Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 11/1017/04. The contractual start date was in January 2013. The final report began editorial review in January 2018 and was accepted for publication in September 2018. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Manthorpe et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Introduction to the report

This report presents the findings of the first UK study of older homeless people living with memory problems or memory problems associated with the disabilities of dementia. It contains findings from literature reviews, and primary data collected from older people living in hostels and hostel staff supporting them. We discuss the prevalence of memory problems among older people accommodated in hostels, a form of temporary accommodation in which they have no security of tenure. We compare the services used by hostel residents with memory problems and services used by those without, using a categorisation developed for this study.

Our first three chapters follow the sequence of presenting the research questions and background to the study (see Chapter 1), the findings from two literature reviews (see Chapter 2) and the study methods (see Chapter 3). The next chapters report our findings: Chapter 4 profiles the research participants and the study sites, Chapter 5 reports our definitions and classifications of memory problems, Chapter 6 reports hostel residents’ health and social care needs and Chapter 7 presents data on their use of health and care services. Chapter 8 forms our discussion chapter and our final chapter (see Chapter 9) outlines the study’s implications for service development, commissioners, providers, practice and researchers.

Background

This unique study investigated four under-researched question areas:

-

To what extent are hostel staff aware of memory problems among their older residents and their prevalence? What impact does this have on their practice or service? How do hostel staff respond to residents’ memory problems?

-

What ‘service pathways’ exist for an older homeless person with memory problems? What are their experiences of these services?

-

What are the gaps in service provision for such individuals, and what are the costs of providing services for them?

-

How do older homeless people with memory problems perceive their quality of life (QoL), and how can this be evaluated? Does this differ from other older people and other older homeless people? What are the implications of this for agreeing desirable outcomes from services?

The background to the study is formed by three different domains: (1) the imperatives of dementia policy and practice, (2) equalities legislation and efforts to reduce health inequalities among older people with long-term conditions, including dementia, and (3) the impact of homelessness on older people with memory problems, including dementia, and their service needs. Little research has been conducted about the problems faced by older homeless people with memory problems (such as dementia), the services and support that they receive and the extent to which their needs are met. Our conversations with different stakeholders working in dementia services and in homelessness services as part of the development of the study proposal revealed that some older homeless people are deemed hard to engage and reluctant to work with services, and are perceived as difficult to assess and help because of persistent alcohol use. We were also told about other problems experienced by professionals in supporting homeless older people; these included accounts of distressed behaviour, complications of physical ill health, and self-neglect. We found little information about any help available to staff working with this client group in homelessness services in the UK and little research evidence about their contacts with other sectors. There were also few reported experiences of working constructively with health and social care services. In our consultations as part of our preparation for this study, professionals from all sectors expressed a desire to gain a greater understanding of this area of practice. These discussions helped frame our study so that it would explore implications for service design through an evidence-based analysis of the barriers to diagnosis, service access, support, treatment and unmet need, and exploration of ways to address the many challenges envisaged. This study, therefore, was designed to investigate these areas. The next section provides more detail of the threefold context to the study.

Dementia

Two major policy documents have shaped dementia services and provide the background to the emerging interests in dementia recognition at patient and society levels in England: the National Dementia Strategy,1 superseded by the Prime Minister’s Challenge on Dementia. 2 Both emphasise the need for earlier or more timely recognition of dementia. Commenting on the progress made under the National Dementia Strategy and the Prime Minister’s Challenge, Knapp et al. 3 reported that the provision and use of memory assessment services (sometimes referred to as memory clinics) has increased, although it is hard to detect what changes there have been and where they have occurred. The development of memory service accreditation has been slow, meaning that commissioners cannot rely on strong evidence of how best to deliver memory services. Knapp et al. 3 added:

Local services will and should respond to local circumstances and be more person-centred, but the wide variations currently seen in staff-mix, methods of clinical assessment and provision of post-diagnostic care are unacceptable if the aim is to equalise access to diagnosis and post-diagnostic support.

P. 2.

Although the National Dementia Strategy1 addressed issues of equalities, generally there has been a lack of focus on people who are homeless who have memory problems or cognitive problems that are indicative of a dementia syndrome. The Ministerial Advisory Group on Dementia Research4 recommended that public and professional awareness and understanding of dementia should be improved. However, whereas it made reference to caring for people with dementia at home, in hospital and in care homes, it contained no mention of those who are homeless or socially excluded from settled accommodation. It also recommended that health and social care staff working in care homes with residents who have dementia should receive appropriate training and continuous professional development, and that community mental health teams (CMHTs) working with older people should provide specialist services to care homes; however, practitioners working in homelessness services were not mentioned. The Ministerial Advisory Group on Dementia Research advised that everyone with dementia should have access to a pathway of care services, including specialist assessment, treatment, care and support, and that this pathway should be responsive to individual need and preferences. It made no reference to possible difficulties in providing care and support to older people with dementia who are homeless, or to the staff groups working with them.

Policy has also promoted broad public health and community development approaches to responses to dementia. Knapp et al. 3 noted the considerable emphasis on improving awareness about and attitudes towards dementia through campaigns such as Dementia Friends and the development of dementia-friendly communities. Such initiatives have generally focused on people living in their own homes. 5

Equalities

Part of the justification for a National Dementia Strategy1 was that dementia has long been overlooked as a health problem, despite its often devastating impact in human terms and its impact on public expenditure. There have been arguments that this lack of priority reflects dementia’s associations with old age and the impact of ageist beliefs and stereotypes; that the condition is stigmatised; and that there is therapeutic nihilism – or a feeling that nothing can be done. 6 There is increasing interest in seeing dementia as needing a rights-based dimension, building on the ideas of the disability movement. 7,8 A report from the Mental Health Foundation suggested that this would bring several benefits, such as greater legal protection and improved service entitlement, thereby promoting cultural shifts to how dementia is perceived that will have benefits to society as well as people with dementia. 9

Thomas and Milligan10 have argued that adapting the social model of disability to people with dementia also encourages us to think beyond the social and institutional disadvantages that may be experienced by people with dementia, and instead notice the impact this can have on the places they live. As people with dementia may lose their sense of orientation of time and space, formerly familiar places may start to seem unfamiliar or frightening to them. 10 The premise that people with dementia may lose their memories of settled and familiar locations overlooks people without settled accommodation or who are unfamiliar with their present neighbourhood.

The premise that people with dementia may lose their memories of settled and familiar locations overlooks people without settled accommodation or who are unfamiliar with their present neighbourhood.

More recently, there has been greater interest in the heterogeneity of the ‘dementia population’ and the possible impact of social inequalities being sustained when a person has dementia or of such inequalities being reproduced or enhanced. Research, for example, has investigated differences in service responses, such as prescriptions of ‘anti-dementia’ medication, by socioeconomic group,11 variations in symptom recognition between ethnic groups,12 fear of prejudice about revealing sexual orientation13 and gender disparities affecting women throughout the dementia trajectory. 14,15 Concluding their literature review, Ludwin and Parker15 observed:

As we have seen throughout the material we reviewed, individuals with dementia are marked by the social locations and identities they occupied prior to diagnosis; these axes of identity may form important parts of individual sense of self. Failing to recognise them in interactions and provision of support may thus contribute to an erosion of personhood and perpetuate marginalisation.

P. 2015

The importance of considering equalities in respect of people who are homeless is not generally recognised, despite the very poor health and QoL of this population. 16 According to the Equality and Human Rights Commission,17 this population is among the most disadvantaged groups in UK society. Although the Equality Act 201018 provides a legal imperative to ensure that ‘protected characteristics’ are addressed in assessments of service impact (many of which are relevant to people with dementia2), homelessness is not readily translated into the ‘characteristics’ for which there is legal protection. Some advocates from the homelessness sector have suggested that the NHS Constitution instead may be an effective lever to ensure the rights of homeless people to health services. 19

Housing people with dementia

There has been growing interest in the living accommodation and housing choices of people with dementia. Much has focused on how to design new accommodation and how to modify existing accommodation so that people with dementia can stay in their own homes or move to better accommodation offering choices over patterns of care and tenure. 20 Several organisations (e.g. the National Federation of Housing21) have argued that dementia-friendly housing must be an integral part of dementia care. Research has also begun to explore particular housing needs of some groups of people with dementia; for example, Lipman and Manthorpe22 investigated how social housing providers (housing associations) were beginning to respond to tenants with dementia from black and minority ethnic groups.

As Knapp et al. 3 reported, local authorities have been encouraged to develop, in collaboration with the Homes and Communities Agency and the Greater London Authority, partnerships with housing associations (social housing providers that may offer housing and care services) and private builders to meet the needs of older people with long-term conditions, including dementia. However, the focus of such developments has been on people with dementia who already have homes, some of whom have considerable assets from home ownership and who are potentially attractive new purchasers to ‘housing with care’ providers.

Older homeless people

The problems and needs of older homeless people and of the effectiveness of services for them were summarised in a review article by Crane and Joly16 and the responses of statutory housing bodies by Alden. 23 There has been little research in the UK about the circumstances and needs of older people who are homeless and have memory problems, although the subject has received some attention in other developed countries, such as the USA24,25 (see Chapter 2 of this report for our review of the relevant literature).

This present study used the former UK Coalition on Older Homelessness26 definition of ‘older’ homeless people as those aged ≥ 50 years, because many homeless people in their fifties have chronic health problems and disabilities normally associated with old age. Those in their fifties who are single and without dependent children are often not regarded by statutory services as ‘elderly’ or particularly vulnerable, meaning that these authorities’ responsibilities may be fulfilled by temporary hostel placement with, increasingly, shorter stays only being permitted. Moreover, at least two-thirds of older homeless people are men in respect of whom problems have been reported if they are rehoused in care homes, which tend to be occupied predominantly by very elderly women. 27 Care home staff have reported difficulties in managing formerly homeless men’s drinking and/or chaotic behaviour, such that some are ‘evicted’ from care homes,27 although there is little direct evidence about this from more recent times.

The number of older homeless people is rising, as is the number of homeless people in England generally, although data quality is not sufficient to provide accurate numbers. 28 In 2017, Homeless Link reported a total of 36,540 bed spaces in 1253 hostels and second-stage accommodation across England. London has the greatest number of projects in total, at 183, and the most bed spaces, with 9647 beds. Reporting on the 1121 accommodation projects for single homeless people in England, Homeless Link29 noted that levels of support, access and inclusion criteria varied between projects. Services that offered lower-level support tended to be for those who were homeless or in need of housing, but deemed to otherwise be capable of living independently. Some other services offered more support for those who had support needs alongside their accommodation needs, and faced many barriers to living independently.

There are expectations that hostel residents will move on from first-stage hostels (those that provide intensive support in a 24-hour hostel) to other accommodation often within 6 to 12 months. 29 (Stage 2 hostels involve shared accommodation and a lower level of support and stage 3 often involves a move to independent living.) Yet some older homeless people with increasing memory impairment and other vulnerabilities may remain in hostels for years, with growing frailty, as there is no suitable alternative accommodation. Most hostels are not designed or staffed to provide long-term housing or a high level of support for this client group or others. In addition, many older homeless people are reported to dislike staying in hostels, fearing intimidation and violence from younger residents. 30

Audits conducted over 20 years ago by homeless sector staff in Blackburn, Brighton, Cambridge, Liverpool, Oxford and Westminster26 suggested that 10–16% of older homeless people known to them had ‘serious memory problems’ or ‘have memory problems/are prone to wander’. Other reports have noted the presence of dementia among older homeless people31 but have not given any estimates of its prevalence. Many of such audits relied on the observations of non-clinical staff, and not on mental health workers’ clinical examinations or tests; various lower age limits were applied (from 45 to 60 years); and profiles of the residents were not collected or not reported. The lack of clinical input in such audits may account for difficulties in analysing what might be contributing to the problems reported: alcohol misuse resulting in vitamin B12 and folate deficiencies, for example, or untreated human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, vascular disease, or chronic or long-standing brain or head injury. There is a strong association between long-standing heavy alcohol consumption and alcohol-related brain damage (ARBD) or injury. 32 Moreover, studies of hostel residents of all ages have revealed multiple health needs; for example, a comprehensive survey of residents in a London hostel for homeless women collected demographic data, and information on past and present psychiatric and social morbidity and on current and premorbid cognitive functioning. 33 This reported that over half of the residents surveyed had ‘severe mental illness’. The associations between poor health and homelessness are becoming better recognised. 19

Quality of life of older homeless people

The research discussed in the previous section is problem focused and does not engage with the individuals of concern and their situations. Thus, although several measures of social functioning and wider QoL have been developed for use with people with long-term mental illnesses,34,35 their development for use with people with dementia is more recent, although there is a long history of measurement of stress and coping among family carers. Work has been undertaken to design measures that better address the social circumstances of older people who are homeless (e.g. the focus group discussions of QoL in a Canadian study included older homeless participants36). These confirm the necessity of taking into account all of the social factors that this marginalisation generally brings (such as lack of family contact or meaningful activities). The QoL measures being developed in social psychiatry are embedded within a strong conceptual framework, including medical and multidimensional, holistic models of functioning,37 wider health and psychosocial needs-based and life satisfaction models,34 but these generally take ‘home’, ‘occupation’ and ‘social contacts’ for granted. The development and use of a robust measurement of QoL among homeless people with dementia may need to take into account the literature on QoL among people with mental illness who are homeless (emphasising maintenance of stable housing, food and clothing, health and risk of victimisation38), and among homeless people per se (emphasising food, shelter, necessities, respect, choice and relationships39). Two particular studies have validated such scales among homeless people: Riley et al. 40 used the SF-36 (Short Form Questionnaire-36 items), although this was confined to a particular subgroup of people infected with HIV who were homeless or marginally housed, whereas Auquier et al. 41 used the same measure with homeless people with schizophrenia living in urban France. These highlighted the need for QoL measures to reflect the priorities of the target population, enabling better understanding of the need for any QoL instrument for those with dementia and who are homeless or ‘hard to house’ to reflect their own needs and priorities. The first part of the present study was therefore designed to examine the appropriateness of existing QoL instruments in reflecting the needs and priorities of this group (see Chapter 2).

Workplace contexts

The subsequent and major part of the present study sought to remedy, in part, the current lack of research evidence and knowledge of the extent of memory problems (used as a general term suggestive of possible dementia and to make a distinction between learning disability-related memory problems and any other mental illnesses) and service use among older homeless people resident in hostels. Other studies have investigated specific health conditions among this group (e.g. Hill et al. ,42 who focused on dental problems). Little is known about how staff working in hostels are involved in identifying memory problems and steering residents into memory services, or how they manage symptoms of possible or recognised dementia among hostel residents in the current context in which dementia is a policy and practice imperative.

The hostel workforce is an under-researched group. 43 In England, most of those working in hostels are employed by not-for-profit or commercial organisations that provide ‘temporary’ accommodation for homeless people. Funding is mainly through local authority housing-related support payments (previously through the Supporting People programme) but also through other income streams and fundraising. Staffing levels in accommodation projects for single homeless people run at an average of nine full-time-equivalent staff,44 although hostels vary greatly in resident numbers, staffing deployment and resources. Staff working in homelessness services generally undertake a range of duties but, in general, receive little continuing professional development and support compared with health-care professionals. 45 They are reported to be uncertain of their positions in local health networks,46 yet they are considered to have much to offer health-care services locally in terms of skills and knowledge. 47 Fitzpatrick and Wygnanska48 argued that hostel staffing and support arrangements can be even more critical to residents’ QoL and future prospects than physical standards, but noted that hostel staff can be poorly qualified, often needing only a basic vocational (non-university) qualification.

Chapter summary

This chapter has located this study in the contexts of policy and practice relating to dementia and homeless older people. It has drawn attention to policy contexts of health inequalities and to the lack of knowledge about the workforce in organisations supporting older homeless people. The discussion of QoL among older homeless people highlights the general lack of information about this important matter, and draws together the contextual themes by noting the importance of this to the individuals concerned, despite difficulties in defining it. The next chapter moves to discuss previous work on this subject on which the present study draws.

Chapter 2 The literature reviewed: the prevalence of memory problems among older people who are homeless and quality of life

Introduction

The previous chapter described the overall aim of this research project as being to investigate service responses to older homeless people with memory problems (consistent with mild cognitive impairment or dementia) and the experiences of those so defined. This chapter presents findings from our two reviews of the literature to set the context for the data collected and analysed. Literature review A aimed to address objective 1 of the study by investigating the prevalence of memory problems among older homeless people. Literature review B aimed to address objective 4 of the study: how homeless people with memory problems perceive their QoL. This has been published49 and so is briefly summarised.

There is emerging, if, at times, varied, UK evidence about the circumstances and needs of older people who are homeless and have memory problems, although, as we report below, the subject has received sustained attention in other developed countries, such as the USA, Canada and Australia. A recent paper commented that ‘(R)eported rates of mild and moderate cognitive impairment in older people experiencing homelessness range from 5–80%’. 50 One explanation for such a vast range may be that several different interpretations of three key terms are being used, namely homelessness, older/old (usually by chronological age, which can start at 45 years) and memory problems (or disability or dementia). International comparisons are rendered even more difficult by national arrangements and terminology relating to locations, with the functions and roles of hostels, flophouses (a term mainly used in North America), shelters (North America in the main) and boarding houses (Australia and North America in the main and approximately equivalent to UK hostels) being variable or overlapping. Other national considerations include whether homeless people are covered by universal health services or systems that are based on insurance (e.g. see Brown et al. 51). There are also differences between people who have been homeless for several years and are reaching older ages, and people who have become homeless for the first time in later life. 52,53

Relatively few homeless people live long. A recent audit of mortality data concerning homeless people in East London who were registered with two specialist primary care practices54 found that the average age at death was 47 years and concluded that most deaths were very premature and preventable. The UK Coalition on Older Homelessness26 defined ‘older’ homeless people as those aged ≥ 50 years, because many people who are homeless at this age already have long-term health problems and disabilities that are normally associated with (very) old age. In Canada, Grenier et al. 55 concluded that ≥ 50 years would be an appropriate threshold. Similarly, Alden23 adopted the age of ≥ 50 years on the basis of evidence that poor health and ‘premature ageing’ are inevitably associated with ‘rooflessness’.

Although official UK statistics on homelessness are acknowledged to be limited in their accuracy,28 approximately one-fifth of homeless people living on the streets and in hostels are aged ≥ 50 years (around 8% are aged ≥ 60 years). 56 The audits reported in Chapter 1 by the former UK Coalition on Older Homelessness26 relied on the observations of staff only, and various lower age limits were applied (from 45 to 60 years), and profiles of the residents were not supplied. Around two-fifths of older homeless men and one-fifth of older homeless women have long histories of alcohol misuse, and there is a strong association between long-standing heavy alcohol consumption and brain damage or Korsakoff syndrome, which is characterised in part by short-term memory loss. 57

Little is known about the problems faced by older homeless people with memory problems, the services and support that they receive, and the extent to which their needs are met. Some are reported to be hard to engage, reluctant to work with services, and difficult to assess and help because of persistent heavy drinking or other challenges and experiences. There are the added problems among some of distressing behaviour, multiple physical health problems and self-neglect. However, Johnson and Chamberlain58 pointed out that it is difficult to help homeless people with their mental health or other problems if they are living in substandard accommodation, such as boarding houses (as noted previously, this term is used in Australia to refer to facilities approximately equivalent to UK hostels), in which they may be at risk of violence and lack control over their environment. There is little information about the help available to homeless-sector staff working with this group, and their knowledge and experiences of accessing health and social care services. Rather than pathologising the older homeless person, there is a perceived need, which many in the homelessness sector acknowledge,59 to gain a greater understanding of these problems, identify the barriers to diagnosis, service access and unmet need, and find out ways in which these might be addressed in services that should be characterised by respect and dignity for older homeless people. 60

Literature review A: a scoping review of prevalence of dementia in older homeless people

Methods

Search strategy

For this scoping review of what is known about the prevalence of dementia among homeless people, we conducted a comprehensive, cross-disciplinary, systematic search of the conceptual and empirical literature across clinical and social sciences, and health, housing and social care. We searched for any type of English-language literature published or written from 1980 to the end of 2016. We included observational studies, controlled evaluations and randomised controlled trials of health and social care interventions relevant to older homeless populations with dementia or memory problems.

Process of the review

The process of the review was that two reviewers independently screened all titles and abstracts that had been retrieved for relevance; disagreements were resolved by consensus. If relevant, the full-text article or publication was obtained. The full text of obtained articles was judged to be potentially relevant by the two reviewers. A list of key questions was generated, and a pro forma (data extraction tool) was developed to address these from the included papers. These were piloted on a small number of selected papers. Owing to the few papers identified, unlike Burra et al. 61 and Ennis et al. 62 we did not adopt a critical appraisal approach to rating the quality of studies, thereby following procedures generally categorised as scoping reviews. 63 One key reason for this is that such an approach risks overlooking studies with small sample sizes and, thus, might exclude individual case study or whole-hostel research if the numbers of older residents were not sizeable. Ennis et al. 62 considered a sample size of over 100 to be ‘good’, but, as discussed below, we found few studies reporting such numbers.

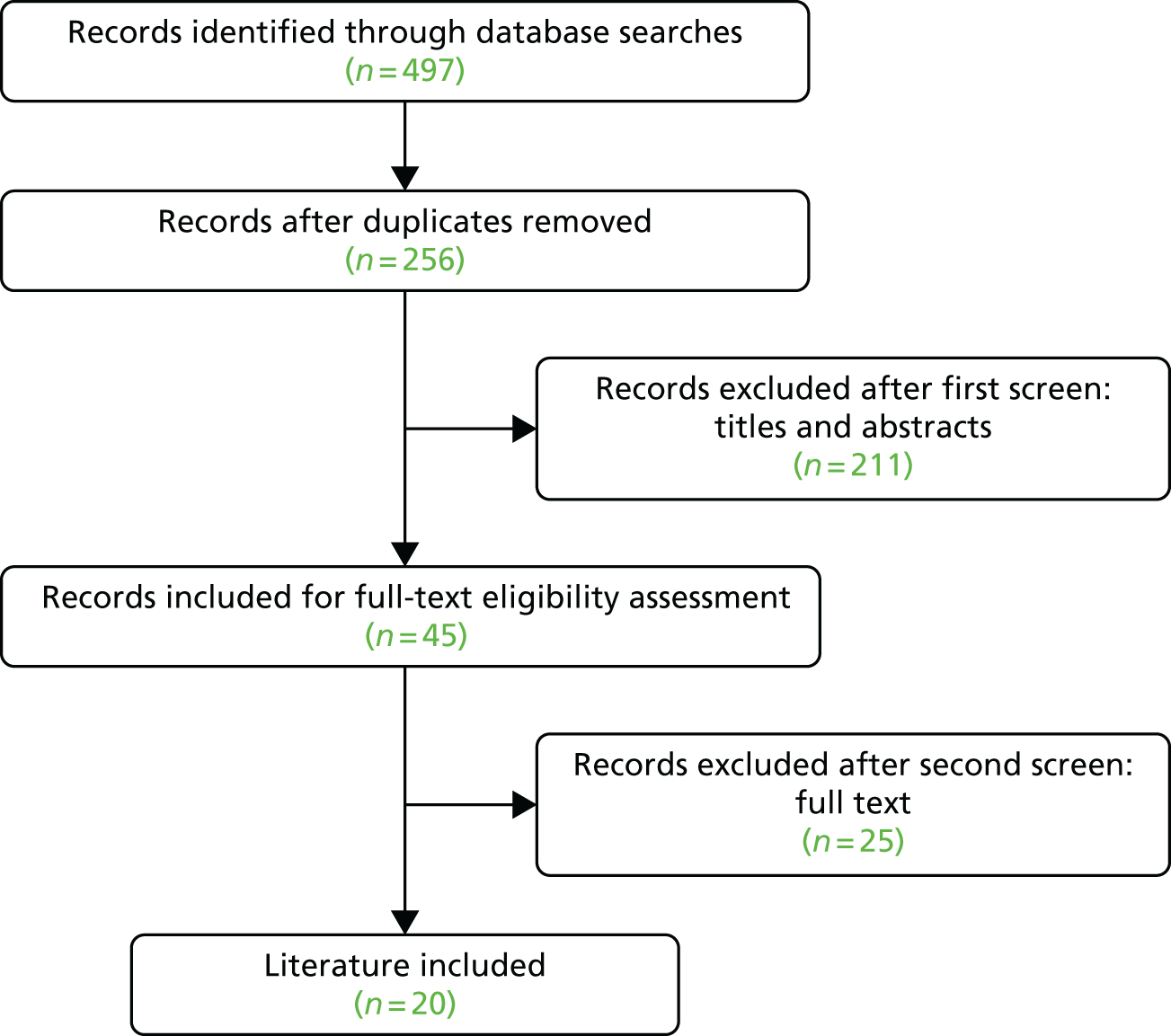

We identified 20 articles for inclusion in the review, after screening 260 articles retrieved from our database searches (the searches were run in May 2016). We searched English-language databases only (Web of Science, Scopus, Social Care Online, PubMed and The Cochrane Collaboration) for material published from 1980 to 2016, including ‘grey’ literature [Figure 1 shows the flow chart – a modified PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) diagram – for the process of literature review].

FIGURE 1.

Literature review A flow chart (a modified PRISMA diagram).

We cross-checked our findings with a recent (2014) literature review from Australia conducted by a researcher at La Trobe University,64 in which the period 2004–14 had been searched for items from English-language literature, using the terms cognitive impairment, dementia, care needs and illness of homeless people. Chenco undertook one search for ‘dementia’ and ‘homeless’ and another for ‘illness’ and ‘homeless’, and then combined the findings into a single larger list. 64 This resulted in the location of 344 references, once Chenco had removed duplicates. Of these, 35 were deemed directly relevant for the purposes of Chenco’s Australian review, which, as noted previously, took a much broader scope than our study by including the term ’illness’. 64 In this search of four main databases, Chenco located the following numbers of items:

-

Social Services Abstracts (via ProQuest) (n = 241)

-

AgeLine (via EBSCOhost) (n = 24)

-

Australian Family & Society Abstracts Database (via Informit) (n = 84)

-

Health & Society Database (via Informit) (n = 73).

In addition to comparing our searches with Chenco’s findings,64 we took particular account of the findings of other scoping and systematic reviews of similar subjects. In the review by Spence et al. ,65 for example, the following terms were searched for in the titles, abstracts and any subject heading fields: ‘homeless*’ or ‘roofless*’ or ‘fixed abode*’ or ‘hostel*’ or ‘bed and breakfast*’ or ‘night shelter*’ or ‘hotel*’ or ‘housing benefit*’ or ‘street dwell*’ or ‘tramp’ or ‘tramps’ or ‘vagrant*’ or ‘vagabond*’ AND ‘cognit*’ or ‘executive function’. We did not search for the terms ‘tramp’ or ‘vagabond’, but it is interesting to note that such terms were evidently in use just over a decade ago in the UK. There are wide variations between services that provide hostel accommodation and night shelters, both internationally and in the UK and in terms of their residents or user profiles; these need to be taken into account in any comparison and are mentioned in Findings.

Findings

Our searches found a small number of studies covering homelessness and memory problems/deficit/dementia and Appendix 1 contains a full table of the studies included in the second literature review. Of these studies, one of the earliest to examine these subjects in terms of prevalence was undertaken in Australia by Teeson and Buhrich. 66 Over 20 years ago, these researchers used the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE),67 which is still commonly used in UK dementia services, and estimated that severe memory problems affected 25% of one hostel’s 65 residents, and another 40% showed signs of mild memory problems.

To establish if the high prevalence of severe memory problems was more commonly borne out in other hostels, and because no women had been included in their 1993 research,66 Buhrich et al. 68 later conducted a broader study of homeless people, again in inner-city Sydney, NSW, Australia. Using the MMSE67 with 204 participants (155 men and 49 women) in seven hostels, they found that 10% (20 people) had some form of memory problems. Of the 14 men with memory problems, five had severe memory problems. The six women had mild memory problems:

The prevalence of cognitive impairment among the homeless subjects in this sample was 10 percent . . . the prevalence of cognitive impairment in the general adult population is 1.7 percent . . .

Buhrich et al. 68

In this study, MMSE scores of 0–17 were interpreted as indicative of severe impairment and scores of 18–23 were interpreted as mild impairment (although six people were not included in these figures as they were unable to complete the MMSE, were deaf, or could not speak English). The researchers found that people with memory problems were likely to stay in the hostel accommodation for longer than those without, postulating that this might be because ‘move on’ accommodation was much harder for them to find, or because their motivations to move on were compromised. 68

Measurements and assessments

Ennis et al. ’s62 review found 11 studies that measured memory impairment among homeless people (of any age) using validated neuropsychiatric tools. They excluded those studies in which memory was assessed by the MMSE,67 as they argued that this does not produce a unique score for items of memory. Eight distinct studies contained unique samples of people who were homeless, a total of 436 participants. The mean age of the studies’ participants was 40.75 years and most participants were male. Most studies had been conducted in the USA. The authors commented that older homeless people were not adequately represented in the studies they reviewed (neither were women, young people or children). They suggested that studies that collect data about ‘memory’ problems without using validated tools are virtually impossible to compare. In respect of their findings of prevalence of memory impairment, they expressed caution in making firm estimates as there were so many variations of assessment, scoring and sample populations. They also highlighted a need for further research on traumatic brain injury, which they concluded is often misdiagnosed or mistaken for other problems. Despite their reservations about using the MMSE, and as the findings reported below show, many other researchers have used this assessment.

Other modes of assessment have explored the presence of serious mental disorders among homeless people. A systematic review (not focusing on older people) identified 29 surveys in which 5684 homeless people had participated through clinical examination or interviews using validated instruments, many of which had good participation or response rates, mostly above 70%. 69 Inner-city Sydney, NSW, Australia, is one research site where several studies with older populations have been undertaken. For example, Rogoz et al. 70 found that 67% of participating homeless older people showed evidence of memory problems. Rogoz and Burke’s later study of 171 older (aged ≥ 45 years) homeless people in inner-city Sydney screened them for memory problems using the MMSE (taking a score of ≤ 26 as indicative of memory problems), or asked them to complete a clock-drawing test, a verbal fluency test and the Trail Making Test (this was the most sensitive). 50 This screening found that 78% (134 out of 171) were cognitively impaired, with 75% showing marked impairment of their frontal lobe functioning. This study recruited from a wide range of sources, including people living on the streets, in temporary accommodation and in marginal or shared facilities. The researchers commented that using one neuropsychological test was easy to administer and appeared acceptable.

In a US study that explored the presence of ‘geriatric syndromes’ among older (age range 50–69 years) homeless people in eight homeless shelters in Boston, MA, USA, Brown et al. 71 found that memory problems (measured by a MMSE score of ≤ 24) were present among 24.3% (n = 247). Other health problems were frequently mentioned, such as incontinence (49.8%), self-reported hearing loss (29.7%), major depression (39.8%) and visual impairment (30%). Comparisons with the general population revealed a higher presence of health problems among the homeless population. Interestingly, to make such comparisons more accurate, the researchers excluded the three eligible participants who were aged ≥ 70 years, meaning that the definition of ‘older’ should not always concentrate on the minimal age of this category (45 years, 50 years, and so forth) but should also enquire about other exclusion criteria on the basis of age.

In a further analysis of the data, Brown et al. 51 explored the factors associated with ‘geriatric syndromes’ among older homeless adults who had participated in the data collection through interviews and physical examinations. These included assessment using the MMSE and the Trail Making Test Part B to measure executive function by the time taken to complete tasks. Joyce and Limbos24 similarly used the MMSE but also used the 15-item Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS-15) among 49 users of a community-based homeless shelter for older men in Toronto, ON, Canada. Study participants were ≥ 55 years of age (mean age 66.4 years) who had been homeless for an average of 8.8 [standard deviation (SD) 10.2] years. The oldest was 89 years. There was a refusal rate of 40.8%; thus, only 29 people completed the depression measures (GDS-15) and the MMSE. One person had a recorded dementia diagnosis before moving to the shelter but within 6 months of moving in another seven people had been so diagnosed (the researchers generally confirmed this) by primary health services. The researchers found a further four participants with mild impairment (MMSE score of 23–27) and one with dementia (MMSE score of ≤ 22) who had not been previously diagnosed. They concluded that brief screening tools seemed to be effective in identifying memory problems (and depression) among this client group. 24

While focusing on ARBD among homeless hostel-dwellers (aged > 34 years, mean age 53 years) in Glasgow, Scotland, Gilchrist and Morrison57 also collected data relating to memory problems using the Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination (ACE). Of their sample, 82% had memory problems as measured by a score of < 88 on the ACE (the researchers estimated that ARBD affected 21%). This study helpfully describes the type of hostels participating, which ranged from large hostels for men and one for women, to a hostel with ‘rapid turnover’. Similarly, in Sydney, NSW, Australia, Conroy et al. 72 found that among the 50 homeless clients of one service they interviewed (average age of ≥ 50 years), all had a history of alcohol abuse and early cognitive decline. They estimated that 39% had scored similarly to people with dementia in their assessments.

In a US study undertaken in California, Brown et al. 73 recruited older homeless people (aged ≥ 50 years) from a variety of homelessness providers, thereby expanding the more usual recruitment source, which, as illustrated above, has often been from shelters and their sometimes transient and heterogeneous populations. They used the Modified MMSE74 to assess cognition and defined memory problems as a score below the seventh percentile or when a participant was unable to complete the assessment. 73 Among their 350 participants, one-quarter (25.8%) had memory problems as measured in this study. However, Rota-Bartelink25 cautioned against using the MMSE with older homeless people, despite it being easy and quick to administer. She considered it an insensitive indicator of memory problems and observed that this may account for the wide variations in detection of memory problems among homeless populations.

Summing up, a recent review of cognitive functioning among homeless people (aged ≥ 18 years) located 24 studies that had tested for cognitive functioning, including performance in the MMSE, abbreviated Mental Test or ACE. 75 The authors observed many inconsistencies across the studies in terms of data collection, definitions, reporting and diagnoses. They pointed to the difficulties of determining associations between homelessness and cognition. Despite this, the authors estimated that among the adults who participated in the studies reviewed (mean age 46 years), the ‘average prevalence of cognitive impairment was about 5–8 times greater than the rate of memory problems in the US population older than 70 years’. 75

However, caution is needed when generalising from this estimate, as difficulties remain in assessing whether or not cognition impairment overlaps with what might be termed dementia. In one of the few studies of homeless people (published in English) from Japan, Nishio et al. 76 explored the overlap between cognitive disability and mental illness in a sample of 114 people living on the streets or in a temporary residence and recruited via a support centre at mealtimes. Although ages ranged from 20 to 78 years, 84% were aged > 50 years (31 were aged 50–59 years, 33 were aged 60–69 years and 10 were aged > 70 years). Their measurements of cognitive disability covered lifelong (congenital) and acquired impairment. In this study, standardised cognitive testing, including reading, was undertaken during semistructured diagnostic interviews. Relevant to the present study was the researchers’ finding of cognitive disability among 34.2% of their sample; but they concluded that half of this group’s cognitive problems were not the result of congenital disability but were age related or had arisen with mental illness. 76

Summary of prevalence studies

This review first sought to determine the prevalence of older homeless people, with and without memory problems, by synthesising audits published as ‘grey’ literature and surveys. The literature suggests a consensus that older homeless people are more likely to have memory problems than other older people and probably more so than younger homeless people. However, there are limitations to each study, as described previously, meaning that an overall prevalence estimate is hard to determine. These complications render comparisons of prevalence near impossible. Although this may be frustrating, it is likely to be more helpful to service providers and service funders to accept that ‘prevalence’ will be affected by the nature of the service from which participants are recruited, their clientele, the definitions of impairment, and the measurements or tests chosen.

We also explored the range of definitions of memory problems used in these studies. Overall, the term cognitive impairment was prominent, but, as noted above, this was largely synonymous with cognitive dysfunction or cognitive deficit. 25 The use of the term dementia is a fairly recent addition to the literature, reflecting perhaps a more social model of dementia but also the wider user of this term in public and health services settings. Alzheimer’s disease is not generally used in the existing research, possibly because the classifications of dementia were broad or simply not considered. In some discussions arising from the reviews’ analyses, the term memory problems appears to be more mild than dementia, as Chenco64 described people with dementia as a group who will need more specialised support or treatment than others with memory problems. The next section of this review discusses the literature related to service models and staffing.

Services

One point implicitly raised by Rota-Bartelink25 was whether or not memory problems matter in the context of providing services to homeless people. She suggested that they do indeed matter because they affect people’s ability to keep or get stable housing and to benefit from support. The person may need support to make decisions and judgements, regulate their behaviour, and build and keep social relationships. A person’s ability to benefit from interventions has to take into account their cognitive abilities and disabilities. Services should beware of devising or agreeing to outcomes that do not reflect these challenges. The thesis that memory problems bring extra vulnerability was echoed in Grenier et al. ’s55 review, which pointed to the likely needs of older homeless people as being for safety and, by extension, the heightened vulnerabilities if a homeless person has dementia.

Two further reviews of the service needs of older homeless people were found. Stergiopoulos and Herrmann77 noted that some researchers had concluded that older homeless people are likely to be missed by studies that recruit from large services because they are ‘hidden’ or do not use such services and sometimes do not access other related services, such as primary health care. The service needs in their review were mainly indicated by reports of surveys and interview-based studies that pointed to the range of problems commonly found among older people who are homeless or the ‘chronically mentally ill elderly’. 77 They noted that better understanding of the events that precipitate homelessness might inform prevention measures or the pathways to homelessness. However, they also suggested that there exist ‘age-specific unmet physical and mental health needs among homeless seniors, particularly among those with mobility and memory problems’. 77 They proposed that it would be helpful to think about services for all homeless people as well as those for older homeless people; the latter experience particular barriers to accessing some services, such as physical inaccessibility, and often have a legacy of dissatisfaction with services and lack of health card identification (proof of entitlement). One concrete suggestion was that local consideration should be given to day centre programmes to engage older homeless people and to provide more acceptable and accessible assistance.

Stergiopoulos and Herrmann’s study77 was one of the few found that collected data from multiple sources, obtaining data from local health and community services in Toronto, ON, Canada, and surveying 11 hostel directors (eight responded) (in addition to completing a literature review). The directors reported that although older (aged > 65 years) male hostel residents were a very small minority of hostel users, and likely to have been homeless long term, the problems that gave rise to most concern among hostel staff were older residents’ memory difficulties, verbal aggression and alcohol misuse. Fewer in number, older female hostel residents were more likely, in the directors’ experiences, to have memory problems, symptoms of paranoia and depression. The directors expressed concern that overall they were not meeting older residents’ memory and mobility needs.

Burra et al. 61 systematically reviewed studies of cognitive deficits in homeless adults, and discussed their implications for services. They found that, among the studies that had administered the MMSE, between 4% and 7% of homeless people were reported as having global cognitive deficits. The consequent implications for services were thought to lie in problems with clients’ adherence to treatment regimes, their difficulties following rehabilitation programmes and their lack of participation in ‘training’.

Likewise, Brown et al. ,73 whose study included older homeless people living in a variety of environments, concluded that there were few differences in the mental and physical health status of older homeless people by location (temporary or rooflessness), many of whom had disproportionately high levels of long-term conditions compared with the general older population, and even when compared with older people living in poverty. These authors suggested that current service efforts in areas such as rehabilitation, environmental adaptation and addressing polypharmacy may not have much traction with older homeless people, whose key need seems to be for permanent supportive housing.

Some researchers concluded that homeless people not only need stable housing but also need support. For example, Lippmann78 argued that older homeless people need to be able to access more of mainstream older people’s (aged care in Australia) resources and funding. Van Wormer79 similarly proposed that older homeless people need assistance with gaining and retaining housing. A review of the literature on housing options for older people80 reported the wide spectrum of housing services, noting the importance of distinguishing between supported and supportive housing, for example the different models of shelters, and the growing evidence base for the ‘housing first’ approach that sees housing as a necessary preliminary for rebuilding people’s lives.

For older people, it is reported to be even more difficult to provide care and resources if they are living on the streets. 81–83 O’Connell et al. 84 noted that diagnosing dementia is difficult ‘on the streets’ as assessment necessitates access to tests and the ability to take details of a person’s history. In this unique longitudinal study of older homeless people in Boston, MA, USA, where the authors followed up 30 people aged ≥ 60 years for 4 years, multidisciplinary teams of health professionals undertook outreach work regularly.

There have been few evaluations of services for older people with dementia or similar conditions who have been rehoused in care facilities. One of the few is of the Wicking Project in Melbourne, VIC, Australia, a model of residential care for older people with dementia and challenging behaviour arising from alcohol-related brain injury. This started in 2006, as described by Rota-Bartlink and Lipmann60 (Lipmann is the chief executive of the provider organisation, Wintringham, a not-for-profit homeless service for people aged ≥ 50 years). Using a household model with an emphasis on harm minimisation and on meeting the needs of people who ‘shuffle transiently between organisations that cannot provide long-term care management solutions,’60 this facility offers individual care plans and specialist case management.

Findings from interviews with 50 stakeholders in Sydney, NSW, Australia, about possible best practice for older homeless people were summed up by Conroy et al. 72 as suggesting the need for persistent engagement with individuals, taking a harm minimisation approach, targeting people for assessment of possible mild cognitive impairment, and improving links and referrals systems between agencies. 72 Backer and Howard85 had earlier noted that, although prevalence estimates of cognitive problems varied, the effects of such impairments were that older homeless people could find it difficult to access help and support or to sustain engagement with services when their housing was at risk.

Barrett et al. ,83 reporting on older homeless service provision in Florida, USA, claimed that there was an increasing need to understand and work on the different ways in which older homeless people gain access to services and the pathways designed. Unsurprisingly, perhaps, they suggested that better collaboration between services and agencies was needed.

In one of the few discussions about distressing or challenging symptoms of dementia that may be experienced in service settings supporting previously homeless older people, the homelessness provider mentioned previously, Wintringham,78 welcomed proposals for a funding supplement to cover the extra costs needed to provide such support. It commended an approach that was ‘behaviour based’, although it queried whether or not the proposed assessment tool would be appropriate for people who had been homeless. Furthermore, it suggested that a wider range of staff be approved to undertake such assessments, noting that, in homelessness services, members of staff were not generally clinically qualified. It further speculated that some people’s behaviour might be so challenging that a ‘top-up’ or an upload to the funding supplement should be considered. Such detailed considerations of cost-effectiveness and service models are rarely encountered in the literature.

Staff training and skills have been considered in some studies, although there does not appear to have been any evaluation of skills development or of training packages or workforce models. Concurring with the conclusions of other studies,81,86,87 Rogoz et al. 70 suggested that improved access and delivery of services to homeless older people with memory problems should be undertaken by specialist, multidisciplinary teams of health professionals. The skills reportedly needed were summarised as spanning the areas of outreach, assessment and multimorbidity management. In addition to advocating for more research on older homeless people following her review, Chenco64 argued the importance of better understanding of the educational, training and resource needs of health professionals who work with homeless older people.

More specifically related to the content of clinical services, Andersen et al. 88 recommended screening for traumatic brain injury after finding that this seemed to explain the poor performance in cognitive testing among a sample of 34 homeless people in Canada, whose average age was 58.8 years. Further related to health services, Abdul-Hamid et al. 89 had earlier raised questions about whether clinical services for older homeless people should be under the responsibility of geriatricians or psychogeriatricians.

However, as reported by other commentators, some older homeless people refuse to be assessed or evaluated, and questions of competency and decision-making autonomy may forestall service engagement. 84 The legal position of having a proxy or court-appointed decision-maker is not generally addressed in most studies, although the first report of the Wicking Initiative60 mentioned briefly that some residents had an administrator appointed to make decisions (in England and Wales this would perhaps be an appointee for benefits because other provisions of the Mental Capacity Act 200590 would apply only if decision capacity was substantially impaired).

Backer et al. ,85 among others, have pointed to the need for services to prevent homelessness by addressing its causes and risk factors. The skills to follow that path are not delineated, nor is how to change service commissioning. The Wicking Initiative, discussed above, remains one of the few service examples of tertiary provision described in any detail. We do not know much about what happens over time to older homeless people in other settings who are recognised as having memory problems or a dementia. As one example of the importance of this, of the 15 older homeless people with dementia contacted by an outreach initiative91 in the city of Tel Aviv, Israel, 11 later moved to a nursing home, with unreported outcomes. More generally, this study recommended intensive outreach and case management to effectively assist older homeless people.

Ending the ‘invisibility’ of memory problems among older homeless people

According to Lipmann,78 founder and chief executive of Wintringham, Australia’s largest aged care provider for homeless people, being homeless limits access to many of the supports that most other people take for granted. He argued that homeless people are often not included in support services because of their sometimes fierce independence and reluctance to push their ‘rights’; in effect, they become invisible or marginalised. Likewise, he observed that homeless people do not come to the attention of ‘aged care’ (the term used in Australia) services and, to some extent, they also remain invisible here. Lipmann78 acknowledged that considerable Australian government funding is provided for dementia research and services for people with dementia, but observed that little of such funding reaches homeless people with dementia. In his view, the reason for this rests on the stigma associated with homelessness and the ‘fact’ that homeless people do not engage with services, particularly the aged care services to which the mainstream funding is allocated. Lipmann argued that funding should be directed towards Australian welfare organisations, such as his own, that provide services to older homeless people. 78

Literature review B: how homeless people with memory problems perceive their quality of life

Although several measures of social functioning and wider QoL have been developed for use with people with long-term mental illnesses,34,35 their development for use with people with dementia has been slower, although stress and coping among carers have been widely studied. None appears to be relevant to the social circumstances of older people who are homeless, with all of the factors that this living situation generally brings (lack of family contact or meaningful activities, and poor health overall). This literature review49 investigated the evidence on how older homeless people with memory problems perceive their QoL, and the potential appropriateness of existing QoL instruments in reflecting the needs and priorities of this group.

Literature review B49 comprised a narrative systematic review and an evidence synthesis of QoL instruments used in assessing people with dementia (all types) to assist investigators and service providers in selecting the optimal measures for their aims and to specifically address issues and life areas that are of particular importance to homeless older people. It noted the presence of a large body of literature in this area (QoL and dementia), and so a narrative review and critical discussion, with tabulated evidence, were undertaken to compare the measurement properties of the QoL instruments identified, their appropriateness for assessing the QoL of homeless people with dementia, and by type and severity of dementia, and sensitivity to the type, organisation, delivery and use of health service interventions.

The objectives of this review were to:

-

assess the scope and domains included in the QoL measures, theoretical and conceptual frameworks, and the extent of user involvement in their development, by type of user

-

assess their sensitivity to different models and settings of care, the process, organisation, delivery and take-up, and outcomes of services (including service skill mix and voluntary-sector interventions)

-

assess how perceived QoL influences decisions about the care of people with dementia, including homeless groups

-

identify the factors that affect reported QoL, and QoL outcomes of people with dementia, including among homeless groups

-

examine the relevance of existing dementia QoL measures, and their appropriateness, in relation to people who are/have been homeless

-

summarise the current data on the QoL of people with dementia, including homeless groups

-

identify research gaps and the need for further primary research.

The findings of this review were published in 201549 and informed our study data collection instruments.

Chapter summary

In summary, literature review A found that studies of the physical and mental health of older people who are homeless or have experienced recent homelessness have collected data on memory problems using different definitions and in different ways either as a focus or in combination with other conditions. As a scoping review, the publications reviewed were not assessed or graded for quality, but a narrative approach has drawn attention to the key features of the studies or descriptive accounts. The review has not only identified the several varied estimates of prevalence and some debate about the most appropriate means of assessment, but, by providing details of the study populations and approaches, it offers a means of interpreting the variations.

Scoping reviews also facilitate understanding of where gaps in the evidence may lie. Notably, service evaluations and trials of interventions are few. The future of homelessness research with older people may need to shift from estimates of prevalence, as there is international consensus that older homeless people experience multiple health problems but we have far fewer data establishing what is effective in care and support or how to implement the findings. Interestingly, there are few personal accounts or qualitative studies of personal experiences and, with one exception from the Melbourne service (Wintringham), very few accounts of practice, service commissioning and outcomes. This review has set the scene for this study; Chapter 3 presents the methods used in the research.

Chapter 3 Study methods

This chapter describes the methods used to conduct the fieldwork that was planned and undertaken to address the research objectives. The chapter begins with an explanation of what was originally planned in the study design during the preparation for the grant application in 2011, including the potential study sites identified and the proposed data collection methods for the two phases of the study. The various challenges that arose during the implementation of the study design are then discussed. The details of data sources are presented. The last section of the chapter provides accounts of the different methods of data analysis undertaken. This includes a descriptive analysis of the participants’ profiles, the analysis of the cognitive assessments, an economic analysis of participants’ service use and an analysis of participants’ intermittent pathways through health and social care services.

The study design

The study was designed to have two distinct phases: (1) a quantitative element to examine the prevalence of memory problems among older homeless people living in hostels and the extent to which homeless-sector staff are aware of and respond to these problems, and (2) a longitudinal case study phase to investigate:

-

the pathways by which older homeless people with suspected cognitive problems are referred to memory assessment services

-

the services and support that this user group receives for cognitive problems, and the cost of these services

-

how existing services can be developed to address any gaps in service provision or unmet need

-

how homeless people with memory problems perceive their QoL and available support.

Phase 1 design

The first phase of the study aimed to recruit and conduct short ‘screening’ interviews with up to 200 older homeless people aged ≥ 50 years living in hostel accommodation in England, with a maximum of 50 people in each of four diverse study sites. These were the Midlands (five hostels), Central London and South London (three hostels) and the North East of England. As noted in Chapter 1, we used the former UK Coalition on Older Homelessness definition of ‘older’ homeless people as those aged ≥ 50 years.

At the time the study was being designed, managers of several hostels in the sample areas were contacted to find out if they had any residents aged ≥ 50 years and to ascertain their interest in participating in the study. There was an enthusiastic response, with the managers welcoming the need for the research as they perceived the needs of older homeless people to be growing. In the North East of England, however, the numbers of older homeless people were thought to be small in the areas approached, and, consequently, four further hostels were identified in the North East of England that potentially could supplement numbers.

The recruitment and screening interviews of older homeless people aimed to obtain a profile of each participant and an overall assessment of their problems and needs. These also aimed to enable the research team to consider whether or not a participant had any memory problems and, if so, to determine whether or not depression was an influencing factor. This enabled participants to be selected for the case study phase (phase 2). These interviews were designed using a semistructured interview schedule to collect the following information: (1) demographic factors (age, gender, ethnicity); (2) brief histories of homelessness (i.e. length of time homeless, duration of stay in present hostel); (3) previous and current employment, education, income and welfare benefits; (4) use of time and family and social contacts; (5) support received with personal care and household tasks, such as obtaining meals and personal hygiene; (6) past and current physical and mental health problems (including administration of a validated depression tool), substance misuse problems, histories of head injuries and other accidents or traumas, other diagnoses including chronic or long-term conditions, past hospitalisations, and medication and treatment; (7) concerns about memory and support or treatment received, and administration of the MMSE; (8) the use of different health services; and (9) QoL, and hopes and plans for the future in terms of housing and support.

We were conscious that older people with memory problems and in marginal living conditions could be a vulnerable group in terms of research as well as in much of their lives. In our application for ethics approvals, we addressed the risks that they might feel obliged to co-operate in the study, might find the questions intrusive or upsetting and might have expectations of more help. Two senior researchers (MC and LJ) had considerable experience of research and practice in the homelessness sector and they supported the wider research team in fieldwork. One ethical challenge was how to acknowledge participants’ time in study participation. We decided that, at the end of each interview, older homeless participants would be offered £5 to thank them for their time, either in cash or as a shopping voucher: the type of incentive was negotiated with each hostel manager.

Once participant baseline interviews were completed in each hostel, each person’s key worker was contacted and invited to take part in the study. An information sheet about the study was designed for hostel workers, and workers were shown the consent form signed by the hostel resident that gave consent for the worker to be interviewed about them. Hostel workers were also required to provide written consent to be interviewed. This interview included questions on (1) the characteristics of the hostel resident; (2) how the worker assessed and planned support for the resident; (3) their perspective on any physical, mental health, substance misuse and memory problems and the support and treatment provided; (4) what assistance, prompting or supervision was provided on a day-to-day basis by hostel staff or other services; and (5) future plans for the hostel resident. If a worker suspected that the participant had memory problems, they were then asked, based on the informant interview questions in the General Practitioner assessment of Cognition (GPCOG) tool,92 the reasons for this, such as whether the person (1) had problems remembering things that had happened recently, (2) could not recall conversations a few days later or (3) had difficulty finding the right word or tended to use the wrong words.

To gain an understanding of the hostel staff’s training and experience, a short structured questionnaire was also designed to be administered at the first interview with each practitioner. Topics were (1) current role, length of time working in the hostel and hours of work; (2) previous experience of working with homeless people; (3) other work experience; (4) training related to working with homeless people and training on supporting someone with mental health or memory problems; and (5) training that was/would be helpful in working with older hostel residents.

To collect background information about the hostel and the services it provided, an interview was also planned with the manager or senior practitioner in each hostel. An interview schedule was designed to collect information about (1) the hostel management, facilities and funding; (2) client groups and access policies; (3) tenure policies; (4) staffing levels and training available for staff; (5) help and support provided to hostel residents; and (6) characteristics of residents with memory difficulties, support provided and services available.

After the baseline interviews were completed with hostel residents and hostel staff, data were summarised so that each participant could be discussed by the research team psychiatrists to enable participants to be allocated to observation or control groups. It was initially intended that decisions regarding allocation to the observation or control group would be made with the 30 hostel residents suspected of having memory problems and a random selection of eight residents not suspected of having memory problems being invited to take part in an interview with the research psychiatrists using the Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination tool version R (ACE-R),93 which would be used to confirm the group allocation. This tool was later replaced by the Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination III (ACE-III) following further discussion. The ACE-III is one of the most popular and commonly used cognitive tests in dementia clinics and in the assessment of other neurological disorders. It provides a sensitive, reliable, secure and easy-to-administer clinical tool to assess cognition as part of the process of assessing for dementia. The ACE-III has five subdomains, which provide a cognitive score out of a maximum of 100: (1) attention, 18 scores; (2) memory, 26 scores; (3) fluency, 14 scores; (4) language, 26 scores; and (5) visuospatial, 16 scores. The assessment also involves asking participants if they have problems with face recognition, remembering names of people or objects, and problems with their short- or long-term memory. As with other hostel residents who participated in interviews, £5 was given for participation.

Phase 2 case study design

The 6-month longitudinal case study phase aimed to conduct case studies of 60 older homeless people – 30 with memory problems and 30 without memory problems – divided between the study sites with the samples matched on age and duration of their stay in the hostel. These 60 participants would be selected from the 200 participants recruited in phase 1. A case study methodology was chosen as it would enable an in-depth exploration of the predominant factors and challenges that staff in homelessness services face in a real-time context,94 which can be especially useful in researching practice settings. 95

Interviews with hostel residents

The case study phase of the study involved interviews being conducted 3 and 6 months after the first ‘screening’ interview with the 60 hostel residents described above. In both interviews, the aim was to collect information relating to their situations during the previous 3 months. Questions covered (1) their use of time and social contacts; (2) courses, training and voluntary work undertaken; (3) contact and support received from hostel staff; (4) everyday tasks and help given; (5) changes to physical, mental health, memory, alcohol and drug use and any associated treatment or support; (6) referrals and use of health, substance misuse and other services including hospital admissions, hospital outpatient drug and alcohol detoxification and rehabilitation services, services accessed from a general practice, urgent and emergency care; and (7) help that they would have liked to have had, but did not receive.

Interviews with hostel staff

Interviews were also planned to be conducted at 3 and 6 months with hostel staff in relation to the participating hostel residents they supported. These interviews focused on the same subject areas as covered in their first interview conducted in phase 1, in particular any changes perceived by the worker in the resident’s physical or mental health, substance misuse or memory problems, the services used by the resident, the support provided by hostel staff or other services and how long they spent providing this support.

It was initially proposed that information about the length of time workers spent supporting an individual could be collected using a self-completion diary sheet. This was piloted in one hostel by members of staff supporting two residents over a 2-day period. Staff were asked to document hourly any support or attention they gave these residents and how many minutes this took. This included help with finances, social activity and personal care, as well as any activities they undertook on a resident’s behalf, such as arranging appointments and dealing with rent payments. However, this proved not to be a very accurate way of collecting these data, as support often involved checking on or keeping an eye on people to monitor their well-being rather than being a specific task, and, as residents often spent large amounts of time in communal areas, such ‘support’ was not provided to a single person. The diary element was, therefore, not pursued.

The final interview with hostel staff at 6 months contained additional questions regarding (1) effective ways of engaging with the hostel resident and any strategies or techniques used, (2) their challenges and difficulties in working with the resident and attempts to overcome the difficulties, (3) experiences of working with other agencies to support the hostel resident and (4) implications for hostel staff and other workers in helping older homeless people with similar problems.

Interviews with other support workers

To obtain as much relevant information about the support needed and provided to each participant, interviews were also planned with other workers providing support. At their 6-month interview, hostel resident participants who received support from a service such as an alcohol misuse or community mental health team were to be asked to provide permission for the worker to be invited to take part in a semistructured interview about the support they provided. Interviews were intended to last about 45 minutes and would be digitally recorded and transcribed. The topic areas were (1) current role and experience in working with older homeless people, (2) help and support provided to the participant, (3) working arrangements with other services to provide this support, (4) challenges or difficulties in providing this support and (5) unmet needs of the participant.

Data collection from participants’ hostel records

It was also planned that, following the 6-month interviews with residents, data would be collected from participants’ hostel records. Information would be collected about (1) length of time in the hostel; (2) welfare benefits received and rent paid to the hostel; (3) mental and physical health conditions, substance use issues and treatment programmes; (4) medication; (5) use of different health services, including general practitioner (GP) and other health-care services, such as emergency department [accident and emergency (A&E)] use and hospital admissions; (6) frequency and duration of receipt of social care services, including domiciliary care/home care; and (7) other service use, such as voluntary services (e.g. day centres).

Data collection from participants’ medical records

At the end of the case study period, data would also be requested from the medical records held by the named GP for each resident. These data would comprise all medical records for the 6-month study period, including active health problems, previous health problems, current medication, hospital admissions and discharges, responses to referrals, use of urgent care and out-of-hours services and hospital outpatient department reports.

Study implementation

This section discusses the challenges involved in implementing the study design and the responses to these.

Recruitment of study sites and participants