Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 15/63/01. The contractual start date was in November 2015. The final report began editorial review in May 2019 and was accepted for publication in January 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Holmes et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background

This report includes direct quotations from media and in places, where copyright permission could not be obtained, comments have been paraphrased by the authors (see Chapter 3). These statements include a range of opinions that relate to the quoted source and do not reflect the views of authors or funders.

Alcohol is a major contributor to global mortality and ill health and is a causal factor in over 200 health conditions including liver disease, heart disease, injuries and seven types of cancer. 1 The Global Burden of Disease study attributed an estimated 2.3 million deaths and 85 million disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) lost to alcohol in 2015. 2 In England, alcohol caused an estimated 24,208 deaths in 2017 and 1.2 million hospital admissions in 2017–18 and was reported by victims as a factor in 39% of violent crimes. 3,4 Estimates of the economic cost to society of alcohol-related health and social harms vary, but the most commonly used estimate is £21B (UK annual estimate). 5

In response to this, successive UK Governments have published a series of alcohol strategies aiming to reduce alcohol consumption and the harm and disruption it causes to drinkers and those around them. 5–7 The most recent strategy was published in 20125 and included the aim to:

Support people to make informed choices about healthier and responsible drinking, so it is no longer considered acceptable to drink excessively.

It further sought to:

Ensure everyone understands the risks around excessive alcohol consumption to help them make the right choices for themselves and their families.

A key policy for achieving these goals was to ask the Chief Medical Officer (CMO) to oversee a review of the country’s low-risk drinking guidelines.

Guidelines for low-risk drinking

Drinking guidelines have proliferated internationally since the 1980s and health authorities in most high-income countries now issue guidelines for alcohol consumption. 8 These usually recommend a quantified level of alcohol consumption that drinkers should not exceed over a specific time period (e.g. per day or per week). The consumption level is usually expressed in standard drinks or units of alcohol. In the UK, 1 unit is 8 g or 10 ml of pure ethanol and is approximately half a pint of beer, 75 ml of wine or one 25-ml shot of spirits, depending on the alcoholic strength of the drink. The guideline consumption threshold is also usually accompanied by textual information that may include, among other things, the source of the guideline (e.g. the CMO recommends . . .), a reason to listen to the advice (e.g. to reduce your risk of alcohol-related disease . . .) and supplementary recommendations (e.g. do not drink every day).

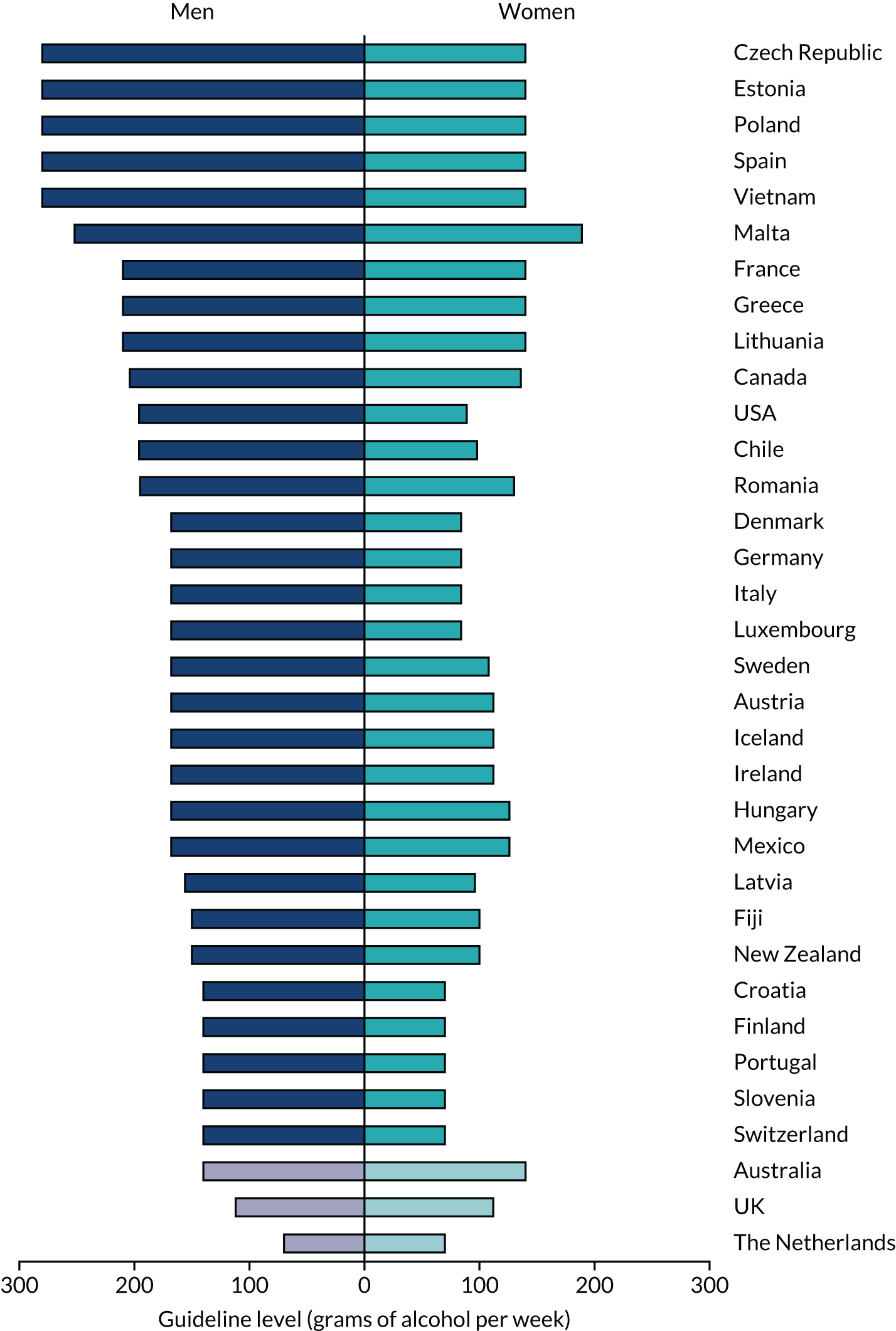

Figure 1 shows that drinking guidelines often vary markedly between countries. There may be a number of reasons for this. First, the purpose of guidelines often differs between countries. For example, Denmark provided guidelines to help people avoid high-risk levels of alcohol consumption until 2010, whereas the UK has tended to issue guidelines to promote low-risk consumption. 8 Other countries use guidelines primarily to inform government policy (e.g. to assess levels of excessive drinking) or clinical practice, rather than as health promotion information for the public. Second, the riskiness of drinking may vary between countries depending on the prevalence of competing or compounding risk factors, such as smoking and obesity. Third, guidelines are usually expressed in units or standard drinks, but these measures vary widely across countries. For example, 1 unit is 8 g of pure ethanol in the UK, 10 g in Ireland, 12 g in Finland, 14 g in the USA and 20 g in Austria. 9 If guidelines are to be easily understood by the public and not expressed in decimals, variation in the definition of 1 unit necessitates variation in drinking guidelines.

FIGURE 1.

Weekly drinking guidelines for women and men in selected countries in 2016. Shaded countries at the bottom of the figure are those with the same guideline for men and women.

Guidelines also vary over time. The earliest quantified guideline dates back to Anstie’s limit of 28–43 g per day, which was developed in the 1860s and used in life assurance in the UK and USA. 10 More recently, UK health authorities published ‘safe limits’ for men of 64 g per day in 1979 and then 144 g per week in 1984, followed by ‘sensible limits’ of 168 g per week in 1987 and then 24–32 g per day in 1995. 11 These changes reflect improvements in epidemiological evidence, societal standards regarding the acceptability of health risks and the purpose of guidelines, as described above. They also reflect changes in how guidelines are set. As described by Holmes et al. ,12 the evidence used by guideline development committees is increasingly likely to include bespoke epidemiological modelling exercises in addition to reviews of scientific literature.

Despite their widespread use, drinking guidelines do not enjoy universal support from public health actors. As discussed below, their effectiveness as a public health intervention is questioned,13,14 and some researchers believe that they are counterproductive. For example, Casswell15 argued in 1996 that guidelines are unlikely to affect behaviour when presented in the context of the pro-alcohol messages that suffuse contemporary media, a view shared by the authors of the leading summary of alcohol policy effectiveness. 13 In 2012, Casswell16 reiterated this point and added that promoting guidelines draws government away from more effective interventions. Similarly, Bellis17 argues that, when implemented in practice, drinking guidelines serve the interests of the alcohol industry as, ‘rather than explaining risks, [they] can read more like an alcohol promotion slogan’ that presents recommended consumption levels.

Other public health actors view guidelines more positively. Heather18 argues that they are essential as the public has a right to know about alcohol-related health risks and they facilitate discussions about alcohol consumption in clinical practice. Marteau19 further suggests that, although guidelines may not lead directly to reductions in alcohol consumption, they increase public concern about the risks of alcohol consumption and may make it easier to introduce effective alcohol control policies.

Drinking guidelines in the UK, 1995–2016

Prior to 2016, the UK drinking guidelines had not changed since 1995, when the Sensible Drinking report20 recommended that men should not regularly consume more than 3–4 units a day and women should not regularly consume more than 2–3 units a day, where regularly means drinking this amount every day or on most days.

The House of Commons Science and Technology Committee launched an inquiry in 2011 to assess whether or not the 1995 guidelines were ‘robust’ as a foundation for alcohol policy. 11 It sought submissions on the evidence underpinning the guidelines, whether or not that evidence could be improved, how well the government communicates the guidelines and how the guidelines compare with other countries. The report concluded that the passage of time, greater evidence on the causal relationship between alcohol and cancer and increased scientific scepticism regarding the health benefits of moderate drinking meant that the guidelines should be reviewed by an expert group.

In 2012, the UK Government published its alcohol strategy5 and announced that the CMO would lead a review of the guidelines, which ran from 2013 to 2016. Although the review was led jointly by the four UK CMOs, it was conducted primarily by a guideline development group (GDG) that mainly comprises civil servants, clinicians and academics with expertise in health and behavioural science. The GDG considered published studies, commissioned new systematic reviews, epidemiological modelling and focus group research, and heard presentations from expert advisors. In 2014, its interim report concluded that that there was sufficient new evidence to justify changes to the guidelines. The CMOs accepted this conclusion.

In 2016, the GDG published its final report21 along with the new draft guidelines,22 which recommended that the guidelines should be revised to state that men and women could keep their risks from alcohol consumption low by consuming no more than 14 units per week. Additional accompanying guidance recommended that drinkers consuming ≥ 14 units per week spread their alcohol consumption across several days and have at least 2 drink-free days per week. These recommendations differed from the 1995 guidelines in three main ways. First, they switched from a daily to a weekly guideline, citing evidence that the previous guideline was often misinterpreted as a limit on consumption on any single occasion and seen as less useful as a result. 23 Second, they set the same guideline for men and women, a decision that triggered substantial comment and criticism as only two other countries take this approach (see Figure 1). Third, they reduced the previous guideline for men. That guideline was often interpreted as ≤ 14 units per week for women and ≤ 21 units for men, a legacy of pre-1995 guidance, and the revisions were, therefore, viewed as reducing the guideline for men by one-third.

The GDG also revised the guidance in two other key areas. First, it updated the guidance on drinking alcohol during pregnancy. Previously, the guidance in Scotland was that women should not drink during pregnancy, whereas the guidance in England was that women should not drink more than 1 or 2 units once or twice per week. The revised guidance removed this inconsistency and took a precautionary approach that recommended:

. . . the safest approach is not to drink alcohol at all, to keep risks to your baby to a minimum.

Second, the GDG provided updated guidance on single occasions of drinking and elected not to provide a specific guideline but instead recommended that drinkers keep their risk to a low level by:

Limiting the total amount of alcohol you drink on any single occasion, drinking more slowly, drinking with food and alternating with water, and planning ahead to avoid problems.

Notably, this guidance did not incorporate the widely used definition of binge drinking as the consumption on a single occasion of more than 6 units (women) or more than 8 units (men). The GDG elected not to set a guideline consumption threshold for single drinking occasions as risks strongly vary substantially between individuals depending on their ability to reduce such risks by other means. 21

The new guidelines were announced publicly by the CMOs in January 2016 and were formally adopted by the UK Government in August 2016 following a public consultation. 25

The effectiveness of drinking guidelines

Little evidence is available on the effects of drinking guidelines, and reviews note that there have been no rigorous evaluations of the impact of producing, revising or promoting drinking guidelines on alcohol consumption or on other factors related to behaviour change. 13,26–28 This is somewhat surprising as public guidance on a wide range of health-related behaviours, including smoking, physical activity, drink-driving and nutrition, has produced small to moderate effects on knowledge, attitudes and behaviour. 28–32

A number of factors may explain the lack of evidence on the effectiveness of drinking guidelines. Opportunities to evaluate the impact of guidelines are rare as revisions take place at intervals of ≥ 10 years and, when they do happen, the new guidelines are often not promoted via large-scale campaigns after the initial announcement. Furthermore, few countries routinely collect data that would facilitate robust evaluation. For example, data on awareness, knowledge or exposure to guidelines are not a common feature of public health surveys, and alcohol consumption data are typically collected on an annual basis only, which makes robust analysis of intervention effects difficult as they are likely to be modest given the scale of promotional activity. For these reasons, the small literature that does attempt to examine effects of promoting drinking guidelines relies on relatively weak research designs.

Studies in several countries have used cross-sectional analyses to examine public knowledge of guidelines. These analyses generally find that large minorities of the population are aware of drinking guidelines and can correctly identify guideline consumption levels, but there is little evidence that this influences drinking behaviours. 33–35 For example, studies in Australia, Denmark and the UK have examined changes in guideline-related knowledge and perceptions over time using annual cross-sectional data. 36–39 In each case, the results suggest that knowledge of guidelines improved over time. In Denmark, this appeared to be linked to annual mass media campaigns to promote the guidelines, but, in Australia, beliefs about what constitutes safe drinking also changed.

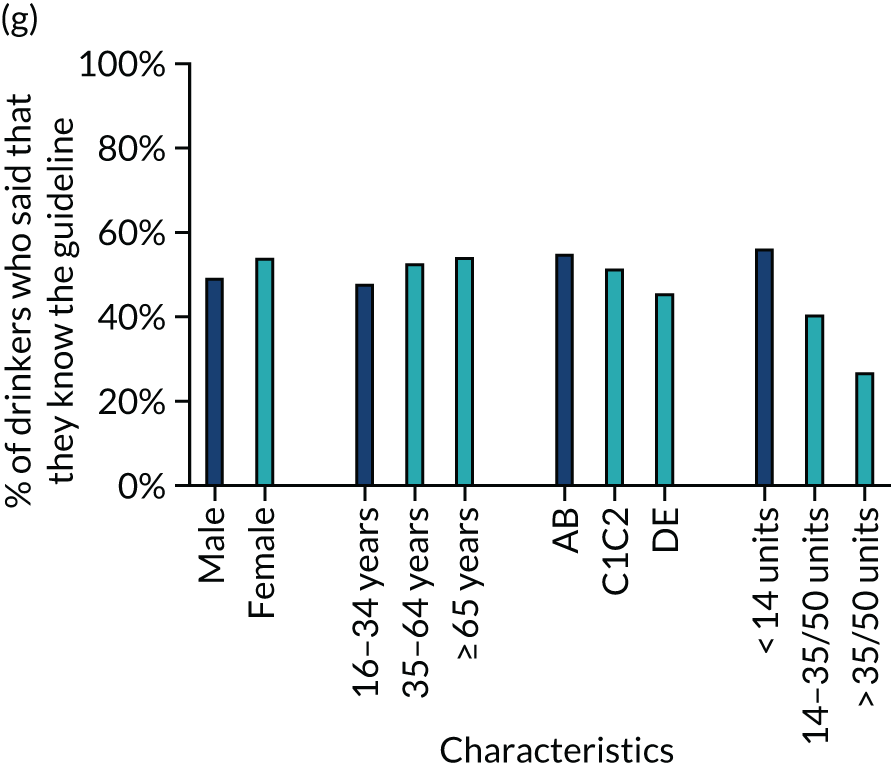

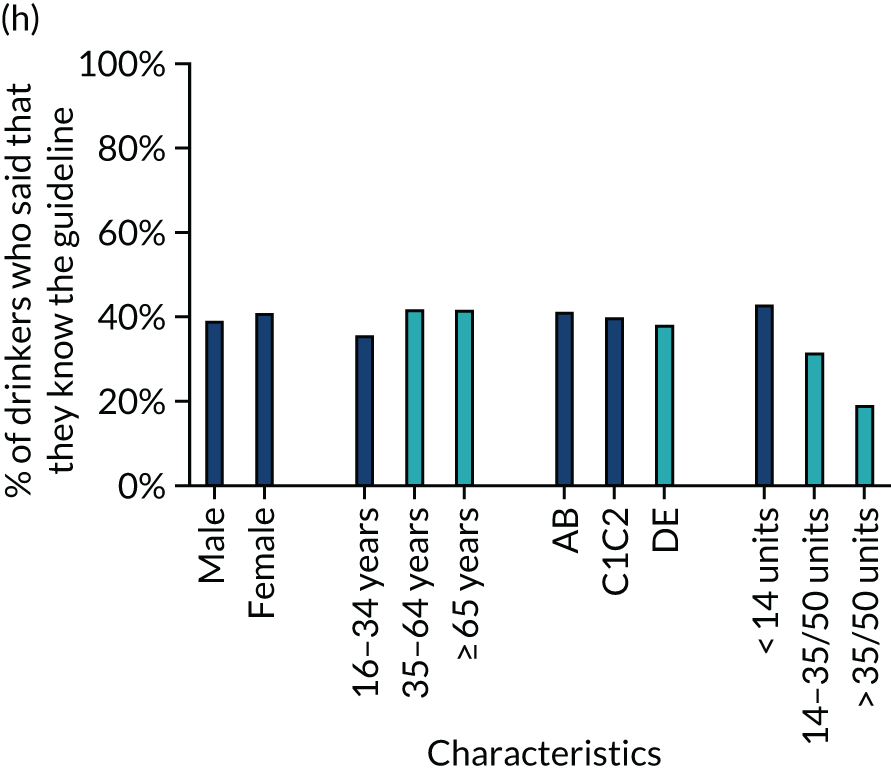

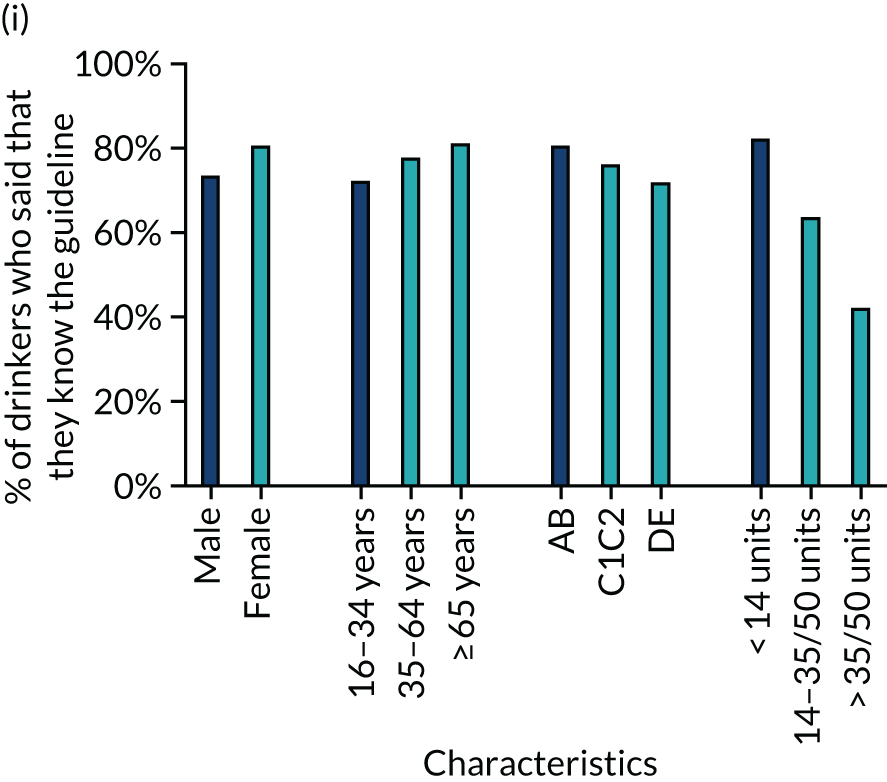

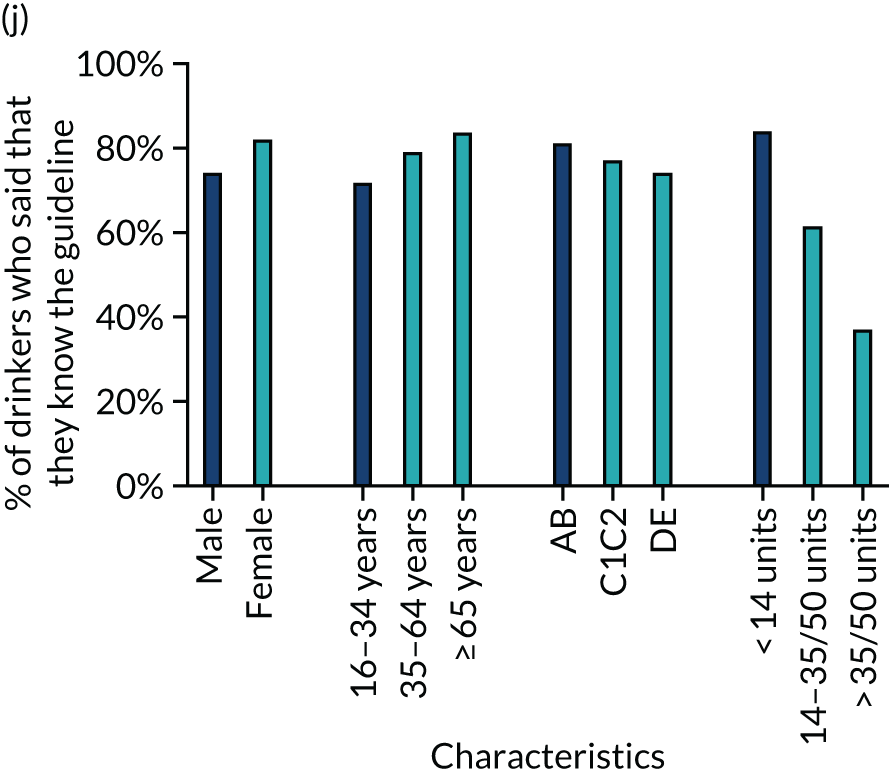

The UK data are particularly relevant to the present study. The Office for National Statistics (ONS) Opinion Survey collected data on knowledge of units and guidelines between 1997 and 2009 and summarised the findings in a 2010 report. 40 The report shows that the proportion of drinkers who had heard of units rose from 79% in 1997 to 90% in 2009. Similarly, the proportion who knew how much beer, wine and spirits constituted 1 unit also rose by up to 10–15 percentage points. In 2009, 63% of respondents knew that 1 unit of beer was approximately half a pint, 69% knew that 1 unit of spirits was a single measure, but only 27% knew that 1 unit of wine was less than a 125-ml glass. The proportion of respondents who had heard of guidelines increased from 54% in 1997 to 75% in 2009. However, only 44% of men and 55% of women in 2009 correctly identified the guideline for their sex, an improvement of only 6 percentage points among men and of 14 percentage points among women over a period of 12 years. Moreover, only 13% of respondents kept a check on their units, with no increase in this proportion between 1997 and 2009. There was little variation in these measures by sex, but heavier drinkers generally showed greater awareness and knowledge of the guidelines and of units.

Prior to the present study, the most detailed evaluation of promoting drinking guidelines focused on an Australian campaign aiming to raise awareness of guidelines and alcohol-related cancer risks. 41 The study used repeat cross-sectional surveys of 150–200 women at three time points over a 15-month period and concluded that multiple waves of advertising led to good recognition and awareness of the campaign content. Promoting drinking guidelines also led to increased cancer risk awareness, knowledge of guidelines and intentions to reduce alcohol consumption among heavier alcohol drinkers in particular. However, there was no evidence of impacts on drinking behaviour.

In addition to these quantitative analyses, a number of qualitative studies have sought to understand how drinkers respond to and use drinking guidelines. These studies report that drinkers typically disregard guidelines as they do not align well with their current drinking practices and rely on drinkers understanding units, which is often not the case. 23,42,43 Instead, drinkers monitor their consumption through embodied means; that is, they make judgements on the riskiness of their drinking based on how intoxicated they feel and their previous experiences of alcohol and its after-effects.

Effectiveness of alcohol health warning labels

Although there is little robust research on the effectiveness of promoting drinking guidelines, a separate body of research exists examining the effectiveness, potential effectiveness and appropriate design of alcohol health warning labels. This literature is important, as approximately 80% of products sold in the UK in 2014 included the CMO’s guidelines on their label,44,45 and this is a key location where drinkers are likely to encounter the guidelines when they are not being promoted via more active means. 46 More generally, information on labels is argued to be a potential influence on social norms around alcohol consumption and increase support for other alcohol policies. 47

The USA introduced mandatory health warning labels on alcoholic products in 1989, which read ‘Government Warning: (1) According to the Surgeon General, women should not drink alcoholic beverages during pregnancy because of the risk of birth defects. (2) Consumption of alcohol impairs your ability to drive a car or operate machinery, and may cause health problems’. 48 Evaluations of the impact of these labels constitute a large proportion of the alcohol labelling literature and the highest-quality evidence on the effectiveness of alcohol health warning labels as a public health intervention. 49 Overall, the evaluations suggest that awareness and recall of USA alcohol warning labels increased initially,48,50,51 but plateaued after around 3–4 years in both adults and adolescents. 52,53 As with drinking guidelines, there was little evidence that these gains in awareness and knowledge translated into changes in alcohol-related behaviours, such as reduced drink-driving or alcohol consumption. 49,53,54

More recent research has used survey, focus group and experimental methods to examine several themes relating to how consumers may use and respond to information and warnings provided on alcohol product labels. For example, focus group research in Australia found that participants favoured labels providing messages related to short-term risks and also found messages with positive rather than fear-based or numerical framings, general health messages rather than ones relating to cancer or specific cancers, and risk-based rather than deterministic messages more believable, convincing and personally relevant. 55 A small experimental study of students at a UK university56 found no significant differences between text-based messages and pictorial messages in terms of fear arousal and intentions to reduce or stop alcohol consumption, and Hobin et al. 57 obtained a similar finding in an experimental study with Canadian adults. This is in contrast to a general view that pictorial messages are more effective,58 although Hobin et al. 57 obtained a similar finding in an experimental study.

The UK’s Royal Society for Public Health surveyed drinkers to determine what information they find most useful. 47 The results revealed that drinkers view alcoholic strength and units as the most important information to include on labels and consider warnings against drink-driving and drinking during pregnancy as moderately important; however, drinking guidelines and links to online information are viewed as substantially less important. 47 Thomson et al. 59 found that drinkers in Australia supported the provision of health information and warnings on product labels, whereas other studies found that drinkers in Australia report poor recall or use of industry-backed logos and weblinks on product labels60 but good awareness of standard drink labels. 61 In Canada, drinkers demonstrate a high level of ability to use standard drink information on product labels, and a focus group study of drinkers in Yukon, Canada, also found that detailed product labels including a health warning, guidelines and standard drink information were seen as of intrinsic value. 57,62 The information provided in this study was viewed by participants as new, useful, important and something they had a right to know. Participants also suggested that it could prompt new conversations and potentially influence behaviour. However, other studies suggest that, particularly among some younger drinkers, standard drink information may be used to maximise the volume of alcohol purchased rather than to moderate consumption. 47,61,63 More broadly, a criticism common across research on alcohol labels is that the information provided on real-world labels is too small, discreet, vague or ambiguous, or otherwise lacking in visual impact, to inform or influence consumer behaviour. 44,55,60

The breadth of findings here and the reliance on small-scale, cross-sectional, focus group or experimental research are perhaps the greatest weaknesses of the literature. Hassan and Shiu64 reviewed studies of the efficacy of alcohol warning labels published between 2000 and 2015 and concluded that the literature is ‘a weak and fragmented evidence base to guide policy-makers or practitioners, which requires further research on most key questions’. 64 They particularly criticise the lack of consistent research approaches and measures, which prevents comparison across studies, and the lack of long-term research on the effects of labels. As with the literature on drinking guidelines, we further note that few of these more recent studies following the US warning label evaluations provide evidence on whether such labels can or do affect drinking behaviour. One exception is Maynard et al. ,63 who found that providing calorie or unit information did not affect alcohol consumption by UK undergraduates in a laboratory study. Maynard et al. ’s63 additional qualitative analyses suggest that this is because such information fits poorly with drinking to get drunk or socialise, echoing findings from previous studies. 23,43

Despite their apparent lack of direct impact on alcohol-related behaviours, alcohol health warning labels may, like drinking guidelines, be important in other ways. The US labels are often viewed by the authors of evaluation studies as important because they inform consumers about alcohol-related risks and reinforce this information, even if they do not affect drinking behaviour. 52 Others note that such labels help to stimulate conversations about alcohol and its risks as well as changing social and cultural norms, potentially leading to behavioural changes in future generations,47,54,62 or greater acceptance of alcohol control measures. 19,47 More simply, warning labels may fulfil consumers’ right to know about the risks of a product they are purchasing. 47,62

The literature on the evaluation of alcohol labels has three main implications for our evaluation of drinking guidelines. First, it supports the evidence from the limited literature on the effectiveness of promoting drinking guidelines in showing that health-related information pertaining to alcohol can be recalled and used by drinkers. Second, it also supports the evidence that such information does not generally lead to changes in alcohol consumption behaviour. As suggested by behaviour change theory, such behaviour changes may require well-designed and implemented messaging. 65 In this context, the text around the numerical guideline consumption level may matter as much as the guideline consumption level itself and the content of promotional activity may be as important as its presence. Third, despite the importance of such design and implementation, there is insufficient evidence available to date to identify clear recommendations regarding what is effective in the design of drinking guidelines or guideline-related messaging. Literature from health promotion in other areas, particularly tobacco warning labels, can provide some guidance, but it is unclear whether or not this can be translated unproblematically to alcohol, the risks of which are smaller in scale, different in nature and interact with more positive public attitudes. 64 This means that it is difficult to assess if we would expect the guidelines as written to be effective or what effects they may have.

Rationale for the present study

Despite concerns about their effectiveness, drinking guidelines still play an important role in alcohol policy debate in the UK and internationally. Successive UK governments have been reluctant to increase regulation of the alcohol market and have focused instead on promoting ‘responsible drinking’ with the support of alcohol producers and retailers. 66 The 2012 alcohol strategy5 initially departed from this approach by promising the introduction of minimum unit pricing (MUP) for alcohol, a greater role for public health within alcohol licensing and possible restrictions on price-based promotional deals for alcohol. However, all of these measures were removed from the strategy following a public consultation,67 leaving the review of the drinking guidelines as one of the headline measures alongside increased attempts to identify and deliver brief interventions to drinkers within primary care. The 2016 revisions to the UK drinking guidelines therefore represented both a central plank of government alcohol policy and a rare opportunity to undertake a prospective evaluation of a widely used but under-researched intervention.

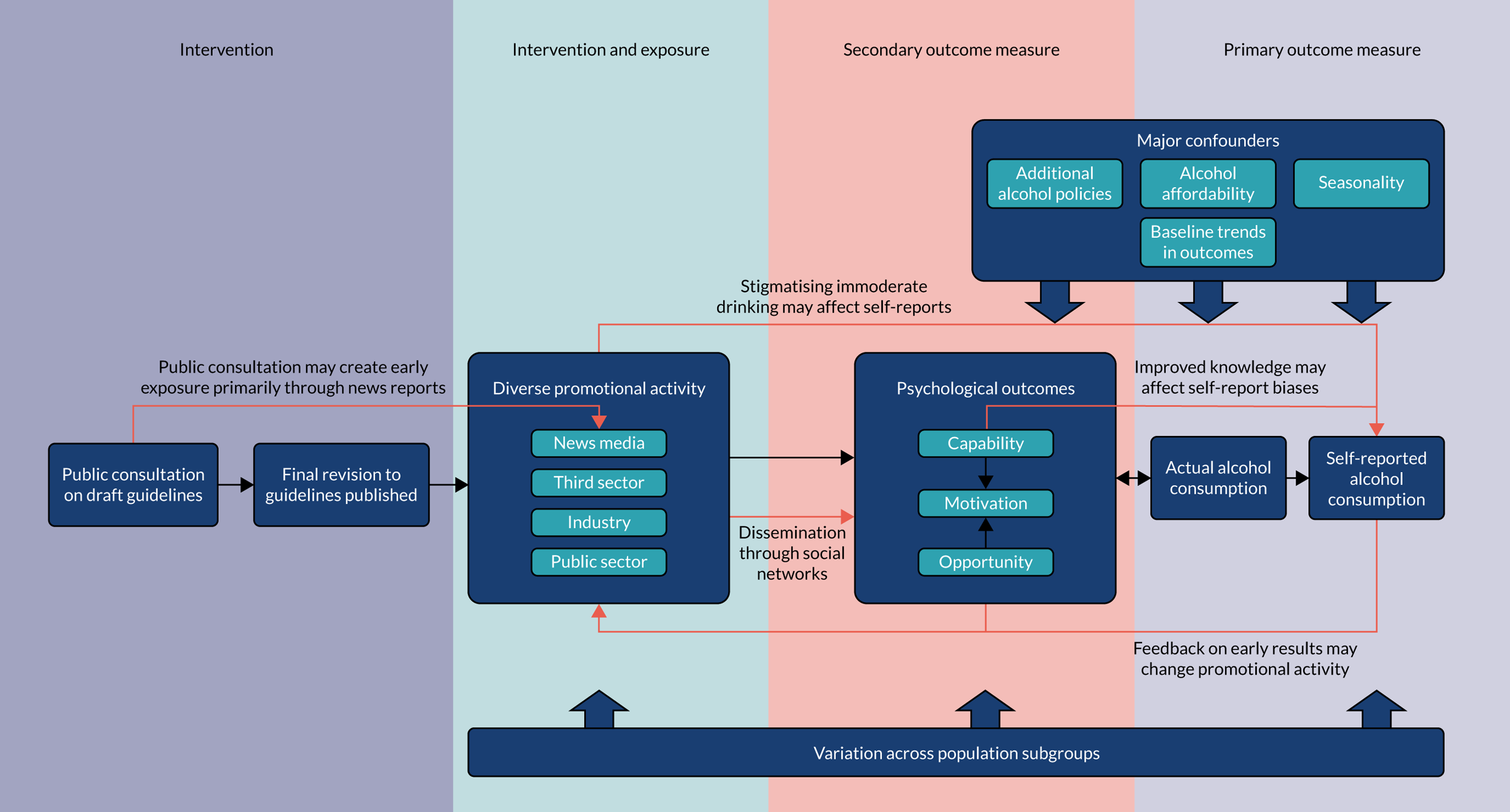

Designing an evaluation is not straightforward as promoting drinking guidelines is a complex intervention. Promotional activity is delivery by many different organisations and actors in varying forms, with an extended causal chain from implementation to outcome. Organisations involved include governmental and non-governmental bodies, such as Public Health England (PHE), the NHS, Drinkaware (London, UK) (an industry-funded charity), alcohol producers, retailers and social aspect organisations, public health charities, and news media. Individual actors include social media users, public commentators, individual politicians and the general public to the extent that each of these discusses the guidelines. Likewise, promotional activity ranges across mass media campaigns, interactive social media, consultations with health professionals, product labels, point-of-sale advertising and general public debate. Behaviour change theory suggests that any changes in alcohol consumption that arise from this network of promoters and promotion will be mediated by changes in behavioural influences, including individuals’ knowledge of the guidelines and alcohol-related risks, their motivations and their social context. 65,68 Therefore, a robust and comprehensive evaluation requires an understanding of not just the effects of promoting drinking guidelines on key outcomes, such as alcohol consumption, but also how and by whom guidelines are promoted and the effects of this promotion on proximal outcomes, such as behavioural influences. Appendix 1 presents a causal logic model indicating our understanding of the connections between these processes and informs the design of the evaluation.

Aims and objectives

The aim of this study was therefore to conduct a prospective evaluation of promoting revised UK drinking guidelines on alcohol consumption behaviour. To do so, it sought to meet the following objectives:

-

to document the timing, audience and content of major promotional activity following the publication of revised drinking guidelines

-

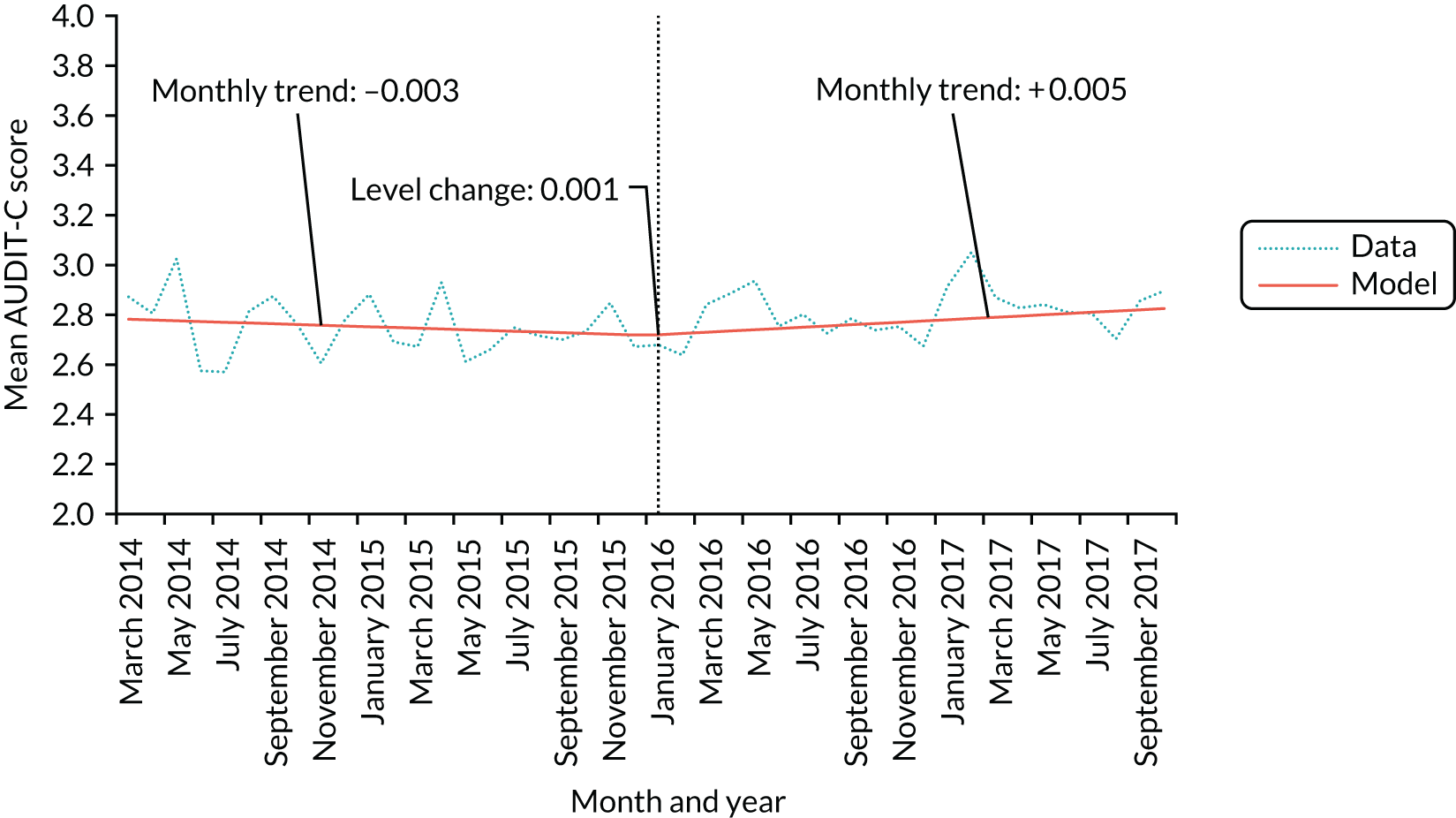

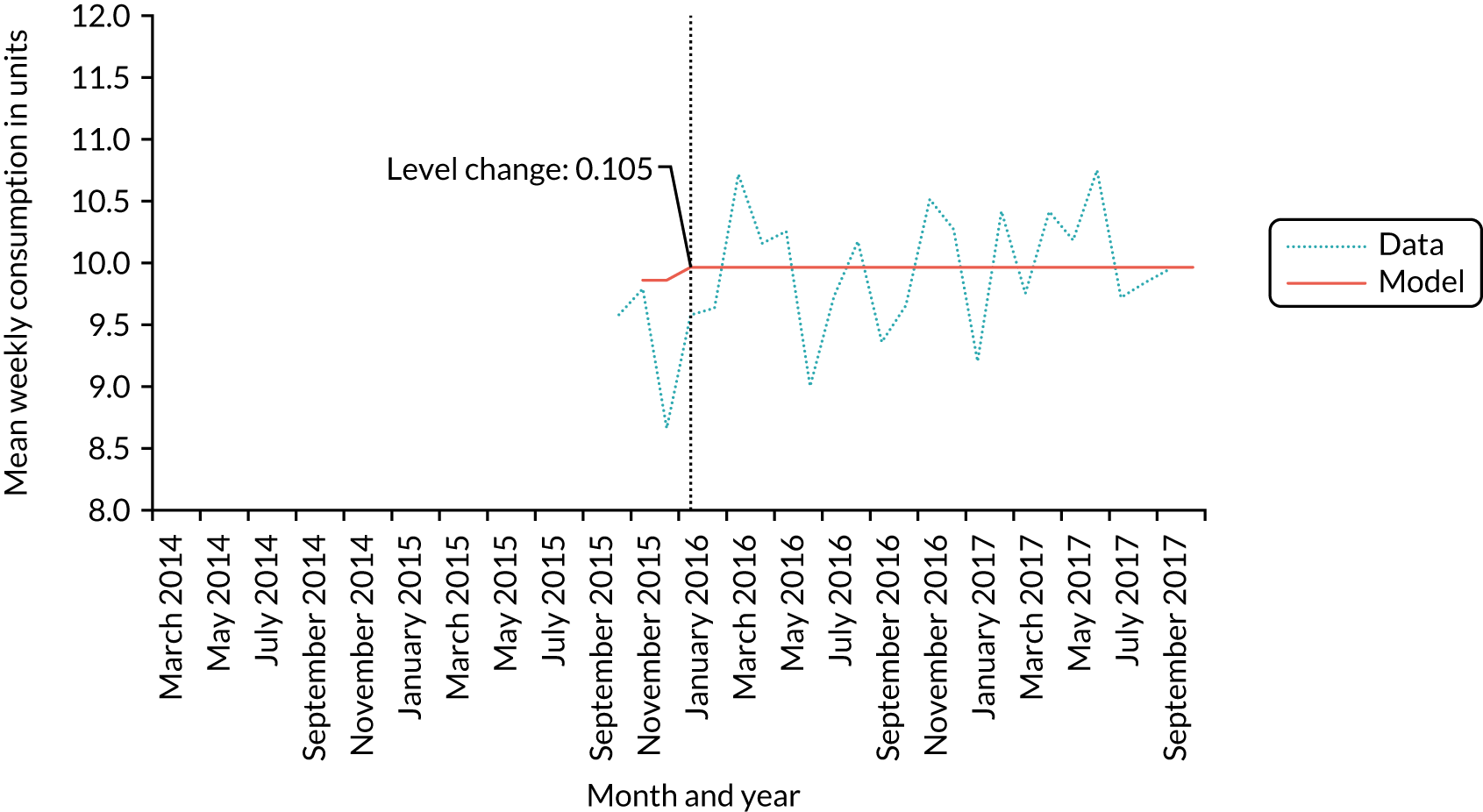

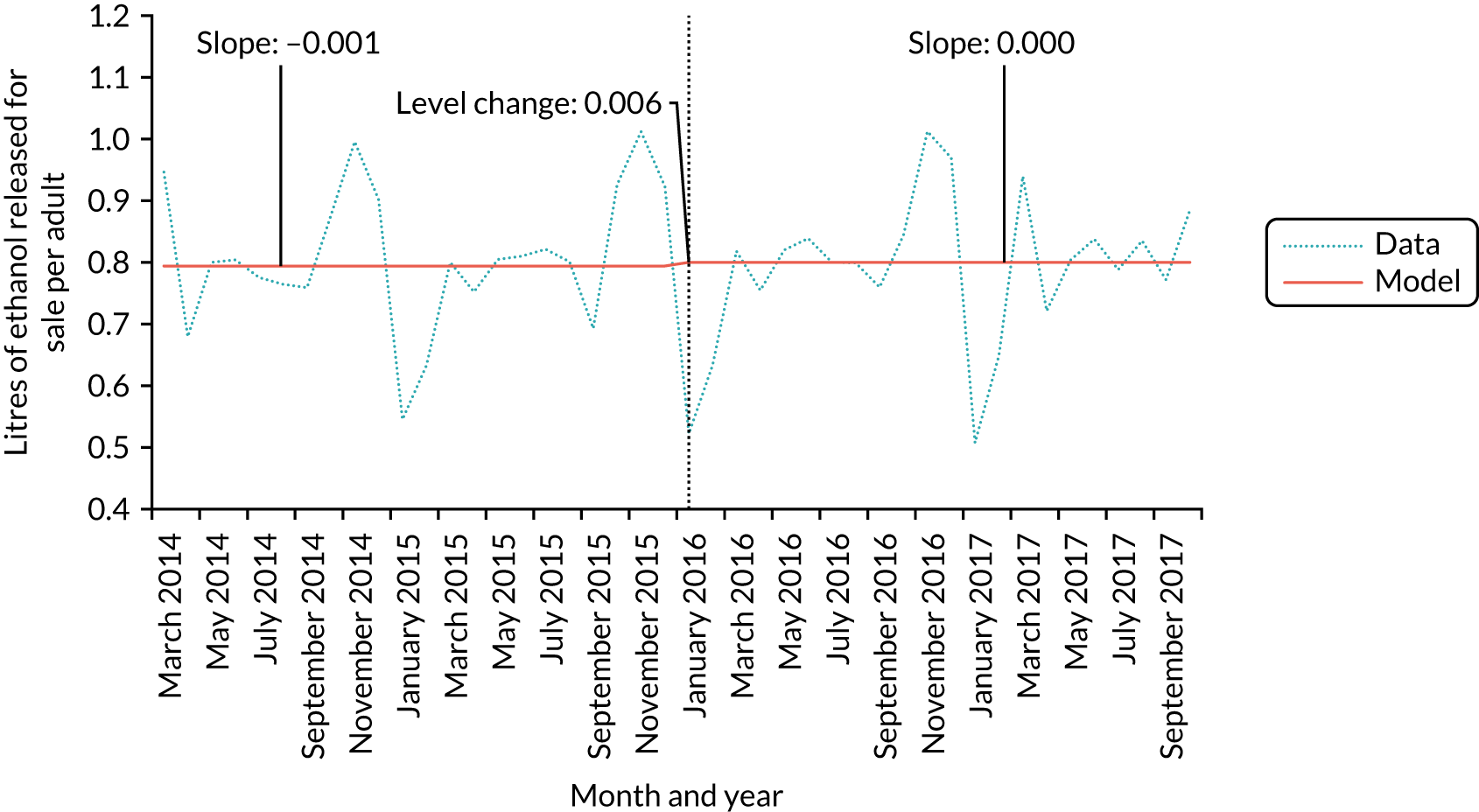

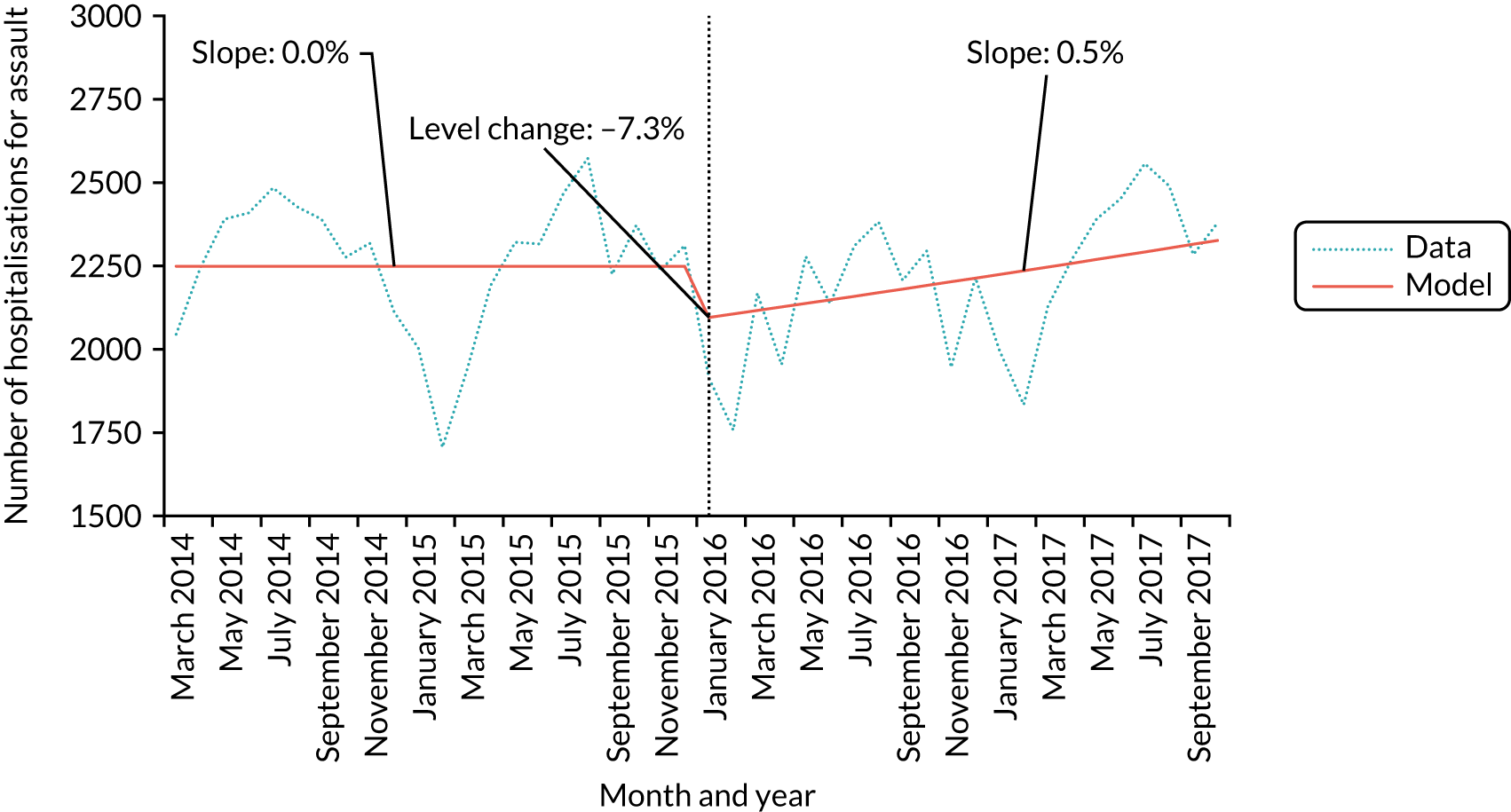

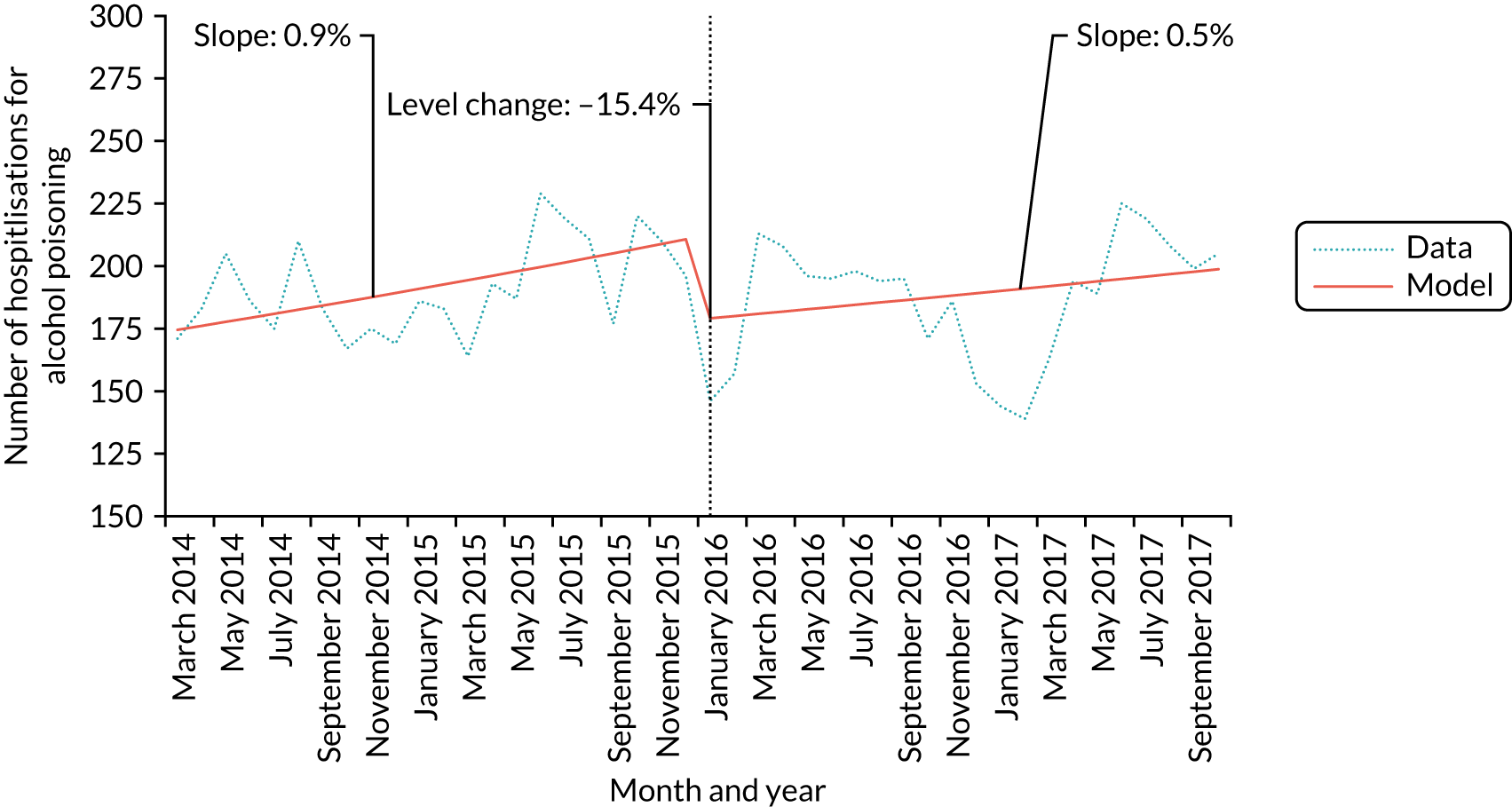

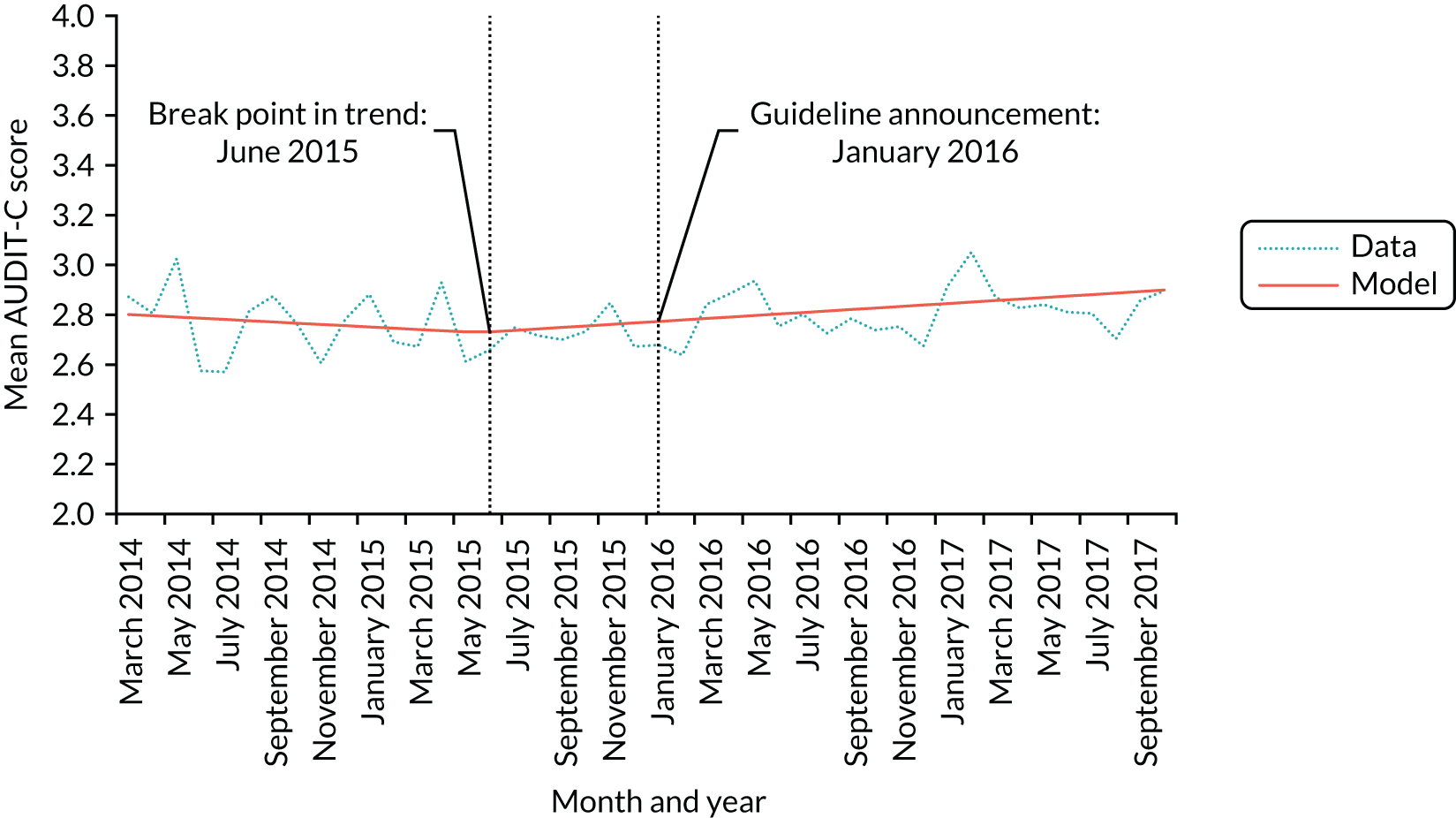

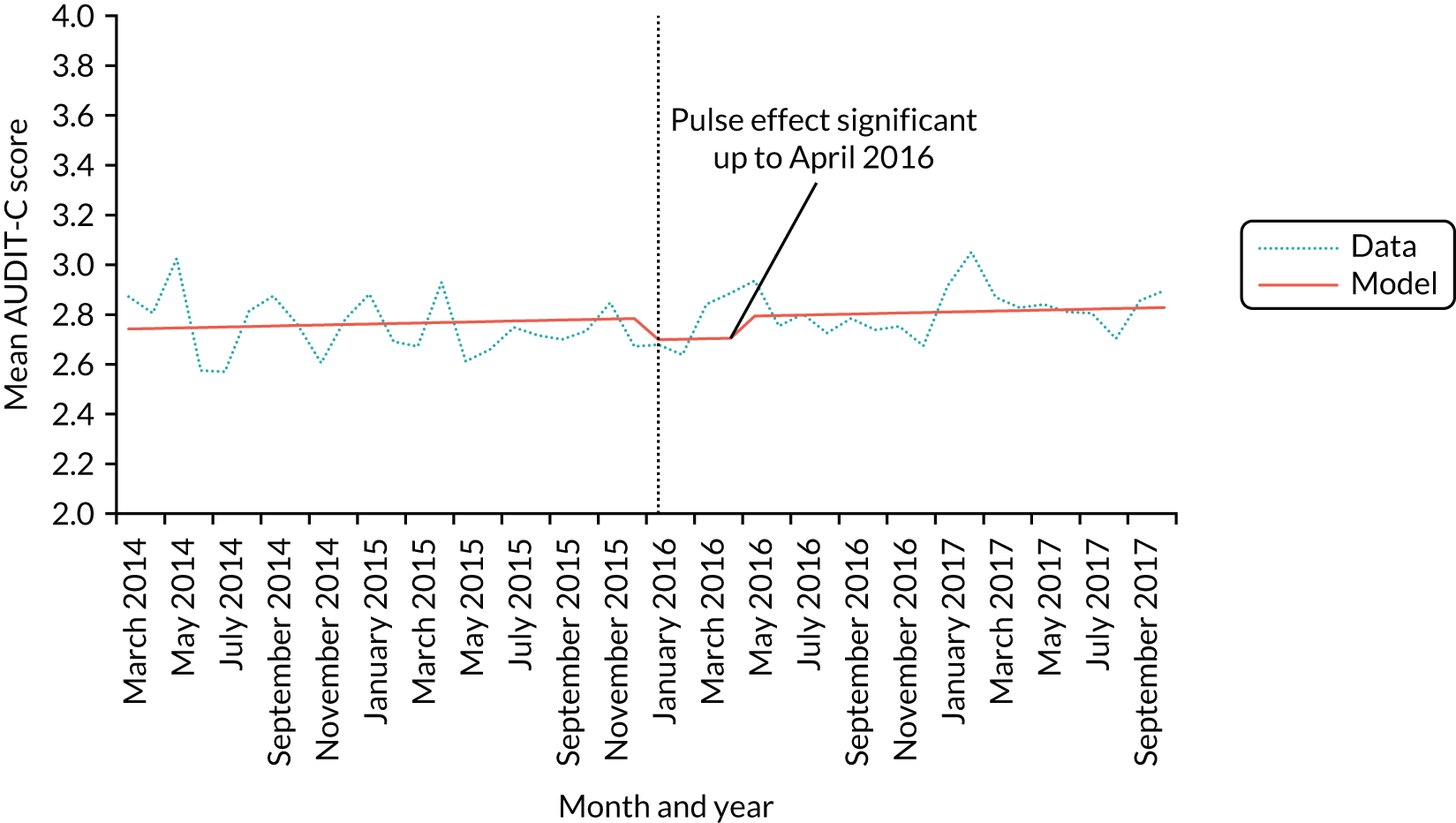

to use interrupted time series analysis of monthly survey data to assess whether or not trends in alcohol consumption behaviour, as a primary outcome, changed following publication and promotion of the revised drinking guidelines

-

to undertake subgroup analyses to examine whether or not there are variations in intervention effects across groups of the population defined by age, sex and socioeconomic status

-

to use difference-in-difference methods to examine whether or not direct and frequent exposure to promotion of drinking guidelines increases their effectiveness

-

to undertake pathway analyses to validate theorised capability, opportunity and motivation to change behaviour and behaviour itself

-

to assess cost-effectiveness of any identified effects on alcohol consumption using the Sheffield Alcohol Policy Model framework. 69

During the project, the objectives were amended as follows in consultation with the Project Steering Committee. First, as we identified no large-scale promotional activity relating to the guidelines beyond the announcement of the revisions, the first objective was abandoned. This was replaced with a new objective: to conduct a review of the scale and content of news media coverage relating to the guidelines. Second, preliminary analyses showed no changes in the primary outcome measure and, in the absence of any promotional activity, we decided not to conduct a cost-effectiveness analysis. Third, the lack of any substantial change in the outcome measures meant that we did not pursue the difference-in-difference analysis or pathway analyses.

At the same time, a decision was also taken to not conduct a cost-effectiveness analysis as preliminary analyses indicated that, in addition to there being no promotional activity that attracted a cost, there was also no change in the primary outcome (alcohol consumption). We judged, in consultation with the Project Steering Committee, that conducting the news media review was a better use of resources. The cost-effectiveness analysis is therefore not discussed further in this report.

Patient and public involvement

The research team conducted two patient and public involvement (PPI) sessions during the project to support the interpretation of the early and final results of the evaluation analyses. In the absence of a pre-existing and appropriate PPI panel in England, we worked with an established PPI panel based in Scotland. The panel comprised approximately 30 adult drinkers from the general population and living in or around Stirling, where the panel meets. The UK Centre for Tobacco and Alcohol Studies recruited the initial panel members in 2014 via social media, with additional members added over time to maintain the group’s size. The panel meets two or three times per year and provides members with a £25 voucher plus an offer to cover travel costs for each meeting attended.

One member of this PPI panel also joined the Project Advisory Group and attended the group’s meetings.

Structure of the report

The remainder of the report comprises a further four chapters. Chapter 2 describes the initial attempt to construct a timeline of promotional activity and the early findings prior to the abandonment of this exercise. Chapter 3 describes the review of print news media coverage of the guidelines. Chapter 4 describes the interrupted time series analyses. Chapter 5 brings together the main findings and discusses the strengths and limitations of the research and its implications for future research, policy and practice before presenting our conclusions.

Chapter 2 Constructing a timeline of activity promoting the revised drinking guidelines

Introduction

As stated in Chapter 1, the promotion of drinking guidelines is a complex intervention. The CMOs announced the UK Government’s revised guidelines in January 2016 and the Government’s Alcohol Strategy5 states that their purpose is to:

Support people to in make informed choices about healthier and responsible drinking.

However, this is an incomplete account of the intervention and its aims. Subsequent promotional activity may be delivered by multiple stakeholders at different points in time, using different techniques and targeting outcomes that may be more or less proximal to alcohol consumption behaviours. These different promotional activities are likely to vary in their effectiveness, and changes in targeted outcomes arising from one activity may also be contingent on the timing and impact of other activities. As a result, identifying a single intervention time point or primary outcome measure for evaluation analyses is not straightforward.

Most previous studies evaluating the effectiveness of drinking guidelines as a public health intervention do not address this point. Many studies use simple before-and-after designs or analyses of annual time series and generic outcome measures, such as drinkers’ awareness of guidelines in general and their knowledge of specific guidelines. They also tend to evaluate the announcement of new or revised guidelines rather than the effects of specific promotional activities promoting those guidelines. As a result, there is little engagement with the actual aims, design or outcomes targeted by such activities. It is often unclear, therefore, whether promotion is ineffective, absent, poorly designed or targeted at outcomes that are not examined by evaluation studies. Exceptions to this include analyses of annual Danish promotional campaigns organised by the National Board of Health, which targeted different groups and used different messages in different years, and this is partly reflected in the interpretation of evaluation results. 37,38 Similarly, Dixon et al. ’s41 evaluation of a campaign in Australia that focused on drinking guidelines as well as alcohol and cancer in women surveyed samples of women on their knowledge of the alcohol–cancer link as well as more generic guideline-related knowledge and drinking behaviours before the campaign and at two time points afterwards.

For the purposes of this study, it is important that evaluation analyses start from a more detailed assessment of promotional activity. The use of a monthly time series within an interrupted time series design means that our results are likely to be sensitive to misspecification of the intervention point. For example, if the guidelines were announced in January 2016 but a large promotional campaign took place in September 2016, we would need to consider the appropriate analytical design to best estimate the effects of these two intervention points. It also clear that health promotion campaigns informed by theory are more effective than those with no clear theoretical basis and that behaviour change arises from multiple factors rather than a single outcome. 65 Therefore, it is important to assess the content and characteristics of promotional campaigns to identify their likely effectiveness, the outcomes in which we would expect to see changes and whether or not we would expect these changes, either alone or in combination with those arising from other promotional activities, to lead to changes in alcohol consumption behaviour.

We therefore aimed to construct a timeline of promotional activity relating to the drinking guidelines, detailing when activities occurred and what they involved. We also sought to identify the cost of activities to inform a planned cost-effectiveness analysis of promotional activity as a whole. For the purpose of this study, we defined promotional activity as any deliberate and planned effect to communicate the drinking guidelines with a view to having a national-level impact of a scale detectable within our analyses, whether directly (e.g. via a mass media campaign) or indirectly (e.g. via education of health professionals). We were interested in capturing promotion of any aspect of the guidelines described in the final documentation. 24 In addition to the guideline consumption threshold, this includes messages around drink-free days and the number of drinking days per week, the disputed cardioprotective benefits of moderate drinking, the cancer risks associated with low levels of alcohol consumption, risks for different adult age groups and drinking in pregnancy. The final example was not a focus of our study but was included in the data collection instruments for completeness.

Methods

Sample

We aimed to survey key stakeholders within organisations in five sectors:

-

government and quasi-non-governmental bodies (e.g. Department of Health and Social Care and PHE)

-

public health advocacy organisations (e.g. Institute of Alcohol Studies and Cancer Research UK)

-

professional bodies (e.g. the Royal College of General Practitioners)

-

non-health-related bodies (e.g. the police and the Local Government Association)

-

industry and industry-related actors (e.g. Drinkaware and the Portman Group).

We generated a list of 23 potential organisations across these sectors and planned to request contacts within each to complete a survey on promotional activity by their organisation. However, during development of the survey, our monitoring of media content relating to guidelines and our informal conversations with stakeholders provided little indication that any organisation was promoting the guidelines in a way that might have a population-level impact. We therefore narrowed our initial survey sample to five key organisations that we judged to be most likely to be engaging in promotional activity. These organisations were also selected for the likelihood that they would also be aware, through their ongoing activities and networks, of promotional activity being undertaken by other organisations.

Known contacts in each of the five organisations were approached initially via e-mail in June 2017 and sent information about the study. The instructions in the e-mail asked individuals, or their nominated alternative, to follow a link to an online questionnaire containing questions about current or planned promotional activity. The questionnaire also asked participants to consent to recontact in 6 months to be asked about any further promotional activity.

Measures

The online questionnaire is provided in Appendix 2 and was informed by a similar tool created for documenting mass media campaigns related to tobacco. 70 It includes questions about each major promotion or communication activity undertaken since January 2016. The questions covered:

-

type of activity (e.g. advertising, distribution of health promotion materials)

-

communication platform [e.g. television (TV), social media]

-

which aspects of the guidelines were communicated (e.g. 14 units per week, number of drinking days)

-

when the activity occurred and how frequently it was repeated

-

any supplementary promotional activity (e.g. social media posts)

-

intended target audience (e.g. national or local, men or women, particular age groups)

-

whether or not the promotional content was interactive

-

actual or estimated cost of the activity (if available)

-

evidence of audience reached (if available)

-

a request for the creative brief or other associated documents that could be shared with the research team.

The survey also asked about press statements released or interviews given by staff in the organisation in relation to drinking guidelines and whether or not respondents were aware of promotional activities by other organisations.

Analyses

Survey results were analysed descriptively.

The following planned analytical work did not take place because of the lack of promotional activity (see Results) and we include a description of it here for completeness. We planned for two members of the research team to review the content of each promotional activity using a structured tool adapted from Langley et al. 71 The tool classifies the thematic, informational and emotional content of campaigns as well as the style of delivery. It was intended to aid identification of the targeted outcomes and likely effectiveness of the campaign with reference to prior research literature. As the tool was designed to look at the content of mass media campaigns, we planned to adapt and expand it iteratively to cover any other activities identified by the survey. We then planned to determine, in discussion with the Project Advisory Group and the PPI group, which promotional activities were important and appropriate to consider when designing the main evaluation analyses described in Chapter 4.

Results

None of the five organisations reported undertaking any substantial promotional activity relating to the revised drinking guidelines between January 2016 and June 2017. Furthermore, none of the organisations reported any knowledge of substantial promotional activity undertaken by other organisations or any awareness of planned activities by their own or other organisations.

Some organisations did report smaller-scale activities. These included news media activities, such as issuing press releases or giving interviews. These activities usually related to the guidelines being announced in January 2016, their formal adoption in August 2016 or other occasional media requests.

Given the lack of substantial activity identified by our respondents or the research team after 19 months of our 22-month study and the lack of indications of any future activity, we decided that surveying the remaining organisations was unwarranted and we discontinued this work after discussions with our Project Advisory Group and the funder.

Discussion

The main finding of this work was that there was no substantial active promotion of the revised drinking guidelines after they were announced in January 2016. This does not mean that no organisation promoted the guidelines at all. It is clear that the guidelines are promoted intermittently on social media by a range of organisations, that organisations such as PHE and Drinkaware provide the guidelines and related information on their websites and in other materials, and that news media routinely mention the guidelines in day-to-day reporting of alcohol-related and health-related topics (see Chapter 3). However, it is unclear that these activities would substantially affect the design or findings of our evaluation analyses as they are unlikely to either reach large audiences or lead on their own to changes in behaviour or in key influences on behaviour change. 65 It is also unclear that they are of sufficient scale or sufficiently different in timing or nature to justify analysis of an additional intervention point beyond January 2016. Our monitoring of stakeholder websites and social media accounts suggests that most organisations changed their messaging on guidelines immediately after the January 2016 announcement and rolled out updated materials in the subsequent months. In the absence of large-scale promotional campaigns, it seems appropriate to regard this activity as part of a general accumulation of drinkers’ exposure to the revised drinking guidelines starting from January 2016 rather than seeking to identify additional intervention points.

Given the above, the remainder of this report proceeds on the basis that there was no significant activity promoting the revised guidelines after the announcement in January 2016. The implications of this for future research, policy and practice are discussed in the main discussion of the project findings in Chapter 5.

Chapter 3 How did news media communicate the revised UK drinking guidelines?

Introduction

News media can play an important role in communicating and shaping public perceptions of social issues, including those related to alcohol. However, the nature of this role is complicated and it is described in many different ways in the literature. For example, Casswell72 describes the media in general terms as ‘key players’ and argues that ‘much of the [public] debate is shaped by the portrayal of alcohol and alcohol policy in mass media’,72 a view broadly shared by several other authors. 73–75 Hansen and Gunter76 suggest that social issues are ‘elaborated, contested, redefined and eventually removed from the public agenda’76 within news media, implying that news media are engaged in multiple sequential or simultaneous processes. Törrönen77 views newspapers in more agentic terms, characterising their editorials as ‘indicators of the opinion climate . . . try[ing] consistently to exert influence . . . evaluate arguments and decisions . . . and make an assessment of them and of situations and attempting to influence policy and public opinion’,77 whereas Nicholls73 addresses only the first aspect of this quotation, noting that ‘news reporting plays a key role in articulating shared cultural values around alcohol’. Mercille78 argues more forcefully that news media deliberately, strategically and inevitably ‘. . . reflect the views of the political and economic establishment on public health measures’. Mercille78 argues this based on the links between media owners and government, their financial links to health-harming industries via advertising and the reliance on establishment contacts for sourcing of news stories and reactions. These different perspectives suggest that the role of news media in alcohol policy debate is complex and multifaceted. As such, it is difficult to capture or demonstrate fully within a single analysis,79 but remains an important area of study when assessing how public perceptions are formed on a particular topic.

Studies of news media coverage of alcohol use are a relatively recent phenomenon. In 2011, Nicholls73 noted that few such studies existed, particularly in the UK; however, a much larger body of literature emerged in subsequent years. This includes analyses of news media reports of policy debates around MUP in the UK,80–82 advertising restrictions and regulation of the night-time economy in Australia,74,83 strategies tackling college drinking in the USA84 and general alcohol policy in several countries. 77,78,85,86 It also includes analysis of news media coverage of contemporary social issues specific to alcohol or with which alcohol intersects, including alcohol’s harm to those other than the drinker,87 alcohol-related health risks,88,89 sex,75,90–93 sexual violence,94,95 parenting96 and personal freedoms. 97 Furthermore, a number of studies examine overall reporting of alcohol-related topics within news media. 73,98–101

A review of this literature in 2007 argued that analyses of news media coverage of alcohol, in addition to being few in number, had failed to draw on relevant theories and techniques developed within the communications and political science literature. 76 In particular, it noted the value of analyses of change over time, a lack of cross-referencing between studies, the mediating role of advocacy within news media or perspective taking by news organisations, the significance of message sources (e.g. individuals quoted within reports) and the medium of the coverage. More recent work has drawn on these arguments to develop rich understandings of how alcohol-related issues are reported in the media. For example, studies have demonstrated that public health actors have successfully positioned themselves as key sources of information within policy debates but provide conflicting findings as to whether or not those actors have also successfully framed debates in public health terms as population-level issues rather than the industry’s favoured individual-level and personal responsibility oriented perspective. 73,74,80 Many studies also identify key frames through which alcohol-related issues are discussed, many of which are replicated across policy debates. For example, men’s drinking is often found to be framed in relation to violence, whereas women’s drinking is linked to a wider set of concerns pertaining to transgression of traditional models of femininity. 73,75 Similarly, in debates about advertising, liberalisation of retail monopolies and MUP, opposition to alcohol policy is framed with reference to individual freedoms or the need to protect industry from an overbearing state. 74,77,80 Analyses of policy debates in Finland and Ireland also suggest that, as agentic actors in policy debate, news media are often unsupportive of public health arguments and alcohol-related problems; even when such problems are identified, the discussion and policies recommended tend to coincide with an underlying view that liberalised alcohol markets are desirable. 77,78

Despite this now-broad literature, only one briefly reported study to date has examined how news media report on drinking guidelines. 102 This is an important oversight as TV, radio, newspapers and magazines are the primary places where the public report seeing drinking guidelines when revisions are announced. 46 At such times, guidelines are discussed prominently by news outlets within ordinary news reports, opinion pieces and editorials. At other times, news media continue to expose the public to drinking guidelines by mentioning them within stories about alcohol-related health risks, drinking trends and lifestyle topics. Such repeated exposure aids awareness and recall of guidelines in the absence of active promotion via mass media campaigns. For example, evaluations of alcohol health warning labels in the USA found higher rates of awareness and recall of the health warnings among heavier drinkers and argued that this was because they see the label more often. 103 Debate within news media may also inform public opinion and responses to drinking guidelines, but, given the wide variety of roles that the media play in public debate, this is unlikely to be a straightforward or unidirectional process. 79 Moreover, differences in news media reports across publications and platforms may play an important role in determining who is exposed to guidelines and informing their attitudes towards them as engagement with news outlets and content is socially patterned. 76

Therefore, the aim of this review was to conduct an exploratory analysis to describe the scale and content of news media coverage of drinking guidelines in England during our study period of February 2014 to October 2017. As this was a retrospective study, broadcast media reports were difficult to access. Therefore, we focused on reviewing print news media, which are searchable via online databases. There were three stages of the review:

-

a systematic search to identify all news articles published in England during the study period that mentioned drinking guidelines or closely related terms

-

a quantitative analysis to develop a timeline of when and where the identified articles were published and to summarise the main content of articles

-

a qualitative analysis to explore the content of articles in more depth.

Methods

Identification of articles

We conducted three searches of the Nexis ‘UK publications’ database across the period from 1 February 2014 to 31 October 2017. Nexis contains all print and online articles published by UK local and national newspapers, including daily and Sunday editions, and a large number of magazines and news websites. As this project focuses on the impact of drinking guidelines in England, we did not search the Scottish editions of UK newspapers (e.g. the Scottish Daily Mail).

Nexis’s news search does not allow users to build complex search strategies and restricts searches to no more than 3000 results, so we conducted three searches using different search terms, across multiple subsections of the search period, if the total results exceeded 3000. Search terms were Alcohol guidelines OR drinking guidelines OR alcohol units (search 1); 14 units OR 21 units OR 2–3 units OR 3–4 units (search 2) and alcohol recommendations OR alcohol limits OR alcohol guidance OR alcohol advice (search 3).

Many members of the public read news on the websites of leading broadcasters, and these are not fully included in the Nexis database. Therefore, we searched the BBC News (British Broadcasting Corporation, London, UK) and Sky News (Sky UK, London, UK) websites by using Google (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA) to find pages within the BBC News website (www.bbc.co.uk/news) and the Sky News website (www.news.sky.com) published during the same study period and including the same search terms as above. The search on the BBC News website was additionally restricted to pages created in the UK.

Articles from both Nexis and Google searches were included in the final sample if they fully or partially mentioned the guidelines (e.g. articles discussing the guidelines for women but not the guidelines for men would be included) or if they commented on the process of developing the guidelines or the guidelines’ content without explicitly stating what the guidelines are. Articles were excluded if they did not mention the guidelines or if they discussed only guidelines or recommendations for drinking in pregnancy or drink-driving. We also excluded articles in local newspapers as we are primarily interested in coverage that would have a national-level impact. It is plausible that a large number of similar stories at a local level in local newspapers could aggregate to have a national-level impact, but analysing patterns of local news coverage is beyond the scope of this study.

Headline and full-text screening was undertaken by one researcher, who discussed any difficult cases with the lead author. We then extracted publication name, source type (e.g. broadsheet/quality press, online only), publication date and period (i.e. before or after the revised guidelines were announced), and what aspects of the guidelines were mentioned (e.g. 2–3 units per day for women or having drink-free days).

Quantitative analysis

As our aim was exploratory, we developed a coding frame from an initial random sample of 50 articles, stratified by source type, and sought to identify their main discriminating features. We then selected a final random sample of approximately half (n = 500) of the identified articles, again stratified by source type, and coded them for the following characteristics.

Primary topic of the article

We coded articles into one of four mutually exclusive categories based on their primary topic:

-

articles primarily discussing drinking guidelines, for example articles that discuss the change in drinking guidelines or opinion pieces that discuss the merit of the guidelines

-

articles that primarily discuss alcohol, but do not focus on the drinking guidelines, for example articles that discuss the relationship between alcohol consumption and certain health outcomes or population statistics on alcohol consumption prevalence

-

articles that primarily discuss health, but do not have alcohol or the drinking guidelines as their main focus, for example articles discussing strategies to prevent certain health outcomes or achieve a healthy lifestyle

-

articles whose primary focus is not the drinking guidelines, alcohol or health, for example articles that use the guidelines as an example of the nanny state or articles presenting gift-giving guides that mention the guidelines when discussing alcohol-related gifts.

Primary role of guidelines within the article

We used five categories to code articles based on our perception of the purpose of mentioning guidelines in the article:

-

articles that mention the guidelines to inform people of the forthcoming or actual change in drinking guidelines

-

articles that discuss the merits of the guidelines in more detail, including articles that discuss information that discredits the guidelines or that discuss the guideline development process in more depth

-

articles that mention the guidelines in the context of promoting health or preventing ill health, including articles providing the guidelines as advice, mentioning them in connection with health outcomes or using them to provide context to a story about health

-

articles that mention the guidelines to illustrate consumption levels of specific groups or individuals, including articles mentioning the guidelines to provide context to alcohol consumption statistics without necessarily linking the guideline to those statistics

-

articles that mention guidelines for another purpose.

Overall tone

We coded the broad tone in which the guidelines were discussed as positive, negative or neutral. An article was coded as positive if a reader who was unfamiliar with the argument could reasonably be expected to have a positive impression of the guidelines after reading the article. Positive articles included those sought to rebut criticism of the guidelines or illustrate how scientific evidence supports them. Articles were coded as negative if the researcher judged that readers unfamiliar with the relevant information could be expected to have a negative impression of the guidelines after reading the article. These included articles that criticised the guidelines without balancing this with support for the guidelines. Articles were coded as neutral if they merely stated the guidelines, or if they balanced supporting and critical information relating to the guidelines.

Qualitative analysis

One researcher (IK) conducted a thematic analysis on a subset of articles sampled for in-depth coding. 104 Articles were coded for quantitative and qualitative analysis simultaneously. First, the researcher coded a random sample of 100 articles, again stratified by source. As saturation had not been reached, the researcher coded another randomly sampled 100 articles. This satisfied the requirement for data saturation and the researcher was confident that no new themes would arise. The researcher organised the codes into themes that describe how the guidelines were covered in the media. Themes were discussed with another researcher (JH) with a strong prior knowledge of media coverage of the guidelines.

Results

Identified articles

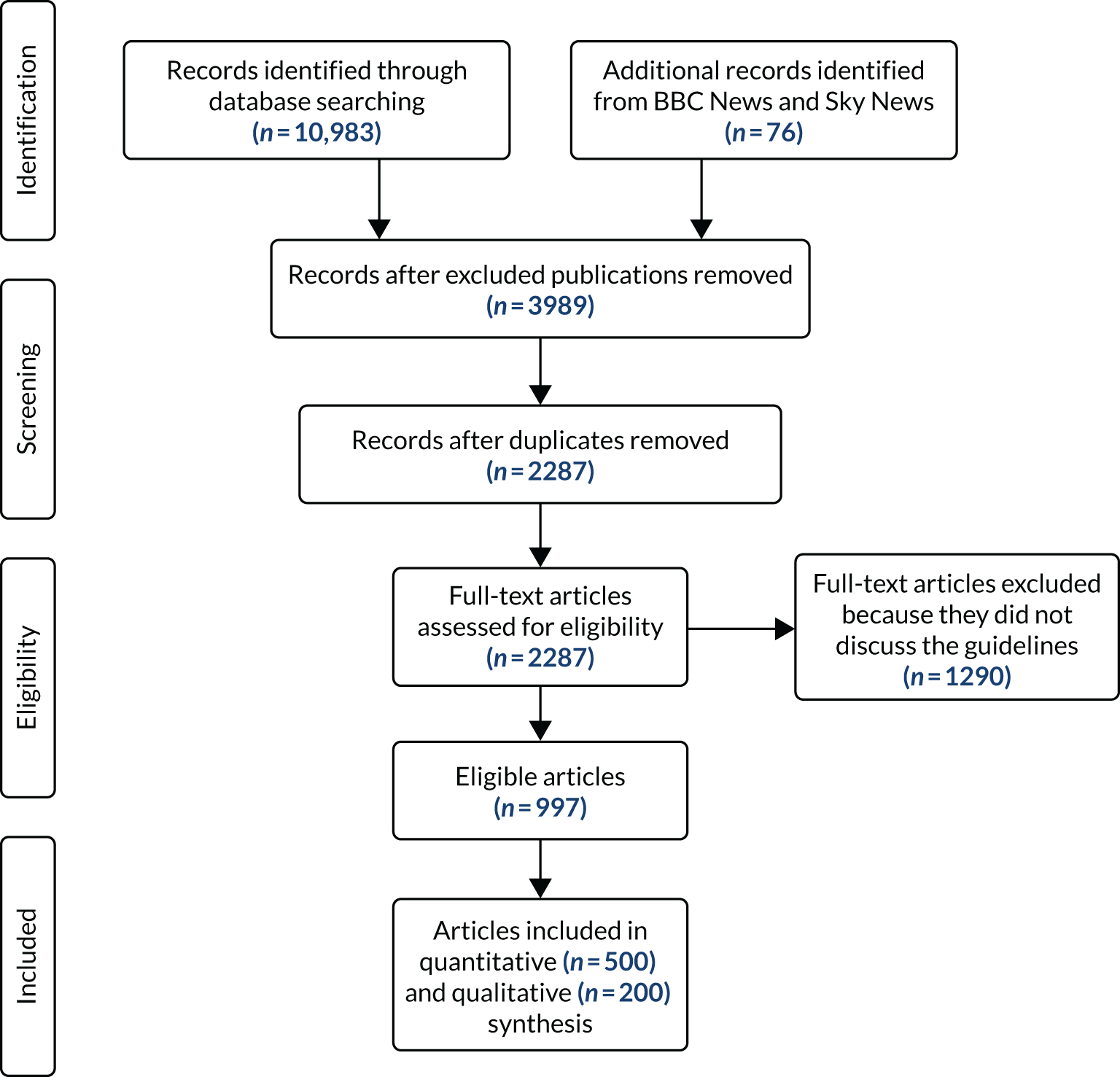

Figure 2 shows the results of the search and selection process. The three Nexis searches yielded 10,983 articles in total. After excluding articles published in local publications or The Associated Press planners (i.e. collections of press releases that are disseminated to journalists and news publications, which are included in the Nexis database; n = 7070) and removing duplicates (n = 1702), we were left with 2211 articles in 41 publications. After concurrent headline and full-text screening of these articles, we excluded a further 1261 articles because they did not discuss the guidelines. The Google searches yielded 70 results on the BBC News website and six on the Sky News website. After headline and full-text screening of these articles, we excluded 29 articles (28 from the BBC) because they did not mention the guidelines. This left 41 further articles in addition to those identified via the Nexis search. After adding the website and Nexis searches together, our final data set comprised 997 eligible articles from 29 publications (Table 1).

FIGURE 2.

The PRISMA flow diagram showing the results of the search for news articles mentioning drinking guidelines.

| Source type | Publication | Number of articles | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n = 997) | Sample (n = 500) | ||

| Broadsheet/quality press | The Daily Telegraph (including telegraph.co.uk) | 112 | 53 |

| The Independent (including the i, The Independent Magazine, independent.co.uk) | 83 | 41 | |

| The Guardian (including The Observer) | 56 | 32 | |

| The Times (including thetimes.co.uk, The Sunday Times) | 88 | 44 | |

| Middle market | Daily Mail (including MailOnline, The Mail on Sunday) | 215 | 99 |

| Daily Express (including Express Online, Sunday Express) | 115 | 66 | |

| Red-top tabloid | Daily Mirror (including mirror.co.uk, The People) | 62 | 29 |

| Daily Star (including Daily Star Online) | 29 | 14 | |

| The Sun (including thesun.co.uk, The Sun on Sunday) | 96 | 52 | |

| Online only | BBC News | 42 | 21 |

| BigHospitality.co.uk | 1 | 0 | |

| FoodNavigator.com | 2 | 1 | |

| Sky News | 13 | 8 | |

| Other | Arts and Book Review | 1 | 0 |

| Convenience Store | 1 | 1 | |

| Financial Wire | 12 | 5 | |

| Good Housekeeping | 9 | 5 | |

| Men’s Health | 4 | 1 | |

| Metro | 11 | 5 | |

| Morning Advertiser | 8 | 3 | |

| New Scientist | 3 | 2 | |

| Nursing Times | 3 | 1 | |

| Prima | 5 | 2 | |

| Runner’s World | 1 | 0 | |

| The Grocer | 12 | 8 | |

| The MCA Report (formerly The M&C Report) | 2 | 1 | |

| UK Government News | 11 | 6 | |

Quantitative analysis

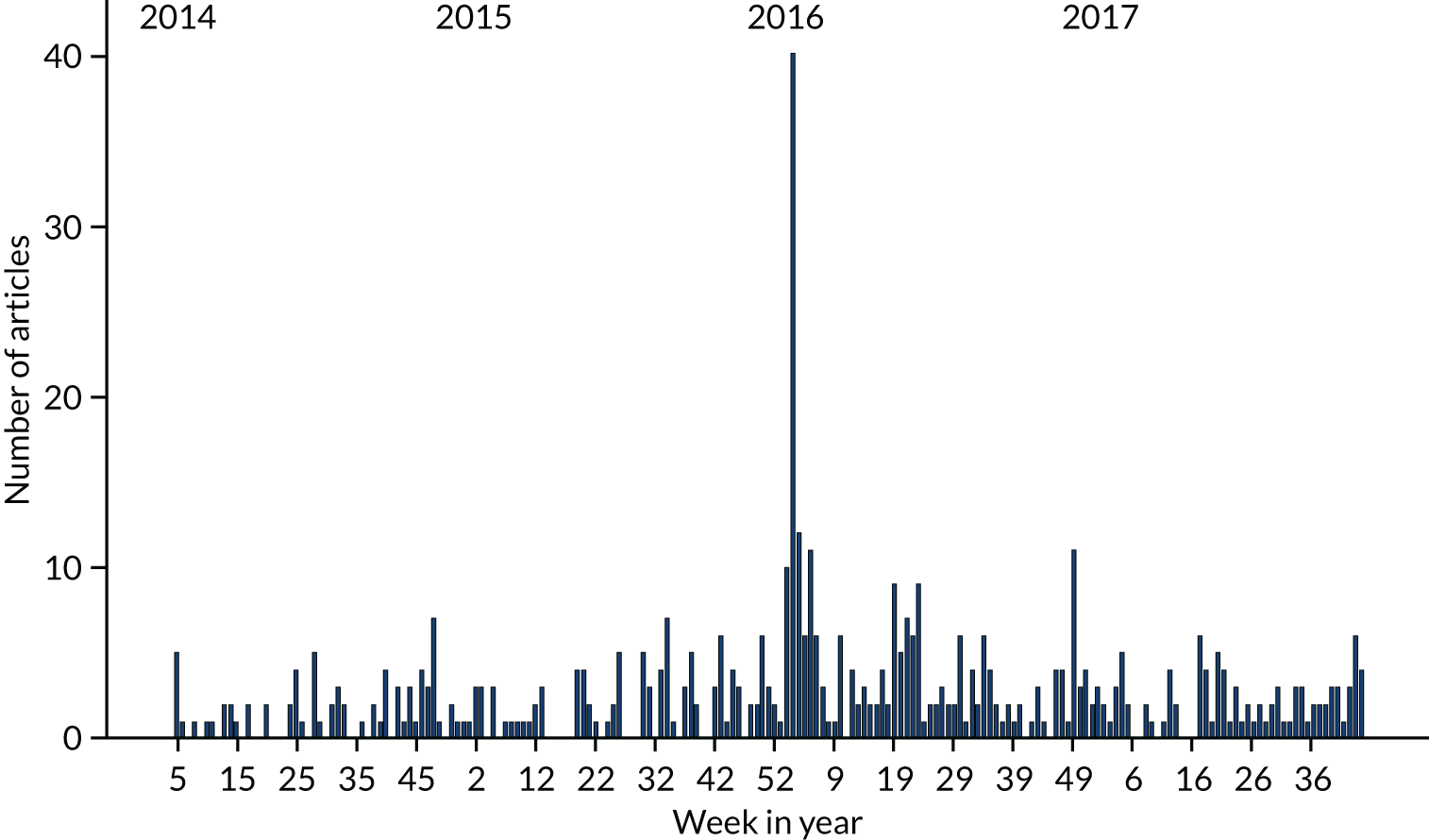

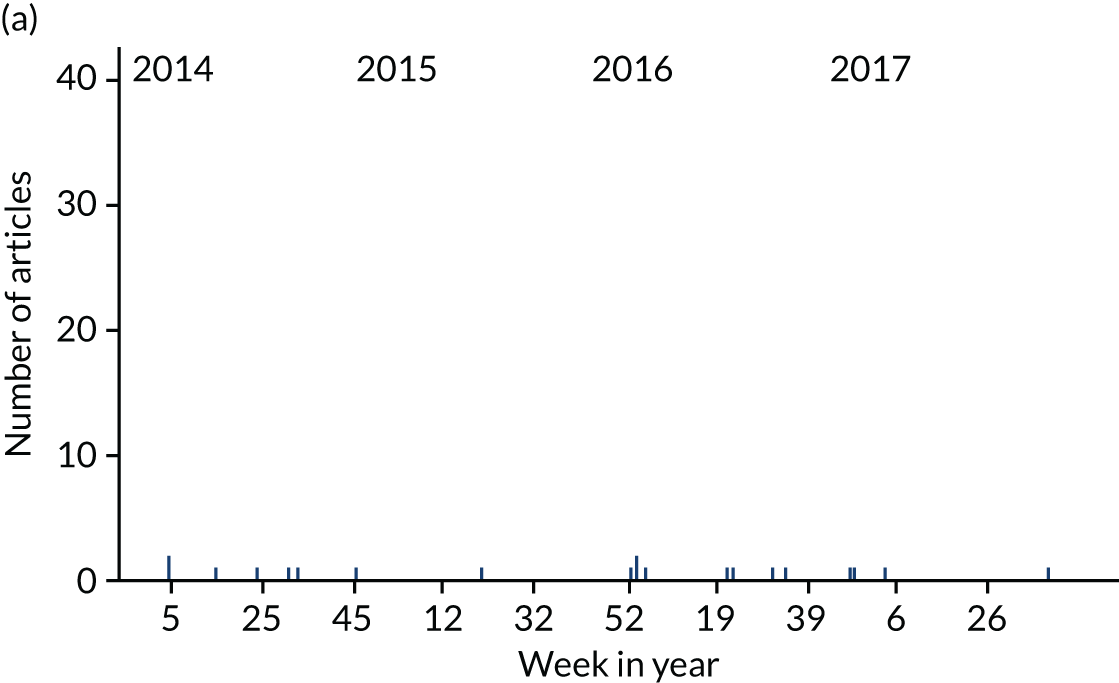

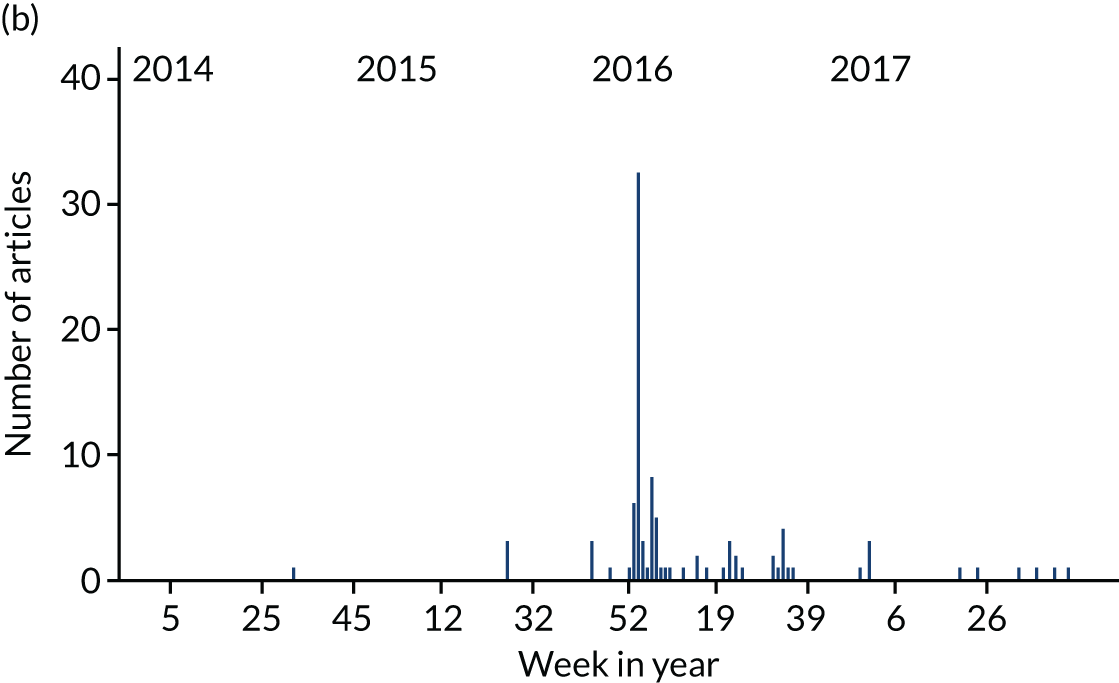

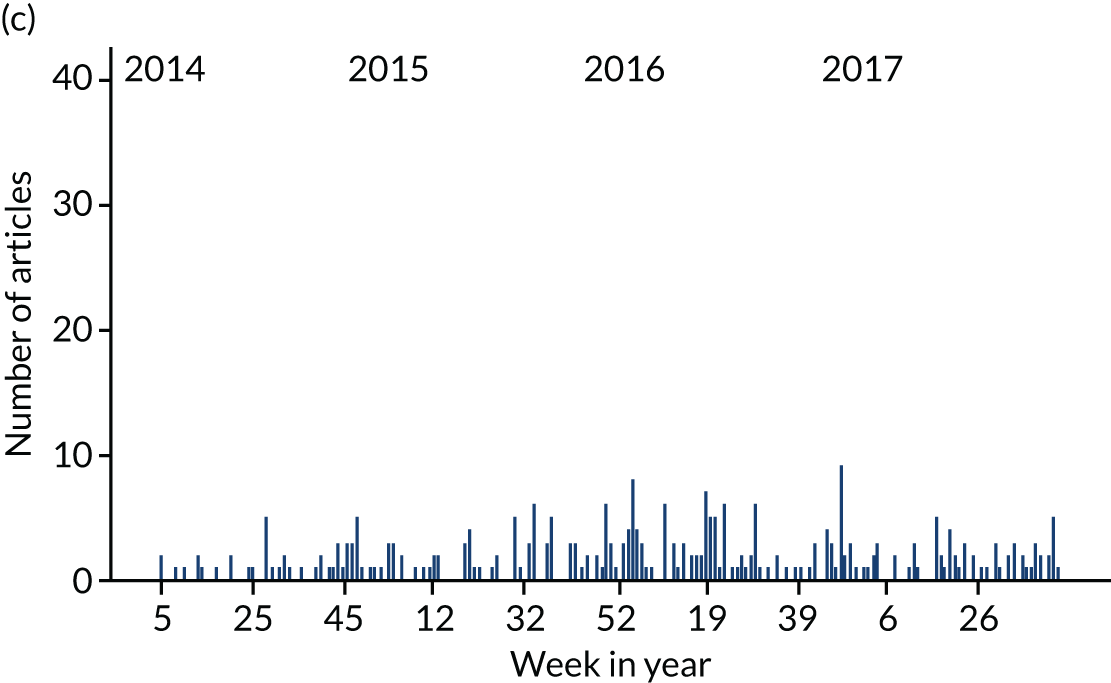

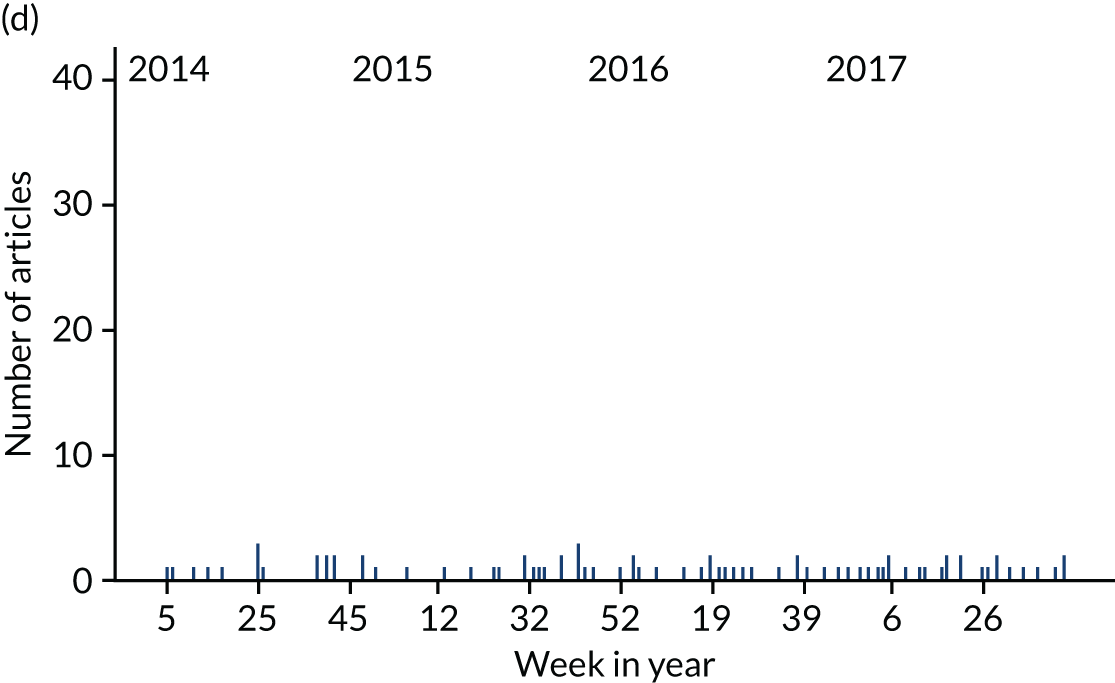

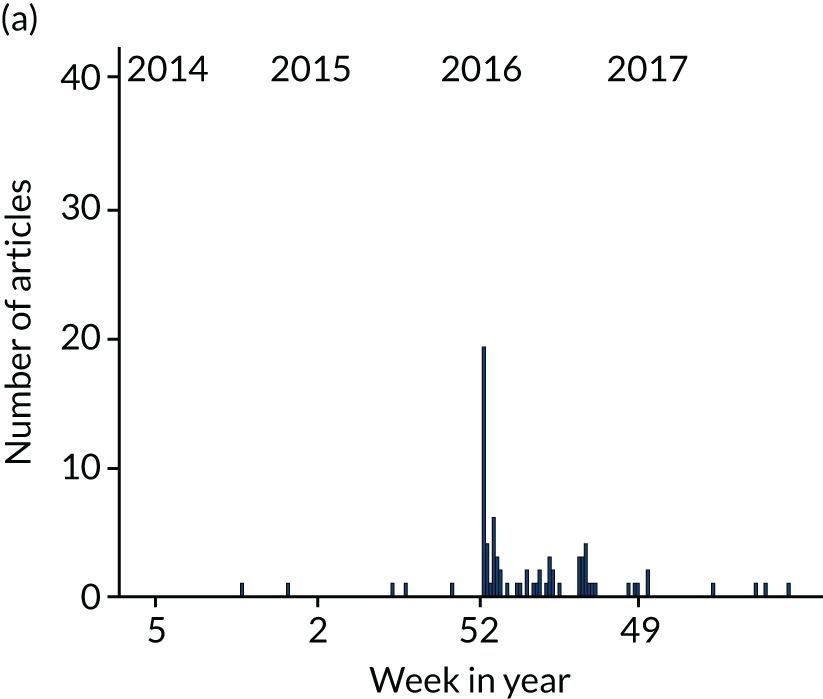

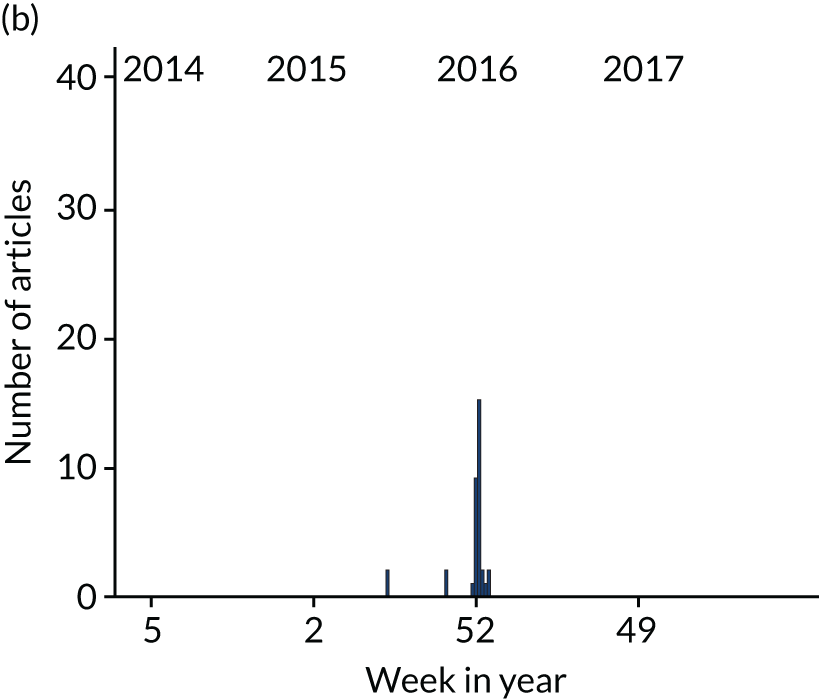

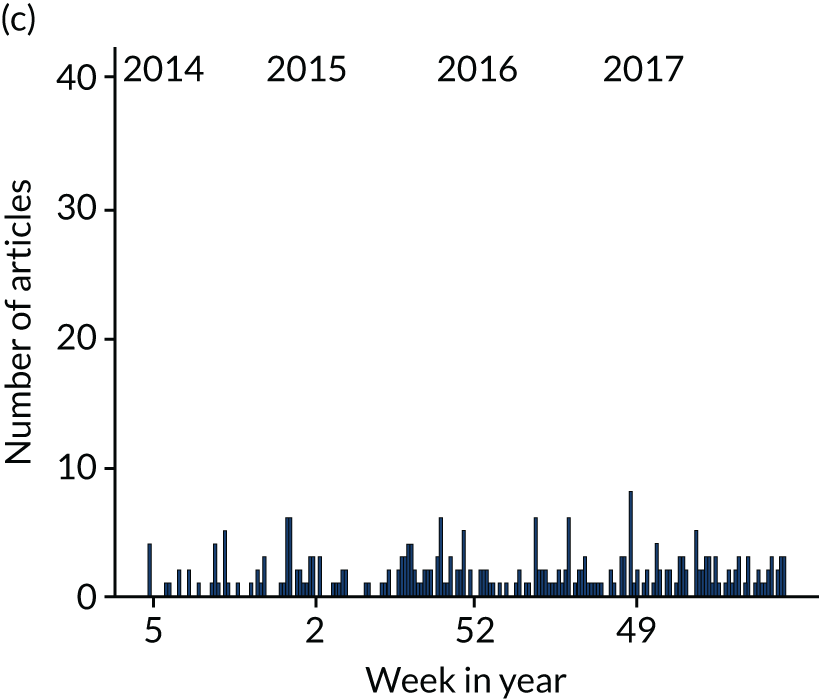

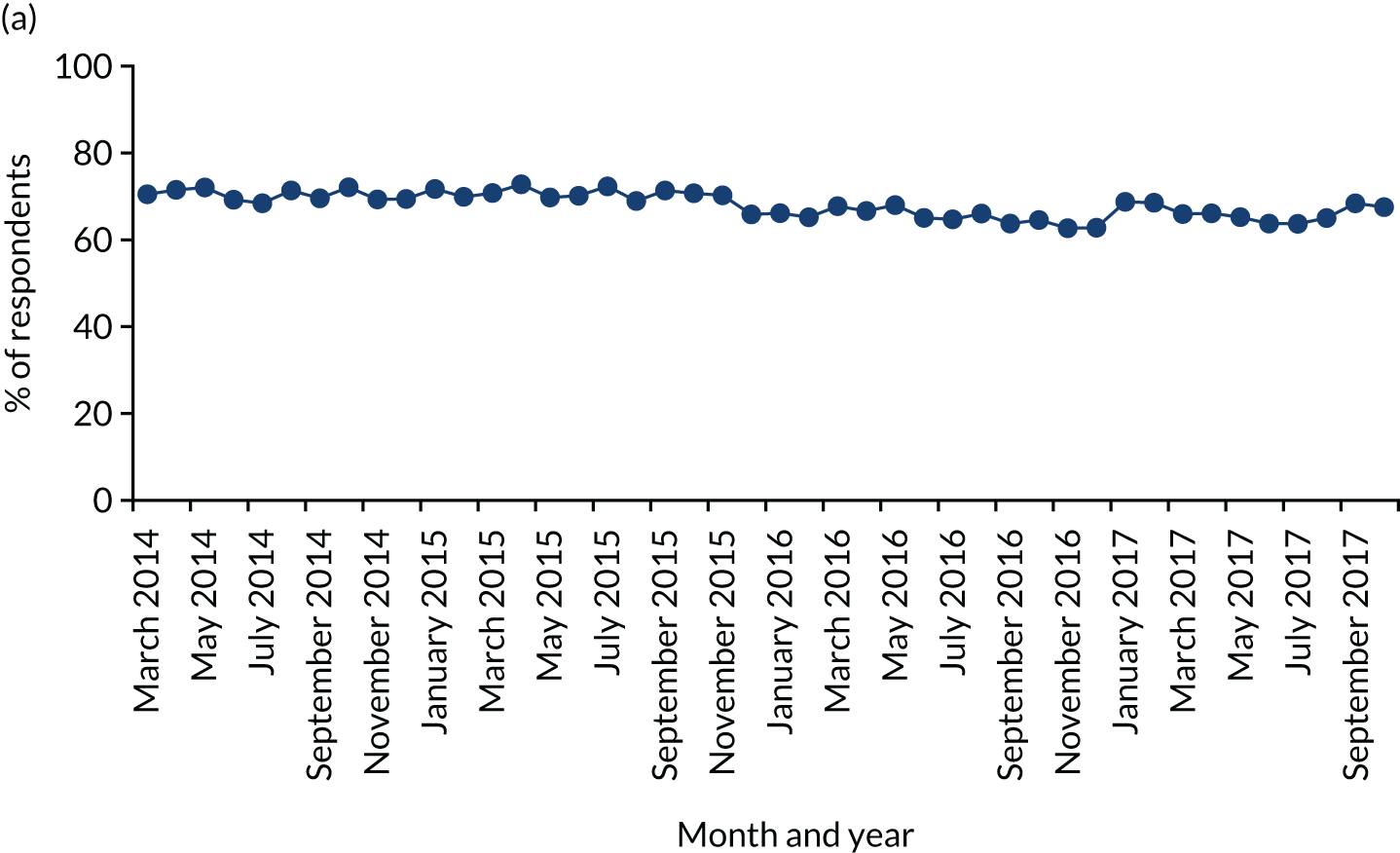

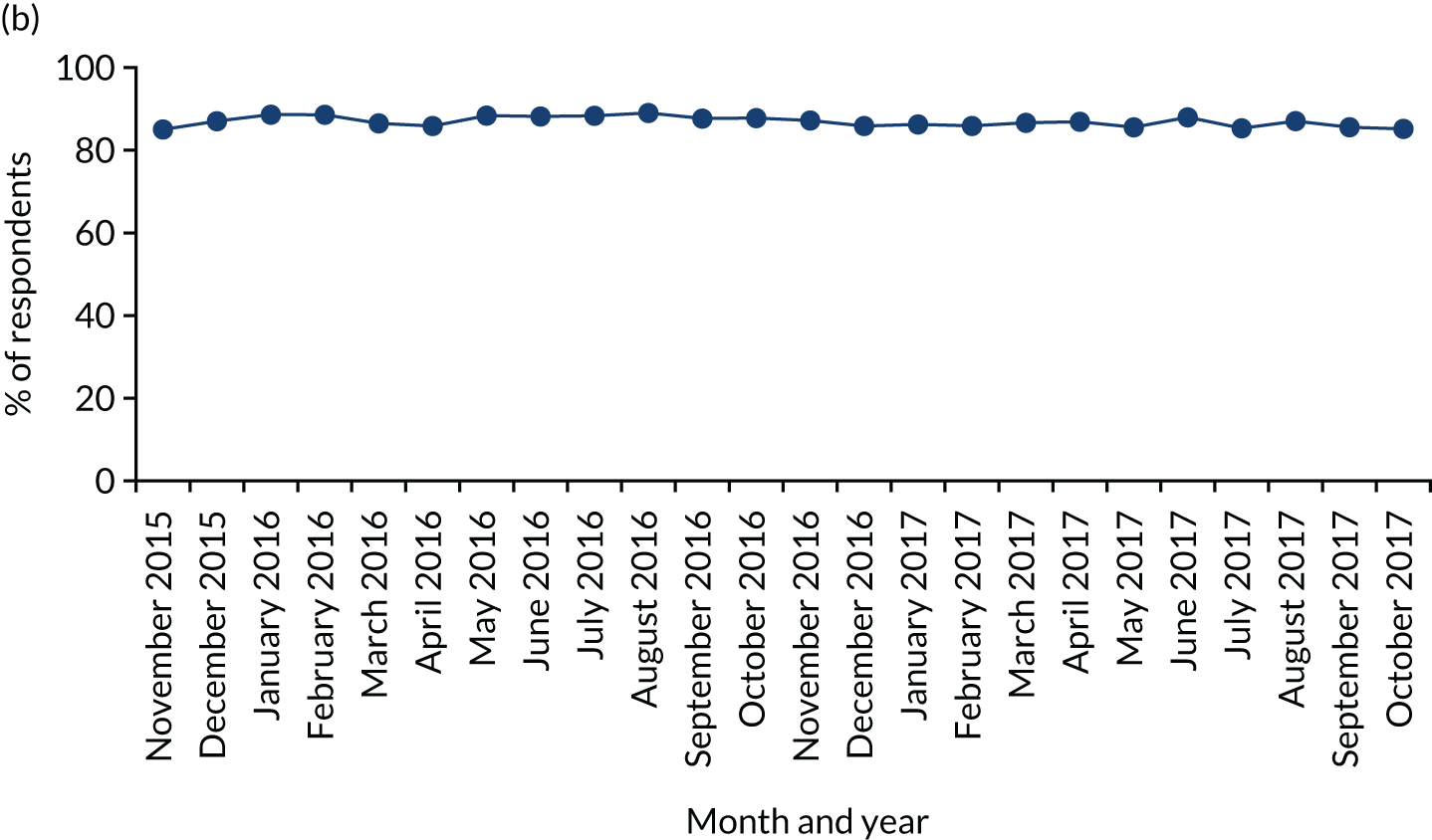

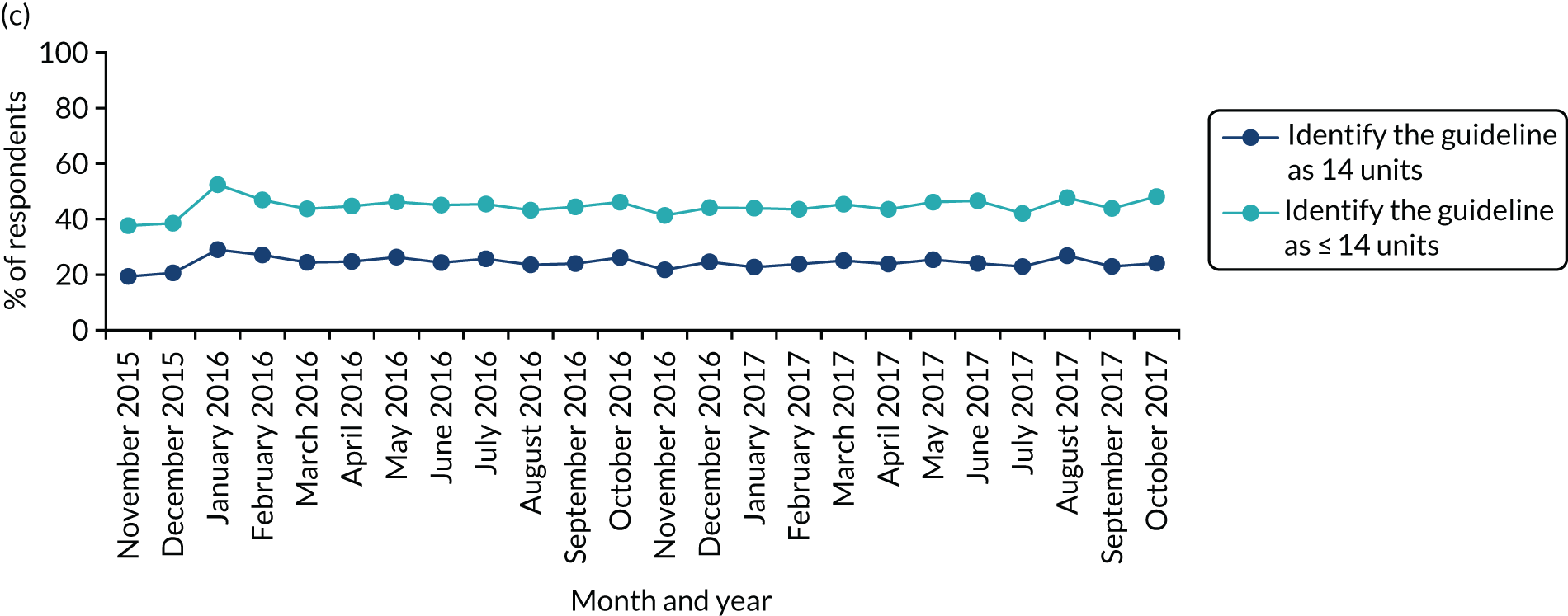

Drinking guidelines were mentioned regularly in news articles across the study period. Figure 3 shows that the number of articles per week peaked when the revised guidelines were announced in January 2016. There were also many smaller peaks that occurred when guidelines were mentioned in articles related to general alcohol- or health-related topics, as shown in Figure 4, whereas guidelines were mentioned only infrequently in articles unrelated to alcohol or health.

FIGURE 3.

Number of news articles mentioning guidelines per week within the analysed sample (n = 500) between 1 February 2014 and 31 October 2017. The guidelines changed in week 2 of 2016.

FIGURE 4.

Number of news articles mentioning guidelines per week within the analysed sample (n = 500) between 1 February 2014 and 31 October 2017, split by primary topic in article. (a) Not related to drinking guidelines of alcohol or health; (b) related to drinking guidelines; (c) related to alcohol but not drinking guidelines; and (d) related to health but not alcohol.

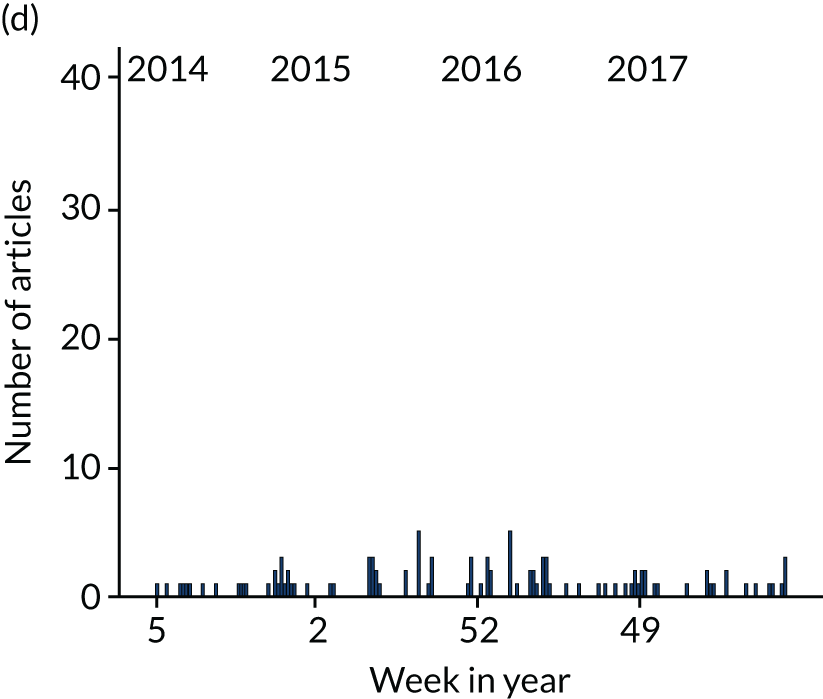

The guidelines were mentioned for different reasons at different time points. Figure 5 shows that a large number of articles mentioned the guidelines in January 2016 to inform the public of the revisions and that there were also a large number of articles that discussed the merits of the guidelines at this time and in the subsequent 23 weeks. However, outside this period, the merits of the guidelines were rarely discussed, and guidelines were mentioned instead to promote health, to prevent ill health and, less often, to provide context to articles discussing alcohol consumption. Around the time that the revised guidelines were announced, there were also a number of articles that mentioned the guidelines for other reasons, including to discuss state intervention in health care and nanny state policies in general, and to criticise UK drinking culture.

FIGURE 5.

Number of news articles mentioning guidelines per week between 1 February 2014 and 31 October 2017, split by primary purpose of guidelines in article. (a) To discuss the merit of guidelines; (b) to inform the public of the change in guidelines; (c) to promote health; (d) to provide context for drinking habits; and (e) other.

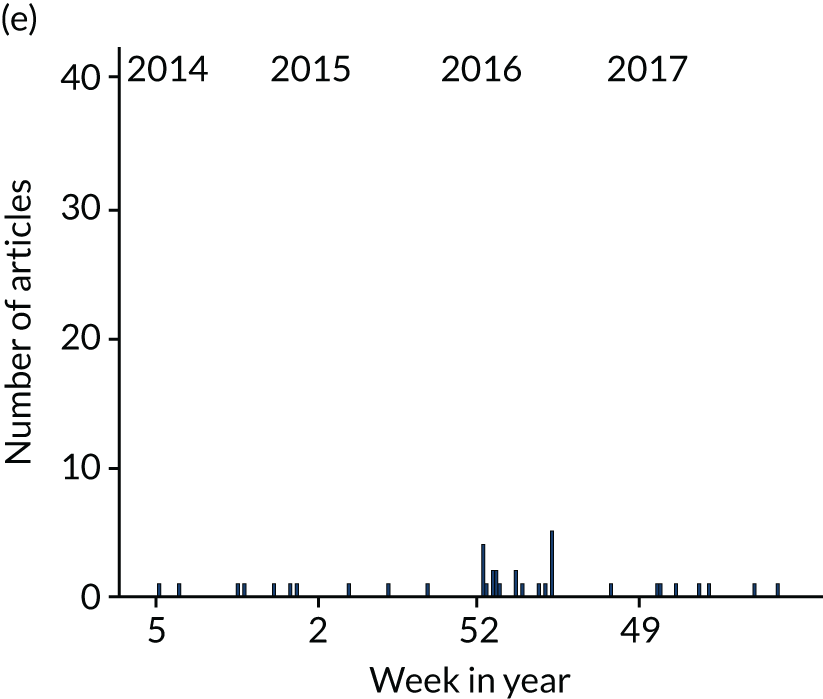

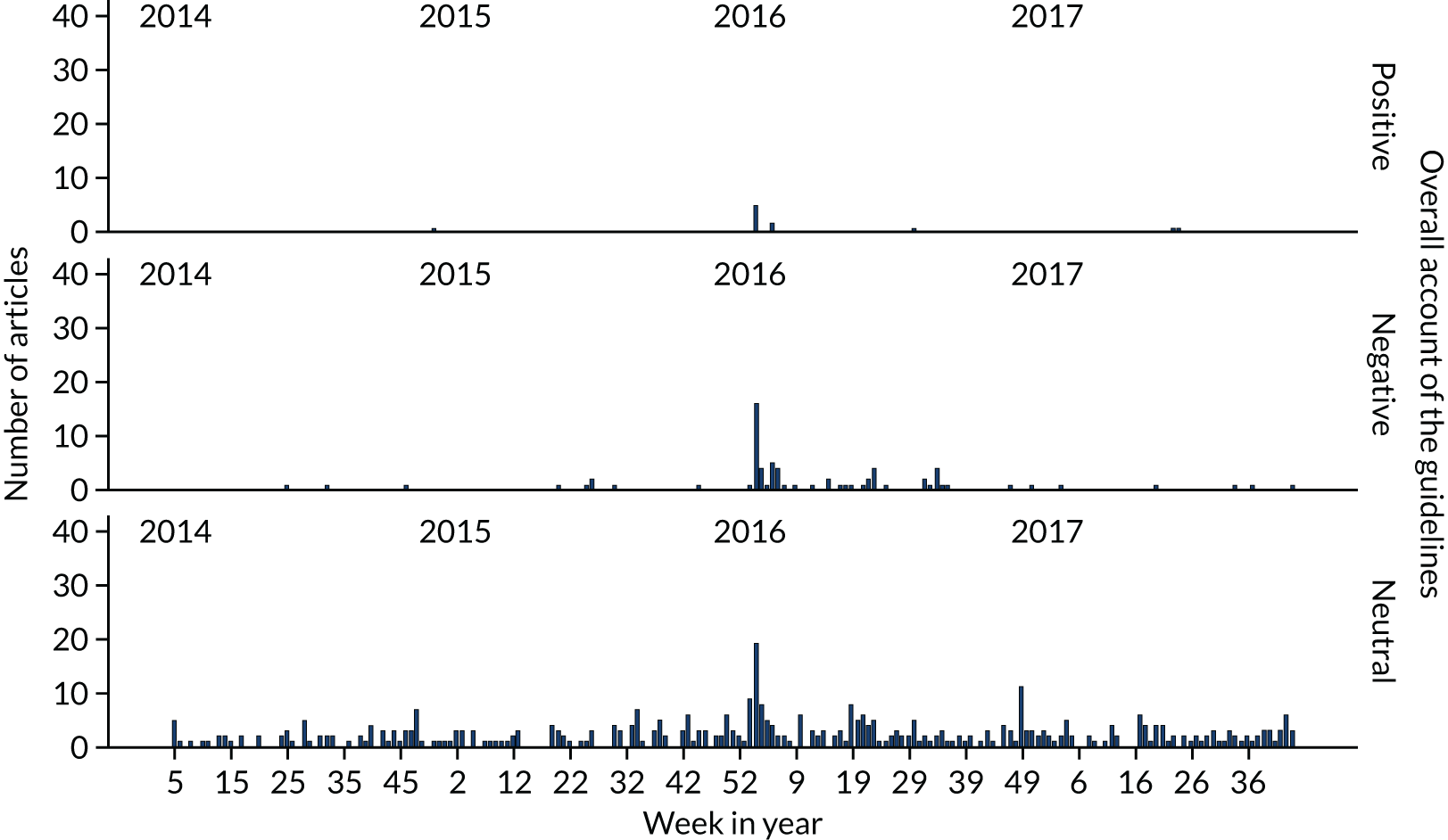

Figure 6 shows that the tone of articles was typically neutral in the overwhelming majority of cases and that articles with a positive tone were rare. Articles with a negative tone were also rare but became more common for several weeks after the revisions were announced.

FIGURE 6.

Numbers of news articles mentioning guidelines per week between 1 February 2014 and 31 October 2017, split by article tone.

Table 2 shows the different aspects of the drinking guidelines that were mentioned in articles and how the aspects mentioned changed before and after the guidelines were revised. Most articles (95.4%) mentioned the guideline threshold, although sometimes this was provided for only one sex. Even after the same guidelines were set for men and women in January 2016, 94.0% of articles mentioned the guideline consumption level but only 88.6% mentioned that it applied to men. Prior to the revisions, the 1995 guidelines of 3–4 units per day for men and 2–3 units per day for women were mentioned in approximately half of the articles, but the pre-1995 guidelines of 21 units per week for men and 14 units per week for women were also mentioned in around one-third of the articles, with both guidelines sometimes mentioned for comparison (e.g. 3–4 units per day or 21 units per week), suggesting that the public was provided with inconsistent information during this time. After the revisions, only 9 out of 296 articles mentioned a guideline other than 14 units per week for men or women. Out of these nine articles, three mentioned the previous daily guidelines, whereas the other six mentioned the previous weekly guidelines.

| Aspect of guidelines communicated | Before (n = 185) | After (n = 315) | Total (n = 500) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (%) | No (%) | Yes (%) | No (%) | Yes (%) | No (%) | |

| Recommended consumption levels (at least one of the following) | 97.8 | 2.2 | 94.0 | 6.0 | 95.4 | 4.6 |

| 3–4 units per day for men | 56.8 | 43.2 | 0.6 | 99.4 | 21.4 | 78.6 |

| 14 units per week for men | 6.5 | 93.5 | 88.6 | 11.4 | 58.2 | 41.8 |

| 21 units per week for men | 35.7 | 64.3 | 1.9 | 38.1 | 14.4 | 85.6 |

| 2–3 units per day for women | 59.5 | 40.5 | 1.0 | 99.0 | 22.6 | 77.4 |

| 14 units per week for women | 36.8 | 63.2 | 88.9 | 11.1 | 69.6 | 30.4 |

| Spread weekly limit over multiple days | 1.1 | 98.9 | 13.7 | 86.3 | 9.0 | 91.0 |

| No alcohol on at least 2 days per week | 9.2 | 90.8 | 10.2 | 89.8 | 9.8 | 90.2 |

| No safe level of drinking | ||||||

| Communicated as part of guidelines | 2.2 | 97.8 | 23.2 | 76.8 | 15.4 | 84.6 |

| Communicated separate from guidelines | 4.9 | 95.1 | 2.5 | 97.5 | 3.4 | 96.6 |

Other aspects of the guidelines were mentioned much less frequently, and the announcement of the revisions did not always lead to increased mentions. The advice to spread the weekly guideline of 14 units across at least 3 days was mentioned in 13.7% of articles after the announcement, compared with 1.1% before. However, the advice to have at least 2 drink-free days per week was mentioned in 10.2% of articles after the revisions and 9.2% before, perhaps because this advice was part of PHE’s Change for Life mass media campaign prior to the guideline review.

Information that was not part of the guidelines was also sometimes presented as though it was. One particular example of this arose because the revised guidelines were announced in conjunction with a report on the relationship between alcohol consumption and cancer, which argued that there was no safe level of drinking with regard to cancer risk. 105 Although the UK CMOs’ report and the report of the GDG discussed evidence on alcohol and cancer and noted the risk at low levels of consumption, the ‘no safe level’ message is not part of the drinking guidelines. 22,24 Despite this, 23.2% of articles published after the revisions stated or implied that this message was part of the guidelines, for example by mentioning it shortly before or after the consumption guidelines without clarifying that it is not part of the guidelines. This compares with 2.5% of articles that mentioned the ‘no safe level’ message as separate to the guidelines (e.g. by stating this explicitly, or by attributing the ‘no safe level’ message to a source other than the guidelines).

Relationship between timing, tone and other article characteristics

We examined the relationship between the tone of articles, whether they were published before or after the guidelines announcement, and their other characteristics. As only 11 out of 500 articles analysed were positive in tone, the analysis focuses on a comparison of articles with a neutral or negative tone.

Table 3 shows that articles were significantly more likely to have a negative tone and less likely to have a neutral tone after the revised guidelines were announced (χ2 = 20.3; p < 0.001). Across the whole study period, articles that had drinking guidelines as the primary topic were more likely to have a negative tone than those related to alcohol in general, those related to health in general or those that were unrelated to guidelines, alcohol or health (χ2 = 179.2; p < 0.001). Guidelines were also more likely to be discussed negatively if the primary purpose of mentioning the guidelines was to discuss their merits (χ2 = 282.8; p < 0.001). There were no significant differences in the likelihood of the guidelines being discussed negatively across source types (χ2 = 4.76; p = 0.31) or their political leanings (χ2 = 0.66; p = 0.72). Articles were, however, more likely to be negative in tone if they communicated the ‘no safe level’ message as part of the guidelines rather than identifying it as a separate message or not mentioning it at all (χ2 = 42.32; p < 0.001).

| Context in which guidelines were communicated | Positive (%) | Negative (%) | Neutral (%) | Total (%) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before (n = 1) | After (n = 10) | Total (n = 11) | Before (n = 10) | After (n = 62) | Total (n = 72) | Before (n = 174) | After (n = 243) | Total (n = 417) | Before (n = 185) | After (n = 315) | Total (n = 500) | |

| Source type | ||||||||||||

| Broadsheet/quality press | 0.0 | 40.0 | 36.4 | 50.0 | 32.3 | 34.7 | 36.8 | 31.7 | 33.8 | 37.3 | 32.1 | 34.0 |

| Middle market | 100.0 | 30.0 | 36.4 | 40.0 | 29.0 | 30.1 | 27.6 | 37.4 | 33.3 | 28.6 | 35.6 | 33.0 |

| Red-top tabloid | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 21.0 | 18.1 | 23.0 | 17.3 | 19.7 | 21.6 | 17.5 | 19.0 |

| Online only | 0.0 | 30.0 | 27.3 | 10.0 | 1.6 | 2.8 | 2.9 | 8.2 | 6.0 | 3.2 | 7.6 | 6.0 |

| Other | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 16.1 | 13.9 | 9.8 | 5.3 | 7.2 | 9.2 | 7.3 | 8.0 |

| Context | ||||||||||||

| Related to drinking guidelines | 0.0 | 60.0 | 54.5 | 40.0 | 80.6 | 75.0 | 6.3 | 10.7 | 8.9 | 8.1 | 26.0 | 19.4 |

| Related to alcohol (but not drinking guidelines) | 0.0 | 40.0 | 36.4 | 40.0 | 11.3 | 15.3 | 69.5 | 67.9 | 68.6 | 67.6 | 55.9 | 60.2 |

| Related to health (but not alcohol) | 100.0 | 0.0 | 9.1 | 10.0 | 4.8 | 5.6 | 19.5 | 17.7 | 18.5 | 19.5 | 14.6 | 16.4 |

| Not related to guidelines, alcohol or health | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 10.0 | 3.2 | 4.2 | 4.6 | 3.7 | 4.1 | 4.9 | 3.5 | 4.0 |

| Role of guidelines within article | ||||||||||||

| To discuss merit of guidelines | 0.0 | 30.0 | 27.3 | 50.0 | 82.3 | 77.8 | 0.0 | 6.2 | 3.6 | 2.7 | 21.9 | 14.8 |

| To inform public of change in guidelines (but not discuss their appropriateness) | 0.0 | 20.0 | 18.2 | 20.0 | 3.2 | 5.6 | 6.9 | 6.6 | 6.7 | 7.6 | 6.3 | 6.8 |

| To promote health | 100.0 | 30.0 | 36.4 | 20.0 | 3.2 | 5.6 | 59.8 | 56.8 | 58.0 | 57.8 | 45.4 | 50.0 |

| To provide context for drinking | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.6 | 1.4 | 28.2 | 22.2 | 24.7 | 26.5 | 17.5 | 20.8 |

| Other | 0.0 | 20.0 | 18.2 | 10.0 | 9.7 | 9.7 | 5.2 | 8.2 | 7.0 | 5.4 | 8.9 | 7.6 |

Qualitative thematic analysis

The analysis identified four main themes: (1) factual reporting of the guidelines, (2) the guidelines are not based on the best available science and should not exist in their current form, (3) the guidelines threaten autonomy and should not exist at all and (4) alcohol advice is changing constantly and it is unclear what advice to follow. Most articles contributed to theme 1, but did not discuss the guidelines in greater detail. The thematic analysis, therefore, was strongly informed by the large minority of articles that discuss guidelines in more detail, and the findings of the analysis reflect that these more discursive articles were primarily negative in tone. Each of these themes is discussed in turn.

Factual reporting of the guidelines

Most articles mention the guidelines very briefly, in a factual manner and without significant linkage to broader themes within the articles. For example, in an article about lifestyle changes to prevent diabetes, only one sentence refers to the guidelines, which tells readers to keep in mind that the recommended guidelines are now only 14 units per week for men and women (paraphrased). 106

Similarly, in a news article about drinking on cruises, the guidelines are mentioned in only one sentence, which states that the average passenger drinks 168 units per week, according to Drinkaware website’s unit calculator, which is eight times the recommended allowance for men (21 units) and 12 times above the recommended level for women (14 units) (paraphrased). 107

In most cases, the reason for sticking to the guidelines (to prevent ill health) was implied rather than explicitly stated. This is achieved by stating the link between alcohol and health outcomes, directly followed by the guidelines or by referring to exceeding the guidelines as drinking at unsafe levels. The vast majority of articles mention the consumption level for both men and women. If an article mentioned the guidelines for only one sex, this was typically because it discussed a condition that affects more men than women or vice versa. For example, Push Doctor’s (an online medical consultation service based in Manchester, UK) medical officer, Dr Dan Robertson, recommended that men stick to the recommended weekly alcohol limit to prevent erectile problems. 108

Many articles reported the guideline amounts in equivalent alcoholic drinks. This information was largely accurate, but there were variations in how it was presented. Most sources opted to provide the equivalent in an integer of drinks, but some sources provided the information in fractions of a glass or how many units are typically contained in a standard-sized drink, such as a bottle of wine or pint of beer:

14 units is equivalent to 14 single measures of spirits at 37.5 per cent ABV [alcohol by volume]; seven pints of 4 per cent strength beer, nine and one-third 125 ml glasses, seven 175 ml glasses, or four and two-thirds 250 ml glasses of 12 per cent-strength wine.

News article, The Independent, 8 January 2016; reproduced with permission from The Independent109

The UK Department of Health recommends that men should drink no more than three to four units of alcohol a day and women should drink no more than two to three units a day. A 750 ml bottle of red, white or rosé wine with an alcohol content of 13.5 per cent contains 10 units. A standard 175 ml glass of red, white or rosé wine contains just over two units and a large 250 ml glass contains three units. A small glass, at 125 ml, contains 1.5 units.

News article, The Independent, 26 November 2015; reproduced with permission from The Independent110

Few articles reported the full set of guidelines including auxiliary advice. Those that did were mainly published around the announcement of the new guidelines. The advice that one should spread alcohol consumption over multiple days and have at least 2 alcohol-free days per week was most often communicated alongside the drinking guidelines. Similar to the recommended consumption levels, this advice is often merely stated without further elaboration:

How much alcohol is too much? Some can probably safely drink more than others; your size, genetics, lifestyle and state of your liver make a difference. But in general, less than 14 units, spread over at least three days a week should be OK. That’s just under a bottle-and-a-half of wine (ABV 13.5%), or an average of one 175 ml glass per day. For beer drinkers, that’s less than five pints of higher strength beer (ABV 5.2%) a week.

News article, The Guardian, 25 January 2016; courtesy of Guardian News & Media Ltd111

Criticism of the scientific basis for the guidelines

Criticism of the scientific basis for the guidelines focused on three main areas: the emphasis on cancer risks while downplaying of the benefits of moderate drinking, the guideline consumption level itself and the integrity of the scientific process.

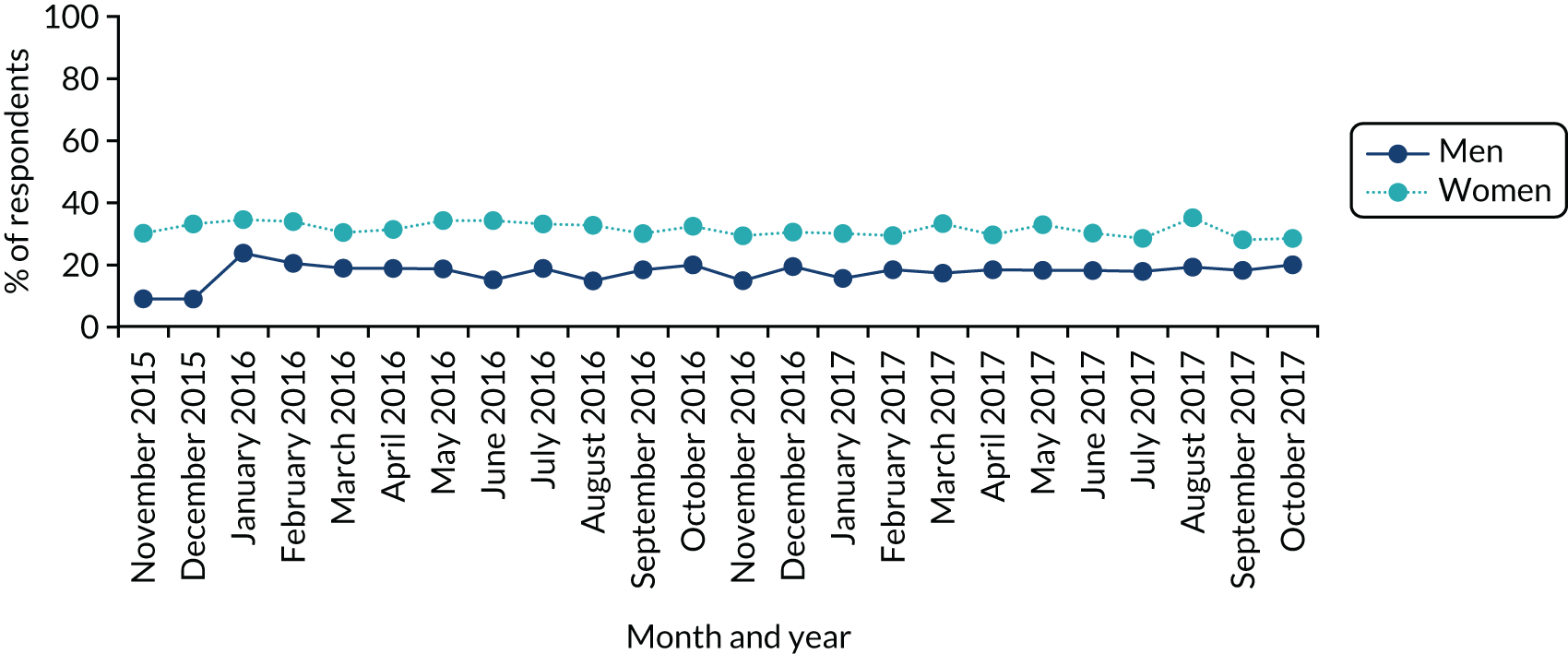

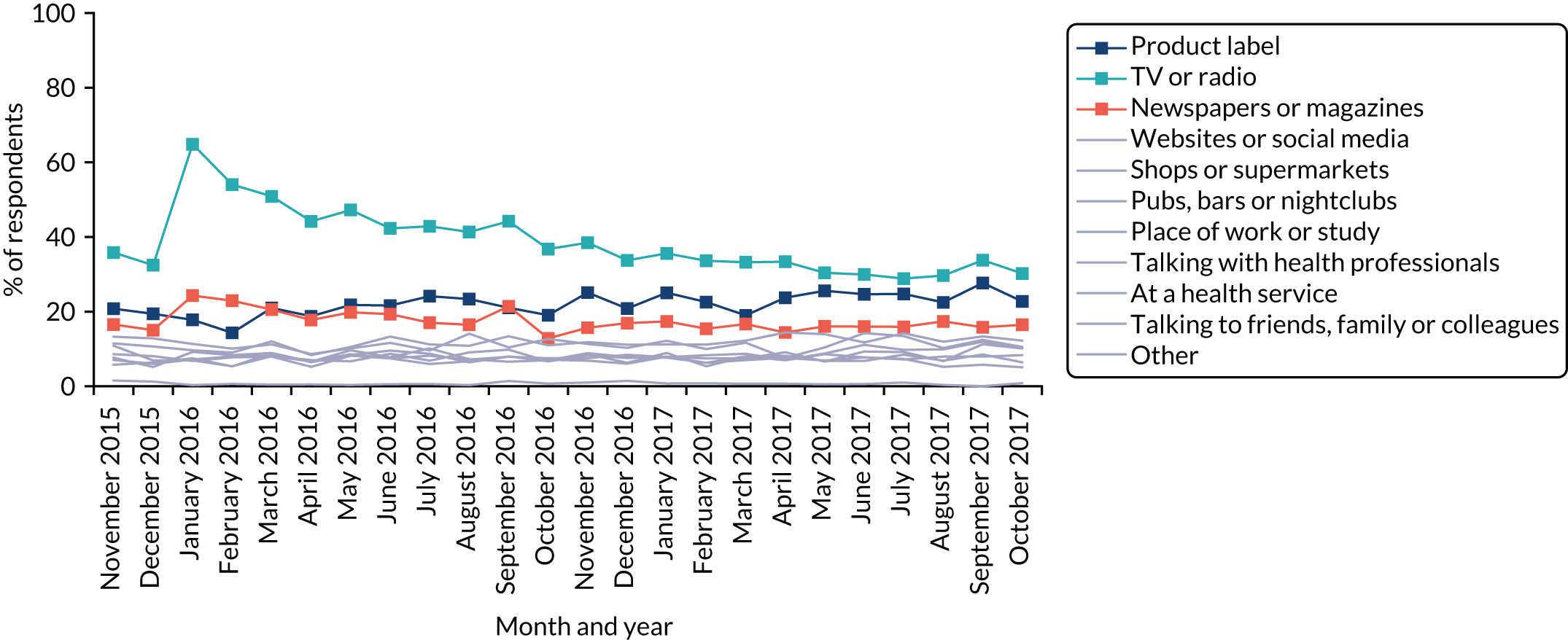

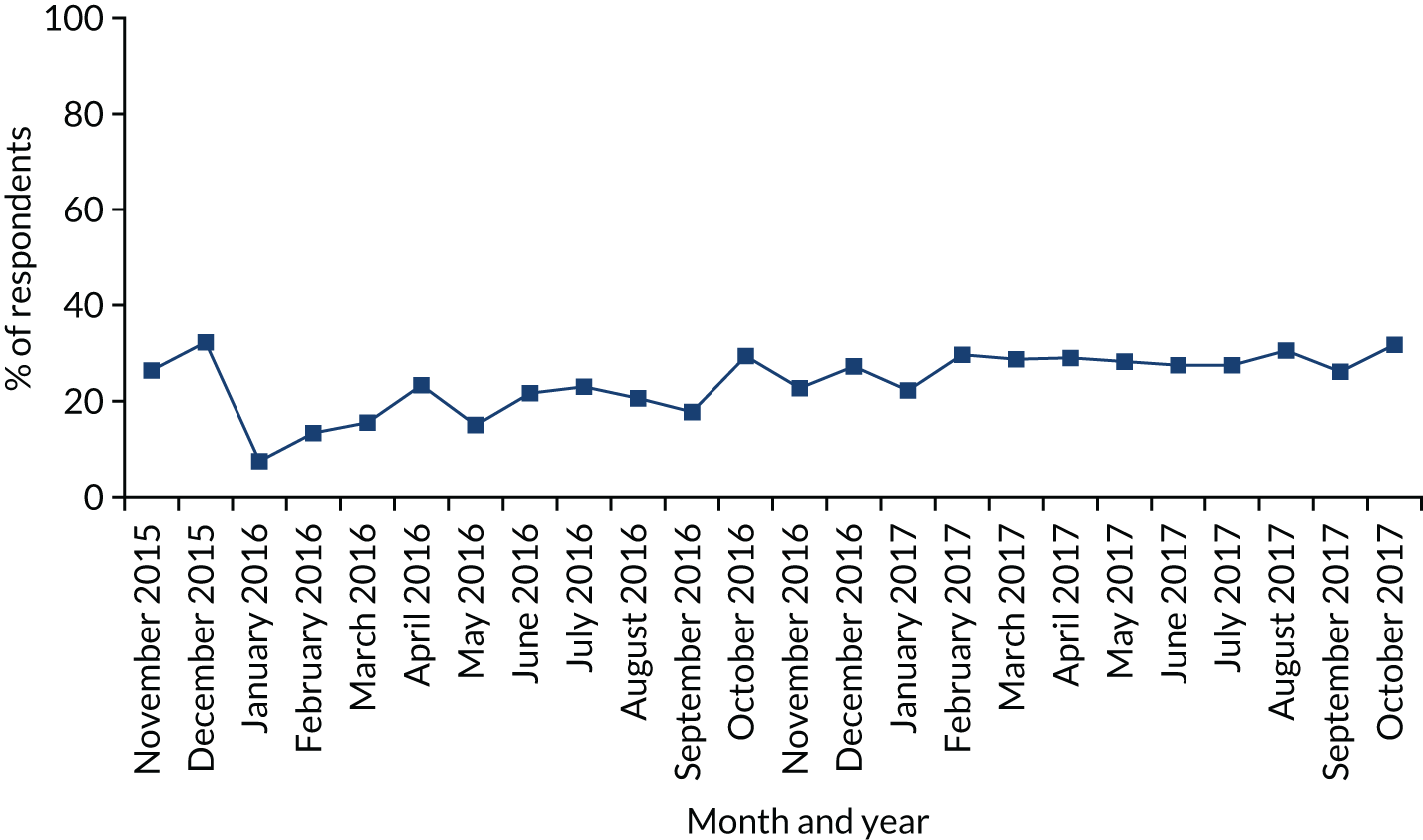

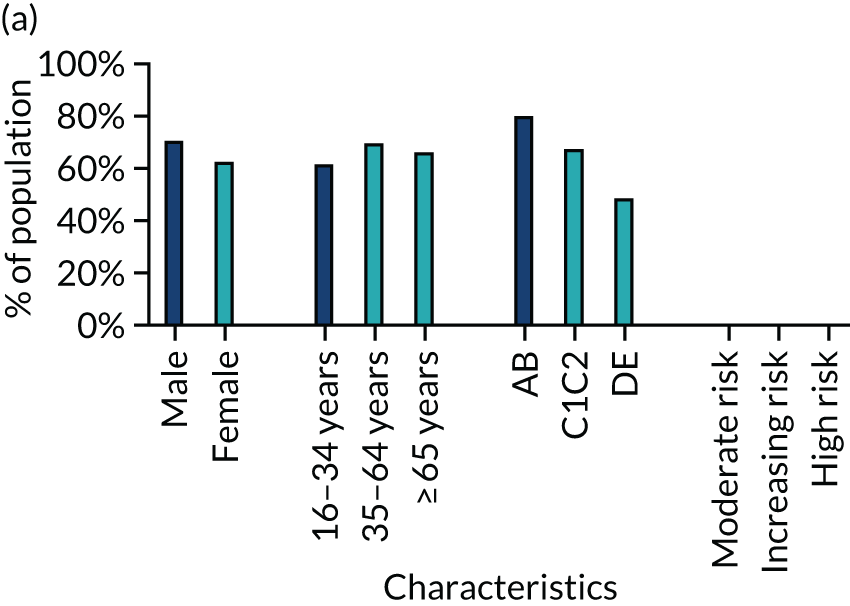

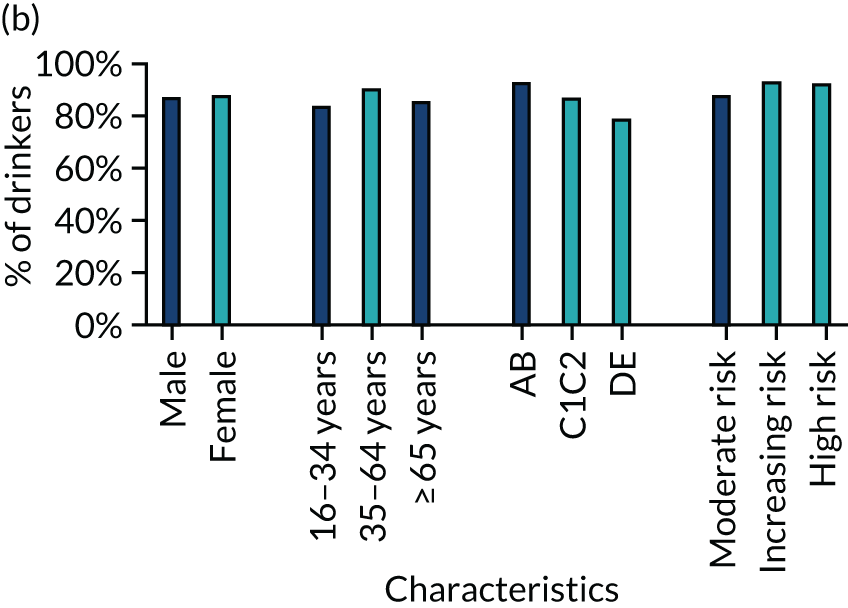

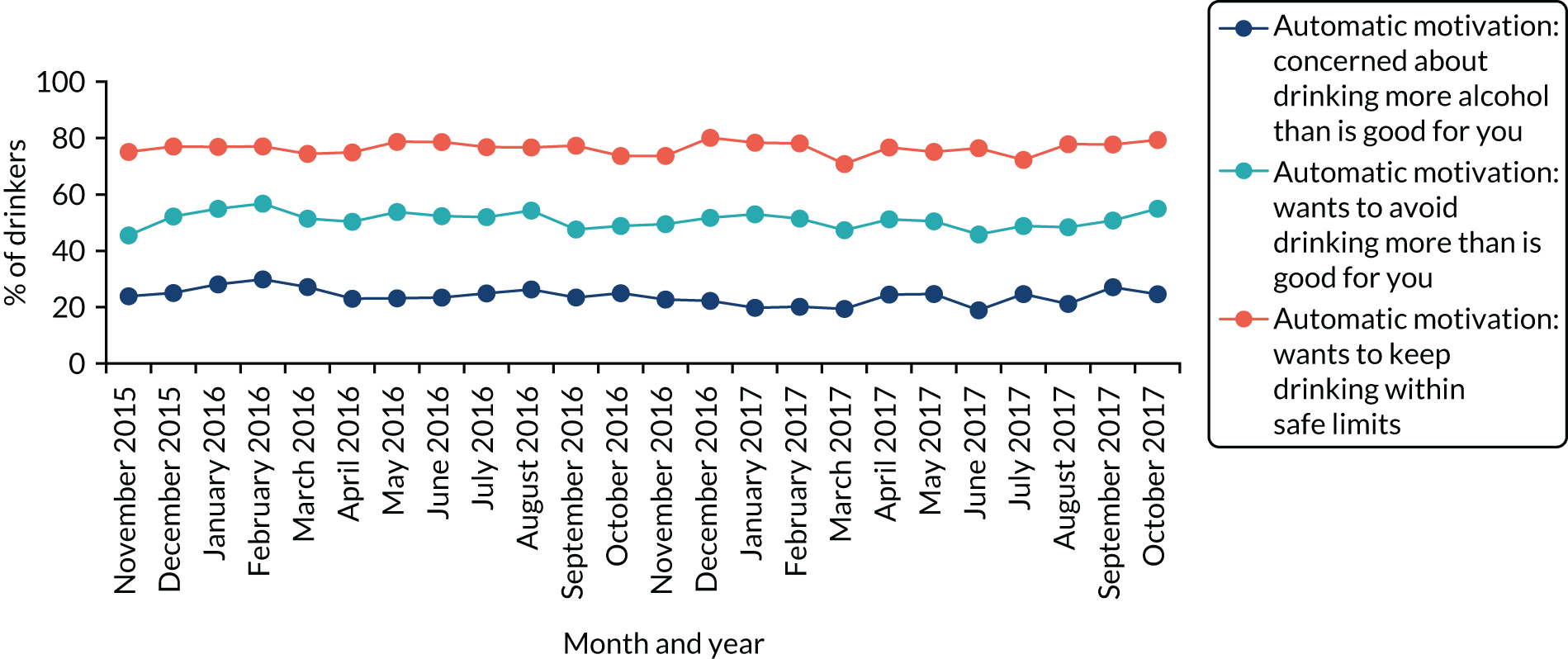

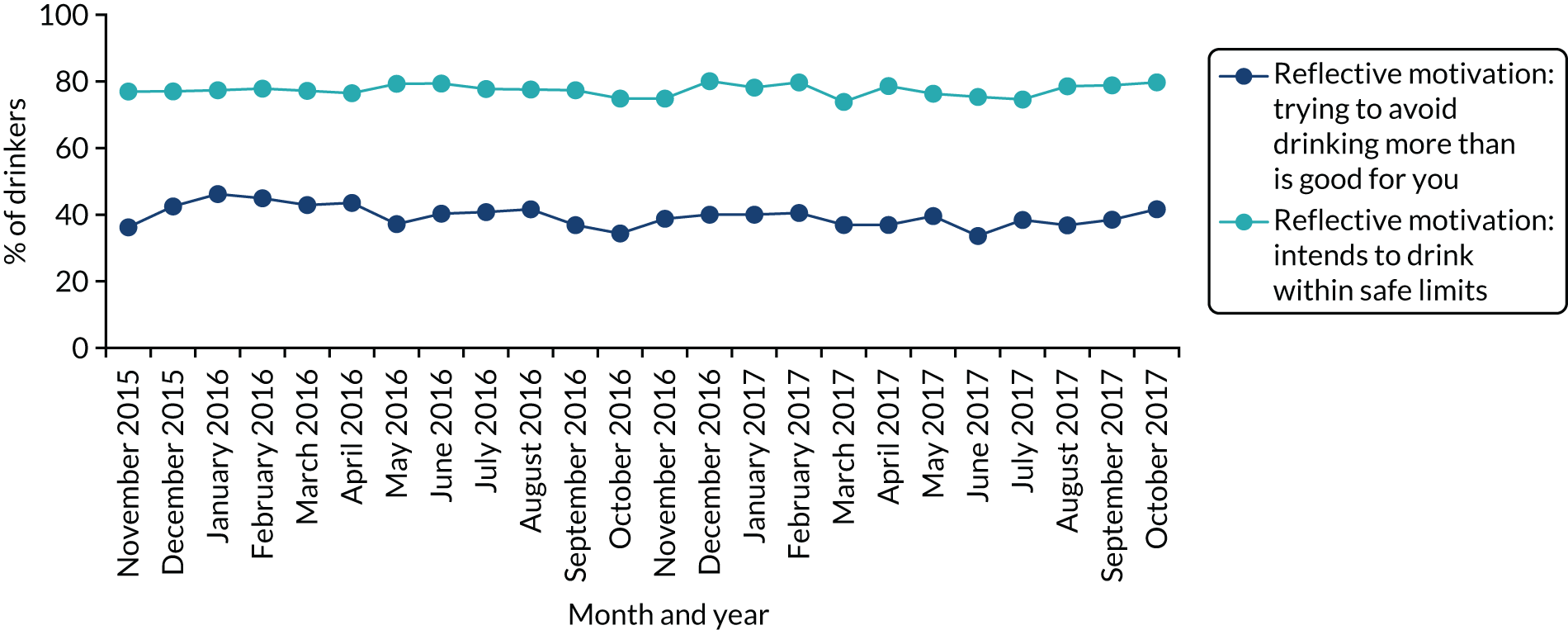

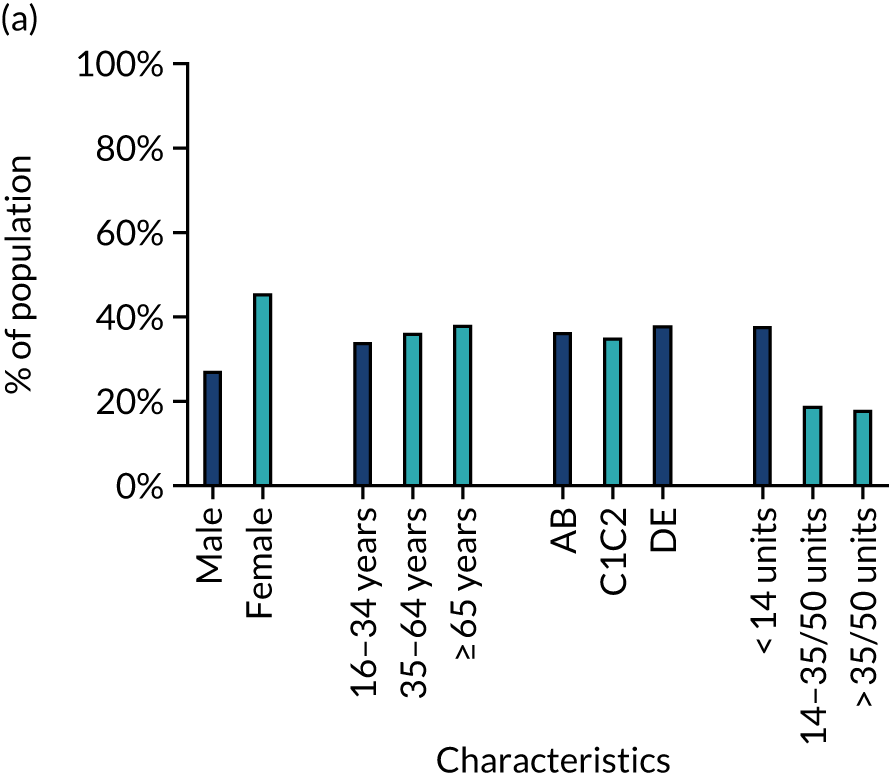

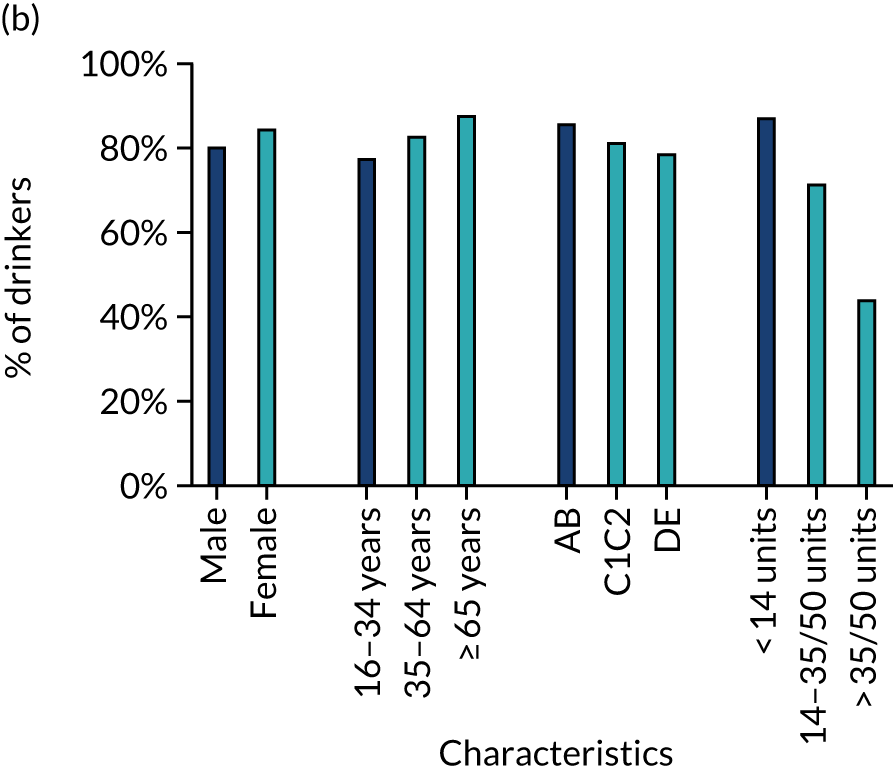

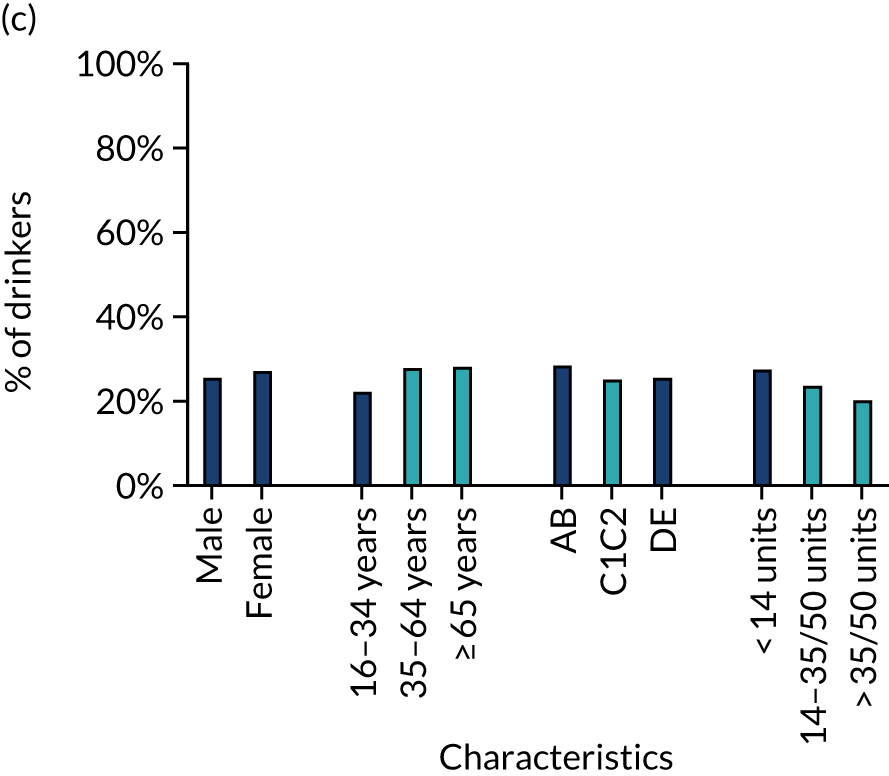

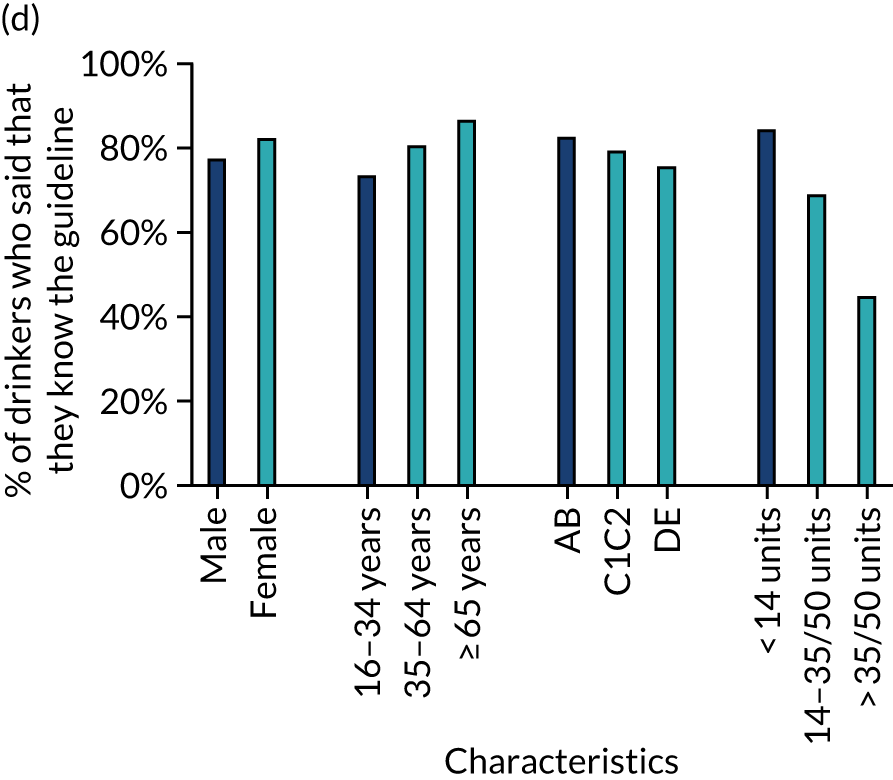

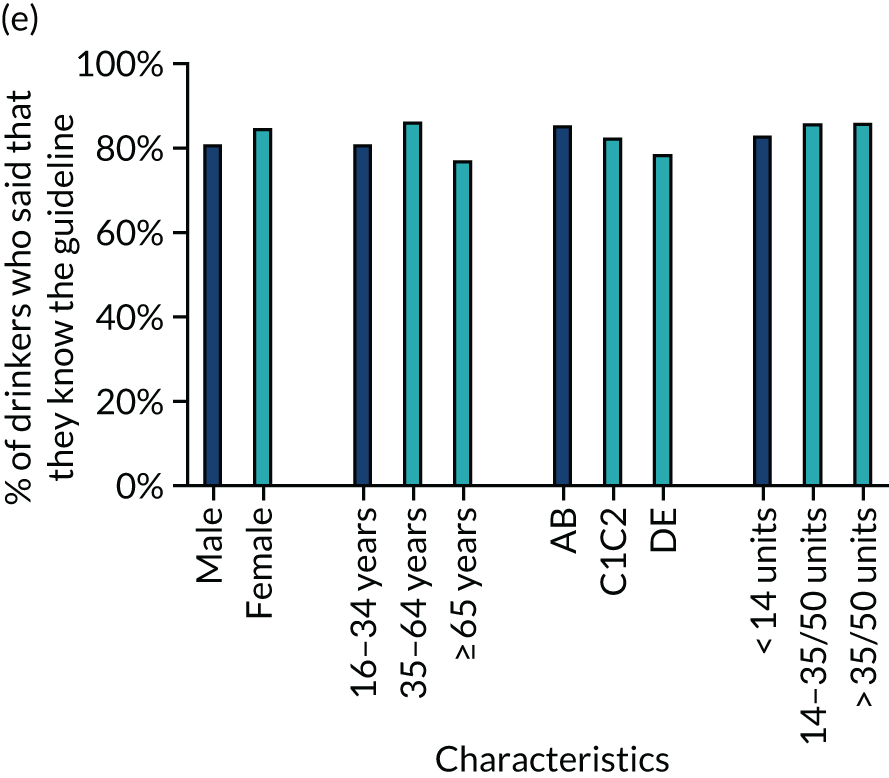

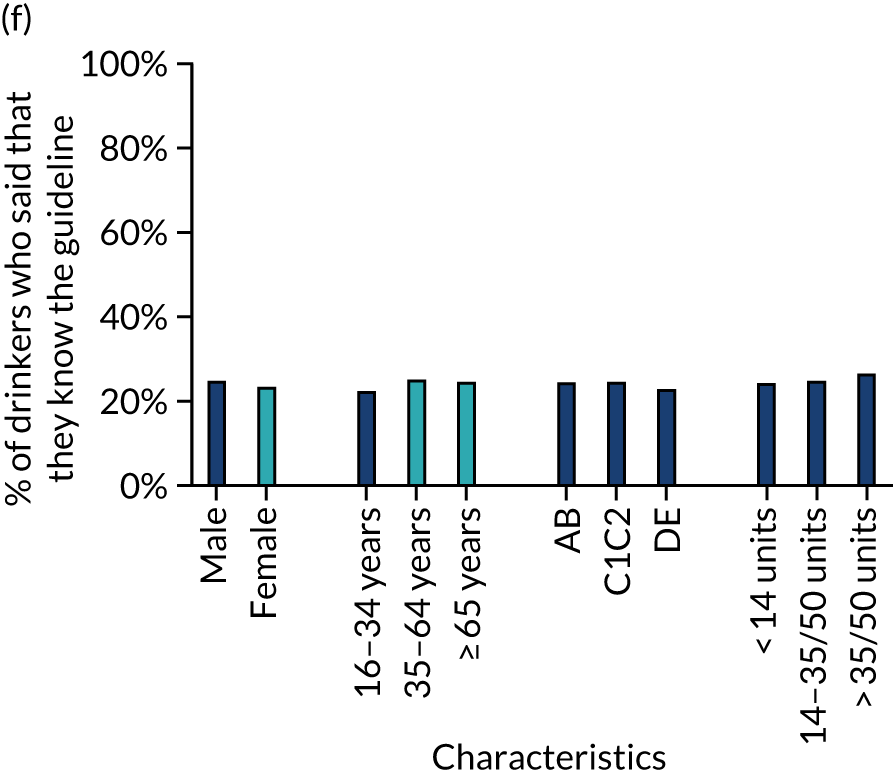

Although not part of the guidelines, much criticism addressed the ‘no safe level’ message, which was prominent in news reports announcing the revision to the guidelines because of the simultaneous release with the cancer report. The no safe level message was given further prominence as public health actors communicating the guidelines also emphasised it in their interviews and other statements. 112 This criticism was often linked to proponents of the guidelines also downplaying previous evidence that moderate drinking benefited cardiovascular health. 113,114 The cancer risk was not challenged directly, but critics allege that the guidelines failed to take into account evidence of benefits to cardiovascular health or that these benefits might outweigh any increased cancer risk. Criticism of this kind comes from a variety of sources, including alcohol industry actors, free-market think tanks and pro-alcohol consumer groups, but also reputable scientists and laypeople. The first quotation below also illustrates how industry actors often criticised the drinking guidelines using multiple arguments within a single sentence, an approach noted in the context of MUP by Hilton et al. 80 A leading drinks producer told The Mail on Sunday that it would send a strongly worded response, stating that the new limits go against decades of scientific research, that having the same limits for men and women contradicts research on how men and women process alcohol, and that the limits are different from almost every other country. He said that there was no discussion about the changes beforehand and the government is consulting only on how the guidelines will be communicated. The drinks producer believes that the content needs to be discussed more, particularly the scientific basis for the guidelines. The Portman Group said that it would also be voicing reservations about the interpretation of the evidence. The group said that more than four in five adults are already drinking within the lower-risk guidelines. Guidelines are important because they help people make informed decisions and the group is concerned that the proposed guidelines are confusing because they are not clear about the relative risks of sensible drinking. 115 Top academics from the Royal Statistical Society criticised the advice, stating that not all alcohol was dangerous and stressing a ‘protective effect’ from small amounts:116