Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 15/49/08. The contractual start date was in October 2016. The final report began editorial review in January 2020 and was accepted for publication in December 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2021. This work was produced by Caldwell et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2021 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background

Parts of this chapter are reproduced or adapted from Caldwell et al. 1 © 2019 The Author(s). Published by Elsevier Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Description of the problem

Common mental disorders are a key cause of morbidity in children and young people (CYP). Globally, depressive disorders are the third largest cause of adolescent disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) lost, and anxiety disorders are the fifth cause of DALYs lost for adolescent girls. 2 In the UK, the most common mental disorders among CYP are anxiety, depressive and conduct disorders. NHS Digital figures from 2017 suggest that 7.2% of 5- to 19-year-olds have an anxiety disorder, 2.1% a depressive disorder and 4.6% a conduct disorder. 3 In this report, we will refer to anxiety, depressive and conduct disorders as ‘common mental disorders’ (CMDs), as these are the disorders with the highest prevalence among CYP in the UK. Although the prevalence of CMDs tends to increase with age, it is noted that rates of anxiety and depressive disorders have increased among CYP in the UK over the last 20 years, in contrast to the stability of diagnoses for conduct and hyperactivity disorders. 3–5 However, as many CYP or their guardians do not seek help,6,7 these figures may represent an underestimate. 8,9

Children and young people with a mental health disorder are more likely to engage in risky behaviours, such as smoking and substance use; are more likely to self-harm; and are more likely to be excluded from school. 10–16 Although the causes are multifactorial, with genetic and environmental factors contributing to susceptibility, the distribution of CMDs is socially and economically patterned. 17 For example, young people with a common mental disorder are nearly twice as likely as those without a disorder to be living with a lone parent, more than twice as likely to have unemployed parents and more likely to have parents with low incomes and fewer qualifications and living in social housing. 11 Evidence from the UK Millennium Cohort18 suggests that children from low-income families are four times more likely to have a mental health problem than those from higher-income families. Longitudinal evidence suggests a linear relationship between the frequency of disorder episodes and the likelihood of adverse social outcomes. In a cohort of CYP aged 16–21 years from New Zealand,19 the odds of later welfare dependence were 1.34 [95% confidence interval (CI) 1.09 to 1.64] times higher among those reporting 1–4 episodes of depression than among those reporting no episodes of major depression. The odds among those reporting ≥ 10 episodes were 2.42 (95% CI 1.31 to 4.45) times higher than among those reporting none.

Although there is ongoing debate about the drivers of increased prevalence,20 there is robust evidence to suggest that lifetime trajectories of CMDs are established by mid-adolescence,21 with half of all disorders recognisable by age 14 years and three-quarters by age 25 years. 22 The Royal College of Psychiatrists has stated that greater personal, social and economic benefits can be generated by intervening early in the life course than by intervening at any other time. 22 However, Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) worldwide are under-resourced. 23 In the UK, the Local Government Association estimates that > 338,000 children were referred to CAMHS in 2017, but fewer than one-third had received treatment within the year. 24 Even in the advent of optimal access and treatment, one economic modelling study has suggested that < 30% of the burden of CMDs could be alleviated by treatment alone. 25

Description of the intervention

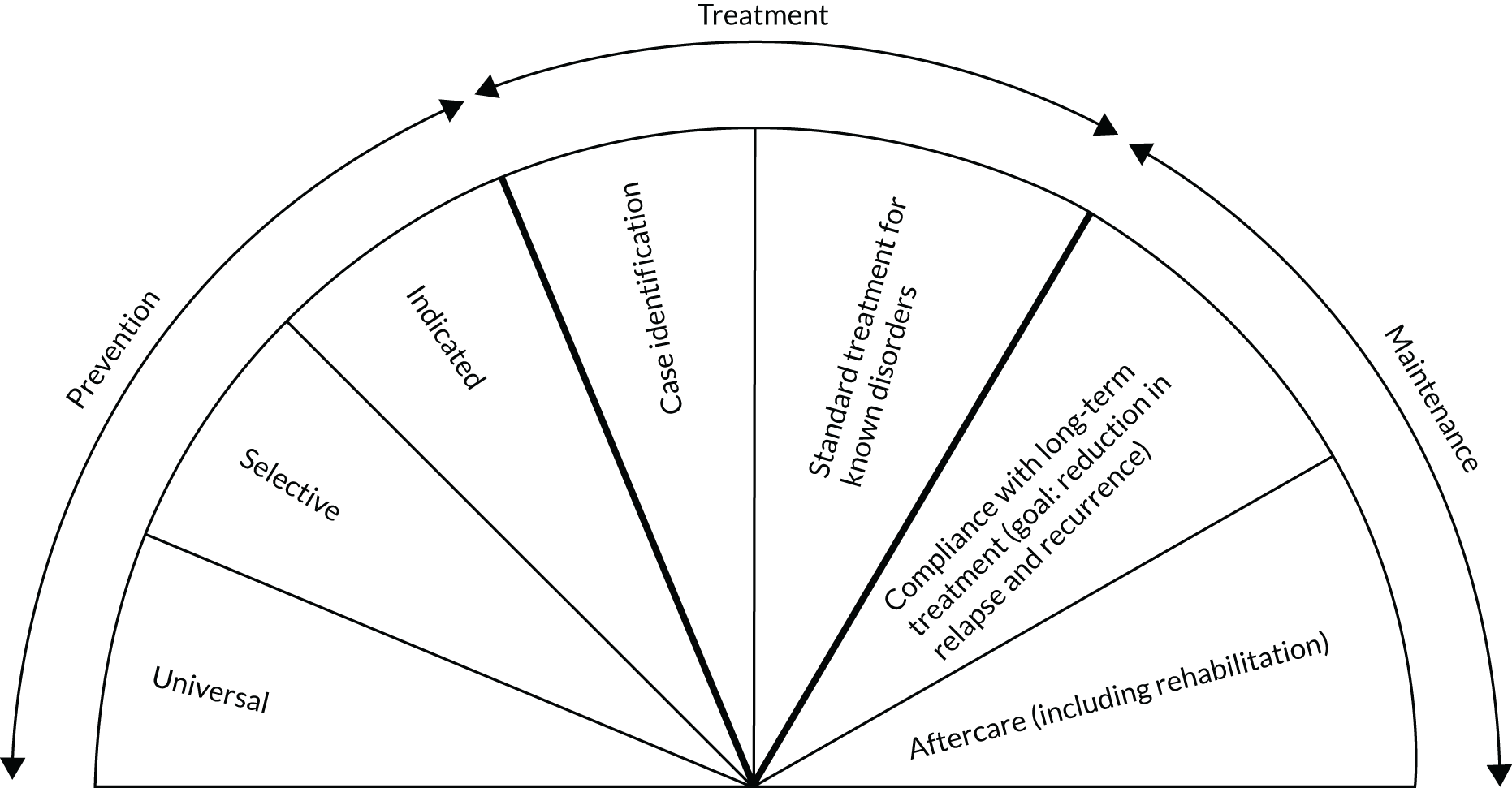

Against this background, there has been a growing focus on the primary prevention of CMDs among CYP. Primary prevention aims to prevent the onset of disease before clinically relevant symptoms are detectable and, therefore, targets a seemingly ‘healthy’ population. According to the National Academy of Medicine (NAM) (formerly known as the Institute of Medicine), primary prevention encompasses the prevention of disorder-specific symptoms, reduction of preclinical symptoms and prevention (or delay) of disorder onset. 26 The NAM definition of primary prevention also refers to universal, selective and indicated prevention26,27 and is distinguished from mental health promotion (Figure 1). Universal prevention addresses whole populations regardless of their risk status or susceptibility to a CMD. Selective prevention targets subgroups with higher than average risk of developing a mental disorder; risk can be defined as biological, psychological or social factors. Indicated prevention focuses on individuals with detectable, but subclinical, symptoms of a CMD. Increasingly, the boundary between indicated prevention and ‘early intervention’ is being blurred by clinicians. 28 The NAM framework views mental health promotion as a focus on encouraging mental health and the enhancement of well-being, rather than the prevention of illness.

FIGURE 1.

The mental health intervention spectrum for mental disorders. Reproduced with permission from Reducing Risks for Mental Disorders: Frontiers for Preventive Intervention Research. 26 Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

In the UK, schools are at the forefront of the prevention agenda. For example, the green paper Transforming Children and Young People’s Mental Health Provision29 calls for mental health leads to be embedded in schools and a greater role for schools in cross-sectoral support teams. The 2019 green paper Advancing our Health: Prevention in the 2020s30 takes this further, with subsequent policy announcements giving schools statutory responsibility for children’s mental health and well-being. Across the UK, school-based education is compulsory between the ages of 5 and 16 years,31 with further statutory provision for 16- to 18-year-olds in England. In 2019, 8.82 million pupils were enrolled in England,32 698,000 in Scotland,33 234,550 in Wales34 and 330,000 in Northern Ireland. 35

Multiple systematic reviews examining school-based preventative interventions for CMDs have been published in recent years, and taken together the results suggest a small but positive effect of psychological and educational interventions. For example, for the prevention of anxiety and depression, Werner-Seidler et al. 36 evaluated both universal and targeted (selective and indicated) interventions in school settings and found a small beneficial effect on both depression (Hedges’ g 0.23, 95% CI 0.19 to 0.28) and anxiety (Hedges’ g 0.20, 95% CI 0.14 to 0.25). Johnstone et al. 37 focused on universal interventions in school settings and observed a positive effect on symptoms of depression (Hedges’ g 0.17, 95% CI 0.06 to 0.28), but not on anxiety (Hedges’ g 0.09, 95% CI –0.07 to 0.26). Stockings et al. 38 included multiple settings in their review, and included both universal and targeted populations. They concluded that universal (Cohen’s d –0.11, 95% CI –0.16 to –0.05) and targeted interventions (Cohen’s d –0.33, 95% CI –0.46 to –0.20) to prevent depression are effective in the short term. They observed that universal prevention had a positive effect on anxiety (Cohen’s d –0.16, 95% CI –0.27 to –0.06), but that indicated prevention did not (Cohen’s d –0.01, 95% CI –0.27 to 0.26). Rasing et al. 39 focused on targeted interventions only, in any setting, and concluded that depression symptoms were reduced [standardised mean difference (SMD) –0.25, 95% CI –0.38 to –0.12], but not anxiety (SMD –0.19, 95% CI –0.36 to 0.03).

Much research into the prevention of conduct disorder has focused on indicated parenting programmes to prevent antisocial/disruptive behaviour in young children. Meta-analyses of indicated parenting programmes suggest that they have a positive effect. For example, Piquero et al. 40 report a medium effect size for preventing antisocial behaviour (Hedges’ g 0.37; p < 0.001). Meta-analyses of school-based universal interventions have focused on reducing broader ‘externalising’ or general behaviour problems, rather than on the prevention of conduct disorder. For example, Lipsey and Wilson41 found that both universal school-based interventions (Hedges’ g 0.21; p < 0.05; Q76 212; p < 0.05) and indicated interventions (Hedges’ g 0.29; p < 0.05; Q108 300; p < 0.05) had a small beneficial effect in terms of preventing outcomes of disruptive behaviour.

Rationale for the current study

It can be argued that no two preventative interventions are exactly alike, as they are made up of combinations of components, each delivered with differing degrees of fidelity and intensity, to slightly different populations and settings. However, in a standard meta-analysis, intervention complexity and variation are overlooked when studies are combined to form a single comparator for analysis (e.g. ‘CMD intervention’ compared with control). This ‘lumping’, or conflating, of potentially disparate interventions can induce statistical heterogeneity. Estimates of statistical heterogeneity (variability across intervention effects) in meta-analyses of preventative CMD interventions can be substantial. Although heterogeneity may be inevitable in public health meta-analyses,42 it should nevertheless be minimised because of the consequences for policy recommendations and decision-making. 43 For example, in a random-effects meta-analysis, the precision (certainty) with which the average intervention effect is estimated decreases as heterogeneity increases, that is CIs are wider.

The need to ‘lump’ interventions, and control conditions, can be avoided by using a network meta-analysis (NMA). 44 A NMA combines direct and indirect estimates of intervention effect to allow the simultaneous comparison of multiple interventions in a single evidence synthesis. Crucially, a NMA retains the distinct identity of each intervention analysed. 45 It also enables the ranking of interventions according to the probability that each is the best, or worst, for a given outcome. The effect of intervention components (individually or in combination) can be modelled in a meta-analysis using metaregression methods. 46 Work since 201447–49 has highlighted the importance and feasibility of NMAs in public health, and how they can be used to explore and minimise heterogeneity in evidence syntheses. A component-level NMA is ideally suited to synthesising preventative CMD interventions, as the complexity of interventions can be incorporated, while providing the coherent and quantitative assessment of effectiveness necessary for decision-making.

Aims and objectives

The overall aim of this project was to identify the most effective and cost-effective intervention component(s), or combination of components, for the universal and targeted prevention of common mental health problems among CYP. For the purposes of this project, CMDs were defined as anxiety, depressive and conduct disorders. This focus was clarified in a protocol update (see the following section and Table 1 for details).

This aim was addressed by the following objectives:

-

consult with CYP and their parents/guardians to inform the outcomes of interest for the systematic review

-

conduct a systematic review of educational setting-based (1) universal and (2) targeted interventions for the primary prevention of anxiety, depression and conduct disorder that have been evaluated in randomised controlled trials (RCTs)

-

develop a classification scheme, or taxonomy, of components used in preventative mental health interventions

-

conduct intervention-level and component-level NMAs to identify effective interventions and components of interventions

-

conduct an economic evaluation to determine the most cost-effective component, or combinations of components, of targeted and universal interventions by condition and setting.

Changes to protocol, clarifications and additional analyses

The protocol was updated in October 2018, to reflect decisions made at the searching and screening stages of the review. These are listed in Searching and screening, with full details and accompanying rationale reported in Table 1 Further changes and clarifications were made at the analysis stage and are listed in Analysis for transparency.

| Deviation or clarification | Proposal or original protocol | Date | Review stage and change | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Project began: October 2016 | ||||

| Deviation | Proposal and protocol | November 2016 | Searching: reduced number of databases searched | The proposal stated that 12 databases would be searched. In consultation with an information specialist, we derived a more efficient approach involving three stages:

|

| Deviation | Proposal and protocol | December 2016 | Screening: change to inclusion criteria | In the original proposal, we stated that the relevant age range would be 5–25 years. To increase relevance to school settings in the UK, the lower age limit was changed to age 4 years. Studies were included if the majority of children were aged ≥ 5 years, or if the mean age was approximately 5 years with a ‘small’ standard deviation. Studies in which the majority of children were < 4 years of age were excluded |

| Deviation | Proposal and protocol | December 2016 | Screening: change to inclusion criteria | In the original proposal, we stated that the relevant age range would be 5–25 years. The original upper age limit was selected to allow sufficient time for multiple follow-ups in tertiary settings, and was not intended to reflect age at baseline (entry to trial). This approach was difficult to operationalise during pilot data extraction, as studies had a wide age range at baseline, spanning the upper age limit (e.g. ages 18–28 years at baseline). Therefore, this was modified to include studies in which the majority of participants were aged ≤ 19 years at baseline |

| Clarification | Proposal and protocol | December 2016 | Screening: clarification of inclusion criteria | ‘Community’ was defined in the protocol inclusion criteria as ‘school affiliated’ and the examples ‘after-school and holiday clubs, church groups, youth clubs and student unions’ given as an illustration. During screening, ‘school affiliated’ was operationalised as ‘attached or linked to a specific school setting’. Studies that used schools as the source of recruitment but that were conducted ‘off-site’ at home or in other community settings were not eligible for inclusion. Multisetting studies that were primarily based in schools were included. This was to ensure that the school was not simply be the point of recruitment for an intervention that was then (entirely) carried out elsewhere |

| Project paused: April 2017 to February 2018 | ||||

| Clarification | Protocol | April 2018 | Data extraction: clarification to conditions included | The original proposal listed CMDs as obsessive–compulsive disorder, phobia, post-traumatic stress, panic disorder, anxiety, depression and conduct disorder. We stated in the proposal that we anticipated focusing on the most common: anxiety, depression and conduct disorder. However, the original protocol did not reflect this anticipated focus clearly enough, and a clarification was needed. After staff absence, to ensure efficiency and expedite the review, a modification was made to the protocol to ensure that the explicit focus was on anxiety, depression and conduct disorder. At the stage this decision was made, data extraction for depression and conduct disorder studies had not started, but was under way for anxiety |

| Clarification | Protocol | January 2019 | Analysis: clarification of analysis plans | Educational settings were divided into UK-specific primary, secondary and tertiary groupings for the purposes of analysis, and studies were grouped on the basis of the mean age (or range) and mapped to a primary, secondary or tertiary setting for analysis. This was not made explicit in the original protocol, which implied that the intervention should be delivered in one of these settings. This would not have been practical from an international perspective, owing to differences in educational systems (e.g. middle and junior-high schools). Studies were grouped on the basis of the mean age (or range) and mapped to a UK-equivalent primary, secondary or tertiary setting for analysis |

| Deviation | Protocol | January 2019 | Analysis: change to analysis plan | We planned to analyse ‘inequality’ as a main outcome. However, few studies reported inequality as a primary outcome; instead, we carried out post hoc subgroup analyses by SES, sex and ethnicity. These characteristics were selected post hoc, on the basis of the most commonly reported study characteristics |

| Deviation | Protocol | January 2019 | Analysis: change to analysis plan | In the protocol, we stated that we would conduct metaregression by intervention intensity, defined as total session time (number of sessions × duration in minutes). However, we determined that this would not be meaningful in a NMA with differing classes of intervention. It would have been possible to conduct the metaregression in a subgroup analysis of psychological therapies only |

| Deviation | Protocol | May 2019 | Analysis: change to outcome measure | In response to reviewer comments on Caldwell et al.,1 we added a post hoc composite ‘internalising’ outcome for inclusion in the NMA. We defined internalising outcomes as combined, or total, scores from depression and anxiety symptom scales. For example, the ‘internalising’ subscale of the SDQ or the total score from the DASS |

| Deviation | Protocol | June 2019 | Analysis: change to analysis plan | Parental reporting of child symptoms was a secondary outcome and, as such, it was not anticipated that we would conduct a NMA. However, based on external evidence of a discrepancy between CYP and parent reports, and that some included studies reported only a parent outcome, we conducted a post hoc analysis of parent-reported outcomes |

| Clarification | Protocol | October 2019 | Analysis: change to analysis plan | In the protocol, we stated that a cost-effectiveness analysis would be conducted if there was sufficient evidence to build and populate a model. If this were not the case, then a cost–consequence analysis would be conducted. We did not identify sufficient evidence to build and populate a model; therefore, we did not conduct a cost-effectiveness analysis. We did, however, conduct a cost–consequence analysis. This, therefore, does not constitute a change from protocol, but we report it here for transparency |

Searching and screening

-

The number of databases searched was reduced from the original proposal. Instead, we followed Cochrane Methodological Expectations of Cochrane Intervention Reviews (MECIR) conduct guidelines50,51 on the selection of primary databases and applied approaches for optimising search strategies. 52–54

-

The protocol stated that the relevant age range for inclusion was 5–25 years. This was difficult to operationalise in practice, and changes were made to the age limits so that the report covers the age range 4–18 years.

-

We clarified the intended intervention setting as ‘educational-setting based’. In the original proposal, we stated that the review would be conducted for ‘school and community based . . . prevention interventions’, and defined ‘community’ as ‘school affiliated’ settings. The clarification here pertains to the definition of ‘school affiliated’, which was operationalised as ‘formally attached or linked to a specific school setting’.

-

A further clarification relates to the definition of CMDs. In this review, CMDs were defined in reference to their prevalence. The updated protocol clarified that the clinical conditions of interest were anxiety, depressive and conduct disorders, as these are the most common across the included age groups.

Analysis

-

The educational setting for each study was categorised as UK-specific primary, secondary and tertiary groupings for the purposes of analysis only. This was not made explicit in the original protocol, which implied that the intervention should be delivered in one of these settings.

-

We planned to analyse ‘inequality’ as a main outcome. However, owing to a lack of data, this was not possible; instead, we considered subgroup analyses by socioeconomic status (SES), sex and ethnicity. These characteristics were selected post hoc, based on participant characteristic data that had been extracted.

-

We planned to conduct a metaregression of intervention intensity, in which intensity was defined as total session time (number of sessions × duration in minutes). However, we determined that this would not be meaningful in a NMA with differing classes of intervention, and so the analysis was not conducted.

-

In response to reviewer comments on Caldwell et al. ,1 we added a post hoc analysis for a composite internalising symptoms outcome (which combined depression and anxiety symptom scores).

-

A post hoc NMA of parent-reported child symptoms was conducted.

-

In the protocol, we stated that a cost-effectiveness analysis would be done if there was sufficient evidence to build and populate a model. As an alternative, we planned a cost–consequence analysis. We found that there was insufficient evidence for a cost-effectiveness analysis, and so a cost–consequence analysis is reported.

Chapter 2 Methods for assessing effectiveness

In this chapter, we describe the methods and process applied for the systematic review and NMA. The protocol for the study was registered with PROSPERO (CRD42016048184). Changes from the protocol and clarifications relating to inclusion criteria are listed in Chapter 1 and are described in detail in Table 1. They are also briefly noted throughout this chapter.

Patient and public involvement

As part of the systematic review process, we consulted with the Advice Leading to Public Health Advancement (ALPHA) research advisory group of young people aged 14–21 years, facilitated by the Development and Evaluation of Complex Interventions for Public Health Improvement (DECIPHer) Centre at Cardiff University. 55 The aim was to identify health and social outcomes of importance to young people that could be considered in the systematic review. On the basis of this focus group, we included a post hoc outcome looking at the impact of prevention interventions on the stigma associated with mental disorders. We also met with members of The Caerphilly County Borough Parent Network to explore their views on young people’s mental health and the role of schools in preventing and identifying problems. 56 There were no outcomes from that focus group that fed directly into this report.

Methods for the systematic review of effectiveness studies

Criteria for considering studies for this review

In the absence of direct head-to-head evidence comparing interventions, indirect comparisons can be made across a connected network of interventions. For example, the effect of intervention C against intervention B (BC) can be obtained indirectly from the effect of C against intervention A (AC), minus the effect of B against A (AB). The combination of indirect and direct evidence across a network of intervention comparisons is known as a NMA.

The following eligibility criteria were specified to address the key consistency assumption required for a valid NMA. In a three-intervention network, the consistency assumption requires the true BC intervention effect estimated in the B versus C trials to be the same as the BC intervention effect estimated by the A versus C and A versus B trials (had they also included the B and C arms). 57 For this to hold, one should check that the populations included across all trials in the analysis are comparable to each other, with respect to any potential effect-modifying characteristics. 58 This requirement has been conceptualised as ‘joint randomisability’ of the interventions for the target population. 59 ‘Joint randomisability’ implies that a hypothetical, multiarm trial of every included intervention would be reasonable, in principle, and that all participants would be randomisable to any of the interventions included. 60 This requires clearly and specifically defined inclusion criteria, to ensure the included studies, populations and interventions are sufficiently comparable. Further details on NMA are provided in Methods for the evidence synthesis of effectiveness studies.

Study design

Parallel-group RCTs and quasi-randomised controlled trials were eligible for inclusion. We defined quasi-randomised trials as those for which allocation was based on a pseudo-random sequence, such as the order in which participants were recruited or their date of birth. Both individually randomised and cluster randomised trials were eligible for inclusion. We did not plan to exclude crossover trials, but only the first period was considered eligible for inclusion.

Population

We followed the NAM’s definition of primary prevention, which refers to universal, selective and indicated populations (see Figure 1). 27 Briefly, universal prevention addresses whole populations not defined on the basis of risk; selective prevention is targeted at subgroups with a higher than average risk of developing a mental disorder; and indicated prevention is targeted at high-risk subgroups and/or individuals with detectable, but subclinical, symptoms of a mental disorder. In the first instance, we used author-reported classifications of the intended prevention level. However, when interventions were delivered to a whole class or school with the same at-risk characteristic (such as schools in low-income areas), they were combined with universal prevention. Studies were excluded if the intervention was described by the author as indicated prevention, but baseline symptoms scores were suggestive of clinically meaningful symptom levels (see Definition of disorder).

Age

As noted in Chapter 1, the eligible age range was modified during the screening stage of the review. Further details of this change to protocol are provided in Table 1.

Studies including participants between the ages of 4 and 18 years (age at study recruitment), in full- or part-time education, were eligible for inclusion. The lower age limit was set in accordance with the de facto school starting age in England and Wales. However, owing to global differences in school starting age, we determined that studies implemented in preschool settings would be eligible for inclusion if (1) the mean age of participants was 5 years or (2) the majority of enrolled children were aged 5 years at the time of the baseline assessment. The upper age limit reflects the minimum age of entry to higher (tertiary) education in England and Wales. However, studies were eligible for inclusion if the mean age of participants at baseline was ≤ 19 years. Studies targeted at young people not in education or training were excluded.

Definition of disorder

The original proposal listed CMDs among CYP as obsessive–compulsive disorder, phobia, post-traumatic stress, panic disorder, anxiety, depression and conduct disorder. However, we anticipated focusing on anxiety, depression and conduct disorder, as they are the most common, and we expected the greatest number of studies for these conditions. The structure and connectivity of a network are important considerations in a NMA, as estimates can be obtained only for connected networks, and sparsely populated networks with few participants can lead to imprecise estimates. 57 Further details of this clarification to the original protocol are provided in Table 1.

Studies were included if they were explicitly aimed at the primary prevention of anxiety, depression and/or conduct disorder as operationalised according to categorical or clinically referenced definitions of disorder [e.g. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5)]. 61 This was to differentiate studies addressing related mental health constructs, such as emotional health or well-being, which were excluded (see Interventions and comparators). Studies were eligible if they focused on either prevention of disorder onset or prevention of symptoms.

However, studies that addressed individual symptoms, or combinations of symptoms, associated with anxiety, depression and conduct disorder, but without explicitly linking these to a clinically identifiable disorder, were excluded. For example, interventions to prevent insomnia, rumination or low self-esteem were excluded, even though these symptoms are associated with depressive and/or anxiety disorders, and interventions to prevent truancy, bullying or aggressive behaviour were excluded, even though these behaviours are associated symptoms of conduct disorder. Studies were included only if they addressed the whole condition, not individual symptoms or combinations of associated symptoms. We consulted trial registrations and protocols, when available, for further information.

Studies in indicated populations were eligible if participants had subclinical mental disorder symptoms as identified by a screening instrument, an interview or a teacher referral. Subclinical symptoms could be defined in reference to diagnostic criteria such as the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10)- or DSM-5-categorised disorders, or ‘in research’ via use of a disorder-specific screening instrument, for example the Children’s Depression Inventory or Revised Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale. The boundary between indicated prevention and early intervention (treatment) is debated,26,27 with no definitive diagnostic threshold. Studies were excluded if baseline measures were suggestive of clinically meaningful symptoms in > 40% of participants, even if the study had been defined as indicated prevention by the author. Young people at risk of comorbid mental health disorders were eligible for inclusion. However, we excluded studies for which > 40% of participants had an identifiable or pre-existing mental disorder. To ensure a clinically homogeneous population for analysis, studies in which the whole population had a diagnosis of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or an autism spectrum disorder were excluded, as these form distinct diagnostic categories.

Setting

As noted in Chapter 1, the operationalisation of setting was clarified from the original proposal. Full details are provided in Table 1.

Interventions implemented in an educational setting were eligible for inclusion. For the purposes of analysis, this was operationalised as being primary, secondary or tertiary educational settings. However, to accommodate global differences in educational systems, we did not restrict to interventions implemented in these settings if the age eligibility criteria were met. For example, an intervention delivered in a kindergarten setting would be eligible for inclusion if the mean age of participants was 5 years, or the majority of enrolled children were aged 5 years at the time of the baseline assessment. Interventions implemented in school-affiliated settings (e.g. after-school and holiday clubs) were eligible for inclusion if they were implemented on school grounds. This clarification from the original protocol is explained in Table 1. Studies that used schools as the source of recruitment but for which the intervention was not school based were excluded.

Health service settings, such as primary care and outpatient and inpatient settings, were excluded. Interventions implemented in young offender institutions and for looked-after children in residential care were also excluded. Interventions implemented in low-income countries (LICs), middle-income countries (MICs) or high-income countries (HICs) were eligible, as defined by 2017 World Bank classifications. 62

Interventions and comparators

Inclusion criteria

Interventions were eligible for inclusion if they addressed a universal, selective or indicated population, and the primary study aim was to prevent anxiety, depression or conduct disorder.

Eligible intervention types included psychological and psychosocial, educational or physical interventions that were implemented in educational settings, either individually or in groups. Inclusion was not restricted by mode of delivery. Interventions were included if delivered by peer educators, teachers, youth workers, clinicians, health visitors, school nurses or counsellors. However, digital and online interventions were eligible for inclusion only if they were primarily delivered in the education setting or were a clear adjunct to a wider programme delivered in the school/educational setting (e.g. as homework).

All relevant non-pharmacological control interventions were considered eligible for inclusion, for example standard provision/usual curriculum, waiting list, no intervention, attention control or ‘placebo’ interventions, and other active psychological and psychosocial, educational or physical interventions. Further details on active and control interventions are provided in Chapter 3.

Exclusion criteria

The following intervention exclusion criteria were informed by the need to ensure the validity of the NMA. The key assumption underpinning a NMA is described in the Cochrane handbook59 as ‘transitivity’, but is also known as the consistency assumption. Regarding the interventions included in the network, transitivity requires ‘all competing interventions of a systematic review to be jointly randomizable’59 and that intervention A is ‘similar’ when it appears in the A versus B and A versus C studies.

Assessment of transitivity for public health interventions is not straightforward. To ensure the validity of the NMA, we included only interventions for which the primary aim in a given study was to prevent anxiety, depression or conduct disorder. Unless the study was explicitly focused on disorder-specific prevention, then mental health promotion, awareness, literacy or information interventions were not eligible for inclusion. Social and emotional well-being and positive psychology interventions to improve mental well-being were also excluded, as research suggests that well-being is a separate construct to mental ill health. 63,64 When possible, we consulted trial protocols or registrations if this was ambiguous in the publication. Interventions designed to target prevention of behaviours or social problems that might be on the causal pathway to a mental disorder (e.g. prevention of stress, anti-bullying interventions, substance abuse prevention) were also excluded. Similarly, classroom management and school readiness interventions were not eligible. ‘Parenting’ interventions such as parent management training or parenting skills interventions were not eligible for inclusion. However, interventions that took place in schools, with a parenting component, were eligible if the parenting component was not > 50% of the whole intervention.

Outcomes

According to the NAM classification of primary prevention, the overall, longer-term aim of preventative interventions ‘is the reduction of the occurrence of new cases’26 of mental disorders. However, it also recognises the importance of shorter-term prevention in terms of reducing symptoms, which, in turn, may delay or reduce the risk of the onset of the disorder. All are considered beneficial at a population level and are ‘worthwhile goals of prevention’. 26 In this report, we focus on the effect of prevention interventions on symptoms of anxiety, depression and conduct disorder. The main outcome was prevention or reduction of disorder-specific symptoms for self-reported anxiety, depression and conduct disorder.

All validated disease-specific measurement scales for CYP were eligible for inclusion. When studies reported multiple outcome measures, we applied a prespecified hierarchy to select the most appropriate outcome for analysis from each study (see Appendix 1). We did not exclude studies reporting a composite mental health scale from the systematic review [e.g. the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ)]; however, they were not combined with disorder-specific scales in the main NMA. In a change from protocol (see Table 1), a post hoc analysis for composite ‘internalising’ symptom scales was conducted. For example, measurement scales reporting a total or combined score across depression and anxiety symptoms, such as a total Revised Children’s Anxiety and Depression Scale (RCADS) score, or a composite outcome such as the SDQ ‘emotional symptoms’ subscale, were included in this post hoc outcome.

The following additional primary and secondary outcomes were also specified a priori. However, in the absence of a core outcome set65 or guidelines for the selection of measurement scales for school-based mental health interventions,66 we determined that an inclusive approach to additional primary and secondary outcomes was appropriate. Therefore, we did not specify how these outcomes should be measured in advance, or which scales should be used. Instead, we extracted outcomes as reported by the study authors.

Additional primary outcomes were as follows:

-

self-reported well-being, as defined by study author(s)

-

self-reported suicidal ideation, behaviour and self-harm, as reported by study author(s)

-

intervention impact on inequalities in health, as defined by study author(s).

The primary time point of interest was immediately post intervention. However, as sustainability of intervention effect is an important question for public mental health,67 we also report results for mid-term (6–12 months) and longer-term (13–24 months) follow-ups. If studies had a follow-up of ≥ 25 months, these results were also extracted.

Secondary outcomes of interest were as follows:

-

Mental health-related stigma, as defined by study author(s). During our initial patient and public involvement (PPI) focus groups, reducing the stigma associated with mental health problems was identified as an important outcome for young people.

-

Acceptability of an intervention to young people, as reported by the study author(s).

-

Parent-reported prevention or reduction of disorder-specific symptoms, as reported by the study author(s).

-

Self-reported problem behaviour, such as substance use or involvement in violence.

-

Academic attainment, as defined by the study author(s).

Study identification, inclusion and data extraction

Identification of studies

As noted in Chapter 1, the approach to searching was modified from that of the original proposal. Full details and explanation are reported in Table 1.

The revised search strategy involved three stages, which might be considered to combine the ‘known items’ and ‘law of diminishing returns’ approaches described by Booth,52 to optimise searching. First, working with an information specialist (SDa) and following the Cochrane MECIR guidance on conducting searches,50,51 we searched MEDLINE, EMBASE, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) and PsycInfo electronic databases. The search strategies for each electronic database are described in Appendix 1. The final searches were carried out on 4 April 2018. Searches were not restricted by language, country or date of publication.

Second, in addition to the database searches, we conducted searches of Epistemonikos (www.epistemonikos.org; Epistemonikos Foundation, Santiago, Chile) to identify published systematic reviews of interventions for the prevention of CMDs among CYP. Epistemonikos was searched on 16 November 2016. The reference lists from these reviews were added to the results of the database searches, ready for screening.

Finally, after screening, we conducted an informal scoping search of the Education Resources Information Center (ERIC) database. This was to check whether further relevant studies could be located, cross-referencing with those already identified from the previously mentioned approaches. If scoping revealed further relevant studies, a formal search was planned. In response to reviewer comments on the draft version of this report, the ERIC scoping searches were formalised and extended to the British Education Index (BEI). Further details are reported in Appendix 1.

Screening for study inclusion/exclusion was independently assessed by two reviewers (SRD, JCP, DMC, PC); disagreement was resolved by a third reviewer if necessary (SRD, JCP, DMC, PC, SEH). Owing to the volume of potentially relevant studies retrieved, reasons for study exclusion were recorded at full-text screening only.

We used a standardised data extraction form in Microsoft Excel® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) to extract information from included studies. Data were extracted by one reviewer and checked by a second (SRD, CF, PC, JCP, DMC). Discrepancies were discussed and a consensus reached. Disagreements were resolved by a third reviewer if necessary. The following information was extracted from the papers:

-

Study design and the target CMD of intervention (i.e. anxiety, depression or conduct disorder); whether the intervention was universal or targeted (indicated or selected); and number of participants recruited, randomised and assessed (or clusters, if a cluster RCT).

-

Details of participants (country, intervention setting, age, sex, ethnicity).

-

Details of intervention as reported by trial author. Narrative description of components and delivery process for experimental and control interventions. This included number of sessions; intervention dose (calculated as intensity of intervention: total session time × duration in minutes); whether the intervention was group or individual, face to face or digital; who facilitated the intervention; and intervention fidelity measures.

-

Outcome(s) assessed and all follow-up time points.

-

Risk-of-bias assessment, including additional assessment for cluster trials.

-

Mean total symptom score and standard deviation (SD) at baseline and follow-up time points for primary measurement scale, change from baseline or mean difference between arms; details on whether results were for completers only or use of methods for handling missing data such as last observation carried forward; and intracluster correlation coefficient (ICC), the statistical model used to account for clustering (if any).

Study authors were contacted for additional data, if necessary.

Classification of interventions and components

Eligible interventions were psychological and psychosocial, educational, or physical interventions. Following previous studies,68–72 and based on author-reported descriptions, the content of psychological and psychosocial interventions was classified into four broad intervention types: cognitive–behavioural, behavioural, third wave and interpersonal. Physical interventions were further classified as exercise or biofeedback. Further categories identified were a combined mindfulness/relaxation intervention, psychoeducational and psychosupportive interventions, and occupational therapy. Control interventions were classified into four categories: no intervention, waiting list, usual curriculum and attention controls. 72–74 A full description of all interventions is given in Chapter 3.

We also conducted an intervention component analysis (ICA)75 to identify features of intervention content and process, influenced by the why, what, who, how, when and how much domains of the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR). 76 We applied the constant comparative method,77 whereby the intervention descriptions reported by authors were used to develop a coding scheme to classify the components of each intervention and control. If necessary, descriptions were supplemented by intervention manuals and/or correspondence with the study author. ICA is an iterative and inductive process. One reviewer (SRD) developed and piloted a list of provisional component codes based on published studies. 46,68,72,78 The components were discussed with a second reviewer and a preliminary coding exercise was then undertaken on a sample of interventions by a wider group (SRD, DMC, JK and SEH), and the coding scheme was further refined based on discussion. The refined coding scheme was then applied inductively by one researcher (SDa) and audited by another (DMC). Iterative coding refinements were made until application failed to reveal any new information and the component categories could be described as ‘saturated’.

The working definitions of each intervention and control classification and the classifications of intervention components are provided in Chapter 3.

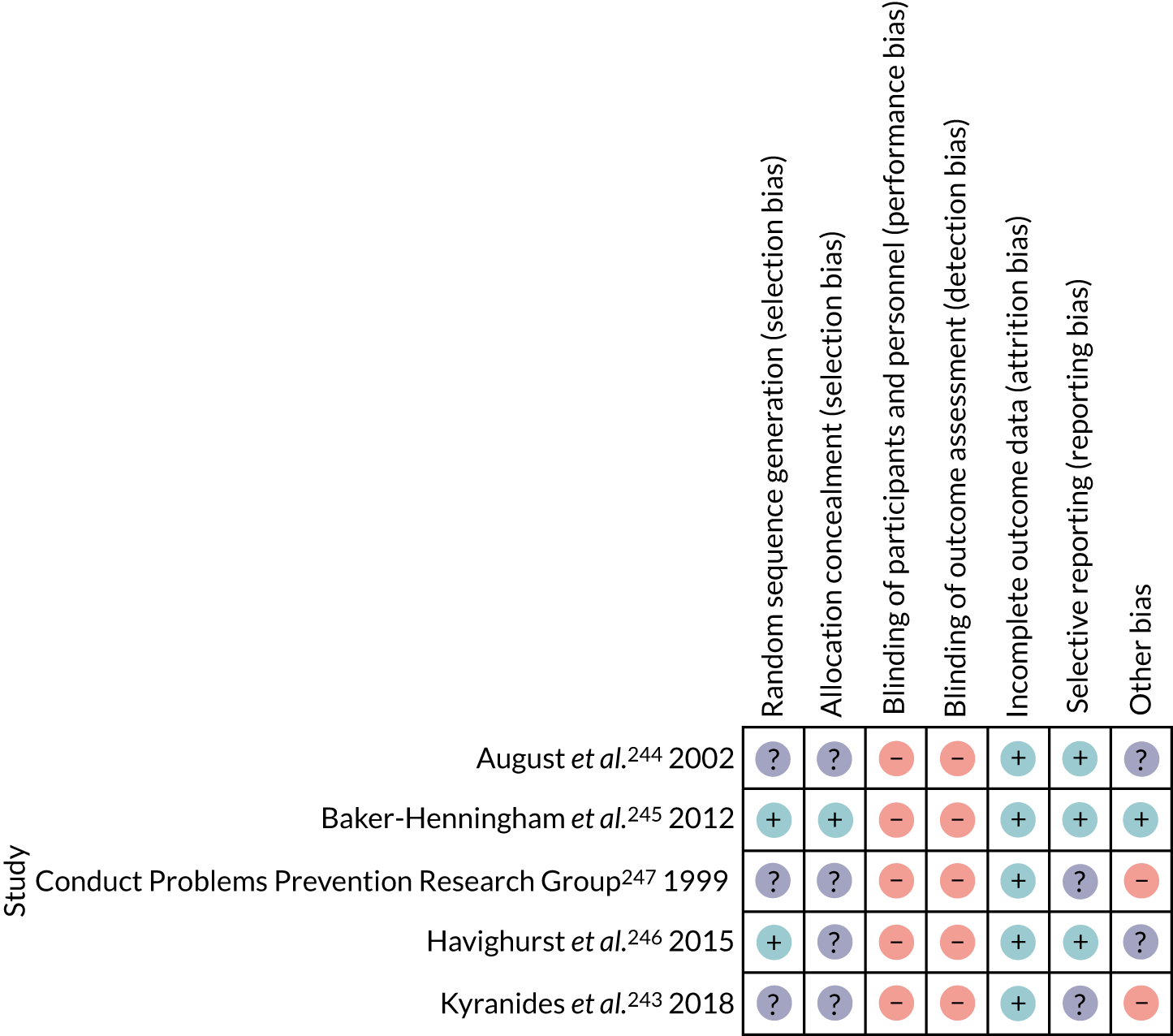

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two reviewers independently used the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool79 to assess whether there was a high, low or unclear risk of bias in the following domains: random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessor, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting and other sources of bias (including cluster-specific issues such as contamination, recruitment bias and unit-of-analysis errors). All eligible studies were included in the NMA regardless of their risk-of-bias classification, and sensitivity analyses examined the impact of excluding studies deemed to be at high and unclear risks of bias for random sequence generation and allocation concealment.

Methods for the evidence synthesis of effectiveness studies

Data preparation

For continuous outcomes, data were extracted for number randomised to each intervention arm at baseline, and baseline mean and SD, and number assessed at follow-up, and follow-up mean and SD (for each time point listed previously). If the mean change from baseline was reported, then this was extracted, together with the standard error (SE) for the mean change from baseline (if reported). Data were extracted for complete cases. However, if authors reported means and SEs from an appropriate model accounting for participant dropout or non-response, this was preferred.

For analysis, we used the standardised mean change from baseline, as a variety of outcome measurement scales were used across the studies. An adjustment for small sample size was applied, following the formula for Hedges’ g. 80 For studies that did not report mean change from baseline, we derived this from reported baseline and follow-up means and SDs. 81 Here we assumed a correlation coefficient of 0.7, based on previous analyses. 82 This value was explored in sensitivity analyses. Results are summarised using SMDs and 95% credible intervals (CrIs).

For dichotomous outcomes, data were extracted for available cases unless authors clearly reported events and number of participants following the intention-to-treat principle. Dichotomous outcomes were summarised using odds ratios (ORs) and 95% CrIs.

If key statistics (e.g. SDs) were not available in the published report, we contacted trial authors for further information. In cases of non-response, or if missing data were not available, we did not impute the data and these studies were excluded from the NMA (but not the systematic review).

For cluster randomised trials that did not account for the effect of clustering, we followed the advice in the Cochrane handbook (section 16.3.4)81 for calculating an approximate sample size. We reviewed reported ICCs from all included papers and used an ICC estimate of 0.03, which is the mean of the values reported and is similar to ICCs used in previous public health systematic reviews. 68,83–85 This value was also explored in sensitivity analyses.

Pairwise and network meta-analyses

Both standard pairwise meta-analyses and NMAs were conducted. A NMA was planned for each primary outcome and for the primary time point only.

A NMA allows data on multiple interventions to be pooled in a single analysis. 86 It is considered a ‘core method’ by Cochrane59 and is routinely used in National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) technology appraisals and guidelines. 87,88 For the novice, the Cochrane handbook81 provides an accessible introduction; for further depth, we recommend consulting tutorials and introductory papers on NMA. 44,45,60,89–92 However, we describe the fundamentals in the following paragraphs.

A NMA requires that the intervention comparisons made in RCTs can be displayed pictorially as a network of comparisons that are ‘connected’ (i.e. there is a path from any one intervention to another formed by RCT evidence). 59,93 In the absence of direct head-to-head evidence comparing interventions, indirect comparisons can be made via common comparator(s) across the network. For example, the effect of intervention C against intervention B can be obtained from the effect of C against A, minus the effect of B against A. The combination of indirect and direct evidence across a network of intervention comparisons is known as a NMA.

The validity of a NMA assumes that there are no differences between studies in factors that might interact with the intervention effect (effect modification). This is the same assumption made in a pairwise meta-analysis,57 but in a NMA applies across intervention comparisons. It is therefore important to consider separate analyses according to factors that may be potential effect modifiers. In the first instance, separate analyses were conducted by population (universal or targeted) and setting (primary, secondary or tertiary education). Separate analyses were run for the main outcomes of self-reported anxiety, self-reported depression and self-reported conduct disorder symptoms. Following research suggesting common mechanisms and pathways within internalising and externalising disorders (transdiagnostic factors),94–97 we ran analyses across (1) all studies aiming to prevent depression and/or anxiety and (2) studies aiming to prevent conduct disorder. That is, studies contributing to either the depression or anxiety outcome analyses could be studies that aimed to prevent (1) anxiety (2) depression or (3) anxiety and depression. Studies contributing to the analysis of the conduct disorder outcome were only those aiming to prevent conduct disorder. We explore this decision further in a subgroup analysis (see Subgroup, metaregression and sensitivity analyses). A visual check of the inclusion/exclusion characteristics of trials in each network was conducted, to ensure that potential effect modifiers were evenly distributed across studies.

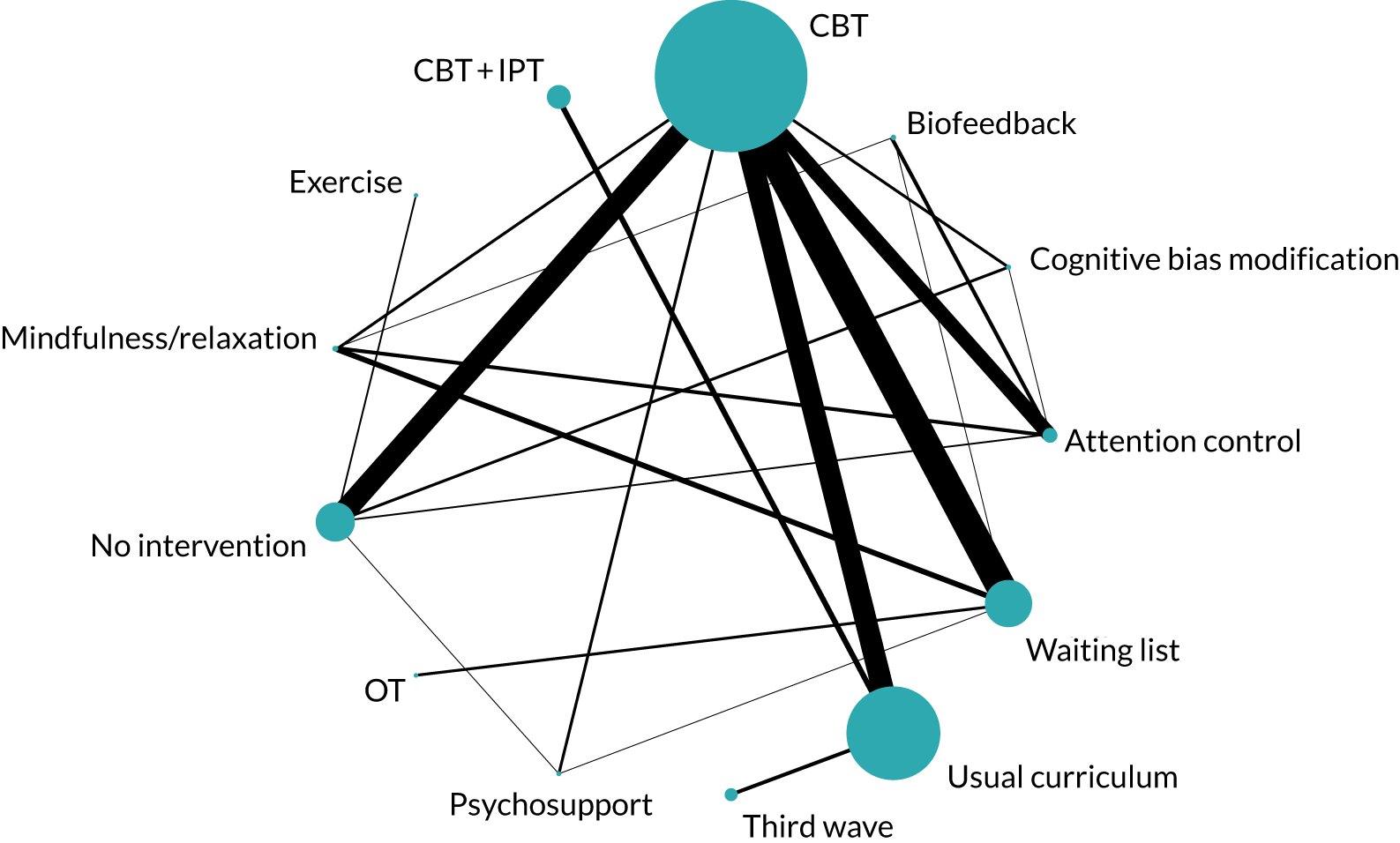

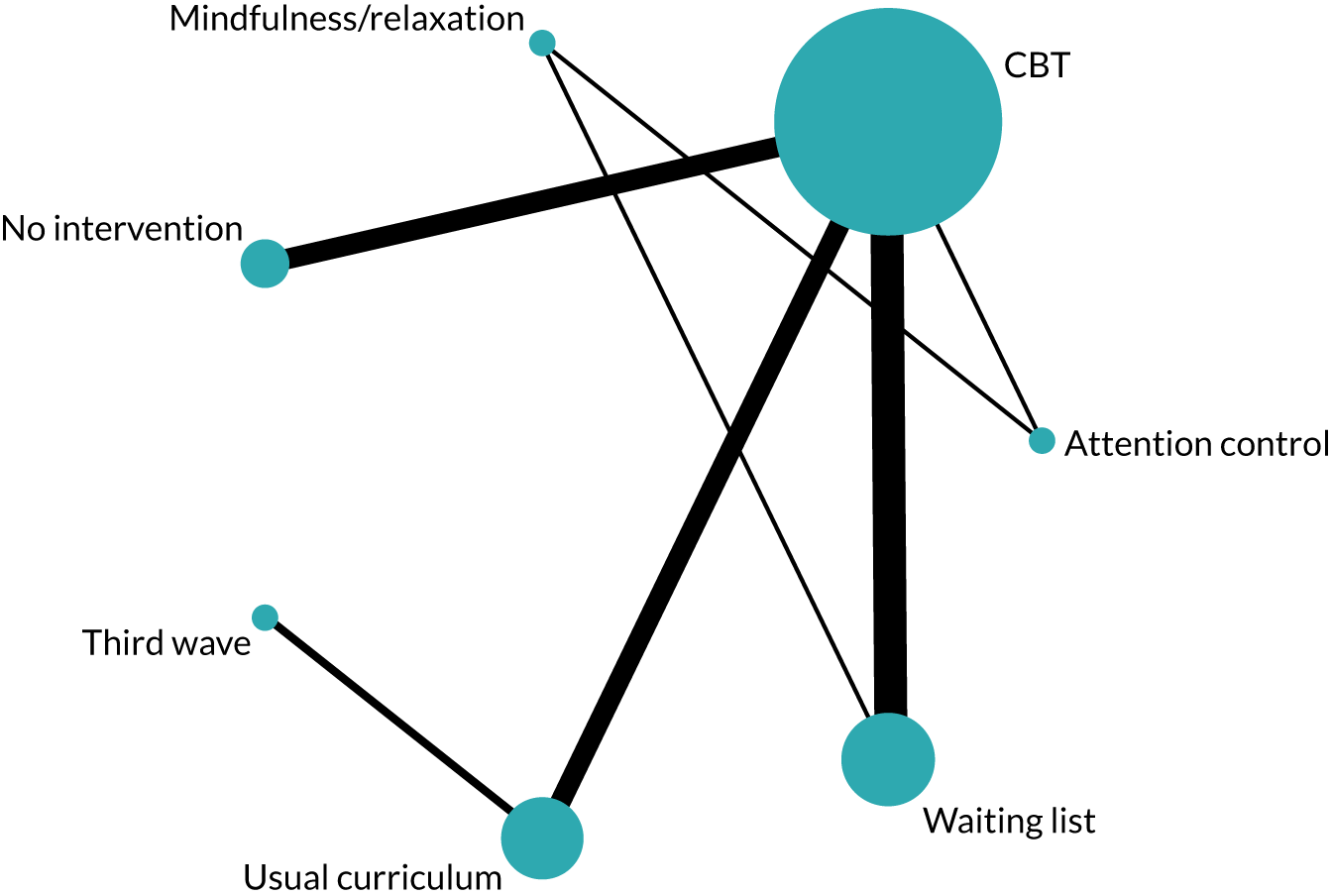

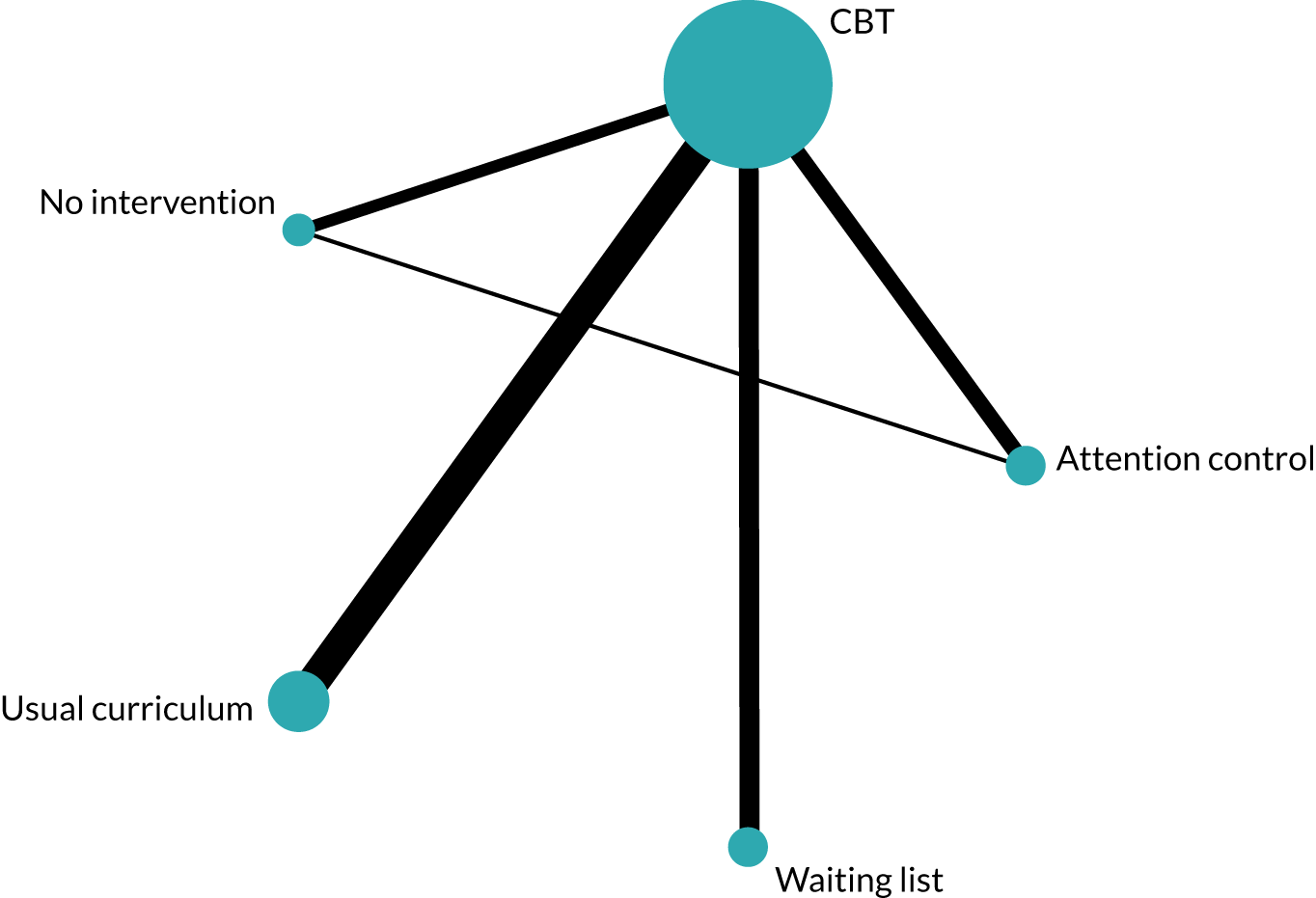

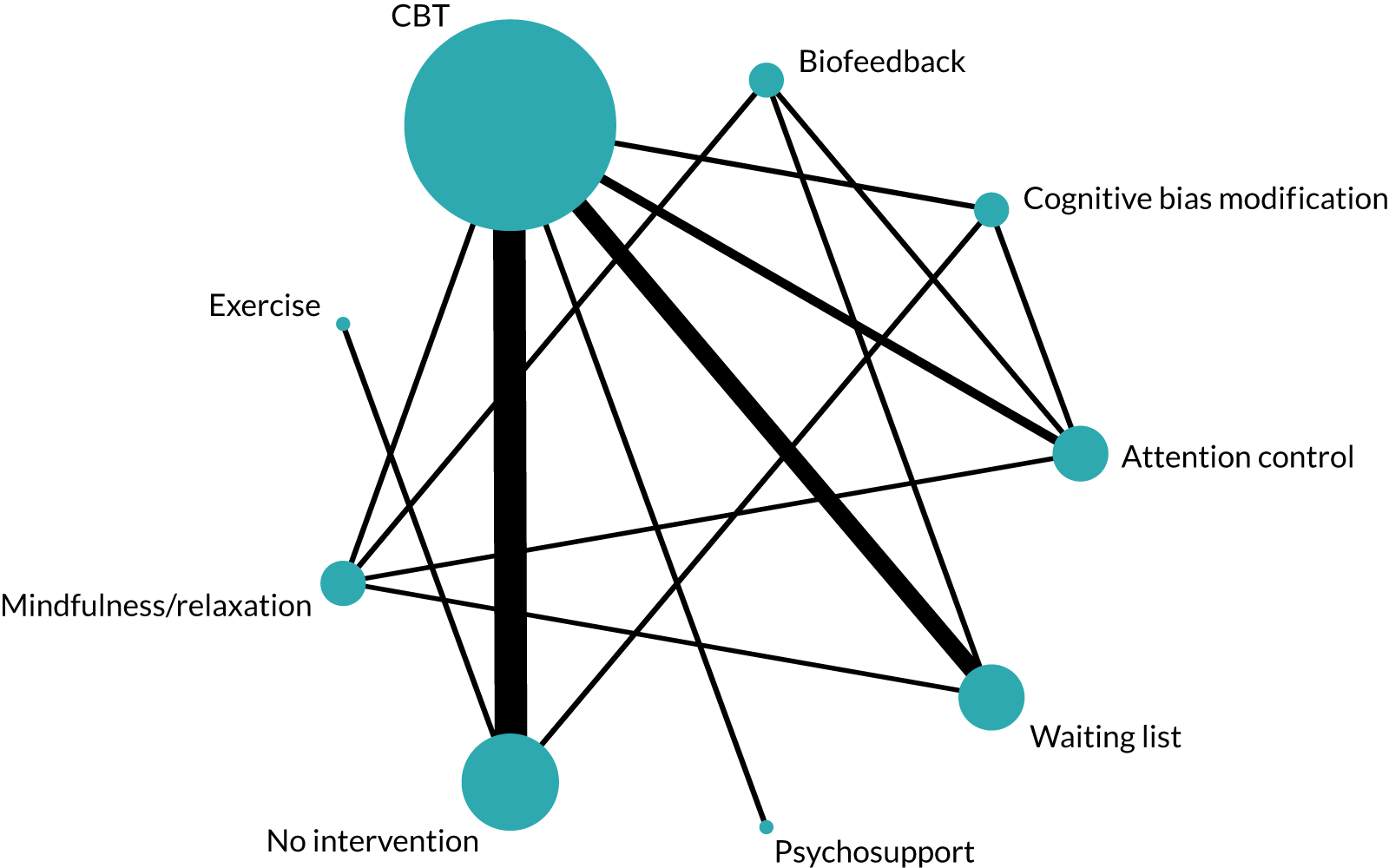

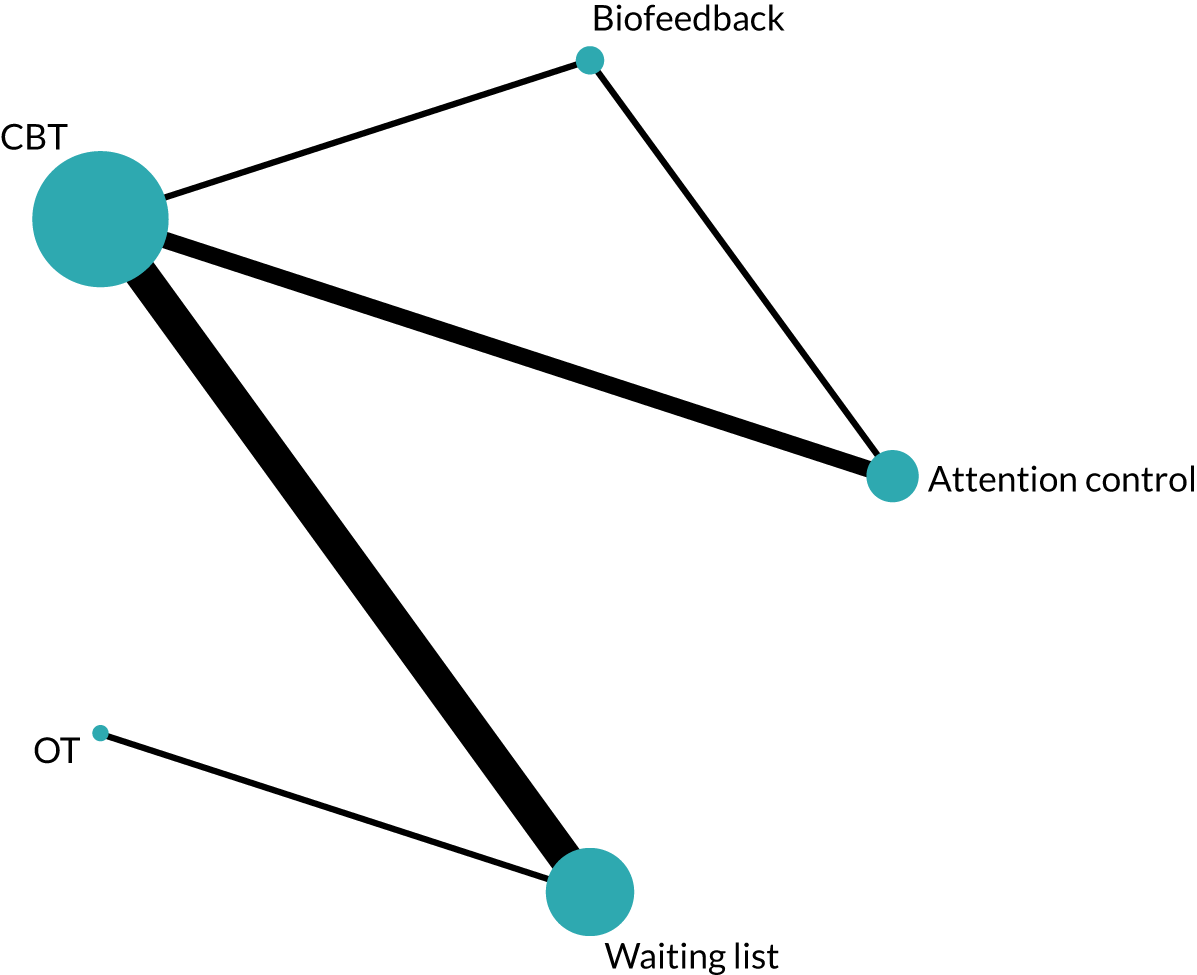

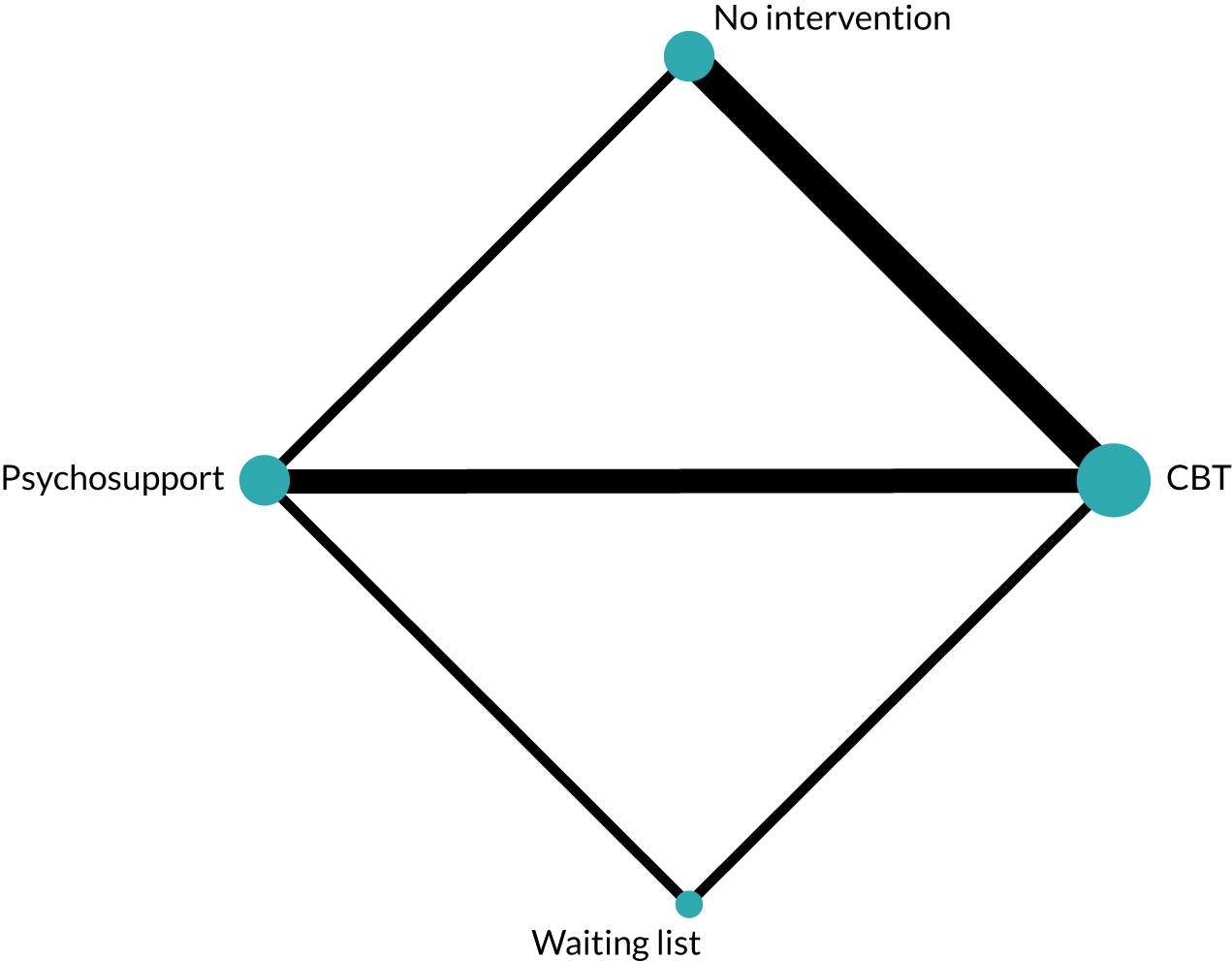

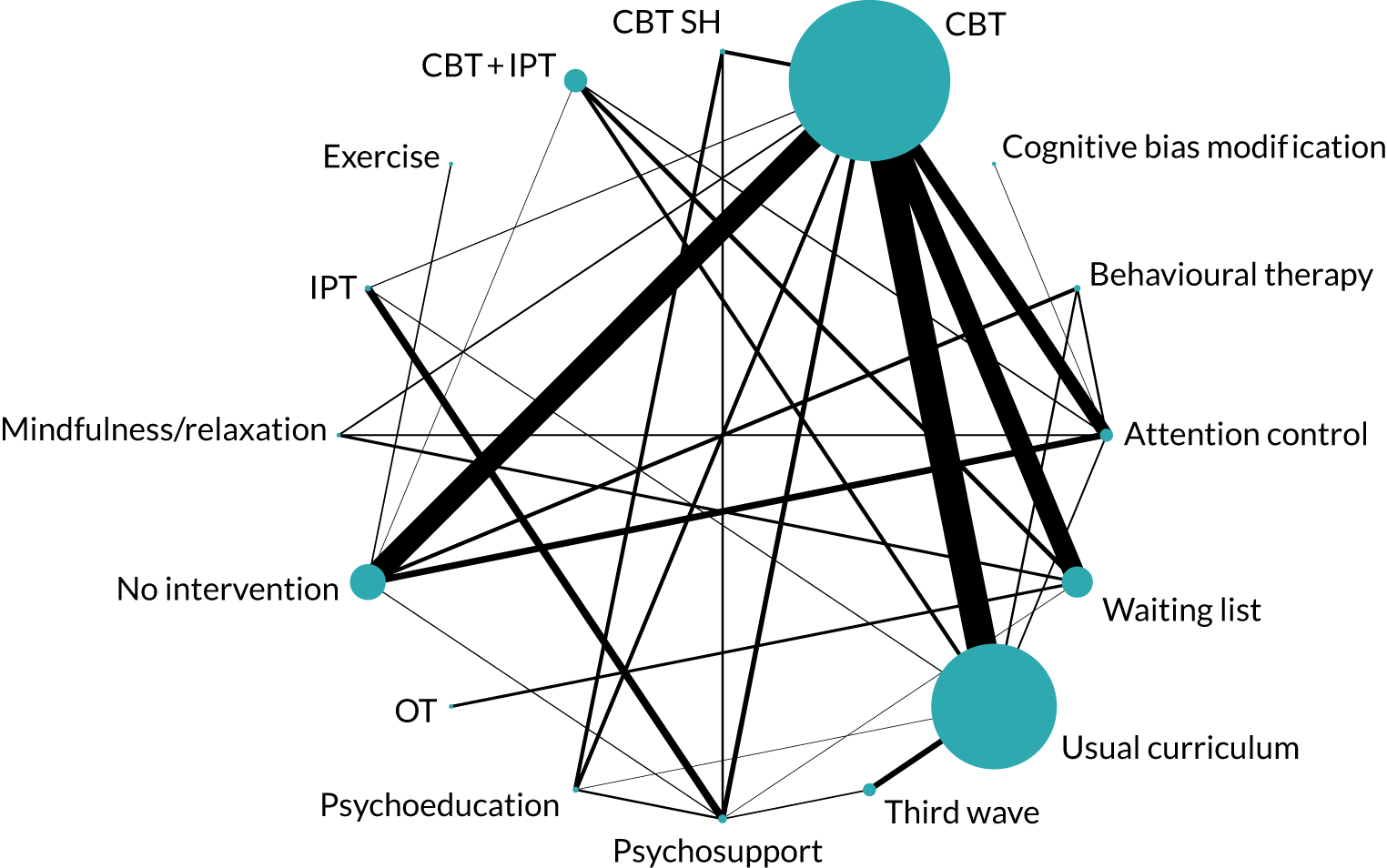

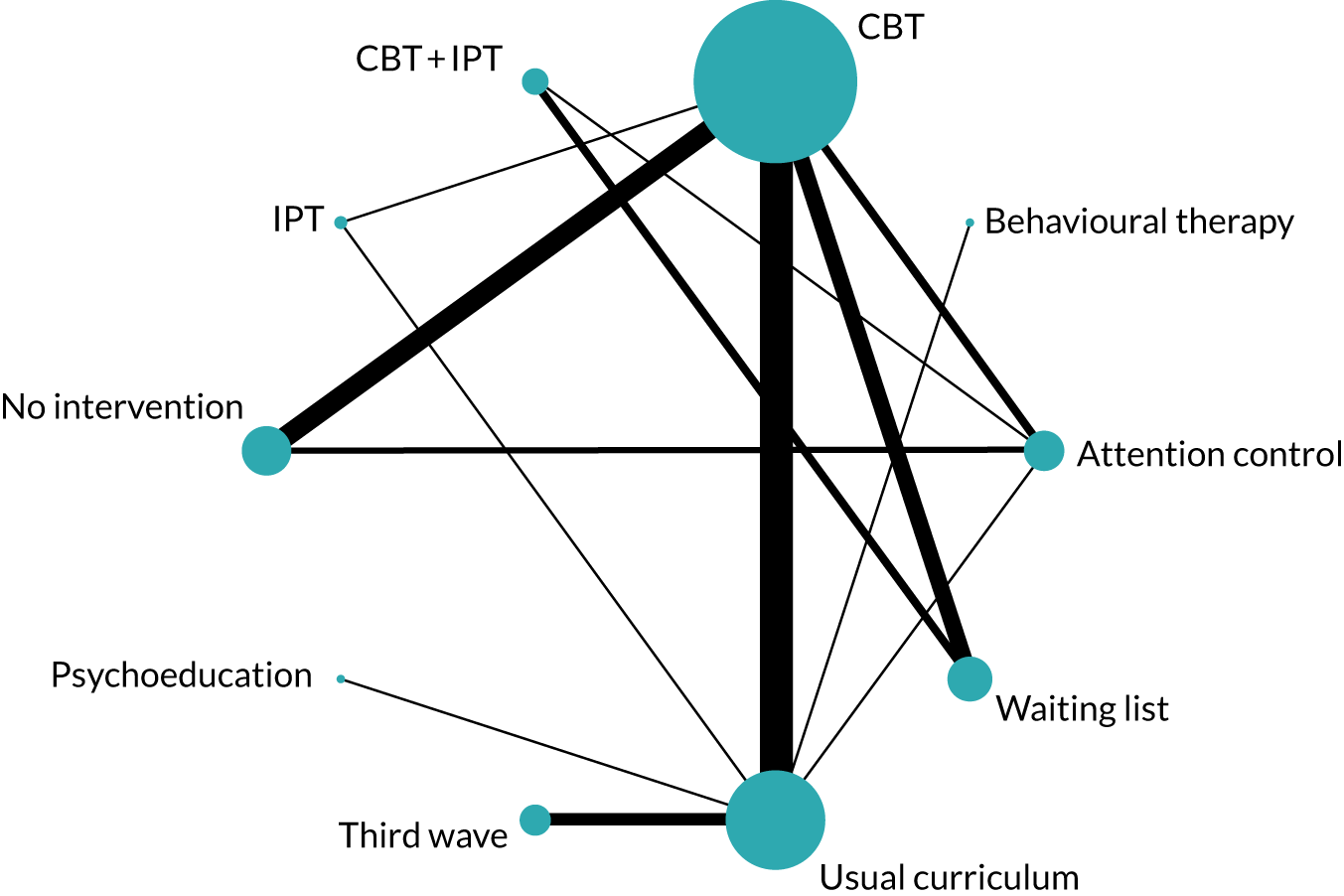

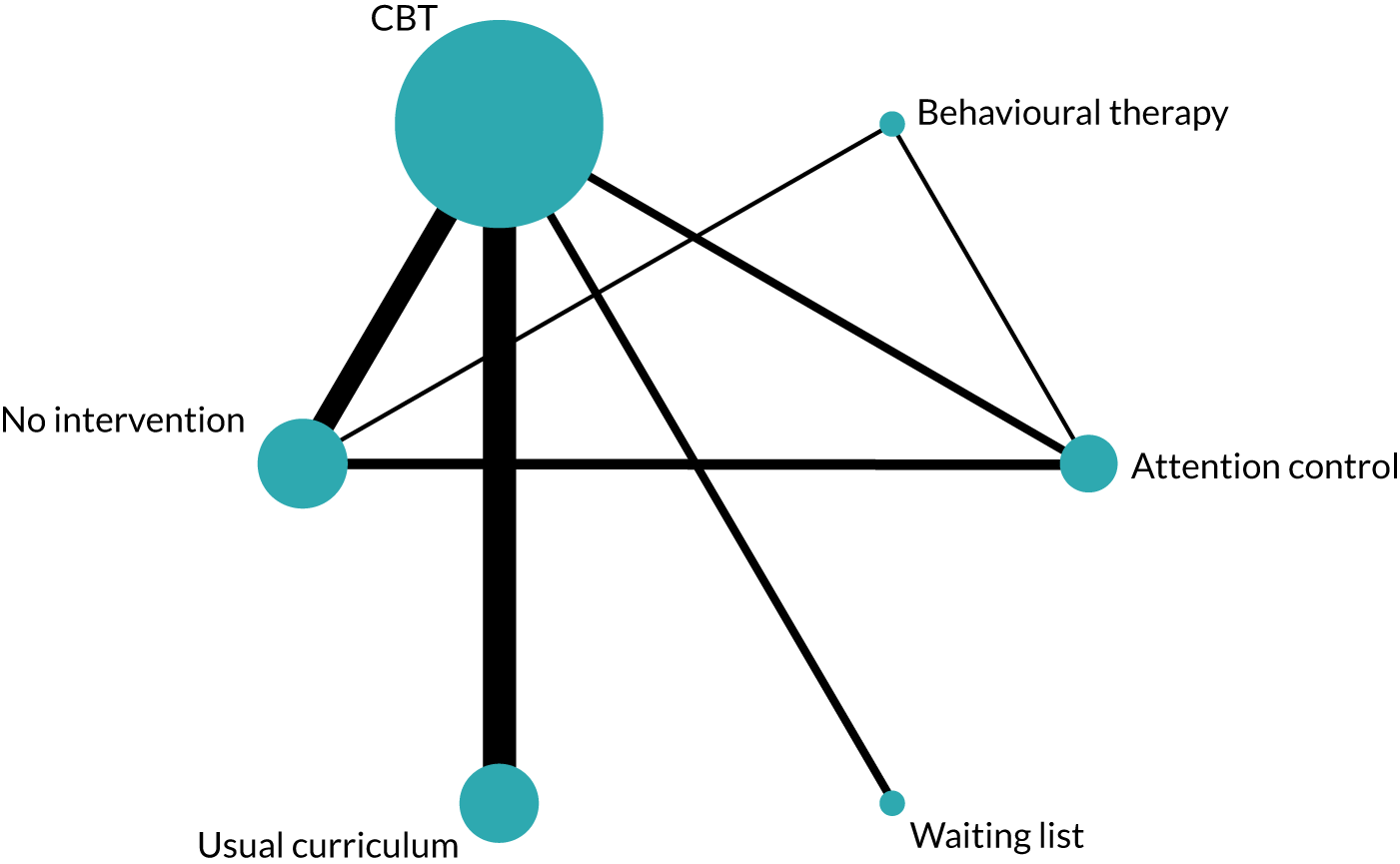

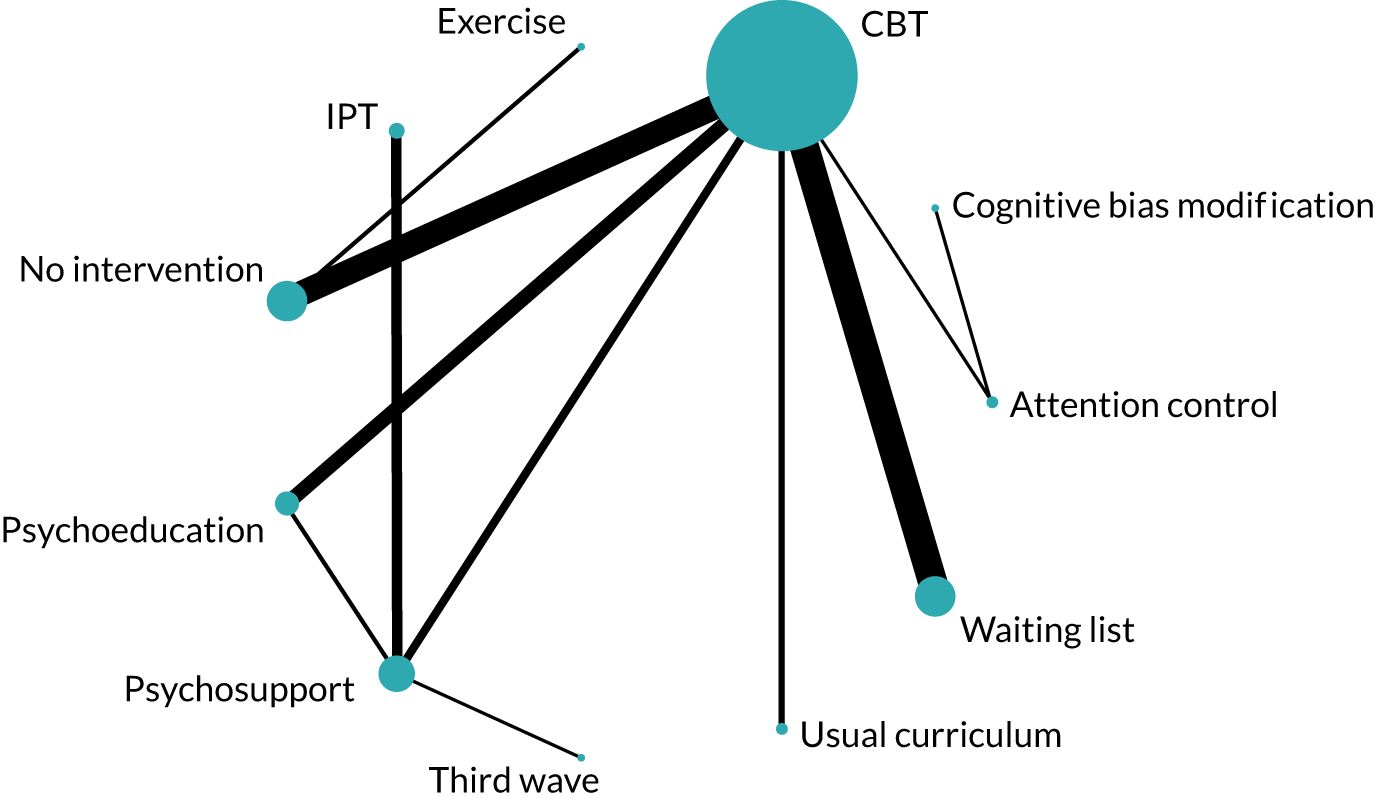

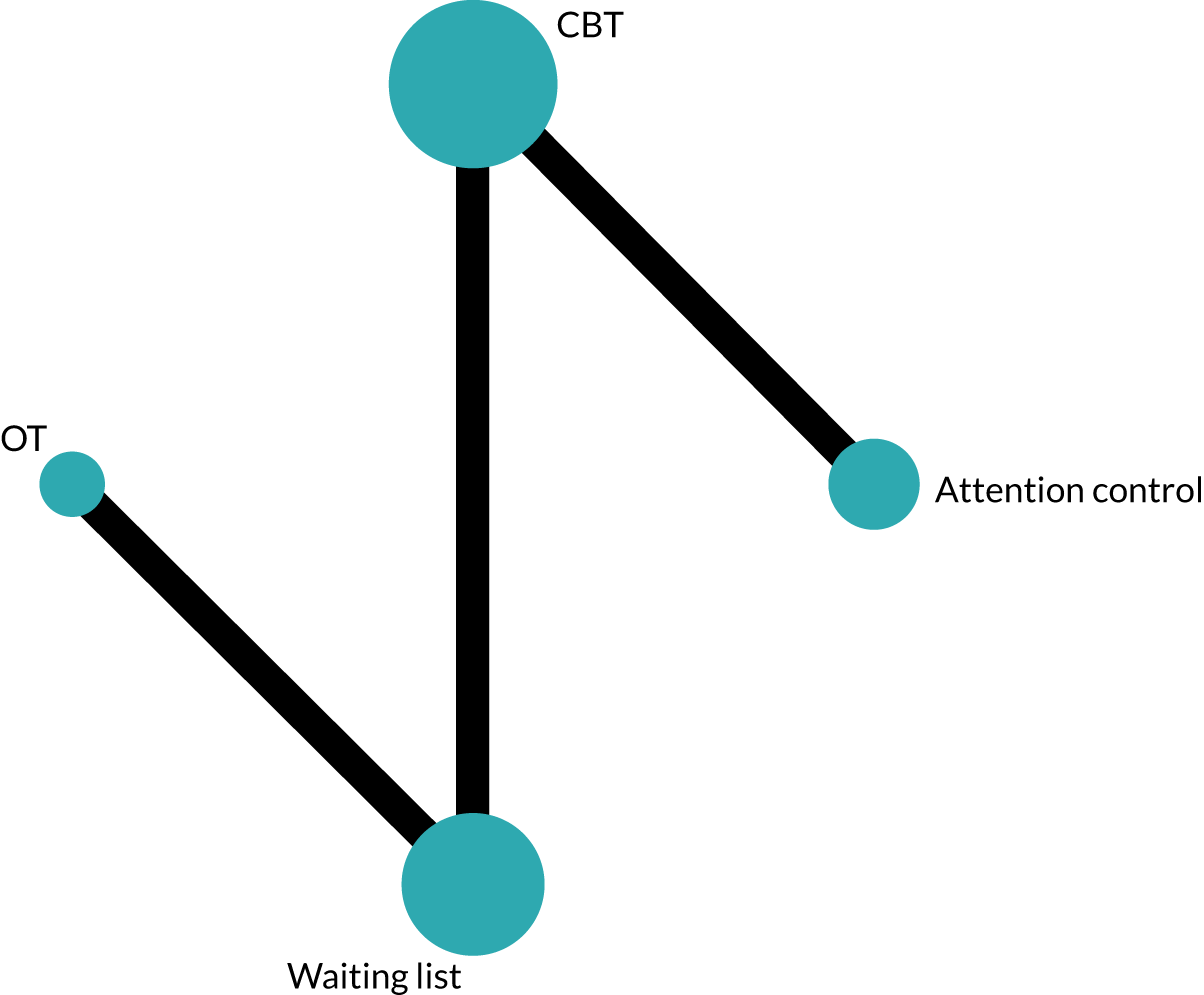

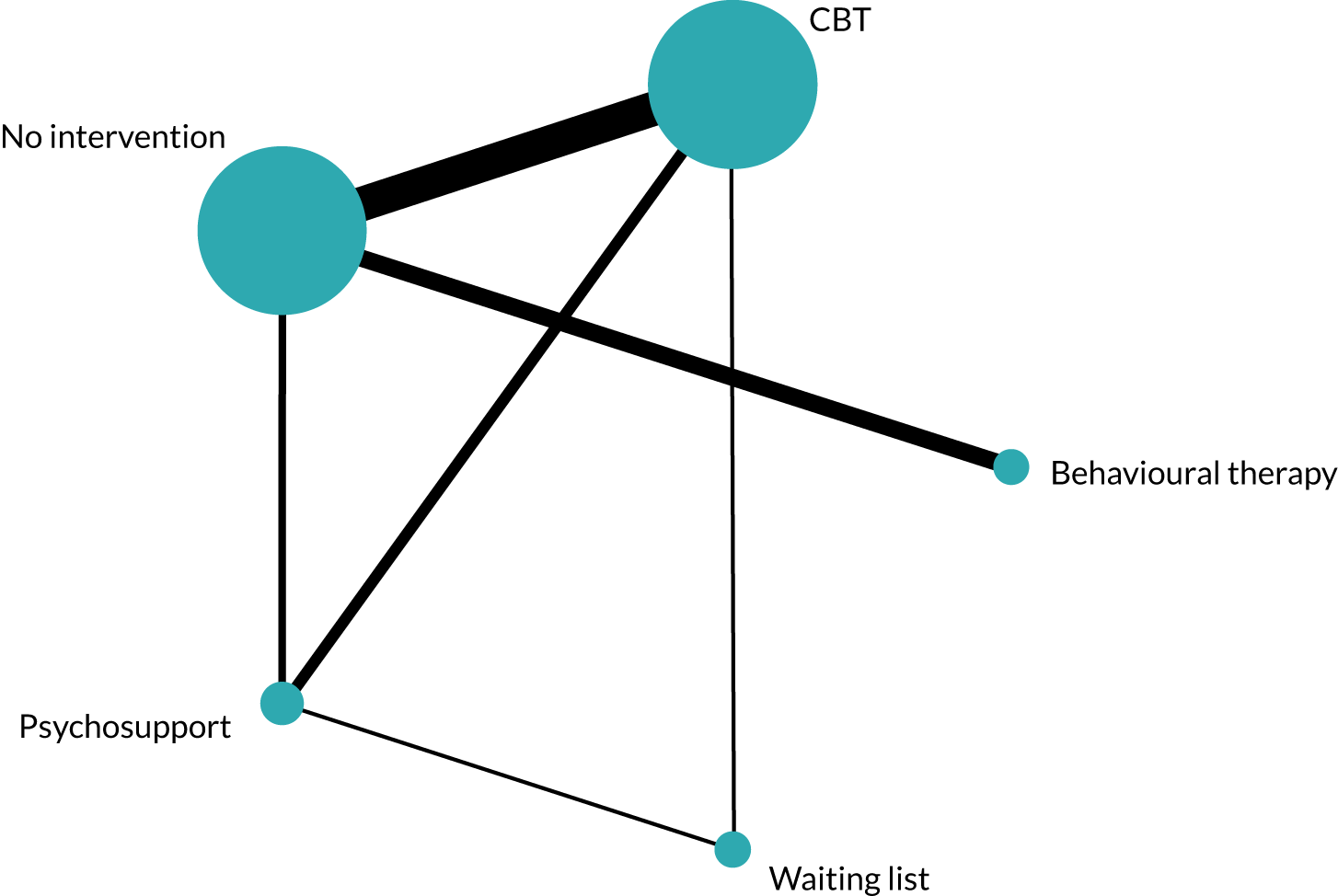

Network plots were drawn in Stata® version 15 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) to allow visual inspection of network connectedness. 98

For the primary time point of post intervention only, we considered three NMA models, each allowing for increasing specificity of intervention detail:46,82

-

Intervention-level model – interventions were analysed as ‘clinically meaningful units’. 48 For example, cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) was analysed as a distinct intervention to psychoeducation or third wave-based interventions.

-

Additive model – components nested within intervention. A main intervention effect was estimated (as per the intervention-level model), plus additional effects for specific components within each intervention. For example, we estimated an overall CBT effect, which represents the effect for CBT interventions with components that were common across all the included CBT interventions, and also estimated the additional effect of CBT interventions containing a psychoeducation component, a mindfulness component and so on.

-

Full interaction model – components nested within intervention: under this model, each unique combination of intervention and components was considered as a separate intervention. For example, CBT with cognitive + behavioural + psychoeducation components was considered a distinct intervention to CBT with cognitive + behavioural + psychoeducation + relaxation components.

For follow-up time points, where we anticipated finding fewer studies, we ran the intervention-level model only as prespecified in the protocol. Intervention-level analyses were implemented in a Bayesian framework using OpenBUGS software (version 3.2.3). Component analyses were implemented in WinBUGS99 (version 1.4.3; MRC Biostatistics Unit, Cambridge, UK). Statistical details are reported in Appendix 1. Data and WinBUGS code can be obtained by contacting the corresponding author. Vague prior distributions were specified for intervention effect and heterogeneity parameters (see Appendices 1 and 3). We assessed convergence for the intervention-level NMA based on three chains using the Brooks–Gelman–Rubin diagnostic tool and history plots in OpenBUGS. Specific convergence details for each model and population/setting analysis are reported in the model fit tables in Appendix 3, Table 29–46.

Random-effects models were run for the main outcomes, assuming a common between-study SD (known as ‘homogeneous variance’). 100 However, we assessed both fixed- and random-effects models on the basis of model fit. Heterogeneity was evaluated by examining the posterior median between-study SD (τ) and 95% CrIs from the random-effects model, and by comparing model fit of the fixed- and random-effects models. Model fit was measured by the posterior mean of residual deviance. In addition, we examined the deviance information criterion (DIC), which penalises model fit with model complexity. Differences of ≥ 5 points in posterior mean residual deviance and the DIC were considered meaningful, with lower values preferred. 101 Model fit statistics are reported in Appendix 3.

As described previously, a key assumption for a valid NMA is that of consistency between the direct and indirect evidence. If the effect estimates from the direct and indirect evidence in a network do not agree, this is known as inconsistency. The strict inclusion/exclusion criteria described previously were specified to avoid inconsistency, but they do not guarantee consistency. For this reason, the statistical agreement of the evidence was formally checked. Consistency was assessed by comparing the goodness of fit of a model assuming consistency with that of one allowing for inconsistency (i.e. a model that provides effect estimates based on direct evidence only). A common between-study SD was also assumed for these inconsistency models. 57

Pairwise meta-analyses were also conducted when head-to-head evidence was available. The method of estimation is similar to the NMA, except that the consistency assumption is removed such that intervention effects for separate comparisons are unrelated and separate intervention effects can be estimated. 57 Estimates are reported for the post-intervention time point only and are from a random-effects model that assumes that the heterogeneity parameter is common across intervention comparisons. This better reflects the assumption made in the NMA and, therefore, allows a fair comparison of the intervention effect estimates obtained from both approaches.

Subgroup, metaregression and sensitivity analyses

Metaregression and subgroup analyses were performed in OpenBUGS following the Evidence Synthesis Technical Support Unit code available from the NICE Decision Support Unit’s website and described in Dias et al. 102,103 Subgroup analyses were conducted to assess whether or not intervention effects differed by intended focus of the intervention, for example if interventions addressing anxiety had a larger effect on anxiety outcomes than interventions intended to focus on depression but which also recorded anxiety outcomes.

Metaregression was planned for the intervention-level NMA and main outcomes only, to examine if intervention effects differed by mode of intervention delivery and who facilitated intervention delivery:

-

Mode of intervention delivery – interventions were categorised as being delivered face to face or via a computer/internet. To explore whether or not intervention effects were modified by mode of delivery, we fitted a metaregression model for face-to-face (covariate value = 0) and computer/internet (covariate = 1) interventions. A random-effects NMA model was fitted. However, the regression coefficient for the covariate was assumed to be a fixed effect across studies. The between-study SD was assumed to be common for face-to-face and computer/internet interventions. Vague priors were specified.

-

Who facilitated intervention delivery – interventions were categorised as being facilitated by a teacher or a mental health professional (MHP). There was considerable variation within the category of ‘MHP’ and it should be regarded as a simplification. Here, MHP included school counsellors, qualified psychotherapists and graduate and post-doctoral psychology students. Graduate and post-doctoral students included those studying general psychology, educational psychology or counselling psychology, when specified. We fitted a metaregression model that enabled us to estimate the intervention effect at each value of the covariate (0 or 1), for each intervention, comparing the effect of each facilitator (e.g. CBT-teacher vs. CBT-MHP vs. usual care). To allow for networks containing multiarm studies with more than two interventions facilitated by a teacher or MHP, a hierarchical model was fitted. In this hierarchical model, a regression coefficient for each intervention was assumed to come from a normal distribution with a common mean and between-intervention SD. The between-intervention SD was assumed to be common for each value of the covariate. Vague priors were specified.

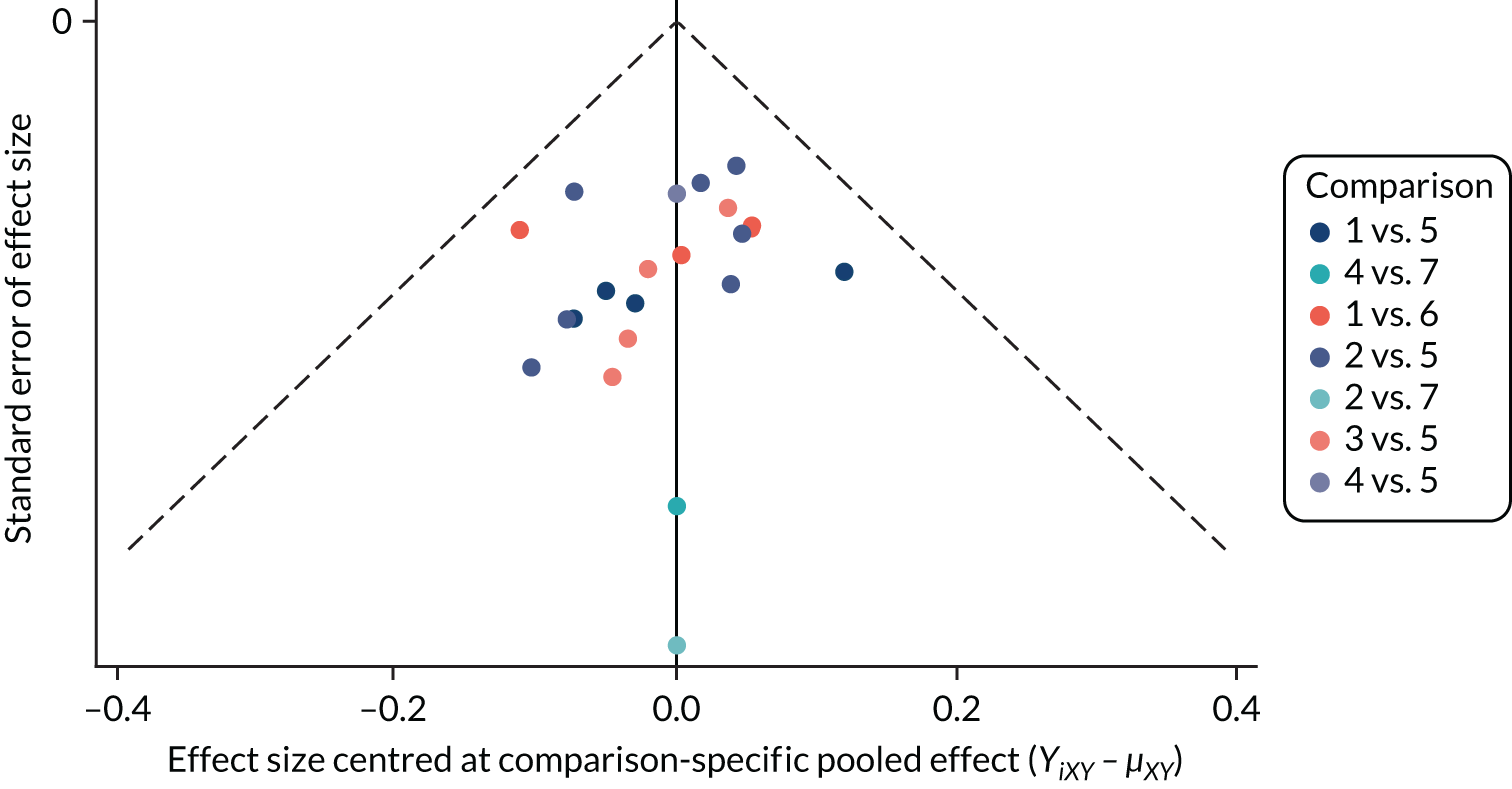

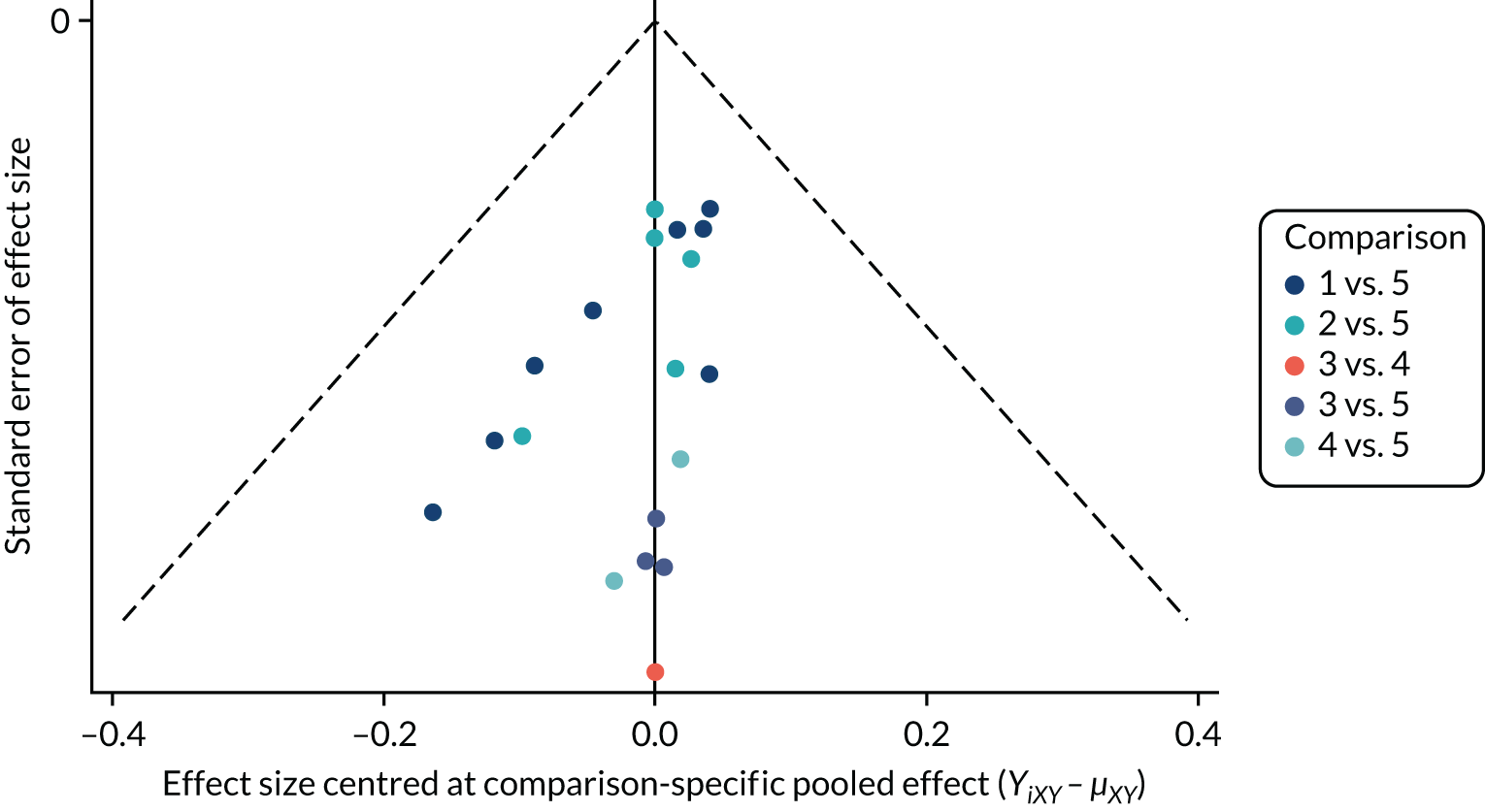

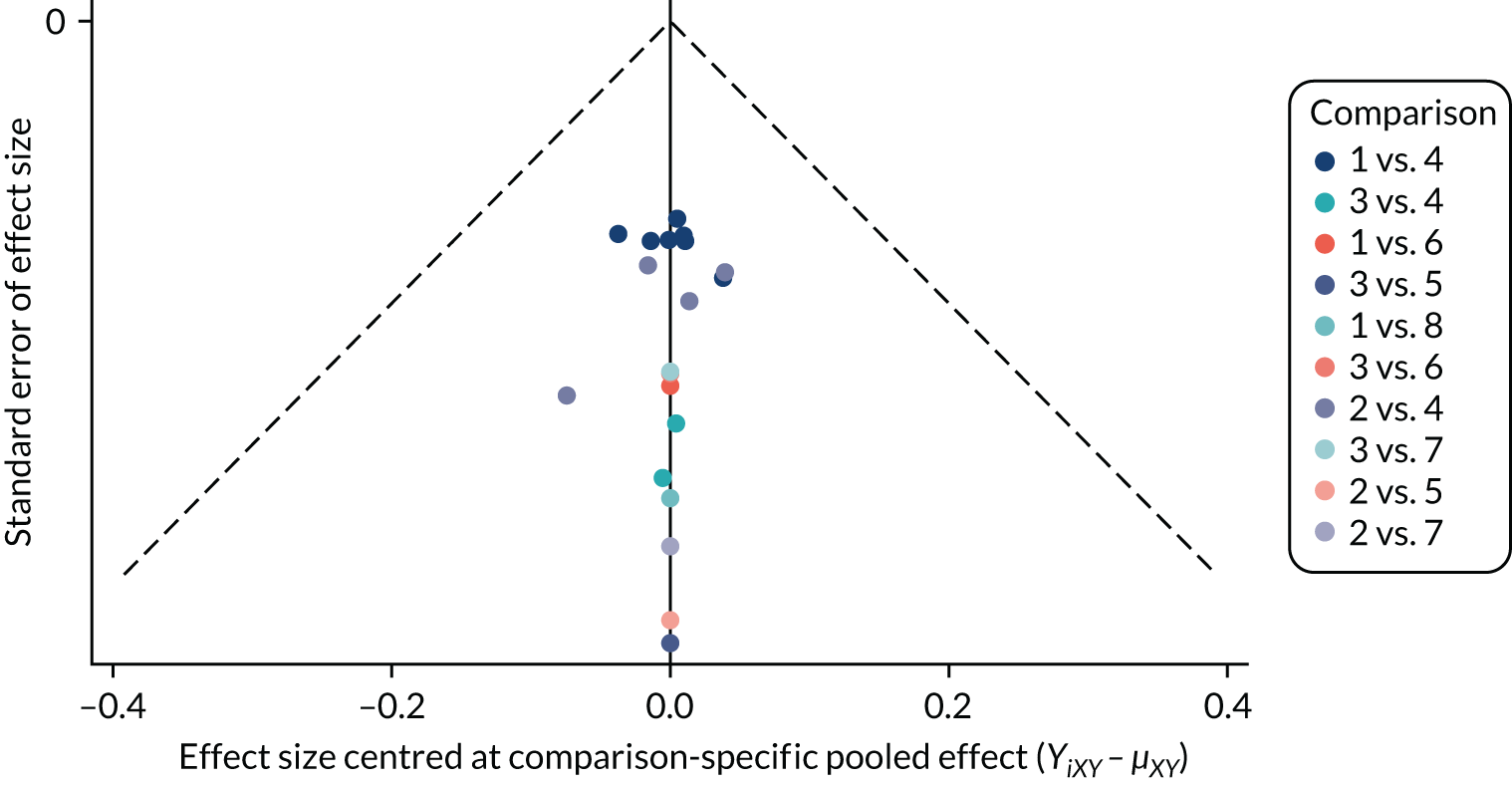

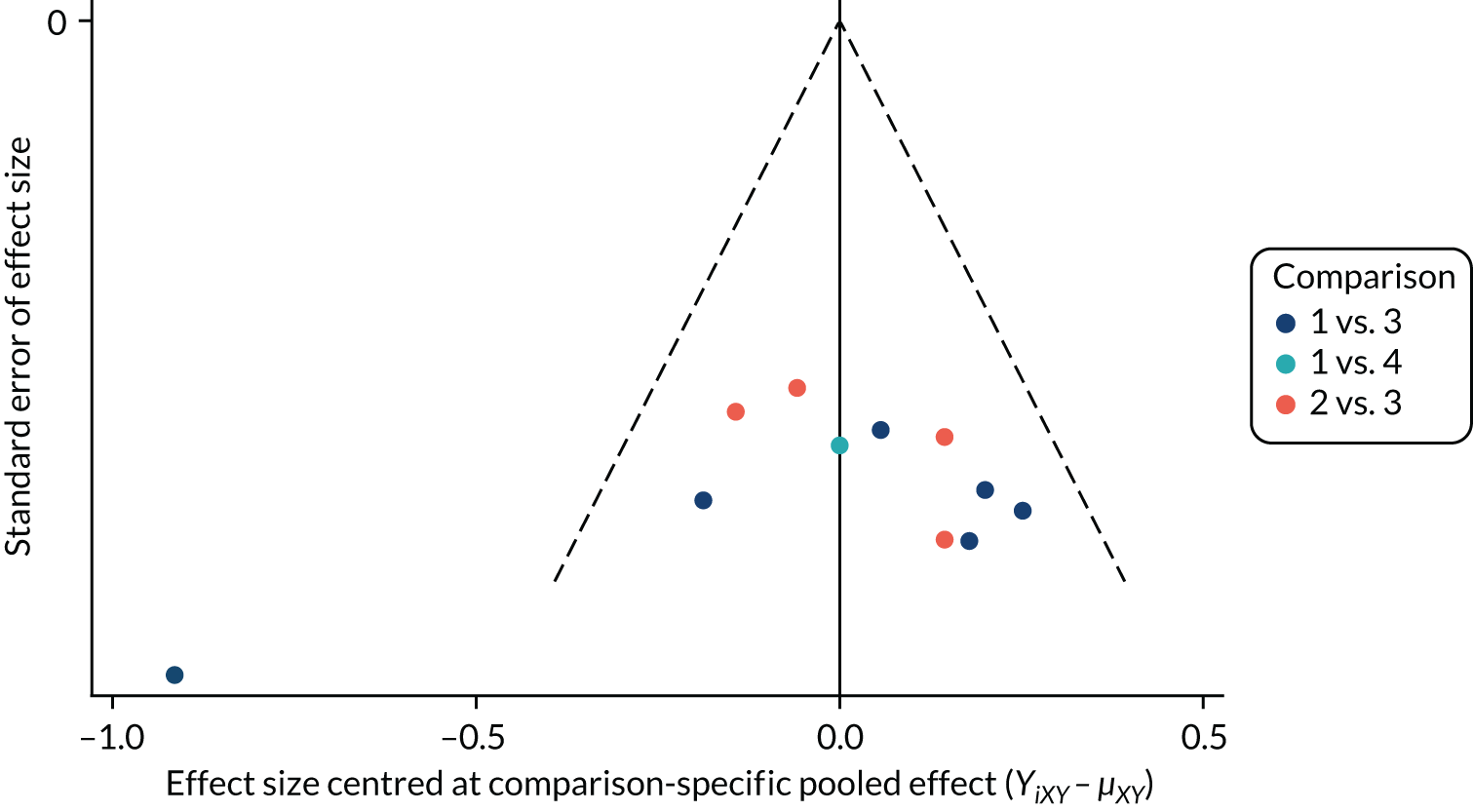

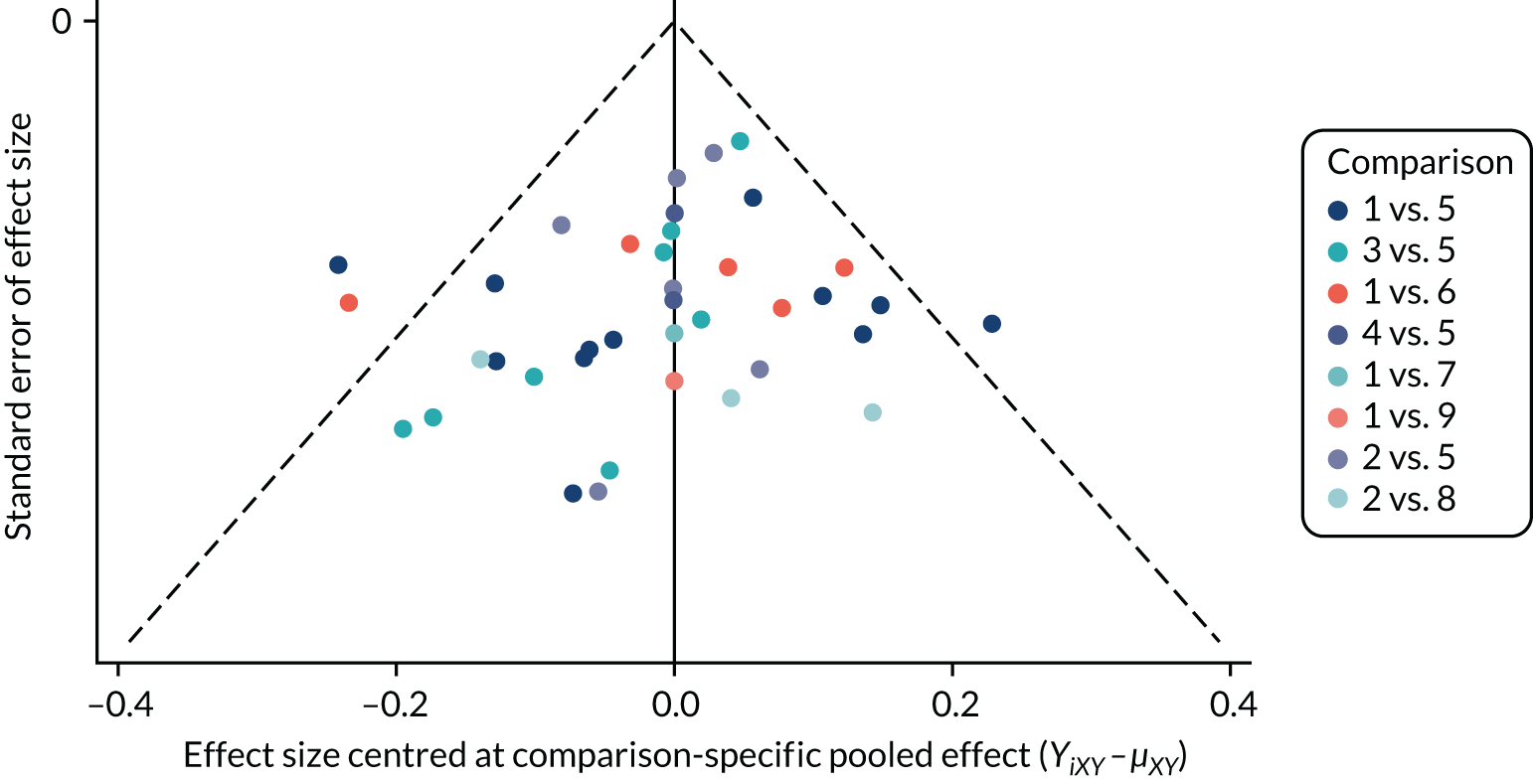

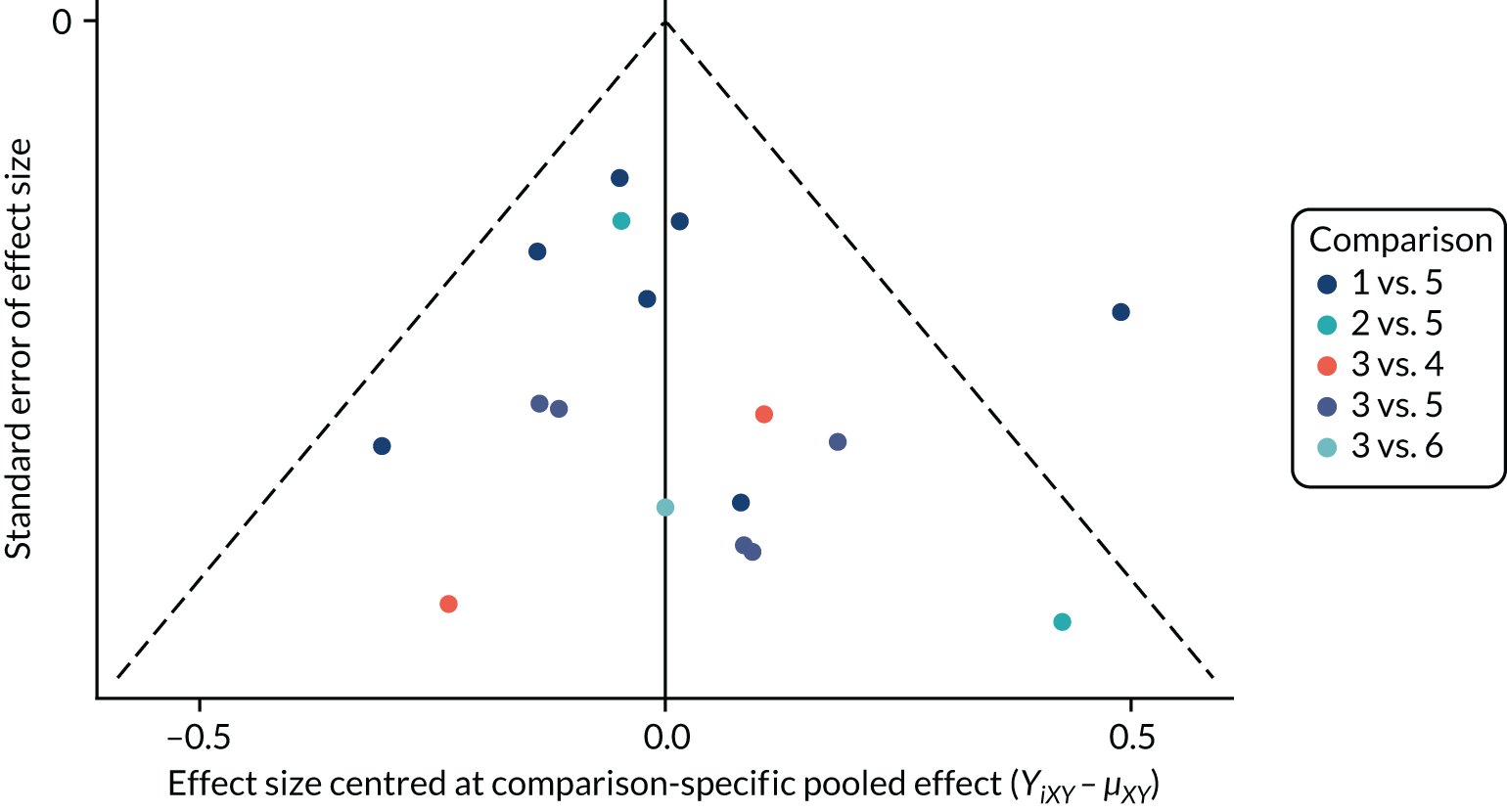

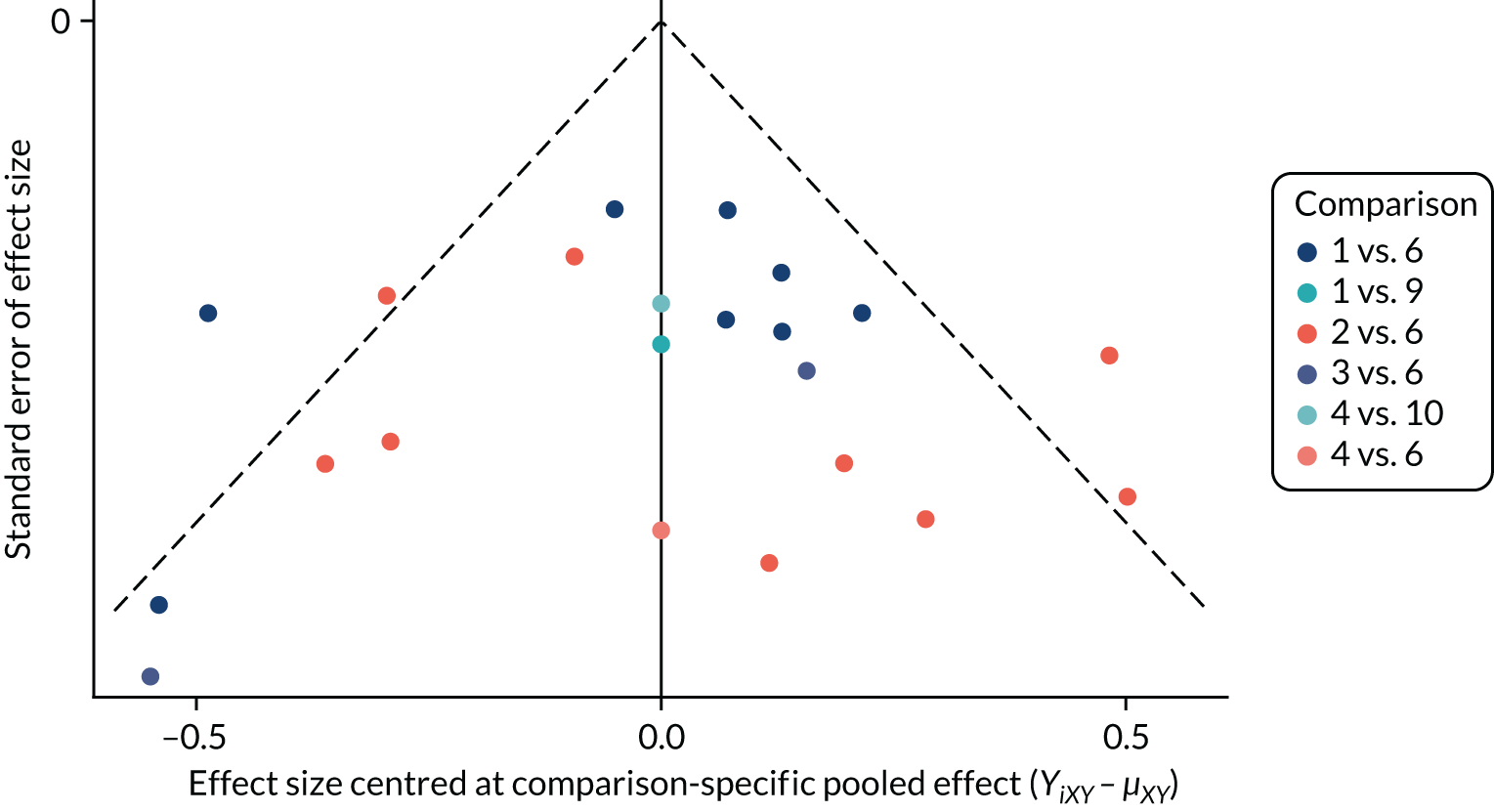

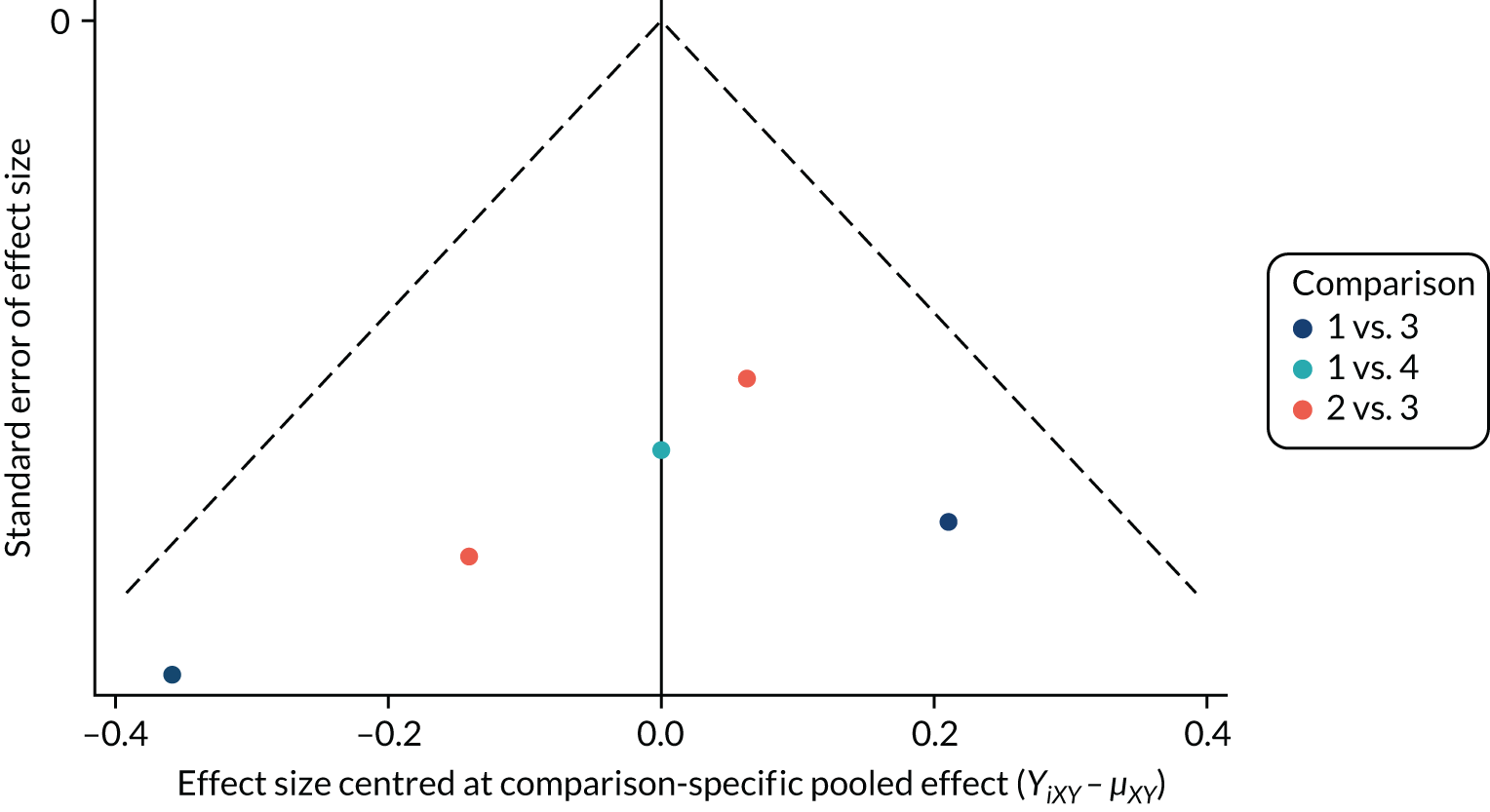

We explored the potential for small-study effects using comparison-adjusted funnel plots. 98

Sensitivity analyses were conducted for the intervention-level NMA, main outcomes and primary time point only. Analyses explored the robustness of results to the following:

-

Excluding studies deemed to have a high/unclear risk of bias on the domains of random sequence generation and allocation concealment.

-

The ICC value of 0.03 for cluster randomised trials. Sensitivity analyses were conducted assuming an ICC of 0.01 and 0.06.

-

The correlation value of 0.7 assumed for calculating change from baseline SD. Sensitivity analyses were conducted assuming a correlation of 0.6 and 0.8.

Interpreting the results and evaluating evidence of effect

As described previously, summary effect estimates and their 95% CrIs from the NMA are reported. In interpreting these statistical findings, we followed the guidance from the Cochrane handbook (section 15.3) that interpretation of results from a meta-analysis should not rely on statements of ‘statistical significance’ or thresholds implying ‘significance’. 104 Instead, we interpret the strength of statistical evidence on a graduated scale from weaker to stronger evidence of an intervention effect. 105,106

In Chapter 9, we also provide a summary of these statistical findings for the primary outcomes of anxiety, depression and conduct disorder symptoms at the primary time point of post intervention. This interpretation forms the basis of the conclusions for the report. The criteria used are based on the considerations outlined in Chapters 14107 and 15104 of the Cochrane handbook. These considerations are informed by the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) domains of imprecision, inconsistency (heterogeneity), risk of bias and publication bias. It is not a formal application of the GRADE rating system, which necessitates up- or downgrading of the evidence on the basis of the assessments to form an overall assessment of ‘quality’. 107

Specifically, our interpretation of the evidence is not solely based on the magnitude and direction of the summary point estimate, but also incorporates an evaluation of all of the following:

-

the precision of the effect estimate, as described by the 95% CrI

-

the extent of the between-study heterogeneity observed in each analysis, as described by τ and its 95% CrI

-

the risk-of-bias assessment

-

the possibility of non-reporting biases or evidence of small-study effects.

Chapter 3 Intervention and component categorisation

In this chapter, we describe the intervention classifications and the components used in the NMAs reported in Chapters 4 and 5.

Main ‘intervention-level’ classification

The main ‘intervention-level’ classifications were assigned based on the trial authors’ descriptions and classifications used in previous systematic reviews. 36–39,68,108–113 Many interventions to prevent anxiety and depression have been adapted from existing clinical interventions for treatment which, in turn, are grounded in identifiable therapeutic traditions. In adapting therapeutic interventions for a prevention context, some developers have retained the reference to the underlying therapy on which they are based, for example cognitive–behavioural therapy. Although these preventative interventions focus on the same techniques, exercises and skills that underpin the clinical ‘therapeutic’ intervention, the term ‘therapy’ may be considered a misnomer in a preventative context. As such, it may be preferable and more accurate to consider these preventative interventions as ‘interventions based on the principles of CBT’. However, for conciseness and consistency with the trial literature we retain the use of ‘therapy’ when using intervention abbreviations throughout the report (e.g. CBT).

Behavioural therapy

Behavioural therapy is a group of allied techniques that focus on behavioural models of psychology and seek to modify overt maladaptive behaviours. In the current review, we categorised interventions based on behavioural activation, self-monitoring, role-playing, exposure to feared stimuli or scheduling pleasant activities as being behavioural in nature.

Cognitive–behavioural therapy

Cognitive–behavioural therapy can be considered a family of allied techniques, based in both behavioural and cognitive models of psychology, that utilise a set of overlapping cognitive and behavioural techniques. CBT is based on the proposition that a person’s behaviour is influenced by their cognitive activity (and vice versa), and that cognitions can be monitored and altered (cognitive restructuring). In turn, emotions and behaviour can be modified via this cognitive change. CBT interventions for treatment of CMDs typically include a psychoeducation component; however, in preventative interventions, this may not always be present.

Third-wave interventions

This was a composite category. Third-wave psychotherapies emphasise mindfulness, acceptance and flexibility. They tend to focus on a person’s relationship to their cognitions and emotions, encouraging an acceptance of thoughts, rather than modifying their content. Interventions that described themselves as mindfulness-based CBT, acceptance and commitment therapy or dialectical behavioural therapy were included in this classification. Third-wave preventative interventions were distinguished from mindfulness meditation or relaxation interventions that did not explicitly address cognitions or behaviours.

Interpersonal therapy

From a treatment perspective, interpersonal therapy (IPT) is based on the relationship between mood symptoms and interpersonal relationships. It seeks to relieve symptoms via resolving interpersonal conflict and difficulties. In the preventative context, IPT addresses the relationship between young people significant adults (e.g. teachers, parents), with regard to avoiding/resolving conflict via improved coping communication skills. The techniques used attempt to improve interpersonal skills may include role play, problem-solving exercises and practising effective communication.

Mindfulness meditation and relaxation-based interventions

In the present review, mindfulness/relaxation is a composite category and is distinct from third-wave interventions. Relaxation includes breathing exercises, muscle relaxation and yoga from the Iyengar or Hatha traditions (as opposed to more vigorous traditions). Mindfulness meditation interventions were included in this category if they focused solely on meditation or relaxation without incorporating aspects of traditional ‘talking’ psychotherapeutic approaches.

Biofeedback

Biofeedback is a mind–body intervention that uses physiological monitoring devices or equipment to learn to control physiological responses, such as heart rate. Users may monitor their heart rate variability using pulse oximetry, for example while completing a standard deep-breathing exercise. The feedback received helps the participant learn how to influence the negative, or undesired, response (e.g. a stress response). Smartphone applications and ‘consumer wearables’ have been developed for monitoring stress, anxiety and sleep problems.

Exercise

In this review, we classified an exercise intervention as a cardiovascular intervention designed to raise heart rate and breathing to (at least) a moderate intensity level, for example dancing, running and team sports.

Cognitive bias modification

Cognitive bias modification (CBM) relates to a group of approaches, including attention and interpretation bias training, that aim to retrain cognitive distortions. CBM evolved from a visual attention task (a dot-probe task), in which a participant is exposed to a series of threatening and neutral stimuli via computer, such as angry and neutral faces, and the speed of their response to a ‘probe’ is measured (e.g. where on the screen the angry or neutral face was displayed). In individuals with a CMD, attention tends to be selectively directed towards the negative image and response times to the probe are slower. CBM for the treatment of anxiety disorders seeks to ‘retrain’ this selective attention bias towards the positive stimulus. In preventative interventions for CYP, CBM tasks may be embedded in engaging and user-friendly formats such as interactive video games (‘CBM gamification’).

Occupational therapy

Occupational therapy interventions are based on engaging CYP in meaningful daily activities or ‘occupations’. Interventions are skill based and aim to enable CYP to successfully engage with, and participate in, developmentally appropriate everyday events. For example, an intervention might focus on a favourite activity to increase self-esteem, or schoolwork may be modified to create a positive learning environment and reduce stress.

Control groups

On the basis of previous research,68,72–74 we distinguished the following separate control groups. We note that, in the included trials, psychoeducation and psychosupport were sometimes considered as active interventions in their own right. Their inclusion under a ‘control group’ heading does not affect the findings.

Psychoeducation

Often a component of CBT-based interventions, psychoeducation can also be used as a distinct intervention. It typically involves a systematic approach to providing background information, for example what the cause or symptoms of a mental disorder are and advice regarding the mental disorder and/or explaining the approaches that can help to mitigate symptoms. Written materials or presentations may be provided.

Psychosupport and counselling

Often a component of other interventions, psychosupportive interventions are also used in a stand-alone format. In the current report, we combined psychosupportive and counselling-based interventions into one category. Here it refers to a non-specific, possibly therapeutic, intervention that could include listening, signposting to further services, or forming an attachment or therapeutic alliance.

Usual curriculum

If an active intervention took place during a regular timetabled class and participants in the control group continued to receive the regular class curriculum, the control intervention was classified as standard provision or ‘usual curriculum’. This included a variety of different classes and could have included a ‘well-being’ or health lesson or a standard timetabled academic lesson (such as history or mathematics).

Waiting list

If participants in the control group were explicitly told (e.g. via informed consent processes) that they would receive the active intervention at a later date, the control condition was categorised as a waiting list. Although participants were also likely to be receiving usual curriculum or a no-intervention control, the use of an explicit waiting list design takes precedence in our categorisation.

No intervention

A no-intervention control categorisation was used to differentiate between a control condition in which participants received something and a control condition in which participants were not involved in any structured activity. This classification was applied when the active intervention was held outside regular timetabled classes (e.g. after school) and the participants were not described as being in a waiting list control.

Attention control

A control was classified as attention control if it was a de novo intervention provided to the participants for the purpose of the research study.

Component classifications

As described in Chapter 2, ICA is a subjective process. We defined an intervention component as a potentially active ingredient or constituent part of a main ‘therapy-level’ intervention. In a NMA, components can be included as indicator variables in a network metaregression; as such, they are pragmatic classifications related to the techniques used, and may not pertain to psychotherapeutic schools or traditions. We did not assume the presence of a component based on the therapy-based intervention-level classification assigned by study authors, but on the details provided about what was done. For example, if an author stated that the intervention was CBT based, we did not assume that it contained a psychoeducation, cognitive or behavioural component unless it was clearly stated in the paper (or intervention manual if applicable). We coded only what was clearly reported, and discuss this further in the limitations section of the discussion (see Chapter 10).

Component classifications should also be read independently from the similar-sounding main intervention-level classifications mentioned previously. For example, an intervention-level CBT classification may be defined by the following illustrative combinations of components, depending on what was reported:

-

CBT intervention 1 – psychoeducation + cognitive + behavioural + relaxation + exercise

-

CBT intervention 2 – cognitive + behavioural

-

CBT intervention 3 – psychoeducation + cognitive.

Behavioural

A behavioural component was one in which techniques included helping participants to practise and acquire new skills to cope or manage difficult emotions, moods or behaviours. This component includes strategies used in behavioural activation, social skills exercises (including how to make friends, be a good friend and support your friends), role play, assertiveness training, interpersonal work and activity scheduling and contingency management including goal-setting, planning and decision-making activities, problem-solving and exposure. Following Hetrick et al. ,68 this component was initially subdivided into four further subcomponents: (1) social skills training, (2) problem-solving, (3) exposure and (4) ‘other’ behavioural categories. However, this resulted in unconnected networks, so results are reported for a ‘lumped’ behavioural component only.

Cognitive

This component label was applied when an intervention included strategies or techniques designed to identify and replace cognitive distortions with more accurate and adaptive ones, for example recognising and understanding thoughts and feelings, using positive self-talk and challenging negative self-talk and thoughts.

Third wave

During the ICA, we observed that standard CBT, third wave interventions and mindfulness/relaxation interventions were often based on combinations of the same components. We included a third wave component category to ensure differentiation between these ‘therapy-level’ interventions. The component definition is the same as described previously for the intervention level analysis.

Mindfulness

Mindfulness techniques included guided meditation, colouring and drawing, and exercises to practise being in the moment and being free from judgemental thoughts and distractions. On completion of the component coding, we observed that a mindfulness component was always present in conjunction with a relaxation component.

Relaxation

Separate mindfulness and relaxation components were specified to allow for relaxation techniques that were not defined as meditation or mindfulness. This included strategies such as progressive muscle relaxation, abdominal breathing exercises, cue-controlled relaxation, and identification of physiological arousal (‘body clues’) approaches.

Physiological

A component was coded as physiological if it involved the process of displaying involuntary or subthreshold physiological processes, usually by electronic instrumentation, and learning to voluntarily influence those processes by making changes in cognition.

Bias modification

This component was present only in the main therapy-level intervention, CBM, as described previously. However, on completion of coding, it was retained as a separate component, as the four studies that could be described as evaluating a CBM intervention were assessed as containing different combinations of components:

Psychoeducation

Psychoeducation was also included as a component of broader interventions. The definition applied at the component level is the same as described previously for the intervention-level analysis.

Additional process and implementation classifications

We also extracted information on the following implementation and process components of interventions: number of sessions, duration of intervention (minutes), mode of delivery (face to face or digital), group or individual delivery, who the facilitator was and whether or not training was provided, and whether or not intervention fidelity was monitored. The characteristics of interventions, the components and process details are provided in Chapters 4 and 5 and in Appendix 2. We did not include the process components in the NMA owing to concerns regarding a lack of power and network connectedness. 82

Chapter 4 Effectiveness of educational setting-based interventions for preventing anxiety

Parts of this chapter are reproduced or adapted from Caldwell et al. 1 © 2019 The Author(s). Published by Elsevier Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes substantial additions and formatting changes to the original text, as well as changes to the reporting approach.

In this chapter, we report the systematic review and NMA results for studies reporting an anxiety outcome only. Studies reporting a depression outcome are reported in Chapter 5 and additional and secondary outcomes are reported in Chapter 6.

Systematic review results

Studies included in the review

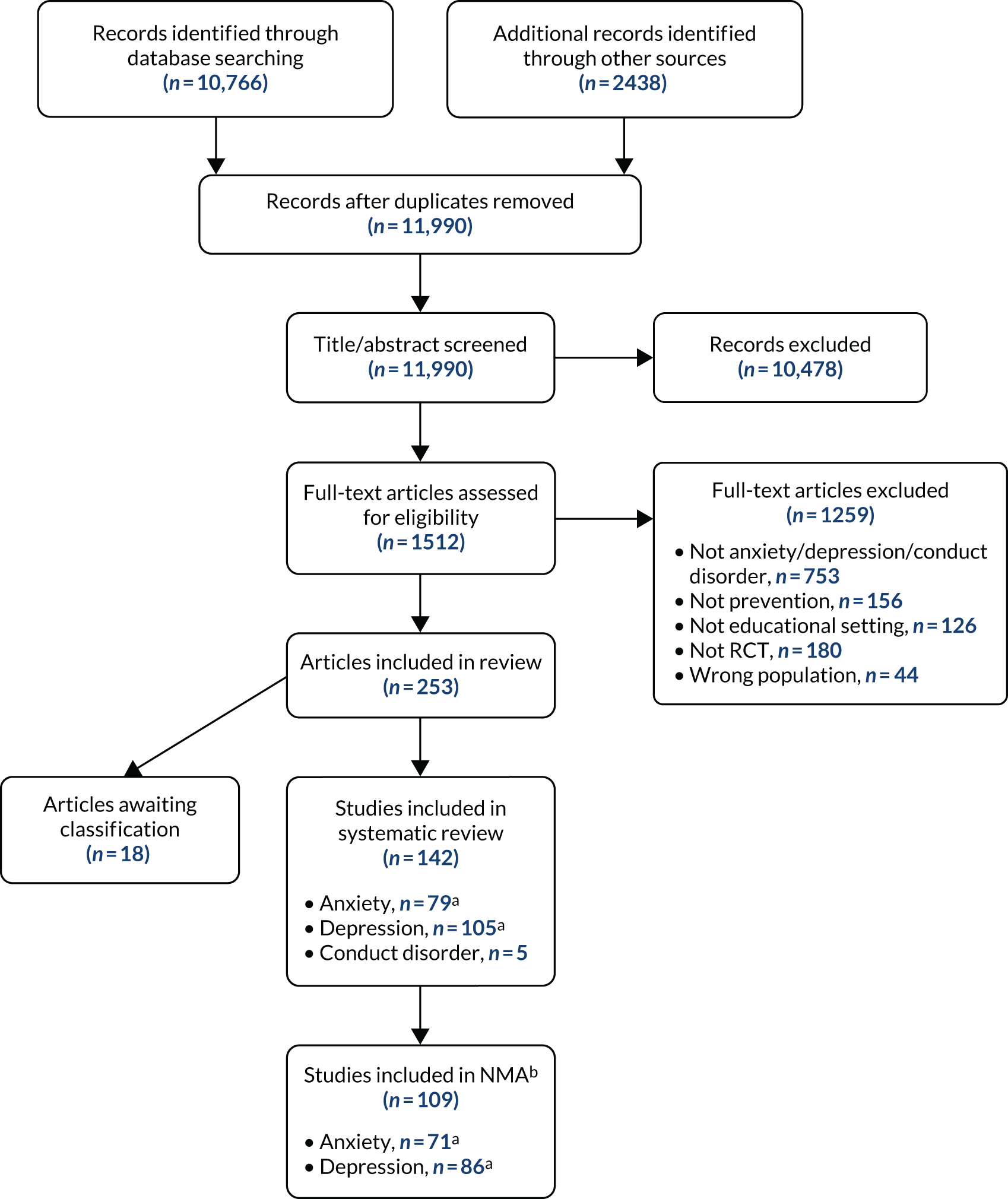

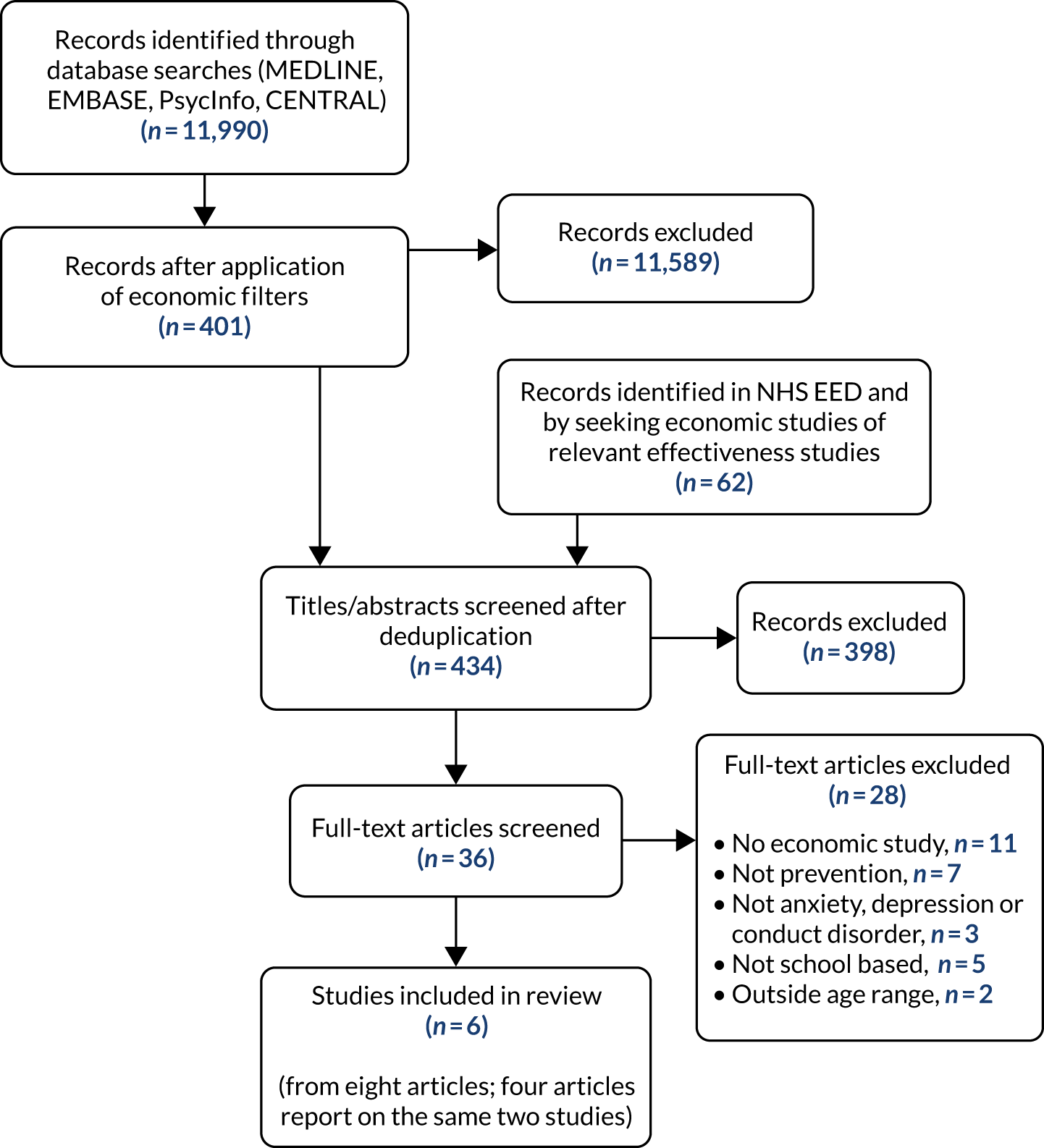

The overall Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram for the whole review is reported in Figure 2. A total of 11,990 citations were screened, and 1512 full-text articles were retrieved for further screening. Of these, 142 studies were identified as eligible for inclusion in either the anxiety, depression or conduct disorder reviews. Fifty-four studies reported both an anxiety and a depression outcome. The full list of included studies can be found in Appendix 2.

FIGURE 2.

Study selection process: PRISMA flow diagram for whole systematic review. a, Not mutually exclusive. Some studies reported both anxiety and depression outcomes. Of 142 studies, 54 reported both anxiety and depression outcomes. Seven did not report either. Forty-eight of 109 studies contributing to the NMA reported both an anxiety and a depression outcome. b, Study was included in the NMA at any of the follow-up time points. Note that references to the main study publication and articles awaiting classification are listed in Appendix 2.