Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 12/128/41. The contractual start date was in January 2014. The final report began editorial review in June 2019 and was accepted for publication in February 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Rob Simister is lead consultant of the hyperacute stroke unit at the University College London Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust. Rob Simister is now Joint Clinical Director of the London Stroke Clinical Network and is part funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre at University College London Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust and University College London. Angus IG Ramsay was an associate board member of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Services and Delivery Research (HSDR) Board (2015–18). Anthony Rudd was the National Clinical Director for Stroke in England from 2010 to 2019 and was the London Stroke Clinical Director from 2009 to 2019. Steve Morris was on the NIHR HSDR Funding Committee (2014–19). Naomi Fulop was a member of the NIHR HSDR Funding Committee (2013–18) and is a NIHR Senior Investigator.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Simister et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Context

Context and rationale for the research

The ‘weekend effect’ and 7-day working policies

In 2001, Bell and Redelmeier1 published a landmark study showing that mortality was higher among people admitted to hospital during weekends or ‘out of hours’ than among those admitted during normal hours on weekdays, based on the health records of 3.8 million Canadian patients. This effect has been repeatedly demonstrated across a range of acute conditions, patient populations and health systems,1–3 such as myocardial infarction4 and stroke,5–9 patients undergoing elective surgery10 and admissions to emergency departments (EDs)11 or intensive care units. 12 However, a number of studies report equivalent or better outcomes in some patients treated outside normal working hours. 10,12–14 Although contested, such studies indicate that high-quality out-of-hours care is possible and that changes in organisation of services might address the current performance gap.

The Secretary of State for Health made this issue a priority in 2015 by suggesting that ‘someone is 15% more likely to die if admitted on a Sunday than on a Wednesday because we do not have as many doctors in our hospitals at the weekends as we have mid-week’ (House of Commons, 2015. Contains Parliamentary information licensed under the Open Parliament Licence v3.0. See https://www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright-parliament/open-parliament-licence/). 15 This led to controversial changes to doctors’ work contracts, provoking large-scale strikes16 and an NHS England policy for a 7-day NHS by 2020. 17 The NHS Long Term Plan18 has identified, in particular, that all stroke units will, over the next 5 years, meet the NHS 7-day standards for stroke care and the national clinical guidelines for stroke over the next 5 years.

Several possible causes for an ‘out-of-hours effect’ are proposed, but many relevant factors are likely to be associated with out-of-hours working, including differences in patient case mix affecting outcomes among patients admitted at different times of the week;19 reduced staffing levels;2,11,20 reduced access to supporting investigations;2,11 lower seniority and clinical experience of available staff;1,2 less familiarity of staff with patients;1 less familiarity with unit-specific processes and policies, and insufficient training to address this;2 and fewer supervisory staff and less supervisor familiarity with the staff they supervise. 1 Systems by which such issues may be identified and addressed, such as clinical governance, and cultures that support staff engagement in these systems, may play an important role in how the out-of-hours effect manifests. Ward and organisational leadership may also represent significant factors in supporting service development, learning and engagement. 21

The controversy raised a number of relevant issues for research: first, that exposure of differences in outcomes across the week was having an impact politically, and that it was necessary to answer the question of whether this was a true effect, or an artefact of the patient mix or the quality of the data; second, that it was important to measure other outcomes and care processes, as well as mortality; and, finally, to change the approach towards acknowledging patterns of temporal variation. 22–25 This movement is characterised by the idea that certain times of the day, or days of the week, are associated with poorer outcomes for the patient, but that this is not necessarily limited to the weekend or night-time. 22 As a result, the concept of ‘out-of-hours’ working or the so-called ‘weekend effect’, which once dominated the discourse of the literature on temporal variation,22,26–28 has been re-evaluated.

It is now recognised that temporal variation results, at least in part, from delivery models of care and the cultural values of the health-care sector, enshrined in everyday practice, funding models, staffing practices and wider policies. 29 Recent research, such as the High-Intensity Specialist-Led Acute Care study,30,31 have taken this approach to examine the intensity of specialist-led care in emergency medical admissions, focusing particularly on the organisation and delivery of care, and medical staffing. 30,31

In the case of urgent stroke care, recent studies have shown that temporal variation in mortality is now decreasing,32,33 including in London’s hyperacute stroke unit (HASU) model. 34 However, there has been no large-scale, organisational research to understand what creates temporal in consistency, particularly in services that aim to operate consistently over 7 days, such as the London stroke services. The current study adds a wealth of information to this gap.

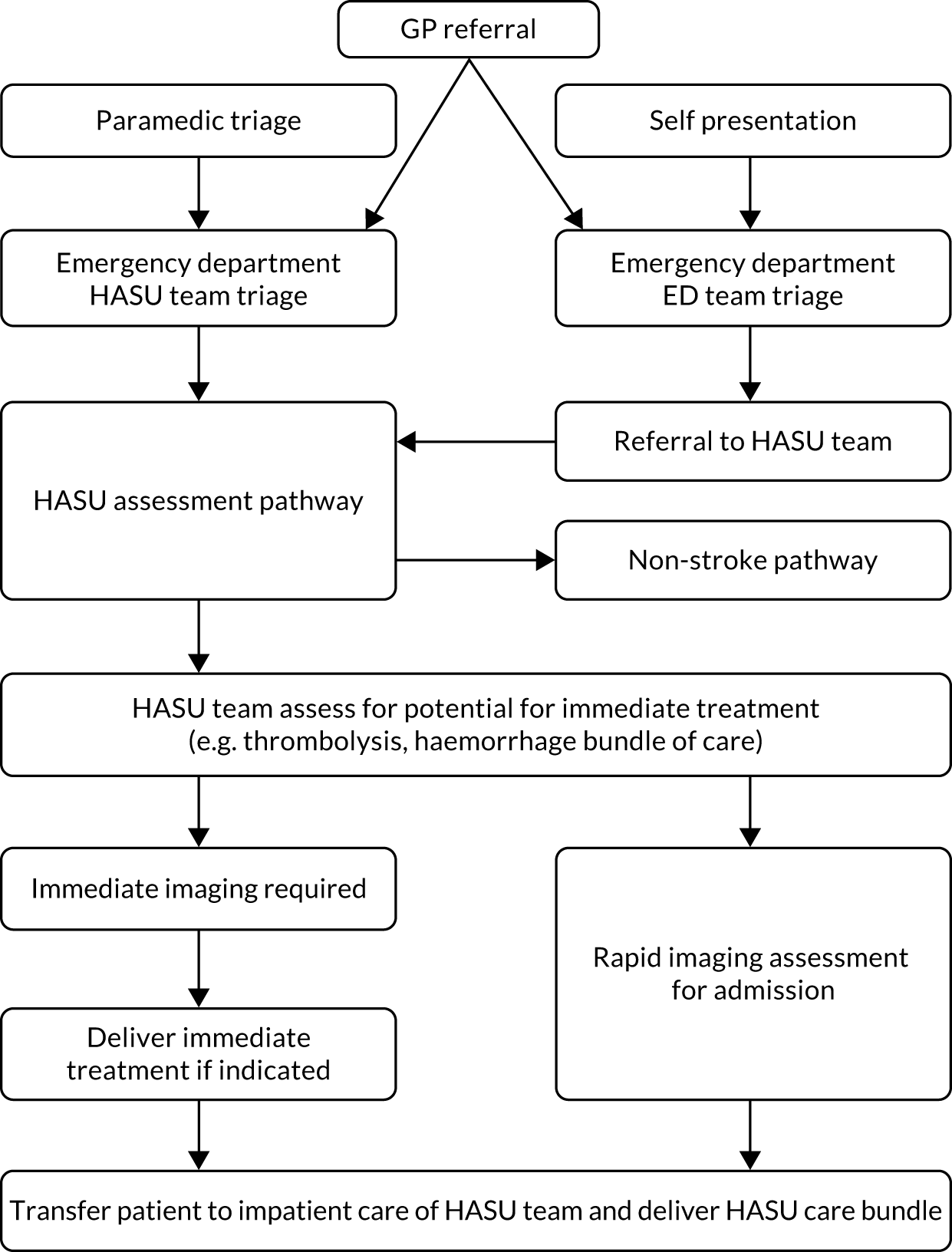

Reconfiguration of stroke services and the aspiration of 7-day working

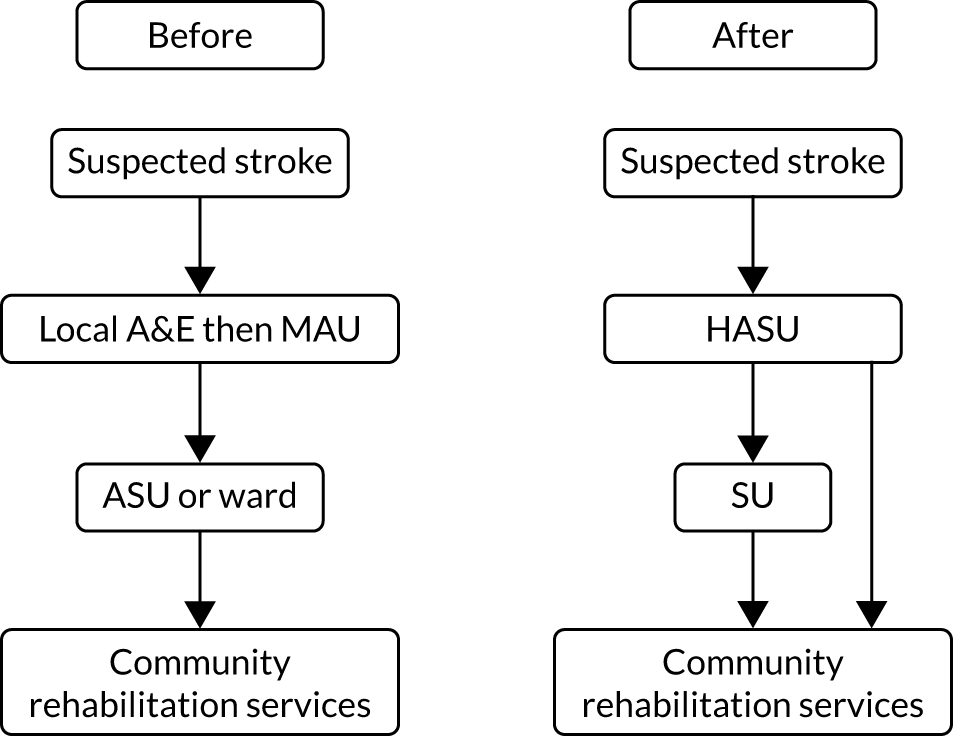

In 2010, acute stroke services in London (population 8.2 million) were centralised. Hospitals were selected to become sites for specialist stroke care (over the first hours following stroke) in a hub-and-spoke network. 35 In London, prior to the reorganisation, 30 hospitals provided acute stroke care. After the reorganisation, initial specialist stroke care was routinely provided to all patients with suspected acute stroke at eight designated HASUs, with all patients being assessed shortly after arrival at the designated hospital by specialised stroke assessment teams able to provide access to immediate brain imaging in all patients and delivering immediate intravenous thrombolysis, when appropriate (Figure 1). The HASU model involved the London Ambulance Service taking all patients with suspected stroke within 48 hours of onset to one of the eight HASUs. 36 Acute stroke patients seen at other medical facilities were similarly transferred as an emergency to a HASU. The aim of the HASUs was to provide specialised care for all acute stroke patients during the first 72 hours after onset of stroke. Twenty-four acute stroke units in London, linked to HASUs, were designated to provide specialist acute stroke care beyond 72 hours for those patients still requiring inpatient treatment. Eight of these were in the same hospital trust as a HASU. 37 On average, across all patients, the quality of acute stroke care in London was better than in the rest of England and increased as a result of the centralisation,38 with a decrease in mortality. 35

FIGURE 1.

Summary of London’s stroke service model before and after reconfiguration. A&E, accident and emergency; ASU, acute stroke unit; MAU, medical admission unit; SU, stroke unit.

Performance standards for HASUs, linked to payments, were initially set by Healthcare for London39,40 and subsequently the London Strategic Clinical Networks to maintain high quality of care across the HASU stay. Standards include staffing quotas, required infrastructure and delivery of care. Some standards were set to provide rapid access to time-critical ‘front-door’ measures [e.g. dysphagia screen within 4 hours of admission, computerised tomography (CT) scan within 1 hour of admission and thrombolysis administration within 60 minutes]. Other standards were set with less stringent time constraints (e.g. stroke specialist consultant physician assessment within 24 hours and physiotherapist assessment within 72 hours). An evaluation of London’s stroke centralisation found that mortality and length of stay (LOS) were reduced, if all stroke patients receive hyperacute care. 35 It has also been shown that these changes are sustainable over time. 41

The London model has been shown to improve clinical outcomes and care provision,35,37,38 and is cost-effective. 42 Beyond London, many regions in the NHS are currently seeking to centralise stroke service organisation in different ways. 43,44 The development of mechanical thrombectomy (surgical removal of a blood clot from a blood vessel) services is an important new development for a subset of stroke patients. As of May 2020, further reorganisation of the London model is currently in progress with the designation of a subset of HASUs that can provide thrombectomy. At the time of our study (2014–15), no HASU was providing a formal thrombectomy service for stroke associated with large vessel occlusion. Therefore, 24/7 availability of scans and assessments by specialists will be vital to enable the correct patients to be transferred to a thrombectomy centre.

Aims and research objectives

Research aims

This study aimed to identify the extent to which London stroke services were providing care 24 hours a day, 7 days a week (24/7), and, if they were, how this was being achieved. The research provides an opportunity to examine how and if a range of organisational factors influence 24/7 provision of stroke care, and to assess the extent to which temporal patterns of provision are reflected in patient outcomes, including mortality, LOS and functional independence. The research also aimed to explore service developments related to temporal consistency. These lessons are of potential value to people who commission, organise and run stroke services, both in London and across any area of the English NHS that seeks to develop or provide 24/7 hyperacute stroke care. They may also have relevance to research in, and provision of, 24/7 care in other health-care settings, such as emergency and intensive care, treatment of myocardial infarction and elective surgery.

Research objectives

Objective 1

To investigate the extent to which evidence-based care received by stroke patients differs between in-hours and out-of-hours services in London HASUs.

Objective 2

To investigate the extent to which clinical outcomes differ between in-hours and out-of-hours services in the London HASUs.

Objective 3

To investigate how in-hours and out-of-hours services are organised and provided in London HASUs.

Objective 4

To investigate how these services are perceived by stakeholders (including stroke clinicians, patients and carers).

Objective 5

To investigate the costs of acute stroke care in London HASUs on different days and at different times of admission.

Overview of the research project

This project was funded by the National Institute for Health Research Health Services and Delivery Research programme, from January 2014, to study the development, provision, effects and cost of 24/7 stroke care in the London HASU system as part of an open call. The project was extended from its original end date of December 2016 to April 2019 due to delays and the eventual inability to obtain the Sentinel Stroke National Audit Programme (SSNAP) data linked to mortality data from the Office for National Statistics (ONS). The reason for this delay was difficulties in formalising data-sharing agreements between the Health and Social Care Information Centre (now NHS Digital, data controller for ONS data) and Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership (data controller for SSNAP data). It was agreed with the funder that we would publish the results based on the SSNAP data we did have, rather than continue to delay the publication of the study. At an early stage of our investigation, we recognised the pivotal roles undertaken by the HASU lead nurses. Understanding these activities and their impact on the functioning of the HASUs required the additional capture of the nursing rotas for each HASU for the period of the study. Our analysis of the impact of nursing numbers and seniority in relationship to temporal variation and clinical outcomes is presented here (see Chapters 3 and 5), and strongly supports our initial observations on the central importance of nurse-led activities to our work. This enabled us to undertake new and originally unplanned analyses to look at the impact of nursing numbers and seniority (see Chapter 5) in relation to temporal variation and clinical outcomes (see Chapter 3).

Structure of the report

The report is structured as follows.

See Chapter 2 for:

-

an overview of the study sites

-

data and analysis methods.

(Detailed methods are provided within each findings chapter.)

See Chapter 3 for:

-

costs of acute stroke care in London HASUs on different days and at different times of admission.

See Chapter 4 for factors that influence, temporally:

-

consistent care

-

inconsistent care.

See Chapter 5 for:

-

nursing roles on the HASU

-

temporal variation in nursing provision

-

associated processes and outcomes.

See Chapter 6 for:

-

temporal structures acting on the HASU patient pathway

-

how this can have an impact on measurement of temporal variation.

See Chapter 7 for:

-

discussion and summary of our findings in relation to our research questions

-

implications for health services, research and 7-day working policies.

Changes to the protocol

We made some changes to the protocol because of difficulties in obtaining access to all our data sources, especially mortality data, as noted in Overview of the research project. Initially, we experienced difficulties gaining access to the HASUs, and later on it proved difficult to recruit patients and carers to our interviews. This is partly because of the long delay periods between recruitment on the wards and patients returning to their homes or care facilities when they would be ready to complete the interview. In addition, there was a significant dropout rate between patients expressing interest in taking part and completing interviews: 80 patients expressed initial interest, but either declined later on or would not respond to communications. Patient recruitment improved with registration of the study on the Clinical Research Network portfolio, which allowed access to the Clinical Research Network research practitioner teams in each HASU and a more systematic approach to patient identification. This released our team to discuss the study with patients who had already expressed interest in taking part.

Lack of access to mortality data or long-term dependency data

The most substantial change made to our protocol is in the absence of 3-month mortality and 6-month modified Rankin Scale (mRS) data. The basis of our data set is the SSNAP. The SSNAP is one of several ongoing mandatory national clinical audits and has contributed significantly to the debates around quality of stroke care at the weekends, by providing a detailed data set to several studies. We had hoped to link this data set to Hospital Episode Statistics and ONS data on mortality after discharge. Similar analyses have been achieved by other research teams (e.g. Bray et al. 22). We estimate that we waited for these linked data for 24 months before we decided to drop these analyses from our study. The delay was due to an ongoing disagreement between NHS Digital and Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership about formalising data-sharing arrangements for our study and similar studies. Follow-up data after discharge from HASU or hospital were collected in the SSNAP for a very small number of patients and it was not feasible to run this analysis.

Without these data our final outputs are weaker, but still important. We are still taking a unique approach to this problem by including within-hospital mortality data, mRS data and nursing rota data, by looking at patterns of temporal variation, rather than binary weekday or weekend patterns, and by incorporating interview and observational data.

Lack of access to carotid surgery data

The consultations about carotid surgery data were made with National Vascular Registry managers. According to the information provided, there was a lag of approximately 18 months between recording of carotid surgery data and their release (as of the end of January 2015 the carotid surgery data were available for linkage up to September 2013). In addition, the SSNAP data requested did not contain patient identifiers and it was not possible to assure the quality of linkage between the SSNAP and the National Vascular Registry data (Table 1).

| In the protocol | What could not be achieved within the term of the grant | Additional content |

|---|---|---|

| Sampling | ||

Covering the period 1 January 2014 to 31 December 2014:

|

|

|

| Analysis | ||

|

We regress our primary and secondary outcomes against different combinations of a series of covariates of interest Primary outcomes:Secondary outcomes: |

We were not able to obtain outcome data on:

|

Additional outcomes:

|

| Independent variables | ||

|

Additional independent variables:

|

|

| Economic element | ||

The cost components will include:

|

Imaging interventions: Surgical and neuroradiological interventions:Post-discharge care: |

|

Chapter 2 Research methods

Overview

In this chapter we provide an overview of our study design, and we outline the quantitative and qualitative data and methods used (note that detailed methods are provided in Chapters 3–6).

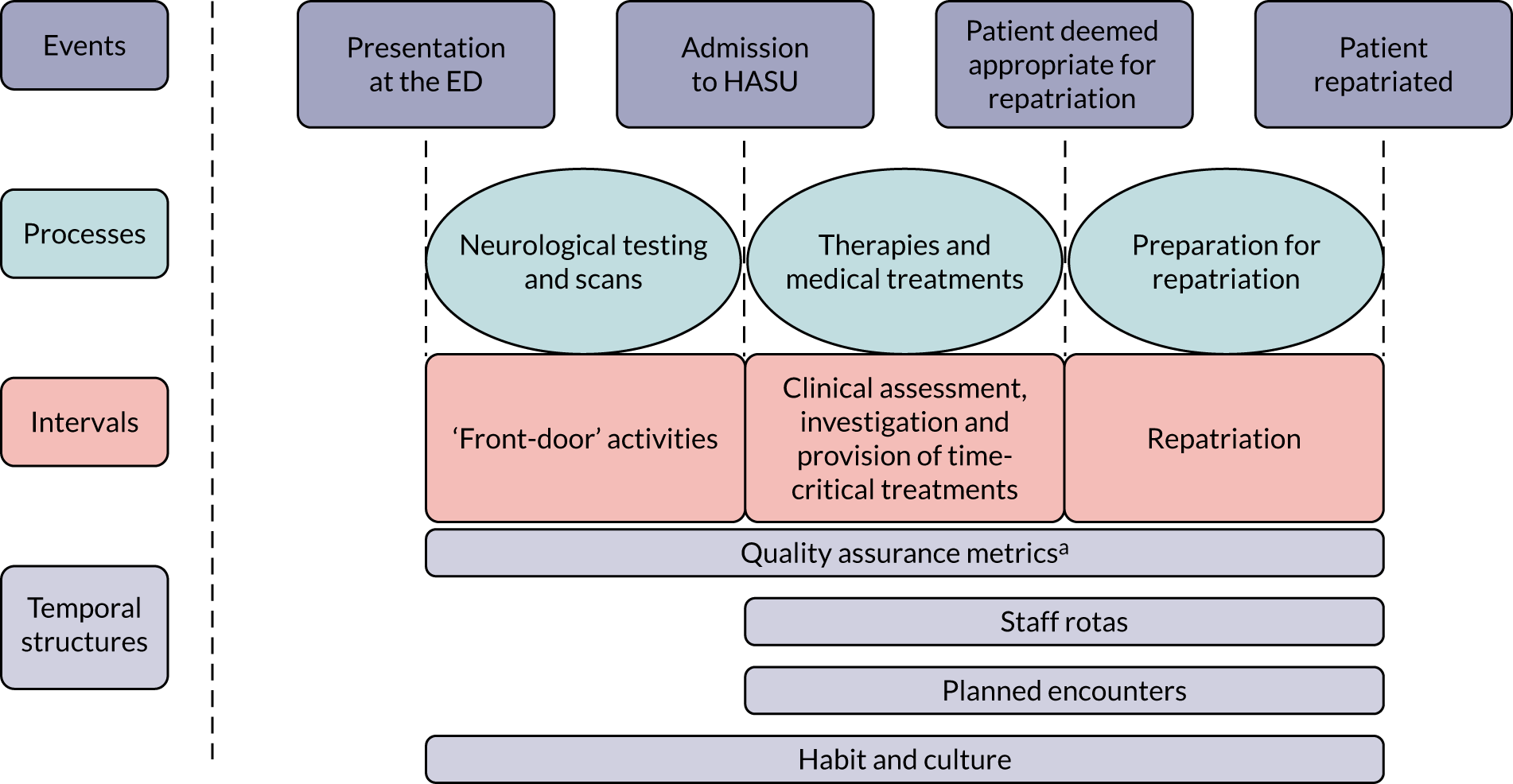

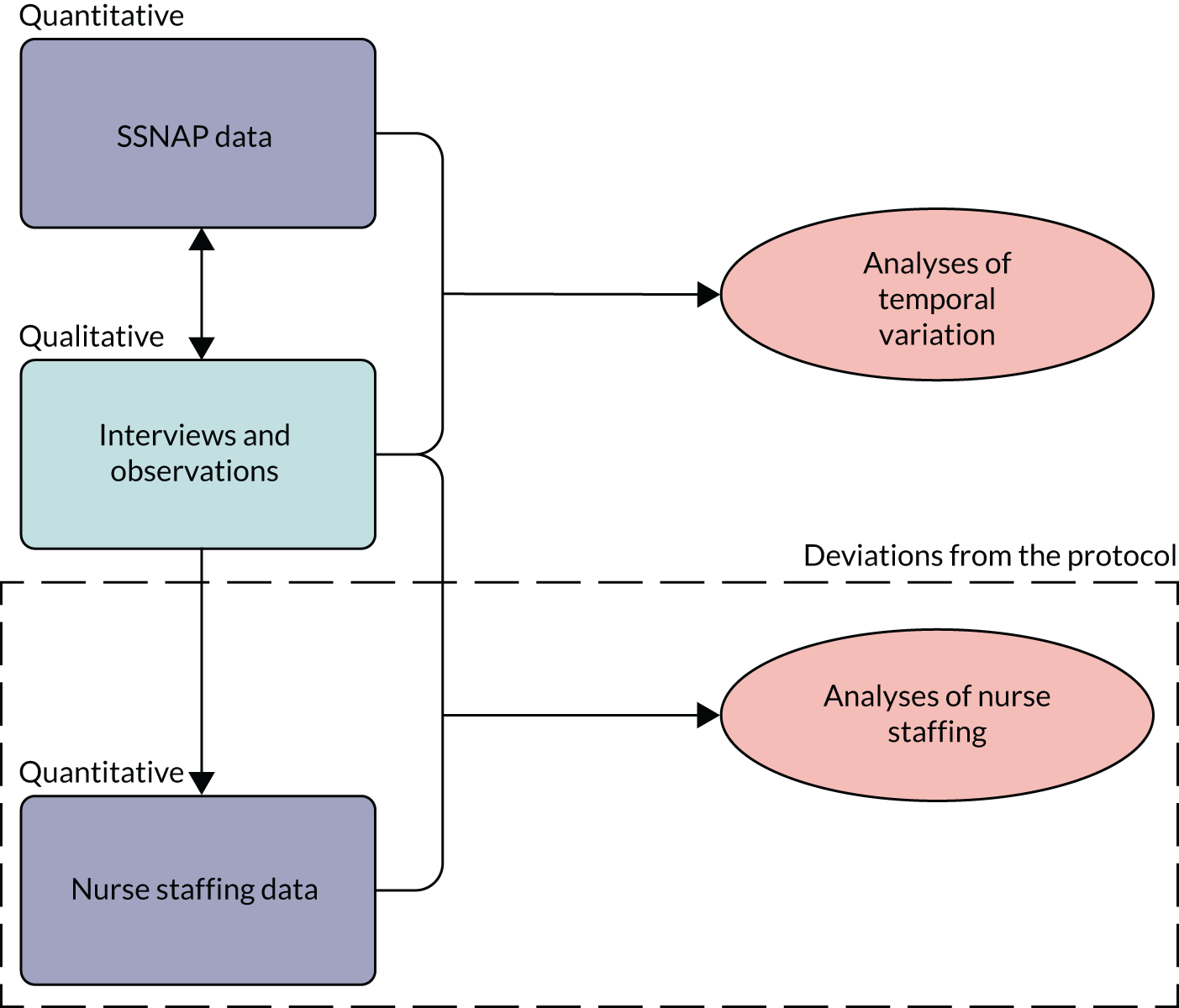

Study design

This study used a mixed-methods design, with findings from planned qualitative and quantitative analyses informing further investigation and analysis throughout the study (see Chapter 1, Structure of the report and Figure 2). 45 The case study method permits development and testing of theories on how efforts to bring about change interact with the context in which they take place. A multiple case study approach, in this case, in which each HASU is a case study, allows the development and testing of theories in several organisational contexts. 46–48 Our large qualitative data set was derived from interviews with HASU staff and patients, and observations on the ward and elsewhere in the eight hospitals. After gaining access to the SSNAP data, we looked at temporal variation (objectives 1 and 2) in the processes and clinical outcomes of HASU care for a 1-year period (from 1 January 2014 to 31 December 2014) (see Chapter 3). Chapter 4 is an analysis of the reasons for the patterns of variation found in our SSNAP data set, derived from dialogues between the quantitative and the qualitative research teams in the study (objective 3). Our third study was informed, in part, by qualitative data, with interviews and observations suggesting that nursing seniority and variation in providing key roles (such as nurse in charge) was perceived to be more important than the number of nurses on the ward (objectives 1–3). Therefore, we examined how nursing roles were provided through different time periods, and the impact on clinical outcomes and processes (see Chapter 5). Chapter 6 reflects the development of our conceptual thinking as a mixed-methods team throughout this project (objectives 3 and 4). We have recognised the limitations of using the SSNAP to assess temporal variation, leading to a qualitative analysis of the forces or structures driving temporal variation, and how this affects measurement of variation in stroke research. Our methods are reported in accordance with the COnsolidated criteria for REporting Qualitative studies (COREQ) (see Appendix 1) and STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guidelines. 49

FIGURE 2.

Interlinkages of the mixed-methods analysis, including deviation from the protocol.

Perspective

We approached this research with a commitment to the study of the HASU system from both a quantitative and a qualitative perspective. Although not an ethnographic study, we adopted some principles of multisited ethnography, such as following people and objects through systems. 50 For example, we based some of our observations around the journey being followed by a stroke patient all the way from the emergency room, through scans and tests, and up to the HASU ward itself. We followed members of staff, such as consultants on their ward rounds and nurses around the hospital. We also focused on relative cultural meanings, such as what 24/7 means from a variety of professional and patient perspectives. We committed to be reflexive and iterative in our approach to data collection, regularly meeting to debrief and make decisions about future plans for data collection, and quantitative and qualitative analysis. 51 Finally, we sought to understand both our qualitative and our quantitative data through our immersion in the services. This led to new additional quantitative analyses being undertaken, such as our analysis of HASU nursing data.

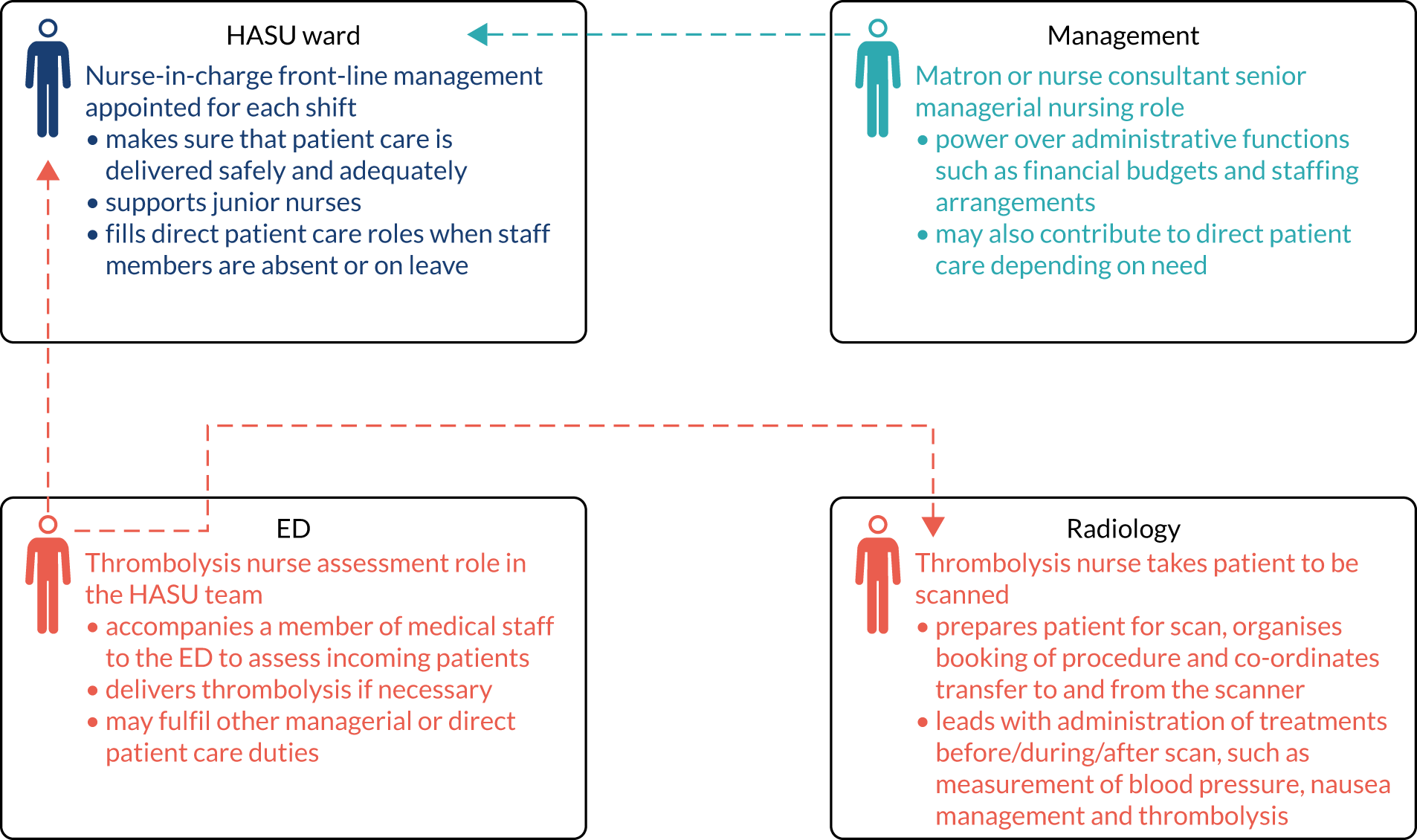

Setting

Our study was set in all eight of the London HASUs. These are dedicated wards, often sited in close proximity to relevant specialties, such as neurology, stroke wards, gerontology, etc. The wards range in size from 18 to 50 beds. We did HASU-specific profiles, noting bed numbers, shift hours, access to scans (e.g. magnetic resonance imaging) (see Tables 11 and 18). In addition to the ward, the HASU teams work in the ED to assess and treat incoming patients. This also includes moving them to scanning facilities and working with radiologists to interpret CT scans. Some patients are either assessed or temporarily situated in other wards when the HASU has inadequate capacity; these are known as ‘outliers’. Therefore, our observational work occurred in all of these locations, but not outside the hospital.

The London HASUs are in the following hospitals:

-

Charing Cross Hospital

-

The Royal London Hospital

-

King’s College Hospital

-

St George’s Hospital

-

Northwick Park Hospital

-

Princess Royal University Hospital

-

Queen’s Hospital

-

University College London Hospital.

Ethics approval

The study received approval from the National Research Ethics Service Committee London, Westminster Branch (reference number 14/LO/1355) and local approvals at each participating trust.

Quantitative data collection

Sentinel Stroke National Audit Programme

We obtained anonymised patient-level data from the SSNAP for all patients treated in London HASUs with a primary diagnosis of stroke (ischaemic stroke or primary intracerebral haemorrhage) between 1 January 2014 and 31 December 2014. The SSNAP collects data on clinical characteristics, care quality (from the time of admission up to 6 months after stroke) and outcomes for all stroke patients admitted to acute care hospitals in England. Data are entered into the SSNAP database by local clinical teams via a secure web interface. During our study period, the case ascertainment in the SSNAP, which is calculated as the proportion of all acute stroke patients admitted to hospitals, was estimated to be 90% for England. 52

Primary outcomes: health outcome measures

Health outcome measures were (1) whether or not the patient died within 3 days of admission to the hospital and (2) functional outcome, measured by a mRS53 score of 3–6 (moderate, moderately severe, severe disability or death) at the end of the inpatient spell. Mortality data in the SSNAP are not available after hospital discharge; therefore, we measured mortality up to 3 days after admission to minimise the number of missed deaths. LOS was measured in the HASU and total LOS in hospital.

Secondary outcomes: quality-of-care measures

Quality-of-care indicators were measured from time of hospital admission or onset of stroke symptoms (the latter used for those who were already in hospital when they had their stroke) (Box 1).

Brain imaging within 1 houra,b and within 12 hours. a,b

Admission to a stroke unit within 4 hours. b

Dysphagia screen within 4 hours. a,b

Assessment by a nurse trained in stroke management within 24 hours. a,b

Administration of intravenous thrombolysis to eligible patients. a,b

Door-to-needle time < 1 hour in patients receiving thrombolysis. a,b

Assessment by a stroke specialist consultant physician within 12 hours and within 24 hours. b

Assessments by a physiotherapist, occupational therapist and SLT within 24 hours and within 72 hours. b

SLT, speech and language therapist.

Measures directly related to stroke nursing care (although not a formal nursing role, dysphagia screening is normally undertaken by a trained nurse), brain scanning and thrombolysis.

Pre-existing quality indicators routinely reported by the SSNAP.

We also included measures with more stringent time constraints to reflect the time-critical nature of acute stroke care.

The denominators used for each measure were consistent with the SSNAP key indicators. 54 Most outcomes were measured for all patients, but there were exceptions: patients who were medically unwell or refused to be screened were excluded from the dysphagia screen measure; patients with only ischaemic stroke who met the Royal College of Physicians’ guideline minimum threshold for thrombolysis were included in the thrombolysis rate; door-to-needle times included only those patients who received thrombolysis; patients who were medically unwell, refused to be assessed or had no relevant deficit were excluded from the therapist measures.

To inform our cost analysis we also created alternative versions of some of these variables that were not time limited, that is whether or not the patient:

-

had brain imaging

-

was admitted to a stroke unit

-

had dysphagia screening

-

was assessed by a nurse trained in stroke management

-

was assessed by a stroke specialist consultant physician

-

was assessed by a physiotherapist, occupational therapist or speech and language therapist (SLT).

Independent variables

In-hours and out-of-hours measures

To examine variations across the week, we initially used a flexible specification of time of admission, measured in six 4-hour periods, 00.00 (midnight) to 03.59, 04.00 to 07.59, 08.00 to 11.59, 12.00 (noon) to 15.59, 16.00 to 19.59 and 20.00 to 23.59, every day of the week (42 periods). We also created a more restrictive measure to examine broad trends across the week: Monday to Friday 08.00 to 19.59, Monday to Friday 20.00 to 07.59, Saturday and Sunday 08.00 to 19.59, and Saturday and Sunday 20.00 to 07.59 (four periods). These specifications were also used by Bray et al. 22

Patient characteristics

In every model we controlled for sex, age (continuous variable), ethnic group (six categories), type of stroke (infarction or primary intracerebral haemorrhage), comorbidities prior to admission, mRS before stroke (0–2, 3–5), level of consciousness on arrival at the hospital (four categories), method of admission to the hospital (three categories), time from onset of stroke symptoms to admission (four categories), month of admission (12 categories) and stroke unit. When analysing mRS scores of 0–2 compared with scores of 3–5 at the end of the inpatient spell, we additionally controlled for the number of days after admission at which the mRS score was measured.

We also computed data from the SSNAP on the number of patients arriving at the hospital in each time period.

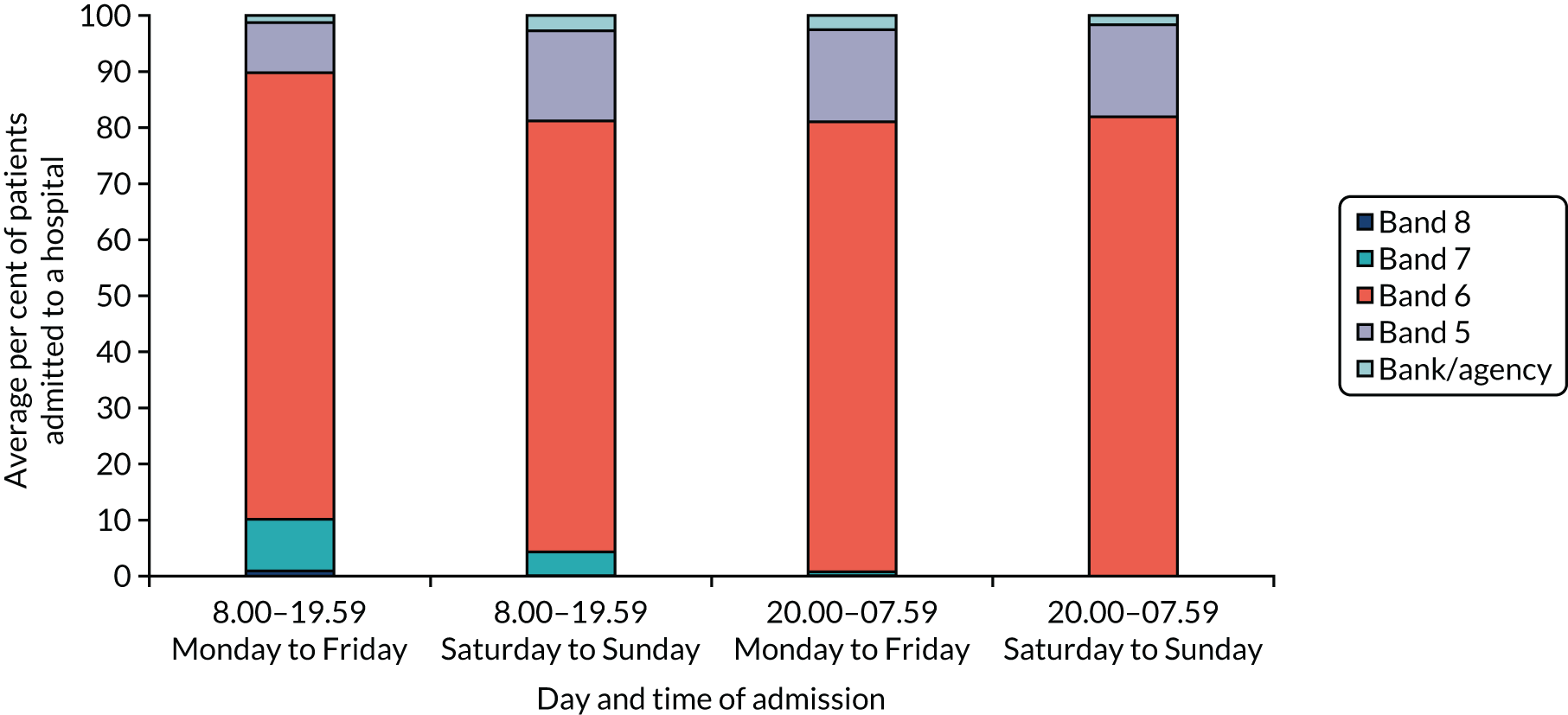

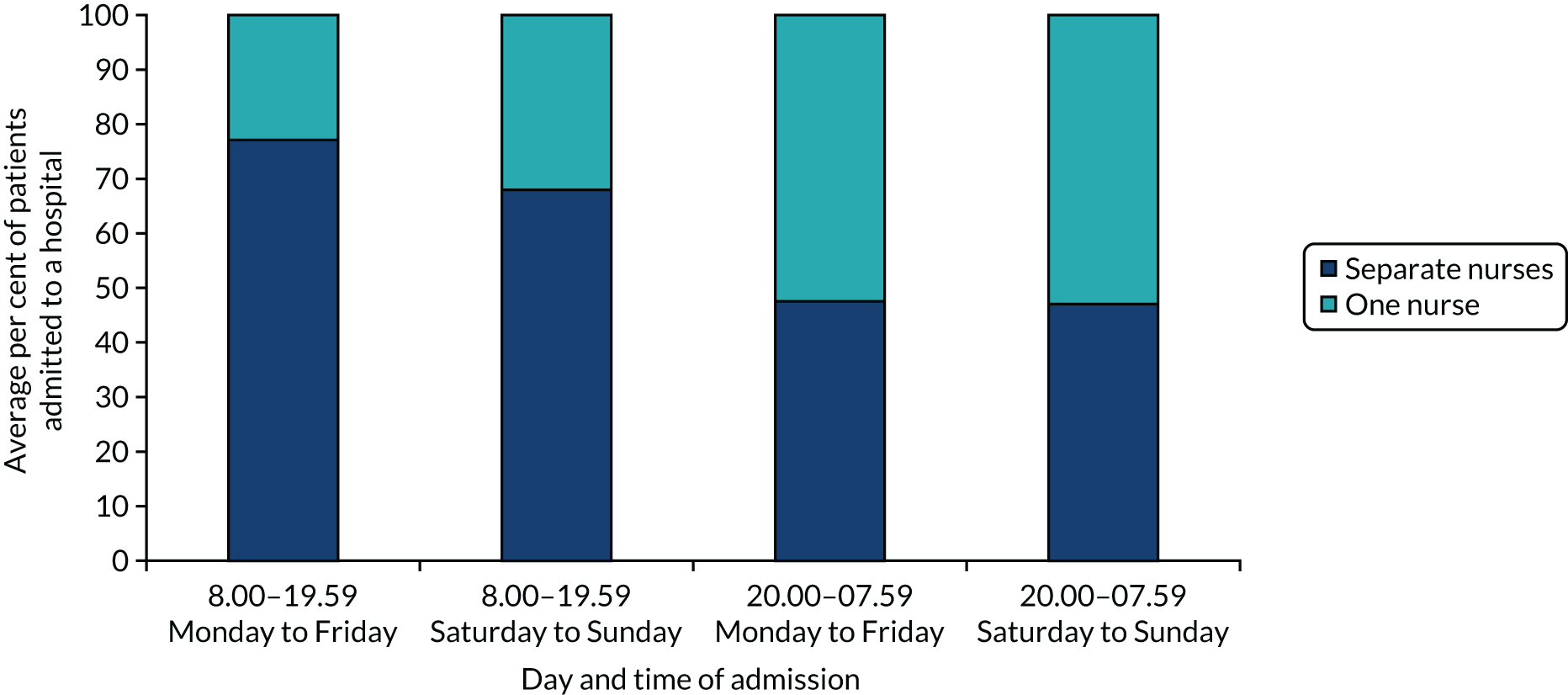

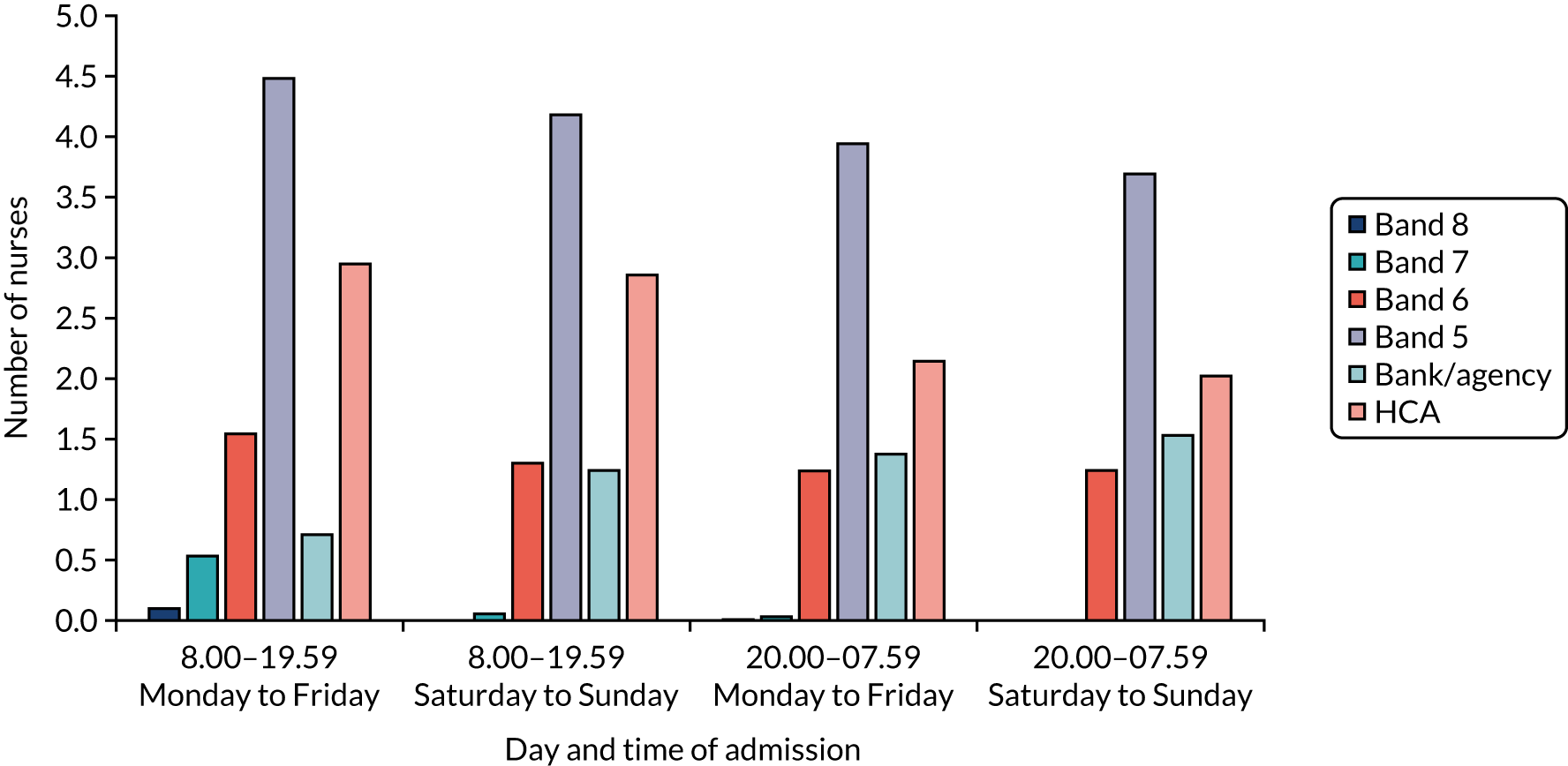

Nurse staffing data

Comprehensive data on nurse staffing were collected from nursing rotas from each of the London HASUs for every time of the day across the 12-month study period (between 1 January and 31 December 2014). Nurse staffing measures comprised the band of the nurse in charge [bands 5–8 and registered bank (or agency) nurse] and whether the nurse in charge was also responsible for administering intravenous thrombolysis or whether there was an additional nurse to perform this activity. We also collected data on the total number of specialised stroke nurse staffing on duty in the HASU by band (as above), the number of beds in each HASU and the times of the nursing shift handover period. These data were combined with the SSNAP data set based on the time of arrival at the hospital, so that for every patient who was admitted to a London HASU during the study period we also knew the characteristics of the nurse staffing at the time that they were admitted to the hospital. Note that we were unable to collect medical staffing data and so did account for this in our analyses (see Chapter 5).

Qualitative data collection

Sampling

Staff were sampled purposively to ensure coverage of a range of professional roles found in the HASUs (Table 2), including medical, nursing, therapy, administrative and managerial staff. Patients were also recruited purposively to reflect variations in sex, age, stroke type, discharge destination and carer perspectives (Table 3). The recruitment procedure was as follows: HASU staff provided researchers with a list of eligible patients in the HASU or stroke unit previously admitted to the HASU (see Recruitment and consent). Patients were introduced by clinical staff and given study information to consider. They were told that the interviewers were not members of current clinical staff and that their participation would not affect their care. Full and informed consent was obtained at the time of the interview. Interviews were conducted at participants’ homes, public places or clinical settings, according to their preference. The interviews were conducted between 6 and 99 days after admission to the HASU (average 38 days, median 33 days).

| Profession | HASU site ID (n) | Total (n) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | H2 | H3 | H4 | H5 | H6 | H7 | H8 | ||

| Lead consultant physician | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Consultant physiciana | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | |||||

| Registrar | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 8 | |

| Senior nurse/ward manager | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | |

| Senior house officer | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | |

| Occupational therapist | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Physiotherapist | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 10 |

| SLT | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Administrator/SSNAP | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||||

| Nurse | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Stroke co-ordinator/facilitator | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | ||

| HASU lead research nurse | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Total completed | 11 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 10 | 9 | 10 | 76 |

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Age in years, mean (range) | 66 (33–90) |

| Female, n/N (%) | 15/31 (48) |

| Interviewee, n/N (%) | |

| Patient and carer | 10/31 (32) |

| Patient alone | 19/31 (62) |

| Carer alone | 2/31 (6) |

| Stroke type, n/N (%) | |

| Ischaemic | 19/31 (61) |

| Haemorrhagic | 2/31 (6) |

| Stroke type not recorded | 10/31 (33) |

| Transfer destination on repatriation from HASU, n/N (%) | |

| Home | 15/31 (48) |

| Stroke unit | 10/31 (32) |

| Rehabilitation unit | 4/31 (12) |

| Died in hospital | 1/31 (3) |

| Discharge unclear | 1/31 (3) |

| Underwent thrombolysis, n/N (%) | 7/31 (23) |

Recruitment and consent

To analyse the organisation of all eight London HASUs during the day and during the night, on weekdays and at weekends, authors GB, ABL, JE and PX conducted 76 interviews with HASU staff and 31 interviews with stroke patients and carers, and undertook 41 non-participant observations of HASU activity over approximately 85 hours. JE also gathered data through informal discussion on staff numbers and seniority on the ward, the composition of staff attending suspected stroke calls in the emergency room and the availability of scans across the week from each site. All interviewers were female and employed as research staff on the project. GB, ABL and PX are postdoctoral researchers with significant interviewing experience and no prior experience of working in stroke. JE was a stroke co-ordinator in a HASU prior to joining the project, with an occupational therapy background. She received research interview and analysis training and feedback from the rest of the team. Qualitative work was overseen by NJF and AIGR, who are experienced in both qualitative research and the London stroke system through previous work.

Patients were approached if they had a provisional or tentative stroke diagnosis and experience of receiving care in the HASU. We excluded patients and carers unable to sufficiently understand spoken or written English, and those who were unable to give informed consent by written or oral methods. Carers were interviewed alone or alongside patients, if patients requested it, and when the patient suffered from severe cognitive impairment or speech difficulty as well as when a patient had died during, or after, admission to a HASU.

The staff interviews were conducted according to a semistructured topic guide. The guide comprised questions about a typical day (see Report Supplementary Material 1), the perceived differences in and attitudes towards working in and out of hours, team working and the HASU environment. The patient interviews followed a broadly biographical topic guide, asking about their journey up to, during and after their HASU stay. We also prompted them to reflect on their experiences in and out of hours. All participants were interviewed only once and interviews were recorded digitally.

Observations

Global written consent for observations was gained initially from service leads and from a selection of staff at team meetings. Thereafter, verbal consent was given by staff members for researchers to make observations of staff meetings and of the stroke care pathway.

Non-participant observations were conducted at least four times at each HASU site, two visits on weekdays, one in the evening during the week and one at the weekend, with some extra visits to certain HASUs to confirm or add to our findings. We aimed to collect information about two dimensions of HASU service organisation and delivery, how (1) a patient progresses through the stroke pathway, assessment in the ED, care on the HASU and HASU repatriation; and (2) HASU staff organise themselves to meet the London specifications in day-to-day delivery operations [e.g. thrombolysis for at least 90% of eligible patients, timely brain scans, direct admission to HASU within 4 hours, daily multidisciplinary team (MDT) meetings]. This research design drew on ongoing research to identify likely service elements and factors influencing the design and implementation of HASU care (Table 4).

| HASU site ID | Ward round | MDT meeting | Admission/thrombolysis | 16.00 catch up | Nurse handover | Bed meeting | Discharge |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | n/a | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ |

| H2 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| H3 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| H4 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | n/a | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| H5 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | n/a | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ |

| H6 | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | n/a | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ |

| H7 | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ |

| H8 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Total | 6/8 | 7/8 | 7/8 | 3/8 | 8/8 | 6/8 | 4/8 |

Modes of analysis

Quantitative analysis

We investigated variations in quality of acute stroke care and outcomes by day and time of admission in London HASUs and evaluated whether or not nurse staffing affected 24/7 access to high-quality acute stroke care in eight London HASUs. For the former, we ran patient-level regressions, regressing each measure against time period of admission. To inform our cost analysis we also tabulated the non-time-dependent measures described above against time period of admission. For the latter, we also included nurse staffing measures in models for London HASUs. In every model we controlled for baseline patient characteristics (sex, age and ethnic group) and case mix (type of stroke, comorbidities prior to admission, mRS before stroke, level of consciousness on arrival at the hospital, method of admission to the hospital, time from onset of stroke symptoms to admission and month of admission). We tested for statistically significant variations using Wald tests and likelihood ratio tests.

Qualitative analysis

The investigation was driven by understanding how London HASUs organise and deliver 24/7 stroke care in practice, how these service patterns have been influenced by workforce and organisational factors, and how stakeholders, including staff, patients and carers, experience these services.

The qualitative analysis drew together interview and observation data using a composite, thematic analysis across HASUs, as well as a comparative case study approach. The thematic approach55 allowed for developing an understanding of the central issues HASUs, as a particular type of service delivery model, face when delivering care in acute trust settings across 24/7 time scales. The comparative case study approach46–48 illuminated similarities and differences between HASUs and across professional groupings.

We used an iterative approach to analysis, following a five-step process to generate thematic and case study insights.

Step 1: data familiarisation

Data were compressed into workable, standardised forms (i.e. transcription formatting) using several initial mapping methods, allowing team members to become familiar with the types of data being collected (e.g. producing tables showing distribution of participants, making lists of information gathered through observations, key components of the service). These were adapted and refined as we became more familiar with the data. Simultaneously, we filled some of the gaps through ongoing data collection.

Step 2: initial framework coding guided by protocol

Three large groupings based on the central objectives of the study were developed as a way to initially sift through data focused by the protocol questions. A handful of patient, carer and staff transcripts were read by each of the four researcher team members (approximately five per researcher), with the groupings then applied and relevant data extracted.

Step 3: initial coding and framework development

The qualitative team met and discussed central issues emerging under the three-capture category rubric. Together, we developed a preliminary framework of codes reflecting central ideas, grouped into seven categories. Each category was defined along with the assigned codes. Codes then guided the extraction of relevant pieces of data in the interviews and observations. Code extracts were sorted by HASU to begin to identify differences by HASU and professional grouping.

Step 4: refining codes and coding framework

The research team met regularly to discuss extracts and codes to both refine and deepen our understanding of ideas emerging from the data. Some ideas led to new or redefined codes and the collapsing of multiple similar codes into one code. It also began the process of prioritising the most important of the codes, getting to the heart of the study’s driving research questions.

The team regularly met with the overall team (principal investigator, advisors and quantitative team) to feed back learning and solicit insights to further develop analytical threads.

Step 5: ‘headlines’ and written memos

The research team moved from the refined codes in iterative fashion to linking them into arguments, combining pieces of evidence to generate convincing answers to the driving research questions. In this process, we elaborated on the comparative case studies by professional groups and HASUs.

Synthesis of approaches

We used our monthly project meetings to bring together observations, queries and suggestions between the qualitative and the quantitative researchers. Interactions centred on key ideas such as:

-

Can we explain why certain variables do and do not show temporal variation?

-

What are the best ways to capture temporal variation?

-

What factors would we expect to influence temporal variation?

-

What further data can we gather or analyse to expand our findings?

Patient and public involvement

Two stroke patient representatives contributed to development of our study protocol and research questions. Over the course of the study patient representatives participated in three Study Steering Committee meetings (in June 2014, June 2015 and July 2016), in which they participated in discussions of interim findings and ongoing development of the study. Lay summaries of our work were produced for each meeting and representatives were offered individual meetings to discuss matters alone before the main Study Steering Committee meeting. Our patient representatives raised issues related to staff handover and confirmed the importance of the interface between hospital and social services, which we incorporated into our analysis.

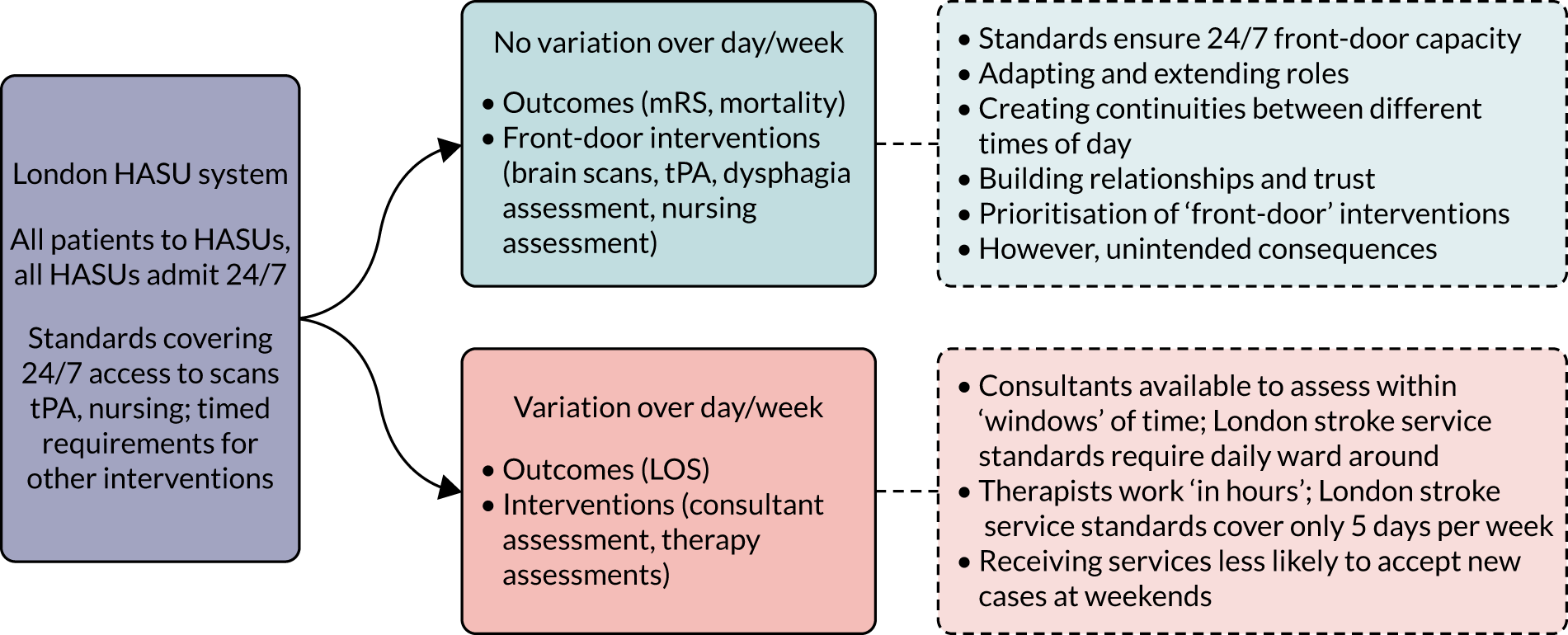

Chapter 3 Variation in quality of acute stroke care by day and time of admission: prospective cohort study of weekday and weekend centralised hyperacute stroke unit care

What is known about this topic?

-

There is conflicting evidence whether patients admitted at weekends have higher or lower quality of acute stroke care and better or worse outcomes than those admitted at other times of the week.

-

Recent analyses have shown that analyses of weekend compared with weekday effects or in-hours effects compared with out-of-hours effects may be flawed, as they do not account for variations by day of the week and time of day.

-

The centralisation of acute stroke services in London was associated, on average, with higher likelihood of providing evidence-based care and greater reductions in mortality.

What this analysis adds

-

London HASUs operate a uniform service across the week, with respect to rapid access to stroke nurse review, brain scans and administration of thrombolysis to eligible patients.

-

Three-day mortality and disability at hospital discharge do not vary by day and time of admission in London HASUs.

-

Other aspects of care are not constant across the week in London HASUs.

-

Costs of acute stroke care in London HASUs are higher for patients admitted at the weekend than for those admitted during the week.

Introduction

There is conflicting evidence whether or not patients presenting with acute stroke symptoms receive lower quality of care and have worse outcomes if admitted to hospital outside normal weekday working hours or at weekends (the so-called ‘weekend effect’). Some studies have shown that acute stroke patients admitted at weekends have lower quality of care and higher mortality,56 whereas others have shown the opposite,10,12,13,57 although there is little evidence in the context of acute stroke care. Evaluation of these studies is further complicated by recent evidence that stroke incidence reporting at the weekend may be unreliable in older studies,58 although this is based on data on patients admitted to a single hospital trust. Recent work based on data from the SSNAP data set further found that care quality and outcomes in acute stroke vary across the week, and concluded that binary comparisons of weekend and weekday, or of in-hours and out-of-hours, processes and effects oversimplify more likely variations by day of week and time of day. 22 Furthermore, no studies have investigated the impact of time of admission on disability following a stroke.

If there is lower quality of care and there are worse outcomes at the weekend, then these could be linked to reduced staffing levels. 59 Nurse staffing levels at weekends have been shown to be a significant predictor of mortality from acute stroke,60 whereas evidence from the USA suggests that specialised stroke units, with round-the-clock availability of specialist stroke teams and rapid access to imaging and thrombolysis, reduce variation in quality of care and outcomes across the week. 61–63 Following these findings, the aim of this study was to investigate variations in the quality of acute stroke care and outcomes by day and time of admission in London HASUs (objectives 1 and 2). We used national audit data for all patients in London HASUs who had a stroke during a 12-month period recorded by the SSNAP. 64 We hypothesised where there would be non-significant variation across the week in care quality measures in London HASUs and that this would also translate into non-significant variation in outcomes.

Methods

This section is based on a paper by Melnychuk et al. 65 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Data and measures

As outlined in Chapter 2, Quantitative data collection, we used anonymised patient-level data from the SSNAP for all patients in London HASUs with a primary diagnosis of stroke between 1 January and 31 December 2014.

Statistical analysis

We ran patient-level logistic regressions by regressing each measure against the time period of admission. For LOS, we used parametric survival models (modelled as time to event of discharge), assuming a log-normal survival distribution. In every model we controlled for baseline patient and case mix characteristics, month of admission (12 categories) and hospital trust. When analysing mRS scores 0–2 compared with 3–5 at the end of the inpatient spell, we additionally controlled for the number of days after admission the mRS score was measured. We were unable to do this for the analysis of mRS score 0–2 compared with 3–6, as date of death was not available. We tested for statistically significant variations across the week using Wald tests and reported the results as joint p-values under the null hypothesis that the regression coefficients for every time period relative to the omitted time period were zero. We calculated the average predicted probability of each outcome (predicted median LOS in the case of the LOS variables) in each time period controlling for the covariates. Patients admitted with a diagnosis of acute stroke in London who were not treated in a HASU were excluded (6% of all London patients in our data set were not treated in a HASU). p-values < 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. Data on National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score, a validated measure of stroke severity on a scale from 0 (no stroke symptoms) to 42 (severe stroke), were available for 93% of patients in London HASUs. Owing to the extent of missing NIHSS data, in our main analysis we controlled for stroke severity using level of consciousness on arrival at the hospital (one component of NIHSS, which was available for all patients in London HASUs). We then re-ran all analyses controlling for NIHSS on arrival at the hospital on the smaller sample, instead of level of consciousness on arrival. The findings using NIHSS score on arrival were qualitatively the same and are presented in the Report Supplementary Material 2, Figures S1–6.

Cost analysis

To investigate the costs of acute stroke care in London HASUs on different days and at different times of admission, we explored whether or not mean costs per patient in the HASU varied by time period of admission. Our cost perspective was the HASU. We examined costs associated with variations in LOS in the HASU. In a secondary analysis, we also included total LOS in the hospital. We re-ran the LOS models, described above, using ordinary least squares and computed adjusted mean HASU and total LOS by time period of admission (although mean costs are affected by skewness and median costs are not, it is the arithmetic mean costs that are most informative for health-care policy decision). 66 We also examined costs associated with variations in the non-time-dependent quality-of-care measures described in Chapter 2 (see Box 1) for patients in London HASUs (whether or not the patient had brain imaging; was admitted to a stroke unit; had dysphagia screening; was assessed by a nurse trained in stroke management, or a stroke specialist consultant physician, physiotherapist, occupational therapist or a SLT). Note that the reason for focusing on the non-time-limited measures was that costs are driven by whether or not the patient received these processes, rather than whether or not they received them within a given time period. We also included receipt of thrombolysis (administration of intravenous thrombolysis to eligible patients). As it was simpler to identify trends, we focused on variations between the four broad time periods across the week (Monday to Friday, 08.00 to 19.59; Monday to Friday, 20.00 to 07.59; Saturday and Sunday, 08.00 to 19.59; and Saturday and Sunday, 20.00 to 07.59). Measures for which there were variations by time period of admission were included in the cost analysis. In this case, we multiplied the incremental volume of resource use associated with each measure for the three other time periods compared with Monday to Friday 08.00 to 19.59 by its unit cost, taken from two published economic evaluations of acute stroke care in London HASUs67,68 and inflated to 2017/18 prices. 69 We assumed that unit costs of the non-time-dependent measures did not vary by the time period of admission, because these are typically provided during normal working hours (see Chapter 6, What this analysis adds).

Results

This section is based on a paper by Melnychuk et al. 65 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

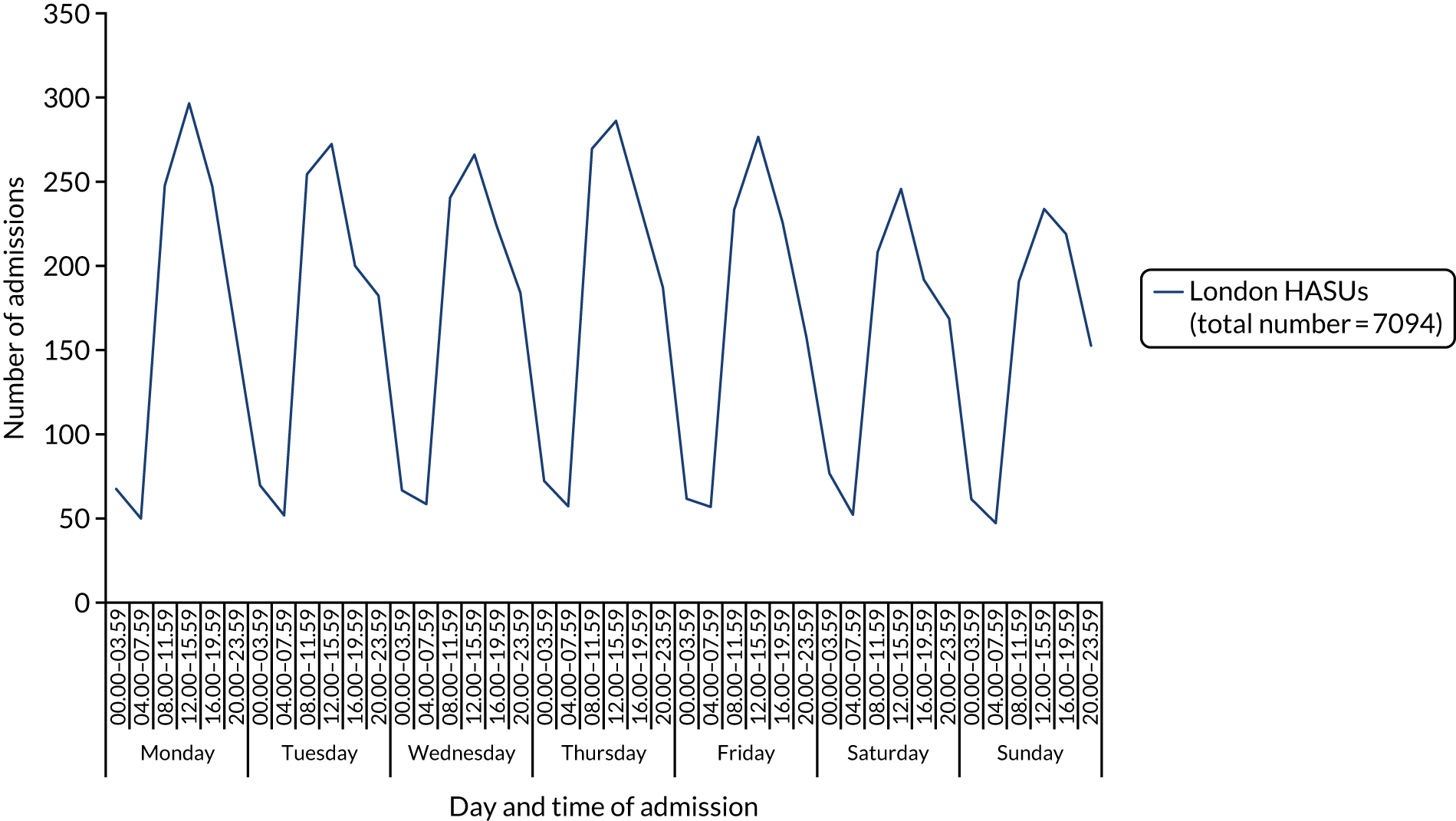

The study cohort comprised 7094 patients from eight London HASUs. The number of admissions varied across the week: admissions peaked during the day then fell at night; there were more admissions during the day through the week than during the day at the weekend; there were similar numbers of admissions during the night each day; and the highest number of admissions was during the day on Monday (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Number of admissions in London HASUs across the 42 time periods in the week. This figure is adapted from Melnychuk et al. 65 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. This figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original figure.

The mean number of admissions per HASU per week in each of the 42 4-hour time periods ranged from 1.03 to 1.44. There was slightly higher proportion of men than women, the mean age was 72 years and 38% of patients were non-white (Table 5). London HASUs case mix was characterised by a large proportion of people with congestive heart failure, hypertension and diabetes. Twenty-two per cent of patients had at least moderate disability according to their mRS score before stroke and 84% of patients arrived at the hospital in an ambulance. Thirty-nine per cent of patients were admitted to the hospital within 3 hours from onset of stroke symptoms, but for 29% of patients the time of symptom onset was unknown.

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Male | 3719 (52) |

| Female | 3375 (48) |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 72 (15) |

| Ethnic group, n (%) | |

| White | 4332 (61) |

| Mixed | 72 (1) |

| Black | 650 (9) |

| Asian | 505 (7) |

| Other | 526 (7) |

| Not available | 1009 (14) |

| Type of stroke, n (%) | |

| Infarction | 6252 (88) |

| Primary intracerebral haemorrhage | 842 (12) |

| Comorbidities prior to admission, n (%) | |

| Congestive heart failure | 439 (6) |

| Hypertension | 4284 (60) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 1229 (17) |

| Diabetes | 1705 (24) |

| Stroke/TIA | 1688 (24) |

| mRS score before stroke, n (%) | |

| Slight or no disability (0–2) | 5552 (78) |

| At least moderate disability (3–5) | 1542 (22) |

| Level of consciousness on arrival at the hospital, n (%)a | |

| Alert | 5991 (84) |

| Not alert, but respond to minor stimulation | 663 (9) |

| Not alert, requires repeated stimulation | 281 (4) |

| Unresponsive | 159 (2) |

| NIHSS score on arrival at the hospital, median (IQR) | 5 (2–11) |

| Method of admission to the hospital, n (%) | |

| Already inpatient | 173 (2) |

| Ambulance | 5966 (84) |

| Walk-in | 955 (14) |

| Time (minutes) from onset of stroke symptoms to admission, n (%) | |

| < 180 | 2741 (39) |

| 180–359 | 759 (11) |

| ≥ 360 | 1516 (21) |

| Time of onset not known | 2078 (29) |

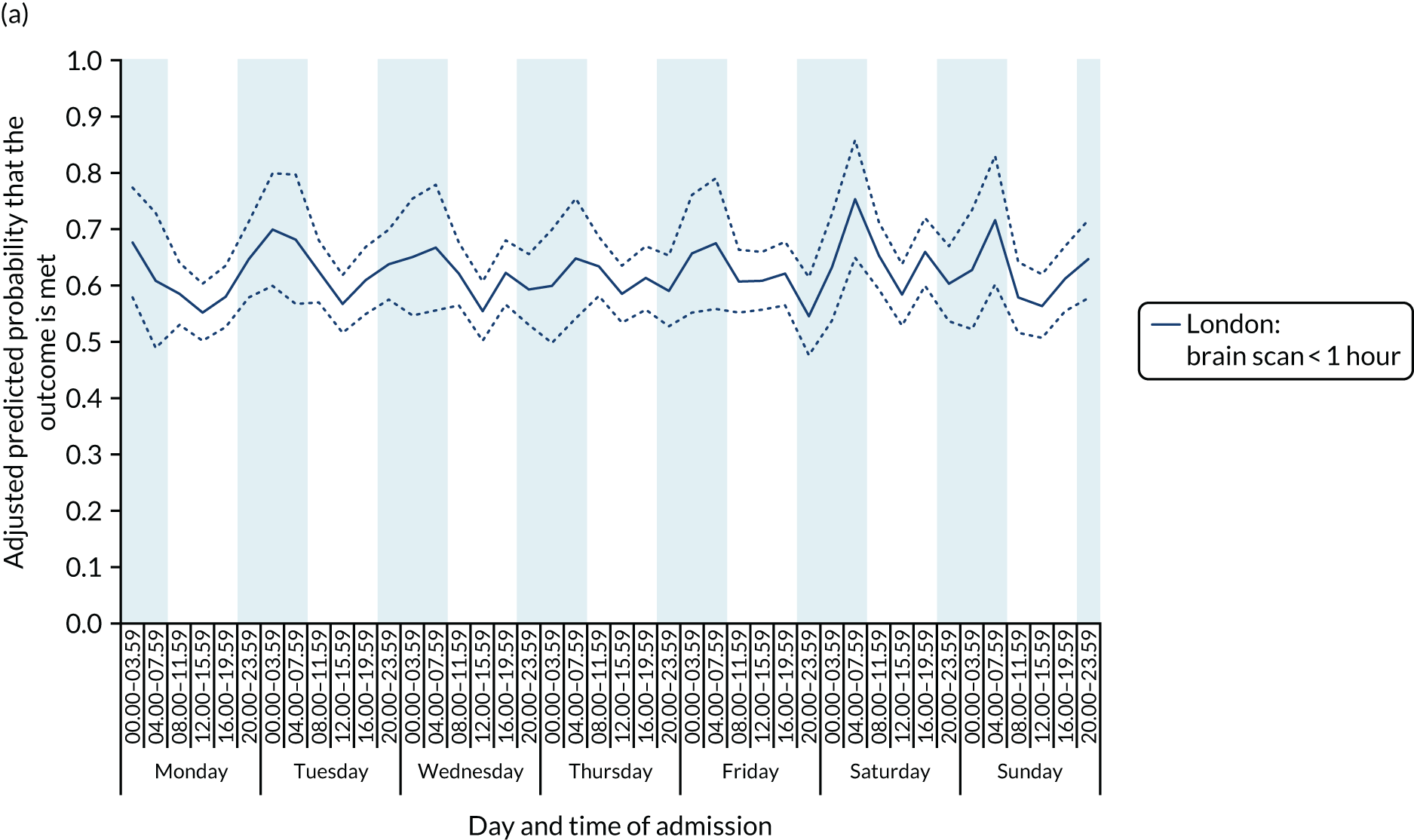

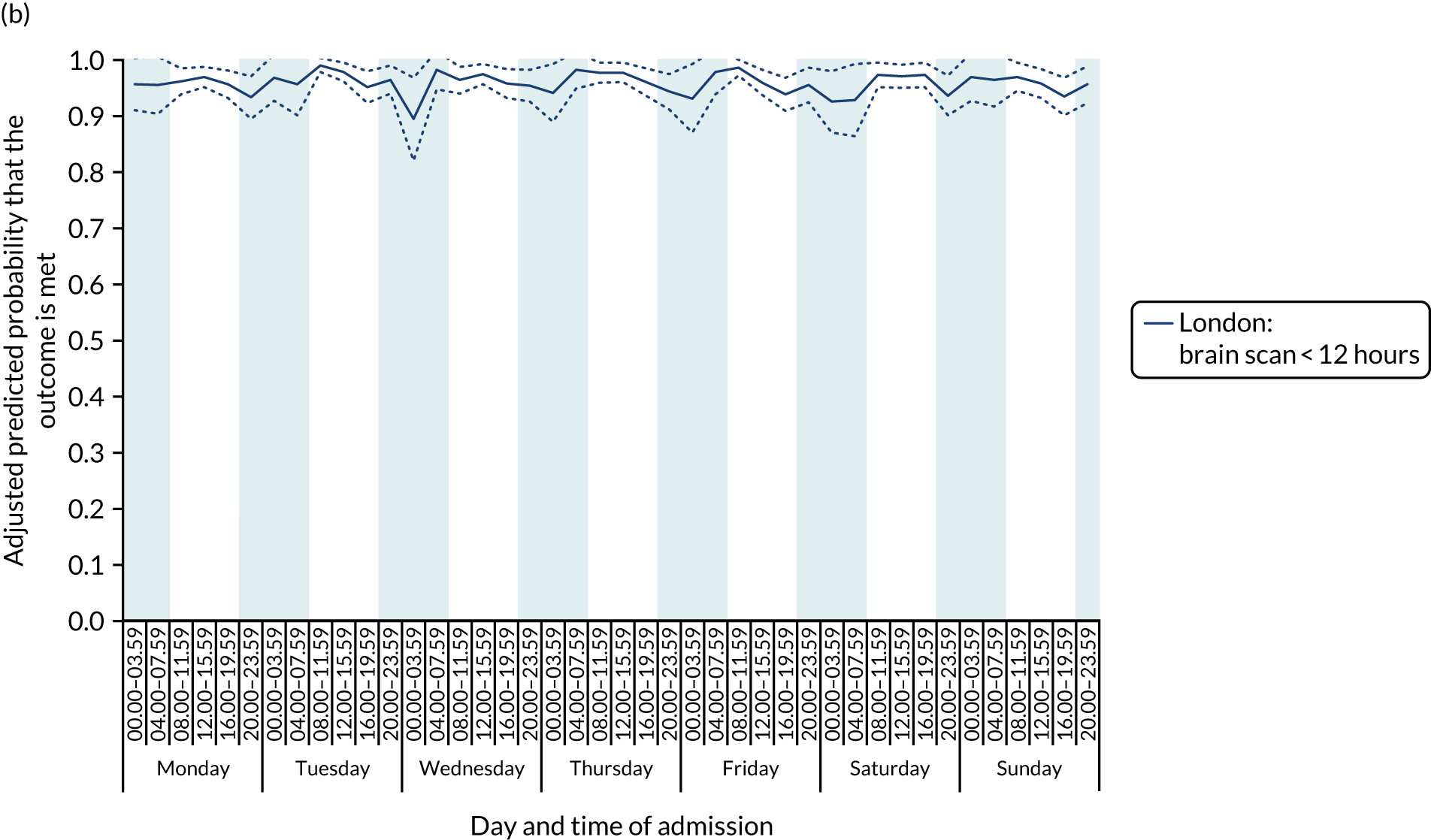

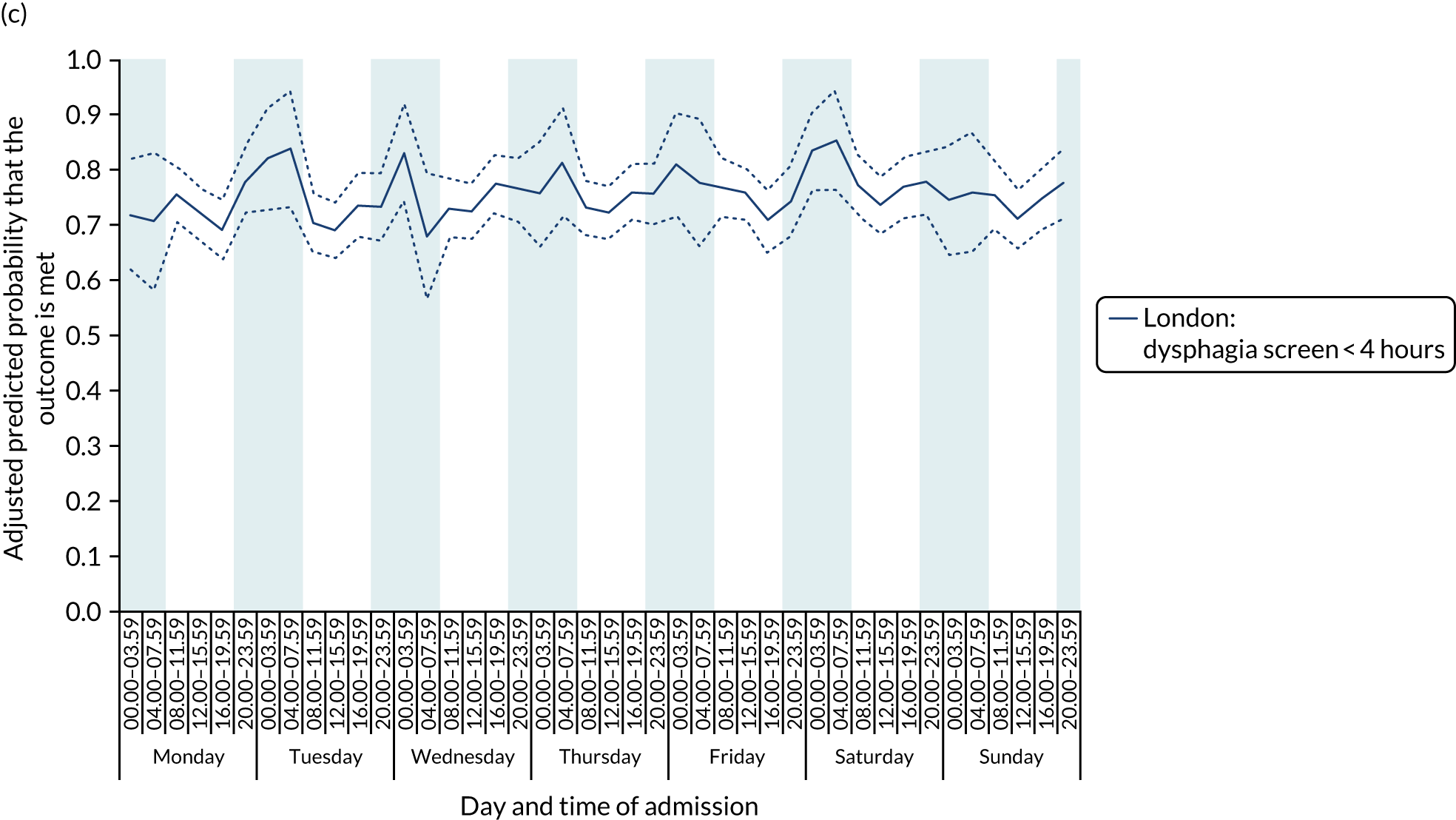

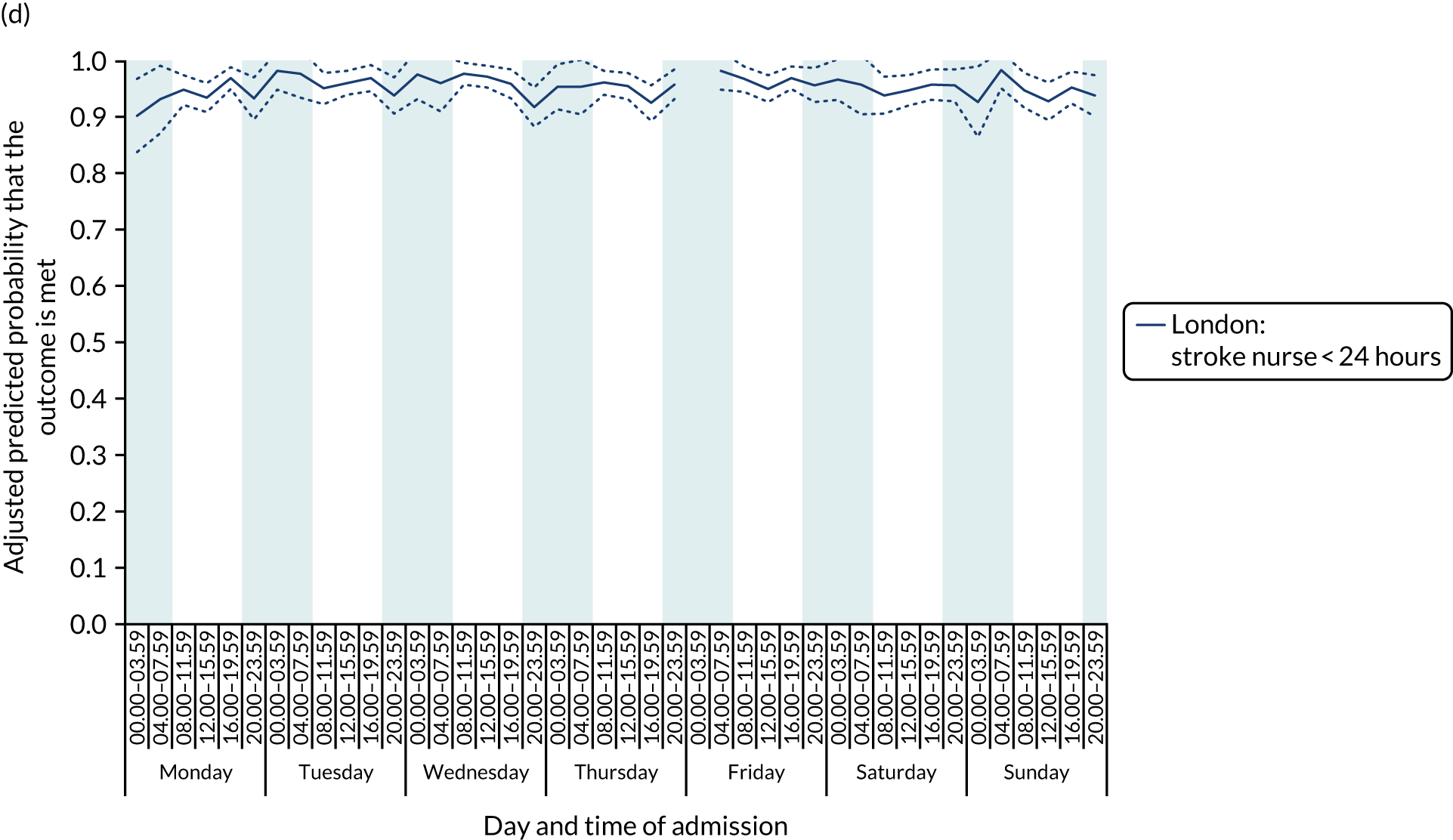

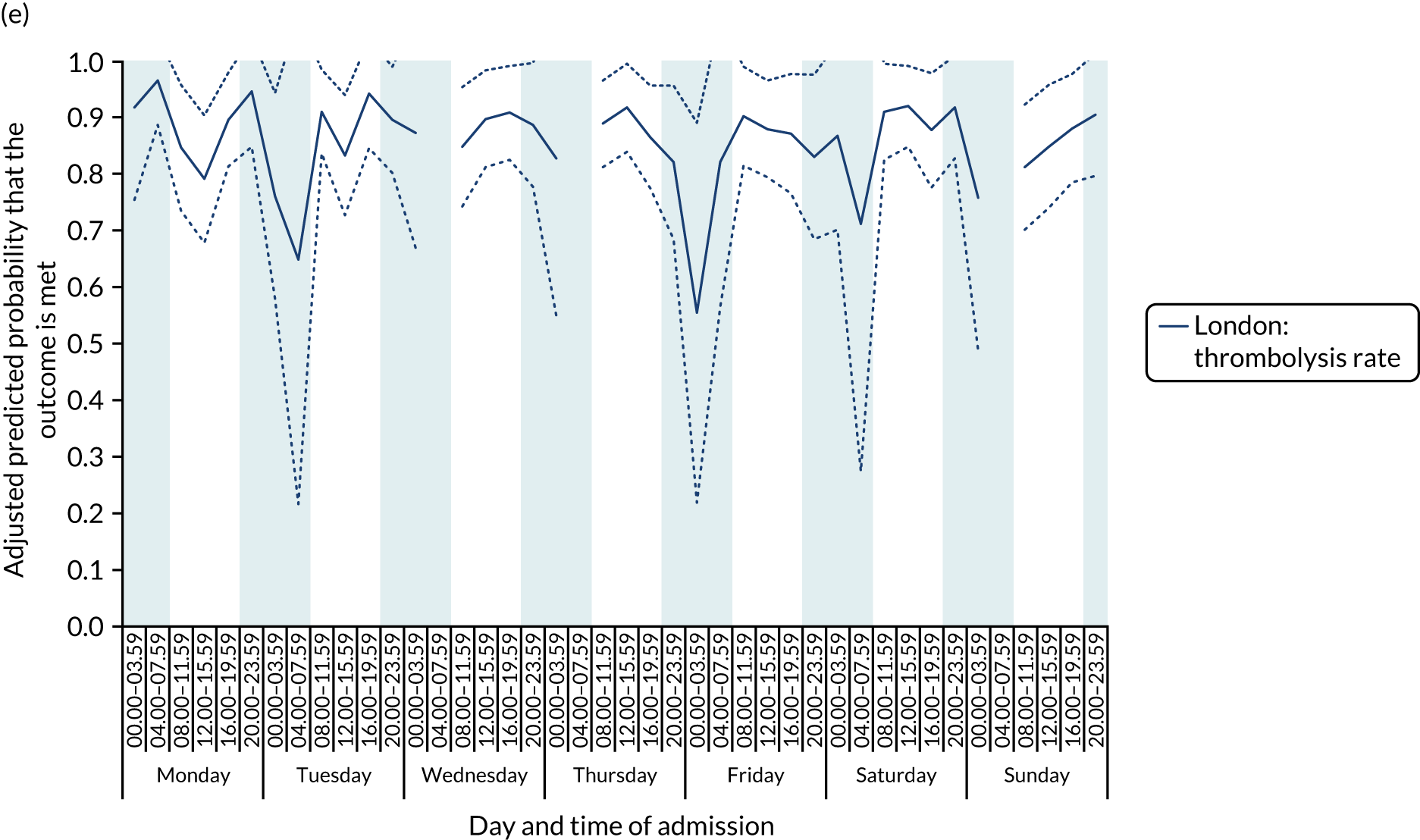

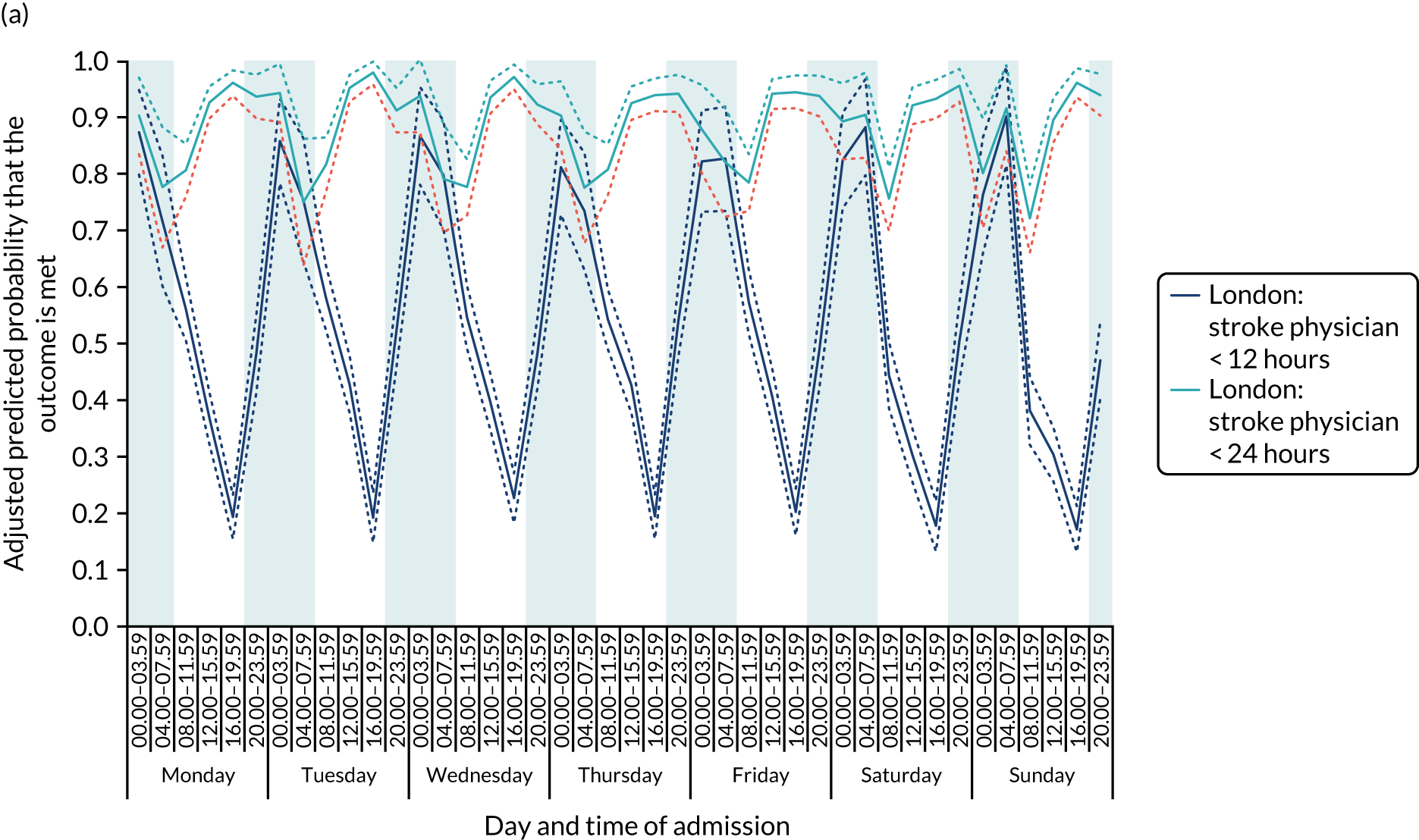

There was no significant variation in care quality across the 42 time periods in any of the measures relating to brain scanning, stroke nursing care and thrombolysis in London HASUs (all p-values > 0.05) (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

Quality of care across the 42 time periods in the week: measures linked to performance standards for London HASUs. (a) Brain scan within 1 hour (p = 0.1372); (b) brain scan within 12 hours (p = 0.1757); (c) dysphagia screen within 4 hours (p = 0.2217); (d) nurse assessment within 24 hours (p = 0.3318); (e) administration of intravenous thrombolysis to eligible patients (p = 0.9233); and (f) door-to-needle time < 1 hour (p = 0.5400). This figure is adapted from Melnychuk et al. 65 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. This figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original figure.

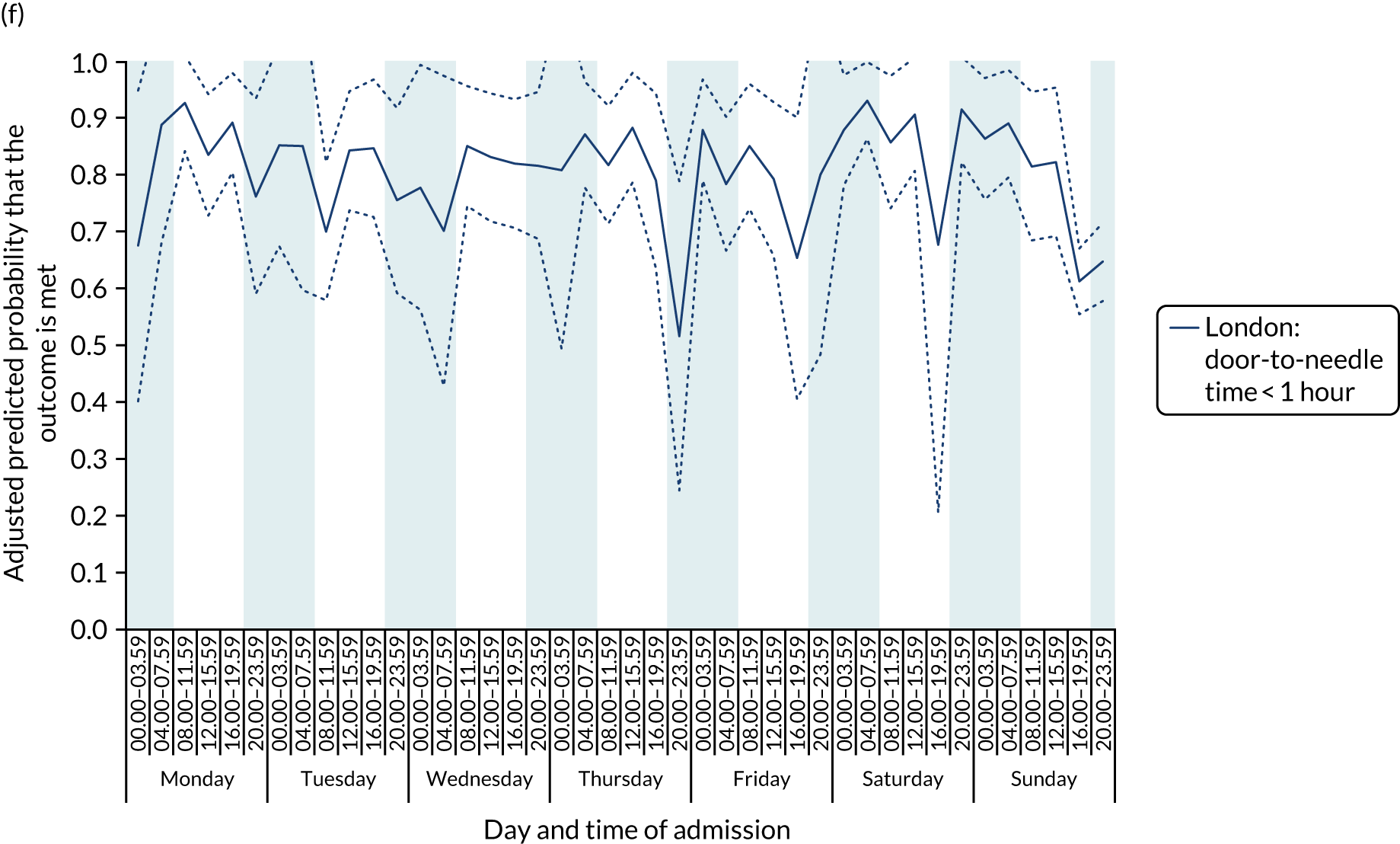

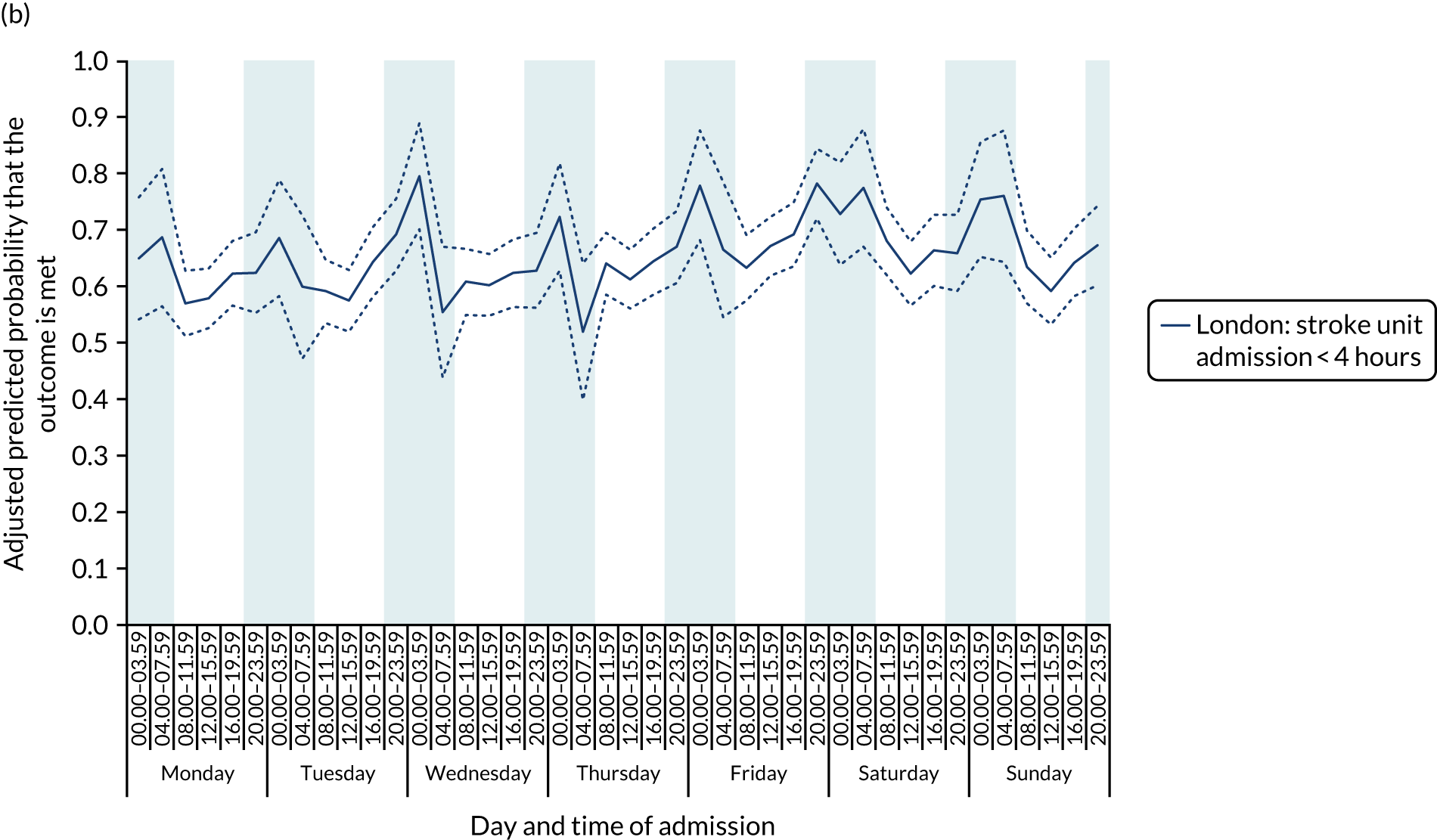

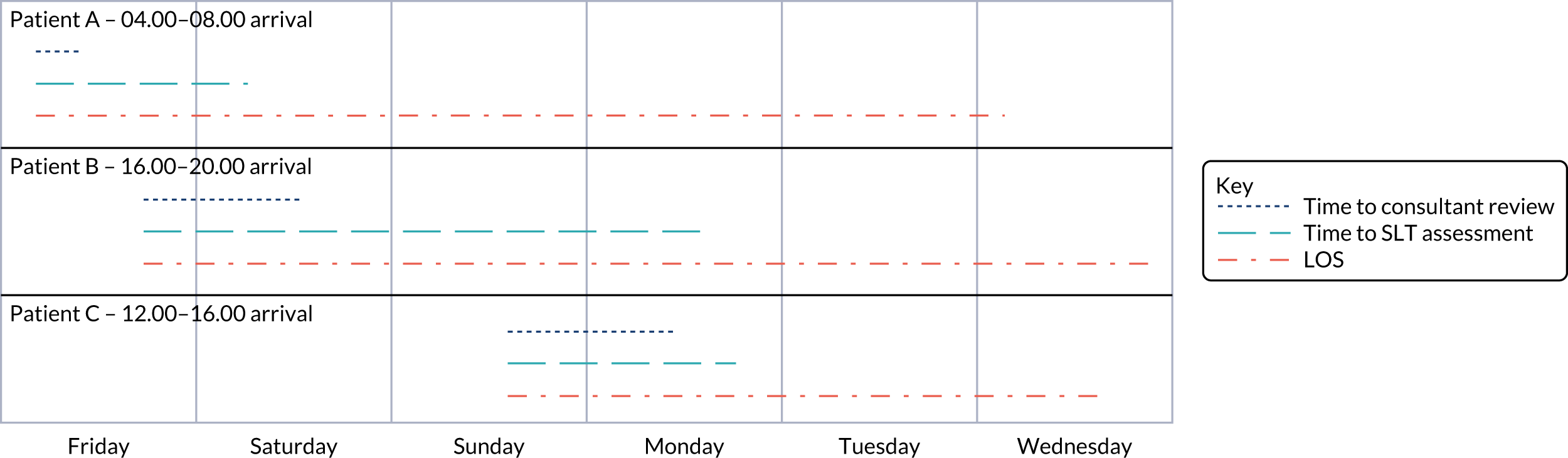

For all the other quality-of care-measures, there was significant variation by time period of admission across the week (all p-values < 0.01). There were three patterns of variation. First, variation by time of day but not day of the week was observed for assessment by a stroke specialist consultant physician within 12 hours and within 24 hours in London HASUs, and admission to a stroke unit within 4 hours (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5.

Quality of care across the 42 time periods in the week in London HASUs: variation by time of day but not day of the week. (a) Assessment by a stroke consultant (stroke physician < 12 hours, p < 0.0001; stroke physician < 24 hours, p = 0.01); and (b) admission to a stroke unit within 4 hours (stroke unit admission < 4 hours, p < 0.0001). This figure is adapted from Melnychuk et al. 65 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. This figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original figure.

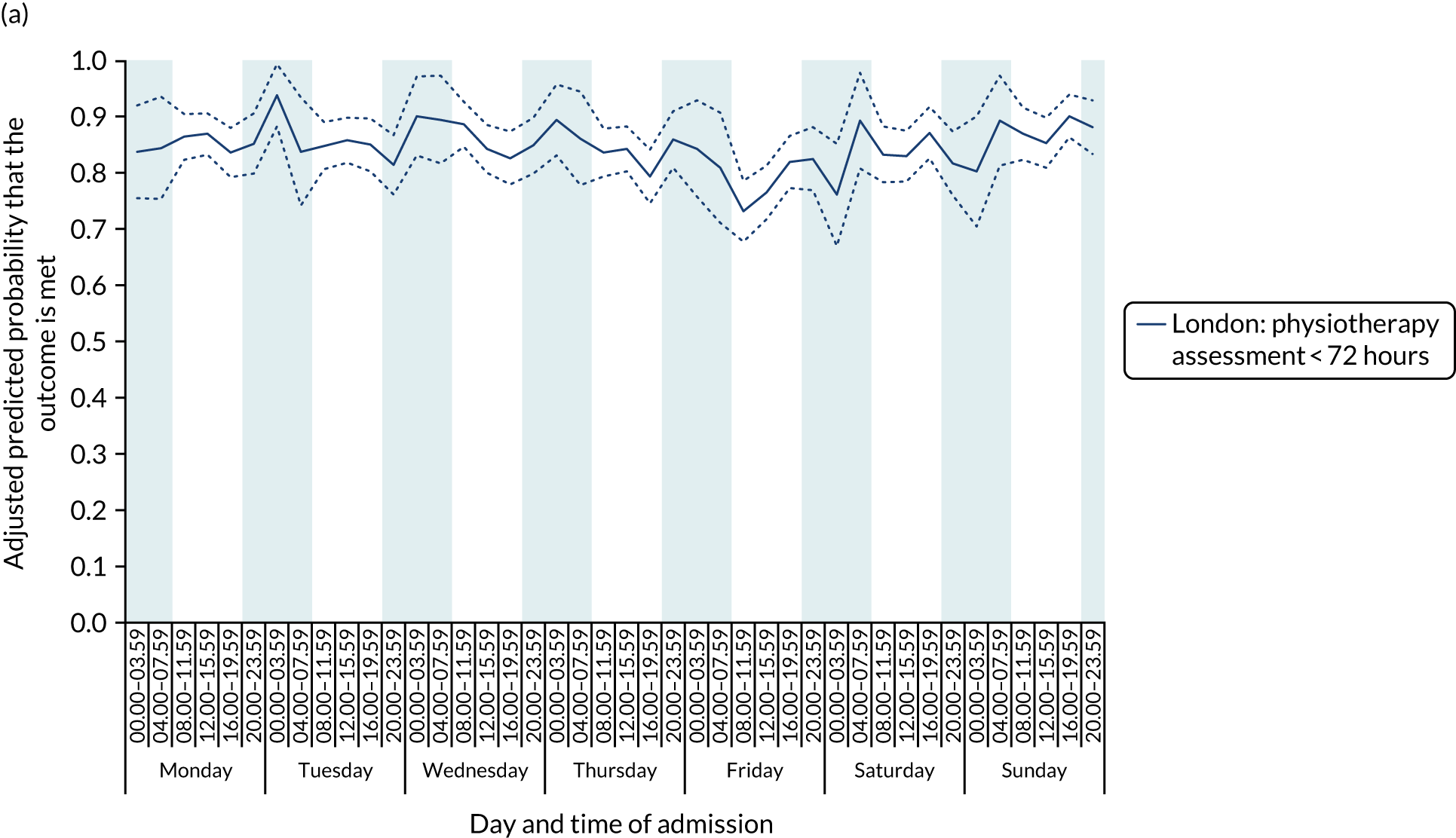

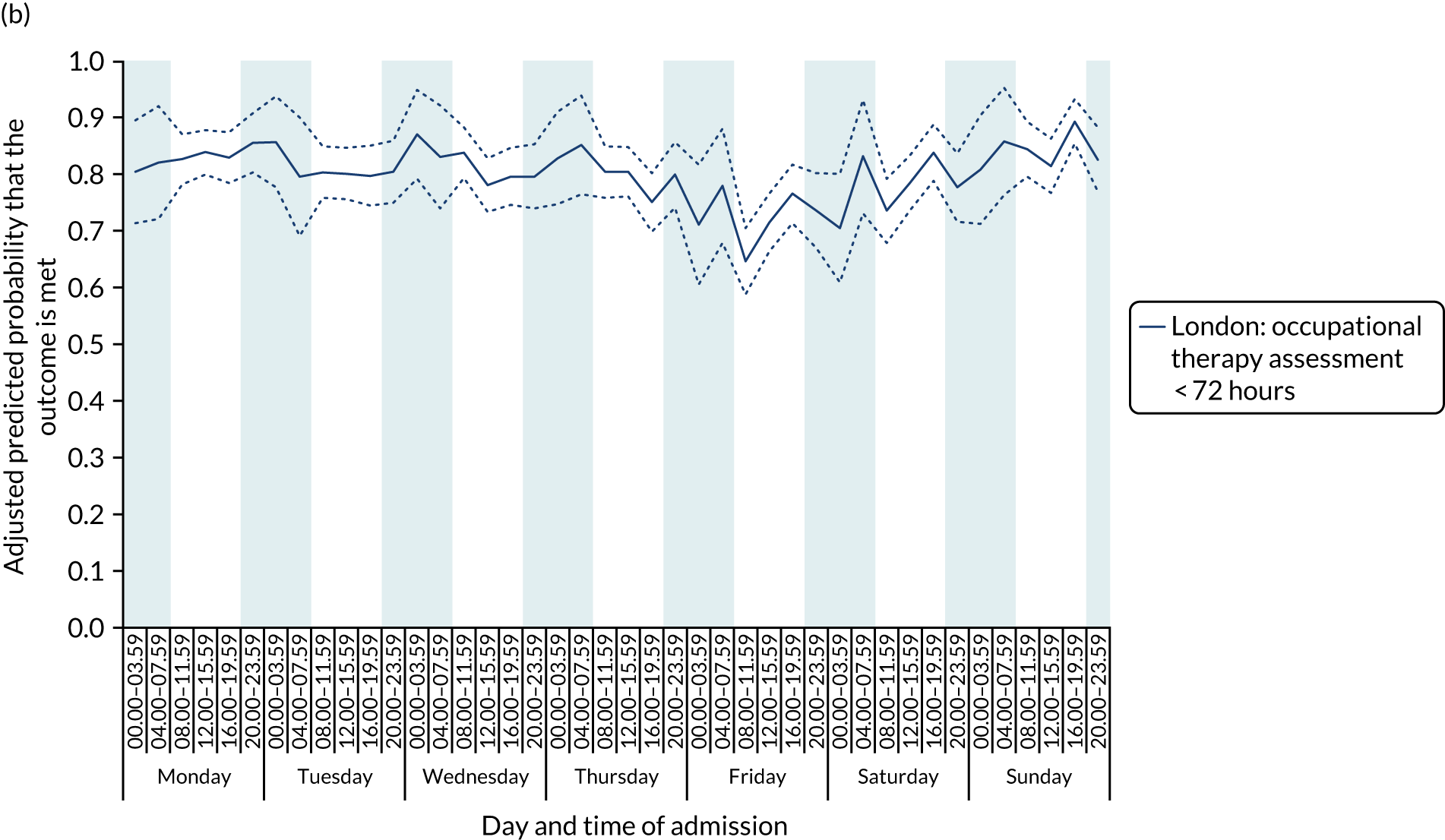

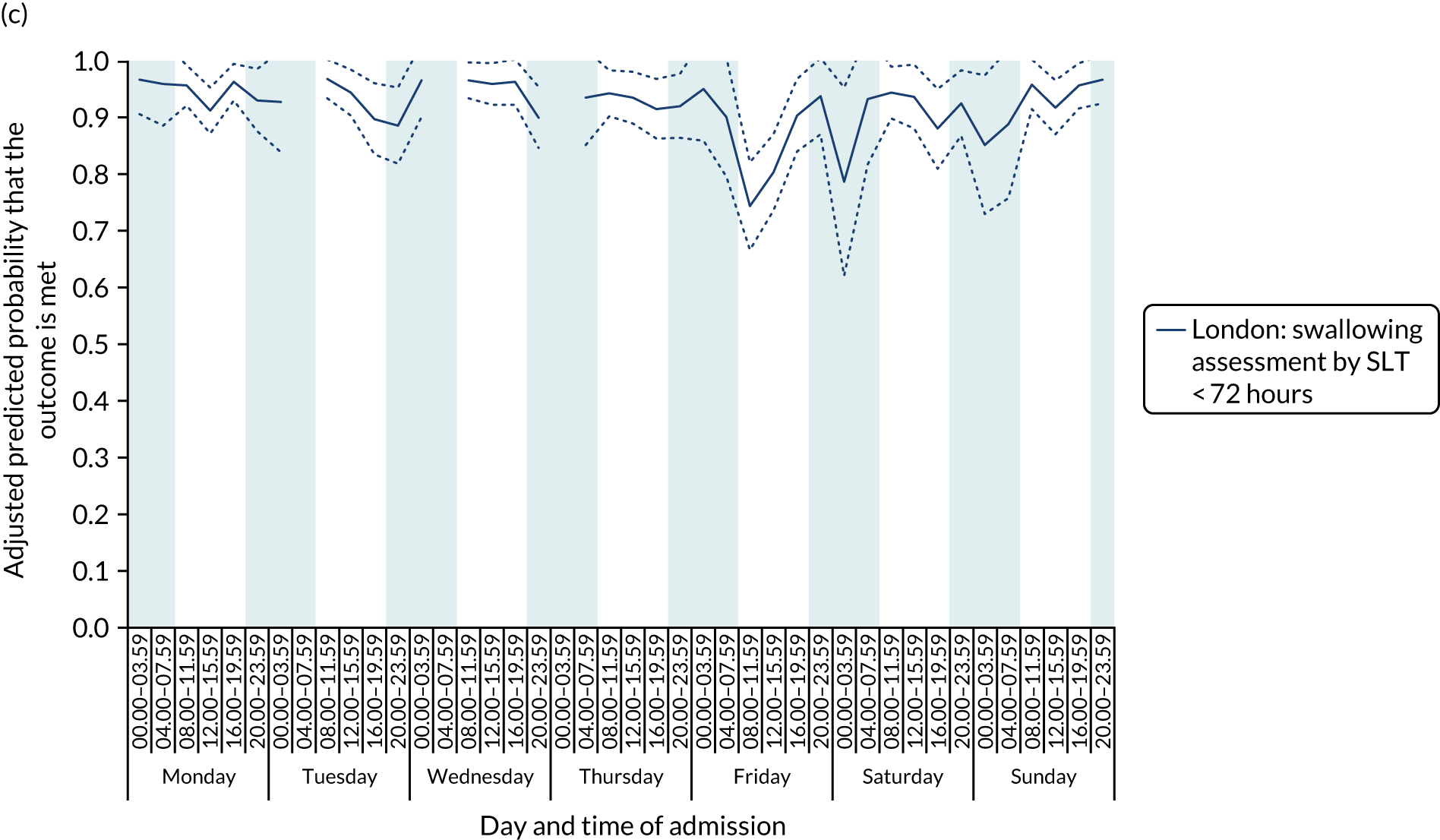

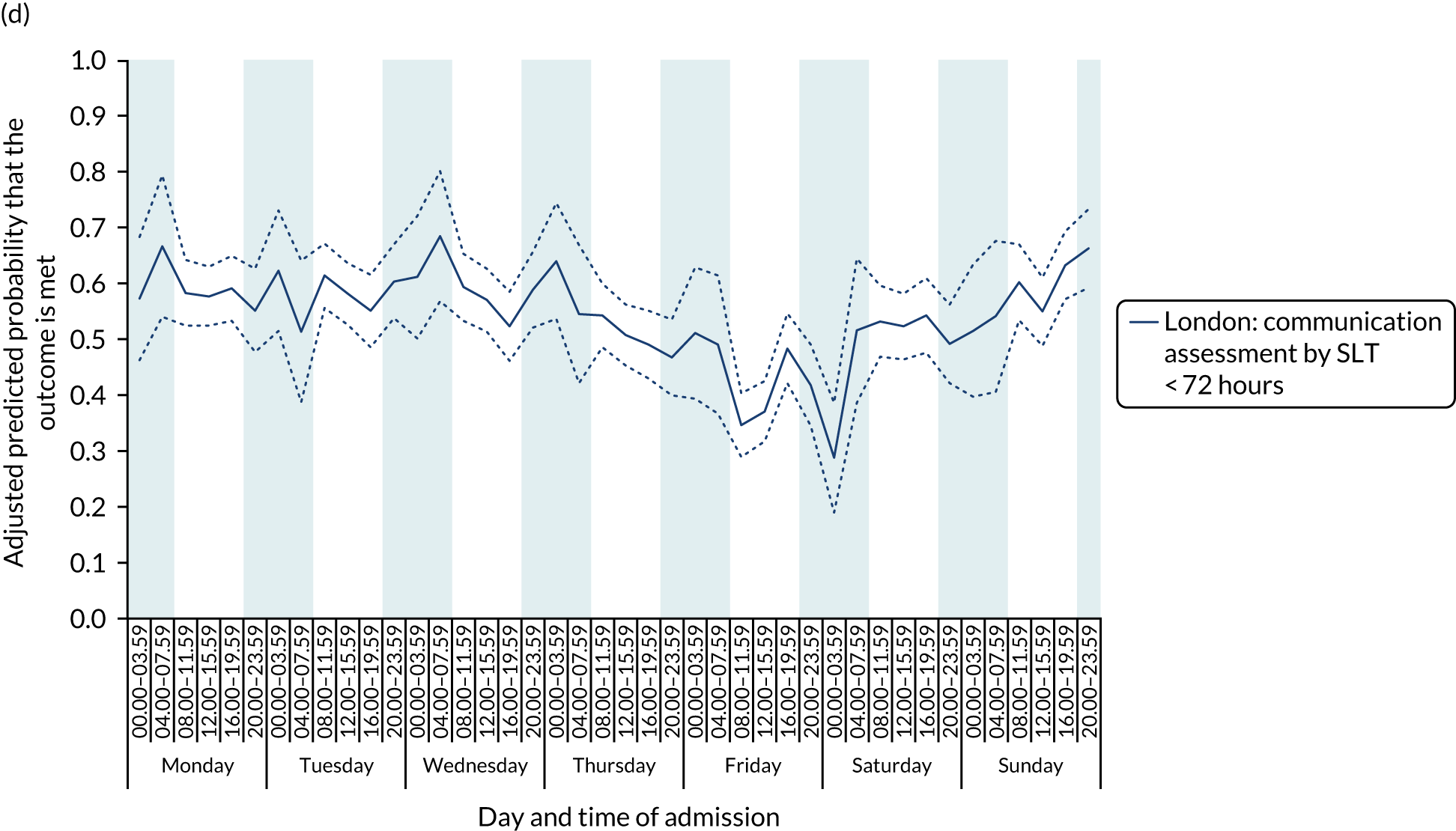

With this pattern, similar variations during the day were found each day of the week. Second, variation by day of the week but not time of day was observed for assessments by a physiotherapist, occupational therapist and SLT within 72 hours in London HASUs (Figure 6).

FIGURE 6.

Quality of care across the 42 time periods in the week in London HASUs: variation by day of the week but not time of day. (a) Physiotherapist assessment within 72 hours (p < 0.0001); (b) occupational therapist assessment within 72 hours (p < 0.0001); (c) swallow assessment by a SLT within 72 hours (p < 0.0001); and (d) communication assessment by a SLT within 72 hours (p < 0.0001). This figure is adapted from Melnychuk et al. 65 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. This figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original figure.

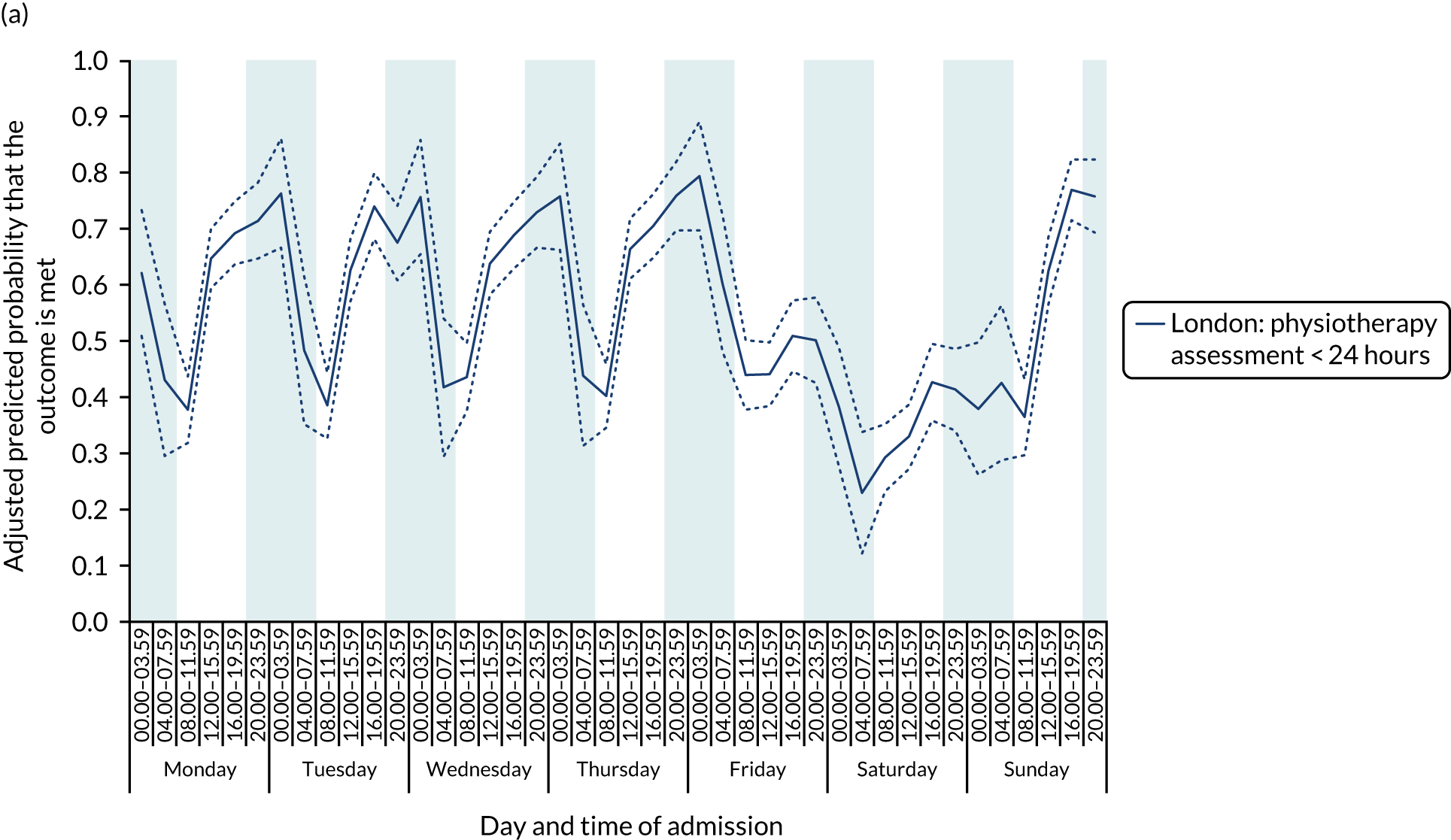

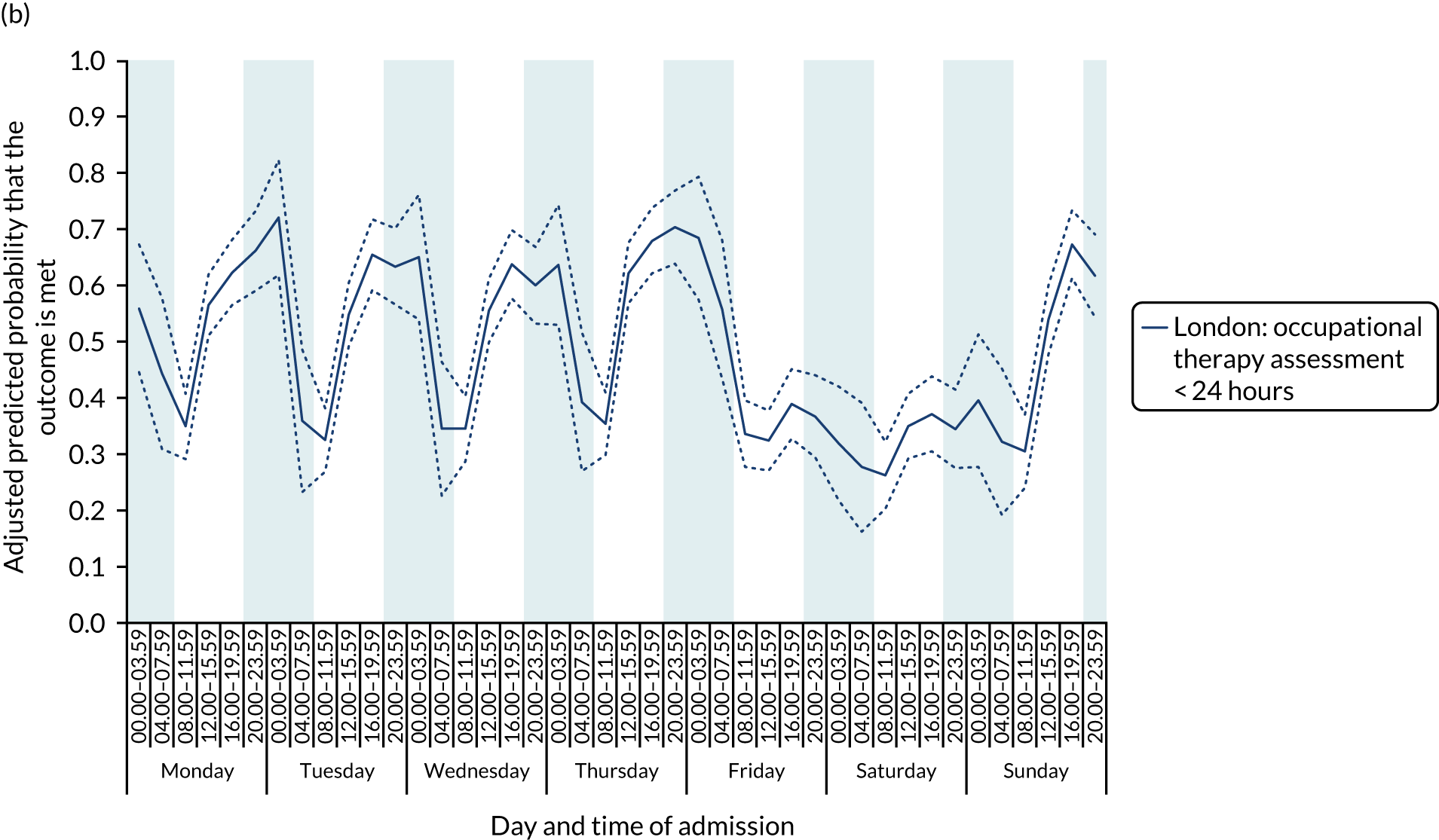

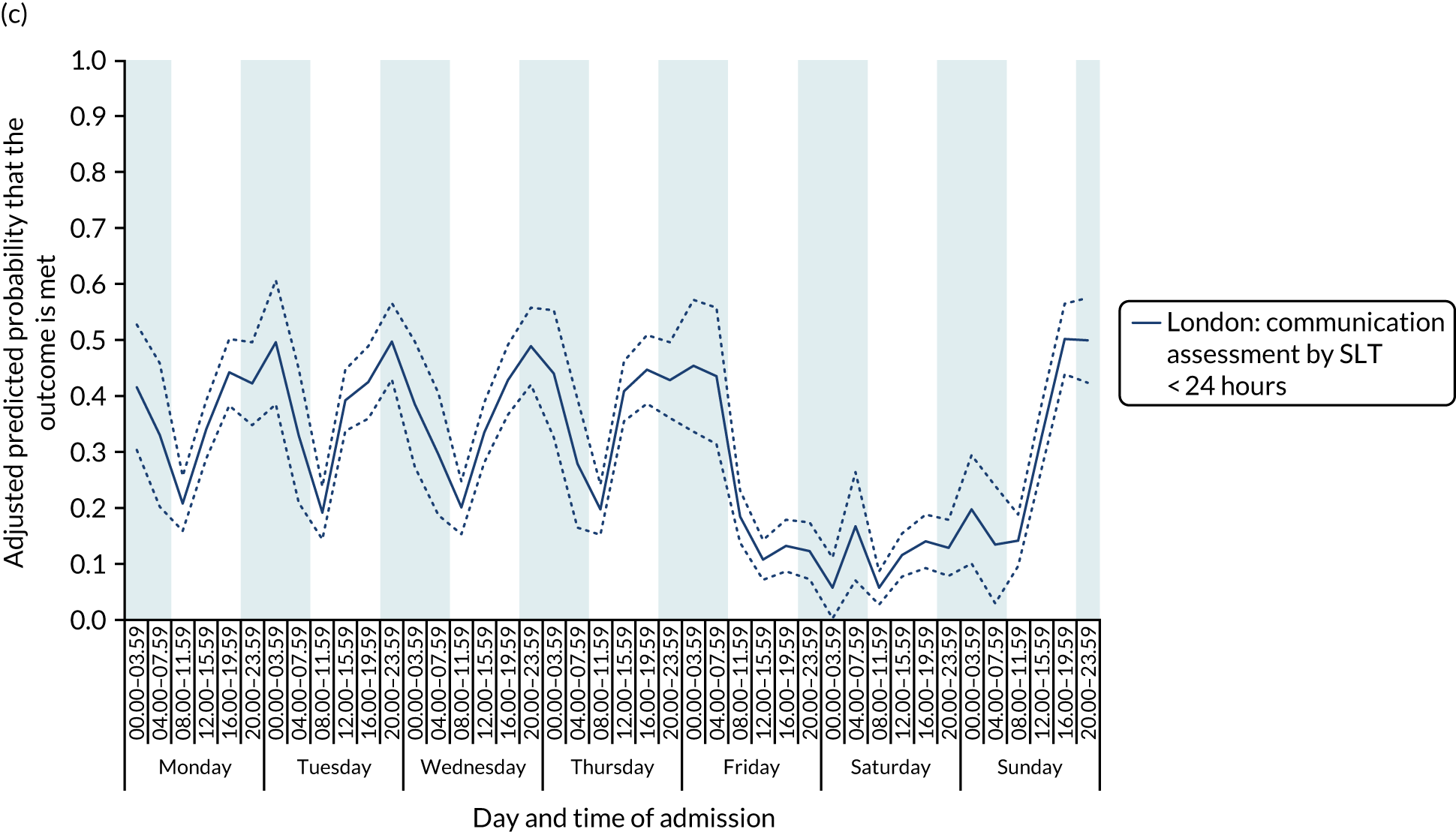

With this pattern, care quality was worse for patients admitted on a Friday. Third, variation by time of day and day of the week was observed for therapist assessments within 24 hours (Figure 7). With this pattern, there was variation during the day on Monday to Friday and care quality was worse at weekends.

FIGURE 7.

Quality of care across the 42 time periods in the week in London HASUs: variation by time of day and day of the week. (a) Physiotherapist assessment within 24 hours (p < 0.0001); (b) occupational therapist assessment within 24 hours (p < 0.0001); and (c) communication assessment by a SLT within 24 hours (p < 0.0001). This figure is adapted from Melnychuk et al. 65 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. This figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original figure.

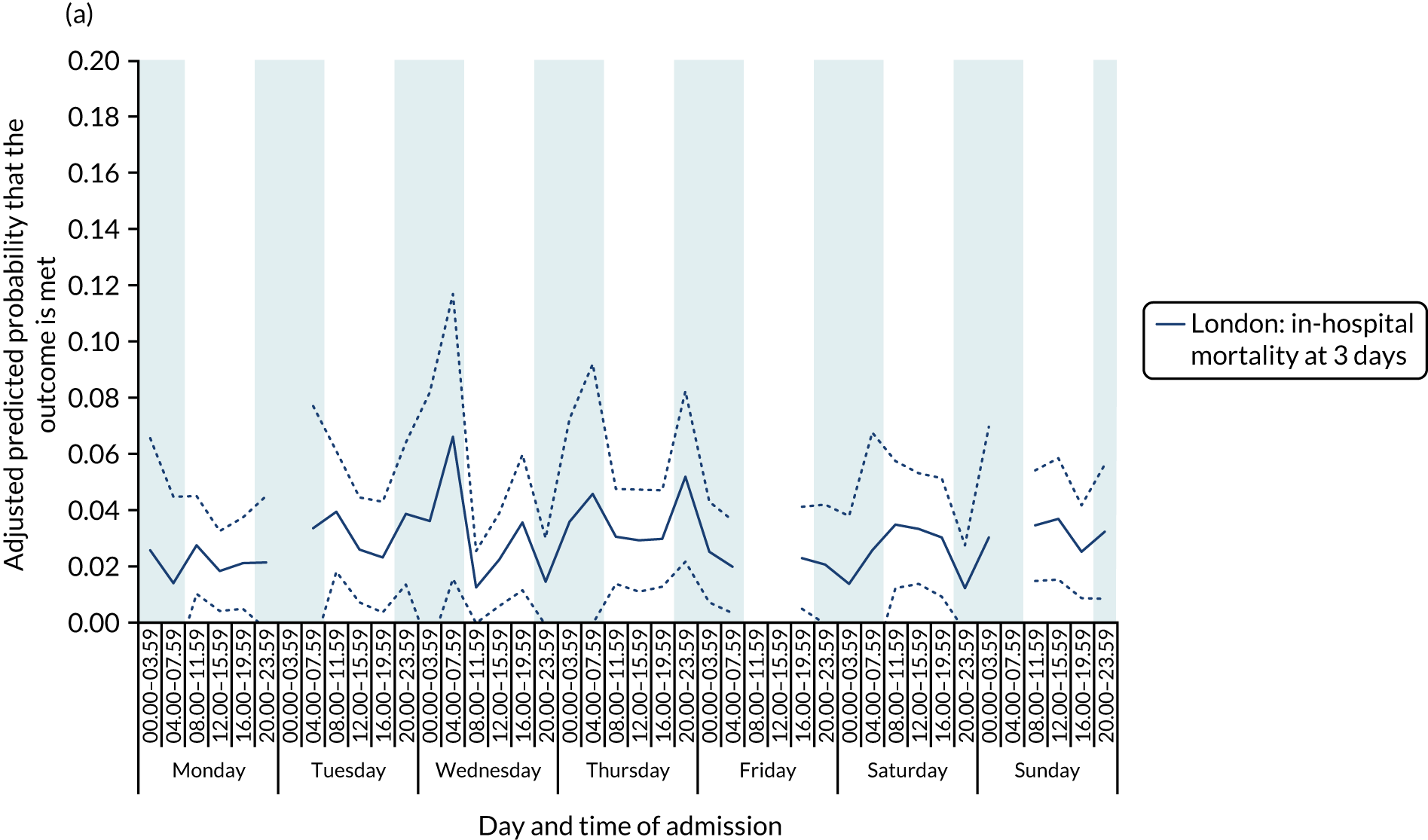

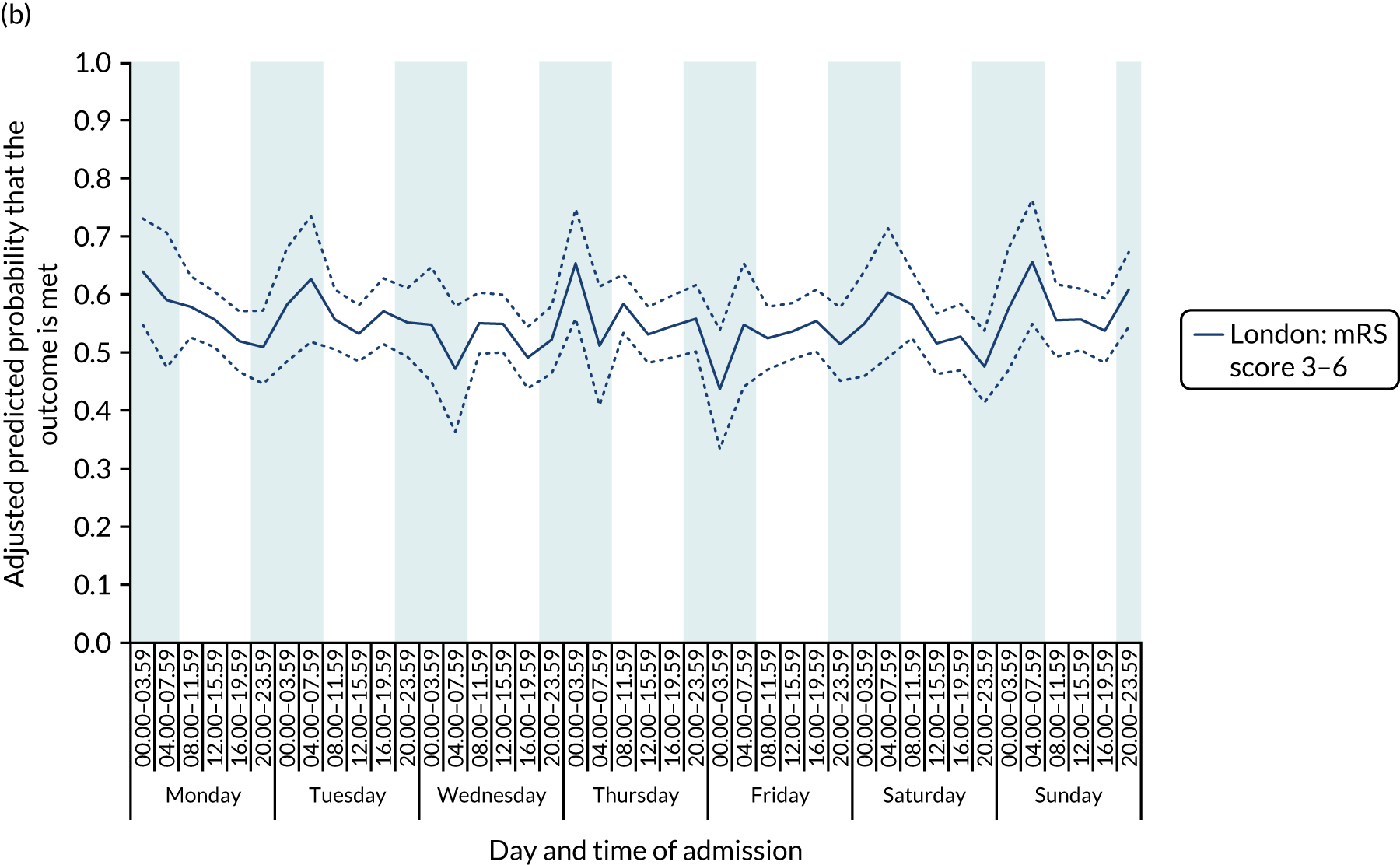

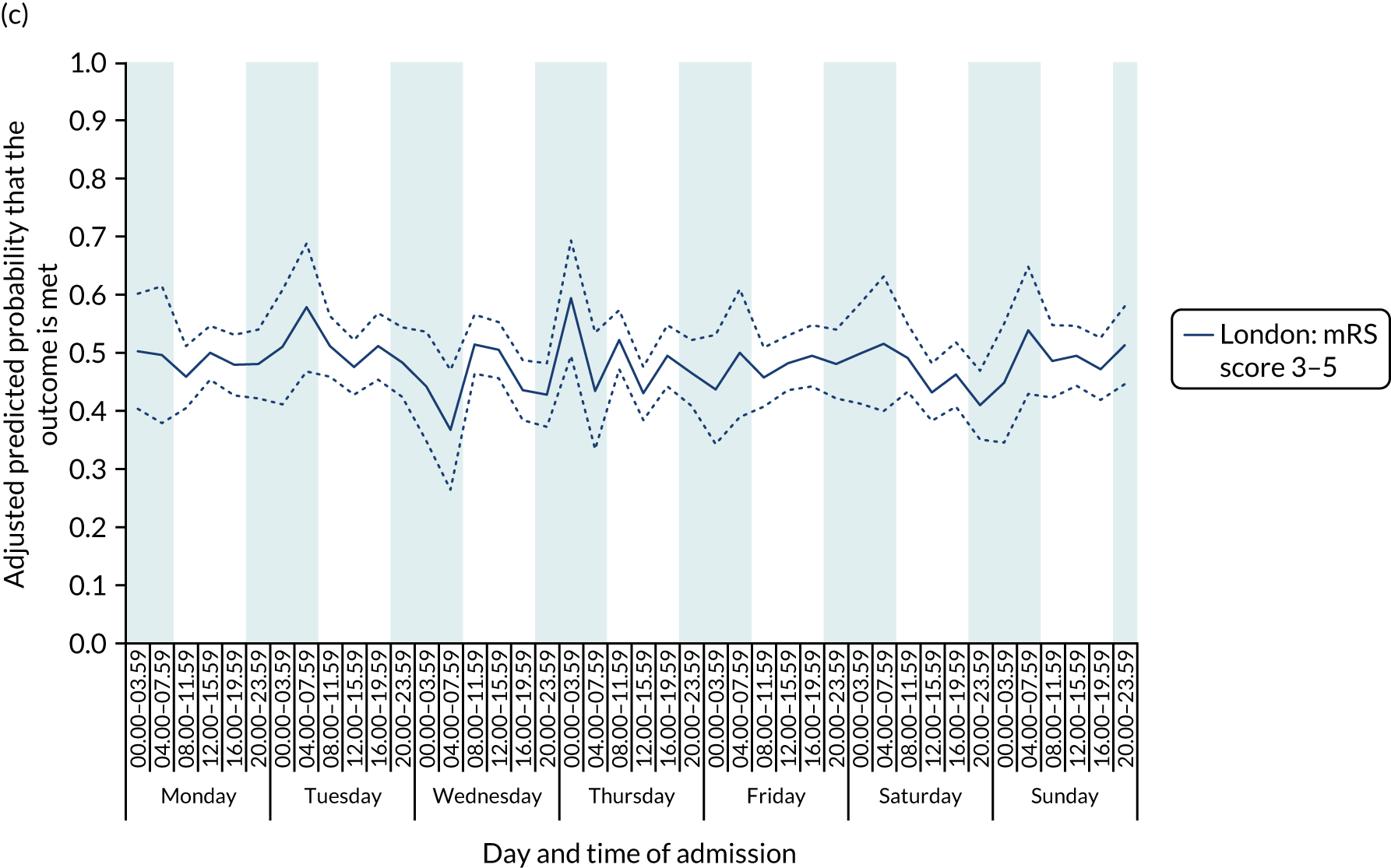

There was no significant variation in outcomes across the 42 time periods in London HASUs (all p > 0.05) (Figure 8).

FIGURE 8.

Outcomes across the 42 time periods in the week in London HASUs. (a) Mortality at 3 days (p = 0.9230); (b) mRS score 3–6 (p = 0.1777); and (c) mRS score 3–5 (p = 0.2015). This figure is adapted from Melnychuk et al. 65 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. This figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original figure.

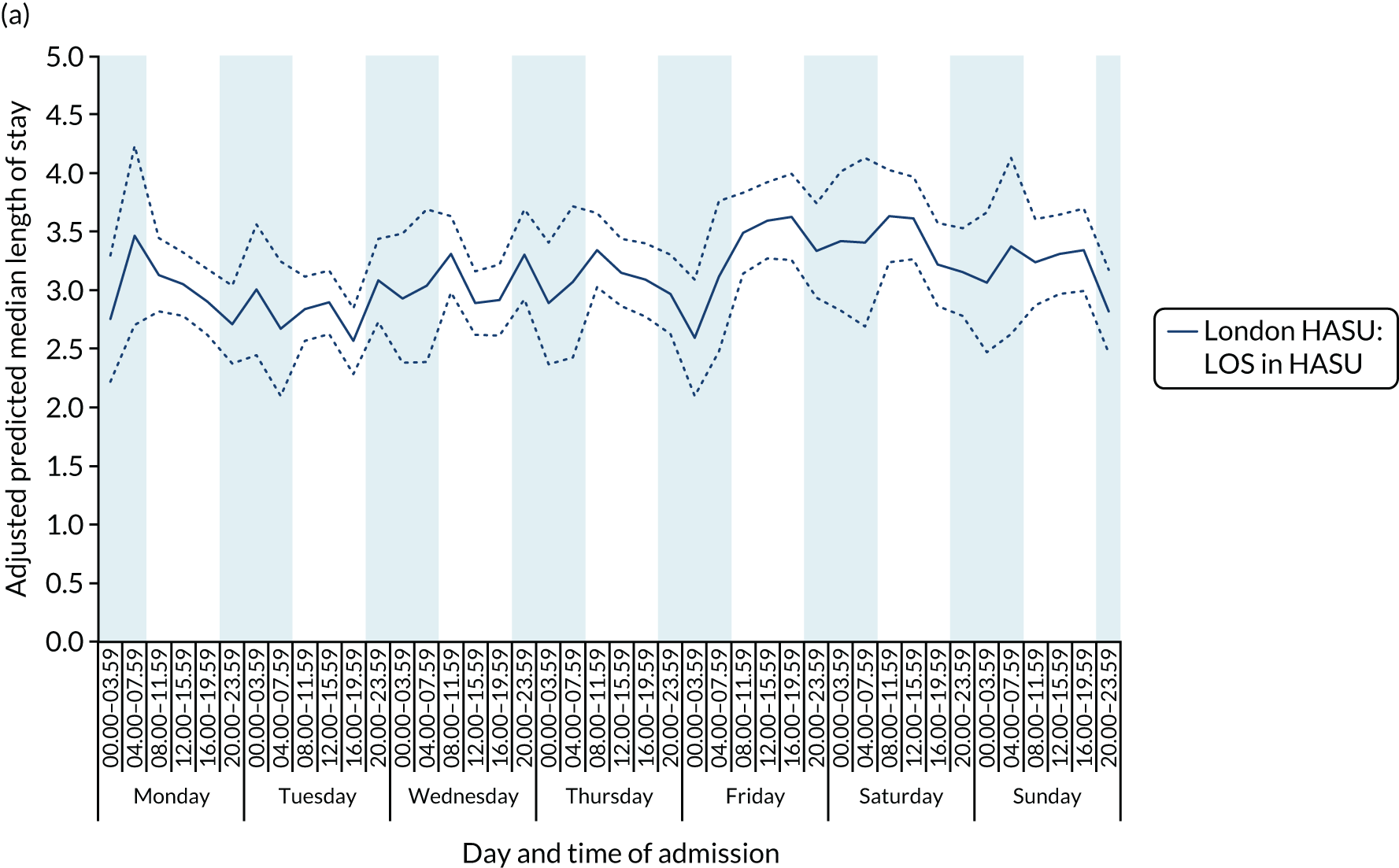

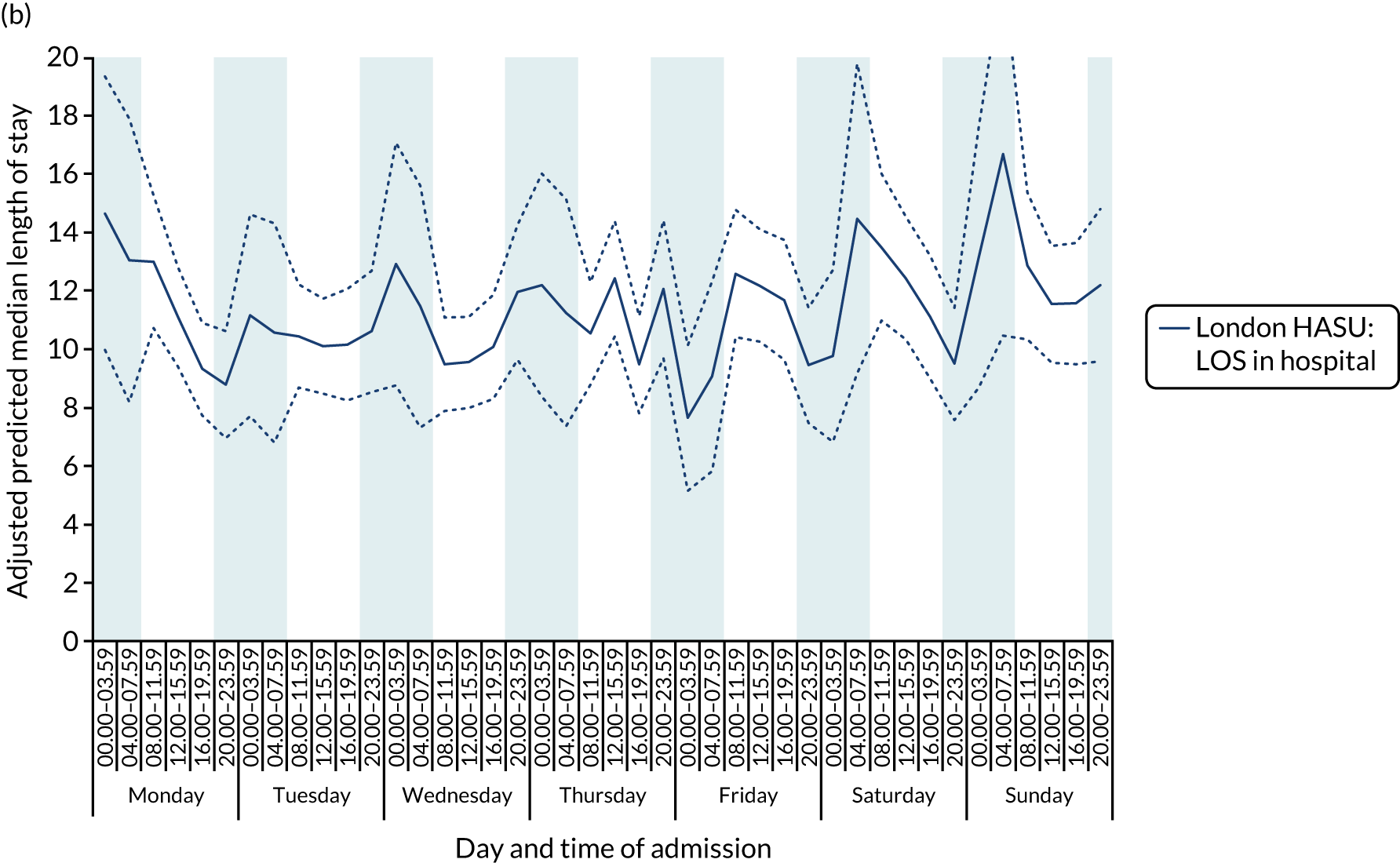

There was significant variation in LOS across the 42 time periods, in terms of both HASU LOS and total inpatient LOS (p < 0.001 for HASU LOS and p = 0.005 for total LOS in hospital) (Figure 9). Median HASU LOS varied between 2.6 and 3.6 days across the 42 time periods. It was difficult to detect a trend by day and time of admission in HASU LOS and inpatient LOS.

FIGURE 9.

Length of stay across the 42 time periods in the week in London HASUs. (a) LOS in HASU (p < 0.0001); and (b) LOS in hospital (p < 0.0001). This figure is adapted from Melnychuk et al. 65 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. This figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original figure.

Results using the four time period specifications (Table 6) were broadly similar to those with the 42 time periods, but pooling time periods meant that the extent of variation during the week for some of the quality-of-care measures was reduced (see Report Supplementary Material 2, Tables S1 and S2, for unadjusted figures and p-values, respectively). In these analyses, there was no significant variation in London HASUs in quality-of-care measures linked to specialist stroke nurse assessments, rapid access to brain scans and administration of thrombolysis to eligible patients for London HASUs, nor was there in the outcome measures. LOS varied significantly for London HASUs: pooling time periods more clearly indicates longer LOS among patients admitted at the weekend.

| Measures | 08.00–19.59 | 20.00–07.59 | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weekday | Weekend | Weekday | Weekend | ||

| Quality-of-care measures that do not vary across the week | |||||

| Brain scan within 1 hour | 0.60 (0.58 to 0.61) | 0.61 (0.58 to 0.63) | 0.63 (0.60 to 0.65) | 0.65 (0.61 to 0.68) | 0.0344 |

| Brain scan within 12 hours | 0.97 (0.96 to 0.97) | 0.96 (0.95 to 0.97) | 0.95 (0.94 to 0.96) | 0.95 (0.93 to 0.96) | 0.0093 |

| Dysphagia screen within 4 hours | 0.74 (0.72 to 0.75) | 0.75 (0.73 to 0.77) | 0.77 (0.75 to 0.79) | 0.79 (0.76 to 0.82) | 0.0029 |

| Assessment by a nurse trained in stroke management within 24 hours | 0.96 (0.95 to 0.96) | 0.94 (0.93 to 0.96) | 0.95 (0.94 to 0.96) | 0.95 (0.94 to 0.97) | 0.1872 |

| Administration of intravenous thrombolysis to eligible patients | 0.88 (0.86 to 0.90) | 0.88 (0.84 to 0.92) | 0.86 (0.82 to 0.91) | 0.88 (0.82 to 0.95) | 0.9327 |

| Door-to-needle time < 1 hour in patients receiving thrombolysis | 0.84 (0.81 to 0.87) | 0.89 (0.85 to 0.93) | 0.79 (0.74 to 0.84) | 0.84 (0.77 to 0.91) | 0.0269 |

| Quality-of-care measures that vary significantly across the week | |||||

| Assessment by a stroke specialist consultant physician within 12 hours | 0.39 (0.38-.40) | 0.30 (0.27 to 0.32) | 0.63 (0.61 to 0.66) | 0.64 (0.60 to 0.68) | < 0.0001 |

| Assessment by a stroke specialist consultant physician within 24 hours | 0.90 (0.89 to 0.91) | 0.87 (0.85 to 0.89) | 0.90 (0.88 to 0.91) | 0.92 (0.90 to 0.94) | 0.0043 |

| Admission to a stroke unit within 4 hours | 0.62 (0.60 to 0.63) | 0.64 (0.61 to 0.66) | 0.67 (0.65 to 0.70) | 0.70 (0.67 to 0.74) | < 0.0001 |

| Physiotherapist assessment within 72 hours | 0.83 (0.82 to 0.84) | 0.86 (0.84 to 0.88) | 0.85 (0.83 to 0.87) | 0.84 (0.81 to 0.87) | 0.0693 |

| Occupational therapist assessment within 72 hours | 0.79 (0.78 to 0.80) | 0.82 (0.80 to 0.84) | 0.81 (0.79 to 0.82) | 0.80 (0.76 to 0.83) | 0.0967 |

| Dysphagia assessment by a SLT within 72 hours | 0.92 (0.91 to 0.93) | 0.93 (0.91 to 0.95) | 0.93 (0.91 to 0.95) | 0.91 (0.88 to 0.95) | 0.5838 |

| Communication assessment by a SLT within 72 hours | 0.53 (0.51 to 0.54) | 0.56 (0.54 to 0.59) | 0.55 (0.53 to 0.58) | 0.52 (0.48 to 0.56) | 0.0739 |

| Physiotherapist assessment within 24 hours | 0.56 (0.54 to 0.57) | 0.47 (0.45 to 0.50) | 0.65 (0.63 to 0.68) | 0.48 (0.44 to 0.52) | < 0.0001 |

| Occupational therapist assessment within 24 hours | 0.49 (0.47 to 0.50) | 0.42 (0.40 to 0.45) | 0.58 (0.55 to 0.60) | 0.41 (0.37 to 0.45) | < 0.0001 |

| Communication assessment by a SLT within 24 hours | 0.29 (0.28 to 0.31) | 0.22 (0.20 to 0.24) | 0.39 (0.37 to 0.42) | 0.23 (0.20 to 0.27) | < 0.0001 |

| Outcome measures | |||||

| Mortality at 3 days | 0.03 (0.02 to 0.03) | 0.03 (0.02 to 0.04) | 0.03 (0.02 to 0.04) | 0.02 (0.01 to 0.03) | 0.3310 |

| mRS score 3–6 | 0.55 (0.53 to 0.56) | 0.55 (0.52 to 0.57) | 0.55 (0.52 to 0.57) | 0.56 (0.53 to 0.59) | 0.8672 |

| mRS score 3–5a | 0.49 (0.47 to 0.50) | 0.47 (0.45 to 0.50) | 0.48 (0.45 to 0.50) | 0.48 (0.44 to 0.51) | 0.7497 |

| LOS | |||||

| LOS in HASU (median days) | 3.1 (3.0–3.2) | 3.4 (3.2–3.5) | 3.0 (2.9–3.1) | 3.1 (2.9–3.3) | 0.0007 |

| LOS in hospital (median days) | 10.8 (10.2–11.3) | 12.1 (11.1–13.1) | 10.8 (10.0–11.7) | 11.5 (10.2–12.9) | 0.0359 |

Cost analysis

Results were similar when controlling for NIHSS score on arrival at hospital, instead of level of consciousness, on the smaller sample of patients with non-missing NIHSS data: results with p-values < 0.05 and trends across the week were unchanged (see Report Supplementary Material 2, Figures S1–S6 and Table S3).

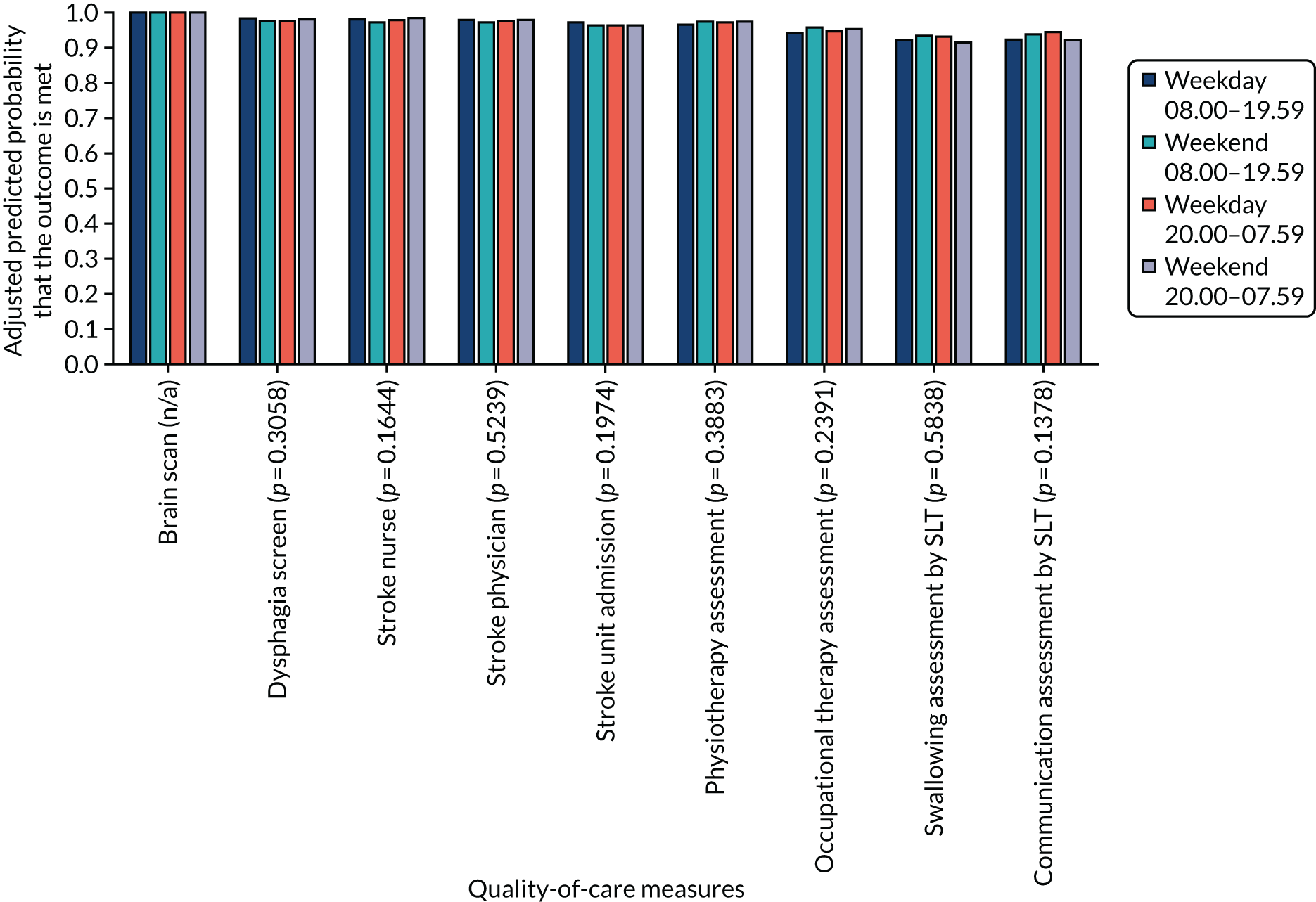

Variations in the non-time-dependent quality-of-care measures by the four time periods are shown in Figure 10).

FIGURE 10.

Non-time-dependent quality-of-care measures across four periods in the week in London HASUs. Figures are average predicted probabilities of each measure in each time period controlling for the covariates. We tested for statistically significant variations across the four time periods using Wald tests and reported the results as joint p-values under the null hypothesis that the regression coefficients for every time period relative to the omitted time period were zero (p-values in parentheses). All patients received a brain scan in every time period. n/a, not applicable.

In contrast to the findings for the time-dependent versions of these measures in Table 6, Figure 10 shows that > 90% of patients receive every measure and that there is little variation across the four time periods. We also note from Table 6 that there is no variation in administration of intravenous thrombolysis across the four time periods. We conclude from these data that the costs of acute care in London HASUs, with respect to these measures, is unlikely to vary on different days and at different times of admission. Table 6 shows significant variation in median LOS for London HASUs, with longer HASU and total LOS among patients admitted at the weekend. Table 7 shows a similar trend for mean LOS (note that the mean values in Table 7 are higher than the corresponding median values in Table 6, indicating skewed data).

| LOS | 08.00–19.59 | 20.00–07.59 | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weekday | Weekend | Weekday | Weekend | ||

| LOS in HASU (mean days) | 4.1 (4.0 to 4.2) | 4.5 (4.3 to 4.7) | 4.0 (3.9 to 4.2) | 4.1 (3.9 to 4.4) | 0.0011 |

| LOS in hospital (mean days) | 23.8 (22.4 to 25.3) | 26.9 (24.6 to 29.2) | 24.0 (22.1 to 26.0) | 25.6 (22.5 to 28.7) | 0.0359 |

In Table 8 we compute the cost implications of the difference in LOS. Focusing on differences in mean LOS, patients who were admitted between 08.00 and 19.59 at the weekend were, on average, £166 more costly to treat in the HASU (£668 when including total LOS) than those admitted between 08.00 and 19.59 on a weekday. Those who were admitted between 20.00 and 07.59 at the weekend were on average no more costly than those admitted between 08.00 and 19.59 on Monday to Friday (£445 more costly when including total LOS). For those admitted between 20.00 and 07.59 on a weekday, the cost difference per patient was small compared with those admitted between 08.00 and 19.59 on a weekday.

| Differences in LOS (days) | Unit cost per day (£) | Differences in costs (£) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 08.00–19.59 | 20.00–07.59 | 08.00–19.59 | 20.00–07.59 | ||||||

| Weekday | Weekend | Weekday | Weekend | Weekday | Weekend | Weekday | Weekend | ||

| Based on median LOS | |||||||||

| HASU | 0.3 | –0.1 | 0 | 415 | 124 | –41 | 0 | ||

| Total hospital minus HASU | 1 | 0.1 | 0.7 | 247 | 247 | 25 | 173 | ||

| Sum (total LOS) | 1.3 | 0 | 0.7 | 372 | –17 | 173 | |||

| Based on mean LOS | |||||||||

| HASU | 0.4 | –0.1 | 0 | 415 | 166 | –41 | 0 | ||

| Total hospital minus HASU | 2.7 | 0.3 | 1.8 | 247 | 668 | 74 | 445 | ||

| Sum (total LOS) | 3.1 | 0.2 | 1.8 | 834 | 33 | 445 | |||

Discussion

This section is based on a paper by Melnychuk et al. 65 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Principal findings

In our study, we found no evidence for an admission effect across the week on early outcomes in acute stroke patients admitted to a London HASU: 3-day mortality and mRS score at hospital discharge did not vary by day and time of admission in London HASUs. This is consistent with a recent study based on administrative data in the UK. 34 The study34 found a steady reduction in in-hospital mortality difference between weekday and weekend stroke admissions in 2008–14 across England, and that this difference is no longer statistically significant in 2014.

There was also no variation by day and time of admission across the week in terms of rapid access to brain scanning, stroke nursing care and thrombolysis in London HASUs. Other quality-of-care measures did significantly vary across the week in London HASUs and three patterns of variation were detected: (1) by time of day, but not day of the week; (2) by day of the week, but not time of day; and (3) by time of day and day of the week. LOS was longer among patients admitted to London HASUs at the weekend. We hypothesised that there would be non-significant variation across the week in care quality measures in London HASUs and that this would translate into non-significant variations in outcomes. The lower variation in care quality measures across the week in London HASUs was confirmed, but only with respect to ‘front-door’ measures of acute stroke care. With respect to the health outcomes, there was no variation in mortality at 3 days and disability at hospital discharge by day and time of admission across the week in London HASUs. This is consistent with previous studies showing that timely access to thrombolysis is associated with good stroke outcomes. 70

We found that patients who were admitted at the weekend were on average more costly than those who were admitted during the week because of their longer LOS. When incorporating total LOS, the additional mean cost per patient was £445–668, depending on when the patient was admitted at the weekend. Those who were admitted between 20.00 and 07.59 on a weekday had similar costs to those who were admitted between 08.00 and 19.59 on a weekday.

Strengths and weaknesses

The main strength of our study is the rich data set we have used, containing detailed information on quality of care, outcomes and patient characteristics. We have examined whether or not time of admission was related to quality of care using a comprehensive set of indicators from across the acute stroke care pathway. Most of the measures were from a pre-existing set of national acute stroke care indicators, and those that were added had more stringent time constraints to reflect the time-critical nature of acute stroke care. Our outcomes were stroke mortality and disability, whereas previous studies have focused on mortality. 6,25,34,71–73 The rich set of patient characteristics in the data set meant that we could control for patient factors likely to affect quality of care and outcomes that vary by day and time of admission across the week. There are several weaknesses. First, although case ascertainment in the SSNAP was 90% during the time period of our study, these data might not be representative of all stroke patients. Second, although analyses of hospital administrative data to investigate weekend effects in stroke may have been undermined by evidence of variations in inaccurate coding across the week,58 in the SSNAP data are inputted voluntarily by hospitals and we cannot exclude the possibility of inaccurate or selective reporting. Particularly problematic for our study would be if this bias was more likely to vary by time of admission. Third, we were unable to measure long-term outcomes, as these were not available in the SSNAP. Mortality data in the SSNAP are currently available only for patients who are in hospital and, therefore, to reduce the risk of bias, we measured mortality at 3 days after admission, when most patients will still be in hospital. Three-day mortality has been used in previous studies to evaluate the centralisation of acute stroke services in London,35 but the focus in our study on in-hospital mortality only is a further limitation. Similarly, long-term disability data are not reliably collected in the SSNAP, and so disability was measured by the mRS at the end of the inpatient spell. Fourth, although the richness of our data set means that we have been able to control for confounding factors, we cannot exclude the possibility of confounding due to unobserved patient characteristics or staffing levels. Fifth, although the sample size of our study is relatively large (n = 7094), when evaluating quality of care and outcomes across the week the number of observations in each of the 42 time periods was considerably smaller (mean of 169). We cannot exclude the possibility that this number of patients resulted in wide confidence intervals (CIs) around the adjusted predicted probabilities in each time period, making it less likely to show significant variation in the measures evaluated. It is difficult to provide sample size calculations for statistical analyses between 42 groups (time periods). However, when we re-ran our analyses of quality of care and outcomes across the four pooled time periods in the week in London HASUs, the results were broadly similar, and this provides some reassurance about the statistical power of our analyses. Sixth, we acknowledge that previous studies have identified that improvements in outcomes following acute stroke in England have been shown to be statistically unrelated to the centralisation of stroke services in London, but are consistent with an overall national focus on improving stroke services. 34 Further research examining whether or not the findings seen in the present study for London HASUs were also achieved in the rest of England would be beneficial.

Comparison with other studies

There is a large literature examining weekend effects in health care across a range of clinical areas. 74 In acute stroke, there is conflicting evidence on whether patients admitted at weekends have higher or lower quality of care and better or worse outcomes. 6,9,40,71,72,75 However, recent analyses have shown that care quality and outcomes in acute stroke vary across the week, and that comparing weekend with weekday or in-hours effects with out-of-hours effects is flawed, as it does not take into account variations by day of the week and time of day. 22 This study,22 using the same data set as ours, but from an earlier time period and analysing the whole of England and Wales, found that quality of care varied across the entire week, not only between weekends and weekdays, with a number quality-of-care measures showing different patterns of variation over the week. What our study adds is analyses of variation in quality of care and outcomes in London HASUs by separately following the centralisation of acute stroke services in London in 2010, which has been shown to increase the quality of care and outcomes overall. 35,38,41

Implications