Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its proceeding programmes as project number 10/1011/19. The contractual start date was in November 2011. The final report began editorial review in October 2013 and was accepted for publication in March 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Norma O’Flynn is seconded to the National Clinical Guideline Centre which is funded by NICE to develop clinical guidelines. Tim Stokes does occasional work for pharmaceutical companies on the work of NICE and primary care; any honoraria received are paid directly to the University of Birmingham. Ray Fitzpatrick is a member of the NIHR Journals Board.

Disclaimer

this report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research, or similar, and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2014. This work was produced by Ziebland et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background

Aim

To identify common, core components of patients’ experiences of the NHS to inform the development, and measurement, of National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) quality standards (QSs) and to examine the reach and limitations of these core components in describing the aspects of care that are important to patients from diverse backgrounds, with experiences of different conditions and NHS care pathways.

Objectives

-

To conduct qualitative secondary analysis of collections of narrative interviews to identify common, core components of patients’ experiences of the NHS.

-

To test these candidate components with (i) further purposive sampling of the interview collections and (ii) a series of focus groups (FGs) with users.

-

To embed the project alongside the development of NICE clinical guidelines (CGs) and QSs.

-

To inform the development of measurement tools on patient experiences.

-

To develop and share resources and skills for secondary analysis of qualitative health research.

In this introductory chapter, we begin by providing a brief overview of the increasing centrality of patient experience in UK health policy, most recently illustrated by the UK coalition government’s White Paper, Equity and Excellence: Liberating the NHS, and the information strategy published by the Department of Health (DH). 1,2 We then describe the process by which NICE produces CGs and QSs, which underpin the development of the proposals outlined in the White Paper. We introduce the Health Experiences Research Group (HERG) interview archive and discuss the methods used in objectives 1 and 2 (secondary analysis of qualitative data and FG research). We discuss how we might understand the ways in which the research knowledge could best be used in practice (objective 3). We also briefly explain the measurement tools used to measure patient experiences and outcomes (objective 4), and, finally, explore the issues surrounding the sharing of qualitative data for secondary analysis (objective 5).

Health policy context: improving patient experience

Improvement of the ‘patient experience’ has been highlighted as a key aim by the DH. The 2012 Health and Social Care Act states that it is the duty of the Secretary of State to ensure continuous improvement in the quality of services including the ‘quality of experience undergone by patients’. 3 The NHS Operating Framework for 2012–13 describes each patient’s experience as ‘the final arbiter in everything the NHS does’. 4 The inquiry into care standards at the Mid Staffordshire Hospitals5 and the subsequent Francis Report6 drew attention to the failures to act on patient and public complaints about poor care, which were recorded, but not acted upon, long before the inquiry.

While the focus of health-care quality improvement appears to have shifted firmly into the territory of patient experience, policies to improve people’s experiences of health care have been introduced by successive governments for decades. These have usually centred on aspects such as the provision of information and patient choice. Other attempts to steer the NHS towards a more patient-centred approach include, for example, the Picker Institute Principles of Patient-Centred Care, which were transformed into the Patient Experience Framework in 2011 by the NHS National Quality Board (NQB). 7 Existing quality frameworks of health care, such as the NICE QS on patient experience in adult NHS services, are formulated as universal statements, describing components of good care that are independent of care setting, condition-specific care pathways or patient characteristics. 8 In a recent critical conceptual synthesis to identify which health-care experiences matter to patients and why, researchers from the Universities of Aberdeen and Dundee reviewed three commonly used health-care quality frameworks: the World Health Organization’s (WHO’s) responsiveness framework, the Institute of Medicine’s domains of health-care quality and the ‘SENSES’ framework of Nolan et al. (Table 1). 9,10 They found that none of these frameworks was sufficiently comprehensive to cover all of the aspects of health-care experience that patients in published research have identified as relevant and important. To catalyse improvements to care, we need a better understanding of why certain aspects of care matter to patients, and how this may differ between individuals, groups and care contexts.

| WHO: responsiveness | |

|---|---|

| Health-care systems ensure | |

| Autonomy | (Of patient/family) via provision of information about health status, risks and treatment options; involvement of individual/family in decision-making if they want this; obtaining of informed consent; existence of rights to treatment refusal |

| Choice | Of health-care providers |

| Clarity of communication | Providers explain illness and treatment options, patients have time to understand and ask questions |

| Confidentiality | Of personal information |

| Dignity | Care is provided in respectful, caring, non-discriminatory settings |

| Prompt attention | Care is provided readily or as soon as necessary |

| Quality of basic amenities | Physical infrastructure of health-care facilities is welcoming and pleasant |

| Access to family and community support | (For hospital inpatients) |

| Institute of Medicine: quality of care | |

| Health services are | |

| Safe | Avoiding injuries to patients from the care that is intended to help them |

| Effective | Providing services based on scientific knowledge . . . avoiding underuse and overuse |

| Patient-centred | Providing care that is respectful of, and responsive to, individual patient preferences, needs and values, and ensuring that patient values guide all clinical decisions |

| Timely | Reducing waits and sometimes harmful delays |

| Efficient | Avoiding waste, including of equipment, supplies, ideas, energy |

| Equitable | Providing care that does not vary in quality because of personal characteristics |

| Nolan et al: SENSES framework | |

| All parties should experience relationships that provide a sense of | |

| Security | To feel safe within relationships |

| Belonging | To feel part of things |

| Continuity | To experience links and consistency |

| Purpose | To have potentially valuable goal(s) |

| Achievement | To make progress towards desired goals(s) |

| Significance | To feel that you matter |

The Health and Social Care Act 2012 was heralded by the UK coalition government’s White Paper, Equity and Excellence: Liberating the NHS, which acknowledges that ‘healthcare systems are in their infancy in putting the experience of the user first’ (p. 13) and many NHS organisations continue to struggle to identify the best way of integrating patients’ experiences into service improvement. 1 The paper proposed ‘an enduring framework for quality and service improvement’ (p. 5). This places patients at the heart of the NHS through ‘an information revolution’ (p. 3), with patients having ‘greater choice and control’ (p. 3). A central component of the government’s vision is the development of national QSs. These provide definitions of good-quality care across a range of clinical pathways and are based on evidence considered during the development of related CGs. The paper states that ‘to achieve our ambition for world-class healthcare outcomes, the service must be focused on outcomes and the quality standards that deliver them’ (p. 4). This ambition was subsequently realised in the Health and Social Care Act 2012, which mandates NICE to develop QSs across a range of health conditions. 3

NICE products

Clinical guidelines

Historically, the DH has commissioned NICE to provide guidance to the NHS and wider public under a number of different programmes. They have produced CGs which set out clear recommendations for the treatment and care of people in England, Wales and Northern Ireland with specific diseases and conditions since 2002. Separate guidelines are produced for Scotland by the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN). NICE commissions guidelines from several National Collaborating Centres (NCCs). The largest of these is the National Clinical Guideline Centre (NCGC) which was established in 2009. The other centres comprise the NCC for Mental Health, the NCC for Women’s and Children’s Health (NCC-WCH) and the NCC for Cancer. NICE also have an internal guidelines programme.

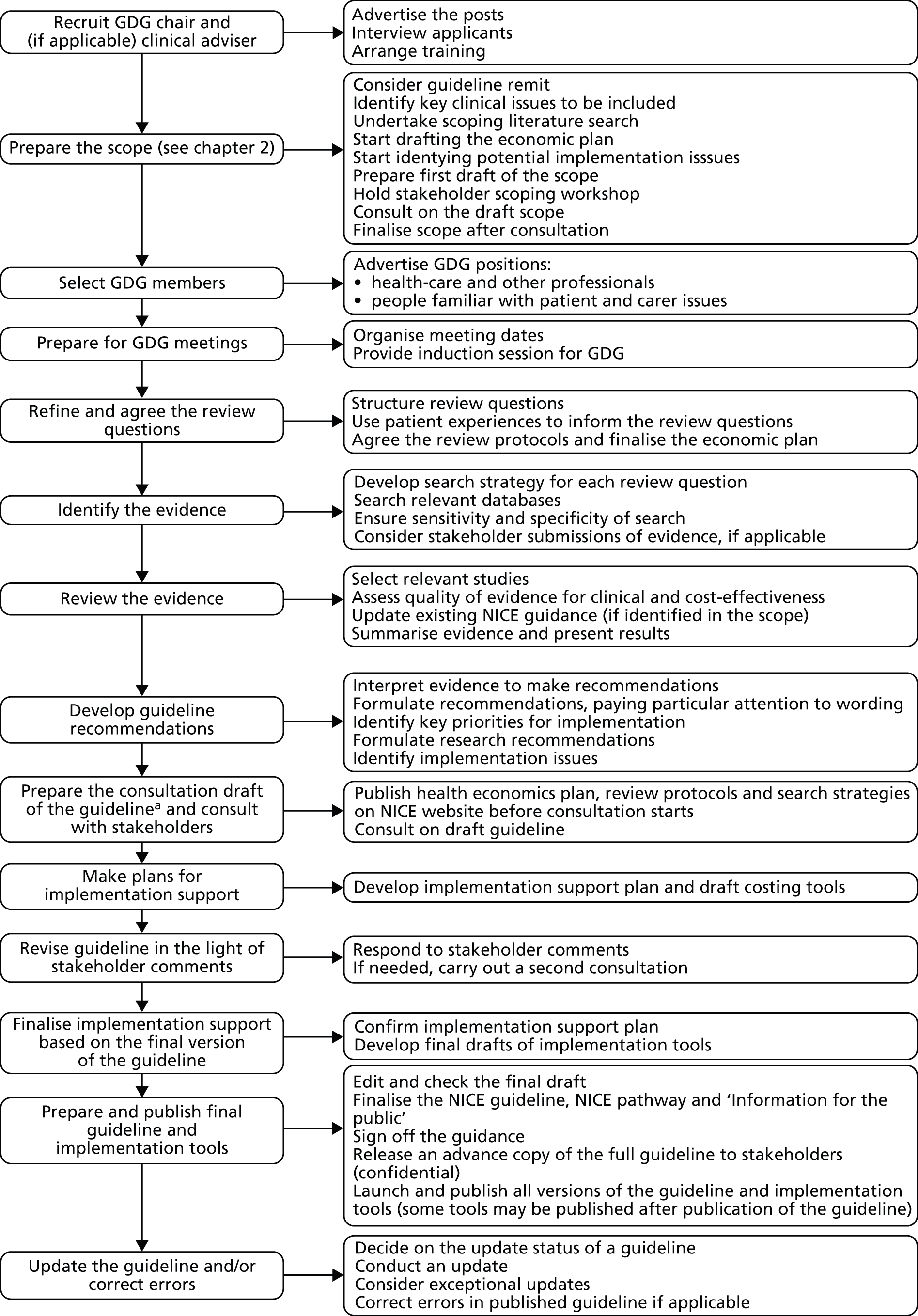

All NICE CGs are based on a review of the best available evidence of the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of treatments for specific diseases and conditions. There are also generic guidelines, which cover subjects such as patient experience and medicines adherence. As each guideline covers a specific condition, or a specific aspect of a condition, there is also extensive cross-referral between guidelines; for example, the guideline on management of obesity is referred to by guidelines on cardiovascular disease and diabetes. The process and methods of developing a guideline is a pre-specified and lengthy process and is described in the NICE guidelines manual. 11 Guideline topics may be suggested by the DH or Welsh Assembly Government, by health professionals, and by patients and the public. Once a topic is referred to NICE, NICE commissions the guideline development centre, who recruit a chairperson and starts to develop the scope of the guideline. This process involves consulting with stakeholders (who register through the NICE website) to determine what will, and what will not, be covered by the guideline. The scope defines areas of clinical management, the target population and important outcome measures. The stakeholder consultation involves a workshop and a formal written consultation process. The scope is finalised and signed off by NICE. The areas included in the scope are converted to a series of clinical ‘review’ questions during guideline development. The chairperson and a guideline development group (GDG) are recruited for each guideline. These groups comprise health professionals [consultants, general practitioners (GPs), nurses and allied health professionals] and lay members (patients, carers, service users) and are supported by a technical team of an information scientist, a health economist, research fellow(s) and a project manager. All GDG members have an interest or expertise relevant to the topic. A systematic review is performed for each clinical question by the technical team. The quality of the evidence is scored and the cost-effectiveness reported if available or original health economic models developed. The GDG meets every 4 to 6 weeks over a period of 16 months to examine this evidence and to make recommendations based on the evidence and their clinical or personal experience. The wording of these recommendations is chosen carefully to reflect the strength of the evidence. The draft guideline is available for a second period of consultation by stakeholders, after which alterations are made by the GDG if needed. The final guideline is reviewed by NICE and published on the NICE website in different formats: the full version (which lists the methods and evidence and details how the recommendations were derived from that evidence); the NICE version, which lists the recommendations alone; and a lay version. NICE produces ‘pathways’ on its website which present guidance in such a way as to allow easy cross-referral between different guidelines that may be relevant to people with a disease or condition.

Quality standards

Quality standards are a set of specific, concise statements that act as markers of high quality, cost-effective patient care, covering the treatment and prevention of different diseases and conditions. They should be aspirational but achievable and define priority areas for quality improvement. 12

NICE were first tasked to develop QSs for the English NHS in the Darzi Review of 2008. 13 In 2010, the profile of NICE QSs was raised significantly, with the new coalition government emphasising the centrality of NICE QSs in the ‘new NHS’ in its 2010 policy paper Liberating the NHS and in the subsequent 2012 Health and Social Care Act. 1,3 Referrals to NICE for QSs are made by NHS England. QSs are intended for use by health-care professionals (to raise standards of care), patients and the public (so that they are informed of the quality that they should expect of the services provided to them), service providers (to enable performance to be assessed) and commissioners (to help them to purchase high-quality services). Audience descriptors append the QS.

Each quality statement is also accompanied by a ‘quality measure’ which defines the proportion of the target population (as a numerator and denominator) to which it applies (for auditing purposes). To keep the administrative burden manageable, each statement specifies only one measurable metric. QSs inform incentive schemes and payment mechanisms – such as the Clinical Commissioning Groups Outcomes Indicator Set, the Quality and Outcomes Framework for general practice, and the Commissioning for Quality and Innovation payment framework – by linking a proportion of the provider’s income to the achievement of quality improvement goals.

The descriptive statements that constitute QSs are derived from three dimensions of quality: effectiveness, patient experience and safety. Equality issues and resource impact are also considered. The process of QS development is still emerging. The first ‘pilot’ QSs comprised approximately 15 statements which described what good-quality care should look like. As the QS programme rapidly expanded, the need to reduce the administrative burden on service providers was recognised (each statement of each QS has to be measured and audited) and the maximum number of permissible statements was reduced first to 10 and then to between six and eight.

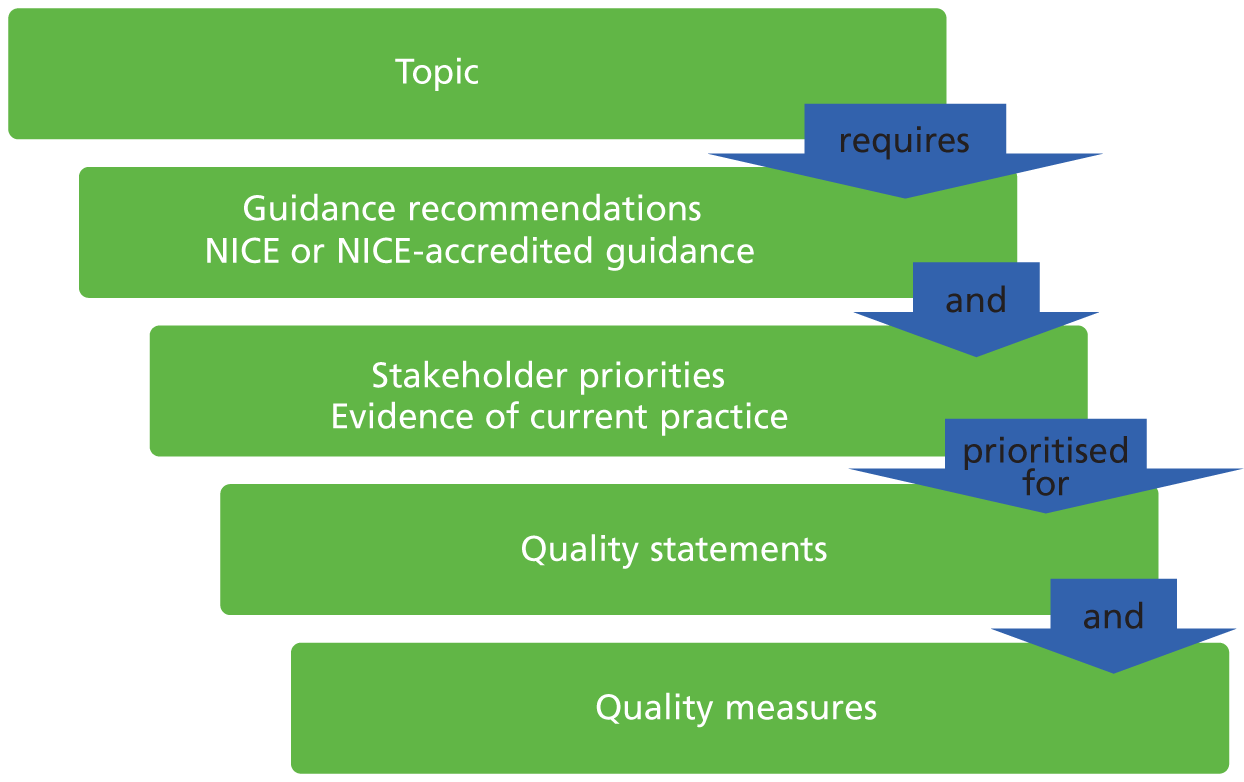

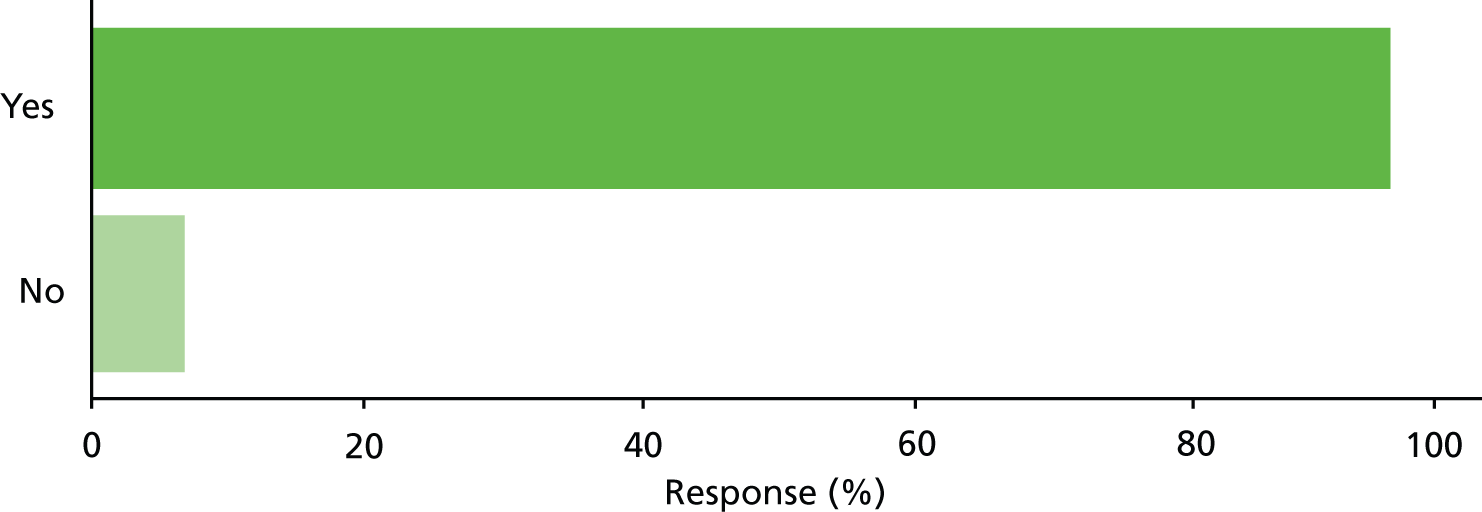

During the lifespan of this study, the process of QS development was as follows (Figure 1): after a QS was referred to NICE, it was developed by a topic expert group (TEG) over three meetings. The TEG, like a GDG, comprised health professionals (consultants, GP, nurses and allied health professionals) and patients and was convened specifically for each QS. During the first meeting, TEG1, the scope of the standard was defined. The scope specified the population groups that would and would not be covered, the health-care settings (primary, secondary, intermediate care and community settings) and areas of care that would and would not be considered. Furthermore, the scope considered economic aspects and designated key development sources (published CGs, guidelines under development, related QSs, other accredited evidence, key policy documents and national audits). Registered stakeholders were invited to comment on the draft scope before it was finalised by NICE.

FIGURE 1.

Overview of the NICE QS development process (at time of fieldwork).

During the second meeting (TEG2), quality statements were discussed and developed with support and guidance from NICE technical teams. The draft QS was also put out to consultation before further development in a third meeting (TEG3). The product was reviewed by NICE before it was finalised and published.

Towards the end of 2012, this process began to be superseded by a standing-committee model. After a topic has been commissioned, a topic overview is developed by a NICE QSs team and published on the NICE website. Registered stakeholders are invited to suggest key areas of care or service provision for quality improvement. A Quality Standards Advisory Committee (QSAC), which again comprises health professionals (consultants, GPs, nurses, allied health professionals), commissioners, experts in quality measurement, NICE representatives, and patient, carer and service user members, meets to prioritise areas for improvement that should be taken forward into draft quality statements. These statements are produced by the QSs team and comment is invited by stakeholders once more. The QSAC meets a second and final time to discuss and modify the draft statements in the light of stakeholder comments. The final product is quality assured and approved by NICE before publication. QSs are reviewed after 5 years. Since April 2013, NICE has an expanded remit to provide guidance and set QSs for social care audiences (further information can be found at www.nice.org.uk/socialcare/).

Although two very different products, the CGs and QSs are related. A major feature of the QS process is agreeing which of the large number of recommendations in a CG should be prioritised for development as a small number of measurable statements. As stated above, the focus is on three dimensions of quality: effectiveness, patient safety and patient experience. There is also a standalone patient experience QS (see Appendix 1), which was developed concurrently with the patient experience CG, with access to the same information. Topic-specific quality statements are not supposed to duplicate material in the patient experience QS. QS development does not include any in-depth discussion of evidence, as this has taken place during the development of the CG, though this may lead to tension when new evidence or changes to practice have emerged in the interim. The NICE manual that was used at the time of our fieldwork contained guidance as to how qualitative evidence might be incorporated into the guidelines development process (see Appendix 2). A detailed figure illustrating the CG development process is appended (see Appendix 3).

The Health Experiences Research Group interview archive: source material for the secondary analysis

The qualitative interviews in the HERG archive are collected as national, purposively sampled collections which aim for maximum variation. The interviews are collected by experienced qualitative social scientists working within HERG. There are currently over 75 collections (60 at the start of the project), each concerning a different health issue (ranging from ‘experiences of pregnancy’ to ‘living with a terminal illness’). Each set comprises 35–50 interviews which are digitally audio or video recorded (depending on the participant’s preference), transcribed, checked by the interview participant and copyrighted to the University of Oxford for a number of non-commercial purposes, including secondary analysis and publication. The research is funded via a peer-reviewed process by bodies including the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) and the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC), and research committees of voluntary organisations (including Arthritis Research UK, Wellcome Trust, Marie Curie Cancer Care).

The projects all share a research question (‘What are the experiences, and information and support needs, of people with health condition X?’) and a common interview method that starts with an appropriate variation on an open-ended question intended to invite a narrative response (e.g ‘Could you tell me all about it from when you first thought there might be a problem?’). When the person has completed their account, a semistructured section of the interview includes questions and prompts about any issues of interest that may not have been fully discussed in the narrative. These typically include questions about treatment decisions, information, support and communication with health professionals. All participants are asked if they have anything they would like to tell other people who are starting out on the same journey and if there is anything they would like to pass on to NHS staff, at all levels, who might learn from the participant’s experiences. These questions often add rich, informative data about how services and communication could be improved. 14

Each of the interview studies starts with a literature and field review and sets up a specialist advisory panel including patients, professionals, researchers, clinicians, and representatives from the voluntary sector and (if appropriate) the funding body. The panel advises on the parameters of the project, including selection and recruitment of participants.

A maximum variation sample is sought to help generate as diverse a sample as possible, including those whose experience might be considered ‘typical’ as well as those with more unusual experiences. 15 As this method seeks to achieve representation of the diversity of experiences, it is not appropriate to present results numerically. For each project, recruits are actively sought through a national network of primary care staff, hospital consultants and specialist nurses, advisory panel members, local and national support groups, advertising online and in local newspapers and snowballing through participants’ and personal contacts. Analysis and data collection proceed simultaneously and continue until ‘data saturation’ is reached to ensure that the widest practical range of experiences has been included. Analyses of the data have been published in peer-reviewed journals over the past 10 years. 16–21 Illustrated lay summaries of the research findings are also disseminated via a website, owned by the DIPEx (Database of Individual Patient Experiences) charity: www.healthtalkonline.org. The website has NHS Information Standard approval and the collections are reviewed every 2 years and updated with further interviews if considered necessary, for example to capture the experiences of people who have used new treatments or therapies. The website is the only public source of patient experience evidence cited in the NHS Evidence Process and Methods Manual (www.evidence.nhs.uk/evidence-search-content/process-and-methods-manual), and is already acknowledged as a source of evidence for use by technical staff as part of their review of evidence when they develop a new CG.

Reusing research data

Two developments in prevailing research cultures particularly favour reuse of existing data. First, synthesising published and unpublished research before (or instead of) conducting new research is now mainstream practice. 22–24 Secondly, following the decision in 2000 by the ESRC to require ‘award holders to offer for archiving and sharing copies of both digital and non-digital data to the Economic and Social Data Service’ (p. 256) and to seek the correct permission to do so when collecting data,25 several funding bodies nationally26,27 and internationally28 have followed suit. Many now have explicit expectations that publicly funded research should be shared to maximise the value of data for the public good and ‘to expedite the translation of research results into knowledge, products, and procedures to improve human health’. 29 There has been a debate in the qualitative research community about the legitimacy of secondary analyses. 30 However, the HERG qualitative interview archive has been widely used, under licence by many established research groups, both nationally and internationally, in work funded by the NIHR, the ESRC and the Medical Research Council (MRC) among others. Articles based on secondary analyses of these data have been published in high-impact journals. 31–35 A secondary analysis of HERG data was commissioned by the General Medical Council (GMC) to contribute patients’ perspectives to the guidelines on end-of-life care. 36

Research methods

In this study, we employed the considerable expertise that exists within the HERG to conduct secondary analyses of interview collections covering selected health conditions so as to identify a candidate list of common components of good health care that was grounded in patients’ experiences (objective 1). The reach of this candidate list was tested through further analyses of other data sets from the archive and through FG work (objective 2). In many cases, we were also able to draw upon the expertise of the primary researcher who could provide additional perspective, insight and contextual information.

Secondary analysis

In a modified version of framework analysis, we used charts to make a summary description of data from each of the interviews across a set of categories, which were later developed into themes for analysis. 37 The process was iterative and flexible enough to accommodate anticipated themes (e.g. areas of care that have been identified in the guideline scope) as well as emergent themes. These themes were then compared across cases and between conditions to identify general and specific aspects of good-quality care. Coding and analysis of the interviews was supported by NVivo qualitative data analysis software (version 9, QSR International, Warrington, UK).

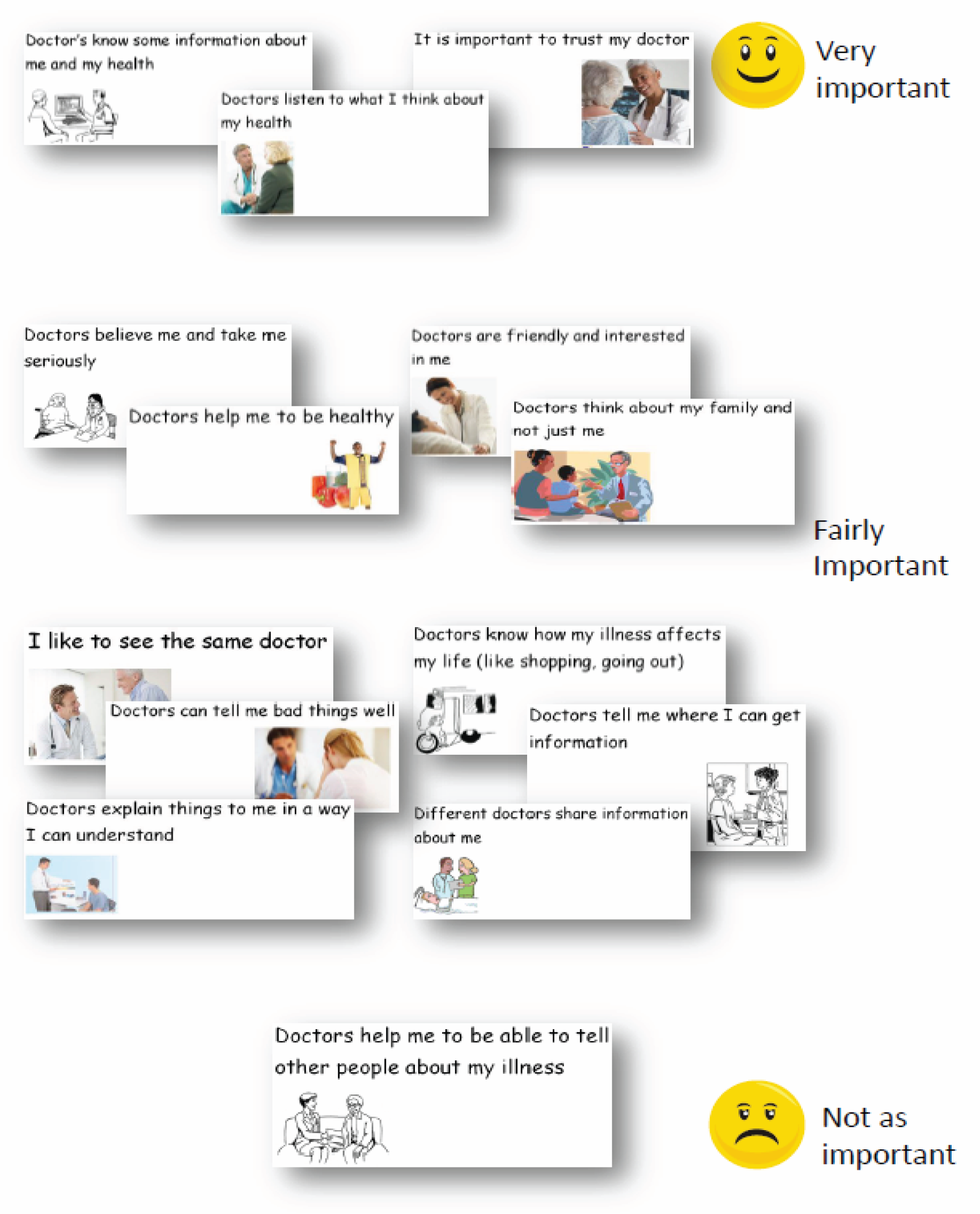

Focus group methods

We used FGs to test the candidate core components with people whose views may have been under-represented in the HERG interviews used for the secondary analysis. FGs have been used previously to research the use of health services by seldom heard groups. 38 Being among similar others, in a supportive and reassuring environment, can encourage the sharing of views openly as well as enabling contradictions, personal or private issues to be more easily raised, discussed and sometimes resolved. 39 On the other hand, FGs can be difficult to use with certain groups; for example, those with mental impairments may find conventional FGs harder to participate in than a one-to-one interview. Flexibility in the structure and comportment of the groups is particularly important when one is seeking to engage participants who might not usually take part in research; too rigid an approach may (further) marginalise some participants.

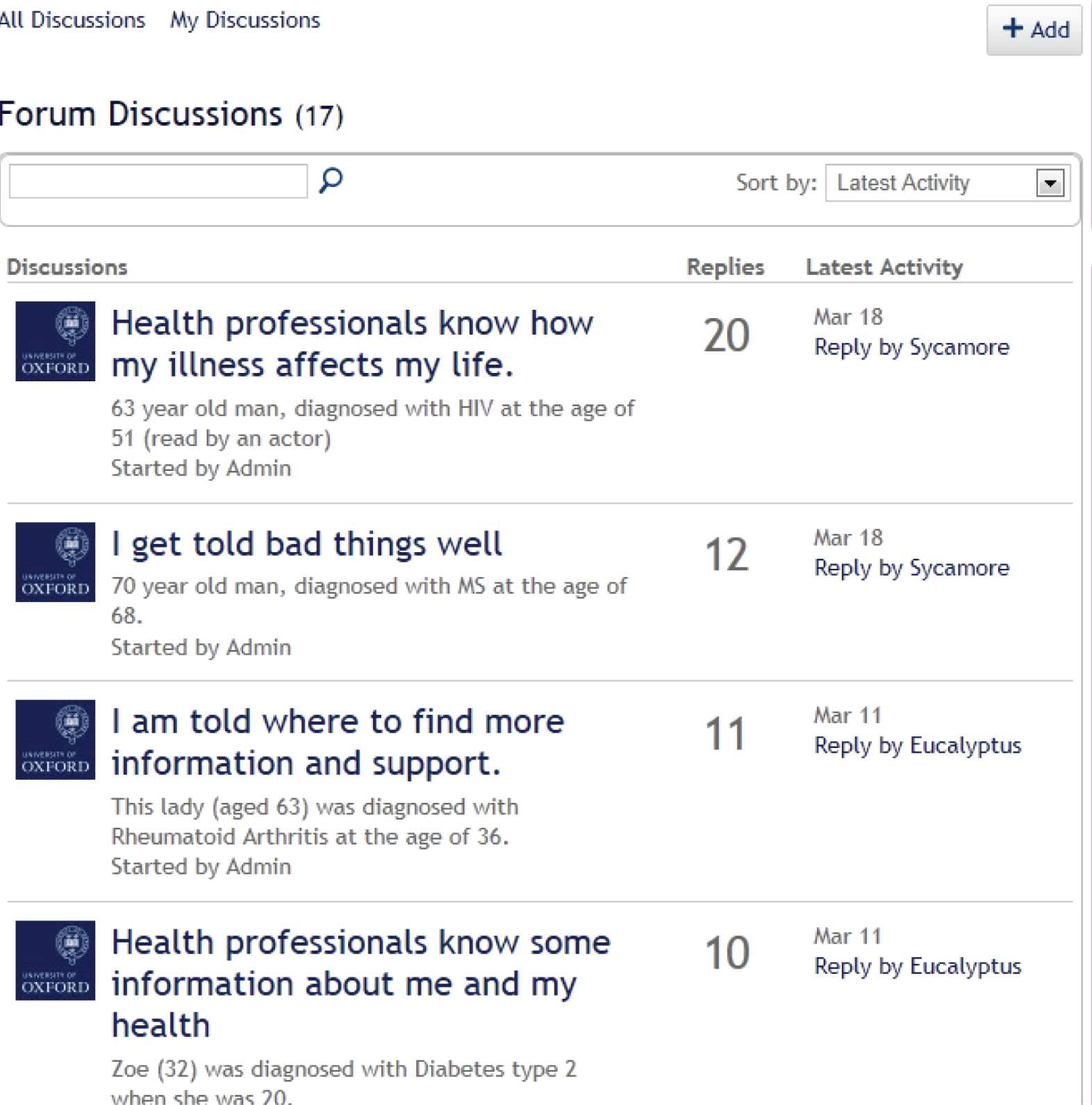

To explore variation in the meaning and importance of components across care settings and social groups, we conducted six FGs with people who we recognise may not be represented in the HERG interview archive (despite striving for maximum variation). In addition to the traditional-format FGs, we designed a webspace in which we held an online discussion forum with patients with long-term conditions (LTCs). The webspace, ‘Good health care’, contained a different forum for each candidate core component and was illustrated with a video clip taken from the archive. The online method allowed us to hear the views of those we could not reach through the FGs, either because of the severity of a LTC or due to a caring role. Our analysis sought to examine and conceptualise the limitations and reach of components of good care and how they may vary between groups.

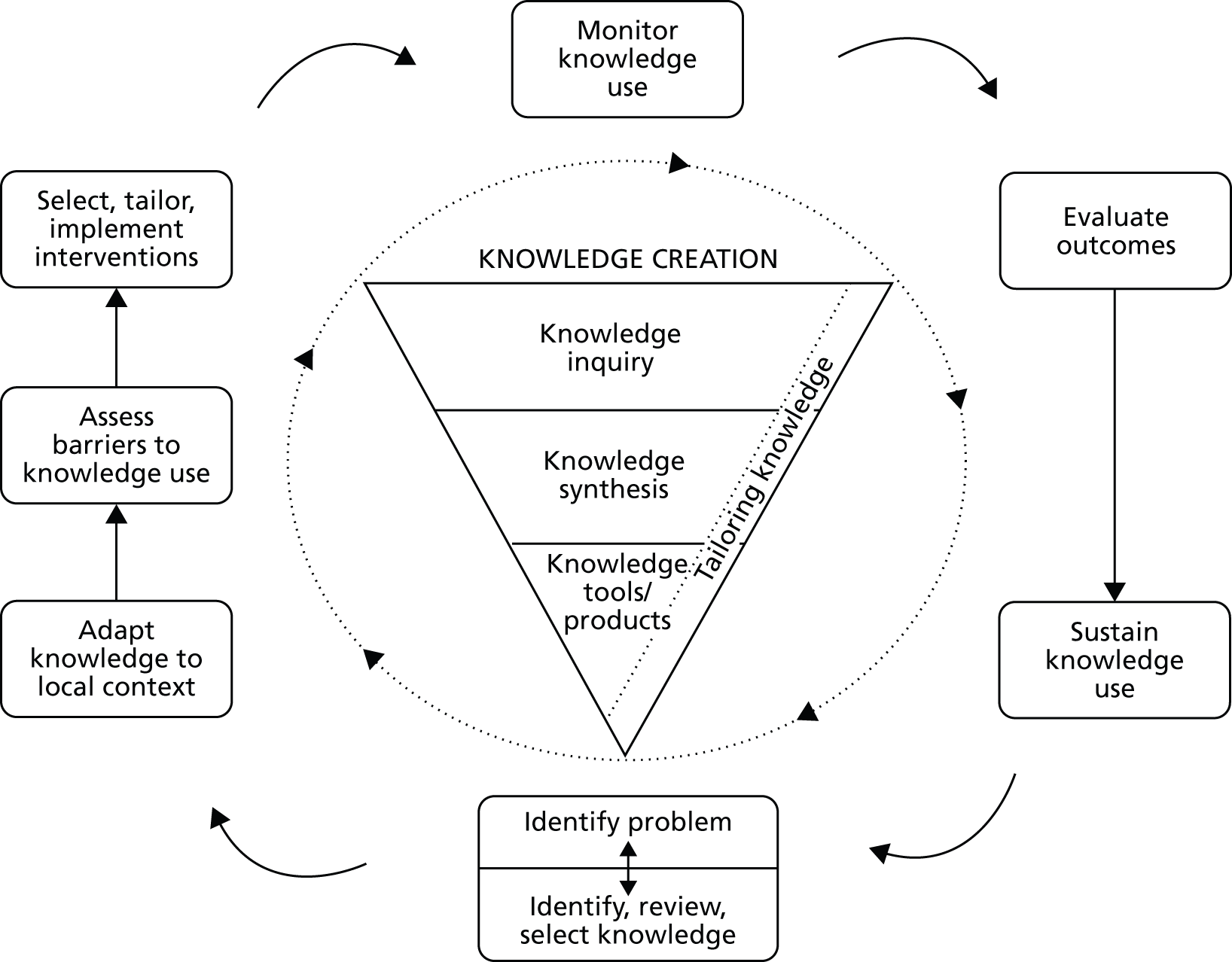

Knowledge transfer

Our third objective was to embed the project alongside the development of the NICE CGs and QSs. In order to meet this objective, the project team planned a ‘knowledge transfer’ intervention comprising three components:

-

the presentation of HERG secondary analyses to chosen CG and QS groups

-

a training programme for NCGC staff

-

a secondment from HERG to the NCGC.

We studied the intervention using a combination of semistructured interviews with HERG and NCGC/NICE staff, non-participant observation of GDG and TEG meetings and an online survey of NCGC staff who attended the training programme. In keeping with our conceptualisation of the three components as being part of a knowledge transfer intervention, we synthesised and analysed our findings using an existing ‘knowledge to action process’ model which distinguishes ‘knowledge creation’ and ‘action’ as two concepts, with each comprising ideal phases or categories. 40 In the context of our study, ‘knowledge creation’ pertains to the work undertaken by HERG staff to conduct the secondary data analyses, while ‘action’ relates to the process by which we sought to embed this knowledge into the CG and QS development process. As the authors of the model indicate ‘In reality, the process is complex and dynamic, and the boundaries between these two concepts and their ideal phases are fluid and permeable. The action phases may occur sequentially or simultaneously, and the knowledge phases may influence the action phases’ (p. 18). 40 Nonetheless, the model provided a useful heuristic to guide our thinking, data collection and analysis.

Measuring patients’ experiences and outcomes

The identification of a set of core topics that are central to patients’ experiences of the NHS is applicable to the development of quality and outcomes measures for health care. This study sought to inform this measurement (objective 4). Here, we briefly explain the tools used to measure patient experiences and outcomes.

The DH is keen to measure the health status or health-related quality of life from the perspective of the patient so as to assess the quality of care and health outcomes of NHS clinical pathways. The government White Paper, Equity and Excellence: Liberating the NHS, encourages ‘much wider use of effective tools like Patient Reported Outcome Measures’ (PROMs). 1 This includes generic tools such as the Short Form questionnaire-36 items (SF-36)41 and European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D)42 which can be used across different conditions, as well as more specific measures such as the Oxford Hip and Knee Score. 43 PROMs are validated questionnaires which may be administered before and after a clinical procedure to measure self-reported health changes and hence the effects of care. Results are used to quantify the performance of providers, clinicians, managers and commissioners, to permit clinical auditing and to inform the choices of patients and GPs. PROM development should ideally include consultation with patients to ensure that the measures include outcomes which matter to patients, as well as those which are regarded as clinically important.

Patient-reported experience measures aim to capture patient experiences of a health-care pathway or service. They include the Picker-15 Patient Experience Questionnaire44 and the national GP Patient Survey,45 for example, but can also be on more specific aspects of care experiences, such as the Patient Evaluation of Emotional Care during Hospitalisation (PEECH). 46

Other mechanisms which seek to capture self-reported aspects of patient experience include patient comment and ratings on websites such as NHS Choices and Patient Opinion, real-time feedback devices in hospital, and brief measures such as the Friends and Family Test.

While experience measures are not about health outcomes as such, it is arguable that experience is in itself a form of outcome of the process of care. There is also an emerging body of literature which suggests that patient experience may be linked to or be predictive of health outcomes. 47

In this study, we discussed with key individuals from the PROM and patient-reported experience measure (PREM) academic community whether or not and how our observations about the reach and limitations of the core components of good-quality care might inform the development and interpretation of quantitative data on patients’ experiences.

Sharing of qualitative data for secondary analysis

The qualitative method of conducting relatively unstructured, in-depth interviews with purposive, maximum variation, national sampling of patients is recognised as an important method for ensuring that patients’ views, opinions and perspectives are understood. 48 However, the method is costly and time-consuming to conduct, and some patient groups are hard to include. An alternative to collecting new data is to use secondary analysis of existing qualitative data sets, which can be a highly efficient and cost-effective alternative, provided that the researcher is aware of the challenges and limitations inherent in a secondary analysis and that the original data have been collected with appropriate rigour and in anticipation that they may inform future work. 49,50 Loss of context and lack of contact with the original researcher has often been cited as a reason to question the validity of a secondary analysis. 51,52

The considerable potential of qualitative research has not been fully realised by policy-makers. Owing to the time pressure inherent in the policy-making process, there is often insufficient time to commission, conduct and analyse new qualitative studies to inform a specific policy. In order for the experiences of patients, relatives and carers to be heard, it is, therefore, imperative that use is made of existing data collections. The reticence of policy-makers to translate qualitative data into a means of informing health policy and improving health service provision may relate to a more general lack of awareness of the qualitative paradigm. 53–56

The aim of the fifth objective was to draw on expertise, both within HERG and of archivists, primary researchers and secondary analysts of qualitative data, in health care and in other disciplines, to discuss and develop recommendations for the archiving and preparation of qualitative data for sharing for secondary analysis. Following the workshop, we have developed a 1-day training course on the secondary analysis of qualitative data for inclusion in the HERG programme of qualitative research methods courses.

Chapter 2 Objective 1: qualitative secondary analysis to identify common core components of patients’ experiences of the NHS to inform NICE clinical guidelines and quality standards

As discussed in the previous chapter, existing quality frameworks do not cover all aspects of care that patients have identified as relevant and important. 7,9,57,58 They have a strong focus on safety, effectiveness and equity, and while these are integral components of health care, they could be considered basic rather than good or aspirational aspects of care. Allied to the development of QSs, our interest in the secondary analysis of patient experience data was to identify what patients perceived to be indicators of ‘good care’, which the Francis Report described as ‘enhanced’ care in contrast to fundamental and developmental. 6

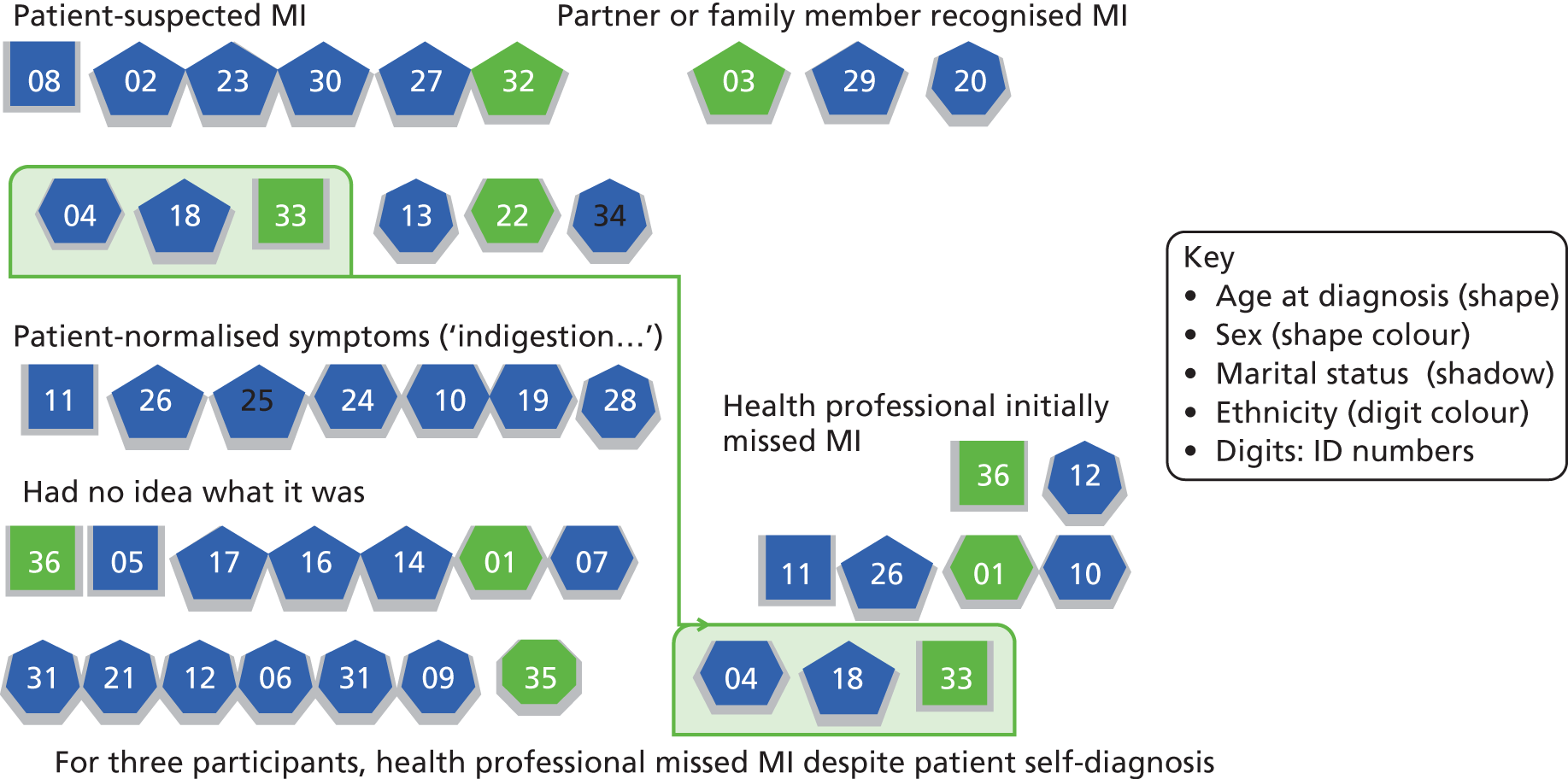

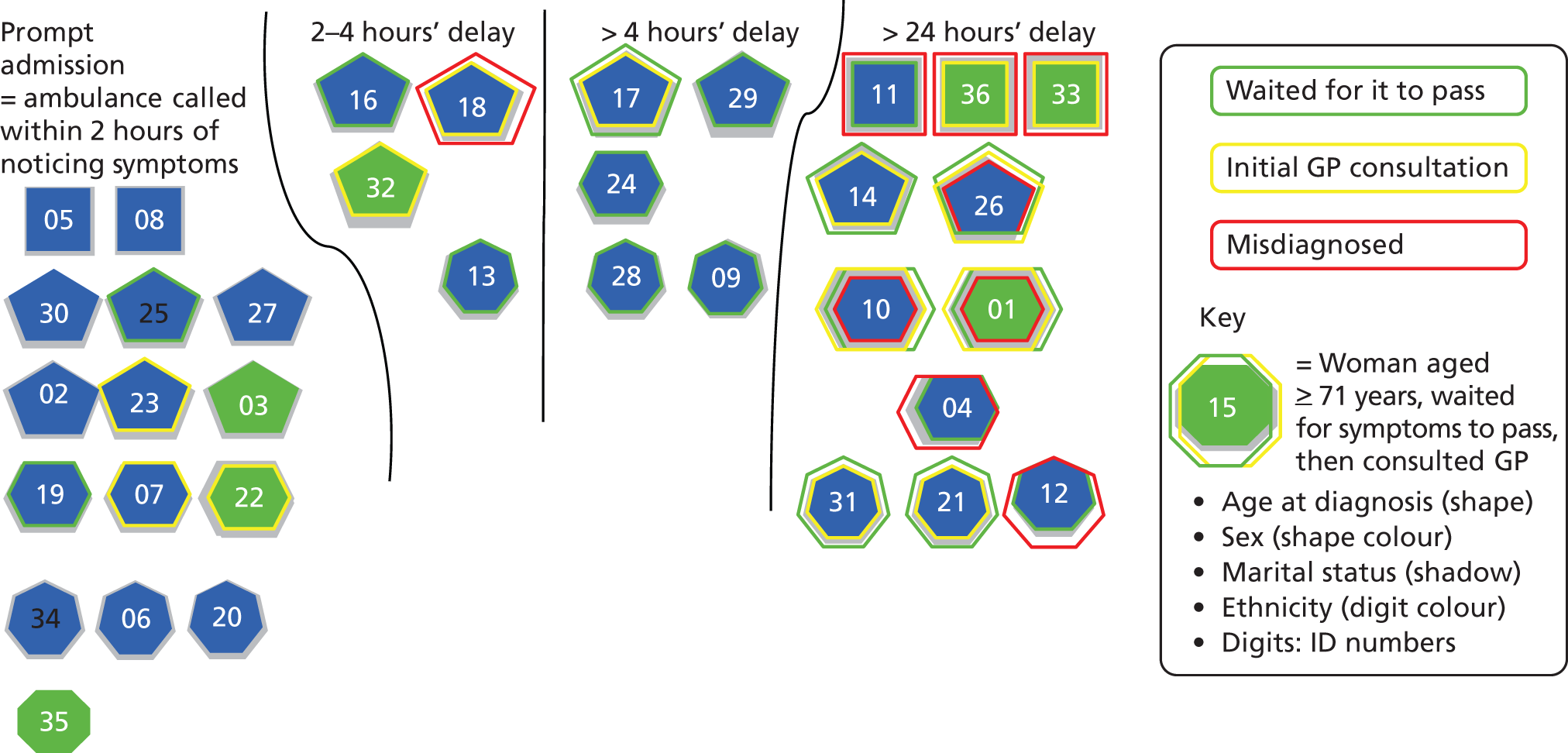

To address the first objective, we conducted a qualitative secondary analysis of four interview collections from the HERG archive. Each collection comprised 37–55 narratives from people with experience of a specific health condition. We began with a complete reanalysis of interviews on myocardial infarction (MI). This analysis sought to identify common core components central to patients’ experiences of the NHS; in accord with the focus of QSs, we focused on good or ‘enhanced care’ rather than fundamental care. The HERG interview collections cover patients’ care experiences in both primary and secondary care, in emergency settings and also after hospital discharge, and can therefore provide insights into how core components of good-quality care might vary across different stations of the care pathway. The analysis of subsequent collections added to the components identified from MI as well as seeking to respond to NICE’s specific needs for specific CGs and QSs (see Asthma, Young people with type 1 Diabetes and Rheumatoid arthritis).

Interview collections were carefully selected to ensure that they matched the development schedules of products that had been commissioned by NICE. Considerations included whether or not the topic and the timing of the analysis could feed into NICE processes to:

-

inform NICE products scheduled for development

-

allow observation and assessment of the transfer of knowledge between NICE/NCCs and HERG (through attendance at GDG and TEG meetings) and scrutiny of the final product

-

permit an examination of the different ways and time points at which the analysis might feed into NICE product development

-

permit an examination of whether or not the type of development process (parallel or sequential) affected the degree to which the research findings influenced the final product. (A QS might be developed in parallel with an update of an existing CG or the development of a new CG, or it might be developed sequentially to a CG that was not due for review, through a tertiary review of the evidence.)

A significant limiting factor was that the choice of topics available in the HERG archive was not as large as anticipated due to the lack of fit of QSs and CGs in development by NICE over the study period.

The 18-month project was too short to follow through an entire NICE product lifespan, although we hoped to be able to learn from examining four topics which were at different stages in the process. Furthermore, uncertainty and emergence of the NICE processes for QSs meant that it was not possible to specify input into pre-selected NICE products at the outset. Agreement of the topic areas for collaboration was an iterative process that required consideration of the scope for the guideline alongside the topic as included in the HERG collection and discussion with teams developing guidelines. This resulted in several ‘blind alleys’ where the opportunity for collaboration with specific technical teams was internally explored by the NICE/NCGC co-applicants, without progression beyond an initial expression of interest.

The final four health areas for the qualitative secondary analysis were MI, asthma, rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and young people with type 1 diabetes (Table 2).

| Topic area | Details of HERG collection used in the analysis | NICE products |

|---|---|---|

| MI | Analysis of interviews with 37 people who had experienced MI between 1989 and 2003 (19 after 2001). Nine had been treated with clot-busting drugs, 10 had had angioplasty (2000–4), nine had had a stent (2001–3), and 11 had experience of bypass surgery. The mean interval between diagnosis and interview was 5 years, ranging from < 1 year to 23 years | New guideline on STEMI |

| Updated guideline on secondary prevention after MI | ||

| Asthma | Analysis of interviews with 38 people diagnosed with asthma during 2011–12 | QS (developed in parallel with accreditation of guideline produced by SIGN and the British Thoracic Society) |

| Young people with type 1 diabetes | Analysis of topic summaries (themes from the primary analysis), peer reviewed and published on www.youthhealthtalk.org, and a subset of six interviews from the full data set | Type 1 diabetes in children (NCC-WCH) and type 2 diabetes in adults (internal guidelines team) |

| RA | Analysis of 52 interviews of people diagnosed with RA (and four partners). A wide range of therapies were included; 20 had experience of surgery and two were waiting for an operation at the time of interview | QS (based on guideline developed in 2009) |

Two further interview collections covering adults with autism and people with fertility problems were used to test the reach of the candidate core components (these last two analyses are discussed in objective 2 and were not intended to contribute to QS development).

There was considerable variation in the time available for each topic (a consequence of accommodating NICE product timelines). Based on the feedback received from the NICE/NCGC co-applicants and technical teams, researchers modified their approach on how to present the findings and experimented with a range of formats. These included relatively intensive secondary analysis of both anticipated and emergent themes (MI) (see Appendix 4); a review of existing analytic reports (diabetes); ‘piggybacking’ the analysis onto the primary analysis (by the original researchers) of a project that was very recently collected; and focusing the analysis on 11 specific aspects of care that had already been identified for discussion as part of the development of a QS (RA). The variation in output styles allowed us to compare the work load, contribution and reception of different models of analysis and reporting.

Analysis of the first interview collection on MI adopted an inductive and exploratory approach to coding data that included emergent themes as well as those anticipated from the literature (see Secondary analysis).

In analysing the subsequent three interview collections (asthma, RA and young people with type 1 diabetes), the mode of analysis was increasingly tailored to the scope of the NICE product and the needs of the technical teams.

The four main secondary analyses and how we reported the findings to NICE

Myocardial infarction

The data collection took place in 2002–3 and participant recruitment aimed for diversity. Most were white British and living with a partner or spouse. The sample included fewer women than men and a higher proportion of younger patients (i.e. aged < 55 years at time of diagnosis) compared with the age profile of patients currently experiencing MI in the UK. The diversity in participants’ ages made it possible to explore adjustment to MI and patients’ information and support needs at different ages and stages of the life course. The sample spanned all socioeconomic groups from all parts of the UK, including urban, small town, rural and remote areas. Recruitment routes included GPs, charities and support groups. Analysis explored accounts of experiences of MI and also adjustment and engagement in secondary prevention from different vantage points in the trajectory of illness and recovery.

Presentation of myocardial infarction findings

It was considered likely that the findings from this collection would inform a guideline being developed on ST segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). A review of the content of the collection suggested that it might also inform the update of another guideline: secondary prevention of MI. Both guidelines were being developed at the NCGC and it was initially envisaged that a report of the findings would be presented to the chairpersons and technical teams responsible for these guidelines. NICE processes require that the evidence used to inform the GDG is publicly available, and so the NCGC requested a written report which could be included in an appendix as part of the evidence presented to the GDG and for public consultation.

The scoping consultation for the STEMI guideline had finished in July and the guideline was in development prior to the start of this project. The scope was highly technical and did not include patient experience but it was anticipated that the report might supplement GDG opinion and clinical data in the discussion part of the guideline. The scope for the secondary prevention guideline included barriers to engagement with cardiac rehabilitation services, and, although the scoping phase was almost complete, the guideline was not yet in development.

An extensive report was sent to both the STEMI and secondary prevention technical teams (see Appendix 4). As agreed with the NCGC, the initial report was extended to include three further chapters of greater relevance to the secondary prevention technical team. The content and format were informed through direct discussion. The NCGC anticipated that the process would be iterative, with the technical team feeding back to the HERG in advance of the document being distributed to the GDG.

Asthma

The analysis of this 2012 collection benefited from the insights of the primary researcher who was able to provide additional contextual information. The sample comprised interviews with 38 people (25 women) diagnosed with asthma during 2011–12. Their ages ranged from 16 to 73 years and included 17 participants with childhood-onset (age at diagnosis 6 months to 12 years). Four of those with adult-onset asthma had been diagnosed over the age of 50 years. Length of time since diagnosis ranged from under 1 year to over 30 years.

Presentation of asthma findings

In order to fit with NICE timelines, analysis was based on an initial coding frame that embedded patients’ NHS experiences within their experience of living with asthma more broadly. These findings were presented to fit with the standard NICE briefing paper format for QS development.

The asthma interviews were still in the process of undergoing primary analysis at the time of the project, and this represented an opportunity to draw directly on that primary analysis to address the secondary questions posed by the team working on the NICE QS for asthma. Rather than a complete analysis of components of good care, for TEG1 the researcher was asked to work through the care pathway and identify headline issues that may indicate where a certain aspect of care was currently poor or variable in terms of delivery by health-care professionals. This was to contribute to prioritising which elements of the British Thoracic Society (BTS)/SIGN guideline would be developed into quality statements. In collaboration with NICE co-investigators, this was reduced considerably and presented in bullet point format, using, primarily, headings drawn from the guideline (such as ‘diagnosis’, ‘non-pharmacological management’ and ‘inhaler devices’) but also a new category, ‘emotions and acceptance’ (see Appendix 5).

The researcher then carried out a more expanded analysis of the original bullet points for TEG1 under these headings. Therefore, the text on emotions and acceptance, for example, was now placed under the statement ‘people with asthma are offered self-management education including a personalised action plan’ (see Appendix 6). The asthma technical team added these components into their full briefing paper for TEG2.

Young people with type 1 diabetes

The secondary analysis drew on peer-reviewed topic summaries (themes from the primary analysis) which had already been published on www.youthhealthtalk.org (the sister site of www.healthtalkonline.org for young people). The full data set comprised 37 young people, aged 15–27 years, diagnosed between 1 year and 24 years of age, mostly interviewed in 2006, with updates in 2010 and 2012.

Presentation of diabetes findings

The report was written in consultation with the HERG researcher who had recently updated the diabetes collection. Themes were tested and further developed by coding selected full interview transcripts from the HERG archive. A summary document was produced for the technical team updating the CG on type 1 diabetes in children, which focused on the areas of care that had been highlighted by NICE (see Appendix 7). This was available at the time of scoping of the diabetes guideline but the final scope was very specific and technical, and despite discussion and meetings between the NICE/NCGC investigators and the technical team updating the guideline, it became clear that the secondary analysis would not be incorporated into the process, and so we did not proceed to prepare a full analysis of the data set.

Rheumatoid arthritis

This collection was based on a core set of 38 interviews conducted in 2004–5 and an update of 14 newer interviews from 2012. The interviews included a wide range of ages at diagnosis from 5 to 74 years, and the time that participants had lived with the condition ranged from very recently diagnosed to 46 years. This diversity in participants’ ages and length of illness experience made it possible to explore how the experience of RA and patients’ information and support needs differed at different ages and what the adjustment to living with RA might require practically and emotionally at different stages of life. The sample reflected the diverse severity of the condition across individuals and time periods and included treatment with disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDS), steroid tablets, injections and intravenous pulses, biological treatments (anti-tumour necrosis factor and B-cell therapies), as well as management with analgesics and non-drug treatments.

Presentation of rheumatoid arthritis findings

A similar model of reporting to that used for the asthma topic was employed following positive feedback from the NICE/NCGC co-investigators. A short summary report was produced after exploratory coding of a subset of interview transcripts (see Appendix 8). Subsequent analysis and coding was focused to generate analytic depth and data saturation in key areas (draft statements) discussed in advance with the NICE technical team. The findings were presented as a second report (see Appendix 9).

Core common components of good health care identified from the four secondary analyses

The analyses of the four health topics allowed us to develop, expand and modify a candidate list of core components of good health care, drawn from the literature (see Table 2) and developed with additions from each collection in turn. In the rest of this section, we describe how these core components were developed through the four secondary analyses.

We begin with a description of the core components of good care identified from the MI interview collection. In subsequent sections on asthma, young people with type 1 diabetes and RA, we consider additional aspects and variations. Results are mapped and summarised in Table 3.

| MI | Asthma | Young people with type 1 diabetes | RA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Being taken seriously (when first presenting with symptoms) | Clarity about when to seek help in event of an asthma attack | Clear rationale for glucose control Also supporting self-care |

Appropriate use of services and referrals Diagnosing the patient’s preferences |

| Kindness and honesty in delivering the diagnosis and implications | Clarity about when a definitive diagnosis has been made (especially adult-onset) | Approachability and friendliness of staff (especially nurses) | Checking knowledge and expectation of the disease |

| Facilitating difficult conversations, e.g. explaining why the MI happened, how to modify life to prevent recurrence | Helping to negotiate responsibilities, e.g. awareness of shifting parent/child dynamics with young people with asthma | Recognition in the consultation of sometimes conflicting agenda between the young person and their parent | Acknowledging uncertainties when seeking effective treatments and the unpredictability of the disease |

| A caring, personal and flexible approach (especially as an inpatient and in early days at home) | Recognising effect on person’s life and relationships as well as the more medical aspects | Helpful if specialist nurses raise topics that may be of concern to young person, e.g. recreational drugs, smoking, alcohol, weight control | Understanding the impact of an unpredictable illness on people’s lives |

| Timely information in a range of formats, including peer support | Repeating information and demonstrating inhaler techniques | Clear, simple but not ‘dumbed-down’ information, given as appropriate over a period of time Peer support important as positive role models and also to exchange tips about living well with diabetes |

Signposting to further information, including peer experiences and support Recognising that younger people have different information and support needs and will use new technologies |

| Building confidence | Recognition of the patient’s own knowledge of their condition | Supporting self-care (also peer support, above) | Entrusting patients with drugs in case of flare-ups, should they wish |

| Continuity of care relationship | Importance of annual reviews Access to specialist asthma nurse |

Back up of personal access to a specialist diabetes nurse | Different consultants known to have different approaches – patients prefer one consultant |

| Smooth transition of information between services | Important if information about diabetes shared when being treated for other illnesses | ||

| Rapid access to specialist advice (especially after leaving hospital) | Access to out-of-hours care in event of an asthma attack | Rapid access to advice and services during hypoglycaemic attacks | Prompt referral from GP to specialist care if needed |

Core components of good health care for patients after a myocardial infarction

People who had had a MI often described feeling shocked and vulnerable and, at least in the short term, lacking confidence in how to manage treatments and other changes to their life. They appreciated kindness and honesty from staff with specialist cardiac knowledge who understood the impact of the illness on the patient’s life. Findings suggested that the relative importance of specific aspects of care varied along the care pathway, reflecting patients’ evolving understanding of, and adjustment to, their condition and their changing information and support needs. We describe below why these aspects of care were important to patients after a MI, with illustrative extracts from the MI interviews.

Being taken seriously when presenting with symptoms

Patients who were later diagnosed as having had a MI were sometimes reluctant to seek help for their symptoms, fearing that they would seem overdramatic. Patients felt well cared for when their GP listened to them, took their concerns seriously and conducted swift and appropriate investigations.

Kindness and honesty in delivering the diagnosis

Myocardial infarction patients usually reported that they had wanted to be fully informed about the possible risks and likely outcomes of their condition and their treatment, but that it was also important to be given hope and encouragement. The following man felt that his consultant gave him a clear explanation as soon as he was admitted to hospital.

He explained [the consultant] – I mean I was very impressed actually because he squatted down and spoke to me at my level. He explained that there were risks attached to this process [. . .] Every intervention was explained to me. [. . .] And, you know, what was very clearly being stated was that, you know, this was the crucial time, you know, that if they were able to intervene successfully now, then my long-term prospects of survival, because I mean, I think there was an explicitness that I wouldn’t necessarily survive.

HA02, male, MI in 2003 aged 54 years

In contrast, another patient described a consultant who was both blunt and pessimistic.

[The consultant] he also wasn’t convinced I’d actually make it through the, the coronary artery bypass. He was surprised that I’d actually made it through that, so like he’s not the sort of guy you want on a football team to gee you up before a game, ‘Hey lads if you keep it down to 10, you’ll do well’. [laughter] He’s not one of those that you want on your team. I think he’s probably going to think he’s trying to give it like it could be, but he probably overdoes how bad it could be.

HA05, male, MI in 2003 aged 37 years

Facilitating difficult conversations

Myocardial infarction patients identified a number of issues that they found difficult to talk to health professionals about, including prognostic information, concern over operation scars and the safety of sexual intercourse after the MI. Patients liked health professionals to guide them through such difficult conversations in a proactive and sensitive manner.

Family members may also be affected by a diagnosis of MI and dynamics may change. Patients sometimes felt ‘mollycoddled’ by an overprotective spouse after returning home. It can be a hard for the patient to explain to other people why they have had a MI and what they can do to avoid another while they are still adjusting to the diagnosis themselves; health professionals can help by including the patients’ partner in discussions about rehabilitation and reassuring them about activities that are safe.

We found that a lot of the stress after the operation derived from the fact that she was more, more worried about, about what I could do than I was. And she was trying to hold me back all the time whereas I was always trying to go. And one of the benefits of joining the support group is precisely this, that the spouse has a chance to speak to other spouses and see you know, what you can do and what you can’t do and that takes away a lot of the stress of rehabilitation. [. . .] [Dr X] was very instrumental in helping me there. He said to my wife, ‘Look he’s got a body and his body’s going to tell him what he can do and what he can’t do’. And my wife took that on board and it was far easier and then from then on we made jokes about it.

HA09, male, MI in 1995 aged 69 years

A caring, personal and flexible approach

After a MI, people often felt very vulnerable and anxious and needed good nursing care. When they were in hospital, people really appreciated feeling that staff were going out of their way to be kind and considerate

I found the staff excellent, you know they said to me ‘you’ll be up and running in a few days you know’. One nurse, an Irish girl if I may say, was on night duty. They used to come down and see me every night about, I used to be awake half the night, and make me a cup of coffee about 3 o’clock in the morning, and we’d have a chat and things like that. They did make life good for me.

HA06, male, MI in 2003 aged 70 years

It was the very attitude of them [that made me feel secure], you know. They were very, they were very caring and they sort of seemed as if they really understood how you were feeling. And I was grateful for that because it wasn’t all this starchy business you know, it was nice.

HA35, female, MI in 2001 aged 77 years

Myocardial infarction means different things to people depending on their awareness of the condition, their life stage, previous health status and caring and work responsibilities. It was appreciated when health professionals showed an understanding of how MI had affected their life, and were willing to be flexible.

The first night I was taken off the monitors, I was actually in little separate room which was fortunate because I’ve a big family and, [um] they thought it’d be, because they’d a room would be easier if I was in that rather than in a general ward, which was lovely of them because it meant that people could come and go.

HA05, male, MI in 2003 aged 37 years

Timely information in a range of formats

Patients usually wanted to understand why they had experienced a MI, whether or not it was likely to happen again and how they might avoid another. Information was not always forthcoming, and some were reluctant to ask busy hospital staff to answer their questions, or were not sure what to ask. It was helpful when health professionals invited questions, provided clear explanations and checked patients’ understanding. A man who had had two MIs had his questions answered but wondered if nursing staff were sometimes a bit cautious about what information they volunteered.

Rushed as they were, they [cardiac ward nurses] always had time to talk to you about what was going on. They would explain procedures to you. I think you have to ask in some cases, but once you have asked, or once I had asked, they were quite willing to go through and tell you. I think they want to be fairly convinced that you aren’t going to panic or misconstrue what they’re saying, so maybe they’ll be a little bit guarded at first.

HA23, male, MIs in 1991 and 1998 aged 49 and 56 years

One woman suggested that a personalised, written record of what exactly had happened to her in hospital, and why, would have been helpful, as it was difficult for her to take in all the information at the time it was given. Having a personal record to revisit over time might also help patients to adjust to their condition, to develop coping strategies and to explain to family and friends.

It was sometimes helpful for patients to hear about how other people had coped. Information about local support groups and recommendations for websites and other resources were appreciated by patients and their families [see Facilitating difficult conversations (HA09)].

Rapid access to appropriate expertise

Myocardial infarction patients usually have to continue to take medicines after being discharged from hospital, but they were not always sure of the purpose of all of their tablets. It was also sometimes hard for them to distinguish between the side effects of treatment and unfamiliar symptoms. Having a telephone number for a cardiac nurse specialist who could be contacted for prompt advice was much appreciated, especially during the early weeks after the MI when the patient and family may have felt particularly anxious.

Building confidence

Health professionals can play a key role in building patients’ confidence after MI and shaping their expectations for the future. This is likely to influence patients’ motivation to make positive lifestyle changes and furnish them with hope for the future. Seeing a rehabilitation exercise class in action was motivating and reassuring for this man and his wife.

Before I was discharged the physiotherapist took me to the gym downstairs and in the gym there were a number of people doing various exercises and she said they were all ex-patients who had had bypass operations and I was, you know, I was pretty impressed. You know, they were doing, they were jumping up and down and they were doing skipping, and they were doing a mild form of press-ups. A number of fairly strenuous looking things and I thought, oh well it must have been 2 or 3 years since they’ve had their bypass and I asked her about that and she said, turned to one of the chaps and she said ‘How long ago have you had your bypass?’ and he said, ‘Oh, just 6 weeks ago now’. So that was, that was a real eye-opener and again something very positive. And really from that moment on I felt, and my wife, we both felt very positive about the whole thing.

HA09, male, MI in 1995 aged 69 years

Smooth information transfer between health professionals and between services

A few patients felt uncertain as to whether or not information about drugs prescribed in primary care reached hospital consultants and vice versa; patients sometimes felt that they needed to take responsibility to ensure smooth information flow between services, but saw it as a marker of good care when information flow was efficient.

Additional perspectives from patients with asthma

Asthma is a chronic condition, often diagnosed in childhood. Below, we describe aspects of good care identified from our interviews with people diagnosed with asthma in childhood or as adults. While many of the components that we have already discussed, such as being taken seriously by health professionals and being treated with kindness and honesty were, of course, also very important to people with asthma, there were particular perspectives on good care that may be more specific to a chronic health issue. These included having one’s own knowledge and experience in managing the condition recognised.

Clarity about when a definitive diagnosis has been made

Patients’ accounts highlighted the need for clarity about when a definite diagnosis of asthma has been made; for example, patients may be required to use inhalers as part of the diagnostic process and this may be confused with the treatment prescribed following diagnosis.

A diagnosis of asthma can come as a surprise to those adults who think of it as a childhood condition; as a result of that perception, some did not take their diagnosis very seriously.

Clarity about when to seek help in event of an asthma attack

An asthma attack can be very alarming to the patient and those around them; people appreciated clear advice about when would be appropriate to seek help from emergency services. Patients sometimes worried that professionals might think they were not using the services appropriately (e.g. if they did not know how to distinguish between a panic attack and an asthma attack).

Access to out-of-hours emergency services

Patients also needed to feel reassured that, if they did require emergency treatment, they knew what to do and that services would be available at any time of the day or night.

Recognition of the patient’s own knowledge of their condition

Information about how their treatment worked and how it could be stepped up or down enabled patients to take a more active role in the management of their condition. Some GPs were willing to pre-prescribe oral steroids for emergency use, thereby showing trust in the patient’s ability to self-manage. Those who had lived with asthma for many years wanted health professionals to respect their expertise and trust them to know when something is wrong, within the context of a regular review.

Repeating information and demonstrating inhaler techniques

‘Good information’ for asthma patients included explanations about the processes leading to a diagnosis, about how oral steroids work and why it is important to take them consistently, as well as when to report side effects. Patients appreciated the repeated provision of information and health professionals taking the time to explain things well. It was helpful when health professionals ‘showed’ rather than just ‘told’, for example demonstrating good inhaler technique.

Patients wanted guidance from health professionals about which sources of information are reliable. Access to specialist primary care asthma nurses was highly valued by those who had experienced it.

Recognising effect on person’s life and relationships

Some asthma patients felt that health professionals could be too focused on medical management at the expense of providing lifestyle advice. Young people appreciated advice on the impact of asthma on their participation in school sports and how to use inhalers preventatively. For adults, consideration of the emotional impact of a diagnosis of asthma was sometimes particularly important.

Helping to negotiate responsibilities and difficult conversations

People who had been diagnosed as children appreciated help from their doctors and nurses in guiding their parents to accept changed responsibilities as they reached young adulthood and the dynamics between the parent and child shifted.

Some health professionals had provided information about asthma and its treatment to schools, and explained to school staff about safety during sports activities and the need for young people with asthma to be able to access medication. This was much appreciated by young people, who had sometimes found it hard to tackle misunderstandings about asthma among school staff.

Additional perspectives on good care from young people with type 1 diabetes

Our analysis of the aspects of good care that were important to young people with diabetes included further parallels with those identified for MI and asthma and also a few topics that were specific to this condition (see Table 3).

Diabetes is a chronic condition which is largely self-managed by patients. All of the young people in this collection had been diagnosed when they were children or young people aged < 25 years and some had experience of the transition from child services to adult services, which raised particular issues for health care.

Communicating a clear rationale for treatment

Getting detailed and intelligible explanations about the condition and its treatment were seen as prerequisites for assuming responsibility for self-management. While type 1 diabetes is a relatively common, chronic condition, there can be long-term complications, such as the amputation of limbs. Hearing about these can frighten young patients (and their parents) rather than motivating them to look after their health. Communication needs to be clear, honest and consistent without being alarmist.

When treatment regimes needed to change, young people liked the doctor (ideally one they had met before) to explain why this was happening.

Information and peer support

Young people sometimes found it hard to raise topics that they were worried about, especially if they were concerned that the nurses and doctors, or their parents, might disapprove. It was helpful if their doctors or specialist nurses raised topics that may be of concern to a young person (e.g. recreational drugs, smoking, alcohol or weight control), rather than waiting until the young person asked or reached 18 years of age.

Hearing about sportspeople who have diabetes could be helpful in providing role models for young people, as could peer support. Patients valued tips and advice about managing the condition from other young people living with diabetes.

Supporting self-care

Young people who had lived with type 1 diabetes for a while were keen for health professionals to recognise their expertise in managing aspects of their own care.

Young people liked health professionals who recognised that it was sometimes a burden to have to monitor their blood glucose and administer insulin. Some staff seemed to be able to empathise with the frustrations of trying to achieve good glucose control. Young people also valued health professionals who recognised changing preferences for autonomy and involvement in decisions as they were growing up and becoming more independent of their parents.

Approachability and friendliness of staff

Genuine friendliness and empathy are very important to young people, some of whom said that they felt guilty or frustrated when their blood sugar levels were not well controlled. It was also helpful if staff recognised that there might sometimes be a conflicting agenda between the young person and their parent, and helped the young person to steer an appropriate course through potential confrontations.

Rapid access to advice and services

Access to specialist support was important especially in the early stages after diagnosis when the young person (and their parent) was learning how to manage the condition. Unforeseen issues sometimes arose; reassurance and reminders about management strategies were needed during hypoglycaemic attacks, especially the first few times they happened.

Access to a specialist diabetes nurse who they knew (especially if they were in mobile, text and e-mail contact) was often greatly appreciated by young people. This was also very useful when they were away from home, for example when travelling abroad.

Additional perspectives on good care from people with rheumatoid arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis is a condition that affects people very differently, which makes a flexible approach to care, including individual assessment of patients’ information and support needs and tailoring of service level, particularly important. Treatments have changed considerably in recent years, with the result that many patients can now avoid disfiguring damage to joints. People with RA experience pain, stiffness and mobility restrictions, the unpredictable nature of which can cause particular difficulties in their relationships, family, work and social lives. Several of the additional perspectives on good care that we identified from this collection relate to these characteristics of the disease. These perspectives are summarised in relation to the other three conditions in Table 3.

Appropriate use of services and referral

Symptoms were often minor, gradual or non-specific when they began – for example, stiff joints in the morning or painful wrists – and were often initially attributed to sports injuries, chilblains or general ageing. GPs who actively encouraged the patient to come back if the symptoms did not go away, or worsened, were appreciated.

Checking knowledge and expectation of the disease

It was helpful if doctors recognised that patients may have fears about RA based on awareness of older patients who had experienced different treatment regimes. Fear of joint deformity or disability was a common feeling in people diagnosed with RA.

Some patients whose acute symptoms had subsided by the time they saw a rheumatologist found it difficult to accept the chronic and recurring nature of the disease and were reluctant to start treatment.

Treatment explanation and preference diagnosis

Patients with RA emphasised the importance of being involved in decisions about treatments, which might include surgery. A worry for some patients was that when they compared notes with other patients they discovered that different consultants had different treatment preferences.

Patients had different priorities and preferences regarding the acceptability of different types of side effects associated with different drugs (e.g. women of child-bearing age did not want drugs that are contraindicated for pregnancy, but doctors cannot guess whether or not this applies to a particular patient).

Those who did not feel that they knew enough to share decision-making appreciated it when doctors took time to explain the options and rationale, for example why it might be the right time to consider surgery. Several patients felt that surgery was ‘the final resort’ when drug treatments had failed to alleviate problems. It was sometimes difficult for patients to accept the need for surgery when pain or mobility problems were still relatively mild; some sought a second opinion before going ahead with surgery.

Acknowledging uncertainties and understanding the impact of an unpredictable illness

Patients found it reassuring when consultants explained that RA affects people differently and that modern interventions are often successful at preventing joint disfigurement. It was also appreciated when doctors took the time to explain about the variable nature of the disease, acknowledged uncertainties in the diagnostic and treatment process, and reassured patients for whom a suitable treatment might take a little while to identify.

Patients felt that they were being well cared for when health professionals seemed to understand the meaning of RA in the context of their lives. At diagnosis, people were often concerned about how their RA may affect their employment or studies. The unpredictability of RA and the uncertainty about when they might get better has major implications for people of working age, who may need help to explain the nature of RA and its implications.

Signposting to further information and access to peer experiences

People with less secure or manual jobs and those raising young children were particularly worried about their ability to continue supporting their families. Signposting to relevant employment laws, information about assistance at work and available benefits was much appreciated. Information needs and preferences varied, but patients now routinely use the internet for information and appreciate being referred to reliable sites and invited to discuss what they find if they have questions. Support groups and group education sessions were also valued.

Hearing other patients’ experiences of using a drug, in combination with other information about the medicine, helped people to decide whether or not to accept the treatment.

Rapid access to specialist support

When experiencing flare-ups, people with RA have particular information and support needs and require rapid specialist access. However, not all people with RA in the sample had adequate arrangements for this in place. Several people said that they typically received steroid injections from their GP to bridge the time it took to see a consultant who could adjust their medication according to disease activity. In one extreme case, a woman was angry that she had to wait for several weeks for her GP to refer her to her consultant once blood tests had shown increased disease activity, and then had to wait further until that consultation took place to receive the medication she knew she needed all along, despite her symptoms getting worse. This was her third experience of a flare-up.

Several other people reported examples of much more rapid and efficient access systems, for example telephoning a helpline to make a clinic appointment.

Supporting self-care

For health professionals to support patients in self-care, there needed to be mutual trust, as well as sufficient knowledge and confidence on the patients’ side. Patients who had experienced group education sessions found them helpful and particularly valued advice on effective use of painkillers, suggestions for lifestyle changes that might improve their symptoms and finding out about the full range of services available to people with RA. Sessions also provided valued opportunities for peer advice and support.

Summary: sourcing the core components of good health care

After completing the secondary analyses for the four HERG interview collections, the researchers merged the findings and key issues highlighted in the outputs produced for NICE/NCC technical teams. We also mapped the similarities and differences in perspectives of good care on a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA), which was updated as each secondary analysis was completed (see Table 3).