Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as award number 17/112/16. The contractual start date was in October 2019. The draft manuscript began editorial review in November 2022 and was accepted for publication in June 2023. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Permissions

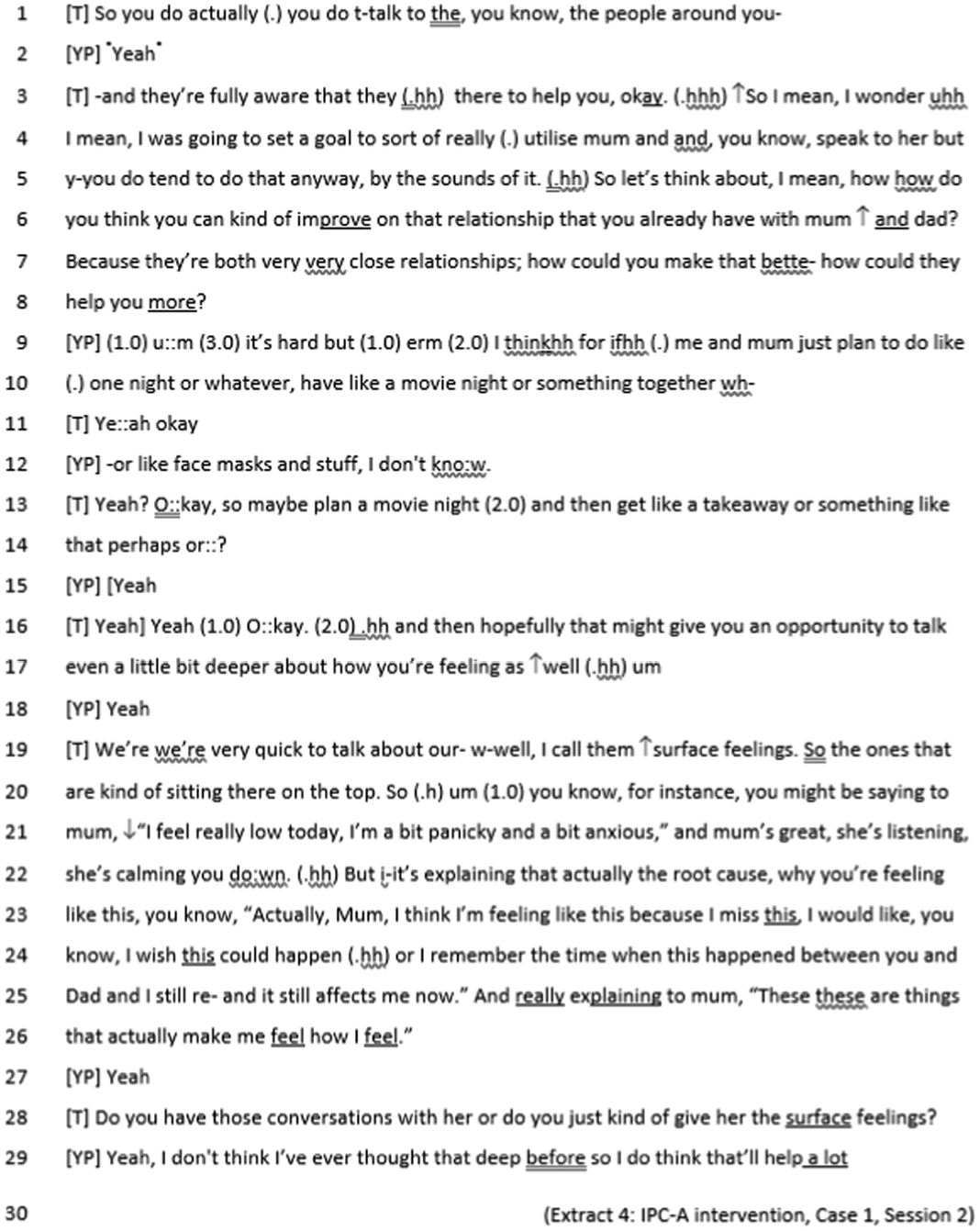

Copyright statement

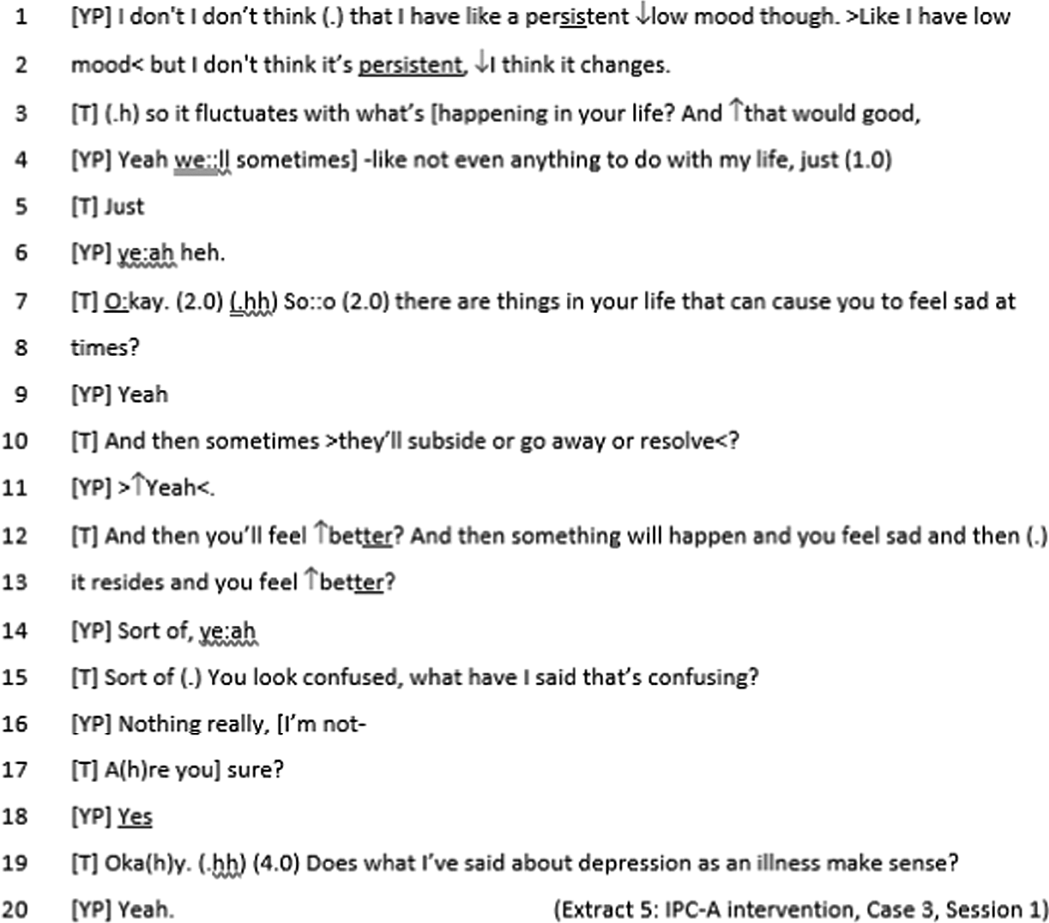

Copyright © 2024 Wilson et al. This work was produced by Wilson et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

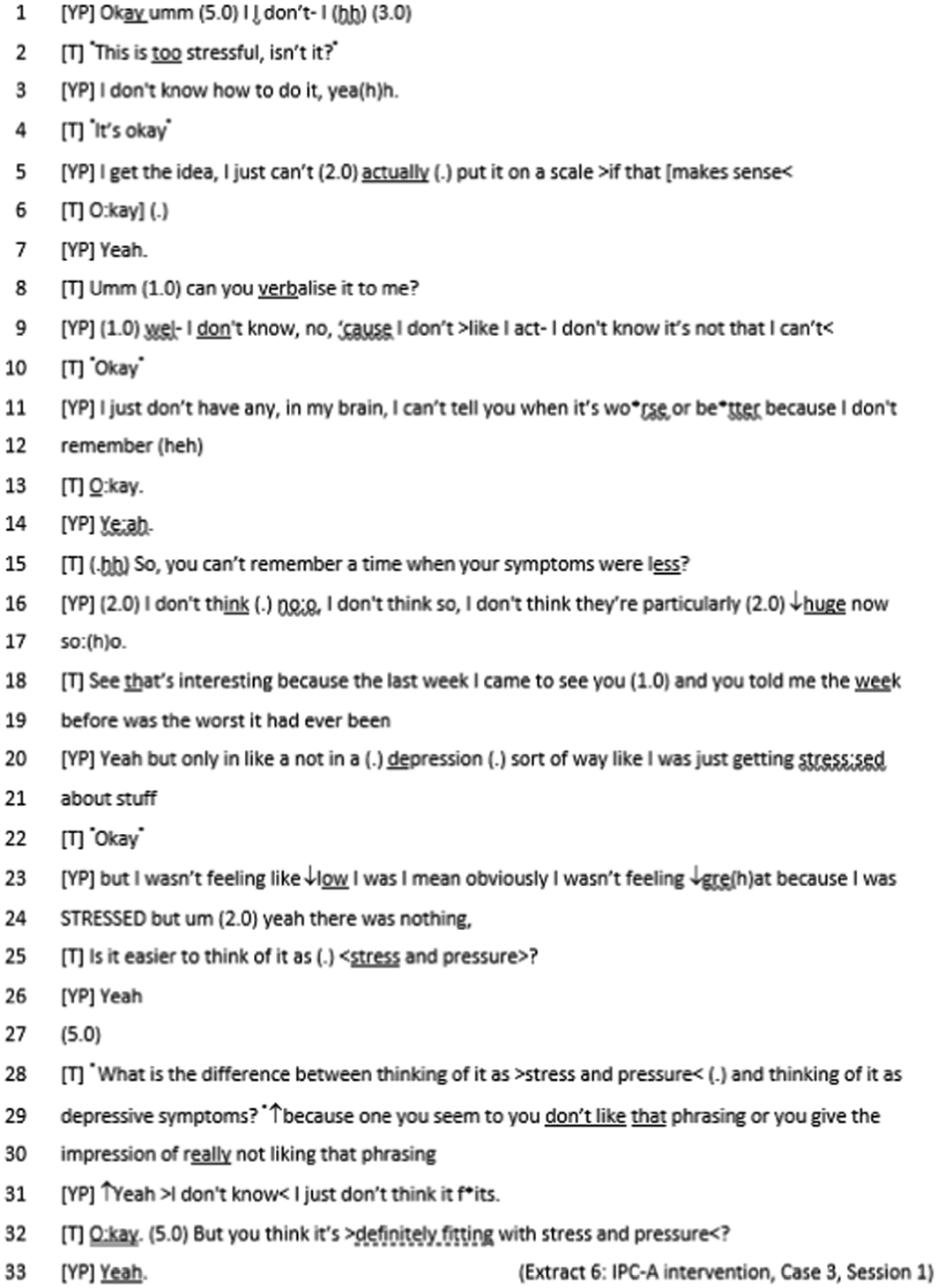

2024 Wilson et al.

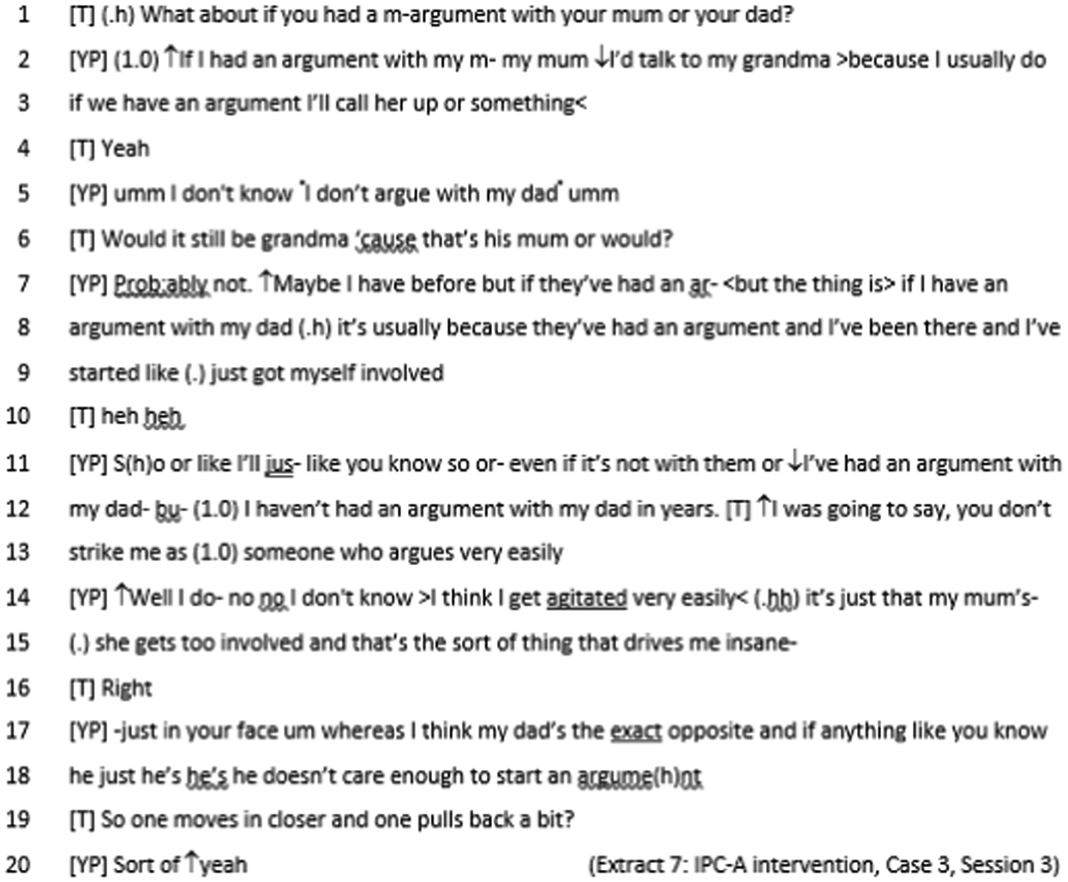

Chapter 1 Introduction

This chapter is adapted from Abotsie et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) licence, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Background

There is extensive and growing demand for services to meet the needs of young people with poor mental health. 2 Depression is a common health problem during adolescence. Adolescent lifetime prevalence of major depressive disorder (MDD) is 11–20%. 3,4 However, mild/subthreshold depression is much more common in adolescents than full MDD. 5 Such mild depression is associated with significant personal and public health consequences6 and is a strong predictor for future onset of full MDD. 7 Depression in adolescence predicts a range of adverse outcomes in adulthood, including ongoing mental health problems,8 poorer physical health9 and social, legal and financial problems,10 and it is the most prevalent psychiatric disorder in young people who die by suicide. 11 The total annual cost of depression in England has been estimated to be at least £20.2B. 12 However, there is evidence that prompt psychological intervention can prevent relapse and recurrence,13 and therefore intervening early, before depression symptoms become severe, could generate substantial savings.

The majority of adolescents seeking treatment for depression have mild disorders. 14 In the UK, such cases of mild depression are not likely to meet treatment thresholds for specialist (tier 3) Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS). Instead, young people with mild depression are seen by staff working in local authority child and family services or tier 2 NHS-funded mental health services often delivered by third-sector/voluntary agencies. Most of those working with depressed young people within these non-specialist services are not qualified mental health professionals and have no formal training in delivering evidence-based treatments for people with depression.

At present, there is not a standard treatment as usual (TAU) in these non-specialist sectors. There is great variation between and within services about what is offered to young people with low mood, for example, psychoeducation, non-directive counselling and/or behavioural activation. There is usually little specific training and supervision for these interventions. There is no evidence as to whether these interventions are effective, nor whether a systematic intervention with manualised training, delivery and supervision would be more effective and cost-effective than the current approach of non-systematic and varied interventions.

Current guidelines for the treatment of mild depression in children and young people (CYP)15 recommend simple, non-specific psychosocial strategies, such as non-directive supportive therapy. A recent, large network meta-analysis has shown that while non-directive supportive therapy is better than a waiting list (i.e. no treatment) for adolescent depression, it is not significantly better than placebo. 16 It is important to note that the primary studies included in this meta-analysis took place in a range of services for a range of severities of depression. No randomised controlled trials (RCTs) have taken place in the services described above, where most cases of mild depression are treated in the UK. Thus, there is a clear lack of evidence as to how to treat young people accessing these services. 17–19

Study rationale

Interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) is a National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)-recommended first-line treatment for adolescents with moderate to severe depression. IPT helps patients to understand the two-way links between their depressive symptoms and current interpersonal relationships. It also helps patients to improve their interpersonal relationships. In doing so, it aims to reduce depressive symptoms. Whereas non-directive supportive therapy aims ‘to help patients accommodate to existing reality rather than try to help them change it’,20 IPT focuses on helping patients to take active steps to improve their relationships in order to decrease their depressive symptoms. Theoretical influences on IPT included Adolf Meyer’s ‘psychobiological’ approach, which emphasised patients’ current interpersonal and psychosocial experiences, and21 Harry Stack Sullivan’s ‘interpersonal’ approach, which conceptualised psychiatry as the scientific study of people and interpersonal processes. 22 Both approaches contrasted with the dominant psychoanalytic approach at that time, which emphasised intrapsychic processes over interpersonal relationships.

Meta-analyses have demonstrated IPT to be superior to control treatments for depression in both adults23 and adolescents16 and to lead to similar outcomes as cognitive–behaviour therapy in both age groups. Crucially, IPT has been shown to be significantly more effective than supportive counselling for depressed adolescents. 24 Given the importance of interpersonal relationships in the causation of adolescent depression,17 and the developmental priority given to interpersonal relationships during adolescence, this approach has high face validity for this age group.

However, in common with other evidence-based treatments for adolescent depression, IPT must be delivered by a qualified mental health professional. As such, it is unlikely to be a feasible treatment option outside of specialist CAMHS. Interpersonal counselling (IPC) is an adaptation of IPT with three main differences: the treatment duration is shorter (three to six sessions); it is designed for clients with mild depression; and it can be delivered by non-mental health professionals after participation in a brief (2-day) training course.

Interpersonal counselling has been found to be an effective treatment for adults with mild to moderate depression. 25,26 A recent trial in Brazil found that staff without prior psychotherapy training were able to successfully deliver IPC to adults with depression. 27 These staff were similarly effective at providing TAU as qualified psychologists. There has yet to be a published trial of the effectiveness or cost effectiveness of this approach in adolescents. An adapted form of IPC designed to meet the needs of young people (IPC-A) has been developed and piloted in a single-arm study by members of the research team. IPC-A was delivered by staff without prior psychotherapy training and was found to be well accepted by staff and young people,28 but its effectiveness as a treatment for adolescent depression has yet to be tested. Although there are many similarities between adult and adolescent depression, there are also important differences, particularly in treatment response. 17 Adult and young people’s services also differ in their organisation, ethos and staff training. 29 Therefore, it cannot be assumed that an effective treatment for adult depression can be transferred to adolescents without evaluation.

There is currently not any evidence to support decision-making regarding which interventions staff members from services providing young people with non-specialist mental health support should be trained to deliver.

Developing skills of staff members by training them to deliver evidence-based interventions will be important to meeting workforce requirements. This study aimed to contribute to this evidence base and is in line with the Department of Health’s Framework for Mental Health Research, which recommends that research should focus on early intervention and involve organisations beyond traditional health services, including local authorities and the voluntary sector. We believed that IPC-A may be effective for young people with mild depression presenting to non-specialist services and may be more effective than current ‘treatment as usual’ (which is not a specific treatment – it is an approach of trying to help young people with one or several strategies that a therapist has learnt about).

It is important to state that while there is a good evidence base for IPT for adolescent depression and evidence that IPC is effective for mild depression in adults, there is minimal evidence that IPT or IPC is more effective than control treatments for anxiety disorders in either age group. 30 This is because depressive and anxiety disorders are different disorders. Although there is increased risk of the second disorder if one is present, they are best conceptualised as different disorders with different core symptoms (low mood vs. anxiety). (For a full discussion of commonalities and differences between depressive and anxiety disorders, please see Wilkinson31) IPT was specifically designed to focus on the link between low mood (and other depressive symptoms) and interpersonal relationships; hence, it should not be assumed that it works for other disorders. Given it is more likely that IPC is effective for depression than anxiety, this initial pilot study focused on young people with mild depression. Given there is no evidence that IPC is effective for depression or anxiety in this clinical setting, we believed it to be ethically acceptable for young people with depression to be randomised to IPC-A or TAU, and for young people with anxiety but not depression to continue to receive TAU, as they would have done before the trial.

This study was intended to provide the information needed to progress to a national full-scale clinical trial of IPC-A delivered by staff without core professional training (referred to in this report as ‘youth mental health workers’). The training (including subsequent supervised casework) required to deliver IPC-A can be completed by staff without prior mental health qualifications in < 12 weeks. Therefore, if found to be an effective treatment, training existing workers as IPC-A therapists could facilitate a rapid and relatively low-cost expansion of the therapy workforce in line with NHS England and government commitments.

Aim and objectives

The research was designed to inform a future trial of the effectiveness and cost effectiveness of the intervention (IPC for adolescents with mild depression). The aim of the research was to answer the following feasibility questions which arose partly from the variability in service models across providers of non-specialist mental health support for young people:

Feasibility question 1

Are trial procedures, including recruitment (of participants and therapists), randomisation, research assessments and follow-up, feasible and acceptable?

Feasibility question 2

How are IPC-A and TAU delivered, and how and why does intervention delivery vary across differing service contexts?

Feasibility question 3

To what extent does contamination of the control arm occur, and should it be mitigated against in a future trial?

Feasibility question 4

Does the interval estimate of benefit of IPC over TAU in depression scores post treatment include a clinically significant effect?

Chapter 2 Feasibility randomised controlled trial – methods

This chapter is adapted from Abotsie et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) licence, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Design

The study was designed to answer the research question: Is a full-scale RCT of IPC for young people with mild depression delivered in non-specialist community services feasible? In this feasibility RCT, we planned to randomise 60 eligible young people in a 1 : 1 ratio to receive IPC-A or TAU. Participants were invited to take part in an assessment at baseline (pre randomisation) (see Supplementary Material 1) and followed up at 10 and 23 weeks. The feasibility trial aimed to recruit young people presenting with low mood who were receiving support from participating services in Norfolk and Suffolk, UK. A health economics component was included to inform the design of the economic evaluation in a future study. A process evaluation was incorporated to explore how the intervention is implemented across the counties. Qualitative data were collected through site profile questionnaires (SPQs) (see Supplementary Material 2), observations of IPC-A training workshops and supervision, video-/audio-recordings of treatment sessions (both IPC-A and TAU), interviews with participants (and parents) from the IPC-A and TAU arms and focus groups with youth mental health workers (YMHWs) and wider stakeholders.

Setting

The trial aimed to be conducted in two counties in England. While the sites are in the area served by one NHS mental health trust, tier 1/2 services or services for mild depression are not delivered by this mental health trust, as the severity of illness of young people is generally below the thresholds for NHS specialist CAMHS. Treatment at this level is delivered by a range of services locally. Within the two counties, some non-specialist mental health support services for CYP are provided by the County Councils. Teams delivering these services include Early Help teams, Young People’s teams, Family Support services, school nurses and NEET (not in education, employment or training) teams. In addition, non-specialist mental health support is provided by publicly commissioned independent counselling organisations. Such tier 1 or 2 services provide early interventions to CYPs with mild mental health problems and/or difficult family circumstances such as parental drug and alcohol dependency, parental poor mental health and domestic abuse. Most practitioners working in these services are not qualified mental health practitioners but may have some training in counselling, family work and social care. Staff delivering the IPC and TAU interventions would be employees of these organisations who support young people with mild depression as part of their usual job role. We believed having a variety of services involved across two counties would give a good balance of increasing the transferability of findings while keeping the scale of the study manageable within the available resources.

Eligibility criteria and recruitment procedure

Participant eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria

-

Age 12–18 years.

-

Seeking help for low mood (as the primary presenting difficulty).

-

Able to provide written informed consent or, for under-16s, written informed assent and parent/guardian consent.

-

Of a level of illness where they would normally receive treatment from the service.

Exclusion criteria

-

Learning disability necessitating non-mainstream schooling.

-

Current psychotic disorder.

-

Current substance dependence.

-

Current significant suicidal ideation (Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia – Present and Lifetime version – ‘suicidal ideation’ threshold – ‘often thinks of suicide and has thought of a specific method’).

In line with the approach used successfully in the pilot, eligibility criteria were kept to a minimum to increase the external validity of the trial in the context of non-specialist services.

Excluded young people would be signposted to appropriate services. Young people would not be excluded based on insufficient English language skills. Interpreting/translation services and foreign language Revised Children’s Anxiety and Depression Scale (RCADS) were available.

There was not a numerical upper severity threshold for depression symptoms or suicidal ideation. However, we anticipated that the criterion ‘of a level of illness where they would normally receive treatment from the service’ would exclude young people presenting with significant suicidal ideation. Participants expressing significant suicidal ideation or planning at the time of screening remained ineligible for the study.

The planned recruitment period for the feasibility RCT was January–December 2020 (12 months). In order to recruit the target 60 participants, it would have been necessary to recruit an average of 5 participants per month across all sites; this was predicted to be lower in early stages of the study and higher in later stages, as more therapists completed training. The aim was to have six IPC therapists trained in each of the two counties who would each treat two to three young people with IPC. With IPC taking around 10 weeks (taking into account holidays), this means that, on average, each participating therapist would have one ongoing IPC case per half of the recruitment year.

Participants would be young people accessing participating services via the service’s standard referral pathways. Young people were triaged and assessed according to each service’s standard procedures. If the assessment identified low mood as a presenting difficulty, the case would be discussed with a clinical member of the research team (without identifying the young person) to ascertain likely suitability for the trial. The service was given the option of using the RCADS depression scale to help determine suitability, with a cut-off of 11 or over suggesting suitability (this cut-off was not an absolute).

Potential suitable young people were invited to participate, and those who expressed an interest met with the trial’s research practitioner, who carried out informed consent procedures and screened the young person to ensure they met the above criteria.

Consent

The Chief Investigator retained overall responsibility for obtaining informed consent but delegated this duty to the study research practitioner who was trained in obtaining valid informed consent according to the ethically approved protocol, principles of Good Clinical Practice and Declaration of Helsinki. The informed consent process included a discussion with the potential participant (and his or her parent/carer if under 16) about the objectives of the study, what he or she would be asked to do if they chose to participate and the possible risks and benefits of participation. Potential participants (and their parent/carer if applicable) were provided with written information and given at least 48 hours to read and consider the information before being asked for consent. Young people and their parents/carers were given the opportunity to ask questions and have these answered in full.

If the young person wished to participate following this process, they were asked to complete a consent form (if 16 or over) or assent form (if under 16) to document the informed consent/assent process and their willingness to participate. For young people under 16, in addition to the child’s assent to participation, the consent of a parent or carer (adult with parental responsibility) was required for the young person to be included in the study. Consent to participate in an interview as part of the process evaluation was sought during the main consent procedures. However, it was not a requirement that a young person consented to a process evaluation interview in order to be included in the study.

We did not include individuals who did not have capacity to give their consent/assent to participation. During the consent process, it was made completely and unambiguously clear that the participant was free to refuse to participate in all or any aspect of the study, at any time, without giving a reason and without incurring any penalty. The participant’s continued willingness to participate was confirmed at each study contact before commencing any research procedures. Participants were free to withdraw from the study at any time up until the time of data analysis without giving a reason and without prejudicing his or her further treatment. Data collected up to the point of withdrawal would be used if the participant (and their parent/carer in the case of participants under 16) consented to this. Every effort was made to ensure that vulnerable young people were protected and participated voluntarily in a safe environment free from coercion or undue influence.

As the reading ages and levels of understanding of potential participants varied and did not necessarily mirror chronological age, and in line with patient and public involvement (PPI) feedback, instead of preparing separate information sheets for children aged 13–15 years and young people aged 16–18 years, we created an ‘easier to read’ version of the information sheet and a ‘detailed’ version. All young people were provided with both versions of the participant information sheet and could choose to read the version they found more accessible or to read both. Members of the Study’s Youth Advisory Panel reviewed the information sheets to ensure the format and language used were appropriate for the target age group.

In addition, informed consent for staff participation was sought prior to the training workshops. All staff members trained in the intervention were given a verbal explanation of the objectives of the study, what he or she would be asked to do if they chose to participate and the possible risks and benefits of participation. Staff were provided with a written information sheet and had the opportunity to ask questions and have these answered in full before deciding whether to participate. If the staff member decided to participate following this process, they were asked to complete a consent form to document this process.

Staff involved in delivering TAU were invited to consent to participation on an individual basis when they were assigned to work with a young participant allocated to the TAU arm. This consenting process was completed by an unblinded member of the research team.

Sample size

We planned to randomise 60 eligible young people in total. The target sample size was not based upon estimation of efficacy but was in keeping with published suggestions32 and was believed to be practically possible within the limits of the project. Further, it was anticipated that a sample of this size would enable the assessment of the rates of recruitment and retention to a reasonable degree of precision. Assuming an attrition rate of around 20%, a sample of 60 would provide a 95% confidence interval (CI) of width 20% (i.e. ± 10%). For a recruitment rate of around 50%, the interval width would be around 25% (i.e. ± 12.5%).

Intervention and control arms

Intervention

Interpersonal counselling for adolescents is a brief, manualised psychological intervention derived from IPT. IPC helps clients to identify the reciprocal interaction between their current depressive symptoms and interpersonal relationships, with a focus on one of four domains: grief, relationship disputes, big changes and loneliness and isolation. The therapist works with the client to identify effective strategies to deal with their interpersonal problems, which should improve depressive symptoms.

Interpersonal counselling for adolescents (IPC-A) is an adapted form of IPC designed to suit the needs of adolescents. The intervention is delivered over three to six (30- to 60-minute) sessions, depending on participant needs. IPC-A is based on the manual developed by Weissman et al.,33 with minor modifications to make it suitable for young people. IPC-A arm participants would also have access to standard health and care provision throughout their participation; the extent to which provision of IPC-A altered use of these services would be monitored using the modified Client Service Receipt Inventory (CSRI).

Staff trained as IPC-A therapists received two full days of initial training. Prior to delivering IPC-A to trial participants, trainees needed to achieve adequate scores on audiotaped ratings of two therapy sessions for each of two cases, write an adequate reflective log of the two cases and attend supervision regularly.

Following successful completion of the training, therapists received clinical supervision weekly, with a maximum of three therapists per group. We intended that supervision would be provided in a group format to allow therapists to explore the theory and practice of IPC through engaging in shared discussions of real-world cases. Each supervision session lasted up to 1.5 hours. There were a number of trained IPC supervisors in the local area who expressed an interest in supervising the delivery of the intervention within the trial. A further two supervisors were trained to supervise IPC: an IPC therapist and IPT practitioner who were trained as IPC leads to supervise trainees in accordance with the treatment manual,28 who would have overall responsibility for co-ordinating the provision of clinical supervision.

Control

The control arm received TAU, the standard support provided by services. At present, there is not a standard TAU in these non-specialist sectors. There is great variation between and within services about what is offered to young people with low mood, for example, psychoeducation, non-directive counselling and/or behavioural activation. There is usually little specific training and supervision for these interventions. Staff received the normal management and supervision that they normally receive for their casework. Hence, treatment was not at a lower standard than before the trial. As therapeutic approach between and within services varies, supervision also varies (as there is not a standard systematic TAU, there is not a standard systematic supervision as usual). Standard supervision for TAU is less frequent and less intense than the systematic supervision for IPC-A. This may affect quality of therapy but may also increase cost (which would be captured in the health economics analysis). Crucially, the trial compared the whole IPC-A package (including training and supervision) against the whole TAU package.

Participants were not denied access to any treatment option available as part of current provision. However, staff providing individual support to TAU participants did not attend any IPC-A training and did not receive any IPC-A supervision to minimise contamination. Staff trained as IPC-A therapists were required to agree not to discuss any aspect of their training or supervision with colleagues not trained in IPC-A. The interventions that constitute TAU for this group were monitored via the modified CSRI and process evaluation.

Although the practitioners who delivered TAU were not qualified mental health professionals (as in the IPC-A arm), they were able to consult with or offer a joint appointment with a mental health professional [e.g. primary mental health worker (PMHW) or clinical psychologist] or signpost/refer the young person to other local services.

Further note on contamination: The relationship between RCT study design in mental health, ethics and contamination is complex. In this case, TAU is the treatment (varied within and across teams) that is currently given as standard to young people with mental health problems. Given the fact that there is no evidence that IPC-A is better than TAU, it is acceptable for this TAU to be given in the study. Contamination would mean that the presence of the trial would mean that young people receiving care in the TAU arm would be receiving IPC-A interventions, which they would not have received if the trial did not exist. This could happen through TAU therapists attending IPC-A training and/or IPC-A therapists in the team talking about IPC-A practice. Such contamination may improve outcomes in the TAU arm, causing a type 2 error. It is ethical to try to avoid contamination because there is no evidence that IPC-A is better than TAU, and we are doing this study to investigate if there could be a difference – we, therefore, need to ensure that TAU really is TAU.

Randomisation and blinding

Randomisation was co-ordinated remotely by the Norwich Clinical Trials Unit (CTU). Participants were randomised in a 1 : 1 allocation ratio, using a stochastic minimisation algorithm to minimise imbalance between groups in baseline symptom severity, gender and study site. Allocation was managed by the Data Management Team at Norwich CTU via a web-based system; it was not accessible by anyone outside of the team, including the research team, trial therapists and participants; thus, allocation concealment was maintained.

Blinding

Research practitioners collecting follow-up data were blind to the participant’s treatment allocation. A second unblinded member of the research team received the outcome of the randomisation via an automated notification from the system set-up and managed by the CTU and passed details of allocation to the clinical service. Given the nature of the intervention, it was not possible for participants and those involved in delivering the intervention to remain blind. Following allocation, all participants in the study and therapists were asked not to reveal the group to which the participants were randomised to the research practitioner. Participants were reminded at the beginning of each contact with the research practitioner post randomisation not to disclose their allocation. Any potentially unblinding data were stored separately in a secured database to which the research practitioner did not have access. As the study’s Chief Investigator and participants’ responsible clinicians were unblind to treatment allocations, no emergency unblinding procedures were required for this study.

Data collection

Participants were young people accessing participating services via the service’s standard referral pathways, as detailed above. Young people were triaged and assessed according to each service’s standard procedures. If this assessment identified low mood as a presenting difficulty, the case would be discussed with a clinical member of the research team (without identifying the young person) to ascertain likely suitability for the trial. Potentially suitable young people (and/or parents/carers) were invited to participate. If they expressed an interest, consent was given to the service to pass on their details to the research team.

Those who expressed an interest met with the trial’s research practitioner who carried out informed consent procedures and screened the young person to ensure they met the eligibility criteria.

Face-to-face, telephone, video call and/or internet-delivered quantitative assessment took place at baseline, 5, 10 and 23 weeks; questionnaires were completed online by the participant with support from the research practitioner. Young people were invited to take part in qualitative interviews at the end of treatment; up to 20 were planned to take part in these. Staff and stakeholders were invited to take part in focus groups.

The following participant data were collected at baseline (face-to-face, telephone and/or video call interview, internet-delivered questionnaires):

-

demographic characteristics of the young person

-

Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia, depression section34,35

-

RCADS36

-

Family Assessment Device37

-

Cambridge Friendships Questionnaire38

-

Employment, Education or Training in previous 4 weeks (NEET status)

-

Short Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (SWEMWBS)32

-

modified CSRI39

-

Child Health Utility Index 9D (CHU-9D). 40

Follow-up assessments

The following participant data were collected at 5-week follow-up (online with telephone support):

The following participant data were collected at 10- and 23-week follow-up (face-to-face, telephone and/or video call interviews, ± internet-delivered questionnaires):

-

RCADS36

-

Family Assessment Device37

-

Cambridge Friendships Questionnaire38

-

Employment, Education or Training in previous 4 weeks (NEET status)

-

SWEMWBS32

-

modified CSRI39

-

CHU-9D40

The proposed primary outcome measure for a future effectiveness trial was the RCADS, which is a continuous self-rated questionnaire of depressive and anxiety symptoms, with six subscales, including depression. The RCADS is used as the primary outcome measure for emotional disorders in CAMHS in England, as recommended in the Department of Health Children and Young People’s Improved Access to Psychological Therapies (CYP-IAPT) programme. The results from this feasibility study could potentially be benchmarked against results from countrywide CAMHS services. The RCADS is also used as the primary measure in routine English IPT for adolescent practice – the depression scale is used at each session as part of routine IPT-A. We extended this to IPC-A in the pilot36 and weekly RCADS depression was a useful part of therapy and certainly acceptable to young people and therapists; and it was a highly useful primary outcome scale in the research evaluation. The original Chief Investigator was part of a review of adolescent depression measures published in 2015 and found the RCADS to have good psychometric properties. 36

We used the observer-administered K-SADS at baseline to test for presence of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders depressive disorders. While not an outcome measure, we used this to help us to describe the sample, in particular what proportion of participants have MDD. The K-SADS is the gold-standard diagnostic interview schedule in adolescents, with excellent validity and reliability. 34

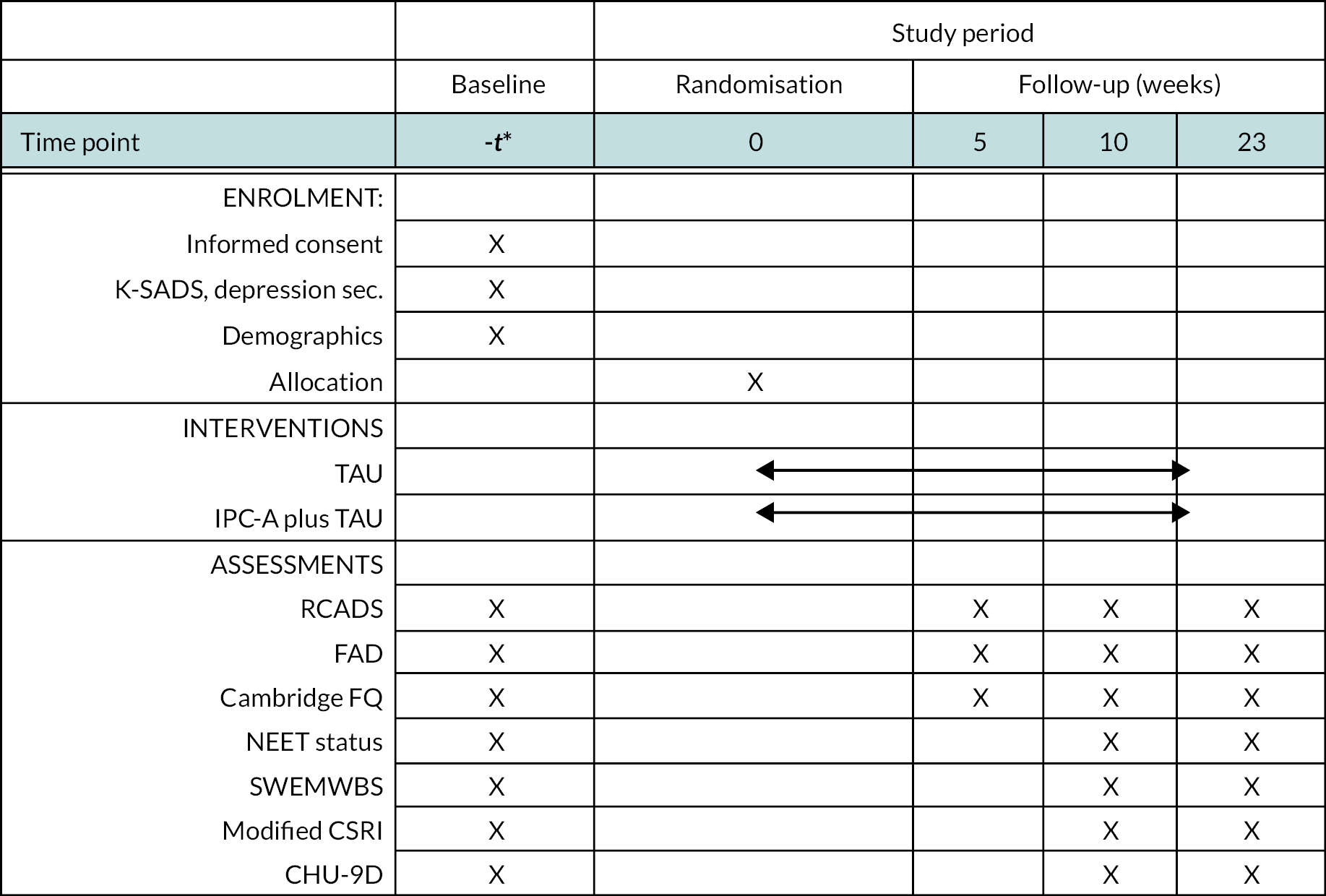

The schedule of enrolment, interventions and assessments in accordance with Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials guidelines is shown in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials figure. FAD, family assessment device; Cambridge FQ, Cambridge Friendship and Relationship Quotient.

Analysis

Statistical analysis plan

Recruitment and retention rates were estimated with 95% CIs. Assuming sufficient information, time until drop-out was analysed using ‘time-to-event’ methods to identify baseline factors likely to be related to drop-out. The proposed primary outcome measure for the definitive RCT was the RCADS depression score at 10 weeks. Although the proposed study was not designed to assess efficacy, the mean between-group difference was estimated using a general linear model including baseline RCADS depression score and treating therapist as a random effect. A 95% CI was constructed to assess whether the treatment benefit was feasibly greater than the minimal clinically significant difference, that is, whether or not it was included within the CI. A similar approach was undertaken for the secondary outcome measures. The rate of completion of each outcome measure was reported. If appropriate, depending on the proportion of missing values, multiple imputation will be undertaken and between-group differences re-estimated as a sensitivity analysis. Further parameters, such as within-group variation, needed for the design of a subsequent full-scale trial, will also be estimated.

A statistical analysis plan (SAP) was written in accordance with Norwich CTU guidance and approved by the independent Data Monitoring Committee (DMC) prior to the formal statistical analysis (see Supplementary Material 3).

Health economic analysis

As this was a feasibility study, it was not considered possible to demonstrate the cost effectiveness of the intervention because the study was not powered to demonstrate effectiveness. However, we collected information to inform the design of an economic evaluation alongside a future definitive trial. The intention was to generate information to inform any future study. Examples would include: the likely cost of the intervention and key components of resource use. It also evaluated the use of the CHU-9D instrument as a potential instrument to use in the future study. 40

The resources required to provide the interventions (IPC and TAU) were recorded. These included training; ongoing clinical supervision; and staff time required to provide the intervention. Each session offered (and its location) in both arms was recorded. Recording of these events was included in the study design in the form of a record sheet. These were combined with appropriate unit cost data to provide an estimate of the cost of providing IPC-A. It is also important to measure any resources related to participants’ mental health in both the intervention and control groups. This was conducted by means of a modified CSRI conducted at baseline, 10 and 23 weeks. Modifications included adjustments to the following aspects of the CSRI. The time frame for recall was adjusted. This was for the last 3 months at baseline and ‘since we last met’ at the 10- and 23-week follow-up. This effectively gave a time frame of the last 10 weeks for the 10-week follow-up and the last 13 weeks for the 23-week follow-up. To reduce burden on participants, the a priori aim was to make the modified CSRI as simple as possible but to still capture relevant and important service use. For this reason, questions were omitted on the following categories: usual living situation; and contacts with criminal justice system. Questions were limited to the following: contacts with specified types of care providers in the school setting; use of inpatient services; use of other secondary care services; contacts with primary care and community health and social services, residential social care services; and use of services by the participants' family. For drugs, named relevant drugs were specified that may have been prescribed for mental health reasons. We also asked about use of other prescribed medicines. For simplicity, no details were recorded of time and travel costs to access services. All demographic data were also deleted from the CSRI, as relevant data were requested elsewhere in the study. Any modifications made were done so in consultation with other ICALM investigators. The CSRI was collected by means of a face-to-face interview, by telephone/teleconference or videocall/video conference, depending on wishes of participants and safety issues arising from COVID-19 infection risk or wider pandemic measures.

The original intention was to analyse resource use data by study arm to highlight any potential areas of differences between trial arms in use of NHS and social care services, including emergency department attendances. However, due to very low numbers, this was not considered to be informative. For this reason, analysis focused on the whole sample, looking at occurrences of missing data, types of resource use reported, patterns over the three time periods and overall performance of the instrument. The measure of health-related quality of life used in the study was the CHU-9D. 40 One important outcome of the feasibility study was an assessment of the suitability of this instrument for use in a future full-scale trial. This was assessed by means of descriptive analysis of the pattern of responses at different time points.

Process evaluation

Please refer to Chapter 4, Data analysis, for details of the analysis for process evaluation.

Progression criteria

The primary intended output of the research was the design of a subsequent trial. The Trial Steering Committee (TSC) planned to assess the trial against the following criteria and make recommendations regarding the suitability of the proposed design for the full-scale trial.

-

Recruitment rate is at least 80% of target.

-

At least 70% of those randomised to receive the intervention attended at least three therapy sessions within the 10-week treatment window.

-

Follow-up assessments are completed by at least 80% of participants at 10 weeks and 70% of participants at 23 weeks.

-

At least 80% of IPC treatment sessions reviewed meet treatment fidelity criteria.

-

Contamination of the control arm can be sufficiently limited for individual randomisation to be justified.

-

The mean RCADS depression scores of the IPC-A and TAU groups at 10 weeks are indicative of a clinically significant difference in depression (3 points).

Governance

Throughout the duration of the study, research processes have been conducted according to the UK Policy Framework for Health and Social Care. A Trial Management Group met on a monthly basis where all aspects of the study were discussed and any issues were identified and resolved. The TSC and DMC were provided with progress reports throughout the duration of the study. Both the committees provided statements of support for the study to be extended beyond the original 2-year timeline due to the suspension of the study during COVID-19.

A provisional SAP was completed at the beginning of the study. Due to the number of changes throughout the study, the SAP was amended following suggestions by the DMC and was approved prior to the analysis being conducted.

Chapter 3 Feasibility randomised controlled trial – results

The project was planned to be conducted over 24 months, beginning on 1 October 2019. Training of identified staff members to deliver IPC-A was planned to commence before the project began and be completed during months 1–3. Recruitment was planned to take place in months 4–15. Follow-up assessments were planned to be completed in month 21. Months 22–24 were to be dedicated to data cleaning, analysis and dissemination.

Although recruitment started as planned in January 2020, the study was suspended in March 2020 due to the first lockdown of the COVID-19 pandemic, which temporarily suspended National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) research activities. The study recommenced in July 2020, with refresher training being offered for therapists. Recruitment then recommenced in September 2020, creating a 7-month delay. By February 2021, however, due to reported impacts on services from continued lockdowns and other COVID-19-related complications, the number of referrals was significantly impacted. Sites had to prioritise urgent cases only or focus only on safeguarding issues. Teams also experienced a change in types of referrals received, reducing the number of trial-eligible young people and lowering the capacity of staff to take on ICALM cases. IPC-A-trained staff also withdrew, citing new pressures resulting from the increased demand and reduced capacity, reducing the number of staff able to carry out the intervention. This difficulty in recruitment prompted changes such as the addition of new delivery sites, offering additional training sessions to train more staff and creating alternative referral pathways (see Recruitment and retention).

In July 2021, due to the ongoing difficulties resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic, and the delay caused by the suspension of the study at the start of the pandemic, an extension was requested and granted by NIHR. According to the revised timeline, recruitment and follow-ups were due to end between December 2021 and February 2022, with March 2022–October 2022 being dedicated to data cleaning, analysis and dissemination. Recruiting sites felt they had begun to normalise and were more positive about their ability to recruit, although the ongoing pressures on the health system limited their ability to prioritise the research trial.

Recruitment and retention

Recruitment of delivery sites

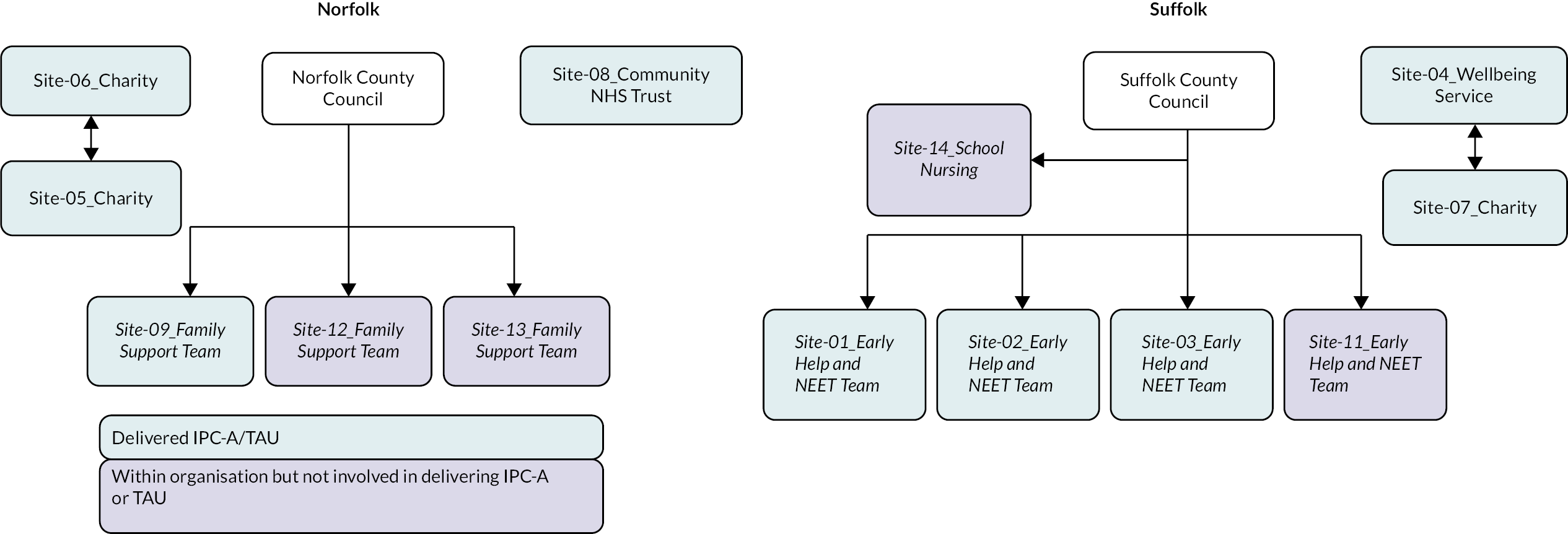

In September 2019, eight teams across Norfolk and Suffolk were approached about taking part in the study. Seven teams (Site-01_Early Help and NEET Team, Site-02_Early Help and NEET Team, Site-03_Early Help and NEET Team, Site-05_Charity, Site-07_Charity, Site-11_Early Help and NEET Team, Site-14_School Nursing) gave their agreement to take part. Six teams were based in Suffolk, and one team was based in Norfolk. The team that declined to take part had previously participated in the single-arm study of IPC-A and stated the reason for declining was that they felt IPC-A did not fit well due to the complexity of their clients.

Site-05_Charity suspended their involvement in December 2020, citing competing pressures and planned to restart their involvement once they had greater capacity; however, this did not happen, and they withdrew from the study in April 2021.

In response to COVID-19, changing team responsibilities and no longer having any teams referring to the study based in Norfolk, it became necessary to recruit further teams to support the study. In May 2021, six additional teams gave their agreement to take part (Site-04_Wellbeing Service, Site-06_Charity, Site-08_Community NHS Trust, Site-09_Family Support Team, Site-12_Family Support Team, Site-13_Family Support Team).

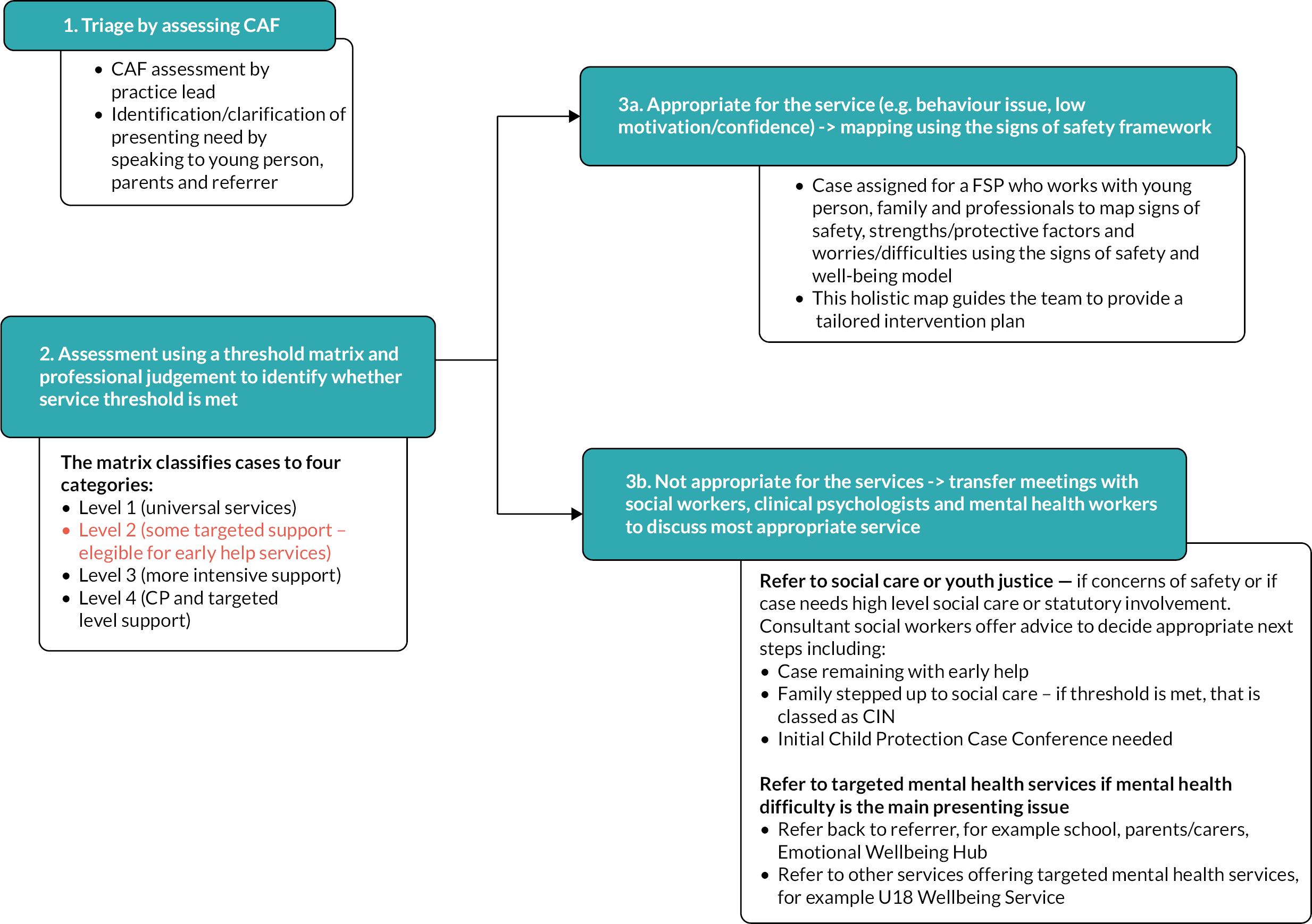

The Family Support Teams provide support through the Family Support Process and child-in-need (CIN) care plans. They work with children and families where there are concerns about the children’s well-being. It is unusual for these teams to get referrals where the only concern is adolescent mental health; there is a much more complex picture, often including a level of relational dysfunction. However, mental health concerns are the norm within their service users. Unlike mental health services, assessments will nearly always include all family members and will most likely be carried out using a Signs of Safety framework.

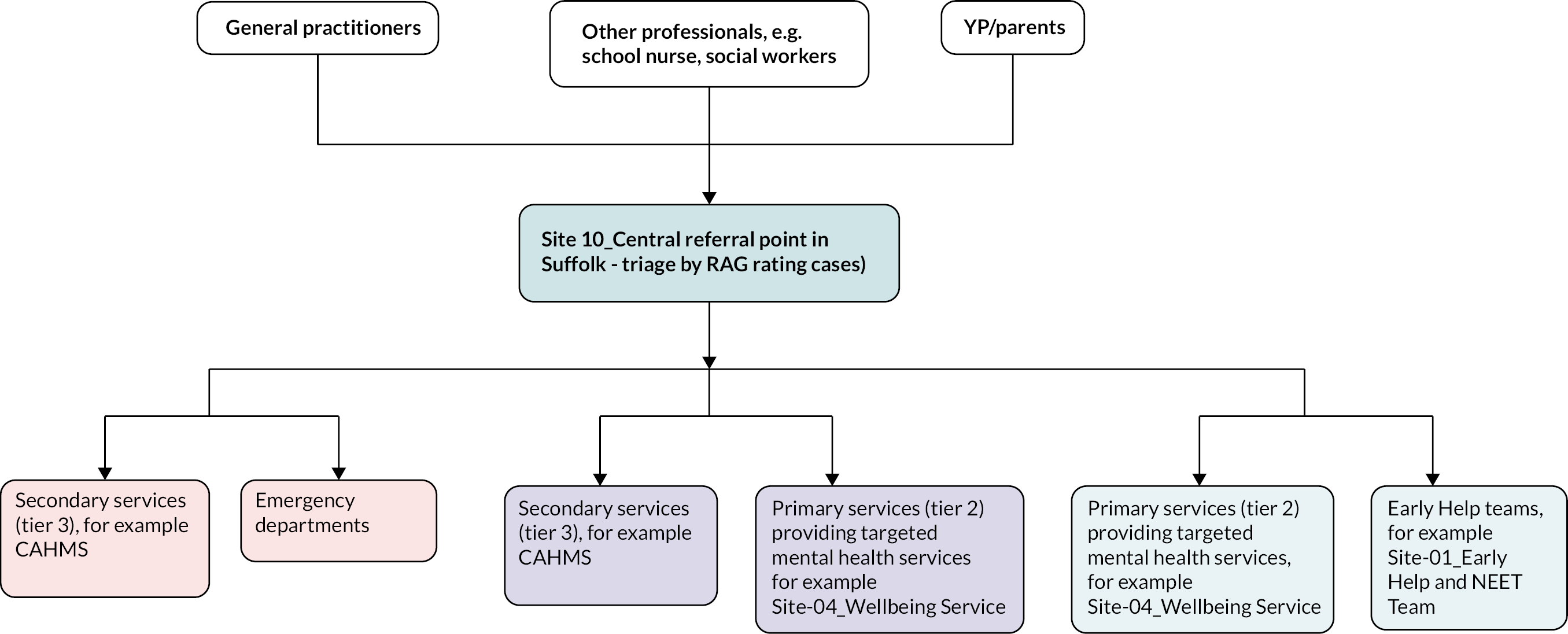

Site-04_Wellbeing Service offer Tier 2 mental health services to young people aged 4–18. The team consists of children’s wellbeing practitioners (CWPs) (without a core professional mental health qualification) and PMHWs (with a core professional mental health qualification) and provides brief interventions to young people with mild/moderate difficulties. Referrals are via the Site-10_Central referral point, the same referral point as Suffolk Early Help teams. As per trial protocol, staff without a core professional mental health qualification delivered IPC-A as part of the trial.

Site-06_Charity sees young people with mild to moderate mental health difficulties aged between 0 and 21 and works closely with Site-05_Charity. The service has a variety of staff without core mental health qualifications, including CWPs and educational mental health practitioners. Referrals to Site-06_Charity come via either professional or self-referral. Site-06_Charity have a track record of actively participating in research and have a keen awareness of what this involves. Site-06_Charity withdrew in September 2021, citing staff turnover and lack of capacity to train more staff as the reasons for withdrawing.

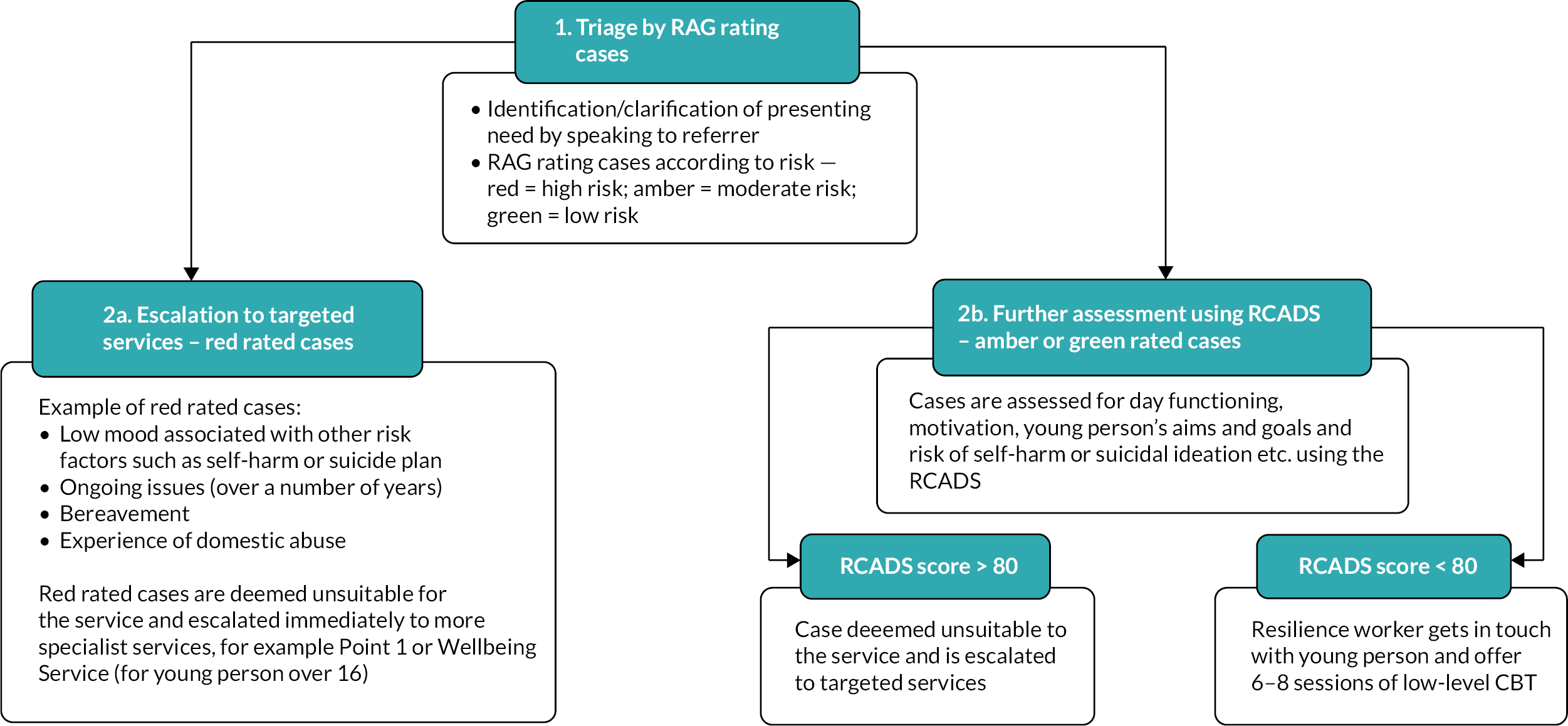

Site-08_Community NHS Trust provide health advice and support for young people at a universal services level. Part of this role involves delivering time-limited interventions to young people aged 12 and above with new and emerging mental health difficulties. Such interventions are offered by resilience and emotional health practitioners (REHPs), who do not have a core mental health qualification. Most referrals to this service are either from the young person themselves, a parent or a school representative.

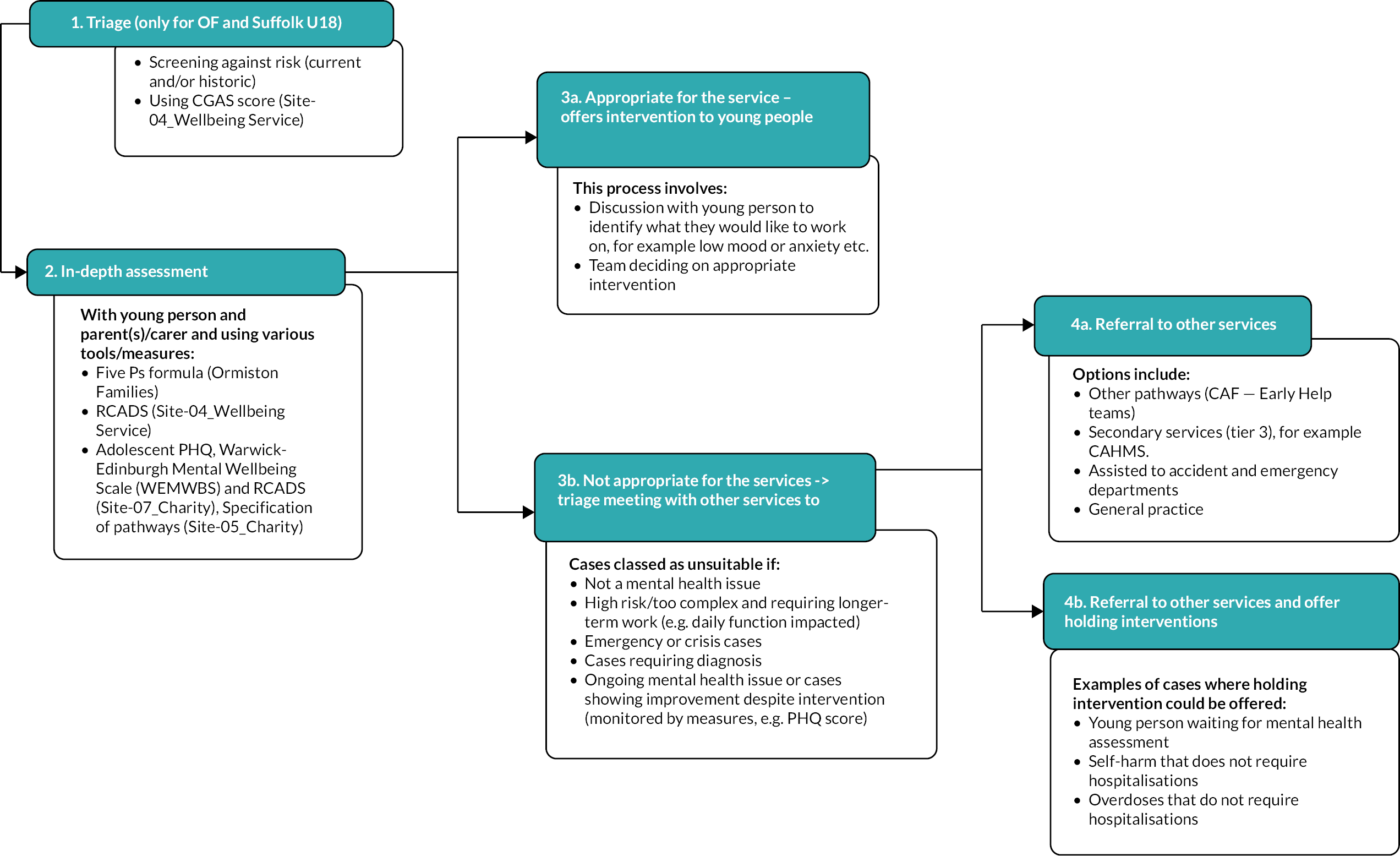

A diagram of the sites can be seen in Figure 5.

Of the 13 teams who were sites for the feasibility trial, 7 made referrals to the study, 3 (Site-02_Early Help and NEET Team, Site-06_Charity and Site-08_Community NHS Trust) delivered IPC-A/TAU of which 2 teams provided recordings (Site-08_Community NHS Trust and Site-02_Early Help and NEET Team).

Changes to referral pathways

Although the majority of teams had agreed to offer both IPC-A and TAU, due to difficulties with retention of trained IPC-A staff, clinical capacity, lack of suitable cases and stagnant waiting lists, there were a number of changes to referral pathways as well as the type of intervention teams were able to offer.

Site-04_Wellbeing Service/Site-14_School Nursing

With difficulties due to many young people being ‘stuck’ on the Site-10_Central referral point waiting list, preventing possible eligible referrals, new pathways were sought. There were difficulties with Site-14_School Nursing having limited capacity to deliver the trial, but having eligible young people, and Site-04_Wellbeing Service who had IPC-A trainees but few eligible young people. It was suggested and agreed with locality managers and commissioners to set up a new pathway to allow referrals to the Site-04_Wellbeing Service from the Site-14_School Nursing. Site-14_School Nursing team checked for eligibility and willingness to take part in the study and then referred to the research team for consent and eligibility checks. Site-14_School Nursing would then transfer the case from Site-14_School Nursing to Site-04_Wellbeing Service. If ineligible, the case remained with Site-14_School Nursing. Only at the point of assessment at the Site-04_Wellbeing Service, if a case withdraws from the study or is no longer suitable, would the case stay with Site-04_Wellbeing Service to finish any treatment, as the case would unlikely be suitable for Site-14_School Nursing. If suitable, the research team would be informed, and the case randomised to Site-04_Wellbeing Service for the intervention and informed if the case is TAU or IPC-A. The intervention and the follow-ups would continue as normal.

Site-04_Wellbeing Service and Site-07_Charity

Similar to the Site-14_School Nursing and Site-04_Wellbeing Service pathways, an agreement was set up for Site-04_Wellbeing Service and Site-07_Charity. Site-07_Charity is a charity that offers brief, ‘light touch’ early interventions to young people experiencing mental health difficulties. In terms of the severity of mental health difficulties they offer treatment for, they sit below Site-04_Wellbeing Service, and young people can self-refer. This service is largely made up of counsellors who, due to their training and qualifications, were deemed ineligible to provide IPC-A as part of this study. However, Site-07_Charity offered to provide additional TAU capacity to Site-04_Wellbeing Service, thereby minimising contamination and offering a clear alternative TAU. Site-04_Wellbeing Service would go through their usual process of checking if appropriate for ICALM and then checking if they were interested. The referral form was then sent to the research team to provide an information sheet and consent form, as well as confirming eligibility. If eligible, the young person was then randomised. If the young person was randomised to the TAU arm of the study, Site-07_Charity and Site-04_Wellbeing Service discussed who would deliver the TAU. The staff member of the respective team then completed the participant consent form, and the intervention and the follow-up continued as normal.

Site-04_Wellbeing Service and Site-07_Charity have a contract, which means that any referrals from Wellbeing will be seen within 4 weeks.

Site-10_Central referral point

In a meeting held with team leaders in August 2021, managers highlighted challenges in getting appropriate referrals from the central referral point as a key barrier to recruitment. Managers fed back that due to pressures at the central referral point, the Early Help teams were being allocated more complex cases, instead of the mild cases they are commissioned to take on.

As a result of this feedback, in November 2021, the ICALM study team initiated discussions with representatives from Site-10_Central referral point, Site-02_Early Help and NEET Team and Site-04_Wellbeing Service to set up a fast-tracked referral pathway for suitable ‘green’-rated (low-risk) cases from Site-10_Central referral point to ICALM. The process also received support from a representative from the commissioning group as it was in line with government agenda. Site-10_Central referral point was not a full site for the study; this site supported referrals to the study only.

Delivery site characteristics

An overview of the characteristics of the 13 sites that agreed to take part in the feasibility study is provided in Table 1. Site-10 has not been included as it was a referring site only. Detailed site characteristics can be found in Table 1.

| Site ID | Service type |

|---|---|

| Site-01 | Early Help and NEET |

| Site-02 a | Early Help and NEET |

| Site-03 | Early Help and NEET |

| Site-04 | Wellbeing Service |

| Site-05 | Charity |

| Site-06 a | Charity |

| Site-07 | Charity |

| Site-08 a | Community NHS Trust |

| Site-09 | Family Support |

| Site-11 | Early Help and NEET |

| Site-12 | Family Support |

| Site-13 | Family Support |

| Site-14 | School Nursing |

Staff participants

In May 2021, the format of IPC-A training was significantly altered by being undertaken online due to COVID-19 restrictions and included several sessions devoted entirely to explaining the trial. This included detailed explanations of equipoise and randomisation. These training materials had been adjusted and routinely delivered and distributed to new teams or new staff when the study was explained. This was changed to help understand randomisation and to support practitioners within therapy delivery teams, as it was observed that the clinical practitioners within these teams were not familiar with research processes such as randomisation, which was seen as a barrier to recruitment.

In total, the study team trained 19 staff members as IPC-A practitioners who all gave consent to take part in the feasibility study. However, subsequently, eight withdrew from the trial. Four consenting IPC-A practitioners were allocated clients. Two IPC-A practitioners delivered the intervention. For those practitioners who did not deliver IPC-A, reasons given were (n = 1) client was offered IPC-A but did not engage with the service and did not attend any IPC-A appointments offered and (n = 1) client was not appropriate for IPC-A due to complexity and risk and was referred for a more appropriate intervention. Staff providing TAU were not consented until they were allocated a client. In total, three staff members providing TAU gave consent to take part in the feasibility trial. Two staff members delivered TAU. One staff member did not deliver TAU as their client withdrew from the study.

Participant flow

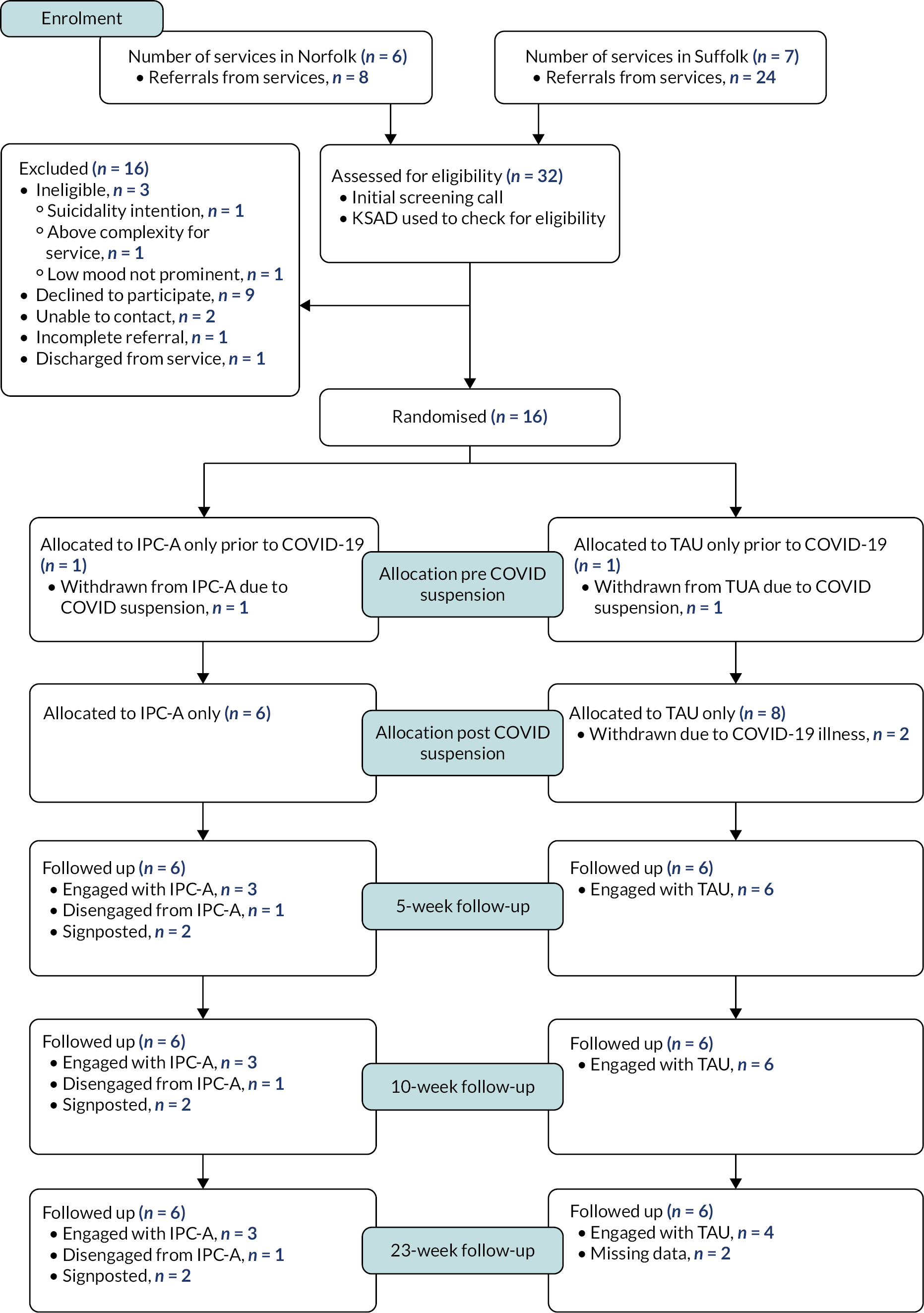

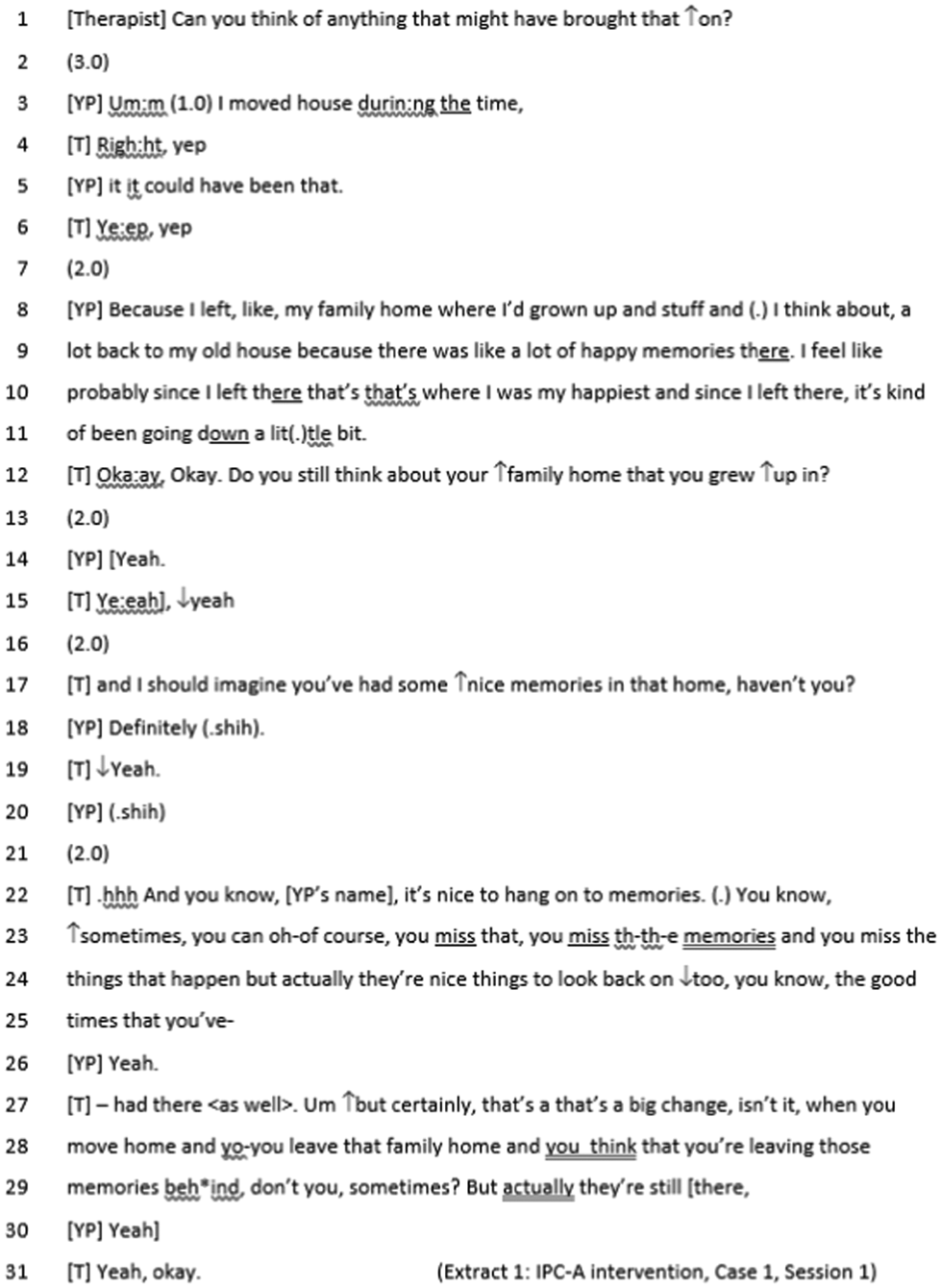

In total, 32 referrals were received, with 16 eligible participants being recruited and randomised (Figure 2). Two of these participants were recruited and randomised before the suspension of the study due to COVID-19. These participants were informed about the decision to discontinue follow-up data collection due to the current COVID-19 crisis causing research to be halted. Therapy (either IPC-A or TAU) continued, but the research practitioner did not contact participants for any more assessments. Of the remaining 14 participants, only 7 received an intervention, with 3 out of 6 participants receiving IPC-A and 4 out of 6 receiving TAU. Among participants who did not complete IPC-A, one did not engage with the service nor attended appointments. Two participants were found inappropriate for ICALM and IPC-A due to complexity and/or risk at rescreening by the IPC-A clinician, highlighting a progression of symptoms between baseline assessment and start of IPC-A. This led to the clients being discharged and signposted to another service. Concerning the two participants who did not complete TAU, not all data were able to be collected as to whether they received any intervention due to staff members not completing the Attendance Questionnaires.

FIGURE 2.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials diagram for feasibility trial (includes two before suspension of study).

Recruitment

Due to remote working, the protocol was changed to allow the young person (or their parent/carer if under 16) to be asked if they are willing to photograph and electronically send a picture of the completed consent form to the research practitioner so that baseline assessments are not delayed by the added complexity caused by postal delivery services. It was also changed to allow interviews/focus groups for the qualitative analysis and treatment and assessment to take place face to face, by telephone/teleconference or videocall/video conference, depending on wishes of participants and safety issues arising from infection risk. Participants were posted copies of the consent form and participant information sheets, with the researcher going through the consent form remotely with the participant. The participant would then take and send a picture of the signed consent form to the research team so further parts of the study could continue. The participant, meanwhile, would post the form back so there was a physical copy for study records. The protocol was changed to accommodate recording online, as this was historically in-person with a dictaphone.

In March 2021, further changes were made in consenting procedures to account for the ongoing changes due to COVID-19. This included having multiple options for carrying out consenting processes, including face to face; via photo and post; and through incorporating the form into the Research Electronic Data Capture system (REDCap) and capturing consent via audio-recording.

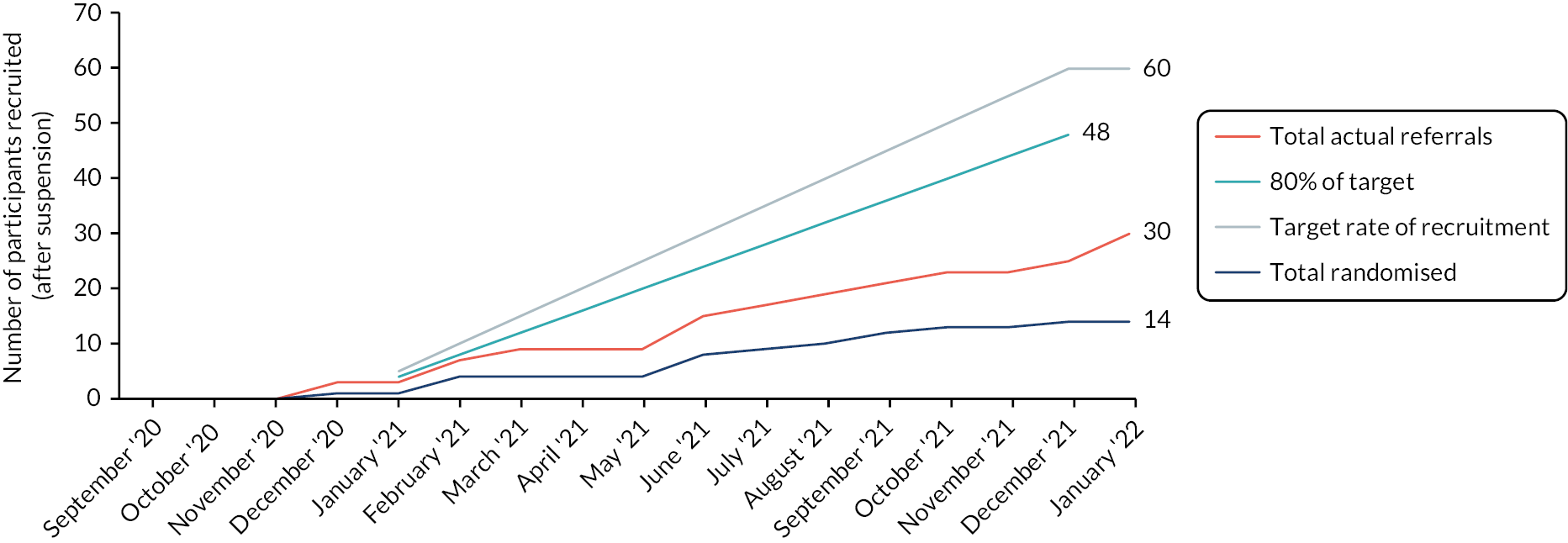

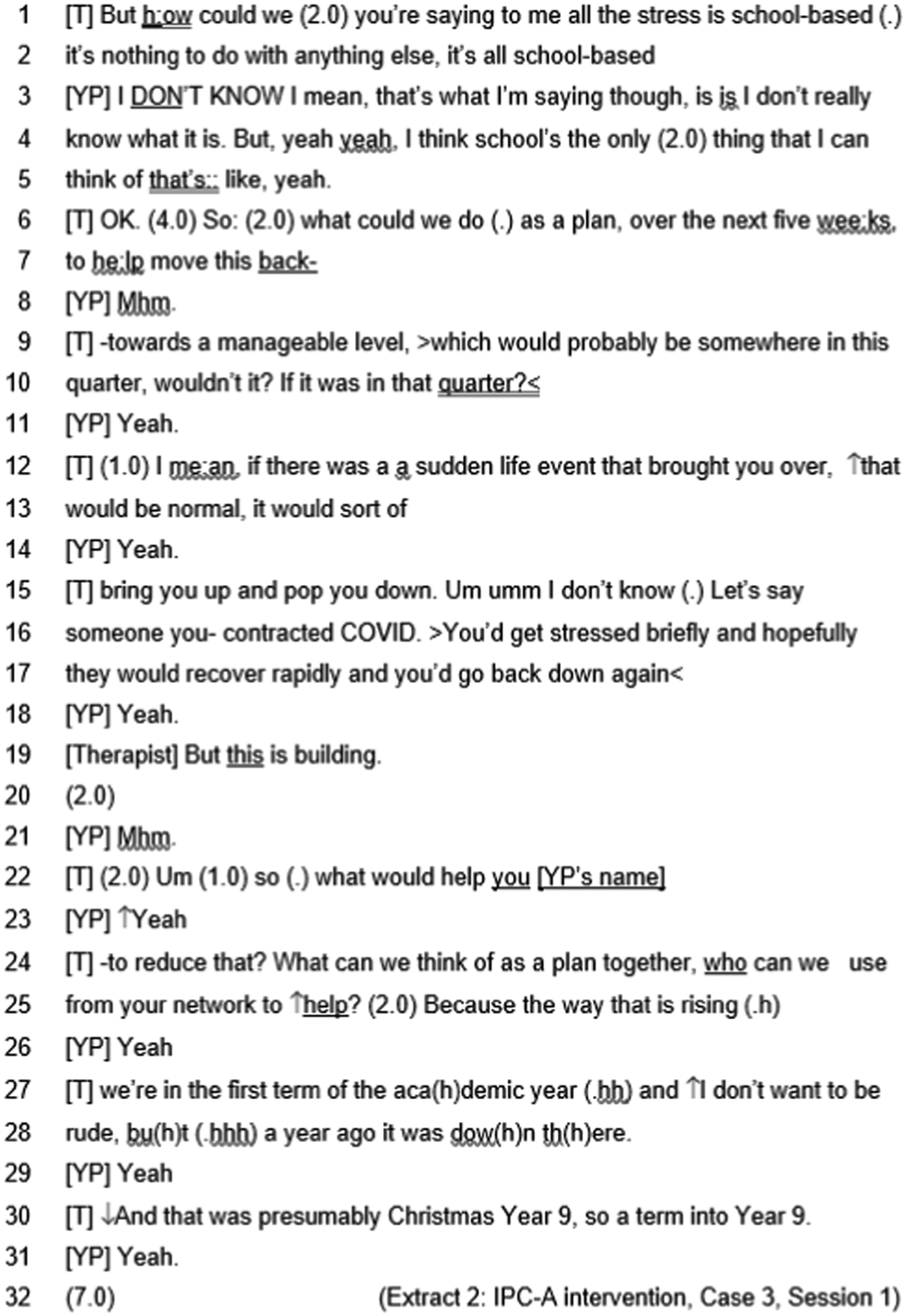

Looking at Figure 3 for those who were recruited after suspension (n = 14), the overall rate of recruitment was slower than anticipated: on average, 1.7 per month (18 months) versus a target recruitment rate of five participants per month (12 months). Recruitment, however, started earlier in September 2020 and ended later than predicted in February 2022, compared to predictions starting in January 2020 and ending in December 2021. The alterations to the referral pathways did not increase the number of referrals made to the study.

FIGURE 3.

Accrual curve for feasibility trial.

Following previous unsuccessful attempts at recruitment, the fast-tracked referral pathway for suitable green-rated cases from Site-10_Central referral point was agreed in November 2021. Prior to this agreement, there were concerns raised from the services around the following areas

Caseloads of therapists

As Early Help managers were aware of the pressures faced by Site-10_Central referral point due to staff shortages and the backlog of cases, they expressed a concern of ‘flooding the services’ by highlighting an incident where approximately 600 cases had been referred from Site-10_Central referral point to another team within a short period of time.

This is an emotive subject for the services because Site-10_Central referral point can see this as a way of offloading cases and may lead to a lot of disquiet. You don’t want to send the message that Site-10_Central referral point is offloading cases. I am concerned that we are not opening the flood gates.

Concerns about the suitability of the cases for their services

The managers felt a number of referrals received from Site-10_Central referral point were not appropriate for their service (even after being advised what the criteria for the service are) and that although they may come through as low mood, there may be other confounding factors which are the cause of this presentation. The main challenge with the referral of cases from Site-10_Central referral point was that there was not a feedback loop which allowed for cases to be returned to the hub if considered inappropriate. The managers of the service therefore felt that there needed to be a feedback loop or support mechanism in place in case the identified cases were beyond the service’s remit.

Site-10_Central referral point not triaging cases before referring

Team managers felt that Site-10_Central referral point did not triage the cases fully, leading to teams not having the full information on the case to decide whether they would be apprioriate for their service. Site-10_Central referral point needed to identify cases that have low-level issues and exclude those that have complexities, for example, violence, safeguarding issues, eating disorders, adoption or learning disabilities.

Usual support

Some teams reported not having TAU for low mood. They would need to ensure provision is made for young people randomised to the TAU arm. This also impacted on practitioners’ willingness to randomise a case they thought suitable for IPC.

Following these concerns from the teams, the plan was to identify a small number of eligible young people (maximum 5) for each of the participating teams based on the capacity of participating therapists and how many cases the practitioners needed to qualify as an IPC-A therapist. The agreed plan was as follows:

Step 1

Site-10_Central referral point clinician to identify potential referrals based on ICALM inclusion and exclusion criteria. Site-10_Central referral point clinician would need to go through the general practitioner (GP) areas to ensure that the cases are being referred to the correct location and right teams. Site-10_Central referral point to refer cases to one of three teams, depending on location: Site-01_Early Help and NEET Team/ Site-02_Early Help and NEET Team/ Site-04_Wellbeing Service to speak to potential participants to see if they would like to find out more about the study:

-

If no – no further action with person for ICALM.

-

If yes – referral is made to the teams.

Step 2

The cases get reviewed by a team manager for appropriateness before assigning them to the team. If appropriate, the team manager will notify Site-10_Central referral point clinician that the case has been assigned to a manager so that it can be closed at the Site-10_Central referral point and noted that it has been assigned to the ICALM study.

Step 3

Team to refer suitable participants to ICALM team for baseline assessment. If they are eligible for ICALM team consent (young person and family), complete baseline measure and randomise participants (this can take up to 3 weeks).

Step 4

ICALM Trial manager to inform the team of the randomisation outcome. When referred to the team, the young people will be in contact with family support practitioners (FSPs) as per usual.

The perceived benefit of the process included reducing the long waiting list for ‘green’ cases while ensuring that services are not inundated with inappropriate referrals.

The Site-10_Central referral point clinician screened 1300 cases, of which only 31 cases were identified as potentially having ‘low mood’.

I filtered out the queues and removed all cases for potential or a diagnosis of ASD or ADHD, l removed learning disabilities, young people suffering from trauma or who are being violent and having anger issues. I also screened the list for the correct GP practices based on the areas of Bury and Ipswich, leaving only 31 cases.

In total I believe there are 19 possible ones for one of the teams and 12 for another – the ones in red (not referring to RAG rating) I am pretty sure on, however this is purely due to a lack of referral info.

For the 1300 referrals that were screened, only 4 young people were then referred to the ICALM team. None of these referrals consented to take part in the study due to not being able to be contacted prior to the recruitment deadline, and one person declined to participate.

Retention

After suspension of the study, of the 14 eligible participants who were randomised to the study, 12 (85.7%) reached the 23-week follow-up, with 2 (14.3%) participants withdrawing from the study at the allocation stage due to testing positive for COVID-19.

Baseline characteristics

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of participants recruited to the feasibility RCT are presented in Tables 2 and 3.

| TAU | Intervention | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | |||

| Participants randomised n | 9 | 7 | |

| Recruiting site | Norfolk | 5 (56) | 2 (29) |

| Suffolk | 4 (44) | 5 (71) | |

| Gender | Male | 1 (11) | 2 (29) |

| Female | 7 (78) | 5 (71) | |

| Undisclosed | 1 (11) | 0 | |

| Age | 13 | 1 (11) | 2 (29) |

| 14 | 2 (22) | 2 (29) | |

| 15 | 3 (33) | 1 (14) | |

| 16 | 2 (22) | 2 (29) | |

| 17 | 1 (11) | 0 | |

| Ethnicity | British | 1 (11) | 0 |

| White British | 5 (56) | 6 (86) | |

| White European | 1 (11) | 0 | |

| White-Afro-Caribbean | 1 (11) | 0 | |

| Undisclosed | 1 (11) | 1 (14) | |

| Symptom severitya | Low | 6 (67) | 2 (29) |

| High | 3 (33) | 5 (71) | |

| TAU | Intervention | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NEET status | NEET status | |||||||||

| n | Further education | School | Paid work | None | n | Further education | School | Paid work | None | |

| Baseline | 9 | 0 | 6 (67%) | 2 (22%) | 1 (11%) | 7 | 0 | 7 (100%) | 0 | 0 |

| 10 weeks | 6 | 0 | 4 (67%) | 1 (17%) | 1 (17%) | 6 | 0 | 6 (100%) | 0 | 0 |

| 23 weeks | 6 | 0 | 5 (83%) | 1 (17%) | 0 | 6 | 0 | 5 (83%) | 0 | 1 (17%) |

Suitability of outcome measures

Rates of completion

Outcome measures were well completed. Of those successfully followed up at 23 weeks, almost all participants (83%) completed all outcome measures; one RCADS measure was missed at week 23. The Trial Manager/Research Assistant was able to check self-reported measures for missing items and follow up with participants to complete the measures. The researchers then facilitated the assessments at week 10 and week 23, which resulted in no measures being missed.

Descriptive statistics for outcome measures collected

The objective of the study was to assess the feasibility of this study to inform a future RCT. This study was not powered to detect any significant changes in outcomes. Mean changes from baseline by allocated arm are presented in Table 4.

| TAU | Intervention | Estimated treatment effect | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean | SD | n | Mean | SD | Effect | 95% CI | p | |

| RCADS | |||||||||

| Baseline | 9 | 19.1 | 4.11 | 7 | 15.1 | 5.55 | |||

| 5 weeks | 6 | 18.3 | 5.13 | 6 | 16.7 | 6.50 | –0.10 | –5.39 to 5.18 | 0.966 |

| 10 weeks | 6 | 16.5 | 7.53 | 6 | 13.5 | 5.47 | 1.14 | –5.31 to 7.58 | 0.699 |

| 23 weeks | 6 | 12.5 | 9.77 | 5 | 7.1 | 1.79 | 2.28 | – 7.32 to 11.89 | 0.599 |

| FAD | |||||||||

| Baseline | 9 | 2.3 | 0.20 | 7 | 2.3 | 0.30 | |||

| 5 weeks | 6 | 2.3 | 0.18 | 6 | 2.4 | 0.23 | –0.03 | 0.26 to 0.21 | 0.803 |

| 10 weeks | 6 | 2.5 | 0.19 | 6 | 2.4 | 0.14 | 0.10 | –0.12 to 0.32 | 0.322 |

| 23 weeks | 6 | 2.5 | 0.20 | 6 | 2.4 | 0.12 | 0.10 | –0.13 to 0.33 | 0.341 |

| Cambridge FQ | |||||||||

| Baseline | 9 | 3.3 | 0.49 | 7 | 3.1 | 0.48 | |||

| 5 weeks | 6 | 3.3 | 0.58 | 6 | 3.0 | 0.47 | 0.02 | –0.52 to 0.56 | 0.936 |

| 10 weeks | 6 | 3.5 | 0.32 | 6 | 3.1 | 0.36 | 0.21 | –0.07 to 0.50 | 0.133 |

| 23 weeks | 6 | 3.2 | 0.25 | 6 | 3.2 | 0.70 | –0.20 | –0.88 to 0.48 | 0.521 |

| SWEMWBS (metric) | |||||||||

| Baseline | 9 | 18.0 | 2.58 | 7 | 18.9 | 2.51 | |||

| 5 weeks | |||||||||

| 10 weeks | 6 | 18.7 | 5.09 | 6 | 20.4 | 2.00 | –1.77 | –5.83 to 2.29 | 0.350 |

| 23 weeks | 6 | 21.2 | 5.51 | 6 | 22.3 | 3.22 | –1.25 | –5.36 to 2.85 | 0.508 |

| CHU-9D (score) | |||||||||

| Baseline | 9 | 2.7 | 0.89 | 7 | 2.3 | 0.80 | |||

| 5 weeks | |||||||||

| 10 weeks | 6 | 2.5 | 1.07 | 6 | 1.9 | 0.49 | 0.65 | –0.10 to 1.40 | 0.080 |

| 23 weeks | 6 | 1.9 | 0.87 | 6 | 1.8 | 0.45 | 0.21 | –0.60 to 1.02 | 0.572 |

Safety and adverse events

There was one serious adverse event (SAE) recorded during the feasibility trial. The SAE was in the IPC-A arm and was an instance of a 3-day hospital admission due to urosepsis. The urosepsis was considered to have been caused by a urinary tract infection. Details of the SAE were reported to the Sponsor’s Participant Sub-Committee for independent review. It was deemed not to be related to the study procedures.

There were five adverse events (AEs) recorded during the feasibility trial, four in the TAU arm and one in the IPC-A arm. The AEs in the TAU arm were a positive test result for coronavirus (COVID-19), bereavement due to the death of an uncle and an ongoing investigation for a gluten allergy. The AE in the IPC-A arm was one instance of perceived difficulty breathing due to anxiety a few hours after baseline measures were taken. It was unclear whether this was related to the baseline assessment.

Health economic assessment

Follow-up was obtained on 12 participants at the 10- and 23-week periods. For a CHU-9D score to be generated, it is required that a valid response be given for all nine of the questions. Only in this case can a summary score be generated. It can be seen from the results outlined in Table 5 that scores could be derived in all but one case. For one participant at baseline, there was one answer to one question missing. In all other instances, complete data were obtained. Although sample sizes are small, the data indicate that health, as determined by the CHU-9D, was increasing over time. The use of t-tests suggests that the baseline and 23-week scores were statistically significantly different. There was no statistically significant difference between baseline and 10-week scores or 10-week and 23-week scores.

| Baseline (N = 15) | 10 weeks (N = 12) | 23 weeks (N = 12) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CHU-9D | 0.716 (0.648–0.784) | 0.78 (0.705–0.855) | 0.833 (0.758–0.909) |

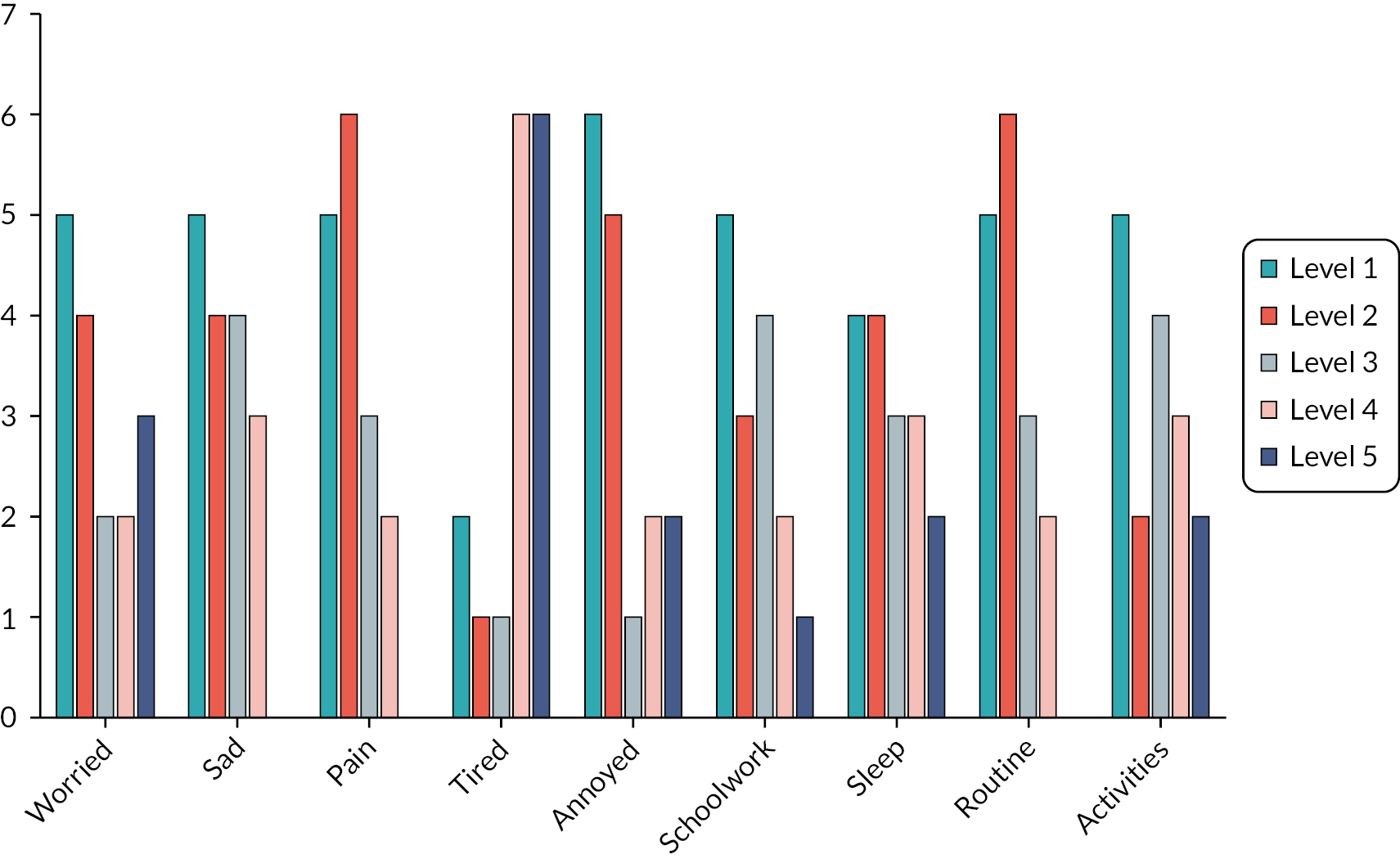

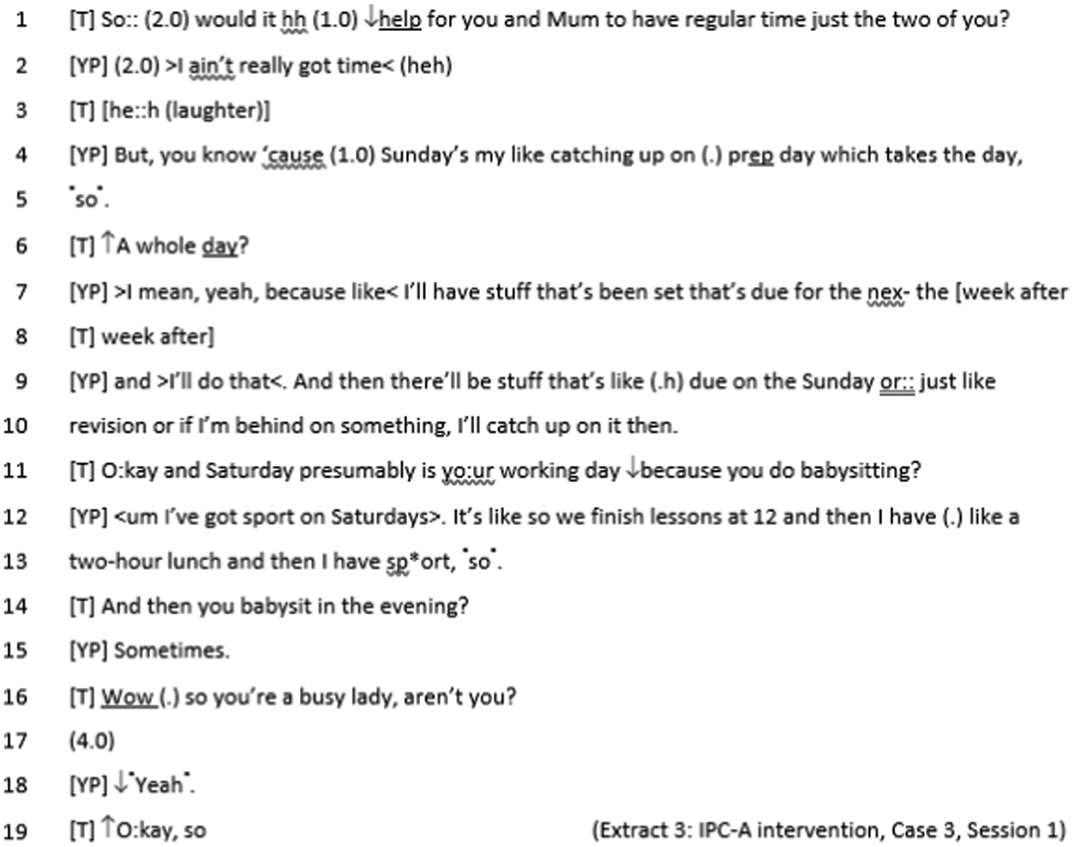

The results of the CHU-9D by individual response to each question are shown in Table 6 and Figure 4 for the baseline responses. The number of responses is given by level for each of the 9 CHU-9D questions. Each question has five possible responses, labelled 1–5 in Table 6 and Figure 4. In all cases, level 1 for each question represents the best response, and level 5 is the worst. Response categories differ by question. For example: level 1 for ‘Worried’ is ‘I don’t feel worried today’, whereas level 1 for ‘Activities’ is ‘I can join in with any activities today’.

FIGURE 4.

Baseline responses by CHU-9D dimension.

| Level | Worried | Sad | Pain | Tired | Annoyed | Schoolwork | Sleep | Routine | Activities |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level 1 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 |

| Level 2 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 2 |

| Level 3 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 |

| Level 4 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 6 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 |

| Level 5 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

Again, numbers are small, so there are limitations in what can be taken from these data. However, there are some observations that can usefully be made. In most cases, there were responses across the entire range of the possible responses, with only ‘sad’, ‘pain’ and ‘routine’ dimensions recording no responses in the worst state. This indicates that baseline responses in ICALM cover the full range of potential responses in the CHU-9D. This would also indicate that the CHU-9D has the potential to show improvements from baseline in this group of individuals. By contrast, if almost all responses had been at level 1, there would have been little opportunity to show improvements. This may also indicate that the CHU-9D is sensitive to changes caused by depression in adolescents. A second point that could be noted with these data is that the question relating to feeling tired appears to show the most negative responses.

Table 7 shows the completion rates for the CSRI and its various questions at the three time points. At least some sections of the CSRI were completed for 16 participants at baseline, 11 at the 10-week follow-up and 12 at the 23-week follow-up. Responses by category of resource use (individual questions) are shown in Table 7, that is, this shows the number of times this section was completed at each follow-up. Where sections do not appear to be completed, it is likely because a question was left blank. This was particularly common for ‘inpatient stays’ and ‘other drugs’. There were more sections/questions left blank at follow-up than at baseline. There was one CSRI form at the 10-week follow-up that was returned but left blank. Generally, the CSRI appeared to have been completed for participants, particularly at baseline.

| Baseline (N = 16) | 10 weeks (N = 12) | 23 weeks (N = 12) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 – School-based support | 14 | 11 | 12 |

| Q2 – Drugs relevant to mental health | 16 | 11 | 9 |

| Q3 – Other drugs | 12 | 6 | 3 |

| Q4 – Inpatient | 10 | 6 | 7 |

| Q5 – Other secondary care | 14 | 11 | 12 |

| Q6 – Community-based health and social care | 14 | 11 | 12 |

| Q7 – Residential social care | 14 | 11 | 12 |

| Q8 – Service use by family related to participants' mental health | 14 | 9 | 11 |

| Any category answered | 16 | 11 | 12 |

Resource use at baseline and follow-up, as indicated by the CSRI, is given in Table 8. Here, categories are only given if there was reported use of that type of resource. The ‘education, other’ category includes items such as personal tutors, attendance officers and success centre support workers. The modified CSRI used asked specifically about a number of named mental health drugs (fluoxetine, sertraline, melatonin/circadin, promethazine, citalopram, propranolol). No participant reported any of these drugs at any time period. The ‘other meds’ category in Table 7 gives a count of the number of different drugs reported. Generally, these are not mental health related. There was only one reported inpatient stay in any time period, corresponding to a 3-day stay. For other uses of secondary care, there was some limited use reported, generally for reasons not related to mental health.

| Resource use type | Resource use | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 10 weeks | 26 weeks | |

| School-based support | |||

| Welfare Officer/Well-being Officer/Pastoral Support Worker/Safeguarding lead | 47 | 13 | 3 |

| Classroom assistant | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Special education needs and disabilities co-ordinator | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| School nurse | 5 | 3 | 4 |

| School counsellor | 4 | 2 | 0 |

| Education, other | 28 | 0 | 1 |

| Other drugs | 13 | 1 | 3 |

| Inpatient stay | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Other secondary care | |||

| A&E – other | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Paediatric OP – MH | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Paediatric OP – not MH | 7 | 0 | 2 |

| Other OP – MH | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Other OP – not MH | 4 | 0 | 1 |

| Day hospital treatment setting – not MH | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Community-based health and social care | |||

| School nurse | 4 | 3 | 4 |

| Mental health nurse | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| GP | 18 | 5 | 4 |

| Paediatrician | 4 | 1 | 2 |

| Physiotherapy | 8 | 2 | 2 |

| Other | 16 | 3 | 1 |

| Counselling | |||

| Family therapist | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| Individual therapy | 18 | 22 | 27 |

| Other | 6 | 33 | |

| Support | |||

| After-school club | 17 | 5 | 1 |

| Other | 9 | 1 | 4 |

| Family use of services – total | 47 | 2 | 0 |

The majority of healthcare uses we asked about were not services that were used by any of the respondents. Contacts were reported for: school nurse, mental health nurse, GP, paediatricians, physiotherapy and other healthcare contacts. There was also reported use of therapist services. Generally, this was reported by a small number of individuals reporting multiple contacts. There was no reported use of social care services, though a few individuals used after-school clubs. There were a number of reported contacts with services by participants’ families – this was mostly in the baseline period.

In general, the CSRI appeared to have been completed by most respondents. There were some categories where the response had been left blank and it was not clear if this was ‘missing’ or zero. However, in the majority of cases, a value of zero was used if there was no reported service use. Generally, there were only one or two missing cases in the data for the majority of data types.

There appears to be a clear pattern of reducing service use over the follow-up period. The exception to this appears to be the use of therapy services.

The number in Table 8 generally corresponds to number of visits or contacts or number of stays. The exception is use of ‘other drugs’ where numbers represent prescriptions.

As part of the economic component, we estimated the costs of providing the IPC-A intervention. Given the very small numbers who had the intervention, it was difficult to estimate what the costs may be if this was applied in a larger sample as it would be in any future trial or if the scheme was rolled out into practice. The costs calculated here can be divided into three categories: costs of providing training; costs of supervision; and costs of providing sessions. In all cases, costs are in UK 2020–1 Great British pounds.