Notes

Article history

The contractual start date for this research was in January 2022. This article began editorial review in May 2023 and was accepted for publication in November 2023. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ article and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on this article document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Hansford et al. This work was produced by Hansford et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Hansford et al.

Background and introduction

Health inequalities in the Peninsula

England’s Chief Medical Officer’s (CMO) Annual Report 2021 identified coastal areas as having the worst health outcomes in England, with low life expectancy and high rates of major diseases. 1 Contributory population factors include retired citizens settling in these areas; oversupply of guest housing and concentrations of deprivation; difficulty in attracting health and social care staff; limited public transport; and scarce/seasonal employment opportunities. The report identified a ‘coastal excess’ of disease, with limited research on health in coastal areas.

The South West Peninsula (SWP) (i.e. Devon, Cornwall and Somerset) has an extensive coastline and is largely rural. The National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Clinical Research Network SWP Business Intelligence Unit analysed Office for National Statistics Subnational Population Projections for England (2018),2 the Rural Urban Classification (2018) of Lower Layer Super Output Areas in England and Wales3 and the English Indices of Deprivation 2019. 4 Data showed that the SWP had the highest percentage of population aged 65 and over (24.2%), the second highest predicted population growth (15.1%) and the highest national average index of multiple deprivation score for rural villages and dispersed populations (17.7%).

Furthermore, Public Health England Health Profiles reveal additional inequalities with differences in life expectancy of up to 6.2 years between the most and least deprived areas, across Cornwall, Devon and Somerset. 5–7 Compared to national data, Cornwall reports significantly lower educational attainment and excess winter deaths. 5 Diagnoses of dementia are significantly higher and educational attainment significantly lower than national averages for both Devon6 and Somerset. 7 In the city of Plymouth, poverty is higher than the national average,8 and there is a 7.5-year difference in average life expectancy between the least and most deprived wards. 8

Challenges in accessing health services in rural and remote areas are exacerbated at the end of life,9 with rural populations and those with a lower socioeconomic status experiencing inequalities in access to palliative care. 10 Populations experiencing inequity in health service access are under-represented in health research, meaning that the voices of those experiencing the highest burden of illness are often overlooked. 11 Hoekstra et al. 12 and Verbeek et al. 13 acknowledge the importance of researcher/stakeholder collaboration in exploring and integrating lived experience in research processes. Such partnerships can centre ‘seldom heard’ voices and improve the relevance and potential impact of research for underserved populations. 14

Local innovations

Local innovation in supporting communities to age, die and grieve well include the St Luke’s Hospice-led initiative in Plymouth to become the first ‘Compassionate City’ in England,15 and Torbay Community Development Trust’s (TCDT) work to support healthy ageing which was highlighted as a case study in the CMO’s Annual Report. 1 The region was noted for its ‘vibrant and an increasingly mature community and voluntary sector, using an Asset Based Community Development approach to empower communities’. The CMO called for actionable research into the health needs of coastal communities.

Forming a cross-sector partnership to build capacity and capability in local communities

In response to these issues, a new South West Peninsula Palliative Care Research Partnership was formed in January 2022, with 15 months funding from NIHR. Recognising local strengths as well as specific challenges, the partnership agreed a theme of community support at the end of life in rural and coastal populations, including a focus on low-income communities. Internationally, interest in public health approaches to palliative care has grown, and involving communities in caring for the dying and bereaved is potentially perceived to be one element of a sustainable solution to these challenges. 16 However, within palliative care research there is little evidence specifically about the needs of rural, coastal and low-income areas, and how communities might best be supported to respond.

The partnership brought together academics from the Cicely Saunders Institute (King’s College London), with extensive experience in palliative care research, and academics from the University of Exeter with experience of community-engaged research into health inequalities. It also included Plymouth University, University College London, the voluntary health sector (all seven regional hospices and Marie Curie’s night sitting service), the voluntary and community sector (two community development infrastructure and support organisations, HealthWatch), local NIHR networks (Clinical Research Network, Research Design Service, Applied Research Collaboration) and the local Clinical Trials Unit (see Report Supplementary Material 1). A steering group with patient and public involvement (PPI) met quarterly.

Aims

The aim was to establish a new, sustainable multisectoral palliative care research partnership that would identify community support needs for underserved rural and coastal patients and families in the SWP. Objectives (outlined below) combined primary (objective 4) and secondary (1) research with activities to build research capacity within the partnership (3, 4), in order to inform and support future research (5, 6).

Objectives

-

To conduct a scoping review of the literature on interventions which enable community members to support the dying.

-

To deliver a research capacity-building programme and enhance access to existing NIHR resources.

-

To co-create public and patient engagement and involvement capacity and structures in the region.

-

To determine the resources and needs for communities to support dying well.

-

To integrate findings from objectives 1 and 4 with regional stakeholders, developing a conceptual framework of optimal community support and to identify research questions for future research.

-

To establish a sustainable research network infrastructure and governance for the longer-term design and delivery of palliative care research in the region.

Methods

Objectives 1–4 involved understanding existing relevant knowledge, understanding needs within the SWP and building research capacity; the last two concern collectively using this knowledge to identify future research priorities and establishing a sustainable research network. We adopted different methodological approaches to meet the first four objectives.

Scoping review

To understand the current state of knowledge in relation to public health palliative care interventions that enable communities to support people who are dying and their carers, a scoping review of such studies which assessed person-centred outcomes was conducted, using the framework developed by Arksey and O’Malley. 17 Following the literature search (September 2022), results were synthesised using narrative synthesis. Inclusion criteria were studies that included: (1) results of a public health palliative care intervention targeting community action or personal skills; (2) an intervention aimed at directly improving the care of adults aged 18 or older at the end of life and/or their carers; (3) outcomes focused on people at the end of life or their carers; and (4) those written in English language. Detailed methodology, the search strategy and results are published separately. 18

Capacity-building programme

The programme of activities to raise awareness of resources available to support the planning and implementation of research and increase confidence in research participation (particularly for organisations primarily involved in clinical palliative care with limited experience of research) included:

-

Funding for two healthcare professionals to attend a Research Methods and Statistics in Palliative Care module delivered by Kings College London as part of their Palliative Care MSc. Course details were disseminated to the partnership with an invitation to apply; two candidates with suitable experience were accepted.

-

A quarterly online journal club, with partner organisations co-leading with rotating academic institutions to select and present a journal paper.

-

Five research skills seminars with input from the local NIHR Clinical Research Network, NIHR Research Design Service and Clinical Trials Units on their purpose, research support available and opportunities for involvement. A partnership hospice taught how to be a research-active clinical service and integrate research recruitment into practice. The PPI group presented on involving community members in research design and delivery.

Patient and public involvement

Expertise included a dedicated PPI worker from the Cicely Saunders Institute, an Exeter University researcher with a professional background in community work, and TCDT. The PPI and community engagement strands of work ran closely in parallel, with PPI members involved in planning and delivering engagement activities.

Partnership members were asked to speak with public contacts (service users, volunteers) and eight individuals were nominated to the new, regional PPI group, all with experience of accessing palliative care services or supporting someone at the end of life. Six individuals from across the SWP regularly took part in PPI activities including the steering group’s discussions, planning and decision-making. PPI members attended an initial face-to-face introductory meeting to get to know each other, learn about the partnership aims and plan their involvement. Members were invited to all (online) Steering Group meetings, and also chose to hold their own separate meetings in person (with an online option), as the group felt this was important to help build relationships. Five dedicated PPI meetings were held, and members also participated in, and helped facilitate, other partnership activities. Members received a payment of £25 per hour for their involvement.

Community engagement to understand needs

To better understand community needs and existing resources that might support living, dying and grieving well, we completed a programme of community engagement from January to October 2022. We aimed to engage with individuals not currently in contact with, or not even necessarily aware of, palliative care services, as well as those with experience of accessing support at end of life or in bereavement. The programme design was pragmatically tailored to available resources (such as the Departure Lounge kit, see below), staffing (one researcher, LH, for 1 day per week), project timescale, and relationships with, and knowledge of, community organisations within the partnership. The programme was planned in two phases: creative, informal engagement activities designed to widen participation, followed by a storytelling project to provide more in-depth illustrations of people’s experiences, and a more traditional research method (focus groups) to further explore issues raised. The inclusion of creative and oral activities (e.g. Community Conversations, storytelling) aimed to broaden participation, and increase accessibility for participants for whom literacy or language may be a barrier.

Strand 1: January–August 2022

The Departure Lounge

The ‘Departure Lounge’ is a pop-up installation produced by the Academy of Medical Science19 to provoke conversations and impart information about death and dying, using the metaphor of an airport departure lounge. We used the display in a range of settings suggested by partnership members, purposively including rural, urban, coastal, inland and low-income neighbourhoods. Four visits were held at specific events (a bereavement open day, a Dying Matters Awareness Week event in a health centre, a family fun day and a PPI meeting), and at five other events the display was available within a community setting while usual activities took place (e.g. community cafes, charity shops). LH made (anonymised) field notes after each session.

Community Conversations

Community Conversations aimed to draw reflections from participants with lived experience of end-of-life care and their carers. As it was not feasible to carry out this workstream across the SWP, Torbay was chosen, as a local authority ranked 48th most deprived district in England (out of 317),4 and an area in which TCDT has strong links within the community. TCDT employs a network of Community Builders (CBs) with established networks in their local neighbourhoods. TCDT commissioned Filament, a local creative producing house that works with communities, to create an engagement tool that CBs could use with people in their own homes to facilitate these conversations.

Filament created a ‘suitcase’ of activities (see Report Supplementary Material 2) – this was a kit comprising a vintage suitcase containing materials for a series of creative activities, to facilitate discussions about individual identity, experiences of end-of-life care, support networks, support needs, the impact of location and neighbourhood, and the essential elements for good connections and support at end of life. Participants could choose not to discuss any of the topics or to answer without engaging with the activities. The initial design was tested with three participants and refined in response to feedback. CBs attended a training session to trial using the suitcase and recording conversations.

Six CBs carried out Community Conversations, using existing contacts to identify potential participants, approach them to explain the project and invite them to take part. Twenty-six individuals participated; see Report Supplementary Material 3 for age, gender and ethnicity demographics. Informed consent was obtained for the notes from the conversation to be used as research data. Most conversations lasted between 90 and 120 minutes, though one ran over three meetings taking a total of 5 hours. Responses from the activities were captured (in text) by the CBs. Notes were pseudonymised and entered onto a database. LH then made summary notes for each ‘case’ under five headings aligned with the research questions: context, key issues, what helped, what could be better and essential elements for supporting end-of-life care within communities.

After completing the Community Conversations, all six CBs were invited to, and attended, a focus group facilitated by the researcher (LH) to elicit their views on the key issues discussed, and to reflect on their experience of facilitating the conversations.

Strand 2: July–October 2022

Focus groups

To explore experiences of end-of-life and bereavement in more depth beyond the Torbay area and reach different cohorts, a convenience sampling approach was used to recruit participants to four focus groups. Community organisations with whom the partnership had existing links or knowledge were approached. Focus groups settings included different geographical areas and included residents from different socioeconomic backgrounds:

-

a community group in a coastal town supporting people living on a low income;

-

a care organisation in a small market town serving a rural inland area;

-

a carers’ organisation in a coastal city;

-

a community café in a low-income neighbourhood in a coastal town.

The focus groups were advertised by the host agencies to their networks and on social media. Interested individuals were invited to contact either the host organisation or researcher and then sent an information sheet. Informed consent was obtained at the beginning of the focus groups. Twenty-two individuals participated; see Report Supplementary Material 3 for age, gender and ethnicity demographics. The groups’ durations ranged from 66 to 116 minutes. Discussions were audio-recorded and transcribed. Participants received a £25 payment.

Storytelling

Filament were commissioned to work with three Community Conversation participants in more depth to create narrative stories about their experiences of living with, or caring for someone with, a life-limiting illness. Recruitment proved difficult, partly because CBs felt that many of the participants had already told their stories, and as there was a significant emotional element to this interaction, they didn’t feel it was appropriate in some cases to ask individuals to repeat their story. Therefore, the stories were created with one previous participant and two new individuals known to TCDT to have supported someone receiving palliative care. Each individual worked with a storyteller and a poet, who after listening to their experiences created narrative scripts. Participants commented on the scripts and, after adaptations, audio materials were recorded. Informed consent was obtained for participation in the project and for the anonymised stories to be disseminated for teaching, training and awareness-raising purposes.

Analysis of community engagement data

Field notes from the Departure Lounge sessions, notes from the Community Conversations and focus group transcripts were all coded by LH using QSR International’s NVivo 11 software. Coding frameworks were devised using both a deductive approach informed by the research questions and topic guides (e.g. codes such as ‘role of community’) and an inductive approach whereby codes were derived from the data (e.g. ‘valuing outdoors’). The resulting coding frameworks from the three sets of data was compared and found to be similar, and the data was assimilated, creating overarching themes and subthemes.

Sense-making workshop

Academics and PPI members co-facilitated an in-person workshop (October 2022) for partnership members and interested local organisations. Early findings from the community engagement activities and the scoping review were presented and discussed. Twenty-seven individuals participated, including 11 staff from 5 hospices, 5 PPI members, 7 academics from the 4 universities, 2 individuals representing community organisations and 2 from end-of-life care charities.

Ethics

Ethics permission for the community engagement work was granted by the University of Exeter College of Humanities Ethics Committee (ID: 493439) in January 2022.

Results

Scoping review

Full details of the scoping review have been published separately18 and summarised briefly here. Eighteen studies of community-based interventions met the inclusion criteria: 10 targeted carers of patients with a life-limiting illness, 3 targeted patients only and 5 targeted dyads. Report Supplementary Material 4 provides a table describing the studies’ key components. There was a marked heterogeneity in the studies’ design, methods and outcomes of interest. Analysis showed that community-engaged palliative care interventions can generate appreciable changes in individual outcomes, though it was difficult to make inferences about which types of approaches work for different communities and why due to differences in outcomes measures and lack of reported contextual information. Of the included studies, nine were conducted in North America, six in Europe (four in the UK), one in Africa, one in Australia and one in Asia. Most focused on urban communities and there was little detail regarding the economic status or rurality of the subject populations. Hence, there was little evidence specifically related to public health approaches to palliative care in rural and coastal areas, and in low-income communities.

Capacity building

Our programme of activities was well-received by organisations within the partnership and beyond, as demonstrated by high levels of participation. Four journal club and five seminar sessions were attended by 15 to 25 partnership participants. Two healthcare professionals successfully completed the Research Methods module. High levels of engagement were sustained throughout the 15-month funded period and are indicative of the value attributed by partners/participants to these opportunities to develop research skills and knowledge.

Building a sustainable partnership

Membership of the partnership grew via word of mouth, with participating organisations sharing information about events and opportunities within their own networks, and through contacts made, for example, with interested health and social care organisations during the engagement events. A mailing list of interested individuals/organisations was generated, with agencies such as the police, the NHS and local care organisations added, and a newsletter was produced and distributed via e-mail to share information more strategically.

One strength of the partnership was to create new relationships between clinical services and research support services. As NIHR funding for the partnership ended in March 2023, arrangements are underway for the SW Peninsula Clinical Research Network to take over the facilitation of the network, creating a ‘Community of Practice’ to ensure its continuation.

Patient and public involvement

Our PPI co-applicant, SM, met with the researcher (LH) before each PPI session to co-create agendas, attended steering group meetings, reported on PPI work and inputted into partnership planning and decision-making.

Patient and public involvement members were involved in planning engagement events and co-creating, for example, the topic guides for focus groups. They ran a partnership training session to input their views on key issues for those needing to access support at end of life. SM jointly chaired the sense-making workshop, and four other PPI members co-facilitated small group discussions. The PPI members remain keen to be involved in palliative care research in the region.

Community engagement

Storytelling

The timescale for this activity was extended, due to the difficulty in recruitment and sensitivity and flexibility needed to work at the pace and availability of the participants. At the time of submission of this paper, Filament were editing the three audio plays, each telling one person’s story, with an accompanying original poem based on a song that was significant for each participant. Steering group meetings are scheduled to discuss how the audio will be used, and to plan next steps for dissemination. Our aspiration is that the audio material can be used for training purposes, and we are exploring how the recordings may be used within and beyond the partnership.

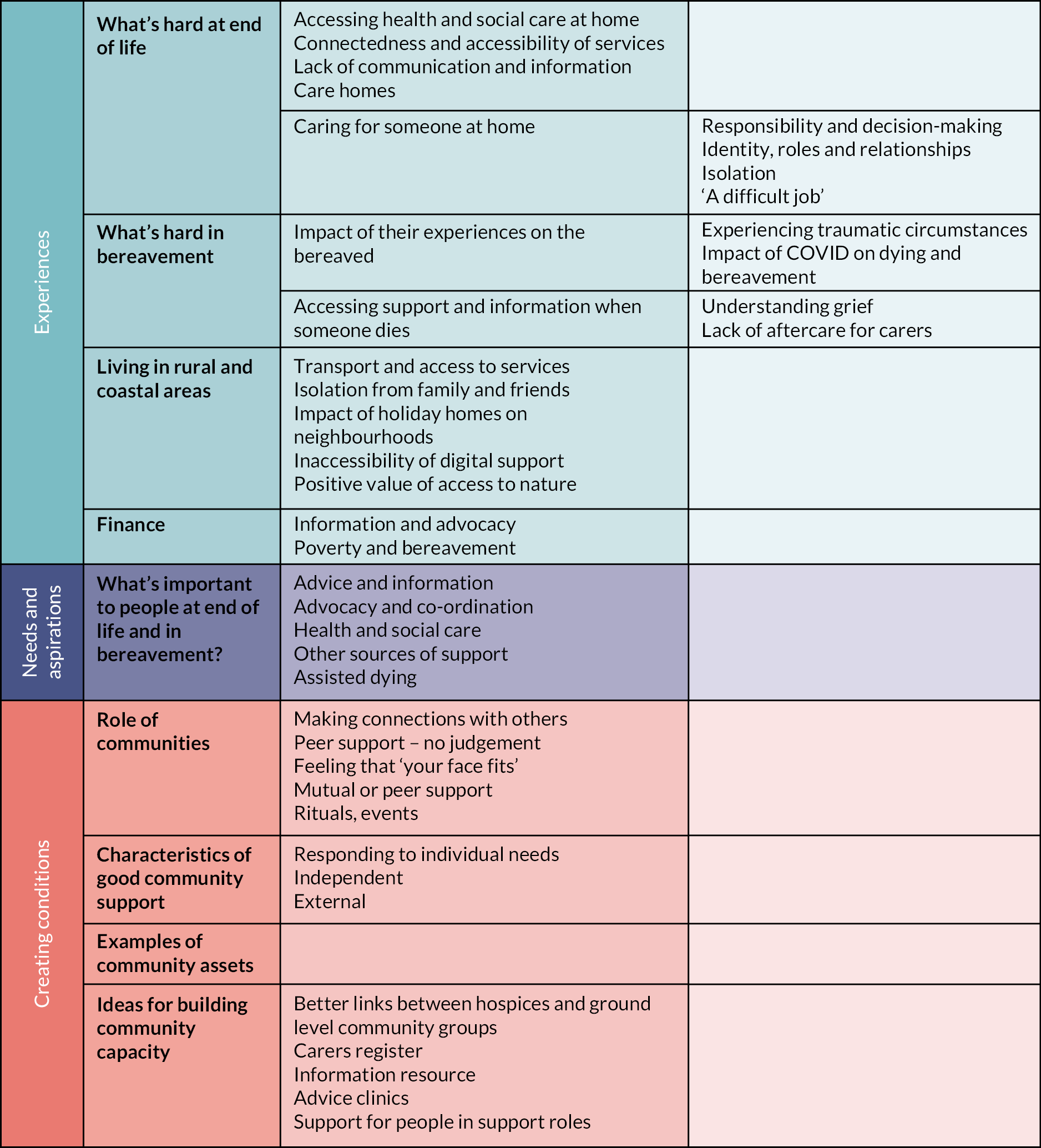

Data from the Community Conversations, Departure Lounge visits and focus groups

Themes from the analysis of the community engagement data are shown in the table below. The data were presented in depth, including local case examples from the Community Conversations, in an unpublished report that was distributed within the region, available on request.

Themes related to creating the conditions for better community support at end of life, including examples of current community assets and ideas for building community capacity, are reported in depth elsewhere, alongside our reflections on the process of engaging with communities about death and dying, and some of the barriers and facilitators to engagement. 20 This paper provides an overview of our findings in relation to the themes ‘experiences’ and ‘needs and aspiration’.

To understand community needs to support dying and grieving well, we listened to what people told us, from their experiences, about current gaps; these are described within the themes ‘what’s hard at end of life’, ‘what’s hard in bereavement’, ‘the impact of living in rural and coastal areas’, and ‘low-income individuals and families’. We also describe the services and support that communities told us were important to them in end of life and bereavement.

What’s hard at end of life

Accessing health and social care for someone at home

The ability to access appropriate health and social care for a patient with a life-limiting illness living at home was a key issue, with mixed experiences reported. Some people discussed the difficulty they experienced in trying to set up a care package that met the needs of their family member, with one participant describing her ‘tears of frustration’. Often people talked of having to ‘fight’ for support when someone was dying at home, including visits from GPs, district nurses and palliative care teams, accessing medical supplies and equipment, and arranging social care. Some people felt they were ‘left to get on with it’ after a family member received a palliative diagnosis.

Some people were concerned about the quality of care their relative had received at home. One person described the lack of consistency and personalisation as ‘like a shopping centre at the till, in, out, in, out’. Others commented on how little time visiting carers and nurses could give, a lack of training or expertise in end-of-life care, and what was perceived as a lack of compassion. The quality of available care sometimes affected whether families chose to continue accessing support.

Knowing what support is available and how to access it was described as very difficult. This lack of clarity related to who would provide care, the role of each agency/professional, what kind of support they would provide and at what stage.

In a more positive example, one bereaved widow described two elements of the care her husband received that were important – both related to continuity of care: (1) having one link person for the palliative care team who knew and understood the family (‘she was the one that sat in the kitchen’) and (2) the availability of a palliative care out-of-hours helpline whose staff were familiar with the patient or could access their notes (‘you don’t have to spend half an hour answering basic questions’).

Several people described negative experiences of using hospital services when a terminally ill family member needed emergency care. As a result, some family carers worried about being in a situation where they needed medical help, particularly in relation to ambulance and Accident and Emergency waiting times. This fear was a commonly shared source of anxiety in the carers’ focus group.

Connectedness and accessibility of statutory, NHS and VCSE (voluntary, community and social enterprise) services

The confusion felt by individuals about what support might be available at end of life was echoed by some professionals who were part of the system. Available hospice support differs by area, as does the provision of other specialist nurses, but these were just some of many differences. Generally, provision was perceived to be inadequate to meet need. Practitioners were aware of the disparity between areas, including the availability of local charities offering support in some areas, fragility of services due to funding cuts or staff recruitment issues, and often a lack of communication between healthcare services.

This frustration and confusion was also felt by some non-specialist community organisations supporting individuals navigating end-of-life systems or bereavement. One community worker described how she, and her organisation, felt overwhelmed when trying to support an older woman after the death of a family member:

It was a lot of admin she needed help with, it was a lot of forms she couldn’t fill out. And it’s just a lot of stuff and it felt like there was no obvious procedure for what needed to happen at that point. We did get her some help with a befriending organisation, but I mean I was guilty of it as well, thinking I don’t know what to do, I don’t know how to deal with this. I don’t know where to go for support. The bigger organisations didn’t want to touch it. So it was a bit like where do we go from there?

(Focus group participant)

Care homes

Perhaps surprisingly, data related to care homes were limited, with only a small number of participants discussing their experiences of family members living in residential care. Some people expressed fears about the costs and availability of care home placements, and implications for their own or a family member’s potential future needs.

Experiences of caring for someone at end of life at home

Many people had mixed feelings about their experience of caring for someone at home; while some people were pleased to have enabled their family member to live at home, many also found it a difficult experience. Issues included the following.

Responsibility and decision-making

Many family carers talked about feeling a heavy burden of responsibility, especially in relation to managing medication and trying to ensure that the person was pain-free. One family member recalled ‘I was asked “are you a nurse?”’ because she had learnt so much medical terminology, and she explained that ‘it feels like you are the only person holding all the information’. Having to make decisions about the person’s care and treatment also weighed heavily. Some people explained that despite knowing that they were carrying out the person’s wishes, it was hard to feel sure that they were doing the right thing, for example if someone didn’t want to go into hospital, and that they would have liked support and reassurance, during and afterwards.

Identity, roles and relationships

Some family members discussed their changed role when caring for someone. One daughter described the relief she felt when her parent decided to go into a hospice, as ‘I could be a daughter again’.

Some also talked about the physical and emotional pressure that they felt when caring for someone who was denying the level of help that they needed or didn’t want to have carers or make arrangements. Some focus group participants also talked about how this affected their relationships. One wife described her experience of caring for her husband who has a progressive illness:

Through the years, I’m becoming emotionally exhausted, mentally exhausted, physically exhausted. The love sometimes turning into hate.

Isolation

Caring for someone at home was commonly experienced as isolating, and described as ‘a lonely process, carrying a lot’. For family carers, finding time, or respite care, to see friends was ‘not easy as you are always on call’. While many found supportive friends invaluable, carers often felt their responsibilities put a strain on other relationships. One CB reflected on the loneliness felt by one Community Conversation participant when caring for her husband:

She said what was really hard is when she was at home with him, he had carers coming in and out at the end, but it would have been really nice for somebody to just sit with her for half an hour. Because she was really, really lonely and she just didn’t know what to […] When the husband was being put to bed – because they put them to bed, the carers, don’t they, about half past six, and that’s another thing, isn’t it – that somebody could have just sat there so she could just reflect or just talk or just get stuff off her chest, instead of sitting there brewing over it. Like maybe a volunteer helper or I don’t know, it could be a nurse, but maybe a volunteer.

Focus group participant

‘A difficult job’

Many family carers described the experience as physically and emotionally exhausting. Two people discussed experiencing ‘burnout’ and the negative impact on their mental health. Self-care was difficult; one participant commented ‘I haven’t bothered to think about myself’; another described their own emotional needs as ‘the least of my worries’.

One person had contacted the Samaritans and was having counselling, but more commonly people felt that it was hard to access mental health support when caring for someone who is dying, and that there are specific issues that are not well understood or provided for, such as the stress of providing constant care and anticipated grief. Carers also described feeling guilt or a sense of shame around finding caring difficult.

What’s hard in bereavement?

Impact of their experiences on the bereaved

Some people talked about the way that their experiences of the death of a loved one were affecting them emotionally, particularly when there had been difficult or traumatic circumstances. Some felt guilty because someone had not received the care that they would have liked them to. Feelings of regret and loss due to COVID restrictions were discussed by some people who had not been allowed to visit a loved one in hospital or a care home, and felt that they had missed opportunities to spend time with them.

Accessing support and/or information after someone dies

Understanding grief

Some people reflected that they hadn’t known what to expect when grieving, or what was ‘normal’, or how to support others. One person commented that they found it difficult to differentiate between the effects of bereavement and mental health issues. Several people had found it difficult to access advice on how to support bereaved children in the family. One community worker talked about their experience of supporting bereaved people in grief cafes:

Another big part of it is that the death of someone was a trauma and part of that is that lack of preparation, lack of expectation, lack of support at the time. What’s involved in caring for and just experiencing death, is a trauma, because we’re not prepared for it. So all these people coming out the other side, are traumatised, and there’s nothing there.

(Focus group participant)

Lack of ‘aftercare’ for carers

Several people felt that immediately after a death there was an absence of both practical help (e.g. dealing with administration, removing equipment) and emotional support; or they didn’t know where to find it. People also discussed how difficult it can be to ask for help. A few people commented that they had received one phone call after a bereavement to ask how they were (e.g. from a hospice) but that it didn’t happen at a time when they felt like talking, and they felt like they had then been ‘ticked off the list’. Although they had then been told to ‘ring any time’ it was hard to make the call, or reach the right person, and they would have preferred more check-ins.

In one rural focus group, a community worker reflected that some people who have not received positive support from services in the past can particularly find it difficult to seek help in bereavement:

I think sometimes people have been so let down that it’s actually easier for them not to ask for help than to manage the sense of being disappointed […] If you haven’t had that experience of being able to form relationships which are supportive, to suddenly find that you have got one, can be unbearably painful as well. So I think it’s a complicated relationship, that you’re asking someone to reach out for help. Because you’re inviting rejection as well, aren’t you? Particularly when they’re feeling vulnerable.

The impact of living in rural and coastal areas

Issues related to living in rural and coastal areas included the accessibility and availability of services, and isolation.

Accessing health, social care and other support services

Limited transport options were cited as a key factor affecting both access to, and provision of, support services. In one coastal town, for example, people discussed how difficult it is to get to hospital appointments, or the local hospice, on public transport. One participant commented:

We’ve got one of the lowest car ownerships in Devon and one of the worst bus services, so how do you get to visit someone at [nearest hospital] when you’ve got work?

Arranging social care at home was commonly described as very hard. Some rural areas were described as a ‘care desert’ not covered by any agencies, citing long travel times and lack of parking in coastal areas. It was also noted that people often don’t realise how difficult it is to get care (either at home or in a hospice) until they are in a crisis situation. Getting hospice support at end of life was described as the ‘golden ticket’.

Isolation

Some participants expressed concern about digital, online or remote information, advice and support replacing face-to-face services, as this can increase exclusion particularly for people in rural areas, older people and those without digital access.

Distance from healthcare services was also found to separate a patient from their family and community. In one focus group in a small coastal town, members of a local community group explained that before the closure of the local community hospital, they would organise a rota to visit a neighbour admitted to hospital, but that now this was not possible:

When it comes to that time for people, it becomes an outside thing and the community, they’re taken away from the community which doesn’t do them any good, and it doesn’t do us any good because of [town] … and how hard it is to get anywhere, and ferries and all the rest of it, they become detached from their community. […] we used to make rotas to visit them, because some have no family […], and we know that from when [name] was ill the next time and our hospital had gone, she was in hospital a long time, she wasn’t getting better, because it was [market town] and we couldn’t get to her, with jobs, and people who wanted to visit her didn’t have cars and there are no bus routes so it detaches people in their time of crisis.

As the SWP is a popular retirement area, a common scenario was described where couples retire away from friends and family, then one person becomes ill or dies and the bereaved partner/carer becomes isolated. The proportion of holiday homes in some areas was also mentioned as contributing to the erosion of neighbourhood networks that would previously have supported older residents towards the end of life.

Access to nature

People mentioned valuing their local environment, often referring to being outdoors as an important positive coping mechanism when living with illness or caring responsibilities. Although some of the frequently mentioned activities (e.g. dog walking, gardening) may have been a common response in any environment, it was noticeable that a number of people referred to the value they placed on being close to coastal or rural areas for their well-being.

Low-income individuals and families

A number of people mentioned the extra costs when someone is dying, such as heating bills, medical supplies or even feeding visitors, as a concern. Several people commented that ‘nobody tells you’ about support that might be available (such as attendance allowance or a bereavement grant) and that they tended to find out through word of mouth, rather than being informed by health or social services.

Being on a restricted income was also mentioned as a contributing factor for people concerned about preparing for end of life – this was in relation to the costs of care homes and funerals, and also worries about how family members will manage after someone dies.

What’s important to people at end of life and in bereavement

Community Conversation participants were asked to identify up to five elements essential for good end-of-life care within the wider community. From these and from relevant Departure Lounge and focus group conversations, we drew out components that people commonly felt were key to better connected support at end of life and in bereavement.

Advice and information

Easier access to information was felt to be key, including:

-

knowing what to expect after a diagnosis;

-

knowing what you are entitled to and how to access it (including benefits), before and after death;

-

understanding healthcare services, roles, who will do what (hospitals, hospice, nurses, GP, carers) and navigating health and social care systems;

-

practical advice about caring for someone, including what will happen when someone dies;

-

help and advice to make dying ‘the best possible way it can be’, ‘tailoring it to the person’ and ‘making the most of the end of life’;

-

individualised social/emotional advice and support, which is there when people need it.

Other sources of support

Other aspects of support that some participants identified as ‘essential elements’ included:

-

enabling carers to take time out for their well-being;

-

emotional support for carers;

-

emotional support for relatives when someone goes into residential care;

-

feeling able to talk to others about loss;

-

finding comfort in finding their own ways of remembering someone, for example through music or visiting special places.

Advocacy and co-ordination

People also recognised that information itself was not always enough – having someone who could advocate for them was also key. This was described as having someone to ‘put it all together’, navigate systems, ‘check you know what you need to know’, co-ordinate between services, help with practical tasks such as form-filling and help ‘fight’ for support. Some also expressed a need for more expert help, such as legal or welfare rights advice in relation to issues such as claiming benefits or organising a power of attorney.

What do people value from community support?

Findings regarding characteristics of good community support for the dying, their families and the bereaved are reported in a forthcoming article;20 key elements of community support that people valued are summarised here.

Connection

Making connections with others reduced feelings of isolation. Some people found relief and comfort from talking to others in a similar situation, whether in person or online. Others appreciated face-to-face interaction and social activities with others in their neighbourhood.

Importantly though, some people talked about needing to feel comfortable and welcome within a group or by an organisation. Some people mentioned support services or charities which hadn’t felt helpful, perhaps because they didn’t share a common background or experience. One young woman, for instance, talked about not feeling able to make a connection with an older volunteer from a bereavement charity after losing her partner. In another example, a community group discussed their feelings about a local care charity, which they perceived to be geared towards residents able to make donations to the charity. Although the organisation did have provision for those unable to pay, the group reported that many people on a low income felt uncomfortable using the service and were unlikely to ask for help as ‘you don’t feel as though your face fits’.

Peer support

Continuing the theme, this group described their own approach as one of mutual support, which also helped them to build resilience as a community. This model was also espoused by others in community groups, often those run by local staff or volunteers in low-income areas, who stressed the importance of people informally supporting each other, rather than professional support. Peer support was felt to be of a different quality because of its voluntary nature, and because people didn’t feel judged, and consequently felt less wary about seeking support. Some described this informal support as being like ‘family’ for those who don’t have one, or don’t feel supported by their own family.

Feeling able to express emotions without feeling judged was highly valued by some carers. In some Community Conversations and focus groups, participants observed that these events had been the first time that they had talked about their experiences of caring or bereavement, and carers particularly welcomed what for some was a rare opportunity to talk ‘openly’.

Discussion

During our sense-making workshop, partners discussed findings and considered ways in which they, as individual organisations and collectively, could respond. Work to develop a conceptual framework of optimal community support is ongoing, as are partnership meetings to identify future research priorities.

Lessons learnt

Findings from our scoping review showed there was no one approach for engaging communities to support end-of-life care, with little evidence regarding community engagement interventions in rural, coastal and low-income areas. In common with the findings, it is clear that in developing capacity within local communities to support the dying and bereaved, careful attention must be paid to understanding contextual factors related to geography and infrastructure (e.g. rural or urban, availability of transport, location of services) and neighbourhood demographics (e.g. proportion of holiday homes, age of population), and also to existing community assets and strengths. While important, this is not only about drawing on existing resources within communities to support palliative care, but also about co-creating responses to local need with those who are experts within their own communities. The example of some residents feeling uncomfortable seeking support from a local care charity illustrates the ways in which socioeconomic inequalities in a small coastal town are reflected in access to care and support. Discussing a lack of awareness within their community about palliative care support, the community group reflected that developing a link with their local hospice, for example through a hospice volunteer regularly visiting to promote a better understanding of, and familiarity with, their services, would be helpful. As in this example, the findings from our community engagement supported the recommendation from our scoping review that future research should be grounded in appropriate theory, should describe contextual differences within communities, and should examine how demographics, resource availability and the relational fabric of the area might impact the design, implementation and results of public health palliative care interventions.

Future research and sustainability

To address the final objective of establishing a sustainable research network, the NIHR SWP Clinical Research Network is planning to facilitate a ‘Community of Practice’ for the region, which current member organisations, PPI members, and others with an interest in palliative care will be invited to join. Ongoing discussions to develop research bids are also underway. However, it is important to acknowledge that sustaining the partnership at the same level of activity has not been feasible beyond the funded period due to a lack of capacity to provide the necessary administrative infrastructure. In our scoping review,18 we found that the long-term sustainability of interventions was rarely reported. Interestingly, in 13 of 18 included studies, community members acted as agents to deliver the intervention and in 7 these were paid members of the research team. This clearly has implications for future viability. The experience of our partnership echoes the finding from our scoping review that future research should address the need to expand community capacity and develop interventions that can continue after the resource and workforce that research teams offer end.

Limitations

Although efforts were made to ensure that the community engagement programme activities took place in different settings (coastal, rural inland, small towns and cities), within the limited resources available it was not possible to cover the large SWP geography, and Cornwall and Somerset were under-represented. There were however PPI members from these counties.

Many people receiving palliative care live in care homes and may benefit from community interventions. Our attempts to involve residential care settings in our engagement programme received no response, and while some participants discussed their relatives’ experiences in care homes, we were unable to elicit the views of care home residents or staff about the potential role of community in supporting end of life. Future research could co-design more tailored community engagement methods to better facilitate the involvement of care home residents and staff in research into this topic.

It was also difficult within the time and resource constraints to engage residents in the most isolated rural areas. Future research to understand needs could consider using resources such as the ‘Community Conversation’ in such areas, but may need a longer time frame to establish contacts in areas where community workers do not have existing links.

We were advised by experienced community workers to limit the amount of demographic data we collected to reduce form-filling/questioning and increase the accessibility of our activities. For the focus group and Conversation participants, we collected age, gender and ethnicity; however, it was not feasible to collect this information for informal interactions such as the Departure Lounge. This limits our ability to evaluate the diversity of individuals reached through engagement activities, and an aim of future research would be to actively target a diverse range of community organisations in terms of age, ethnicity and other cultural factors.

Membership of the PPI group was limited in diversity, in that the individuals who chose to participate were all female and of white UK origin. Recruitment to this group was conducted pragmatically based on partner contacts, due to the need for the project to begin quickly once funding was confirmed, and our desire for PPI involvement from the outset. Any future research network should look to further broaden the range of experience and demographic background of its PPI group.

Conclusions

This study adds to the body of evidence supporting public health approaches to palliative care and demonstrates:

-

That populations in rural and coastal areas, and low-income communities within those populations, face particular challenges in accessing care and support at end of life. These include transport issues and distance from services, the erosion of neighbourhood networks, isolation from family and friends, the ‘patchiness’ of palliative care services and a lack of social care provision.

-

The potential for creative methods of engagement to help researchers and practitioners understand the experiences, needs and priorities of underserved populations, particularly when discussing sensitive issues.

-

That existing community organisations are often best placed, because of their trusted position within communities, to co-produce such methodologies for involving underserved populations in research.

-

The potential for successful partnerships between voluntary and community sector organisations, specialist palliative care providers, health and social care providers and academics to design future research and public health interventions taking into local contextual factors and the needs and priorities of local communities.

-

The need to develop an evidence base for approaches which enable communities to form partnerships with health and social care providers to support people at the end of life and those caring for them.

-

The need for system-level measures to assess how we capture the effectiveness of such approaches in changing health and social care systems.

Additional information

Acknowledgements

We thank all of the partner organisations (listed Report Supplementary Material 1), their representatives, and the members of the Patient and Public Involvement Group who were key contributors to the partnership and provided critical reflections throughout the project on the planning of the programme and the interpretation of findings, and co-facilitated training and events. We also thank all of the Community Conversation, focus group and storytelling participants, and those who took part in community engagement activities, for being willing to share their experiences and views.

KW and SC are partially supported by the National Institute for Health Research Applied Research Collaboration South West Peninsula.

Contribution of authors

Lorraine Hansford (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8795-117X) (Co-lead applicant, Research Fellow) developed the project protocol, planned and delivered the community engagement strategy, analysed data from the engagement programme, and drafted the manuscript.

Katrina Wyatt (https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7099-159X) (Co-applicant, Professor of Relational Health) developed the project protocol and provided support to analyse data from the engagement programme.

Siobhan Creanor (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7373-8263) (Co-applicant, Professor of Medical Statistics and Clinical Trials) developed the project protocol.

Sheena McCready (https://orcid.org/0009-0007-9875-2719) (Co-applicant, PPI representative) developed the project protocol and provided support to analyse data from the engagement programme.

Richard Harding (https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9653-8689) (Principal Investigator, Professor of Palliative Care and Rehabilitation) developed the project protocol and supervised the scoping review.

All authors had access to all study data, discussed the interpretation of findings, provided critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content and take responsibility for data integrity and analysis.

Disclosure of interests

Full disclosure of interests: Completed ICMJE forms for all authors, including all related interests, are available in the toolkit on the NIHR Journals Library report publication page at https://doi.org/10.3310/ATFA4287.

Primary conflicts of interest: None declared.

Data-sharing statement

All data requests should be submitted to the corresponding author for consideration. Access to anonymised data may be granted following review.

Ethics statement

Ethics permission for the community engagement programme was granted by the University of Exeter College of Humanities Ethics Committee (ID: 493439) in January 2022.

Information governance statement

The University of Exeter is committed to handling all personal information in line with the UK Data Protection Act (2018) and the General Data Protection Regulation (EU GDPR) 2016/679. Under the Data Protection legislation, University of Exeter is the Data Controller, and you can find out more about how we handle personal data, including how to exercise your individual rights and the contact details for our Data Protection Officer here: www.exeter.ac.uk/dataprotection.

Department of Health and Social Care disclaimer

This publication presents independent research commissioned by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR). The views and opinions expressed by the interviewees in this publication are those of the interviewees and do not necessarily reflect those of the authors, those of the NHS, the NIHR, MRC, NIHR Coordinating Centre, the PHR programme or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Publications

Hansford L, Wyatt K, Creanor S, Davies J, Horne G, Lynn A, et al. Engaging with communities in rural, coastal and low-income areas to understand barriers to palliative care and bereavement support: reflections on a community engagement programme in South West England. Palliative Care and Social Practice. 2023;17. https://doi:10.1177/26323524231212514

Peeler A, Doran A, Winter-Dean L, Ijaz M, Brittain M, Hansford L, et al. Public health palliative care interventions that enable communities to support people who are dying and their carers: a scoping review of studies that assess person-centered outcomes. Front Public Health 2023;11:1180571. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1180571

Funding

This article presents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Public Health Research programme as award number NIHR135312. The views and opinions expressed by authors in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the NHS, the NIHR, the PHR programme or the Department of Health and Social Care. If there are verbatim quotations included in this publication the views and opinions expressed by the interviewees are those of the interviewees and do not necessarily reflect those of the authors, those of the NHS, the NIHR, the PHR programme or the Department of Health and Social Care.

About this article

The contractual start date for this research was in January 2022. This article began editorial review in May 2023 and was accepted for publication in November 2023. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ article and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on this article document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

This article reports on one component of the research award Multi-sectoral partnership building in the South West Peninsula: palliative and end-of-life care research in rural, coastal and low-income communities. For more information about this research please view the award page [https://www.fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/NIHR135312].

Notes

-

South West Peninsula Palliative Care Research Partnership list of members

-

Community Conversation and Focus Group participant demographics

-

Table of studies included in the Scoping Review showing key components

Supplementary material can be found on the NIHR Journals Library report page (https://doi.org/10.3310/ATFA4287).

Supplementary material has been provided by the authors to support the report and any files provided at submission will have been seen by peer reviewers, but not extensively reviewed. Any supplementary material provided at a later stage in the process may not have been peer reviewed.

List of abbreviations

- CB

- Community Builder

- CMO

- Chief Medical Officer

- NIHR

- National Institute for Health and Care Research

- PPI

- patient and public involvement

- SWP

- South West Peninsula

- TCDT

- Torbay Community Development Trust

References

- Whitty C. Chief Medical Officer’s Annual Report 2021: Health in Coastal Communities 2021. www.gov.uk/government/publications/chief-medical-officers-annual-report-2021-health-in-coastal-communities (accessed 1 April 2023).

- Office for National Statistics . Subnational Population Projections for England: 2018-Based 2020. www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/populationprojections/bulletins/subnationalpopulationprojectionsforengland/2018based (accessed 1 April 2023).

- Office for National Statistics . Rural Urban Classification (2011) of Lower Layer Super Output Areas in England and Wales 2018. www.ons.gov.uk/methodology/geography/geographicalproducts/ruralurbanclassifications/2011ruralurbanclassification (accessed 1 April 2023).

- Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government . English Indices of Deprivation 2019 2019. www.gov.uk/government/statistics/english-indices-of-deprivation-2019 (accessed 1 April 2023).

- Public Health England . Cornwall: Local Authority Health Profile 2019 2020. https://fingertips.phe.org.uk/static-reports/health-profiles/2019/E06000052.html?area-name=Cornwall (accessed 1 April 2023).

- Public Health England . Devon: Local Authority Health Profile 2019 2020. https://fingertips.phe.org.uk/static-reports/health-profiles/2019/E10000008.html?area-name=Devon (accessed 1 April 2023).

- Public Health England . Somerset: Local Authority Health Profile 2019 2020. https://fingertips.phe.org.uk/static-reports/health-profiles/2019/e10000027.html?area-name=somerset (accessed 1 April 2023).

- Plymouth City Council . Plymouth Report. www.plymouth.gov.uk/sites/default/files/Plymouth%20Report_2019.pdf (accessed 1 April 2023).

- Hospice UK . Equality in Hospice and End of Life Care: Challenges and Change 2021.

- Tobin J, Rogers A, Winterburn I, Tullie S, Kalyanasundaram A, Kuhn I, et al. Hospice care access inequalities: a systematic review and narrative synthesis. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2021;12:142-51. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjspcare-2020-002719.

- Bonevski B, Randell M, Paul C, Chapman K, Twyman L, Bryant J, et al. Reaching the hard-to-reach: a systematic review of strategies for improving health and medical research with socially disadvantaged groups. BMC Med Res Methodol 2014;14. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-14-42.

- Hoekstra F, Mrklas KJ, Sibley KM, Nguyen T, Vis-Dunbar M, Neilson CJ, et al. A review protocol on research partnerships: a Coordinated Multicenter Team approach. Syst Rev 2018;7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-018-0879-2.

- Verbeek H, Zwakhalen SMG, Schols J, Kempen GIJM, Hamers JPH. The living lab in ageing and long-term care: a sustainable model for translational research improving quality of life, quality of care and quality of work. J Nutr Health Aging 2020;24:43-7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-019-1288-5.

- Drahota A, Meza RD, Brikho B, Naaf M, Estabillo JA, Gomez ED, et al. Community–academic partnerships: a systematic review of the state of the literature and recommendations for future research. Milbank Q 2016;94:163-214. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0009.12184.

- St Lukes Hospice . Plymouth: A Compassionate City 2018. www.stlukes-hospice.org.uk/plymouth-a-compassionate-city/ (accessed 1 April 2023).

- Sallnow L, Richardson H, Murray SA, Kellehear A. The impact of a new public health approach to end-of-life care: a systematic review. Palliat Med 2016;30:200-11. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216315599869.

- Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol 2005;8:19-32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616.

- Peeler A, Doran A, Winter-Dean L, Ijaz M, Brittain M, Hansford L, et al. Public health palliative care interventions that enable communities to support people who are dying and their carers: a scoping review of studies that assess person-centered outcomes. Front Publ Health 2023;11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1180571.

- The Academy of Medical Sciences . The Departure Lounge n.d. https://acmedsci.ac.uk/policy/policy-projects/the-departure-lounge (accessed 1 April 2023).

- Hansford L, Wyatt K, Creanor S, Davies J, Horne G, Lynn A, et al. Engaging with communities in rural, coastal and low-income areas to understand barriers to palliative care and bereavement support: reflections on a community engagement programme in South West England. Palliat Care Soc Pract 2023;17. https://doi:10.1177/26323524231212514.