Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number NIHR129968. The contractual start date was in November 2020. The final report began editorial review in August 2022 and was accepted for publication in March 2023. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2023 Pesola et al. This work was produced by Pesola et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2023

Chapter 1 Introduction

The key current controversy surrounding reduced-risk alternative nicotine-delivery products (ANDs), comprising electronic cigarettes (ECs), snus and heated tobacco products (HTPs), concerns their effect on smoking prevalence. On one hand, there is a fear that ANDs could be acting as a gateway into smoking by enticing adolescents to cigarette use, reducing quitting in smokers (by allowing them to circumvent smoke-free regulation), or both. On the other hand, it is possible that ANDs act as a gateway out of smoking by helping smokers to quit and steering adolescents who would otherwise become smokers away from smoking to use ANDs instead.

Various governments have adopted different legislative approaches to the regulation of ANDs globally. Some countries ban or restrict AND sales, while others allow their use or even encourage smokers to switch to them, as in the UK.

The existing evidence on the effects of ANDs on cigarette smoking is mixed. Two studies examined the effects of access to ECs on youth uptake of smoking in selected US states and reported higher smoking prevalence where ECs are banned. 1,2 The samples’ representativeness is unclear though and longer-term time trends were not taken into account. A trend line analysis of data from the USA suggests that increase in vaping experimentation (use in past 30 days) has been accompanied by a decline in smoking experimentation among youth and young adults. 3 A UK study found no association between vaping and smoking uptake in youth. 4 In Sweden, there is some evidence of an association between an increase in snus use and a decrease in smoking prevalence over time. 5,6 Similarly, a Japanese study found that sales of IQOS (a leading brand of HTP) were associated with a decline in cigarettes sales for years 2014–8. 7 On the other hand, the 2018 National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine Report review of studies of use of cigarettes and ECs in youth concluded that there is substantial evidence that vaping by youth is strongly associated with an increased risk of smoking. 8

Routinely collected data on trends in the prevalence of smoking, AND use and the sales of these products can contribute to answering the gateway question. Apart from analyses of within-countries time trends in smoking and AND prevalence, and cigarette and AND sales, countries with different policies on ANDs provide an ongoing natural experiment that could further clarify any links between AND use and smoking. If the decline in smoking rates and cigarette sales is slower (or even reversed) in countries where AND use is allowed and popular, compared to countries where it is discouraged or banned, this would be consistent with the ‘gateway into smoking’ hypothesis. The opposite pattern would support the ‘gateway out of smoking hypothesis’. It is also possible that ANDs have had no clear effect on smoking prevalence and cigarette sales so far, or that currently available data do not provide a clear answer, for example, due to low prevalence of AND use or insufficient data points. Such a finding would also have implications both for policies (needing to take account of uncertainty) and for future research (aiming to fill the gaps).

Here we examined existing data sets to answer the following research questions (RQs).

Research questions

-

Is there an association between prevalence of smoking and prevalence of AND use (in the population in general, in young adults, and in different socioeconomic groups), in different countries and for different AND products?

-

Is there an association between AND sales and cigarette sales?

-

Are there any differences in time trends of smoking prevalence (overall and in young adults) and cigarette sales between countries that had similar tobacco control measures prior to ANDs emerging locally, but that have allowed EC sales (the UK and USA) or banned them (Australia)?

The results can provide an indication of which types of regulatory frameworks concerning ANDs (restrictive or liberal) are more likely to reduce rates of smoking.

Chapter 2 Methods

Overview of study design

This was a project which analysed existing data from several countries to address the above RQs. Individual-level data were aggregated to obtain population-level estimates.

We explored trends in cigarette smoking and AND use prevalence (RQ1) and sales (RQ2), how smoking and AND use covaried over time (RQ1 and RQ2), and whether trends in smoking prevalence over time differed in the UK and USA, where EC use was allowed, versus Australia, where sales of nicotine-containing ECs are banned (RQ3).

Changes to study design

The statistical analysis plan (SAP) was reviewed by the independent study steering committee (SSC) and submitted to the funder prior to any analysis being conducted. Changes that occurred between the finalised grant application and finalised SAP are detailed in the SAP, which can be found here: https://osf.io/j38uf. Lack of available data meant RQ4, which was planned in the original proposal, could not be addressed reliably. There were no changes to the overall study design once the SAP was finalised, but when the available data sets were examined, we had to make changes to the definitions used for ‘young users’ and socioeconomic status (SES), and to the time periods used in some analyses. These changes are detailed in the relevant sections below.

Countries chosen

Regarding ECs, we examined data from the UK and USA. These countries have a similar history of smoking and tobacco control and conduct repeated representative surveys that allow modelling of long-term trajectories of smoking prevalence and EC use, while controlling for other tobacco control policies and their timing. To examine differences in changes in smoking prevalence over time between countries that allow and disallow EC use, we contrasted UK and US data with those from Australia, which has similar tobacco control policies but bans the sale of nicotine-containing ECs. While there are other countries that ban ECs, such as India and Thailand, they have different histories of tobacco use and control and less comprehensive data on smoking prevalence, which would make comparative interpretation difficult.

Regarding snus, we used data from Sweden as this is the only EU country where snus is legally available, and data from Sweden are available that monitor the prevalence of smoking and snus use.

Regarding HTPs, these became popular particularly in Japan and South Korea. In both countries, data are available that to our knowledge are not available elsewhere. In both countries, the state operates tobacco monopolies and publishes domestic sales data, and HTP sales data can be accessed too.

Survey data chosen

Where more than one survey was available per country, we selected the survey to use based on:

-

quality of smoking and AND use measures

-

years covered

-

representativeness of samples and weighting

-

number of time points (monthly/quarterly breakdown)

-

sample size

-

quality of SES information.

For the UK, we used the Health Survey for England (HSE) https://ukdataservice.ac.uk/9 for prevalence and www.gov.uk/government/statistics/tobacco-bulletin for cigarette sales data.

For the USA we used the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/about_nhis.htm10 and the National Youth Tobacco Survey (NYTS) www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/surveys/nyts/index.htm for prevalence, and NielsenIQ data purchased from Chicago Booth www.chicagobooth.edu/research/kilts/datasets/nielsenIQ-nielsen for cigarette sales data.

For Australia, we used the National Drug Strategy Household Survey (NDSHS), which is owned and managed by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare www.aihw.gov.au/about-our-data/accessing-data-through-the-aihw for prevalence and www.euromonitor.com/tobacco11 for cigarette sales data.

For Japan, we used the National Health and Nutrition Survey www.mhlw.go.jp/bunya/kenkou/kenkou_eiyou_chousa.html for prevalence, Tobacco Institute of Japan (TIOJ) www.tioj.or.jp/data/ for cigarettes sales and Philip Morris International www.pmi.com/investor-relations/reports-filings for HTP sales data.

For South Korea, we used the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KHANES) https://knhanes.cdc.go.kr/knhanes/main.do for prevalence, and Korea Tobacco and Ginseng Corporation (KT&G) https://en.ktng.com/report?cmsCd=CM0044 for sales data.

For Sweden, we used the Swedish Council for Information on Alcohol and Other Drugs (CAN): Monitor Studies www.can.se/publikationer/tobaksvanor-i-sverige-2003-2019/ for prevalence, and Swedish Match AB provided cigarette and snus sales data directly by e-mail contact.

The details of the surveys used are shown in Tables 1 and 2. In the SAP (available here: https://osf.io/j38uf/), Supplementary Table 1 shows all the surveys that we examined and the reasons for selecting the surveys in Table 1.

| Country, survey, N surveyed, and weights | Access to survey data | Age of respondents | Years used, frequency of data collection, N of data pointsa | Smoking variables | AND use variables | SES variables |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health Survey for England (HSE)b N per year ~ 8000 Weights: Yes |

Free after registering at: https://ukdataservice.ac.uk/ | 16+ | 2005–18c Quarterlyd Time series = 56 |

Daily: smoke nowadays = yes and at least one cigarette per day Current: smoke nowadays = current cigarette smoker |

Daily: use nowadays = yes and reports everyday use Current: use nowadays = currently uses ECs |

Manual versus non-manual (NS-SEC): Managerial and intermediate versus routine |

| USA National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) N per year ~ 87,500 Weights: Yes |

Free from: www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/about_nhis.htm | 18+ | 2005–19 Quarterlyd Time series = 60 |

Daily: smoking frequency = every day Current: smoking frequency = some days |

Daily: EC frequency = every day Current: EC frequency = some days |

Occupation classificatione |

| USA National Youth Tobacco Survey (NYTS) N ~ 20,000 Weights: Yes |

Free from: www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/surveys/nyts/index.htm | 11–18 | 2005, 2006, 2009, 2011, 2012–19 Biannual to 2011 then annual Time series = 15 |

Daily: smoked on 30 days in the past month Current: smoked on 20–30 days in the past month |

Daily: used on 30 days in the past month Current: used on 20–30 days in the past month |

N/A |

| Australia National Drug Strategy Household Survey (NDSHS) N ~ 22,000 Weights: Yes |

Free from the Australian Institute if Health and Welfare after an application and approvals process: www.aihw.gov.au/about-our-data/accessing-data-through-the-aihw | 14+ | 2004, 2007, 2010, 2013, 2016 and 2019 Triennial Time series = 6 |

Daily: have you ever smoked on a daily basis? = yes I smoke daily now Current: category not covered |

Questions on ANDs not available | Individual incomef |

| Japan National Health and Nutrition Survey (NHNS) N ~ 9000 Summary tables by year Weights: No |

Free from: www.mhlw.go.jp/bunya/kenkou/kenkou_eiyou_chousa.html | 20+ | 2005–18 Annual Time series = 14 |

Daily: ‘smoke daily/every day’ Current: ‘currently smoking habitually’ |

2018 only: Current tobacco product use reported as: ‘heated tobacco only’ or ‘cigarettes and heated tobacco’ |

No SES data available |

| Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KHANES) N per year ~ 10,000 Weights: Yes |

Free from: https://knhanes.cdc.go.kr/knhanes/main.do | 19+ | 2005, 2007–9, 2010–19 Annual Time series = 15 |

Daily: reports smoking every day Current: reports smoking occasionally |

No questions on HTPs available | Income quartile individualg |

| Swedish council for information on alcohol and other drugs (CAN): monitor studies N per year ~ 3500 Summary tables by year |

Free from: www.can.se/publikationer/tobaksvanor-i-sverige-2003-2019/ | 17+ | 2005–19 Annual Time series = 15 |

Daily: smoking daily in last 30 days Current: category not covered |

Daily: used snus daily in last 30 days Current: category not covered |

No SES data available |

| Policy implemented | Year implemented | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | Japan | South Korea | USA | UK | Sweden | |

| Smoking ban in public places | 1986–2006 phased in bans on smoking in public places and officesa | April 2020 | 1995 partial ban in workplaces and transportation. Ban in restaurants, coffee shops etc. 2015 | January 1995 in California, most states between 2004 and 2007b | July 2007 | June 2005 |

| Steep price increase | A one off 25% (vs. usual 12.5%) increase in 201014 | 37% increase in October 201015 | Increase by 80% in January 201516 | 14% increase in federal tax in April 200917 | 11% increase in recommended retail price March 201518 | N/A |

We focused on prevalence and sales data rather than on youth surveys that show incidence of new use because product experimentation will only have any impact if it translates into regular use. Prevalence and sales data over a 15-year period were expected to show the effects of early experimentation on any later regular use.

Time periods chosen

For analyses looking at the interplay between cigarettes and EC/HTP use (RQ1), we included data on smoking from 2005 until the most recent available year up to 2019, the year before the COVID-19 epidemic started. The same timeframe was used, where available, for analyses exploring the interplay of cigarettes and EC/HTP sales (RQ2). This allowed for modelling of smoking and cigarette sales for at least 5 years before the emergence of these newer products.

For snus, we analysed data from 2007 to 2019. We had initially planned to analyse earlier data as snus use has a longer history,5,12 but these data were not available. For analysis looking at trends in cigarette smoking for the UK, USA and Australia we used data from 2004 onwards as the NDSHS is triennial and we wanted to include 2004 as a proxy for 2005. Similarly, for the NYTS, which used to be conducted every 2 years, we included 2004 as a proxy for 2005. For analysis looking at trends in cigarette sales for the UK, USA and Australia, we used data from 2010 as sales data for Australia were only available from 2010.

For analyses looking at trends in cigarette smoking in the UK, USA and Australia, we used data from 2004 onwards as the NDSHS is triennial and we wanted to include 2004 as a proxy for 2005. Similarly, for the NYTS, which used to be biannual, we included 2004 as a proxy for 2005. For analyses looking at trends in cigarette sales for the UK, USA and Australia we looked at data from 2010 as sales data for Australia were only available from 2010.

Measures

The specific survey questions used to define daily and current use for each survey are provided in Table 1.

The following definitions were used:

Daily smoker: someone smoking at least one cigarette daily.

Current smoker: someone smoking ‘weekly’, ‘some days’ or ‘smoking nowadays’. The definition included daily smokers.

Daily AND user: someone using ANDs daily.

Current AND user: someone using ANDs ‘weekly’, ‘some days’ or ‘smoking nowadays’. The definition included daily users.

The prevalence of cigarette and AND use was obtained by dividing the number of respondents meeting the definition of daily or current use by the total number of respondents providing information on their product use.

Dual users: in all surveys, prevalence of smoking and product rates were calculated on the entire sample of respondents and, hence, participants using cigarettes as well as ANDs were included when calculating both rates.

Young users: for England, we originally anticipated data for ages 16–21 from the HSE would be available. However, from 2015 age was available in bands 16–19, 20–24 etc. We therefore used < 20 years.

For the USA, we used data for ages 14–18 from the NYTS.

For Australia, we used data for ages 14–21 from the NDSHS.

For Korea, we used data for ages 19–21 from the KHANES.

For Sweden and Japan, we could only access tabulated data which did not include age categories.

Gender: male/female.

SES categories: we originally planned to use job classifications for England (manual vs. non-manual) and household income for the USA and Australia, dichotomised using a median split. However, in 2004 only individual income was available for Australia. Individual income was therefore used, so that we could include 2004. Income was recorded via bands indicating a minimum and maximum so the average of the minimum and maximum bound for each band was calculated and the median of these averages was used to identify the cut-off between lower and higher earners. Similarly, for the USA, there were no income measures post-2005. An occupation classification was therefore used, based on the Standard Occupation Classification. This consists of 23 categories which can be dichotomised into managerial and intermediate (categories 1 to 17) and manual and routine (categories 18 to 22), with military left out. 13

For South Korea, we combined low and middle-low social class versus middle, middle-high and high social class. For Sweden and Japan, we could only access tabulated data which did not include SES categories.

Table 1 shows which data on product use, age and SES were available in each survey.

Tobacco control policy variables

The analyses took into account two variables which are believed to affect smoking prevalence and cigarette sales (see Table 2). Each policy was modelled as a step level change, coded as one after the introduction of the policy and zero before. When monthly data were available, we were also able to assess if there was a potential delay (i.e. lag) between the policy implementation and its impact on sales/use. We compared models with 1 to 3 month lags and selected the one that best fitted the data. This is presented together with the no-lag model. Models were compared using the Bayesian information criterion (BIC) and Akaike information criterion (AIC). Smaller AIC and BIC values indicate better-fitting models. The AIC is the primary measure of model fit and drives decisions in the case of disagreements between AIC and BIC.

Sales data

Sales data were selected based on availability, number of years available and number of time points. The sales data sets used for different countries are presented in Table 3. For RQ1 and RQ2, we focused on cigarette sales, as this was available for all countries. For RQ3 (between-countries comparison), we included data on all smoked tobacco, as this was available and roll-your-own (RYO) cigarettes in particular now form a substantial part of cigarette sales in Australia and the UK. For all markets, major tobacco companies have much richer sales data available, including precise estimates of changes in market shares of cigarettes and ANDs. One of the co-authors, DS, has tried repeatedly to have these data released, but has not been successful.

| Data source | Access to sales data | Country | Frequency of collection | Years used | Number of data points |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NielsenIQ | Purchased after an application and approvals process via: www.chicagobooth.edu/research/kilts/datasets/nielsenIQ-nielsen | USA | Yearly | 2006–18 | Cigarettes ($ value; quarterly time series = 52) |

| Euromonitor International | One off purchases from www.euromonitor.com/tobacco | Australia | Yearly | 2007–19 | Cigarettes, cigars and cigarillos (volume; time series = 13) |

| HM Revenue and Customs (HMRC) | Free from www.gov.uk/government/statistics/tobacco-bulletin | UK | Yearly (tax year) | 2005–19 | Clearance data (cigarettes, volume); (quarterly time series = 60) |

| Korea Tobacco and Ginseng Corporation (KT&G) | Free from https://en.ktng.com/report?cmsCd=CM0044 | South Korea | Yearly | 2005–20 | Cigarettes (volume; time series = 16) HTP from 2018 only |

| Philip Morris International (PMI) | Free from www.pmi.com/investor-relations/reports-filings | Japan | Yearly | HTPs: 2011–20 | HTPs (volume; time series = 10) |

| Tobacco Institute of Japan (TIOJ) | Free from www.tioj.or.jp/data/ | Japan | Yearly | 2011–20 | Cigarettes (volume; time series = 10) |

| Swedish Match | Free directly from Swedish Match AB | Sweden | Yearly | 2005–19 | Cigarettes, snus (volume; time series = 15) |

Chapter 3 Statistical methods

We pre-specified in our SAP (https://osf.io/j38uf/) that we would use dynamic time series approaches applying generalised least squares (GLS) models to explore the association between prevalence of smoking and product use, and cigarette sales and product sales. Regression analyses were used to compare trends in smoking prevalence in different countries.

Unfortunately, the time series were shorter and less granular than required for time series analyses and the available data had suboptimal data points for the planned statistical modelling. We carried out the pre-specified analyses to adhere to the original plan, but the results are vulnerable to the effects of dominant points and low statistical power and need to be considered as tentative and interpreted with caution.

Current and daily use was identified using responses to the relevant questions in each survey, as described above. Data were weighted to reflect the national population, where raw data and weights were available, using Stata’s suite of survey data commands. Data were grouped quarterly for UK and US surveys. In the HSE, data had a monthly breakdown until 2014 and quarterly afterwards, so data pre-2015 were aggregated to quarterly data. Data from Australia, South Korea and Sweden were available at yearly intervals.

Some of the yearly surveys provided too few data points to meet the requirements for autoregressive integrated moving average with explanatory variable (ARIMAX) analyses, which were originally proposed in the project application. Hence, all analyses were conducted using GLS models instead as pre-specified in the SAP. The same statistical approach was used in comparisons between countries.

Generalised least squares models can take into account autoregressive (AR) and moving average (MA) autocorrelation, if present in the data. Where we found no evidence of autocorrelation, we planned to use linear regression models. The presence of simple autocorrelation (autoregressive-1 autocorrelation) was assessed with the Durbin–Watson test and more complex AR and MA autocorrelation was assed using the autocorrelation function (ACF19,20) and partial autocorrelation function (PACF). For longer time series with quarterly data, we assessed whether seasonal adjustment was necessary by comparing a model with no seasonal adjustment and a model where we adjusted for seasonality, modelled using natural cubic splines. The latter consists of piecewise third-order polynomials which allow us to capture seasonal trends. Lastly, the sample cross-correlation function on pre-whitened data was used to determine whether there was a delay (i.e. lag) of the effect of prevalence of predictor (i.e. EC use and policies) on cigarette smoking when quarterly data were available. After fitting the model, residuals were plotted to ensure they were normally distributed and to assess the need to include additional MA or AR using ACF plots.

Models were compared using the BIC and AIC. The latter was the primary measure of model fit and drive decisions. For data sets that provided monthly information, we repeated our main analysis using more complex time series analysis (e.g. ARIMAX) as part of our sensitivity analysis. 19

Non-significant p-values (i.e. p > 0.05) do not tell us whether we can conclude that there is no effect, or whether there is insufficient evidence to decide whether there is an effect or not. We calculated Bayes factors (BF), the ratios of the likelihood of a specified hypothesis (e.g. an effect) to another hypothesis (e.g. no effect). BF determine whether a negative finding is due to there being no association, or whether it reflects insufficient or insensitive data. 21,22 BF between 1/3 and 1 are interpreted as suggesting no or weak evidence (i.e. insensitive data), BF between 1/3 and 1/10 as moderate evidence, and 1/10 or lower as strong evidence for the null hypothesis. We also calculated BF for significant findings to assess the possible impact of low power and data issues discussed above. A half-Gaussian distribution was specified with the mode at zero (no effect), and the standard deviation equal to the alternative hypothesis.

We used a BF calculator (run on R code), developed by our collaborators at University College London (www.bayesfactor.info). This approach requires the specification of an expected effect size (i.e. a plausible range of predicted values based on previous studies, judgement or clinical significance), the effect size from the analysis (e.g. mean difference or log odds ratio) and standard error of this parameter. It assumes that the sampling distribution of the parameter estimate is distributed normally (hence the need to use the natural logs of odds ratios). The expected effect sizes were derived as follows. For RQ1 and RQ2, we based our estimates on results reported in a previous paper which explored the association between EC use and quit attempts and attempt success. 20 Results showed that a 1% increase in EC use is associated with an increase in quit attempts by 0.098% and an increase in quit success by 0.058% amongst those who attempt to quit. We multiplied these estimates to obtain a population estimate of impact of ECs on smoking prevalence among all smokers (0.098*0.058, b = 0.006). We assumed a similar effect size would be observed for sales because there is a correspondence between survey-measured smoking prevalence and cigarette sales. 23 We estimated the rate of change in prevalence/sales of cigarette since ECs became popular in the UK and USA by looking at changes in routinely collected data for RQ3. Based on existing data, we were expecting a compound annual reduction rate (CARR) of 4–4.5% in the UK (observed between 2011 and 2019 in the Annual Population Survey)24 and the USA (observed between 2010 and 2018 in NIHS25) and a lower rate in Australia (3% between 2001 and 2019 and 2% observed between 2010 and 201926).

Data from different countries were analysed separately. For between-countries comparisons, unstandardised and standardised regression coefficients are presented and, where appropriate, formal statistical comparison conducted. 27–29

The approach we used focuses on whether short-term changes in the use/sales of the two products moved in the same direction. The potential problem with this approach is that if there is a longer-term trend, that is, if the increase in AND use is accompanied by an increase or decrease in cigarette use that develops gradually over time, such effects are removed (detrending). The rationale for this approach is that under some circumstances, long-term trends can be driven by external factors while short-term changes can indicate immediate causal interactions. Under other circumstances, however, short-term changes could be driven by external factors depressing or stimulating use of both products, or of one product when the other product is not involved (e.g. economic downturns or upturns or product availability issues). In some scenarios, long-term trends can provide a better indication of any real product substitution or facilitation effects. The issue of ‘dual use’ can contribute to this problem. Most smokers do not switch to exclusively using ANDs immediately but use both ANDs and cigarettes for some period of time. Prevalence surveys list them among both cigarette and AND users, which may make product interactions harder to discern over short time periods.

Models for each research question

The following statistical approaches were used to address each RQ.

RQ1 and RQ2 were addressed using multiple time series analysis and regressing smoking prevalence rates/cigarette sales (RQ1; sales for RQ2) onto time and AND prevalence/sales, for each country separately using GLS to account for autocorrelation, if present. The use of ACF plots allowed us to assess if the data followed a trend. Where present, we used differencing to render the data stationary. The models were adjusted for policies likely to affect smoking, that is, bans in smoking in public indoor venues and large cigarette price increases.

In the original application, we had planned to assess the association between HTPs and smoking prevalence (RQ1) for Japan and South Korea; however, having obtained the data, we realised this was not possible as no HTP prevalence data were available for South Korea, and only 2018 HTP prevalence data were available for Japan. Therefore, we pre-specified in the SAP that our focus for Japan and South Korea was examining the association between product sales (RQ2) and we also explored the associations between HTP sales and smoking prevalence.

Analyses of prevalence of use (RQ1) were conducted for the overall sample and repeated for young users only (i.e. < 22) to explore the gateway theory in this age group. Analysis for RQ1 was also stratified by SES to assess the equity impact of ANDs. Standardised coefficients are reported to allow comparisons between SES groups.

We also planned to explore the impact of the ‘electronic cigarette or vaping use-associated lung injury’ scare on AND use and on cigarette smoking and sales by comparing 2019 and any 2020 figures with those in previous years, but the COVID-19 epidemic disrupted the standard data collection and probably also product use trajectories and so this analysis was not conducted.

Sample size

Based on the decision to conduct our primary analysis using GLS, we estimated power using a power simulation programme developed in R.

Assuming 40 data points, we would have 80% power to detect a decline or increase in smoking prevalence of −0.43% for every 1% increase in the prevalence of EC use, assuming a baseline smoking prevalence of 15%, an underlying decline of 0.1 for each unit in time, and increases in EC use from 0% to 15% over the study period.

Sensitivity analyses

Sensitivity analyses were conducted for data sets with monthly data, including HSE for the UK and NHIS for the USA, using ARIMAX models. ARIMAX is an extension of autoregressive integrated moving average analysis (ARIMA), which produces forecasts based upon prior values in the time series analysis (AR autocorrelation terms) and the errors made by previous predictions (MA terms). These models adjust for underlying trends, seasonality and autocorrelation.

We used the following procedures to select the ARIMAX models:19,30 first, we assessed each time series analysis for outlying values which may bias the results and the presence of exogeneity (i.e. no reverse causality of Y on X) using the Granger causality test. Secondly, plots of the differenced data and unit root tests (Osborn–Chui–Smith–Birchenhall test and Kwiatkowski, Phillips, Schmidt, and Shin tests) were used to determine the number of seasonal and non-seasonal differences required for the time series analyses to be made stationary. These were then confirmed by the augmented Dickey-Fuller test.

To identify the most appropriate transfer function for the continuous explanatory variables, we checked the sample cross-correlation function using pre-whitened data to remove autocorrelation. Additionally, we compared univariate ARIMAX models with variations for the transfer function.

To determine the initial values of the AR and MA terms, we assessed the ACF and the PACF. Additional models with various fitted AR and MA terms were then compared. According to the Box-Jenkins method, in ARIMA (p, d, q) the total number of parameters should be less than four30 and, therefore, we only checked ARIMAX models for p and q values of three or less. We selected the models with lower AIC values. Using the ACF and PACF, we also assessed whether seasonal differencing was needed.

Finally, we checked the ACF for the residuals to check for normality and assess the need for additional MA/AR terms. We also checked whether the coefficients fell within the bounds of stationarity and invertibility. The model residuals assessed for normality.

RQ3: The objective of RQ3 was to compare trends in countries that allow EC sales (USA and UK) with those which have banned them (Australia).

The first analysis we conducted compared the three countries’ smoking prevalence trajectories between 2005 and 2018. Firstly, smoking prevalence (and cigarette sales) were regressed onto time, adjusting for factors that may affect relevant trends. As described above, we tested whether autocorrelation was present via plots using the Durbin–Watson test, the ACF and PACF, and if present GLS models. The need to adjust for seasonality within GLS models was also assessed as described above.

We subsequently explored several additional models: (1) polynomial regression with terms up to an order of three (i.e. quadratic trend and cubic trend model), (2) power regression (log–log model or power trend model), (3) exponential regression (log-level model or exponential trend model) and (4) logarithmic regression (level-log model or logarithmic trend model). For the quadratic and cubic trend models, orthogonal polynomials were used in the model selection phase, as they solve the multicollinearity problem, while raw polynomials were used for the final model. Other functions were excluded a priori, such as quartic and quantic polynomial regressions, as they were unlikely to reflect plausible underlying trends in prevalence and could lead to overfitting.

For each regression model, we determined the initial values of the autocorrelation and MA terms by comparing varying AR and MA terms as described for RQ1 and RQ2. Similarly, for quarterly data, the need to adjust for seasonality was assessed following the same procedures described for RQ1.

Models were compared using the BIC and AIC. Where the finding is that a linear trend is the best-fitting model for one output series and a power trend for another, it is clear that the trends differ between the countries. We were able to identify the point of change where non-linear functions were used. We used standardised coefficients to aid comparison, with formal comparison undertaken using t-tests to compare slopes of regression lines. This, of course, was only possible in instances where the same function was applied.

Final models were adjusted for smoking ban and price increase, when appropriate, modelled as a step level change, coded as one after the introduction of the policy and zero before. Linear models offered a good fit to the data overall and therefore results based on this simpler model are also presented in the report. Using linear models allows us to compare slopes between countries and estimate CARRs, which can be compared to the prior CARRs specified to estimate BFs (see page 26).

Analyses were conducted using R Statistical Software version 4.0.5 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). 31

Results were also stratified by SES and age (overall vs. young users).

Exploratory ‘hybrid’ analyses

The main analyses examined the associations between sales of cigarettes and sales of ANDs and between prevalence of smoking and prevalence of AND use. We also conducted two pre-specified exploratory analyses of links between smoking prevalence and AND sales data, when AND prevalence data were not available (RQ1). For Japan, we had information on HTP prevalence for 2018 only. We therefore used HTP sales data as a proxy for prevalence and examined the link between prevalence of smoking and sales of HTP. The same approach was implemented for South Korea in RQ1 as no data on HTP were available in KHANES. Similarly, as we did not have good data on EC sales in the UK and USA, we explored the association between prevalence of EC use and cigarette sales in these two countries (RQ2).

Missing data

Most surveys started collecting information on EC use between 2011 and 2016. Data for previous years were imputed by using the available data to estimate prevalence back to 2010. We assumed linear growth and estimated the average growth change between 2010 (assuming 0.1% prevalence) and the first available year. Some surveys had missing data for specific years or quarters (e.g. 2015 in NHIS; 2004 in KT&G for sales). In this case, we imputed the missing information using the average observed in the previous and following years.

Approvals and independent oversight

As this was a study based on existing data and involving no human participants, ethics approval was not required.

The project was overseen by the SSC, comprising four independent international experts, two independent UK experts and a lay member. The committee met twice and reviewed both the SAP and the final report. Details of the committee membership are in the Acknowledgements section.

Chapter 4 Results

For each RQ a description of model fit is given in Report Supplementary Material 1 – Supplementary results.

RQ1: Association between prevalence of smoking and prevalence of AND use

Results from the analyses using the pre-specified GLS approach are summarised in Table 4. For surveys with quarterly data breakdown, sensitivity analyses were conducted using ARIMAX approaches (see Supplementary Table 1, Report Supplementary Material 1).

| Country (survey, AND type, time points) GLS (p, I, q)f a |

Coefficient (SE), 95% CI, and p-value | |

|---|---|---|

| UK (HSE, ECs, N = 56) | Primary | Adjusted for policies |

| Daily use GLS (0, 1, 1)4 |

−0.10 (0.42) −0.93 to 0.73 p = 0.81 |

−0.35 (0.53) −1.40 to 0.69 p = 0.51 |

| Current use GLS (0, 1, 1)4 |

−0.13 (0.23) −0.58 to 0.32 p = 0.58 |

−0.33 (0.21) −0.74 to 0.08 p = 0.11 |

| USA (NIHS, ECs, N = 60) | Primary | Adjusted for policies |

| Daily use GLS (0, 1, 1)4 |

0.76 (0.50) −0.23 to 1.75 p = 0.13 |

0.94 (0.51) −0.07 to 1.94 p = 0.07 |

| Current use GLS (0, 1, 1)4 |

0.29 (0.23) −0.16 to 0.74 p = 0.21 |

0.33 (0.21) −0.09 to 0.75 p = 0.12 |

| Sweden (CAN, snus, N = 15) | Primary | Adjusted for policies |

| Daily use GLS (0, 1, 1)1 |

0.34 (0.24) −0.14 to 0.81 p = 0.17 |

n/cb |

| Japan (HTPs, N = 14) | Primary | Adjusted for policies |

| Current use GLS (0, 1, 1)1 |

0.06 (0.03) −0.001 to 0.12 p = 0.06 |

0.04 (0.04) −0.04 to 0.11 p = 0.36 |

| Daily use GLS (0, 1, 1)1 |

0.05 (0.03) −0.01 to 0.11 p = 0.12 |

0.02 (0.04) −0.06 to 0.09 p = 0.66 |

| Korea (HTPs, N = 15) c | Primary | Adjusted for policies |

| Current use GLS (0, 1, 0)1 |

0.06 (0.18) −0.29 to 0.41 p = 0.75 |

0.02 (0.22) −0.42 to 0.46 p = 0.94 |

| Daily use GLS (1, 1, 0)1 |

0.06 (0.11) −0.16 to 0.28 p = 0.59 |

−0.05 (0.18) −0.40 to 0.29 p = 0.76 |

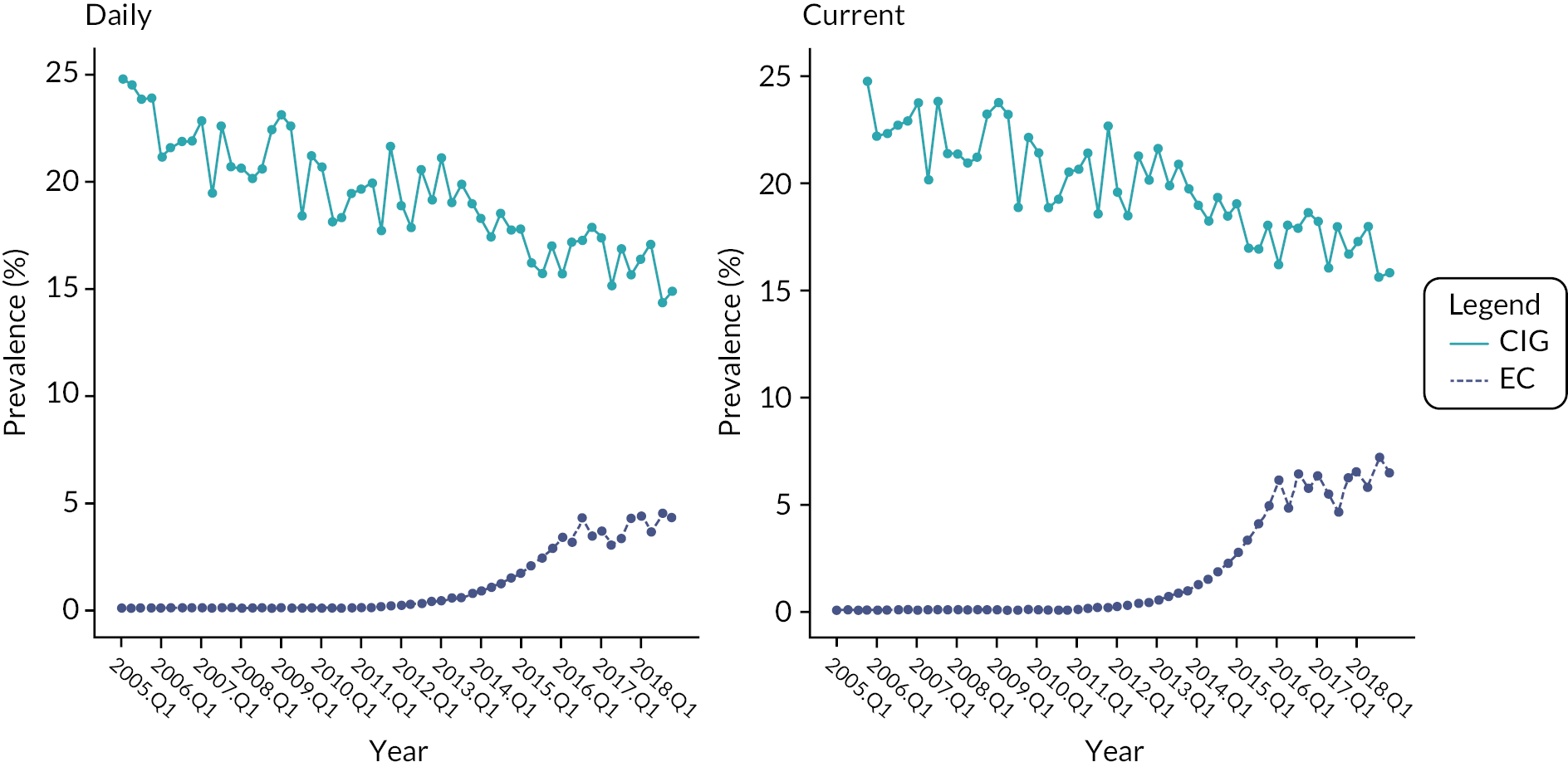

United Kingdom (Health Survey for England)

Figure 1 shows the prevalence of daily and current smoking and vaping over time in the UK.

FIGURE 1.

Prevalence of daily and current smoking and vaping over time in the UK. CIG, cigarette; EC, electronic cigarette.

We did not find an association between smoking and vaping (see Table 4). The BF = 1 indicated inconclusive evidence, potentially due to the analyses being underpowered.

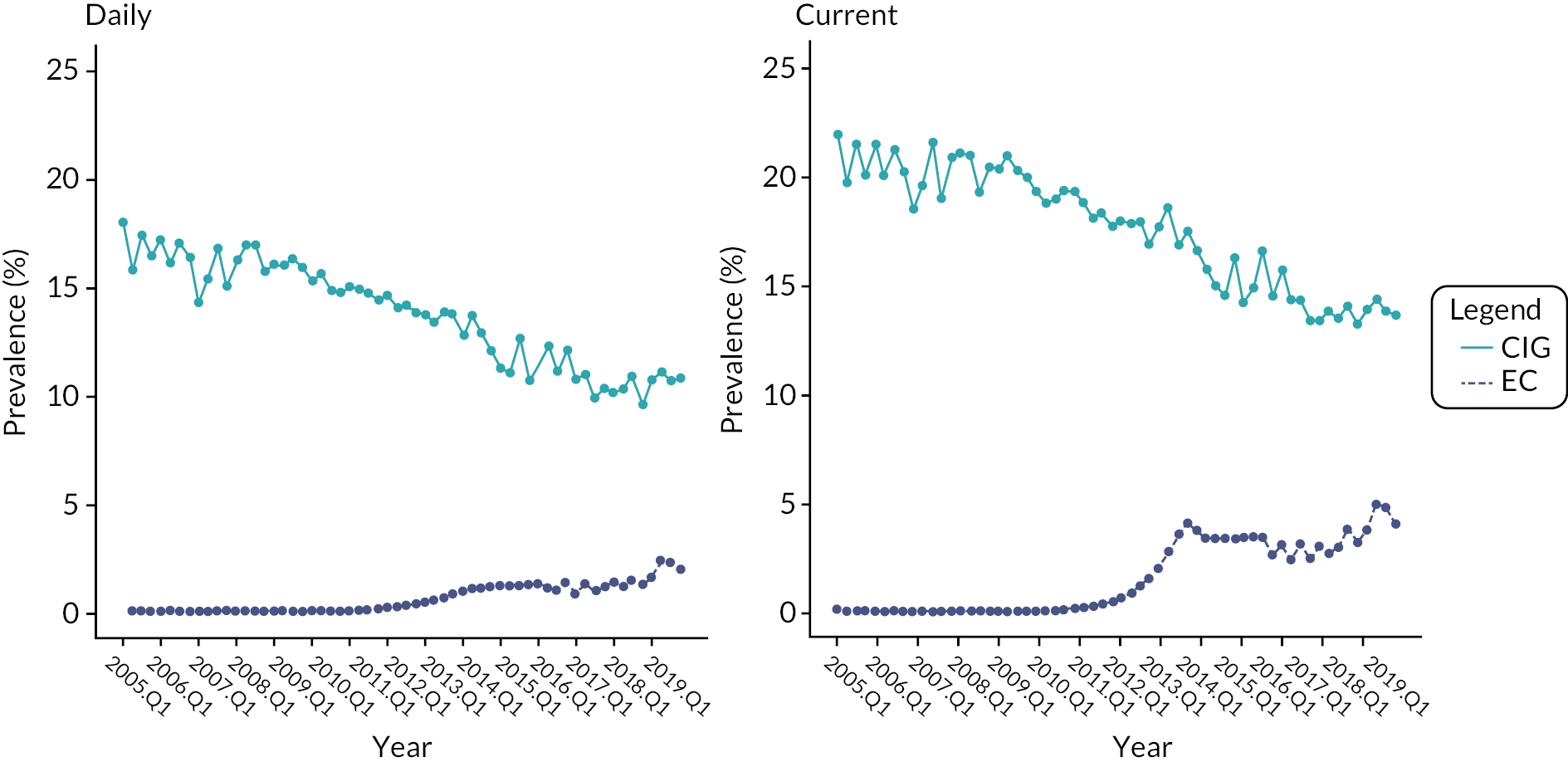

USA (National Health Interview Survey)

Figure 2 shows the prevalence of daily and current smoking and vaping over time in the USA.

FIGURE 2.

Prevalence of daily and current smoking and vaping over time in the USA. CIG, cigarette; EC, electronic cigarette.

We did not find an association between smoking and vaping prevalence (see Table 4), with the BF = 1 indicating inconclusive evidence, potentially due to the analyses being underpowered.

Sensitivity analyses using ARIMAX mirrored the results of the primary analysis (see Supplementary Table 2, Report Supplementary Material 1).

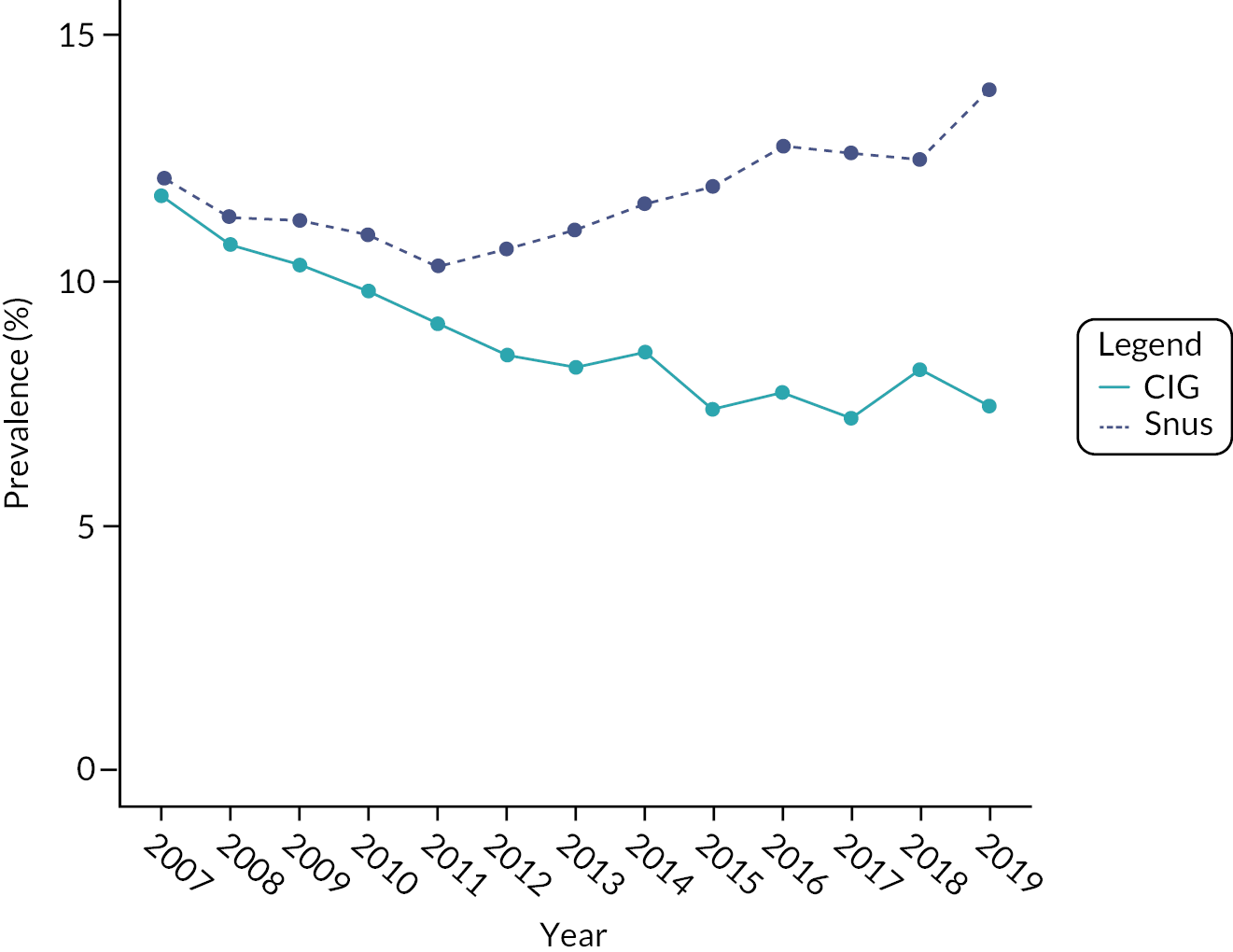

Sweden (CAN)

Figure 3 shows the prevalence of daily smoking and snus use over time in Sweden.

FIGURE 3.

Prevalence of daily smoking and snus use over time in Sweden. CIG, cigarette.

No association was found between the prevalence of smoking and prevalence of snus use (see Table 4). The BF = 1 indicates there is inconclusive evidence, potentially due to the analyses being underpowered.

South Korea

In the ‘hybrid’ analysis looking at prevalence of smoking and sales of HTPs over time in South Korea, there was no association between HTP sales and prevalence of smoking (see Table 4). The BF = 1 indicates there is inconclusive evidence, potentially due to the analyses being underpowered.

Japan

In the ‘hybrid’ analysis looking at prevalence of smoking and sales of HTPs over time in Japan, there was no association between HTP sales and prevalence of smoking (see Table 4). The BF = 1 indicates there is inconclusive evidence, potentially due to the analyses being underpowered.

RQ1: Association between prevalence of smoking and prevalence of AND use stratified by SES and age

Analyses stratified by SES and age were underpowered and no association reached statistical significance (see Supplementary Tables 3 and 4, Report Supplementary Material 1).

RQ2: Association between cigarette sales and the prevalence of AND use and AND sales

United Kingdom

We explored the ‘hybrid’ association between current vaping rates and cigarettes sales, based on the HMRC clearance data (billion sticks). Both data sets allowed for a quarterly breakdown, but in these ‘hybrid’ analyses the chance of detecting an effect of early low prevalence of predominantly light and occasional use of ANDs on cigarette sales was small.

No association was found between cigarette sales and the prevalence of EC use (b = −0.24, p = 0.17). The BF = 1 indicates there is inconclusive evidence, potentially due to the analyses being underpowered.

United States of America

Pre-specified ‘hybrid’ exploratory analyses assessed the association between the prevalence of current vaping and sales of cigarettes (in billion dollars). Both data sets allowed for a quarterly breakdown.

As the NielsenIQ data included a curious anomaly in 2019 when sales in a mature market increased 2.5-fold, suggesting a substantial change in the survey method, we excluded 2019 from the analysis.

There was no association between cigarettes sales and EC prevalence (unadjusted: b = 0.05, p = 0.17). The BF = 1 indicates there is inconclusive evidence, potentially due to the analyses being underpowered.

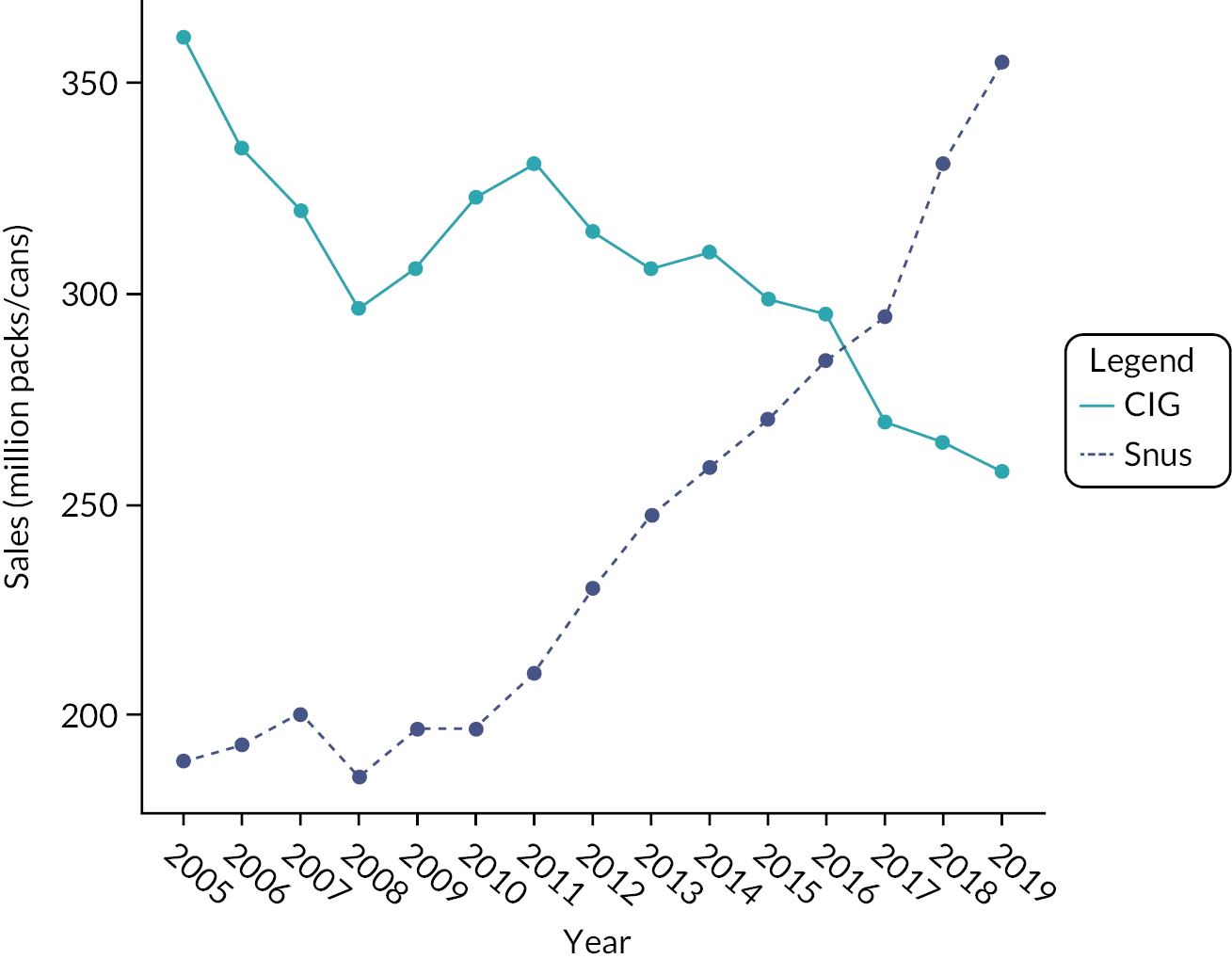

Sweden

We explored the association between sales of cigarettes (in million packs) and sales of snus products (million cans). Figure 4 presents the time series for the sales of the two products.

FIGURE 4.

Sales of snus and cigarettes over time in Sweden. CIG, cigarette.

No association was found between cigarette and snus sales (b = 0.19, p = 0.55). The BF = 1 indicates there is inconclusive evidence, potentially due to the analyses being underpowered.

Japan

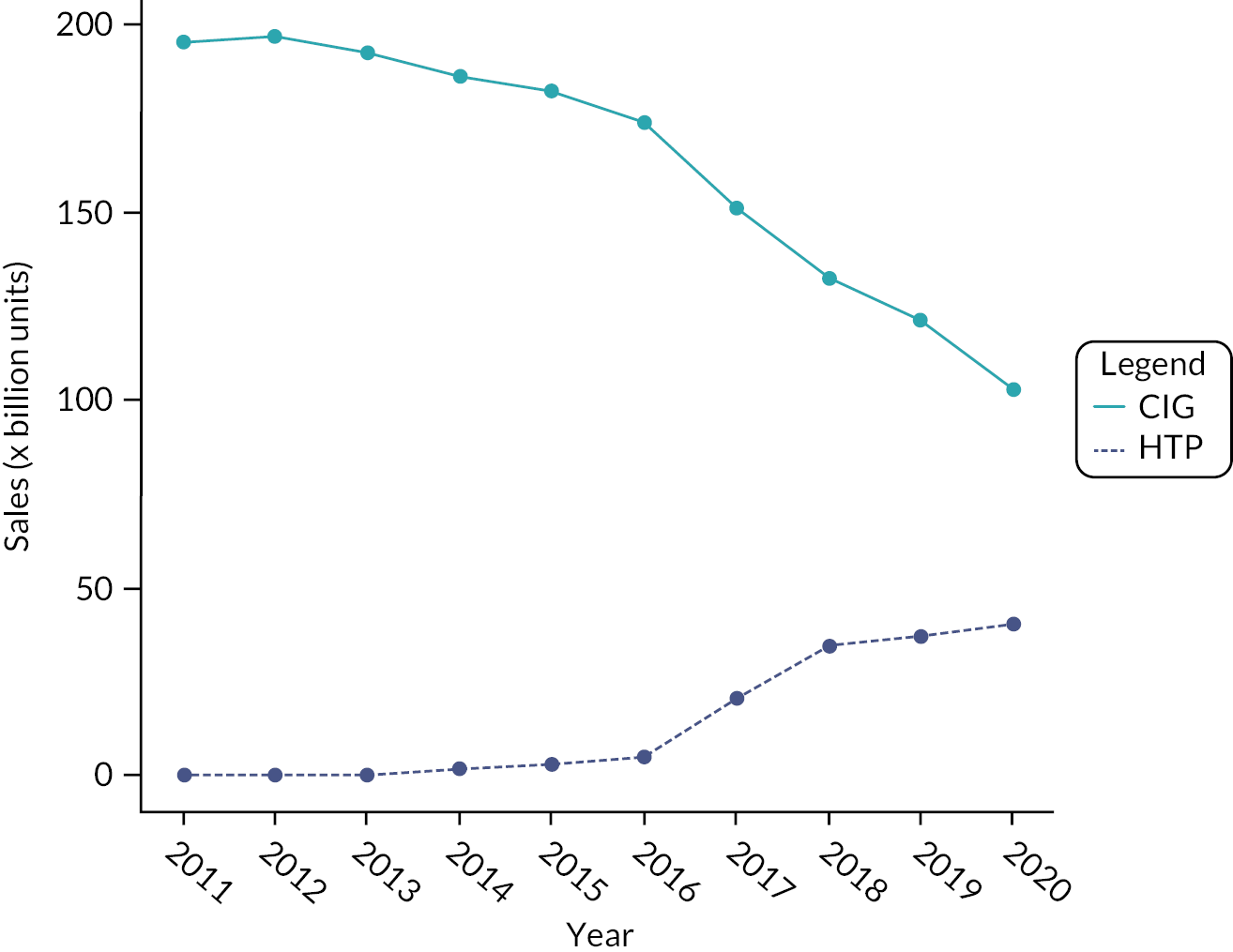

We explored the association between volume of sales of cigarettes and HTPs (in billion units), based on data collected by PMI.

Figure 5 presents the time series for both measures separately.

FIGURE 5.

Sales of HTPs and cigarettes over time in Japan. CIG, cigarette; HTP, heated tobacco product.

There was a negative association between cigarette and HTP sales (b = −1.09, p < 0.001). Based on the expected effect size, the BF = 1 indicates that the results are inconclusive.

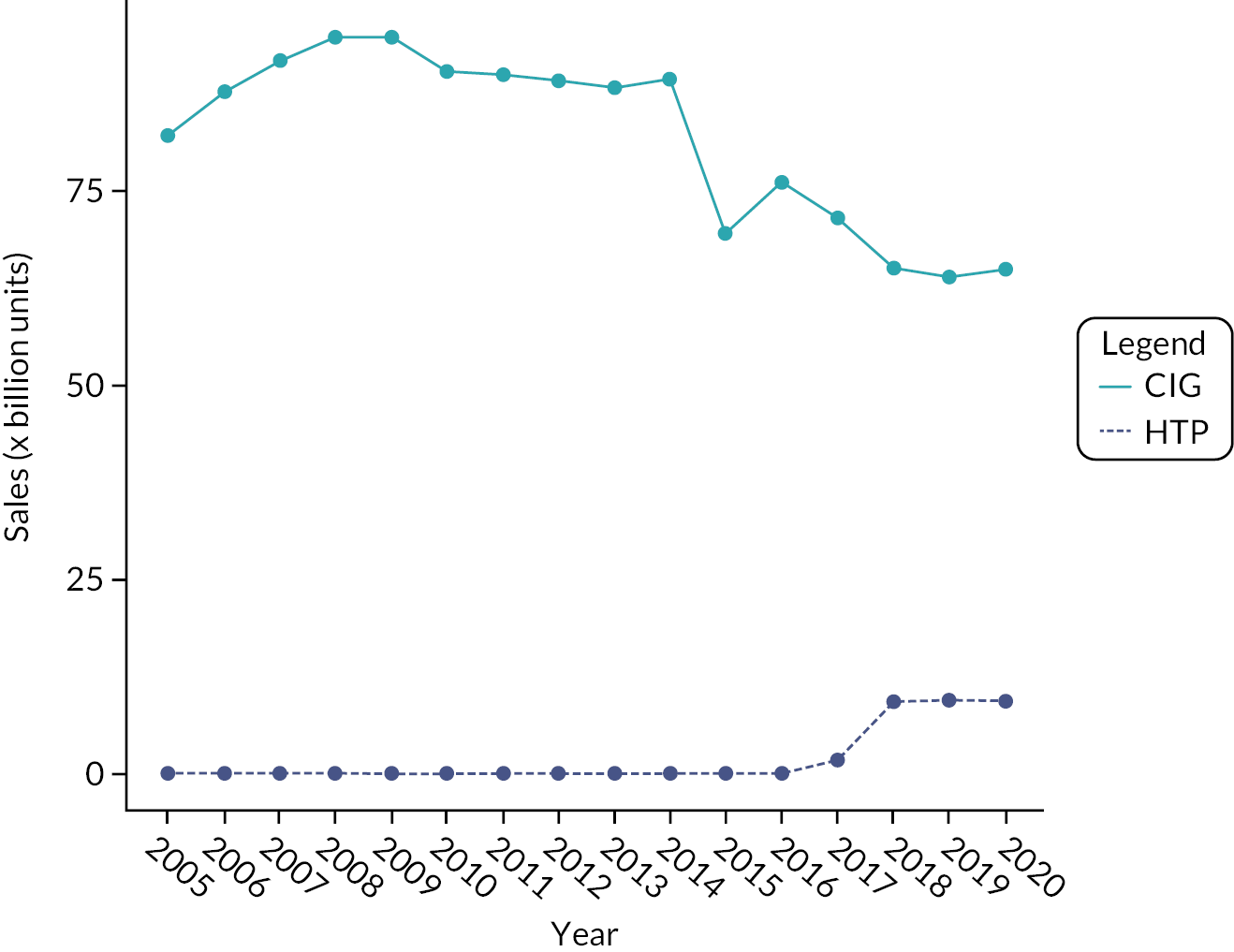

South Korea

We explored the association between sales volume of cigarettes and HTPs (billion units), based on data collected by KT&G.

Figure 6 presents the time series for both measures separately.

FIGURE 6.

Sales of HTPs and cigarettes over time in South Korea. CIG, cigarette; HTP, heated tobacco product.

No association was found between cigarette and HTP sales (b = −0.12, p = 0.89). The BF = 1 indicates there is inconclusive evidence, potentially due to the analyses being underpowered.

Table 5 shows the results of the analyses referred to above.

| Country (AND type, time points) GLS (p, I, q)fa |

Coefficient (SE), 95% CI and p-value | |

|---|---|---|

| UK (ECs, N = 56) b | Primary | Adjusted for policies |

| GLS (0, 1, 2)4 with seasonality (hybrid) | −0.18 (0.21) −0.59 to 0.23 p = 0.39 |

−0.25 (0.26) −0.77 to 0.26 p = 0.33 |

| USA (ECs, N = 52) c | Primary | Adjusted for policies |

| GLS (2, 1, 0)4 with seasonality (hybrid) |

0.04 (0.03) −0.02 to 0.11 p = 0.19 |

0.05 (0.03) −0.02 to 0.011 p = 0.16 |

| Sweden (snus, N = 15) | Primary | Adjusted for policies |

| GLS (0, 1, 0)1 | 0.19 (0.32) −0.44 to 0.82 p = 0.55 |

n/ad |

| Japan (HTPs, N = 10) | Primary | Adjusted for policies |

| GLS (0, 1, 1)1 | −1.09 (0.30) −1.67 to −0.50 p < 0.001 |

n/ae |

| South Korea (HTPs, N = 16) | Primary | Adjusted for policies |

| GLS (0, 1, 0)1 | −0.89 (0.89) −2.64 to 0.85 p = 0.32 |

−1.22 (1.04) −3.26 to 0.82 p = 0.24 |

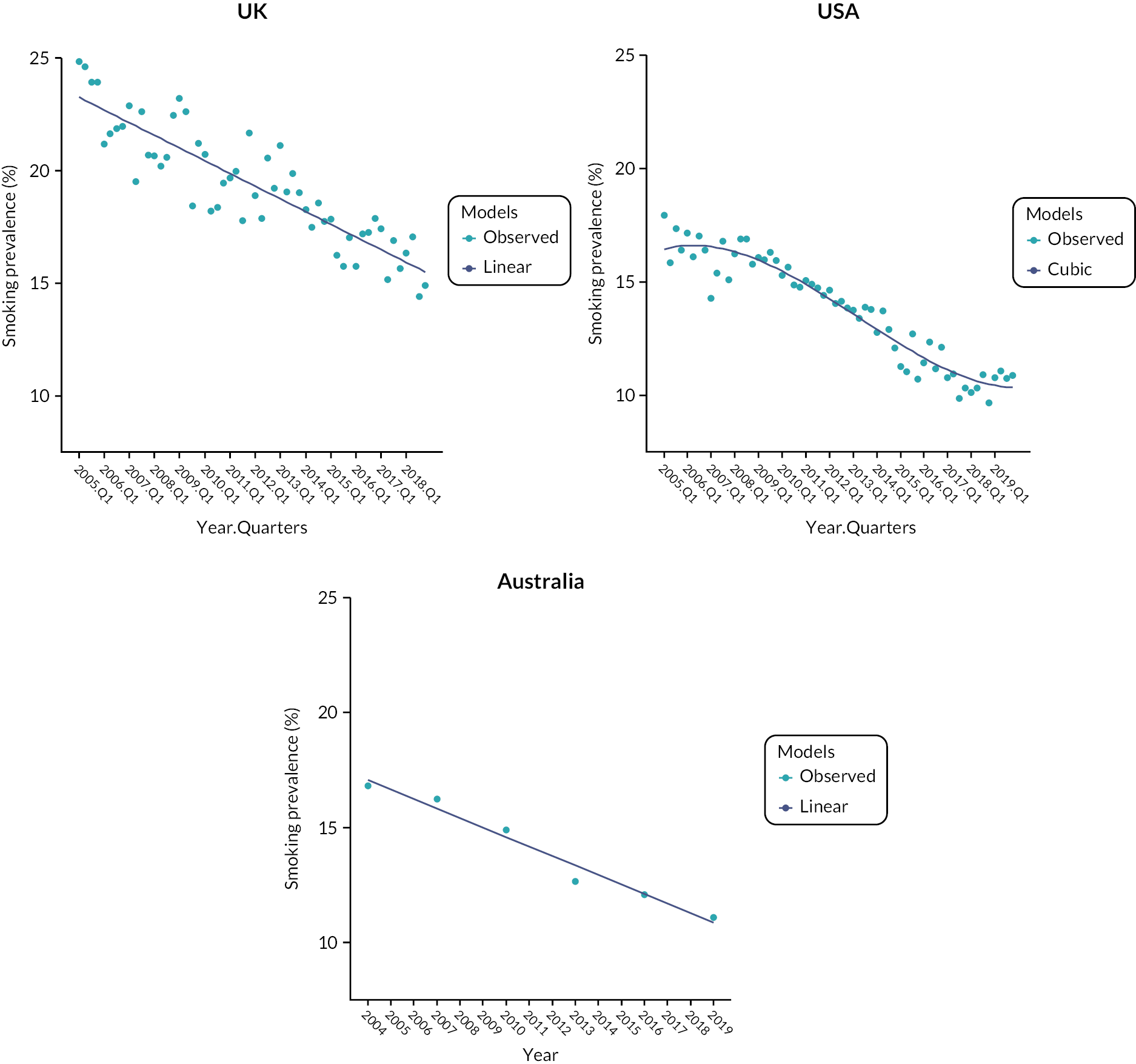

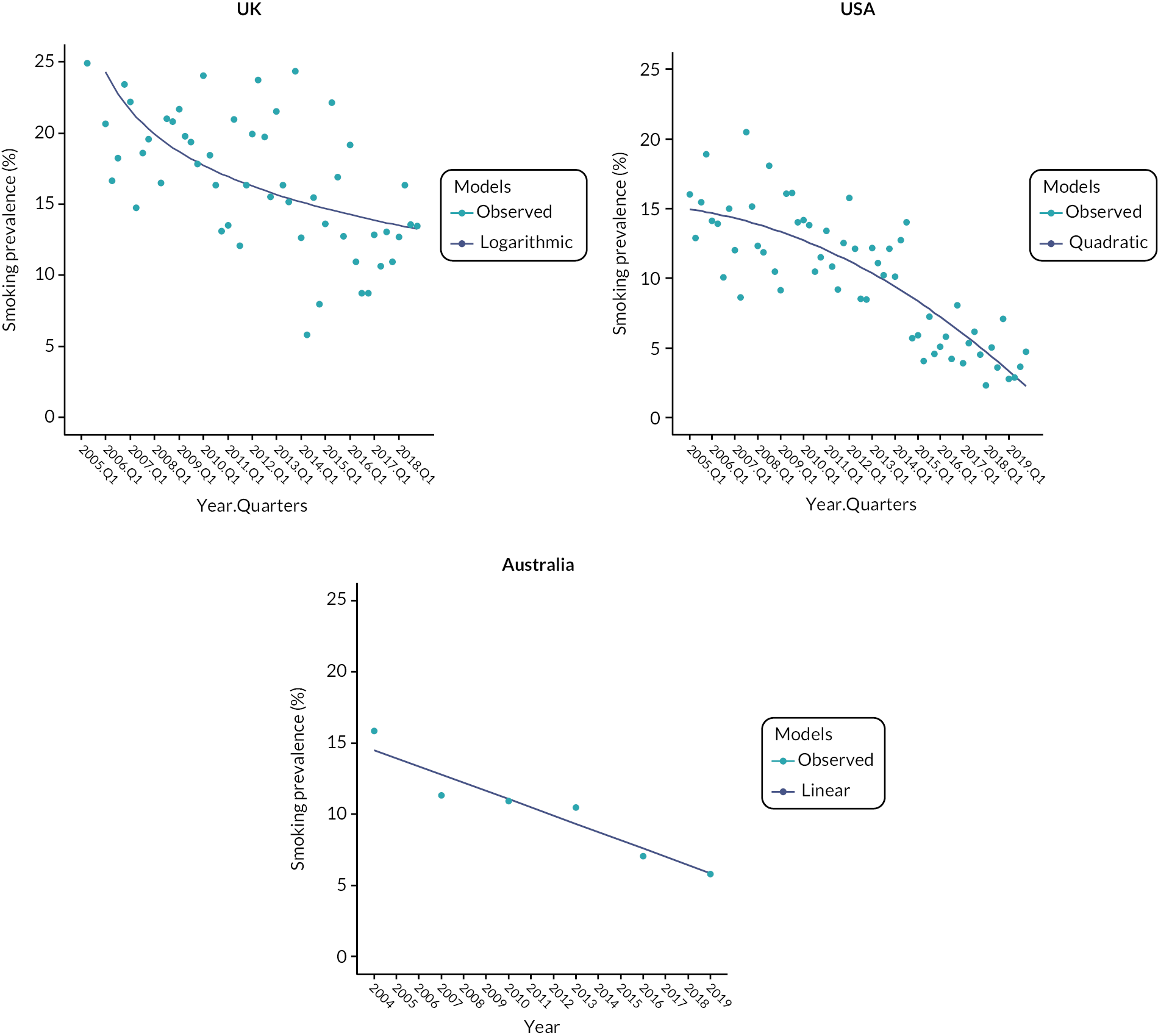

RQ3: Time trends of smoking prevalence and cigarette sales in the UK and USA versus Australia

Since cigarette prevalence was only available for daily use in the Australian data set, only daily smoking rates were used for the UK and the USA as well.

Supplementary Table 5, Report Supplementary Material 1 summarises the model fit indices for the various models and indicates those selected. Supplementary Figures 1, 2 and 3, Report Supplementary Material 1 show the observed versus fitted values for daily smoking for each model in each country (UK, USA and Australia).

Results from the best-fitting models are presented in Figure 7 and summarised in Supplementary Table 6, Report Supplementary Material 1. A linear model offered the best fit to the UK data, indicating a decline in smoking rates over the period of interest. Data from the USA and Australia were instead best fitted by a cubic model; however, due to the few years of observations available for Australia we considered that a cubic model may be overfitting the data and instead report results based on the linear model, which shows a decreasing smoking trend. For the USA, the model suggests that there was an initial increase in smoking rates up to the fourth quarter of 2008, followed by a steady decrease in smoking rates up to the first quarter of 2018, when it appears to have reached a plateau.

FIGURE 7.

Smoking prevalence raw data and best-fitting model for the UK, USA and Australia.

While a cubic model best fitted the US data, linear models also appeared to offer a good fit (see Supplementary Figures 2 and 3, Report Supplementary Material 1) and so we report the results fitting the data using a linear model for all three countries (Table 6).

| Country (time points) GLS (p, q)fa |

Coefficient (SE), p-value, 95% CI and CARR (SE) | |

|---|---|---|

| UK ( N = 56) | Unadjusted | Adjusted for policies |

| GLS (0, 0)4 Time |

−0.14 (0.01) p < 0.001 −0.16 to −0.12 CARR = 0.73% (0.06) |

−0.12 (0.02) p < 0.001 −0.17 to −0.07 |

| USA ( N = 60) | Unadjusted | Adjusted for policies |

| GLS (1, 1)4 Time |

−0.12 (0.02) p < 0.001 −0.15 to −0.08 CARR = 0.84% (0.17%) |

−0.12 (0.02) p < 0.001 −0.16 to −0.08 |

| Australia ( N = 6) | Unadjusted | Adjusted for policies |

| GLS (0, 0)1 Timeb |

−0.10 (0.01) p < 0.001 −0.12 to −0.09 CARR = 0.7% (0.1) |

−0.10 (0.02) p < 0.001 −0.13 to −0.06 |

Based on the linear model results, all countries had a decreasing trend in smoking, with the rates of smoking decreasing at a faster rate in the UK than in Australia (slope difference = 0.04, 95% CI 0.02 to 0.06). There was no difference between Australia and USA (slope difference = 0.02, 95% CI −0.2 to 0.06).

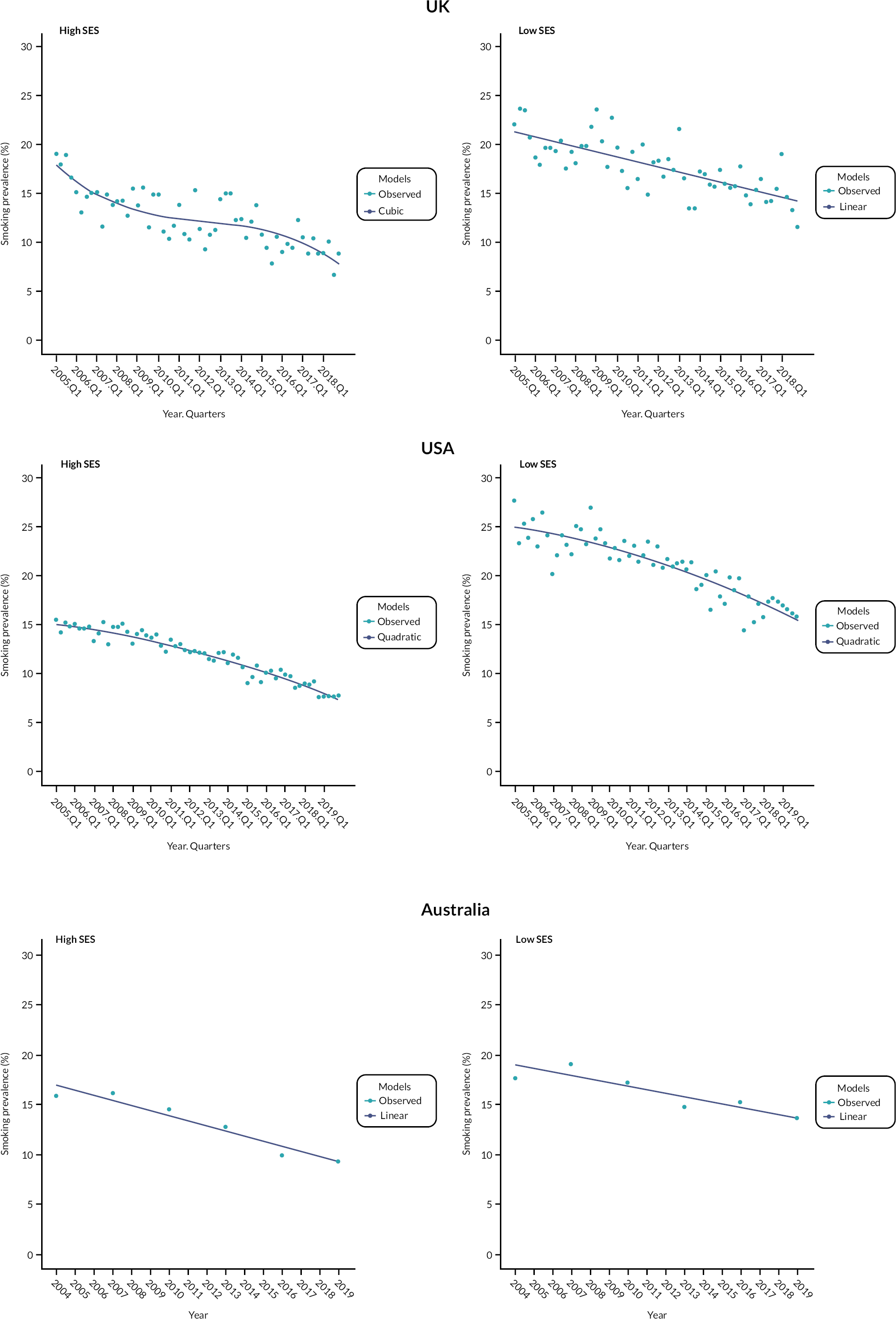

RQ3: Trends in smoking prevalence in the UK and USA versus Australia, stratified by SES

Supplementary Figure 4, Report Supplementary Material 1 captures the observed and fitted data for each country by SES. Supplementary Table 7, Report Supplementary Material 1 presents the model fit (AIC) for the analyses stratified by SES, and Supplementary Table 8, Report Supplementary Material 1 shows time trends in the three countries stratified by SES.

A cubic model offered a good fit to the UK data for high SES, indicating a decreasing trend up until the first quarter of 2008, followed by a plateau in smoking rates until the first quarter of 2015, when rates start to decrease again. For low SES, we found a linear model offered a good fit, with overall decreasing trends in smoking prevalence. A quadratic model offered a good fit to the US data for both low and high SES, indicating a curvilinear decreasing trend throughout the time series. For Australia, we report results from the linear model, indicating a decrease in smoking rates as for the main analysis. Results are summarised in Figure 8.

FIGURE 8.

Smoking prevalence raw data and best-fitting model for the UK, USA and Australia broken down by SES (high vs. low). SES, socioeconomic status.

The results based on linear models are presented in Supplementary Table 9, Report Supplementary Material 1 for comparison. A decreasing trend in smoking rates is observed and for high SES the slopes are of similar magnitude in all three countries. Among low SES, the prevalence of smoking was decreasing faster in the UK and USA than in Australia (UK vs. Australia: slope difference = 0.04, 95% CI 0.02 to 0.06; USA vs. Australia: slope difference = 0.07; 95% CI 0.05 to 0.09).

RQ3: Time trends of smoking prevalence in the UK and USA versus Australia, in young users

Supplementary Table 10, Report Supplementary Material 1 presents the model fit (AIC) for the analyses on young users only and Supplementary Figure 5, Report Supplementary Material 1 captures the observed and fitted data for each country.

Decreasing trends were observed in all three countries. Supplementary Table 11, Report Supplementary Material 1 shows trends in daily smoking prevalence in young users (< 22 years old) in the UK, USA and Australia based on the best-fitting model. A logarithmic model offered a good fit to the UK data. For a 1% increase in the independent variable (time) smoking prevalence decreased by about 0.05. A quadratic model offered good fit to the US data, indicating a curvilinear decreasing trend. For Australia a linear model offered the best fit to the data, indicating a decreasing trend over time. The results based on linear models are presented in Supplementary Table 12, Report Supplementary Material 1 for comparison.

Based on the results from the linear models, the rates of smoking in young users were decreasing at a slower rate in Australia than in both the UK (slope difference = 0.09, 95% CI 0.01 to 0.17) and USA (slope difference = 0.07, 95% CI 0.01 to 0.13), see Figure 9.

FIGURE 9.

Smoking prevalence raw data and best-fitting model for the UK, USA and Australia in young users only.

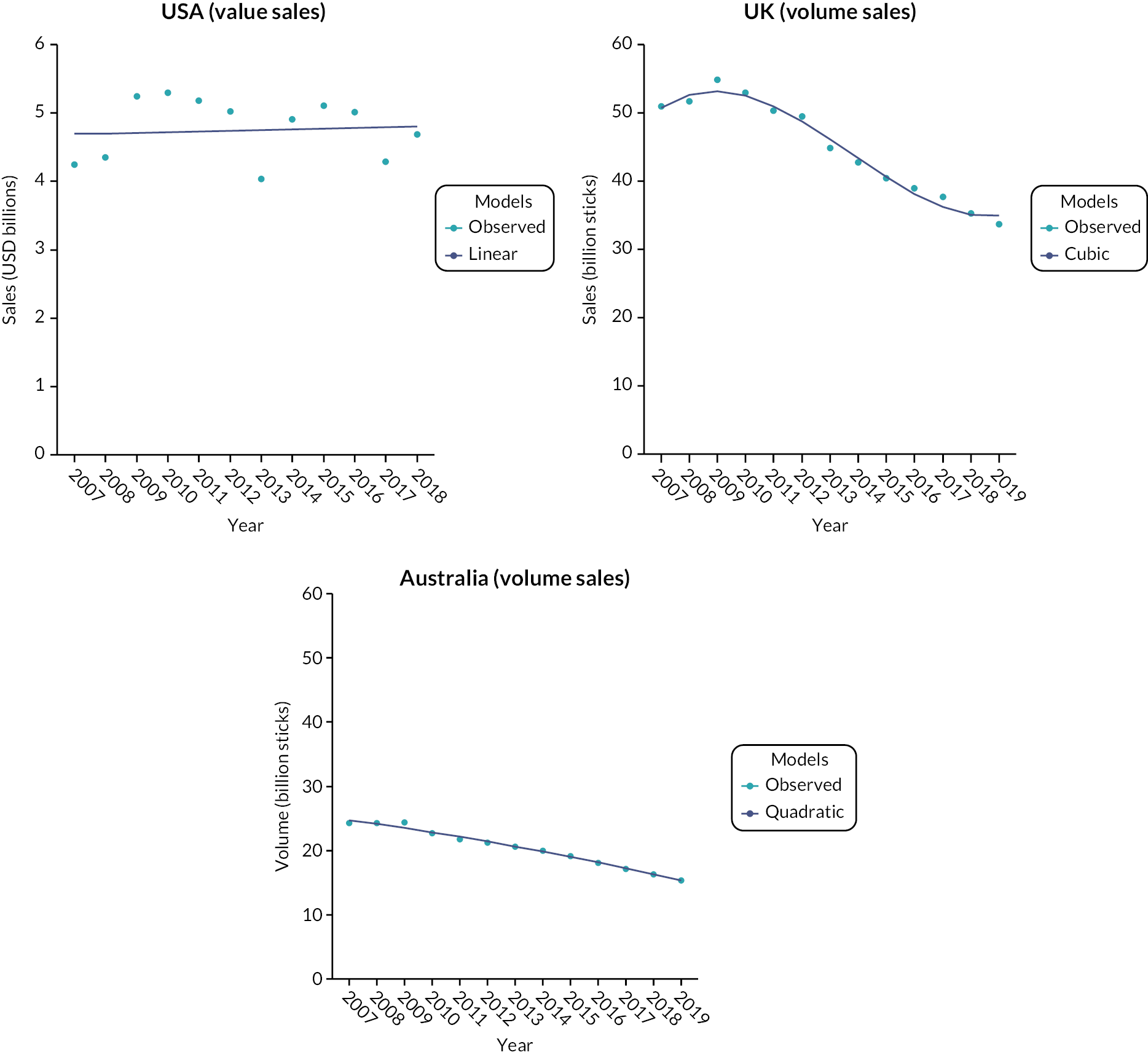

RQ3: Cigarette sales in the UK and USA versus Australia

The UK and Australian sales are measured in retail volume (billions of sticks), while US sales are measured in value (US dollars). For all three countries we modelled data for cigarettes (manufactured and RYO). For RYO data, tonnes were converted to sticks assuming 0.7 g of tobacco corresponds to one RYO cigarette.

US sales expressed in value are affected by changes in price rather than just by volume of sales. We adjusted the figures for inflation using the Consumer Price Index (www.bls.gov/cpi/data.htm) and present them for illustration, but do not compare them statistically with the UK and Australian data.

Various models were compared and the best-fitting model was identified (see Supplementary Table 13, Report Supplementary Material 1). Supplementary Figures 6–8, Report Supplementary Material 1 show the observed versus fitted values based on the best-fitting model for the UK, USA and Australia, respectively. Quarterly sales data for the USA and UK are summed to show total annual sales for ease of comparison to Australian data in the figures, but data are modelled using quarterly breakdown.

Figure 10 and Supplementary Table 14, Report Supplementary Material 1 show the time trends of cigarette sales in the UK, USA and Australia based on best-fitting models.

FIGURE 10.

Raw sales data and best-fitting model for the UK, USA and Australia.

For comparison, we also conducted analysis using the linear model as it offered a fairly good fit to the UK (see Table 7). The linear model did not offer a good fit to the US data, so sensitivity analyses are only presented for reference (see Supplementary Figure 7, Report Supplementary Material 1).

| Country (time points) GLS (p, q)fa |

Coefficient (SE), p-value, 95% CI and CARR (SE) | |

|---|---|---|

| UK ( N = 52) b | Unadjusted | Adjusted for policies |

| GLS (1, 0)4 with seasonality Time |

−0.11 (0.01) p < 0.001 −0.13 to −0.09 CARR = −1.00% (0.09) |

−0.09 (0.02) p < 0.001 −0.13 to −0.05 |

| USA to 2018 ( N = 48) c | Unadjusted | Adjusted for policies |

| GLS (1, 0)4 with seasonality Time |

0.0004 (0.004) p = 0.91 −0.006 to 0.007 CARR = 0.08% (0.25) |

−0.003 (0.003) p < 0.23 −0.008 to 0.002 |

| Australia ( N = 13) d | Unadjusted | Adjusted for policies |

| GLS (0, 0)1 Time |

−0.05 (0.002) p < 0.001 −0.053 to −0.045 CARR = −0.25% (0.01) |

−0.05 (0.003) p < 0.001 −0.055 to −0.044 |

The linear model shows the sale of cigarettes decreasing at a faster rate in the UK than in Australia [slope difference = 0.06 (0.04 to 0.08)]. In the USA the value of cigarette sales has not changed over time. The estimated CARR is 0.08%. Based on the expected effect size (CARR = 4–4.5%), the BF = 0.08 suggests a lack of trend over time.

Chapter 5 Discussion

The analyses using the pre-specified GLS approach found only a few statistically significant associations between the prevalence of use of cigarettes and ANDs and between the sales of the two products. Regarding prevalence data, the decline in smoking prevalence seems to have been slower in Australia than in the UK overall, and slower than in both the UK and USA among young people. Regarding sales data, the decline in cigarette sales has accelerated faster in the UK than in Australia, and the increase in sales of HTPs in Japan was accompanied by a decrease in sales of cigarettes. For most results, significant and non-significant, BF indicated inconclusive evidence related to the analyses being underpowered.

The findings are subject to serious limitations. We pre-specified in our SAP that we would use dynamic time series applying GLS models. Unfortunately, most of the available data series had insufficient data points for robust time series analyses and the results need to be considered as only tentative and interpreted cautiously. It is recommended that at least 50, but preferably more than 100, time points are included for dynamic time series. 19,32 Power simulations included in our SAP assumed that at least 40 time points would be available for each data set, but all but two surveys, which had 50–60 time points, consisted of 20 or fewer time points. Furthermore, for most analyses, early data on ANDs needed to be imputed.

In addition, the GLS approach assumes that causal interactions are more likely to be detected when long-term changes are screened out, and so underlying long-term trends are removed. In product replacement scenarios, however, short-term fluctuations can be caused by external factors such as fluctuations in prosperity or product supplies, while product interactions may require longer time periods to develop. If the increase in AND use is accompanied by an increase or decrease in cigarette use that develops gradually over time, the ‘detrending’ may in fact remove the effect that the analysis is trying to detect. These issues are further aggravated if time series are not long enough.

There is also another factor that is likely to have reduced the robustness of the analyses. ANDs are used predominantly by smokers, and established smokers rarely switch fully to the alternative product straight away. In the initial phases of the increase in AND use, the majority of AND users also smoke. The prevalence data do not separate ‘dual users’ and ‘single product users’, which means that most AND users are counted among both smokers and AND users. For example, if a survey reports that 30% of the population smoke and 5% use ANDs, ANDs cannot be expected to have made a proportional impact on cigarette use, as there may be only perhaps 2% of people who only use ANDs at that stage. There needs to be a sufficient population-level use of the new product for the analysis to be able to assess if its use is affecting the use of the incumbent product.

The problem of dual use should not affect sales figures to the same extent as prevalence figures. This is because even occasional use of ANDs can be expected to reduce use of cigarettes, though for this to generate a significant signal in the data, sufficient numbers of smokers need to start using ANDs. Monitoring sales figures over the initial increase in AND use is thus likely to be more informative.

The time series analyses, which explored the interplay between AND use and cigarette smoking over time, is a form of ecological study design which groups data at the population level. This may be seen as another limitation, as finding an association does not necessarily mean that vaping is facilitating or replacing smoking at the individual level. However, these would be the most likely scenarios, as regular vaping in non-smokers is rare.

Different national surveys also used slightly different methods (e.g. different wordings of relevant questions), but as long as the same methods were used over time, such differences should not have a major impact on time trends that are the focus of this study.

During our work on the project, several studies were published that examined some of the questions we were interested in, with some studies using different statistical methods.

Several studies focused on vaping and smoking among US youth, using mostly NYTS data. A study looking at years 2004–14 found no effect of vaping on smoking,33 but although ECs entered the US market in 2007, their use was negligible until 2014. Using data from 2004 to 2018, the same authors reported a slowing decline in current smoking but an accelerated decline in ever smoking. 34 A study using data on youth cigarette use from five different surveys reported that the decline in smoking has markedly accelerated when vaping increased from 2014 onwards. 3 Similarly, a study using joinpoint regression analyses reported that the prevalence of smoking among adolescents decreased more rapidly during years when EC use increased (2011 to 2019) than in previous years. 35 A study using NYTS youth smoking and vaping prevalence data and National Retail Solutions (NRS) cigarette and EC price data concluded that ECs and cigarettes are economic substitutes, replacing each other in response to cost. 36

Several studies using data from the UK Smoking Toolkit Study, which used a similar approach to the present study, found limited associations between vaping and smoking. The dynamic time series analyses using ARIMAX found no association between vaping and quit attempts or cigarette consumption, but reported that vaping enhanced quit success rates. 37 Modelling smoking and EC use using segmented regressions to compare patterns over time suggested that EC use did not influence the reduction in smoking prevalence. 38 An analysis using ARIMAX found no association between smoking and vaping in young people. 4

Two studies examined links between cigarettes and AND sales in Japan. One analysed sales data from the TIOJ and PMI from 2011 to 2019, using joinpoint regression models that test the statistical significance of no joinpoints (straight line) compared to one or more joinpoints. Cigarette sales declined at accelerated pace since 2016 following the introduction of HTPs. Between 2011 and 2015, the annual per cent change (APC) for cigarette sales was –3.10, while between 2016 and 2019 the APC was –16.38 (p = 0.003), a fivefold increase compared to the pre-HTP period. 39 The second study used 2014 to 2018 monthly retailer panel data from 11 Japanese regions. Linear trends were fitted to the per capita cigarette sales by each region, using a fixed-effects model. The ‘Changing growth’ time-trend model showed that cigarette sales began to substantially decline at the time of the introduction of IQOS in each of the regions (Chow tests p < 0.001). 7

As another alternative to the GLS approach we used, some studies implemented simulation models. A recent UK study suggested that reductions in smoking from 2012 to 2019 were linked to growth in vaping. 40 The study used a simulation model indirectly estimating the impact of vaping on smoking prevalence, using data from three separate national surveys. Data from 2000 to 2011 were used to estimate counterfactual smoking rates in the absence of vaping between 2012 and 2019. Comparing counterfactual and observed prevalence rates allowed an estimate of the relative reduction in smoking due to vaping. The same approach was used to model smoking prevalence in young adults in the USA and similarly found that vaping was associated with reduced smoking prevalence rates. 41 A similar approach modelled nicotine use in adolescents (aged 12 to 17) using data from the NYTS. Between 2010 and 2018, while cigarette use had been declining, total nicotine use was maintained. This was interpreted as suggesting that adolescents who would otherwise smoke were diverted to vaping. 42 A complex dynamic model using NYTS data for adolescents (aged 12 to 17) similarly showed a substantial diversion rather than catalyst effect of vaping on smoking in the USA. 43 More recently age-period-cohort models were used to describe secular trends using survey data. 44–46 Age-period-cohort models examine trends in relation to chronological age, cohort (i.e. generational differences), and period (i.e. social and cultural changes at the population level) effects. They require large data sets with long time series but should be able to provide robust estimates of the impact of ANDs on smoking.

Regarding the between-countries comparison, an interrupted time series analysis that examined data from four Canadian provinces, the UK and Australia reported that in jurisdictions with permissive policies, the introduction of vaping has generally accelerated the decline in smoking. 47 Our tentative findings that the more liberal approach to ECs in the UK and USA may have led to a faster decline in smoking in both countries compared to banning nicotine-containing ECs in Australia tally with this.

Overall, our analytical method did not detect some of the effects reported above, but the results tally with other findings regarding the impact of HTPs on reducing smoking in Japan and with other indications that the more liberal approach to ECs in the UK and USA may have led to a faster decline in smoking compared to banning sales of nicotine-containing ECs in Australia.

In our between-countries comparisons of the cigarette sales trajectory following the introduction of ANDs in the UK and USA, we were only able to compare Australia and the UK, as US data used value sales rather than volume of sales. It is striking that sales of cigarettes seem to have been declining at a slower rate in Australia than in the UK, despite the cost of cigarettes increasing much more in Australia (by 12.5% per year, reaching the cost of a packet of cigarettes of > £20 in 2019, compared to < £9 in the UK).

Regulatory implications

In the original study protocol, we planned a synthesis of the implications of the results for deciding which types of regulatory frameworks (restrictive or liberal) are more likely to reduce rates of smoking. The results are not clear enough for strong policy recommendations, but some general conclusions can be drawn. There are some indications that ANDs compete with cigarettes and that regulations restricting access to ANDs may slow down the decline in smoking compared to regulations that allow access to ANDs, although given the limitations discussed above, these results are only tentative. The strength of the substitution effect in particular remains unclear. The evidence, however, seems clear that allowing ANDs on the market has not been associated with increased smoking rates. Limiting access to ANDs out of the concern that they promote smoking generally, or do so specifically in young people, is thus not justified.

Research recommendations

The overall picture will become clearer when further data accrue. Unfortunately, the COVID-19 epidemic has disrupted some of the data collection and may have also affected both smoking and AND use. This is likely to make prevalence data collected over the past 2 years more difficult to integrate and interpret. Sales data, on the other hand, should be more informative. Prevalence data are subject to sampling issues, changes in sampling and data collection procedures, phrasing of the questions, representativeness of samples reached and issues with double counting of dual users.

Our main research recommendation is to analyse sales data. Sales volumes avoid most of these issues, are likely to include much more frequent data points, and can provide clearer information on whether the alternative products are facilitating cigarette sales, replacing them or attracting new nicotine users without affecting smoking. Major tobacco companies have extensive relevant data. In many markets the major tobacco companies regularly report precise estimates of market share for alternative products, which requires awareness of associated changes in cigarette sales. One of the co-authors, DS, has tried repeatedly to have these data released, but has not been successful. Given the importance to policy-makers of knowing what impact ANDs are having on cigarette sales, accessing such data should be a future research priority. If tobacco companies continue to refuse to share them, it may be possible to examine tax receipt data from national treasuries and shipment data from customs and excise authorities instead.

Regarding the statistical approaches, future studies should consider using age-period-cohort models to understand changes in smoking trends over time and modelling to compare estimated smoking prevalence and cigarette sales in the absence of AND products (i.e. counterfactual scenario) with observed figures.

Equality, diversity and inclusion

This was a study using pre-existing data. As a result, equality, diversity and inclusion were limited to characteristics captured within the data available.

Patient and public involvement

The project was discussed with 46 stop-smoking advisors who attended an annual UK stop smoking service (SSS) update and supervision event in December 2018 and with 52 advisors who attended the event in 2019. There was an agreement that knowing whether permissive regulations of ANDs promotes smoking or helps to drive it out is of primary importance for informing attitudes towards ECs and other such products within the SSSs.

The project was also discussed with a panel of six ex-smokers who stopped smoking with the help of SSSs. Panel members were aware of assertions that vaping lures young people to smoking and thought that clarifying the effects of vaping on smoking prevalence is a high priority issue.

The SSC included an ex-smoker who stopped smoking with the help of a UK SSS (recruited from one of our existing panels). The report was discussed with the lay committee member and they are assisting in drafting plain language summaries.

Conclusion

We detected some indications that ANDs are competing against cigarettes rather than facilitating cigarette use. The decline in smoking prevalence seems to have been slower in Australia than in the UK overall, and slower than in both the UK and USA among young users, suggesting that liberal AND regulations may be more conducive to reducing rates of smoking. The increase in sales of HTPs in Japan was accompanied by a decrease in sales of cigarettes, suggesting that HTPs are replacing rather than facilitating smoking. However, for most results, BF indicated inconclusive evidence. Due to insufficient data points and short time series, the findings are only tentative. As further data on prevalence and especially on sales of different nicotine products emerge, the analyses will become more informative.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the following international SSC members for their oversight and guidance throughout the project:

Professor Tim Coleman (Chair) – Professor of Primary Care, UK

Professor Joan Morris – Professor of Medical Statistics, UK

Ms Tanya Francis – PPI member, UK

Dr Ivan Berlin – Associate Professor in Clinical Pharmacology, France

Dr Carlos A Jiménez-Ruiz – Chair of Smoking Cessation Service, Spain

Dr Masakazu Nakamura – General Manager of Health Promotion Research Center, Japan

Dr Yuri Ito – Associate Professor of Medical Statistics, Japan

Professor Wayne Hall – Emeritus Professor at National Centre for Youth Substance Use Research, Australia

We would like to thank the owners of the original survey and sales data for allowing us to use the data. All analyses, interpretations and conclusions in this report have been made by the authors and not the data owners. With regard to the NielsenIQ data specifically, researcher(s) own analyses calculated (or derived) based in part on data from Nielsen Consumer LLC and marketing databases provided through the NielsenIQ Datasets at the Kilts Center for Marketing Data Center at The University of Chicago Booth School of Business.

The conclusions drawn from the NielsenIQ data are those of the researcher(s) and do not reflect the views of NielsenIQ. NielsenIQ is not responsible for, had no role in, and was not involved in analysing and preparing the results reported herein.

This report presents independent research commissioned by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). The views and opinions expressed by authors in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the NHS, the NIHR, MRC, CCF, NETSCC, the PHR programme or the Department of Health.

Contributions of authors

Francesca Pesola (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2054-7930) (Research Fellow in Statistics) led the statistical analysis plan, analysed the project data and led on the drafting of study results.

Anna Phillips-Waller (https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6856-6439) (Clinical Project Manager) was a co-investigator. She co-wrote the original grant application, managed the project and co-led drafting of the report.

Emma Beard (https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8586-1261) (Lecturer in Statistics and Quantitative Methods) was a co-investigator. She co-wrote the original grant application and assisted with analysis and interpretation of the project findings and drafting of the report.

Lion Shahab (https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4033-442X) (Professor of Health Psychology) was a co-investigator. He co-wrote the original grant application and assisted with interpretation of the project findings and drafting of the report.

David Sweanor (https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1076-041X) (Independent) was a co-investigator. He co-wrote the original grant application and assisted with interpretation of the project findings and drafting of the report.

Martin Jarvis (https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9238-8038) (Emeritus Professor of Health Psychology) was a co-investigator. He co-wrote the original grant application and assisted with interpretation of the project findings and drafting of the report.

Peter Hajek (https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9160-4296) (Professor of Clinical Psychology) was the lead investigator. He led the original grant application, designed the project and led the drafting of the study report.

Data-sharing statement

This is a study based on existing data sets and only the results contained within the report can be shared. Further information can be obtained from the corresponding author.

Disclaimers

This report presents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR). The views and opinions expressed by authors in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the NHS, the NIHR, the PHR programme or the Department of Health and Social Care. If there are verbatim quotations included in this publication the views and opinions expressed by the interviewees are those of the interviewees and do not necessarily reflect those of the authors, those of the NHS, the NIHR, the PHR programme or the Department of Health and Social Care.

References

- Friedman AS. How does electronic cigarette access affect adolescent smoking?. J Health Econ 2015;44:300-8.

- Pesko MF, Hughes JM, Faisal FS. The influence of electronic cigarette age purchasing restrictions on adolescent tobacco and marijuana use. Prev Med 2016;87:207-12.

- Levy DT, Warner KE, Cummings KM, Hammond D, Kuo C, Fong GT, et al. Examining the relationship of vaping to smoking initiation among US youth and young adults: a reality check. Tob Control 2019;28:629-35.

- Beard E, Brown J, Shahab L. Association of quarterly prevalence of e‐cigarette use with ever regular smoking among young adults in England: a time-series analysis between 2007 and 2018. Addiction 2022;117:2283-93.

- Foulds J, Ramstrom L, Burke M, Fagerström K. Effect of smokeless tobacco (snus) on smoking and public health in Sweden. Tob Control 2003;12:349-59. https://doi.org/10.1136/tc.12.4.349.

- Ramström L, Borland R, Wikmans T. Patterns of smoking and snus use in Sweden: implications for public health. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2016;13.

- Stoklosa M, Cahn Z, Liber A, Nargis N, Drope J. Effect of IQOS introduction on cigarette sales: evidence of decline and replacement. Tob Control 2020;29:381-7.

- Eaton DL, Kwan LY, Stratton K. Public Health Consequences of e-Cigarettes. 2018.

- NatCen Social Research, University College London, Department of Epidemiology and Public Health . Health Survey for England 2023. http://doi.org/10.5255/UKDA-Series-2000021 (accessed 24 February 2023).

- Statistics NCfH . National Health Interview Survey 2020. Public-Use Data File and Documentation 2020.

- Euromonitor International . Market Size Tobacco, Australia 2022. https://www.euromonitor.com/ (accessed 24 February 2023).

- Clarke E, Thompson K, Weaver S, Thompson J, O’Connell G. Snus: a compelling harm reduction alternative to cigarettes. Harm Reduct J 2019;16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-019-0335-1.

- Krieger N, Barbeau EM, Soobader M-J. Class matters: US versus UK measures of occupational disparities in access to health services and health status in the 2000 US National Health Interview Survey. Int J Health Serv 2005;35:213-36.

- Scollo M, Bayly M. The Price of Tobacco Products in Australia. Tobacco in Australia: Facts and Issues. Melbourne: Cancer Council Victoria; 2020.

- Tabuchi T, Nakamura M, Nakayama T, Miyashiro I, Mori J-I, Tsukuma H. Tobacco price increase and smoking cessation in Japan, a developed country with affordable tobacco: a national population-based observational study. J Epidemiol 2016;26:14-21. https://doi.org/10.2188/jea.JE20140183.

- Lee B, Seo D-C. Effects of an 80% cigarette price increase on quit attempts, successful quitting and smoking intensity among Korean adult smokers: results from nationally representative longitudinal panel data. Tob Control 2020;30:336-43. https://doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2019-055518.

- CDC 2009. www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5819a2.htm (accessed 9 February 2021).

- Hiscock R, Branston JR, Partos TR, McNeill A, Hitchman SC, Gilmore AB. UK tobacco price increases: driven by industry or public health?. Tob Control 2019;28:e148-50. https://doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2019-054969.

- Beard E, Marsden J, Brown J, Tombor I, Stapleton J, Michie S, et al. Understanding and using time series analyses in addiction research. Addiction 2019;114:1866-84.

- Beard E, West R, Michie S, Brown J. Association between electronic cigarette use and changes in quit attempts, success of quit attempts, use of smoking cessation pharmacotherapy, and use of stop smoking services in England: time series analysis of population trends. BMJ 2016;354.

- Beard E, West R. Using Bayesian statistics in health psychology: a comment on Depaoli et al. (2017). Health Psychol Rev 2017;11:298-301.

- Beard E, Dienes Z, Muirhead C, West R. Using Bayes factors for testing hypotheses about intervention effectiveness in addictions research. Addiction 2016;111:2230-47.