Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 13/90/18. The contractual start date was in September 2015. The final report began editorial review in March 2020 and was accepted for publication in November 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2021. This work was produced by Corder et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2021 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction and background

This report includes text from the authors’ published articles. 1–6 All of these articles are Open Access articles distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Adolescent physical activity

Physical inactivity is the fourth largest cause of death worldwide. 7 Globally, physical activity levels are low and are continuing to decline, with less than 1 in 10 adolescents meeting current World Health Organization physical activity recommendations of 60 minutes of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) daily. 8,9 Physical activity declines during adolescence10 and inactive adolescents are at greater risk of long-term ill health. 11 Not only is inactivity associated with poor health and well-being during childhood, but it may have implications for health into adulthood. 12 More physically active adolescents are likely to become active, healthy and successful adults,12 and so tackling the decline in physical activity during adolescence is a major public health priority. 7

Schools should provide an ideal setting for reaching large numbers of young people across a range of differing backgrounds and are therefore an attractive route for adolescent physical activity promotion. Although the reduction in physical activity during adolescence mainly occurs outside school, it is pragmatic to utilise the school setting for recruitment and delivery. 13

The challenge of effectively delivering physical activity interventions in this setting is highlighted by a review13 of school-based trials that were largely ineffective at increasing accelerometer-measured physical activity over the whole day. Of the 17 studies included in this review,13 only one study included participants with a mean age > 13 years at baseline (13.2 years). In another review14 that examined the impact of school-based interventions on objectively measured activity among adolescents, this applied to only 3 of 13 included studies. Lack of intervention fidelity and poor implementation may explain the null findings in many school-based interventions. 15 Taken together, this indicates the need for activity promotion strategies among older adolescents.

Concurrent with physical activity declines, adolescence is also a period of increased risk of mental health problems16 and around half of mental health disorders will have emerged by the age of 14 years. 17 In 2017, it was estimated that 24% of British adolescent girls and 9% of boys experienced depressive symptoms,18 and suicide is one of the major causes of mortality in adolescence and young adulthood. 19 The benefit of physical activity for mental health has been repeatedly observed through meta-analysis of observational studies, as well as in intervention trials, and does not appear to be explained by reverse causality. 20–23 There is increasing consensus on the benefits of physical activity for mental health. These benefits may not be limited to the physiological consequences of physical activity itself, and the wider social and intra/interpersonal aspects of activity should also be considered. 24

Together, this evidence indicated the need for the development and evaluation of an inclusive physical activity promotion initiative that targets adolescents, and this formed the basis for the Get Others Active (GoActive) intervention.

Development of the GoActive intervention

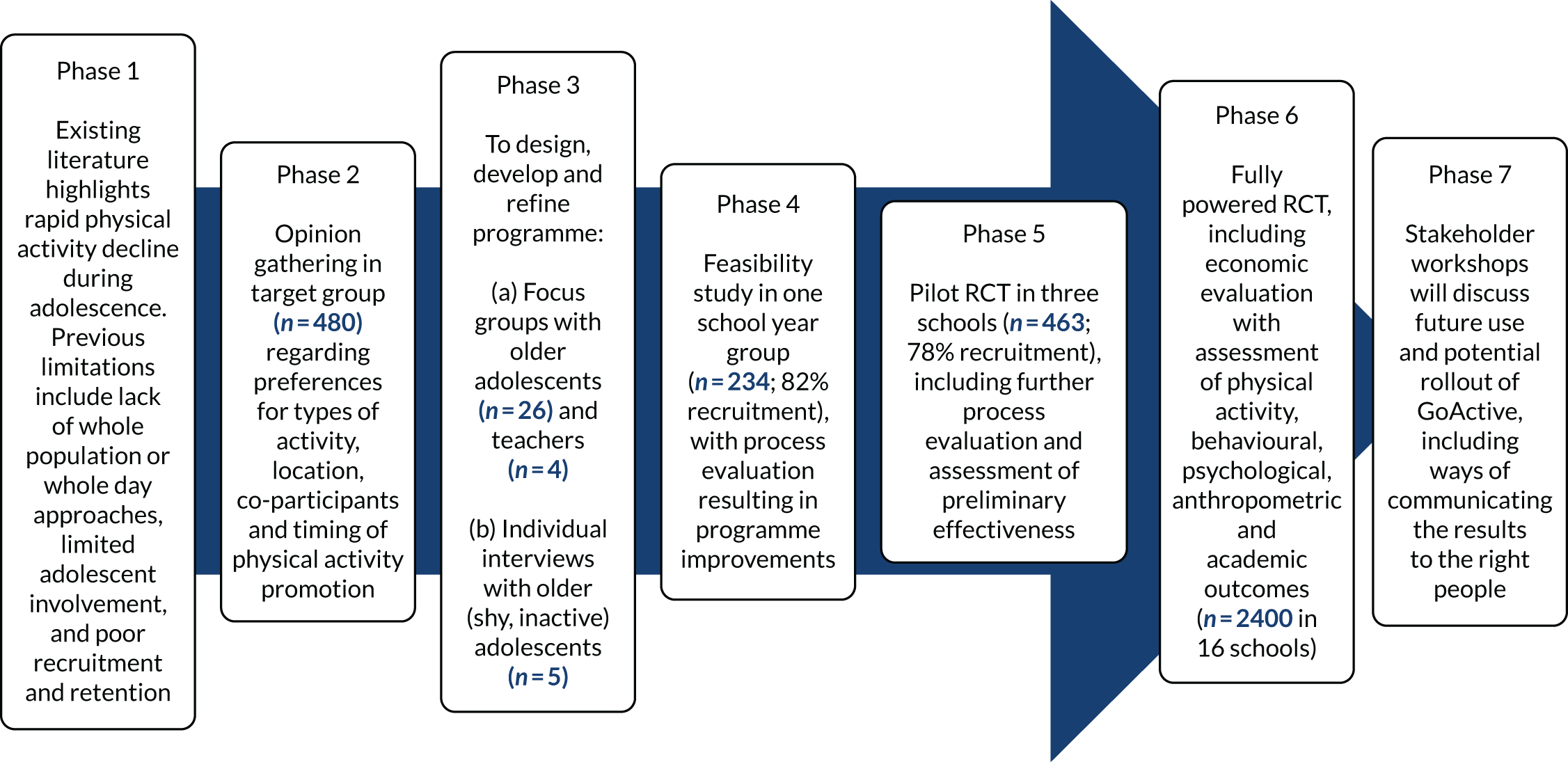

The GoActive physical activity promotion intervention was developed with substantial involvement from adolescents and teachers, and was based on gaps in the existing evidence (Table 1 and Figure 1). Qualitative work with adolescents25 suggested six key themes that may encourage Year 9 students to do more physical activity: (1) choice, (2) novelty, (3) mentorship, (4) competition, (5) rewards and (6) flexibility (Table 2). Although the intervention was broadly aligned with self-determination theory,47 our priority was to co-design the intervention with students and teachers. Therefore, we used theory flexibility to enable the incorporation of components strongly suggested in the development work, irrespective of whether or not they aligned with theory, such as rewards. 6

| Gap in evidence | Key rationale |

|---|---|

| Need for physical activity promotion in older adolescents | Most adolescents are inactive25 and this inactivity tracks into adulthood,26,27 increasing their risk of diabetes, cancer and mortality.28,29 Over 10 minutes/day of physical activity every year is replaced by sedentary time between 9/10 years and 13/14 years25 and a 10-minute increase in MVPA was associated with a smaller waist circumference and lower fasting insulin among young people in a large worldwide meta-analysis.30 Pubertal, brain and social development during adolescence leads to a new capacity for health behaviours,31 increasing the likelihood of long-term change |

| Lack of effective interventions in target group | Reviews highlight limited effectiveness of adolescent physical activity promotion,32–35 with a 4 minutes/day effect size estimated from studies with objective outcomes.35 Only two of these studies included adolescents aged ≥ 13 years,36,37 showing a lack of high-quality research in this important group |

| Lack of whole-population approach | Activity declines among all groups,25 but many interventions target subgroups only.38 A whole-population approach to health promotion overcomes stigmatisation of target groups25 |

| Lack of whole-day approach | The activity decline mainly occurs out of school,39 but many interventions target specific times only (e.g. school time),34,40 PE lessons41 or after-school time |

| Few interventions involve adolescents in intervention development | Adolescent focus groups are mainly used to feedback on existing interventions42 and little research uses adolescent views to develop strategies25 |

| Need for improved adolescent engagement with health promotion interventions | Participation is vital to intervention success, but engaging adolescents to take part in health promotion interventions has challenges,43,44 including transitioning social priorities, biological changes and engagement with minors through schools31,45 |

FIGURE 1.

The GoActive development model.

| Concept | Supporting evidence | Component |

|---|---|---|

| Choice | Adolescents who are given an activity choice have better programme attendance.46 Choice may improve intrinsic motivation, self-efficacy and self-esteem, all of which are important for long-term activity maintenance47,48 | Each tutor group chooses two different activities weekly |

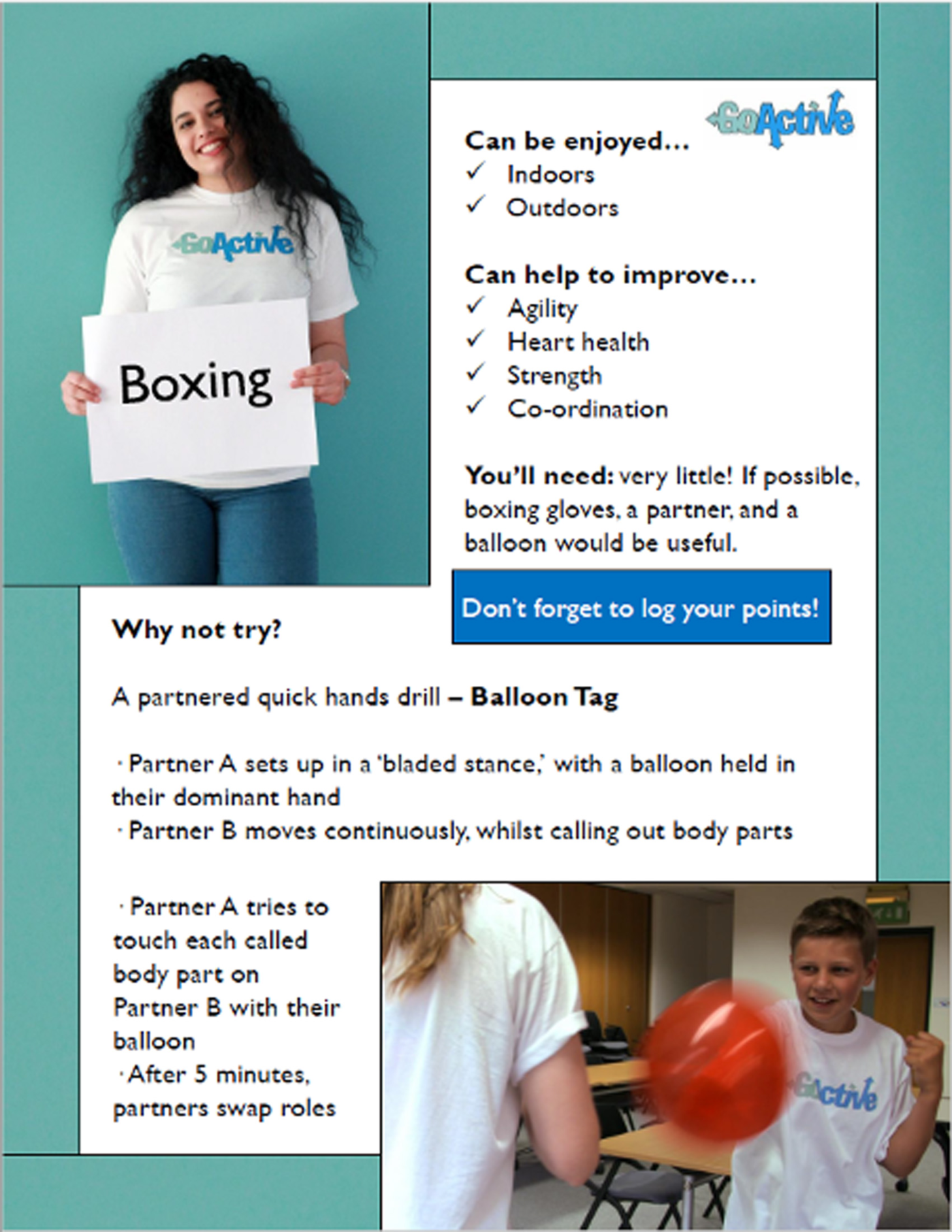

| Novelty | Introducing adolescents to new activities is important. Those given the opportunity to try new activities are more likely to want to do more25 | There are 19 activities available that are designed to utilise little or no equipment. Intervention materials are available on the study website, including Quick Cards (i.e. overviews of chosen activities) |

| Mentorship | Peers are crucial for adolescents to attain the best health behaviours in the transition to adulthood.31 Cross-age mentorship can successfully improve adolescent health behaviours (e.g. substance use,49,50 sexual health51 and nutrition52), but is understudied in physical activity research,53 particularly in young people54 | Older adolescents in the school (i.e. mentors) are paired with each Year 9 class and are responsible for encouraging their class to participate in new activities. Mentors are helped by Year 9 in-class leaders, who change weekly |

| Competition | Competitions improve engagement and retention in health promotion55 | Students gain points every time they do an activity. There is no time limit, students just have to try an activity to get points. Individual points are kept private, with class-level totals announced to encourage interclass competition. Students can enter their points on the GoActive website with individual passwords and login details |

| Rewards | Reward-based interventions appear effective in improving weight management behaviours in children56 | Students gain small individual prizes for reaching certain points levels. Everyone gaining a certain amount of points is entered into a prize draw for a bike |

| Flexibility | A range of co-participants, timing and locations for activity are preferred by Year 9 adolescents, with preferences differing on an individual level25 | One period of tutor time per week was used to do an activity during the feasibility and pilot work. Participants were also encouraged to do activities at other times, especially out of school |

We translated these themes into a physical activity promotion intervention that aimed to increase physical activity among the whole of Year 9.

Feasibility and pilot testing

Feasibility and pilot testing of the GoActive programme was important to demonstrate intervention acceptability, feasibility of recruitment, randomisation and measurement of Year 9 students. 5 Data on preliminary effectiveness was also necessary to inform a realistic estimate of the resources needed for the evaluation of a fully powered randomised controlled trial (RCT). We conducted a feasibility study of the GoActive intervention in one secondary school and a pilot cluster RCT in three schools (two intervention schools and one control school) (ISRCTN31583496). Ethics approval, including for the consent procedures, was obtained for the feasibility and pilot cluster RCT from the Cambridge Psychology Research Ethics Committee, Cambridge, UK (Pre.2013.40).

Feasibility results

The intervention was delivered by one school to the whole of Year 9 for 8 weeks during the summer term of 2013, with limited researcher assistance. Despite initially agreeing to do so, the school was unable to provide mentors, as the older students had examinations. Year 9 form teachers were trained to deliver the intervention prior to the programme commencing. The teachers delivered the intervention with the help of one GoActive team member during tutor time once per week. A total of 234 Year 9 students were exposed to the intervention, as reported by the school, with nine parents (representing 3.8% of eligible students) and 13 students (5.6% of eligible students) opting out of participation in study measures. A total of 183 (78.2%) students assented to participate in measurements, with 29 (12.4%) students not attending a measurement session (because of absence or apathy).

Pilot results

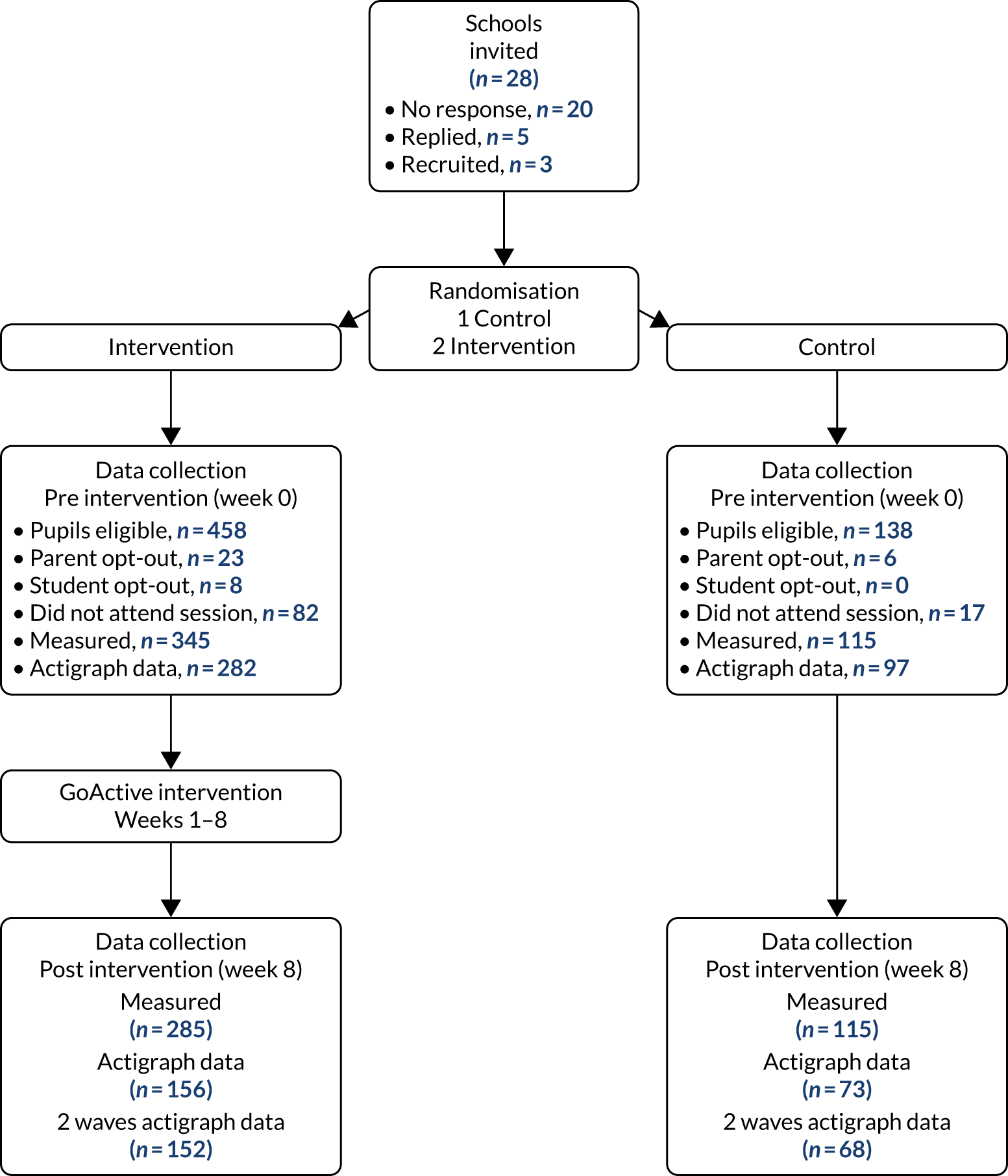

Across the three pilot schools, 596 Year 9 students were invited to participate in the evaluation of GoActive. A total of 458 students provided valid written informed assent and were measured (76.8% response rate; an average of 153 students per school) (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Pilot study recruitment flow chart. All measures include accelerometry, anthropometry and outcomes questionnaire (student-reported physical activity participation, self-efficacy, peer support, friendship quality and mood).

Of the 458 baseline participants, 87.3% attended the follow-up measurement. Of these students, 400 (55%) were available for analysis of the primary outcome [n = 220; ≥ 1 day of ActiGraph data at pre and post intervention (ActiGraph, LLC, Pensacola, FL, USA)] and all 400 completed the questionnaire-based measures that assessed the secondary outcomes. Average days of accelerometer wear were 4.9 (SD 1.8) days pre intervention and 3.8 (SD 1.8) days post intervention.

The results of this pilot cluster RCT provided an indication of the potential effect of GoActive on the main outcome measure (i.e. average daily minutes in MVPA). Change in MVPA was –6.5 (SD 14.0) minutes per day in the control group and –2.5 (SD 15.4) minutes per day in the intervention group, with a change adjusted for baseline of 5.1 [95% confidence interval (CI) 1.1 to 9.2] minutes per day in favour of the intervention group. Furthermore, the results of the questionnaire-based measures indicated tentative positive effects for some secondary outcomes, including well-being and social support.

Year 9 participants

Questionnaire data showed that for boys and girls, respectively, 71% and 74% agreed that taking part in the intervention was ‘fun’ and 56% and 69%, respectively, said that it encouraged them to do more activity. Moreover, 61% of intervention participants indicated that it was fairly likely that they would continue with an activity they had tried during GoActive (boys, 64%; girls, 59%). Of those who had been involved as peer leaders, 81% reported that they thought that it was ‘fun’, 54% said that it had ‘improved their leadership skills’ and 38% said that it took up a lot of time.

Mentors

In focus groups, mentors indicated that although they found it difficult ‘to get their head around’ the GoActive intervention, they quickly picked it up and enjoyed it. Out of the 16 mentors who completed a questionnaire (16 mentors invited), 14 (88%) mentors agreed that GoActive was fun, 15 (94%) mentors said that it improved leadership skills and four (25%) mentors said that it took up a lot of time. Useful suggestions for improvements were made regarding the need for refined points collection, more comprehensive activity explanations, the importance of teacher involvement and more initial training, which were incorporated in the full trial and are summarised in Table 3.

| Issue from feasibility study | Improvements (between feasibility and pilot) | Changes required after pilot | Supporting quotes from student focus groups |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention design | |||

| Lack of mentors | |||

| Mentors were not recruited as they had exams |

|

|

. . . so for instance a sixth former came into our form and we was not very motivated, didn’t really want to do it and he’s in there saying, right, we’re all going to go outside, we’re all going to do this, I think probably, I don’t know, I’d probably give it more effort . . .Male participant, post feasibility focus groupMentors would have been helpful especially with large tutor groupsTeacher, post pilot questionnaire |

| Lack of clarity at start | |||

| Researchers did a launch assembly at the beginning of the project, but students suggested the need for clearer initial intervention explanation |

|

|

It was just difficult to get them started but once they were into it, it was fineYear 11 mentor, post pilotNot very sure what was going on, so form [teachers] looked disorganisedTeacher, post pilot |

| Points recording was complicated | |||

| The students found the system for recording points on ‘points cards’ too complicated. This was also a burden for study staff entering the points | Simplified points entry system:

|

|

They [points cards] were like complicated, there was too many like days and numbers and you didn’t know where to like put itFemale participant, post feasibility |

| Activity preferences | |||

| Participant focus groups revealed occasional gender imbalance in activity choices and, with that, differential motivation to participate | Boy and girl leaders each week:

|

|

Yeah, like our sports is for what like the leaders want to do, not the whole class, ‘cos all the boys would pick like boxing and the girls want to do like dancing and Zumba but the boys don’t want to do that so we all go for the boys one, but ‘cos we have a girl and a boy we should like the boys do their thing and the girls do their thing with their leadersFemale Year 9 participant, post feasibility |

| Issue | Proposed change | Changes required after pilot | Supporting information |

| Study design | |||

| Questionnaires | |||

| Some students had difficulty completing questionnaires | Word substitutions and font/colour change:

|

|

Informed by teachers’ suggestions during measurement sessions Rationale for adding additional questions: 44% of pilot participants stated that they asked someone to do physical activity with them during the intervention |

| Measurement session attendance | |||

| A total of 12.4% of eligible students in feasibility study did not attend a measurement session because of absences, illnesses, forgetfulness and apathy |

|

|

In pilot, non-attendance varied (excluding students who opt-out):

|

| Measurement incentives | |||

| Students did not realise that they were receiving vouchers for participating in measurements in feasibility study | No monetary incentives:

|

No further changes | Recruitment and retention was similar in feasibility study and pilot trial |

| Accelerometer data | |||

| Not all participants could be issued with an accelerometer because of resource limitations and 6% of monitors were lost | Strategies for monitor return:

|

|

Pilot study return rate and compliance needs improvement. A total of 36.9% students returned two waves of valid accelerometer data and monitor losses were 8%, 3% and 3% across the three schools |

Teachers

One school had vertical forms, with Year 9 students spread across 66 school forms. The other intervention school had a traditional form structure, with eight Year 9 forms. Eleven teachers completed the questionnaire, five (63%) teachers from the traditional school and six (9%) teachers from the vertical school. Across both schools, 10 (91%) teachers enjoyed the programme, eight (73%) teachers thought that their class did more activity, 11 (100%) teachers thought that their class found it fun, two (18%) teachers thought that it was a lot of work and none (0%) of the teachers thought that their class found it boring. Similar to the feasibility study, most of the free-text comments highlighted the need for improved information provision between the research team and the school. Teacher suggestions are included in Table 3.

Feasibility and pilot summary

The feasibility study and pilot trial of the GoActive intervention showed feasibility of recruitment, measurement, randomisation and the ability to deliver GoActive to a whole-school year group of 13- to 14-year-olds. Both of these stages prompted several key improvements to the intervention and to the study design, including emphasis on monitor return, mentor recruitment, adequate mentor training, clearer and more consistent intervention explanations, and an improved points recording systems. The lessons learnt from each phase of this research were taken forward to the trial reported on here, aiming to evaluate the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the GoActive intervention to increase MVPA among 13- to 14-year-olds.

The GoActive study

As outlined, the development of the GoActive intervention followed previous research suggestions. This included basing activity promotion strategies on behaviour change theory, incorporating existing research evidence and including pre-trial qualitative work within the target population in intervention development. 13,16 A further consideration is that whole-group approaches may help overcome some of the stigma associated with targeting particular at-risk groups (particularly shy and inactive adolescents). 17 The overall objective of the GoActive study was to assess the effectiveness of the GoActive intervention in increasing daily MVPA in 13- to 14-year-old (Year 9) adolescents and to establish the cost-effectiveness of the programme. However, responding to calls for more in-depth evaluations of the mechanisms of intervention delivery and effectiveness, the trial was designed to enable the study of mediators of intervention effectiveness and included a comprehensive mixed-methods process evaluation.

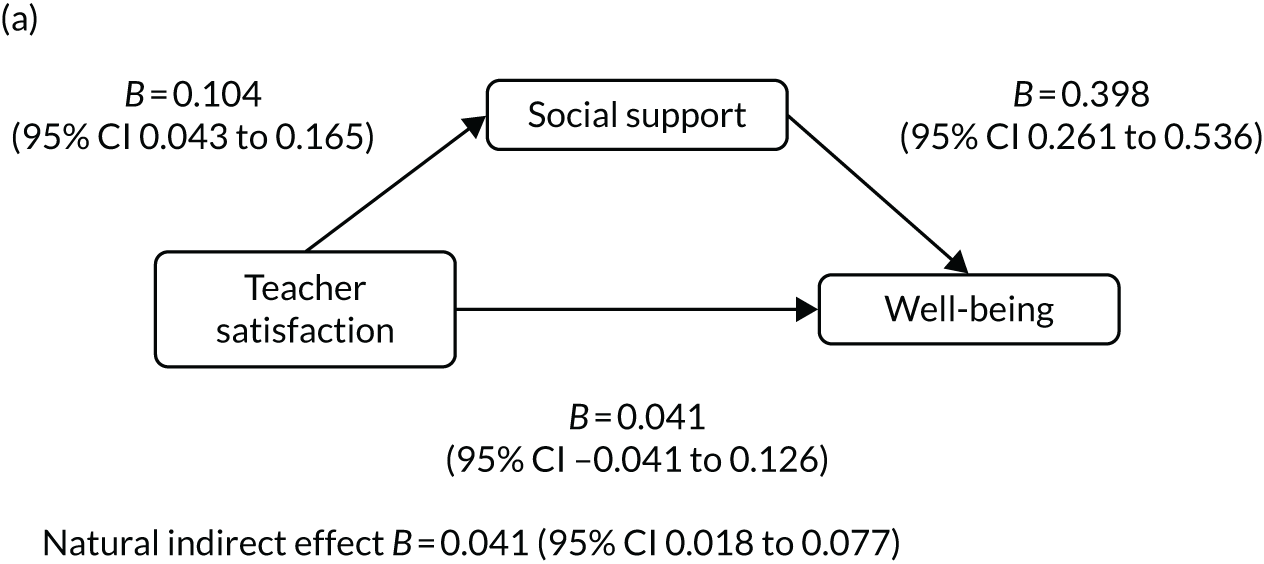

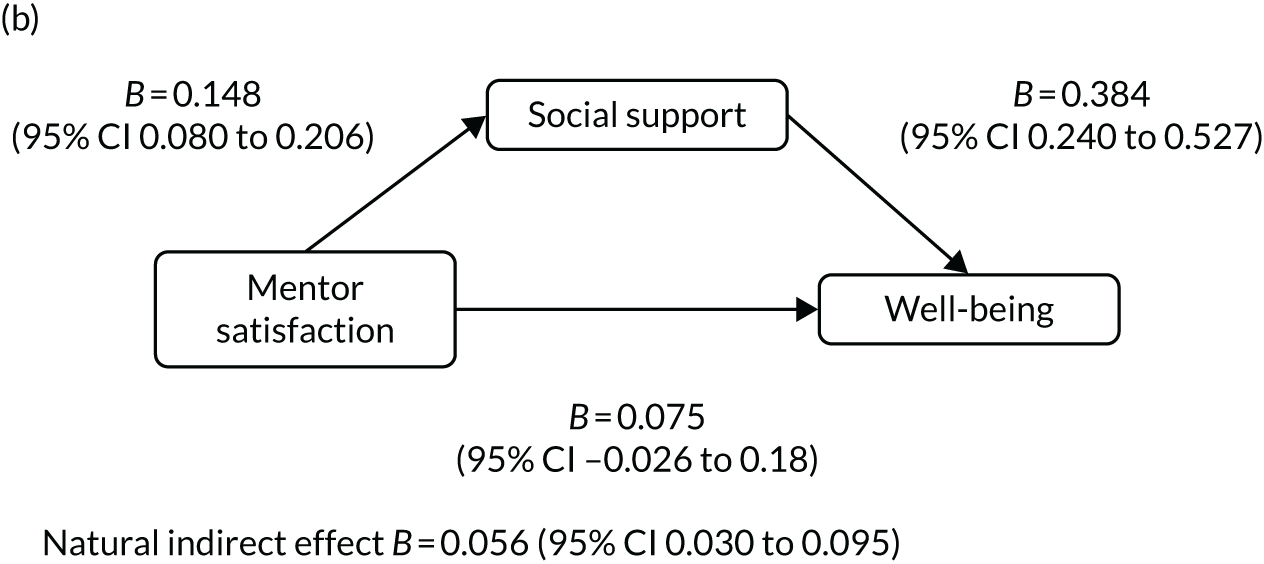

Studying mechanisms

We hypothesised that the GoActive intervention components suggested by students and teachers (including mentorship, leadership, teacher support, class-based activity sessions, competition, rewards and online activity tracking) would also influence well-being through social support, self-efficacy, group cohesion, friendship quality and self-esteem. We wanted to investigate if particular engagement with components of GoActive may be associated with mediators and outcomes, for example encouragement provided by older adolescent mentors could be associated with increased self-efficacy and social support, which may be associated with changes in physical activity and mental well-being. 57,58

Mixed-methods process evaluation

The literature on school-based physical activity interventions highlights the need to critically examine the delivery of each component and the processes of any complex intervention. 59 Process evaluation provides detailed evaluative information about the delivery of an intervention from the perspective of participants, mentors, teachers and facilitators, with the aim of contextualising and interpreting its potential effects, providing greater confidence in conclusions about effectiveness. 60

It is also important to understand the primary recipients’ experiences and perspectives of the intervention, as this can not only help to determine the effectiveness of the intervention and its individual components, but can also produce new insights regarding intervention design. There is limited published research of the experiences of those directly involved in receiving these interventions,61–63 particularly using qualitative research methods. Process evaluations of school-based interventions have mainly focused on other stakeholder groups, notably parents and teachers. The process evaluations note the importance of child engagement and autonomy over their own behaviour,64 embedding diet and physical activity across the curriculum and school,64 school resources,64 parental and community engagement,61,64 and the importance of adult role models61,64 in delivering school-based physical activity interventions. However, such stakeholder perspectives cannot replace the sharing of views and experiences of adolescents themselves.

In recent decades, literature and policy have emphasised the importance of capturing views, experiences and actions of those who are the focus of the research. 65 Moore et al. 60 states that the success of an intervention is dependent on the response of the intended audience. This is traditionally considered ‘dose received’,66 and more specifically ‘dose received: satisfaction’. 67 It is argued that ‘dose received’ is a passive term, privileging quantitative measures. 60 Moore et al. 60 advocate for the critical assessment of aspects of dose received, including ‘acceptability’ and ‘satisfaction’, to examine participants’ relationships to the mechanisms through which the intervention works. Additionally, they call for the inclusion of qualitative methods as an effective approach to illuminating participant experiences. Although GoActive was designed as a whole-population approach, aiming to overcome stigmatisation and the potential detrimental mental health consequences of targeting particular subgroups in health promotion strategies,68 we wanted to ensure that the intervention was acceptable to those least likely to engage in physical activity. As such, the intervention was developed to include the opinions of those with characteristics that were deemed as common in those hard to reach for physical activity promotion (including girls, and those with low activity levels and high shyness). 6 Therefore, participants for our process evaluation were purposively sampled to account for perspectives of individuals with those characteristics.

Chapter 2 Methods

GoActive intervention description

Overview

The intervention is titled ‘GoActive’, which stands for ‘Get Others Active’. Each Year 9 class (i.e. tutor group/home room class) are asked to choose 2 of 20 available activities each week. These activities require little or no equipment, and are designed to be appealing to a wide variety of students (e.g. ultimate frisbee, Zumba and hula hoop). Materials available on the GoActive website include activity instructions (Quick Cards), which offer an overview of the chosen activity, a short explanation and suggestions for adaptations, and provide advice, safety tips and ‘factoids’ about each activity (see Appendix 1).

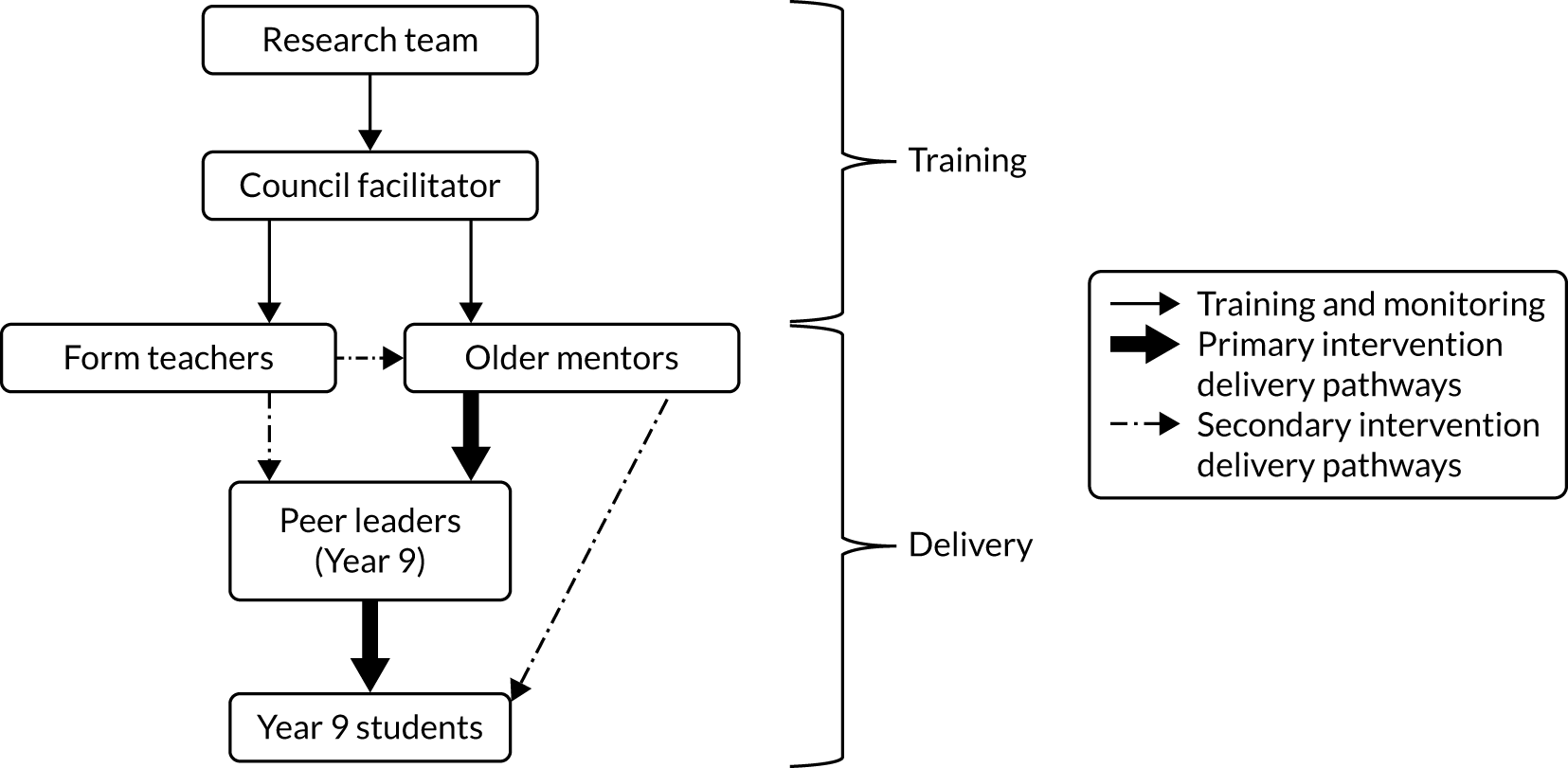

The GoActive intervention is implemented using a tiered leadership system, led by a council-funded facilitator. Schools were requested to select mentors. Mentors (i.e. older adolescents within the school) and peer leaders (i.e. select pupils within each class) encouraged students to try these activities each week (Figure 3). The mentors remain paired with each class for the duration of the intervention, whereas the in-class peer leaders (two per class each week, one male and one female) change every week. Teachers are encouraged to use one period of tutor time (registration/roll call) weekly to do one of the chosen activities as a class; however, students gain points for trying these new activities in or out of school. Points are gained every time a student tries an activity. There is no expectation of time spent in the activity, as points are rewarded for the taking part itself. Individual students keep track of their own points privately on the study website and their points are entered into the between-class competition so that each class competes against each other. Class rankings are circulated each week to encourage teacher support and students receive small rewards (e.g. frisbee, sports bag) for reaching points thresholds (such as 20/50/100 points). As GoActive runs on a weekly cycle, the length of the intervention can vary as appropriate for each individual school.

FIGURE 3.

The GoActive tiered delivery system.

The full intervention ran for 12 weeks, with 6 weeks of weekly facilitator visits and a further 6 weeks with reduced facilitator support. The role of the facilitator was to provide training for mentors and teachers, provide instructions/prompts to teachers, mentors and Year 9 leaders for intervention delivery, support teachers, mentors and leaders to deliver the intervention, provide activity Quick Cards that give overviews and examples of activities, provide basic equipment to facilitate activities if relevant/needed, collect point cards, update points boards in school communal area and class rooms, and to provide prizes. As described in Chapter 1 and clarified in Table 3, several intervention improvements were identified following the pilot intervention and these were incorporated into GoActive. The main differences between the intervention delivered in the pilot evaluation and the GoActive intervention delivered in the trial reported on here were (1) the use of the GoActive website to track points and facilitate communication with the mentor, and (2) delivery was led by a local council-funded facilitator instead of by a member of the research team.

The teachers, mentors and peer leaders delivered the intervention after training from a facilitator (see Facilitator and mentor training). Quick Cards provided information that allows any of these individuals to lead the 20 activities. For example, we suggested using YouTube (YouTube, LLC, San Bruno, CA, USA) for Zumba instruction, as we want the students to be able to try activities without the barrier of needing a specific class. Similarly, we suggested doing these activities at home with a friend or relative to encourage out of school participation.

Table 4 summarises the behaviour change techniques applied in GoActive. Table 5 describes the GoActive intervention’s essential functions (i.e. components of the intervention) that schools were asked to implement. Importantly, these essential functions could be adapted to suit individual settings, offering the schools flexibility to adapt the intervention and its implementation to their context.

| GoActive tenet | Behaviour change technique label | Application in the GoActive intervention |

|---|---|---|

| Novelty, choice, mentorship | 1.1: goal-setting (behaviour) | Form group sets goal to try one new activity per week. Mentors encourage Year 9 students to plan when and with whom they will try the activity |

| Competition | 2.3: self-monitoring of behaviour | Year 9 students record their participation in weekly new activities by entering points online |

| Mentorship | 3.1: social support (unidentified) | Mentors, in-class Year 9 leaders, form teachers and peers provide encouragement and support |

| 4.1: instruction on how to perform behaviour | Quick Cards (i.e. laminated print out resources) and mentors provide activity instructions/tips | |

| 6.1: demonstration of the behaviour | Mentors are encouraged to model the behaviour. Quick Cards show examples of adolescents engaging in the behaviour | |

| Competition | 6.2: social comparison | Points are awarded for trying activities. Anonymised individual points ranking will allow individual-level comparison and class-level competition will be open through the use of school graphs that denote form group leader boards |

| Rewards | 10.1: material incentive (behaviour) | Year 9 students will be informed of the GoActive reward system |

| 10.2: material reward (behaviour) | Year 9 students will be rewarded for obtaining points | |

| 10.4: social reward | Rewards are given out in front of peers. Awards are handed out at full-year assembly at programme end | |

| Mentorship | 10.5: social incentive | Year 9 students are informed that verbal praise will be provided |

| 12.2: restructuring the social environment | A regular short (≈ 20-minute) intervention session is incorporated into the school timetable | |

| 13.1: identification of self as role model | Weekly elected Year 9 peer leaders act as role models. They support and encourage fellow students to try the chosen activities | |

| Rewards | 14.9: reduce reward frequency | Year 9 students receive individual rewards on reaching point milestones [e.g. a sports bag (15 points), t-shirt (50 points) or hoodie (150 points)] |

| Intervention element | Brief description |

|---|---|

| GoActive sessions |

Each tutor group chooses two different activities weekly. Twenty example activities are available, utilising little or no equipment and appealing to a wide variety of students (e.g. ultimate frisbee, Zumba and hula hoop). Materials are available on the GoActive website or in resources provided to schools Teachers are encouraged to use one period of tutor time per week to do one of the chosen GoActive activities as a class |

| Mentors | Older adolescents within the school are paired with each Year 9 tutor group to encourage them to participate in the chosen activities. Mentors remain paired with each class for the duration of the intervention |

| In-class Year 9 leaders | Peer-leaders (two per class each week, one male and one female) assist mentors to encourage students to try activities in GoActive sessions. Peer leaders change every week |

| GoActive website use |

Points: points are gained every time students try a GoActive activity. There is no expectation of time spent in the activity, as points are rewarded for the taking part itself. Individual students keep track of their own points privately on the study website and their points are entered into the between-class competition so that each class competes against each other School graphs: class rankings are circulated each week to encourage teacher support Claiming rewards: students can claim small rewards on reaching individual point thresholds [e.g. a sports bag (15 points), t-shirt (50 points) or hoodie (150 points)] |

Facilitator and mentor training

All facilitators took part in a 1-day training session before the start of the GoActive intervention. Training was provided by members of the GoActive research team and an external consultant specialised in adapting physical activity promotion to different contexts. The contents of the training focused on providing background information on GoActive and its evaluation, a detailed overview of the intervention and the role of the facilitator in intervention delivery, the options for flexibility in intervention implementation, and the resources available to the facilitators and teachers/mentors. All facilitators additionally received a 33-page manual and the research team was available throughout the intervention delivery phase if any questions or concerns arose.

The role of the GoActive intervention facilitator included training teachers and mentors. The audience of this training included Year 9 form tutors and/or house leaders, GoActive mentors and a selected school contact [often physical education (PE) or Year 9 lead]. Training sessions were scheduled for 1 hour. The sessions first provided an overview of the GoActive programme, followed by a question and answer session, during which the audience was encouraged to ask questions or clarify details. Practical training (including role playing, if appropriate) was given for (1) daily intervention delivery, (2) ideas for motivating leaders, (3) overcoming problems and (4) ideas for planning and organising activities. A slide deck and a suggested training schedule were provided to each facilitator to support training and all mentors/teachers received a manual. It was stressed that expectations should be made clear during teacher/mentor training, and the importance of and process for risk assessments was discussed.

Study objective and aims

Overall study

The overall objective was to assess the clinical effectiveness of the GoActive intervention in increasing daily MVPA in 13- to 14-year-old (Year 9) adolescents and to establish the cost-effectiveness of the programme.

The specific aims of the project were as follows:

-

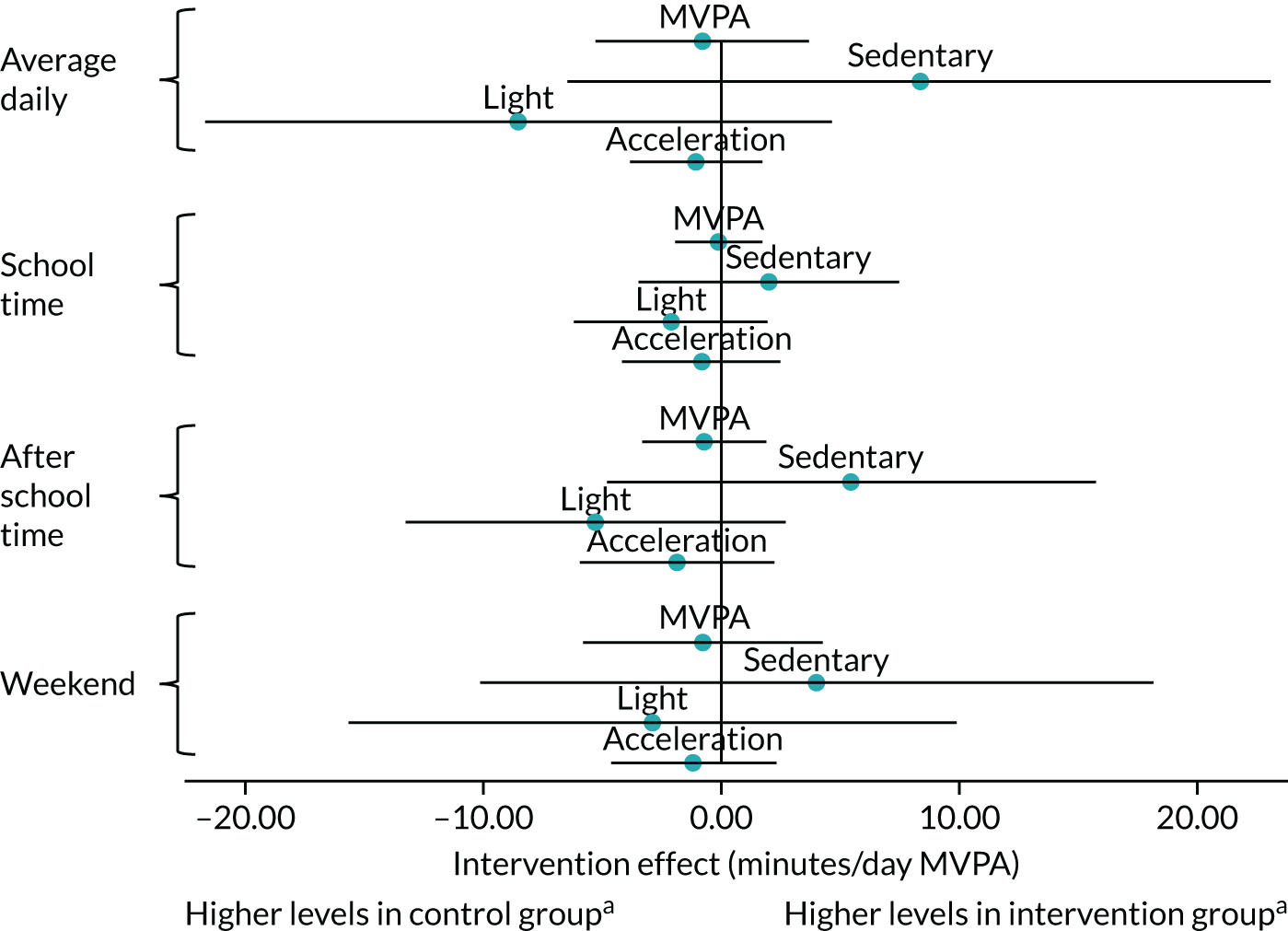

To assess the post-intervention and 10-month effectiveness of the GoActive programme in increasing average daily accelerometer-assessed MVPA among 13- to 14-year-old adolescents.

-

To assess the effect of GoActive on the following secondary outcomes:

-

accelerometer-assessed sedentary time, light physical activity (LPA) and overall physical activity during school time, weekday evenings and weekends

-

student-reported physical activity participation, self-efficacy, peer support, self-esteem, friendship quality and well-being

-

body composition [i.e. body fat percentage and body mass index (BMI) z-score].

-

-

To assess the short-term (within-trial) and potential long-term cost-effectiveness of the programme.

-

To assess programme acceptability, uptake, maintenance and dose.

-

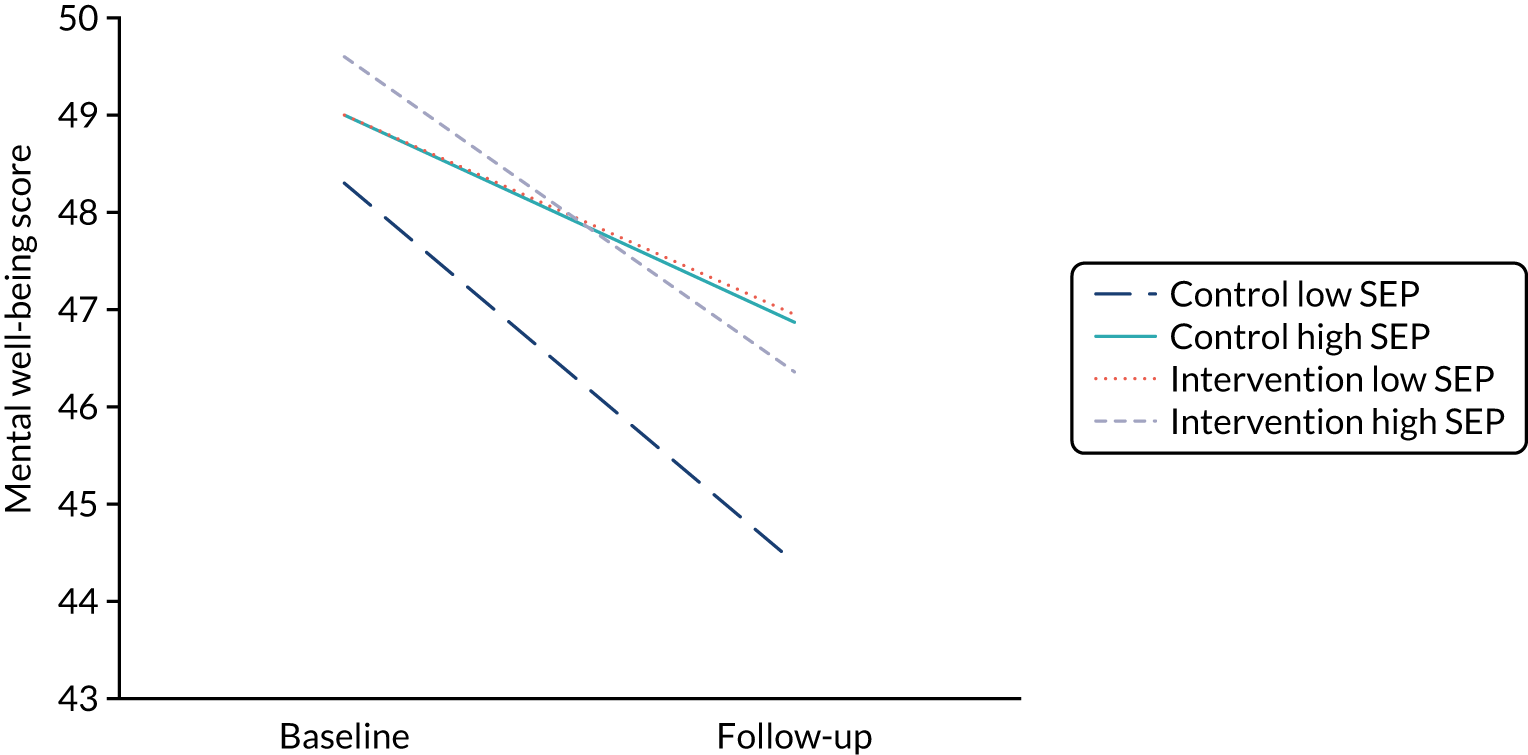

To investigate potential moderation of intervention effects (by gender, socioeconomic status, ethnicity, baseline activity level and weight status) and potential mechanisms of effect by proposed mediators, including peer support, friendship quality, self-efficacy and self-esteem, using a mixed-methods approach.

Mixed-methods process evaluation

Process evaluation is key to being able to assess fidelity and quality of implementation, clarify causal mechanisms and identify contextual factors associated with variation in outcomes. 69 By conducting a thorough process evaluation, combining both quantitative and qualitative data collection methods and insights from different stakeholder groups, it is possible to identify the barriers and facilitators that influence the delivery of the intervention within different contexts, investigating successes and failures of implementation to maximise the learning from the trial delivery of an intervention. 70

The implementation of the programme in each school was assessed through a mixed-methods process evaluation, which included focus groups with and questionnaires completed by students and mentors, as well as individual student, teacher and facilitator interviews and observations of GoActive sessions. The process evaluation protocol has been published previously25 and part of the process evaluation was published prior to analysing intervention efficacy to avoid interpretation bias. 21

The specific objectives of the GoActive process evaluation were as follows:

-

To assess the reach, dose and fidelity of intervention delivery, to document how the intervention was implemented and to ascertain whether or not the intervention’s essential functions (i.e. components of the intervention) were adapted to suit individual settings (see Table 5).

-

To explore the GoActive intervention from the perspective of Year 9 students, mentors, teachers and facilitators, and to describe participants’ views of the intervention (including intervention acceptance).

-

To consider the maintenance and sustainability of the intervention and, if proven effective, the possible dissemination of the GoActive intervention.

The process evaluation was designed to observe the implementation of GoActive and was not used to intervene in how schools implemented the GoActive intervention where deviations from the intervention protocol were detected. The design of the process evaluation was informed by the Medical Research Council (MRC) guidance on the process evaluation of complex interventions. 60,69,71

Study design

We conducted a two-arm cluster RCT with an embedded mixed-methods process evaluation comparing the GoActive intervention with the control condition (i.e. where schools continued to provide their usual physical activity offering). After baseline measurements, participating schools were randomised to the intervention arm or the no-treatment control arm. Allocation used a randomisation list that was prepared in advance by the trial statistician, who was independent from the measurement team, using a random number generator in Stata® version 15.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). Randomisation was stratified by school-level pupil premium (below or above the county-specific median) and county (Cambridgeshire or Essex). Information on pupil premium is described in Appendix 2.

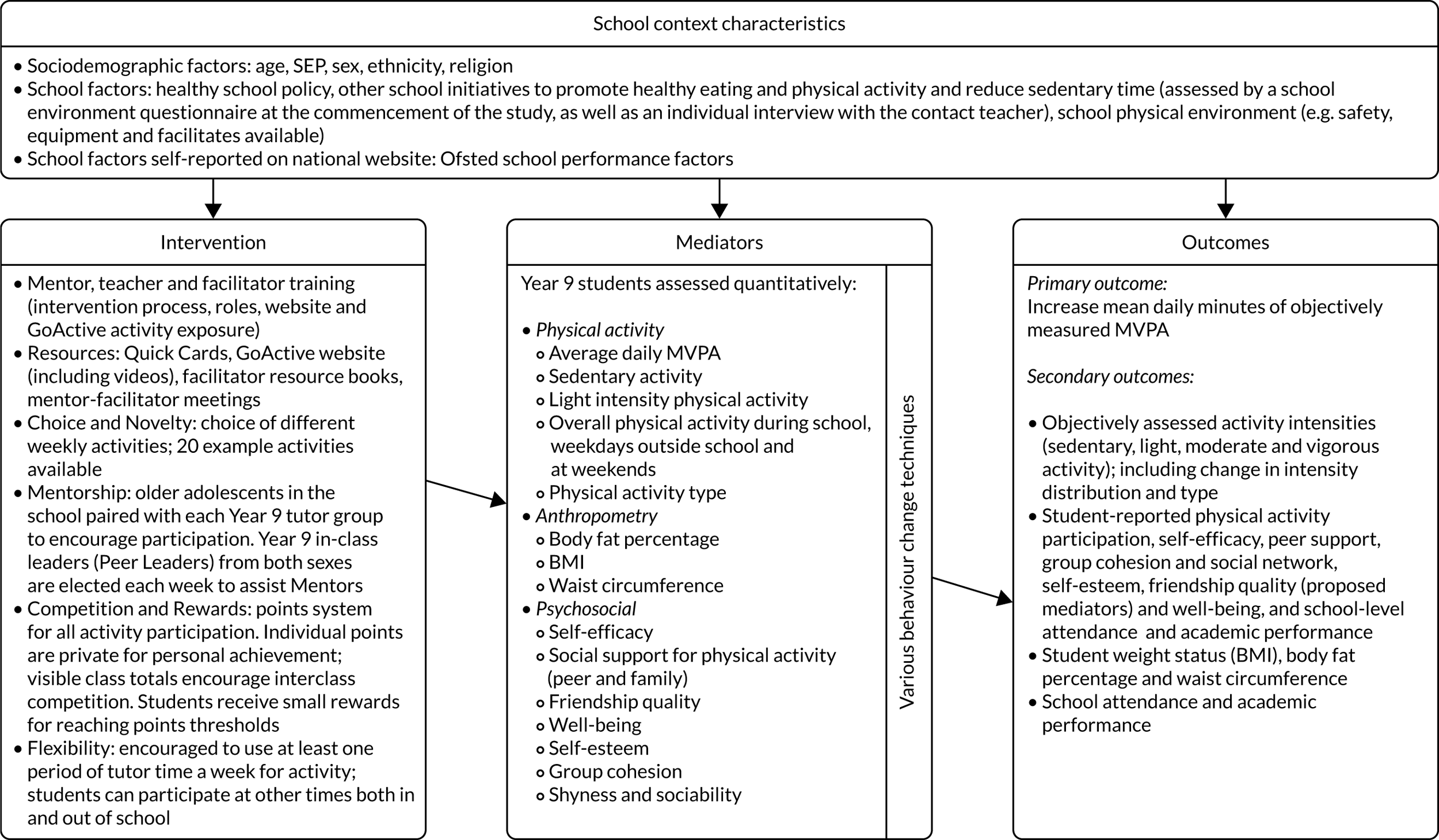

Figure 4 shows the GoActive logic model developed for the overall evaluation.

FIGURE 4.

The GoActive logic model. SEP, socioeconomic position.

Ethics approval was obtained from the University of Cambridge Psychology Research Ethics Committee, Cambridge, UK (PRE.126.2016). The protocol was conducted and reported in accordance with SPIRIT (Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials) guidance. 27–29 The trial was registered with the ISRCTN registry (trial registration number ISRCTN31583496).

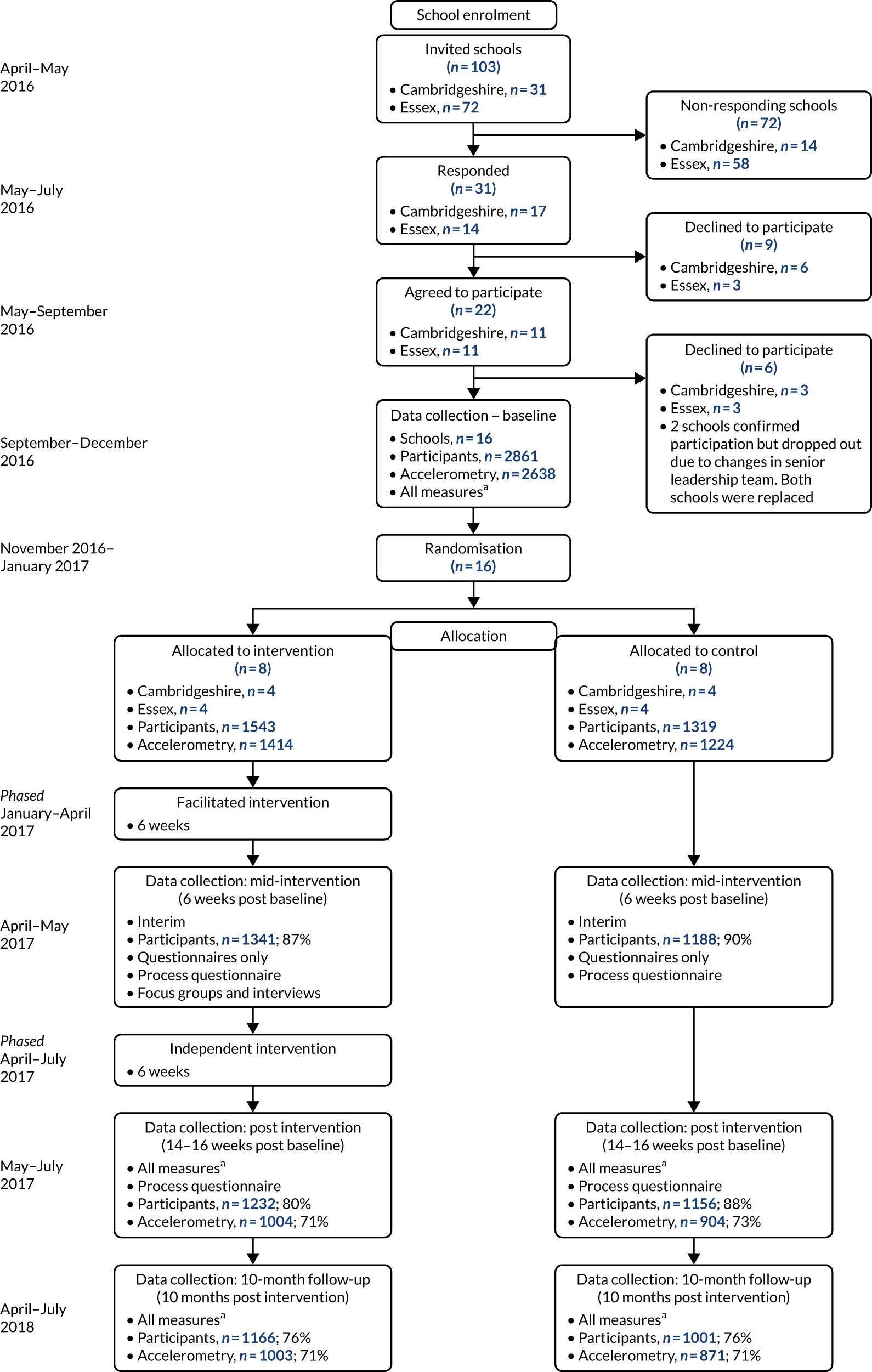

School and participant recruitment

All state-maintained schools that included Year 9 students across Cambridgeshire and Essex (n = 103) were invited to take part in the study between April and July 2016. Although Cambridgeshire and Essex have lower deprivation than the UK median, the areas included wide socioeconomic diversity, including the most deprived place in the UK,20 as well as a mix of urban and rural areas. Schools that expressed interest were provided with further information and senior school staff met with the GoActive study team. Sixteen schools agreed to take part.

All students within Year 9 in the 2016–17 academic year in participating schools were eligible for participation in the study. Students and their parents/guardians/carers were provided with study information. Parents were asked to provide passive consent (meaning that they had to actively opt out their child from study participation). Students provided written informed assent on the data collection day. Parents were provided with information packs that were sent home with students; the packs could also be accessed electronically through the usual school communication channels. Parents were given a 2-week deadline to respond, with the option to respond by telephone or e-mail if they had not returned a form to opt out their child. All those involved in intervention delivery (i.e. mentors, teachers and facilitators) provided informed consent, which was collected by researchers trained in Good Clinical Practice.

Intervention delivery

Irrespective of whether or not students participated in measurements, intervention delivery was at the school tutor group level to all eligible students in intervention schools. Parents were encouraged to speak with the school if they wanted to opt their child out of intervention participation, but no parents chose this option. Control schools received no intervention.

The intervention was delivered over 12 weeks. During the first 6 weeks, a facilitator was provided; however, during the second 6 weeks, external support for the programme was reduced to encourage school-led sustainability. The GoActive intervention targeted peer-led class-based activity, with participation encouraged outside school. Intervention facilitators (i.e. health trainers employed and funded by local councils) provided school staff and older mentors with training, support and resources for intervention delivery. Training sessions consisted of an initial session between facilitators and mentors, lasting at least 1 hour, followed by six 30-minute meetings every week during the first 6 weeks and meetings approximately every 2 weeks thereafter. Mentors were asked to meet with peer leaders weekly.

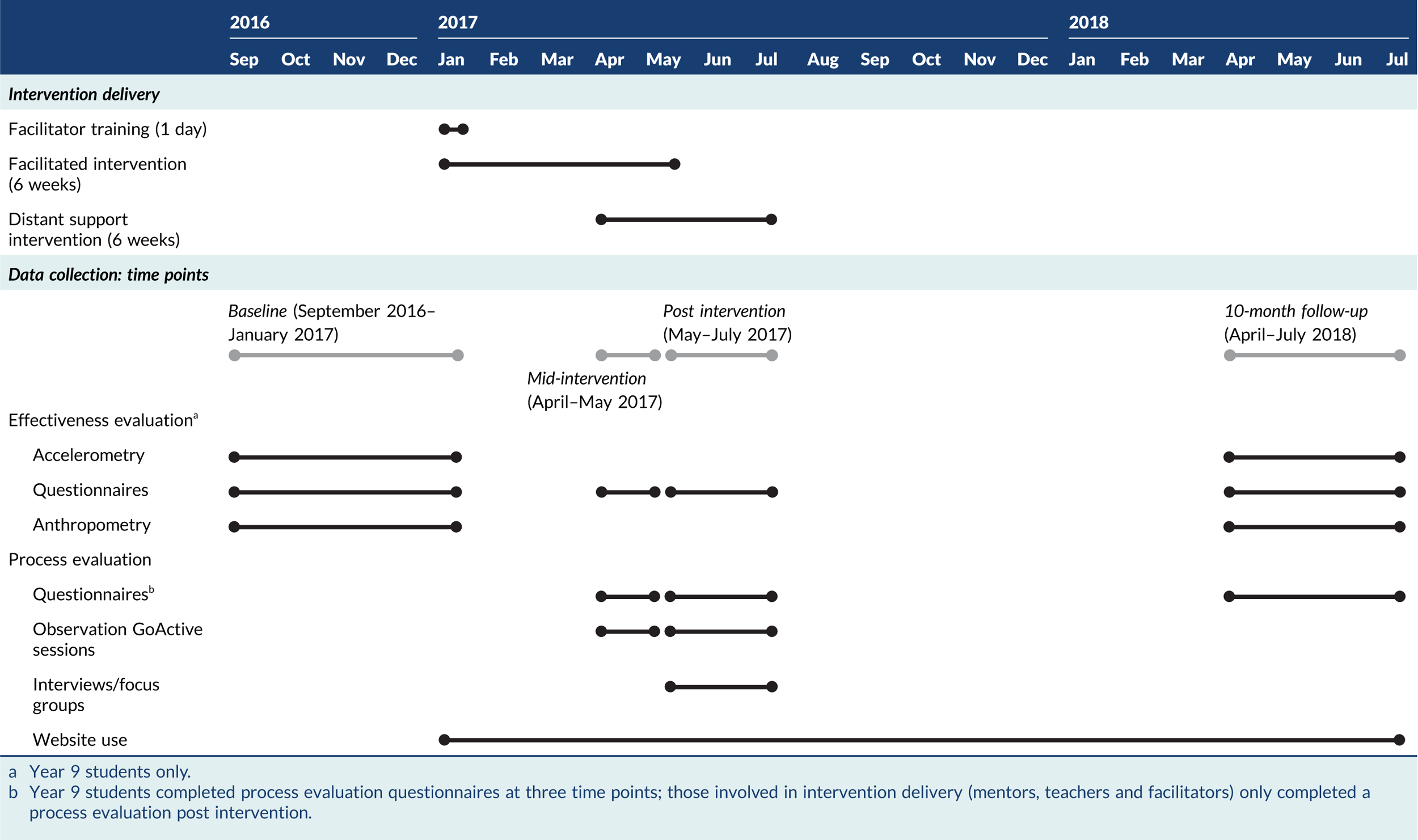

Data collection overview

Baseline assessments took place early in the academic year for Year 9 students (September 2016–January 2017), which is the school year in which students will reach 14 years of age.

Measurements were taken at four time points:

-

baseline – early in Year 9 (September 2016–January 2017)

-

mid-intervention – 6 weeks after intervention start (April–May 2017)

-

post intervention – 14–16 weeks after intervention start (May–July 2017)

-

10-month follow-up – 10 months after the end of the intervention (April–July 2018).

Outcome assessments using identical procedures were undertaken at baseline and at 10-month follow-up, and these included objective assessment of physical activity for 7 days [i.e. the primary outcome, using a wrist-worn Axivity monitor (Axivity Ltd, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK)], anthropometry (measured), social networks (computer-based assessment), and questionnaires regarding secondary outcomes, including self-reported physical activity, social support, self-efficacy, friendship quality, self-esteem, shyness and sociability. Participant demographic characteristics were additionally included in questionnaires at baseline. Social network data collection, secondary outcomes and objective physical activity assessment were conducted post intervention. Trained measurement staff, blinded to allocation, conducted measurements using standardised protocols and instruments, as detailed in the protocol. 19 Measurement staff were blinded to allocation and our dedicated process evaluation researcher independently verified the success of this blinding by e-mail correspondence shortly after the 10-month follow-up measurements.

Process evaluation measures were collected mid-intervention, post intervention and at 10-month follow-up (Table 6). With regard to quantitative data, all Year 9 participants, regardless of intervention allocation, completed questionnaire-based measures at all time points. In the intervention schools, mentors, facilitators and teachers completed process evaluation questionnaires post intervention. Website analytics were also retrieved from the website, as were facilitator and mentor logs.

| Method of data collection | Data collection participants | Number completed | Response rate | Data collection time frame | Data collected |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase 1 | |||||

| Questionnaire | Year 9 students (control and intervention) | 1341 | 86.9% of 1543 baseline participants | Mid-intervention | Experience with the GoActive programme |

| Phase 2 | |||||

| Observation | Form group, mentors and teachers in intervention schools | Eight | Eight out of eight intervention schools had an observation in phase 2 |

During the first 6 weeks of the intervention/during the 12-week intervention Sessions ran from January–July 2017 |

Details on the venue used for the intervention, the number of mentors within the classroom for the intervention and the number of Year 9 students participating in the intervention Delivery and content of GoActive activity Year 9 student engagement and understanding Detailed description of activities Questions, issues or statements from Year 9 students |

| Individual interviews | Year 9 students at intervention schools identified as shy and inactive based on baseline data questionnaire (n = 16) | Two per school | Semistructured interview questions on the following:

|

||

| Contact teacher at each intervention school | Nine (one per school and one school had two contact teachers) | Semistructured interview questions on the following:

|

|||

| Phase 3 | |||||

| Observation | Form group, mentors and teachers in intervention schools | Eight | Eight out of eight schools had an observation |

During the last 6 weeks of the intervention/during the 12-week intervention Sessions ran from April–July 2017 |

Details on the venue used for the intervention and the number of Year 9 students participating in the intervention Delivery and content of GoActive activity Year 9 student engagement and understanding Detailed description of activities Questions, issues or statements from Year 9 students |

| Throughout intervention | |||||

| Website use | Year 9 students (intervention) | 714 | 46.2% of intervention participants | From intervention start to July 2017 |

Proportion of students logging points Number of points logged Number of rewards claimed |

Qualitative process evaluation data were collected from intervention schools only. Qualitative data collection was conducted between April and July 2017 (aligned with post intervention) and included purposively sampled, semistructured individual interviews (participants, teachers and facilitators) and focus group interviews (participants and mentors). Direct observations of two GoActive sessions at each school were conducted.

Table 7 provides an overview of the timing of intervention delivery and data collection in the GoActive study.

TABLE 7.

GoActive study overview

Description of data collection methods

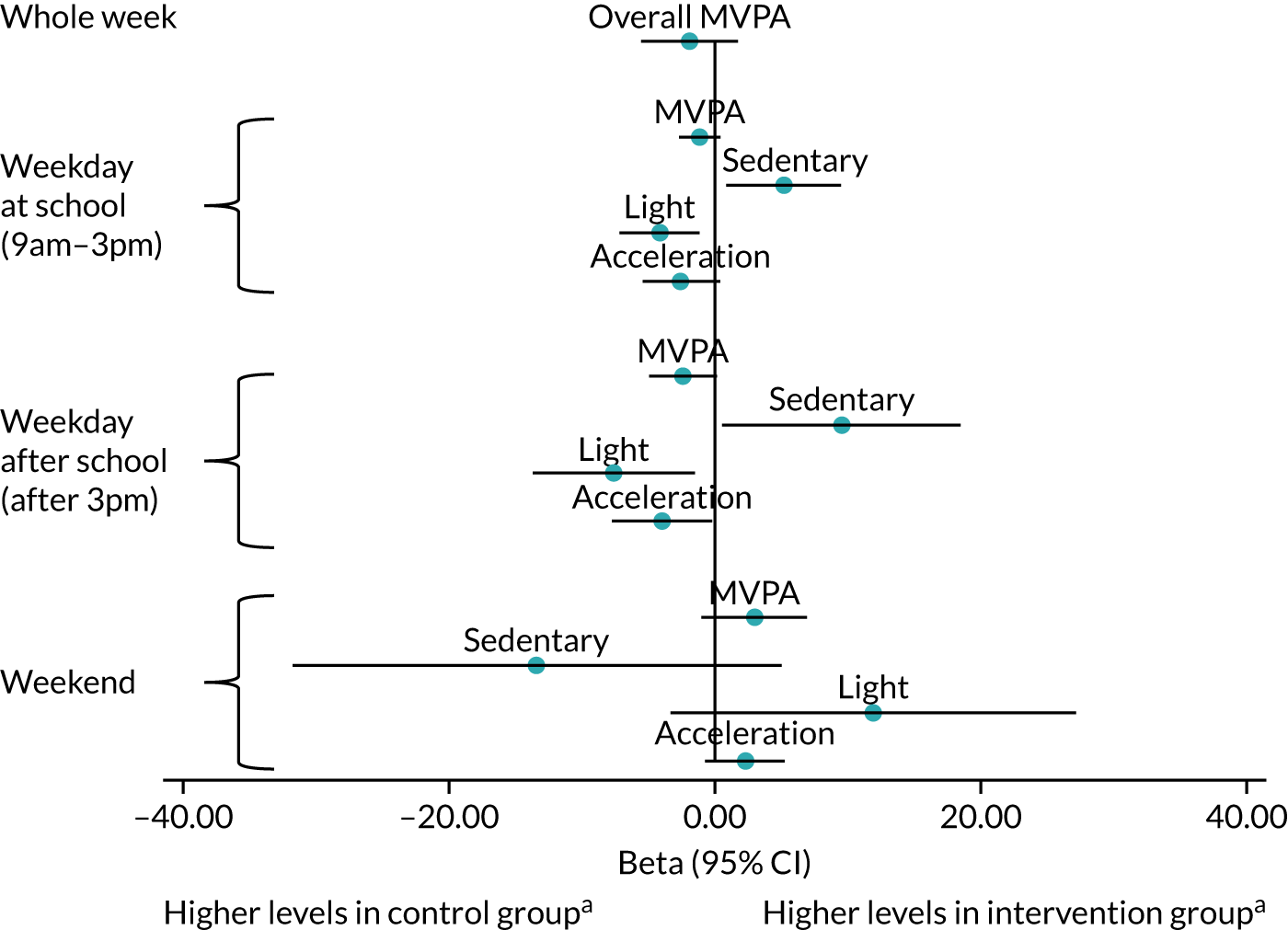

Accelerometer-assessed outcomes (including primary outcome)

The prespecified primary outcome for effectiveness was average daily minutes of MVPA at 10-month follow-up. We measured MVPA at baseline, post intervention and 10-month follow-up using wrist-worn activity monitors (Axivity) that assess acceleration (continuous waveform data). As a change to the published protocol, wrist-worn monitors were used instead of the originally proposed hip-worn ActiGraph monitors (Axivity Ltd, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK) because of the increased likelihood of protocol adherence in the target group compared with what was seen in our pilot work. Participants were asked to wear the monitors continuously for 7 days, 24 hours a day on their non-dominant wrist. Monitor output was processed to provide minutes spent in MVPA and secondary outcomes.

Accelerometery validity and processing

The Axivity monitor has been validated to assess physical activity energy expenditure72 and to have better wear time adherence and acceptability than commonly used hip-worn monitors, among adolescents. 73 Given the 24-hour wear time protocol of the Axivity monitors, a diurnal adjustment was used to reduce any bias caused by imbalances of protocol deviations regarding non-wear. 74 Each day of possible wear was divided into four time quadrants: morning (06.00 to 12.00), afternoon (12.00 to 18.00), evening (20.00 to 24.00) and night (24.00 to 06.00). For participants to be included in analyses, over 6 hours of wear time spread over at least 2 days was required from the possible 42 hours in each daytime quadrant (i.e. ≥ 6 hours from 7 possible mornings, ≥ 6 hours from 7 possible afternoons and ≥ 6 hours from 7 possible evenings). The ‘night’ quadrant (i.e. 24.00 to 06.00) was considered as sleep time and was included in the denominator when calculating daily averages of MVPA, for consistency across all participants. Where individuals did not wear the monitor for ≥ 6 hours at night-time, despite the protocol requesting them to wear it continuously for 7 days, average night-time values were imputed using population averages (n = 91 at baseline and n = 463 at follow-up), created from GoActive participants with 100% protocol compliance regarding monitor wear, to avoid inflation of MVPA estimates. This method was verified by running simulations that exclude night data for a subsample of participants with 100% protocol compliance. For an individual hour to be included for analysis, at least 70% of possible wear time was required, with non-wear time within the hour considered as missing. 74

Monitor output was processed to provide minutes spent in MVPA equivalent to ≥ 2000 ActiGraph counts per minute (c.p.m.). 4 Additional secondary accelerometry-derived outcomes were average daily minutes of sedentary time (equivalent to ≤ 100 ActiGraph c.p.m.), average daily minutes of LPA (equivalent to 101–1999 ActiGraph c.p.m.) and average daily activity (represented by average acceleration). In addition to daily averages, all intensity outcomes (including MVPA) were derived during school time (09.00 to 15.00), during weekday after school time (after 15.00) and at weekends. Participants who met the inclusion criteria for average daily MVPA were included in any analyses for which they had sufficient data (≥ 2 days). 75 As the criteria for deriving average daily MVPA did not require both weekend and weekdays of valid data,76 participant numbers varied by outcome.

Reported demographic data

Participant descriptive characteristics, including prespecified effect modifiers [e.g. gender, individual socioeconomic position (SEP) and ethnicity] were self-reported at baseline. Ethnicity was self-reported by participants who were given 20 response options and additional free-text completion options. For descriptive purposes, the reported values were recoded to five categories in accordance with recommendations:77 (1) ‘white’, (2) ‘mixed ethnicity’ (i.e. identifying with multiple ethnicities), (3) ‘Asian’ (including South Asian and Chinese), (4) ‘African and/or Caribbean’ and (5) ‘other’. Ethnicity was subsequently dichotomised for prespecified moderation analyses (‘white’ vs. remaining categories). Participants completed six items from the Family Affluence Scale (FAS) that relate to family car ownership, holidays, computers, availability of bathrooms, dishwasher ownership and having their own bedroom, which was used as a proxy of individual SEP by summing answers (possible range: 0–13) and dividing into predefined affluence groups (low = 0–6, medium = 7–9 and high = 10–13). 78,79 Shyness and sociability were assessed using five items in the Emotionality, Activity, Shyness and Sociability Scale. 80

Self-reported outcomes

Secondary outcomes were assessed at baseline, post intervention and 10-month follow-up using questionnaires that included measures validated for use in the population (e.g. social support for activity, self-efficacy, group cohesion, friendship quality, self-esteem, shyness, sociability and mental well-being). GoActive questionnaires are available as additional material [see NIHR Journals Library, URL: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/phr/139018 (accessed 12 January 2020)]. Social support for physical activity was a mean derived from nine self-reported items (response range: 1–4) from the European Youth Heart Study. 81 Self-efficacy was a mean of eight self-reported items from Reynolds’ Psychosocial Predictors of Physical Activity: Self-efficacy scale82 (response categories: 1–6). Group cohesion was assessed by an adapted social network modelling tool in which participants were provided with a list of tutor group members on a laptop and were asked to select the names of up to five of their friends from the list provided. These data were used to derive in-degrees (i.e. the number of people identifying the participant as a friend) and out-degrees (i.e. the number of friends that participant lists as a friend). 83 Friendship quality was a mean score of eight self-reported items used in the ‘ROOTS’ study (equally weighted),84 with a response range of 1–5. Self-esteem was a mean score of self-reported items using the 10-item Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale,85 which had original response options of 1–4. Self-reported physical activity was assessed using the Youth Physical Activity Questionnaire (YPAQ). 86 Activity frequency was calculated as sessions per week of all reported activities (range: 0–160).

The Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale was used to assess mental well-being. 87 The 14-item scale asks participants to indicate what best describes their experiences of a collection of statements over the past 2 weeks. Items relate to both hedonic and eudemonic experiences of mental health, including positive affect (e.g. ‘I’ve been feeling optimistic about the future’), relationships (e.g. ‘I’ve been feeling close to other people’) and emotional functioning (e.g. ‘I’ve been dealing with problems well’), each rated on a five-point Likert scale with responses ‘none of the time’, ‘rarely’, ‘some of the time’, ‘often’ and ‘all of the time’ scored 1–5, respectively. The scale has shown good content validity, and correlates well with other mental health and well-being scales, including the Positive and Negative Affect Scale,88,89 Short Depression-Happiness Scale90 and the World Health Organization (Five) Well-Being Index. 91 Cronbach’s alpha has been shown to be 0.89 among a student sample and 0.91 in a population sample. 87 Overall, the scale has shown good internal consistency, good test–retest reliability and good face validity. 92 Participants who responded to all 14 items on the scale were included in the mediation analysis and their score was the average of the item responses (out of a possible 1–5).

Anthropometry

Anthropometry (i.e. height, weight, waist circumference, bioimpedance) was assessed at baseline and at 10-month follow-up by trained staff. BMI z-score was calculated from height, weight, age and gender. 93 BMI z-score was also used to identify participants with overweight or obesity. 94 As a change to the published protocol,4 anthropometry was not assessed at post intervention to reduce the burden on schools and participants, and because no meaningful short-term effect on anthropometry was expected.

Appendix 3 lists further details regarding all outcome variables, including for the primary outcome and all secondary outcome measures.

Process evaluation data collection

As stated earlier, process evaluation measures were collected mid-intervention, post intervention and at 10-month follow-up. Details on the quantitative and qualitative data collected are provided below. An overview of the process evaluation data collected is presented in Table 6.

Quantitative process evaluation data

Quantitative process evaluation data were collected in post-intervention questionnaires adapted from those used in the feasibility study. 5,6 To assess engagement with mentors, students were asked:

Within the GoActive programme, mentors . . . (a) motivated me to be active, (b) were enthusiastic about GoActive, (c) offered lots of different activities to take part in, (d) came in to run GoActive almost every week and (e) explained activities clearly.

Students were also asked to assess engagement with their form tutors (teachers):

Within the GoActive programme, teachers . . . (a) motivated me to be active and (b) were enthusiastic about GoActive.

Response options were from 1, ‘strongly agree’ to 4, ‘strongly disagree’. Items were reverse coded so that higher values were indicative of more positive responses and a mean was calculated. Perception of other intervention components, including class sessions (mean of trying new activities and using tutor time), rewards (individual prizes), competition (mean of class and individual competition) and peer leaders (mean of reported leadership and engagement), were assessed using Likert scales [‘do not like it at all’ (1) to ‘like it a lot’ (5)].

Mentors, teachers and facilitators were also given questionnaires asking them to rate their opinions of the programme and the implementation. All mentors and facilitators involved with the delivery of GoActive were also asked to complete intervention delivery logs on the GoActive website. These logs sought information on, for example, the date each lesson took place, how long it lasted, how many Year 9 students were active in their participation and any comments on the delivery of the session.

Use of the GoActive website was assessed using the points entered on the study website. Participant scores were dichotomised as having entered points compared with not entering points. The website analytics that were included for process evaluation were individual points logged, rewards claimed, activities selected and messages to mentors.

Qualitative process evaluation data

Six process evaluation components were assessed: (1) fidelity, (2) dose delivered, (3) dose received, (4) reach, (5) recruitment and (6) context. 67 Process evaluation quantitative data collection occured in both the control and intervention arms of the trial, whereas qualitative data were collected in the intervention arm only. 3

Qualitative data collection occurred between mid-intervention and 12–14 weeks post baseline (April–July 2017). Data were collected to evaluate the process evaluation measures, to note if findings were consistent with how the intervention was theorised to act in our logic model (see Figure 4) and to note any potential barriers to wider dissemination, should it have proved effective. Qualitative data were collected from all eight intervention schools towards the end of the 12-week intervention. Individual and focus group interviews were conducted by the same experienced qualitative researcher. The interview materials are available as additional material (with color) [see NIHR Journals Library, URL: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/phr/139018 (accessed 12 January 2020)].

Eleven semistructured focus groups with Year 9 students were conducted in a school space familiar to them (total group, n = 48 participants; mean group size, n = 4 participants; range 2–7 participants). Mid-intervention, Year 9 students at intervention schools indicated whether or not they would be willing to be contacted about participating in an interview and those who responded positively were provided with an additional information sheet to clarify the interview procedure (both individual and focus group). Participants for qualitative data collection were purposively sampled to gain information-rich responses, exploring diverse experiences. Focus group participants were grouped by level of participation [determined by tertiles of website points entered: 150 (high), 10–100 (medium), ≤ 10 (low)] and purposively sampled to aim for a mix of gender. An interview guide was developed and iteratively updated as new issues emerged throughout focus groups. 3 Focus groups for six schools were mixed gender. Critical reflection after the first few focus groups led to separating the remaining focus groups by gender, where possible, to maximise the chances of participants feeling comfortable to share experiences openly. Focus groups lasted between 22 and 46 minutes.

Shy/inactive participants were identified using shyness data, and self-reported physical activity participation data (YPAQ) from baseline. Students in the highest tertile for shyness80 and the lowest tertile for self-reported physical activity frequency86 were invited. It was felt that a one-to-one interview may be more comfortable for these individuals. Sixteen individual interviews were conducted (lasting 10–26 minutes). Interviews were semistructured, using a flexible interview guide specifically designed for the interviews.

Interviews focused on the perceptions of the GoActive intervention from diverse student perspectives, including those with high shyness and low physical activity, who may be less likely to engage with physical activity promotion interventions. Both of the interview guides for the focus groups and individual interviews included discussion points on the experience of participating in the GoActive trial, the process of what had been implemented around the GoActive trial within the school and in each class, the depictions of the in-class Year 9 leader, mentor and teacher roles, and perceived barriers to and facilitators of running the GoActive intervention.

Qualitative data were also collected from all of those involved in intervention delivery. Data collection methods included purposively sampled, semistructured individual interviews (teachers and facilitators) and 10 focus group interviews (58 mentors) with individuals involved in intervention delivery. Interview topics included experience of facilitating the GoActive intervention in the school, the process of what had been implemented around the GoActive trial, the depictions of the mentor, teacher and facilitator roles (including self-perceptions), and perceived barriers to and facilitators of running the GoActive intervention. Facilitators implementing across more than one school were asked to discuss school-specific responses.

GoActive sessions observations

Direct observations of two GoActive sessions at each school running the intervention (n = 8) were arranged by contact teachers. Teachers and most mentors that were to be observed were informed of when observations would take place. Data collected during observations comprised detailed written notes that described what took place, where in the school setting, any informal conversation, the role of the mentor, teacher engagement and level of engagement from Year 9 students.

Trial sample size calculation

We estimated that a total of 1310 participants would be required to have 85% power to detect a 5-minute difference in change in MVPA between baseline and 10-month follow-up as significant at the 5% level,4 assuming a standard deviation (SD) of MVPA of 17.8 minutes and a correlation of 0.59 between baseline and follow-up. 19 Assuming a within-school (intraclass) correlation of 0.034 and 30–40% loss to follow-up, we aimed to recruit 16 schools with 150 participants per school. 19

Analytical approach

Analysis of effects on primary and secondary outcomes

The statistical analysis plan was approved by the Trial Steering Committee (TSC) prior to analyses being performed. The full statistical analysis plan is available from the GoActive study website [URL: www.mrc-epid.cam.ac.uk/research/studies/goactive/ (accessed 28 February 2020)]. Statistical quantitative analyses were performed using Stata.

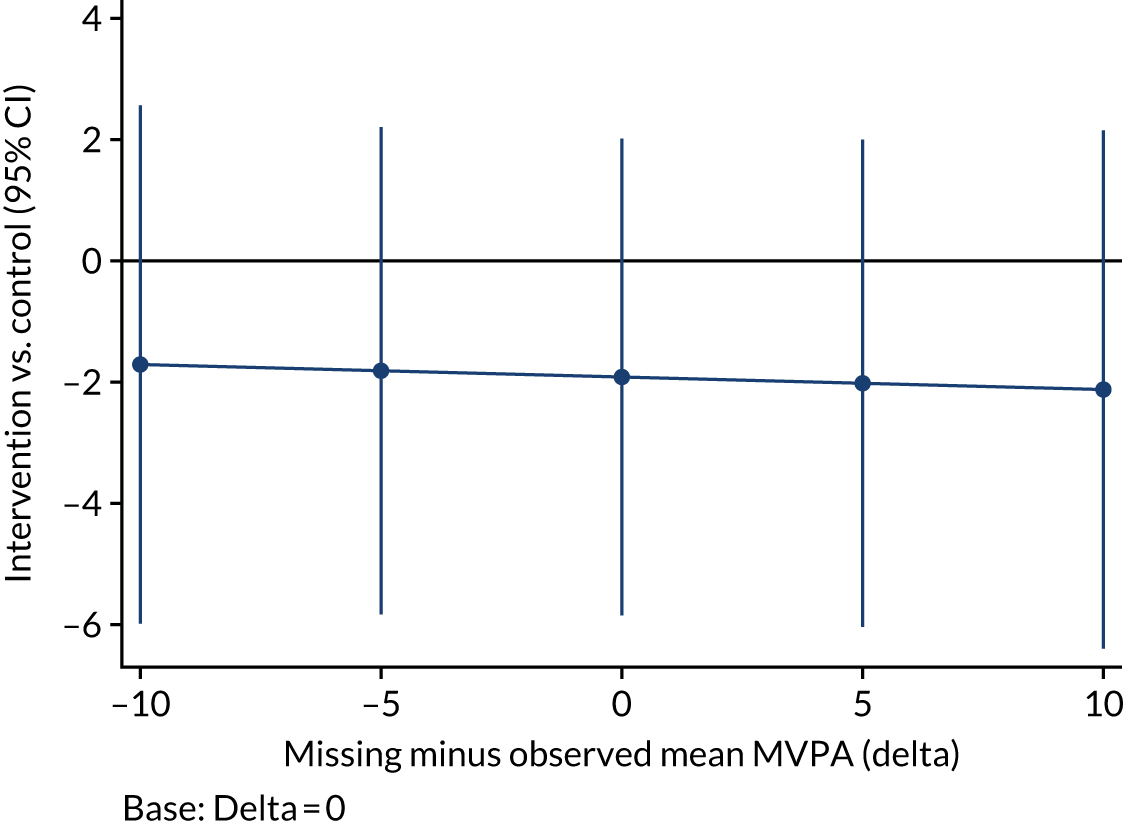

For MVPA at 10-month follow-up (i.e. the primary outcome), the intervention effect, representing the baseline-adjusted difference in change from baseline between the intervention and control groups, was estimated from a linear regression model, including randomisation group, baseline value of the outcome [i.e. analysis of covariance (ANCOVA)] and the randomisation stratifiers (i.e. pupil premium funding and county). Robust standard errors (SEs) were calculated to allow for the non-independence of individuals within schools and the missing indicator method95 was used to ensure the inclusion of participants with a missing baseline value of the outcome variable. All secondary outcome variables were analysed using the same method.

We conducted a complete-case analysis in which participants and schools were included in the group to which they were randomised, although participants with a missing value of an outcome at follow-up were excluded from the analysis of that particular variable. This is a complete-case analysis that is valid under the assumption that the outcome is missing at random, conditional on randomised group and the baseline value of the outcome.

Per-protocol analysis

A further analysis of the primary outcome was performed in a per-protocol population, defined as intervention group participants reporting ‘being active during tutor times at least twice during the last 2 weeks’ [i.e. self-reported intervention engagement mid-intervention (week 6 of the intensely facilitated phase of the intervention)] and logging activity points on the study website at least once during the entire intervention period. This definition was based on a review of quantitative process evaluation data prior to the main analyses and reflects the group with highest intervention engagement, as opposed to delivery of the protocol with fidelity.

Sensitivity analyses

Post hoc sensitivity analyses recommended by the TSC were performed, in which the primary outcome was calculated (1) excluding time between 24.00 and 06.00 and (2) using a stricter inclusion criterion of 12 hours of wear time per quadrant.

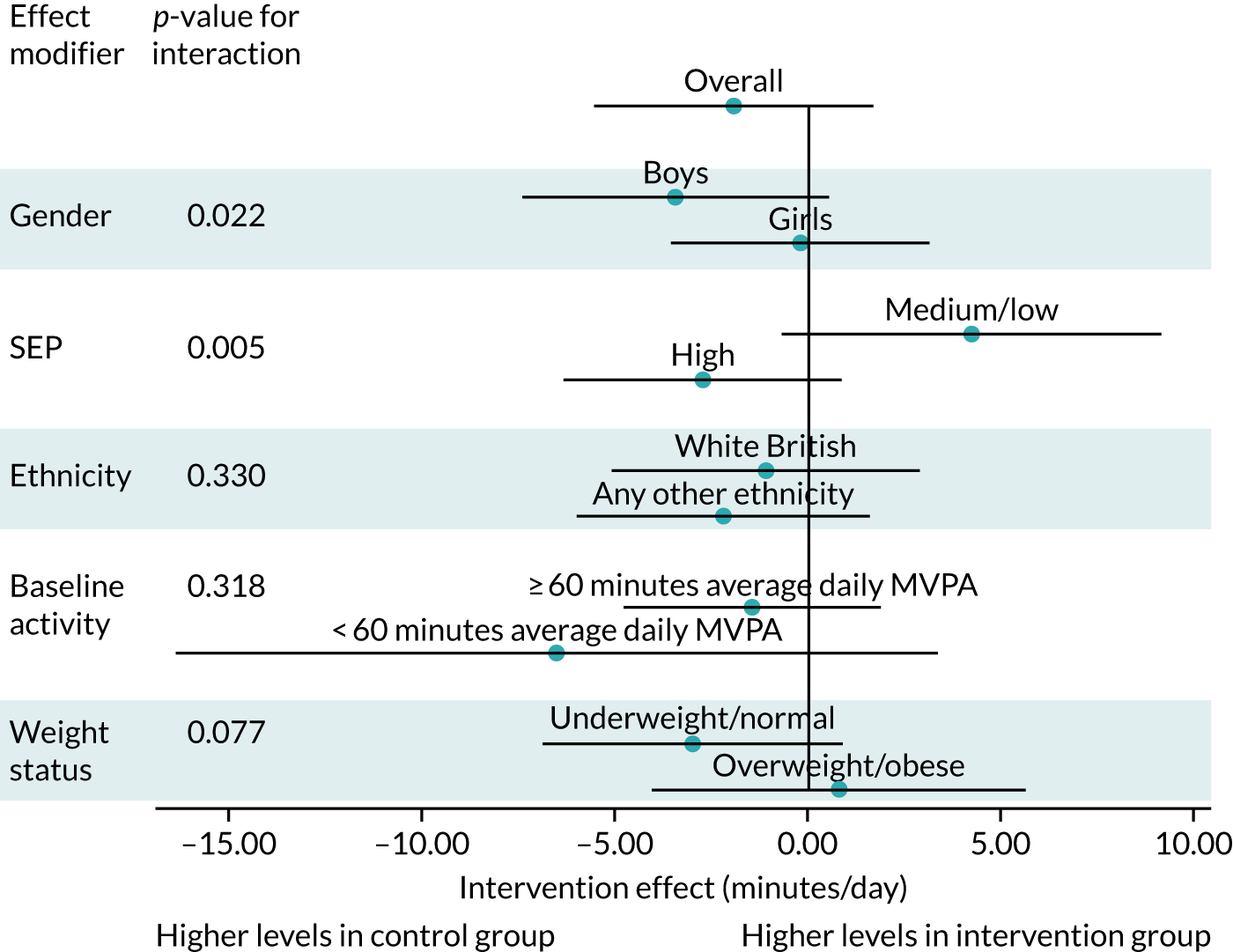

Effect modification

For the primary outcome and secondary accelerometer-assessed physical activity outcomes, effect modification was conducted by (1) gender, (2) socioeconomic status (medium or lower vs. high, according to FAS score), (3) ethnicity (white vs. any other ethnic background), (4) baseline physical activity (≥ 60 minutes MVPA/day vs. < 60 minutes) and (5) weight status (with normal weight vs. with overweight or obesity) and was tested with an F-test of the relative multiplicative interaction parameter in the ANCOVA model. Effect modifiers were selected based on previous evidence of potential differential effects. 13,14 Subgroup analyses were performed within all categories defined by these variables.

We used baseline accelerometer-assessed activity data to classify participants’ activity level using 30 and 60 minutes of MVPA, using (average) thresholds. The 60-minute threshold was applied to be consistent with UK physical activity guidelines, whereas the additional 30-minute threshold was applied to achieve greater heterogeneity in the moderator, as activity levels were low at baseline (minutes of MVPA at baseline for whole group: 35.6 ± 18.6 minutes/day). Subgroup analyses were performed for the primary outcome within all categories defined by these variables, but only where interactions showed p < 0.05 for secondary outcomes.

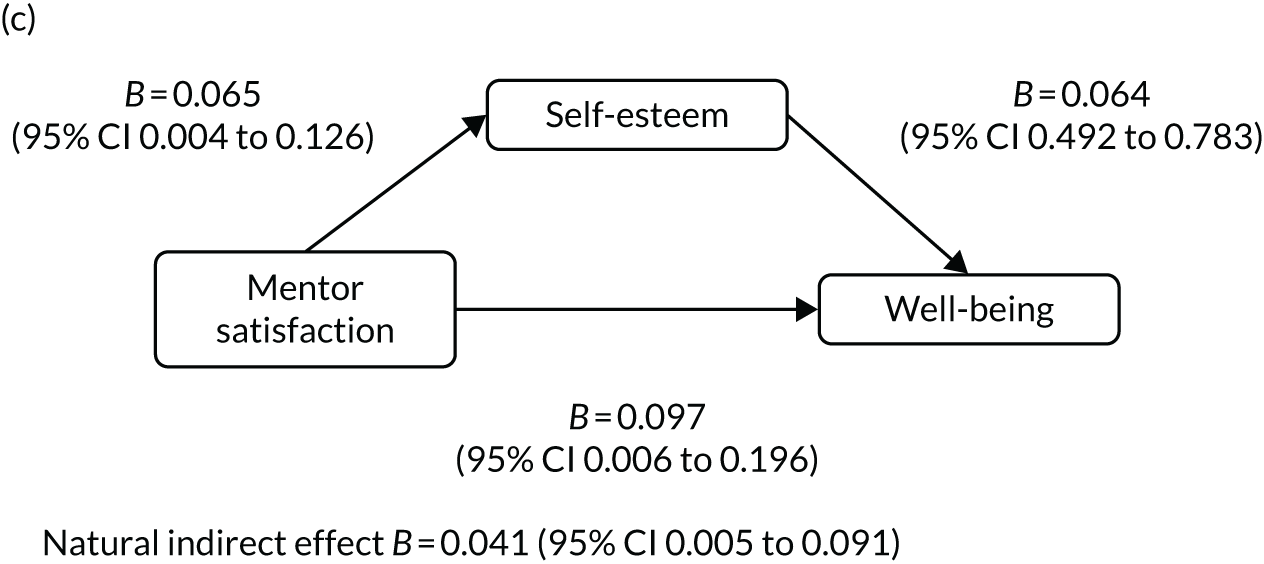

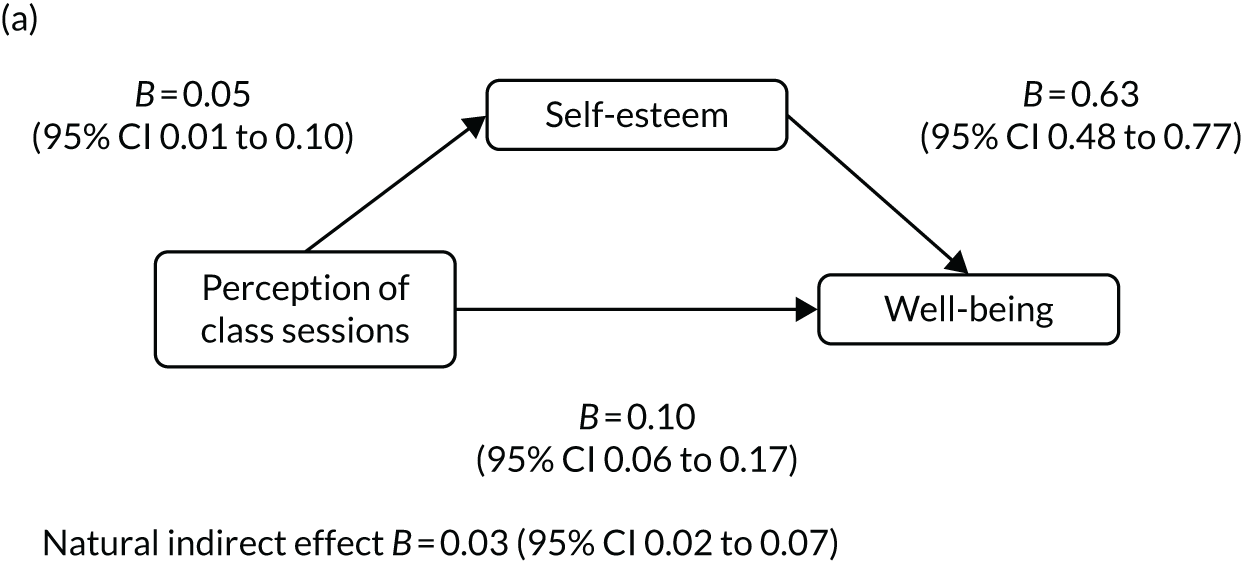

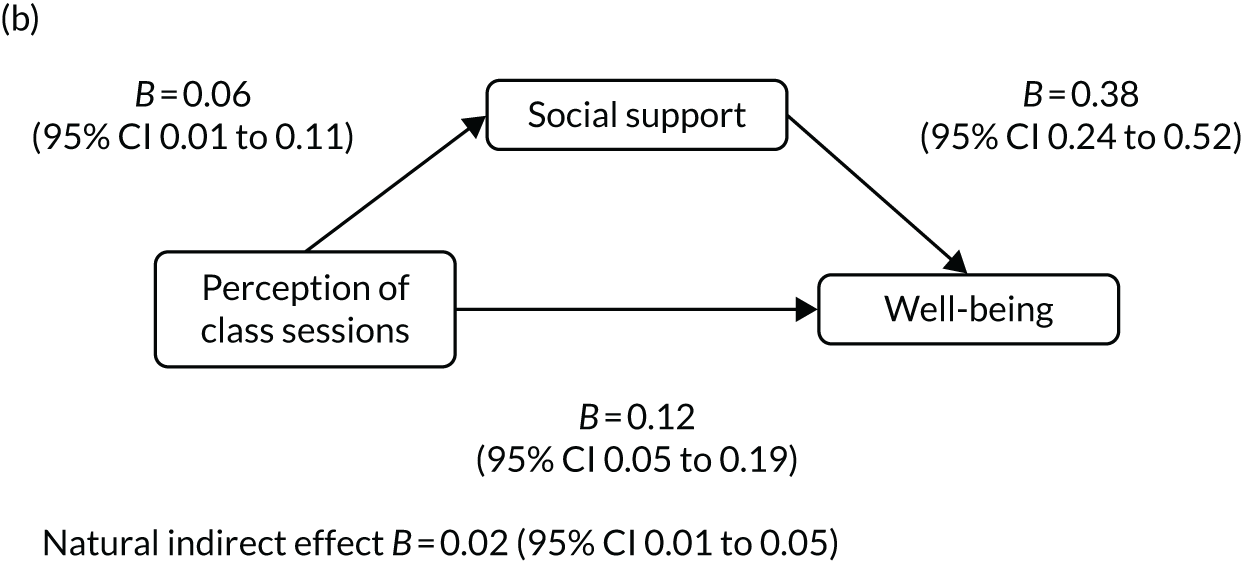

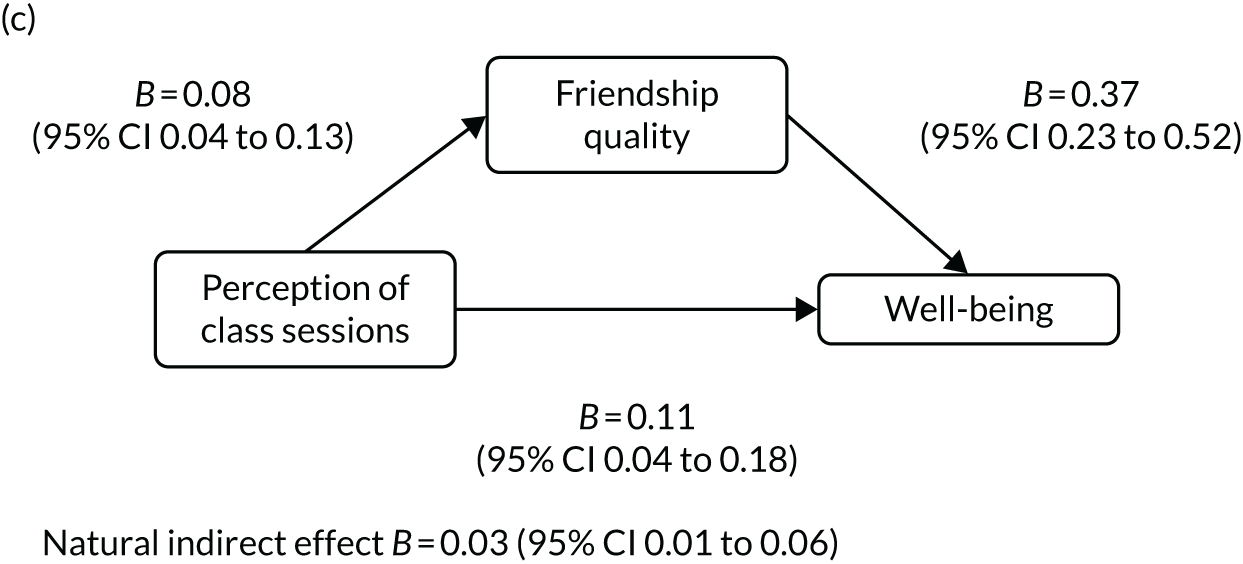

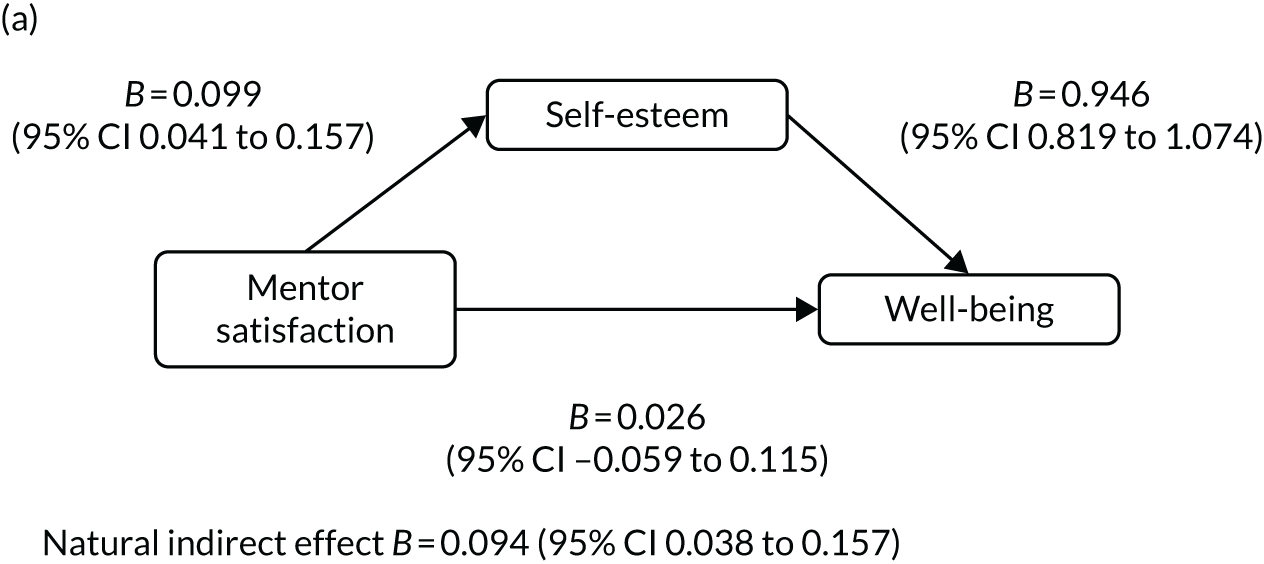

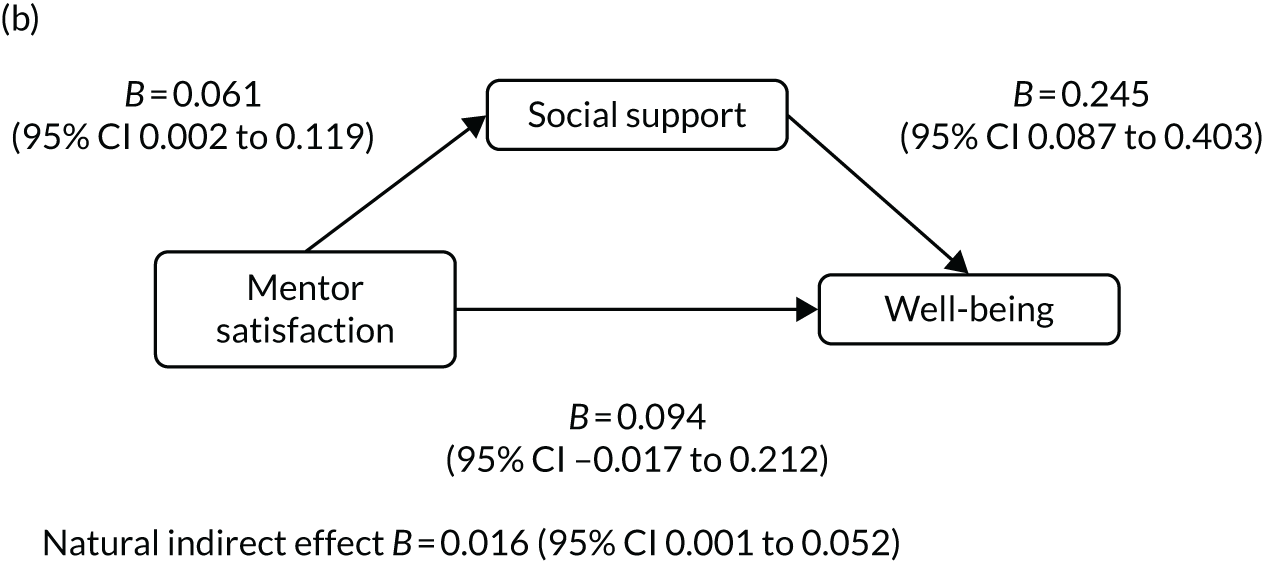

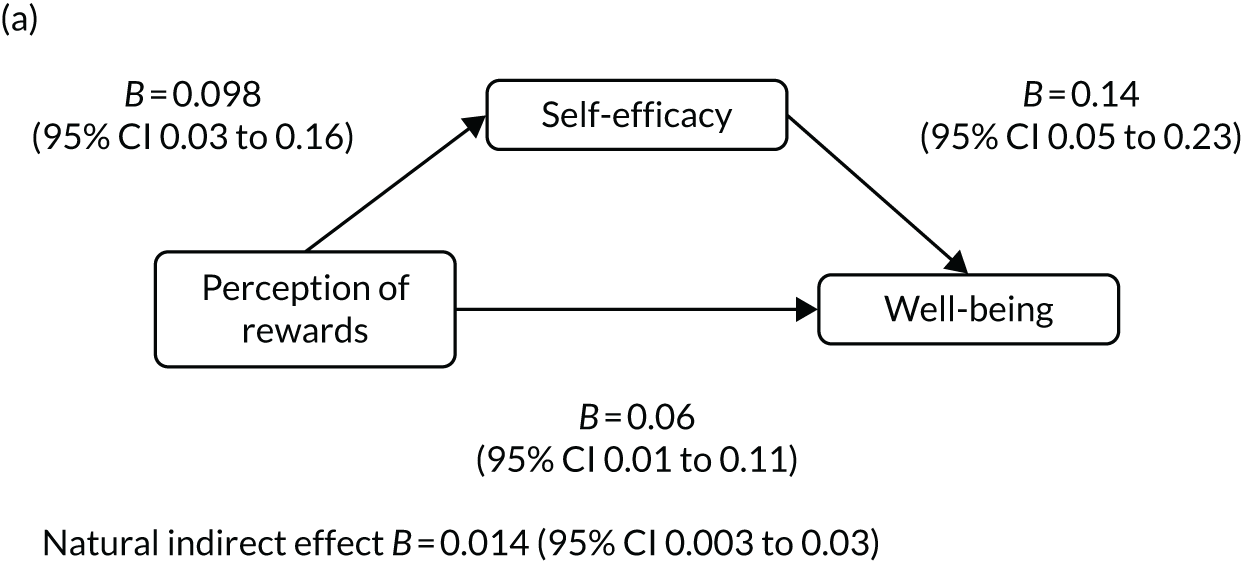

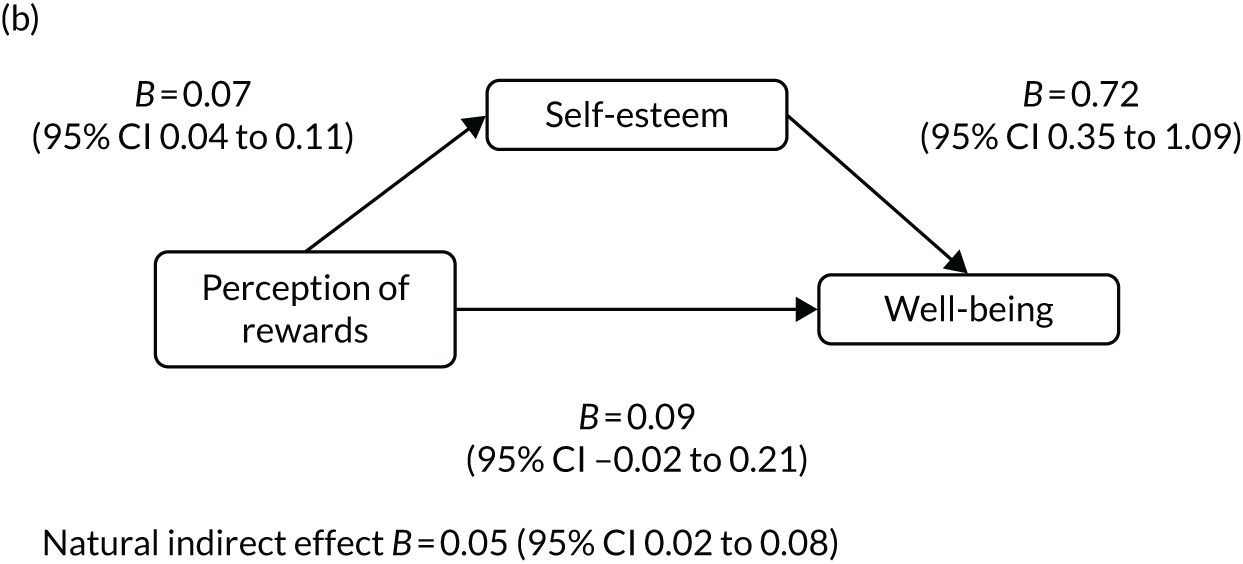

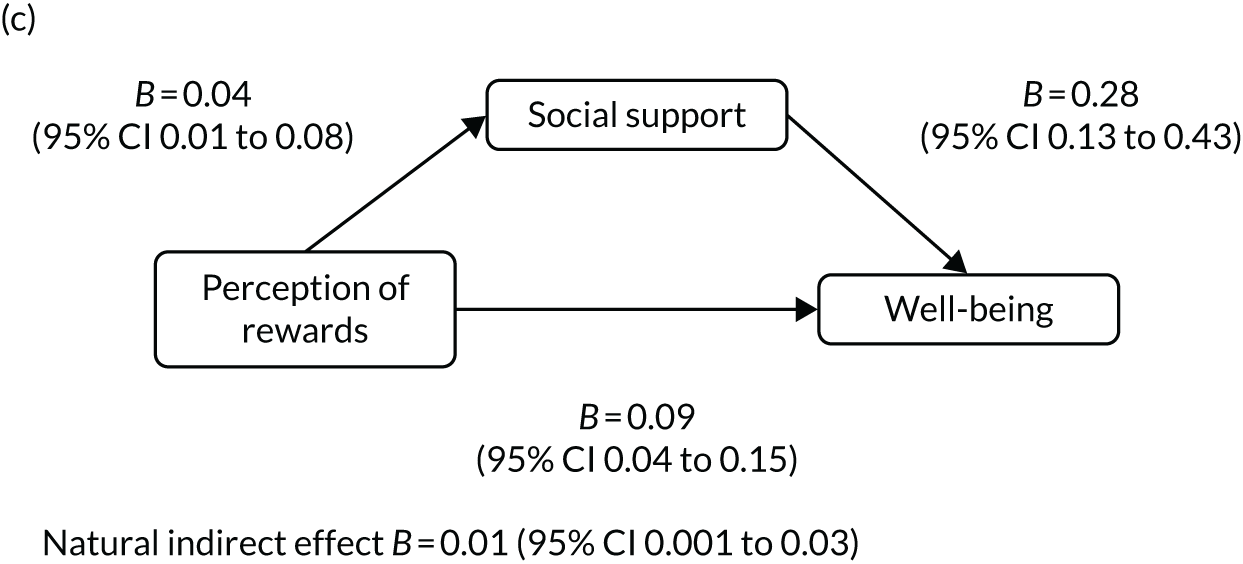

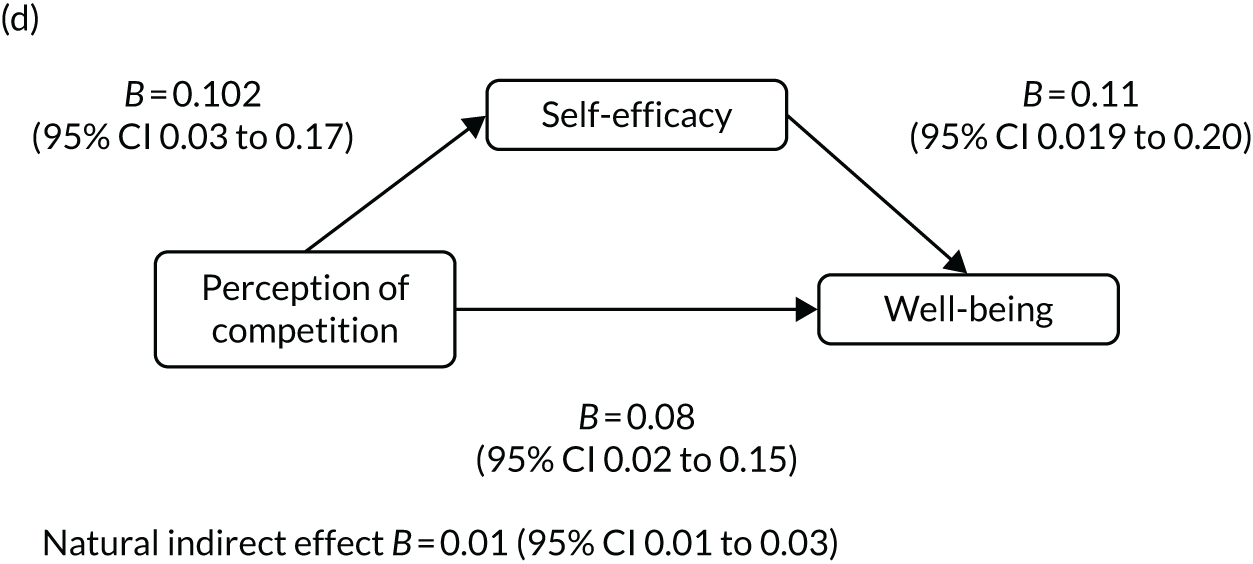

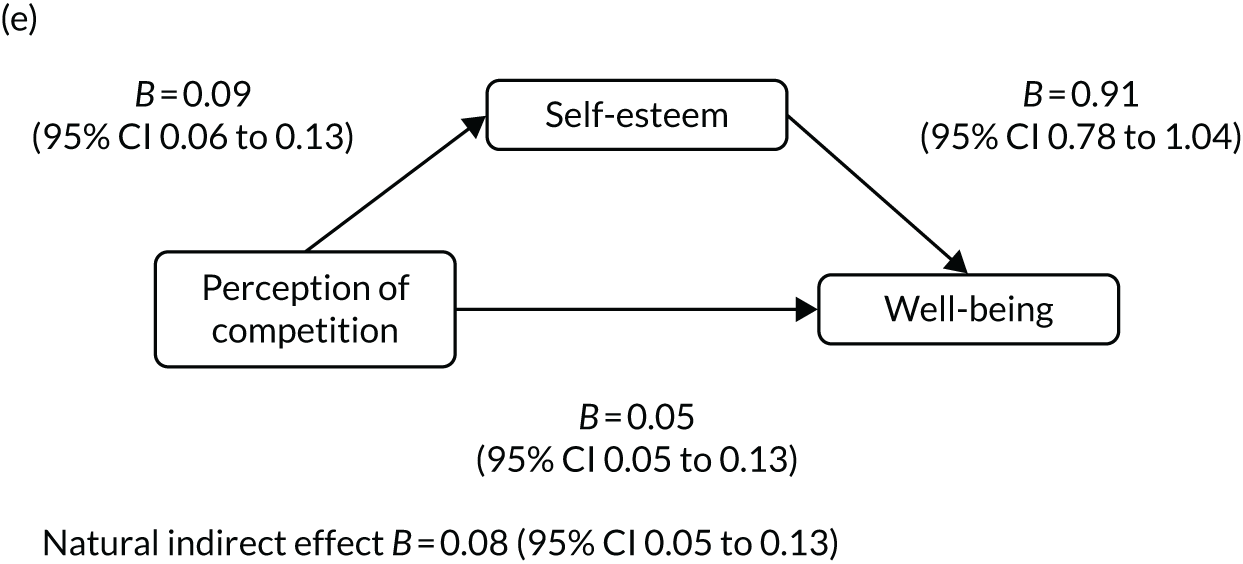

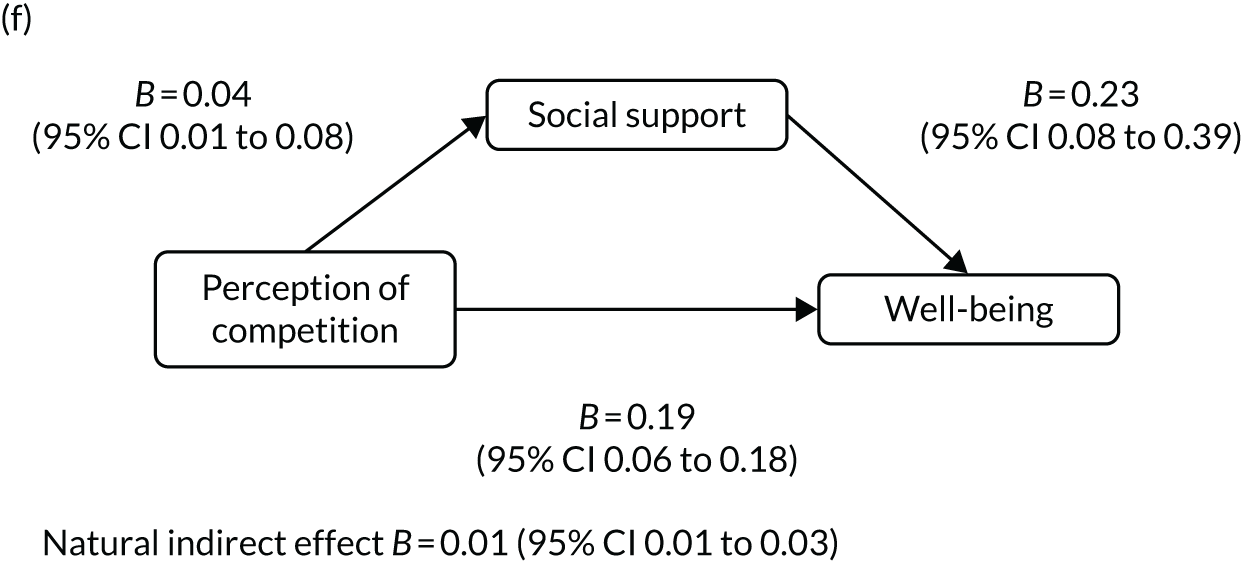

Mediation analyses

We aimed to use mediation analysis as a novel approach to evaluate the potential mediating role of psychosocial factors in the association between engagement in the intervention components suggested by students in our intervention co-design process and changes in physical activity and well-being.

Mediation of effects on the primary outcome (i.e. MVPA) and well-being was assessed using linear regression models stratified by gender (adjusted for age, ethnicity, language, school, BMI z-score and baseline values), assessing associations between (1) exposures and mediators, (2) exposures and outcomes (without mediators) and (3) exposures and mediators with outcomes, using bootstrap resampling.

Economic analysis and cost-effectiveness

A within-trial cost-effectiveness analysis comparing the GoActive intervention with the control was conducted from the perspective of the school funder (assumed to be the local authority). Cost per school and per participant was calculated for intervention group participants based on facilitator and teacher time input, and materials. Quantities of inputs were based on the protocol, supplemented by study records, and unit costs reported in 2019 Great British pounds. As costings considered the additional costs associated with the GoActive intervention only, there were zero costs associated with control.

Outcomes in the economic analysis were the primary outcome (i.e. change in minutes of MVPA) and quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs). QALYs are useful as they measure overall health-related quality and quantity of life. QALYs were assessed using the Child Health Utility-9D, which has been validated for use in adolescents24 and was included in the participant questionnaire at all follow-up time points. Responses were converted to utilities using the recommended published algorithm96 and QALYs were calculated as the area under the curve, with straight-line interpolation between time periods. Total accrued time from baseline to 10-month follow-up, and hence the time horizon for the study, is approximately 2 academic years. Undiscounted and discounted QALYs (at 3.5%) are calculated and an unadjusted and adjusted imputed analysis reported. The latter analysis adjusted for age, socioeconomic status and other demographic variables. Multiple imputation with chained equations was carried out on missing utility data using the predictive mean matching method and five imputed data sets. Analysis was conducted in R (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Code is available from the corresponding author on request.

Exploratory economic modelling

The study protocol stated that long-term modelling would be undertaken only if a positive effect on physical activity was observed, on the basis than it is highly unlikely for the intervention to be (cost-) effective in the long term if it is not so in the short term. However, irrespective of the point estimate, incorporating the uncertainty in study results into a previously developed, longer-term model enables analysis of where uncertainties in longer-term cost-effectiveness lie and can be used to guide further research via value-of-information analysis. For example, the treatment effect of the GoActive intervention may be uncertain, which a priori might suggest that further research was warranted. However, the modelling may reveal that greater value would be obtained from a research project investigating, for example, the link between physical activity and blood pressure, or blood pressure and risk of cardiovascular event.

We therefore conducted an exploratory analysis, inserting the results from the GoActive trial into the previously developed PACE (physical activity cost-effectiveness) model,97 adapted to this study question, reporting longer-term costs and QALYs accrued as per the protocol, but also incorporating a value-of-information analysis. Adapting the model to the study question simply comprised converting the study results from minutes of MVPA to metabolic equivalent of task (MET)-hour equivalents. 98

The PACE model has been described previously,97 but, briefly, it generates a cohort of individuals based on English demographic data. The model follows them for a defined number of years under a base case of average physical activity levels, tracking BMI, blood pressure, glucose (glycated haemoglobin) and lipids, the incidence and prevalence of type 2 diabetes and associated complications, cardiovascular events and certain cancers according to a set of risk equations extracted from the literature. Costs and health state utilities are assigned to these events, resulting in a measure of accrued costs and QALYs over the time horizon of the model. A second-order Monte Carlo simulation propagates parameter uncertainty (i.e. uncertainty in coefficients of the risk equations) to decision uncertainty (i.e. uncertainty in costs and QALYs). The model is then repeated under alternative physical activity scenarios, input as mean and SE of difference in MET-hours per day, with assumptions as to the ‘decay’ rate of the intervention effect (base case assumed 55% per annum), yielding a mean and SE cost and QALY gained from each intervention, from which incremental cost-effectiveness ratios can be calculated.

The model simulated a cohort of 10,000 14-year-olds and followed them for a period of 10 years under a ‘do nothing’/control scenario, repeated 10,000 times. This was then repeated, incorporating the distribution of intervention effect described above.

Costs included in the PACE model are health service costs, to which we added the cost to local authorities of the intervention. The cost perspective of the modelled analysis is therefore the public sector.

Results are reported as mean and 95% credibility intervals for costs and QALYs in each arm, as well as increments between the arms, net monetary benefit from each arm and incremental net monetary benefit calculated at £20,000 per QALY gained. Value-of-information analysis estimates the expected value of perfect information (EVPI) and expected value of perfect parameter information (EVPPI), providing a guide as to where future research is likely to be of most value. Population EVPI and EVPPI are calculated based on population projections of the numbers of 14-year-olds in the UK from 2020 to 2029 (i.e. 10-year time horizon), discounted at 3.5%. This yields a beneficial population of 7,169,651.

Analysis of process evaluation data

Quantitative data

Data are presented descriptively as means (SD) or medians (interquartile range) for continuous variables, and as proportions for categorical variables. Between-group differences (boys vs. girls, and shy/inactive vs. others) in data from process evaluation questionnaires, including enjoyment and satisfaction with individual components, were tested, with multilevel linear regression models clustered by school.

Website data collected from Year 9 students entering individual points through the GoActive website (a point per activity completed) included the number of user logins, as well as logs of the pages visited within the GoActive website. Website analytics of the GoActive website were used to generate descriptive statistics to explore the fidelity and dose received of the intervention.

Qualitative data

Qualitative data were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim and managed using NVivo11 (QSR International, Warrington, UK). Qualitative data were analysed using a realist thematic approach to report the experiences, meanings and reality of participants. 99 Two researchers independently coded a subsample of transcripts. Data were organised into manageable segments of text,100 and patterns and connections between them were identified. 101 All codes were compared, discussed and agreed on prior to coding all other interviews. Interim themes were discussed by members of the research team to reach consensus. Codes were revisited and abridged into broader themes. At first, individual and focus group data were analysed separately; however, because of the identification of common themes, the two data sets were subsequently reviewed together to identify and map overarching themes related to participants experiences of the intervention. A deductive thematic approach was used to provide a focused analysis of the GoActive components.

All data from the website logs, and data from interviews and focus groups from mentors, teachers and facilitators, were analysed using NVivo, using a six-step thematic approach. 99 Codes were generated both from the topics in the interview guides and iteratively from the data. All codes were discussed with another researcher and were categorised as a series of themes. The themes were discussed, refined and agreed by two researchers. Taken with data from participants, the themes exemplify the process evaluation components. These themes combine with an inductive analysis to attain the facilitators and challenges of the intervention. Illustrative anonymised quotes typify the data from interviews. Observation qualitative data were used to provide context, or to support, reaffirm or contradict data from interviews, and were documented as text extracts.

Mixed-methods process evaluation

Qualitative and quantitative data were merged during analysis and interpreted using a mixed-methods convergence matrix, where appropriate. Components were assessed for convergence (i.e. agreement between both sets of results) or dissonance (i.e. disagreement between the sets of results on either the relevance or direction of the determinant/theme under consideration). 102 The process of developing a convergence matrix allowed data sets to be compared, triangulating the data to address completeness, convergence and dissonance of key themes.

Additional mixed-methods analysis included sorting findings based on the process evaluation components (i.e. reach, recruitment, dose and fidelity). Findings were reviewed and compared to assess convergence and dissonance between the data sets, and specific examples of qualitative data were gathered to reflect this convergence or dissonance, or to explain particular process evaluation components. The two researchers involved in the analysis clarified interpretations of the findings, where required. Results were discussed with the research team for review and clarification.

GoActive project management