Notes

Article history

The contractual start date for this research was in November 2021. This article began editorial review in June 2023 and was accepted for publication in June 2024. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The Public Health Research editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ article and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Bonell et al. This work was produced by Bonell et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Bonell et al.

Introduction

Mental disorders are the largest cause of disability in the UK1 with about half starting by age 18 and a third before age 14 years. 2 In 2022, 18.0% of children and young people aged 7–16 years had a probable mental health disorder. 3 About 40% of adolescent girls have disordered eating4 and 20% report self-harm. 5 In the UK, the Green Paper ‘Transforming Children and Young People’s Mental Health Provision’ identified a central role for schools. 6 Schools aim to implement effective programmes but have lacked specialist expertise, access to evidence-based interventions, and resources. This is changing as schools become part of mental health support teams with access to a new workforce of educational mental health practitioners. 6 However, the focus of these initiatives is largely responding to, rather than preventing, mental health problems. There is therefore a continuing need to develop and evaluate universal prevention interventions. 7 Such interventions are of even greater importance since COVID-19 as there is evidence of worsened mental health post the pandemic. 8,9

Multiple reviews support a role for school programmes in addressing young people’s mental health and disruptive behaviours,10–13 with evidence across anxiety and depression,11 body image and disordered eating,14 and self-harm, and supportive capacities such as self-regulation. 15 A promising approach is the use of whole-school interventions, which include classroom curricula plus components aiming to transform the wider school environment to make this more health-promoting. Such interventions aim to address multiple determinants of mental health in the school environment. They also aim to build ownership among school leaders, staff, and students, which should promote implementation fidelity. Observational studies suggest that school environments can influence mental health in multiple ways through a sense of school belonging and commitment; exposure to prosocial or antisocial peers, bullying and social-support networks; and learning of social and emotional skills. 16–19 Whole-school interventions addressing such factors have been found to be effective for a range of health outcomes. 7,20,21 However, such interventions have received only limited attention in the field of mental health and the evidence base supporting implementation is therefore weak. 20 The existing evidence on school-based interventions to promote mental health is also limited by: small effect sizes;10 interventions focused on single aspects of mental health;22 lack of interventions being co-created with young people; promising interventions failing to be effective at scale;7 and lack of flexibility in implementation. 23

We previously led a cluster-randomised trial of the Learning Together (LT) intervention across 40 English secondary schools. 24 Learning Together is a multicomponent, whole-school intervention aiming to modify the school environment to reduce bullying. The key elements of LT are as follows: survey of students to identify needs; action groups comprising staff and students (supported by an external facilitator) to review needs data and use this to plan and co-ordinate local delivery, and revise school policies and rules; training for school staff in restorative practices; and a social and emotional learning (SEL) classroom curriculum. Restorative practice addresses bullying, antisocial behaviour or conflict by bringing together victims and perpetrators, victims describing the harms caused, perpetrators taking responsibility, and work to improve the relationship and avoid further harms.

The theory of change postulated that implementing these interventions components triggers a mechanism involving: building of student sense of belonging at school via recentring provision on student needs, and improving relationships between staff and students and between students’ academic and personal development; and developing students’ social and emotional skills. Building sense of school belonging and commitment, and providing students with social and emotional skills were theorised to increase student investment in prosocial groups and behaviours, and decrease investment in antischool groups and behaviours including bullying. 24,25 We found that the intervention was implemented with fidelity (other than for the SEL curriculum), with significant effects on reduced bullying victimisation (primary outcome) as well as improved mental well-being and health-related quality of life, and reduced psychological distress and substance use (secondary outcomes), with high cost-effectiveness. 24 Effect sizes for impacts on mental health and well-being were approximately 0.1 standard deviation (SD) despite the intervention not directly addressing mental health other than through the poorly delivered SEL curriculum. Refocusing LT to address mental health more directly may enable even greater impact on such outcomes.

This paper reports on how we refined LT to produce the Learning Together for Mental Health (LT-MH) intervention. The LT-MH intervention retained key elements of LT while focusing more directly on mental health, including emotional and behavioural issues, self-esteem, body image and eating problems, substance use, and self-harm. We also aimed to replace our poorly delivered SEL curriculum with an improved curriculum. We set out our initial plans for LT-MH in a proposal for a refinement and feasibility study, which was funded by the National Institute for Health and Care Research. Such studies ensure that interventions can be optimised prior to phase III trials. 26 The initial stage of the funded work was aimed at refining and elaborating intervention materials prior to feasibility testing. Existing frameworks for intervention development and refinement suggest that this should be based on understanding: the problem to be addressed and what factors influence its occurrence; which of these factors are modifiable and how this will benefit the target population and its subgroups; what mechanisms of change will be harnessed to modify these factors; and how these will pragmatically be triggered. 26,27 As noted above, we had a clear understanding of the problem to be addressed and the school factors to be influenced. Learning Together’s theory of change also outlined the broad mechanisms of change to modify these factors. We thus had an existing sense of how the intervention would work and sought further information to elaborate and optimise the methods we would use to do this.

We conducted a systematic review of reviews to inform our menu of evidence-based actions to promote mental health, which is reported separately. All other aspects of adaptation are reported in this paper. We reviewed existing evidence to inform our choice of a new SEL curriculum and the measures to use in the needs survey, which are reported in this paper. We aimed to use patient and public involvement and engagement (PPIE) to inform refinement, ensuring that the intervention was feasible and acceptable on the ground. Patient and public involvement and engagement aims to ensure that the views and experiences of service users, citizens, and practitioners inform interventions. 28,29 This orientation is grounded in a recognition that academics are liable to develop unfeasible and ineffective interventions if these are based merely on academic theories which are inattentive to local contextual contingencies. 30 Patient and public involvement and engagement is intended to enable the development of more feasible and acceptable interventions by involving those with experience and understanding of local contexts. 31 However, the use of PPIE to inform interventions is complex and challenging, involving different groups and various processes. 32 In this paper, we report on how we refined the LT intervention components to design LT-MH through a review of research evidence and PPIE.

Methods

Overall design

We refined LT-MH in collaboration with Place2Be (a charity specialising in promoting young people’s mental health, which subsequently supported delivery of LT-MH in schools); the National Children’s Bureau (NCB) Young NCB, a group exclusively for children and young people; staff and students from one secondary school; and a group of school senior leadership team members.

Refinement was conducted from November 2021 to September 2022. As described above, the key elements of the intervention were determined at the stage of writing the funding proposal. These are described below. After this, we turn to the main focus of the paper, how we drew on evidence and PPIE to refine LT-MH.

Initial plans for intervention

Theory of change

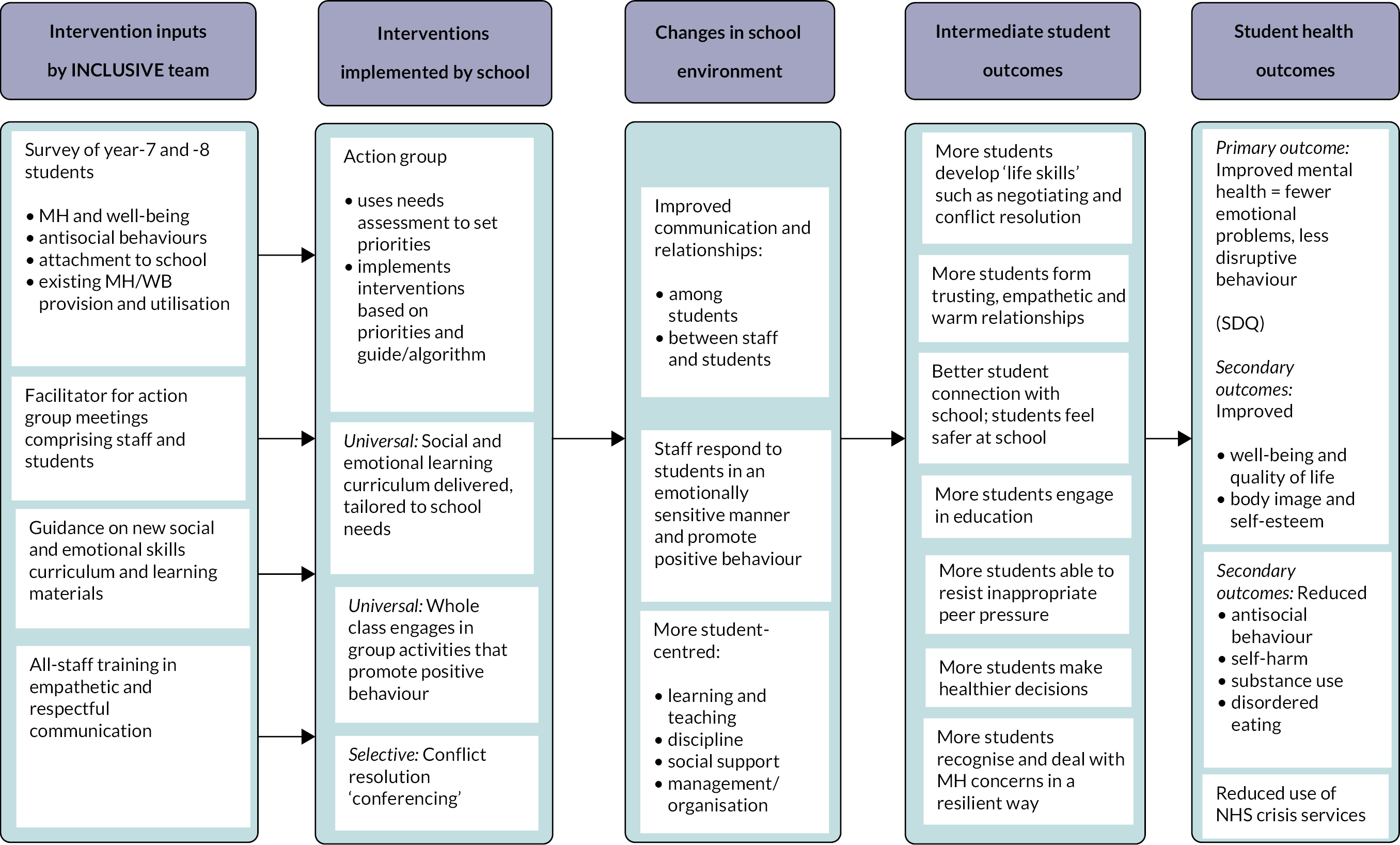

The LT-MH intervention was underpinned by a theory of change based on that used in the LT intervention (Figure 1) and drawing on the theory of human functioning and school organisation. 25 We also drew on evidence of the effects of other whole-school mental health interventions. 10–13 Our intervention inputs (described below) were intended to enable implementation of an action group, SEL curriculum, and restorative practice. Together these would modify schools’ social environments to: improve relationships among and between students and staff; provide more student-centred provision; increase social support for mental well-being; and teach social and emotional skills. 33 These were theorised to increase student sense of school belonging and engagement, and increase social and emotional skills. Through this, students would develop: increased emotional security in school; more trusting, empathetic, forgiving and accepting relationships with students and staff; increased self-belief (including belief in the ability to manage and resolve difficulties when they arise); and increased ability to resolve conflict, avoid peer pressure and seek support for one’s own and others’ mental health needs. These changes were theorised to mediate intervention impacts on mental health: fewer emotional problems and less disruptive behaviour; improved well-being and quality of life; improved body image and self-esteem; reduced antisocial behaviour, self-harm, substance use and disordered eating; and reduced use of NHS crisis services.

FIGURE 1.

Logic model.

Intervention inputs

-

Needs assessment: We retained the original LT focus on antisocial behaviours and: (a) strengthened assessment of various mental health issues as described above; (b) strengthened translation of needs assessment into actions through use of guidance for schools on matching needs to actions; and (c) guided and enabled the action group to draw on existing data to audit existing mental health and well-being provision in the school. 34

-

Facilitator and manual: We updated the manual to detail all refined intervention components. We modified the external facilitation of the action group (identified as being critically important in the successful implementation and mechanism of impact for LT35,36) to be provided by a Place2Be practitioner with mental health expertise.

-

Whole-school training in restorative practice. This component was not modified because it was accredited training, was rated highly by staff in the original trial and its focus remained on preventing bullying and conflict. 36

-

The SEL curriculum: we retained a curriculum because of evidence for the effectiveness of SEL curricula on mental well-being37 but identified a new evidence-based curriculum in the refinement phase because the LT trial and process evaluation indicated that the LT curriculum was poorly delivered and unpopular in schools. 24

School processes

-

Action group: In each school, a group would be convened to enable staff and students to work together to review data on mental health needs, choose options from a menu of evidence-based actions, revise policy to support mental health promotion, and plan and co-ordinate intervention delivery. The external facilitator would assist the school staff member chairing the meetings in terms of convening the group, interpreting the school’s needs assessment data, setting initial priorities for action and reviewing progress. By identifying student needs, providing an external facilitator and having the action group plan and co-ordinate actions, we hoped to build school commitment and hence optimise implementation. The funding proposal was informed by initial reviews of evidence and preliminary consultation with the Young NCB, identifying the following areas and actions likely to be relevant: self-esteem and body image (via single38 or multiple lessons39); anxiety and depression (via teacher-delivered curricula22 and single-session interventions40); digital health; inclusion of LGBTQ+ young people (via inclusion policies, champions and support groups41); increasing student voice; mental health awareness sessions; physical activity opportunities;42 mental health first aid (MHFA) training; and various other activities such as well-being workshops, mental health monitoring, mental health literacy education, support for exam stress and signposting services. These were reviewed and finalised during the refinement stage informed by review of systematic reviews (reported in a separate paper).

-

Restorative practice – this was to be implemented largely unchanged from LT, but would be situated within a broader focus on mental health and well-being.

-

Learning social and emotional skills – this was to occur in classes led by trained teachers using the materials described above.

Intervention refinement

Refinement was informed by an existing framework for intervention development,43 occurring in phases. Firstly, the intervention theory of change, logic model, and overall approaches were reviewed to identify required changes. Secondly, the student needs survey, the manual guiding the action group, and needs assessment guide were refined. Thirdly, an evidence-based SEL curriculum was identified. For each phase, refinement occurred through a systematic process involving: reflection on the intervention plans in light of existing evidence;7,10–13,20,21,44,45 discussions with PPIE stakeholders; drafting of resources by the research team informed by PPIE, and research team expertise and experience; and refinement of resources informed by PPIE.

Patient and public involvement and engagement involved multiple activities to provide diverse perspectives. It was consultative in orientation given that the aim was to adapt an intervention with existing evidence of mental health benefits to maximise these benefits. We felt that a more thoroughgoing reappraisal of the intervention involving more participant-led PPIE was not appropriate given the importance of maintaining the existing theory of change and effective components. Because this was PPIE and not research, formal consent was not sought for participation, and sessions were not audio-recorded. Instead, the team checked that participants were content to be involved and took detailed notes of views and suggestions. Each meeting was attended by two researchers, one leading facilitation and one taking notes. We held two meetings with Young NCB members. This is a membership group for children and young people in England, providing opportunities to speak about and contribute to matters relevant to them. The first meeting involved presentation of the aims of the LT-MH intervention by the research team. The Young NCB group was then split into two breakout rooms to discuss what young people worry about, distinguishing between new and existing worries, guided by slides indicating these topics. One researcher joined each subgroup. Again, guided by slides, Young NCB members were then asked for their views on the feasibility and acceptability in schools of the following intervention components: the student needs survey; the manual; and the manual section offering guidance on using the needs assessment to identify evidence-based actions. The second meeting involved presentation of the draft components of the LT-MH intervention and how the intervention was being refined to address mental health. The draft of the menu of evidence-based actions was presented. The Young NCB members were split into two breakout groups to: discuss the pros and cons of each intervention component; identify any gaps; and identify the best three actions and their reasons for choosing these. The group was then asked to further discuss the feasibility and acceptability of workshops on how to handle stress and of MHFA to ascertain young people’s views on how these could be delivered.

We also conducted two meetings with a purposively sampled secondary school, one with students and one with staff. We aimed to involve a school with student free-school-meal eligibility (as a proxy for student need) above the national average of 27.1% and a government school inspectorate rating of good or excellent (as a proxy for the school having sufficient organisational capacity to participate). This school was recruited via our existing contacts. The student meeting involved five boys and girls across years 8–11 and the staff meeting comprised four teachers from the senior leadership team and with pastoral responsibilities. Schools were asked to involve a diversity of students and staff, reflecting diversity across the school. Both meetings involved presentation of the intervention theory of change and overall components. Guided by the research team with slides indicating points to discuss, students were asked: whether the components made sense as an overall programme; whether students would be interested in participating; what information schools would need about student needs to inform choice of actions; and what information schools would need in order to deliver actions. Staff were asked: how the intervention should be presented to maximise school take-up and student participation; whether the intervention activities looked appropriate and manageable; whether they made sense as an overall programme; whether schools would agree to involve students in decision-making; whether students would be interested to participate; what information schools would need to deliver specific actions; whether schools would value local evidence about need and what needs they would want evidence about; and what support they would want from a facilitator and whether this should be face to face or online. We used standard operating procedures to deal with any potential safeguarding concerns becoming apparent during consultation with students but none arose.

We held one meeting with senior leadership team members from two different schools. Five schools were initially contacted for this meeting based on previously indicated interest. However, only two were able to participate in the meeting due to COVID-19-related challenges. One senior leader member per school attended. This meeting involved presentations to the staff members attending about the draft manual and menu of evidence-based actions, as well as how the results of previous meetings had informed these. Guided by researchers, senior leadership team members were asked whether: the manual guidance and menu of actions looked appropriate and manageable; these provided the right information; and participants thought these would impact on student mental health. Senior leadership team members were also asked what comparators would be most useful when benchmarking mental health needs.

After PPIE, researchers separately discussed views and suggestions of PPIE participants from notes, to decide which suggestions could be incorporated into research plans. As far as possible, suggestions were taken onboard, except where they contradicted existing evidence or were unfeasible.

Results

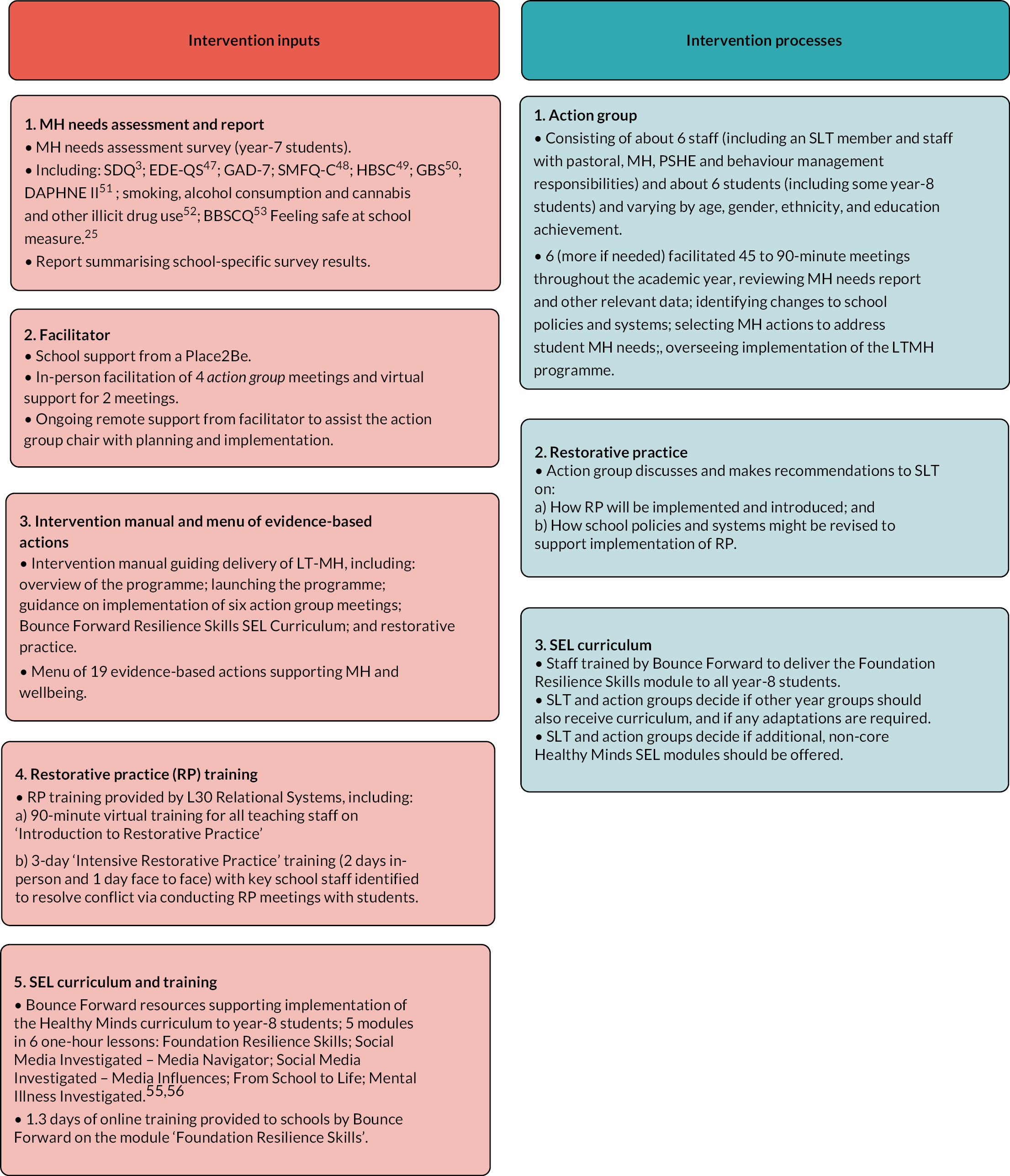

Appendix 1 presents the final LT-MH intervention design. The PPIE suggestions and responses are described below and summarised in Appendix 2.

Consultation with Young National Children’s Bureau members

We first met with the Young NCB members in January 2022. This session involved approximately eight members. Participants reported various worries, such as body image and self-esteem. Participants mentioned other worries, including: social media and online reputation; lack of sense of community; lack of trust in government and other institutions; sexism and misogyny; the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic; the climate emergency; and education and exams pressure. In commenting on LT-MH components, participants suggested that the need survey would need to include mostly closed-response questions. Participants suggested that the manual guiding actions groups should be read by, and include actions for, young people to maximise students’ participation.

We held a second meeting with eight Young NCB members in April 2022. In terms of improving LGBTQ+ inclusion, young people agreed that this was a good idea because they felt that LGBTQ+ young people sometimes did not feel comfortable coming out to others. However, participants thought that such activities should also encompass other groups, such as disabled students. Participants suggested that support should not be restricted to one-off events, and should include activities such as ongoing lunchtime clubs and presentations by guest speakers with lived experiences. The group felt it important that students involved in such work be well supported.

The group discussed student-led clubs focused on mindfulness, meditation, dance, and martial arts for mental health. Participants felt that the success of these would depend on who led them (possibly a role for older students) and how well they were supervised. The group discussed lessons on mental health literacy. Several thought this was a good idea but suggested that there might not be enough time in the school day. The group also discussed lessons on online safety and well-being, as well as lessons on ethnicity and mental health, there being limited support for the latter. There was not much support for an expansion of tutor time.

The group discussed stress-management workshops. All participants supported this option. Participants commented that stress comes from a variety of sources, connected to exams and life in general. They felt that this option would need to explore all potential sources of stress. Participants suggested that it might include activities such as aromatherapy sessions.

The group discussed the potential for expanding school extracurricular activities, with some participants commenting that students have very different interests so diverse options would need to be available. The group considered MHFA. One participant pointed out that this option is not preventative in nature. There was, however, widespread support for this option as many of the young people felt that their peers currently would not be properly equipped to deal with a peer who was, for example, having a panic attack. The group suggested that there could be a role for older students delivering this. The group discussed yoga, with some young people viewing this as a helpful option. However, others pointed out that this would not be suitable for all young people, such as those with disabilities. Therefore, a meditation option might be helpful.

There was little support for additional support for students transitioning from primary schools as participants felt that there was already provision in this area. The group discussed outdoors lessons and the use of physical activity in lessons. Although there was some support for these in that they would make lessons more engaging, participants highlighted that the time required should be considered.

The group discussed themed mental health weeks. Participants felt that mental health should be a priority all of the time and not just in particular weeks or months. They reported that the volume of awareness weeks in schools meant that they were not perceived as effective by students. When discussing posters and other resources on mental health, young people expressed some interest but believed that the quality of these would need to be improved. Of the options identified above, participants nominated the following as priorities: improving LGBTQ+ inclusion; lessons on mental health literacy; workshop on how to handle stress (including exam stress); MHFA; and posters and other resources on mental health.

The group then further discussed workshops on how to handle stress and MHFA, to ascertain young people’s views on how these activities could be best delivered. Regarding workshops on how to handle stress, participants thought that two sessions per week of between 30- and 60-minute duration would be appropriate. The group recommended that sessions would need to be delivered outside normal lessons by an external professional. Regarding MHFA, the group recommended that this should be delivered yearly or twice yearly, and should be for a whole day. One participant believed that a minimum level of training should be available for everyone, with optional training for selected students. All agreed that training needed to be delivered by external specialists.

Consultation with school students and staff

The school originally selected to participate matched our criteria of rate of free-school-meal entitlement above 27.1% and outstanding Ofsted inspection but dropped out at the last minute. We replaced this school at short notice. The school recruited to participate had an outstanding government inspectorate rating but below-average rate (approximately 15%) of free-school-meal entitlement. The meetings with students and staff occurred in May 2022 and involved presentations by the team followed by discussion. A staff member from Place2Be also helped facilitate discussions.

The student meeting involved discussion with two boys and three girls from across years 8–11. In terms of needs assessment, the students indicated that they would be happy for the needs survey to include mental health scales. The students emphasised the importance of participant anonymity. Students were concerned that surveying only one year group would not identify all mental health needs across different age groups. Participants thought that comparing each schools’ prevalence of mental health needs with broader data would be useful.

In terms of the action group, students agreed that it would be valuable to have staff and students meeting together. Students thought that, if participation were on the basis of students coming forward to volunteer, this would make for less-diverse participation. There was a suggestion that students could be approached to participate and could initially observe the meeting without committing to participate, as way to encourage participation among a broader group. There was a concern that selecting students on the basis of their mental health could cause participants to feel stigmatised. Participants thought that the action groups should be as student-led as possible. They suggested that meetings should be monthly and comprise six staff, six students, and the external facilitator.

In terms of the menu of actions, students were supportive of these addressing: physical activity sessions; stress management; and lessons or other activities occurring outdoors. Physical activity was viewed as something that might help improve some students’ attitudes to learning. Students commented that some of the planned activities were things already done in schools, though not linked together as a coherent programme. Students thought that there was no need for activities to be labelled as explicitly focused on mental health promotion. Some participants described stress as a problem linked to studying, not just exams, and that mindfulness or walks might help. Yoga was viewed as something that would appeal to some students. Participants also proposed that doing more group activities in classes might help promote mental health, ensuring that all students participated. In terms of restorative practice, students were supportive of this but suggested it should only be done when all parties to a conflict consented. Finally, students suggested that ‘Learning Together for Mental Health’ was too long a name.

The meeting with teachers involved four staff from the senior leadership team and with pastoral responsibilities. In terms of needs assessment, the teachers said that they would expect students to answer questions differently at different ages. There was a concern that results from year-7 students would not be representative of other year groups. Teachers thought that a different year group, such as year 8 or 9, might be better. There was also concern about survey overload, given that the school already carried out surveys.

In terms of action groups, staff thought that schools would be willing to involve students in decision-making. While they said that participation should be voluntary, they cautioned that the group should not comprise only the most vocal. It was important that membership of the group was not stigmatising of those with mental health needs. Staff suggested that students from a range of year groups should be included to give insights from across the school and, if necessary, compensate for the narrowness of focus of the needs survey on year-7 students. Teachers commented that, in terms of staff participation, all schools should have a mental health lead, who should be included in the group.

In terms of choice of actions, staff liked the idea of presenting a menu of evidence-based actions with indications of the strength of evidence, size of effects and costs. Staff were also interested in knowing where there was little or no evidence for other actions. They liked the idea that guidance should advise that if there were a certain need apparent then this would suggest the value of implementing a particular activity. It should be clear whether an action aimed to target a particular group or address the broader ethos and culture of the school. Teachers thought that actions should address the whole school, such as school rules, policies and staff training. There were some concerns about the implications of actions for teachers’ time. Teachers identified bullying prevention as a key priority and said that they would like to see evidence for interventions to address this. In terms of the SEL curriculum, staff said their school would be unlikely to adopt a new curriculum because they had already developed a curriculum meeting their requirements.

Teachers said that they would value an external facilitator for the action group. They suggested it should be provided for at least 2 years. Participants thought that in-person facilitation would be preferable but thought that a hybrid approach could work with half of meetings in person and half online. Staff felt that the facilitator should act as a critical friend, motivating and supporting implementation, and providing expertise about how to maximise outcomes. The facilitator should set and monitor success criteria for each meeting.

Consultation with school senior leadership team members

This meeting occurred in June 2022 and involved presentations by our team to a staff member each from two schools about the draft contents of the manual and the menu of evidence-based actions, as well as how the results of previous meetings had informed these.

Participants liked the whole-school, universal approach, suggesting that targeted interventions could sometimes miss those students in most need. One participant commented that the intervention and manual provided the outline and direction of what was required. Participants commented that schools would then need to identify what was required of them to implement the intervention and determine who would be responsible for delivery and oversight. The group recommended a greater emphasis on engaging parents. One participant commented that the needs assessment was very useful in quantifying need, given schools sometimes had to rely on anecdotal information. Comparisons, especially with national data, would be useful. Participants commented that the resources could be presented during Ofsted inspections, showing data on student needs and how these had been addressed.

Commenting on the menu of evidence-based actions, both participants liked the presentation of the menu and the links to all resources. A participant liked the format, given that schools were familiar with that of the Educational Endowment Foundation menu of evidence-based interventions to promote attainment. Participants agreed that it was also useful to summarise costs. One participant asked whether it could be made clear whether the evidence base referred to the actions in general or the specific materials linked to. A participant also suggested that the menu should include a disclaimer indicating that the intervention team did not necessarily endorse every resource. One participant commented that, in relation to MHFA, it would be useful to have guidance materials. This participant reported that, although many staff already received training in this, they were often unsure how to implement it without written guidance. Participants also supported the inclusion of daily miles and mental health check-ins. These have been used more in primary schools but secondary schools could also implement them.

Refinement of the intervention theory of change, logic model and overall approaches

No further refinements were made based on our review of existing systematic reviews and PPIE to the intervention theory of change and overall approach. The evidence from systematic reviews had already informed our theory of change as described above. Most PPIE comments aligned with our existing plans but some suggested possible changes, some of which we made. We did not, as one student suggested, shorten the name of the intervention as the name was judged to represent a link with an existing effective intervention and signalled the new focus on mental health. In response to a comment from senior leadership team participants to increase the focus on parents, we included various suggestions in the manual on how to win support from and involve parents but did not amend the overall theory of change or components.

Modifications to needs survey and guidance for determining actions

We retained the needs survey despite one staff member commenting that it would overload schools. This was both because it was a core component of tailoring the intervention to the school and because other participants were positive about its usefulness. We also could not act on the suggestions that the survey should broaden its focus from only year-7 students. This was because the survey of year-7 students was a central part of the evaluation protocol. However, we amended the manual so that it recommended schools draw on other data, including from other year groups, as part of the needs assessment. In response to a comment from senior leadership team participants, the manual also encouraged schools to share needs assessment findings with Ofsted inspectors where appropriate. Other comments from PPIE aligned with our existing plans.

The needs questionnaire retained the following measures, which had been included in the LT questionnaire: the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ);3 the Gatehouse Bullying Victimisation Scale;46 questions on smoking, alcohol consumption, cannabis and other illicit drug use;47 the Beyond Blue School Climate Questionnaire (BBSCQ);48 and the Feeling Safe at School measure. 24 The following items were added: the Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire Short (EDE-QS) (which included questions on body image);49 the Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) Scale; the Short Mood and Feelings Questionnaire (Child Report – Depression);50 the Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) measure of self-harm;51 and the DAPHNE II measure of cyberbulling. 52 Decisions about which measures to include were informed by our expertise in young people’s mental health and current evidence about children and young people’s mental needs. 53

In the needs assessment report, we included plans to report on the following measures overall and stratified by gender: SDQ as a measure of general mental health as well as its subscales; EDE-QS as a measure of eating disorders; GAD-7 as a measure of anxiety; SMFQ-C as a measure of depressive symptoms; the HBSC measure of self-harm; the GBS measure of bullying victimisation; the DAPHNE II measure of cyberbullying; our measures of smoking, alcohol use and drug use; the BBSCQ measure of school commitment and its subscales; and our Feeling Safe at School measure. Where possible, we would compare school prevalence to national comparative data. Where no national data were available, we would refer to prevalence across all LT-MH schools as the comparator. We did not report mental well-being as we felt that that this overall measure would not provide useful information for schools in determining what mental health actions to take.

Drafting the intervention manual

We drafted the manual informed by the previous LT manual, the recommendations emerging from PPIE and experience within the research team developing group-facilitation manuals. The systematic reviews were not informative because they did not contain the necessary detailed information about interventions. Guidance on implementing and facilitating the action group was elaborated and given a more prominent role in the manual, given the action group’s central role in implementation of the programme. Meeting objectives, agenda items and practical exercises and tools were added to guide action groups. As recommended by students and staff, we refined the manual so that this supported the recruitment of diverse students to the action group. In response to student comments, the manual was worded to encourage schools to include students both with and without mental health problems, but did not aim to encourage staff to target students with mental health problems for recruitment.

We did not act on the suggestions that action groups should meet monthly or be student-led. The former contradicted evidence from the LT trial that meetings should not occur too frequently. 24 While students were to be empowered to actively contribute to decision-making, we decided the groups should be chaired by senior staff to support implementation of decisions, informed by the LT trial. 24 In response to staff comments, we included meeting-specific objectives in the suggested agenda, included as part of the manual. We also moved to a mixture of face-to-face and virtual external facilitation as this had been normalised post the pandemic and would enhance efficiency and scalability, which was supported by staff views. Other PPIE comments aligned with our existing plans.

Drafting of the menu of evidence-based actions

The systematic review of reviews that informed the menu is described in a separate paper. The PPIE comments were very helpful in drafting the menu. The PPIE participants supported our plans to indicate the strength of evidence, size of effects and costs of recommended actions. Our menu distinguished between general approaches and specific guidance materials and interventions, and indicated the level at which actions were to be delivered, as suggested by senior leadership team participants. We did not act on a staff suggestion that the menu should also indicate which actions were not supported by evidence since this would not be possible to do comprehensively within a short document. Most of the mental health topics and actions suggested in PPIE did feature in our menu. However, some, such as aromatherapy and mental health check-ins, did not feature because there was no evidence that these were effective. We also did not address some of the more upstream determinants of mental health suggested by students, such as lack of trust in government, since there is a lack of evidenced interventions to address these. We did not act on suggestions from Young NCB members about what specific actions should look like, such as how many sessions stress workshops should involve, because we were guided instead by the evidence base regarding the details of implementation. We amended the manual to encourage schools to consider the implications of actions in terms of staff time and their ability to continue other activities.

Refinement of restorative practice

We made few changes to the restorative practice component informed by PPIE since the suggestions aligned with our existing plans. We changed some terminology to ensure this was suitable for secondary-school students. For example, ‘circle time’ was instead referred to as ‘class group activities that promote positive behaviour and peer-to-peer support’. Informed by PPIE, we decided that the training on restorative practice should be delivered via a mixture of face-to-face and virtual sessions to reduce costs and enhance scalability.

Identification of evidence-based social and emotional learning curriculum

We retained our plans for a SEL curriculum despite one staff member commenting that their school would be unlikely to use this since they had developed their own. We judged that other schools would welcome this component given its effectiveness. The team identified and assessed various curricula cited in the systematic reviews, and assessed these based on criteria of: evidence of effectiveness; quality of materials; cost; age focus; training availability; and number of lessons. The Healthy Minds curriculum was judged most appropriate on ground of: involving a manageable number of lessons; having strong evidence in promoting multiple health outcomes,54 being inexpensive according to Education Endowment Foundation criteria; being suitable for students in years 8 and 9; and being deliverable by teachers with training provided by experts. The Healthy Minds curriculum is informed by the Penn Resilience Program and other evidence-based interventions. 55

All schools would be provided with training to deliver the six-lesson ‘Bounce Forward Resilience Skills’ section of the SEL curriculum. Teachers would be provided with 1.3 days of online training to support delivery. Schools could, if they deemed it appropriate, also deliver other Healthy Minds lessons: ‘Social Media Investigated’ (six lessons for 10- to 12-year-olds and eight lessons for 12- to 14-year olds); ‘Resilience Revisited’ (six lessons designed for 10- to 12-year-olds); ‘From School to Life’ (nine lessons designed for 12- to 14-year-olds); and/or ‘Mental Illness Investigated’ (seven lessons designed for 13- to 14-year-olds). Training and materials were provided by the Bounce Forward charity.

Discussion

Summary of key findings

The finalised LT-MH intervention is a novel whole-school mental health intervention in that, like some existing whole-school interventions17,20,21 but unlike previous mental health interventions,10–13 it uses an evidence-based menu to inform local decision-making. We refined and elaborated the initial plans for LT-MH to generate an intervention supported by full materials, training and external facilitation. In line with this, we retained key components and did not modify the theory of change. The reviews of existing evidence proved useful in informing the questions on mental health included in the needs assessment survey (as well as in developing the menu of evidence-based actions which are described in a separate, forthcoming paper). However, the reviews of existing evidence did not prove very useful in informing refinement of other aspects of the intervention. These aspects of refinement involved detailed questions about delivery in English schools and existing research was generally conducted in other countries and did not engage at this level of detail concerning delivery. However, existing evidence had earlier proved useful in developing the initial plans for LT-MH in terms of what broad approaches to promoting mental health in schools had previously been effective. 7,20,21

Patient and public involvement and engagement proved valuable in informing refinement of LT-MH in terms of ensuring its feasibility, acceptability, and inclusiveness. The PPIE participants were well placed to comment on some aspects of our planned intervention. Teachers and senior leadership team members were well placed to comment on the likely feasibility of LT-MH in their schools. For example, they offered useful suggestions about the need to consider the implications of schools choosing actions from the menu. Students had a good understanding of student mental health needs, exemplified by the close alignment between the mental health topics suggested by the students and those emerging from our review of research evidence.

However, we did not act on some recommendations from PPIE. Sometimes this occurred when recommendations ran counter to the evidence, for example when students suggested the value of aromatherapy for mental health, an intervention for which there is little evidence of effectiveness. 56 It was also sometimes necessary to prioritise the evidence base over PPIE suggestions when it came to the detail of particular evidence-based actions, such as our not acting on student recommendations of how many sessions stress workshops should involve. We also did not act on PPIE recommendations when these were practically unfeasible. Our proposal had been funded based on a clear initial plan for the intervention. We could amend some aspects of this but did not feel we had the scope to radically change the intervention. Therefore, we could not act on recommendations that proposed radical reformulations, such as those proposing dropping the needs assessment survey or broadening which student year groups were surveyed. Finally, we did not act on some comments when we judged that these took an overly conservative approach to defining what is and is not possible in a setting. This was illustrated in some staffs’ view that needs assessment surveys would overload schools when there was no evidence that this was the case from previous evaluation. 24

Limitations

There is a spectrum of participation for PPIE, ranging from consultation to fully participative co-production. 29 The processes we describe here are appropriate but not innovative, and nearer the consultation than the co-production end of this spectrum. This was appropriate given our aim to adapt an intervention with existing evidence of mental health effectiveness. The research team maintained control over final decisions. However, the refinement was done ‘with’ members of the public. With the exception of the Young NCB members, the engagements with PPIE stakeholders were one-offs, not sustained over time. Sustained engagement might have allowed a more participative approach, in which we used repeated meetings to present how we had reflected on earlier advice and which suggestions from participants we had made use of and which we had not. This could have allowed discussion with participants about whether they thought that these decisions were reasonable. Nonetheless, participant views did influence how we refined LT-MH. Despite the meetings with most stakeholders being one-offs, we still took a phased approach to PPIE with sessions occurring at different points during the process of refinement of the intervention. This enabled us not only to get stakeholders’ initial views but also to seek stakeholders’ opinions on the emerging plans. A consultation approach is appropriate where there is limited scope for adapting interventions. The numbers of participants involved in PPIE was in line with protocol and appropriate given these aims.

The PPIE work was affected by its occurring during the recovery period of the COVID-19 pandemic when schools were more stressed than normal. We had planned for the school involved in PPIE to be above average in student free-school-meals eligibility but the school initially recruited dropped out and its replacement had a lower-than-average rate of entitlement. This may have resulted in the students involved being less disadvantaged and educationally disengaged. Participation at the meeting for senior leadership team members was also lower than anticipated due to COVID-19-related challenges faced by schools. We did not record demographic characteristics for participants given that this was PPIE and not research.

Implications for policy and research

It is possible to refine interventions and elaborate them to provide full materials and support via processes drawing on evidence review and PPIE. 29,57 Patient and public involvement and engagement is extremely useful in addressing questions of feasibility, acceptability and equity. 29 In this regard, the views of those who would participate in an intervention as providers or participants are critically important. Patient and public involvement and engagement is also useful in assessing whether intervention components are likely to align with the felt needs of the population being involved in or targeted by an intervention.

Not all the suggestions from PPIE can or should be accepted and acted on. 32 It can be challenging to use PPIE to refine or co-produce interventions in parallel to drawing on existing evidence when the recommendations emerging from these diverge. 30 Neither providers nor affected populations will necessarily know what interventions are likely to be most effective in meeting population needs. It makes most sense to be guided by the evidence of what has proven effective while listening to PPIE views about how things might need to be refined to maximise the likelihood of success in a new context.

Patient and public involvement and engagement recommendations are challenging to incorporate when they do not align with existing plans for the intervention. 32 Those facilitating PPIE should be clear with stakeholders about which aspects of intervention design are negotiable and which are non-negotiable. It may be that, in some cases, funding proposals need to be less prescriptive so that there is more scope for intervention refinement informed by PPIE. Patient and public involvement and engagement recommendations can also sometimes be challenging to incorporate when there is a feeling that they might simply reflect participants thinking aloud or where stakeholders might be moving beyond their area of expertise or experience when offering comments. As with some previous analyses of public participation in health decision-making,58 we recommend that PPIE involves more open dialogues between researchers and PPIE stakeholders. Researchers and PPIE stakeholders should feel able to probe and challenge each other’s views, and examine what light evidence can shed on the questions being discussed. Patient and public involvement and engagement would also benefit from sustained engagement so that, where recommendations are not accepted, this can be reported back to participants and further discussed if necessary.

The approach to adaptation was not informed by recent guidance59 because it was planned prior to publication of this. Furthermore, the focus was slightly different: adapting an existing intervention to maximise its effects on mental health rather than adapting it to a new context. Nevertheless, the approach was consistent with this guidance in terms of: involving diverse participants; being clear about decision-making authority; ensuring appropriate consistency with the intended theory of change; considering contextual influences on feasibility and acceptability; and ensuring intervention materials are amended appropriately. Despite the consultative approach to PPIE and the challenge recruiting a disadvantaged school, PPIE was useful in informing the limited adaptation of LT-MH required. Future work will include a feasibility study to optimise the intervention and assess whether progression to a full trial is justified.

Equality, diversity and inclusion

School environment interventions such as that adapted in this study have reach across the whole school to influence all students regardless of socioeconomic status. This universal reach avoids the tendency for individual-level interventions to have greater uptake and benefits among the more educated and affluent. Given the previous LT intervention had greater impact on those with greater behavioural problems, this intervention may particularly benefit those from more disadvantaged families, given the strong association between deprivation and mental health problems. All intervention materials were designed to be accessible and appropriate for individuals regardless of socioeconomic status, gender, ethnicity and sexual identity. The intervention is universal but aims to benefit those with most baseline need. The pilot phase will assess how socioeconomic status as well as other characteristics affect the experience of implementation and receipt. The research team was diverse in terms of gender, ethnicity, nationality, seniority, and discipline.

Patient and public involvement

Patient and public involvement and engagement is at the heart of the work reported in this paper. We worked collaboratively with the staff and students from one secondary school, children and young people from the Young NCB and a group of senior staff from other schools to inform adaptation of the intervention. This is described in full throughout the paper.

Additional information

CRediT contribution statement

Chris Bonell (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6253-6498): Conceptualisation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualisation, Writing – original draft.

Steven Hope (https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4159-9518): Data curation, Formal analysis, Project administration, Writing – editing and reviewing.

Neisha Sundaram (https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4159-9518): Formal analysis, Writing – editing and reviewing.

Oliver Lloyd-Houldey (https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6081-3546): Data curation, Project administration, Writing – editing and reviewing.

Semina Michalopoulou (https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3198-0411): Project administration, Writing – editing and reviewing.

Stephen Scott (https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4680-6213): Conceptualisation, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – editing and reviewing.

Dasha Nicholls (https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7257-6605): Conceptualisation, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – editing and reviewing.

Russell Viner (https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3047-2247): Conceptualisation, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualisation, Writing – editing and reviewing.

Acknowledgements

We thank all those who participated in our PPIE.

Data-sharing statement

PPIE sessions were not recorded there is therefore no data that can be shared. All queries should be submitted to the corresponding author in the first instance.

Ethics statement

The research was conducted in accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. Regulatory approval for the overall research project was given by the research ethics committees of University College London (reference 21179/001 on 30 May 2021) and the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (reference 27994 on 26 August 2022). Participation in the PPIE subcomponent of the overall study was deemed not to be research participation by these ethics committees and so formal written consent was not sought. However, participants were given verbal information about the work and freely agreed to participation. No PPIE sessions were recorded other than via written notes, which did not attribute any statements to individuals.

Information governance statement

All personal information was managed in line with the Data Protection Act (2018) and General Data Protection Regulation (EU GDPR) 2016/679. University College London was the data controller and data processor.

Disclosure of interests

Full disclosure of interests: Completed ICMJE forms for all authors, including all related interests, are available in the toolkit on the NIHR Journals Library report publication page at https://doi.org/10.3310/JWGT4863.

Primary conflicts of interest: Chris Bonell was a member of the Research Funding Board, NIHR Public Health Research Programme between 2013 and 2019. Fifteen per cent of Stephen Scott’s time is funded by NIHR for a RCT of personalised Programme for Children with conduct problems.

Department of Health and Social Care disclaimer

This publication presents independent research commissioned by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR). The views and opinions expressed by authors in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the NHS, the NIHR, MRC, NIHR Coordinating Centre, the Public Health Research programme or the Department of Health and Social Care.

This article was published based on current knowledge at the time and date of publication. NIHR is committed to being inclusive and will continually monitor best practice and guidance in relation to terminology and language to ensure that we remain relevant to our stakeholders.

Study registration

This study is registered as Current Controlled Trials ISRCTN15301591.

Funding

This article presents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Public Health Research programme as award number NIHR131594.

This article reports on one component of the research award Learning Together to promote mental health and wellbeing (LTMH). Other articles published as part of this thread are: [LINKS to other articles]. For more information about this research please view the award page (https://fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/NIHR131594)

About this article

The contractual start date for this research was in November 2021. This article began editorial review in June 2023 and was accepted for publication in June 2024. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The Public Health Research editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ article and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Copyright

Copyright © 2024 Bonell et al. This work was produced by Bonell et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

List of abbreviations

- BBSCQ

- Beyond Blue School Climate Questionnaire

- EDE-QS

- Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire Short

- GAD-7

- Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7

- HBSC

- Health Behaviour in School-aged Children

- LT

- Learning Together

- LT-MH

- Learning Together for Mental Health

- MHFA

- mental health first aid

- NCB

- National Children Bureau

- PPIE

- patient and public involvement and engagement

- SDQ

- Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire

- SEL

- social and emotional learning

References

- NHS England Mental Health Taskforce . The Five Year Forward View for Mental Health 2016.

- Solmi M, Radua J, Olivola M, Croce E, Soardo L, Salazar de Pablo G, et al. Age at onset of mental disorders worldwide: large-scale meta-analysis of 192 epidemiological studies. Mol Psychiatry 2022;27:281-95.

- Newlove-Delgado T, Marcheselli F, Williams T, Mandalia D, Davis J, McManus S, et al. Mental Health of Children and Young People in England. Leeds: NHS Digital; 2022.

- Bould H, De Stavola B, Lewis G, Micali N. Do disordered eating behaviours in girls vary by school characteristics? A UK cohort study. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2018;27:1473-81. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-018-1133-0.

- McManus SBP, Jenkins R, Brugha T. Mental Health and Wellbeing in England: Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey 2014. Leeds: NHS Digital; 2016.

- Transforming Children and Young People’s Mental Health Provision: A Green Paper. London: Department of Health and Department for Education, England; 2017.

- O’Reilly M, Svirydzenka N, Adams S, Dogra N. Review of mental health promotion interventions in schools. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2018;53:647-62. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-018-1530-1.

- Pearcey S, Shum A, Waite P, Patalay P, Creswell C. Report 04: Changes in Children and Young People’s Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties Through Lockdown. Oxford: CoSPACE study; 2020.

- Levita L. Initial Research Findings on the Impact of COVID-19 on the Well-being of Young People Aged 13 to 24 in the UK. Sheffield: COVID-19 Psychological Research Consortium (C19PRC), University of Sheffield; 2020.

- Caldwell DM, Davies SR, Hetrick SE, Palmer JC, Caro P, López-López JA, et al. School-based interventions to prevent anxiety and depression in children and young people: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 2019;6:1011-20.

- Neil AL, Christensen H. Efficacy and effectiveness of school-based prevention and early intervention programs for anxiety. Clin Psychol Rev 2009;29:208-15.

- Sanchez AL, Cornacchio D, Poznanski B, Golik AM, Chou T, Comer JS. The effectiveness of school-based mental health services for elementary-aged children: a meta-analysis. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2018;57:153-65.

- Paulus FW, Ohmann S, Popow C. Practitioner review: school-based interventions in child mental health. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2016;57:1337-59.

- Yager Z, Diedrichs PC, Ricciardelli LA, Halliwell E. What works in secondary schools? A systematic review of classroom-based body image programs. Body Image 2013;10:271-81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2013.04.001.

- Pandey A, Hale D, Das S, Goddings A-L, Blakemore S-J, Viner RM. Effectiveness of universal self-regulation-based interventions in children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatrics 2018;172:566-75. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.0232.

- Baker DP, Leon J, Smith Greenaway EG, Collins J, Movit M. The education effect on population health: a reassessment. Popul Dev Rev 2011;37:307-32. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2011.00412.x.

- Bonell C, Wells H, Harden A, Jamal F, Fletcher A, Thomas J, et al. The effects on student health of interventions modifying the school environment: systematic review. J Epidemiol Community Health 2013;67:677-81. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2012-202247.

- Leurent B, Dodd M, Allen E, Viner R, Scott S, Bonell C. Is positive school climate associated with better adolescent mental health? Longitudinal study of young people in England. SSM Mental Health 2021;1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmmh.2021.100033.

- Humphrey N. Are the kids alright? Examining the intersection between education and mental health. Psychol Educ Rev 2018;1:4-16.

- Langford R, Bonell C, Jones H, Pouliou T, Murphy S, Waters E, et al. The World Health Organization’s Health Promoting Schools framework: a Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 2015;15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-1360-y.

- Bonell C, Jamal F, Harden A, Wells H, Parry W, Fletcher A, et al. Systematic review of the effects of schools and school environment interventions on health: evidence mapping and synthesis. Public Health Res 2013;1:1-320.

- Stallard P, Skryabina E, Taylor G, Phillips R, Daniels H, Anderson R, et al. Classroom-based cognitive behaviour therapy (FRIENDS): a cluster randomised controlled trial to Prevent Anxiety in Children through Education in Schools (PACES). Lancet Psychiatry 2014;1:185-92. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(14)70244-5.

- Herlitz L, MacIntyre H, Osborn T, Bonell C. The sustainability of public health interventions in schools: a systematic review. Implement Sci 2020;15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-019-0961-8.

- Bonell C, Allen E, Warren E, McGowan J, Bevilacqua L, Jamal F, et al. Initiating change in the school environment to reduce bullying and aggression: a cluster randomised controlled trial of the Learning Together (LT) intervention in English secondary schools. The Lancet 2018;392:2452-64.

- Markham WA, Aveyard P. A new theory of health promoting schools based on human functioning, school organisation and pedagogic practice. Soc Sci Med 2003;56:1209-20.

- Wight D, Wimbush E, Jepson R, Doi L. Six steps in quality intervention development (6SQuID). J Epidemiol Community Health 2016;70:520-5.

- Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, Michie S, Nazareth I, Petticrew M. Medical Research Council Guidance . Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. Br Med J 2008;337.

- Jackson T, Pinnock H, Liew SM, Horne E, Ehrlich E, Fulton O, et al. Patient and public involvement in research: from tokenistic box ticking to valued team members. BMC Med 2020;18.

- NHS England/Public Participation Team . Patient and Public Participation Policy 2015.

- Moore GF, Evans RE. What theory, for whom and in which context? Reflections on the application of theory in the development and evaluation of complex population health interventions. SSM – Popul Health 2017;3:132-5.

- Moore GF, Evans RE, Hawkins J, Littlecott H, Melendez-Torres GJ, Bonell C, et al. From complex social interventions to interventions in complex social systems: future directions and unresolved questions for intervention development and evaluation. Evaluation (Lond) 2019;25:23-45.

- Williams O, Sarre S, Constantina Papoulias S, Knowles S, Robert G, Beresford P, et al. Lost in the shadows: reflections on the dark side of co-production. Health Res Policy Syst 2020;18.

- Bandura A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory. Hoboken (NJ): Prentice Hall; 1986.

- Murphy S, Littlecott H, Hewitt G, MacDonald S, Roberts J, Bishop J, et al. A Transdisciplinary Complex Adaptive Systems (T-CAS) approach to developing a national school-based culture of prevention for health improvement: the School Health Research Network (SHRN) in Wales. Prev Sci 2018;22:50-61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-018-0969-3.

- Warren EBL, Opondo C, Allen E, Mathiot A, West G, Jamal F, et al. Action groups as a participative strategy for leading whole-school health promotion: results on implementation from the INCLUSIVE trial in English secondary schools. Br Educ Res J 2019;45:748-62.

- Bonell C, Allen E, Warren E, McGowan J, Bevilacqua L, Jamal F, et al. Initiating change locally in bullying and aggression through the school environment: the INCLUSIVE cluster RCT. Public Health Res 2019;7:1-196.

- Durlak JA, Weissberg RP, Dymnicki AB, Taylor RD, Schellinger KB. The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: a meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions. Child Dev 2011;82:405-32. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01564.x.

- Diedrichs PC, Atkinson MJ, Steer RJ, Garbett KM, Rumsey N, Halliwell E. Effectiveness of a brief school-based body image intervention ‘Dove Confident Me: Single Session’ when delivered by teachers and researchers: results from a cluster randomised controlled trial. Behav Res Ther 2015;74:94-104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2015.09.004.

- Chua JYX, Tam W, Shorey S. Research Review: Effectiveness of universal eating disorder prevention interventions in improving body image among children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2019;61:522-35. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.13164.

- Schleider JL, Abel MR, Weisz JR. Do immediate gains predict long-term symptom change? findings from a randomized trial of a single-session intervention for youth anxiety and depression. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 2019;50:868-81. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-019-00889-2.

- Marx RA, Kettrey HH. Gay-straight alliances are associated with lower levels of school-based victimization of LGBTQ+ youth: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Youth Adolesc 2016;45:1269-82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-016-0501-7.

- Liu M, Wu L, Ming Q. How does physical activity intervention improve self-esteem and self-concept in children and adolescents? evidence from a meta-analysis. PLoS One 2015;10. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0134804.

- Hawkins J, Madden K, Fletcher A, Midgley L, Grant A, Cox G, et al. Development of a framework for the co-production and prototyping of public health interventions. BMC Public Health 2017;17.

- Kidger J, Araya R, Donovan J, Gunnell D. The effect of the school environment on the emotional health of adolescents: a systematic review. Pediatrics 2012;129:925-49.

- Farahmand FK, Grant KE, Polo AJ, Duffy SN, Dubois DL. School-based mental health and behavioral programs for low‐income, urban youth: a systematic and meta-analytic review. Clin Psychol Sci Pract 2011;18:372-90.

- Engelsen BK, Laberg JC. A comparison of three questionnaires (EAT-12, EDI, and EDE-Q) for assessment of eating problems in healthy female adolescents. Nord J Psychiatry 2001;55:129-35.

- Currie C, Molcho M, Boyce W, Holstein B, Torsheim T, Richter M. Researching health inequalities in adolescents: the development of the Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children (HBSC) Family Affluence Scale. Soc Sci Med 2008;66:1429-36.

- Smith PK, Mahdavi J, Carvalho M, Fisher S, Russell S, Tippett N. Cyberbullying: its nature and impact in secondary school pupils. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2008;49:376-85. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01846.x.

- Bond L, Wolfe S, Tollit M, Butler H, Patton G. A comparison of the Gatehouse Bullying Scale and the peer relations questionnaire for students in secondary school. J Sch Health 2007;77:75-9.

- Bridges S, Gill V, Omole T, Sutton R, Wright V. Smoking, Drinking and Drug Use Among Young People in England in 2010. London: NHS Information Centre for Health and Social Care; 2011.

- Sawyer MG, Pfeiffer S, Spence SH, Bond L, Graetz B, Kay D, et al. School-based prevention of depression: a randomised controlled study of the beyondblue schools research initiative. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2010;51:199-20.

- Deighton J, Lereya ST, Morgan E, Breedvelt J, Martin K, Feltham A, et al. Measuring and Monitoring Children and Young People’s Mental Wellbeing: A Toolkit for Schools and Colleges. London: Anna Freud Centre and Public Health England; 2016.

- NHS Digital . Mental Health of Children and Young People in England, 2020: Wave 1 Follow up to the 2017 Survey Official Statistics 2020.

- Lordan G, McGuire A. Healthy Minds: Health Outcomes Evaluation Report and Executive Summary. London: Education Endowment Foundation; 2019.

- Coleman J, Hale D, Layard R. A Model for the Delivery of Evidence-Based PSHE (Personal Wellbeing) in Secondary Schools. London: London School of Economics; 2011.

- Cooke B, Ernst E. Aromatherapy: a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract 2000;50:493-6.

- Harrison JD, Auerbach AD, Anderson W, Fagan M, Carnie M, Hanson C, et al. Patient stakeholder engagement in research: a narrative review to describe foundational principles and best practice activities. Health Expect 2019;22:307-16.

- Strøm Synnevåg E, Amdam R, Fosse E. Intersectoral planning for public health: dilemmas and challenges. Int J Health Policy Manag 2018;7:982-92.

- Moore G, Campbell M, Copeland L, Craig P, Movsisyan A, Hoddinott P, et al. Adapting interventions to new contexts-the ADAPT guidance. Br Med J 2021;374.

Appendix 1 Learning Together for Mental Health design as piloted

Appendix 2 Patient and public involvement and engagement suggestions and responses

| Intervention component | Suggestion/comment | Source | Accepted (✓) or not (X) | Details of how addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | Learning Together for Mental Health is too long a name | Students | X | We kept the name to retain the link to an effective intervention and emphasise the new focus on mental health |

| Whole-school approach is good given targeted interventions can miss those most in need | Senior leadership team | ✓ | This aligned with the existing plans | |

| Increase the focus on parents | Senior leadership team | ✓ | The manual now refers to consulting with parents, marketing the intervention to parents, dealing with any parental opposition, using other data from parent surveys, encouraging parents to sit on the action group and involving parents in restorative practice. The menu of actions includes yoga led by parent volunteers | |

| Needs assessment | Very useful in quantifying need | Senior leadership team | ✓ | This aligned with the existing plans |

| Will be useful to share with Ofsted inspectors | Senior leadership team | ✓ | The manual now refers to Ofsted inspections | |

| Surveying one year group will not identify needs across other year groups | Students Staff |

X | It was not possible to broaden the survey due to this being part of the evaluation protocol | |

| ✓ | The manual now recommends schools drawing on other data as part of needs assessment | |||

| Surveying year-8 or -9 students might be a better guide | Staff | X | It was not possible to modify this due to this being part of the evaluation protocol | |

| ✓ | The manual now recommends schools drawing on other data as part of needs assessment | |||

| Survey should include mental health questions | Students | ✓ | This aligned with the existing plans | |

| Survey should mostly include closed-response questions | Young NCB members | ✓ | This aligned with the existing plans | |

| Participant anonymity is important | Students | ✓ | This aligned with the existing plans | |

| Comparison with broader data on mental health indicators is useful | Students Senior leadership team |

This aligned with the existing plans | ||

| Risk of survey overload in schools | Staff | X | Given other positive views on needs assessment, we retained this component | |

| Manual – action group | Should include actions for teachers and young people | Young NCB members | ✓ | This aligned with the existing plans |

| The manual provides the necessary outline and direction | Senior leadership team | ✓ | This aligned with the existing plans | |

| Valuable for staff and students to meet together | Students | ✓ | This aligned with the existing plans | |

| Schools willing to involve students in decision-making | Staff | ✓ | This aligned with the existing plans | |

| Groups should be student-led | Students | X | The groups involve and empower students but are chaired by a staff member since there is evidence from the LT trial that the chair needs to have the authority to make and implement decisions | |

| Monthly meetings comprising 6 staff, 6 students, and a facilitator would be good | Students | X | Monthly meetings would be too frequent according to the LT trial | |

| ✓ | The recommended membership aligned with the existing plans | |||

| Action groups should not comprise only the most vocal students | Staff | ✓ | This aligned with the existing plans | |

| Students could be approached to participate | Students | ✓ | The manual now encourages recruitment of diverse students including via direct invitation | |

| Selecting students on basis of mental health would lead to stigma | Students | ✓ | The manual now indicates that the group can consist of students with or without self-expressed mental health challenges; does not recommend pro-actively recruiting those with known mental health challenges | |

| Students from various year groups should be included to compensate for survey focus on year-7 students | Staff | ✓ | The manual recommends recruitment of students diverse by year group | |

| School mental health lead should be member of the action group | Staff | ✓ | The manual recommends this | |

| External facilitator | Valuable and should be provided for at least 2 years | Staff | ✓ | External facilitation is to be provided for 2 years in the phase III trial (but not in this 1-year pilot) |

| Should act as critical friend: motivating, supporting and providing expertise | Staff | ✓ | This aligned with the existing plans | |

| Should set/monitor success criteria for each meeting | Staff | ✓ | Outcomes have been incorporated into draft agenda for each meeting included in the manual | |

| Hybrid approach to facilitation could work with half meetings in person and half online | Staff | ✓ | This approach has been adopted for this pilot | |

| Menu of actions | Good that guidance links identified needs to recommended actions | Staff | ✓ | This aligned with the existing plans |

| Valuable and liked indicators of strength of evidence, size of effects and costs | Staff Senior leadership team |

✓ | This aligned with the existing plans | |