Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 15/183/26. The contractual start date was in March 2018. The final report began editorial review in March 2020 and was accepted for publication in October 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2021. This work was produced by Fulton et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2021 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

Although UK smoking rates have hit an all-time low, 6.1 million adults in the UK are current smokers. 1 The significant role of smoking as a cause of chronic illness and preventable death endures worldwide. 2 UK NHS Stop Smoking Services (SSS) offer free behavioural and pharmacological interventions proven to increase the likelihood of quitting compared with ‘going it alone’. 3 SSS are typically offered within general practice and pharmacy settings, although increasingly they are offered as part of a package of lifestyle services hosted in a variety of community settings (CSs), such as supermarkets, libraries and community centres. 4

The effectiveness of SSS is determined by smoking abstinence 4 weeks after the quit date set, confirmed by standard carbon monoxide (CO) testing. 5 Studies indicate that 4-week quit rates are a reliable predictor of long-term abstinence, with 6-month follow-up data revealing only a small increase in the accuracy of such predictions. 6

Service uptake by smokers is, however, in decline. 7 Potential explanations for this include reduced economic resources for promoting services, and that smokers now favour the use of electronic cigarettes (ECs) over behavioural support for cessation, although this remains unclear. 8 Nonetheless, a survey of stop smoking advisors found that the majority (95%) had encountered smokers who were also using ECs. 9 This suggests that smokers may recognise ECs as an adjunct rather than an alternative to behavioural support for smoking cessation, and the effectiveness of ECs as a stop-smoking aid is likely to be enhanced when coupled with SSS behavioural support. 10 The growing use of ECs need not impede SSS access if services promote a clear EC-friendly approach, with consistent training and policy. 11

Despite significant budget cuts, sustained investment in SSS is being called for by the All Party Parliamentary Group on Smoking and Health,12 to support the ambition of achieving a smoke-free population by 2030. 13 However, evidence suggests that SSS reach only 5–10% of current smokers. 14 Investment in promotion and interventions to increase uptake of SSS is warranted. The UK Government funded a series of mass media tobacco control campaigns between 1999 and 2010 to emphasise smoking harms and SSS support. These campaigns were suspended owing to significant costs associated with delivery in 2010, enabling analysis of their impact on SSS uptake. Although calls to stop-smoking telephone lines, smoke-free website visits and requests for cessation support packs decreased significantly, there was no effect on SSS attendance,15 suggesting that the campaigns were not effective in enhancing SSS uptake.

Digital interventions promoting SSS help-seeking by smokers offer a potentially cost-effective solution. Current data suggest that internet access and smartphone use are increasingly widespread, with an estimated 96% of 16- to 24-year-olds, 98% of 25- to 34-year-olds, 94% of 35- to 44-year-olds, 87% of 45- to 54-year-olds and 71% of 55- to 64-year-olds owning a smartphone. 16 However, questions remain regarding whether or not they increase health inequalities if users of digital technologies are principally from higher socioeconomic status (SES) groups. Interventions require careful testing to ensure that they do not promote a ‘digital divide’. This is pertinent given that smoking is most prevalent in more deprived communities. 17 However, a trial of ‘StopAdvisor’,18 a digital smoking cessation intervention, found that it was effective at achieving cessation for smokers from lower but not higher SES groups, suggesting that digital interventions can help to reduce rather than increase health inequalities.

The uptake of SSS from lower SES groups remains varied across geographical localities. 19 Several studies suggest that smokers from more deprived groups are less aware that SSS exist, or of the services that they offer. 20–24 Negative beliefs about SSS include uncertainties about whether or not they will help or if they will be stigmatising, guilt-inducing or judgemental. 20–23 Concerns from smokers about a lack of information and perceived availability of services have been highlighted, alongside work commitments and time constraints, which can impede attendance. 25 The authors conducted studies to explore these perceived barriers and facilitators in depth,26 and discovered similar findings, including beliefs that needing support to quit smoking is a sign of weakness27 and that smokers should not need help. Therefore, an understanding of the potential barriers to access, particularly in lower SES groups, is paramount, and should be addressed within the development and evaluation of interventions designed to increase SSS access.

These barriers to accessing SSS have not, to the authors’ knowledge, been addressed sufficiently within interventions or health promotion campaigns targeted at smokers. Research has shown that providing information about SSS may increase access; for example, when booklets explaining how and why services help smokers are given to those who have registered with SSS, this can increase attendance rates. 28 A more recent trial (Start2quit) provided letters to smokers with personalised risk information and the offer of SSS taster sessions, resulting in improved SSS uptake. 29

Given that public health budgets are under increasing pressure, and evidence suggests that smokers seeking help themselves are more successful at stopping than those referred by others,30 it will become increasingly important that SSS are promoted to smokers who otherwise may not have recognised the benefits of attending. This will also involve ensuring that there is informed decision-making and encouragement to attend, to reduce ‘did-not-attend’ (DNA) rates and the costs that these incur. Implementing inexpensive strategies to address these factors will maximise effectiveness in a resource-restricted public health context.

StopApp™ (Coventry University, Coventry, UK) is a brief, digital behaviour change intervention [web application (app)] developed with the aim of increasing booking and attendance at SSS, especially by those from more deprived groups. Based on evidence about the barriers to service access and designed using the Behaviour Change Wheel,31 it first aims to enhance motivation to attend SSS using a series of behaviour change techniques (BCTs)32 derived from a systematic assessment of the barriers and facilitators that smokers typically experience. 27 StopApp then supports instant appointment booking, providing choice regarding time and location via an application programming interface (API). This infrastructure is supported by pharmacy and general practice data management software (PharmOutcomes and Outcomes4Health, both owned by Pinnacle Healthcare Ltd, Teddington, UK) that is used extensively by UK pharmacists and general practices to manage SSS use data. For the purpose of this feasibility trial, we had access only to pharmacy-based SSS data software (PharmOutcomes) to test the trial methods. However, StopApp could be used to increase attendance at any SSS for which it is possible to embed an API link to the SSS data software system.

Although increasing numbers of digital interventions for smoking cessation support exist,33,34 to our knowledge, StopApp is the first digital intervention to target increased uptake of SSS. If effective, StopApp could provide an important contribution to maximise SSS uptake. Given the novel digital approach that StopApp represents, and the challenges of recruiting smokers into research studies,35 it is unclear from the current evidence base whether or not it is possible to recruit the required sample size for a full randomised controlled trial (RCT). In addition, given concerns around the potential for digital interventions to contribute to health inequalities, the extent to which a trial of StopApp would reach and engage smokers from a range of sociodemographic backgrounds, including those most at risk of poor health outcomes from smoking, needs to be established. Therefore, a feasibility RCT was deemed necessary in order to assess whether or not a future, definitive RCT is possible.

Aims and objectives

The aim was to establish the viability of a future, larger, multicentre RCT of the StopApp intervention. The specific objectives are outlined below.

Primary objective

The primary objective was to conduct a feasibility trial of StopApp to estimate recruitment and attrition rates of participants across three settings, namely general practitioner (GP) surgeries, CSs and online, at baseline, intervention access and 2 months’ follow-up.

Secondary objectives

The secondary objectives of the MyWay feasibility trial were to estimate:

-

the acceptability of randomisation and the StopApp intervention for participants

-

the acceptability of the outcome measures and measures required for cost-effectiveness analyses in a future trial

-

the key costs that would be incurred in delivering the intervention and usual care, including a comparison of DNA rates between each arm of the trial

-

the feasibility of accessing SSS and GP data (if recruited via a GP) on attendance, quit dates set and 4-week abstinence rates for trial participants

-

any differential recruitment and attrition rates across socioeconomic groups, age and sex

-

the rate of SSS booking and attendance in the intervention and control groups to estimate the event rate of the primary outcome measure for a future trial, and to support future trial sample size calculations.

Chapter 2 Methods

Design

This was a two-arm, 1 : 1 allocation, double-blinded, parallel-group, individual participant randomised feasibility RCT of StopApp (intervention) compared with usual promotion of and provision of contact details for SSS via an online leaflet (control; see Report Supplementary Material 1). The study included a nested qualitative process evaluation with participants and staff involved in participant recruitment across the three settings to assess the acceptability of the research processes, randomisation, measures and the intervention.

Study population for feasibility trial

Eligible participants were current smokers (of any tobacco amount and type) aged ≥ 16 years who were either (1) registered with one of six participating GP surgeries in Warwickshire, (2) accessing participating Warwickshire-based local community services (e.g. children’s centres, libraries, well-being hubs) or (3) viewing open-access advertising for the study on Warwickshire-based social media (SM) platforms [e.g. Twitter feed (Twitter, Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA; www.twitter.com) of local public health department; Facebook page (Facebook, Inc., Menlo Park, CA, USA; www.facebook.com) of ‘What’s on in Warwickshire’]. Participants were not excluded if they had previously attended SSS. Eligible participants had to be able to comprehend written English, have access to the internet and have a mobile phone to complete study measures, view intervention or control content, and be able to receive short message service (SMS) reminders. As SSS appointments were available only in Warwickshire, participants had to live or work in Warwickshire.

Study population for process interviews

Process interview participants comprised (1) smokers who had taken part in the main study who were willing to participate in an interview, and (2) professional staff from the pharmacies offering SSS appointments and two of the recruitment settings, including GPs and practice managers and staff from local community services.

Study protocol and intervention

The study protocol was approved by the NHS West Midlands – Edgbaston Research Ethics Committee (reference 18/WM/0170) and was later published. 36

Control

Participants received a link to a web page displaying Warwickshire’s standard stop smoking service provision information (‘Quit4Good’). The control website does not include behavioural science theory or BCTs to facilitate booking or attendance, nor does it include the facility to book an appointment online; rather, participants can telephone for an appointment.

Intervention

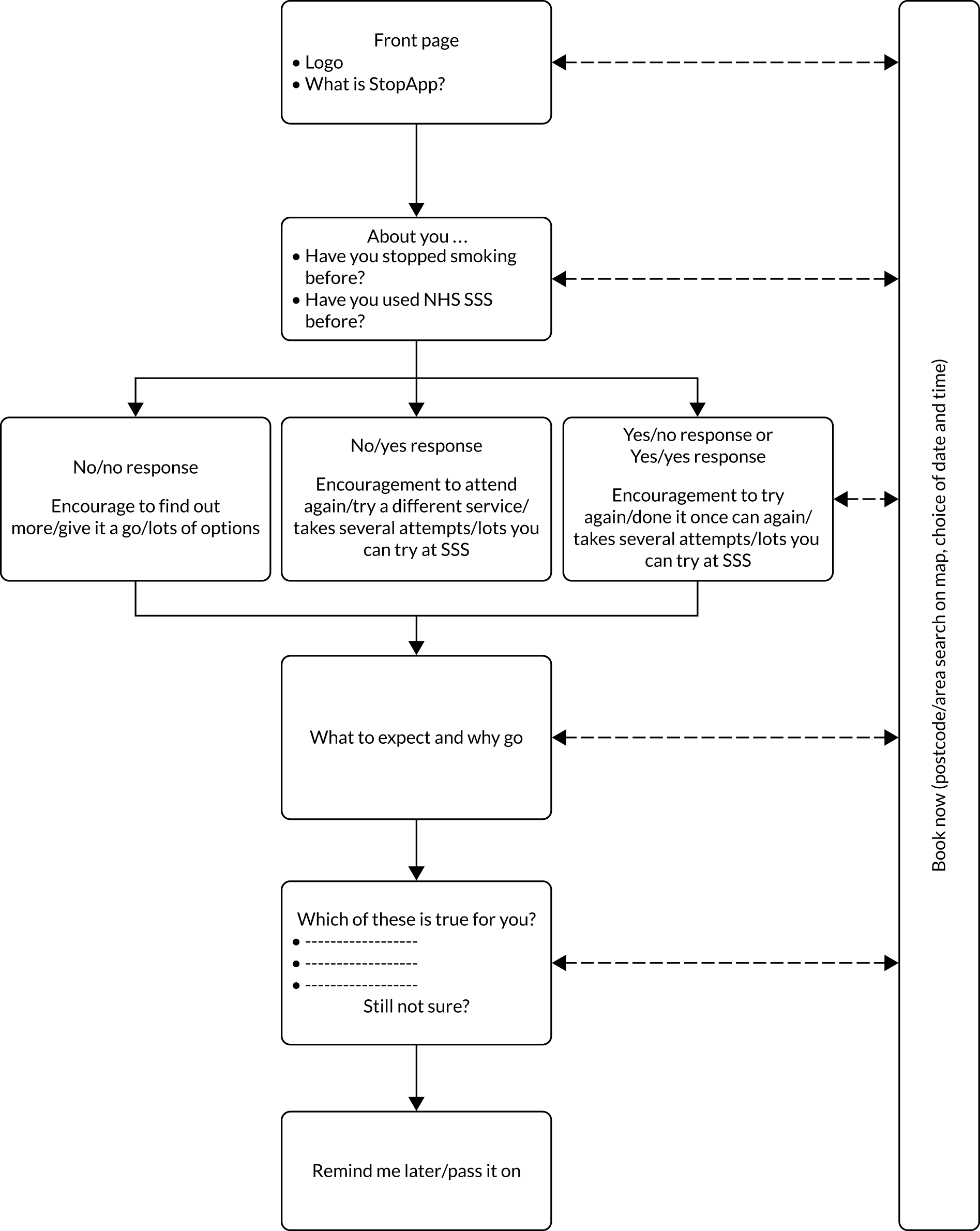

StopApp is a brief web app intervention designed to be used on a single occasion to address the psychological and practical barriers smokers may experience when considering help from SSS [Figure 1; see Report Supplementary Material 2]. It is intended to improve the reach and effectiveness of standard SSS promotion that local authorities (LAs) and SSS may use to recruit smokers. The process involved in the development of the StopApp, in terms of its theory and evidence base, and patient and public involvement (PPI) in content and functionality design, has been described elsewhere. 26,27,37 Figure 2 illustrates the participant flow and message tailoring content that StopApp recipients experienced. Initially, StopApp users are given persuasive messages applying BCTs tailored to past experiences of quit attempts and SSS use. They are given clear information about what to expect from the services and the benefits of SSS use; for example, the intervention provides key messages about the services and the multiple strategies for quitting that are available, the benefits of attending and the non-judgemental, friendly support provided. Some message content is derived from genuine feedback from SSS users. Subsequently, users are asked to select barriers to SSS use that they may be experiencing, and further persuasive content employing BCTs is tailored to personal perceptions. At all times, the opportunity to ‘book now’ is provided and anyone who does not yet feel ready but remains interested can request a reminder to come back to StopApp in the subsequent month. Navigation and user experience were designed using behavioural science insights to ensure that the intervention was intuitive, attractive and easy to use. To operationalise the ‘book now’ facility, StopApp was connected to the online outcomes reporting systems owned by Pinnacle Healthcare Ltd and used by SSS in pharmacies (PharmOutcomes) and GP surgeries (Outcomes4Health) in Warwickshire and other UK LAs. These secure systems support appointment booking and record SSS outcome data such as quit dates and CO-verified 4-week quit rates for service commissioners. StopApp was programmed to ‘talk to’ these systems and access live data about which services had appointment availability. StopApp users could then choose a location and could see appointment availability over the following 2 weeks. Participants selected an appointment time and received confirmation (date and location) via their mobile phone. In future, through collaboration with other providers of similar data management systems, StopApp could be adapted to link to a range of systems used by other types of service provider such as ‘QuitManager’ (Bionical Solutions Ltd, Willington, UK).

FIGURE 1.

Image of StopApp as viewed on a mobile phone.

FIGURE 2.

User flow and message tailoring within StopApp.

Recruitment settings

To assess the best method for recruitment in a potential future definitive RCT of StopApp, recruitment across three settings was trialled. The settings were recruiting (1) via participating GP practices at which smokers were registered, (2) via advertising and information provided in community services and settings, and (3) via SM channels.

The West Midlands Clinical Research Network (CRN) recruited a total of six GP surgeries and identified smokers on their patient lists. Where more than one smoker cohabited, the smoker whose first name was alphabetically first was selected for invitation to the study to avoid contamination across trial arms. Other members of the household who were smokers were sent control arm information about SSS at the end of the recruitment and follow-up period. Four surgeries sent study invites to smokers by text message containing a link to the study website. The two surgeries that were not enabled to send communications to patients by text message or e-mail sent invitations with study website details by post using ‘Docmail’ services (CFH Docmail Ltd, Radstock).

A wide variety of CSs were identified to promote the study. Initially, these included libraries, leisure centres, well-being hubs, children’s centres, the family information service and the registrar’s office, and, during recruitment, we also advertised via workplaces including the Warwickshire County Council’s intranet, newsagents and public houses. There was also a bus advert campaign, with adverts appearing at bus stops and inside buses in Warwickshire.

The marketing and communications department at Warwickshire County Council supported the SM campaign and promoted the study via a range of Warwickshire-based SM channels. They also set up paid targeted advertising via Google Ads (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA) and Facebook Ads. The study team supported the online promotion via ‘retweets’ and posts of their own on relevant Facebook pages, with permission from administrators.

Recruitment and randomisation procedure

Smokers who received or viewed study invitations or promotional materials and were interested in participating in the research could access more information by clicking on or entering a link to the study web page online. Each recruitment setting had a different study URL in order to monitor where recruits were from. The study web page was delivered via secure, bespoke study management software (‘eNgage’) and this is where individuals could access the participant information sheet. Those who chose to participate were required to endorse mandatory consent statements before signing up (involving creating an account with their name and e-mail address) and were then directed by eNgage (St Louis, MO, USA) to complete the baseline measures set up in Qualtrics (Provo, UT, USA) survey software. On completion of the baseline survey, participants were routed back to eNgage, where the preprogrammed randomisation algorithm assigned participants to either the intervention arm or the control arm. Researchers and participants were blind to allocation. Randomisation used a 1 : 1 ratio, stratified by age, sex and level of deprivation, with pure minimisation to ensure balance. The randomisation algorithm was tested and approved by the Clinical Trials Unit at the University of Warwick. Our statistician regularly monitored allocation by condition using a dashboard in eNgage each week to ensure that a balance was achieved. Following randomisation, both groups received a near-identical message and web link. The web link took participants to either the control website or StopApp. At the same time, an e-mail containing the link, assigned to the participant’s unique identification number, was sent to participants to allow them to access the material at a later date. In relation to StopApp, participants could, therefore, go back and book at a later date. A reminder e-mail was sent to participants 2 weeks later. In the participant information sheet within eNgage, participants in both conditions were told that if they wished to book an appointment at the SSS they were free to do so, but, in taking part, were under no obligation to do so. An e-mail with a link to the control ‘Quit4Good’ leaflet was sent to anyone who contacted us after recruitment until the study ended.

Challenges with recruitment and deviation from planned protocol

Recruitment began on 7 January 2019 and, after an initial flood of participants in weeks 1 and 2, enrolment trailed off. We therefore sought approval for an amendment to the protocol from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) and NHS research ethics committees to provide an e-voucher payment of £5 per completed survey. This amendment to the protocol was included in the published study protocol. 36 Participants who had already participated were contacted and offered the e-voucher. At the same time as the e-voucher payment was introduced, our monitoring of participant access to the study website via linked analytics software demonstrated that there was a high ‘bounce’ rate (people clicking the link to the study and then immediately leaving the web page). Exploration of why that might be revealed that 86% of those accessing the study website were doing so on a mobile phone, and some information was difficult to read in this format. We therefore paused study recruitment for 1 week while the mobile optimisation features of eNgage were improved. Recruitment resumed and these amendments resulted in an improved recruitment rate.

Recruitment monitoring at the onset of the eighth week revealed a sudden influx of participants via the SM URL. Initial investigation of the data revealed that the majority of those recruited at this sudden point of influx were fraudulent and ineligible participants from other countries, most likely to be attempting to access the e-vouchers. Recruitment was paused again for a total of 4 weeks while further investigations took place and remedial action was taken. A clear set of indicators of ineligible participants were identified and then applied to the data in order to select and remove these cases. These indicators included checking the geographical location where each case had originated, the timestamp of the response, the e-mail address given and data provided in baseline questionnaires, to see if they were viable responses. It was generally very clear when ‘participants’ were completing several questionnaires in quick succession, as these responses were logged in batches with e-mail addresses that bore no resemblance to the name of the participant supplied in their eNgage account. These cases were removed and additional clarification was placed on the study website and the sign-up page explaining that only eligible participants who were smokers living and/or working in Warwickshire could be accepted into the study and given e-vouchers. We also included messages stating that evidence of eligibility may be necessary, to further deter ineligible participation. These pauses to recruitment resulted in the total period for baseline recruitment running until 31 May 2019, which included a total of 116 days on which recruitment via the study website was live.

Prior to the commencement of the feasibility trial, a data-sharing agreement (DSA) was drawn up between Coventry University and Warwickshire County Council, which commissions the SSS, in order to obtain access to the data on participants’ SSS use that are recorded by Pinnacle Healthcare Ltd. This was a requirement from Pinnacle Healthcare Ltd to ensure that permissions had been granted by Warwickshire County Council for it to release a report of the data it holds to Coventry University, to coincide with participant consent. We also sought written permission from the participating pharmacies at the point of inviting them to join the trial to ensure that they gave their approval for using SSS data. However, after the trial had commenced, concerns were raised about who owned the SSS data, and whether it was in fact the individual pharmacies that should give this more formal permission and, therefore, be required to sign a DSA to release their SSS data. As a result, it became necessary for the research team to action the creation of a series of DSAs between the council, Coventry University and each of the participating pharmacies.

Baseline measures

Baseline data included demographic information [including age, sex, profession, ethnicity and postcode – to identify Indices of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) score], current smoking status and tobacco products used (type and quantity), EC use, previous use of SSS, ease of internet access, and motivation to quit (measured using the one-item ‘Motivation to Stop Scale’38 and a single-item Likert scale39). Pregnancy status was collected to identify participants who would experience a separate NHS care pathway specifically for smoking in pregnancy. Level of social and economic deprivation was measured in several ways to identify the most suitable method for a full trial. This included using postcodes to calculate the standard IMD and quintile scores40 and a five-point version of the National Statistics Socio-economic Classification (NS-SEC)41 based on employment status. Health-related quality-of-life data were measured using the EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L),42 and the ICECAP-A (ICEpop CAPability measure for Adults)43,44 instrument to inform the health economic analysis.

Measurement of engagement with StopApp

The eNgage system was programmed to provide individual-level data about StopApp use from Matomo (https://matomo.org; accessed March 2021) web analytics software. This allowed us to access individual participant-level information about whether or not StopApp was accessed, and how long participants spent on each page of the intervention, including whether or not they reached the booking confirmation page.

Follow-up procedure

Two months after each participant had been recruited to baseline and randomised, eNgage automatically sent them an e-mail with a request to complete an online follow-up questionnaire. Reminders to complete the questionnaire were sent again 2 weeks later. No further attempt to collect follow-up measures was made. Researchers checked that the automated procedures were functioning as planned, with no problems detected.

Outcome measures at follow-up

At the 2-month follow-up, participants were asked to provide self-reports of current smoking behaviour, any SSS appointment bookings made and how they were made (e.g. StopApp, booked with their own GP), and attendance at SSS in the last 2 months, quit dates set and if 4-week abstinence had been reached. Questions about resource use were also given to those who reported any service use, to verify costs to individuals and the public purse in conjunction with using StopApp compared with the control. This included costs and resource use associated with promoting the intervention and usual care (e.g SM marketing, bus advertising), delivering the intervention (e.g. web hosting, text messages) and delivering usual care (e.g. telephone calls to book appointments).

Data collection at participating Stop Smoking Services

The original plan for trial set-up had involved recruiting all GPs and pharmacies able to offer SSS appointments across Warwickshire to participate in offering appointments in StopApp during the trial; however, although GP surgeries were in the process of transferring to the Pinnacle Healthcare Ltd software when trial funding was awarded, they had not completed this process in time to support the trial. In addition, some pharmacies (n = 11) offering SSS appointments in Warwickshire declined to be involved in the trial and did not feature as venues in StopApp.

It had also been our original intention to collect consent to access the objective SSS data of trial participants at study sign-up in eNgage, and provide evidence of this along with a list of study participant names via secure means to Pinnacle Healthcare Ltd (the PharmOutcomes owners). Pinnacle Healthcare Ltd could then search for participants (who had given consent) in its secure database to provide evidence regarding any bookings, attendances, DNAs, quit dates set and 4-week quits achieved, by the end of the trial. Pinnacle Healthcare Ltd decided, however, that it wanted to re-collect consent at the point of service access. In order to facilitate this, all participating pharmacies (n = 28) adopted a procedure for checking the trial participation status of those attending appointments during data collection. Stop smoking advisors were requested to ask participants at the first appointment (1) to confirm that they were taking part in the MyWay study/trial, and, if they did so, (2) whether or not they consented to the research team accessing data on their SSS use, which would be stored anonymously, and (3) how they heard about the research study. To facilitate this process, Pinnacle Healthcare Ltd added these three questions as drop-down menu items in the ‘first appointment’ section of its PharmOutcomes software. This ensured that Pinnacle Healthcare Ltd, as the data controller, could create a report on SSS use by trial participants who consented to their data being shared at the end of the trial. The report identified appointments booked via StopApp, attendance at appointments, quit dates set and CO-tested 4-week quit rates. This report was sent to a secure nhs.net e-mail address within the research team, to match with the questionnaire data. After matching, all identifying information and the e-mail report were deleted. It should be noted that because there were alternative venues where smokers could seek a SSS appointment (i.e. their own GP practice or one of 11 pharmacies who did not agree to support the trial), objective data about SSS use from pharmacies were not considered complete. We had to also rely on self-report data to collect an assessment of numbers of bookings that occurred outside StopApp.

Process evaluation interviews

Participants were asked at the end of the baseline survey whether or not they would be willing to participate in an interview about their trial experience. Willing participants provided contact details. To ensure that a cross-section of views was captured, a sample of approximately 20 participants was targeted, with participants from both arms and different demographic groups represented. The intention was to oversample participants from more deprived backgrounds, as measured by their IMD scores and quintiles. This was to ensure that any factors potentially associated with deprivation (which may have influenced engagement with the intervention or the research process) were fully explored.

Staff from CSs, GP practices and pharmacies who took part were also invited to participate in telephone interviews about their trial involvement. Selected participants and staff were invited to participate in a telephone interview via a link that was sent by e-mail. The link took them back to eNgage, where they could view information about participating in the interviews and complete online consent statements. Participants who gave consent were then contacted by telephone to arrange a suitable time for the interview to take place. In some instances, this took place immediately. The interviews explored participants’ experiences of taking part in the trial, barriers to and facilitators of the process, suggestions for improvement, beliefs about the value of the research methods and the overall impact that it had on them. Interviews were conducted by KK and LS, were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim, and qualitative data were subject to thematic analysis45 by EAF with input from KK and LS. A pragmatic, hybrid approach was used to conduct the analysis in that we were concerned with identifying positive and negative experiences with various predetermined processes within the study, but were open to identifying themes and ideas which summarised the data that had not been predetermined. All researchers involved were experienced in applying this thematic analysis approach to qualitative data. EAF, KK and LS analysed a 10% subset of the interview transcripts independently and met to consider their level of agreement and discrepancies. The transcripts were read in their entirety to gain familiarity with the data and then re-read to highlight examples of ‘meaning’, such as ideas, comments and descriptions, to form codes. Notes regarding these initial codes were made in the margin, for reflection and discussion with the other two researchers. Agreements about discrepancies were reached, and EAF applied agreed principles in all subsequent analyses. A complete list of codes, with example quotes from the text, from all the interviews by subgroup (e.g. all the codes for participants only) were reviewed and grouped together by commonality to create a list of overarching themes (based on the research questions) to describe the data. If themes could be grouped further to create higher-order themes, this was conducted. The final themes were reviewed a final time to ensure that codes were included in the most appropriate theme, and theme names were assigned.

Sample size

Based on RCT data investigating the recruitment of smokers to SSS via letters from their GPs,46 we would need to enrol 980 smokers to detect a 7% difference in attendance at SSS between control and intervention arms in a definitive trial. Based on this estimate, any trial would need to recruit 1.8 participants per day in total to achieve the required recruitment in 18 months. We planned to recruit for 3 months in a single LA provider of SSS, requiring one-sixth of the sample and providing a target of 162 participants in this time frame.

As a result of the challenges experienced during recruitment, outlined in Challenges with recruitment and deviation from planned protocol, a revised target of 120 participants was agreed with the NIHR Public Health Research (PHR) programme manager. This target adhered to recommendations from Teare et al. 47 about having a minimum of 60 participants per arm of a feasibility trial with a dichotomous primary outcome measure. 47 Given that this feasibility study was conducted in a single LA area and any future definitive RCT would be delivered as a multisite trial, a target of 120 participants still represents a conservative target for what may be possible in a national multicentre trial. With a sample size of 120 participants, the recruitment rate of smokers for a full RCT was calculated as estimable with a precision (95% confidence interval width) of ± 5%.

Data analysis

Data from Qualtrics were downloaded and analysed using the Statistical Product and Service Solutions (SPSS v25). The overall recruitment rate was calculated as the total number of participants recruited divided by the number of days recruitment was live, to provide a recruit per day figure for one LA. To enable comparison across recruitment settings, the same calculation was made for each of the different settings, and for GP surgeries the rate was also calculated as the proportion of those recruited from those identified as smokers and invited to participate, expressed as a percentage. Cost per baseline recruit was calculated by summing the total costs spent to promote and advertise in each setting divided by the number of recruits achieved there. Attrition rates across all three settings were calculated as the proportion of those lost to the 2-month follow-up, expressed as a percentage. Attrition at baseline (i.e. consented but no completion of measures) and at intervention access was also calculated in this way. Owing to low frequencies of data in some of the ethnicity categories, which would impair statistical analysis, the variable was reduced to four categories: ‘white British’, ‘white other’, ‘all mixed background’ and ‘African/Asian background’.

An analysis of variance (ANOVA) test was conducted for continuous data and the Kruskal–Wallis test was conducted for ordinal data, to assess any differential recruitment between the three settings. Statistical assessments were conducted at the 5% level of significance or 95% confidence intervals. We also asked participants in the process evaluation how they felt about the randomisation process and their experience of the study methods. To assess the acceptability of the StopApp intervention, we explored engagement using Matomo analytics and asked participants randomised to the StopApp arm for their views during the process evaluation interviews.

To assess the acceptability of measures, including outcome measures and measures needed to evaluate cost-effectiveness in a potential future definitive RCT, we considered the proportion of missing data across study measures. Missing value analysis identified data missing at > 5% on any single measure. Those interviewed were also asked about the acceptability of the questionnaires that they completed.

To assess the health equity of the study methods, we report on the spread of age, sex, ethnicity and SES represented in baseline recruits; those who completed follow-up and those who did not; and the differential attrition by sociodemographic characteristics of the sample.

To assess the feasibility of accessing SSS data on booking, attendance, quit dates set and 4-week quit rates, we report on the challenges experienced around data access. We also report rates of booking, attendance and quit rates from both the self-report data and the objective data, and have calculated the event rate of booking in the intervention arm in support of a future trial sample size calculation.

The key costs incurred in delivering the intervention and the usual-care data are examined in Chapter 5.

Data analytics

Data analytics software (Matomo) was used to measure the attrition rate at intervention access and the level of engagement with the intervention. This software enabled us to observe the number of StopApp pages viewed, where participants exited and the interactions they had with the intervention, including button clicks.

Patient and public involvement group

A PPI group of 11 smokers from a range of SES backgrounds was invited to support the delivery of the MyWay trial. A number from this group (n = 3) had previously been involved in the co-design and end-user testing of StopApp and were instrumental in contributing to several waves of improvements made to the content, functionality and user experience. We recruited new members to this group (n = 8) during preparation for our funding application, and we consulted and engaged with the wider group regularly on the design of this feasibility study. With the help of a NIHR Research Design Service PPI grant of £500, we held a workshop with and sent follow-up e-mail communications to the group to consult on study design. Payment via vouchers for all contributions was provided. In addition to several suggestions about locations and ways to recruit (e.g. through bus stop and public transport-based advertising), and recruitment messages, attendees also suggested that the follow-up measures should be collected at 2 months post baseline to encourage responding; any longer was deemed problematic, and would lead to a loss of interest and disengagement. The PPI group also read and approved the lay summary of the project for the funding application. A further three meetings were carried out following the commencement of the trial to (1) review the study materials and protocols to ensure that they were as inclusive and acceptable as possible, (2) discuss recruitment issues with suggestions for improvements and (3) review the acceptability of trial methods in the format of ‘think aloud’ sessions (members participated in the sessions as dummy participants). We provided training in research processes and met with members at regular intervals either face to face or via online methods, to consult and gain their input. Two representatives from the group also attended and contributed to the Study Steering Committee meetings. Detailed minutes and notes were taken by a co-facilitator throughout the PPI group sessions to record ideas and suggestions.

Chapter 3 Quantitative results

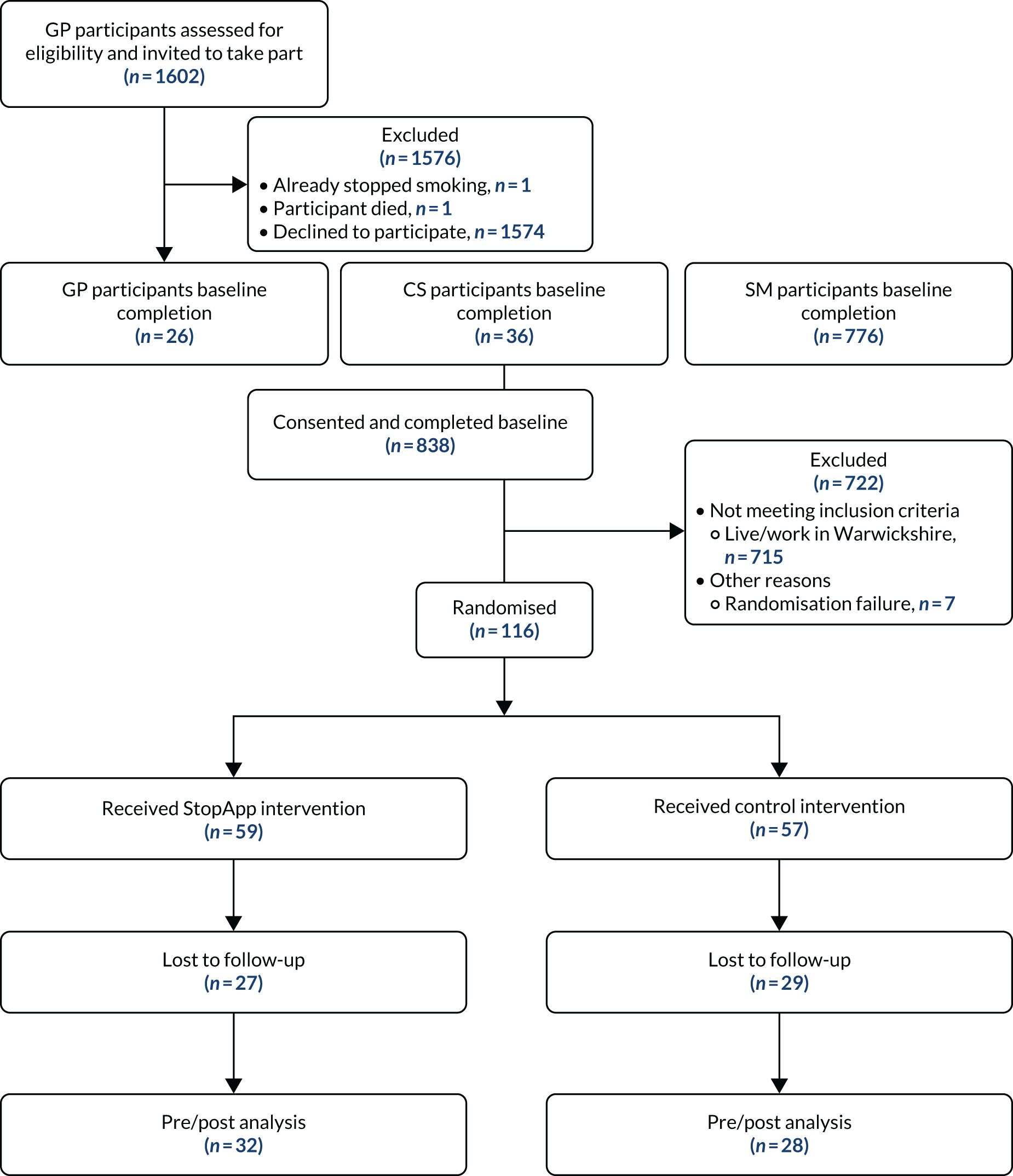

Recruitment took place between 7 January and 31 May 2019. Six GP practices with a combined patient list size of 52,608 identified 1602 smokers who met the eligibility criteria. A total of 1602 initial invitation texts or letters were sent, and 1597 reminders were sent 2 weeks later. Five participants were excluded before reminders were sent because they had stopped smoking, had contacted their GP to state they did not wish to take part, or had died (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Participant flow diagram.

A total of 78 community sites were recruited to promote the study to the Warwickshire population. Researchers sent posters and fliers out to sites by post, and attended major sites (e.g. children’s centres, libraries) to brief staff and provide additional support for recruitment (see Report Supplementary Material 3). Fliers for the study were distributed to newsagents that sold cigarettes, and to pubs and restaurants in Warwickshire. A bus and billboard campaign was also run in the Warwickshire area.

The online recruitment strategy comprised study invitation advertisements using Facebook Ads, Twitter Ads (Twitter, Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA), Google Ads and Gumtree (Gumtree.com, London, UK) for the duration of the recruitment period. The invitation was also posted on SM channels [including Twitter, Facebook and LinkedIn (LinkedIn Corporation, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) accounts] hosted by Coventry University, Warwickshire County Council and the local public health authority, and was added to a County Council online newsletter. These activities resulted in 721,602 SM ‘impressions’ and 3355 advert clicks.

Primary objective: recruitment and attrition rates across three settings (general practitioner, community setting, social media) at baseline, intervention access and follow-up

A total of 838 participants signed up on the study website, consented to take part in the study and completed the baseline measures. Of these, 715 (all accessing the study via SM) were excluded because they did not meet the eligibility criterion of living or working in Warwickshire (see Challenges with recruitment and deviation from planned protocol for details). A total of 123 eligible participants were, therefore, recruited over a period of 116 days and included in the baseline analyses (overall recruitment rate of 1.06 participants per day). Sixty-one participants were recruited via SM (0.53 per day), 36 from CSs (0.31 per day) and 26 from GP practices (0.22 per day). Using text messages and letters sent by post to recruit people from GP practices, we were able to identify that only 1.62% of those who received an invitation were recruited. All recruits were obtained via text message. Five participants were not computer randomised within the trial and were instead randomised manually by our statistician. Seven participants were not randomised. Interrogation of web analytics suggest that these seven participants completed the baseline measures but closed their browser before being assigned.

Of the 123 participants recruited, 116 were randomised (59 to the StopApp arm, and 57 to the control arm). A total of 60 participants completed the follow-up questionnaire (60/123; 48.8%) (n = 32, 54.2%, in the StopApp arm and n = 28, 49.1%, in the control arm) at 2 months post baseline (see Figure 3). This revealed an attrition rate of 51.2%. Loss to follow-up by site was as follows: SM (n = 24; 39.3%), CSs (n = 18; 50.0%) and GP (n = 21; 80.8%).

The demographic characteristics of participants are presented in Table 1. The distribution of participants by age, sex, ethnicity, SES and health-related quality of life between the two groups appeared balanced.

| Characteristic | Total (N = 123a) | StopApp (N = 59) | Control (N = 57) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 38.10 (12.6) | 38.27 (12.7) | 37.82 (12.4) |

| Minimum, maximum | 16, 70 | 19, 70 | 16, 69 |

| Sex (male), n (%) | 39 (31.7) | 19 (34.5) | 17 (30.4) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| White British | 98 (79.7) | 43 (78.2) | 46 (82.1) |

| White other | 6 (4.9) | 4 (7.3) | 2 (3.6) |

| African/Asian | 6 (4.9) | 3 (5) | 3 (5.3) |

| All mixed background | 10 (8.1) | 5 (8.4) | 5 (8.8) |

| Have you done any paid work in the last 12 months? n (%) | |||

| Yes | 103 (83.7) | 46 (83.6) | 45 (80.4) |

| No | 20 (16.3) | 9 (16.4) | 11 (19.6) |

| Current job description, n (%) | |||

| Professional | 33 (26.8) | 9 (16.4) | 19 (33.9) |

| Intermediate position | 23 (18.7) | 14 (25.5) | 6 (10.7) |

| Routine and manual | 8 (6.5) | 4 (7.3) | 4 (7.1) |

| Student | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Long-term employed/never worked | 20 (16.3) | 9 (16.4) | 11 (19.6) |

| IMD score, n (%) | |||

| < 8.49 (least deprived) | 16 (13.0) | 9 (16.4) | 7 (12.5) |

| 8.50–13.79 | 18 (14.6) | 7 (12.7) | 7 (12.5) |

| 13.80–21.35 | 36 (29.3) | 18 (32.7) | 17 (30.4) |

| 21.86–34.17 | 20 (16.3) | 8 (14.5) | 8 (14.3) |

| > 34.18 (most deprived) | 18 (14.6) | 9 (16.4) | 8 (14.3) |

| Recruitment source, n (%) | |||

| GP practices | 26 (21.1) | 9 (16.4) | 13 (23.2) |

| CSs | 36 (29.3) | 21 (39.6) | 20 (35.7) |

| SM | 61 (49.6) | 23 (14.8) | 23 (41.1) |

| How often do you usually smoke? n (%) | |||

| Every day | 106 (86.2) | 45 (81.8) | 52 (92.9) |

| Most days (3–5 days per week) | 8 (6.5) | 5 (9.1) | 1 (1.8) |

| Fewer than most days (1–2 days per week) | 9 (7.3) | 5 (9.1) | 3 (5.4) |

| How soon after waking do you smoke? n (%) | |||

| Within 5 minutes | 29 (23.6) | 12 (21.8) | 15 (26.8) |

| 5–30 minutes | 55 (44.7) | 25 (45.5) | 26 (46.4) |

| 31–60 minutes | 22 (17.9) | 11 (20.0) | 7 (12.5) |

| > 60 minutes | 17 (13.8) | 7 (12.7) | 8 (14.3) |

| How likely is it that you will stop smoking in the next 6 months? n (%) | |||

| Very unlikely | 13 (10.6) | 6 (10.9) | 6 (10.7) |

| Unlikely | 16 (13.0) | 9 (16.4) | 6 (10.7) |

| Maybe, maybe not | 48 (39.0) | 19 (34.5) | 25 (44.6) |

| Likely | 31 (25.2) | 16 (29.1) | 13 (23.2) |

| Very likely | 15 (12.2) | 5 (9.1) | 6 (10.7) |

| Intentions to stop smoking, n (%) | |||

| I don’t want to stop | 5 (4.1) | 2 (3.6) | 2 (3.6) |

| I think I should stop smoking but I don’t know how | 18 (14.6) | 9 (16.4) | 9 (16.1) |

| I want to stop smoking but haven’t thought about when | 15 (12.2) | 5 (9.1) | 8 (14.3) |

| I really want to stop smoking but I don’t know when I will | 22 (17.9) | 10 (18.2) | 8 (14.3) |

| I want to stop smoking and hope to soon | 31 (25.2) | 15 (27.3) | 15 (26.8) |

| I really want to stop and intend to in the next 3 months | 11 (8.9) | 7 (12.7) | 4 (7.1) |

| I really want to stop and intend to in the next month | 21 (17.1) | 7 (12.7) | 10 (17.9) |

| Feeling settled and secure in all aspects of life, n (%) | |||

| I feel settled and secure in all aspects of my life | 29 (23.6) | 11 (20.0) | 12 (21.4) |

| I feel settled and secure in many aspects of my life | 50 (40.7) | 24 (43.6) | 24 (42.9) |

| I feel settled and secure in a few aspects of my life | 32 (26.0) | 14 (25.5) | 16 (28.6) |

| I feel unable to feel settled and secure in any aspects of my life | 12 (9.8) | 6 (10.9) | 4 (7.1) |

| Having love and friendship, n (%) | |||

| I can have a lot of love, friendship and support | 44 (35.8) | 21 (38.2) | 19 (33.9) |

| I can have quite a lot of love, friendship and support | 46 (37.4) | 21 (38.2) | 20 (35.7) |

| I can have a little love, friendship and support | 29 (23.6) | 12 (21.8) | 15 (26.8) |

| I do not have any love, friendship and support | 3 (2.4) | 1 (1.8) | 2 (3.6) |

| Being independent, n (%) | |||

| I am able to be completely independent | 78 (63.4) | 38 (69.1) | 34 (60.7) |

| I am able to be independent | 30 (24.4) | 12 (21.8) | 13 (23.2) |

| I am able to be independent in many things | 8 (6.5) | 3 (5.5) | 5 (8.9) |

| I am able to be independent in a few things | 4 (3.3) | 2 (3.6) | 2 (3.6) |

| Having achievement and progress, n (%) | |||

| I can have achievement and progress in all aspects of my life | 37 (30.1) | 17 (30.9) | 16 (28.6) |

| I can have achievement and progress in many aspects of my life | 58 (47.2) | 24 (43.6) | 28 (50.0) |

| I can have achievement and progress in a few aspects of my life | 24 (19.5) | 11 (20.0) | 11 (19.6) |

| I cannot achieve in any aspects of my life | 4 (3.3) | 3 (5.5) | 1 (1.8) |

| Having enjoyment and pleasure, n (%) | |||

| I can have a lot of enjoyment and pleasure | 40 (32.5) | 18 (32.7) | 19 (33.9) |

| I can have quite a lot of enjoyment and pleasure | 50 (40.7) | 23 (41.8) | 22 (39.3) |

| I can have a little enjoyment and pleasure | 29 (23.6) | 12 (21.8) | 14 (25) |

| I cannot have any enjoyment and pleasure | 3 (2.4) | 2 (3.6) | 1 (1.8) |

Data analytics findings

Matomo analytics data indicated that there were 60 unique views of the StopApp home page, which illustrated that one of the 59 participants in the intervention arm viewed the content more than once. Of these, nine proceeded to the next page(s) and 51 exited before interacting (e.g. clicking a button), indicating an attrition rate at intervention access of 85%. This meant that 15% of participants proceeded past the first page and were able to book an appointment; therefore, the majority of StopApp arm participants did not see information about SSS and how to book.

Secondary objectives

Acceptability of randomisation and the StopApp intervention for participants

Table 2 shows the demographic characteristics of participants by trial arm and compares baseline with follow-up. Similar rates of attrition were seen across trial arms, suggesting that being assigned to the control arm was as acceptable as being assigned to the StopApp intervention arm.

| Characteristic | Baseline (N = 116)a | Follow-up (N = 56)a | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| StopApp (N = 59) | Control (N = 57) | StopApp (N = 31) | Control (N = 24) | |

| Age (years) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 38.27 (12.7) | 37.82 (12.4) | 38.13 (12.53) | 35.29 (8.42) |

| Minimum, maximum | 19, 70 | 16, 69 | 19, 70 | 20, 48 |

| Sex (male), n (%) | 19 (34.5) | 17 (30.4) | 10 (32.3) | 6 (25.0) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||||

| White British | 43 (78.2) | 46 (82.1) | 27 (87.1) | 22 (91.7) |

| White other | 4 (7.3) | 2 (3.6) | 3 (9.7) | 0 (0) |

| African/Asian | 3 (5.0) | 3 (5.3) | 0 (0) | 2 (8.3) |

| All mixed background | 5 (8.4) | 5 (8.8) | 1 (3.2) | 0 (0) |

| Have you done any paid work in the last 12 months? n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 46 (83.6) | 45 (80.4) | 25 (80.6) | 21 (87.5) |

| No | 9 (16.4) | 11 (19.6) | 6 (19.4) | 3 (12.5) |

| Current job description, n (%) | ||||

| Professional | 9 (16.4) | 19 (33.9) | 4 (12.9) | 7 (29.2) |

| Intermediate position | 14 (25.5) | 6 (10.7) | 9 (29.0) | 3 (12.5) |

| Routine and manual | 4 (7.3) | 4 (7.1) | 2 (6.4) | 3 (12.5) |

| Student | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Long-term employed/never worked | 9 (16.4) | 11 (19.6) | 6 (19.4) | 3 (12.5) |

| IMD score,b n (%) | ||||

| < 8.49 (least deprived) | 9 (16.4) | 7 (12.5) | 3 (9.7) | 1 (4.1) |

| 8.50–13.79 | 7 (12.7) | 7 (12.5) | 1 (3.2) | 2 (8.2) |

| 13.80–21.35 | 18 (32.7) | 17 (30.4) | 3 (9.7) | 2 (8.2) |

| 21.86–34.17 | 8 (14.5) | 8 (14.3) | 0 | 1 (4.1) |

| > 34.18 (most deprived) | 9 (16.4) | 8 (14.3) | 1 (3.2) | 1 (4.1) |

Acceptability of randomisation and the StopApp intervention was discussed during the process interviews. Participants understood the need for randomisation and thought it was acceptable. One participant expressed disappointment at being allocated to the control arm when this was disclosed during the process interviews (see Chapter 4, Acceptability of randomisation and self-report measures). StopApp was considered acceptable by those randomised to receive it, although some suggestions for improvements were also made [see Chapter 4, Acceptability of StopApp (for intervention arm participants only)].

Acceptability of primary and secondary outcome measures and measures required for cost-effectiveness and cost–utility analyses in a future trial

Missing data were interrogated to assess measure acceptability. Most questionnaire items had fully complete or near-complete data, with the latter defined as < 5% missing data from 123 questionnaire responses at baseline and 61 responses at follow-up. There was > 5% missing data for the following items: self-report data on whether or not the participant had booked an SSS appointment at follow-up (48.8% of participants did not respond); questions about job status: ‘Do you work as an employee or are you self-employed?’ (16.3% missing), ‘Do you supervise?’ (20.3% missing) and ‘Please read the following job descriptions, which best describes your role?’ (33.3% missing). Questions about whether or not participants were pregnant revealed missing data for 31.7% of female participants. Two items regarding smoking status, namely ‘Please tell us what you smoke’ and ‘How many cigarettes per day?’, each had 17.1% missing data.

There were also very few data entered in open-text boxes (e.g. 11.2% of participants listed that they smoked ‘other’ in a question about tobacco products, but no participants provided detail in the open-text box). Measure acceptability was also discussed during the process interviews. Participants in the trial who also took part in the process evaluation interview found the measures acceptable (see Chapter 4, Acceptability of randomisation and self-report measures).

Key costs that would be incurred in delivering the intervention and usual care including a comparison of did-not-attend rates between each arm of the trial

Key costs incurred are provided in Chapter 5. It was not possible to compare DNA rates between arms as a result of being able to confirm only two DNAs from the intervention arm in the objective SSS data.

Rate of Stop Smoking Services attendance in the intervention and control groups to estimate the event rate of the primary outcome measure for a future trial and support future trial sample size calculations

Self-report booking and attendance at Stop Smoking Services, quit dates set and 4-week quits

At follow-up, eight participants (6.9%) self-reported having made an NHS SSS appointment (Table 3). Six of these participants were randomised to the StopApp intervention arm and two to the control arm. Of these six participants, one had made an appointment in StopApp verified via the objective SSS data. The remaining participants made appointments outside StopApp. One participant made a face-to-face appointment (intervention arm), five made a telephone appointment (three from intervention arm and two from control arm) and two made a face-to-face and a telephone appointment (both intervention arm). Only three participants from the total study sample answered questions about how they booked these appointments. One reported to have telephoned (control arm) and two said that they had booked via StopApp (intervention arm, for which one was not recorded on the objective SSS data). Three participants said that they had set a quit date (one control participant and two intervention participants). One control participant said that they achieved a 4-week quit, one intervention participant said that they achieved a 4-week quit, and one intervention participant said that they did not achieve a 4-week quit.

| Data source | StopApp, n (%) | Control, n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Booked | DNA | Booked | DNA | |

| Objective SSS data | 5 (8.5) | 2/5 (40) | 0a | 0a |

| Self-report data | 5 (8.5)b | 1/5 (20)a | 2 (3.5) | 1/2 (50)a |

| Total | 10 (16.9) | 3/10 (30) | 2 | 1/2 (50) |

Objective data about Stop Smoking Services booking, attendance, quit dates set and 4-week quits

The objective data accessed through the Pinnacle Healthcare Ltd system, PharmOutcomes, identified five MyWay trial participants who had booked an appointment in StopApp. Of these, two participants DNA and three attended their appointments. Of the three people who attended their appointments, only one is recorded as having responded ‘yes’ to the drop-down menu questions about participating in the MyWay trial and consenting to sharing their service use data with the research team. There was no indication in the objective SSS data that this participant set a quit date or achieved a 4-week quit.

Event rate calculation

Based on objective SSS data of five definitive bookings in StopApp (out of 59 participants randomised to this arm of the trial), the event rate is calculated to be 0.08 or 8% of those randomised. A standard margin of error calculation was employed [Z × √P(1 − P)/n], where Z is a constant 1.96, P is the booking rate (i.e. 5/59 = 0.08) and n is the potential sample size. Assuming a future trial recruitment size of 1000 and a future observed sample booking rate of 8%, we have calculated the margin of error to be 8% ± 1.68%, meaning that the true booking event rate at 95% confidence would lie between 6.32% and 9.68% of those randomised to StopApp. Applying the same calculation to the less conservative combination of objective and self-report data in the intervention arm provides a booking rate of 17%. Again, assuming a future trial sample size of 1000 and a future observed sample booking rate of 17%, the margin of error is ± 2.33%, suggesting that the true booking event rate at 95% confidence would lie between 14.7% and 19.3%.

In the control arm, the best indication we have is a booking rate of two out of 57 participants randomised to this arm. This provides a booking rate of 3.5%. Applying the margin of error calculation outlined above with an assumed sample size of 1000 and a future observed sample booking rate of 3.5%, the margin of error is ± 1.14%; suggesting that the true booking rate for the control arm would be between 2.36% and 4.64%.

Being conservative, if the difference was split between the lower of the two estimates of the event rate for the intervention arm (6.3% and 14.7%), which is 10.5%, and the higher estimate for the control arm event rate (4.6%) was deducted, this would result in a difference of 5.9% in the expected event rate of the control arm versus the intervention arm. A future definitive trial sample size calculation can be based on this percentage difference.

G*Power 3.1.9.448 was used to determine the sample size required to be able to detect a difference of 5.9% (where the event rates are 10.5% and 4.6%) for a dichotomous outcome. With the significance level held at 0.05 and power at a commonly accepted standard of 90%, we would need an overall sample size of 840 participants (420 in each arm) for a definitive trial. With the significance level held at 0.05, the power to detect a 5.9% difference would be increased to 95% with an overall sample size of 1038 participants (519 in each arm) for a definitive trial. Rounding the difference to be detected to 6% would push the required sample size down to 998 participants (499 in each arm).

Feasibility of accessing Stop Smoking Services data on attendance, quit dates set and 4-week quits for trial participants (including after the trial at the request of the National Institute for Health Research Public Health Research board)

Challenges with accessing objective service use data required for a full trial were identified in this feasibility study. One issue concerned the providers of SSS appointments within Warwickshire and the fact that not all of them were willing to support the trial. GPs were not involved in offering appointments at all, and some pharmacies also declined to be involved in providing appointments via StopApp. This should not have caused problems with accessing objective service data in isolation, but, in combination with the issues outlined below, trial participants booking appointments outside StopApp (at a non-participating venue) would only be reported using self-report.

A further issue relates to the fact that Pinnacle Healthcare Ltd, as the data controller for the SSS service user data, required consent from each participant for their service use data to be shared with the research team. Consent was required at the point of service access and at sign-up to the study online. To achieve this, Pinnacle Healthcare Ltd added three drop-down questions to its PharmOutcomes system in Warwickshire to establish whether or not service users attending during the trial period were trial participants and, if so, whether or not participants were willing to share their service use data with the research team. This created several issues. First, it transferred responsibility for obtaining consent to access important data to the participating pharmacists. Although the pharmacists were aware of these responsibilities, and had received training and support for setting up the trial, the research team cannot be certain that the pharmacists asked these questions, or asked them in a way that was understood. Some people were clearly study participants because they booked using StopApp and either answered ‘no’ to the question about being in the trial (in which case consent was not requested) or did not provide consent to their data being shared. We cannot be certain if they did not consent purely because of the way in which the questions were put to them or for another reason. This also highlighted that participants may not have understood what was meant by ‘participating in the MyWay trial’. A third issue is that, in the case of participants who booked but DNA an appointment, it was not possible to match the objective service data held in PharmOutcomes with self-report data because such participants DNA to provide consent.

Any differential recruitment and attrition rates across socioeconomic groups, ethnicity, age and sex

Baseline representativeness of the sample

The demographic characteristics of the sample were presented in Table 1. At baseline, females were over-represented in the sample (84/123, 68.3%). A large proportion of the sample were also white British (98/123, 79.7%). The most recent population census data show, however, that the population of Warwickshire is 93% white British, which suggests that we had over-represented black, Asian and minority ethnic groups in our sample. The mean age was 38.27 years [standard deviation (SD) 12.59 years] with a good representation across age groups (range 16–70 years). One participant reported being pregnant. Participant level of deprivation scores based on postcode (IMD quintiles) were evenly distributed between least and most deprived, with 38 (30.9%) participants in the two most deprived quintiles. In the NS-SEC item relating to job role and level of seniority/responsibility, the spread was relatively even, with 33 (26.8%) participants in a professional role, eight (6.5%) participants in a routine and manual role, and 29 (16.3%) participants who had never worked or were long-term unemployed. Most participants had undergone paid employment within the last 12 months (103; 83.7%) and most were employed (96; 78.0%) rather than self-employed (7; 5.7%). The data therefore demonstrated good reach across population groups and did not suggest that there were problems with health equity at study recruitment. Table 2 suggests, however, that there may have been a greater attrition rate in those from black, Asian and minority ethnic groups. Amendments to follow-up procedures for a full trial should aim to address this.

Analyses to assess any differential recruitment by the three settings

Demographic differences

Age, ethnicity and SES data by recruitment source are presented in Table 4. There were no significant differences in ethnicity [χ2 = 1.58, degrees of freedom (df) = 6; p = 0.950], measures of SES including NS-SEC (H = 0.335, df = 2; p = 0.846) and IMD quintiles (H = 1.566, df = 2; p = 0.457) between the three settings. However, there were significant differences in age between the three settings (F = 3.13, df = 2120; p = 0.047). The mean age was highest in the GP group (43.38 years) and lowest in the CSs group (37.16 years). However, the ANOVA test revealed only a very borderline significant difference in mean age between the three recruitment settings (F = 3.13, df = 2120; p = 0.047). These findings suggest that a slightly different age demographic was recruited dependent on recruitment setting. Further exploratory analyses were conducted to assess whether or not there were any further differences in relevant clinical outcomes by recruitment setting.

| Characteristic | Recruitment source | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| GP practices | CSs | SM | |

| Age (years) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 43.4 (13.1) | 35.9 (10.6) | 37.2 (13) |

| Minimum, maximum | 17, 67 | 16, 58 | 16, 70 |

| Ethnicity (n) | |||

| White British | 20 | 30 | 48 |

| White other | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| African/Asian | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| All mixed background | 2 | 3 | 5 |

| IMD score, n (%) | |||

| < 8.49 (least deprived) | 2 (7.7) | 0 | 4 (6.6) |

| 8.50–13.79 | 1 (3.8) | 3 (8.3) | 4 (6.6) |

| 13.80–21.35 | 0 | 2 (5.6) | 6 (9.8) |

| 21.86–34.17 | 1 (3.8) | 2 (5.6) | 3 (4.9) |

| > 34.18 (most deprived) | 4 (15.4) | 1 (2.8) | 2 (3.3) |

Clinical differences by recruitment setting

There were no significant differences in the mean health-related quality-of-life measure among the three recruitment settings (F = 1.29, df = 2115; p = 0.280). There were no significant differences in how soon after waking participants smoked, whether or not they had ever made an appointment at SSS, or made an appointment within the last 2 months. There were, however, significant differences in smoking frequency (H = 6.80, df = 2; p = 0.033) between the recruitment sites, with CS participants reporting the highest frequency, and GP the lowest (mean rank score 69.28 and 55.67, respectively). Intentions to stop smoking were also significantly different across sites (H = 6.60, df = 2; p = 0.037). GP participants had the greatest intentions to stop, and CS participants had the least (mean rank score 69.13 and 49.49, respectively). Perceptions about how likely it was that participants would stop smoking in the next 6 months were also significantly different across recruitment sites (H = 5.44, df = 2; p = 0.066). CS participants perceived that they were the least likely to stop, and GP recruits reported being the most likely to stop (mean rank score 50.89 and 67.96, respectively).

Differential attrition by socioeconomic status, ethnicity, age and sex

For sex or ethnicity, there was no significant association between participants who had completed follow-up data collection and those lost to follow-up. There were no significant differences in age (t = –0.203, df = 114; p = 0.839) between follow-up completers and non-completers. There were also no significant differences in any of the measures of SES (NS-SEC, IMD quintile and job description).

Participation in the MyWay process evaluation

There were significant differences in whether or not participants agreed to being contacted about the MyWay process evaluation among the three recruitment sites (H = 7.30, df = 2; p = 0.026). The mean rank scores indicated that CS participants were most likely to agree, and GP participants were least likely to agree.

Additional exploratory analyses

A range of exploratory analyses were carried out to identify any other differences or associations in the data. A significant association was found between internet access and ethnicity (χ2 = 21.56, df = 6; p = 0.001). Review of the frequencies suggests that participants of white background had greater access to the internet than those from mixed background, and African/Asian ethnicity. No other significant findings were found.

Harms

There were no known harms or unintended consequences to participants as a result of taking part in the MyWay trial.

Chapter 4 Process evaluation results

In addition to telephone interviews, there were several items completed by all participants on the self-report questionnaires that assessed items relevant to the process of participating. All participants described being happy with their level of access to the internet. Ninety-one (74%) participants had access on their mobile phone, 30 (24.4%) participants had access at home but not on their phone, and two (1.6%) participants had access at work but not at home or on their phone. Participants reported that they found out about the study in the following ways: online (51, 41.5%), by GP letter or text (28, 22.8%), via poster or leaflet (27, 22.0%), via word of mouth (13, 10.6%), from ‘the news’ (1, 0.8%) and via bus adverts (1, 0.8%). The majority of participants (91.3%) reported being happy for the researchers to access their data about SSS attendance and quit attempts. In the StopApp arm, 55 of 59 participants (93.2%) gave consent for this, compared with 50 out of 57 (87.7%) participants in the control arm. A total of 22 participants stated that they were happy to be contacted about the MyWay evaluation study process interviews.

Process interview results

Eleven process evaluation interviews were conducted, involving five trial participants and six members of staff involved in supporting the study.

Trial participant interviews

Twenty-two participants from the trial stated that they were willing to be contacted about taking part. All 22 participants were contacted, but only five (22.7%) agreed to take part; the remainder were unresponsive (lack of response to two e-mails, a telephone call and a voicemail) and were not pursued further. Two process study participants had been originally recruited via their GP, two via CSs and one via SM. Two participants had been assigned to the intervention arm and three participants had been assigned to the control arm. Participants reported that they struggled to recall what they had seen and the questions that they were asked because of the time delay since participation. Interviews lasted between 17 and 36 minutes and were all conducted over the telephone. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Analysis was conducted using the interview transcripts.

Participant interview results

Method for inviting to research

Participants described how they found out about the study. Responses included an e-mail (that was not provided by the research team) sent around the workplace from management, which the participants assumed was part of a ‘work health kick’ (804CS, lines 18–20). Text messaging was also mentioned (846GP, line 10) and was viewed as acceptable (846GP, line 32) and preferable to a letter:

When it’s a text you automatically look at it and read it and it’s saved on your phone so you can’t lose it. With a letter you just throw it in the bin.

846GP, lines 37–39

A SM participant was introduced to the study by friends (1003SM, line 7), and they later shared it (1003SM, lines 19–21). One participant reported a method the study team had not anticipated, in which their GP asked for the participant’s e-mail address during a consultation and sent something to them following this interaction (867GP, lines 2 and 3).

Reasons for taking part

Participants gave several reasons for choosing to take part. These reasons included the fact that the information was interesting (804CS, lines 26 and 27), they were happy to help and provide an opinion (867GP, lines 16 and 17) and they felt that the research might ‘help improve services’ (867GP, line 117):

You could gather more data of what things tend to be working for people, and what wasn’t.

867GP, lines 130–133

Participants noted how participation might aid smoking cessation attempts and be ‘worth a go’ (804CS, line 9; 743CS, line 6):

When I hear things about smoking it just puts me off and makes me think about quitting more.

846GP, lines 17 and 18

The provision of vouchers was also deemed a motivator for participation (846GP, line 14):

It pushes people who want to do it though, doesn’t it?

1003SM, line 284

Secondary reason was free money from Amazon [Amazon.com, Inc., Seattle, WA, USA].

743CS, line 8

Ease of participation, comprehension and time to complete

Ease of participation was mentioned, with some expressing that the process was not problematic (804CS, line 35):

I’d just say it was easy, easy to follow, straightforward.

846GP, lines 47–49

No part in it was difficult that I came across anyway.

1003SM, line 54

The log-in process within eNgage was described as ‘familiar’ and therefore something participants were accustomed to (804CS, line 55). Equally, one participant expressed that the process made it clear that they did not have to take part:

It was my choice to give my e-mail address. I don’t think in a way it forced anybody to do it.

867GP, lines 42–44

However, a lack of clarity about how the study would be conducted was conveyed (743CS, line 52), and concerns were expressed about the usability of the study research platform eNgage:

[The] website is not good so stopped using it, not user friendly and could not log on so gave up.

743CS, lines 87 and 88

Poor website access, poor communication, poor follow-up, incorrect platform.

743CS, lines 113–115

The online process was clunky, and it was difficult to participate in.

743CS, line 120

[Study hosted on] ineffective platform . . .

743CS, line 173

It leads to people disengaging.

743CS, line 190

Participants felt that the survey questions were relatively quick to complete:

. . . was just right – if it was too short you wouldn’t have taken the information in. If it had been long, you’d have probably given up before you deleted it.

804CS, lines 49–51

Literally takes you 5 minutes, not even that.

1003SM, lines 50, 51 and 67

Relatively quick and simple.

867GP, line 93

The number of questions was also deemed appropriate by participants:

There wasn’t too many questions, they were very easy to go through.

1003SM, lines 69–71

[It was] quite simple, quite understanding, and there was a lot of information on there about what it was on about and what it was for.

867GP, lines 29 and 30

Just the right amount.

867GP, line 71

Participants reported that they found the questions easy to comprehend (846GP, line 83) and were clear about what was being asked:

They were brilliant they were.

1003SM, line 105

Really explanatory, really simple, the questions were put in simple form. There was nothing too complicated about it.

867GP, lines 53 and 54

Participants all agreed that the level of personal detail collected was appropriate, relevant and not excessive:

I thought that it was easy and it was just enough to target what you were asking.

867GP, lines 75–77

Reminders and amount of contact from researchers

Reminders to complete the survey were seen as beneficial rather than obtrusive:

You get reminders which is good. Yeah I felt like since I did it there’s been a lot of contact after.

846GP, lines 47–49

They kept in touch, but you weren’t getting 100 e-mails a day.

846GP, line 65

You don’t feel like you’re being hounded but you don’t feel like you’re being ignored either.

846GP, lines 72 and 73

It was keeping me informed at times of what was happening, if I needed to do more, if I was to have telephone calls, so it kept me in the loop the whole time.

867GP, lines 180 and 181

There was an expectation about follow-up contact as participants all knew to expect further questionnaires, so this was deemed ‘fine’ (804CS, line 187). One participant felt it effectively nudged them to complete the survey again, which was good (1003SM, lines 221–223).

The role of participation on stopping smoking

A number of participants described how the process of taking part had spurred thoughts about stopping:

Made you think as you were completing it . . . I liked that.

804CS, lines 43–46

I think there should be more things out there like this that’ll encourage people to think about changing their life or giving up smoking . . . but yeah it was really good. Excellent [taking part in the study].

804CS, lines 273–281

It’s kind of made me urge to stop smoking a bit more. I booked as soon as I did them, its actually pushed me into going to the doctors. Taking part prompts you to stop – it sort of triggers me really to want to stop again.

846GP, line 210

It’s nice to have little reminders about smoking, it puts you off.

846GP, line 212

Its [the study] brought to light more in a way of how much I want to do it obviously for my children . . . I have cut down.

867GP, lines 195–198 and 200

One participant described how participation led to them booking a SSS GP appointment and nudged them closer to their goal with increased motivation:

It did prompt me to go to the SSS which actually, to be fair, has put it in my mind that even though I haven’t maintained that that I will be quitting smoking by the end of the year, because I don’t want to be a smoker . . . so it helped me in that way to resolve in my mind psychologically that when I hit that point of having I’m ready, that I will actually go and quit smoking.

743CS, lines 297–299

Acceptability of randomisation and self-report measures