Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its proceeding programmes as project number 10/2001/41. The contractual start date was in October 2011. The final report began editorial review in May 2013 and was accepted for publication in November 2013. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Two co-authors (names anonymised to protect confidentiality of participants) have received funding from various health service organisations to act as a service user research partner, including some initiatives which were assessed as part of this study. Jane Coad was employed on a partner contract with Coventry University. Rosemary Davies received a University of the West of England bursary for a PhD focused on public involvement in health research.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2014. This work was produced by Evans et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

This study was concerned with developing the evidence base for public involvement in research in health and social care. From as early as 1993 there was policy commitment to ‘consumer involvement’ (later called ‘public involvement’) in research in the English NHS,1 and there now is significant support for public involvement within the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), including the work of the INVOLVE Advisory Group and Coordinating Centre. 2 For example, researchers applying for NIHR grants are now strongly encouraged to involve the public in research projects, and lay people are involved in NIHR commissioning groups and as reviewers.

Despite this strong policy commitment, the evidence for the benefits of public involvement within the research and development (R&D) world remains limited. From the early days of the NHS R&D strategy there was some concern to build the evidence base. One of the first acts of the Standing Advisory Group on Consumer Involvement in the NHS R&D programme, established in 1996, was to commission a report on lay involvement in the R&D programme. 3 But such surveys did not overcome the scepticism of many researchers regarding the lack of robust evidence for the impact of involvement. The desire for evidence on the impact of public involvement on research has grown along with wider interest in evidence-based policy making. 4,5

Interest in the evidence base for public involvement in research has grown over the same period, alongside an increasing interest in the evidence regarding public involvement in health care more generally. A number of research projects and evidence reviews on the impact of public involvement in health care have been commissioned by the Department of Health, the NIHR, the NHS and other official and professional bodies over the last decade. 6–10

The first literature reviews commissioned specifically on the impact of public involvement in health research did not appear until 2009–10. 11,12 These reviews identified a number of gaps in the evidence, in particular the lack of primary studies on the impact of involvement and the uneven quality of much of the published literature in this area. Partly in response, the Medical Research Council (MRC) and NIHR commissioned new research on the impact of public involvement in research in 2009 and 2010 respectively, of which this study is one; at the time of writing, however, none of these studies has yet reported.

As with the concept of evidence, the term ‘public involvement’ is often used in R&D policy documents uncritically and generically to encompass a range of very different involvement activities and approaches. People can be involved in research across a wide spectrum of activity including initial priority setting, advising on the design of research, and participating in data collection, analysis and dissemination. A number of authors have sought to conceptualise public involvement in terms of hierarchical levels; for example INVOLVE have previously distinguished between consultation, collaboration and user control. 11 Such models are problematic, however, as public involvement is not well defined in English health policy, either in health services generally10 or in R&D in particular. 12 See Terminology for a further discussion of some of the issues around definition and the terminology we have chosen to use in this report.

The best evidence for the impact of public involvement in research at the start of our study was provided by two recent literature reviews by Staley11 for INVOLVE and Brett et al. 12 for the UK Clinical Research Collaboration. These reviews both independently found that there was huge variation in how the evidence of the impact of involvement had been assessed and reported. Equally, they both found that the impact of involvement was highly context-specific, making it difficult to judge the quality of the evidence or draw general conclusions. Almost all the evidence of impact was based on the retrospective views of researchers and (less commonly) the public. Although there had been no consistent approach to assessing impact, similar benefits and costs were consistently reported. The two reviews concluded that involvement has had a variety of impacts, including on the research, on the public who were involved, on the researchers, on participants, on community organisations and on the wider community. Public involvement has been reported to help identify topics for research, shape research questions and help decide which projects to fund. For research design and delivery, public involvement has helped improve research tools such as questionnaires, and improved recruitment rates by aiding access to potential participants, improving information provided and encouraging people to take part. Many other examples of benefits are given in the two reviews. Most of the identified impacts have been viewed as positive, but some negative impacts of public involvement have been identified, such as additional costs to research projects.

The two reviews reported that there were a number of factors that appeared to influence whether involvement made a difference. 11,12 These included long-term involvement, involvement throughout a project, and training and support for people involved. The reviews concluded with discussions of the difficulties of assessing the impact of public involvement and calls for further research. They noted that public involvement in research was characterised as an area with no economic evaluation and both reviews recommended the development of such approaches. What have been missing in the literature are prospective evaluations of public involvement in research, where the objectives and methods for the evaluation of involvement are identified at the beginning of the studies, and the impact and outcomes are recorded in real time and with robust mechanisms for validating the self-assessments of researchers and the public involved.

There is currently no objective measure of what counts as effective and cost-effective public involvement. In developing an approach to costing public involvement for this study, we found no previous full or partial economic evaluations or economic analyses in which either costs or benefits/impacts have been measured and valued. Such costs include fixed financial costs (e.g. funding for institutional involvement facilitation or training events) and variable costs (e.g. time spent by staff engaging with members of the public or negative impacts such as delay in progressing a project due to conflict between researchers and the public involved).

Aims and objectives

The aim of this project was to assess the impact of public involvement in research through a ‘realist evaluation’13 which emphasises the importance of hypothesising regularities of context, mechanism and outcome (CMO). We examined implementation by asking what context factors (e.g. institutional support for involvement) enable which mechanisms (e.g. training) to lead to what outcomes (e.g. improved research design, cost-effectiveness). We then sought to compare these configurations of ‘CMO regularities’ in a range of research types, for example, qualitative research and clinical trials. We undertook this impact assessment using eight case studies, and special emphasis was given to the involvement of young people and families with children in the research process, as these groups have been relatively neglected in previous literature on public involvement in research.

To date there has been little robust evidence on the effectiveness or cost-effectiveness of public involvement in research. The Staley review recommended strengthening the evidence base by finding more robust ways of assessing the impact of such involvement. 11 The Brett et al. 12 systematic review, which examined the conceptualisation, measurement, impact and outcomes, and cost-effectiveness of public involvement in research, provided a framework to devise a structure for economic evaluation in this area as well as concluding ‘a need to develop economic appraisal of patient and public involvement (PPI) impact’. 12 Our approach to impact assessment and economic evaluation aimed to encompass these recommendations.

Given the finding of these two recent major literature reviews that the impact of public involvement in research is highly context-specific, this proposal adopted a realist evaluation framework in which we sought to map regularities of CMOs. Thus the overarching aim of this research was to identify the contextual factors and mechanisms that are regularly associated with effective and cost-effective public involvement in research. In order to achieve this aim we sought to pursue the following objectives:

-

to identify a sample of eight NIHR and other quality-assured research projects that are diverse in terms of research methodology, participants and extent of public involvement in research

-

to identify the desired outputs and outcomes of public involvement in research in the sample from multiple stakeholder perspectives (e.g. members of the public, researchers, research managers)

-

to track the impact of public involvement in research in this sample from project inception through to completion where possible and, at a minimum, for complete stages of the research process (design, recruitment, data collection, analysis, dissemination)

-

to compare the contextual factors and mechanisms associated with public involvement in research and their impact on desired outcomes of research from stakeholder perspectives, and to make a judgement of the costs of different mechanisms for public involvement in research

-

to undertake a consensus exercise among stakeholders to assess the merit of the realist evaluation approach to ascertain the impact of public involvement in research, and our logic for the measurement and valuation of economic costs of public involvement in research.

Organisation of this report

This report is organised into nine chapters. Following this introduction we describe the project design and research methodology, in particular our realist evaluation approach. In Chapter 3 we describe how our theory of public involvement in research developed over the course of our study. We then present summaries of our eight case studies. The main chapter of the report follows using our case study data to test our emerging theory of public involvement in research. There follows a reflective chapter on our learning from the public involvement in this study. This is followed by a specific chapter on our economic analysis. We then bring all our data and theory development together in our discussion chapter to present our current theory of public involvement in research in terms of our observed regularities of CMO, and our theory’s relationship to the wider literature on public involvement in research. Finally, we present our conclusions and recommendations for future research.

Terminology

We recognise that terminology in public involvement is problematic and sometimes contested, and there is no agreed terminology to describe those members of the public who are actively involved in research. A range of terminology is used (consumer, patient, user, involvement, engagement, participation) with overlapping and sometimes conflicting meanings, and changes over time which sometimes but not always represent policy shifts. 14 We follow the INVOLVE definition of the ‘public’ to include patients, carers, family, service users and those targeted by public health interventions. 2 Thus we use ‘public involvement in research’ as our overarching term rather than the many alternatives such as ‘PPI’ or ‘user involvement’. Where members of the public are actively involved in research we use the term ‘research partner’ to differentiate them from other members of the public, and in particular from research participants or subjects who contribute data but are not involved in design and delivery of research. This terminology is used by some of our case study participants but by no means all, and we recognise that it is not in wide usage, but then neither are any of the alternative terms we might have chosen. From our perspective it is the most all-encompassing term that covers the spectrum of involvement from user researchers who are actively integrated into research teams to members of the public who are infrequently consulted in a project advisory group.

This is not of course just a matter of terminology. There are substantive questions here about the diversity of roles members of the public may play in research, and whether one overarching term is useful to describe all these roles. Some members of the public may be ‘professionalised’, that is, they have developed substantial research expertise as well as the lived experience they bring as a patient or service user. Some researchers are cautious about involving such professionalised research partners, concerned that they may have lost some of the newness to research that enables them to ask seemingly naive but actually profoundly helpful questions. Experienced research partners sometimes have a different concern, that naive members of the public may sometimes be asked to be involved in complex discussions or high-level meetings where their inexperience means they are unable to express a meaningful voice. Whatever terminology we choose, we need to be mindful that such terms as ‘public’ or ‘research partner’ cover a multitude and diversity of roles and experiences.

Finally a note about our usage in describing the research partners in our own project. We originally had four research partner co-applicants, and at a later stage two young people joined us as additional research partners to contribute to case studies concerning young people. Because the original research partners are co-applicants and have been involved from the initial design stages, they have played slightly different roles from the more recently joined young research partners (although those differences have lessened over time). We therefore felt it was sometimes important to distinguish their roles in this report and have struggled to find the right terms to do so. In the end we have settled on the perhaps obvious distinction between our ‘original research partners’ and our ‘young research partners’ and this usage is applied where appropriate, in particular in the reflective Chapter 6.

Chapter 2 Project design and methodology

Introduction

This project was initially designed by a group of academic researchers and research partners drawn from the Service User and Carer Involvement in Research (SUCIR) group at the University of the West of England (UWE). An outline application was submitted in May 2010 to a joint funding call for proposals from the NIHR Health Services and Delivery Research programme (HS&DR) and INVOLVE on public involvement in research (see Research brief). The team were invited to submit a full proposal, which was submitted in October 2010 and approved in February 2011. The HS&DR Board asked the team to consider three points relating to the economic evaluation, the involvement of children and young people and the total number of interviews to be conducted, and changes were made in response in redrafting the project protocol in July 2011 prior to submission for ethical review. A second version of the protocol was drafted once the research fellow was in post in November 2011 and recruitment of case studies had been completed. The overall design and methodology remained similar, but some minor changes were made. In particular, the research fellow appointed was an anthropologist who argued the need for more informal visits at the beginning of the study and observation of case study processes. Because of the time between application, approval and commencing the project other factors became apparent that required additional minor modifications of the planned design. In particular the timescales for public involvement in the agreed case studies were not always optimal for our planned data collection processes and timescales and, as discussed below, research governance processes led to some delays in our starting data collection in some case studies.

Research brief

The NIHR HS&DR Programme and INVOLVE jointly invited proposals in 2010 to address the gap in evidence around the impact of public involvement in research. 15 A background paper summarised the evidence then available, particularly drawing on the reviews by Staley11 and Brett et al. 12 The invitation expressed three key aims for the research: to collect evidence on the impact of public involvement in research, to identify methods of evaluating this involvement, and to identify effective ways of involving the public in research (implementation). The call was open to a range of methodological approaches.

Methodology

Realist evaluation framework

Our research design was based on the application of realist theory of evaluation, particularly drawing on the work of Ray Pawson,13,16,17 which argues that social programmes (in this case public involvement in research) are driven by an underlying vision of change – a ‘programme theory’ of how the programme is supposed to work. The role of the evaluator is to compare the theory and the practice: ‘It is the realist evaluator’s task, and the added value of social science, to identify and explain the precise circumstances under which each theory holds.’17 Moreover, the outcomes of social programmes can be understood by identifying regularities of CMO. Thus the key question for the evaluator is ‘What works for whom in what circumstances . . . and why?’17 The realist approach is increasingly used in the evaluation of complex health programmes, and producing useful analyses. 18,19 After our study began, Staley et al. published a paper calling for the application of realist evaluation to the study of the impact of public involvement in research. 20 The development of our realist theory of public involvement in research over the course of our study is described in more detail in Chapter 3.

Our realist theory of public involvement in research was based on the two recently published literature reviews,11,12 which allowed us to identify a number of contextual factors and mechanisms that we believe were intended by policy-makers and other stakeholders in research policy to enable desired outcomes to be achieved. There has not previously been a robust testing of the underlying ‘programme theory’ of public involvement in research; our study was designed to allow an independent prospective testing of this underlying programme theory for the first time. We included an economic evaluation, designed to complement a realist evaluation design, estimating the resources used for public involvement across eight case studies.

Case study sampling

The setting for this project was within organisations hosting health and social care-related research studies (i.e. universities, NHS trusts and third-sector organisations) in the west of England. Our aim was to recruit a methodologically diverse sample of eight case studies which would have significant elements of public involvement during the period January to December 2012. There was no existing database or other source of routinely available data that enabled such upcoming studies to be identified. To meet our aims the studies needed only to be diverse, not representative, so we took the pragmatic decision to sample through our existing knowledge of studies with public involvement in the west of England and to ‘snowball’ through our existing networks, including the People and Research West of England consortium.

We developed a pro forma to identify from network stakeholders upcoming studies they were involved in or aware of with what they identified as ‘significant’ elements of public involvement. Our key inclusion criterion was evidence of some ongoing public involvement in key stages of the research process (design, recruitment, data collection, analysis, dissemination). A key exclusion criterion was that no study would be included unless both the principal investigator (PI) and at least one research partner agreed to take part. In order to identify generalisable regularities of CMO for public involvement in research, we wanted to identify a maximum variety sample of studies in terms of study type, stages of the research process and public involved. In a relatively small-scale study such as this, however, we knew we would not be able to achieve full diversity in all three dimensions. We therefore prioritised diversity of study type, as different study types can drive very different priorities for public involvement (e.g. emphasis on participant information and recruitment in clinical trials). We also prioritised including some studies involving young people and families with children because they make up a substantial minority of health service users but are underrepresented in the literature on public involvement in research. Our case studies are described in Chapter 4.

In deciding the number of case studies to undertake we recognise that there is always a trade-off between the depth of exploration (which suggests a small number of case studies) and identification of regularities (which benefits from a larger number). There are many ways to categorise research studies (e.g. basic science vs. applied, qualitative vs. quantitative, pilot studies vs. full trials, clinical vs. epidemiological, primary vs. secondary data, action research, translational research) and we could not hope to cover the full diversity in our case studies. From previous experience of case study research,21 we believed that eight case studies would enable us both to examine the CMO regularities in depth and to look for generalisable regularities across the case studies. This number of case studies did not enable us to examine all potential types of research study, but did enable us to include the most common, for example qualitative, mixed methods, feasibility and clinical trials. We received agreement from four PIs with appropriate funded studies taking place in the west of England at the application stage of our study, and the final four between approval and the early months of our study.

Case study data collection

The first stage of data collection involved initial mapping of the eight case studies through informal visits, encompassing observation of research settings and team meetings (where possible) and unstructured interviews.

Intelligence from the informal visits, together with previous findings from the two literature reviews and the CMO configuration, was then used to design an interview guide for semistructured interviews with case study project stakeholders. For each case study we aimed to carry out semistructured interviews with approximately five stakeholders (PIs, other researchers, research managers and two research partners) on three occasions over the course of the year of data collection, January–December 2012 (three interviews × five participants × eight case studies = 120 interviews in total during the year). Potential interviewees were identified in discussion with PIs and invitations forwarded via the PI or an administrative member of the PI’s team.

Interviews were broadly structured around our CMO hypothesis. Data collected include measurable elements (e.g. resources allocated for supporting public involvement and actual spend) and stakeholder perceptions (e.g. respective views of researchers and research partners on whether research partner contributions influenced project decisions). In addition, some of the stakeholders were given a resource log to record over 2 weeks, chosen at random, the amount of time spent contributing to a range of activities linked to public involvement in each case study. These were then costed using prices taken from published or recognised sources (see Chapter 7). Interviews were intended to take place at three broadly evenly spaced times over the 12-month data collection period.

In practice the number and timing of interviews varied widely across the case studies for a variety of reasons including delays in research governance approvals, illness among case study participants and research team members, delays in one research project commencing, and general logistical issues. In two case studies it was possible to carry out only two rounds of interviews rather than three, and the total number of interviews completed was 88 with 42 participants rather than the 120 with 40 participants initially envisaged. Table 1 summarises the total number of interviews (and research partner interviews) undertaken in each round across the case studies.

| Case study | First-round interviews | Second-round interviews | Final interviews | Total interviews |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5 (2) | 2 (0) | 4 (1) | 11 (3) |

| 2 | 6 (2) | 4 (1) | 6 (2) | 16 (5) |

| 3 | 5 (2) | 3 (2) | 4 (2) | 12 (6) |

| 4 | 3 (1) | – | 1 (0) | 4 (1) |

| 5 | 7 (3) | 4 (0) | 4 (2) | 15 (5) |

| 6 | 4 (2) | – | 4 (1) | 8 (3) |

| 7 | 4 (2) | 2 (2) | 2 (0) | 8 (4) |

| 8 | 6 (2) | 3 (1) | 5 (1) | 14 (4) |

| Total | 40 (16) | 18 (6) | 30 (9) | 88 (31) |

Case study 4 was exceptional in that, unexpectedly, no public involvement activity took place during the year. Thus the PI, a research manager and one research partner were interviewed initially and only the research manager at the end of the year. The other case studies where numbers of interviews were relatively low were case study 6, which started much later in the year than expected and where only one research partner chose to participate, and case study 7, where the research team was relatively small, there was relatively little involvement activity, and illness prevented final interviews with the two research partners. The relatively low completion rates on the initially planned 120 interviews were not a problem in themselves, so much as a symptom of lack of involvement activity for long periods in some of the case studies.

Given the small numbers of research partners overall, and the fact that some case studies targeted particular socioeconomic or age groups, we do not believe it would be meaningful to present demographic data on these participants. Our perception was, however, that our experience echoed other reports that those members of the public who choose to get involved in research tend to have attained a higher educational level than the population as a whole.

We recognise that a few interviewees do not fall easily into the categories of researcher, research manager or research partner, but we have kept to a limited number of categories to ensure anonymity.

Each case study was intended to be conducted by pairing an academic researcher and a research partner, under the overall supervision of the PI and co-ordinated by the research fellow. In one case, for logistical reasons, the research fellow undertook the data collection on his own. In the other cases, interviews were conducted by both an academic and research partner, usually separately but on occasion interviewing together.

The first round of interviews focused particularly on understanding the context of the case study and the mechanisms for public involvement planned for the remainder of the year. The second round of interviews was ‘light touch’, intended to capture developments in public involvement since the first round and to identify members of the research team able to nominate at least one research partner per case study who could be approached to complete the resource logs for economic costing. The final round of interviews focused on capturing outcomes and learning from the year, to enable us to assess how the researchers’ initial intentions and aspirations for public involvement turned out in practice. In addition to the semistructured interviews, a flexible approach to capturing data included observation of meetings where possible and/or other group tasks directly related to public involvement, and collection of project documents related to involvement processes. Observations were carried out in case studies 1, 2, 5, 7 and 8 but were not possible in case studies 3, 4 or 6, either because of internal case study project considerations or because no public involvement activity took place during the study period.

Developing a methodology for the economic costing of public involvement

There has been minimal exploration and there is little evidence for the costs and benefits of public involvement in research. El Ansari and Andersson conclude that analysis of the costs and benefits of participatory activities should form part of an overall evaluation of public participation. 22 They state that, for participation to move forward as a field, a broader ‘set of analytical frameworks is required, which captures the richness and unique qualities of participation, [and] that recognises and values the different perspectives that led to its initial development.’22

Our work here is an attempt to develop an analytical framework of how to assess the economic costs of involvement in research. Planning the budget for public involvement in research at the outset is crucial. The budget needs to include all planned research involvement work to be completed by research partners (for example participating in patient advisory groups or undertaking data analysis) as well as time for academics to facilitate research partners. Two key aspects of budgeting for public involvement are the researcher and research partner relationship and contingency planning. For example, research partners may be asked to contribute their expertise to respond to problems arising during a research project, for example poor recruitment of participants to a study (there were several examples of this among our case studies). These contributions generally arose during the research process and were not foreseen.

Payment and reward issues have generally proved controversial. At our second consensus event our case study participants debated the nature of payment and reward for public involvement vigorously, revealing a wide range of strongly held views on this subject. INVOLVE has developed guidelines on payments for involvement research work to respond to these issues. A recent document outlines the issues to bear in mind in paying research partners, gives examples of payments and provides general tips about issues connected with payment and ‘payments in kind’ that need to be carefully considered by project managers. 23 A range of pay rates for different research activities connected with public involvement are mentioned in INVOLVE documents, including a flat rate payment of £19.40 per hour. 23

Our economic analysis aimed to collect data from each case study team, in order to:

-

identify all activities relating to public involvement

-

measure the amounts of activities using a resource log

-

value or put a price on these activities using prices from published or established sources.

Identifying and measuring involvement activity

To gather data from our eight case studies for our economic analysis, we asked selected members of the case study teams (researchers, research managers and research partners) to log all the resources that were used in public involvement work/activities over a snapshot 2-week period. During the 2 weeks each person recorded/logged:

-

all involvement-related activities

-

length of time spent on each activity.

We asked them to include all activities (or inputs) that were undertaken as contributing to or enabling the central objective (or output) of public involvement in research. A sample log sheet for research partners on 1 day is in Appendix 1. Our ethical approval letter stipulated that research staff within each case study were to nominate research partners to provide our data, so we were dependent on these nominations being made successfully from within our case studies, as we were not able to make direct contact with research partners.

We issued user-friendly guidance for completing our resource log, and supported respondents over a 2-week period by e-mail and providing a telephone helpline. Our guidance document for research partners to complete resource logs is in Appendix 2. Our contact and ongoing dialogue with the academics and research partners who used our guidance and completed our resource logs enabled us to become familiar with how involvement activities were working within each case study from the point of view of both academics and their nominated research partners. These exchanges helped us gain a rounded understanding of the nature and diversity of involvement activity and the relationships and issues within each case study.

Economic valuation/costing of involvement activities

We translated the knowledge we had accrued of each case study into some working assumptions about each one. These assumptions are significant but complex, so we have detailed them in Appendices 3–5.

We then used the completed 2-week resource logs to estimate involvement costs for a projected 12-month period. From there we scaled up the 12-month projected costs to the length of each case study. This enabled us to compare the actual budgeted costs from each grant with the projected costs on a like-for-like basis.

We followed a standard economic approach to treat resource use and prices separately to arrive at a cost.

For example:

Ideally the price applied should come from a published source or the next best alternative, a recognised or established source. There are illustrative examples within INVOLVE guidelines of a range of prices for different research activities connected with public involvement. In our own project we had previously paid research partners at a ‘meeting rate’ of £19.77 per hour, but early in this project it became obvious that most work was being done outside meetings, so a lower ‘research associate’ rate of £14.02 per hour was agreed. Research partners kept records of all their work for the project (including e-mails, collecting and analysing data, and writing) and submitted claim forms regularly. Our project did not have a means of costing researcher time for public involvement activities, as working alongside research partners was a continuous process during our project.

A new set of guidelines from INVOLVE to budget for involvement was incomplete at the time of our analysis, but we saw the draft document, which again gave the example of the flat rate payment of £19.40 per hour for public involvement participation, so we used this price when costing research partners’ activities for our case studies. 23

Reflective practice

Data were captured on our reflective learning on the impact of public involvement in our own study. This was done by facilitating and audio-recording short reflective sessions during team meetings on our own experiences as a project team of academic researchers and research partners working together.

Consensus events

Two consensus workshops were organised as part of our plans to develop and test a theory of public involvement in research. Initially we aimed to hold the first event prior to the first round of data collection to inform the interview schedules for this round. As the project developed, however, we realised that this would not be practical in terms of the length of time research governance approval was taking from some NHS trusts and, more importantly, that an event after the first round would be more fruitful in terms of theory development. Thus, the decision was taken to hold the first consensus event between the first and second rounds of data collection.

At the first workshop we presented an overview of our initial findings from our first round of interviews and visits in the eight case studies. The overview was in the form of 12 statements drawn from our initial mapping of the case studies. The statements identify key contextual factors and mechanisms for public involvement in research that we hypothesised were regularly linked to positive impacts on research design and delivery.

The aim of the workshop was to test these statements with case study participants and steering group members, drawing on their experiences and insights regarding public involvement in research, in order to refine or replace the statements, to inform the next phase of data collection and analysis. The workshop was limited to one afternoon in the hope that this relatively short time commitment would make it more feasible for case study participants to attend.

Nineteen participants took part in the first consensus workshop. Six of the eight case studies were represented. The intention had been that all case studies would be represented by both research staff and research partners in their projects, but it was not possible to achieve this because of participants’ other commitments and some last-minute illness.

Participants first voted electronically on the 12 statements with the choices ‘agree’, ‘disagree’ or ‘abstain’. Participants were then divided into three groups, with each group asked to look in depth at four of the statements, discuss and revise them as necessary and identify any omissions, connections or other comments. The groups then fed back to a plenary session and participated in a final discussion.

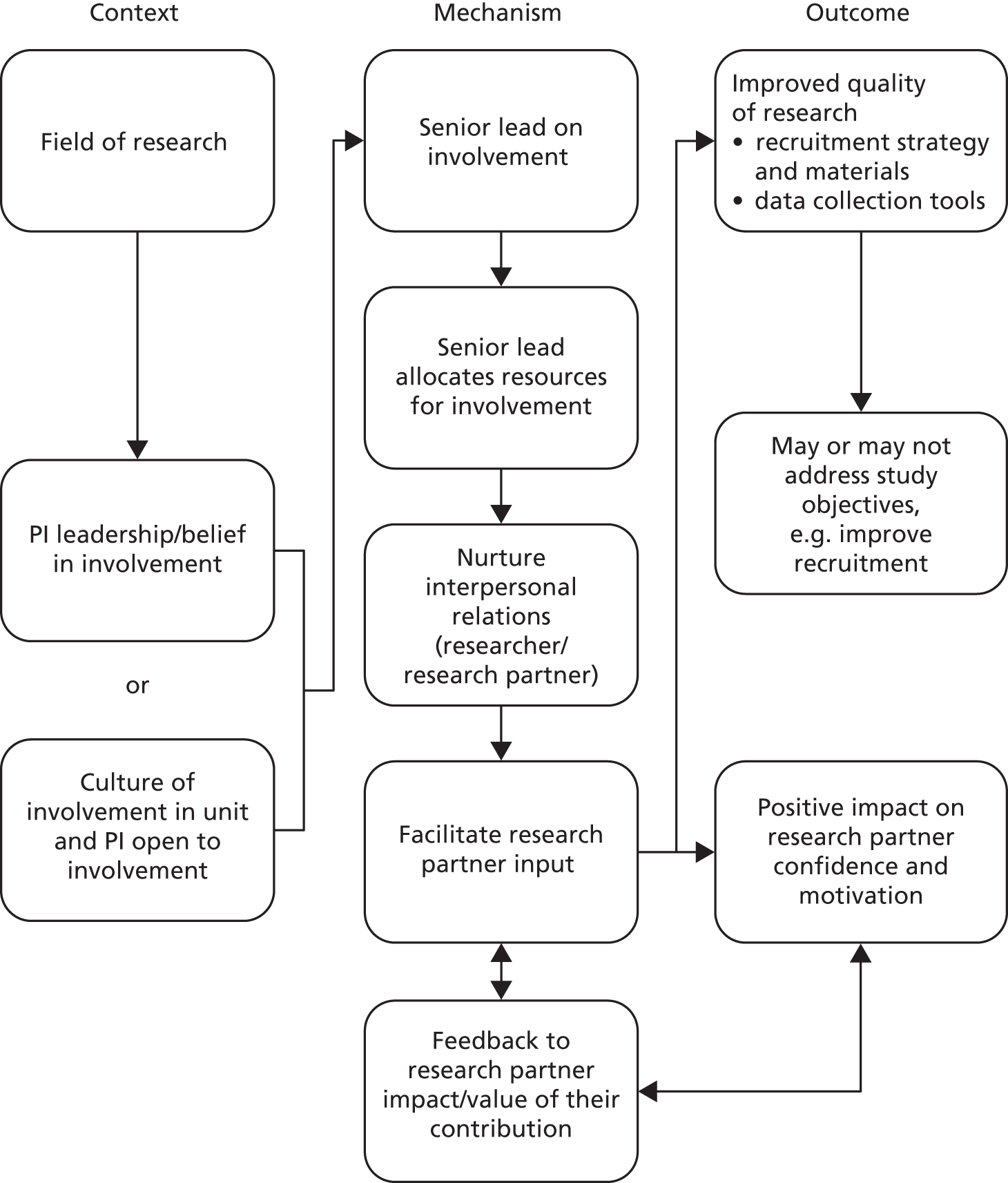

A second half-day consensus workshop was held at the end of the third round of data collection. On this occasion all eight case studies were represented with a total of 29 participants. Our emerging theory of public involvement was presented in graphic form in a set of four slides covering different aspects of CMO regularities (field of research, leadership and culture, relationships and structures of involvement). Participants were asked to discuss, amend and comment on A1 printed versions of the slides. The output of the workshop was amended slides with marginal commentary, which were further analysed by the project team and used to form the basis of the analysis of findings presented in Chapter 5 and the development of our theory of public involvement as described in Chapter 8, Our revised theory of public involvement in research.

Case study data analysis

All interview data were transcribed and entered into an NVivo 10 database (QSR International, Warrington, Cheshire, UK). A key team discussion was how to most fully involve our research partners in the analysis of these data given that only one of them had experience of using any version of the NVivo software. The decision was made to offer NVivo 10 training to research partners but not to require this, as some did not feel confident of learning and using the programme effectively in the time available. A manual coding alternative was therefore made available. In order to make this practical, we limited the number of codes we identified to a minimum necessary to allow meaningful analysis. Those team members coding in NVivo 10 were supplied with this coding framework. Those coding manually were given a numerical code to use with transcripts and the coding was entered into the NVivo 10 database by the project research associate. For each case study, at least one transcript was coded independently by a researcher and research partner, and any divergence discussed and a joint approach agreed.

Data analysis focused on identifying CMO regularities across our case studies. From the initial CMO configuration identified in the proposal, with amendments from the first consensus workshop, a coding framework was devised with 38 codes (see Appendix 6) organised into six broad themes: relationships, leadership and culture, field of research, structures of involvement, resources and outcomes. We agreed as a team that the codes were the primary unit of analysis and the themes were provisional. Following coding of data, team discussion lead to the codes being reordered in terms of hypothesised CMO regularities presented in Chapter 5. This coding framework was then validated by one academic team member not involved in the case studies, who independently undertook a framework analysis24 of a sample of transcripts and compared her emerging framework with that drawn from the CMO configuration.

Verification of coding

Initial data were analysed by team members identifying codes within interviews. NVivo 10 software was used for data storage, retrieval, coding, analysis, memo writing and theme building across the CMO approach. This was useful in that data coding and development of findings was a collective team activity but an overall verification process was also established. One senior team member, who had not been party to the initial coding discussions, undertook a second verification to ensure consistency and rigor. The coding verification consisted of five transcripts randomly chosen across the case studies and involved two activities: naive reading and structured coding review analysis.

First, transcripts were repeatedly read, blindly from assigned codes, by the independent reviewer, with memo writing with regard to potential codes. Next, data were coded line by line, and each sentence or group of sentences was given a code using the direct meaning of the text. The second reviewer then read the transcripts with the allocated codes assigned by the initial coder. Similarities and differences were recorded. Comparing and contrasting meanings across and within transcripts through the use of memos was used. There was very high agreement found between the coder and second reviewer, which was a very positive result.

Narrative review

There were many issues of agreement in the broader level of understanding. For example, leadership emerged in all five transcripts, as did common terms such as culture (team and organisational), PI beliefs or senior lead issues. Feeling valued, trust and interpersonal relationships and other ‘emotional’-type codes were allocated by coders in all five transcripts. The second reviewer found similar patterns and this showed good overall broad agreement of coders. Power emerged in three transcripts more clearly and repeatedly but was in all five transcripts in some form.

There were minor issues of differences in coding where coders had consistently coded information in a similar way in terms of the value of public involvement. There was only one research partner who coded public involvement not just in terms of value but in terms of impact.

The thematic analysis of each code across the case studies was then used as the basis for the thematic analysis used to test our theory of public involvement in research as presented in Chapter 5.

Research ethics and governance

The study team took the importance of ethical practice extremely seriously and considered whether it raised any substantive ethical issues. As the study was primarily qualitative and did not involve questions around particularly personal health status or behaviours, we came to the view that it was relatively low risk. However, we recognised that, in asking researchers and research partners from the same studies about what was working and not working in terms of public involvement, we could potentially be raising some sensitive interpersonal relationship issues. We therefore sought to address these issues in our study design, participant information sheets and processes for ensuring confidentiality and anonymity. Following the screening questions on the Integrated Research Application System form, our study was identified as eligible for proportionate review. Ethical approval for the study was therefore sought from the County Durham & Tees Valley Research Ethics Committee prior to the commencement of the study and approval was given with minor conditions in August 2011. An application for a substantive amendment was made in December 2011 to include observation of case study meetings, which had not been included in the original application. Approval was given in February 2012.

Research governance approval, which was sought from the three NHS trusts hosting the four NHS-based case studies, proved much more time-consuming and problematic to obtain than expected. This was particularly because of our desire to enable research partners to participate fully in data collection, which required taking them through the NHS research passport system, something that neither the university nor the NHS trust human resources departments appeared familiar with. Final research governance approval for all three NHS trusts was not obtained until late March 2012, thus delaying our planned date for data collection in some case studies by around 3 months.

Throughout the study we sought to adhere to our ethical and research governance approvals by ensuring informed consent for all participants and fully complying with all conditions of our approvals. All case study participants were sent copies of the report in draft form and invited to comment on how their data had been used and any inaccuracies or other comments on their case studies.

Public involvement in our team

Our aim throughout this project has been to model good practice in our own research while studying the impact of public involvement in our case studies. The project was developed by the SUCIR group at UWE, which had strong service user representation. One research partner co-applicant was the cochair of SUCIR. Three other research partner co-applicants had previously worked with the PI and other academic co-applicants on developing the SUCIR scheme and/or on other research projects.

The four research partner co-applicants were involved in all aspects of the project including design, data collection, analysis and dissemination. The case studies were designed to be undertaken by four subteams, each consisting of one academic researcher and one research partner working together on two case studies. The research partners also formed a separate research partner reference group meeting bimonthly.

The initial intention was for two academic co-applicants with extensive experience in working with young people to recruit and support a young persons’ advisory group to work on the two case studies where participants were young people. In the end it did not prove feasible to recruit such a group and a decision was made to develop an alternative model of involving young people in the project. Two young people, one of whom who had worked on a previous study, were recruited to join the project as research partners. Over time they came to play a similar role to the original four research partners, attending team meetings, research partner meetings and other events, and participating in data collection and analysis in their two case studies.

Research partners were involved in our team’s reflective process on what worked well and what did not work well in terms of our own processes around public involvement. A period of approximately 15 minutes was set aside at the beginning of each team meeting and research partner meeting to share reflections and learning about public involvement in our own project. Research partners have co-authored and presented our outputs at the INVOLVE conference and elsewhere, and have contributed to ensuring that this final report is as user-friendly as possible, and that our wider dissemination plans include outputs specifically designed to be accessible to a wide public. The plain English summary of this report was drafted by research partners. Chapter 6 of this report includes the synthesis, led by one research partner, of the shared reflections on public involvement in our project by both the academic researchers and the research partners.

Chapter 3 Developing our realist theory

Introduction

Realist theory needs to be developed and refined by a cumulative process of synthesising the evidence, using the evidence to develop theory and testing theory empirically against new evidence. Our starting point needed to be the best existing synthesis of current evidence, the two recent literature reviews on the impact of public involvement in research. 11,12

Neither review adopted an explicitly realist framework. Staley11 emphasised the importance of context in assessing the impact of public involvement in research but did not seek to provide an explicit conceptual framework linking context with outcomes. Of key relevance was section 4.10, ‘Factors that influence the impact of involvement’, summarised in Box 1. 11

The evidence suggests that public involvement has had the greatest impact when people have been involved throughout an entire research project, rather than just at discrete stages.

Long-term involvementOver a longer term, involvement is reported to have more impact because:

-

members of the public gain more insight into research

-

members of the public and researchers develop more constructive, ongoing dialogue

-

a general ethos of learning from each other is established.

Public involvement is reported to be more likely to have a positive impact if members of the public receive appropriate training and continued support.

Linking involvement to decision-makingSome research projects have established advisory groups. Integrating these groups into the management structure of a project can ensure the public’s views actually influence decisions.

Brett et al. argued the need to develop explicit theory and suggest a model linking context, process and outcome. 12 They did not, however, differentiate between those factors they saw as contextual and those they saw as process. Their table of ‘the architecture of PPI: context and process factors’ contained a single list of undifferentiated context and process factors (Box 2). 12

-

Budget appropriately for the service users’ involvement. This may include contributions to service users for their time, expenses and cost of training.

-

Consider additional time needed for PPI activity in time scales for the study.

-

Involve service users as early as possible in the research, preferably at the beginning of the study and maintain involvement throughout.

-

Define roles of service users and researchers in the PPI activity.

-

Provide service users with adequate training on research skills required for their involvement in the study.

-

Provide service users with the additional knowledge of the disease/condition that is necessary in order for them to contribute.

-

Provide researchers with training on how to involve service users in research and encourage a positive attitude to PPI.

-

Establish good relationships between service users and researchers over time, and avoid recruiting service users in a hurry.

-

Respect the skills, knowledge and experience that service users bring to a research study.

-

Provide personal support and supervision of service users.

-

Encourage good communication to manage conflict and avoid isolation.

-

Involve service users in developing invitation letters, information sheets, consent forms, questionnaires and interview schedules, as service users will assist in developing this information in a patient-relevant way.

-

Involve service users in decisions as to how participants are recruited.

-

If sufficient training is provided, service users can assist in data collection.

-

Service users can identify patient-important themes in the data.

-

Detail in reports/publications how PPI was conducted.

-

Produce a lay summary of the final report so it can be easily understood by the target population.

-

Develop service user advocacies for dissemination and implementation of research to assist in making the results more poignant and more relevant to the target population.

Our initial realist theory of public involvement in research

In developing our realist theory we needed to be clear about what aspects of public involvement in research we were seeking to investigate. Mechanisms to support public involvement have been introduced at many levels within English NHS research systems, for example in strategic leadership, commissioning research, peer review of applications, and supporting research through NIHR research networks. Our focus has been specifically on public involvement within research programmes and projects led by academic and clinical researchers. Thus we were mainly interested in public involvement in the design and conduct of research, for example decision-making around research questions, methods, instrument development, selection of outcomes for measurement, sampling, recruitment, data collection and analysis.

Pawson16 writes that ‘in general, realist analysis admits to the shaping influence of at least four contextual layers’. These layers are:

-

the individual capacities of the key actors

-

the interpersonal relationships supporting the intervention

-

the institutional setting

-

the wider infrastructural system.

These four layers provide a useful framework for structuring the key contextual factors drawn from Staley11 and Brett et al. 12, as summarised in Table 2, first column.

| Context | Mechanism | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|

| Leadership on public involvement by the PI or other senior member of the research team (individual capacities of the key actors) Attitudes of trust and respect towards public involved (interpersonal relationships supporting the intervention) Culture of valuing and support for involvement (institutional setting) Infrastructure that supports involvement, e.g. policy on payment and expenses (wider infrastructural system) |

Involvement throughout a research project Long-term involvement Training and support for the people involved Linking involvement to decision-making Budget for involvement Defined roles |

Impact on research design and delivery – improved quality of:

|

Mechanisms of public involvement can be conceptualised in many different ways. As Brett et al. 12 make clear, there are no agreed definitions or theories of public involvement in research. One of the simplest ways to differentiate the various mechanisms would be in terms of the organisational arrangement by which members of the public are involved in the research process, for example:

-

public (patient/user) advisory groups or panels

-

public membership of a multidisciplinary project steering or advisory group

-

working in partnership with service user-led organisations

-

research partners (working individually alongside researchers but not actually conducting data collection or analysis)

-

coresearchers (conducting data collection and/or analysis).

However, such structures are likely to be specific to different settings, professional disciplines or client groups and so focusing our understanding of mechanisms on them would be unlikely to lead to generalisable learning. Moreover, the reports of the reviews of Staley11 and Brett et al. 12 did not focus on these structures and so do not easily allow us to compare outcomes from these different organisational arrangements for public involvement.

The alternative approach we initially adopted was to define mechanisms in terms of other process factors identified by both Staley11 and Brett et al. 12 such as involvement throughout a research project, training and support offered, and the nature and/or extent of role definition, as indicated in Table 2, second column.

In terms of outcome, both reviews identify very similar areas of impact for public involvement in research, which Staley11 summarised as impact on (1) the research agenda, (2) research design and delivery, (3) research ethics, (4) the public involved, (5) researchers, (6) research participants, (7) the wider community, (8) community organisations and (9) implementation/change. In a relatively small-scale study such as this, it was not possible to assess impact in all of these domains and we chose to focus on impact on (2) research design and delivery and (4) the public involved, as these impacts reflect the policy priorities of improving the quality of research and giving voice to the public involved. For both of these areas there are a number of more specific aspects of impact that can be identified from the two reviews as indicated in Table 2, third column.

Table 2 integrates and synthesises the key context and process factors identified by Staley11 in Box 1 and Brett et al. 12 in Box 2, and summarises key elements of our initial framing of a programme theory for public involvement in research for testing in our case studies. It is recognised that a number of these factors could be broken down into multiple and more specific factors, and that this matrix could be extensively expanded. The temptation to include all relevant specific factors must be balanced, however, with the need to develop a statement of theory that is sufficiently focused to be testable in case studies. The factors identified in Table 2 were not necessarily all explicitly named by both Staley11 and Brett et al. 12 For example, the contextual factor identified here of leadership on public involvement was not explicitly listed by either Staley11 or Brett et al. ,12 but it was implicit in other factors they identify such as linking involvement with decision-making11 and providing researchers with training on how to involve service users. 12

What neither Staley11 nor Brett et al. 12 indicated was whether or not all these factors need to be present (or to what level) to achieve desired outcomes. For example, Brett et al. 12 identified a ‘budget appropriate for the service users’ involvement’ as the first factor in their architecture of public involvement, but did not specify how one might judge appropriateness. 12 This was not a factor explicitly identified by Staley, although it was implicit in her identification of ‘training and support’ as a key factor,11 as these cannot easily be provided without a budget. We thus lacked an evidence base to be able to say that all the identified context and mechanism factors must be present to achieve the desired outcomes. At most we could say that, the more such factors are present, the more likely the desired outcomes were to be achieved. It would require further empirical testing to be able to say more about whether any one or more factors were essential to achieve the desired outcomes or, indeed, if we (and Staley11 and Brett et al. 12) had missed other fundamentally important factors not listed here which need to be incorporated into future revisions of the model.

It is probable that, where one contextual factor is present, others are also likely to be. In particular, if there is leadership supportive of involvement in a department or research team, then it might be expected that culture and the attitudes of other team members are equally likely to be supportive of it. If there is involvement throughout a research project there is also likely to be long-term involvement. Some factor may thus be partly or wholly dependent or contingent on others, and further iterations of our model would therefore need to incorporate such complexities.

This then was the state of play with our theory as we approached the analysis of our case study data in early 2013. The next chapter describes our eight case studies before we go on in Chapter 5 to report the extent to which our case study data supported or challenged our developing theory of public involvement in research.

Chapter 4 Case studies

Introduction

Eight diverse case studies were recruited as described in Chapter 2. Each of the case studies was followed up over the calendar year 2012. Where possible, three rounds of data collection were completed. Because of research governance approvals and logistical factors, data collection did not begin as early as expected, so that in most cases 9 months rather than 12 months separated the first and last rounds of data collection. In two cases (case studies 4 and 6) only two rounds of data collection were possible because of factors internal to the case studies. Key contextual factors, mechanisms and outcomes of involvement are summarised in Table 3 before the CMOs for each case study are described in brief in the rest of this chapter.

| Case study 1 | Case study 2 | Case study 3 | Case study 4 | Case study 5 | Case study 6 | Case study 7 | Case study 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Context | ||||||||

| Project focus | Evaluation of care provided to first-time mothers | Interventions for preschool children with speech and language impairment | Prevention of recurrent unintentional injury in preschool children | Improving the management of BSIs | Evaluation of personal budgets | Patients’ definition of recovery from chronic pain | Foot problems in people with RA | Longitudinal health research with young people |

| Time period | 5 years 2008–14 |

3 years 2011–13 |

2 years 2011–13 |

6 years 2009–15 |

3 years 2010–13 |

2 years 2012–14 |

5 years 2010–15 |

20 years and ongoing |

| Total funding | £4M | £1.2M | £400,000 | £2M | £430,000 | US$180,000 | £248,000 | Tens of millions of pounds |

| Funding for public involvement | £42,000 | £27,000 stakeholder involvement (£7000 parent involvement) | Not specified separately in bid | Not specified separately in bid | £22,000 | US$15,000 | £2970 | Part of £91,000 for participation |

| Methodology | RCT | Mixed methods | Feasibility RCT | Mixed methods | Mixed methods | Qualitative/Delphi | Mixed methods | Mixed methods/epidemiological |

| Stage of research | Data collection and analysis | Phase 1 parent focus groups | Recruitment, data collection and analysis | Work package 2 – RCT | Phase 2 interview data collection | Phase 1 data collection | Phase 2 survey data collection | Wide range of research in progress |

| Host institution | University | NHS trust | University | NHS trust | Charity | NHS trust | NHS trust | University |

| Collaborating institution | Three universities | Three universities and a third sector organisation | Three universities and one NHS trust | Two universities and five NHS trusts | Two universities and four local authorities | NHS trust and seven international hospitals | NHS trust and two universities | Numerous universities and NHS organisations |

| Mechanism | ||||||||

| Approach to public involvement | Third-sector partners on steering group; involvement of pre-existing groups of young mothers | Parent research panel; rotating parental representation on advisory group | Parent advisory group based in a children’s centre | Patient/carer advisory group | Working with four local service user organisations | Individual research partners at each study site | Two research partners as members of research team | Young people’s advisory group; one young person on ethics committee |

| Frequency of public involvement | Variable | Meeting every 2 months plus ad hoc events | Variable, six in early stages, long gap, final meeting at end of project | Variable, frequent meetings in 2011, none in 2012 | Biannual national meetings; variable local involvement | Once yearly 2-day meeting of research teams; variable in local teams | Variable, two or three times per year | Monthly meetings and regular social media |

| Type of public | Young mothers | Parents of preschool children | Parents of preschool children | Past patients with BSI and their carers | Mental health service users and carers | Patients with complex regional pain syndrome | Patients with RA | Young people involved in cohort |

| Key roles in public involvement | Co-applicant lead on involvement; designated person to support young people | PI, third-sector co-applicant, programme manager, andco-ordinator all with PPI roles | Co-applicant with previous PPI experience leading on PPI | Programme manager lead role | All four researchers had involvement roles | Lead role for junior programme manager | PI lead for PPI, supported by unit director with extensive PPI experience | Executive director, participation team |

| Recruitment of research partners | Approach to existing young mothers’ groups | New group through open advertisement | Via children’s centre staff | Recruited through NHS trust, mainly ITU | Local organisations invited to tender for involvement work | One UK research partner via local user group; others via study hospitals | Recruited through existing involvement process in unit | Invitation to study participants |

| Point involvement began | Early in project life | Third-sector from beginning of bid; parents from early in phase 1 | One parent advised on bid; group recruited early in life of project | Once programme manager came into post (2010) | Individual users involved in bid design; local organisations invited to tender early in project | From early in project life | One research partner involved from beginning; second recruited in phase 1 | Previous ad hoc involvement; group meetings for last 6 years |

| Reward for research partners | Contribution to educational studies | Vouchers and expenses for each meeting | Vouchers given as ‘thank you’ at last meeting | Reimbursed for expenses | Payment to each local organisation and individual payment and expenses for national meetings | Expenses paid for meetings; training in qualitative analysis for three research partners | Honorarium/expenses paid; opportunities for co-authorship | Expenses paid for meetings |

| Outcome | ||||||||

| Research design and delivery | Designed poster for use in recruitment Suggested ideas for retention Contributed to participant website and leaflets Commented on questionnaires |

Advice on parental recruitment strategy taken up by researchers Helped design/redraft recruitment materials Suggested promoting focus groups as play session taken up by researchers Suggested change to telephone interviewing taken up by researchers Commented on bids for future funding Developed and presented a conference poster Helped develop the infrastructure for parental involvement in future projects Helped the researchers work out how best to involve other parents in future |

Suggestions on strategy for trial recruitment taken up by team Supported idea that intervention should be delivered in children’s centres Commented on participant info sheet prior to ethical review Suggestions on draft recruitment poster and proposed injury calendar led to substantial revisions by team |

No outcomes during 2012 as no involvement activity during case study period (In 2011 contributed to ethics application, shaping approach to consent. Commented on bid for future funding) |

Provided local intelligence and insight to the research team Contributed to development of data collection approach and tools Helped recruit and support study participants, including holding two recruitment events Suggested changes to instruments and processes taken up by the team Contributed to data analysis Reviewed and commented on selected excerpts from transcripts Contributed to planning dissemination strategies and designing materials |

Contributed to development of data collection approach and tools Suggestions for design of questionnaire (e.g. splitting questionnaire into two) and changing wording taken up by researchers Insights provided on how questions would be answered, how long it would take to complete |

Contributed to design of questionnaire (changes in layout, order, wording and the inclusion of additional questions) Suggested changes to information sheets and letters taken up by researchers Contributed to planning data collection process |

Contributed to design of individual research projects, suggesting major changes in some projects which were accepted by the programme Contributed to developing policy and practice for the overall programme, e.g. developing generic guidance for consent forms and information sheets Contributed to participant leaflets and data collection tools including on questionnaires Contributed to dissemination through presenting at conferences, making videos and other dissemination materials |

Case studies

Case study 1

Context of public involvement

This research project was a 5-year randomised controlled trial (RCT) involving 1645 young mothers across 18 sites. The PI expressed a strong commitment to public involvement. He had previous experience of working on studies that had a strong element of public involvement and was very committed to public involvement in this project and to having it embedded in the project from the beginning. The PI and his team are based in a clinical trials unit that has had previous experience of public involvement in research and a working group on PPI. A co-applicant based at another university also had significant experience of stakeholder and public involvement in other projects and was identified to lead in this area for the project. Stakeholder organisations have been part of the project from the beginning. A stakeholder management group was therefore an important part of the project.

Another member of the team had interviewed people who belonged to patient organisations and a reason why she was attracted to working for this trial was the fact that public involvement was built into the proposal from the start.

Mechanisms of public involvement

This project had public involvement built into the proposal. Adult stakeholders were part of the stakeholder management group of the project from the beginning and young people were represented at this level through representatives of young people’s organisations. This group met every 2 or 3 months.

The project also worked with a group of young mothers who were already an established and well-supported group who were working together to obtain educational qualifications. Two members of the project team were responsible for engaging directly with this group of young people and supporting their contribution to the project. However, this group closed when funding was cut and so a new group had to be found. There was a goodbye party and presentation of certificates to say thank you for their work and contribution to the project.

A second group was then approached. This was also a well-supported group and the young people were given some information about the project. At the start of our case study period this group had met with the researchers on only one occasion, when the researchers had asked them for some ideas about leaflets. They met a second time during the course of the case study period, but as the RCT was at that point approaching the analysis stage there was less need to seek their input. However, the researchers responsible for the participation of the young people were going to look at ways young people could be involved in dissemination, with the help of a stakeholder group representative from a young people’s organisation.

Outcomes of involvement

The first young people’s group was approached to assist the project in a number of ways – some of which contributed to their educational credits. A poster for the project was designed by the group, supported by a local arts teacher, and this was used during the recruitment phase in all the trial sites. At different points in the trial the group assisted with ideas for retention, a participant website, leaflets and questionnaires. This group worked closely with the project and reportedly had a big impact on how young mothers were recruited and retained in the study. It was too soon to gauge the outcomes of involvement of the second group.

Case study 2

Context of public involvement

Case study 2 took place in a research group with institutional connections to both an NHS trust and a university and with research interests in speech and language therapy (SLT). The PI had a long-term interest in and philosophical commitment to involving parents and children in research, and had previously collaborated with a parent-led third-sector organisation in research, but had relatively little previous experience directly involving parents or children in research. The PI led a small and cohesive team within the group based together in one geographical site. Both the NHS trust and the university had existing initiatives to support public involvement in research, and were collaborating in a subregional initiative to support public involvement. There was no wider experience or culture of public involvement in research in the research group. The PI saw this grant as an opportunity to develop parental involvement not just in the specific programme of SLT research but more widely in the future research work of the group.

As well as the PI and the co-applicant from the parent-led organisation, a research manager was seconded from the NHS trust R&D team to the project team to manage the research programme including taking a strategic lead on parental involvement. Part of her role within the R&D team was to advise other researchers on good practice in public involvement, but she had limited direct experience of it, having previously been in an advisory role, so the SLT role gave her a development opportunity to learn from applying her theoretical knowledge in practice.

The research programme aimed to improve the quality of SLT for preschool children, to develop an evidence-based approach to interventions and to develop a model to support the appropriate targeting of interventions. It was designed to include two phases over 3 years. In the first phase, covered by this case study, the team undertook systematic literature reviews, surveys and case studies involving focus groups with SLT professionals, other health professionals and parents. The second phase will involve the development of an evidence-based typology of interventions. The research programme was funded by a major national funding agency which expected evidence of public involvement in all its funded projects.

Mechanisms of public involvement

The key mechanism for public involvement was the parent research panel, which was set up specifically for this research programme. Parents of preschool children (not necessarily those specifically with speech and language difficulties) were recruited through an advertised open process to establish a panel which met every 2 months. This was a new group of parents who did not previously know each other, and therefore had to form as a new group both with each other and with the research team. It was recognised by the research team that the panel was not diverse and did not include many parents of children with speech and language difficulties or marginalised groups. The research team set the agenda and circulated it prior to the meeting, and facilitated the discussion at each meeting. Activities for the panel included discussing and commenting on recruitment materials and strategies, and on data collection, for the parent focus groups.

The SLT office manager co-ordinated the parent panel and the parental involvement more widely. Halfway through the case study, the post holder left the unit and a new office manager (recruited from within the unit’s administrative team) took on this co-ordination role. Facilitation of the parent panel meetings was shared between the PI and the programme manager, with several research team staff attending each parent panel meeting. The programme manager also produced a written involvement strategy for the research programme.

The parents were not involved in the early design of the research programme, but the intention was that they would help shape later stages of the research programme. Parents were also involved in the study advisory group, with different parents representing the parent panel at different advisory group meetings. Parents were also offered the opportunity to represent the study at conferences and other events, including by presenting a poster on parental involvement. Parents were rewarded with vouchers rather than direct payment as well as in non-monetary ways (e.g. invitation to present at events, thanks).

Outcomes of involvement