Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 09/3001/19. The contractual start date was in November 2009. The final report began editorial review in May 2013 and was accepted for publication December 2013. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Janet E Cade is a personal member of the Royal Horticultural Society. Janet E Cade and Charlotte EL Evans received funding from Kids Company to undertake some subsequent analysis of this data set (results not presented in this report).

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2014. This work was produced by Christian et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Fruit and vegetables are fundamental components of a healthy diet, providing vital micronutrients. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that we should eat at least 400 g of a variety of fruit and non-starchy vegetables every day. 1 A standard portion of fruit or vegetables is assumed to be 80 g. 1 Consuming low energy density foods such as vegetables could help prevent obesity. 2

Epidemiological evidence indicates that, in adults, a diet rich in fruit and vegetables can decrease the risk of developing cardiovascular disease, stroke, hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, obesity and several forms of cancer. 3,4 A diet low in fruit and vegetables is one of the top 10 risk factors for global mortality. 5 Research has also revealed that dietary habits are developed in childhood and persist throughout life; therefore, it is vital that children at a young age consume adequate levels of fruit and vegetables. 6,7 Several studies indicate that children’s fruit and vegetable intake is positively associated with their parents’ intake. 8

The impact of poor nutrition in children is causing major public health concerns across the globe. 4 Of particular public concern is the rise of obesity in children. 9 Diet plays a fundamental role in weight management; having a healthy diet rich in fruit and vegetables, which have a low energy density, could help tackle the obesity epidemic. 10 A diet rich in fruit and vegetables is key for children to develop mentally and physically. 4 The importance of childhood eating patterns has been illustrated through longitudinal research concluding that eating fruit and vegetables in childhood has positive health benefits in terms of cardiovascular disease, asthma and other respiratory diseases. 11–14 Public health interventions need to change children’s lifestyles to reduce the intake of non-essential foods which are high in fat, sugar and salt, and to encourage increased intake of a variety of fruit and vegetables. Strategies to reduce obesity in children are urgently required. 15

Current consumption levels

Currently, children’s consumption of fruit and vegetables is low in the USA, Australia and most European countries. 12,16,17 The average intake of fruit and vegetables for children in the UK is around 2.8 servings per day – approximately 224 g. 18 In British children, the main sources of energy intake are chips, biscuits and crisps;19 the need for public health intervention to improve children’s overall diet habits is evident. 20 Children from low-income families consume even less fruit and vegetables than the average. Boys consume only 64 g, or 0.8 of a portion, and girls consume 1.1 portions (approximately 88 g) of fruit and vegetables daily. 19

Interventions to improve children’s fruit and vegetable intake from across the globe: what is already known?

Nutrition education programmes have been developed for school, home and community settings in an attempt to improve children’s diets. 21–28 Evidence suggests that the most effective interventions are multicomponent, with both school- and home-based components. 29–31 Successful intervention studies have included a variety of components: integrating teaching about fruit and vegetables into the curriculum;23,29,30,32–34 training teachers in theories of behaviour change and nutritional education;35,36 increasing fruit and vegetable availability at school and in school meals;34,36,37 training of catering staff (verbal encouragement);29,30,37 hands-on exposure (tasting and preparation sessions);23,33,35 parental involvement through newsletters and homework activities;23,29,30,33,34 a whole-school approach (developing a nutrition policy, evening activities)30,36,37 and community involvement (involving the local fruit and vegetable industry). 23,29,34 These intervention programmes report a moderate increase in children’s fruit and vegetable consumption of approximately one-third of a portion of fruit and/or vegetables per day. 22,38,39

The psychological theory behind school gardens is based on the social cognition theory (SCT), which works on the assumption that to successfully change a person’s behaviour requires changing their knowledge, values and beliefs. 40 It is believed that rather than being a quantitative effect, active engagement in gardening activities can reinforce healthy messages about eating, and increase children’s willingness to try different fruit and vegetables. Planting, growing and eating vegetables can improve children’s consumption patterns. However, there is now a gap between the implementation of school gardens and the academic evaluation of their effectiveness. Previous studies of school gardening are limited and none have been randomised controlled trials (RCTs). Studies have had issues with their design and the use of convenience sampling with relatively small sample sizes. 41–43 A number of the trials only had one school or club implementing the intervention. 41,44,45 Statistical analysis was also limited, with only three studies46–48 using a statistical methodology that adjusted for baseline differences. None of the studies took into consideration the hierarchical structures of school data through multilevel analysis. These factors could compromise reliability of statistical outcomes, limiting the generalisability of the results.

Potential barriers to changing children’s fruit and vegetable consumption

Changing children’s fruit and vegetable consumption is a challenging task. Academic literature shows that the main barriers to increasing children’s fruit and vegetable intake are availability, accessibility, convenience, taste preferences, peer pressure, parental/school support and knowledge. 49 The successful implementation of an intervention is often determined by the time allocated to the programme and the perception of its importance by teachers and parents. For teachers, the main barrier to implementing school-based interventions is preparation time. For parents, the cost of fruit and vegetables is often cited as being too high, with many opting to buy items of food that are less nutrient rich but are guaranteed to be consumed, such as biscuits, sweets and crisps. 50

Research has attempted to design complex interventions to improve the understanding and education of children regarding the importance of healthy eating. The complexity of these interventions is matched by the complexity of our relationship with food. Children’s desires, and their understanding and knowledge of nutrition, come not only from the school and family environments, but also from different types of media, supermarkets, packaging and television advertising, all of which influence their nutritional preferences. Literature suggests that in highly populated areas, such as inner cities, a gap has been created between children’s understanding of the processes of agriculture and the end result – the supermarket. 51,52 To increase children’s intake of fruit and vegetables, it is necessary to increase children’s general knowledge of fruit and vegetables. There is increasing evidence to suggest that gardening might be a vehicle for facilitating fruit and vegetable intake. 52–55

Barriers to implementing a school garden

School gardens require long-term commitment from the schools, and often need community assistance from parents if they are to be sustained. 54 Another issue found is that some schools under study took too long to establish their school gardens, affecting the period of time available during the studies for plants to germinate and grow edible fruit or vegetables. 54 Environmental factors will also play an important role in the amount of food harvested. Schools are closed over the summer, which is the peak harvesting season; without organising staff to water the garden and carry out general garden maintenance, the hard work during term time can be lost. The length of time spent in the interventions will also affect the chances of long-term change in children’s fruit and vegetable intake. Their consumption patterns are unlikely to be affected if their involvement in the actual intervention is limited.

The Royal Horticultural Society ‘Campaign for School Gardening’

This report describes two RCTs designed to evaluate an existing gardening programme run by the Royal Horticultural Society (RHS) in England. The RHS is the largest gardening charity in the UK and has existed for over 200 years. 56 The ‘Campaign for School Gardening’ programme was launched in 2007, and since then has recruited over 11,500 primary schools in England. The main aims of the programme are to encourage schools to be involved in growing fruit and vegetables, to enrich the curriculum activities of the schools and to educate children in the values of gardening, such as ‘healthy living’ and ’sustainability of the natural world’. 56 The RHS intervention is delivered using two different approaches: a trained RHS advisor or class teachers. The RHS advisor provides intensive, hands-on support to a small number of schools. The advisor also trains class teachers to develop the school garden in twilight after-school training sessions.

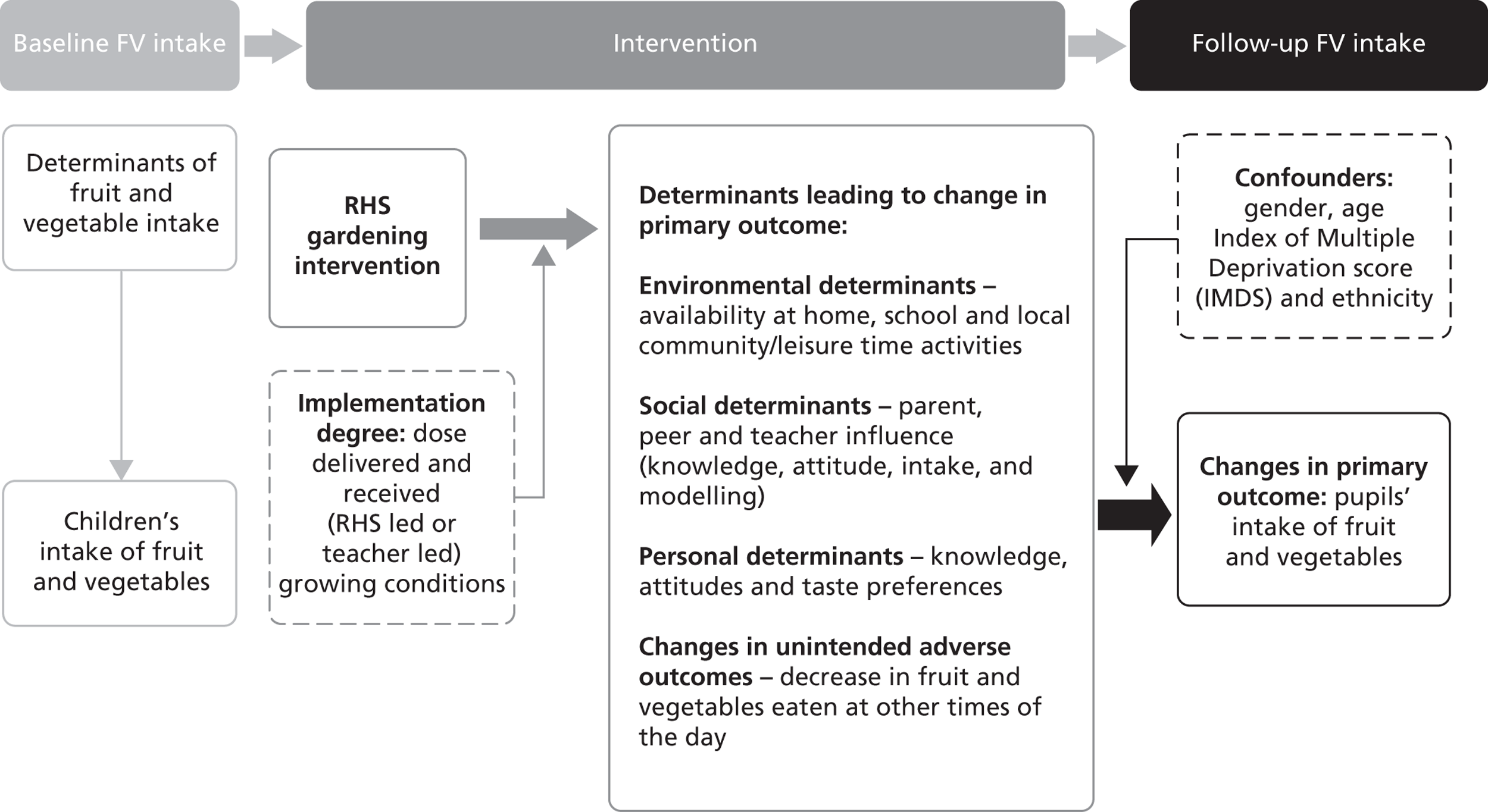

Figure 1, based on the work conducted by Krølner et al. ,57 illustrates the theoretical foundation for this study. It explores some of the factors that could assist or prevent the success of the intervention in affecting the primary outcome, highlighting important environmental, social and personal determinants that affect children’s nutritional behaviour. There are several determinants that are essential to changing a person’s health behaviour. 58 Without changing a child’s environment and access to fruit and vegetables, it would not be possible to change his or her overall intake. Watching parents, peers and teachers eating fruit and vegetables is pivotal in influencing children’s dietary habits and preferences. 59 In addition, nutrition education, presented in the form of a gardening intervention, should aim to increase children’s knowledge, creating the mechanisms necessary to increase overall intake. 60

FIGURE 1.

Path analysis diagram showing how the intervention could change children’s fruit and vegetable consumption. FV, fruit and vegetable.

Nevertheless, to be able to determine the effect of the intervention it is necessary to explore its implementation. The method by which the intervention is implemented, in this case delivered to the schools by the RHS advisor or conducted by the teacher, can have an influence on the primary outcome. Understanding the degree of implementation of the intervention in each school is fundamental in explaining the effect of the intervention. 61 Finally, the information in Figure 1 also illustrates the possible confounders (gender, age, ethnicity and socioeconomic status) that are associated with an effect on children’s fruit and vegetable intake.

Summary

School gardening programmes may provide an interactive environment with the potential to change children’s self-efficacy and willingness to try different fruit and vegetables. These changes in attitudes towards fruit and vegetables could lead to an increase in their actual consumption. Limitations of the existing research are the lack of RCTs and evaluation tools, and inadequate follow-up time. With the variability in quality of study design and validated tools to measure children’s nutritional intake, further research is needed to determine the potential impact gardening interventions have on children’s diets.

Chapter 2 Development and piloting of questionnaires

This chapter outlines the development of, modifications to and piloting of the data collection tools used in this study: the dietary assessment tool and DVD, child knowledge and attitudes questionnaire and the gardening process measures. It describes in detail the tools used to assess the primary and secondary outcome measures of the two trials. It also describes a pilot study conducted to confirm the suitability of language used in the questionnaires and to confirm the final data collection methodology for the trials.

The development of the data collection tools took place over two months from December 2009 until the end of January 2010. Ethical approval for the two trials was granted by the Leeds Institute of Health Sciences and the Leeds Institute of Genetics, Health and Therapeutics (LIHS/LIGHT) Joint Ethics Committee on 10 December 2009 (ref. number HSLT/09/012). The pilot study took place in two primary schools in Leeds in November 2009.

Primary outcome questionnaire

The Child And Diet Evaluation Tool

The primary aim of the two linked trials is to determine whether or not children who participate in the RHS advisor-led gardening intervention increase their fruit and vegetable consumption more than those who receive the teacher-led gardening intervention; or whether the teacher-led intervention increases their fruit and vegetable consumption more than no intervention at all. The effectiveness of either intervention (RHS advisor-led or teacher-led) will be determined by an increase in mean intake of one of the following: mean intake of fruit, mean intake of vegetables, or mean intake of fruit and vegetables at follow-up, after adjusting for baseline intake. Dietary intake, with a focus on fruit and vegetable intake, was measured using a modified version of the Child And Diet Evaluation Tool (CADET) questionnaire. 62 The main aim of the CADET diary is to collect accurate information on children’s fruit and vegetable intake, whilst also collecting information on all foods that the children consumed in a 24-hour period.

Part one of the CADET diary comprises a list of 115 separate food and drink types, divided into 15 categories. The categories of foods are cereal (five items); sandwich/bread/cake/biscuit (10 items); spreads/sauces/soup (seven items); cheese/egg (six items); chicken/turkey (three items); other meat (nine items); fish (five items); vegetarian (three items); pizza/pasta/rice (eight items); desserts/puddings (three items); sweets/crisps (four items); vegetables and beans (18 items); potato (two items); fruit (13 items); and drinks (nine items). Part two consists of food-related questions to identify daily consumption of milk, bread, sugar, spreads and fruit juice. It also includes general demographic questions about the family household, questions about the children’s and parents’ attitudes towards fruit and vegetables, and the availability of fruit and vegetables at home.

Data collection methodology

To complete the diary, participants tick each item consumed under the appropriate mealtime heading within the 24-hour period. In previous research with children aged 3–7 years, trained fieldworkers filled in the CADET diary during the school day, and parents were asked to complete the diary for evening and morning food consumption. 63,64 CADET has been validated for use in children aged 4–7 years in comparison with a semi-weighed food diary collected on a school day, but it has not been used in children aged 8–11 years, the age group of children in this study. After evaluation of previous studies,63,65 the following modifications to the data collection methodology were made:

-

The CADET diary was split into two: a school diary to record all food consumed at school, and a home diary to record all food consumed at home. These two versions of CADET were renamed as the school food diary and home food diary.

-

Additional demographic questions were added to explore the home food environment.

-

On the day after the food-recording day, the fieldworker went back to the school to collect the home food diary, and checked that it had been completed accurately. If a child forgot to return the home food diary a retrospective recall was taken by the fieldworker to record all evening meals and breakfast.

Justification for these changes came from the response rate of a previous study, ‘Project Tomato’. 66 At baseline of Project Tomato, 3159 children took part in the study. Of these children, 280 never returned the CADET diary after it was sent home to be completed by their parents. This meant that the data collected during the whole day were lost, and no data were collected on these children. An additional 170 CADET diaries sent home to be completed by parents were returned without any of the sections completed. This reduced the sample size to 2709 – a loss of 450 children or 14%. Furthermore, when analysing the data collected from this study, children with a total energy intake of < 500 kcal or > 3500 kcal on the day of CADET administration were excluded. This led to a further 179 children being excluded. It was anticipated that some of these errors in data collection would be rectified after splitting the CADET diary into two diaries and having the fieldworker revisit the school to check that the home food diary had been completed.

Portion sizes for children aged 8–11 years

The dietary information from the CADET diary was transferred to a Microsoft Access spreadsheet (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) using our established in-house software, named Diet And Nutrition Tool for Evaluation (DANTE) (Nutritional Epidemiology Group, Leeds). This used standard predefined algorithms to convert food items into total daily nutrient values for each child, based on the composition of foods. 67 Although the CADET diary upon which the school and home food diaries were based has previously been validated in children aged 3–7 years, it has not been used to collect dietary information in 8- to 11-year-olds. As this study includes children aged 7–10 years, it was necessary to change the standard portion sizes in DANTE to reflect the children’s intake for each year of age (i.e. 8, 9, 10 and 11 years), and to account for differences in intake for boys and girls.

Methodology

Protocol for determining portion sizes for children aged 8, 9, 10 and 11 years

The portion sizes for ages 8, 9, 10 and 11 years were obtained from the National Diet and Nutrition Survey (NDNS) of young people aged 4–18 years. 68 The NDNS was conducted to explore food consumption and nutrient intake in the general population living in privately owned houses across Britain. The NDNS data are based on an interview and a 4-day food diary as well as blood and urine samples. The NDNS is the most detailed nutrition survey conducted across Britain. A recent update of the report (2008/09–2009/10) confirmed that the overall diet intake was similar to the previous findings. Owing to the validity of these data, it was decided that they would be used to update the CADET portion sizes for older children. 18

From the NDNS data, the mean portion size, number of participants, standard deviation (SD), and maximum and minimum values were extracted. Nearly all the food items used in the CADET were available from the NDNS data and were then further broken down into each age category by gender. Whereas commonly consumed items such as apples and bananas were consumed by, on average, a higher number of participants in each age group (32 and 24 children on average per age group, respectively), several items were consumed by, on average, fewer than five participants per age group. For these foods, the portions had notably higher variation compared with those foods with a higher number of observations. The likelihood that these portion sizes reflected those of the general population that consumed them was questionable. Furthermore, some food items, once broken down into age/gender categories, were found to have missing data. To improve the validity of those foods with low or missing numbers of participants, the rules in the following sections were applied.

Missing data

If any foods included in the CADET dairy were not available as specific codes/items on the NDNS database, then a similar food item was substituted.

Food items with, on average, fewer than five participants per age/gender category

If the item was consumed by fewer than five participants, on average, per age/gender category, an appropriate nutritionally similar food with an average of 10 or more participants per age/gender category would be obtained. The average of the two means would then be calculated in an attempt to reflect actual intake for each category.

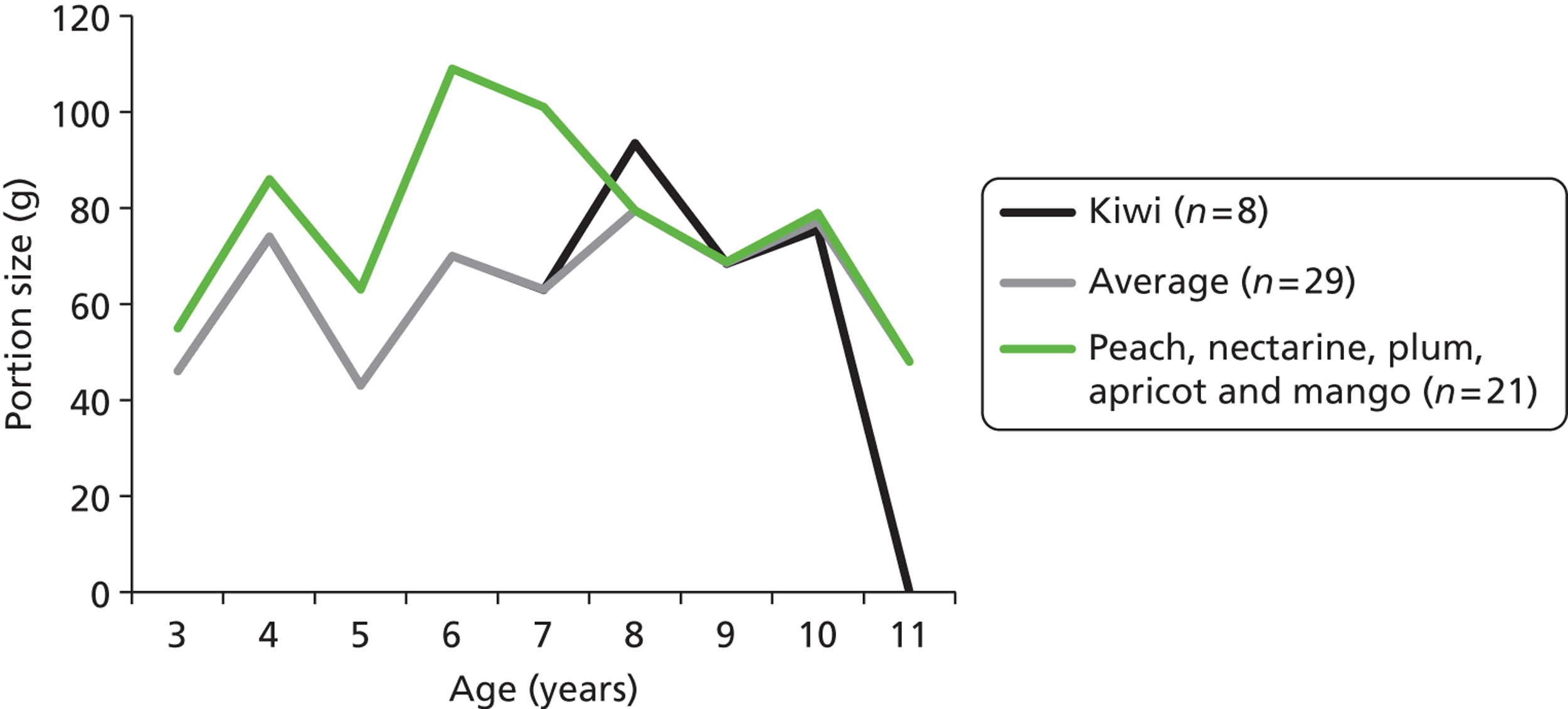

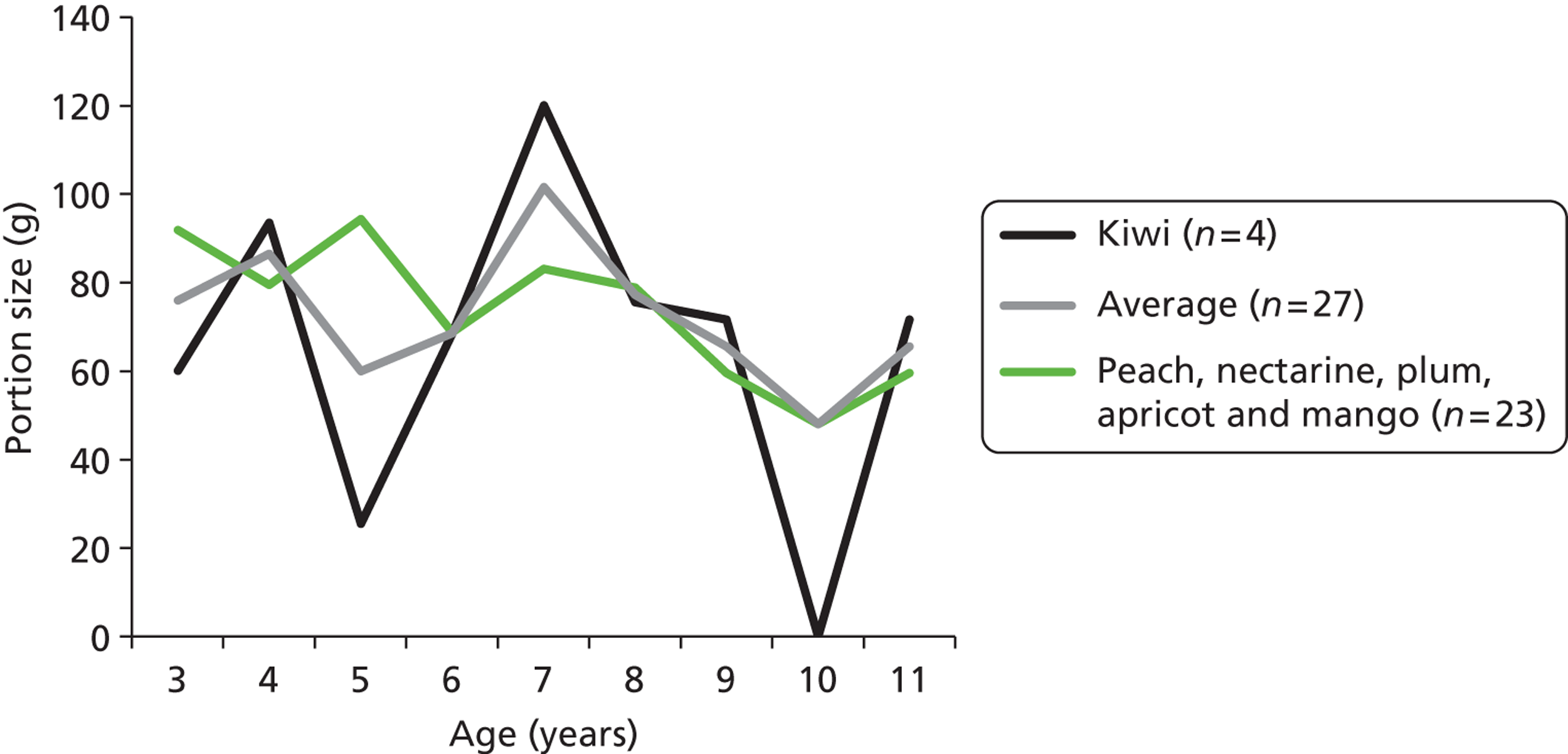

An example of this is kiwi, which had, on average, only one person per age/gender category. It also had no value for girls aged 8 years. For kiwi, an average of kiwi and peach, nectarine, plum, apricot and mango was used to ensure a better representation of the average portion sizes for the different age groups consuming them, based on gender. The aim was to smooth out the data where there were extreme values based on one person, and to gain a more valid estimation of intake. For each food that was changed, a line graph was produced containing both the pre-existing food, for example ‘kiwi’, and the modified food, for example ‘average of kiwi and peach, nectarine, plum, apricot and mango’, to visually confirm that the portion sizes looked appropriate. The reason for doing so was to confirm the direction of change in consumption, as at different ages and for different foods, children can not only increase, but also decrease their consumption. Tables 1 and 2 along with Figures 2 and 3 show the portion sizes for children aged 3–11 years, to demonstrate the overall change in portion sizes by age. The calculations of portion sizes as consumed were made only for children aged 8–11 years.

| Food item | Portion size (g) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age 3 years | Age 4 years | Age 5 years | Age 6 years | Age 7 years | Age 8 years | Age 9 years | Age 10 years | Age 11 years | |

| Kiwi fruit (n = 8) | 46 | 74 | 43 | 70 | 63 | 93 | 68 | 75 | 0 |

| Peach, nectarine, plum, apricot and mango (n = 21) | 55 | 86 | 63 | 109 | 101 | 79 | 68 | 78 | 48 |

| Average (n = 29) | 46 | 74 | 43 | 70 | 63 | 86 | 68 | 76 | 48 |

| Food item | Portion size (g) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age 3 years | Age 4 years | Age 5 years | Age 6 years | Age 7 years | Age 8 years | Age 9 years | Age 10 years | Age 11 years | |

| Kiwi fruit (n = 4) | 60 | 94 | 26 | 68 | 120 | 76 | 72 | 0 | 72 |

| Peach, nectarine, plum, apricot and mango (n = 23) | 92 | 80 | 94 | 69 | 83 | 79 | 60 | 48 | 60 |

| Average (n = 27) | 76 | 87 | 60 | 69 | 102 | 74 | 66 | 48 | 69 |

FIGURE 2.

Girls’ portion sizes by age, for different fruits in CADET.

FIGURE 3.

Boys’ portion sizes by age, for different fruits in CADET.

Modifications

Of the 115 foods in the school and home food diaries, 21 had no dietary examples from the NDNS data and 16 had an average sample size of fewer than five participants. Table 3 lists the food items from CADET that did not have a NDNS portion size, and the food groups used as a substitute to create an appropriate portion size for consumers. Table 4 lists the foods with an average of five or fewer participants per age group in the NDNS data, and the food groups that were used as a substitute.

| Food group | Substitute food portion | Portion size (g) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boys aged 8 years | Girls aged 8 years | Boys aged 9 years | Girls aged 9 years | Boys aged 10 years | Girls aged 10 years | Boys aged 11 years | Girls aged 11 years | ||

| Chapatti/pitta bread/wrap/roti | Bread sticks and garlic bread/naan/paratha | 42 | 23 | 32 | 44 | 31 | 52 | 26 | 45 |

| Cottage cheese | Cheese spread, triangles | 26 | 22 | 24 | 22 | 26 | 23 | 36 | 25 |

| Chicken in a creamy sauce | Other meats: stew, casserole, mince, curry or keema | 139 | 159 | 144 | 118 | 115 | 115 | 164 | 151 |

| Vegetable pie/pasty | Sausage roll, meat pie, pasty, fried dumplings | 118 | 126 | 126 | 127 | 138 | 122 | 148 | 143 |

| Samosa/pakora/bhajee | Vegetable pie, pasty | 118 | 126 | 126 | 127 | 138 | 122 | 148 | 143 |

| Quorn™/vegetarian mince/sausages | Sausage roll, meat pie, pasty, fried dumplings | 66 | 69 | 64 | 69 | 77 | 69 | 82 | 72 |

| Paneer (cheese curry) | Other meats: stew, casserole, mince, curry or keema | 139 | 159 | 144 | 118 | 115 | 115 | 167 | 151 |

| Fried rice | Boiled rice | 132 | 100 | 143 | 120 | 151 | 134 | 172 | 122 |

| Pasta with meat/fish and sauce | Average of pasta with a cheese sauce and pasta with tomato sauce | 164 | 155 | 170 | 231 | 238 | 160 | 144 | 185 |

| Stir-fried vegetables | Average of carrots, cauliflower and peas | 46 | 47 | 53 | 56 | 67 | 63 | 61 | 53 |

| Courgettes | Average of carrots, cauliflower and peas | 46 | 47 | 53 | 56 | 67 | 63 | 61 | 53 |

| Spinach | Lettuces | 19 | 16 | 21 | 35 | 25 | 22 | 22 | 28 |

| Parsnips | Carrots | 44 | 38 | 44 | 52 | 55 | 54 | 49 | 47 |

| Radishes | Average of peppers and salad | 11 | 11 | 12 | 10 | 24 | 22 | 26 | 36 |

| Leeks | Onions | 15 | 15 | 15 | 28 | 26 | 23 | 35 | 20 |

| Other vegetables | Average of carrots, cauliflower and peas/sweetcorn | 46 | 47 | 53 | 56 | 67 | 63 | 61 | 53 |

| Lentils/dahl | Peas and sweetcorn | 42 | 36 | 59 | 55 | 69 | 46 | 59 | 52 |

| Other beans | Brussels sprouts | 42 | 36 | 59 | 55 | 69 | 46 | 59 | 52 |

| Pineapples | Grapes | 84 | 58 | 61 | 105 | 40 | 90 | 85 | 90 |

| Other fresh fruit | Peaches, nectarines, plums, apricots, mangoes and average of strawberries/grapes | 100 | 92 | 111 | 72 | 88 | 89 | 71 | 97 |

| Mousse/milk/rice puddings | Custard | 97 | 91 | 109 | 105 | 112 | 80 | 146 | 104 |

| Food group | Substitute food | Portion size (g) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boys aged 8 years | Girls aged 8 years | Boys aged 9 years | Girls aged 9 years | Boys aged 10 years | Girls aged 10 years | Boys aged 11 years | Girls aged 11 years | ||

| Croissants/waffles/Pop-Tarts® | Crumpets/pikelets/scotch pancakes | 52 | 54 | 52 | 53 | 67 | 57 | 65 | 52 |

| Nuts | Dried fruit | 35 | 54 | 23 | 36 | 31 | 38 | 49 | 34 |

| Quiche | Sausage roll, meat pie, pasty, fried dumplings | 77 | 80 | 77 | 79 | 76 | 81 | 79 | 84 |

| Corned beef, luncheon meats/salami | Ham | 52 | 31 | 32 | 39 | 64 | 52 | 49 | 40 |

| White fish (not fried) | Fish in breadcrumbs and fishcakes | 80 | 78 | 112 | 81 | 83 | 79 | 83 | 62 |

| Shellfish, e.g. prawns/mussels | Tuna and other oily fish | 44 | 33 | 56 | 50 | 54 | 54 | 45 | 47 |

| Offal | Ham | 24 | 18 | 28 | 27 | 63 | 47 | 38 | 39 |

| Celery | Salad vegetables | 27 | 8 | 17 | 33 | 24 | 22 | 26 | 36 |

| Peppers (red, green, yellow) | Salad vegetables | 15 | 8 | 15 | 38 | 23 | 19 | 16 | 25 |

| Strawberries/raspberries | Grapes | 107 | 104 | 128 | 105 | 93 | 99 | 82 | 90 |

| Pears | Apples | 130 | 123 | 127 | 95 | 108 | 114 | 123 | 115 |

| Melons/watermelons | Bananas | 199 | 167 | 138 | 220 | 171 | 133 | 102 | 140 |

| Kiwi fruits | Peaches, nectarines, plums, apricots, mangoes | 76 | 87 | 60 | 69 | 102 | 77 | 66 | 48 |

| Sugar-coated cereals | High-fibre cereals, e.g. bran flakes, Weetabix®, Shreddies® | 43 | 40 | 18 | 36 | 17 | 38 | 46 | 46 |

Table 5 shows the final portion sizes for all vegetables, as used in DANTE for the CADET diaries, for boys and girls across the different age groups. Overall, there is a general trend towards a small increase in vegetable consumption for both boys and girls. However, there is more variability between the different ages for both boys and girls in fruit intake (Table 6). Melon and watermelon portion sizes vary greatly between year groups; this could be a consequence of the infrequent consumption of both of these fruits. It was decided not to overmanipulate the data and to leave these portion sizes as they are, as the NDNS data are based on weighed intakes from a nationally representative sample.

| Food | Portion size (g) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boys aged 8 years | Girls aged 8 years | Boys aged 9 years | Girls aged 9 years | Boys aged 10 years | Girls aged 10 years | Boys aged 11 years | Girls aged 11 years | |

| Baked beans | 95 | 97 | 112 | 97 | 113 | 92 | 104 | 104 |

| Broccoli, Brussels sprouts, cabbages | 50 | 59 | 53 | 52 | 68 | 56 | 60 | 67 |

| Carrots | 42 | 32 | 40 | 58 | 54 | 56 | 41 | 42 |

| Cauliflowers | 52 | 66 | 54 | 61 | 78 | 88 | 75 | 61 |

| Celery | 27 | 8 | 17 | 33 | 24 | 22 | 26 | 36 |

| Coleslaw | 47 | 44 | 47 | 35 | 42 | 38 | 64 | 42 |

| Courgettes | 46 | 47 | 53 | 56 | 67 | 63 | 61 | 53 |

| Cucumbers | 32 | 27 | 25 | 34 | 23 | 31 | 25 | 28 |

| Leeks | 15 | 15 | 15 | 28 | 26 | 23 | 35 | 20 |

| Lentils, dahl | 42 | 36 | 59 | 55 | 69 | 46 | 59 | 52 |

| Mixed vegetables | 42 | 36 | 59 | 55 | 69 | 46 | 46 | 52 |

| Other beans, pulses | 42 | 36 | 59 | 55 | 69 | 46 | 59 | 52 |

| Other salad vegetables | 19 | 16 | 21 | 35 | 25 | 22 | 22 | 28 |

| Other vegetables | 46 | 47 | 53 | 56 | 67 | 63 | 61 | 53 |

| Parsnips | 44 | 38 | 44 | 52 | 55 | 54 | 49 | 47 |

| Peas, sweetcorn | 42 | 36 | 59 | 55 | 69 | 46 | 59 | 52 |

| Peppers (red, green, yellow, etc.) | 15 | 8 | 15 | 38 | 23 | 19 | 16 | 25 |

| Radishes | 11 | 11 | 12 | 10 | 24 | 22 | 26 | 36 |

| Spinach | 19 | 16 | 21 | 35 | 25 | 22 | 22 | 28 |

| Stir-fried vegetables | 46 | 47 | 53 | 56 | 67 | 63 | 61 | 53 |

| Tomatoes | 69 | 75 | 24 | 64 | 33 | 69 | 47 | 41 |

| Food | Portion size (g) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boys aged 8 years | Girls aged 8 years | Boys aged 9 years | Girls aged 9 years | Boys aged 10 years | Girls aged 10 years | Boys aged 11 years | Girls aged 11 years | |

| Apples | 123 | 117 | 117 | 122 | 120 | 114 | 123 | 115 |

| Bananas | 104 | 93 | 110 | 119 | 114 | 119 | 102 | 116 |

| Dried fruit | 35 | 54 | 23 | 36 | 31 | 38 | 49 | 67 |

| Fruit salad (tinned or fresh) | 107 | 104 | 128 | 105 | 93 | 99 | 82 | 90 |

| Grapes | 84 | 58 | 61 | 105 | 40 | 90 | 85 | 90 |

| Kiwi fruits | 76 | 87 | 60 | 69 | 102 | 77 | 66 | 48 |

| Melons | 199 | 167 | 138 | 220 | 171 | 133 | 102 | 140 |

| Oranges, satsumas, etc. | 132 | 160 | 117 | 137 | 105 | 140 | 84 | 57 |

| Other fruit | 100 | 92 | 111 | 72 | 88 | 89 | 71 | 97 |

| Peaches, nectarines, plums, apricots, mangoes | 92 | 80 | 94 | 69 | 83 | 79 | 60 | 48 |

| Pears | 130 | 123 | 127 | 95 | 108 | 114 | 123 | 115 |

| Pineapples | 84 | 58 | 61 | 105 | 40 | 90 | 85 | 90 |

| Strawberries, raspberries, etc. | 107 | 104 | 128 | 105 | 93 | 99 | 82 | 90 |

Additional demographic questions

There were several questions added to part two of the CADET diary. The first set of questions explored the availability of fruit and vegetables at home, and children’s and parents’ fruit and vegetable consumption habits. An example question is ‘do you buy a specific fruit/vegetable because your child asked for it?’ The parents were presented with the response options of ‘yes, always’, ‘yes, most days/often’, ’sometimes’, ‘rarely’ and ‘never’. These questions were based on the existing literature. 69 This research explored the availability and accessibility of fruit and vegetables in the home environment. Test–retest reliability was conducted in five different European countries: Norway, Spain, Denmark, Portugal and Belgium. The intraclass correlation coefficient was 0.6, suggesting that it is a reliable tool to use in primary school-aged children. 70

A second set of six questions was added regarding the family’s fruit and vegetable intake. These questions were developed from a previous study,71 and addressed parents’ reasons for buying fruit and vegetables for their families and the importance of buying fruit and vegetables. One such question addressed the ‘price of fruit and vegetables’; parents were provided with the options of ‘very important’, ‘important’, ‘neither unimportant or important’, ‘unimportant’ and ‘very unimportant’.

The third and final question that was added to the home food diary was a request for an inventory of fruit and vegetables that were in the house on the evening the diary was completed. This question listed common fruit and vegetables consumed and asked the parents to tick any that were currently in their food cupboards or fridge. There was also a section designated ‘other’ for any items that were not listed.

These questions in part two were included to provide some understanding of the home food environment, providing us with insight into the availability of fruit and vegetables, and parents’ attitudes towards fruit and vegetables. This insight is crucial, as the home food environment is a key influence on children’s food intake. 72

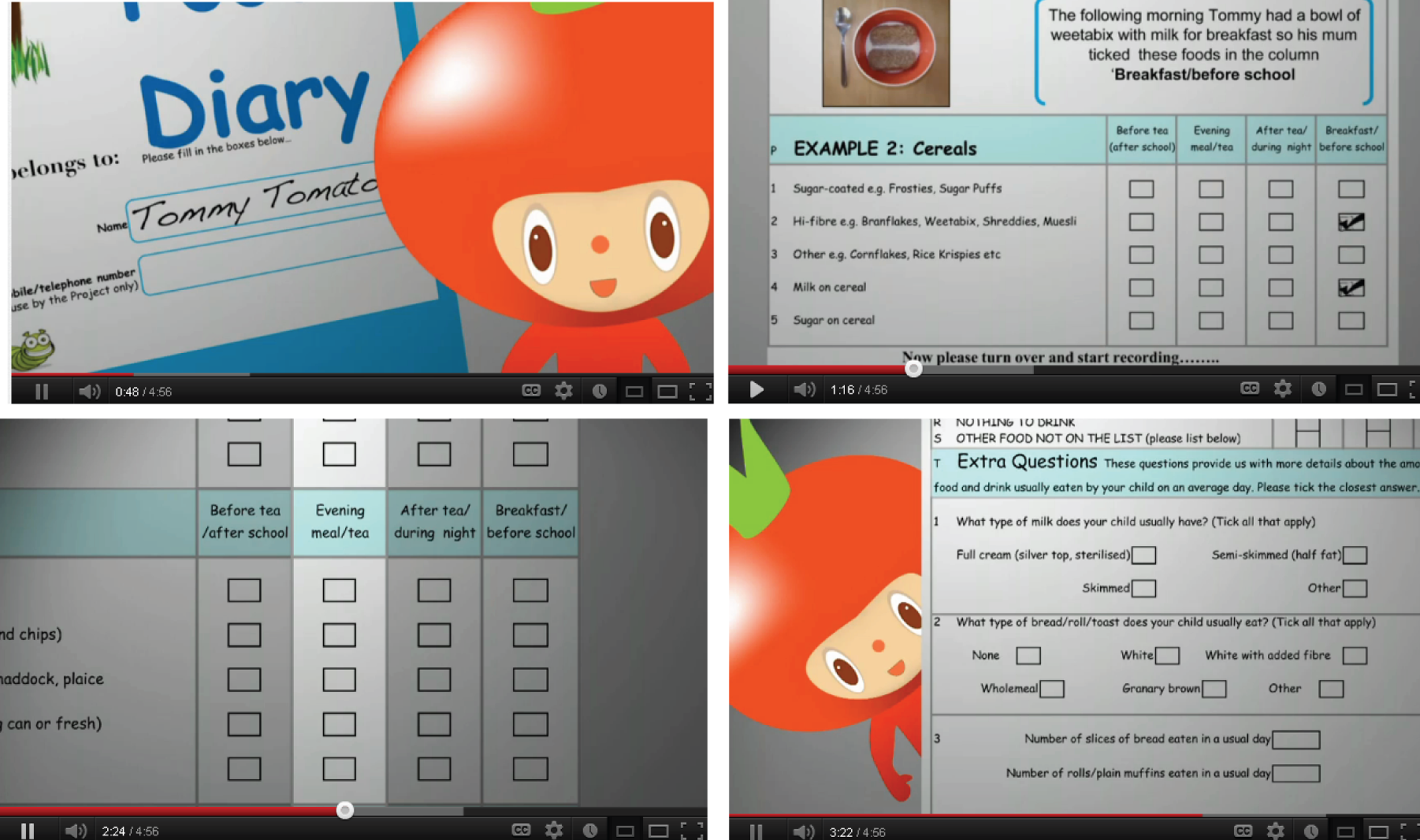

Development of the home food diary instruction DVD

Previous studies that have implemented the CADET diary to measure dietary intake have identified that parents and children with low literacy or English as a second language struggle to complete the diary. 64 Although the CADET diary had two pages of simple instructions on how to complete it, it was evident that some participants still did not understand what was required of them. Sometimes children or parents would complete the diary, ticking every item in the diary that the child liked, rather than only those foods that the child had eaten that day. Some did not complete the CADET at all, and simply did not return it to the school, despite several reminders. To improve accuracy and completion of the home food diary, the concept of creating an instructional DVD for parents and children to watch was developed (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

Images from the CADET DVD. © University of Leeds. Reproduced with permission.

The DVD script was written with the aim of encouraging children and parents to watch the DVD together. It used a cartoon character to explain each step of the diary, while showing the actual diary on-screen for parents and children to follow. The script was written by MSC with input from PhD supervisors, with the aim of introducing the study to the audience and explaining how to complete the home food diary, step by step. The main aims of the script were to introduce the study, remind the children to make sure their parents were watching, demonstrate how to complete the diary for each meal, explain what ‘part two’ questions consisted of and remind participants to return the diary to school the next day. It also provided a contact number for parents to ring if they had any queries.

It was decided that a cartoon character would be the narrator and would resemble the characters used by the Nintendo Wii™ console. The cartoon character was a tomato called ‘Tom the Tomato’, which had a head like a tomato and a red body, alive in a plant pot. The concept behind using a cartoon character was to make the DVD child-friendly so that hopefully children and parents would find it interesting. To construct the DVD, Leeds Media Service were contracted. It was decided that the voice of Tom the Tomato would be a child’s voice, and Emily Cade, who was 16 years of age, was recruited as she had a clear speaking voice with very little regional accent. The total length of the instruction DVD is 5 minutes. The end product is a useful tool for anyone completing the home food diary questionnaire as it both ‘verbally tells you’ and ‘visually shows you’ how to be complete the form (see https://youtube.googleapis.com/v/AIbzqaJiHq0%26hl=en_US%26fs=1%26rel=0%26hd=1).

Secondary outcome questionnaires

Development of the questionnaire on knowledge and attitudes towards fruit and vegetables

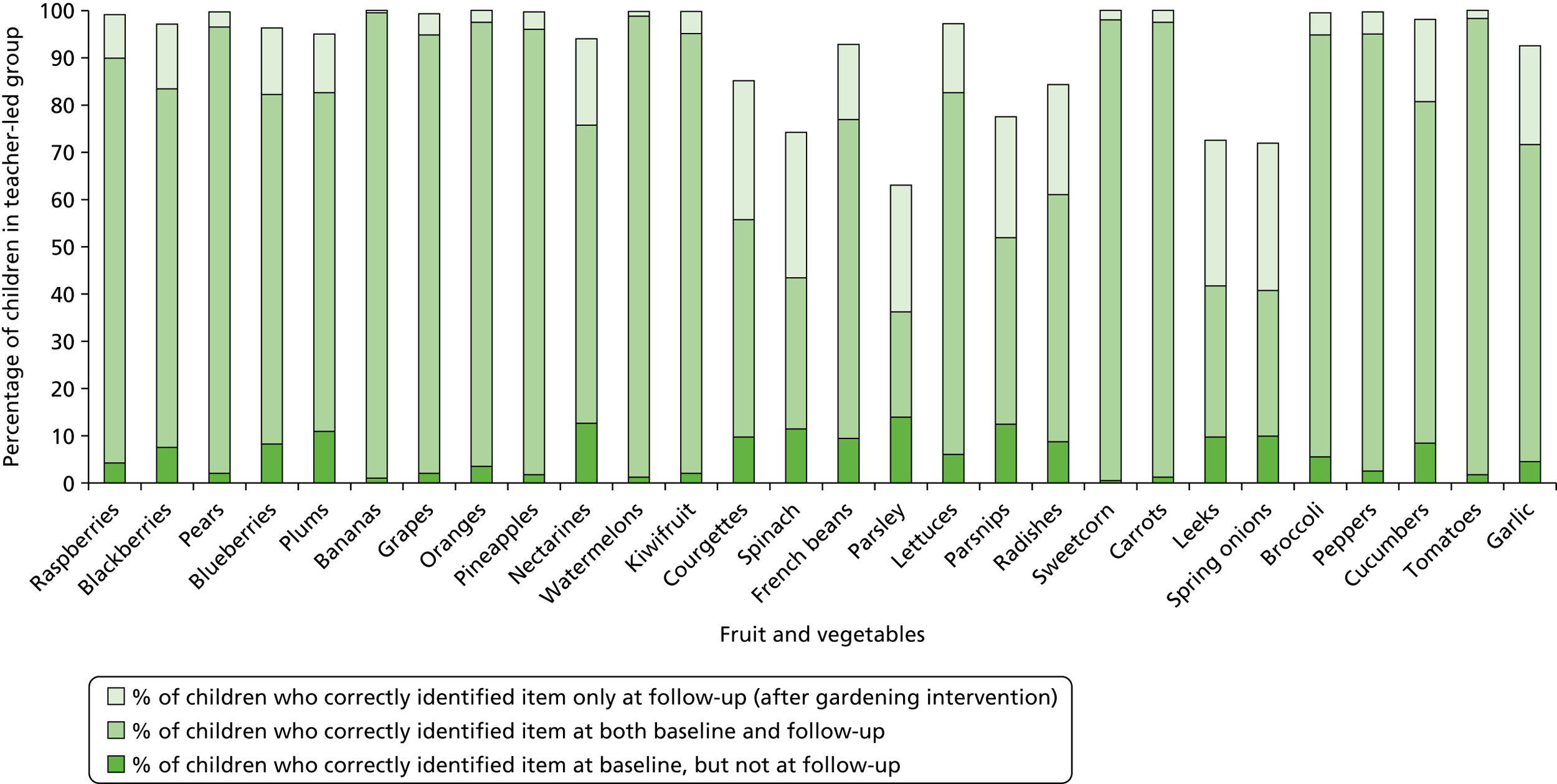

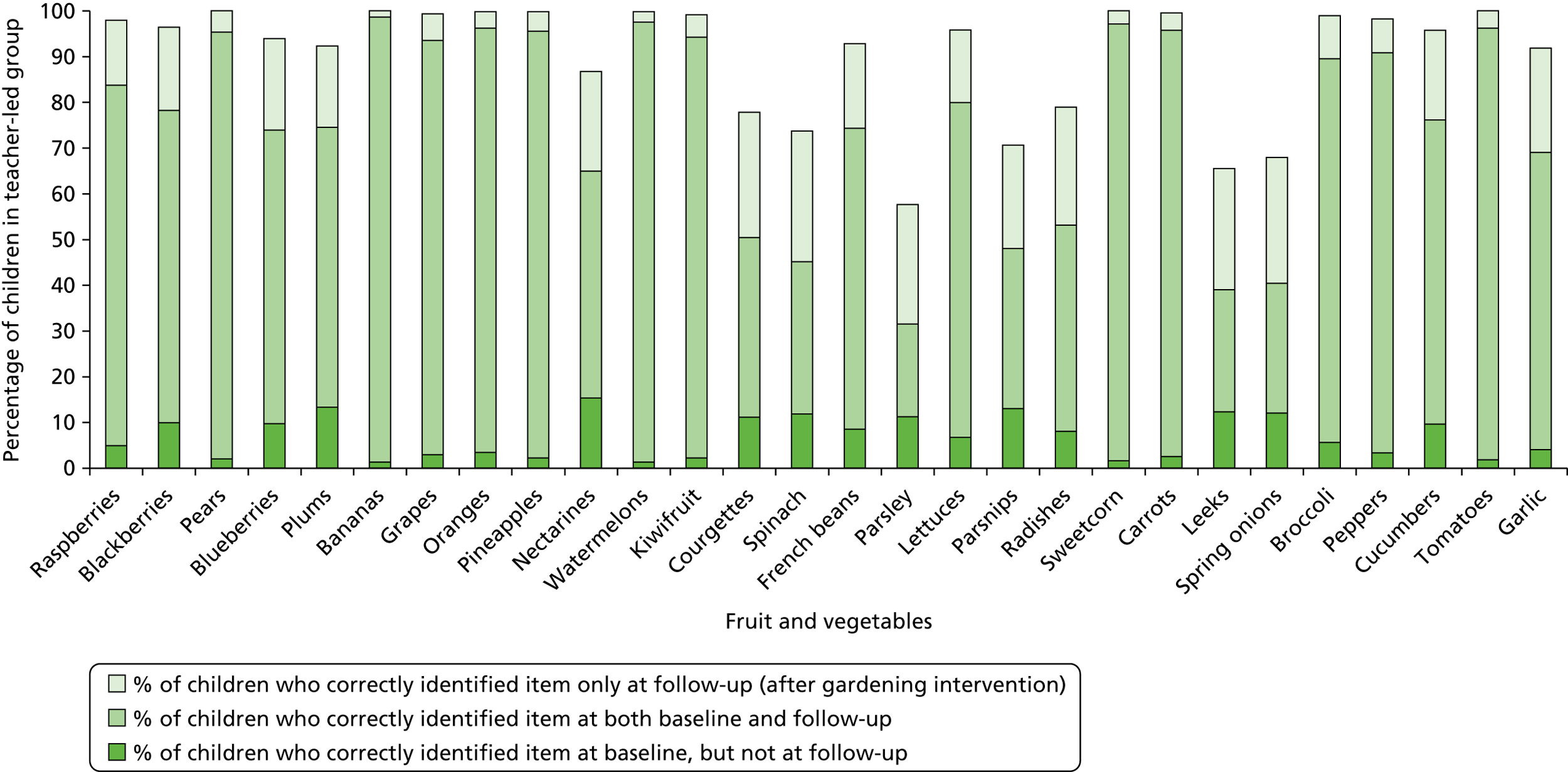

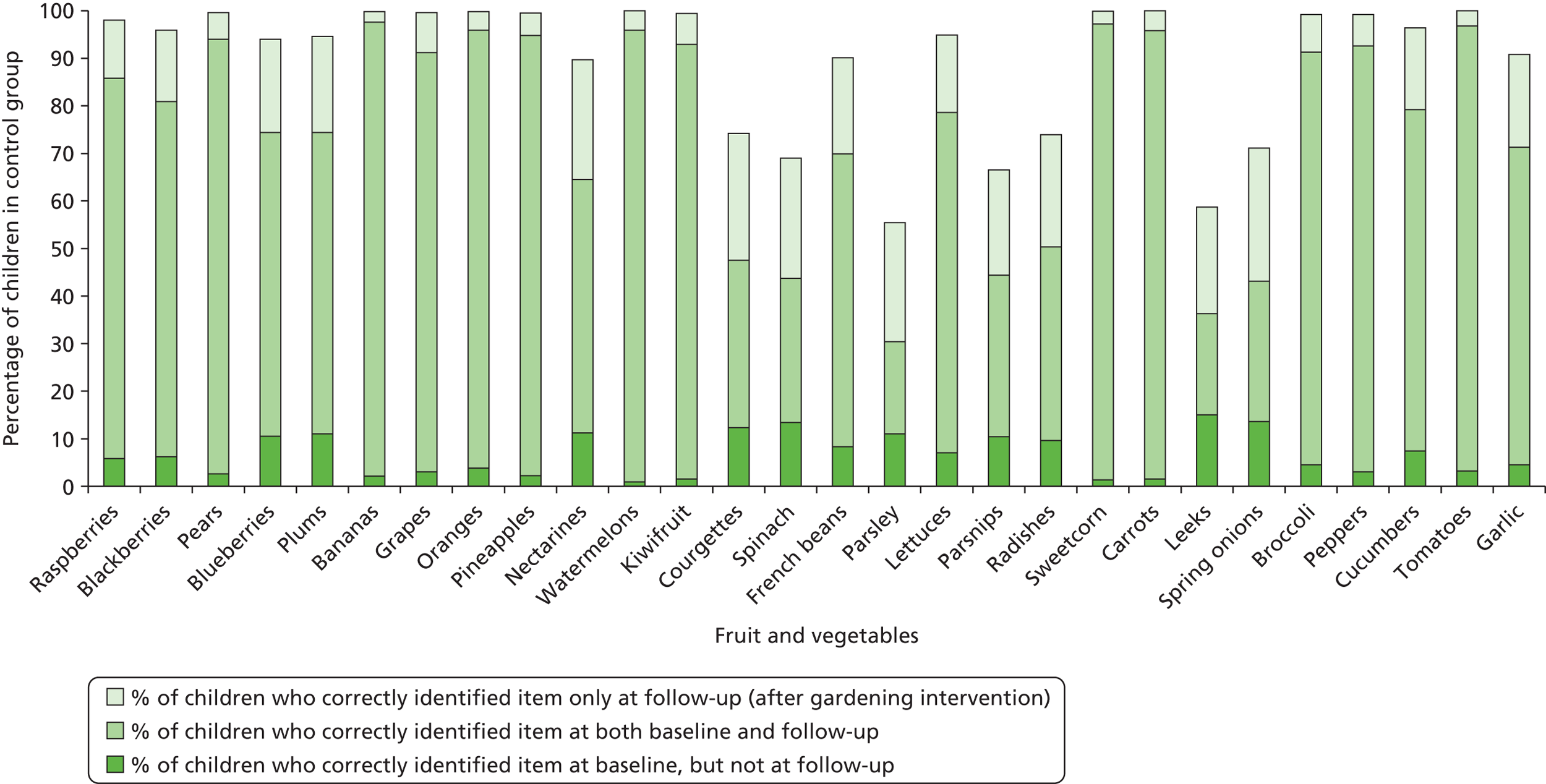

One of the secondary outcome measures was ‘Can participating in a school gardening intervention improve children’s ability to identify specific fruit and vegetables and their attitudes towards fruit and vegetables?’

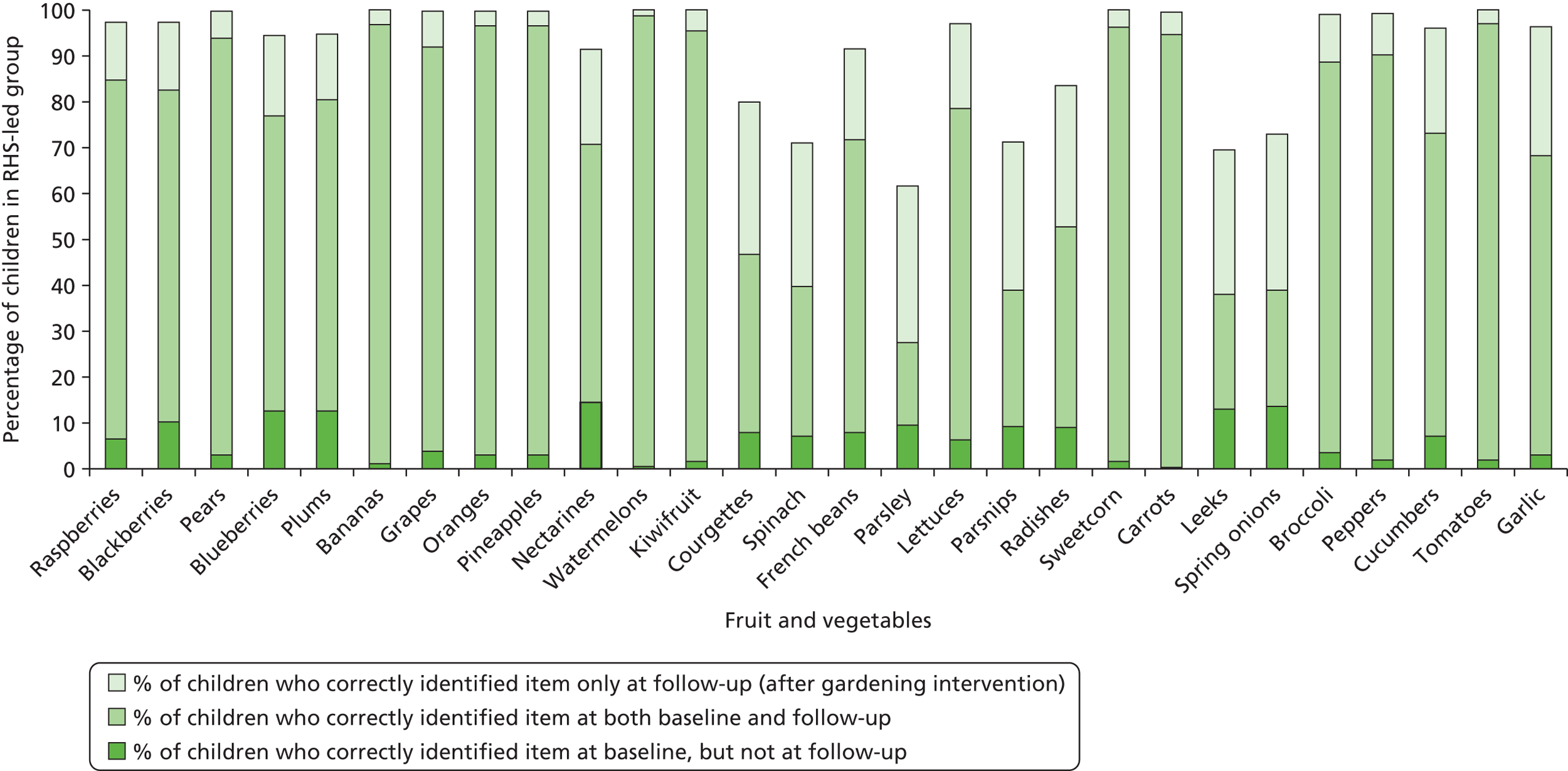

Since the RHS gardening intervention is an educational resource that teaches children about fruit and vegetables through gardening, it has the potential to have an impact on children’s general knowledge of fruit and vegetables. Therefore, one of the other main aims of this study was to explore change in children’s knowledge and attitudes towards fruit and vegetables, to see if there was a difference from baseline to follow-up. A short questionnaire was developed to identify children’s knowledge and attitudes towards fruit and vegetable consumption, and to assess gardening activity levels (see Appendix 1, Child knowledge and attitudes questionnaire). The knowledge questions assessed children’s ability to recognise different fruit and vegetables. Children were presented with a list of 13 fruits, 17 vegetables and one herb, with a colour picture for each, and were asked to draw a line connecting each name with the right picture. The attitude questions were based on previously validated research. 73 Children were asked if they agreed or disagreed with ideas about fruit and vegetables, and were presented with a list of 10 statements, five of these about fruit and five about vegetables. An example is ‘I enjoy eating fruit’. The children had to circle one of four options: ‘agree a lot’, ‘agree a little’, ‘disagree a lot’ or ‘disagree a little’. Images of smiley, neutral or sad faces were presented above each statement to help the children work out their response.

The gardening questions assessed the children’s gardening experience, in terms of what they have grown and what they have tasted. The children were asked to confirm if they had done any gardening (‘yes’ or ‘no’) and then write in the space provided if they had grown any fruit or vegetables. They were then asked to confirm if they had tasted any of the fruit or vegetables they had grown (‘yes’ or ‘no’) and to write down what they had tasted.

To assist with the varying levels of reading ability, this questionnaire was read out to the children as a class, to help them with any difficult words. Furthermore, the teachers and teaching assistants were encouraged to help those children who might struggle with this task, and children were encouraged to put their hands up if they had any questions.

Process measures questionnaires

There were two process measures components for this study; the first was a gardening telephone interview, to identify current level of gardening activities within the school (see Appendix 1); the second was a gardening activity process measures questionnaire to identify the gardening activities that had taken place in each academic year in each school.

School gardening questionnaire

The school gardening questionnaire was a telephone interview. It was designed to identify the school’s baseline gardening level. This questionnaire was based on the RHS benchmarking scheme, which ranks schools in the following categories: (1) planning, (2) getting started, (3) growing and diversifying, (4) sharing best practice and (5) celebrating with the wider community. The schools were asked a series of questions to identify different aspects of gardening currently occurring in their school garden. The questions were focused on the following aspects of gardening in schools: school culture and ethos, the school garden, teaching and learning, and community. Within each of these areas there were several questions that reflected different levels of development within school gardening relating to the five stages of developing a school garden. These questions were adapted as simple ‘yes or no’ questions to be used in a telephone interview. The interviewee was the school staff member who was most involved in the school garden within each school. The questions were structured according to the five categories.

Gardening activity process measures questionnaire

The aim of the gardening activity questionnaire was to identify the level of adherence to the intervention by the schools involved, and to identify any gardening activities that are being undertaken by the control schools. The main aim of the process evaluations was to capture which fruit and vegetables each school grows and harvests. They also aimed to identify which year groups had been involved in the garden each year, whether or not they had started a growing or environmental club, and to find out if the schools had any success or failure stories around the school garden. This information was captured via e-mail in September 2010 for trial years 1 and 2, and again in September 2011 for both trials.

For the schools involved in the RHS intervention, more in-depth information about their intervention activities was captured by the regional advisor and was used to outline changes in school gardening. From this, the level of involvement in the intervention by each school and their adherence to the intervention was identified, as well as success and failure stories reported by the regional advisor himself.

For trial 2 intervention schools, another process measure captured was the level of involvement in the twilight sessions, whereby the regional advisor kept a record of the teacher’s attendance. With this type of intervention, schools were expected to tailor the intervention to their individual needs. By monitoring what activities are undertaken in the school garden, aspects of the intervention that could be associated with dietary change were identified.

Questionnaire development summary

The main aim of the dietary assessment tool was to collect information on children’s fruit and vegetable intake, while also collecting information on all the food the children consumed in one 24-hour period. Whereas one 24-hour food diary has been used previously, for this study CADET was changed and modified into a school food diary and a home food diary, to improve the response rate for the home food diary. Furthermore, the portion sizes used to analyse the children’s food intake were changed to reflect the age- and gender-related portion sizes of the sample. A DVD was also designed to help parents and children understand how to complete the home food diary. The final modification was a change in the administration of the diaries, with the fieldworkers returning to each school the day after collection, to collate and check the diaries and to identify any that had not been completed properly. An additional step was to collect a dietary recall of food and drink consumed at home from children who had not returned their diaries that day.

To ensure that these portion sizes reflected actual dietary intake, it was necessary to test this instrument – the home and school food diaries – against an appropriate reference measurement, such as a 1-day weighed record in children of the relevant ages in Years 3, 4, 5 and 6. 19,74

Additional questionnaires were designed to measure the secondary outcome measures for this study:

-

a child knowledge and attitudes questionnaire

-

a gardening telephone interview questionnaire

-

a gardening in schools process measures questionnaire.

These questionnaires were designed to capture important information to evaluate the effectiveness of the RHS gardening intervention, through evaluating children’s learning and knowledge with a focus on fruit and vegetables, capturing change in schools’ gardening involvement based on RHS gardening levels and assessing implementation of the intervention or other gardening activities in schools. Examples of all questionnaires can be found in Appendix 1.

Piloting baseline materials

Owing to the changes made to the original CADET diary, the collection method and the development of the new questionnaires (including the child knowledge and attitudes questionnaire) as well as the instruction DVD, it was necessary to pilot these materials. Two primary schools in West Yorkshire were recruited to be involved in a pilot study of the collection procedure and the new materials, namely the school and home food diaries, the child knowledge and attitudes questionnaire, the school gardening questionnaire and the instructional DVD.

The aims and objectives of the pilot study were:

-

to determine whether the DVD should be shown in the classroom at school, or sent home with the children for them and their parents to watch together

-

to confirm that the questionnaire was age-appropriate in terms of language used and layout, and to identify whether or not there were any questions that children struggled to answer

-

to test the new data collection protocol and explore the potential benefits of having the fieldworkers check the home food diary the following day.

Methodology

Study population

A total of 74 Year 3 and 4 children from two local primary schools in Leeds (mean age 8.4 years) participated in the pilot study. This involved three different class groups: one Year 3, one Year 4 and a mixed Year 3 and 4 class. To evaluate whether the DVD should be sent home or viewed in school, one class was allocated to receive the DVD to watch in class, another was allocated to be given the DVD to take home and the third class was allocated not to receive the DVD at all.

Masters students in nutrition were recruited and trained to administer the CADET diaries and the child knowledge and attitudes questionnaire. The students were asked to record everything the children ate at school by completing the school food diary, and then to go through the child knowledge and attitudes questionnaire as a class. At the end of the school day, one class of children was given the home food diary, one class was asked to watch the DVD before they were given the home food diary, and the final class was given the DVD and the home food diary and asked to watch the DVD with their parents.

Results

A total of 74 children were invited to participate in the pilot study, of which 62 parents agreed to let their children participate. The results from this study are presented in Table 7.

| Allocation of DVD | Response rate, n (%) | Boys, n (%) | Year level | Returned the home food diary, n (%) | Home food diary recalls, n (%) | 5 A DAY ‘correct’ answer, n (%)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Received the DVD to take home (n = 33) | 30 (90) | 13 (43) | 3 and 4 | 25 (83) | 5 (17) | 19 (63) |

| Watched the DVD at school (n = 22) | 15 (68) | 9 (60) | 3 | 11 (73) | 4 (27) | 8 (53) |

| No DVD given (n = 19) | 17 (89) | 10 (59) | 4 | 8 (42) | 9 (53) | 9 (53) |

Home food diary and instruction DVD

One of the aims of the pilot study was to evaluate whether the DVD should be shown in the classroom at school, or sent home with the children for them and their parents to watch together; there were concerns about children forgetting to return the DVD to the school the next day, and losing the DVD. The results indicated that children who received the DVD to take home and watch with their parents had a higher home food diary return rate (83%) compared with those who watched the DVD in class (73%) or did not receive the DVD (52%). Of those parents who confirmed that they had watched the DVD, all completed the home food diary correctly. Therefore, it was decided that all children should receive the DVD to take home and watch with their parents to improve the quality of the data collected.

School food diary

The fieldworkers were also required to complete the school food diary for all the children in the pilot study. It was brought to our attention that Yorkshire pudding was not included in the school food diary, as one school had it as part of its school dinners; it was then added to both the school and home food diaries. There was also a comment from one of the parents about the home food diary; they stated that they would prefer their ethnicity to be classified as ‘British Asian’ rather than ‘Asian British’. This was rectified.

Data collection protocol

On the second day of data collection, the fieldworkers had two tasks: (1) to check that the home food diary was completed properly, and (2) to complete a diet recall for those children who did not return the home food diary. These results reveal that 25% of the total sample did not return the home food diary. Of the children who were allocated to watch the DVD with their parents, only 17% needed a diet recall to be taken, compared with 27% of those who watched the DVD at school and 42% of those who did not receive the DVD.

Knowledge and attitudes questionnaire results

To assist with the psychological questions and the variability in children’s reading ability, the knowledge and attitudes questionnaire was read aloud to the children and completed together as a class. Teachers were encouraged to assist any children who they thought might struggle with completing the questionnaire.

Administration of the questionnaires was successfully completed. There were six different sections in the child questionnaire. There was only one section which children struggled to complete; this was section 4, containing psychological questions about gardening and fruit and vegetable self-efficacy. Children were asked to respond ‘agree a lot’, ‘agree a little’, ‘disagree a little’ or ‘disagree a lot’ to each of these questions (presented in Table 8). In view of the feedback from fieldworkers, five of the questions were removed. Furthermore, a smiley face or sad face was added under the different options (‘agree a little’, etc.) to help children choose how to respond to each of these questions.

| Question | Question removed? |

|---|---|

| I like trying new fruits | No |

| I like trying new veg | No |

| Eating fruit and veg every day keeps me healthy | No |

| Most fruit tastes bad | Yes |

| We have veg with dinner most nights | Yes |

| There’s usually lots of fruit and veg snacks at home | Yes |

| I’m good at preparing fruit and veg | No |

| I like raw veg | Yes |

| We grow fruit or veg at home | Yes |

| My parents encourage me to eat fruit and veg | No |

| I enjoy eating fruit | No |

| I enjoy eating vegetables | No |

| I try to eat lots of fruit | No |

| I try to eat lots of vegetables | No |

| I find it easy to eat lots of fruit | No |

| I find it easy to eat lots of vegetables | No |

The results also revealed that, on average, when asked how many fruit and vegetables one should eat every day to stay healthy, 52% of the children were not aware that they should consume at least five portions of fruit and vegetables a day.

Discussion

Accurately measuring children’s energy and nutrient intake is challenging, especially in a large trial such as this, as there are always benefits and limitations of any nutritional assessment tool. Research suggests that children are aware of what they consume from around 8 years old. 75 For primary school-aged children, parents are often used to collect the dietary information as the children themselves are considered too young to collect accurate dietary data. However, dietary analysis is prone to many forms of measurement error. 76 CADET has been validated in an ethnically diverse population62 and has been used to evaluate large intervention studies. These include the national free school fruit scheme in primary school children,63 and a large national RCT of an intervention to maintain fruit and vegetable eating in Year 3 children once they are no longer eligible for free fruit. 77,78 The style of CADET, using a simple tick-box list, is considered an appropriate tool for people with low literacy who struggle to record or weigh what they eat. The main benefit of using a 24-hour tool is that it is easy to complete in a large sample at a relatively low cost. 79 This style of nutrition analysis will capture the mean intake of a population, and is the standard method used for intervention evaluation. The disadvantage of 24-hour data is that they cannot be used to analyse individual intake, as the instrument is not sensitive enough to identify individual differences in dietary patterns. 50,79 Nevertheless, CADET has been proven to be a valid tool for evaluating intervention studies in trials,62,64,77 and it is an effective way to capture fruit and vegetable intake in children.

There were three main aims of the pilot study. The first was to determine whether the children should take the DVD home to watch, or watch it at school. The results revealed that children and parents who watched the DVD together had a higher response rate than children who watched the DVD at home on their own, or who did not watch the DVD at all. The second aim was to test the child knowledge and attitudes questionnaire, to confirm that the questionnaire was age-appropriate in terms of language used and to identify whether or not there were any questions that children struggled to answer. This identified that children struggled with some of the psychological questions, such as ‘We have veg with dinner most nights’ and ‘There’s usually lots of fruit and veg snacks at home’; therefore, these questions were removed. The final aim of the pilot study was to test the new protocol methodology. On the second day of data collection, 18 (25%) of the children did not bring back a home food diary; if the fieldworkers had not conducted a recall, then 25% of the sample diet data would have been lost. The fieldworkers also provided positive comments regarding conducting the diet recall. This is supported by other research which states that children are aware of what they consume from around 8 years of age, the mean age of the trial children. 80

Overall, the aims of the pilot study were achieved, and the results were able to provide important feedback in the development of the necessary tools needed to evaluate the RHS gardening intervention.

Summary

This chapter has discussed the methodology used in designing the data collection tools for this study. It also discussed the pilot study conducted in Leeds and the changes made as a consequence of this process.

The pilot study revealed that it was beneficial for parents to watch the DVD at home with their children, when compared with children who watched the DVD at school or not at all. It also highlights some of the psychological questions that children in Years 3 and 4 struggled to understand, and some minor changes made to the food diaries. These changes and additions to the collection methodology aim to improve the overall response rate and quality of the data collected.

Chapter 3 Methodology

This chapter outlines the general methodological components that applied to both trials. It will discuss:

-

sampling and recruitment of schools (inclusion and exclusion criteria)

-

sample size calculation

-

randomisation methodology

-

training of fieldworkers to collect the baseline and follow-up data

-

the two interventions: RHS-led and teacher-led

-

data cleaning methodology.

It should also be noted that this chapter is based on a published protocol written by MSC. 81

Sampling and recruitment of schools

It is RHS policy to provide support to all schools that register an interest in the campaign. As a consequence of this, two linked trials were required. All schools in the London boroughs supported by the RHS (Tower Hamlets, Greenwich, Wandsworth and Sutton) would be given access to either the regional advisor or twilight teacher training sessions. These boroughs represent two relatively deprived areas and two less deprived regions in London. A second set of schools from adjacent boroughs was recruited by the research team into trial 2 and randomised to receive the twilight teacher training or no RHS gardening intervention.

Addresses of all schools were supplied by the local education authority of the nominated London boroughs for each trial; the schools were then sent a recruitment letter (see example provided in Appendix 2). Schools were asked to reply, providing information on their gardening activities. These responses were checked by both the University of Leeds team and the RHS Campaign for School Gardening manager before randomising the schools to one of the interventions or the comparison group.

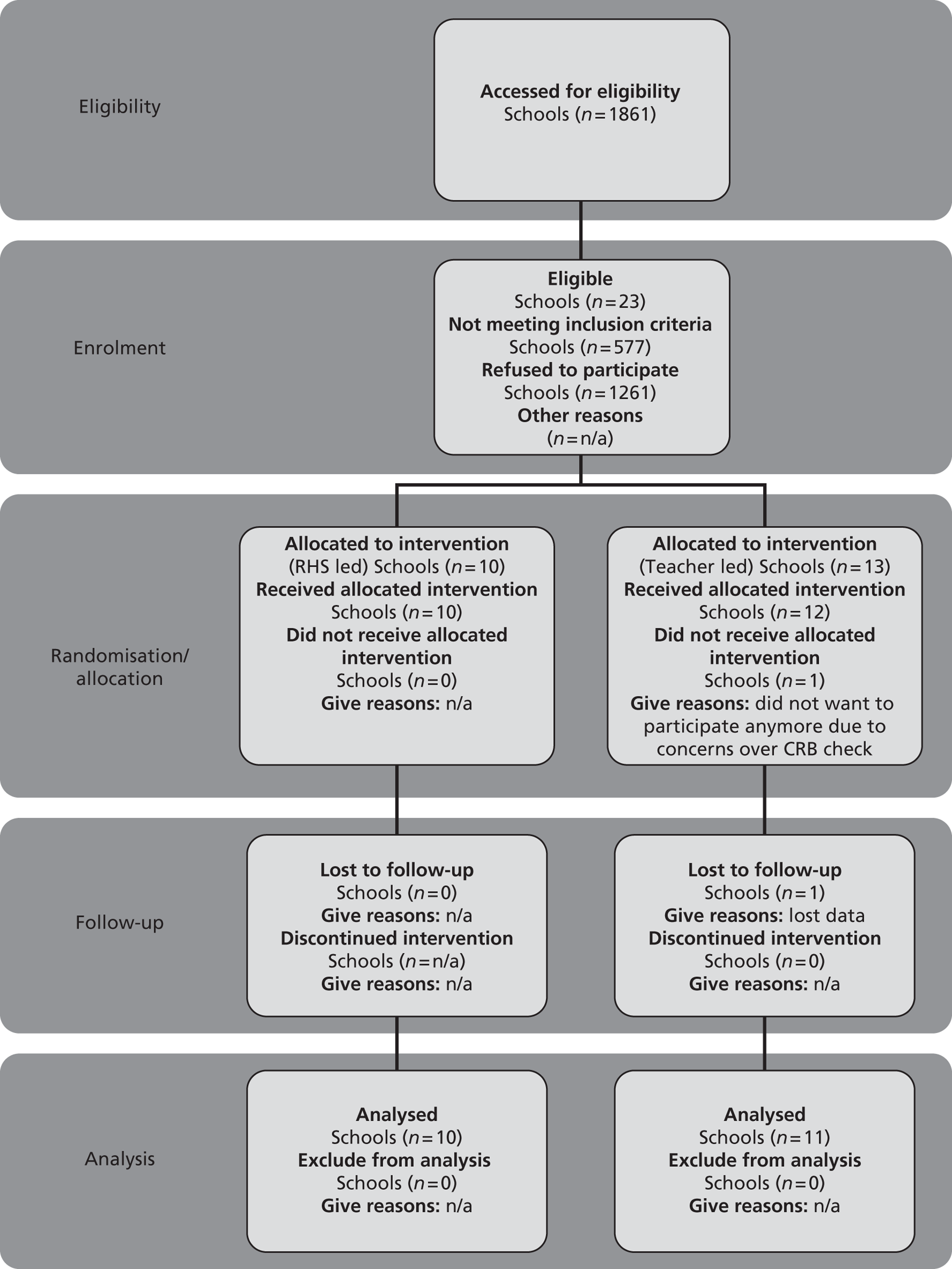

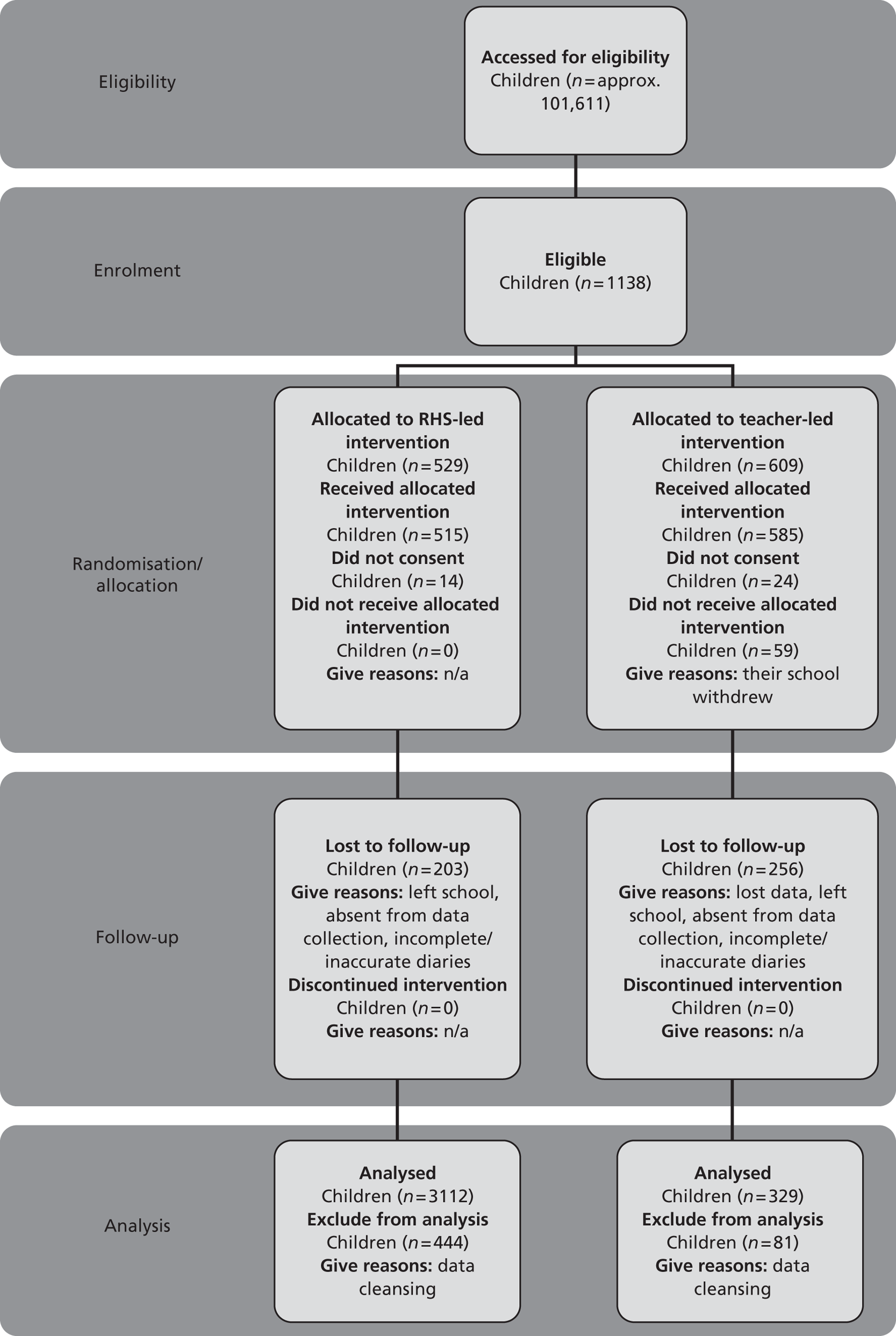

Trial 1: Royal Horticultural Society-led intervention versus teacher-led intervention

The RHS introduced its Campaign for School Gardening to schools in the London region in the autumn of 2009. The RHS campaign provided intensive support to 10 schools in each region through support from an RHS School Gardening Regional Advisor (the RHS-led intervention). The remaining schools had access to support through twilight training sessions for staff and other activities (the teacher-led intervention). A sample size of 10 schools received the RHS-led intervention, as this was the maximum number of schools that could be supported by one regional advisor. Further details of the intervention components are discussed later in this chapter.

Twenty-six schools from four boroughs in London (Wandsworth, Tower Hamlets, Greenwich and Sutton) were recruited for trial 1. Of the 26 schools, 10 were randomly allocated to receive the RHS-led and 16 to receive the teacher-led intervention. The allocation sequence was generated using Stata Version 11 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). All schools were allocated at the same time. It was not possible to randomise schools in trial 1 to receive no intervention at all owing to RHS policy.

Rationale for trial 2

In trial 1 it was not possible to randomise schools to receive no intervention at all (control/comparison group) as it is RHS policy to provide support to all schools who register an interest in the campaign. As a consequence of this, the second set of schools was recruited into a linked trial, trial 2, to provide a ‘no intervention’ arm, i.e. a comparison group.

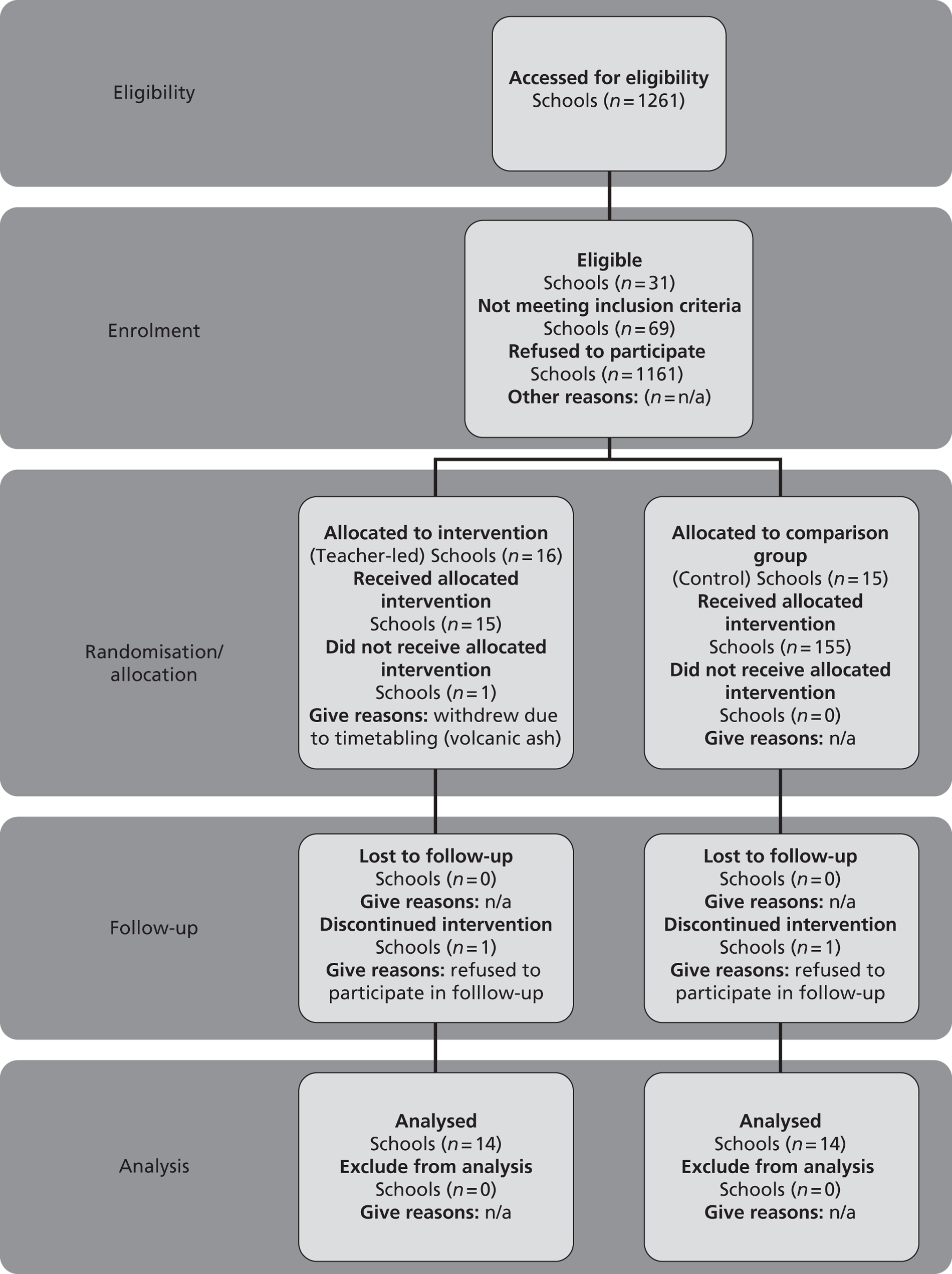

Trial 2: teacher-led versus delayed intervention

Thirty-two schools from four boroughs in London (Lewisham, Lambeth, Merton and Newham) were recruited for trial 2. These boroughs are adjacent to the trial 1 boroughs. Of these schools, 16 were randomly allocated to receive the teacher-led intervention and 16 were used as comparison schools. The comparison schools received no active intervention during the trial. However, they were informed that once the study ended follow-up collection in February 2012, they would be able to attend the twilight sessions offered to the teacher-led schools.

It was not possible to blind the schools to their intervention group because of the nature of the intervention. The fieldworkers were blinded to the allocation of schools to the intervention (RHS-led or teacher-led) and comparison arms of the study.

Study population

Trial 1 inclusion criteria

All non-fee-paying primary schools within four London boroughs (Wandsworth, Tower Hamlets, Greenwich and Sutton) with classes in Key Stage 2 (Years 3–6; children aged 8–11 years) were invited to take part in the study.

Trial 2 inclusion criteria

All non-fee-paying primary schools within four London boroughs (Lewisham, Lambeth, Merton and Newham) with classes in Key Stage 2 (Years 3–6; children aged 8–11 years) were invited to take part in the study.

Exclusion criteria for trials 1 and 2

Independent schools, special schools, schools without all four year groups in Key Stage 2 at primary school (Years 3–6) and small schools with fewer than 15 pupils per year group were excluded.

Proposed sample size

Based on our previous school-based trial, Project Tomato,65 the SD for daily consumption in this age group was estimated to be 85 g for vegetables and 143 g for fruit, with an associated intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.125 for vegetables and 0.114 for fruit. With the proposed sample of one Year 3 class and one Year 4 class from each school, the sample size needed to detect a half-portion (40 g) difference in vegetable intake with 90% power would be 627 children per group, approximately 13 schools. 82 To have 90% power to detect a one-portion difference in fruit intake (one portion = 80 g), 482 children per group would be required, i.e. about 10 schools.

The Project Tomato research identified that approximately 75% of participants completed the dietary questionnaire at baseline and follow-up; therefore, to allow for possible withdrawals and children changing schools, it was decided that 16 schools would be randomly allocated to each group, except for the RHS-led intervention, where the sample size requirements were determined by the staffing levels at the RHS. As a consequence, the RHS-led group had a sample size of 10 randomised schools only, which was carried out by the trial research team.

Discontinuation criteria

Analysis followed the principle of intention to treat. Therefore all schools and children are included in the analysis according to the group to which they were initially randomised. All reasonable and ethical steps were taken to ensure completeness of follow-up of outcome measures.

School withdrawal

If a school wished to withdraw from the trial, the study team would post a data collection form to the head/class teacher along with a freepost envelope. The data collection form would record the following: reasons for withdrawal; whether or not anything could have been done to make taking part in the study easier; confirmation that they no longer wanted to take part in the intervention and receive information/training/materials; and whether or not they still allowed us to use data collected to date and to collect data at round two (i.e. follow-up collection) in October 2011.

Child withdrawal

This occurred if a parent requested to remove their child from the trial. It was anticipated that this request would go to the school, the RHS or the study team at the University of Leeds. Whoever was the first point of contact with the parent was required to inform the other relevant groups (school/RHS/University of Leeds) by telephone, letter or e-mail. A record of any child withdrawals was kept in the database. On receipt of this information, the study team would send a letter to inform the class teacher that the child was to be withdrawn from the study. A data collection form and freepost envelope would be sent via the class teacher to the parent. A covering letter would make it clear to the parent that although the child would not receive any self-study or home-based materials, he or she would not be left out of whole-class activities, as to do so would involve taking the child out of the class while these activities were occurring. The parent would be asked to complete the data collection form and post it back to the Nutritional Epidemiology Group at the University of Leeds in the freepost envelope.

Assessment of harm

On rare occasions, children or schools may need to discontinue the randomised intervention. This may, in most cases, be only a temporary withdrawal; for example, if a child injures him or herself with a spade. Minor adverse reactions were not considered grounds for discontinuing. However, these events were captured either by the RHS regional advisor for the RHS-led schools, or by the Nutritional Epidemiology Group team, through the process measures e-mail, for the teacher-led schools. All adverse events were reported to the Trial Steering Committee. The same notification procedures applied for school or individual withdrawal.

Interim analysis and stopping rules

No interim analyses of trial outcomes were planned.

Randomisation

Cluster randomisation, with school location and borough to identify each ‘cluster’, was used to randomise the schools. The schools were randomised by the study team by geographic location of their London borough and using Stata. From each primary school, one Year 3 class and one Year 4 class was asked to consent to be part of the trial. These classes were randomly selected if there was more than one class in that particular year group.

General considerations

All data collected from these two trials have been reported and presented according to the revised CONSORT statement in Chapter 6. 83

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was obtained through the University of Leeds Research Ethics Committee in 2009. Written informed consent was obtained first from all schools and then from all parents whose children were in the classes chosen to participate in the trial data collection. Schools and parents were informed about the potential risks and benefits of participating in the trial through the information sheet. Participants’ parents gave informed consent, with the opportunity to ‘opt out’ of the study if they did not wish their child to take part. If the parents did not wish their child to participate in the study, the child was still able to take part in the growing activities in the class; however, his or her food intake and child knowledge and attitudes questionnaire were not recorded.

The intervention: the Royal Horticultural Society Campaign for School Gardening

Intervention definitions

-

RHS-led intervention These schools received an intervention delivered by the RHS regional advisor.

-

Teacher-led intervention Staff from these schools attended twilight sessions of the garden programme at a nearby participating school. The twilight sessions were run by the RHS regional advisor.

The Campaign for School Gardening aims to:

-

inspire and empower schools to get growing and to give children the chance to grow and create gardens

-

demonstrate the value of gardening in enriching the curriculum, teaching life skills and contributing to children’s mental and physical health

-

convince everyone involved with education in schools of the value of gardening in developing active citizens and carers for the environment

-

understand the importance of plants and show how gardening can contribute to a sustainable environment.

The Royal Horticultural Society-led intervention

The RHS Campaign for School Gardening consisted of two programmes. The RHS-led intervention schools received the following:

-

a day visit from the RHS regional advisor each half-term to work in the garden with teachers and children (summer term 2010 to summer term 2011 inclusive)

-

follow-up visits to aid planning by the teachers who were leading the gardening activity (autumn term 2011 to autumn term 2012)

-

general ongoing advice on the school garden, and free seeds and tools

-

one twilight teacher training session each term (summer term 2010 to summer term 2011 inclusive), based on seasonal tasks in the school garden (open to RHS-led schools’ teachers and others from local schools)

-

free access to a wide range of teacher resources at www.rhs.org.uk/schoolgardening/.

The role of the regional advisor was to assist the schools in developing a successful garden, through working directly with teachers and pupils to give them support and practical advice (Figure 5). They were also expected to help overcome barriers to developing gardening within schools. The regional advisor had the expertise and experience to tie in gardening and growing activities with the national curriculum and to run staff training sessions for teachers. The key tasks of the regional advisor were to:

-

deliver advice and support to schools in setting up school gardens and growing projects

-

promote the RHS Campaign for School Gardening by contacting schools, local education authorities and partner organisations and by giving talks and demonstrations

-

train teachers in practical skills to grow plants and harvest crops

-

build community links and recruit volunteers to enable the wider community to support and get involved in school growing projects

-

contact, advise and support schools within the region by means of visits, e-mails and phone calls

-

make links with partner organisations and recruit volunteers to support schools in setting up school gardens and growing plants

-

run termly twilight training session courses at 10 school venues throughout the year.

FIGURE 5.

The RHS regional advisor seed sowing at one of the RHS-led schools. Photograph © RHS. Reproduced with permission.

An example of some of the work conducted in one of the RHS-led schools is described below.

-

Embedding gardening in the school in order to attain all the benefits which that brings (e.g. most pupils never have access to gardening, as they do not have gardens themselves).

-

Establishing a community garden which helps to deal with some of the difficult issues faced in the ‘forgotten estate’.

-

Redeveloping the school garden (to be used for class growing).

-

Creating simple beds, paths, a fence, and later possibly a greenhouse.

-

Digging a pit for the nursery to prevent the raised bed being ‘dug’.

-

Clearing the community allotment garden (‘secret garden’). The community garden is to be used for project work, teaching (e.g. about life cycles in a wildlife area) and community beds, and for use by learning mentors to work with children who have learning difficulties and/or behavioural issues.

The two images in Figure 6 below demonstrate the before-and-after effect of the RHS-led intervention in one of the 10 RHS-led schools.

FIGURE 6.

Before-and-after images of the development of the school garden at a RHS-led school. Photographs © RHS. Reproduced with permission.

The teacher-led intervention (‘teacher-led schools’)

The teacher-led intervention schools worked with the RHS by attending termly twilight training at a nearby RHS-led school, to help support them in developing and using their school gardens. Unlike the RHS-led schools, the teacher-led schools did not have direct support from the regional advisor. The regional advisor ran these twilight sessions for them, and provided the teacher-led schools with advice as needed for their school gardens. The following is an example of some of the topics taught in the twilight sessions.

Summer term 2010

-

Planning your school garden.

-

What and when to grow for the school term.

-

Watering in the school garden.

-

Introduction to garden pests.

Autumn term 2010

-

Garden site assessment and plans.

-

Bulb planting (including practical session, with free bulbs supplied).

-

School garden risk assessment templates.

-

Soil types and texture.

Spring term 2011

-

Safe tool use.

-

Seed sowing.

-

Growing for the school years.

-

Composting.

Summer term 2011

-

Watering.

-

Pricking out.

-

Garden tours.

Trial 1 consisted of schools participating in both intervention groups mentioned above, whereas for trial 2 schools were involved in either the teacher-led intervention or a comparison group. The comparison group did not receive any support from the regional advisor during the period of the trial. However, these schools were able to receive the twilight sessions for the summer of 2012, once the study had completed follow-up data collection.

Data collection methods

Data sources

The data used in this study came from the following sources.

Child-level data

-

School food diary, April 2010.

-

Home food diary, April 2010.

-

Child knowledge and attitudes questionnaire, April 2010.

School-level data

-

School gardening level questionnaire, June 2010.

-

Gardening in schools – process measures e-mail dated October 2010.

-

Information collated from the RHS advisor on school gardening in the intervention schools.

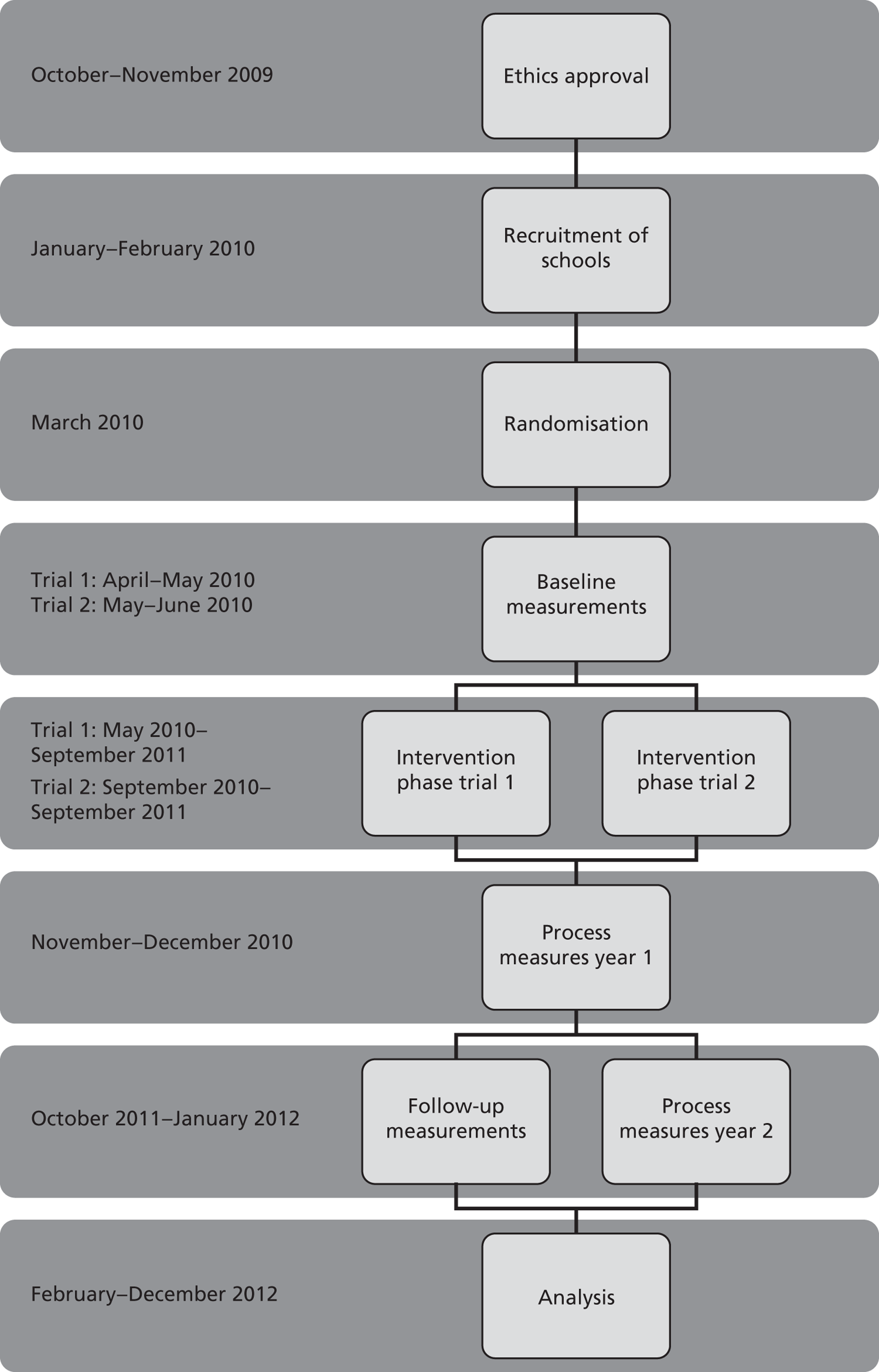

The main outcome measurements were collected at baseline in May and June 2010, when the children were in Years 3 and 4 (aged 7–8 years). The follow-up measurements were collected between October 2011 and January 2012, when the children were in Years 5 and 6 (aged 9–11 years). A breakdown of the different phases of these two trials is illustrated in Figure 7.

FIGURE 7.

Trial phases.

Training the fieldworkers: nutrition students

The primary schools were spread throughout London, and therefore a large sample of undergraduate or masters nutrition students were recruited to undertake baseline collection. These sessions were designed and led by MSC with assistance from one of the research assistants on the trial. The students were recruited from King’s College London and Roehampton University. The students were offered £70 payment per school, and were informed that in order to participate it would be necessary for them to attend one of the two training sessions offered in London. The first training session was at Roehampton University on 9 April 2010; the second was at King’s College London on 12 April 2010. Baseline collection took place from mid-April to July 2010. The students were not informed as to which intervention group the schools they visited were allocated.

Most of the students who registered an interest in the study were dietetic students, who had little data collection experience. In order to ensure that the standard of data collected was consistently high, training was provided to the students to teach them how to complete not only the school and home food diaries, but the child knowledge and attitudes questionnaire as well.

An important quality needed to work with children is presentation skills, the ability to speak confidently in a room full of young children. To assess the students on their ability to complete the baseline collection, the first part of the training required them to introduce themselves and explain how to play one of their favourite childhood games.

The next component of the training was a presentation by MSC introducing the students to the study, and what exactly their tasks would be if they were involved in the data collection. This was the first time the students had seen the questionnaires, so each section was explained to them in detail to help them familiarise themselves with the questionnaires. They were also shown the instructional DVD. The main part of the training consisted of two activities which are explained in detail below.

Sample diet exercise

This exercise involved giving the students examples of children’s food intake for the whole day. The aim was for the students to correctly code each food and categorise it in the right section of either the school or home food diary. An example of a child’s diet is presented in Table 9, shown with the correct school food diary codes. There were always some challenging food items included, which were typical for children to eat but not adults, such as the Dairylea Lunchables and Dunkers ham wrap.

| Breakfast/before school | Morning break | Lunchtime | Before tea/after school | Evening meal/tea | After tea/during night |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White bread toasted (C1)a with Utterly Butterly® (D1) Glass of apple juice (A6) |

Fruit and nut bar (B3) | Tropical-flavoured spring water (A4) Cheese and onion crisps (B1) Dairylea Lunchables – ham (E2, B5, G5) |

Satsuma (M5) | Chicken nuggets (F2) Chips (L2) Tomato ketchup (D2) Salt Vinegar |

Jaffa cakes (N5) White bread toasted (C1) with Utterly Butterly® (D1) |

Right or wrong

In the second activity, the students were presented with 10 completed home food diaries and were asked to identify whether the diaries had been completed by the parents correctly or incorrectly. The aim of this exercise was to show the students what to expect on day 2 of the baseline collection, and to identify when it is necessary to take a recall from a child due to serious errors in completion of the home food diary.

At the end of the session, the students had the opportunity to ask questions and raise queries about completing the different questionnaires and the overall structure of the data collection process.

Baseline collection

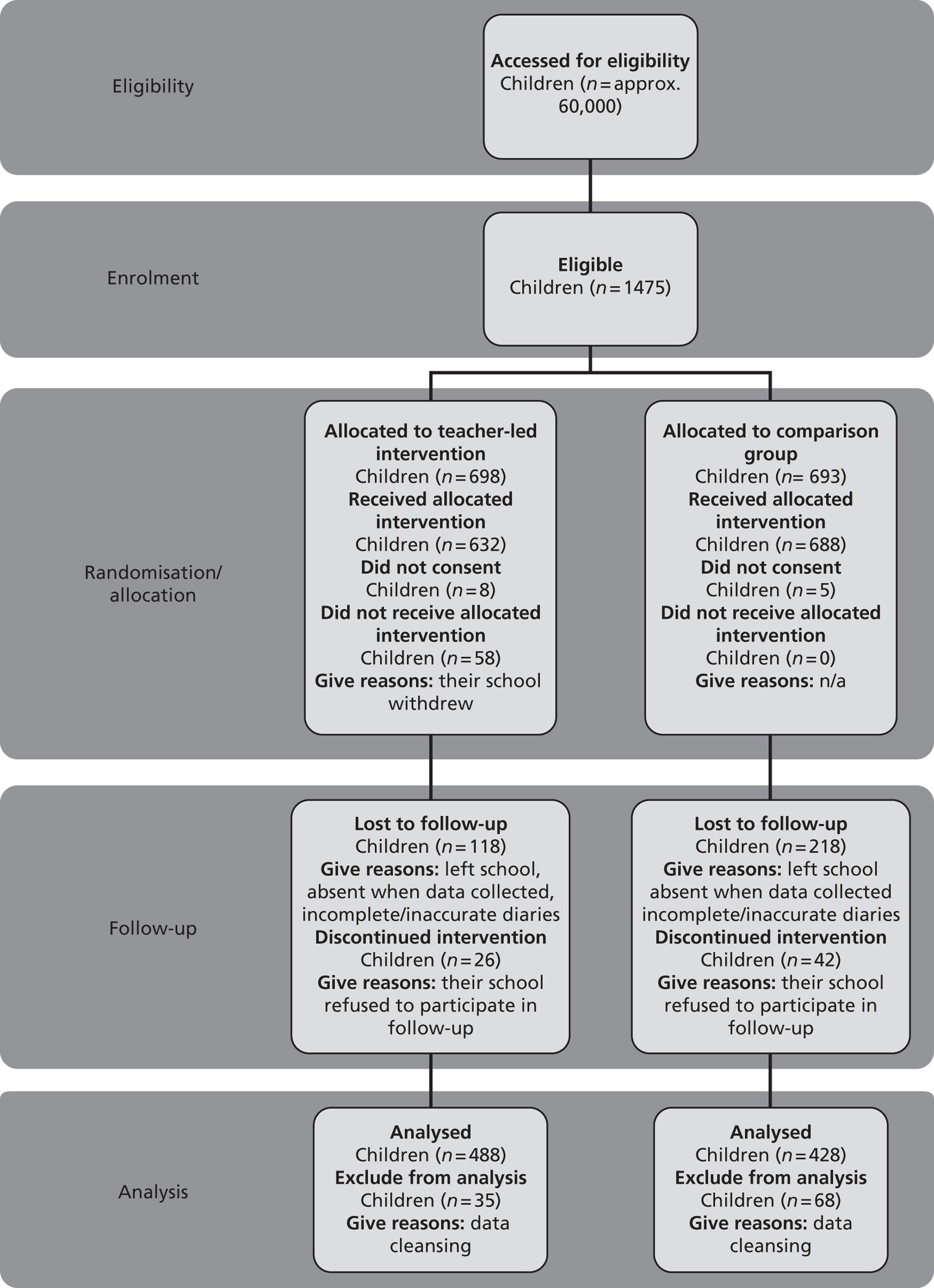

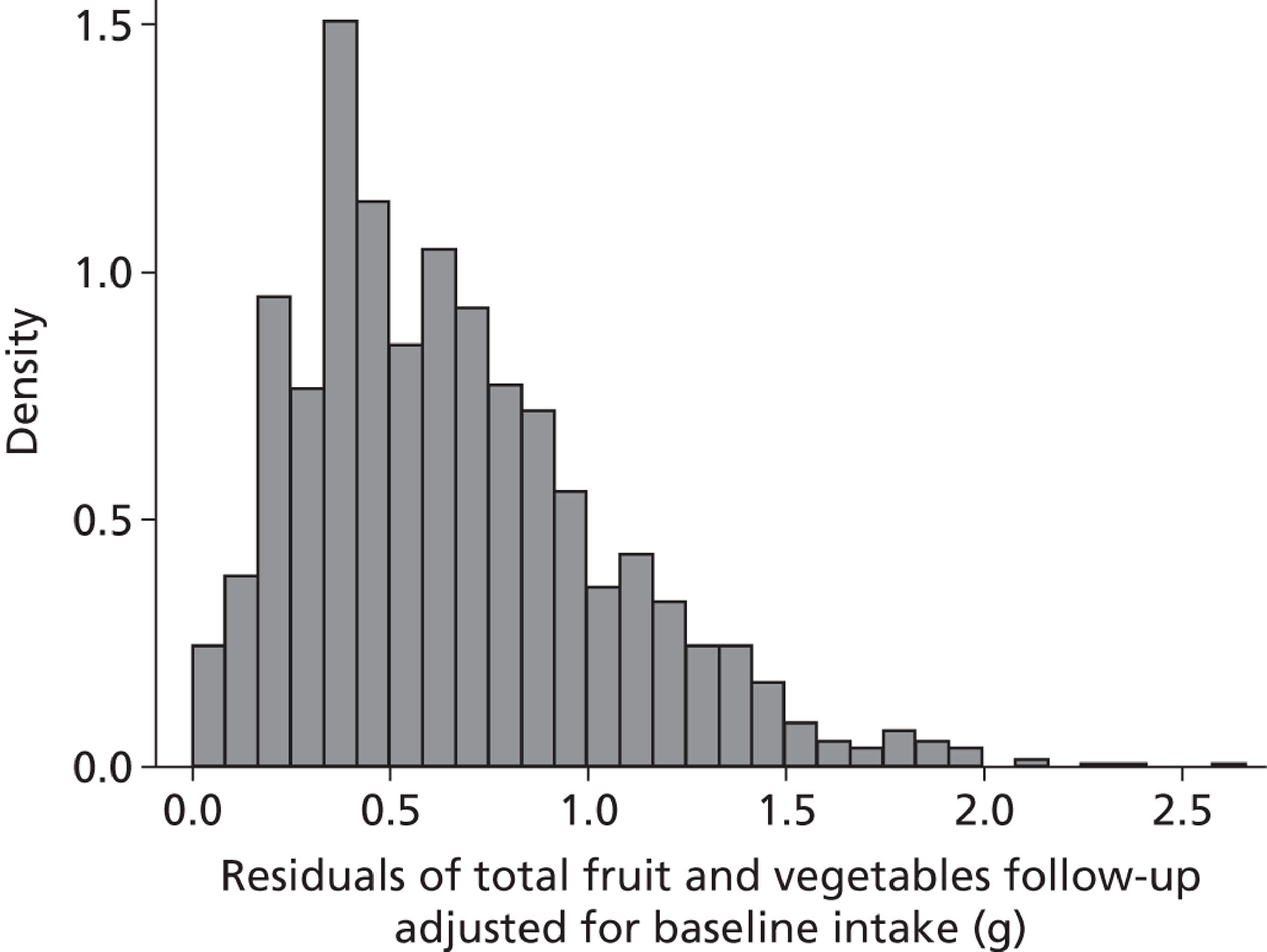

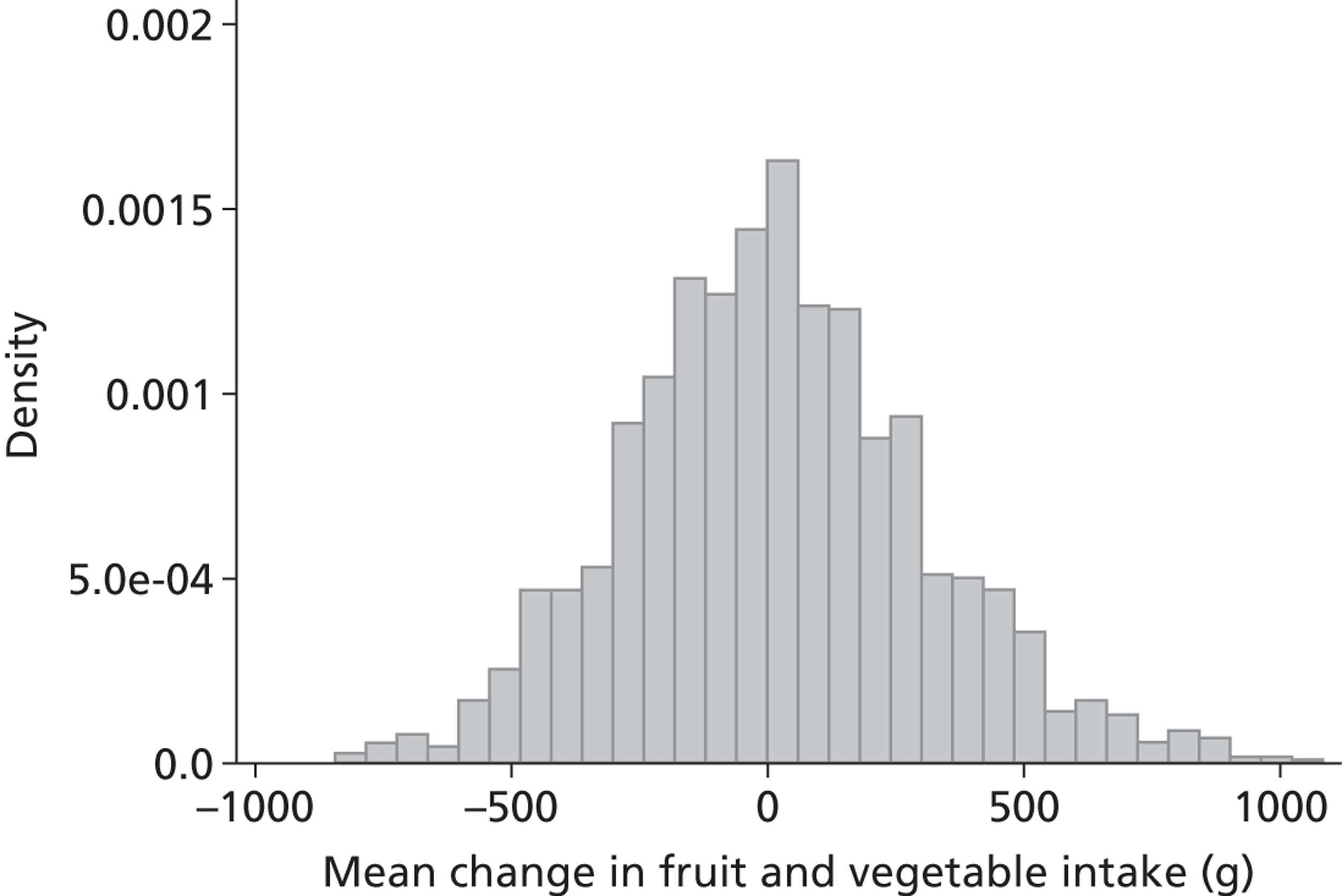

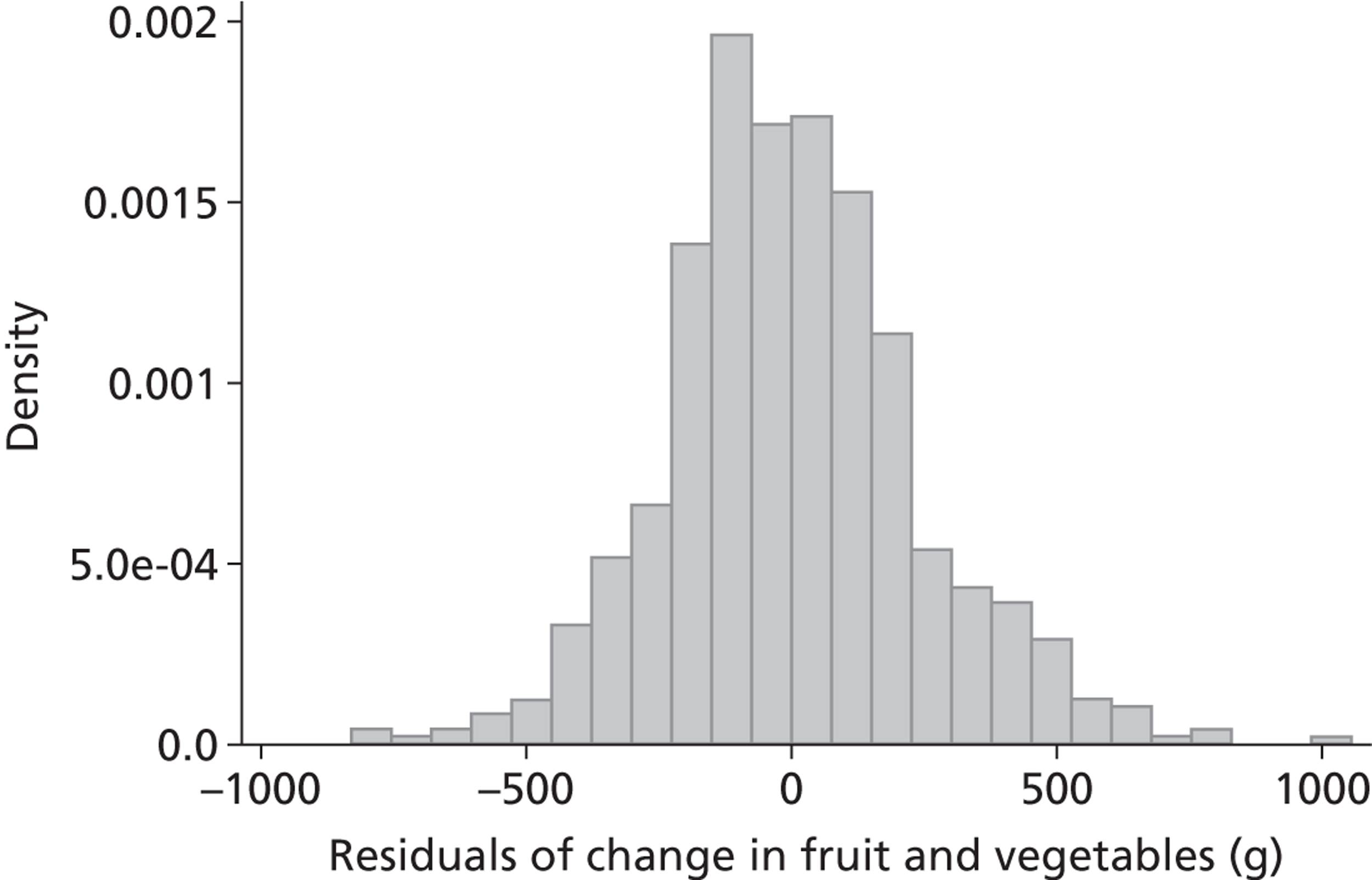

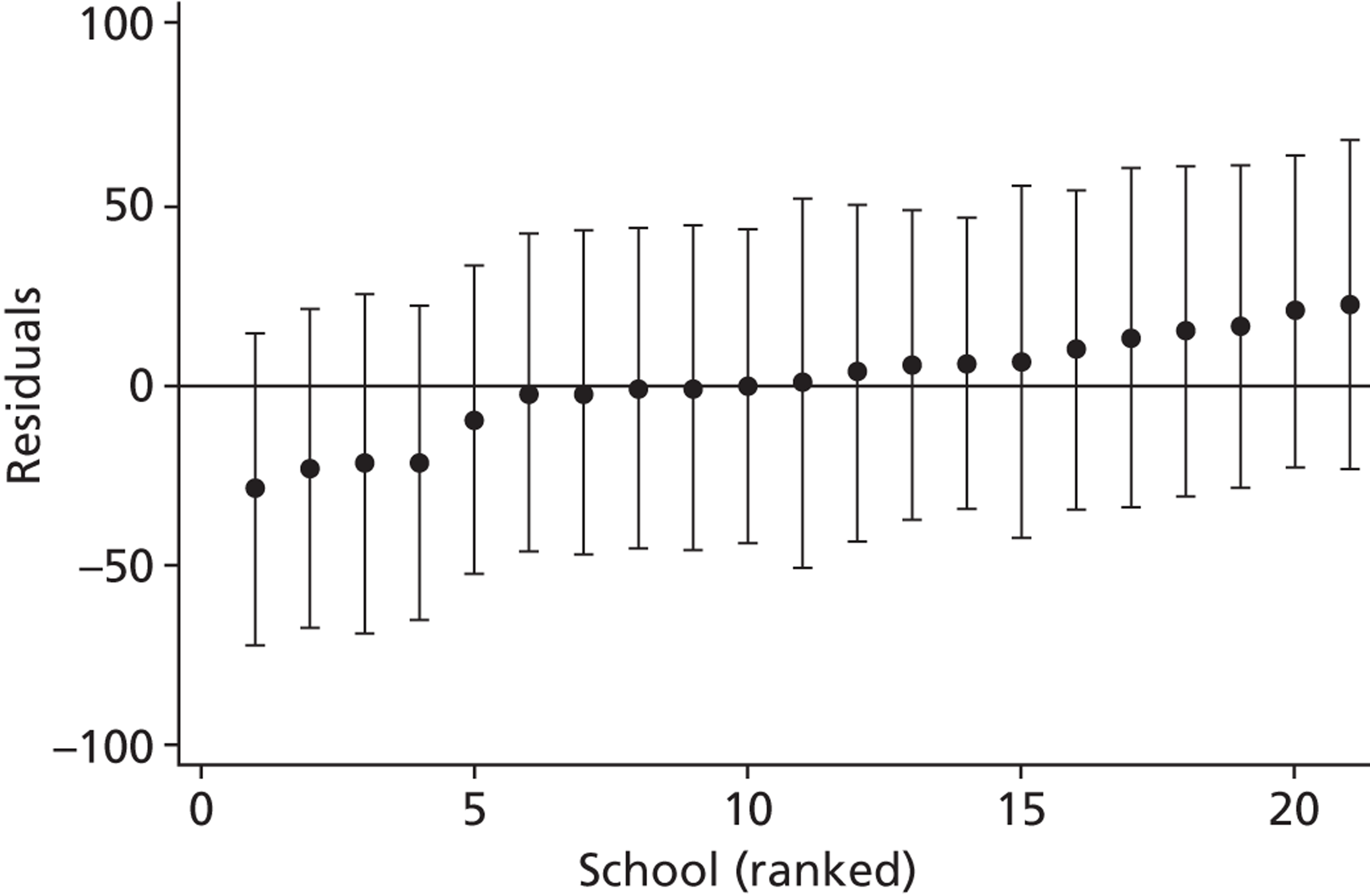

Baseline collection of the school and home food diaries, child questionnaire and school gardening telephone interview took place between April and July 2010. The baseline process measures e-mails were sent out in November 2010 followed by reminders in December 2010.