Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 11/1014/04. The contractual start date was in April 2012. The final report began editorial review in June 2013 and was accepted for publication in December 2013. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Gemma Pearce received expenses from the World Stroke Organization to present this research at their international conference. Hilary Pinnock chairs the self-management evidence review group for the British Thoracic Society/Scottish Intercollegiate Guideline Network Asthma Guideline. No other author has any competing interest to declare.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2014. This work was produced by Taylor et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 The brief and overview of the project

This study was formulated in response to the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Services and Delivery Research (HS&DR) commissioning brief (NIHR HS&DR project: 11/1014/04): ‘A rapid synthesis of the evidence on interventions supporting self-management for people with long-term conditions’ (LTCs),1 and took place during 2012 and 2013.

Commissioning brief

The HS&DR brief highlighted that despite the growing interest in supporting self-management for people with LTCs, the ‘huge range of self-care activities’ makes it difficult for decision-makers to identify what works. 2 Some conditions (such as asthma and diabetes) have a reasonable evidence base, whereas other patient groups are relatively overlooked. In addition, the literature on self-management is often condition-specific, making it difficult to generalise from one disease area to another.

The brief called for a single evidence synthesis on key findings on self-management, specifically focusing on the information needs of commissioners to identify effective strategies to support people with LTCs at a population level, and covering:

-

Models of care: who for?

-

At a population level, what models work best and for whom? What is the impact on service use?

-

-

Skill mix: who by?

-

What is the role of specialists, generalists, case managers or peer-led facilitators in providing self-management support?

-

-

Intervention: what?

-

From the broad range of interventions, what works to improve outcomes? What is the role of telehealthcare?

-

-

Delivery of care: how?

-

How should interventions be delivered? How can professionals be motivated to support effective self-management?

-

The brief stated that the completed synthesis should describe the key components of effective programmes to support self-management for people with LTCs, and identify gaps in the existing knowledge base.

The project in relation to the brief

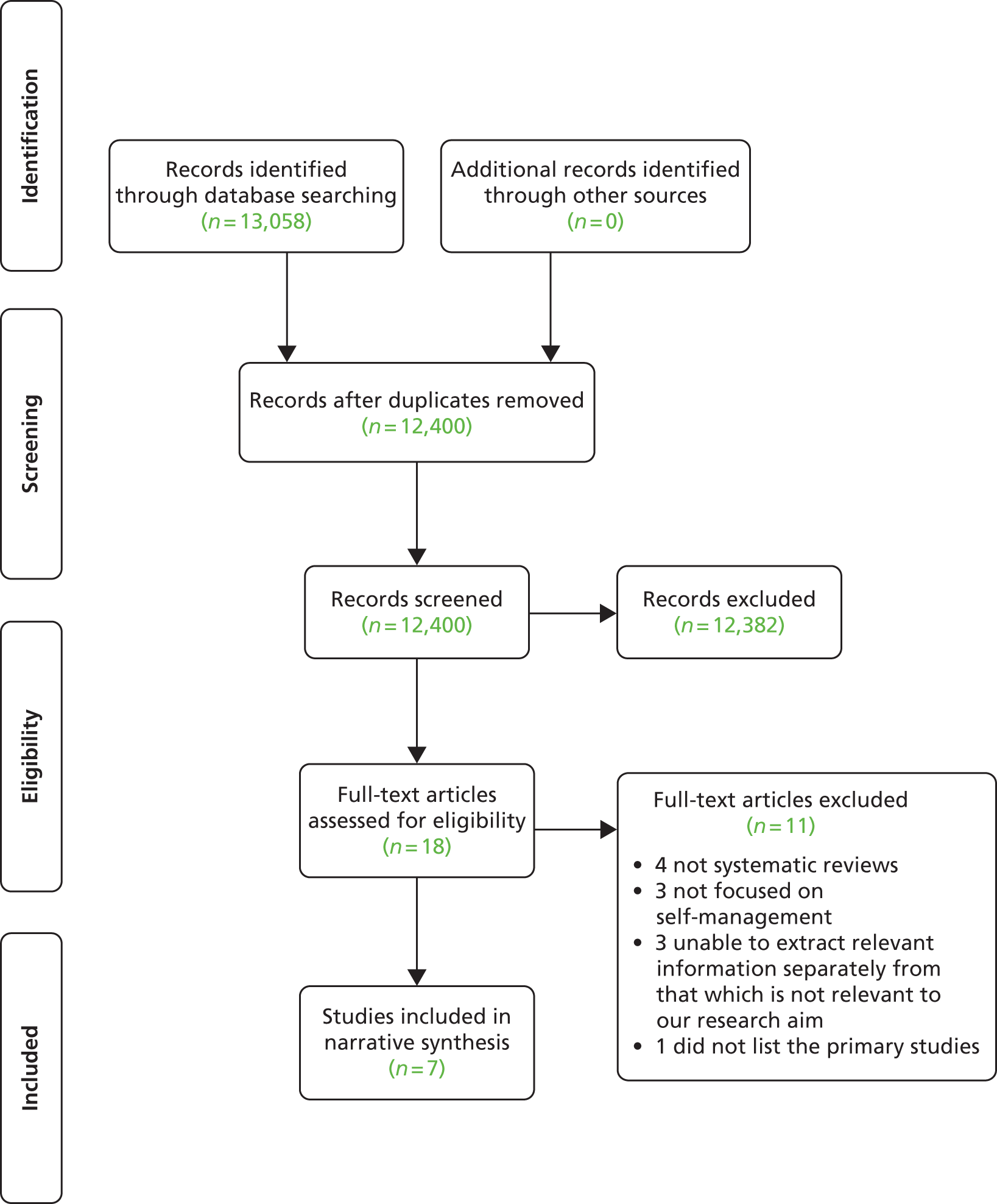

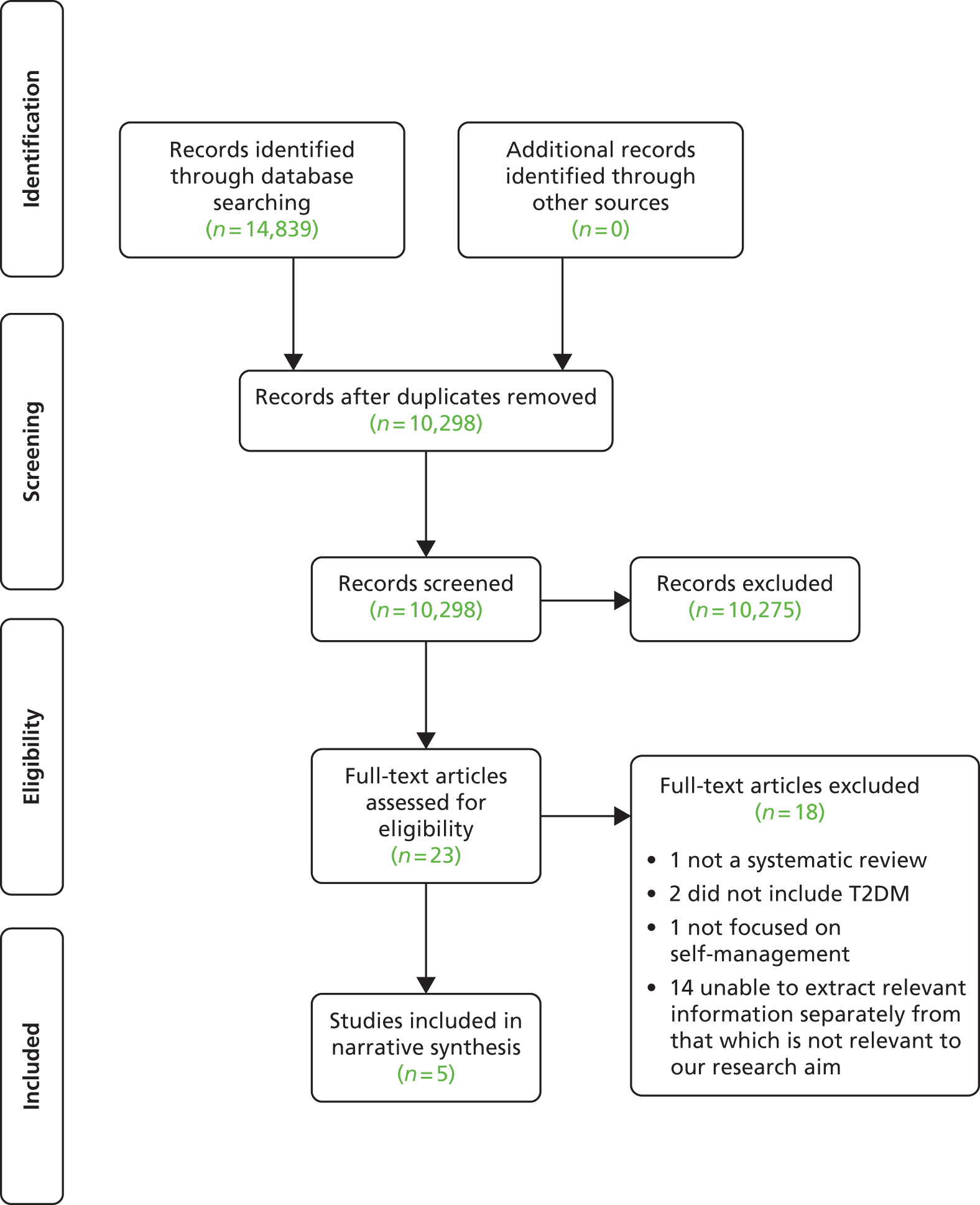

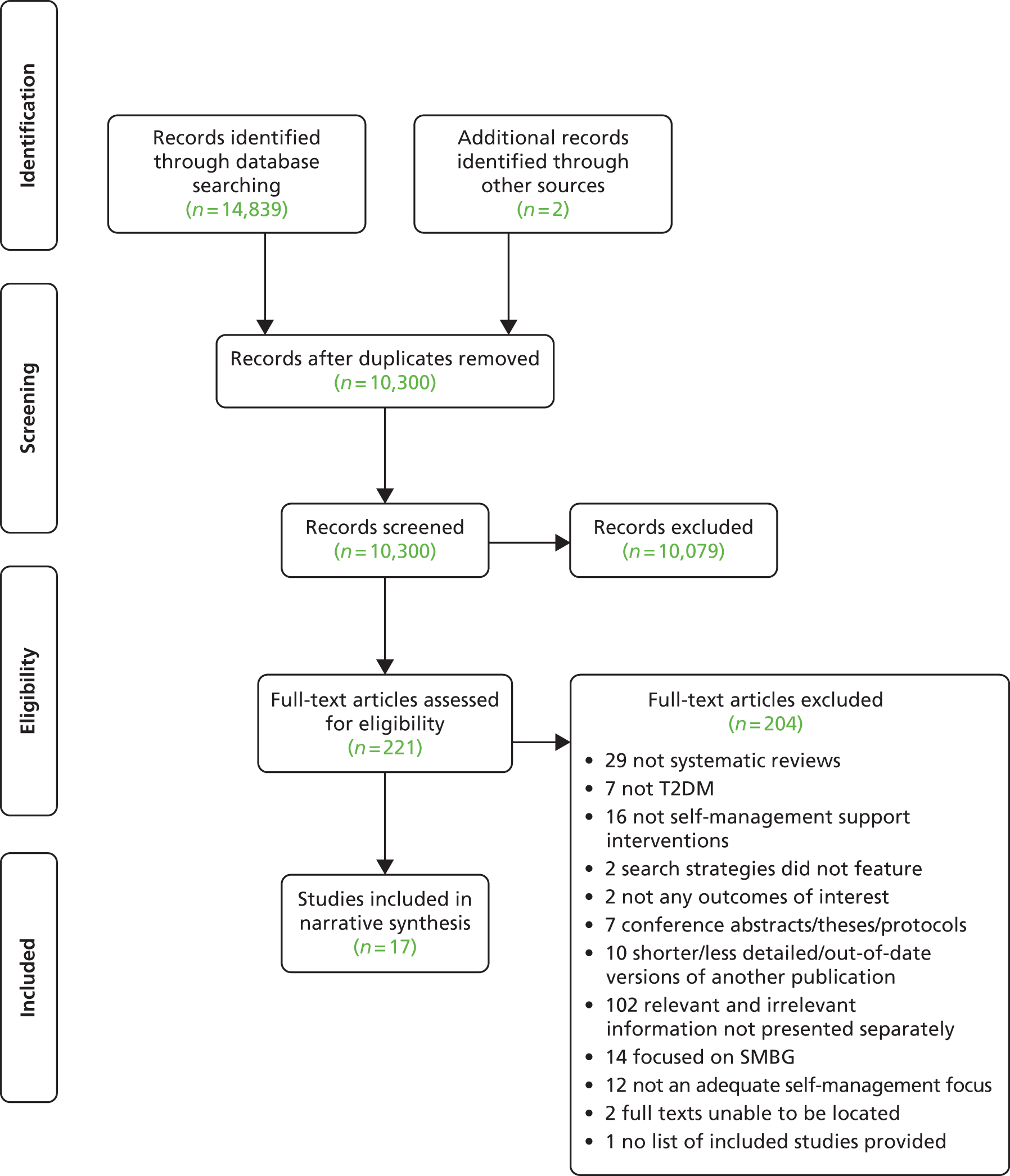

Our systematic overview of self-management support interventions had three phases (Figure 1):

-

Phase 1 involved an External Advisory Group workshop to identify potential components and important characteristics of self-management support interventions (to assist the development of a taxonomy of self-management support interventions), to agree the clusters of LTCs with similar features and to identify the best representative LTCs within each cluster for detailed study in phase 2.

-

Phase 2 involved extracting effectiveness evidence and other relevant evidence from systematic reviews, qualitative syntheses and Phase IV implementation studies on the LTCs identified for detailed study. We then used a series of matrices of LTC clusters and self-management support interventions in an attempt to synthesise the evidence from these sources. Following this, we conducted an overarching narrative synthesis of all this material and developed provisional summaries and recommendations for commissioners.

-

Phase 3 involved a second stakeholder conference at which we presented our findings and recommendations to be discussed and refined by the multidisciplinary delegates.

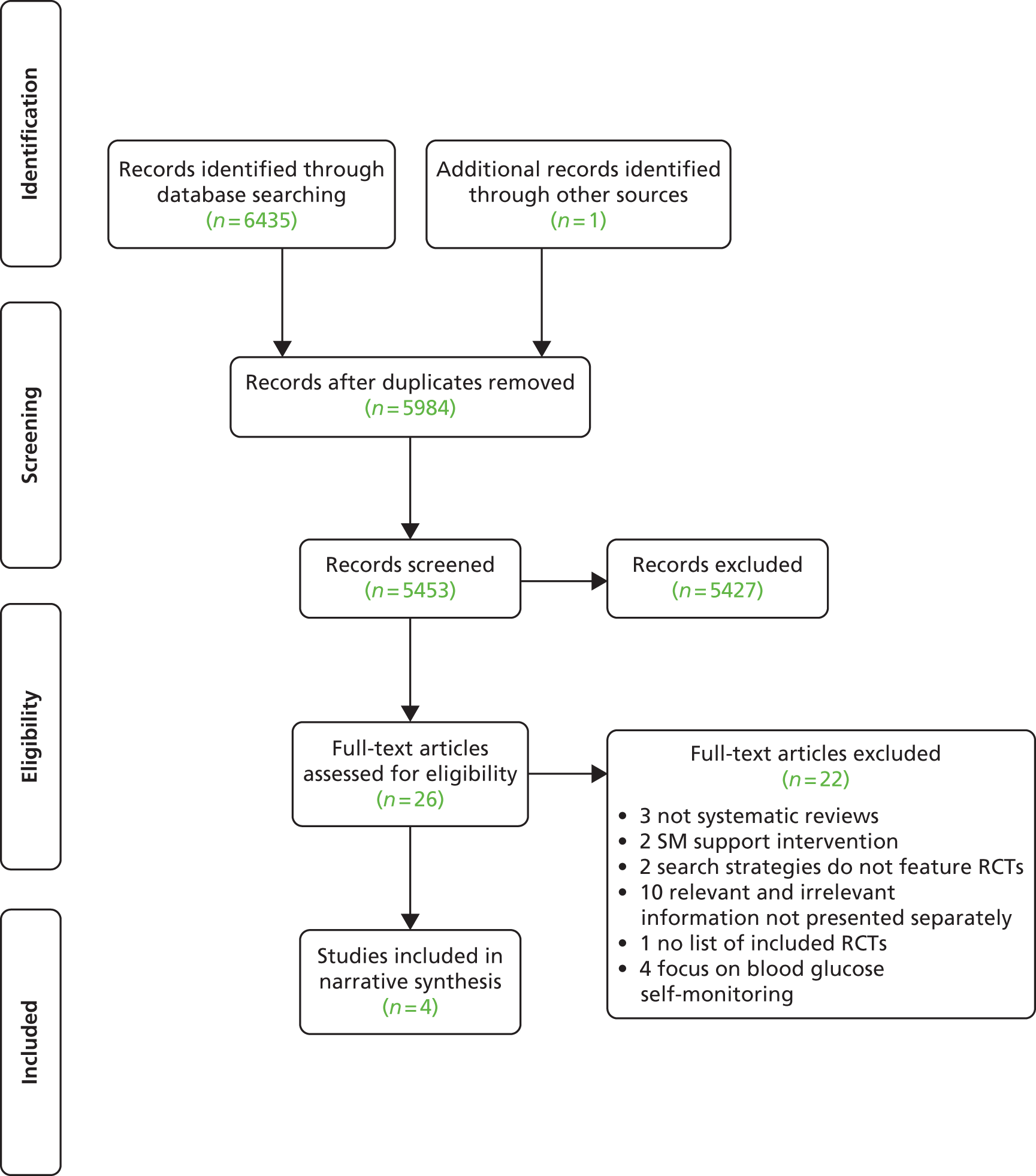

FIGURE 1.

Overview of study design. RCT, randomised controlled trial.

Rationale for changes from the original protocol

Some iterative changes to our original protocol were made during the project; these are described in relation to the original protocol in Table 1.

| Change | Description |

|---|---|

| Taxonomy of self-management interventions (see Chapter 4) | As a result of our preparations for the Expert Advisory Group workshop, it became clear that it would not be feasible to create a taxonomy for self-management interventions at the beginning of this project. We therefore set out to collate a descriptive list of self-management components and features from workshop attendees and the reviews |

| LTCs (see Chapter 4) | It became clear from the first Expert Advisory Group workshop that LTC characteristics should be considered as spectra rather than absolutes enabling more flexible classification. Additionally, the experts at the workshop helped us to pick the LTCs on which to focus our review. Following this we identified four priority LTCs for more in-depth systematic meta-reviews, and an additional 10 LTCs for more rapid and focused systematic meta-reviews |

| Implementation review (see Chapter 21) |

|

| Collaboration with RECURSIVE | We anticipated a high level of collaboration with Professor Peter Bowers and his Reducing Care Utilisation through Self-management Interventions (RECURSIVE) review team. Although we did invite the team to both of the PRISMS workshops, and liaised via regular teleconference, we did not achieve the level of collaboration which we would have liked. This is a result of the time pressures which both teams were under |

Chapter 2 Background

The policy context

As the population ages,3 the prevalence of LTCs is increasing,4,5 resulting in major challenges to the adequate provision of health and social care. 6 Promotion of self-care is a core response of health-care systems globally to this challenge. 7–10

In England and Wales, self-care is promoted by leading health organisations, including The King’s Fund and the Health Foundation,11 as an indispensable component of modern health care. The intense interest in support for self-care, driven by a desire to reduce unscheduled care, shrink costs and improve patient outcomes, has contributed to a plethora of Department of Health (DH) policies and initiatives including the Expert Patients Programme,12 the Quality, Innovation, Productivity and Prevention workstream,13 the whole-system demonstrator telehealth project,14 the annual national Self Care Week,15 NHS Direct,16 NHS Choices (including, for example, a library of downloadable ‘health apps’, see http://apps.nhs.uk/),17 and personalised care planning. 18 Implementation of these initiatives, however, remains patchy or disjointed. 19 Indeed, the Secretary of State for Health regards current systems as inadequate to meet growing burden from LTCs, and called recently for the development of a more proactive approach, definitions and scope of self-management support. 20

The fluidity of terminology in this area21 and the diversity of definitions are symptomatic of the current lack of clarity about what constitutes a clinically effective and cost-effective self-management programme. The diversity of the LTCs that may benefit from self-management, the spectrum of disease severity, and range of professional and lay contexts in which these complex interventions might be delivered, are further challenges to defining self-management.

Self-care and self-management

Although the DH sometimes appears to use the terms ‘self-care’ and ‘self-management’ interchangeably, they are commonly seen as different. In this report we have maintained the distinction adopted by Parsons et al. :22

. . . we give preference to the term ‘self-management’ in order to refer to those actions individuals and others take to mitigate the effects of a long term condition and to maintain the best possible quality of life. ‘Self-care’ refers to a wider set of behaviours which both the healthy and the not so healthy take to prevent the onset of illness or disability, and, again to maintain quality of life.

We have thus adopted the definition of self-management proposed by the US Institute of Medicine. 23

Self-management is defined as the tasks that individuals must undertake to live with one or more chronic conditions. These tasks include having the confidence to deal with medical management, role management and emotional management of their conditions.

This is echoed by the DH who describe their Expert Patients Programme as being ‘based on developing the confidence and motivation of patients to use their own skills and knowledge to take effective control over life with a chronic illness’ and ‘not simply about educating or instructing patients about their condition’. 12

Tasks, skills and self-efficacy

The tasks of medical, role and emotional management were outlined by Corbin and Strauss as the core components of chronic disease self-management. 24 To facilitate these tasks, Lorig and Holman identified five core self-management skills: problem-solving; decision-making; appropriate resource utilisation; forming a partnership with a health-care provider; and taking necessary actions. 25

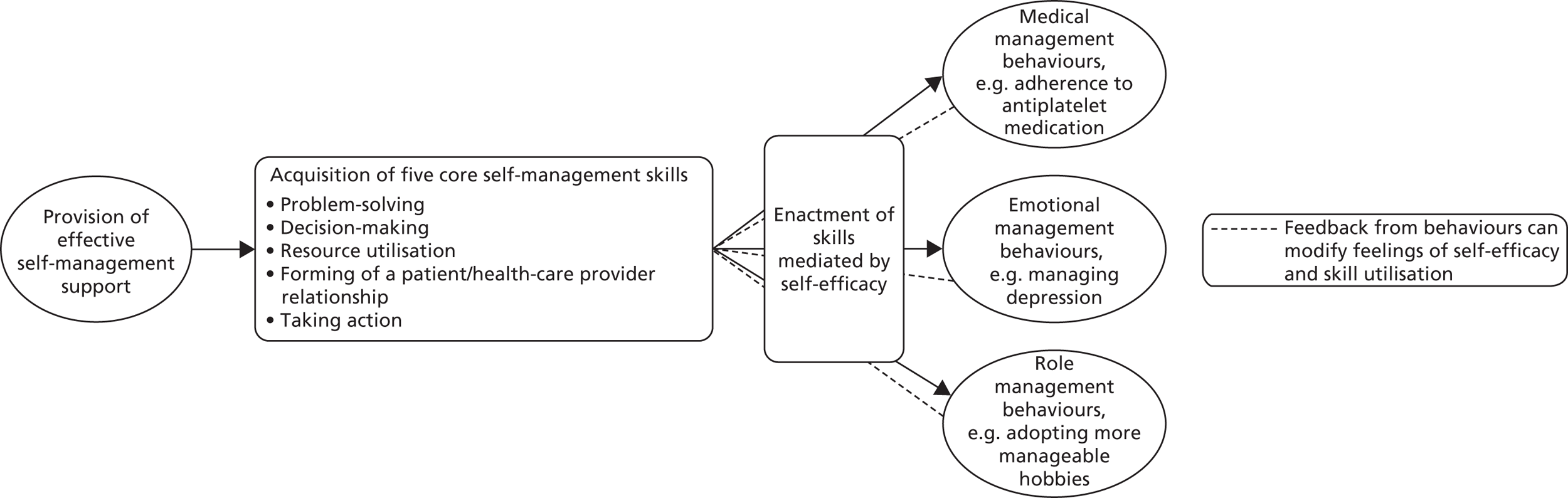

Self-efficacy is commonly viewed as the mediator between the acquisition of self-management skills, and the enactment of self-management behaviours,26 as illustrated in Figure 2. Self-efficacy, one of the core concepts of Bandura’s social–cognitive theory, focuses on increasing an individual’s confidence in their ability to carry out a certain task or behaviour, thereby empowering the individual to self-manage. 27

The range of self-management interventions

Self-management support may range from the provision of disease-specific information via a website or leaflet, to extensive generic programmes such as the Expert Patients Programme which aim to promote behavioural change by building the confidence of individuals to manage their condition and the biopsychosocial effects of LTCs. 12 ‘Personalised Care Planning’ is an ambitious programme involving improved access to, and provision of, information for the 15 million people living with LTCs,28 which emphasises personal involvement and choice in health care (‘no decisions about me without me’). 29,30 A key component of personalised care planning is support for self-management.

Other initiatives include interactive educational projects, complex interventions involving repeated contact with health-care professionals (HCPs) from a variety of disciplines in a range of settings (home, clinic, physician’s office). Telemonitoring for a broad range of LTCs is seen as a means of promoting self-management,31 though the inter-relationship is complex. 32

The inter-relationship between professional and self-management

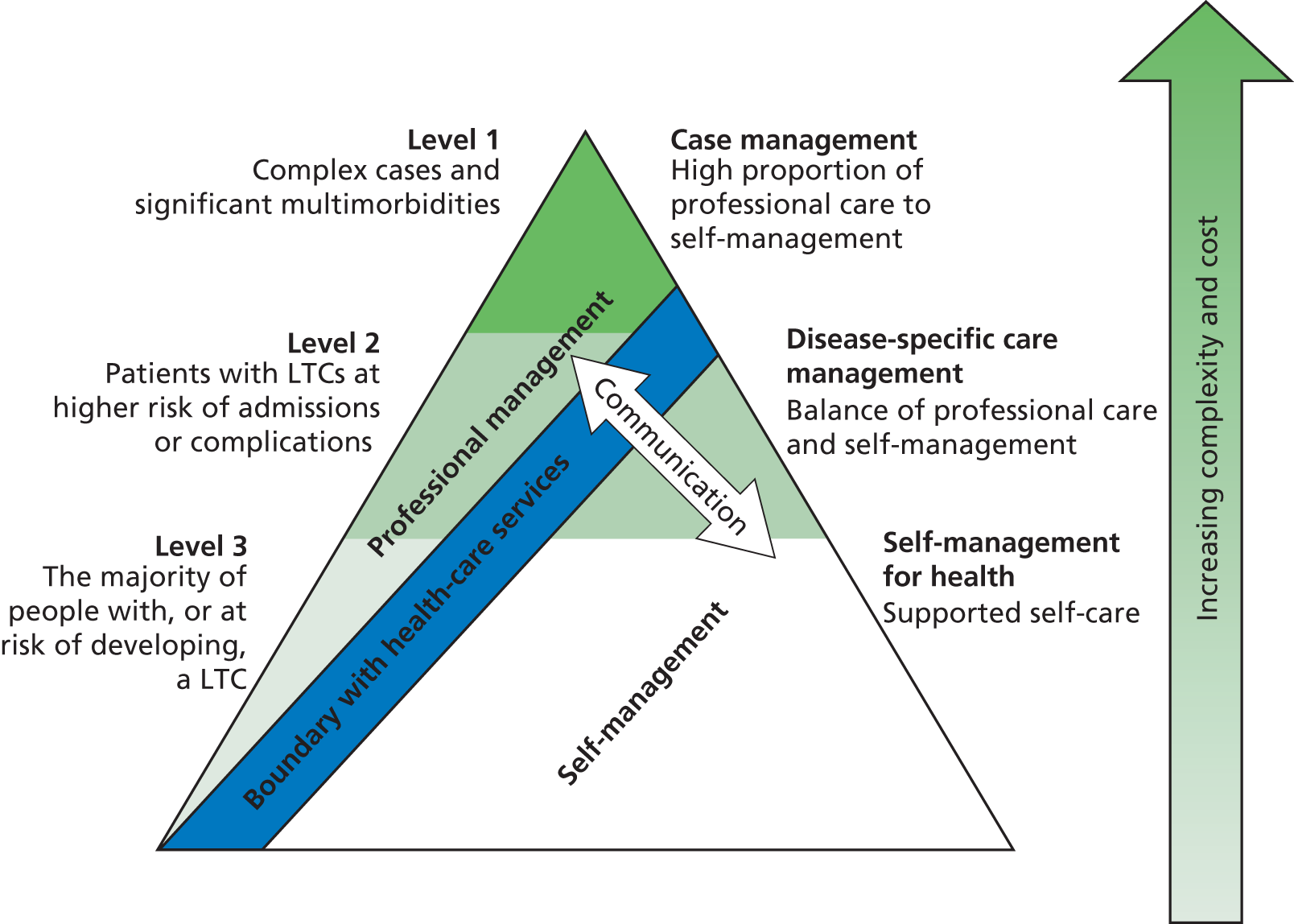

The DH has developed and refined a generic LTC model which stratifies the local population into three levels of need, often depicted using the ‘Kaiser pyramid’ (Figure 3). 33 Level 1 focuses on those with complex needs and accounts for around 5% of people. Level 2 in the middle has a medium level of need (around 25%) and the bottom level represents the 70% of patients with a typically low level of need and well controlled LTCs. The relative importance of self-management compared with professional care at each level has been proposed as low for those with complex problems, and high for those with well-controlled LTCs, with ‘equally shared care’ in the middle level. 34

The inter-relationship at an individual level

Central to our thinking is the concept that patients are de facto responsible for day-to-day lifestyle choices, adhering (or not) to medication advice, monitoring their condition, recognising deterioration and deciding on the action(s) they will take. The role of professionals within the health service is to inform and support the patient so that positive behaviours are enabled and decisions are (clinically) appropriate and enacted with increased confidence.

This is exemplified in the specific context of monitoring by the theoretical model developed by Glasziou et al. 35 that describes the complementary and evolving roles of periodic professional reviews and on-going patient self-monitoring. A newly diagnosed condition is assessed and brought under control with professional support before the patient assumes responsibility for self-management as the stable maintenance phase is established. If symptoms or a physiological measurement subsequently fall outside pre-defined limits, the patient is empowered to act (either by initiating treatment or seeking appropriate professional advice) in order to regain control. Self-management programmes aim to ensure that the patient has the knowledge and confidence to take appropriate and timely action.

A whole-systems approach at population level

Kennedy et al. 36 argue for a whole-systems approach to the provision of effective support for self-care, yet most of the evidence supporting self-management is derived from Medical Research Council Phase III randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of complex interventions delivered to individual patients. 37 Phase IV implementation studies which accommodate the diversity of patient, professional and structural contexts are relatively uncommon. Echoing Kennedy et al. ’s framework, qualitative data in the context of chronic respiratory disease highlight the importance of availability of relevant information for patients and a patient-centred attitude from trusted professionals working within a health-care service. This enables flexible access to professional advice in order to support self-management. 38,39

Commissioning systems to support self-management

The DH estimates that around 15 million people in England (including half of all those aged > 60 years) are living with at least one LTC. 40 There is, however, no definitive list of LTCs, and the potential range of diseases of interest is both extensive and diverse. Commissioners face the daunting challenge of developing commissioning briefs that facilitate the development of services to support self-management across the full range of LTCs. A key goal of our synthesis is therefore to make the task of commissioners easier by summarising the key components of effective programmes to support self-management for people with LTCs.

Chapter 3 Aim and objectives

Aim

To undertake a systematic overview of the evidence on self-management support in people with one or more exemplar LTCs in order to inform commissioners and health-care providers about what works, for whom, in what contexts, how and why.

Objectives

Workshop: phase 1

To agree in discussion with our Expert Advisory Group:

-

a taxonomy of LTCs based on the presence, variability and persistence of symptoms, the risk of exacerbations and the risk of LTCs

-

a taxonomy of self-management support interventions for people with LTCs based on consideration of models of care, skill-mix, components of the intervention and process of delivery of care

-

the selection of exemplar conditions for detailed investigation in phase 2.

Systematic reviews: phase 2

To undertake meta-syntheses of the evidence around interventions for self-management support in the exemplar conditions (for both priority and additional LTCs identified as a result of the workshop) from:

-

published systematic reviews of RCTs

-

syntheses of qualitative studies

-

primary studies specifically concerned with the implementation of interventions in populations with one or more LTCs (i.e. Phase IV implementation trials).

To synthesise these meta-reviews in an overarching narrative synthesis, to determine what is known about their likely effectiveness with respect to health service resource use (including unscheduled use of health-care services and hospital admission rates), health outcomes [including quality of life (QoL), symptoms and biological markers of disease] and equity (including different ethnic populations, minority groups and hard-to-reach groups).

National end-of-project workshop: phase 3

To organise a national, multidisciplinary workshop as a result of the work undertaken in phases 1 and 2. This will enable us to discuss, debate and derive practical recommendations for commissioners and providers seeking to implement effective population level self-management support services for people with a range of LTCs.

To identify research gaps for future primary research or research synthesis.

Chapter 4 Expert Advisory Group workshop

In the first phase of our study we worked with an Expert Advisory Group both to inform our understanding of self-management support for LTCs and to reach consensus on an appropriate focus for our reviews. The three specific objectives of the workshop were to:

-

group LTCs according to characteristics that influence the type of self-management support they might need

-

identify features of self-management support interventions that might reflect these needs

-

select exemplar LTCs for the project reviews.

Preliminary scoping of the literature

We undertook a preliminary scoping of the literature to inform the content and process of the Expert Advisory Group workshop. We obtained national/international clinical guidelines for a range of common LTCs in order to identify whether (or not) self-management interventions were promoted as potentially useful management techniques in that disease area, and any recommendations on component parts of those self-management interventions. The extent and nature of the supporting research evidence were also assessed.

Recruitment of the Expert Advisory Group

We invited a range of stakeholders encompassing a broad range of LTCs to be members of a multidisciplinary Expert Advisory Group. We sent invitations to a total of 83 people (including both representatives of relevant organisations and named individuals) representing a wide range of experts, policy-makers, commissioners, self-management providers, HCPs, academics, patients and people from charities, professionals from the NIHR Service Delivery and Organisation Network (now the NIHR HS&DR Programme Network) and colleagues from the parallel health economics project led by Professor Peter Bower at Manchester University. The experts were invited specifically to contribute to a pre-workshop open round and attend the workshop, but also to attend the end-of-project stakeholder conference.

Pre-workshop open round

In the pre-workshop open round, members of the Expert Advisory Group were invited to complete a survey consisting of three tasks in line with the three workshop objectives (see Appendix 1). Respondents were asked to:

-

list characteristics that they felt should be taken into account when grouping LTCs from the perspective of health-care services seeking to support self-management

-

list components of self-management support they thought should be taken into account when developing services for people with LTCs

-

compile a list of common and/or important LTCs.

We collated the free-text suggestions for characteristics of LTCs and components of self-management support using thematic analysis. Themes were abstracted separately by each member of the team and then discussed as a group. They formed the basis of the introduction to the workshop and the exercises carried out throughout the day.

Workshop methods

The 1-day workshop, held at a central London venue, aimed to reach consensus on the three tasks to inform and direct the subsequent foci of the project (for the agenda see Appendix 2).

Presentations incorporating definitions of key terms, explanations of the rationale and usefulness of each activity and feedback from the pre-workshop survey were used to set the scene for the day and as introductions to each of the tasks. Delegates were then allocated to one of three groups ensuring that each group included members with different professional or lay backgrounds and experiences.

Building on the themes emerging from the pre-workshop open round and in line with the three workshop objectives, delegates were asked to consider from the perspective of commissioners and providers of services:

-

the significance of identified LTC characteristics for the design of services to support self-management and the (lack of) potential for these to be used to cluster LTCs

-

the components of self-management interventions which could be considered for inclusion in services to support self-management and their importance with regard to the proposed clusters of LTCs

-

exemplar LTCs representing the proposed LTC clusters for our review.

Group work was designed to allow participants to provide judgements, discuss, clarify and/or evolve ideas before rating the relative importance of items with a view to moving towards a consensus. The ethos of the workshop was to encourage an iterative process that enabled perceptions to be refined in the light of participants’ diverse views. For example, the specific details of the task for the final session (selection of exemplar LTCs), were not finalised until the outcomes of the earlier discussions (on characteristics of LTCs and components of self-management interventions) were known.

Task one: identification of characteristics of long-term conditions of relevance to the provision of self-management support

-

The LTC characteristics suggested in the pre-workshop open round were presented to the whole group (see Appendix 3).

-

Delegates then completed a score sheet (see Appendix 4) on which they individually rated the importance (one = not important, five = crucially important) of each characteristic in terms of potential relevance to designing services to support self-management. Responses were collated and numerical scores entered onto a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) which calculated the median score for each item.

-

In a 50-minute facilitated group discussion, delegates shared their perceptions of the LTC characteristics suggested during the open round.

-

At the end of the group discussions, the original score sheets, to which the median scores for each LTC characteristic had been added, were returned to delegates. They were then asked to revise their original score in the light of the workshop delegates’ median score and the outcomes of the group discussion.

-

The revised scores were entered onto an Excel spreadsheet and the degree of consensus calculated. Consensus was defined as 60% agreement using a five-point Likert scale, with higher scores representing higher levels of importance. These results were used to inform task three (selection of exemplar LTCs).

Task two: identification of components of self-management support interventions

-

The components of self-management interventions suggested in the pre-workshop open round were presented to the whole group (see Appendix 5).

-

Delegates were asked to form informal groups of between three and six people to complete a worksheet (see Appendix 6). They scored the importance (one = not important, five = crucially important) of self-management components for four different example LTCs (epilepsy, arthritis, dementia and heart failure). The example LTCs were derived from the list suggested in the pre-workshop open round and were selected to reflect a range of LTC characteristics (e.g. potential self-management, variability, complexity and severity of symptoms). A free-text box was provided to highlight any additional components which might be important when developing self-management interventions for people with LTCs.

-

After the workshop, median scores were calculated for the relevance of each component in each of the four conditions: epilepsy, arthritis, dementia and heart failure. The degree of agreement was assessed by counting the proportion with scores of four or five across the four disease areas.

Task three: selection of exemplar long-term conditions

-

The results from task one (characteristics of LTCs) and task two (components of self-management interventions) were presented to the workshop. The LTC characteristics that reached consensus were presented as the agreed ‘primary’ characteristics, with the remaining presented as ‘secondary’ characteristics (see Appendix 7).

-

Working in the same three multidisciplinary groups as the first session, the groups were asked to decide which exemplar LTCs should be used as topics for the systematic overviews. In order to inform discussion, groups were provided with the long list of LTCs suggested in the pre-workshop open round (see Appendix 8). This was annotated with UK prevalence, outline demographics, a brief summary of symptoms and management and an estimate of the extent of the literature on self-management.

-

Delegates were asked to select LTCs that reflected the high and low extremes of the primary characteristic’s continuum. For example, the highest ranking characteristic was ‘potential of (self)-treatment/management (in this chapter shortened to self-management) to improve symptoms’. Groups were asked to identify LTCs which stood to gain substantial benefit from self-management, and those where benefits might be limited. Factors to consider when deciding which LTCs to select included the burden of disease and the availability of evidence for that LTC.

-

Initially, group facilitators attempted to gain consensus on between three and five LTCs which could represent each end of the spectrum for the primary characteristics. Once this task was completed, the groups considered if they could allocate their selected LTCs to populate the spectra for any/all of the secondary LTC characteristics.

Results

Response rate

The pre-workshop open round was completed by 19 out of the 83 invited (23%) people, 14 of whom attended the workshop. A total of 27 (33%) delegates attended the conference, encompassing health-care managers, commissioners, policy-makers, patients and HCPs (Table 2).

| Sector | Role of delegatea | LTC(s) represented |

|---|---|---|

| Policy-makers | Head of Respiratory, Diabetes, Liver and Kidney Programmes, DH | Asthma, COPD, diabetes, chronic liver disease, CKD |

| DH | All | |

| Commissioner | Director of Public Health, NHS East London and The City Alliance | All |

| Self-management providers | (Clinician) Clinical Lead for the Year of Care project | Diabetes |

| (Social Enterprise Organisation) Social Action for Health | All | |

| Self-management support providers | (Training of HCPs) Education for Health | All |

| Chairman, Expert Patients Programme Community Interest Company | All | |

| Patients | Patient | Not supplied |

| Patient representative | Not supplied | |

| Professional stakeholder | Professional stakeholder | Not supplied |

| PPI expertise/HCP | PPI in Research Advisor, RCN | All |

| Voluntary sector | Service Improvement Manager, Diabetes UK | Diabetes |

| Chef Executive, The Stroke Association | Stroke | |

| Head of Research, British Lung Foundation | Asthma, COPD | |

| Social enterprise | Tuke Institute | All |

| HCP | LTC Adviser, RCN | All |

| Academic/HCP | Professor of Clinical Diabetes, Director of Research and Development | Diabetes |

| Academics | Project Manager, Irish College of General Practitioners | All |

| Senior Research Analyst, Social Care Institute for Excellence | All | |

| Senior Research Fellow, Applied Research Centre in Health and Lifestyle Interventions | All | |

| Senior Lecturer in Health Policy Research, QMUL | All | |

| Senior Lecturer, Medical Sociology, QMUL | All | |

| Health Foundation Self-Management Support Fellow | All | |

| Reader, NPCRDC, University of Manchester | All | |

| Senior Research Fellow, NPCRDC, University of Manchester | All | |

| Senior Research Fellow, QMUL | All | |

| Research Assistant, QMUL | All |

Results of task one: identification of the long-term conditions characteristics of relevance to the provision of self-management support

Pre-workshop open round

The characteristics of LTCs suggested by respondents during the open round as important considerations when developing services to support self-management were grouped thematically into 16 characteristics (Table 3). For the workshop we listed each characteristic across a spectrum to illustrate how they might be expressed to very different extents in different conditions. We also included delegates’ comments from the pre-workshop exercise to aid understanding and illustrate the different perspectives on the characteristics (see Appendix 3).

| Themes | Subthemes |

|---|---|

| Presence or absence of ongoing symptoms |

|

| Impact of symptoms on lifestyle |

|

| Risk of future progression/mortality necessitating self-monitoring |

|

| Risk of significant complications or comorbidity needing self-monitoring |

|

| Significant variability/risk of (serious/high-cost) exacerbations |

|

| Potential of self-management to improve symptoms |

|

| Potential of self-management to be disease modifying |

|

| Impact on ability to self-manage and/or requiring significant assistance from (informal) carers |

|

| Who provides care: predominantly self-management or reliant on professional input |

|

| Degree of complexity of medical/clinical/social/lifestyle self-management regimes |

|

| Genetics/familial nature of condition |

|

| Age at onset |

|

| Presence of comorbidities (including depression) |

|

| Stigma/social class/medically unexplained symptoms |

|

| Prevalence (burden to health-care system/society) |

|

| Evidence base/existing tools/skills required |

|

Consensus process

Following discussion and two rounds of scoring, consensus was reached for two characteristics: ‘the potential of self-management to improve symptoms’ and ‘the impact of symptoms on lifestyle’ (Table 4). There was then a substantial gap before a group of characteristics scoring 24–34% agreement. Many of these scored highly when the data were reanalysed using consensus for scores of four or five (see final column in Table 4). Two were particularly poorly scored: ‘the age at onset’, and ‘the genetics/familial nature of condition’.

| Characteristic | Spectrum | Proportion (%) awarded a score of five | Proportion (%) awarded scores of four or five | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Achieved pre-defined consensus | |||||

| Potential of self-management to improve symptoms | Very effective treatment | ← → | Limited benefit | 72 | 90 |

| Impact of symptoms on lifestyle | Normal activities (including work) | ← → | Severely limited (including housebound) | 62 | 90 |

| Did not achieve pre-defined consensus | |||||

| Significant variability/risk of (serious/high cost) exacerbations | Highly variable | ← → | Minimal variability | 34 | 79 |

| Degree of complexity of clinical/social/lifestyle self-management regimes | Simple tasks | ← → | Complex daily regimes | 34 | 66 |

| Risk of significant complications or comorbidity necessitating self-monitoring | Unlikely/not serious | ← → | Likely/significant | 31 | 93 |

| Presence of comorbidities (including depression) | No comorbid conditions | ← → | Significant comorbidity | 31 | 86 |

| Potential of treatment/self-management to modify disease | Very effective treatment | ← → | Limited benefit | 31 | 83 |

| Prevalence (burden to health-care system/society) | Common condition | ← → | Rare condition | 31 | 72 |

| Risk of future progression/mortality necessitating self-monitoring | Unlikely/not serious | ← → | Common/potentially fatal | 28 | 79 |

| Who provides care: predominantly self-management or reliant on professional input | Largely self-care | ← → | High level of professional care | 28 | 66 |

| Impact on ability to self-manage and/or requiring assistance from (informal) carers | Self-caring | ← → | Highly dependent | 25 | 79 |

| Presence or absence of ongoing symptoms | Asymptomatic | ← → | Persistent symptoms | 24 | 76 |

| Evidence base/existing tools/skills required | No evidence about self-management | ← → | Extensive evidence base | 14 | 76 |

| Stigma/social class/medically unexplained symptoms | No stigma/inequity issues | ← → | Stigma | 14 | 59 |

| Age at onset | Onset in childhood | ← → | Onset as adult | 7 | 28 |

| Genetics/familial nature of condition | No significant familial component | ← → | Clear genetic condition | 3 | 17 |

Results of task two: prioritisation of components of self-management support interventions

Pre-workshop open round

Potential components of self-management support suggested by the respondents as important to the open round were collated and analysed thematically into 10 categories (Table 5; for respondents’ verbatim comments see Appendix 5). We recognised that the respondents had in fact suggested both components and features of self-management support intervention in this exercise.

| Themes | Subthemes |

|---|---|

| Training and education |

|

| Access to information | |

| Monitoring |

|

| Environmental adaptations | |

| Care planning | |

| Access to specialist team | |

| Emotional/social/psychological support |

|

| Users having financial control |

|

| Large-scale public initiatives |

In addition, respondents also highlighted the importance of considering the following features of a self-management support intervention: patient centredness, complexity, multidisciplinary approach, disruption to the individual, involvement of carer/families, generic/disease-specific, duration, accessibility, integrated care and monitoring of outcomes.

Workshop exercise

The components of self-management support interventions considered by the delegates as most important with a median score of five (highest priority) for all four diseases were ‘training and education’; ‘access to information’ and the overarching characteristic of ‘patient centredness’ (Table 6).

| Component of self-management support interventions | Epilepsy | Arthritis | Dementia | Heart failure | Total with median score four or five |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Training and education | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 |

| Access to information | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 |

| Patient centredness | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 |

| Care planning | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 |

| Emotional/social/psychological support | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 |

| Accessibility | 5 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4 |

| Involvement of carers/family | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 4 |

| Integration into mainstream health care | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 4 |

| Duration | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Generic/disease-specific | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Access to specialist team | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 |

| Multidisciplinarity | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 |

| Environmental adaptations | 2 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 2 |

| Monitoring | 4 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 2 |

| Users having financial control | 2 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 1 |

| Large-scale public health initiatives | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 1 |

| Complexity | 2 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 1 |

| Disruption to individual | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 0 |

| Financial incentives | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

Results of task three: selection of exemplar long-term conditions

A list of over 100 LTCs was compiled during the pre-workshop open round (see Appendix 9). Using the characteristics identified in the first workshop exercise, delegates allocated potential exemplar LTCs to these characteristics.

The LTCs highlighted by the three groups as exemplar conditions for the meta-reviews and implementation systematic review were asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), chronic kidney disease (CKD), dementia, depression, epilepsy, hypertension, inflammatory arthropathies (IAs) [rheumatoid arthritis (RA), psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)], irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), low back pain (LBP), progressive neurological disorders (PNDs) [motor neurone disease (MND), multiple sclerosis (MS) and Parkinson’s disease (PD)], stroke, type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM).

Conclusions from the workshop

Final decision on the exemplar long-term conditions with selection of four priority conditions

The team reviewed the recommendations of the three groups, taking into account:

-

the frequency with which they were suggested by the groups (e.g. asthma was suggested by all three groups)

-

the extent of the evidence base for each LTC identified in our scoping of the literature

-

the potential of individual LTCs to represent a number of the characteristics of LTCs (e.g. asthma was not only applicable to the spectrum ‘potential of (self)-treatment/management to improve symptoms’ as a condition with ‘very effective treatment’, but was also ‘highly variable’, ‘common’ and ‘largely self-caring’) (see Table 4)

-

where possible, the advantage of ensuring a range of LTCs from various disease areas.

In this way a final list of four priority LTCs was derived and used to inform the ‘priority meta-reviews’ (stroke, T2DM, asthma and depression). Table 7 maps the LTCs to the two LTC characteristics that reached consensus, and the next five highest scoring characteristics, all of which are presented as spectra. We recognise that our positioning of conditions on these spectra is subjective and that at different stages in the natural history of some LTCs they might be placed at different positions on the spectra. We carried out a slightly simplified version of the meta-reviews, ‘additional reviews’, to test our emerging themes by examining the literature from the other 10 highlighted disease areas [COPD, CKD, dementia, epilepsy, hypertension, IAs, IBS, LBP, PNDs (MND, MS and PD) and T1DM]. The implementation review covers all 14 LTCs.

| Low ◄––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––► high | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stroke | T2DM | Epilepsy | Depression | T1DM |

| Dementia | CKD | IAs | IBS | Asthma |

| PNDs | COPD | LBP | ||

| Hypertension | ||||

| Low ◄––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––► high | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypertension | T2DM | Epilepsy | IAs | Dementia |

| CKD | Asthma | IBS | Stroke | |

| LBP | PNDs | |||

| T1DM | COPD | |||

| Depression | ||||

| Low ◄––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––► high | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stroke | T2DM | IBS | Epilepsy | COPD |

| Dementia | CKD | IAs | Depression | Asthma |

| PNDs | LBP | T1DM | ||

| Hypertension | ||||

| Low ◄–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––► high | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypertension | CKD | IBS | IAs | T1DM |

| Epilepsy | Stroke | T2DM | ||

| LBP | Dementia | PNDs | ||

| Depression | COPD | |||

| Asthma | ||||

| Low ◄–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––► high | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stroke | Depression | CKD | IAs | T1DM |

| IBS | Epilepsy | PNDs | Hypertension | T2DM |

| Dementia | LBP | Asthma | COPD | |

| Low ◄–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––► high | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epilepsy | Depression | CKD | Stroke | COPD |

| Asthma | Hypertension | LBP | T1DM | T2DM |

| PNDs | IBS | Dementia | ||

| IAs | ||||

| Low ◄–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––► high | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epilepsy | Hypertension | LBP | T1DM | T2DM |

| Stroke | IBS | Depression | Asthma | IAs |

| PNDs | Dementia | COPD | CKD | |

Components of self-management support interventions

The components and features of self-management support interventions suggested by the respondents were incorporated in our search strategies for all of the reviews, and the components contributed to our proposed taxonomy of components of self-management support interventions which was used in the final overarching synthesis. We revisited some of the proposed features of self-management support interventions when considering the results of our meta-reviews and our implementation review.

Chapter 5 Methods

We undertook a systematic overview of the evidence related to self-management support in the exemplar LTCs. Papers identified through a common search strategy were analysed in three parallel streams.

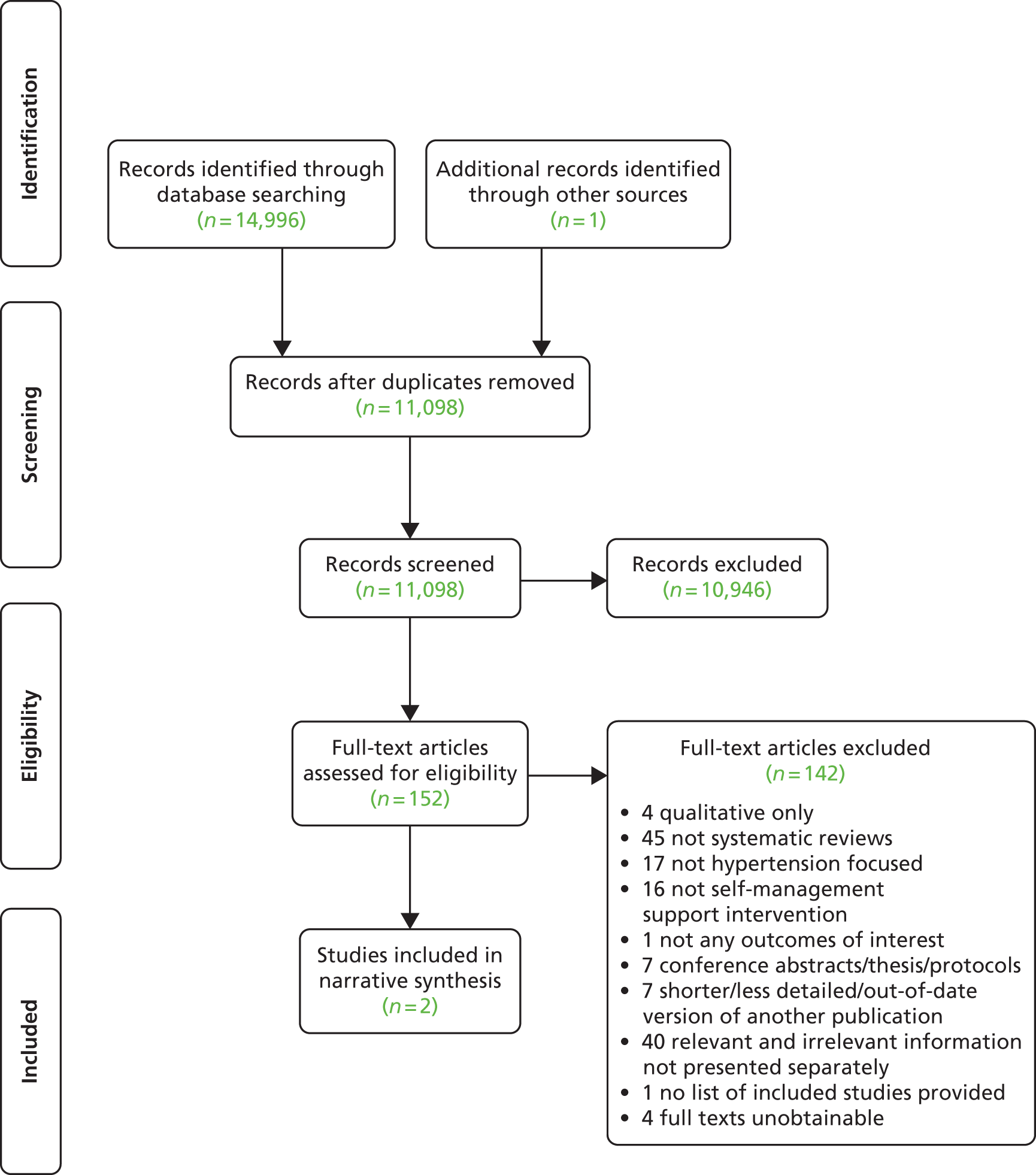

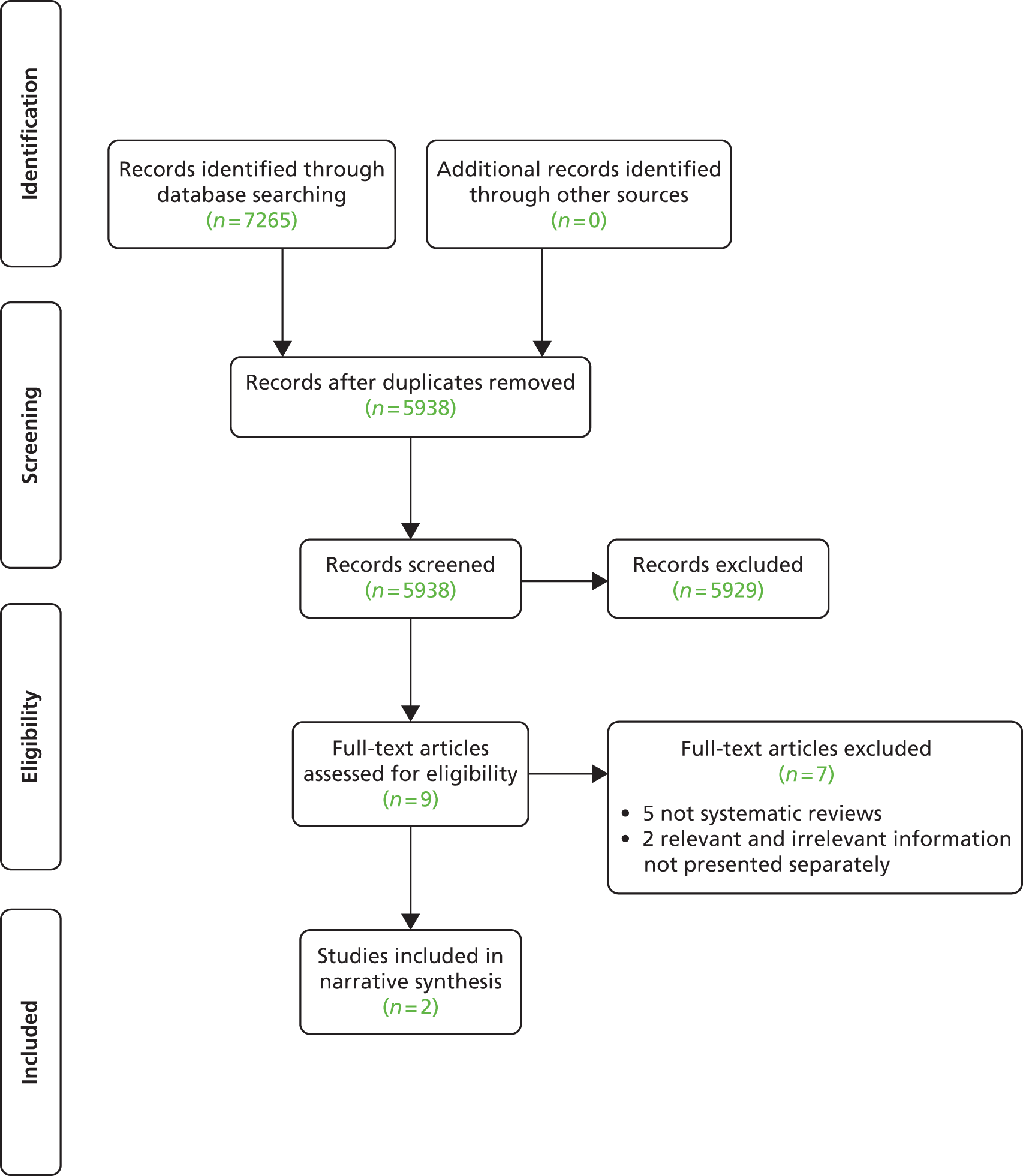

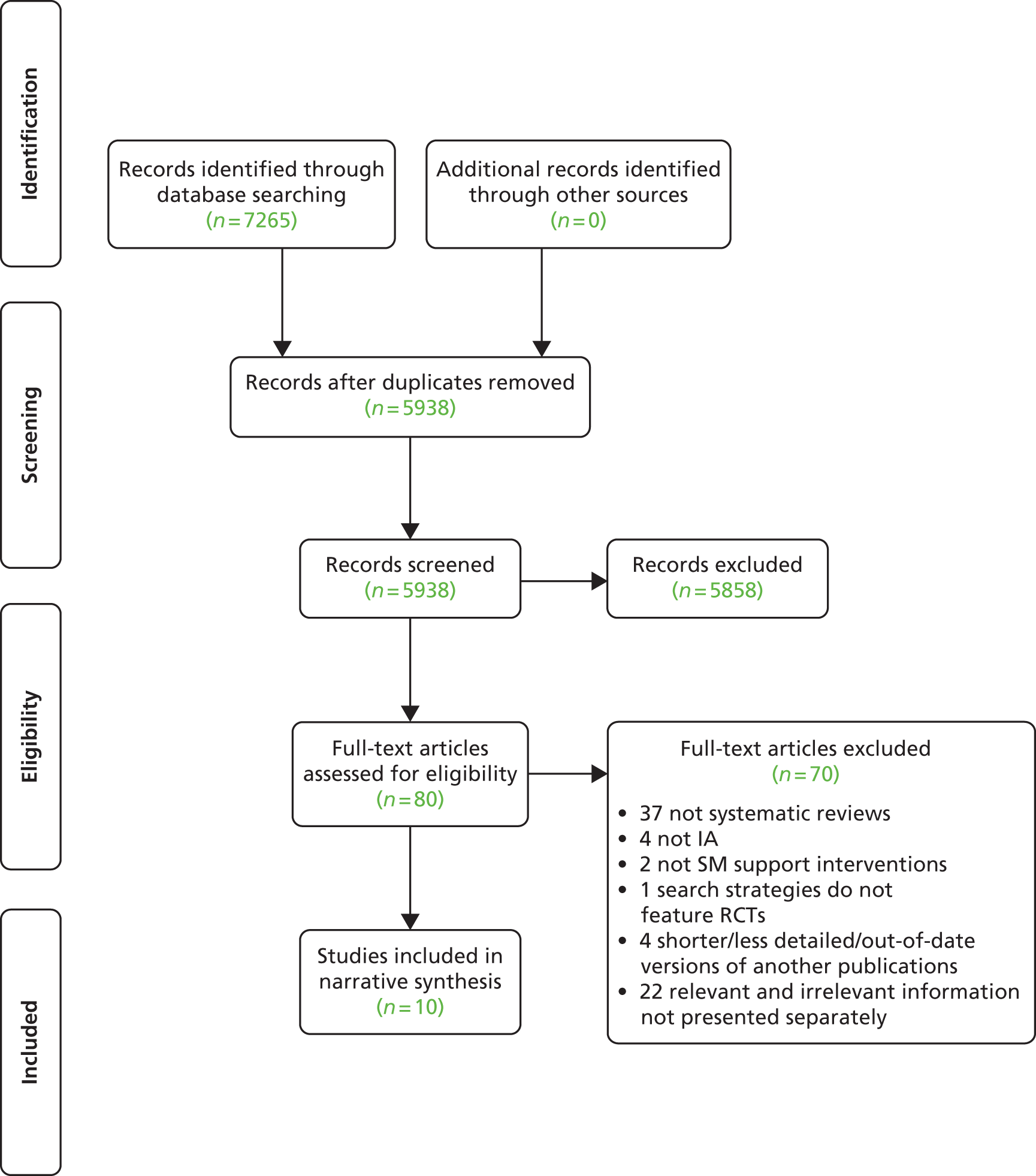

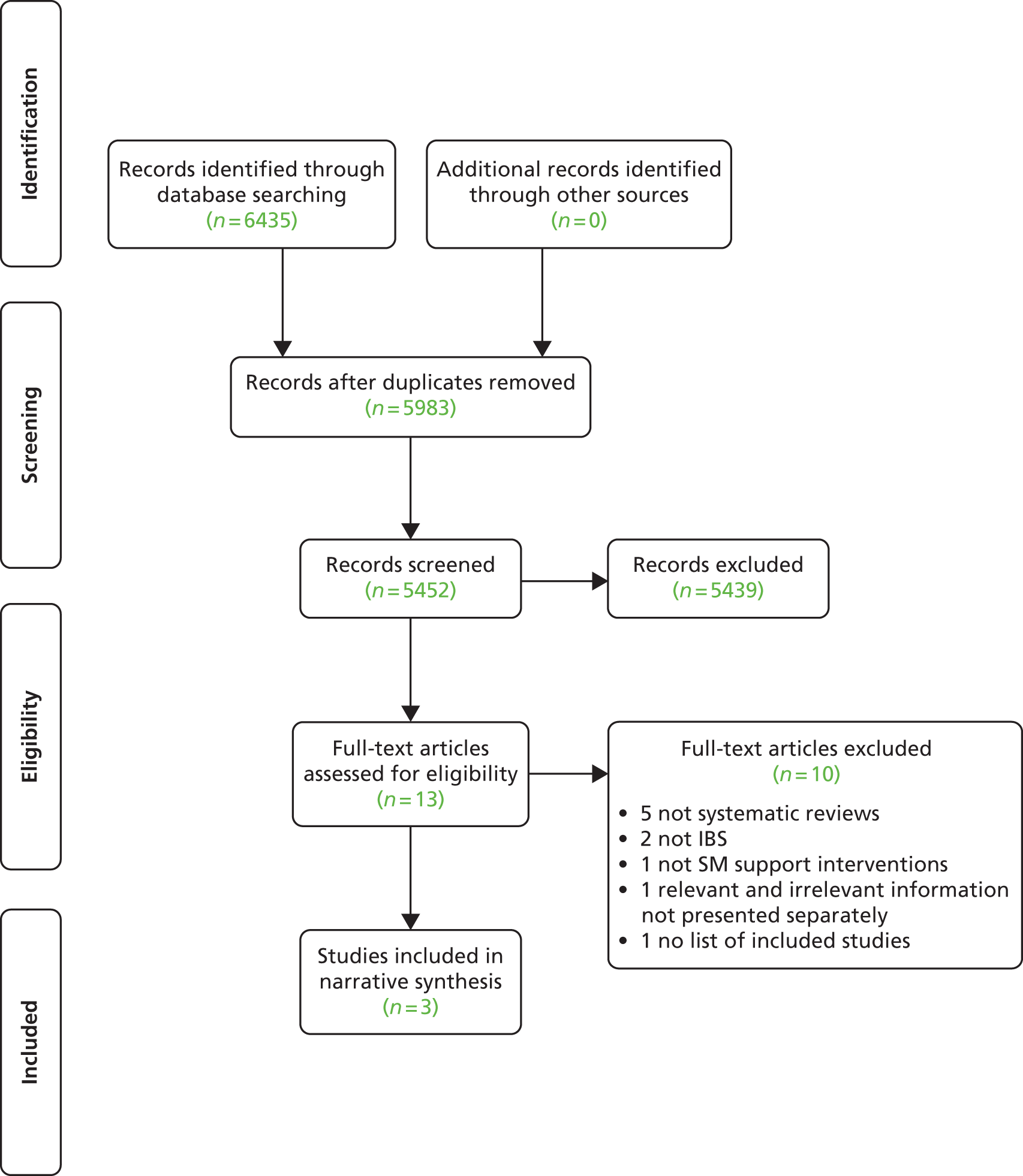

Priority meta-reviews Includes two types: quantitative and qualitative meta-reviews. A quantitative meta-review is an overview of systematic reviews of RCTs. A qualitative meta-review is an overview of systematic syntheses of qualitative studies. These were carried out for the four LTCs identified as priority conditions (stroke, T2DM, asthma and depression).

Additional meta-reviews Simplified versions of the quantitative and qualitative meta-reviews for the remaining 10 conditions (COPD, CKD, dementia, epilepsy, hypertension, IAs, IBS, LBP, PNDs and T1DM).

Implementation review Systematic review of Phase IV implementation studies for all 14 exemplar conditions.

Our overarching analysis synthesised the findings of all the above streams into the spectra of LTC characteristics produced in the Expert Advisory Group workshop (see Chapter 23). Additionally, the self-management components identified in the initial workshop were developed into a taxonomy of self-management interventions based on the evidence collated from the existing literature, the two Expert Advisory Group workshops and the Practical Reviews of Self-Management Support (PRISMS) reviews (see Chapter 6).

We adapted established systematic review and qualitative synthesis methodology for the quantitative and qualitative meta-reviews41,42 and the systematic implementation review. 43 The protocol for the systematic implementation review was registered with PROSPERO (registration number: CRD42012002898). Meta-reviews cannot be registered with PROSPERO but all the protocols are available on the PRISMS website (http://blizard.qmul.ac.uk/research-generation/609-prisms.html).

Search strategy

Search strategy and databases

The priority meta-reviews used a tailored ‘PICOS’ (patients/population; intervention; comparison; outcome; setting) search strategy43 (Table 8). Our basic search strategy was: ‘self-management support’ and ‘LTC’ and ‘systematic review’ terms. Self-management support search terms included ‘confidence’, ‘self-efficacy’, ‘responsib*’, ‘autonom*’, ‘educat*’, ‘knowledge’, ‘(peer or patient) ADJ1 (support or group)’ and ‘(lifestyle or occupational) ADJ1 (intervention* or modification* or therapy)’ as well as relevant medical subject heading (MeSH) terms (see Appendix 10 for the full search strategy). The additional meta-reviews had a simplified version of this search strategy (see Appendix 11).

| Priority meta-reviews | Additional meta-reviews | Implementation review | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quantitative | Qualitative | Quantitative | Qualitative | ||

| Population | Priority exemplar LTCs: stroke, T2DM, asthma and depression | Additional exemplar LTCs: COPD, CKD, dementia, epilepsy, hypertension, IAs, IBS, LBP, PNDs and T1DM | All 14 exemplar LTCs | ||

| Studies were included if self-management support was delivered to populations with one or more of the exemplar LTCs. Generic self-management support was included if one or more of the exemplar LTCs were specified and subgroup data for that condition was provided. As appropriate, we included adults and/or children, ethnic minorities and groups who were perceived as finding services ‘hard to reach’ | |||||

| Intervention | We were interested in any systematic review which focused on, or incorporated, strategies to support self-management | We were interested in any qualitative primary studies that either informed or provided feedback for interventions which focused on, or incorporated, strategies to support self-management | We were interested in any systematic review which focused on, or incorporated, strategies to support self-management | We were interested in any qualitative primary studies that either informed or provided feedback for interventions which focused on, or incorporated, strategies to support self-management | We were interested in any Phase IV implementation intervention which focused on, or incorporated, strategies to support self-management, and which were delivered as part of routine clinical service |

| Comparator | Typically ‘usual care’. The nature of the control service was noted and accommodated within our analysis, but papers were not excluded on this basis | N/A | Typically ‘usual care’. The nature of the control service was noted and accommodated within our analysis, but papers were not excluded on this basis | N/A | Typically ‘usual care’, though definition of ‘usual care’ will vary between trials. The nature of control service was noted and accommodated within our analysis |

| Outcomes | Use of health-care services (including unscheduled use of health-care services and hospital admission rates), health outcomes (including biological markers of disease), symptoms, health behaviour, QoL or self-efficacy | N/A | The reviews’ primary outcome (if supplied), use of health-care services (if supplied), and the two most important health outcomes for each condition (usually a disease-specific outcome, and a measure of patient experience or process outcome) | N/A | Use of health-care services (including unscheduled use of health-care services and hospital admission rates), health outcomes (including biological markers of disease), symptoms, health behaviour, QoL or self-efficacy |

| Settings | Any health-care setting: hospital (inpatient or outpatient), community or remote (e.g. web-based) settings | ||||

| Study design | Systematic reviews which had explicitly searched for RCTs. To be classified as a systematic review the following must be present:

|

Systematic reviews which had explicitly searched for qualitative primary studies | Systematic reviews which had explicitly searched for RCTs. To be classified as a systematic review the following must be present:

|

Systematic reviews which had explicitly searched for qualitative primary studies | Phase IV implementation studies. Where possible, we prioritised cluster randomised trials, quasi-experimental studies, interrupted time series, case–control, controlled before-and-after studies. If these more robust designs were not available, we included uncontrolled before-and-after studies and observational studies |

For the implementation review we used the same self-management and LTC search terms used in the priority meta-reviews along with implementation design terms, i.e. ‘real world’, ‘routine clinical care’, ‘Phase IV’ (see Appendix 12). For the implementation review we also completed a search for unpublished and in-progress studies using general self-management terms.

For the priority and additional meta-reviews, database searches commenced in 1993 (the year in which The Cochrane Collaboration was established; this marked the widespread initiation of high-quality systematic reviews). The end dates of the searches are given in Table 9. No limits in publication year were applied for the implementation review. We searched nine databases for the priority meta-reviews and eight for the implementation review (see Table 9). For reasons of efficiency in the additional meta-reviews, we selected the two databases with the highest sensitivity and specificity (see Appendix 11 for details of the rationale for this decision). Snowball searches and manual searches were applied in all reviews. Forward citation searches were also run for the implementation review and the priority meta-reviews, but not for the additional meta-reviews because of their rapid methodology.

| Priority meta-reviews | Additional meta-reviews | Implementation review | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quantitative | Qualitative | Quantitative | Qualitative | ||

| Databases | MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, PsycINFO, AMED, BNI, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects and ISI Proceedings (Web of Science) | MEDLINE, CINAHL, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects | MEDLINE (1980 onwards), EMBASE (1974 onwards), CINAHL (1982 onwards), PsycINFO, AMED (1985 onwards), BNI, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects and ISI Proceedings (Web of Science) | ||

| Dates | All from January 1993 Stroke to June 2012 Asthma to July 2012 T2DM to August 2012 Depression to October 2012 |

All from January 1993 COPD, CKD, dementia, epilepsy, IBS, LBP, PND and T1DM to January 2013 Hypertension to October 2012 IAs to November 2012 |

Database searches were completed between 7 and 13 August 2012; searches for unpublished and in-progress studies were completed between 21 and 28 November 2012 | ||

| Manual searching | Systematic Reviews, Health Education and Behaviour, Health Education Research, Journal of Behavioural Medicine and Patient Education and Counseling | Patient Education and Counseling, Health Education and Behaviour and Health Education Research | |||

| Forward citations | A forward citation search was performed on all included systematic reviews using ISI Proceedings (Web of Science). The bibliographies of all eligible studies were scrutinised to identify additional possible studies | None | A forward citation search was performed on all included papers using ISI Proceedings (Web of Science). The bibliographies of all eligible studies were scrutinised to identify additional possible studies | ||

| Unpublished and in-progress studies | N/A | UK Clinical Research Network Study Portfolio (www.clinicaltrials.gov) and the Meta Register of Controlled Trials (www.controlled-trials.com) | |||

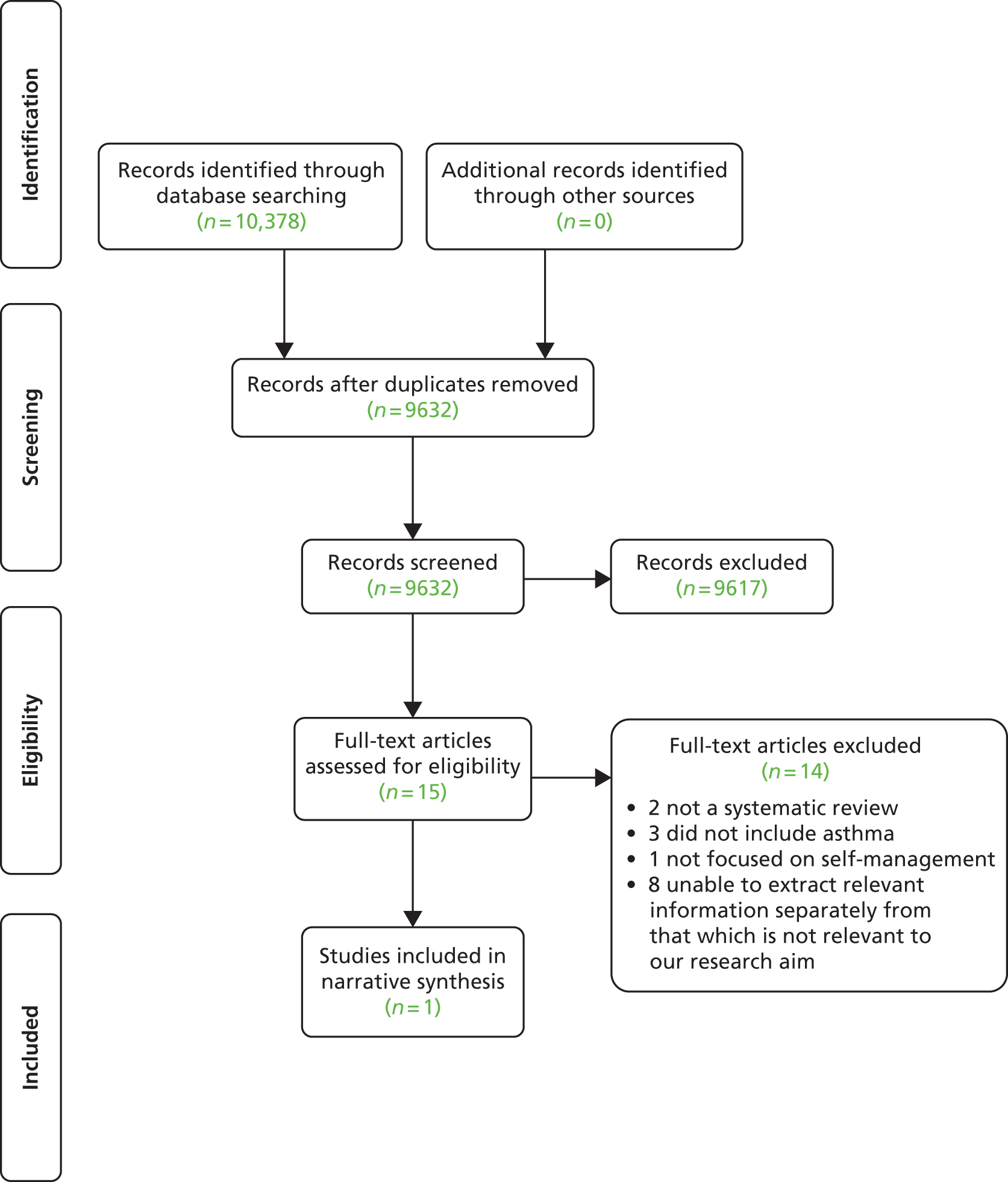

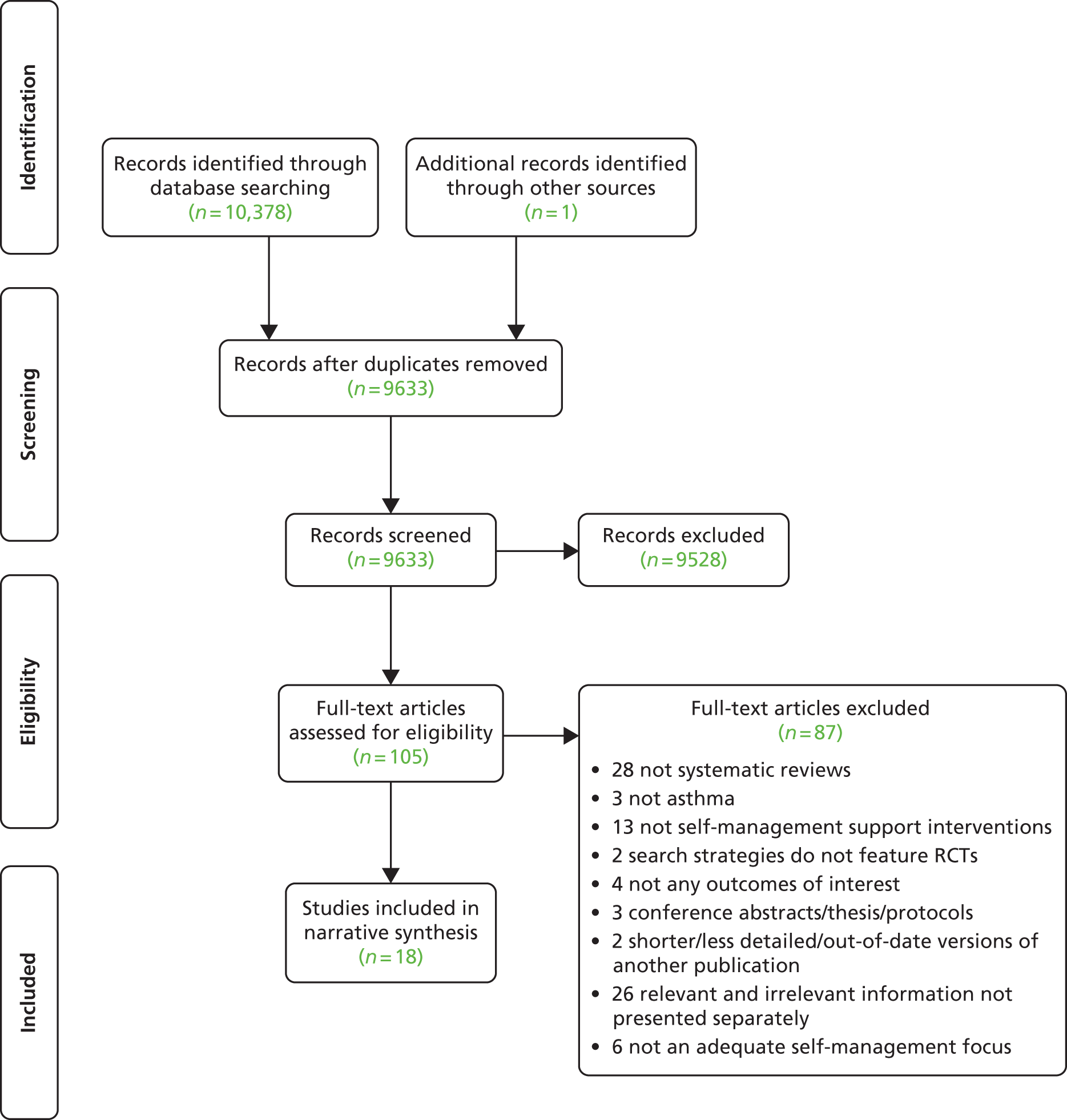

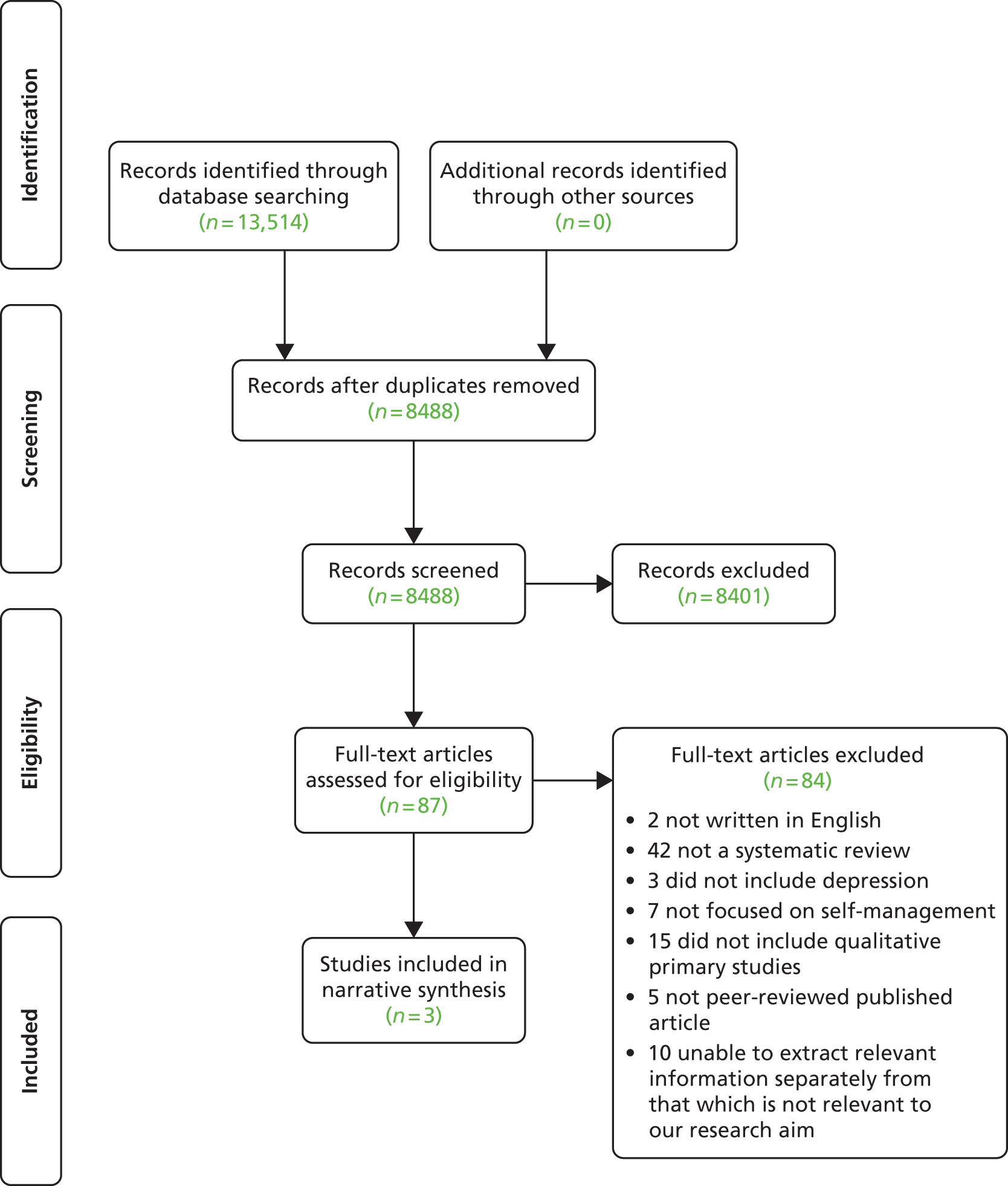

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We excluded papers not published in English (translation was impractical within the time scale of the project), or if we were unable to extract data on self-management support in one or more of the exemplar conditions. Reviews of multiple interventions were included where the focus of the review incorporated self-management, and where data from the RCTs of self-management interventions could be extracted separately, regardless of how many RCTs had this focus. For all of the meta-reviews, we excluded papers published before 1993, or papers which were a shorter and less detailed version of another included review, or if a more recent updated version had been published. The quantitative meta-reviews only included systematic reviews of RCTs (or mixed-method reviews in which the RCT data were presented separately), the qualitative meta-reviews only included systematic reviews reporting a qualitative synthesis (or mixed-method reviews in which the qualitative data were presented separately), and the implementation review only included Phase IV primary studies in which the self-management support intervention was implemented in routine practice. From a practical perspective, when screening papers this meant the studies had to include outcomes from whole populations, define eligibility to the service (not the research), recruit patients to the new service (as opposed to consenting to research), report uptake and attrition, be delivered by service personnel (though they could be trained specifically to deliver the intervention). For the implementation review qualitative studies and RCTs were not included as they were considered to be included in the meta-reviews. The detailed exclusion process for the meta-reviews is detailed in Appendix 13 and for the implementation review in Appendix 14.

Training and quality control

Three reviewers (EE, GPe and HLP) and the joint lead applicants (ST and HP) independently reviewed a sample of 100 titles and abstracts from the searches. The team then compared which titles and abstracts had been selected for further scrutiny. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion and consultation with the Steering Group, if required. This process was repeated on further samples of 100 titles and abstracts until the level of agreement between the joint leads and all reviewers was deemed satisfactory.

Screening of titles and abstracts

Following training, one reviewer (HLP, GPe, EE, SJ, AS or NP) reviewed titles and abstracts from the literature searches and selected possible relevant studies addressing our research question. A random 10% sample of titles and abstracts were examined by a second reviewer (ST or HP) working independently as a quality check. The agreements for the meta-reviews were stroke = 96%; T2DM = 96%; asthma = 97%; depression = 98%; hypertension = 99%; IAs = 99%; and the remaining additional reviews together = 95%. In the case of any disagreements between reviewers, this was resolved by discussion between the two reviewers; in the case of consensus not being reached, a third reviewer (ST or HP) became involved and, if necessary, arbitrated.

Full-text screening

The full texts of all potentially eligible studies were retrieved and assessed against the exclusion criteria (see Appendices 13 and 14) by one reviewer (EE, HLP, GPe, AS or NP). At this stage a 10% check was again implemented (ST or HP). The agreements were stroke = 81%; T2DM = 89%; asthma = 83%; depression = 88%; hypertension = 67%; IAs = 67%; and the remaining additional reviews together = 86%. Disagreements were resolved by discussion with a third reviewer (ST or HP) arbitrating if necessary.

Dealing with multiple publications

Multiple papers may be published for a number of reasons, including translations, results at different follow-up periods or reporting of different outcomes. In the meta-reviews, we only included either the most recent or most comprehensive version of the research (based on exclusion criteria 10), but may make reference to other relevant publications where considered useful.

Implementation review

A random 25% control check was implemented where a second reviewer working independently examined the sample. Disagreements between the reviewers were resolved by discussion between them and sometimes with a third reviewer arbitrating if deemed necessary. Due to the challenges in identifying Phase IV implementation studies, all papers considered relevant to the review were rescreened by ST or HP. Any disagreements or uncertainties between the reviewers were resolved but if deemed necessary a third reviewer arbitrated. The percentage of agreement was calculated separately for diabetes, asthma and depression due to the high volume of relevant papers and a joint percentage of agreement was implemented for the remaining conditions.

Assessment of methodological quality

Meta-reviews

The quality of a systematic review is assessed at two levels:41

-

Quality of systematic review: this reflects the quality of the review process, including an assessment of the methodology of searching, selection of studies, data extraction and synthesis. 44

-

Quality of evidence included within systematic review: this reflects the rigour with which the reviews assessed the quality of the studies included in each of the reviews, looking for potential bias, conflicting results across individual studies, sparse evidence or a lack of relevance to the review question. 41

We used the Revised Assessment of Multiple Systematic Reviews (R-AMSTAR) quality appraisal tool to assess the methodological quality of all included systematic reviews45 (see Appendix 15). Assessment of Multiple Systematic Reviews (AMSTAR) has good face and content validity but is unable to produce quantifiable assessments of quality. 46,47 R-AMSTAR is a revised version of the AMSTAR instrument which can quantify the quality of systematic reviews. 45 Due to the dearth of tools to assess quality of qualitative systematic reviews, we adapted the R-AMSTAR for this purpose (see Appendix 16). The qualitative tool was assessed out of 40 and papers were judged to be high quality if scored as ≥ 30 and low quality if scored < 30.

Quality assessment was undertaken by one reviewer (GPe, HLP, SJ, AS or NP), with a random 10% conducted independently by a second reviewer (EE, GPe, HLP, ST or EH). Disagreements were resolved by discussion and, if necessary, with the involvement of a third reviewer.

Implementation review

We used the checklist described by Black and Downs,48 which was developed to assess the methodological quality of both randomised and non-randomised studies of health-care interventions (see Appendix 17). This checklist was chosen on the basis of being one of the best in assessing non-randomised controlled studies. 49 Quality assessment was undertaken by one reviewer (EE), with a random 10% conducted independently by a second reviewer (HP). Disagreements were resolved by discussion and, if necessary, with the involvement of a third reviewer.

Extraction of data

Meta-reviews

Data were extracted by one reviewer (GPe, HLP, SJ, AS or NP) using a piloted data extraction table and 10% of the completed data extraction tables were checked by a second reviewer (HP or ST) for integrity and accuracy. We resolved any disagreements by discussion between reviewers; in the case of consensus not being reached, a third reviewer (HP or ST) became involved and, if necessary, arbitrated.

We extracted data under the headings of review rationale, research question(s), inclusion criteria, definition of self-management support component reviewed, definition of the LTC(s) reviewed, completeness of search strategy, screening procedure, method of data analysis, number and reference of all relevant primary studies included (either RCTs or qualitative studies), participant demographics, study details, descriptive results and synthesised results. Additionally, the quantitative meta-reviews extracted specific information reported in the reviews on the range of comparison groups, settings, service arrangements, delivery modes of intervention, duration and intensity of self-management component(s), and follow-ups within the included RCTs. We extracted the findings and conclusions as synthesised by the authors of the systematic reviews, and specifically avoided going back to the individual primary studies.

Implementation review

Data were extracted by one reviewer (EE) using a piloted data extraction table and the completed data extraction tables were checked by a second reviewer (HP or ST) for integrity and accuracy. We resolved any disagreements by discussion between reviewers; in the case of consensus not being reached, a third reviewer became involved and, if necessary, arbitrated.

We extracted data under the headings of: at whom the intervention is directed (HCPs, patients, carers, mixture); setting; mode of delivery (group, individual, professional, lay led, joint led, face to face, telehealthcare); group allocation (if applicable); components (education, action plans, techniques to support behaviour change); (tele)monitoring; support materials (written/electronic information); duration and intensity of components; follow-up (frequency and mode); service arrangements (‘usual’ primary/additional care, dedicated service); and any cost-effectiveness data.

Data analysis

Priority quantitative meta-reviews

Detailed description

The initial step was to compile a detailed descriptive summary of the evidence for self-management support in each of the priority exemplar LTCs (stroke, T2DM, asthma and depression).

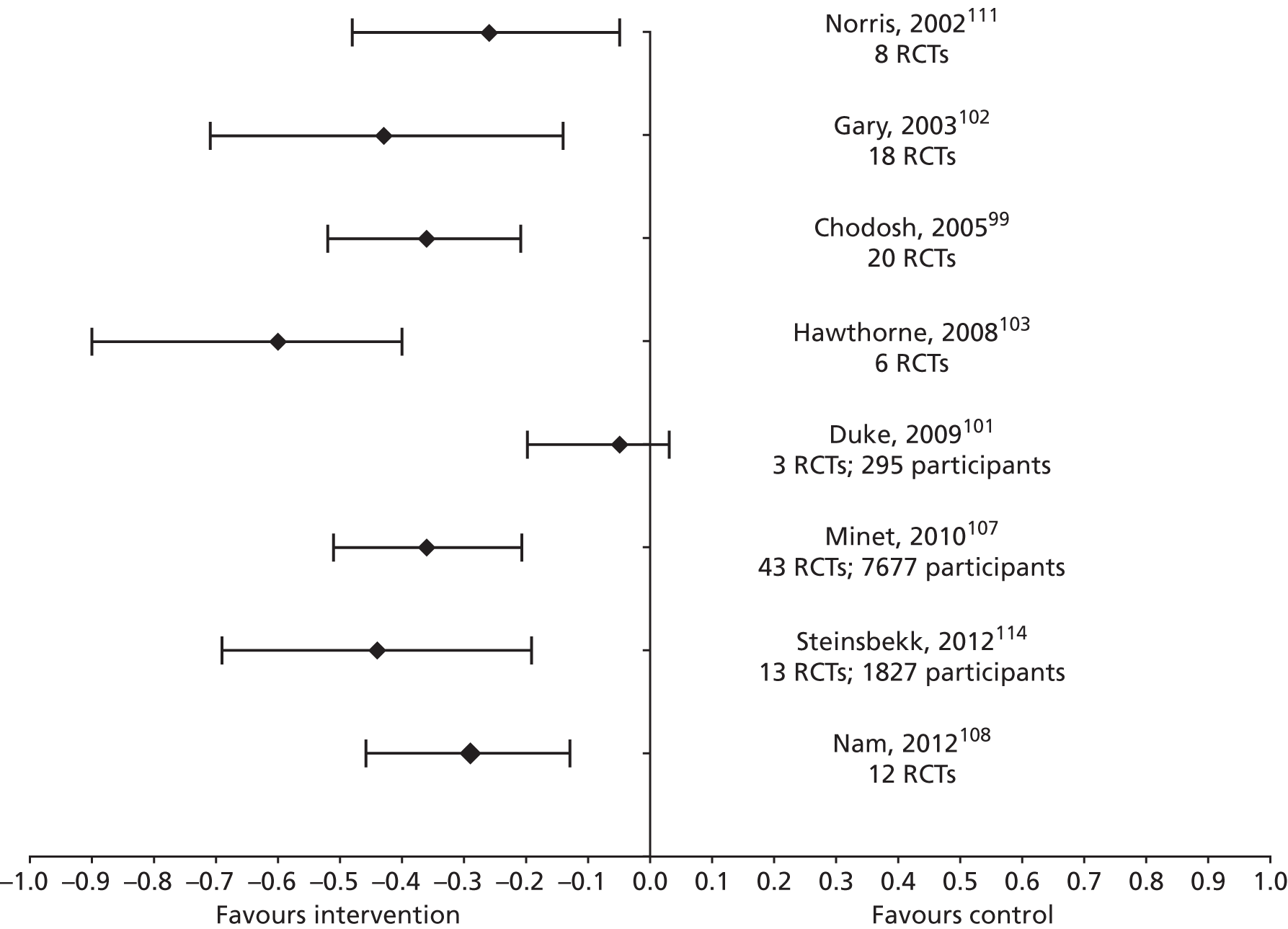

Synthesis

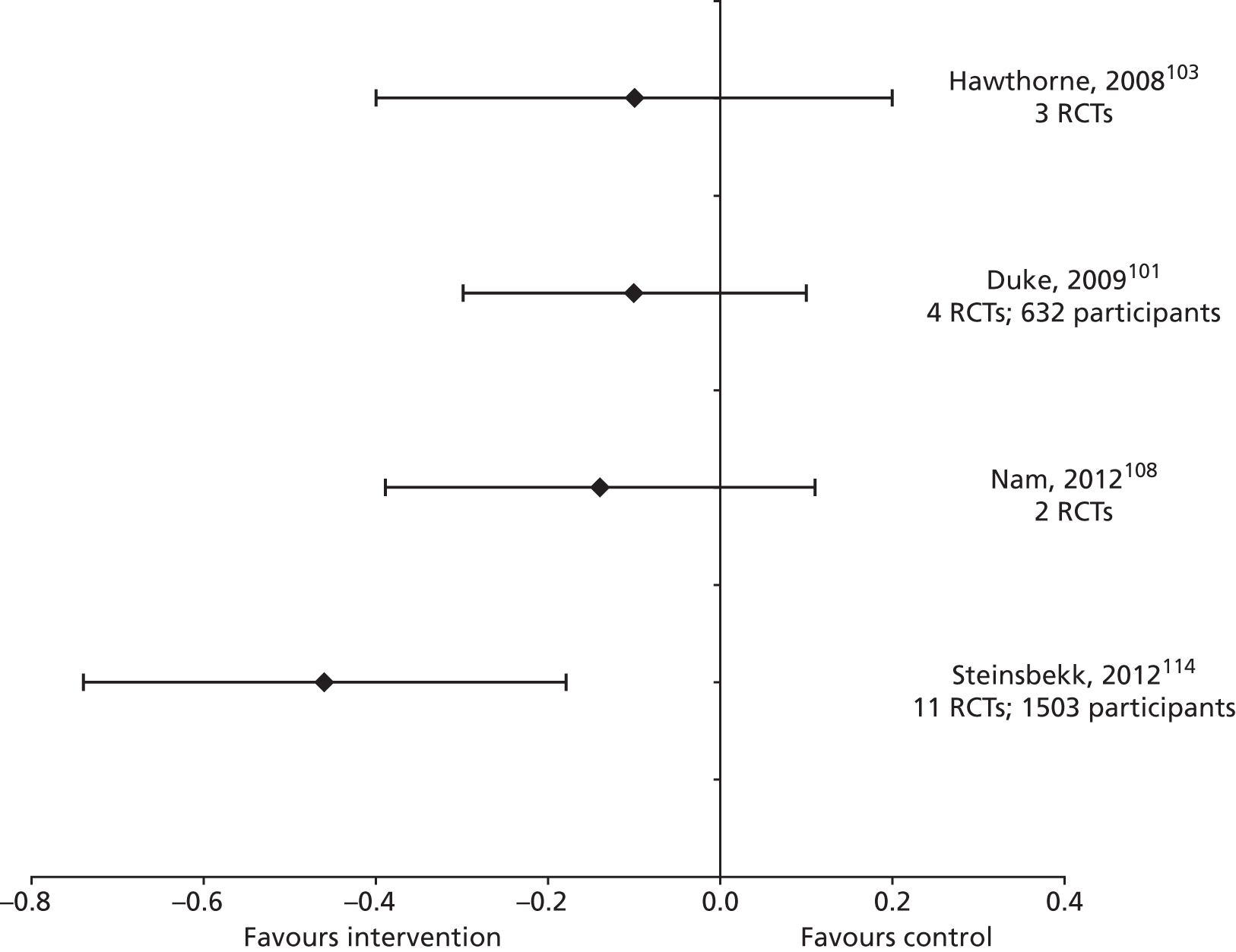

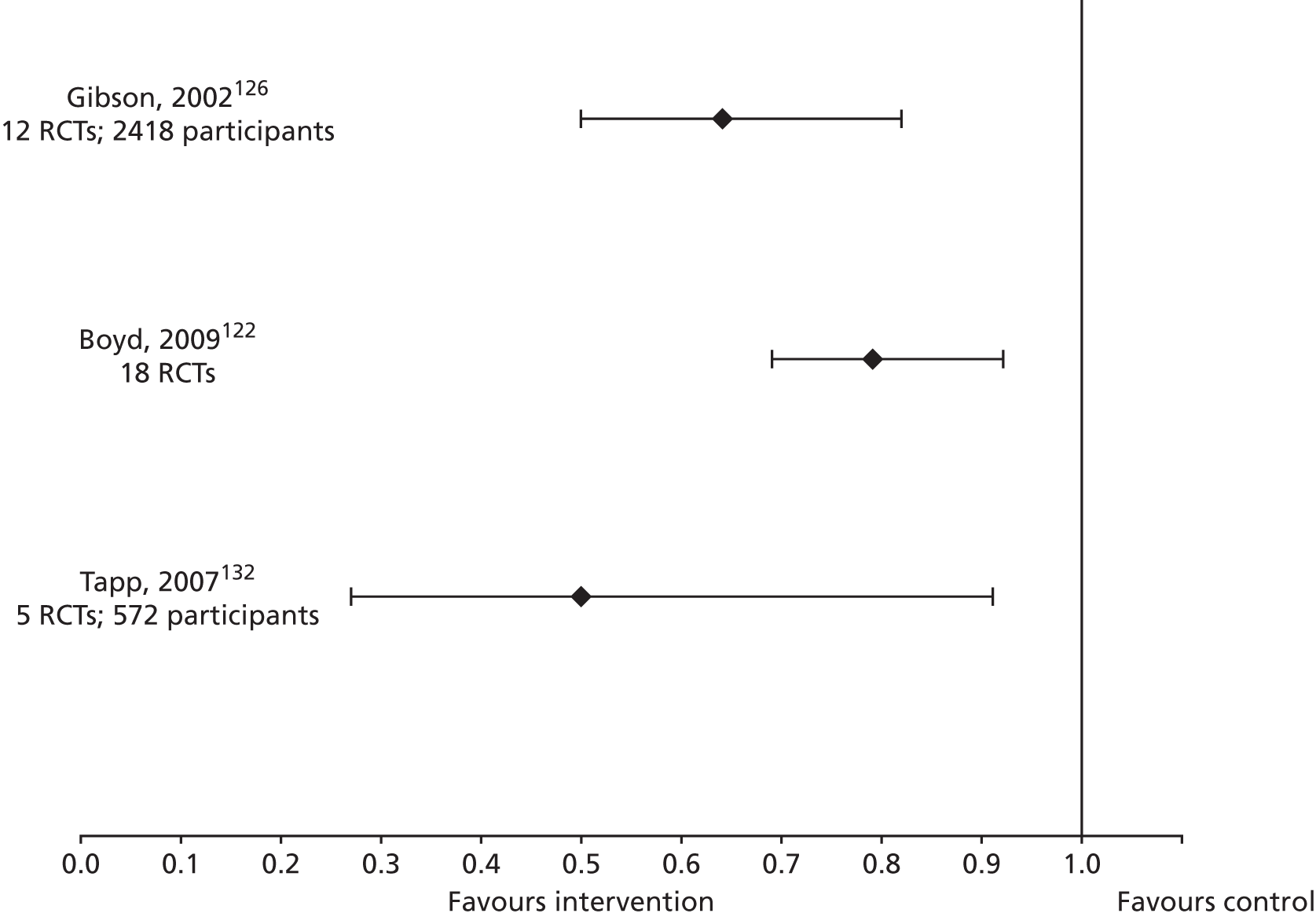

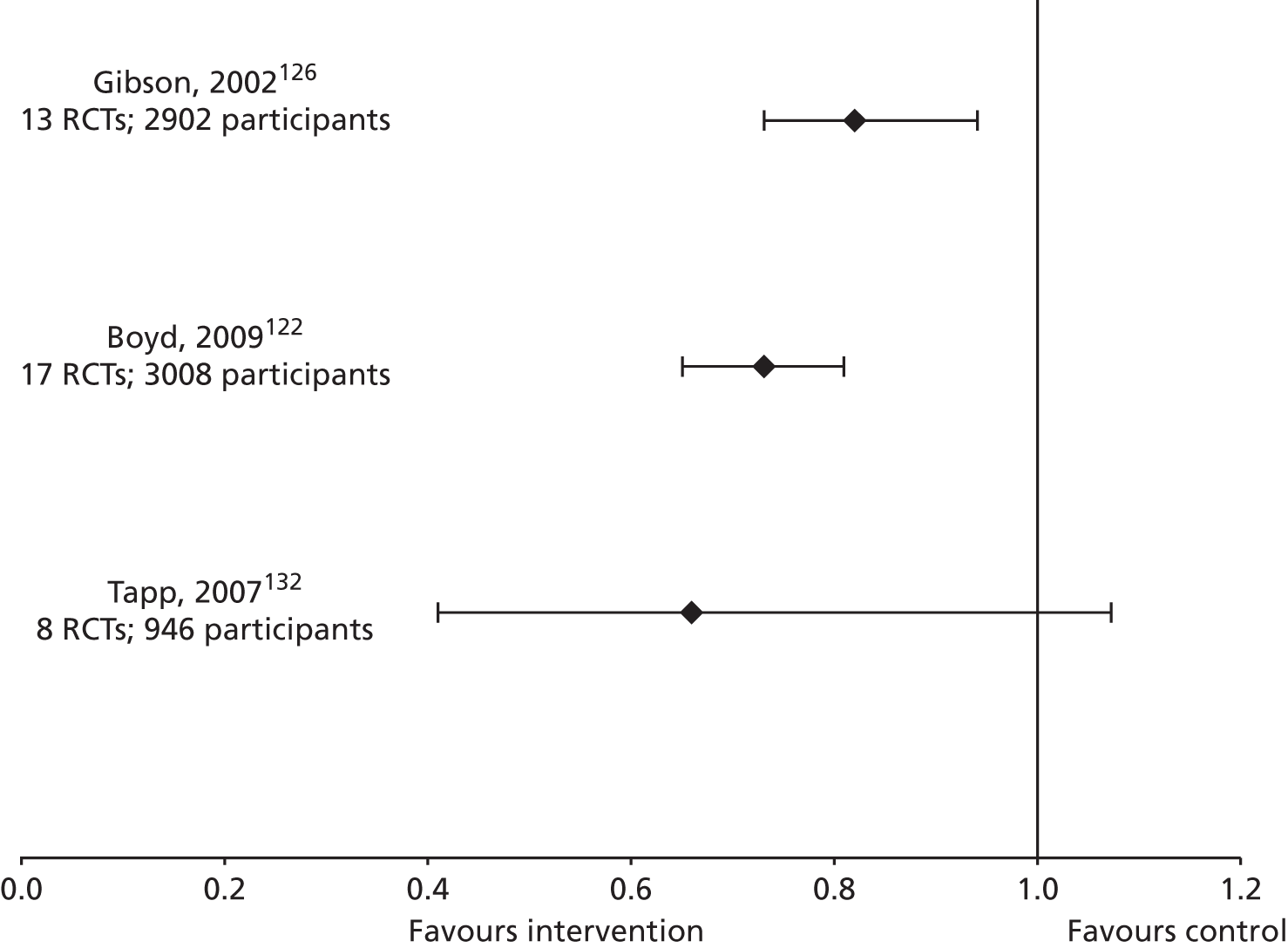

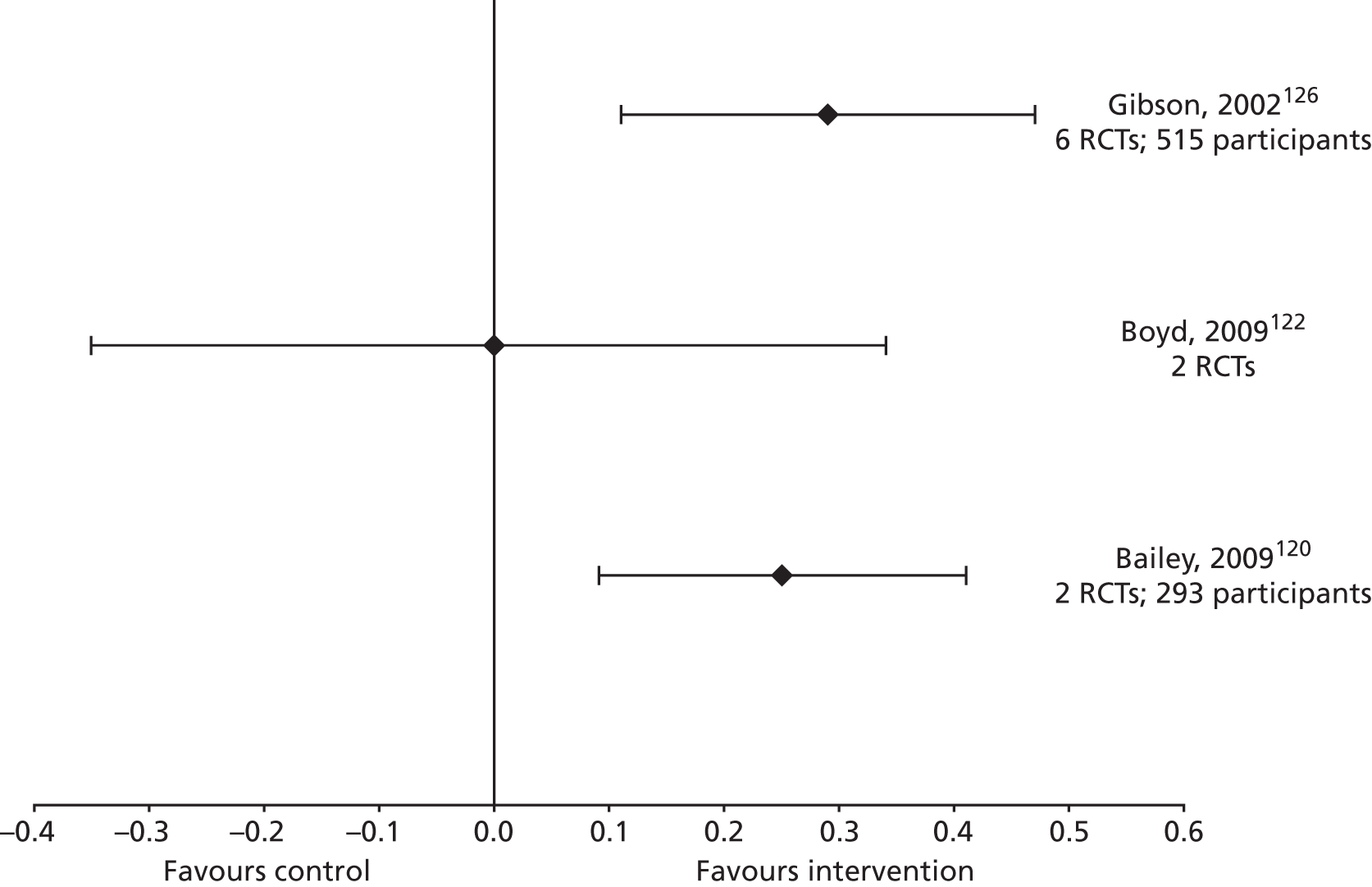

Meta-analysis is inappropriate at the meta-review level due to the overlap of included RCTs between reviews. However, for any primary outcomes where three or more systematic reviews present pooled statistics, results were displayed graphically by creating ‘meta-forest plots’. These graphical representations do not attempt to create overall pooled statistics, as this would require going back to the original RCTs. They provide a visual representation of results instead, allowing for more straightforward interpretation of data. Where there was heterogeneity between the included reviews for each LTC, we undertook a narrative synthesis. Interpretation of results was facilitated by discussion among the multidisciplinary study team. Interpretation of systematic review results was weighted by consideration of study quality and the total number of participants included in the systematic review.

Priority qualitative meta-reviews

Levels of interpretation

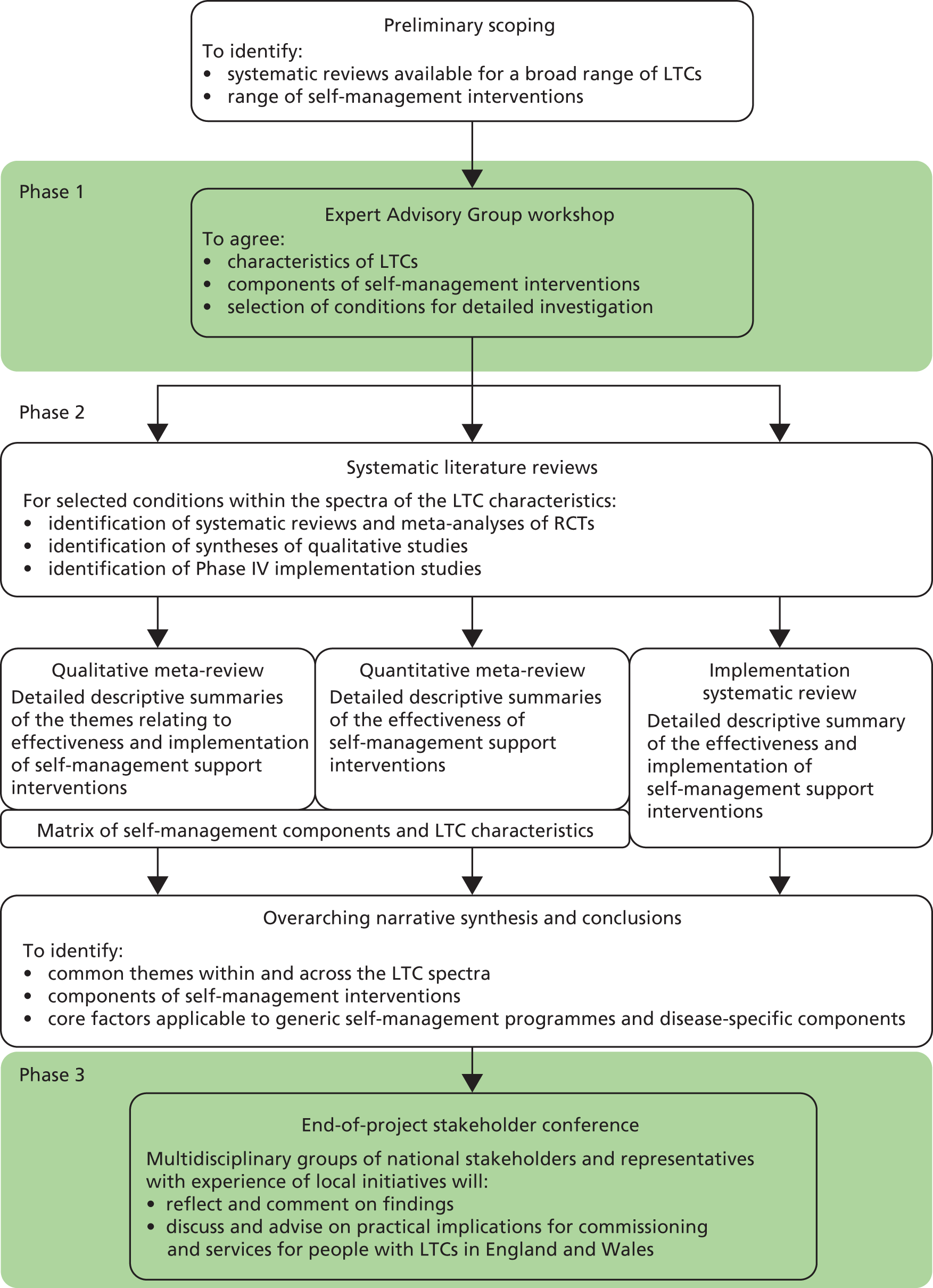

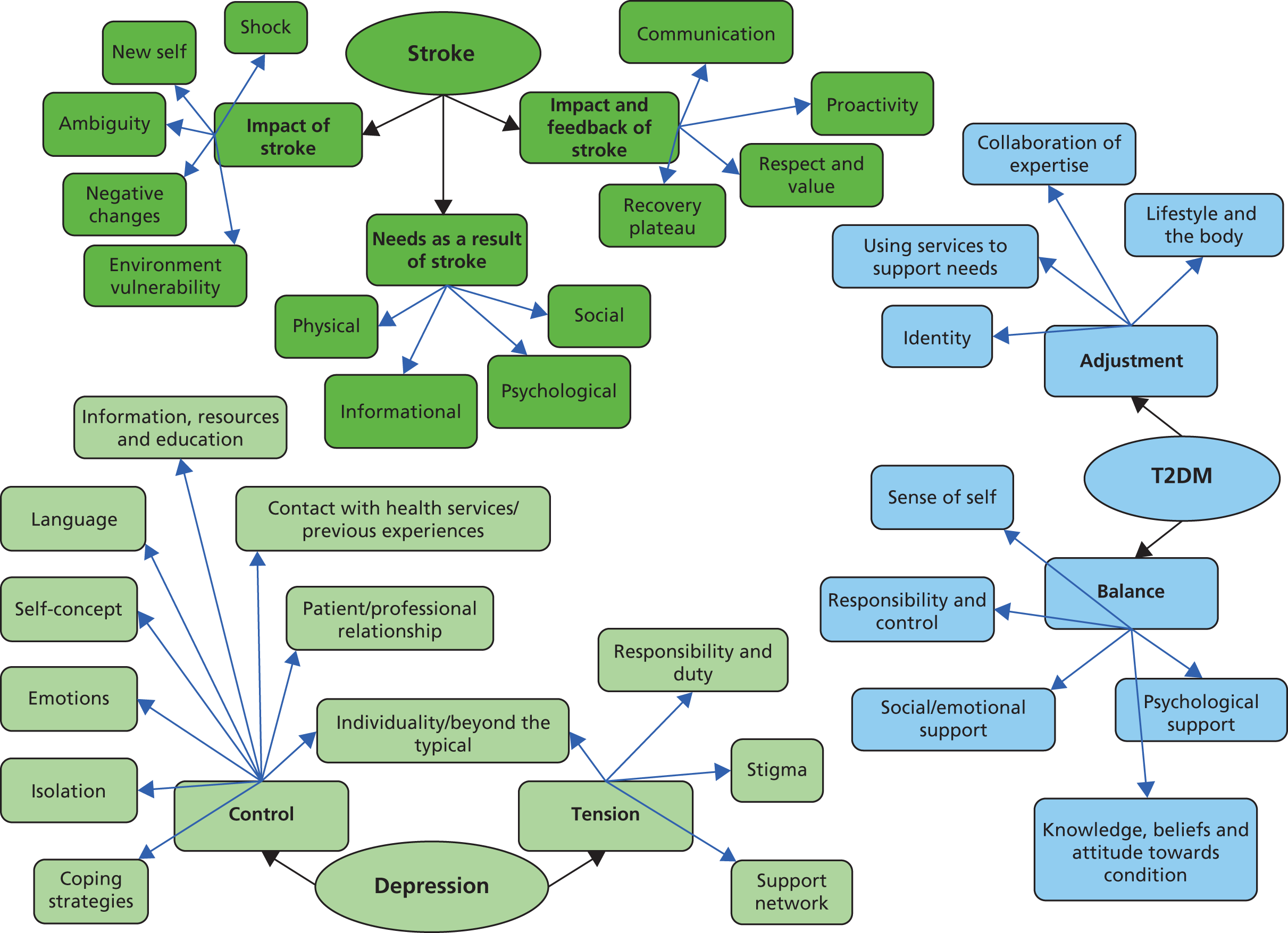

It is important to acknowledge the four main levels of interpretation and hermeneutic philosophy50 (a quadruple hermeneutic) involved when carrying out a meta-review of qualitative reviews. The first is the participant’s interpretation of their own experiences when discussing them during the interview in the course of the primary research project; the second relates to the researcher’s reflections and report in the primary study; the third level involves the synthesis of all the findings from the primary studies included in a systematic review; and the last is the meta-review level (Figure 4). For this final level, our aim was to only analyse the summaries and syntheses of the existing evidence in the included reviews [i.e. the second (as reported in the systematic reviews) and third hermeneutic levels], rather than to investigate or analyse data from the primary studies or individual interviews.

FIGURE 4.

Levels of interpretation: the four levels of collected data, of which the meta-review is the fourth. It aims to synthesise the systematic reviews’ findings and conclusions only, and not to examine the individual interview or primary study level of data.

A meta-ethnographic framework

We were concerned not only to examine the arising patterns within these data, but also to integrate the findings together in relation to our aim of informing the commissioning of health services. As a result, we employed a meta-ethnographic framework to meta-synthesise these data. 51 Our qualitative meta-review questions were (i) how can people with a specific LTC be effectively supported in their self-management; and (ii) how can this inform commissioners and health-care providers about what works, for whom, in what contexts, how and why?

In order to address the first question, reciprocal translation51 was used to examine patterns and identify arising metaphors within the included reviews. In meta-ethnographic framework, reciprocal translation is specifically focused on translating similarities across data in order to organise the concepts taking place. This was followed by a lines-of-argument synthesis51 to examine the second question. Lines-of-argument synthesis is a technique used to interpret and infer at a whole level, such as at an organisational or cultural level. In these particular meta-reviews the key purpose of the lines-of-argument synthesis was to translate the findings into a broader understanding about their meaning in the commissioning context. The analysis and quality assessment were carried out by two reviewers (GPe, SJ, EH, ST or HP) working independently; findings were cross checked and discrepancies resolved through discussion.

Data saturation

In meta-reviews where the data arising reached a point where no additional data were being found and each arising theme was a repetition of a previous one, a conclusion of data saturation was made. 52

Additional meta-reviews

This analysis was similar to the priority meta-reviews, but for the additional exemplar LTCs (COPD, CKD, dementia, epilepsy, hypertension, IAs, IBS, LBP, PND and T1DM) a more focused approach to analysis was adopted.

In order to simplify the quantitative data extraction and analysis, we focused on:

-

the primary outcome as defined by the systematic review (if supplied)

-

any measures of health-care utilisation (if supplied)

-

a disease-specific outcome – this was usually a measure of disease control (e.g. number of seizures in epilepsy, number of hospitalisations in COPD)

-

a measure of patient experience or process measure of self-management (e.g. QoL, ownership of action plans or self-efficacy).

We synthesised the quantitative and qualitative data, focusing on (though not limited to) issues raised by the analysis of our priority meta-reviews. We specifically looked for evidence which confirmed or refuted our conclusions from previous analyses.

Implementation review

Detailed description

The initial step was to compile a descriptive summary of the evidence for implementing self-management support in each of the exemplar LTCs.

Narrative synthesis

The eligible trials were characterised by a substantial heterogeneity and thus meta-analysis was not appropriate. We used narrative analysis53 and adopted the whole-systems approach as a framework for the analysis. 36 This considers interventions from a multilevel perspective, engaging patients, professionals and the organisation in a collaborative approach.

Over-arching synthesis

We then developed matrices that mapped the evidence for, and where possible the components of, effective self-management support interventions, to the characteristics of the exemplar LTCs as defined by the Expert Advisory Group. The highlighted areas where there was a paucity of evidence enabled us to see any patterns of evidence for effectiveness and ineffectiveness of self-management support interventions.

Interpretation of the findings

Multidisciplinary discussion

Throughout the process of undertaking the reviews, the multidisciplinary team met regularly (normally weekly) to discuss the emerging findings. The monthly Steering Group meetings provided further opportunities to discuss and refine preliminary conclusions. Regular teleconferences with Professor Bower enabled synergy with the findings of the complementary HS&DR programme-commissioned health economics project. 54

This enabled the analysis to develop iteratively as the work progressed. For example, the outcomes of the priority quantitative meta-reviews dictated the primary outcomes for our additional quantitative meta-reviews. Building on the findings of the quantitative meta-reviews, the Phase IV implementation review sought evidence of effectiveness (or not) of models of supported self-management which had been shown to be effective in RCTs.

End-of-project workshop

The findings and over-arching conclusions from our programme of reviews were presented to 34 multidisciplinary stakeholders (including the initial Expert Advisory Group) at an end-of-project stakeholder conference. Small discussion groups reflected on findings and discussed and advised on practical implications for commissioning and providing services for people with LTCs in England and Wales. The conclusions of the discussion groups were used to refine the priorities for practice, research and policy, and to inform the final report and publications.

Long-term condition-specific methods

In some LTCs, methods varied from those described previously (Table 10).

| LTC | Condition-specific methods |

|---|---|

| Stroke | The aims of both the included systematic reviews and the studies they included did not always completely match the aims of our review. To address this, we assessed the potential relevance of the individual studies to our aim and used this, in combination with the quality assessment results, to guide the weight we attached to the conclusions of each review |

| T2DM – qualitative | After the completion of full-text screening for qualitative reviews exploring T2DM, we were left with the decision about whether to only include those explicitly including T2DM only, or whether to include those that did not separate types of diabetes as well (e.g. not separately including or analysing T1DM and T2DM, or insulin-dependent diabetics with non-insulin-dependent diabetics). As there was only one paper fitting the description of the former, the team decided to include the latter as well to add depth and breadth to the findings. This was based on Campbell et al.’s rationale that ‘qualitative health research synthesis should not be driven by medical considerations but should rather concern itself with the way in which patients experience disease and illness’.55 We included all of the findings from the included reviews unless the paper explicitly referred to an aspect specific to T1DM, such as children and families learning to use insulin. However, comparing these findings with each other was carried out with caution. The following exclusion criteria were revised to explicate the changes: Exclude 5. Exclude if the review does not focus on or include adults’ self-management of diabetes mellitus or self-management by those that have been diagnosed with T2DM (include diabetes mellitus papers that mix T1DM and T2DM or insulin- and non-insulin-dependent diabetes together if they focus on self-management in populations that are relevant to adults with diabetes mellitus). As the review was not focusing on T1DM alone, we excluded reviews that focused on T1DM only Exclude 11. Exclude if unable to data extract the information on qualitative primary studies in the selected LTCs separately from the rest of the findings (unless it is between T1DM and T2DM or insulin- and non-insulin-dependent diabetes: these will be included) |

| T2DM – quantitative | Although the focus of this meta-review was T2DM, and reviews combining data for T1DM and T2DM were excluded, an exception was made for reviews of interventions specifically targeting self-management in foot ulcer care or DKD as these two conditions require broadly the same self-management regardless of whether the individual has a diagnosis of T1DM or T2DM56 A significant number of retrieved reviews were concerned exclusively with SMBG. NICE guidelines recommend offering SMBG to individuals newly diagnosed with T2DM as an integral part of self-management education.57 A recent Cochrane review on this subject observed that the efficacy of SMBG in T2DM has been the focus of a large number of systematic reviews and meta-analyses over time, most including RCTs only. This most recent review reached similar conclusions to the NICE guidelines, finding SMBG to be beneficial in individuals newly diagnosed with T2DM, but finding less effect when diabetes mellitus duration was over 1 year.58 The research team decided to exclude all reviews focusing purely on SMBG as it is a thoroughly researched area with up-to-date clinical recommendations already in place. Furthermore, where SMBG formed part of a self-management package which included other components such as education, peer support, counselling, etc., we hoped that studies would be picked up by reviews with a broader self-management support focus |

| T1DM – quantitative | As discussed with regards to T2DM, we acknowledge SMBG as an important aspect of self-management support. However, due to the huge body of evidence which already exists to support the effectiveness of this single aspect of self-management in T1DM, the review team decided to exclude reviews which focused solely on SMBG. This is in keeping with our decision not to review monocomponent self-management support interventions, apart from education. Where reviews explored SMBG alongside other self-management support components they were still considered for inclusion in our meta-review |

| Depression | After removing duplicates, a total of 8570 titles and abstracts were identified through systematic searching of the following databases: AMED, BNI, CINAHL, EMBASE, MEDLINE and PsycINFO. In addition, 2865 titles and abstracts were identified through searching the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects. All databases were searched from 1993 onwards To familiarise the review team with the emerging forms of self-management delivered within the context of depression, scoping of a randomly selected 1000 titles and abstracts was performed. This scoping was undertaken concurrently with title and abstract screening, and involved the reviewer (GPe) keeping an open mind as to what self-management support might mean within the context of depression. The idea behind this broad and inclusive screening of 1000 titles and abstracts was to facilitate discussion between the review team, and to ensure reviewers were in agreement before further screening continued. A basic search of the EndNote file (Thomson Reuters, CA, USA) containing all references was also undertaken, searching for the key words ‘self-management’ and ‘self management’ In addition to the screening of a random sample of 1000 titles and abstracts and the basic key word search, all 2865 titles and abstracts identified from the search of the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects were screened |

| Hypertension and IAs | Although these were additional meta-reviews, the search strategy and screening process carried out for them were the same as for the priority reviews. The analysis remained at the level of the additional meta-reviews |

Layout of the rest of this report

The next chapter describes the development of a proposed taxonomy for self-management support – this work was conducted in parallel with the reviews which comprise the main bulk of this report.

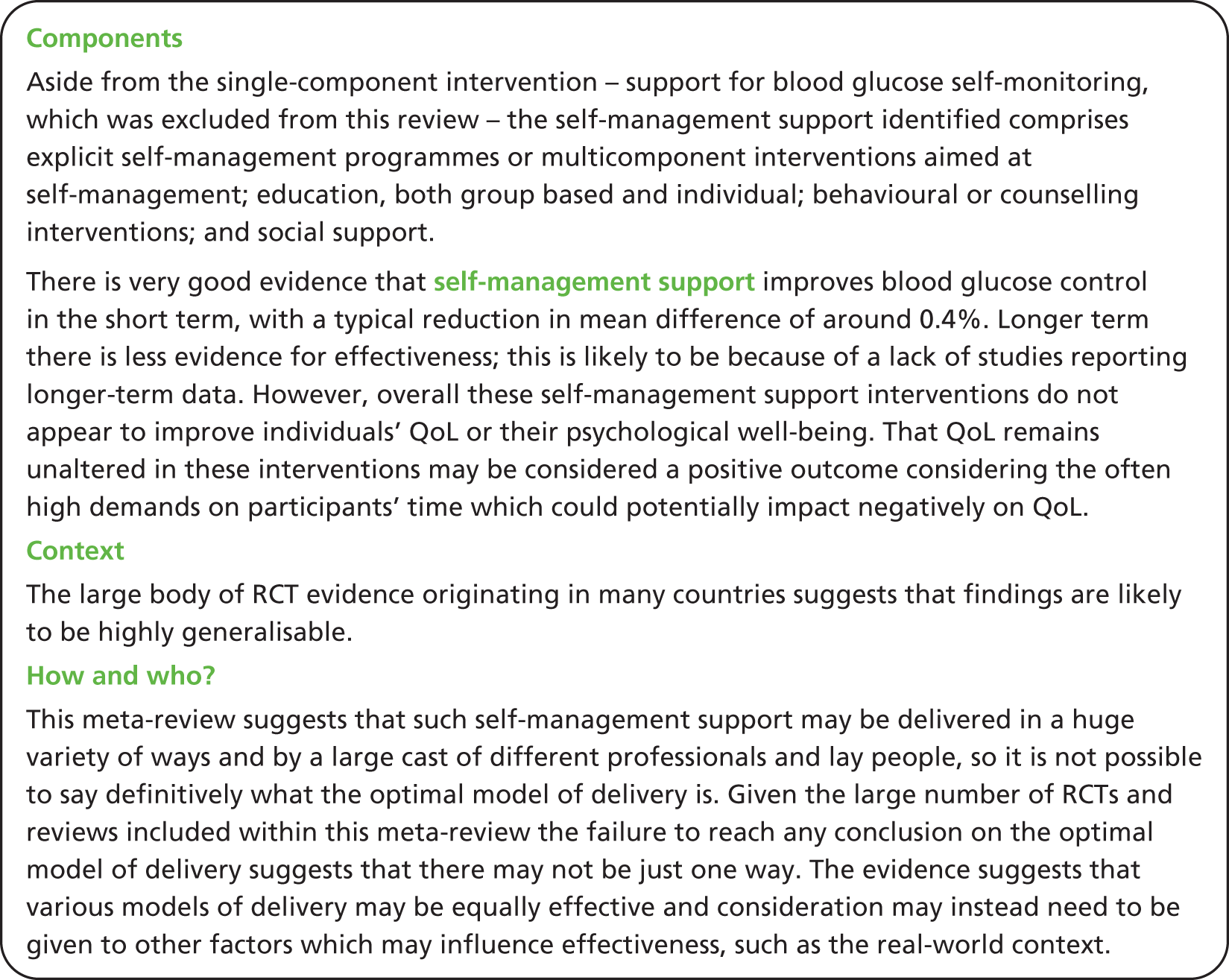

The four priority meta-review chapters follow (see Chapters 7–10). Each chapter reports a meta-review of qualitative systematic reviews with a line of argument synthesis, followed by a meta-review of quantitative systematic reviews. The overall quantitative evidence on self-management support and the effective components of multicomponent interventions, any evidence about context and how and by whom such interventions should be delivered is summarised in a figure and this is followed by a mixed-methods synthesis which combines the quantitative and qualitative meta-review findings.

Ten additional chapters on different LTCs follow (see Chapters 11–20). Again, each chapter reports a meta-review of qualitative systematic reviews, but this simply presents key themes arising from the qualitative systematic reviews, rather than attempting a line of argument synthesis. Each chapter also presents a quantitative meta-review, but this is limited to two or three carefully chosen health outcomes rather than examining all possible health-related outcomes. Again, any evidence including that about context and how and by whom such interventions should be delivered is summarised in a figure and this is followed by a mixed-methods synthesis which combines the quantitative and qualitative meta-review findings.

The report is deliberately structured so that those interested in self-management support in a particular LTC can get a detailed summary of the systematic review evidence on that LTC in the respective chapter.

The next chapter (see Chapter 21) is an original systematic review of implementation research relating to all the conditions studied in the earlier chapters.

This is followed by an overarching synthesis chapter (see Chapter 22) which attempts to bring all the review findings together. The final chapter (see Chapter 23), includes our conclusions in relation to the brief and recommendations for future research.

Chapter 6 Proposed taxonomy for self-management support interventions

Background and rationale