Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 14/231/20. The contractual start date was in October 2016. The final report began editorial review in September 2018 and was accepted for publication in June 2019. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Stacy A Clemes, Daniel D Bingham, Natalie Pearson, Yu-Ling Chen, Charlotte Edwardson, Keith Tolfrey, Lorraine Cale, Mike Fray and Sally E Barber report non-financial support from Ergotron, Inc. (Saint Paul, MN, USA), during the conduct of the study. Keith Tolfrey reports non-financial support from Iwantastandingdesk.com (Clitheroe, UK) for EIGER™ student standing desks for other independent sedentary behaviour research in secondary schools.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Clemes et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background and rationale

Sedentary behaviour, physical activity and health in children

Childhood is a critical period for the establishment of healthy lifestyle behaviours, including physical activity. Continual advances in modern technology, economic progress and changes to our environments have resulted in reductions in physical activities associated with daily living, and in sedentary behaviour becoming ubiquitous within all settings of daily life. Sedentary behaviour is a behaviour distinct from physical (in)activity and is currently defined as ‘any waking behaviour characterised by an energy expenditure of ≤ 1.5 metabolic equivalents (METs) while in a sitting, reclining or lying posture’. 1 Although reclining and lying postures are included in the definition, most of the time an individual (young people and adults) spends sedentary will be in a sitting position during waking hours. Participation in regular physical activity has numerous short- and longer-term physiological, psychological and social benefits for young people. 2–4 For example, reviews have shown that physical activity can improve blood pressure, weight status and bone mineral density, and lead to improvements in self-esteem and depression, and, in the longer term, can prevent chronic disease. 2,4 It is acknowledged that physical activity is beneficial to health, and sedentary behaviour has been shown to adversely affect health.

Sedentary time is associated with an increased risk of metabolic syndrome,5 cardiovascular disease,6–8 type 2 diabetes mellitus,7,8 all-cause mortality9 and depression10 in adults. Although the evidence for associations between objectively assessed sedentary time and health outcomes in young people is less consistent,11–13 the proxy sedentary behaviours of television viewing and screen time (the most prolific area of sedentary behaviour research) are unfavourably associated with body composition, fitness, self-esteem, cognitive development, pro-social behaviour, academic achievement in children13,14 and cholesterol in adulthood. 15 Sedentary behaviours in children have, furthermore, been shown to coexist with lower levels of physical activity16 and other ‘unhealthy’ behaviours, such as increased consumption of energy-dense foods, lower intakes of fruits and vegetables,17 and inadequate sleep. 18 Furthermore, recent evidence suggests an association between sedentary behaviour and several markers of inflammation and endothelial dysfunction,19 signalling potential mechanistic links with poor cardiovascular health in children. In addition, the emergence of an increased cardiometabolic health risk profile in some population groups is evident during the first decade of life. 20 For example, British South Asian children have demonstrated higher levels of glycated haemoglobin, fasting insulin and triglycerides, and lower high-density lipoprotein cholesterol than white British children, as well as having a higher sum of all skinfolds and fat mass percentage. 21,22 Therefore, these populations may be more vulnerable to the adverse affects of excessive sedentary time. Indeed, evidence of the influence of sedentary behaviour on the health of young people has prompted many countries to establish public health recommendations for sedentary behaviour. The UK, USA, Canada, Australia and the Netherlands, for example, now recommend that young people should reduce sitting time and break up long periods of sitting as frequently as possible. 23–27

Prevalence of sedentary behaviour in children

In the UK, sitting is the most prevalent behaviour exhibited during waking hours in children, accounting for > 65% of their waking time (or 7.5 hours),28 with some children reportedly sitting for > 10 hours per day (> 70% of waking hours). 29 Accelerometer data from the Health Survey for England have shown that young people (aged 5–15 years) spend, on average, 7 hours per day sedentary. 30 International research shows similar prevalence rates, with data from the International Study of Childhood Obesity, Lifestyle and the Environment (ISCOLE)31 showing that children across 12 geographically and culturally diverse countries spend an average of 8.6 hours per day sedentary. 31 Similar proportions of waking hours spent sedentary have also been reported in children and adolescents from Canada and the USA. 32,33

Objective (accelerometry) sedentary behaviour data further suggest that children spend the majority of their school time sedentary. 34,35 For example, in children aged 10–12 years, across five European countries, 65% of the time spent at school was sedentary. 35 More recently, research has turned to inclinometer devices to more accurately measure total sedentary time (or sitting specifically), with data from these devices from British, Australian and Malaysian children (aged 8–12 years) further confirming that the majority of their time at school (70–71%), on weekdays (53–69%) and weekend days (60–73%) is spent sitting. 29,36–38

The rising prevalence of sedentary behaviour (and sitting) is of further public health concern because this behaviour in childhood has been shown to increase across key transitions in children’s lives (i.e. from primary to secondary school),39 and has been shown to track into adolescence40 and adulthood. 15 Given the physiological and psychosocial risks related to sedentary behaviour, and the evidence that sedentary behaviour increases as children get older, there is a need for interventions to reduce sedentary behaviour and increase movement in children.

Interventions to reduce sedentary behaviour in young people

The environments and social norms that children are exposed to have dominant influences on their activity behaviour. Given that children spend half of their waking hours at school, it is plausible that the school environment may be a critical influence on their health behaviour patterns41–43 and be a most appropriate target environment for interventions. A plethora of physical activity interventions aimed at young people have been conducted over the past two decades. 44,45 School-based interventions promoting physical activity have been successfully implemented during physical education classes, break times and before and after school hours, and have revealed positive effects on physical activity. 44 Furthermore, there is now growing evidence supporting the use of physical activity as a teaching tool (e.g. physically active learning) and classroom movement breaks, as a means of facilitating classroom management, student attention and focus on task. 46 However, teachers, education departments and organisations frequently cite a crowded curriculum, alongside other barriers, such as lack of knowledge or confidence, as reasons for not implementing physical activity programmes. Thus, alternative methods that do not add to teachers’ workload and require minimal specialist knowledge are required.

With an increasing interest in sedentary behaviour, a number of systematic reviews and meta-analyses have been published, synthesising the interventions that focus on young people. 47,48 Although most interventions specifically targeting sedentary behaviour have been home or school based, sedentary behaviour has typically been targeted as screen time and via behaviour change strategies within non-school settings (i.e. screen time at home),48 the effects of which have been inconclusive. 47 Most interventions specifically targeting sedentary behaviour have not been based on a behaviour change framework or theory. 48 In a recent review of interventions targeting sedentary behaviour, only 10 out of 21 interventions included studies that were theory based. 48 Theoretical frameworks provide a scaffold for intervention development from being an evidence-based source for understanding the behaviour of interest and possible levers of change,49 allowing a systematic evaluation of the intervention outcomes. Theories and frameworks typically utilised in sedentary behaviour interventions to date, again which have largely targeted screen time, include social cognitive theory, behavioural choice theory, the social ecological model and the chronic care model. 48

Although there is an abundance of behaviour change theories, models and frameworks for researchers to use (indeed 83 were identified in a recent systematic review49), the behaviour change wheel (BCW)50 has increasingly received attention within the sedentary behaviour literature. 51,52 The BCW synthesises 19 pre-existing frameworks of behaviour change into a single interface, incorporating a theory of behaviour, intervention functions and associated policy categories, and can be applied to any behaviour in any setting. 50 As policy can only influence behaviour through interventions, which in turn act through capability, opportunity and motivation, the framework is represented as a wheel with an outer layer (policy categories) influencing the next layer (intervention functions), until behaviour is changed at the very centre of the wheel. 50

The capability, opportunity, motivation – behaviour model (COM-B) (sources of behaviour) hypothesises that for specific behaviours to occur, the individual must have both the physical and psychological capability to perform the given behaviour, along with the social and physical opportunity to perform the behaviour, and be motivated to perform the specific behaviour more so than any other behaviours within that moment in time. Within the context of sedentary behaviour, the only interventions that have consistently demonstrated a reduction in sedentary time in younger populations are those utilising a standing desks design within the classroom (i.e. environmental restructuring),53 thus providing a physical opportunity for children to stand and/or break up their sitting time. As children spend up to 6 hours per day in the school environment and owing to the potential reach of school-based interventions to tackle inequalities (i.e. demographic and social/cultural), changing the traditional classroom environment to an activity-permissive one by reducing sitting in this environment (rather than the traditional focus on leisure time screen use) is a promising area of research. Indeed, environmental restructuring to provide a physical opportunity to stand rather than sit would certainly be essential within the classroom environment, as traditional furniture dictates that children spend most of their class time sitting. However, implementing new practices and/or changing existing practices in organisations, such as schools, require changes in individual behaviour (i.e. pupil) and collective behaviour (i.e. teachers/school staff and pupils), and changing behaviour requires an understanding of the influences on behaviour in the context in which they occur. Our understanding of these factors can be enhanced through the theoretical domains framework,54 which provides a theoretical lens through which to view the cognitive, affective, social and environmental influences on behaviour. 55

Interventions to reduce sitting within the classroom environment

There are now a growing number of environmental interventions that aim to reduce classroom sitting time and increase standing and movement, which have been implemented in schools and evaluated for effectiveness through systematic reviews. 56,57 Feasibility studies, including our own,29,58,59 have demonstrated the effectiveness of incorporating sit–stand desks in primary school classrooms over the short term (< 12 weeks). For example, sit–stand desks have been shown to enable pupils to alternate between sitting and standing without disruption to teaching, learning or behaviour. 56 Furthermore, sit–stand desks in classrooms have been shown to be effective in increasing energy expenditure60,61 and standing and movement62 during the school day. In addition, studies have shown that sit–stand desks in classrooms lead to improvements in children’s posture and musculoskeletal comfort,63,64 levels of academic engagement65 and achievement,64 and improved cognitive function. 66 Sitting time has been shown to be reduced by between 44 and 60 minutes per day and standing time increased by between 18 and 55 minutes per day during classroom time at school, over 4 and 9 weeks’ follow-up. 29,59,67 More recently, the impact of standing desks on sitting time in the classroom has been assessed over 16 weeks’ follow-up, with results suggesting a 13% reduction in sitting and a 31% increase in standing at school, relative to baseline. 68 Clearly, incorporating standing desks in classrooms shows great promise for reducing children’s sitting time. However, systematic reviews have concluded that the majority of studies conducted to date have included relatively small samples, have been short in duration, have not included a randomised controlled design and have not assessed the impact of standing desks on academic performance. 56,57,69 Further exploration in this area of research is thus warranted.

Development of the Stand Out in Class study

The feasibility of incorporating sit–stand desks in the classroom environment over a 9-week period was demonstrated in an earlier intervention study we conducted with Year 5 Bradford primary school children. 29 In this feasibility study, we verified a number of our outcome measures (objectively determined sitting time and physical activity, body composition, blood pressure and teacher-reported pupil behaviour). In a novel approach, we replaced three standard desks (sitting six children) with six sit–stand desks. The teacher rotated the children assigned to the intervention group around the classroom in groups of six, according to the lesson being taught, using naturally occurring breaks between lessons to do so, ensuring that each child was exposed to the sit–stand desks once a day for at least 1 hour. Children in the control group continued with their usual practice, with no environmental changes to their classroom. Reductions in classroom sitting of 52 minutes per day were observed within the intervention group and reductions in total daily sitting of 81 minutes per day on school days after 9 weeks were seen. Teachers reported improvements in behaviour and no perceived negative effects on teaching or learning were observed. As part of this feasibility work, we also compared the changes in classroom sitting observed in our sample with data from a related feasibility study conducted in a primary school in Melbourne, Australia. 29 In the Melbourne study,29 every child in the intervention classroom had a sit–stand desk. Despite differences in desk provision, no significant differences in reductions in sitting time were observed between the two studies. Reductions in classroom sitting of 44 minutes per day and reductions in total daily sitting of 68 minutes per day were observed in the Melbourne intervention class. This early work demonstrates the potential of sit–stand desks in the classroom as a way of reducing sitting in children over the short term, irrespective of the type of sit–stand desk provision.

Following this successful feasibility work, the next logical step required was the development of the Stand Out in Class intervention. With the aim of informing a future definitive trial, the Stand Out in Class pilot study was developed to establish procedures for school and participant recruitment, and the acceptability of the intervention and outcome measures, and attrition rates. This intervention was informed by our feasibility work and public and patient involvement (PPI) with teachers and children through informal interviews and workshops (children only), in which our earlier work was described and their feedback on the intervention and proposed measures was obtained. This present study therefore comprises a pilot evaluation of the implementation of standing desks in the classroom through a cluster randomised controlled trial (RCT), with objective measures of sitting and activity, and a range of health- and education-related outcome measures. Rapid increases in sedentary time have been observed in children aged ≥ 11 years, relative to younger age groups. 70 This study targets Year 5 classrooms, comprising children just below this age (9- to 10-year-olds), with the goal of reducing the typical rise in sedentary time seen during the transition into adolescence,39 given also that sedentary behaviours track from childhood into adolescence and adulthood. 40 Furthermore, evidence suggests that children in Year 5 upwards are active participants in their own learning, making them an optimal target for classroom interventions that may facilitate learning. 71 A cluster design is considered appropriate because the intervention is delivered at the classroom level, rather than at an individual level.

Aims and objectives

The aim of this study is to undertake a pilot cluster RCT of the introduction of sit–stand desks in primary school classrooms to inform a future definitive trial.

Pilot trial study objectives

-

Establish and refine a recruitment strategy for schools and pupils.

-

Determine attrition in the trial (schools and children).

-

Determine completion rates for outcome measures (and whether or not these are sufficiently high to provide accurate data in a full trial).

-

Assess whether or not there are any differences in trial recruitment, retention and acceptability between ethnic groups.

-

Assess the acceptability of randomisation to schools.

-

Assess the acceptability of measurement instruments to teachers, children and parents, including the activPAL™ (PAL Technologies Ltd, Glasgow, UK) inclinometer, as the tool for the measurement of the primary outcome.

-

Assess the acceptability of the intervention to teachers, children and parents.

-

Monitor any adverse effects, such as musculoskeletal discomfort and/or disruption to the classroom/learning, to inform the design of a full trial and minimise or eliminate any such effects.

-

Assess intervention fidelity.

-

Derive preliminary estimates of the effect of the intervention on children’s total daily sitting time, physical activity, indicators of health (markers of adiposity and blood pressure), cognitive function, and academic performance, engagement and behaviour.

-

Estimate the standard deviation (SD) of the primary outcome to inform a sample size calculation for a full RCT.

-

Determine the availability and completeness of economic data, and conduct a preliminary assessment of potential cost-effectiveness.

Chapter 2 Study design and methods

This chapter summarises the study protocol for this pilot RCT as originally funded. Some of the material has already appeared in a published format72 and is reproduced here. Reproduced from Clemes et al. 72 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Study design

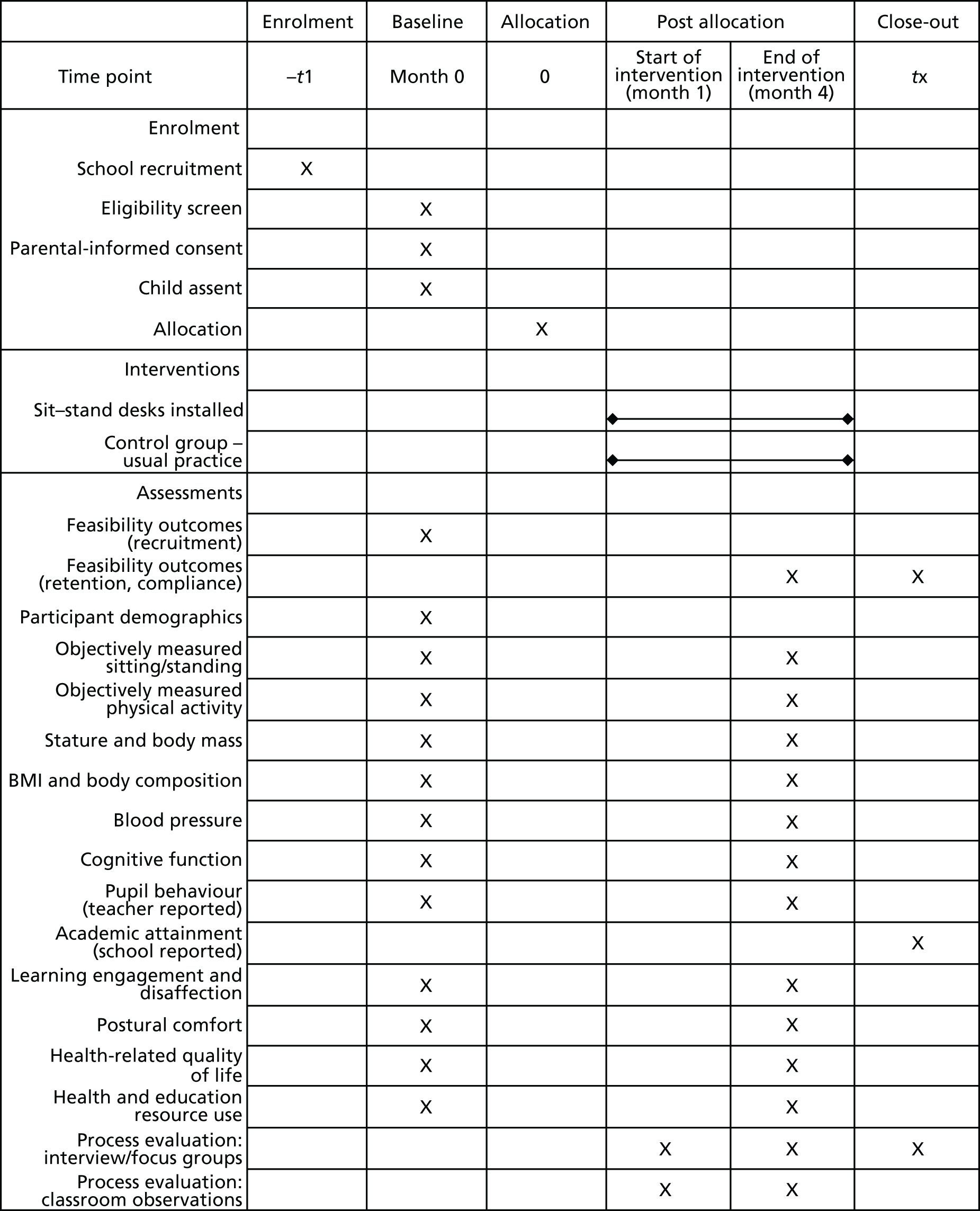

This was a school-based, pilot, two-armed, cluster RCT with economic and process evaluations. Individuals (Year 5 children, aged 9–10 years) were the unit of analysis and schools (clusters) were randomly assigned to one of two conditions: (1) six manually adjustable sit–stand desks incorporated into the classroom environment (intervention condition) or (2) current practice (control condition). Baseline measurements preceded randomisation and the sit–stand desks were installed into the intervention classrooms following this. An identical set of outcome measurements were taken from all participants approximately 7 months after the baseline measures, at the end of Year 5. Figure 1 shows the schedule of enrolment, intervention and outcome measurements.

FIGURE 1.

Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials (SPIRIT) diagram illustrating the design and time scales of the pilot Stand Out in Class RCT. BMI, body mass index. Arrows indicate start and end points of intervention and control period. Reproduced from Clemes et al. 72 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval for this study was obtained from Loughborough University’s Ethical Advisory Committee (reference R16-P027). All members of the measurement team were required to have a current enhanced disclosure and barring service check and all employees of the Bradford Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust who undertook data collection completed online training in safeguarding children and information governance.

Study setting

The study was conducted in primary schools in Bradford, UK. Bradford was chosen as the study location given its ethnic composition (predominantly South Asian and white British) and high levels of deprivation, health inequalities and childhood morbidity. 73 Half of all babies born in Bradford are of South Asian origin and 60% of babies are born into the poorest 20% of the population,73 with elevated risk factors for chronic diseases seen in South Asian children in comparison with white children. 20,22 Furthermore, in 2016–17, 38% of Year 6 children in Bradford were overweight or obese according to the National Child Measurement Programme. 74 The setting of this study, therefore, is fundamental in addressing the important issue of health inequalities, in that the intervention will be accessible to all children. In addition, the location enables us to pilot the intervention under challenging circumstances, meaning that, if it proves acceptable, it is likely to be transferable to most schools. At the planning stages of the trial, PPI with local teachers, parents and children demonstrated widespread support for the study, with all of those informally interviewed stating that they would be keen to try sit–stand desks in their classrooms (teachers and children).

Sample size

A recruitment target of eight primary schools, each with at least 15 child participants (approximately 50% of a typical class), was set, giving a minimum total sample of 120 participants. This matches the minimum of four clusters per arm recommended for a definitive cluster RCT75 and exceeds the target minimum sample size recommended for pilot trials. 76 Consequently, the sample should be sufficient to provide clear estimates of recruitment and follow-up for a definitive trial.

School and participant recruitment and eligibility criteria

Government-funded primary schools located in the city of Bradford were invited to take part in the trial. Private and designated special schools and schools with < 25 pupils in Year 5 were not eligible to participate. Schools running a sitting time reduction programme, or with a unique characteristic that precluded comparisons with another school, were also not eligible for participation. The study was publicised to primary schools through existing local networks (e.g. Bradford Primary Improvement Partnership and Bradford’s Public Forum for Education). We aimed to recruit four schools with predominantly South Asian pupils (> 50%) and four with predominantly white British pupils (> 50%). The ethnic composition of the pupils was determined using local school census data.

The following three-stage process was adopted, informed by our earlier feasibility work and PPI with teachers and head teachers, for contacting schools about the study: (1) head teachers/senior teachers were sent an e-mail detailing the study, with the e-mail including a copy of the information sheet for schools; (2) 2 days after sending the e-mail, the school was telephoned and the reception team was asked whether or not the e-mail had been received by the head teacher/senior teachers; and (3) a follow-up telephone call was made to the school to arrange a time for the research team to meet either with the head teacher or with a senior teacher, either over the telephone or in person, to discuss the study in more detail, or to confirm that the school was not interested in participating in the study. Schools interested in participating were sent/given further information about the study, including an information sheet for teachers, and during the follow-up conversations the head teacher, or a nominated senior teacher, was requested to provide written informed consent to participate on behalf of the school. During recruitment, schools were requested to identify a designated lead teacher and were informed that they may be randomised to a current practice control condition in which they would be asked to maintain their usual classroom practice.

Following school recruitment, a member of the research team contacted the designated lead teacher directly via e-mail. The school was then provided with an invitation pack for the parents or guardians of eligible children (9- to 10-year-olds within the nominated Year 5 class of participating schools). The invitation pack contained a detailed information sheet for parents/guardians about the study, an opt-in consent form for the parent or guardian to complete and return if they were happy for their child to participate in the evaluation and an information sheet for children. The packs were given to eligible Year 5 children, who were asked to give them to their parents or guardians. In consultation with the participating Year 5 teachers within the schools, it was agreed that members of the research team, and the teacher, would be present at the school gates during school drop-off and collection times over a 4-day period (after children were given their packs to take home) to speak to parents and guardians about the study, should they have any questions. Completed consent forms were returned by pupils to their teacher, who informed the research team of the children who were to be involved in the evaluation measures.

At the beginning of the baseline measurement session, all methods were fully explained to the participants by a team member who was suitably qualified and experienced, and who was authorised to do so by the principal investigator (PI). Children were then asked to provide verbal and written assent that they were happy to participate, and this was requested again at the start of the follow-up measurement sessions. Children without parental consent or those who did not give their assent to participate in the evaluation were excluded from the evaluation measures, described in Outcome measurements, although they were still able to use the sit–stand desks in their classrooms. Any children in the intervention schools with known contraindications (e.g. those with a musculoskeletal injury, wheelchair users) that would preclude periods of standing were invited to participate in the evaluation measures and encouraged to use the sit–stand desks in a seated posture for inclusivity. These individuals were, however, excluded from the analyses.

Changes from the original protocol/grant application

The original grant application proposed that the intervention would run throughout the entire academic year (≈10 months) while the participants were in Year 5. The intended start date of the grant was originally 1 April 2016 and the desk installation was planned for September 2016. However, owing to delays at the project approval stage, the study did not officially commence until 1 November 2016 and the sit–stand desks were installed in the intervention schools between 27 February 2017 and 3 March 2017 (due to further delays caused by desk availability from the manufacturer). The intervention was therefore shorter (4.5 months) than originally proposed. As one of the project goals was to build on the previous evidence and assess the longer-term acceptability of using sit–stand desks in primary school classrooms, the study team discussed with the Trial Steering Committee (TSC) the possibility of extending the duration of the intervention until December 2017, with the desks remaining with the children as they entered Year 6. The TSC, however, recommended that the intervention be completed as originally planned in July 2017, and this recommendation was supported by expert advisors within the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). It was felt that extending the trial into Year 6, particularly in terms of the scheduling of a further set of follow-up measures, would place added pressure on the new Year 6 teachers and schools at a critical time when the children would be preparing for and taking their Standard Assessment Tests (SATs). It was also felt that, as a pilot study, the team would still have an adequate number of data to assess the acceptability of the trial following 4.5 months.

The Stand Out in Class intervention

Six sit–stand desks were placed in one Year 5 classroom (replacing three standard desks sitting six children) in each intervention school for two school terms. The research team supported teachers in the development of a classroom rotation plan to ensure that all children in their class were exposed to the sit–stand desks for at least 1 hour per day, on average, across the week. Stools or chairs remained in the classroom and children were free to choose whether they sat or stood when using the sit–stand desks.

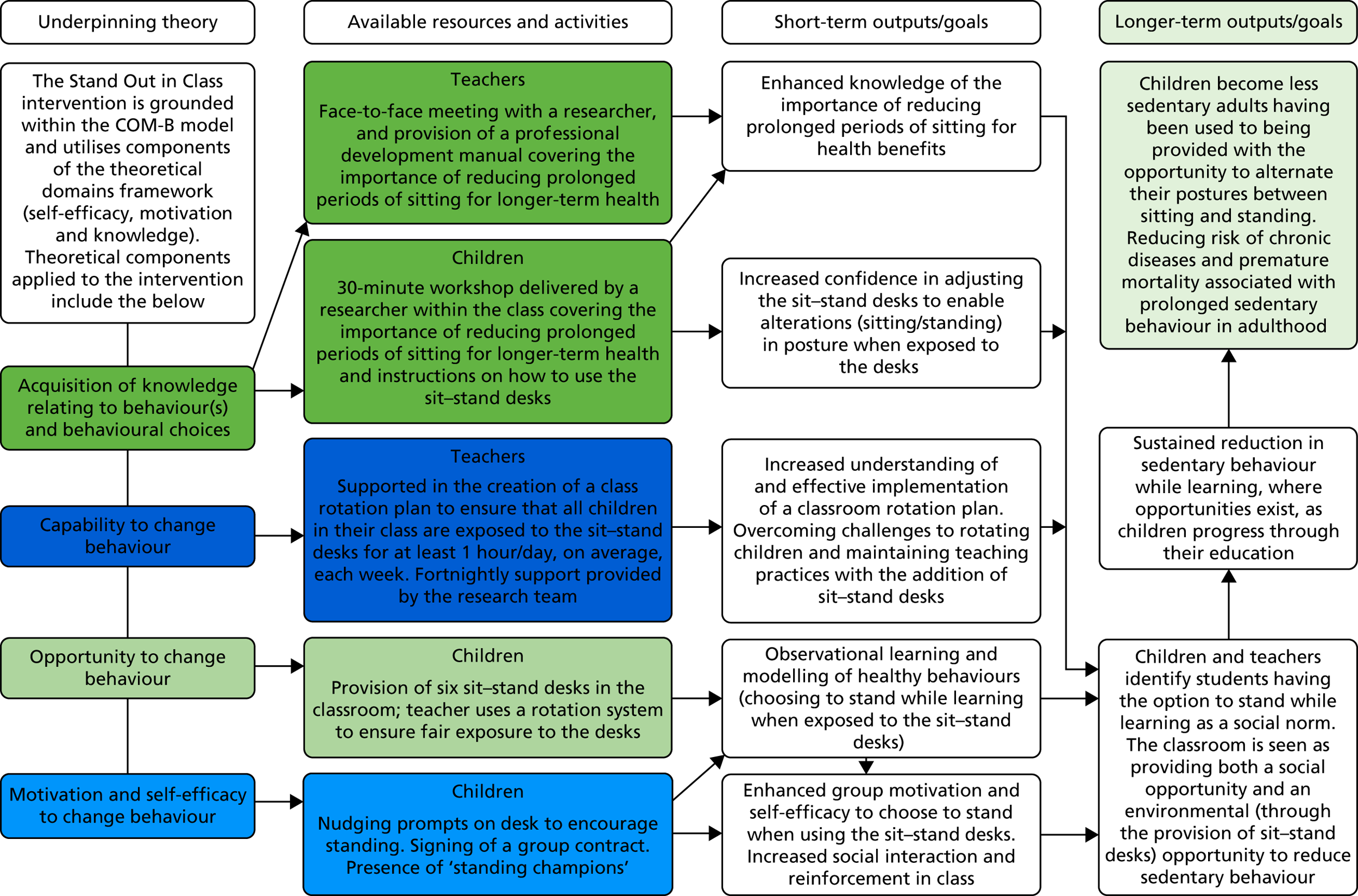

Teachers and pupils in the intervention classrooms received training on sit–stand desk use by the research team and teachers also received a professional development manual (see Report Supplementary Material 1) containing information on the health benefits of reducing prolonged sitting and on correct posture when standing at the desks. The manual and training focused on encouraging correct adoption of the intervention, targeting key barriers to and facilitators of sit–stand desk use. These were identified from our previous work,29,77 from the COM-B, within the BCW,78 and from the theoretical domains framework79 (e.g. self-efficacy, motivation and knowledge). Standardised behaviour change techniques (e.g. goal-setting, instruction)80 were also used during the training with teachers and pupils. A summary of the intervention components is shown in Table 1 and a logic model for the Stand Out in Class intervention, applicable for a definitive trial, is presented in Figure 2. Appendix 1, Table 23, details potential intervention barriers, solutions and hypothesised mediating processes informed by the above theoretical frameworks.

| Intervention component | Target domain | Mediating variable | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adjustable sit–stand desks | Environment | Six adjustable sit–stand desks introduced into the classroom | |

| Nudging prompts | Environment | Children choose to stand rather than sit when using desks |

Stickers placed on each of the sit–stand desks Examples: |

| 2-hour one-to-one meeting | Teacher | Exposure to desks | 2-hour meeting with teacher covering:

|

| Professional development manual | Teacher | Exposure to desks | Covering topics such as:

|

| Planned weekly rotation plan | Teacher | Exposure to desks | Teacher creates a predetermined rotation plan and keeps a record of whether this was adhered to or not (simple tick sheet) |

| Fortnightly support with practitioners | Teacher | Exposure to desks | Telephone or face-to-face meeting with researchers/practitioners to discuss any issues around implementation of rotation plans |

| 30-minute workshop | Children |

Exposure to desks Children choose to stand rather than sit when using desks |

Covering topics such as:

|

| Standing champion/leader | Children |

Exposure to desks Children choose to stand rather than sit when using desks |

One child in a group is chosen as a standing champion, with responsibility of reminding the teacher of the rotation plan |

| Group contract | Children |

Exposure to desks Children choose to stand rather than sit when using desks |

Children asked to sign a class contract that states that I will try my best to:

|

FIGURE 2.

A logic model for the Stand Out in Class intervention, which is applicable for a definitive trial. Adapted with permission from Clemes et al. 81 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

The usual practice control arm

To compare the effects of the intervention against usual practice (i.e. the provision of standard classroom desks), schools assigned to the control arm were requested to continue with their usual practice and lesson delivery, and no environmental changes were made to their classrooms. The Year 5 participants in the control schools were asked to complete the same study measurements as those in the intervention schools, at the same time points. On completion of the study, control schools were offered a report summarising the collected data of their pupils.

Allocation to treatment groups

To assess the acceptability of the intervention and proposed outcome measures for use in a definitive trial across an ethnically diverse sample, recruited schools were stratified based on the ethnic composition of their pupils (see School and participant recruitment and eligibility criteria). Following the completion of baseline measurements, schools within each stratum were randomised by an independent statistician at the Leicester Clinical Trials Unit into the two trial arms [intervention and control, with an allocation ratio of 1 : 1 using a randomisation list in SAS® software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). [SAS and all other SAS Institute Inc. product or service names are registered trademarks or trademarks of SAS Institute Inc. in the USA and other countries. ® indicates USA registration.] Two schools with predominantly South Asian pupils and two schools with predominantly white British pupils were randomised into the intervention and control arms (four schools in each trial arm). This stratification enabled the examination of whether or not there were differences between South Asian and white British pupils in terms of recruitment and retention, adherence to the outcome measures and preliminary effects of the intervention on outcome measures (objective 4). The statistician performing the analyses was blinded to the schools’ allocation to the study arms, as were the community researchers undertaking the outcome measurements.

Outcome measurements

Trial feasibility-related outcomes

The primary aim of this pilot study was to establish school and participant recruitment and retention rates, the acceptability of the intervention and proposed outcome measures, intervention and measurement fidelity, and the availability and completeness of economic data for an estimation of potential cost-effectiveness, to inform the development of a definitive trial. Study uptake was monitored by recording the number of schools and pupils approached, and the number agreeing to participate (objective 1). Withdrawal rates of schools and children (objective 2) and completion rates for outcome measures were recorded (objective 3), and these feasibility outcomes were compared between ethnic groups (objective 4).

Process evaluation

A series of interviews and focus groups with teachers, children and parents were conducted following the completion of the baseline measures and randomisation to explore the acceptability of the trial procedures, including randomisation (objective 5), and the acceptability of the measurement instruments (objective 6). The acceptability of the intervention (objective 7) and children’s, teachers’ and parents’ perceptions and experiences of the intervention and outcome measures were determined during the intervention through a further set of interviews (n = 4 with teachers from the intervention schools) and focus groups (n = 4 with children from the intervention schools) (objective 8). Potential differences in the trial and intervention acceptability between ethnic groups were explored as part of the analyses from the focus groups (objective 4). Towards the end of the intervention, four one-to-one interviews were also conducted (one per intervention school) with senior staff (head teachers/deputy head teachers) to further examine the acceptability of the intervention (objective 7).

To assess intervention fidelity, intervention classrooms were observed by a member of the research team for the duration of at least half a school day during the spring and summer terms. Field notes were taken to document the occurrence of any intervention components (i.e. use of prompt cards, engagement with a standing champion; see Table 1) during the observation period. In addition, children’s postures during sit–stand desk use were recorded using a postural analysis recording system based on the portable ergonomic observation63 to assess any potential future risk of musculoskeletal injury (objectives 8 and 9). Full details of the process evaluation methods, analyses and results are described in Chapter 5.

Health- and education-related outcome measures

All health-related outcome measurements were taken twice: at baseline prior to randomisation and approximately 7 months after baseline when pupils were at the end of Year 5 (the sit–stand desks remained in the intervention classes until the end of Year 5, while the follow-up measures were taking place).

Proposed primary outcome in a full trial: activPAL-determined sitting time

The likely primary outcome in a definitive trial would be change in average daily school day sitting time. Sitting was measured objectively for 7 consecutive days during each measurement period using the activPAL3 micro accelerometer (PAL Technologies Ltd, Glasgow, UK). All activPALs were initialised and downloaded using manufacturer proprietary software (activPAL Professional v.7.2.32, PAL Technologies Ltd, Glasgow, UK) and data were processed using the freely available ProcessingPAL software (version 1.1, University of Leicester, Leicester, UK; https://github.com/UOL-COLS/ProcessingPAL). The activPAL3 was waterproofed [using a nitrile sleeve and hypoallergenic Hypafix® (BSN medical, Hull, UK) dressing] and participants were requested to wear the device continuously (24 hours/day) on the anterior aspect of their right thigh during each measurement period. Participants were provided with a brief diary during each monitoring period, in which they were requested to document time in bed and any periods of non-wear.

The use of the activPAL to objectively measure sitting has increased in recent years82 and the device is recommended for use in interventions when the primary outcome measure is sitting. 83 It is regarded as the most accurate method of assessing sitting behaviour in free-living settings,84 and has been shown to be almost 100% accurate in measuring sitting, standing, walking and postural transitions in children. 85,86 The device has also been successfully used as a primary outcome measure in previous school-based sedentary behaviour interventions. 29,59,67

Although total daily school day sitting time is likely to be the primary outcome for a future trial, we also extracted classroom and leisure time sitting, standing and stepping times from the activPAL data. This allowed us to specifically examine the impact of the intervention on these behaviours during class time (the environment in which the intervention was administered). Furthermore, any positive (i.e. reductions in sitting) or compensatory effects (increases in sitting) of the intervention on children’s sitting, standing or stepping time out of school hours were examined by extracting activPAL data collected during leisure time.

Periods of non-wear and sleep time were excluded from the analyses using an automated algorithm,87 (applied within the ProcessingPAL software) and supplemented with cross-checking against participants’ diary entries. Owing to the exploratory nature of this study, children were included in the analyses if they had worn the activPAL for at least 8 hours on at least 1 weekday at baseline and follow-up, as applied elsewhere. 29 To assess whether or not the number of valid days of activPAL wear had an effect on the primary outcome (to inform wear time criteria in a definitive trial), sensitivity analyses were undertaken to examine the impact of the number of included days (see Statistical analysis). The variability (SD) of the data from the proposed primary outcome was used to inform a sample size calculation for a definitive trial (objective 11).

Proposed secondary outcomes in a full trial

ActiGraph-determined physical activity

Proposed secondary outcomes for a definitive trial include objectively measured physical activity. Although the activPAL provides a valid measure of posture, it has not been well validated for assessment of various physical activity intensities among children. Therefore, participants were requested to wear the ActiGraph GT3X+ accelerometer (ActiGraph, Pensacola, FL, USA) on the waist continuously (24 hours/day) for 7 consecutive days, concurrently with the activPAL, during each measurement period. The feasibility of collecting ActiGraph data, in addition to activPAL data, was examined in the present study to inform a definitive trial, in which this device could be used as a secondary outcome to examine any positive or negative (i.e. compensatory) effects of the intervention on physical activity, either during or after school hours. ActiGraphs were initialised to record data at 15-second epochs, the devices were initialised and downloaded using ActiLife version 6.13.3 (ActiGraph) and the data were processed using specifically developed and commercially available software (KineSoft version 3.3.20, Loughborough, UK). Periods of non-wear were documented in a brief diary provided with the activPAL and ActiGraph.

Waist-worn accelerometers have traditionally been considered the criterion measure of children’s physical activity. 88 The ActiGraph is the most commonly used accelerometer in field-based research and has been shown to have acceptable reliability and validity in paediatric populations. 89 Times spent in light (26–573 counts/15-second epoch) and moderate- to vigorous-intensity (≥ 574 counts/15-second epoch) activity throughout the day, and during and out of school hours, were extracted from the ActiGraph data using the Evenson cut-off points. 90 ActiGraph-determined sedentary time (≤ 25 counts/15-second epoch) was also extracted for descriptive purposes. In a comparative study examining the classification accuracy of five different ActiGraph cut-off points for determining children’s and adolescents’ physical activity intensity, against indirect calorimetry, the Evenson cut-off points were found to be the most accurate across all intensity levels and are therefore recommended for use in this age group. 91 Periods of non-wear and sleep time were excluded from the analyses during the processing of the ActiGraph data, and supplemented with cross-checking against participants’ diary entries. Owing to the 24-hour wear protocol of the ActiGraphs, a blanket removal of sleep time between 23.00 and 05.59 was undertaken when processing these data. However, to identify periods of sleep occurring outside this time period (i.e. after 06.00 and before 23.00), the three-axis acceleration data from the ActiGraph were used to detect periods of no movement. If these periods exceeded 20 minutes of zero counts, then this additional period was excluded as non-wear/sleep time. The same wear time criteria as applied to the activPAL data (a minimum of 8 hours of wear on at least 1 weekday) was also applied to the ActiGraph data.

Anthropometry

At each measurement point, children’s stature and body mass (both assessed without shoes) were measured directly using standard procedures by trained research staff. Body mass index (BMI) (kg/m2) was calculated and converted to a BMI percentile based on UK reference data. 92 Body composition (percentage body fat and fat mass) was assessed via bioelectrical impedance analysis using Tanita DC-360S body composition scales (Tanita, Tokyo, Japan) which contain specific algorithms for children.

Blood pressure

Blood pressure was measured from the left arm after at least a 5-minute period of quiet sitting using a semi-automated recorder (Omron HEM-907; Omron Corporation, Kyoto, Japan) with a paediatric cuff, in accordance with current recommendations. 93 Three measurements of blood pressure were taken with each measurement, separated by a 2-minute rest period. The mean systolic and diastolic blood pressures recorded from the second and third assessments were calculated and used in the analyses.

Cognitive function

A set of objective cognitive function tests were administered via a validated software package. The software was installed on school computers, enabling study participants to undertake these assessments collectively in the classroom, under the supervision of two researchers. Participants undertook a practice run-through of the cognitive function test battery a day before the test day. The test battery took children approximately 15 minutes to complete and included the Corsi block-tapping test,94 the Stroop test95 and the rapid visual information processing (RVIP) task. 96

The Corsi block-tapping test measures visuospatial working memory capacity. 94 Performance on the Corsi block-tapping test is linearly associated with age in typically developing children97 and the original version has exhibited a test–retest reliability coefficient of 0.7 (Pearson’s correlation coefficient) in 11-year-olds. 98 The test involves participants repeating a sequence of blocks, displayed on a 3 × 3 grid, which individually change colour. The test begins with a sequence of three blocks and proceeds to a maximum of 12. The sequence length increases or decreases by one with every correctly or incorrectly reproduced sequence, respectively. The outcome measure was the mean correctly recalled sequence length, assessed across 12 attempts.

The Stroop test measures sensitivity to interference and the ability to suppress an automated response (by reading colour names in favour of naming the font colour), and is a commonly used measure of selective attention and executive function. 99 The current test comprised two levels: a simple level and a complex level. The simple level involved reading a name of a colour in black font and identifying the colour using the right or left arrow keys on the keyboard. In the complex level, participants were presented with a colour name (i.e. red, green or blue) in a different font colour (e.g. the word ‘red’ in blue font) and were required to identify the colour name (i.e. red in the example given above). The average reaction time of all correct responses for the simple and complex levels were calculated. The complex reaction time measure within this computerised test has been shown to exhibit a test–retest reliability of 0.55 (Pearson’s correlation coefficient) in a combined sample of children and adults. 100

The RVIP task measures sustained attention and has been shown to exhibit an internal reliability coefficient (assessed using Cronbach’s alpha) of 0.49 in school-aged children. 101 The test involves detecting sequences of three consecutive even or odd numbers presented on the screen. Each number is presented individually and changes every 600 milliseconds. Outcomes from this test include the true-positive rate (i.e. the number of correctly identified sequences out of all identifiable sequences) and the miss rate (i.e. the number of missed sequences out of all identifiable sequences), with scores for both measures ranging between 0 and 1. The true-positive rate is considered a measure of accuracy, whereas the miss rate is considered a measure of alertness, with higher and lower values indicating better performance, respectively. Mean reaction times for each correctly identified sequence were also recorded.

Academic progress and attainment

Measures of participants’ academic progress across maths, reading and writing were collected using routine assessment data recorded by the schools. As collecting data relating to pupils’ progress across these key subject areas is not a requirement of the national curriculum, the participating schools did not have a standardised method of collecting these data. Through consultation with participating teachers, attainment data were dichotomised for the purposes of this study into binary classifications of whether or not each participating pupil was meeting expectations in these three key subject areas at a particular time of development and education. With teachers’ guidance, we transformed the attainment data collected by each school, for each participating pupil, into the following variables: ‘yes – pupil is meeting expectations (for maths/writing/reading) of children of that age’ or ‘no – pupil is not meeting expectations (for maths/writing/reading) of children of that age’. Each school’s attainment data collected at the start of the spring term (2016/17 academic year), coinciding with before the intervention commenced, and at the end of the school year (July 2017), were collected and transformed in this way, to ensure standardised data across the eight participating schools. The binary scores calculated for baseline were subtracted from the follow-up scores for maths, reading and writing separately, leading to a nominal variable of ‘change of subject expectation’, which led to three categorical levels: (1) decreased level of expectation (pupil was meeting expected level for the subject, but is no longer meeting expectations); (2) no change in expected level; and (3) increased level of expectation (pupil was not meeting level of expectation, but is now).

Questionnaire measures

The impact of the intervention on participants’ behaviour was assessed using the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire, completed by teachers at baseline and follow-up. This questionnaire, when completed by teachers, has been shown to provide a valid indicator of children’s behaviour (convergent validity: Pearson’s correlation coefficient with the Rutter Children Behaviour Questionnaire = 0.92102). In addition, children self-reported their engagement and disaffection with their own learning via the Engagement Versus Disaffection with Learning Questionnaire103 (correlation coefficients between pupil and teacher reports of the components of engagement using this measure range from 0.26 to 0.44104). Postural comfort was reported by participants using a further brief questionnaire. 63

Children completed the Paediatric Quality of Life Inventory (PEDS-QL)105 and EuroQol-5 Dimensions Youth (EQ-5D-Y)106 at each measurement point, to provide a measure of self-reported quality of life. The construct validity of the PEDS-QL has been previously demonstrated, with healthy children displaying significantly higher scores on this measure than acutely or chronically ill children. 105 Responses on the EQ-5D-Y have also been shown to correlate with other measures of children’s health-related quality of life (convergent validity correlation coefficients up to 0.56107). To inform the economic analysis described in more detail in Economic Analysis (objective 12), teachers and parents completed a questionnaire72 created for the purpose of this study, which assessed participants’ health- and education-related resource use at baseline and follow-up.

Basic demographic information (sex, age, ethnicity and postcode, to determine Index of Multiple Deprivation as an indicator of socioeconomic status) was collected at baseline.

School and participant appreciation

As a thank you for participating in this pilot trial, all schools (intervention and control) received a donation of £200 at the end of the study period. A £5 gift voucher was also given to each child following the completion of both the baseline and follow-up measures to encourage a timely return of the accelerometers.

Economic analysis

The availability and completeness of economic data were established as part of this pilot study (objective 12). Resource use information was collected, which included the cost of the sit–stand desks, along with participants’ health-related [e.g. general practitioner (GP) visits] and education-related resource use (e.g. requirements for additional tutoring). Proposed outcomes within a definitive trial were based on two sectors: health and education. For the former, as described in Questionnaire measures, the PEDS-QL105 and EQ-5D-Y106 were collected at baseline and follow-up to assess children’s health-related quality of life. For the latter, the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire completed by school teachers for each pupil was used. A preliminary cost-effectiveness analysis was conducted (see Chapter 4) to inform the value of, and to make recommendations for, the design of a full trial. All outcomes collected were presented as a within-trial analysis at baseline and follow-up; however, no formal comparison of the cost and benefit of providing sit–stand desks was conducted for within-trial outcomes. A brief scoping review was conducted to identify existing model(s) that link short-term health outcomes to long-term health effects with this model, informing a preliminary assessment of the long-term health costs and benefits associated with the intervention.

Statistical analysis

The analysis and reporting of this pilot RCT was in line with the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) statement for cluster RCTs. 108 Data were analysed on a complete-case basis. The purpose of the primary analysis was to assess the feasibility of recruitment and adherence/retention of primary schools and pupils to the sit–stand desk intervention. As this was a pilot trial, the primary analyses mainly utilised descriptive statistics. The number of schools approached, the number agreeing to participate, the proportion of children within each school with parental consent to participate in the study evaluation, the number of children completing the study protocol, retention rates and the number providing valid outcome measurement data at baseline and follow-up are described in Chapter 3. Study acceptability data are presented for the sample as a whole and stratified according to study arm (intervention and control) and ethnicity (South Asian and white British).

Although the main aim of this study was to establish acceptability, feasibility, recruitment rates and sample size to inform a definitive trial, and although effectiveness was unlikely to be established with the small sample size, we examined the proposed primary and secondary outcomes for a definitive trial to mimic practice in such a trial. The results from this analysis should, however, be treated as preliminary and interpreted with caution. 109,110 As the number of clusters is low, cluster summary statistics were used rather than multilevel modelling. 111,112 The analyses were conducted using children as the unit of analysis, with change in average total school day sitting time as the primary outcome. A weighted linear regression model was used to compare the intervention arms weighted by the number of participants followed up in each cluster, and adjusted for baseline total daily sitting time on school days and average weekday wear time when awake across the two time points (baseline and 7 months). To examine preliminary effects of the intervention on the secondary outcomes, the same analytical approach was adopted as for the proposed primary outcome (objective 10). These analyses were intended to provide preliminary evidence of the effectiveness of the intervention to, in part, inform the decision of whether or not a definitive trial should be undertaken.

Sensitivity analyses were performed on the proposed primary outcome for a full trial of average weekday sitting time. This was achieved by including pupils who wore the activPAL (with a minimum valid wear time of 8 hours/day) for at least 2, 3 and 4 weekdays, at baseline and follow-up.

An objective of this pilot study was to estimate the SD of the primary outcome to inform a full trial. The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) to inform the sample size calculation of a definitive trial was estimated from published literature. The ICC was not estimated from this pilot study because multilevel modelling was considered to be an unsuitable analysis method for the present study, due to the small number of clusters, and an ICC estimate from such a model would not be sufficiently robust to inform a sample size calculation for a definitive trial.

Data management and research governance

Anonymised data were entered into a secure and validated clinical data management system provided by the Leicester Clinical Trials Unit; this database (InferMed Macro v4; Elsevier Ltd, Oxford, UK) included a series of quality control mechanisms to ensure that the data collected were complete and accurate. The study was sponsored by Loughborough University and two groups were created to oversee the research: an independent TSC and a Project Committee. As the study was regarded as low risk, the TSC took on the role of a Data Monitoring Committee, with the intention of reviewing any serious adverse events, should they have arisen, and monitored progress with data collection. The TSC met every 6 months and included the PIs (Stacy A Clemes and Sally E Barber), an independent chairperson, two independent external members (including a statistician) and two school representatives (public members who were teachers from schools separate to those participating in the trial). The Project Committee comprised the PIs, all co-investigators and those concerned with the day-to-day running of the study, and provided update reports for the TSC.

Chapter 3 Results

This chapter presents the quantitative findings from the Stand Out in Class pilot study. This study was primarily designed to address issues surrounding school and participant recruitment, acceptability of the measurement tools and intervention, and school and participant attrition rates and compliance with the measurement tools to inform a future definitive trial. Although the study was not powered to provide information on a treatment effect, preliminary estimates of the effect of the intervention are reported herein to further aid the design of a definitive trial. This chapter reports on the following study objectives:

-

Objective 1 – establish and refine a recruitment strategy for schools and pupils.

-

Objective 2 – determine attrition in the trial (schools and children).

-

Objective 3 – determine completion rates for outcome measures (and whether or not these are sufficiently high to provide accurate data in a full trial).

-

Objective 4 – assess whether or not there are any differences in trial recruitment, retention and acceptability between ethnic groups.

-

Objective 8 – monitor any adverse effects, such as musculoskeletal discomfort and/or disruption to the classroom/learning, to inform the design of a full trial and minimise or eliminate any such effects.

-

Objective 10 – derive preliminary estimates of the effect of the intervention on children’s total daily sitting time, physical activity, indicators of health (markers of adiposity and blood pressure), cognitive function, and academic performance, engagement and behaviour.

-

Objective 11 – estimate the SD of the primary outcome to inform a sample size calculation for a full RCT.

Objective 1: school and participant recruitment

A total of 24 eligible schools were approached for recruitment into this pilot study. Of these 24 schools, the study target number of eight schools consented to take part in the study, with the overall recruitment rate being 33% [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.16% to 0.55%]. Twelve out of the 24 schools did not consent to enter the study (50%) and four out of the 24 schools approached did not respond to the initial e-mail (17%). The characteristics of the participating schools are described in Table 2.

| Trial arm (school number) | Location | Percentage of pupils | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eligible for free school meals | Classified as white British ethnic origin | Classified as South Asian ethnic origin | Whose first language is not English | ||

| Control (1) | Bradford South | 16.9 | 63.2 | 17.5 | 16.3 |

| Control (2) | Bradford West | 21.2 | 10.8 | 76.3 | 69.5 |

| Control (3) | Bradford East | 23.8 | 30.8 | 54.9 | 57.1 |

| Control (4) | Bradford East | 13.1 | 1.1 | 88.3 | 88.6 |

| Intervention (1) | Bradford East | 26.4 | 11.1 | 51 | 74.3 |

| Intervention (2) | Bradford East | 18.2 | 0.6 | 91.8 | 92 |

| Intervention (3) | Bradford South | 14.9 | 89 | 2.8 | 3.9 |

| Intervention (4) | Shipley | 2.3 | 83.5 | 5.6 | 9.1 |

Data from the 2016–17 school census113 show that the proportion of children eligible for free school meals was similar across the recruited schools and declined schools [mean 17.1% (range 2.3–26.4%) vs. mean 17.4% (range 9.6–28.5%), respectively] for the 2016/17 academic year and across the previous 6 years [mean 31.1% (range 6.4–52.4%) vs. mean 29.6% (range 17.4–48.2%), respectively]. There was, however, a difference between the proportion of children whose first language was not English between the recruited and declined schools [mean 51.4% (range 3.9–92%) vs. mean 38.4% (range 0–93.5%), respectively], with eight of the 12 declined schools predominantly containing white British children.

Overall, the proportion of pupils at the eight schools with parental consent to participate in the trial evaluation was 75% (176/234), exceeding the target minimum sample size of 120 participants (see Chapter 2, Sample size).

Objective 2: determine attrition in the trial (schools and children)

All eight participating schools completed the trial; the overall school retention rate was therefore 100%.

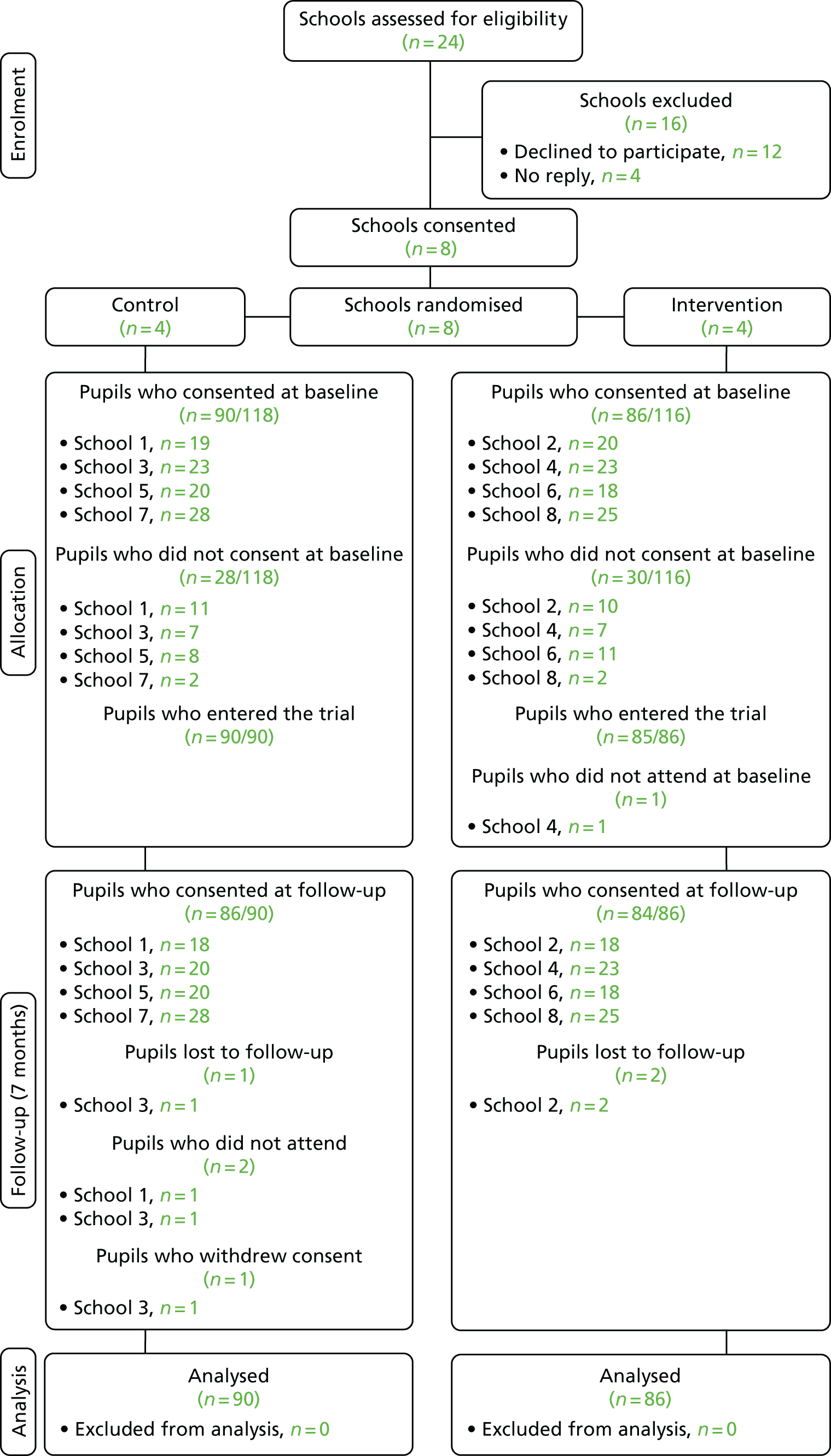

At 7 months’ follow-up, the overall retention of participating children was 97% (170/176). The retention rate of children in the control group was 96% (86/90) and the retention rate of the intervention group was 98% (84/86). A CONSORT flow diagram for the study is shown in Figure 3. Two participants in the control group (2.2%) did not attend the follow-up measures because they were absent from school during the days in which these measures took place. Three participants [one control (1.1%), two intervention (2.3%)] moved away from the area during the study and hence changed schools. One participant in the control group (1.1%) withdrew their assent prior to the follow-up measures. The demographic characteristics of the participating children are shown in Table 3.

FIGURE 3.

A CONSORT flow diagram for the Stand Out in Class pilot RCT. Reproduced with permission from Clemes et al. 81 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

| Demographic characteristic | Trial arm | Overall (N = 176) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control (N = 90) | Intervention (N = 86) | ||

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Male | 50 (55.6) | 48 (55.8) | 98 (55.7) |

| Female | 44 (44.4) | 38 (44.2) | 78 (44.3) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| White British | 18 (20.0) | 45 (52.3) | 63 (35.8) |

| South Asian | 59 (65.6) | 26 (30.2) | 85 (48.3) |

| Other | 13 (14.4) | 15 (17.4) | 28 (15.9) |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 9.3 (0.5) | 9.3 (0.4) | 9.3 (0.5) |

Objective 3: determine completion rates for outcome measures

Overall completion rates for the outcome measures at 7 months’ follow-up (including participants who provided valid data at both baseline and follow-up) were as follows:

-

≥ 63% for activPAL data (proposed primary outcome in a definitive trial)

-

≥ 83% for ActiGraph data

-

≥ 94% for anthropometric measures

-

≥ 69% for blood pressure

-

≥ 89% for cognitive function

-

≥ 97% for the child-reported Body Comfort Survey

-

≥ 97% for the Engagement Versus Disaffection with Learning Questionnaire

-

≥ 91% for teacher-reported Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire data.

Objective 4: assess whether or not there are any differences in trial recruitment, retention and acceptability between ethnic groups

Table 24 in Appendix 2 displays the recruitment and retention rates for the whole sample and according to ethnic group. Ninety-eight per cent of both white British children and South Asian children provided parental consent and written assent to participate within the trial evaluation. Similarly, 98% of white British children and South Asian children completed the trial. The impact of ethnic group on acceptability of the trial overall is discussed in Chapter 5 as part of the full process evaluation, alongside discussion of objectives 5–7.

Objective 8: monitor any adverse effects, such as musculoskeletal discomfort and/or disruption to the classroom/learning, to inform the design of a full trial and minimise or eliminate any such effects

There were no serious adverse events or adverse events reported throughout the duration of the trial. Specifically, there were no reported adverse effects associated with the intervention that related to musculoskeletal discomfort and/or disruption to the classroom or to learning. Teachers’ and children’s perceptions and experiences of the intervention are discussed in detail in the process evaluation described in Chapter 5. Descriptive statistics summarising preliminary evidence of the impact of the intervention on musculoskeletal comfort, classroom behaviour, engagement with learning and markers of attainment are presented under objective 10 (objective 9, the assessment of intervention fidelity, is also covered in Chapter 5).

Objective 10: derive preliminary estimates of the effect of the intervention on children’s total daily sitting time, physical activity, indicators of health (markers of adiposity and blood pressure), cognitive function, and academic performance, engagement and behaviour

Primary outcome for a subsequent definitive trial

The proposed primary outcome for a future definitive trial is change in mean daily sitting time on weekdays (school days). Mean daily sitting time on weekdays was chosen, given that the intervention was school based. Sitting time measured across the whole school day/weekday was proposed, as this measure encompasses school hours and out-of-school hours and factors in any compensatory effects of the intervention, should any beneficial effects of the intervention experienced during school hours be cancelled out by an increase in sitting after school, for example. Table 4 displays the descriptive statistics for all activPAL variables recorded throughout waking hours on weekdays for the control and intervention groups.

| Waking hours on weekdays | Time point, mean (SD) | Change, mean (SD) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Follow-up | |||||

| Control (n = 57) | Intervention (n = 52) | Control (n = 58) | Intervention (n = 52) | Control (n = 57) | Intervention (n = 52) | |

| Wear time (minutes/day) | 836.3 (88.5) | 843.8 (47.8) | 830.9 (78.6) | 835.4 (64.2) | –3.7 (121.6) | –8.4 (62.3) |

| Time spent sitting (minutes/day) | 520.1 (83.6) | 514 (61.5) | 504.4 (94.0) | 472.0 (73.5) | –15.2 (107.5) | –42.0 (76.6) |

| Time spent standing (minutes/day) | 179.9 (58.6) | 195.4 (38.7) | 176.5 (45.7) | 197.1 (49.4) | –3.0 (50.2) | 1.6 (52.0) |

| Time spent stepping (minutes/day) | 136.3 (44.9) | 134.4 (30.4) | 150.0 (42.1) | 166.4 (41.9) | 14.4 (44.8) | 32.0 (41.1) |

| Percentage of wear time spent sitting | 62.4 (8.8) | 60.9 (5.9) | 60.5 (8.6) | 56.5 (8.2) | –2.0 (8.7) | –4.3 (8.6) |

| Percentage of wear time spent standing | 21.4 (6.3) | 23.2 (4.5) | 21.5 (6.1) | 23.6 (5.7) | 0.1 (5.9) | 0.4 (5.8) |

| Percentage of wear time spent stepping | 16.2 (4.7) | 15.9 (3.5) | 18.1 (4.8) | 19.9 (4.6) | 1.9 (4.6) | 3.9 (4.6) |

| Number of sit to stand transitions | 102.5 (28.7) | 106.4 (23.6) | 104.1 (26.5) | 106.2 (21.4) | 1.6 (25.0) | 0.2 (20.5) |

| Number of days worn | 3.7 (1.3) | 3.5 (0.9) | 3.2 (1.2) | 3.5 (1.4) | –0.5 (1.4) | 0.0 (1.8) |

A weighted linear regression model was calculated to compare the primary outcome for the subsequent definitive trial (change in average weekday sitting time between baseline and 7 months’ follow-up) between pupils in the control group and those in the intervention group. The model was weighted by the number of participants followed up in each cluster (sum of weight = 110 observations). The model was adjusted for baseline average weekday sitting time for each cluster and for average weekday wear time when awake across the two time points (baseline and 7 months). Owing to the exploratory nature of the trial, the results are presented as weighted mean differences with 95% CIs. As the variables in the regression model reflect cluster means rather than individual observations, analytically weighted least squares was the method of estimation used, in which cluster sizes were the weights.

The model revealed that children in the intervention group spent less time sitting than children in the control group. The mean difference (weighted by school size) in change in sitting time (in minutes) adjusted as described above was –30.6 minutes per day (95% CI –56.42 to –4.83 minutes per day).

The addition of baseline season of activPAL data collection to the weighted linear regression model did not affect the difference in sitting time between groups. When follow-up season was included in the model, the adjusted difference in sitting time between groups was –26.64 minutes per day (95% CI –73.08 to 19.79 minutes per day).

Sensitivity analyses of the proposed primary outcome in a definitive trial

Owing to the exploratory nature of this pilot study, participants were included in the preliminary analyses presented in Primary outcome for a subsequent definitive trial if they wore the activPAL for a minimum of 8 hours on at least 1 weekday. To assess whether or not the number of valid days of activPAL wear had an effect on the estimates (to inform wear time criteria in a definitive trial), the preliminary primary outcome analysis described in Primary outcome for a subsequent definitive trial was rerun to include only those participants with specific days of valid activPAL data. These results are presented in Table 5. Similar differences to those described in Primary outcome for a subsequent definitive trial between groups were observed for participants providing at least 2 and 3 valid days of wear; however, these differences appear to be attenuated when considering only participants with at least 4 valid days of activPAL data.

| Days of valid data | Time point, mean (SD) | Change, mean (SD) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Follow-up | |||||

| Control | Intervention | Control | Intervention | Control | Intervention | |

| At least 1 weekday (control, n = 58; intervention, n = 52) | 520.1 (83.6) | 514 (61.5) | 504.4 (94.0) | 472.0 (73.5) | –15.2 (107.5) | –42.0 (76.6) |

| Intervention vs. control weighted mean difference –30.6 minutes/day (95% CI –56.42 to –4.83 minutes/day) | ||||||

| At least 2 weekdays (control, n = 47; intervention, n = 41) | 522.8 (79.3) | 513.3 (57.5) | 507.1 (92.6) | 471.7 (76.9) | –15.7 (98.1) | –41.6 (71.2) |

| Intervention vs. control weighted mean difference –23.96 minutes/day (95% CI –67.47 to 19.54 minutes/day) | ||||||

| At least 3 weekdays (control, n = 34; intervention, n = 34) | 508.6 (78.9) | 513.9 (58.9) | 511.2 (74.3) | 480.2 (77.7) | 2.5 (80.2) | –33.6 (70.5) |

| Intervention vs. control weighted mean difference –29.17 minutes/day (95% CI –85.57 to 27.24 minutes/day) | ||||||

| At least 4 weekdays (control, n = 26; intervention, n = 19) | 493.0 (73.8) | 525.5 (52.1) | 508.8 (73.3) | 509.4 (63.5) | 15.8 (82.2) | –16.0 (70.7) |

| Intervention vs. control weighted mean difference –6.71 minutes/day (95% CI –77.48 to 64.06 minutes/day) | ||||||

Secondary outcomes for a subsequent definitive trial

activPAL accelerometer secondary outcomes

Table 6 displays the descriptive statistics for activPAL-determined time spent sitting, standing and stepping during school class time for the control and intervention groups. The change in time spent sitting during class time was the main secondary activPAL outcome of interest. On average, control participants experienced an increase in class time sitting at 7 months’ follow-up, whereas a reduction in class time sitting was observed in the intervention group (see Table 6).

| Class time | Time point, mean (SD) | Change, mean (SD) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Follow-up | |||||

| Control (n = 57) | Intervention (n = 52) | Control (n = 58) | Intervention (n = 52) | Control (n = 57) | Intervention (n = 52) | |

| Wear time (minutes/day) | 278.7 (58.1) | 274.5 (48.3) | 291.8 (42.0) | 290.0 (19.0) | 13.4 (67.0) | 11.8 (61.3) |

| Time spent sitting (minutes/day) | 180.2 (47.7) | 188.3 (40.4) | 206.4 (48.3) | 176.4 (41.2) | 25.7 (59.0) | –14.5 (56.6) |

| Time spent standing (minutes/day) | 64.5 (34.0) | 59.2 (21.5) | 56.3 (22.1) | 72.3 (28.6) | –7.8 (28.9) | 12.5 (31.5) |

| Time spent stepping (minutes/day) | 34.0 (15.5) | 27.0 (10.1) | 29.1 (10.7) | 41.4 (17.0) | –4.5 (13.8) | 13.8 (17.2) |

| Percentage of wear time spent sitting | 65.5 (13.2) | 68.8 (9.0) | 70.1 (11.4) | 60.8 (13.5) | 4.4 (12.4) | –7.7 (13.2) |

| Percentage of wear time spent standing | 22.5 (10.4) | 21.4 (6.8) | 19.7 (8.8) | 25.0 (10.0) | –2.7 (9.5) | 3.3 (9.9) |

| Percentage of wear time spent stepping | 12.0 (4.7) | 9.7 (3.2) | 10.1 (4.5) | 14.3 (5.9) | –1.7 (5.3) | 4.4 (5.9) |

In addition, participants in the intervention group experienced an increase in standing and stepping time during class time at follow-up, whereas reductions in these behaviours were observed at follow-up in the control group (see Table 6).

Table 7 displays the descriptive statistics for activPAL-determined time spent sitting, standing and stepping measured after school for the control and intervention groups. On average, both groups experienced reductions in sitting and increases in standing and stepping after school at the 7-month follow-up, suggesting no compensatory effects of the intervention (such as increases in sitting outside of school) in the intervention group.

| After school | Time point, mean (SD) | Change, mean (SD) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Follow-up | |||||

| Control (n = 56) | Intervention (n = 52) | Control (n = 57) | Intervention (n = 52) | Control (n = 56) | Intervention (n = 52) | |

| Wear time (minutes/day) | 381.6 (63.2) | 363.0 (60.4) | 376.0 (84.7) | 367.6 (72.8) | –0.3 (88.0) | 6.8 (59.6) |

| Time spent sedentary (minutes/day) | 258.9 (49.9) | 239.9 (49.9) | 221.8 (76.0) | 217.2 (56.2) | –33.9 (75.2) | –19.6 (59.2) |

| Time spent standing (minutes/day) | 68.6 (25.5) | 72.6 (22.1) | 77.1 (30.6) | 76.0 (28.4) | 9.5 (32.0) | 3.6 (29.6) |

| Time spent stepping (minutes/day) | 54.1 (28.8) | 50.6 (18.5) | 77.1 (37.2) | 74.4 (32.6) | 24.1 (39.7) | 22.8 (31.2) |

| Percentage of wear time spent sedentary | 68.2 (9.3) | 66.0 (7.0) | 58.5 (13.8) | 59.3 (10.7) | –9.6 (14.0) | –6.4 (12.5) |

| Percentage of wear time spent standing | 17.8 (5.6) | 20.0 (5.4) | 20.9 (7.4) | 20.6 (5.8) | 2.9 (7.4) | 0.5 (6.8) |

| Percentage of wear time spent stepping | 14.0 (5.9) | 13.9 (4.5) | 20.7 (8.8) | 20.1 (6.9) | 6.7 (8.6) | 5.9 (7.2) |

Table 25 in Appendix 2 summarises the descriptive statistics for all activPAL variables recorded throughout waking hours across all monitoring days, including both weekdays and weekend days. The trends observed in this table match those reported in Table 4, which summarise the mean daily activPAL variables calculated across weekdays only.

ActiGraph accelerometer secondary outcomes