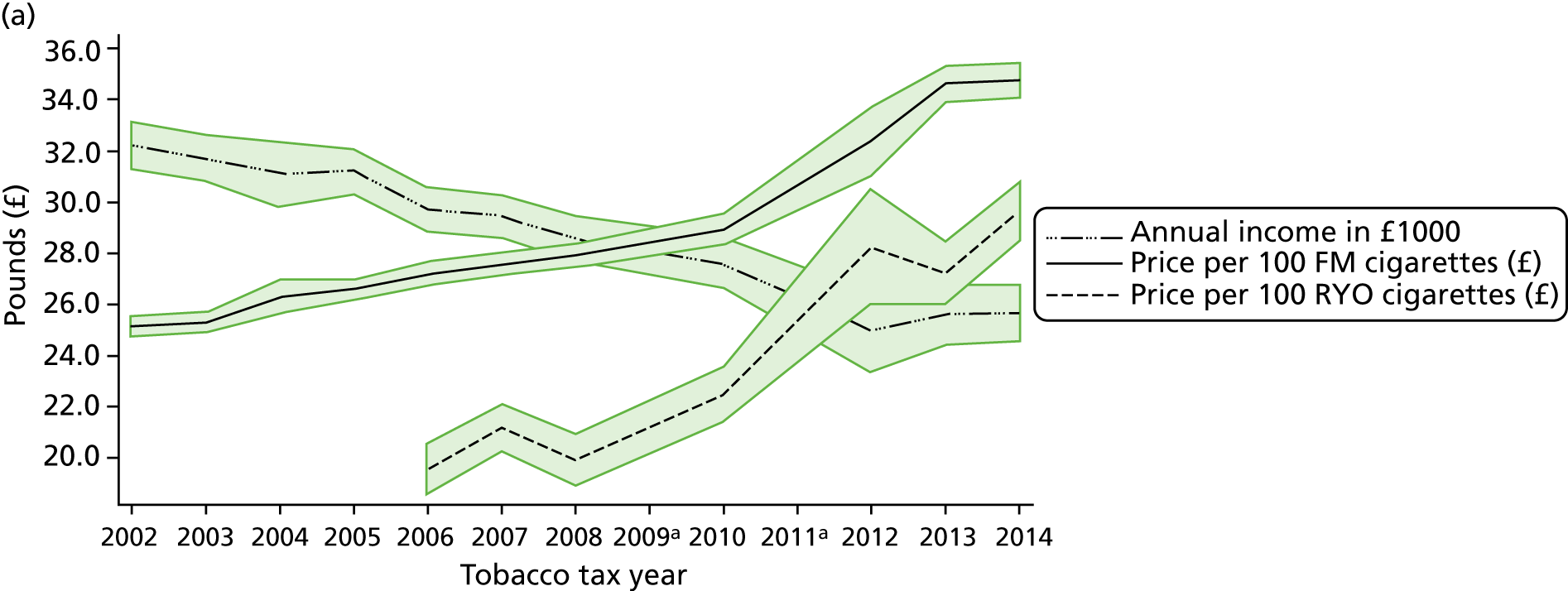

The impact of price rises is also modified by changes in incomes and inflation rates, and, hence, it is important to measure affordability (i.e. smokers’ purchasing power for tobacco in relation to their real incomes). There are many different types of ‘aggregate’ tobacco affordability measures: the ‘Big Mac® index’ representing the number of cigarettes purchased for the price of one McDonald’s Big Mac hamburger (McDonald’s Corporation, San Bernardino, CA, USA);64 the ‘minutes of labour’ needed to purchase a pack of 20 Marlboro cigarettes or an equivalent local brand;65 the ‘relative income price’ (RIP), representing the percentage of per capita gross domestic product (GDP) required to purchase 100 packs of cigarettes (Marlboro or local brand);66 and the cigarette price–daily income ratio, which divides the price of one pack of cigarettes (Marlboro or local brand) by daily income. 67 These measures have different strengths and weaknesses and their merits, particularly when compared across high-, middle- and low-income countries, have been discussed elsewhere. 68

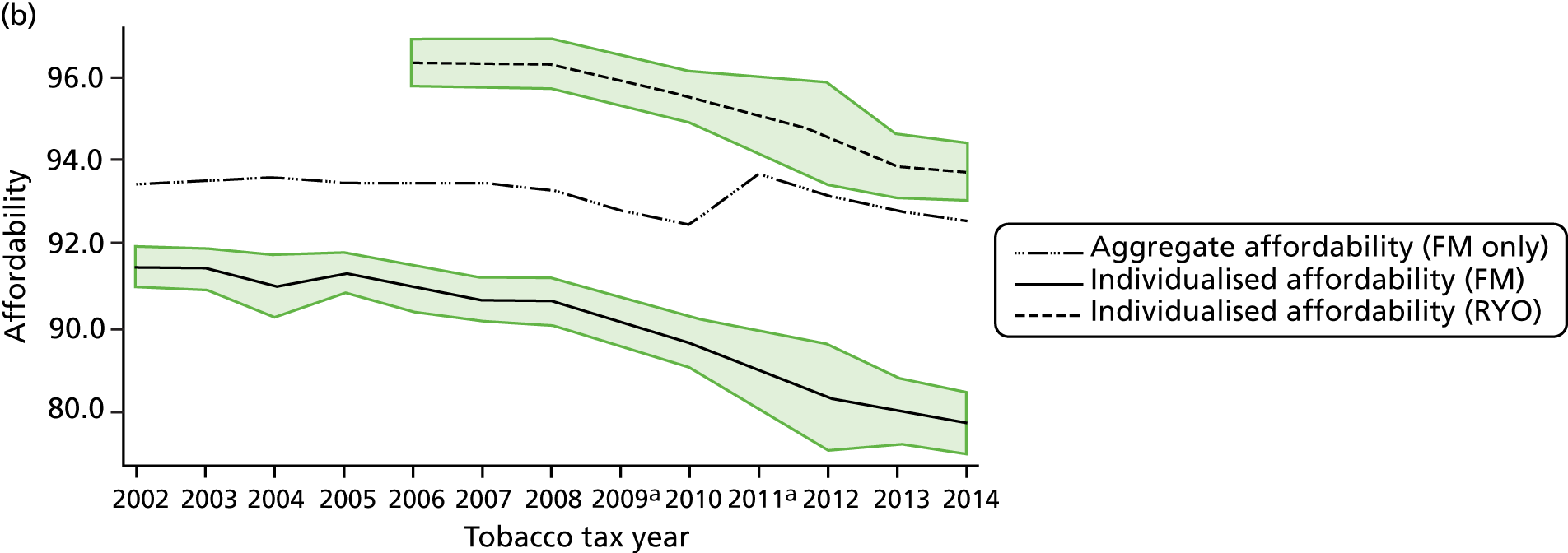

Studies using these methods indicate that cigarettes in the UK have became less affordable since the 1990s, although the rate of decline in affordability appears to be slowing. Between 1991 and 2002 the annual decrease in tobacco affordability was around 5.5%,65 but only around 2–3% between 2003 and 2009. 69 Similarly, estimates using the RIP indicate an annual decrease in affordability of around 2.5–3% between 1990 and 2001,66 but only 1–2% between 2004 and 2010. 70 No studies have examined tobacco affordability in the UK since 2010.

A major limitation of aggregate affordability measures is that they rely on average cigarette prices, usually derived from a small number of brands, and on average national income estimates. However, there are wide income inequalities observed within many countries, including the UK, and, as shown in Tobacco industry segmentation and pricing strategies, a large range of prices between and within different tobacco products. In addition, aggregate measures do not capture the strategies that smokers use to minimise costs, such as buying from cheaper sources or buying in bulk.

Illicit tobacco: tobacco industry complicity and UK government strategies

There is overwhelming evidence of the TI’s historical involvement in the global illicit tobacco trade. 47,71–73 In the UK in the 1990s, tobacco companies were accused of facilitating smuggling by deliberately oversupplying their brands to countries with no demand for them. 74 Although the nature of the illicit tobacco market has since changed substantially and the TI now claims that it has addressed the problem, evidence suggests that the TI has continued to be involved in illicit trade and failed to control their supply chain,73,75,76 despite signing legal agreements to address both these issues. 47 In the UK, Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs (HMRC) estimated that in 2011 the aggregate supply of certain brands of RYO tobacco to some countries exceeded legitimate demand by 240%. 77 Similarly, massive TI overproduction of cigarettes in the Ukraine has been shown to fuel the illicit market in Europe,78 a finding supported by our pan-European survey, which showed that illicit tobacco use was greatest for those living in countries that shared a land or sea border with the Ukraine, Russia, Moldova or Belarus. 52 Furthermore, PMI’s own data suggest that in 2010 around one-quarter of illicit cigarettes in Europe were genuine PMI brands. 79

Despite this, the TI continues to use the threat of increases in illicit tobacco use to argue against key tobacco control policies, including tax increases. 33,79–81 Although these arguments are intuitive and price is one driver of illicit tobacco use, it is not the main driver; supply-side issues (such as levels of corruption and TI complicity) are more important and are key to controlling illicit trade. 82 Nevertheless, the industry has used these arguments extensively in the UK, despite evidence that much of the price increases is directly attributable to industry price increases rather than tax increases, no observed association between tobacco prices and illicit tobacco use across countries in Europe,52 and an observed overall decline in levels of illicit tobacco in the UK despite continued tax increases. 83

The UK government implemented a number of strategies to reduce illicit tobacco use during the study period. In 2000, the UK launched its first illicit tobacco strategy, including £201M of additional funding, new customs staff, freight scanners, stronger penalties for tobacco smuggling and new ‘UK duty paid’ markings on tobacco packs. Government co-operated with tobacco companies to reduce illicit tobacco and implemented a publicity campaign to raise awareness of illicit tobacco use dangers. 84 In 2006, 2011 and 2015, the strategy was updated and refreshed. A regional programme in the north of England, launched in 2009, also aimed to reduce demand for illicit tobacco. 85

UK government tobacco taxation

In the UK, three types of tax are applied to tobacco: (1) specific tax (a fixed amount per 1000 cigarettes or 1000 grams of RYO tobacco); (2) ad valorem tax (set as a percentage of the retail price and only applied to FM cigarettes); and (3) value-added tax (VAT) (another ad valorem tax applied to most goods and services and applied to both FM cigarettes and RYO tobacco). Compared with ad valorem taxes, specific taxes tend to narrow the price range between expensive and cheaper brands, maximise the impact of tobacco taxes24,86,87 and raise more revenue. 88

Since our previous work, UK tobacco taxes have increased annually, their structure has changed somewhat and the rate of VAT has varied [Table 1, and for further details see the fact sheet published by Action on Smoking and Health (ASH) England89 and UK Budget documents90–98]. Two significant changes occurred in March 2011. For FM cigarettes, there was a shift away from ad valorem taxes,99,100 which were reduced from 24% to 16.5% of the retail price. Instead, specific taxes on FM cigarettes were increased from £119 to £155 per 1000 sticks. Ad valorem taxes generally increase the price range between cheap and expensive products and this move was intended to narrow the price range between different FM brands. For RYO tobacco, there was a sudden increase of 10% above the Retail Price Index (RPI) in tax from £130 to £152 per kilogram. This was intended to narrow the price range between RYO and FM products. A third significant change occurred in March 2012, when the tax escalator (which was otherwise set between 0% and 2% above RPI throughout the study period) increased to 5% above RPI for 1 year. It should be noted that, although the RPI (a measure of private household spending from survey data) is still employed in relation to tobacco taxation changes,101 it was de-designated as a national statistic in March 2013 and replaced with the Consumer Price Index (CPI), which meets international standards and is comparable with other European countries. 90 The RPI, unlike the CPI, includes housing costs, is more volatile than the CPI and rises more quickly. 102 We used the CPI to adjust our FM and RYO prices for inflation (see Chapter 2).

| Time point | Specific dutya | Ad valoremb (%) (FM only) | VATc (%) | Tax escalator (%) | Inflationd | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| £/1000 FM cigarettes | £/kg of RYO tobacco | CPI | RPI | ||||

| March 2001 | 92.25 | 96.81 | 22.0 | 17.5 | 0 | ||

| April 2002 | 94.24 | 98.66 | 22.0 | 17.5 | 0 | ||

| April 2003 | 96.88 | 101.42 | 22.0 | 17.5 | 0 | ||

| March 2004 | 99.80 | 104.47 | 22.0 | 17.5 | 0 | ||

| April 2005 | 102.39 | 107.18 | 22.0 | 17.5 | 0 | ||

| March 2006 | 105.10 | 110.02 | 22.0 | 17.5 | 0 | ||

| March 2007 | 108.65 | 113.74 | 22.0 | 17.5 | 0 | 2.8 | 4.6 |

| March 2008 | 112.07 | 117.32 | 22.0 | 17.5 | 0 | 2.5 | 3.8 |

| November/Decembere 2008 | 112.07 | 122.01 | 24.0 | 15.0 | 0 | 4.5 | 4.2 |

| April 2009 | 114.31 | 124.45 | 24.0 | 15.0 | 0 | 2.3 | –1.2 |

| January 2010 | 17.5 | ||||||

| March 2010 | 119.03 | 129.59 | 24.0 | 17.5 | 1 | 3.4 | 4.4 |

| January 2011 | 20.0 | ||||||

| Marchf 2011 | 154.95 (25% > RPI) | 151.90 (12% > RPI) | 16.5f | 20.0 | 2 | 4.0 | 5.3 |

| March 2012 | 167.41 | 164.11 | 16.5 | 20.0 | 5 | 3.5 | 3.6 |

| March 2013 | 176.22 | 172.74 | 16.5 | 20.0 | 2 | 2.8 | 3.3 |

| March 2014 | 184.10 | 180.46 | 16.5 | 20.0 | 2 | 1.6 | 2.5 |

| March 2015 | 189.49 | 185.74 | 16.5 | 20.0 | 2 | 0.0 | 0.9 |

European Union tax changes

Since the 1970s, tobacco product regulations have been introduced in European countries. 103 Two pieces of legislation were introduced in the last decade that are relevant to this study: EU Council Directives 2008/118/EC and 2011/64/EU, which define categories for tobacco and tax structures, including minimum tobacco tax rates. Of relevance here are cigarettes (Article 3), cigars and cigarillos (Article 4) and RYO tobacco (Article 5). The regulations require countries to apply a specific excise tax and an ad valorem tax on cigarettes, as well as a minimum excise duty. Countries have more flexibility for other tobacco product categories and can apply specific and/or ad valorem tax. Mandatory minimum tax rates are set out. 104 The European Commission also changed the price benchmark from the most popular price category (MPPC) to a weighted average price (WAP) in each member state in January 2011.

Rationale for current study

The increased use of cheap legal tobacco products coinciding with the widening price range between expensive and cheap manufactured cigarettes in the UK, and the relatively high (although declining) use of illicit tobacco, raised concerns that tax increases in the UK were perhaps not as effective as assumed, particularly for smokers with low socioeconomic status (SES). An additional concern was that the government’s willingness to increase tobacco taxes was constrained by fear that tax and price rises would fuel the illicit tobacco trade. There was a clear need, therefore, for greater understanding of the effectiveness of tobacco tax increases, the extent to which their public health impact is undermined by TI pricing and whether or not the threat of the illicit trade is a genuine concern that needs to be considered when setting tobacco duties. There were three inter-related issues that we identified as evidence gaps.

Roll-your-own pricing strategies

To the best of our knowledge, no studies had examined TI pricing of RYO tobacco in the UK, despite its growing market share. Furthermore, the work on FM cigarette pricing dated only to 2009. Up-to-date data on RYO tobacco and cigarette pricing were essential, because TI pricing strategies could evolve over time to reflect market, economic and policy developments, and should be considered when setting tobacco duties.

Tobacco industry pricing strategies and socioeconomic inequalities

There was limited evidence on the impact of TI pricing on levels of cheap tobacco use in the UK. Evidence was also limited on differences in smoking outcomes (including quit attempts and success) among those using expensive compared with cheap cigarettes and the extent to which this explains inequalities in smoking. Further research was therefore needed to examine how UK smokers respond to TI pricing strategies, including the extent to which they engage in price-minimising behaviours, reduce consumption or quit, and whether or not these responses vary by SES.

The prevalence of illicit tobacco use

Although the argument that the TI most frequently uses to prevent tobacco tax increases is the claim that they will lead to an increase in the illicit tobacco trade,105 to the best of our knowledge no study had directly examined links between tax increases and trends in tax evasion or avoidance by smokers in the UK. Furthermore, as the TI uses the illicit trade to argue against tobacco tax increases and other tobacco control measures using its own data,47,81,105 it is important that assessments of the level and nature of illicit use in the UK are conducted independently of the TI. The only recent, independent studies estimating illicit use in the UK covered only England, or regions therein, and did not provide a measure of uncertainty with the estimate. 49,50,52 Some also did not break the data down by FM and RYO. 49 Further independent studies were therefore essential.

Research objectives

The main intended public health impacts of tobacco taxation are, first, to reduce tobacco smoking and, second, to raise revenue to deal with the public health costs attributable to smoking. Central to this is the intent that taxation-based interventions are socially equitable, that is, they do not widen (and ideally help to reduce) the sociodemographic disparities associated with smoking. This study aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of tobacco tax increases in reducing tobacco use and minimising inequalities in tobacco use in the UK, and the extent to which this was influenced (undermined or enhanced) by TI pricing strategies.

Objectives

-

Provide up-to-date knowledge of TI pricing and the extent to which this modifies the impact of tobacco taxation on public health, by examining:

-

how the TI segments manufactured cigarettes and RYO tobacco on price

-

the extent to which the TI undershifts, overshifts or fully shifts tobacco tax increases on to consumers, whether or not this varies by product, price segment and over time, and what proportion of price increases by segment is explained by TI price increases versus tax increases.

-

-

To explore the impact of tobacco tax increases, as moderated by TI pricing strategies, on smokers’ behaviour, by examining:

-

the impact of the price range (the difference in price between the most and least expensive products) and price changes (annual tax increases modified via TI pricing) on quitting or switching between products or price segments

-

the impact of the price range and price changes on tobacco consumption

-

whether these behaviours differ by smokers’ previous product or price choices.

-

-

To explore the impact of tobacco tax increases, as moderated by TI pricing strategies, on inequalities in smoking, by examining:

-

the characteristics (socioeconomic, geographic, etc.) of smokers using each product/price segment

-

whether or not behavioural choices (quitting, switching between price segments and reducing consumption) differ by smokers’ SES

-

the proportion of change in smoking inequalities over time attributable to cheap (legal) tobacco use.

-

-

To explore whether or not cheap (legal) products are a means of market entry for the young, by examining:

-

the age of smokers using each product or price segment

-

trends in youth usage of cheap products

-

whether or not young people initiate smoking via cheap products, later upgrading to more expensive products.

-

-

To increase understanding of trends in and the nature of tax avoidance and evasion, by examining:

-

trends in the proportion of smokers engaging in tax avoidance and evasion and their socioeconomic and other characteristics (where they acquire their tobacco and trends therein)

-

whether or not tax/price increases, particularly larger tax increases, are linked to tax avoidance and/or evasion

-

which products are most frequently acquired via tax avoidance and evasion, and from which sources.

-

-

To synthesise findings and develop recommendations to improve the effectiveness of tobacco taxation as a public health intervention.

Once the project was under way, we realised that it was not possible to address the fourth objective [to explore whether or not cheap (legal) products are a means of market entry for the young], as insufficient numbers of young people were enrolled in the ITC. Instead, the ITC data were useful for supplementary analyses on tobacco affordability and weight of RYO cigarettes, which enhanced our understanding of the public health effectiveness of tobacco tax increases.

Patient and public involvement

We did not initially plan patient and public involvement, as the research focused on secondary data analysis. However, we did set up a Stakeholder Group for the project (see Acknowledgements), consisting of stakeholders, including Her Majesty’s Treasury, Public Health England and ASH, which met annually during the project, and we also invited two lay members to join the group. The lay members were two representatives from the then current UK Centre for Tobacco and Alcohol Studies (UKCTAS) Smokers’ Panel: Matthew Alford and Dan Griffin. The UKCTAS Smokers’ Panel is a group of both active smokers and those trying to quit, or recent quitters, who provide lay input into the work of the UKCTAS. At the time our project started, the Panel was recruited from the Bath area. The Stakeholder Group reviewed and commented on preliminary findings and directed the focus of ongoing work so that it was relevant to policy and smokers’ lives. Our two lay members provided critically important and useful input, which helped us to interpret our research findings. In particular, they helped us to assess affordability issues, alerted us to new tobacco packs being marketed and also stimulated us to address the weight of RYO tobacco used. We were enormously grateful for their input.

Chapter 2 General methodology

Introduction

This chapter describes the three main data sources used for our programme of research: (1) tobacco sector commercial literature (hereafter ‘commercial literature’), (2) Nielsen tobacco sales data (hereafter ‘Nielsen data’) and (3) the ITC data. Nielsen is a retail measurement service providing sales data on a range of consumer goods. The ITC conducts longitudinal cohort surveys in 29 countries (including the UK), aimed at systematic evaluation of key tobacco control policies, including assessing the impact of tobacco prices [see URL: www.itcproject.org (accessed 25 August 2019)].

Commercial literature

The commercial literature was used to give a comprehensive overview on the TI pricing strategy for tobacco products and to describe how the industry segmented FM and RYO markets (also identifying brand names in each identified segment).

Sources

The commercial literature included TI documents, industry monitoring reports and trade magazines, from the years 2008 to 2014, with a few articles from early 2015 included when they were reviews of 2014. TI documents included annual reports from BAT, Imperial Tobacco, JTI and PMI, and presentations from BAT, Imperial Tobacco and PMI (JTI does not make presentations available). Industry monitoring reports were from Euromonitor International Ltd (London, UK), Mintel (London, UK) and Keynote (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA), and for 2014 only from Bank of America (Charlotte, NC, USA)/Merrill Lynch (New York, NY, USA) (Imperial Tobacco bought some American brands from Reynolds American at this time). Trade magazines included Retail News (online as Talkingretail.com), The Grocer, Wholesale News and Tobacco Journal International (including the supplement Tobacco Profiles). Online and/or paper copies of trade magazines were searched, depending on availability. Additional trade magazines (2014 editions of Forecourt Trader, Convenience Store and Asian Trader), available from a related literature review for a previous project, were also searched. One article on Imperial Tobacco price segmentation from the Scottish Grocer, found via a post hoc Google (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA) search for segment names, was also included.

Analyses

From articles mentioning tobacco products, we collated the following information in a database: segment name, tobacco company, brand name, pack size, price, price type [recommended retail price (RRP) or price marked], date referred to, date of article, source of article, title of article, reporter, geography and relevant quotations. The number of articles/reports extracted was 517. Each article was searched for mentions of brands and brand variants, alongside segment information and any text relevant to understanding segmentation. An article could mention one or several brands and brand variants and/or could provide one or more quotations regarding segmentation. This resulted in 1892 entries in the final main database, of which 1700 concerned 347 brand and brand variants. The remainder of the entries were articles that discussed price segmentation generally without referring to specific brands.

We also conducted a qualitative analysis to explore how the industry maintained profitability through brand segmentation, in the context of other price-limiting strategies, between 2008 and 2014. For this, 557 quotations about brand segments and tobacco pricing were collected from the commercial literature and analysed. The quotations were imported into NVivo 10 (QSR International, Warrington, UK) and coded at various nodes. There were two super-nodes: ‘market conditions that the TI was experiencing’ and ‘TI actions and responses to these market conditions’. Within each super-node, subnodes were developed iteratively during data collection. Queries for each subnode by year were used to assess patterns over time.

Limitations and strengths

Strengths of the commercial literature are that it can provide unique insights into industry attempts to maintain and enhance profitability. This was also the only data source available which included cigars and cigarillos. However, this literature may also obscure the TI’s real intentions (e.g. to promote sales) and fears (e.g. of declining premium sales and profits), and it will tend to report industry rather than public health viewpoints. The flip side of this is that as this literature is aimed at current and potential investors, rather than government and regulatory bodies that seek to regulate its promotional activities, it often contains illuminating examples of TI efforts to promote sales, sales figures and profitability.

Studies using the commercial literature

The commercial literature was often used as a background to inform our investigations, but three specific studies were also conducted.

Nielsen data

These sales data were primarily used to finalise the allocation of FM and RYO brands to price segments [a process that was begun in the commercial literature study 2, building on our earlier Pricing Policies and Control of Tobacco in Europe (PPACTE) project32], and then to identify trends in the price, sales volumes and TI revenue of FM cigarettes and RYO tobacco by price segment. We were also interested in the extent to which the TI was overshifting or undershifting tax increases by segment.

Source

Nielsen’s Scantrak data were based on electronic point-of-sale (EPOS) system data (i.e. information obtained when tobacco products are scanned at the till in sales outlets). 106 Data are collated by Nielsen on grocery sales, which include sales in supermarkets and convenience stores. Nielsen collates 100% of sales data from four supermarkets [Tesco (Welwyn Garden City, UK), Sainsbury’s (London, UK), Morrisons (Bradford, UK) and Asda (Leeds, UK)] and conducts stratified random sampling with replacement from other outlets [e.g. Co-op (Manchester, UK)]. 107 For remaining retail outlets, sales could only be modelled. As an example, in November 2015, Nielsen collected EPOS data from 87% of the UK’s supermarkets, 15% of its convenience stores (including 83% supermarket-owned convenience stores, 59% petrol station shops, 6% convenience store chains and 4% independents) and 17% of Northern Ireland stores with grocery sales (Northern Ireland represents 2.8% of the UK population). 107 The outlets that provide Nielsen data vary over time and changes to the cigarettes being sold by the outlets may also mean that databases need adjusting. Nielsen updates its market coverage and thus its estimation of prices and volumes twice a year. In the UK, Nielsen collates EPOS data on grocery sales from 15,000 shops across all food and drink trade channels, and the total grocery market measured was £145B in 2015. 108 Other estimates of the total UK grocery market vary from £99.2B109 to £179.1B;110 thus, Nielsen’s estimate is consistent with these.

Nielsen data consists of a list of stock-keeping units (SKUs). A SKU is identified through an individual electronic barcode. Each SKU comprises seven different descriptors:

-

product type (e.g. RYO tobacco vs. FM cigarettes)

-

trading company (e.g. BAT)

-

house (e.g. Pall Mall)

-

brand (e.g. Pall Mall Blue king size)

-

pack size (e.g. the number of FM sticks or grams of RYO per pack)

-

sales unit contents – the number of packs sold together (e.g. in a carton)

-

packaging type – whether or not price promoted (i.e. sold in a price-marked pack).

Stock-keeping units are thus the lowest level element within a hierarchical classification system. We compared this Nielsen hierarchical brand typology with other alternatives,111,112 producing one to be used for our study (Table 2). Nielsen provides monthly sales data and for this study we used data from November 2008 to February 2016.

| Level | Generic brand hierarchya | Nielsen (UK data) | PMI | Australiab | Our study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Family brand (e.g. Buick) | Parent anchoring brand (e.g. Marlboro) | Brand family (e.g. JPS) | Brand [e.g. (1) Marlboro and (2) Benson & Hedges] | |

| 2 | Individual brand (e.g. Buick Regal) | Housec (e.g. Marlboro Bright Leaf) | Brand family (e.g. Marlboro Fresh) | Brand/brand extension (e.g. JPS Duo) | Brand family [e.g. (1) Marlboro Bright Leaf and (2) Benson & Hedges Blue] |

| 3 | Modifier (e.g. Buick Regal GS) | Brand (e.g. Marlboro Bright Leaf Platinum) | Brand variant (e.g. Marlboro Fresh Ice Blast or Marlboro Fresh Kretek Mint) | Products (e.g. JPS Duo Gold) | Brand variant [e.g. (1) Marlboro Bright Leaf Platinum and (2) Benson & Hedges Sky Blue Superkings] |

| 4 | Product description (e.g. mid-size luxury sport sedan automobile) | SKU (e.g. Marlboro Bright Leaf Platinum 10s carton, not price marked) | SKU (e.g. JPS Duo Gold 20s) | SKU [e.g. (1) Marlboro Bright Leaf Platinum 10s carton not price marked and (2) Benson & Hedges Sky Blue Superkings 19-stick price-marked single pack] |

Analyses

Nielsen provided six overlapping data sets of monthly data: 1 (November 2008–October 2011), 2 (January 2009–December 2011), 3 (August 2011–July 2013), 4 (July 2012–December 2014), 5 (January 2013–November 2015) and 6 (March 2013–February 2016). Nielsen updates its estimates (market coverage and thus sales volumes and prices) twice yearly. Hence, the most recent data sets are likely to reflect the market most accurately, so when data for a month were available from multiple data sets, we used the most recent (e.g. we took data for November 2008–December 2008 from data set 1, January 2009–July 2011 from data set 2). We thus created a data set with the most recently provided monthly data, spanning from November 2008 to February 2016.

Up to five types of sales information were provided by Nielsen for each SKU every month:

-

number of units (usually packs) sold

-

price of each unit

-

total value of SKUs sold

-

total volume sold (sticks of FM or kilograms of RYO)

-

percentage of sampled stores to which each SKU was distributed.

Sometimes tobacco companies change the names of brands. We used this sales information, together with the commercial literature and Google searches, to check whether an apparent new brand, family or variant in a data set previously existed under a different name. Thus, SKU behaviour over the entire analysis period was identifiable.

It should be noted that not all five types of sales information were provided for all the data sets. Volumes were not provided for data sets 1 and 2 (used for our estimates between November 2008 and July 2011), so we imputed volume based on number of units sold. When provided, the volume variable showed evidence of modelling by Nielsen, so there may be some discrepancy between earlier and later data sets here. Distribution data were provided only for data sets 5 and 6 (used for our estimates between January 2013 and February 2016).

Data validity and exclusions

Nielsen state that data are valid only when a SKU is distributed to ≥ 10% of retailers in its sample. However, given that distribution data were not available for the earlier data sets, this could not be used as our exclusion criterion. Thus, we instead attempted to model 10% distribution using market share (dividing volume of sticks or 0.5-g RYO stick equivalents sold for each SKU by total volume) for conducting our FM segmentation (see Chapter 3). We did this using a selection of months for which we had distribution information available, namely January 2013, February 2013, March 2013, January 2016 and February 2016 (January 2013 and February 2016 were the first and last months, respectively, for which we had distribution information). For our modelling we explored market shares for FM SKUs between 0.02% and 0.06%, and compared these to Nielsen’s ≥ 10% distribution criteria (Table 3). We wanted to identify the market share value that minimised the number of SKUs misclassified (see Table 3, ‘F’ rows) and provided a number of valid SKUs as close as possible to that using Nielsen’s ≥ 10% distribution criterion (see Table 3, comparison of ‘A’ and ‘E’ rows). The resulting optimal outcome was a market share of > 0.05%, which we therefore applied uniformly over our entire data set as the criterion for identifying valid SKUs for brand segmentation each month (we ended our modelling with 0.06 because the number of misclassified SKUs was rising). Given that the 10% distribution criterion was also suggested by Nielsen for RYO products, we used the same criterion of > 0.05% market share for conducting our RYO segmentation.

| Market shares for FM SKUs | Time point | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| January 2013 | February 2013 | March 2013 | January 2016 | February 2016 | |

| Total number of SKUs available | 221 | 221 | 218 | 387 | 387 |

| A. Valid SKUs based on distribution (B + D) (Nielsen criterion: distributed to ≥ 10% of stores) | 87 | 88 | 88 | 102 | 98 |

| 1. Market share > 0.02% | |||||

| B. Only distribution valid | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| C. Only market share valid | 28 | 29 | 29 | 39 | 43 |

| D. Distribution and market share valid | 87 | 88 | 88 | 102 | 98 |

| E. Any market share valid (C + D) | 115 | 117 | 117 | 141 | 141 |

| F. Total misclassified (B + C) | 28 | 29 | 29 | 39 | 43 |

| 2. Market share > 0.03% | |||||

| B. Only distribution valid | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 0 |

| C. Only market share valid | 14 | 15 | 18 | 26 | 29 |

| D. Distribution and market share valid | 86 | 87 | 86 | 99 | 98 |

| E. Any market share valid (C + D) | 100 | 102 | 104 | 125 | 127 |

| F. Total misclassified (B + C) | 15 | 16 | 20 | 29 | 29 |

| 3. Market share > 0.04% | |||||

| B. Only distribution valid | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 0 |

| C. Only market share valid | 12 | 12 | 12 | 18 | 24 |

| D. Distribution and market share valid | 84 | 84 | 85 | 98 | 98 |

| E. Any market share valid (C + D) | 96 | 96 | 97 | 116 | 122 |

| F. Total misclassified (B + C) | 15 | 16 | 15 | 22 | 24 |

| 4. Market share > 0.05% | |||||

| B. Only distribution valid | 6 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 4 |

| C. Only market share valid | 7 | 6 | 7 | 13 | 15 |

| D. Distribution and market share valid | 81 | 82 | 81 | 95 | 94 |

| E. Any market share valid (C + D) | 88 | 88 | 88 | 108 | 109 |

| F. Total misclassified (B + C) | 13 | 12 | 14 | 20 | 19 |

| 5. Market share > 0.06% | |||||

| B. Only distribution valid | 9 | 13 | 12 | 10 | 8 |

| C. Only market share valid | 6 | 6 | 6 | 10 | 14 |

| D. Distribution and market share valid | 78 | 75 | 76 | 92 | 90 |

| E. Any market share valid (C + D) | 84 | 81 | 82 | 102 | 104 |

| F. Total misclassified | 15 | 19 | 18 | 20 | 22 |

For the segmentation development, the FM and RYO data sets were kept separate, but for the price analyses, these data sets were merged so that we could compare market share changes of RYO tobacco and FM cigarettes. On merging these data sets, the exclusion criterion of 0.05% market share was no longer applicable because the total number of SKUs was larger. We found that changing the criterion to 0.008% market share allowed all SKUs that were valid in the separate FM and RYO data sets to be also valid in the combined data set. However, other SKUs now reached sufficient market share to be included that had not done so for the segmentation process. To prevent random fluctuations from being influential, new SKUs were included only if they reached sufficient market share for 3 months. To avoid incorrectly excluding SKUs that were present for < 3 months because they were arriving on or leaving the market at the beginning or end of the data series, respectively (rather than due to random fluctuations), the price analyses using the merged data sets were restricted to January 2009–December 2015. The allocation of these extra SKUs to segments is described in Chapter 3.

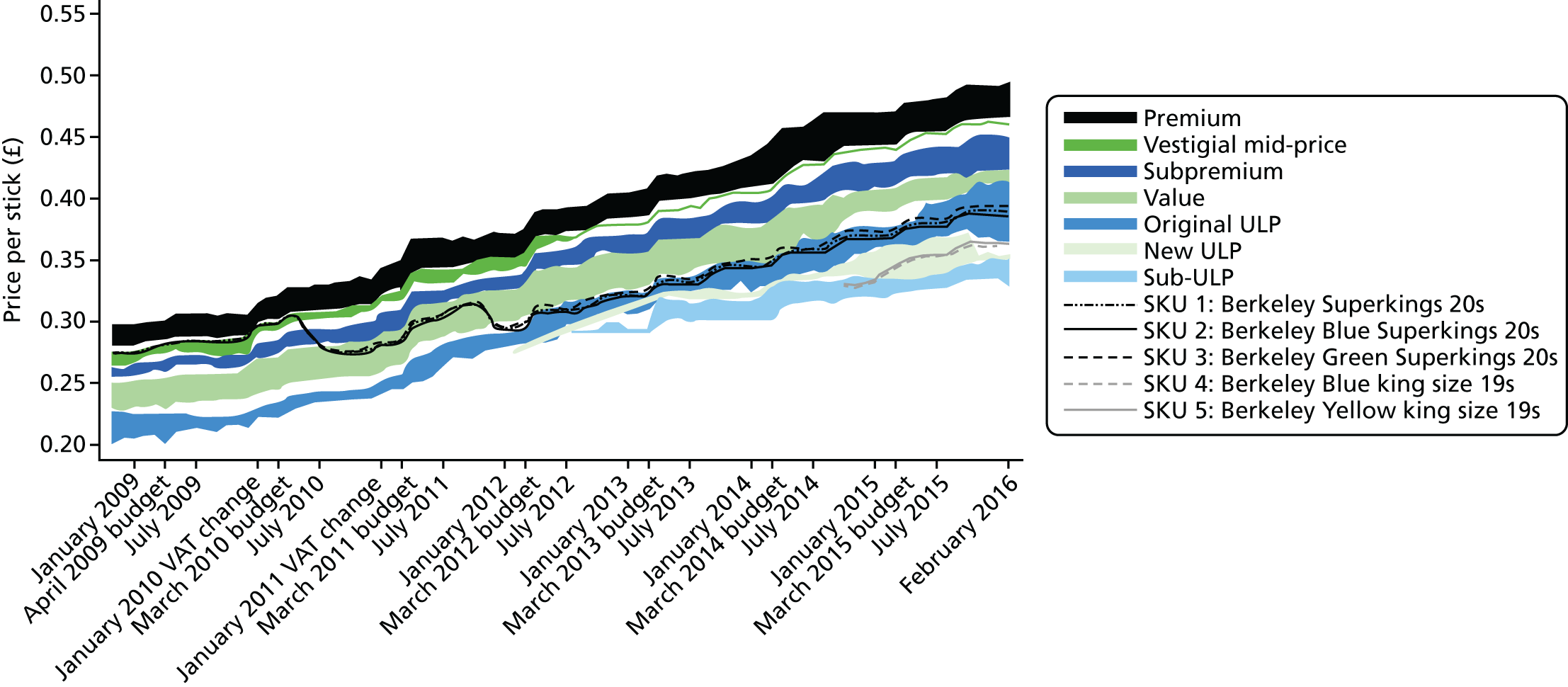

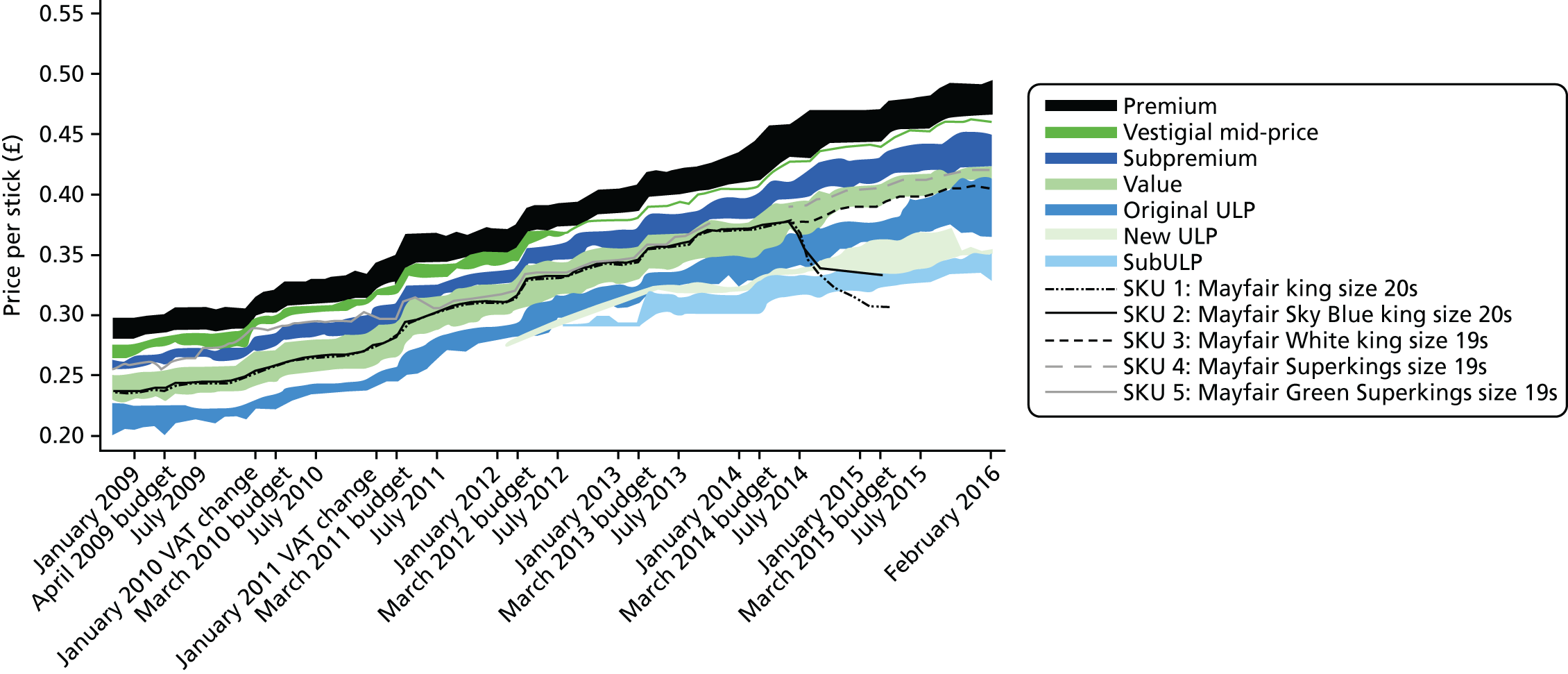

To identify consistent pricing patterns, some atypically priced and/or rare SKUs were excluded. Retailer and wholesaler brands and cartons (sometimes known as ‘multipacks’) were excluded from all analyses because they rarely reached valid distribution during the time period that distribution data were available. We also excluded make your own (when smokers purchase empty cigarette tubes and a small machine that fills these tubes with tobacco) and combi-packs (packs of RYO tobacco sold together with rolling papers and/or filters) from all analyses, as they were consistently priced higher than other SKUs in their brand family. From the segmentation analyses only, we excluded price-marked packs and FM packs containing < 17 or > 20 sticks, due to their rarity (e.g. 14 stick packs) or consistently different pricing than other SKUs in their segment (e.g. 10 sticks packs were priced higher), and RYO packs of uncommon sizes (we included only 10-g, 12.5-g, 25-g and 50-g packs). From the pricing analyses only, we excluded Berkeley and Swan brands due to idiosyncratic pricing. Unless otherwise noted (e.g. for revenue analyses; see Chapter 4) and unlike the segmentation analyses, price-marked packs, 10-stick FM packs and RYO packs of all sizes were included in the pricing analyses.

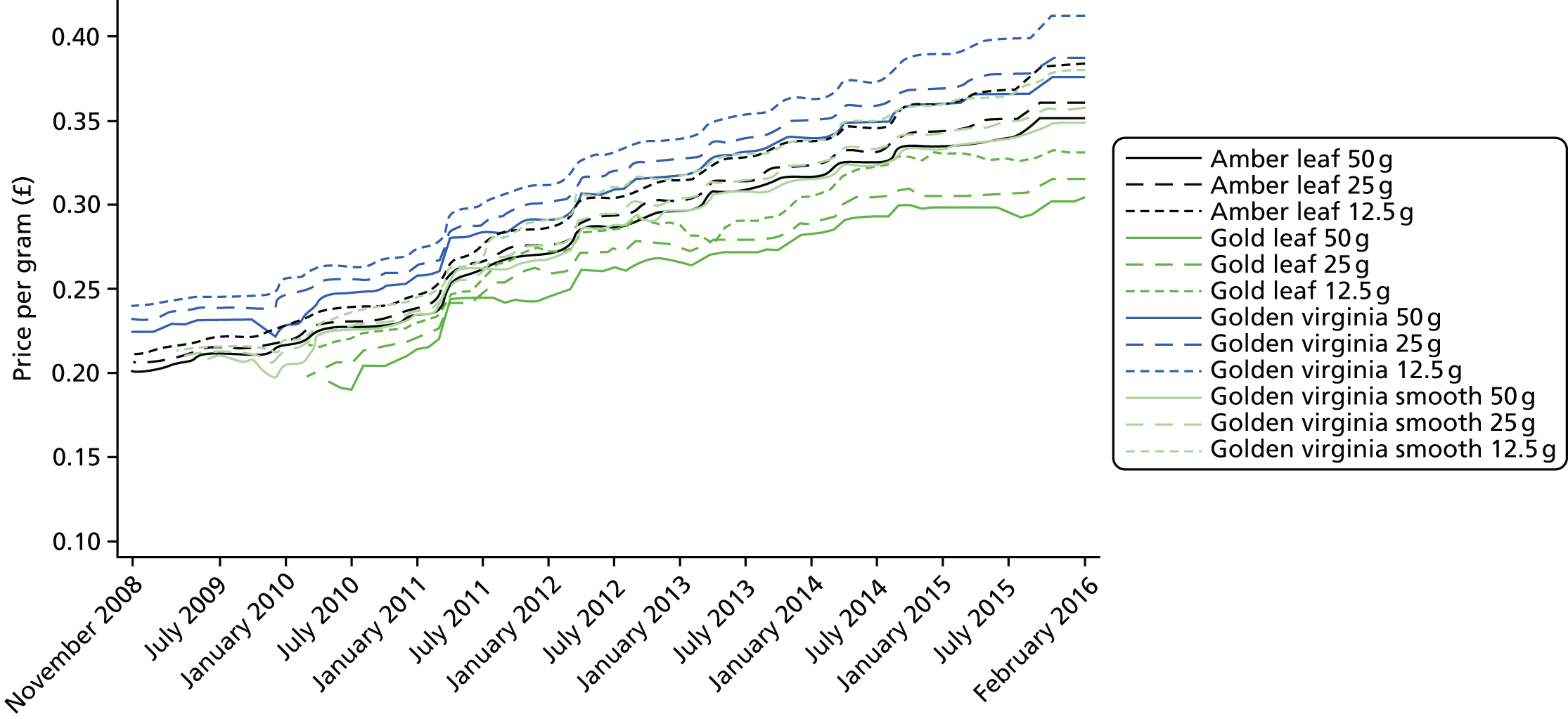

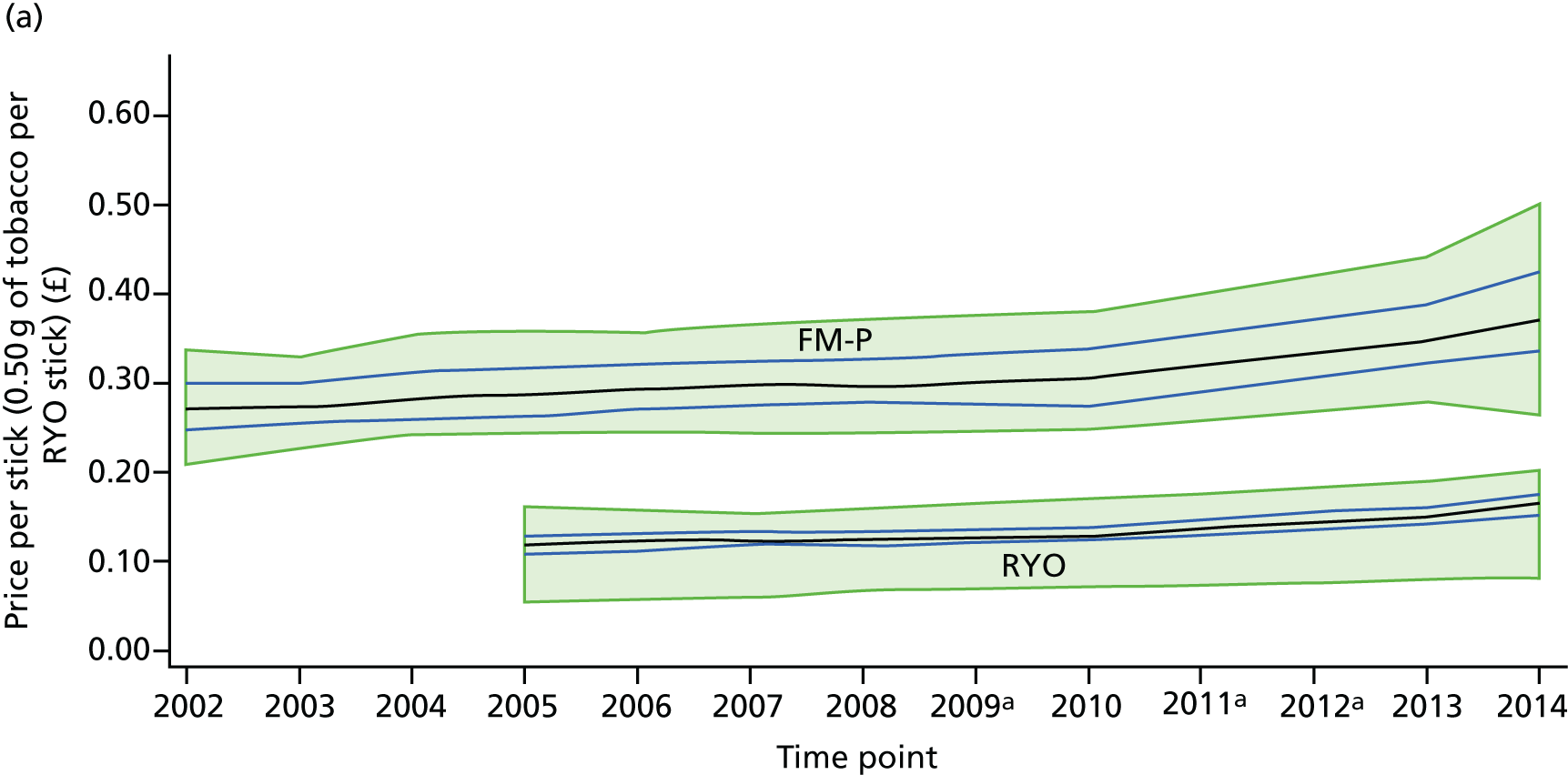

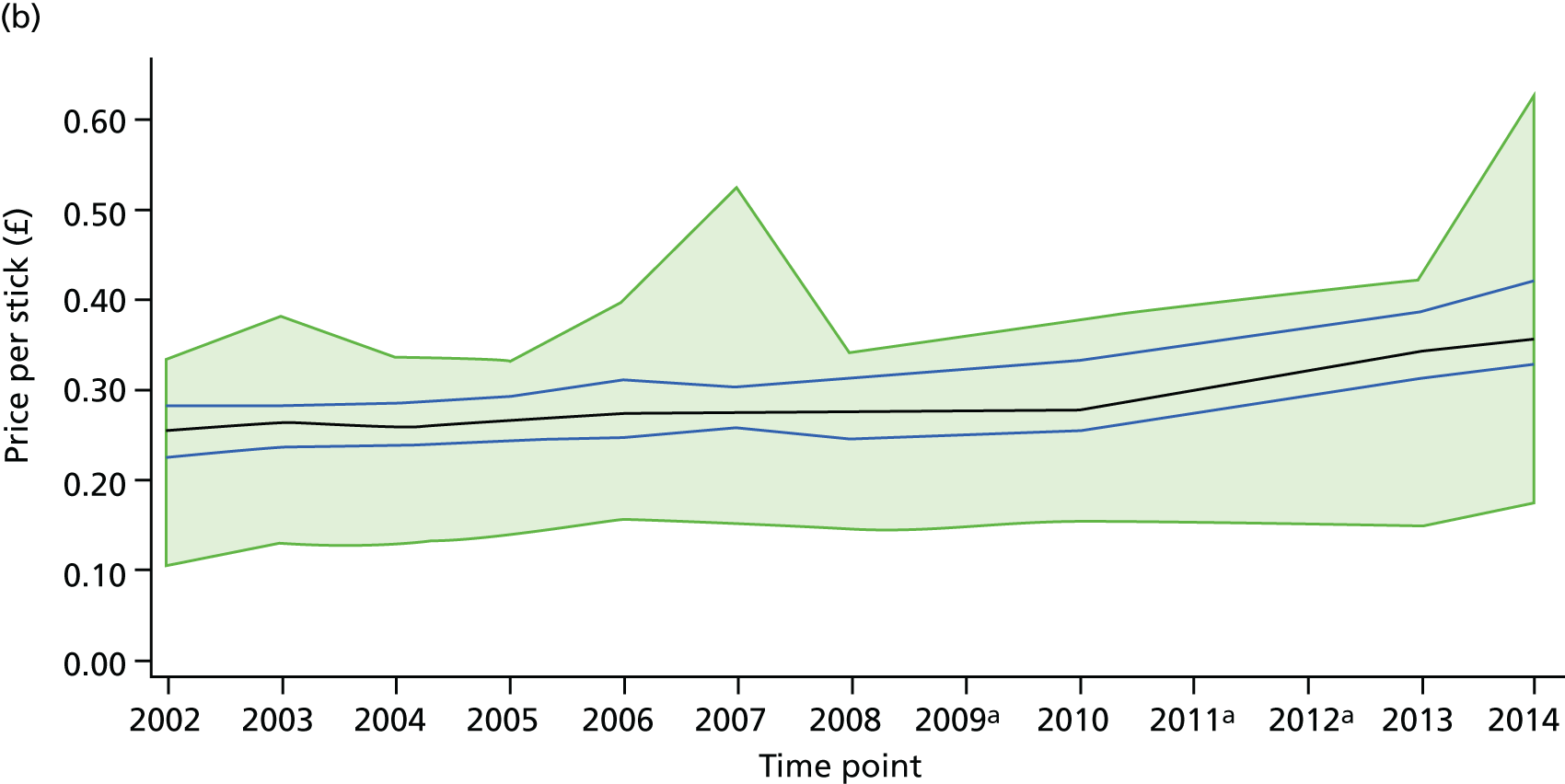

Prices per stick and roll-your-own ‘stick equivalents’

After literature review and analysis of consumption patterns in the ITC data (see Chapter 7), we defined one RYO cigarette (‘stick equivalent’) as containing 0.5 g of tobacco. Price per stick (one FM cigarette or 0.5-g RYO stick equivalent) was calculated by dividing the price per unit (pack) by the number of sticks or stick equivalents per pack. It is worth reiterating here that, in the UK, specific duty on FM cigarettes is calculated per 1000 cigarettes, whereas on RYO tobacco it is calculated per 1000 g of tobacco, and these rates are comparable (e.g. in 2015, specific duty was £189.49 for 1000 FM sticks and £185.74 for 1000 g of RYO tobacco, see Table 1). Implicit in this, is the notion that one FM cigarette is comparable to 1 g of RYO tobacco; however, our data indicate that 1 g of RYO tobacco is more comparable to two FM cigarettes, which means that specific duty on RYO tobacco is effectively half that on FM cigarettes.

Limitations and strengths

Nielsen tobacco data are increasingly being used for academic, as well as commercial, research. 14,113–116 They have also been validated for policy evaluation. 117 Only legal grocery store sales are included, but such sales (including supermarkets and convenience stores) represent up to 80% of the total market [see Chapter 6, ITC data study 3: smokers’ tobacco purchasing behaviours by product and store type (licit purchases)] and, as we shall see, illicit and non-grocery store sales are declining (see Chapter 8). 81,118 In this project, we did not differentiate Nielsen sales data in terms of the percentage of tobacco sales that came from supermarkets compared with convenience stores; thus, although Nielsen samples overall grocery sales from around 87% of UK supermarkets and 15% of its convenience stores, we do not have the data to determine what percentage of the tobacco sales came from those supermarkets compared with convenience stores. However, in more recent work (covering the period from May 2015 to April 2018), we have found that about 80% of tobacco sales were from convenience stores (data not shown). This was higher than in this study using the ITC data (41% of legal tobacco sales were from convenience stores; see Chapter 6). Thus, assuming that convenience stores have higher tobacco prices, it might be the case that our Nielsen analyses would provide slightly higher estimates of tobacco prices than our ITC data; however, given that we can triangulate the findings from these two sources, we are confident that we will obtain an accurate estimate of tobacco prices in this project.

Only RYO tobacco prices are included, not papers or filters (which currently cost between £0.002 and £0.006 and between £0.002 and £0.008 each, respectively),119,120 which would add between £0.004 and £0.014 per cigarette.

Wider changes in the competitive landscape may also have contributed to price changes, but this seems unlikely: the e-cigarette market in 2015 was only a twentieth of the size of the tobacco market in the UK121 and four transnational tobacco companies collectively accounted for > 90% of the market, with only relatively small changes in their respective market shares. 122

Studies using the Nielsen data set

-

Study 1 (see Chapter 3): allocation of SKUs to segments.

-

Study 2 (see Chapter 4): TI pricing strategies.

-

Study 3 (see Chapter 4): what proportion of price increases by segment are explained by TI price increases versus tax increases?

-

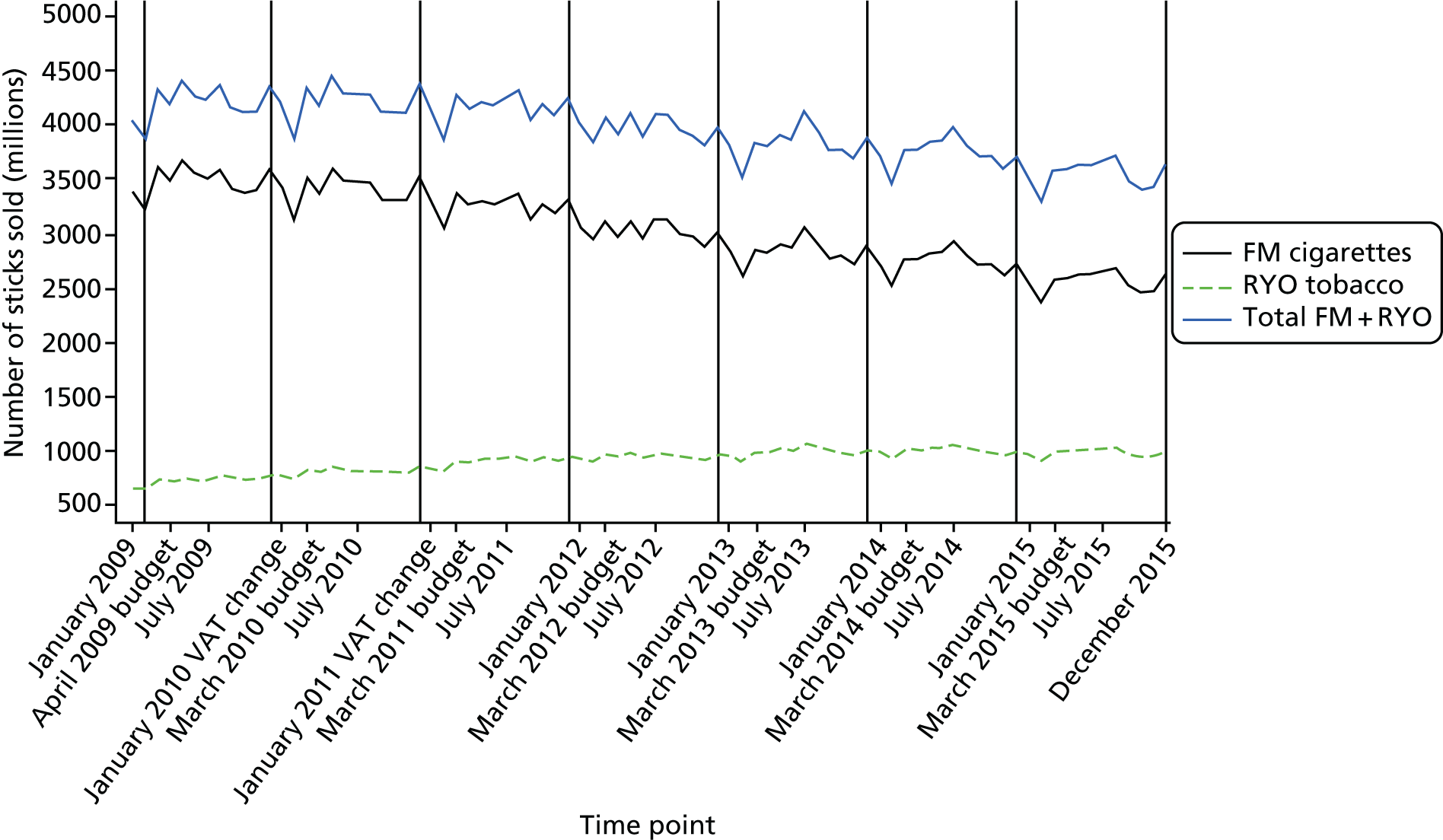

Study 4 (see Chapter 6): what are sales volumes overall and by tobacco type over time?

-

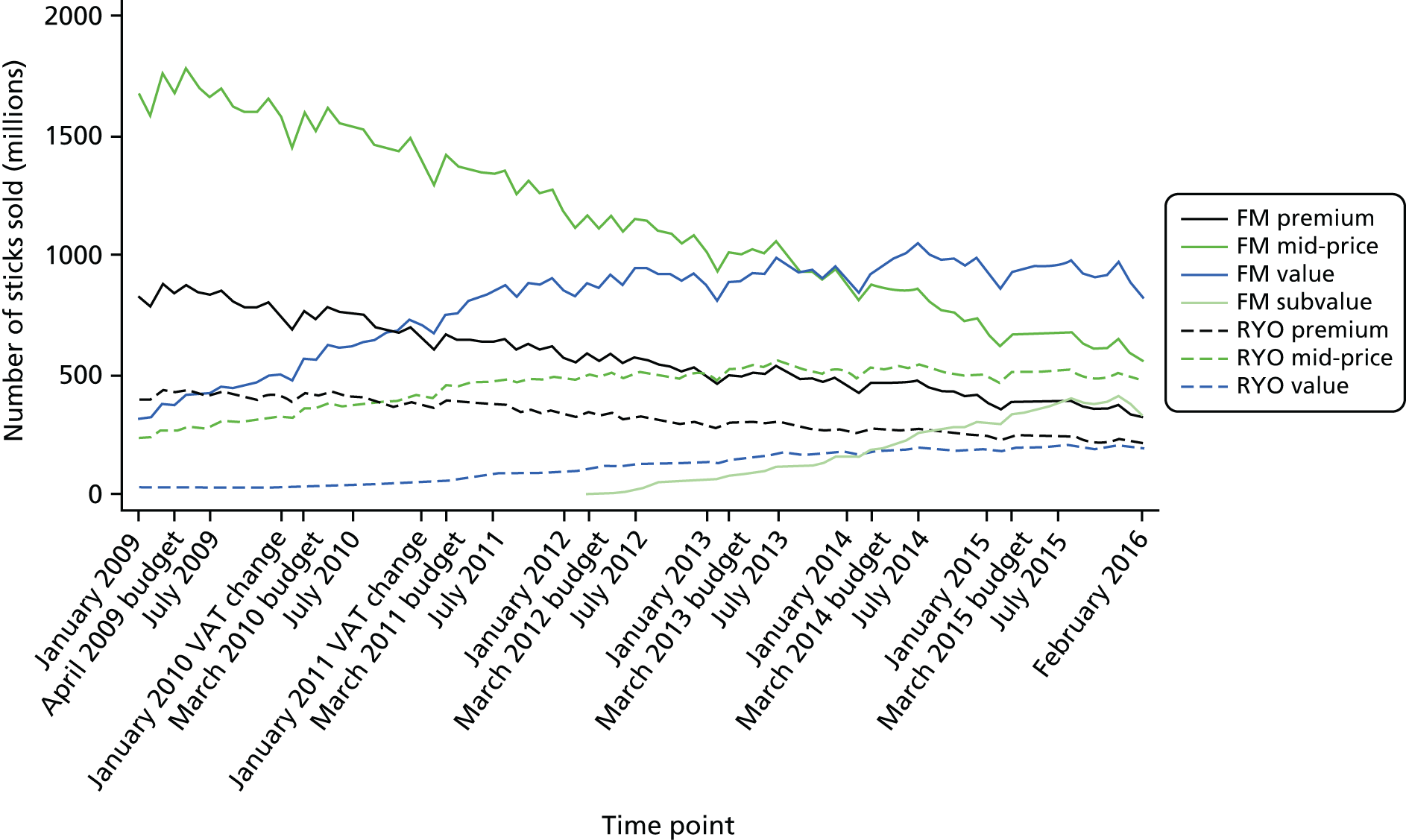

Study 5 (see Chapter 6): what are sales volumes by differently priced segments over time?

ITC data

The ITC was used to explore the impact of tobacco taxation and TI pricing strategies on smokers’ behaviour. This included the extent to which smokers were switching between different products (FM and RYO) or FM brand families (e.g. trading up or trading down), purchasing from different sources (e.g. licit/illicit), or changing their consumption patterns (e.g. reducing cigarettes smoked or quitting smoking). We were also able to explore differences by smoking dependence and sociodemographics.

Data source and sampling characteristics

This research predominantly used the UK data from the ITC. This includes Canada, the USA, the UK and Australia. It is a longitudinal cohort study of adult smokers (aged ≥ 18 years) who are initially recruited as smokers (at least 100 cigarettes smoked in their lifetime and smoking at least monthly at the time of the survey). They are subsequently retained in the study for as long as possible, even if they quit smoking. At each survey, a new ‘replenishment’ sample of smokers are also recruited to compensate for those lost to follow-up (ranging for the UK between 22% and 34%), maintaining sample sizes at around 1500 for each country at each survey. This research mostly used the first 10 surveys or ‘waves’ of the UK ITC, conducted approximately annually between 2002 and 2014 (Table 4) (for some analyses, a subset of these surveys was used). More recent data were excluded because the methodology, sampling and questionnaires changed.

| Survey | Start date | End date | Sample (n) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recontact | Replenishment | Total | |||

| 1 | 21 October 2002 | 9 December 2002 | 2401 | 2401 | |

| 2 | 17 May 2003 | 5 August 2003 | 1865 | 255 | 2120 |

| 3 | 12 June 2004 | 21 December 2004 | 1494 | 586 | 2080 |

| 4 | 11 October 2005 | 30 January 2006 | 1540 | 503 | 2043 |

| 5 | 19 October 2006 | 17 February 2007 | 1406 | 613 | 2019 |

| 6 | 27 September 2007 | 13 February 2008 | 1484 | 523 | 2007 |

| 7 | 30 October 2008 | 29 March 2009 | 1453 | 370 | 1823 |

| 8 | 13 July 2010 | 13 January 2011 | 1325 | 1325 | |

| 9 | 7 February 2013 | 9 September 2013 | 870 | 533 | 1403 |

| 10 | 28 August 2014 | 14 December 2014 | 1018 | 452 | 1470 |

The ITC surveys were administered via computer-aided telephone interviewing or online (the online version was piloted at survey 7 in 2008 and then introduced gradually from survey 8 in 2010 onwards). Stratified random sampling was used to obtain samples broadly representative of national distributions of age, sex and geographical region for each of the four countries at the time of each survey. At each survey, cross-sectional sampling weights were also calculated to be representative of these characteristics, as well as longitudinal weights that were adjusted for attrition. Detailed methodological information about the ITC has been published elsewhere. 123,124

Measures

Not all studies used all measures and details will be provided in subsequent chapters when appropriate.

Sample design control variables

A variable was included to differentiate between the recontact sample (those who had been recruited in a previous ITC survey) and the replenishment sample (those who were completing their first ITC survey). A variable to indicate the survey mode (telephone or online) was also included.

Demographics

Demographic data were stratified to contain logical subgroups that were also large enough for analysis.

Sex

Sex was dichotomised as male or female.

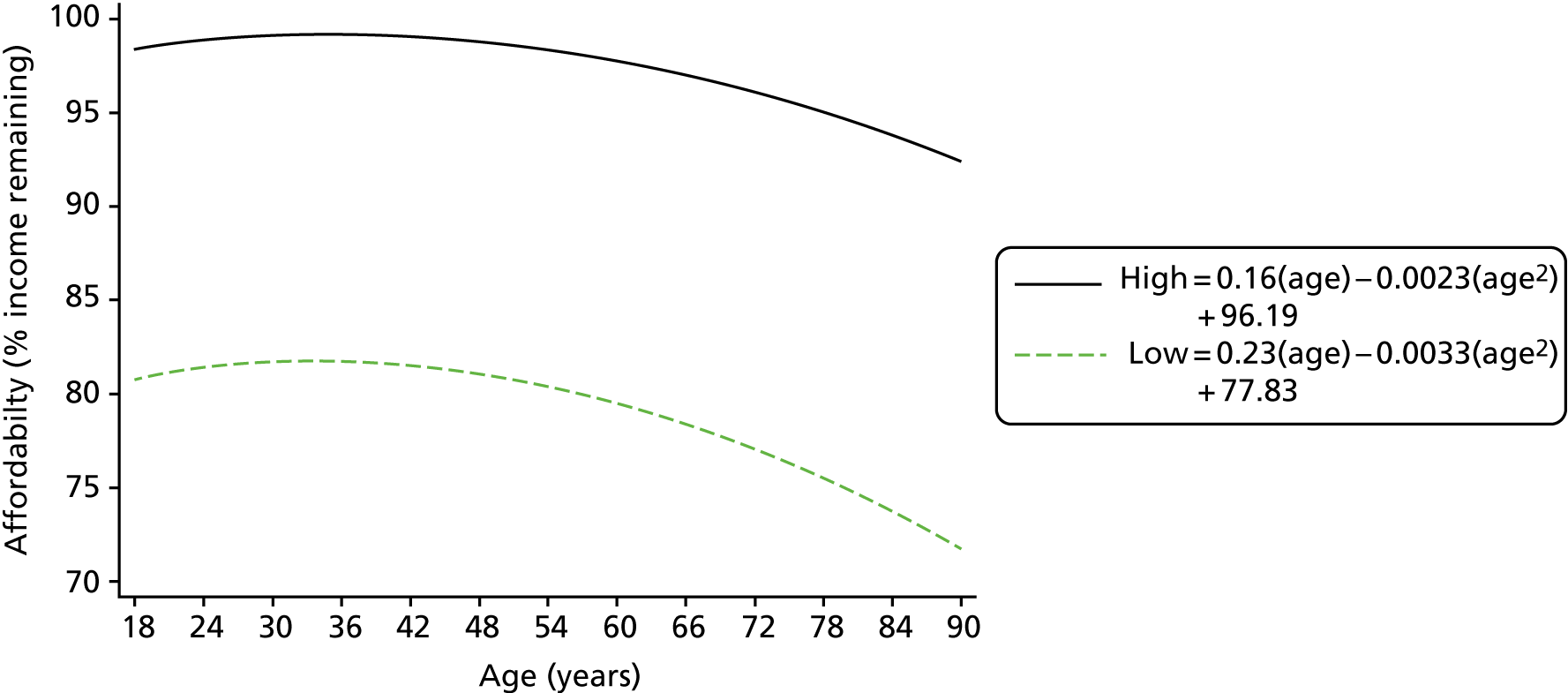

Age

All participants were asked their age, in years, at the time of their recruitment survey. Their age at each subsequent survey was estimated by adding the number of days that had elapsed between their recruitment survey and the survey in question (based on survey dates) to their age at recruitment. Implicit in this methodology was the assumption that all participants were surveyed on their birthdays. This was not considered to be problematic as it was consistently applied to all participants and the margins of error were < 1 year. As age was usually stratified for analysis, the impact of this assumption on our findings was considered to be negligible. Unless otherwise noted, age was stratified into three groups: 18–39 years, 40–54 years and ≥ 55 years.

Geographical region of residence

UK analyses: London, Northern (Yorkshire and The Humber, North East and North West), Midlands and Eastern (East Midlands, West Midlands and Eastern), Southern (South East and South West) and outside England (Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland). Four-country analyses: Australia, Canada, the UK and the USA.

Ethnicity

Ethnicity was dichotomised as white or not white.

Relationship status

Relationship status was dichotomised as single (separated, divorced, widowed or single) or partnered (married or de facto).

Education

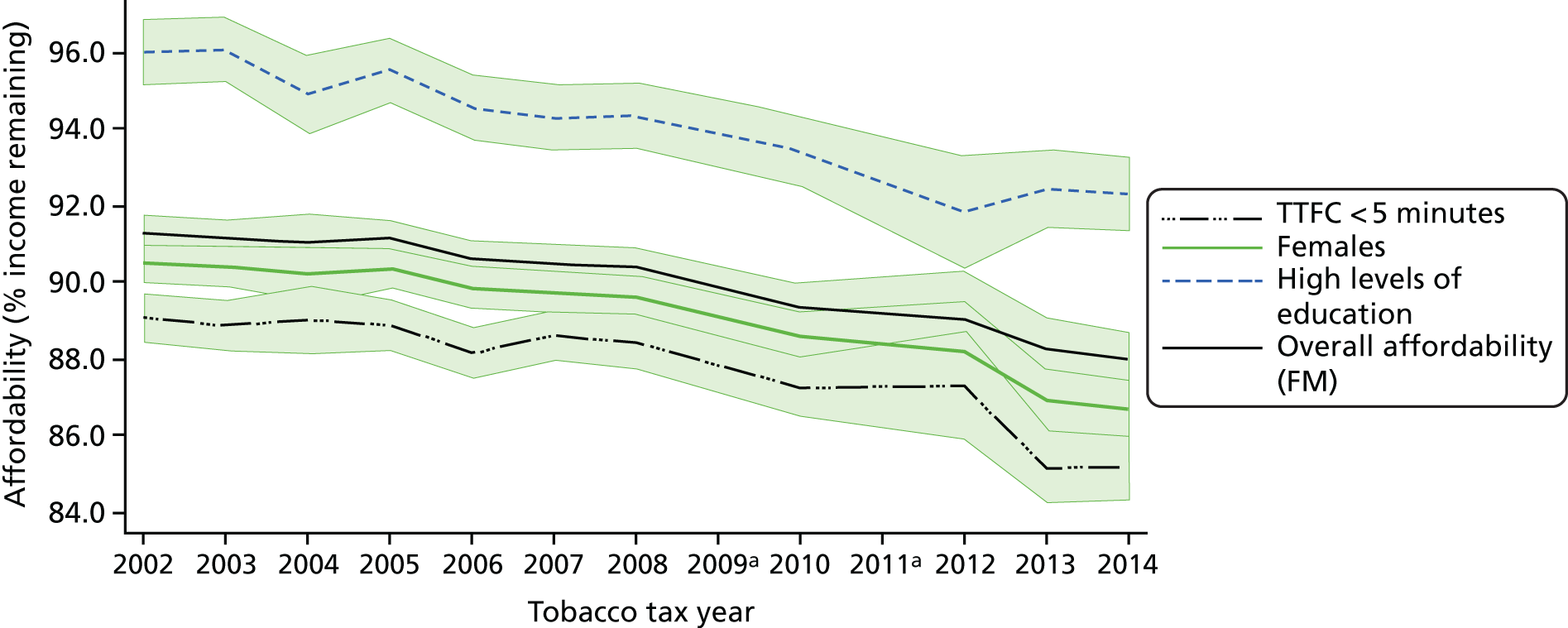

Participants’ highest level of education was coded as low (secondary school/vocational level 3 or less), moderate (some college or university, but no degree) or high (completed university or post graduate degree).

Income

The ITC asks about income and household composition. Gross annual household income is assessed in ranges (£0–6499, £6500–15,000, £15,001–30,000, £30,001–40,000, £40,001–50,000, £50,001–65,000, £65,001–95,000 and ≥ £95,001). For the affordability calculation (ITC study 2), the mid-point of each range was used and £95,001 for the highest value. Participants also reported their household composition, which was used to derive ‘equivalised’ annual income (adjusted for household composition) using the modified Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (mOECD) scale. 125 Equivalisation weights were modified slightly because children’s ages in the ITC questionnaire were stratified somewhat differently to the mOECD strata. Income was converted to 2014 values for all ITC studies, using CPI data from the Office for National Statistics. 126 For some analyses, income was stratified to low, moderate, high or not disclosed. Further details on income equivalisation are available in Report Supplementary Material 1.

Nicotine dependence measures

Time to first cigarette after waking

This was stratified to within 5 minutes (most dependent), 6–30 minutes, 31–60 minutes and after 60 minutes (least dependent).

Cigarettes per day

This ranged between 1 and 100 [mean around 16 cigarettes per day (CPD) and standard deviation (SD) around 8.5 CPD] for the daily smokers in our UK sample.

Heaviness of Smoking Index

This was a combination of time to first cigarette (TTFC) and CPD. 127 This was slightly modified to minimise exclusions due to missing data. For participants who had valid data on both CPD and TTFC (constituting 95.7% of observations), the Heaviness of Smoking Index (HSI) was computed as normal and then stratified to low (0–2), moderate (3–4) and high (5–6). Participants with valid data on CPD only (3.8%) were classified as low (0–20), moderate (21–30) and high (≥ 31), and participants with valid data on TTFC only (0.5%) were classified as low (≥ 31 minutes), moderate (6–30 minutes) and high (within 5 minutes).

Tobacco use and purchase measures

Usual tobacco product type (product loyalty)

This was measured by asking ‘Do you now smoke . . . (packet/FM cigarettes only, RYO cigarettes only, or both)?’. For the measure of product loyalty, those who responded ‘both’ were classified as non-product-loyal ‘mixed’ users; and those who responded as ‘FM cigarettes only’ or ‘RYO tobacco only’ were classified as product-loyal ‘non-mixed’ users.

Last tobacco purchase type

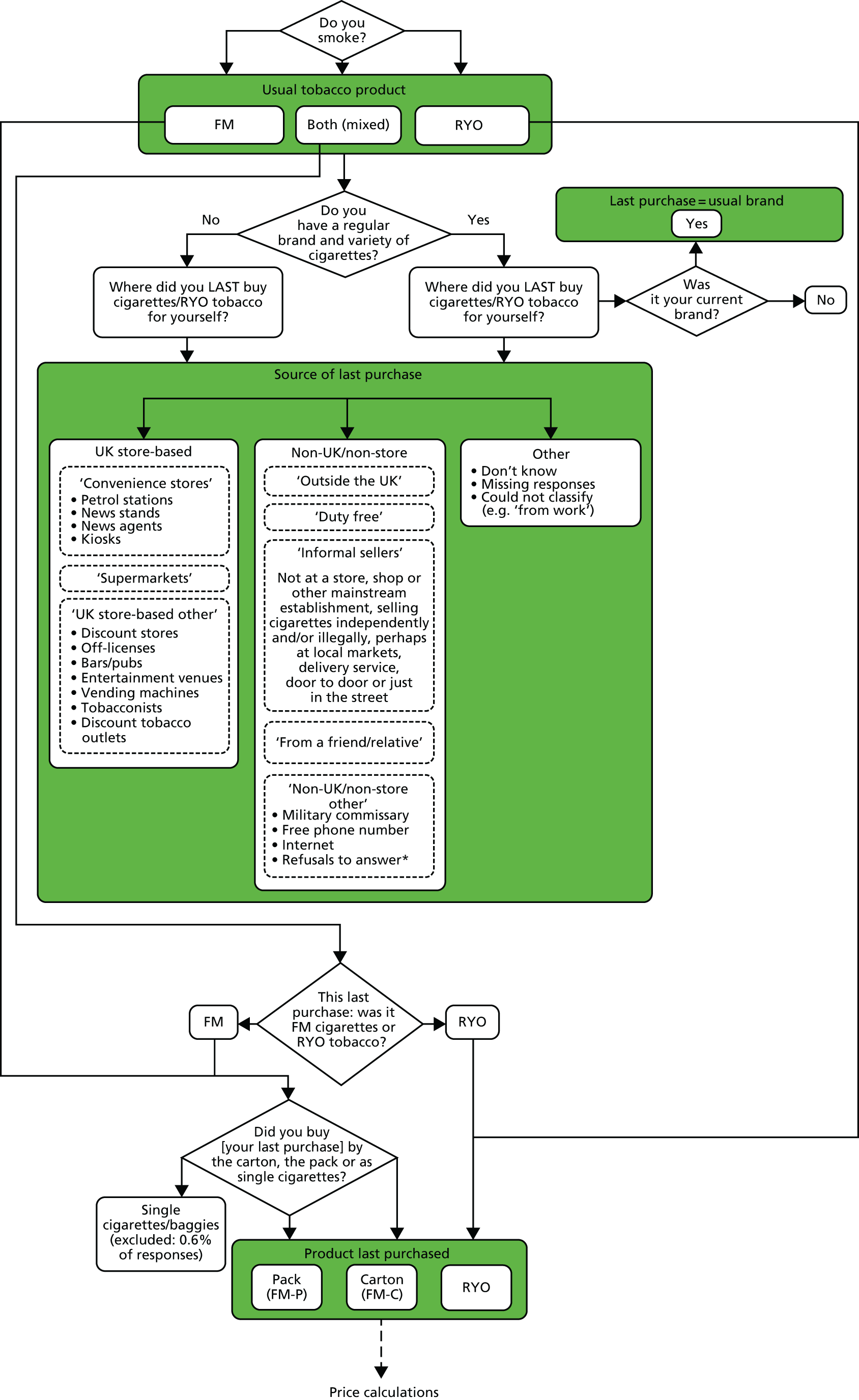

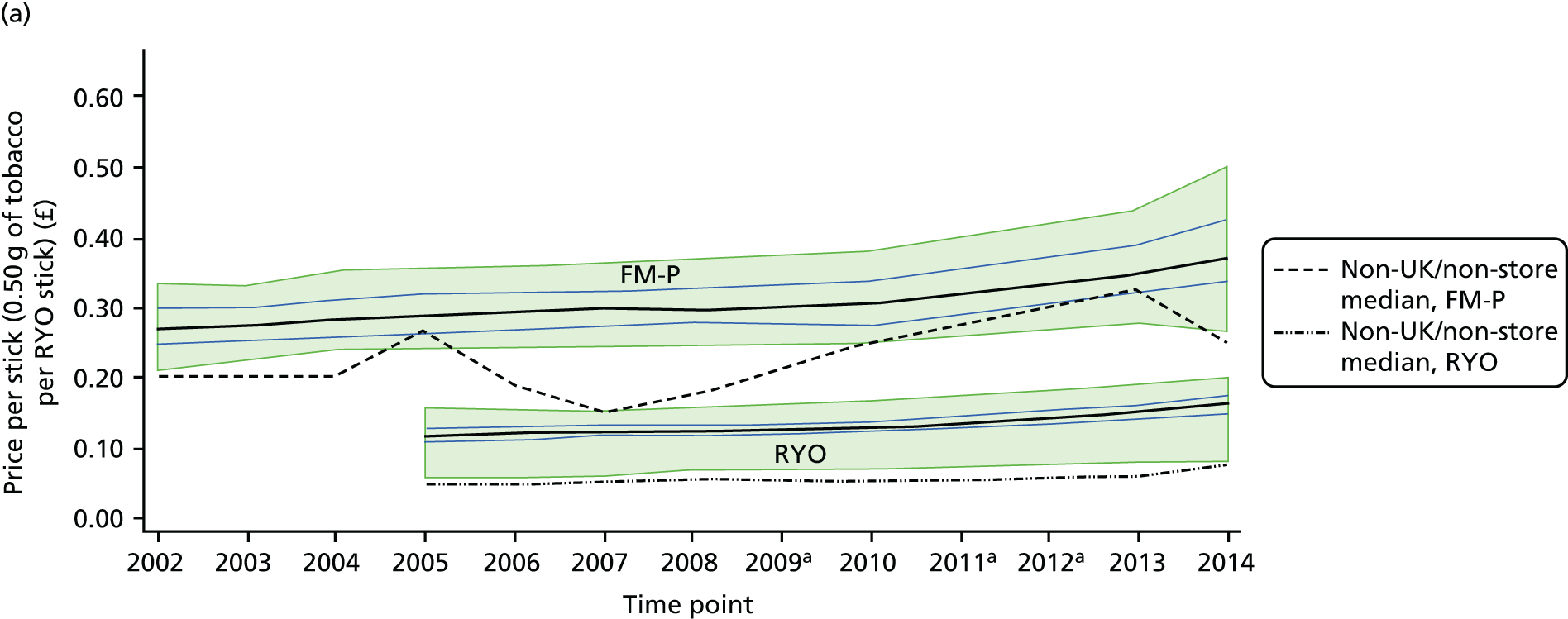

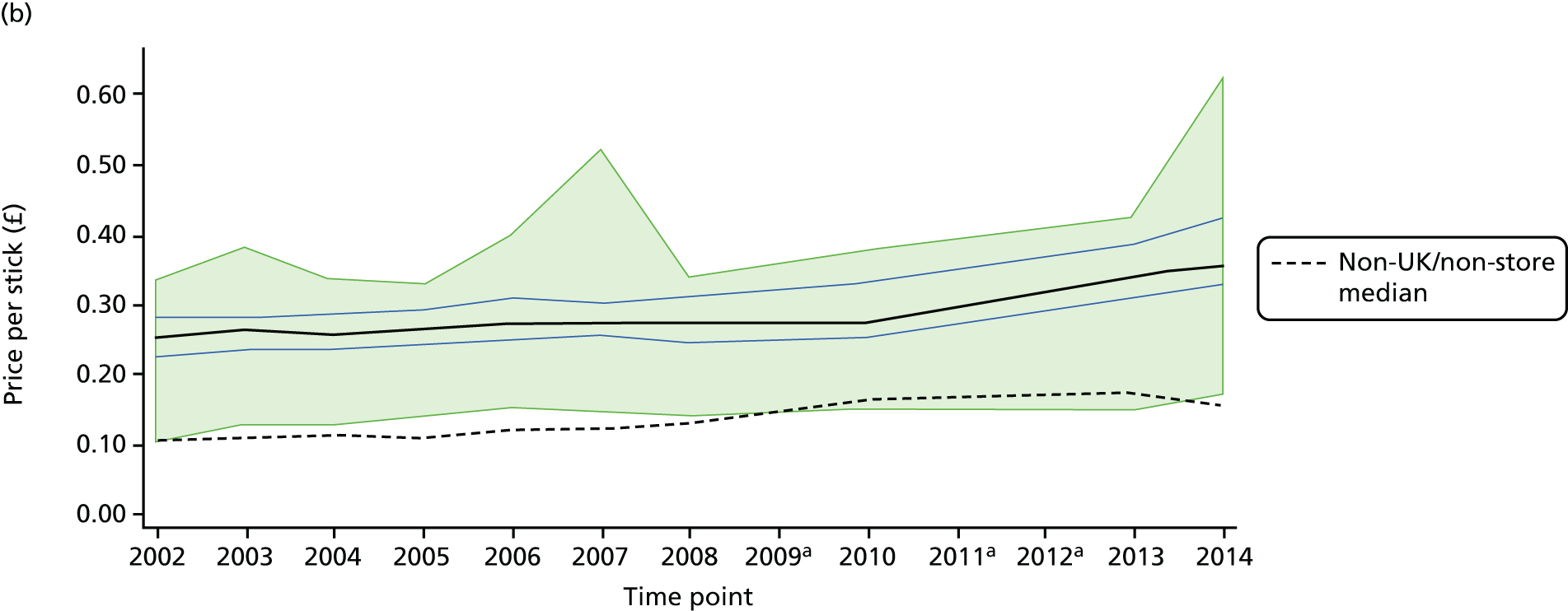

This was coded as factory-made (cigarettes sold in) packs (FM-P); factory-made (cigarettes sold in) cartons (FM-C) or RYO (Figure 1). For participants who reported having a usual brand of tobacco, they were asked if this was the same as their last purchase. Those purchasing other products may be less brand-loyal and potentially more influenced by price promotions or discounts.

FIGURE 1.

International Tobacco Control Policy Evaluation Project survey questions and response categorisation for tobacco product purchases.

Brand loyalty

Participants were asked ‘Do you have a regular brand and variety of cigarettes (yes/no)?’.

Purchase source (differentiating full duties paid, tax avoidance and tax evasion)

In the ITC, we use a number of different measures to assess tax evasion and avoidance in relation to tobacco purchases, depending on what aspect of this we are interested in. When we are interested in the price smokers pay for their tobacco products, we need to determine tax evasion/avoidance using the source of the last tobacco product they purchased, as ITC ascertains only prices paid for the last product purchased. The ITC also asks about the frequency of tobacco purchases likely to be illicit, and when we are not interested in assessing the price of products from different sources, we are able to use this more direct measure as an indicator of likely illicit use instead.

Purchase sources (UK store based vs. non-UK/non-store)

We devised a novel way of assessing potentially illicit tobacco purchases, via categorising the purchase sources of participants’ most recent tobacco purchase into two categories. Purchases from convenience stores, supermarkets and tobacconists were classified as ‘UK store-based sources’ (deemed likely to be licit tobacco with full UK duties paid), and purchases from overseas or duty free (deemed likely to be tax avoidance), friends/relatives or informal sellers (deemed likely to be tax evasion, although see further discussion in Chapter 8) and the internet were classified as ‘non-UK/non-store’ sources. Remaining sources that we were unable to code into one of these two categories (e.g. ‘do not know’ or ‘from work’), were classified as ‘other’ (see Figure 1).

Frequency of purchasing from cheap (probably illicit) sources

In a series of questions, participants were asked directly whether or not, in the past 6 months, they had purchased cigarettes from (1) the internet, (2) phone order, (3) mail order or (4) people selling independently (e.g. door to door, in the street or at local markets) and, if yes, how often (only once, a few times, many times or all of the time). In addition, in surveys 9 and 10 only, participants were also asked if and how often in the last 6 months they had purchased tobacco that had been (5) smuggled, lacked proper health warnings or did not have all government taxes paid (no, once or twice a year, every few months, a couple of times a month or at least once a week). Anyone who responded ‘no/never’, ‘only once/once or twice a year’ or ‘a few times/every few months’ to all of the above sources was classified as having a low frequency of cheap purchases, whereas anyone who responded ‘many times/a couple of times a month’ or ‘all of the time/at least once a week’ to any of the above five sources was classified as having a high frequency of cheap purchases.

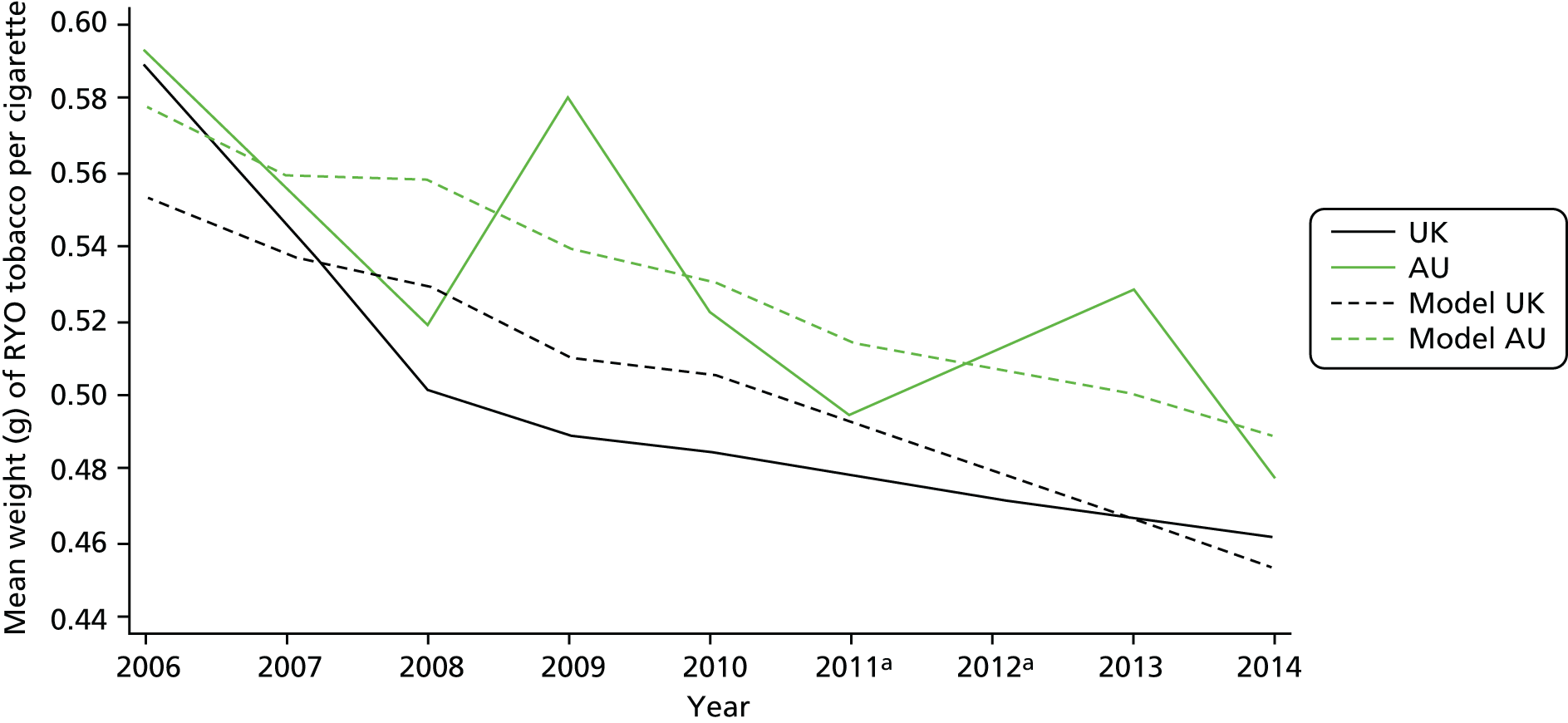

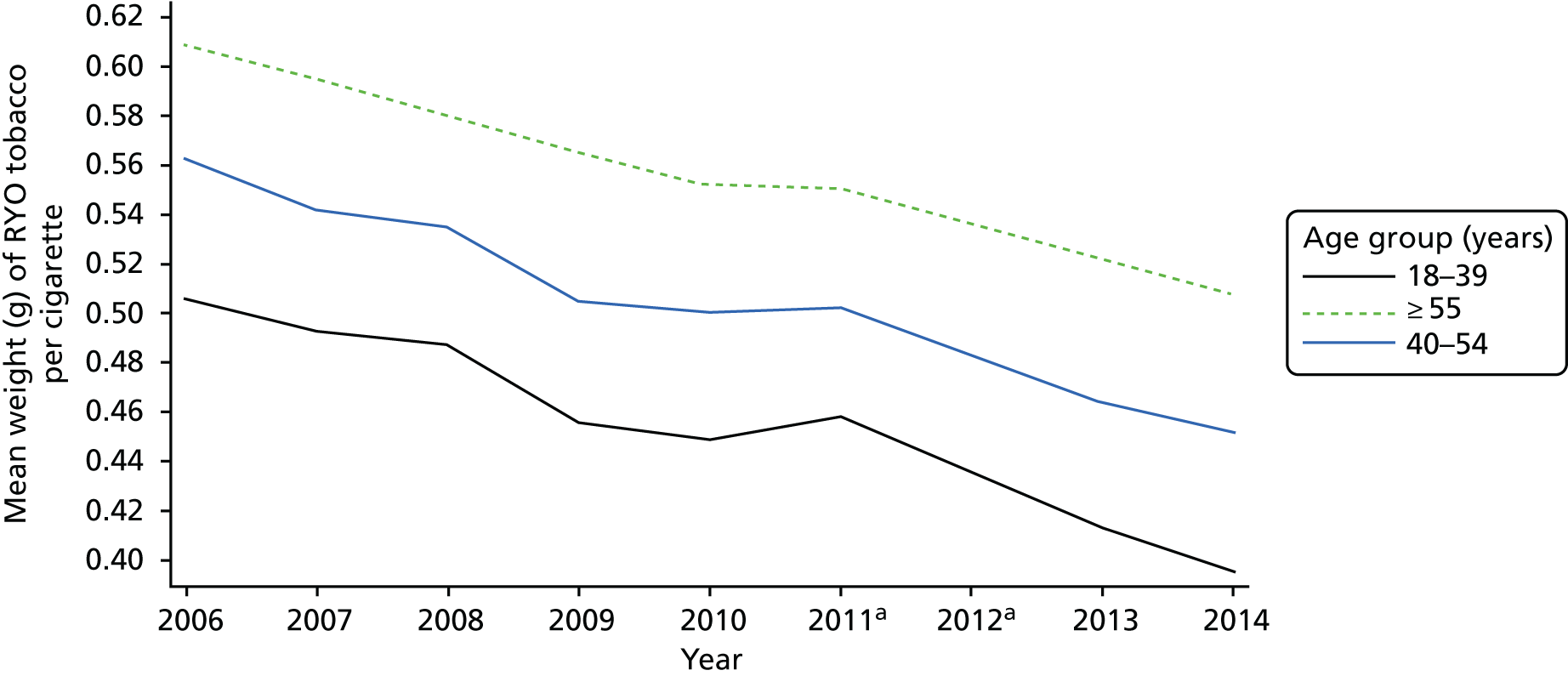

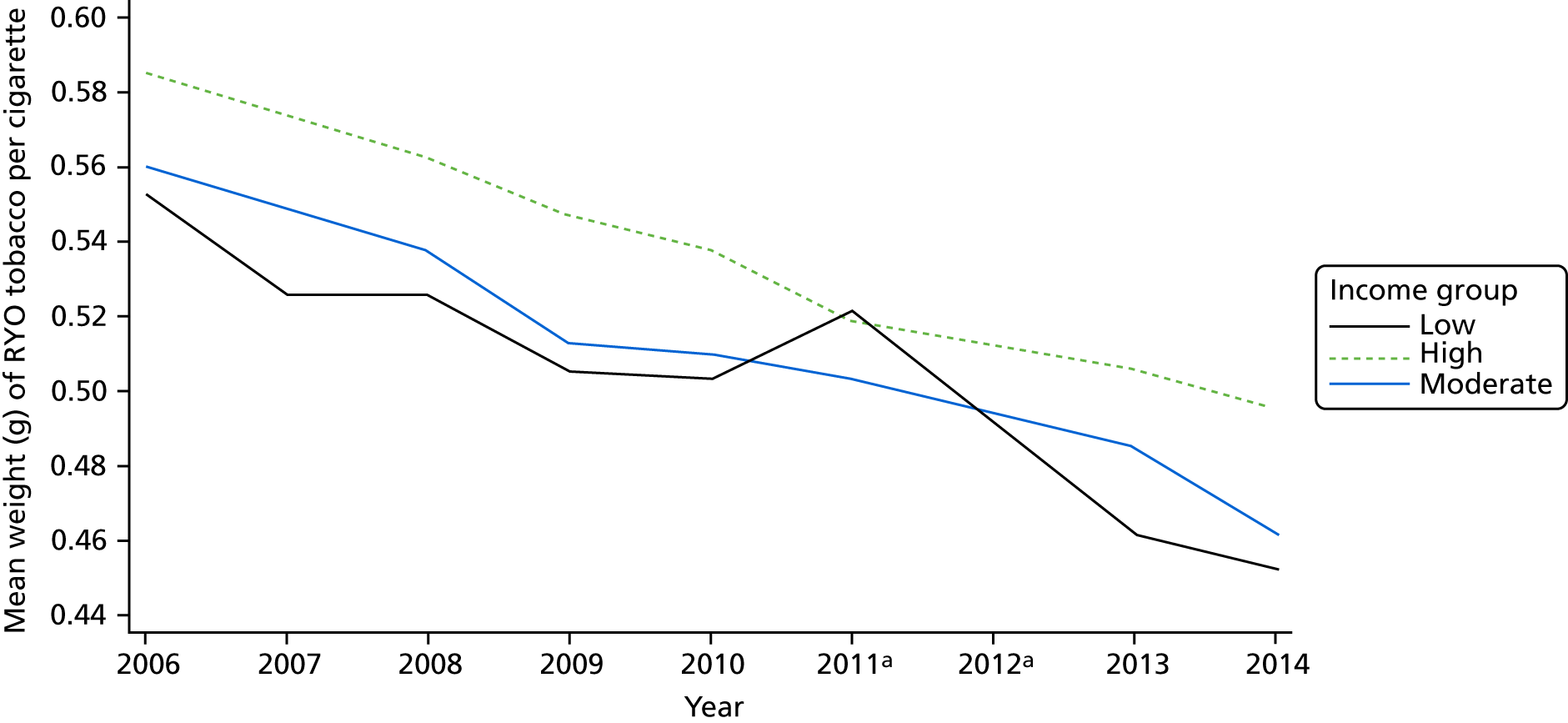

Weight of tobacco in roll-your-own cigarettes

We used participants’ last reported tobacco purchase (because the relevant data were available only for last rather than usual purchase) to derive the average weight of tobacco per RYO cigarette for each participant. We felt that this was justified as 95.4% of our sample of RYO users indicated that their last purchase was the same as their usual purchase. Using the reported weight of the pouch of RYO tobacco they had last purchased, the reported days it usually took them to smoke this amount and how many cigarettes, on average, they smoked per day (CPD), we then calculated their average weight per RYO cigarette, in grams, by dividing the total pouch weight by the days taken to smoke it and by their CPD. The average grams of tobacco per RYO cigarette over the survey period for which these data were available (from survey 5 in 2005 to survey 10 in 2014) ranged between 0.45 g and 0.55 g (data not shown). We therefore chose the mid-point (0.50 g) for use throughout this project as the RYO ‘stick equivalent’ to one FM cigarette.

Tobacco price

The price per stick (for both FM and RYO) was also calculated using last purchase data. The price of FM cigarettes was available for all ITC surveys, the price of RYO was available only from survey 5 (2006) onwards. A series of questions was asked, depending on the tobacco product type (e.g. how many cartons purchased, packs per carton, cigarettes per pack, or RYO weight and number of packs). Participants could give the price they paid for a single carton, pack or pouch, or the total they paid. Prices were converted into 2014 values using CPI126 data (see Equation 1).

The CPI values we used in Equation 1 for each ITC survey year were 95.4 (2002), 96.7 (2003), 98 (2004), 100.0 (2005), 102.3 (2006), 104.7 (2007), 108.5 (2008), 114.5 (2010), 126.1 (2013), and 128 (2014) (see also Report Supplementary Material 1 for more information relating to the calculation of real prices). We then calculated the median reported price for each product type last purchased within each source and, for UK store-based sources only, the ‘price range’ for each product type was also calculated. Some exclusions were agreed on a priori to remove improbable responses from the data and this was done prior to converting to 2014 values, these were any prices per FM stick or 1.0 g of RYO tobacco obtained from any source > £0.50 (before survey 6) or > £0.80 (survey 6 onwards); prices per FM stick or 1.0 g of RYO obtained from UK store-based sources only < £0.07 (before survey 6) or < £0.10 (survey 6 onwards); and any FM packs containing > 50 cigarettes obtained from UK store-based sources only. We also truncated the price range from UK store-based sources to lie between the 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles, in order to have a more representative range by capturing 95% of all prices (thus excluding the extreme, low-frequency cases).

Annual tobacco spend

Annual tobacco spend for all participants was calculated by multiplying the price per stick (0.5-g RYO stick equivalent) by CPD and by 365. As before, we felt it reasonable to extrapolate annual expenditure from participants’ most recent purchase, as the large majority of our sample (92.2% of FM users and 95.4% of RYO users) indicated that their most recent purchase was their usual brand.

Time (tobacco tax year)

The ITC survey collection periods occurred at differing times of year and spanned varying numbers of months for each survey (see Table 4), whereas UK tobacco tax changes were usually enacted during the annual Budget update, typically in March (sometimes April) of each year (see Table 1). For certain analyses, we therefore assigned participants to the appropriate ‘tobacco tax year’, corresponding to the timing of their survey responses relative to when the tobacco tax changes were implemented. No ITC survey data were collected in the 2009 or 2011 tobacco tax years.

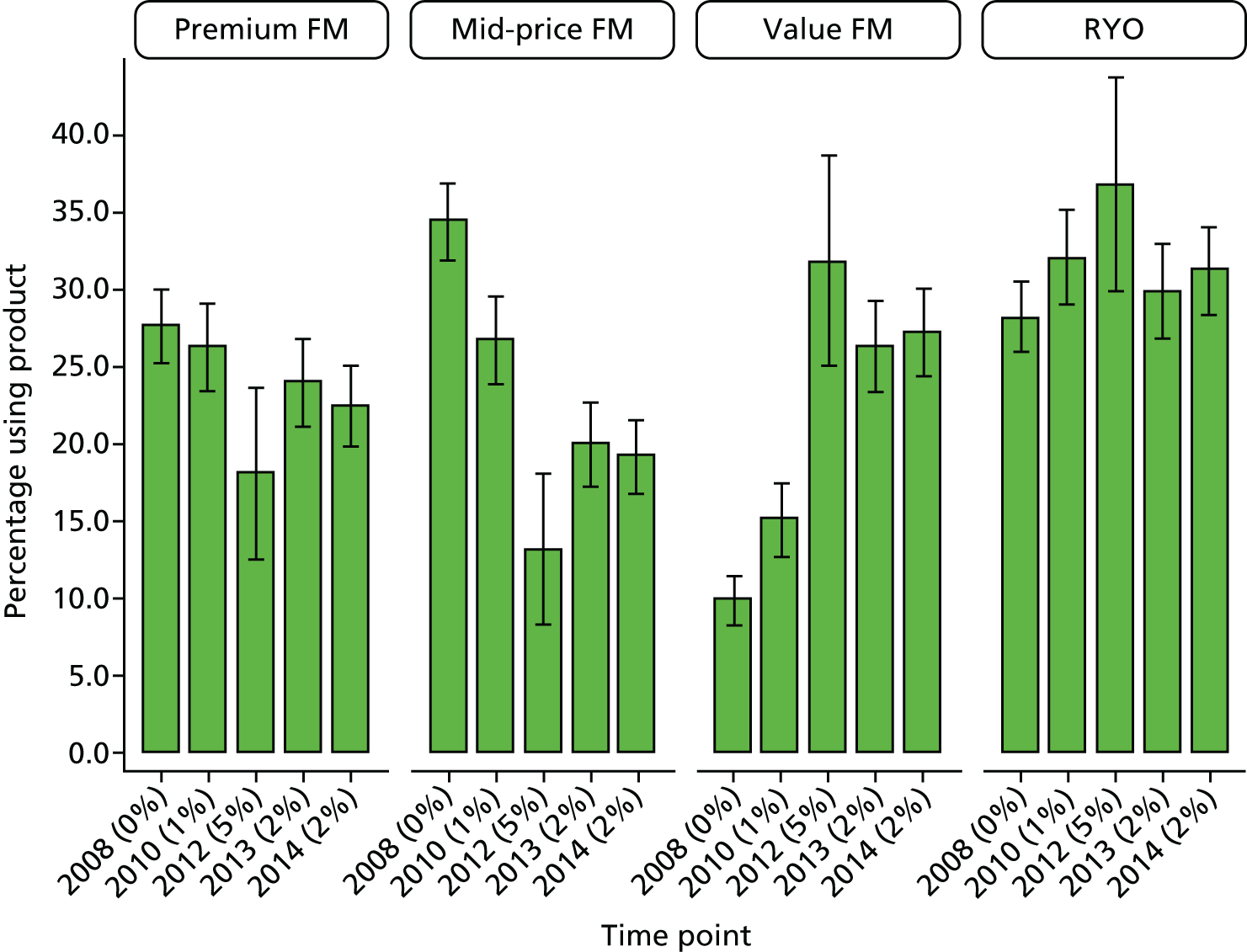

Tobacco taxation increase rates

For some analyses involving surveys 7–10 of the ITC data (see Table 4), we were interested in the impact of different tobacco taxation increase rates. Using a similar strategy as for tobacco tax year [see Time (tobacco tax year)], tobacco taxation increase rates based on tax changes outlined in annual Budget statements (see Chapter 1 and Table 1) were allocated to these ITC surveys as follows: 0% (equivalent to inflation) for all data from survey 7 (October 2008–March 2009); 1% above inflation for all data from survey 8 (July 2010–January 2011); 2% above inflation for the majority of data from survey 9 (February 2013–September 2013) and all data from survey 10 (August 20 –December 2014); and 5% above inflation for the remainder of the data from survey 9 (February 2013). Tobacco taxation increase rates for longitudinal analyses were those applicable at the follow-up (not baseline) surveys.

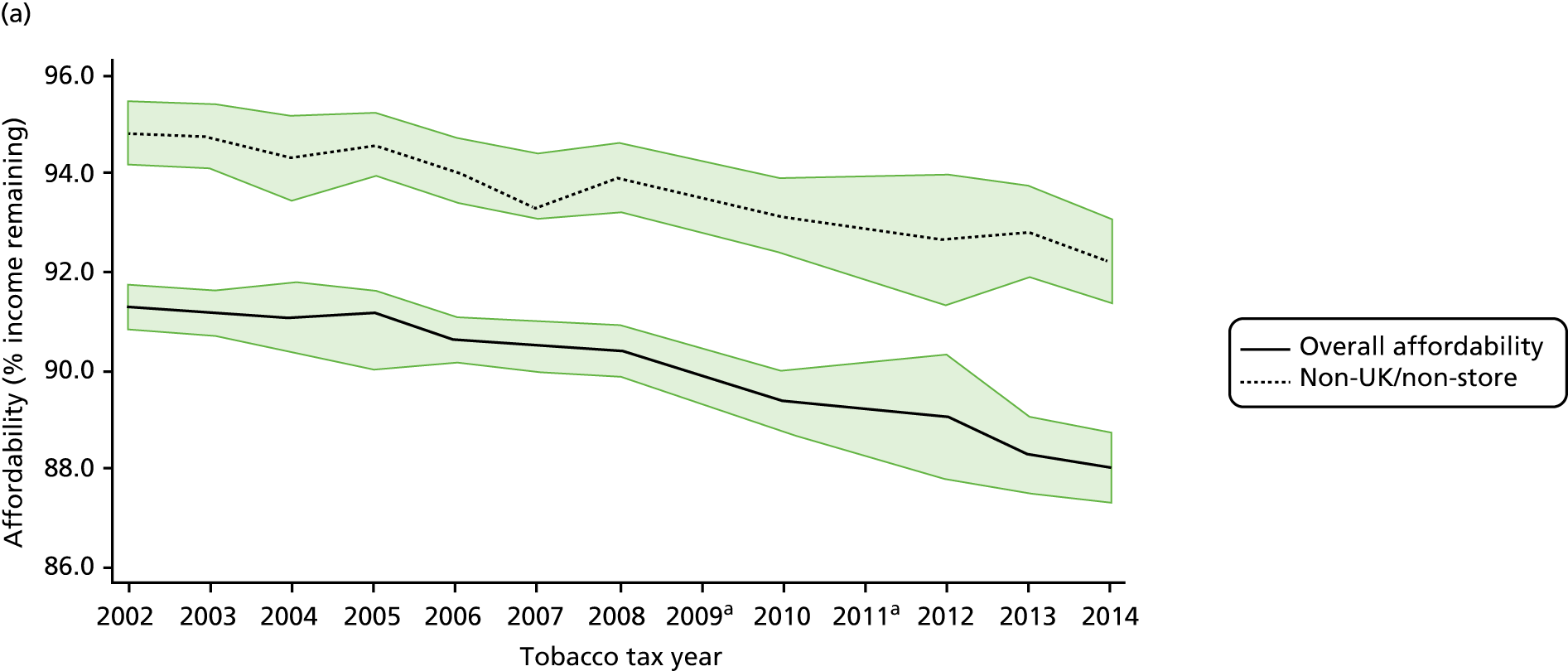

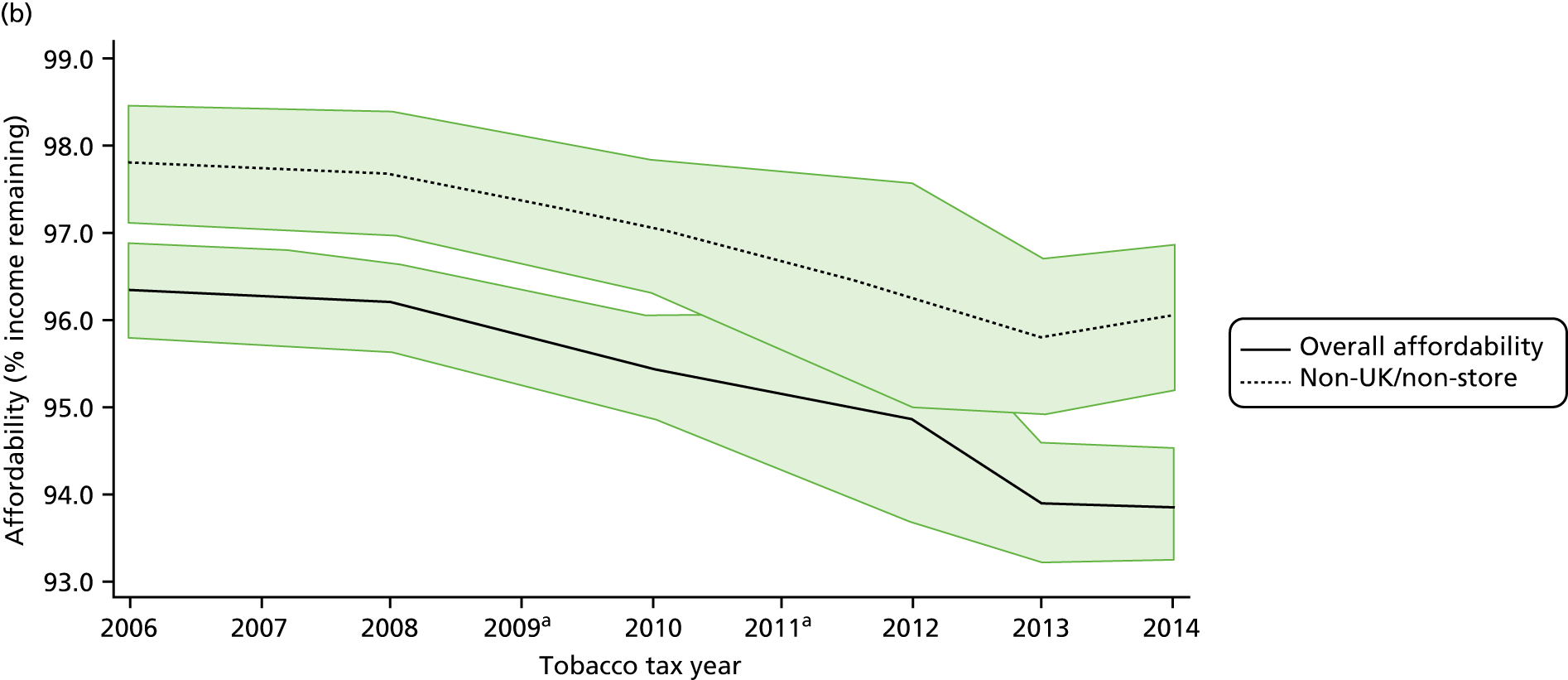

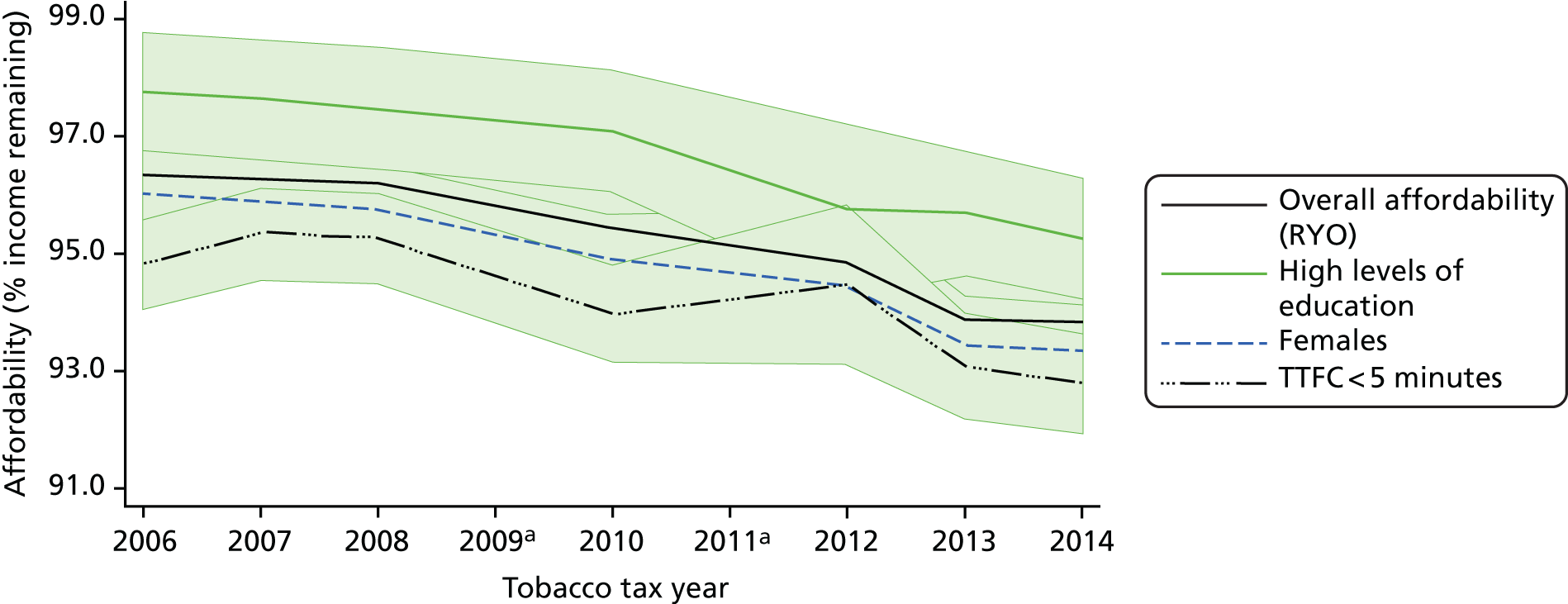

Affordability

We developed a new individualised affordability measure: the percentage of a smoker’s annual gross income remaining after subtracting their annual tobacco spend (see Equation 2), with higher values representing more affordable tobacco. Values theoretically ranged between 0% and 100%, but after excluding outliers (the top and bottom percentile of the data), affordability ranged between 35.3% and 99.9%.

For comparison, an aggregate version of this affordability measure was also calculated (see Equation 3), based on average tobacco prices and national estimates of income, but this was possible only for FM cigarettes. An existing methodology was adapted, the RIP,66 which is the percentage of per-capita GDP required to purchase 100 packs of 20 FM cigarettes (2000 cigarettes). We made two adjustments to make comparable with our individualised method, in magnitude and direction: (1) we tripled the number of cigarettes (to 6000 cigarettes or 300 packs of 20), which corresponded more closely to the average annual cigarette consumption of our sample (mean 6074 cigarettes, SD 2913 cigarettes); and (2) we inverted the equation so that higher values would indicate more affordable cigarettes (as in the individualised measure). It should be noted that our new methodology for calculating affordability (both the individualised and aggregate versions) also differed from traditional measures, such as the RIP, in that we incorporated consumption into our measure, whereas traditional measures usually assess only the ratio of price to income (see Chapter 7 for a more detailed discussion of this issue). UK FM cigarette prices for our aggregate version of affordability were based on the MPPC from 2002 to 2010 or the WAP from 2011 to 2014, as these were the European Commission published data128 on which UK tobacco taxes were based. Cigarette prices and yearly GDP figures were adjusted for inflation to 2014 values using the CPI. GDP and CPI data were obtained from the Office for National Statistics. 126,129 For income, we took the mid-point of each range and £95,001 for the highest value. Owing to the complexities and slight deviations from the published methodologies involved in equivalising income (see Report Supplementary Material 1), sensitivity analyses were carried out using a version of income that was not equivalised for household composition. The results of these analyses did not deviate substantially from the results presented using equivalised income and did not alter the conclusions drawn from the data (data not shown).

Analyses

The ITC data analyses were conducted using the Stata® software package, Stata SE version 12.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA), unless otherwise indicated. When relevant, more detailed analytical plans are discussed for each study in the relevant chapters. In general, for analyses in which we were interested in simple overall population trends (e.g. in prices paid for different products over time, or changes in the proportions of participants purchasing tobacco from different sources), we used generalised estimating equations (GEEs) with population-weighted data. However, the estimates provided by GEE analyses are not well suited for predictive modelling (e.g. for simulating or predicting responses of individuals or different groups of individuals),130 so for analyses in which we were interested in examining the role of other factors (e.g. nicotine dependence, sociodemographics or taxation rates) on our outcomes from our particular sample, we instead used random-effects regression analyses with unweighted data.

The ITC data are hierarchical, in that the same individual can provide multiple responses by participating in more than one survey, so the data are responses clustered within individuals, with a large number of small clusters (an average of around two responses per individual) and even some ‘clusters’ of size 1. GEEs require that the nature of the correlation between responses in the same cluster (in the ITC data that is the correlation between responses made by the same individual in different surveys) be specified. Stata allows for seven different types of correlation structure (independent, exchangeable, unstructured, autoregressive, stationary, non-stationary and fixed). From the outset, the autoregressive, stationary and non-stationary options were ruled out for our data, as these rely on equally spaced timing of observations with no gaps, which was not the case for our data. For the remaining options, we made our selection using a theory-driven, rather than a data-driven, approach. The fixed option allows for the user to specify a correlation matrix; however, we had no theoretical basis for producing such a matrix, so this option was also ruled out. The independent option assumes that responses provided by the same individual at different time points are independent (uncorrelated). We felt that this was highly unlikely and thus ruled out the independent correlation structure also. The likeliest scenario for our data, we felt, was that participants’ responses at different time points would be related in such a way that responses made closer together would be more closely related than those made further apart. The exchangeable correlation structure imposes the same relationship at all time points and does not allow for this scenario. This left only the unstructured correlation option, in which correlations are estimated for each time point from the data themselves. We thought that, theoretically, this was the best option to fit our data and therefore used this as the default option (the exchangeable structure was the next best option and, thus, we used this when the unstructured method failed to converge). In addition, the standard errors (SEs) provided by GEE are quite robust to mis-specification of the correlation structure if robust SEs are specified, which we did routinely. However, we did also use a data-driven method to compare model fit of the unstructured compared with exchangeable options, using the quasi-likelihood under the independence criterion (QIC), and the results of this are presented in Table S1 in Report Supplementary Material 2. The QIC statistic indicated an equivalent or better fit using the unstructured correlation matrix in all cases, with one exception, and the implications of this are discussed in Chapter 8.

Our reasons for choosing random- (and not fixed-) effects regression were both practical and theoretical. Our objective was to make inferences at the group level, controlling for the correlation of responses provided by the same individual (e.g. exploring the effect of time or age on tobacco affordability). Fixed-effects regression focuses on cluster-level analysis, in which the clusters themselves are of interest (e.g. in data in which pupils are clustered in schools, looking at the effect of different schools on academic outcomes), and clusters of large sizes are desirable. Random-effects regression is more focused on the group-level effects and can handle large numbers of small clusters and clusters of 1 (as in our data). Fixed-effects regression therefore also requires a higher degree of within-cluster variability than was present in our data. Furthermore, we were also often interested in the effects of time-invariant variables (e.g. sex, ethnicity), and fixed-effects regression does not allow for this. 130

We note also that we have not, in any of our analyses, adjusted our alpha levels for multiple comparisons, as we agree with others that this is not a meaningful or useful strategy. 131 We have, however, provided p-values throughout the report, enabling interested readers to make their own adjustments if so desired.

Limitations

The ITC data are based on self-reported details of smoking behaviour, so the results are dependent on the accuracy of that reporting. In general, several steps are taken to minimise bias and maximise response rates (e.g. through using different times of the day and days of the week for recruitment calls). Multiple contact information is collected to minimise attrition, with up to 25 attempts at follow-up, using different methods. Demographic profiles of the unweighted samples are compared with benchmark surveys and weights calculated, so that weighted data are consistent with corresponding national benchmarks. Full details of methods and weighting are given elsewhere. 123,124 Data from single countries can be used to examine how smoking behaviour changes over time in response to specific policies. Given the commonality of methods, study design and questionnaires across different countries, comparisons across countries can also be made using other countries as controls. The ITC conceptual model123 focuses on how single policies affect behaviour, rather than how combinations of policies and other factors interact to influence behaviour.

Similarly to the limitations discussed with the Nielsen data, the ITC survey did not ascertain whether or not RYO pouches were purchased as part of a bundle, including filters and/or rolling papers. However, the impact of this on our price estimates is likely to be minimal, with papers and filters contributing only between £0.004 to £0.014 to the prices per RYO cigarette, and any resulting biases would be consistently applicable over the study period, thus not affecting time-related trends.

A particular strength of the ITC is that it has been subject to consideration by ethics committees in multiple organisations and the hundreds of outputs from ITC data have been subjected to extensive peer review. As an international collaboration, all the processes and practices are subject to ongoing quality improvement. Specific limitations pertaining to particular analyses and subsamples are described in the relevant chapters.

Studies using ITC data

-

Study 1 (see Chapters 4 and 8): prices paid for tobacco by smokers over time from both licit and tax avoidance/tax evasion sources.

-

Study 2 (see Chapters 5–9): changes in tobacco affordability over time among smokers.

-

Study 3 (see Chapters 6 and 8): smokers’ tobacco purchasing behaviours by product and store type, for both licit and tax avoidance/evasion sources.

-

Study 4 (see Chapters 6, 8 and 9): impact of tobacco pricing changes on smokers’ purchasing patterns and product choices (analysis 4a) and smoking behaviour (analysis 4b).

-

Study 5 (see Chapters 7–9): impact of tobacco pricing changes and product choices on smokers’ quit attempts (analysis 5a) and sustained abstinence (analysis 5b).

-

Study 6 (see Chapter 7): weight of RYO tobacco cigarettes, analysis over time and international comparison.

Structure of report

The chapters that follow discuss the research in relation to the objectives set out in the Introduction and the studies set out above. Chapter 3 assesses TI pricing strategies and how the industry segments its tobacco market for FM and RYO cigarettes using commercial literature and Nielsen data. Chapter 4 uses ITC data for an analysis of how much smokers pay for their tobacco and have paid between 2002 and 2014, and how prices paid differed by the type of product purchased. Nielsen data are also used to assess the price of products by price segment and then to analyse what proportion of price increases by segment are explained by TI price increases compared with tax increases. Chapter 5 uses the commercial literature and ITC data to assess changes in tobacco affordability over time among smokers, using a new individualised measure of affordability. Chapter 6 examines the impact of tobacco tax increases, as moderated by TI pricing, on smokers’ legal purchasing patterns. Commercial and Nielsen data are used to examine patterns of product use and sales volumes over time. We then use ITC data to examine purchasing behaviours by product and store type. Then, using Nielsen data, we assess sales volumes of differently priced segments over time. Utilising ITC data, we then examine the impact of tobacco pricing changes (taxation) on product choices and purchasing patterns. In Chapter 7, we analyse the impact of tobacco tax increases, as moderated by TI pricing, on smokers’ quitting and reducing behaviours. We examine quit attempts and 6-month abstinence using ITC data and then the impact of tobacco pricing changes on cigarette consumption over time. As smokers of RYO cigarettes can reduce either the number of cigarettes or the amount of tobacco in their cigarettes, we also examine the weight of RYO tobacco cigarettes over time and in comparison with other countries that have different RYO taxation strategies. Chapter 8 examines tax avoidance and evasion using smokers’ sources for their cigarettes. We look at the proportion of tobacco purchases that are from non-UK/non-store sources and the prices paid from different sources. The impact of tax and price on sociodemographic inequalities is assessed in Chapter 9. Finally, we synthesise all the results with implications for practice in Chapter 10.

Chapter 3 Tobacco industry pricing strategies and price segmentation of the UK tobacco market

Introduction