Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 13/10/14. The contractual start date was in February 2015. The final report began editorial review in May 2018 and was accepted for publication in January 2019. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Gavin Perkins reports grants from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) during the conduct of the study and non-financial support from Intensive Care Foundation (Camberwell, VIC, Australia) outside the submitted work. Karen Rees reports grants from NIHR during the conduct of the study. Helen Parsons reports grants from NIHR during the conduct of the study. Zoe Fritz has received grant funding from the Wellcome Trust (London, UK) outside this study and is on the executive committee of the Resuscitation Council (UK) (London, UK); expenses are covered for meetings. Zoe Fritz is also chairperson of the Strategic Steering Group for ReSPECT (Recommended Summary Plan for Emergency Care and Treatment); expenses are covered for meetings. Sarah Symons is a member of the Bath Clinical Ethics Advisory Group and has received payment from the University of Warwick for time taken to comment on the study documents as patient and public involvement co-investigator. Anne Slowther is a member of the Board of Trustees of the UK Clinical Ethics Network (Newcastle upon Tyne, UK) and the Institute of Medical Ethics (St Helens, UK). She has received funding in grants from NIHR as a co-investigator outside this study.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Bassford et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Throughout this report we have used the term intensive care (rather than critical care) to describe both the physical location [intensive care unit (ICU)] and the health-care professional (intensive care doctor) making decisions about admission to the unit. We consider the terms intensive care and critical care to be synonymous.

Intensive care

An ICU is ‘a specifically staffed and equipped, separate and self-contained area of a hospital dedicated to the management and monitoring of patients with life-threatening conditions’ (reproduced with permission from Faculty of Intensive Care Medicine/Intensive Care Society). 1 Timely admission to an ICU is associated with more favourable outcomes. 2 It is thought that admission to intensive care gives a critically ill patient a 17–23% increase in their chances of surviving their acute illness. 3

Treatments delivered in intensive care include invasive monitoring of physiological parameters, renal replacement therapy, cardiovascular support and invasive and non-invasive ventilatory support. These treatments, although potentially life-saving, can place significant burdens on an individual patient. In the UK, the mortality rate for patients whose hospital stay involves admission to ICU is around 20%, and 10% of those who survive ICU die before leaving hospital. 4 Following ICU discharge, patients have an increased mortality rate that persists for at least 15 years. 5,6 In addition, ICU survivors have ongoing morbidity compared with their peers; among patients who require renal replacement therapy on ICU, only 28% survive for 1 year and 12% of survivors require ongoing renal dialysis. 7 Long-term psychological morbidity after ICU admission is also widely recognised. 8

Treatment in intensive care may not always be in the best interests of a critically ill patient. If intensive care does not return a critically ill patient to a life they value, then the intervention may have harmed rather than benefited that patient. For patients who do not survive ICU, an opportunity may have been missed for them to have a peaceful and dignified death.

Deciding whether to refer and/or admit a patient

When a patient is assessed as having a life-threatening illness, an initial decision must be made about whether or not they should be referred to ICU. This decision is made by the clinical team caring for the patient. The decision whether or not a patient should be admitted to ICU is usually made by the ICU doctor, although critical care outreach (CCOR) or emergency medical treatment teams may also contribute to the decision. Both the referral and the admission decision require clinical teams to consider the benefits and burdens of ICU treatment for the individual patient in question. Treatments delivered in an ICU may not be required or the burdens of ICU treatment, both short and long term, may outweigh any potential benefit. In some cases, palliative care may provide the best option for treatment of the patient’s condition. These decisions are not easy and require good clinical and ethical judgement.

Assessing the clinical situation

A patient’s acute clinical condition and the severity and nature of their past medical history are important considerations when making a decision about admitting him or her to ICU. Our previous scoping review found several studies confirming that these factors have an impact on the decision. 9–14 However, there is often uncertainty about prognostic indicators and the extent of chronic illness in an acute situation. Other, more value-laden factors also appear to influence the assessment of the clinical situation, including the age of the patient13,15–17 or the doctor’s assessment of the patient’s functional status or quality of life,14,18–20 whether a patient has a medical or a surgical diagnosis3,12,21 and whether they are assessed by a junior or a senior physician. 10,16,22–24

Evidence and prognostic indicators

Although prognostic information from observational studies is available to guide decision-making, the likelihood of death for a critically ill individual remains difficult to predict with an acceptable degree of certainty. Several prognostic tools for application to critically ill patients have been developed, the most widely used in the UK being the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE-II) score. 25 However, this is calculated after the patient has been admitted to ICU, so it is of limited value for referral or admission decisions. Most prognostic models predict either ICU or hospital mortality, rather than long-term survival (or quality of life). Therefore, prognostic models are primarily used to assess ICU quality and performance rather than as a framework for decision-making in individual cases. 26

Some individual patient-related factors have been found to be associated with increased mortality in ICU patients after hospital discharge, namely severity of illness, age and presence of comorbidities. 5 This information can inform the risk–benefit analysis when considering admission, but it does not provide a definitive prognosis for an individual patient.

There is evidence to suggest that, even if clinicians are provided with patient-specific prognostic information about end of life at the time of decision-making, this does not materially alter their clinical decision-making. 27

Patient’s values and wishes

The ethical principle of respect for patient autonomy is reflected in legal and professional regulation of clinical decision-making. 28,29 A person should be provided with relevant information and given an appropriate time to contribute to a decision about their treatment. However, when the decision is about whether to refer or admit a person to ICU, that person is often unable to take part in the discussion, and in most cases will lack the capacity to consent to, refuse or request treatment because of the severity of their illness. Guidance on how to use a shared decision-making model in the context of critical illness has been produced;30 however, it is still the clinician’s responsibility to operationalise the shared decision-making model within a specific context, including the urgency of the situation and the extent to which the patient and/or their family or surrogate decision-maker are able to participate. In the UK, if a patient lacks capacity, it is the responsibility of the clinician caring for them to first determine if there is any relevant advance statement or legal proxy to make decisions on the patient’s behalf, and then to make a decision that is in the patient’s best interests, consulting where possible with the patient’s family and those who know the patient well in order to understand what the patient’s wishes might be. 28

Critical illness often develops with little warning and the decision whether or not to admit a patient to ICU often needs to be made in an emergency situation or when a patient’s condition is deteriorating rapidly. Family members may not be present and, even if they are, there may be little time for extensive discussion with them. When families are consulted about the patient’s values and wishes, they are not always accurate in predicting what the patient might want in this situation. There is evidence that families acting as surrogate decision-makers poorly predict what the patient would wish for themselves, and may prioritise their own values and wishes, rather than those of the patient, when asked for their views on future therapy. 31

Resources and external influences

The safe delivery of intensive care treatments requires a high concentration of staff and resources. In an ICU, the nurse-to-patient ratio is 1 : 1 for a ‘level 3’ patient or 1 : 2 for a ‘level 2 patient’,1,32 compared with a standard ward where one nurse will look after nine patients. 33 In 2006 in Europe the cost of an intensive care bed was between €1168 and €2025 per day. 34 Delivering this level of nursing for all patients would quickly overwhelm the resources of any health-care system, and therefore access must be limited. 35 The UK has relatively few intensive care beds compared with many other countries,36 and pressure on the UK’s available ICU resources is a regular occurrence. A survey by the Faculty of Intensive Care Medicine in 201837 showed that 21% of ICUs regularly moved patients to other hospitals because of a lack of local intensive care resources. Surveys and cross-sectional studies10,38–43 of patients admitted to ICU have previously shown that the availability of ICU resources influences whether or not a patient is admitted.

Decision-making within intensive care is set in the context of wider organisational policies and priorities. Some hospitals have specific priority programmes, such as transplant surgery or major trauma, and institutional policy may prioritise these patient pathways for intensive care admission. 44,45 The behaviour of other clinicians (e.g. failure to specify end-of-life treatment plans or to secure an ICU bed before elective surgery) and family demands for life support can also create a perceived pressure to admit a patient to ICU. 46

These organisational and situational pressures add a further ethical dimension to the decision-making, in addition to the difficulty of balancing benefits and burdens of ICU treatment for a particular patient.

The views and values of the decision-maker

As evidence-based prognostic indicators are seen to be of limited value, and as the patients’ views may not be known, it is likely that other values and perceptions will have a bearing on the decision about whether or not to admit a patient to ICU. Previous experience of treating patients with similar conditions may influence the clinician’s perception of a patient’s potential to benefit from a particular treatment. A phenomenon known as ‘prognostic pessimism’ has been demonstrated in ICU clinicians assessing patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Patients with the most severe disease were found to benefit most from ICU treatment and valued the resultant extension to their life after hospital discharge, contrary to the expectations of clinicians who predicted that they would fare badly. 47 Similar findings have also been seen in patients with heart failure. 48,49 A large European study50 of decisions to admit to ICU found that, although older people were less likely to be admitted to ICU, the mortality benefit (mortality without ICU compared with that with ICU) was greater for older patients than for their younger counterparts. The authors concluded that ‘physicians should consider changing their intensive care triage practices for the elderly’. 50

Personal moral values and religious values have also been shown to influence clinicians’ decisions about withholding or withdrawing life-prolonging treatment, of which intensive care can be considered an example. 51

Fair access to intensive care

Given the diversity of values and external factors that influence decisions to admit to ICU, the lack of an effective prognostic tool and the relative lack of relevant guidance, it seems likely that decision-making will vary. Studies have shown variation in ICU admission decisions among individual ICU clinicians,47,52 between ICU staff and referring clinicians,9,53 between institutions in the same country18,50 and between physicians in different countries. 43 Although some variation in decision-making is inevitable, this could lead to inequity in the provision of ICU care. Currently in the UK, not all patients who would benefit from ICU receive it. The 2012 National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcomes and Death report54 Time to Intervene? noted that 37 out of the 392 patients studied who were admitted to a standard ward should have received ICU/high-dependency unit care. There is an ethical requirement to be fair to every patient when making decisions about their care, which means that there should be consistency in the reasons for making the decision and that these reasons should be explicit so that they can be justified if challenged.

Current guidance on decisions to admit patients to the intensive care unit

There is very little specific professional guidance on decision-making about admitting patients to intensive care. In 1996, the then UK Department of Health published guidelines55 on patients’ admissions to and discharge from ICU and high-dependency units. The main criteria for ICU admission in this guidance are whether or not the condition is reversible and the absence of a significant comorbidity, in addition to the need for ventilator or multiple organ support. The guidance does not define what constitutes reversibility or significant comorbidity. This document, although 22 years old, remains the only national UK guidance on admission to ICU. A Department of Health and Social Care report,56 published in 2000, on the organisation of critical care services in the UK did not further develop admission policy for intensive care but called for further guidance to be developed and implemented locally and nationally. Although some regional critical care networks have developed admission policies,57,58 the national guidance has not been updated to take into account new evidence or developments in professional guidance and legal frameworks such as the Mental Capacity Act 2005. 29

In 2016, the Society of Critical Care Medicine in the USA provided definitions of ‘inappropriate’ and ‘futile’ treatments, with the aim of resolving disagreement about these terms. They suggested that a treatment should generally be considered inappropriate:

when there is no reasonable expectation that the patient will improve sufficiently to survive outside the acute care setting, or when there is no reasonable expectation that the patient’s neurologic function will improve sufficiently to allow the patient to perceive the benefits of treatment.

Nates et al. 59

The Society of Critical Care Medicine also produced administrative guidance59 for developing services for best practice in ICU admissions. This guidance highlights the importance of the processes surrounding admission to ICU but offers little guidance for individual decision-making. Also in 2016, the World Federation of Societies of Intensive and Critical Care Medicine produced a summary60 of available evidence addressing four key questions relevant to decisions about intensive care admission: who will benefit from intensive care?; who makes the decision whether or not a patient will be admitted to intensive care?; what in-hospital factors limit patient access to intensive care; and what other factors should influence whether or not a patient is admitted to intensive care? Their conclusions did not provide specific guidance for decision-makers but gave more general points about the importance of fair allocation of ICU resources, the need to weigh the benefits and burdens of ICU for the individual patient, the importance of multidisciplinary input into decisions, and the limited usefulness of prognostic algorithms.

Decision-making for intensive care admissions: addressing the issue

Decisions about the provision of potentially life-saving but extremely burdensome treatment are clinically complex and ethically challenging. The clinicians who make these decisions are faced with clinical uncertainty, limited knowledge of the patient and external constraints which may preclude their preferred option, as well as being under pressure to make a decision quickly if the patient is deteriorating. They also have an ethical obligation to treat all patients fairly. Critically ill patients and their families may be unaware of how or why the decision has been made and have little opportunity to contribute to or challenge the process, yet the families have to live with the consequences of these decisions and may be very distressed if they feel that the decision was the wrong one, especially where the patient does not survive. There is a clear need for guidance and support for both clinicians and patients and their families when faced with these difficult decisions.

Therefore, this project focuses on understanding the decision-making process around referral and admission to the ICU in order to develop an intervention to support decision-makers, patients and their families, and to improve the decision-making process.

The project was designed to answer the research question:

-

What is required for an ethically justifiable, patient-centred decision-making process for unplanned and emergency admissions to adult intensive care?

The project aims were threefold:

-

to explore how decisions about whether or not to refer or admit a patient to adult intensive care are made in the acute and emergency situation

-

to identify and critically analyse the factors that should inform ICU referral and admission decisions from the perspective of patients and their families and the clinical decision-makers

-

to facilitate ethically justifiable, patient- and family-centred decision-making in these situations.

We sought to achieve these aims through a series of work packages (WPs) addressing specific objectives:

-

to describe current practice in decision-making for referral and admission to ICU (WP1)

-

to explore the experience of patients, families and clinicians involved in the decision-making process and their views on how these decisions should be made (WP1)

-

to determine the influence of different factors on decisions to admit a patient to ICU from the perspective of ICU clinicians and the general public (WP2)

-

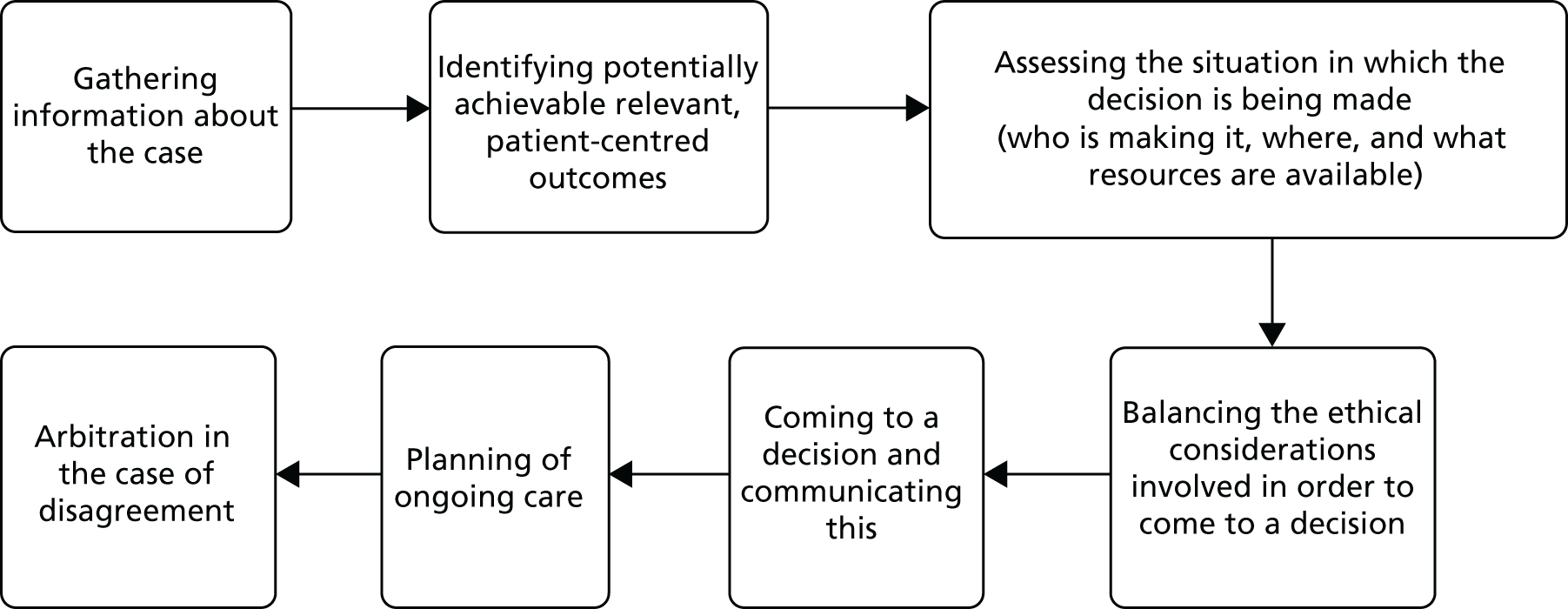

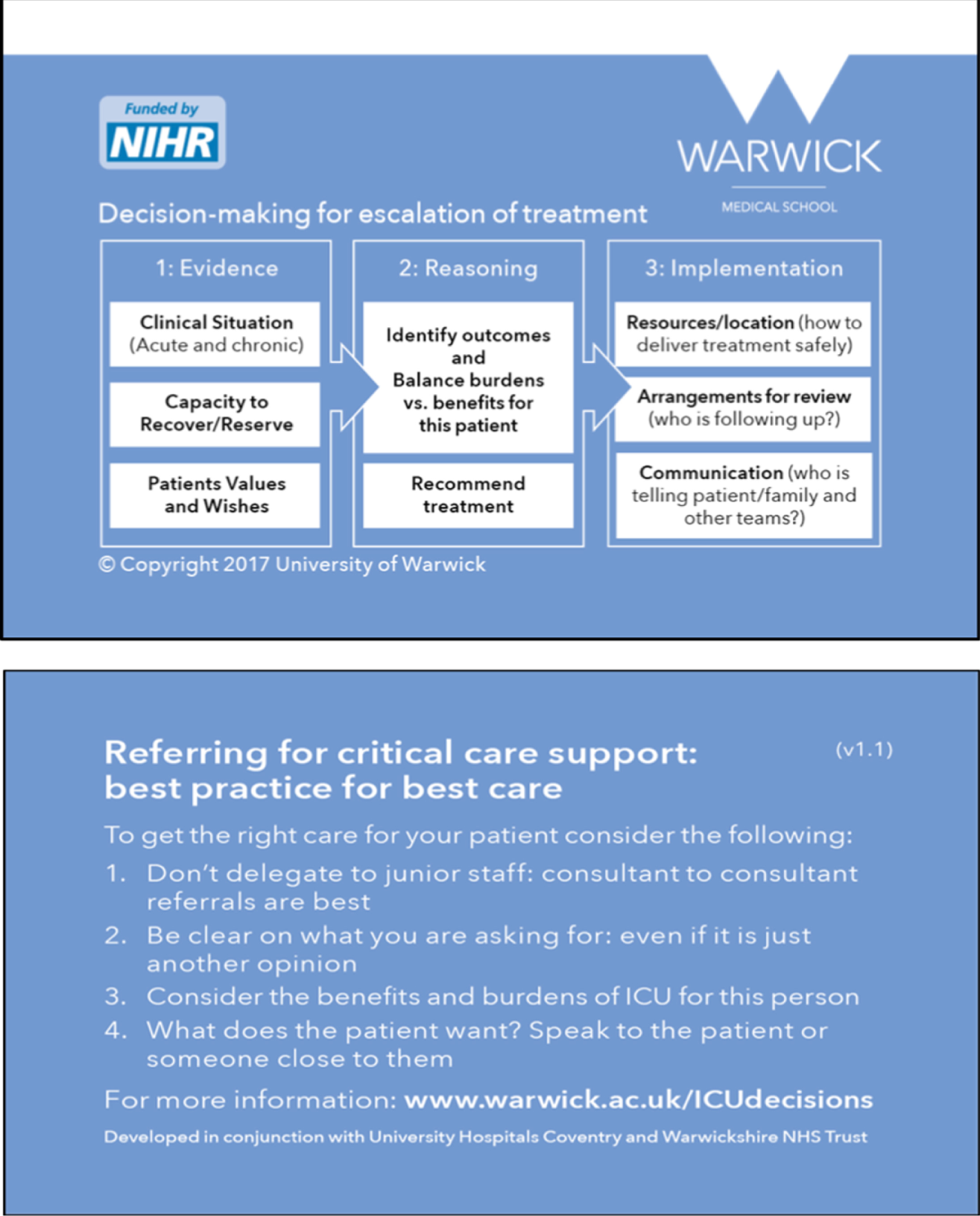

to develop and test a decision-support framework (DSF), including education and support materials, that will facilitate ethically informed decision-making, including reasons and process (WP3)

-

to develop information for patients and families to help them understand and contribute to the decision-making process (WP3)

-

to develop and test a tool for assessing the impact of the DSF on ICU referral and admission decisions (WP4).

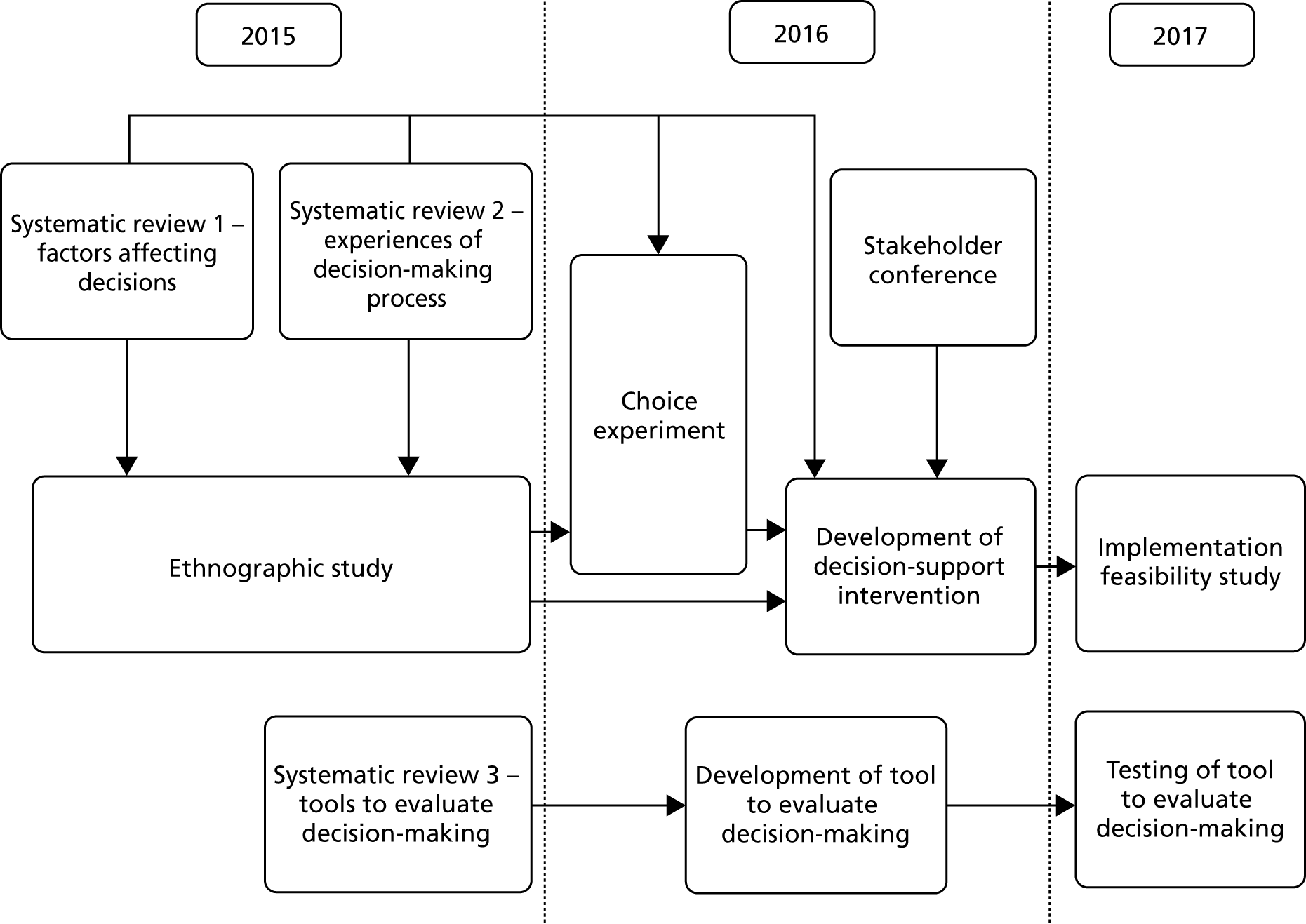

The project used a mixed-methods approach, including systematic reviews, a focused ethnographic study of current practice, a choice experiment questionnaire survey of intensive care consultants and CCOR nurses, a stakeholder conference and an implementation feasibility study. Figure 1 provides an overview of the study.

FIGURE 1.

Study diagram.

Ethics considerations

This project raised a number of ethical issues, particularly in terms of recruitment and consent to our ethnographic study. For the observation process, it was not possible to obtain consent from everyone who might be observed; therefore, information was provided in all clinical areas, consent was obtained from the ICU doctor being shadowed and specific agreement was obtained from the patient or family members for individual case observation. The approach to patients and/or family members at the time of decision-making was through the clinical team to minimise distress and protect privacy. A comprehensive system of tracking, recruitment and consent was developed to ensure that patients who regained capacity were informed of the study and gave appropriate consent for participation, and to approach family members for late-stage interviews (see Report Supplementary Material 1 and 2). Site-specific contacts for support for patients and families were identified. A protocol for responding to disclosures or observation of unsafe or unethical practice was developed and approved by the research ethics committee. In developing the evaluation tool, we accessed sections of anonymised patient records without explicit consent being obtained. We received approval for this from the Confidentiality Advisory Group of the Health Research Authority (15/CAG/0116). The whole project was approved by the Coventry and Warwickshire Research Ethics Committee (15/WM/0025) on 18 February 2015.

Chapter 2 Patient and public involvement

Introduction

Decisions about referral or admission to intensive care can have life-changing implications for patients and their families, and any project investigating these decisions must consider this impact in both the design and the conduct of the project. A project that involves critically ill patients and their families raises challenges for researchers around how to involve them while not adding to their existing distress. Given these two major considerations, the embedding of patient and public involvement (PPI) at every stage was identified as vital to the successful running and meaningful reporting of the project. We therefore included PPI in the design, development, analysis, reporting and oversight of the project.

Scope of patient and public involvement

Project design

Before submitting the application for funding, we held a patient and public engagement meeting. Attendees were recruited from a national ICU patient support charity, ICUsteps; patients from a NHS post-ICU clinic; and the University of Warwick’s Teaching and Research Action Partnership (UNTRAP). The purpose of this meeting was to seek input from the group on framing and prioritising the research questions and identifying appropriate methods for conducting the research that would be acceptable to patients and their families. During the meeting, the participants were presented with background information about referrals and admissions to intensive care and why there was a perceived need for a study. The presentation concluded with the proposed broad aim of the research. The group was asked to identify what they saw as important issues for the research to address, what the specific research questions might be and how to conduct the research in a way that was sensitive to patients and their families.

The group thought that this was an important area of research as it was crucial for patients and families in an extremely vulnerable situation to be able to trust both the professionals making these decisions and the decision-making process. Key questions identified by the group included how patients and families were involved in these decisions and communicated with; who was involved in making the decisions; how decisions about quality of life were made; and if ICU resources were important in the decision-making process. The group also offered suggestions on the timing and the number of interviews with family members to balance the needs of data collection with reducing family distress. These fed into the final project design.

Investigator team

Our investigator team included two PPI co-investigators (CW and SS), who were involved in the design and development of the project, provided guidance on the acceptability of the methods, commented on and amended all patient and family information materials (both study and intervention documents) and contributed to the writing and editing of reports from the different WPs.

Advisory group

We convened a patient and public involvement advisory group (PPIAG) of six members, some of whom had either been patients themselves or had experience of a relative being in an ICU. The group met 6-monthly throughout the project for updates from the project team and to provide advice on the conduct and findings of the project as it progressed. Individual members of the group also contributed more directly to specific WPs.

Project oversight

The project’s independent steering committee included two PPI members, one of whom had been a patient in an ICU. The committee met at 6-monthly intervals throughout the project to provide support to and oversight of the project.

Project development

The PPI co-investigators worked closely with the project team on developing information for patient and family participants and recruitment and consent processes in the ethnographic study. Two members of the PPIAG participated in the development of the draft decision-support intervention (DSI), attending project meetings and commenting on each stage of the process. One member led on initial drafting of patient and family information leaflets to be used as part of the intervention. Members of patient representative groups and the PPIAG attended the stakeholder conference and participated in focus groups to refine the content of the DSI. One of our PPI co-investigators (CW) chaired a session at the conference. Following the stakeholder conference, further extensive revision of patient and family information leaflets was overseen by the PPI co-investigators. Translated versions of these documents were checked for cultural acceptability among native speakers of the languages through our PPIAG contacts.

We were unable to obtain sufficient representation at the stakeholder conference for patients with mental health disorders and for elderly patients. We therefore attended local advocate group meetings to seek feedback on the DSI and its implementation.

Analysis

Two members of the PPIAG and one PPI co-investigator (CW) contributed to the analysis of the qualitative data in our ethnographic study. They attended data analysis meetings, read a selection of interview transcripts and contributed to the refinement of interview schedules and the development of an analysis framework.

Dissemination

Patient and public involvement co-investigators, members of the PPIAG and patient organisation representatives who attended the stakeholder conference were invited to the dissemination event at the end of the project. One PPI co-investigator (CW) gave a response to and reflection on the project findings from the patient and family perspective.

Summary

The importance of PPI was recognised at an early stage of development of the project and was integral to its development, conduct, delivery and successful completion. Involving PPI members in analysis raised issues of data protection, which were addressed using confidentiality agreements and standard operating procedures. PPI was occasionally challenging, as the involvement of individuals with different experiences and perspectives can create dissonance and disagreement. However, disagreement was always constructive and enriched the overall project development. The presence of PPI throughout the project also helped to ensure that the work retained its focus on the patients at the heart of the decision-making process, and that language and communication were consistently clear and accessible. Without PPI throughout the project, the outputs would have been less acceptable and credible as guides for patient-centred clinical decision-making. We were fortunate to have such engaged PPI co-investigators and advisory group members so that we were able to create an environment for meaningful PPI.

Chapter 3 Systematic literature reviews to explore existing evidence

Introduction

To identify what was already known about the subject, we carried out two systematic reviews to answer the following research questions:

-

What are the patient- and clinician-related factors that affect decisions around unplanned admissions to an ICU? (Factors review: PROSPERO CRD42015019711.)

-

What are the experiences of clinicians, patients and families of the process of referral and admission to an ICU? (Experiences review: PROSPERO CRD42015019714.)

Methods

Study identification

Because both reviews focused on the process of decision-making about referral and admission to ICU, we used the same search strategy and abstract screening process to avoid duplication between them. At the full-paper screening stage, we identified studies relevant to (1) the factors review, (2) the experiences review and (3) both reviews. The search strategy was informed by an initial scoping review of the literature, and had three broad areas using a combination of the following MeSH (medical subject heading) headings and keywords: (1) critical and intensive care, intensive care units and critical illness; (2) patient admission, transfer, triage and refusal to treat; and (3) professional decision-making and judgement, professional–family relations, choice behaviour and medical futility. Papers that referred to paediatrics or neonates were excluded. The following databases were searched: MEDLINE, EMBASE, Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ASSIA), all sections of The Cochrane Library, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), PsycINFO and Web of Science. ‘Grey literature’ (Dissertation Abstracts Online, Index to Theses, OpenGrey) and references from key papers were also screened. We used forward and backward citation tracking from our full-text papers to identify further studies that our initial search had missed. Our full searches are presented in Appendix 1 (see Tables 25 and 26). We included papers published between 1980 and 2015 describing empirical research that focused on the process of decision-making about referral or admission of adult patients to ICU, and that investigated either factors affecting decision-making or the experiences of clinicians, patients or families. The search was run on 11 May 2015.

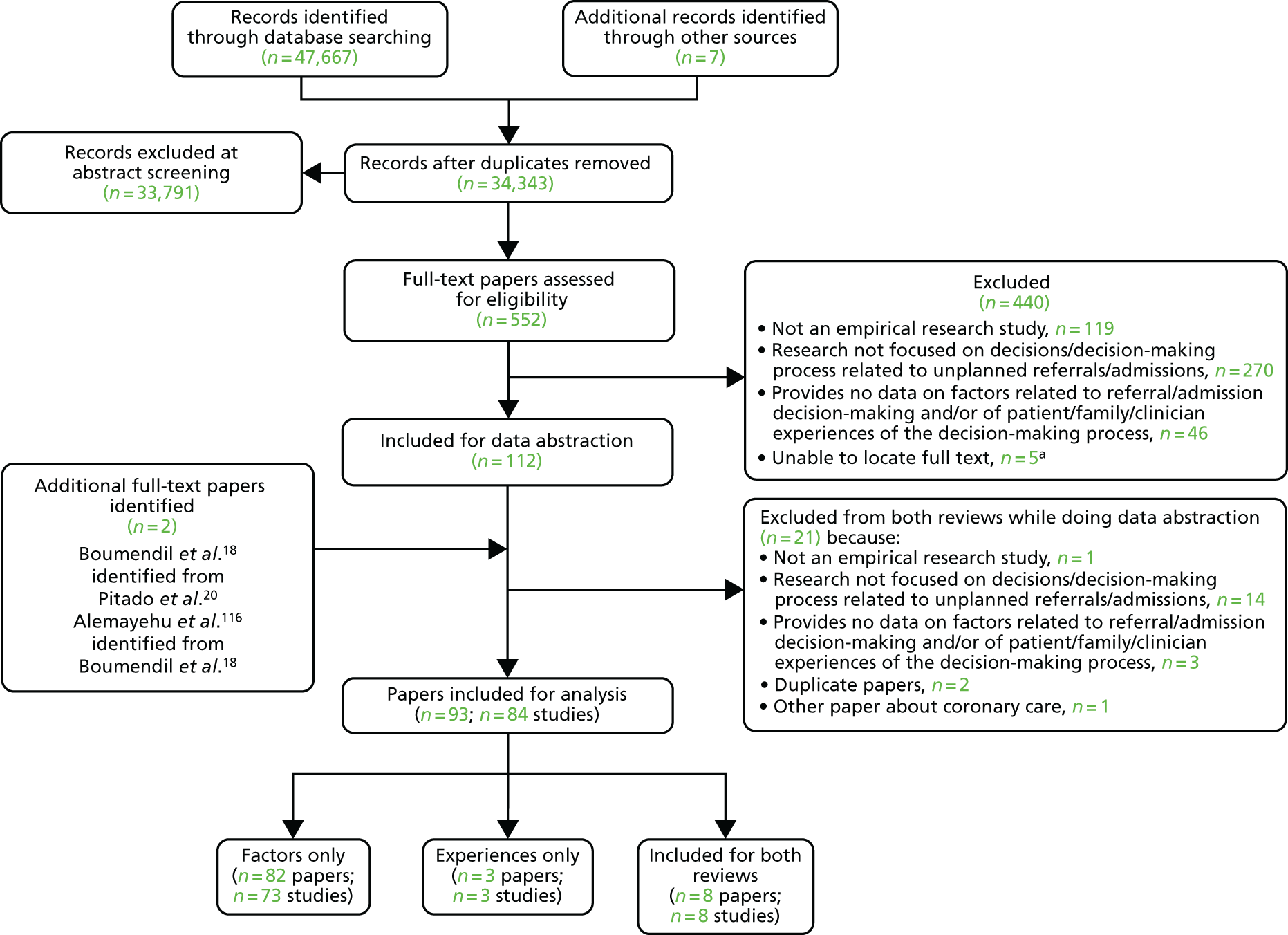

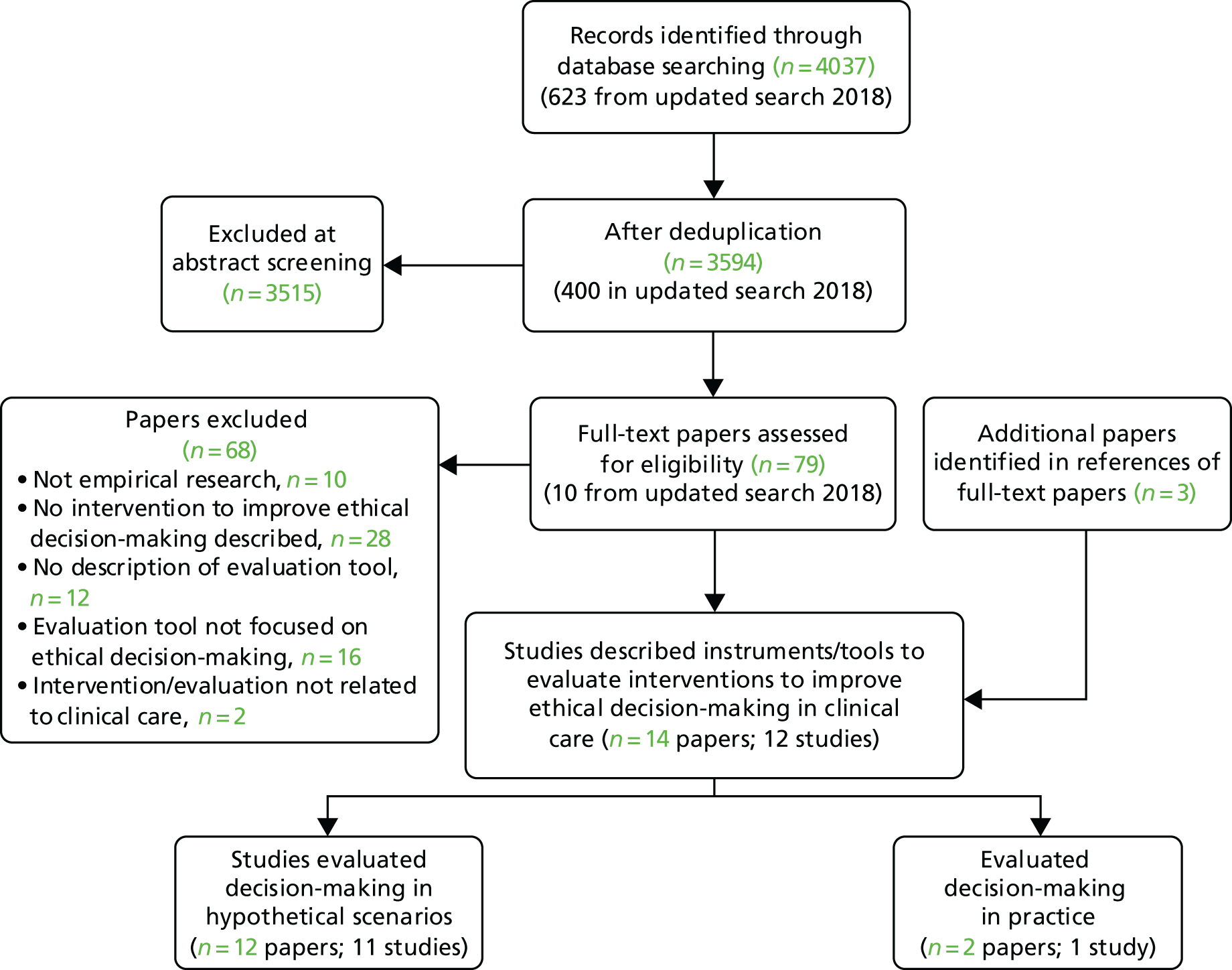

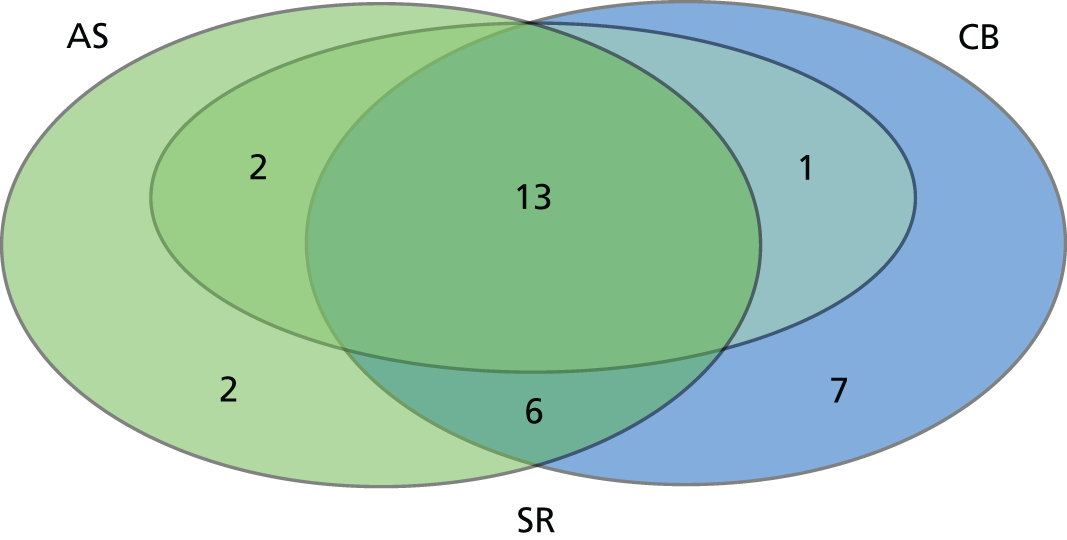

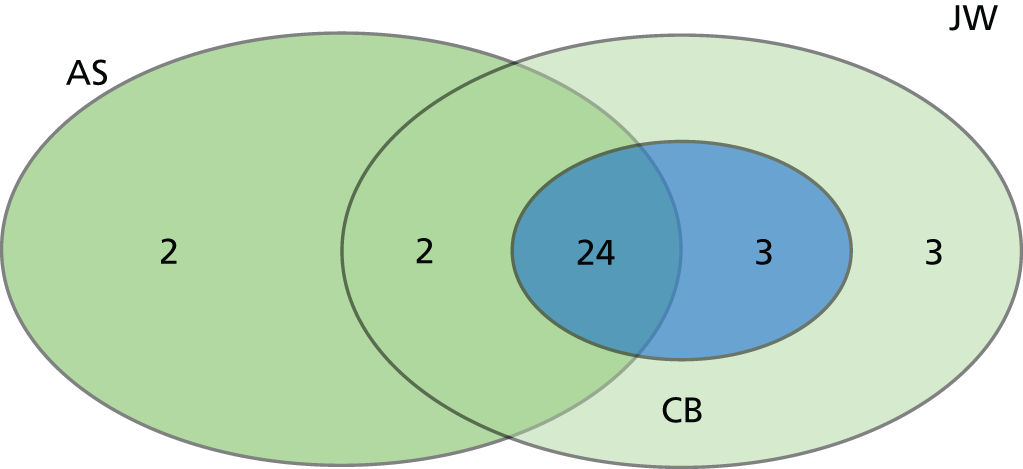

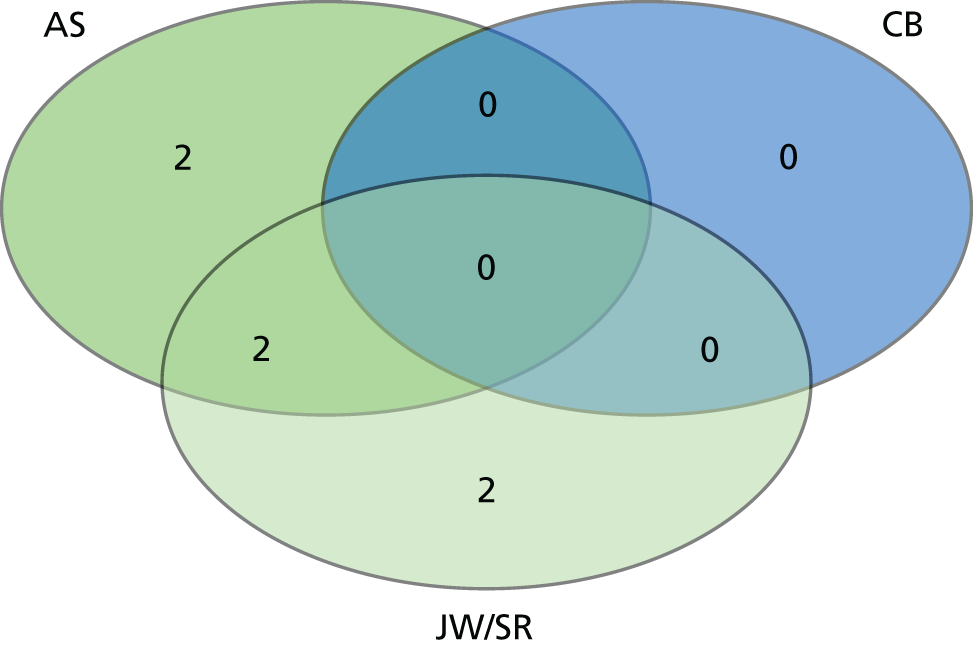

We identified 47,674 records, 34,343 after duplicates were removed. Abstracts were double-screened by a team of 13 reviewers [three members of the study team (CB, AS and HH) and 10 medical students trained in the process], and 552 records went forward for full-text retrieval and formal inclusion in/exclusion from the review (Figure 2). Full-text papers were also double screened by six members of the research team (CB, AS, ZF, HH, JT and MB).

FIGURE 2.

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram for the main systematic review. a, We were unable to source these five full texts for a variety of reasons, including being unable to make contact with the author even after internet searching, e-mail-based invitation and telephoning, where possible; the author of two related conference abstracts also did not follow up in the end with further details on their unpublished full study findings (as promised earlier). Reproduced with permission from Rees et al. 61

In March 2018, we completed a brief update review to identify any relevant studies that had been published since our initial searches. A re-run of the original searches yielded over 10,000 returns. Given time constraints, we chose not to repeat the full review process. Instead, we adopted a pragmatic approach using the following method:

-

We searched PubMed for papers published between 1 May 2015 and 31 December 2017 using the search terms Critical care/CCU or intensive care/ICU AND decision-making AND admissions OR referrals.

-

We hand-searched the contents of the six journals that had provided more than one included paper in our original review. We searched all issues published from 1 May 2015 to 1 January 2018.

-

We searched the reference lists of any identified papers to check for further papers, as well as the reference list of a published review. 62

Ten papers were identified at abstract screening stage for full-text assessment by two reviewers (AS/KR or AS/CB). Three further papers were identified from the reference list of the published review. Eight studies (seven for factors and one for experiences) were added to the total number of studies included for analysis in the main systematic review.

Methodological quality assessment

Cohort studies were assessed using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale. 63 The majority of studies were cross-sectional, and we used an adapted version of the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale to assess quality for this study design. 64 Clinical trials were assessed with the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool65 and qualitative studies were assessed using May and Pope’s qualitative evaluation criteria. 66 Each included study was scored for quality by two reviewers (AS/HH, CB/JT or ZF/MB) and any discrepancies were referred to a third reviewer for final decision (KR or FG) (see Appendix 2, Tables 27–29).

Data extraction

For studies relevant to the factors review, we grouped identified factors using the following process. We identified an initial list of factors based on our previous scoping review of the literature and categorised these into patient factors (medical/non-medical), clinician factors, organisational factors and others. These categories were further subdivided; for example, patient-related medical factors included type of acute illness, severity of acute illness and type of chronic illness. During data abstraction, we mapped each factor identified in a paper onto our predefined subcategories and collected any factors that did not map onto the category of ‘other’. Three members of the team (KR, CB and AS) then either categorised factors in the ‘other’ category into existing categories or created additional subcategories. For the experiences review, any relevant qualitative data were copied and pasted into a Microsoft Word (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) document for analysis.

Analysis

The majority of data for the factors review were quantitative, but a small number of studies had descriptive qualitative data. When possible, we combined studies statistically using a meta-analysis. Owing to the potential confounding effects of each of the factors examined on the others, we focused on studies reporting multivariate analyses of independent factors affecting admission decisions. Where these were lacking, we explored descriptive associations but were cautious in our interpretation because of biases and confounding.

If there were sufficient studies, effect sizes from multivariate analyses for each factor were pooled using the generic inverse variance method using RevMan software (version 5.3; The Cochrane Collaboration, The Nordic Cochrane Centre, Copenhagen, Denmark). 67 The results from cohort studies were pooled together with the results from cross-sectional studies as we were concerned not with longitudinal associations but with decisions to admit and the factors affecting these that occur concurrently. The remaining studies were described narratively.

For the experiences review, a thematic analysis of any relevant qualitative data from the identified studies was conducted. Two research team members (SR and AS) read all of the data and developed initial codes from which themes were developed during discussion. The themes were tested in a further research meeting with a third member of the team (FG).

Results

From the initial review, 84 studies (93 papers) were included for analysis in both reviews, of which 81 studies (90 papers) were included in the factors review and 11 studies were included in the experiences review (see Figure 2). A further eight studies (seven for factors and one for experiences) were included from the brief update review. Overall, the quality of studies was moderate or poor, with 14 out of 19 cohort studies and 17 out of 61 cross-sectional studies being rated as high quality (see Appendix 2, Tables 27 and 28).

Factors review

The characteristics of the 88 included studies and the factors each study investigated are documented in Appendix 3 (see Table 31). The vast majority were observational.

The findings are reported under factor headings grouped as patient-related medical, patient-related non-medical, clinician-related and organisation-related (Table 1). For each of the factors analysed, the results are presented first for multivariate analyses. A summary of multivariate analysis results is presented in Appendix 4 (see Table 32). For factors for which there are no multivariate analyses, we report findings of descriptive studies. If multivariate analyses are present, we note the presence of descriptive studies.

| Factor | Studies with multivariate analyses (n) | Studies with univariate analyses (n) | Descriptive studies (n) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient related | |||

| Medical | |||

| Type of acute illness | 9 | 1 | 14 |

| Severity of acute illness | 8 | 1 | 36 |

| Presence of chronic illness | 6 | 1 | 21 |

| Severity of chronic illness | 5 | – | 14 |

| Functional status/quality of life measures | 14 | – | 25 |

| Nutritional status | 1 | – | 1 |

| Length of hospital stay | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| Trajectory of illness | 3 | – | 4 |

| Presence of DNACPR order | 3 | – | 6 |

| Non-medical | |||

| Age | 18 | – | 35 |

| Gender | 7 | 1 | 22 |

| Ethnicity | 4 | – | 5 |

| Patient preference | 3 | – | 15 |

| Family preference | 1 | – | 13 |

| Health insurance status | 2 | – | 4 |

| Clinician related | |||

| Seniority of ICU clinician | 2 | – | – |

| Seniority of referring clinician | – | – | – |

| Demography of ICU clinician | – | – | – |

| Physician’s attitude | – | – | – |

| Prognostic pessimism | 2 | – | – |

| Organisation related | |||

| ICU bed availability | 12 | – | 27 |

| Decision-maker present | 2 | ||

| Specialty of patient | 5 | – | 4 |

| Time of day | 2 | – | 5 |

| Experience/expertise of ward team | 1 | – | – |

| Hospital characteristics | 2 | – | 3 |

| Avoid conflict/litigation | – | – | 2 |

| Other | 3 | – | – |

Patient-related medical factors

Type of acute illness

Nine studies12,14,16,41,68–70,72,73 reported multivariate analyses of type of acute illness as a factor affecting decisions about patient admission to ICU. The types of acute illnesses considered between studies varied enormously and precluded meta-analyses. Distinct groupings were possible in the following categories: respiratory, cardiac/vascular, neurological, infections and emergency surgery. Three studies14,16,69 reported respiratory diagnoses as a factor associated with reduced likelihood of refusal or increased odds of admission, whereas one study70,71 found respiratory diagnoses to be associated with an increased odds of refusal. Cardiac or vascular diseases were reported in six studies,12,16,41,69,72,73 with increased odds of admission reported in four studies. 12,16,69,73 One study72 showed less likelihood of refusal to ICU with a diagnosis of cardiac failure than with a diagnosis of respiratory failure. In another study,41 cardiac disease was associated with refusal to admit. Four studies16,41,69–71 reported on neurological disease, with inconsistent results. Two of the studies16,69 showed that admission was more likely with a diagnosis of neurological disease, whereas the other two studies41,70,71 showed that the same diagnosis was associated with refusal to admit. Three studies68,69,72 reported that infections were an independent factor associated with ICU admission, and two studies12,72 reported independent effects of emergency surgery on admission decisions (see Appendix 4, Table 32).

Other diagnoses as independent predictors of admission decisions in multivariate models included shock and coma, which reduced the likelihood of refusal. 14 Haematologic etiology,68 injuries/poisonings/toxic effects of drugs,69 trauma and haematological malignancy12 and ‘worried’16 were all associated with increased likelihood of admission.

One study13 reported diagnosis to be a significant factor in multivariate analyses affecting refusal to admit to ICU, but it is unclear which individual diagnoses had the most impact. Another study20 reported univariate associations between categories of acute illness and odds of ICU refusal in an elderly cohort, but type of acute illness was not an independent predictor in the multivariate model. Fourteen further studies10,11,18,19,24,74–82 reported descriptive associations between types of acute illness and decisions about admission to ICU.

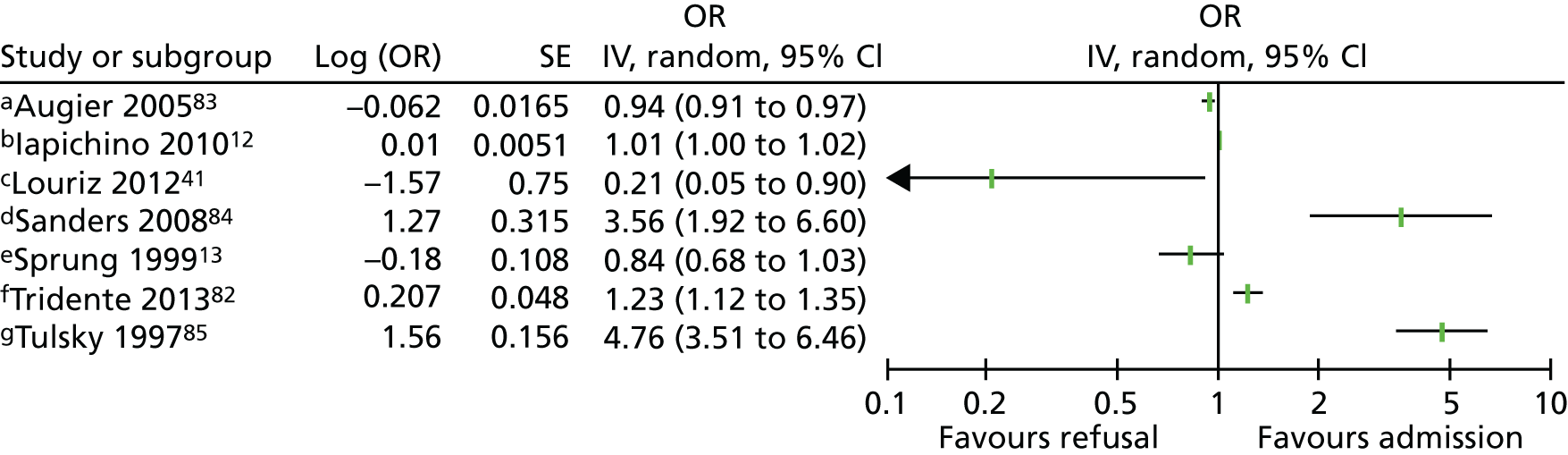

Severity of acute illness

Eight studies12,13,41,76,82–85 reported multivariate analyses of severity of acute illness as a factor. A number of different scales were used to assess severity of acute illness (see Appendix 4, Table 32). Results from individual studies were plotted, but the studies were not combined statistically because of considerable heterogeneity (I2 = 96%) and inconsistent direction of effect (Figure 3). There were no clear effects of severity of acute illness and decisions to admit patients to ICU (see Appendix 4, Table 32). It is possible that the heterogeneity and inconsistent direction of effect relates to questions around patients being too ill or too well to benefit from ICU care.

FIGURE 3.

Forest plot of studies reporting severity of acute illness scales in multivariate analyses. The pooled effect estimate is suppressed as heterogeneity is considerable (I2 = 97%) and the direction of effect is inconsistent between studies. a, APACHE II score; b, APS II score (Simplified Acute Physiology Score II without age, comorbidity and type of admission); c, MPM-0 (mortality predicted model at admission); d, All Patient Refined Diagnosis Related Group (APR DRG) grouper (measures chronic and acute disease severity); e, APACHE II (SE imputed); f, EWS; and g, severity of illness stage 2 (as defined by the authors): selective population – patients with AIDS with pneumonia. AIDS, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome; EWS, Early Warning Score; IV, instrumental variable; OR, odds ratio; SE, standard error.

One further study20 reported a reduced odds of refusal of admission with increasing SOFA (Sequential Organ Failure Assessment) score [odds ratio (OR) 0.93, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.87 to 1.0] in a univariate analysis, although this was not an independent predictor in the multivariate model. Thirty-six further studies10,19,21,22,24,42,44,72,73,75–77,80,81,86–107 reported descriptive associations between severity of acute illness and decisions about admission to the ICU.

Presence of chronic illness

Seven studies10,14,18,70,71,76,108 reported multivariate analyses of presence of chronic illness as a factor. Chronic illnesses investigated included dementia,108 metastatic cancer,10,18,76 mental disorder (psychotropic drug use),18 a combined category of chronic respiratory or heart failure or metastatic cancer without hope of remission,14 and a general category of ‘underlying chronic disease’70,71 (see Appendix 4, Table 32).

One study20 reported univariate associations between prior cognitive status and odds of ICU refusal, where refusal was associated with worse cognitive status, but this was not an independent predictor in the multivariate model. Twenty-one studies11,12,15,17,22,41,74,78,80,88–91,93,98,101,105,106,109–111 reported descriptive associations between the presence of chronic illness and decisions about admission to the ICU.

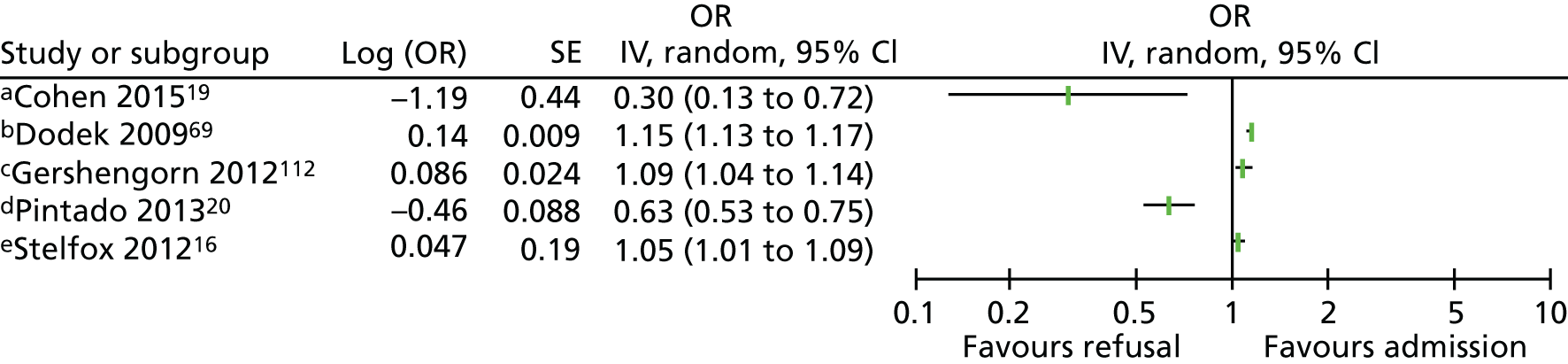

Severity of chronic illness

Five studies16,19,20,69,112 reported multivariate analyses for severity of chronic illness as a factor. Four studies16,20,69,112 assessed the severity of chronic illness using the Charlson Comorbidity Index. Results from individual studies have been plotted but not combined statistically because of considerable heterogeneity (I2 = 95%) and inconsistent direction of effect (Figure 4). Sensitivity analyses combining scales of the same type and removing selective populations had no effect on the very high level of heterogeneity. There are no clear effects from multivariate studies of severity of chronic illness and decisions to admit patients to the ICU. Fourteen further studies10,24,41,74,80,81,86,87,91,92,95,100,101,113 reported descriptive associations between the severity of chronic illness and decisions about admission to the ICU.

FIGURE 4.

Forest plot of studies reporting severity of chronic illness scales in multivariate analyses. The pooled effect estimate is suppressed as heterogeneity is considerable (I2 = 95%) and the direction of effect is inconsistent between studies. a, Elixhauser scale; b, Quan’s adaptation of Charlson Index; c, Charlson Comorbidity Index, selective population – diabetic ketoacidosis; d, Charlson Comorbidity Index, selective population – elderly cohort; and e, Charlson Comorbidity Index; IV, instrumental variable; OR, odds ratio; SE, standard error.

Functional status/quality of life

Fourteen studies10,12,14,15,17–21,68,70,76,82,114 reported multivariate analyses for functional status/quality of life as a factor using a number of different scales and measures, so we were unable to pool data statistically. Most studies reported on patient data from real-world settings but three reported simulation studies,17 surveys to health-care professionals using clinical vignettes114 or the theoretical future need of ICU in elderly patients admitted to emergency departments (EDs). 15

Measures of dependency/self-caring status related independently to admission decisions in the 11 studies10,12,14,18–21,68,70,76,82 in real-world settings; in most studies, increased dependency was associated with reduced odds of admission (see Appendix 4, Table 32).

Twenty-five further studies11,22,24,42,46,74,76,78,80,81,87-91,99–105,111,114,115 reported descriptive associations between functional status/quality of life and decisions about admission to the ICU.

Nutritional status

Only one study18 reported multivariate analyses of nutritional status on admission decisions. In this elderly cohort of patients aged > 80 years, nutritional status was independently associated with eligibility for ICU admission (see Appendix 4, Table 32). One descriptive study76 in patients aged > 80 years found no statistically significant differences in nutritional status between those referred and those not referred to ICU.

Pre-admission length of hospital stay

One study16 reported multivariate analyses for pre-admission length of hospital stay as a factor. One study84 reported univariate analyses where length of hospital stay of > 7 days increased the odds of ICU transfer compared with 1 or 2 days, but this was not an independent predictor in the multivariate model. Five additional descriptive studies12,18,50,68,110 reported previous length of hospital stay and admission decisions to the ICU with conflicting results.

Trajectory of illness

Three studies16,17,76 reported multivariate analyses of trajectory of illness as a factor. Previous hospitalisation in the past year was associated with reduced odds of admission to the ICU in one study,17 but hospitalisation in the past 6 months showed no difference in another. 76 Previous ICU admission during the hospitalisation was associated with increased odds of admission within 2 hours of medical emergency team (MET) activation16 (see Appendix 4, Table 32). Four further studies90,91,105,111 reported descriptive associations between trajectory of illness and ICU admission.

Presence of do-not-resuscitate order (variously described in studies as DNR/DNAR/DNACPR)

Three studies19,68,97 reported multivariate analyses of do not resuscitate orders and admission decisions to the ICU. All three studies showed that patients were less likely to be admitted with a do not resuscitate order.

Six descriptive studies78,89,92,98,116,117 reported associations between presence of do not resuscitate order and admission decisions. Three studies found that it resulted in significantly fewer ICU admissions. 89,116,117 In the others, do not attempt resuscitation status was seen as important98 or clinicians said that they would comply with a do not attempt resuscitation order. 78,92

Patient-related non-medical factors

Age

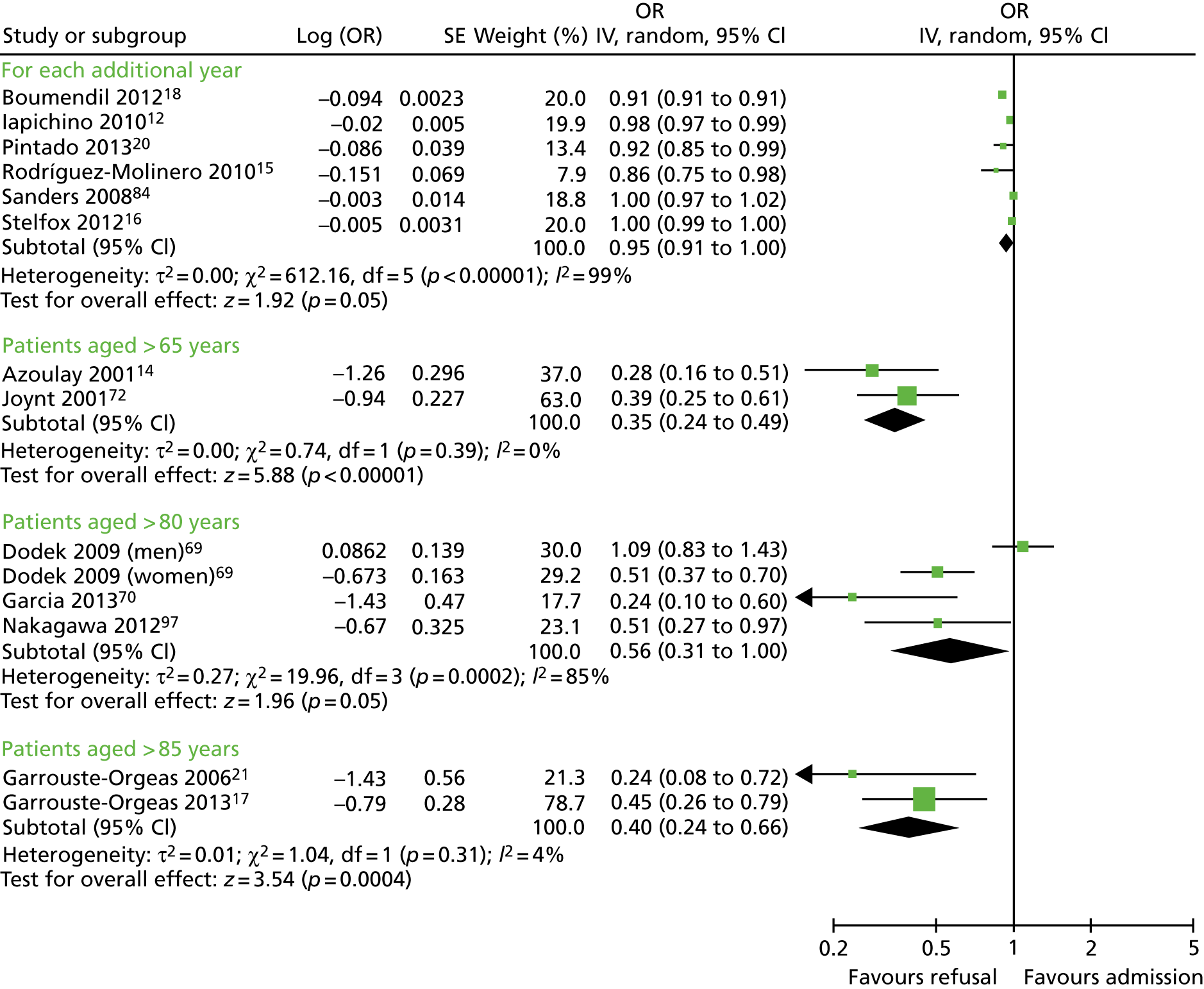

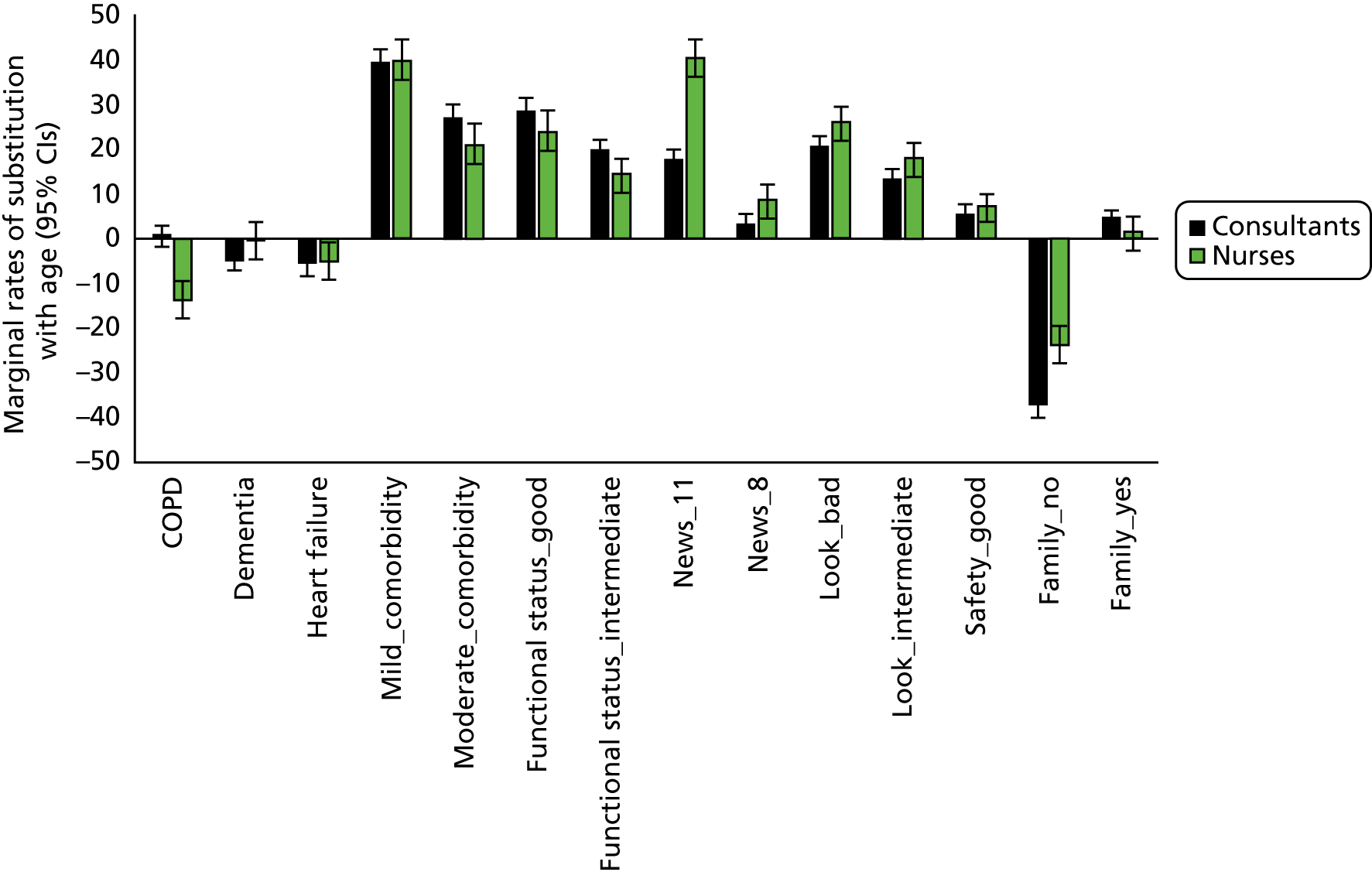

Eighteen studies12–18,20,21,69–73,76,84,97,106,112 examined age as a factor in multivariate analyses. Data on age were inconsistently reported. Six studies12,15,16,18,20,84 reported admission decisions per year increase in age, and data from these studies were pooled statistically (Figure 5). There was considerable heterogeneity (I2 = 99%), but magnitude and direction of effect between studies were similar, showing an increased odds of refusal to ICU with increasing age (OR 0.95, 95% CI 0.91 to 1.0; p = 0.05). Five studies12,16,18,20,84 were conducted in real-world settings and one15 was theoretical.

FIGURE 5.

Forest plot of studies reporting age in multivariate analyses, for each year increase in age and by age bands. IV, instrumental variable; OR, odds ratio; SE, standard error.

Other studies reported specifically on elderly cohorts or similar cut-off points and, where possible, we have pooled these statistically (see Figure 5). All multivariate analyses are summarised in Appendix 4, Table 32.

A further 35 studies (39 publications)10,11,19,22,24,41,68,74,75,77,78,80–83,87–91,93–95,99–101,105,107,109–111,114,118–124 looked at the association between age and admission to ICU in descriptive analyses.

Sex

Seven studies69,72,73,84,112,125,126 examined sex as a factor in multivariate analyses. Results were inconsistent between studies, with different age groups and ethnicity also playing a role.

Three studies73,84,112 reported no difference in admission decisions by sex when controlling for other covariates. One study72 found that being female reduced the odds of refusal to ICU compared with being male (the reference), but this did not reach statistical significance. Three studies69,125,126 found that men were more likely to be admitted than women (see Appendix 4, Table 32).

One study20 reported univariate associations between sex and ICU admission decisions and found no differences between men and women (OR 0.83, 95% CI 0.52 to 1.43). Twenty-two further studies10–13,18,19,21,24,41,50,68,70,74–76,79,81,89,94,106,110,127 reported descriptive associations between sex and decisions around admission to the ICU.

Ethnicity

Four studies73,85,112,125 reported multivariate analyses for ethnicity as a factor, with inconsistent findings. All studies were conducted in the USA.

Five additional studies11,68,75,109,110 reported the effects of ethnicity on admission decisions in descriptive analyses. Ethnic origin did not have an impact on admission decisions in these studies.

Patient preference

Three studies16,17,114 reported multivariate analyses of patient preferences and admission decisions to the ICU. Two studies16,17 of patient cohorts found increased odds of ICU admission when patient preferences for ICU care were considered (resuscitative vs. comfort care, and I accept vs. I refuse ICU care) (see Appendix 4, Table 32). A survey of health-care professionals,114 using a clinical vignette to determine decisions about admission to the last available ICU bed, found that the prior wishes of the patient were not an independent predictor for either physicians or nurses in predicting choice of patient for admission.

No further studies reported the effects of patient preference in univariate analyses, but 15 additional studies22,71,78,80,81,87,90,100,101,105,107,111,116,128,129 reported its effect on admission decisions in descriptive analyses, the majority being questionnaire studies of physician attitudes.

Family preference

One study114 reported multivariate analyses of family preferences and admission decisions to the ICU. This study was regarded as being of low methodological quality and did not show family considerations as an independent factor in affecting admission decisions in a clinical vignette study.

Thirteen additional studies38,46,71,78,80,81,91,96,100,101,105,130,131 reported the effects of family preference on admission decisions in descriptive analyses. The majority of these were questionnaire studies of physician attitudes and perceptions that variably reported the effect of family wishes on decision-making.

Health insurance

Two cohort studies73,112 reported multivariate analyses of health insurance and admission decisions to the ICU, one of which was in a population of patients with diabetic ketoacidosis. Both were US studies and explored differences between types of health insurance (see Appendix 4, Table 32).

Four additional studies22,68,91,98 reported the effects of health insurance on admission decisions in descriptive analyses.

Clinician-related factors

Seniority of intensive care unit clinician

Two studies16,68 reported multivariate analyses of clinician seniority and the effects on ICU admission decisions. One study16 found that attending physicians were more likely than more junior physicians to admit patients, whereas the other68 found that less experienced attending physicians (defined as those spending < 25% of their time in the ICU) were more likely to admit patients to ICU (see Appendix 4, Table 32).

Ten additional studies10,21,22,24,41,74,76,78,116,130 were found with descriptive analyses reporting variable results.

Seniority of referrer

No studies reported multivariate or univariate analyses of the effects of the seniority of the referrer on ICU admission decisions, but four descriptive studies11,120,132,133 were found reporting associations between referrer seniority and ICU admissions.

Personal characteristics/demography of intensive care unit clinician

No multivariate or univariate studies reported on the personal characteristics/demography of ICU clinicians and their association with ICU admission decisions, but two descriptive studies22,116 were found that were rated as being of low methodological quality. No consistent association was found with physician age, sex and whether or not they had children in responses to a number of clinical vignettes and importance of a number of criteria when considering admission. 22 Country of practice had an impact on decision-making, with Brazilian and US physicians choosing more aggressive treatment in response to clinical vignettes than Australian, Scottish and Welsh physicians. 116

Physician’s attitude

Three descriptive studies86,90,111 were found that were rated as being of low methodological quality. In one study,86 12% of physicians cited alcohol dependency as a ‘lifestyle decision’ when considering ICU admission. In the other studies,90,111 56% of Israeli physicians90 and 19% of US physicians111 thought that their personal attitude was important in deciding admission to the last ICU bed.

Prognostic pessimism

Two studies24,72 reported multivariate analyses of prognostic pessimism and admission decisions to the ICU. A high chance of mortality from the mortality prediction model was associated with increased odds of refusal to the ICU, as was physician-predicted risk of death of > 50% in the coming month. No further studies were found reporting on prognostic pessimism.

Organisational-related factors

Intensive care unit resource/bed availability

Twelve studies10,12,13,16,17,20,21,24,41,83,112,134,135 examined ICU bed availability as a factor. Results were reported variably by number of beds available and unit full/not full, so we were unable to pool data statistically. In eight studies,10,12,13,16,17,20,21,41 ICU bed availability was associated with likelihood of admission to ICU. Conversely, ICU occupancy levels had no significant effect or were only weakly predictive of likelihood of admission in three studies. 83,112,135,136 One study134 found that an increase in the use of mechanical ventilation in hospitalised nursing home residents with advanced dementia was associated with an increased number of ICU beds in a hospital (see Appendix 4, Table 32).

An additional 27 studies11,24,42,44,46,68,74,75,77,78,80,81,86–88,100,103,104,107,115,122,128–130,137–140 reported the effects of ICU bed availability on admission decisions in descriptive analyses.

Decision-maker present

Only two studies10,21 were found that reported circumstances in which an ICU clinician undertook triage, whether over the telephone or by examination. Both studies found that patients who were refused ICU admission were more likely to have been examined by an ICU clinician.

Specialty of patient

Five studies12,21,24,82,106 reported multivariate analyses of specialty of patient and admission decisions to the ICU. These found that patients referred from medical specialties were less likely to be admitted to ICU than those referred from surgical specialties.

Four further studies10,11,16,120 reporting descriptive analyses were found, reporting variable results.

Time of day

Two studies10,16,118,119 reported multivariate analyses of time of day and admission decisions to the ICU. These had conflicting results, with one10 reporting increased admissions during the day and the other16 reporting increased admissions at night (see Appendix 4, Table 32).

Five descriptive studies21,24,41,76,81 found no significant association between time of day and admission decisions, but one study120 found that patients referred out of hours were more likely to be admitted to the ICU (p = 0.005).

Experience and expertise of ward team

One study84 reporting multivariate analyses examined the effect of experience and expertise of the ward team on admission decisions. Registered nurse certification in a nursing specialty did not significantly predict ICU transfer after controlling for severity of illness (OR 0.43, 95% CI 0.1 to 1.73).

Hospital characteristics

Two studies85,112 reporting multivariate analyses examined the effect of hospital characteristics on admission decisions. The number of hospital beds, hospital percentage occupancy, ICU percentage occupancy, location (metropolitan, non-metropolitan) or teaching status of the hospital did not have an effect. 112 Among patients with AIDS (acquired immunodeficiency syndrome), admission was more likely in a Veterans Health Administration hospital than in a government hospital. 85

Three further descriptive studies73,113,131 found associations with characteristics of the hospital and decisions to admit to ICU.

Avoid conflict/litigation

Two descriptive studies38,78 were found that reported the effect of litigation on ICU admission decisions. In a survey38 of ICU clinicians in Milan exploring reasons for inappropriate admission, 5% cited threat of legal action as a reason. The other study78 found no association with admission to ICU.

Other

Three empirical studies12,97,112 reported multivariate analyses of other organisational factors not captured in the categories above (see Appendix 4, Table 32).

Experiences review

We identified 12 studies (14 publications), presented in Table 2. Eleven44,46,92,115,128,130,141–145 used qualitative and one100 used quantitative methods. Interviews were most commonly used for data collection. Two studies used questionnaires and four used multiple methods (including interviews, focus groups, observation, and analysis of documents). Five of the studies44,46,128,143,144 were carried out in North America and seven92,100,115,130,141,142,145 were carried out in Europe (including three92,141,142 in the UK). In general, the quality of the studies was mixed (see Appendix 2 for a review of quality assessment of studies). All but two of the qualitative studies were single-site or single-participant studies.

| Study (first author, year) | Objective of study | Data collection | Location | Participants | Number of participants | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cullati, 2014130 | Importance of advanced care planning for seriously ill patients | Interviews | Switzerland | Health-care professionals | 24 | Single site; conference abstract and presentation |

| Hart, 2011128 | ICU clinicians’ reasons for bed rationing | Questionnaire (free text) | USA | Health-care professionals | 1086 | Abstract only; questionnaire |

| Santana Cabrera, 2008100 | Non-ICU doctors’ perceptions of ICU | Questionnaire | Spain | Health-care professionals | 116 | Single site; questionnaire |

| Hancock, 200792 | A CCOR nurse’s decision-making | Reflective piece | UK | Health-care professionals | 1 | One participant |

| Todres, 2000141 | Being a patient in ICU | Interview | UK | Patient (also an ICU nurse) | 1 | One participant |

| Oerlemans, 2015115 | Ethical dilemmas influencing admission and discharge | Interviews and focus groups | Netherlands | Health-care professionals | 44 | |

| Mielke, 200344 | Priority setting in ICU: evaluated in an ethical framework | Interviews, documents, observations | USA | Health-care professionals | 20 interviews | Single site |

| Fulbrook, 1999142 | Being a relative of a patient in ICU | Interview | UK | Relative (also an ICU nurse) | 1 | One participant |

| Cooper, 201346 | Scarcity in ICU context | Interviews | Canada | Health-care professionals | 22 | Single site |

| Martin, 2003143 | Neurosurgery patients’ access to ICU in an ethical framework | Interviews, documents, observations | Canada | Health-care professionals | 13 interviews | Single site |

| Danjoux Meth, 2009144 | Conflicts in the ICU | Interviews | Canada | Health-care professionals | 42 | |

| Charlesworth, 2017145 | ICU doctors’ decision-making practices in response to patient referrals | Ethnography (observations, interviews) | UK | Health-care professionals | 71 ICU reviews observed, 10 interviews | Single site |

Of the 12 studies, two looked at patients’ or relatives’ experiences (having only one participant each): Fulbrook et al. 142 and Todres et al. 141 The other 10 explored the experiences of health-care professionals, including ICU and general ward doctors and nurses, CCOR nurses, medical directors, respiratory technicians, hospital administrators, social workers and bioethicists. One study92 contained a detailed reflection of how a CCOR nurse made her clinical decisions based on one case, rather than a reflection on the wider process. We did not find any papers that focused solely on experiences of the process of referral and admission to ICU, but in these 12 we were able to identify data relevant to our research question.

Findings

Thematic analysis of the data from these studies identified three main themes: professional relationships, communication and working within external constraints. An overarching theme relevant to health-care professionals, patients and relatives was lack of agency or control.

Professional relationships

The existing and past relationships with clinical colleagues in the context of referring a patient to ICU had a substantial impact on how health-care professionals, specifically ICU doctors, referring doctors and ward nurses, experienced the decision-making process. Previous experience of having had a patient refused admission made some referrers less likely to refer, either because they assumed that the referral would be refused again or because the process had made them feel undervalued:100,115,130

And then you think, well as they are always aggressive, you are, you are a little afraid of calling them, yes. A dire consequence is you don’t dare ask for the consultation.

Medical doctor 6, Cullati et al. 130

One study115 reported that terms such as ‘arrogant’, ‘ivory tower’ and ‘island’ were used often to describe ICU consultants. Interprofessional relationships were often strained because of a lack of shared understanding about what ICU could achieve and what life was like caring for patients on a general ward. 44,115,144 This can lead to frustration and resentment. When professional relationships work well, the process runs smoothly. 44

Communication

Good communication between clinicians was seen as facilitating the referral and decision-making process, but poor communication was often described, leading to tensions between staff and harmful consequences for patients:

[You] go to see a patient and you don’t know what the therapeutic plan is, the patient is ill and we sometimes bring the patient down to the unit and then discover that actually the patient was for palliative care.

ICU team member, Cooper et al. 46

Concerns about communication were particularly noted in relation to patients and relatives. 44,46,115,141,142 ICU doctors commented that referring teams often avoided conversations about treatment goals and what transfer to ICU would mean for the patient, so the ICU team was put in the position of having to initiate those conversations.

However, ICU doctors also avoided conversations with relatives about the decision:

The ICU resident would have come down, done the consult and said to the ward team, ‘no.’ Or they may have said to the family, en passant, ‘Sorry, no,’ and then disappeared and then the family would have said, ‘Why?’

Nurse manager, Danjoux Meth et al. 144

By contrast, we found one study145 that reported a highly collaborative environment at their site, and this was seen as improving the experience of making decisions about ICU:

The other change that has come on in the last few years that is probably worthy of talking to you about is the collaborative way in which we make the decisions now . . . It is a supportive thing.

ICU consultant, Charlesworth et al. 145

Working within resource constraints

Several studies115,130,144,145 described the need for ICU and referring clinicians to negotiate limited availability of ICU beds, and the impact of this on both clinicians’ decision-making and patient care. External pressures included unrealistic expectations from the patient’s family,46,130 pressure from referring clinicians,46,143 and hospital policies on priority programme patients. 44 ICU doctors sometimes stretched ICU resources by reducing the nurse-to-patient ratio, creating conflict with nursing staff:144

We all knew that it [ICU treatment] wasn’t gonna make any difference . . . So it was hard for us to understand, given that our resources are very tight . . . why we were proceeding with the care of this patient.

Nurse manager, Danjoux Meth et al. 144

Lack of agency

An overarching theme of lack of agency was identified running through the studies. ICU doctors feel constrained by policies and pressure from other clinicians and families,44,46,143 referring teams feel that they are not listened to by ICU colleagues,100,115,130 and nurses are left caring for the critically ill, deteriorating patient with no power to challenge the doctor’s decision. 141,142,144 Patients and relatives are often excluded from the decision-making process. 44,141,142

The body of literature indicated a major gap in relation to patient and relative experiences, as these were included in only two studies, each of which contained the account of one participant. Furthermore, these participants were both ICU nurses by profession. The data in these two studies indicated that patients/relatives were not adequately involved in the process of referral and admission.

Summary

Our systematic reviews identified a large number of studies exploring a wide range of factors associated with decisions to admit a patient to ICU. There was marked heterogeneity among these studies, making it difficult to pool results, and many of the studies were of poor quality. The clearest associations identified were with age, sex, type of acute illness, presence of chronic illness, functional status, presence of do not attempt cardiopulmonary resuscitation (DNACPR) order, referring specialty, seniority of referrer and ICU bed availability. No clear association across studies was found with severity of acute or chronic illness. Few studies looked at the experience of stakeholders in the decision-making process and none had specifically explored this. Key themes identified in the data related to experience were communication, interprofessional relationships and perceived loss of control. One study we reviewed reported a positive, collaborative environment for ICU decision-making, in contrast to our overall findings. Very little is known about patients’ and families’ experience of this potentially life-changing decision.

Chapter 4 Understanding current practice

Introduction

This chapter reports a focused ethnographic study (observation and interviews) to explore current practice and inform subsequent WPs. We chose focused ethnography as this allows observation of what happens in a particular context, which for this study is hospitals with ICUs, and exploration of patterns of practice, ideas, beliefs, norms and values. 146,147

Our research questions were:

-

How are decisions about whether or not to admit a patient to an ICU made?

-

What are the experiences of patients, families and doctors involved in the decision-making process, and what are their views on how these decisions should be made?

-

What would constitute an ethically justifiable process for these decisions?

We first report the methods of data collection and analysis. We then report the analysis undertaken to inform the discrete choice experiment, followed by the analysis undertaken to inform the design of the DSF, accompanying training and professional support. We draw the analysis together at the end of the chapter to respond to our research questions.

Methods

In consultation with our PPI co-investigators and PPIAG, we designed detailed flow charts of participant recruitment and consent (see Report Supplementary Material 1 and 2).

We used a focused ethnography technique to observe and describe what happened before and after a decision was made whether or not to admit a patient to ICU. 148 We chose, as our main data collection, to observe decision-making events and interview doctors about these specific events as this keeps data collection grounded in what is actually happening and how doctors think at the time about decisions. The aim was to reduce social desirability bias of self-reported data from health professionals. 149 However, when asking about the ideal process, we wanted the doctors to think beyond the constraints of a specific case.

To gain understanding of the decision and what happened from the perspectives of those involved, we interviewed the observed intensive care doctors, patients or family members where possible, and referring doctors (see Report Supplementary Material 3–6 for interview schedules and observation template).

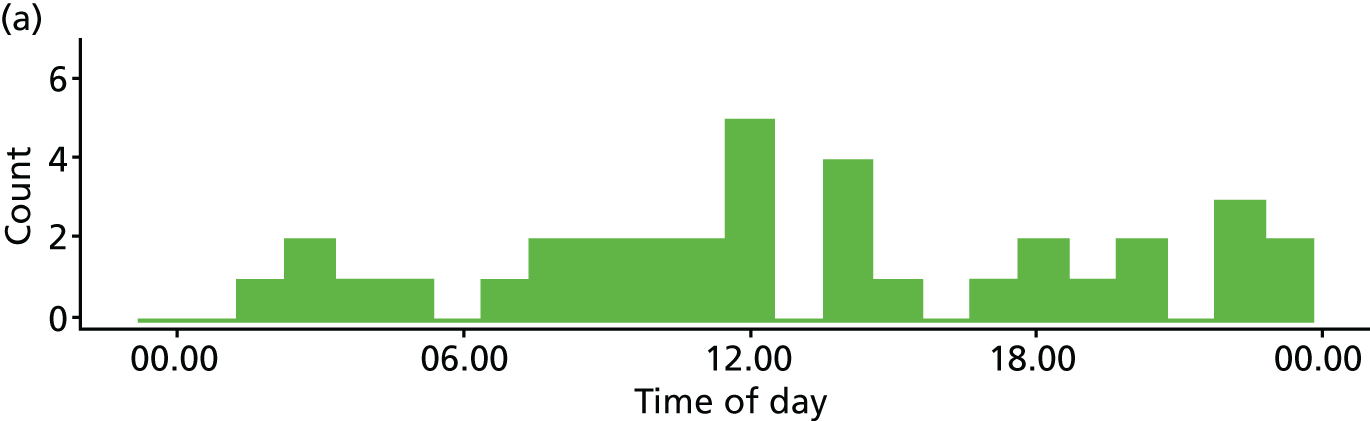

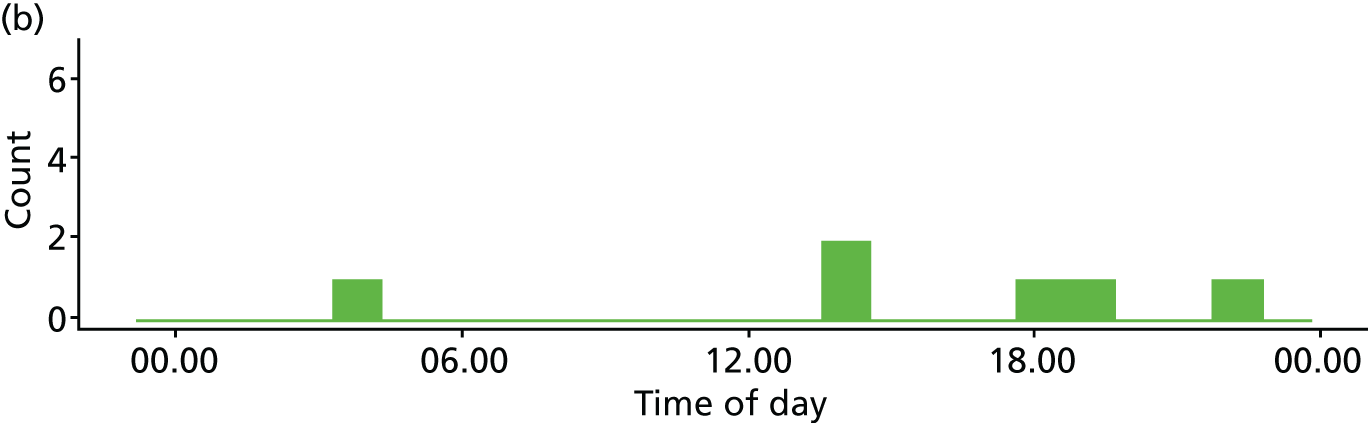

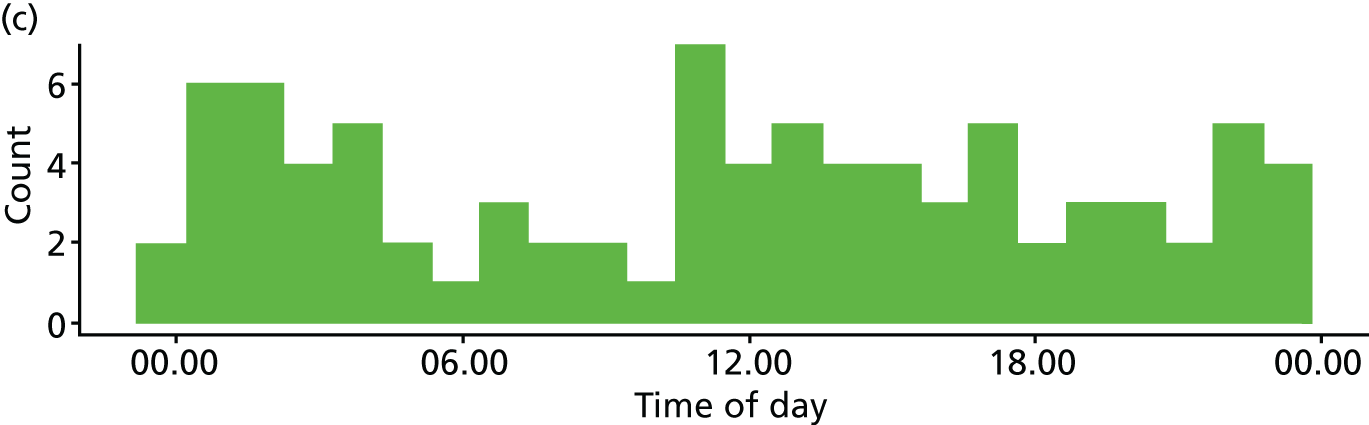

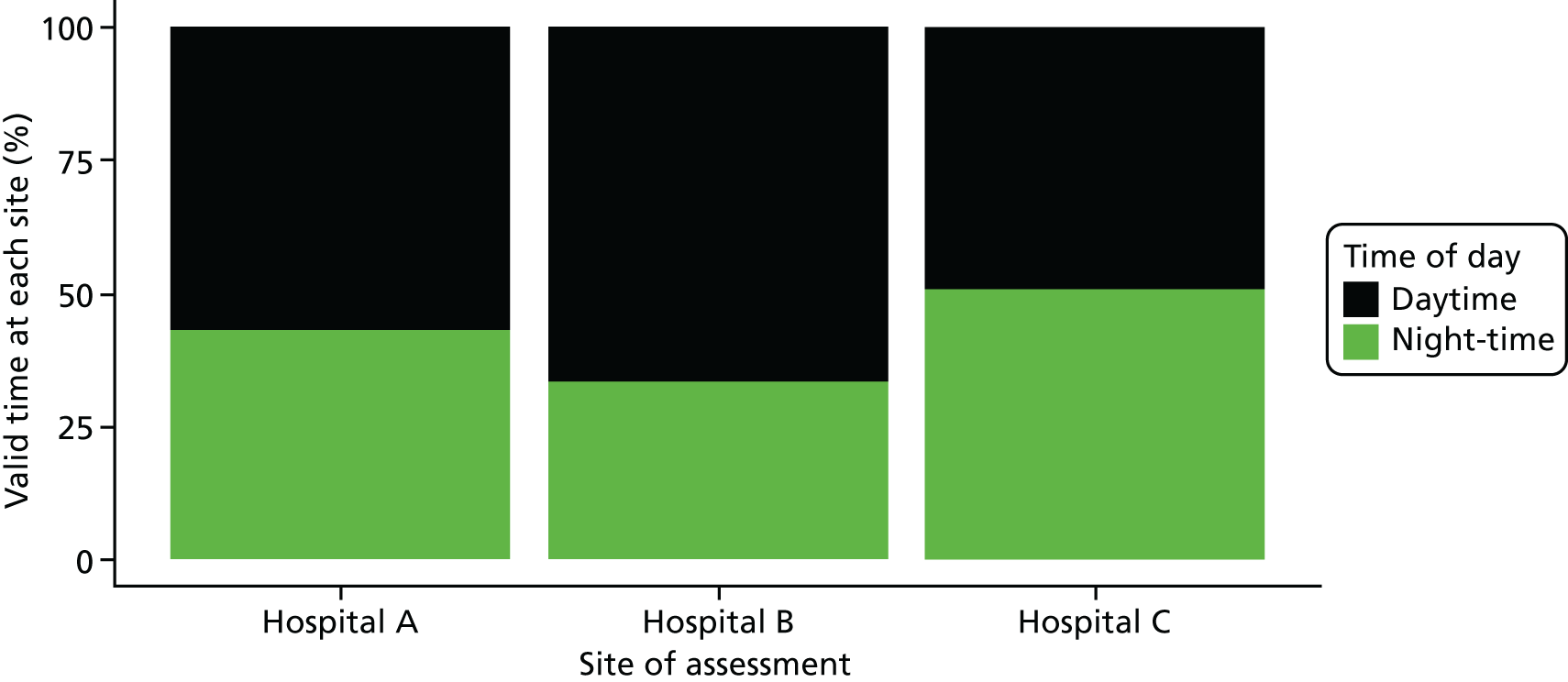

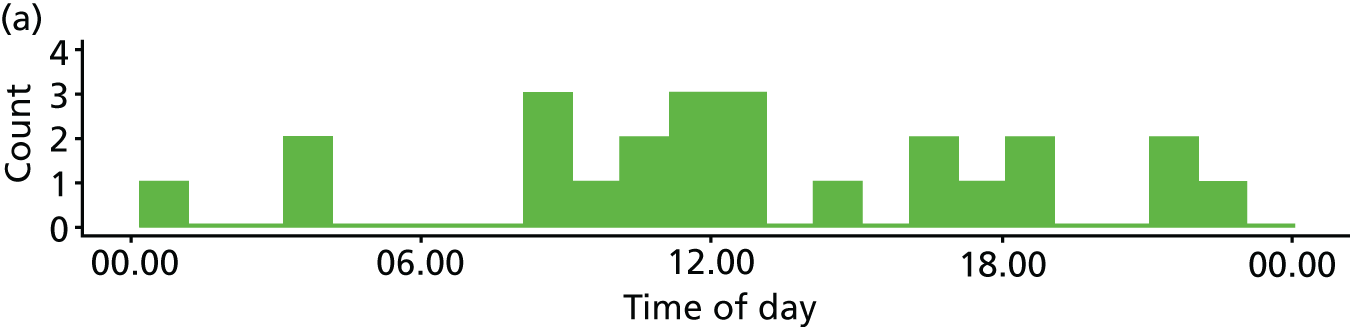

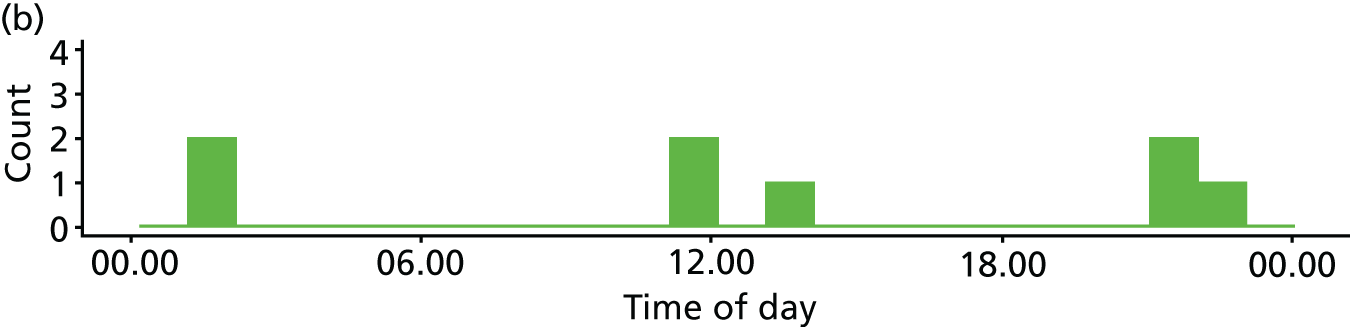

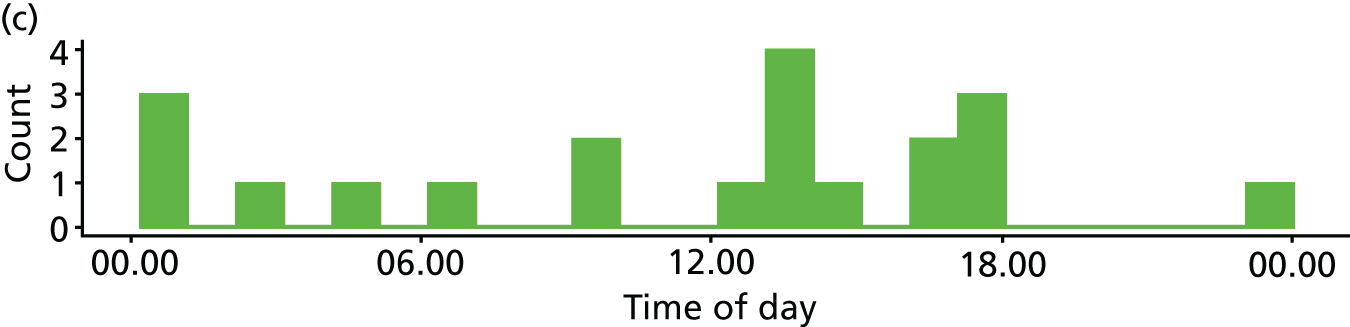

Six NHS hospitals across the East and West Midlands of England were sampled for diversity of type of hospital (university/district general) and ICU unit size (bed numbers: up to 20/21–40/> 40). The researcher, Mia Svantesson (a qualitative researcher with ethics training and ICU nursing experience in Sweden), undertook observation sessions over a 3-week period at each site. These were timetabled to include as many different ICU doctors as possible and to cover the whole 24-hour period and all days of the week. Mia Svantesson met the doctor to be shadowed at the start of the observation period and agreed a process that would not interfere with the clinician’s other work. Usually Mia Svantesson sat in or next to the ICU in a place where the doctor would remain aware of her, and when the doctor received a referral they signalled to Mia Svantesson to join them. The time spent waiting for referrals ranged from 8 to 16 hours. Mia Svantesson observed one to three decisions in each session, except for one session in which she observed five. The time spent with the doctor while the decision was made ranged from 10 minutes to 1.5 hours, except for one decision where the duration was 3.5 hours. Twelve of the 28 sessions were out of hours (between 17.00 and 24.00 or during a weekend).

Patients and family members seen by the doctor during observation were given the option of asking the researcher to leave the room. The limits we placed on observation minimised the burden on the clinical team but allowed sufficient time to include diverse participants and times of day/week, and to reach data saturation.

Interviews with the ICU and referring doctors occurred as soon as possible after the observed decision. Additionally, we interviewed specialist doctors who refer to ICU but did not refer during observation periods. For logistical reasons the interviews with these doctors were undertaken by Mia Svantesson and other team members, Frances Griffiths (a UK general practitioner and sociologist) and Anne Slowther (a UK general practitioner and ethicist). Patients with capacity at the time of their referral to ICU were given brief information about the study and asked if they agreed to a family member being interviewed. Before leaving hospital, surviving patients with capacity were asked for their consent to include data from any family interview already obtained, consent to approach a family member for an interview in 3 months and consent to be personally contacted 3 months later for an interview. Family members were approached by a member of the clinical team for interview within 48 hours of the observed decision. Early in the study, we realised that very few family members had been approached because of practical reasons, such as the family not being available, and because the clinical teams were concerned about causing distress. In consultation with our PPI advisors, and with ethics approval, the time window for approaching family members was extended to 72 hours in an attempt to increase recruitment. If the clinical team thought that an approach would cause distress, no approach was made. Patient and family member interviews were undertaken by Mia Svantesson. Patients and family members unable to engage in an interview in English were excluded.

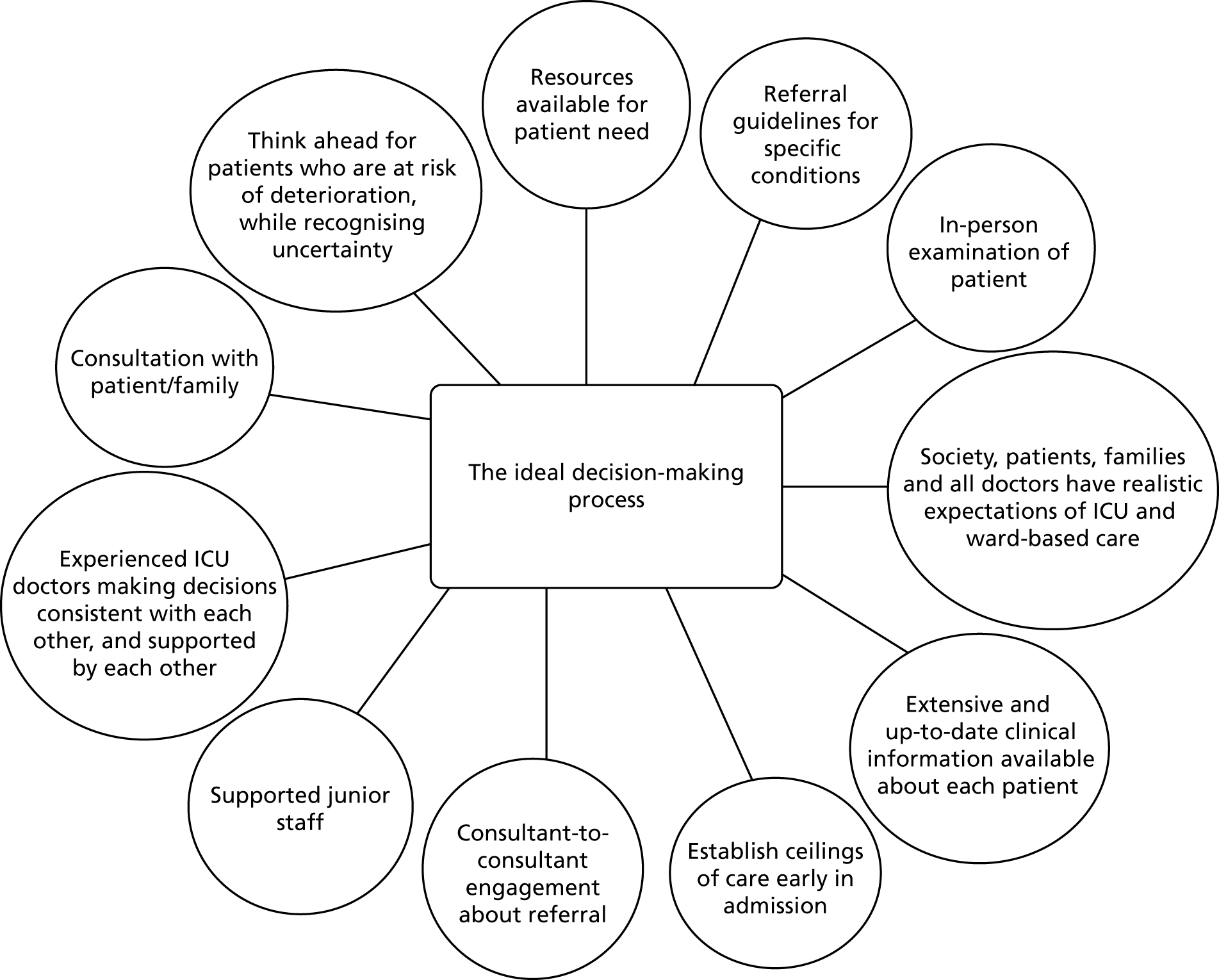

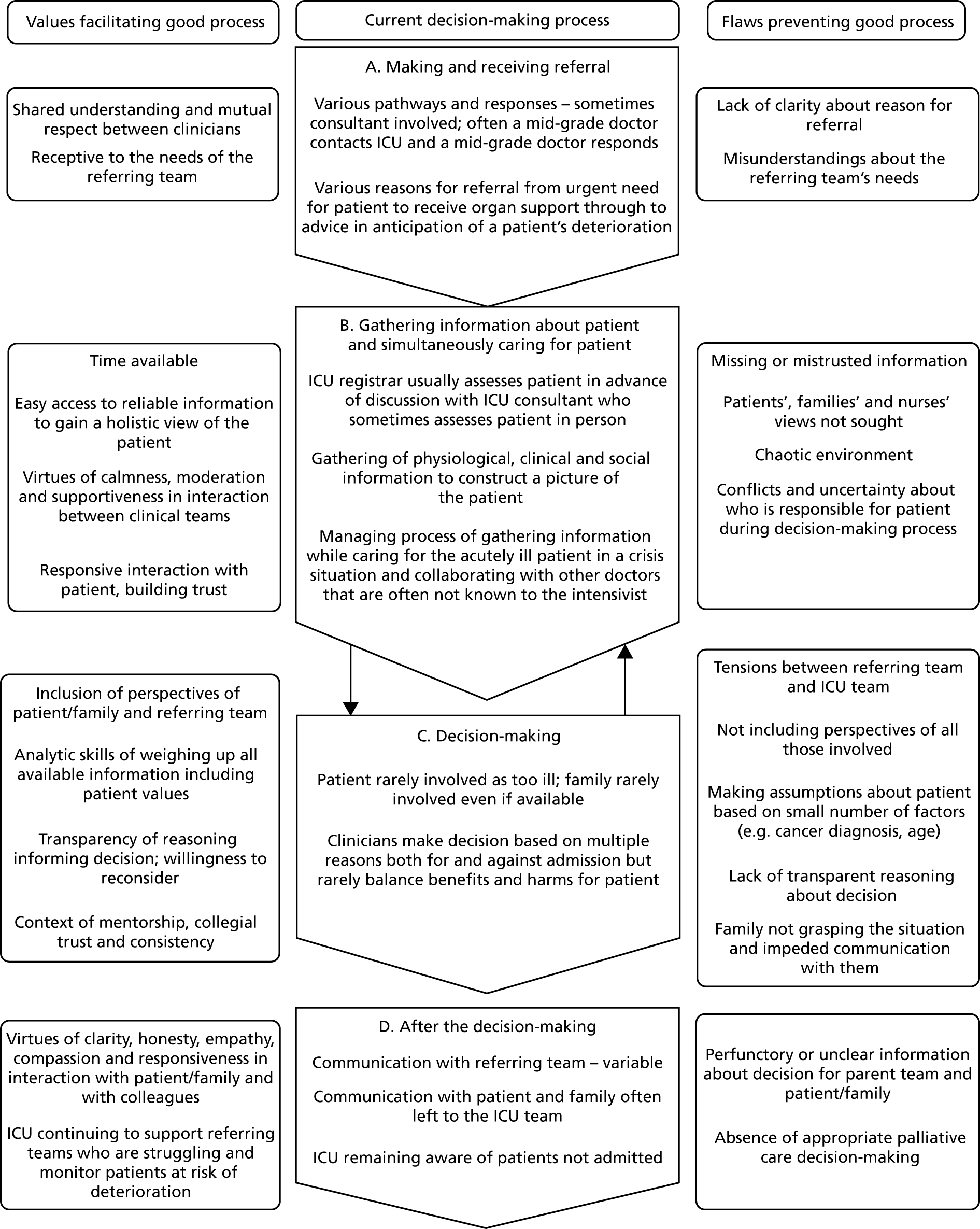

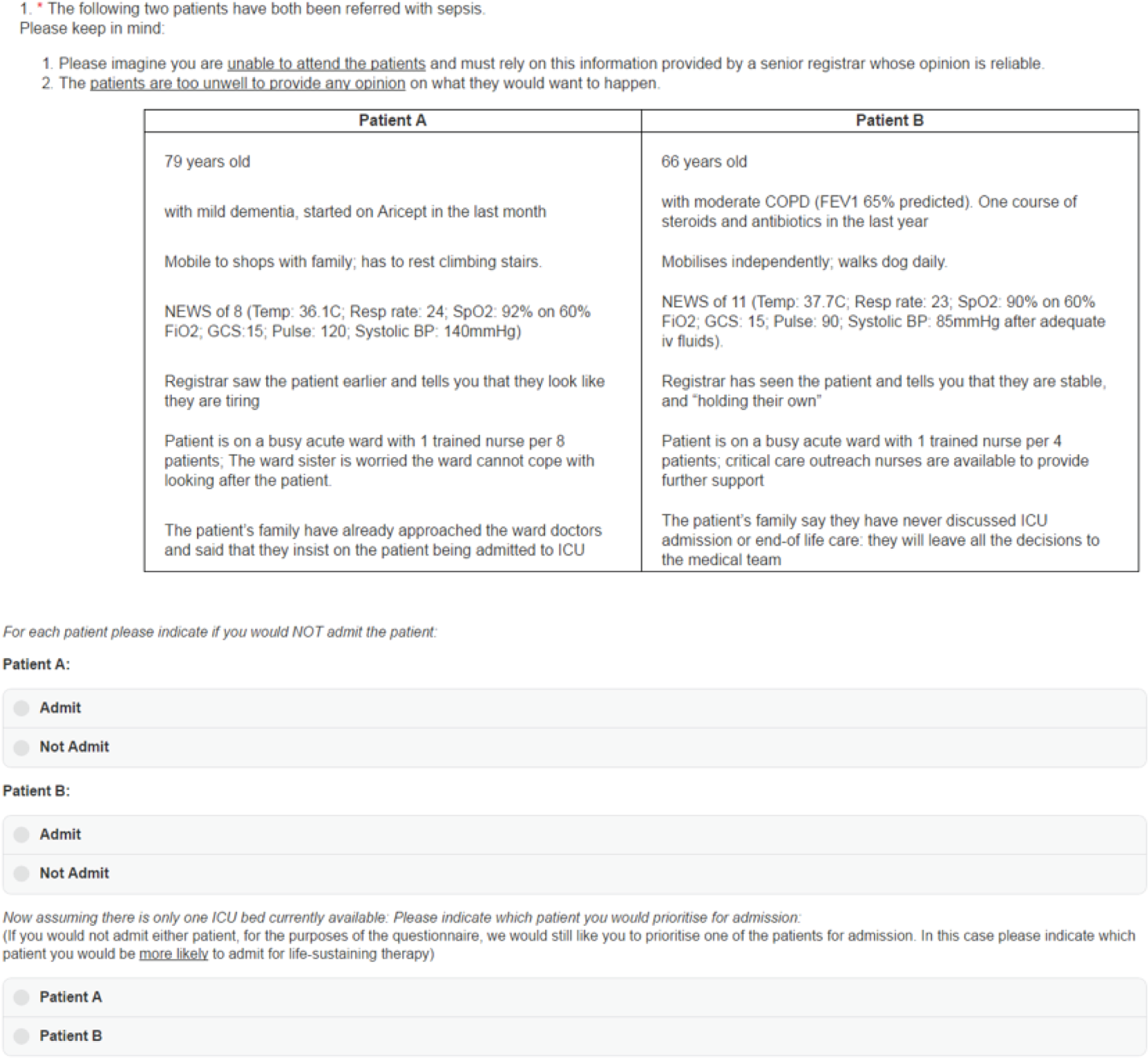

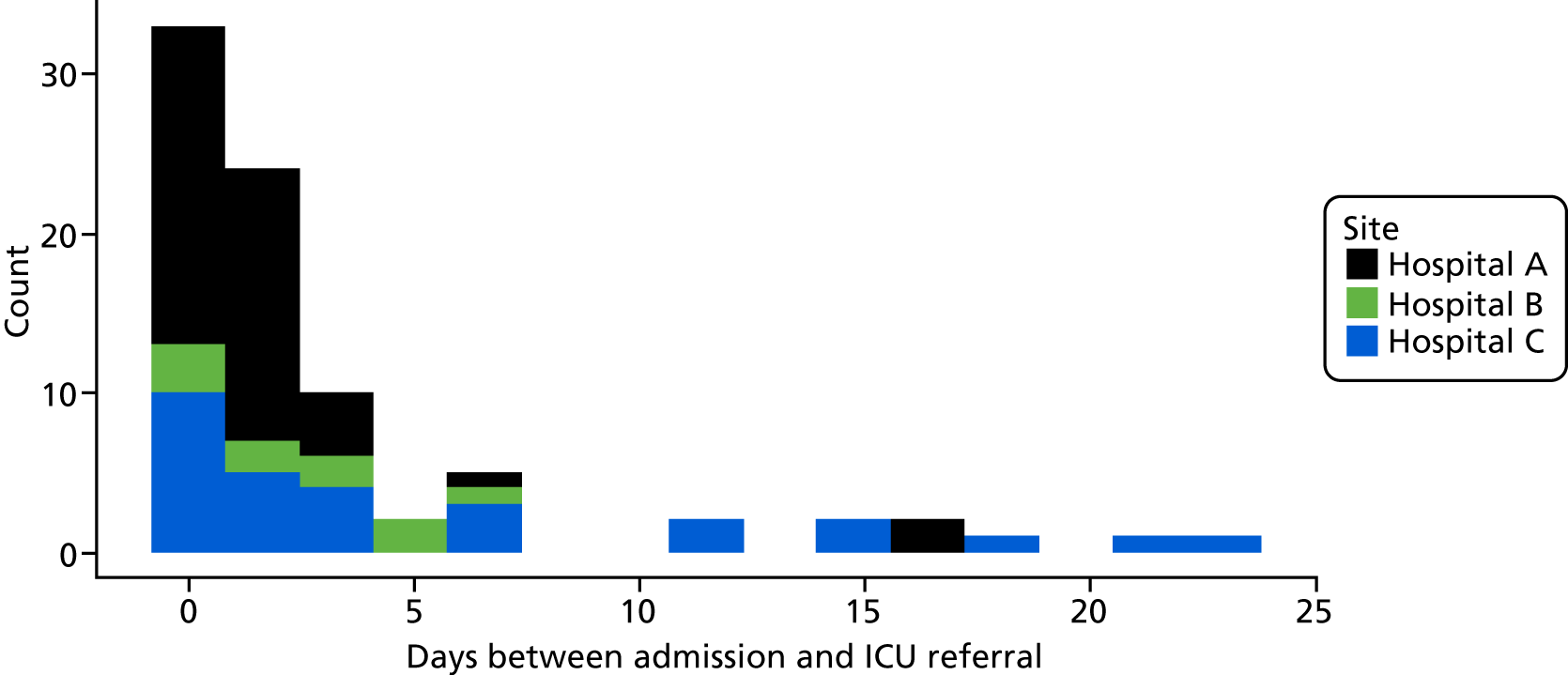

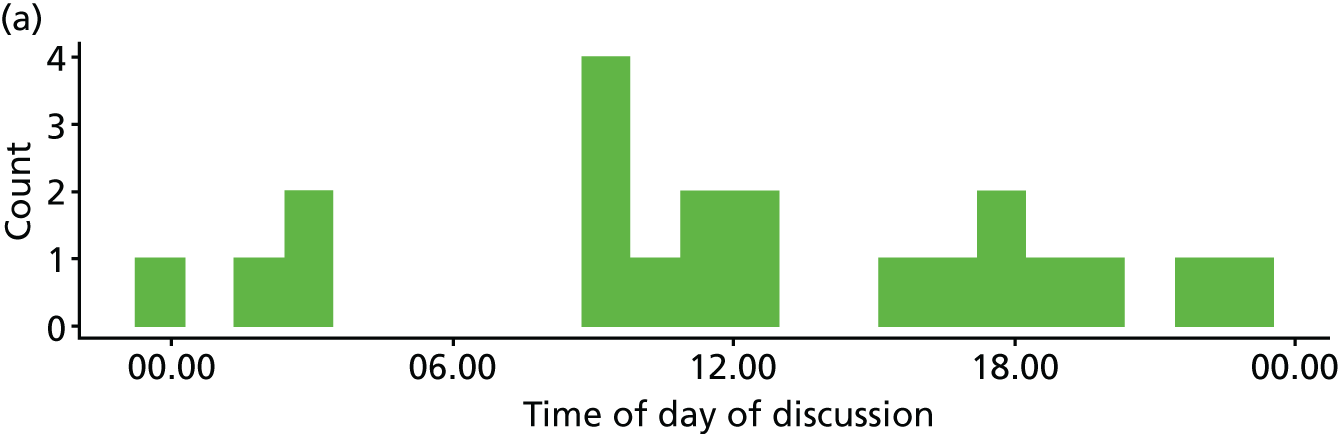

Field notes were taken during observation about what was happening and Mia Svantesson’s impressions of whether or not a process was a good experience for patients and family members and for doctors, and what influenced this, including underlying values. We used a broad definition of values to include procedural values such as communication, time and mentoring, as well as ethical/moral values such as respect for persons, minimising harm, honesty and fairness. Mia Svantesson drew on ethical, professional and legal frameworks to inform her identification and exploration of ethical/moral values in the field. She checked her impressions through conversations with the observed doctors. The field notes were typed up and expanded immediately after each observation session. Doctors were asked during interview to describe their decision-making process related to an observed decision to admit or not to admit a patient to ICU (or their most recent decision if they had not been involved in an observed decision), including any communication with the patient/family, what they took into account in the process and how the process could be improved. The researcher explored what participants thought made a good decision-making process, and what hindered this. Patients/family members were asked during interview (initial interview and 3-month interview) to describe what they remembered of the situation they were in, the decision about admission to ICU, and their involvement, and whether or not they thought that the process could be improved. Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim and anonymised. Observation and interview guides were refined based on analysis of initial data (see Report Supplementary Material 3–6). Data collection started in June 2015 and was complete by May 2016.